User login

Malignancy risk of tocilizumab and TNF inhibitors found similar

AMSTERDAM – , according to an analysis of three large databases presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“When we combined the databases, the incidence of any malignancy excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer was 13.09 per 1,000 patient years in the tocilizumab group and 13.46 in the TNF-inhibitor group,” reported Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, ScD, of the division of pharmacoepidemiology & pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The study was conducted with data from 10,393 adult RA patients treated with tocilizumab and 26,357 patients treated with TNFi in the Medicare, QuintilesIMS PharMetrics Plus, and Truven Health MarketScan databases. All patients were new starts on tocilizumab or the TNFi on which they were evaluated, but all were required to have been exposed to at least one different biologic prior to starting the treatment. A diagnosis of RA at least 365 days prior to inclusion in this analysis was required to rule out prevalent cancers, which was an exclusion criterion.

More than 60 covariates were employed in the analysis to minimize the risk of confounders. These included demographics, RA characteristics, comorbidities, and other medications.

There also was no difference in the rates of the 12 most common cancer types when those exposed to tocilizumab were compared with those exposed to TNFi in a secondary analysis of these data, according to Dr. Kim. When expressed as hazard ratios, there were some numerical differences in relative risk among these cancers on both as-treated and intention-to-treat analyses, but confidence intervals were large, and none approached significance.

RA itself has been associated with an increased risk of some malignancies, such as lung cancer, but the relationship between the proinflammatory state of RA, its treatments, and the risk of cancer has been unclear, according to Dr. Kim. She said, “There is some concern relative to use of TNFi or other biologics in regard to developing malignancy, but studies have been inconsistent.”

Dr. Kim conceded that a lack of data on patients’ disease duration or activity is one limitation of this analysis. Another is that residual confounding can never be ruled out from a retrospective analysis. However, she said that, because the two biologics were compared for the same indication in patients exposed to at least one previous biologic, the confounding may be less than it would be if tocilizumab was compared with a conventional synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD), such as methotrexate. Again, there also was a requirement for exposure to at least one prior biologic, and this also is reassuring for the final conclusion.

“In other words, even among RA patients who were exposed to more than one biologic, the risk of cancer was similar between tocilizumab and TNF-inhibitor initiators,” Dr. Kim reported.

Roche provided funding for the study. Dr. Kim reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Roche.

AMSTERDAM – , according to an analysis of three large databases presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“When we combined the databases, the incidence of any malignancy excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer was 13.09 per 1,000 patient years in the tocilizumab group and 13.46 in the TNF-inhibitor group,” reported Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, ScD, of the division of pharmacoepidemiology & pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The study was conducted with data from 10,393 adult RA patients treated with tocilizumab and 26,357 patients treated with TNFi in the Medicare, QuintilesIMS PharMetrics Plus, and Truven Health MarketScan databases. All patients were new starts on tocilizumab or the TNFi on which they were evaluated, but all were required to have been exposed to at least one different biologic prior to starting the treatment. A diagnosis of RA at least 365 days prior to inclusion in this analysis was required to rule out prevalent cancers, which was an exclusion criterion.

More than 60 covariates were employed in the analysis to minimize the risk of confounders. These included demographics, RA characteristics, comorbidities, and other medications.

There also was no difference in the rates of the 12 most common cancer types when those exposed to tocilizumab were compared with those exposed to TNFi in a secondary analysis of these data, according to Dr. Kim. When expressed as hazard ratios, there were some numerical differences in relative risk among these cancers on both as-treated and intention-to-treat analyses, but confidence intervals were large, and none approached significance.

RA itself has been associated with an increased risk of some malignancies, such as lung cancer, but the relationship between the proinflammatory state of RA, its treatments, and the risk of cancer has been unclear, according to Dr. Kim. She said, “There is some concern relative to use of TNFi or other biologics in regard to developing malignancy, but studies have been inconsistent.”

Dr. Kim conceded that a lack of data on patients’ disease duration or activity is one limitation of this analysis. Another is that residual confounding can never be ruled out from a retrospective analysis. However, she said that, because the two biologics were compared for the same indication in patients exposed to at least one previous biologic, the confounding may be less than it would be if tocilizumab was compared with a conventional synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD), such as methotrexate. Again, there also was a requirement for exposure to at least one prior biologic, and this also is reassuring for the final conclusion.

“In other words, even among RA patients who were exposed to more than one biologic, the risk of cancer was similar between tocilizumab and TNF-inhibitor initiators,” Dr. Kim reported.

Roche provided funding for the study. Dr. Kim reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Roche.

AMSTERDAM – , according to an analysis of three large databases presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“When we combined the databases, the incidence of any malignancy excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer was 13.09 per 1,000 patient years in the tocilizumab group and 13.46 in the TNF-inhibitor group,” reported Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, ScD, of the division of pharmacoepidemiology & pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The study was conducted with data from 10,393 adult RA patients treated with tocilizumab and 26,357 patients treated with TNFi in the Medicare, QuintilesIMS PharMetrics Plus, and Truven Health MarketScan databases. All patients were new starts on tocilizumab or the TNFi on which they were evaluated, but all were required to have been exposed to at least one different biologic prior to starting the treatment. A diagnosis of RA at least 365 days prior to inclusion in this analysis was required to rule out prevalent cancers, which was an exclusion criterion.

More than 60 covariates were employed in the analysis to minimize the risk of confounders. These included demographics, RA characteristics, comorbidities, and other medications.

There also was no difference in the rates of the 12 most common cancer types when those exposed to tocilizumab were compared with those exposed to TNFi in a secondary analysis of these data, according to Dr. Kim. When expressed as hazard ratios, there were some numerical differences in relative risk among these cancers on both as-treated and intention-to-treat analyses, but confidence intervals were large, and none approached significance.

RA itself has been associated with an increased risk of some malignancies, such as lung cancer, but the relationship between the proinflammatory state of RA, its treatments, and the risk of cancer has been unclear, according to Dr. Kim. She said, “There is some concern relative to use of TNFi or other biologics in regard to developing malignancy, but studies have been inconsistent.”

Dr. Kim conceded that a lack of data on patients’ disease duration or activity is one limitation of this analysis. Another is that residual confounding can never be ruled out from a retrospective analysis. However, she said that, because the two biologics were compared for the same indication in patients exposed to at least one previous biologic, the confounding may be less than it would be if tocilizumab was compared with a conventional synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD), such as methotrexate. Again, there also was a requirement for exposure to at least one prior biologic, and this also is reassuring for the final conclusion.

“In other words, even among RA patients who were exposed to more than one biologic, the risk of cancer was similar between tocilizumab and TNF-inhibitor initiators,” Dr. Kim reported.

Roche provided funding for the study. Dr. Kim reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Roche.

REPORTING FROM THE EULAR 2018 CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Tocilizumab was not associated with a higher cancer risk in rheumatoid arthritis than TNFi treatment in a cohort study.

Major finding: Relative to TNFI, the hazard ratio for malignancy was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.80-1.19) for tocilizumab relative to TNFi.

Study details: Cohort study with propensity matching with data from 10,393 adult RA patients treated with tocilizumab and 26,357 patients treated with TNFi.

Disclosures: Roche provided funding for the study. Dr. Kim reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Roche.

FDA approves pembrolizumab for relapsed/refractory PMBCL

The immune checkpoint inhibitor in adult and pediatric patients.

The Food and Drug Administration based the accelerated approval on results from 53 patients with relapsed or refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma in the KEYNOTE-170 trial. In the phase 2 trial, patients received 200 mg of pembrolizumab intravenously for 3 weeks until unacceptable toxicity or documented disease progression occurred. This continued for up to 24 months in patients who did not display progression. The overall response rate to pembrolizumab was 45% (95% CI, 32-60), which included both complete (11%) and partial (34%) responses. The median duration of response was not met within the follow-up period (median, 9.7 months) and the median time to first objective response was 2.8 months.

The recommended dose for pembrolizumab in adults is 200 mg every 3 weeks. It is recommended that pediatric patients receive 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks, with a maximum dose of 200 mg.

The most common adverse reactions to pembrolizumab were musculoskeletal pain, upper respiratory tract infection, pyrexia, fatigue, cough, dyspnea, diarrhea, nausea, arrhythmia, and headache. In total, a quarter of patients with adverse reactions required systemic treatment with a corticosteroid and 26% of patients had serious adverse reactions.

Pembrolizumab was approved via the FDA’s accelerated approval process, which allows for earlier approval of drugs that treat serious medical conditions and fulfill an unmet medical need. The drug was approved based on tumor response rate and durability of response, the FDA noted.

The immune checkpoint inhibitor in adult and pediatric patients.

The Food and Drug Administration based the accelerated approval on results from 53 patients with relapsed or refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma in the KEYNOTE-170 trial. In the phase 2 trial, patients received 200 mg of pembrolizumab intravenously for 3 weeks until unacceptable toxicity or documented disease progression occurred. This continued for up to 24 months in patients who did not display progression. The overall response rate to pembrolizumab was 45% (95% CI, 32-60), which included both complete (11%) and partial (34%) responses. The median duration of response was not met within the follow-up period (median, 9.7 months) and the median time to first objective response was 2.8 months.

The recommended dose for pembrolizumab in adults is 200 mg every 3 weeks. It is recommended that pediatric patients receive 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks, with a maximum dose of 200 mg.

The most common adverse reactions to pembrolizumab were musculoskeletal pain, upper respiratory tract infection, pyrexia, fatigue, cough, dyspnea, diarrhea, nausea, arrhythmia, and headache. In total, a quarter of patients with adverse reactions required systemic treatment with a corticosteroid and 26% of patients had serious adverse reactions.

Pembrolizumab was approved via the FDA’s accelerated approval process, which allows for earlier approval of drugs that treat serious medical conditions and fulfill an unmet medical need. The drug was approved based on tumor response rate and durability of response, the FDA noted.

The immune checkpoint inhibitor in adult and pediatric patients.

The Food and Drug Administration based the accelerated approval on results from 53 patients with relapsed or refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma in the KEYNOTE-170 trial. In the phase 2 trial, patients received 200 mg of pembrolizumab intravenously for 3 weeks until unacceptable toxicity or documented disease progression occurred. This continued for up to 24 months in patients who did not display progression. The overall response rate to pembrolizumab was 45% (95% CI, 32-60), which included both complete (11%) and partial (34%) responses. The median duration of response was not met within the follow-up period (median, 9.7 months) and the median time to first objective response was 2.8 months.

The recommended dose for pembrolizumab in adults is 200 mg every 3 weeks. It is recommended that pediatric patients receive 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks, with a maximum dose of 200 mg.

The most common adverse reactions to pembrolizumab were musculoskeletal pain, upper respiratory tract infection, pyrexia, fatigue, cough, dyspnea, diarrhea, nausea, arrhythmia, and headache. In total, a quarter of patients with adverse reactions required systemic treatment with a corticosteroid and 26% of patients had serious adverse reactions.

Pembrolizumab was approved via the FDA’s accelerated approval process, which allows for earlier approval of drugs that treat serious medical conditions and fulfill an unmet medical need. The drug was approved based on tumor response rate and durability of response, the FDA noted.

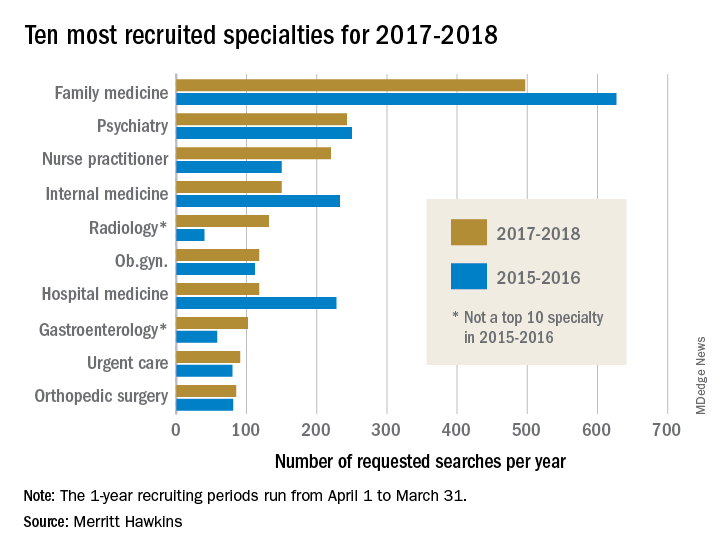

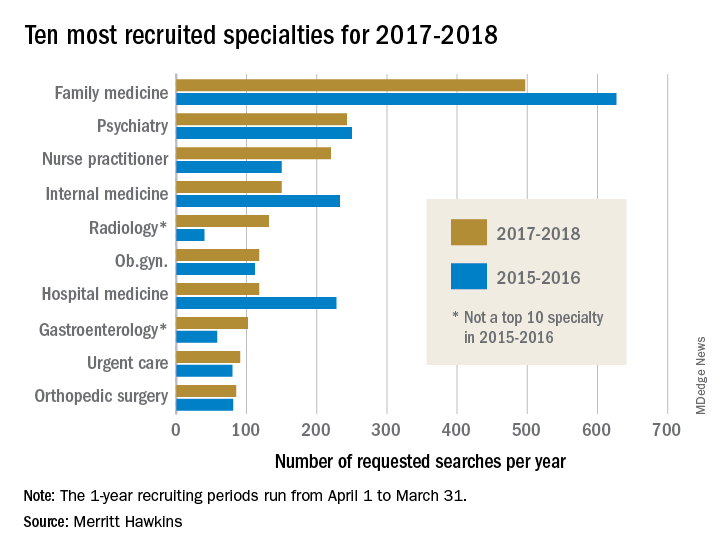

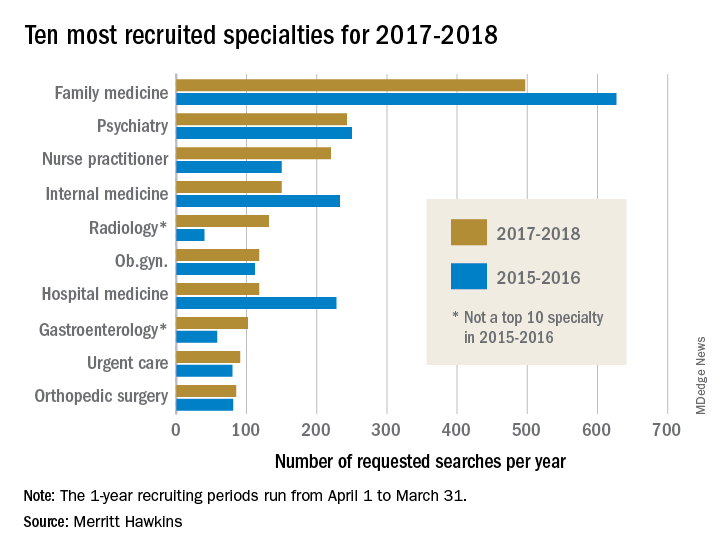

Family medicine remains first in recruiting demand

according to physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The company conducted 497 searches for family physicians from April 1, 2017, to March 31, 2018, marking the third straight year of decline for the specialty but still more than double the 243 searches conducted for psychiatrists, the medical specialty that was second more frequently requested for recruitment, Merritt Hawkins wrote in its 2018 Survey of Physician and Advanced Practitioners Recruiting Incentives.

Gastroenterology, with an eighth-place finish in 2017-2018, also showed strong growth by increasing 55% from the year before and rising 137% over the past 3 years. The rise of gastroenterology and radiology over the past 2 years came at the expense of pediatrics, which went from 10th in 2015-2016 to 13th this year, and neurology, which dropped from 7th to 15th, Merritt Hawkins wrote in the report, which was based on a total of 3,045 search assignments conducted in 2017-2018.

“While demand for primary care physicians remains robust, hospitals, medical groups, and other health care facilities are shifting their recruiting efforts to medical specialists,” the company wrote, noting that recruiting assignments for medical specialists have risen from 67% of all searches 3 years ago to 74% in the past year.

“It’s a matter of demographic destiny,” Travis Singleton, senior vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a written statement accompanying the report. “Americans are getting older, and it is medical specialists who will be taking care of our aging and ailing bodies and brains. We still need more primary care doctors, but a growing emphasis is being placed on recruiting specialists.”

according to physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The company conducted 497 searches for family physicians from April 1, 2017, to March 31, 2018, marking the third straight year of decline for the specialty but still more than double the 243 searches conducted for psychiatrists, the medical specialty that was second more frequently requested for recruitment, Merritt Hawkins wrote in its 2018 Survey of Physician and Advanced Practitioners Recruiting Incentives.

Gastroenterology, with an eighth-place finish in 2017-2018, also showed strong growth by increasing 55% from the year before and rising 137% over the past 3 years. The rise of gastroenterology and radiology over the past 2 years came at the expense of pediatrics, which went from 10th in 2015-2016 to 13th this year, and neurology, which dropped from 7th to 15th, Merritt Hawkins wrote in the report, which was based on a total of 3,045 search assignments conducted in 2017-2018.

“While demand for primary care physicians remains robust, hospitals, medical groups, and other health care facilities are shifting their recruiting efforts to medical specialists,” the company wrote, noting that recruiting assignments for medical specialists have risen from 67% of all searches 3 years ago to 74% in the past year.

“It’s a matter of demographic destiny,” Travis Singleton, senior vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a written statement accompanying the report. “Americans are getting older, and it is medical specialists who will be taking care of our aging and ailing bodies and brains. We still need more primary care doctors, but a growing emphasis is being placed on recruiting specialists.”

according to physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The company conducted 497 searches for family physicians from April 1, 2017, to March 31, 2018, marking the third straight year of decline for the specialty but still more than double the 243 searches conducted for psychiatrists, the medical specialty that was second more frequently requested for recruitment, Merritt Hawkins wrote in its 2018 Survey of Physician and Advanced Practitioners Recruiting Incentives.

Gastroenterology, with an eighth-place finish in 2017-2018, also showed strong growth by increasing 55% from the year before and rising 137% over the past 3 years. The rise of gastroenterology and radiology over the past 2 years came at the expense of pediatrics, which went from 10th in 2015-2016 to 13th this year, and neurology, which dropped from 7th to 15th, Merritt Hawkins wrote in the report, which was based on a total of 3,045 search assignments conducted in 2017-2018.

“While demand for primary care physicians remains robust, hospitals, medical groups, and other health care facilities are shifting their recruiting efforts to medical specialists,” the company wrote, noting that recruiting assignments for medical specialists have risen from 67% of all searches 3 years ago to 74% in the past year.

“It’s a matter of demographic destiny,” Travis Singleton, senior vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a written statement accompanying the report. “Americans are getting older, and it is medical specialists who will be taking care of our aging and ailing bodies and brains. We still need more primary care doctors, but a growing emphasis is being placed on recruiting specialists.”

Benefits of nicotine preloading undercut by reduced varenicline usage

Nicotine preloading with patches 4 weeks before making a quit attempt was not significantly associated with according to Paul Aveyard, PhD, and his associates at Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford (England).

The primary study outcome, biochemically validated abstinence at 6 months, was achieved by 17.5% of the 899 people who preloaded with a 21-mg/24-hr nicotine patch for 4 weeks and by 14.4% of the 893 in the control group. After 1 year, 14.0% of people in the preloading group maintained long-term abstinence, compared with 11.3% in the control group. In addition, 35.5% of the preloading group and 32.3% of the control group achieved abstinence 4 weeks from baseline.

The unadjusted odds ratio for the effect of preloading at 6 months was 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 0.97-1.62; P = .08) and not statistically significant. However, when reduced varenicline usage in the preloading group was taken into account, the effect of preloading did reach statistical significance (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.03-1.73; P = .03). Similar results were found at 1 year and at 4 weeks, where the preloading effect did not reach significance until adjusted for varenicline usage.

“Nicotine preloading with a 21-mg/24-hr nicotine patch for 4 weeks seems to be efficacious, safe, and well tolerated, but probably deters the use of varenicline, the most effective smoking cessation drug. If it were possible to overcome this unintended consequence, preloading could lead to a worthwhile increase in long-term smoking abstinence,” the investigators concluded.

SOURCE: Aveyard P et al. BMJ. 2018 Jun 13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2164.

Nicotine preloading with patches 4 weeks before making a quit attempt was not significantly associated with according to Paul Aveyard, PhD, and his associates at Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford (England).

The primary study outcome, biochemically validated abstinence at 6 months, was achieved by 17.5% of the 899 people who preloaded with a 21-mg/24-hr nicotine patch for 4 weeks and by 14.4% of the 893 in the control group. After 1 year, 14.0% of people in the preloading group maintained long-term abstinence, compared with 11.3% in the control group. In addition, 35.5% of the preloading group and 32.3% of the control group achieved abstinence 4 weeks from baseline.

The unadjusted odds ratio for the effect of preloading at 6 months was 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 0.97-1.62; P = .08) and not statistically significant. However, when reduced varenicline usage in the preloading group was taken into account, the effect of preloading did reach statistical significance (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.03-1.73; P = .03). Similar results were found at 1 year and at 4 weeks, where the preloading effect did not reach significance until adjusted for varenicline usage.

“Nicotine preloading with a 21-mg/24-hr nicotine patch for 4 weeks seems to be efficacious, safe, and well tolerated, but probably deters the use of varenicline, the most effective smoking cessation drug. If it were possible to overcome this unintended consequence, preloading could lead to a worthwhile increase in long-term smoking abstinence,” the investigators concluded.

SOURCE: Aveyard P et al. BMJ. 2018 Jun 13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2164.

Nicotine preloading with patches 4 weeks before making a quit attempt was not significantly associated with according to Paul Aveyard, PhD, and his associates at Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford (England).

The primary study outcome, biochemically validated abstinence at 6 months, was achieved by 17.5% of the 899 people who preloaded with a 21-mg/24-hr nicotine patch for 4 weeks and by 14.4% of the 893 in the control group. After 1 year, 14.0% of people in the preloading group maintained long-term abstinence, compared with 11.3% in the control group. In addition, 35.5% of the preloading group and 32.3% of the control group achieved abstinence 4 weeks from baseline.

The unadjusted odds ratio for the effect of preloading at 6 months was 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 0.97-1.62; P = .08) and not statistically significant. However, when reduced varenicline usage in the preloading group was taken into account, the effect of preloading did reach statistical significance (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.03-1.73; P = .03). Similar results were found at 1 year and at 4 weeks, where the preloading effect did not reach significance until adjusted for varenicline usage.

“Nicotine preloading with a 21-mg/24-hr nicotine patch for 4 weeks seems to be efficacious, safe, and well tolerated, but probably deters the use of varenicline, the most effective smoking cessation drug. If it were possible to overcome this unintended consequence, preloading could lead to a worthwhile increase in long-term smoking abstinence,” the investigators concluded.

SOURCE: Aveyard P et al. BMJ. 2018 Jun 13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2164.

FROM THE BMJ

Bisphosphonate ‘holidays’ exceeding 2 years linked to increased fractures

AMSTERDAM – Older women on bisphosphonate treatment for at least 3 years who then stopped taking the drug showed a 40% increased risk for hip fracture after they were off the bisphosphonate for more than 2 years, compared with women who never stopped using the drug, according to an analysis of more than 150,000 women in a Medicare database.

The implication of this observational-data finding is that drug holidays from a bisphosphonate regimen “may not be appropriate for all patients,” Kenneth G. Saag, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

The finding seems to dispute a recent recommendation from the American College of Physicians (Ann Intern Med. 2017 June 6;166[11]:818-39) that drug treatment to prevent bone fractures in osteoporotic women should stop after 5 years, noted Dr. Saag, a rheumatologist and professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. The median duration of bisphosphonate treatment in the studied cohort before the drug use stopped was 5.5 years.

“Drug holidays [from a bisphosphonate] have become increasingly common” because of concerns about potential adverse effects from prolonged, continuous bisphosphonate treatment, especially the risk for osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures, he said. These bisphosphonate stoppages are sometimes permanent and sometimes temporary, Dr. Saag noted. Ideally, assessment of the risks and benefits from a bisphosphonate drug holiday should occur in a randomized study, but in current U.S. practice such a trial would be “impossible because there is not equipoise around the decision of whether or not to stop,” he said.

To try to gain insight into the impact of halting bisphosphonate treatment with observational data, Dr. Saag and his associates used records collected by Medicare on 153,236 women who started a new course of bisphosphonate treatment and remained on it for at least 3 years during 2006 to 2014. When selecting these women, the researchers also focused on those with at least 80% adherence to their bisphosphonate regimen, based on prescription coverage data. The analysis censored women who also received other treatments that can affect bone density, such as estrogen or denosumab (Prolia, Xgeva). The average age of the women was 79 years; two-thirds were aged 75 years or older. The median duration of follow-up information after bisphosphonate stoppage was 2.1 years. Forty percent of the women stopped their bisphosphonate treatment for at least 6 months, and 13% of the women who stopped treatment subsequently restarted a bisphosphonate drug. The most commonly used bisphosphonate was alendronate (Fosamax, Binosto), used by 72%, followed by zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa), used by 16%.

The analysis divided women who stopped their bisphosphonate treatment into subgroups based on the duration of stoppage, and showed that the rate of hip fracture was 40% higher among women who stopped treatment for more than 2 years but not more than 3 years, compared with the women who never interrupted their bisphosphonate treatment, a statistically significant difference, Dr. Saag said. In contrast, among women who halted bisphosphonate treatment for more than 1 year but not more than 2 years, the hip fracture risk was 20% higher than that of nonstoppers, also a statistically significant difference. These and all the other analyses the researchers ran adjusted for the possible impact from baseline differences in several demographic and clinical variables.

Dr. Saag cautioned that while the relatively increased risk for hip fracture from a prolonged halt to bisphosphonate treatment was 40%, the absolute increase in risk was “relatively modest,” representing an increased fracture rate of 0.5-1 additional fractures during every 100 patient years of follow-up.

For the endpoint of major osteoporotic fracture at any location, the risk was 10% higher among women who stopped treatment for more than 2 years but not for longer than 3 years, compared with nonstoppers.

The researchers also focused on two key subgroups. Among women who only took alendronate, a drug holiday of more than 2 years was linked with a statistically significant 20% rise in hip fractures, compared with women who never stopped the drug. And among the 4% of studied women who had a history of a bone fracture because of bone fragility, stoppage of their bisphosphonate treatment for more than 2 years doubled their hip fracture rate, compared with similar women who did not stop their treatment.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Saag has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Amgen, Lilly, and Radius.

SOURCE: Curtis J et al. EULAR 2018 Congress, abstract OP0017.

AMSTERDAM – Older women on bisphosphonate treatment for at least 3 years who then stopped taking the drug showed a 40% increased risk for hip fracture after they were off the bisphosphonate for more than 2 years, compared with women who never stopped using the drug, according to an analysis of more than 150,000 women in a Medicare database.

The implication of this observational-data finding is that drug holidays from a bisphosphonate regimen “may not be appropriate for all patients,” Kenneth G. Saag, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

The finding seems to dispute a recent recommendation from the American College of Physicians (Ann Intern Med. 2017 June 6;166[11]:818-39) that drug treatment to prevent bone fractures in osteoporotic women should stop after 5 years, noted Dr. Saag, a rheumatologist and professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. The median duration of bisphosphonate treatment in the studied cohort before the drug use stopped was 5.5 years.

“Drug holidays [from a bisphosphonate] have become increasingly common” because of concerns about potential adverse effects from prolonged, continuous bisphosphonate treatment, especially the risk for osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures, he said. These bisphosphonate stoppages are sometimes permanent and sometimes temporary, Dr. Saag noted. Ideally, assessment of the risks and benefits from a bisphosphonate drug holiday should occur in a randomized study, but in current U.S. practice such a trial would be “impossible because there is not equipoise around the decision of whether or not to stop,” he said.

To try to gain insight into the impact of halting bisphosphonate treatment with observational data, Dr. Saag and his associates used records collected by Medicare on 153,236 women who started a new course of bisphosphonate treatment and remained on it for at least 3 years during 2006 to 2014. When selecting these women, the researchers also focused on those with at least 80% adherence to their bisphosphonate regimen, based on prescription coverage data. The analysis censored women who also received other treatments that can affect bone density, such as estrogen or denosumab (Prolia, Xgeva). The average age of the women was 79 years; two-thirds were aged 75 years or older. The median duration of follow-up information after bisphosphonate stoppage was 2.1 years. Forty percent of the women stopped their bisphosphonate treatment for at least 6 months, and 13% of the women who stopped treatment subsequently restarted a bisphosphonate drug. The most commonly used bisphosphonate was alendronate (Fosamax, Binosto), used by 72%, followed by zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa), used by 16%.

The analysis divided women who stopped their bisphosphonate treatment into subgroups based on the duration of stoppage, and showed that the rate of hip fracture was 40% higher among women who stopped treatment for more than 2 years but not more than 3 years, compared with the women who never interrupted their bisphosphonate treatment, a statistically significant difference, Dr. Saag said. In contrast, among women who halted bisphosphonate treatment for more than 1 year but not more than 2 years, the hip fracture risk was 20% higher than that of nonstoppers, also a statistically significant difference. These and all the other analyses the researchers ran adjusted for the possible impact from baseline differences in several demographic and clinical variables.

Dr. Saag cautioned that while the relatively increased risk for hip fracture from a prolonged halt to bisphosphonate treatment was 40%, the absolute increase in risk was “relatively modest,” representing an increased fracture rate of 0.5-1 additional fractures during every 100 patient years of follow-up.

For the endpoint of major osteoporotic fracture at any location, the risk was 10% higher among women who stopped treatment for more than 2 years but not for longer than 3 years, compared with nonstoppers.

The researchers also focused on two key subgroups. Among women who only took alendronate, a drug holiday of more than 2 years was linked with a statistically significant 20% rise in hip fractures, compared with women who never stopped the drug. And among the 4% of studied women who had a history of a bone fracture because of bone fragility, stoppage of their bisphosphonate treatment for more than 2 years doubled their hip fracture rate, compared with similar women who did not stop their treatment.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Saag has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Amgen, Lilly, and Radius.

SOURCE: Curtis J et al. EULAR 2018 Congress, abstract OP0017.

AMSTERDAM – Older women on bisphosphonate treatment for at least 3 years who then stopped taking the drug showed a 40% increased risk for hip fracture after they were off the bisphosphonate for more than 2 years, compared with women who never stopped using the drug, according to an analysis of more than 150,000 women in a Medicare database.

The implication of this observational-data finding is that drug holidays from a bisphosphonate regimen “may not be appropriate for all patients,” Kenneth G. Saag, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

The finding seems to dispute a recent recommendation from the American College of Physicians (Ann Intern Med. 2017 June 6;166[11]:818-39) that drug treatment to prevent bone fractures in osteoporotic women should stop after 5 years, noted Dr. Saag, a rheumatologist and professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. The median duration of bisphosphonate treatment in the studied cohort before the drug use stopped was 5.5 years.

“Drug holidays [from a bisphosphonate] have become increasingly common” because of concerns about potential adverse effects from prolonged, continuous bisphosphonate treatment, especially the risk for osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures, he said. These bisphosphonate stoppages are sometimes permanent and sometimes temporary, Dr. Saag noted. Ideally, assessment of the risks and benefits from a bisphosphonate drug holiday should occur in a randomized study, but in current U.S. practice such a trial would be “impossible because there is not equipoise around the decision of whether or not to stop,” he said.

To try to gain insight into the impact of halting bisphosphonate treatment with observational data, Dr. Saag and his associates used records collected by Medicare on 153,236 women who started a new course of bisphosphonate treatment and remained on it for at least 3 years during 2006 to 2014. When selecting these women, the researchers also focused on those with at least 80% adherence to their bisphosphonate regimen, based on prescription coverage data. The analysis censored women who also received other treatments that can affect bone density, such as estrogen or denosumab (Prolia, Xgeva). The average age of the women was 79 years; two-thirds were aged 75 years or older. The median duration of follow-up information after bisphosphonate stoppage was 2.1 years. Forty percent of the women stopped their bisphosphonate treatment for at least 6 months, and 13% of the women who stopped treatment subsequently restarted a bisphosphonate drug. The most commonly used bisphosphonate was alendronate (Fosamax, Binosto), used by 72%, followed by zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa), used by 16%.

The analysis divided women who stopped their bisphosphonate treatment into subgroups based on the duration of stoppage, and showed that the rate of hip fracture was 40% higher among women who stopped treatment for more than 2 years but not more than 3 years, compared with the women who never interrupted their bisphosphonate treatment, a statistically significant difference, Dr. Saag said. In contrast, among women who halted bisphosphonate treatment for more than 1 year but not more than 2 years, the hip fracture risk was 20% higher than that of nonstoppers, also a statistically significant difference. These and all the other analyses the researchers ran adjusted for the possible impact from baseline differences in several demographic and clinical variables.

Dr. Saag cautioned that while the relatively increased risk for hip fracture from a prolonged halt to bisphosphonate treatment was 40%, the absolute increase in risk was “relatively modest,” representing an increased fracture rate of 0.5-1 additional fractures during every 100 patient years of follow-up.

For the endpoint of major osteoporotic fracture at any location, the risk was 10% higher among women who stopped treatment for more than 2 years but not for longer than 3 years, compared with nonstoppers.

The researchers also focused on two key subgroups. Among women who only took alendronate, a drug holiday of more than 2 years was linked with a statistically significant 20% rise in hip fractures, compared with women who never stopped the drug. And among the 4% of studied women who had a history of a bone fracture because of bone fragility, stoppage of their bisphosphonate treatment for more than 2 years doubled their hip fracture rate, compared with similar women who did not stop their treatment.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Saag has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Amgen, Lilly, and Radius.

SOURCE: Curtis J et al. EULAR 2018 Congress, abstract OP0017.

REPORTING FROM THE EULAR 2018 CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Stopping a bisphosphonate for more than 2 years boosts hip fracture risk.

Major finding: Women stopping bisphosphonate use for more than 2 years had a 40% higher rate of hip fractures compared with women who didn’t stop the drug.

Study details: Review of data collected by Medicare for 153,236 women treated with a bisphosphonate drug.

Disclosures: The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Saag has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Amgen, Lilly, and Radius.

Source: Curtis J et al. EULAR 2018 Congress, abstract OP0017.

FDA approves bevacizumab for advanced ovarian cancer

The Food and Drug Administration has approved bevacizumab (Avastin) for treating stage III or IV ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following initial surgical resection, first in combination with chemotherapy (carboplatin and paclitaxel), then as monotherapy.

The approval was based on an improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in the phase 3, three-arm GOG-0218 trial, evaluating the addition of bevacizumab to carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with stage III or IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following initial surgical resection, the FDA said in a press statement.

The most serious adverse events of bevacizumab included gastrointestinal perforation, wounds that don’t heal, and serious bleeding. Other possible adverse events included kidney problems, fistula, severe high blood pressure, severe stroke or heart problems, and problems of the nervous system and vision. Less serious events included headache, nosebleeds, rectal bleeding, and dry skin.

The recommended bevacizumab dose for stage III or IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following initial surgical resection is 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks with carboplatin and paclitaxel for up to 6 cycles, followed by 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks as a single agent, for a total of up to 22 cycles, the FDA said.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved bevacizumab (Avastin) for treating stage III or IV ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following initial surgical resection, first in combination with chemotherapy (carboplatin and paclitaxel), then as monotherapy.

The approval was based on an improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in the phase 3, three-arm GOG-0218 trial, evaluating the addition of bevacizumab to carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with stage III or IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following initial surgical resection, the FDA said in a press statement.

The most serious adverse events of bevacizumab included gastrointestinal perforation, wounds that don’t heal, and serious bleeding. Other possible adverse events included kidney problems, fistula, severe high blood pressure, severe stroke or heart problems, and problems of the nervous system and vision. Less serious events included headache, nosebleeds, rectal bleeding, and dry skin.

The recommended bevacizumab dose for stage III or IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following initial surgical resection is 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks with carboplatin and paclitaxel for up to 6 cycles, followed by 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks as a single agent, for a total of up to 22 cycles, the FDA said.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved bevacizumab (Avastin) for treating stage III or IV ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following initial surgical resection, first in combination with chemotherapy (carboplatin and paclitaxel), then as monotherapy.

The approval was based on an improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in the phase 3, three-arm GOG-0218 trial, evaluating the addition of bevacizumab to carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with stage III or IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following initial surgical resection, the FDA said in a press statement.

The most serious adverse events of bevacizumab included gastrointestinal perforation, wounds that don’t heal, and serious bleeding. Other possible adverse events included kidney problems, fistula, severe high blood pressure, severe stroke or heart problems, and problems of the nervous system and vision. Less serious events included headache, nosebleeds, rectal bleeding, and dry skin.

The recommended bevacizumab dose for stage III or IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following initial surgical resection is 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks with carboplatin and paclitaxel for up to 6 cycles, followed by 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks as a single agent, for a total of up to 22 cycles, the FDA said.

Lung volume reduction procedures on the rise since 2011

SAN DIEGO – The number of has been increasing since 2011, according to a large national analysis.

Lung volume–reduction surgery (LVRS) has been available for decades, but results from the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) in 2003 (N Engl J Med 2003;348:2059-73) demonstrated that certain COPD patients benefited from the surgery, Amy Attaway, MD, said at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society.

In that trial, overall mortality at 30 days was 3.6% for the surgical group. “If you excluded high-risk patients, the 30-day mortality was only 2.2%,” said Dr. Attaway, a staff physician at the Cleveland Clinic Respiratory Institute. “If you look at the upper lobe–predominant, low-exercise group, their mortality at 30 days was 1.4%.”

Subsequent studies that evaluated NETT patients over time showed continued improvements in their mortality. For example, one study found that in the upper lobe–predominant patients who received surgery in the NETT trial, their survival at 3 years was 81% vs. 74% in the medical group (P = .05), while survival at 5 years was 70% in the surgery group vs. 60% in the medical group (P = .02; J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140[3]:564-72). Despite this improved mortality, other studies have shown that LVRS remains underutilized. Once such analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample showed a logarithmic drop from 2000 to 2010 (Chest 2014;146[6]:e228-9). The authors also noted that the overall mortality was 6% and that the need for a tracheostomy was 7.9%. Age greater than 65 years was associated with increased mortality (odds ratio 2.8).

Dr. Attaway and her associates hypothesized that availability of the long-term survival data from the NETT, support from GOLD guidelines, and the lack of a Food and Drug Administration–approved alternative may have increased utilization of this surgery from 2007 through 2013. With data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for 2007-2013, the researchers performed a retrospective cohort analysis of 2,805 patients who underwent LVRS. The composite primary outcome was mortality or need for tracheostomy. Logistic regression was performed to analyze factors associated with the composite primary outcome.

The average patient age was 59 years, and 64% were male. Medicare was the payer in nearly half of cases, in-hospital mortality and need for tracheostomy were both 5.5%, and the risk for tracheostomy or mortality was 10.5%. Linear regression analysis showed a significant increase in LVRS over time, with the 320 surgeries in 2007 and 605 in 2013 (P = .0016).

On univariate analysis, the following factors were found to be significantly associated with the composite primary outcome: in-hospital mortality or the need for tracheostomy (P less than .001), respiratory failure (P less than .001), septicemia (P = .01), shock (P less than .001), acute kidney injury (P less than .001), secondary pulmonary hypertension (P less than .001), and a higher mean number of diagnoses or number of chronic conditions on admission (P less than .001 and P = .017, respectively).

On multivariate logistic regression, only two factors were found to be significantly associated with the composite primary outcome: a higher number of diagnoses (adjusted OR of 1.17 per additional diagnosis), and the presence of secondary pulmonary hypertension (adjusted OR 4.4).

“Availability of long-term survival data from NETT, support from the GOLD guidelines, and lack of current FDA-approved alternatives are potential reasons for increased utilization [of LVRS],” Dr. Attaway said. “However, our study showed that in-hospital mortality and morbidity is high, compared to the NETT results. We also found that secondary pulmonary hypertension and comorbidities are associated with poor outcomes. This is important to keep in mind for patient selection.”

Dr. Attaway and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Attaway A et al. ATS 2018, Abstract 4436.

SAN DIEGO – The number of has been increasing since 2011, according to a large national analysis.

Lung volume–reduction surgery (LVRS) has been available for decades, but results from the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) in 2003 (N Engl J Med 2003;348:2059-73) demonstrated that certain COPD patients benefited from the surgery, Amy Attaway, MD, said at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society.

In that trial, overall mortality at 30 days was 3.6% for the surgical group. “If you excluded high-risk patients, the 30-day mortality was only 2.2%,” said Dr. Attaway, a staff physician at the Cleveland Clinic Respiratory Institute. “If you look at the upper lobe–predominant, low-exercise group, their mortality at 30 days was 1.4%.”

Subsequent studies that evaluated NETT patients over time showed continued improvements in their mortality. For example, one study found that in the upper lobe–predominant patients who received surgery in the NETT trial, their survival at 3 years was 81% vs. 74% in the medical group (P = .05), while survival at 5 years was 70% in the surgery group vs. 60% in the medical group (P = .02; J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140[3]:564-72). Despite this improved mortality, other studies have shown that LVRS remains underutilized. Once such analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample showed a logarithmic drop from 2000 to 2010 (Chest 2014;146[6]:e228-9). The authors also noted that the overall mortality was 6% and that the need for a tracheostomy was 7.9%. Age greater than 65 years was associated with increased mortality (odds ratio 2.8).

Dr. Attaway and her associates hypothesized that availability of the long-term survival data from the NETT, support from GOLD guidelines, and the lack of a Food and Drug Administration–approved alternative may have increased utilization of this surgery from 2007 through 2013. With data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for 2007-2013, the researchers performed a retrospective cohort analysis of 2,805 patients who underwent LVRS. The composite primary outcome was mortality or need for tracheostomy. Logistic regression was performed to analyze factors associated with the composite primary outcome.

The average patient age was 59 years, and 64% were male. Medicare was the payer in nearly half of cases, in-hospital mortality and need for tracheostomy were both 5.5%, and the risk for tracheostomy or mortality was 10.5%. Linear regression analysis showed a significant increase in LVRS over time, with the 320 surgeries in 2007 and 605 in 2013 (P = .0016).

On univariate analysis, the following factors were found to be significantly associated with the composite primary outcome: in-hospital mortality or the need for tracheostomy (P less than .001), respiratory failure (P less than .001), septicemia (P = .01), shock (P less than .001), acute kidney injury (P less than .001), secondary pulmonary hypertension (P less than .001), and a higher mean number of diagnoses or number of chronic conditions on admission (P less than .001 and P = .017, respectively).

On multivariate logistic regression, only two factors were found to be significantly associated with the composite primary outcome: a higher number of diagnoses (adjusted OR of 1.17 per additional diagnosis), and the presence of secondary pulmonary hypertension (adjusted OR 4.4).

“Availability of long-term survival data from NETT, support from the GOLD guidelines, and lack of current FDA-approved alternatives are potential reasons for increased utilization [of LVRS],” Dr. Attaway said. “However, our study showed that in-hospital mortality and morbidity is high, compared to the NETT results. We also found that secondary pulmonary hypertension and comorbidities are associated with poor outcomes. This is important to keep in mind for patient selection.”

Dr. Attaway and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Attaway A et al. ATS 2018, Abstract 4436.

SAN DIEGO – The number of has been increasing since 2011, according to a large national analysis.

Lung volume–reduction surgery (LVRS) has been available for decades, but results from the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) in 2003 (N Engl J Med 2003;348:2059-73) demonstrated that certain COPD patients benefited from the surgery, Amy Attaway, MD, said at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society.

In that trial, overall mortality at 30 days was 3.6% for the surgical group. “If you excluded high-risk patients, the 30-day mortality was only 2.2%,” said Dr. Attaway, a staff physician at the Cleveland Clinic Respiratory Institute. “If you look at the upper lobe–predominant, low-exercise group, their mortality at 30 days was 1.4%.”

Subsequent studies that evaluated NETT patients over time showed continued improvements in their mortality. For example, one study found that in the upper lobe–predominant patients who received surgery in the NETT trial, their survival at 3 years was 81% vs. 74% in the medical group (P = .05), while survival at 5 years was 70% in the surgery group vs. 60% in the medical group (P = .02; J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140[3]:564-72). Despite this improved mortality, other studies have shown that LVRS remains underutilized. Once such analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample showed a logarithmic drop from 2000 to 2010 (Chest 2014;146[6]:e228-9). The authors also noted that the overall mortality was 6% and that the need for a tracheostomy was 7.9%. Age greater than 65 years was associated with increased mortality (odds ratio 2.8).

Dr. Attaway and her associates hypothesized that availability of the long-term survival data from the NETT, support from GOLD guidelines, and the lack of a Food and Drug Administration–approved alternative may have increased utilization of this surgery from 2007 through 2013. With data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for 2007-2013, the researchers performed a retrospective cohort analysis of 2,805 patients who underwent LVRS. The composite primary outcome was mortality or need for tracheostomy. Logistic regression was performed to analyze factors associated with the composite primary outcome.

The average patient age was 59 years, and 64% were male. Medicare was the payer in nearly half of cases, in-hospital mortality and need for tracheostomy were both 5.5%, and the risk for tracheostomy or mortality was 10.5%. Linear regression analysis showed a significant increase in LVRS over time, with the 320 surgeries in 2007 and 605 in 2013 (P = .0016).

On univariate analysis, the following factors were found to be significantly associated with the composite primary outcome: in-hospital mortality or the need for tracheostomy (P less than .001), respiratory failure (P less than .001), septicemia (P = .01), shock (P less than .001), acute kidney injury (P less than .001), secondary pulmonary hypertension (P less than .001), and a higher mean number of diagnoses or number of chronic conditions on admission (P less than .001 and P = .017, respectively).

On multivariate logistic regression, only two factors were found to be significantly associated with the composite primary outcome: a higher number of diagnoses (adjusted OR of 1.17 per additional diagnosis), and the presence of secondary pulmonary hypertension (adjusted OR 4.4).

“Availability of long-term survival data from NETT, support from the GOLD guidelines, and lack of current FDA-approved alternatives are potential reasons for increased utilization [of LVRS],” Dr. Attaway said. “However, our study showed that in-hospital mortality and morbidity is high, compared to the NETT results. We also found that secondary pulmonary hypertension and comorbidities are associated with poor outcomes. This is important to keep in mind for patient selection.”

Dr. Attaway and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Attaway A et al. ATS 2018, Abstract 4436.

AT ATS 2018

Key clinical point: Lung volume–reduction surgery remains an evidence-based therapy for a cohort of severe COPD patients.

Major finding: Linear regression analysis showed a significant increase in LVRS over time, with the 320 surgeries in 2007 and 605 in 2013 (P = .0016).

Study details: A retrospective cohort analysis of 2,805 patients who underwent LVRS.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Attaway A et al. Abstract 4436, ATS 2018.

Protein activation could predict renal cell carcinoma recurrence

Levels of activity of a protein linked to malignancy could help predict if and when patients with renal cell carcinoma are likely to experience a recurrence, investigators report.

In a retrospective cohort study, the researchers looked at surgical specimens from 303 patients with localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma who had surgery between 1993 and 2011. The specimens were stained for antibodies against three key proteins; eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1), and phospho eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (p-4EBP1), reported Osamu Ichiyanagi, MD, of Yamagata (Japan) University, and colleagues. The study was published in Clinical Genitourinary Cancer.

The 4EBP1/eIF4E axis is known to regulate protein synthesis associated with malignant behavior. Researchers found that while the expression levels for the three proteins were similar between the recurrence-free and recurrence groups, patients who did not experience a recurrence had significantly lower activity in the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis.

The analysis showed that having intermediate or strong activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis was an independent predictor of the risk of recurrence, as was Fuhrman grade 3/4 and pathological T stage of pT1b or above.

Only two patients who had weak activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis experienced a recurrence (one early, one late).

Overall, 31 patients experienced an early recurrence – defined as recurrence within 5 years – and 16 patients experienced a recurrence after 5 years. Strong activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis was an independent predictor of early recurrence.

About one-third of patients with nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma who are curatively treated with nephrectomy experience a tumor recurrence, most commonly a distant metastasis. Late recurrence is known to occur in 6%-12% of patients.

“We show here for the first time that activation level of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis in localised ccRCC may contribute not only to tumour recurrence but also to the timing of recurrence following curative nephrectomy,” wrote Dr. Ichiyanagi and coauthors. “Our data indicate that this activation may impact ER [early recurrence] and LR [late recurrence] events differentially.”

The study also found that more patients experienced recurrence after curative nephrectomy, suggesting that the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis became strongly activated after this.

The study was supported by Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine and the Japan Society for Promotion of Science. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Ichiyanagi O et al. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 June 8. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.06.002.

Levels of activity of a protein linked to malignancy could help predict if and when patients with renal cell carcinoma are likely to experience a recurrence, investigators report.

In a retrospective cohort study, the researchers looked at surgical specimens from 303 patients with localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma who had surgery between 1993 and 2011. The specimens were stained for antibodies against three key proteins; eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1), and phospho eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (p-4EBP1), reported Osamu Ichiyanagi, MD, of Yamagata (Japan) University, and colleagues. The study was published in Clinical Genitourinary Cancer.

The 4EBP1/eIF4E axis is known to regulate protein synthesis associated with malignant behavior. Researchers found that while the expression levels for the three proteins were similar between the recurrence-free and recurrence groups, patients who did not experience a recurrence had significantly lower activity in the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis.

The analysis showed that having intermediate or strong activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis was an independent predictor of the risk of recurrence, as was Fuhrman grade 3/4 and pathological T stage of pT1b or above.

Only two patients who had weak activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis experienced a recurrence (one early, one late).

Overall, 31 patients experienced an early recurrence – defined as recurrence within 5 years – and 16 patients experienced a recurrence after 5 years. Strong activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis was an independent predictor of early recurrence.

About one-third of patients with nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma who are curatively treated with nephrectomy experience a tumor recurrence, most commonly a distant metastasis. Late recurrence is known to occur in 6%-12% of patients.

“We show here for the first time that activation level of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis in localised ccRCC may contribute not only to tumour recurrence but also to the timing of recurrence following curative nephrectomy,” wrote Dr. Ichiyanagi and coauthors. “Our data indicate that this activation may impact ER [early recurrence] and LR [late recurrence] events differentially.”

The study also found that more patients experienced recurrence after curative nephrectomy, suggesting that the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis became strongly activated after this.

The study was supported by Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine and the Japan Society for Promotion of Science. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Ichiyanagi O et al. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 June 8. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.06.002.

Levels of activity of a protein linked to malignancy could help predict if and when patients with renal cell carcinoma are likely to experience a recurrence, investigators report.

In a retrospective cohort study, the researchers looked at surgical specimens from 303 patients with localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma who had surgery between 1993 and 2011. The specimens were stained for antibodies against three key proteins; eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1), and phospho eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (p-4EBP1), reported Osamu Ichiyanagi, MD, of Yamagata (Japan) University, and colleagues. The study was published in Clinical Genitourinary Cancer.

The 4EBP1/eIF4E axis is known to regulate protein synthesis associated with malignant behavior. Researchers found that while the expression levels for the three proteins were similar between the recurrence-free and recurrence groups, patients who did not experience a recurrence had significantly lower activity in the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis.

The analysis showed that having intermediate or strong activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis was an independent predictor of the risk of recurrence, as was Fuhrman grade 3/4 and pathological T stage of pT1b or above.

Only two patients who had weak activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis experienced a recurrence (one early, one late).

Overall, 31 patients experienced an early recurrence – defined as recurrence within 5 years – and 16 patients experienced a recurrence after 5 years. Strong activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis was an independent predictor of early recurrence.

About one-third of patients with nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma who are curatively treated with nephrectomy experience a tumor recurrence, most commonly a distant metastasis. Late recurrence is known to occur in 6%-12% of patients.

“We show here for the first time that activation level of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis in localised ccRCC may contribute not only to tumour recurrence but also to the timing of recurrence following curative nephrectomy,” wrote Dr. Ichiyanagi and coauthors. “Our data indicate that this activation may impact ER [early recurrence] and LR [late recurrence] events differentially.”

The study also found that more patients experienced recurrence after curative nephrectomy, suggesting that the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis became strongly activated after this.

The study was supported by Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine and the Japan Society for Promotion of Science. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Ichiyanagi O et al. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 June 8. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.06.002.

FROM CLINICAL GENITOURINARY CANCER

Key clinical point: Protein activation levels of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis may predict renal cell carcinoma recurrence.

Major finding: Strong protein activation of the 4EBP1/eIF4E axis may be linked to early recurrence of renal cell carcinoma.

Study details: Retrospective cohort study in 303 patients with localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine and the Japan Society for Promotion of Science. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Ichiyanagi O et al. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 June 8. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.06.002.

Make the Diagnosis - June 2018

Different types of steatocystoma multiplex have been described: localized, generalized, facial, acral, and suppurative (in which the lesions resemble hidradenitis suppurativa).

This condition is autosomal dominant and is linked to defects in KRT17 gene, which instructs the production of keratin 17. However, some cases of steatocystoma multiplex occur sporadically with no mutation in the KRT17 gene; in them, the cause is unknown. Steatocystoma multiplex may be associated with eruptive vellus hair cysts and pachyonychia congenita (nail and teeth abnormalities and palmoplantar keratoderma). Lesions often appear during adolescence, when an individual hits puberty. Hormones likely influence the development of the cysts from the pilosebaceous unit. If there is a single steatocystoma, it is called steatocystoma simplex.

Steatocystomas do not resolve on their own. The small, benign cysts are located fairly superficial in the dermis. If punctured, they drain a yellow, oily liquid sebum. Lesions may become inflamed and may heal with scarring, as in acne. They may be treated by incision and drainage or excision to remove the cyst wall. Electrosurgery and cryotherapy may be used. Oral antibiotics may improve inflamed lesions. There are reports in the literature in which isotretinoin has helped; however, it is not curative. In some cases, the lesions can reoccur and may even be worse.

Case and photo submitted by: Donna Bilu Martin, MD; Premier Dermatology, MD; Aventura, Fla.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Different types of steatocystoma multiplex have been described: localized, generalized, facial, acral, and suppurative (in which the lesions resemble hidradenitis suppurativa).

This condition is autosomal dominant and is linked to defects in KRT17 gene, which instructs the production of keratin 17. However, some cases of steatocystoma multiplex occur sporadically with no mutation in the KRT17 gene; in them, the cause is unknown. Steatocystoma multiplex may be associated with eruptive vellus hair cysts and pachyonychia congenita (nail and teeth abnormalities and palmoplantar keratoderma). Lesions often appear during adolescence, when an individual hits puberty. Hormones likely influence the development of the cysts from the pilosebaceous unit. If there is a single steatocystoma, it is called steatocystoma simplex.

Steatocystomas do not resolve on their own. The small, benign cysts are located fairly superficial in the dermis. If punctured, they drain a yellow, oily liquid sebum. Lesions may become inflamed and may heal with scarring, as in acne. They may be treated by incision and drainage or excision to remove the cyst wall. Electrosurgery and cryotherapy may be used. Oral antibiotics may improve inflamed lesions. There are reports in the literature in which isotretinoin has helped; however, it is not curative. In some cases, the lesions can reoccur and may even be worse.

Case and photo submitted by: Donna Bilu Martin, MD; Premier Dermatology, MD; Aventura, Fla.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Different types of steatocystoma multiplex have been described: localized, generalized, facial, acral, and suppurative (in which the lesions resemble hidradenitis suppurativa).

This condition is autosomal dominant and is linked to defects in KRT17 gene, which instructs the production of keratin 17. However, some cases of steatocystoma multiplex occur sporadically with no mutation in the KRT17 gene; in them, the cause is unknown. Steatocystoma multiplex may be associated with eruptive vellus hair cysts and pachyonychia congenita (nail and teeth abnormalities and palmoplantar keratoderma). Lesions often appear during adolescence, when an individual hits puberty. Hormones likely influence the development of the cysts from the pilosebaceous unit. If there is a single steatocystoma, it is called steatocystoma simplex.

Steatocystomas do not resolve on their own. The small, benign cysts are located fairly superficial in the dermis. If punctured, they drain a yellow, oily liquid sebum. Lesions may become inflamed and may heal with scarring, as in acne. They may be treated by incision and drainage or excision to remove the cyst wall. Electrosurgery and cryotherapy may be used. Oral antibiotics may improve inflamed lesions. There are reports in the literature in which isotretinoin has helped; however, it is not curative. In some cases, the lesions can reoccur and may even be worse.

Case and photo submitted by: Donna Bilu Martin, MD; Premier Dermatology, MD; Aventura, Fla.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Seeking the chair

“Before you are a leader, success is all about growing yourself. When you become a leader, success is all about growing others.” – Jack Welch

Serving my colleagues as chairman of the department of hematology and medical oncology at the Cleveland Clinic has been my greatest honor and privilege. I am humbled to lead such compassionate, inquisitive, and accomplished clinician scientists during a time of great change in academic medicine. From the introduction of new therapies to the implementation of new operational processes, my team inspires me to extend my capability beyond what I ever thought possible. I am grateful for the opportunity to grow with them.

Serving as chair can be extraordinarily satisfying, but there are some parts of the job description that an aspiring chairperson should be aware of before seeking the position. These less savory – though necessary – aspects of the job are not explicitly stated in the advertisements in the back of a trade journal. Allow me to translate a typical advertisement. I copied this text from the first advertisement for a department chairperson that I found with a Google search:

Knowledge of and ability to apply professional medical principles, procedures, and techniques. Thorough knowledge of pharmacological agents used in patient treatment. Able to effectively manage and direct medical staff support activities while providing quality medical care. Able to receive detailed information through oral communications; express or exchange ideas by verbal communications. Excellent written and verbal communications, listening, and social skills. Able to interact effectively with people of varied educational, socioeconomic, and ethnic backgrounds, skill levels, and value systems. Performs in a tactful and professional manner. A wide degree of creativity and latitude is expected. Relies on experience and judgment to plan and accomplish goals.

1. “Knowledge of and ability to apply professional medical principles, procedures, and techniques. Thorough knowledge of pharmacological agents used in patient treatment.” You better be a good doctor because …

2. “Able to effectively manage and direct medical staff support activities while providing quality medical care.” You will still be seeing patients while supporting everybody else’s career development, signing off on vacations, setting call schedules, attesting to conflicts of interest, certifying competence, approving research projects, and attending administrative meetings.

3. “Able to receive detailed information through oral communications; express or exchange ideas by verbal communications.” Your team will be paging, calling, and knocking on your door whenever they want to immediately address their latest irritation. Responding to irritation with email is a mistake.

4. “Excellent written and verbal communications, listening, and social skills.” You will write email more than you can possibly imagine, with each one precisely worded and politically correct. When you inevitably screw up one of these communications, often because you responded to someone else’s irritation, you will accept the criticism, apologize to the offended party, and correct the error without being defensive.

5. “Able to interact effectively with people of varied educational, socioeconomic, and ethnic backgrounds, skill levels, and value systems.” You will work with people who do not share your worldview, have problems you cannot begin to fathom, display behavior you cannot understand, and expect you to remember their names.

6. “Performs in a tactful and professional manner.” No matter how much someone angers you, you cannot be a jerk like the last chairperson.

7. “A wide degree of creativity and latitude is expected.” This one is confusing, but I think it means that you need to avoid immediate dismissal of stupid ideas.

8. “Relies on experience and judgment to plan and accomplish goals.” Failure to reach goals set by others is your fault because of inadequate planning.

Who would apply for that job? The only people who should apply are those who are ready to leave their personal comforts behind for the comfort of others.

For those undaunted by the job description, I am frequently asked how a career should develop to maximize the chances of promotion to leadership positions. Should I get my MBA? What committees should I sit on? Who should I get to know and collaborate with? When is the best time to seek promotion? How should I position myself for advantage?

I’m sorry to disappoint, but I find that those who seek promotion the most are the ones least likely to be promoted to the position they want. I recommend being yourself while pursuing goals that interest you, seeking education that stimulates you, working with people who engage with you, and helping others succeed instead of yourself. Promotions will follow.

The key is a serving mindset. No MBA, committee, collaboration, event, or positioning will determine your willingness to serve. All may contribute to a chair’s skill set, but the sense of obligation to develop and lead a team can only come from an altruistic resolve to put others first. It is hard work that requires sacrifice and a willingness to fail so that others may succeed. I recommend it.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

“Before you are a leader, success is all about growing yourself. When you become a leader, success is all about growing others.” – Jack Welch

Serving my colleagues as chairman of the department of hematology and medical oncology at the Cleveland Clinic has been my greatest honor and privilege. I am humbled to lead such compassionate, inquisitive, and accomplished clinician scientists during a time of great change in academic medicine. From the introduction of new therapies to the implementation of new operational processes, my team inspires me to extend my capability beyond what I ever thought possible. I am grateful for the opportunity to grow with them.

Serving as chair can be extraordinarily satisfying, but there are some parts of the job description that an aspiring chairperson should be aware of before seeking the position. These less savory – though necessary – aspects of the job are not explicitly stated in the advertisements in the back of a trade journal. Allow me to translate a typical advertisement. I copied this text from the first advertisement for a department chairperson that I found with a Google search:

Knowledge of and ability to apply professional medical principles, procedures, and techniques. Thorough knowledge of pharmacological agents used in patient treatment. Able to effectively manage and direct medical staff support activities while providing quality medical care. Able to receive detailed information through oral communications; express or exchange ideas by verbal communications. Excellent written and verbal communications, listening, and social skills. Able to interact effectively with people of varied educational, socioeconomic, and ethnic backgrounds, skill levels, and value systems. Performs in a tactful and professional manner. A wide degree of creativity and latitude is expected. Relies on experience and judgment to plan and accomplish goals.

1. “Knowledge of and ability to apply professional medical principles, procedures, and techniques. Thorough knowledge of pharmacological agents used in patient treatment.” You better be a good doctor because …

2. “Able to effectively manage and direct medical staff support activities while providing quality medical care.” You will still be seeing patients while supporting everybody else’s career development, signing off on vacations, setting call schedules, attesting to conflicts of interest, certifying competence, approving research projects, and attending administrative meetings.

3. “Able to receive detailed information through oral communications; express or exchange ideas by verbal communications.” Your team will be paging, calling, and knocking on your door whenever they want to immediately address their latest irritation. Responding to irritation with email is a mistake.