User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Patient Navigators for Serious Illnesses Can Now Bill Under New Medicare Codes

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How to explain physician compounding to legislators

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Best Practices: Protecting Dry Vulnerable Skin with CeraVe® Healing Ointment

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

Photodermatoses: Exploring Clinical Presentations, Causative Factors, Differential Diagnoses, and Treatment Strategies

Photodermatoses: Exploring Clinical Presentations, Causative Factors, Differential Diagnoses, and Treatment Strategies

Photosensitivity refers to clinical manifestations arising from exposure to sunlight. Photodermatoses encompass a group of skin diseases caused by varying degrees of radiation exposure, including UV radiation and visible light. Photodermatoses can be categorized into 5 main types: primary, exogenous, photoexacerbated, metabolic, and genetic.1 The clinical features of photodermatoses vary depending on the underlying cause but often include pruritic flares, wheals, or dermatitis on sun-exposed areas of the skin.2 While photodermatoses typically are not life threatening, they can greatly impact patients’ quality of life. It is crucial to emphasize the importance of photoprotection and sunlight avoidance to patients as preventive measures against the manifestations of these skin diseases. Furthermore, we present a case of photocontact dermatitis (PCD) and discuss common causative agents, diagnostic mimickers, and treatment options.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash on the neck and under the eyes of 6 days’ duration. The rash was intermittently pruritic but otherwise asymptomatic. The patient reported that she had spent extensive time on the golf course the day of the rash onset and noted that a similar rash had occurred one other time 2 to 3 months prior, also following a prolonged period on the golf course. She had been using over-the-counter fexofenadine 180 mg and over-the-counter lidocaine spray for symptom relief.

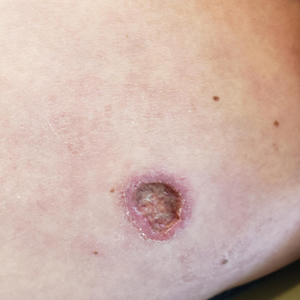

Upon physical examination, erythematous patches were appreciated in a photodistributed pattern on the arms, legs, neck, face, and chest—areas that were not covered by clothing (Figures 1-3). Due to the distribution and morphology of the erythematous patches along with clinical course of onset following exposure to various environmental agents including pesticides, herbicides, oak, and pollen, a diagnosis of PCD was made. The patient was prescribed hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%, and methylprednisolone in addition to the antihistamine. Improvement was noted after 3 days with complete resolution of the skin manifestations. She was counseled on wearing clothing with a universal protection factor rating of 50+ when on the golf course and when sun exposure is expected for an extended period of time.

Causative Agents

Photodermatoses are caused by antigenic substances that lead to photosensitization acquired by either contact or oral ingestion with subsequent sensitization to UV radiation. Halogenated salicylanilide, fenticlor, hexachlorophene, bithionol and, in rare cases, sunscreens, have been reported as triggers.3 In a study performed in 2010, sunscreens, antimicrobial agents, medications, fragrances, plants/plant derivatives, and pesticides were the most commonly reported offending agents listed from highest to lowest frequency. Of the antimicrobial agents, fenticlor, a topical antimicrobial and antifungal that is now mostly used in veterinary medicine, was the most common culprit, causing 60% of cases.4,5

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of photodermatoses vary depending upon the specific type of reaction. Examples of primary photodermatoses include polymorphous light eruption (PMLE) and solar urticaria. The cardinal symptoms of PMLE consist of severely pruritic skin lesions that can have macular, papular, papulovesicular, urticarial, multiformelike, and plaquelike variants that develop hours to days after sun exposure.3 Conversely, solar urticaria commonly develops more abruptly, with indurated plaques and wheals appearing on the arms and neck within 30 minutes of sun exposure. The lesions typically resolve within 24 hours.1

Examples of the exogenous subtype include drug-induced photosensitivity, PCD, and pseudoporphyria, with the common clinical presentation of eruption following contact with the causative agent. Drug-induced photosensitivity primarily manifests as a severe sunburnlike rash commonly caused by systemic drugs such as tetracyclines. Photocontact dermatitis is limited to sun-exposed areas of the skin and is caused by a reactive irritant such as chemicals or topical creams. Pseudoporphyria, usually caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can manifest with skin fragility and subepidermal blisters.6

Photoexacerbated photodermatoses encompass a variety of conditions ranging from hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma to autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and dermatomyositis (DM). Common clinical features of these diseases include photodistributed erythema, often involving the cheeks, upper back, and anterior neck. Photo-exposed areas of the dorsal hands also are commonplace for both SLE and DM. Clinical manifestations of PCD are limited to sun-exposed areas of the body, specifically those that come into contact with photoallergic triggers.3 Manifestations of PCD can include pruritic eczematous eruptions resembling those of contact dermatitis 1 to 2 days after sun exposure.1

Photocontact dermatitis represents a specific sensitization via contact or oral ingestion acquired prior to sunlight exposure. It can be broken down into 2 distinct subtypes: photoallergic and photoirritant dermatitis, dependent on whether an allergic or irritant reaction is invoked.2 Plants are known to be a common trigger of photoirritant reactions, while extrinsic triggers include psoralens and medications such as tetracycline antibiotics or sulfonamides. Photoallergic reactions commonly can be caused by topical application of sunscreen or medications, namely nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.2 Clinical manifestations that may point to photoirritant dermatitis include a photodistributed eruption and classic morphology showing erythema and edema with bullae present in severe cases. These can be contrasted with the clinical manifestations of photoallergic reactions, which usually do not correlate to sun-exposed areas and consist of a monomorphous distribution pattern similar to that of eczema. Although there are distinguishing features of both subtypes of PCD, the overlapping clinical features can mimic those of solar urticaria, PMLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and more systemic conditions such as SLE and DM.7

Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with a broad range of cutaneous manifestations.8 Exposure to UV radiation is a common trigger for lupus and has the propensity to cause a malar (butterfly) rash that covers the cheeks and nasal bridge but classically spares the nasolabial folds. The rash may display confluent reddish-purple discoloration with papules and/or edema and typically is present at diagnosis in 40% to 52% of patients with SLE.8 Discoid lupus erythematosus, one of the most common cutaneous forms of lupus, manifests with various-sized coin-shaped plaques with adherent follicular hyperkeratosis and plugging. These lesions usually develop on the face, scalp, and ears but also may appear in non–sun-exposed areas.8 Dermatomyositis can manifest with photodistributed erythema affecting classic areas such as the upper back (shawl sign), anterior neck and upper chest (V-sign), and a malar rash similar to that seen in lupus, though DM classically does not spare the nasolabial folds.8,9

Because SLE and DM manifest with photodistributed rashes, it can be difficult to distinguish them from the classic symptoms of photoirritant dermatitis.9 Thus, it is imperative that providers have a high clinical index of suspicion when dealing with patients of similar presentations, as the treatment regimens vastly differ. Approaching the patient with a thorough medical history review, review of systems, biopsy (including immunofluorescence), and appropriate laboratory workup may aid in excluding more complex differential diagnoses such as SLE and DM.

Metabolic and genetic photodermatoses are more rare but can include conditions such as porphyria cutanea tarda and xeroderma pigmentosum, both of which demonstrate fragile skin, slow wound healing, and bullae on photo-exposed skin.1 Although the manifestations can be similar in these systemic conditions, they are caused by very different mechanisms. Porphyria cutanea tarda is caused by deficiencies in enzymes involved in the heme synthesis pathway, whereas xeroderma pigmentosum is caused by an alteration in DNA repair mechanisms.7

Prevalence and the Need for Standardized Testing

Most practicing dermatologists see cases of PCD due to its multiple causative agents; however, little is known about its overall prevalence. The incidence of PCD is fairly low in the general population, but this may be due to its clinical diagnosis, which excludes diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing.10 While the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis also is fairly unknown, the inception of testing modalities has allowed statistics to be drawn. Research conducted in the United States has disclosed that the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis in individuals with a history of a prior photosensitivity eruption is approximately 10% to 20%.10 The development of guidelines and a registry for photopatch testing would aid in a greater understanding of the incidence of PCD and overall consistency of diagnosis.7 Regardless of this lack of consensus, these conditions can be properly managed and prevented if recognized clinically, while newer testing modalities would allow for confirmation of the diagnosis. It is important that any patient presenting with a history of photosensitivity be seen as a candidate for photopatch testing, especially today, as the general population is increasingly exposed to new chemicals entering the market and new social trends.7,10

Diagnosis and Treatment

It is important to consider a detailed history, including the timing, location, duration, family history, and seasonal variation of suspected photodermatoses. A thorough skin examination that takes note of the specific areas affected, morphology, and involvement of the rash or lesions can be helpful.1 Further diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing can be employed and is especially important when distinguishing photoallergy from phototoxicity.11 Phototesting involves exposing the patient’s skin to different doses of UVA, UVB, and visible light, followed by an immediate clinical reading of the results and then a delayed reading conducted after 24 hours.1 Photopatch testing involves the application of 2 sets of identical photoallergens to prepped skin (typically cleansed with isopropyl alcohol), with one being irradiated with UVA after 24 hours and one serving as the control. A clinical assessment is conducted at 24 hours and repeated 7 days later.1 In photodermatoses, a visible reaction can be appreciated on the treatment arm while the control arm remains clear. When both sides reveal a visible reaction, this is more indicative of a light-independent allergic contact dermatitis.1

Photodermatoses occur only if there has been a specific sensitization, and therefore it is important to work with the patient to discover any new products that have been introduced into their regimen. Though many photosensitizers in personal care products (eg, antiseptics in soap and topical creams) have been discontinued, certain allergenic ingredients may remain.12 It also is important to note that sensitization to a substance that previously was not a known allergen for a particular patient can occur later in life. Avoiding further sun exposure can rapidly improve the dermatitis, and it is possible for spontaneous remission without further intervention; however, as photoallergic reactions can cause severely pruritic skin lesions, the mainstay of symptomatic treatment consists of topical corticosteroids. Oral and topical antihistamines may help alleviate the pruritus but should not be heavily relied on as this can lead to medication resistance and diminishing efficacy.3 Use of short-term oral steroids also may be considered for rapid improvement of symptoms when the patient is in moderate distress and there are no contraindications. By identifying a temporal association between the introduction of new products and the emergence of dermatitis, it may be possible to identify the causative agent. The patient should promptly discontinue the suspected agent and remain under close observation by the clinician for any further eruptions, especially following additional sun exposure.

Prevention Strategies

In the case of PCD, prevention is key. As PCD indicates a photoallergy, it is important to inform patients that the allergy will persist for a lifetime, much like in contact dermatitis; therefore, the causative agent should be avoided indefinitely.3 Patients with PCD should make intentional efforts to read ingredient lists when purchasing new personal care products to ensure they do not contain the specific causative allergen if one has been identified. Further steps should be taken to ensure proper photoprotection, including use of dense clothing and sunscreen with UVA and UVB filters (broad spectrum).3 It has also been suggested that utilizing sunscreen with ectoin, an amino acid–derived molecule, may result in increased protection against UVA-induced photodermatoses.13

Final Thoughts

Photodermatoses are a group of skin diseases caused by exposure to UV radiation. Photocontact dermatitis/photoallergy is a form of allergic contact dermatitis that results from exposure to an allergen, whether topical, oral, or environmental. The allergen is activated by exposure to UV radiation to sensitize the allergic response, resulting in a rash characterized by confluent erythematous patches or plaques, papular vesicles, and rarely blisters.3 Photocontact dermatitis, although rare, is an important differential diagnosis to consider when the presenting rash is restricted to sun-exposed areas of the skin such as the arms, legs, neck, and face. Diagnosis remains a challenge; however, new testing modalities such as photopatch testing may open the door for further confirmation and aid in proper diagnosis leading to earlier treatment times for patients. It is recommended that the clinician and patient work together to identify the possible causative agent to prevent further eruptions.

- Santoro FA, Lim HW. Update on photodermatoses. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30:229-238.

- Gimenez-Arnau A, Maurer M, De La Cuadra J, et al. Immediate contact skin reactions, an update of contact urticaria, contact urticaria syndrome and protein contact dermatitis—“a never ending story.” Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:555-562.

- Lehmann P, Schwarz T. Photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:135-141.

- Victor FC, Cohen DE, Soter NA. A 20-year analysis of previous and emerging allergens that elicit photoallergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:605-610.

- Fenticlor (Code 65671). National Cancer Institute EVS Explore. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://ncithesaurus.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/ConceptReport.jsp?dictionary=NCIThesaurus&ns=ncit&code=C65671

- Elmets CA. Photosensitivity disorders (photodermatoses): clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. UptoDate. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/photosensitivity-disorders-photodermatoses-clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-and-treatment

- Snyder M, Turrentine JE, Cruz PD Jr. Photocontact dermatitis and its clinical mimics: an overview for the allergist. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:32-40.

- Cooper EE, Pisano CE, Shapiro SC. Cutaneous manifestations of “lupus”: systemic lupus erythematosus and beyond. Int J Rheumatol. 2021;2021:6610509.

- Christopher-Stine L, Amato AA, Vleugels RA. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of dermatomyositis and polymyositis in adults. UptoDate. Updated March 3, 2025. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-and-differential-diagnosis-of-dermatomyositis-and-polymyositis-in-adults?search=Diagnosis%20and%20differential%20diagnosis%20of%20dermatomyositis%20and%20polymyositis%20in%20adults&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Deleo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:279-288.

- Gonçalo M. Photopatch testing. In: Johansen J, Frosch P, Lepoittevin JP, eds. Contact Dermatitis. Springer; 2011:519-531.

- Enta T. Dermacase. Contact photodermatitis. Can Fam Physician. 1995;41:577,586-587.

- Duteil L, Queille-Roussel C, Aladren S, et al. Prevention of polymophic light eruption afforded by a very high broad-spectrum protection sunscreen containing ectoin. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:1603-1613.

Photosensitivity refers to clinical manifestations arising from exposure to sunlight. Photodermatoses encompass a group of skin diseases caused by varying degrees of radiation exposure, including UV radiation and visible light. Photodermatoses can be categorized into 5 main types: primary, exogenous, photoexacerbated, metabolic, and genetic.1 The clinical features of photodermatoses vary depending on the underlying cause but often include pruritic flares, wheals, or dermatitis on sun-exposed areas of the skin.2 While photodermatoses typically are not life threatening, they can greatly impact patients’ quality of life. It is crucial to emphasize the importance of photoprotection and sunlight avoidance to patients as preventive measures against the manifestations of these skin diseases. Furthermore, we present a case of photocontact dermatitis (PCD) and discuss common causative agents, diagnostic mimickers, and treatment options.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash on the neck and under the eyes of 6 days’ duration. The rash was intermittently pruritic but otherwise asymptomatic. The patient reported that she had spent extensive time on the golf course the day of the rash onset and noted that a similar rash had occurred one other time 2 to 3 months prior, also following a prolonged period on the golf course. She had been using over-the-counter fexofenadine 180 mg and over-the-counter lidocaine spray for symptom relief.

Upon physical examination, erythematous patches were appreciated in a photodistributed pattern on the arms, legs, neck, face, and chest—areas that were not covered by clothing (Figures 1-3). Due to the distribution and morphology of the erythematous patches along with clinical course of onset following exposure to various environmental agents including pesticides, herbicides, oak, and pollen, a diagnosis of PCD was made. The patient was prescribed hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%, and methylprednisolone in addition to the antihistamine. Improvement was noted after 3 days with complete resolution of the skin manifestations. She was counseled on wearing clothing with a universal protection factor rating of 50+ when on the golf course and when sun exposure is expected for an extended period of time.

Causative Agents

Photodermatoses are caused by antigenic substances that lead to photosensitization acquired by either contact or oral ingestion with subsequent sensitization to UV radiation. Halogenated salicylanilide, fenticlor, hexachlorophene, bithionol and, in rare cases, sunscreens, have been reported as triggers.3 In a study performed in 2010, sunscreens, antimicrobial agents, medications, fragrances, plants/plant derivatives, and pesticides were the most commonly reported offending agents listed from highest to lowest frequency. Of the antimicrobial agents, fenticlor, a topical antimicrobial and antifungal that is now mostly used in veterinary medicine, was the most common culprit, causing 60% of cases.4,5

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of photodermatoses vary depending upon the specific type of reaction. Examples of primary photodermatoses include polymorphous light eruption (PMLE) and solar urticaria. The cardinal symptoms of PMLE consist of severely pruritic skin lesions that can have macular, papular, papulovesicular, urticarial, multiformelike, and plaquelike variants that develop hours to days after sun exposure.3 Conversely, solar urticaria commonly develops more abruptly, with indurated plaques and wheals appearing on the arms and neck within 30 minutes of sun exposure. The lesions typically resolve within 24 hours.1

Examples of the exogenous subtype include drug-induced photosensitivity, PCD, and pseudoporphyria, with the common clinical presentation of eruption following contact with the causative agent. Drug-induced photosensitivity primarily manifests as a severe sunburnlike rash commonly caused by systemic drugs such as tetracyclines. Photocontact dermatitis is limited to sun-exposed areas of the skin and is caused by a reactive irritant such as chemicals or topical creams. Pseudoporphyria, usually caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can manifest with skin fragility and subepidermal blisters.6

Photoexacerbated photodermatoses encompass a variety of conditions ranging from hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma to autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and dermatomyositis (DM). Common clinical features of these diseases include photodistributed erythema, often involving the cheeks, upper back, and anterior neck. Photo-exposed areas of the dorsal hands also are commonplace for both SLE and DM. Clinical manifestations of PCD are limited to sun-exposed areas of the body, specifically those that come into contact with photoallergic triggers.3 Manifestations of PCD can include pruritic eczematous eruptions resembling those of contact dermatitis 1 to 2 days after sun exposure.1

Photocontact dermatitis represents a specific sensitization via contact or oral ingestion acquired prior to sunlight exposure. It can be broken down into 2 distinct subtypes: photoallergic and photoirritant dermatitis, dependent on whether an allergic or irritant reaction is invoked.2 Plants are known to be a common trigger of photoirritant reactions, while extrinsic triggers include psoralens and medications such as tetracycline antibiotics or sulfonamides. Photoallergic reactions commonly can be caused by topical application of sunscreen or medications, namely nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.2 Clinical manifestations that may point to photoirritant dermatitis include a photodistributed eruption and classic morphology showing erythema and edema with bullae present in severe cases. These can be contrasted with the clinical manifestations of photoallergic reactions, which usually do not correlate to sun-exposed areas and consist of a monomorphous distribution pattern similar to that of eczema. Although there are distinguishing features of both subtypes of PCD, the overlapping clinical features can mimic those of solar urticaria, PMLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and more systemic conditions such as SLE and DM.7

Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with a broad range of cutaneous manifestations.8 Exposure to UV radiation is a common trigger for lupus and has the propensity to cause a malar (butterfly) rash that covers the cheeks and nasal bridge but classically spares the nasolabial folds. The rash may display confluent reddish-purple discoloration with papules and/or edema and typically is present at diagnosis in 40% to 52% of patients with SLE.8 Discoid lupus erythematosus, one of the most common cutaneous forms of lupus, manifests with various-sized coin-shaped plaques with adherent follicular hyperkeratosis and plugging. These lesions usually develop on the face, scalp, and ears but also may appear in non–sun-exposed areas.8 Dermatomyositis can manifest with photodistributed erythema affecting classic areas such as the upper back (shawl sign), anterior neck and upper chest (V-sign), and a malar rash similar to that seen in lupus, though DM classically does not spare the nasolabial folds.8,9

Because SLE and DM manifest with photodistributed rashes, it can be difficult to distinguish them from the classic symptoms of photoirritant dermatitis.9 Thus, it is imperative that providers have a high clinical index of suspicion when dealing with patients of similar presentations, as the treatment regimens vastly differ. Approaching the patient with a thorough medical history review, review of systems, biopsy (including immunofluorescence), and appropriate laboratory workup may aid in excluding more complex differential diagnoses such as SLE and DM.

Metabolic and genetic photodermatoses are more rare but can include conditions such as porphyria cutanea tarda and xeroderma pigmentosum, both of which demonstrate fragile skin, slow wound healing, and bullae on photo-exposed skin.1 Although the manifestations can be similar in these systemic conditions, they are caused by very different mechanisms. Porphyria cutanea tarda is caused by deficiencies in enzymes involved in the heme synthesis pathway, whereas xeroderma pigmentosum is caused by an alteration in DNA repair mechanisms.7

Prevalence and the Need for Standardized Testing

Most practicing dermatologists see cases of PCD due to its multiple causative agents; however, little is known about its overall prevalence. The incidence of PCD is fairly low in the general population, but this may be due to its clinical diagnosis, which excludes diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing.10 While the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis also is fairly unknown, the inception of testing modalities has allowed statistics to be drawn. Research conducted in the United States has disclosed that the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis in individuals with a history of a prior photosensitivity eruption is approximately 10% to 20%.10 The development of guidelines and a registry for photopatch testing would aid in a greater understanding of the incidence of PCD and overall consistency of diagnosis.7 Regardless of this lack of consensus, these conditions can be properly managed and prevented if recognized clinically, while newer testing modalities would allow for confirmation of the diagnosis. It is important that any patient presenting with a history of photosensitivity be seen as a candidate for photopatch testing, especially today, as the general population is increasingly exposed to new chemicals entering the market and new social trends.7,10

Diagnosis and Treatment

It is important to consider a detailed history, including the timing, location, duration, family history, and seasonal variation of suspected photodermatoses. A thorough skin examination that takes note of the specific areas affected, morphology, and involvement of the rash or lesions can be helpful.1 Further diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing can be employed and is especially important when distinguishing photoallergy from phototoxicity.11 Phototesting involves exposing the patient’s skin to different doses of UVA, UVB, and visible light, followed by an immediate clinical reading of the results and then a delayed reading conducted after 24 hours.1 Photopatch testing involves the application of 2 sets of identical photoallergens to prepped skin (typically cleansed with isopropyl alcohol), with one being irradiated with UVA after 24 hours and one serving as the control. A clinical assessment is conducted at 24 hours and repeated 7 days later.1 In photodermatoses, a visible reaction can be appreciated on the treatment arm while the control arm remains clear. When both sides reveal a visible reaction, this is more indicative of a light-independent allergic contact dermatitis.1

Photodermatoses occur only if there has been a specific sensitization, and therefore it is important to work with the patient to discover any new products that have been introduced into their regimen. Though many photosensitizers in personal care products (eg, antiseptics in soap and topical creams) have been discontinued, certain allergenic ingredients may remain.12 It also is important to note that sensitization to a substance that previously was not a known allergen for a particular patient can occur later in life. Avoiding further sun exposure can rapidly improve the dermatitis, and it is possible for spontaneous remission without further intervention; however, as photoallergic reactions can cause severely pruritic skin lesions, the mainstay of symptomatic treatment consists of topical corticosteroids. Oral and topical antihistamines may help alleviate the pruritus but should not be heavily relied on as this can lead to medication resistance and diminishing efficacy.3 Use of short-term oral steroids also may be considered for rapid improvement of symptoms when the patient is in moderate distress and there are no contraindications. By identifying a temporal association between the introduction of new products and the emergence of dermatitis, it may be possible to identify the causative agent. The patient should promptly discontinue the suspected agent and remain under close observation by the clinician for any further eruptions, especially following additional sun exposure.

Prevention Strategies

In the case of PCD, prevention is key. As PCD indicates a photoallergy, it is important to inform patients that the allergy will persist for a lifetime, much like in contact dermatitis; therefore, the causative agent should be avoided indefinitely.3 Patients with PCD should make intentional efforts to read ingredient lists when purchasing new personal care products to ensure they do not contain the specific causative allergen if one has been identified. Further steps should be taken to ensure proper photoprotection, including use of dense clothing and sunscreen with UVA and UVB filters (broad spectrum).3 It has also been suggested that utilizing sunscreen with ectoin, an amino acid–derived molecule, may result in increased protection against UVA-induced photodermatoses.13

Final Thoughts

Photodermatoses are a group of skin diseases caused by exposure to UV radiation. Photocontact dermatitis/photoallergy is a form of allergic contact dermatitis that results from exposure to an allergen, whether topical, oral, or environmental. The allergen is activated by exposure to UV radiation to sensitize the allergic response, resulting in a rash characterized by confluent erythematous patches or plaques, papular vesicles, and rarely blisters.3 Photocontact dermatitis, although rare, is an important differential diagnosis to consider when the presenting rash is restricted to sun-exposed areas of the skin such as the arms, legs, neck, and face. Diagnosis remains a challenge; however, new testing modalities such as photopatch testing may open the door for further confirmation and aid in proper diagnosis leading to earlier treatment times for patients. It is recommended that the clinician and patient work together to identify the possible causative agent to prevent further eruptions.

Photosensitivity refers to clinical manifestations arising from exposure to sunlight. Photodermatoses encompass a group of skin diseases caused by varying degrees of radiation exposure, including UV radiation and visible light. Photodermatoses can be categorized into 5 main types: primary, exogenous, photoexacerbated, metabolic, and genetic.1 The clinical features of photodermatoses vary depending on the underlying cause but often include pruritic flares, wheals, or dermatitis on sun-exposed areas of the skin.2 While photodermatoses typically are not life threatening, they can greatly impact patients’ quality of life. It is crucial to emphasize the importance of photoprotection and sunlight avoidance to patients as preventive measures against the manifestations of these skin diseases. Furthermore, we present a case of photocontact dermatitis (PCD) and discuss common causative agents, diagnostic mimickers, and treatment options.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash on the neck and under the eyes of 6 days’ duration. The rash was intermittently pruritic but otherwise asymptomatic. The patient reported that she had spent extensive time on the golf course the day of the rash onset and noted that a similar rash had occurred one other time 2 to 3 months prior, also following a prolonged period on the golf course. She had been using over-the-counter fexofenadine 180 mg and over-the-counter lidocaine spray for symptom relief.

Upon physical examination, erythematous patches were appreciated in a photodistributed pattern on the arms, legs, neck, face, and chest—areas that were not covered by clothing (Figures 1-3). Due to the distribution and morphology of the erythematous patches along with clinical course of onset following exposure to various environmental agents including pesticides, herbicides, oak, and pollen, a diagnosis of PCD was made. The patient was prescribed hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%, and methylprednisolone in addition to the antihistamine. Improvement was noted after 3 days with complete resolution of the skin manifestations. She was counseled on wearing clothing with a universal protection factor rating of 50+ when on the golf course and when sun exposure is expected for an extended period of time.

Causative Agents

Photodermatoses are caused by antigenic substances that lead to photosensitization acquired by either contact or oral ingestion with subsequent sensitization to UV radiation. Halogenated salicylanilide, fenticlor, hexachlorophene, bithionol and, in rare cases, sunscreens, have been reported as triggers.3 In a study performed in 2010, sunscreens, antimicrobial agents, medications, fragrances, plants/plant derivatives, and pesticides were the most commonly reported offending agents listed from highest to lowest frequency. Of the antimicrobial agents, fenticlor, a topical antimicrobial and antifungal that is now mostly used in veterinary medicine, was the most common culprit, causing 60% of cases.4,5

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of photodermatoses vary depending upon the specific type of reaction. Examples of primary photodermatoses include polymorphous light eruption (PMLE) and solar urticaria. The cardinal symptoms of PMLE consist of severely pruritic skin lesions that can have macular, papular, papulovesicular, urticarial, multiformelike, and plaquelike variants that develop hours to days after sun exposure.3 Conversely, solar urticaria commonly develops more abruptly, with indurated plaques and wheals appearing on the arms and neck within 30 minutes of sun exposure. The lesions typically resolve within 24 hours.1

Examples of the exogenous subtype include drug-induced photosensitivity, PCD, and pseudoporphyria, with the common clinical presentation of eruption following contact with the causative agent. Drug-induced photosensitivity primarily manifests as a severe sunburnlike rash commonly caused by systemic drugs such as tetracyclines. Photocontact dermatitis is limited to sun-exposed areas of the skin and is caused by a reactive irritant such as chemicals or topical creams. Pseudoporphyria, usually caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can manifest with skin fragility and subepidermal blisters.6

Photoexacerbated photodermatoses encompass a variety of conditions ranging from hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma to autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and dermatomyositis (DM). Common clinical features of these diseases include photodistributed erythema, often involving the cheeks, upper back, and anterior neck. Photo-exposed areas of the dorsal hands also are commonplace for both SLE and DM. Clinical manifestations of PCD are limited to sun-exposed areas of the body, specifically those that come into contact with photoallergic triggers.3 Manifestations of PCD can include pruritic eczematous eruptions resembling those of contact dermatitis 1 to 2 days after sun exposure.1