User login

Assessment of Automated vs Conventional Blood Pressure Measurements in a Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice Setting

Assessment of Automated vs Conventional Blood Pressure Measurements in a Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice Setting

Hypertension remains one of the most important modifiable risk factors for the prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events. According to a population-based study, 25% of CV events (CV death, heart disease, coronary revascularization, stroke, or heart failure) are attributable to hypertension.1 Recent guidelines have emphasized the importance of accurate blood pressure (BP) measurement in facilitating appropriate hypertension diagnosis and management.2-4

Currently, there are different BP measurement methods endorsed by practice guidelines. These include conventional in-office measurement, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), home BP monitoring (HBPM), and automated office BP (AOBP) measurement.2-4 AOBP device protocols vary but generally involve devices automatically taking multiple BP measurements while the patient is unattended. These measurements are then presented as a single averaged reading, with individual BP values available for review by the clinician.

Researchers have found that AOBP measurements have a greater association with ABPM values and can mitigate the white coat effect observed in a substantial proportion of patients during in-clinic BP measurement.5 A meta-analysis found that the use of AOBP was associated with a 10.5 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP (SBP) compared with traditional office-based BP assessments.5 Similarly, a separate meta-analysis found that AOBP SBP measures were on average 14.5 mm Hg lower than routine office or research setting values.6 In addition, CV risk outcomes data support the use of AOBP to screen and manage patients with hypertension. The Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) study used AOBP values to determine the risk for CV events (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke) in community-based patients aged ≥ 65 years.7 The study showed a significantly higher risk of CV events in patients with an SBP of 135 to 144 mm Hg and a diastolic BP (DBP) of 80 to 89 mm Hg. Therefore, the CHAP study researchers suggested an AOBP target of < 135/85 mm Hg to decrease the risk of CV events.7The landmark SPRINT trial, which was a major contributor to the development of BP target recommendations in guidelines, utilized AOBP to classify hypertension and guide management.2-4,8 SPRINT ultimately showed that intensive BP-lowering treatment (to SBP < 120 mm Hg) was associated with a 25% reduction in major CV events and a 27% reduction in all-cause mortality.8 Other evaluations found a close association between AOBP values and left ventricular mass index and carotid artery wall thickness as surrogate markers for end-organ damage.9,10 These data show AOBP as a reliable method to guide antihypertensive therapy interventions in the clinical setting.

Considering these proposed advantages, the 2017 Canadian guidelines for hypertension management recommend AOBP as the preferred method for clinic-based BP measurement, and the 2018 European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension blood pressure guidelines recommend the use of AOBP when feasible.3,4 The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults also discusses AOBP as a method to minimize potential confounders in BP values.2

This study evaluated the difference between AOBP and conventional in-office BP measurements obtained during cardiology clinic visits at the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WPBVAMC).

METHODS

A retrospective review of AOBP measurements was performed at the WPBVAMC cardiology clinic between May 26, 2017, and February 19, 2019. These AOBP measurements were taken at the discretion of a nurse or other clinician after initial, conventional BP measurements had been taken as part of clinic check-in procedures. No formal protocols dictated the use or timing of AOBP measurements. Similarly, the AOBP results were factored into clinical care decisions.

Clinicians at the cardiology clinic used AOBP averages that were derived using the BpTRU BPM-100 (BpTRU Medical Devices) meter, which averaged 5 BP readings taken at 1-minute intervals. Clinicians selected cuff size based on manufacturer recommendations. The testing was done with the patient seated alone in either a nursing triage area or a clinic office.

Data collected during the retrospective review included the clinician associated with the visit, the patient’s physical location and accompaniment status during AOBP measurement, conventionally measured BP and heart rates, and AOBP-derived BP and heart rate averages. Differences in BP values were compared with the paired t test, while binary comparisons were conducted through the McNemar test. Data collection and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel.

During data collection, all information was stored in a secure drive accessible only to the investigators. The project was approved by the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Research and Development Committee as a nonresearch activity in accordance with Veterans Health Administration Handbook 1058.05; thus, institutional review board approval was not required.

RESULTS

Ninety-five nonconsecutive patients were included in the analysis. AOBP measurements were taken with the patient sitting alone in either a clinic office (n = 83) or nursing triage area (n = 12). Most patients were coming in for follow-up appointments; 13 patients (14%) had appointments related to a 24-hour ABPM session.

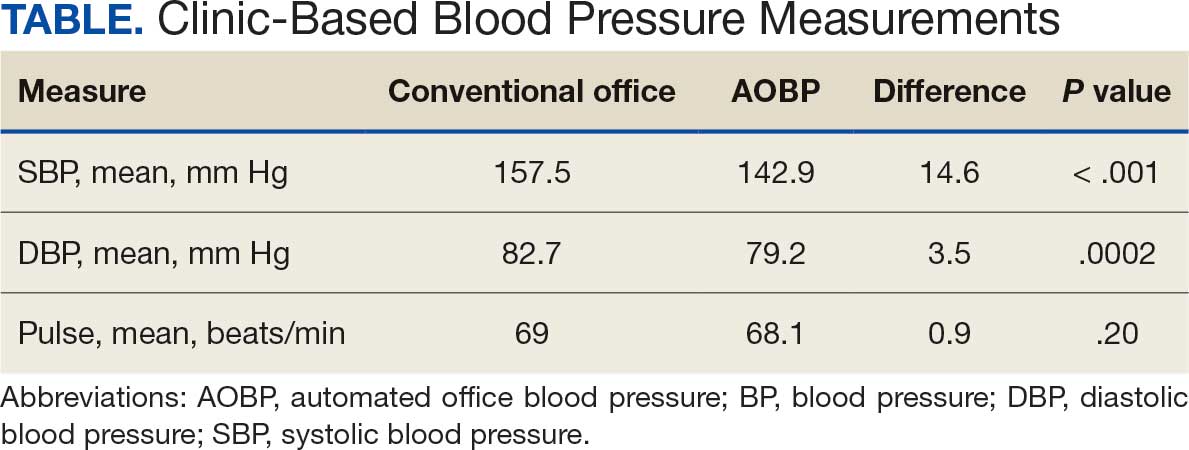

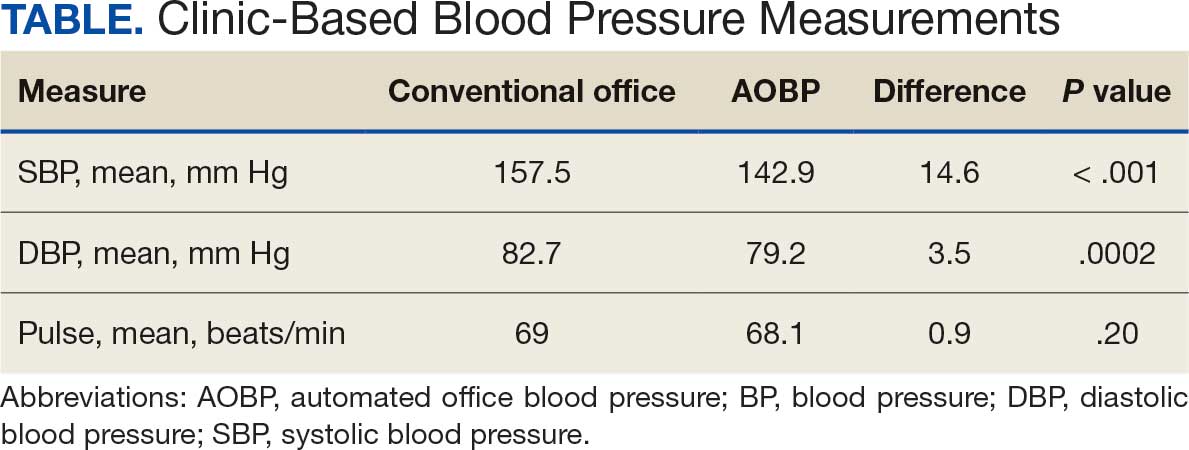

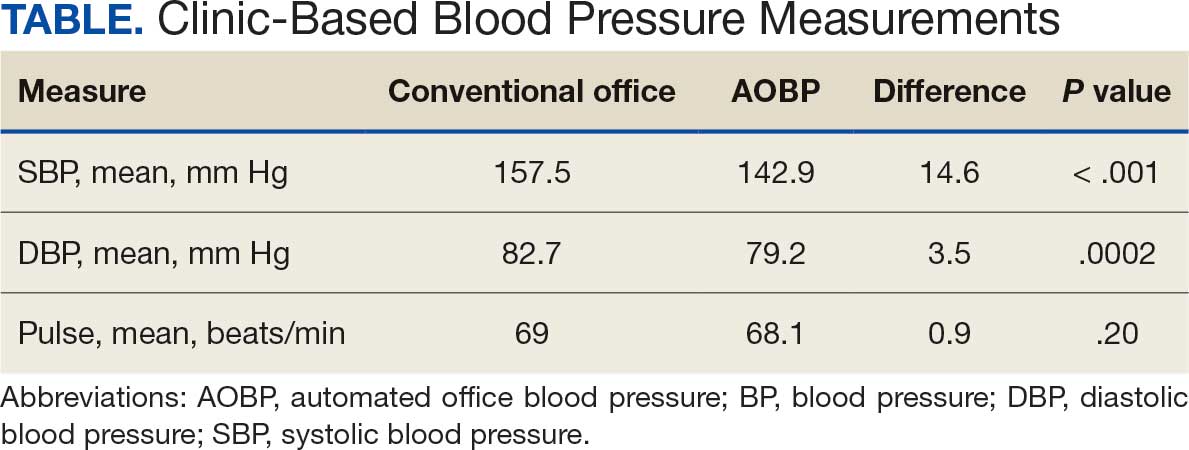

The mean SBP and DBP values were lower for the AOBP measurements vs the conventional BP measurements (mean SBP difference, 14.6 mm Hg; P < .001; mean DBP difference, 3.5 mm Hg; P = .0002) (Table). There were no appreciable differences in heart rates. The white coat effect was suggested based on an SBP reduction of > 20 mm Hg from conventional to AOBP measurements in 22 patients (23%), a DBP reduction of > 10 mm Hg in 21 patients (22%), and a reduction in both values in 8 patients (8%).

A controlled BP (< 130/80 mm Hg) was more common in the AOBP group than in the conventional group (22% vs 7%, respectively; P =.001).2 Review of conventional BP measurements indicated that 11 patients had systolic readings ≥ 180 mm Hg, 2 had diastolic readings ≥ 110 mm Hg, and 1 had a reading that was ≥ 180/110 mm Hg. AOBP measurements indicated that these 14 patients had SBP readings < 180 mm Hg and DBP readings < 110 mm Hg. The use of AOBP measurements may have mitigated unnecessary emergency room visits for these patients.

On review of clinic notes and actions associated with episodes of AOBP testing during routine follow-up clinic appointments, AOBP was determined to be useful with regard to clinical decision-making for 65 (79%) patients. Impacts of AOBP inclusion vs conventional BP assessments included clinician notation of AOBP, support for making changes that would have been considered based on conventional BP assessment. AOBP results gave support to forgoing a therapeutic intervention (ie, therapy addition or intensification) that may have been pursued based on conventional BP measurements in 25 of 82 patients (30%). These data suggest that AOBP readings can be useful and actionable by clinicians.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study add to the growing evidence regarding AOBP use, application, and advantages in clinical practice. In this evaluation, the mean difference in SBP and DBP was 14.6 mm Hg and 3.5 mm Hg, respectively, from the conventional office measurements to the AOBP measurements. This difference is similar to that reported by the CAMBO trial and other evaluations, where the use of AOBP measurements corresponded to a reduction in SBP of between 10 and 20 mm Hg vs conventional measures.5,11-18

These findings showed a significantly higher percentage of controlled BP values (< 130/80 mm Hg) with AOBP values compared with conventional office measurements. The data supported the decision to defer antihypertensive therapy intervention in 30% of patients. Without AOBP data, patients may have been classified as uncontrolled, prompting therapy addition or intensification that could increase the risk of adverse events. Additionally, 14 patients would have met the criteria for hypertensive urgency under the guidelines at that time.2 With the use of AOBP readings, none of these patients were identified as having a hypertensive urgency, and they avoided an acute care referral or urgent intervention.

The discrepancy between AOBP and conventional office BP measurements suggested a white coat effect based on SBP and DBP readings in 22 (23%) and 21 (22%) patients, respectively. Practice guidelines recommend ABPM to mitigate a potential white coat effect.2-4 However, ABPM can be inconvenient for patients, as they need to travel to and from the clinic for fitting and removal (assuming that a facility has the device available for patient use). In addition, some patients may find it uncomfortable. Based on the correlation between AOBP and awake ABPM values, AOBP represents a feasible way to identify a white coat effect.

AOBP monitoring does not appear to be affected by the type of practice setting, as it has been evaluated in a variety of locations, including community-based pharmacies, primary care offices, and waiting rooms.12,19-22 However, potential AOBP implementation challenges may include office space constraints, clinician perception that it will delay workflow, and device cost. Costs associated with an AOBP meter vary widely based on device and procurement source, but have been estimated to range from $650 to > $2000.23 Published reports have described how to overcome AOBP implementation barriers.24,25

Limitations

The results of this evaluation should be interpreted cautiously due to several limitations. First, the retrospective study was conducted at a single clinic that may not be representative of other Veterans Health Administration or community-based populations. In addition, patient data such as age, sex, and body mass index were not available. AOBP measurements were obtained at the discretion of the clinician and not according to a prespecified protocol.

Conclusions

This analysis showed AOBP measurement leads to a greater percentage of controlled BP values compared with conventional office BP measurement, positioning it as a way to reduce BP misclassification, prevent potentially unnecessary therapeutic interventions, and mitigate the white coat effect.

- Cheng S, Claggett B, Correia AW, et al. Temporal Trends in the Population Attributable Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2014;130:820-828. doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008506

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(5):557-576. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.005

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-3104. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339

- Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, et al. Comparison of automated office blood pressure with office and out-off-office measurement techniques. Hypertension. 2019;73(2):481-490. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12079

- Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension - a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551

- Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Karwalajtys T, et al. Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP): a community cluster-randomised trial among elderly Canadians. Prev Med. 2008;46(6):537-544. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.005

- SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103-2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Andreadis EA, Agaliotis GD, Angelopoulos ET, et al. Automated office blood pressure and 24-h ambulatory measurements are equally associated with left ventricular mass index. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(6):661-666. doi:10.1038/ajh.2011.38

- Campbell NRC, McKay DW, Conradson H, et al. Automated oscillometric blood pressure versus auscultatory blood pressure as a predictor of carotid intima-medial thickness in male firefighters. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21(7):588-590. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1002190

- Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M et al. Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: randomised parallel design controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d286. doi:10.1136/bmj.d286

- Beckett L, Godwin M. The BpTRU automatic blood pressure monitor compared to 24 hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the assessment of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5(1):18. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-5-18

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27(2):280-286. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831b9e6b

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Consistent relationship between automated office blood pressure recorded in different settings. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14(3):108-111. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e32832c5167

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Optimum frequency of office blood pressure measurement using an automated sphygmomanometer. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13(6):333-338. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283104247

- Myers MG. A proposed algorithm for diagnosing hypertension using automated office blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2010;28(4):703-708. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d091

- Godwin M, Birtwhistle R, Delva D, et al. Manual and automated office measurements in relation to awake ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Fam Pract. 2011;28(1):110-117. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmq067

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Chessman M, Kiss A. Can sphygmomanometers designed for self-measurement of blood pressure in the home be used in office practice? Blood Press Monit. 2010;15(6):300-304. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e328340d128

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian hypertension education program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):569-588. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.02.066

- Myers MG. A short history of automated office blood pressure - 15 years to SPRINT. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(8):721-724. doi:10.1111/jch.12820

- Myers MG, Kaczorowski J, Dawes M, Godwin M. Automated office blood pressure measurement in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(2):127-132.

- Armstrong D, Matangi M, Brouillard D, Myers MG. Automated office blood pressure - being alone and not location is what matters most. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20(4):204-208. doi:10.1097/MBP.0000000000000133

- Yarows SA. What is the Cost of Measuring a Blood Pressure? Ann Clin Hypertens. 2018;2:59-66. doi:10.29328/journal.ach.1001012

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. doi:10.1001/jama.282.15.1458

- Doane J, Buu J, Penrod MJ, et al. Measuring and managing blood pressure in a primary care setting: a pragmatic implementation study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):375-388. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.03.170450

Hypertension remains one of the most important modifiable risk factors for the prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events. According to a population-based study, 25% of CV events (CV death, heart disease, coronary revascularization, stroke, or heart failure) are attributable to hypertension.1 Recent guidelines have emphasized the importance of accurate blood pressure (BP) measurement in facilitating appropriate hypertension diagnosis and management.2-4

Currently, there are different BP measurement methods endorsed by practice guidelines. These include conventional in-office measurement, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), home BP monitoring (HBPM), and automated office BP (AOBP) measurement.2-4 AOBP device protocols vary but generally involve devices automatically taking multiple BP measurements while the patient is unattended. These measurements are then presented as a single averaged reading, with individual BP values available for review by the clinician.

Researchers have found that AOBP measurements have a greater association with ABPM values and can mitigate the white coat effect observed in a substantial proportion of patients during in-clinic BP measurement.5 A meta-analysis found that the use of AOBP was associated with a 10.5 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP (SBP) compared with traditional office-based BP assessments.5 Similarly, a separate meta-analysis found that AOBP SBP measures were on average 14.5 mm Hg lower than routine office or research setting values.6 In addition, CV risk outcomes data support the use of AOBP to screen and manage patients with hypertension. The Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) study used AOBP values to determine the risk for CV events (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke) in community-based patients aged ≥ 65 years.7 The study showed a significantly higher risk of CV events in patients with an SBP of 135 to 144 mm Hg and a diastolic BP (DBP) of 80 to 89 mm Hg. Therefore, the CHAP study researchers suggested an AOBP target of < 135/85 mm Hg to decrease the risk of CV events.7The landmark SPRINT trial, which was a major contributor to the development of BP target recommendations in guidelines, utilized AOBP to classify hypertension and guide management.2-4,8 SPRINT ultimately showed that intensive BP-lowering treatment (to SBP < 120 mm Hg) was associated with a 25% reduction in major CV events and a 27% reduction in all-cause mortality.8 Other evaluations found a close association between AOBP values and left ventricular mass index and carotid artery wall thickness as surrogate markers for end-organ damage.9,10 These data show AOBP as a reliable method to guide antihypertensive therapy interventions in the clinical setting.

Considering these proposed advantages, the 2017 Canadian guidelines for hypertension management recommend AOBP as the preferred method for clinic-based BP measurement, and the 2018 European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension blood pressure guidelines recommend the use of AOBP when feasible.3,4 The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults also discusses AOBP as a method to minimize potential confounders in BP values.2

This study evaluated the difference between AOBP and conventional in-office BP measurements obtained during cardiology clinic visits at the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WPBVAMC).

METHODS

A retrospective review of AOBP measurements was performed at the WPBVAMC cardiology clinic between May 26, 2017, and February 19, 2019. These AOBP measurements were taken at the discretion of a nurse or other clinician after initial, conventional BP measurements had been taken as part of clinic check-in procedures. No formal protocols dictated the use or timing of AOBP measurements. Similarly, the AOBP results were factored into clinical care decisions.

Clinicians at the cardiology clinic used AOBP averages that were derived using the BpTRU BPM-100 (BpTRU Medical Devices) meter, which averaged 5 BP readings taken at 1-minute intervals. Clinicians selected cuff size based on manufacturer recommendations. The testing was done with the patient seated alone in either a nursing triage area or a clinic office.

Data collected during the retrospective review included the clinician associated with the visit, the patient’s physical location and accompaniment status during AOBP measurement, conventionally measured BP and heart rates, and AOBP-derived BP and heart rate averages. Differences in BP values were compared with the paired t test, while binary comparisons were conducted through the McNemar test. Data collection and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel.

During data collection, all information was stored in a secure drive accessible only to the investigators. The project was approved by the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Research and Development Committee as a nonresearch activity in accordance with Veterans Health Administration Handbook 1058.05; thus, institutional review board approval was not required.

RESULTS

Ninety-five nonconsecutive patients were included in the analysis. AOBP measurements were taken with the patient sitting alone in either a clinic office (n = 83) or nursing triage area (n = 12). Most patients were coming in for follow-up appointments; 13 patients (14%) had appointments related to a 24-hour ABPM session.

The mean SBP and DBP values were lower for the AOBP measurements vs the conventional BP measurements (mean SBP difference, 14.6 mm Hg; P < .001; mean DBP difference, 3.5 mm Hg; P = .0002) (Table). There were no appreciable differences in heart rates. The white coat effect was suggested based on an SBP reduction of > 20 mm Hg from conventional to AOBP measurements in 22 patients (23%), a DBP reduction of > 10 mm Hg in 21 patients (22%), and a reduction in both values in 8 patients (8%).

A controlled BP (< 130/80 mm Hg) was more common in the AOBP group than in the conventional group (22% vs 7%, respectively; P =.001).2 Review of conventional BP measurements indicated that 11 patients had systolic readings ≥ 180 mm Hg, 2 had diastolic readings ≥ 110 mm Hg, and 1 had a reading that was ≥ 180/110 mm Hg. AOBP measurements indicated that these 14 patients had SBP readings < 180 mm Hg and DBP readings < 110 mm Hg. The use of AOBP measurements may have mitigated unnecessary emergency room visits for these patients.

On review of clinic notes and actions associated with episodes of AOBP testing during routine follow-up clinic appointments, AOBP was determined to be useful with regard to clinical decision-making for 65 (79%) patients. Impacts of AOBP inclusion vs conventional BP assessments included clinician notation of AOBP, support for making changes that would have been considered based on conventional BP assessment. AOBP results gave support to forgoing a therapeutic intervention (ie, therapy addition or intensification) that may have been pursued based on conventional BP measurements in 25 of 82 patients (30%). These data suggest that AOBP readings can be useful and actionable by clinicians.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study add to the growing evidence regarding AOBP use, application, and advantages in clinical practice. In this evaluation, the mean difference in SBP and DBP was 14.6 mm Hg and 3.5 mm Hg, respectively, from the conventional office measurements to the AOBP measurements. This difference is similar to that reported by the CAMBO trial and other evaluations, where the use of AOBP measurements corresponded to a reduction in SBP of between 10 and 20 mm Hg vs conventional measures.5,11-18

These findings showed a significantly higher percentage of controlled BP values (< 130/80 mm Hg) with AOBP values compared with conventional office measurements. The data supported the decision to defer antihypertensive therapy intervention in 30% of patients. Without AOBP data, patients may have been classified as uncontrolled, prompting therapy addition or intensification that could increase the risk of adverse events. Additionally, 14 patients would have met the criteria for hypertensive urgency under the guidelines at that time.2 With the use of AOBP readings, none of these patients were identified as having a hypertensive urgency, and they avoided an acute care referral or urgent intervention.

The discrepancy between AOBP and conventional office BP measurements suggested a white coat effect based on SBP and DBP readings in 22 (23%) and 21 (22%) patients, respectively. Practice guidelines recommend ABPM to mitigate a potential white coat effect.2-4 However, ABPM can be inconvenient for patients, as they need to travel to and from the clinic for fitting and removal (assuming that a facility has the device available for patient use). In addition, some patients may find it uncomfortable. Based on the correlation between AOBP and awake ABPM values, AOBP represents a feasible way to identify a white coat effect.

AOBP monitoring does not appear to be affected by the type of practice setting, as it has been evaluated in a variety of locations, including community-based pharmacies, primary care offices, and waiting rooms.12,19-22 However, potential AOBP implementation challenges may include office space constraints, clinician perception that it will delay workflow, and device cost. Costs associated with an AOBP meter vary widely based on device and procurement source, but have been estimated to range from $650 to > $2000.23 Published reports have described how to overcome AOBP implementation barriers.24,25

Limitations

The results of this evaluation should be interpreted cautiously due to several limitations. First, the retrospective study was conducted at a single clinic that may not be representative of other Veterans Health Administration or community-based populations. In addition, patient data such as age, sex, and body mass index were not available. AOBP measurements were obtained at the discretion of the clinician and not according to a prespecified protocol.

Conclusions

This analysis showed AOBP measurement leads to a greater percentage of controlled BP values compared with conventional office BP measurement, positioning it as a way to reduce BP misclassification, prevent potentially unnecessary therapeutic interventions, and mitigate the white coat effect.

Hypertension remains one of the most important modifiable risk factors for the prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events. According to a population-based study, 25% of CV events (CV death, heart disease, coronary revascularization, stroke, or heart failure) are attributable to hypertension.1 Recent guidelines have emphasized the importance of accurate blood pressure (BP) measurement in facilitating appropriate hypertension diagnosis and management.2-4

Currently, there are different BP measurement methods endorsed by practice guidelines. These include conventional in-office measurement, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), home BP monitoring (HBPM), and automated office BP (AOBP) measurement.2-4 AOBP device protocols vary but generally involve devices automatically taking multiple BP measurements while the patient is unattended. These measurements are then presented as a single averaged reading, with individual BP values available for review by the clinician.

Researchers have found that AOBP measurements have a greater association with ABPM values and can mitigate the white coat effect observed in a substantial proportion of patients during in-clinic BP measurement.5 A meta-analysis found that the use of AOBP was associated with a 10.5 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP (SBP) compared with traditional office-based BP assessments.5 Similarly, a separate meta-analysis found that AOBP SBP measures were on average 14.5 mm Hg lower than routine office or research setting values.6 In addition, CV risk outcomes data support the use of AOBP to screen and manage patients with hypertension. The Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) study used AOBP values to determine the risk for CV events (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke) in community-based patients aged ≥ 65 years.7 The study showed a significantly higher risk of CV events in patients with an SBP of 135 to 144 mm Hg and a diastolic BP (DBP) of 80 to 89 mm Hg. Therefore, the CHAP study researchers suggested an AOBP target of < 135/85 mm Hg to decrease the risk of CV events.7The landmark SPRINT trial, which was a major contributor to the development of BP target recommendations in guidelines, utilized AOBP to classify hypertension and guide management.2-4,8 SPRINT ultimately showed that intensive BP-lowering treatment (to SBP < 120 mm Hg) was associated with a 25% reduction in major CV events and a 27% reduction in all-cause mortality.8 Other evaluations found a close association between AOBP values and left ventricular mass index and carotid artery wall thickness as surrogate markers for end-organ damage.9,10 These data show AOBP as a reliable method to guide antihypertensive therapy interventions in the clinical setting.

Considering these proposed advantages, the 2017 Canadian guidelines for hypertension management recommend AOBP as the preferred method for clinic-based BP measurement, and the 2018 European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension blood pressure guidelines recommend the use of AOBP when feasible.3,4 The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults also discusses AOBP as a method to minimize potential confounders in BP values.2

This study evaluated the difference between AOBP and conventional in-office BP measurements obtained during cardiology clinic visits at the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WPBVAMC).

METHODS

A retrospective review of AOBP measurements was performed at the WPBVAMC cardiology clinic between May 26, 2017, and February 19, 2019. These AOBP measurements were taken at the discretion of a nurse or other clinician after initial, conventional BP measurements had been taken as part of clinic check-in procedures. No formal protocols dictated the use or timing of AOBP measurements. Similarly, the AOBP results were factored into clinical care decisions.

Clinicians at the cardiology clinic used AOBP averages that were derived using the BpTRU BPM-100 (BpTRU Medical Devices) meter, which averaged 5 BP readings taken at 1-minute intervals. Clinicians selected cuff size based on manufacturer recommendations. The testing was done with the patient seated alone in either a nursing triage area or a clinic office.

Data collected during the retrospective review included the clinician associated with the visit, the patient’s physical location and accompaniment status during AOBP measurement, conventionally measured BP and heart rates, and AOBP-derived BP and heart rate averages. Differences in BP values were compared with the paired t test, while binary comparisons were conducted through the McNemar test. Data collection and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel.

During data collection, all information was stored in a secure drive accessible only to the investigators. The project was approved by the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Research and Development Committee as a nonresearch activity in accordance with Veterans Health Administration Handbook 1058.05; thus, institutional review board approval was not required.

RESULTS

Ninety-five nonconsecutive patients were included in the analysis. AOBP measurements were taken with the patient sitting alone in either a clinic office (n = 83) or nursing triage area (n = 12). Most patients were coming in for follow-up appointments; 13 patients (14%) had appointments related to a 24-hour ABPM session.

The mean SBP and DBP values were lower for the AOBP measurements vs the conventional BP measurements (mean SBP difference, 14.6 mm Hg; P < .001; mean DBP difference, 3.5 mm Hg; P = .0002) (Table). There were no appreciable differences in heart rates. The white coat effect was suggested based on an SBP reduction of > 20 mm Hg from conventional to AOBP measurements in 22 patients (23%), a DBP reduction of > 10 mm Hg in 21 patients (22%), and a reduction in both values in 8 patients (8%).

A controlled BP (< 130/80 mm Hg) was more common in the AOBP group than in the conventional group (22% vs 7%, respectively; P =.001).2 Review of conventional BP measurements indicated that 11 patients had systolic readings ≥ 180 mm Hg, 2 had diastolic readings ≥ 110 mm Hg, and 1 had a reading that was ≥ 180/110 mm Hg. AOBP measurements indicated that these 14 patients had SBP readings < 180 mm Hg and DBP readings < 110 mm Hg. The use of AOBP measurements may have mitigated unnecessary emergency room visits for these patients.

On review of clinic notes and actions associated with episodes of AOBP testing during routine follow-up clinic appointments, AOBP was determined to be useful with regard to clinical decision-making for 65 (79%) patients. Impacts of AOBP inclusion vs conventional BP assessments included clinician notation of AOBP, support for making changes that would have been considered based on conventional BP assessment. AOBP results gave support to forgoing a therapeutic intervention (ie, therapy addition or intensification) that may have been pursued based on conventional BP measurements in 25 of 82 patients (30%). These data suggest that AOBP readings can be useful and actionable by clinicians.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study add to the growing evidence regarding AOBP use, application, and advantages in clinical practice. In this evaluation, the mean difference in SBP and DBP was 14.6 mm Hg and 3.5 mm Hg, respectively, from the conventional office measurements to the AOBP measurements. This difference is similar to that reported by the CAMBO trial and other evaluations, where the use of AOBP measurements corresponded to a reduction in SBP of between 10 and 20 mm Hg vs conventional measures.5,11-18

These findings showed a significantly higher percentage of controlled BP values (< 130/80 mm Hg) with AOBP values compared with conventional office measurements. The data supported the decision to defer antihypertensive therapy intervention in 30% of patients. Without AOBP data, patients may have been classified as uncontrolled, prompting therapy addition or intensification that could increase the risk of adverse events. Additionally, 14 patients would have met the criteria for hypertensive urgency under the guidelines at that time.2 With the use of AOBP readings, none of these patients were identified as having a hypertensive urgency, and they avoided an acute care referral or urgent intervention.

The discrepancy between AOBP and conventional office BP measurements suggested a white coat effect based on SBP and DBP readings in 22 (23%) and 21 (22%) patients, respectively. Practice guidelines recommend ABPM to mitigate a potential white coat effect.2-4 However, ABPM can be inconvenient for patients, as they need to travel to and from the clinic for fitting and removal (assuming that a facility has the device available for patient use). In addition, some patients may find it uncomfortable. Based on the correlation between AOBP and awake ABPM values, AOBP represents a feasible way to identify a white coat effect.

AOBP monitoring does not appear to be affected by the type of practice setting, as it has been evaluated in a variety of locations, including community-based pharmacies, primary care offices, and waiting rooms.12,19-22 However, potential AOBP implementation challenges may include office space constraints, clinician perception that it will delay workflow, and device cost. Costs associated with an AOBP meter vary widely based on device and procurement source, but have been estimated to range from $650 to > $2000.23 Published reports have described how to overcome AOBP implementation barriers.24,25

Limitations

The results of this evaluation should be interpreted cautiously due to several limitations. First, the retrospective study was conducted at a single clinic that may not be representative of other Veterans Health Administration or community-based populations. In addition, patient data such as age, sex, and body mass index were not available. AOBP measurements were obtained at the discretion of the clinician and not according to a prespecified protocol.

Conclusions

This analysis showed AOBP measurement leads to a greater percentage of controlled BP values compared with conventional office BP measurement, positioning it as a way to reduce BP misclassification, prevent potentially unnecessary therapeutic interventions, and mitigate the white coat effect.

- Cheng S, Claggett B, Correia AW, et al. Temporal Trends in the Population Attributable Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2014;130:820-828. doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008506

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(5):557-576. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.005

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-3104. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339

- Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, et al. Comparison of automated office blood pressure with office and out-off-office measurement techniques. Hypertension. 2019;73(2):481-490. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12079

- Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension - a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551

- Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Karwalajtys T, et al. Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP): a community cluster-randomised trial among elderly Canadians. Prev Med. 2008;46(6):537-544. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.005

- SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103-2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Andreadis EA, Agaliotis GD, Angelopoulos ET, et al. Automated office blood pressure and 24-h ambulatory measurements are equally associated with left ventricular mass index. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(6):661-666. doi:10.1038/ajh.2011.38

- Campbell NRC, McKay DW, Conradson H, et al. Automated oscillometric blood pressure versus auscultatory blood pressure as a predictor of carotid intima-medial thickness in male firefighters. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21(7):588-590. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1002190

- Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M et al. Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: randomised parallel design controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d286. doi:10.1136/bmj.d286

- Beckett L, Godwin M. The BpTRU automatic blood pressure monitor compared to 24 hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the assessment of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5(1):18. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-5-18

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27(2):280-286. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831b9e6b

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Consistent relationship between automated office blood pressure recorded in different settings. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14(3):108-111. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e32832c5167

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Optimum frequency of office blood pressure measurement using an automated sphygmomanometer. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13(6):333-338. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283104247

- Myers MG. A proposed algorithm for diagnosing hypertension using automated office blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2010;28(4):703-708. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d091

- Godwin M, Birtwhistle R, Delva D, et al. Manual and automated office measurements in relation to awake ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Fam Pract. 2011;28(1):110-117. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmq067

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Chessman M, Kiss A. Can sphygmomanometers designed for self-measurement of blood pressure in the home be used in office practice? Blood Press Monit. 2010;15(6):300-304. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e328340d128

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian hypertension education program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):569-588. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.02.066

- Myers MG. A short history of automated office blood pressure - 15 years to SPRINT. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(8):721-724. doi:10.1111/jch.12820

- Myers MG, Kaczorowski J, Dawes M, Godwin M. Automated office blood pressure measurement in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(2):127-132.

- Armstrong D, Matangi M, Brouillard D, Myers MG. Automated office blood pressure - being alone and not location is what matters most. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20(4):204-208. doi:10.1097/MBP.0000000000000133

- Yarows SA. What is the Cost of Measuring a Blood Pressure? Ann Clin Hypertens. 2018;2:59-66. doi:10.29328/journal.ach.1001012

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. doi:10.1001/jama.282.15.1458

- Doane J, Buu J, Penrod MJ, et al. Measuring and managing blood pressure in a primary care setting: a pragmatic implementation study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):375-388. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.03.170450

- Cheng S, Claggett B, Correia AW, et al. Temporal Trends in the Population Attributable Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2014;130:820-828. doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008506

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(5):557-576. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.005

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-3104. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339

- Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, et al. Comparison of automated office blood pressure with office and out-off-office measurement techniques. Hypertension. 2019;73(2):481-490. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12079

- Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension - a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551

- Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Karwalajtys T, et al. Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP): a community cluster-randomised trial among elderly Canadians. Prev Med. 2008;46(6):537-544. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.005

- SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103-2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Andreadis EA, Agaliotis GD, Angelopoulos ET, et al. Automated office blood pressure and 24-h ambulatory measurements are equally associated with left ventricular mass index. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(6):661-666. doi:10.1038/ajh.2011.38

- Campbell NRC, McKay DW, Conradson H, et al. Automated oscillometric blood pressure versus auscultatory blood pressure as a predictor of carotid intima-medial thickness in male firefighters. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21(7):588-590. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1002190

- Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M et al. Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: randomised parallel design controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d286. doi:10.1136/bmj.d286

- Beckett L, Godwin M. The BpTRU automatic blood pressure monitor compared to 24 hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the assessment of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5(1):18. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-5-18

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27(2):280-286. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831b9e6b

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Consistent relationship between automated office blood pressure recorded in different settings. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14(3):108-111. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e32832c5167

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Optimum frequency of office blood pressure measurement using an automated sphygmomanometer. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13(6):333-338. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283104247

- Myers MG. A proposed algorithm for diagnosing hypertension using automated office blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2010;28(4):703-708. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d091

- Godwin M, Birtwhistle R, Delva D, et al. Manual and automated office measurements in relation to awake ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Fam Pract. 2011;28(1):110-117. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmq067

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Chessman M, Kiss A. Can sphygmomanometers designed for self-measurement of blood pressure in the home be used in office practice? Blood Press Monit. 2010;15(6):300-304. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e328340d128

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian hypertension education program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):569-588. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.02.066

- Myers MG. A short history of automated office blood pressure - 15 years to SPRINT. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(8):721-724. doi:10.1111/jch.12820

- Myers MG, Kaczorowski J, Dawes M, Godwin M. Automated office blood pressure measurement in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(2):127-132.

- Armstrong D, Matangi M, Brouillard D, Myers MG. Automated office blood pressure - being alone and not location is what matters most. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20(4):204-208. doi:10.1097/MBP.0000000000000133

- Yarows SA. What is the Cost of Measuring a Blood Pressure? Ann Clin Hypertens. 2018;2:59-66. doi:10.29328/journal.ach.1001012

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. doi:10.1001/jama.282.15.1458

- Doane J, Buu J, Penrod MJ, et al. Measuring and managing blood pressure in a primary care setting: a pragmatic implementation study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):375-388. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.03.170450

Assessment of Automated vs Conventional Blood Pressure Measurements in a Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice Setting

Assessment of Automated vs Conventional Blood Pressure Measurements in a Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice Setting

Anticoagulation Stewardship Efforts Via Indication Reviews at a Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Anticoagulation Stewardship Efforts Via Indication Reviews at a Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Due to the underlying mechanism of atrial fibrillation (Afib), clots can form within the left atrial appendage. Clots that become dislodged may lead to ischemic stroke and possibly death. The 2023 guidelines for atrial fibrillation from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend anticoagulation therapy for patients with an Afib diagnosis and a CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes, stroke/vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and female sex) score pertinent for ≥ 1 non–sex-related factor (score ≥ 2 for women; ≥ 1 for men) to prevent stroke-related complications. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is a 9-point scoring tool based on comorbidities and conditions that increase risk of stroke in patients with Afib. Each value correlates to an annualized stroke risk percentage that increases as the score increases.

In clinical practice, patients meeting these thresholds are indicated for anticoagulation and are considered for indefinite use unless ≥ 1 of the following conditions are present: bleeding risk outweighs the stroke prevention benefit, Afib is episodic (< 48 hours) or a nonpharmacologic intervention, such as a left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) device is present.1

In patients with a diagnosed venous thromboembolism (VTE), such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation is used to treat the current thrombosis and prevent embolization that can ultimately lead to death. The 2021 guideline for VTE from the American College of Chest Physicians identifies certain risk factors that increase risk for VTE and categorizes them as transient or persistent. Transient risk factors include hospitalization > 3 days, major trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel > 8 hours. Persistent risk factors include malignancy, thrombophilia, and certain medications.

The guideline recommends therapy durations based on event frequency, the presence and classification of provoking risk factors, and bleeding risk. As the risk of recurrent thrombosis and other potential complications is greatest in the first 3 to 6 months after a diagnosed event, at least 3 months anticoagulation therapy is recommended following VTE diagnosis. At the 3-month mark, all regimens are suggested to be re-evaluated and considered for extended treatment duration if the event was unprovoked, recurrent, secondary to a persistent risk factor, or low bleed risk.2Anticoagulation is an important guideline-recommended pharmacologic intervention for various disease states, although its use is not without risks. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices has classified oral anticoagulants as high-alert medications. This designation was made because anticoagulant medications have the potential to cause harm when used or omitted in error and lead to life-threatening bleed or thrombotic complications.3Anticoagulation stewardship ensures that anticoagulation therapy is appropriately initiated, maintained, and discontinued when indicated. Because of the potential for harm, anticoagulation stewardship is an important part of Afib and VTE management. Pharmacists can help verify and evaluate anticoagulation therapies. Research suggests that pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship efforts may play a role in ensuring safer patient outcomes.4The purpose of this quality improvement (QI) study was to implement pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship practices at Veterans Affairs Phoenix Health Care System (VAPHCS) to identify veterans with Afib not currently on anticoagulation, as well as to identify veterans with a history of VTE events who have completed a sufficient treatment duration.

Methods

Anticoagulation stewardship efforts were implemented in 2 cohorts of patients: those with Afib who may be indicated to initiate anticoagulation, and those with a history of VTE events who may be indicated to consider anticoagulation discontinuation. Patient records were reviewed using a standardized note template, and recommendations to either initiate or discontinue anticoagulation therapy were documented. The VAPHCS Research Service reviewed this study and determined that it was not research and was exempt from institutional review board review.

Atrial Fibrillation Cohort

A population health dashboard created by the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter Targeting the uNTreated: a focus on health care disparities (SPAFF-TNT-D) national VA study team was used to identify veterans at VAPHCS with a diagnosis of Afib without an active VA prescription for an anticoagulant. The dashboard filtered and produced data points from the medical record that correlated to the components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. All veterans identified by the dashboard with scores of 7 or 8 were included. No patients had a score of 9. Comprehensive chart reviews of available VA and non–VA-provided care records were conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template designed by the SPAFF-TNT-D team (eAppendix 1) was used to document findings within the electronic health record (EHR). If anticoagulation was deemed to be indicated, the assigned primary care practitioner (PCP) as listed in the EHR was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of prescribing anticoagulation.

Venous Thromboembolism Cohort

VAPHCS pharmacy informatics pulled data that included veterans with documented VTE and an active VA anticoagulant prescription between November 2022 and November 2023. Veterans were reviewed in chronological order based on when the anticoagulant prescription was written. All veterans were included until an equal number of charts were reviewed in both the Afib and VTE cohorts. Comprehensive chart review of available VA- and non–VA-provided care records was conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template as designed by the investigators (eAppendix 2) was used to document findings within the EHR. If the duration of anticoagulation therapy was deemed sufficient, the assigned anticoagulation clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of discontinuing anticoagulation.

EHR reviews were conducted in October and November 2023 and lasted about 10 to 20 minutes per patient. To evaluate completeness and accuracy of the documented findings within the EHR, both investigators reviewed and cosigned the completed note template and verified the correct PCP was alerted to the recommendation for appropriate continuity of care. Results were reviewed in March 2024.

Outcomes

Atrial fibrillation cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with Afib who were recommended to start anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes evaluated included the number of interventions completed, action taken by PCPs in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending initiation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Venous thromboembolism cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with a history of VTE events recommended to discontinue anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes included number of interventions completed, action taken by the anticoagulation CPP in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Analysis

Sample size was determined by the inclusion criteria and was not designed to attain statistical power. Data embedded in the Afib cohort standardized note template, also known as health factors, were later used for data analysis. Recommendations in the VTE cohort were manually tracked and recorded by the investigators. Results for this study were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

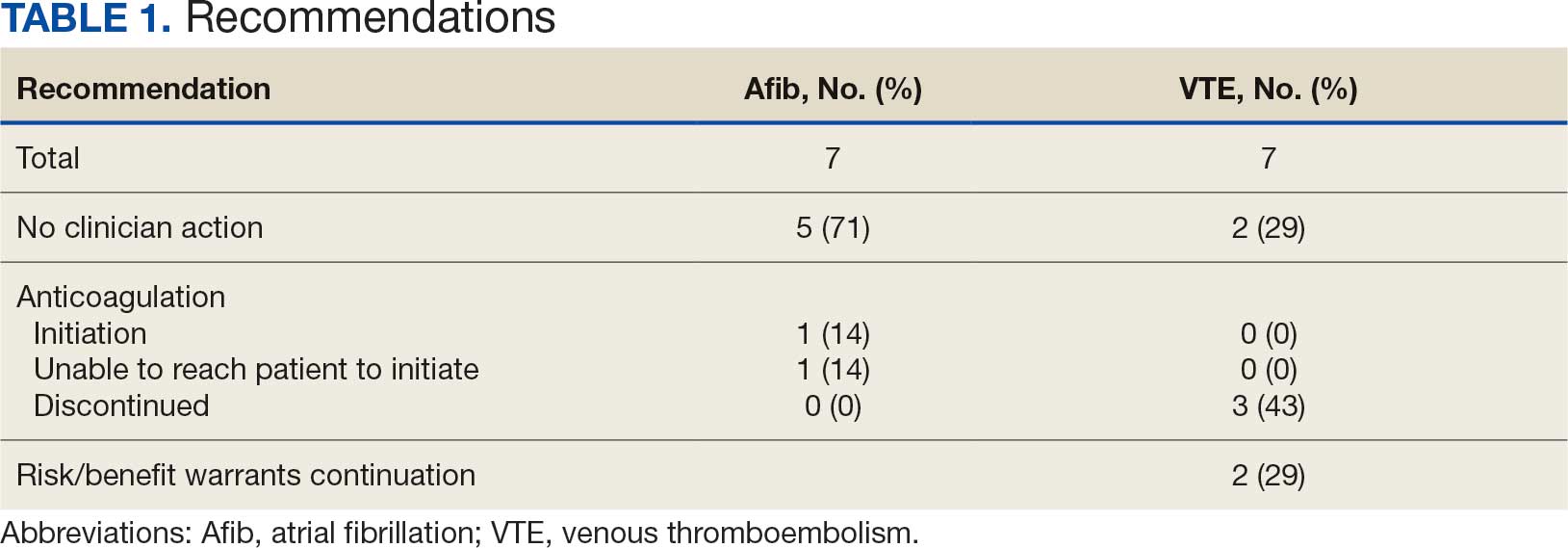

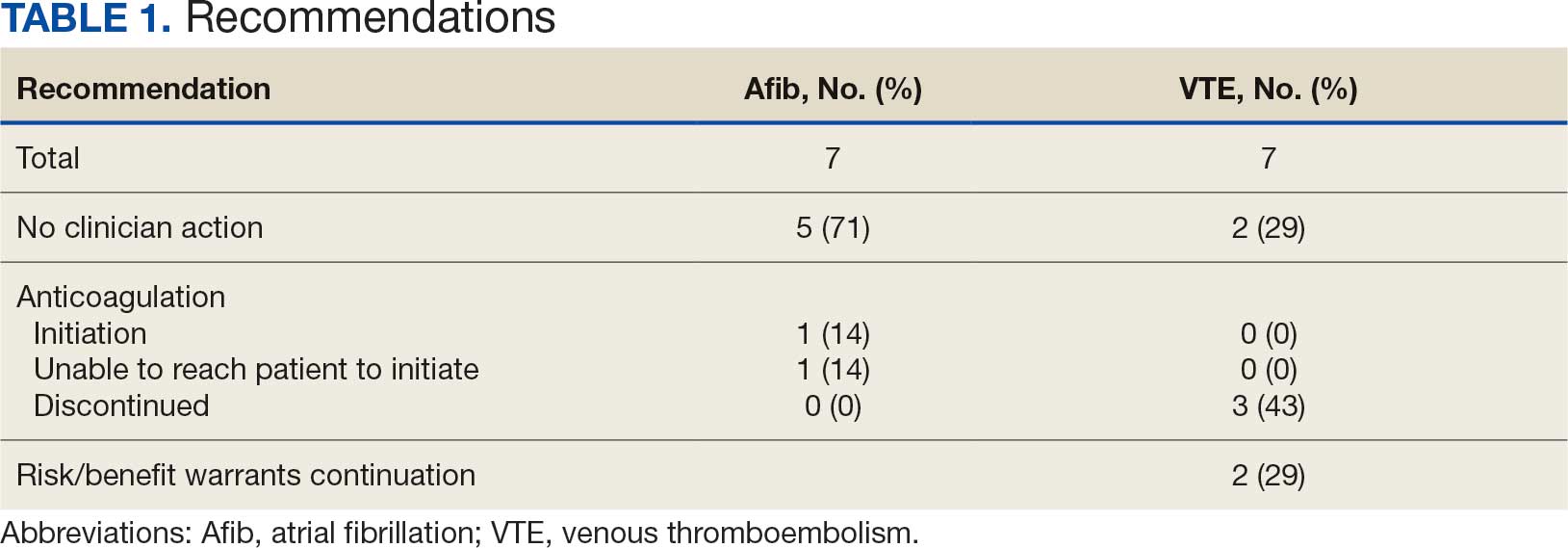

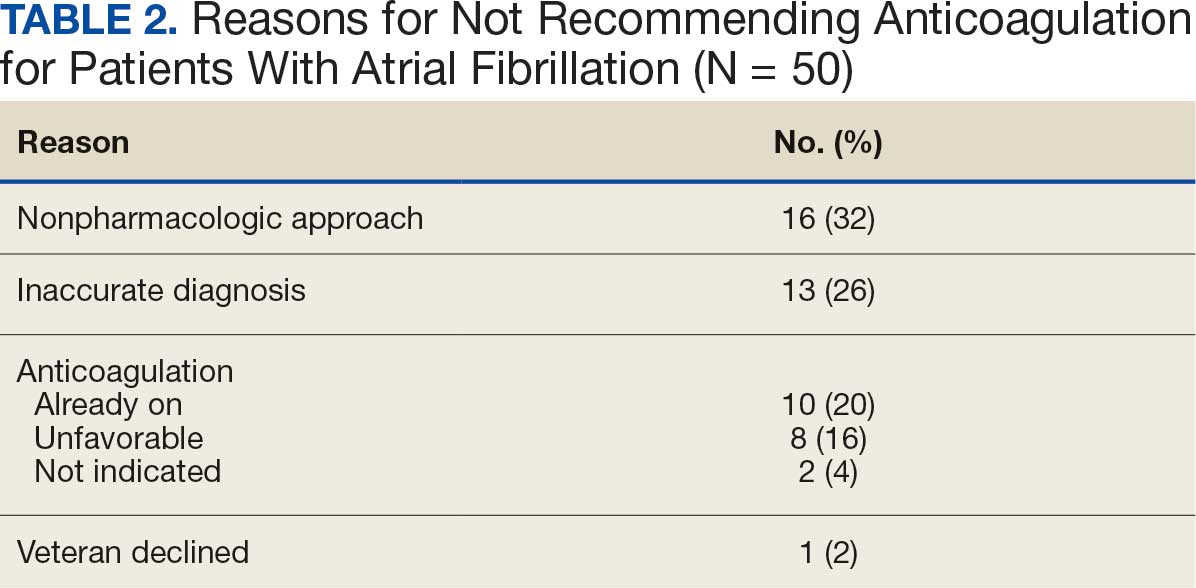

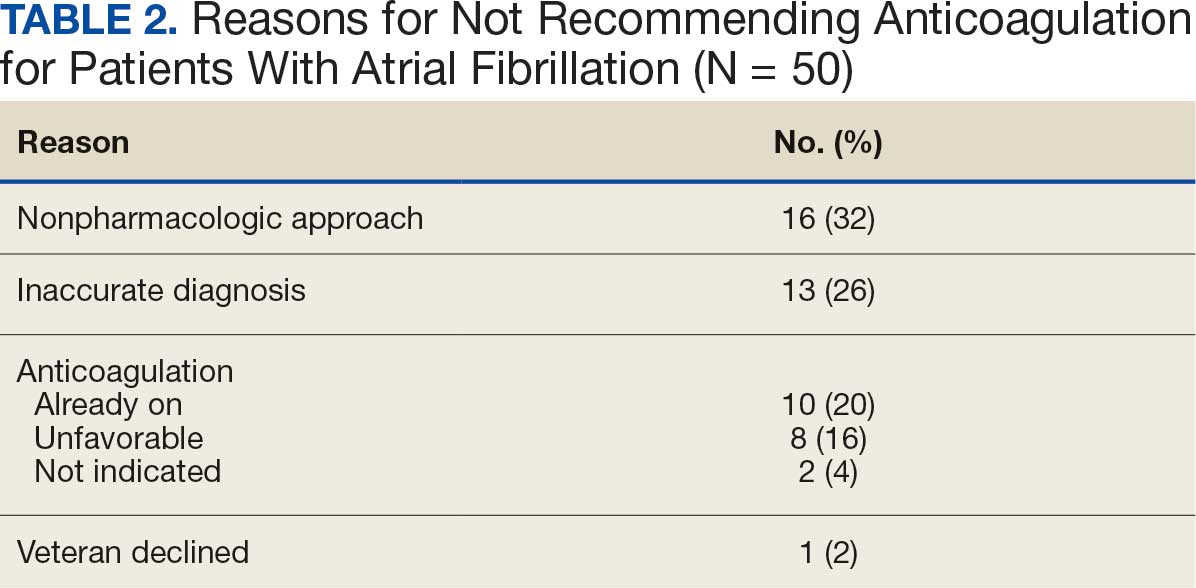

A total of 114 veterans were reviewed and included in this study: 57 in each cohort. Seven recommendations were made regarding anticoagulation initiation for patients with Afib and 7 were made for anticoagulation discontinuation for patients with VTE (Table 1).

In the Afib cohort, 1 veteran was successfully initiated on anticoagulation therapy and 1 veteran was deemed appropriate for initiation of anticoagulation but was not reachable. Of the 5 recommendations with no action taken, 4 PCPs acknowledged the alert with no further documentation, and 1 PCP deferred the decision to cardiology with no further documentation. In the VTE cohort, 3 veterans successfully discontinued anticoagulation therapy and 2 veterans were further evaluated by the anticoagulation CPP and deemed appropriate to continue therapy based on potential for malignancy. Of the 2 recommendations with no action taken, 1 anticoagulation CPP acknowledged the alert with no further documentation and 1 anticoagulation CPP suggested further evaluation by PCP with no further documentation.

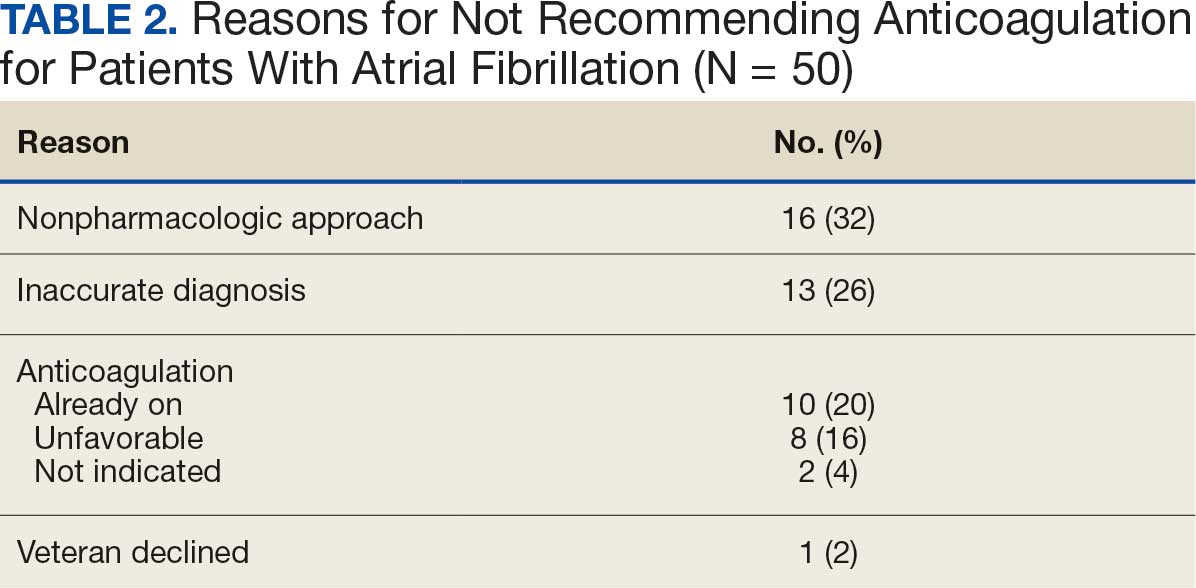

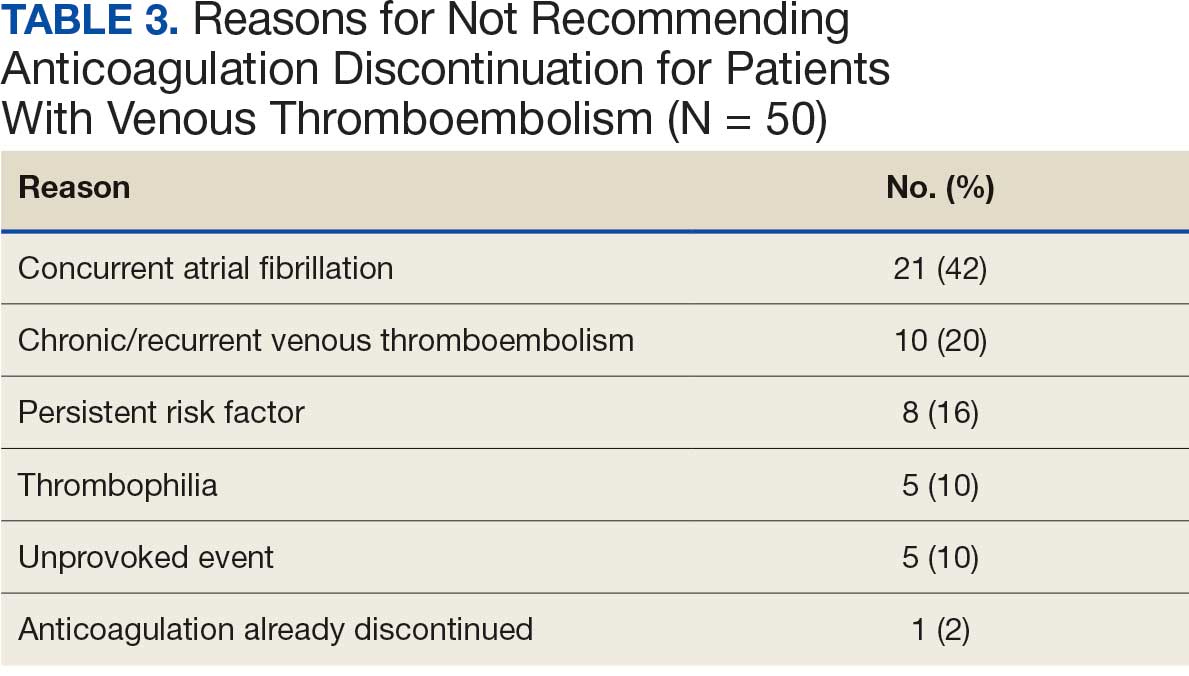

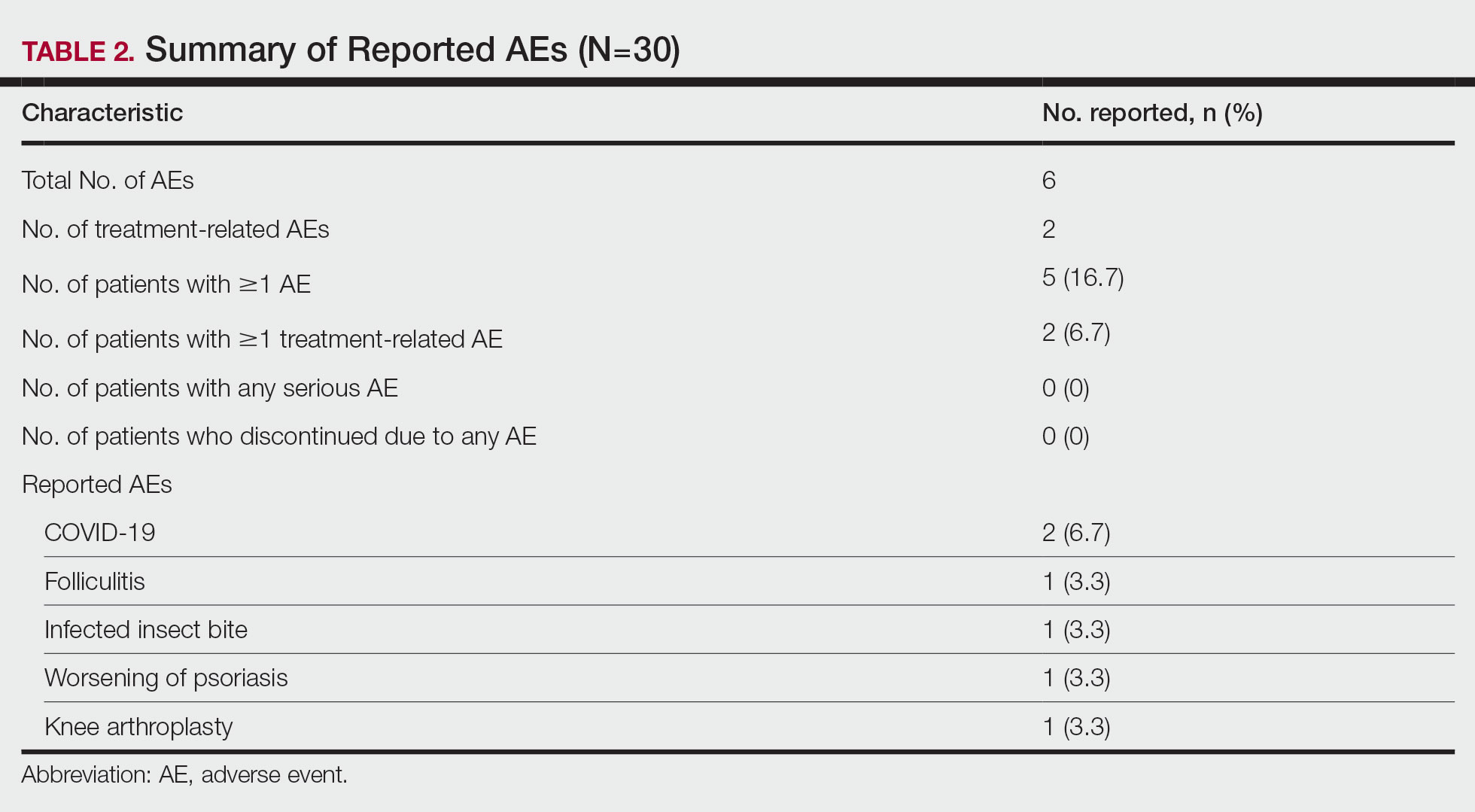

In the Afib cohort, a nonpharmacologic approach was defined as documentation of a LAAO device. An inaccurate diagnosis was defined as an Afib diagnosis being used in a previous visit, although there was no further confirmation of diagnosis via chart review. Veterans classified as already being on anticoagulation had documentation of non–VA-written anticoagulant prescriptions or receiving a supply of anticoagulants from a facility such as a nursing home. Anticoagulation was defined as unfavorable if a documented risk/benefit conversation was found via EHR review. Anticoagulation was defined as not indicated if the Afib was documented as transient, episodic, or historical (Table 2).

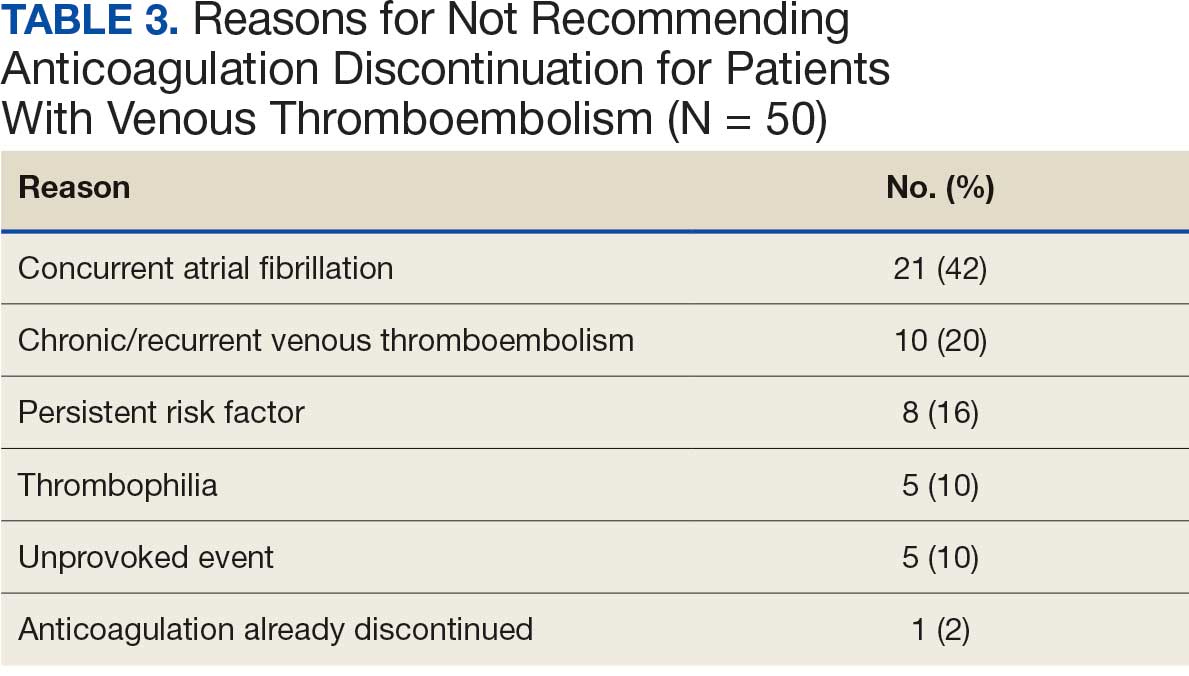

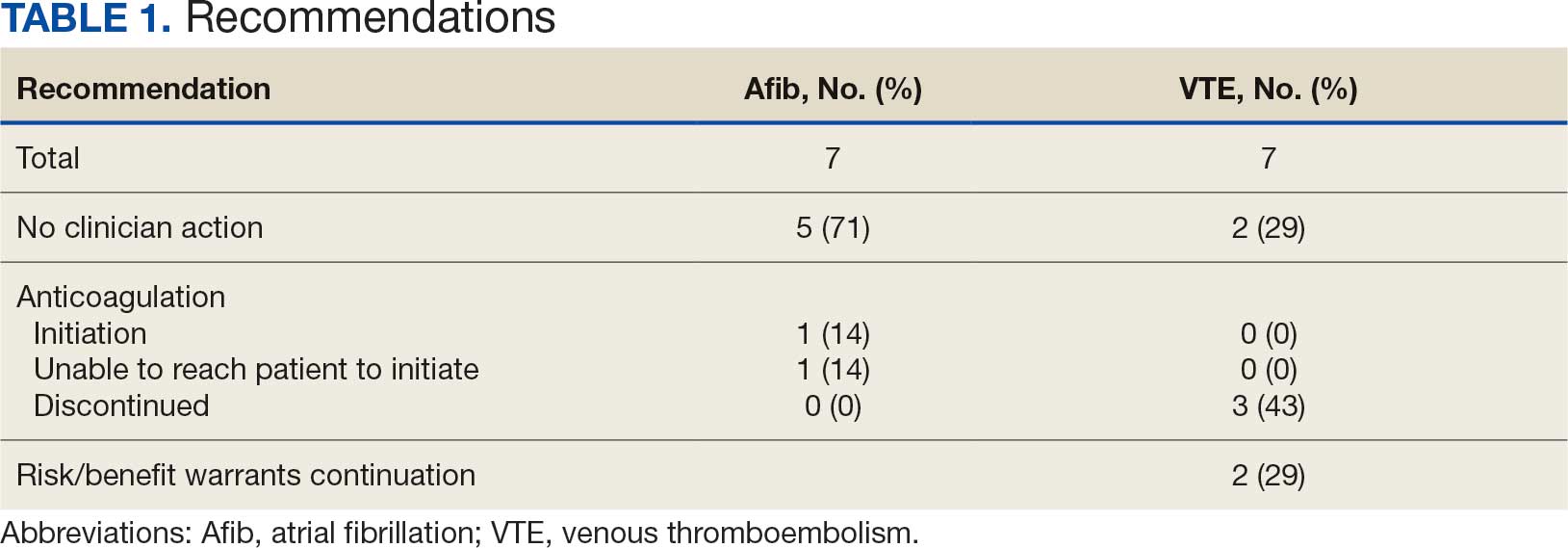

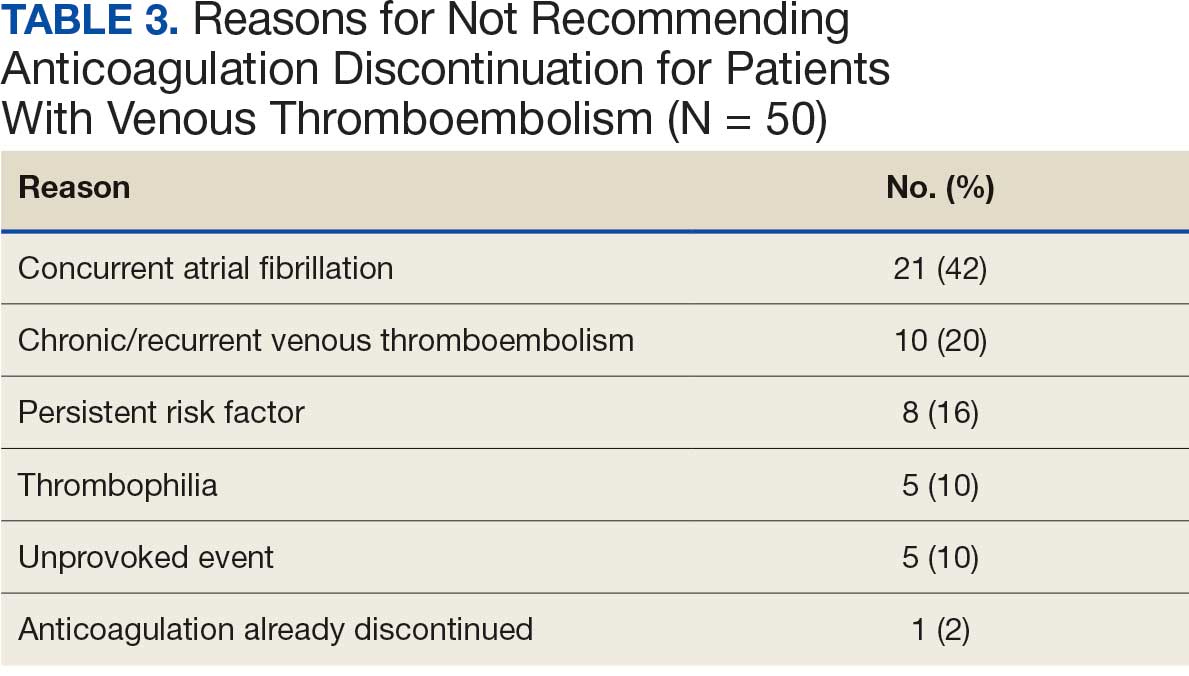

In the VTE cohort, no recommendations for discontinuation were made for veterans indicated to continue anticoagulation due to a concurrent Afib diagnosis. Chronic or recurrent events were defined as documentation of multiple VTE events and associated dates in the EHR. Persistent risk factors included malignancy or medications contributing to hypercoagulable states. Thrombophilia was defined as having documentation of a diagnosis in the EHR. An unprovoked event was defined as VTE without any documented transient risk factors (eg, hospitalization, trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel). Anticoagulation had already been discontinued in 1 veteran after the data were collected but before chart review occurred (Table 3).

Discussion

Pharmacy-led indication reviews resulted in appropriate recommendations for anticoagulation use in veterans with Afib and a history of VTE events. Overall, 12.3% of chart reviews in each cohort resulted in a recommendation being made, which was similar to the rate found by Koolian et al.5 In that study, 10% of recommendations were related to initiation or interruption of anticoagulation. This recommendation category consisted of several subcategories, including “suggesting therapeutic anticoagulation when none is currently ordered” and “suggesting anticoagulation cessation if no longer indicated,” but specific numerical prevalence was not provided.5

Online dashboard use allowed for greater population health management and identification of veterans with Afib who were not on active anticoagulation, providing opportunities to prevent stroke-related complications. Wang et al completed a similarly designed study that included a population health tool to identify patients with Afib who were not on anticoagulation and implemented pharmacist-led chart review and facilitation of recommendations to the responsible clinician. This study reviewed 1727 patients and recommended initiation of anticoagulation therapy for 75 (4.3%).6 The current study had a higher percentage of patients with recommendations for changes despite its smaller size.

Evaluating the duration of therapy for anticoagulation in veterans with a history of VTE events provided an opportunity to reduce unnecessary exposure to anticoagulation and minimize bleeding risks. Using a chart review process and standardized note template enabled the documentation of pertinent information that could be readily reviewed by the PCP. This process is a step toward ensuring VAPHCS PCPs provide guideline-recommended care and actively prevent stroke and bleeding complications. Adoption of this process into the current VAPHCS Anticoagulation Clinic workflow for review of veterans with either Afib or VTE could lead to more EHRs being reviewed and recommendations made, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Therapeutic interventions based on the recommendations were completed for 1 of 7 veterans (14%) and 3 of 7 veterans (43%) in the Afib and VTE cohorts, respectively. The prevalence of completed interventions in this anticoagulation stewardship study was higher than those in Wang et al, who found only 9% of their recommendations resulted in PCPs considering action related to anticoagulation, and only 4% were successfully initiated.6

In the Afib cohort, veterans identified by the dashboard with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 7 or 8 were prioritized for review. Reviewing these veterans ensured that patients with the highest stroke risk were sufficiently evaluated and started on anticoagulation as needed to reduce stroke-related complications. In contrast, because these veterans had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, they may have already been evaluated for anticoagulation in the past and had a documented rationale for not being placed on anticoagulation (LAAO device placement was the most common rationale). Focusing on veterans with a lower CHA2DS2-VASc score such as 1 for men or 2 for women could potentially include more opportunities for recommendations. Although stroke risk may be lower in this population compared with those with higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, guideline-recommended anticoagulation use may be missed for these patients.

In the VTE cohort, veterans with an anticoagulant prescription written 12 months before data collection were prioritized for review. Reviewing these veterans ensured that anticoagulation therapy met guideline recommendations of at least 3 months, with potential for extended duration upon further evaluation by a provider at that time. Based on collected results, most veterans were already reevaluated and had documented reasons why anticoagulation was still indicated; concurrent Afib was most common followed by chronic or recurrent VTE. Reviewing veterans with more recent prescriptions just over the recommended 3-month duration could potentially include more opportunities for recommendations to be made. It is more likely that by 3 months another PCP had not already weighed in on the duration of therapy, and the anticoagulation CPP could ensure a thorough review is conducted with guideline-based recommendations.

Most published literature on anticoagulation stewardship efforts is focused on inpatient management and policy changes, or concentrate on attributes of therapy such as appropriate dosing and drug interactions. This study highlighted that gaps in care related to anticoagulation use and discontinuation are present in the VAPHCS population and can be appropriately addressed via pharmacist-led indication reviews. Future studies designed to focus on initiating anticoagulation where appropriate, and discontinuing where a sufficient treatment period has been completed, are warranted to minimize this gap in care and allow health systems to work toward process changes to ensure safe and optimized care is provided for the patients they serve.

Limitations

In the Afib cohort, 5 of 7 recommendations (71%) had no further action taken by the PCP, which may represent a barrier to care. In contrast, 2 of 7 recommendations (29%) had no further action in the VTE cohort. It is possible that the difference can be attributed to the anticoagulation CPP receiving VTE alerts and PCPs receiving Afib alerts. The anticoagulation CPP was familiar with this QI study and may have better understood the purpose of the chart review and the need to provide a timely response. PCPs may have been less likely to take action because they were unfamiliar with the anticoagulation stewardship initiative and standardized note template or overwhelmed by too many EHR alerts.

The lack of PCP response to a virtual alert or message also was observed by Wang et al, whereas Koolian et al reported higher intervention completion rates, with verbal recommendations being made to the responsible clinicians. To further ensure these pertinent recommendations for anticoagulation initiation in veterans with Afib are properly reviewed and evaluated, future research could include intentional follow-up with the PCP regarding the alert, PCP-specific education about the anticoagulation stewardship initiative and the role of the standardized note template, and collaboration with PCPs to identify alternative ways to relay recommendations in a way that would ensure the completion of appropriate and timely review.

Conclusions

This study identified gaps in care related to anticoagulation needs in the VAPHCS veteran population. Utilizing a standardized indication review process allows pharmacists to evaluate anticoagulant use for both appropriate indication and duration of therapy. Providing recommendations via chart review notes and alerting respective PCPs and CPPs results in veterans receiving safe and optimized care regarding their anticoagulation needs.

- Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149:e1-e156. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

- Stevens SM, Woller SC, Kreuziger LB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160:e545-e608. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.055

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). List of high-alert medications in community/ambulatory care settings. ISMP. September 30, 2021. Accessed September 11, 2025. https://home.ecri.org/blogs/ismp-resources/high-alert-medications-in-community-ambulatory-care-settings

- Burnett AE, Barnes GD. A call to action for anticoagulation stewardship. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12757. doi:10.1002/rth2.12757

- Koolian M, Wiseman D, Mantzanis H, et al. Anticoagulation stewardship: descriptive analysis of a novel approach to appropriate anticoagulant prescription. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12758. doi:10.1002/rth2.12758

- Wang SV, Rogers JR, Jin Y, et al. Stepped-wedge randomised trial to evaluate population health intervention designed to increase appropriate anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:835-842. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009367

Due to the underlying mechanism of atrial fibrillation (Afib), clots can form within the left atrial appendage. Clots that become dislodged may lead to ischemic stroke and possibly death. The 2023 guidelines for atrial fibrillation from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend anticoagulation therapy for patients with an Afib diagnosis and a CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes, stroke/vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and female sex) score pertinent for ≥ 1 non–sex-related factor (score ≥ 2 for women; ≥ 1 for men) to prevent stroke-related complications. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is a 9-point scoring tool based on comorbidities and conditions that increase risk of stroke in patients with Afib. Each value correlates to an annualized stroke risk percentage that increases as the score increases.

In clinical practice, patients meeting these thresholds are indicated for anticoagulation and are considered for indefinite use unless ≥ 1 of the following conditions are present: bleeding risk outweighs the stroke prevention benefit, Afib is episodic (< 48 hours) or a nonpharmacologic intervention, such as a left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) device is present.1

In patients with a diagnosed venous thromboembolism (VTE), such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation is used to treat the current thrombosis and prevent embolization that can ultimately lead to death. The 2021 guideline for VTE from the American College of Chest Physicians identifies certain risk factors that increase risk for VTE and categorizes them as transient or persistent. Transient risk factors include hospitalization > 3 days, major trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel > 8 hours. Persistent risk factors include malignancy, thrombophilia, and certain medications.

The guideline recommends therapy durations based on event frequency, the presence and classification of provoking risk factors, and bleeding risk. As the risk of recurrent thrombosis and other potential complications is greatest in the first 3 to 6 months after a diagnosed event, at least 3 months anticoagulation therapy is recommended following VTE diagnosis. At the 3-month mark, all regimens are suggested to be re-evaluated and considered for extended treatment duration if the event was unprovoked, recurrent, secondary to a persistent risk factor, or low bleed risk.2Anticoagulation is an important guideline-recommended pharmacologic intervention for various disease states, although its use is not without risks. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices has classified oral anticoagulants as high-alert medications. This designation was made because anticoagulant medications have the potential to cause harm when used or omitted in error and lead to life-threatening bleed or thrombotic complications.3Anticoagulation stewardship ensures that anticoagulation therapy is appropriately initiated, maintained, and discontinued when indicated. Because of the potential for harm, anticoagulation stewardship is an important part of Afib and VTE management. Pharmacists can help verify and evaluate anticoagulation therapies. Research suggests that pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship efforts may play a role in ensuring safer patient outcomes.4The purpose of this quality improvement (QI) study was to implement pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship practices at Veterans Affairs Phoenix Health Care System (VAPHCS) to identify veterans with Afib not currently on anticoagulation, as well as to identify veterans with a history of VTE events who have completed a sufficient treatment duration.

Methods

Anticoagulation stewardship efforts were implemented in 2 cohorts of patients: those with Afib who may be indicated to initiate anticoagulation, and those with a history of VTE events who may be indicated to consider anticoagulation discontinuation. Patient records were reviewed using a standardized note template, and recommendations to either initiate or discontinue anticoagulation therapy were documented. The VAPHCS Research Service reviewed this study and determined that it was not research and was exempt from institutional review board review.

Atrial Fibrillation Cohort

A population health dashboard created by the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter Targeting the uNTreated: a focus on health care disparities (SPAFF-TNT-D) national VA study team was used to identify veterans at VAPHCS with a diagnosis of Afib without an active VA prescription for an anticoagulant. The dashboard filtered and produced data points from the medical record that correlated to the components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. All veterans identified by the dashboard with scores of 7 or 8 were included. No patients had a score of 9. Comprehensive chart reviews of available VA and non–VA-provided care records were conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template designed by the SPAFF-TNT-D team (eAppendix 1) was used to document findings within the electronic health record (EHR). If anticoagulation was deemed to be indicated, the assigned primary care practitioner (PCP) as listed in the EHR was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of prescribing anticoagulation.

Venous Thromboembolism Cohort

VAPHCS pharmacy informatics pulled data that included veterans with documented VTE and an active VA anticoagulant prescription between November 2022 and November 2023. Veterans were reviewed in chronological order based on when the anticoagulant prescription was written. All veterans were included until an equal number of charts were reviewed in both the Afib and VTE cohorts. Comprehensive chart review of available VA- and non–VA-provided care records was conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template as designed by the investigators (eAppendix 2) was used to document findings within the EHR. If the duration of anticoagulation therapy was deemed sufficient, the assigned anticoagulation clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of discontinuing anticoagulation.

EHR reviews were conducted in October and November 2023 and lasted about 10 to 20 minutes per patient. To evaluate completeness and accuracy of the documented findings within the EHR, both investigators reviewed and cosigned the completed note template and verified the correct PCP was alerted to the recommendation for appropriate continuity of care. Results were reviewed in March 2024.

Outcomes

Atrial fibrillation cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with Afib who were recommended to start anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes evaluated included the number of interventions completed, action taken by PCPs in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending initiation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Venous thromboembolism cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with a history of VTE events recommended to discontinue anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes included number of interventions completed, action taken by the anticoagulation CPP in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Analysis

Sample size was determined by the inclusion criteria and was not designed to attain statistical power. Data embedded in the Afib cohort standardized note template, also known as health factors, were later used for data analysis. Recommendations in the VTE cohort were manually tracked and recorded by the investigators. Results for this study were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

A total of 114 veterans were reviewed and included in this study: 57 in each cohort. Seven recommendations were made regarding anticoagulation initiation for patients with Afib and 7 were made for anticoagulation discontinuation for patients with VTE (Table 1).

In the Afib cohort, 1 veteran was successfully initiated on anticoagulation therapy and 1 veteran was deemed appropriate for initiation of anticoagulation but was not reachable. Of the 5 recommendations with no action taken, 4 PCPs acknowledged the alert with no further documentation, and 1 PCP deferred the decision to cardiology with no further documentation. In the VTE cohort, 3 veterans successfully discontinued anticoagulation therapy and 2 veterans were further evaluated by the anticoagulation CPP and deemed appropriate to continue therapy based on potential for malignancy. Of the 2 recommendations with no action taken, 1 anticoagulation CPP acknowledged the alert with no further documentation and 1 anticoagulation CPP suggested further evaluation by PCP with no further documentation.

In the Afib cohort, a nonpharmacologic approach was defined as documentation of a LAAO device. An inaccurate diagnosis was defined as an Afib diagnosis being used in a previous visit, although there was no further confirmation of diagnosis via chart review. Veterans classified as already being on anticoagulation had documentation of non–VA-written anticoagulant prescriptions or receiving a supply of anticoagulants from a facility such as a nursing home. Anticoagulation was defined as unfavorable if a documented risk/benefit conversation was found via EHR review. Anticoagulation was defined as not indicated if the Afib was documented as transient, episodic, or historical (Table 2).

In the VTE cohort, no recommendations for discontinuation were made for veterans indicated to continue anticoagulation due to a concurrent Afib diagnosis. Chronic or recurrent events were defined as documentation of multiple VTE events and associated dates in the EHR. Persistent risk factors included malignancy or medications contributing to hypercoagulable states. Thrombophilia was defined as having documentation of a diagnosis in the EHR. An unprovoked event was defined as VTE without any documented transient risk factors (eg, hospitalization, trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel). Anticoagulation had already been discontinued in 1 veteran after the data were collected but before chart review occurred (Table 3).

Discussion

Pharmacy-led indication reviews resulted in appropriate recommendations for anticoagulation use in veterans with Afib and a history of VTE events. Overall, 12.3% of chart reviews in each cohort resulted in a recommendation being made, which was similar to the rate found by Koolian et al.5 In that study, 10% of recommendations were related to initiation or interruption of anticoagulation. This recommendation category consisted of several subcategories, including “suggesting therapeutic anticoagulation when none is currently ordered” and “suggesting anticoagulation cessation if no longer indicated,” but specific numerical prevalence was not provided.5