User login

Advances in Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Advances in Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Click to view more from Gastroenterology Data Trends 2025.

- Vantanasiri K, Kamboj AK, Kisiel JB, Iyer PG. Advances in Screening for Barrett Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2024;99(3):459-473. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.07.014

- Cancer Stat Facts: Esophageal Cancer. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 12, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/esoph.html

- Seer*Explorer: Esophagus. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html

- Kolb JM, Chen M, Tavakkoli A, et al. Understanding Compliance, Practice Patterns, and Barriers Among Gastroenterologists and Primary Care Providers Is Crucial for Developing Strategies to Improve Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(6):1568-1573.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.003

- Kunzmann AT, Thrift AP, Cardwell CR, et al. Model for Identifying Individuals at Risk for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(8):1229-1236.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.014

- Rubenstein JH, Evans RR, Burns JA, et al. Patients With Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Esophagogastric Junction Frequently Have Potential Screening Opportunities. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(4):1349-1351.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.255

- Xie S-H, Ness-Jensen E, Medefelt N, Lagergren J. Assessing the feasibility of targeted screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma based on individual risk assessment in a population-based cohort study in Norway (The HUNT Study). Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(6):829-835. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0069-9

- Rubenstein JH, Fontaine S, MacDonald PW, et al. Predicting Incident Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Gastric Cardia Using Machine Learning of Electronic Health Records. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(6):1420-1429.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.011

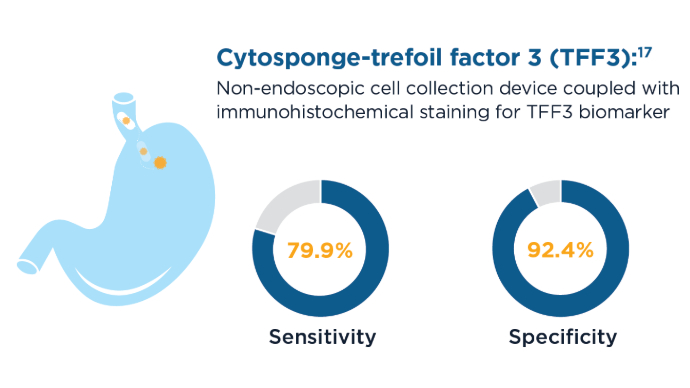

- Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, O’Donovan M, et al. Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify Barrett’s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):333-344. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31099-0

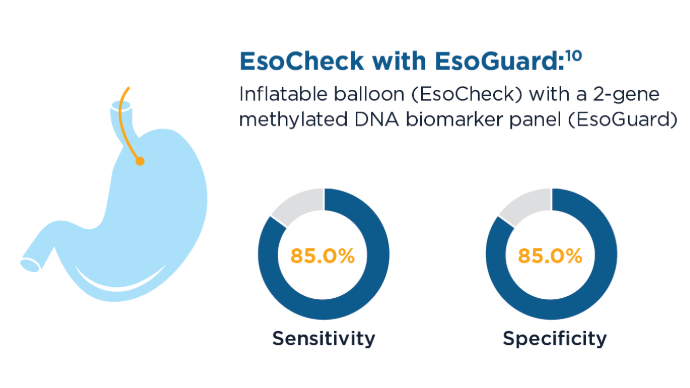

- Moinova HR, Verma S, Dumot J, et al. Multicenter, Prospective Trial of Nonendoscopic

Biomarker-Driven Detection of Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119(11):2206-2214. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002850 - Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus: An Updated ACG Guideline. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(4):559-587. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001680

- ASGE STANDARDS OF PRACTICE COMMITTEE; Qumseya B, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(3):335-359.e2. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2019.05.012

- Muthusamy VR, Wani S, Gyawali CP, Komanduri S. CGIT Barrett’s Esophagus Consensus Conference Participants. AGA Clinical Practice Update on New Technology and Innovation for Surveillance and Screening in Barrett’s Esophagus: Expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(12):2696-2706. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.06.003

- Xie SH, Lagergren J. A model for predicting individuals’ absolute risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma: Moving toward tailored screening and prevention. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(12):2813-2819. doi:10.1002/ijc.29988

- Rubenstein JH, McConnell D, Waljee AK, et al. Validation and Comparison of Tools for Selecting Individuals to Screen for Barrett’s Esophagus and Early Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(8):2082-2092. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.037

- Iyer PG, Sachdeva K, Leggett CL, et al. Development of Electronic Health Record–Based Machine Learning Models to Predict Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Risk. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023;14(10):e00637. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000637

- Ross-Innes CS, Debiram-Beecham I, O’Donovan M, et al; BEST2 Study Group. Evaluation of a minimally invasive cell sampling device coupled with assessment of trefoil factor 3 expression for diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus: a multicenter case-control study. PLoS Med. 2015;12(1):e1001780. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001780

Click to view more from Gastroenterology Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Gastroenterology Data Trends 2025.

- Vantanasiri K, Kamboj AK, Kisiel JB, Iyer PG. Advances in Screening for Barrett Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2024;99(3):459-473. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.07.014

- Cancer Stat Facts: Esophageal Cancer. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 12, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/esoph.html

- Seer*Explorer: Esophagus. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html

- Kolb JM, Chen M, Tavakkoli A, et al. Understanding Compliance, Practice Patterns, and Barriers Among Gastroenterologists and Primary Care Providers Is Crucial for Developing Strategies to Improve Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(6):1568-1573.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.003

- Kunzmann AT, Thrift AP, Cardwell CR, et al. Model for Identifying Individuals at Risk for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(8):1229-1236.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.014

- Rubenstein JH, Evans RR, Burns JA, et al. Patients With Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Esophagogastric Junction Frequently Have Potential Screening Opportunities. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(4):1349-1351.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.255

- Xie S-H, Ness-Jensen E, Medefelt N, Lagergren J. Assessing the feasibility of targeted screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma based on individual risk assessment in a population-based cohort study in Norway (The HUNT Study). Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(6):829-835. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0069-9

- Rubenstein JH, Fontaine S, MacDonald PW, et al. Predicting Incident Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Gastric Cardia Using Machine Learning of Electronic Health Records. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(6):1420-1429.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.011

- Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, O’Donovan M, et al. Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify Barrett’s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):333-344. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31099-0

- Moinova HR, Verma S, Dumot J, et al. Multicenter, Prospective Trial of Nonendoscopic

Biomarker-Driven Detection of Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119(11):2206-2214. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002850 - Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus: An Updated ACG Guideline. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(4):559-587. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001680

- ASGE STANDARDS OF PRACTICE COMMITTEE; Qumseya B, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(3):335-359.e2. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2019.05.012

- Muthusamy VR, Wani S, Gyawali CP, Komanduri S. CGIT Barrett’s Esophagus Consensus Conference Participants. AGA Clinical Practice Update on New Technology and Innovation for Surveillance and Screening in Barrett’s Esophagus: Expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(12):2696-2706. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.06.003

- Xie SH, Lagergren J. A model for predicting individuals’ absolute risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma: Moving toward tailored screening and prevention. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(12):2813-2819. doi:10.1002/ijc.29988

- Rubenstein JH, McConnell D, Waljee AK, et al. Validation and Comparison of Tools for Selecting Individuals to Screen for Barrett’s Esophagus and Early Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(8):2082-2092. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.037

- Iyer PG, Sachdeva K, Leggett CL, et al. Development of Electronic Health Record–Based Machine Learning Models to Predict Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Risk. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023;14(10):e00637. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000637

- Ross-Innes CS, Debiram-Beecham I, O’Donovan M, et al; BEST2 Study Group. Evaluation of a minimally invasive cell sampling device coupled with assessment of trefoil factor 3 expression for diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus: a multicenter case-control study. PLoS Med. 2015;12(1):e1001780. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001780

- Vantanasiri K, Kamboj AK, Kisiel JB, Iyer PG. Advances in Screening for Barrett Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2024;99(3):459-473. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.07.014

- Cancer Stat Facts: Esophageal Cancer. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 12, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/esoph.html

- Seer*Explorer: Esophagus. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html

- Kolb JM, Chen M, Tavakkoli A, et al. Understanding Compliance, Practice Patterns, and Barriers Among Gastroenterologists and Primary Care Providers Is Crucial for Developing Strategies to Improve Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(6):1568-1573.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.003

- Kunzmann AT, Thrift AP, Cardwell CR, et al. Model for Identifying Individuals at Risk for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(8):1229-1236.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.014

- Rubenstein JH, Evans RR, Burns JA, et al. Patients With Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Esophagogastric Junction Frequently Have Potential Screening Opportunities. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(4):1349-1351.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.255

- Xie S-H, Ness-Jensen E, Medefelt N, Lagergren J. Assessing the feasibility of targeted screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma based on individual risk assessment in a population-based cohort study in Norway (The HUNT Study). Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(6):829-835. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0069-9

- Rubenstein JH, Fontaine S, MacDonald PW, et al. Predicting Incident Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Gastric Cardia Using Machine Learning of Electronic Health Records. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(6):1420-1429.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.011

- Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, O’Donovan M, et al. Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify Barrett’s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):333-344. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31099-0

- Moinova HR, Verma S, Dumot J, et al. Multicenter, Prospective Trial of Nonendoscopic

Biomarker-Driven Detection of Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119(11):2206-2214. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002850 - Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus: An Updated ACG Guideline. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(4):559-587. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001680

- ASGE STANDARDS OF PRACTICE COMMITTEE; Qumseya B, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(3):335-359.e2. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2019.05.012

- Muthusamy VR, Wani S, Gyawali CP, Komanduri S. CGIT Barrett’s Esophagus Consensus Conference Participants. AGA Clinical Practice Update on New Technology and Innovation for Surveillance and Screening in Barrett’s Esophagus: Expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(12):2696-2706. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.06.003

- Xie SH, Lagergren J. A model for predicting individuals’ absolute risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma: Moving toward tailored screening and prevention. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(12):2813-2819. doi:10.1002/ijc.29988

- Rubenstein JH, McConnell D, Waljee AK, et al. Validation and Comparison of Tools for Selecting Individuals to Screen for Barrett’s Esophagus and Early Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(8):2082-2092. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.037

- Iyer PG, Sachdeva K, Leggett CL, et al. Development of Electronic Health Record–Based Machine Learning Models to Predict Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Risk. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023;14(10):e00637. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000637

- Ross-Innes CS, Debiram-Beecham I, O’Donovan M, et al; BEST2 Study Group. Evaluation of a minimally invasive cell sampling device coupled with assessment of trefoil factor 3 expression for diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus: a multicenter case-control study. PLoS Med. 2015;12(1):e1001780. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001780

Advances in Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Advances in Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

New Model Estimates Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B

The model, called Revised REACH-B or reREACH-B, stems from cohort studies in Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan, and looks at the nonlinear parabolic association between serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA levels and HCC risk.

“Current clinical practice guidelines don’t advocate antiviral treatment for patients with CHB who don’t show elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, even in those with high HBV viral loads,” said coauthor Young-Suk Lim, MD, PhD, professor of gastroenterology at the University of Ulsan College of Medicine and Asan Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea.

“This stance is rooted in the notion that patients in the immune-tolerant phase are at very low risk for developing HCC,” Lim said. “However, the immune-tolerant phase includes patients with HBV DNA levels who face the highest risk for HCC, and many patients with moderate HBV viremia fall into an undefined gray zone.”

The study was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Validating reREACH-B

During a course of CHB, HBV viral loads and HCC risks evolve over time because of viral replication and host immune responses, Lim explained. Most patients typically move to seroclearance and an “inactive hepatitis” phase, but about 10%-20% can progress to a “reactivation” phase, where HBV DNA levels and ALT levels increase, which can increase HCC risk as well.

In a previous cohort study in Taiwan, a prognostic model called Risk Estimation for HCC in CHB — or REACH-B — found the risk for HCC increases tenfold with increasing levels of HBV DNA up to 5 log10IU/mL in noncirrhotic patients with CHB, regardless of ALT levels. Another cohort study in South Korea found a nonlinear parabolic association between HCC risk and HBV DNA levels up to 9 log10 IU/mL, with the highest risks found for moderate HBV DNA levels around 6 log10 IU/mL.

In this study, Lim and colleagues developed a prognostic model to integrate the nonlinear relationship and validated it externally, as well as compared it with the previous REACH-B model. The Revised REACH-B model incorporates six variables: age, sex, platelet count, HBV DNA level, ALT, and hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg).

The study included 14,378 treatment-naive, noncirrhotic adults with CHB and serum ALT levels < two times the upper limit of normal for at least 1 year and serum hepatitis B surface antigen for at least 6 months. The internal validation cohort included 6,949 patients from Asan Medical Center, and the external validation cohort included 7,429 patients from previous studies in Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Among the Asan cohort, the mean age was 45 years, 29.9% were HBeAg positive, median HBV DNA levels were 3.1 log10 IU/mL, and the median ALT level was 25 U/L. In the external cohort, the mean age was 46 years, 21% were HBeAg positive, median HBV DNA levels were 3.4 log10 IU/mL, and the median ALT level was 20 U/L.

In the Asan cohort, 435 patients (6.3%) developed HCC during a median follow-up of 10 years. The annual HCC incidence rate was 0.63 per 100 person-years, and the estimated cumulative probability of developing HCC at 10 years was 6.4%.

In the external cohort, 467 patients (6.3%) developed HCC during a median follow-up of 12 years. The annual HCC incidence rate was 0.42 per 100 person-years, and the estimated cumulative probability of developing HCC at 10 years was 3.1%.

Overall, the association between HBV viral load and HCC risk was linear in the HBeAg-negative groups and inverse in the HBeAg-positive groups, with the association between HBV viral load and HCC risk showing a nonlinear parabolic pattern.

Across both cohorts, patients with HBV DNA levels between 5 and 6 log10 IU/mL had the highest risk for HCC in both the HBeAg-negative and HBeAg-positive groups, which was more than eight times higher than those HBV DNA levels ≤ 3 log10 IU/mL.

For internal validation, the Revised REACH-B model had a c-statistic of 0.844 and 5-year area under the curve of 0.864. For external validation across the three external cohorts, the reREACH-B had c-statistics of 0.804, 0.808, and 0.813, and 5-year area under the curve of 0.839, 0.860, and 0.865.

In addition, the revised model yielded a greater positive net benefit than the REACH-B model in the threshold probability range between 0% and 18%.

“These analyses indicate the reREACH-B model can be a valuable tool in clinical practice, aiding in timely management decisions,” Lim said.

Considering Prognostic Models

This study highlights the importance of recognizing that the association between HBV DNA viral load and HCC risk isn’t linear, said Norah Terrault, MD, chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“In contrast to most chronic liver diseases where liver cancer develops only among those with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis, people with chronic hepatitis B are at risk prior to the development of cirrhosis,” she said. “Risk prediction scores for HCC can be a useful means of identifying those without cirrhosis who should be enrolled in HCC surveillance programs.”

For instance, patients with HBV DNA levels < 3 log10 IU/mL or > 8 log10 IU/mL don’t have an increased risk, Terrault noted. However, the highest risk group appears to be around 5-6 log10 IU/mL.

“Future risk prediction models should acknowledge that relationship in modeling HCC risk,” she said. “The re-REACH-B provides modest improvement over the REACH-B, but further validation of this score in more diverse cohorts is essential.”

The study received financial support from the Korean government and grants from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center of the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency and the National R&D Program for Cancer Control through the National Cancer Center, which is funded by Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare. Lim and Terrault reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The model, called Revised REACH-B or reREACH-B, stems from cohort studies in Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan, and looks at the nonlinear parabolic association between serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA levels and HCC risk.

“Current clinical practice guidelines don’t advocate antiviral treatment for patients with CHB who don’t show elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, even in those with high HBV viral loads,” said coauthor Young-Suk Lim, MD, PhD, professor of gastroenterology at the University of Ulsan College of Medicine and Asan Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea.

“This stance is rooted in the notion that patients in the immune-tolerant phase are at very low risk for developing HCC,” Lim said. “However, the immune-tolerant phase includes patients with HBV DNA levels who face the highest risk for HCC, and many patients with moderate HBV viremia fall into an undefined gray zone.”

The study was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Validating reREACH-B

During a course of CHB, HBV viral loads and HCC risks evolve over time because of viral replication and host immune responses, Lim explained. Most patients typically move to seroclearance and an “inactive hepatitis” phase, but about 10%-20% can progress to a “reactivation” phase, where HBV DNA levels and ALT levels increase, which can increase HCC risk as well.

In a previous cohort study in Taiwan, a prognostic model called Risk Estimation for HCC in CHB — or REACH-B — found the risk for HCC increases tenfold with increasing levels of HBV DNA up to 5 log10IU/mL in noncirrhotic patients with CHB, regardless of ALT levels. Another cohort study in South Korea found a nonlinear parabolic association between HCC risk and HBV DNA levels up to 9 log10 IU/mL, with the highest risks found for moderate HBV DNA levels around 6 log10 IU/mL.

In this study, Lim and colleagues developed a prognostic model to integrate the nonlinear relationship and validated it externally, as well as compared it with the previous REACH-B model. The Revised REACH-B model incorporates six variables: age, sex, platelet count, HBV DNA level, ALT, and hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg).

The study included 14,378 treatment-naive, noncirrhotic adults with CHB and serum ALT levels < two times the upper limit of normal for at least 1 year and serum hepatitis B surface antigen for at least 6 months. The internal validation cohort included 6,949 patients from Asan Medical Center, and the external validation cohort included 7,429 patients from previous studies in Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Among the Asan cohort, the mean age was 45 years, 29.9% were HBeAg positive, median HBV DNA levels were 3.1 log10 IU/mL, and the median ALT level was 25 U/L. In the external cohort, the mean age was 46 years, 21% were HBeAg positive, median HBV DNA levels were 3.4 log10 IU/mL, and the median ALT level was 20 U/L.

In the Asan cohort, 435 patients (6.3%) developed HCC during a median follow-up of 10 years. The annual HCC incidence rate was 0.63 per 100 person-years, and the estimated cumulative probability of developing HCC at 10 years was 6.4%.

In the external cohort, 467 patients (6.3%) developed HCC during a median follow-up of 12 years. The annual HCC incidence rate was 0.42 per 100 person-years, and the estimated cumulative probability of developing HCC at 10 years was 3.1%.

Overall, the association between HBV viral load and HCC risk was linear in the HBeAg-negative groups and inverse in the HBeAg-positive groups, with the association between HBV viral load and HCC risk showing a nonlinear parabolic pattern.

Across both cohorts, patients with HBV DNA levels between 5 and 6 log10 IU/mL had the highest risk for HCC in both the HBeAg-negative and HBeAg-positive groups, which was more than eight times higher than those HBV DNA levels ≤ 3 log10 IU/mL.

For internal validation, the Revised REACH-B model had a c-statistic of 0.844 and 5-year area under the curve of 0.864. For external validation across the three external cohorts, the reREACH-B had c-statistics of 0.804, 0.808, and 0.813, and 5-year area under the curve of 0.839, 0.860, and 0.865.

In addition, the revised model yielded a greater positive net benefit than the REACH-B model in the threshold probability range between 0% and 18%.

“These analyses indicate the reREACH-B model can be a valuable tool in clinical practice, aiding in timely management decisions,” Lim said.

Considering Prognostic Models

This study highlights the importance of recognizing that the association between HBV DNA viral load and HCC risk isn’t linear, said Norah Terrault, MD, chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“In contrast to most chronic liver diseases where liver cancer develops only among those with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis, people with chronic hepatitis B are at risk prior to the development of cirrhosis,” she said. “Risk prediction scores for HCC can be a useful means of identifying those without cirrhosis who should be enrolled in HCC surveillance programs.”

For instance, patients with HBV DNA levels < 3 log10 IU/mL or > 8 log10 IU/mL don’t have an increased risk, Terrault noted. However, the highest risk group appears to be around 5-6 log10 IU/mL.

“Future risk prediction models should acknowledge that relationship in modeling HCC risk,” she said. “The re-REACH-B provides modest improvement over the REACH-B, but further validation of this score in more diverse cohorts is essential.”

The study received financial support from the Korean government and grants from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center of the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency and the National R&D Program for Cancer Control through the National Cancer Center, which is funded by Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare. Lim and Terrault reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The model, called Revised REACH-B or reREACH-B, stems from cohort studies in Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan, and looks at the nonlinear parabolic association between serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA levels and HCC risk.

“Current clinical practice guidelines don’t advocate antiviral treatment for patients with CHB who don’t show elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, even in those with high HBV viral loads,” said coauthor Young-Suk Lim, MD, PhD, professor of gastroenterology at the University of Ulsan College of Medicine and Asan Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea.

“This stance is rooted in the notion that patients in the immune-tolerant phase are at very low risk for developing HCC,” Lim said. “However, the immune-tolerant phase includes patients with HBV DNA levels who face the highest risk for HCC, and many patients with moderate HBV viremia fall into an undefined gray zone.”

The study was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Validating reREACH-B

During a course of CHB, HBV viral loads and HCC risks evolve over time because of viral replication and host immune responses, Lim explained. Most patients typically move to seroclearance and an “inactive hepatitis” phase, but about 10%-20% can progress to a “reactivation” phase, where HBV DNA levels and ALT levels increase, which can increase HCC risk as well.

In a previous cohort study in Taiwan, a prognostic model called Risk Estimation for HCC in CHB — or REACH-B — found the risk for HCC increases tenfold with increasing levels of HBV DNA up to 5 log10IU/mL in noncirrhotic patients with CHB, regardless of ALT levels. Another cohort study in South Korea found a nonlinear parabolic association between HCC risk and HBV DNA levels up to 9 log10 IU/mL, with the highest risks found for moderate HBV DNA levels around 6 log10 IU/mL.

In this study, Lim and colleagues developed a prognostic model to integrate the nonlinear relationship and validated it externally, as well as compared it with the previous REACH-B model. The Revised REACH-B model incorporates six variables: age, sex, platelet count, HBV DNA level, ALT, and hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg).

The study included 14,378 treatment-naive, noncirrhotic adults with CHB and serum ALT levels < two times the upper limit of normal for at least 1 year and serum hepatitis B surface antigen for at least 6 months. The internal validation cohort included 6,949 patients from Asan Medical Center, and the external validation cohort included 7,429 patients from previous studies in Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Among the Asan cohort, the mean age was 45 years, 29.9% were HBeAg positive, median HBV DNA levels were 3.1 log10 IU/mL, and the median ALT level was 25 U/L. In the external cohort, the mean age was 46 years, 21% were HBeAg positive, median HBV DNA levels were 3.4 log10 IU/mL, and the median ALT level was 20 U/L.

In the Asan cohort, 435 patients (6.3%) developed HCC during a median follow-up of 10 years. The annual HCC incidence rate was 0.63 per 100 person-years, and the estimated cumulative probability of developing HCC at 10 years was 6.4%.

In the external cohort, 467 patients (6.3%) developed HCC during a median follow-up of 12 years. The annual HCC incidence rate was 0.42 per 100 person-years, and the estimated cumulative probability of developing HCC at 10 years was 3.1%.

Overall, the association between HBV viral load and HCC risk was linear in the HBeAg-negative groups and inverse in the HBeAg-positive groups, with the association between HBV viral load and HCC risk showing a nonlinear parabolic pattern.

Across both cohorts, patients with HBV DNA levels between 5 and 6 log10 IU/mL had the highest risk for HCC in both the HBeAg-negative and HBeAg-positive groups, which was more than eight times higher than those HBV DNA levels ≤ 3 log10 IU/mL.

For internal validation, the Revised REACH-B model had a c-statistic of 0.844 and 5-year area under the curve of 0.864. For external validation across the three external cohorts, the reREACH-B had c-statistics of 0.804, 0.808, and 0.813, and 5-year area under the curve of 0.839, 0.860, and 0.865.

In addition, the revised model yielded a greater positive net benefit than the REACH-B model in the threshold probability range between 0% and 18%.

“These analyses indicate the reREACH-B model can be a valuable tool in clinical practice, aiding in timely management decisions,” Lim said.

Considering Prognostic Models

This study highlights the importance of recognizing that the association between HBV DNA viral load and HCC risk isn’t linear, said Norah Terrault, MD, chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“In contrast to most chronic liver diseases where liver cancer develops only among those with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis, people with chronic hepatitis B are at risk prior to the development of cirrhosis,” she said. “Risk prediction scores for HCC can be a useful means of identifying those without cirrhosis who should be enrolled in HCC surveillance programs.”

For instance, patients with HBV DNA levels < 3 log10 IU/mL or > 8 log10 IU/mL don’t have an increased risk, Terrault noted. However, the highest risk group appears to be around 5-6 log10 IU/mL.

“Future risk prediction models should acknowledge that relationship in modeling HCC risk,” she said. “The re-REACH-B provides modest improvement over the REACH-B, but further validation of this score in more diverse cohorts is essential.”

The study received financial support from the Korean government and grants from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center of the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency and the National R&D Program for Cancer Control through the National Cancer Center, which is funded by Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare. Lim and Terrault reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Red Wine May Not Be a Health Tonic, But Is It a Cancer Risk?

Earlier this month, US surgeon general Vivek Murthy, MD, issued an advisory, calling for alcoholic beverages to carry a warning label about cancer risk. The advisory flagged alcohol as the third leading preventable cause of cancer in the United States, after tobacco and obesity, and highlighted people’s limited awareness about the relationship between alcohol and cancer risk.

But, when it comes to cancer risk, are all types of alcohol created equal?

For many years, red wine seemed to be an outlier, with studies indicating that, in moderation, it might even be good for you. Red wine has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties — most notably, it contains the antioxidant resveratrol. Starting in the 1990s, research began to hint that the compound might protect against heart disease, aging, and cancer, though much of this work was done in animals or test tubes.

The idea that red wine carries health benefits, however, has been called into question more recently. A recent meta-analysis, for instance, suggests that many previous studies touting the health benefits of more moderate drinking were likely biased, potentially leading to “misleading positive health associations.” And one recent study found that alcohol consumption, largely red wine and beer, at all levels was linked to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

Although wine’s health halo is dwindling, there might be an exception: Cancer risk.

Overall, research shows that even light to moderate drinking increases the risk for at least seven types of cancer, but when focusing on red wine, in particular, that risk calculus can look different.

“It’s very complicated and nuanced,” said Timothy Rebbeck, PhD, professor of cancer prevention, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “And ‘complicated and nuanced’ doesn’t work very well in public health messages.”

The Knowns About Alcohol and Cancer Risk

Some things about the relationship between alcohol and cancer risk are crystal clear. “There’s no question that alcohol is a group 1 carcinogen,” Rebbeck said. “Alcohol can cause cancer.”

Groups including the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and American Cancer Society agree that alcohol use is an established cause of seven types of cancer: Those of the oral cavity, larynx, pharynx, esophagus (squamous cell carcinoma), liver (hepatocellular carcinoma), breast, and colon/rectum. Heavy drinking — at least 8 standard drinks a week for women and 15 for men — and binge drinking — 4 or more drinks in 2 hours for women and 5 or more for men — only amplify that risk. (A “standard” drink has 14 g of alcohol, which translates to a 5-oz glass of wine.)

“We’re most concerned about high-risk drinking — more than 2 drinks a day — and/or binge drinking,” said Noelle LoConte, MD, of the Division of Hematology, Medical Oncology and Palliative Care, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, who authored a 2018 statement on alcohol and cancer risk from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Compared with not drinking, heavy drinking is linked with a roughly fivefold increase in the risk for oral cavity, pharyngeal, and esophageal cancers, and a 61% increase in the risk for breast cancer, according to LoConte and colleagues.

Things get murkier when it comes to moderate drinking — defined as up to 1 standard drink per day for women and 2 per day for men. There is evidence, LoConte said, that moderate drinking is associated with increased cancer risks, though the magnitude is generally much less than heavier drinking.

Cancer type also matters. One analysis found that the risk for breast cancer increased with even light to moderate alcohol consumption. Compared with no drinking, light to moderate drinking has also been linked to increased risks for oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and esophageal cancers.

As for whether the type of alcoholic beverage matters, LoConte said, there’s no clear physiological reason that wine would be less risky than beer or liquor. Research indicates that ethanol is the problematic ingredient: Once ingested, it’s metabolized into acetaldehyde, a DNA-damaging substance that’s considered a probable human carcinogen. Ethanol can also alter circulating levels of estrogens and androgens, LoConte said, which is thought to drive its association with breast cancer risk.

“It likely doesn’t matter how you choose to get your ethanol,” she said. “It’s a question of volume.”

Hints That Wine Is an Outlier

Still, some studies suggest that how people ingest ethanol could make a difference.

A study published in August in JAMA Network Open is a case in point. The study found that, among older adults, light to heavy drinkers had an increased risk of dying from cancer, compared with occasional drinkers (though the increased risk among light to moderate drinkers occurred only among people who also had chronic health conditions, such as diabetes or high blood pressure, or were of lower socioeconomic status).

Wine drinkers fared differently. Most notably, drinkers who “preferred” wine — consuming over 80% of total ethanol from wine — or those who drank only with meals showed a small reduction in their risk for cancer mortality and all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 0.94 for both). The small protective association was somewhat stronger among people who reported both patterns (HR, 0.88), especially if they were of lower socioeconomic status (HR, 0.79).

The findings are in line with other research suggesting that wine drinkers may be outliers when it comes to cancer risk. A 2023 meta-analysis of 26 observational studies, for instance, found no association between wine consumption and any cancer type, with the caveat that there was «substantial» heterogeneity among the studies.

This heterogeneity caveat speaks to the inherent limitations of observational research, said Tim Stockwell, PhD, of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada.

“Individual studies of alcohol and cancer risk do find differences by type of drink, or patterns of drinking,” Stockwell said. “But it’s so hard to unpack the confounding that goes along with the type of person who’s a wine drinker or a beer drinker or a spirit drinker. The beverage of choice seems to come with a lot of baggage.”

Compared with people who favor beer or liquor, he noted, wine aficionados are typically higher-income, exercise more often, smoke less, and have different diets, for example. The “best” studies, Rebbeck said, try to adjust for those differences, but it’s challenging.

The authors of the 2023 meta-analysis noted that “many components in wine could have anticarcinogenic effects” that theoretically could counter the ill effects of ethanol. Besides resveratrol, which is mainly found in red wine, the list includes anthocyanins, quercetin, and tannins. However, the authors also acknowledged that they couldn’t account for whether other lifestyle habits might explain why wine drinkers, overall, showed no increased cancer risks and sometimes lower risks.

Still, groups such as the IARC and ASCO hold that there is no known “safe” level, or type, of alcohol when it comes to cancer.

In the latest Canadian guidelines on alcohol use, the scientific panel calculated that people who have 6 drinks a week throughout adulthood (whatever the source of the alcohol) could shave 11 weeks from their life expectancy, on average, said Stockwell, who was on the guideline panel. Compare that with heavy drinking, where 4 drinks a day could rob the average person of 2 or 3 years. “If you’re drinking a lot, you could get huge benefits from cutting down,” Stockwell explained. “If you’re a moderate drinker, the benefits would obviously be less.”

Stockwell said that choices around drinking and breast cancer risk, specifically, can be “tough.” Unlike many of the other alcohol-associated cancers, he noted, breast cancer is common — so even small relative risk increases may be concerning. Based on a 2020 meta-analysis of 22 cohort studies, the risk for breast cancer rises by about 10%, on average, for every 10 g of alcohol a woman drinks per day. This study also found no evidence that wine is any different from other types of alcohol.

In real life, the calculus around wine consumption and cancer risk will probably vary widely from person to person, Rebbeck said. One woman with a family history of breast cancer might decide that having wine with dinner isn’t worth it. Another with the same family history might see that glass of wine as a stress reliever and opt to focus on other ways to reduce her breast cancer risk — by exercising and maintaining a healthy weight, for example.

“The bottom line is, in human studies, the data on light to moderate drinking and cancer are limited and messy, and you can’t draw firm conclusions from them,” Rebbeck said. “It probably raises risk in some people, but we don’t know who those people are. And the risk increases are relatively small.”

A Conversation Few Are Having

Even with many studies highlighting the connection between alcohol consumption and cancer risk, most people remain unaware about this risk.

A 2023 study by the National Cancer Institute found that only a minority of US adults knew that drinking alcohol is linked to increased cancer risk, and they were much less likely to say that was true of wine: Only 20% did, vs 31% who said that liquor can boost cancer risk. Meanwhile, 10% believed that wine helps prevent cancer. Other studies show that even among cancer survivors and patients undergoing active cancer treatment, many drink — often heavily.

“What we know right now is, physicians almost never talk about this,” LoConte said.

That could be due to time constraints, according to Rebbeck, or clinicians’ perceptions that the subject is too complicated and/or their own confusion about the data. There could also be some “cognitive dissonance” at play, LoConte noted, because many doctors drink alcohol.

It’s critical, she said, that conversations about drinking habits become “normalized,” and that should include informing patients that alcohol use is associated with certain cancers. Again, LoConte said, it’s high-risk drinking that’s most concerning and where reducing intake could have the biggest impact on cancer risk and other health outcomes.

“From a cancer prevention standpoint, it’s probably best not to drink,” she said. “But people don’t make choices based solely on cancer risk. We don’t want to come out with recommendations saying no one should drink. I don’t think the data support that, and people would buck against that advice.”

Rebbeck made a similar point. Even if there’s uncertainty about the risks for a daily glass of wine, he said, people can use that information to make decisions. “Everybody’s preferences and choices are going to be different,” Rebbeck said. “And that’s all we can really do.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Earlier this month, US surgeon general Vivek Murthy, MD, issued an advisory, calling for alcoholic beverages to carry a warning label about cancer risk. The advisory flagged alcohol as the third leading preventable cause of cancer in the United States, after tobacco and obesity, and highlighted people’s limited awareness about the relationship between alcohol and cancer risk.

But, when it comes to cancer risk, are all types of alcohol created equal?

For many years, red wine seemed to be an outlier, with studies indicating that, in moderation, it might even be good for you. Red wine has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties — most notably, it contains the antioxidant resveratrol. Starting in the 1990s, research began to hint that the compound might protect against heart disease, aging, and cancer, though much of this work was done in animals or test tubes.

The idea that red wine carries health benefits, however, has been called into question more recently. A recent meta-analysis, for instance, suggests that many previous studies touting the health benefits of more moderate drinking were likely biased, potentially leading to “misleading positive health associations.” And one recent study found that alcohol consumption, largely red wine and beer, at all levels was linked to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

Although wine’s health halo is dwindling, there might be an exception: Cancer risk.

Overall, research shows that even light to moderate drinking increases the risk for at least seven types of cancer, but when focusing on red wine, in particular, that risk calculus can look different.

“It’s very complicated and nuanced,” said Timothy Rebbeck, PhD, professor of cancer prevention, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “And ‘complicated and nuanced’ doesn’t work very well in public health messages.”

The Knowns About Alcohol and Cancer Risk

Some things about the relationship between alcohol and cancer risk are crystal clear. “There’s no question that alcohol is a group 1 carcinogen,” Rebbeck said. “Alcohol can cause cancer.”

Groups including the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and American Cancer Society agree that alcohol use is an established cause of seven types of cancer: Those of the oral cavity, larynx, pharynx, esophagus (squamous cell carcinoma), liver (hepatocellular carcinoma), breast, and colon/rectum. Heavy drinking — at least 8 standard drinks a week for women and 15 for men — and binge drinking — 4 or more drinks in 2 hours for women and 5 or more for men — only amplify that risk. (A “standard” drink has 14 g of alcohol, which translates to a 5-oz glass of wine.)

“We’re most concerned about high-risk drinking — more than 2 drinks a day — and/or binge drinking,” said Noelle LoConte, MD, of the Division of Hematology, Medical Oncology and Palliative Care, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, who authored a 2018 statement on alcohol and cancer risk from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Compared with not drinking, heavy drinking is linked with a roughly fivefold increase in the risk for oral cavity, pharyngeal, and esophageal cancers, and a 61% increase in the risk for breast cancer, according to LoConte and colleagues.

Things get murkier when it comes to moderate drinking — defined as up to 1 standard drink per day for women and 2 per day for men. There is evidence, LoConte said, that moderate drinking is associated with increased cancer risks, though the magnitude is generally much less than heavier drinking.

Cancer type also matters. One analysis found that the risk for breast cancer increased with even light to moderate alcohol consumption. Compared with no drinking, light to moderate drinking has also been linked to increased risks for oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and esophageal cancers.

As for whether the type of alcoholic beverage matters, LoConte said, there’s no clear physiological reason that wine would be less risky than beer or liquor. Research indicates that ethanol is the problematic ingredient: Once ingested, it’s metabolized into acetaldehyde, a DNA-damaging substance that’s considered a probable human carcinogen. Ethanol can also alter circulating levels of estrogens and androgens, LoConte said, which is thought to drive its association with breast cancer risk.

“It likely doesn’t matter how you choose to get your ethanol,” she said. “It’s a question of volume.”

Hints That Wine Is an Outlier

Still, some studies suggest that how people ingest ethanol could make a difference.

A study published in August in JAMA Network Open is a case in point. The study found that, among older adults, light to heavy drinkers had an increased risk of dying from cancer, compared with occasional drinkers (though the increased risk among light to moderate drinkers occurred only among people who also had chronic health conditions, such as diabetes or high blood pressure, or were of lower socioeconomic status).

Wine drinkers fared differently. Most notably, drinkers who “preferred” wine — consuming over 80% of total ethanol from wine — or those who drank only with meals showed a small reduction in their risk for cancer mortality and all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 0.94 for both). The small protective association was somewhat stronger among people who reported both patterns (HR, 0.88), especially if they were of lower socioeconomic status (HR, 0.79).

The findings are in line with other research suggesting that wine drinkers may be outliers when it comes to cancer risk. A 2023 meta-analysis of 26 observational studies, for instance, found no association between wine consumption and any cancer type, with the caveat that there was «substantial» heterogeneity among the studies.

This heterogeneity caveat speaks to the inherent limitations of observational research, said Tim Stockwell, PhD, of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada.

“Individual studies of alcohol and cancer risk do find differences by type of drink, or patterns of drinking,” Stockwell said. “But it’s so hard to unpack the confounding that goes along with the type of person who’s a wine drinker or a beer drinker or a spirit drinker. The beverage of choice seems to come with a lot of baggage.”

Compared with people who favor beer or liquor, he noted, wine aficionados are typically higher-income, exercise more often, smoke less, and have different diets, for example. The “best” studies, Rebbeck said, try to adjust for those differences, but it’s challenging.

The authors of the 2023 meta-analysis noted that “many components in wine could have anticarcinogenic effects” that theoretically could counter the ill effects of ethanol. Besides resveratrol, which is mainly found in red wine, the list includes anthocyanins, quercetin, and tannins. However, the authors also acknowledged that they couldn’t account for whether other lifestyle habits might explain why wine drinkers, overall, showed no increased cancer risks and sometimes lower risks.

Still, groups such as the IARC and ASCO hold that there is no known “safe” level, or type, of alcohol when it comes to cancer.

In the latest Canadian guidelines on alcohol use, the scientific panel calculated that people who have 6 drinks a week throughout adulthood (whatever the source of the alcohol) could shave 11 weeks from their life expectancy, on average, said Stockwell, who was on the guideline panel. Compare that with heavy drinking, where 4 drinks a day could rob the average person of 2 or 3 years. “If you’re drinking a lot, you could get huge benefits from cutting down,” Stockwell explained. “If you’re a moderate drinker, the benefits would obviously be less.”

Stockwell said that choices around drinking and breast cancer risk, specifically, can be “tough.” Unlike many of the other alcohol-associated cancers, he noted, breast cancer is common — so even small relative risk increases may be concerning. Based on a 2020 meta-analysis of 22 cohort studies, the risk for breast cancer rises by about 10%, on average, for every 10 g of alcohol a woman drinks per day. This study also found no evidence that wine is any different from other types of alcohol.

In real life, the calculus around wine consumption and cancer risk will probably vary widely from person to person, Rebbeck said. One woman with a family history of breast cancer might decide that having wine with dinner isn’t worth it. Another with the same family history might see that glass of wine as a stress reliever and opt to focus on other ways to reduce her breast cancer risk — by exercising and maintaining a healthy weight, for example.

“The bottom line is, in human studies, the data on light to moderate drinking and cancer are limited and messy, and you can’t draw firm conclusions from them,” Rebbeck said. “It probably raises risk in some people, but we don’t know who those people are. And the risk increases are relatively small.”

A Conversation Few Are Having

Even with many studies highlighting the connection between alcohol consumption and cancer risk, most people remain unaware about this risk.

A 2023 study by the National Cancer Institute found that only a minority of US adults knew that drinking alcohol is linked to increased cancer risk, and they were much less likely to say that was true of wine: Only 20% did, vs 31% who said that liquor can boost cancer risk. Meanwhile, 10% believed that wine helps prevent cancer. Other studies show that even among cancer survivors and patients undergoing active cancer treatment, many drink — often heavily.

“What we know right now is, physicians almost never talk about this,” LoConte said.

That could be due to time constraints, according to Rebbeck, or clinicians’ perceptions that the subject is too complicated and/or their own confusion about the data. There could also be some “cognitive dissonance” at play, LoConte noted, because many doctors drink alcohol.

It’s critical, she said, that conversations about drinking habits become “normalized,” and that should include informing patients that alcohol use is associated with certain cancers. Again, LoConte said, it’s high-risk drinking that’s most concerning and where reducing intake could have the biggest impact on cancer risk and other health outcomes.

“From a cancer prevention standpoint, it’s probably best not to drink,” she said. “But people don’t make choices based solely on cancer risk. We don’t want to come out with recommendations saying no one should drink. I don’t think the data support that, and people would buck against that advice.”

Rebbeck made a similar point. Even if there’s uncertainty about the risks for a daily glass of wine, he said, people can use that information to make decisions. “Everybody’s preferences and choices are going to be different,” Rebbeck said. “And that’s all we can really do.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Earlier this month, US surgeon general Vivek Murthy, MD, issued an advisory, calling for alcoholic beverages to carry a warning label about cancer risk. The advisory flagged alcohol as the third leading preventable cause of cancer in the United States, after tobacco and obesity, and highlighted people’s limited awareness about the relationship between alcohol and cancer risk.

But, when it comes to cancer risk, are all types of alcohol created equal?

For many years, red wine seemed to be an outlier, with studies indicating that, in moderation, it might even be good for you. Red wine has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties — most notably, it contains the antioxidant resveratrol. Starting in the 1990s, research began to hint that the compound might protect against heart disease, aging, and cancer, though much of this work was done in animals or test tubes.

The idea that red wine carries health benefits, however, has been called into question more recently. A recent meta-analysis, for instance, suggests that many previous studies touting the health benefits of more moderate drinking were likely biased, potentially leading to “misleading positive health associations.” And one recent study found that alcohol consumption, largely red wine and beer, at all levels was linked to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

Although wine’s health halo is dwindling, there might be an exception: Cancer risk.

Overall, research shows that even light to moderate drinking increases the risk for at least seven types of cancer, but when focusing on red wine, in particular, that risk calculus can look different.

“It’s very complicated and nuanced,” said Timothy Rebbeck, PhD, professor of cancer prevention, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “And ‘complicated and nuanced’ doesn’t work very well in public health messages.”

The Knowns About Alcohol and Cancer Risk

Some things about the relationship between alcohol and cancer risk are crystal clear. “There’s no question that alcohol is a group 1 carcinogen,” Rebbeck said. “Alcohol can cause cancer.”

Groups including the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and American Cancer Society agree that alcohol use is an established cause of seven types of cancer: Those of the oral cavity, larynx, pharynx, esophagus (squamous cell carcinoma), liver (hepatocellular carcinoma), breast, and colon/rectum. Heavy drinking — at least 8 standard drinks a week for women and 15 for men — and binge drinking — 4 or more drinks in 2 hours for women and 5 or more for men — only amplify that risk. (A “standard” drink has 14 g of alcohol, which translates to a 5-oz glass of wine.)

“We’re most concerned about high-risk drinking — more than 2 drinks a day — and/or binge drinking,” said Noelle LoConte, MD, of the Division of Hematology, Medical Oncology and Palliative Care, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, who authored a 2018 statement on alcohol and cancer risk from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Compared with not drinking, heavy drinking is linked with a roughly fivefold increase in the risk for oral cavity, pharyngeal, and esophageal cancers, and a 61% increase in the risk for breast cancer, according to LoConte and colleagues.

Things get murkier when it comes to moderate drinking — defined as up to 1 standard drink per day for women and 2 per day for men. There is evidence, LoConte said, that moderate drinking is associated with increased cancer risks, though the magnitude is generally much less than heavier drinking.

Cancer type also matters. One analysis found that the risk for breast cancer increased with even light to moderate alcohol consumption. Compared with no drinking, light to moderate drinking has also been linked to increased risks for oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and esophageal cancers.

As for whether the type of alcoholic beverage matters, LoConte said, there’s no clear physiological reason that wine would be less risky than beer or liquor. Research indicates that ethanol is the problematic ingredient: Once ingested, it’s metabolized into acetaldehyde, a DNA-damaging substance that’s considered a probable human carcinogen. Ethanol can also alter circulating levels of estrogens and androgens, LoConte said, which is thought to drive its association with breast cancer risk.

“It likely doesn’t matter how you choose to get your ethanol,” she said. “It’s a question of volume.”

Hints That Wine Is an Outlier

Still, some studies suggest that how people ingest ethanol could make a difference.

A study published in August in JAMA Network Open is a case in point. The study found that, among older adults, light to heavy drinkers had an increased risk of dying from cancer, compared with occasional drinkers (though the increased risk among light to moderate drinkers occurred only among people who also had chronic health conditions, such as diabetes or high blood pressure, or were of lower socioeconomic status).

Wine drinkers fared differently. Most notably, drinkers who “preferred” wine — consuming over 80% of total ethanol from wine — or those who drank only with meals showed a small reduction in their risk for cancer mortality and all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 0.94 for both). The small protective association was somewhat stronger among people who reported both patterns (HR, 0.88), especially if they were of lower socioeconomic status (HR, 0.79).

The findings are in line with other research suggesting that wine drinkers may be outliers when it comes to cancer risk. A 2023 meta-analysis of 26 observational studies, for instance, found no association between wine consumption and any cancer type, with the caveat that there was «substantial» heterogeneity among the studies.

This heterogeneity caveat speaks to the inherent limitations of observational research, said Tim Stockwell, PhD, of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada.

“Individual studies of alcohol and cancer risk do find differences by type of drink, or patterns of drinking,” Stockwell said. “But it’s so hard to unpack the confounding that goes along with the type of person who’s a wine drinker or a beer drinker or a spirit drinker. The beverage of choice seems to come with a lot of baggage.”

Compared with people who favor beer or liquor, he noted, wine aficionados are typically higher-income, exercise more often, smoke less, and have different diets, for example. The “best” studies, Rebbeck said, try to adjust for those differences, but it’s challenging.

The authors of the 2023 meta-analysis noted that “many components in wine could have anticarcinogenic effects” that theoretically could counter the ill effects of ethanol. Besides resveratrol, which is mainly found in red wine, the list includes anthocyanins, quercetin, and tannins. However, the authors also acknowledged that they couldn’t account for whether other lifestyle habits might explain why wine drinkers, overall, showed no increased cancer risks and sometimes lower risks.

Still, groups such as the IARC and ASCO hold that there is no known “safe” level, or type, of alcohol when it comes to cancer.

In the latest Canadian guidelines on alcohol use, the scientific panel calculated that people who have 6 drinks a week throughout adulthood (whatever the source of the alcohol) could shave 11 weeks from their life expectancy, on average, said Stockwell, who was on the guideline panel. Compare that with heavy drinking, where 4 drinks a day could rob the average person of 2 or 3 years. “If you’re drinking a lot, you could get huge benefits from cutting down,” Stockwell explained. “If you’re a moderate drinker, the benefits would obviously be less.”

Stockwell said that choices around drinking and breast cancer risk, specifically, can be “tough.” Unlike many of the other alcohol-associated cancers, he noted, breast cancer is common — so even small relative risk increases may be concerning. Based on a 2020 meta-analysis of 22 cohort studies, the risk for breast cancer rises by about 10%, on average, for every 10 g of alcohol a woman drinks per day. This study also found no evidence that wine is any different from other types of alcohol.

In real life, the calculus around wine consumption and cancer risk will probably vary widely from person to person, Rebbeck said. One woman with a family history of breast cancer might decide that having wine with dinner isn’t worth it. Another with the same family history might see that glass of wine as a stress reliever and opt to focus on other ways to reduce her breast cancer risk — by exercising and maintaining a healthy weight, for example.

“The bottom line is, in human studies, the data on light to moderate drinking and cancer are limited and messy, and you can’t draw firm conclusions from them,” Rebbeck said. “It probably raises risk in some people, but we don’t know who those people are. And the risk increases are relatively small.”

A Conversation Few Are Having

Even with many studies highlighting the connection between alcohol consumption and cancer risk, most people remain unaware about this risk.

A 2023 study by the National Cancer Institute found that only a minority of US adults knew that drinking alcohol is linked to increased cancer risk, and they were much less likely to say that was true of wine: Only 20% did, vs 31% who said that liquor can boost cancer risk. Meanwhile, 10% believed that wine helps prevent cancer. Other studies show that even among cancer survivors and patients undergoing active cancer treatment, many drink — often heavily.

“What we know right now is, physicians almost never talk about this,” LoConte said.

That could be due to time constraints, according to Rebbeck, or clinicians’ perceptions that the subject is too complicated and/or their own confusion about the data. There could also be some “cognitive dissonance” at play, LoConte noted, because many doctors drink alcohol.

It’s critical, she said, that conversations about drinking habits become “normalized,” and that should include informing patients that alcohol use is associated with certain cancers. Again, LoConte said, it’s high-risk drinking that’s most concerning and where reducing intake could have the biggest impact on cancer risk and other health outcomes.

“From a cancer prevention standpoint, it’s probably best not to drink,” she said. “But people don’t make choices based solely on cancer risk. We don’t want to come out with recommendations saying no one should drink. I don’t think the data support that, and people would buck against that advice.”

Rebbeck made a similar point. Even if there’s uncertainty about the risks for a daily glass of wine, he said, people can use that information to make decisions. “Everybody’s preferences and choices are going to be different,” Rebbeck said. “And that’s all we can really do.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Dietary Calcium Cuts Colorectal Cancer Risk by 17%

Cancer Research UK (CRUK), which funded the study, said that it demonstrated the benefits of a healthy, balanced diet for lowering cancer risk.

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide. Incidence rates vary markedly, with higher rates observed in high-income countries. The risk increases for individuals who migrate from low- to high-incidence areas, suggesting that lifestyle and environmental factors contribute to its development.

While alcohol and processed meats are established carcinogens, and red meat is classified as probably carcinogenic, there is a lack of consensus regarding the relationships between other dietary factors and colorectal cancer risk. This uncertainty may be due, at least in part, to relatively few studies giving comprehensive results on all food types, as well as dietary measurement errors, and/or small sample sizes.

Study Tracked 97 Dietary Factors

To address these gaps, the research team, led by the University of Oxford in England, tracked the intake of 97 dietary factors in 542,778 women from 2001 for an average of 16.6 years. During this period 12,251 participants developed colorectal cancer. The women completed detailed dietary questionnaires at baseline, with 7% participating in at least one subsequent 24-hour online dietary assessment.

Women diagnosed with colorectal cancer were generally older, taller, more likely to have a family history of bowel cancer, and have more adverse health behaviors, compared with participants overall.

Calcium Intake Showed the Strongest Protective Association

Relative risks (RR) for colorectal cancer were calculated for intakes of all 97 dietary factors, with significant associations found for 17 of them. Calcium intake showed the strongest protective effect, with each additional 300 mg per day – equivalent to a large glass of milk – associated with a 17% reduced RR.

Six dairy-related factors associated with calcium – dairy milk, yogurt, riboflavin, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium intakes – also demonstrated inverse associations with colorectal cancer risk. Weaker protective effects were noted for breakfast cereal, fruit, wholegrains, carbohydrates, fibre, total sugars, folate, and vitamin C. However, the team commented that these inverse associations might reflect residual confounding from other lifestyle or other dietary factors.

Calcium’s protective role was independent of dairy milk intake. The study, published in Nature Communications, concluded that, while “dairy products help protect against colorectal cancer,” that protection is “driven largely or wholly by calcium.”

Alcohol and Processed Meat Confirmed as Risk Factors

As expected, alcohol showed the reverse association, with each additional 20 g daily – equivalent to one large glass of wine – associated with a 15% RR increase. Weaker associations were seen for the combined category of red and processed meat, with each additional 30 g per day associated with an 8% increased RR for colorectal cancer. This association was minimally affected by diet and lifestyle factors.

Commenting to the Science Media Centre (SMC), Tom Sanders, professor emeritus of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, England, said: “One theory is that the calcium may bind to free bile acids in the gut, preventing the harmful effects of free bile acids on gut mucosa.” However, the lactose content in milk also has effects on large bowel microflora, which may in turn affect risk.

Also commenting to the SMC, David Nunan, senior research fellow at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Evidence Based Medicine, who was not involved in the study, cautioned that the findings were subject to the bias inherent in observational studies. “These biases often inflate the estimated associations compared to controlled experiments,” he said. Nunan advised caution in interpreting the findings, as more robust research, such as randomized controlled trials, would be needed to establish causation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer Research UK (CRUK), which funded the study, said that it demonstrated the benefits of a healthy, balanced diet for lowering cancer risk.

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide. Incidence rates vary markedly, with higher rates observed in high-income countries. The risk increases for individuals who migrate from low- to high-incidence areas, suggesting that lifestyle and environmental factors contribute to its development.

While alcohol and processed meats are established carcinogens, and red meat is classified as probably carcinogenic, there is a lack of consensus regarding the relationships between other dietary factors and colorectal cancer risk. This uncertainty may be due, at least in part, to relatively few studies giving comprehensive results on all food types, as well as dietary measurement errors, and/or small sample sizes.

Study Tracked 97 Dietary Factors

To address these gaps, the research team, led by the University of Oxford in England, tracked the intake of 97 dietary factors in 542,778 women from 2001 for an average of 16.6 years. During this period 12,251 participants developed colorectal cancer. The women completed detailed dietary questionnaires at baseline, with 7% participating in at least one subsequent 24-hour online dietary assessment.

Women diagnosed with colorectal cancer were generally older, taller, more likely to have a family history of bowel cancer, and have more adverse health behaviors, compared with participants overall.

Calcium Intake Showed the Strongest Protective Association

Relative risks (RR) for colorectal cancer were calculated for intakes of all 97 dietary factors, with significant associations found for 17 of them. Calcium intake showed the strongest protective effect, with each additional 300 mg per day – equivalent to a large glass of milk – associated with a 17% reduced RR.

Six dairy-related factors associated with calcium – dairy milk, yogurt, riboflavin, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium intakes – also demonstrated inverse associations with colorectal cancer risk. Weaker protective effects were noted for breakfast cereal, fruit, wholegrains, carbohydrates, fibre, total sugars, folate, and vitamin C. However, the team commented that these inverse associations might reflect residual confounding from other lifestyle or other dietary factors.

Calcium’s protective role was independent of dairy milk intake. The study, published in Nature Communications, concluded that, while “dairy products help protect against colorectal cancer,” that protection is “driven largely or wholly by calcium.”

Alcohol and Processed Meat Confirmed as Risk Factors

As expected, alcohol showed the reverse association, with each additional 20 g daily – equivalent to one large glass of wine – associated with a 15% RR increase. Weaker associations were seen for the combined category of red and processed meat, with each additional 30 g per day associated with an 8% increased RR for colorectal cancer. This association was minimally affected by diet and lifestyle factors.

Commenting to the Science Media Centre (SMC), Tom Sanders, professor emeritus of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, England, said: “One theory is that the calcium may bind to free bile acids in the gut, preventing the harmful effects of free bile acids on gut mucosa.” However, the lactose content in milk also has effects on large bowel microflora, which may in turn affect risk.

Also commenting to the SMC, David Nunan, senior research fellow at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Evidence Based Medicine, who was not involved in the study, cautioned that the findings were subject to the bias inherent in observational studies. “These biases often inflate the estimated associations compared to controlled experiments,” he said. Nunan advised caution in interpreting the findings, as more robust research, such as randomized controlled trials, would be needed to establish causation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer Research UK (CRUK), which funded the study, said that it demonstrated the benefits of a healthy, balanced diet for lowering cancer risk.

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide. Incidence rates vary markedly, with higher rates observed in high-income countries. The risk increases for individuals who migrate from low- to high-incidence areas, suggesting that lifestyle and environmental factors contribute to its development.

While alcohol and processed meats are established carcinogens, and red meat is classified as probably carcinogenic, there is a lack of consensus regarding the relationships between other dietary factors and colorectal cancer risk. This uncertainty may be due, at least in part, to relatively few studies giving comprehensive results on all food types, as well as dietary measurement errors, and/or small sample sizes.

Study Tracked 97 Dietary Factors

To address these gaps, the research team, led by the University of Oxford in England, tracked the intake of 97 dietary factors in 542,778 women from 2001 for an average of 16.6 years. During this period 12,251 participants developed colorectal cancer. The women completed detailed dietary questionnaires at baseline, with 7% participating in at least one subsequent 24-hour online dietary assessment.

Women diagnosed with colorectal cancer were generally older, taller, more likely to have a family history of bowel cancer, and have more adverse health behaviors, compared with participants overall.

Calcium Intake Showed the Strongest Protective Association

Relative risks (RR) for colorectal cancer were calculated for intakes of all 97 dietary factors, with significant associations found for 17 of them. Calcium intake showed the strongest protective effect, with each additional 300 mg per day – equivalent to a large glass of milk – associated with a 17% reduced RR.

Six dairy-related factors associated with calcium – dairy milk, yogurt, riboflavin, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium intakes – also demonstrated inverse associations with colorectal cancer risk. Weaker protective effects were noted for breakfast cereal, fruit, wholegrains, carbohydrates, fibre, total sugars, folate, and vitamin C. However, the team commented that these inverse associations might reflect residual confounding from other lifestyle or other dietary factors.

Calcium’s protective role was independent of dairy milk intake. The study, published in Nature Communications, concluded that, while “dairy products help protect against colorectal cancer,” that protection is “driven largely or wholly by calcium.”

Alcohol and Processed Meat Confirmed as Risk Factors

As expected, alcohol showed the reverse association, with each additional 20 g daily – equivalent to one large glass of wine – associated with a 15% RR increase. Weaker associations were seen for the combined category of red and processed meat, with each additional 30 g per day associated with an 8% increased RR for colorectal cancer. This association was minimally affected by diet and lifestyle factors.

Commenting to the Science Media Centre (SMC), Tom Sanders, professor emeritus of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, England, said: “One theory is that the calcium may bind to free bile acids in the gut, preventing the harmful effects of free bile acids on gut mucosa.” However, the lactose content in milk also has effects on large bowel microflora, which may in turn affect risk.

Also commenting to the SMC, David Nunan, senior research fellow at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Evidence Based Medicine, who was not involved in the study, cautioned that the findings were subject to the bias inherent in observational studies. “These biases often inflate the estimated associations compared to controlled experiments,” he said. Nunan advised caution in interpreting the findings, as more robust research, such as randomized controlled trials, would be needed to establish causation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

MRI-Invisible Prostate Lesions: Are They Dangerous?

MRI-invisible prostate lesions. It sounds like the stuff of science fiction and fantasy, a creation from the minds of H.G. Wells, who wrote The Invisible Man, or J.K. Rowling, who authored the Harry Potter series.

But MRI-invisible prostate lesions are real. And what these lesions may, or may not, indicate is the subject of intense debate.

MRI plays an increasingly important role in detecting and diagnosing prostate cancer, staging prostate cancer as well as monitoring disease progression. However, on occasion, a puzzling phenomenon arises. Certain prostate lesions that appear when pathologists examine biopsied tissue samples under a microscope are not visible on MRI. The prostate tissue will, instead, appear normal to a radiologist’s eye.

Some experts believe these MRI-invisible lesions are nothing to worry about.

If the clinician can’t see the cancer on MRI, then it simply isn’t a threat, according to Mark Emberton, MD, a pioneer in prostate MRIs and director of interventional oncology at University College London, England.

Laurence Klotz, MD, of the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, agreed, noting that “invisible cancers are clinically insignificant and don’t require systematic biopsies.”

Emberton and Klotz compared MRI-invisible lesions to grade group 1 prostate cancer (Gleason score ≤ 6) — the least aggressive category that indicates the cancer that is not likely to spread or kill. For patients on active surveillance, those with MRI-invisible cancers do drastically better than those with visible cancers, Klotz explained.

But other experts in the field are skeptical that MRI-invisible lesions are truly innocuous.

Although statistically an MRI-visible prostate lesion indicates a more aggressive tumor, that is not always the case for every individual, said Brian Helfand, MD, PhD, chief of urology at NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, Illinois.