User login

Team-Based Care is Crucial for Head-and-Neck Cancer Cases

Team-Based Care is Crucial for Head-and-Neck Cancer Cases

PHOENIX – A 70-year-old Vietnam veteran with oropharyngeal cancer presented challenges beyond his disease.

He couldn’t afford transportation for daily radiation treatments and had lost > 10% of his body weight due to pain and eating difficulties, recalled radiation oncologist Vinita Takiar, MD, PhD, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology.

To make matters more difficult, his wife held medical power of attorney despite his apparent competence to make decisions, said Takiar, who formerly worked with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Cincinnati Healthcare System and is now chair of radiation oncology at Penn State University.

All these factors would likely have derailed his treatment if not for a coordinated team intervention, Takiar said. Fortunately, the clinic launched a multifaceted effort involving representatives from the social work, dentistry, ethics, nutrition, and chaplaincy departments.

When surgery became impossible because the patient couldn’t lie on the operating table for adequate tumor exposure, she said, the existing team framework enabled a seamless and rapid transition to radiation with concurrent chemotherapy.

The patient completed treatment with an excellent response, offering a lesson in the importance of multidisciplinary care in head-and-neck cancers, she said.

In fact, when it comes to these forms of cancer, coordinated care “is probably more impactful than any treatment that we’re going to come up with,” she said. “The data show that when we do multidisciplinary care and we do it well, it actually improves the patient experience and outcomes.”

As Takiar noted, teamwork matters in many ways. It leads to better logistics and can address disparities, reduce financial burden and stigma, and even increase clinical trial involvement.

She pointed to studies linking teamwork to better outcomes, support for patients, and overall survival.

Takiar highlighted different parts of teams headed by radiation oncologists who act as “a node to improve multimodal care delivery.”

Speech and swallowing specialists, for example, are helpful in head-and-neck cancer because “there’s an impact on speech, swallowing, and appearance. Our patients don’t want to go out to dinner with friends because they can’t do it.”

Dentists and prosthodontists are key team members too: “I have dentists who have my cell phone number. They just call me: ‘Can I do this extraction? Was this in your radiation field? What was the dose?’”

Other team members include ear, nose, and throat specialists, palliative and supportive care specialists, medical oncologists, nurses, pathologists, transportation workers, and service connection specialists. She noted that previous military experience can affect radiation therapy. For example, the physical restraints required during treatment present particular challenges for veterans who’ve had wartime trauma. These patients may require therapy adjustments.

What’s next on the horizon? Takiar highlighted precision oncology and molecular profiling, artificial intelligence in care decisions and in radiation planning, telemedicine and virtual tumor boards, and expanded survivorship programs.

As for now, she urged colleagues to not be afraid to chat with radiation oncologists. “Please talk to us. We prioritize open communication and shared decision-making with the entire team,” she said. “If you see something and think your radiation oncologist should know about it, you think it was caused by the radiation, you should reach out to us.”

Takiar reported no disclosures.

PHOENIX – A 70-year-old Vietnam veteran with oropharyngeal cancer presented challenges beyond his disease.

He couldn’t afford transportation for daily radiation treatments and had lost > 10% of his body weight due to pain and eating difficulties, recalled radiation oncologist Vinita Takiar, MD, PhD, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology.

To make matters more difficult, his wife held medical power of attorney despite his apparent competence to make decisions, said Takiar, who formerly worked with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Cincinnati Healthcare System and is now chair of radiation oncology at Penn State University.

All these factors would likely have derailed his treatment if not for a coordinated team intervention, Takiar said. Fortunately, the clinic launched a multifaceted effort involving representatives from the social work, dentistry, ethics, nutrition, and chaplaincy departments.

When surgery became impossible because the patient couldn’t lie on the operating table for adequate tumor exposure, she said, the existing team framework enabled a seamless and rapid transition to radiation with concurrent chemotherapy.

The patient completed treatment with an excellent response, offering a lesson in the importance of multidisciplinary care in head-and-neck cancers, she said.

In fact, when it comes to these forms of cancer, coordinated care “is probably more impactful than any treatment that we’re going to come up with,” she said. “The data show that when we do multidisciplinary care and we do it well, it actually improves the patient experience and outcomes.”

As Takiar noted, teamwork matters in many ways. It leads to better logistics and can address disparities, reduce financial burden and stigma, and even increase clinical trial involvement.

She pointed to studies linking teamwork to better outcomes, support for patients, and overall survival.

Takiar highlighted different parts of teams headed by radiation oncologists who act as “a node to improve multimodal care delivery.”

Speech and swallowing specialists, for example, are helpful in head-and-neck cancer because “there’s an impact on speech, swallowing, and appearance. Our patients don’t want to go out to dinner with friends because they can’t do it.”

Dentists and prosthodontists are key team members too: “I have dentists who have my cell phone number. They just call me: ‘Can I do this extraction? Was this in your radiation field? What was the dose?’”

Other team members include ear, nose, and throat specialists, palliative and supportive care specialists, medical oncologists, nurses, pathologists, transportation workers, and service connection specialists. She noted that previous military experience can affect radiation therapy. For example, the physical restraints required during treatment present particular challenges for veterans who’ve had wartime trauma. These patients may require therapy adjustments.

What’s next on the horizon? Takiar highlighted precision oncology and molecular profiling, artificial intelligence in care decisions and in radiation planning, telemedicine and virtual tumor boards, and expanded survivorship programs.

As for now, she urged colleagues to not be afraid to chat with radiation oncologists. “Please talk to us. We prioritize open communication and shared decision-making with the entire team,” she said. “If you see something and think your radiation oncologist should know about it, you think it was caused by the radiation, you should reach out to us.”

Takiar reported no disclosures.

PHOENIX – A 70-year-old Vietnam veteran with oropharyngeal cancer presented challenges beyond his disease.

He couldn’t afford transportation for daily radiation treatments and had lost > 10% of his body weight due to pain and eating difficulties, recalled radiation oncologist Vinita Takiar, MD, PhD, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology.

To make matters more difficult, his wife held medical power of attorney despite his apparent competence to make decisions, said Takiar, who formerly worked with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Cincinnati Healthcare System and is now chair of radiation oncology at Penn State University.

All these factors would likely have derailed his treatment if not for a coordinated team intervention, Takiar said. Fortunately, the clinic launched a multifaceted effort involving representatives from the social work, dentistry, ethics, nutrition, and chaplaincy departments.

When surgery became impossible because the patient couldn’t lie on the operating table for adequate tumor exposure, she said, the existing team framework enabled a seamless and rapid transition to radiation with concurrent chemotherapy.

The patient completed treatment with an excellent response, offering a lesson in the importance of multidisciplinary care in head-and-neck cancers, she said.

In fact, when it comes to these forms of cancer, coordinated care “is probably more impactful than any treatment that we’re going to come up with,” she said. “The data show that when we do multidisciplinary care and we do it well, it actually improves the patient experience and outcomes.”

As Takiar noted, teamwork matters in many ways. It leads to better logistics and can address disparities, reduce financial burden and stigma, and even increase clinical trial involvement.

She pointed to studies linking teamwork to better outcomes, support for patients, and overall survival.

Takiar highlighted different parts of teams headed by radiation oncologists who act as “a node to improve multimodal care delivery.”

Speech and swallowing specialists, for example, are helpful in head-and-neck cancer because “there’s an impact on speech, swallowing, and appearance. Our patients don’t want to go out to dinner with friends because they can’t do it.”

Dentists and prosthodontists are key team members too: “I have dentists who have my cell phone number. They just call me: ‘Can I do this extraction? Was this in your radiation field? What was the dose?’”

Other team members include ear, nose, and throat specialists, palliative and supportive care specialists, medical oncologists, nurses, pathologists, transportation workers, and service connection specialists. She noted that previous military experience can affect radiation therapy. For example, the physical restraints required during treatment present particular challenges for veterans who’ve had wartime trauma. These patients may require therapy adjustments.

What’s next on the horizon? Takiar highlighted precision oncology and molecular profiling, artificial intelligence in care decisions and in radiation planning, telemedicine and virtual tumor boards, and expanded survivorship programs.

As for now, she urged colleagues to not be afraid to chat with radiation oncologists. “Please talk to us. We prioritize open communication and shared decision-making with the entire team,” she said. “If you see something and think your radiation oncologist should know about it, you think it was caused by the radiation, you should reach out to us.”

Takiar reported no disclosures.

Team-Based Care is Crucial for Head-and-Neck Cancer Cases

Team-Based Care is Crucial for Head-and-Neck Cancer Cases

Head and Neck Cancer: VA Dietitian Advocates Whole Foods Over Supplements

PHOENIX — Patients with head and neck cancer face high rates of malnutrition during treatment, and oral supplements are often recommended. But they are not the entire answer, a dietician told colleagues at the Association of Veterans Affairs (VA) Hematology/Oncology annual meeting.

“Patients should consume the most liberal diet possible throughout treatment,” said advanced practice oncology dietician Brittany Leneweaver, RD, CSO, CES, at the VA Washington DC Healthcare System. “This means not solely relying on oral nutrition supplements like Ensure if possible.”

While Leneweaver said many patients will need supplements, she stressed these products “are meant to supplement the diet and not be the sole source of nutrition, ideally.” Encouraging the intake of whole foods “is really key to make the transition back to solid foods after they’re done with treatment. This makes it so much easier when they’re already swallowing those thicker textures, rather than just liquid the entire time.”

Malnutrition: Common and Damaging

As Leneweaver noted, malnutrition is common in patients with head and neck cancer, and can lead to “increased treatment toxicity, increased risk of infection, decreased survival, increased surgical complication, delayed healing, decreased physical function, and decreased quality of life.”

Malnutrition data in patients with head and neck cancer in the US is sparse. However, a 2024 study found malnutrition in 20% of patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery and linked the condition to increased length of stay (β, 5.20 additional days), higher costs (β, $15,722) higher odds of potentially preventable complications (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.04), and lower odds of discharge to home (aOR, 0.34).

Leneweaver said her role involves addressing “nutrition impact symptoms” that reduce veteran food intake such as difficulty swallowing, taste disorders, dry mouth, and inflammation of the mucus membranes.

“I can’t tell you how much time I spend just talking to the patient about their medication regimens, making sure they have antiemetics on board, letting the radiation oncologist know, ‘Hey, it’s probably time for medicine,’” she said. “We’re constantly looking at side effects and addressing to alert the team as quickly as possible so that we can prevent further weight loss.”

Better Diets Lead to Better Outcomes

Leneweaver noted that “many times, patients will continue to rely on oral supplements as their primary source of nutrition over the long term. They may be missing out on several health benefits as a result.”

Research shows that high-quality diets matter in this patient group, she said. They’re associated with “decreased symptoms during treatment, reduced head and neck cancer risk, and reduced risk of those chronic nutrition impact symptoms,” Leneweaver said.

Diets before and after cancer diagnosis can make a difference. A 2019 study examined patient diets prior to diagnosis of head and neck cancer. It found that patients with better diet quality were less likely to experience overall nutrition impact symptoms (OR 0.45). However, “studies have found that the majority of our patients with head and neck cancer have an inadequate diet prior to diagnosis,” Leneweaver said.

As for postdiagnosis nutrition, a 2022 study linked healthier diets in patients with head and neck cancer to 93% lower 3-year risk of all-cause mortality and 85% lower risk of cancer-specific mortality.

What’s in a High-Quality Diet?

Regarding specific food recommendations, Leneweaver prefers the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) nutrition guidelines over the US Department of Agriculture’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The AICR “more clearly recommends plant-based diet with at least two-thirds of each meal coming from a variety of plant sources” and recommends avoiding alcohol entirely and limiting red meat, she said.

Leneweaver said she recognizes that dietary change can be gradual.

“It’s not going to happen overnight,” she said. “We know that lifestyle change takes a lot of work.”

Basic interventions can be effective, she said: “This can be just as simple as recommending a plant-based diet to your patient or recommending they eat the rainbow. And I don’t mean Skittles, I mean actual plants. If you just mention these couple of things to the patients, this can really go a long way, especially if they’re hearing that consistent messaging.”

Team-Based Follow-Up Is Key

Leneweaver emphasized the importance of following up over time even if patients do not initially accept referrals to nutritional services. Dieticians ideally see patients before or during initial treatment and then weekly during radiation therapy. Posttreatment follow-up continues “until they’re nutritionally stable. This can be anywhere from weekly to monthly.”

Leneweaver emphasized collaborating with other team members. For example, she works with a speech pathologist at joint visits, either weekly or monthly, “so that they can get off of that feeding tube or get back to a solid consistency diet, typically before that 3-month PET scan.”

It is also important to understand barriers to healthy eating in the veteran population, including transportation challenges and poor access to healthy food, Leneweaver said.

“Make sure you’re utilizing your social worker, your psychologist, other resources, and food pantries, if you have them.”

Even when the most ideal choices are not available, she said, “if they only have access to canned vegetables, I’d much rather them eat that than have nothing.”

No disclosures for Leneweaver were provided.

PHOENIX — Patients with head and neck cancer face high rates of malnutrition during treatment, and oral supplements are often recommended. But they are not the entire answer, a dietician told colleagues at the Association of Veterans Affairs (VA) Hematology/Oncology annual meeting.

“Patients should consume the most liberal diet possible throughout treatment,” said advanced practice oncology dietician Brittany Leneweaver, RD, CSO, CES, at the VA Washington DC Healthcare System. “This means not solely relying on oral nutrition supplements like Ensure if possible.”

While Leneweaver said many patients will need supplements, she stressed these products “are meant to supplement the diet and not be the sole source of nutrition, ideally.” Encouraging the intake of whole foods “is really key to make the transition back to solid foods after they’re done with treatment. This makes it so much easier when they’re already swallowing those thicker textures, rather than just liquid the entire time.”

Malnutrition: Common and Damaging

As Leneweaver noted, malnutrition is common in patients with head and neck cancer, and can lead to “increased treatment toxicity, increased risk of infection, decreased survival, increased surgical complication, delayed healing, decreased physical function, and decreased quality of life.”

Malnutrition data in patients with head and neck cancer in the US is sparse. However, a 2024 study found malnutrition in 20% of patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery and linked the condition to increased length of stay (β, 5.20 additional days), higher costs (β, $15,722) higher odds of potentially preventable complications (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.04), and lower odds of discharge to home (aOR, 0.34).

Leneweaver said her role involves addressing “nutrition impact symptoms” that reduce veteran food intake such as difficulty swallowing, taste disorders, dry mouth, and inflammation of the mucus membranes.

“I can’t tell you how much time I spend just talking to the patient about their medication regimens, making sure they have antiemetics on board, letting the radiation oncologist know, ‘Hey, it’s probably time for medicine,’” she said. “We’re constantly looking at side effects and addressing to alert the team as quickly as possible so that we can prevent further weight loss.”

Better Diets Lead to Better Outcomes

Leneweaver noted that “many times, patients will continue to rely on oral supplements as their primary source of nutrition over the long term. They may be missing out on several health benefits as a result.”

Research shows that high-quality diets matter in this patient group, she said. They’re associated with “decreased symptoms during treatment, reduced head and neck cancer risk, and reduced risk of those chronic nutrition impact symptoms,” Leneweaver said.

Diets before and after cancer diagnosis can make a difference. A 2019 study examined patient diets prior to diagnosis of head and neck cancer. It found that patients with better diet quality were less likely to experience overall nutrition impact symptoms (OR 0.45). However, “studies have found that the majority of our patients with head and neck cancer have an inadequate diet prior to diagnosis,” Leneweaver said.

As for postdiagnosis nutrition, a 2022 study linked healthier diets in patients with head and neck cancer to 93% lower 3-year risk of all-cause mortality and 85% lower risk of cancer-specific mortality.

What’s in a High-Quality Diet?

Regarding specific food recommendations, Leneweaver prefers the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) nutrition guidelines over the US Department of Agriculture’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The AICR “more clearly recommends plant-based diet with at least two-thirds of each meal coming from a variety of plant sources” and recommends avoiding alcohol entirely and limiting red meat, she said.

Leneweaver said she recognizes that dietary change can be gradual.

“It’s not going to happen overnight,” she said. “We know that lifestyle change takes a lot of work.”

Basic interventions can be effective, she said: “This can be just as simple as recommending a plant-based diet to your patient or recommending they eat the rainbow. And I don’t mean Skittles, I mean actual plants. If you just mention these couple of things to the patients, this can really go a long way, especially if they’re hearing that consistent messaging.”

Team-Based Follow-Up Is Key

Leneweaver emphasized the importance of following up over time even if patients do not initially accept referrals to nutritional services. Dieticians ideally see patients before or during initial treatment and then weekly during radiation therapy. Posttreatment follow-up continues “until they’re nutritionally stable. This can be anywhere from weekly to monthly.”

Leneweaver emphasized collaborating with other team members. For example, she works with a speech pathologist at joint visits, either weekly or monthly, “so that they can get off of that feeding tube or get back to a solid consistency diet, typically before that 3-month PET scan.”

It is also important to understand barriers to healthy eating in the veteran population, including transportation challenges and poor access to healthy food, Leneweaver said.

“Make sure you’re utilizing your social worker, your psychologist, other resources, and food pantries, if you have them.”

Even when the most ideal choices are not available, she said, “if they only have access to canned vegetables, I’d much rather them eat that than have nothing.”

No disclosures for Leneweaver were provided.

PHOENIX — Patients with head and neck cancer face high rates of malnutrition during treatment, and oral supplements are often recommended. But they are not the entire answer, a dietician told colleagues at the Association of Veterans Affairs (VA) Hematology/Oncology annual meeting.

“Patients should consume the most liberal diet possible throughout treatment,” said advanced practice oncology dietician Brittany Leneweaver, RD, CSO, CES, at the VA Washington DC Healthcare System. “This means not solely relying on oral nutrition supplements like Ensure if possible.”

While Leneweaver said many patients will need supplements, she stressed these products “are meant to supplement the diet and not be the sole source of nutrition, ideally.” Encouraging the intake of whole foods “is really key to make the transition back to solid foods after they’re done with treatment. This makes it so much easier when they’re already swallowing those thicker textures, rather than just liquid the entire time.”

Malnutrition: Common and Damaging

As Leneweaver noted, malnutrition is common in patients with head and neck cancer, and can lead to “increased treatment toxicity, increased risk of infection, decreased survival, increased surgical complication, delayed healing, decreased physical function, and decreased quality of life.”

Malnutrition data in patients with head and neck cancer in the US is sparse. However, a 2024 study found malnutrition in 20% of patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery and linked the condition to increased length of stay (β, 5.20 additional days), higher costs (β, $15,722) higher odds of potentially preventable complications (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.04), and lower odds of discharge to home (aOR, 0.34).

Leneweaver said her role involves addressing “nutrition impact symptoms” that reduce veteran food intake such as difficulty swallowing, taste disorders, dry mouth, and inflammation of the mucus membranes.

“I can’t tell you how much time I spend just talking to the patient about their medication regimens, making sure they have antiemetics on board, letting the radiation oncologist know, ‘Hey, it’s probably time for medicine,’” she said. “We’re constantly looking at side effects and addressing to alert the team as quickly as possible so that we can prevent further weight loss.”

Better Diets Lead to Better Outcomes

Leneweaver noted that “many times, patients will continue to rely on oral supplements as their primary source of nutrition over the long term. They may be missing out on several health benefits as a result.”

Research shows that high-quality diets matter in this patient group, she said. They’re associated with “decreased symptoms during treatment, reduced head and neck cancer risk, and reduced risk of those chronic nutrition impact symptoms,” Leneweaver said.

Diets before and after cancer diagnosis can make a difference. A 2019 study examined patient diets prior to diagnosis of head and neck cancer. It found that patients with better diet quality were less likely to experience overall nutrition impact symptoms (OR 0.45). However, “studies have found that the majority of our patients with head and neck cancer have an inadequate diet prior to diagnosis,” Leneweaver said.

As for postdiagnosis nutrition, a 2022 study linked healthier diets in patients with head and neck cancer to 93% lower 3-year risk of all-cause mortality and 85% lower risk of cancer-specific mortality.

What’s in a High-Quality Diet?

Regarding specific food recommendations, Leneweaver prefers the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) nutrition guidelines over the US Department of Agriculture’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The AICR “more clearly recommends plant-based diet with at least two-thirds of each meal coming from a variety of plant sources” and recommends avoiding alcohol entirely and limiting red meat, she said.

Leneweaver said she recognizes that dietary change can be gradual.

“It’s not going to happen overnight,” she said. “We know that lifestyle change takes a lot of work.”

Basic interventions can be effective, she said: “This can be just as simple as recommending a plant-based diet to your patient or recommending they eat the rainbow. And I don’t mean Skittles, I mean actual plants. If you just mention these couple of things to the patients, this can really go a long way, especially if they’re hearing that consistent messaging.”

Team-Based Follow-Up Is Key

Leneweaver emphasized the importance of following up over time even if patients do not initially accept referrals to nutritional services. Dieticians ideally see patients before or during initial treatment and then weekly during radiation therapy. Posttreatment follow-up continues “until they’re nutritionally stable. This can be anywhere from weekly to monthly.”

Leneweaver emphasized collaborating with other team members. For example, she works with a speech pathologist at joint visits, either weekly or monthly, “so that they can get off of that feeding tube or get back to a solid consistency diet, typically before that 3-month PET scan.”

It is also important to understand barriers to healthy eating in the veteran population, including transportation challenges and poor access to healthy food, Leneweaver said.

“Make sure you’re utilizing your social worker, your psychologist, other resources, and food pantries, if you have them.”

Even when the most ideal choices are not available, she said, “if they only have access to canned vegetables, I’d much rather them eat that than have nothing.”

No disclosures for Leneweaver were provided.

Epidemiology and Survival of Parotid Gland Malignancies With Brain Metastases: A Population- Based Study

Background

Parotid gland malignancies are a rare subset of salivary gland tumors, comprising approximately 1–3% of all head and neck cancers. While distant metastases commonly involve the lungs, brain metastases are exceedingly rare and remain poorly characterized. Management typically includes stereotactic radiosurgery or whole-brain radiation. This study evaluates the incidence, clinicopathologic features, and survival outcomes of patients with parotid gland tumors and brain metastases using data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Methods

SEER database (2010–2022) was queried for patients diagnosed with primary malignant neoplasms of the parotid gland (ICD-O-3 site code C07.9). Cases of brain metastases were identified using SEER metastatic site variables. Age-adjusted incidence rates (IR) per 100,000 population were calculated using SEER*Stat 8.4.5. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism, and survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test.

Results

Among 12,951 patients diagnosed with parotid malignancy, 47 (0.36%) had brain metastases. The median age at diagnosis was 67 years, and 77.5% were male. The overall incidence rate (IR) of brain metastases was 0.00235 per 100,000 population, with a significantly higher rate observed in males compared to females (p < 0.0001). The most common histologic subtype associated with brain involvement was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, n=10), followed by adenocarcinoma. Median overall survival (mOS) for patients with brain metastases was 2 months (hazard ratio [HR] 6.28; 95% CI: 2.71–14.55), compared to 131 months for those without brain involvement (p < 0.001). 1-year cancer-specific survival for patients with brain metastases was 38%. Among patients with parotid SCC and brain metastases, mOS was 3 months, compared to 39 months in those without brain involvement (HR 5.70; 95% CI: 1.09–29.68; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Brain metastases from parotid gland cancers, though rare, are associated with markedly poor outcomes. This highlights the importance of early neurologic assessment and brain imaging in high-risk patients, particularly with SCC histology. Prior studies have shown that TP53 mutations are common in parotid SCC, but their role in CNS spread remains unclear. Future research should explore molecular pathways underlying neurotropism in parotid cancers and investigate targeted systemic therapies with CNS penetration to improve outcomes.

Background

Parotid gland malignancies are a rare subset of salivary gland tumors, comprising approximately 1–3% of all head and neck cancers. While distant metastases commonly involve the lungs, brain metastases are exceedingly rare and remain poorly characterized. Management typically includes stereotactic radiosurgery or whole-brain radiation. This study evaluates the incidence, clinicopathologic features, and survival outcomes of patients with parotid gland tumors and brain metastases using data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Methods

SEER database (2010–2022) was queried for patients diagnosed with primary malignant neoplasms of the parotid gland (ICD-O-3 site code C07.9). Cases of brain metastases were identified using SEER metastatic site variables. Age-adjusted incidence rates (IR) per 100,000 population were calculated using SEER*Stat 8.4.5. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism, and survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test.

Results

Among 12,951 patients diagnosed with parotid malignancy, 47 (0.36%) had brain metastases. The median age at diagnosis was 67 years, and 77.5% were male. The overall incidence rate (IR) of brain metastases was 0.00235 per 100,000 population, with a significantly higher rate observed in males compared to females (p < 0.0001). The most common histologic subtype associated with brain involvement was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, n=10), followed by adenocarcinoma. Median overall survival (mOS) for patients with brain metastases was 2 months (hazard ratio [HR] 6.28; 95% CI: 2.71–14.55), compared to 131 months for those without brain involvement (p < 0.001). 1-year cancer-specific survival for patients with brain metastases was 38%. Among patients with parotid SCC and brain metastases, mOS was 3 months, compared to 39 months in those without brain involvement (HR 5.70; 95% CI: 1.09–29.68; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Brain metastases from parotid gland cancers, though rare, are associated with markedly poor outcomes. This highlights the importance of early neurologic assessment and brain imaging in high-risk patients, particularly with SCC histology. Prior studies have shown that TP53 mutations are common in parotid SCC, but their role in CNS spread remains unclear. Future research should explore molecular pathways underlying neurotropism in parotid cancers and investigate targeted systemic therapies with CNS penetration to improve outcomes.

Background

Parotid gland malignancies are a rare subset of salivary gland tumors, comprising approximately 1–3% of all head and neck cancers. While distant metastases commonly involve the lungs, brain metastases are exceedingly rare and remain poorly characterized. Management typically includes stereotactic radiosurgery or whole-brain radiation. This study evaluates the incidence, clinicopathologic features, and survival outcomes of patients with parotid gland tumors and brain metastases using data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Methods

SEER database (2010–2022) was queried for patients diagnosed with primary malignant neoplasms of the parotid gland (ICD-O-3 site code C07.9). Cases of brain metastases were identified using SEER metastatic site variables. Age-adjusted incidence rates (IR) per 100,000 population were calculated using SEER*Stat 8.4.5. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism, and survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test.

Results

Among 12,951 patients diagnosed with parotid malignancy, 47 (0.36%) had brain metastases. The median age at diagnosis was 67 years, and 77.5% were male. The overall incidence rate (IR) of brain metastases was 0.00235 per 100,000 population, with a significantly higher rate observed in males compared to females (p < 0.0001). The most common histologic subtype associated with brain involvement was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, n=10), followed by adenocarcinoma. Median overall survival (mOS) for patients with brain metastases was 2 months (hazard ratio [HR] 6.28; 95% CI: 2.71–14.55), compared to 131 months for those without brain involvement (p < 0.001). 1-year cancer-specific survival for patients with brain metastases was 38%. Among patients with parotid SCC and brain metastases, mOS was 3 months, compared to 39 months in those without brain involvement (HR 5.70; 95% CI: 1.09–29.68; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Brain metastases from parotid gland cancers, though rare, are associated with markedly poor outcomes. This highlights the importance of early neurologic assessment and brain imaging in high-risk patients, particularly with SCC histology. Prior studies have shown that TP53 mutations are common in parotid SCC, but their role in CNS spread remains unclear. Future research should explore molecular pathways underlying neurotropism in parotid cancers and investigate targeted systemic therapies with CNS penetration to improve outcomes.

Analysis of the Frequency of level 1 OncoKB Genomic Alterations in Veterans With Various Solid Organ Malignancies

Purpose

The aim of this study is to quantify the frequency of Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Precision Oncology Knowledge Base (OncoKB) Level 1 genetic alterations in Veterans with various solid organ malignancies and evaluate the clinical benefit and impact of testing on treatment of these patients.

Background

The VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) facilitates comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) testing of Veterans with advanced cancer. While CGP is increasingly utilized and routinely ordered in patients with advanced solid organ malignancies, the clinical utility and value has not been proven in certain cancers. We present data from 5,979 patients with head and neck (H&N), pancreatic, hepatocellular (HCC), esophageal and kidney cancers who underwent CGP.

Methods

Our cohort consists of Veterans that received CGP testing to identify somatic variants between 1/1/2019 and 4/2/2025. Identified variants and biomarkers were formatted for use with oncoKB-annotator, a publicly available tool to annotate genomic variants with FDA approved drug recommendations stored as Level 1 annotations in OncoKB, and prescribed drugs were extracted from the Veteran Health Administration’s (VHA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Cancers were grouped by MSK’s OncoTree codes, and summary counts of Veterans tested, Veterans recommended, Veterans prescribed recommended FDA approved drugs were determined. Percentages were calculated using the total number of Veterans tested as the denominator.

Results

Level 1 OncoKB alterations were infrequent in H&N (0.94%), kidney (0.45%), HCC(0.28%), and pancreatic adenocarcinomas (1%). The frequency of Level 1 alterations in esophageal adenocarcinomas (EAC) was 20%. Approximately 98% of the Level 1 alterations in EAC patients were HER2 positivity or MSI-High status, which can be determined by other diagnostic methodologies such as IHC. The remaining 2% of EAC patients with level 1 alterations had BRAF V600E or NTRK rearrangements.

Conclusions

The incidence of level 1 genetic variants in H&N, kidney, HCC and pancreatic adenocarcinoma is very low and would very uncommonly result in clinical benefit. Although there is an expanding number of precision oncology-based therapies available, the proportion of patients with the aforementioned solid organ malignancies who benefitted from CGP was low, suggesting CGP has minimal impact on the treatment of Veterans with these malignancies.

Purpose

The aim of this study is to quantify the frequency of Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Precision Oncology Knowledge Base (OncoKB) Level 1 genetic alterations in Veterans with various solid organ malignancies and evaluate the clinical benefit and impact of testing on treatment of these patients.

Background

The VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) facilitates comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) testing of Veterans with advanced cancer. While CGP is increasingly utilized and routinely ordered in patients with advanced solid organ malignancies, the clinical utility and value has not been proven in certain cancers. We present data from 5,979 patients with head and neck (H&N), pancreatic, hepatocellular (HCC), esophageal and kidney cancers who underwent CGP.

Methods

Our cohort consists of Veterans that received CGP testing to identify somatic variants between 1/1/2019 and 4/2/2025. Identified variants and biomarkers were formatted for use with oncoKB-annotator, a publicly available tool to annotate genomic variants with FDA approved drug recommendations stored as Level 1 annotations in OncoKB, and prescribed drugs were extracted from the Veteran Health Administration’s (VHA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Cancers were grouped by MSK’s OncoTree codes, and summary counts of Veterans tested, Veterans recommended, Veterans prescribed recommended FDA approved drugs were determined. Percentages were calculated using the total number of Veterans tested as the denominator.

Results

Level 1 OncoKB alterations were infrequent in H&N (0.94%), kidney (0.45%), HCC(0.28%), and pancreatic adenocarcinomas (1%). The frequency of Level 1 alterations in esophageal adenocarcinomas (EAC) was 20%. Approximately 98% of the Level 1 alterations in EAC patients were HER2 positivity or MSI-High status, which can be determined by other diagnostic methodologies such as IHC. The remaining 2% of EAC patients with level 1 alterations had BRAF V600E or NTRK rearrangements.

Conclusions

The incidence of level 1 genetic variants in H&N, kidney, HCC and pancreatic adenocarcinoma is very low and would very uncommonly result in clinical benefit. Although there is an expanding number of precision oncology-based therapies available, the proportion of patients with the aforementioned solid organ malignancies who benefitted from CGP was low, suggesting CGP has minimal impact on the treatment of Veterans with these malignancies.

Purpose

The aim of this study is to quantify the frequency of Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Precision Oncology Knowledge Base (OncoKB) Level 1 genetic alterations in Veterans with various solid organ malignancies and evaluate the clinical benefit and impact of testing on treatment of these patients.

Background

The VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) facilitates comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) testing of Veterans with advanced cancer. While CGP is increasingly utilized and routinely ordered in patients with advanced solid organ malignancies, the clinical utility and value has not been proven in certain cancers. We present data from 5,979 patients with head and neck (H&N), pancreatic, hepatocellular (HCC), esophageal and kidney cancers who underwent CGP.

Methods

Our cohort consists of Veterans that received CGP testing to identify somatic variants between 1/1/2019 and 4/2/2025. Identified variants and biomarkers were formatted for use with oncoKB-annotator, a publicly available tool to annotate genomic variants with FDA approved drug recommendations stored as Level 1 annotations in OncoKB, and prescribed drugs were extracted from the Veteran Health Administration’s (VHA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Cancers were grouped by MSK’s OncoTree codes, and summary counts of Veterans tested, Veterans recommended, Veterans prescribed recommended FDA approved drugs were determined. Percentages were calculated using the total number of Veterans tested as the denominator.

Results

Level 1 OncoKB alterations were infrequent in H&N (0.94%), kidney (0.45%), HCC(0.28%), and pancreatic adenocarcinomas (1%). The frequency of Level 1 alterations in esophageal adenocarcinomas (EAC) was 20%. Approximately 98% of the Level 1 alterations in EAC patients were HER2 positivity or MSI-High status, which can be determined by other diagnostic methodologies such as IHC. The remaining 2% of EAC patients with level 1 alterations had BRAF V600E or NTRK rearrangements.

Conclusions

The incidence of level 1 genetic variants in H&N, kidney, HCC and pancreatic adenocarcinoma is very low and would very uncommonly result in clinical benefit. Although there is an expanding number of precision oncology-based therapies available, the proportion of patients with the aforementioned solid organ malignancies who benefitted from CGP was low, suggesting CGP has minimal impact on the treatment of Veterans with these malignancies.

GATA3-Positive Metastatic Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: A Rare Diagnostic Challenge

Background

GATA3 is a zinc finger transcription factor most commonly used as an immunohistochemical marker in breast and urothelial carcinomas, though it has also been detected—albeit infrequently—in other malignancies. While GATA3 expression is well established in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, it is rarely documented in esophageal adenocarcinoma. We present a unique case of widely metastatic, strongly GATA3-positive esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Case Presentation

A 59-year-old male smoker with gastroesophageal reflux disease and a history of alcohol use disorder presented with progressive right hip pain following a fall. Imaging revealed multiple lytic bone lesions and a soft tissue mass near the right acetabulum. PET-CT demonstrated widespread osseous metastases and FDG-avid uptake in the distal esophagus and perigastric lymph nodes. Laboratory findings included a PSA of 14. Biopsy of the right pubic ramus revealed adenocarcinoma positive for GATA3, CK7, CK20 (patchy), CK40, and P63, and negative for PSA. Given the unexpected GATA3 positivity, the differential diagnosis included primary urothelial cancer. However, cystoscopy and urine cytology were unremarkable. EGD revealed Barrett’s esophagus without a discrete mass. Biopsy of the distal esophagus confirmed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with underlying dysplasia. Molecular profiling showed HER2-negative, microsatellite stable (MSS) disease with PD-L1 expression of 10%. Due to an ECOG performance status ≥3 and extensive metastatic burden, the patient was not a candidate for systemic therapy and was transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A large tissue microarray study of over 16,000 tumors found weak GATA3 expression in only 2.4% of esophageal adenocarcinomas, with strong or diffuse positivity virtually undocumented. In this case, the unusual immunoprofile initially raised concern for a primary urothelial tumor, but endoscopic biopsy confirmed an esophageal origin. Aberrant GATA3 expression in poorly differentiated gastrointestinal tumors may complicate diagnosis and has been associated with worse prognosis. Awareness of such atypical patterns is critical for accurate tumor classification and appropriate management in metastatic disease.

Conclusions

This case highlights a rare presentation of GATA3-positive esophageal adenocarcinoma. Further reporting may improve diagnostic accuracy and inform future therapeutic strategies for this unique subset of tumors.

Background

GATA3 is a zinc finger transcription factor most commonly used as an immunohistochemical marker in breast and urothelial carcinomas, though it has also been detected—albeit infrequently—in other malignancies. While GATA3 expression is well established in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, it is rarely documented in esophageal adenocarcinoma. We present a unique case of widely metastatic, strongly GATA3-positive esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Case Presentation

A 59-year-old male smoker with gastroesophageal reflux disease and a history of alcohol use disorder presented with progressive right hip pain following a fall. Imaging revealed multiple lytic bone lesions and a soft tissue mass near the right acetabulum. PET-CT demonstrated widespread osseous metastases and FDG-avid uptake in the distal esophagus and perigastric lymph nodes. Laboratory findings included a PSA of 14. Biopsy of the right pubic ramus revealed adenocarcinoma positive for GATA3, CK7, CK20 (patchy), CK40, and P63, and negative for PSA. Given the unexpected GATA3 positivity, the differential diagnosis included primary urothelial cancer. However, cystoscopy and urine cytology were unremarkable. EGD revealed Barrett’s esophagus without a discrete mass. Biopsy of the distal esophagus confirmed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with underlying dysplasia. Molecular profiling showed HER2-negative, microsatellite stable (MSS) disease with PD-L1 expression of 10%. Due to an ECOG performance status ≥3 and extensive metastatic burden, the patient was not a candidate for systemic therapy and was transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A large tissue microarray study of over 16,000 tumors found weak GATA3 expression in only 2.4% of esophageal adenocarcinomas, with strong or diffuse positivity virtually undocumented. In this case, the unusual immunoprofile initially raised concern for a primary urothelial tumor, but endoscopic biopsy confirmed an esophageal origin. Aberrant GATA3 expression in poorly differentiated gastrointestinal tumors may complicate diagnosis and has been associated with worse prognosis. Awareness of such atypical patterns is critical for accurate tumor classification and appropriate management in metastatic disease.

Conclusions

This case highlights a rare presentation of GATA3-positive esophageal adenocarcinoma. Further reporting may improve diagnostic accuracy and inform future therapeutic strategies for this unique subset of tumors.

Background

GATA3 is a zinc finger transcription factor most commonly used as an immunohistochemical marker in breast and urothelial carcinomas, though it has also been detected—albeit infrequently—in other malignancies. While GATA3 expression is well established in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, it is rarely documented in esophageal adenocarcinoma. We present a unique case of widely metastatic, strongly GATA3-positive esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Case Presentation

A 59-year-old male smoker with gastroesophageal reflux disease and a history of alcohol use disorder presented with progressive right hip pain following a fall. Imaging revealed multiple lytic bone lesions and a soft tissue mass near the right acetabulum. PET-CT demonstrated widespread osseous metastases and FDG-avid uptake in the distal esophagus and perigastric lymph nodes. Laboratory findings included a PSA of 14. Biopsy of the right pubic ramus revealed adenocarcinoma positive for GATA3, CK7, CK20 (patchy), CK40, and P63, and negative for PSA. Given the unexpected GATA3 positivity, the differential diagnosis included primary urothelial cancer. However, cystoscopy and urine cytology were unremarkable. EGD revealed Barrett’s esophagus without a discrete mass. Biopsy of the distal esophagus confirmed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with underlying dysplasia. Molecular profiling showed HER2-negative, microsatellite stable (MSS) disease with PD-L1 expression of 10%. Due to an ECOG performance status ≥3 and extensive metastatic burden, the patient was not a candidate for systemic therapy and was transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A large tissue microarray study of over 16,000 tumors found weak GATA3 expression in only 2.4% of esophageal adenocarcinomas, with strong or diffuse positivity virtually undocumented. In this case, the unusual immunoprofile initially raised concern for a primary urothelial tumor, but endoscopic biopsy confirmed an esophageal origin. Aberrant GATA3 expression in poorly differentiated gastrointestinal tumors may complicate diagnosis and has been associated with worse prognosis. Awareness of such atypical patterns is critical for accurate tumor classification and appropriate management in metastatic disease.

Conclusions

This case highlights a rare presentation of GATA3-positive esophageal adenocarcinoma. Further reporting may improve diagnostic accuracy and inform future therapeutic strategies for this unique subset of tumors.

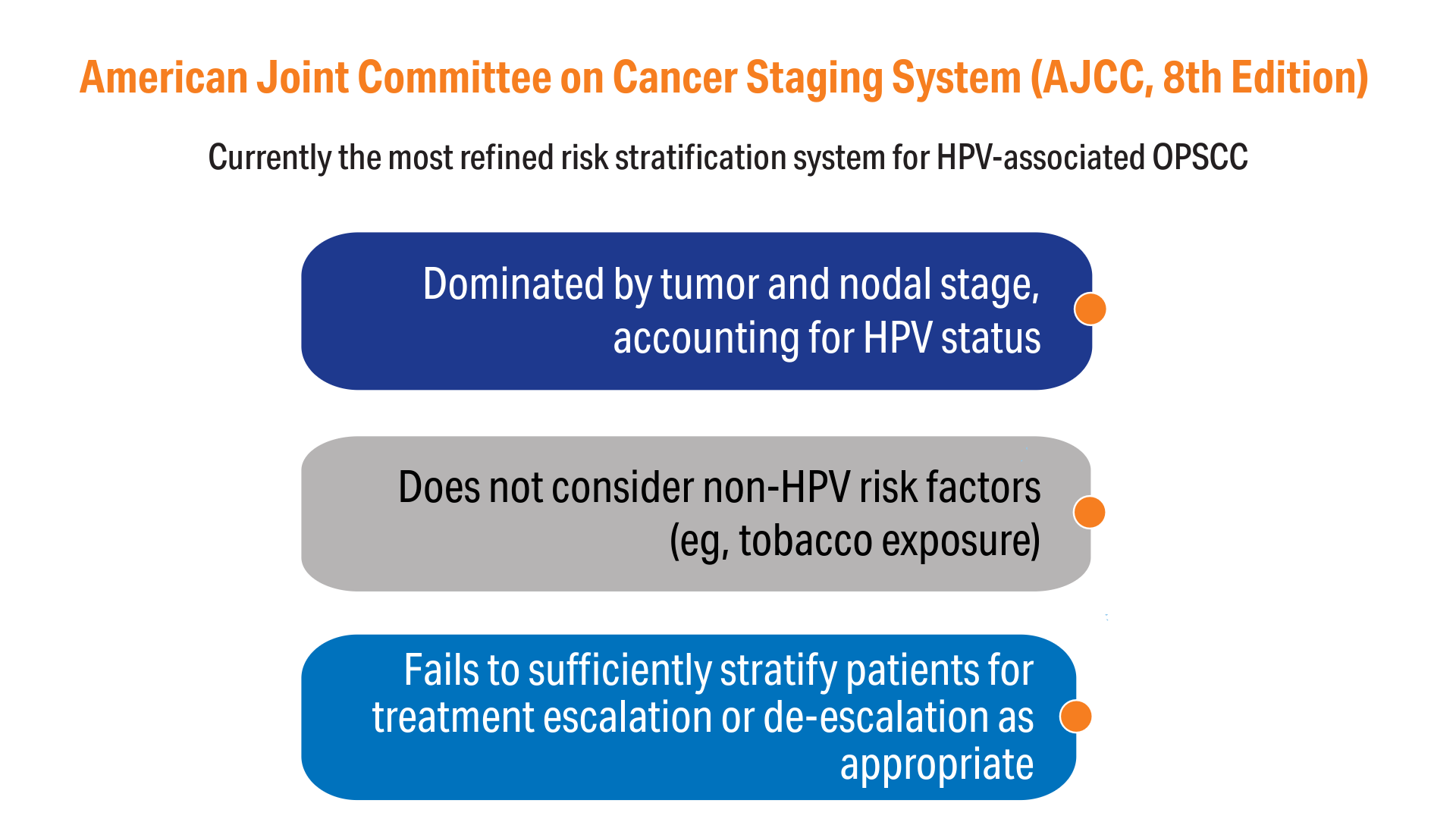

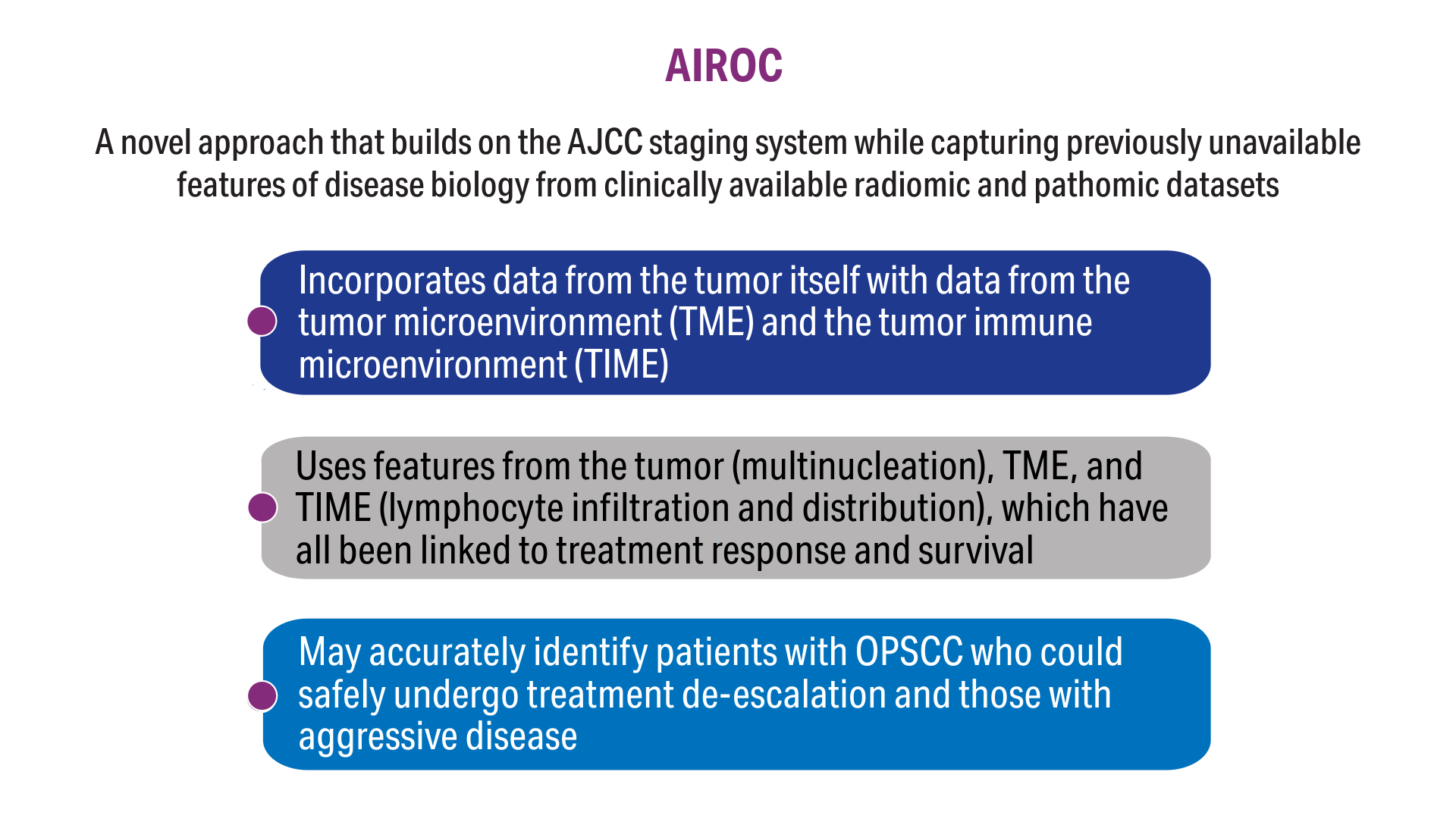

AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

1. Zevallos JP, Kramer JR, Sandulache VC, et al. National trends in oropharyngeal cancer incidence and survival within the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

2. Fakhry C, Blackford AL, Neuner G, et al. Association of oral human papillomavirus DNA persistence with cancer progression after primary treatment for oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):985-992. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0439

3. Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Gillison ML, et al. Validation of NRG oncology/RTOG-0129 risk groups for HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer: implications for risk-based therapeutic intensity trials. Cancer. 2019;125(12):2027-2038. doi:10.1002/cncr.32025

4. O'Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J, et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):440-451. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00560-4

5. Koyuncu CF, Lu C, Bera K, et al. Computerized tumor multinucleation index (MuNI) is prognostic in p16+ oropharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(8):e145488. doi:10.1172/JCI145488

6. Lu C, Lewis JS Jr, Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr, Janowczyk A, Madabhushi A. An oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma quantitative histomorphometric-based image classifier of nuclear morphology can risk stratify patients for disease-specific survival. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(12):1655-1665. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2017.98

7. Corredor G, Toro P, Koyuncu C, et al. An imaging biomarker of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to risk-stratify patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(4):609-617. doi:10.1093/jnci/djab215

8. Cancer stat facts: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html

9. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 18, 2024. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/united-states-cancer-statistics/publications/hpv-associated-cancers.html

10. Chidambaram S, Chang SH, Sandulache VC, Mazul AL, Zevallos JP. Human papillomavirus vaccination prevalence and disproportionate cancer burden among US veterans. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(5):712-714. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

11. Corredor G, Wang X, Zhou Y, et al. Spatial architecture and arrangement of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for predicting likelihood of recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(5):1526-1534. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2013

12. Alilou M, Orooji M, Beig N, et al. Quantitative vessel tortuosity: a potential CT imaging biomarker for distinguishing lung granulomas from adenocarcinomas. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15290. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33473-0

13. Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93-99. doi:10.3322/caac.21388

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

1. Zevallos JP, Kramer JR, Sandulache VC, et al. National trends in oropharyngeal cancer incidence and survival within the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

2. Fakhry C, Blackford AL, Neuner G, et al. Association of oral human papillomavirus DNA persistence with cancer progression after primary treatment for oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):985-992. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0439

3. Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Gillison ML, et al. Validation of NRG oncology/RTOG-0129 risk groups for HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer: implications for risk-based therapeutic intensity trials. Cancer. 2019;125(12):2027-2038. doi:10.1002/cncr.32025

4. O'Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J, et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):440-451. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00560-4

5. Koyuncu CF, Lu C, Bera K, et al. Computerized tumor multinucleation index (MuNI) is prognostic in p16+ oropharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(8):e145488. doi:10.1172/JCI145488

6. Lu C, Lewis JS Jr, Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr, Janowczyk A, Madabhushi A. An oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma quantitative histomorphometric-based image classifier of nuclear morphology can risk stratify patients for disease-specific survival. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(12):1655-1665. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2017.98

7. Corredor G, Toro P, Koyuncu C, et al. An imaging biomarker of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to risk-stratify patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(4):609-617. doi:10.1093/jnci/djab215

8. Cancer stat facts: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html

9. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 18, 2024. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/united-states-cancer-statistics/publications/hpv-associated-cancers.html

10. Chidambaram S, Chang SH, Sandulache VC, Mazul AL, Zevallos JP. Human papillomavirus vaccination prevalence and disproportionate cancer burden among US veterans. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(5):712-714. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

11. Corredor G, Wang X, Zhou Y, et al. Spatial architecture and arrangement of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for predicting likelihood of recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(5):1526-1534. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2013

12. Alilou M, Orooji M, Beig N, et al. Quantitative vessel tortuosity: a potential CT imaging biomarker for distinguishing lung granulomas from adenocarcinomas. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15290. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33473-0

13. Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93-99. doi:10.3322/caac.21388

1. Zevallos JP, Kramer JR, Sandulache VC, et al. National trends in oropharyngeal cancer incidence and survival within the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

2. Fakhry C, Blackford AL, Neuner G, et al. Association of oral human papillomavirus DNA persistence with cancer progression after primary treatment for oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):985-992. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0439

3. Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Gillison ML, et al. Validation of NRG oncology/RTOG-0129 risk groups for HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer: implications for risk-based therapeutic intensity trials. Cancer. 2019;125(12):2027-2038. doi:10.1002/cncr.32025

4. O'Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J, et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):440-451. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00560-4

5. Koyuncu CF, Lu C, Bera K, et al. Computerized tumor multinucleation index (MuNI) is prognostic in p16+ oropharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(8):e145488. doi:10.1172/JCI145488

6. Lu C, Lewis JS Jr, Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr, Janowczyk A, Madabhushi A. An oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma quantitative histomorphometric-based image classifier of nuclear morphology can risk stratify patients for disease-specific survival. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(12):1655-1665. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2017.98

7. Corredor G, Toro P, Koyuncu C, et al. An imaging biomarker of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to risk-stratify patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(4):609-617. doi:10.1093/jnci/djab215

8. Cancer stat facts: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html

9. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 18, 2024. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/united-states-cancer-statistics/publications/hpv-associated-cancers.html

10. Chidambaram S, Chang SH, Sandulache VC, Mazul AL, Zevallos JP. Human papillomavirus vaccination prevalence and disproportionate cancer burden among US veterans. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(5):712-714. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

11. Corredor G, Wang X, Zhou Y, et al. Spatial architecture and arrangement of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for predicting likelihood of recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(5):1526-1534. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2013

12. Alilou M, Orooji M, Beig N, et al. Quantitative vessel tortuosity: a potential CT imaging biomarker for distinguishing lung granulomas from adenocarcinomas. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15290. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33473-0

13. Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93-99. doi:10.3322/caac.21388

AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

Can Adjuvant Immunotherapy Boost Survival Outcomes in Advanced Nasopharyngeal Cancer?

TOPLINE:

Adjuvant therapy with camrelizumab significantly improved 3-year event-free survival in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma compared with observation, according to findings from the phase 3 DIPPER trial.

METHODOLOGY:

- About 20%-30% of patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma experience disease relapse after definitive chemoradiotherapy. Camrelizumab plus chemotherapy can improve progression-free survival in patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma, but its effectiveness as adjuvant therapy in locoregionally advanced disease remains unclear.

- Researchers conducted the randomized phase 3 DIPPER trial at 11 centers in China, enrolling 450 patients with T4N1M0 or T1-4N2-3M0 nasopharyngeal carcinoma who had completed induction-concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

- Participants were randomly assigned to receive either adjuvant camrelizumab (200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks for 12 cycles; n = 226) or observation (n = 224). The median follow-up duration was 39 months.

- The primary endpoint was event-free survival, defined as freedom from distant metastasis, locoregional relapse, or death due to any cause; secondary endpoints included distant metastasis–free survival, locoregional relapse–free survival, overall survival, and safety.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received camrelizumab had a higher 3-year event-free survival rate than those who underwent observation (86.9% vs 77.3%; stratified hazard ratio [HR], 0.56; P = .01).

- The 3-year distant metastasis–free survival was also higher in the camrelizumab group (92.4% vs 84.5%; stratified HR, 0.54; P = .04).

- Patients in the camrelizumab group had higher locoregional relapse–free survival at 3 years than those in the observation group (92.8% vs 87.0%; stratified HR, 0.53; P = .046). However, the difference in overall survival between the groups was not significant.

- The safety analysis included 426 patients; 97.1% of those who received camrelizumab experienced at least one adverse event of any grade, the most common being reactive capillary endothelial proliferation compared with 85.5% of those in the observation group. Further, 11.2% of patients taking camrelizumab reported grade 3 or 4 events, including leukopenia and neutropenia compared with 3% in the observation group.

IN PRACTICE:

“The DIPPER trial demonstrated that adjuvant camrelizumab following induction-concurrent chemoradiotherapy significantly improved event-free survival by 9.6% with a favorable safety profile in patients with locoregionally advanced [nasopharyngeal carcinoma],” the authors wrote.

“If survival is eventually proven to be improved with induction chemoimmunotherapy, can we begin asking about de-escalation of chemoradiotherapy” for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma? “This question is exceptionally important, given the significant long-term consequences of radiotherapy on survivors,” the author of an accompanying editorial wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ye-Lin Liang, MD, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, and was published online in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included patients from an endemic region where nasopharyngeal carcinoma is predominantly linked to Epstein-Barr virus infection, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings to nonendemic populations. The open-label design may have introduced bias. Additionally, combined positive scores for programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) were unavailable for some patients, potentially affecting the analysis of the correlation between PD-L1 expression and clinical outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Guangzhou Municipal Health Commission, Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province, Overseas Expertise Introduction Project for Discipline Innovation, and Cancer Innovative Research Program of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adjuvant therapy with camrelizumab significantly improved 3-year event-free survival in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma compared with observation, according to findings from the phase 3 DIPPER trial.

METHODOLOGY:

- About 20%-30% of patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma experience disease relapse after definitive chemoradiotherapy. Camrelizumab plus chemotherapy can improve progression-free survival in patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma, but its effectiveness as adjuvant therapy in locoregionally advanced disease remains unclear.

- Researchers conducted the randomized phase 3 DIPPER trial at 11 centers in China, enrolling 450 patients with T4N1M0 or T1-4N2-3M0 nasopharyngeal carcinoma who had completed induction-concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

- Participants were randomly assigned to receive either adjuvant camrelizumab (200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks for 12 cycles; n = 226) or observation (n = 224). The median follow-up duration was 39 months.

- The primary endpoint was event-free survival, defined as freedom from distant metastasis, locoregional relapse, or death due to any cause; secondary endpoints included distant metastasis–free survival, locoregional relapse–free survival, overall survival, and safety.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received camrelizumab had a higher 3-year event-free survival rate than those who underwent observation (86.9% vs 77.3%; stratified hazard ratio [HR], 0.56; P = .01).

- The 3-year distant metastasis–free survival was also higher in the camrelizumab group (92.4% vs 84.5%; stratified HR, 0.54; P = .04).

- Patients in the camrelizumab group had higher locoregional relapse–free survival at 3 years than those in the observation group (92.8% vs 87.0%; stratified HR, 0.53; P = .046). However, the difference in overall survival between the groups was not significant.

- The safety analysis included 426 patients; 97.1% of those who received camrelizumab experienced at least one adverse event of any grade, the most common being reactive capillary endothelial proliferation compared with 85.5% of those in the observation group. Further, 11.2% of patients taking camrelizumab reported grade 3 or 4 events, including leukopenia and neutropenia compared with 3% in the observation group.

IN PRACTICE:

“The DIPPER trial demonstrated that adjuvant camrelizumab following induction-concurrent chemoradiotherapy significantly improved event-free survival by 9.6% with a favorable safety profile in patients with locoregionally advanced [nasopharyngeal carcinoma],” the authors wrote.

“If survival is eventually proven to be improved with induction chemoimmunotherapy, can we begin asking about de-escalation of chemoradiotherapy” for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma? “This question is exceptionally important, given the significant long-term consequences of radiotherapy on survivors,” the author of an accompanying editorial wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ye-Lin Liang, MD, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, and was published online in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included patients from an endemic region where nasopharyngeal carcinoma is predominantly linked to Epstein-Barr virus infection, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings to nonendemic populations. The open-label design may have introduced bias. Additionally, combined positive scores for programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) were unavailable for some patients, potentially affecting the analysis of the correlation between PD-L1 expression and clinical outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Guangzhou Municipal Health Commission, Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province, Overseas Expertise Introduction Project for Discipline Innovation, and Cancer Innovative Research Program of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adjuvant therapy with camrelizumab significantly improved 3-year event-free survival in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma compared with observation, according to findings from the phase 3 DIPPER trial.

METHODOLOGY:

- About 20%-30% of patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma experience disease relapse after definitive chemoradiotherapy. Camrelizumab plus chemotherapy can improve progression-free survival in patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma, but its effectiveness as adjuvant therapy in locoregionally advanced disease remains unclear.

- Researchers conducted the randomized phase 3 DIPPER trial at 11 centers in China, enrolling 450 patients with T4N1M0 or T1-4N2-3M0 nasopharyngeal carcinoma who had completed induction-concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

- Participants were randomly assigned to receive either adjuvant camrelizumab (200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks for 12 cycles; n = 226) or observation (n = 224). The median follow-up duration was 39 months.

- The primary endpoint was event-free survival, defined as freedom from distant metastasis, locoregional relapse, or death due to any cause; secondary endpoints included distant metastasis–free survival, locoregional relapse–free survival, overall survival, and safety.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received camrelizumab had a higher 3-year event-free survival rate than those who underwent observation (86.9% vs 77.3%; stratified hazard ratio [HR], 0.56; P = .01).

- The 3-year distant metastasis–free survival was also higher in the camrelizumab group (92.4% vs 84.5%; stratified HR, 0.54; P = .04).

- Patients in the camrelizumab group had higher locoregional relapse–free survival at 3 years than those in the observation group (92.8% vs 87.0%; stratified HR, 0.53; P = .046). However, the difference in overall survival between the groups was not significant.

- The safety analysis included 426 patients; 97.1% of those who received camrelizumab experienced at least one adverse event of any grade, the most common being reactive capillary endothelial proliferation compared with 85.5% of those in the observation group. Further, 11.2% of patients taking camrelizumab reported grade 3 or 4 events, including leukopenia and neutropenia compared with 3% in the observation group.

IN PRACTICE:

“The DIPPER trial demonstrated that adjuvant camrelizumab following induction-concurrent chemoradiotherapy significantly improved event-free survival by 9.6% with a favorable safety profile in patients with locoregionally advanced [nasopharyngeal carcinoma],” the authors wrote.

“If survival is eventually proven to be improved with induction chemoimmunotherapy, can we begin asking about de-escalation of chemoradiotherapy” for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma? “This question is exceptionally important, given the significant long-term consequences of radiotherapy on survivors,” the author of an accompanying editorial wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ye-Lin Liang, MD, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, and was published online in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included patients from an endemic region where nasopharyngeal carcinoma is predominantly linked to Epstein-Barr virus infection, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings to nonendemic populations. The open-label design may have introduced bias. Additionally, combined positive scores for programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) were unavailable for some patients, potentially affecting the analysis of the correlation between PD-L1 expression and clinical outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Guangzhou Municipal Health Commission, Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province, Overseas Expertise Introduction Project for Discipline Innovation, and Cancer Innovative Research Program of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Postoperative RT Plus Cetuximab Showed Mixed Results in Head and Neck Cancer Trial

TOPLINE:

Adding cetuximab (C) to postoperative radiotherapy (RT) improves disease-free survival (DFS) but not overall survival (OS) in intermediate-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Benefits were specifically observed in human papillomavirus–negative patients, who represented 80.2% of the study participants.

METHODOLOGY:

- Previous research showed that adding high-dose cisplatin to postoperative RT in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) improved outcomes in those with positive margins and nodal extracapsular extension of the tumor.

- The new phase 3 randomized trial, which enrolled patients from November 2009 to March 2018 included 577 individuals with resected SCCHN of the oral cavity, oropharynx, or larynx, specifically.

- Participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive either intensity-modulated RT (60-66 Gy) with weekly C (400 mg/m2 loading dose, followed by 250 mg/m2 weekly) or RT alone.

- The primary endpoint was OS in randomly assigned eligible patients, with DFS and toxicity as secondary endpoints.

- Analysis included stratified log-rank test for OS and DFS, while toxicity was compared using Fisher’s exact test.

TAKEAWAY:

- OS was not significantly improved with RT plus C vs RT alone (hazard ratio [HR], 0.81; 95% CI, 0.60-1.08; P = .0747), though 5-year OS rates were 76.5% vs 68.7%.

- DFS showed significant improvement with combined therapy (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57-0.98; P = .0168), with 5-year rates of 71.7% vs 63.6%.

- Grade 3-4 acute toxicity rates were significantly higher with combination therapy (70.3% vs 39.7%; P < .0001), primarily affecting skin and mucosa, though late toxicity rates were similar (33.2% vs 29.0%; P = .3101).

- The benefit of RT plus C was only observed in those patients who were human papillomavirus–negative, which comprised 80.2% of trial participants.

IN PRACTICE:

RT plus C “significantly improved DFS, but not OS, with no increase in long-term toxicity, compared with RT alone for resected, intermediate-risk SCCHN. RT plus C is an appropriate option for carefully selected patients with HPV-negative disease,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Mitchell Machtay, MD, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania. It was published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

According to the researchers, the OS in the control group was higher than predicted, resulting in the trial being underpowered to detect the initial targeted HR. The authors noted that the better-than-expected survival rates could be attributed to improvements in surgical and radiotherapeutic techniques, including mandatory intensity-modulated RT for all patients. Additionally, the researchers pointed out that patient selection may have influenced outcomes, as only 30% of study participants had more than two risk factors.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute and Eli Lilly Inc. Machtay received grants from Lilly/ImClone, AstraZeneca, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adding cetuximab (C) to postoperative radiotherapy (RT) improves disease-free survival (DFS) but not overall survival (OS) in intermediate-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Benefits were specifically observed in human papillomavirus–negative patients, who represented 80.2% of the study participants.

METHODOLOGY:

- Previous research showed that adding high-dose cisplatin to postoperative RT in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) improved outcomes in those with positive margins and nodal extracapsular extension of the tumor.

- The new phase 3 randomized trial, which enrolled patients from November 2009 to March 2018 included 577 individuals with resected SCCHN of the oral cavity, oropharynx, or larynx, specifically.

- Participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive either intensity-modulated RT (60-66 Gy) with weekly C (400 mg/m2 loading dose, followed by 250 mg/m2 weekly) or RT alone.