User login

Epstein-Barr ‘Switches On” Autoimmune Genes

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) protein can “switch on” risk genes for autoimmune diseases, according to researchers from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. They found that when EBV infects human immune cells, the virus produces a protein (EBNA2) that “recruits” human proteins (transcription factors) to bind to regions of both the EBV genome and the cell’s own genome. Together the viral protein and the human transcription factors change the expression of neighboring viral genes.

In the study, EBNA2 and its related transcription factors activated some of the genes associated with the risk for lupus, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and celiac disease.

Previous research had also suggested that EBV infection plays a role in autoimmune diseases, particularly lupus. The researchers in the current study speculated that genetic analysis could further explain the relationship. They used a new computational and biochemical technique to sift through genetic and protein data, looking for potential regulatory regions in genes associated with the risk of developing lupus that also bound to EBNA2 and its transcription factors.

“We were surprised to see that nearly half of the locations on the human genome known to contribute to lupus risk were also binding sites for EBNA2,” said John Harley, MD, PhD, lead investigator.

The researchers caution, however, that many of the regulatory genes that contribute to lupus and other autoimmune disorders did not interact with EBNA2, and some individuals with activated regulatory genes do not develop disease.

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) protein can “switch on” risk genes for autoimmune diseases, according to researchers from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. They found that when EBV infects human immune cells, the virus produces a protein (EBNA2) that “recruits” human proteins (transcription factors) to bind to regions of both the EBV genome and the cell’s own genome. Together the viral protein and the human transcription factors change the expression of neighboring viral genes.

In the study, EBNA2 and its related transcription factors activated some of the genes associated with the risk for lupus, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and celiac disease.

Previous research had also suggested that EBV infection plays a role in autoimmune diseases, particularly lupus. The researchers in the current study speculated that genetic analysis could further explain the relationship. They used a new computational and biochemical technique to sift through genetic and protein data, looking for potential regulatory regions in genes associated with the risk of developing lupus that also bound to EBNA2 and its transcription factors.

“We were surprised to see that nearly half of the locations on the human genome known to contribute to lupus risk were also binding sites for EBNA2,” said John Harley, MD, PhD, lead investigator.

The researchers caution, however, that many of the regulatory genes that contribute to lupus and other autoimmune disorders did not interact with EBNA2, and some individuals with activated regulatory genes do not develop disease.

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) protein can “switch on” risk genes for autoimmune diseases, according to researchers from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. They found that when EBV infects human immune cells, the virus produces a protein (EBNA2) that “recruits” human proteins (transcription factors) to bind to regions of both the EBV genome and the cell’s own genome. Together the viral protein and the human transcription factors change the expression of neighboring viral genes.

In the study, EBNA2 and its related transcription factors activated some of the genes associated with the risk for lupus, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and celiac disease.

Previous research had also suggested that EBV infection plays a role in autoimmune diseases, particularly lupus. The researchers in the current study speculated that genetic analysis could further explain the relationship. They used a new computational and biochemical technique to sift through genetic and protein data, looking for potential regulatory regions in genes associated with the risk of developing lupus that also bound to EBNA2 and its transcription factors.

“We were surprised to see that nearly half of the locations on the human genome known to contribute to lupus risk were also binding sites for EBNA2,” said John Harley, MD, PhD, lead investigator.

The researchers caution, however, that many of the regulatory genes that contribute to lupus and other autoimmune disorders did not interact with EBNA2, and some individuals with activated regulatory genes do not develop disease.

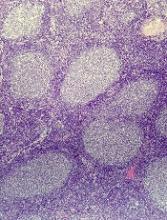

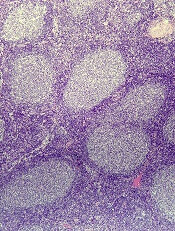

‘Excellent’ survival with HCT despite early treatment failure in FL

Autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) both offer excellent long-term survival in follicular lymphoma (FL) patients who experience early treatment failure, an analysis of a large transplant registry suggests.

Five-year survival rates exceeded 70% for patients who received autologous or matched sibling donor (MSD) transplants, according to the analysis of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database. The database included 440 patients who underwent a procedure between 2002 and 2014.

“Until better risk-stratification tools are available for FL, auto-HCT and MSD allo-HCT should be considered as effective treatment options with excellent long-term survival for high-risk patients as defined by early treatment failure,” Sonali M. Smith, MD, of the University of Chicago, and co-investigators wrote in the journal Cancer.

Early treatment failure in FL is associated with worse overall survival. In the National LymphoCare Study (NLCS), patients who received upfront R-CHOP therapy and progressed within 24 months had a 5-year overall survival of 50%, versus 90% for patients without early progression.

By contrast, survival figures in the present study are “provocatively higher” than those in the NLCS, in which only 8 out of 110 patients underwent HCT, Dr Smith and co-authors said.

Dr Smith’s study showed that with a median follow-up of 69 to 73 months, adjusted probability of 5-year overall survival was 70% for autologous and 73% for MSD HCT, versus 49% for matched unrelated donor HCT (P=0.0008).

Ryan C. Lynch, MD, and Ajay K. Gopal, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, said that the finding “convincingly demonstrates” the benefit of transplant in the setting of early treatment failure.

“Select patients (particularly younger patients) with chemoresponsive disease who understand the risk-benefit ratio in comparison with currently approved and experimental therapies still remain good candidates for autologous HCT,” Drs Lynch and Gopal said in an editorial.

“For older patients or patients with comorbidities, we would continue to recommend clinical trials or treatment with an approved PI3K inhibitor,” they added.

The study by Dr Smith and colleagues is not the first to show a benefit of HCT in this clinical scenario. In a recent NLCS/CIBMTR analysis of FL patients, 5-year overall survival was 73% for those undergoing autologous HCT done within a year of early treatment failure, versus 60% for those who did not (P=0.05).

The two studies “collectively suggest that transplantation should be considered in this high-risk group of patients with early relapse,” Dr Smith and co-authors wrote.

Autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) both offer excellent long-term survival in follicular lymphoma (FL) patients who experience early treatment failure, an analysis of a large transplant registry suggests.

Five-year survival rates exceeded 70% for patients who received autologous or matched sibling donor (MSD) transplants, according to the analysis of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database. The database included 440 patients who underwent a procedure between 2002 and 2014.

“Until better risk-stratification tools are available for FL, auto-HCT and MSD allo-HCT should be considered as effective treatment options with excellent long-term survival for high-risk patients as defined by early treatment failure,” Sonali M. Smith, MD, of the University of Chicago, and co-investigators wrote in the journal Cancer.

Early treatment failure in FL is associated with worse overall survival. In the National LymphoCare Study (NLCS), patients who received upfront R-CHOP therapy and progressed within 24 months had a 5-year overall survival of 50%, versus 90% for patients without early progression.

By contrast, survival figures in the present study are “provocatively higher” than those in the NLCS, in which only 8 out of 110 patients underwent HCT, Dr Smith and co-authors said.

Dr Smith’s study showed that with a median follow-up of 69 to 73 months, adjusted probability of 5-year overall survival was 70% for autologous and 73% for MSD HCT, versus 49% for matched unrelated donor HCT (P=0.0008).

Ryan C. Lynch, MD, and Ajay K. Gopal, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, said that the finding “convincingly demonstrates” the benefit of transplant in the setting of early treatment failure.

“Select patients (particularly younger patients) with chemoresponsive disease who understand the risk-benefit ratio in comparison with currently approved and experimental therapies still remain good candidates for autologous HCT,” Drs Lynch and Gopal said in an editorial.

“For older patients or patients with comorbidities, we would continue to recommend clinical trials or treatment with an approved PI3K inhibitor,” they added.

The study by Dr Smith and colleagues is not the first to show a benefit of HCT in this clinical scenario. In a recent NLCS/CIBMTR analysis of FL patients, 5-year overall survival was 73% for those undergoing autologous HCT done within a year of early treatment failure, versus 60% for those who did not (P=0.05).

The two studies “collectively suggest that transplantation should be considered in this high-risk group of patients with early relapse,” Dr Smith and co-authors wrote.

Autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) both offer excellent long-term survival in follicular lymphoma (FL) patients who experience early treatment failure, an analysis of a large transplant registry suggests.

Five-year survival rates exceeded 70% for patients who received autologous or matched sibling donor (MSD) transplants, according to the analysis of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database. The database included 440 patients who underwent a procedure between 2002 and 2014.

“Until better risk-stratification tools are available for FL, auto-HCT and MSD allo-HCT should be considered as effective treatment options with excellent long-term survival for high-risk patients as defined by early treatment failure,” Sonali M. Smith, MD, of the University of Chicago, and co-investigators wrote in the journal Cancer.

Early treatment failure in FL is associated with worse overall survival. In the National LymphoCare Study (NLCS), patients who received upfront R-CHOP therapy and progressed within 24 months had a 5-year overall survival of 50%, versus 90% for patients without early progression.

By contrast, survival figures in the present study are “provocatively higher” than those in the NLCS, in which only 8 out of 110 patients underwent HCT, Dr Smith and co-authors said.

Dr Smith’s study showed that with a median follow-up of 69 to 73 months, adjusted probability of 5-year overall survival was 70% for autologous and 73% for MSD HCT, versus 49% for matched unrelated donor HCT (P=0.0008).

Ryan C. Lynch, MD, and Ajay K. Gopal, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, said that the finding “convincingly demonstrates” the benefit of transplant in the setting of early treatment failure.

“Select patients (particularly younger patients) with chemoresponsive disease who understand the risk-benefit ratio in comparison with currently approved and experimental therapies still remain good candidates for autologous HCT,” Drs Lynch and Gopal said in an editorial.

“For older patients or patients with comorbidities, we would continue to recommend clinical trials or treatment with an approved PI3K inhibitor,” they added.

The study by Dr Smith and colleagues is not the first to show a benefit of HCT in this clinical scenario. In a recent NLCS/CIBMTR analysis of FL patients, 5-year overall survival was 73% for those undergoing autologous HCT done within a year of early treatment failure, versus 60% for those who did not (P=0.05).

The two studies “collectively suggest that transplantation should be considered in this high-risk group of patients with early relapse,” Dr Smith and co-authors wrote.

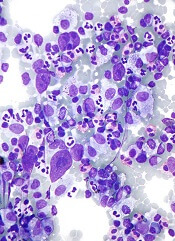

Interim PET scans identify HL patients with better outcomes

CHICAGO—Interim PET scans can identify a subset of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients with a better outcome suitable for de-escalation treatment after upfront BEACOPP without impairing disease control, according to final results of the AHL2011-LYSA study.

BEACOPP, compared to ABVD, improves progression-free survival (PFS) but not overall survival (OS) and is associated with a higher risk of myelodysplasia, acute leukemia, and infertility.

Investigators evaluated whether some patients might be able to reduce treatment intensity without compromising the effectiveness of their therapy.

Olivier Casasnovas, MD, of CHU Le Bocage Service d'Hématologie Clinique, Dijon, France, presented the final analysis at the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7503).

AHL2011-LYSA study (NCT01358747)

The randomized phase 3 study compared an early PET-driven treatment de-escalation to a non-PET-monitored strategy in patients with advanced-stage HL.

The study included 823 previously untreated patients, median age 30 years (range 16 – 60), with stage III, IV, or high-risk IIB HL.

The PET-driven strategy consisted of 2 BEACOPP* cycles (PET2), followed by 4 cycles of ABVD** for PET2-negative patients, and 4 cycles of BEACOPP for PET2-positive patients.

The experimental PET-driven strategy (410 patients) was randomly compared to a standard treatment delivering 6 cycles of BEACOPP (413 patients). PFS was the primary endpoint with a hypothesis of non-inferiority of the PET-driven arm compared to the standard arm.

Patients characteristics were well balanced between the arms, Dr Casasnovas said. PET2-positivity rate was similar in both arms (experimental 13%, standard 12%).

Based on PET2 results, 346 (84%) patients received 4 cycles of ABVD and 51 (12%) patients received 4 additional cycles of BEACOPP in the experimental arm.

Results

With a median follow-up of 50 months, the 5-year PFS was similar in the standard (86.2%) and the PET-driven arms (85.7%). The 5-year PFS for PET 2-negative/PET 4-negative patients was 90.9%, for PET 2-positive/PET4-negative patients was 75.4%, and for PET 4-positive patients was 46.5%.

The 5-year OS was similar in both arms (96.4% experimental, 95.2% standard).

The treatment toxicity was significantly higher in patients receiving 6 cycles of BEACOPP as compared to those who received 2 cycles of BEACOPP plus 4 cycles of ABVD.

Those who received more cycles of BEACOPP had more frequent grade 3 or higher adverse events than those with fewer cycles, including anemia (11% vs 2%), leukopenia (85% vs 74%), thrombocytopenia (44% vs 15%), and sepsis (7% vs 3%), as well as in serious adverse events (45% vs 28%).

“After 4 cycles of chemotherapy, it [PET positivity] identifies a subset of patients with a particularly poor outcome,” Dr Casasnovas said, “encouraging researchers to develop new treatment options in these patients.”

“PET performed after 2 cycles of BEACOPP escalation can be safely used to guide subsequent treatment,” he concluded.

“This approach allows clinicians to reduce the treatment-related immediate toxicity in most patients,” he added, “and provides similar patient outcomes compared to standard BEACOPP escalation treatment.”

* Bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone

**Adriamycin (doxorubicin), bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine

CHICAGO—Interim PET scans can identify a subset of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients with a better outcome suitable for de-escalation treatment after upfront BEACOPP without impairing disease control, according to final results of the AHL2011-LYSA study.

BEACOPP, compared to ABVD, improves progression-free survival (PFS) but not overall survival (OS) and is associated with a higher risk of myelodysplasia, acute leukemia, and infertility.

Investigators evaluated whether some patients might be able to reduce treatment intensity without compromising the effectiveness of their therapy.

Olivier Casasnovas, MD, of CHU Le Bocage Service d'Hématologie Clinique, Dijon, France, presented the final analysis at the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7503).

AHL2011-LYSA study (NCT01358747)

The randomized phase 3 study compared an early PET-driven treatment de-escalation to a non-PET-monitored strategy in patients with advanced-stage HL.

The study included 823 previously untreated patients, median age 30 years (range 16 – 60), with stage III, IV, or high-risk IIB HL.

The PET-driven strategy consisted of 2 BEACOPP* cycles (PET2), followed by 4 cycles of ABVD** for PET2-negative patients, and 4 cycles of BEACOPP for PET2-positive patients.

The experimental PET-driven strategy (410 patients) was randomly compared to a standard treatment delivering 6 cycles of BEACOPP (413 patients). PFS was the primary endpoint with a hypothesis of non-inferiority of the PET-driven arm compared to the standard arm.

Patients characteristics were well balanced between the arms, Dr Casasnovas said. PET2-positivity rate was similar in both arms (experimental 13%, standard 12%).

Based on PET2 results, 346 (84%) patients received 4 cycles of ABVD and 51 (12%) patients received 4 additional cycles of BEACOPP in the experimental arm.

Results

With a median follow-up of 50 months, the 5-year PFS was similar in the standard (86.2%) and the PET-driven arms (85.7%). The 5-year PFS for PET 2-negative/PET 4-negative patients was 90.9%, for PET 2-positive/PET4-negative patients was 75.4%, and for PET 4-positive patients was 46.5%.

The 5-year OS was similar in both arms (96.4% experimental, 95.2% standard).

The treatment toxicity was significantly higher in patients receiving 6 cycles of BEACOPP as compared to those who received 2 cycles of BEACOPP plus 4 cycles of ABVD.

Those who received more cycles of BEACOPP had more frequent grade 3 or higher adverse events than those with fewer cycles, including anemia (11% vs 2%), leukopenia (85% vs 74%), thrombocytopenia (44% vs 15%), and sepsis (7% vs 3%), as well as in serious adverse events (45% vs 28%).

“After 4 cycles of chemotherapy, it [PET positivity] identifies a subset of patients with a particularly poor outcome,” Dr Casasnovas said, “encouraging researchers to develop new treatment options in these patients.”

“PET performed after 2 cycles of BEACOPP escalation can be safely used to guide subsequent treatment,” he concluded.

“This approach allows clinicians to reduce the treatment-related immediate toxicity in most patients,” he added, “and provides similar patient outcomes compared to standard BEACOPP escalation treatment.”

* Bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone

**Adriamycin (doxorubicin), bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine

CHICAGO—Interim PET scans can identify a subset of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients with a better outcome suitable for de-escalation treatment after upfront BEACOPP without impairing disease control, according to final results of the AHL2011-LYSA study.

BEACOPP, compared to ABVD, improves progression-free survival (PFS) but not overall survival (OS) and is associated with a higher risk of myelodysplasia, acute leukemia, and infertility.

Investigators evaluated whether some patients might be able to reduce treatment intensity without compromising the effectiveness of their therapy.

Olivier Casasnovas, MD, of CHU Le Bocage Service d'Hématologie Clinique, Dijon, France, presented the final analysis at the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7503).

AHL2011-LYSA study (NCT01358747)

The randomized phase 3 study compared an early PET-driven treatment de-escalation to a non-PET-monitored strategy in patients with advanced-stage HL.

The study included 823 previously untreated patients, median age 30 years (range 16 – 60), with stage III, IV, or high-risk IIB HL.

The PET-driven strategy consisted of 2 BEACOPP* cycles (PET2), followed by 4 cycles of ABVD** for PET2-negative patients, and 4 cycles of BEACOPP for PET2-positive patients.

The experimental PET-driven strategy (410 patients) was randomly compared to a standard treatment delivering 6 cycles of BEACOPP (413 patients). PFS was the primary endpoint with a hypothesis of non-inferiority of the PET-driven arm compared to the standard arm.

Patients characteristics were well balanced between the arms, Dr Casasnovas said. PET2-positivity rate was similar in both arms (experimental 13%, standard 12%).

Based on PET2 results, 346 (84%) patients received 4 cycles of ABVD and 51 (12%) patients received 4 additional cycles of BEACOPP in the experimental arm.

Results

With a median follow-up of 50 months, the 5-year PFS was similar in the standard (86.2%) and the PET-driven arms (85.7%). The 5-year PFS for PET 2-negative/PET 4-negative patients was 90.9%, for PET 2-positive/PET4-negative patients was 75.4%, and for PET 4-positive patients was 46.5%.

The 5-year OS was similar in both arms (96.4% experimental, 95.2% standard).

The treatment toxicity was significantly higher in patients receiving 6 cycles of BEACOPP as compared to those who received 2 cycles of BEACOPP plus 4 cycles of ABVD.

Those who received more cycles of BEACOPP had more frequent grade 3 or higher adverse events than those with fewer cycles, including anemia (11% vs 2%), leukopenia (85% vs 74%), thrombocytopenia (44% vs 15%), and sepsis (7% vs 3%), as well as in serious adverse events (45% vs 28%).

“After 4 cycles of chemotherapy, it [PET positivity] identifies a subset of patients with a particularly poor outcome,” Dr Casasnovas said, “encouraging researchers to develop new treatment options in these patients.”

“PET performed after 2 cycles of BEACOPP escalation can be safely used to guide subsequent treatment,” he concluded.

“This approach allows clinicians to reduce the treatment-related immediate toxicity in most patients,” he added, “and provides similar patient outcomes compared to standard BEACOPP escalation treatment.”

* Bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone

**Adriamycin (doxorubicin), bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine

Azar blames PBMs for no drop in prescription prices

“The president said that, in reaction to the release of the drug pricing blueprint, drug companies would be ‘announcing voluntary massive drops in prices within 2 weeks,’ ” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) said during a hearing of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee to review the administration’s plan to lower drug costs.

Sen. Warren said she, along with Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.), sent letters to the top 10 drug manufacturers to get a pricing update and see what products were going to be the recipient of price cuts in response to the blueprint.

She then asked Alex Azar, Health & Human Services secretary and the hearing’s only witness, which manufacturers the president was referring to when he said drug companies would be reducing prices.

“There are actually several drug companies that are looking at substantial and material decreases of drug prices in competitive classes and actually competing with each other and looking to do that,” Mr. Azar testified. “They are working right now with the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and distributors.”

He went on to blame the PBMs for the inability to lower prices.

“What they are trying to do is work to ensure they are not discriminated against,” he said. “Oddly, the fear is that they would be discriminated against for decreasing their price.”

He noted during the hearing that PBMs get paid based on the rebates they negotiate and could retaliate against manufacturers by placing products on a higher tier or dropping them from formularies in total if manufacturers were to impact the PBM bottom line by dropping prices. He added that one of the options in the blueprint was to ban any financial transactions between the manufacturer and the PBM to ensure there is no conflict of interest and that the PBM is working on behalf of the insurers only to negotiate the best prices for drugs.

Panel Democrats used the hearing to hammer the administration for not following up on President Trump’s campaign promise to allow the government to negotiate Medicare Part D drug pricing. Part of that discussion focused on using government leverage to get “best price” contracts using prices for drugs in other countries, an exercise that Mr. Azar said would theoretically result in manufacturers yanking their drugs out of foreign markets and jacking the prices even more in the United States.

When pressed to try it on a pilot basis with one or two drugs, he pushed back, suggesting that even a pilot trial of it could result in “irreparable harm.”

“The president said that, in reaction to the release of the drug pricing blueprint, drug companies would be ‘announcing voluntary massive drops in prices within 2 weeks,’ ” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) said during a hearing of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee to review the administration’s plan to lower drug costs.

Sen. Warren said she, along with Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.), sent letters to the top 10 drug manufacturers to get a pricing update and see what products were going to be the recipient of price cuts in response to the blueprint.

She then asked Alex Azar, Health & Human Services secretary and the hearing’s only witness, which manufacturers the president was referring to when he said drug companies would be reducing prices.

“There are actually several drug companies that are looking at substantial and material decreases of drug prices in competitive classes and actually competing with each other and looking to do that,” Mr. Azar testified. “They are working right now with the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and distributors.”

He went on to blame the PBMs for the inability to lower prices.

“What they are trying to do is work to ensure they are not discriminated against,” he said. “Oddly, the fear is that they would be discriminated against for decreasing their price.”

He noted during the hearing that PBMs get paid based on the rebates they negotiate and could retaliate against manufacturers by placing products on a higher tier or dropping them from formularies in total if manufacturers were to impact the PBM bottom line by dropping prices. He added that one of the options in the blueprint was to ban any financial transactions between the manufacturer and the PBM to ensure there is no conflict of interest and that the PBM is working on behalf of the insurers only to negotiate the best prices for drugs.

Panel Democrats used the hearing to hammer the administration for not following up on President Trump’s campaign promise to allow the government to negotiate Medicare Part D drug pricing. Part of that discussion focused on using government leverage to get “best price” contracts using prices for drugs in other countries, an exercise that Mr. Azar said would theoretically result in manufacturers yanking their drugs out of foreign markets and jacking the prices even more in the United States.

When pressed to try it on a pilot basis with one or two drugs, he pushed back, suggesting that even a pilot trial of it could result in “irreparable harm.”

“The president said that, in reaction to the release of the drug pricing blueprint, drug companies would be ‘announcing voluntary massive drops in prices within 2 weeks,’ ” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) said during a hearing of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee to review the administration’s plan to lower drug costs.

Sen. Warren said she, along with Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.), sent letters to the top 10 drug manufacturers to get a pricing update and see what products were going to be the recipient of price cuts in response to the blueprint.

She then asked Alex Azar, Health & Human Services secretary and the hearing’s only witness, which manufacturers the president was referring to when he said drug companies would be reducing prices.

“There are actually several drug companies that are looking at substantial and material decreases of drug prices in competitive classes and actually competing with each other and looking to do that,” Mr. Azar testified. “They are working right now with the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and distributors.”

He went on to blame the PBMs for the inability to lower prices.

“What they are trying to do is work to ensure they are not discriminated against,” he said. “Oddly, the fear is that they would be discriminated against for decreasing their price.”

He noted during the hearing that PBMs get paid based on the rebates they negotiate and could retaliate against manufacturers by placing products on a higher tier or dropping them from formularies in total if manufacturers were to impact the PBM bottom line by dropping prices. He added that one of the options in the blueprint was to ban any financial transactions between the manufacturer and the PBM to ensure there is no conflict of interest and that the PBM is working on behalf of the insurers only to negotiate the best prices for drugs.

Panel Democrats used the hearing to hammer the administration for not following up on President Trump’s campaign promise to allow the government to negotiate Medicare Part D drug pricing. Part of that discussion focused on using government leverage to get “best price” contracts using prices for drugs in other countries, an exercise that Mr. Azar said would theoretically result in manufacturers yanking their drugs out of foreign markets and jacking the prices even more in the United States.

When pressed to try it on a pilot basis with one or two drugs, he pushed back, suggesting that even a pilot trial of it could result in “irreparable harm.”

6 ways to reduce liability by improving doc-nurse teams

Positive relationships between physicians and nurses not only make for a smoother work environment, they also may reduce medical errors and lower the risk of lawsuits.

A recent study of closed claims by national medical malpractice insurer The Doctors Company found that poor physician oversight is a key contributor to lawsuits against nurses. Investigators analyzed 67 nurse practitioner (NP) claims from January 2011 to December 2016 and compared them with 1,358 claims against primary care physicians during the same time period.

Diagnostic and medication errors were the most common allegations against NPs, the study found, a trend that matched the most frequent allegations against primary care (internal medicine and family medicine) doctors. Top administrative factors that prompted lawsuits against nurses included inadequate physician supervision, failure to adhere to scope of practice, and absence of or deviation from written protocols.

The findings illustrate the importance of effective collaboration between physicians and NPs, said Darrell Ranum, vice president for patient safety and risk management for The Doctors Co. Below, legal experts share six ways to strengthen the physician-nurse relationship and at the same time, reduce liability:

1. Foster open dialogue. Cultivating a comfortable environment where nurses and physicians feel at ease sharing concerns and problems is a key step, says Louise B. Andrew, MD, JD, a physician and attorney who specializes in litigation stress management. A common scenario is a nurse who notices an abnormal vital sign but fails to mention it to the supervising physician because they feel they can handle it themselves or because they believe the doctor is too busy or too tired to be bothered, she said. The patient’s condition then worsens, resulting in a poor outcome that could have been avoided with better communication among providers. Delayed/wrong diagnosis accounted for 41% of claims against primary care physicians and 48% of claims against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

Set the tone early by exemplifying positive and clear communication, practicing good listening, and remaining empathetic, yet firm when making your needs known, Dr. Andrew advised.

“In the medical setting, you are always communicating for the benefit of the patient, and it is good to both keep this in mind, and to say it out loud,” she said.

2. Stick to the scope. When hiring an NP, make sure their scope of practice is clearly understood by all parties and respect their limitations, said Melanie L. Balestra, a Newport Beach, Calif., attorney and nurse practitioner who represents health providers.

Nurses practitioners must refrain from overstepping their authority, but physicians also must be careful not to ask too much of their NPs, experts stress. Ms. Balestra notes there is frequent confusion among doctors and NPs over how and whether scope of practice can be expanded as needed.

“This happens all the time,” Ms. Balestra said. “I get at least two questions on this every week [from nurses] asking, ‘Can I do this? Can I do that?’ ”

The answer depends on the circumstances, the nurse’s training, and the type of practice being broadened, Ms. Balestra said. For example, an NP in cardiology care may be allowed to perform more procedures in that field after internal training, but an NP who is trained in the care of adults can see pediatric patients only by going back to school.

“Know who you’re hiring, where their expertise lies, and where they feel comfortable,” she emphasized.

3. Preplan reviews. Early in the doctor-NP relationship, discuss and decide what type of medical cases warrant physician review, Mr. Ranum said. This includes agreeing on the type of patient conditions that will require a physician review and determining the types and percentage of medical records the doctor will evaluate, he said.

“The numbers should be higher at the beginning of the relationship until the physician gains an understanding of the NP’s experience and competence,” Mr. Ranum said. “Setting expectations will open the door to more frequent and more effective communication.”

NPs, meanwhile, should feel confident in requesting the physician’s assistance when a patient’s presentation is complex or a patient has returned with the same complaints, he added.

4. Convene regularly. Schedule regular meetings to catch up and discuss patient cases – not just when something goes awry, said Ms. Balestra. During weekly or monthly meetings, physicians, NPs, and other team members can converse in a more relaxed atmosphere and share any concerns or ideas for improvements.

“Have a meeting, whether by phone or in person, just to see how things are going,” she said. “That way, the NP may be able to take some things off the plate for the physician and the physician can see how [he or she] can assist the NP.”

Short huddles at the start of each day also help clinicians and staff prepare for patients and discuss approaches to managing complex conditions or challenging patient personalities, Mr. Ranum said.

“It is often helpful to debrief on patients who were seen during that day and who represent complex conditions,” he said. “Physicians may see opportunities to improve care following the NP’s assessment and diagnosis.”

5. Consider noncompliant policy. Create a noncompliant patient policy and work together to address uncooperative patients. Noncompliant patients are a top lawsuit risk, Ms. Balestra said. A noncompliant patient for instance, may provide conflicting information to different health professionals or attempt to blame providers for adverse events, she said.

“Your noncompliant patient is your easiest patient for a lawsuit because they’re not following [instructions] and then something happens, and they say, ‘It’s your fault, you didn’t treat me right.’”

Physician and NPs should be on the same page about noncompliant patients, including taking time to discuss when and how to terminate them from the practice if necessary, she said. Consistent documentation about patients by both physician and NPs is also critical, experts emphasize. Insufficient or lack of documentation led to patient injuries in 17% of cases against primary care doctors and in 19% of cases against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

6. Keep patients out of it. When disagreements or grievances occur, discuss the problem in private and ensure all staff members do the same, Dr. Andrew said. Refrain from letting anger or annoyance with another team member carry into patient care or worse, trigger a negative comment about a staff member in front of a patient, she said.

“All it takes is for something to go wrong and a patient or family who has heard such sentiments is tuned into the fact there may be some culpability,” she said. “This is probably a key factor in many a claimant’s decision to seek redress for a bad outcome.”

Instead, address problems or differences as soon as possible and work toward a resolution. It may help to create a conflict resolution policy that outlines behavioral expectations from all team members and suggested solutions when concerns arise.

“We have to put our egos aside,” Ms. Balestra said. “The ultimate goal is the best care of the patient.”

Positive relationships between physicians and nurses not only make for a smoother work environment, they also may reduce medical errors and lower the risk of lawsuits.

A recent study of closed claims by national medical malpractice insurer The Doctors Company found that poor physician oversight is a key contributor to lawsuits against nurses. Investigators analyzed 67 nurse practitioner (NP) claims from January 2011 to December 2016 and compared them with 1,358 claims against primary care physicians during the same time period.

Diagnostic and medication errors were the most common allegations against NPs, the study found, a trend that matched the most frequent allegations against primary care (internal medicine and family medicine) doctors. Top administrative factors that prompted lawsuits against nurses included inadequate physician supervision, failure to adhere to scope of practice, and absence of or deviation from written protocols.

The findings illustrate the importance of effective collaboration between physicians and NPs, said Darrell Ranum, vice president for patient safety and risk management for The Doctors Co. Below, legal experts share six ways to strengthen the physician-nurse relationship and at the same time, reduce liability:

1. Foster open dialogue. Cultivating a comfortable environment where nurses and physicians feel at ease sharing concerns and problems is a key step, says Louise B. Andrew, MD, JD, a physician and attorney who specializes in litigation stress management. A common scenario is a nurse who notices an abnormal vital sign but fails to mention it to the supervising physician because they feel they can handle it themselves or because they believe the doctor is too busy or too tired to be bothered, she said. The patient’s condition then worsens, resulting in a poor outcome that could have been avoided with better communication among providers. Delayed/wrong diagnosis accounted for 41% of claims against primary care physicians and 48% of claims against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

Set the tone early by exemplifying positive and clear communication, practicing good listening, and remaining empathetic, yet firm when making your needs known, Dr. Andrew advised.

“In the medical setting, you are always communicating for the benefit of the patient, and it is good to both keep this in mind, and to say it out loud,” she said.

2. Stick to the scope. When hiring an NP, make sure their scope of practice is clearly understood by all parties and respect their limitations, said Melanie L. Balestra, a Newport Beach, Calif., attorney and nurse practitioner who represents health providers.

Nurses practitioners must refrain from overstepping their authority, but physicians also must be careful not to ask too much of their NPs, experts stress. Ms. Balestra notes there is frequent confusion among doctors and NPs over how and whether scope of practice can be expanded as needed.

“This happens all the time,” Ms. Balestra said. “I get at least two questions on this every week [from nurses] asking, ‘Can I do this? Can I do that?’ ”

The answer depends on the circumstances, the nurse’s training, and the type of practice being broadened, Ms. Balestra said. For example, an NP in cardiology care may be allowed to perform more procedures in that field after internal training, but an NP who is trained in the care of adults can see pediatric patients only by going back to school.

“Know who you’re hiring, where their expertise lies, and where they feel comfortable,” she emphasized.

3. Preplan reviews. Early in the doctor-NP relationship, discuss and decide what type of medical cases warrant physician review, Mr. Ranum said. This includes agreeing on the type of patient conditions that will require a physician review and determining the types and percentage of medical records the doctor will evaluate, he said.

“The numbers should be higher at the beginning of the relationship until the physician gains an understanding of the NP’s experience and competence,” Mr. Ranum said. “Setting expectations will open the door to more frequent and more effective communication.”

NPs, meanwhile, should feel confident in requesting the physician’s assistance when a patient’s presentation is complex or a patient has returned with the same complaints, he added.

4. Convene regularly. Schedule regular meetings to catch up and discuss patient cases – not just when something goes awry, said Ms. Balestra. During weekly or monthly meetings, physicians, NPs, and other team members can converse in a more relaxed atmosphere and share any concerns or ideas for improvements.

“Have a meeting, whether by phone or in person, just to see how things are going,” she said. “That way, the NP may be able to take some things off the plate for the physician and the physician can see how [he or she] can assist the NP.”

Short huddles at the start of each day also help clinicians and staff prepare for patients and discuss approaches to managing complex conditions or challenging patient personalities, Mr. Ranum said.

“It is often helpful to debrief on patients who were seen during that day and who represent complex conditions,” he said. “Physicians may see opportunities to improve care following the NP’s assessment and diagnosis.”

5. Consider noncompliant policy. Create a noncompliant patient policy and work together to address uncooperative patients. Noncompliant patients are a top lawsuit risk, Ms. Balestra said. A noncompliant patient for instance, may provide conflicting information to different health professionals or attempt to blame providers for adverse events, she said.

“Your noncompliant patient is your easiest patient for a lawsuit because they’re not following [instructions] and then something happens, and they say, ‘It’s your fault, you didn’t treat me right.’”

Physician and NPs should be on the same page about noncompliant patients, including taking time to discuss when and how to terminate them from the practice if necessary, she said. Consistent documentation about patients by both physician and NPs is also critical, experts emphasize. Insufficient or lack of documentation led to patient injuries in 17% of cases against primary care doctors and in 19% of cases against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

6. Keep patients out of it. When disagreements or grievances occur, discuss the problem in private and ensure all staff members do the same, Dr. Andrew said. Refrain from letting anger or annoyance with another team member carry into patient care or worse, trigger a negative comment about a staff member in front of a patient, she said.

“All it takes is for something to go wrong and a patient or family who has heard such sentiments is tuned into the fact there may be some culpability,” she said. “This is probably a key factor in many a claimant’s decision to seek redress for a bad outcome.”

Instead, address problems or differences as soon as possible and work toward a resolution. It may help to create a conflict resolution policy that outlines behavioral expectations from all team members and suggested solutions when concerns arise.

“We have to put our egos aside,” Ms. Balestra said. “The ultimate goal is the best care of the patient.”

Positive relationships between physicians and nurses not only make for a smoother work environment, they also may reduce medical errors and lower the risk of lawsuits.

A recent study of closed claims by national medical malpractice insurer The Doctors Company found that poor physician oversight is a key contributor to lawsuits against nurses. Investigators analyzed 67 nurse practitioner (NP) claims from January 2011 to December 2016 and compared them with 1,358 claims against primary care physicians during the same time period.

Diagnostic and medication errors were the most common allegations against NPs, the study found, a trend that matched the most frequent allegations against primary care (internal medicine and family medicine) doctors. Top administrative factors that prompted lawsuits against nurses included inadequate physician supervision, failure to adhere to scope of practice, and absence of or deviation from written protocols.

The findings illustrate the importance of effective collaboration between physicians and NPs, said Darrell Ranum, vice president for patient safety and risk management for The Doctors Co. Below, legal experts share six ways to strengthen the physician-nurse relationship and at the same time, reduce liability:

1. Foster open dialogue. Cultivating a comfortable environment where nurses and physicians feel at ease sharing concerns and problems is a key step, says Louise B. Andrew, MD, JD, a physician and attorney who specializes in litigation stress management. A common scenario is a nurse who notices an abnormal vital sign but fails to mention it to the supervising physician because they feel they can handle it themselves or because they believe the doctor is too busy or too tired to be bothered, she said. The patient’s condition then worsens, resulting in a poor outcome that could have been avoided with better communication among providers. Delayed/wrong diagnosis accounted for 41% of claims against primary care physicians and 48% of claims against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

Set the tone early by exemplifying positive and clear communication, practicing good listening, and remaining empathetic, yet firm when making your needs known, Dr. Andrew advised.

“In the medical setting, you are always communicating for the benefit of the patient, and it is good to both keep this in mind, and to say it out loud,” she said.

2. Stick to the scope. When hiring an NP, make sure their scope of practice is clearly understood by all parties and respect their limitations, said Melanie L. Balestra, a Newport Beach, Calif., attorney and nurse practitioner who represents health providers.

Nurses practitioners must refrain from overstepping their authority, but physicians also must be careful not to ask too much of their NPs, experts stress. Ms. Balestra notes there is frequent confusion among doctors and NPs over how and whether scope of practice can be expanded as needed.

“This happens all the time,” Ms. Balestra said. “I get at least two questions on this every week [from nurses] asking, ‘Can I do this? Can I do that?’ ”

The answer depends on the circumstances, the nurse’s training, and the type of practice being broadened, Ms. Balestra said. For example, an NP in cardiology care may be allowed to perform more procedures in that field after internal training, but an NP who is trained in the care of adults can see pediatric patients only by going back to school.

“Know who you’re hiring, where their expertise lies, and where they feel comfortable,” she emphasized.

3. Preplan reviews. Early in the doctor-NP relationship, discuss and decide what type of medical cases warrant physician review, Mr. Ranum said. This includes agreeing on the type of patient conditions that will require a physician review and determining the types and percentage of medical records the doctor will evaluate, he said.

“The numbers should be higher at the beginning of the relationship until the physician gains an understanding of the NP’s experience and competence,” Mr. Ranum said. “Setting expectations will open the door to more frequent and more effective communication.”

NPs, meanwhile, should feel confident in requesting the physician’s assistance when a patient’s presentation is complex or a patient has returned with the same complaints, he added.

4. Convene regularly. Schedule regular meetings to catch up and discuss patient cases – not just when something goes awry, said Ms. Balestra. During weekly or monthly meetings, physicians, NPs, and other team members can converse in a more relaxed atmosphere and share any concerns or ideas for improvements.

“Have a meeting, whether by phone or in person, just to see how things are going,” she said. “That way, the NP may be able to take some things off the plate for the physician and the physician can see how [he or she] can assist the NP.”

Short huddles at the start of each day also help clinicians and staff prepare for patients and discuss approaches to managing complex conditions or challenging patient personalities, Mr. Ranum said.

“It is often helpful to debrief on patients who were seen during that day and who represent complex conditions,” he said. “Physicians may see opportunities to improve care following the NP’s assessment and diagnosis.”

5. Consider noncompliant policy. Create a noncompliant patient policy and work together to address uncooperative patients. Noncompliant patients are a top lawsuit risk, Ms. Balestra said. A noncompliant patient for instance, may provide conflicting information to different health professionals or attempt to blame providers for adverse events, she said.

“Your noncompliant patient is your easiest patient for a lawsuit because they’re not following [instructions] and then something happens, and they say, ‘It’s your fault, you didn’t treat me right.’”

Physician and NPs should be on the same page about noncompliant patients, including taking time to discuss when and how to terminate them from the practice if necessary, she said. Consistent documentation about patients by both physician and NPs is also critical, experts emphasize. Insufficient or lack of documentation led to patient injuries in 17% of cases against primary care doctors and in 19% of cases against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

6. Keep patients out of it. When disagreements or grievances occur, discuss the problem in private and ensure all staff members do the same, Dr. Andrew said. Refrain from letting anger or annoyance with another team member carry into patient care or worse, trigger a negative comment about a staff member in front of a patient, she said.

“All it takes is for something to go wrong and a patient or family who has heard such sentiments is tuned into the fact there may be some culpability,” she said. “This is probably a key factor in many a claimant’s decision to seek redress for a bad outcome.”

Instead, address problems or differences as soon as possible and work toward a resolution. It may help to create a conflict resolution policy that outlines behavioral expectations from all team members and suggested solutions when concerns arise.

“We have to put our egos aside,” Ms. Balestra said. “The ultimate goal is the best care of the patient.”

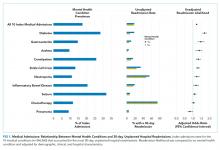

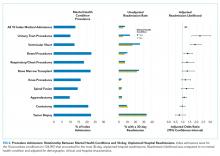

The Inpatient Blindside: Comorbid Mental Health Conditions and Readmissions among Hospitalized Children

To ensure hospital quality, the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services have tied payments to performance measures, including readmissions.1 One readmission metric, the Potentially Preventable Readmission measure (3M, PPR), was initially developed for Medicare and defined as readmissions related to an index admission, excluding those for treatment of cancer, related to trauma or burns, or following neonatal hospitalization. The PPR includes readmissions for both primary mental health conditions (MHCs) and for other hospitalizations with comorbid MHCs.2 Although controversies surround equating a hospital’s quality with its rate of readmissions, the PPR has been expanded to include numerous states. Since the PPR is also used for the Medicaid population in these states, it also measures pediatric readmissions. Hospitals in states adopting PPR calculations, including children’s hospitals, must either meet these new quality metrics or risk financial penalties. In light of evidence of high readmission rates among adult patients with MHCs, several states have modified the PPR to exclude MHCs and claims for mental health services.3–9

In their study, “Mental Health Conditions and Unplanned Hospital Readmissions in Children,” Doupnik et al. provided compelling evidence that MHCs in children (similar to adults) are closely associated with readmissions.10 MHCs are possibly underappreciated risk factors for readmission penalties and therefore represent a necessary point for increased awareness. Doupnik et al. calculated 30-day unplanned hospital readmissions of children with versus without comorbid MHCs using another standard measure, the Pediatric All-Condition Readmission (PACR) measure. The PACR measure excludes index admissions with a MHC as primary diagnosis but includes children with comorbid MHCs.

Doupnik et al. used a nationally representative cohort of all index hospitalizations of children aged 3–21 years from the 2013 Nationwide Readmission Database that allowed for estimates of MHC prevalence in the study population.11 A comorbid MHC was identified in almost 1 in 5 medical admissions and 1 in 7 procedural admissions. Comorbid substance abuse was identified in 5.4% of medical admissions and 4.7% of procedure admissions, making this diagnosis the most frequently coded stand-alone MHC. The authors’ findings are particularly noteworthy given that diagnosis of MHCs is highly dependent upon coding and is therefore almost certainly underreported. In pediatric inpatient populations, the true prevalence of comorbid MHCs is probably higher.

Doupnik et al. observed that comorbid MHCs are a significant risk factor for readmission. After adjustment for demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics, children with MHCs presented a nearly 25% higher chance of readmission for both medical and procedural hospitalizations. Children admitted with medical conditions and multiple MHCs yielded odds of readmission 50% higher than that of children without MHCs. Overall, the presence of MHCs was associated with more than 2,500 medical and 200 procedure readmissions.

Previous studies in adult populations have also found that comorbid MHCs are an important risk factor for readmissions.12,13 Other research describes that children with MHCs have increased hospital resource use, including longer lengths of stay and higher hospitalization costs.14-17 Further, children with MHCs as a primary diagnosis are more prone to readmission, with readmission rates approaching those observed in children with medical complexity in some cases.18,19 MHCs are common among hospitalized children and have become an increasingly present comorbidity in primary medical or surgical admissions.17

One particular strength of this study lies in its description of the relationship between comorbid (not primary) MHCs and readmission following medical or surgical procedures in hospitalized children. This relationship has been examined in adult inpatient populations but less so in pediatric inpatient populations.12,13 This study provides insights into the relationships between specific MHCs and unplanned readmissions for certain primary medical or surgical diagnoses, including those for attention deficit disorder and autism that are not well-recognized in adult populations.

High-quality inpatient pediatric practice depends not only upon recognition of concurrent MHCs during hospitalizations but also assurance of follow-up outside of such institutions. During the inpatient care of children, pediatric hospitalists often perform myopic inpatient care which fails to routinely address underlying MHCs.20 For example, among children who are admitted with primary medical or procedure diagnoses, it is possible, or perhaps likely, that providers give little attention to an underlying MHC outside of continuation of a current medication. Comorbid MHCs are not accounted for within readmission calculations that directly affect hospital reimbursement. This study suggests that comorbid MHCs in hospitalized children may worsen readmission penalty status. In this manner, comorbid MHCs may represent a hospital’s blindside.

We agree with Doupnik et al. that an integrated approach with medical and mental health professionals may improve the care of children with MHCs in hospitalized settings. This improvement in care may eventually affect hospital-level national quality metrics, such as readmissions. The findings of Doupnik et al. also provide a strong argument that pediatric inpatient providers should consider mental health consultations for patients with frequent admissions associated with chronic conditions, as comorbid MHCs are associated with worsened disease states and account for a disproportionate share of admissions for children with chronic conditions.21,22 Recognition of comorbid MHCs may improve baseline chronic disease states for hospitalized children.

We assert that the current silos in inpatient pediatrics of medical and mental healthcare are outdated. Pediatric hospitalists need to assess for and access effective MHC treatment options in the inpatient setting. In addition to the provision of mental health care within hospital settings, providers should also ensure that appropriate follow-up is arranged at the time of discharge. From a health policy standpoint, providers should clarify how both primary and comorbid MHCs are included within readmission measures while considering the close association of these conditions with readmission. Although the care of children with MHCs requires a long-term and coordinated approach, identification and treatment during hospitalization offer unique opportunities to modify outcomes of MHCs and coexistent medical and surgical diagnoses.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/HRRP/Hospital-Readmission-Reduction-Program.html. Published September 28, 2015. Accessed February 9, 2018.

2. 3M. Potentially Preventable Readmissions Classification System. http://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1042610O/resources-and-references-his-2015.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2018.

3. Illinois Department of Family and Healthcare Services. Hospital Inpatient Potentially Preventable Readmissions Information and Reports. https://www.illinois.gov/hfs/MedicalProviders/hospitals/PPRReports/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed February 9, 2018.

4. New York State Department of Health. Potentially preventable hospital readmissions among medicaid recipients with mental health and/or substance abuse health conditions compared with all others: New York State, 2007. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/managed_care/reports/statistics_data/3hospital_readmissions_mentahealth.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2018.

5. Texas Health and Human Services Commission. Potentially preventable readmissions in Texas Medicaid and CHIP Programs, Fiscal Year 2013. https://hhs.texas.gov/reports/2016/08/potentially-preventable-readmissions-texas-medicaid-and-chip-programs-fiscal-year-2013. Accessed February 9, 2018.

6. Oklahoma Healthcare Association. Provider reimbursement notice. https://www.okhca.org/providers.aspx?id=2538. Accessed February 9, 2018.

7. Washington State Hospital Association. Potentially preventable readmission (PPR) adjustments. http://www.wsha.org/articles/hca-implements-potentially-preventable-readmission-ppr-adjustments/. Accessed February 9, 2018.

8. State of Colorado. HQIP 30-day All cause readmission. https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/2016%20March%20HQIP%2030-day%20all-cause%20readmission%20measure.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2018.

9. Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission. Readmission reduction incentive program. http://www.hscrc.state.md.us/Pages/init-readm-rip.aspx. Accessed February 9, 2018.

10. Doupnik SK, Lawlor J, Zima BT, et al. Mental health conditions and unplanned hospital readmissions in children. J Hosp Med. 2018(13):445-452. PubMed

11. NRD Overview. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nrdoverview.jsp. Accessed February 9, 2018.

12. Singh G, Zhang W, Kuo Y-F, Sharma G. Association of psychological disorders with 30-day readmission rates in patients with COPD. Chest. 2016;149(4):905-915. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0449 PubMed

13. McIntyre LK, Arbabi S, Robinson EF, Maier RV. Analysis of risk factors for patient readmission 30 days following discharge from general surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(9):855-861. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1258 PubMed

14. Bardach NS, Coker TR, Zima BT, et al. Common and costly hospitalizations for pediatric mental health disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):602-609. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3165 PubMed

15. Doupnik SK, Lawlor J, Zima BT, et al. Mental health conditions and medical and surgical hospital utilization. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6): e20162416. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2416 PubMed

16. Doupnik SK, Mitra N, Feudtner C, Marcus SC. The influence of comorbid mood and anxiety disorders on outcomes of pediatric patients hospitalized for pneumonia. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(3):135-142. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2015-0177 PubMed

17. Zima BT, Rodean J, Hall M, Bardach NS, Coker TR, Berry JG. Psychiatric disorders and trends in resource use in pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5): e20160909. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0909 PubMed

18. Feng JY, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, Nakamura MM, Schuster MA. Readmission after pediatric mental health admissions. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20171571. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-1571 PubMed

19. Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, Anderson G, Wodchis W, Guttmann A. Patterns and costs of health care use of children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1463-e1470. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0175 PubMed

20. Doupnik SK, Walter JK. Collaboration is key to improving hospital care for patients with medical and psychiatric comorbidity. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(12):760-762. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2016-0165 PubMed

21. Richardson LP, Russo JE, Lozano P, McCauley E, Katon W. The effect of comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders on health care utilization and costs among adolescents with asthma. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):398-406. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.06.004 PubMed

22. Malik FS, Hall M, Mangione-Smith R, et al. Patient characteristics associated with differences in admission frequency for diabetic ketoacidosis in United States children’s hospitals. J Pediatr. 2016;171:104-110. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.015 PubMed

To ensure hospital quality, the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services have tied payments to performance measures, including readmissions.1 One readmission metric, the Potentially Preventable Readmission measure (3M, PPR), was initially developed for Medicare and defined as readmissions related to an index admission, excluding those for treatment of cancer, related to trauma or burns, or following neonatal hospitalization. The PPR includes readmissions for both primary mental health conditions (MHCs) and for other hospitalizations with comorbid MHCs.2 Although controversies surround equating a hospital’s quality with its rate of readmissions, the PPR has been expanded to include numerous states. Since the PPR is also used for the Medicaid population in these states, it also measures pediatric readmissions. Hospitals in states adopting PPR calculations, including children’s hospitals, must either meet these new quality metrics or risk financial penalties. In light of evidence of high readmission rates among adult patients with MHCs, several states have modified the PPR to exclude MHCs and claims for mental health services.3–9

In their study, “Mental Health Conditions and Unplanned Hospital Readmissions in Children,” Doupnik et al. provided compelling evidence that MHCs in children (similar to adults) are closely associated with readmissions.10 MHCs are possibly underappreciated risk factors for readmission penalties and therefore represent a necessary point for increased awareness. Doupnik et al. calculated 30-day unplanned hospital readmissions of children with versus without comorbid MHCs using another standard measure, the Pediatric All-Condition Readmission (PACR) measure. The PACR measure excludes index admissions with a MHC as primary diagnosis but includes children with comorbid MHCs.

Doupnik et al. used a nationally representative cohort of all index hospitalizations of children aged 3–21 years from the 2013 Nationwide Readmission Database that allowed for estimates of MHC prevalence in the study population.11 A comorbid MHC was identified in almost 1 in 5 medical admissions and 1 in 7 procedural admissions. Comorbid substance abuse was identified in 5.4% of medical admissions and 4.7% of procedure admissions, making this diagnosis the most frequently coded stand-alone MHC. The authors’ findings are particularly noteworthy given that diagnosis of MHCs is highly dependent upon coding and is therefore almost certainly underreported. In pediatric inpatient populations, the true prevalence of comorbid MHCs is probably higher.

Doupnik et al. observed that comorbid MHCs are a significant risk factor for readmission. After adjustment for demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics, children with MHCs presented a nearly 25% higher chance of readmission for both medical and procedural hospitalizations. Children admitted with medical conditions and multiple MHCs yielded odds of readmission 50% higher than that of children without MHCs. Overall, the presence of MHCs was associated with more than 2,500 medical and 200 procedure readmissions.

Previous studies in adult populations have also found that comorbid MHCs are an important risk factor for readmissions.12,13 Other research describes that children with MHCs have increased hospital resource use, including longer lengths of stay and higher hospitalization costs.14-17 Further, children with MHCs as a primary diagnosis are more prone to readmission, with readmission rates approaching those observed in children with medical complexity in some cases.18,19 MHCs are common among hospitalized children and have become an increasingly present comorbidity in primary medical or surgical admissions.17

One particular strength of this study lies in its description of the relationship between comorbid (not primary) MHCs and readmission following medical or surgical procedures in hospitalized children. This relationship has been examined in adult inpatient populations but less so in pediatric inpatient populations.12,13 This study provides insights into the relationships between specific MHCs and unplanned readmissions for certain primary medical or surgical diagnoses, including those for attention deficit disorder and autism that are not well-recognized in adult populations.

High-quality inpatient pediatric practice depends not only upon recognition of concurrent MHCs during hospitalizations but also assurance of follow-up outside of such institutions. During the inpatient care of children, pediatric hospitalists often perform myopic inpatient care which fails to routinely address underlying MHCs.20 For example, among children who are admitted with primary medical or procedure diagnoses, it is possible, or perhaps likely, that providers give little attention to an underlying MHC outside of continuation of a current medication. Comorbid MHCs are not accounted for within readmission calculations that directly affect hospital reimbursement. This study suggests that comorbid MHCs in hospitalized children may worsen readmission penalty status. In this manner, comorbid MHCs may represent a hospital’s blindside.

We agree with Doupnik et al. that an integrated approach with medical and mental health professionals may improve the care of children with MHCs in hospitalized settings. This improvement in care may eventually affect hospital-level national quality metrics, such as readmissions. The findings of Doupnik et al. also provide a strong argument that pediatric inpatient providers should consider mental health consultations for patients with frequent admissions associated with chronic conditions, as comorbid MHCs are associated with worsened disease states and account for a disproportionate share of admissions for children with chronic conditions.21,22 Recognition of comorbid MHCs may improve baseline chronic disease states for hospitalized children.

We assert that the current silos in inpatient pediatrics of medical and mental healthcare are outdated. Pediatric hospitalists need to assess for and access effective MHC treatment options in the inpatient setting. In addition to the provision of mental health care within hospital settings, providers should also ensure that appropriate follow-up is arranged at the time of discharge. From a health policy standpoint, providers should clarify how both primary and comorbid MHCs are included within readmission measures while considering the close association of these conditions with readmission. Although the care of children with MHCs requires a long-term and coordinated approach, identification and treatment during hospitalization offer unique opportunities to modify outcomes of MHCs and coexistent medical and surgical diagnoses.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

To ensure hospital quality, the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services have tied payments to performance measures, including readmissions.1 One readmission metric, the Potentially Preventable Readmission measure (3M, PPR), was initially developed for Medicare and defined as readmissions related to an index admission, excluding those for treatment of cancer, related to trauma or burns, or following neonatal hospitalization. The PPR includes readmissions for both primary mental health conditions (MHCs) and for other hospitalizations with comorbid MHCs.2 Although controversies surround equating a hospital’s quality with its rate of readmissions, the PPR has been expanded to include numerous states. Since the PPR is also used for the Medicaid population in these states, it also measures pediatric readmissions. Hospitals in states adopting PPR calculations, including children’s hospitals, must either meet these new quality metrics or risk financial penalties. In light of evidence of high readmission rates among adult patients with MHCs, several states have modified the PPR to exclude MHCs and claims for mental health services.3–9

In their study, “Mental Health Conditions and Unplanned Hospital Readmissions in Children,” Doupnik et al. provided compelling evidence that MHCs in children (similar to adults) are closely associated with readmissions.10 MHCs are possibly underappreciated risk factors for readmission penalties and therefore represent a necessary point for increased awareness. Doupnik et al. calculated 30-day unplanned hospital readmissions of children with versus without comorbid MHCs using another standard measure, the Pediatric All-Condition Readmission (PACR) measure. The PACR measure excludes index admissions with a MHC as primary diagnosis but includes children with comorbid MHCs.

Doupnik et al. used a nationally representative cohort of all index hospitalizations of children aged 3–21 years from the 2013 Nationwide Readmission Database that allowed for estimates of MHC prevalence in the study population.11 A comorbid MHC was identified in almost 1 in 5 medical admissions and 1 in 7 procedural admissions. Comorbid substance abuse was identified in 5.4% of medical admissions and 4.7% of procedure admissions, making this diagnosis the most frequently coded stand-alone MHC. The authors’ findings are particularly noteworthy given that diagnosis of MHCs is highly dependent upon coding and is therefore almost certainly underreported. In pediatric inpatient populations, the true prevalence of comorbid MHCs is probably higher.

Doupnik et al. observed that comorbid MHCs are a significant risk factor for readmission. After adjustment for demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics, children with MHCs presented a nearly 25% higher chance of readmission for both medical and procedural hospitalizations. Children admitted with medical conditions and multiple MHCs yielded odds of readmission 50% higher than that of children without MHCs. Overall, the presence of MHCs was associated with more than 2,500 medical and 200 procedure readmissions.

Previous studies in adult populations have also found that comorbid MHCs are an important risk factor for readmissions.12,13 Other research describes that children with MHCs have increased hospital resource use, including longer lengths of stay and higher hospitalization costs.14-17 Further, children with MHCs as a primary diagnosis are more prone to readmission, with readmission rates approaching those observed in children with medical complexity in some cases.18,19 MHCs are common among hospitalized children and have become an increasingly present comorbidity in primary medical or surgical admissions.17

One particular strength of this study lies in its description of the relationship between comorbid (not primary) MHCs and readmission following medical or surgical procedures in hospitalized children. This relationship has been examined in adult inpatient populations but less so in pediatric inpatient populations.12,13 This study provides insights into the relationships between specific MHCs and unplanned readmissions for certain primary medical or surgical diagnoses, including those for attention deficit disorder and autism that are not well-recognized in adult populations.

High-quality inpatient pediatric practice depends not only upon recognition of concurrent MHCs during hospitalizations but also assurance of follow-up outside of such institutions. During the inpatient care of children, pediatric hospitalists often perform myopic inpatient care which fails to routinely address underlying MHCs.20 For example, among children who are admitted with primary medical or procedure diagnoses, it is possible, or perhaps likely, that providers give little attention to an underlying MHC outside of continuation of a current medication. Comorbid MHCs are not accounted for within readmission calculations that directly affect hospital reimbursement. This study suggests that comorbid MHCs in hospitalized children may worsen readmission penalty status. In this manner, comorbid MHCs may represent a hospital’s blindside.

We agree with Doupnik et al. that an integrated approach with medical and mental health professionals may improve the care of children with MHCs in hospitalized settings. This improvement in care may eventually affect hospital-level national quality metrics, such as readmissions. The findings of Doupnik et al. also provide a strong argument that pediatric inpatient providers should consider mental health consultations for patients with frequent admissions associated with chronic conditions, as comorbid MHCs are associated with worsened disease states and account for a disproportionate share of admissions for children with chronic conditions.21,22 Recognition of comorbid MHCs may improve baseline chronic disease states for hospitalized children.

We assert that the current silos in inpatient pediatrics of medical and mental healthcare are outdated. Pediatric hospitalists need to assess for and access effective MHC treatment options in the inpatient setting. In addition to the provision of mental health care within hospital settings, providers should also ensure that appropriate follow-up is arranged at the time of discharge. From a health policy standpoint, providers should clarify how both primary and comorbid MHCs are included within readmission measures while considering the close association of these conditions with readmission. Although the care of children with MHCs requires a long-term and coordinated approach, identification and treatment during hospitalization offer unique opportunities to modify outcomes of MHCs and coexistent medical and surgical diagnoses.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/HRRP/Hospital-Readmission-Reduction-Program.html. Published September 28, 2015. Accessed February 9, 2018.

2. 3M. Potentially Preventable Readmissions Classification System. http://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1042610O/resources-and-references-his-2015.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2018.