User login

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

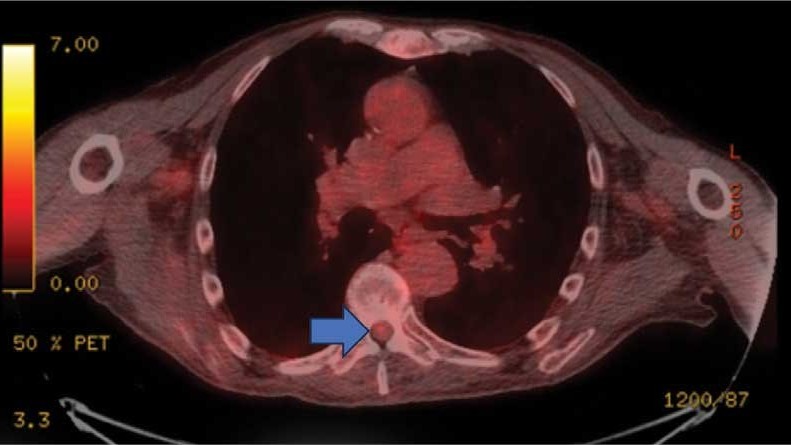

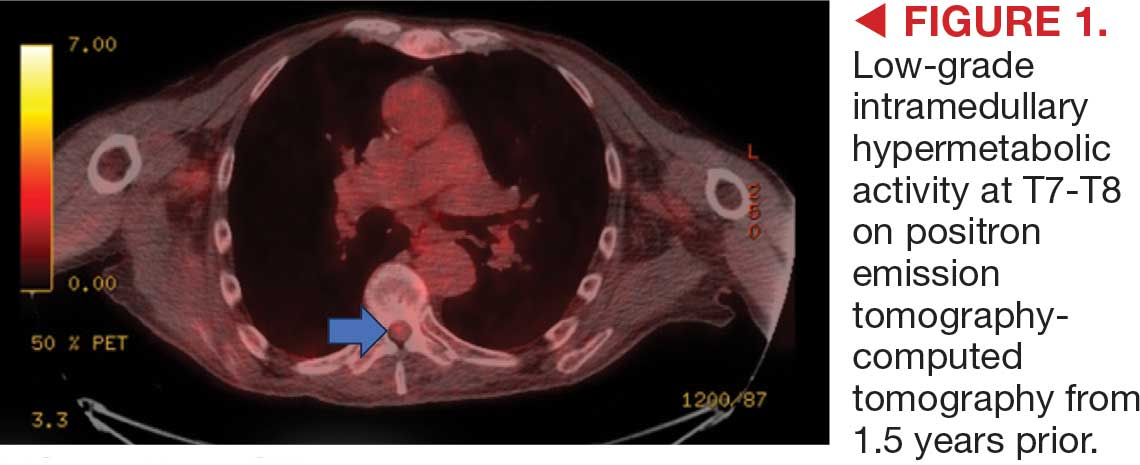

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

An 87-year-old man presented to the emergency department reporting a 1-month history of right lower extremity weakness, progressing to an inability to ambulate. The patient had a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, low-grade right urothelial carcinoma status postbiopsy 2 years earlier, and atrial fibrillation following cardioversion 6 years earlier without anticoagulation therapy. He also reported severe right groin pain and increasing urinary obstruction.

On admission, neurology evaluated the patient’s lower extremity strength as 5/5 on his left, 1/5 on his right hip, and 2/5 on his right knee, with hypoesthesia of his right lower extremity. Computed tomography (CT) with contrast of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated moderate to severe right-sided hydronephrosis, possibly due to a proximal right ureteric mass; no evidence of systemic metastases was found. He underwent a gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, which showed a mass at T7-T8, a mass effect in the central cord, and abnormal spinal cord enhancement from T7 through the conus medullaris. A review of fluorodeoxyglucose- 18 (FDG-18) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT imaging from 1.5 years prior showed a low-grade focus (Figures 1-3). A gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI did not demonstrate any intracranial metastatic disease, acute infarct, hemorrhage, mass effect, or extra-axial fluid collections.

Atrophic Areas on the Axillary and Anogenital Anatomy

Atrophic Areas on the Axillary and Anogenital Anatomy

Discussion

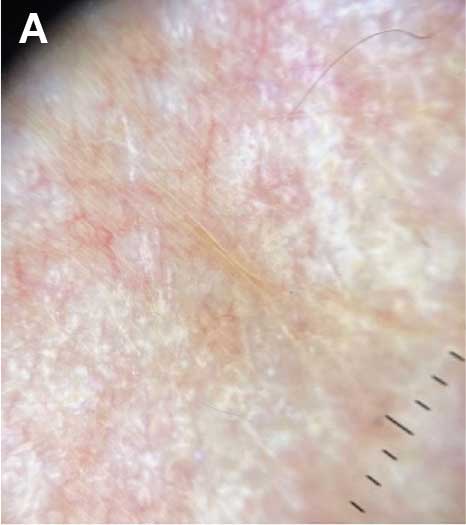

A diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS) was made based on clinical and dermoscopic features, followed by confirmation with histology. The patient’s presentation included typical signs and symptoms of LS: itching, burning, intermittent bleeding, perianal hemorrhage, fusion of the clitoral head, and fissures. Other presentations can include dyspareunia, erosions, and excoriations; however, these symptoms and signs were not reported or seen in this patient.

LS typically affects the anogenital region and has 2 peak incidences: in preadolescent teens and during the fifth to sixth decade of life.1 This patient presented with a case of extragenital LS, which is less common than the classic presentation of LS that affects the genitals. This variant’s epidemiology differs, as it is less common in children and more common in postmenopausal women.2 Extragenital LS presents as white, atrophic plaques with a predilection for sites including the trunk, breasts, upper arms, and sites of physical trauma, with symptoms of dryness and pruritus. Over time, the papules can coalesce and form ivory, scar-like papules or plaques with a wrinkled surface. In advanced stages, telangiectasia or follicular plugging can be present, along with flattening of the dermal-epidermal junction. This flat interface is fragile and can result in bullae that may become hemorrhagic.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) may infrequently arise from LS, similar to other chronic inflammatory dermatoses.3 Lichen planus is typically not associated with an increased risk of SCC, except in the oral and hypertrophic variants. However, LS may be considered a premalignant process, and many vulvar SCC cases are noted to have adjacent LS lesions.3

Autoimmune and genetic factors contribute to the pathogenesis of LS. Extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1) binds molecules of the basement membrane zone and dermis, contributing to the structure and integrity of skin. Autoantibodies against ECM1 and other antigens of the basement membrane zone, including BP180 and BP320, were found in LS.2 HLA-DQ7 major histocompatibility complex class II antigens have been associated with LS.1

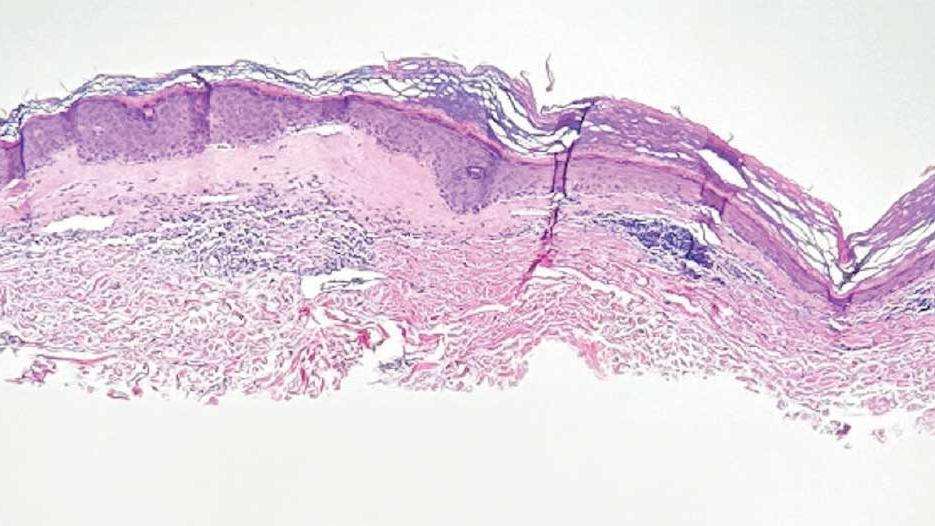

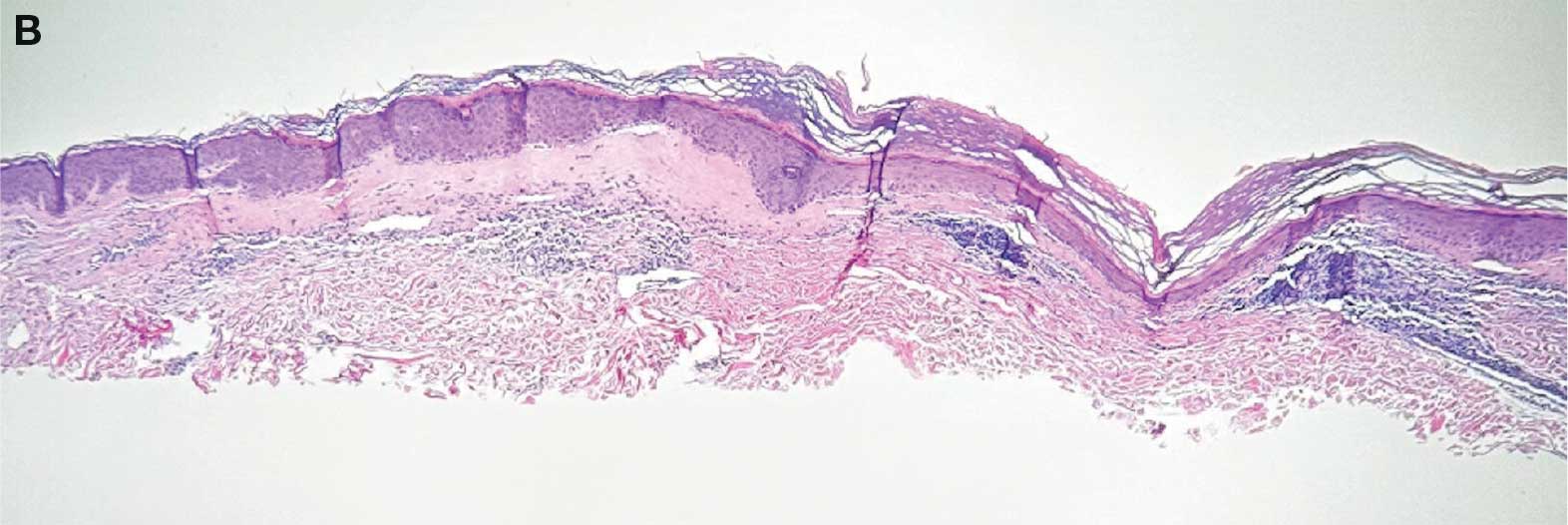

On histologic examination, the epidermis of LS is atrophic with hyperkeratosis. The dermis shows homogenization and sclerosis of superficial collagen with a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate below the sclerosis. The basal layer is thickened, showing basal cell vacuolization and hydropic degeneration.4

First-line treatment for genital and extragenital variants of LS is high-potency topical steroids for 3 months or until the skin texture and color resolve (ie, clobetasol 0.05% cream or ointment). The second-line treatment is a topical calcineurin inhibitor. These treatments are used for management. They are not cures for LS, as relapse is possible after the initial treatment course is completed. Adverse effects of high potency topical steroids are skin burning, skin atrophy, and fragility, telangiectasia. The adverse effects of topical calcineurin inhibitors are stinging and burning on application.

Other Diagnostic Considerations

Inverse psoriasis (IP) is a variant of psoriasis that presents as erythematous, well-demarcated plaques with minimal scale in intertriginous areas and flexural surfaces. Localized dermatophyte, candidal, or bacterial infections can trigger IP.5 It occurs in about 3% to 7% of patients with plaque psoriasis and is thought to form due to koebnerization via mechanical friction of flexural zones.6 The patient described in this case did not have IP because IP would be more likely to present as a well-demarcated erythematous plaque rather than a patch.

Histologically, IP shows regular psoriasiform acanthosis and hypogranulosis of the epidermis, Munro microabscess, spongiform pustules of Kogoj, dilated tortuous dermal vessels, and thinning of the suprapapillary plates.5

Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI) is also known as lichen planus pigmentosus—intertriginous variant. This variant of lichen planus pigmentosus presents as multiple gray to dark brown macules and patches with poorly defined borders in a linear distribution limited to intertriginous areas, flexural surfaces, or following the lines of Blaschko.7 About 20% of cases present with frontal fibrosing alopecia. It is most common in individuals with intermediate and darker skin pigmentation, has a higher prevalence in females, and typically occurs within the third and fifth decades of life. Friction is a common trigger of LPPI.7 A diagnosis of LPPI is incorrect because the lesions would present as gray to dark brown macules, as opposed to the shiny white atrophic thin papules with surrounding pink and purple patches seen in this case.

Histologically, while both LS and LPPI share band-like lymphocytic infiltrate and basal cell vacuolization, findings in the dermis differ. LPPI shows melanophages and prominent melanin incontinence, while LS shows homogenization and sclerosis of superficial collagen.1,8 LPPI also shows absence of compensatory keratinocyte proliferation.

Morphea is an inflammatory disease that affects the dermis and subcutaneous fat, resulting in sclerosis that appears scarlike. Its prevalence increases with age and has a 4:1 prevalence in females, with the plaque type being the most common variant. 9 The typical presentation of plaque-type morphea is an insidious onset of asymptomatic, slightly elevated, erythematous or violaceous, slightly edematous plaques with centrifugal expansion. The center of the plaque may become sclerotic and indurated, acquiring a shiny white color with a peripheral “lilac” ring. Trunk and upper extremity involvement is common. Morphea is associated with increased antisingle-stranded DNA, antitopoisomerase IIa, antiphospholipid, antifibrillin-1, and antihistone antibodies. Triggers of morphea are believed to be localized insults to the skin, including mechanical trauma, injections, vaccinations, and irradiation.9 This answer is incorrect because the patient’s lesions were pruritic and had genital involvement, which are not typical of morphea. Morphea can be differentiated with based on symptoms (lack of pruritus, pain, burning), morphology of lesions (induration versus atrophy), dermoscopy (fibrotic beams with less scale and hemorrhage vs keratotic follicular plugs), and histopathology (depth of inflammation in superficial and deep dermis).

Histology of morphea can differ based on the stage, whether the lesion is sampled in the inflammatory margin or central sclerosis, and the depth of affected skin. At the inflammatory margin, vascular changes, including endothelial swelling and edema, are present, as well as CD4+ T cells, eosinophils, plasma cells, and mast cells surrounding smaller blood vessels. In late stages, the inflammatory infiltrate is no longer present, the epidermis appears regular, and there is a flattened dermal-epidermal junction. Distinct features include homogenous collagen bundles that replace many dermal structures, with atrophic eccrine glands that appear “trapped” in the thickened dermis, and homogenized and hyalinized subcutis.9

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and presents as annular, erythematous or hypopigmented patches and plaques with fine scale and tumors on the buttocks and sun-protected areas of the limbs and trunk. Lesions can appear with prominent poikiloderma or atrophic or lichenified skin.10 It is most common in males of African descent aged 50 to 55 years. The etiology is largely unknown but believed to be multifactorial. This answer is incorrect because the lesions in this patient appeared more atrophic, were less well demarcated, and lacked the scale that would be present in MF.

On histology, both LS and MF show band-like lymphocytic infiltrate, however MF lacks the homogenization and sclerosis of superficial collagen that is present in the dermis of LS. Also, MF demonstrates epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes forming Pautrier microabscess.10

Primary Care Role

Primary care physicians can diagnose and treat LS. Referral to dermatology is not mandatory. Note that topical steroids can be used daily for up to 12 weeks. In LS, early treatment is associated with improved outcomes and minimizes the risk of irreversible skin changes.11 Follow-up during the treatment period is recommended to monitor subjective and objective response to treatment. Follow-up after the initial treatment is recommended since LS is typically chronic, can relapse, and SCC can infrequently arise from LS lesions.11

- Tran DA, Tan X, Macri CJ, Goldstein AT, Fu SW. Lichen sclerosus: an autoimmunopathogenic and genomic enigma with emerging genetic and immune targets. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1429-1439. doi:10.7150/ijbs.34613

- De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, et al. Lichen sclerosus: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106318. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1106318

- Kuraitis D, Murina A. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in chronic inflammatory dermatoses. Cutis. 2024;113:29-34. doi:10.12788/cutis.0914

- Gaertner E, Elstein W. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: case report and review of an unusual entity. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Micali G, Verzì AE, Giuffrida G, et al. Inverse psoriasis: from diagnosis to current treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:953-959. doi:10.2147/CCID.S189000

- Syed ZU, Khachemoune A. Inverse psoriasis: case presentation and review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:143-146. doi:10.2165/11532060-000000000-00000

- Robles-Méndez JC, Rizo-Frías P, Herz-Ruelas ME, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus and its variants: review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:505-514. doi:10.1111/ijd.13806

- Vinay K, Kumar S, Bishnoi A, et al. A clinico-demographic study of 344 patients with lichen planus pigmentosus seen in a tertiary care center in India over an 8-year period. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:245-252. doi:10.1111/ijd.14540

- Papara C, De Luca DA, Bieber K, et al. Morphea: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1108623. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1108623

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJ, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Cri t Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1061-1067. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0643

Discussion

A diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS) was made based on clinical and dermoscopic features, followed by confirmation with histology. The patient’s presentation included typical signs and symptoms of LS: itching, burning, intermittent bleeding, perianal hemorrhage, fusion of the clitoral head, and fissures. Other presentations can include dyspareunia, erosions, and excoriations; however, these symptoms and signs were not reported or seen in this patient.

LS typically affects the anogenital region and has 2 peak incidences: in preadolescent teens and during the fifth to sixth decade of life.1 This patient presented with a case of extragenital LS, which is less common than the classic presentation of LS that affects the genitals. This variant’s epidemiology differs, as it is less common in children and more common in postmenopausal women.2 Extragenital LS presents as white, atrophic plaques with a predilection for sites including the trunk, breasts, upper arms, and sites of physical trauma, with symptoms of dryness and pruritus. Over time, the papules can coalesce and form ivory, scar-like papules or plaques with a wrinkled surface. In advanced stages, telangiectasia or follicular plugging can be present, along with flattening of the dermal-epidermal junction. This flat interface is fragile and can result in bullae that may become hemorrhagic.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) may infrequently arise from LS, similar to other chronic inflammatory dermatoses.3 Lichen planus is typically not associated with an increased risk of SCC, except in the oral and hypertrophic variants. However, LS may be considered a premalignant process, and many vulvar SCC cases are noted to have adjacent LS lesions.3

Autoimmune and genetic factors contribute to the pathogenesis of LS. Extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1) binds molecules of the basement membrane zone and dermis, contributing to the structure and integrity of skin. Autoantibodies against ECM1 and other antigens of the basement membrane zone, including BP180 and BP320, were found in LS.2 HLA-DQ7 major histocompatibility complex class II antigens have been associated with LS.1

On histologic examination, the epidermis of LS is atrophic with hyperkeratosis. The dermis shows homogenization and sclerosis of superficial collagen with a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate below the sclerosis. The basal layer is thickened, showing basal cell vacuolization and hydropic degeneration.4

First-line treatment for genital and extragenital variants of LS is high-potency topical steroids for 3 months or until the skin texture and color resolve (ie, clobetasol 0.05% cream or ointment). The second-line treatment is a topical calcineurin inhibitor. These treatments are used for management. They are not cures for LS, as relapse is possible after the initial treatment course is completed. Adverse effects of high potency topical steroids are skin burning, skin atrophy, and fragility, telangiectasia. The adverse effects of topical calcineurin inhibitors are stinging and burning on application.

Other Diagnostic Considerations

Inverse psoriasis (IP) is a variant of psoriasis that presents as erythematous, well-demarcated plaques with minimal scale in intertriginous areas and flexural surfaces. Localized dermatophyte, candidal, or bacterial infections can trigger IP.5 It occurs in about 3% to 7% of patients with plaque psoriasis and is thought to form due to koebnerization via mechanical friction of flexural zones.6 The patient described in this case did not have IP because IP would be more likely to present as a well-demarcated erythematous plaque rather than a patch.

Histologically, IP shows regular psoriasiform acanthosis and hypogranulosis of the epidermis, Munro microabscess, spongiform pustules of Kogoj, dilated tortuous dermal vessels, and thinning of the suprapapillary plates.5

Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI) is also known as lichen planus pigmentosus—intertriginous variant. This variant of lichen planus pigmentosus presents as multiple gray to dark brown macules and patches with poorly defined borders in a linear distribution limited to intertriginous areas, flexural surfaces, or following the lines of Blaschko.7 About 20% of cases present with frontal fibrosing alopecia. It is most common in individuals with intermediate and darker skin pigmentation, has a higher prevalence in females, and typically occurs within the third and fifth decades of life. Friction is a common trigger of LPPI.7 A diagnosis of LPPI is incorrect because the lesions would present as gray to dark brown macules, as opposed to the shiny white atrophic thin papules with surrounding pink and purple patches seen in this case.

Histologically, while both LS and LPPI share band-like lymphocytic infiltrate and basal cell vacuolization, findings in the dermis differ. LPPI shows melanophages and prominent melanin incontinence, while LS shows homogenization and sclerosis of superficial collagen.1,8 LPPI also shows absence of compensatory keratinocyte proliferation.

Morphea is an inflammatory disease that affects the dermis and subcutaneous fat, resulting in sclerosis that appears scarlike. Its prevalence increases with age and has a 4:1 prevalence in females, with the plaque type being the most common variant. 9 The typical presentation of plaque-type morphea is an insidious onset of asymptomatic, slightly elevated, erythematous or violaceous, slightly edematous plaques with centrifugal expansion. The center of the plaque may become sclerotic and indurated, acquiring a shiny white color with a peripheral “lilac” ring. Trunk and upper extremity involvement is common. Morphea is associated with increased antisingle-stranded DNA, antitopoisomerase IIa, antiphospholipid, antifibrillin-1, and antihistone antibodies. Triggers of morphea are believed to be localized insults to the skin, including mechanical trauma, injections, vaccinations, and irradiation.9 This answer is incorrect because the patient’s lesions were pruritic and had genital involvement, which are not typical of morphea. Morphea can be differentiated with based on symptoms (lack of pruritus, pain, burning), morphology of lesions (induration versus atrophy), dermoscopy (fibrotic beams with less scale and hemorrhage vs keratotic follicular plugs), and histopathology (depth of inflammation in superficial and deep dermis).

Histology of morphea can differ based on the stage, whether the lesion is sampled in the inflammatory margin or central sclerosis, and the depth of affected skin. At the inflammatory margin, vascular changes, including endothelial swelling and edema, are present, as well as CD4+ T cells, eosinophils, plasma cells, and mast cells surrounding smaller blood vessels. In late stages, the inflammatory infiltrate is no longer present, the epidermis appears regular, and there is a flattened dermal-epidermal junction. Distinct features include homogenous collagen bundles that replace many dermal structures, with atrophic eccrine glands that appear “trapped” in the thickened dermis, and homogenized and hyalinized subcutis.9

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and presents as annular, erythematous or hypopigmented patches and plaques with fine scale and tumors on the buttocks and sun-protected areas of the limbs and trunk. Lesions can appear with prominent poikiloderma or atrophic or lichenified skin.10 It is most common in males of African descent aged 50 to 55 years. The etiology is largely unknown but believed to be multifactorial. This answer is incorrect because the lesions in this patient appeared more atrophic, were less well demarcated, and lacked the scale that would be present in MF.

On histology, both LS and MF show band-like lymphocytic infiltrate, however MF lacks the homogenization and sclerosis of superficial collagen that is present in the dermis of LS. Also, MF demonstrates epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes forming Pautrier microabscess.10

Primary Care Role

Primary care physicians can diagnose and treat LS. Referral to dermatology is not mandatory. Note that topical steroids can be used daily for up to 12 weeks. In LS, early treatment is associated with improved outcomes and minimizes the risk of irreversible skin changes.11 Follow-up during the treatment period is recommended to monitor subjective and objective response to treatment. Follow-up after the initial treatment is recommended since LS is typically chronic, can relapse, and SCC can infrequently arise from LS lesions.11

Discussion

A diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS) was made based on clinical and dermoscopic features, followed by confirmation with histology. The patient’s presentation included typical signs and symptoms of LS: itching, burning, intermittent bleeding, perianal hemorrhage, fusion of the clitoral head, and fissures. Other presentations can include dyspareunia, erosions, and excoriations; however, these symptoms and signs were not reported or seen in this patient.

LS typically affects the anogenital region and has 2 peak incidences: in preadolescent teens and during the fifth to sixth decade of life.1 This patient presented with a case of extragenital LS, which is less common than the classic presentation of LS that affects the genitals. This variant’s epidemiology differs, as it is less common in children and more common in postmenopausal women.2 Extragenital LS presents as white, atrophic plaques with a predilection for sites including the trunk, breasts, upper arms, and sites of physical trauma, with symptoms of dryness and pruritus. Over time, the papules can coalesce and form ivory, scar-like papules or plaques with a wrinkled surface. In advanced stages, telangiectasia or follicular plugging can be present, along with flattening of the dermal-epidermal junction. This flat interface is fragile and can result in bullae that may become hemorrhagic.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) may infrequently arise from LS, similar to other chronic inflammatory dermatoses.3 Lichen planus is typically not associated with an increased risk of SCC, except in the oral and hypertrophic variants. However, LS may be considered a premalignant process, and many vulvar SCC cases are noted to have adjacent LS lesions.3

Autoimmune and genetic factors contribute to the pathogenesis of LS. Extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1) binds molecules of the basement membrane zone and dermis, contributing to the structure and integrity of skin. Autoantibodies against ECM1 and other antigens of the basement membrane zone, including BP180 and BP320, were found in LS.2 HLA-DQ7 major histocompatibility complex class II antigens have been associated with LS.1

On histologic examination, the epidermis of LS is atrophic with hyperkeratosis. The dermis shows homogenization and sclerosis of superficial collagen with a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate below the sclerosis. The basal layer is thickened, showing basal cell vacuolization and hydropic degeneration.4

First-line treatment for genital and extragenital variants of LS is high-potency topical steroids for 3 months or until the skin texture and color resolve (ie, clobetasol 0.05% cream or ointment). The second-line treatment is a topical calcineurin inhibitor. These treatments are used for management. They are not cures for LS, as relapse is possible after the initial treatment course is completed. Adverse effects of high potency topical steroids are skin burning, skin atrophy, and fragility, telangiectasia. The adverse effects of topical calcineurin inhibitors are stinging and burning on application.

Other Diagnostic Considerations

Inverse psoriasis (IP) is a variant of psoriasis that presents as erythematous, well-demarcated plaques with minimal scale in intertriginous areas and flexural surfaces. Localized dermatophyte, candidal, or bacterial infections can trigger IP.5 It occurs in about 3% to 7% of patients with plaque psoriasis and is thought to form due to koebnerization via mechanical friction of flexural zones.6 The patient described in this case did not have IP because IP would be more likely to present as a well-demarcated erythematous plaque rather than a patch.

Histologically, IP shows regular psoriasiform acanthosis and hypogranulosis of the epidermis, Munro microabscess, spongiform pustules of Kogoj, dilated tortuous dermal vessels, and thinning of the suprapapillary plates.5

Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI) is also known as lichen planus pigmentosus—intertriginous variant. This variant of lichen planus pigmentosus presents as multiple gray to dark brown macules and patches with poorly defined borders in a linear distribution limited to intertriginous areas, flexural surfaces, or following the lines of Blaschko.7 About 20% of cases present with frontal fibrosing alopecia. It is most common in individuals with intermediate and darker skin pigmentation, has a higher prevalence in females, and typically occurs within the third and fifth decades of life. Friction is a common trigger of LPPI.7 A diagnosis of LPPI is incorrect because the lesions would present as gray to dark brown macules, as opposed to the shiny white atrophic thin papules with surrounding pink and purple patches seen in this case.

Histologically, while both LS and LPPI share band-like lymphocytic infiltrate and basal cell vacuolization, findings in the dermis differ. LPPI shows melanophages and prominent melanin incontinence, while LS shows homogenization and sclerosis of superficial collagen.1,8 LPPI also shows absence of compensatory keratinocyte proliferation.

Morphea is an inflammatory disease that affects the dermis and subcutaneous fat, resulting in sclerosis that appears scarlike. Its prevalence increases with age and has a 4:1 prevalence in females, with the plaque type being the most common variant. 9 The typical presentation of plaque-type morphea is an insidious onset of asymptomatic, slightly elevated, erythematous or violaceous, slightly edematous plaques with centrifugal expansion. The center of the plaque may become sclerotic and indurated, acquiring a shiny white color with a peripheral “lilac” ring. Trunk and upper extremity involvement is common. Morphea is associated with increased antisingle-stranded DNA, antitopoisomerase IIa, antiphospholipid, antifibrillin-1, and antihistone antibodies. Triggers of morphea are believed to be localized insults to the skin, including mechanical trauma, injections, vaccinations, and irradiation.9 This answer is incorrect because the patient’s lesions were pruritic and had genital involvement, which are not typical of morphea. Morphea can be differentiated with based on symptoms (lack of pruritus, pain, burning), morphology of lesions (induration versus atrophy), dermoscopy (fibrotic beams with less scale and hemorrhage vs keratotic follicular plugs), and histopathology (depth of inflammation in superficial and deep dermis).

Histology of morphea can differ based on the stage, whether the lesion is sampled in the inflammatory margin or central sclerosis, and the depth of affected skin. At the inflammatory margin, vascular changes, including endothelial swelling and edema, are present, as well as CD4+ T cells, eosinophils, plasma cells, and mast cells surrounding smaller blood vessels. In late stages, the inflammatory infiltrate is no longer present, the epidermis appears regular, and there is a flattened dermal-epidermal junction. Distinct features include homogenous collagen bundles that replace many dermal structures, with atrophic eccrine glands that appear “trapped” in the thickened dermis, and homogenized and hyalinized subcutis.9

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and presents as annular, erythematous or hypopigmented patches and plaques with fine scale and tumors on the buttocks and sun-protected areas of the limbs and trunk. Lesions can appear with prominent poikiloderma or atrophic or lichenified skin.10 It is most common in males of African descent aged 50 to 55 years. The etiology is largely unknown but believed to be multifactorial. This answer is incorrect because the lesions in this patient appeared more atrophic, were less well demarcated, and lacked the scale that would be present in MF.

On histology, both LS and MF show band-like lymphocytic infiltrate, however MF lacks the homogenization and sclerosis of superficial collagen that is present in the dermis of LS. Also, MF demonstrates epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes forming Pautrier microabscess.10

Primary Care Role

Primary care physicians can diagnose and treat LS. Referral to dermatology is not mandatory. Note that topical steroids can be used daily for up to 12 weeks. In LS, early treatment is associated with improved outcomes and minimizes the risk of irreversible skin changes.11 Follow-up during the treatment period is recommended to monitor subjective and objective response to treatment. Follow-up after the initial treatment is recommended since LS is typically chronic, can relapse, and SCC can infrequently arise from LS lesions.11

- Tran DA, Tan X, Macri CJ, Goldstein AT, Fu SW. Lichen sclerosus: an autoimmunopathogenic and genomic enigma with emerging genetic and immune targets. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1429-1439. doi:10.7150/ijbs.34613

- De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, et al. Lichen sclerosus: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106318. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1106318

- Kuraitis D, Murina A. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in chronic inflammatory dermatoses. Cutis. 2024;113:29-34. doi:10.12788/cutis.0914

- Gaertner E, Elstein W. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: case report and review of an unusual entity. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Micali G, Verzì AE, Giuffrida G, et al. Inverse psoriasis: from diagnosis to current treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:953-959. doi:10.2147/CCID.S189000

- Syed ZU, Khachemoune A. Inverse psoriasis: case presentation and review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:143-146. doi:10.2165/11532060-000000000-00000

- Robles-Méndez JC, Rizo-Frías P, Herz-Ruelas ME, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus and its variants: review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:505-514. doi:10.1111/ijd.13806

- Vinay K, Kumar S, Bishnoi A, et al. A clinico-demographic study of 344 patients with lichen planus pigmentosus seen in a tertiary care center in India over an 8-year period. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:245-252. doi:10.1111/ijd.14540

- Papara C, De Luca DA, Bieber K, et al. Morphea: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1108623. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1108623

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJ, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Cri t Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1061-1067. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0643

- Tran DA, Tan X, Macri CJ, Goldstein AT, Fu SW. Lichen sclerosus: an autoimmunopathogenic and genomic enigma with emerging genetic and immune targets. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1429-1439. doi:10.7150/ijbs.34613

- De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, et al. Lichen sclerosus: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106318. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1106318

- Kuraitis D, Murina A. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in chronic inflammatory dermatoses. Cutis. 2024;113:29-34. doi:10.12788/cutis.0914

- Gaertner E, Elstein W. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: case report and review of an unusual entity. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Micali G, Verzì AE, Giuffrida G, et al. Inverse psoriasis: from diagnosis to current treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:953-959. doi:10.2147/CCID.S189000

- Syed ZU, Khachemoune A. Inverse psoriasis: case presentation and review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:143-146. doi:10.2165/11532060-000000000-00000

- Robles-Méndez JC, Rizo-Frías P, Herz-Ruelas ME, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus and its variants: review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:505-514. doi:10.1111/ijd.13806

- Vinay K, Kumar S, Bishnoi A, et al. A clinico-demographic study of 344 patients with lichen planus pigmentosus seen in a tertiary care center in India over an 8-year period. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:245-252. doi:10.1111/ijd.14540

- Papara C, De Luca DA, Bieber K, et al. Morphea: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1108623. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1108623

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJ, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Cri t Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1061-1067. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0643

Atrophic Areas on the Axillary and Anogenital Anatomy

Atrophic Areas on the Axillary and Anogenital Anatomy

A 62-year-old woman presented for a fullbody skin examination and was found to have a rash in her axillae and inframammary regions. The rash was intermittently pruritic, and the patient felt that the inframammary rash had started from contact with brassiere underwires. She had no oral lesions but noted intermittent burning and itching of the vaginal folds and intermittent bleeding near her anus. Physical examination revealed confluent, shiny, white, atrophic, thin papules with surrounding pink and purple patches on bilateral axillae, bilateral inframammary folds, bilateral inner thighs, and on the clitoral hood and labia minora. There was also an hourglass-shaped erythematous patch involving the vagina and anus. A small fissure was noted perianally, and small hemorrhage was noted on the clitoral head, with fusion of the clitoral head and superior labia minora (Figures 1 and 2).

lesion from punch biopsy of the patient’s left axilla.

sclerosus plaque showing bright white grouped dots

on a pink background with follicular plugging and linear

branching vessels.

showing a compact corneal layer with a pale papillary

dermis and an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate. These

findings give the “red, white, and blue” appearance.

Low power 20× magnification.

nsbp;

An 81-Year-Old White Woman Presented With a 2-Week History of a Painful Lesion on Her Left Calf

Calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare condition most commonly observed in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Because of the non-healing nature of the wounds and need for frequent hospitalizations, there is a significant risk of sepsis with a 1-year mortality rate greater than 50%.

Beyond ESRD, calciphylaxis is also associated with obesity, diabetes, hypoalbuminemia, autoimmune conditions, hepatic disease, malignancies, and dialysis. Rates in patients on dialysis have been increasing, ranging from 1% to 4%. Certain medications have also been implicated in the development of calciphylaxis, including warfarin, steroids, calcium-based phosphate binders, vitamin D, and iron. There is also an association with White individuals and more cases have been reported in females.

Pathophysiology of this condition includes calcification of the medial layer of arterioles and small arteries near the skin. Damage to vessel endothelium and formation of microthrombi contribute to the ischemia, which results in necrosis and ulceration of the skin. Elevated calcium and phosphate have been associated with these findings; however, these lab abnormalities alone are typically not enough to cause calciphylaxis. Vascular calcification inhibitors such as fetuin-A, osteoprotegerin, and matrix G1a protein may play a role in pathogenesis, with individuals lacking these factors potentially being at a greater risk. Specifically, matrix G1a protein is dependent on vitamin K dependent carboxylation, which may elucidate why warfarin has been implicated in the development of calciphylaxis because of interference with this pathway.

Upon presentation, patients will have painful ischemic plaques on the skin or painful subcutaneous nodules. Long-standing lesions may have a necrotic eschar or secondary infection, or may be associated with livedo reticularis. Areas with a greater concentration of adipose tissue such as the abdomen, thighs, and buttocks are most commonly affected, but lesions may appear anywhere. A biopsy may be done, but a clinical diagnosis is often sufficient as biopsies carry risks of prolonged healing and infection.

The differential diagnosis includes warfarin skin necrosis, cholesterol embolization, vasculitis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and cellulitis. Although this is a cutaneous manifestation, calciphylaxis is indicative of a systemic problem and requires multidisciplinary intervention.

Patients who present with calciphylaxis require a complete metabolic panel, liver function tests, coagulation studies, and albumin tests. Depending on the presentation, imaging studies such as nuclear medicine scans may be used if extensive soft tissue involvement is suspected.

Clinical management includes carefully avoiding electrolyte imbalances, initiating dialysis if necessary, discontinuing potentially offending supplements and medications, and administering proper wound care and pain management. Debridement of necrotic tissue may be necessary and should be initiated early as this has been associated with a 6-month increase in survival. Physicians should have a low threshold for starting antibiotics if secondary infection is suspected, but prophylaxis is not recommended. Sodium thiosulfate has been used off-label, but the mechanism of action is unknown and some meta-analyses indicate this treatment is not significantly associated with improvement of skin lesions. Interventions such as hyperbaric oxygen have also been used, but there is still more research to be done on these modalities.

The case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, Fort Lauderdale, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Kodumudi V et al. Adv Ther. 2020 Dec;37(12):4797-4807. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01504-w.

Seethapathy H et al. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019 Nov;26(6):484-490. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2019.09.005.

Turek M et al. Am J Case Rep. 2021 Jun 7:22:e930026. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.930026.

Wen W at al. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e2310068. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.10068.

Westphal SG, Plumb T. Calciphylaxis. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519020/.

Calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare condition most commonly observed in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Because of the non-healing nature of the wounds and need for frequent hospitalizations, there is a significant risk of sepsis with a 1-year mortality rate greater than 50%.

Beyond ESRD, calciphylaxis is also associated with obesity, diabetes, hypoalbuminemia, autoimmune conditions, hepatic disease, malignancies, and dialysis. Rates in patients on dialysis have been increasing, ranging from 1% to 4%. Certain medications have also been implicated in the development of calciphylaxis, including warfarin, steroids, calcium-based phosphate binders, vitamin D, and iron. There is also an association with White individuals and more cases have been reported in females.

Pathophysiology of this condition includes calcification of the medial layer of arterioles and small arteries near the skin. Damage to vessel endothelium and formation of microthrombi contribute to the ischemia, which results in necrosis and ulceration of the skin. Elevated calcium and phosphate have been associated with these findings; however, these lab abnormalities alone are typically not enough to cause calciphylaxis. Vascular calcification inhibitors such as fetuin-A, osteoprotegerin, and matrix G1a protein may play a role in pathogenesis, with individuals lacking these factors potentially being at a greater risk. Specifically, matrix G1a protein is dependent on vitamin K dependent carboxylation, which may elucidate why warfarin has been implicated in the development of calciphylaxis because of interference with this pathway.

Upon presentation, patients will have painful ischemic plaques on the skin or painful subcutaneous nodules. Long-standing lesions may have a necrotic eschar or secondary infection, or may be associated with livedo reticularis. Areas with a greater concentration of adipose tissue such as the abdomen, thighs, and buttocks are most commonly affected, but lesions may appear anywhere. A biopsy may be done, but a clinical diagnosis is often sufficient as biopsies carry risks of prolonged healing and infection.

The differential diagnosis includes warfarin skin necrosis, cholesterol embolization, vasculitis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and cellulitis. Although this is a cutaneous manifestation, calciphylaxis is indicative of a systemic problem and requires multidisciplinary intervention.

Patients who present with calciphylaxis require a complete metabolic panel, liver function tests, coagulation studies, and albumin tests. Depending on the presentation, imaging studies such as nuclear medicine scans may be used if extensive soft tissue involvement is suspected.

Clinical management includes carefully avoiding electrolyte imbalances, initiating dialysis if necessary, discontinuing potentially offending supplements and medications, and administering proper wound care and pain management. Debridement of necrotic tissue may be necessary and should be initiated early as this has been associated with a 6-month increase in survival. Physicians should have a low threshold for starting antibiotics if secondary infection is suspected, but prophylaxis is not recommended. Sodium thiosulfate has been used off-label, but the mechanism of action is unknown and some meta-analyses indicate this treatment is not significantly associated with improvement of skin lesions. Interventions such as hyperbaric oxygen have also been used, but there is still more research to be done on these modalities.

The case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, Fort Lauderdale, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Kodumudi V et al. Adv Ther. 2020 Dec;37(12):4797-4807. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01504-w.

Seethapathy H et al. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019 Nov;26(6):484-490. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2019.09.005.

Turek M et al. Am J Case Rep. 2021 Jun 7:22:e930026. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.930026.

Wen W at al. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e2310068. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.10068.

Westphal SG, Plumb T. Calciphylaxis. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519020/.

Calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare condition most commonly observed in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Because of the non-healing nature of the wounds and need for frequent hospitalizations, there is a significant risk of sepsis with a 1-year mortality rate greater than 50%.

Beyond ESRD, calciphylaxis is also associated with obesity, diabetes, hypoalbuminemia, autoimmune conditions, hepatic disease, malignancies, and dialysis. Rates in patients on dialysis have been increasing, ranging from 1% to 4%. Certain medications have also been implicated in the development of calciphylaxis, including warfarin, steroids, calcium-based phosphate binders, vitamin D, and iron. There is also an association with White individuals and more cases have been reported in females.

Pathophysiology of this condition includes calcification of the medial layer of arterioles and small arteries near the skin. Damage to vessel endothelium and formation of microthrombi contribute to the ischemia, which results in necrosis and ulceration of the skin. Elevated calcium and phosphate have been associated with these findings; however, these lab abnormalities alone are typically not enough to cause calciphylaxis. Vascular calcification inhibitors such as fetuin-A, osteoprotegerin, and matrix G1a protein may play a role in pathogenesis, with individuals lacking these factors potentially being at a greater risk. Specifically, matrix G1a protein is dependent on vitamin K dependent carboxylation, which may elucidate why warfarin has been implicated in the development of calciphylaxis because of interference with this pathway.

Upon presentation, patients will have painful ischemic plaques on the skin or painful subcutaneous nodules. Long-standing lesions may have a necrotic eschar or secondary infection, or may be associated with livedo reticularis. Areas with a greater concentration of adipose tissue such as the abdomen, thighs, and buttocks are most commonly affected, but lesions may appear anywhere. A biopsy may be done, but a clinical diagnosis is often sufficient as biopsies carry risks of prolonged healing and infection.

The differential diagnosis includes warfarin skin necrosis, cholesterol embolization, vasculitis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and cellulitis. Although this is a cutaneous manifestation, calciphylaxis is indicative of a systemic problem and requires multidisciplinary intervention.

Patients who present with calciphylaxis require a complete metabolic panel, liver function tests, coagulation studies, and albumin tests. Depending on the presentation, imaging studies such as nuclear medicine scans may be used if extensive soft tissue involvement is suspected.