User login

Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Treatment for Glomerulopathy: Case Report and Review of Literature

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, highly specialized cells located in juxtaposition to the basement membrane over the abluminal surfaces of endothelial cells within the glomerular tuft. This triad structure is the site of the filtration barrier, which forms highly delicate and tightly regulated architecture to carry out the ultrafiltration function of the kidney.1 The filtration barrier is characterized by foot processes that are connected by specialized junctions called slit diaphragms.

Insults to components of the filtration barrier can initiate cascading events and perpetuate structural alterations that may eventually result in sclerotic changes.2 Common causes among children include minimal change disease (MCD) with the collapse of foot processes resulting in proteinuria, Alport syndrome due to mutation of collagen fibers within the basement membrane leading to hematuria and proteinuria, immune complex mediated nephropathy following common infections or autoimmune diseases, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) that can show variable histopathology toward eventual glomerular scarring.3,4 These children often clinically have minimal, if any, signs of systemic inflammation.3-5 This has been a limiting factor for the commitment to immunomodulatory treatment, except for steroids for the treatment of MCD.6 Although prolonged steroid treatment may be efficacious, adverse effects are significant in a growing child. Alternative treatments, such as tacrolimus and rituximab have been suggested as second-line steroid-sparing agents.7,8 Not uncommonly, however, these cases are managed by supportive measures only during the progression of the natural course of the disease, which may eventually lead to renal failure, requiring transplant for survival.8,9

This case report highlights a child with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes involved in Alport syndrome and FSGS who developed an abrupt onset of proteinuria and hematuria after a respiratory illness. To our knowledge, he represents the youngest case demonstrating the benefit of targeted treatment against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for glomerulopathy using biologic response modifiers.

Case Description

This is currently a 7-year-old male patient who was born at 39 weeks gestation to gravida 3 para 3 following induced labor due to elevated maternal blood pressure. During the first 2 years of life, his growth and development were normal and his immunizations were up to date. The patient's medical history included upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), respiratory syncytial virus, as well as 3 bouts of pneumonia and multiple otitis media that resulted in 18 rounds of antibiotics. The child was also allergic to nuts and milk protein. The patient’s parents are of Northern European and Native American descent. There is no known family history of eye, ear, or kidney diseases.

Renal concerns were first noted at the age of 2 years and 6 months when he presented to an emergency department in Fall 2019 (week 0) for several weeks of intermittent dark-colored urine. His mother reported that the discoloration recently progressed in intensity to cola-colored, along with the onset of persistent vomiting without any fever or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient had normal vitals: weight 14.8 kg (68th percentile), height 91 cm (24th percentile), and body surface area 0.6 m2. There was no edema, rash, or lymphadenopathy, but he appeared pale.

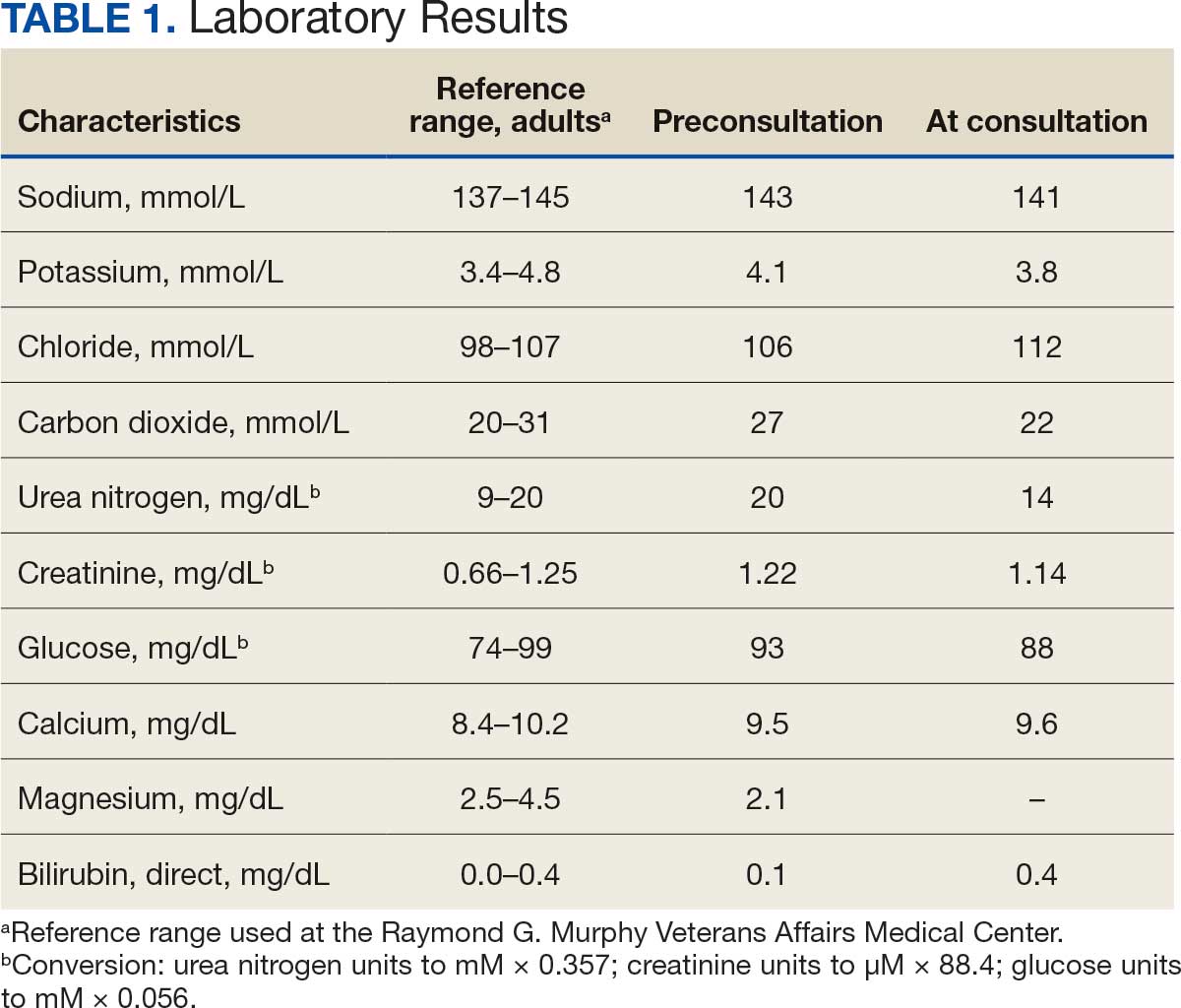

The patient’s initial laboratory results included: complete blood count with white blood cells (WBC) 10 x 103/L (reference range, 4.5-13.5 x 103/L); differential lymphocytes 69%; neutrophils 21%; hemoglobin 10 g/dL (reference range, 12-16 g/dL); hematocrit, 30%; (reference range, 37%-45%); platelets 437 103/L (reference range, 150-450 x 103/L); serum creatinine 0.46 mg/dL (reference range, 0.5-0.9 mg/dL); and albumin 3.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL). Serum electrolyte levels and liver enzymes were normal. A urine analysis revealed 3+ protein and 3+ blood with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBC) and RBC casts without WBC. The patient's spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 4.3 and his renal ultrasound was normal. The patient was referred to Nephrology.

During the next 2 weeks, his protein-to-creatinine ratio progressed to 5.9 and serum albumin fell to 2.7 g/dL. His urine remained red colored, and a microscopic examination with RBC > 500 and WBC up to 10 on a high powered field. His workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antistreptolysin-O (ASO) and anti-DNase B. Serum C3 was low at 81 mg/dL (reference range, 90-180 mg/dL), C4 was 13.3 mg/dL (reference range, 10-40 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G was low at 452 mg/dL (reference range 719-1475 mg/dL). A baseline audiology test revealed normal hearing.

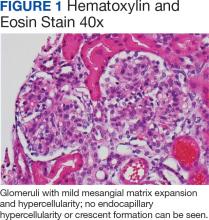

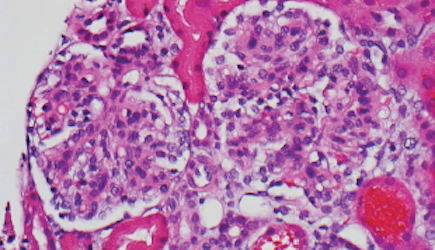

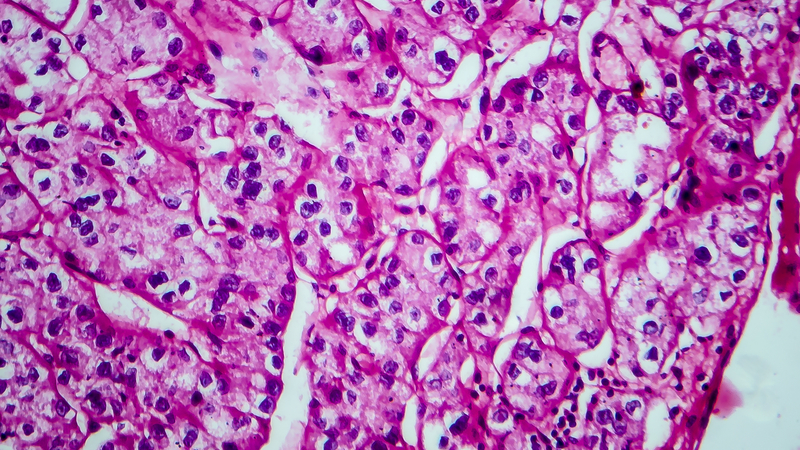

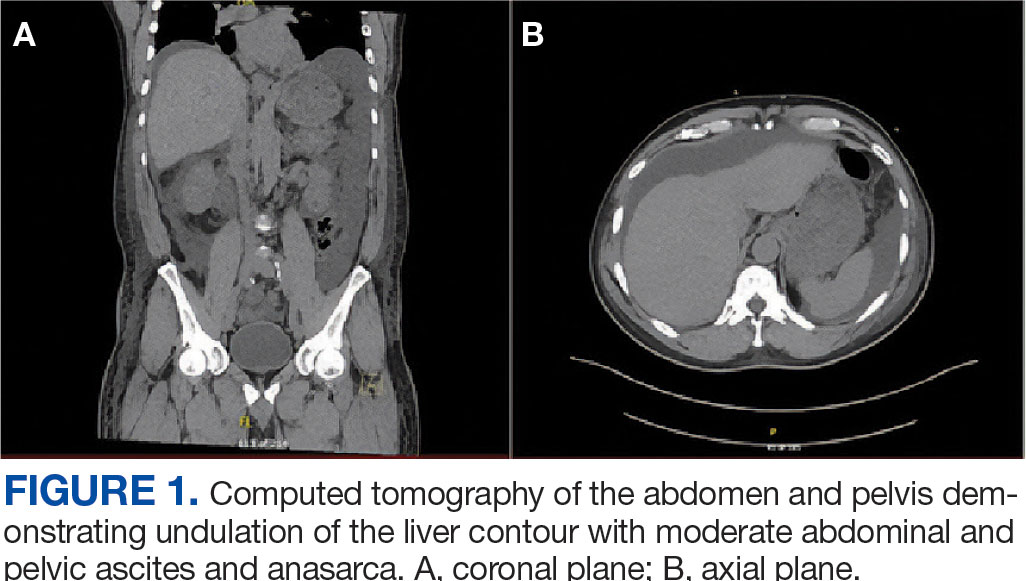

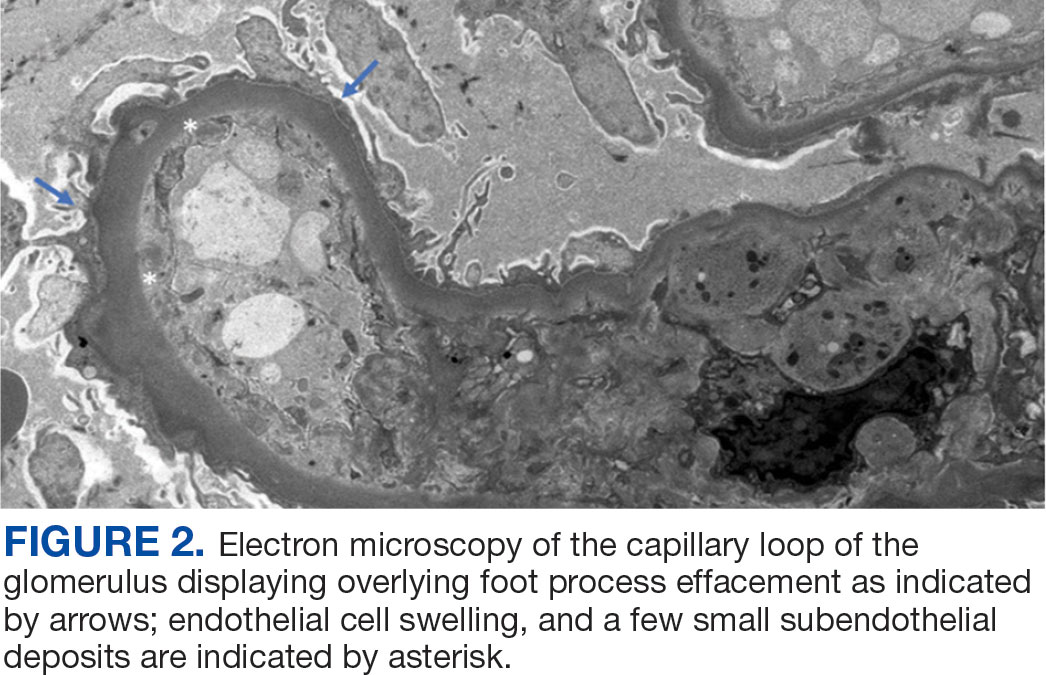

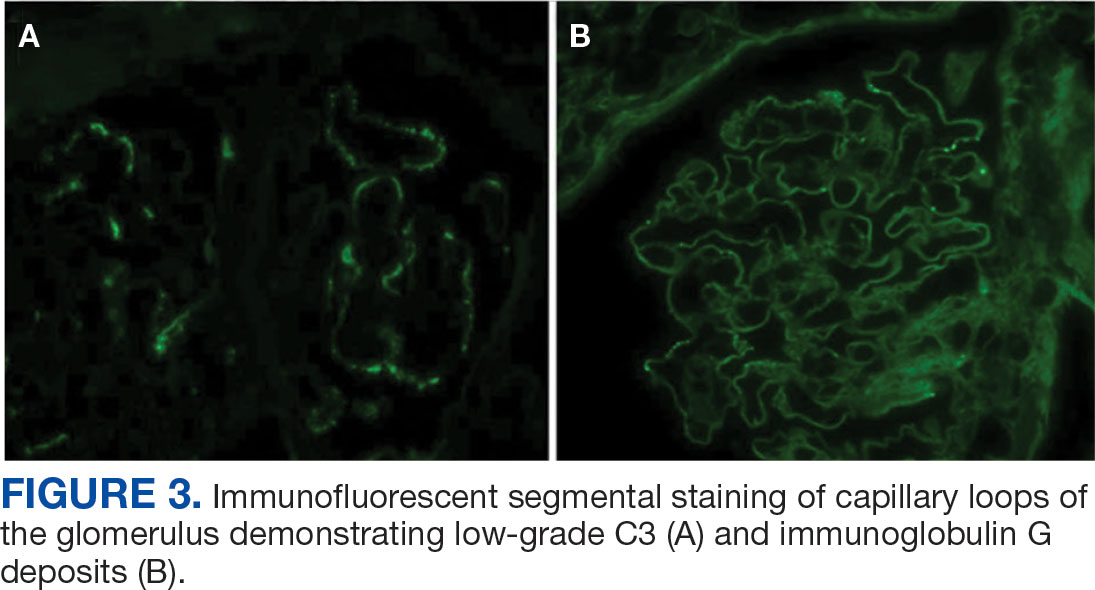

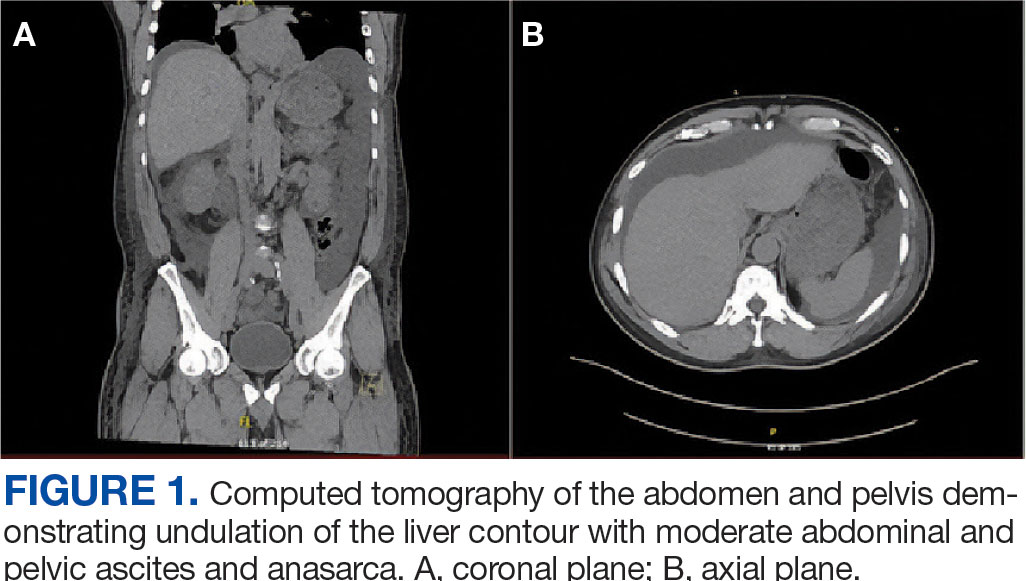

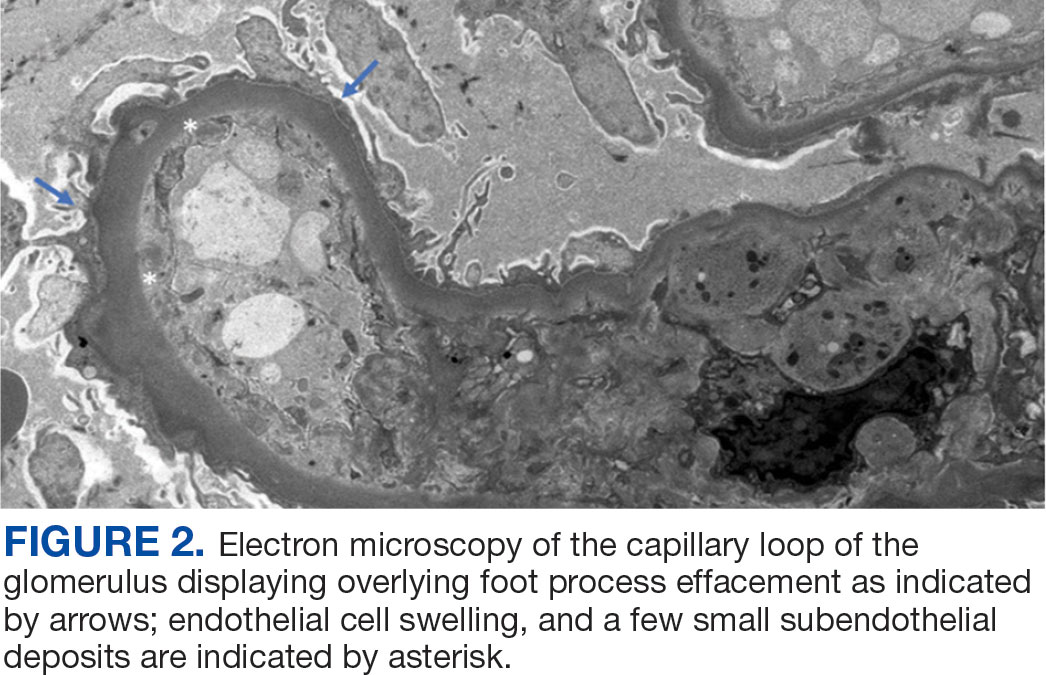

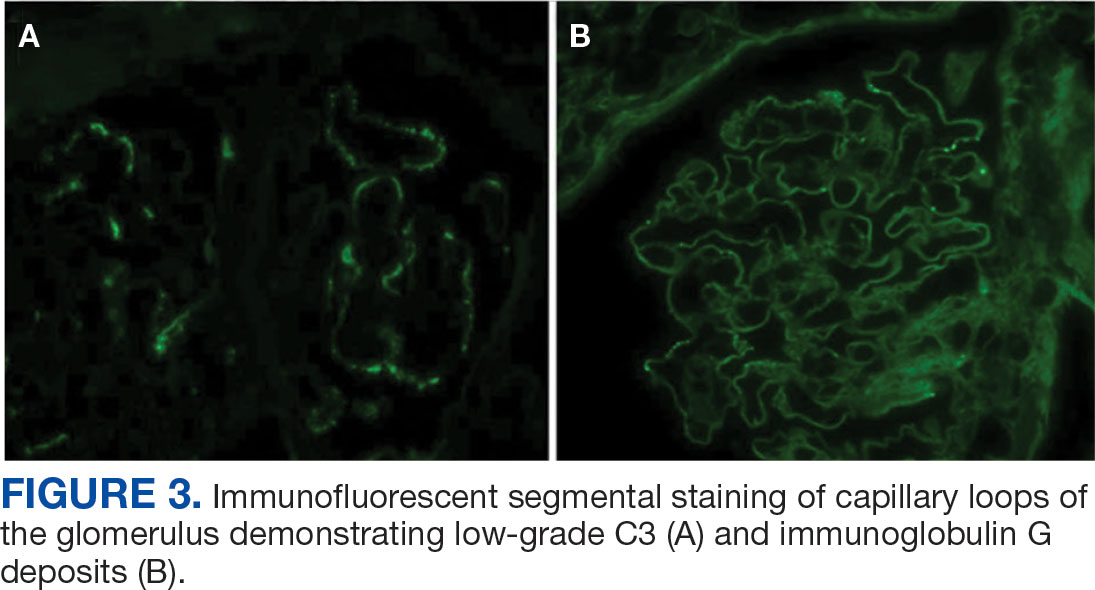

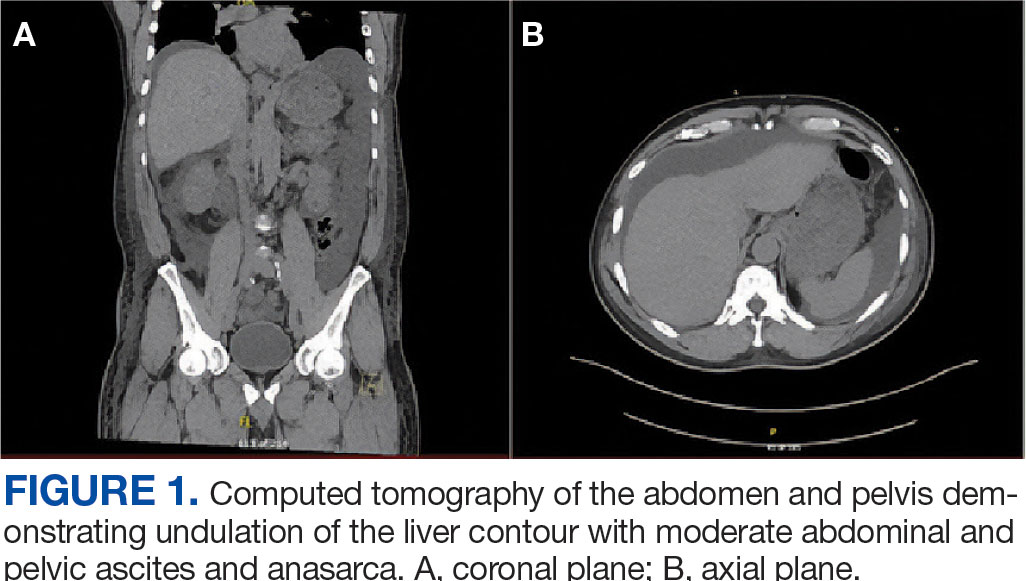

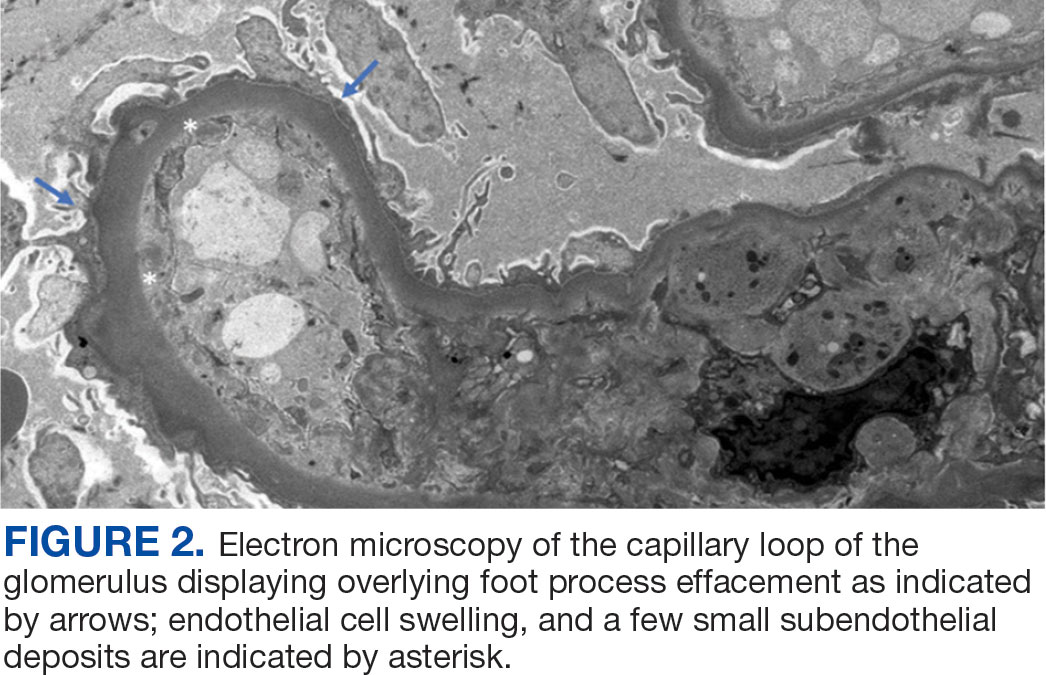

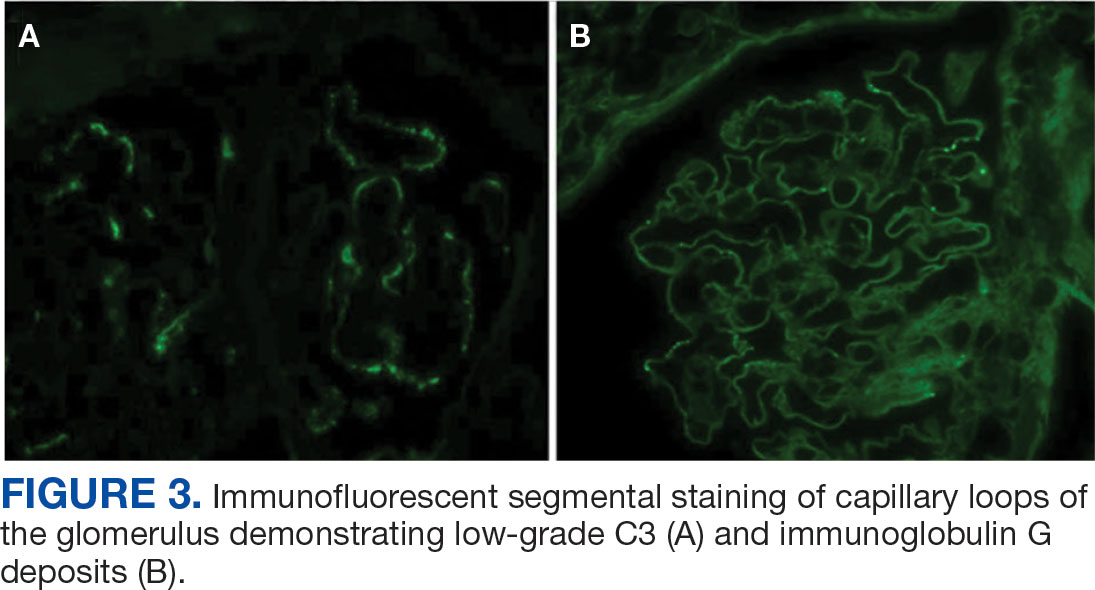

Percutaneous renal biopsy yielded about 12 glomeruli, all exhibiting mild mesangial matrix expansion and hypercellularity (Figure 1). One glomerulus had prominent parietal epithelial cells without endocapillary hypercellularity or crescent formation. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence studies showed no evidence of immune complex deposition with negative staining for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, C3 and C1q. Staining for α 2 and α 5 units of collagen was normal. Electron microscopy showed patchy areas of severe basement membrane thinning with frequent foci of mild to moderate lamina densa splitting and associated visceral epithelial cell foot process effacement (Figure 2).

These were reported as concerning findings for possible Alport syndrome by 3 independent pathology teams. The genetic testing was submitted at a commercial laboratory to screen 17 mutations, including COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5. Results showed the presence of a heterozygous VUS in the COL4A4 gene (c.1055C > T; p.Pro352Leu; dbSNP ID: rs371717486; PolyPhen-2: Probably Damaging; SIFT: Deleterious) as well as the presence of a heterozygous VUS in TRPC6 gene (c2463A>T; p.Lys821Asn; dbSNP ID: rs199948731; PolyPhen-2: Benign; SIFT: Tolerated). Further genetic investigation by whole exome sequencing on approximately 20,000 genes through MNG Laboratories showed a new heterozygous VUS in the OSGEP gene [c.328T>C; p.Cys110Arg]. Additional studies ruled out mitochondrial disease, CoQ10 deficiency, and metabolic disorders upon normal findings for mitochondrial DNA, urine amino acids, plasma acylcarnitine profile, orotic acid, ammonia, and homocysteine levels.

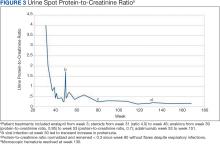

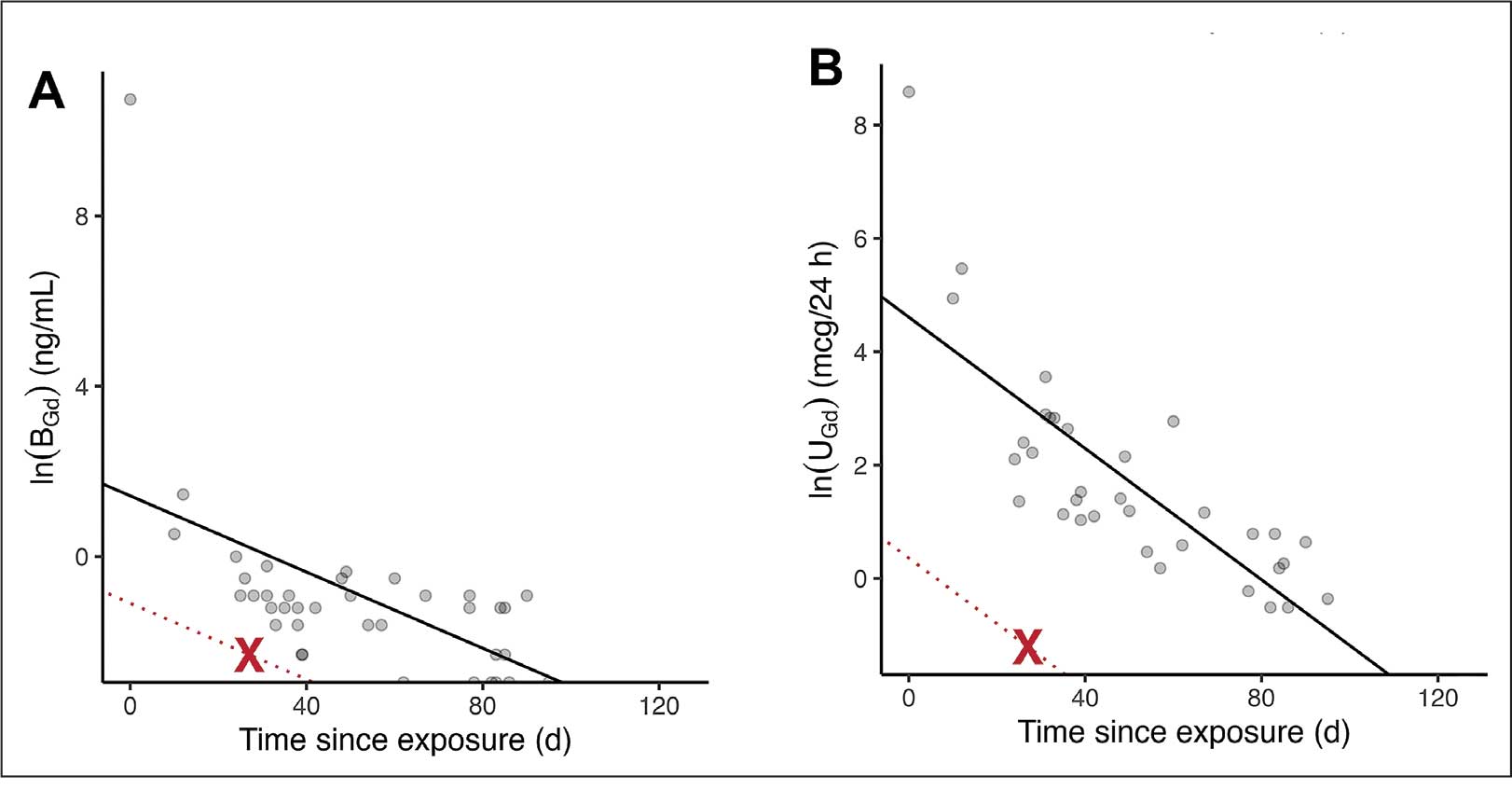

Figure 3 summarizes the patient’s treatment response during 170 weeks of follow-up (Fall 2019 to Summer 2023). The patient was started on enalapril 0.6 mg/kg daily at week 3, which continued throughout treatment. Following a rheumatology consult at week 30, the patient was started on prednisolone 3 mg/mL to assess the role of inflammation through the treatment response. An initial dose of 2 mg/kg daily (9 mL) for 1 month was followed by every other day treatment that was tapered off by week 48. To control mild but noticeably increasing proteinuria in the interim, subcutaneous anakinra 50 mg (3 mg/kg daily) was added as a steroid

DISCUSSION

This case describes a child with rapidly progressive proteinuria and hematuria following a URI who was found to have VUS mutations in 3 different genes associated with chronic kidney disease. Serology tests on the patient were negative for streptococcal antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, ruling out poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. His renal biopsy findings were concerning for altered podocytes, mesangial cells, and basement membrane without inflammatory infiltrate, immune complex, complements, immunoglobulin A, or vasculopathy. His blood inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were normal when his care team initiated daily steroids.

Overall, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathology findings were suggestive of Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy with a high potential to progress into FSGS.10-12 Alport syndrome affects 1 in 5000 to 10,000 children annually due to S-linked inheritance of COL4A5, or autosomal recessive inheritance of COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes. It presents with hematuria and hearing loss.10 Our patient had a single copy COL4A4 gene mutation that was classified as VUS. He also had 2 additional VUS affecting the TRPC6 and OSGEP genes. TRPC6 gene mutation can be associated with FSGS through autosomal dominant inheritance. Both COL4A4 and TRPC6 gene mutations were paternally inherited. Although the patient’s father not having renal disease argues against the clinical significance of these findings, there is literature on the potential role of heterozygous COL4A4 variant mimicking thin basement membrane nephropathy that can lead to renal impairment upon copresence of superimposed conditions.13 The patient’s rapidly progressing hematuria and changes in the basement membrane were worrisome for emerging FSGS. Furthermore, VUS of TRPC6 has been reported in late onset autosomal dominant FSGS and can be associated with early onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children.14 This concern was voiced by 3 nephrology consultants during the initial evaluation, leading to the consensus that steroid treatment for podocytopathy would not alter the patient’s long-term outcomes (ie, progression to FSGS).

Immunomodulation

Our rationale for immunomodulatory treatment was based on the abrupt onset of renal concerns following a URI, suggesting the importance of an inflammatory trigger causing altered homeostasis in a genetically susceptible host. Preclinical models show that microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides can lead to podocytopathy by several mechanisms through activation of toll-like receptor signaling. It can directly cause apoptosis by downregulation of the intracellular Akt survival pathway.15 Lipopolysaccharide can also activate the NF-αB pathway and upregulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and TNF-α in mesangial cells.16,17

Both cytokines can promote mesangial cell proliferation.18 Through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, proinflammatory cytokines can further perpetuate somatic tissue changes and contribute to the development of podocytopathy. For instance, TNF-α can promote podocyte injury and proteinuria by downregulation of the slit diaphragm protein expression (ie, nephrin, ezrin, or podocin), and disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton.19,20 TNF-α promotes the influx and activation of macrophages and inflammatory cells. It is actively involved in chronic alterations within the glomeruli by the upregulation of matrix metalloproteases by integrins, as well as activation of myofibroblast progenitors and extracellular matrix deposition in crosstalk with transforming growth factor and other key mediators.17,21,22

For the patient described in this case report, initial improvement on steroids encouraged the pursuit of additional treatment to downregulate inflammatory pathways within the glomerular milieu. However, within the COVID-19 environment, escalating the patient’s treatment using traditional immunomodulators (ie, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil) was not favored due to the risk of infection. Initially, anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was preferred as a steroid-sparing agent for its short life and safety profile during the pandemic. At first, the patient responded well to anakinra and was allowed a steroid wean when the dose was titrated up to 6 mg/kg daily. However, anakinra did not prevent the escalation of proteinuria following a URI. After the treatment was changed to adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, the patient continued to improve and reach full remission despite experiencing a cold and the flu in the following months.

Literature Review

There is a paucity of literature on applications of biological response modifiers for idiopathic NS and FSGS.23,24 Angeletti and colleagues reported that 3 patients with severe long-standing FSGS benefited from anakinra 4 mg/kg daily to reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function. All the patients had positive C3 staining in renal biopsy and treatment response, which supported the role of C3a in inducing podocyte injury through upregulated expression of IL-1 and IL-1R.23 Trachtman and colleagues reported on the phase II FONT trial that included 14 of 21 patients aged < 18 years with advanced FSGS who were treated with adalimumab 24 mg/m2, or ≤ 40 mg every other week.24 Although, during a 6-month period, none of the 7 patients met the endpoint of reduced proteinuria by ≥ 50%, and the authors suggested that careful patient selection may improve the treatment response in future trials.24

A recent study involving transcriptomics on renal tissue samples combined with available pathology (fibrosis), urinary markers, and clinical characteristics on 285 patients with MCD or FSGS from 3 different continents identified 3 distinct clusters. Patients with evidence of activated kidney TNF pathway (n = 72, aged > 18 years) were found to have poor clinical outcomes.25 The study identified 2 urine markers associated with the TNF pathway (ie, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), which aligns with the preclinical findings previously mentioned.25

Conclusions

The patient’s condition in this case illustrates the complex nature of biologically predetermined cascading events in the emergence of glomerular disease upon environmental triggers under the influence of genetic factors.

Chronic kidney disease affects 7.7% of veterans annually, illustrating the need for new therapeutics.26 Based on our experience and literature review, upregulation of TNF-α is a root cause of glomerulopathy; further studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of anti-TNF biologic response modifiers for the treatment of these patients. Long-term postmarketing safety profile and steroid-sparing properties of adalimumab should allow inclusion of pediatric cases in future trials. Results may also contribute to identifying new predictive biomarkers related to the basement membrane when combined with precision nephrology to further advance patient selection and targeted treatment.25,27

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s mother for providing consent to allow publication of this case report.

1. Arif E, Nihalani D. Glomerular filtration barrier assembly: an insight. Postdoc J. 2013;1(4):33-45.

2. Garg PA. Review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(suppl 1):3-13. doi:10.1159/000481633SUPPL

3. Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, et al. Alport syndrome classification and management. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):639-649. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014

4. Angioi A, Pani A. FSGS: from pathogenesis to the histological lesion. J Nephrol. 2016;29(4):517-523. doi:10.1007/s40620-016-0333-2

5. Roca N, Martinez C, Jatem E, Madrid A, Lopez M, Segarra A. Activation of the acute inflammatory phase response in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: association with clinicopathological phenotypes and with response to corticosteroids. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1207-1215. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa247

6. Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332-345.

7. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lawrence C, Condon M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of tacrolimus and prednisolone monotherapy for adults with De Novo minimal change disease: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(2):209-218. doi:10.2215/CJN.06290420

8. Ye Q, Lan B, Liu H, Persson PB, Lai EY, Mao J. A critical role of the podocyte cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of glomerular proteinuria and autoimmune podocytopathies. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2022;235(4):e13850. doi:10.1111/apha.13850

9. Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Ziμtkiewicz BS, et al. Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3055-3065. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016101121

10. Kashtan CE, Gross O. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711-719. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6

11. Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY. Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1169-78. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00234.x

12. Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(3):502-517. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960616

13. Savige J. Should we diagnose autosomal dominant Alport syndrome when there is a pathogenic heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 variant? Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1239-1241. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.08.002

14. Gigante M, Caridi G, Montemurno E, et al. TRPC6 mutations in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and atypical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1626-1634. doi:10.2215/CJN.07830910

15. Saurus P, Kuusela S, Lehtonen E, et al. Podocyte apoptosis is prevented by blocking the toll-like receptor pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(5):e1752. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.125

16. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1111-1118. doi:10.1038/ki.1989.98

17. White S, Lin L, Hu K. NF-κB and tPA signaling in kidney and other diseases. Cells. 2020;9(6):1348. doi:10.3390/cells9061348

18. Tesch GH, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Role of interleukin-1 in mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition in experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(1):141-150.

19. Lai KN, Leung JCK, Chan LYY, et al. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62-72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn441

20. Saleem MA, Kobayashi Y. Cell biology and genetics of minimal change disease. F1000 Res. 2016;5: F1000 Faculty Rev-412. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7300.1

21. Kim KP, Williams CE, Lemmon CA. Cell-matrix interactions in renal fibrosis. Kidney Dial. 2022;2(4):607-624. doi:10.3390/kidneydial2040055

22. Zvaifler NJ. Relevance of the stroma and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):210. doi:10.1186/ar1963

23. Angeletti A, Magnasco A, Trivelli A, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):121-124. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018

24. Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:111. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0094-5

25. Mariani LH, Eddy S, AlAkwaa FM, et al. Precision nephrology identified tumor necrosis factor activation variability in minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.023

26. Korshak L, Washington DL, Powell J, Nylen E, Kokkinos P. Kidney Disease in Veterans. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

27. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.305

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, highly specialized cells located in juxtaposition to the basement membrane over the abluminal surfaces of endothelial cells within the glomerular tuft. This triad structure is the site of the filtration barrier, which forms highly delicate and tightly regulated architecture to carry out the ultrafiltration function of the kidney.1 The filtration barrier is characterized by foot processes that are connected by specialized junctions called slit diaphragms.

Insults to components of the filtration barrier can initiate cascading events and perpetuate structural alterations that may eventually result in sclerotic changes.2 Common causes among children include minimal change disease (MCD) with the collapse of foot processes resulting in proteinuria, Alport syndrome due to mutation of collagen fibers within the basement membrane leading to hematuria and proteinuria, immune complex mediated nephropathy following common infections or autoimmune diseases, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) that can show variable histopathology toward eventual glomerular scarring.3,4 These children often clinically have minimal, if any, signs of systemic inflammation.3-5 This has been a limiting factor for the commitment to immunomodulatory treatment, except for steroids for the treatment of MCD.6 Although prolonged steroid treatment may be efficacious, adverse effects are significant in a growing child. Alternative treatments, such as tacrolimus and rituximab have been suggested as second-line steroid-sparing agents.7,8 Not uncommonly, however, these cases are managed by supportive measures only during the progression of the natural course of the disease, which may eventually lead to renal failure, requiring transplant for survival.8,9

This case report highlights a child with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes involved in Alport syndrome and FSGS who developed an abrupt onset of proteinuria and hematuria after a respiratory illness. To our knowledge, he represents the youngest case demonstrating the benefit of targeted treatment against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for glomerulopathy using biologic response modifiers.

Case Description

This is currently a 7-year-old male patient who was born at 39 weeks gestation to gravida 3 para 3 following induced labor due to elevated maternal blood pressure. During the first 2 years of life, his growth and development were normal and his immunizations were up to date. The patient's medical history included upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), respiratory syncytial virus, as well as 3 bouts of pneumonia and multiple otitis media that resulted in 18 rounds of antibiotics. The child was also allergic to nuts and milk protein. The patient’s parents are of Northern European and Native American descent. There is no known family history of eye, ear, or kidney diseases.

Renal concerns were first noted at the age of 2 years and 6 months when he presented to an emergency department in Fall 2019 (week 0) for several weeks of intermittent dark-colored urine. His mother reported that the discoloration recently progressed in intensity to cola-colored, along with the onset of persistent vomiting without any fever or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient had normal vitals: weight 14.8 kg (68th percentile), height 91 cm (24th percentile), and body surface area 0.6 m2. There was no edema, rash, or lymphadenopathy, but he appeared pale.

The patient’s initial laboratory results included: complete blood count with white blood cells (WBC) 10 x 103/L (reference range, 4.5-13.5 x 103/L); differential lymphocytes 69%; neutrophils 21%; hemoglobin 10 g/dL (reference range, 12-16 g/dL); hematocrit, 30%; (reference range, 37%-45%); platelets 437 103/L (reference range, 150-450 x 103/L); serum creatinine 0.46 mg/dL (reference range, 0.5-0.9 mg/dL); and albumin 3.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL). Serum electrolyte levels and liver enzymes were normal. A urine analysis revealed 3+ protein and 3+ blood with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBC) and RBC casts without WBC. The patient's spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 4.3 and his renal ultrasound was normal. The patient was referred to Nephrology.

During the next 2 weeks, his protein-to-creatinine ratio progressed to 5.9 and serum albumin fell to 2.7 g/dL. His urine remained red colored, and a microscopic examination with RBC > 500 and WBC up to 10 on a high powered field. His workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antistreptolysin-O (ASO) and anti-DNase B. Serum C3 was low at 81 mg/dL (reference range, 90-180 mg/dL), C4 was 13.3 mg/dL (reference range, 10-40 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G was low at 452 mg/dL (reference range 719-1475 mg/dL). A baseline audiology test revealed normal hearing.

Percutaneous renal biopsy yielded about 12 glomeruli, all exhibiting mild mesangial matrix expansion and hypercellularity (Figure 1). One glomerulus had prominent parietal epithelial cells without endocapillary hypercellularity or crescent formation. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence studies showed no evidence of immune complex deposition with negative staining for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, C3 and C1q. Staining for α 2 and α 5 units of collagen was normal. Electron microscopy showed patchy areas of severe basement membrane thinning with frequent foci of mild to moderate lamina densa splitting and associated visceral epithelial cell foot process effacement (Figure 2).

These were reported as concerning findings for possible Alport syndrome by 3 independent pathology teams. The genetic testing was submitted at a commercial laboratory to screen 17 mutations, including COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5. Results showed the presence of a heterozygous VUS in the COL4A4 gene (c.1055C > T; p.Pro352Leu; dbSNP ID: rs371717486; PolyPhen-2: Probably Damaging; SIFT: Deleterious) as well as the presence of a heterozygous VUS in TRPC6 gene (c2463A>T; p.Lys821Asn; dbSNP ID: rs199948731; PolyPhen-2: Benign; SIFT: Tolerated). Further genetic investigation by whole exome sequencing on approximately 20,000 genes through MNG Laboratories showed a new heterozygous VUS in the OSGEP gene [c.328T>C; p.Cys110Arg]. Additional studies ruled out mitochondrial disease, CoQ10 deficiency, and metabolic disorders upon normal findings for mitochondrial DNA, urine amino acids, plasma acylcarnitine profile, orotic acid, ammonia, and homocysteine levels.

Figure 3 summarizes the patient’s treatment response during 170 weeks of follow-up (Fall 2019 to Summer 2023). The patient was started on enalapril 0.6 mg/kg daily at week 3, which continued throughout treatment. Following a rheumatology consult at week 30, the patient was started on prednisolone 3 mg/mL to assess the role of inflammation through the treatment response. An initial dose of 2 mg/kg daily (9 mL) for 1 month was followed by every other day treatment that was tapered off by week 48. To control mild but noticeably increasing proteinuria in the interim, subcutaneous anakinra 50 mg (3 mg/kg daily) was added as a steroid

DISCUSSION

This case describes a child with rapidly progressive proteinuria and hematuria following a URI who was found to have VUS mutations in 3 different genes associated with chronic kidney disease. Serology tests on the patient were negative for streptococcal antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, ruling out poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. His renal biopsy findings were concerning for altered podocytes, mesangial cells, and basement membrane without inflammatory infiltrate, immune complex, complements, immunoglobulin A, or vasculopathy. His blood inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were normal when his care team initiated daily steroids.

Overall, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathology findings were suggestive of Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy with a high potential to progress into FSGS.10-12 Alport syndrome affects 1 in 5000 to 10,000 children annually due to S-linked inheritance of COL4A5, or autosomal recessive inheritance of COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes. It presents with hematuria and hearing loss.10 Our patient had a single copy COL4A4 gene mutation that was classified as VUS. He also had 2 additional VUS affecting the TRPC6 and OSGEP genes. TRPC6 gene mutation can be associated with FSGS through autosomal dominant inheritance. Both COL4A4 and TRPC6 gene mutations were paternally inherited. Although the patient’s father not having renal disease argues against the clinical significance of these findings, there is literature on the potential role of heterozygous COL4A4 variant mimicking thin basement membrane nephropathy that can lead to renal impairment upon copresence of superimposed conditions.13 The patient’s rapidly progressing hematuria and changes in the basement membrane were worrisome for emerging FSGS. Furthermore, VUS of TRPC6 has been reported in late onset autosomal dominant FSGS and can be associated with early onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children.14 This concern was voiced by 3 nephrology consultants during the initial evaluation, leading to the consensus that steroid treatment for podocytopathy would not alter the patient’s long-term outcomes (ie, progression to FSGS).

Immunomodulation

Our rationale for immunomodulatory treatment was based on the abrupt onset of renal concerns following a URI, suggesting the importance of an inflammatory trigger causing altered homeostasis in a genetically susceptible host. Preclinical models show that microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides can lead to podocytopathy by several mechanisms through activation of toll-like receptor signaling. It can directly cause apoptosis by downregulation of the intracellular Akt survival pathway.15 Lipopolysaccharide can also activate the NF-αB pathway and upregulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and TNF-α in mesangial cells.16,17

Both cytokines can promote mesangial cell proliferation.18 Through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, proinflammatory cytokines can further perpetuate somatic tissue changes and contribute to the development of podocytopathy. For instance, TNF-α can promote podocyte injury and proteinuria by downregulation of the slit diaphragm protein expression (ie, nephrin, ezrin, or podocin), and disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton.19,20 TNF-α promotes the influx and activation of macrophages and inflammatory cells. It is actively involved in chronic alterations within the glomeruli by the upregulation of matrix metalloproteases by integrins, as well as activation of myofibroblast progenitors and extracellular matrix deposition in crosstalk with transforming growth factor and other key mediators.17,21,22

For the patient described in this case report, initial improvement on steroids encouraged the pursuit of additional treatment to downregulate inflammatory pathways within the glomerular milieu. However, within the COVID-19 environment, escalating the patient’s treatment using traditional immunomodulators (ie, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil) was not favored due to the risk of infection. Initially, anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was preferred as a steroid-sparing agent for its short life and safety profile during the pandemic. At first, the patient responded well to anakinra and was allowed a steroid wean when the dose was titrated up to 6 mg/kg daily. However, anakinra did not prevent the escalation of proteinuria following a URI. After the treatment was changed to adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, the patient continued to improve and reach full remission despite experiencing a cold and the flu in the following months.

Literature Review

There is a paucity of literature on applications of biological response modifiers for idiopathic NS and FSGS.23,24 Angeletti and colleagues reported that 3 patients with severe long-standing FSGS benefited from anakinra 4 mg/kg daily to reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function. All the patients had positive C3 staining in renal biopsy and treatment response, which supported the role of C3a in inducing podocyte injury through upregulated expression of IL-1 and IL-1R.23 Trachtman and colleagues reported on the phase II FONT trial that included 14 of 21 patients aged < 18 years with advanced FSGS who were treated with adalimumab 24 mg/m2, or ≤ 40 mg every other week.24 Although, during a 6-month period, none of the 7 patients met the endpoint of reduced proteinuria by ≥ 50%, and the authors suggested that careful patient selection may improve the treatment response in future trials.24

A recent study involving transcriptomics on renal tissue samples combined with available pathology (fibrosis), urinary markers, and clinical characteristics on 285 patients with MCD or FSGS from 3 different continents identified 3 distinct clusters. Patients with evidence of activated kidney TNF pathway (n = 72, aged > 18 years) were found to have poor clinical outcomes.25 The study identified 2 urine markers associated with the TNF pathway (ie, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), which aligns with the preclinical findings previously mentioned.25

Conclusions

The patient’s condition in this case illustrates the complex nature of biologically predetermined cascading events in the emergence of glomerular disease upon environmental triggers under the influence of genetic factors.

Chronic kidney disease affects 7.7% of veterans annually, illustrating the need for new therapeutics.26 Based on our experience and literature review, upregulation of TNF-α is a root cause of glomerulopathy; further studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of anti-TNF biologic response modifiers for the treatment of these patients. Long-term postmarketing safety profile and steroid-sparing properties of adalimumab should allow inclusion of pediatric cases in future trials. Results may also contribute to identifying new predictive biomarkers related to the basement membrane when combined with precision nephrology to further advance patient selection and targeted treatment.25,27

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s mother for providing consent to allow publication of this case report.

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, highly specialized cells located in juxtaposition to the basement membrane over the abluminal surfaces of endothelial cells within the glomerular tuft. This triad structure is the site of the filtration barrier, which forms highly delicate and tightly regulated architecture to carry out the ultrafiltration function of the kidney.1 The filtration barrier is characterized by foot processes that are connected by specialized junctions called slit diaphragms.

Insults to components of the filtration barrier can initiate cascading events and perpetuate structural alterations that may eventually result in sclerotic changes.2 Common causes among children include minimal change disease (MCD) with the collapse of foot processes resulting in proteinuria, Alport syndrome due to mutation of collagen fibers within the basement membrane leading to hematuria and proteinuria, immune complex mediated nephropathy following common infections or autoimmune diseases, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) that can show variable histopathology toward eventual glomerular scarring.3,4 These children often clinically have minimal, if any, signs of systemic inflammation.3-5 This has been a limiting factor for the commitment to immunomodulatory treatment, except for steroids for the treatment of MCD.6 Although prolonged steroid treatment may be efficacious, adverse effects are significant in a growing child. Alternative treatments, such as tacrolimus and rituximab have been suggested as second-line steroid-sparing agents.7,8 Not uncommonly, however, these cases are managed by supportive measures only during the progression of the natural course of the disease, which may eventually lead to renal failure, requiring transplant for survival.8,9

This case report highlights a child with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes involved in Alport syndrome and FSGS who developed an abrupt onset of proteinuria and hematuria after a respiratory illness. To our knowledge, he represents the youngest case demonstrating the benefit of targeted treatment against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for glomerulopathy using biologic response modifiers.

Case Description

This is currently a 7-year-old male patient who was born at 39 weeks gestation to gravida 3 para 3 following induced labor due to elevated maternal blood pressure. During the first 2 years of life, his growth and development were normal and his immunizations were up to date. The patient's medical history included upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), respiratory syncytial virus, as well as 3 bouts of pneumonia and multiple otitis media that resulted in 18 rounds of antibiotics. The child was also allergic to nuts and milk protein. The patient’s parents are of Northern European and Native American descent. There is no known family history of eye, ear, or kidney diseases.

Renal concerns were first noted at the age of 2 years and 6 months when he presented to an emergency department in Fall 2019 (week 0) for several weeks of intermittent dark-colored urine. His mother reported that the discoloration recently progressed in intensity to cola-colored, along with the onset of persistent vomiting without any fever or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient had normal vitals: weight 14.8 kg (68th percentile), height 91 cm (24th percentile), and body surface area 0.6 m2. There was no edema, rash, or lymphadenopathy, but he appeared pale.

The patient’s initial laboratory results included: complete blood count with white blood cells (WBC) 10 x 103/L (reference range, 4.5-13.5 x 103/L); differential lymphocytes 69%; neutrophils 21%; hemoglobin 10 g/dL (reference range, 12-16 g/dL); hematocrit, 30%; (reference range, 37%-45%); platelets 437 103/L (reference range, 150-450 x 103/L); serum creatinine 0.46 mg/dL (reference range, 0.5-0.9 mg/dL); and albumin 3.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL). Serum electrolyte levels and liver enzymes were normal. A urine analysis revealed 3+ protein and 3+ blood with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBC) and RBC casts without WBC. The patient's spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 4.3 and his renal ultrasound was normal. The patient was referred to Nephrology.

During the next 2 weeks, his protein-to-creatinine ratio progressed to 5.9 and serum albumin fell to 2.7 g/dL. His urine remained red colored, and a microscopic examination with RBC > 500 and WBC up to 10 on a high powered field. His workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antistreptolysin-O (ASO) and anti-DNase B. Serum C3 was low at 81 mg/dL (reference range, 90-180 mg/dL), C4 was 13.3 mg/dL (reference range, 10-40 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G was low at 452 mg/dL (reference range 719-1475 mg/dL). A baseline audiology test revealed normal hearing.

Percutaneous renal biopsy yielded about 12 glomeruli, all exhibiting mild mesangial matrix expansion and hypercellularity (Figure 1). One glomerulus had prominent parietal epithelial cells without endocapillary hypercellularity or crescent formation. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence studies showed no evidence of immune complex deposition with negative staining for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, C3 and C1q. Staining for α 2 and α 5 units of collagen was normal. Electron microscopy showed patchy areas of severe basement membrane thinning with frequent foci of mild to moderate lamina densa splitting and associated visceral epithelial cell foot process effacement (Figure 2).

These were reported as concerning findings for possible Alport syndrome by 3 independent pathology teams. The genetic testing was submitted at a commercial laboratory to screen 17 mutations, including COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5. Results showed the presence of a heterozygous VUS in the COL4A4 gene (c.1055C > T; p.Pro352Leu; dbSNP ID: rs371717486; PolyPhen-2: Probably Damaging; SIFT: Deleterious) as well as the presence of a heterozygous VUS in TRPC6 gene (c2463A>T; p.Lys821Asn; dbSNP ID: rs199948731; PolyPhen-2: Benign; SIFT: Tolerated). Further genetic investigation by whole exome sequencing on approximately 20,000 genes through MNG Laboratories showed a new heterozygous VUS in the OSGEP gene [c.328T>C; p.Cys110Arg]. Additional studies ruled out mitochondrial disease, CoQ10 deficiency, and metabolic disorders upon normal findings for mitochondrial DNA, urine amino acids, plasma acylcarnitine profile, orotic acid, ammonia, and homocysteine levels.

Figure 3 summarizes the patient’s treatment response during 170 weeks of follow-up (Fall 2019 to Summer 2023). The patient was started on enalapril 0.6 mg/kg daily at week 3, which continued throughout treatment. Following a rheumatology consult at week 30, the patient was started on prednisolone 3 mg/mL to assess the role of inflammation through the treatment response. An initial dose of 2 mg/kg daily (9 mL) for 1 month was followed by every other day treatment that was tapered off by week 48. To control mild but noticeably increasing proteinuria in the interim, subcutaneous anakinra 50 mg (3 mg/kg daily) was added as a steroid

DISCUSSION

This case describes a child with rapidly progressive proteinuria and hematuria following a URI who was found to have VUS mutations in 3 different genes associated with chronic kidney disease. Serology tests on the patient were negative for streptococcal antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, ruling out poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. His renal biopsy findings were concerning for altered podocytes, mesangial cells, and basement membrane without inflammatory infiltrate, immune complex, complements, immunoglobulin A, or vasculopathy. His blood inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were normal when his care team initiated daily steroids.

Overall, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathology findings were suggestive of Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy with a high potential to progress into FSGS.10-12 Alport syndrome affects 1 in 5000 to 10,000 children annually due to S-linked inheritance of COL4A5, or autosomal recessive inheritance of COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes. It presents with hematuria and hearing loss.10 Our patient had a single copy COL4A4 gene mutation that was classified as VUS. He also had 2 additional VUS affecting the TRPC6 and OSGEP genes. TRPC6 gene mutation can be associated with FSGS through autosomal dominant inheritance. Both COL4A4 and TRPC6 gene mutations were paternally inherited. Although the patient’s father not having renal disease argues against the clinical significance of these findings, there is literature on the potential role of heterozygous COL4A4 variant mimicking thin basement membrane nephropathy that can lead to renal impairment upon copresence of superimposed conditions.13 The patient’s rapidly progressing hematuria and changes in the basement membrane were worrisome for emerging FSGS. Furthermore, VUS of TRPC6 has been reported in late onset autosomal dominant FSGS and can be associated with early onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children.14 This concern was voiced by 3 nephrology consultants during the initial evaluation, leading to the consensus that steroid treatment for podocytopathy would not alter the patient’s long-term outcomes (ie, progression to FSGS).

Immunomodulation

Our rationale for immunomodulatory treatment was based on the abrupt onset of renal concerns following a URI, suggesting the importance of an inflammatory trigger causing altered homeostasis in a genetically susceptible host. Preclinical models show that microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides can lead to podocytopathy by several mechanisms through activation of toll-like receptor signaling. It can directly cause apoptosis by downregulation of the intracellular Akt survival pathway.15 Lipopolysaccharide can also activate the NF-αB pathway and upregulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and TNF-α in mesangial cells.16,17

Both cytokines can promote mesangial cell proliferation.18 Through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, proinflammatory cytokines can further perpetuate somatic tissue changes and contribute to the development of podocytopathy. For instance, TNF-α can promote podocyte injury and proteinuria by downregulation of the slit diaphragm protein expression (ie, nephrin, ezrin, or podocin), and disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton.19,20 TNF-α promotes the influx and activation of macrophages and inflammatory cells. It is actively involved in chronic alterations within the glomeruli by the upregulation of matrix metalloproteases by integrins, as well as activation of myofibroblast progenitors and extracellular matrix deposition in crosstalk with transforming growth factor and other key mediators.17,21,22

For the patient described in this case report, initial improvement on steroids encouraged the pursuit of additional treatment to downregulate inflammatory pathways within the glomerular milieu. However, within the COVID-19 environment, escalating the patient’s treatment using traditional immunomodulators (ie, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil) was not favored due to the risk of infection. Initially, anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was preferred as a steroid-sparing agent for its short life and safety profile during the pandemic. At first, the patient responded well to anakinra and was allowed a steroid wean when the dose was titrated up to 6 mg/kg daily. However, anakinra did not prevent the escalation of proteinuria following a URI. After the treatment was changed to adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, the patient continued to improve and reach full remission despite experiencing a cold and the flu in the following months.

Literature Review

There is a paucity of literature on applications of biological response modifiers for idiopathic NS and FSGS.23,24 Angeletti and colleagues reported that 3 patients with severe long-standing FSGS benefited from anakinra 4 mg/kg daily to reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function. All the patients had positive C3 staining in renal biopsy and treatment response, which supported the role of C3a in inducing podocyte injury through upregulated expression of IL-1 and IL-1R.23 Trachtman and colleagues reported on the phase II FONT trial that included 14 of 21 patients aged < 18 years with advanced FSGS who were treated with adalimumab 24 mg/m2, or ≤ 40 mg every other week.24 Although, during a 6-month period, none of the 7 patients met the endpoint of reduced proteinuria by ≥ 50%, and the authors suggested that careful patient selection may improve the treatment response in future trials.24

A recent study involving transcriptomics on renal tissue samples combined with available pathology (fibrosis), urinary markers, and clinical characteristics on 285 patients with MCD or FSGS from 3 different continents identified 3 distinct clusters. Patients with evidence of activated kidney TNF pathway (n = 72, aged > 18 years) were found to have poor clinical outcomes.25 The study identified 2 urine markers associated with the TNF pathway (ie, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), which aligns with the preclinical findings previously mentioned.25

Conclusions

The patient’s condition in this case illustrates the complex nature of biologically predetermined cascading events in the emergence of glomerular disease upon environmental triggers under the influence of genetic factors.

Chronic kidney disease affects 7.7% of veterans annually, illustrating the need for new therapeutics.26 Based on our experience and literature review, upregulation of TNF-α is a root cause of glomerulopathy; further studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of anti-TNF biologic response modifiers for the treatment of these patients. Long-term postmarketing safety profile and steroid-sparing properties of adalimumab should allow inclusion of pediatric cases in future trials. Results may also contribute to identifying new predictive biomarkers related to the basement membrane when combined with precision nephrology to further advance patient selection and targeted treatment.25,27

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s mother for providing consent to allow publication of this case report.

1. Arif E, Nihalani D. Glomerular filtration barrier assembly: an insight. Postdoc J. 2013;1(4):33-45.

2. Garg PA. Review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(suppl 1):3-13. doi:10.1159/000481633SUPPL

3. Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, et al. Alport syndrome classification and management. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):639-649. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014

4. Angioi A, Pani A. FSGS: from pathogenesis to the histological lesion. J Nephrol. 2016;29(4):517-523. doi:10.1007/s40620-016-0333-2

5. Roca N, Martinez C, Jatem E, Madrid A, Lopez M, Segarra A. Activation of the acute inflammatory phase response in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: association with clinicopathological phenotypes and with response to corticosteroids. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1207-1215. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa247

6. Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332-345.

7. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lawrence C, Condon M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of tacrolimus and prednisolone monotherapy for adults with De Novo minimal change disease: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(2):209-218. doi:10.2215/CJN.06290420

8. Ye Q, Lan B, Liu H, Persson PB, Lai EY, Mao J. A critical role of the podocyte cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of glomerular proteinuria and autoimmune podocytopathies. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2022;235(4):e13850. doi:10.1111/apha.13850

9. Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Ziμtkiewicz BS, et al. Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3055-3065. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016101121

10. Kashtan CE, Gross O. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711-719. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6

11. Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY. Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1169-78. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00234.x

12. Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(3):502-517. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960616

13. Savige J. Should we diagnose autosomal dominant Alport syndrome when there is a pathogenic heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 variant? Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1239-1241. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.08.002

14. Gigante M, Caridi G, Montemurno E, et al. TRPC6 mutations in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and atypical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1626-1634. doi:10.2215/CJN.07830910

15. Saurus P, Kuusela S, Lehtonen E, et al. Podocyte apoptosis is prevented by blocking the toll-like receptor pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(5):e1752. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.125

16. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1111-1118. doi:10.1038/ki.1989.98

17. White S, Lin L, Hu K. NF-κB and tPA signaling in kidney and other diseases. Cells. 2020;9(6):1348. doi:10.3390/cells9061348

18. Tesch GH, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Role of interleukin-1 in mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition in experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(1):141-150.

19. Lai KN, Leung JCK, Chan LYY, et al. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62-72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn441

20. Saleem MA, Kobayashi Y. Cell biology and genetics of minimal change disease. F1000 Res. 2016;5: F1000 Faculty Rev-412. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7300.1

21. Kim KP, Williams CE, Lemmon CA. Cell-matrix interactions in renal fibrosis. Kidney Dial. 2022;2(4):607-624. doi:10.3390/kidneydial2040055

22. Zvaifler NJ. Relevance of the stroma and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):210. doi:10.1186/ar1963

23. Angeletti A, Magnasco A, Trivelli A, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):121-124. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018

24. Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:111. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0094-5

25. Mariani LH, Eddy S, AlAkwaa FM, et al. Precision nephrology identified tumor necrosis factor activation variability in minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.023

26. Korshak L, Washington DL, Powell J, Nylen E, Kokkinos P. Kidney Disease in Veterans. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

27. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.305

1. Arif E, Nihalani D. Glomerular filtration barrier assembly: an insight. Postdoc J. 2013;1(4):33-45.

2. Garg PA. Review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(suppl 1):3-13. doi:10.1159/000481633SUPPL

3. Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, et al. Alport syndrome classification and management. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):639-649. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014

4. Angioi A, Pani A. FSGS: from pathogenesis to the histological lesion. J Nephrol. 2016;29(4):517-523. doi:10.1007/s40620-016-0333-2

5. Roca N, Martinez C, Jatem E, Madrid A, Lopez M, Segarra A. Activation of the acute inflammatory phase response in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: association with clinicopathological phenotypes and with response to corticosteroids. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1207-1215. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa247

6. Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332-345.

7. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lawrence C, Condon M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of tacrolimus and prednisolone monotherapy for adults with De Novo minimal change disease: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(2):209-218. doi:10.2215/CJN.06290420

8. Ye Q, Lan B, Liu H, Persson PB, Lai EY, Mao J. A critical role of the podocyte cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of glomerular proteinuria and autoimmune podocytopathies. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2022;235(4):e13850. doi:10.1111/apha.13850

9. Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Ziμtkiewicz BS, et al. Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3055-3065. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016101121

10. Kashtan CE, Gross O. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711-719. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6

11. Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY. Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1169-78. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00234.x

12. Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(3):502-517. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960616

13. Savige J. Should we diagnose autosomal dominant Alport syndrome when there is a pathogenic heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 variant? Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1239-1241. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.08.002

14. Gigante M, Caridi G, Montemurno E, et al. TRPC6 mutations in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and atypical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1626-1634. doi:10.2215/CJN.07830910

15. Saurus P, Kuusela S, Lehtonen E, et al. Podocyte apoptosis is prevented by blocking the toll-like receptor pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(5):e1752. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.125

16. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1111-1118. doi:10.1038/ki.1989.98

17. White S, Lin L, Hu K. NF-κB and tPA signaling in kidney and other diseases. Cells. 2020;9(6):1348. doi:10.3390/cells9061348

18. Tesch GH, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Role of interleukin-1 in mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition in experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(1):141-150.

19. Lai KN, Leung JCK, Chan LYY, et al. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62-72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn441

20. Saleem MA, Kobayashi Y. Cell biology and genetics of minimal change disease. F1000 Res. 2016;5: F1000 Faculty Rev-412. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7300.1

21. Kim KP, Williams CE, Lemmon CA. Cell-matrix interactions in renal fibrosis. Kidney Dial. 2022;2(4):607-624. doi:10.3390/kidneydial2040055

22. Zvaifler NJ. Relevance of the stroma and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):210. doi:10.1186/ar1963

23. Angeletti A, Magnasco A, Trivelli A, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):121-124. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018

24. Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:111. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0094-5

25. Mariani LH, Eddy S, AlAkwaa FM, et al. Precision nephrology identified tumor necrosis factor activation variability in minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.023

26. Korshak L, Washington DL, Powell J, Nylen E, Kokkinos P. Kidney Disease in Veterans. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

27. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.305

Following the Hyperkalemia Trail: A Case Report of ECG Changes and Treatment Responses

Following the Hyperkalemia Trail: A Case Report of ECG Changes and Treatment Responses

Hyperkalemia involves elevated serum potassium levels (> 5.0 mEq/L) and represents an important electrolyte disturbance due to its potentially severe consequences, including cardiac effects that can lead to dysrhythmia and even asystole and death.1,2 In a US Medicare population, the prevalence of hyperkalemia has been estimated at 2.7% and is associated with substantial health care costs.3 The prevalence is even more marked in patients with preexisting conditions such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) and heart failure.4,5

Hyperkalemia can result from multiple factors, including impaired renal function, adrenal disease, adverse drug reactions of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and other medications, and heritable mutations.6 Hyperkalemia poses a considerable clinical risk, associated with adverse outcomes such as myocardial infarction and increased mortality in patients with CKD.5,7,8 Electrocardiographic (ECG) changes associated with hyperkalemia play a vital role in guiding clinical decisions and treatment strategies.9 Understanding the pathophysiology, risk factors, and consequences of hyperkalemia, as well as the significance of ECG changes in its management, is essential for health care practitioners.

Case Presentation

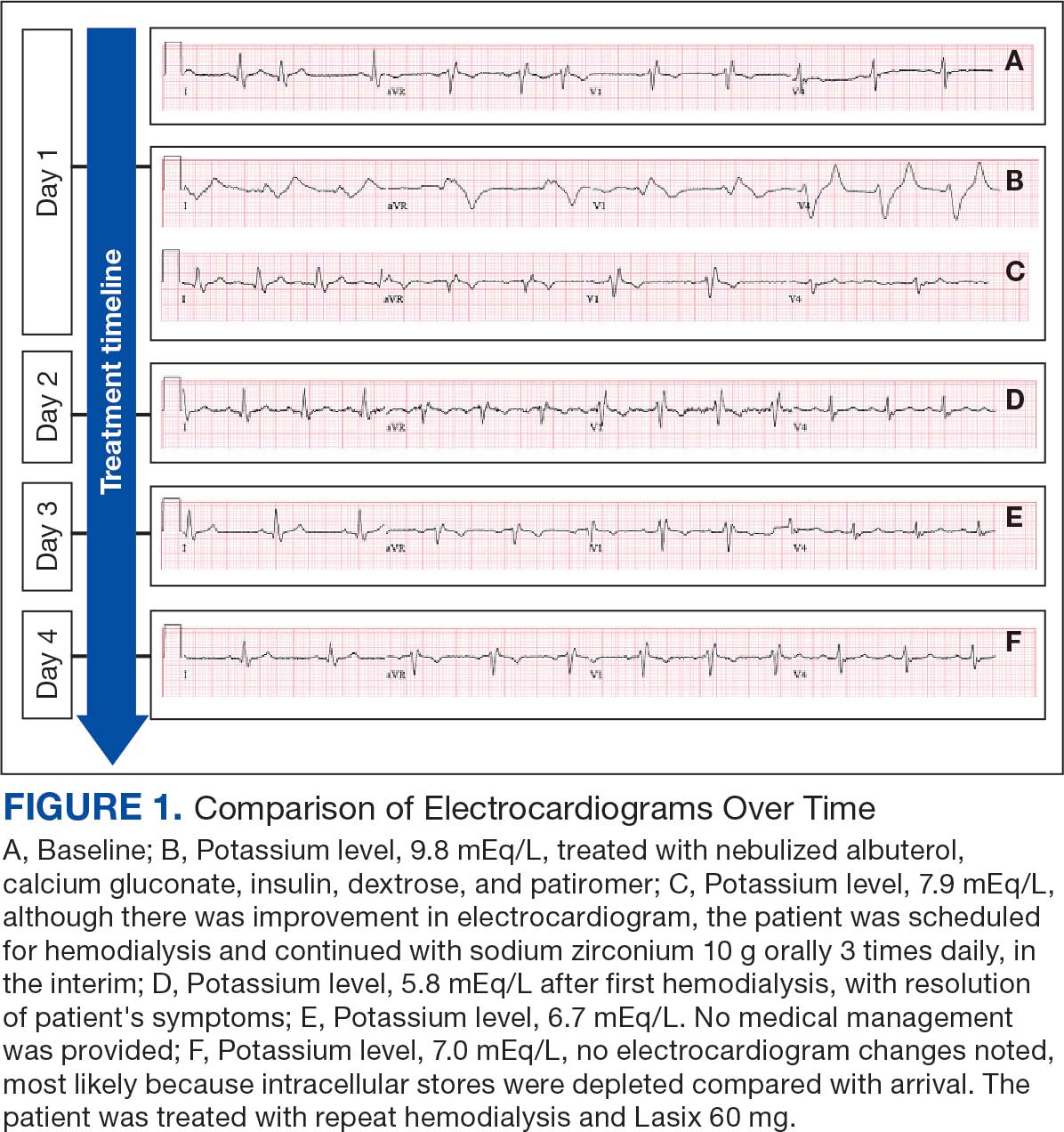

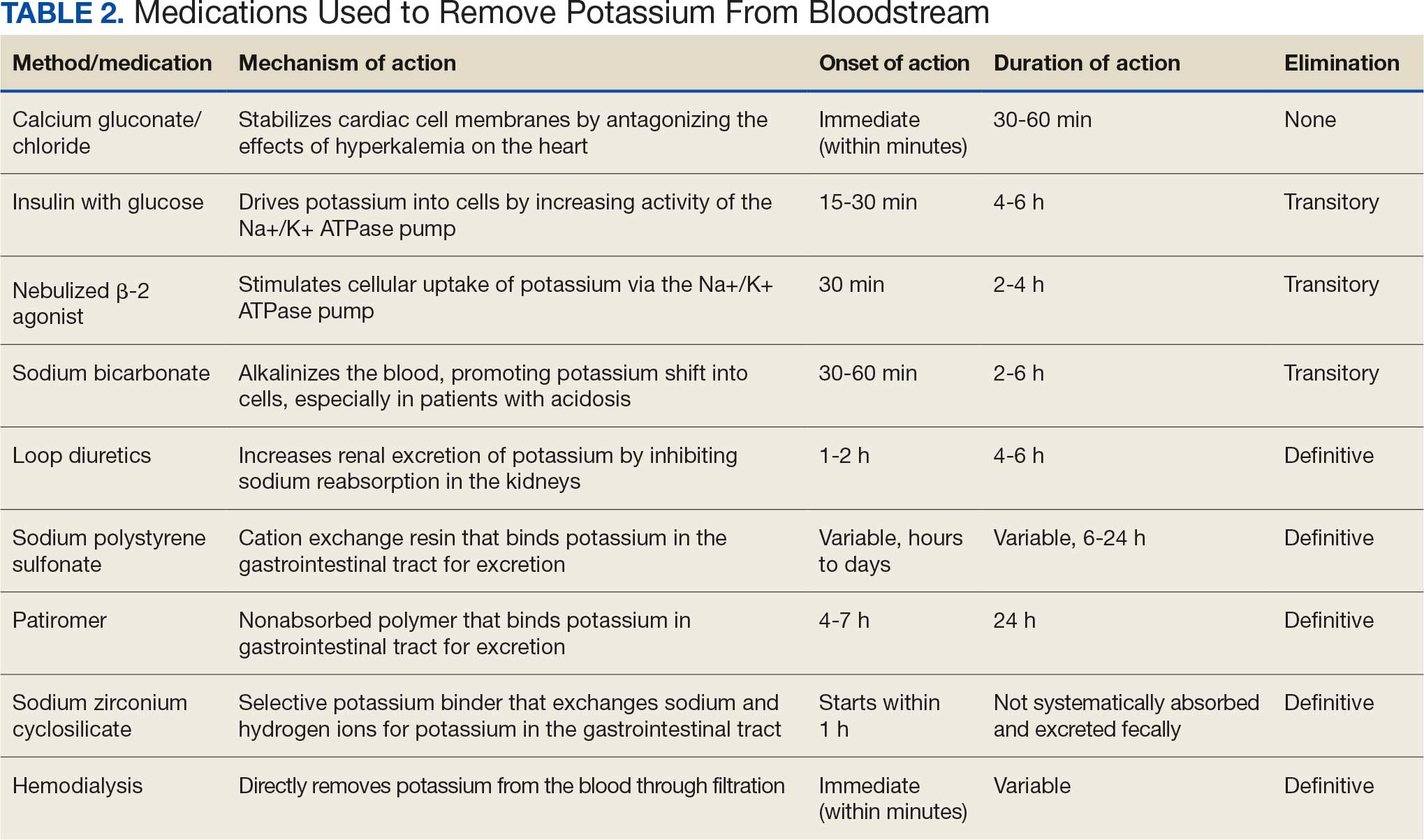

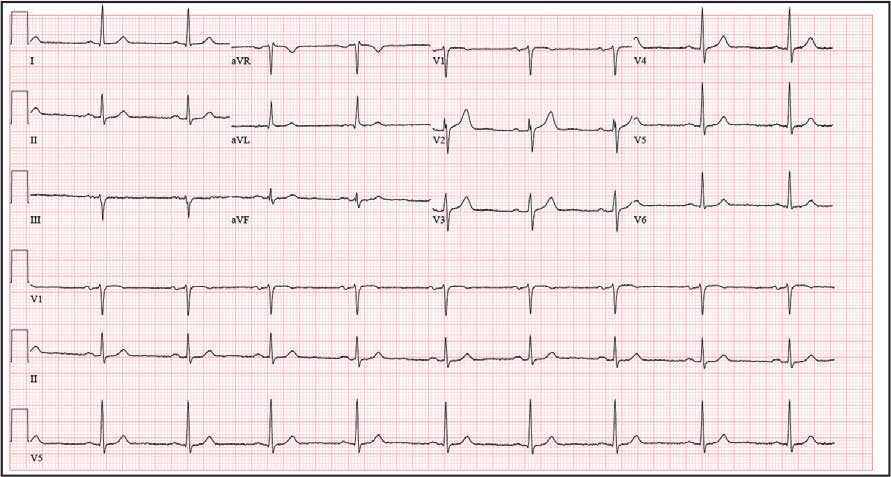

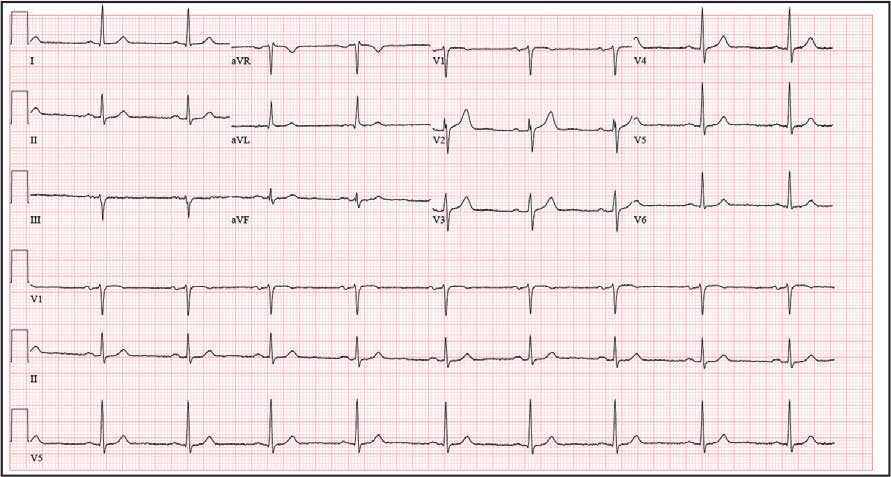

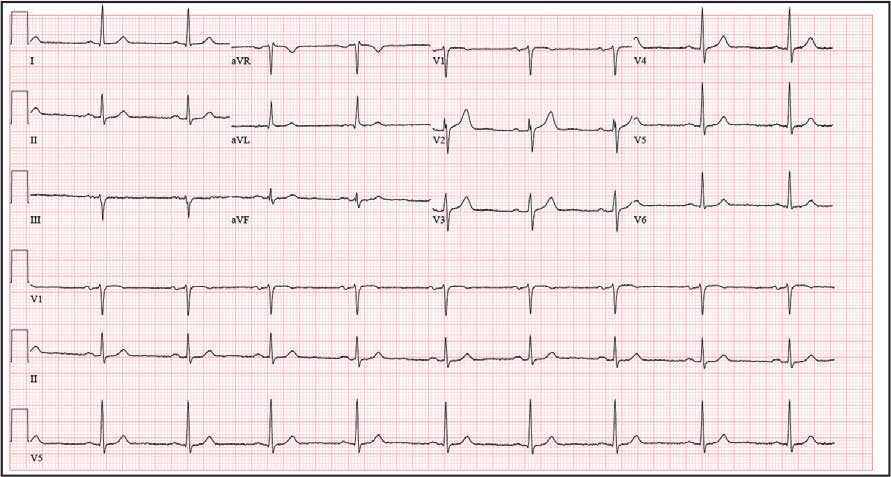

An 81-year-old Hispanic man with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, gout, and CKD stage 3B presented to the emergency department with progressive weakness resulting in falls and culminating in an inability to ambulate independently. Additional symptoms included nausea, diarrhea, and myalgia. His vital signs were notable for a pulse of 41 beats/min. The physical examination was remarkable for significant weakness of the bilateral upper extremities, inability to bear his own weight, and bilateral lower extremity edema. His initial ECG upon arrival showed bradycardia with wide QRS, absent P waves, and peaked T waves (Figure 1a). These findings differed from his baseline ECG taken 1 year earlier, which showed sinus rhythm with premature atrial complexes and an old right bundle branch block (Figure 1b).

Medication review revealed that the patient was currently prescribed 100 mg allopurinol daily, 2.5 mg amlodipine daily, 10 mg atorvastatin at bedtime, 4 mg doxazosin daily, 112 mcg levothyroxine daily, 100 mg losartan daily, 25 mg metoprolol daily, and 0.4 mg tamsulosin daily. The patient had also been taking over-the-counter indomethacin for knee pain.

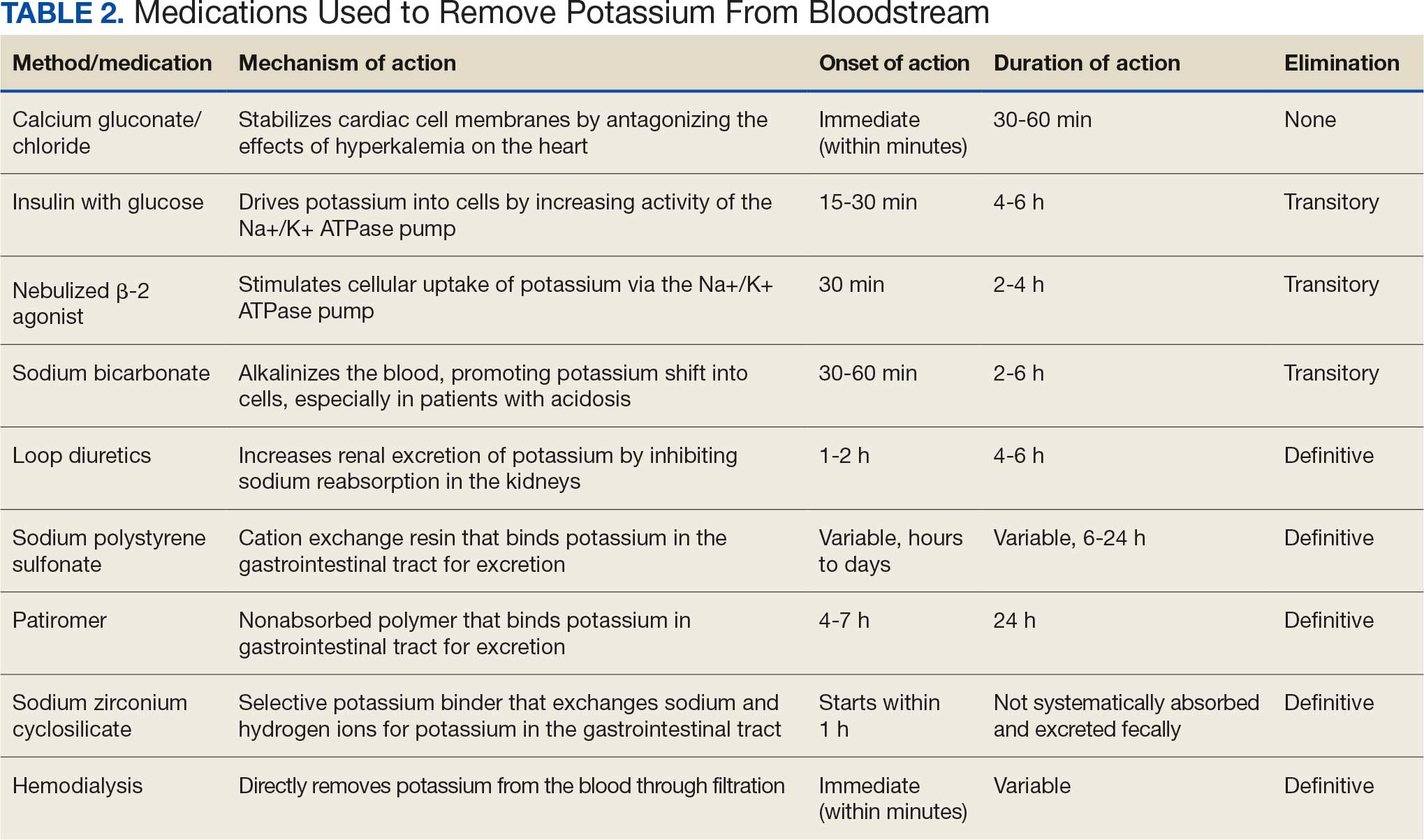

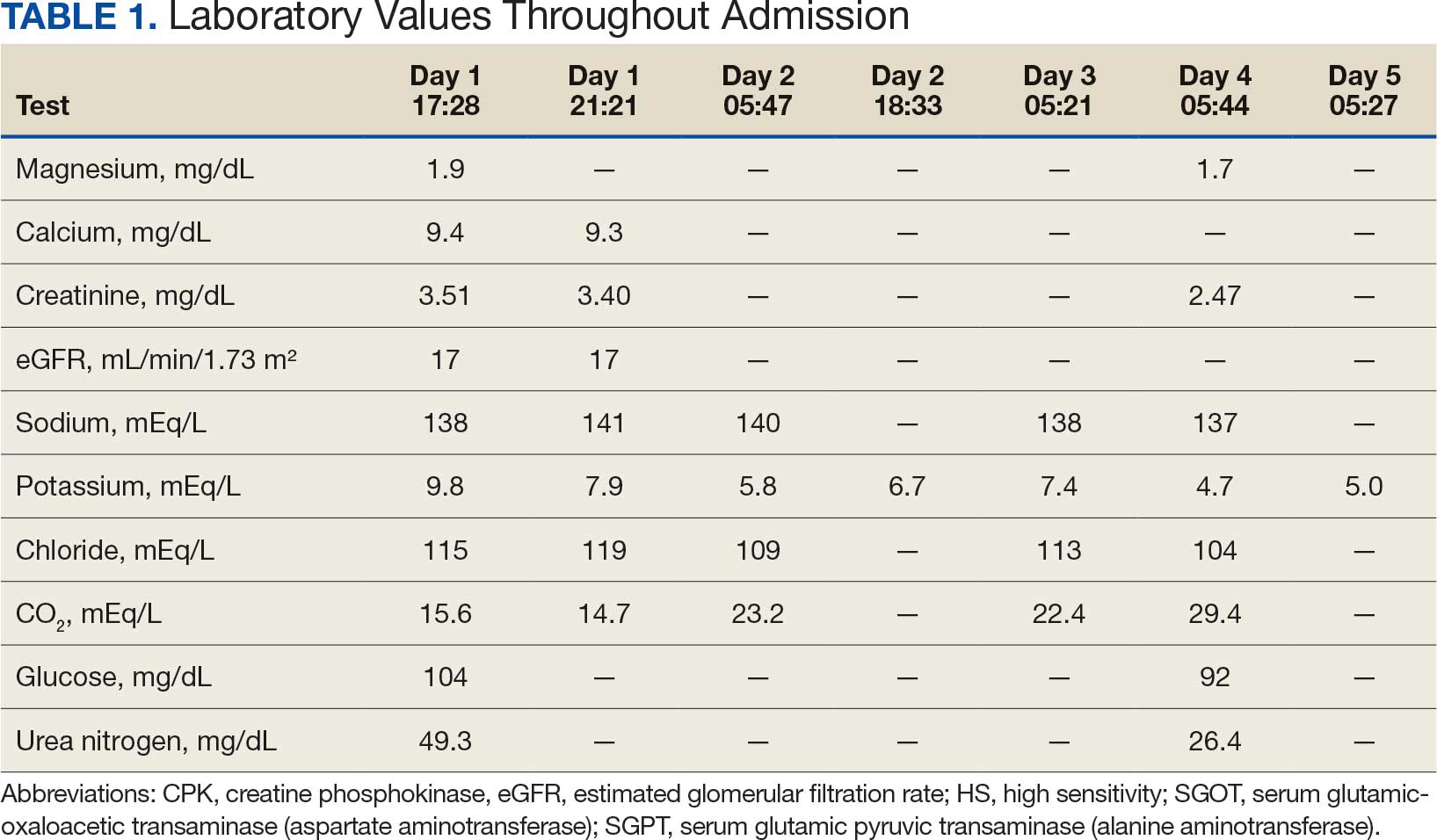

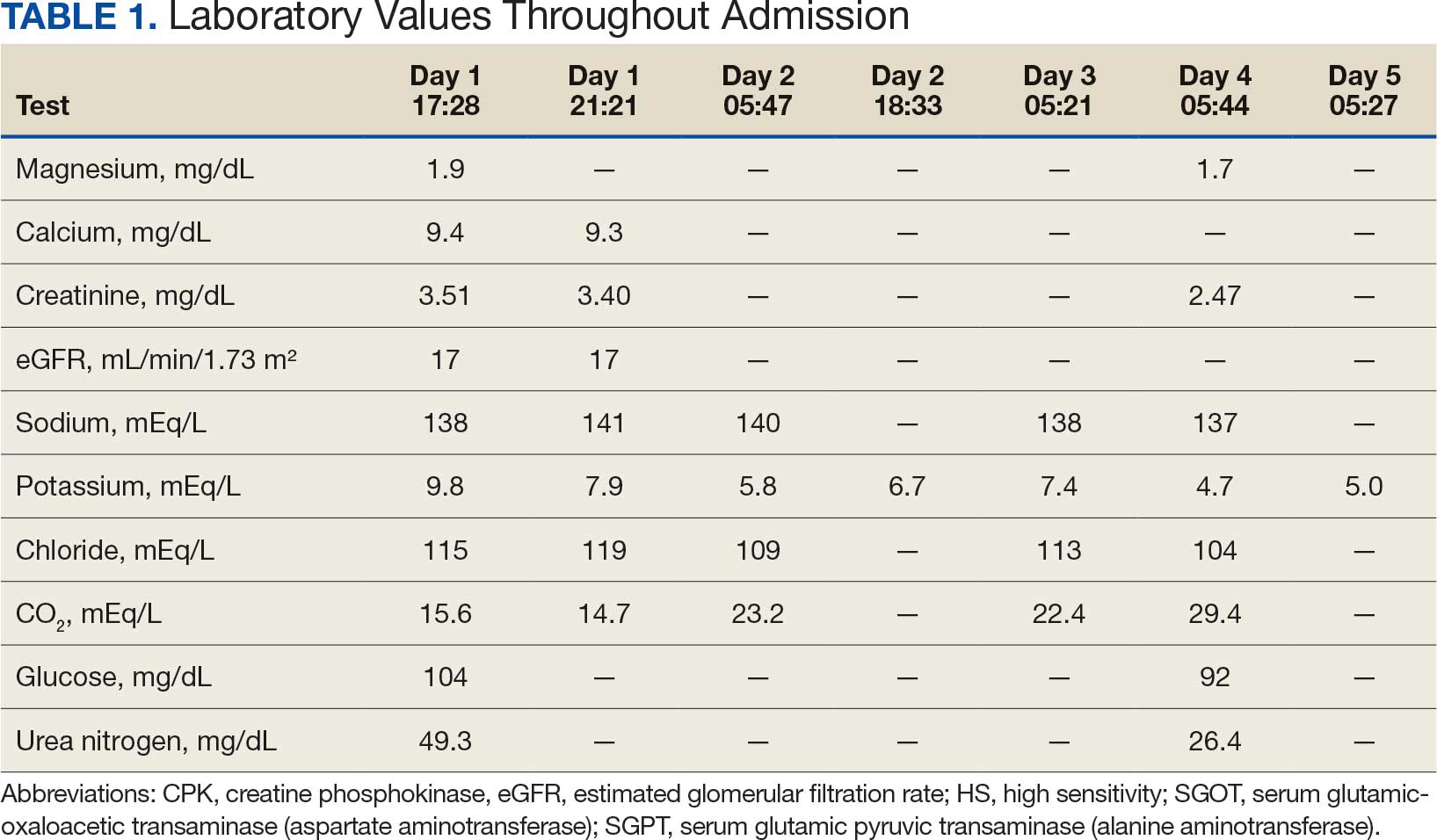

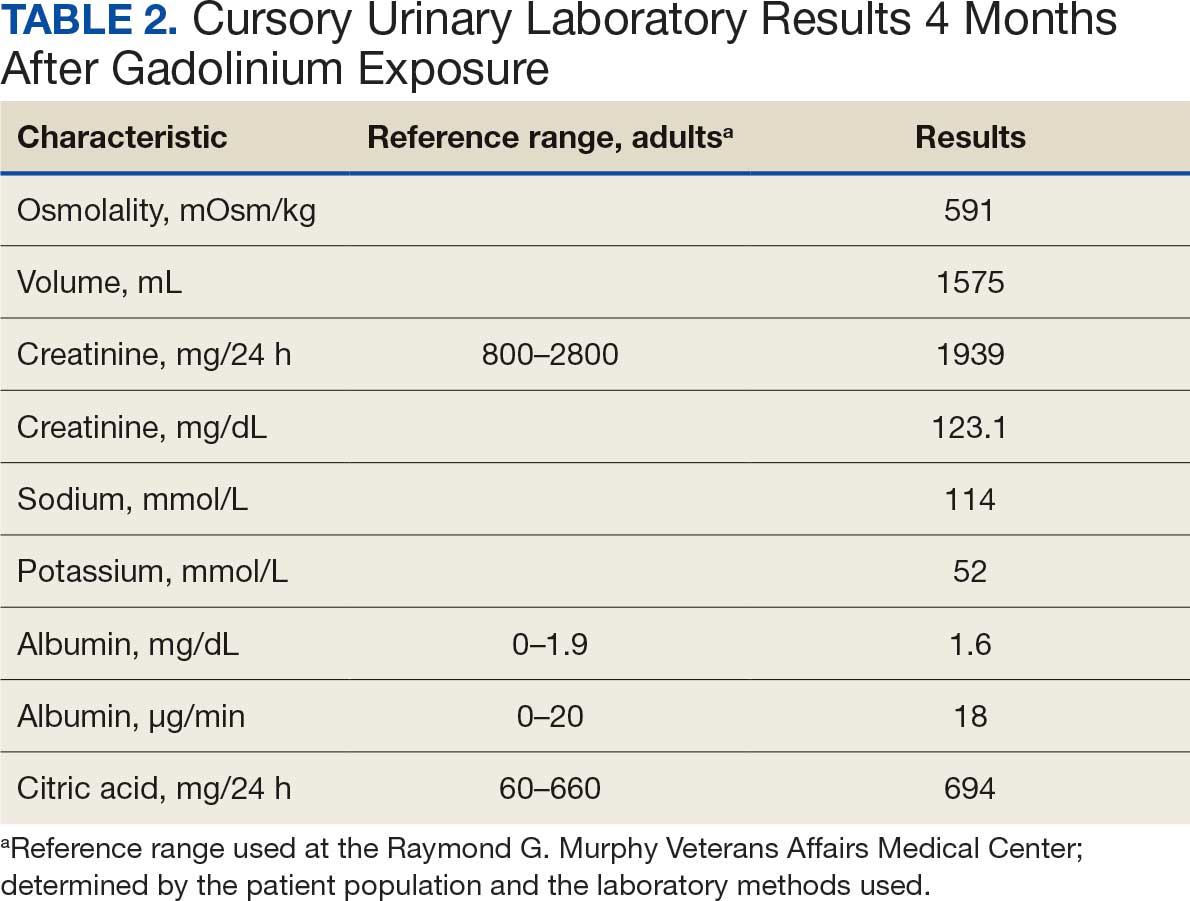

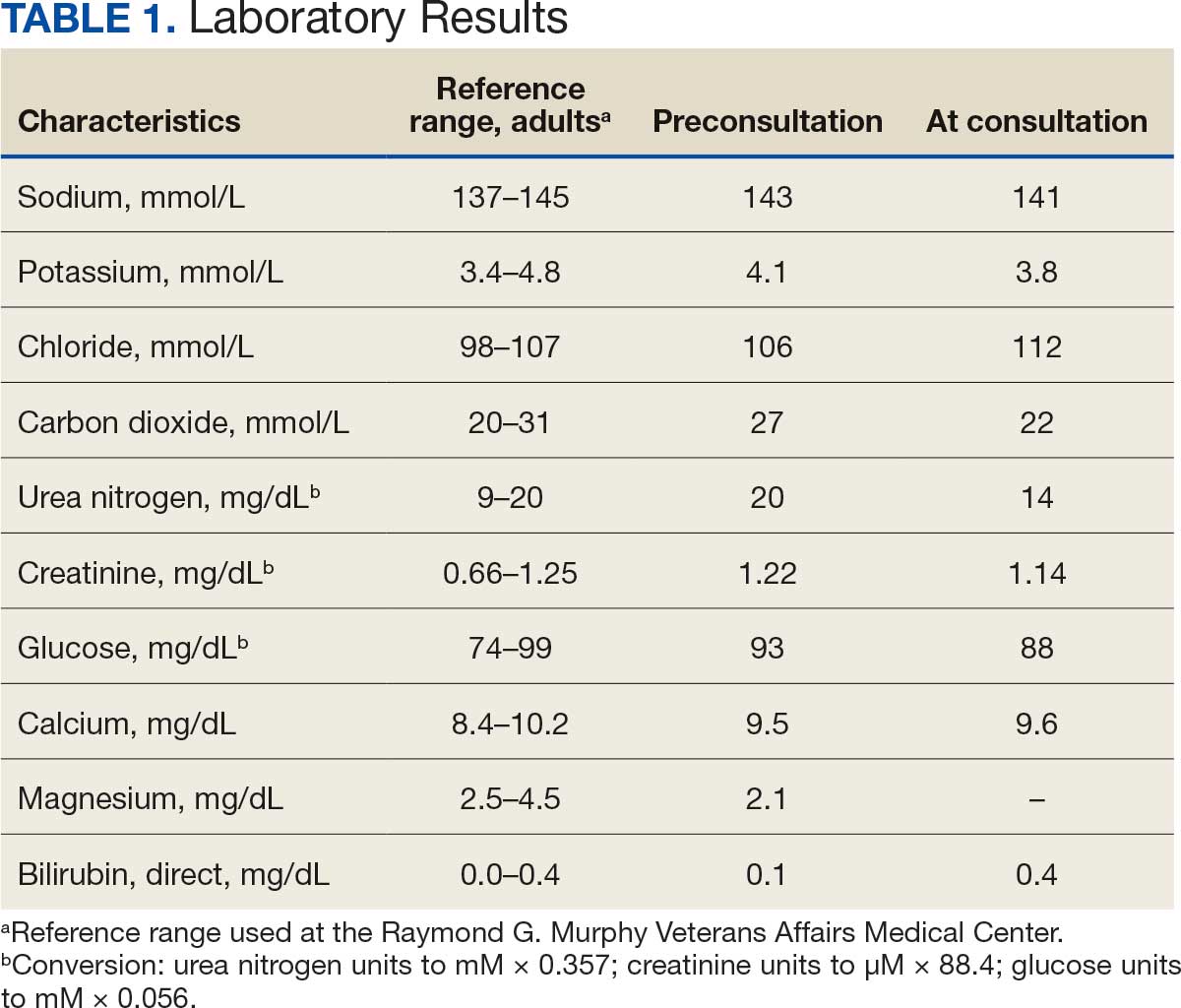

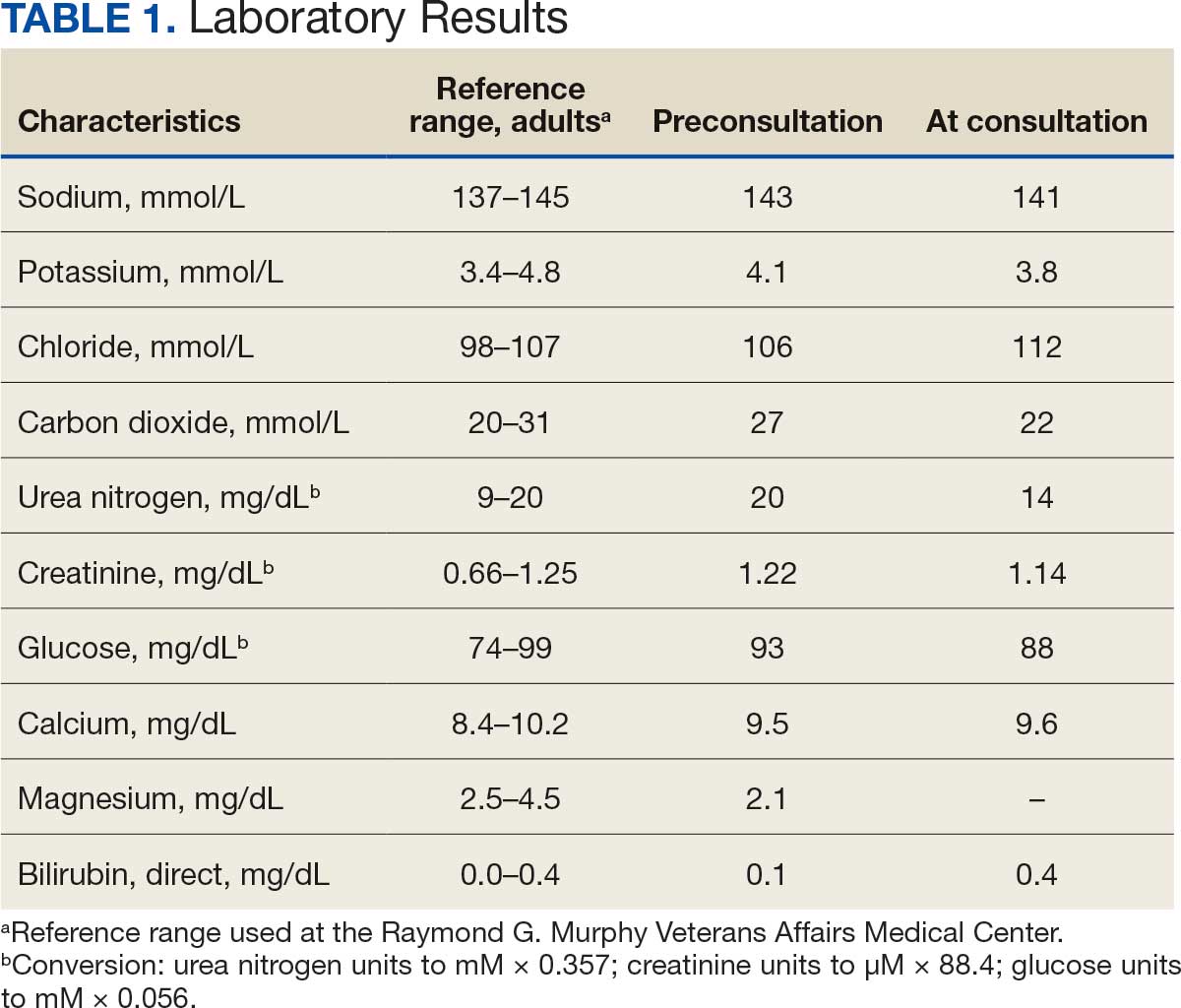

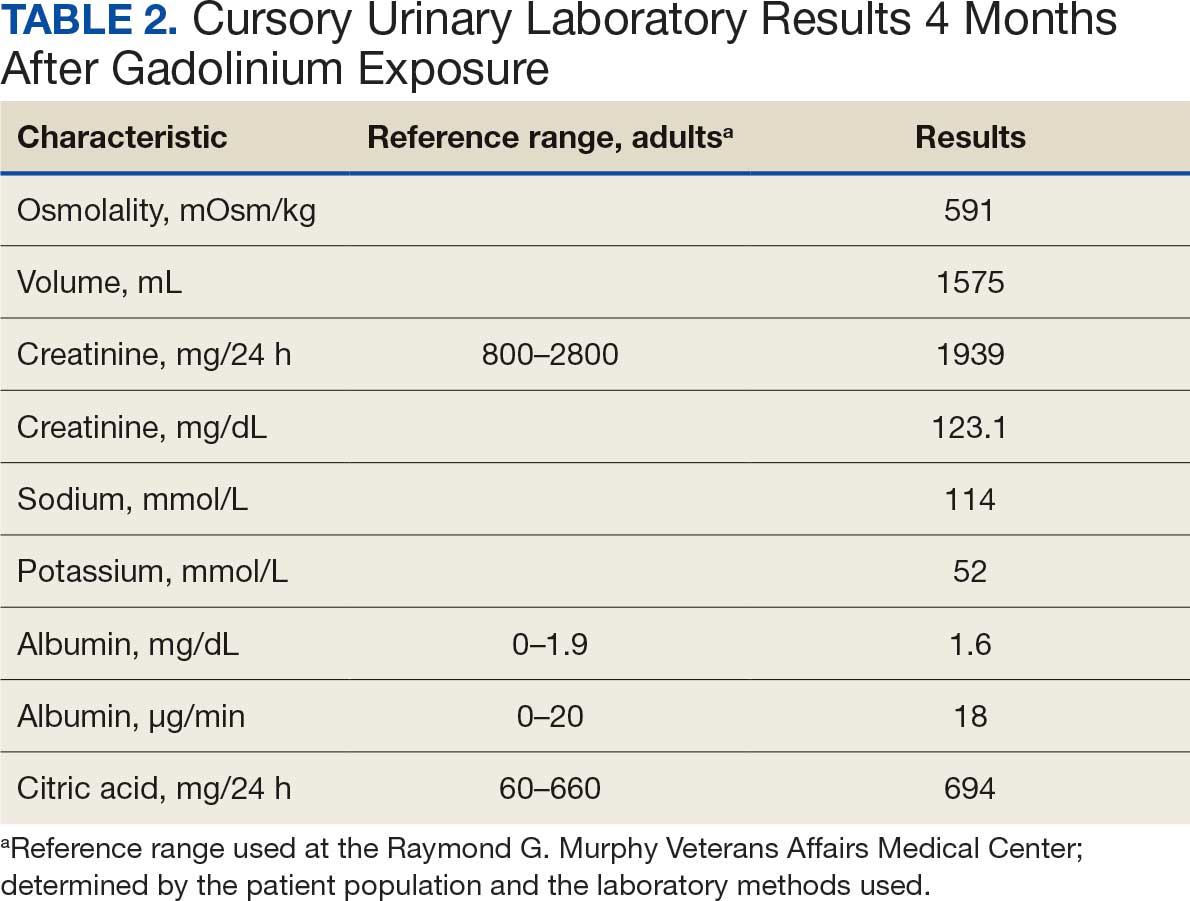

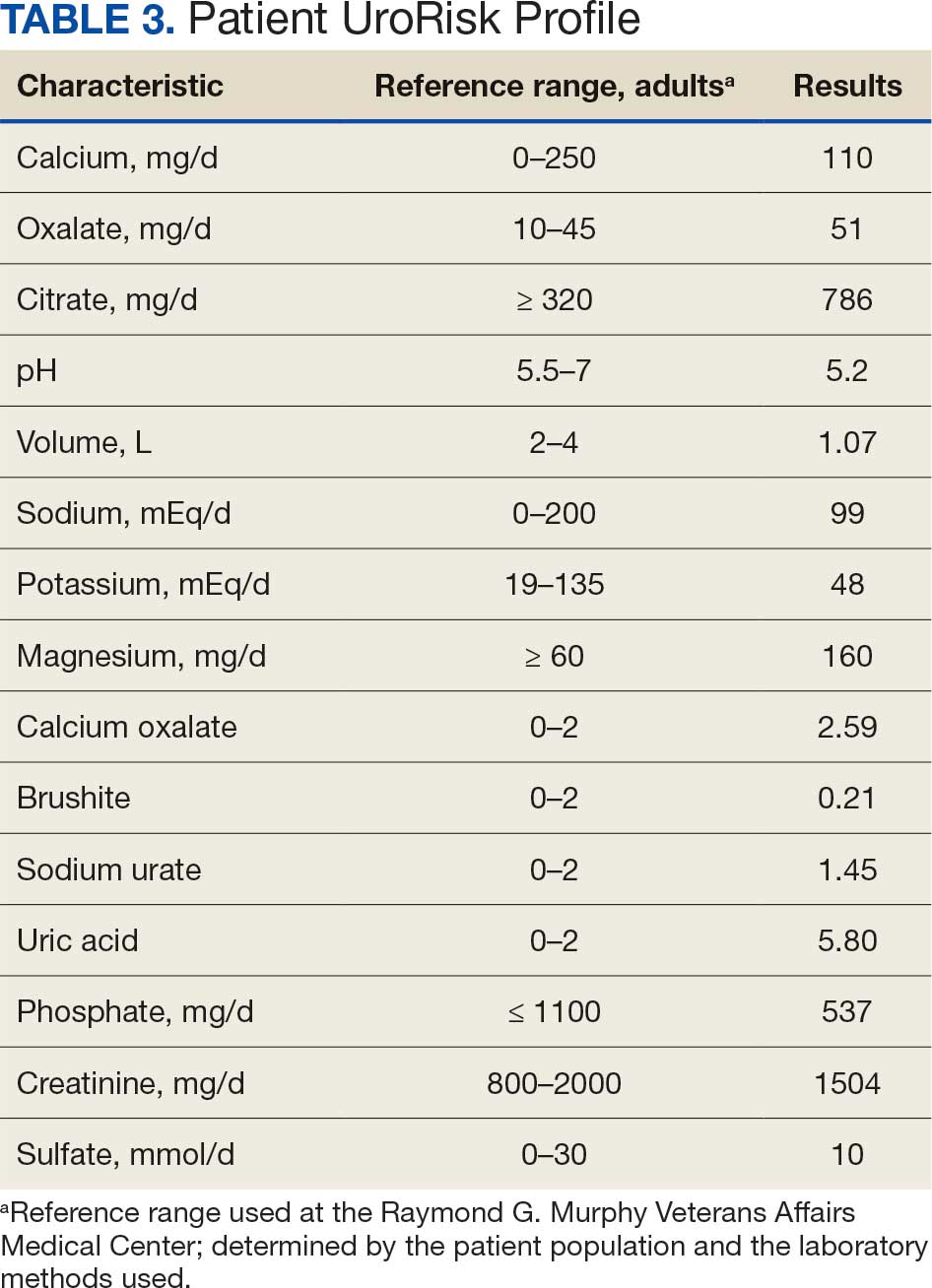

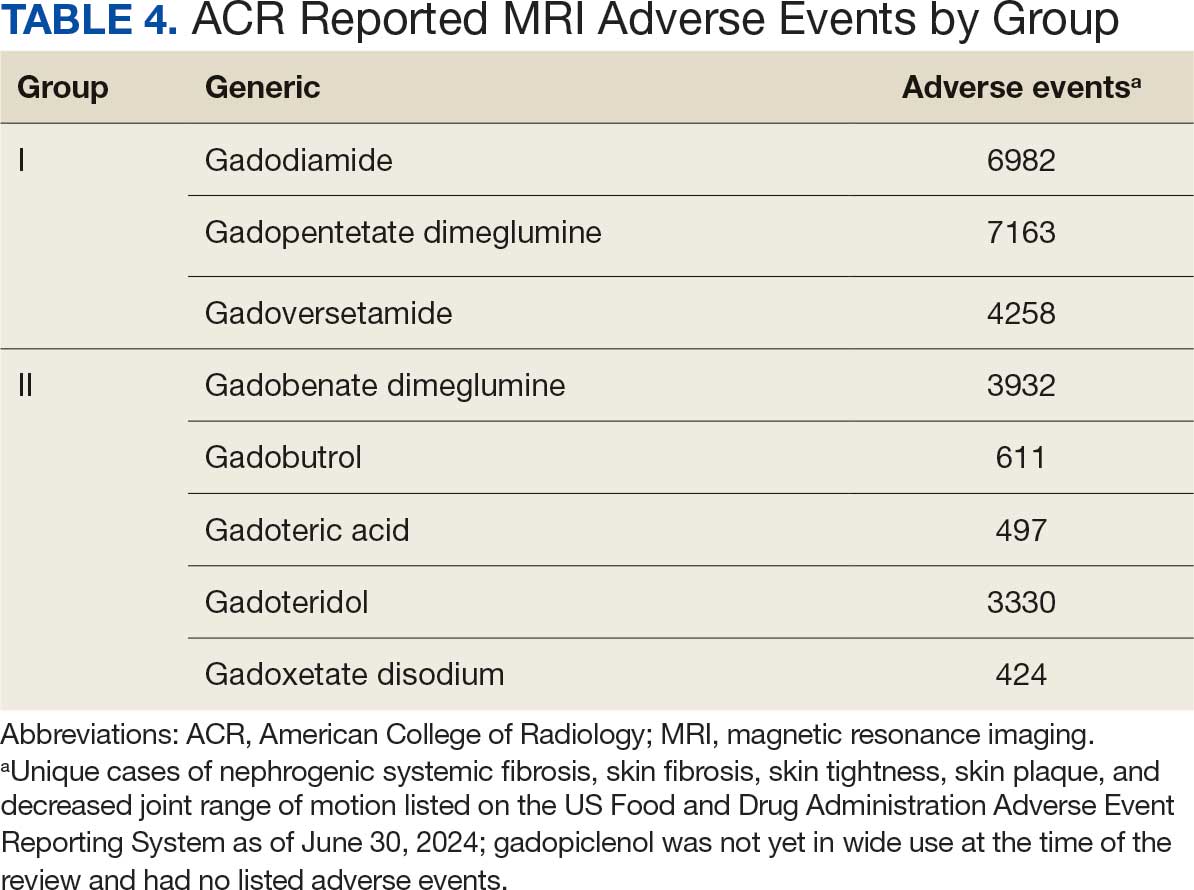

Based on the ECG results, he was treated with 0.083%/6 mL nebulized albuterol, 4.65 Mq/250 mL saline solution intravenous (IV) calcium gluconate, 10 units IV insulin with concomitant 50%/25 mL IV dextrose and 8.4 g of oral patiromer suspension. IV furosemide was held due to concern for renal function. The decision to proceed with hemodialysis was made. Repeat laboratory tests were performed, and an ECG obtained after treatment initiation but prior to hemodialysis demonstrated improvement of rate and T wave shortening (Figure 1c). The serum potassium level dropped from 9.8 mEq/L to 7.9 mEq/L (reference range, 3.5-5.0 mEq/L) (Table 1).

In addition to hemodialysis, sodium zirconium 10 g orally 3 times daily was added. Laboratory test results and an ECG was performed after dialysis continued to demonstrate improvement (Figure 1d). The patient’s potassium level decreased to 5.8 mEq/L, with the ECG demonstrating stability of heart rate and further improvement of the PR interval, QRS complex, and T waves.

Despite the established treatment regimen, potassium levels again rose to 6.7 mEq/L, but there were no significant changes in the ECG, and thus no medication changes were made (Figure 1e). Subsequent monitoring demonstrated a further increase in potassium to 7.4 mEq/L, with an ECG demonstrating a return to the baseline of 1 year prior. The patient underwent hemodialysis again and was given oral furosemide 60 mg every 12 hours. The potassium concentration after dialysis decreased to 4.7 mEq/L and remained stable, not going above 5.0 mEq/L on subsequent monitoring. The patient had resolution of all symptoms and was discharged.

Discussion

We have described in detail the presentation of each pathology and mechanisms of each treatment, starting with the patient’s initial condition that brought him to the emergency room—muscle weakness. Skeletal muscle weakness is a common manifestation of hyperkalemia, occurring in 20% to 40% of cases, and is more prevalent in severe elevations of potassium. Rarely, the weakness can progress to flaccid paralysis of the patient’s extremities and, in extreme cases, the diaphragm.

Muscle weakness progression occurs in a manner that resembles Guillain-Barré syndrome, starting in the lower extremities and ascending toward the upper extremities.10 This is known as secondary hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. Hyperkalemia lowers the transmembrane gradient in neurons, leading to neuronal depolarization independent of the degree of hyperkalemia. If the degree of hyperkalemia is large enough, this depolarization inactivates voltage-gated sodium channels, making neurons refractory to excitation. Electromyographical studies have shown reduction in the compounded muscle action potential.11 The transient nature of this paralysis is reflected by rapid correction of weakness and paralysis when the electrolyte disorder is corrected.

The patient in this case also presented with bradycardia. The ECG manifestations of hyperkalemia can include atrial asystole, intraventricular conduction disturbances, peaked T waves, and widened QRS complexes. However, some patients with renal insufficiency may not exhibit ECG changes despite significantly elevated serum potassium levels.12

The severity of hyperkalemia is crucial in determining the associated ECG changes, with levels > 6.0 mEq/L presenting with abnormalities.13 ECG findings alone may not always accurately reflect the severity of hyperkalemia, as up to 60% of patients with potassium levels > 6.0 mEq/L may not show ECG changes.14 Additionally, extreme hyperkalemia can lead to inconsistent ECG findings, making it challenging to rely solely on ECG for diagnosis and monitoring.8 The level of potassium that causes these effects varies widely through patient populations.

The main mechanism by which hyperkalemia affects the heart’s conduction system is through voltage differences across the conduction fibers and eventual steady-state inactivation of sodium channels. This combination of mechanisms shortens the action potential duration, allowing more cardiomyocytes to undergo synchronized depolarization. This amalgamation of cardiomyocytes repolarizing can be reflected on ECGs as peaked T waves. As the action potential decreases, there is a period during which cardiomyocytes are prone to tachyarrhythmias and ventricular fibrillation.

A reduced action potential may lead to increased rates of depolarization and thus conduction, which in some scenarios may increase heart rate. As the levels of potassium rise, intracellular accumulation impedes the entry of sodium by decreasing the cation gradient across the cell membrane. This effectively slows the sinus nodes and prolongs the QRS by slowing the overall propagation of action potentials. By this mechanism, conduction delays, blocks, or asystole are manifested. The patient in this case showed conduction delays, peaked T waves, and disappearance of P waves when he first arrived.

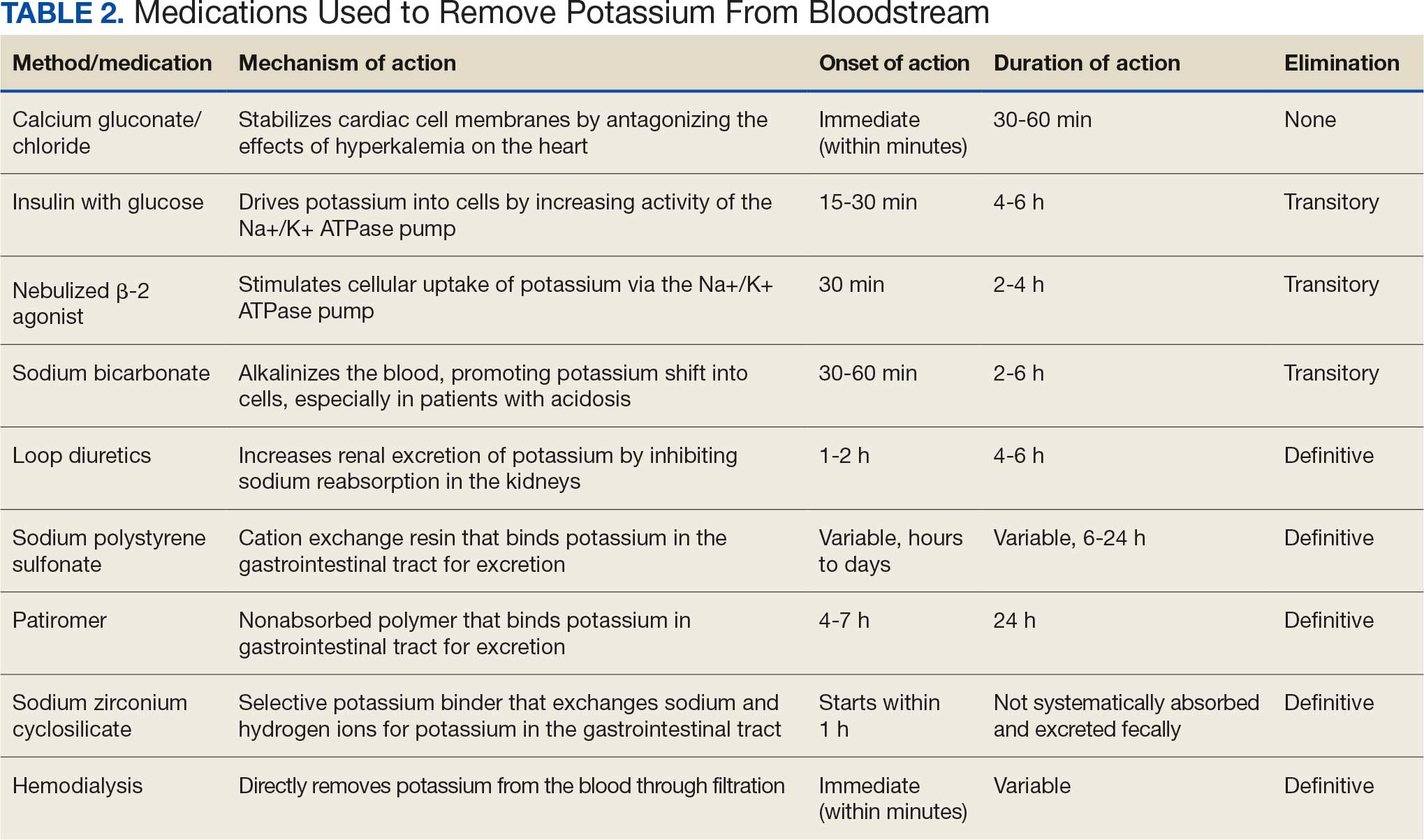

Hyperkalemia Treatment

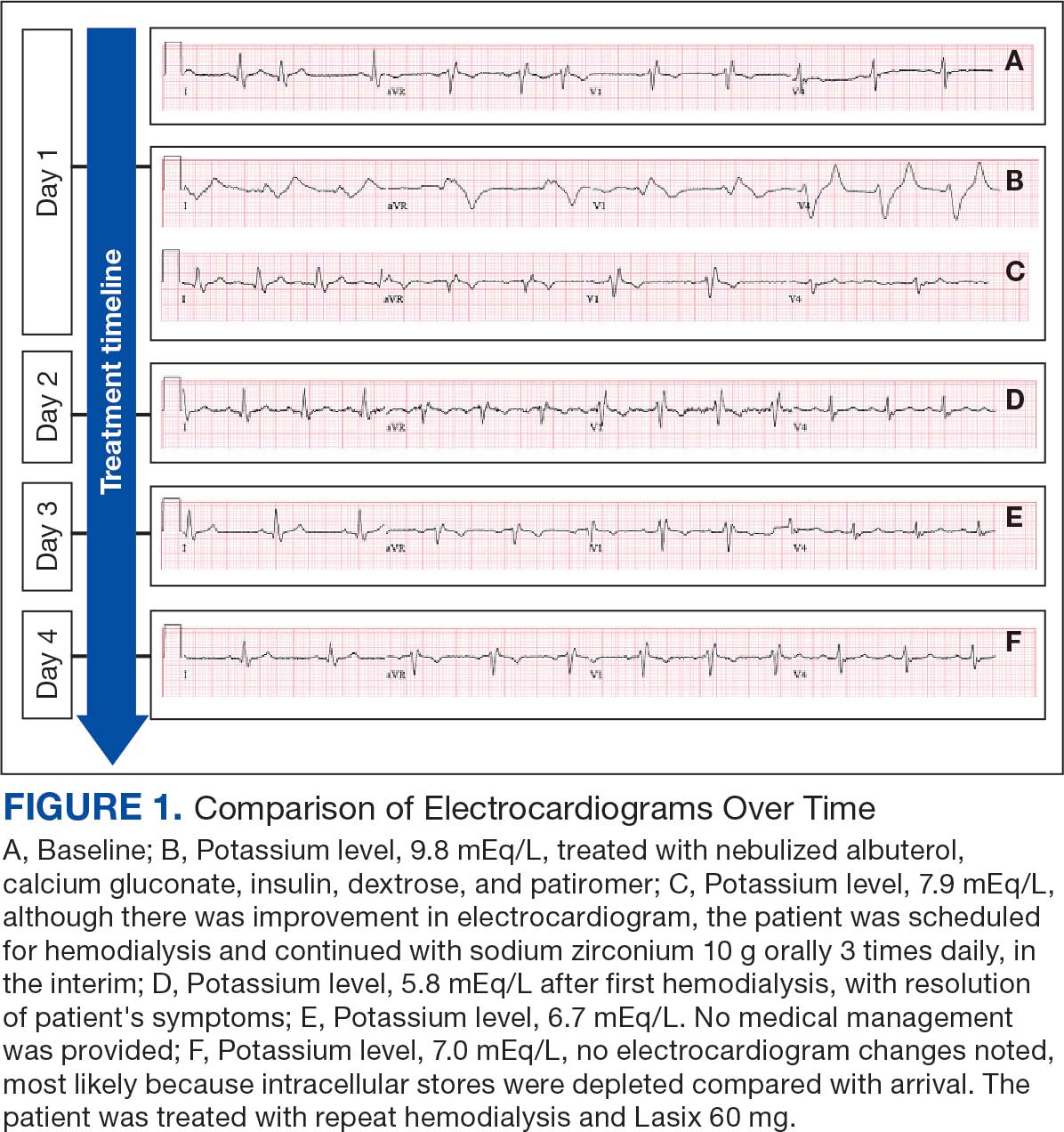

Hyperkalemia develops most commonly due to acute or chronic kidney diseases, as was the case with this patient. The patient’s hyperkalemia was also augmented by the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which can directly affect renal function. A properly functioning kidney is responsible for excretion of up to 90% of ingested potassium, while the remainder is excreted through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Definitive treatment of hyperkalemia is mitigated primarily through these 2 organ systems. The treatment also includes transitory mechanisms of potassium reduction. The goal of each method is to preserve the action potential of cardiomyocytes and myocytes. This patient presented with acute symptomatic hyperkalemia and received various medications to acutely, transitorily, and definitively treat it.

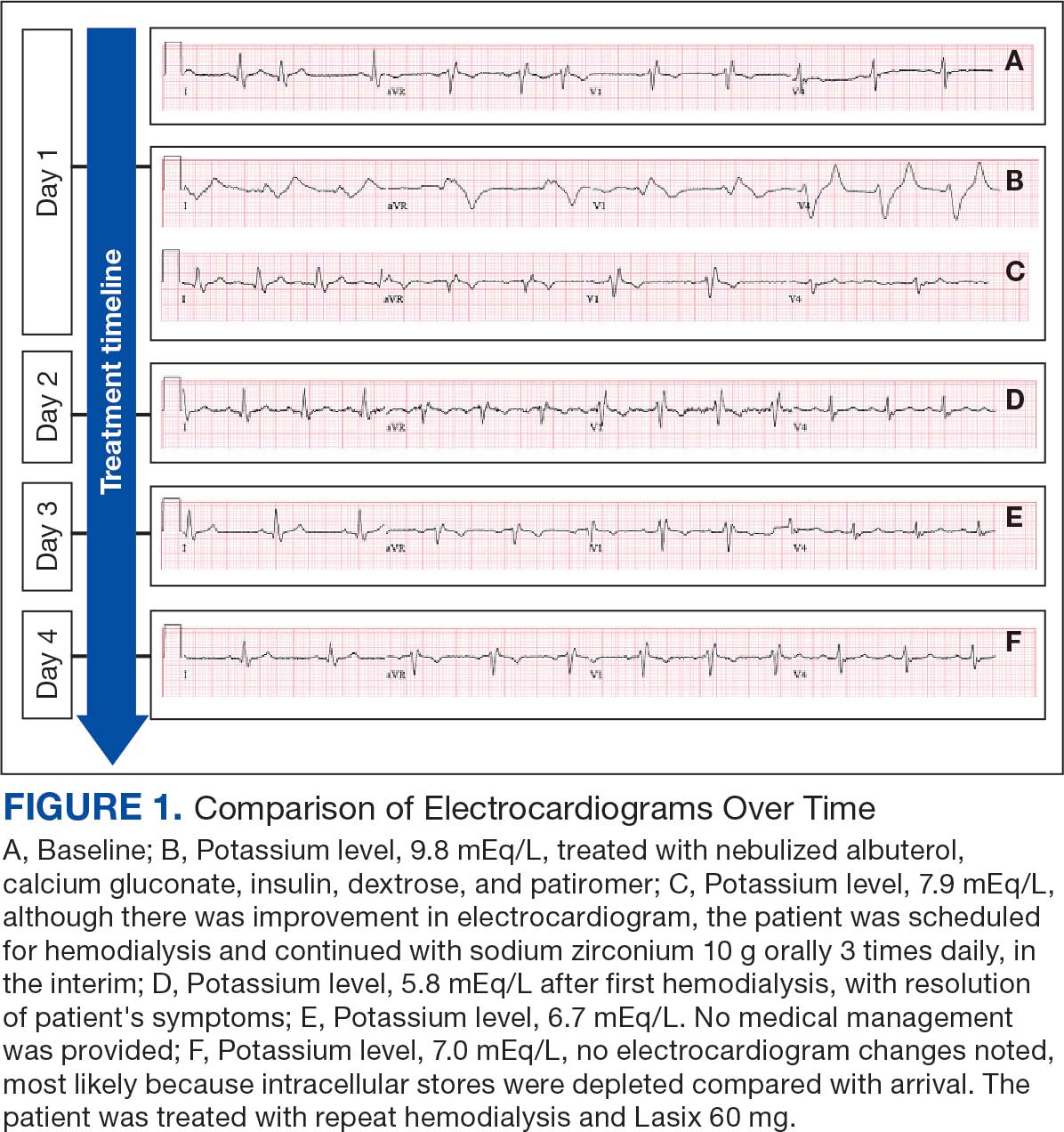

Initial therapy included calcium gluconate, which functions to stabilize the myocardial cell membrane. Hyperkalemia decreases the resting membrane action potential of excitable cells and predisposes them to early depolarization and thus dysrhythmias. Calcium decreases the threshold potential across cells and offsets the overall gradient back to near normal levels.15 Calcium can be delivered through calcium gluconate or calcium chloride. Calcium chloride is not preferred because extravasation can cause pain, blistering and tissue ischemia. Central venous access is required, potentially delaying prompt treatment. Calcium acts rapidly after administration—within 1 to 3 minutes—but only lasts 30 to 60 minutes.16 Administration of calcium gluconate can be repeated as often as necessary, but patients must be monitored for adverse effects of calcium such as nausea, abdominal pain, polydipsia, polyuria, muscle weakness, and paresthesia. Care must be taken when patients are taking digoxin, because calcium may potentiate toxicity.17 Although calcium provides immediate benefits it does little to correct the underlying cause; other medications are required to remove potassium from the body.

Two medication classes have been proven to shift potassium intracellularly. The first are β-2 agonists, such as albuterol/levalbuterol, and the second is insulin. Both work through sodium-potassium-ATPase in a direct manner. β-2 agonists stimulate sodium-potassium-ATPase to move more potassium intracellularly, but these effects have been seen only with high doses of albuterol, typically 4× the standard dose of 0.5 mg in nebulized solutions to achieve decreases in potassium of 0.3 to 0.6 mEq/L, although some trials have reported decreases of 0.62 to 0.98 mEq/L.15,18 These potassium-lowering effects of β-2 agonist are modest, but can be seen 20 to 30 minutes after administration and persist up to 1 to 2 hours. β-2 agonists are also readily affected by β blockers, which may reduce or negate the desired effect in hyperkalemia. For these reasons, a β-2 agonist should not be given as monotherapy and should be provided as an adjuvant to more independent therapies such as insulin. Insulin binds to receptors on muscle cells and increases the quantity of sodium-potassium-ATPase and glucose transporters. With this increase in influx pumps, surrounding tissues with higher resting membrane potentials can absorb the potassium load, thereby protecting cardiomyocytes.

Potassium Removal

Three methods are currently available to remove potassium from the body: GI excretion, renal excretion, and direct removal from the bloodstream. Under normal physiologic conditions, the kidneys account for about 90% of the body’s ability to remove potassium. Loop diuretics facilitate the removal of potassium by increasing urine production and have an additional potassium-wasting effect. Although the onset of action of loop diuretics is typically 30 to 60 minutes after oral administration, their effect can last for several hours. In this patient, furosemide was introduced later in the treatment plan to manage recurring hyperkalemia by enhancing renal potassium excretion.

Potassium binders such as patiromer act in the GI tract, effectively reducing serum potassium levels although with a slower onset of action than furosemide, generally taking hours to days to exert its effect. Both medications illustrate a tailored approach to managing potassium levels, adapted to the evolving needs and renal function of the patient. The last method is using hemodialysis—by far the most rapid method to remove potassium, but also the most invasive. The different methods of treating hyperkalemia are summarized in Table 2. This patient required multiple days of hemodialysis to completely correct the electrolyte disorder. Upon discharge, the patient continued oral furosemide 40 mg daily and eventually discontinued hemodialysis due to stable renal function.

Often, after correcting an inciting event, potassium stores in the body eventually stabilize and do not require additional follow-up. Patients prone to hyperkalemia should be thoroughly educated on medications to avoid (NSAIDs, ACEIs/ARBs, trimethoprim), an adequate low potassium diet, and symptoms that may warrant medical attention.19

Conclusions

This case illustrates the importance of recognizing the spectrum of manifestations of hyperkalemia, which ranged from muscle weakness to cardiac dysrhythmias. Management strategies for the patient included stabilization of cardiac membranes, potassium shifting, and potassium removal, each tailored to the patient’s individual clinical findings.

The case further illustrates the critical role of continuous monitoring and dynamic adjustment of therapeutic strategies in response to evolving clinical and laboratory findings. The initial and subsequent ECGs, alongside laboratory tests, were instrumental in guiding the adjustments needed in the treatment regimen, ensuring both the efficacy and safety of the interventions. This proactive approach can mitigate the risk of recurrent hyperkalemia and its complications.

- Youn JH, McDonough AA. Recent advances in understanding integrative control of potassium homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:381-401. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163241 2.

- Simon LV, Hashmi MF, Farrell MW. Hyperkalemia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; September 4, 2023. Accessed October 22, 2025.

- Mu F, Betts KA, Woolley JM, et al. Prevalence and economic burden of hyperkalemia in the United States Medicare population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36:1333-1341. doi:10.1080/03007995.2020.1775072

- Loutradis C, Tolika P, Skodra A, et al. Prevalence of hyperkalemia in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a nested case-control study. Am J Nephrol. 2015;42:351-360. doi:10.1159/000442393

- Grodzinsky A, Goyal A, Gosch K, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of hyperkalemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2016;129:858-865. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.03.008

- Hunter RW, Bailey MA. Hyperkalemia: pathophysiology, risk factors and consequences. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(suppl 3):iii2-iii11. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfz206

- Luo J, Brunelli SM, Jensen DE, Yang A. Association between serum potassium and outcomes in patients with reduced kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:90-100. doi:10.2215/CJN.01730215

- Montford JR, Linas S. How dangerous is hyperkalemia? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3155-3165. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016121344

- Mattu A, Brady WJ, Robinson DA. Electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperkalemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:721-729. doi:10.1053/ajem.2000.7344

- Kimmons LA, Usery JB. Acute ascending muscle weakness secondary to medication-induced hyperkalemia. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:789529. doi:10.1155/2014/789529

- Naik KR, Saroja AO, Khanpet MS. Reversible electrophysiological abnormalities in acute secondary hyperkalemic paralysis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:339-343. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.104354

- Montague BT, Ouellette JR, Buller GK. Retrospective review of the frequency of ECG changes in hyperkalemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:324-330. doi:10.2215/CJN.04611007

- Larivée NL, Michaud JB, More KM, Wilson JA, Tennankore KK. Hyperkalemia: prevalence, predictors and emerging treatments. Cardiol Ther. 2023;12:35-63. doi:10.1007/s40119-022-00289-z

- Shingarev R, Allon M. A physiologic-based approach to the treatment of acute hyperkalemia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:578-584. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.014

- Parham WA, Mehdirad AA, Biermann KM, Fredman CS. Hyperkalemia revisited. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33:40-47.

- Ng KE, Lee CS. Updated treatment options in the management of hyperkalemia. U.S. Pharmacist. February 16, 2017. Accessed October 1, 2025. www.uspharmacist.com/article/updated-treatment-options-in-the-management-of-hyperkalemia

- Quick G, Bastani B. Prolonged asystolic hyperkalemic cardiac arrest with no neurologic sequelae. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:305-311. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70144-x 18.

- Allon M, Dunlay R, Copkney C. Nebulized albuterol for acute hyperkalemia in patients on hemodialysis. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:426-429. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-110-6-42619.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024;105(4 suppl):S117-S314. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018

Hyperkalemia involves elevated serum potassium levels (> 5.0 mEq/L) and represents an important electrolyte disturbance due to its potentially severe consequences, including cardiac effects that can lead to dysrhythmia and even asystole and death.1,2 In a US Medicare population, the prevalence of hyperkalemia has been estimated at 2.7% and is associated with substantial health care costs.3 The prevalence is even more marked in patients with preexisting conditions such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) and heart failure.4,5

Hyperkalemia can result from multiple factors, including impaired renal function, adrenal disease, adverse drug reactions of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and other medications, and heritable mutations.6 Hyperkalemia poses a considerable clinical risk, associated with adverse outcomes such as myocardial infarction and increased mortality in patients with CKD.5,7,8 Electrocardiographic (ECG) changes associated with hyperkalemia play a vital role in guiding clinical decisions and treatment strategies.9 Understanding the pathophysiology, risk factors, and consequences of hyperkalemia, as well as the significance of ECG changes in its management, is essential for health care practitioners.

Case Presentation

An 81-year-old Hispanic man with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, gout, and CKD stage 3B presented to the emergency department with progressive weakness resulting in falls and culminating in an inability to ambulate independently. Additional symptoms included nausea, diarrhea, and myalgia. His vital signs were notable for a pulse of 41 beats/min. The physical examination was remarkable for significant weakness of the bilateral upper extremities, inability to bear his own weight, and bilateral lower extremity edema. His initial ECG upon arrival showed bradycardia with wide QRS, absent P waves, and peaked T waves (Figure 1a). These findings differed from his baseline ECG taken 1 year earlier, which showed sinus rhythm with premature atrial complexes and an old right bundle branch block (Figure 1b).

Medication review revealed that the patient was currently prescribed 100 mg allopurinol daily, 2.5 mg amlodipine daily, 10 mg atorvastatin at bedtime, 4 mg doxazosin daily, 112 mcg levothyroxine daily, 100 mg losartan daily, 25 mg metoprolol daily, and 0.4 mg tamsulosin daily. The patient had also been taking over-the-counter indomethacin for knee pain.

Based on the ECG results, he was treated with 0.083%/6 mL nebulized albuterol, 4.65 Mq/250 mL saline solution intravenous (IV) calcium gluconate, 10 units IV insulin with concomitant 50%/25 mL IV dextrose and 8.4 g of oral patiromer suspension. IV furosemide was held due to concern for renal function. The decision to proceed with hemodialysis was made. Repeat laboratory tests were performed, and an ECG obtained after treatment initiation but prior to hemodialysis demonstrated improvement of rate and T wave shortening (Figure 1c). The serum potassium level dropped from 9.8 mEq/L to 7.9 mEq/L (reference range, 3.5-5.0 mEq/L) (Table 1).