User login

Elusive Edema: A Case of Nephrotic Syndrome Mimicking Decompensated Cirrhosis

Elusive Edema: A Case of Nephrotic Syndrome Mimicking Decompensated Cirrhosis

Histology is the gold standard for cirrhosis diagnosis. However, a combination of clinical history, physical examination findings, and supportive laboratory and radiographic features is generally sufficient to make the diagnosis. Routine ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) imaging often identifies a nodular liver contour with sequelae of portal hypertension, including splenomegaly, varices, and ascites, which can suggest cirrhosis when supported by laboratory parameters and clinical features. As a result, the diagnosis is typically made clinically.1 Many patients with compensated cirrhosis go undetected. The presence of a decompensation event (ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy) often leads to index diagnosis when patients were previously compensated. When a patient presents with suspected decompensated cirrhosis, it is important to consider other diagnoses with similar presentations and ensure that multiple disease processes are not contributing to the symptoms.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 64-year-old male with a history of intravenous (IV) methamphetamine use and prior incarceration presented with a 3-week history of progressively worsening generalized swelling. Prior to the onset of his symptoms, the patient injured his right lower extremity (RLE) in a bicycle accident, resulting in edema that progressed to bilateral lower extremity (BLE) edema and worsening fatigue, despite resolution of the initial injury. The patient gained weight though he could not quantify the amount. He experienced progressive hunger, thirst, and fatigue as well as increased sleep. Additionally, the patient experienced worsening dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea. He started using 2 pillows instead of 1 pillow at night.

The patient reported no fevers, chills, sputum production, chest pain, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He had no known history of sexually transmitted infections, no significant history of alcohol use, and occasional tobacco and marijuana use. He had been incarcerated > 10 years before and last used IV methamphetamine 3 years before. He did not regularly take any medications.

The patient’s vital signs included a temperature of 98.2 °F; 78/min heart rate; 15/min respiratory rate; 159/109 mm Hg blood pressure; and 98% oxygen saturation on room air. He had gained 20 lbs in the past 4 months. He had pitting edema in both legs and arms, as well as periorbital swelling, but no jugular venous distention, abnormal heart sounds, or murmurs. Breath sounds were distant but clear to auscultation. His abdomen was distended with normal bowel sounds and no fluid wave; mild epigastric tenderness was present, but no intra-abdominal masses were palpated. He had spider angiomata on the upper chest but no other stigmata of cirrhosis, such as caput medusae or jaundice. Tattoos were noted.

Laboratory test results showed a platelet count of 178 x 103/μL (reference range, 140- 440 ~ 103μL).Creatinine was 0.80 mg/dL (reference range, < 1.28 mg/dL), with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 99 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology equation (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and Cystatin C was 1.14 mg/L (reference range, < 1.15 mg/L). His electrolytes and complete blood count were within normal limits, including sodium, 134 mmol/L; potassium, 4.4 mmol/L; chloride, 108 mmol/L; and carbon dioxide, 22.5 mmol/L.

Additional test results included alkaline phosphatase, 126 U/L (reference range, < 94 U/L); alanine transaminase, 41 U/L (reference range, < 45 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 70 U/L (reference range, < 35 U/L); total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL (reference range, < 1 mg/dL); albumin, 1.8 g/dL (reference range, 3.2-4.8 g/dL); and total protein, 6.3 g/dL (reference range, 5.9-8.3 g/dL). The patient’s international normalized ratio was 0.96 (reference range, 0.8-1.1), and brain natriuretic peptide was normal at 56 pg/mL. No prior laboratory results were available for comparison.

Urine toxicology was positive for amphetamines. Urinalysis demonstrated large occult blood, with a red blood cell count of 26/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF) and proteinuria (100 mg/dL; reference range, negative), without bacteria, nitrites, or leukocyte esterase. Urine white blood cell count was 10/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF), and fine granular casts and hyaline casts were present.

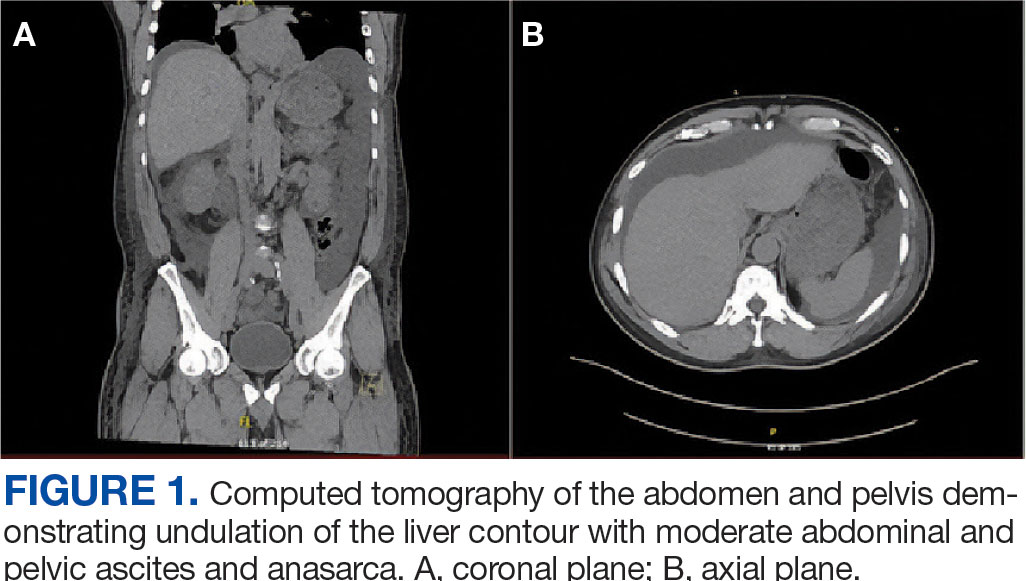

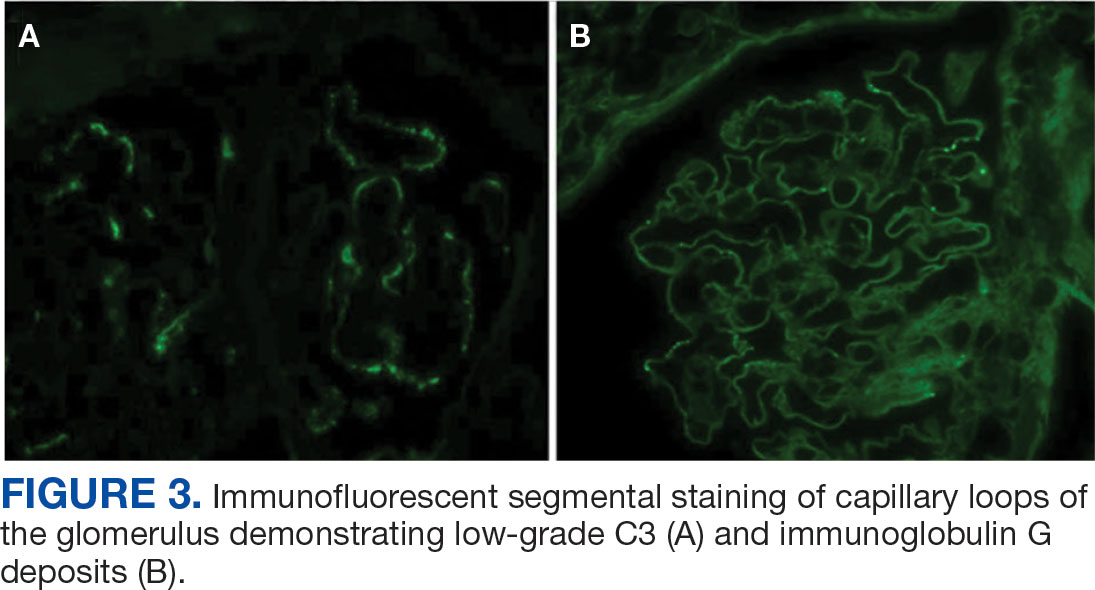

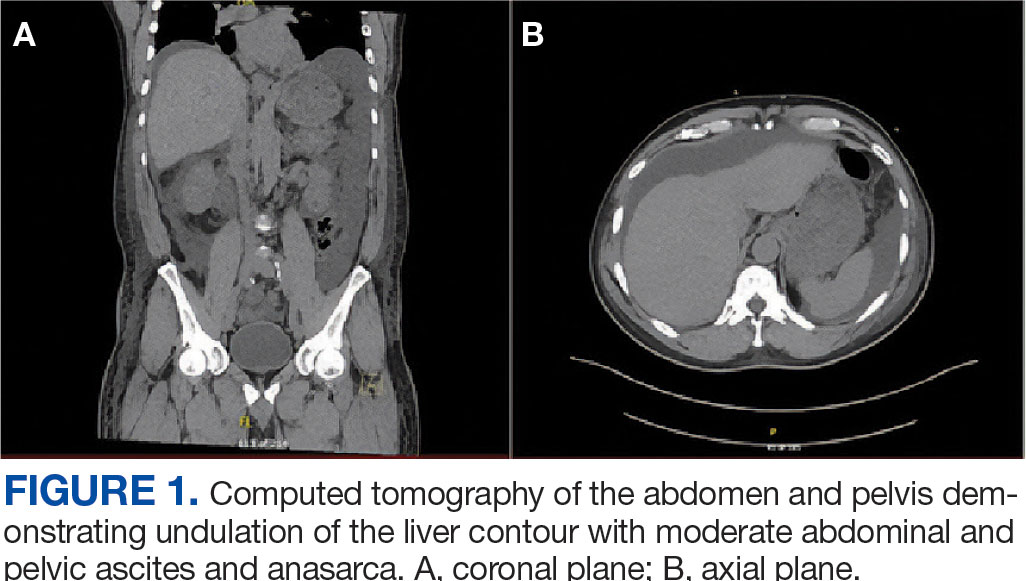

A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis in the emergency department showed an irregular liver contour with diffuse nodularity, multiple portosystemic collaterals, moderate abdominal and pelvic ascites, small bilateral pleural effusions with associated atelectasis, and anasarca consistent with cirrhosis (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the internal medicine service for workup and management of newly diagnosed cirrhosis.

Paracentesis revealed straw-colored fluid with an ascitic fluid neutrophil count of 17/μL, a protein level of < 3 g/dL and albumin level of < 1.5 g/dL. Gram stain of the ascitic fluid showed a moderate white blood cell count with no organisms. Fluid culture showed no microbial growth.

Initial workup for cirrhosis demonstrated a positive total hepatitis A antibody. The patient had a nonreactive hepatitis B surface antigen and surface antibody, but a reactive hepatitis B core antibody; a hepatitis B DNA level was not ordered. He had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 4,490,000 II/mL (genotype 1a). The patient’s iron level was 120 μg/dL, with a calculated total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) of 126.2 μg/dL. His transferrin saturation (TSAT) (serum iron divided by TIBC) was 95%. The patient had nonreactive antinuclear antibody and antimitochondrial antibody tests and a positive antismooth muscle antibody test with a titer of 1:40. His α-fetoprotein (AFP) level was 505 ng/mL (reference range, < 8 ng/mL).

Follow-up MRI of the abdomen and pelvis showed cirrhotic morphology with large volume ascites and portosystemic collaterals, consistent with portal hypertension. Additionally, it showed multiple scattered peripheral sub centimeter hyperenhancing foci, most likely representing benign lesions.

The patient's spot urine protein-creatinine ratio was 3.76. To better quantify proteinuria, a 24-hour urine collection was performed and revealed 12.8 g/d of urine protein (reference range, 0-0.17 g/d). His serum triglyceride level was 175 mg/dL (reference range, 40-60 mg/dL); total cholesterol was 177 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 200 mg/dL); low density lipoprotein cholesterol was 98 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 130 mg/dL); and highdensity lipoprotein cholesterol was 43.8 mg/ dL (reference range, ≥ 40 mg/dL); C3 complement level was 71 mg/dL (reference range, 82-185 mg/dL); and C4 complement level was 22 mg/dL (reference range, 15-53 mg/ dL). His rheumatoid factor was < 14 IU/mL. Tests for rapid plasma reagin and HIV antigen- antibody were nonreactive, and the phospholipase A2 receptor antibody test was negative. The patient tested positive for QuantiFERON-TB Gold and qualitative cryoglobulin, which indicated a cryocrit of 1%.

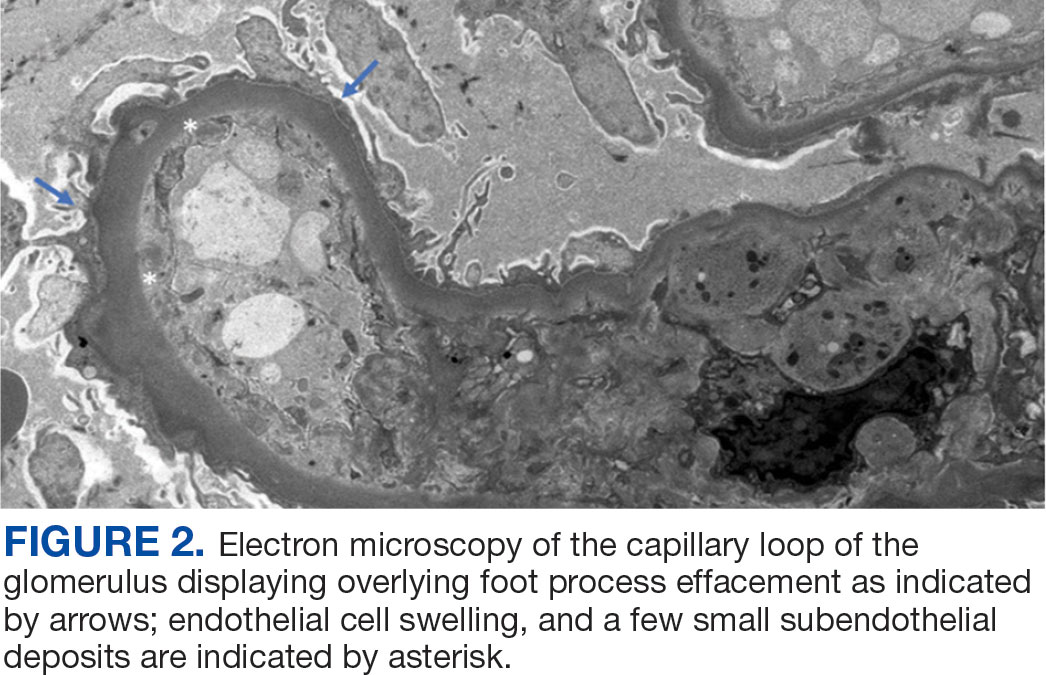

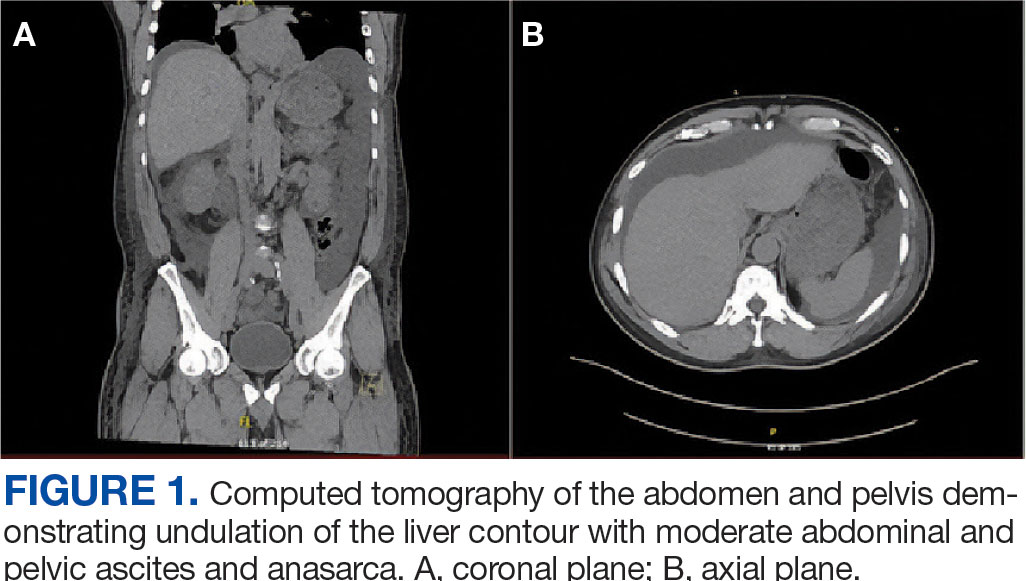

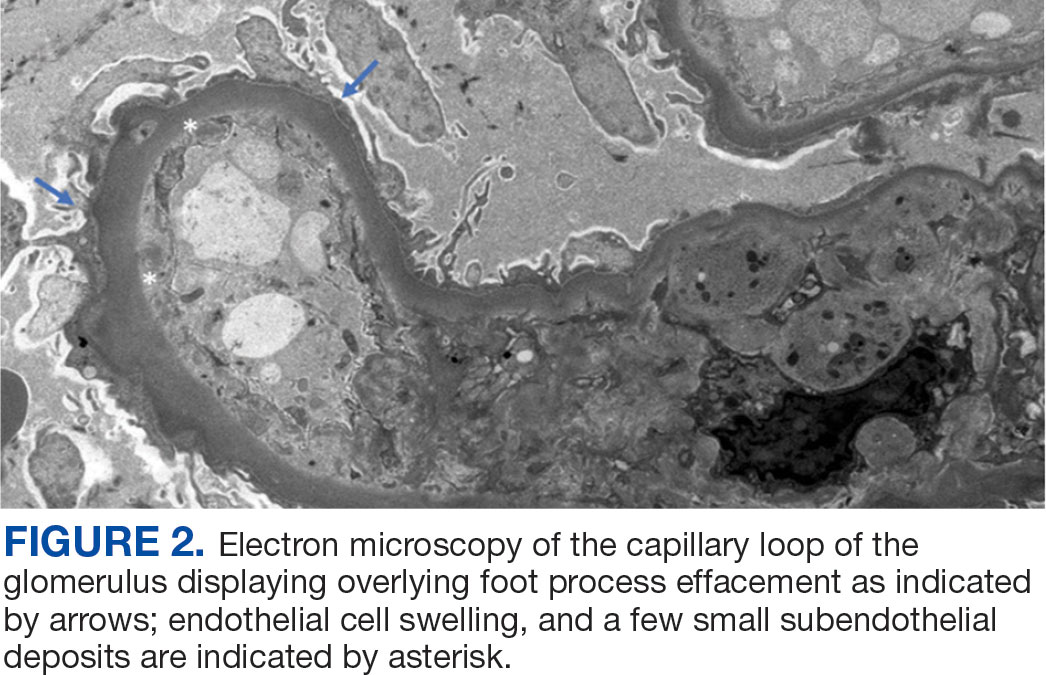

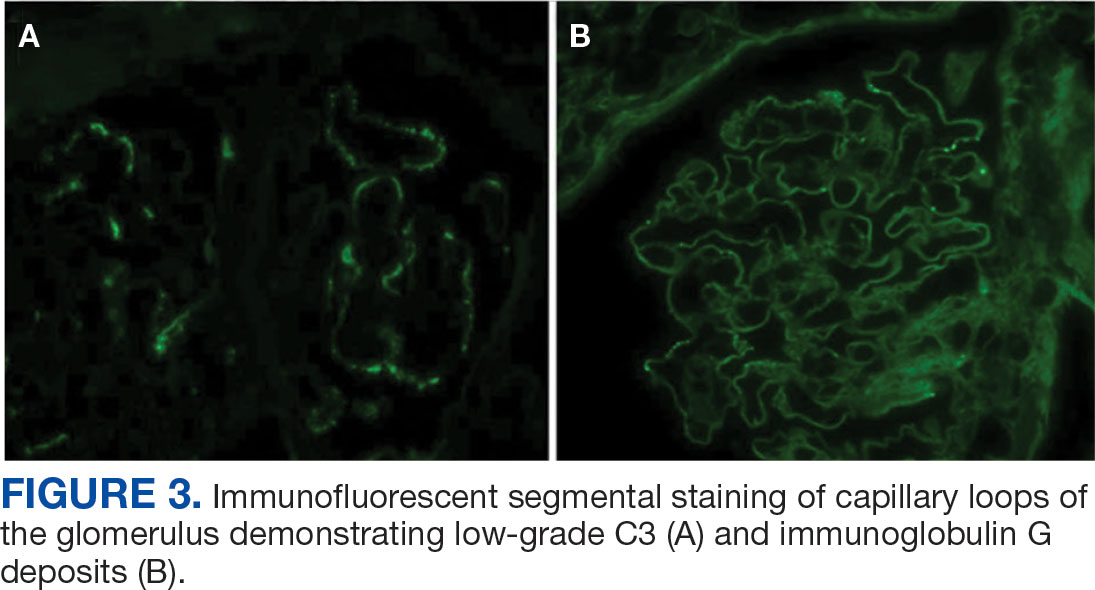

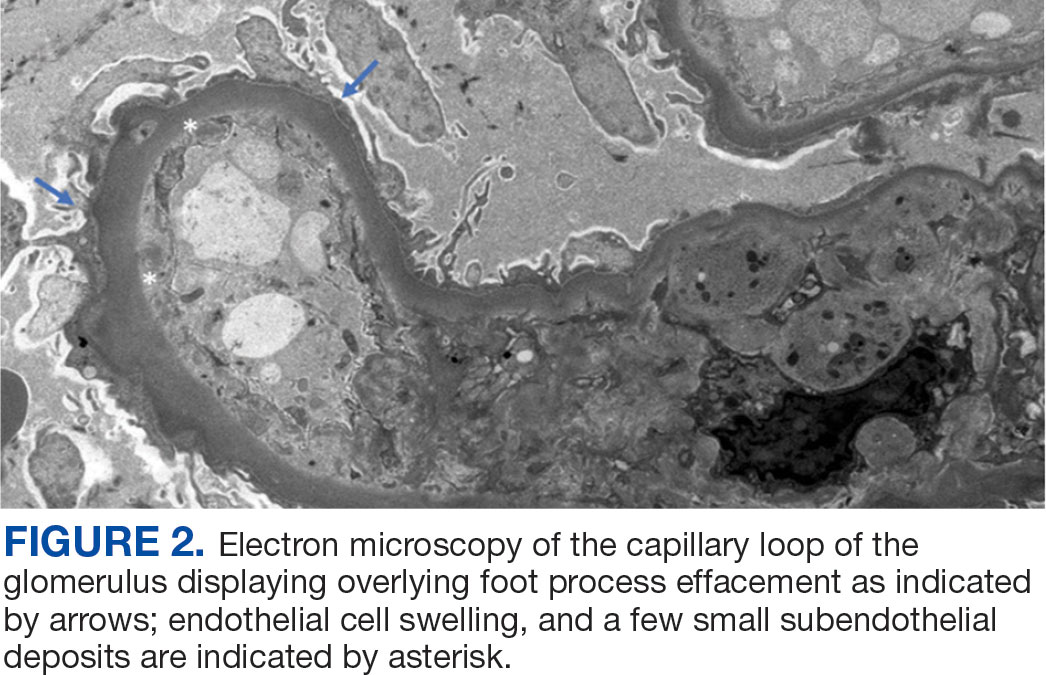

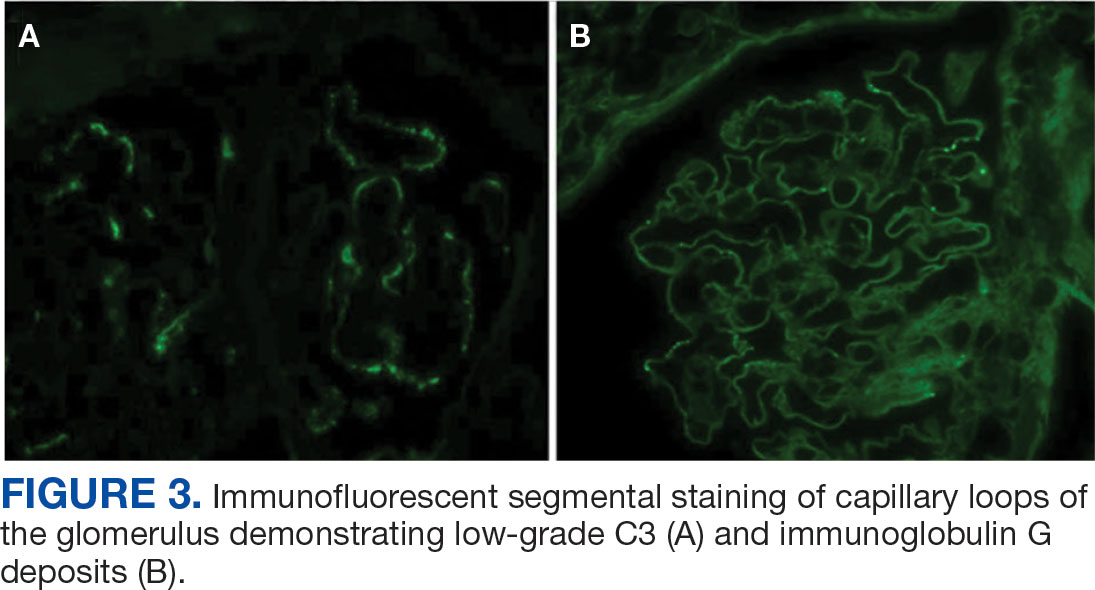

A renal biopsy was performed, revealing diffuse podocyte foot process effacement and glomerulonephritis with low-grade C3 and immunoglobulin (Ig) G deposits, consistent with early membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) (Figures 2 and 3).

The patient was initially diuresed with IV furosemide without significant urine output. He was then diuresed with IV 25% albumin (total, 25 g), followed by IV furosemide 40 mg twice daily, which led to significant urine output and resolution of his anasarca. Given the patient’s hypoalbuminemic state, IV albumin was necessary to deliver furosemide to the proximal tubule. He was started on lisinopril for renal protection and discharged with spironolactone and furosemide for fluid management in the context of cirrhosis.

The patient was evaluated by the Liver Nodule Clinic, which includes specialists from hepatology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, interventional radiology, and diagnostic radiology. The team considered the patient’s medical history and characteristics of the nodules on imaging. Notable aspects of the patient’s history included hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and an elevated AFP level, although imaging showed no lesion concerning for malignancy. Given these findings, the patient was scheduled for a liver biopsy to establish a tissue diagnosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology, nephrology, and infectious disease specialists coordinated to plan the management and treatment of latent tuberculosis (TB), chronic HCV, MPGN, compensated cirrhosis, and suspicious liver lesions.

The patient chose to handle management and treatment as an outpatient. He was discharged with furosemide and spironolactone for anasarca management, and amlodipine and lisinopril for his hypertension and MPGN. Follow-up appointments were scheduled with infectious disease for management of latent TB and HCV, nephrology for MPGN, gastroenterology for cirrhosis, and interventional radiology for liver biopsy. Unfortunately, the patient was unhoused with limited access to transportation, which prevented timely follow-up. Given these social factors, immunosuppression was not started. Additionally, he did not start on HCV therapy because the viral load was still pending at time of discharge.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis was prematurely established, resulting in a diagnostic delay, a form of diagnostic error. However, on hospital day 2, the initial hypothesis of decompensated cirrhosis as the sole driver of the patient’s presentation was reconsidered due to the disconnect between the severity of hypoalbuminemia and diffuse edema (anasarca), and the absence of laboratory evidence of hepatic decompensation (normal international normalized ratio, bilirubin, and low but normal platelet count). Although image findings supported cirrhosis, laboratory markers did not indicate hepatic decompensation. The severity of hypoalbuminemia and anasarca, along with an indeterminate Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient, prompted the patient’s care team to consider other causes, specifically, nephrotic syndrome.

The patien’s spot protein-to-creatinine ratio was 3.76 (reference range < 0.2 mg/mg creatinine), but a 24-hour urine protein collection was 12.8 g/day (reference range < 150 mg/day). While most spot urine protein- to-creatinine ratios (UPCR) correlate with a 24-hour urine collection, discrepancies can occur, as in this case. It is important to recognize that the spot UPCR assumes that patients are excreting 1000 mg of creatinine daily in their urine, which is not always the case. In addition, changes in urine osmolality can lead to different values. The gold standard for proteinuria is a 24-hour urine collection for protein and creatinine.

The patient’s nephrotic-range proteinuria and severe hypoalbuminemia are not solely explained by cirrhosis. In addition, the patient’s lower extremity edema pointed to nephrotic syndrome. The differential diagnosis for nephrotic syndrome includes both primary and secondary forms of membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and MPGN, a histopathological diagnosis that requires distinguishing between immune complex-mediated and complement-mediated forms. Other causes of nephrotic syndrome that do not fit in any of these buckets include amyloidosis, IgA nephropathy, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Despite DM being a common cause of nephrotic range proteinuria, it rarely leads to full nephrotic syndrome.

When considering the diagnosis, we reframed the patient’s clinical syndrome as compensated cirrhosis plus nephrotic syndrome. This approach prioritized identifying a cause that could explain both cirrhosis (from any cause) leading to IgA nephropathy or injection drug use serving as a risk factor for cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome through HCV or AA amyloidosis, respectively. This problem representation guided us to the correct diagnosis. There are multiple renal diseases associated with HCV infection, including MPGN, membranous nephropathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and IgA nephropathy.2 MPGN and mixed cryoglobulinemia are the most common. In the past, MPGN was classified as type I, II, and III.

The patient’s urine toxicology revealed recent amphetamine use, which can also lead to acute kidney injury through rhabdomyolysis or acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).3 In the cases of rhabdomyolysis, urinalysis would show positive heme without any red blood cell on microscopic analysis, which was not present in this case. AIN commonly manifests as acute kidney injury, pyuria, and proteinuria but without a decrease in complement levels.4 While the patient’s urine sediment included white blood cell (10/high-power field), the presence of microscopic hematuria, decreased complement levels, and proteinuria in the context of HCV positivity makes MPGN more likely than AIN.

Recently, there has been greater emphasis on using immunofluorescence for kidney biopsies. MPGN is now classified into 2 main categories: MPGN with mesangial immunoglobulins and C3 deposits in the capillary walls, and MPGN with C3 deposits but without Ig.5 MPGN with Ig-complement deposits is seen in autoimmune diseases and infections and is associated with dysproteinemias.

The renal biopsy in this patient was consistent with MPGN with immunofluorescence, a common finding in patients with infection. By synthesizing these data, we concluded that the patient represented a case of chronic HCV infection that led to MPGN with cryoglobulinemia. The normal C4 and negative RF do not suggest cryoglobulinemic crisis. Compensated cirrhosis was seen on imaging, pending liver biopsy.

Treatment

The management of MPGN secondary to HCV infection relies on the treatment of the underlying infection and clearance of viral load. Direct-acting antivirals have been used successfully in the treatment of HCV-associated MPGN. When cryoglobulinemia is present, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended. These regimens commonly include rituximab and steroids.5 Rituximab is also used for nephrotic syndrome associated with MPGN, as recommended in the 2018 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.6

When initiating rituximab therapy in a patient who tests positive for hepatitis B (HBcAb positive or HBsAb positive), it is recommended to follow the established guidelines, which include treating them with entecavir for prophylaxis to prevent reactivation or a flare of hepatitis B.7 The patient in this case needed close follow-up in the nephrology and hepatology clinic. Immunosuppressive therapy was not pursued while the patient was admitted to the hospital due to instability with housing, transportation, and difficulty in ensuring close follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians should maintain a broad differential even in the face of confirmatory imaging and other objective findings. In the case of anasarca, nephrotic syndrome should be considered. Key causes of nephrotic syndromes include MPGN, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. MPGN is a histopathological diagnosis, and it is essential to identify if it is secondary to immune complexes or only complement mediated because Ig-complement deposits are seen in autoimmune disease and infection. The management of MPGN due to HCV infection relies on antiviral therapy. In the presence of cryoglobulinemia, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended.

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Diagnosis and management of cirrhosis and its complications: a review. JAMA. 2023;329(18):1589–1602. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5997

- Ozkok A, Yildiz A. Hepatitis C virus associated glomerulopathies. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7544-7554. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7544

- Foley RJ, Kapatkin K, Vrani R, Weinman EJ. Amphetamineinduced acute renal failure. South Med J. 1984;77(2):258- 260. doi:10.1097/00007611-198402000-00035

- Rossert J. Drug - induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2001;60(2):804-817. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002804.x

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: pathogenetic heterogeneity and proposal for a new classification. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31(4):341-348. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.06.005

- Jadoul M, Berenguer MC, Doss W, et al. Executive summary of the 2018 KDIGO hepatitis C in CKD guideline: welcoming advances in evaluation and management. Kidney Int. 2018;94(4):663-673. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2018.06.011

- Myint A, Tong MJ, Beaven SW. Reactivation of hepatitis b virus: a review of clinical guidelines. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020;15(4):162-167. doi:10.1002/cld.883

Histology is the gold standard for cirrhosis diagnosis. However, a combination of clinical history, physical examination findings, and supportive laboratory and radiographic features is generally sufficient to make the diagnosis. Routine ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) imaging often identifies a nodular liver contour with sequelae of portal hypertension, including splenomegaly, varices, and ascites, which can suggest cirrhosis when supported by laboratory parameters and clinical features. As a result, the diagnosis is typically made clinically.1 Many patients with compensated cirrhosis go undetected. The presence of a decompensation event (ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy) often leads to index diagnosis when patients were previously compensated. When a patient presents with suspected decompensated cirrhosis, it is important to consider other diagnoses with similar presentations and ensure that multiple disease processes are not contributing to the symptoms.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 64-year-old male with a history of intravenous (IV) methamphetamine use and prior incarceration presented with a 3-week history of progressively worsening generalized swelling. Prior to the onset of his symptoms, the patient injured his right lower extremity (RLE) in a bicycle accident, resulting in edema that progressed to bilateral lower extremity (BLE) edema and worsening fatigue, despite resolution of the initial injury. The patient gained weight though he could not quantify the amount. He experienced progressive hunger, thirst, and fatigue as well as increased sleep. Additionally, the patient experienced worsening dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea. He started using 2 pillows instead of 1 pillow at night.

The patient reported no fevers, chills, sputum production, chest pain, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He had no known history of sexually transmitted infections, no significant history of alcohol use, and occasional tobacco and marijuana use. He had been incarcerated > 10 years before and last used IV methamphetamine 3 years before. He did not regularly take any medications.

The patient’s vital signs included a temperature of 98.2 °F; 78/min heart rate; 15/min respiratory rate; 159/109 mm Hg blood pressure; and 98% oxygen saturation on room air. He had gained 20 lbs in the past 4 months. He had pitting edema in both legs and arms, as well as periorbital swelling, but no jugular venous distention, abnormal heart sounds, or murmurs. Breath sounds were distant but clear to auscultation. His abdomen was distended with normal bowel sounds and no fluid wave; mild epigastric tenderness was present, but no intra-abdominal masses were palpated. He had spider angiomata on the upper chest but no other stigmata of cirrhosis, such as caput medusae or jaundice. Tattoos were noted.

Laboratory test results showed a platelet count of 178 x 103/μL (reference range, 140- 440 ~ 103μL).Creatinine was 0.80 mg/dL (reference range, < 1.28 mg/dL), with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 99 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology equation (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and Cystatin C was 1.14 mg/L (reference range, < 1.15 mg/L). His electrolytes and complete blood count were within normal limits, including sodium, 134 mmol/L; potassium, 4.4 mmol/L; chloride, 108 mmol/L; and carbon dioxide, 22.5 mmol/L.

Additional test results included alkaline phosphatase, 126 U/L (reference range, < 94 U/L); alanine transaminase, 41 U/L (reference range, < 45 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 70 U/L (reference range, < 35 U/L); total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL (reference range, < 1 mg/dL); albumin, 1.8 g/dL (reference range, 3.2-4.8 g/dL); and total protein, 6.3 g/dL (reference range, 5.9-8.3 g/dL). The patient’s international normalized ratio was 0.96 (reference range, 0.8-1.1), and brain natriuretic peptide was normal at 56 pg/mL. No prior laboratory results were available for comparison.

Urine toxicology was positive for amphetamines. Urinalysis demonstrated large occult blood, with a red blood cell count of 26/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF) and proteinuria (100 mg/dL; reference range, negative), without bacteria, nitrites, or leukocyte esterase. Urine white blood cell count was 10/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF), and fine granular casts and hyaline casts were present.

A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis in the emergency department showed an irregular liver contour with diffuse nodularity, multiple portosystemic collaterals, moderate abdominal and pelvic ascites, small bilateral pleural effusions with associated atelectasis, and anasarca consistent with cirrhosis (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the internal medicine service for workup and management of newly diagnosed cirrhosis.

Paracentesis revealed straw-colored fluid with an ascitic fluid neutrophil count of 17/μL, a protein level of < 3 g/dL and albumin level of < 1.5 g/dL. Gram stain of the ascitic fluid showed a moderate white blood cell count with no organisms. Fluid culture showed no microbial growth.

Initial workup for cirrhosis demonstrated a positive total hepatitis A antibody. The patient had a nonreactive hepatitis B surface antigen and surface antibody, but a reactive hepatitis B core antibody; a hepatitis B DNA level was not ordered. He had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 4,490,000 II/mL (genotype 1a). The patient’s iron level was 120 μg/dL, with a calculated total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) of 126.2 μg/dL. His transferrin saturation (TSAT) (serum iron divided by TIBC) was 95%. The patient had nonreactive antinuclear antibody and antimitochondrial antibody tests and a positive antismooth muscle antibody test with a titer of 1:40. His α-fetoprotein (AFP) level was 505 ng/mL (reference range, < 8 ng/mL).

Follow-up MRI of the abdomen and pelvis showed cirrhotic morphology with large volume ascites and portosystemic collaterals, consistent with portal hypertension. Additionally, it showed multiple scattered peripheral sub centimeter hyperenhancing foci, most likely representing benign lesions.

The patient's spot urine protein-creatinine ratio was 3.76. To better quantify proteinuria, a 24-hour urine collection was performed and revealed 12.8 g/d of urine protein (reference range, 0-0.17 g/d). His serum triglyceride level was 175 mg/dL (reference range, 40-60 mg/dL); total cholesterol was 177 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 200 mg/dL); low density lipoprotein cholesterol was 98 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 130 mg/dL); and highdensity lipoprotein cholesterol was 43.8 mg/ dL (reference range, ≥ 40 mg/dL); C3 complement level was 71 mg/dL (reference range, 82-185 mg/dL); and C4 complement level was 22 mg/dL (reference range, 15-53 mg/ dL). His rheumatoid factor was < 14 IU/mL. Tests for rapid plasma reagin and HIV antigen- antibody were nonreactive, and the phospholipase A2 receptor antibody test was negative. The patient tested positive for QuantiFERON-TB Gold and qualitative cryoglobulin, which indicated a cryocrit of 1%.

A renal biopsy was performed, revealing diffuse podocyte foot process effacement and glomerulonephritis with low-grade C3 and immunoglobulin (Ig) G deposits, consistent with early membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) (Figures 2 and 3).

The patient was initially diuresed with IV furosemide without significant urine output. He was then diuresed with IV 25% albumin (total, 25 g), followed by IV furosemide 40 mg twice daily, which led to significant urine output and resolution of his anasarca. Given the patient’s hypoalbuminemic state, IV albumin was necessary to deliver furosemide to the proximal tubule. He was started on lisinopril for renal protection and discharged with spironolactone and furosemide for fluid management in the context of cirrhosis.

The patient was evaluated by the Liver Nodule Clinic, which includes specialists from hepatology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, interventional radiology, and diagnostic radiology. The team considered the patient’s medical history and characteristics of the nodules on imaging. Notable aspects of the patient’s history included hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and an elevated AFP level, although imaging showed no lesion concerning for malignancy. Given these findings, the patient was scheduled for a liver biopsy to establish a tissue diagnosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology, nephrology, and infectious disease specialists coordinated to plan the management and treatment of latent tuberculosis (TB), chronic HCV, MPGN, compensated cirrhosis, and suspicious liver lesions.

The patient chose to handle management and treatment as an outpatient. He was discharged with furosemide and spironolactone for anasarca management, and amlodipine and lisinopril for his hypertension and MPGN. Follow-up appointments were scheduled with infectious disease for management of latent TB and HCV, nephrology for MPGN, gastroenterology for cirrhosis, and interventional radiology for liver biopsy. Unfortunately, the patient was unhoused with limited access to transportation, which prevented timely follow-up. Given these social factors, immunosuppression was not started. Additionally, he did not start on HCV therapy because the viral load was still pending at time of discharge.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis was prematurely established, resulting in a diagnostic delay, a form of diagnostic error. However, on hospital day 2, the initial hypothesis of decompensated cirrhosis as the sole driver of the patient’s presentation was reconsidered due to the disconnect between the severity of hypoalbuminemia and diffuse edema (anasarca), and the absence of laboratory evidence of hepatic decompensation (normal international normalized ratio, bilirubin, and low but normal platelet count). Although image findings supported cirrhosis, laboratory markers did not indicate hepatic decompensation. The severity of hypoalbuminemia and anasarca, along with an indeterminate Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient, prompted the patient’s care team to consider other causes, specifically, nephrotic syndrome.

The patien’s spot protein-to-creatinine ratio was 3.76 (reference range < 0.2 mg/mg creatinine), but a 24-hour urine protein collection was 12.8 g/day (reference range < 150 mg/day). While most spot urine protein- to-creatinine ratios (UPCR) correlate with a 24-hour urine collection, discrepancies can occur, as in this case. It is important to recognize that the spot UPCR assumes that patients are excreting 1000 mg of creatinine daily in their urine, which is not always the case. In addition, changes in urine osmolality can lead to different values. The gold standard for proteinuria is a 24-hour urine collection for protein and creatinine.

The patient’s nephrotic-range proteinuria and severe hypoalbuminemia are not solely explained by cirrhosis. In addition, the patient’s lower extremity edema pointed to nephrotic syndrome. The differential diagnosis for nephrotic syndrome includes both primary and secondary forms of membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and MPGN, a histopathological diagnosis that requires distinguishing between immune complex-mediated and complement-mediated forms. Other causes of nephrotic syndrome that do not fit in any of these buckets include amyloidosis, IgA nephropathy, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Despite DM being a common cause of nephrotic range proteinuria, it rarely leads to full nephrotic syndrome.

When considering the diagnosis, we reframed the patient’s clinical syndrome as compensated cirrhosis plus nephrotic syndrome. This approach prioritized identifying a cause that could explain both cirrhosis (from any cause) leading to IgA nephropathy or injection drug use serving as a risk factor for cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome through HCV or AA amyloidosis, respectively. This problem representation guided us to the correct diagnosis. There are multiple renal diseases associated with HCV infection, including MPGN, membranous nephropathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and IgA nephropathy.2 MPGN and mixed cryoglobulinemia are the most common. In the past, MPGN was classified as type I, II, and III.

The patient’s urine toxicology revealed recent amphetamine use, which can also lead to acute kidney injury through rhabdomyolysis or acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).3 In the cases of rhabdomyolysis, urinalysis would show positive heme without any red blood cell on microscopic analysis, which was not present in this case. AIN commonly manifests as acute kidney injury, pyuria, and proteinuria but without a decrease in complement levels.4 While the patient’s urine sediment included white blood cell (10/high-power field), the presence of microscopic hematuria, decreased complement levels, and proteinuria in the context of HCV positivity makes MPGN more likely than AIN.

Recently, there has been greater emphasis on using immunofluorescence for kidney biopsies. MPGN is now classified into 2 main categories: MPGN with mesangial immunoglobulins and C3 deposits in the capillary walls, and MPGN with C3 deposits but without Ig.5 MPGN with Ig-complement deposits is seen in autoimmune diseases and infections and is associated with dysproteinemias.

The renal biopsy in this patient was consistent with MPGN with immunofluorescence, a common finding in patients with infection. By synthesizing these data, we concluded that the patient represented a case of chronic HCV infection that led to MPGN with cryoglobulinemia. The normal C4 and negative RF do not suggest cryoglobulinemic crisis. Compensated cirrhosis was seen on imaging, pending liver biopsy.

Treatment

The management of MPGN secondary to HCV infection relies on the treatment of the underlying infection and clearance of viral load. Direct-acting antivirals have been used successfully in the treatment of HCV-associated MPGN. When cryoglobulinemia is present, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended. These regimens commonly include rituximab and steroids.5 Rituximab is also used for nephrotic syndrome associated with MPGN, as recommended in the 2018 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.6

When initiating rituximab therapy in a patient who tests positive for hepatitis B (HBcAb positive or HBsAb positive), it is recommended to follow the established guidelines, which include treating them with entecavir for prophylaxis to prevent reactivation or a flare of hepatitis B.7 The patient in this case needed close follow-up in the nephrology and hepatology clinic. Immunosuppressive therapy was not pursued while the patient was admitted to the hospital due to instability with housing, transportation, and difficulty in ensuring close follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians should maintain a broad differential even in the face of confirmatory imaging and other objective findings. In the case of anasarca, nephrotic syndrome should be considered. Key causes of nephrotic syndromes include MPGN, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. MPGN is a histopathological diagnosis, and it is essential to identify if it is secondary to immune complexes or only complement mediated because Ig-complement deposits are seen in autoimmune disease and infection. The management of MPGN due to HCV infection relies on antiviral therapy. In the presence of cryoglobulinemia, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended.

Histology is the gold standard for cirrhosis diagnosis. However, a combination of clinical history, physical examination findings, and supportive laboratory and radiographic features is generally sufficient to make the diagnosis. Routine ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) imaging often identifies a nodular liver contour with sequelae of portal hypertension, including splenomegaly, varices, and ascites, which can suggest cirrhosis when supported by laboratory parameters and clinical features. As a result, the diagnosis is typically made clinically.1 Many patients with compensated cirrhosis go undetected. The presence of a decompensation event (ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy) often leads to index diagnosis when patients were previously compensated. When a patient presents with suspected decompensated cirrhosis, it is important to consider other diagnoses with similar presentations and ensure that multiple disease processes are not contributing to the symptoms.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 64-year-old male with a history of intravenous (IV) methamphetamine use and prior incarceration presented with a 3-week history of progressively worsening generalized swelling. Prior to the onset of his symptoms, the patient injured his right lower extremity (RLE) in a bicycle accident, resulting in edema that progressed to bilateral lower extremity (BLE) edema and worsening fatigue, despite resolution of the initial injury. The patient gained weight though he could not quantify the amount. He experienced progressive hunger, thirst, and fatigue as well as increased sleep. Additionally, the patient experienced worsening dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea. He started using 2 pillows instead of 1 pillow at night.

The patient reported no fevers, chills, sputum production, chest pain, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He had no known history of sexually transmitted infections, no significant history of alcohol use, and occasional tobacco and marijuana use. He had been incarcerated > 10 years before and last used IV methamphetamine 3 years before. He did not regularly take any medications.

The patient’s vital signs included a temperature of 98.2 °F; 78/min heart rate; 15/min respiratory rate; 159/109 mm Hg blood pressure; and 98% oxygen saturation on room air. He had gained 20 lbs in the past 4 months. He had pitting edema in both legs and arms, as well as periorbital swelling, but no jugular venous distention, abnormal heart sounds, or murmurs. Breath sounds were distant but clear to auscultation. His abdomen was distended with normal bowel sounds and no fluid wave; mild epigastric tenderness was present, but no intra-abdominal masses were palpated. He had spider angiomata on the upper chest but no other stigmata of cirrhosis, such as caput medusae or jaundice. Tattoos were noted.

Laboratory test results showed a platelet count of 178 x 103/μL (reference range, 140- 440 ~ 103μL).Creatinine was 0.80 mg/dL (reference range, < 1.28 mg/dL), with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 99 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology equation (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and Cystatin C was 1.14 mg/L (reference range, < 1.15 mg/L). His electrolytes and complete blood count were within normal limits, including sodium, 134 mmol/L; potassium, 4.4 mmol/L; chloride, 108 mmol/L; and carbon dioxide, 22.5 mmol/L.

Additional test results included alkaline phosphatase, 126 U/L (reference range, < 94 U/L); alanine transaminase, 41 U/L (reference range, < 45 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 70 U/L (reference range, < 35 U/L); total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL (reference range, < 1 mg/dL); albumin, 1.8 g/dL (reference range, 3.2-4.8 g/dL); and total protein, 6.3 g/dL (reference range, 5.9-8.3 g/dL). The patient’s international normalized ratio was 0.96 (reference range, 0.8-1.1), and brain natriuretic peptide was normal at 56 pg/mL. No prior laboratory results were available for comparison.

Urine toxicology was positive for amphetamines. Urinalysis demonstrated large occult blood, with a red blood cell count of 26/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF) and proteinuria (100 mg/dL; reference range, negative), without bacteria, nitrites, or leukocyte esterase. Urine white blood cell count was 10/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF), and fine granular casts and hyaline casts were present.

A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis in the emergency department showed an irregular liver contour with diffuse nodularity, multiple portosystemic collaterals, moderate abdominal and pelvic ascites, small bilateral pleural effusions with associated atelectasis, and anasarca consistent with cirrhosis (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the internal medicine service for workup and management of newly diagnosed cirrhosis.

Paracentesis revealed straw-colored fluid with an ascitic fluid neutrophil count of 17/μL, a protein level of < 3 g/dL and albumin level of < 1.5 g/dL. Gram stain of the ascitic fluid showed a moderate white blood cell count with no organisms. Fluid culture showed no microbial growth.

Initial workup for cirrhosis demonstrated a positive total hepatitis A antibody. The patient had a nonreactive hepatitis B surface antigen and surface antibody, but a reactive hepatitis B core antibody; a hepatitis B DNA level was not ordered. He had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 4,490,000 II/mL (genotype 1a). The patient’s iron level was 120 μg/dL, with a calculated total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) of 126.2 μg/dL. His transferrin saturation (TSAT) (serum iron divided by TIBC) was 95%. The patient had nonreactive antinuclear antibody and antimitochondrial antibody tests and a positive antismooth muscle antibody test with a titer of 1:40. His α-fetoprotein (AFP) level was 505 ng/mL (reference range, < 8 ng/mL).

Follow-up MRI of the abdomen and pelvis showed cirrhotic morphology with large volume ascites and portosystemic collaterals, consistent with portal hypertension. Additionally, it showed multiple scattered peripheral sub centimeter hyperenhancing foci, most likely representing benign lesions.

The patient's spot urine protein-creatinine ratio was 3.76. To better quantify proteinuria, a 24-hour urine collection was performed and revealed 12.8 g/d of urine protein (reference range, 0-0.17 g/d). His serum triglyceride level was 175 mg/dL (reference range, 40-60 mg/dL); total cholesterol was 177 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 200 mg/dL); low density lipoprotein cholesterol was 98 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 130 mg/dL); and highdensity lipoprotein cholesterol was 43.8 mg/ dL (reference range, ≥ 40 mg/dL); C3 complement level was 71 mg/dL (reference range, 82-185 mg/dL); and C4 complement level was 22 mg/dL (reference range, 15-53 mg/ dL). His rheumatoid factor was < 14 IU/mL. Tests for rapid plasma reagin and HIV antigen- antibody were nonreactive, and the phospholipase A2 receptor antibody test was negative. The patient tested positive for QuantiFERON-TB Gold and qualitative cryoglobulin, which indicated a cryocrit of 1%.

A renal biopsy was performed, revealing diffuse podocyte foot process effacement and glomerulonephritis with low-grade C3 and immunoglobulin (Ig) G deposits, consistent with early membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) (Figures 2 and 3).

The patient was initially diuresed with IV furosemide without significant urine output. He was then diuresed with IV 25% albumin (total, 25 g), followed by IV furosemide 40 mg twice daily, which led to significant urine output and resolution of his anasarca. Given the patient’s hypoalbuminemic state, IV albumin was necessary to deliver furosemide to the proximal tubule. He was started on lisinopril for renal protection and discharged with spironolactone and furosemide for fluid management in the context of cirrhosis.

The patient was evaluated by the Liver Nodule Clinic, which includes specialists from hepatology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, interventional radiology, and diagnostic radiology. The team considered the patient’s medical history and characteristics of the nodules on imaging. Notable aspects of the patient’s history included hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and an elevated AFP level, although imaging showed no lesion concerning for malignancy. Given these findings, the patient was scheduled for a liver biopsy to establish a tissue diagnosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology, nephrology, and infectious disease specialists coordinated to plan the management and treatment of latent tuberculosis (TB), chronic HCV, MPGN, compensated cirrhosis, and suspicious liver lesions.

The patient chose to handle management and treatment as an outpatient. He was discharged with furosemide and spironolactone for anasarca management, and amlodipine and lisinopril for his hypertension and MPGN. Follow-up appointments were scheduled with infectious disease for management of latent TB and HCV, nephrology for MPGN, gastroenterology for cirrhosis, and interventional radiology for liver biopsy. Unfortunately, the patient was unhoused with limited access to transportation, which prevented timely follow-up. Given these social factors, immunosuppression was not started. Additionally, he did not start on HCV therapy because the viral load was still pending at time of discharge.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis was prematurely established, resulting in a diagnostic delay, a form of diagnostic error. However, on hospital day 2, the initial hypothesis of decompensated cirrhosis as the sole driver of the patient’s presentation was reconsidered due to the disconnect between the severity of hypoalbuminemia and diffuse edema (anasarca), and the absence of laboratory evidence of hepatic decompensation (normal international normalized ratio, bilirubin, and low but normal platelet count). Although image findings supported cirrhosis, laboratory markers did not indicate hepatic decompensation. The severity of hypoalbuminemia and anasarca, along with an indeterminate Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient, prompted the patient’s care team to consider other causes, specifically, nephrotic syndrome.

The patien’s spot protein-to-creatinine ratio was 3.76 (reference range < 0.2 mg/mg creatinine), but a 24-hour urine protein collection was 12.8 g/day (reference range < 150 mg/day). While most spot urine protein- to-creatinine ratios (UPCR) correlate with a 24-hour urine collection, discrepancies can occur, as in this case. It is important to recognize that the spot UPCR assumes that patients are excreting 1000 mg of creatinine daily in their urine, which is not always the case. In addition, changes in urine osmolality can lead to different values. The gold standard for proteinuria is a 24-hour urine collection for protein and creatinine.

The patient’s nephrotic-range proteinuria and severe hypoalbuminemia are not solely explained by cirrhosis. In addition, the patient’s lower extremity edema pointed to nephrotic syndrome. The differential diagnosis for nephrotic syndrome includes both primary and secondary forms of membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and MPGN, a histopathological diagnosis that requires distinguishing between immune complex-mediated and complement-mediated forms. Other causes of nephrotic syndrome that do not fit in any of these buckets include amyloidosis, IgA nephropathy, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Despite DM being a common cause of nephrotic range proteinuria, it rarely leads to full nephrotic syndrome.

When considering the diagnosis, we reframed the patient’s clinical syndrome as compensated cirrhosis plus nephrotic syndrome. This approach prioritized identifying a cause that could explain both cirrhosis (from any cause) leading to IgA nephropathy or injection drug use serving as a risk factor for cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome through HCV or AA amyloidosis, respectively. This problem representation guided us to the correct diagnosis. There are multiple renal diseases associated with HCV infection, including MPGN, membranous nephropathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and IgA nephropathy.2 MPGN and mixed cryoglobulinemia are the most common. In the past, MPGN was classified as type I, II, and III.

The patient’s urine toxicology revealed recent amphetamine use, which can also lead to acute kidney injury through rhabdomyolysis or acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).3 In the cases of rhabdomyolysis, urinalysis would show positive heme without any red blood cell on microscopic analysis, which was not present in this case. AIN commonly manifests as acute kidney injury, pyuria, and proteinuria but without a decrease in complement levels.4 While the patient’s urine sediment included white blood cell (10/high-power field), the presence of microscopic hematuria, decreased complement levels, and proteinuria in the context of HCV positivity makes MPGN more likely than AIN.

Recently, there has been greater emphasis on using immunofluorescence for kidney biopsies. MPGN is now classified into 2 main categories: MPGN with mesangial immunoglobulins and C3 deposits in the capillary walls, and MPGN with C3 deposits but without Ig.5 MPGN with Ig-complement deposits is seen in autoimmune diseases and infections and is associated with dysproteinemias.

The renal biopsy in this patient was consistent with MPGN with immunofluorescence, a common finding in patients with infection. By synthesizing these data, we concluded that the patient represented a case of chronic HCV infection that led to MPGN with cryoglobulinemia. The normal C4 and negative RF do not suggest cryoglobulinemic crisis. Compensated cirrhosis was seen on imaging, pending liver biopsy.

Treatment

The management of MPGN secondary to HCV infection relies on the treatment of the underlying infection and clearance of viral load. Direct-acting antivirals have been used successfully in the treatment of HCV-associated MPGN. When cryoglobulinemia is present, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended. These regimens commonly include rituximab and steroids.5 Rituximab is also used for nephrotic syndrome associated with MPGN, as recommended in the 2018 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.6

When initiating rituximab therapy in a patient who tests positive for hepatitis B (HBcAb positive or HBsAb positive), it is recommended to follow the established guidelines, which include treating them with entecavir for prophylaxis to prevent reactivation or a flare of hepatitis B.7 The patient in this case needed close follow-up in the nephrology and hepatology clinic. Immunosuppressive therapy was not pursued while the patient was admitted to the hospital due to instability with housing, transportation, and difficulty in ensuring close follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians should maintain a broad differential even in the face of confirmatory imaging and other objective findings. In the case of anasarca, nephrotic syndrome should be considered. Key causes of nephrotic syndromes include MPGN, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. MPGN is a histopathological diagnosis, and it is essential to identify if it is secondary to immune complexes or only complement mediated because Ig-complement deposits are seen in autoimmune disease and infection. The management of MPGN due to HCV infection relies on antiviral therapy. In the presence of cryoglobulinemia, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended.

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Diagnosis and management of cirrhosis and its complications: a review. JAMA. 2023;329(18):1589–1602. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5997

- Ozkok A, Yildiz A. Hepatitis C virus associated glomerulopathies. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7544-7554. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7544

- Foley RJ, Kapatkin K, Vrani R, Weinman EJ. Amphetamineinduced acute renal failure. South Med J. 1984;77(2):258- 260. doi:10.1097/00007611-198402000-00035

- Rossert J. Drug - induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2001;60(2):804-817. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002804.x

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: pathogenetic heterogeneity and proposal for a new classification. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31(4):341-348. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.06.005

- Jadoul M, Berenguer MC, Doss W, et al. Executive summary of the 2018 KDIGO hepatitis C in CKD guideline: welcoming advances in evaluation and management. Kidney Int. 2018;94(4):663-673. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2018.06.011

- Myint A, Tong MJ, Beaven SW. Reactivation of hepatitis b virus: a review of clinical guidelines. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020;15(4):162-167. doi:10.1002/cld.883

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Diagnosis and management of cirrhosis and its complications: a review. JAMA. 2023;329(18):1589–1602. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5997

- Ozkok A, Yildiz A. Hepatitis C virus associated glomerulopathies. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7544-7554. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7544

- Foley RJ, Kapatkin K, Vrani R, Weinman EJ. Amphetamineinduced acute renal failure. South Med J. 1984;77(2):258- 260. doi:10.1097/00007611-198402000-00035

- Rossert J. Drug - induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2001;60(2):804-817. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002804.x

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: pathogenetic heterogeneity and proposal for a new classification. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31(4):341-348. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.06.005

- Jadoul M, Berenguer MC, Doss W, et al. Executive summary of the 2018 KDIGO hepatitis C in CKD guideline: welcoming advances in evaluation and management. Kidney Int. 2018;94(4):663-673. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2018.06.011

- Myint A, Tong MJ, Beaven SW. Reactivation of hepatitis b virus: a review of clinical guidelines. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020;15(4):162-167. doi:10.1002/cld.883

Elusive Edema: A Case of Nephrotic Syndrome Mimicking Decompensated Cirrhosis

Elusive Edema: A Case of Nephrotic Syndrome Mimicking Decompensated Cirrhosis

A Tough Egg to Crack

A 68-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with altered mental status. On the morning prior to admission, she was fully alert and oriented. Over the course of the day, she became more confused and somnolent, and by the evening, she was unarousable to voice. She had not fallen and had no head trauma.

Altered mental status may arise from metabolic (eg, hyponatremia), infectious (eg, urinary tract infection), structural (eg, subdural hematoma), or toxin-related (eg, adverse medication effect) processes. Any of these categories of encephalopathy can develop gradually over the course of a day.

One year prior, the patient was admitted for a similar episode of altered mental status. Asterixis and elevated transaminases prompted an abdominal ultrasound, which revealed a nodular liver and ascites. Paracentesis revealed a high serum-ascites albumin gradient. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was made based on these findings. Testing for viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, and Wilson’s disease were negative. Although steatosis was not detected on ultrasound, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was suspected based on the patient’s risk factors of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. She had four additional presentations of altered mental status with asterixis; each episode resolved with lactulose.

Other medical history included end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. Her medications were labetalol, amlodipine, insulin, propranolol, lactulose, and rifaximin. She was originally from China and moved to the United States 10 years earlier. Given concerns about her ability to consistently take medications, she had moved to a long-term facility. She did not use alcohol, tobacco, or illicit substances.

The normalization of the patient’s mental status after lactulose treatment, especially in the context of recurrent episodes, is characteristic of hepatic encephalopathy, in which ammonia and other substances bypass hepatic metabolism and impair cerebral function. Hepatic encephalopathy is the most common cause of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy, and may recur in the setting of infection or nonadherence with lactulose and rifaximin. Other causes of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy include hyperammonemia caused by urease-producing bacterial infection (eg, Proteus), valproic acid toxicity, and urea cycle abnormalities.

Other causes of confusion with a self-limited course should be considered for the current episode. A postictal state is possible, but convulsions were not reported. The patient is at risk of hypoglycemia from insulin use and impaired gluconeogenesis due to cirrhosis and ESRD, but low blood sugar would have likely been detected at the time of hospitalization. Finally, she might have experienced episodic encephalopathy from ingestion of unreported medications or toxins, whose effects may have resolved with abstinence during hospitalization.

The patient’s temperature was 37.8°C, pulse 73 beats/minute, blood pressure 133/69 mmHg, respiratory rate 12 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on ambient air. Her body mass index (BMI) was 19 kg/m2. She was somnolent but was moving all four extremities spontaneously. Her pupils were symmetric and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. Biceps and patellar reflexes were 2+ bilaterally. Babinski sign was absent bilaterally. The patient could not cooperate with the assessment for asterixis. Her sclerae were anicteric. The jugular venous pressure was estimated at 13 cm of water. Her heart was regular with no murmurs. Her lungs were clear. She had a distended, nontender abdomen with caput medusae. She had symmetric pitting edema in her lower extremities up to the shins.

The elevated jugular venous pressure, lower extremity edema, and distended abdomen suggest volume overload. Jugular venous distention with clear lungs is characteristic of right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular myocardial infarction, tricuspid regurgitation, or constrictive pericarditis. However, chronic biventricular heart failure often presents in this manner and is more common than the aforementioned conditions. ESRD and cirrhosis may be contributing to the hypervolemia.

Although Asian patients may exhibit metabolic syndrome and NAFLD at a lower BMI than non-Asians, her BMI is uncharacteristically low for NAFLD, especially given the increased weight expected from volume overload. There are no signs of infection to account for worsening of hepatic encephalopathy.

Laboratory tests demonstrated a white blood cell count of 4400/µL with a normal differential, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count of 108,000 per cubic millimeter. Mean corpuscular volume was 103 fL. Basic metabolic panel was normal with the exception of blood urea nitrogen of 46 mg/dL and a creatinine of 6.4 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase was 34 units/L, alanine aminotransferase 34 units/L, alkaline phosphatase 289 units/L (normal, 31-95), gamma-glutamyl transferase 104 units (GGT, normal, 12-43), total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL, and albumin 2.5 g/dL (normal, 3.5-4.5). Pro-brain natriuretic peptide was 1429 pg/mL (normal, <100). The international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.0. Urinalysis showed trace proteinuria. The chest x-ray was normal. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head demonstrated no intracranial pathology. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal-sized nodular liver, a nonocclusive portal vein thrombus (PVT), splenomegaly (15 cm in length), and trace ascites. There was no biliary dilation, hepatic steatosis, or hepatic mass.

The evolving data set presents a mixed picture about the state of the liver. The distended abdominal wall veins, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly are commonly observed in advanced cirrhosis, but these findings reflect the associated portal hypertension and not the liver disease itself. The normal bilirubin and INR suggest preserved liver function and decrease the likelihood of cirrhosis being responsible for the portal hypertension. However, the elevated alkaline phosphatase and GGT levels suggest an infiltrative liver disease, such as lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis.

Furthermore, while a nodular liver on imaging is consistent with cirrhosis, no steatosis was noted to support the presumed diagnosis of NAFLD. One explanation for this discrepancy is that fatty infiltration may be absent when NAFLD-associated cirrhosis develops. In summary, there is evidence of liver disease, and there is evidence of portal hypertension, but there is no evidence of liver parenchymal failure. The key features of the latter – spider angiomata, palmar erythema, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy – are absent.

Noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is an alternative explanation for the patient’s findings. NCPH is an elevation in the portal venous system pressure that arises from intrahepatic (but noncirrhotic) disease or from extrahepatic disease. Hepatic schistosomiasis is an example of intrahepatic but noncirrhotic portal hypertension. PVT that arises on account of a hypercoagulable condition (eg, abdominal malignancy, pancreatitis, or myeloproliferative disorders) is a prototype of extrahepatic NCPH. At this point, it is impossible to know if the PVT is a complication of NCPH or a cause of NCPH. PVT as a complication of cirrhosis is less likely.

An abdominal CT scan would better assess the hepatic parenchyma and exclude abdominal malignancies such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma. An echocardiogram is indicated to evaluate the cause of the elevated jugular venous pressure. A liver biopsy and measurement of portal venous pressure would help distinguish between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

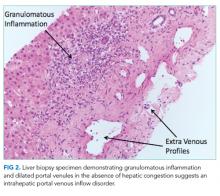

Hepatitis A, B, and C serologies were negative as were antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies. Ferritin and ceruloplasmin levels were normal. A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast demonstrated a nodular liver contour, splenomegaly, and a nonocclusive PVT (Figure 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal biventricular systolic function and size, normal diastolic function, a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 57 mmHg (normal, < 25), moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and no pericardial effusion or thickening. The patient’s confusion and somnolence resolved after two days of lactulose therapy. She denied the use of other medications, supplements, or herbs.

Pulmonary hypertension is usually a consequence of cardiopulmonary disease, but there is no exam or imaging evidence for left ventricular failure, mitral stenosis, obstructive lung disease, or interstitial lung disease. Portopulmonary hypertension (a form of pulmonary hypertension) can develop as a consequence of end-stage liver disease. The most common cause of hepatic encephalopathy due to portosystemic shunting is cirrhosis, but such shunting also arises in NCPH.

Schistosomiasis is the most common cause of NCPH worldwide. Parasite eggs trapped within the terminal portal venules cause inflammation, leading to fibrosis and intrahepatic portal hypertension. The liver becomes nodular on account of these changes, but the overall hepatic function is typically preserved. Portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, and pulmonary hypertension are common complications. The latter can arise from portosystemic shunting, which leads to embolization of schistosome eggs into the pulmonary circulation, where a granulomatous reaction ensues.

A percutaneous liver biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and dilated portal venules consistent with increased resistance to venous inflow (Figure 2). There was no sinusoidal congestion to indicate impaired hepatic venous outflow. Mild sinusoidal and portal fibrosis and increased iron in Kupffer cells were noted. There was no evidence of cirrhosis or steatohepatitis. Stains for acid-fast bacilli and fungi were negative. 16S rDNA (a test assessing for bacterial DNA) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reactions were negative. The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Hepatic granulomas can arise from infectious, immunologic, toxic, and malignant diseases. In the United States, immunologic disorders, such as sarcoidosis and primary biliary cholangitis, are the most common causes of granulomatous hepatitis. The patient lacks extrahepatic features of the former. The absence of bile duct injury and negative antimitochondrial antibody exclude the latter. None of the listed medications are commonly associated with hepatic granulomas. The ultrasound, CT scan, and biopsy did not reveal a granulomatous malignancy such as lymphoma.

Infections, such as brucellosis, Q fever, and tuberculosis, are common causes of granulomatous hepatitis in the developing world. Tuberculosis is prevalent in China, but the test results do not support tuberculosis as a unifying diagnosis.

Schistosomiasis accounts for the major clinical features (portal and pulmonary hypertension and preserved liver function) and hepatic pathology (ie, portal venous fibrosis with granulomatous inflammation) in this case and is prevalent in China, where the patient emigrated from. The biopsy specimen should be re-examined for schistosome eggs and serologic tests for schistosomiasis pursued.

Antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus, Brucella, Bartonella quintana, Bartonella henselae, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, and Histoplasma were negative. Cryptococcal antigen and rapid plasma reagin were negative. IgG antibodies to Schistosoma were 0.21 units (normal, < 0.19 units). Based on the patient’s epidemiology, biopsy findings, and serology results, hepatic schistosomiasis was diagnosed. Praziquantel was prescribed. She continues to receive daily lactulose and rifaximin and has not had any episodes of encephalopathy in the year after discharge.

COMMENTARY

Portal hypertension arises when there is resistance to flow in the portal venous system. It is defined as a pressure gradient greater than 5 mmHg between the portal vein and the intra-abdominal portion of the inferior vena cava.1 Clinicians are familiar with the manifestations of portal hypertension – portosystemic shunting leading to encephalopathy and variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and splenomegaly with thrombocytopenia – because of their close association with cirrhosis. In developed countries, cirrhosis accounts for over 90% of cases of portal hypertension.1 In the remaining 10%, conditions such as portal vein thrombosis primarily affect the portal vasculature and increase resistance to portal blood flow while leaving hepatic synthetic function relatively spared (Figure 3). Therefore, cirrhosis cannot be inferred with certainty from signs of portal hypertension alone.

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of cirrhosis, but this method is increasingly being replaced by noninvasive assessments of liver fibrosis, including imaging and scoring systems.2 Clinicians often infer cirrhosis from the combination of a known cause of liver injury, abnormal liver biochemical tests, evidence of liver dysfunction, and signs of portal hypertension.3 However, when signs of portal hypertension are present, but liver dysfunction cannot be established on physical exam (eg, palmar erythema, spider nevi, gynecomastia, and testicular atrophy) or laboratory testing (eg, low albumin, elevated INR, and elevated bilirubin), noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension should be considered. In this case, the biopsy showed vascular changes that suggested impaired venous inflow without bridging fibrosis, which pointed to NCPH.

NCPH is categorized based on the location of resistance to blood flow: prehepatic (eg, portal vein thrombosis), intrahepatic (eg, schistosomiasis), and posthepatic (eg, right-sided heart failure).1 In our patient, the dilated portal venules (inflow) in the presence of normal hepatic vein outflow suggested an increased intrahepatic resistance to blood flow. This finding excluded a causal role of the portal vein thrombosis and prompted testing for schistosomiasis.

Schistosomiasis affects more than 200 million people worldwide and is prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, Egypt, China, and Southeast Asia.4,5 Transmission occurs in fresh water, where the infectious form of the parasite is released from snails.4,6 Schistosome worms are not found in the United States, but as a result of immigration and travel, more than 400,000 people in the United States are estimated to be infected.5

Chronic schistosomiasis develops from the host’s granulomatous reaction to schistosome eggs whose location (depending on the species) leads to genitourinary, intestinal, hepatic, or rarely, neurologic disease.6 Hepatic schistosomiasis arises when eggs released in the portal venous system lodge in small portal venules and cause granulomatous inflammation, periportal fibrosis, and microvascular obstruction.6 The resultant portal hypertension develops insidiously, but the architecture and synthetic function of the liver is maintained until the very late stages of disease.6,7 Pulmonary hypertension can arise from the embolization of eggs to the pulmonary arterioles via portosystemic collaterals.

The demonstration of eggs in stool is the gold standard for the diagnosis of hepatic schistosomiasis, which is most commonly caused by Schistosoma mansoni and S. japonicum.7 Serologic assays provide evidence of infection or exposure but may cross-react with other helminths. Liver biopsy may reveal characteristic histopathologic findings, including granulomatous inflammation, distorted vasculature, and the deposition of collagen deposits in the periportal space, leading to “pipestem fibrosis.”8,9 If eggs cannot be detected on stool or histology, then serology, secondary histologic changes, and sometimes PCR are used to diagnose hepatic schistosomiasis. In our patient, the epidemiology, Schistosoma antibody titer, pulmonary hypertension, and liver biopsy with granulomatous inflammation, periportal fibrosis, and intrahepatic portal venule dilation were diagnostic of hepatic schistosomiasis.

The recurrent episodes of confusion which resolved with lactulose therapy were suggestive of hepatic encephalopathy, which results from shunting and accumulation of neurotoxic substances that would otherwise undergo hepatic metabolism.10 Clinicians are most familiar with hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis, where multiple liver functions – synthesis, excretion, metabolism, and circulation – simultaneously fail. NCPH represents a scenario where only the circulation is impaired, but this is sufficient to cause the portosystemic shunting that leads to encephalopathy. Our patient’s recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, despite adherence to lactulose and rifaximin and its resolution after praziquantel treatment, underscores the importance of addressing the underlying cause of portosystemic shunting.Associating portal hypertension with cirrhosis is efficient and accurate in many cases. However, when specific manifestations of cirrhosis are lacking, clinicians must decouple this association and pursue an alternative explanation for portal hypertension. The presence of some intrahepatic pathology (from schistosomiasis) but no cirrhosis made this case a particularly tough egg to crack.

Teaching Points

- In the developed world, 90% of portal hypertension is due to cirrhosis. Hepatic schistosomiasis is the most common cause of NCPH worldwide.

- Chronic schistosomiasis affects the gastrointestinal, hepatic, and genitourinary systems and causes significant global morbidity and mortality.

- Visualization of schistosome eggs is the diagnostic gold standard. Indirect testing such as schistosoma antibodies and secondary histologic changes may be required for the diagnosis in patients with a low burden of eggs.

Disclosures

Dr. Geha has no disclosures. Dr. Dhaliwal reports receiving honoraria from ISMIE Mutual Insurance Company and Physicians’ Reciprocal Insurers. Dr. Peters’ spouse is employed by Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Manesh is supported by the Jeremiah A. Barondess Fellowship in the Clinical Transaction of the New York Academy of Medicine, in collaboration with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

1. Sarin SK, Khanna R. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18(2):451-76. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2014.01.009. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Lok AS. Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):756-768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1610570. PubMed

3. Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis? JAMA. 2012;307(8):832-42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.186. PubMed

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites–Schistosomiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/schistosomiasis/. Accessed December 2, 2017.

5. Bica I, Hamer DH, Stadecker MJ. Hepatic schistosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2000;14(3):583-604. PubMed

6. Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, et al. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(16):1212-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012396. PubMed

7. Gray DJ, Ross AG, Li YS, McManus DP. Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. BMJ. 2011;342: 2561-2561. doi: doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2651. PubMed

8. Manzella A, Ohtomo K, Monzawa S, Lim JH. Schistosomiasis of the liver. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(2):144-50. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9329-7. PubMed

9. Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368(9541):1106-18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. PubMed

10. Blei AT, Córdoba J. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):1968. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03964.x. PubMed

A 68-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with altered mental status. On the morning prior to admission, she was fully alert and oriented. Over the course of the day, she became more confused and somnolent, and by the evening, she was unarousable to voice. She had not fallen and had no head trauma.

Altered mental status may arise from metabolic (eg, hyponatremia), infectious (eg, urinary tract infection), structural (eg, subdural hematoma), or toxin-related (eg, adverse medication effect) processes. Any of these categories of encephalopathy can develop gradually over the course of a day.

One year prior, the patient was admitted for a similar episode of altered mental status. Asterixis and elevated transaminases prompted an abdominal ultrasound, which revealed a nodular liver and ascites. Paracentesis revealed a high serum-ascites albumin gradient. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was made based on these findings. Testing for viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, and Wilson’s disease were negative. Although steatosis was not detected on ultrasound, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was suspected based on the patient’s risk factors of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. She had four additional presentations of altered mental status with asterixis; each episode resolved with lactulose.

Other medical history included end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. Her medications were labetalol, amlodipine, insulin, propranolol, lactulose, and rifaximin. She was originally from China and moved to the United States 10 years earlier. Given concerns about her ability to consistently take medications, she had moved to a long-term facility. She did not use alcohol, tobacco, or illicit substances.

The normalization of the patient’s mental status after lactulose treatment, especially in the context of recurrent episodes, is characteristic of hepatic encephalopathy, in which ammonia and other substances bypass hepatic metabolism and impair cerebral function. Hepatic encephalopathy is the most common cause of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy, and may recur in the setting of infection or nonadherence with lactulose and rifaximin. Other causes of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy include hyperammonemia caused by urease-producing bacterial infection (eg, Proteus), valproic acid toxicity, and urea cycle abnormalities.

Other causes of confusion with a self-limited course should be considered for the current episode. A postictal state is possible, but convulsions were not reported. The patient is at risk of hypoglycemia from insulin use and impaired gluconeogenesis due to cirrhosis and ESRD, but low blood sugar would have likely been detected at the time of hospitalization. Finally, she might have experienced episodic encephalopathy from ingestion of unreported medications or toxins, whose effects may have resolved with abstinence during hospitalization.

The patient’s temperature was 37.8°C, pulse 73 beats/minute, blood pressure 133/69 mmHg, respiratory rate 12 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on ambient air. Her body mass index (BMI) was 19 kg/m2. She was somnolent but was moving all four extremities spontaneously. Her pupils were symmetric and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. Biceps and patellar reflexes were 2+ bilaterally. Babinski sign was absent bilaterally. The patient could not cooperate with the assessment for asterixis. Her sclerae were anicteric. The jugular venous pressure was estimated at 13 cm of water. Her heart was regular with no murmurs. Her lungs were clear. She had a distended, nontender abdomen with caput medusae. She had symmetric pitting edema in her lower extremities up to the shins.

The elevated jugular venous pressure, lower extremity edema, and distended abdomen suggest volume overload. Jugular venous distention with clear lungs is characteristic of right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular myocardial infarction, tricuspid regurgitation, or constrictive pericarditis. However, chronic biventricular heart failure often presents in this manner and is more common than the aforementioned conditions. ESRD and cirrhosis may be contributing to the hypervolemia.

Although Asian patients may exhibit metabolic syndrome and NAFLD at a lower BMI than non-Asians, her BMI is uncharacteristically low for NAFLD, especially given the increased weight expected from volume overload. There are no signs of infection to account for worsening of hepatic encephalopathy.

Laboratory tests demonstrated a white blood cell count of 4400/µL with a normal differential, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count of 108,000 per cubic millimeter. Mean corpuscular volume was 103 fL. Basic metabolic panel was normal with the exception of blood urea nitrogen of 46 mg/dL and a creatinine of 6.4 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase was 34 units/L, alanine aminotransferase 34 units/L, alkaline phosphatase 289 units/L (normal, 31-95), gamma-glutamyl transferase 104 units (GGT, normal, 12-43), total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL, and albumin 2.5 g/dL (normal, 3.5-4.5). Pro-brain natriuretic peptide was 1429 pg/mL (normal, <100). The international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.0. Urinalysis showed trace proteinuria. The chest x-ray was normal. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head demonstrated no intracranial pathology. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal-sized nodular liver, a nonocclusive portal vein thrombus (PVT), splenomegaly (15 cm in length), and trace ascites. There was no biliary dilation, hepatic steatosis, or hepatic mass.

The evolving data set presents a mixed picture about the state of the liver. The distended abdominal wall veins, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly are commonly observed in advanced cirrhosis, but these findings reflect the associated portal hypertension and not the liver disease itself. The normal bilirubin and INR suggest preserved liver function and decrease the likelihood of cirrhosis being responsible for the portal hypertension. However, the elevated alkaline phosphatase and GGT levels suggest an infiltrative liver disease, such as lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis.

Furthermore, while a nodular liver on imaging is consistent with cirrhosis, no steatosis was noted to support the presumed diagnosis of NAFLD. One explanation for this discrepancy is that fatty infiltration may be absent when NAFLD-associated cirrhosis develops. In summary, there is evidence of liver disease, and there is evidence of portal hypertension, but there is no evidence of liver parenchymal failure. The key features of the latter – spider angiomata, palmar erythema, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy – are absent.

Noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is an alternative explanation for the patient’s findings. NCPH is an elevation in the portal venous system pressure that arises from intrahepatic (but noncirrhotic) disease or from extrahepatic disease. Hepatic schistosomiasis is an example of intrahepatic but noncirrhotic portal hypertension. PVT that arises on account of a hypercoagulable condition (eg, abdominal malignancy, pancreatitis, or myeloproliferative disorders) is a prototype of extrahepatic NCPH. At this point, it is impossible to know if the PVT is a complication of NCPH or a cause of NCPH. PVT as a complication of cirrhosis is less likely.

An abdominal CT scan would better assess the hepatic parenchyma and exclude abdominal malignancies such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma. An echocardiogram is indicated to evaluate the cause of the elevated jugular venous pressure. A liver biopsy and measurement of portal venous pressure would help distinguish between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Hepatitis A, B, and C serologies were negative as were antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies. Ferritin and ceruloplasmin levels were normal. A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast demonstrated a nodular liver contour, splenomegaly, and a nonocclusive PVT (Figure 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal biventricular systolic function and size, normal diastolic function, a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 57 mmHg (normal, < 25), moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and no pericardial effusion or thickening. The patient’s confusion and somnolence resolved after two days of lactulose therapy. She denied the use of other medications, supplements, or herbs.