User login

Millipede Burns: An Unusual Cause of Purplish Toes

To the Editor:

Millipedes do not have nearly as many feet as their name would suggest; most have fewer than 100.1 They are not actually insects; they are a wormlike arthropod in the Diplopoda class. Generally these harmless animals can be a welcome resident in gardens because they break down decaying plant material and rejuvenate the soil.1 However, they are less welcome in the home or underfoot because of what happens when these invertebrates are threatened or crushed.2

Millipedes, which typically have at least 30 pairs of legs, have 2 defense mechanisms: (1) body coiling to withstand external pressure, and (2) secretion of fluids with insecticidal properties from specialized glands distributed along their body.3 These secretions, which are used by the millipede to defend against predators, contain organic compounds including benzoquinone. When these secretions come into contact with skin, pigmentary changes resembling a burn or necrosis and irritation to the skin (pain, burning, itching) occur.4,5

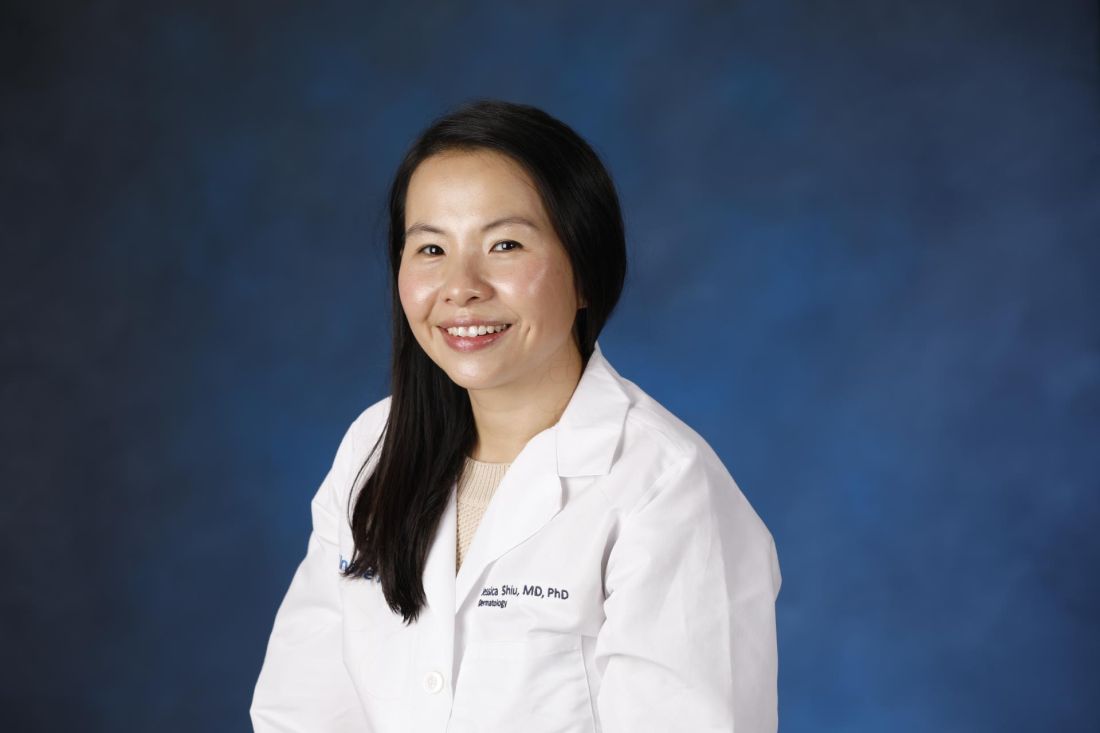

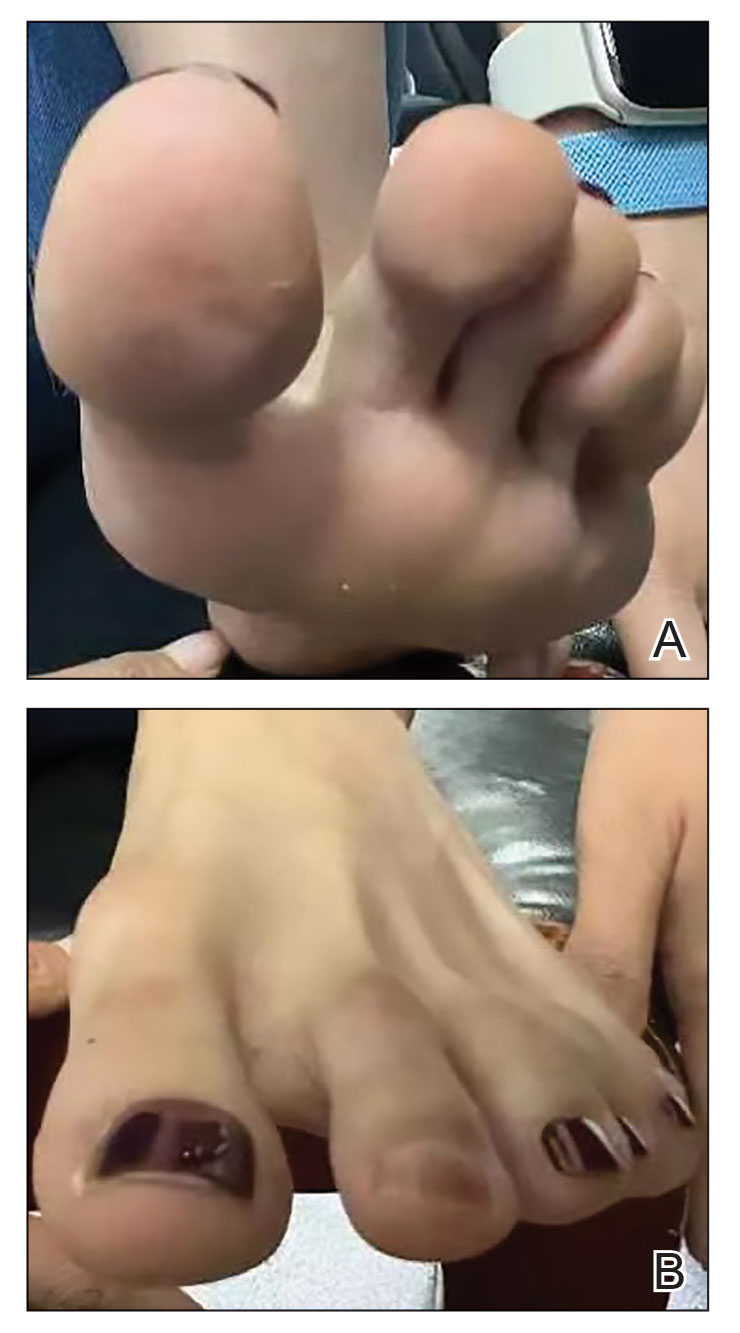

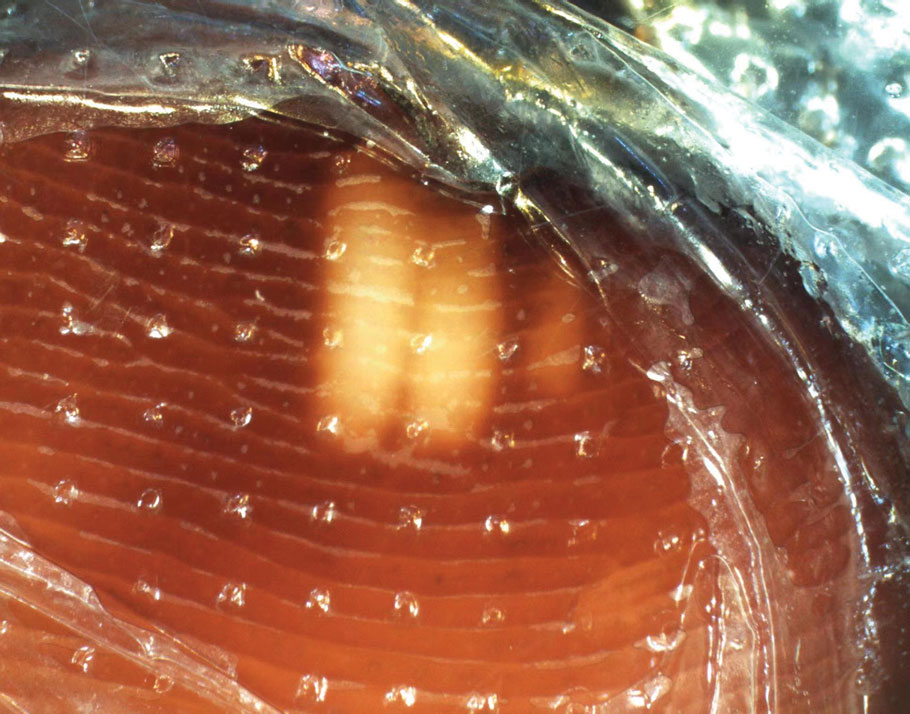

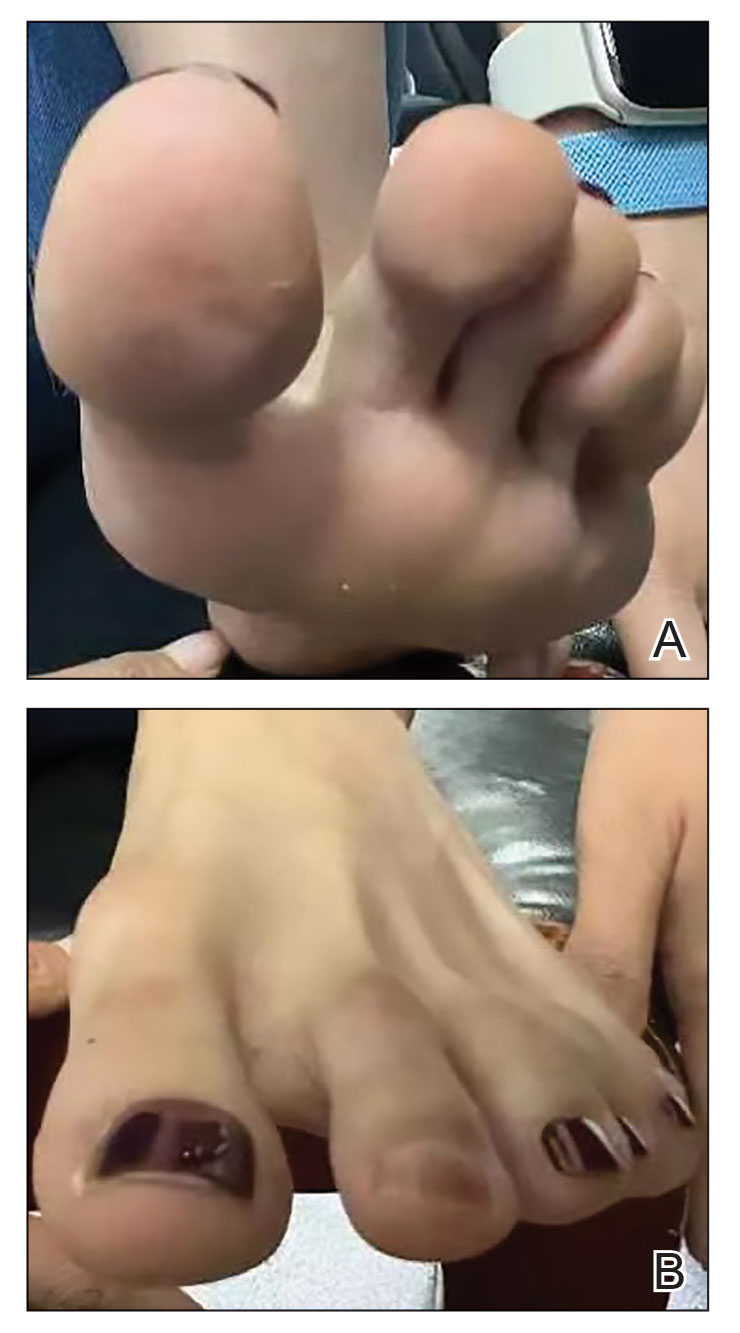

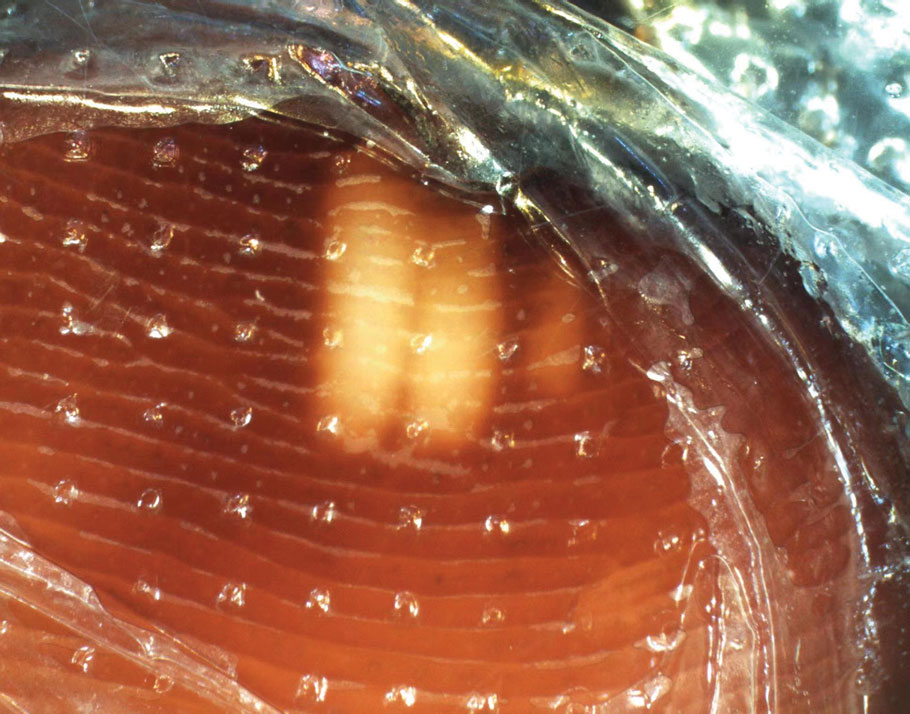

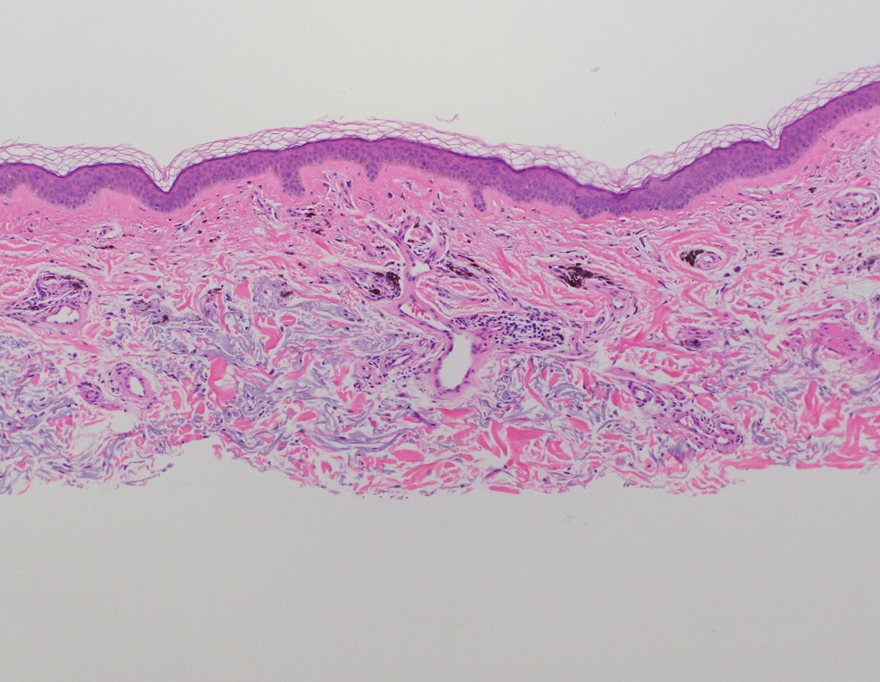

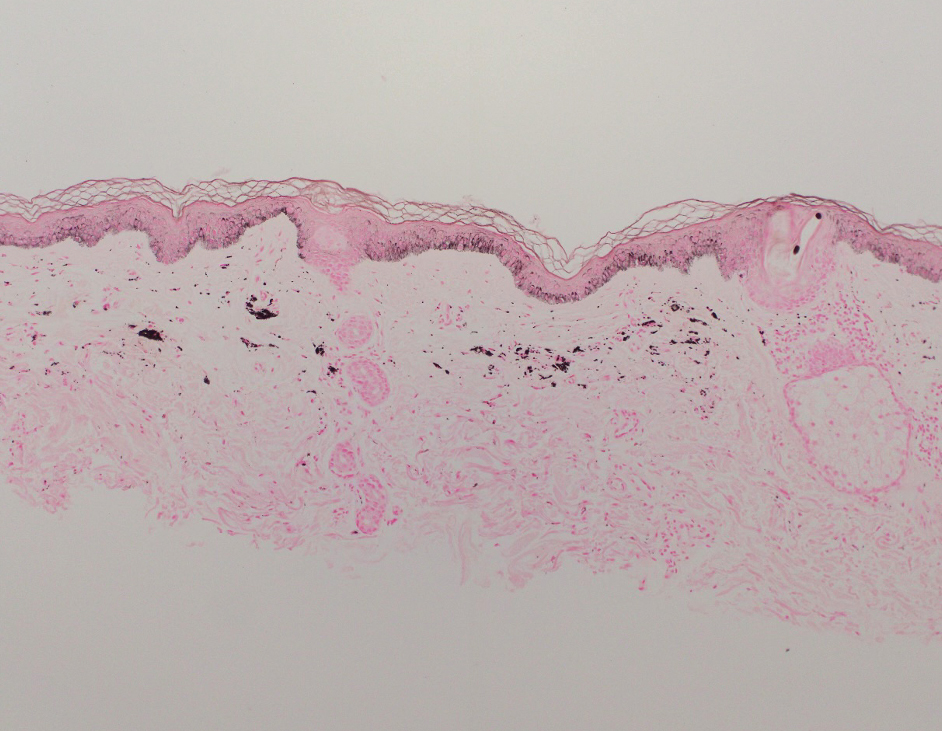

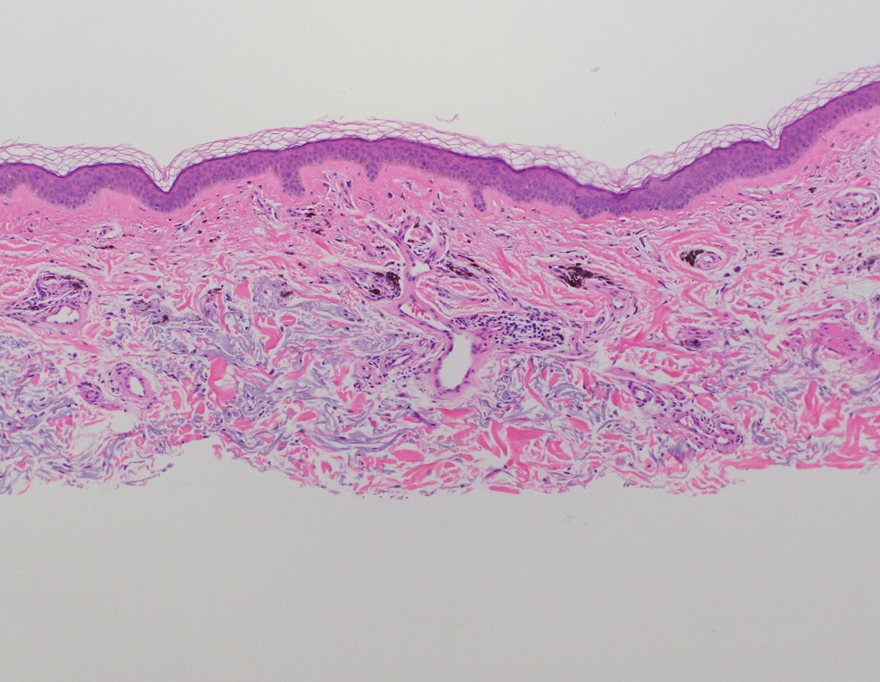

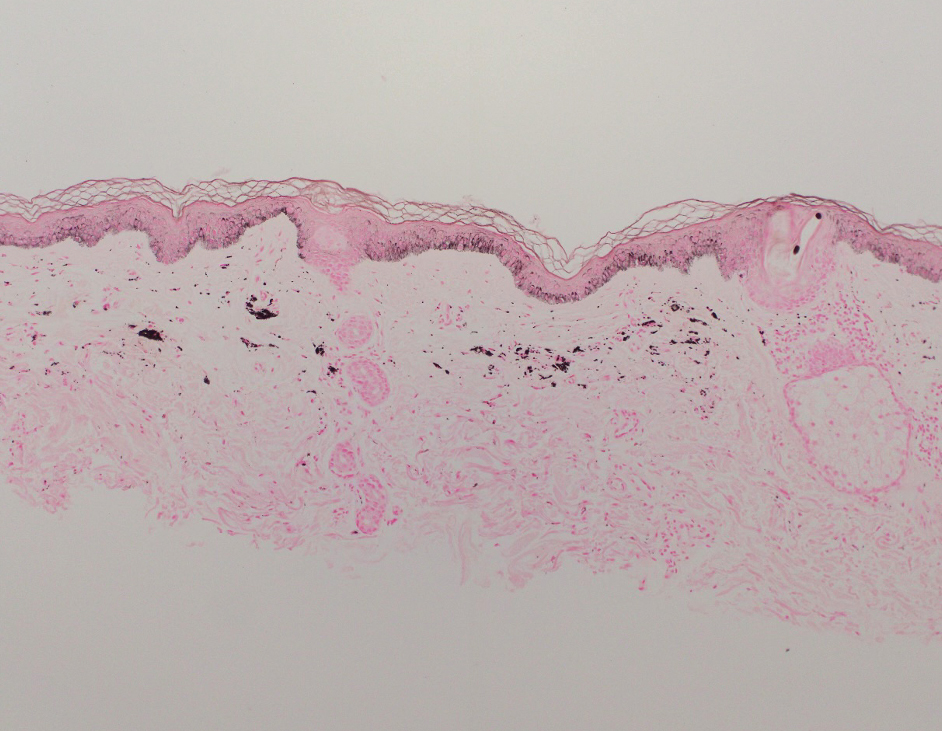

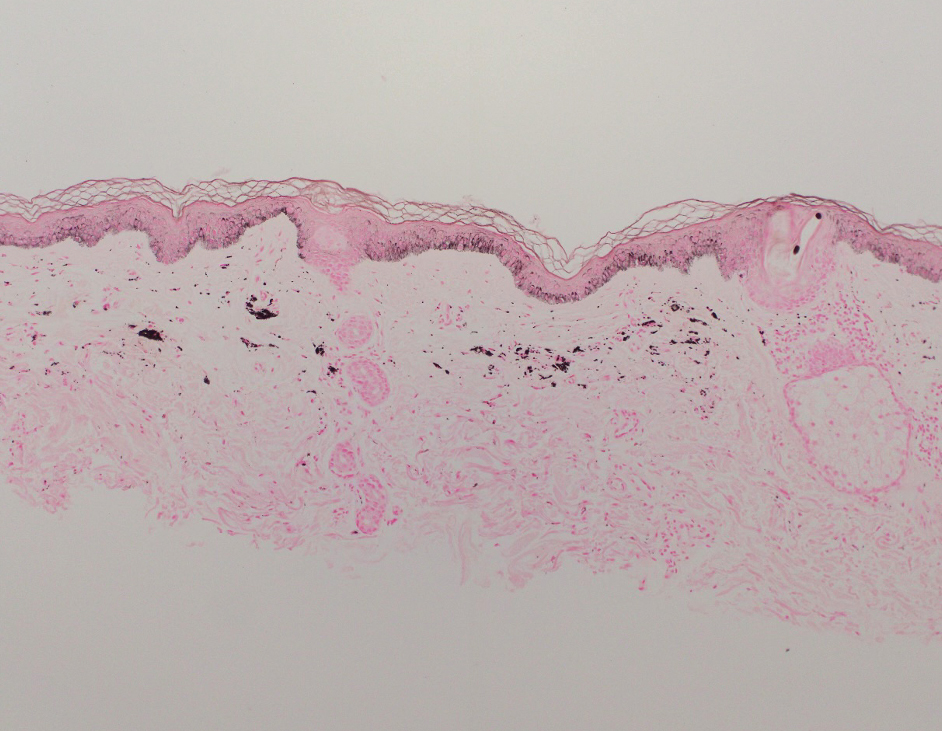

Millipedes typically are found in tropical and temperate regions worldwide, such as the Amazon rainforest, Southeast Asia, tropical areas of Africa, forests, grasslands, and gardens in North America and Europe.6 They also are found in every US state as well as Puerto Rico.1 Millipedes are nocturnal, favor dark places, and can make their way into residential areas, including homes, basements, gardens, and yards.2,6 Although millipede burns commonly are reported in tropical regions, we present a case in China.6A 33-year-old woman presented with purplish-red discoloration on all 5 toes on the left foot. The patient recounted that she discovered a millipede in her shoe earlier in the day, removed it, and crushed it with her bare foot. That night, while taking a bath, she noticed that the toes had turned purplish-red (Figure 1). The patient brought the crushed millipede with her to the emergency department where she sought treatment. The dermatologist confirmed that it was a millipede; however, the team was unable to determine the specific species because it had been crushed (Figure 2).

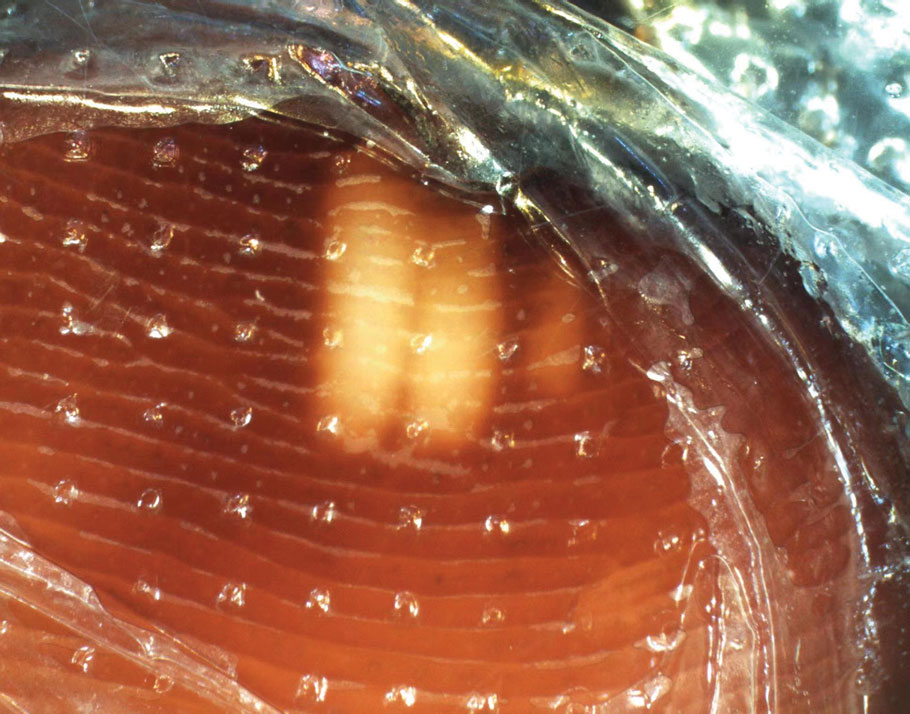

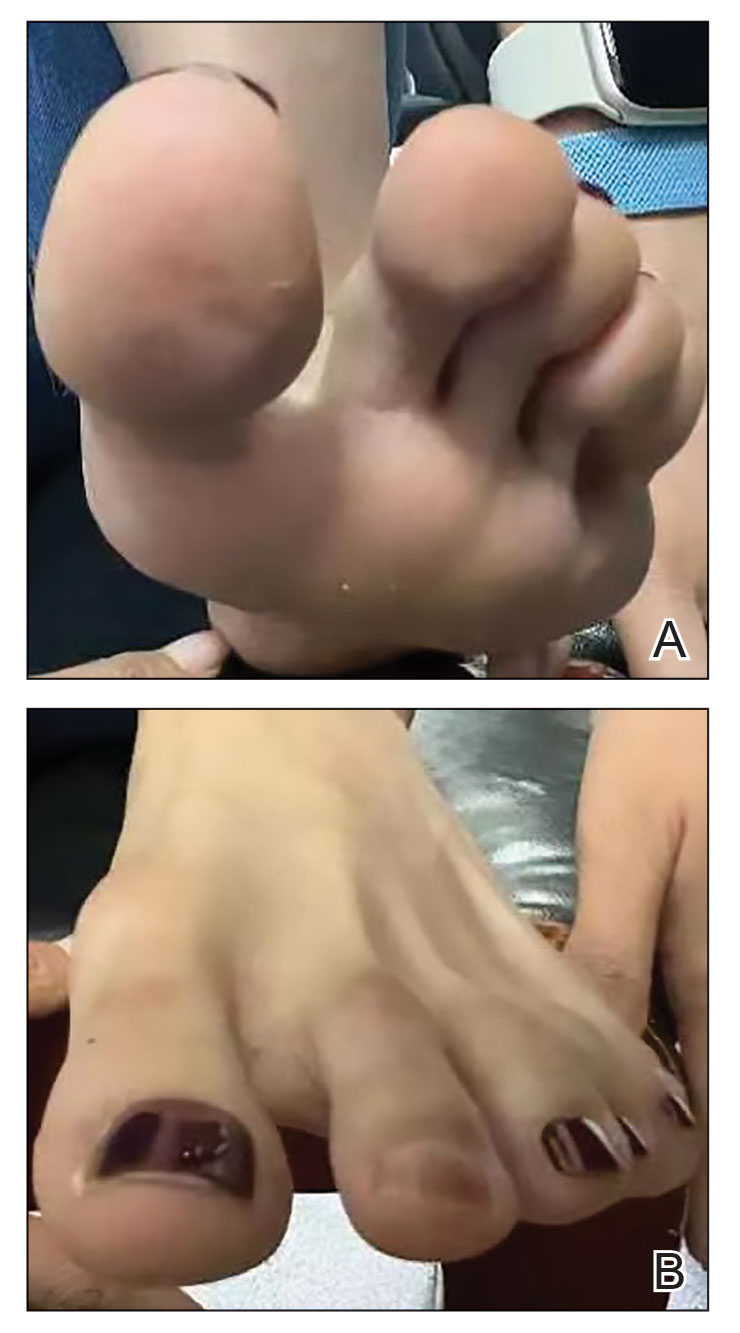

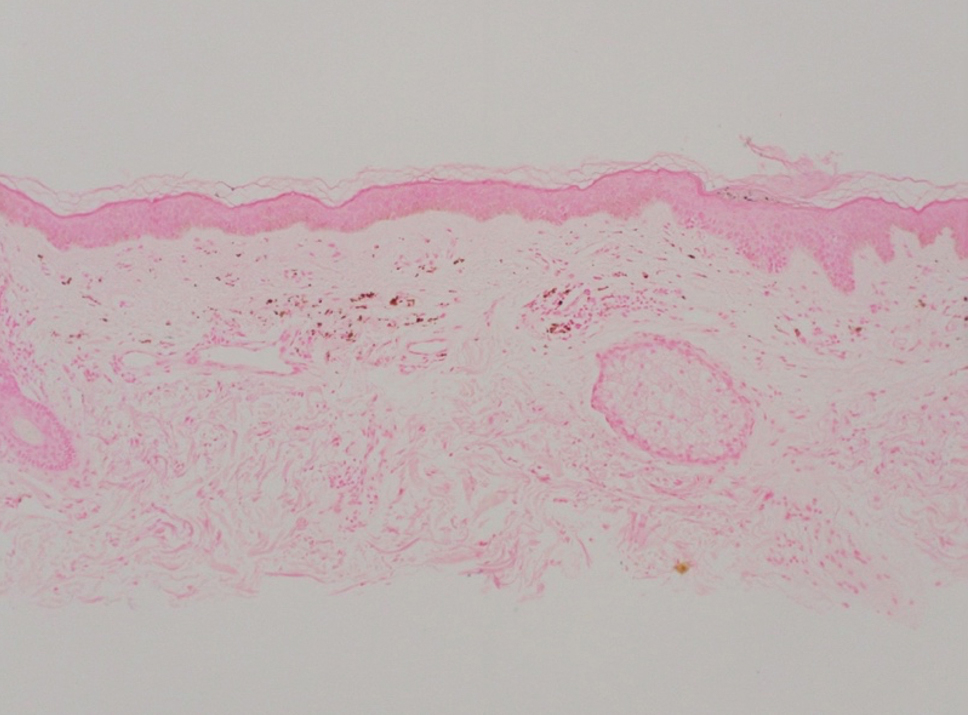

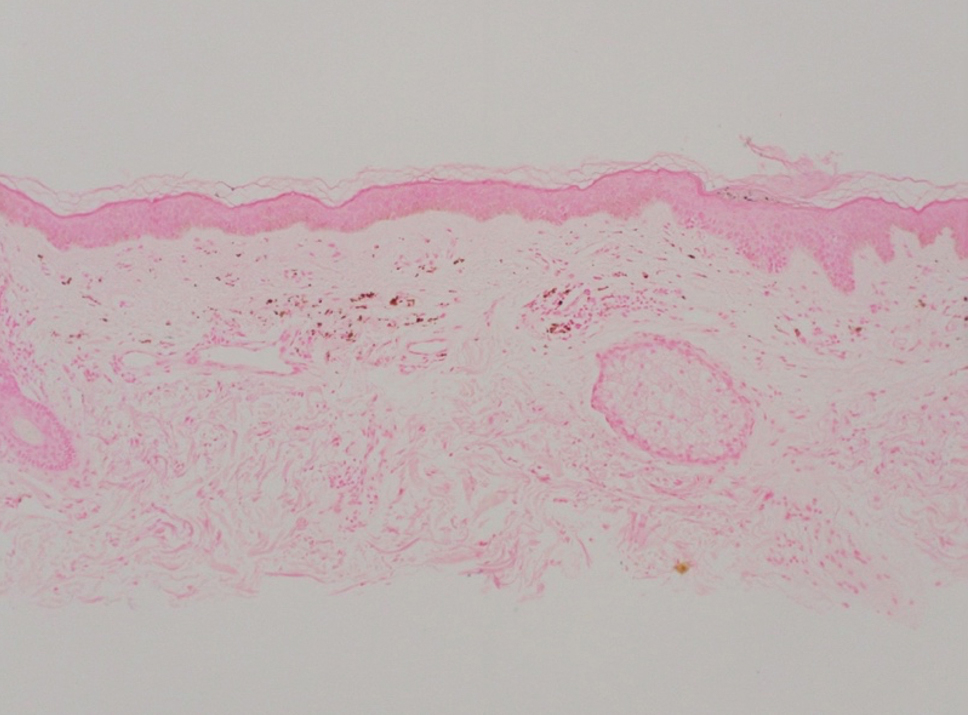

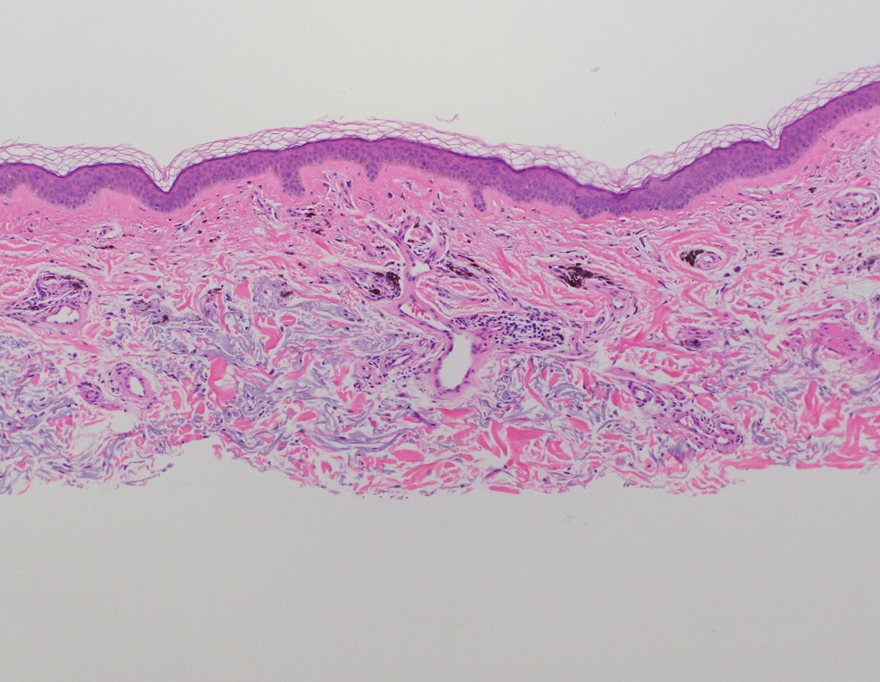

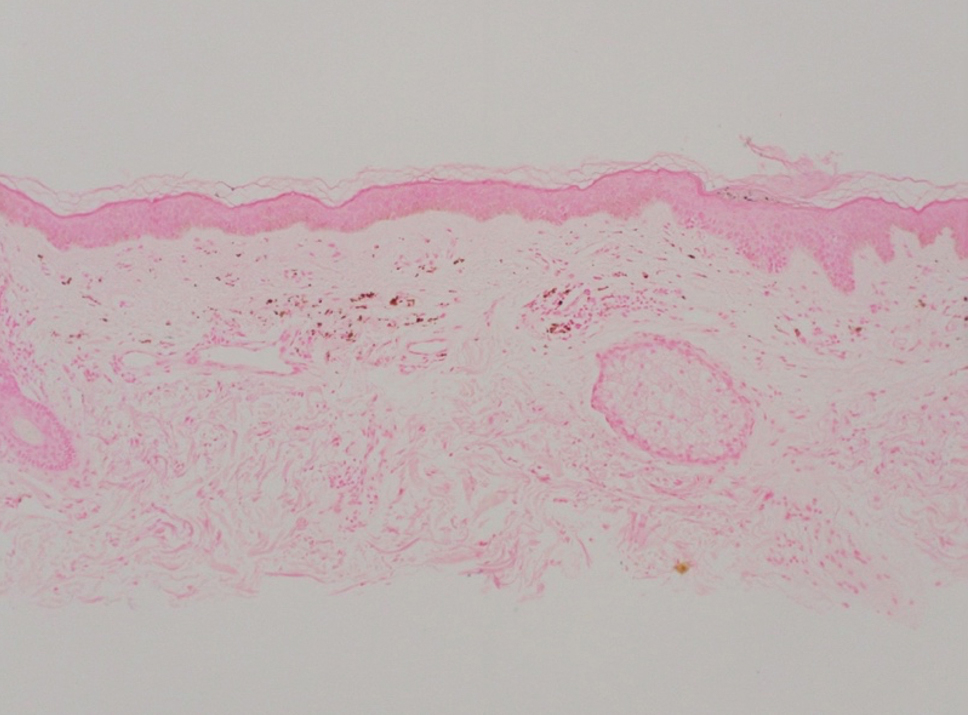

Physical examination of the affected toes showed a clear boundary and iodinelike staining. The patient did not report pain. The stained skin had a normal temperature, pulse, texture, and sensation. Dermoscopy revealed multiple black-brown patches on the toes (Figure 3). The pigmented area gradually faded over a 1-month period. Superficial damage to the toenail revealed evidence of black-brown pigmentation on both the nail and the skin underneath. The diagnosis in the dermoscopy report suggested exogenous pigmentation of the toes. The patient was advised that no treatment was needed and that the condition would resolve on its own. At 1-month follow-up, the patient’s toes had returned to their normal color (Figure 4).

The feet are common sites of millipede burns; other exposed areas, such as the arms, face, and eyes, also are potential sites of involvement.5 The cutaneous pigmentary changes seen on our patient’s foot were a result of the millipede’s defense mechanism—secreted toxic chemicals that stained the foot. It is important to note that the pigmentation was not associated with the death of the millipede, as the millipede was still alive upon initial contact with the patient’s foot in her shoe.

When a patient presents with pigmentary changes, several conditions must be ruled out—notably acute arterial thrombosis. Patients with this condition will describe acute pain and weakness in the area of involvement. Physicians inspecting the area will note coldness and pallor in the affected limb as well as a diminished or absent pulse. In severe cases, the skin may exhibit a purplish-red appearance.5 Millipede burns also should be distinguished from bacterial endocarditis and cryoglobulinemia.7 All 3 conditions can manifest with redness, swelling, blisters, and purpuralike changes. Positive blood culture is an important diagnostic basis for bacterial endocarditis; in addition, routine blood tests will demonstrate a decrease in red blood cells and hemoglobin, and routine urinalysis may show proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. Patients with cryoglobulinemia will have a positive cryoglobulin assay, increased IgM, and often decreased complement.7 It also is worth noting that millipede burns might resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, necessitating further evaluation.5

It is unusual to see a millipede burn in nontropical regions. Therefore, the identification of our patient’s millipede burn was notable and serves as a reminder to keep this diagnosis in the differential when caring for patients with pigmentary changes. An accurate diagnosis hinges on being alert to a millipede exposure history and recognizing the clinical manifestations. For affected patients, it may be beneficial to recommend they advise friends and relatives to avoid skin contact with millipedes and most importantly to avoid stepping on them with bare feet.

Millipedes. National Wildlife Federation. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/Millipedes

Pennini SN, Rebello PFB, Guerra MdGVB, et al. Millipede accident with unusual dermatological lesion. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:765-767. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.10.003

Lima CAJ, Cardoso JLC, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda Class (“millipedes“). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962910000300018

De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.560855

Lacy FA, Elston DM. What’s eating you? millipede burns. Cutis. 2019;103:195-196.

Neto ASH, Filho FB, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0212-2013

Sampaio FMS, Valviesse VRGdA, Lyra-da-Silva JO, et al. Pain and hyperpigmentation of the toes: a quiz. hyperpigmentation of the toes caused by millipedes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:253-254. doi:10.2340/00015555-1645

To the Editor:

Millipedes do not have nearly as many feet as their name would suggest; most have fewer than 100.1 They are not actually insects; they are a wormlike arthropod in the Diplopoda class. Generally these harmless animals can be a welcome resident in gardens because they break down decaying plant material and rejuvenate the soil.1 However, they are less welcome in the home or underfoot because of what happens when these invertebrates are threatened or crushed.2

Millipedes, which typically have at least 30 pairs of legs, have 2 defense mechanisms: (1) body coiling to withstand external pressure, and (2) secretion of fluids with insecticidal properties from specialized glands distributed along their body.3 These secretions, which are used by the millipede to defend against predators, contain organic compounds including benzoquinone. When these secretions come into contact with skin, pigmentary changes resembling a burn or necrosis and irritation to the skin (pain, burning, itching) occur.4,5

Millipedes typically are found in tropical and temperate regions worldwide, such as the Amazon rainforest, Southeast Asia, tropical areas of Africa, forests, grasslands, and gardens in North America and Europe.6 They also are found in every US state as well as Puerto Rico.1 Millipedes are nocturnal, favor dark places, and can make their way into residential areas, including homes, basements, gardens, and yards.2,6 Although millipede burns commonly are reported in tropical regions, we present a case in China.6A 33-year-old woman presented with purplish-red discoloration on all 5 toes on the left foot. The patient recounted that she discovered a millipede in her shoe earlier in the day, removed it, and crushed it with her bare foot. That night, while taking a bath, she noticed that the toes had turned purplish-red (Figure 1). The patient brought the crushed millipede with her to the emergency department where she sought treatment. The dermatologist confirmed that it was a millipede; however, the team was unable to determine the specific species because it had been crushed (Figure 2).

Physical examination of the affected toes showed a clear boundary and iodinelike staining. The patient did not report pain. The stained skin had a normal temperature, pulse, texture, and sensation. Dermoscopy revealed multiple black-brown patches on the toes (Figure 3). The pigmented area gradually faded over a 1-month period. Superficial damage to the toenail revealed evidence of black-brown pigmentation on both the nail and the skin underneath. The diagnosis in the dermoscopy report suggested exogenous pigmentation of the toes. The patient was advised that no treatment was needed and that the condition would resolve on its own. At 1-month follow-up, the patient’s toes had returned to their normal color (Figure 4).

The feet are common sites of millipede burns; other exposed areas, such as the arms, face, and eyes, also are potential sites of involvement.5 The cutaneous pigmentary changes seen on our patient’s foot were a result of the millipede’s defense mechanism—secreted toxic chemicals that stained the foot. It is important to note that the pigmentation was not associated with the death of the millipede, as the millipede was still alive upon initial contact with the patient’s foot in her shoe.

When a patient presents with pigmentary changes, several conditions must be ruled out—notably acute arterial thrombosis. Patients with this condition will describe acute pain and weakness in the area of involvement. Physicians inspecting the area will note coldness and pallor in the affected limb as well as a diminished or absent pulse. In severe cases, the skin may exhibit a purplish-red appearance.5 Millipede burns also should be distinguished from bacterial endocarditis and cryoglobulinemia.7 All 3 conditions can manifest with redness, swelling, blisters, and purpuralike changes. Positive blood culture is an important diagnostic basis for bacterial endocarditis; in addition, routine blood tests will demonstrate a decrease in red blood cells and hemoglobin, and routine urinalysis may show proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. Patients with cryoglobulinemia will have a positive cryoglobulin assay, increased IgM, and often decreased complement.7 It also is worth noting that millipede burns might resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, necessitating further evaluation.5

It is unusual to see a millipede burn in nontropical regions. Therefore, the identification of our patient’s millipede burn was notable and serves as a reminder to keep this diagnosis in the differential when caring for patients with pigmentary changes. An accurate diagnosis hinges on being alert to a millipede exposure history and recognizing the clinical manifestations. For affected patients, it may be beneficial to recommend they advise friends and relatives to avoid skin contact with millipedes and most importantly to avoid stepping on them with bare feet.

To the Editor:

Millipedes do not have nearly as many feet as their name would suggest; most have fewer than 100.1 They are not actually insects; they are a wormlike arthropod in the Diplopoda class. Generally these harmless animals can be a welcome resident in gardens because they break down decaying plant material and rejuvenate the soil.1 However, they are less welcome in the home or underfoot because of what happens when these invertebrates are threatened or crushed.2

Millipedes, which typically have at least 30 pairs of legs, have 2 defense mechanisms: (1) body coiling to withstand external pressure, and (2) secretion of fluids with insecticidal properties from specialized glands distributed along their body.3 These secretions, which are used by the millipede to defend against predators, contain organic compounds including benzoquinone. When these secretions come into contact with skin, pigmentary changes resembling a burn or necrosis and irritation to the skin (pain, burning, itching) occur.4,5

Millipedes typically are found in tropical and temperate regions worldwide, such as the Amazon rainforest, Southeast Asia, tropical areas of Africa, forests, grasslands, and gardens in North America and Europe.6 They also are found in every US state as well as Puerto Rico.1 Millipedes are nocturnal, favor dark places, and can make their way into residential areas, including homes, basements, gardens, and yards.2,6 Although millipede burns commonly are reported in tropical regions, we present a case in China.6A 33-year-old woman presented with purplish-red discoloration on all 5 toes on the left foot. The patient recounted that she discovered a millipede in her shoe earlier in the day, removed it, and crushed it with her bare foot. That night, while taking a bath, she noticed that the toes had turned purplish-red (Figure 1). The patient brought the crushed millipede with her to the emergency department where she sought treatment. The dermatologist confirmed that it was a millipede; however, the team was unable to determine the specific species because it had been crushed (Figure 2).

Physical examination of the affected toes showed a clear boundary and iodinelike staining. The patient did not report pain. The stained skin had a normal temperature, pulse, texture, and sensation. Dermoscopy revealed multiple black-brown patches on the toes (Figure 3). The pigmented area gradually faded over a 1-month period. Superficial damage to the toenail revealed evidence of black-brown pigmentation on both the nail and the skin underneath. The diagnosis in the dermoscopy report suggested exogenous pigmentation of the toes. The patient was advised that no treatment was needed and that the condition would resolve on its own. At 1-month follow-up, the patient’s toes had returned to their normal color (Figure 4).

The feet are common sites of millipede burns; other exposed areas, such as the arms, face, and eyes, also are potential sites of involvement.5 The cutaneous pigmentary changes seen on our patient’s foot were a result of the millipede’s defense mechanism—secreted toxic chemicals that stained the foot. It is important to note that the pigmentation was not associated with the death of the millipede, as the millipede was still alive upon initial contact with the patient’s foot in her shoe.

When a patient presents with pigmentary changes, several conditions must be ruled out—notably acute arterial thrombosis. Patients with this condition will describe acute pain and weakness in the area of involvement. Physicians inspecting the area will note coldness and pallor in the affected limb as well as a diminished or absent pulse. In severe cases, the skin may exhibit a purplish-red appearance.5 Millipede burns also should be distinguished from bacterial endocarditis and cryoglobulinemia.7 All 3 conditions can manifest with redness, swelling, blisters, and purpuralike changes. Positive blood culture is an important diagnostic basis for bacterial endocarditis; in addition, routine blood tests will demonstrate a decrease in red blood cells and hemoglobin, and routine urinalysis may show proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. Patients with cryoglobulinemia will have a positive cryoglobulin assay, increased IgM, and often decreased complement.7 It also is worth noting that millipede burns might resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, necessitating further evaluation.5

It is unusual to see a millipede burn in nontropical regions. Therefore, the identification of our patient’s millipede burn was notable and serves as a reminder to keep this diagnosis in the differential when caring for patients with pigmentary changes. An accurate diagnosis hinges on being alert to a millipede exposure history and recognizing the clinical manifestations. For affected patients, it may be beneficial to recommend they advise friends and relatives to avoid skin contact with millipedes and most importantly to avoid stepping on them with bare feet.

Millipedes. National Wildlife Federation. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/Millipedes

Pennini SN, Rebello PFB, Guerra MdGVB, et al. Millipede accident with unusual dermatological lesion. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:765-767. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.10.003

Lima CAJ, Cardoso JLC, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda Class (“millipedes“). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962910000300018

De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.560855

Lacy FA, Elston DM. What’s eating you? millipede burns. Cutis. 2019;103:195-196.

Neto ASH, Filho FB, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0212-2013

Sampaio FMS, Valviesse VRGdA, Lyra-da-Silva JO, et al. Pain and hyperpigmentation of the toes: a quiz. hyperpigmentation of the toes caused by millipedes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:253-254. doi:10.2340/00015555-1645

Millipedes. National Wildlife Federation. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/Millipedes

Pennini SN, Rebello PFB, Guerra MdGVB, et al. Millipede accident with unusual dermatological lesion. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:765-767. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.10.003

Lima CAJ, Cardoso JLC, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda Class (“millipedes“). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962910000300018

De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.560855

Lacy FA, Elston DM. What’s eating you? millipede burns. Cutis. 2019;103:195-196.

Neto ASH, Filho FB, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0212-2013

Sampaio FMS, Valviesse VRGdA, Lyra-da-Silva JO, et al. Pain and hyperpigmentation of the toes: a quiz. hyperpigmentation of the toes caused by millipedes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:253-254. doi:10.2340/00015555-1645

PRACTICE POINTS

- Millipede burns can resemble ischemia. The most common site of a millipede burn is the feet.

- Diagnosing a millipede burn hinges on obtaining a detailed history, viewing the site under a dermatoscope, and carefully assessing the temperature and pulse of the affected area.

Emerging Insights in Vitiligo Therapeutics: A Focus on Oral and Topical JAK Inhibitors

Emerging Insights in Vitiligo Therapeutics: A Focus on Oral and Topical JAK Inhibitors

Vitiligo is a common autoimmune disorder characterized by cutaneous depigmentation that has a substantial impact on patient quality of life.1 Vitiligo affects approximately 28.5 million individuals globally, with the highest lifetime prevalence occurring in Central Europe and South Asia.2 In the United States, Asian American and Hispanic/Latine populations most commonly are affected.3 The accompanying psychosocial burdens of vitiligo are particularly substantial among individuals with darker skin types, as evidenced by higher rates of concomitant anxiety and depression in these patients.4 Despite this, patients with skin of color are underrepresented in vitiligo research.2

Treatment algorithms developed based on worldwide expert consensus recommendations provide valuable insights into the management of segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo.5 The mainstay therapeutics include topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and phototherapy. While vitiligo pathogenesis is not completely understood, recent advances have focused on the role of the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway. Interferon gamma drives vitiligo pathogenesis through this pathway, upregulating C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 and promoting CD8+ T-cell recruitment, resulting in targeted melanocyte destruction.6 The emergence of targeted therapeutics may address equity and inclusion gaps. Herein, we highlight innovations in vitiligo treatment with a focus on oral and topical JAK inhibitors.

Oral JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

The therapeutic potential of JAK inhibitors for vitiligo was first reported when patients with alopecia areata and comorbid vitiligo experienced repigmentation of the skin following administration of oral ruxolitinib.7 Since this discovery, other oral JAK inhibitors have been investigated for vitiligo treatment. A phase 2b randomized clinical trial (RCT) of 364 patients examined oral ritlecitinib, a JAK3 inhibitor, and found it to be effective in treating active nonsegmental vitiligo.8 Patients aged 18 to 65 years with active nonsegmental vitiligo that had been present for 3 months or more as well as 4% to 50% body surface area (BSA) affected excluding acral surfaces and at least 0.25% facial involvement were included. Treatment groups received 50 mg (with or without a 100- or 200- mg loading dose), 30 mg, or 10 mg daily for 24 weeks. The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI) score. Significant differences in F-VASI percentage change compared with placebo occurred for those in the 50-mg group who received a loading dose (-21.2 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) and those who did not receive a loading dose (–18.5 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) as well as the 30-mg group (-14.6 vs 2.1 [P=.01]). Continued repigmentation of the skin was observed in the 24-week extension period, indicating that longer treatment periods may be necessary for optimal repigmentation results. Ritlecitinib generally was well tolerated, and the most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis (15.9%), upper respiratory tract infection (11.5%), and headache (8.8%). Most patients identified as White (67.6%), with 23.6% identifying as Asian and 2.7% identifying as Black. The authors stated that continued improvement was observed in the extension period across all skin types; however, the data were not reported.8

Upadacitnib, an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor, also has demonstrated efficacy in nonsegmental vitiligo in a phase 2 RCT.9 Adult patients (N=185) with nonsegmental vitiligo were randomized to receive upadacitinib 6 mg, 11 mg, or 22 mg or placebo (the placebo group subsequently was switched to upadacitinib 11 mg or 22 mg after 24 weeks). The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in F-VASI score at 24 weeks. The higher doses of upadacitinib resulted in significant changes in F-VASI scored compared with placebo (6 mg: -7.60 [95% CI, -22.18 to 6.97][P=.30]; 11 mg: -21.27 [95% CI, -36.02 to -6.52][P=.01]; 22 mg: -19.60 [95% CI, -35.04 to –4.16][P=.01]). As with ritlecitinib, continued repigmentation was observed beyond the initial 24-week period. Of the 185 participants, 5.9% identified as Black and 13.5% identified as Asian. The investigators reported that the percentage change in F-VASI score was consistent across skin types.9 The results of these phase 2 RCTs are encouraging, and we anticipate the findings of 2 phase 3 RCTs for ritlecitinib and upadacitinib that currently are underway (Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers NCT05583526 and NCT06118411).

Topical JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

Tofacitinib cream 2%, a selective JAK3 inhibitor, has shown therapeutic potential for treatment of vitiligo. One of the earliest pilot studies on topical tofacitinib examined the efficacy of tofacitinib cream 2% applied twice daily combined with narrowband UVB therapy 3 times weekly for facial vitiligo. The investigators reported repigmentation of the skin in all 11 patients (which included 4 Asian patients and 1 Hispanic patient), with a mean improvement of 70% in F-VASI score (range, 50%-87%).10 In a nonrandomized cohort study of 16 patients later that year, twice-daily application of tofacitinib cream 2% on facial and nonfacial vitiligo lesions resulted in partial repigmentation in 81.3% of patients: 4 (25%) achieved greater than 90% improvement, 5 (31.3%) achieved improvement of 25% to 75%, and 4 (25%) achieved 5% to 15% improvement.11 The researchers also found that tofacitinib cream 2% was significantly more effective in facial than nonfacial lesions (P=.02).

While tofacitinib has shown promise in early studies, recent advancements have led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, another topical JAK inhibitor that has undergone robust clinical testing for vitiligo.12-14 Ruxolitinib, a JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitor, is the first and only US Food and Drug Administration–approved topical JAK inhibitor for vitiligo.14,15 Two phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials of identical design conducted across 101 centers in North America and Europe (TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2) assessed the efficacy of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% in 674 patients aged 12 years and older with nonsegmental vitiligo covering 10% or lower total BSA.13 In both trials, twice-daily application of topical ruxolitinib resulted in greater facial repigmentation and improvement in F-VASI75 score (ie, a reduction of at least 75% from baseline) at 24 weeks in 29.9% (66/221) and 30.1% (69/222) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. Continued application through 52 weeks resulted in F-VASI75 response in 52.6% (91/173) and 48.0% (85/177) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. The most frequently reported adverse events were acne (6.3% [14/221] and 6.6% [15/228]), nasopharyngitis (5.4% [12/221] and 6.1% [14/228]), and pruritus (5.4% [12/221] and 5.3% [12/228]). These findings align with prior subgroup analyses of an earlier phase 2 double- blind RCT of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% that indicated similar improvement in vitiligo among patients with differing skin tones.17

There are no additional large-scale RCTs examining topical JAK inhibitors with intentional subanalysis of diverse skin tones.16,17,18 Studies examining topical JAK inhibitors have expanded to be more inclusive, providing hope for the future of topical vitiligo therapeutics for all patients.

Final Thoughts

It is imperative to increase racial/ethnic and skin type diversity in research on JAK inhibitors for vitiligo. While the studies mentioned here are inclusive of an array of races and skin tones, it is crucial that future research continue to expand the number of diverse participants, especially given the increased psychosocial burdens of vitiligo in patients with darker skin types.4 Intentional subgroup analyses across skin tones are vital to characterize and unmask potential differences between lighter and darker skin types. This point was exemplified by a 2024 RCT that investigated ritlecitinib efficacy with biomarker analysis across skin types.19 For patients receiving ritlecitinib 50 mg, IL-9 and IL-22 expression were decreased in darker vs lighter skin tones (P<.05). This intentional and inclusive analysis revealed a potential immunologic mechanism for why darker skin tones respond to JAK inhibitor therapy earlier than lighter skin tones.19

In the expanding landscape of oral and topical JAK inhibitors for vitiligo, continued efforts to assess these therapies across a range of skin tones and racial/ ethnic groups are critical. The efficacy of JAK inhibitors in other populations, including pediatric patients and patients with refractory segmental disease, have been reported.20,21 As larger studies are developed based on the success of individual cases, researchers should investigate the efficacy of JAK inhibitors for various vitiligo subtypes (eg, segmental, nonsegmental) and recalcitrant disease and conduct direct comparisons with traditional treatments across diverse skin tones and racial/ethnic subgroup analyses to ensure broad therapeutic applicability.

- Alikhan Ali, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview. part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2010.11.061

- Akl J, Lee S, Ju HJ, et al. Estimating the burden of vitiligo: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:E386-E396. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00026-4

- Mastacouris N, Strunk A, Garg A. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed vitiligo according to race and ethnicity, age, and sex in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:986-990. doi:10.1001/jama dermatol.2023.2162

- Bibeau K, Ezzedine K, Harris JE, et al. Mental health and psychosocial quality-of-life burden among patients with vitiligo: findings from the global VALIANT study. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1124-1128. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2787

- van Geel N, Speeckaert R, Taïeb A, et al. Worldwide expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vitiligo: position statement from the International Vitiligo Task Force part 1: towards a new management algorithm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023; 37:2173-2184. doi:10.1111/jdv.19451

- Rashighi M, Agarwal P, Richmond JM, et al. CXCL10 is critical for the progression and maintenance of depigmentation in a mouse model of vitiligo. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:223ra23. doi:10.1126 /scitranslmed.3007811

- Harris JE, Rashighi M, Nguyen N, et al. Rapid skin repigmentation on oral ruxolitinib in a patient with coexistent vitiligo and alopecia areata (AA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:370-371. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2015.09.073

- Ezzedine K, Peeva E, Yamguchi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ritlecitinib for the treatment of active nonsegmental vitiligo: a randomized phase 2b clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:395-403. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.005

- Passeron T, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adults with extensive non-segmental vitiligo: a phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;73:102655. doi:10.1016 /j.eclinm.2024.102655

- McKesey J, Pandya AG. A pilot study of 2% tofacitinib cream with narrowband ultraviolet B for the treatment of facial vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:646-648. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.032

- Mobasher P, Guerra R, Li SJ, et al. Open-label pilot study of tofacitinib 2% for the treatment of refractory vitiligo. Brit J Dermatol. 2020;182:1047-1049. doi:10.1111/bjd.18606

- Rosmarin D, Pandya AG, Lebwohl M, et al. Ruxolitinib cream for treatment of vitiligo: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:110-120. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30609-7

- Rosmarin D, Passeron T, Pandya AG, et al; TRuE-V Study Group. Two phase 3, randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1445-1455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2118828

- FDA. FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. Published July 19, 2022. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical-treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients-aged-12-and-older

- Quintás-Cardama A, Vaddi K, Liu P, et al. Preclinical characterization of the selective JAK1/2 inhibitor INCB018424: therapeutic implications for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;115:3109-3117. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-04-214957

- Seneschal J, Wolkerstorfer A, Desai SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo by patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics: week 52 pooled subgroup analysis from two randomized phase 3 studies. Brit J Dermatol. 2023;188 (suppl 1):ljac106.006. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljac106.006

- Hamzavi I, Rosmarin D, Harris JE, et al. Efficacy of ruxolitinib cream in vitiligo by patient characteristics and affected body areas: descriptive subgroup analyses from a phase 2, randomized, double-blind trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1398-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.047

- Inoue S, Suzuki T, Sano S, et al. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of vitiligo. J Dermatol Sci. 2024;113:86-92. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2023.12.008

- Peeva E, Yamaguchi Y, Ye Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in vitiligo patients across Fitzpatrick skin types with biomarker analyses. Exp Dermatol. 2024;33:E15177. doi:10.1111/exd.15177

- Mu Y, Pan T, Chen L. Treatment of refractory segmental vitiligo and alopecia areata in a child with upadacitinib and NB-UVB: a case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2024;17:1789-1792. doi:10.2147 /CCID.S467026

- Shah RR, McMichael A. Resistant vitiligo treated with tofacitinib and sustained repigmentation after discontinuation. Skinmed. 2024;22:384-385.

Vitiligo is a common autoimmune disorder characterized by cutaneous depigmentation that has a substantial impact on patient quality of life.1 Vitiligo affects approximately 28.5 million individuals globally, with the highest lifetime prevalence occurring in Central Europe and South Asia.2 In the United States, Asian American and Hispanic/Latine populations most commonly are affected.3 The accompanying psychosocial burdens of vitiligo are particularly substantial among individuals with darker skin types, as evidenced by higher rates of concomitant anxiety and depression in these patients.4 Despite this, patients with skin of color are underrepresented in vitiligo research.2

Treatment algorithms developed based on worldwide expert consensus recommendations provide valuable insights into the management of segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo.5 The mainstay therapeutics include topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and phototherapy. While vitiligo pathogenesis is not completely understood, recent advances have focused on the role of the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway. Interferon gamma drives vitiligo pathogenesis through this pathway, upregulating C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 and promoting CD8+ T-cell recruitment, resulting in targeted melanocyte destruction.6 The emergence of targeted therapeutics may address equity and inclusion gaps. Herein, we highlight innovations in vitiligo treatment with a focus on oral and topical JAK inhibitors.

Oral JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

The therapeutic potential of JAK inhibitors for vitiligo was first reported when patients with alopecia areata and comorbid vitiligo experienced repigmentation of the skin following administration of oral ruxolitinib.7 Since this discovery, other oral JAK inhibitors have been investigated for vitiligo treatment. A phase 2b randomized clinical trial (RCT) of 364 patients examined oral ritlecitinib, a JAK3 inhibitor, and found it to be effective in treating active nonsegmental vitiligo.8 Patients aged 18 to 65 years with active nonsegmental vitiligo that had been present for 3 months or more as well as 4% to 50% body surface area (BSA) affected excluding acral surfaces and at least 0.25% facial involvement were included. Treatment groups received 50 mg (with or without a 100- or 200- mg loading dose), 30 mg, or 10 mg daily for 24 weeks. The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI) score. Significant differences in F-VASI percentage change compared with placebo occurred for those in the 50-mg group who received a loading dose (-21.2 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) and those who did not receive a loading dose (–18.5 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) as well as the 30-mg group (-14.6 vs 2.1 [P=.01]). Continued repigmentation of the skin was observed in the 24-week extension period, indicating that longer treatment periods may be necessary for optimal repigmentation results. Ritlecitinib generally was well tolerated, and the most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis (15.9%), upper respiratory tract infection (11.5%), and headache (8.8%). Most patients identified as White (67.6%), with 23.6% identifying as Asian and 2.7% identifying as Black. The authors stated that continued improvement was observed in the extension period across all skin types; however, the data were not reported.8

Upadacitnib, an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor, also has demonstrated efficacy in nonsegmental vitiligo in a phase 2 RCT.9 Adult patients (N=185) with nonsegmental vitiligo were randomized to receive upadacitinib 6 mg, 11 mg, or 22 mg or placebo (the placebo group subsequently was switched to upadacitinib 11 mg or 22 mg after 24 weeks). The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in F-VASI score at 24 weeks. The higher doses of upadacitinib resulted in significant changes in F-VASI scored compared with placebo (6 mg: -7.60 [95% CI, -22.18 to 6.97][P=.30]; 11 mg: -21.27 [95% CI, -36.02 to -6.52][P=.01]; 22 mg: -19.60 [95% CI, -35.04 to –4.16][P=.01]). As with ritlecitinib, continued repigmentation was observed beyond the initial 24-week period. Of the 185 participants, 5.9% identified as Black and 13.5% identified as Asian. The investigators reported that the percentage change in F-VASI score was consistent across skin types.9 The results of these phase 2 RCTs are encouraging, and we anticipate the findings of 2 phase 3 RCTs for ritlecitinib and upadacitinib that currently are underway (Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers NCT05583526 and NCT06118411).

Topical JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

Tofacitinib cream 2%, a selective JAK3 inhibitor, has shown therapeutic potential for treatment of vitiligo. One of the earliest pilot studies on topical tofacitinib examined the efficacy of tofacitinib cream 2% applied twice daily combined with narrowband UVB therapy 3 times weekly for facial vitiligo. The investigators reported repigmentation of the skin in all 11 patients (which included 4 Asian patients and 1 Hispanic patient), with a mean improvement of 70% in F-VASI score (range, 50%-87%).10 In a nonrandomized cohort study of 16 patients later that year, twice-daily application of tofacitinib cream 2% on facial and nonfacial vitiligo lesions resulted in partial repigmentation in 81.3% of patients: 4 (25%) achieved greater than 90% improvement, 5 (31.3%) achieved improvement of 25% to 75%, and 4 (25%) achieved 5% to 15% improvement.11 The researchers also found that tofacitinib cream 2% was significantly more effective in facial than nonfacial lesions (P=.02).

While tofacitinib has shown promise in early studies, recent advancements have led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, another topical JAK inhibitor that has undergone robust clinical testing for vitiligo.12-14 Ruxolitinib, a JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitor, is the first and only US Food and Drug Administration–approved topical JAK inhibitor for vitiligo.14,15 Two phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials of identical design conducted across 101 centers in North America and Europe (TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2) assessed the efficacy of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% in 674 patients aged 12 years and older with nonsegmental vitiligo covering 10% or lower total BSA.13 In both trials, twice-daily application of topical ruxolitinib resulted in greater facial repigmentation and improvement in F-VASI75 score (ie, a reduction of at least 75% from baseline) at 24 weeks in 29.9% (66/221) and 30.1% (69/222) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. Continued application through 52 weeks resulted in F-VASI75 response in 52.6% (91/173) and 48.0% (85/177) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. The most frequently reported adverse events were acne (6.3% [14/221] and 6.6% [15/228]), nasopharyngitis (5.4% [12/221] and 6.1% [14/228]), and pruritus (5.4% [12/221] and 5.3% [12/228]). These findings align with prior subgroup analyses of an earlier phase 2 double- blind RCT of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% that indicated similar improvement in vitiligo among patients with differing skin tones.17

There are no additional large-scale RCTs examining topical JAK inhibitors with intentional subanalysis of diverse skin tones.16,17,18 Studies examining topical JAK inhibitors have expanded to be more inclusive, providing hope for the future of topical vitiligo therapeutics for all patients.

Final Thoughts

It is imperative to increase racial/ethnic and skin type diversity in research on JAK inhibitors for vitiligo. While the studies mentioned here are inclusive of an array of races and skin tones, it is crucial that future research continue to expand the number of diverse participants, especially given the increased psychosocial burdens of vitiligo in patients with darker skin types.4 Intentional subgroup analyses across skin tones are vital to characterize and unmask potential differences between lighter and darker skin types. This point was exemplified by a 2024 RCT that investigated ritlecitinib efficacy with biomarker analysis across skin types.19 For patients receiving ritlecitinib 50 mg, IL-9 and IL-22 expression were decreased in darker vs lighter skin tones (P<.05). This intentional and inclusive analysis revealed a potential immunologic mechanism for why darker skin tones respond to JAK inhibitor therapy earlier than lighter skin tones.19

In the expanding landscape of oral and topical JAK inhibitors for vitiligo, continued efforts to assess these therapies across a range of skin tones and racial/ ethnic groups are critical. The efficacy of JAK inhibitors in other populations, including pediatric patients and patients with refractory segmental disease, have been reported.20,21 As larger studies are developed based on the success of individual cases, researchers should investigate the efficacy of JAK inhibitors for various vitiligo subtypes (eg, segmental, nonsegmental) and recalcitrant disease and conduct direct comparisons with traditional treatments across diverse skin tones and racial/ethnic subgroup analyses to ensure broad therapeutic applicability.

Vitiligo is a common autoimmune disorder characterized by cutaneous depigmentation that has a substantial impact on patient quality of life.1 Vitiligo affects approximately 28.5 million individuals globally, with the highest lifetime prevalence occurring in Central Europe and South Asia.2 In the United States, Asian American and Hispanic/Latine populations most commonly are affected.3 The accompanying psychosocial burdens of vitiligo are particularly substantial among individuals with darker skin types, as evidenced by higher rates of concomitant anxiety and depression in these patients.4 Despite this, patients with skin of color are underrepresented in vitiligo research.2

Treatment algorithms developed based on worldwide expert consensus recommendations provide valuable insights into the management of segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo.5 The mainstay therapeutics include topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and phototherapy. While vitiligo pathogenesis is not completely understood, recent advances have focused on the role of the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway. Interferon gamma drives vitiligo pathogenesis through this pathway, upregulating C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 and promoting CD8+ T-cell recruitment, resulting in targeted melanocyte destruction.6 The emergence of targeted therapeutics may address equity and inclusion gaps. Herein, we highlight innovations in vitiligo treatment with a focus on oral and topical JAK inhibitors.

Oral JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

The therapeutic potential of JAK inhibitors for vitiligo was first reported when patients with alopecia areata and comorbid vitiligo experienced repigmentation of the skin following administration of oral ruxolitinib.7 Since this discovery, other oral JAK inhibitors have been investigated for vitiligo treatment. A phase 2b randomized clinical trial (RCT) of 364 patients examined oral ritlecitinib, a JAK3 inhibitor, and found it to be effective in treating active nonsegmental vitiligo.8 Patients aged 18 to 65 years with active nonsegmental vitiligo that had been present for 3 months or more as well as 4% to 50% body surface area (BSA) affected excluding acral surfaces and at least 0.25% facial involvement were included. Treatment groups received 50 mg (with or without a 100- or 200- mg loading dose), 30 mg, or 10 mg daily for 24 weeks. The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI) score. Significant differences in F-VASI percentage change compared with placebo occurred for those in the 50-mg group who received a loading dose (-21.2 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) and those who did not receive a loading dose (–18.5 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) as well as the 30-mg group (-14.6 vs 2.1 [P=.01]). Continued repigmentation of the skin was observed in the 24-week extension period, indicating that longer treatment periods may be necessary for optimal repigmentation results. Ritlecitinib generally was well tolerated, and the most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis (15.9%), upper respiratory tract infection (11.5%), and headache (8.8%). Most patients identified as White (67.6%), with 23.6% identifying as Asian and 2.7% identifying as Black. The authors stated that continued improvement was observed in the extension period across all skin types; however, the data were not reported.8

Upadacitnib, an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor, also has demonstrated efficacy in nonsegmental vitiligo in a phase 2 RCT.9 Adult patients (N=185) with nonsegmental vitiligo were randomized to receive upadacitinib 6 mg, 11 mg, or 22 mg or placebo (the placebo group subsequently was switched to upadacitinib 11 mg or 22 mg after 24 weeks). The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in F-VASI score at 24 weeks. The higher doses of upadacitinib resulted in significant changes in F-VASI scored compared with placebo (6 mg: -7.60 [95% CI, -22.18 to 6.97][P=.30]; 11 mg: -21.27 [95% CI, -36.02 to -6.52][P=.01]; 22 mg: -19.60 [95% CI, -35.04 to –4.16][P=.01]). As with ritlecitinib, continued repigmentation was observed beyond the initial 24-week period. Of the 185 participants, 5.9% identified as Black and 13.5% identified as Asian. The investigators reported that the percentage change in F-VASI score was consistent across skin types.9 The results of these phase 2 RCTs are encouraging, and we anticipate the findings of 2 phase 3 RCTs for ritlecitinib and upadacitinib that currently are underway (Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers NCT05583526 and NCT06118411).

Topical JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

Tofacitinib cream 2%, a selective JAK3 inhibitor, has shown therapeutic potential for treatment of vitiligo. One of the earliest pilot studies on topical tofacitinib examined the efficacy of tofacitinib cream 2% applied twice daily combined with narrowband UVB therapy 3 times weekly for facial vitiligo. The investigators reported repigmentation of the skin in all 11 patients (which included 4 Asian patients and 1 Hispanic patient), with a mean improvement of 70% in F-VASI score (range, 50%-87%).10 In a nonrandomized cohort study of 16 patients later that year, twice-daily application of tofacitinib cream 2% on facial and nonfacial vitiligo lesions resulted in partial repigmentation in 81.3% of patients: 4 (25%) achieved greater than 90% improvement, 5 (31.3%) achieved improvement of 25% to 75%, and 4 (25%) achieved 5% to 15% improvement.11 The researchers also found that tofacitinib cream 2% was significantly more effective in facial than nonfacial lesions (P=.02).

While tofacitinib has shown promise in early studies, recent advancements have led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, another topical JAK inhibitor that has undergone robust clinical testing for vitiligo.12-14 Ruxolitinib, a JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitor, is the first and only US Food and Drug Administration–approved topical JAK inhibitor for vitiligo.14,15 Two phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials of identical design conducted across 101 centers in North America and Europe (TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2) assessed the efficacy of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% in 674 patients aged 12 years and older with nonsegmental vitiligo covering 10% or lower total BSA.13 In both trials, twice-daily application of topical ruxolitinib resulted in greater facial repigmentation and improvement in F-VASI75 score (ie, a reduction of at least 75% from baseline) at 24 weeks in 29.9% (66/221) and 30.1% (69/222) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. Continued application through 52 weeks resulted in F-VASI75 response in 52.6% (91/173) and 48.0% (85/177) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. The most frequently reported adverse events were acne (6.3% [14/221] and 6.6% [15/228]), nasopharyngitis (5.4% [12/221] and 6.1% [14/228]), and pruritus (5.4% [12/221] and 5.3% [12/228]). These findings align with prior subgroup analyses of an earlier phase 2 double- blind RCT of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% that indicated similar improvement in vitiligo among patients with differing skin tones.17

There are no additional large-scale RCTs examining topical JAK inhibitors with intentional subanalysis of diverse skin tones.16,17,18 Studies examining topical JAK inhibitors have expanded to be more inclusive, providing hope for the future of topical vitiligo therapeutics for all patients.

Final Thoughts

It is imperative to increase racial/ethnic and skin type diversity in research on JAK inhibitors for vitiligo. While the studies mentioned here are inclusive of an array of races and skin tones, it is crucial that future research continue to expand the number of diverse participants, especially given the increased psychosocial burdens of vitiligo in patients with darker skin types.4 Intentional subgroup analyses across skin tones are vital to characterize and unmask potential differences between lighter and darker skin types. This point was exemplified by a 2024 RCT that investigated ritlecitinib efficacy with biomarker analysis across skin types.19 For patients receiving ritlecitinib 50 mg, IL-9 and IL-22 expression were decreased in darker vs lighter skin tones (P<.05). This intentional and inclusive analysis revealed a potential immunologic mechanism for why darker skin tones respond to JAK inhibitor therapy earlier than lighter skin tones.19

In the expanding landscape of oral and topical JAK inhibitors for vitiligo, continued efforts to assess these therapies across a range of skin tones and racial/ ethnic groups are critical. The efficacy of JAK inhibitors in other populations, including pediatric patients and patients with refractory segmental disease, have been reported.20,21 As larger studies are developed based on the success of individual cases, researchers should investigate the efficacy of JAK inhibitors for various vitiligo subtypes (eg, segmental, nonsegmental) and recalcitrant disease and conduct direct comparisons with traditional treatments across diverse skin tones and racial/ethnic subgroup analyses to ensure broad therapeutic applicability.

- Alikhan Ali, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview. part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2010.11.061

- Akl J, Lee S, Ju HJ, et al. Estimating the burden of vitiligo: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:E386-E396. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00026-4

- Mastacouris N, Strunk A, Garg A. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed vitiligo according to race and ethnicity, age, and sex in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:986-990. doi:10.1001/jama dermatol.2023.2162

- Bibeau K, Ezzedine K, Harris JE, et al. Mental health and psychosocial quality-of-life burden among patients with vitiligo: findings from the global VALIANT study. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1124-1128. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2787

- van Geel N, Speeckaert R, Taïeb A, et al. Worldwide expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vitiligo: position statement from the International Vitiligo Task Force part 1: towards a new management algorithm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023; 37:2173-2184. doi:10.1111/jdv.19451

- Rashighi M, Agarwal P, Richmond JM, et al. CXCL10 is critical for the progression and maintenance of depigmentation in a mouse model of vitiligo. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:223ra23. doi:10.1126 /scitranslmed.3007811

- Harris JE, Rashighi M, Nguyen N, et al. Rapid skin repigmentation on oral ruxolitinib in a patient with coexistent vitiligo and alopecia areata (AA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:370-371. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2015.09.073

- Ezzedine K, Peeva E, Yamguchi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ritlecitinib for the treatment of active nonsegmental vitiligo: a randomized phase 2b clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:395-403. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.005

- Passeron T, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adults with extensive non-segmental vitiligo: a phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;73:102655. doi:10.1016 /j.eclinm.2024.102655

- McKesey J, Pandya AG. A pilot study of 2% tofacitinib cream with narrowband ultraviolet B for the treatment of facial vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:646-648. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.032

- Mobasher P, Guerra R, Li SJ, et al. Open-label pilot study of tofacitinib 2% for the treatment of refractory vitiligo. Brit J Dermatol. 2020;182:1047-1049. doi:10.1111/bjd.18606

- Rosmarin D, Pandya AG, Lebwohl M, et al. Ruxolitinib cream for treatment of vitiligo: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:110-120. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30609-7

- Rosmarin D, Passeron T, Pandya AG, et al; TRuE-V Study Group. Two phase 3, randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1445-1455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2118828

- FDA. FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. Published July 19, 2022. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical-treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients-aged-12-and-older

- Quintás-Cardama A, Vaddi K, Liu P, et al. Preclinical characterization of the selective JAK1/2 inhibitor INCB018424: therapeutic implications for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;115:3109-3117. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-04-214957

- Seneschal J, Wolkerstorfer A, Desai SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo by patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics: week 52 pooled subgroup analysis from two randomized phase 3 studies. Brit J Dermatol. 2023;188 (suppl 1):ljac106.006. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljac106.006

- Hamzavi I, Rosmarin D, Harris JE, et al. Efficacy of ruxolitinib cream in vitiligo by patient characteristics and affected body areas: descriptive subgroup analyses from a phase 2, randomized, double-blind trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1398-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.047

- Inoue S, Suzuki T, Sano S, et al. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of vitiligo. J Dermatol Sci. 2024;113:86-92. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2023.12.008

- Peeva E, Yamaguchi Y, Ye Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in vitiligo patients across Fitzpatrick skin types with biomarker analyses. Exp Dermatol. 2024;33:E15177. doi:10.1111/exd.15177

- Mu Y, Pan T, Chen L. Treatment of refractory segmental vitiligo and alopecia areata in a child with upadacitinib and NB-UVB: a case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2024;17:1789-1792. doi:10.2147 /CCID.S467026

- Shah RR, McMichael A. Resistant vitiligo treated with tofacitinib and sustained repigmentation after discontinuation. Skinmed. 2024;22:384-385.

- Alikhan Ali, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview. part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2010.11.061

- Akl J, Lee S, Ju HJ, et al. Estimating the burden of vitiligo: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:E386-E396. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00026-4

- Mastacouris N, Strunk A, Garg A. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed vitiligo according to race and ethnicity, age, and sex in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:986-990. doi:10.1001/jama dermatol.2023.2162

- Bibeau K, Ezzedine K, Harris JE, et al. Mental health and psychosocial quality-of-life burden among patients with vitiligo: findings from the global VALIANT study. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1124-1128. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2787

- van Geel N, Speeckaert R, Taïeb A, et al. Worldwide expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vitiligo: position statement from the International Vitiligo Task Force part 1: towards a new management algorithm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023; 37:2173-2184. doi:10.1111/jdv.19451

- Rashighi M, Agarwal P, Richmond JM, et al. CXCL10 is critical for the progression and maintenance of depigmentation in a mouse model of vitiligo. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:223ra23. doi:10.1126 /scitranslmed.3007811

- Harris JE, Rashighi M, Nguyen N, et al. Rapid skin repigmentation on oral ruxolitinib in a patient with coexistent vitiligo and alopecia areata (AA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:370-371. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2015.09.073

- Ezzedine K, Peeva E, Yamguchi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ritlecitinib for the treatment of active nonsegmental vitiligo: a randomized phase 2b clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:395-403. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.005

- Passeron T, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adults with extensive non-segmental vitiligo: a phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;73:102655. doi:10.1016 /j.eclinm.2024.102655

- McKesey J, Pandya AG. A pilot study of 2% tofacitinib cream with narrowband ultraviolet B for the treatment of facial vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:646-648. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.032

- Mobasher P, Guerra R, Li SJ, et al. Open-label pilot study of tofacitinib 2% for the treatment of refractory vitiligo. Brit J Dermatol. 2020;182:1047-1049. doi:10.1111/bjd.18606

- Rosmarin D, Pandya AG, Lebwohl M, et al. Ruxolitinib cream for treatment of vitiligo: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:110-120. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30609-7

- Rosmarin D, Passeron T, Pandya AG, et al; TRuE-V Study Group. Two phase 3, randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1445-1455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2118828

- FDA. FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. Published July 19, 2022. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical-treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients-aged-12-and-older

- Quintás-Cardama A, Vaddi K, Liu P, et al. Preclinical characterization of the selective JAK1/2 inhibitor INCB018424: therapeutic implications for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;115:3109-3117. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-04-214957

- Seneschal J, Wolkerstorfer A, Desai SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo by patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics: week 52 pooled subgroup analysis from two randomized phase 3 studies. Brit J Dermatol. 2023;188 (suppl 1):ljac106.006. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljac106.006

- Hamzavi I, Rosmarin D, Harris JE, et al. Efficacy of ruxolitinib cream in vitiligo by patient characteristics and affected body areas: descriptive subgroup analyses from a phase 2, randomized, double-blind trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1398-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.047

- Inoue S, Suzuki T, Sano S, et al. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of vitiligo. J Dermatol Sci. 2024;113:86-92. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2023.12.008

- Peeva E, Yamaguchi Y, Ye Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in vitiligo patients across Fitzpatrick skin types with biomarker analyses. Exp Dermatol. 2024;33:E15177. doi:10.1111/exd.15177

- Mu Y, Pan T, Chen L. Treatment of refractory segmental vitiligo and alopecia areata in a child with upadacitinib and NB-UVB: a case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2024;17:1789-1792. doi:10.2147 /CCID.S467026

- Shah RR, McMichael A. Resistant vitiligo treated with tofacitinib and sustained repigmentation after discontinuation. Skinmed. 2024;22:384-385.

Emerging Insights in Vitiligo Therapeutics: A Focus on Oral and Topical JAK Inhibitors

Emerging Insights in Vitiligo Therapeutics: A Focus on Oral and Topical JAK Inhibitors

Vitiligo: Updated Guidelines, New Treatments Reviewed

of the disease, delegates heard at a recent conference, the Dermatology Days of Paris 2024, organized by the French Society of Dermatology.

A Distinct Disease

An estimated 65% of patients with vitiligo in Europe have been told that their disease is untreatable, according to a recent international study, and this figure rises to 75% in France, Julien Seneschal, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Bordeaux University Hospital in Bordeaux, France, told the audience during his presentation.

“This is a message we must change,” he said.

The survey also revealed that in France, even when treatment is offered, 80% of patients do not receive appropriate care. However, treatments do exist, and novel approaches are revolutionizing the management of patients, whatever the degree of severity, he explained.

As a specialist in inflammatory and autoimmune skin diseases, he stressed that these advances are important because vitiligo is a distinct disease and not merely a cosmetic issue. When widespread, it has a significant impact on quality of life and can lead to depression, anxiety, and even suicidal thoughts, even though it does not affect life expectancy.

Updated Guidelines

Since October 2023, new international guidelines for vitiligo management have defined a therapeutic algorithm.

“Nowadays, we place the patient at the center of therapeutic decision-making,” Seneschal said. It is essential to educate patients about the disease and take the time to understand their treatment goals.

For patients with mild vitiligo that does not affect quality of life, simple monitoring may suffice.

However, when a decision is made to pursue treatment, its goals should be:

- Halting disease progression and melanocyte loss

- Achieving repigmentation (a process that can take 6-24 months)

- Preventing relapse after treatment discontinuation

For moderate cases affecting less than 10% of the skin surface, localized treatment is recommended. Previously, topical corticosteroids were used for body lesions, while tacrolimus 0.1% (off-label) was often prescribed for the face and neck. However, as of March 2024, tacrolimus has been officially approved for use in patients aged ≥ 2 years.

In more severe, generalized, and/or active cases, oral treatments such as corticosteroids taken twice weekly for 12-24 weeks can stabilize the disease in 80% of cases (off-label use). Other off-label options include methotrexate, cyclosporine, and tetracyclines.

Targeted Therapies

Recent targeted therapies have significantly advanced the treatment of moderate to severe vitiligo. Since January 2024, the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1)/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib cream has been available in community pharmacies after previously being restricted to hospital use, Seneschal said, and can have spectacular results if previous treatments have failed.

Ruxolitinib is approved for patients aged > 12 years with nonsegmental vitiligo and facial involvement, covering up to 10% of the body surface area. Treatment typically lasts 6 months to 1 year.

Key Findings

The cream-formulated drug has been demonstrated effective in reducing inflammation in two phase 3 clinical trials published in the New England Journal of Medicine that demonstrated its efficacy and safety in patients aged ≥ 12 years. The treatment was well tolerated despite some mild acne-like reactions in 8% of patients. It was shown to be very effective on the face, with a reduction of over 75% in facial lesions in more than 50% of patients, and had good effectiveness on the body, with a 50% decrease in lesions in more than 50% of patients on the body, trunk, arms, and legs, excluding hands and feet.

“Areas like the underarms, hands, and feet are more resistant to treatment,” Seneschal noted.

Although some improvement continues after 1 year, disease recurrence is common if treatment is stopped: Only 40% of patients maintain therapeutic benefits in the year following discontinuation.

“It is therefore important to consider the value of continuing treatment in order to achieve better efficacy or to maintain the repigmentation obtained,” Seneschal said.

He stressed that all treatments should be paired with phototherapy, typically narrowband UVB, to accelerate repigmentation. “There is no increased skin cancer risk in vitiligo patients treated with narrowband UVB,” Seneschal said.

New Therapies

Emerging treatments under development, including injectable biologics alone or in combination with phototherapy, show great promise, he said. Oral JAK inhibitors such as ritlecitinib, upadacitinib, and povorcitinib are also under investigation.

In particular, ritlecitinib, a JAK3/TEC pathway inhibitor, has shown significant reductions in affected skin area in severely affected patients in a phase 2b trial. Phase 3 trials are now underway.

On the safety profile of JAK inhibitors, Seneschal said that studies are reassuring but highlighted the need to monitor cardiovascular, thromboembolic, and infectious risks.

“The question of safety is important because vitiligo is a visible but nonsevere condition, and we do not want to expose patients to unnecessary risks,” added Gaëlle Quéreux, MD, PhD, president of the French Society of Dermatology.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

of the disease, delegates heard at a recent conference, the Dermatology Days of Paris 2024, organized by the French Society of Dermatology.

A Distinct Disease

An estimated 65% of patients with vitiligo in Europe have been told that their disease is untreatable, according to a recent international study, and this figure rises to 75% in France, Julien Seneschal, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Bordeaux University Hospital in Bordeaux, France, told the audience during his presentation.

“This is a message we must change,” he said.

The survey also revealed that in France, even when treatment is offered, 80% of patients do not receive appropriate care. However, treatments do exist, and novel approaches are revolutionizing the management of patients, whatever the degree of severity, he explained.

As a specialist in inflammatory and autoimmune skin diseases, he stressed that these advances are important because vitiligo is a distinct disease and not merely a cosmetic issue. When widespread, it has a significant impact on quality of life and can lead to depression, anxiety, and even suicidal thoughts, even though it does not affect life expectancy.

Updated Guidelines

Since October 2023, new international guidelines for vitiligo management have defined a therapeutic algorithm.

“Nowadays, we place the patient at the center of therapeutic decision-making,” Seneschal said. It is essential to educate patients about the disease and take the time to understand their treatment goals.

For patients with mild vitiligo that does not affect quality of life, simple monitoring may suffice.

However, when a decision is made to pursue treatment, its goals should be:

- Halting disease progression and melanocyte loss

- Achieving repigmentation (a process that can take 6-24 months)

- Preventing relapse after treatment discontinuation

For moderate cases affecting less than 10% of the skin surface, localized treatment is recommended. Previously, topical corticosteroids were used for body lesions, while tacrolimus 0.1% (off-label) was often prescribed for the face and neck. However, as of March 2024, tacrolimus has been officially approved for use in patients aged ≥ 2 years.

In more severe, generalized, and/or active cases, oral treatments such as corticosteroids taken twice weekly for 12-24 weeks can stabilize the disease in 80% of cases (off-label use). Other off-label options include methotrexate, cyclosporine, and tetracyclines.

Targeted Therapies

Recent targeted therapies have significantly advanced the treatment of moderate to severe vitiligo. Since January 2024, the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1)/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib cream has been available in community pharmacies after previously being restricted to hospital use, Seneschal said, and can have spectacular results if previous treatments have failed.

Ruxolitinib is approved for patients aged > 12 years with nonsegmental vitiligo and facial involvement, covering up to 10% of the body surface area. Treatment typically lasts 6 months to 1 year.

Key Findings

The cream-formulated drug has been demonstrated effective in reducing inflammation in two phase 3 clinical trials published in the New England Journal of Medicine that demonstrated its efficacy and safety in patients aged ≥ 12 years. The treatment was well tolerated despite some mild acne-like reactions in 8% of patients. It was shown to be very effective on the face, with a reduction of over 75% in facial lesions in more than 50% of patients, and had good effectiveness on the body, with a 50% decrease in lesions in more than 50% of patients on the body, trunk, arms, and legs, excluding hands and feet.

“Areas like the underarms, hands, and feet are more resistant to treatment,” Seneschal noted.

Although some improvement continues after 1 year, disease recurrence is common if treatment is stopped: Only 40% of patients maintain therapeutic benefits in the year following discontinuation.

“It is therefore important to consider the value of continuing treatment in order to achieve better efficacy or to maintain the repigmentation obtained,” Seneschal said.

He stressed that all treatments should be paired with phototherapy, typically narrowband UVB, to accelerate repigmentation. “There is no increased skin cancer risk in vitiligo patients treated with narrowband UVB,” Seneschal said.

New Therapies

Emerging treatments under development, including injectable biologics alone or in combination with phototherapy, show great promise, he said. Oral JAK inhibitors such as ritlecitinib, upadacitinib, and povorcitinib are also under investigation.

In particular, ritlecitinib, a JAK3/TEC pathway inhibitor, has shown significant reductions in affected skin area in severely affected patients in a phase 2b trial. Phase 3 trials are now underway.

On the safety profile of JAK inhibitors, Seneschal said that studies are reassuring but highlighted the need to monitor cardiovascular, thromboembolic, and infectious risks.

“The question of safety is important because vitiligo is a visible but nonsevere condition, and we do not want to expose patients to unnecessary risks,” added Gaëlle Quéreux, MD, PhD, president of the French Society of Dermatology.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

of the disease, delegates heard at a recent conference, the Dermatology Days of Paris 2024, organized by the French Society of Dermatology.

A Distinct Disease

An estimated 65% of patients with vitiligo in Europe have been told that their disease is untreatable, according to a recent international study, and this figure rises to 75% in France, Julien Seneschal, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Bordeaux University Hospital in Bordeaux, France, told the audience during his presentation.

“This is a message we must change,” he said.

The survey also revealed that in France, even when treatment is offered, 80% of patients do not receive appropriate care. However, treatments do exist, and novel approaches are revolutionizing the management of patients, whatever the degree of severity, he explained.

As a specialist in inflammatory and autoimmune skin diseases, he stressed that these advances are important because vitiligo is a distinct disease and not merely a cosmetic issue. When widespread, it has a significant impact on quality of life and can lead to depression, anxiety, and even suicidal thoughts, even though it does not affect life expectancy.

Updated Guidelines

Since October 2023, new international guidelines for vitiligo management have defined a therapeutic algorithm.

“Nowadays, we place the patient at the center of therapeutic decision-making,” Seneschal said. It is essential to educate patients about the disease and take the time to understand their treatment goals.

For patients with mild vitiligo that does not affect quality of life, simple monitoring may suffice.

However, when a decision is made to pursue treatment, its goals should be:

- Halting disease progression and melanocyte loss

- Achieving repigmentation (a process that can take 6-24 months)

- Preventing relapse after treatment discontinuation

For moderate cases affecting less than 10% of the skin surface, localized treatment is recommended. Previously, topical corticosteroids were used for body lesions, while tacrolimus 0.1% (off-label) was often prescribed for the face and neck. However, as of March 2024, tacrolimus has been officially approved for use in patients aged ≥ 2 years.

In more severe, generalized, and/or active cases, oral treatments such as corticosteroids taken twice weekly for 12-24 weeks can stabilize the disease in 80% of cases (off-label use). Other off-label options include methotrexate, cyclosporine, and tetracyclines.

Targeted Therapies

Recent targeted therapies have significantly advanced the treatment of moderate to severe vitiligo. Since January 2024, the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1)/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib cream has been available in community pharmacies after previously being restricted to hospital use, Seneschal said, and can have spectacular results if previous treatments have failed.

Ruxolitinib is approved for patients aged > 12 years with nonsegmental vitiligo and facial involvement, covering up to 10% of the body surface area. Treatment typically lasts 6 months to 1 year.

Key Findings

The cream-formulated drug has been demonstrated effective in reducing inflammation in two phase 3 clinical trials published in the New England Journal of Medicine that demonstrated its efficacy and safety in patients aged ≥ 12 years. The treatment was well tolerated despite some mild acne-like reactions in 8% of patients. It was shown to be very effective on the face, with a reduction of over 75% in facial lesions in more than 50% of patients, and had good effectiveness on the body, with a 50% decrease in lesions in more than 50% of patients on the body, trunk, arms, and legs, excluding hands and feet.

“Areas like the underarms, hands, and feet are more resistant to treatment,” Seneschal noted.

Although some improvement continues after 1 year, disease recurrence is common if treatment is stopped: Only 40% of patients maintain therapeutic benefits in the year following discontinuation.

“It is therefore important to consider the value of continuing treatment in order to achieve better efficacy or to maintain the repigmentation obtained,” Seneschal said.

He stressed that all treatments should be paired with phototherapy, typically narrowband UVB, to accelerate repigmentation. “There is no increased skin cancer risk in vitiligo patients treated with narrowband UVB,” Seneschal said.

New Therapies

Emerging treatments under development, including injectable biologics alone or in combination with phototherapy, show great promise, he said. Oral JAK inhibitors such as ritlecitinib, upadacitinib, and povorcitinib are also under investigation.

In particular, ritlecitinib, a JAK3/TEC pathway inhibitor, has shown significant reductions in affected skin area in severely affected patients in a phase 2b trial. Phase 3 trials are now underway.

On the safety profile of JAK inhibitors, Seneschal said that studies are reassuring but highlighted the need to monitor cardiovascular, thromboembolic, and infectious risks.

“The question of safety is important because vitiligo is a visible but nonsevere condition, and we do not want to expose patients to unnecessary risks,” added Gaëlle Quéreux, MD, PhD, president of the French Society of Dermatology.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Break the Itch-Scratch Cycle to Treat Prurigo Nodularis

Break the Itch-Scratch Cycle to Treat Prurigo Nodularis