User login

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (<1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, >35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

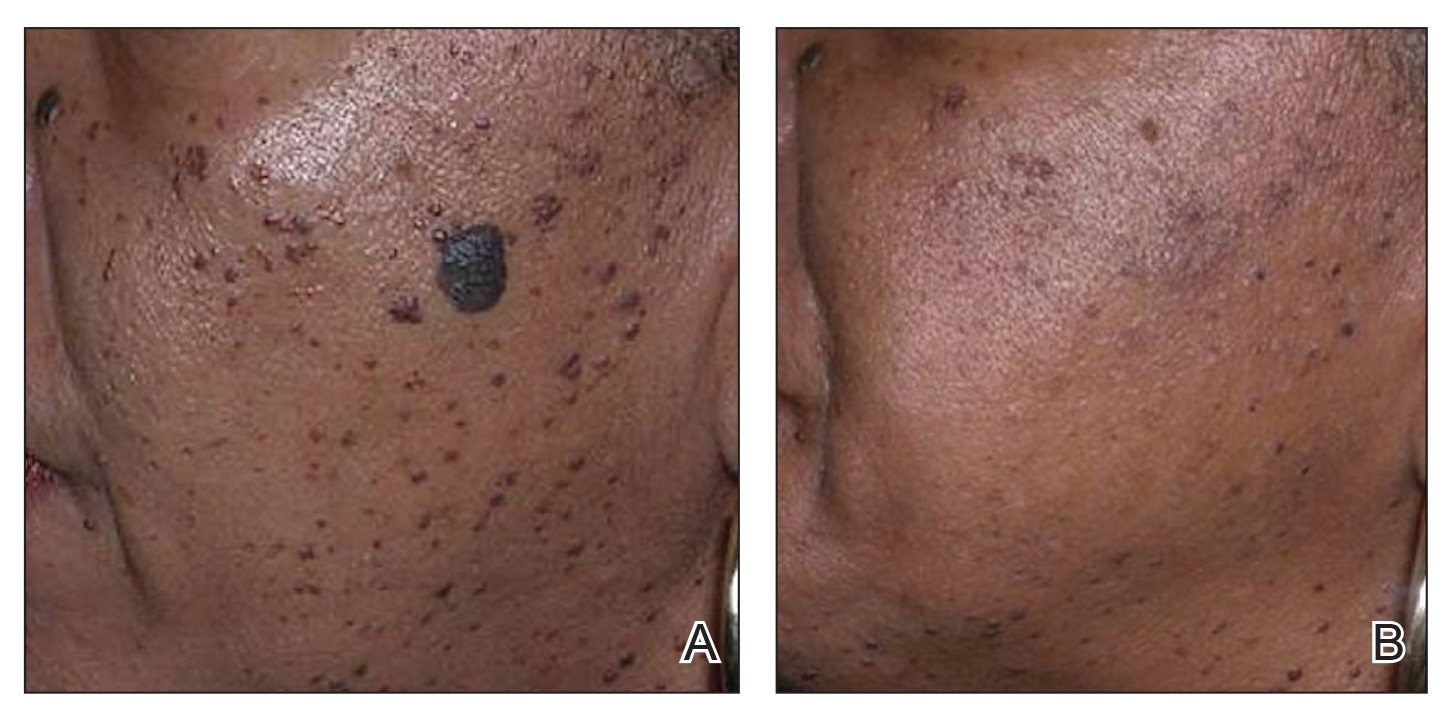

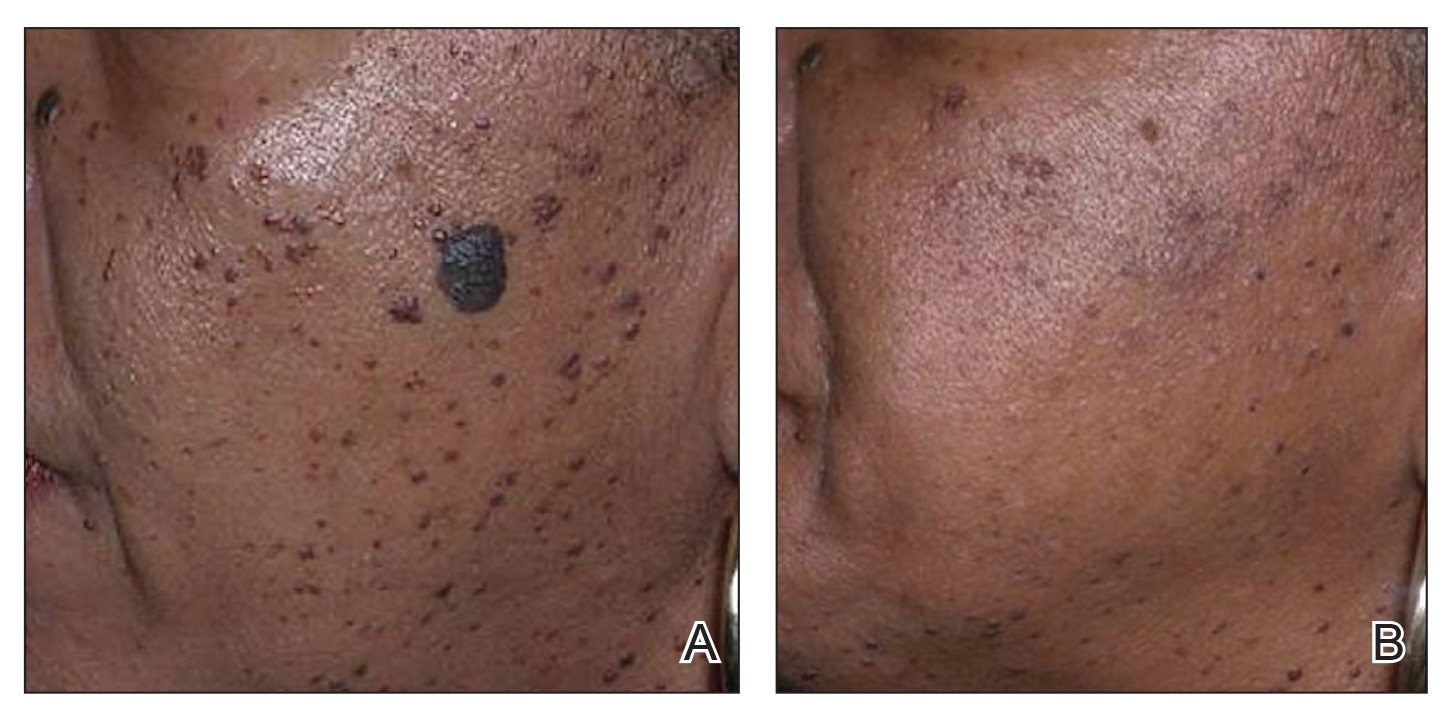

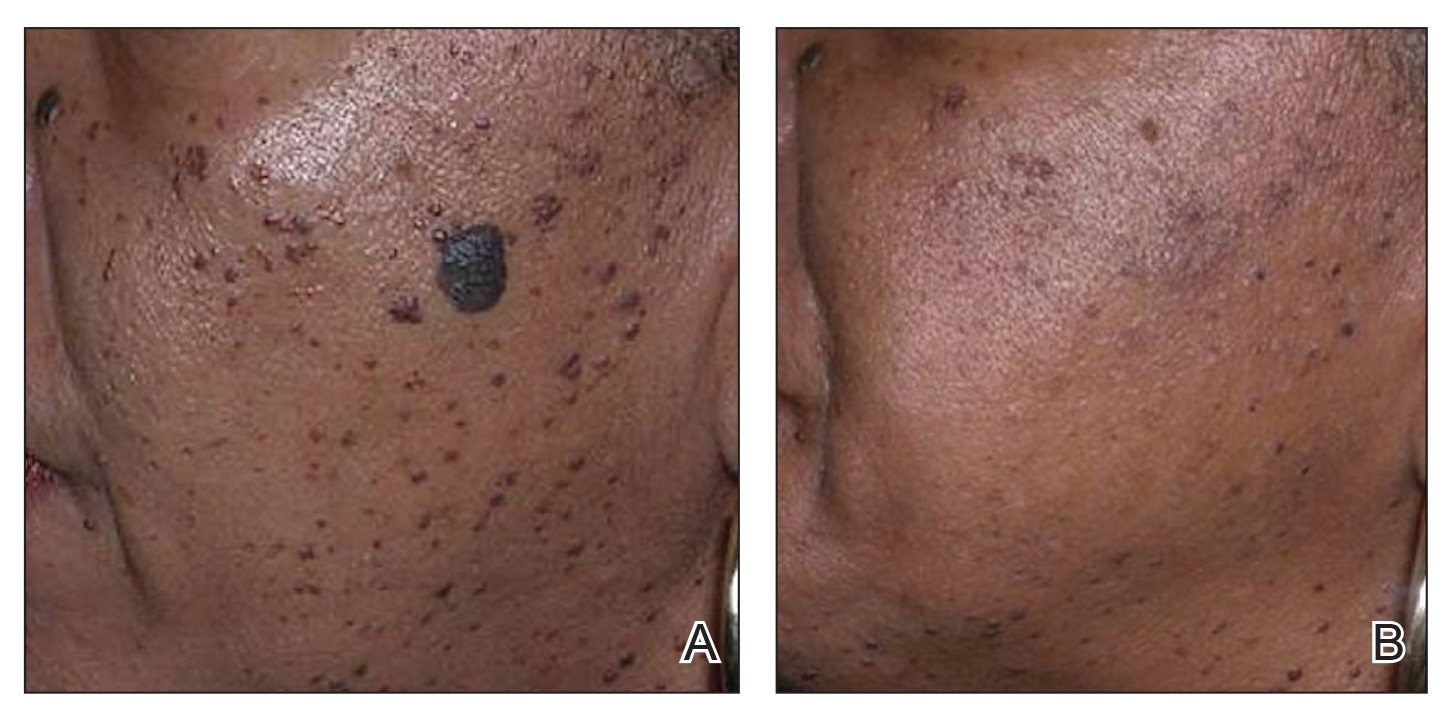

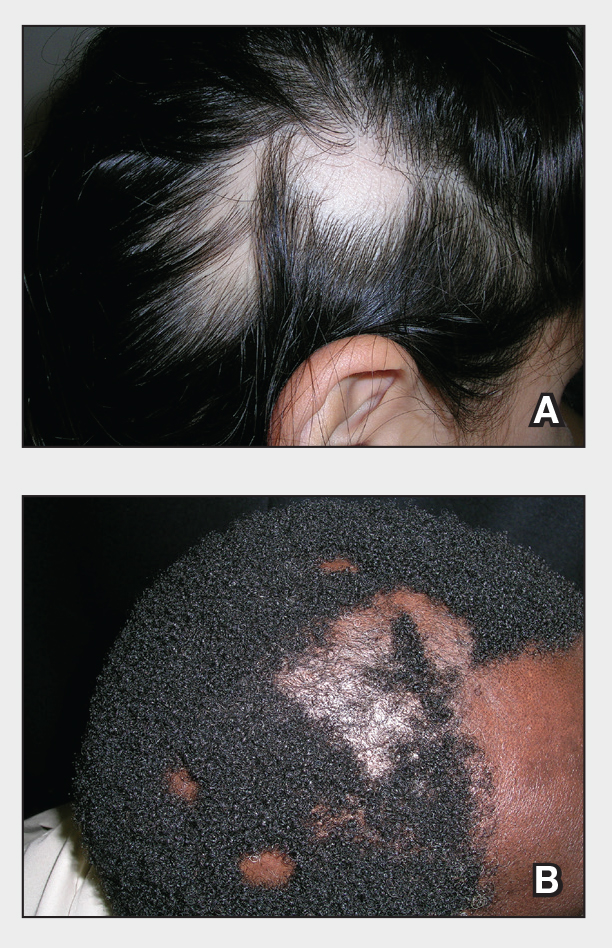

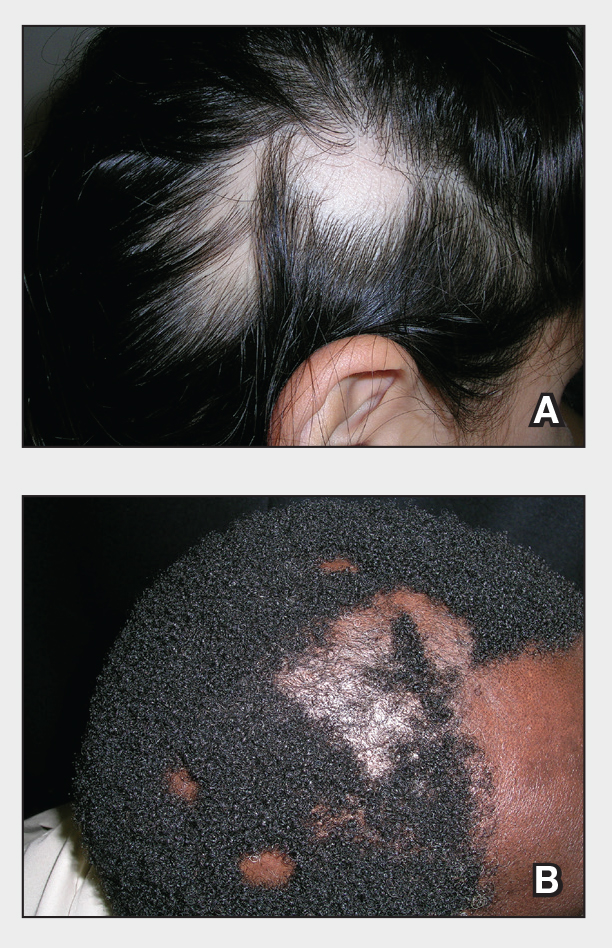

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (>5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (<1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, >35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (>5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (<1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, >35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (>5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Assessing the Merit of the Apple Cider Vinegar Rinse Method for Synthetic Hair Extensions

Assessing the Merit of the Apple Cider Vinegar Rinse Method for Synthetic Hair Extensions

Synthetic hair extensions are made from various plastic polymers (eg, modacrylic, vinyl chloride, and acrylonitrile) shaped into thin strands that mimic human hair and are used to add fullness, length, and manageability in individuals with textured hair.1-3 The plastic polymers used to make synthetic hair, most notably acrylonitrile and vinyl chloride, are known to be toxic to humans.1-4 The US Environmental Protection Agency classifies acrylonitrile as a probable carcinogen, and vinyl chloride is associated with the development of lymphoma; leukemia; and rare malignancies of the brain, liver, and lungs.1,4 According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the maximum exposure limits of vinyl chloride and acrylonitrile vapor or gas over an 8-hour period are 1 ppm (0.001 g/L) and 2 ppm (0.002 g/L), respectively.5 Exposure levels from wearing synthetic hair extensions easily exceed these maximums; for example, a full head of braids requires application of multiple packets of synthetic hair, resulting in continuous exposure to carcinogenic materials that can last for weeks to months at a time.1 Furthermore, individuals as young as 3 years old can begin to style their hair with synthetic extensions, which not only leads to potentially harmful carcinogenic exposure in young children but also yields notably high levels of lifetime exposure in individuals who regularly style their hair with these products.

There currently are no regulations barring the use of potentially harmful materials from the manufacturing process for synthetic hair extensions.1 As a result, rinsing with apple cider vinegar (ACV) is a popular remedy that many users claim can effectively remove harmful chemicals from synthetic hair.6,7 As this is the only known remedy that aims to address this issue,

Methods

We conducted a search of Google Scholar, JSTOR, Science Direct, the Public Library of Science, and PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ACV, apple cider vinegar rinse, ACV rinse, synthetic hair carcinogens, synthetic fiber carcinogens, synthetic hair extension carcinogens, modacrylic fibers, Kanekalon (a flame-retardant modacrylic fiber), acrylonitrile, and vinyl chloride fibers to identify primary research articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions for inclusion in our review. To broaden our search, we did not establish a time frame for publication of the articles included in the study. Articles investigating the ACV rinse that were unrelated to carcinogenicity and synthetic hair extensions were excluded from this study.

Results

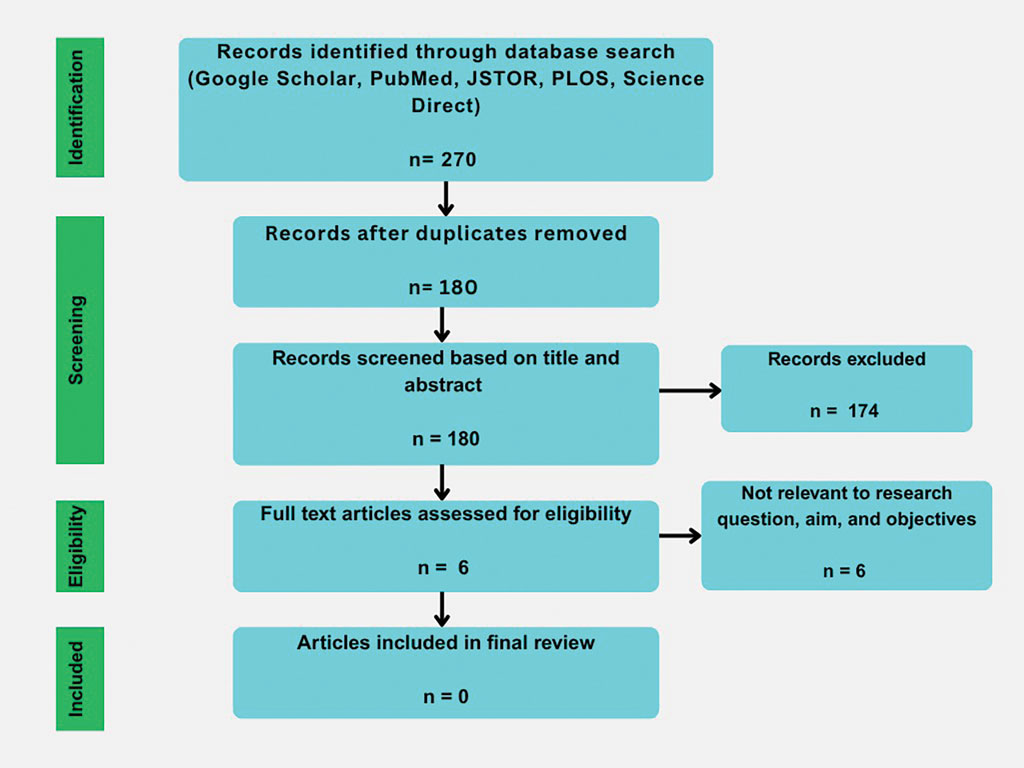

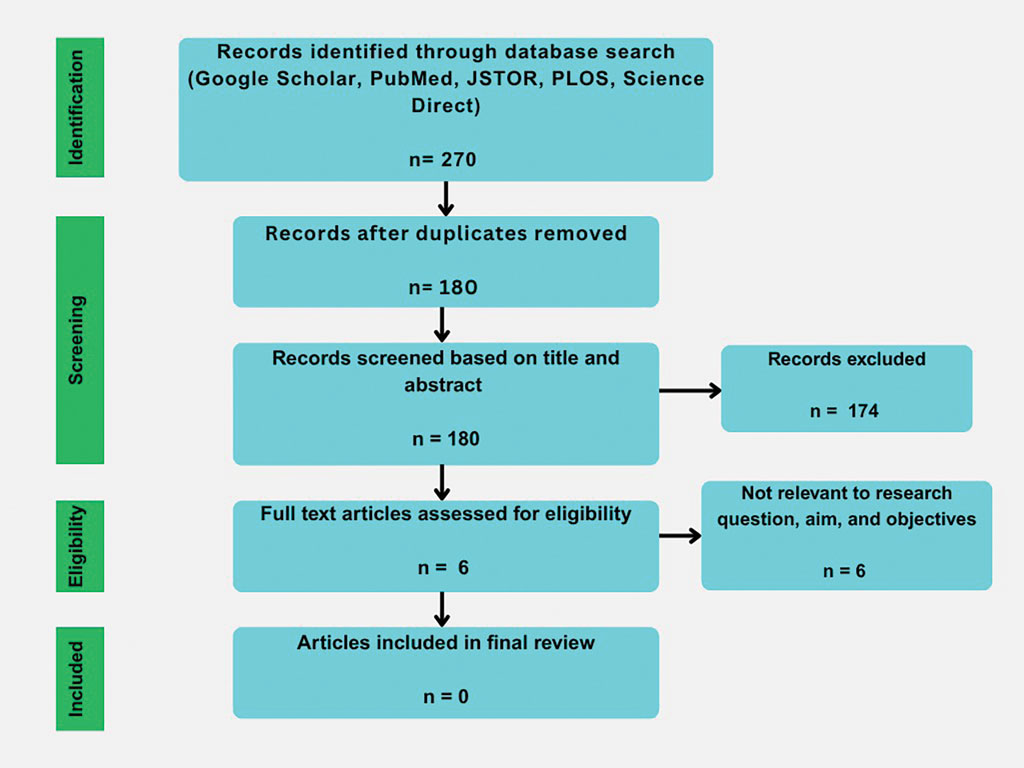

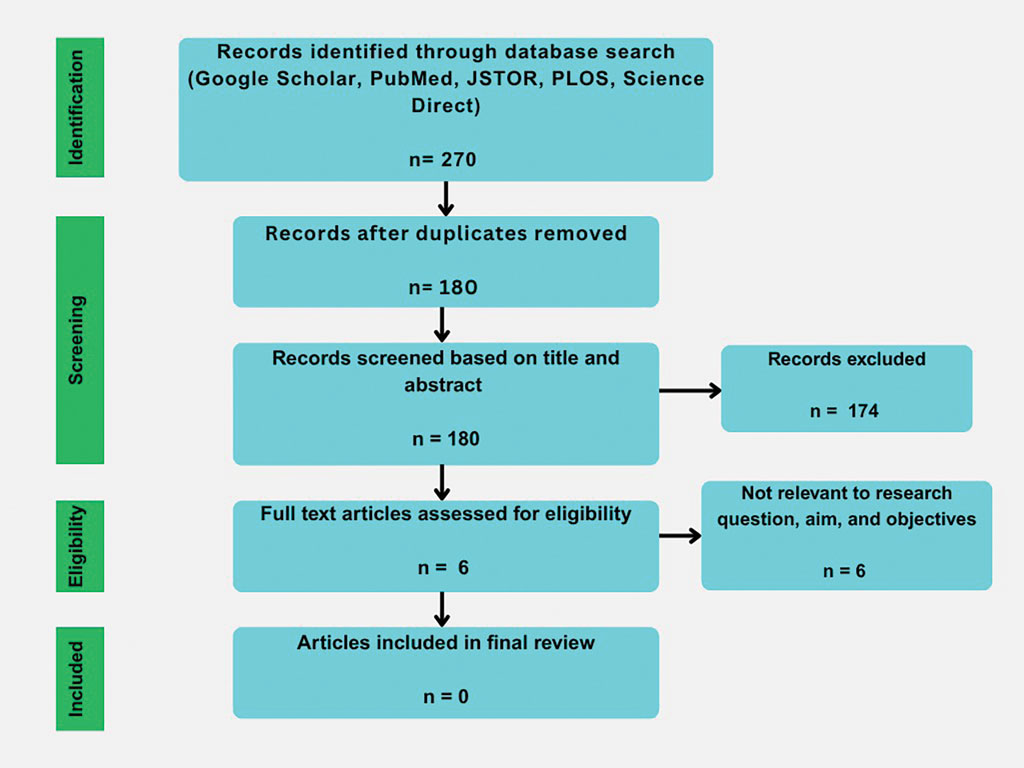

Our initial literature search identified 270 articles, which decreased to 180 after removal of duplicates. These 180 articles were screened for relevance based on title and abstract, which yielded 6 articles. None of the 6 articles identified through our literature search discussed synthetic hair and carcinogenicity in the context of the ACV rinse and were subsequently excluded from our review (eFigure 1).

Comment

Potentially harmful chemicals and ingredients in hair care products marketed for textured hair are now established topics in public discourse among those familiar with textured hair care and maintenance1,8; however, the discourse remains limited. Our search for scientific articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions revealed a notable deficit in the literature regarding scientific studies assessing this practice. While the likelihood that the ACV rinse effectively alters the carcinogenicity of plastic polymers found in synthetic hair extensions and improves their safety seems improbable, the deficit of empirical data evaluating this practice is concerning given both the prevalence of this remedy and the sizable demographic of patients who practice styling with synthetic hair.1 Of the potential adverse outcomes (eg, contact dermatitis, traction alopecia) that are possible from styling with synthetic hair that have been reported in the literature, carcinogenic exposure from synthetic hair extensions is relatively absent, with the exception of a few publications,2,3,9 despite its potential to cause serious long-term consequences for hair stylists and those who regularly use these products.

Interestingly, individuals who style their hair with synthetic hair extensions frequently tout the efficacy of the ACV rinse for removal of mostly unidentified irritants, although the effects are unverified.6,7 While the ACV rinse may be an effective means of removing toxic chemicals from synthetic hair extensions, without verifiable data this method remains an unproven remedy whose perceived benefits could result from factors unrelated to the rinse itself. Theoretically, simply rinsing synthetic hair extensions with plain water prior to use may demonstrate similar efficacy to that of the ACV rinse.

An additional factor worth mentioning is the lack of government regulations concerning the manufacturing practices of synthetic hair extensions. Flame-retardant materials such as trichloroethylene, polyvinyl chloride, and hexabromocyclododecane frequently are used in synthetic hair extensions despite their known adverse effects, which include reproductive organ toxicity and links to various cancers, leading to them being banned in 5 states.1,10-12 With no federal ban on these materials, individuals using synthetic hair remain at risk.

It is unclear what chemicals, irritants, or toxic substances the ACV rinse method could potentially remove from synthetic hair. In general, manufacturers of synthetic hair extensions are not forthcoming with information regarding materials used in the processing of their products despite public inquiries into their manufacturing practices.6 Although Whitehurst’s3 curriculum details the process of making synthetic polymer fibers, the overall processes by which these plastics are made to resemble human hair have not been reviewed in academic publications. Should this information be made available to the public, consumers could potentially avoid specific irritants when purchasing synthetic hair extensions.

The most common management strategy observed in the literature for adverse outcomes attributable to synthetic hair is discontinuation of use2; however, the prevalence and cultural significance of styling with synthetic hair extensions, along with the convenience these styles offer, make this option suboptimal. The scarcity of publications concerning the management of adverse outcomes related to the use of synthetic hair extensions may explain the absence of alternative management recommendations in the literature. Notably, new synthetic hair extensions from manufacturers that exclude plastic polymers and other harmful additives are now available to the public13; however, these hair extensions are cost prohibitive and are less accessible compared to synthetic extensions made from modacrylic fibers (eFigures 2 and 3).1,13-16

Final Thoughts

- Thomas CG. Carcinogenic materials in synthetic braids: an unrecognized risk of hair products for Black women. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;22:100517.

- Dlova NC, Ferguson NN, Rorex JN, et al. Synthetic hair extensions causing irritant contact dermatitis in patients with a history of atopy: a report of 10 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:141-145.

- Whitehurst L. Polytails and urban tumble weaves: the chemistry of synthetic hair fibers. Yale National Initiative. September 2011. Accessed September 29, 2025. teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_11.05.10_u

- Acrylonitrile. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. April 1992. Updated January 2000. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/acrylonitrile.pdf

- Permissible exposure limits – annotated tables. OSHA annotated table Z-1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.osha.gov/annotated-pels/table-z-1

- Adesina P. Braids are causing unbearable itching & there’s a sinister reason behind it. Refinery29. August 19, 2019. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.refinery29.com/en-gb/itchy-braids-hair

- Boakye O. Here’s why you should always wash plastic synthetic braiding extensions. InStyle. February 27, 2023. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.instyle.com/synthetic-braiding-extensions-upkeep-7151722

- James-Todd T, Connolly L, Preston EV, et al. Hormonal activity in commonly used Black hair care products: evaluating hormone disruption as a plausible contribution to health disparities. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021;31:476-486.

- Ijere ND, Okereke JN, Ezeji EU. Potential hazards associated with wearing of synthetic hairs (wigs, weavons, hair extensions/attachments) in Nigeria. J Environ Sci Public Health. 2022;6:299-313.

- Kaminsky T. An act to amend the environmental conservation law, in relation to the regulation of chemicals in upholstered furniture, mattresses and electronic enclosures. S4630B (2021). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S4630

- Shen Y. Hair extension standards and regulations in the US: an overview. Compliance Gate. December 20, 2022. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.compliancegate.com/hair-extension-regulations-united-states/

- Lienke J, Rothschild R. Regulating Risk From Toxic Substances: Best Practices for Economic Analysis of Risk Management Options Under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Institute of Policy Integrity; 2021.

- Rebundle. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://rebundle.co/

- About us. Kanekalon. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.kanekalon-hair.com/en/about

- Julianna wholesale smooth Kanekalon futura natural fiber heat resistant bone straight synthetic bundle weft hair extensions. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/Julianna-wholesale-Smooth-Kanekalon-Futura-Natural_1601335996748.html

- AIDUSA solid colors braiding hair 5pcs synthetic Afro braid hair extensions 24 inch 1 tone for women braids twist crochet braids 100g(#1B Natural Black). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.amazon.com/AIDUSA-Braiding-Synthetic-Extensions-Crochet/dp/B09TNB9LC8

Synthetic hair extensions are made from various plastic polymers (eg, modacrylic, vinyl chloride, and acrylonitrile) shaped into thin strands that mimic human hair and are used to add fullness, length, and manageability in individuals with textured hair.1-3 The plastic polymers used to make synthetic hair, most notably acrylonitrile and vinyl chloride, are known to be toxic to humans.1-4 The US Environmental Protection Agency classifies acrylonitrile as a probable carcinogen, and vinyl chloride is associated with the development of lymphoma; leukemia; and rare malignancies of the brain, liver, and lungs.1,4 According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the maximum exposure limits of vinyl chloride and acrylonitrile vapor or gas over an 8-hour period are 1 ppm (0.001 g/L) and 2 ppm (0.002 g/L), respectively.5 Exposure levels from wearing synthetic hair extensions easily exceed these maximums; for example, a full head of braids requires application of multiple packets of synthetic hair, resulting in continuous exposure to carcinogenic materials that can last for weeks to months at a time.1 Furthermore, individuals as young as 3 years old can begin to style their hair with synthetic extensions, which not only leads to potentially harmful carcinogenic exposure in young children but also yields notably high levels of lifetime exposure in individuals who regularly style their hair with these products.

There currently are no regulations barring the use of potentially harmful materials from the manufacturing process for synthetic hair extensions.1 As a result, rinsing with apple cider vinegar (ACV) is a popular remedy that many users claim can effectively remove harmful chemicals from synthetic hair.6,7 As this is the only known remedy that aims to address this issue,

Methods

We conducted a search of Google Scholar, JSTOR, Science Direct, the Public Library of Science, and PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ACV, apple cider vinegar rinse, ACV rinse, synthetic hair carcinogens, synthetic fiber carcinogens, synthetic hair extension carcinogens, modacrylic fibers, Kanekalon (a flame-retardant modacrylic fiber), acrylonitrile, and vinyl chloride fibers to identify primary research articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions for inclusion in our review. To broaden our search, we did not establish a time frame for publication of the articles included in the study. Articles investigating the ACV rinse that were unrelated to carcinogenicity and synthetic hair extensions were excluded from this study.

Results

Our initial literature search identified 270 articles, which decreased to 180 after removal of duplicates. These 180 articles were screened for relevance based on title and abstract, which yielded 6 articles. None of the 6 articles identified through our literature search discussed synthetic hair and carcinogenicity in the context of the ACV rinse and were subsequently excluded from our review (eFigure 1).

Comment

Potentially harmful chemicals and ingredients in hair care products marketed for textured hair are now established topics in public discourse among those familiar with textured hair care and maintenance1,8; however, the discourse remains limited. Our search for scientific articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions revealed a notable deficit in the literature regarding scientific studies assessing this practice. While the likelihood that the ACV rinse effectively alters the carcinogenicity of plastic polymers found in synthetic hair extensions and improves their safety seems improbable, the deficit of empirical data evaluating this practice is concerning given both the prevalence of this remedy and the sizable demographic of patients who practice styling with synthetic hair.1 Of the potential adverse outcomes (eg, contact dermatitis, traction alopecia) that are possible from styling with synthetic hair that have been reported in the literature, carcinogenic exposure from synthetic hair extensions is relatively absent, with the exception of a few publications,2,3,9 despite its potential to cause serious long-term consequences for hair stylists and those who regularly use these products.

Interestingly, individuals who style their hair with synthetic hair extensions frequently tout the efficacy of the ACV rinse for removal of mostly unidentified irritants, although the effects are unverified.6,7 While the ACV rinse may be an effective means of removing toxic chemicals from synthetic hair extensions, without verifiable data this method remains an unproven remedy whose perceived benefits could result from factors unrelated to the rinse itself. Theoretically, simply rinsing synthetic hair extensions with plain water prior to use may demonstrate similar efficacy to that of the ACV rinse.

An additional factor worth mentioning is the lack of government regulations concerning the manufacturing practices of synthetic hair extensions. Flame-retardant materials such as trichloroethylene, polyvinyl chloride, and hexabromocyclododecane frequently are used in synthetic hair extensions despite their known adverse effects, which include reproductive organ toxicity and links to various cancers, leading to them being banned in 5 states.1,10-12 With no federal ban on these materials, individuals using synthetic hair remain at risk.

It is unclear what chemicals, irritants, or toxic substances the ACV rinse method could potentially remove from synthetic hair. In general, manufacturers of synthetic hair extensions are not forthcoming with information regarding materials used in the processing of their products despite public inquiries into their manufacturing practices.6 Although Whitehurst’s3 curriculum details the process of making synthetic polymer fibers, the overall processes by which these plastics are made to resemble human hair have not been reviewed in academic publications. Should this information be made available to the public, consumers could potentially avoid specific irritants when purchasing synthetic hair extensions.

The most common management strategy observed in the literature for adverse outcomes attributable to synthetic hair is discontinuation of use2; however, the prevalence and cultural significance of styling with synthetic hair extensions, along with the convenience these styles offer, make this option suboptimal. The scarcity of publications concerning the management of adverse outcomes related to the use of synthetic hair extensions may explain the absence of alternative management recommendations in the literature. Notably, new synthetic hair extensions from manufacturers that exclude plastic polymers and other harmful additives are now available to the public13; however, these hair extensions are cost prohibitive and are less accessible compared to synthetic extensions made from modacrylic fibers (eFigures 2 and 3).1,13-16

Final Thoughts

Synthetic hair extensions are made from various plastic polymers (eg, modacrylic, vinyl chloride, and acrylonitrile) shaped into thin strands that mimic human hair and are used to add fullness, length, and manageability in individuals with textured hair.1-3 The plastic polymers used to make synthetic hair, most notably acrylonitrile and vinyl chloride, are known to be toxic to humans.1-4 The US Environmental Protection Agency classifies acrylonitrile as a probable carcinogen, and vinyl chloride is associated with the development of lymphoma; leukemia; and rare malignancies of the brain, liver, and lungs.1,4 According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the maximum exposure limits of vinyl chloride and acrylonitrile vapor or gas over an 8-hour period are 1 ppm (0.001 g/L) and 2 ppm (0.002 g/L), respectively.5 Exposure levels from wearing synthetic hair extensions easily exceed these maximums; for example, a full head of braids requires application of multiple packets of synthetic hair, resulting in continuous exposure to carcinogenic materials that can last for weeks to months at a time.1 Furthermore, individuals as young as 3 years old can begin to style their hair with synthetic extensions, which not only leads to potentially harmful carcinogenic exposure in young children but also yields notably high levels of lifetime exposure in individuals who regularly style their hair with these products.

There currently are no regulations barring the use of potentially harmful materials from the manufacturing process for synthetic hair extensions.1 As a result, rinsing with apple cider vinegar (ACV) is a popular remedy that many users claim can effectively remove harmful chemicals from synthetic hair.6,7 As this is the only known remedy that aims to address this issue,

Methods

We conducted a search of Google Scholar, JSTOR, Science Direct, the Public Library of Science, and PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ACV, apple cider vinegar rinse, ACV rinse, synthetic hair carcinogens, synthetic fiber carcinogens, synthetic hair extension carcinogens, modacrylic fibers, Kanekalon (a flame-retardant modacrylic fiber), acrylonitrile, and vinyl chloride fibers to identify primary research articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions for inclusion in our review. To broaden our search, we did not establish a time frame for publication of the articles included in the study. Articles investigating the ACV rinse that were unrelated to carcinogenicity and synthetic hair extensions were excluded from this study.

Results

Our initial literature search identified 270 articles, which decreased to 180 after removal of duplicates. These 180 articles were screened for relevance based on title and abstract, which yielded 6 articles. None of the 6 articles identified through our literature search discussed synthetic hair and carcinogenicity in the context of the ACV rinse and were subsequently excluded from our review (eFigure 1).

Comment

Potentially harmful chemicals and ingredients in hair care products marketed for textured hair are now established topics in public discourse among those familiar with textured hair care and maintenance1,8; however, the discourse remains limited. Our search for scientific articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions revealed a notable deficit in the literature regarding scientific studies assessing this practice. While the likelihood that the ACV rinse effectively alters the carcinogenicity of plastic polymers found in synthetic hair extensions and improves their safety seems improbable, the deficit of empirical data evaluating this practice is concerning given both the prevalence of this remedy and the sizable demographic of patients who practice styling with synthetic hair.1 Of the potential adverse outcomes (eg, contact dermatitis, traction alopecia) that are possible from styling with synthetic hair that have been reported in the literature, carcinogenic exposure from synthetic hair extensions is relatively absent, with the exception of a few publications,2,3,9 despite its potential to cause serious long-term consequences for hair stylists and those who regularly use these products.

Interestingly, individuals who style their hair with synthetic hair extensions frequently tout the efficacy of the ACV rinse for removal of mostly unidentified irritants, although the effects are unverified.6,7 While the ACV rinse may be an effective means of removing toxic chemicals from synthetic hair extensions, without verifiable data this method remains an unproven remedy whose perceived benefits could result from factors unrelated to the rinse itself. Theoretically, simply rinsing synthetic hair extensions with plain water prior to use may demonstrate similar efficacy to that of the ACV rinse.

An additional factor worth mentioning is the lack of government regulations concerning the manufacturing practices of synthetic hair extensions. Flame-retardant materials such as trichloroethylene, polyvinyl chloride, and hexabromocyclododecane frequently are used in synthetic hair extensions despite their known adverse effects, which include reproductive organ toxicity and links to various cancers, leading to them being banned in 5 states.1,10-12 With no federal ban on these materials, individuals using synthetic hair remain at risk.

It is unclear what chemicals, irritants, or toxic substances the ACV rinse method could potentially remove from synthetic hair. In general, manufacturers of synthetic hair extensions are not forthcoming with information regarding materials used in the processing of their products despite public inquiries into their manufacturing practices.6 Although Whitehurst’s3 curriculum details the process of making synthetic polymer fibers, the overall processes by which these plastics are made to resemble human hair have not been reviewed in academic publications. Should this information be made available to the public, consumers could potentially avoid specific irritants when purchasing synthetic hair extensions.

The most common management strategy observed in the literature for adverse outcomes attributable to synthetic hair is discontinuation of use2; however, the prevalence and cultural significance of styling with synthetic hair extensions, along with the convenience these styles offer, make this option suboptimal. The scarcity of publications concerning the management of adverse outcomes related to the use of synthetic hair extensions may explain the absence of alternative management recommendations in the literature. Notably, new synthetic hair extensions from manufacturers that exclude plastic polymers and other harmful additives are now available to the public13; however, these hair extensions are cost prohibitive and are less accessible compared to synthetic extensions made from modacrylic fibers (eFigures 2 and 3).1,13-16

Final Thoughts

- Thomas CG. Carcinogenic materials in synthetic braids: an unrecognized risk of hair products for Black women. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;22:100517.

- Dlova NC, Ferguson NN, Rorex JN, et al. Synthetic hair extensions causing irritant contact dermatitis in patients with a history of atopy: a report of 10 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:141-145.

- Whitehurst L. Polytails and urban tumble weaves: the chemistry of synthetic hair fibers. Yale National Initiative. September 2011. Accessed September 29, 2025. teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_11.05.10_u

- Acrylonitrile. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. April 1992. Updated January 2000. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/acrylonitrile.pdf

- Permissible exposure limits – annotated tables. OSHA annotated table Z-1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.osha.gov/annotated-pels/table-z-1

- Adesina P. Braids are causing unbearable itching & there’s a sinister reason behind it. Refinery29. August 19, 2019. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.refinery29.com/en-gb/itchy-braids-hair

- Boakye O. Here’s why you should always wash plastic synthetic braiding extensions. InStyle. February 27, 2023. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.instyle.com/synthetic-braiding-extensions-upkeep-7151722

- James-Todd T, Connolly L, Preston EV, et al. Hormonal activity in commonly used Black hair care products: evaluating hormone disruption as a plausible contribution to health disparities. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021;31:476-486.

- Ijere ND, Okereke JN, Ezeji EU. Potential hazards associated with wearing of synthetic hairs (wigs, weavons, hair extensions/attachments) in Nigeria. J Environ Sci Public Health. 2022;6:299-313.

- Kaminsky T. An act to amend the environmental conservation law, in relation to the regulation of chemicals in upholstered furniture, mattresses and electronic enclosures. S4630B (2021). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S4630

- Shen Y. Hair extension standards and regulations in the US: an overview. Compliance Gate. December 20, 2022. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.compliancegate.com/hair-extension-regulations-united-states/

- Lienke J, Rothschild R. Regulating Risk From Toxic Substances: Best Practices for Economic Analysis of Risk Management Options Under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Institute of Policy Integrity; 2021.

- Rebundle. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://rebundle.co/

- About us. Kanekalon. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.kanekalon-hair.com/en/about

- Julianna wholesale smooth Kanekalon futura natural fiber heat resistant bone straight synthetic bundle weft hair extensions. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/Julianna-wholesale-Smooth-Kanekalon-Futura-Natural_1601335996748.html

- AIDUSA solid colors braiding hair 5pcs synthetic Afro braid hair extensions 24 inch 1 tone for women braids twist crochet braids 100g(#1B Natural Black). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.amazon.com/AIDUSA-Braiding-Synthetic-Extensions-Crochet/dp/B09TNB9LC8

- Thomas CG. Carcinogenic materials in synthetic braids: an unrecognized risk of hair products for Black women. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;22:100517.

- Dlova NC, Ferguson NN, Rorex JN, et al. Synthetic hair extensions causing irritant contact dermatitis in patients with a history of atopy: a report of 10 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:141-145.

- Whitehurst L. Polytails and urban tumble weaves: the chemistry of synthetic hair fibers. Yale National Initiative. September 2011. Accessed September 29, 2025. teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_11.05.10_u

- Acrylonitrile. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. April 1992. Updated January 2000. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/acrylonitrile.pdf

- Permissible exposure limits – annotated tables. OSHA annotated table Z-1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.osha.gov/annotated-pels/table-z-1

- Adesina P. Braids are causing unbearable itching & there’s a sinister reason behind it. Refinery29. August 19, 2019. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.refinery29.com/en-gb/itchy-braids-hair

- Boakye O. Here’s why you should always wash plastic synthetic braiding extensions. InStyle. February 27, 2023. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.instyle.com/synthetic-braiding-extensions-upkeep-7151722

- James-Todd T, Connolly L, Preston EV, et al. Hormonal activity in commonly used Black hair care products: evaluating hormone disruption as a plausible contribution to health disparities. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021;31:476-486.

- Ijere ND, Okereke JN, Ezeji EU. Potential hazards associated with wearing of synthetic hairs (wigs, weavons, hair extensions/attachments) in Nigeria. J Environ Sci Public Health. 2022;6:299-313.

- Kaminsky T. An act to amend the environmental conservation law, in relation to the regulation of chemicals in upholstered furniture, mattresses and electronic enclosures. S4630B (2021). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S4630

- Shen Y. Hair extension standards and regulations in the US: an overview. Compliance Gate. December 20, 2022. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.compliancegate.com/hair-extension-regulations-united-states/

- Lienke J, Rothschild R. Regulating Risk From Toxic Substances: Best Practices for Economic Analysis of Risk Management Options Under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Institute of Policy Integrity; 2021.

- Rebundle. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://rebundle.co/

- About us. Kanekalon. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.kanekalon-hair.com/en/about

- Julianna wholesale smooth Kanekalon futura natural fiber heat resistant bone straight synthetic bundle weft hair extensions. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/Julianna-wholesale-Smooth-Kanekalon-Futura-Natural_1601335996748.html

- AIDUSA solid colors braiding hair 5pcs synthetic Afro braid hair extensions 24 inch 1 tone for women braids twist crochet braids 100g(#1B Natural Black). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.amazon.com/AIDUSA-Braiding-Synthetic-Extensions-Crochet/dp/B09TNB9LC8

Assessing the Merit of the Apple Cider Vinegar Rinse Method for Synthetic Hair Extensions

Assessing the Merit of the Apple Cider Vinegar Rinse Method for Synthetic Hair Extensions

Practice Points

- Synthetic hair extensions are made from materials that can expose patients to high levels of carcinogens beginning in early childhood.

- The apple cider vinegar rinse method is an anecdotal remedy lacking data validating its ability to mitigate adverse reactions and complications associated with synthetic hair extensions, including carcinogenic exposure to materials they comprise.

- Dermatologists should inform patients of the potential exposure risks when using synthetic hair extensions to help patients make informed decisions regarding future styling habits and hair care choices.

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in the Military: Policy, Stigma, and Practical Solutions

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in the Military: Policy, Stigma, and Practical Solutions

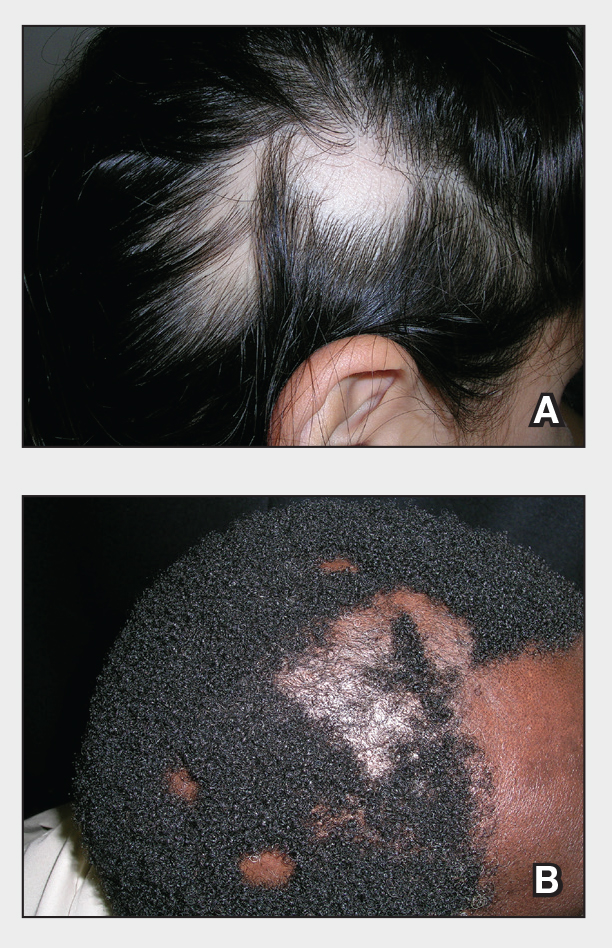

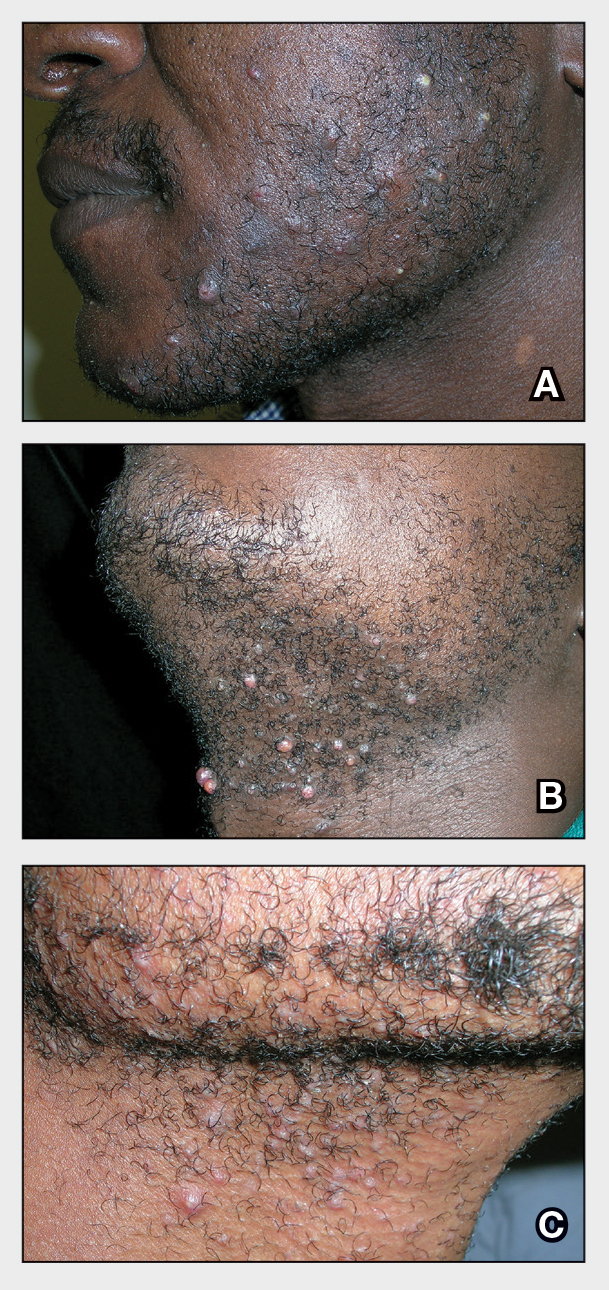

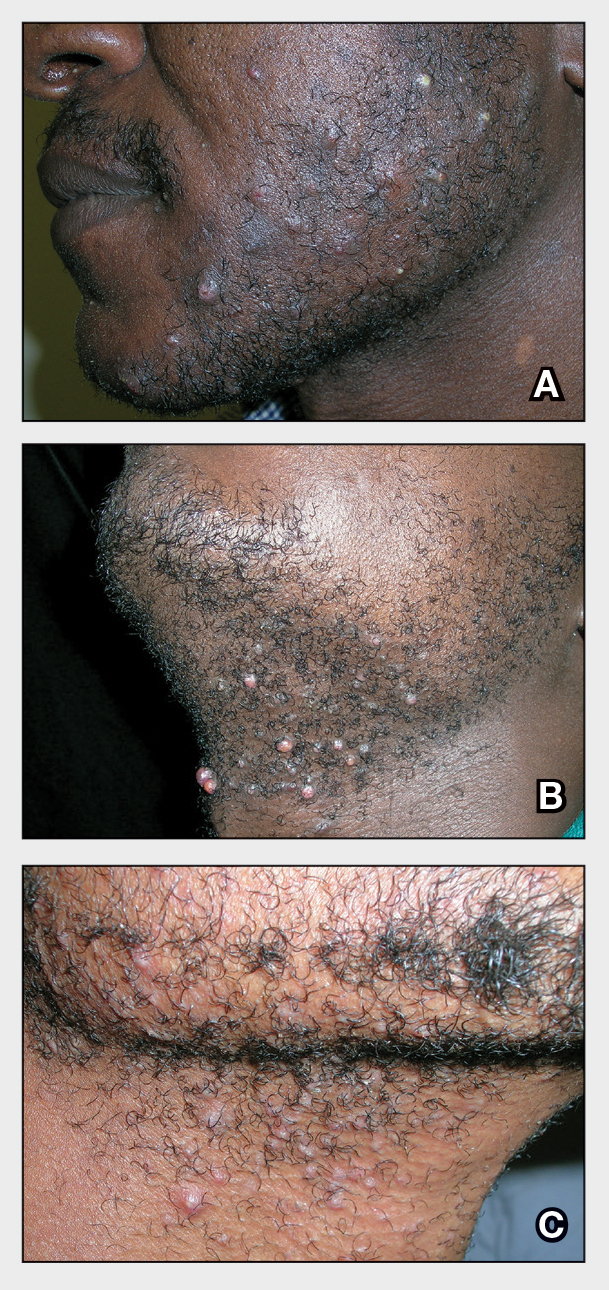

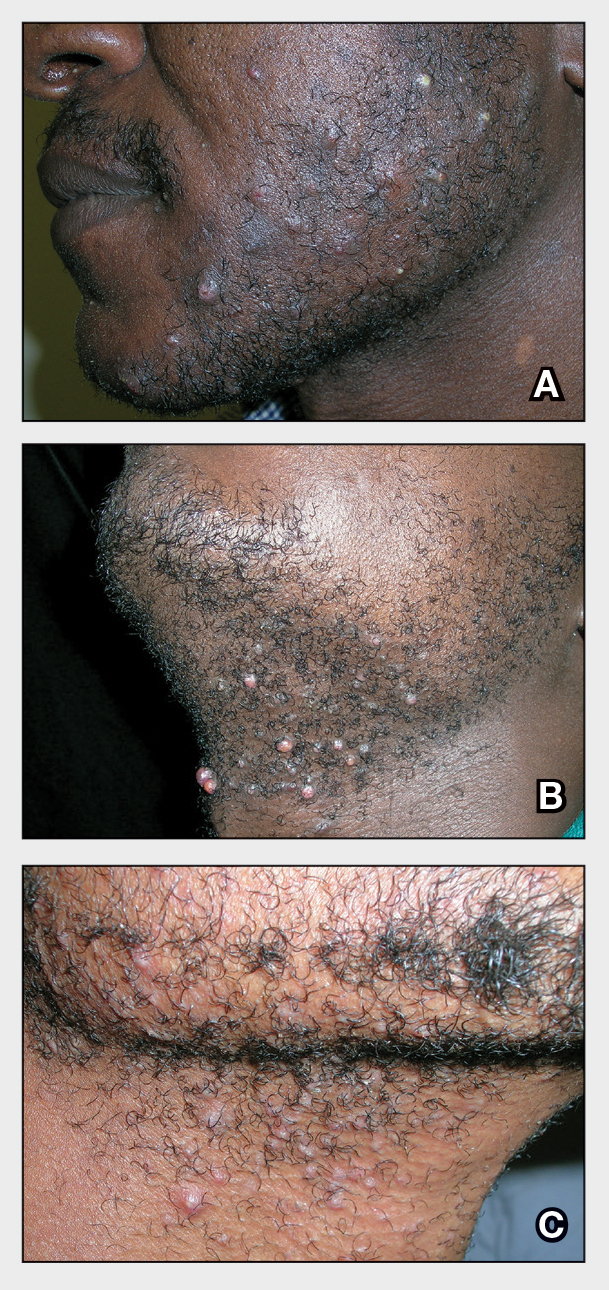

The impact of pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) on military service members and other uniformed professionals has been a topic of recent interest due to the announcement of the US Army’s new shaving rule in July 2025.1 The policy prohibits permanent shaving waivers, requires medical re-evaluation of shaving profiles within 90 days, and allows for administrative separation if a service member accumulates shaving exceptions totaling more than 12 months over a 24-month period.2 A common skin condition triggered or worsened by shaving, PFB causes painful bumps, pustules, and hyperpigmentation most often in the beard and cheek areas and negatively impacts quality of life. It disproportionately affects 45% to 83% of men in the United States, particularly those of African, Hispanic, or Middle Eastern descent.3,4 Genetic factors, particularly tightly coiled or coarse curly hair, can predispose individuals to PFB. The most successful treatment for PFB is to stop shaving, but this conflicts with military shaving standards and interferes with the use of protective equipment (eg, masks). Herein, we highlight the adverse impact of PFB on military career progression and provide context for clinicians who treat patients with PFB, especially as policies recently have shifted to allow nonmilitary clinicians to evaluate PFB in service members.5

Shaving Waivers and Advancement

Pseudofolliculitis barbae disproportionately prolongs the time to advancement of many service members, and those with PFB also are overburdened by policy changes related to shaving.6 In the US military, nearly 18% of the active-duty force is Black,7 a population that is more susceptible to PFB. Military personnel may request PFB-related accommodations, including medical shaving waivers that vary by branch. Through a formal documentation process, waivers allow service members to maintain facial hair up to one-quarter inch in length.5 Previously, waivers could be temporary (eg, up to 90 days) or permanent as subjectively determined based on clinician-documented disease severity. Almost 65% of US Air Force medical shaving waivers are held by Black men, and PFB is one of the most common reasons.6 Notably, the US Navy discontinued permanent shaving waivers in October 2019.8 A US Marine Corps policy issued in March 2025 now allows administrative separation of service members with PFB if symptoms do not improve after a 1-year medical shaving waiver due to “incompatibility with service.”9 This change reversed a 2022 policy that protected Marines from separation based on PFB.10 A Marine Corps spokesperson stated that this change aims to clarify how medical conditions can impact uniform compliance and standardize medical condition management while prioritizing compliance and duty readiness.1

Even in the absence of policy changes, obtaining a medical shaving waiver for PFB can be challenging. Service members may have little to no access to military dermatologists who specialize in management of PFB and experience long wait times for civilian network deferment. Service members seen in civilian clinics may have restricted treatment options due to limited insurance coverage for laser hair reduction, even in the most difficult-to-manage areas (eg, neck, jawline). Expanding access to military dermatologists, civilian dermatologists who are experienced with PFB and understand the impact and necessity of military waivers, and teledermatology services could help improve and streamline care. Other challenges include the subjective nature of documenting PFB disease severity, the need for validated assessment tools, a lack of standardized policies across military branches, and stigma. A standardized approach to documentation may reduce variability in how shaving waivers are evaluated across service branches, but at a minimum, clinicians should document the diagnosis, clinical findings, severity of PFB, and the treatment used. Having a waiver would help these service members focus on mastering critical skillsets and performing duties without the time pressures, angst, and expense dedicated to caring for and managing PFB.

Clinical and Policy Barriers

Unfortunately, service members with PFB or shaving waivers often face stigma that can hinder career advancement.6 In a recent analysis of 9339 US Air Force personnel, those with shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion compared to those without waivers: in the waiver group, 94.47% were enlisted and 5.53% were officers; in the nonwaiver group, 72.11% were enlisted and 27.89% were officers (P=.0003).6 While delays in promotion were consistent across racial groups, most of the waiver holders identified as Black (64.8%), despite this demographic group representing only a small portion of the overall cohort (12.9%).6 Promotion delays may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism and exclusion from high-profile assignments, which notably require “the highest standards of military appearance and professional conduct.”11 The burden of career-limiting shaving policies falls disproportionately on military personnel with PFB who self-identify as Black. Perceptions about unprofessional appearance or job readiness often unintentionally introduce bias, unjustly restricting career advancement.6

Safety Equipment and Shaving Standards

Conditions that potentially affect the use of masks and chemical defense equipment extend beyond the military. Firefighters and law enforcement officers generally are required to maintain a clean-shaven face for proper fit of respirator masks; the standard is that no respirator fit test shall be conducted if hair—including stubble, beards, mustaches, or sideburns—grows between the skin and the facepiece sealing surface, and any apparel interfering with a proper seal must be altered or removed.12 This creates challenges for uniformed professionals with PFB who must manage their condition while adhering to safety requirements. Some endure long-term pain and scarring in order to comply, while others seek waivers to treat and prevent symptoms while also facing the stigma of doing so.13 One of the most effective treatments for PFB is to discontinue shaving,14 which may not be feasible for those in uniformed professions with strict grooming standards. Research on mask seal effectiveness in individuals with neatly trimmed beards or PFB remains limited.5 Studies evaluating mask fit across facial hair types and lengths are needed, along with the development of protective equipment that accommodates career-limiting conditions such as PFB, cystic acne, and acne keloidalis nuchae. This also may encourage development of equipment that does not induce such conditions (eg, mechanical acne from friction). These efforts would promote safety, scientific innovation for dermatologic follicular-based disorders, and overall quality of life for service members as well as increase their ability to serve without stigma. These developments also would positively impact other fields that require intermittent or full-time use of masks, including health care and some food service industries.

Final Thoughts

The disproportionate impact of PFB in the military highlights the need for improved access to treatment, culturally informed care, and policies that avoid penalizing service members with tightly coiled hair and a desire to serve. We discussed PFB management strategies, clinical features, and implications across various skin tones in a previous publication.14 It is important to consider insights from individuals with PFB who are serving in the military as well as the medical personnel who care for them. Ensuring or creating effective treatment options drives innovation, and evidence-based accommodation plans can help individuals in uniformed professions avoid choosing between PFB management and their career. Promoting awareness about the impact of PFB beyond the razor is key to reducing disparities and supporting excellence among those who serve and desire to continue to do so.

- Lawrence DF. Marines with skin condition affecting mostly black men could now be booted under new policy. Military.com. March 14, 2025. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2025/03/14/marines-can-now-be-kicked-out-skin-condition-affects-mostly-black-men.html

- Secretary of the Army. Army directive 2025-13 (facial hair grooming standards). Published July 7, 2025. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://lyster.tricare.mil/Portals/61/ARN44307-ARMY_DIR_2025-13-000.pdf

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.12.001

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:24-27. doi:10.1111/ics.12331

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302. doi:10.12788/cutis.0907

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab272

- Defense Manpower Data Center. Active-duty military personnel master file and reserve components common personnel data system. Military OneSource. September 2023. Accessed May 3, 2025. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2023-demographics-report.pdf

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US. Military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa243

- US Marine Corps. Uniform and grooming standards for medical conditions (MARADMINS number: 124/25). Published March 13, 2025. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/4119098/uniform-and-grooming-standards-for-medical-conditions/

- US Marine Corps. Advance notification of change to MCO 6310.1C (Pseudofolliculitis Barbae), MCO 1900.16 CH2 (Marine Corps Retirement and Separation Manual), and MCO 1040.31 (Enlisted Retention and Career Development Program). Published January 21, 2022. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/2907104/advance-notification-of-change-to-mco-63101c-pseudofolliculitis-barbae-mco-1900/

- US Department of Defense. Special duty catalog (SPECAT). Published August 15, 2013. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://share.google/iuMrVMIASWx4EFLVN

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Appendix A to §1910.134—fit testing procedures (mandatory). Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.134AppA

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195. doi:10.1017/jme.2023.55

- Welch D, Usatine R, Heath C. Implications of PFB beyond the razor. Cutis. 2025;115:135-136. doi:10.12788/cutis.1194

The impact of pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) on military service members and other uniformed professionals has been a topic of recent interest due to the announcement of the US Army’s new shaving rule in July 2025.1 The policy prohibits permanent shaving waivers, requires medical re-evaluation of shaving profiles within 90 days, and allows for administrative separation if a service member accumulates shaving exceptions totaling more than 12 months over a 24-month period.2 A common skin condition triggered or worsened by shaving, PFB causes painful bumps, pustules, and hyperpigmentation most often in the beard and cheek areas and negatively impacts quality of life. It disproportionately affects 45% to 83% of men in the United States, particularly those of African, Hispanic, or Middle Eastern descent.3,4 Genetic factors, particularly tightly coiled or coarse curly hair, can predispose individuals to PFB. The most successful treatment for PFB is to stop shaving, but this conflicts with military shaving standards and interferes with the use of protective equipment (eg, masks). Herein, we highlight the adverse impact of PFB on military career progression and provide context for clinicians who treat patients with PFB, especially as policies recently have shifted to allow nonmilitary clinicians to evaluate PFB in service members.5

Shaving Waivers and Advancement

Pseudofolliculitis barbae disproportionately prolongs the time to advancement of many service members, and those with PFB also are overburdened by policy changes related to shaving.6 In the US military, nearly 18% of the active-duty force is Black,7 a population that is more susceptible to PFB. Military personnel may request PFB-related accommodations, including medical shaving waivers that vary by branch. Through a formal documentation process, waivers allow service members to maintain facial hair up to one-quarter inch in length.5 Previously, waivers could be temporary (eg, up to 90 days) or permanent as subjectively determined based on clinician-documented disease severity. Almost 65% of US Air Force medical shaving waivers are held by Black men, and PFB is one of the most common reasons.6 Notably, the US Navy discontinued permanent shaving waivers in October 2019.8 A US Marine Corps policy issued in March 2025 now allows administrative separation of service members with PFB if symptoms do not improve after a 1-year medical shaving waiver due to “incompatibility with service.”9 This change reversed a 2022 policy that protected Marines from separation based on PFB.10 A Marine Corps spokesperson stated that this change aims to clarify how medical conditions can impact uniform compliance and standardize medical condition management while prioritizing compliance and duty readiness.1

Even in the absence of policy changes, obtaining a medical shaving waiver for PFB can be challenging. Service members may have little to no access to military dermatologists who specialize in management of PFB and experience long wait times for civilian network deferment. Service members seen in civilian clinics may have restricted treatment options due to limited insurance coverage for laser hair reduction, even in the most difficult-to-manage areas (eg, neck, jawline). Expanding access to military dermatologists, civilian dermatologists who are experienced with PFB and understand the impact and necessity of military waivers, and teledermatology services could help improve and streamline care. Other challenges include the subjective nature of documenting PFB disease severity, the need for validated assessment tools, a lack of standardized policies across military branches, and stigma. A standardized approach to documentation may reduce variability in how shaving waivers are evaluated across service branches, but at a minimum, clinicians should document the diagnosis, clinical findings, severity of PFB, and the treatment used. Having a waiver would help these service members focus on mastering critical skillsets and performing duties without the time pressures, angst, and expense dedicated to caring for and managing PFB.

Clinical and Policy Barriers

Unfortunately, service members with PFB or shaving waivers often face stigma that can hinder career advancement.6 In a recent analysis of 9339 US Air Force personnel, those with shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion compared to those without waivers: in the waiver group, 94.47% were enlisted and 5.53% were officers; in the nonwaiver group, 72.11% were enlisted and 27.89% were officers (P=.0003).6 While delays in promotion were consistent across racial groups, most of the waiver holders identified as Black (64.8%), despite this demographic group representing only a small portion of the overall cohort (12.9%).6 Promotion delays may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism and exclusion from high-profile assignments, which notably require “the highest standards of military appearance and professional conduct.”11 The burden of career-limiting shaving policies falls disproportionately on military personnel with PFB who self-identify as Black. Perceptions about unprofessional appearance or job readiness often unintentionally introduce bias, unjustly restricting career advancement.6

Safety Equipment and Shaving Standards

Conditions that potentially affect the use of masks and chemical defense equipment extend beyond the military. Firefighters and law enforcement officers generally are required to maintain a clean-shaven face for proper fit of respirator masks; the standard is that no respirator fit test shall be conducted if hair—including stubble, beards, mustaches, or sideburns—grows between the skin and the facepiece sealing surface, and any apparel interfering with a proper seal must be altered or removed.12 This creates challenges for uniformed professionals with PFB who must manage their condition while adhering to safety requirements. Some endure long-term pain and scarring in order to comply, while others seek waivers to treat and prevent symptoms while also facing the stigma of doing so.13 One of the most effective treatments for PFB is to discontinue shaving,14 which may not be feasible for those in uniformed professions with strict grooming standards. Research on mask seal effectiveness in individuals with neatly trimmed beards or PFB remains limited.5 Studies evaluating mask fit across facial hair types and lengths are needed, along with the development of protective equipment that accommodates career-limiting conditions such as PFB, cystic acne, and acne keloidalis nuchae. This also may encourage development of equipment that does not induce such conditions (eg, mechanical acne from friction). These efforts would promote safety, scientific innovation for dermatologic follicular-based disorders, and overall quality of life for service members as well as increase their ability to serve without stigma. These developments also would positively impact other fields that require intermittent or full-time use of masks, including health care and some food service industries.

Final Thoughts

The disproportionate impact of PFB in the military highlights the need for improved access to treatment, culturally informed care, and policies that avoid penalizing service members with tightly coiled hair and a desire to serve. We discussed PFB management strategies, clinical features, and implications across various skin tones in a previous publication.14 It is important to consider insights from individuals with PFB who are serving in the military as well as the medical personnel who care for them. Ensuring or creating effective treatment options drives innovation, and evidence-based accommodation plans can help individuals in uniformed professions avoid choosing between PFB management and their career. Promoting awareness about the impact of PFB beyond the razor is key to reducing disparities and supporting excellence among those who serve and desire to continue to do so.

The impact of pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) on military service members and other uniformed professionals has been a topic of recent interest due to the announcement of the US Army’s new shaving rule in July 2025.1 The policy prohibits permanent shaving waivers, requires medical re-evaluation of shaving profiles within 90 days, and allows for administrative separation if a service member accumulates shaving exceptions totaling more than 12 months over a 24-month period.2 A common skin condition triggered or worsened by shaving, PFB causes painful bumps, pustules, and hyperpigmentation most often in the beard and cheek areas and negatively impacts quality of life. It disproportionately affects 45% to 83% of men in the United States, particularly those of African, Hispanic, or Middle Eastern descent.3,4 Genetic factors, particularly tightly coiled or coarse curly hair, can predispose individuals to PFB. The most successful treatment for PFB is to stop shaving, but this conflicts with military shaving standards and interferes with the use of protective equipment (eg, masks). Herein, we highlight the adverse impact of PFB on military career progression and provide context for clinicians who treat patients with PFB, especially as policies recently have shifted to allow nonmilitary clinicians to evaluate PFB in service members.5

Shaving Waivers and Advancement