User login

Cosmetic Laser Procedures and Nonsurgical Body Contouring in Patients With Skin of Color

Cosmetic Laser Procedures and Nonsurgical Body Contouring in Patients With Skin of Color

Cosmetic laser procedures as well as energy-based fat reduction and body-contouring devices are increasingly popular among individuals with skin of color (SOC). Innovations in cosmetic devices and procedures tailored for SOC have allowed for the optimization of outcomes in this patient population. In this article, SOC is defined as darker skin types, including Fitzpatrick skin types (FSTs) IV to VI and ethnic backgrounds such as LatinX, African American, Southeast Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, Asian, and African. Indications for laser treatment include dermatosis papulosa nigrans (DPN), acne scars, skin rejuvenation, and hyperpigmentation. There currently are 6 procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): high-frequency focused ultrasound, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring (Supplementary Table S1).1

In this review, our initial focus is cosmetic laser procedures, encompassing FDA-cleared indications along with the associated risks and benefits in SOC populations. Subsequently, we delve into the realms of energy-based fat reduction and body contouring, offering a comprehensive overview of these noninvasive therapies and addressing considerations for efficacy and safety in these patients.

Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

In patients with SOC, scissor excision, curettage, or electrodesiccation are the mainstay treatments for removal of DPN (Figure 1). Curettage and electrodesiccation can cause temporary postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) in these populations, while cryotherapy is not a preferred method in patients with SOC due to the possibility of cryotherapy-induced depigmentation. In a 14-patient split-face study comparing the 532-nm potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser vs electrodesiccation in FSTs IV to VI, the KTP-treated side showed an improvement rate of 96%, while the electrodesiccation side showed an improvement rate of 79%. There was a statistically significant favorable experience for KTP with regard to pain tolerability (P=.002).2 Complete resolution of lesions may be seen after 3 to 4 sessions at 4-week intervals. Additionally, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser was assessed for treatment of DPN in 2 patients, with 70% to 90% of lesions resolved after a single treatment with no complications.3

Most dermatologists still rely on curettage and electrodesiccation instead of laser therapy to remove DPNs in patients with SOC. The use of the Nd:YAG laser is promising yet expensive for the provider both to purchase and maintain. Electrodesiccation has been used by dermatology practices for decades and can be used without permanent discoloration. To minimize the risk for PIH, we recommend application of a healing ointment such as petroleum jelly or aloe vera gel to the treated lesions as well as lightening agents for PIH and daily use of sunscreen. Overall, providers do not need to purchase an expensive laser device for DPN removal.

Acne Scars

The invention of fractional technology in the early 2000s and its favorable safety profile have changed how dermatologists treat scarring in patients with SOC.

In one study of the short-pulsed nonablative Nd:YAG laser, 9 patients with FSTs I to V and 2 patients with FSTs IV to V underwent 8 treatments at 2-week intervals. Three blinded observers found a 29% improvement in the Global Acne Scar Severity score, while 89% (8/9) of patients self-reported subjective improvement in their acne scars.10

The 755-nm picosecond laser and diffractive lens array also have been shown to reduce the appearance of acne scars in patients with SOC, as shown via serial photography in a retrospective study of 56 patients with FSTs IV to VI. Transient hyperpigmentation, erythema, and edema were reported.11

Nonablative laser therapy is preferred for skin rejuvenation in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.11 Ablative resurfacing (eg, CO2 laser) poses major risks for postprocedural hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scar formation and therefore should be avoided in these populations.12,13 A study involving 30 Asian patients (FSTs III-IV) demonstrated that the 1550-nm fractional laser was well tolerated, though higher treatment densities and fluences may lead to temporary adverse effects such as increased redness, swelling, and pain (P<.01).14 Furthermore, greater density was shown to cause higher levels of redness, hyperpigmentation, and swelling in comparison to higher fluence settings. Of note, patient satisfaction was markedly higher in patients who underwent treatment with higher fluence settings but not in patients with higher densities (P<.05). Postprocedural hyperpigmentation was noted in 6.7% (2/30) of patients studied.14 In another study, 8 patients with FSTs II to V were treated with either the 1064-nm long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser or the grid fractional monopolar radiofrequency laser.15 All participants experienced a significant decrease in mean wrinkle count using the Lemperle wrinkle assessment (P<.05). A significant decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score from 3.5 to 3.17 in clinical assessment and a decrease from 3.165 to 2.33 for photographic assessment was noted in patients treated with the grid laser (P<.05). A similar decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score was observed in the Nd:YAG group, with a mean decrease of 3.665 to 2.83 after 2 months for clinical assessment and 3.5 to 2.67 for photographic assessment. Among all patients in the study, 68% (6/8) experienced erythema, 25% (2/8) had a burning sensation, and 25% (2/8) experienced urticaria immediately postprocedure.15

Nonablative fractional resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC. Adverse effects such as hyperpigmentation typically are transient, and the risk may be minimized with strict photoprotective practices following the procedure. Furthermore, avoidance of topicals containing exfoliants or α-hydroxy acids applied to the treated area following the procedure also may mitigate the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.16 If hyperpigmentation does occur, use of topical melanogenesis inhibitors such as hydroquinone, kojic acid, or azelaic acid has shown some utility in practice.

Skin Rejuvenation

Nonablative fractional lasers (NAFLs) continue to be popular for treatment of photoaging. One study including 10 Asian patients (FSTs III-V) assessed the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser for facial rejuvenation.17 After 4 sessions at 2-week intervals, 80% (8/10) of patients reported decreased skin roughness after both the second and third treatments, while 90% (9/10) had improved texture 1 month after the final procedure. Adverse effects included moderate facial edema and one case of transient hyperpigmentation.17 Another study reported a significant reduction in pore score (P<.002), with patients noting an overall improvement in skin appearance with minimal erythema, dryness, and flaking following 6 sessions at 2-week intervals using the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser.18

The 1550-nm diode fractional laser significantly improved skin pigmentation (P<.001) and texture (P<.001) in 10 patients with FSTs II to IV following 5 sessions at 2- to 3-week intervals, with self-resolving erythema and edema posttreatment (Supplementary Table S2).19 Overall, NAFLs for the treatment of photoaging are effective with minimal adverse effects (eg, facial edema), which can be reduced with application of cold compression to the face and elevation of the head following treatment as well as the use of additional pillows during overnight sleep.

Laser Treatment for Hyperpigmentation Disorders

Melasma—The FDA recently approved fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of melasma; however, due to the risk for hyperpigmentation given its pathogenesis linked to hyperactive melanocytes, this laser is not considered a first-line therapy for melasma.20 In a split-face, randomized study, 22 patients with FSTs III to V who were diagnosed with either dermal or mixed-type melasma were treated with a low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser combined with hydroquinone 2% vs hydroquinone 2% alone (Supplementary Table S3).21 Each patient was treated weekly for 5 consecutive weeks. The laser-treated side was found to reach an average of 92.5% improvement compared with 19.7% on the hydroquinone-only side. Three of the 22 (13.6%) patients developed mottled hypopigmentation after 5 laser treatments, and 8 (36.4%) developed confetti-type hypopigmentation. Four (18.2%) patients developed rebound hyperpigmentation, and all 22 patients experienced recurrence of melasma by 12 weeks posttreatment.21

First-line treatment for melasma involves the application of topical lightening agents such as hydroquinone, azelaic acid, kojic acid, retinoids, or mild topical steroids. Combining laser technology with topical medications can enhance treatment outcomes, particularly yielding positive results for patients with persistent pigmentation concerns. Notably, utilization of 650-microsecond technology with the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser is considered superior in clinical practice, especially for patients with FSTs IV through VI.

Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation—A retrospective evaluation of 61 patients with FSTs IV to VI with PIH treated with a 1927-nm NAFL showed a mean improvement of 43.24%, as assessed by 2 dermatologists.22 Additionally, the Nd:YAG 1064-nm 650-microsecond pulse duration laser is an emerging treatment that delivers high and low fluences between 4 J/cm2 and 255 J/cm2 within a single 650-microsecond pulse duration.23 The short-pulse duration avoids overheating the skin, mitigating procedural discomfort and the risk for adverse effects commonly seen with the previous generation of low-pulsed lasers. In addition to PIH, this laser has been successfully used to treat pseudofolliculitis barbae.24

Solar Lentigos—In a split-face study treating solar lentigos in Asian patients, 4 treatments with a low-pulsed KTP 532-nm laser were administered with and without a second treatment with a low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.25 Scoring of a modified pigment severity index and measurement of the melanin index showed that skin treated with the low-pulsed 532-nm laser alone and in combination with the low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser resulted in improvement at 3 months’ follow-up. However, there was no difference between the 2 sides of the face, leading the researchers to conclude that the low-pulsed 532-nm laser appears to be safe and effective for treatment of solar lentigos in Asian patients and does not require the addition of the low-pulsed 1064-nm laser.25

To avoid hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, strict photoprotection to the treated areas should be advised. Proper cooling of the laser-treated area is required to minimize PIH, as cooling decreases tissue damage and excessive thermal injury. Test spots should be considered prior to initiation of the full laser treatment. Hydroquinone in a 4% concentration applied daily for 2 weeks preprocedure commonly is employed to reduce the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation in clinical practice.26,27

Skin Tightening and Body Contouring

In general, skin-tightening and body-contouring devices are among the most sought-after procedures. Studies performed in patients with SOC are limited. Herein, we provide background on why these devices are favorable for patients with SOC and our experiences in using them. A summary of these devices can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Radiofrequency Skin Tightening—Radiofrequency devices are utilized for skin tightening as well as mild fat reduction; they commonly are used on the abdomen, thighs, buttocks, and face.28 People with SOC are more responsive to radiofrequency skin-tightening therapy due to higher baseline collagen content and dermal thickness, more sebaceous activity and skin elasticity, and more melanin content which offers protective thermal buffering.29,30 As the radiofrequency device emits heat, penetrating deep into the dermis, it generates collagen remodeling and synthesis within 4 to 6 months posttreatment.

Nonsurgical Fat Reduction

Procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction are favorable due to minimal recovery time, manageable cost, and an in-office procedure setting. As noted previously, there are 6 FDA-indicated interventions for nonsurgical fat reduction: ultrasonography, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring.31

Ultrasonography—Ultrasound devices designed for body contouring are used for skin tightening and mild fat reduction through the use of acoustic energy.32 These devices can be divided into 2 categories: high frequency and low frequency, with the high-frequency devices being the most popular. High-frequency ultrasound energy produces heat at target sites, which induces necrosis of adipocytes and stimulates collagen remodeling within the tissue matrix.33 Tissue temperatures above 56°C stimulate adipocyte necrosis while sparing nearby nerves and vessels.28 Because of the short duration of the procedure, the risk for epidermal damage is minimal. Contrary to high-frequency ultrasonography, focus-pulsed ultrasonography employs low-frequency waves to induce the mechanical disruption of adipocytes, which is generally better tolerated due to its nonthermal mechanism. The latter may be advantageous in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for thermal injury to the epidermis. Multiple treatments often are needed at 3- to 4-week intervals, resulting in gradual improvement observed over 2 to 6 months. One study of microfocused ultrasonography in 25 Asian patients for treatment of face and neck laxity reported that skin laxity was improved or much improved in 84% (21/25) of patients following treatment.34 Adverse effects were reported as mild and transient, resolving within 90 days.34 Ultrasound devices also were shown to improve wrinkles, texture, and overall appearance of the skin in a 71-year-old African American woman 4 months following treatment (Figure 2). These photographs highlight the clinical utility of a microfocused ultrasound skin-tightening treatment in African American patients.

Cryolipolysis—Cryolipolysis is a noninvasive body contouring procedure that employs controlled cooling to induce subcutaneous panniculitis. Through cold-induced apoptosis of adipocytes, this procedure selectively reduces adipose tissue in localized areas such as the flank, abdomen, thighs, buttocks, back, submental area, and upper arms. The temperature used in cryolipolysis is approximately –10°C.35 The lethal temperature for melanocytes is –4 °C, below which melanocyte apoptosis may be induced, resulting in depigmentation. Given the prolonged contact of the skin with a cryolipolysis device for up to 60 minutes during a body-contouring procedure, there is a risk for resultant depigmentation in darker skin types. Controlled studies are needed to fully evaluate the safety and efficacy of cryolipolysis in patients with SOC. One retrospective study of cryolipolysis applied to the abdomen and upper arm of 4122 Asian patients reported a significant (P<.05) reduction in the circumference of the abdomen and the upper-arm areas. No long-term adverse effects were reported.36

Laser Lipolysis—The 1060-nm diode laser for body contouring selectively destroys adipose tissue, resulting in body contouring via thermally induced inflammation. Hyperthermic exposure for 15 minutes selectively elevates adipocyte temperature between 42°C to 47°C, which triggers apoptosis and the eventual clearance of destroyed cells from the interstitial space.37 The selectivity of the 1060-nm wavelength coupled with the device’s contact cooling system preserves the overlying skin and adnexa during the procedure,37 which would minimize epidermal damage that may induce dyspigmentation in patients with SOC. No notable adverse effects or dyspigmentation have been reported using this device.

Injection Lipolysis—Deoxycholic acid is an injectable adipocytolytic for the reduction of submental fat. It nonselectively lyses muscle and other adjacent nonfatty tissue. One study of 50 Indian patients demonstrated a substantial reduction of submental fat in 90% (45/50).38 For each treatment, 5 mL of 30 mg/mL deoxycholic acid was injected. Serial sessions were conducted at 2-month intervals, and most (64% [32/50]) patients required 3 sessions to see a treatment effect. Adverse effects included transient swelling, lumpiness, and tenderness. A phase 2a investigation of the novel injectable small-molecule drug CBL-514 in 43 Asian and White participants found a significant improvement in the reduction in abdominal fat volume (P<.00001) and thickness (P<.0001) relative to baseline at higher doses (unit dose, 2.0 mg/cm2 and 1.6 mg/cm2).39 In addition to the adverse effects mentioned previously, pruritus, repeated urticaria, body rash, and fever also were reported.39

Radiofrequency Lipolysis—Radiofrequency is used for adipolysis through heat-induced apoptosis. To achieve this effect, adipose tissue must sustain a temperature of 42 °C to 45 °C for at least 15 minutes.40 In one study, 4 treatments performed at 7-day intervals resulted in a statistically significant reduction in circumference to the treated areas of the inner and outer thighs without any reported adverse effects (P<0.001).41 Of note, there was 1 cm of distance between the applicator and the skin. The absence of direct contact with the skin is likely to reduce the risk for postprocedural complications in patients with SOC.

Magnetic Resonance Contouring—Magnetic resonance contouring with high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology is an emerging treatment modality for noninvasive body contouring. One distinguishing characteristic from other currently available noninvasive fat-reduction therapies is that magnetic resonance may improve strength, tone, and muscle thickness.42 This modality is FDA approved for contouring of the buttocks and abdomen and employs electromagnetic energy to stimulate approximately 20,000 muscle contractions within a time frame of 30 minutes. Though the mechanisms causing benefits to muscular and adipose tissue have not been elucidated, current findings suggest that the contractions stimulate substantial lipolysis of adipocytes, resulting in the release of large amounts of free fatty acids that cause damage to nearby adipose tissue.43 Multiple treatments are required over time to maintain effect. No major adverse effects have been reported. The likely mechanism of action of magnetic resonance contouring does not appear to pose an increased risk to patients with SOC.

Final Thoughts

One of the major roadblocks in distilling indications along with associated risks and benefits for nonsurgical cosmetic practices for patients with SOC is a void in the primary literature involving these populations. Clinical experience serves to address this deficit in combination with a thorough review of the literature. The 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser has shown clinical utility in the treatment of DPN, melanoma, and acne scars, but it poses financial constraints to the provider in comparison to modalities used for many years. Notably, NAF resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC and continues to gain popularity for the treatment of photoaging. Regarding skin-tightening and body-contouring devices, studies performed in patients with SOC are limited and affected by factors such as small sample sizes, underrepresentation of FSTs IV through VI, short follow-up durations, and a lack of standardized outcome measures. Additionally, few studies assess pigmentary adverse effects or stratify results by skin type, which is critical given the higher risk for PIH in SOC. Ultrasound devices showed clinical utility in improvement of skin laxity, texture, and overall improvement. Patients with SOC respond well to skin-tightening devices due to the increased collagen synthesis. Regarding emerging devices for reduction of adipocytes, deoxycholic acid when injected showed notable improvement in fat reduction but also had adverse effects. As additional studies on cosmetic procedures in SOC emerge, an expansion of treatment options could be offered to this demographic group with confidence, provided proper treatment and follow-up protocols are in place.

Cosmetic laser procedures as well as energy-based fat reduction and body-contouring devices are increasingly popular among individuals with skin of color (SOC). Innovations in cosmetic devices and procedures tailored for SOC have allowed for the optimization of outcomes in this patient population. In this article, SOC is defined as darker skin types, including Fitzpatrick skin types (FSTs) IV to VI and ethnic backgrounds such as LatinX, African American, Southeast Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, Asian, and African. Indications for laser treatment include dermatosis papulosa nigrans (DPN), acne scars, skin rejuvenation, and hyperpigmentation. There currently are 6 procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): high-frequency focused ultrasound, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring (Supplementary Table S1).1

In this review, our initial focus is cosmetic laser procedures, encompassing FDA-cleared indications along with the associated risks and benefits in SOC populations. Subsequently, we delve into the realms of energy-based fat reduction and body contouring, offering a comprehensive overview of these noninvasive therapies and addressing considerations for efficacy and safety in these patients.

Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

In patients with SOC, scissor excision, curettage, or electrodesiccation are the mainstay treatments for removal of DPN (Figure 1). Curettage and electrodesiccation can cause temporary postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) in these populations, while cryotherapy is not a preferred method in patients with SOC due to the possibility of cryotherapy-induced depigmentation. In a 14-patient split-face study comparing the 532-nm potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser vs electrodesiccation in FSTs IV to VI, the KTP-treated side showed an improvement rate of 96%, while the electrodesiccation side showed an improvement rate of 79%. There was a statistically significant favorable experience for KTP with regard to pain tolerability (P=.002).2 Complete resolution of lesions may be seen after 3 to 4 sessions at 4-week intervals. Additionally, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser was assessed for treatment of DPN in 2 patients, with 70% to 90% of lesions resolved after a single treatment with no complications.3

Most dermatologists still rely on curettage and electrodesiccation instead of laser therapy to remove DPNs in patients with SOC. The use of the Nd:YAG laser is promising yet expensive for the provider both to purchase and maintain. Electrodesiccation has been used by dermatology practices for decades and can be used without permanent discoloration. To minimize the risk for PIH, we recommend application of a healing ointment such as petroleum jelly or aloe vera gel to the treated lesions as well as lightening agents for PIH and daily use of sunscreen. Overall, providers do not need to purchase an expensive laser device for DPN removal.

Acne Scars

The invention of fractional technology in the early 2000s and its favorable safety profile have changed how dermatologists treat scarring in patients with SOC.

In one study of the short-pulsed nonablative Nd:YAG laser, 9 patients with FSTs I to V and 2 patients with FSTs IV to V underwent 8 treatments at 2-week intervals. Three blinded observers found a 29% improvement in the Global Acne Scar Severity score, while 89% (8/9) of patients self-reported subjective improvement in their acne scars.10

The 755-nm picosecond laser and diffractive lens array also have been shown to reduce the appearance of acne scars in patients with SOC, as shown via serial photography in a retrospective study of 56 patients with FSTs IV to VI. Transient hyperpigmentation, erythema, and edema were reported.11

Nonablative laser therapy is preferred for skin rejuvenation in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.11 Ablative resurfacing (eg, CO2 laser) poses major risks for postprocedural hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scar formation and therefore should be avoided in these populations.12,13 A study involving 30 Asian patients (FSTs III-IV) demonstrated that the 1550-nm fractional laser was well tolerated, though higher treatment densities and fluences may lead to temporary adverse effects such as increased redness, swelling, and pain (P<.01).14 Furthermore, greater density was shown to cause higher levels of redness, hyperpigmentation, and swelling in comparison to higher fluence settings. Of note, patient satisfaction was markedly higher in patients who underwent treatment with higher fluence settings but not in patients with higher densities (P<.05). Postprocedural hyperpigmentation was noted in 6.7% (2/30) of patients studied.14 In another study, 8 patients with FSTs II to V were treated with either the 1064-nm long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser or the grid fractional monopolar radiofrequency laser.15 All participants experienced a significant decrease in mean wrinkle count using the Lemperle wrinkle assessment (P<.05). A significant decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score from 3.5 to 3.17 in clinical assessment and a decrease from 3.165 to 2.33 for photographic assessment was noted in patients treated with the grid laser (P<.05). A similar decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score was observed in the Nd:YAG group, with a mean decrease of 3.665 to 2.83 after 2 months for clinical assessment and 3.5 to 2.67 for photographic assessment. Among all patients in the study, 68% (6/8) experienced erythema, 25% (2/8) had a burning sensation, and 25% (2/8) experienced urticaria immediately postprocedure.15

Nonablative fractional resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC. Adverse effects such as hyperpigmentation typically are transient, and the risk may be minimized with strict photoprotective practices following the procedure. Furthermore, avoidance of topicals containing exfoliants or α-hydroxy acids applied to the treated area following the procedure also may mitigate the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.16 If hyperpigmentation does occur, use of topical melanogenesis inhibitors such as hydroquinone, kojic acid, or azelaic acid has shown some utility in practice.

Skin Rejuvenation

Nonablative fractional lasers (NAFLs) continue to be popular for treatment of photoaging. One study including 10 Asian patients (FSTs III-V) assessed the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser for facial rejuvenation.17 After 4 sessions at 2-week intervals, 80% (8/10) of patients reported decreased skin roughness after both the second and third treatments, while 90% (9/10) had improved texture 1 month after the final procedure. Adverse effects included moderate facial edema and one case of transient hyperpigmentation.17 Another study reported a significant reduction in pore score (P<.002), with patients noting an overall improvement in skin appearance with minimal erythema, dryness, and flaking following 6 sessions at 2-week intervals using the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser.18

The 1550-nm diode fractional laser significantly improved skin pigmentation (P<.001) and texture (P<.001) in 10 patients with FSTs II to IV following 5 sessions at 2- to 3-week intervals, with self-resolving erythema and edema posttreatment (Supplementary Table S2).19 Overall, NAFLs for the treatment of photoaging are effective with minimal adverse effects (eg, facial edema), which can be reduced with application of cold compression to the face and elevation of the head following treatment as well as the use of additional pillows during overnight sleep.

Laser Treatment for Hyperpigmentation Disorders

Melasma—The FDA recently approved fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of melasma; however, due to the risk for hyperpigmentation given its pathogenesis linked to hyperactive melanocytes, this laser is not considered a first-line therapy for melasma.20 In a split-face, randomized study, 22 patients with FSTs III to V who were diagnosed with either dermal or mixed-type melasma were treated with a low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser combined with hydroquinone 2% vs hydroquinone 2% alone (Supplementary Table S3).21 Each patient was treated weekly for 5 consecutive weeks. The laser-treated side was found to reach an average of 92.5% improvement compared with 19.7% on the hydroquinone-only side. Three of the 22 (13.6%) patients developed mottled hypopigmentation after 5 laser treatments, and 8 (36.4%) developed confetti-type hypopigmentation. Four (18.2%) patients developed rebound hyperpigmentation, and all 22 patients experienced recurrence of melasma by 12 weeks posttreatment.21

First-line treatment for melasma involves the application of topical lightening agents such as hydroquinone, azelaic acid, kojic acid, retinoids, or mild topical steroids. Combining laser technology with topical medications can enhance treatment outcomes, particularly yielding positive results for patients with persistent pigmentation concerns. Notably, utilization of 650-microsecond technology with the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser is considered superior in clinical practice, especially for patients with FSTs IV through VI.

Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation—A retrospective evaluation of 61 patients with FSTs IV to VI with PIH treated with a 1927-nm NAFL showed a mean improvement of 43.24%, as assessed by 2 dermatologists.22 Additionally, the Nd:YAG 1064-nm 650-microsecond pulse duration laser is an emerging treatment that delivers high and low fluences between 4 J/cm2 and 255 J/cm2 within a single 650-microsecond pulse duration.23 The short-pulse duration avoids overheating the skin, mitigating procedural discomfort and the risk for adverse effects commonly seen with the previous generation of low-pulsed lasers. In addition to PIH, this laser has been successfully used to treat pseudofolliculitis barbae.24

Solar Lentigos—In a split-face study treating solar lentigos in Asian patients, 4 treatments with a low-pulsed KTP 532-nm laser were administered with and without a second treatment with a low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.25 Scoring of a modified pigment severity index and measurement of the melanin index showed that skin treated with the low-pulsed 532-nm laser alone and in combination with the low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser resulted in improvement at 3 months’ follow-up. However, there was no difference between the 2 sides of the face, leading the researchers to conclude that the low-pulsed 532-nm laser appears to be safe and effective for treatment of solar lentigos in Asian patients and does not require the addition of the low-pulsed 1064-nm laser.25

To avoid hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, strict photoprotection to the treated areas should be advised. Proper cooling of the laser-treated area is required to minimize PIH, as cooling decreases tissue damage and excessive thermal injury. Test spots should be considered prior to initiation of the full laser treatment. Hydroquinone in a 4% concentration applied daily for 2 weeks preprocedure commonly is employed to reduce the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation in clinical practice.26,27

Skin Tightening and Body Contouring

In general, skin-tightening and body-contouring devices are among the most sought-after procedures. Studies performed in patients with SOC are limited. Herein, we provide background on why these devices are favorable for patients with SOC and our experiences in using them. A summary of these devices can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Radiofrequency Skin Tightening—Radiofrequency devices are utilized for skin tightening as well as mild fat reduction; they commonly are used on the abdomen, thighs, buttocks, and face.28 People with SOC are more responsive to radiofrequency skin-tightening therapy due to higher baseline collagen content and dermal thickness, more sebaceous activity and skin elasticity, and more melanin content which offers protective thermal buffering.29,30 As the radiofrequency device emits heat, penetrating deep into the dermis, it generates collagen remodeling and synthesis within 4 to 6 months posttreatment.

Nonsurgical Fat Reduction

Procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction are favorable due to minimal recovery time, manageable cost, and an in-office procedure setting. As noted previously, there are 6 FDA-indicated interventions for nonsurgical fat reduction: ultrasonography, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring.31

Ultrasonography—Ultrasound devices designed for body contouring are used for skin tightening and mild fat reduction through the use of acoustic energy.32 These devices can be divided into 2 categories: high frequency and low frequency, with the high-frequency devices being the most popular. High-frequency ultrasound energy produces heat at target sites, which induces necrosis of adipocytes and stimulates collagen remodeling within the tissue matrix.33 Tissue temperatures above 56°C stimulate adipocyte necrosis while sparing nearby nerves and vessels.28 Because of the short duration of the procedure, the risk for epidermal damage is minimal. Contrary to high-frequency ultrasonography, focus-pulsed ultrasonography employs low-frequency waves to induce the mechanical disruption of adipocytes, which is generally better tolerated due to its nonthermal mechanism. The latter may be advantageous in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for thermal injury to the epidermis. Multiple treatments often are needed at 3- to 4-week intervals, resulting in gradual improvement observed over 2 to 6 months. One study of microfocused ultrasonography in 25 Asian patients for treatment of face and neck laxity reported that skin laxity was improved or much improved in 84% (21/25) of patients following treatment.34 Adverse effects were reported as mild and transient, resolving within 90 days.34 Ultrasound devices also were shown to improve wrinkles, texture, and overall appearance of the skin in a 71-year-old African American woman 4 months following treatment (Figure 2). These photographs highlight the clinical utility of a microfocused ultrasound skin-tightening treatment in African American patients.

Cryolipolysis—Cryolipolysis is a noninvasive body contouring procedure that employs controlled cooling to induce subcutaneous panniculitis. Through cold-induced apoptosis of adipocytes, this procedure selectively reduces adipose tissue in localized areas such as the flank, abdomen, thighs, buttocks, back, submental area, and upper arms. The temperature used in cryolipolysis is approximately –10°C.35 The lethal temperature for melanocytes is –4 °C, below which melanocyte apoptosis may be induced, resulting in depigmentation. Given the prolonged contact of the skin with a cryolipolysis device for up to 60 minutes during a body-contouring procedure, there is a risk for resultant depigmentation in darker skin types. Controlled studies are needed to fully evaluate the safety and efficacy of cryolipolysis in patients with SOC. One retrospective study of cryolipolysis applied to the abdomen and upper arm of 4122 Asian patients reported a significant (P<.05) reduction in the circumference of the abdomen and the upper-arm areas. No long-term adverse effects were reported.36

Laser Lipolysis—The 1060-nm diode laser for body contouring selectively destroys adipose tissue, resulting in body contouring via thermally induced inflammation. Hyperthermic exposure for 15 minutes selectively elevates adipocyte temperature between 42°C to 47°C, which triggers apoptosis and the eventual clearance of destroyed cells from the interstitial space.37 The selectivity of the 1060-nm wavelength coupled with the device’s contact cooling system preserves the overlying skin and adnexa during the procedure,37 which would minimize epidermal damage that may induce dyspigmentation in patients with SOC. No notable adverse effects or dyspigmentation have been reported using this device.

Injection Lipolysis—Deoxycholic acid is an injectable adipocytolytic for the reduction of submental fat. It nonselectively lyses muscle and other adjacent nonfatty tissue. One study of 50 Indian patients demonstrated a substantial reduction of submental fat in 90% (45/50).38 For each treatment, 5 mL of 30 mg/mL deoxycholic acid was injected. Serial sessions were conducted at 2-month intervals, and most (64% [32/50]) patients required 3 sessions to see a treatment effect. Adverse effects included transient swelling, lumpiness, and tenderness. A phase 2a investigation of the novel injectable small-molecule drug CBL-514 in 43 Asian and White participants found a significant improvement in the reduction in abdominal fat volume (P<.00001) and thickness (P<.0001) relative to baseline at higher doses (unit dose, 2.0 mg/cm2 and 1.6 mg/cm2).39 In addition to the adverse effects mentioned previously, pruritus, repeated urticaria, body rash, and fever also were reported.39

Radiofrequency Lipolysis—Radiofrequency is used for adipolysis through heat-induced apoptosis. To achieve this effect, adipose tissue must sustain a temperature of 42 °C to 45 °C for at least 15 minutes.40 In one study, 4 treatments performed at 7-day intervals resulted in a statistically significant reduction in circumference to the treated areas of the inner and outer thighs without any reported adverse effects (P<0.001).41 Of note, there was 1 cm of distance between the applicator and the skin. The absence of direct contact with the skin is likely to reduce the risk for postprocedural complications in patients with SOC.

Magnetic Resonance Contouring—Magnetic resonance contouring with high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology is an emerging treatment modality for noninvasive body contouring. One distinguishing characteristic from other currently available noninvasive fat-reduction therapies is that magnetic resonance may improve strength, tone, and muscle thickness.42 This modality is FDA approved for contouring of the buttocks and abdomen and employs electromagnetic energy to stimulate approximately 20,000 muscle contractions within a time frame of 30 minutes. Though the mechanisms causing benefits to muscular and adipose tissue have not been elucidated, current findings suggest that the contractions stimulate substantial lipolysis of adipocytes, resulting in the release of large amounts of free fatty acids that cause damage to nearby adipose tissue.43 Multiple treatments are required over time to maintain effect. No major adverse effects have been reported. The likely mechanism of action of magnetic resonance contouring does not appear to pose an increased risk to patients with SOC.

Final Thoughts

One of the major roadblocks in distilling indications along with associated risks and benefits for nonsurgical cosmetic practices for patients with SOC is a void in the primary literature involving these populations. Clinical experience serves to address this deficit in combination with a thorough review of the literature. The 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser has shown clinical utility in the treatment of DPN, melanoma, and acne scars, but it poses financial constraints to the provider in comparison to modalities used for many years. Notably, NAF resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC and continues to gain popularity for the treatment of photoaging. Regarding skin-tightening and body-contouring devices, studies performed in patients with SOC are limited and affected by factors such as small sample sizes, underrepresentation of FSTs IV through VI, short follow-up durations, and a lack of standardized outcome measures. Additionally, few studies assess pigmentary adverse effects or stratify results by skin type, which is critical given the higher risk for PIH in SOC. Ultrasound devices showed clinical utility in improvement of skin laxity, texture, and overall improvement. Patients with SOC respond well to skin-tightening devices due to the increased collagen synthesis. Regarding emerging devices for reduction of adipocytes, deoxycholic acid when injected showed notable improvement in fat reduction but also had adverse effects. As additional studies on cosmetic procedures in SOC emerge, an expansion of treatment options could be offered to this demographic group with confidence, provided proper treatment and follow-up protocols are in place.

Cosmetic laser procedures as well as energy-based fat reduction and body-contouring devices are increasingly popular among individuals with skin of color (SOC). Innovations in cosmetic devices and procedures tailored for SOC have allowed for the optimization of outcomes in this patient population. In this article, SOC is defined as darker skin types, including Fitzpatrick skin types (FSTs) IV to VI and ethnic backgrounds such as LatinX, African American, Southeast Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, Asian, and African. Indications for laser treatment include dermatosis papulosa nigrans (DPN), acne scars, skin rejuvenation, and hyperpigmentation. There currently are 6 procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): high-frequency focused ultrasound, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring (Supplementary Table S1).1

In this review, our initial focus is cosmetic laser procedures, encompassing FDA-cleared indications along with the associated risks and benefits in SOC populations. Subsequently, we delve into the realms of energy-based fat reduction and body contouring, offering a comprehensive overview of these noninvasive therapies and addressing considerations for efficacy and safety in these patients.

Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

In patients with SOC, scissor excision, curettage, or electrodesiccation are the mainstay treatments for removal of DPN (Figure 1). Curettage and electrodesiccation can cause temporary postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) in these populations, while cryotherapy is not a preferred method in patients with SOC due to the possibility of cryotherapy-induced depigmentation. In a 14-patient split-face study comparing the 532-nm potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser vs electrodesiccation in FSTs IV to VI, the KTP-treated side showed an improvement rate of 96%, while the electrodesiccation side showed an improvement rate of 79%. There was a statistically significant favorable experience for KTP with regard to pain tolerability (P=.002).2 Complete resolution of lesions may be seen after 3 to 4 sessions at 4-week intervals. Additionally, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser was assessed for treatment of DPN in 2 patients, with 70% to 90% of lesions resolved after a single treatment with no complications.3

Most dermatologists still rely on curettage and electrodesiccation instead of laser therapy to remove DPNs in patients with SOC. The use of the Nd:YAG laser is promising yet expensive for the provider both to purchase and maintain. Electrodesiccation has been used by dermatology practices for decades and can be used without permanent discoloration. To minimize the risk for PIH, we recommend application of a healing ointment such as petroleum jelly or aloe vera gel to the treated lesions as well as lightening agents for PIH and daily use of sunscreen. Overall, providers do not need to purchase an expensive laser device for DPN removal.

Acne Scars

The invention of fractional technology in the early 2000s and its favorable safety profile have changed how dermatologists treat scarring in patients with SOC.

In one study of the short-pulsed nonablative Nd:YAG laser, 9 patients with FSTs I to V and 2 patients with FSTs IV to V underwent 8 treatments at 2-week intervals. Three blinded observers found a 29% improvement in the Global Acne Scar Severity score, while 89% (8/9) of patients self-reported subjective improvement in their acne scars.10

The 755-nm picosecond laser and diffractive lens array also have been shown to reduce the appearance of acne scars in patients with SOC, as shown via serial photography in a retrospective study of 56 patients with FSTs IV to VI. Transient hyperpigmentation, erythema, and edema were reported.11

Nonablative laser therapy is preferred for skin rejuvenation in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.11 Ablative resurfacing (eg, CO2 laser) poses major risks for postprocedural hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scar formation and therefore should be avoided in these populations.12,13 A study involving 30 Asian patients (FSTs III-IV) demonstrated that the 1550-nm fractional laser was well tolerated, though higher treatment densities and fluences may lead to temporary adverse effects such as increased redness, swelling, and pain (P<.01).14 Furthermore, greater density was shown to cause higher levels of redness, hyperpigmentation, and swelling in comparison to higher fluence settings. Of note, patient satisfaction was markedly higher in patients who underwent treatment with higher fluence settings but not in patients with higher densities (P<.05). Postprocedural hyperpigmentation was noted in 6.7% (2/30) of patients studied.14 In another study, 8 patients with FSTs II to V were treated with either the 1064-nm long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser or the grid fractional monopolar radiofrequency laser.15 All participants experienced a significant decrease in mean wrinkle count using the Lemperle wrinkle assessment (P<.05). A significant decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score from 3.5 to 3.17 in clinical assessment and a decrease from 3.165 to 2.33 for photographic assessment was noted in patients treated with the grid laser (P<.05). A similar decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score was observed in the Nd:YAG group, with a mean decrease of 3.665 to 2.83 after 2 months for clinical assessment and 3.5 to 2.67 for photographic assessment. Among all patients in the study, 68% (6/8) experienced erythema, 25% (2/8) had a burning sensation, and 25% (2/8) experienced urticaria immediately postprocedure.15

Nonablative fractional resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC. Adverse effects such as hyperpigmentation typically are transient, and the risk may be minimized with strict photoprotective practices following the procedure. Furthermore, avoidance of topicals containing exfoliants or α-hydroxy acids applied to the treated area following the procedure also may mitigate the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.16 If hyperpigmentation does occur, use of topical melanogenesis inhibitors such as hydroquinone, kojic acid, or azelaic acid has shown some utility in practice.

Skin Rejuvenation

Nonablative fractional lasers (NAFLs) continue to be popular for treatment of photoaging. One study including 10 Asian patients (FSTs III-V) assessed the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser for facial rejuvenation.17 After 4 sessions at 2-week intervals, 80% (8/10) of patients reported decreased skin roughness after both the second and third treatments, while 90% (9/10) had improved texture 1 month after the final procedure. Adverse effects included moderate facial edema and one case of transient hyperpigmentation.17 Another study reported a significant reduction in pore score (P<.002), with patients noting an overall improvement in skin appearance with minimal erythema, dryness, and flaking following 6 sessions at 2-week intervals using the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser.18

The 1550-nm diode fractional laser significantly improved skin pigmentation (P<.001) and texture (P<.001) in 10 patients with FSTs II to IV following 5 sessions at 2- to 3-week intervals, with self-resolving erythema and edema posttreatment (Supplementary Table S2).19 Overall, NAFLs for the treatment of photoaging are effective with minimal adverse effects (eg, facial edema), which can be reduced with application of cold compression to the face and elevation of the head following treatment as well as the use of additional pillows during overnight sleep.

Laser Treatment for Hyperpigmentation Disorders

Melasma—The FDA recently approved fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of melasma; however, due to the risk for hyperpigmentation given its pathogenesis linked to hyperactive melanocytes, this laser is not considered a first-line therapy for melasma.20 In a split-face, randomized study, 22 patients with FSTs III to V who were diagnosed with either dermal or mixed-type melasma were treated with a low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser combined with hydroquinone 2% vs hydroquinone 2% alone (Supplementary Table S3).21 Each patient was treated weekly for 5 consecutive weeks. The laser-treated side was found to reach an average of 92.5% improvement compared with 19.7% on the hydroquinone-only side. Three of the 22 (13.6%) patients developed mottled hypopigmentation after 5 laser treatments, and 8 (36.4%) developed confetti-type hypopigmentation. Four (18.2%) patients developed rebound hyperpigmentation, and all 22 patients experienced recurrence of melasma by 12 weeks posttreatment.21

First-line treatment for melasma involves the application of topical lightening agents such as hydroquinone, azelaic acid, kojic acid, retinoids, or mild topical steroids. Combining laser technology with topical medications can enhance treatment outcomes, particularly yielding positive results for patients with persistent pigmentation concerns. Notably, utilization of 650-microsecond technology with the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser is considered superior in clinical practice, especially for patients with FSTs IV through VI.

Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation—A retrospective evaluation of 61 patients with FSTs IV to VI with PIH treated with a 1927-nm NAFL showed a mean improvement of 43.24%, as assessed by 2 dermatologists.22 Additionally, the Nd:YAG 1064-nm 650-microsecond pulse duration laser is an emerging treatment that delivers high and low fluences between 4 J/cm2 and 255 J/cm2 within a single 650-microsecond pulse duration.23 The short-pulse duration avoids overheating the skin, mitigating procedural discomfort and the risk for adverse effects commonly seen with the previous generation of low-pulsed lasers. In addition to PIH, this laser has been successfully used to treat pseudofolliculitis barbae.24

Solar Lentigos—In a split-face study treating solar lentigos in Asian patients, 4 treatments with a low-pulsed KTP 532-nm laser were administered with and without a second treatment with a low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.25 Scoring of a modified pigment severity index and measurement of the melanin index showed that skin treated with the low-pulsed 532-nm laser alone and in combination with the low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser resulted in improvement at 3 months’ follow-up. However, there was no difference between the 2 sides of the face, leading the researchers to conclude that the low-pulsed 532-nm laser appears to be safe and effective for treatment of solar lentigos in Asian patients and does not require the addition of the low-pulsed 1064-nm laser.25

To avoid hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, strict photoprotection to the treated areas should be advised. Proper cooling of the laser-treated area is required to minimize PIH, as cooling decreases tissue damage and excessive thermal injury. Test spots should be considered prior to initiation of the full laser treatment. Hydroquinone in a 4% concentration applied daily for 2 weeks preprocedure commonly is employed to reduce the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation in clinical practice.26,27

Skin Tightening and Body Contouring

In general, skin-tightening and body-contouring devices are among the most sought-after procedures. Studies performed in patients with SOC are limited. Herein, we provide background on why these devices are favorable for patients with SOC and our experiences in using them. A summary of these devices can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Radiofrequency Skin Tightening—Radiofrequency devices are utilized for skin tightening as well as mild fat reduction; they commonly are used on the abdomen, thighs, buttocks, and face.28 People with SOC are more responsive to radiofrequency skin-tightening therapy due to higher baseline collagen content and dermal thickness, more sebaceous activity and skin elasticity, and more melanin content which offers protective thermal buffering.29,30 As the radiofrequency device emits heat, penetrating deep into the dermis, it generates collagen remodeling and synthesis within 4 to 6 months posttreatment.

Nonsurgical Fat Reduction

Procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction are favorable due to minimal recovery time, manageable cost, and an in-office procedure setting. As noted previously, there are 6 FDA-indicated interventions for nonsurgical fat reduction: ultrasonography, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring.31

Ultrasonography—Ultrasound devices designed for body contouring are used for skin tightening and mild fat reduction through the use of acoustic energy.32 These devices can be divided into 2 categories: high frequency and low frequency, with the high-frequency devices being the most popular. High-frequency ultrasound energy produces heat at target sites, which induces necrosis of adipocytes and stimulates collagen remodeling within the tissue matrix.33 Tissue temperatures above 56°C stimulate adipocyte necrosis while sparing nearby nerves and vessels.28 Because of the short duration of the procedure, the risk for epidermal damage is minimal. Contrary to high-frequency ultrasonography, focus-pulsed ultrasonography employs low-frequency waves to induce the mechanical disruption of adipocytes, which is generally better tolerated due to its nonthermal mechanism. The latter may be advantageous in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for thermal injury to the epidermis. Multiple treatments often are needed at 3- to 4-week intervals, resulting in gradual improvement observed over 2 to 6 months. One study of microfocused ultrasonography in 25 Asian patients for treatment of face and neck laxity reported that skin laxity was improved or much improved in 84% (21/25) of patients following treatment.34 Adverse effects were reported as mild and transient, resolving within 90 days.34 Ultrasound devices also were shown to improve wrinkles, texture, and overall appearance of the skin in a 71-year-old African American woman 4 months following treatment (Figure 2). These photographs highlight the clinical utility of a microfocused ultrasound skin-tightening treatment in African American patients.

Cryolipolysis—Cryolipolysis is a noninvasive body contouring procedure that employs controlled cooling to induce subcutaneous panniculitis. Through cold-induced apoptosis of adipocytes, this procedure selectively reduces adipose tissue in localized areas such as the flank, abdomen, thighs, buttocks, back, submental area, and upper arms. The temperature used in cryolipolysis is approximately –10°C.35 The lethal temperature for melanocytes is –4 °C, below which melanocyte apoptosis may be induced, resulting in depigmentation. Given the prolonged contact of the skin with a cryolipolysis device for up to 60 minutes during a body-contouring procedure, there is a risk for resultant depigmentation in darker skin types. Controlled studies are needed to fully evaluate the safety and efficacy of cryolipolysis in patients with SOC. One retrospective study of cryolipolysis applied to the abdomen and upper arm of 4122 Asian patients reported a significant (P<.05) reduction in the circumference of the abdomen and the upper-arm areas. No long-term adverse effects were reported.36

Laser Lipolysis—The 1060-nm diode laser for body contouring selectively destroys adipose tissue, resulting in body contouring via thermally induced inflammation. Hyperthermic exposure for 15 minutes selectively elevates adipocyte temperature between 42°C to 47°C, which triggers apoptosis and the eventual clearance of destroyed cells from the interstitial space.37 The selectivity of the 1060-nm wavelength coupled with the device’s contact cooling system preserves the overlying skin and adnexa during the procedure,37 which would minimize epidermal damage that may induce dyspigmentation in patients with SOC. No notable adverse effects or dyspigmentation have been reported using this device.

Injection Lipolysis—Deoxycholic acid is an injectable adipocytolytic for the reduction of submental fat. It nonselectively lyses muscle and other adjacent nonfatty tissue. One study of 50 Indian patients demonstrated a substantial reduction of submental fat in 90% (45/50).38 For each treatment, 5 mL of 30 mg/mL deoxycholic acid was injected. Serial sessions were conducted at 2-month intervals, and most (64% [32/50]) patients required 3 sessions to see a treatment effect. Adverse effects included transient swelling, lumpiness, and tenderness. A phase 2a investigation of the novel injectable small-molecule drug CBL-514 in 43 Asian and White participants found a significant improvement in the reduction in abdominal fat volume (P<.00001) and thickness (P<.0001) relative to baseline at higher doses (unit dose, 2.0 mg/cm2 and 1.6 mg/cm2).39 In addition to the adverse effects mentioned previously, pruritus, repeated urticaria, body rash, and fever also were reported.39

Radiofrequency Lipolysis—Radiofrequency is used for adipolysis through heat-induced apoptosis. To achieve this effect, adipose tissue must sustain a temperature of 42 °C to 45 °C for at least 15 minutes.40 In one study, 4 treatments performed at 7-day intervals resulted in a statistically significant reduction in circumference to the treated areas of the inner and outer thighs without any reported adverse effects (P<0.001).41 Of note, there was 1 cm of distance between the applicator and the skin. The absence of direct contact with the skin is likely to reduce the risk for postprocedural complications in patients with SOC.

Magnetic Resonance Contouring—Magnetic resonance contouring with high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology is an emerging treatment modality for noninvasive body contouring. One distinguishing characteristic from other currently available noninvasive fat-reduction therapies is that magnetic resonance may improve strength, tone, and muscle thickness.42 This modality is FDA approved for contouring of the buttocks and abdomen and employs electromagnetic energy to stimulate approximately 20,000 muscle contractions within a time frame of 30 minutes. Though the mechanisms causing benefits to muscular and adipose tissue have not been elucidated, current findings suggest that the contractions stimulate substantial lipolysis of adipocytes, resulting in the release of large amounts of free fatty acids that cause damage to nearby adipose tissue.43 Multiple treatments are required over time to maintain effect. No major adverse effects have been reported. The likely mechanism of action of magnetic resonance contouring does not appear to pose an increased risk to patients with SOC.

Final Thoughts

One of the major roadblocks in distilling indications along with associated risks and benefits for nonsurgical cosmetic practices for patients with SOC is a void in the primary literature involving these populations. Clinical experience serves to address this deficit in combination with a thorough review of the literature. The 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser has shown clinical utility in the treatment of DPN, melanoma, and acne scars, but it poses financial constraints to the provider in comparison to modalities used for many years. Notably, NAF resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC and continues to gain popularity for the treatment of photoaging. Regarding skin-tightening and body-contouring devices, studies performed in patients with SOC are limited and affected by factors such as small sample sizes, underrepresentation of FSTs IV through VI, short follow-up durations, and a lack of standardized outcome measures. Additionally, few studies assess pigmentary adverse effects or stratify results by skin type, which is critical given the higher risk for PIH in SOC. Ultrasound devices showed clinical utility in improvement of skin laxity, texture, and overall improvement. Patients with SOC respond well to skin-tightening devices due to the increased collagen synthesis. Regarding emerging devices for reduction of adipocytes, deoxycholic acid when injected showed notable improvement in fat reduction but also had adverse effects. As additional studies on cosmetic procedures in SOC emerge, an expansion of treatment options could be offered to this demographic group with confidence, provided proper treatment and follow-up protocols are in place.

Cosmetic Laser Procedures and Nonsurgical Body Contouring in Patients With Skin of Color

Cosmetic Laser Procedures and Nonsurgical Body Contouring in Patients With Skin of Color

- Mazzoni D, Lin MJ, Dubin DP, et al. Review of non-invasive body contouring devices for fat reduction, skin tightening and muscle definition. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:278-283. doi:10.1111/ajd.13090

- Kundu RV, Joshi SS, Suh KY, et al. Comparison of electrodesiccation and potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser for treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1079-1083. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01186.x&

- Schweiger ES, Kwasniak L, Aires DJ. Treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra with a 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser: report of two cases. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10:120-122. doi:10.1080/14764170801950070

- Manstein D, Herron GS, Sink RK, et al. Fractional photothermolysis: a new concept for cutaneous remodeling using microscopic patterns of thermal injury. Lasers Surg Med. 2004;34:426-438. doi:10.1002/lsm.20048

- Alajlan AM, Alsuwaidan SN. Acne scars in ethnic skin treated with both non-ablative fractional 1,550 nm and ablative fractional CO2 lasers: comparative retrospective analysis with recommended guidelines. Lasers Surg Med. 2011;43effi:787-791. doi:10.1002/lsm.21092

- Ke R, Cai B, Ni X, et al. Efficacy and safety of non-ablative vs. ablative lasers for acne scarring: a meta-analysis. J Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. Published online March 11, 2025. doi: 10.1111/ddg.15651

- Goel A, Krupashankar DS, Aurangabadkar S, et al. Fractional lasers in dermatology—current status and recommendations. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:369. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.79732

- Lee HS, Lee JH, Ahn GY, et al. Fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of acne scars: a report of 27 Korean patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:45-49. doi:10.1080/09546630701691244

- Zhang AD, Clovie J, Lazar M, et al. Treatment of benign pigmented lesions using lasers: a scoping review. J Clin Med. 2025;14li:3985. doi:10.3390/jcm14113985

- Lipper GM, Perez M. Nonablative acne scar reduction after a series of treatments with a short-pulsed 1,064-nm neodymium:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:998-1006. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32222.x

- Mar K, Khalid B, Maazi M, et al. Treatment of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in skin of colour: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2024;28:473-480. doi:10.1177/12034754241265716

- Kono T, Chan HH, Groff WF, et al. Prospective direct comparison study of fractional resurfacing using different fluences and densities for skin rejuvenation in Asians. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:311-314. doi:10.1002/lsm.20484

- Sharkey JR, Sharf BF, St John JA. “Una persona derechita (staying right in the mind)”: perceptions of Spanish-speaking Mexican American older adults in South Texas colonias. Gerontologist. 2009;49 suppl 1:S79-85. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp086

- Wu X, Cen Q, Jin J, et al. An effective and safe laser treatment strategy of fractional carbon dioxide laser for Chinese populations with periorbital wrinkles: a randomized split-face trial. Dermatol Therapy. 2025;15:1307-1317.

- Milante RR, Doria-Ruiz MJ, Beloso MB, et al. Split-face comparison of grid fractional radiofrequency vs 1064-nm Nd-YAG laser treatment of periorbital rhytides among Filipino patients. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14031. doi:10.1111/dth.14031

- Alexis AF, Andriessen A, Beach RA, et al. Periprocedural skincare for nonenergy and nonablative energy-based aesthetic procedures in patients with skin of color. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2025;24:E16712. doi:10.1111/jocd.16712

- Marmon S, Shek SYN, Yeung CK, et al. Evaluating the safety and efficacy of the 1,440-nm laser in the treatment of photodamage in Asian skin. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:375-379. doi:10.1002/lsm.22242

- Saedi N, Petrell K, Arndt K, et al. Evaluating facial pores and skin texture after low-energy nonablative fractional 1440-nm laser treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:113-118. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.08.041

- Jih MH, Goldberg LH, Kimyai-Asadi A. Fractional photothermolysis for photoaging of hands. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:73-78. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34011.x

- Prohaska J, Hohman MH. Laser complications. StatPearls. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed July 23, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532248/

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.01.004

- Brauer JA, Kazlouskaya V, Alabdulrazzaq H, et al. Use of a picosecond pulse duration laser with specialized optic for treatment of facial acne scarring. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:278-284. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3045

- Greywal T, Ortiz A. Treating melasma with the 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser with a 650-microsecond pulse duration: a clinical evaluation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3889-3892. doi:10.1111/jocd.14558

- Weaver SM, Sagaral EC. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae using the long-pulse Nd:YAG laser on skin types V and VI. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1187-1191. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2003.29387.x

- Negishi K, Tanaka S, Tobita S. Prospective, randomized, evaluator-blinded study of the long pulse 532-nm KTP laser alone or in combination with the long pulse 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser on facial rejuvenation in Asian skin. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:844-851. doi:10.1002/lsm.22582

- Kaushik S, Alexis AF. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in skin of color: evidence-based review. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2017;10:51-67.

- Garg S, Vashisht KR, Garg D, et al. Advancements in laser therapies for dermal hyperpigmentation in skin of color: a comprehensive literature review and experience of sequential laser treatments in a cohort of 122 Indian patients. J Clin Med. 2024;13:2116. doi:10.3390/jcm13072116

- Alizadeh Z, Halabchi F, Mazaheri R, et al. Review of the mechanisms and effects of noninvasive body contouring devices on cellulite and subcutaneous fat. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;14:e36727. doi:10.5812/ijem.36727

- Rawlings AV. Ethnic skin types: are there differences in skin structure and function? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006;28:79-93. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2494.2006.00302.x

- El-Domyati M, El-Ammawi TS, Medhat W, et al. Radiofrequency facial rejuvenation: Evidence-based effect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:524-535. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.045

- US Food and Drug Administration. Non-invasive body contouring technologies. Published December 7, 2022. Accessed July 23, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/aesthetic-cosmetic-devices/non-invasive-body-contouring-technologies

- Robinson DM, Kaminer MS, Baumann L, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound for the reduction of subcutaneous adipose tissue using multiple treatment techniques. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:641-651. doi:10.1111/dsu.0000000000000022

- Biskanaki F, Tertipi N, Sfyri E, et al. Complications and risks of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) in esthetic procedures: a review. Applied Sciences. 2025;15:4958. doi:10.3390/app15094958

- Lu PH, Yang CH, Chang YC. Quantitative analysis of face and neck skin tightening by microfocused ultrasound with visualization in Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1332-1338. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001181

- Avram MM, Harry RS. Cryolipolysis for subcutaneous fat layer reduction. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41:703-708. doi:10.1002/lsm.20864

- Nishikawa A, Aikawa Y. Quantitative assessment of the cryolipolysis method for body contouring in Asian patients. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:1773-1781. doi:10.2147/CCID.S337487

- Bass LS, Doherty ST. Safety and efficacy of a non-invasive 1060 nm diode laser for fat reduction of the abdomen. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:106-112

- Shome D, Khare S, Kapoor R. The use of deoxycholic acid for the clinical reduction of excess submental fat in Indian patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:266-272.

- Goodman GJ, Ho WWS, Chang KJ, et al. Efficacy of a novel injection lipolysis to induce targeted adipocyte apoptosis: a randomized, phase IIa study of CBL-514 injection on abdominal subcutaneous fat reduction. Aesthetic Surg J. 2022;42:NP662-NP674. doi:10.1093/asj/sjac162

- McDaniel D, Lozanova P. Human adipocyte apoptosis immediately following high frequency focused field radio frequency: case study.J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:622-623.

- Fritz K, Samková P, Salavastru C, et al. A novel selective RF applicator for reducing thigh circumference: a clinical evaluation. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:92-95. doi:10.1111/dth.12304

- Kinney BM, Lozanova P. High intensity focused electromagnetic therapy evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging: safety and efficacy study of a dual tissue effect based non-invasive abdominal body shaping. Lasers Surg Med. 2019;51:40-46. doi:10.1002/lsm.23024

- Negosanti F, Cannarozzo G, Zingoni T, et al. Is it possible to reshape the body and tone it at the same time? Schwarzy: the new technology for body sculpting. Bioengineering (Basel). 2022;9:284. doi:10.3390/bioengineering9070284

PRACTICE POINTS

- Nonablative fractional lasers are preferred for acne scars in skin of color (SOC), minimizing hyperpigmentation risk.

- The 1064-nm Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe and effective when used with SOC-appropriate settings.

- Photoprotection and topical lightening agents reduce postprocedure pigmentation risks.

Treatment of Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia in Black Patients: A Systematic Review

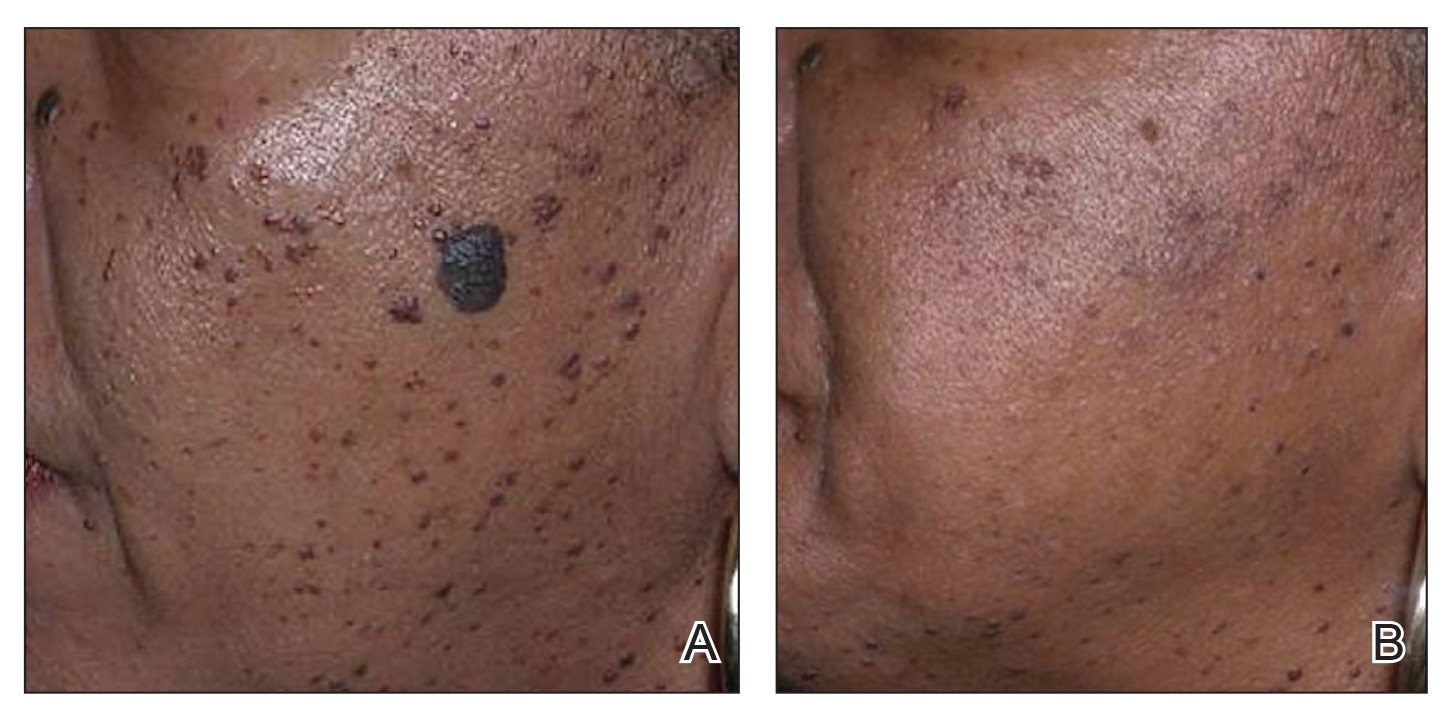

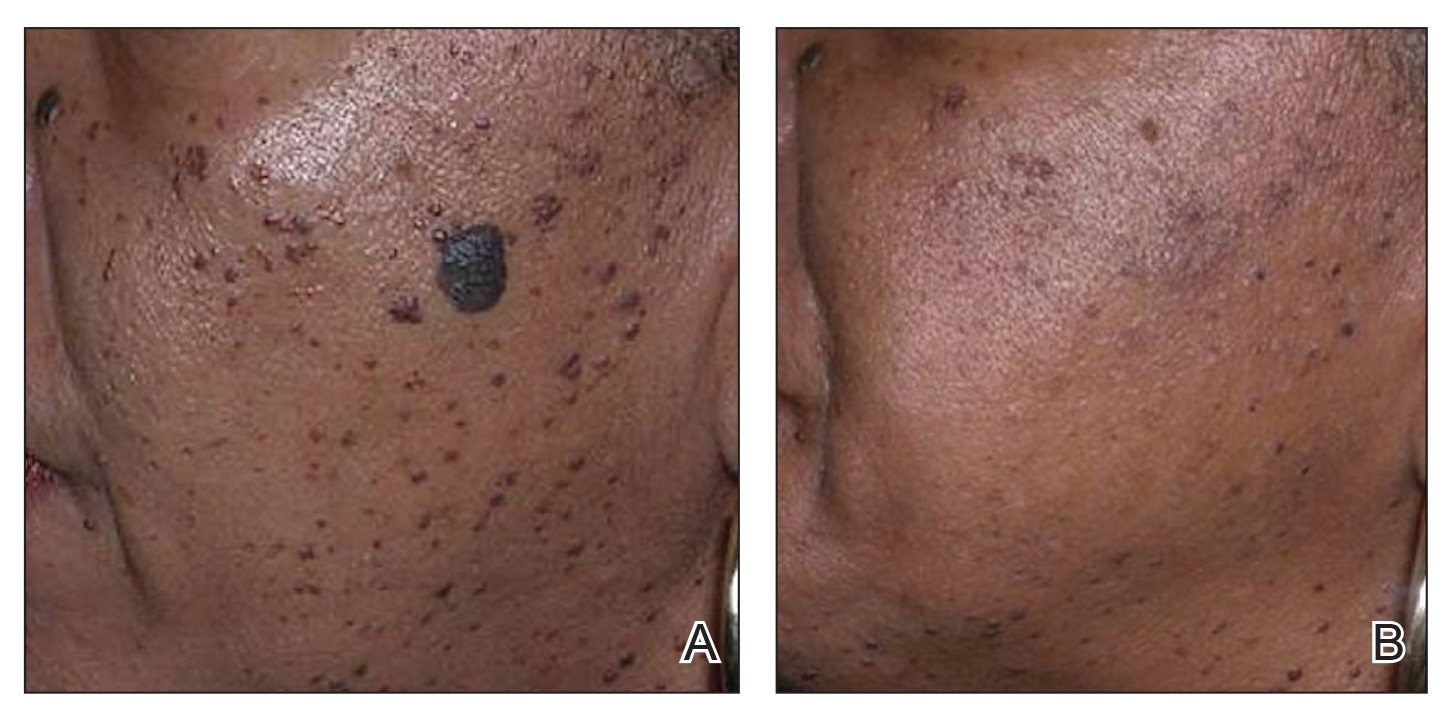

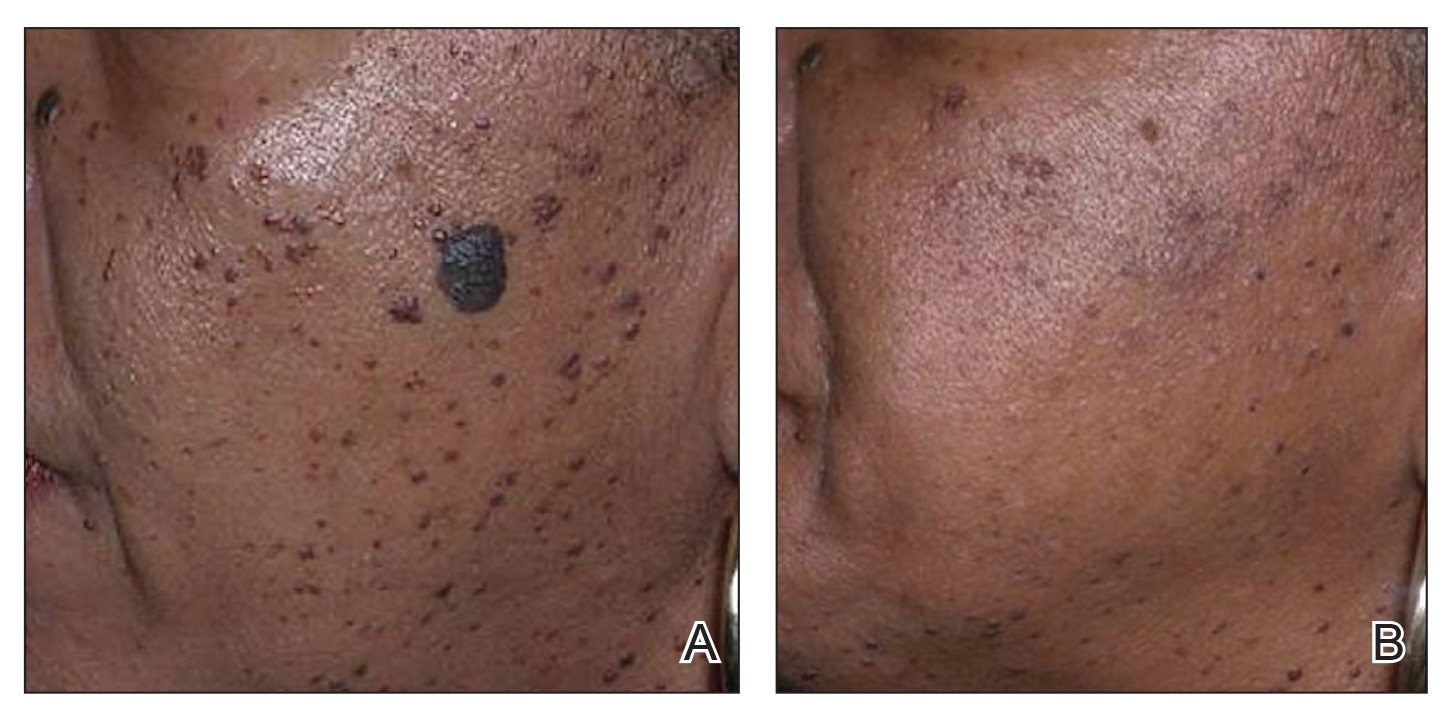

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that primarily affects postmenopausal women. Considered a subtype of lichen planopilaris (LPP), FFA is histologically identical but presents as symmetric frontotemporal hairline recession rather than the multifocal distribution typical of LPP (Figure 1). Patients also may experience symptoms such as itching, facial papules, and eyebrow loss. As a progressive and scarring alopecia, early management of FFA is necessary to prevent permanent hair loss; however, there still are no clear guidelines regarding the efficacy of different treatment options for FFA due to a lack of randomized controlled studies in the literature. Patients with skin of color (SOC) also may have varying responses to treatment, further complicating the establishment of any treatment algorithm. Furthermore, symptoms, clinical findings, and demographics of FFA have been observed to vary across different ethnicities, especially among Black individuals. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on FFA in Black patients, with an analysis of demographics, clinical findings, concomitant skin conditions, treatments given, and treatment responses.

Methods

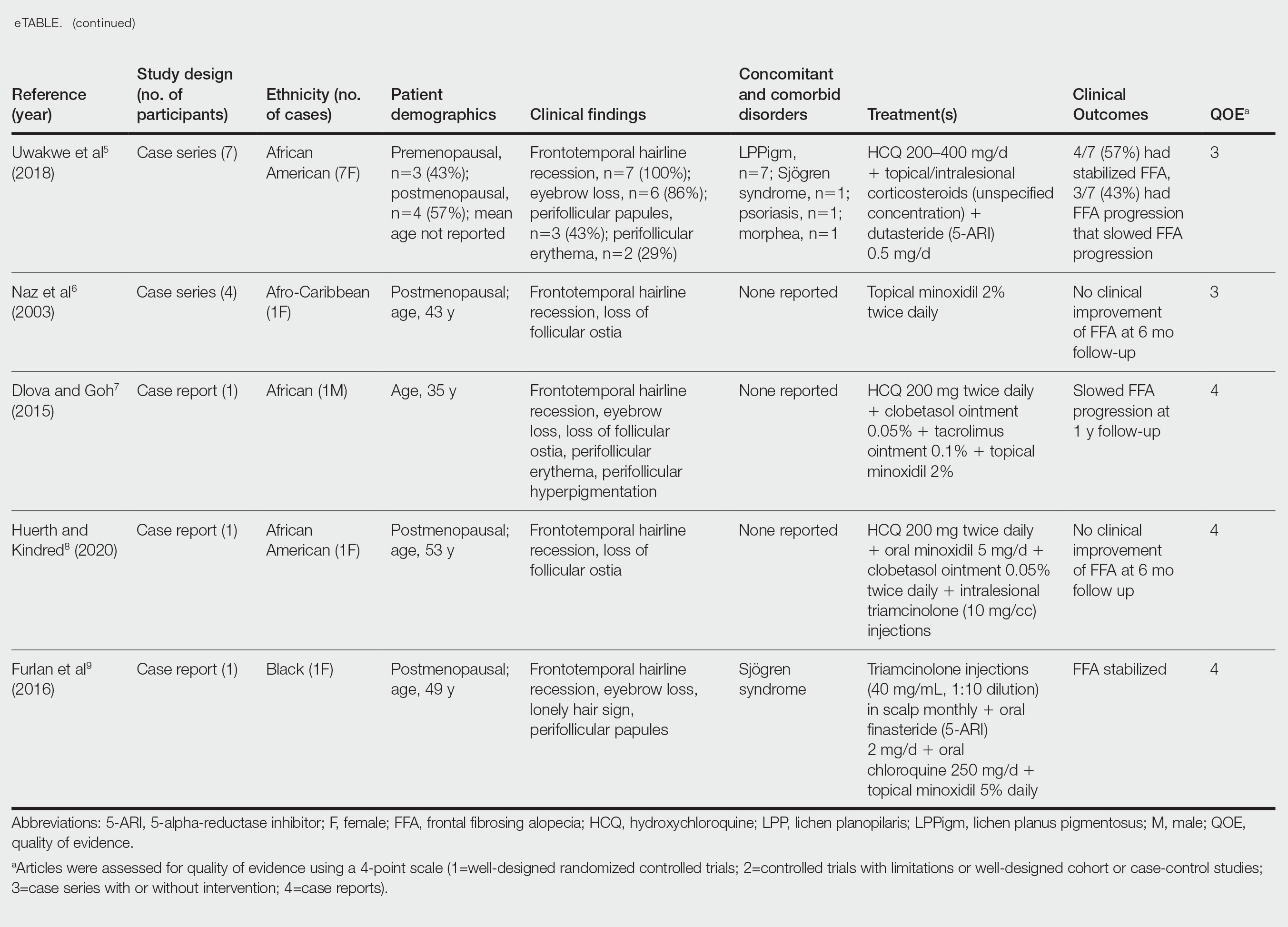

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted of studies investigating FFA in patients with SOC from January 1, 2000, through November 30, 2020, using the terms frontal fibrosing alopecia, ethnicity, African, Black, Asian, Indian, Hispanic, and Latino. Articles were included if they were available in English and discussed treatment and clinical outcomes of FFA in Black individuals. The reference lists of included studies also were reviewed. Articles were assessed for quality of evidence using a 4-point scale (1=well-designed randomized controlled trials; 2=controlled trials with limitations or well-designed cohort or case-control studies; 3=case series with or without intervention; 4=case reports). Variables related to study type, patient demographics, treatments, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

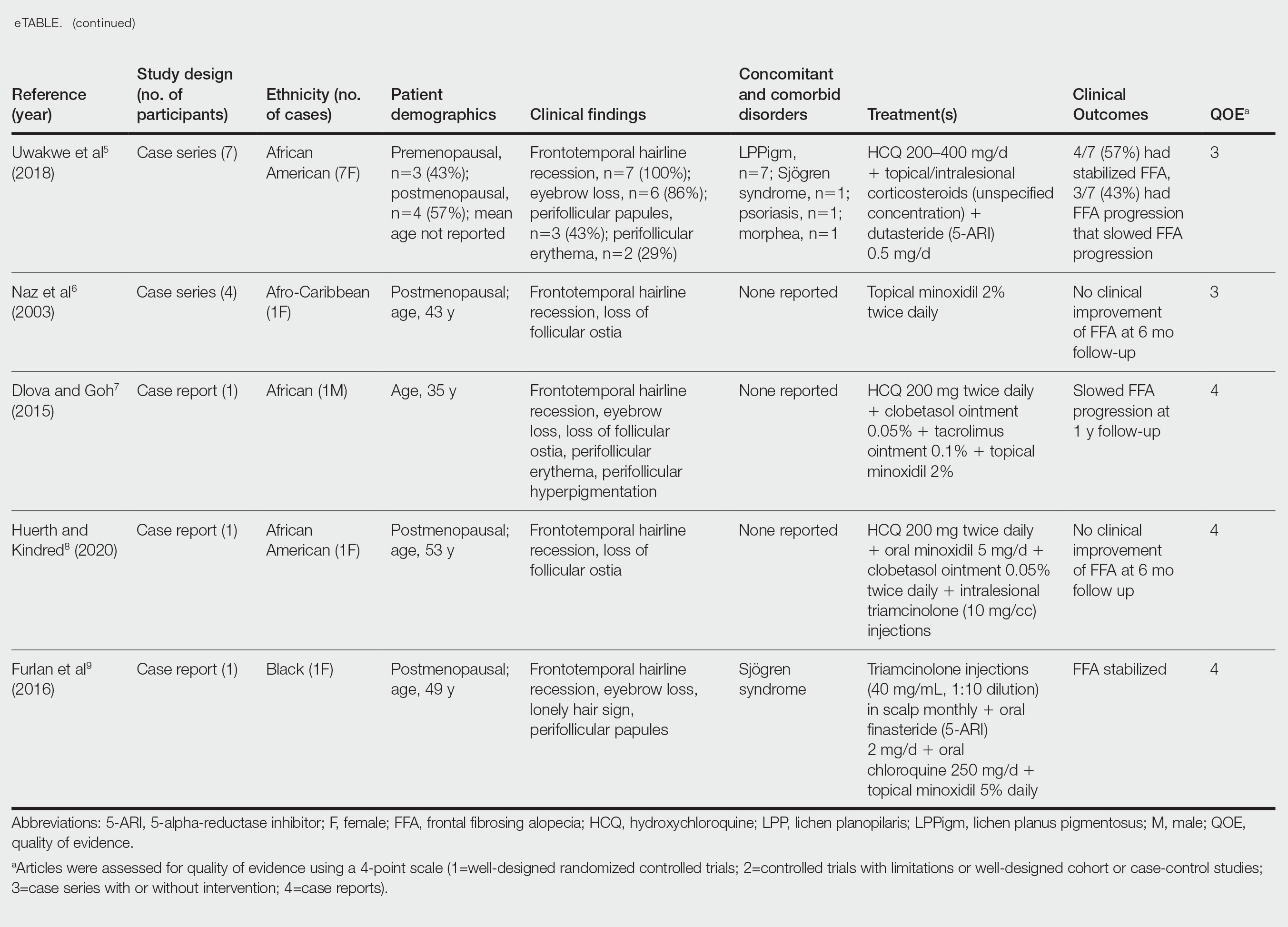

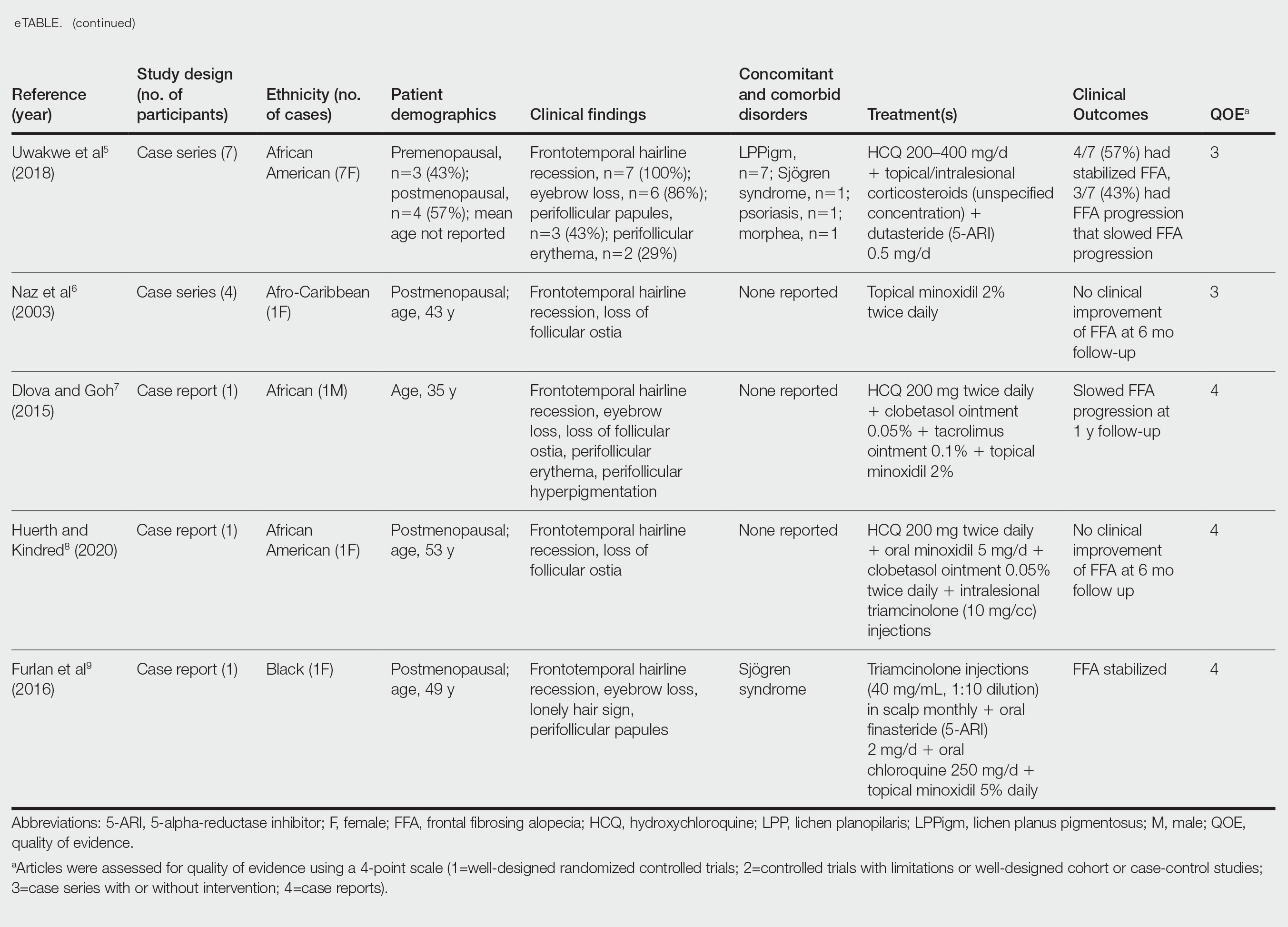

Of the 69 search results, 8 studies—2 retrospective cohort studies, 3 case series, and 3 case reports—describing 51 Black individuals with FFA were included in our review (eTable). Of these, 49 (96.1%) were female and 2 (3.9%) were male. Of the 45 females with data available for menopausal status, 24 (53.3%) were premenopausal and 21 (46.7%) were postmenopausal; data were not available for 4 females. Patients identified as African or African American in 27 (52.9%) cases, South African in 19 (37.3%), Black in 3 (5.9%), Indian in 1 (2.0%), and Afro-Caribbean in 1 (2.0%). The average age of FFA onset was 43.8 years in females (raw data available in 24 patients) and 35 years in males (raw data available in 2 patients). A family history of hair loss was reported in 15.7% (8/51) of patients.

Involved areas of hair loss included the frontotemporal hairline (51/51 [100%]), eyebrows (32/51 [62.7%]), limbs (4/51 [7.8%]), occiput (4/51 [7.8%]), facial hair (2/51 [3.9%]), vertex scalp (1/51 [2.0%]), and eyelashes (1/51 [2.0%]). Patchy alopecia suggestive of LPP was reported in 2 (3.9%) patients.

Patients frequently presented with scalp pruritus (26/51 [51.0%]), perifollicular papules or pustules (9/51 [17.6%]), and perifollicular hyperpigmentation (9/51 [17.6%]). Other associated symptoms included perifollicular erythema (6/51 [11.8%]), scalp pain (5/51 [9.8%]), hyperkeratosis or flaking (3/51 [5.9%]), and facial papules (2/51 [3.9%]). Loss of follicular ostia, prominent follicular ostia, and the lonely hair sign (Figure 2) was described in 21 (41.2%), 5 (9.8%), and 15 (29.4%) of patients, respectively. Hairstyles that involve scalp traction (19/51 [37.3%]) and/or chemicals (28/51 [54.9%]), such as hair dye or chemical relaxers, commonly were reported in patients prior to the onset of FFA.

The most commonly reported dermatologic comorbidities included traction alopecia (17/51 [33.3%]), followed by lichen planus pigmentosus (LLPigm)(7/51 [13.7%]), LPP (2/51 [3.9%]), psoriasis (1/51 [2.0%]), and morphea (1/51 [2.0%]). Reported comorbid diseases included Sjögren syndrome (2/51 [3.9%]), hypothyroidism (2/51 [3.9%]), HIV (1/51 [2.0%]), and diabetes mellitus (1/51 [2.0%]).

Of available reports (n=32), the most common histologic findings included perifollicular fibrosis (23/32 [71.9%]), lichenoid lymphocytic inflammation (22/23 [95.7%]) primarily affecting the isthmus and infundibular areas of the follicles, and decreased follicular density (21/23 [91.3%]).

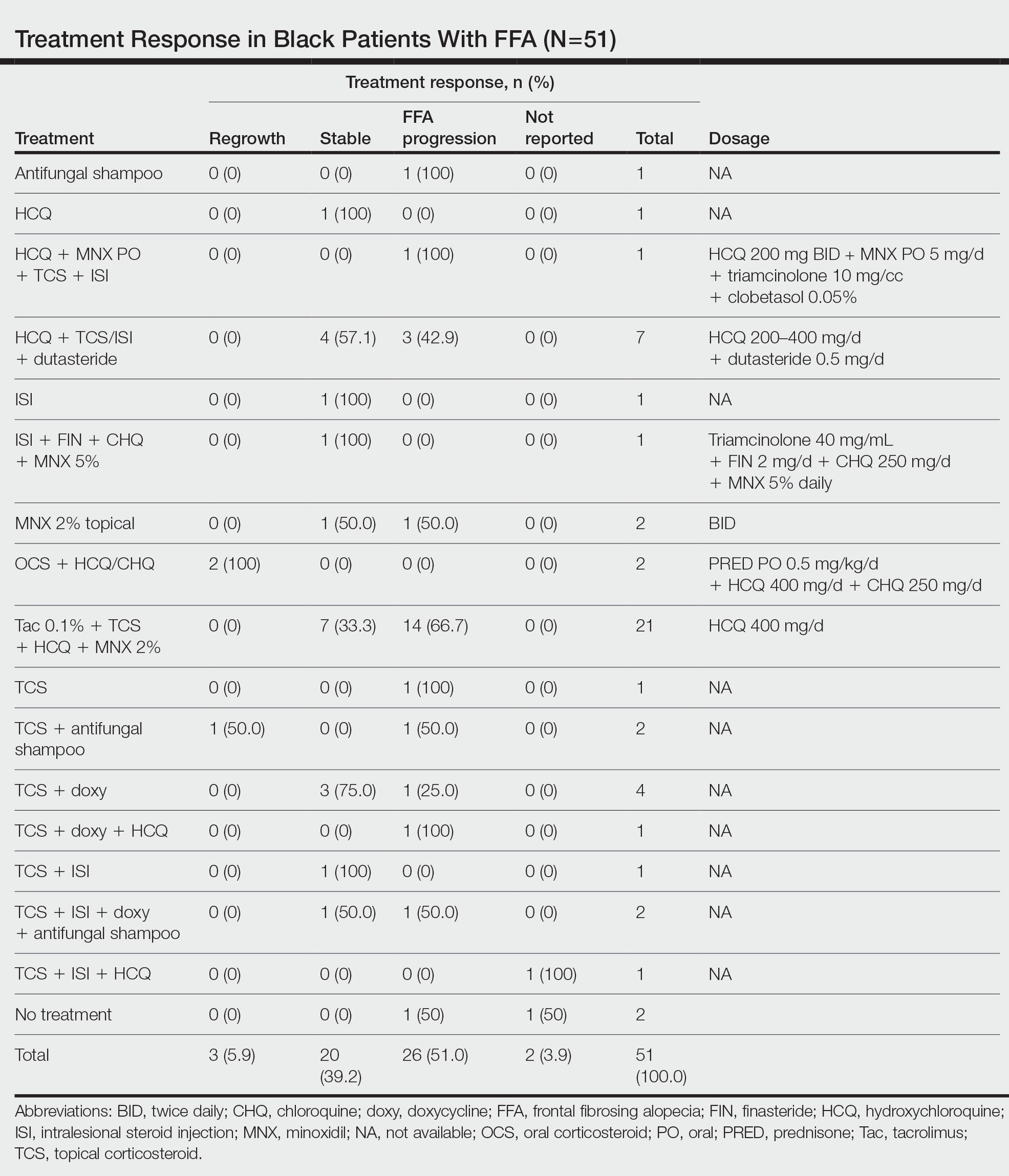

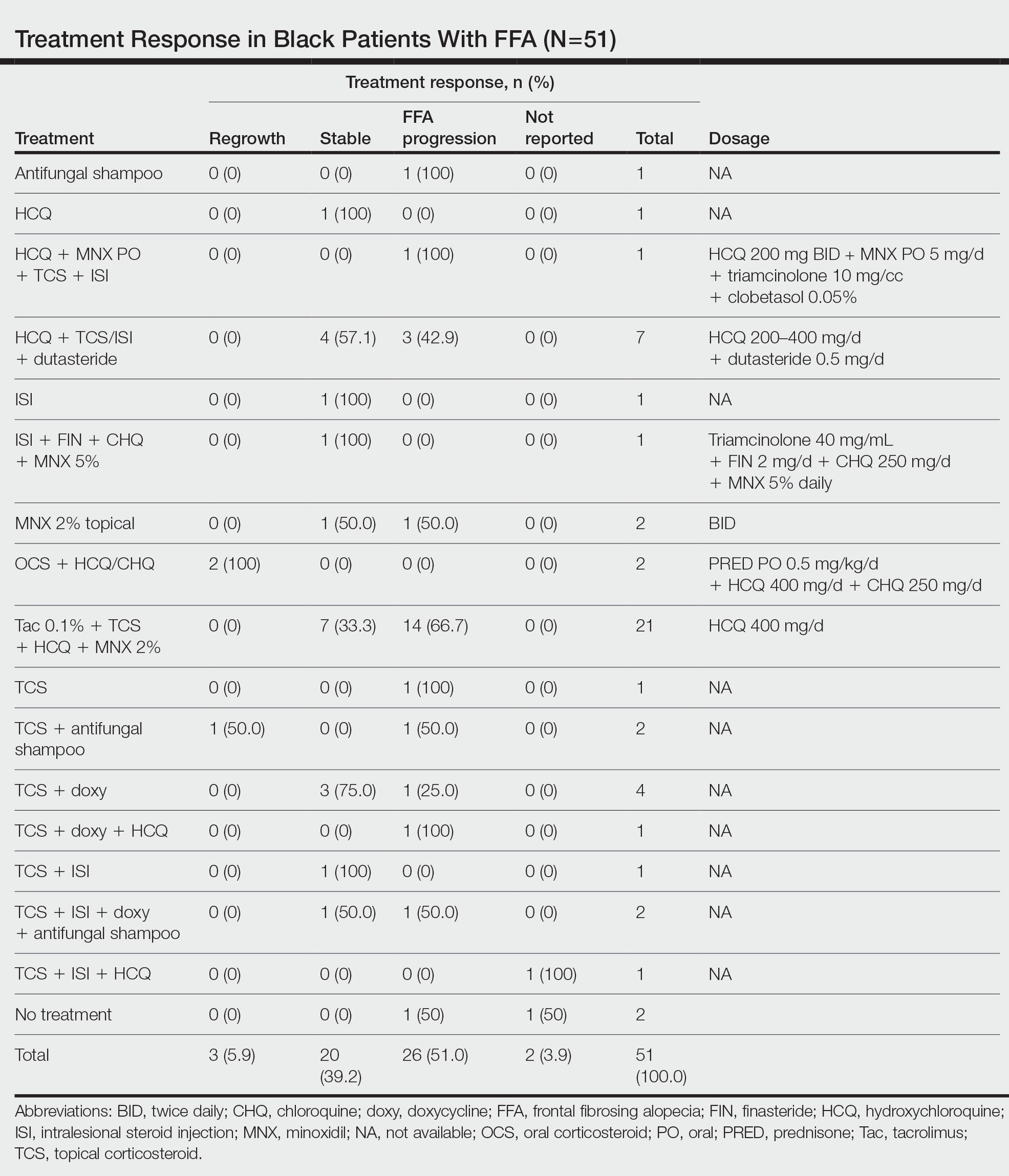

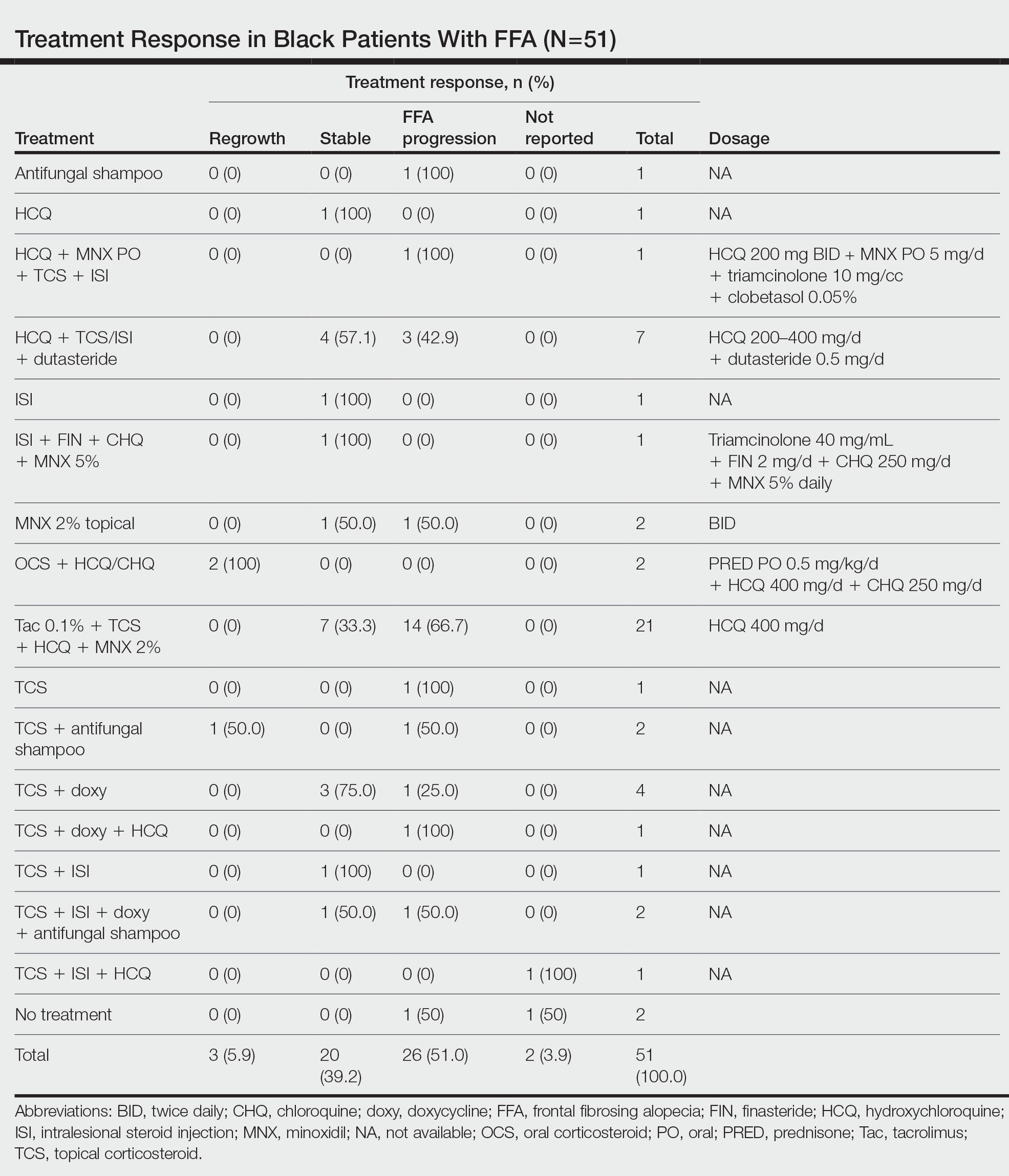

The average time interval from treatment initiation to treatment assessment in available reports (n=25) was 1.8 years (range, 0.5–2 years). Response to treatment included regrowth of hair in 5.9% (3/51) of patients, FFA stabilization in 39.2% (20/51), FFA progression in 51.0% (26/51), and not reported in 3.9% (2/51). Combination therapy was used in 84.3% (43/51) of patients, while monotherapy was used in 11.8% (6/51), and 3.9% (2/51) did not have any treatment reported. Response to treatment was highly variable among patients, as were the combinations of therapeutic agents used (Table). Regrowth of hair was rare, occurring in only 2 (100%) patients treated with oral prednisone plus hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or chloroquine (CHQ), and in 1 (50.0%) patient treated with topical corticosteroids plus antifungal shampoo, while there was no response in the other patient treated with this combination.

Improvement in hair loss, defined as having at least slowed progression of FFA, was observed in 100% (2/2) of patients who had oral steroids as part of their treatment regimen, followed by 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs)(finasteride and dutasteride; 62.5% [5/8]), intralesional steroids (57.1% [8/14]), HCQ/CHQ (42.9% [15/35]), topical steroids (41.5% [17/41]), antifungal shampoo (40.0% [2/5]), topical/oral minoxidil (36.0% [9/25]), and tacrolimus (33.3% [7/21]).

Comment

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a progressive scarring alopecia and a clinical variant of LPP. First described in 1994 by Kossard,1 it initially was thought to be a disease of postmenopausal White women. Although still most prevalent in White individuals, there has been a growing number of reports describing FFA in patients with SOC, including Black individuals.10 Despite the increasing number of cases over the years, studies on the treatment of FFA remain sparse. Without expert guidelines, treatments usually are chosen based on clinician preferences. Few observational studies on these treatment modalities and their clinical outcomes exist, and the cohorts largely are composed of White patients.10-12 However, Black individuals may respond differently to these treatments, just as they have been shown to exhibit unique features of FFA.3

Demographics of Patients With FFA—Consistent with our findings, prior studies have found that Black patients are more likely to be younger and premenopausal at FFA onset than their White counterparts.13-15 Among the Black individuals included in our review, the majority were premenopausal (53%) with an average age of FFA onset of 46.7 years. Conversely, only 5% of 60 White females with FFA reported in a retrospective review were premenopausal and had an older mean age of FFA onset of 64 years,1 substantiating prior reports.