User login

Assessing the Merit of the Apple Cider Vinegar Rinse Method for Synthetic Hair Extensions

Assessing the Merit of the Apple Cider Vinegar Rinse Method for Synthetic Hair Extensions

Synthetic hair extensions are made from various plastic polymers (eg, modacrylic, vinyl chloride, and acrylonitrile) shaped into thin strands that mimic human hair and are used to add fullness, length, and manageability in individuals with textured hair.1-3 The plastic polymers used to make synthetic hair, most notably acrylonitrile and vinyl chloride, are known to be toxic to humans.1-4 The US Environmental Protection Agency classifies acrylonitrile as a probable carcinogen, and vinyl chloride is associated with the development of lymphoma; leukemia; and rare malignancies of the brain, liver, and lungs.1,4 According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the maximum exposure limits of vinyl chloride and acrylonitrile vapor or gas over an 8-hour period are 1 ppm (0.001 g/L) and 2 ppm (0.002 g/L), respectively.5 Exposure levels from wearing synthetic hair extensions easily exceed these maximums; for example, a full head of braids requires application of multiple packets of synthetic hair, resulting in continuous exposure to carcinogenic materials that can last for weeks to months at a time.1 Furthermore, individuals as young as 3 years old can begin to style their hair with synthetic extensions, which not only leads to potentially harmful carcinogenic exposure in young children but also yields notably high levels of lifetime exposure in individuals who regularly style their hair with these products.

There currently are no regulations barring the use of potentially harmful materials from the manufacturing process for synthetic hair extensions.1 As a result, rinsing with apple cider vinegar (ACV) is a popular remedy that many users claim can effectively remove harmful chemicals from synthetic hair.6,7 As this is the only known remedy that aims to address this issue,

Methods

We conducted a search of Google Scholar, JSTOR, Science Direct, the Public Library of Science, and PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ACV, apple cider vinegar rinse, ACV rinse, synthetic hair carcinogens, synthetic fiber carcinogens, synthetic hair extension carcinogens, modacrylic fibers, Kanekalon (a flame-retardant modacrylic fiber), acrylonitrile, and vinyl chloride fibers to identify primary research articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions for inclusion in our review. To broaden our search, we did not establish a time frame for publication of the articles included in the study. Articles investigating the ACV rinse that were unrelated to carcinogenicity and synthetic hair extensions were excluded from this study.

Results

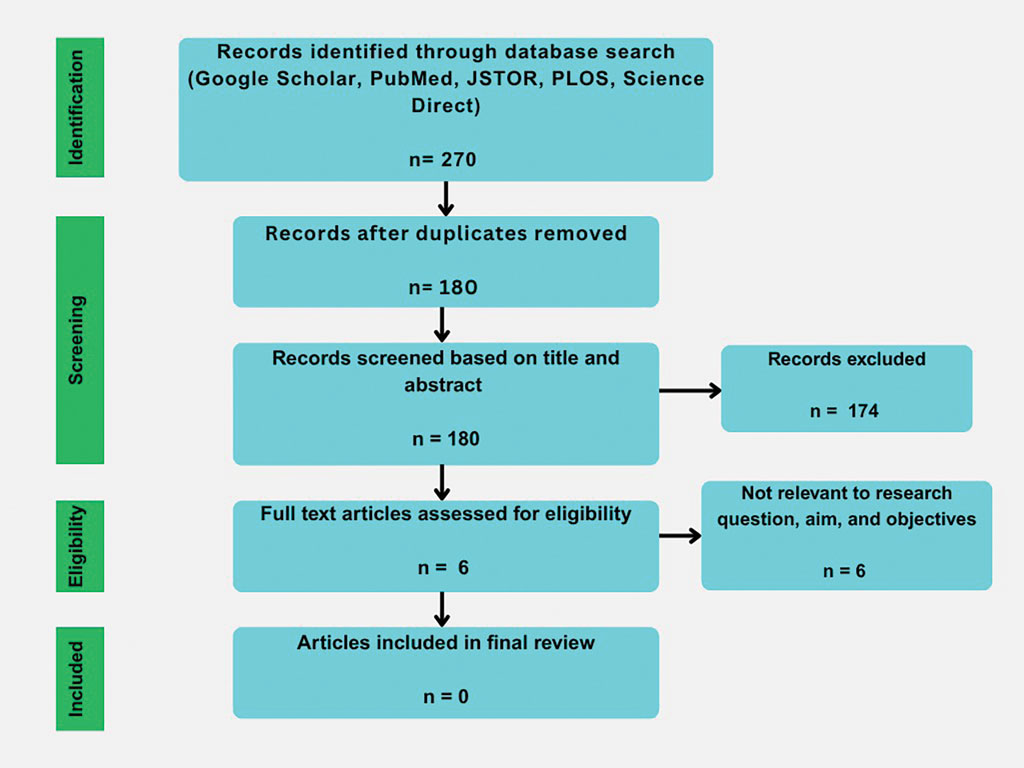

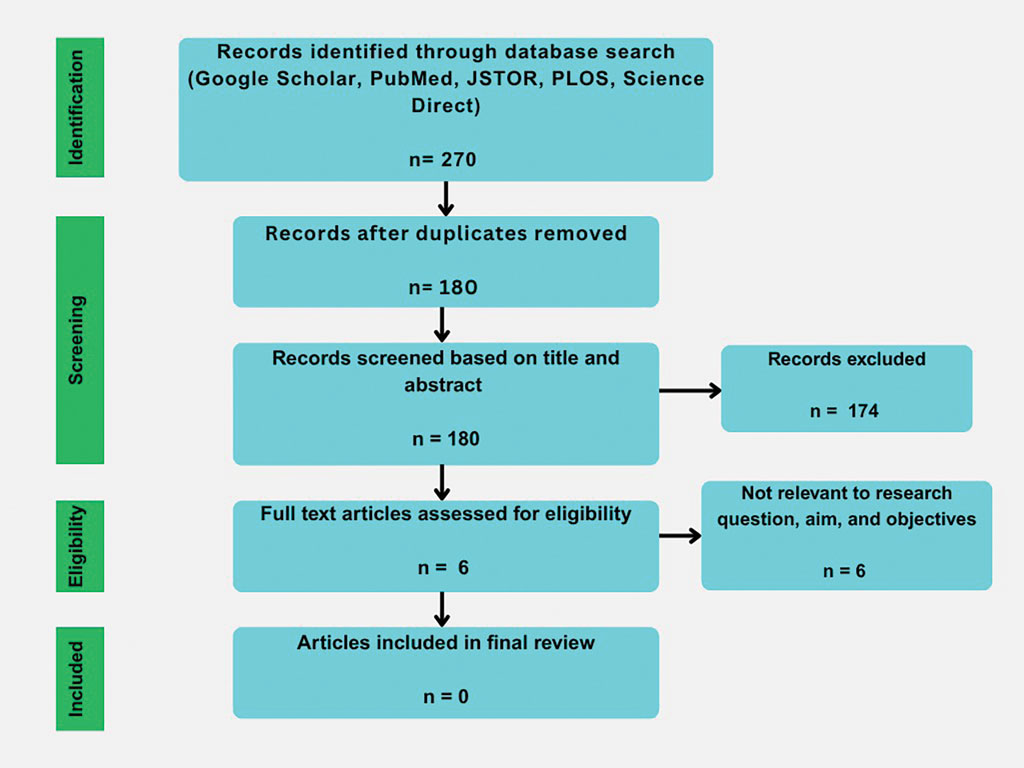

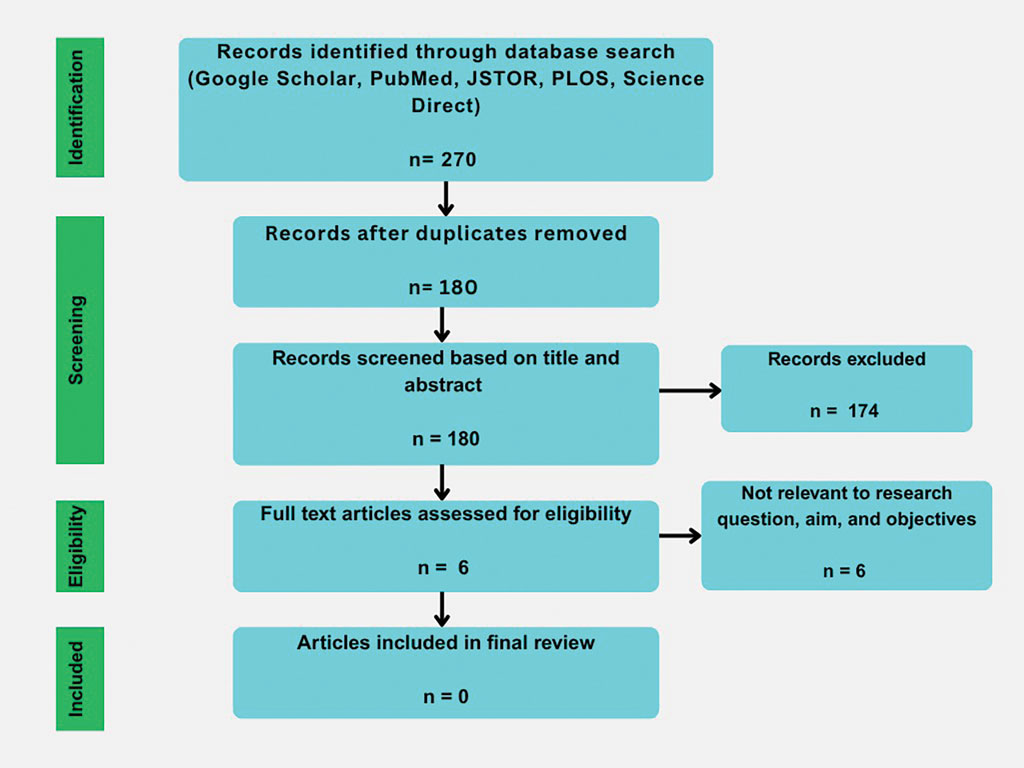

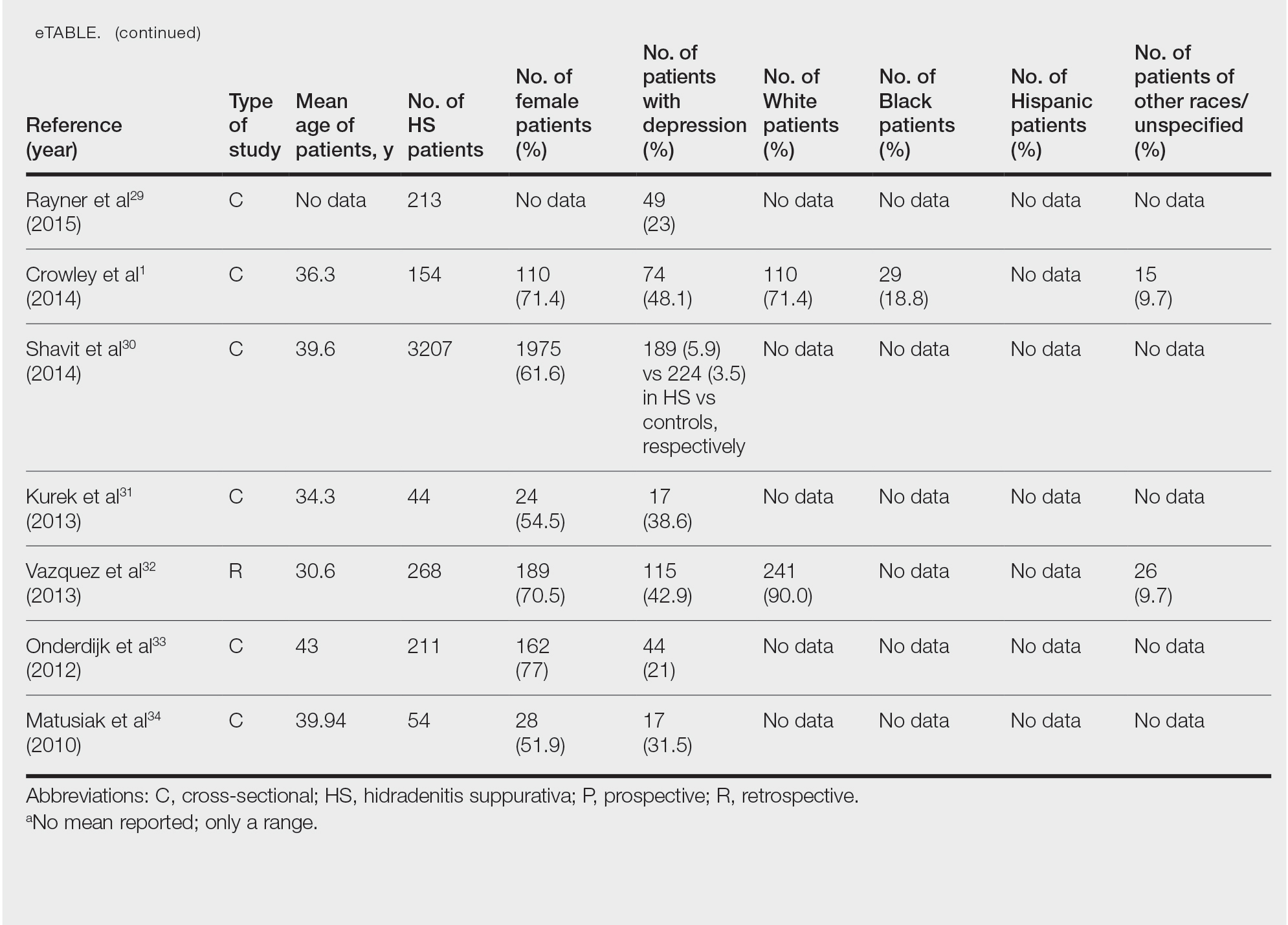

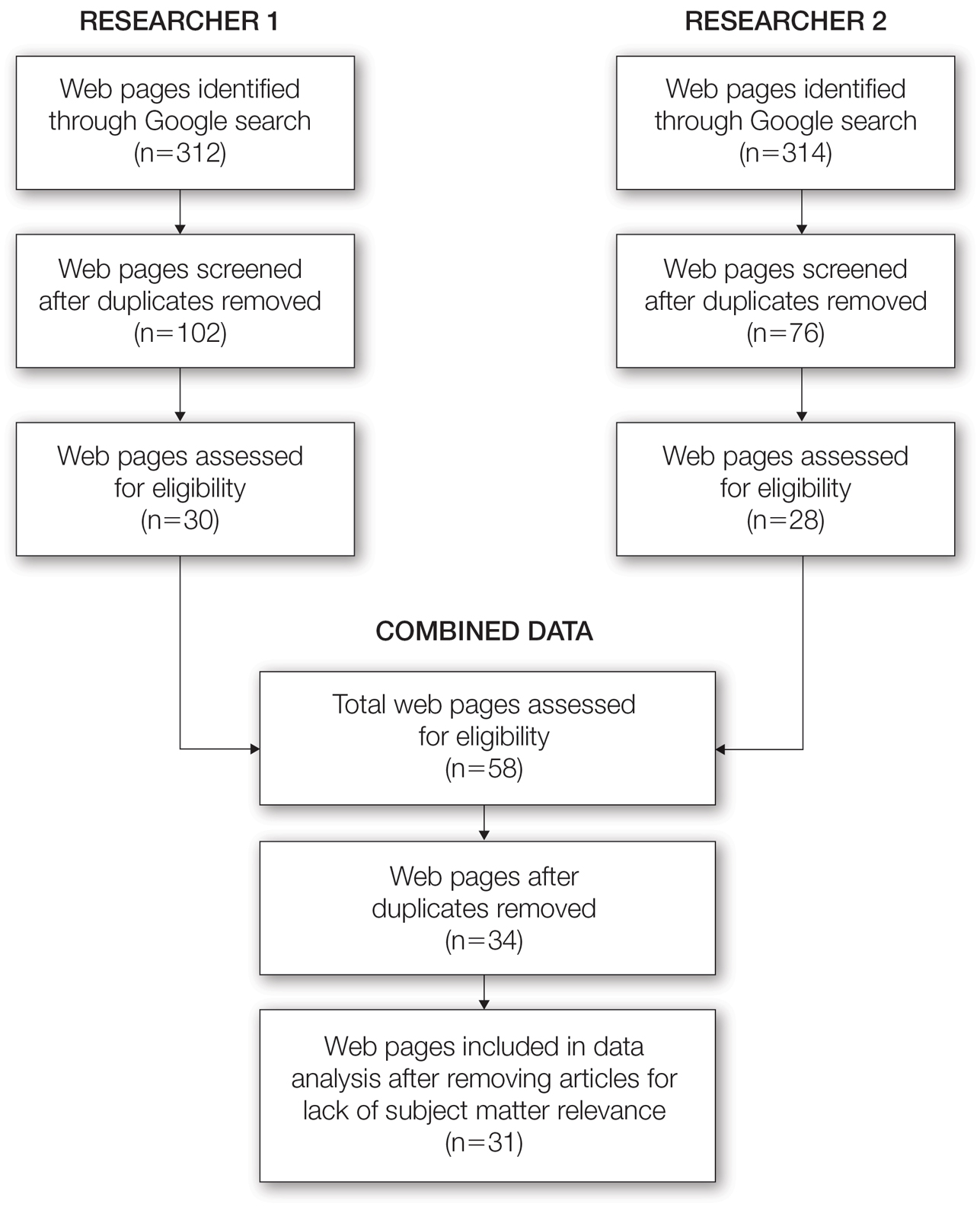

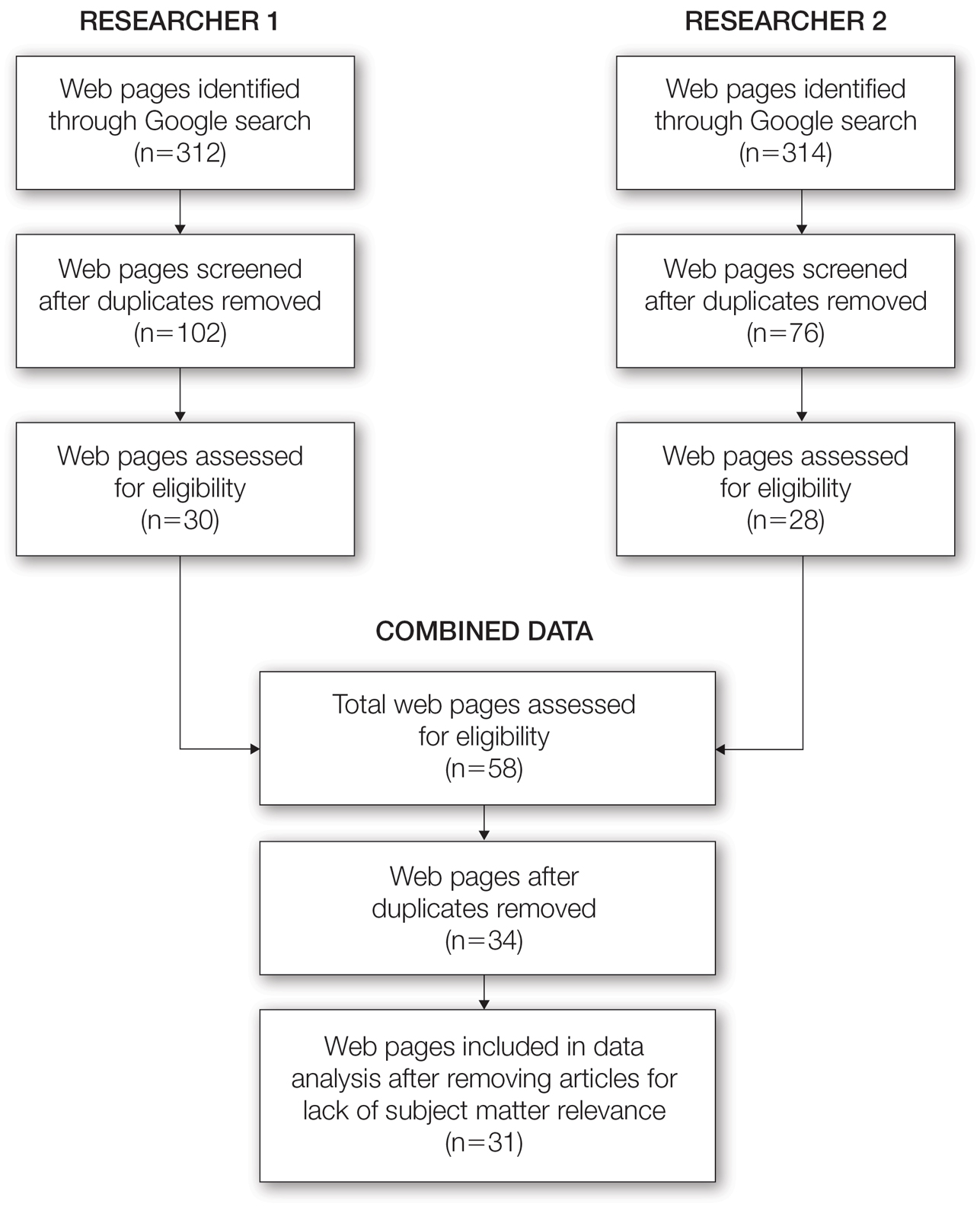

Our initial literature search identified 270 articles, which decreased to 180 after removal of duplicates. These 180 articles were screened for relevance based on title and abstract, which yielded 6 articles. None of the 6 articles identified through our literature search discussed synthetic hair and carcinogenicity in the context of the ACV rinse and were subsequently excluded from our review (eFigure 1).

Comment

Potentially harmful chemicals and ingredients in hair care products marketed for textured hair are now established topics in public discourse among those familiar with textured hair care and maintenance1,8; however, the discourse remains limited. Our search for scientific articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions revealed a notable deficit in the literature regarding scientific studies assessing this practice. While the likelihood that the ACV rinse effectively alters the carcinogenicity of plastic polymers found in synthetic hair extensions and improves their safety seems improbable, the deficit of empirical data evaluating this practice is concerning given both the prevalence of this remedy and the sizable demographic of patients who practice styling with synthetic hair.1 Of the potential adverse outcomes (eg, contact dermatitis, traction alopecia) that are possible from styling with synthetic hair that have been reported in the literature, carcinogenic exposure from synthetic hair extensions is relatively absent, with the exception of a few publications,2,3,9 despite its potential to cause serious long-term consequences for hair stylists and those who regularly use these products.

Interestingly, individuals who style their hair with synthetic hair extensions frequently tout the efficacy of the ACV rinse for removal of mostly unidentified irritants, although the effects are unverified.6,7 While the ACV rinse may be an effective means of removing toxic chemicals from synthetic hair extensions, without verifiable data this method remains an unproven remedy whose perceived benefits could result from factors unrelated to the rinse itself. Theoretically, simply rinsing synthetic hair extensions with plain water prior to use may demonstrate similar efficacy to that of the ACV rinse.

An additional factor worth mentioning is the lack of government regulations concerning the manufacturing practices of synthetic hair extensions. Flame-retardant materials such as trichloroethylene, polyvinyl chloride, and hexabromocyclododecane frequently are used in synthetic hair extensions despite their known adverse effects, which include reproductive organ toxicity and links to various cancers, leading to them being banned in 5 states.1,10-12 With no federal ban on these materials, individuals using synthetic hair remain at risk.

It is unclear what chemicals, irritants, or toxic substances the ACV rinse method could potentially remove from synthetic hair. In general, manufacturers of synthetic hair extensions are not forthcoming with information regarding materials used in the processing of their products despite public inquiries into their manufacturing practices.6 Although Whitehurst’s3 curriculum details the process of making synthetic polymer fibers, the overall processes by which these plastics are made to resemble human hair have not been reviewed in academic publications. Should this information be made available to the public, consumers could potentially avoid specific irritants when purchasing synthetic hair extensions.

The most common management strategy observed in the literature for adverse outcomes attributable to synthetic hair is discontinuation of use2; however, the prevalence and cultural significance of styling with synthetic hair extensions, along with the convenience these styles offer, make this option suboptimal. The scarcity of publications concerning the management of adverse outcomes related to the use of synthetic hair extensions may explain the absence of alternative management recommendations in the literature. Notably, new synthetic hair extensions from manufacturers that exclude plastic polymers and other harmful additives are now available to the public13; however, these hair extensions are cost prohibitive and are less accessible compared to synthetic extensions made from modacrylic fibers (eFigures 2 and 3).1,13-16

Final Thoughts

- Thomas CG. Carcinogenic materials in synthetic braids: an unrecognized risk of hair products for Black women. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;22:100517.

- Dlova NC, Ferguson NN, Rorex JN, et al. Synthetic hair extensions causing irritant contact dermatitis in patients with a history of atopy: a report of 10 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:141-145.

- Whitehurst L. Polytails and urban tumble weaves: the chemistry of synthetic hair fibers. Yale National Initiative. September 2011. Accessed September 29, 2025. teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_11.05.10_u

- Acrylonitrile. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. April 1992. Updated January 2000. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/acrylonitrile.pdf

- Permissible exposure limits – annotated tables. OSHA annotated table Z-1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.osha.gov/annotated-pels/table-z-1

- Adesina P. Braids are causing unbearable itching & there’s a sinister reason behind it. Refinery29. August 19, 2019. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.refinery29.com/en-gb/itchy-braids-hair

- Boakye O. Here’s why you should always wash plastic synthetic braiding extensions. InStyle. February 27, 2023. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.instyle.com/synthetic-braiding-extensions-upkeep-7151722

- James-Todd T, Connolly L, Preston EV, et al. Hormonal activity in commonly used Black hair care products: evaluating hormone disruption as a plausible contribution to health disparities. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021;31:476-486.

- Ijere ND, Okereke JN, Ezeji EU. Potential hazards associated with wearing of synthetic hairs (wigs, weavons, hair extensions/attachments) in Nigeria. J Environ Sci Public Health. 2022;6:299-313.

- Kaminsky T. An act to amend the environmental conservation law, in relation to the regulation of chemicals in upholstered furniture, mattresses and electronic enclosures. S4630B (2021). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S4630

- Shen Y. Hair extension standards and regulations in the US: an overview. Compliance Gate. December 20, 2022. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.compliancegate.com/hair-extension-regulations-united-states/

- Lienke J, Rothschild R. Regulating Risk From Toxic Substances: Best Practices for Economic Analysis of Risk Management Options Under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Institute of Policy Integrity; 2021.

- Rebundle. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://rebundle.co/

- About us. Kanekalon. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.kanekalon-hair.com/en/about

- Julianna wholesale smooth Kanekalon futura natural fiber heat resistant bone straight synthetic bundle weft hair extensions. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/Julianna-wholesale-Smooth-Kanekalon-Futura-Natural_1601335996748.html

- AIDUSA solid colors braiding hair 5pcs synthetic Afro braid hair extensions 24 inch 1 tone for women braids twist crochet braids 100g(#1B Natural Black). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.amazon.com/AIDUSA-Braiding-Synthetic-Extensions-Crochet/dp/B09TNB9LC8

Synthetic hair extensions are made from various plastic polymers (eg, modacrylic, vinyl chloride, and acrylonitrile) shaped into thin strands that mimic human hair and are used to add fullness, length, and manageability in individuals with textured hair.1-3 The plastic polymers used to make synthetic hair, most notably acrylonitrile and vinyl chloride, are known to be toxic to humans.1-4 The US Environmental Protection Agency classifies acrylonitrile as a probable carcinogen, and vinyl chloride is associated with the development of lymphoma; leukemia; and rare malignancies of the brain, liver, and lungs.1,4 According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the maximum exposure limits of vinyl chloride and acrylonitrile vapor or gas over an 8-hour period are 1 ppm (0.001 g/L) and 2 ppm (0.002 g/L), respectively.5 Exposure levels from wearing synthetic hair extensions easily exceed these maximums; for example, a full head of braids requires application of multiple packets of synthetic hair, resulting in continuous exposure to carcinogenic materials that can last for weeks to months at a time.1 Furthermore, individuals as young as 3 years old can begin to style their hair with synthetic extensions, which not only leads to potentially harmful carcinogenic exposure in young children but also yields notably high levels of lifetime exposure in individuals who regularly style their hair with these products.

There currently are no regulations barring the use of potentially harmful materials from the manufacturing process for synthetic hair extensions.1 As a result, rinsing with apple cider vinegar (ACV) is a popular remedy that many users claim can effectively remove harmful chemicals from synthetic hair.6,7 As this is the only known remedy that aims to address this issue,

Methods

We conducted a search of Google Scholar, JSTOR, Science Direct, the Public Library of Science, and PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ACV, apple cider vinegar rinse, ACV rinse, synthetic hair carcinogens, synthetic fiber carcinogens, synthetic hair extension carcinogens, modacrylic fibers, Kanekalon (a flame-retardant modacrylic fiber), acrylonitrile, and vinyl chloride fibers to identify primary research articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions for inclusion in our review. To broaden our search, we did not establish a time frame for publication of the articles included in the study. Articles investigating the ACV rinse that were unrelated to carcinogenicity and synthetic hair extensions were excluded from this study.

Results

Our initial literature search identified 270 articles, which decreased to 180 after removal of duplicates. These 180 articles were screened for relevance based on title and abstract, which yielded 6 articles. None of the 6 articles identified through our literature search discussed synthetic hair and carcinogenicity in the context of the ACV rinse and were subsequently excluded from our review (eFigure 1).

Comment

Potentially harmful chemicals and ingredients in hair care products marketed for textured hair are now established topics in public discourse among those familiar with textured hair care and maintenance1,8; however, the discourse remains limited. Our search for scientific articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions revealed a notable deficit in the literature regarding scientific studies assessing this practice. While the likelihood that the ACV rinse effectively alters the carcinogenicity of plastic polymers found in synthetic hair extensions and improves their safety seems improbable, the deficit of empirical data evaluating this practice is concerning given both the prevalence of this remedy and the sizable demographic of patients who practice styling with synthetic hair.1 Of the potential adverse outcomes (eg, contact dermatitis, traction alopecia) that are possible from styling with synthetic hair that have been reported in the literature, carcinogenic exposure from synthetic hair extensions is relatively absent, with the exception of a few publications,2,3,9 despite its potential to cause serious long-term consequences for hair stylists and those who regularly use these products.

Interestingly, individuals who style their hair with synthetic hair extensions frequently tout the efficacy of the ACV rinse for removal of mostly unidentified irritants, although the effects are unverified.6,7 While the ACV rinse may be an effective means of removing toxic chemicals from synthetic hair extensions, without verifiable data this method remains an unproven remedy whose perceived benefits could result from factors unrelated to the rinse itself. Theoretically, simply rinsing synthetic hair extensions with plain water prior to use may demonstrate similar efficacy to that of the ACV rinse.

An additional factor worth mentioning is the lack of government regulations concerning the manufacturing practices of synthetic hair extensions. Flame-retardant materials such as trichloroethylene, polyvinyl chloride, and hexabromocyclododecane frequently are used in synthetic hair extensions despite their known adverse effects, which include reproductive organ toxicity and links to various cancers, leading to them being banned in 5 states.1,10-12 With no federal ban on these materials, individuals using synthetic hair remain at risk.

It is unclear what chemicals, irritants, or toxic substances the ACV rinse method could potentially remove from synthetic hair. In general, manufacturers of synthetic hair extensions are not forthcoming with information regarding materials used in the processing of their products despite public inquiries into their manufacturing practices.6 Although Whitehurst’s3 curriculum details the process of making synthetic polymer fibers, the overall processes by which these plastics are made to resemble human hair have not been reviewed in academic publications. Should this information be made available to the public, consumers could potentially avoid specific irritants when purchasing synthetic hair extensions.

The most common management strategy observed in the literature for adverse outcomes attributable to synthetic hair is discontinuation of use2; however, the prevalence and cultural significance of styling with synthetic hair extensions, along with the convenience these styles offer, make this option suboptimal. The scarcity of publications concerning the management of adverse outcomes related to the use of synthetic hair extensions may explain the absence of alternative management recommendations in the literature. Notably, new synthetic hair extensions from manufacturers that exclude plastic polymers and other harmful additives are now available to the public13; however, these hair extensions are cost prohibitive and are less accessible compared to synthetic extensions made from modacrylic fibers (eFigures 2 and 3).1,13-16

Final Thoughts

Synthetic hair extensions are made from various plastic polymers (eg, modacrylic, vinyl chloride, and acrylonitrile) shaped into thin strands that mimic human hair and are used to add fullness, length, and manageability in individuals with textured hair.1-3 The plastic polymers used to make synthetic hair, most notably acrylonitrile and vinyl chloride, are known to be toxic to humans.1-4 The US Environmental Protection Agency classifies acrylonitrile as a probable carcinogen, and vinyl chloride is associated with the development of lymphoma; leukemia; and rare malignancies of the brain, liver, and lungs.1,4 According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the maximum exposure limits of vinyl chloride and acrylonitrile vapor or gas over an 8-hour period are 1 ppm (0.001 g/L) and 2 ppm (0.002 g/L), respectively.5 Exposure levels from wearing synthetic hair extensions easily exceed these maximums; for example, a full head of braids requires application of multiple packets of synthetic hair, resulting in continuous exposure to carcinogenic materials that can last for weeks to months at a time.1 Furthermore, individuals as young as 3 years old can begin to style their hair with synthetic extensions, which not only leads to potentially harmful carcinogenic exposure in young children but also yields notably high levels of lifetime exposure in individuals who regularly style their hair with these products.

There currently are no regulations barring the use of potentially harmful materials from the manufacturing process for synthetic hair extensions.1 As a result, rinsing with apple cider vinegar (ACV) is a popular remedy that many users claim can effectively remove harmful chemicals from synthetic hair.6,7 As this is the only known remedy that aims to address this issue,

Methods

We conducted a search of Google Scholar, JSTOR, Science Direct, the Public Library of Science, and PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ACV, apple cider vinegar rinse, ACV rinse, synthetic hair carcinogens, synthetic fiber carcinogens, synthetic hair extension carcinogens, modacrylic fibers, Kanekalon (a flame-retardant modacrylic fiber), acrylonitrile, and vinyl chloride fibers to identify primary research articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions for inclusion in our review. To broaden our search, we did not establish a time frame for publication of the articles included in the study. Articles investigating the ACV rinse that were unrelated to carcinogenicity and synthetic hair extensions were excluded from this study.

Results

Our initial literature search identified 270 articles, which decreased to 180 after removal of duplicates. These 180 articles were screened for relevance based on title and abstract, which yielded 6 articles. None of the 6 articles identified through our literature search discussed synthetic hair and carcinogenicity in the context of the ACV rinse and were subsequently excluded from our review (eFigure 1).

Comment

Potentially harmful chemicals and ingredients in hair care products marketed for textured hair are now established topics in public discourse among those familiar with textured hair care and maintenance1,8; however, the discourse remains limited. Our search for scientific articles investigating the effects of the ACV rinse on the carcinogenicity of synthetic hair extensions revealed a notable deficit in the literature regarding scientific studies assessing this practice. While the likelihood that the ACV rinse effectively alters the carcinogenicity of plastic polymers found in synthetic hair extensions and improves their safety seems improbable, the deficit of empirical data evaluating this practice is concerning given both the prevalence of this remedy and the sizable demographic of patients who practice styling with synthetic hair.1 Of the potential adverse outcomes (eg, contact dermatitis, traction alopecia) that are possible from styling with synthetic hair that have been reported in the literature, carcinogenic exposure from synthetic hair extensions is relatively absent, with the exception of a few publications,2,3,9 despite its potential to cause serious long-term consequences for hair stylists and those who regularly use these products.

Interestingly, individuals who style their hair with synthetic hair extensions frequently tout the efficacy of the ACV rinse for removal of mostly unidentified irritants, although the effects are unverified.6,7 While the ACV rinse may be an effective means of removing toxic chemicals from synthetic hair extensions, without verifiable data this method remains an unproven remedy whose perceived benefits could result from factors unrelated to the rinse itself. Theoretically, simply rinsing synthetic hair extensions with plain water prior to use may demonstrate similar efficacy to that of the ACV rinse.

An additional factor worth mentioning is the lack of government regulations concerning the manufacturing practices of synthetic hair extensions. Flame-retardant materials such as trichloroethylene, polyvinyl chloride, and hexabromocyclododecane frequently are used in synthetic hair extensions despite their known adverse effects, which include reproductive organ toxicity and links to various cancers, leading to them being banned in 5 states.1,10-12 With no federal ban on these materials, individuals using synthetic hair remain at risk.

It is unclear what chemicals, irritants, or toxic substances the ACV rinse method could potentially remove from synthetic hair. In general, manufacturers of synthetic hair extensions are not forthcoming with information regarding materials used in the processing of their products despite public inquiries into their manufacturing practices.6 Although Whitehurst’s3 curriculum details the process of making synthetic polymer fibers, the overall processes by which these plastics are made to resemble human hair have not been reviewed in academic publications. Should this information be made available to the public, consumers could potentially avoid specific irritants when purchasing synthetic hair extensions.

The most common management strategy observed in the literature for adverse outcomes attributable to synthetic hair is discontinuation of use2; however, the prevalence and cultural significance of styling with synthetic hair extensions, along with the convenience these styles offer, make this option suboptimal. The scarcity of publications concerning the management of adverse outcomes related to the use of synthetic hair extensions may explain the absence of alternative management recommendations in the literature. Notably, new synthetic hair extensions from manufacturers that exclude plastic polymers and other harmful additives are now available to the public13; however, these hair extensions are cost prohibitive and are less accessible compared to synthetic extensions made from modacrylic fibers (eFigures 2 and 3).1,13-16

Final Thoughts

- Thomas CG. Carcinogenic materials in synthetic braids: an unrecognized risk of hair products for Black women. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;22:100517.

- Dlova NC, Ferguson NN, Rorex JN, et al. Synthetic hair extensions causing irritant contact dermatitis in patients with a history of atopy: a report of 10 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:141-145.

- Whitehurst L. Polytails and urban tumble weaves: the chemistry of synthetic hair fibers. Yale National Initiative. September 2011. Accessed September 29, 2025. teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_11.05.10_u

- Acrylonitrile. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. April 1992. Updated January 2000. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/acrylonitrile.pdf

- Permissible exposure limits – annotated tables. OSHA annotated table Z-1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.osha.gov/annotated-pels/table-z-1

- Adesina P. Braids are causing unbearable itching & there’s a sinister reason behind it. Refinery29. August 19, 2019. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.refinery29.com/en-gb/itchy-braids-hair

- Boakye O. Here’s why you should always wash plastic synthetic braiding extensions. InStyle. February 27, 2023. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.instyle.com/synthetic-braiding-extensions-upkeep-7151722

- James-Todd T, Connolly L, Preston EV, et al. Hormonal activity in commonly used Black hair care products: evaluating hormone disruption as a plausible contribution to health disparities. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021;31:476-486.

- Ijere ND, Okereke JN, Ezeji EU. Potential hazards associated with wearing of synthetic hairs (wigs, weavons, hair extensions/attachments) in Nigeria. J Environ Sci Public Health. 2022;6:299-313.

- Kaminsky T. An act to amend the environmental conservation law, in relation to the regulation of chemicals in upholstered furniture, mattresses and electronic enclosures. S4630B (2021). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S4630

- Shen Y. Hair extension standards and regulations in the US: an overview. Compliance Gate. December 20, 2022. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.compliancegate.com/hair-extension-regulations-united-states/

- Lienke J, Rothschild R. Regulating Risk From Toxic Substances: Best Practices for Economic Analysis of Risk Management Options Under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Institute of Policy Integrity; 2021.

- Rebundle. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://rebundle.co/

- About us. Kanekalon. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.kanekalon-hair.com/en/about

- Julianna wholesale smooth Kanekalon futura natural fiber heat resistant bone straight synthetic bundle weft hair extensions. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/Julianna-wholesale-Smooth-Kanekalon-Futura-Natural_1601335996748.html

- AIDUSA solid colors braiding hair 5pcs synthetic Afro braid hair extensions 24 inch 1 tone for women braids twist crochet braids 100g(#1B Natural Black). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.amazon.com/AIDUSA-Braiding-Synthetic-Extensions-Crochet/dp/B09TNB9LC8

- Thomas CG. Carcinogenic materials in synthetic braids: an unrecognized risk of hair products for Black women. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;22:100517.

- Dlova NC, Ferguson NN, Rorex JN, et al. Synthetic hair extensions causing irritant contact dermatitis in patients with a history of atopy: a report of 10 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:141-145.

- Whitehurst L. Polytails and urban tumble weaves: the chemistry of synthetic hair fibers. Yale National Initiative. September 2011. Accessed September 29, 2025. teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_11.05.10_u

- Acrylonitrile. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. April 1992. Updated January 2000. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/acrylonitrile.pdf

- Permissible exposure limits – annotated tables. OSHA annotated table Z-1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.osha.gov/annotated-pels/table-z-1

- Adesina P. Braids are causing unbearable itching & there’s a sinister reason behind it. Refinery29. August 19, 2019. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.refinery29.com/en-gb/itchy-braids-hair

- Boakye O. Here’s why you should always wash plastic synthetic braiding extensions. InStyle. February 27, 2023. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.instyle.com/synthetic-braiding-extensions-upkeep-7151722

- James-Todd T, Connolly L, Preston EV, et al. Hormonal activity in commonly used Black hair care products: evaluating hormone disruption as a plausible contribution to health disparities. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021;31:476-486.

- Ijere ND, Okereke JN, Ezeji EU. Potential hazards associated with wearing of synthetic hairs (wigs, weavons, hair extensions/attachments) in Nigeria. J Environ Sci Public Health. 2022;6:299-313.

- Kaminsky T. An act to amend the environmental conservation law, in relation to the regulation of chemicals in upholstered furniture, mattresses and electronic enclosures. S4630B (2021). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S4630

- Shen Y. Hair extension standards and regulations in the US: an overview. Compliance Gate. December 20, 2022. Accessed September 29, 2025. www.compliancegate.com/hair-extension-regulations-united-states/

- Lienke J, Rothschild R. Regulating Risk From Toxic Substances: Best Practices for Economic Analysis of Risk Management Options Under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Institute of Policy Integrity; 2021.

- Rebundle. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://rebundle.co/

- About us. Kanekalon. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.kanekalon-hair.com/en/about

- Julianna wholesale smooth Kanekalon futura natural fiber heat resistant bone straight synthetic bundle weft hair extensions. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/Julianna-wholesale-Smooth-Kanekalon-Futura-Natural_1601335996748.html

- AIDUSA solid colors braiding hair 5pcs synthetic Afro braid hair extensions 24 inch 1 tone for women braids twist crochet braids 100g(#1B Natural Black). Accessed October 2, 2025. www.amazon.com/AIDUSA-Braiding-Synthetic-Extensions-Crochet/dp/B09TNB9LC8

Assessing the Merit of the Apple Cider Vinegar Rinse Method for Synthetic Hair Extensions

Assessing the Merit of the Apple Cider Vinegar Rinse Method for Synthetic Hair Extensions

Practice Points

- Synthetic hair extensions are made from materials that can expose patients to high levels of carcinogens beginning in early childhood.

- The apple cider vinegar rinse method is an anecdotal remedy lacking data validating its ability to mitigate adverse reactions and complications associated with synthetic hair extensions, including carcinogenic exposure to materials they comprise.

- Dermatologists should inform patients of the potential exposure risks when using synthetic hair extensions to help patients make informed decisions regarding future styling habits and hair care choices.

Cosmetic Laser Procedures and Nonsurgical Body Contouring in Patients With Skin of Color

Cosmetic Laser Procedures and Nonsurgical Body Contouring in Patients With Skin of Color

Cosmetic laser procedures as well as energy-based fat reduction and body-contouring devices are increasingly popular among individuals with skin of color (SOC). Innovations in cosmetic devices and procedures tailored for SOC have allowed for the optimization of outcomes in this patient population. In this article, SOC is defined as darker skin types, including Fitzpatrick skin types (FSTs) IV to VI and ethnic backgrounds such as LatinX, African American, Southeast Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, Asian, and African. Indications for laser treatment include dermatosis papulosa nigrans (DPN), acne scars, skin rejuvenation, and hyperpigmentation. There currently are 6 procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): high-frequency focused ultrasound, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring (Supplementary Table S1).1

In this review, our initial focus is cosmetic laser procedures, encompassing FDA-cleared indications along with the associated risks and benefits in SOC populations. Subsequently, we delve into the realms of energy-based fat reduction and body contouring, offering a comprehensive overview of these noninvasive therapies and addressing considerations for efficacy and safety in these patients.

Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

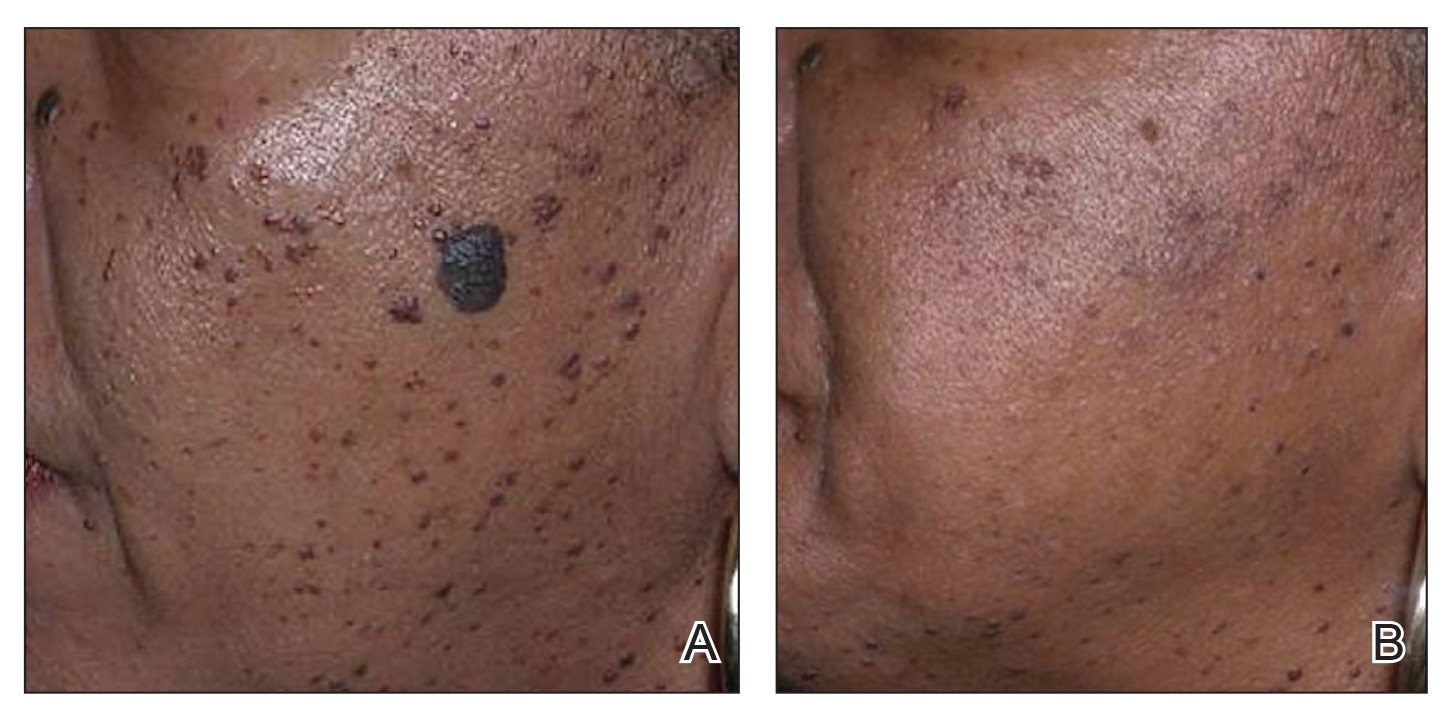

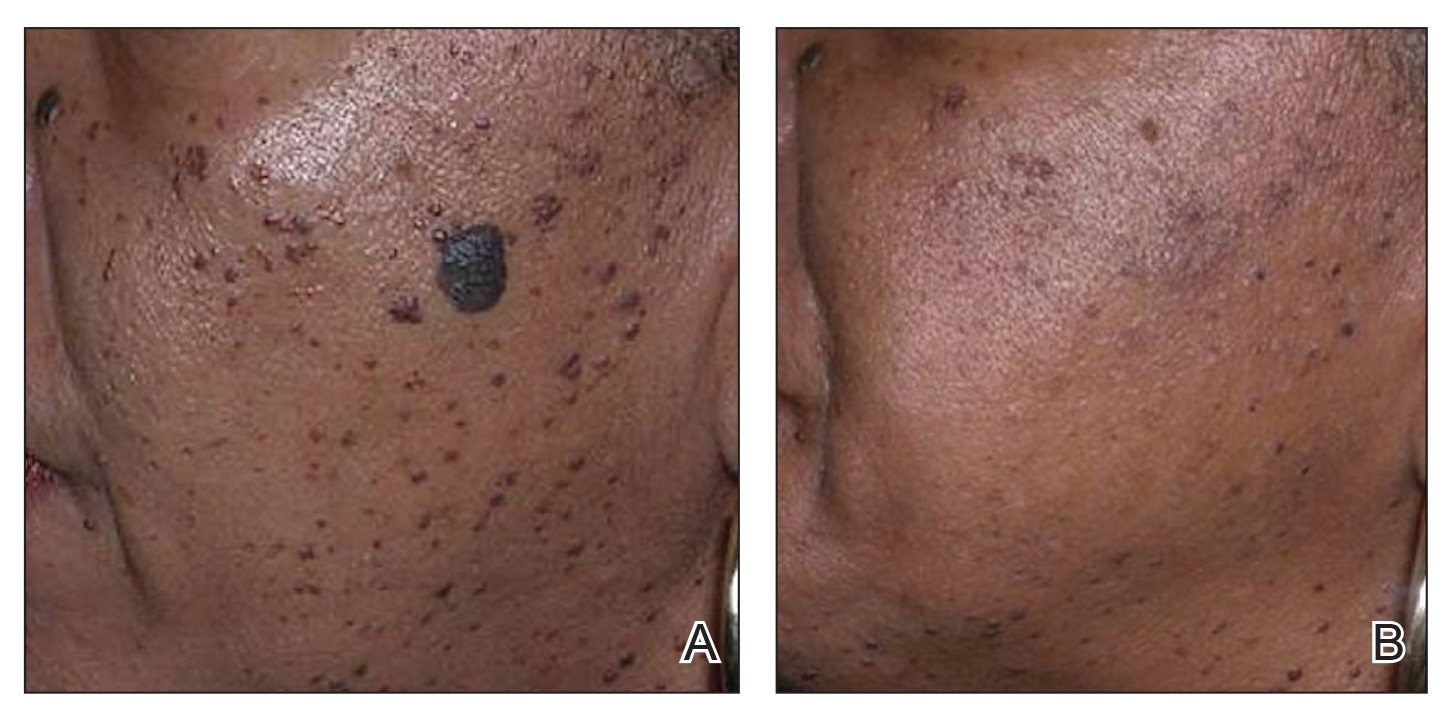

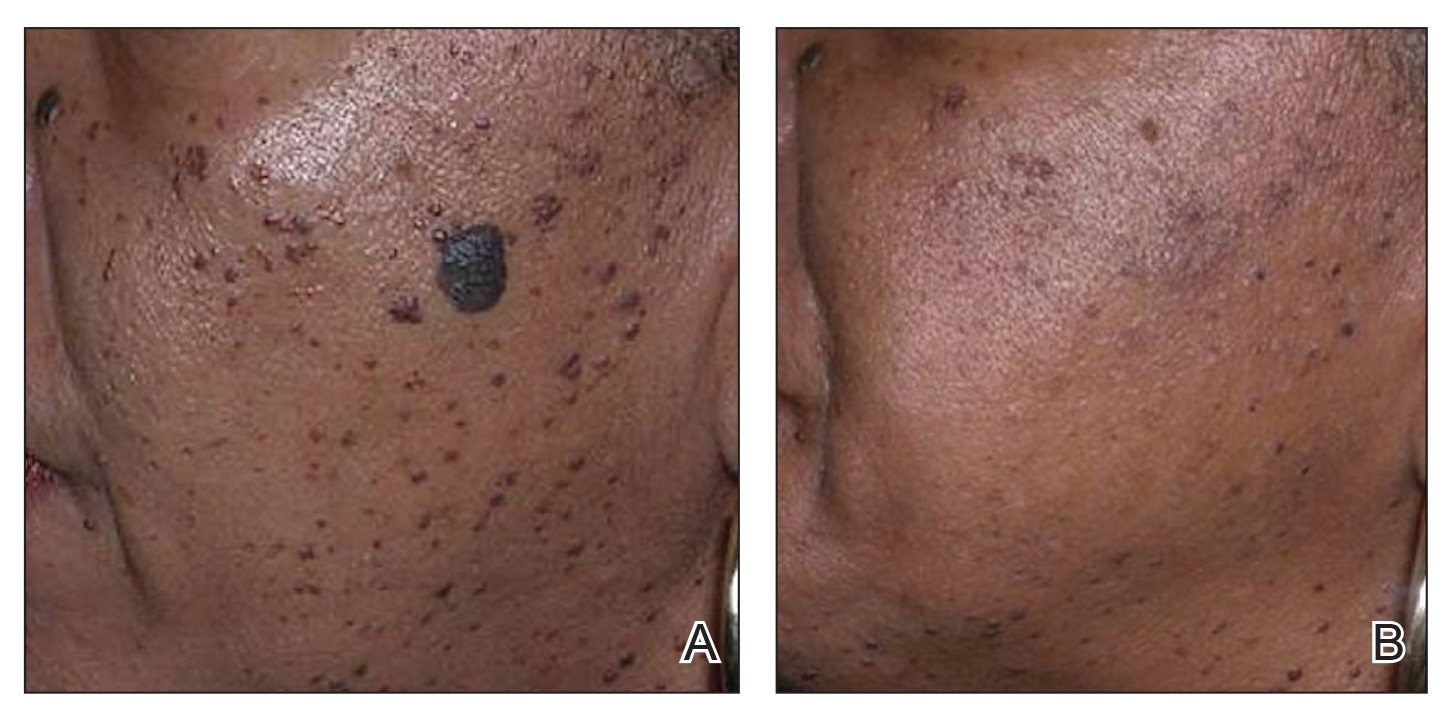

In patients with SOC, scissor excision, curettage, or electrodesiccation are the mainstay treatments for removal of DPN (Figure 1). Curettage and electrodesiccation can cause temporary postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) in these populations, while cryotherapy is not a preferred method in patients with SOC due to the possibility of cryotherapy-induced depigmentation. In a 14-patient split-face study comparing the 532-nm potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser vs electrodesiccation in FSTs IV to VI, the KTP-treated side showed an improvement rate of 96%, while the electrodesiccation side showed an improvement rate of 79%. There was a statistically significant favorable experience for KTP with regard to pain tolerability (P=.002).2 Complete resolution of lesions may be seen after 3 to 4 sessions at 4-week intervals. Additionally, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser was assessed for treatment of DPN in 2 patients, with 70% to 90% of lesions resolved after a single treatment with no complications.3

Most dermatologists still rely on curettage and electrodesiccation instead of laser therapy to remove DPNs in patients with SOC. The use of the Nd:YAG laser is promising yet expensive for the provider both to purchase and maintain. Electrodesiccation has been used by dermatology practices for decades and can be used without permanent discoloration. To minimize the risk for PIH, we recommend application of a healing ointment such as petroleum jelly or aloe vera gel to the treated lesions as well as lightening agents for PIH and daily use of sunscreen. Overall, providers do not need to purchase an expensive laser device for DPN removal.

Acne Scars

The invention of fractional technology in the early 2000s and its favorable safety profile have changed how dermatologists treat scarring in patients with SOC.

In one study of the short-pulsed nonablative Nd:YAG laser, 9 patients with FSTs I to V and 2 patients with FSTs IV to V underwent 8 treatments at 2-week intervals. Three blinded observers found a 29% improvement in the Global Acne Scar Severity score, while 89% (8/9) of patients self-reported subjective improvement in their acne scars.10

The 755-nm picosecond laser and diffractive lens array also have been shown to reduce the appearance of acne scars in patients with SOC, as shown via serial photography in a retrospective study of 56 patients with FSTs IV to VI. Transient hyperpigmentation, erythema, and edema were reported.11

Nonablative laser therapy is preferred for skin rejuvenation in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.11 Ablative resurfacing (eg, CO2 laser) poses major risks for postprocedural hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scar formation and therefore should be avoided in these populations.12,13 A study involving 30 Asian patients (FSTs III-IV) demonstrated that the 1550-nm fractional laser was well tolerated, though higher treatment densities and fluences may lead to temporary adverse effects such as increased redness, swelling, and pain (P<.01).14 Furthermore, greater density was shown to cause higher levels of redness, hyperpigmentation, and swelling in comparison to higher fluence settings. Of note, patient satisfaction was markedly higher in patients who underwent treatment with higher fluence settings but not in patients with higher densities (P<.05). Postprocedural hyperpigmentation was noted in 6.7% (2/30) of patients studied.14 In another study, 8 patients with FSTs II to V were treated with either the 1064-nm long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser or the grid fractional monopolar radiofrequency laser.15 All participants experienced a significant decrease in mean wrinkle count using the Lemperle wrinkle assessment (P<.05). A significant decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score from 3.5 to 3.17 in clinical assessment and a decrease from 3.165 to 2.33 for photographic assessment was noted in patients treated with the grid laser (P<.05). A similar decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score was observed in the Nd:YAG group, with a mean decrease of 3.665 to 2.83 after 2 months for clinical assessment and 3.5 to 2.67 for photographic assessment. Among all patients in the study, 68% (6/8) experienced erythema, 25% (2/8) had a burning sensation, and 25% (2/8) experienced urticaria immediately postprocedure.15

Nonablative fractional resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC. Adverse effects such as hyperpigmentation typically are transient, and the risk may be minimized with strict photoprotective practices following the procedure. Furthermore, avoidance of topicals containing exfoliants or α-hydroxy acids applied to the treated area following the procedure also may mitigate the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.16 If hyperpigmentation does occur, use of topical melanogenesis inhibitors such as hydroquinone, kojic acid, or azelaic acid has shown some utility in practice.

Skin Rejuvenation

Nonablative fractional lasers (NAFLs) continue to be popular for treatment of photoaging. One study including 10 Asian patients (FSTs III-V) assessed the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser for facial rejuvenation.17 After 4 sessions at 2-week intervals, 80% (8/10) of patients reported decreased skin roughness after both the second and third treatments, while 90% (9/10) had improved texture 1 month after the final procedure. Adverse effects included moderate facial edema and one case of transient hyperpigmentation.17 Another study reported a significant reduction in pore score (P<.002), with patients noting an overall improvement in skin appearance with minimal erythema, dryness, and flaking following 6 sessions at 2-week intervals using the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser.18

The 1550-nm diode fractional laser significantly improved skin pigmentation (P<.001) and texture (P<.001) in 10 patients with FSTs II to IV following 5 sessions at 2- to 3-week intervals, with self-resolving erythema and edema posttreatment (Supplementary Table S2).19 Overall, NAFLs for the treatment of photoaging are effective with minimal adverse effects (eg, facial edema), which can be reduced with application of cold compression to the face and elevation of the head following treatment as well as the use of additional pillows during overnight sleep.

Laser Treatment for Hyperpigmentation Disorders

Melasma—The FDA recently approved fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of melasma; however, due to the risk for hyperpigmentation given its pathogenesis linked to hyperactive melanocytes, this laser is not considered a first-line therapy for melasma.20 In a split-face, randomized study, 22 patients with FSTs III to V who were diagnosed with either dermal or mixed-type melasma were treated with a low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser combined with hydroquinone 2% vs hydroquinone 2% alone (Supplementary Table S3).21 Each patient was treated weekly for 5 consecutive weeks. The laser-treated side was found to reach an average of 92.5% improvement compared with 19.7% on the hydroquinone-only side. Three of the 22 (13.6%) patients developed mottled hypopigmentation after 5 laser treatments, and 8 (36.4%) developed confetti-type hypopigmentation. Four (18.2%) patients developed rebound hyperpigmentation, and all 22 patients experienced recurrence of melasma by 12 weeks posttreatment.21

First-line treatment for melasma involves the application of topical lightening agents such as hydroquinone, azelaic acid, kojic acid, retinoids, or mild topical steroids. Combining laser technology with topical medications can enhance treatment outcomes, particularly yielding positive results for patients with persistent pigmentation concerns. Notably, utilization of 650-microsecond technology with the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser is considered superior in clinical practice, especially for patients with FSTs IV through VI.

Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation—A retrospective evaluation of 61 patients with FSTs IV to VI with PIH treated with a 1927-nm NAFL showed a mean improvement of 43.24%, as assessed by 2 dermatologists.22 Additionally, the Nd:YAG 1064-nm 650-microsecond pulse duration laser is an emerging treatment that delivers high and low fluences between 4 J/cm2 and 255 J/cm2 within a single 650-microsecond pulse duration.23 The short-pulse duration avoids overheating the skin, mitigating procedural discomfort and the risk for adverse effects commonly seen with the previous generation of low-pulsed lasers. In addition to PIH, this laser has been successfully used to treat pseudofolliculitis barbae.24

Solar Lentigos—In a split-face study treating solar lentigos in Asian patients, 4 treatments with a low-pulsed KTP 532-nm laser were administered with and without a second treatment with a low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.25 Scoring of a modified pigment severity index and measurement of the melanin index showed that skin treated with the low-pulsed 532-nm laser alone and in combination with the low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser resulted in improvement at 3 months’ follow-up. However, there was no difference between the 2 sides of the face, leading the researchers to conclude that the low-pulsed 532-nm laser appears to be safe and effective for treatment of solar lentigos in Asian patients and does not require the addition of the low-pulsed 1064-nm laser.25

To avoid hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, strict photoprotection to the treated areas should be advised. Proper cooling of the laser-treated area is required to minimize PIH, as cooling decreases tissue damage and excessive thermal injury. Test spots should be considered prior to initiation of the full laser treatment. Hydroquinone in a 4% concentration applied daily for 2 weeks preprocedure commonly is employed to reduce the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation in clinical practice.26,27

Skin Tightening and Body Contouring

In general, skin-tightening and body-contouring devices are among the most sought-after procedures. Studies performed in patients with SOC are limited. Herein, we provide background on why these devices are favorable for patients with SOC and our experiences in using them. A summary of these devices can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Radiofrequency Skin Tightening—Radiofrequency devices are utilized for skin tightening as well as mild fat reduction; they commonly are used on the abdomen, thighs, buttocks, and face.28 People with SOC are more responsive to radiofrequency skin-tightening therapy due to higher baseline collagen content and dermal thickness, more sebaceous activity and skin elasticity, and more melanin content which offers protective thermal buffering.29,30 As the radiofrequency device emits heat, penetrating deep into the dermis, it generates collagen remodeling and synthesis within 4 to 6 months posttreatment.

Nonsurgical Fat Reduction

Procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction are favorable due to minimal recovery time, manageable cost, and an in-office procedure setting. As noted previously, there are 6 FDA-indicated interventions for nonsurgical fat reduction: ultrasonography, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring.31

Ultrasonography—Ultrasound devices designed for body contouring are used for skin tightening and mild fat reduction through the use of acoustic energy.32 These devices can be divided into 2 categories: high frequency and low frequency, with the high-frequency devices being the most popular. High-frequency ultrasound energy produces heat at target sites, which induces necrosis of adipocytes and stimulates collagen remodeling within the tissue matrix.33 Tissue temperatures above 56°C stimulate adipocyte necrosis while sparing nearby nerves and vessels.28 Because of the short duration of the procedure, the risk for epidermal damage is minimal. Contrary to high-frequency ultrasonography, focus-pulsed ultrasonography employs low-frequency waves to induce the mechanical disruption of adipocytes, which is generally better tolerated due to its nonthermal mechanism. The latter may be advantageous in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for thermal injury to the epidermis. Multiple treatments often are needed at 3- to 4-week intervals, resulting in gradual improvement observed over 2 to 6 months. One study of microfocused ultrasonography in 25 Asian patients for treatment of face and neck laxity reported that skin laxity was improved or much improved in 84% (21/25) of patients following treatment.34 Adverse effects were reported as mild and transient, resolving within 90 days.34 Ultrasound devices also were shown to improve wrinkles, texture, and overall appearance of the skin in a 71-year-old African American woman 4 months following treatment (Figure 2). These photographs highlight the clinical utility of a microfocused ultrasound skin-tightening treatment in African American patients.

Cryolipolysis—Cryolipolysis is a noninvasive body contouring procedure that employs controlled cooling to induce subcutaneous panniculitis. Through cold-induced apoptosis of adipocytes, this procedure selectively reduces adipose tissue in localized areas such as the flank, abdomen, thighs, buttocks, back, submental area, and upper arms. The temperature used in cryolipolysis is approximately –10°C.35 The lethal temperature for melanocytes is –4 °C, below which melanocyte apoptosis may be induced, resulting in depigmentation. Given the prolonged contact of the skin with a cryolipolysis device for up to 60 minutes during a body-contouring procedure, there is a risk for resultant depigmentation in darker skin types. Controlled studies are needed to fully evaluate the safety and efficacy of cryolipolysis in patients with SOC. One retrospective study of cryolipolysis applied to the abdomen and upper arm of 4122 Asian patients reported a significant (P<.05) reduction in the circumference of the abdomen and the upper-arm areas. No long-term adverse effects were reported.36

Laser Lipolysis—The 1060-nm diode laser for body contouring selectively destroys adipose tissue, resulting in body contouring via thermally induced inflammation. Hyperthermic exposure for 15 minutes selectively elevates adipocyte temperature between 42°C to 47°C, which triggers apoptosis and the eventual clearance of destroyed cells from the interstitial space.37 The selectivity of the 1060-nm wavelength coupled with the device’s contact cooling system preserves the overlying skin and adnexa during the procedure,37 which would minimize epidermal damage that may induce dyspigmentation in patients with SOC. No notable adverse effects or dyspigmentation have been reported using this device.

Injection Lipolysis—Deoxycholic acid is an injectable adipocytolytic for the reduction of submental fat. It nonselectively lyses muscle and other adjacent nonfatty tissue. One study of 50 Indian patients demonstrated a substantial reduction of submental fat in 90% (45/50).38 For each treatment, 5 mL of 30 mg/mL deoxycholic acid was injected. Serial sessions were conducted at 2-month intervals, and most (64% [32/50]) patients required 3 sessions to see a treatment effect. Adverse effects included transient swelling, lumpiness, and tenderness. A phase 2a investigation of the novel injectable small-molecule drug CBL-514 in 43 Asian and White participants found a significant improvement in the reduction in abdominal fat volume (P<.00001) and thickness (P<.0001) relative to baseline at higher doses (unit dose, 2.0 mg/cm2 and 1.6 mg/cm2).39 In addition to the adverse effects mentioned previously, pruritus, repeated urticaria, body rash, and fever also were reported.39

Radiofrequency Lipolysis—Radiofrequency is used for adipolysis through heat-induced apoptosis. To achieve this effect, adipose tissue must sustain a temperature of 42 °C to 45 °C for at least 15 minutes.40 In one study, 4 treatments performed at 7-day intervals resulted in a statistically significant reduction in circumference to the treated areas of the inner and outer thighs without any reported adverse effects (P<0.001).41 Of note, there was 1 cm of distance between the applicator and the skin. The absence of direct contact with the skin is likely to reduce the risk for postprocedural complications in patients with SOC.

Magnetic Resonance Contouring—Magnetic resonance contouring with high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology is an emerging treatment modality for noninvasive body contouring. One distinguishing characteristic from other currently available noninvasive fat-reduction therapies is that magnetic resonance may improve strength, tone, and muscle thickness.42 This modality is FDA approved for contouring of the buttocks and abdomen and employs electromagnetic energy to stimulate approximately 20,000 muscle contractions within a time frame of 30 minutes. Though the mechanisms causing benefits to muscular and adipose tissue have not been elucidated, current findings suggest that the contractions stimulate substantial lipolysis of adipocytes, resulting in the release of large amounts of free fatty acids that cause damage to nearby adipose tissue.43 Multiple treatments are required over time to maintain effect. No major adverse effects have been reported. The likely mechanism of action of magnetic resonance contouring does not appear to pose an increased risk to patients with SOC.

Final Thoughts

One of the major roadblocks in distilling indications along with associated risks and benefits for nonsurgical cosmetic practices for patients with SOC is a void in the primary literature involving these populations. Clinical experience serves to address this deficit in combination with a thorough review of the literature. The 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser has shown clinical utility in the treatment of DPN, melanoma, and acne scars, but it poses financial constraints to the provider in comparison to modalities used for many years. Notably, NAF resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC and continues to gain popularity for the treatment of photoaging. Regarding skin-tightening and body-contouring devices, studies performed in patients with SOC are limited and affected by factors such as small sample sizes, underrepresentation of FSTs IV through VI, short follow-up durations, and a lack of standardized outcome measures. Additionally, few studies assess pigmentary adverse effects or stratify results by skin type, which is critical given the higher risk for PIH in SOC. Ultrasound devices showed clinical utility in improvement of skin laxity, texture, and overall improvement. Patients with SOC respond well to skin-tightening devices due to the increased collagen synthesis. Regarding emerging devices for reduction of adipocytes, deoxycholic acid when injected showed notable improvement in fat reduction but also had adverse effects. As additional studies on cosmetic procedures in SOC emerge, an expansion of treatment options could be offered to this demographic group with confidence, provided proper treatment and follow-up protocols are in place.

Cosmetic laser procedures as well as energy-based fat reduction and body-contouring devices are increasingly popular among individuals with skin of color (SOC). Innovations in cosmetic devices and procedures tailored for SOC have allowed for the optimization of outcomes in this patient population. In this article, SOC is defined as darker skin types, including Fitzpatrick skin types (FSTs) IV to VI and ethnic backgrounds such as LatinX, African American, Southeast Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, Asian, and African. Indications for laser treatment include dermatosis papulosa nigrans (DPN), acne scars, skin rejuvenation, and hyperpigmentation. There currently are 6 procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): high-frequency focused ultrasound, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring (Supplementary Table S1).1

In this review, our initial focus is cosmetic laser procedures, encompassing FDA-cleared indications along with the associated risks and benefits in SOC populations. Subsequently, we delve into the realms of energy-based fat reduction and body contouring, offering a comprehensive overview of these noninvasive therapies and addressing considerations for efficacy and safety in these patients.

Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

In patients with SOC, scissor excision, curettage, or electrodesiccation are the mainstay treatments for removal of DPN (Figure 1). Curettage and electrodesiccation can cause temporary postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) in these populations, while cryotherapy is not a preferred method in patients with SOC due to the possibility of cryotherapy-induced depigmentation. In a 14-patient split-face study comparing the 532-nm potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser vs electrodesiccation in FSTs IV to VI, the KTP-treated side showed an improvement rate of 96%, while the electrodesiccation side showed an improvement rate of 79%. There was a statistically significant favorable experience for KTP with regard to pain tolerability (P=.002).2 Complete resolution of lesions may be seen after 3 to 4 sessions at 4-week intervals. Additionally, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser was assessed for treatment of DPN in 2 patients, with 70% to 90% of lesions resolved after a single treatment with no complications.3

Most dermatologists still rely on curettage and electrodesiccation instead of laser therapy to remove DPNs in patients with SOC. The use of the Nd:YAG laser is promising yet expensive for the provider both to purchase and maintain. Electrodesiccation has been used by dermatology practices for decades and can be used without permanent discoloration. To minimize the risk for PIH, we recommend application of a healing ointment such as petroleum jelly or aloe vera gel to the treated lesions as well as lightening agents for PIH and daily use of sunscreen. Overall, providers do not need to purchase an expensive laser device for DPN removal.

Acne Scars

The invention of fractional technology in the early 2000s and its favorable safety profile have changed how dermatologists treat scarring in patients with SOC.

In one study of the short-pulsed nonablative Nd:YAG laser, 9 patients with FSTs I to V and 2 patients with FSTs IV to V underwent 8 treatments at 2-week intervals. Three blinded observers found a 29% improvement in the Global Acne Scar Severity score, while 89% (8/9) of patients self-reported subjective improvement in their acne scars.10

The 755-nm picosecond laser and diffractive lens array also have been shown to reduce the appearance of acne scars in patients with SOC, as shown via serial photography in a retrospective study of 56 patients with FSTs IV to VI. Transient hyperpigmentation, erythema, and edema were reported.11

Nonablative laser therapy is preferred for skin rejuvenation in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.11 Ablative resurfacing (eg, CO2 laser) poses major risks for postprocedural hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scar formation and therefore should be avoided in these populations.12,13 A study involving 30 Asian patients (FSTs III-IV) demonstrated that the 1550-nm fractional laser was well tolerated, though higher treatment densities and fluences may lead to temporary adverse effects such as increased redness, swelling, and pain (P<.01).14 Furthermore, greater density was shown to cause higher levels of redness, hyperpigmentation, and swelling in comparison to higher fluence settings. Of note, patient satisfaction was markedly higher in patients who underwent treatment with higher fluence settings but not in patients with higher densities (P<.05). Postprocedural hyperpigmentation was noted in 6.7% (2/30) of patients studied.14 In another study, 8 patients with FSTs II to V were treated with either the 1064-nm long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser or the grid fractional monopolar radiofrequency laser.15 All participants experienced a significant decrease in mean wrinkle count using the Lemperle wrinkle assessment (P<.05). A significant decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score from 3.5 to 3.17 in clinical assessment and a decrease from 3.165 to 2.33 for photographic assessment was noted in patients treated with the grid laser (P<.05). A similar decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score was observed in the Nd:YAG group, with a mean decrease of 3.665 to 2.83 after 2 months for clinical assessment and 3.5 to 2.67 for photographic assessment. Among all patients in the study, 68% (6/8) experienced erythema, 25% (2/8) had a burning sensation, and 25% (2/8) experienced urticaria immediately postprocedure.15

Nonablative fractional resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC. Adverse effects such as hyperpigmentation typically are transient, and the risk may be minimized with strict photoprotective practices following the procedure. Furthermore, avoidance of topicals containing exfoliants or α-hydroxy acids applied to the treated area following the procedure also may mitigate the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.16 If hyperpigmentation does occur, use of topical melanogenesis inhibitors such as hydroquinone, kojic acid, or azelaic acid has shown some utility in practice.

Skin Rejuvenation

Nonablative fractional lasers (NAFLs) continue to be popular for treatment of photoaging. One study including 10 Asian patients (FSTs III-V) assessed the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser for facial rejuvenation.17 After 4 sessions at 2-week intervals, 80% (8/10) of patients reported decreased skin roughness after both the second and third treatments, while 90% (9/10) had improved texture 1 month after the final procedure. Adverse effects included moderate facial edema and one case of transient hyperpigmentation.17 Another study reported a significant reduction in pore score (P<.002), with patients noting an overall improvement in skin appearance with minimal erythema, dryness, and flaking following 6 sessions at 2-week intervals using the 1440-nm diode-based fractional laser.18

The 1550-nm diode fractional laser significantly improved skin pigmentation (P<.001) and texture (P<.001) in 10 patients with FSTs II to IV following 5 sessions at 2- to 3-week intervals, with self-resolving erythema and edema posttreatment (Supplementary Table S2).19 Overall, NAFLs for the treatment of photoaging are effective with minimal adverse effects (eg, facial edema), which can be reduced with application of cold compression to the face and elevation of the head following treatment as well as the use of additional pillows during overnight sleep.

Laser Treatment for Hyperpigmentation Disorders

Melasma—The FDA recently approved fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of melasma; however, due to the risk for hyperpigmentation given its pathogenesis linked to hyperactive melanocytes, this laser is not considered a first-line therapy for melasma.20 In a split-face, randomized study, 22 patients with FSTs III to V who were diagnosed with either dermal or mixed-type melasma were treated with a low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser combined with hydroquinone 2% vs hydroquinone 2% alone (Supplementary Table S3).21 Each patient was treated weekly for 5 consecutive weeks. The laser-treated side was found to reach an average of 92.5% improvement compared with 19.7% on the hydroquinone-only side. Three of the 22 (13.6%) patients developed mottled hypopigmentation after 5 laser treatments, and 8 (36.4%) developed confetti-type hypopigmentation. Four (18.2%) patients developed rebound hyperpigmentation, and all 22 patients experienced recurrence of melasma by 12 weeks posttreatment.21

First-line treatment for melasma involves the application of topical lightening agents such as hydroquinone, azelaic acid, kojic acid, retinoids, or mild topical steroids. Combining laser technology with topical medications can enhance treatment outcomes, particularly yielding positive results for patients with persistent pigmentation concerns. Notably, utilization of 650-microsecond technology with the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser is considered superior in clinical practice, especially for patients with FSTs IV through VI.

Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation—A retrospective evaluation of 61 patients with FSTs IV to VI with PIH treated with a 1927-nm NAFL showed a mean improvement of 43.24%, as assessed by 2 dermatologists.22 Additionally, the Nd:YAG 1064-nm 650-microsecond pulse duration laser is an emerging treatment that delivers high and low fluences between 4 J/cm2 and 255 J/cm2 within a single 650-microsecond pulse duration.23 The short-pulse duration avoids overheating the skin, mitigating procedural discomfort and the risk for adverse effects commonly seen with the previous generation of low-pulsed lasers. In addition to PIH, this laser has been successfully used to treat pseudofolliculitis barbae.24

Solar Lentigos—In a split-face study treating solar lentigos in Asian patients, 4 treatments with a low-pulsed KTP 532-nm laser were administered with and without a second treatment with a low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.25 Scoring of a modified pigment severity index and measurement of the melanin index showed that skin treated with the low-pulsed 532-nm laser alone and in combination with the low-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser resulted in improvement at 3 months’ follow-up. However, there was no difference between the 2 sides of the face, leading the researchers to conclude that the low-pulsed 532-nm laser appears to be safe and effective for treatment of solar lentigos in Asian patients and does not require the addition of the low-pulsed 1064-nm laser.25

To avoid hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, strict photoprotection to the treated areas should be advised. Proper cooling of the laser-treated area is required to minimize PIH, as cooling decreases tissue damage and excessive thermal injury. Test spots should be considered prior to initiation of the full laser treatment. Hydroquinone in a 4% concentration applied daily for 2 weeks preprocedure commonly is employed to reduce the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation in clinical practice.26,27

Skin Tightening and Body Contouring

In general, skin-tightening and body-contouring devices are among the most sought-after procedures. Studies performed in patients with SOC are limited. Herein, we provide background on why these devices are favorable for patients with SOC and our experiences in using them. A summary of these devices can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Radiofrequency Skin Tightening—Radiofrequency devices are utilized for skin tightening as well as mild fat reduction; they commonly are used on the abdomen, thighs, buttocks, and face.28 People with SOC are more responsive to radiofrequency skin-tightening therapy due to higher baseline collagen content and dermal thickness, more sebaceous activity and skin elasticity, and more melanin content which offers protective thermal buffering.29,30 As the radiofrequency device emits heat, penetrating deep into the dermis, it generates collagen remodeling and synthesis within 4 to 6 months posttreatment.

Nonsurgical Fat Reduction

Procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction are favorable due to minimal recovery time, manageable cost, and an in-office procedure setting. As noted previously, there are 6 FDA-indicated interventions for nonsurgical fat reduction: ultrasonography, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring.31

Ultrasonography—Ultrasound devices designed for body contouring are used for skin tightening and mild fat reduction through the use of acoustic energy.32 These devices can be divided into 2 categories: high frequency and low frequency, with the high-frequency devices being the most popular. High-frequency ultrasound energy produces heat at target sites, which induces necrosis of adipocytes and stimulates collagen remodeling within the tissue matrix.33 Tissue temperatures above 56°C stimulate adipocyte necrosis while sparing nearby nerves and vessels.28 Because of the short duration of the procedure, the risk for epidermal damage is minimal. Contrary to high-frequency ultrasonography, focus-pulsed ultrasonography employs low-frequency waves to induce the mechanical disruption of adipocytes, which is generally better tolerated due to its nonthermal mechanism. The latter may be advantageous in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for thermal injury to the epidermis. Multiple treatments often are needed at 3- to 4-week intervals, resulting in gradual improvement observed over 2 to 6 months. One study of microfocused ultrasonography in 25 Asian patients for treatment of face and neck laxity reported that skin laxity was improved or much improved in 84% (21/25) of patients following treatment.34 Adverse effects were reported as mild and transient, resolving within 90 days.34 Ultrasound devices also were shown to improve wrinkles, texture, and overall appearance of the skin in a 71-year-old African American woman 4 months following treatment (Figure 2). These photographs highlight the clinical utility of a microfocused ultrasound skin-tightening treatment in African American patients.

Cryolipolysis—Cryolipolysis is a noninvasive body contouring procedure that employs controlled cooling to induce subcutaneous panniculitis. Through cold-induced apoptosis of adipocytes, this procedure selectively reduces adipose tissue in localized areas such as the flank, abdomen, thighs, buttocks, back, submental area, and upper arms. The temperature used in cryolipolysis is approximately –10°C.35 The lethal temperature for melanocytes is –4 °C, below which melanocyte apoptosis may be induced, resulting in depigmentation. Given the prolonged contact of the skin with a cryolipolysis device for up to 60 minutes during a body-contouring procedure, there is a risk for resultant depigmentation in darker skin types. Controlled studies are needed to fully evaluate the safety and efficacy of cryolipolysis in patients with SOC. One retrospective study of cryolipolysis applied to the abdomen and upper arm of 4122 Asian patients reported a significant (P<.05) reduction in the circumference of the abdomen and the upper-arm areas. No long-term adverse effects were reported.36

Laser Lipolysis—The 1060-nm diode laser for body contouring selectively destroys adipose tissue, resulting in body contouring via thermally induced inflammation. Hyperthermic exposure for 15 minutes selectively elevates adipocyte temperature between 42°C to 47°C, which triggers apoptosis and the eventual clearance of destroyed cells from the interstitial space.37 The selectivity of the 1060-nm wavelength coupled with the device’s contact cooling system preserves the overlying skin and adnexa during the procedure,37 which would minimize epidermal damage that may induce dyspigmentation in patients with SOC. No notable adverse effects or dyspigmentation have been reported using this device.

Injection Lipolysis—Deoxycholic acid is an injectable adipocytolytic for the reduction of submental fat. It nonselectively lyses muscle and other adjacent nonfatty tissue. One study of 50 Indian patients demonstrated a substantial reduction of submental fat in 90% (45/50).38 For each treatment, 5 mL of 30 mg/mL deoxycholic acid was injected. Serial sessions were conducted at 2-month intervals, and most (64% [32/50]) patients required 3 sessions to see a treatment effect. Adverse effects included transient swelling, lumpiness, and tenderness. A phase 2a investigation of the novel injectable small-molecule drug CBL-514 in 43 Asian and White participants found a significant improvement in the reduction in abdominal fat volume (P<.00001) and thickness (P<.0001) relative to baseline at higher doses (unit dose, 2.0 mg/cm2 and 1.6 mg/cm2).39 In addition to the adverse effects mentioned previously, pruritus, repeated urticaria, body rash, and fever also were reported.39

Radiofrequency Lipolysis—Radiofrequency is used for adipolysis through heat-induced apoptosis. To achieve this effect, adipose tissue must sustain a temperature of 42 °C to 45 °C for at least 15 minutes.40 In one study, 4 treatments performed at 7-day intervals resulted in a statistically significant reduction in circumference to the treated areas of the inner and outer thighs without any reported adverse effects (P<0.001).41 Of note, there was 1 cm of distance between the applicator and the skin. The absence of direct contact with the skin is likely to reduce the risk for postprocedural complications in patients with SOC.

Magnetic Resonance Contouring—Magnetic resonance contouring with high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology is an emerging treatment modality for noninvasive body contouring. One distinguishing characteristic from other currently available noninvasive fat-reduction therapies is that magnetic resonance may improve strength, tone, and muscle thickness.42 This modality is FDA approved for contouring of the buttocks and abdomen and employs electromagnetic energy to stimulate approximately 20,000 muscle contractions within a time frame of 30 minutes. Though the mechanisms causing benefits to muscular and adipose tissue have not been elucidated, current findings suggest that the contractions stimulate substantial lipolysis of adipocytes, resulting in the release of large amounts of free fatty acids that cause damage to nearby adipose tissue.43 Multiple treatments are required over time to maintain effect. No major adverse effects have been reported. The likely mechanism of action of magnetic resonance contouring does not appear to pose an increased risk to patients with SOC.

Final Thoughts

One of the major roadblocks in distilling indications along with associated risks and benefits for nonsurgical cosmetic practices for patients with SOC is a void in the primary literature involving these populations. Clinical experience serves to address this deficit in combination with a thorough review of the literature. The 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser has shown clinical utility in the treatment of DPN, melanoma, and acne scars, but it poses financial constraints to the provider in comparison to modalities used for many years. Notably, NAF resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC and continues to gain popularity for the treatment of photoaging. Regarding skin-tightening and body-contouring devices, studies performed in patients with SOC are limited and affected by factors such as small sample sizes, underrepresentation of FSTs IV through VI, short follow-up durations, and a lack of standardized outcome measures. Additionally, few studies assess pigmentary adverse effects or stratify results by skin type, which is critical given the higher risk for PIH in SOC. Ultrasound devices showed clinical utility in improvement of skin laxity, texture, and overall improvement. Patients with SOC respond well to skin-tightening devices due to the increased collagen synthesis. Regarding emerging devices for reduction of adipocytes, deoxycholic acid when injected showed notable improvement in fat reduction but also had adverse effects. As additional studies on cosmetic procedures in SOC emerge, an expansion of treatment options could be offered to this demographic group with confidence, provided proper treatment and follow-up protocols are in place.

Cosmetic laser procedures as well as energy-based fat reduction and body-contouring devices are increasingly popular among individuals with skin of color (SOC). Innovations in cosmetic devices and procedures tailored for SOC have allowed for the optimization of outcomes in this patient population. In this article, SOC is defined as darker skin types, including Fitzpatrick skin types (FSTs) IV to VI and ethnic backgrounds such as LatinX, African American, Southeast Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, Asian, and African. Indications for laser treatment include dermatosis papulosa nigrans (DPN), acne scars, skin rejuvenation, and hyperpigmentation. There currently are 6 procedures for nonsurgical fat reduction that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): high-frequency focused ultrasound, cryolipolysis, laser lipolysis, injection lipolysis, radiofrequency lipolysis, and magnetic resonance contouring (Supplementary Table S1).1

In this review, our initial focus is cosmetic laser procedures, encompassing FDA-cleared indications along with the associated risks and benefits in SOC populations. Subsequently, we delve into the realms of energy-based fat reduction and body contouring, offering a comprehensive overview of these noninvasive therapies and addressing considerations for efficacy and safety in these patients.

Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

In patients with SOC, scissor excision, curettage, or electrodesiccation are the mainstay treatments for removal of DPN (Figure 1). Curettage and electrodesiccation can cause temporary postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) in these populations, while cryotherapy is not a preferred method in patients with SOC due to the possibility of cryotherapy-induced depigmentation. In a 14-patient split-face study comparing the 532-nm potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser vs electrodesiccation in FSTs IV to VI, the KTP-treated side showed an improvement rate of 96%, while the electrodesiccation side showed an improvement rate of 79%. There was a statistically significant favorable experience for KTP with regard to pain tolerability (P=.002).2 Complete resolution of lesions may be seen after 3 to 4 sessions at 4-week intervals. Additionally, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser was assessed for treatment of DPN in 2 patients, with 70% to 90% of lesions resolved after a single treatment with no complications.3

Most dermatologists still rely on curettage and electrodesiccation instead of laser therapy to remove DPNs in patients with SOC. The use of the Nd:YAG laser is promising yet expensive for the provider both to purchase and maintain. Electrodesiccation has been used by dermatology practices for decades and can be used without permanent discoloration. To minimize the risk for PIH, we recommend application of a healing ointment such as petroleum jelly or aloe vera gel to the treated lesions as well as lightening agents for PIH and daily use of sunscreen. Overall, providers do not need to purchase an expensive laser device for DPN removal.

Acne Scars

The invention of fractional technology in the early 2000s and its favorable safety profile have changed how dermatologists treat scarring in patients with SOC.

In one study of the short-pulsed nonablative Nd:YAG laser, 9 patients with FSTs I to V and 2 patients with FSTs IV to V underwent 8 treatments at 2-week intervals. Three blinded observers found a 29% improvement in the Global Acne Scar Severity score, while 89% (8/9) of patients self-reported subjective improvement in their acne scars.10

The 755-nm picosecond laser and diffractive lens array also have been shown to reduce the appearance of acne scars in patients with SOC, as shown via serial photography in a retrospective study of 56 patients with FSTs IV to VI. Transient hyperpigmentation, erythema, and edema were reported.11

Nonablative laser therapy is preferred for skin rejuvenation in patients with SOC due to a reduced risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.11 Ablative resurfacing (eg, CO2 laser) poses major risks for postprocedural hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scar formation and therefore should be avoided in these populations.12,13 A study involving 30 Asian patients (FSTs III-IV) demonstrated that the 1550-nm fractional laser was well tolerated, though higher treatment densities and fluences may lead to temporary adverse effects such as increased redness, swelling, and pain (P<.01).14 Furthermore, greater density was shown to cause higher levels of redness, hyperpigmentation, and swelling in comparison to higher fluence settings. Of note, patient satisfaction was markedly higher in patients who underwent treatment with higher fluence settings but not in patients with higher densities (P<.05). Postprocedural hyperpigmentation was noted in 6.7% (2/30) of patients studied.14 In another study, 8 patients with FSTs II to V were treated with either the 1064-nm long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser or the grid fractional monopolar radiofrequency laser.15 All participants experienced a significant decrease in mean wrinkle count using the Lemperle wrinkle assessment (P<.05). A significant decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score from 3.5 to 3.17 in clinical assessment and a decrease from 3.165 to 2.33 for photographic assessment was noted in patients treated with the grid laser (P<.05). A similar decrease in mean wrinkle assessment score was observed in the Nd:YAG group, with a mean decrease of 3.665 to 2.83 after 2 months for clinical assessment and 3.5 to 2.67 for photographic assessment. Among all patients in the study, 68% (6/8) experienced erythema, 25% (2/8) had a burning sensation, and 25% (2/8) experienced urticaria immediately postprocedure.15

Nonablative fractional resurfacing is preferred for the management of acne scars in patients with SOC. Adverse effects such as hyperpigmentation typically are transient, and the risk may be minimized with strict photoprotective practices following the procedure. Furthermore, avoidance of topicals containing exfoliants or α-hydroxy acids applied to the treated area following the procedure also may mitigate the risk for postprocedural hyperpigmentation.16 If hyperpigmentation does occur, use of topical melanogenesis inhibitors such as hydroquinone, kojic acid, or azelaic acid has shown some utility in practice.

Skin Rejuvenation