User login

To the Editor:

Millipedes do not have nearly as many feet as their name would suggest; most have fewer than 100.1 They are not actually insects; they are a wormlike arthropod in the Diplopoda class. Generally these harmless animals can be a welcome resident in gardens because they break down decaying plant material and rejuvenate the soil.1 However, they are less welcome in the home or underfoot because of what happens when these invertebrates are threatened or crushed.2

Millipedes, which typically have at least 30 pairs of legs, have 2 defense mechanisms: (1) body coiling to withstand external pressure, and (2) secretion of fluids with insecticidal properties from specialized glands distributed along their body.3 These secretions, which are used by the millipede to defend against predators, contain organic compounds including benzoquinone. When these secretions come into contact with skin, pigmentary changes resembling a burn or necrosis and irritation to the skin (pain, burning, itching) occur.4,5

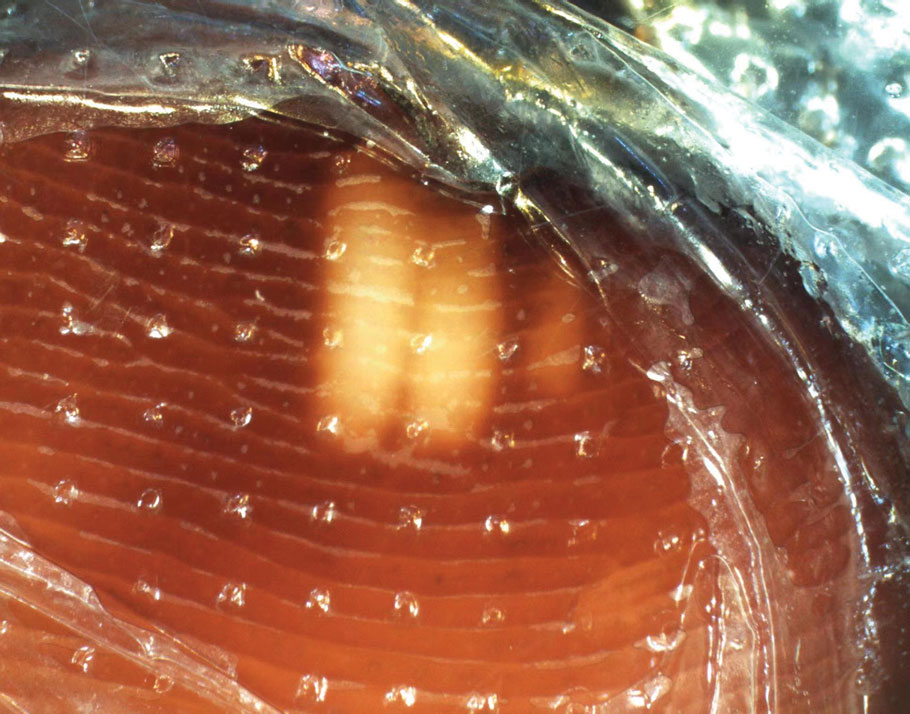

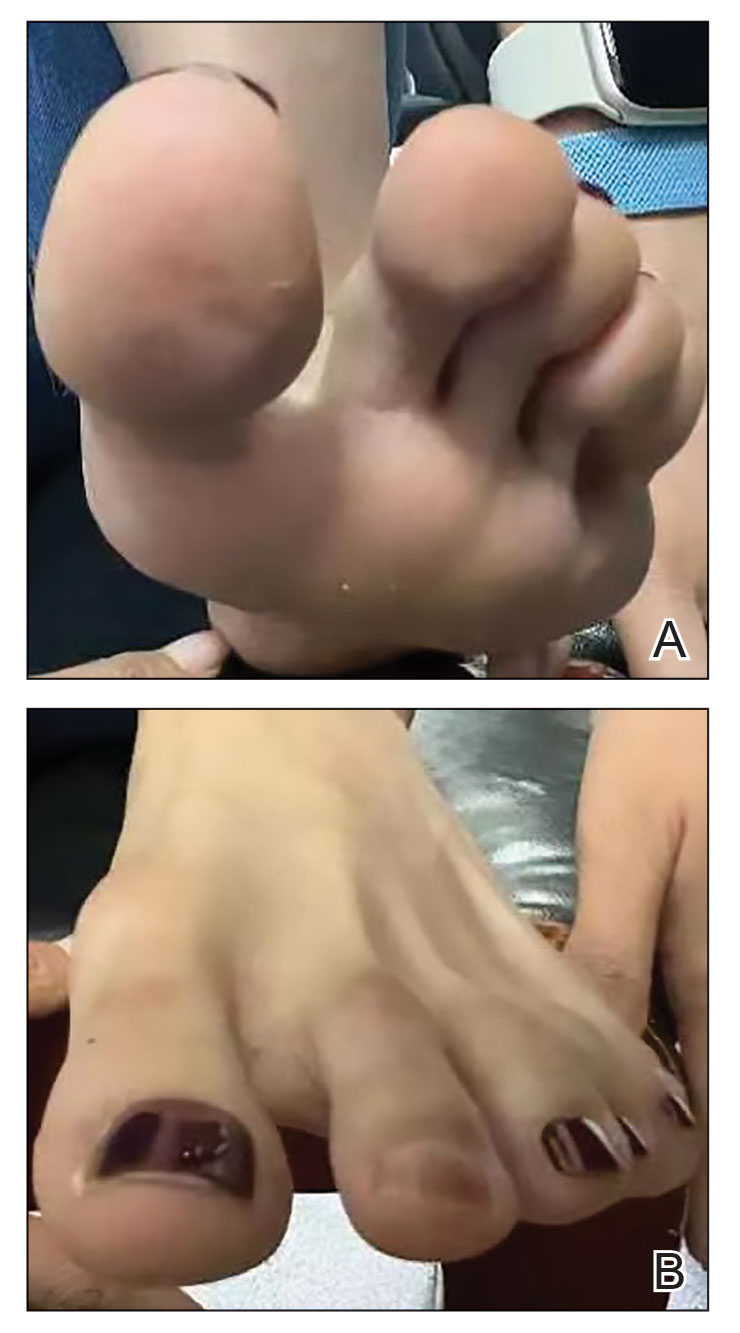

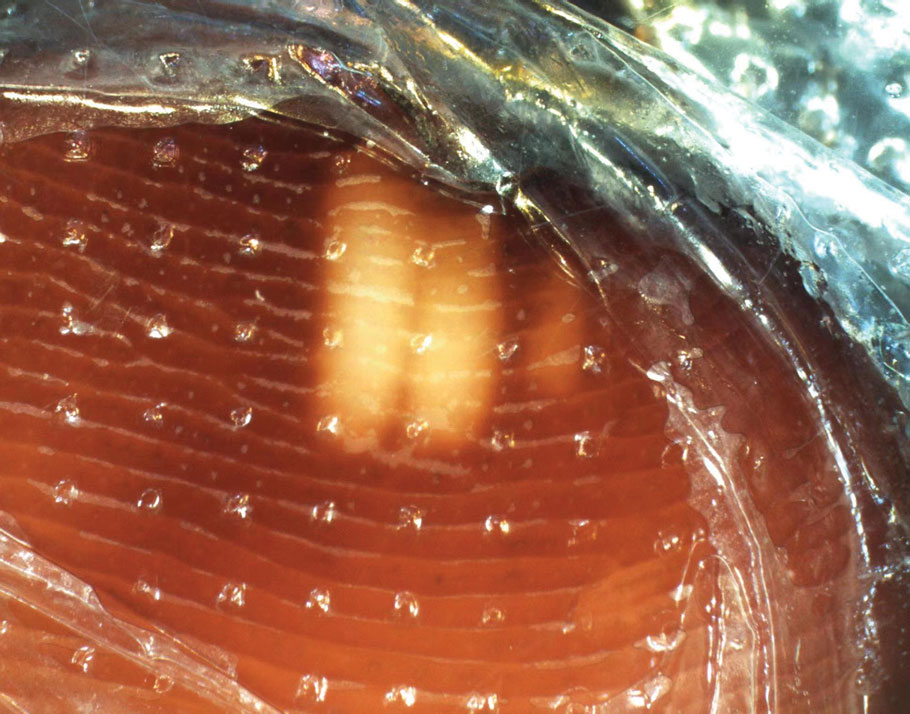

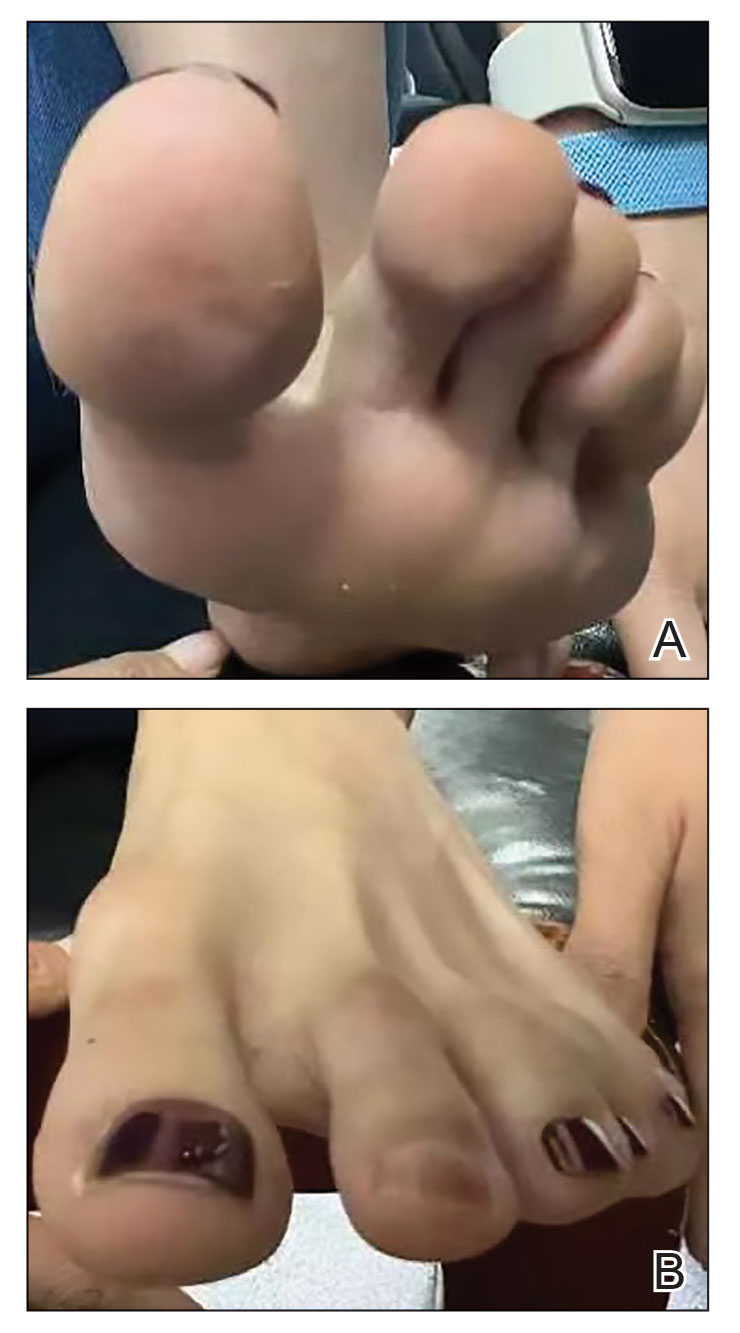

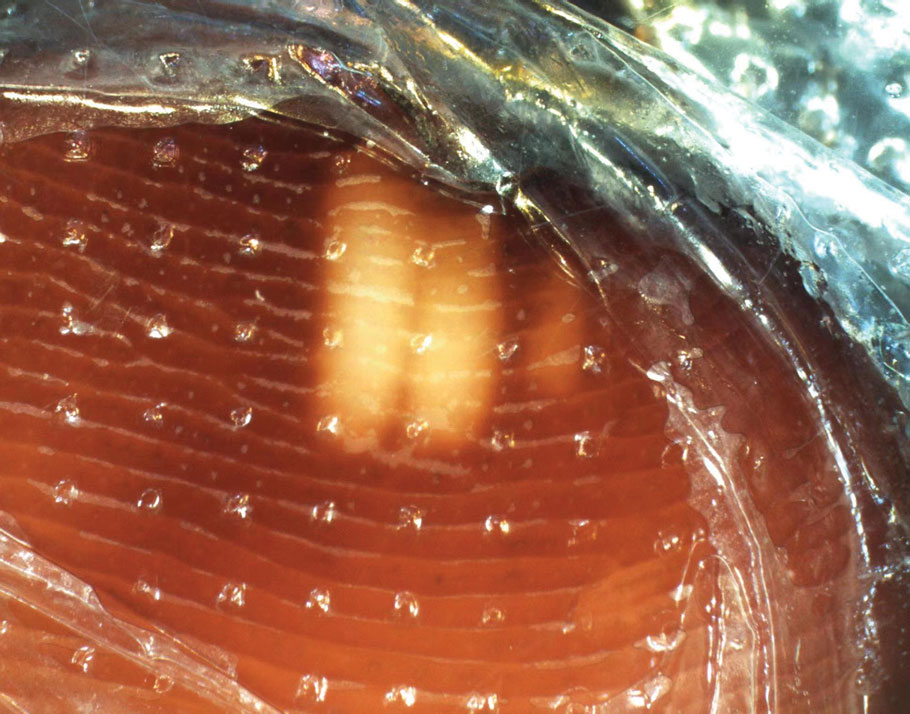

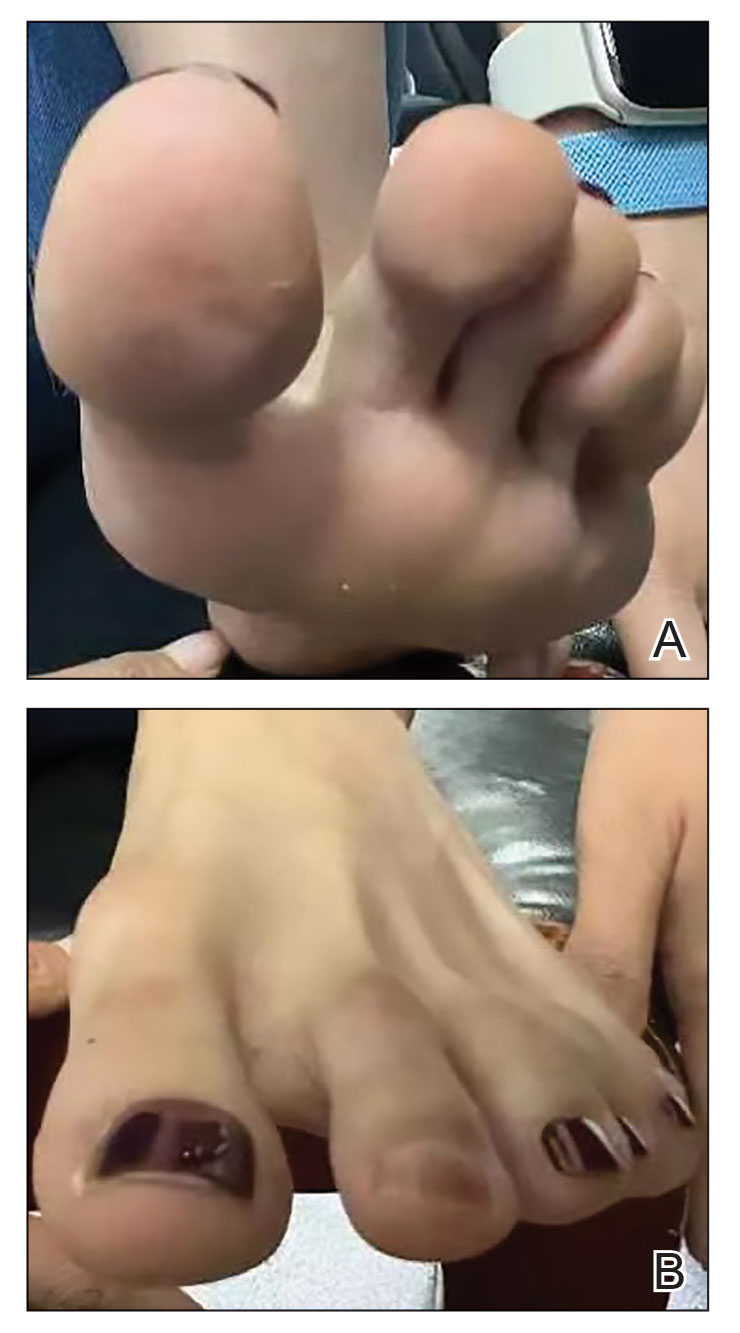

Millipedes typically are found in tropical and temperate regions worldwide, such as the Amazon rainforest, Southeast Asia, tropical areas of Africa, forests, grasslands, and gardens in North America and Europe.6 They also are found in every US state as well as Puerto Rico.1 Millipedes are nocturnal, favor dark places, and can make their way into residential areas, including homes, basements, gardens, and yards.2,6 Although millipede burns commonly are reported in tropical regions, we present a case in China.6A 33-year-old woman presented with purplish-red discoloration on all 5 toes on the left foot. The patient recounted that she discovered a millipede in her shoe earlier in the day, removed it, and crushed it with her bare foot. That night, while taking a bath, she noticed that the toes had turned purplish-red (Figure 1). The patient brought the crushed millipede with her to the emergency department where she sought treatment. The dermatologist confirmed that it was a millipede; however, the team was unable to determine the specific species because it had been crushed (Figure 2).

Physical examination of the affected toes showed a clear boundary and iodinelike staining. The patient did not report pain. The stained skin had a normal temperature, pulse, texture, and sensation. Dermoscopy revealed multiple black-brown patches on the toes (Figure 3). The pigmented area gradually faded over a 1-month period. Superficial damage to the toenail revealed evidence of black-brown pigmentation on both the nail and the skin underneath. The diagnosis in the dermoscopy report suggested exogenous pigmentation of the toes. The patient was advised that no treatment was needed and that the condition would resolve on its own. At 1-month follow-up, the patient’s toes had returned to their normal color (Figure 4).

The feet are common sites of millipede burns; other exposed areas, such as the arms, face, and eyes, also are potential sites of involvement.5 The cutaneous pigmentary changes seen on our patient’s foot were a result of the millipede’s defense mechanism—secreted toxic chemicals that stained the foot. It is important to note that the pigmentation was not associated with the death of the millipede, as the millipede was still alive upon initial contact with the patient’s foot in her shoe.

When a patient presents with pigmentary changes, several conditions must be ruled out—notably acute arterial thrombosis. Patients with this condition will describe acute pain and weakness in the area of involvement. Physicians inspecting the area will note coldness and pallor in the affected limb as well as a diminished or absent pulse. In severe cases, the skin may exhibit a purplish-red appearance.5 Millipede burns also should be distinguished from bacterial endocarditis and cryoglobulinemia.7 All 3 conditions can manifest with redness, swelling, blisters, and purpuralike changes. Positive blood culture is an important diagnostic basis for bacterial endocarditis; in addition, routine blood tests will demonstrate a decrease in red blood cells and hemoglobin, and routine urinalysis may show proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. Patients with cryoglobulinemia will have a positive cryoglobulin assay, increased IgM, and often decreased complement.7 It also is worth noting that millipede burns might resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, necessitating further evaluation.5

It is unusual to see a millipede burn in nontropical regions. Therefore, the identification of our patient’s millipede burn was notable and serves as a reminder to keep this diagnosis in the differential when caring for patients with pigmentary changes. An accurate diagnosis hinges on being alert to a millipede exposure history and recognizing the clinical manifestations. For affected patients, it may be beneficial to recommend they advise friends and relatives to avoid skin contact with millipedes and most importantly to avoid stepping on them with bare feet.

Millipedes. National Wildlife Federation. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/Millipedes

Pennini SN, Rebello PFB, Guerra MdGVB, et al. Millipede accident with unusual dermatological lesion. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:765-767. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.10.003

Lima CAJ, Cardoso JLC, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda Class (“millipedes“). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962910000300018

De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.560855

Lacy FA, Elston DM. What’s eating you? millipede burns. Cutis. 2019;103:195-196.

Neto ASH, Filho FB, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0212-2013

Sampaio FMS, Valviesse VRGdA, Lyra-da-Silva JO, et al. Pain and hyperpigmentation of the toes: a quiz. hyperpigmentation of the toes caused by millipedes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:253-254. doi:10.2340/00015555-1645

To the Editor:

Millipedes do not have nearly as many feet as their name would suggest; most have fewer than 100.1 They are not actually insects; they are a wormlike arthropod in the Diplopoda class. Generally these harmless animals can be a welcome resident in gardens because they break down decaying plant material and rejuvenate the soil.1 However, they are less welcome in the home or underfoot because of what happens when these invertebrates are threatened or crushed.2

Millipedes, which typically have at least 30 pairs of legs, have 2 defense mechanisms: (1) body coiling to withstand external pressure, and (2) secretion of fluids with insecticidal properties from specialized glands distributed along their body.3 These secretions, which are used by the millipede to defend against predators, contain organic compounds including benzoquinone. When these secretions come into contact with skin, pigmentary changes resembling a burn or necrosis and irritation to the skin (pain, burning, itching) occur.4,5

Millipedes typically are found in tropical and temperate regions worldwide, such as the Amazon rainforest, Southeast Asia, tropical areas of Africa, forests, grasslands, and gardens in North America and Europe.6 They also are found in every US state as well as Puerto Rico.1 Millipedes are nocturnal, favor dark places, and can make their way into residential areas, including homes, basements, gardens, and yards.2,6 Although millipede burns commonly are reported in tropical regions, we present a case in China.6A 33-year-old woman presented with purplish-red discoloration on all 5 toes on the left foot. The patient recounted that she discovered a millipede in her shoe earlier in the day, removed it, and crushed it with her bare foot. That night, while taking a bath, she noticed that the toes had turned purplish-red (Figure 1). The patient brought the crushed millipede with her to the emergency department where she sought treatment. The dermatologist confirmed that it was a millipede; however, the team was unable to determine the specific species because it had been crushed (Figure 2).

Physical examination of the affected toes showed a clear boundary and iodinelike staining. The patient did not report pain. The stained skin had a normal temperature, pulse, texture, and sensation. Dermoscopy revealed multiple black-brown patches on the toes (Figure 3). The pigmented area gradually faded over a 1-month period. Superficial damage to the toenail revealed evidence of black-brown pigmentation on both the nail and the skin underneath. The diagnosis in the dermoscopy report suggested exogenous pigmentation of the toes. The patient was advised that no treatment was needed and that the condition would resolve on its own. At 1-month follow-up, the patient’s toes had returned to their normal color (Figure 4).

The feet are common sites of millipede burns; other exposed areas, such as the arms, face, and eyes, also are potential sites of involvement.5 The cutaneous pigmentary changes seen on our patient’s foot were a result of the millipede’s defense mechanism—secreted toxic chemicals that stained the foot. It is important to note that the pigmentation was not associated with the death of the millipede, as the millipede was still alive upon initial contact with the patient’s foot in her shoe.

When a patient presents with pigmentary changes, several conditions must be ruled out—notably acute arterial thrombosis. Patients with this condition will describe acute pain and weakness in the area of involvement. Physicians inspecting the area will note coldness and pallor in the affected limb as well as a diminished or absent pulse. In severe cases, the skin may exhibit a purplish-red appearance.5 Millipede burns also should be distinguished from bacterial endocarditis and cryoglobulinemia.7 All 3 conditions can manifest with redness, swelling, blisters, and purpuralike changes. Positive blood culture is an important diagnostic basis for bacterial endocarditis; in addition, routine blood tests will demonstrate a decrease in red blood cells and hemoglobin, and routine urinalysis may show proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. Patients with cryoglobulinemia will have a positive cryoglobulin assay, increased IgM, and often decreased complement.7 It also is worth noting that millipede burns might resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, necessitating further evaluation.5

It is unusual to see a millipede burn in nontropical regions. Therefore, the identification of our patient’s millipede burn was notable and serves as a reminder to keep this diagnosis in the differential when caring for patients with pigmentary changes. An accurate diagnosis hinges on being alert to a millipede exposure history and recognizing the clinical manifestations. For affected patients, it may be beneficial to recommend they advise friends and relatives to avoid skin contact with millipedes and most importantly to avoid stepping on them with bare feet.

To the Editor:

Millipedes do not have nearly as many feet as their name would suggest; most have fewer than 100.1 They are not actually insects; they are a wormlike arthropod in the Diplopoda class. Generally these harmless animals can be a welcome resident in gardens because they break down decaying plant material and rejuvenate the soil.1 However, they are less welcome in the home or underfoot because of what happens when these invertebrates are threatened or crushed.2

Millipedes, which typically have at least 30 pairs of legs, have 2 defense mechanisms: (1) body coiling to withstand external pressure, and (2) secretion of fluids with insecticidal properties from specialized glands distributed along their body.3 These secretions, which are used by the millipede to defend against predators, contain organic compounds including benzoquinone. When these secretions come into contact with skin, pigmentary changes resembling a burn or necrosis and irritation to the skin (pain, burning, itching) occur.4,5

Millipedes typically are found in tropical and temperate regions worldwide, such as the Amazon rainforest, Southeast Asia, tropical areas of Africa, forests, grasslands, and gardens in North America and Europe.6 They also are found in every US state as well as Puerto Rico.1 Millipedes are nocturnal, favor dark places, and can make their way into residential areas, including homes, basements, gardens, and yards.2,6 Although millipede burns commonly are reported in tropical regions, we present a case in China.6A 33-year-old woman presented with purplish-red discoloration on all 5 toes on the left foot. The patient recounted that she discovered a millipede in her shoe earlier in the day, removed it, and crushed it with her bare foot. That night, while taking a bath, she noticed that the toes had turned purplish-red (Figure 1). The patient brought the crushed millipede with her to the emergency department where she sought treatment. The dermatologist confirmed that it was a millipede; however, the team was unable to determine the specific species because it had been crushed (Figure 2).

Physical examination of the affected toes showed a clear boundary and iodinelike staining. The patient did not report pain. The stained skin had a normal temperature, pulse, texture, and sensation. Dermoscopy revealed multiple black-brown patches on the toes (Figure 3). The pigmented area gradually faded over a 1-month period. Superficial damage to the toenail revealed evidence of black-brown pigmentation on both the nail and the skin underneath. The diagnosis in the dermoscopy report suggested exogenous pigmentation of the toes. The patient was advised that no treatment was needed and that the condition would resolve on its own. At 1-month follow-up, the patient’s toes had returned to their normal color (Figure 4).

The feet are common sites of millipede burns; other exposed areas, such as the arms, face, and eyes, also are potential sites of involvement.5 The cutaneous pigmentary changes seen on our patient’s foot were a result of the millipede’s defense mechanism—secreted toxic chemicals that stained the foot. It is important to note that the pigmentation was not associated with the death of the millipede, as the millipede was still alive upon initial contact with the patient’s foot in her shoe.

When a patient presents with pigmentary changes, several conditions must be ruled out—notably acute arterial thrombosis. Patients with this condition will describe acute pain and weakness in the area of involvement. Physicians inspecting the area will note coldness and pallor in the affected limb as well as a diminished or absent pulse. In severe cases, the skin may exhibit a purplish-red appearance.5 Millipede burns also should be distinguished from bacterial endocarditis and cryoglobulinemia.7 All 3 conditions can manifest with redness, swelling, blisters, and purpuralike changes. Positive blood culture is an important diagnostic basis for bacterial endocarditis; in addition, routine blood tests will demonstrate a decrease in red blood cells and hemoglobin, and routine urinalysis may show proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. Patients with cryoglobulinemia will have a positive cryoglobulin assay, increased IgM, and often decreased complement.7 It also is worth noting that millipede burns might resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, necessitating further evaluation.5

It is unusual to see a millipede burn in nontropical regions. Therefore, the identification of our patient’s millipede burn was notable and serves as a reminder to keep this diagnosis in the differential when caring for patients with pigmentary changes. An accurate diagnosis hinges on being alert to a millipede exposure history and recognizing the clinical manifestations. For affected patients, it may be beneficial to recommend they advise friends and relatives to avoid skin contact with millipedes and most importantly to avoid stepping on them with bare feet.

Millipedes. National Wildlife Federation. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/Millipedes

Pennini SN, Rebello PFB, Guerra MdGVB, et al. Millipede accident with unusual dermatological lesion. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:765-767. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.10.003

Lima CAJ, Cardoso JLC, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda Class (“millipedes“). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962910000300018

De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.560855

Lacy FA, Elston DM. What’s eating you? millipede burns. Cutis. 2019;103:195-196.

Neto ASH, Filho FB, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0212-2013

Sampaio FMS, Valviesse VRGdA, Lyra-da-Silva JO, et al. Pain and hyperpigmentation of the toes: a quiz. hyperpigmentation of the toes caused by millipedes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:253-254. doi:10.2340/00015555-1645

Millipedes. National Wildlife Federation. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/Millipedes

Pennini SN, Rebello PFB, Guerra MdGVB, et al. Millipede accident with unusual dermatological lesion. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:765-767. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.10.003

Lima CAJ, Cardoso JLC, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda Class (“millipedes“). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962910000300018

De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.560855

Lacy FA, Elston DM. What’s eating you? millipede burns. Cutis. 2019;103:195-196.

Neto ASH, Filho FB, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0212-2013

Sampaio FMS, Valviesse VRGdA, Lyra-da-Silva JO, et al. Pain and hyperpigmentation of the toes: a quiz. hyperpigmentation of the toes caused by millipedes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:253-254. doi:10.2340/00015555-1645

PRACTICE POINTS

- Millipede burns can resemble ischemia. The most common site of a millipede burn is the feet.

- Diagnosing a millipede burn hinges on obtaining a detailed history, viewing the site under a dermatoscope, and carefully assessing the temperature and pulse of the affected area.