User login

A new way to classify endometrial cancer

We classify endometrial cancer so that we can communicate and define each patient’s disease status, the potential for harm, and the likelihood that adjuvant therapies might provide help. Traditional forms of classification have clearly fallen short in achieving this aim, as we all know of patients with apparent low-risk disease (such as stage IA grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma) who have had recurrences and died from their disease, and we know that many patients have been subjected to overtreatment for their cancer and have acquired lifelong toxicities of therapy. This column will explore the newer, more sophisticated molecular-based classifications that are being validated for endometrial cancer, and the ways in which this promises to personalize the treatment of endometrial cancer.

Breast cancer and melanoma are examples of the inclusion of molecular data such as hormone receptor status, HER2/neu status, or BRAF positivity resulting in advancements in personalizing therapeutics. We are now moving toward this for endometrial cancer.

What is the Cancer Genome Atlas?

In 2006 the National Institutes of Health announced an initiative to coordinate work between the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute taking information about the human genome and analyzing it for key genomic alterations found in 33 common cancers. These data were combined with clinical information (such as survival) to classify the behaviors of those cancers with respect to their individual genomic alternations, in order to look for patterns in mutations and behaviors. The goal of this analysis was to shift the paradigm of cancer classification from being centered around primary organ site toward tumors’ shared genomic patterns.

In 2013 the Cancer Genome Atlas published their results of complete gene sequencing in endometrial cancer.3 The authors identified four discrete subgroups of endometrial cancer with distinct molecular mutational profiles and distinct clinical outcomes: polymerase epsilon (POLE, pronounced “pole-ee”) ultramutated, microsatellite instability (MSI) high, copy number high, and copy number low.

POLE ultramutated

An important subgroup identified in the Cancer Genome Atlas was a group of patients with a POLE ultramutated state. POLE encodes for a subunit of DNA polymerase, the enzyme responsible for replicating the leading DNA strand. Nonfunctioning POLE results in proofreading errors and a subsequent ultramutated cellular state with a predominance of single nucleotide variants. POLE proofreading domain mutations in endometrial cancer and colon cancer are associated with excellent prognosis, likely secondary to the immune response that is elicited by this ultramutated state from creation of “antigenic neoepitopes” that stimulate T-cell response. Effectively, the very mutated cell is seen as “more foreign” to the body’s immune system.

Approximately 10% of patients with endometrial cancer have a POLE ultramutated state, and, as stated above, prognosis is excellent, even if coexisting with a histologic cell type (such as serous) that is normally associated with adverse outcomes. These women tend to be younger, with a lower body mass index, higher-grade endometrioid cell type, the presence of lymphovascular space invasion, and low stage.

MSI high

MSI (microsatellite instability) is a result of epigenetic/hypermethylations or loss of expression in mismatch repair genes (such as MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2). These genes code for proteins critical in the repair of mismatches in short repeated sequences of DNA. Loss of their function results in an accumulation of errors in these sequences: MSI. It is a feature of the Lynch syndrome inherited state, but is also found sporadically in endometrial tumors. These tumors accumulate a number of mutations during cell replication that, as in POLE hypermutated tumors, are associated with eliciting an immune response.

These tumors tend to be associated with a higher-grade endometrioid cell type, the presence of lymphovascular space invasion, and an advanced stage. Patients with tumors that have been described as MSI high are candidates for “immune therapy” with the PDL1 inhibitor pembrolizumab because of their proinflammatory state and observed favorable responses in clinical trials.4

Copy number high/low

Copy number (CN) high and low refers to the results of microarrays in which hierarchical clustering was applied to identify reoccurring amplification or deletion regions. The CN-high group was associated with the poorest outcomes (recurrence and survival). There is significant overlap with mutations in TP53. Most serous carcinomas were CN high; however, 25% of patients with high-grade endometrioid cell type shared the CN-high classification. These tumors shared great molecular similarity to high-grade serous ovarian cancers and basal-like breast cancer.

Those patients who did not possess mutations that classified them as POLE hypermutated, MSI high, or CN high were classified as CN low. This group included predominantly grades 1 and 2 endometrioid adenocarcinomas of an early stage and had a favorable prognostic profile, though less favorable than those with a POLE ultramutated state, which appears to be somewhat protective.

Molecular/metabolic interactions

While molecular data are clearly important in driving a cancer cell’s behavior, other clinical and metabolic factors influence cancer behavior. For example, body mass index, adiposity, glucose, and lipid metabolism have been shown to be important drivers of cellular behavior and responsiveness to targeted therapies.5,6 Additionally age, race, and other metabolic states contribute to oncologic behavior. Future classifications of endometrial cancer are unlikely to use molecular profiles in isolation but will need to incorporate these additional patient-specific data to better predict and prognosticate outcomes.

Clinical applications

If researchers can better define and describe a patient’s endometrial cancer from the time of their biopsy, important clinical decisions might be able to be tackled. For example, in a premenopausal patient with an endometrial cancer who is considering fertility-sparing treatments, preoperative knowledge of a POLE ultramutated state (and therefore an anticipated good prognosis) might favor fertility preservation or avoid comprehensive staging which may be of limited value. Similarly, if an MSI-high profile is identified leading to a Lynch syndrome diagnosis, she may be more inclined to undergo a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging as she is at known increased risk for a more advanced endometrial cancer, as well as the potential for ovarian cancer.

Postoperative incorporation of molecular data promises to be particularly helpful in guiding adjuvant therapies and sparing some women from unnecessary treatments. For example, women with high-grade endometrioid tumors who are CN high were historically treated with radiotherapy but might do better treated with systemic adjuvant therapies traditionally reserved for nonendometrioid carcinomas. Costly therapies such as immunotherapy can be directed toward those with MSI-high tumors, and the rare patient with a POLE ultramutated state who has a recurrence or advanced disease. Clinical trials will be able to cluster enrollment of patients with CN-high, serouslike cancers with those with serous cancers, rather than combining them with patients whose cancers predictably behave much differently.

Much work is still needed to validate this molecular profiling in endometrial cancer and define the algorithms associated with treatment decisions; however, it is likely that the way we describe endometrial cancer in the near future will be quite different.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no disclosures.

References

1. Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983;15(1):10-7.

2. Clarke BA et al. Endometrial carcinoma: controversies in histopathological assessment of grade and tumour cell type. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(5):410-5.

3. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67-73.

4. Ott PA et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced endometrial cancer: Preliminary results from the phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl):Abstract 5581.

5. Roque DR et al. Association between differential gene expression and body mass index among endometrial cancers from the Cancer Genome Atlas Project. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142(2):317-22.

6. Talhouk A et al. New classification of endometrial cancers: The development and potential applications of genomic-based classification in research and clinical care. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2016 Dec;3:14.

We classify endometrial cancer so that we can communicate and define each patient’s disease status, the potential for harm, and the likelihood that adjuvant therapies might provide help. Traditional forms of classification have clearly fallen short in achieving this aim, as we all know of patients with apparent low-risk disease (such as stage IA grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma) who have had recurrences and died from their disease, and we know that many patients have been subjected to overtreatment for their cancer and have acquired lifelong toxicities of therapy. This column will explore the newer, more sophisticated molecular-based classifications that are being validated for endometrial cancer, and the ways in which this promises to personalize the treatment of endometrial cancer.

Breast cancer and melanoma are examples of the inclusion of molecular data such as hormone receptor status, HER2/neu status, or BRAF positivity resulting in advancements in personalizing therapeutics. We are now moving toward this for endometrial cancer.

What is the Cancer Genome Atlas?

In 2006 the National Institutes of Health announced an initiative to coordinate work between the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute taking information about the human genome and analyzing it for key genomic alterations found in 33 common cancers. These data were combined with clinical information (such as survival) to classify the behaviors of those cancers with respect to their individual genomic alternations, in order to look for patterns in mutations and behaviors. The goal of this analysis was to shift the paradigm of cancer classification from being centered around primary organ site toward tumors’ shared genomic patterns.

In 2013 the Cancer Genome Atlas published their results of complete gene sequencing in endometrial cancer.3 The authors identified four discrete subgroups of endometrial cancer with distinct molecular mutational profiles and distinct clinical outcomes: polymerase epsilon (POLE, pronounced “pole-ee”) ultramutated, microsatellite instability (MSI) high, copy number high, and copy number low.

POLE ultramutated

An important subgroup identified in the Cancer Genome Atlas was a group of patients with a POLE ultramutated state. POLE encodes for a subunit of DNA polymerase, the enzyme responsible for replicating the leading DNA strand. Nonfunctioning POLE results in proofreading errors and a subsequent ultramutated cellular state with a predominance of single nucleotide variants. POLE proofreading domain mutations in endometrial cancer and colon cancer are associated with excellent prognosis, likely secondary to the immune response that is elicited by this ultramutated state from creation of “antigenic neoepitopes” that stimulate T-cell response. Effectively, the very mutated cell is seen as “more foreign” to the body’s immune system.

Approximately 10% of patients with endometrial cancer have a POLE ultramutated state, and, as stated above, prognosis is excellent, even if coexisting with a histologic cell type (such as serous) that is normally associated with adverse outcomes. These women tend to be younger, with a lower body mass index, higher-grade endometrioid cell type, the presence of lymphovascular space invasion, and low stage.

MSI high

MSI (microsatellite instability) is a result of epigenetic/hypermethylations or loss of expression in mismatch repair genes (such as MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2). These genes code for proteins critical in the repair of mismatches in short repeated sequences of DNA. Loss of their function results in an accumulation of errors in these sequences: MSI. It is a feature of the Lynch syndrome inherited state, but is also found sporadically in endometrial tumors. These tumors accumulate a number of mutations during cell replication that, as in POLE hypermutated tumors, are associated with eliciting an immune response.

These tumors tend to be associated with a higher-grade endometrioid cell type, the presence of lymphovascular space invasion, and an advanced stage. Patients with tumors that have been described as MSI high are candidates for “immune therapy” with the PDL1 inhibitor pembrolizumab because of their proinflammatory state and observed favorable responses in clinical trials.4

Copy number high/low

Copy number (CN) high and low refers to the results of microarrays in which hierarchical clustering was applied to identify reoccurring amplification or deletion regions. The CN-high group was associated with the poorest outcomes (recurrence and survival). There is significant overlap with mutations in TP53. Most serous carcinomas were CN high; however, 25% of patients with high-grade endometrioid cell type shared the CN-high classification. These tumors shared great molecular similarity to high-grade serous ovarian cancers and basal-like breast cancer.

Those patients who did not possess mutations that classified them as POLE hypermutated, MSI high, or CN high were classified as CN low. This group included predominantly grades 1 and 2 endometrioid adenocarcinomas of an early stage and had a favorable prognostic profile, though less favorable than those with a POLE ultramutated state, which appears to be somewhat protective.

Molecular/metabolic interactions

While molecular data are clearly important in driving a cancer cell’s behavior, other clinical and metabolic factors influence cancer behavior. For example, body mass index, adiposity, glucose, and lipid metabolism have been shown to be important drivers of cellular behavior and responsiveness to targeted therapies.5,6 Additionally age, race, and other metabolic states contribute to oncologic behavior. Future classifications of endometrial cancer are unlikely to use molecular profiles in isolation but will need to incorporate these additional patient-specific data to better predict and prognosticate outcomes.

Clinical applications

If researchers can better define and describe a patient’s endometrial cancer from the time of their biopsy, important clinical decisions might be able to be tackled. For example, in a premenopausal patient with an endometrial cancer who is considering fertility-sparing treatments, preoperative knowledge of a POLE ultramutated state (and therefore an anticipated good prognosis) might favor fertility preservation or avoid comprehensive staging which may be of limited value. Similarly, if an MSI-high profile is identified leading to a Lynch syndrome diagnosis, she may be more inclined to undergo a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging as she is at known increased risk for a more advanced endometrial cancer, as well as the potential for ovarian cancer.

Postoperative incorporation of molecular data promises to be particularly helpful in guiding adjuvant therapies and sparing some women from unnecessary treatments. For example, women with high-grade endometrioid tumors who are CN high were historically treated with radiotherapy but might do better treated with systemic adjuvant therapies traditionally reserved for nonendometrioid carcinomas. Costly therapies such as immunotherapy can be directed toward those with MSI-high tumors, and the rare patient with a POLE ultramutated state who has a recurrence or advanced disease. Clinical trials will be able to cluster enrollment of patients with CN-high, serouslike cancers with those with serous cancers, rather than combining them with patients whose cancers predictably behave much differently.

Much work is still needed to validate this molecular profiling in endometrial cancer and define the algorithms associated with treatment decisions; however, it is likely that the way we describe endometrial cancer in the near future will be quite different.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no disclosures.

References

1. Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983;15(1):10-7.

2. Clarke BA et al. Endometrial carcinoma: controversies in histopathological assessment of grade and tumour cell type. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(5):410-5.

3. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67-73.

4. Ott PA et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced endometrial cancer: Preliminary results from the phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl):Abstract 5581.

5. Roque DR et al. Association between differential gene expression and body mass index among endometrial cancers from the Cancer Genome Atlas Project. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142(2):317-22.

6. Talhouk A et al. New classification of endometrial cancers: The development and potential applications of genomic-based classification in research and clinical care. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2016 Dec;3:14.

We classify endometrial cancer so that we can communicate and define each patient’s disease status, the potential for harm, and the likelihood that adjuvant therapies might provide help. Traditional forms of classification have clearly fallen short in achieving this aim, as we all know of patients with apparent low-risk disease (such as stage IA grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma) who have had recurrences and died from their disease, and we know that many patients have been subjected to overtreatment for their cancer and have acquired lifelong toxicities of therapy. This column will explore the newer, more sophisticated molecular-based classifications that are being validated for endometrial cancer, and the ways in which this promises to personalize the treatment of endometrial cancer.

Breast cancer and melanoma are examples of the inclusion of molecular data such as hormone receptor status, HER2/neu status, or BRAF positivity resulting in advancements in personalizing therapeutics. We are now moving toward this for endometrial cancer.

What is the Cancer Genome Atlas?

In 2006 the National Institutes of Health announced an initiative to coordinate work between the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute taking information about the human genome and analyzing it for key genomic alterations found in 33 common cancers. These data were combined with clinical information (such as survival) to classify the behaviors of those cancers with respect to their individual genomic alternations, in order to look for patterns in mutations and behaviors. The goal of this analysis was to shift the paradigm of cancer classification from being centered around primary organ site toward tumors’ shared genomic patterns.

In 2013 the Cancer Genome Atlas published their results of complete gene sequencing in endometrial cancer.3 The authors identified four discrete subgroups of endometrial cancer with distinct molecular mutational profiles and distinct clinical outcomes: polymerase epsilon (POLE, pronounced “pole-ee”) ultramutated, microsatellite instability (MSI) high, copy number high, and copy number low.

POLE ultramutated

An important subgroup identified in the Cancer Genome Atlas was a group of patients with a POLE ultramutated state. POLE encodes for a subunit of DNA polymerase, the enzyme responsible for replicating the leading DNA strand. Nonfunctioning POLE results in proofreading errors and a subsequent ultramutated cellular state with a predominance of single nucleotide variants. POLE proofreading domain mutations in endometrial cancer and colon cancer are associated with excellent prognosis, likely secondary to the immune response that is elicited by this ultramutated state from creation of “antigenic neoepitopes” that stimulate T-cell response. Effectively, the very mutated cell is seen as “more foreign” to the body’s immune system.

Approximately 10% of patients with endometrial cancer have a POLE ultramutated state, and, as stated above, prognosis is excellent, even if coexisting with a histologic cell type (such as serous) that is normally associated with adverse outcomes. These women tend to be younger, with a lower body mass index, higher-grade endometrioid cell type, the presence of lymphovascular space invasion, and low stage.

MSI high

MSI (microsatellite instability) is a result of epigenetic/hypermethylations or loss of expression in mismatch repair genes (such as MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2). These genes code for proteins critical in the repair of mismatches in short repeated sequences of DNA. Loss of their function results in an accumulation of errors in these sequences: MSI. It is a feature of the Lynch syndrome inherited state, but is also found sporadically in endometrial tumors. These tumors accumulate a number of mutations during cell replication that, as in POLE hypermutated tumors, are associated with eliciting an immune response.

These tumors tend to be associated with a higher-grade endometrioid cell type, the presence of lymphovascular space invasion, and an advanced stage. Patients with tumors that have been described as MSI high are candidates for “immune therapy” with the PDL1 inhibitor pembrolizumab because of their proinflammatory state and observed favorable responses in clinical trials.4

Copy number high/low

Copy number (CN) high and low refers to the results of microarrays in which hierarchical clustering was applied to identify reoccurring amplification or deletion regions. The CN-high group was associated with the poorest outcomes (recurrence and survival). There is significant overlap with mutations in TP53. Most serous carcinomas were CN high; however, 25% of patients with high-grade endometrioid cell type shared the CN-high classification. These tumors shared great molecular similarity to high-grade serous ovarian cancers and basal-like breast cancer.

Those patients who did not possess mutations that classified them as POLE hypermutated, MSI high, or CN high were classified as CN low. This group included predominantly grades 1 and 2 endometrioid adenocarcinomas of an early stage and had a favorable prognostic profile, though less favorable than those with a POLE ultramutated state, which appears to be somewhat protective.

Molecular/metabolic interactions

While molecular data are clearly important in driving a cancer cell’s behavior, other clinical and metabolic factors influence cancer behavior. For example, body mass index, adiposity, glucose, and lipid metabolism have been shown to be important drivers of cellular behavior and responsiveness to targeted therapies.5,6 Additionally age, race, and other metabolic states contribute to oncologic behavior. Future classifications of endometrial cancer are unlikely to use molecular profiles in isolation but will need to incorporate these additional patient-specific data to better predict and prognosticate outcomes.

Clinical applications

If researchers can better define and describe a patient’s endometrial cancer from the time of their biopsy, important clinical decisions might be able to be tackled. For example, in a premenopausal patient with an endometrial cancer who is considering fertility-sparing treatments, preoperative knowledge of a POLE ultramutated state (and therefore an anticipated good prognosis) might favor fertility preservation or avoid comprehensive staging which may be of limited value. Similarly, if an MSI-high profile is identified leading to a Lynch syndrome diagnosis, she may be more inclined to undergo a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging as she is at known increased risk for a more advanced endometrial cancer, as well as the potential for ovarian cancer.

Postoperative incorporation of molecular data promises to be particularly helpful in guiding adjuvant therapies and sparing some women from unnecessary treatments. For example, women with high-grade endometrioid tumors who are CN high were historically treated with radiotherapy but might do better treated with systemic adjuvant therapies traditionally reserved for nonendometrioid carcinomas. Costly therapies such as immunotherapy can be directed toward those with MSI-high tumors, and the rare patient with a POLE ultramutated state who has a recurrence or advanced disease. Clinical trials will be able to cluster enrollment of patients with CN-high, serouslike cancers with those with serous cancers, rather than combining them with patients whose cancers predictably behave much differently.

Much work is still needed to validate this molecular profiling in endometrial cancer and define the algorithms associated with treatment decisions; however, it is likely that the way we describe endometrial cancer in the near future will be quite different.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no disclosures.

References

1. Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983;15(1):10-7.

2. Clarke BA et al. Endometrial carcinoma: controversies in histopathological assessment of grade and tumour cell type. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(5):410-5.

3. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67-73.

4. Ott PA et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced endometrial cancer: Preliminary results from the phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl):Abstract 5581.

5. Roque DR et al. Association between differential gene expression and body mass index among endometrial cancers from the Cancer Genome Atlas Project. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142(2):317-22.

6. Talhouk A et al. New classification of endometrial cancers: The development and potential applications of genomic-based classification in research and clinical care. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2016 Dec;3:14.

Marijuana use is affecting the job market

I have a friend who owns a large paving and excavating company. He currently is turning away large contracts because he can’t find employees to drive his dump trucks and operate his heavy machinery. The situation is so dire that he has begun to explore the possibility of recruiting employees out of the corrections system.

Like much of the country, Maine is experiencing a low level of unemployment that few of us over the age of 50 years can recall. Coupled with a confused and unwelcoming immigration policy at the federal level many small and large companies are struggling to find employees. The employment opportunities my friend’s company is offering are well above minimum wage, paying in the $30,000-$70,000 range with benefits. While the jobs require some special skills, his company is large enough that it can provide in-house training.

Maine residents recently have voted to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of marijuana. It is unclear exactly how this change in the official position of the state government will translate into a distribution network and a system of local codes. However, it does reflect a more tolerant attitude toward marijuana use. It also suggests that job seekers who are avoiding positions that require drug testing are not worried about the stigma of being identified as a user. They understand enough pharmacology to know that marijuana is detectable days and even weeks after it was last ingested or inhaled. Even the recreational users realize that the chances of being able to pass a drug test before employment and at any subsequent random testing are slim.

The problem is that these good-paying jobs are going unfilled because of the pharmacologic properties of a drug, and our current inability to devise a test that can accurately and consistently correlate a person’s blood level and his or her ability to safely operate a motor vehicle or piece of heavy equipment (“Establishing legal limit for driving under the influence of marijuana,” Inj Epidemiol. 2014 Dec.;1[1]: 26). There is some correlation between blood levels and whether a person is a heavy or infrequent user. Laws that rely on a zero tolerance philosophy are not bringing us any closer to a solution. And it is probably unrealistic to hope that in the near future scientists will develop a single, simply administered test that can provide a clear yes or no to the issue of impairment in the workplace.

I can envision a two-tier system in which all employees are blood or urine tested on a 3-month schedule. Those with a positive test must then take a 10-minute test on a laptop computer simulator with a joy stick each morning that they arrive on the job to demonstrate that, despite a history of marijuana use, they are not impaired.

Even if such a test is developed, we still owe our patients the reminder that, despite its decriminalization, marijuana is a drug and like any drug has side effects. One of them is that it can put limits on your employment opportunities.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I have a friend who owns a large paving and excavating company. He currently is turning away large contracts because he can’t find employees to drive his dump trucks and operate his heavy machinery. The situation is so dire that he has begun to explore the possibility of recruiting employees out of the corrections system.

Like much of the country, Maine is experiencing a low level of unemployment that few of us over the age of 50 years can recall. Coupled with a confused and unwelcoming immigration policy at the federal level many small and large companies are struggling to find employees. The employment opportunities my friend’s company is offering are well above minimum wage, paying in the $30,000-$70,000 range with benefits. While the jobs require some special skills, his company is large enough that it can provide in-house training.

Maine residents recently have voted to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of marijuana. It is unclear exactly how this change in the official position of the state government will translate into a distribution network and a system of local codes. However, it does reflect a more tolerant attitude toward marijuana use. It also suggests that job seekers who are avoiding positions that require drug testing are not worried about the stigma of being identified as a user. They understand enough pharmacology to know that marijuana is detectable days and even weeks after it was last ingested or inhaled. Even the recreational users realize that the chances of being able to pass a drug test before employment and at any subsequent random testing are slim.

The problem is that these good-paying jobs are going unfilled because of the pharmacologic properties of a drug, and our current inability to devise a test that can accurately and consistently correlate a person’s blood level and his or her ability to safely operate a motor vehicle or piece of heavy equipment (“Establishing legal limit for driving under the influence of marijuana,” Inj Epidemiol. 2014 Dec.;1[1]: 26). There is some correlation between blood levels and whether a person is a heavy or infrequent user. Laws that rely on a zero tolerance philosophy are not bringing us any closer to a solution. And it is probably unrealistic to hope that in the near future scientists will develop a single, simply administered test that can provide a clear yes or no to the issue of impairment in the workplace.

I can envision a two-tier system in which all employees are blood or urine tested on a 3-month schedule. Those with a positive test must then take a 10-minute test on a laptop computer simulator with a joy stick each morning that they arrive on the job to demonstrate that, despite a history of marijuana use, they are not impaired.

Even if such a test is developed, we still owe our patients the reminder that, despite its decriminalization, marijuana is a drug and like any drug has side effects. One of them is that it can put limits on your employment opportunities.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I have a friend who owns a large paving and excavating company. He currently is turning away large contracts because he can’t find employees to drive his dump trucks and operate his heavy machinery. The situation is so dire that he has begun to explore the possibility of recruiting employees out of the corrections system.

Like much of the country, Maine is experiencing a low level of unemployment that few of us over the age of 50 years can recall. Coupled with a confused and unwelcoming immigration policy at the federal level many small and large companies are struggling to find employees. The employment opportunities my friend’s company is offering are well above minimum wage, paying in the $30,000-$70,000 range with benefits. While the jobs require some special skills, his company is large enough that it can provide in-house training.

Maine residents recently have voted to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of marijuana. It is unclear exactly how this change in the official position of the state government will translate into a distribution network and a system of local codes. However, it does reflect a more tolerant attitude toward marijuana use. It also suggests that job seekers who are avoiding positions that require drug testing are not worried about the stigma of being identified as a user. They understand enough pharmacology to know that marijuana is detectable days and even weeks after it was last ingested or inhaled. Even the recreational users realize that the chances of being able to pass a drug test before employment and at any subsequent random testing are slim.

The problem is that these good-paying jobs are going unfilled because of the pharmacologic properties of a drug, and our current inability to devise a test that can accurately and consistently correlate a person’s blood level and his or her ability to safely operate a motor vehicle or piece of heavy equipment (“Establishing legal limit for driving under the influence of marijuana,” Inj Epidemiol. 2014 Dec.;1[1]: 26). There is some correlation between blood levels and whether a person is a heavy or infrequent user. Laws that rely on a zero tolerance philosophy are not bringing us any closer to a solution. And it is probably unrealistic to hope that in the near future scientists will develop a single, simply administered test that can provide a clear yes or no to the issue of impairment in the workplace.

I can envision a two-tier system in which all employees are blood or urine tested on a 3-month schedule. Those with a positive test must then take a 10-minute test on a laptop computer simulator with a joy stick each morning that they arrive on the job to demonstrate that, despite a history of marijuana use, they are not impaired.

Even if such a test is developed, we still owe our patients the reminder that, despite its decriminalization, marijuana is a drug and like any drug has side effects. One of them is that it can put limits on your employment opportunities.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Accuracy of Distal Femoral Valgus Deformity Correction: Fixator-Assisted Nailing vs Fixator-Assisted Locked Plating

ABSTRACT

Fixator-assisted nailing (FAN) and fixator-assisted locked plating (FALP) are 2 techniques that can be used to correct distal femoral valgus deformities. The fixator aids in achieving an accurate adjustable initial reduction, which is then made permanent with either nail or plate insertion. FALP can be performed with the knee held in a neutral extended position, whereas FAN requires 30° to 90° of knee flexion to insert the nail, which may cause some alignment loss. We hypothesized that FAN may yield less accurate correction than FALP. Prospectively collected data of a consecutive cohort of patients who underwent valgus deformity femoral correction with FAN or FALP at a single institution over an 8-year period were retrospectively evaluated. Twenty extremities (18 patients) were treated using FAN (median follow-up, 5 years; range, 1-10 years), and 7 extremities (6 patients) were treated with FALP (median follow-up, 5 years; range, 1-8 years). In the FAN cohort, the mean preoperative and postoperative mechanical lateral distal femoral angles (mLDFAs) were 81° (range, 67°-86°) and 89° (range, 80°-100°), respectively (P = .009). In the FALP cohort, the mean preoperative and postoperative mLDFAs were 80° (range, 71°-87°) and 88° (range, 81°-94°), respectively (P < .001). Although the average mechanical axis deviation correction for the FALP group was greater than for the FAN group (32 mm and 27 mm, respectively), the difference was not significant (P = .66). Both methods of femoral deformity correction can be considered safe and effective. On the basis of our results, FAN and FALP are comparable in accuracy for deformity correction in the distal femur.

Multiple etiologies for distal femoral valgus deformity have been described in the literature.1-3 These can be congenital, developmental, secondary to lateral compartmental arthritis, or posttraumatic.4 If not corrected, femoral deformities alter the axial alignment and orientation of the joints, and may lead to early degenerative joint disease and abnormal leg kinematics.3,5 After correcting these deformities, the goal of treatment is to obtain anatomic distal femoral angles and neutral mechanical axis deviation (MAD), but without overcorrecting into varus. Numerous techniques to fix these deformities, such as progressive correction with external fixation or acute correction open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF), have been described.6 Modern external fixation allows for a gradual, adjustable, and more accurate correction but may produce discomfort and complications for patients.7-10 In contrast, ORIF may be more tolerable for the patient, but to achieve a precise correction, considerable technical skills and expertise are required.1,11-14

Two techniques used to correct these valgus femoral deformities in adults are fixator-assisted nailing (FAN) and fixator-assisted locked plating (FALP).1 FAN and FALP combine the advantage of external fixation (accuracy, adjustability) with the benefits of internal fixation (patient comfort), because the osteotomy and correction are performed with the guidance of a temporary external fixator and then permanently fixated by an intramedullary (IM) nail or a locking plate.1,8,11-13,15-18 Both techniques have the possibility to correct varus and valgus deformities, but whenever correcting sagittal plane angulation, the FAN technique may be more challenging. The paucity of studies available involving FAN and FALP do not lead to a conclusive preference of one technique over the other relative to the accuracy and success of correction.15,19,20

Continue to: In both FAN and FALP

In both FAN and FALP, the external fixator is applied and adjusted after the osteotomy for accurate alignment. In FALP, the plate is added without moving the leg from its straight position. However, in FAN, the knee must be flexed to 30° to 90° for insertion of the retrograde knee nail, and the alignment may be lost if the external fixation is not fully stable. Therefore, we hypothesized that FAN would be less accurate than FALP. Hence, the purposes of this study is to compare the correction achieved with FAN and FALP in patients with distal femoral valgus deformities and to describe the intraoperative complications associated with both techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After proper Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a consecutive cohort of 35 patients who underwent femoral deformity correction with either FAN or FALP during an 8-year period (January 2002 to December 2010) was retrospectively reviewed. Eleven patients had to be excluded because of inadequate follow-up (<12 months) or because additional procedures were simultaneously performed. A total of 24 patients (27 femora) who had a mean age of 26 years (range, 14-68 years) were included in the final study cohort. Specifically, 20 femora (18 patients) were corrected using the FAN technique (7 males and 11 females; mean age, 36 years; range, 14-68 years), and 7 femora (6 patients) were fixed using the FALP technique (2 males and 4 females; mean age, 16 years; range, 15-19 years). The median follow-up in the FAN cohort was 5 years (range, 1-10 years), and the median follow-up in the FALP cohort was 5 years (range, 1-8 years) (Table 1).

| Table 1. Study Details and Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Detail | Overall | FAN | FALP |

| Number of patients | 24 | 18 | 6 |

| Number of femurs | 27 | 20 | 7 |

| Age in years (range) | 26 (14 to 68) | 36 (14 to 68) | 16 (15 to 19) |

| Male:Female | 9:15 | 7:11 | 2:4 |

| Median follow-up in years (range) | 5 (1 to 10) | 5 (1 to 10) | 5 (1 to 8) |

Abbreviations: FALP, fixator assisted locked plating; FAN, fixator assisted nailing

The specific measurements performed in all patients were MAD, mechanical lateral distal femoral angle (mLDFA), and medial proximal tibia angle (MPTA). These were measured from standing anteroposterior radiographs of the knee that included the femur.21 All outcome data were collected from the medical charts, operative reports, and radiographic evaluations. To ensure accuracy, all measurements were performed by 2 authors blinded to each other’s measurements. If a variation of <5% was obtained, the results were averaged and used for further analysis. Whenever a difference of >5% was obtained, the measurement was repeated by both authors for confirmation.

SURGICAL FAN TECHNIQUE

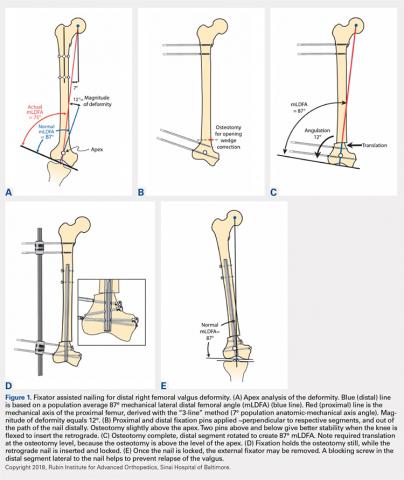

After measuring the deformity (Figure 1A) with the patient under general anesthesia on a radiolucent table, the involved lower limb is prepared and draped. Two half-pins are inserted medially, 1 proximal and 1 distal to the planned osteotomy site (Figure 1B), and then connected loosely with a monolateral external fixator. Special care is taken while placing the half-pins, not to interfere with the insertion path of the IM rod. When performing the preoperative planning, the level of osteotomy is chosen to enable the placement of at least 2 interlocking screws distal to the osteotomy. Then, a percutaneous osteotomy is performed from a lateral approach, and the bone ends are manipulated (translation and then angulation) to achieve the desired deformity correction. The external fixator is then stabilized and locked in the exact position (Figure 1C). Subsequently, retrograde reaming, nail insertion, and placement of proximal and distal locking screws are performed (Figure 1D). Blocking screws may give additional stability. The removal of the external fixator is the final step (Figure 1E).20

Continue to: When using the FAN technique...

When using the FAN technique, special attention is paid to reducing the risk of fat embolism. This can be reduced but not totally eradicated with the use of reaming irrigation devices.22-24 In our technique of FAN, the bone is cut and displaced prior to reaming so that the pressure of reaming is vented out through the osteotomy, along with the reaming contents, which theoretically can then act as a “prepositioned bone graft” that may speed healing.

SURGICAL FALP TECHNIQUE

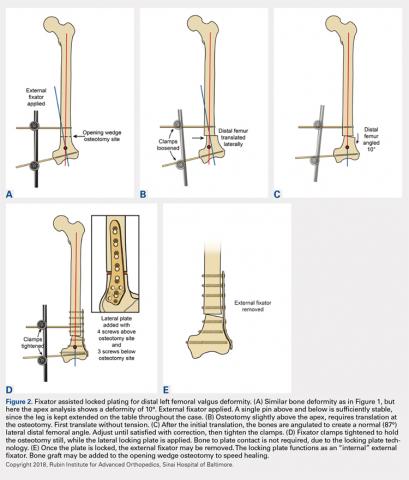

Preoperatively, a decision concerning the planned osteotomy and the correct locking plate size is made. In addition, the outline of the plate is marked on the skin. Under general anesthesia, the patients are prepared and draped. A tourniquet is elevated around the upper thigh. Then, 2 half-pins are medially inserted, 1 proximal and 1 distal to the planned osteotomy site, and are then connected loosely with a monolateral external fixator (Figure 2A). A lateral approach to the distal femur is done, preserving the periosteum, except at the level of the osteotomy. After the osteotomy is performed (through an open lateral incision), both segments are translated (Figure 2B) and then the distal segment is angulated to achieve the desired deformity correction, and the desired position is then stabilized by tightening the external fixator connectors (Figure 2C). Subsequently, a locking plate is inserted in the submuscular-extraperiostal plane. The plate does not require being in full contact (flush) with the bone. At least 3 screws are placed on both sides of the osteotomy through a long lateral incision (Figure 2D). Bone graft may be added to the osteotomy site to encourage healing. Then, the external fixator is removed, and all incisions are closed (Figure 2E).15,19

During each of the procedures, we aimed at having “perfect alignment” with a MAD of 0 mm, in which a Bovie cord is used and passed through the center of the femoral head, knee, and ankle. However, to confirm that the surgery was successful, the actual measurements were performed on standing long-leg films. These films were obtained preoperatively and at latest follow-up. They were performed with the patella aiming forward, the toes straight ahead, feet separated enough for good balance, knees fully extended, and weight equally distributed on the feet. Postoperatively, in both cohorts, partial weight-bearing was encouraged immediately with crutches; physical therapy was instituted daily for knee range of motion. Radiographs were scheduled every 4 weeks to monitor callus formation. Full weight-bearing was allowed when at least 3 cortices were consolidated.1,15,19,20,25,26

All statistical analyses were performed with the aid of the SPSS statistical software package (SPSS). Average values and standard error of the mean were assigned to each variable. A nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used, and a 2-tailed P < .05 was considered significant. Correlation of continuous variables was determined by Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Also, multivariate Cox regression analyses after adjustment for age, sex, and deformity correction were used to detect associations within the study population. To evaluate whether our data were normally distributed, Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed.

Continue to: Results...

RESULTS

The mLDFA significantly improved in the FAN cohort from a mean of 81° to a mean of 89° (ranges, 67°-86° and 80°-100°; respectively; P = .001) (Figures 3A, 3B).

| Table 2. Deformity Correction | ||||

| Measurement | Cohort | Preoperative | Postoperative | P Value |

| mLDFA in degrees (range) | FAN | 81 (67 to 86) | 89 (80 to 100) | 0.001 |

| FALP | 80 (71 to 87) | 90 (88 to 94) | <0.001 | |

| Mechanical axis deviation in mm (range) | FAN | 32 (6 to 64) | 10 (0 to 22) | 0.001 |

| FALP | 34 (17 to 62) | 4 (0 to 11) | 0.002 | |

Abbreviations: FALP, fixator assisted locked plating; FAN, fixator assisted nailing; mLDFA, mechanical lateral distal femoral angle

After evaluating the MPTA, in the FAN cohort, we found that the mean pre- and postoperative MPTAs were not modified. These patients had a mean preoperative angle of 88° (range, 62°-100°), which was kept postoperatively to a mean of 88° (range, 78°-96°). In the FALP cohort, a slight change from 90° to 88° was observed (ranges, 82°-97° and 83°-94°, respectively). None of these changes in MPTA were significant (P > .05).

When evaluating correction of the MAD, we observed that the FAN cohort changed from a preoperative MAD of 32 mm (range, 6-64 mm) to a postoperative mean of 10 mm (range, 0-22 mm), and this correction was statistically significant. (P = .001). The FALP cohort changed from a mean of 34 mm (range, 17-62 mm) preoperatively to 4 mm (range, 0-11 mm) postoperatively, and this was also statistically significant (P = .002). The mean MAD correction for the FAN group vs FALP group was 27 mm vs 32 mm, respectively (Table 2).

In patients with valgus femoral deformity, the MAD is usually lateralized; however, in the FAN cohort, we included 3 patients with medial MADs (10 mm, 13 mm, and 40 mm). This is justified in these patients because a complex deformity of the distal femur and the proximal tibia was present. In the extreme case of a 40-mm medial MAD, the presurgery mLDFA was 76°, and the presurgery MPTA was 62°. The amount of deformity correction in this patient was 16°.

During the follow-up period, 2 complications occurred in the FAN group. One patient developed gait disturbance that resolved with physical therapy. Another had an infection at the osteotomy site. This was addressed with intravenous antibiotic therapy, surgical irrigation and débridement, hardware removal, and antegrade insertion of an antibiotic-coated nail. In the FALP group, 1 patient developed a persistent incomplete peroneal nerve palsy attributed to a 17° correction from valgus to varus, despite prophylactic peroneal nerve decompression. Nonetheless, the patient was satisfied with the result, recovered partial nerve function, and returned for correction of the contralateral leg deformity. When comparing the complications between both cohorts, no significant differences were found: 2 of 18 cases (11%) in the FAN group vs 1 of 6 cases (17%) in the FALP group (P = .78).

Continue to: The goal of this study...

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to compare the accuracy of deformity corrections achieved with either FAN or FALP. A number of authors have described results after deformity correction with several plating and nailing techniques; however, the information derived from comparing these 2 techniques is limited. We hypothesized that FALP would be more accurate, because less mobilization during fixation is required. However, we found no significant differences between these 2 techniques.

This study has several limitations. First, the small size of our cohort had to be further reduced owing to limited data; nevertheless, this pathology and the treatment methods used are not commonly performed, which make this cohort 1 of the largest of its type described in the literature. Also, the procedures were performed by multiple surgeons in a population with a wide age range, creating multiple additional variables that complicate the comparison of the sole differences between FAN and FALP. However, owing to these variables, the generalizability of this study may be increased, and similar outcomes can potentially be obtained by other institutions/surgeons. In addition, the variability of our follow-up period is another limitation; however, these patients were all assessed until bony union after skeletal maturity was achieved. Hence, the development of additional deformity is not expected. The lack of clinical outcome with a standardized questionnaire may also be seen as a limitation. However, because the purpose of our study was to assess both surgeries in terms of their ability to achieve angular correction, the addition of patient-reported outcomes may have increased the variability of our data.

The foremost objective in valgus deformity correction is to establish joint orientation angles within anatomic range to prevent overloading of the lateral joint and thereby prevent lateral compartmental osteoarthritis.2,20,27-29 There are 2 categories of fixation: internal and external. With FAN and FALP, we strive to have the adjustability and accuracy of external fixation with the comfort (for the patient) of internal fixation. Accurate osteotomy correction requires an accurate preoperative analysis and osteotomy close to the apex of the deformity.16,21,30-33 The most commonly used osteotomy techniques are drill-hole,31 focal dome,34 rotation, and open- or closed-wedge osteotomies.35,36 After the osteotomy, the resultant correction has to be stabilized. In recent years, the popularity of plates instead of an IM nail for internal fixation has been driven by the rapid development of low contact locking plates.16,19,26,30,37-40

There are certain advantages of using FAN over FALP. In older patients who may require a subsequent total knee arthroplasty (TKA), the midline incision used for retrograde FAN technique is identical to that made for TKA. In contrast, in a younger and more active population, with a longer life expectancy, the extra-articular FALP approach has the advantage of not violating the knee joint. In addition, locking plates may achieve a more rigid fixation than IM nails; however, the stability of IM nails can be augmented with blocking screws.

Continue to: In 20 patients, including children...

In 20 patients, including children and young adults, with frontal and sagittal plane deformities, Marangoz and colleagues7 reported on correction of valgus, varus, and procurvatum deformities using a Taylor Spatial Frame (TSF). Successful correction of severe deformities was achieved gradually with the TSF, resulting in a postoperative deformity (valgus group) of mLDFA 88.9° (range, 85°-95°).7 In a more recent study, Bar-On and colleagues15 described a series of 11 patients (18 segments) with corrective lower limb osteotomies in which all were corrected to within 2° of the planned range. Similarly, Gugenheim and Brinker20 described the use of the FAN technique to correct distal varus and valgus deformities in 14 femora. The final mean mLDFA and MAD in the valgus group were 89° (range, 88°-90°) and 5 mm (range, 0-14 mm medial), respectively.

In their comparative study, Seah and colleagues11 described monolateral frame vs FALP deformity correction in a series of 34 extremities (26 patients) that required distal femoral osteotomy. No differences related to knee range of motion or the ability to correct the deformity between internal and external fixation were reported (P > .05). Similarly, Eidelman and colleagues1 evaluated the outcomes of 6 patients (7 procedures) who underwent surgery performed with the FALP technique for distal femoral valgus deformity. They concluded that this technique is minimally invasive and can provide a precise deformity correction with minimal morbidity.

Other methods of fixation while performing FAN have been described by Jasiewicz and colleagues,22 who evaluated possible differences between the classic Ilizarov device and monolateral fixators in 19 femoral lengthening procedures. The authors concluded that there is no difference between concerning complication rate and treatment time. The use of FAN has also been described in patients with metabolic disease who required deformity correction. In this regard, Kocaoglu and colleagues12 described the use of a monolateral external fixator in combination with an IM nail in a series of 17 patients with metabolic bone disease. The authors concluded that the use of the IM nail prevented recurrence of deformity and refracture.12 Kocaoglu and colleagues14 also published a series of 25 patients treated with the FAN and LON (lengthening over a nail) technique for lengthening and deformity correction. The mean MAD improved from 33.9 mm to11.3 mm (range, 0-30 mm). In contrast, Erlap and colleagues13 compared FAN with circular external fixator for bone realignment of the lower extremity for deformities in patients with rickets. Although no significant difference was found between both groups, FAN was shown to be accurate and to provide great comfort to patients, and it also shortened the total treatment time.13 Finally, the advent of newer technologies could also provide alternatives for correcting valgus deformities. For example, Saragaglia and Chedal-Bornu6 performed 29 computer-assisted valgus knees osteotomies (27 patients) and reported that the goal hip-knee angle was achieved in 86% of patients and that the goal MPTA was achieved in 100% of patients.6

CONCLUSION

Both the FALP and FAN methods of femoral deformity correction are safe and effective surgical techniques. In our opinion, the advantages of the FALP technique result from the easy lateral surgical approach under medial external fixation and stabilization of the osteotomy without bending the knee. Ultimately, the decision to use FAN may be influenced by the surgeon’s perception of the potential need for future TKA. In such cases, a midline anterior approach with nailing is very compatible with subsequent TKA. The surgeon’s experience and preference, while keeping in mind the patient’s predilection, will play an important role in the decision-making process. Larger prospective clinical trials with larger cohorts have to be conducted to confirm our findings.

1. Eidelman M, Keren Y, Norman D. Correction of distal femoral valgus deformities in adolescents and young adults using minimally invasive fixator-assisted locking plating (FALP). J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012;21(6):558-562. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e328358f884.

2. Pelletier JP, Raynauld JP, Berthiaume MJ, et al. Risk factors associated with the loss of cartilage volume on weight-bearing areas in knee osteoarthritis patients assessed by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(4):R74. doi:10.1186/ar2272.

3. Solomin LN, Paley D, Shchepkina EA, Vilensky VA, Skomoroshko PV. A comparative study of the correction of femoral deformity between the Ilizarov apparatus and ortho-SUV Frame. Int Orthop. 2014;38(4):865-872. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2247-0.

4. Meric G, Gracitelli GC, Aram LJ, Swank ML, Bugbee WD. Variability in distal femoral anatomy in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: measurements on 13,546 computed tomography scans. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(10):1835-1838. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2015.04.024.

5. Cameron JI, McCauley JC, Kermanshahi AY, Bugbee WD. Lateral opening-wedge distal femoral osteotomy: pain relief, functional improvement, and survivorship at 5 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2009-2015. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-4106-8.

6. Saragaglia D, Chedal-Bornu B. Computer-assisted osteotomy for valgus knees: medium-term results of 29 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(5):527-530. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2014.04.002.

7. Marangoz S, Feldman DS, Sala DA, Hyman JE, Vitale MG. Femoral deformity correction in children and young adults using Taylor Spatial Frame. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(12):3018-3024. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0490-2.

8. Rogers MJ, McFadyen I, Livingstone JA, Monsell F, Jackson M, Atkins RM. Computer hexapod assisted orthopaedic surgery (CHAOS) in the correction of long bone fracture and deformity. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(5):337-342. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e3180463103.

9. Feldman DS, Madan SS, Ruchelsman DE, Sala DA, Lehman WB. Accuracy of correction of tibia vara: acute versus gradual correction. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(6):794-798. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000242375.64854.3d.

10. Manner HM, Huebl M, Radler C, Ganger R, Petje G, Grill F. Accuracy of complex lower-limb deformity correction with external fixation: a comparison of the Taylor Spatial Frame with the Ilizarov ring fixator. J Child Orthop. 2007;1(1):55-61. doi:10.1007/s11832-006-0005-1.

11. Seah KT, Shafi R, Fragomen AT, Rozbruch SR. Distal femoral osteotomy: is internal fixation better than external? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):2003-2011. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1755-0.

12. Kocaoglu M, Bilen FE, Sen C, Eralp L, Balci HI. Combined technique for the correction of lower-limb deformities resulting from metabolic bone disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):52-56. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.24788.

13. Eralp L, Kocaoglu M, Toker B, Balcı HI, Awad A. Comparison of fixator-assisted nailing versus circular external fixator for bone realignment of lower extremity angular deformities in rickets disease. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(5):581-589. doi:10.1007/s00402-010-1162-8.

14. Kocaoglu M, Eralp L, Bilen FE, Balci HI. Fixator-assisted acute femoral deformity correction and consecutive lengthening over an intramedullary nail. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):152-159. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00114.

15. Bar-On E, Becker T, Katz K, Velkes S, Salai M, Weigl DM. Corrective lower limb osteotomies in children using temporary external fixation and percutaneous locking plates. J Child Orthop. 2009;3(2):137-143. doi:10.1007/s11832-009-0165-x.

16. Herzenberg JE, Kovar FM. External fixation assisted nailing (EFAN) and external fixation assisted plating (EFAP) for deformity correction. In: Solomin LN, ed. The Basic Principles of External Fixation Using the Ilizarov and Other Devices. 2nd ed. Italy: Springer-Verlag; 2012:1363-1378.

17. Eralp L, Kocaoglu M, Cakmak M, Ozden VE. A correction of windswept deformity by fixator assisted nailing. A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(7):1065-1068.

18. Eralp L, Kocaoglu M. Distal tibial reconstruction with use of a circular external fixator and an intramedullary nail. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 2):181-194. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00467.

19. Gautier E, Sommer C. Guidelines for the clinical application of the LCP. Injury. 2003;34(Suppl 2):B63-B76. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2003.09.026.

20. Gugenheim JJ Jr, Brinker MR. Bone realignment with use of temporary external fixation for distal femoral valgus and varus deformities. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85–A(7):1229-1237. doi:10.2106/00004623-200307000-00008.

21. Paley D, Herzenberg JE, Tetsworth K, McKie J, Bhave A. Deformity planning for frontal and sagittal plane corrective osteotomies. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25(3):425-465.

22. Jasiewicz B, Kacki W, Tesiorowski M, Potaczek T. Results of femoral lengthening over an intramedullary nail and external fixator. Chir Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol. 2008;73(3):177-183.

23. Pape HC, Giannoudis P. The biological and physiological effects of intramedullary reaming. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(11):1421-1426. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B11.19570.

24. Wozasek GE, Simon P, Redl H, Schlag G. Intramedullary pressure changes and fat intravasation during intramedullary nailing: an experimental study in sheep. J Trauma. 1994;36(2):202-207. doi:10.1097/00005373-199402000-00010.

25. Gordon JE, Goldfarb CA, Luhmann SJ, Lyons D, Schoenecker PL. Femoral lengthening over a humeral intramedullary nail in preadolescent children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84–A(6):930-937. doi:10.2106/00004623-200206000-00006.

26. Oh CW, Song HR, Kim JW, et al. Deformity correction with submuscular plating technique in children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19(1):47-54. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e32832f5b06.

27. Guettler J, Glisson R, Stubbs A, Jurist K, Higgins L. The triad of varus malalignment, meniscectomy, and chondral damage: a biomechanical explanation for joint degeneration. Orthopedics. 2007;30(7):558-566.

28. Sharma L, Eckstein F, Song J, et al. Relationship of meniscal damage, meniscal extrusion, malalignment, and joint laxity to subsequent cartilage loss in osteoarthritic knees. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(6):1716-1726. doi:10.1002/art.23462.

29. Tanamas S, Hanna FS, Cicuttini FM, Wluka AE, Berry P, Urquhart DM. Does knee malalignment increase the risk of development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(4):459-467. doi:10.1002/art.24336.

30. Paley D, HJ, Bor N. Fixator-assisted nailing of femoral and tibial deformities. Tech Orthop. 1997;12(4):260-275.

31. Eralp L, Kocaoğlu M, Ozkan K, Türker M. A comparison of two osteotomy techniques for tibial lengthening. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(5):298-300. doi:10.1007/s00402-004-0646-9.

32. Strecker W, Kinzl L, Keppler P. Corrective osteotomies of the distal femur with retrograde intramedullary nail. Unfallchirurg. 2001;104(10):973-983. doi:10.1007/s001130170040.

33. Watanabe K, Tsuchiya H, Sakurakichi K, Matsubara H, Tomita K. Acute correction using focal dome osteotomy for deformity about knee joint. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(12):1373-1378. doi:10.1007/s00402-008-0574-1.

34. Hankemeier S, Paley D, Pape HC, Zeichen J, Gosling T, Krettek C. Knee para-articular focal dome osteotomy. Orthopade. 2004;33(2):170-177. doi:10.1007/s00132-003-0588-x.

35. Brinkman JM, Luites JW, Wymenga AB, van Heerwaarden RJ. Early full weight bearing is safe in open-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(2):193-198. doi:10.3109/17453671003619003.

36. Hankemeier S, Mommsen P, Krettek C, et al. Accuracy of high tibial osteotomy: comparison between open- and closed-wedge technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(10):1328-1333. doi:10.1007/s00167-009-1020-9.

37. Hedequist D, Bishop J, Hresko T. Locking plate fixation for pediatric femur fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28(1):6-9. doi:10.1097/bpo.0b013e31815ff301.

38. Iobst CA, Dahl MT. Limb lengthening with submuscular plate stabilization: a case series and description of the technique. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(5):504-509. doi:10.1097/01.bpb.0000279020.96375.88.

39. Uysal M, Akpinar S, Cesur N, Hersekli MA, Tandoğan RN. Plating after lengthening (PAL): technical notes and preliminary clinical experiences. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127(10):889-893. doi:10.1007/s00402-007-0442-4.

40. Smith WR, Ziran BH, Anglen JO, Stahel PF. Locking plates: tips and tricks. Instr Course Lect. 2008;57:25-36.

ABSTRACT

Fixator-assisted nailing (FAN) and fixator-assisted locked plating (FALP) are 2 techniques that can be used to correct distal femoral valgus deformities. The fixator aids in achieving an accurate adjustable initial reduction, which is then made permanent with either nail or plate insertion. FALP can be performed with the knee held in a neutral extended position, whereas FAN requires 30° to 90° of knee flexion to insert the nail, which may cause some alignment loss. We hypothesized that FAN may yield less accurate correction than FALP. Prospectively collected data of a consecutive cohort of patients who underwent valgus deformity femoral correction with FAN or FALP at a single institution over an 8-year period were retrospectively evaluated. Twenty extremities (18 patients) were treated using FAN (median follow-up, 5 years; range, 1-10 years), and 7 extremities (6 patients) were treated with FALP (median follow-up, 5 years; range, 1-8 years). In the FAN cohort, the mean preoperative and postoperative mechanical lateral distal femoral angles (mLDFAs) were 81° (range, 67°-86°) and 89° (range, 80°-100°), respectively (P = .009). In the FALP cohort, the mean preoperative and postoperative mLDFAs were 80° (range, 71°-87°) and 88° (range, 81°-94°), respectively (P < .001). Although the average mechanical axis deviation correction for the FALP group was greater than for the FAN group (32 mm and 27 mm, respectively), the difference was not significant (P = .66). Both methods of femoral deformity correction can be considered safe and effective. On the basis of our results, FAN and FALP are comparable in accuracy for deformity correction in the distal femur.

Multiple etiologies for distal femoral valgus deformity have been described in the literature.1-3 These can be congenital, developmental, secondary to lateral compartmental arthritis, or posttraumatic.4 If not corrected, femoral deformities alter the axial alignment and orientation of the joints, and may lead to early degenerative joint disease and abnormal leg kinematics.3,5 After correcting these deformities, the goal of treatment is to obtain anatomic distal femoral angles and neutral mechanical axis deviation (MAD), but without overcorrecting into varus. Numerous techniques to fix these deformities, such as progressive correction with external fixation or acute correction open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF), have been described.6 Modern external fixation allows for a gradual, adjustable, and more accurate correction but may produce discomfort and complications for patients.7-10 In contrast, ORIF may be more tolerable for the patient, but to achieve a precise correction, considerable technical skills and expertise are required.1,11-14

Two techniques used to correct these valgus femoral deformities in adults are fixator-assisted nailing (FAN) and fixator-assisted locked plating (FALP).1 FAN and FALP combine the advantage of external fixation (accuracy, adjustability) with the benefits of internal fixation (patient comfort), because the osteotomy and correction are performed with the guidance of a temporary external fixator and then permanently fixated by an intramedullary (IM) nail or a locking plate.1,8,11-13,15-18 Both techniques have the possibility to correct varus and valgus deformities, but whenever correcting sagittal plane angulation, the FAN technique may be more challenging. The paucity of studies available involving FAN and FALP do not lead to a conclusive preference of one technique over the other relative to the accuracy and success of correction.15,19,20

Continue to: In both FAN and FALP

In both FAN and FALP, the external fixator is applied and adjusted after the osteotomy for accurate alignment. In FALP, the plate is added without moving the leg from its straight position. However, in FAN, the knee must be flexed to 30° to 90° for insertion of the retrograde knee nail, and the alignment may be lost if the external fixation is not fully stable. Therefore, we hypothesized that FAN would be less accurate than FALP. Hence, the purposes of this study is to compare the correction achieved with FAN and FALP in patients with distal femoral valgus deformities and to describe the intraoperative complications associated with both techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After proper Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a consecutive cohort of 35 patients who underwent femoral deformity correction with either FAN or FALP during an 8-year period (January 2002 to December 2010) was retrospectively reviewed. Eleven patients had to be excluded because of inadequate follow-up (<12 months) or because additional procedures were simultaneously performed. A total of 24 patients (27 femora) who had a mean age of 26 years (range, 14-68 years) were included in the final study cohort. Specifically, 20 femora (18 patients) were corrected using the FAN technique (7 males and 11 females; mean age, 36 years; range, 14-68 years), and 7 femora (6 patients) were fixed using the FALP technique (2 males and 4 females; mean age, 16 years; range, 15-19 years). The median follow-up in the FAN cohort was 5 years (range, 1-10 years), and the median follow-up in the FALP cohort was 5 years (range, 1-8 years) (Table 1).

| Table 1. Study Details and Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Detail | Overall | FAN | FALP |

| Number of patients | 24 | 18 | 6 |

| Number of femurs | 27 | 20 | 7 |

| Age in years (range) | 26 (14 to 68) | 36 (14 to 68) | 16 (15 to 19) |

| Male:Female | 9:15 | 7:11 | 2:4 |

| Median follow-up in years (range) | 5 (1 to 10) | 5 (1 to 10) | 5 (1 to 8) |

Abbreviations: FALP, fixator assisted locked plating; FAN, fixator assisted nailing

The specific measurements performed in all patients were MAD, mechanical lateral distal femoral angle (mLDFA), and medial proximal tibia angle (MPTA). These were measured from standing anteroposterior radiographs of the knee that included the femur.21 All outcome data were collected from the medical charts, operative reports, and radiographic evaluations. To ensure accuracy, all measurements were performed by 2 authors blinded to each other’s measurements. If a variation of <5% was obtained, the results were averaged and used for further analysis. Whenever a difference of >5% was obtained, the measurement was repeated by both authors for confirmation.

SURGICAL FAN TECHNIQUE

After measuring the deformity (Figure 1A) with the patient under general anesthesia on a radiolucent table, the involved lower limb is prepared and draped. Two half-pins are inserted medially, 1 proximal and 1 distal to the planned osteotomy site (Figure 1B), and then connected loosely with a monolateral external fixator. Special care is taken while placing the half-pins, not to interfere with the insertion path of the IM rod. When performing the preoperative planning, the level of osteotomy is chosen to enable the placement of at least 2 interlocking screws distal to the osteotomy. Then, a percutaneous osteotomy is performed from a lateral approach, and the bone ends are manipulated (translation and then angulation) to achieve the desired deformity correction. The external fixator is then stabilized and locked in the exact position (Figure 1C). Subsequently, retrograde reaming, nail insertion, and placement of proximal and distal locking screws are performed (Figure 1D). Blocking screws may give additional stability. The removal of the external fixator is the final step (Figure 1E).20

Continue to: When using the FAN technique...

When using the FAN technique, special attention is paid to reducing the risk of fat embolism. This can be reduced but not totally eradicated with the use of reaming irrigation devices.22-24 In our technique of FAN, the bone is cut and displaced prior to reaming so that the pressure of reaming is vented out through the osteotomy, along with the reaming contents, which theoretically can then act as a “prepositioned bone graft” that may speed healing.

SURGICAL FALP TECHNIQUE

Preoperatively, a decision concerning the planned osteotomy and the correct locking plate size is made. In addition, the outline of the plate is marked on the skin. Under general anesthesia, the patients are prepared and draped. A tourniquet is elevated around the upper thigh. Then, 2 half-pins are medially inserted, 1 proximal and 1 distal to the planned osteotomy site, and are then connected loosely with a monolateral external fixator (Figure 2A). A lateral approach to the distal femur is done, preserving the periosteum, except at the level of the osteotomy. After the osteotomy is performed (through an open lateral incision), both segments are translated (Figure 2B) and then the distal segment is angulated to achieve the desired deformity correction, and the desired position is then stabilized by tightening the external fixator connectors (Figure 2C). Subsequently, a locking plate is inserted in the submuscular-extraperiostal plane. The plate does not require being in full contact (flush) with the bone. At least 3 screws are placed on both sides of the osteotomy through a long lateral incision (Figure 2D). Bone graft may be added to the osteotomy site to encourage healing. Then, the external fixator is removed, and all incisions are closed (Figure 2E).15,19

During each of the procedures, we aimed at having “perfect alignment” with a MAD of 0 mm, in which a Bovie cord is used and passed through the center of the femoral head, knee, and ankle. However, to confirm that the surgery was successful, the actual measurements were performed on standing long-leg films. These films were obtained preoperatively and at latest follow-up. They were performed with the patella aiming forward, the toes straight ahead, feet separated enough for good balance, knees fully extended, and weight equally distributed on the feet. Postoperatively, in both cohorts, partial weight-bearing was encouraged immediately with crutches; physical therapy was instituted daily for knee range of motion. Radiographs were scheduled every 4 weeks to monitor callus formation. Full weight-bearing was allowed when at least 3 cortices were consolidated.1,15,19,20,25,26

All statistical analyses were performed with the aid of the SPSS statistical software package (SPSS). Average values and standard error of the mean were assigned to each variable. A nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used, and a 2-tailed P < .05 was considered significant. Correlation of continuous variables was determined by Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Also, multivariate Cox regression analyses after adjustment for age, sex, and deformity correction were used to detect associations within the study population. To evaluate whether our data were normally distributed, Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed.

Continue to: Results...

RESULTS

The mLDFA significantly improved in the FAN cohort from a mean of 81° to a mean of 89° (ranges, 67°-86° and 80°-100°; respectively; P = .001) (Figures 3A, 3B).

| Table 2. Deformity Correction | ||||

| Measurement | Cohort | Preoperative | Postoperative | P Value |

| mLDFA in degrees (range) | FAN | 81 (67 to 86) | 89 (80 to 100) | 0.001 |

| FALP | 80 (71 to 87) | 90 (88 to 94) | <0.001 | |

| Mechanical axis deviation in mm (range) | FAN | 32 (6 to 64) | 10 (0 to 22) | 0.001 |

| FALP | 34 (17 to 62) | 4 (0 to 11) | 0.002 | |

Abbreviations: FALP, fixator assisted locked plating; FAN, fixator assisted nailing; mLDFA, mechanical lateral distal femoral angle

After evaluating the MPTA, in the FAN cohort, we found that the mean pre- and postoperative MPTAs were not modified. These patients had a mean preoperative angle of 88° (range, 62°-100°), which was kept postoperatively to a mean of 88° (range, 78°-96°). In the FALP cohort, a slight change from 90° to 88° was observed (ranges, 82°-97° and 83°-94°, respectively). None of these changes in MPTA were significant (P > .05).

When evaluating correction of the MAD, we observed that the FAN cohort changed from a preoperative MAD of 32 mm (range, 6-64 mm) to a postoperative mean of 10 mm (range, 0-22 mm), and this correction was statistically significant. (P = .001). The FALP cohort changed from a mean of 34 mm (range, 17-62 mm) preoperatively to 4 mm (range, 0-11 mm) postoperatively, and this was also statistically significant (P = .002). The mean MAD correction for the FAN group vs FALP group was 27 mm vs 32 mm, respectively (Table 2).