User login

VAM is Next Week – Are you Registered?

Don’t miss the vascular surgery world’s headline event! Join colleagues and friends in Boston for this year’s Vascular Annual Meeting, June 20 to 23. Scientific sessions are June 21-23 and the Exhibit Hall is open June 21 to 22. Click here to register. To get a full schedule and begin creating your own personal agenda, complete with marking sessions as favorites, see the VAM Planner.

Don’t miss the vascular surgery world’s headline event! Join colleagues and friends in Boston for this year’s Vascular Annual Meeting, June 20 to 23. Scientific sessions are June 21-23 and the Exhibit Hall is open June 21 to 22. Click here to register. To get a full schedule and begin creating your own personal agenda, complete with marking sessions as favorites, see the VAM Planner.

Don’t miss the vascular surgery world’s headline event! Join colleagues and friends in Boston for this year’s Vascular Annual Meeting, June 20 to 23. Scientific sessions are June 21-23 and the Exhibit Hall is open June 21 to 22. Click here to register. To get a full schedule and begin creating your own personal agenda, complete with marking sessions as favorites, see the VAM Planner.

The VA Cannot Be Privatized

As usual, it was a hectic Monday on the psychiatry consult service. All the trainees, from medical student to fellow, were seeing other patients when the call came from the surgery clinic. One of the pleasures of being a VA clinician is the ability to teach and supervise medical students and residents. The attending in that busy clinic said, “There is a patient down here who is refusing care for a gangrenous leg, but he is also talking about his life not being worth living. Could someone evaluate him?” That patient, Mr. S, declined to go to either the emergency department or the urgent care psychiatry clinic, so I went to see him. I realized that I had seen this patient in the hospital several times before.

One of the great clinical benefits of working in the VA, as opposed to in academic or community hospitals, is continuity. In my nearly 20 years at the same medical center, I have had the privilege of following many patients through multiple courses of treatment. This continuity is a huge advantage when there is what Hippocrates called a “critical day,” as on that Monday in the surgery clinic.2 Also, in many cases the continuity allows me to have a reservoir of trust that I can draw on for challenging consultations, like that of Mr. S.

The surgery resident and attending had spent more than an hour talking to Mr. S when I arrived but still they joined me for the conversation. Mr. S was a veteran in his sixties, and after a few minutes of listening to him, it was clear he was talking about ending his life because of its poor quality. He told us that he had acquired the infection in his leg secondary to unsanitary living conditions. The veteran was quite a storyteller, intelligent, and had a wry sense of humor, which only made his point that his living conditions were intolerable more poignant. He apparently had tried to talk to someone about his situation but felt frustrated that he had not obtained more help.

The surgery attending had already told Mr. S that he would respect his right to refuse the amputation but he feared that Mr. S’s refusal was an expression of his depression and hopelessness, hence, the psychiatry consult. Although Mr. S was not acutely suicidal, something about the combination of his despair and deliberation worried me.

The surgery attending offered to admit Mr. S to do a further workup of his leg. I encouraged him to accept this option and added that I would make sure a social worker saw him and the psychiatry service department also would follow him. Mr. S declined even a 24-hour admission, saying that he had just moved to a new apartment and “everything I have in the world is there and I don’t want to lose it.” This comment suggested to me that he was ambivalent about his wish to die and provided an opening to reduce his risk of harming himself either directly or indirectly.

After the discussion, Mr. S seemed to believe we cared about him and was more willing to participate in treatment planning. He agreed to let the surgeons draw blood and to pick up oral antibiotics from the pharmacy. I promised him that if he would come back to clinic that week, I would make sure a social worker met with him and that my team would talk with him more about his depression. Mr. S picked Friday for his return and assured me that now that he knew we were going to try and improve his situation, he would not hurt himself. Obviously, this was a risk on my part—but the show of compassion combined with flexibility had created a therapeutic alliance that I believed was sufficient to protect Mr. S until we met again.

I returned to my office and called the chief of social work: The dedication of career VA employees forges effective working relationships that can be leveraged for the benefit of the patients. At my facility and many others, many of the staff members who are now in positions of leadership rose through the ranks together, giving us a solidarity of purpose and mutual reliance that are rare in community health care settings. The chief of social work looked at the patient’s chart with me on the phone while I explained the circumstances and within a few minutes said, “We can help him. It looks like he is eligible for an increased pension, and I think we can find him better housing.”

I admit to some anxiety on Friday. One of the psychiatry residents on the service had volunteered to see Mr. S after studying his chart in the morning. Most of us are aware that the aging VA electronic health record system is due to be replaced. But having access to more than 20 years of medical history from episodes of inpatient, outpatient, and residential care all over the country is an unrivaled asset that brings a unique breadth that sharpens, deepens, and humanizes diagnosis and treatment planning.

Sure enough at 10

The social worker arranged new housing for Mr. S that day and help to move into his new place. The paperwork was submitted for the pension increase, and help for shopping and meals as well as transportation was either put in place or applied for. As he left to pack, Mr. S told the surgeon he might not want hospice just yet.

The coda to this narrative is equally uplifting. Several weeks after Mr. S was seen in the surgery clinic, I received a call from a midlevel psychiatric practitioner in the urgent care clinic who had been on leave for several weeks. He too had seen Mr. S before and shared my concern about his state of mind and well-being. He thanked me for having the consult service see him and remarked that it was a relief to know Mr. S had been taken care of and was in a better place in every sense of the word.

In response to a rising media tide of concern about the direction VA care is headed, Congress and the VA have issued a strong statements, “debunking” what they called the “myth” of privatization.3 Yet for the first time in my career, many thoughtful people discern a constellation of forces that could eventuate in this reality in our lifetimes. The title and message of this column is that the VA cannot be privatized, not that it will not be privatized. Also, I did not say that it should not be privatized. As I have written in other columns, that is because ethically I do not believe this is even a question.4 Privatization breaks President Abraham Lincoln’s promise to veterans, “to care for him who has borne the battle.” A promise that was kept for Mr. S and is fulfilled for thousands of other veterans every day all over this nation. A promise that far exceeds payments for medical services.

I also do not mean the title to be a rejection of the Veterans Choice Program. The VA has always provided—and should continue to offer—community-based care for veterans that complements VA care. For example, I live in one of the most rural states in the union and recognize that a patient should not have to drive 300 miles to get a routine colonoscopy.

The VA cannot be privatized because of the comprehensive care that it provides: the degree of integration; the wealth of resources; and the level of expertise in caring for the complex medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems of veterans cannot be replicated. Nor is this just my opinion—a recent RAND Corporation study documents the evidence.5 There are many medical services in the private sector that may be delivered more efficiently, and Congress has just passed the Mission Act to allocate the funds needed to ensure our veterans have wider and easier access to private care resources.6 Yet someone must coordinate, monitor, and center all these services on the veteran. It is not likely Mr. S’s story would have had this kind of ending in the community. The continuity of care, the access to staff with the knowledge of veterans benefits and health care needs, and the ability to listen and follow up without time or performance constraints is just not possible outside VA.

The other evening in the parking lot of the hospital, I encountered a physician who had left the VA to work in several other large health care organizations. He had some good things to say about their business processes and the volume of patients they saw. He came back to the VA, he said, because “No one else can provide this quality of care for the individual veteran.”

1. Conway E, Batalden P. Like magic? (“Every system is perfectly designed…”). http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/o rigin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Published August 21, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

2. Lloyd GER, ed. Hippocratic Writings . London: Penguin Books ; 1983.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Debunking the VA privatization myth [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4034. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

4. Geppert CMA. Lessons from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):6-7.

5. Tanielian T, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Duffy EL, Messan Setodji C. Ready or Not? Assessing the Capacity of New York State Health Care Providers to Meet the Needs of Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018, S 2372, 115th Congress, 2nd Sess (2018).

As usual, it was a hectic Monday on the psychiatry consult service. All the trainees, from medical student to fellow, were seeing other patients when the call came from the surgery clinic. One of the pleasures of being a VA clinician is the ability to teach and supervise medical students and residents. The attending in that busy clinic said, “There is a patient down here who is refusing care for a gangrenous leg, but he is also talking about his life not being worth living. Could someone evaluate him?” That patient, Mr. S, declined to go to either the emergency department or the urgent care psychiatry clinic, so I went to see him. I realized that I had seen this patient in the hospital several times before.

One of the great clinical benefits of working in the VA, as opposed to in academic or community hospitals, is continuity. In my nearly 20 years at the same medical center, I have had the privilege of following many patients through multiple courses of treatment. This continuity is a huge advantage when there is what Hippocrates called a “critical day,” as on that Monday in the surgery clinic.2 Also, in many cases the continuity allows me to have a reservoir of trust that I can draw on for challenging consultations, like that of Mr. S.

The surgery resident and attending had spent more than an hour talking to Mr. S when I arrived but still they joined me for the conversation. Mr. S was a veteran in his sixties, and after a few minutes of listening to him, it was clear he was talking about ending his life because of its poor quality. He told us that he had acquired the infection in his leg secondary to unsanitary living conditions. The veteran was quite a storyteller, intelligent, and had a wry sense of humor, which only made his point that his living conditions were intolerable more poignant. He apparently had tried to talk to someone about his situation but felt frustrated that he had not obtained more help.

The surgery attending had already told Mr. S that he would respect his right to refuse the amputation but he feared that Mr. S’s refusal was an expression of his depression and hopelessness, hence, the psychiatry consult. Although Mr. S was not acutely suicidal, something about the combination of his despair and deliberation worried me.

The surgery attending offered to admit Mr. S to do a further workup of his leg. I encouraged him to accept this option and added that I would make sure a social worker saw him and the psychiatry service department also would follow him. Mr. S declined even a 24-hour admission, saying that he had just moved to a new apartment and “everything I have in the world is there and I don’t want to lose it.” This comment suggested to me that he was ambivalent about his wish to die and provided an opening to reduce his risk of harming himself either directly or indirectly.

After the discussion, Mr. S seemed to believe we cared about him and was more willing to participate in treatment planning. He agreed to let the surgeons draw blood and to pick up oral antibiotics from the pharmacy. I promised him that if he would come back to clinic that week, I would make sure a social worker met with him and that my team would talk with him more about his depression. Mr. S picked Friday for his return and assured me that now that he knew we were going to try and improve his situation, he would not hurt himself. Obviously, this was a risk on my part—but the show of compassion combined with flexibility had created a therapeutic alliance that I believed was sufficient to protect Mr. S until we met again.

I returned to my office and called the chief of social work: The dedication of career VA employees forges effective working relationships that can be leveraged for the benefit of the patients. At my facility and many others, many of the staff members who are now in positions of leadership rose through the ranks together, giving us a solidarity of purpose and mutual reliance that are rare in community health care settings. The chief of social work looked at the patient’s chart with me on the phone while I explained the circumstances and within a few minutes said, “We can help him. It looks like he is eligible for an increased pension, and I think we can find him better housing.”

I admit to some anxiety on Friday. One of the psychiatry residents on the service had volunteered to see Mr. S after studying his chart in the morning. Most of us are aware that the aging VA electronic health record system is due to be replaced. But having access to more than 20 years of medical history from episodes of inpatient, outpatient, and residential care all over the country is an unrivaled asset that brings a unique breadth that sharpens, deepens, and humanizes diagnosis and treatment planning.

Sure enough at 10

The social worker arranged new housing for Mr. S that day and help to move into his new place. The paperwork was submitted for the pension increase, and help for shopping and meals as well as transportation was either put in place or applied for. As he left to pack, Mr. S told the surgeon he might not want hospice just yet.

The coda to this narrative is equally uplifting. Several weeks after Mr. S was seen in the surgery clinic, I received a call from a midlevel psychiatric practitioner in the urgent care clinic who had been on leave for several weeks. He too had seen Mr. S before and shared my concern about his state of mind and well-being. He thanked me for having the consult service see him and remarked that it was a relief to know Mr. S had been taken care of and was in a better place in every sense of the word.

In response to a rising media tide of concern about the direction VA care is headed, Congress and the VA have issued a strong statements, “debunking” what they called the “myth” of privatization.3 Yet for the first time in my career, many thoughtful people discern a constellation of forces that could eventuate in this reality in our lifetimes. The title and message of this column is that the VA cannot be privatized, not that it will not be privatized. Also, I did not say that it should not be privatized. As I have written in other columns, that is because ethically I do not believe this is even a question.4 Privatization breaks President Abraham Lincoln’s promise to veterans, “to care for him who has borne the battle.” A promise that was kept for Mr. S and is fulfilled for thousands of other veterans every day all over this nation. A promise that far exceeds payments for medical services.

I also do not mean the title to be a rejection of the Veterans Choice Program. The VA has always provided—and should continue to offer—community-based care for veterans that complements VA care. For example, I live in one of the most rural states in the union and recognize that a patient should not have to drive 300 miles to get a routine colonoscopy.

The VA cannot be privatized because of the comprehensive care that it provides: the degree of integration; the wealth of resources; and the level of expertise in caring for the complex medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems of veterans cannot be replicated. Nor is this just my opinion—a recent RAND Corporation study documents the evidence.5 There are many medical services in the private sector that may be delivered more efficiently, and Congress has just passed the Mission Act to allocate the funds needed to ensure our veterans have wider and easier access to private care resources.6 Yet someone must coordinate, monitor, and center all these services on the veteran. It is not likely Mr. S’s story would have had this kind of ending in the community. The continuity of care, the access to staff with the knowledge of veterans benefits and health care needs, and the ability to listen and follow up without time or performance constraints is just not possible outside VA.

The other evening in the parking lot of the hospital, I encountered a physician who had left the VA to work in several other large health care organizations. He had some good things to say about their business processes and the volume of patients they saw. He came back to the VA, he said, because “No one else can provide this quality of care for the individual veteran.”

As usual, it was a hectic Monday on the psychiatry consult service. All the trainees, from medical student to fellow, were seeing other patients when the call came from the surgery clinic. One of the pleasures of being a VA clinician is the ability to teach and supervise medical students and residents. The attending in that busy clinic said, “There is a patient down here who is refusing care for a gangrenous leg, but he is also talking about his life not being worth living. Could someone evaluate him?” That patient, Mr. S, declined to go to either the emergency department or the urgent care psychiatry clinic, so I went to see him. I realized that I had seen this patient in the hospital several times before.

One of the great clinical benefits of working in the VA, as opposed to in academic or community hospitals, is continuity. In my nearly 20 years at the same medical center, I have had the privilege of following many patients through multiple courses of treatment. This continuity is a huge advantage when there is what Hippocrates called a “critical day,” as on that Monday in the surgery clinic.2 Also, in many cases the continuity allows me to have a reservoir of trust that I can draw on for challenging consultations, like that of Mr. S.

The surgery resident and attending had spent more than an hour talking to Mr. S when I arrived but still they joined me for the conversation. Mr. S was a veteran in his sixties, and after a few minutes of listening to him, it was clear he was talking about ending his life because of its poor quality. He told us that he had acquired the infection in his leg secondary to unsanitary living conditions. The veteran was quite a storyteller, intelligent, and had a wry sense of humor, which only made his point that his living conditions were intolerable more poignant. He apparently had tried to talk to someone about his situation but felt frustrated that he had not obtained more help.

The surgery attending had already told Mr. S that he would respect his right to refuse the amputation but he feared that Mr. S’s refusal was an expression of his depression and hopelessness, hence, the psychiatry consult. Although Mr. S was not acutely suicidal, something about the combination of his despair and deliberation worried me.

The surgery attending offered to admit Mr. S to do a further workup of his leg. I encouraged him to accept this option and added that I would make sure a social worker saw him and the psychiatry service department also would follow him. Mr. S declined even a 24-hour admission, saying that he had just moved to a new apartment and “everything I have in the world is there and I don’t want to lose it.” This comment suggested to me that he was ambivalent about his wish to die and provided an opening to reduce his risk of harming himself either directly or indirectly.

After the discussion, Mr. S seemed to believe we cared about him and was more willing to participate in treatment planning. He agreed to let the surgeons draw blood and to pick up oral antibiotics from the pharmacy. I promised him that if he would come back to clinic that week, I would make sure a social worker met with him and that my team would talk with him more about his depression. Mr. S picked Friday for his return and assured me that now that he knew we were going to try and improve his situation, he would not hurt himself. Obviously, this was a risk on my part—but the show of compassion combined with flexibility had created a therapeutic alliance that I believed was sufficient to protect Mr. S until we met again.

I returned to my office and called the chief of social work: The dedication of career VA employees forges effective working relationships that can be leveraged for the benefit of the patients. At my facility and many others, many of the staff members who are now in positions of leadership rose through the ranks together, giving us a solidarity of purpose and mutual reliance that are rare in community health care settings. The chief of social work looked at the patient’s chart with me on the phone while I explained the circumstances and within a few minutes said, “We can help him. It looks like he is eligible for an increased pension, and I think we can find him better housing.”

I admit to some anxiety on Friday. One of the psychiatry residents on the service had volunteered to see Mr. S after studying his chart in the morning. Most of us are aware that the aging VA electronic health record system is due to be replaced. But having access to more than 20 years of medical history from episodes of inpatient, outpatient, and residential care all over the country is an unrivaled asset that brings a unique breadth that sharpens, deepens, and humanizes diagnosis and treatment planning.

Sure enough at 10

The social worker arranged new housing for Mr. S that day and help to move into his new place. The paperwork was submitted for the pension increase, and help for shopping and meals as well as transportation was either put in place or applied for. As he left to pack, Mr. S told the surgeon he might not want hospice just yet.

The coda to this narrative is equally uplifting. Several weeks after Mr. S was seen in the surgery clinic, I received a call from a midlevel psychiatric practitioner in the urgent care clinic who had been on leave for several weeks. He too had seen Mr. S before and shared my concern about his state of mind and well-being. He thanked me for having the consult service see him and remarked that it was a relief to know Mr. S had been taken care of and was in a better place in every sense of the word.

In response to a rising media tide of concern about the direction VA care is headed, Congress and the VA have issued a strong statements, “debunking” what they called the “myth” of privatization.3 Yet for the first time in my career, many thoughtful people discern a constellation of forces that could eventuate in this reality in our lifetimes. The title and message of this column is that the VA cannot be privatized, not that it will not be privatized. Also, I did not say that it should not be privatized. As I have written in other columns, that is because ethically I do not believe this is even a question.4 Privatization breaks President Abraham Lincoln’s promise to veterans, “to care for him who has borne the battle.” A promise that was kept for Mr. S and is fulfilled for thousands of other veterans every day all over this nation. A promise that far exceeds payments for medical services.

I also do not mean the title to be a rejection of the Veterans Choice Program. The VA has always provided—and should continue to offer—community-based care for veterans that complements VA care. For example, I live in one of the most rural states in the union and recognize that a patient should not have to drive 300 miles to get a routine colonoscopy.

The VA cannot be privatized because of the comprehensive care that it provides: the degree of integration; the wealth of resources; and the level of expertise in caring for the complex medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems of veterans cannot be replicated. Nor is this just my opinion—a recent RAND Corporation study documents the evidence.5 There are many medical services in the private sector that may be delivered more efficiently, and Congress has just passed the Mission Act to allocate the funds needed to ensure our veterans have wider and easier access to private care resources.6 Yet someone must coordinate, monitor, and center all these services on the veteran. It is not likely Mr. S’s story would have had this kind of ending in the community. The continuity of care, the access to staff with the knowledge of veterans benefits and health care needs, and the ability to listen and follow up without time or performance constraints is just not possible outside VA.

The other evening in the parking lot of the hospital, I encountered a physician who had left the VA to work in several other large health care organizations. He had some good things to say about their business processes and the volume of patients they saw. He came back to the VA, he said, because “No one else can provide this quality of care for the individual veteran.”

1. Conway E, Batalden P. Like magic? (“Every system is perfectly designed…”). http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/o rigin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Published August 21, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

2. Lloyd GER, ed. Hippocratic Writings . London: Penguin Books ; 1983.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Debunking the VA privatization myth [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4034. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

4. Geppert CMA. Lessons from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):6-7.

5. Tanielian T, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Duffy EL, Messan Setodji C. Ready or Not? Assessing the Capacity of New York State Health Care Providers to Meet the Needs of Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018, S 2372, 115th Congress, 2nd Sess (2018).

1. Conway E, Batalden P. Like magic? (“Every system is perfectly designed…”). http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/o rigin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Published August 21, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

2. Lloyd GER, ed. Hippocratic Writings . London: Penguin Books ; 1983.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Debunking the VA privatization myth [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4034. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

4. Geppert CMA. Lessons from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):6-7.

5. Tanielian T, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Duffy EL, Messan Setodji C. Ready or Not? Assessing the Capacity of New York State Health Care Providers to Meet the Needs of Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018, S 2372, 115th Congress, 2nd Sess (2018).

NAMDRC Legislative and Regulatory Agenda Once Again Focuses on Patient Access

NAMDRC’s Mission Statement declares, “NAMDRC’s primary mission is to improve access to quality care for patients with respiratory disease by removing regulatory and legislative barriers to appropriate treatment.” This mission is clear as we review our legislative and regulatory agenda on an ongoing and continuing basis.

Home Mechanical Ventilation: Close to 20 years ago, HCFA (now CMS) was faced with an important reality: advances in technology related to home mechanical ventilation are triggering an exponential growth in availability of these life supporting devices, but a price would be paid. At that time, Medicare law was quite explicit, indicating that certain ventilators would be paid under a “frequent and substantial servicing” payment methodology, authorizing payment on an ongoing basis as long as the prescribing physician documented medical necessity. To circumvent that statutory reality, the agency created a new category of medical device – a respiratory assist device/RAD – and declared that these devices are no longer ventilators and are now subject to capped rental rules and regulations.

NAMDRC was determined to work within the system, but roadblocks were consistently encountered, ie, contractor policies that did not reflect current medical standards of care, peer reviewed literature, etc. Even defining a “respiratory assist device” was (and still is) a challenge, as the term does not appear in the medical literature or in FDA vernacular.

Spin forward to 2018 and numerous realities come into play. Physicians still struggle with the concept of RADs without a definitive, consistent definition and no FDA language to guide usage. Today, it is easier to secure a ventilator if a physician documents the patient experiences some level of respiratory failure than it is to prescribe a simple ventilator with a back-up rate. Because of that dichotomy, the growth of life support ventilator usage is well documented.

If one takes the approach that a device should be paired with the actual clinical characteristics/medical need of the patient, changes in policy are necessary. While CMS clearly has the authority to act to improve policy and match clinical need to patient access, years and years of back and forth have signaled a definite unwillingness of the agency to move in that direction; therefore, the only genuine recourse is to seek legislative relief.

NAMDRC is working closely with the United States Senate, particularly the Finance Committee, Senator Cassidy (R-LA), and the Office of Senate Legislative Counsel to craft legislative language to address the myriad of issues associated with home mechanical ventilation.

Home Oxygen Therapy: In 1986, Congress revamped the statute governing coverage and payment of home oxygen. Pondering the reality of a segment of pulmonary medicine that has seen dramatic technological improvements and enhancements over the past 30-plus years, coupled with a payment system that is stuck with e-cylinders and competitive bidding, it is no wonder that both patients and physicians experience ongoing frustration trying to match a patient’s needs with an oxygen system that reflects the patient’s needs.

It’s a challenge to even consider where to start a reasonable discussion of home oxygen therapy. While the concept of supplemental oxygen is well accepted, the actual clinical evidence relies heavily on a very small number of studies. While virtually no one challenges the concept of the therapy, the actual science has progressed modestly in 30-plus years. But the technology surrounding oxygen therapy has become an industry all to itself. There are concentrators, portable oxygen concentrators, liquid systems, transfill systems, transtracheal oxygen therapy, and so on.

Add to the environment the growing demand for high flow systems that would deliver continuous flow oxygen at rates in excess of 4 L/min, and you begin to realize that the current payment system is a barrier to access. After all, the current payment system has problematic characteristics:

1. A flawed competitive bidding methodology;

2. Payment tied to liter flow pegged at a baseline of 2 L/min, regardless of actual patient need;

3. The major shift from a “delivery model” of care to a nondelivery model that reflects these newer technologies;

4. Virtual disappearance of liquid system availability as an option for physicians/patients;

5. The total failure of CMS to monitor, let alone act on, patient concerns.

Again, taking the NAMDRC Mission Statement into context, NAMDRC is working with all the key societies to craft a broad strategy to address these problems, acknowledging that it will likely take a mix of legislative and regulatory actions to bring home oxygen therapy into the 21st century, let alone to reflect realities of care in 2018.

NAMDRC’s Mission Statement declares, “NAMDRC’s primary mission is to improve access to quality care for patients with respiratory disease by removing regulatory and legislative barriers to appropriate treatment.” This mission is clear as we review our legislative and regulatory agenda on an ongoing and continuing basis.

Home Mechanical Ventilation: Close to 20 years ago, HCFA (now CMS) was faced with an important reality: advances in technology related to home mechanical ventilation are triggering an exponential growth in availability of these life supporting devices, but a price would be paid. At that time, Medicare law was quite explicit, indicating that certain ventilators would be paid under a “frequent and substantial servicing” payment methodology, authorizing payment on an ongoing basis as long as the prescribing physician documented medical necessity. To circumvent that statutory reality, the agency created a new category of medical device – a respiratory assist device/RAD – and declared that these devices are no longer ventilators and are now subject to capped rental rules and regulations.

NAMDRC was determined to work within the system, but roadblocks were consistently encountered, ie, contractor policies that did not reflect current medical standards of care, peer reviewed literature, etc. Even defining a “respiratory assist device” was (and still is) a challenge, as the term does not appear in the medical literature or in FDA vernacular.

Spin forward to 2018 and numerous realities come into play. Physicians still struggle with the concept of RADs without a definitive, consistent definition and no FDA language to guide usage. Today, it is easier to secure a ventilator if a physician documents the patient experiences some level of respiratory failure than it is to prescribe a simple ventilator with a back-up rate. Because of that dichotomy, the growth of life support ventilator usage is well documented.

If one takes the approach that a device should be paired with the actual clinical characteristics/medical need of the patient, changes in policy are necessary. While CMS clearly has the authority to act to improve policy and match clinical need to patient access, years and years of back and forth have signaled a definite unwillingness of the agency to move in that direction; therefore, the only genuine recourse is to seek legislative relief.

NAMDRC is working closely with the United States Senate, particularly the Finance Committee, Senator Cassidy (R-LA), and the Office of Senate Legislative Counsel to craft legislative language to address the myriad of issues associated with home mechanical ventilation.

Home Oxygen Therapy: In 1986, Congress revamped the statute governing coverage and payment of home oxygen. Pondering the reality of a segment of pulmonary medicine that has seen dramatic technological improvements and enhancements over the past 30-plus years, coupled with a payment system that is stuck with e-cylinders and competitive bidding, it is no wonder that both patients and physicians experience ongoing frustration trying to match a patient’s needs with an oxygen system that reflects the patient’s needs.

It’s a challenge to even consider where to start a reasonable discussion of home oxygen therapy. While the concept of supplemental oxygen is well accepted, the actual clinical evidence relies heavily on a very small number of studies. While virtually no one challenges the concept of the therapy, the actual science has progressed modestly in 30-plus years. But the technology surrounding oxygen therapy has become an industry all to itself. There are concentrators, portable oxygen concentrators, liquid systems, transfill systems, transtracheal oxygen therapy, and so on.

Add to the environment the growing demand for high flow systems that would deliver continuous flow oxygen at rates in excess of 4 L/min, and you begin to realize that the current payment system is a barrier to access. After all, the current payment system has problematic characteristics:

1. A flawed competitive bidding methodology;

2. Payment tied to liter flow pegged at a baseline of 2 L/min, regardless of actual patient need;

3. The major shift from a “delivery model” of care to a nondelivery model that reflects these newer technologies;

4. Virtual disappearance of liquid system availability as an option for physicians/patients;

5. The total failure of CMS to monitor, let alone act on, patient concerns.

Again, taking the NAMDRC Mission Statement into context, NAMDRC is working with all the key societies to craft a broad strategy to address these problems, acknowledging that it will likely take a mix of legislative and regulatory actions to bring home oxygen therapy into the 21st century, let alone to reflect realities of care in 2018.

NAMDRC’s Mission Statement declares, “NAMDRC’s primary mission is to improve access to quality care for patients with respiratory disease by removing regulatory and legislative barriers to appropriate treatment.” This mission is clear as we review our legislative and regulatory agenda on an ongoing and continuing basis.

Home Mechanical Ventilation: Close to 20 years ago, HCFA (now CMS) was faced with an important reality: advances in technology related to home mechanical ventilation are triggering an exponential growth in availability of these life supporting devices, but a price would be paid. At that time, Medicare law was quite explicit, indicating that certain ventilators would be paid under a “frequent and substantial servicing” payment methodology, authorizing payment on an ongoing basis as long as the prescribing physician documented medical necessity. To circumvent that statutory reality, the agency created a new category of medical device – a respiratory assist device/RAD – and declared that these devices are no longer ventilators and are now subject to capped rental rules and regulations.

NAMDRC was determined to work within the system, but roadblocks were consistently encountered, ie, contractor policies that did not reflect current medical standards of care, peer reviewed literature, etc. Even defining a “respiratory assist device” was (and still is) a challenge, as the term does not appear in the medical literature or in FDA vernacular.

Spin forward to 2018 and numerous realities come into play. Physicians still struggle with the concept of RADs without a definitive, consistent definition and no FDA language to guide usage. Today, it is easier to secure a ventilator if a physician documents the patient experiences some level of respiratory failure than it is to prescribe a simple ventilator with a back-up rate. Because of that dichotomy, the growth of life support ventilator usage is well documented.

If one takes the approach that a device should be paired with the actual clinical characteristics/medical need of the patient, changes in policy are necessary. While CMS clearly has the authority to act to improve policy and match clinical need to patient access, years and years of back and forth have signaled a definite unwillingness of the agency to move in that direction; therefore, the only genuine recourse is to seek legislative relief.

NAMDRC is working closely with the United States Senate, particularly the Finance Committee, Senator Cassidy (R-LA), and the Office of Senate Legislative Counsel to craft legislative language to address the myriad of issues associated with home mechanical ventilation.

Home Oxygen Therapy: In 1986, Congress revamped the statute governing coverage and payment of home oxygen. Pondering the reality of a segment of pulmonary medicine that has seen dramatic technological improvements and enhancements over the past 30-plus years, coupled with a payment system that is stuck with e-cylinders and competitive bidding, it is no wonder that both patients and physicians experience ongoing frustration trying to match a patient’s needs with an oxygen system that reflects the patient’s needs.

It’s a challenge to even consider where to start a reasonable discussion of home oxygen therapy. While the concept of supplemental oxygen is well accepted, the actual clinical evidence relies heavily on a very small number of studies. While virtually no one challenges the concept of the therapy, the actual science has progressed modestly in 30-plus years. But the technology surrounding oxygen therapy has become an industry all to itself. There are concentrators, portable oxygen concentrators, liquid systems, transfill systems, transtracheal oxygen therapy, and so on.

Add to the environment the growing demand for high flow systems that would deliver continuous flow oxygen at rates in excess of 4 L/min, and you begin to realize that the current payment system is a barrier to access. After all, the current payment system has problematic characteristics:

1. A flawed competitive bidding methodology;

2. Payment tied to liter flow pegged at a baseline of 2 L/min, regardless of actual patient need;

3. The major shift from a “delivery model” of care to a nondelivery model that reflects these newer technologies;

4. Virtual disappearance of liquid system availability as an option for physicians/patients;

5. The total failure of CMS to monitor, let alone act on, patient concerns.

Again, taking the NAMDRC Mission Statement into context, NAMDRC is working with all the key societies to craft a broad strategy to address these problems, acknowledging that it will likely take a mix of legislative and regulatory actions to bring home oxygen therapy into the 21st century, let alone to reflect realities of care in 2018.

Using Simulation to Enhance Care of Older Veterans

Enhancing patient-centered care is an important priority for caregivers in all settings but particularly in long-term care (LTC) where patients also are residents. Simulation is a potential strategy to effect cultural change for health care providers at LTC facilities. In a clinical setting, simulation is an educational model that allows staff to practice behaviors or skills without putting patients at risk. Due to limited time, staffing, and budget resources, the use of simulation for training is not common at LTC facilities.

Background

The simulation model is considered an effective teaching and learning strategy for replicating experiences in nursing practice.1,2 The interactive experience provides the learner with opportunities to engage with patients through psychomotor participation, critical thinking, reflection, and debriefing. Prelicensure nursing education programs and acute care hospitals are the most common users of simulation learning. However, there is a paucity of literature addressing the use of simulation in LTC.

One study was conducted in 2002 by P.K. Beville called the Virtual Dementia Tour, a program using evidence-based simulation. Beville found that study participants using the simulation model had a heightened awareness of the challenges of confused elderly as well as unrealistic expectations by caregivers.3 Although the Virtual Dementia Tour is available for a fee for training professional caregivers, lay people, family, and first responders, many LTC facilities do not have sufficient funding for simulation and simulation equipment, and many do not have dedicated staff for nursing education. Most staff in LTC facilities are unlicensed and may not have had simulation training experience. Additionally, due to staffing and budget constraints, staff education may be limited.

This article will describe the successful implementation of a simulation-based quality improvement project created by and used at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center (LSCVAMC) LTC facility. The LSCVAMC has acute care beds and is adjacent to its LTC facility. Also, a previously successful simulation educational program to improve delirium care was conducted at this acute care hospital.4

Experiential Learning Opportunity

Many residents in a LTC facility have been diagnosed with dementia. As part of a cultural transformation at LSCVAMC, a simulation program was used to help sensitize LTC caregivers to the many sensory changes that occur in older veterans with dementia. The program was guided by the Kolb model.5

The Kolb model of experiential learning includes 4 elements: abstract conceptualization (knowledge), active experimentation (application), concrete experience (engagement), and reflective observation (self-evaluation).5 A simulation program can touch all 4 elements of the Kolb model by providing an educational experience for all learning styles as well as facilitating critical thinking. Nursing homes that provide care to residents with dementia are required to include dementia education annually to staff.6 Long-term care facilities can take advantage of using simulation education along with their traditional educational programs to provide staff with exposure to realistic resident care conditions.7

Methods

The simulation learning experience was provided to all nursing, recreation therapy, and rehabilitation services staff at the LTC facility. The goal was to create an affective, psychomotor learning experience that refreshed, reminded, and sensitized the staff to the challenges that many residents face. The LSCVAMC LTC leadership was supportive of this simulation model because it was not time intensive for direct care staff, and the materials needed were inexpensive. The only equipment that was purchased were several eyeglass readers, popcorn kernels, and Vaseline, resulting in a budget of about $10. The simulation program was scheduled on all shifts. In addition to the simulation experience, the model consists of pre- and postsurveys and a dementia review handout. Staff were able to complete a pre- and postsurvey as well as a debriefing all within a 30-minute time slot.

The pre- and posteducation surveys used were designed to measure learnings and provide data for future education planning. The surveys required only a yes/no and short answers. To reduce the total time of participants’ involvement in the simulation program, an online survey was used. Presurvey questions were designed to identify basic knowledge and experience with dementia, both at work and in personal life. The postsurvey questions sought to identify affective feelings about the participants experience as well as lessons learned and how that could impact future care.

The dementia review handout that was provided to staff 2 weeks before the simulation provided an overview of dementia. It included communication techniques and care planning suggestions.8 The time spent in the simulation room was about 10 to 15 minutes but depended on the activity. The total in-service time was about 30 minutes, depending on the time allotted for debriefing. Room choice was influenced by the number of participants performing the simulation at the same time. Activity stations/tables generally provided 1 experience at a time.

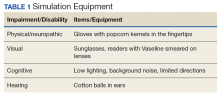

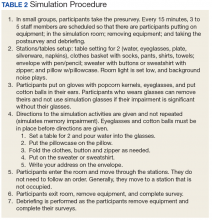

The room that was used had adjustable lighting with the ability to provide a low light setting. Activities were chosen based on the goals for the physical and cognitive disabilities to be simulated. Table 1 identifies equipment used with success and chosen with consideration for ease and expense in describing the disability.

Simulation activities were based on the staff learning needs determined by the presimulation survey. Simulated deficits impacted activities of daily living, mood, and cognition. Neuropathy, arthritis, paralysis, dementia, glaucoma, cataracts, and hearing loss are conditions that are easily represented in a simulation.

Participants also gained additional knowledge of dementia through the Kolb process, which was included in the debriefing. The survey followed the completion of the simulation session to identify knowledge deficits for general remediation and program development and expansion.

Discussion

During the dementia simulation, active experimentation or application learning may be counterintuitive. Staff do not apply their knowledge of dementia directly as in other education settings where they can practice or demonstrate a skill. Instead, participants experience care from the perspective of residents. This learning transitions well into reflective observation as the participants begin to understand the challenges of the cognitively impaired resident, which are manifested in the residents’ behaviors.

Debriefing and a postsimulation survey provide a guided reflection to assimilate new knowledge and revise presimulation attitudes about dementia.9 Reflective observation or self-evaluation is a learning activity that is not a routine part of staff education but can be a powerful learning tool. The postsimulation survey incorporated Bloom’s taxonomy: the affective domain of learning by challenging staff to organize their values with the experience and resolving in their mind any conflicts.10 The goal of the process is to help internalize the education by encouraging changes in behavior (in this case dementia care) and considering the new experience.

Survey Results

The 30-minute program allowed 155 staff to experience cognitive and physical impairment while completing tasks. The pre- and postsurveys were analyzed by 2 learning and dementia survey content experts. The survey questions were open-ended with the intention of eliciting affective behavior responses and staff could provide comments (See eTables 1 and 2 at www.mdedge.com/fedprac). All participants indicated they had knowledge of dementia before the simulation, but 70% acknowledged in the postsimulation survey that they did not have the dementia knowledge that they thought they had. Patience and understanding were most commonly reported in the reflective observation/affective domain (values are internalized leading to changes in behavior).

Participants also described success in closing the loop of experiential learning as a result of the simulation. Some participants verbalized experiencing emotional distress when they realized that their temporary, frustrating impairment was a permanent condition for the residents. Postexperience comments supported the success of the Kolb model experiential learning activity.

Conclusion

Dementia simulation can augment didactic education for improving the quality of dementia care. The virtual dementia simulation was an inexpensive educational program that did not adversely impact scheduling or patient care in a LTC facility. Care providers provided anecdotal feedback that suggested that the program increased their awareness of the difficulty of performing activities of daily living for patients with dementia. The simulation touched all 4 elements of the Kolb Model. The participants had gained new knowledge or reinforced existing knowledge. The simulation activities addressed the application and engagement parts of the model. Self-evaluation resulted from the debriefing time and postsurvey questions. The virtual dementia simulation will be repeated with additional debrief time and a long-term follow-up survey to identify additional learning needs and changes in professional practice.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nurse Educator Lisa Weber, MSN, RN-BC, for her contribution to the manuscript.

1. Aebersold M, Tschannen D. Simulation in nursing practice: the impact on patient care. Online J Issues Nurs. 2013;18(2):6.

2. Mariani B, Doolen J. Nursing simulation research: what are the perceived gaps? Clin Simulation in Nurs. 2016;12(1):30-36.

3. Beville PK. Virtual Dementia Tour helps sensitize health care providers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2002;17(3):183-190.

4. Kresevic D, Heath B, Fine-Smilovich E, et al. Simulation training, coaching, and cue cards improve delirium care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(12):22-28.

5. Chmil JV, Turk M, Adamson K, Larew C. Effects of an experiential learning simulation design on clinical nursing judgment development. Nurse Educ. 2015;40(5):228-232.

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid programs; reform of requirements for long-term care facilities, final rule. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/10/04/2016-23503/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-reform-of-requirements-for-long-term-care-facilities. Published October 4, 2016. Accessed May 22, 2018.

7. Donahoe J, Moon L, VanCleave K. Increasing student empathy toward older adults using the virtual dementia tour. J Baccalaureate Soc Work. 2014;19(1):S23-S40.

8. Coggins MD. Behavioral expressions in dementia patients. http://www.todaysgeriatricmedicine.com/archive/0115p6.shtml. Published 2015. Accessed May 10, 2018.

9. Al Sabei SD, Lasater K. Simulation debriefing for clinical judgment development: a concept analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;45:42-47.

10. Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS, eds. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman; 2001.

Enhancing patient-centered care is an important priority for caregivers in all settings but particularly in long-term care (LTC) where patients also are residents. Simulation is a potential strategy to effect cultural change for health care providers at LTC facilities. In a clinical setting, simulation is an educational model that allows staff to practice behaviors or skills without putting patients at risk. Due to limited time, staffing, and budget resources, the use of simulation for training is not common at LTC facilities.

Background

The simulation model is considered an effective teaching and learning strategy for replicating experiences in nursing practice.1,2 The interactive experience provides the learner with opportunities to engage with patients through psychomotor participation, critical thinking, reflection, and debriefing. Prelicensure nursing education programs and acute care hospitals are the most common users of simulation learning. However, there is a paucity of literature addressing the use of simulation in LTC.

One study was conducted in 2002 by P.K. Beville called the Virtual Dementia Tour, a program using evidence-based simulation. Beville found that study participants using the simulation model had a heightened awareness of the challenges of confused elderly as well as unrealistic expectations by caregivers.3 Although the Virtual Dementia Tour is available for a fee for training professional caregivers, lay people, family, and first responders, many LTC facilities do not have sufficient funding for simulation and simulation equipment, and many do not have dedicated staff for nursing education. Most staff in LTC facilities are unlicensed and may not have had simulation training experience. Additionally, due to staffing and budget constraints, staff education may be limited.

This article will describe the successful implementation of a simulation-based quality improvement project created by and used at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center (LSCVAMC) LTC facility. The LSCVAMC has acute care beds and is adjacent to its LTC facility. Also, a previously successful simulation educational program to improve delirium care was conducted at this acute care hospital.4

Experiential Learning Opportunity

Many residents in a LTC facility have been diagnosed with dementia. As part of a cultural transformation at LSCVAMC, a simulation program was used to help sensitize LTC caregivers to the many sensory changes that occur in older veterans with dementia. The program was guided by the Kolb model.5

The Kolb model of experiential learning includes 4 elements: abstract conceptualization (knowledge), active experimentation (application), concrete experience (engagement), and reflective observation (self-evaluation).5 A simulation program can touch all 4 elements of the Kolb model by providing an educational experience for all learning styles as well as facilitating critical thinking. Nursing homes that provide care to residents with dementia are required to include dementia education annually to staff.6 Long-term care facilities can take advantage of using simulation education along with their traditional educational programs to provide staff with exposure to realistic resident care conditions.7

Methods

The simulation learning experience was provided to all nursing, recreation therapy, and rehabilitation services staff at the LTC facility. The goal was to create an affective, psychomotor learning experience that refreshed, reminded, and sensitized the staff to the challenges that many residents face. The LSCVAMC LTC leadership was supportive of this simulation model because it was not time intensive for direct care staff, and the materials needed were inexpensive. The only equipment that was purchased were several eyeglass readers, popcorn kernels, and Vaseline, resulting in a budget of about $10. The simulation program was scheduled on all shifts. In addition to the simulation experience, the model consists of pre- and postsurveys and a dementia review handout. Staff were able to complete a pre- and postsurvey as well as a debriefing all within a 30-minute time slot.

The pre- and posteducation surveys used were designed to measure learnings and provide data for future education planning. The surveys required only a yes/no and short answers. To reduce the total time of participants’ involvement in the simulation program, an online survey was used. Presurvey questions were designed to identify basic knowledge and experience with dementia, both at work and in personal life. The postsurvey questions sought to identify affective feelings about the participants experience as well as lessons learned and how that could impact future care.

The dementia review handout that was provided to staff 2 weeks before the simulation provided an overview of dementia. It included communication techniques and care planning suggestions.8 The time spent in the simulation room was about 10 to 15 minutes but depended on the activity. The total in-service time was about 30 minutes, depending on the time allotted for debriefing. Room choice was influenced by the number of participants performing the simulation at the same time. Activity stations/tables generally provided 1 experience at a time.

The room that was used had adjustable lighting with the ability to provide a low light setting. Activities were chosen based on the goals for the physical and cognitive disabilities to be simulated. Table 1 identifies equipment used with success and chosen with consideration for ease and expense in describing the disability.

Simulation activities were based on the staff learning needs determined by the presimulation survey. Simulated deficits impacted activities of daily living, mood, and cognition. Neuropathy, arthritis, paralysis, dementia, glaucoma, cataracts, and hearing loss are conditions that are easily represented in a simulation.

Participants also gained additional knowledge of dementia through the Kolb process, which was included in the debriefing. The survey followed the completion of the simulation session to identify knowledge deficits for general remediation and program development and expansion.

Discussion

During the dementia simulation, active experimentation or application learning may be counterintuitive. Staff do not apply their knowledge of dementia directly as in other education settings where they can practice or demonstrate a skill. Instead, participants experience care from the perspective of residents. This learning transitions well into reflective observation as the participants begin to understand the challenges of the cognitively impaired resident, which are manifested in the residents’ behaviors.

Debriefing and a postsimulation survey provide a guided reflection to assimilate new knowledge and revise presimulation attitudes about dementia.9 Reflective observation or self-evaluation is a learning activity that is not a routine part of staff education but can be a powerful learning tool. The postsimulation survey incorporated Bloom’s taxonomy: the affective domain of learning by challenging staff to organize their values with the experience and resolving in their mind any conflicts.10 The goal of the process is to help internalize the education by encouraging changes in behavior (in this case dementia care) and considering the new experience.

Survey Results

The 30-minute program allowed 155 staff to experience cognitive and physical impairment while completing tasks. The pre- and postsurveys were analyzed by 2 learning and dementia survey content experts. The survey questions were open-ended with the intention of eliciting affective behavior responses and staff could provide comments (See eTables 1 and 2 at www.mdedge.com/fedprac). All participants indicated they had knowledge of dementia before the simulation, but 70% acknowledged in the postsimulation survey that they did not have the dementia knowledge that they thought they had. Patience and understanding were most commonly reported in the reflective observation/affective domain (values are internalized leading to changes in behavior).

Participants also described success in closing the loop of experiential learning as a result of the simulation. Some participants verbalized experiencing emotional distress when they realized that their temporary, frustrating impairment was a permanent condition for the residents. Postexperience comments supported the success of the Kolb model experiential learning activity.

Conclusion

Dementia simulation can augment didactic education for improving the quality of dementia care. The virtual dementia simulation was an inexpensive educational program that did not adversely impact scheduling or patient care in a LTC facility. Care providers provided anecdotal feedback that suggested that the program increased their awareness of the difficulty of performing activities of daily living for patients with dementia. The simulation touched all 4 elements of the Kolb Model. The participants had gained new knowledge or reinforced existing knowledge. The simulation activities addressed the application and engagement parts of the model. Self-evaluation resulted from the debriefing time and postsurvey questions. The virtual dementia simulation will be repeated with additional debrief time and a long-term follow-up survey to identify additional learning needs and changes in professional practice.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nurse Educator Lisa Weber, MSN, RN-BC, for her contribution to the manuscript.

Enhancing patient-centered care is an important priority for caregivers in all settings but particularly in long-term care (LTC) where patients also are residents. Simulation is a potential strategy to effect cultural change for health care providers at LTC facilities. In a clinical setting, simulation is an educational model that allows staff to practice behaviors or skills without putting patients at risk. Due to limited time, staffing, and budget resources, the use of simulation for training is not common at LTC facilities.

Background

The simulation model is considered an effective teaching and learning strategy for replicating experiences in nursing practice.1,2 The interactive experience provides the learner with opportunities to engage with patients through psychomotor participation, critical thinking, reflection, and debriefing. Prelicensure nursing education programs and acute care hospitals are the most common users of simulation learning. However, there is a paucity of literature addressing the use of simulation in LTC.

One study was conducted in 2002 by P.K. Beville called the Virtual Dementia Tour, a program using evidence-based simulation. Beville found that study participants using the simulation model had a heightened awareness of the challenges of confused elderly as well as unrealistic expectations by caregivers.3 Although the Virtual Dementia Tour is available for a fee for training professional caregivers, lay people, family, and first responders, many LTC facilities do not have sufficient funding for simulation and simulation equipment, and many do not have dedicated staff for nursing education. Most staff in LTC facilities are unlicensed and may not have had simulation training experience. Additionally, due to staffing and budget constraints, staff education may be limited.

This article will describe the successful implementation of a simulation-based quality improvement project created by and used at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center (LSCVAMC) LTC facility. The LSCVAMC has acute care beds and is adjacent to its LTC facility. Also, a previously successful simulation educational program to improve delirium care was conducted at this acute care hospital.4

Experiential Learning Opportunity

Many residents in a LTC facility have been diagnosed with dementia. As part of a cultural transformation at LSCVAMC, a simulation program was used to help sensitize LTC caregivers to the many sensory changes that occur in older veterans with dementia. The program was guided by the Kolb model.5

The Kolb model of experiential learning includes 4 elements: abstract conceptualization (knowledge), active experimentation (application), concrete experience (engagement), and reflective observation (self-evaluation).5 A simulation program can touch all 4 elements of the Kolb model by providing an educational experience for all learning styles as well as facilitating critical thinking. Nursing homes that provide care to residents with dementia are required to include dementia education annually to staff.6 Long-term care facilities can take advantage of using simulation education along with their traditional educational programs to provide staff with exposure to realistic resident care conditions.7

Methods

The simulation learning experience was provided to all nursing, recreation therapy, and rehabilitation services staff at the LTC facility. The goal was to create an affective, psychomotor learning experience that refreshed, reminded, and sensitized the staff to the challenges that many residents face. The LSCVAMC LTC leadership was supportive of this simulation model because it was not time intensive for direct care staff, and the materials needed were inexpensive. The only equipment that was purchased were several eyeglass readers, popcorn kernels, and Vaseline, resulting in a budget of about $10. The simulation program was scheduled on all shifts. In addition to the simulation experience, the model consists of pre- and postsurveys and a dementia review handout. Staff were able to complete a pre- and postsurvey as well as a debriefing all within a 30-minute time slot.

The pre- and posteducation surveys used were designed to measure learnings and provide data for future education planning. The surveys required only a yes/no and short answers. To reduce the total time of participants’ involvement in the simulation program, an online survey was used. Presurvey questions were designed to identify basic knowledge and experience with dementia, both at work and in personal life. The postsurvey questions sought to identify affective feelings about the participants experience as well as lessons learned and how that could impact future care.

The dementia review handout that was provided to staff 2 weeks before the simulation provided an overview of dementia. It included communication techniques and care planning suggestions.8 The time spent in the simulation room was about 10 to 15 minutes but depended on the activity. The total in-service time was about 30 minutes, depending on the time allotted for debriefing. Room choice was influenced by the number of participants performing the simulation at the same time. Activity stations/tables generally provided 1 experience at a time.

The room that was used had adjustable lighting with the ability to provide a low light setting. Activities were chosen based on the goals for the physical and cognitive disabilities to be simulated. Table 1 identifies equipment used with success and chosen with consideration for ease and expense in describing the disability.

Simulation activities were based on the staff learning needs determined by the presimulation survey. Simulated deficits impacted activities of daily living, mood, and cognition. Neuropathy, arthritis, paralysis, dementia, glaucoma, cataracts, and hearing loss are conditions that are easily represented in a simulation.

Participants also gained additional knowledge of dementia through the Kolb process, which was included in the debriefing. The survey followed the completion of the simulation session to identify knowledge deficits for general remediation and program development and expansion.

Discussion

During the dementia simulation, active experimentation or application learning may be counterintuitive. Staff do not apply their knowledge of dementia directly as in other education settings where they can practice or demonstrate a skill. Instead, participants experience care from the perspective of residents. This learning transitions well into reflective observation as the participants begin to understand the challenges of the cognitively impaired resident, which are manifested in the residents’ behaviors.

Debriefing and a postsimulation survey provide a guided reflection to assimilate new knowledge and revise presimulation attitudes about dementia.9 Reflective observation or self-evaluation is a learning activity that is not a routine part of staff education but can be a powerful learning tool. The postsimulation survey incorporated Bloom’s taxonomy: the affective domain of learning by challenging staff to organize their values with the experience and resolving in their mind any conflicts.10 The goal of the process is to help internalize the education by encouraging changes in behavior (in this case dementia care) and considering the new experience.

Survey Results

The 30-minute program allowed 155 staff to experience cognitive and physical impairment while completing tasks. The pre- and postsurveys were analyzed by 2 learning and dementia survey content experts. The survey questions were open-ended with the intention of eliciting affective behavior responses and staff could provide comments (See eTables 1 and 2 at www.mdedge.com/fedprac). All participants indicated they had knowledge of dementia before the simulation, but 70% acknowledged in the postsimulation survey that they did not have the dementia knowledge that they thought they had. Patience and understanding were most commonly reported in the reflective observation/affective domain (values are internalized leading to changes in behavior).

Participants also described success in closing the loop of experiential learning as a result of the simulation. Some participants verbalized experiencing emotional distress when they realized that their temporary, frustrating impairment was a permanent condition for the residents. Postexperience comments supported the success of the Kolb model experiential learning activity.

Conclusion

Dementia simulation can augment didactic education for improving the quality of dementia care. The virtual dementia simulation was an inexpensive educational program that did not adversely impact scheduling or patient care in a LTC facility. Care providers provided anecdotal feedback that suggested that the program increased their awareness of the difficulty of performing activities of daily living for patients with dementia. The simulation touched all 4 elements of the Kolb Model. The participants had gained new knowledge or reinforced existing knowledge. The simulation activities addressed the application and engagement parts of the model. Self-evaluation resulted from the debriefing time and postsurvey questions. The virtual dementia simulation will be repeated with additional debrief time and a long-term follow-up survey to identify additional learning needs and changes in professional practice.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nurse Educator Lisa Weber, MSN, RN-BC, for her contribution to the manuscript.

1. Aebersold M, Tschannen D. Simulation in nursing practice: the impact on patient care. Online J Issues Nurs. 2013;18(2):6.

2. Mariani B, Doolen J. Nursing simulation research: what are the perceived gaps? Clin Simulation in Nurs. 2016;12(1):30-36.

3. Beville PK. Virtual Dementia Tour helps sensitize health care providers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2002;17(3):183-190.

4. Kresevic D, Heath B, Fine-Smilovich E, et al. Simulation training, coaching, and cue cards improve delirium care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(12):22-28.

5. Chmil JV, Turk M, Adamson K, Larew C. Effects of an experiential learning simulation design on clinical nursing judgment development. Nurse Educ. 2015;40(5):228-232.

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid programs; reform of requirements for long-term care facilities, final rule. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/10/04/2016-23503/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-reform-of-requirements-for-long-term-care-facilities. Published October 4, 2016. Accessed May 22, 2018.

7. Donahoe J, Moon L, VanCleave K. Increasing student empathy toward older adults using the virtual dementia tour. J Baccalaureate Soc Work. 2014;19(1):S23-S40.

8. Coggins MD. Behavioral expressions in dementia patients. http://www.todaysgeriatricmedicine.com/archive/0115p6.shtml. Published 2015. Accessed May 10, 2018.

9. Al Sabei SD, Lasater K. Simulation debriefing for clinical judgment development: a concept analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;45:42-47.

10. Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS, eds. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman; 2001.

1. Aebersold M, Tschannen D. Simulation in nursing practice: the impact on patient care. Online J Issues Nurs. 2013;18(2):6.

2. Mariani B, Doolen J. Nursing simulation research: what are the perceived gaps? Clin Simulation in Nurs. 2016;12(1):30-36.

3. Beville PK. Virtual Dementia Tour helps sensitize health care providers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2002;17(3):183-190.

4. Kresevic D, Heath B, Fine-Smilovich E, et al. Simulation training, coaching, and cue cards improve delirium care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(12):22-28.

5. Chmil JV, Turk M, Adamson K, Larew C. Effects of an experiential learning simulation design on clinical nursing judgment development. Nurse Educ. 2015;40(5):228-232.

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid programs; reform of requirements for long-term care facilities, final rule. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/10/04/2016-23503/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-reform-of-requirements-for-long-term-care-facilities. Published October 4, 2016. Accessed May 22, 2018.

7. Donahoe J, Moon L, VanCleave K. Increasing student empathy toward older adults using the virtual dementia tour. J Baccalaureate Soc Work. 2014;19(1):S23-S40.

8. Coggins MD. Behavioral expressions in dementia patients. http://www.todaysgeriatricmedicine.com/archive/0115p6.shtml. Published 2015. Accessed May 10, 2018.

9. Al Sabei SD, Lasater K. Simulation debriefing for clinical judgment development: a concept analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;45:42-47.

10. Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS, eds. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman; 2001.

bb2121 demonstrates durable responses, manageable toxicity in MM

CHICAGO—bb2121, the anti-BCMA chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, induced deep and durable ongoing responses in heavily pretreated multiple myeloma (MM) patients, updated results of a phase 1 study show.

At active doses (≥150 x 108 CAR+ T cells), the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-targeted therapy produced an overall response rate of 95.5%, including a 50% rate of complete response (CR) or stringent CR, with a median duration of response of 10.8 months.

Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 11.8 months in the dose-escalation cohort.

Noopur S. Raje, MD, of the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, reported these results at the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 8007*). The study is sponsored by Celgene Corporation and bluebird bio.

To date, bb2121 has been manageable for patients at doses as high as 800 x 108 CAR T cells, Dr Raje noted.

She updated the findings of CRB-401 (NCT02658929), which included 43 patients with relapsed/refractory MM, including 21 in a dose-escalation (DE) cohort and 22 in a dose-expansion (Exp) cohort.

Patients received one infusion of bb2121 anti-BCMA CAR T cells after a lymphodepleting conditioning regimen including fludarabine and cyclophosphamide.

Patients were a median age of 58 (range, 37 – 74) and 65 (range, 44 – 75) in the DE and Exp cohorts, respectively.

Eight patients (38%) in the DE cohort and 9 (41%) in the Exp cohort had high-risk cytogenetics and had received a median of 7 (range, 3 – 14) and 8 (range, 3 – 23) prior regimens, respectively.