User login

Allergies linked to autism spectrum disorder in children

The prevalence of food, respiratory, and skin allergy is greater in U.S. children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) than in U.S. children without the disorder, according to findings published June 8 in JAMA Network Open.

An analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey found that the weighted prevalence of food, respiratory, and skin allergies was 11.25%, 18.73%, and 16.81%, respectively, in children with ASD, compared with 4.25%, 12.08%, and 9.84%, respectively, in children without ASD (P less than .001).

Survey data were collected between 1997 and 2016, and included patients aged 3-17 years. Allergic conditions were defined by the respondent, usually a parent, answering in the affirmative that the child had any kind of food, digestive, respiratory, or skin allergy in the past 12 months. ASD was defined based on an affirmative response to a question asking whether the child received an ASD diagnosis from a health professional. The question was asked as part of a 10-condition checklist from 1997 to 2013, and as a standalone item from 2014 onward, with revised wording to distinguish autism, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive developmental disorder, and ASD, wrote Guifeng Xu, MD, of the department of epidemiology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and her coauthors.

Of the 199,520 children included in the study, 8,734 had food allergy, 24,555 had respiratory allergy, and 19,399 had skin allergy. An ASD diagnosis was reported in 1,868 children. The weighted prevalence was 4.31% for food allergy (95% confidence interval, 4.20%-4.43%), 12.15% for respiratory allergy (95% CI, 11.92%-12.38%), and 9.91% for skin allergy (95% CI, 9.72%-10.10%), the authors said.

Children with ASD were more likely than were children without ASD to have food allergy, respiratory allergy, and skin allergy (P less than .001). After adjustment for factors including age, sex, ethnicity, and family education level, the odds ratio of ASD was more than double among children with food allergy, compared with those without food allergy (odds ratio, 2.72; 95% CI, 2.26-3.28; P less than .001).

Respiratory allergy and skin allergy also were significantly associated with ASD, but to a lesser degree, with an OR of 1.53 (95% CI, 1.32-1.78; P less than .001) for respiratory allergy and 1.80 (95% CI, 1.55-2.09; P less than .001) for skin allergy, Dr. Xu and her colleagues reported.

,” though the underlying mechanisms still need to be identified, the authors wrote.

Particularly striking were the connections found between ASD and food allergy. “Although the underlying mechanisms for the observed association between food allergy and ASD remain to be elucidated, the gut-brain-behavior axis could be one of the potential mechanisms,” Dr. Xu and her coauthors wrote. “Previous studies found higher prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms among children with ASD.”

Limitations to the study include possible recall bias and misreporting, as well as an absence of information about onset of allergy and ASD diagnosis.

“Large prospective cohort studies starting from birth or early life are needed to confirm our findings,” the authors concluded.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Guifeng X et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018 Jun 8. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0279.

The results of this study add to a “growing body of literature supporting an immune-mediated subtype of autism spectrum disorder (ASD),” Christopher J. McDougle, MD, wrote in an editorial published with the study.

Although prior studies have identified an association between ASD and respiratory and skin allergy, this study is “the first to document the association of food allergy with ASD with confidence, in part based on the large sample size they accessed,” he said (JAMA Network Open. 2018;1[2]:e180280. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0280).

Dr. McDougle is affiliated with the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The results of this study add to a “growing body of literature supporting an immune-mediated subtype of autism spectrum disorder (ASD),” Christopher J. McDougle, MD, wrote in an editorial published with the study.

Although prior studies have identified an association between ASD and respiratory and skin allergy, this study is “the first to document the association of food allergy with ASD with confidence, in part based on the large sample size they accessed,” he said (JAMA Network Open. 2018;1[2]:e180280. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0280).

Dr. McDougle is affiliated with the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The results of this study add to a “growing body of literature supporting an immune-mediated subtype of autism spectrum disorder (ASD),” Christopher J. McDougle, MD, wrote in an editorial published with the study.

Although prior studies have identified an association between ASD and respiratory and skin allergy, this study is “the first to document the association of food allergy with ASD with confidence, in part based on the large sample size they accessed,” he said (JAMA Network Open. 2018;1[2]:e180280. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0280).

Dr. McDougle is affiliated with the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The prevalence of food, respiratory, and skin allergy is greater in U.S. children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) than in U.S. children without the disorder, according to findings published June 8 in JAMA Network Open.

An analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey found that the weighted prevalence of food, respiratory, and skin allergies was 11.25%, 18.73%, and 16.81%, respectively, in children with ASD, compared with 4.25%, 12.08%, and 9.84%, respectively, in children without ASD (P less than .001).

Survey data were collected between 1997 and 2016, and included patients aged 3-17 years. Allergic conditions were defined by the respondent, usually a parent, answering in the affirmative that the child had any kind of food, digestive, respiratory, or skin allergy in the past 12 months. ASD was defined based on an affirmative response to a question asking whether the child received an ASD diagnosis from a health professional. The question was asked as part of a 10-condition checklist from 1997 to 2013, and as a standalone item from 2014 onward, with revised wording to distinguish autism, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive developmental disorder, and ASD, wrote Guifeng Xu, MD, of the department of epidemiology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and her coauthors.

Of the 199,520 children included in the study, 8,734 had food allergy, 24,555 had respiratory allergy, and 19,399 had skin allergy. An ASD diagnosis was reported in 1,868 children. The weighted prevalence was 4.31% for food allergy (95% confidence interval, 4.20%-4.43%), 12.15% for respiratory allergy (95% CI, 11.92%-12.38%), and 9.91% for skin allergy (95% CI, 9.72%-10.10%), the authors said.

Children with ASD were more likely than were children without ASD to have food allergy, respiratory allergy, and skin allergy (P less than .001). After adjustment for factors including age, sex, ethnicity, and family education level, the odds ratio of ASD was more than double among children with food allergy, compared with those without food allergy (odds ratio, 2.72; 95% CI, 2.26-3.28; P less than .001).

Respiratory allergy and skin allergy also were significantly associated with ASD, but to a lesser degree, with an OR of 1.53 (95% CI, 1.32-1.78; P less than .001) for respiratory allergy and 1.80 (95% CI, 1.55-2.09; P less than .001) for skin allergy, Dr. Xu and her colleagues reported.

,” though the underlying mechanisms still need to be identified, the authors wrote.

Particularly striking were the connections found between ASD and food allergy. “Although the underlying mechanisms for the observed association between food allergy and ASD remain to be elucidated, the gut-brain-behavior axis could be one of the potential mechanisms,” Dr. Xu and her coauthors wrote. “Previous studies found higher prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms among children with ASD.”

Limitations to the study include possible recall bias and misreporting, as well as an absence of information about onset of allergy and ASD diagnosis.

“Large prospective cohort studies starting from birth or early life are needed to confirm our findings,” the authors concluded.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Guifeng X et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018 Jun 8. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0279.

The prevalence of food, respiratory, and skin allergy is greater in U.S. children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) than in U.S. children without the disorder, according to findings published June 8 in JAMA Network Open.

An analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey found that the weighted prevalence of food, respiratory, and skin allergies was 11.25%, 18.73%, and 16.81%, respectively, in children with ASD, compared with 4.25%, 12.08%, and 9.84%, respectively, in children without ASD (P less than .001).

Survey data were collected between 1997 and 2016, and included patients aged 3-17 years. Allergic conditions were defined by the respondent, usually a parent, answering in the affirmative that the child had any kind of food, digestive, respiratory, or skin allergy in the past 12 months. ASD was defined based on an affirmative response to a question asking whether the child received an ASD diagnosis from a health professional. The question was asked as part of a 10-condition checklist from 1997 to 2013, and as a standalone item from 2014 onward, with revised wording to distinguish autism, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive developmental disorder, and ASD, wrote Guifeng Xu, MD, of the department of epidemiology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and her coauthors.

Of the 199,520 children included in the study, 8,734 had food allergy, 24,555 had respiratory allergy, and 19,399 had skin allergy. An ASD diagnosis was reported in 1,868 children. The weighted prevalence was 4.31% for food allergy (95% confidence interval, 4.20%-4.43%), 12.15% for respiratory allergy (95% CI, 11.92%-12.38%), and 9.91% for skin allergy (95% CI, 9.72%-10.10%), the authors said.

Children with ASD were more likely than were children without ASD to have food allergy, respiratory allergy, and skin allergy (P less than .001). After adjustment for factors including age, sex, ethnicity, and family education level, the odds ratio of ASD was more than double among children with food allergy, compared with those without food allergy (odds ratio, 2.72; 95% CI, 2.26-3.28; P less than .001).

Respiratory allergy and skin allergy also were significantly associated with ASD, but to a lesser degree, with an OR of 1.53 (95% CI, 1.32-1.78; P less than .001) for respiratory allergy and 1.80 (95% CI, 1.55-2.09; P less than .001) for skin allergy, Dr. Xu and her colleagues reported.

,” though the underlying mechanisms still need to be identified, the authors wrote.

Particularly striking were the connections found between ASD and food allergy. “Although the underlying mechanisms for the observed association between food allergy and ASD remain to be elucidated, the gut-brain-behavior axis could be one of the potential mechanisms,” Dr. Xu and her coauthors wrote. “Previous studies found higher prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms among children with ASD.”

Limitations to the study include possible recall bias and misreporting, as well as an absence of information about onset of allergy and ASD diagnosis.

“Large prospective cohort studies starting from birth or early life are needed to confirm our findings,” the authors concluded.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Guifeng X et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018 Jun 8. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0279.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Key clinical point: The prevalence of food, respiratory, and skin allergy was greater in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Major finding: The weighted prevalence of food, respiratory, and skin allergies was 11.25%, 18.73%, and 16.81%, respectively, in children with ASD, compared with 4.25%, 12.08%, and 9.84%, respectively, in children without ASD (P less than .001).

Study details: A population-based study of 199,520 children aged 3-17 years in the National Health Interview Survey.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Guifeng X et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018 Jun 8. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0279.

Cladribine Tablets Improve MRI Outcomes in Patients With Highly Active Relapsing-Remitting MS

The relative risk ratio for cumulative new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions was significantly lower in the cladribine 3.5 mg/kg group, compared with placebo.

NASHVILLE—Treatment with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg reduces MRI markers of disease activity in patients with highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), according to research described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. Results of a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY study indicated that in patients with relapsing MS who were selected for further study based on high disease activity, treatment with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg showed efficacy in reducing MRI markers of disease activity comparable with the overall CLARITY study population.

In the CLARITY study, treatment with cladribine tablets versus placebo showed strong efficacy in a large cohort of patients with relapsing MS over two years. Because patients with high disease activity have a high risk of relapses and disability, Gavin Giovannoni, MBBCh, PhD, and his CLARITY collaborators conducted a post hoc analysis to compare the effects of cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg versus placebo on outcomes assessed by MRI in subgroups of CLARITY patients with evidence of high disease activity at study entry. Professor Giovannoni is Chair of Neurology at the Blizard Institute of Cell and Molecular Science, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry at Queen Mary University of London.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed CLARITY participants randomized to cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg or placebo using the following two sets of high disease activity criteria based on relapse history, prior treatment, and MRI characteristics: 1) high relapse activity, which was defined as two or more relapses during the year before study entry whether on disease-modifying therapy or not; 2) high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse, in which treatment nonresponse was defined as one or more relapses and one or more T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions or nine or more T2 lesions during the year before study entry and while on therapy with other disease-modifying therapy.

For cumulative new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions, the relative risk ratio in the high relapse activity subgroup (0.087) was significantly lower in favor of cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (n = 130) over placebo (n = 131). In the high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse subgroup, the relative risk ratio (0.077) also significantly favored cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (n = 140) versus placebo (n = 149). The risk reductions (91% and 92%, respectively) were similar to the 90% reduction in the overall CLARITY population (0.097), said the researchers.

For cumulative active T2 lesions, the relative risk ratio also significantly favored cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg versus placebo for the high relapse activity (0.263) and the high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse subgroups (0.254), with risk reductions of 74% and 75%, reflecting the 73% reduction in the overall population (0.272).

The relative risk ratio for cumulative combined unique active lesions significantly favored cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg versus placebo for high relapse activity (0.212) and high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse (0.203) with risk reductions of 79% and 80%, reflecting the 77% overall population reduction (0.234). Comparable results were observed in the non-high-disease activity counterparts, with no significant treatment-subgroup interactions.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Giovannoni G, Soelberg Sorensen P, Cook S, et al. Efficacy of cladribine tablets in high disease activity subgroups of patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: A post hoc analysis of the CLARITY Study. Mult Scler. 2018 April 1 [Epub ahead of print].

The relative risk ratio for cumulative new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions was significantly lower in the cladribine 3.5 mg/kg group, compared with placebo.

The relative risk ratio for cumulative new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions was significantly lower in the cladribine 3.5 mg/kg group, compared with placebo.

NASHVILLE—Treatment with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg reduces MRI markers of disease activity in patients with highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), according to research described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. Results of a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY study indicated that in patients with relapsing MS who were selected for further study based on high disease activity, treatment with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg showed efficacy in reducing MRI markers of disease activity comparable with the overall CLARITY study population.

In the CLARITY study, treatment with cladribine tablets versus placebo showed strong efficacy in a large cohort of patients with relapsing MS over two years. Because patients with high disease activity have a high risk of relapses and disability, Gavin Giovannoni, MBBCh, PhD, and his CLARITY collaborators conducted a post hoc analysis to compare the effects of cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg versus placebo on outcomes assessed by MRI in subgroups of CLARITY patients with evidence of high disease activity at study entry. Professor Giovannoni is Chair of Neurology at the Blizard Institute of Cell and Molecular Science, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry at Queen Mary University of London.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed CLARITY participants randomized to cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg or placebo using the following two sets of high disease activity criteria based on relapse history, prior treatment, and MRI characteristics: 1) high relapse activity, which was defined as two or more relapses during the year before study entry whether on disease-modifying therapy or not; 2) high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse, in which treatment nonresponse was defined as one or more relapses and one or more T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions or nine or more T2 lesions during the year before study entry and while on therapy with other disease-modifying therapy.

For cumulative new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions, the relative risk ratio in the high relapse activity subgroup (0.087) was significantly lower in favor of cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (n = 130) over placebo (n = 131). In the high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse subgroup, the relative risk ratio (0.077) also significantly favored cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (n = 140) versus placebo (n = 149). The risk reductions (91% and 92%, respectively) were similar to the 90% reduction in the overall CLARITY population (0.097), said the researchers.

For cumulative active T2 lesions, the relative risk ratio also significantly favored cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg versus placebo for the high relapse activity (0.263) and the high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse subgroups (0.254), with risk reductions of 74% and 75%, reflecting the 73% reduction in the overall population (0.272).

The relative risk ratio for cumulative combined unique active lesions significantly favored cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg versus placebo for high relapse activity (0.212) and high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse (0.203) with risk reductions of 79% and 80%, reflecting the 77% overall population reduction (0.234). Comparable results were observed in the non-high-disease activity counterparts, with no significant treatment-subgroup interactions.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Giovannoni G, Soelberg Sorensen P, Cook S, et al. Efficacy of cladribine tablets in high disease activity subgroups of patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: A post hoc analysis of the CLARITY Study. Mult Scler. 2018 April 1 [Epub ahead of print].

NASHVILLE—Treatment with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg reduces MRI markers of disease activity in patients with highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), according to research described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. Results of a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY study indicated that in patients with relapsing MS who were selected for further study based on high disease activity, treatment with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg showed efficacy in reducing MRI markers of disease activity comparable with the overall CLARITY study population.

In the CLARITY study, treatment with cladribine tablets versus placebo showed strong efficacy in a large cohort of patients with relapsing MS over two years. Because patients with high disease activity have a high risk of relapses and disability, Gavin Giovannoni, MBBCh, PhD, and his CLARITY collaborators conducted a post hoc analysis to compare the effects of cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg versus placebo on outcomes assessed by MRI in subgroups of CLARITY patients with evidence of high disease activity at study entry. Professor Giovannoni is Chair of Neurology at the Blizard Institute of Cell and Molecular Science, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry at Queen Mary University of London.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed CLARITY participants randomized to cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg or placebo using the following two sets of high disease activity criteria based on relapse history, prior treatment, and MRI characteristics: 1) high relapse activity, which was defined as two or more relapses during the year before study entry whether on disease-modifying therapy or not; 2) high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse, in which treatment nonresponse was defined as one or more relapses and one or more T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions or nine or more T2 lesions during the year before study entry and while on therapy with other disease-modifying therapy.

For cumulative new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions, the relative risk ratio in the high relapse activity subgroup (0.087) was significantly lower in favor of cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (n = 130) over placebo (n = 131). In the high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse subgroup, the relative risk ratio (0.077) also significantly favored cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (n = 140) versus placebo (n = 149). The risk reductions (91% and 92%, respectively) were similar to the 90% reduction in the overall CLARITY population (0.097), said the researchers.

For cumulative active T2 lesions, the relative risk ratio also significantly favored cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg versus placebo for the high relapse activity (0.263) and the high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse subgroups (0.254), with risk reductions of 74% and 75%, reflecting the 73% reduction in the overall population (0.272).

The relative risk ratio for cumulative combined unique active lesions significantly favored cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg versus placebo for high relapse activity (0.212) and high relapse activity plus treatment nonresponse (0.203) with risk reductions of 79% and 80%, reflecting the 77% overall population reduction (0.234). Comparable results were observed in the non-high-disease activity counterparts, with no significant treatment-subgroup interactions.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Giovannoni G, Soelberg Sorensen P, Cook S, et al. Efficacy of cladribine tablets in high disease activity subgroups of patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: A post hoc analysis of the CLARITY Study. Mult Scler. 2018 April 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Caring for the offensive patient

“I only see Jewish doctors.”

The middle-aged lady across my desk repeated that several times during her visit, apparently hoping to get some response from me. I just ignored it each time.

Imagine if she’d said, “I only see white doctors,” or “I only see black doctors.” To say you came to a doctor solely because of his or her ethnicity is, to me, ignorant at best and blatant discrimination at worst.

Of course, I continued the appointment. While I found her comment offensive, I’m a doctor. Unlike a restaurant owner, I can’t refuse to serve someone because of their personal beliefs, no matter how much I disagree. I took an oath to provide equal care to all, regardless of personal differences. I try hard to measure up to that.

We live in a world that seems to be increasingly divided along tribal lines. Us against them. Me against you. Everyone for themselves.

I’m not going to play that game. For better or worse, I’ll take the high road and continue treating all people as equal. If you want to believe that religion, or color, or any other difference makes someone a better or worse physician (or person, for that matter), you’re entitled to your opinion.

I may not be able to change your mind, but that’s not going to stop me from trying to be the best doctor I can to everyone who comes to me, regardless of who they are.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“I only see Jewish doctors.”

The middle-aged lady across my desk repeated that several times during her visit, apparently hoping to get some response from me. I just ignored it each time.

Imagine if she’d said, “I only see white doctors,” or “I only see black doctors.” To say you came to a doctor solely because of his or her ethnicity is, to me, ignorant at best and blatant discrimination at worst.

Of course, I continued the appointment. While I found her comment offensive, I’m a doctor. Unlike a restaurant owner, I can’t refuse to serve someone because of their personal beliefs, no matter how much I disagree. I took an oath to provide equal care to all, regardless of personal differences. I try hard to measure up to that.

We live in a world that seems to be increasingly divided along tribal lines. Us against them. Me against you. Everyone for themselves.

I’m not going to play that game. For better or worse, I’ll take the high road and continue treating all people as equal. If you want to believe that religion, or color, or any other difference makes someone a better or worse physician (or person, for that matter), you’re entitled to your opinion.

I may not be able to change your mind, but that’s not going to stop me from trying to be the best doctor I can to everyone who comes to me, regardless of who they are.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“I only see Jewish doctors.”

The middle-aged lady across my desk repeated that several times during her visit, apparently hoping to get some response from me. I just ignored it each time.

Imagine if she’d said, “I only see white doctors,” or “I only see black doctors.” To say you came to a doctor solely because of his or her ethnicity is, to me, ignorant at best and blatant discrimination at worst.

Of course, I continued the appointment. While I found her comment offensive, I’m a doctor. Unlike a restaurant owner, I can’t refuse to serve someone because of their personal beliefs, no matter how much I disagree. I took an oath to provide equal care to all, regardless of personal differences. I try hard to measure up to that.

We live in a world that seems to be increasingly divided along tribal lines. Us against them. Me against you. Everyone for themselves.

I’m not going to play that game. For better or worse, I’ll take the high road and continue treating all people as equal. If you want to believe that religion, or color, or any other difference makes someone a better or worse physician (or person, for that matter), you’re entitled to your opinion.

I may not be able to change your mind, but that’s not going to stop me from trying to be the best doctor I can to everyone who comes to me, regardless of who they are.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Everolimus/exemestane improves PFS of ER+/HER2– breast cancer vs. everolimus alone

CHICAGO – For women with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer resistant to endocrine therapy, the combination of everolimus and exemestane had better efficacy than did everolimus alone, but single-agent capecitabine appeared to offer benefit comparable to that of the combination therapy, results of the BOLERO-6 trial suggest.

Among 309 postmenopausal women with ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, the combination of everolimus (Afinitor) and exemestane (Aromasin and generics) was associated with a 26% improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) compared with everolimus alone, reported Guy Jerusalem, MD, PhD, of Liege University, Belgium.

There was also, however, a numerical but not statistically significant difference in PFS favoring capecitabine (Xeloda and generics) “which may be attributed to various baseline characteristics favoring capecitabine, and potential informative censoring,” he said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“We have noted in BOLERO-6 a better-than-expected outcome in median progression-free survival of capecitabine compared with the previously reported 4.1 to 7.9 months median progression-free survival,” he said.

BOLERO-6, results of which were published online June 3 in JAMA Oncology, was a postmarketing study by the sponsors to fulfill commitments to both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to estimate the treatment benefit with combined everolimus and exemestane vs. monotherapy with everolimus or capecitabine in patients with ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer that progressed during nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor therapy.

Patients from 83 centers in 18 countries were enrolled in the open label, phase 2 study and randomly assigned to receive oral everolimus 10 mg daily with oral exemestane 25 mg daily, everolimus at the same dose alone, or oral capecitabine 1,250 mg/m2 twice daily for 2 weeks on, 1 week off.

The trial was not powered for statistical comparisons between arms, but was instead designed with the primary objective of estimated investigator-assessed PFS for the combination vs. everolimus alone.

At baseline, more patients assigned to capecitabine vs. everolimus-containing regimens were younger than 65, white, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status of 0 (fully active), and had bone-only metastases. In addition, fewer patients in the capecitabine arm had three or more metastatic sites, Dr. Jerusalem noted,

For the primary analysis, the median PFS with everolimus/exemestane was 8.4 months, compared with 6.8 months for everolimus alone. The estimated hazard ratio (HR) for PFS with everolimus/exemestane vs. everolimus alone was 0.74 (90% confidence interval [CI], 0.57-0.97)

In contrast, median PFS with capecitabine was 9.6 months, with a nonsignificant hazard ratio of 1.26 for the combination (90% CI, 0.96-1.66).

A stratified multivariate Cox regression model controlling for baseline difference and known prognostic factor yielded an HR for PFS of 1.15 (90% CI, 0.86-1.52) for the combination.

Censoring of patients was more frequent in the capecitabine arm (33% vs. 23% in the combination arm), which included 20% of patients on capecitabine who were censored for starting on a new antineoplastic therapy vs. 9% of patients on everolimus/exemestane.

The median time to treatment failure was 5.8 months with the combination, vs. 4.2 months with everolimus alone (HR, 0.66, 90% CI, 0.52-0.4), and 6.2 months with capecitabine alone (HR, 1.03, 90% CI, 0.81-1.31).

Median overall survival was 23.1 months in the combination arm, 29.3 months in the everolimus arm, and 25.6 months in the capecitabine arm. There were no statistically significant differences in overall survival among the groups.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events were more frequent in the combination vs. everolimus arms, and comparable between the combination and capecitabine arms, Dr. Jerusalem said.

Serious adverse events of any grade were more frequent in the combination arm than in the other two arms, but there were no significant differences in discontinuations due to adverse events

“The results of the present study suggest that mTOR inhibitor and endocrine therapy combinations remain important for aromatase inhibitor–refractory disease. Safety and PFS with everolimus plus exemestane in this study were consistent with BOLERO-2 and are now supported by real-world evidence,” the investigators wrote.

“The take home from the BOLERO-6 trial is that the progression-free survival for the combination of everolimus and exemestane is superior to everolimus alone, and is in line with data from the BOLERO-2 trial, and also the PrE0102 study, demonstrating the consistent activity of mTOR inhibition in combination with endocrine therapy in the aromatase inhibitor resistance setting, and this supports our use of the combination in the endocrine resistant patients,” said Cynthia X. Ma, MD, PhD, of Washington University, St. Louis, the invited discussant.

Novartis funded the study. Dr Jerusalem received research funding from Novartis and Roche; honoraria from Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, Celgene, Amgen, BMS, and Puma Technology; and nonfinancial support from Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, Amgen, and BMS. Dr. Ma reported consulting/advising, travel expenses, and institutional research funding from Novartis and others.

SOURCE: Jerusalem G et al. ASCO 2018 Abstract 1005

CHICAGO – For women with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer resistant to endocrine therapy, the combination of everolimus and exemestane had better efficacy than did everolimus alone, but single-agent capecitabine appeared to offer benefit comparable to that of the combination therapy, results of the BOLERO-6 trial suggest.

Among 309 postmenopausal women with ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, the combination of everolimus (Afinitor) and exemestane (Aromasin and generics) was associated with a 26% improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) compared with everolimus alone, reported Guy Jerusalem, MD, PhD, of Liege University, Belgium.

There was also, however, a numerical but not statistically significant difference in PFS favoring capecitabine (Xeloda and generics) “which may be attributed to various baseline characteristics favoring capecitabine, and potential informative censoring,” he said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“We have noted in BOLERO-6 a better-than-expected outcome in median progression-free survival of capecitabine compared with the previously reported 4.1 to 7.9 months median progression-free survival,” he said.

BOLERO-6, results of which were published online June 3 in JAMA Oncology, was a postmarketing study by the sponsors to fulfill commitments to both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to estimate the treatment benefit with combined everolimus and exemestane vs. monotherapy with everolimus or capecitabine in patients with ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer that progressed during nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor therapy.

Patients from 83 centers in 18 countries were enrolled in the open label, phase 2 study and randomly assigned to receive oral everolimus 10 mg daily with oral exemestane 25 mg daily, everolimus at the same dose alone, or oral capecitabine 1,250 mg/m2 twice daily for 2 weeks on, 1 week off.

The trial was not powered for statistical comparisons between arms, but was instead designed with the primary objective of estimated investigator-assessed PFS for the combination vs. everolimus alone.

At baseline, more patients assigned to capecitabine vs. everolimus-containing regimens were younger than 65, white, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status of 0 (fully active), and had bone-only metastases. In addition, fewer patients in the capecitabine arm had three or more metastatic sites, Dr. Jerusalem noted,

For the primary analysis, the median PFS with everolimus/exemestane was 8.4 months, compared with 6.8 months for everolimus alone. The estimated hazard ratio (HR) for PFS with everolimus/exemestane vs. everolimus alone was 0.74 (90% confidence interval [CI], 0.57-0.97)

In contrast, median PFS with capecitabine was 9.6 months, with a nonsignificant hazard ratio of 1.26 for the combination (90% CI, 0.96-1.66).

A stratified multivariate Cox regression model controlling for baseline difference and known prognostic factor yielded an HR for PFS of 1.15 (90% CI, 0.86-1.52) for the combination.

Censoring of patients was more frequent in the capecitabine arm (33% vs. 23% in the combination arm), which included 20% of patients on capecitabine who were censored for starting on a new antineoplastic therapy vs. 9% of patients on everolimus/exemestane.

The median time to treatment failure was 5.8 months with the combination, vs. 4.2 months with everolimus alone (HR, 0.66, 90% CI, 0.52-0.4), and 6.2 months with capecitabine alone (HR, 1.03, 90% CI, 0.81-1.31).

Median overall survival was 23.1 months in the combination arm, 29.3 months in the everolimus arm, and 25.6 months in the capecitabine arm. There were no statistically significant differences in overall survival among the groups.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events were more frequent in the combination vs. everolimus arms, and comparable between the combination and capecitabine arms, Dr. Jerusalem said.

Serious adverse events of any grade were more frequent in the combination arm than in the other two arms, but there were no significant differences in discontinuations due to adverse events

“The results of the present study suggest that mTOR inhibitor and endocrine therapy combinations remain important for aromatase inhibitor–refractory disease. Safety and PFS with everolimus plus exemestane in this study were consistent with BOLERO-2 and are now supported by real-world evidence,” the investigators wrote.

“The take home from the BOLERO-6 trial is that the progression-free survival for the combination of everolimus and exemestane is superior to everolimus alone, and is in line with data from the BOLERO-2 trial, and also the PrE0102 study, demonstrating the consistent activity of mTOR inhibition in combination with endocrine therapy in the aromatase inhibitor resistance setting, and this supports our use of the combination in the endocrine resistant patients,” said Cynthia X. Ma, MD, PhD, of Washington University, St. Louis, the invited discussant.

Novartis funded the study. Dr Jerusalem received research funding from Novartis and Roche; honoraria from Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, Celgene, Amgen, BMS, and Puma Technology; and nonfinancial support from Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, Amgen, and BMS. Dr. Ma reported consulting/advising, travel expenses, and institutional research funding from Novartis and others.

SOURCE: Jerusalem G et al. ASCO 2018 Abstract 1005

CHICAGO – For women with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer resistant to endocrine therapy, the combination of everolimus and exemestane had better efficacy than did everolimus alone, but single-agent capecitabine appeared to offer benefit comparable to that of the combination therapy, results of the BOLERO-6 trial suggest.

Among 309 postmenopausal women with ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, the combination of everolimus (Afinitor) and exemestane (Aromasin and generics) was associated with a 26% improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) compared with everolimus alone, reported Guy Jerusalem, MD, PhD, of Liege University, Belgium.

There was also, however, a numerical but not statistically significant difference in PFS favoring capecitabine (Xeloda and generics) “which may be attributed to various baseline characteristics favoring capecitabine, and potential informative censoring,” he said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“We have noted in BOLERO-6 a better-than-expected outcome in median progression-free survival of capecitabine compared with the previously reported 4.1 to 7.9 months median progression-free survival,” he said.

BOLERO-6, results of which were published online June 3 in JAMA Oncology, was a postmarketing study by the sponsors to fulfill commitments to both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to estimate the treatment benefit with combined everolimus and exemestane vs. monotherapy with everolimus or capecitabine in patients with ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer that progressed during nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor therapy.

Patients from 83 centers in 18 countries were enrolled in the open label, phase 2 study and randomly assigned to receive oral everolimus 10 mg daily with oral exemestane 25 mg daily, everolimus at the same dose alone, or oral capecitabine 1,250 mg/m2 twice daily for 2 weeks on, 1 week off.

The trial was not powered for statistical comparisons between arms, but was instead designed with the primary objective of estimated investigator-assessed PFS for the combination vs. everolimus alone.

At baseline, more patients assigned to capecitabine vs. everolimus-containing regimens were younger than 65, white, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status of 0 (fully active), and had bone-only metastases. In addition, fewer patients in the capecitabine arm had three or more metastatic sites, Dr. Jerusalem noted,

For the primary analysis, the median PFS with everolimus/exemestane was 8.4 months, compared with 6.8 months for everolimus alone. The estimated hazard ratio (HR) for PFS with everolimus/exemestane vs. everolimus alone was 0.74 (90% confidence interval [CI], 0.57-0.97)

In contrast, median PFS with capecitabine was 9.6 months, with a nonsignificant hazard ratio of 1.26 for the combination (90% CI, 0.96-1.66).

A stratified multivariate Cox regression model controlling for baseline difference and known prognostic factor yielded an HR for PFS of 1.15 (90% CI, 0.86-1.52) for the combination.

Censoring of patients was more frequent in the capecitabine arm (33% vs. 23% in the combination arm), which included 20% of patients on capecitabine who were censored for starting on a new antineoplastic therapy vs. 9% of patients on everolimus/exemestane.

The median time to treatment failure was 5.8 months with the combination, vs. 4.2 months with everolimus alone (HR, 0.66, 90% CI, 0.52-0.4), and 6.2 months with capecitabine alone (HR, 1.03, 90% CI, 0.81-1.31).

Median overall survival was 23.1 months in the combination arm, 29.3 months in the everolimus arm, and 25.6 months in the capecitabine arm. There were no statistically significant differences in overall survival among the groups.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events were more frequent in the combination vs. everolimus arms, and comparable between the combination and capecitabine arms, Dr. Jerusalem said.

Serious adverse events of any grade were more frequent in the combination arm than in the other two arms, but there were no significant differences in discontinuations due to adverse events

“The results of the present study suggest that mTOR inhibitor and endocrine therapy combinations remain important for aromatase inhibitor–refractory disease. Safety and PFS with everolimus plus exemestane in this study were consistent with BOLERO-2 and are now supported by real-world evidence,” the investigators wrote.

“The take home from the BOLERO-6 trial is that the progression-free survival for the combination of everolimus and exemestane is superior to everolimus alone, and is in line with data from the BOLERO-2 trial, and also the PrE0102 study, demonstrating the consistent activity of mTOR inhibition in combination with endocrine therapy in the aromatase inhibitor resistance setting, and this supports our use of the combination in the endocrine resistant patients,” said Cynthia X. Ma, MD, PhD, of Washington University, St. Louis, the invited discussant.

Novartis funded the study. Dr Jerusalem received research funding from Novartis and Roche; honoraria from Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, Celgene, Amgen, BMS, and Puma Technology; and nonfinancial support from Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, Amgen, and BMS. Dr. Ma reported consulting/advising, travel expenses, and institutional research funding from Novartis and others.

SOURCE: Jerusalem G et al. ASCO 2018 Abstract 1005

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2018

Key clinical point: The combination of everolimus and exemestane had better efficacy than did everolimus alone in women with ER+/HER2– breast cancer resistant to endocrine therapy.

Major finding: Median PFS with everolimus/exemestane was 8.4 months vs 6.8 months for everolimus.

Study details: Randomized, open label, phase 2 trial of 309 women with ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer that progressed during nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor therapy.

Disclosures: Novartis funded the study. Dr Jerusalem received research funding from Novartis and Roche; honoraria from Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, Celgene, Amgen, BMS, and Puma Technology; and nonfinancial support from Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, Amgen, and BMS. Dr. Ma reported consulting/advising, travel expenses, and institutional research funding from Novartis and others.

Source: Jerusalem G et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 1005.

FDA approves rituximab for treating pemphigus vulgaris

Rituximab (Rituxan) has been approved for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris, the manufacturer announced on June 7.

Rituximab is the first biologic approved for treating pemphigus vulgaris, Genentech, a member of the Roche group, stated in a press release announcing the approval.

The prospective, multicenter, open-label, randomized trial, conducted in France, compared the rituximab product approved in the European Union, plus short-term corticosteroid therapy (1,000 mg rituximab administered intravenously at baseline and day 14, then 500 mg at 12 and 18 months, plus 0.5 mg/kg or 1.0 mg/kg per day of prednisone tapered over 3 or 6 months) to corticosteroid therapy alone (oral prednisone 1.0 or 1.5 mg/kg per day tapered over 12 or 18 months), in 90 patients newly diagnosed with moderate to severe pemphigus.

At 24 months, 89% of those in the rituximab group met the primary endpoint, complete remission off therapy at 24 months, compared with 34% of those on corticosteroids (P less than .0001), the investigators reported (Lancet. 2017 May 20;389[10083]:2031-40). Severe adverse events were more commonly reported in the prednisone-only group.

First approved in 1997, rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, is approved for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. The prescribing information includes a boxed warning about the risks of fatal infusion reactions, severe mucocutaneous reactions, hepatitis B virus reactivation, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

The study published in the Lancet was funded by Roche, the French Ministry of Health, and the French Society of Dermatology.

Rituximab (Rituxan) has been approved for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris, the manufacturer announced on June 7.

Rituximab is the first biologic approved for treating pemphigus vulgaris, Genentech, a member of the Roche group, stated in a press release announcing the approval.

The prospective, multicenter, open-label, randomized trial, conducted in France, compared the rituximab product approved in the European Union, plus short-term corticosteroid therapy (1,000 mg rituximab administered intravenously at baseline and day 14, then 500 mg at 12 and 18 months, plus 0.5 mg/kg or 1.0 mg/kg per day of prednisone tapered over 3 or 6 months) to corticosteroid therapy alone (oral prednisone 1.0 or 1.5 mg/kg per day tapered over 12 or 18 months), in 90 patients newly diagnosed with moderate to severe pemphigus.

At 24 months, 89% of those in the rituximab group met the primary endpoint, complete remission off therapy at 24 months, compared with 34% of those on corticosteroids (P less than .0001), the investigators reported (Lancet. 2017 May 20;389[10083]:2031-40). Severe adverse events were more commonly reported in the prednisone-only group.

First approved in 1997, rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, is approved for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. The prescribing information includes a boxed warning about the risks of fatal infusion reactions, severe mucocutaneous reactions, hepatitis B virus reactivation, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

The study published in the Lancet was funded by Roche, the French Ministry of Health, and the French Society of Dermatology.

Rituximab (Rituxan) has been approved for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris, the manufacturer announced on June 7.

Rituximab is the first biologic approved for treating pemphigus vulgaris, Genentech, a member of the Roche group, stated in a press release announcing the approval.

The prospective, multicenter, open-label, randomized trial, conducted in France, compared the rituximab product approved in the European Union, plus short-term corticosteroid therapy (1,000 mg rituximab administered intravenously at baseline and day 14, then 500 mg at 12 and 18 months, plus 0.5 mg/kg or 1.0 mg/kg per day of prednisone tapered over 3 or 6 months) to corticosteroid therapy alone (oral prednisone 1.0 or 1.5 mg/kg per day tapered over 12 or 18 months), in 90 patients newly diagnosed with moderate to severe pemphigus.

At 24 months, 89% of those in the rituximab group met the primary endpoint, complete remission off therapy at 24 months, compared with 34% of those on corticosteroids (P less than .0001), the investigators reported (Lancet. 2017 May 20;389[10083]:2031-40). Severe adverse events were more commonly reported in the prednisone-only group.

First approved in 1997, rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, is approved for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. The prescribing information includes a boxed warning about the risks of fatal infusion reactions, severe mucocutaneous reactions, hepatitis B virus reactivation, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

The study published in the Lancet was funded by Roche, the French Ministry of Health, and the French Society of Dermatology.

Multi-Modal Pain Control in Ambulatory Hand Surgery

ABSTRACT

We evaluated postoperative pain control and narcotic usage after thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) arthroplasty or open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the distal radius in patients given opiates with or without other non-opiate medication using a specific dosing regimen. A prospective, randomized study of 79 patients undergoing elective CMC arthroplasty or ORIF of the distal radius evaluated postoperative pain in the first 5 postoperative days. Patients were divided into 4 groups: Group 1, oxycodone and acetaminophen PRN; Group 2, oxycodone and acetaminophen with specific dosing; Group 3, oxycodone, acetaminophen, and OxyContin with specific dosing; and Group 4, oxycodone, acetaminophen, and ketorolac with specific dosing. During the first 5 postoperative days, we recorded pain levels according to a numeric pain scale, opioid usage, and complications. Although differences in our data did not reach statistical significance, overall pain scores, opioid usage, and complication rates were less prevalent in the oxycodone, acetaminophen, and ketorolac group. Postoperative pain following ambulatory hand and wrist surgery under regional anesthesia was more effectively controlled with fewer complications using a combination of oxycodone, acetaminophen, and ketorolac with a specific dosing regimen.

Continue to: Regional anesthesia...

Regional anesthesia is a safe and effective modality of perioperative pain control in patients undergoing ambulatory hand procedures.1-10 Often, as the regional block wears off, patients experience a rebound pain effect that can be challenging to manage.

We sought to determine if an organized, multimodal approach in patients undergoing thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) arthroplasty or open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of distal radius fractures would provide better postoperative pain control. We hypothesized that this approach would significantly reduce postoperative pain and the need for narcotic pain medication compared with PRN dosing of oxycodone/acetaminophen alone.11-14

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our study was approved by our Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from each patient. Patients presenting for elective thumb CMC arthroplasty or ORIF of the distal radius were screened for inclusion in a prospective, randomized study. Inclusion criteria included patients aged 18 to 65 years who could provide informed consent. Patients with chronic pain syndromes, long-term narcotic usage, chronic medical conditions precluding the use of opiates or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and those who did not have a complete sensory and motor block postoperatively were excluded.

Patients were randomly divided into 1 of 4 study arms. Randomization was performed via sealed envelopes, which were opened in the recovery area when postoperative prescriptions were written. The group distribution was as follows: Group 1, Percocet 5 mg/325 mg alone (control); Group 2, oxycodone 5 mg, acetaminophen 325 mg administered separately; Group 3, oxycodone 5 mg, acetaminophen 325 mg, and oxycodone SR (OxyContin) 10 mg; and Group 4, oxycodone 5 mg, acetaminophen 325 mg, and ketorolac (Toradol) 10 mg (Table 1). Patients in the control group were instructed to take 1 or 2 tablets every 4 to 6 hours as needed for pain. Patients in the 3 experimental groups were given detailed instructions regarding when and how to take their medications. All patients were instructed to take 650 mg of acetaminophen every 6 hours. Patients were provided a sliding scale to assist in dosing their opioid medications according to their numeric pain score (NPS) (Table 2). Group 2 patients were given oxycodone 10 mg in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) and instructed to take oxycodone 10 mg with acetaminophen 650 mg every 6 hours on a scheduled basis until their block wore off, then dose themselves using the NPS.

Table 1. Patient Groups

Group | Anesthesia | Pain Medications |

1 (standard treatment) | Brachial plexus block | Percocet (oxycodone and acetaminophen) 5-10 mg every 4-6 hours as needed for pain. |

2 | Brachial plexus block | 1. Oxycodone 0-15 mg every 4-6 hours as needed for pain based on pain scale score. 2. Tylenol (Acetaminophen) 650 mg every 6 hours, scheduled. |

3 | Brachial plexus block | 1. Oxycodone 0-15 mg every 4-6 hours as needed for pain based on numeric pain scale. 2. Tylenol (Acetaminophen) 650 mg every 6 hours, scheduled. 3. OxyContin (oxycodone sustained release) 10 mg twice a day, scheduled. |

4 | Brachial plexus block | 1. Oxycodone 0-15 mg every 4-6 hours as needed for pain based on pain scale score. 2. Tylenol (Acetaminophen) 650 mg every 6 hours, scheduled. 3. Toradol (Ketorolac) 10mg every 6 hours, scheduled. |

Table 2. Sliding Scale for Pain Control in the Experimental Groups

Pain Score | Oxycodone Dose |

0-3 | 5 mg (1 tablet) |

4-7 | 10 mg (2 tablets) |

8-10 | 15 mg (3 tablets) |

Group 3 patients were given oxycodone 10 mg in the PACU and instructed to take oxycodone 10 mg with acetaminophen 650 mg every 6 hours and OxyContin 10 mg every 12 hours on a scheduled basis until their block wore off, then dose themselves using NPS. Group 4 patients were given oxycodone 10 mg postoperatively and ketorolac 30 mg intravenously in the PACU and instructed to take oxycodone 10 mg, acetaminophen 650 mg, and ketorolac 10 mg every 6 hours on a scheduled basis until their block wore off, then dose themselves using the NPS.

Patients were provided with a journal and asked to record their medication usage, NPS, and any adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, and uncontrolled pain were specifically mentioned) or complications for 5 days after their procedure. We also attempted to contact patients by telephone on each of the 5 days after their procedure to remind them to complete their logs. They were asked specifically if they were having difficulty with their medications. They were also asked specifically about nausea, vomiting, and over-sedation. If patients requested additional medication to help treat their pain, they were instructed to add an over-the-counter NSAID of their choice based on the label’s suggested dosing.

Continue to: All patients received a supraclavicular...

All patients received a supraclavicular brachial plexus block using 0.75% ropivacaine under the supervision of an attending anesthesiologist experienced in regional anesthesia. Patients underwent thumb CMC arthroplasty utilizing complete resection of the trapezium followed by abductor pollicis longus suspensionplasty under the supervision of 1 of 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons. ORIF of the distal radius was completed utilizing a volar approach and distal radius locking plate under the supervision of 1 of 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons.

Primary outcome measures were the total number of oxycodone tablets taken daily and the average daily NPS. Secondary outcomes measured included adverse effects as noted above and the need for a trip to the emergency department for unrelieved pain.

A power analysis was completed prior to the beginning of the study. To detect a difference of at least 1 on the NPS, we determined that 18 patients per group would provide 80% power. This was based on literature utilizing the visual analog scale (VAS), a 100-mm line on which patients can place a mark to describe the intensity of their pain. The standard deviation on the VAS is approximately 15 mm. To account for potential dropout, we elected to recruit 20 patients per group. Non-paired t tests were used to compare groups.

RESULTS

One hundred and eighteen patients enrolled in the study. Of those, 79 patients completed and returned their summary logs (by group: 18 control, 20 oxycodone, 17 OxyContin, and 24 ketorolac). The remaining patients were excluded from the final analysis because they did not return their summary logs. Only 1 patient was excluded from the analysis because he did not have adequate regional anesthesia. Demographic data were analyzed and showed no significant differences between groups at the P < .05 level of significance. Surgical procedures were completed by 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons. Distal radius fractures were performed using a volar approach. CMC arthroplasty was performed using a procedure that was standardized across surgeons. There were no between-surgeon differences in outcomes.

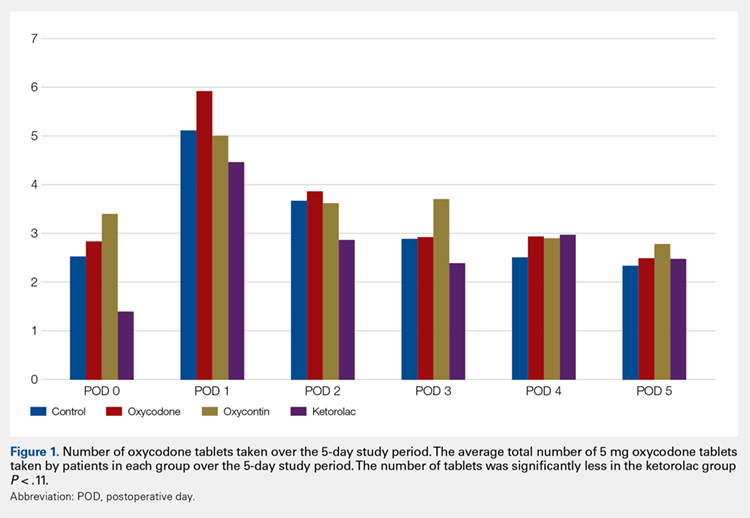

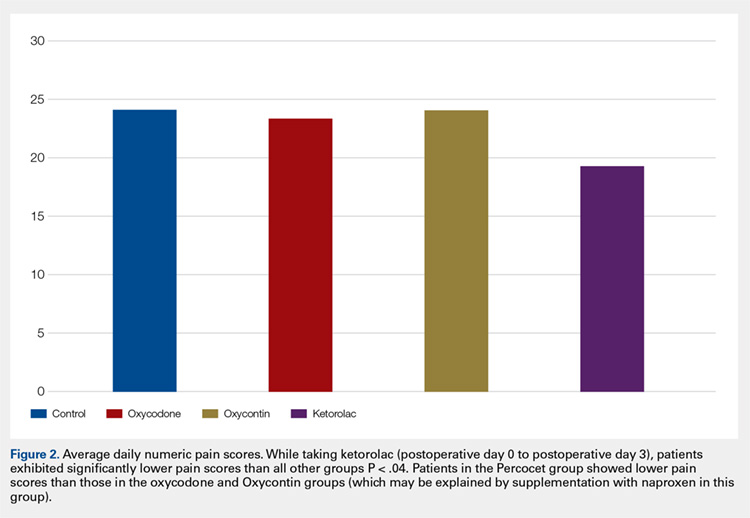

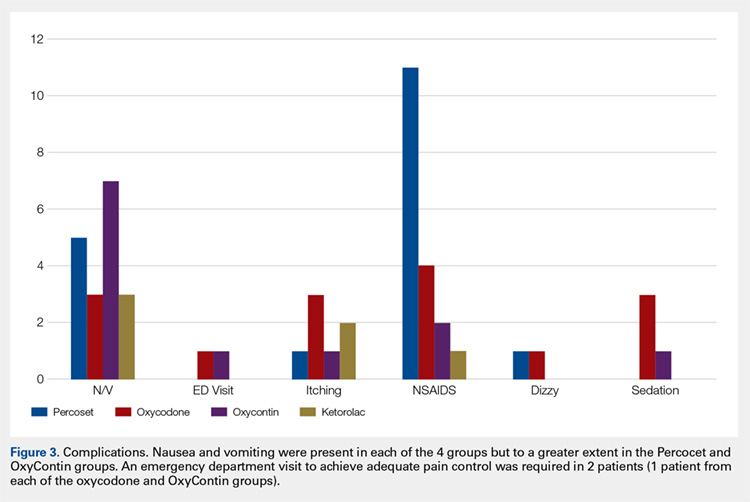

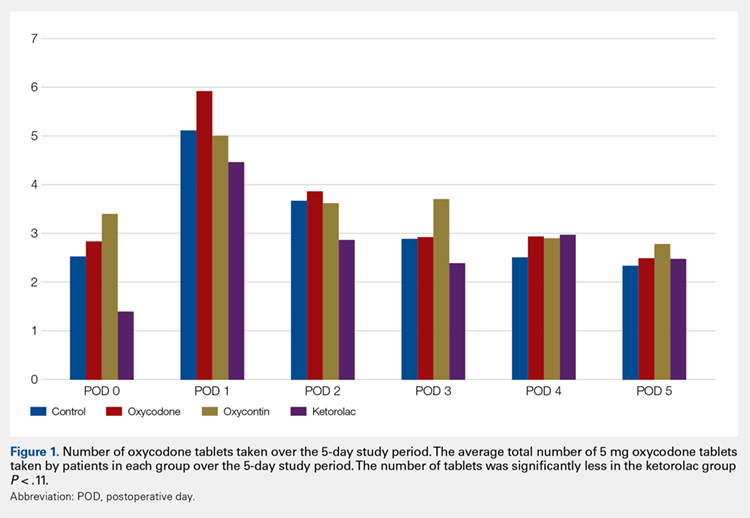

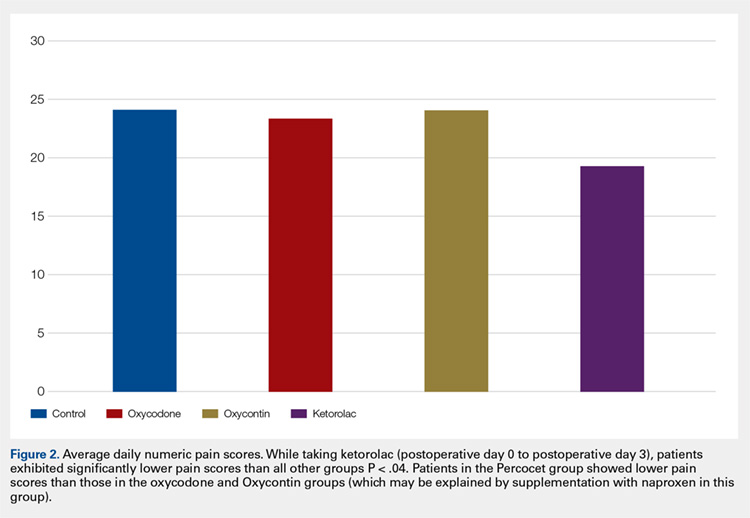

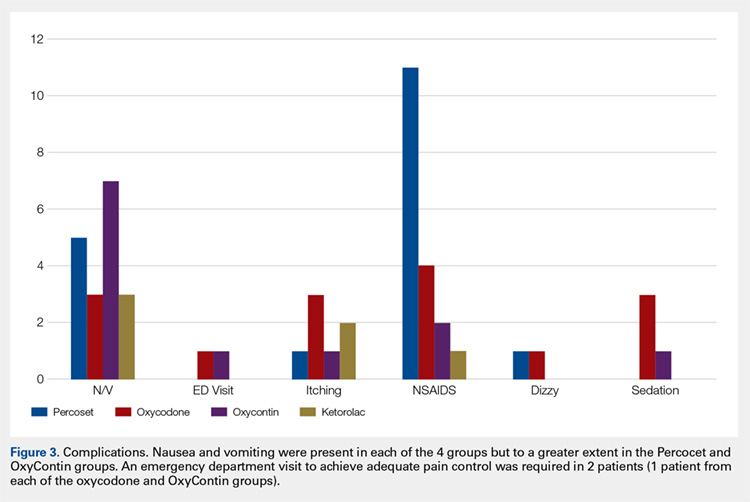

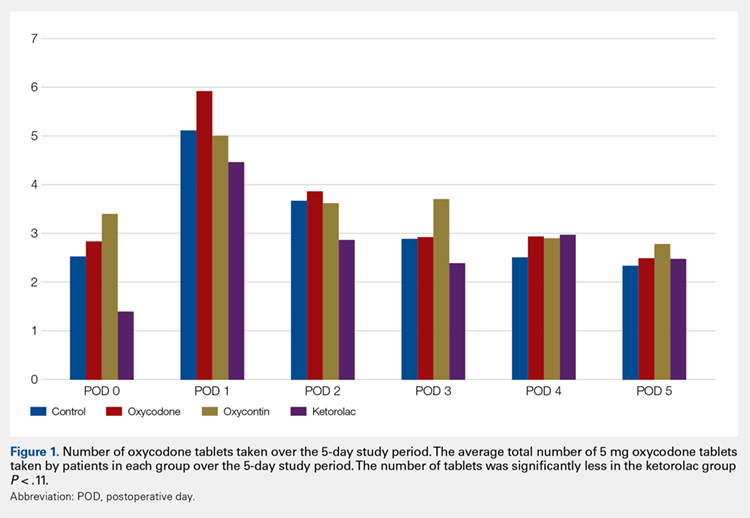

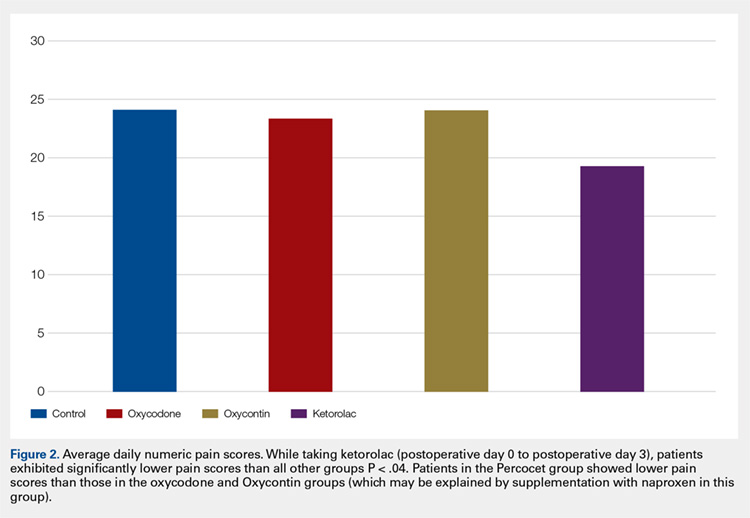

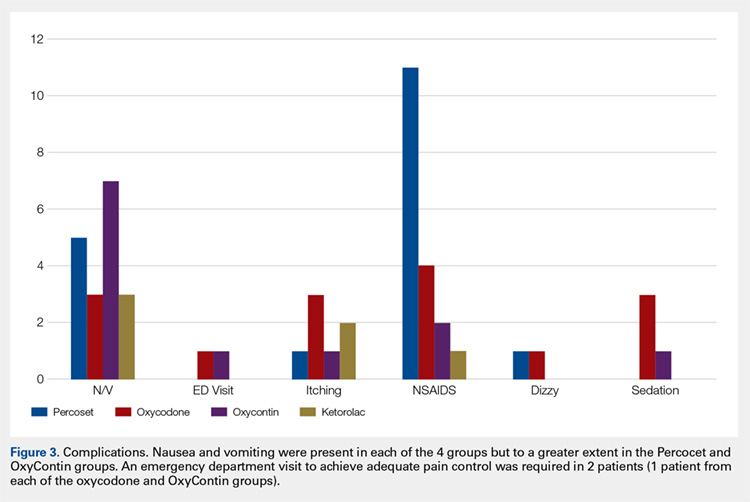

Average daily NPS (Figure 1) and the total number of oxycodone tablets taken (Figure 2) over the 5-day study period were recorded. Patients in the ketorolac group used fewer oxycodone tablets (19.3) than patients in the other 3 groups (24.4), P =.11, but the difference was not statistically significant. The maximum number of oxycodone tablets used was 71 in the Percocet group, 57 in the oxycodone and ketorolac groups, and 73 in the OxyContin group. The average daily NPS was lower in the ketorolac group during the period of medication use. This value only reached statistical significance on postoperative day 0 when the ketorolac group was compared with the OxyContin group (P = .01) and on postoperative day 1 when the ketorolac group was compared with the oxycodone group (P = .04). Complications (Figure 3) were greater in the non-ketorolac groups. One patient each in the oxycodone and OxyContin groups required a trip to the emergency department for pain control after their block wore off. Nausea and vomiting were present in each of the 4 groups but to a much greater degree in the Percocet and OxyContin groups; however, these results did not reach statistical significance (P = .129). Eleven of the 18 patients in the Percocet group required an additional NSAID (naproxen) and still did not achieve pain control similar to the other groups. This may explain why the average daily pain score in the Percocet group was lower than that in the oxycodone group, in which only 4 of the 20 patients supplemented with naproxen. Patients did, however, require many more oxycodone tablets to achieve pain control in the Percocet group. Over-sedation was reported in 3 patients in the oxycodone group and in 1 patient in the OxyContin group. No patients were found to have bleeding, renal, or other systemic complications.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION

In this prospective, randomized study, we sought to determine whether a more organized approach to treating postoperative pain using a specific dosing regimen or opiates in conjunction with non-opiate medications would lead to improved pain control and a decreased need for opiates. We found that adding ketorolac to the postoperative pain regimen and outlining a more detailed set of instructions could lower narcotic usage in the first 4 postoperative days. In addition, adding ketorolac decreased other complications commonly seen with narcotic usage and was shown to be safe in our patient population.

Ketorolac has been shown to decrease narcotic pain medication usage in several surgical settings and across different surgical specialties. It is hypothesized that ketorolac potentiates the effects of narcotics.11 Ketorolac given alone has a potent analgesic effect by acting as a strong non-selective cyclooxygenase inhibitor. The major drawback to ketorolac use has been its well-known side-effect profile. Ketorolac is renally excreted, and as such, should not be used in patients with renal insufficiency. In addition, ketorolac has been shown to cause increased gastrointestinal bleeding when used for >5 days.15 Caution should be taken when combining ketorolac with thromboprophylactic medications, especially in older patients.

Many surgeons use NSAIDs along with narcotics as part of a postoperative pain regimen. While this is often adequate for some procedures, when the surgery involves manipulating fractures, internal fixation, or resection arthroplasty, the variation in individual patient pain may call for a more robust protocol. Additionally, as surgeons expand to more complex procedures performed in the outpatient setting, evaluating different combinations of analgesics taken in a more structured manner may provide for improved pain control.

A major component of patient satisfaction is postoperative pain control.3-8,12,16,17 Regional anesthesia is an important tool that allows patients to undergo a surgical procedure with a greatly reduced amount of opioid pain medications. In addition, regional anesthesia can provide significant pain control after the patient has left the ambulatory surgery center, but this relief is short-lived because the medication is designed to lose effectiveness over time. As the effects of regional anesthesia wear off, patients can experience “rebound pain” with severe levels of pain that, on occasion, cannot be controlled with oral analgesics alone. The addition of ketorolac provided improved pain control when compared with the other regimens during this transition period when the regional anesthesia was becoming ineffective. In addition, because patients taking ketorolac used less narcotic medication, they experienced less nausea, vomiting, and over-sedation.

Additionally, patients were instructed to record their medication usage and pain scores on a prospective basis, with the hope of eliminating recall bias. A potential weakness is the inability to show significance for pain relief and reduced narcotic usage with the addition of ketorolac, although there was a trend toward significance. Many of the patients who enrolled in the trial did not return their medication logs. While these patients had to be excluded from data analysis, we continued enrollment until we obtained an adequate number of patients in each group. In addition, in the OxyContin group (Group 3), we could only recruit 17 participants, instead of the 18 needed based on our power study. Although this has a potential to alter the significance of our results, we do not feel this had a substantial impact on our results.

Many patients in the non-ketorolac groups supplemented their medication regimens with NSAIDs, which may have falsely lowered pain scores and narcotic usage. While this confounds our study results, we do not believe that it invalidates the conclusion that ketorolac can be an effective adjunct pain medication for use in patients undergoing ambulatory hand surgery.

The study examined postoperative pain control for only 2 procedures, thumb basal joint arthroplasty and distal radius fracture fixation, both commonly performed in the outpatient setting under regional anesthesia and both typically requiring narcotic pain medication. Perhaps the utilization of these medication regimens with different surgical procedures would have differing results.

We conclude that ketorolac potentially provides patients with improved pain control over the use of narcotic pain medications alone in the setting of ambulatory hand surgery.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

- Boezaart AP, Davis G, Le-Wendling L. Recovery after orthopedic surgery: techniques to increase duration of pain control. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2012;25(6):665-672. doi:10.1097/ACO.0b013e328359ab5a.

- Buvanendran A, Kroin JS. Useful adjuvants for postoperative pain management. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007;21(1):31-49. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2006.12.003.

- Coluzzi F, Bragazzi L, Di Bussolo E, Pizza G, Mattia C. Determinants of patient satisfaction in postoperative pain management following hand ambulatory day-surgery. Minerva Med. 2011;102(3):177-186.

- Elvir-Lazo OL, White PF. Postoperative pain management after ambulatory surgery: role of multimodal analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2010;28(2):217-224. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2010.02.011.

- Kopp SL, Horlocker TT. Regional anaesthesia in day-stay and short-stay surgery. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(Suppl 1):84-96. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06204.x.

- Rawal N. Postoperative pain treatment for ambulatory surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007;21(1):129-148. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2006.11.005.

- Schug SA, Chong C. Pain management after ambulatory surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22(6):738-743. doi:10.1097/ACO.0b013e32833020f4.

- Sripada R, Bowens C Jr. Regional anesthesia procedures for shoulder and upper arm surgery upper extremity update--2005 to present. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2012;50(1):26-46. doi:10.1097/AIA.0b013e31821a0284.

- Trompeter A, Camilleri G, Narang K, Hauf W, Venn R. Analgesia requirements after interscalene block for shoulder arthroscopy: the 5 days following surgery. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(3):417-421. doi:10.1007/s00402-009-0959-9.

- Dufeu N, Marchand-Maillet F, Atchabahian A, et al. Efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided distal blocks for analgesia without motor blockade after ambulatory hand surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(4):737-743. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.01.011.

- Gutta R, Koehn CR, James LE. Does ketorolac have a preemptive analgesic effect? A randomized, double-blind, control study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(12):2029-2034. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2013.06.220.

- Nossaman VE, Ramadhyani U, Kadowitz PJ, Nossaman BD. Advances in perioperative pain management: use of medications with dual analgesic mechanisms, tramadol & tapentadol. Anesthesiol Clin. 2010;28(4):647-666. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2010.08.009.

- Warren-Stomberg M, Brattwall M, Jakobsson JG. Non-opioid analgesics for pain management following ambulatory surgery: a review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013;79(9):1077-1087.

- Wickerts L, Warrén Stomberg M, Brattwall M, Jakobsson JJ. Coxibs: is there a benefit when compared to traditional non-selective NSAIDs in postoperative pain management? Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77(11):1084-1098.

- Strom BL, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, et al. Parenteral ketorolac and risk of gastrointestinal and operative site bleeding. A postmarketing surveillance study. JAMA. 1996;275(5):376-382. doi:10.1001/jama.275.5.376.

- Hegarty M, Calder A, Davies K, et al. Does take-home analgesia improve postoperative pain after elective day case surgery? A comparison of hospital vs parent-supplied analgesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(5):385-389. doi:10.1111/pan.12077.

- Weber SC, Jain R, Parise C. Pain scores in the management of postoperative pain in shoulder surgery. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(1):65-72. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2006.11.002.

ABSTRACT

We evaluated postoperative pain control and narcotic usage after thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) arthroplasty or open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the distal radius in patients given opiates with or without other non-opiate medication using a specific dosing regimen. A prospective, randomized study of 79 patients undergoing elective CMC arthroplasty or ORIF of the distal radius evaluated postoperative pain in the first 5 postoperative days. Patients were divided into 4 groups: Group 1, oxycodone and acetaminophen PRN; Group 2, oxycodone and acetaminophen with specific dosing; Group 3, oxycodone, acetaminophen, and OxyContin with specific dosing; and Group 4, oxycodone, acetaminophen, and ketorolac with specific dosing. During the first 5 postoperative days, we recorded pain levels according to a numeric pain scale, opioid usage, and complications. Although differences in our data did not reach statistical significance, overall pain scores, opioid usage, and complication rates were less prevalent in the oxycodone, acetaminophen, and ketorolac group. Postoperative pain following ambulatory hand and wrist surgery under regional anesthesia was more effectively controlled with fewer complications using a combination of oxycodone, acetaminophen, and ketorolac with a specific dosing regimen.

Continue to: Regional anesthesia...

Regional anesthesia is a safe and effective modality of perioperative pain control in patients undergoing ambulatory hand procedures.1-10 Often, as the regional block wears off, patients experience a rebound pain effect that can be challenging to manage.

We sought to determine if an organized, multimodal approach in patients undergoing thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) arthroplasty or open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of distal radius fractures would provide better postoperative pain control. We hypothesized that this approach would significantly reduce postoperative pain and the need for narcotic pain medication compared with PRN dosing of oxycodone/acetaminophen alone.11-14

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our study was approved by our Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from each patient. Patients presenting for elective thumb CMC arthroplasty or ORIF of the distal radius were screened for inclusion in a prospective, randomized study. Inclusion criteria included patients aged 18 to 65 years who could provide informed consent. Patients with chronic pain syndromes, long-term narcotic usage, chronic medical conditions precluding the use of opiates or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and those who did not have a complete sensory and motor block postoperatively were excluded.

Patients were randomly divided into 1 of 4 study arms. Randomization was performed via sealed envelopes, which were opened in the recovery area when postoperative prescriptions were written. The group distribution was as follows: Group 1, Percocet 5 mg/325 mg alone (control); Group 2, oxycodone 5 mg, acetaminophen 325 mg administered separately; Group 3, oxycodone 5 mg, acetaminophen 325 mg, and oxycodone SR (OxyContin) 10 mg; and Group 4, oxycodone 5 mg, acetaminophen 325 mg, and ketorolac (Toradol) 10 mg (Table 1). Patients in the control group were instructed to take 1 or 2 tablets every 4 to 6 hours as needed for pain. Patients in the 3 experimental groups were given detailed instructions regarding when and how to take their medications. All patients were instructed to take 650 mg of acetaminophen every 6 hours. Patients were provided a sliding scale to assist in dosing their opioid medications according to their numeric pain score (NPS) (Table 2). Group 2 patients were given oxycodone 10 mg in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) and instructed to take oxycodone 10 mg with acetaminophen 650 mg every 6 hours on a scheduled basis until their block wore off, then dose themselves using the NPS.

Table 1. Patient Groups

Group | Anesthesia | Pain Medications |

1 (standard treatment) | Brachial plexus block | Percocet (oxycodone and acetaminophen) 5-10 mg every 4-6 hours as needed for pain. |

2 | Brachial plexus block | 1. Oxycodone 0-15 mg every 4-6 hours as needed for pain based on pain scale score. 2. Tylenol (Acetaminophen) 650 mg every 6 hours, scheduled. |

3 | Brachial plexus block | 1. Oxycodone 0-15 mg every 4-6 hours as needed for pain based on numeric pain scale. 2. Tylenol (Acetaminophen) 650 mg every 6 hours, scheduled. 3. OxyContin (oxycodone sustained release) 10 mg twice a day, scheduled. |

4 | Brachial plexus block | 1. Oxycodone 0-15 mg every 4-6 hours as needed for pain based on pain scale score. 2. Tylenol (Acetaminophen) 650 mg every 6 hours, scheduled. 3. Toradol (Ketorolac) 10mg every 6 hours, scheduled. |

Table 2. Sliding Scale for Pain Control in the Experimental Groups

Pain Score | Oxycodone Dose |

0-3 | 5 mg (1 tablet) |

4-7 | 10 mg (2 tablets) |

8-10 | 15 mg (3 tablets) |

Group 3 patients were given oxycodone 10 mg in the PACU and instructed to take oxycodone 10 mg with acetaminophen 650 mg every 6 hours and OxyContin 10 mg every 12 hours on a scheduled basis until their block wore off, then dose themselves using NPS. Group 4 patients were given oxycodone 10 mg postoperatively and ketorolac 30 mg intravenously in the PACU and instructed to take oxycodone 10 mg, acetaminophen 650 mg, and ketorolac 10 mg every 6 hours on a scheduled basis until their block wore off, then dose themselves using the NPS.

Patients were provided with a journal and asked to record their medication usage, NPS, and any adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, and uncontrolled pain were specifically mentioned) or complications for 5 days after their procedure. We also attempted to contact patients by telephone on each of the 5 days after their procedure to remind them to complete their logs. They were asked specifically if they were having difficulty with their medications. They were also asked specifically about nausea, vomiting, and over-sedation. If patients requested additional medication to help treat their pain, they were instructed to add an over-the-counter NSAID of their choice based on the label’s suggested dosing.

Continue to: All patients received a supraclavicular...

All patients received a supraclavicular brachial plexus block using 0.75% ropivacaine under the supervision of an attending anesthesiologist experienced in regional anesthesia. Patients underwent thumb CMC arthroplasty utilizing complete resection of the trapezium followed by abductor pollicis longus suspensionplasty under the supervision of 1 of 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons. ORIF of the distal radius was completed utilizing a volar approach and distal radius locking plate under the supervision of 1 of 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons.

Primary outcome measures were the total number of oxycodone tablets taken daily and the average daily NPS. Secondary outcomes measured included adverse effects as noted above and the need for a trip to the emergency department for unrelieved pain.

A power analysis was completed prior to the beginning of the study. To detect a difference of at least 1 on the NPS, we determined that 18 patients per group would provide 80% power. This was based on literature utilizing the visual analog scale (VAS), a 100-mm line on which patients can place a mark to describe the intensity of their pain. The standard deviation on the VAS is approximately 15 mm. To account for potential dropout, we elected to recruit 20 patients per group. Non-paired t tests were used to compare groups.

RESULTS

One hundred and eighteen patients enrolled in the study. Of those, 79 patients completed and returned their summary logs (by group: 18 control, 20 oxycodone, 17 OxyContin, and 24 ketorolac). The remaining patients were excluded from the final analysis because they did not return their summary logs. Only 1 patient was excluded from the analysis because he did not have adequate regional anesthesia. Demographic data were analyzed and showed no significant differences between groups at the P < .05 level of significance. Surgical procedures were completed by 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons. Distal radius fractures were performed using a volar approach. CMC arthroplasty was performed using a procedure that was standardized across surgeons. There were no between-surgeon differences in outcomes.