User login

Beyond the sleeve and RYGB: The frontier of bariatric procedures

BOSTON – Though are the bariatric procedures most patients will receive, other surgical approaches to weight loss are occasionally performed. Knowing these various techniques and their likely efficacy and safety can help physicians who care for patients with obesity, whether a patient is considering a less common option, or whether a post-vagal blockade patient shows up on the schedule with long-term issues.

A common theme among many of these procedures is that overall numbers are low, long-term follow-up may be lacking, and research quality is variable, said Travis McKenzie, MD, speaking at a bariatric surgery-focused session of the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

One minimally invasive approach targets stomach functions and the appetite and satiety signaling system. In vagal blockade via an electronic implant (vBloc), an indwelling, removable device produces electronically-induced intermittent blockade of the vagal nerve.

In one randomized controlled trial, excess weight loss in patients receiving this procedure was 24%, significantly more than the 16% seen in the group that received a sham procedure (P = .002); both groups received regular follow-up and counseling, according to the study protocol. Overall, at 1 year, 52% of those in the treatment group had seen at least 20% reduction in excess weight; just 3.7% of vBloc recipients had adverse events, mostly some dyspepsia and pain at the implant site, said Dr. McKenzie, an endocrine surgeon at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The vBloc procedure, said Dr. McKenzie, “demonstrated modest weight loss at 2 years, with a reasonable risk profile.”

A variation of the duodenal switch is known as single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy, or SADI-S. This procedure both resects the greater curve of the stomach to create a gastric sleeve, and uses a single intestinal anastomosis to create a common channel of 200, 250 or 300 cm, bypassing most of the small intestine.

In this procedure, also known as the one-anastomosis duodenal switch (OADS), weight loss occurs both because of intestinal malabsorption and because of the reduced stomach volume.

Parsing safety and efficacy of this procedure isn’t easy, given the studies at hand, said Dr. McKenzie: “The data are plagued by short follow-up, low numbers, and inconsistent quality.” Of the 14 case series following 1,045 patients, none include randomized controlled data, he said.

The data that are available show total body weight loss in the 34%-39% range, with little difference between losses seen at 1 year and 2 years.

However, said Dr. McKenzie, one 100-patient case series showed that SADI-S patients averaged 2.5 bowel movements daily after the procedure, and two patients needed surgical revision because they were experiencing malnutrition. Anemia, vitamin B12 and D deficiencies, and folate deficiency are all commonly seen two years after SADI-S procedures, he said.

“The OADS procedure is very effective, although better data are needed before drawing conclusions,” said Dr. McKenzie.

A gastric bypass variation known as the “mini” bypass, or the one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), is another less common bariatric technique. In this procedure, a small gastric pouch is created that forms the working stomach, which is then connected to the duodenum with bypassing of a significant portion (up to 200 cm) of the small intestine. This procedure causes both restrictive and malabsorptive weight loss, and is usually performed using minimally invasive surgery.

Four randomized controlled trials exist, said Dr. McKenzie, that compare OAGB variously to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and to sleeve gastrectomy. In an 80-patient study that compared OAGB with RYGB at two years post-procedure, excess weight loss was similar, at 60% for OAGB versus 64% for RYGB ( Ann Surg. 2005;24[1]20-8). However, morbidity was less for OAGB recipients (8% vs 20%, P less than .05).

Another study looked at OAGB and sleeve gastrectomy in 60 patients, following them for 5 years. Total body weight loss was similar between groups at 20%-23%, said Dr. McKenzie (Obes Surg. 2014;24[9]1552-62).

“But what about bile reflux?” asked Dr. McKenzie. He pointed out that in OAGB, digestive juices enter the digestive path very close to the outlet of the new, surgically created stomach, affording the potential for significant reflux. Calling for further study of the frequency of bile reflux and potential long-term sequelae, he advised caution with this otherwise attractive procedure.

Those caring for bariatric patients may also see the consequences of “rogue” procedures on occasion: “Interest in metabolic surgery has led to some ‘original’ procedures, many of which are not based on firm science,” said Dr. McKenzie. An exemplar of an understudied procedure is the sleeve gastrectomy with a loop bipartition, with results that have been published in case reports, but whose longer-term outcomes are unknown.

“Caution is advised regarding operations that are devised outside of study protocols,” said Dr. McKenzie.

Dr. McKenzie reported that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McKenzie, T. AACE 2018, presentation SGS4.

BOSTON – Though are the bariatric procedures most patients will receive, other surgical approaches to weight loss are occasionally performed. Knowing these various techniques and their likely efficacy and safety can help physicians who care for patients with obesity, whether a patient is considering a less common option, or whether a post-vagal blockade patient shows up on the schedule with long-term issues.

A common theme among many of these procedures is that overall numbers are low, long-term follow-up may be lacking, and research quality is variable, said Travis McKenzie, MD, speaking at a bariatric surgery-focused session of the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

One minimally invasive approach targets stomach functions and the appetite and satiety signaling system. In vagal blockade via an electronic implant (vBloc), an indwelling, removable device produces electronically-induced intermittent blockade of the vagal nerve.

In one randomized controlled trial, excess weight loss in patients receiving this procedure was 24%, significantly more than the 16% seen in the group that received a sham procedure (P = .002); both groups received regular follow-up and counseling, according to the study protocol. Overall, at 1 year, 52% of those in the treatment group had seen at least 20% reduction in excess weight; just 3.7% of vBloc recipients had adverse events, mostly some dyspepsia and pain at the implant site, said Dr. McKenzie, an endocrine surgeon at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The vBloc procedure, said Dr. McKenzie, “demonstrated modest weight loss at 2 years, with a reasonable risk profile.”

A variation of the duodenal switch is known as single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy, or SADI-S. This procedure both resects the greater curve of the stomach to create a gastric sleeve, and uses a single intestinal anastomosis to create a common channel of 200, 250 or 300 cm, bypassing most of the small intestine.

In this procedure, also known as the one-anastomosis duodenal switch (OADS), weight loss occurs both because of intestinal malabsorption and because of the reduced stomach volume.

Parsing safety and efficacy of this procedure isn’t easy, given the studies at hand, said Dr. McKenzie: “The data are plagued by short follow-up, low numbers, and inconsistent quality.” Of the 14 case series following 1,045 patients, none include randomized controlled data, he said.

The data that are available show total body weight loss in the 34%-39% range, with little difference between losses seen at 1 year and 2 years.

However, said Dr. McKenzie, one 100-patient case series showed that SADI-S patients averaged 2.5 bowel movements daily after the procedure, and two patients needed surgical revision because they were experiencing malnutrition. Anemia, vitamin B12 and D deficiencies, and folate deficiency are all commonly seen two years after SADI-S procedures, he said.

“The OADS procedure is very effective, although better data are needed before drawing conclusions,” said Dr. McKenzie.

A gastric bypass variation known as the “mini” bypass, or the one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), is another less common bariatric technique. In this procedure, a small gastric pouch is created that forms the working stomach, which is then connected to the duodenum with bypassing of a significant portion (up to 200 cm) of the small intestine. This procedure causes both restrictive and malabsorptive weight loss, and is usually performed using minimally invasive surgery.

Four randomized controlled trials exist, said Dr. McKenzie, that compare OAGB variously to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and to sleeve gastrectomy. In an 80-patient study that compared OAGB with RYGB at two years post-procedure, excess weight loss was similar, at 60% for OAGB versus 64% for RYGB ( Ann Surg. 2005;24[1]20-8). However, morbidity was less for OAGB recipients (8% vs 20%, P less than .05).

Another study looked at OAGB and sleeve gastrectomy in 60 patients, following them for 5 years. Total body weight loss was similar between groups at 20%-23%, said Dr. McKenzie (Obes Surg. 2014;24[9]1552-62).

“But what about bile reflux?” asked Dr. McKenzie. He pointed out that in OAGB, digestive juices enter the digestive path very close to the outlet of the new, surgically created stomach, affording the potential for significant reflux. Calling for further study of the frequency of bile reflux and potential long-term sequelae, he advised caution with this otherwise attractive procedure.

Those caring for bariatric patients may also see the consequences of “rogue” procedures on occasion: “Interest in metabolic surgery has led to some ‘original’ procedures, many of which are not based on firm science,” said Dr. McKenzie. An exemplar of an understudied procedure is the sleeve gastrectomy with a loop bipartition, with results that have been published in case reports, but whose longer-term outcomes are unknown.

“Caution is advised regarding operations that are devised outside of study protocols,” said Dr. McKenzie.

Dr. McKenzie reported that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McKenzie, T. AACE 2018, presentation SGS4.

BOSTON – Though are the bariatric procedures most patients will receive, other surgical approaches to weight loss are occasionally performed. Knowing these various techniques and their likely efficacy and safety can help physicians who care for patients with obesity, whether a patient is considering a less common option, or whether a post-vagal blockade patient shows up on the schedule with long-term issues.

A common theme among many of these procedures is that overall numbers are low, long-term follow-up may be lacking, and research quality is variable, said Travis McKenzie, MD, speaking at a bariatric surgery-focused session of the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

One minimally invasive approach targets stomach functions and the appetite and satiety signaling system. In vagal blockade via an electronic implant (vBloc), an indwelling, removable device produces electronically-induced intermittent blockade of the vagal nerve.

In one randomized controlled trial, excess weight loss in patients receiving this procedure was 24%, significantly more than the 16% seen in the group that received a sham procedure (P = .002); both groups received regular follow-up and counseling, according to the study protocol. Overall, at 1 year, 52% of those in the treatment group had seen at least 20% reduction in excess weight; just 3.7% of vBloc recipients had adverse events, mostly some dyspepsia and pain at the implant site, said Dr. McKenzie, an endocrine surgeon at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The vBloc procedure, said Dr. McKenzie, “demonstrated modest weight loss at 2 years, with a reasonable risk profile.”

A variation of the duodenal switch is known as single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy, or SADI-S. This procedure both resects the greater curve of the stomach to create a gastric sleeve, and uses a single intestinal anastomosis to create a common channel of 200, 250 or 300 cm, bypassing most of the small intestine.

In this procedure, also known as the one-anastomosis duodenal switch (OADS), weight loss occurs both because of intestinal malabsorption and because of the reduced stomach volume.

Parsing safety and efficacy of this procedure isn’t easy, given the studies at hand, said Dr. McKenzie: “The data are plagued by short follow-up, low numbers, and inconsistent quality.” Of the 14 case series following 1,045 patients, none include randomized controlled data, he said.

The data that are available show total body weight loss in the 34%-39% range, with little difference between losses seen at 1 year and 2 years.

However, said Dr. McKenzie, one 100-patient case series showed that SADI-S patients averaged 2.5 bowel movements daily after the procedure, and two patients needed surgical revision because they were experiencing malnutrition. Anemia, vitamin B12 and D deficiencies, and folate deficiency are all commonly seen two years after SADI-S procedures, he said.

“The OADS procedure is very effective, although better data are needed before drawing conclusions,” said Dr. McKenzie.

A gastric bypass variation known as the “mini” bypass, or the one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), is another less common bariatric technique. In this procedure, a small gastric pouch is created that forms the working stomach, which is then connected to the duodenum with bypassing of a significant portion (up to 200 cm) of the small intestine. This procedure causes both restrictive and malabsorptive weight loss, and is usually performed using minimally invasive surgery.

Four randomized controlled trials exist, said Dr. McKenzie, that compare OAGB variously to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and to sleeve gastrectomy. In an 80-patient study that compared OAGB with RYGB at two years post-procedure, excess weight loss was similar, at 60% for OAGB versus 64% for RYGB ( Ann Surg. 2005;24[1]20-8). However, morbidity was less for OAGB recipients (8% vs 20%, P less than .05).

Another study looked at OAGB and sleeve gastrectomy in 60 patients, following them for 5 years. Total body weight loss was similar between groups at 20%-23%, said Dr. McKenzie (Obes Surg. 2014;24[9]1552-62).

“But what about bile reflux?” asked Dr. McKenzie. He pointed out that in OAGB, digestive juices enter the digestive path very close to the outlet of the new, surgically created stomach, affording the potential for significant reflux. Calling for further study of the frequency of bile reflux and potential long-term sequelae, he advised caution with this otherwise attractive procedure.

Those caring for bariatric patients may also see the consequences of “rogue” procedures on occasion: “Interest in metabolic surgery has led to some ‘original’ procedures, many of which are not based on firm science,” said Dr. McKenzie. An exemplar of an understudied procedure is the sleeve gastrectomy with a loop bipartition, with results that have been published in case reports, but whose longer-term outcomes are unknown.

“Caution is advised regarding operations that are devised outside of study protocols,” said Dr. McKenzie.

Dr. McKenzie reported that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McKenzie, T. AACE 2018, presentation SGS4.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AACE 2018

Aclidinium bromide for COPD: No impact on MACE

SAN DIEGO – The use of aclidinium bromide 400 mcg b.i.d. did not increase the risk of major adverse cardiac events or mortality in patients with moderate to very severe , compared with placebo.

Those are two key findings from the ASCENT COPD trial presented by Robert A. Wise, MD, at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. “Cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities are prevalent in patients with COPD, and about 30% of COPD patients die of cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Wise, who serves as director of research for the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. “However, patients who have cardiovascular disease are often excluded from, or not enrolled in, COPD clinical trials. Moreover, there has been controversy as to whether or not treatment with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. That’s been seen in randomized trials, meta-analyses, as well as in observational studies.”

Aclidinium bromide 400 mcg b.i.d., administered by the Pressair inhaler, is approved as a maintenance treatment for patients with COPD. However, during the registration studies, there were not an adequate number of cardiovascular events in order to ascertain clearly whether or not the drug was associated with increased risk, Dr. Wise said. Therefore, he and his associates in the ASCENT COPD study set out to assess the long-term cardiovascular safety profile of aclidinium 400 mcg b.i.d. in patients with moderate to very severe COPD at risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) for up to 3 years (Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5[1]:5-15). For the randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study, patients received treatment with aclidinium bromide or a placebo inhaler of similar appearance. The study was designed to be terminated when at least 122 patients experienced an adjudicated MACE. The primary safety endpoint was time to first MACE during follow-up of up to 3 years, while the primary efficacy endpoint was the rate of moderate to severe exacerbations per patient per year during the first year of treatment.

To be included in the study, patients had to be at least 40 years of age with moderate to very severe stable COPD, have a smoking history of at least 10 pack-years, and have at least one of the following significant risk factors: cerebrovascular disease; coronary artery disease; peripheral vascular disease, or history of claudication; or at least two atherothrombotic risk factors (male at least 65 years of age, female at least 70 years of age; waist circumference of at least 40 inches among males or at least 38 inches among females; an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min and microalbuminuria; dyslipidemia; or hypertension).

The researchers randomized 1,791 patients to the aclidinium group and 1,798 to the placebo group. Their mean age was 67 years, and about 60% of patients had an exacerbation in the preceding year. Nearly two-thirds of patients (63%) were receiving concomitant long-acting beta 2-agonists (LABA) or LABA/inhaled corticosteroid therapy. In addition, 44% of patients entered the study with a history of a prior cardiovascular event plus at least two atherothrombotic risk factors, 52% reported at least two atherothrombotic risk factors without any prior cardiovascular events, and 4% had a history of a prior cardiovascular event only.

Dr. Wise reported that aclidinium did not increase the risk of MACE in patients with moderate to very severe COPD with significant cardiovascular risk factors, compared with placebo (hazard ratio 0.89; P = .469); non-inferiority was concluded as the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval was less than 1.8). In terms of all-cause mortality, aclidinium did not increase the risk of death, compared with placebo (HR 0.99; P = .929).

During the first year of treatment, Dr. Wise and his associates also observed a 22% reduction in COPD exacerbation rate for aclidinium vs. placebo groups (HR 0.44 vs. 0.57, respectively; P less than .001), and a 35% reduction in the rate of COPD exacerbations leading to hospitalizations (HR 0.07 vs. 0.10; P = .006). “The reduction in exacerbation risk was similar, whether or not patients had an exacerbation in the past year,” Dr. Wise said. He reported being a consultant to, and receiving research support from, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and ContraFect.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Wise, R., et al., Abstract 7711, ATS 2018.

SAN DIEGO – The use of aclidinium bromide 400 mcg b.i.d. did not increase the risk of major adverse cardiac events or mortality in patients with moderate to very severe , compared with placebo.

Those are two key findings from the ASCENT COPD trial presented by Robert A. Wise, MD, at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. “Cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities are prevalent in patients with COPD, and about 30% of COPD patients die of cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Wise, who serves as director of research for the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. “However, patients who have cardiovascular disease are often excluded from, or not enrolled in, COPD clinical trials. Moreover, there has been controversy as to whether or not treatment with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. That’s been seen in randomized trials, meta-analyses, as well as in observational studies.”

Aclidinium bromide 400 mcg b.i.d., administered by the Pressair inhaler, is approved as a maintenance treatment for patients with COPD. However, during the registration studies, there were not an adequate number of cardiovascular events in order to ascertain clearly whether or not the drug was associated with increased risk, Dr. Wise said. Therefore, he and his associates in the ASCENT COPD study set out to assess the long-term cardiovascular safety profile of aclidinium 400 mcg b.i.d. in patients with moderate to very severe COPD at risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) for up to 3 years (Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5[1]:5-15). For the randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study, patients received treatment with aclidinium bromide or a placebo inhaler of similar appearance. The study was designed to be terminated when at least 122 patients experienced an adjudicated MACE. The primary safety endpoint was time to first MACE during follow-up of up to 3 years, while the primary efficacy endpoint was the rate of moderate to severe exacerbations per patient per year during the first year of treatment.

To be included in the study, patients had to be at least 40 years of age with moderate to very severe stable COPD, have a smoking history of at least 10 pack-years, and have at least one of the following significant risk factors: cerebrovascular disease; coronary artery disease; peripheral vascular disease, or history of claudication; or at least two atherothrombotic risk factors (male at least 65 years of age, female at least 70 years of age; waist circumference of at least 40 inches among males or at least 38 inches among females; an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min and microalbuminuria; dyslipidemia; or hypertension).

The researchers randomized 1,791 patients to the aclidinium group and 1,798 to the placebo group. Their mean age was 67 years, and about 60% of patients had an exacerbation in the preceding year. Nearly two-thirds of patients (63%) were receiving concomitant long-acting beta 2-agonists (LABA) or LABA/inhaled corticosteroid therapy. In addition, 44% of patients entered the study with a history of a prior cardiovascular event plus at least two atherothrombotic risk factors, 52% reported at least two atherothrombotic risk factors without any prior cardiovascular events, and 4% had a history of a prior cardiovascular event only.

Dr. Wise reported that aclidinium did not increase the risk of MACE in patients with moderate to very severe COPD with significant cardiovascular risk factors, compared with placebo (hazard ratio 0.89; P = .469); non-inferiority was concluded as the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval was less than 1.8). In terms of all-cause mortality, aclidinium did not increase the risk of death, compared with placebo (HR 0.99; P = .929).

During the first year of treatment, Dr. Wise and his associates also observed a 22% reduction in COPD exacerbation rate for aclidinium vs. placebo groups (HR 0.44 vs. 0.57, respectively; P less than .001), and a 35% reduction in the rate of COPD exacerbations leading to hospitalizations (HR 0.07 vs. 0.10; P = .006). “The reduction in exacerbation risk was similar, whether or not patients had an exacerbation in the past year,” Dr. Wise said. He reported being a consultant to, and receiving research support from, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and ContraFect.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Wise, R., et al., Abstract 7711, ATS 2018.

SAN DIEGO – The use of aclidinium bromide 400 mcg b.i.d. did not increase the risk of major adverse cardiac events or mortality in patients with moderate to very severe , compared with placebo.

Those are two key findings from the ASCENT COPD trial presented by Robert A. Wise, MD, at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. “Cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities are prevalent in patients with COPD, and about 30% of COPD patients die of cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Wise, who serves as director of research for the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. “However, patients who have cardiovascular disease are often excluded from, or not enrolled in, COPD clinical trials. Moreover, there has been controversy as to whether or not treatment with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. That’s been seen in randomized trials, meta-analyses, as well as in observational studies.”

Aclidinium bromide 400 mcg b.i.d., administered by the Pressair inhaler, is approved as a maintenance treatment for patients with COPD. However, during the registration studies, there were not an adequate number of cardiovascular events in order to ascertain clearly whether or not the drug was associated with increased risk, Dr. Wise said. Therefore, he and his associates in the ASCENT COPD study set out to assess the long-term cardiovascular safety profile of aclidinium 400 mcg b.i.d. in patients with moderate to very severe COPD at risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) for up to 3 years (Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5[1]:5-15). For the randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study, patients received treatment with aclidinium bromide or a placebo inhaler of similar appearance. The study was designed to be terminated when at least 122 patients experienced an adjudicated MACE. The primary safety endpoint was time to first MACE during follow-up of up to 3 years, while the primary efficacy endpoint was the rate of moderate to severe exacerbations per patient per year during the first year of treatment.

To be included in the study, patients had to be at least 40 years of age with moderate to very severe stable COPD, have a smoking history of at least 10 pack-years, and have at least one of the following significant risk factors: cerebrovascular disease; coronary artery disease; peripheral vascular disease, or history of claudication; or at least two atherothrombotic risk factors (male at least 65 years of age, female at least 70 years of age; waist circumference of at least 40 inches among males or at least 38 inches among females; an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min and microalbuminuria; dyslipidemia; or hypertension).

The researchers randomized 1,791 patients to the aclidinium group and 1,798 to the placebo group. Their mean age was 67 years, and about 60% of patients had an exacerbation in the preceding year. Nearly two-thirds of patients (63%) were receiving concomitant long-acting beta 2-agonists (LABA) or LABA/inhaled corticosteroid therapy. In addition, 44% of patients entered the study with a history of a prior cardiovascular event plus at least two atherothrombotic risk factors, 52% reported at least two atherothrombotic risk factors without any prior cardiovascular events, and 4% had a history of a prior cardiovascular event only.

Dr. Wise reported that aclidinium did not increase the risk of MACE in patients with moderate to very severe COPD with significant cardiovascular risk factors, compared with placebo (hazard ratio 0.89; P = .469); non-inferiority was concluded as the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval was less than 1.8). In terms of all-cause mortality, aclidinium did not increase the risk of death, compared with placebo (HR 0.99; P = .929).

During the first year of treatment, Dr. Wise and his associates also observed a 22% reduction in COPD exacerbation rate for aclidinium vs. placebo groups (HR 0.44 vs. 0.57, respectively; P less than .001), and a 35% reduction in the rate of COPD exacerbations leading to hospitalizations (HR 0.07 vs. 0.10; P = .006). “The reduction in exacerbation risk was similar, whether or not patients had an exacerbation in the past year,” Dr. Wise said. He reported being a consultant to, and receiving research support from, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and ContraFect.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Wise, R., et al., Abstract 7711, ATS 2018.

AT ATS 2018

Key clinical point: Researchers found no increased risk of MACE in at-risk patients with COPD receiving aclidinium.

Major finding: MACE risk and mortality in COPD patients with significant cardiovascular risk given aclidinium bromide had a hazard ratio 0.89 (P = .469), compared to placebo.

Study details: A randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of 3,589 patients with moderate to very severe COPD at risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.

Disclosures: Dr. Wise reported being a consultant to, and receiving research support from, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and ContraFect.

Source: Wise, R. et al, ATS 2018, Abstract 7711.

Education sessions upped COPD patients’ knowledge of their disease

A brief patient-directed education program delivered at the time of hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) improved disease-specific knowledge, according to results of a pilot randomized trial.

Patients who participated in education sessions had a significant improvement in their scores on the Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ), compared with control patients who received no education, study investigators reported in the journal Chest.

“Early education may be a bridge to more active approaches and could provide an important contribution to self-management interventions post-AECOPD,” wrote first author Tania Janaudis-Ferreira, PhD, of the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, McGill University, Montreal, and her co-authors.

In the study, patients admitted to a community hospital with an AECOPD were randomized to standard care plus brief education or standard care alone. The education consisted of two 30-minute sessions delivered by a physiotherapist, either in the hospital or at home up to 2 weeks after the admission.

Before and after the intervention period, participant knowledge was measured using both the BCKQ and the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire (LINQ).

A total of 31 patients participated, including 15 in the intervention group and 16 in the control group, although 3 patients in the control group did not complete the follow-up testing, investigators said in their report.

The mean change in BCKQ was 8 points for the educational intervention group, and 3.4 for the control group (P = 0.02). That result was in keeping with findings of a previous randomized study noting an 8.3-point change in BCKQ scores for COPD patients who received education in the primary care setting, Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors said.

“The change itself is relatively modest, suggesting more frequent sessions might result in greater improvements,” they wrote. For example, they said, an 8-week educational intervention delivered in the context of pulmonary rehabilitation program in one study yielded a mean change of 18.3 points on the BCKQ in the intervention group.

By contrast, the investigators found no significant difference in LINQ score changes between the intervention and control groups (P = .8).

That may indicate that two 30-minute sessions were not sufficient to attend to patients’ learning needs, authors said, though it could also have been an issue with the instrument itself in the setting of this study.

“The majority of the questions in the LINQ ask whether or not a doctor or nurse has explained a specific question to the patient,” authors explained. “Since a physiotherapist delivered the program, had the wording been altered to include physiotherapists or a more general term for healthcare professionals, we may have seen a change in these results.”

Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals, which did not have input in research or manuscript development.

SOURCE: Janaudis-Ferreira T, et al. Chest

A brief patient-directed education program delivered at the time of hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) improved disease-specific knowledge, according to results of a pilot randomized trial.

Patients who participated in education sessions had a significant improvement in their scores on the Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ), compared with control patients who received no education, study investigators reported in the journal Chest.

“Early education may be a bridge to more active approaches and could provide an important contribution to self-management interventions post-AECOPD,” wrote first author Tania Janaudis-Ferreira, PhD, of the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, McGill University, Montreal, and her co-authors.

In the study, patients admitted to a community hospital with an AECOPD were randomized to standard care plus brief education or standard care alone. The education consisted of two 30-minute sessions delivered by a physiotherapist, either in the hospital or at home up to 2 weeks after the admission.

Before and after the intervention period, participant knowledge was measured using both the BCKQ and the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire (LINQ).

A total of 31 patients participated, including 15 in the intervention group and 16 in the control group, although 3 patients in the control group did not complete the follow-up testing, investigators said in their report.

The mean change in BCKQ was 8 points for the educational intervention group, and 3.4 for the control group (P = 0.02). That result was in keeping with findings of a previous randomized study noting an 8.3-point change in BCKQ scores for COPD patients who received education in the primary care setting, Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors said.

“The change itself is relatively modest, suggesting more frequent sessions might result in greater improvements,” they wrote. For example, they said, an 8-week educational intervention delivered in the context of pulmonary rehabilitation program in one study yielded a mean change of 18.3 points on the BCKQ in the intervention group.

By contrast, the investigators found no significant difference in LINQ score changes between the intervention and control groups (P = .8).

That may indicate that two 30-minute sessions were not sufficient to attend to patients’ learning needs, authors said, though it could also have been an issue with the instrument itself in the setting of this study.

“The majority of the questions in the LINQ ask whether or not a doctor or nurse has explained a specific question to the patient,” authors explained. “Since a physiotherapist delivered the program, had the wording been altered to include physiotherapists or a more general term for healthcare professionals, we may have seen a change in these results.”

Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals, which did not have input in research or manuscript development.

SOURCE: Janaudis-Ferreira T, et al. Chest

A brief patient-directed education program delivered at the time of hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) improved disease-specific knowledge, according to results of a pilot randomized trial.

Patients who participated in education sessions had a significant improvement in their scores on the Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ), compared with control patients who received no education, study investigators reported in the journal Chest.

“Early education may be a bridge to more active approaches and could provide an important contribution to self-management interventions post-AECOPD,” wrote first author Tania Janaudis-Ferreira, PhD, of the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, McGill University, Montreal, and her co-authors.

In the study, patients admitted to a community hospital with an AECOPD were randomized to standard care plus brief education or standard care alone. The education consisted of two 30-minute sessions delivered by a physiotherapist, either in the hospital or at home up to 2 weeks after the admission.

Before and after the intervention period, participant knowledge was measured using both the BCKQ and the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire (LINQ).

A total of 31 patients participated, including 15 in the intervention group and 16 in the control group, although 3 patients in the control group did not complete the follow-up testing, investigators said in their report.

The mean change in BCKQ was 8 points for the educational intervention group, and 3.4 for the control group (P = 0.02). That result was in keeping with findings of a previous randomized study noting an 8.3-point change in BCKQ scores for COPD patients who received education in the primary care setting, Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors said.

“The change itself is relatively modest, suggesting more frequent sessions might result in greater improvements,” they wrote. For example, they said, an 8-week educational intervention delivered in the context of pulmonary rehabilitation program in one study yielded a mean change of 18.3 points on the BCKQ in the intervention group.

By contrast, the investigators found no significant difference in LINQ score changes between the intervention and control groups (P = .8).

That may indicate that two 30-minute sessions were not sufficient to attend to patients’ learning needs, authors said, though it could also have been an issue with the instrument itself in the setting of this study.

“The majority of the questions in the LINQ ask whether or not a doctor or nurse has explained a specific question to the patient,” authors explained. “Since a physiotherapist delivered the program, had the wording been altered to include physiotherapists or a more general term for healthcare professionals, we may have seen a change in these results.”

Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals, which did not have input in research or manuscript development.

SOURCE: Janaudis-Ferreira T, et al. Chest

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Two 30-minute education sessions improved patients’ disease-specific knowledge for an acute exacerbation of COPD.

Major finding: Mean change on the Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ) was 8 points for the educational intervention, and 3.4 for controls.

Study details: A pilot randomized controlled trial of 31 patients admitted to a community hospital.

Disclosures: Authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals, which did not have input in research or manuscript development.

Source: Janaudis-Ferreira T, et al. Chest 2018 Jun 4.

The IHS Helps Youth Transition Safely Back to the Community

When young people successfully complete an Indian Health Service (IHS) Youth Regional Treatment Center (YRTC) program, they often leave the structured environment to return to a community and family that cannot provide them with the necessary aftercare. The IHS has launched the YRTC Aftercare Pilot Project to fill that gap.

The 12 federal and tribal YRTCs provide a range of clinical services “rooted in culturally relevant, holistic models of care” to American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) adolescents who abuse alcohol or drugs. But without aftercare and case management, the young people are at risk for falling back into old ways.

The YRTC project will identify transitional services that can be culturally adapted to meet the needs of AI/AN youth to support resiliency and coping skills and provide support systems. The project developers aim to establish community-based approaches to reduce relapse and encourage reintegration.

The IHS has awarded $1.62 million for YRTC Aftercare Pilot Projects to Healing Lodge of the Seven Nations in Spokane Valley, Washington, and Desert Sage Youth Wellness Center in Hemet, California. The awards are for 3 years. Both sites will develop innovative, collaborative strategies to improve the health of Native youth as they transition back to their communities.

When young people successfully complete an Indian Health Service (IHS) Youth Regional Treatment Center (YRTC) program, they often leave the structured environment to return to a community and family that cannot provide them with the necessary aftercare. The IHS has launched the YRTC Aftercare Pilot Project to fill that gap.

The 12 federal and tribal YRTCs provide a range of clinical services “rooted in culturally relevant, holistic models of care” to American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) adolescents who abuse alcohol or drugs. But without aftercare and case management, the young people are at risk for falling back into old ways.

The YRTC project will identify transitional services that can be culturally adapted to meet the needs of AI/AN youth to support resiliency and coping skills and provide support systems. The project developers aim to establish community-based approaches to reduce relapse and encourage reintegration.

The IHS has awarded $1.62 million for YRTC Aftercare Pilot Projects to Healing Lodge of the Seven Nations in Spokane Valley, Washington, and Desert Sage Youth Wellness Center in Hemet, California. The awards are for 3 years. Both sites will develop innovative, collaborative strategies to improve the health of Native youth as they transition back to their communities.

When young people successfully complete an Indian Health Service (IHS) Youth Regional Treatment Center (YRTC) program, they often leave the structured environment to return to a community and family that cannot provide them with the necessary aftercare. The IHS has launched the YRTC Aftercare Pilot Project to fill that gap.

The 12 federal and tribal YRTCs provide a range of clinical services “rooted in culturally relevant, holistic models of care” to American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) adolescents who abuse alcohol or drugs. But without aftercare and case management, the young people are at risk for falling back into old ways.

The YRTC project will identify transitional services that can be culturally adapted to meet the needs of AI/AN youth to support resiliency and coping skills and provide support systems. The project developers aim to establish community-based approaches to reduce relapse and encourage reintegration.

The IHS has awarded $1.62 million for YRTC Aftercare Pilot Projects to Healing Lodge of the Seven Nations in Spokane Valley, Washington, and Desert Sage Youth Wellness Center in Hemet, California. The awards are for 3 years. Both sites will develop innovative, collaborative strategies to improve the health of Native youth as they transition back to their communities.

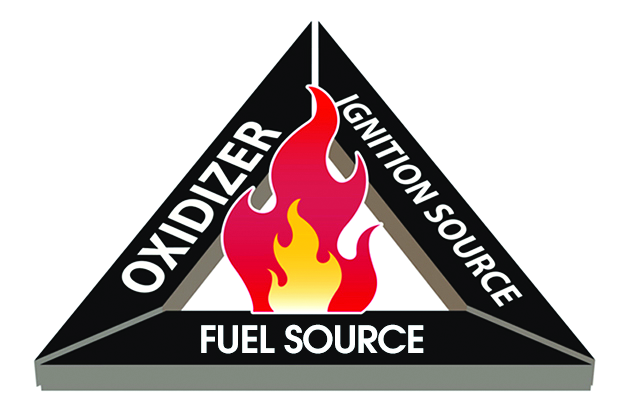

FDA issues recommendations to avoid surgical fires

The Food and Drug Administration on May 29 issued a set of recommendations to medical professionals and health care facility staff to reduce the occurrence of surgical fires on or near a patient.

Surgical fires most often occur when there is an oxygen-enriched environment (a concentration of greater than 30%). In addition to an oxygen source, the other two necessary elements of the “fire triangle” are an ignition source and a fuel source.

The recommendations discuss the safe use of devices or items that may serve as a source of any one of those three elements.

Oxygen: Evaluate if supplemental oxygen is needed. If it is, titrate to the minimum concentration needed for adequate saturation. Closed oxygen delivery systems (such as a laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube) are safer than open oxygen delivery systems (such as a nasal cannula or mask). If you must use an open system, take additional precautions to exclude oxygen and flammable/combustible gases from the operative field, such as draping techniques that avoid accumulation of oxygen.

Ignition sources: Consider alternatives to using an ignition source for surgery of the head, neck, and upper chest if high concentrations of supplemental oxygen are being delivered. Check for insulation failure before use, and keep devices clean of char and tissue. When not in use, place the devices safely away from the patient and drapes. Devices are safer to use if you can allow time for the oxygen concentration in the room to decrease.

Fuel sources: Ensure dry conditions prior to draping, avoiding pooling of alcohol-based antiseptics during skin preparation. Use the appropriate-sized applicator for the surgical site. Be aware of products that may serve as a fuel source, such as oxygen-trapping gauze, plastic laryngeal masks, and aware of potential patient sources such as hair or gastrointestinal gases.

Training should include how to manage fires that do occur – stop the ignition source, then extinguish the fire – and evacuation procedures.

Read the full recommendations here.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 29 issued a set of recommendations to medical professionals and health care facility staff to reduce the occurrence of surgical fires on or near a patient.

Surgical fires most often occur when there is an oxygen-enriched environment (a concentration of greater than 30%). In addition to an oxygen source, the other two necessary elements of the “fire triangle” are an ignition source and a fuel source.

The recommendations discuss the safe use of devices or items that may serve as a source of any one of those three elements.

Oxygen: Evaluate if supplemental oxygen is needed. If it is, titrate to the minimum concentration needed for adequate saturation. Closed oxygen delivery systems (such as a laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube) are safer than open oxygen delivery systems (such as a nasal cannula or mask). If you must use an open system, take additional precautions to exclude oxygen and flammable/combustible gases from the operative field, such as draping techniques that avoid accumulation of oxygen.

Ignition sources: Consider alternatives to using an ignition source for surgery of the head, neck, and upper chest if high concentrations of supplemental oxygen are being delivered. Check for insulation failure before use, and keep devices clean of char and tissue. When not in use, place the devices safely away from the patient and drapes. Devices are safer to use if you can allow time for the oxygen concentration in the room to decrease.

Fuel sources: Ensure dry conditions prior to draping, avoiding pooling of alcohol-based antiseptics during skin preparation. Use the appropriate-sized applicator for the surgical site. Be aware of products that may serve as a fuel source, such as oxygen-trapping gauze, plastic laryngeal masks, and aware of potential patient sources such as hair or gastrointestinal gases.

Training should include how to manage fires that do occur – stop the ignition source, then extinguish the fire – and evacuation procedures.

Read the full recommendations here.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 29 issued a set of recommendations to medical professionals and health care facility staff to reduce the occurrence of surgical fires on or near a patient.

Surgical fires most often occur when there is an oxygen-enriched environment (a concentration of greater than 30%). In addition to an oxygen source, the other two necessary elements of the “fire triangle” are an ignition source and a fuel source.

The recommendations discuss the safe use of devices or items that may serve as a source of any one of those three elements.

Oxygen: Evaluate if supplemental oxygen is needed. If it is, titrate to the minimum concentration needed for adequate saturation. Closed oxygen delivery systems (such as a laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube) are safer than open oxygen delivery systems (such as a nasal cannula or mask). If you must use an open system, take additional precautions to exclude oxygen and flammable/combustible gases from the operative field, such as draping techniques that avoid accumulation of oxygen.

Ignition sources: Consider alternatives to using an ignition source for surgery of the head, neck, and upper chest if high concentrations of supplemental oxygen are being delivered. Check for insulation failure before use, and keep devices clean of char and tissue. When not in use, place the devices safely away from the patient and drapes. Devices are safer to use if you can allow time for the oxygen concentration in the room to decrease.

Fuel sources: Ensure dry conditions prior to draping, avoiding pooling of alcohol-based antiseptics during skin preparation. Use the appropriate-sized applicator for the surgical site. Be aware of products that may serve as a fuel source, such as oxygen-trapping gauze, plastic laryngeal masks, and aware of potential patient sources such as hair or gastrointestinal gases.

Training should include how to manage fires that do occur – stop the ignition source, then extinguish the fire – and evacuation procedures.

Read the full recommendations here.

The case for bariatric surgery to manage CV risk in diabetes

BOSTON – For patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes ( health over the lifespan.

“Behavioral changes in diet and activity may be effective over the short term, but they are often ineffective over the long term,” said Daniel L. Hurley, MD. By contrast, “Bariatric surgery is very effective long-term,” he said.

At the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Dr. Hurley made the case for bariatric surgery in effective and durable management of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk, weighing risks and benefits for those with higher and lower levels of obesity.

Speaking during a morning session focused on bariatric surgery, Dr. Hurley, an endocrionologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., noted that bariatric surgery reduces not just weight, but also visceral adiposity. This, he said, is important when thinking about type 2 diabetes (T2D), because diabetes prevalence has climbed in the United States as obesity has also increased, according to examination of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Additionally, increased abdominal adiposity is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular-related deaths, myocardial infarctions, and all-cause deaths. Some of this relationship is mediated by T2D, which itself “is a major cause of cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Hurley.

From a population health perspective, the increased prevalence of T2D – expected to reach 10% in the United States by 2030 – will also boost cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, said Dr. Hurley. Those with T2D die 5 to 10 years earlier, and have double the risk for heart attack and stroke of their peers without diabetes. The risk of lower limb amputation can be as much as 40 times greater for an individual with T2D across the lifespan, he said.

The National Institutes of Health recognizes bariatric surgery as an appropriate weight loss therapy for individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 35 kg/m2 and comorbidity. Whether bariatric surgery might be appropriate for individuals with T2D and BMIs of less than 35 kg/m2 is less settled, though at least some RCTs support the surgical approach, said Dr. Hurley.

The body of data that support long-term metabolic and cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery as obesity therapy is growing, said Dr. Hurley. A large prospective observational study by the American College of Surgeons’ Bariatric Surgery Center Network followed 28,616 patients, finding that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was most effective in improving or resolving CVD comorbidities. At 1 year post surgery, 83% of RYGB patients saw improvement or resolution of T2D; the figure was 79% for hypertension and 66% for dyslipidemia (Ann Surg. 2011;254[3]:410-20).

Weight loss for patients receiving bariatric procedures has generally been durable: for laparoscopic RYGB patients tracked to 7 years after surgery, 75% had maintained at least a 20% weight loss (JAMA Surg. 2018;153[5]427-34).

Longer-term clinical follow-up points toward favorable metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes, said Dr. Hurley, citing data from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial. This study followed over 4,000 patients with high BMIs (at least 34 kg/m2 for men and 38 kg/m2 for women) over 10 years. At that point, 36% of gastric bypass patients, compared with 13% of non-surgical high BMI patients, saw resolution of T2D, a significant difference. Triglyceride levels also fell significantly more for the bypass recipients. Hypertension was resolved in just 19% of patients at 10 years, a non-significant difference from the 11% of control patients. Data from the same patient set also showed a significant reduction in total cardiovascular events in the surgical versus non-surgical patients (n = 49 vs. 28, hazard ratio 0.83, log-rank P = .05). Fatal cardiovascular events were significantly lower for patients who had received bariatric surgery, with a 24% decline in mortality for bariatric surgery patients at about 11 years post surgery.

Canadian data showed even greater reductions in mortality, with an 89% decrease in mortality after RYGB, compared with non-surgical patients at the 5-year mark (Ann Surg 2004;240:416-24).

In trials that afforded a direct comparison of medical therapy and bariatric surgery obesity and diabetes, Dr. Hurley said that randomized trials generally show no change to modest change in HbA1c levels with medical management. By contrast, patients in the surgical arms showed a range of improvement ranging from a reduction of just under 1% to reductions of over 5%, with an average reduction of more than 2% across the trials.

Separating out data from the randomized controlled trials with patient BMIs averaging 35 kg/m2 or less, odds ratios still favored bariatric surgery over medication therapy for diabetes-related outcomes in this lower-BMI population, said Dr. Hurley (Diabetes Care 2016;39:924-33).

More data come from a recently reported randomized trial that assigned patients with T2D and a mean BMI of 37 kg/m2 (range, 27-43) to intensive medical therapy, or either sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or RYGB. The study, which had a 90% completion rate at the 5-year mark, found that both surgical procedures were significantly more effective at reducing HbA1c to 6% or less 12 months into the study (P less than .001).

At the 60-month mark, 45% of the RYGB and 25% of the SG patients were on no diabetes medications, while just 2% of the medical therapy arm had stopped all medications, and 40% of this group remained on insulin 5 years into the study, said Dr. Hurley (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651).

“For treatment of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular co-morbidities, long-term goals often are met following bariatric surgery versus behavior change,” said Dr. Hurley.

Dr. Hurley reported that he had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Hurley, D. AACE 2018, Session SGS-4.

BOSTON – For patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes ( health over the lifespan.

“Behavioral changes in diet and activity may be effective over the short term, but they are often ineffective over the long term,” said Daniel L. Hurley, MD. By contrast, “Bariatric surgery is very effective long-term,” he said.

At the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Dr. Hurley made the case for bariatric surgery in effective and durable management of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk, weighing risks and benefits for those with higher and lower levels of obesity.

Speaking during a morning session focused on bariatric surgery, Dr. Hurley, an endocrionologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., noted that bariatric surgery reduces not just weight, but also visceral adiposity. This, he said, is important when thinking about type 2 diabetes (T2D), because diabetes prevalence has climbed in the United States as obesity has also increased, according to examination of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Additionally, increased abdominal adiposity is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular-related deaths, myocardial infarctions, and all-cause deaths. Some of this relationship is mediated by T2D, which itself “is a major cause of cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Hurley.

From a population health perspective, the increased prevalence of T2D – expected to reach 10% in the United States by 2030 – will also boost cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, said Dr. Hurley. Those with T2D die 5 to 10 years earlier, and have double the risk for heart attack and stroke of their peers without diabetes. The risk of lower limb amputation can be as much as 40 times greater for an individual with T2D across the lifespan, he said.

The National Institutes of Health recognizes bariatric surgery as an appropriate weight loss therapy for individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 35 kg/m2 and comorbidity. Whether bariatric surgery might be appropriate for individuals with T2D and BMIs of less than 35 kg/m2 is less settled, though at least some RCTs support the surgical approach, said Dr. Hurley.

The body of data that support long-term metabolic and cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery as obesity therapy is growing, said Dr. Hurley. A large prospective observational study by the American College of Surgeons’ Bariatric Surgery Center Network followed 28,616 patients, finding that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was most effective in improving or resolving CVD comorbidities. At 1 year post surgery, 83% of RYGB patients saw improvement or resolution of T2D; the figure was 79% for hypertension and 66% for dyslipidemia (Ann Surg. 2011;254[3]:410-20).

Weight loss for patients receiving bariatric procedures has generally been durable: for laparoscopic RYGB patients tracked to 7 years after surgery, 75% had maintained at least a 20% weight loss (JAMA Surg. 2018;153[5]427-34).

Longer-term clinical follow-up points toward favorable metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes, said Dr. Hurley, citing data from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial. This study followed over 4,000 patients with high BMIs (at least 34 kg/m2 for men and 38 kg/m2 for women) over 10 years. At that point, 36% of gastric bypass patients, compared with 13% of non-surgical high BMI patients, saw resolution of T2D, a significant difference. Triglyceride levels also fell significantly more for the bypass recipients. Hypertension was resolved in just 19% of patients at 10 years, a non-significant difference from the 11% of control patients. Data from the same patient set also showed a significant reduction in total cardiovascular events in the surgical versus non-surgical patients (n = 49 vs. 28, hazard ratio 0.83, log-rank P = .05). Fatal cardiovascular events were significantly lower for patients who had received bariatric surgery, with a 24% decline in mortality for bariatric surgery patients at about 11 years post surgery.

Canadian data showed even greater reductions in mortality, with an 89% decrease in mortality after RYGB, compared with non-surgical patients at the 5-year mark (Ann Surg 2004;240:416-24).

In trials that afforded a direct comparison of medical therapy and bariatric surgery obesity and diabetes, Dr. Hurley said that randomized trials generally show no change to modest change in HbA1c levels with medical management. By contrast, patients in the surgical arms showed a range of improvement ranging from a reduction of just under 1% to reductions of over 5%, with an average reduction of more than 2% across the trials.

Separating out data from the randomized controlled trials with patient BMIs averaging 35 kg/m2 or less, odds ratios still favored bariatric surgery over medication therapy for diabetes-related outcomes in this lower-BMI population, said Dr. Hurley (Diabetes Care 2016;39:924-33).

More data come from a recently reported randomized trial that assigned patients with T2D and a mean BMI of 37 kg/m2 (range, 27-43) to intensive medical therapy, or either sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or RYGB. The study, which had a 90% completion rate at the 5-year mark, found that both surgical procedures were significantly more effective at reducing HbA1c to 6% or less 12 months into the study (P less than .001).

At the 60-month mark, 45% of the RYGB and 25% of the SG patients were on no diabetes medications, while just 2% of the medical therapy arm had stopped all medications, and 40% of this group remained on insulin 5 years into the study, said Dr. Hurley (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651).

“For treatment of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular co-morbidities, long-term goals often are met following bariatric surgery versus behavior change,” said Dr. Hurley.

Dr. Hurley reported that he had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Hurley, D. AACE 2018, Session SGS-4.

BOSTON – For patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes ( health over the lifespan.

“Behavioral changes in diet and activity may be effective over the short term, but they are often ineffective over the long term,” said Daniel L. Hurley, MD. By contrast, “Bariatric surgery is very effective long-term,” he said.

At the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Dr. Hurley made the case for bariatric surgery in effective and durable management of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk, weighing risks and benefits for those with higher and lower levels of obesity.

Speaking during a morning session focused on bariatric surgery, Dr. Hurley, an endocrionologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., noted that bariatric surgery reduces not just weight, but also visceral adiposity. This, he said, is important when thinking about type 2 diabetes (T2D), because diabetes prevalence has climbed in the United States as obesity has also increased, according to examination of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Additionally, increased abdominal adiposity is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular-related deaths, myocardial infarctions, and all-cause deaths. Some of this relationship is mediated by T2D, which itself “is a major cause of cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Hurley.

From a population health perspective, the increased prevalence of T2D – expected to reach 10% in the United States by 2030 – will also boost cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, said Dr. Hurley. Those with T2D die 5 to 10 years earlier, and have double the risk for heart attack and stroke of their peers without diabetes. The risk of lower limb amputation can be as much as 40 times greater for an individual with T2D across the lifespan, he said.

The National Institutes of Health recognizes bariatric surgery as an appropriate weight loss therapy for individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 35 kg/m2 and comorbidity. Whether bariatric surgery might be appropriate for individuals with T2D and BMIs of less than 35 kg/m2 is less settled, though at least some RCTs support the surgical approach, said Dr. Hurley.

The body of data that support long-term metabolic and cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery as obesity therapy is growing, said Dr. Hurley. A large prospective observational study by the American College of Surgeons’ Bariatric Surgery Center Network followed 28,616 patients, finding that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was most effective in improving or resolving CVD comorbidities. At 1 year post surgery, 83% of RYGB patients saw improvement or resolution of T2D; the figure was 79% for hypertension and 66% for dyslipidemia (Ann Surg. 2011;254[3]:410-20).

Weight loss for patients receiving bariatric procedures has generally been durable: for laparoscopic RYGB patients tracked to 7 years after surgery, 75% had maintained at least a 20% weight loss (JAMA Surg. 2018;153[5]427-34).

Longer-term clinical follow-up points toward favorable metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes, said Dr. Hurley, citing data from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial. This study followed over 4,000 patients with high BMIs (at least 34 kg/m2 for men and 38 kg/m2 for women) over 10 years. At that point, 36% of gastric bypass patients, compared with 13% of non-surgical high BMI patients, saw resolution of T2D, a significant difference. Triglyceride levels also fell significantly more for the bypass recipients. Hypertension was resolved in just 19% of patients at 10 years, a non-significant difference from the 11% of control patients. Data from the same patient set also showed a significant reduction in total cardiovascular events in the surgical versus non-surgical patients (n = 49 vs. 28, hazard ratio 0.83, log-rank P = .05). Fatal cardiovascular events were significantly lower for patients who had received bariatric surgery, with a 24% decline in mortality for bariatric surgery patients at about 11 years post surgery.

Canadian data showed even greater reductions in mortality, with an 89% decrease in mortality after RYGB, compared with non-surgical patients at the 5-year mark (Ann Surg 2004;240:416-24).

In trials that afforded a direct comparison of medical therapy and bariatric surgery obesity and diabetes, Dr. Hurley said that randomized trials generally show no change to modest change in HbA1c levels with medical management. By contrast, patients in the surgical arms showed a range of improvement ranging from a reduction of just under 1% to reductions of over 5%, with an average reduction of more than 2% across the trials.

Separating out data from the randomized controlled trials with patient BMIs averaging 35 kg/m2 or less, odds ratios still favored bariatric surgery over medication therapy for diabetes-related outcomes in this lower-BMI population, said Dr. Hurley (Diabetes Care 2016;39:924-33).

More data come from a recently reported randomized trial that assigned patients with T2D and a mean BMI of 37 kg/m2 (range, 27-43) to intensive medical therapy, or either sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or RYGB. The study, which had a 90% completion rate at the 5-year mark, found that both surgical procedures were significantly more effective at reducing HbA1c to 6% or less 12 months into the study (P less than .001).

At the 60-month mark, 45% of the RYGB and 25% of the SG patients were on no diabetes medications, while just 2% of the medical therapy arm had stopped all medications, and 40% of this group remained on insulin 5 years into the study, said Dr. Hurley (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651).

“For treatment of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular co-morbidities, long-term goals often are met following bariatric surgery versus behavior change,” said Dr. Hurley.

Dr. Hurley reported that he had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Hurley, D. AACE 2018, Session SGS-4.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AACE 2018

Dasatinib outcomes similar to imatinib in pediatric Ph+ ALL

Dasatinib used during induction and consolidation in the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL0622 trial provided early response rates for children with Ph-positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to investigators.

But the early response rates did not improve event-free survival (EFS) compared to the use of consolidation imatinib in the AALL0031 study.

Incidence of cranial relapse was more than doubled in AALL0622 compared to AALL0031.

The investigators believe the incidence of cranial relapse may explain the results of AALL0622.

“We cannot yet conclude that the current dasatinib plus chemotherapy combination is better than imatinib plus chemotherapy,” the authors stated.

AALL0622 was designed to be an improvement on AALL0031, which demonstrated that adding the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib to intensive chemotherapy in the consolidation phase significantly improved survival for children with Ph+ ALL.

In AALL0622 dasatinib was given early in induction (day 15) and then in consolidation with the hope that patients could achieve early remission.

Another departure from AALL0031 was that cranial irradiation was not provided for control of central nervous system (CNS) metastasis. Because dasatinib accumulates in the CNS, which is a ‘sanctuary site’ for leukemia, it was presumed that patients could benefit from a TKI yet be spared from cranial irradiation.

As expected, adding dasatinib mid-induction provided a complete remission rate of 98% at the end of induction (day 29), which was better than the 89% seen in AALL0031.

In addition, more patients in AALL0622 showed minimal residual disease (MRD) <0.01% at the end of induction: 59% vs 25% in AALL0031 (P <0.001). At the end of consolidation, corresponding rates were 89% vs 71% for AALL0031.

For the primary outcome, 3-year EFS was 84.6% for patients in AALL0622 in standard-risk patients. Five-year OS and EFS rates were 86% and 60%, respectively.

In patients with overt brain metastasis (CNS3 status), 5-year CNS relapse was 15% for patients in the AALL0622 study vs 6.6% for patients in the AALL031 study.

However, 5-year OS rates were similar in the two groups of patients: 86% for AALL0622 vs 81% for AALL0031.

HSCT

AALL0622 allowed the use of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in high-risk patients as well as in standard-risk patients with a sibling donor.

Five-year OS and EFS for standard-risk patients (19% underwent HSCT at first remission) and high-risk patients (91% underwent HSCT in first remission) were similar.

Children who did not undergo HSCT had a similar 5-year OS of 88%, which suggested that children with Ph+ ALL should not undergo transplantation at first remission.

Samples from a subset of patients was analyzed for IKZF1 mutations and correlated with outcomes.

Five-year OS was 80% in those harboring the mutation versus 100% who had the wild-type gene (P=0.04); 4-year EFS was also significantly lower—10% vs 82% (P=0.04).

Screening for IKZF1 may be used to identify high-risk patients suitable for HSCT and/or alternate treatment, the authors note.

The investigators reported their findings in The Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Dasatinib used during induction and consolidation in the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL0622 trial provided early response rates for children with Ph-positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to investigators.

But the early response rates did not improve event-free survival (EFS) compared to the use of consolidation imatinib in the AALL0031 study.

Incidence of cranial relapse was more than doubled in AALL0622 compared to AALL0031.

The investigators believe the incidence of cranial relapse may explain the results of AALL0622.

“We cannot yet conclude that the current dasatinib plus chemotherapy combination is better than imatinib plus chemotherapy,” the authors stated.

AALL0622 was designed to be an improvement on AALL0031, which demonstrated that adding the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib to intensive chemotherapy in the consolidation phase significantly improved survival for children with Ph+ ALL.

In AALL0622 dasatinib was given early in induction (day 15) and then in consolidation with the hope that patients could achieve early remission.

Another departure from AALL0031 was that cranial irradiation was not provided for control of central nervous system (CNS) metastasis. Because dasatinib accumulates in the CNS, which is a ‘sanctuary site’ for leukemia, it was presumed that patients could benefit from a TKI yet be spared from cranial irradiation.

As expected, adding dasatinib mid-induction provided a complete remission rate of 98% at the end of induction (day 29), which was better than the 89% seen in AALL0031.

In addition, more patients in AALL0622 showed minimal residual disease (MRD) <0.01% at the end of induction: 59% vs 25% in AALL0031 (P <0.001). At the end of consolidation, corresponding rates were 89% vs 71% for AALL0031.

For the primary outcome, 3-year EFS was 84.6% for patients in AALL0622 in standard-risk patients. Five-year OS and EFS rates were 86% and 60%, respectively.

In patients with overt brain metastasis (CNS3 status), 5-year CNS relapse was 15% for patients in the AALL0622 study vs 6.6% for patients in the AALL031 study.

However, 5-year OS rates were similar in the two groups of patients: 86% for AALL0622 vs 81% for AALL0031.

HSCT

AALL0622 allowed the use of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in high-risk patients as well as in standard-risk patients with a sibling donor.

Five-year OS and EFS for standard-risk patients (19% underwent HSCT at first remission) and high-risk patients (91% underwent HSCT in first remission) were similar.

Children who did not undergo HSCT had a similar 5-year OS of 88%, which suggested that children with Ph+ ALL should not undergo transplantation at first remission.

Samples from a subset of patients was analyzed for IKZF1 mutations and correlated with outcomes.

Five-year OS was 80% in those harboring the mutation versus 100% who had the wild-type gene (P=0.04); 4-year EFS was also significantly lower—10% vs 82% (P=0.04).

Screening for IKZF1 may be used to identify high-risk patients suitable for HSCT and/or alternate treatment, the authors note.

The investigators reported their findings in The Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Dasatinib used during induction and consolidation in the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL0622 trial provided early response rates for children with Ph-positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to investigators.

But the early response rates did not improve event-free survival (EFS) compared to the use of consolidation imatinib in the AALL0031 study.

Incidence of cranial relapse was more than doubled in AALL0622 compared to AALL0031.

The investigators believe the incidence of cranial relapse may explain the results of AALL0622.

“We cannot yet conclude that the current dasatinib plus chemotherapy combination is better than imatinib plus chemotherapy,” the authors stated.

AALL0622 was designed to be an improvement on AALL0031, which demonstrated that adding the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib to intensive chemotherapy in the consolidation phase significantly improved survival for children with Ph+ ALL.

In AALL0622 dasatinib was given early in induction (day 15) and then in consolidation with the hope that patients could achieve early remission.

Another departure from AALL0031 was that cranial irradiation was not provided for control of central nervous system (CNS) metastasis. Because dasatinib accumulates in the CNS, which is a ‘sanctuary site’ for leukemia, it was presumed that patients could benefit from a TKI yet be spared from cranial irradiation.

As expected, adding dasatinib mid-induction provided a complete remission rate of 98% at the end of induction (day 29), which was better than the 89% seen in AALL0031.

In addition, more patients in AALL0622 showed minimal residual disease (MRD) <0.01% at the end of induction: 59% vs 25% in AALL0031 (P <0.001). At the end of consolidation, corresponding rates were 89% vs 71% for AALL0031.

For the primary outcome, 3-year EFS was 84.6% for patients in AALL0622 in standard-risk patients. Five-year OS and EFS rates were 86% and 60%, respectively.

In patients with overt brain metastasis (CNS3 status), 5-year CNS relapse was 15% for patients in the AALL0622 study vs 6.6% for patients in the AALL031 study.

However, 5-year OS rates were similar in the two groups of patients: 86% for AALL0622 vs 81% for AALL0031.

HSCT

AALL0622 allowed the use of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in high-risk patients as well as in standard-risk patients with a sibling donor.

Five-year OS and EFS for standard-risk patients (19% underwent HSCT at first remission) and high-risk patients (91% underwent HSCT in first remission) were similar.

Children who did not undergo HSCT had a similar 5-year OS of 88%, which suggested that children with Ph+ ALL should not undergo transplantation at first remission.

Samples from a subset of patients was analyzed for IKZF1 mutations and correlated with outcomes.

Five-year OS was 80% in those harboring the mutation versus 100% who had the wild-type gene (P=0.04); 4-year EFS was also significantly lower—10% vs 82% (P=0.04).

Screening for IKZF1 may be used to identify high-risk patients suitable for HSCT and/or alternate treatment, the authors note.

The investigators reported their findings in The Journal of Clinical Oncology.

DOJ won’t defend ACA from lawsuit challenging constitutionality