User login

FLT3-L level may point to relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma

FLT3-ligand (FLT3-L) levels exceeding 92 pg/mL in bone marrow and 121 pg/mL in peripheral blood are associated with relapsed and refractory disease in patients with multiple myeloma, Normann Steiner, MD, and his colleagues report in a study published in PLoS ONE.

In the study of 14 patients with monoclonal gamm opathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), 42 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, and 27 patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma, there was a 61% probability that patients with FLT3-L levels above 92 pg/mL in bone marrow had relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma and a 79% probability that those with FLT3-L levels of 92 pg/mL or less had not relapsed and were not refractory. Based on FLT3-L levels in peripheral blood, values of 121 pg/mL or more were associated with a 71% probability of relapsed or refractory disease. The likelihood of not having relapses or refractory disease was 87% for patients with values less than 121 pg/mL.

“FLT3-L could be useful as a marker to identify (relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma) patients and should be evaluated as a potential target for future therapy strategies,” Dr. Steiner of Innsbruck (Austria) Medical University, and his fellow researchers wrote in PLoS ONE.

The researchers obtained bone marrow aspirates from all patients. Peripheral blood was examined from 4 MGUS patients, 31 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, and 16 patients with relapsed or refractory myeloma. Peripheral blood was also obtained from 16 control subjects.

The levels of four potential risk factors were measured – soluble TIE2, FLT3-L, endostatin, and osteoactivin. The most significant association with risk was seen with FLT3-L levels.

Expression of soluble TIE2 in bone marrow differed significantly among the three patient cohorts and may be driven by the same factors that influence FLT3-L levels. However, soluble TIE2 levels were not as effective at differentiating patients at risk for disease progression, the researchers wrote.

Soluble TIE2 expression in bone marrow was highest in MGUS patients (median 4003.97 pg/mL) in comparison to relapsed or refractory disease (median 2223.26 pg/mL; P = .03) and to newly diagnosed patients with myeloma (median 861.98 pg/mL; P less than .001). A statistically significant difference among bone marrow levels of soluble TIE2 was observed for newly diagnosed patients and those with relapsed or refractory disease (P = .03).

However, soluble TIE2 in peripheral blood plasma did not differ significantly in the three cohorts nor did it differ between patients and controls.

In contrast to TIE2 and FLT3-L, levels of endostatin were lowest (median 146.50 ng/mL) in bone marrow plasma samples of patients with relapsed or refractory disease. Levels were higher in MGUS patients (median 190.37 mg/dL) than in newly diagnosed myeloma patients (median 170.15 mg/mL; P = .5).

Similar to soluble TIE2, plasma levels of endostatin in peripheral blood did not differ significantly in the three patient cohorts. Measurements of endostatin in bone marrow and peripheral blood correlated significantly (P less than .001), and peripheral blood levels differed significantly (P less than .001) for patients and control persons.

Osteoactivin expression was highest in the MGUS cohort, with median bone marrow plasma levels of 36 ng/mL as compared with median levels of 24.92 ng/mL in newly diagnosed myeloma patients and 22.30 ng/mL in patients with relapsed or refractory myeloma. Osteoactivin levels in peripheral blood did not differ significantly in the three cohorts, but differed between patients and control subjects. Osteoactivin measures in bone marrow and peripheral blood correlated significantly.

Citation: Steiner N, et al. High levels of FLT3-ligand in bone marrow and peripheral blood of patients with advanced multiple myeloma. PLoS ONE 2017 Jul 20;12:e0181487. doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181487.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

FLT3-ligand (FLT3-L) levels exceeding 92 pg/mL in bone marrow and 121 pg/mL in peripheral blood are associated with relapsed and refractory disease in patients with multiple myeloma, Normann Steiner, MD, and his colleagues report in a study published in PLoS ONE.

In the study of 14 patients with monoclonal gamm opathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), 42 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, and 27 patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma, there was a 61% probability that patients with FLT3-L levels above 92 pg/mL in bone marrow had relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma and a 79% probability that those with FLT3-L levels of 92 pg/mL or less had not relapsed and were not refractory. Based on FLT3-L levels in peripheral blood, values of 121 pg/mL or more were associated with a 71% probability of relapsed or refractory disease. The likelihood of not having relapses or refractory disease was 87% for patients with values less than 121 pg/mL.

“FLT3-L could be useful as a marker to identify (relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma) patients and should be evaluated as a potential target for future therapy strategies,” Dr. Steiner of Innsbruck (Austria) Medical University, and his fellow researchers wrote in PLoS ONE.

The researchers obtained bone marrow aspirates from all patients. Peripheral blood was examined from 4 MGUS patients, 31 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, and 16 patients with relapsed or refractory myeloma. Peripheral blood was also obtained from 16 control subjects.

The levels of four potential risk factors were measured – soluble TIE2, FLT3-L, endostatin, and osteoactivin. The most significant association with risk was seen with FLT3-L levels.

Expression of soluble TIE2 in bone marrow differed significantly among the three patient cohorts and may be driven by the same factors that influence FLT3-L levels. However, soluble TIE2 levels were not as effective at differentiating patients at risk for disease progression, the researchers wrote.

Soluble TIE2 expression in bone marrow was highest in MGUS patients (median 4003.97 pg/mL) in comparison to relapsed or refractory disease (median 2223.26 pg/mL; P = .03) and to newly diagnosed patients with myeloma (median 861.98 pg/mL; P less than .001). A statistically significant difference among bone marrow levels of soluble TIE2 was observed for newly diagnosed patients and those with relapsed or refractory disease (P = .03).

However, soluble TIE2 in peripheral blood plasma did not differ significantly in the three cohorts nor did it differ between patients and controls.

In contrast to TIE2 and FLT3-L, levels of endostatin were lowest (median 146.50 ng/mL) in bone marrow plasma samples of patients with relapsed or refractory disease. Levels were higher in MGUS patients (median 190.37 mg/dL) than in newly diagnosed myeloma patients (median 170.15 mg/mL; P = .5).

Similar to soluble TIE2, plasma levels of endostatin in peripheral blood did not differ significantly in the three patient cohorts. Measurements of endostatin in bone marrow and peripheral blood correlated significantly (P less than .001), and peripheral blood levels differed significantly (P less than .001) for patients and control persons.

Osteoactivin expression was highest in the MGUS cohort, with median bone marrow plasma levels of 36 ng/mL as compared with median levels of 24.92 ng/mL in newly diagnosed myeloma patients and 22.30 ng/mL in patients with relapsed or refractory myeloma. Osteoactivin levels in peripheral blood did not differ significantly in the three cohorts, but differed between patients and control subjects. Osteoactivin measures in bone marrow and peripheral blood correlated significantly.

Citation: Steiner N, et al. High levels of FLT3-ligand in bone marrow and peripheral blood of patients with advanced multiple myeloma. PLoS ONE 2017 Jul 20;12:e0181487. doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181487.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

FLT3-ligand (FLT3-L) levels exceeding 92 pg/mL in bone marrow and 121 pg/mL in peripheral blood are associated with relapsed and refractory disease in patients with multiple myeloma, Normann Steiner, MD, and his colleagues report in a study published in PLoS ONE.

In the study of 14 patients with monoclonal gamm opathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), 42 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, and 27 patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma, there was a 61% probability that patients with FLT3-L levels above 92 pg/mL in bone marrow had relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma and a 79% probability that those with FLT3-L levels of 92 pg/mL or less had not relapsed and were not refractory. Based on FLT3-L levels in peripheral blood, values of 121 pg/mL or more were associated with a 71% probability of relapsed or refractory disease. The likelihood of not having relapses or refractory disease was 87% for patients with values less than 121 pg/mL.

“FLT3-L could be useful as a marker to identify (relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma) patients and should be evaluated as a potential target for future therapy strategies,” Dr. Steiner of Innsbruck (Austria) Medical University, and his fellow researchers wrote in PLoS ONE.

The researchers obtained bone marrow aspirates from all patients. Peripheral blood was examined from 4 MGUS patients, 31 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, and 16 patients with relapsed or refractory myeloma. Peripheral blood was also obtained from 16 control subjects.

The levels of four potential risk factors were measured – soluble TIE2, FLT3-L, endostatin, and osteoactivin. The most significant association with risk was seen with FLT3-L levels.

Expression of soluble TIE2 in bone marrow differed significantly among the three patient cohorts and may be driven by the same factors that influence FLT3-L levels. However, soluble TIE2 levels were not as effective at differentiating patients at risk for disease progression, the researchers wrote.

Soluble TIE2 expression in bone marrow was highest in MGUS patients (median 4003.97 pg/mL) in comparison to relapsed or refractory disease (median 2223.26 pg/mL; P = .03) and to newly diagnosed patients with myeloma (median 861.98 pg/mL; P less than .001). A statistically significant difference among bone marrow levels of soluble TIE2 was observed for newly diagnosed patients and those with relapsed or refractory disease (P = .03).

However, soluble TIE2 in peripheral blood plasma did not differ significantly in the three cohorts nor did it differ between patients and controls.

In contrast to TIE2 and FLT3-L, levels of endostatin were lowest (median 146.50 ng/mL) in bone marrow plasma samples of patients with relapsed or refractory disease. Levels were higher in MGUS patients (median 190.37 mg/dL) than in newly diagnosed myeloma patients (median 170.15 mg/mL; P = .5).

Similar to soluble TIE2, plasma levels of endostatin in peripheral blood did not differ significantly in the three patient cohorts. Measurements of endostatin in bone marrow and peripheral blood correlated significantly (P less than .001), and peripheral blood levels differed significantly (P less than .001) for patients and control persons.

Osteoactivin expression was highest in the MGUS cohort, with median bone marrow plasma levels of 36 ng/mL as compared with median levels of 24.92 ng/mL in newly diagnosed myeloma patients and 22.30 ng/mL in patients with relapsed or refractory myeloma. Osteoactivin levels in peripheral blood did not differ significantly in the three cohorts, but differed between patients and control subjects. Osteoactivin measures in bone marrow and peripheral blood correlated significantly.

Citation: Steiner N, et al. High levels of FLT3-ligand in bone marrow and peripheral blood of patients with advanced multiple myeloma. PLoS ONE 2017 Jul 20;12:e0181487. doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181487.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM PLOS ONE

Key clinical point: .

Major finding: There was a 61% probability that patients with FLT3-L levels above 92 pg/mL in bone marrow had relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma and a 79% probability that those with FLT3-L levels of 92 pg/mL or less had not relapsed and were not refractory.

Data source: A study of 14 patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, 42 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, and 27 patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma, plus 16 control subjects.

Disclosures: The study was not sponsored, and the authors had no relevant disclosures.

Citation: Steiner N, et al. High levels of FLT3-ligand in bone marrow and peripheral blood of patients with advanced multiple myeloma. PLoS ONE 2017 Jul 20;12:e0181487. doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181487

Modifiable risk factors account for most of the dementia risk imposed by low socioeconomic status

LONDON – Twelve modifiable risk factors appear to account for more than half of the variation in dementia risk associated with socioeconomic status.

When integrated into an 18-point risk score, dubbed the “Lifestyle for Brain Health” (LIBRA) index, they accurately predicted dementia risk in more than 6,300 subjects who were followed for 7 years: Dementia risk increased by 30% for every 1-point increase on the LIBRA score, Sebastian Koehler, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

According to Public Health England, 52% of citizens choose dementia prevention as a top health priority, but almost the same number believe that “there is nothing anyone can do to reduce their risk of getting dementia.” The LIBRA score could be employed as a public health measure to counteract that misunderstanding, he said.

“We can reduce the gap in risk that’s related to low socioeconomic status by improving health in that group. But we know that public health measures and messages are taken up much better by those with higher socioeconomic status. We think the first step is to raise awareness among this group that there is something we can do about dementia risk. And then we can reach out to this vulnerable group and design measures and messages that speak to both their needs and their resources.”

The 12 risk and protective factors were originally identified by epidemiologist Kay Deckers of Maastricht University, who drew them from a large meta-analysis published in 2015 (Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015 Mar;30[3]:234-46).

They are the following:

• Diabetes.

• Hypertension.

• High cholesterol.

• Smoking.

• Obesity.

• Physical inactivity.

• Depression.

• Coronary heart disease.

• Kidney disease.

• Diet.

• Alcohol.

• Mental activity.

Dr. Koehler and his colleagues used them to create the weighted LIBRA score, which computes an 18-point risk level ranging from –5.9 (lower risk) to 12.7 (higher risk). Among the factors that reduce dementia risk are high cognitive activity, healthy diet or Mediterranean diet, and low-moderate alcohol intake. The others all increased risk. Each of the factors was assigned a point value based on its percentage of risk reduction or increase. For example, high cognitive activity reduced risk by more than 3 points, but depression increased it by 2 points. The investigators then validated this score on 6,346 participants in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, who were followed for up to 7 years.

Dr. Koehler’s study, however, was not just a LIBRA validation study. He wanted to correlate these protective and endangering factors with each subject’s socioeconomic status, and determine how much of the risk difference generally accredited to wealth was related to the LIBRA factors.

After 7 years, about 9% of the study sample developed incident dementia. These subjects were significantly older than those who didn’t (77 vs. 64 years). They were more likely to have lower education attainment (58% vs. 37%), and more likely to be poor (44% vs. 29%).

On the LIBRA risk factors, the participants who developed dementia were significantly more likely to have heart disease, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and depression, although not significantly more likely to be obese or to smoke.

On the LIBRA protective factors, they were significantly less likely to be low-moderate alcohol users (37% vs. 57%), to have high cognitive activity (17% vs. 45%), and significantly more likely to be physically inactive (59% vs. 24%).

Two survival curves compared the incidence of dementia related to wealth and LIBRA score. Subjects of low socioeconomic status experienced an increase in dementia risk very similar to those with high LIBRA scores. Dr. Koehler also conducted three analyses that examined the effects of wealth on dementia risk: the total effect of wealth, the direct effect of wealth, and what he called the “indirect wealth effect.” This examined the impact of wealth on LIBRA scores, followed by the effect of these scores on dementia risk.

This final model concluded that 56% of the risk imposed by low socioeconomic status was actually attributable to LIBRA scores. In other words, low socioeconomic status was directly tied to both increases in physical and mental risk factors, and decreases in physical and mental protective factors.

“Health inequalities influencing dementia risk exist because of socioeconomic differences between people,” Dr. Koehler said. “People with less wealth have a higher frequency of being exposed to risk factors for dementia that are potentially treatable.”

The LIBRA study is part of a larger dementia prevention study called Innovative, Midlife Intervention for Dementia Deterrence (In-MINDD). Dr. Koehler had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

LONDON – Twelve modifiable risk factors appear to account for more than half of the variation in dementia risk associated with socioeconomic status.

When integrated into an 18-point risk score, dubbed the “Lifestyle for Brain Health” (LIBRA) index, they accurately predicted dementia risk in more than 6,300 subjects who were followed for 7 years: Dementia risk increased by 30% for every 1-point increase on the LIBRA score, Sebastian Koehler, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

According to Public Health England, 52% of citizens choose dementia prevention as a top health priority, but almost the same number believe that “there is nothing anyone can do to reduce their risk of getting dementia.” The LIBRA score could be employed as a public health measure to counteract that misunderstanding, he said.

“We can reduce the gap in risk that’s related to low socioeconomic status by improving health in that group. But we know that public health measures and messages are taken up much better by those with higher socioeconomic status. We think the first step is to raise awareness among this group that there is something we can do about dementia risk. And then we can reach out to this vulnerable group and design measures and messages that speak to both their needs and their resources.”

The 12 risk and protective factors were originally identified by epidemiologist Kay Deckers of Maastricht University, who drew them from a large meta-analysis published in 2015 (Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015 Mar;30[3]:234-46).

They are the following:

• Diabetes.

• Hypertension.

• High cholesterol.

• Smoking.

• Obesity.

• Physical inactivity.

• Depression.

• Coronary heart disease.

• Kidney disease.

• Diet.

• Alcohol.

• Mental activity.

Dr. Koehler and his colleagues used them to create the weighted LIBRA score, which computes an 18-point risk level ranging from –5.9 (lower risk) to 12.7 (higher risk). Among the factors that reduce dementia risk are high cognitive activity, healthy diet or Mediterranean diet, and low-moderate alcohol intake. The others all increased risk. Each of the factors was assigned a point value based on its percentage of risk reduction or increase. For example, high cognitive activity reduced risk by more than 3 points, but depression increased it by 2 points. The investigators then validated this score on 6,346 participants in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, who were followed for up to 7 years.

Dr. Koehler’s study, however, was not just a LIBRA validation study. He wanted to correlate these protective and endangering factors with each subject’s socioeconomic status, and determine how much of the risk difference generally accredited to wealth was related to the LIBRA factors.

After 7 years, about 9% of the study sample developed incident dementia. These subjects were significantly older than those who didn’t (77 vs. 64 years). They were more likely to have lower education attainment (58% vs. 37%), and more likely to be poor (44% vs. 29%).

On the LIBRA risk factors, the participants who developed dementia were significantly more likely to have heart disease, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and depression, although not significantly more likely to be obese or to smoke.

On the LIBRA protective factors, they were significantly less likely to be low-moderate alcohol users (37% vs. 57%), to have high cognitive activity (17% vs. 45%), and significantly more likely to be physically inactive (59% vs. 24%).

Two survival curves compared the incidence of dementia related to wealth and LIBRA score. Subjects of low socioeconomic status experienced an increase in dementia risk very similar to those with high LIBRA scores. Dr. Koehler also conducted three analyses that examined the effects of wealth on dementia risk: the total effect of wealth, the direct effect of wealth, and what he called the “indirect wealth effect.” This examined the impact of wealth on LIBRA scores, followed by the effect of these scores on dementia risk.

This final model concluded that 56% of the risk imposed by low socioeconomic status was actually attributable to LIBRA scores. In other words, low socioeconomic status was directly tied to both increases in physical and mental risk factors, and decreases in physical and mental protective factors.

“Health inequalities influencing dementia risk exist because of socioeconomic differences between people,” Dr. Koehler said. “People with less wealth have a higher frequency of being exposed to risk factors for dementia that are potentially treatable.”

The LIBRA study is part of a larger dementia prevention study called Innovative, Midlife Intervention for Dementia Deterrence (In-MINDD). Dr. Koehler had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

LONDON – Twelve modifiable risk factors appear to account for more than half of the variation in dementia risk associated with socioeconomic status.

When integrated into an 18-point risk score, dubbed the “Lifestyle for Brain Health” (LIBRA) index, they accurately predicted dementia risk in more than 6,300 subjects who were followed for 7 years: Dementia risk increased by 30% for every 1-point increase on the LIBRA score, Sebastian Koehler, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

According to Public Health England, 52% of citizens choose dementia prevention as a top health priority, but almost the same number believe that “there is nothing anyone can do to reduce their risk of getting dementia.” The LIBRA score could be employed as a public health measure to counteract that misunderstanding, he said.

“We can reduce the gap in risk that’s related to low socioeconomic status by improving health in that group. But we know that public health measures and messages are taken up much better by those with higher socioeconomic status. We think the first step is to raise awareness among this group that there is something we can do about dementia risk. And then we can reach out to this vulnerable group and design measures and messages that speak to both their needs and their resources.”

The 12 risk and protective factors were originally identified by epidemiologist Kay Deckers of Maastricht University, who drew them from a large meta-analysis published in 2015 (Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015 Mar;30[3]:234-46).

They are the following:

• Diabetes.

• Hypertension.

• High cholesterol.

• Smoking.

• Obesity.

• Physical inactivity.

• Depression.

• Coronary heart disease.

• Kidney disease.

• Diet.

• Alcohol.

• Mental activity.

Dr. Koehler and his colleagues used them to create the weighted LIBRA score, which computes an 18-point risk level ranging from –5.9 (lower risk) to 12.7 (higher risk). Among the factors that reduce dementia risk are high cognitive activity, healthy diet or Mediterranean diet, and low-moderate alcohol intake. The others all increased risk. Each of the factors was assigned a point value based on its percentage of risk reduction or increase. For example, high cognitive activity reduced risk by more than 3 points, but depression increased it by 2 points. The investigators then validated this score on 6,346 participants in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, who were followed for up to 7 years.

Dr. Koehler’s study, however, was not just a LIBRA validation study. He wanted to correlate these protective and endangering factors with each subject’s socioeconomic status, and determine how much of the risk difference generally accredited to wealth was related to the LIBRA factors.

After 7 years, about 9% of the study sample developed incident dementia. These subjects were significantly older than those who didn’t (77 vs. 64 years). They were more likely to have lower education attainment (58% vs. 37%), and more likely to be poor (44% vs. 29%).

On the LIBRA risk factors, the participants who developed dementia were significantly more likely to have heart disease, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and depression, although not significantly more likely to be obese or to smoke.

On the LIBRA protective factors, they were significantly less likely to be low-moderate alcohol users (37% vs. 57%), to have high cognitive activity (17% vs. 45%), and significantly more likely to be physically inactive (59% vs. 24%).

Two survival curves compared the incidence of dementia related to wealth and LIBRA score. Subjects of low socioeconomic status experienced an increase in dementia risk very similar to those with high LIBRA scores. Dr. Koehler also conducted three analyses that examined the effects of wealth on dementia risk: the total effect of wealth, the direct effect of wealth, and what he called the “indirect wealth effect.” This examined the impact of wealth on LIBRA scores, followed by the effect of these scores on dementia risk.

This final model concluded that 56% of the risk imposed by low socioeconomic status was actually attributable to LIBRA scores. In other words, low socioeconomic status was directly tied to both increases in physical and mental risk factors, and decreases in physical and mental protective factors.

“Health inequalities influencing dementia risk exist because of socioeconomic differences between people,” Dr. Koehler said. “People with less wealth have a higher frequency of being exposed to risk factors for dementia that are potentially treatable.”

The LIBRA study is part of a larger dementia prevention study called Innovative, Midlife Intervention for Dementia Deterrence (In-MINDD). Dr. Koehler had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT AAIC 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The factors accounted for 56% of the risk imposed by low SES.

Data source: The LIBRA validation study comprised more than 6,300 subjects.

Disclosures: The LIBRA study is part of a larger dementia prevention study called In-MINDD. Dr. Koehler had no financial disclosures.

Abiraterone plus ADT boosts prostate cancer survival

In findings that are being hailed as practice changing, men with metastatic prostate cancer had a near 40% lower risk of death when they were treated with a combination of abiraterone acetate (Zytiga), androgen deprivation therapy, and prednisone or prednisolone, compared with ADT alone.

After a median follow-up of 30.4 months, median overall survival for men with newly diagnosed metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer treated with ADT plus dual placebos was 34.7 months, vs. not reached for men treated with ADT, abiraterone, and prednisone in the LATITUDE trial. Similarly, in the STAMPEDE trial, men with newly diagnosed locally advanced or metastatic disease who were randomized to ADT with abiraterone and prednisolone had a 37% reduction in their risk for death and a 79% reduction in their risk for treatment failure, compared with men randomized to ADT alone.

The majority of men with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer who are started on androgen deprivation therapy with a luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) analog with or without a first-generation androgen receptor inhibitor will have responses to therapy, but within a median of 1-year most will progress to castration-resistant disease, noted Karim Fizazi, MD, from the Gustave Roussy Cancer Institute at the University of Paris Sud, Villejuif, France, and coinvestigators of the LATITUDE trial.

“Resistance to androgen-deprivation therapy is largely driven by the reactivation of androgen receptor signaling through persistent adrenal androgen production, upregulation of intratumoral testosterone production, modification of the biologic characteristics of androgen receptors, and steroidogenic parallel pathways,” they wrote.

Although ADT and docetaxel is the standard of care for men with metastatic castration-sensitive disease who are eligible for chemotherapy, data from real-world practice suggest that patients with this presentation are older than those enrolled in clinical trials, and may not be able to tolerate the toxicities that occur when docetaxel is added to ADT, they noted.

Abiraterone, in combination with prednisone, has been shown to increase overall survival (OS) in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who have not undergone chemotherapy, and among patients who had previously been treated with docetaxel.

The drug is thought to exert its antitumor effects through a combination of androgen receptor antagonism and blockade of steroidogenic enzymes, the investigators wrote.

The LATITUDE trial

LATITUDE investigators from 235 sites in 34 countries in Europe, Asia/Pacific, Latin America and Canada enrolled 1,199 patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer and randomly assigned them to receive either abiraterone and prednisone plus ADT (597 patients), or ADT plus dual placebos (602).

At a planned interim analysis at a median follow-up of 30.4 months, after 406 patients had died, median OS, a co-primary end point, had not been reached among patients in the abiraterone group, compared with 34.7 months for patients assigned to ADT/placebo. This difference translates into a hazard ratio for death of 0.62 (P less than .001).

The median duration of radiographic progression-free survival (PFS), the other primary end point, was 33.0 months among patients treated with abiraterone vs. 14.8 months for those treated with placebo (HR for disease progression or death, 0.47; P less than .001)

Abiraterone was also associated with significantly better outcomes in all secondary endpoints, including time until pain progression, subsequent therapy, initiation of chemotherapy, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression (P less than .001 for each comparison).

The frequency of adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation was 12% for patients in the abiraterone group vs. 10% for those in the placebo group. Rates of grade 3 or 4 hypertension and hypokalemia were higher among patients who received abiraterone.

Based on the trial results, the independent data and safety monitoring committee unanimously recommended unblinding of the trial and allowing patients in the placebo group to receive abiraterone.

The STAMPEDE trial

The STAMPEDE (Systemic Therapy in Advancing or Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy) trial was designed to test whether adding other therapies to ADT can improve OS in the first-line setting for men with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer.

The investigators enrolled 1,917 patients with either newly diagnosed node-positive or metastatic prostate cancer, high-risk locally advanced disease, or relapsed, high-risk disease following radical surgery or radiotherapy.

In all, 95% of patients had newly diagnosed disease; 52% had metastatic disease, 20% had node-positive or node-indeterminate nonmetastatic disease, and 28% had node-negative nonmetastatic disease.

After a median follow-up of 40 months, there had been 184 deaths among the 960 patients assigned to received ADT plus abiraterone and prednisolone, compared with 262 deaths among 957 patients assigned to ADT alone. The respective 3-year survival rates were 83% vs. 76%, translating into a HR of 0.63 (P less than .001) favoring abiraterone. The respective hazard ratios for abiraterone in patients with metastatic and nonmetastatic disease were 0.75 and 0.61, respectively.

Failure-free survival (no radiologic, clinical, or prostate-specific antigen progression or prostate cancer death) also favored abiraterone, with a HR of 0.29, compared with ADT alone (P less than .001). The respective hazard ratios for patients with nonmetastatic disease and metastatic disease were 0.21 and 0.31, respectively.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events occurred in 47% of patients on abiraterone, and in 33% of patients treated with ADT alone. There nine deaths on treatment in the abiraterone group, including two cases of pneumonia (one with sepsis), two strokes, and one case each of dyspnea, lower respiratory tract infection, liver failure, pulmonary hemorrhage, and chest infections.

There were three deaths in the ADT alone group, two from myocardial infarctions and one from bronchopneumonia.

LATITUDE was supported by Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Fizazi reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. Multiple coauthors reported personal fees or other support from Janssen and other companies. STAMPEDE was supported by Cancer Research UK, Medical Research Council, Astellas Pharma, Clovis Oncology, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis. Lead author Nicholas D. James, PhD, reports receiving support, fees, grants and/or other considerations from Astellas Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Clovis Oncology, and Sanofi-Aventis. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships with various entities.

The LATITUDE and STAMPEDE research teams report encouraging improvements in the initial treatment of men with advanced prostate cancer. Metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer is diagnosed in a small proportion of men with prostate cancer at initial presentation and is disproportionately represented in lethal prostate cancer. The findings of these two trials suggest that therapeutically relevant biologic features of this form of cancer are shared with castration-resistant prostate cancer and raise the broader question of whether earlier application of approved life-prolonging therapies will further improve outcomes.

The reports support the hypothesis that more complete suppression of androgen signaling with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone added to a luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist lengthens survival of men with metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. The findings are in line with the efficacy of abiraterone plus LHRH agonist therapy as a preoperative treatment. Confidence in the conclusion stems from the observation that treatment with abiraterone plus an LHRH agonist was superior to an LHRH agonist alone in these two large studies among patients with distant metastases, including those with nonosseous visceral metastases. The reported toxic effects of the combination therapy relative to those observed with the LHRH agonist alone did not adversely affect outcomes. The findings may extend to second-generation androgen-receptor inhibitors or combinations with abiraterone currently under study. This practice-changing evidence supports the conclusion that men with metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer, particularly those with more than three bone metastases on conventional imaging, should be treated with abiraterone plus an LHRH agonist.

Christopher J. Logothetis, MD, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. This comment is excerpted from an editorial accompanying the studies (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1704992).

The LATITUDE and STAMPEDE research teams report encouraging improvements in the initial treatment of men with advanced prostate cancer. Metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer is diagnosed in a small proportion of men with prostate cancer at initial presentation and is disproportionately represented in lethal prostate cancer. The findings of these two trials suggest that therapeutically relevant biologic features of this form of cancer are shared with castration-resistant prostate cancer and raise the broader question of whether earlier application of approved life-prolonging therapies will further improve outcomes.

The reports support the hypothesis that more complete suppression of androgen signaling with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone added to a luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist lengthens survival of men with metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. The findings are in line with the efficacy of abiraterone plus LHRH agonist therapy as a preoperative treatment. Confidence in the conclusion stems from the observation that treatment with abiraterone plus an LHRH agonist was superior to an LHRH agonist alone in these two large studies among patients with distant metastases, including those with nonosseous visceral metastases. The reported toxic effects of the combination therapy relative to those observed with the LHRH agonist alone did not adversely affect outcomes. The findings may extend to second-generation androgen-receptor inhibitors or combinations with abiraterone currently under study. This practice-changing evidence supports the conclusion that men with metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer, particularly those with more than three bone metastases on conventional imaging, should be treated with abiraterone plus an LHRH agonist.

Christopher J. Logothetis, MD, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. This comment is excerpted from an editorial accompanying the studies (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1704992).

The LATITUDE and STAMPEDE research teams report encouraging improvements in the initial treatment of men with advanced prostate cancer. Metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer is diagnosed in a small proportion of men with prostate cancer at initial presentation and is disproportionately represented in lethal prostate cancer. The findings of these two trials suggest that therapeutically relevant biologic features of this form of cancer are shared with castration-resistant prostate cancer and raise the broader question of whether earlier application of approved life-prolonging therapies will further improve outcomes.

The reports support the hypothesis that more complete suppression of androgen signaling with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone added to a luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist lengthens survival of men with metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. The findings are in line with the efficacy of abiraterone plus LHRH agonist therapy as a preoperative treatment. Confidence in the conclusion stems from the observation that treatment with abiraterone plus an LHRH agonist was superior to an LHRH agonist alone in these two large studies among patients with distant metastases, including those with nonosseous visceral metastases. The reported toxic effects of the combination therapy relative to those observed with the LHRH agonist alone did not adversely affect outcomes. The findings may extend to second-generation androgen-receptor inhibitors or combinations with abiraterone currently under study. This practice-changing evidence supports the conclusion that men with metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer, particularly those with more than three bone metastases on conventional imaging, should be treated with abiraterone plus an LHRH agonist.

Christopher J. Logothetis, MD, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. This comment is excerpted from an editorial accompanying the studies (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1704992).

In findings that are being hailed as practice changing, men with metastatic prostate cancer had a near 40% lower risk of death when they were treated with a combination of abiraterone acetate (Zytiga), androgen deprivation therapy, and prednisone or prednisolone, compared with ADT alone.

After a median follow-up of 30.4 months, median overall survival for men with newly diagnosed metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer treated with ADT plus dual placebos was 34.7 months, vs. not reached for men treated with ADT, abiraterone, and prednisone in the LATITUDE trial. Similarly, in the STAMPEDE trial, men with newly diagnosed locally advanced or metastatic disease who were randomized to ADT with abiraterone and prednisolone had a 37% reduction in their risk for death and a 79% reduction in their risk for treatment failure, compared with men randomized to ADT alone.

The majority of men with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer who are started on androgen deprivation therapy with a luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) analog with or without a first-generation androgen receptor inhibitor will have responses to therapy, but within a median of 1-year most will progress to castration-resistant disease, noted Karim Fizazi, MD, from the Gustave Roussy Cancer Institute at the University of Paris Sud, Villejuif, France, and coinvestigators of the LATITUDE trial.

“Resistance to androgen-deprivation therapy is largely driven by the reactivation of androgen receptor signaling through persistent adrenal androgen production, upregulation of intratumoral testosterone production, modification of the biologic characteristics of androgen receptors, and steroidogenic parallel pathways,” they wrote.

Although ADT and docetaxel is the standard of care for men with metastatic castration-sensitive disease who are eligible for chemotherapy, data from real-world practice suggest that patients with this presentation are older than those enrolled in clinical trials, and may not be able to tolerate the toxicities that occur when docetaxel is added to ADT, they noted.

Abiraterone, in combination with prednisone, has been shown to increase overall survival (OS) in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who have not undergone chemotherapy, and among patients who had previously been treated with docetaxel.

The drug is thought to exert its antitumor effects through a combination of androgen receptor antagonism and blockade of steroidogenic enzymes, the investigators wrote.

The LATITUDE trial

LATITUDE investigators from 235 sites in 34 countries in Europe, Asia/Pacific, Latin America and Canada enrolled 1,199 patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer and randomly assigned them to receive either abiraterone and prednisone plus ADT (597 patients), or ADT plus dual placebos (602).

At a planned interim analysis at a median follow-up of 30.4 months, after 406 patients had died, median OS, a co-primary end point, had not been reached among patients in the abiraterone group, compared with 34.7 months for patients assigned to ADT/placebo. This difference translates into a hazard ratio for death of 0.62 (P less than .001).

The median duration of radiographic progression-free survival (PFS), the other primary end point, was 33.0 months among patients treated with abiraterone vs. 14.8 months for those treated with placebo (HR for disease progression or death, 0.47; P less than .001)

Abiraterone was also associated with significantly better outcomes in all secondary endpoints, including time until pain progression, subsequent therapy, initiation of chemotherapy, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression (P less than .001 for each comparison).

The frequency of adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation was 12% for patients in the abiraterone group vs. 10% for those in the placebo group. Rates of grade 3 or 4 hypertension and hypokalemia were higher among patients who received abiraterone.

Based on the trial results, the independent data and safety monitoring committee unanimously recommended unblinding of the trial and allowing patients in the placebo group to receive abiraterone.

The STAMPEDE trial

The STAMPEDE (Systemic Therapy in Advancing or Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy) trial was designed to test whether adding other therapies to ADT can improve OS in the first-line setting for men with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer.

The investigators enrolled 1,917 patients with either newly diagnosed node-positive or metastatic prostate cancer, high-risk locally advanced disease, or relapsed, high-risk disease following radical surgery or radiotherapy.

In all, 95% of patients had newly diagnosed disease; 52% had metastatic disease, 20% had node-positive or node-indeterminate nonmetastatic disease, and 28% had node-negative nonmetastatic disease.

After a median follow-up of 40 months, there had been 184 deaths among the 960 patients assigned to received ADT plus abiraterone and prednisolone, compared with 262 deaths among 957 patients assigned to ADT alone. The respective 3-year survival rates were 83% vs. 76%, translating into a HR of 0.63 (P less than .001) favoring abiraterone. The respective hazard ratios for abiraterone in patients with metastatic and nonmetastatic disease were 0.75 and 0.61, respectively.

Failure-free survival (no radiologic, clinical, or prostate-specific antigen progression or prostate cancer death) also favored abiraterone, with a HR of 0.29, compared with ADT alone (P less than .001). The respective hazard ratios for patients with nonmetastatic disease and metastatic disease were 0.21 and 0.31, respectively.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events occurred in 47% of patients on abiraterone, and in 33% of patients treated with ADT alone. There nine deaths on treatment in the abiraterone group, including two cases of pneumonia (one with sepsis), two strokes, and one case each of dyspnea, lower respiratory tract infection, liver failure, pulmonary hemorrhage, and chest infections.

There were three deaths in the ADT alone group, two from myocardial infarctions and one from bronchopneumonia.

LATITUDE was supported by Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Fizazi reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. Multiple coauthors reported personal fees or other support from Janssen and other companies. STAMPEDE was supported by Cancer Research UK, Medical Research Council, Astellas Pharma, Clovis Oncology, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis. Lead author Nicholas D. James, PhD, reports receiving support, fees, grants and/or other considerations from Astellas Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Clovis Oncology, and Sanofi-Aventis. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships with various entities.

In findings that are being hailed as practice changing, men with metastatic prostate cancer had a near 40% lower risk of death when they were treated with a combination of abiraterone acetate (Zytiga), androgen deprivation therapy, and prednisone or prednisolone, compared with ADT alone.

After a median follow-up of 30.4 months, median overall survival for men with newly diagnosed metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer treated with ADT plus dual placebos was 34.7 months, vs. not reached for men treated with ADT, abiraterone, and prednisone in the LATITUDE trial. Similarly, in the STAMPEDE trial, men with newly diagnosed locally advanced or metastatic disease who were randomized to ADT with abiraterone and prednisolone had a 37% reduction in their risk for death and a 79% reduction in their risk for treatment failure, compared with men randomized to ADT alone.

The majority of men with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer who are started on androgen deprivation therapy with a luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) analog with or without a first-generation androgen receptor inhibitor will have responses to therapy, but within a median of 1-year most will progress to castration-resistant disease, noted Karim Fizazi, MD, from the Gustave Roussy Cancer Institute at the University of Paris Sud, Villejuif, France, and coinvestigators of the LATITUDE trial.

“Resistance to androgen-deprivation therapy is largely driven by the reactivation of androgen receptor signaling through persistent adrenal androgen production, upregulation of intratumoral testosterone production, modification of the biologic characteristics of androgen receptors, and steroidogenic parallel pathways,” they wrote.

Although ADT and docetaxel is the standard of care for men with metastatic castration-sensitive disease who are eligible for chemotherapy, data from real-world practice suggest that patients with this presentation are older than those enrolled in clinical trials, and may not be able to tolerate the toxicities that occur when docetaxel is added to ADT, they noted.

Abiraterone, in combination with prednisone, has been shown to increase overall survival (OS) in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who have not undergone chemotherapy, and among patients who had previously been treated with docetaxel.

The drug is thought to exert its antitumor effects through a combination of androgen receptor antagonism and blockade of steroidogenic enzymes, the investigators wrote.

The LATITUDE trial

LATITUDE investigators from 235 sites in 34 countries in Europe, Asia/Pacific, Latin America and Canada enrolled 1,199 patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer and randomly assigned them to receive either abiraterone and prednisone plus ADT (597 patients), or ADT plus dual placebos (602).

At a planned interim analysis at a median follow-up of 30.4 months, after 406 patients had died, median OS, a co-primary end point, had not been reached among patients in the abiraterone group, compared with 34.7 months for patients assigned to ADT/placebo. This difference translates into a hazard ratio for death of 0.62 (P less than .001).

The median duration of radiographic progression-free survival (PFS), the other primary end point, was 33.0 months among patients treated with abiraterone vs. 14.8 months for those treated with placebo (HR for disease progression or death, 0.47; P less than .001)

Abiraterone was also associated with significantly better outcomes in all secondary endpoints, including time until pain progression, subsequent therapy, initiation of chemotherapy, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression (P less than .001 for each comparison).

The frequency of adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation was 12% for patients in the abiraterone group vs. 10% for those in the placebo group. Rates of grade 3 or 4 hypertension and hypokalemia were higher among patients who received abiraterone.

Based on the trial results, the independent data and safety monitoring committee unanimously recommended unblinding of the trial and allowing patients in the placebo group to receive abiraterone.

The STAMPEDE trial

The STAMPEDE (Systemic Therapy in Advancing or Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy) trial was designed to test whether adding other therapies to ADT can improve OS in the first-line setting for men with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer.

The investigators enrolled 1,917 patients with either newly diagnosed node-positive or metastatic prostate cancer, high-risk locally advanced disease, or relapsed, high-risk disease following radical surgery or radiotherapy.

In all, 95% of patients had newly diagnosed disease; 52% had metastatic disease, 20% had node-positive or node-indeterminate nonmetastatic disease, and 28% had node-negative nonmetastatic disease.

After a median follow-up of 40 months, there had been 184 deaths among the 960 patients assigned to received ADT plus abiraterone and prednisolone, compared with 262 deaths among 957 patients assigned to ADT alone. The respective 3-year survival rates were 83% vs. 76%, translating into a HR of 0.63 (P less than .001) favoring abiraterone. The respective hazard ratios for abiraterone in patients with metastatic and nonmetastatic disease were 0.75 and 0.61, respectively.

Failure-free survival (no radiologic, clinical, or prostate-specific antigen progression or prostate cancer death) also favored abiraterone, with a HR of 0.29, compared with ADT alone (P less than .001). The respective hazard ratios for patients with nonmetastatic disease and metastatic disease were 0.21 and 0.31, respectively.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events occurred in 47% of patients on abiraterone, and in 33% of patients treated with ADT alone. There nine deaths on treatment in the abiraterone group, including two cases of pneumonia (one with sepsis), two strokes, and one case each of dyspnea, lower respiratory tract infection, liver failure, pulmonary hemorrhage, and chest infections.

There were three deaths in the ADT alone group, two from myocardial infarctions and one from bronchopneumonia.

LATITUDE was supported by Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Fizazi reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. Multiple coauthors reported personal fees or other support from Janssen and other companies. STAMPEDE was supported by Cancer Research UK, Medical Research Council, Astellas Pharma, Clovis Oncology, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis. Lead author Nicholas D. James, PhD, reports receiving support, fees, grants and/or other considerations from Astellas Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Clovis Oncology, and Sanofi-Aventis. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships with various entities.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Adding abiraterone acetate to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) significantly improved overall survival in men with metastatic prostate cancer.

Major finding: The hazard ratio for death with abiraterone/ADT vs. ADT alone in LATITUDE was 0.62, and in STAMPEDE was 0.63.

Data source: Randomized LATITUDE study in 1,199 men with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Randomized STAMPEDE trial in 1,917 patients with newly diagnosed node-positive or metastatic prostate cancer, high-risk locally advanced disease, or relapsed, high-risk disease.

Disclosures: LATITUDE was supported by Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Fizazi reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. Multiple coauthors reported personal fees or other support from Janssen and other companies. STAMPEDE was supported by Cancer Research UK, Medical Research Council, Astellas Pharma, Clovis Oncology, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis. Lead author Nicholas D. James, PhD, reports receiving support, fees, grants and/or other considerations from Astellas Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Clovis Oncology, and Sanofi-Aventis. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships with various entities.

Developments in celiac disease and wheat-sensitivity disorders

Celiac disease remained a rare disease until this century. “When I went to medical school, people from Ireland, the Netherlands, and other Northern Europeans had celiac disease. The prevalence of celiac disease has increased in the United States and worldwide.

Advances have been made in the understanding of celiac disease pathogenesis over the past few decades regarding the host genotype, currently restricted to the HLA genes, the delivery mode of gluten, type of feeding, time of feeding, and possibly antibiotics modulating the microbiome. The DQ2 genes are necessary but are insufficient to explain the development of celiac disease. About 40% of the burden of celiac disease is related to the HLA-DQ2.2, 2.5, and 8 genes. In spite of many genomewide association studies, no key molecules have been identified that play a significant role in causing the disease to date.

The association of enteric infections and celiac disease may explain why genetically susceptible individuals that are exposed to gluten from childhood do not all develop the disease in early childhood. The average age of diagnosis of celiac disease in modern times is the mid-40s, and the individuals have been eating gluten all their lives, so it’s not clear why and when people develop celiac disease. It has been postulated that enteric infection could modulate the immune system, cause breaches in the mucosal barrier, and alters of the microbiome, thus triggering the disease. A study recently published in Science supports the role of reovirus as a trigger for celiac disease and results from the TEDDY study group published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology suggest that rotavirus vaccination could reduce celiac disease autoimmunity in susceptible children.

While the mechanisms underlying nonceliac gluten sensitivity or wheat sensitivity are still unclear, the terms “encompass individuals who report symptoms or alterations in health that are related to perceived gluten or wheat ingestion.” These symptoms could stem from fructose or fructans in wheat starch (FODMAPs), which could lead to symptoms similar to irritable bowel syndrome or other functional GI disorders. North American data show that more and more people without a diagnosis of celiac disease are consuming gluten-free products. Researchers have postulated that the pathophysiology of these conditions could include activation of the innate immune system, increased permeability, mucosal inflammation, basophil and eosinophil activation, antigliadin antibody elevation, and wheat amyloid trypsin inhibitors, but data have been inconsistent. The recommendation for diagnosing nonceliac gluten or wheat sensitivity is a double-blind placebo-controlled gluten trial to assess gluten-induced symptoms after excluding celiac disease or wheat allergy, but this testing is rarely available in North America. A recent study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology demonstrated the limitations of this testing. The gluten-free diet is now very popular, but some drawbacks have emerged. These include an increased risk for cardiovascular disorders linked to the diet according to a recent study published in BMJ, and increased levels of heavy metals in urine and blood found in insecticide used on rice, according to a recent study published in Epidemiology. Further studies are needed to corroborate these recall diet studies.

Dr. Crowe is a clinical professor of medicine in the department of gastroenterology, University of California, San Diego. She reports financial relationships with UpToDate, Ferring, and Otsuka. She made her comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the Annual Digestive Disease Week.

Celiac disease remained a rare disease until this century. “When I went to medical school, people from Ireland, the Netherlands, and other Northern Europeans had celiac disease. The prevalence of celiac disease has increased in the United States and worldwide.

Advances have been made in the understanding of celiac disease pathogenesis over the past few decades regarding the host genotype, currently restricted to the HLA genes, the delivery mode of gluten, type of feeding, time of feeding, and possibly antibiotics modulating the microbiome. The DQ2 genes are necessary but are insufficient to explain the development of celiac disease. About 40% of the burden of celiac disease is related to the HLA-DQ2.2, 2.5, and 8 genes. In spite of many genomewide association studies, no key molecules have been identified that play a significant role in causing the disease to date.

The association of enteric infections and celiac disease may explain why genetically susceptible individuals that are exposed to gluten from childhood do not all develop the disease in early childhood. The average age of diagnosis of celiac disease in modern times is the mid-40s, and the individuals have been eating gluten all their lives, so it’s not clear why and when people develop celiac disease. It has been postulated that enteric infection could modulate the immune system, cause breaches in the mucosal barrier, and alters of the microbiome, thus triggering the disease. A study recently published in Science supports the role of reovirus as a trigger for celiac disease and results from the TEDDY study group published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology suggest that rotavirus vaccination could reduce celiac disease autoimmunity in susceptible children.

While the mechanisms underlying nonceliac gluten sensitivity or wheat sensitivity are still unclear, the terms “encompass individuals who report symptoms or alterations in health that are related to perceived gluten or wheat ingestion.” These symptoms could stem from fructose or fructans in wheat starch (FODMAPs), which could lead to symptoms similar to irritable bowel syndrome or other functional GI disorders. North American data show that more and more people without a diagnosis of celiac disease are consuming gluten-free products. Researchers have postulated that the pathophysiology of these conditions could include activation of the innate immune system, increased permeability, mucosal inflammation, basophil and eosinophil activation, antigliadin antibody elevation, and wheat amyloid trypsin inhibitors, but data have been inconsistent. The recommendation for diagnosing nonceliac gluten or wheat sensitivity is a double-blind placebo-controlled gluten trial to assess gluten-induced symptoms after excluding celiac disease or wheat allergy, but this testing is rarely available in North America. A recent study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology demonstrated the limitations of this testing. The gluten-free diet is now very popular, but some drawbacks have emerged. These include an increased risk for cardiovascular disorders linked to the diet according to a recent study published in BMJ, and increased levels of heavy metals in urine and blood found in insecticide used on rice, according to a recent study published in Epidemiology. Further studies are needed to corroborate these recall diet studies.

Dr. Crowe is a clinical professor of medicine in the department of gastroenterology, University of California, San Diego. She reports financial relationships with UpToDate, Ferring, and Otsuka. She made her comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the Annual Digestive Disease Week.

Celiac disease remained a rare disease until this century. “When I went to medical school, people from Ireland, the Netherlands, and other Northern Europeans had celiac disease. The prevalence of celiac disease has increased in the United States and worldwide.

Advances have been made in the understanding of celiac disease pathogenesis over the past few decades regarding the host genotype, currently restricted to the HLA genes, the delivery mode of gluten, type of feeding, time of feeding, and possibly antibiotics modulating the microbiome. The DQ2 genes are necessary but are insufficient to explain the development of celiac disease. About 40% of the burden of celiac disease is related to the HLA-DQ2.2, 2.5, and 8 genes. In spite of many genomewide association studies, no key molecules have been identified that play a significant role in causing the disease to date.

The association of enteric infections and celiac disease may explain why genetically susceptible individuals that are exposed to gluten from childhood do not all develop the disease in early childhood. The average age of diagnosis of celiac disease in modern times is the mid-40s, and the individuals have been eating gluten all their lives, so it’s not clear why and when people develop celiac disease. It has been postulated that enteric infection could modulate the immune system, cause breaches in the mucosal barrier, and alters of the microbiome, thus triggering the disease. A study recently published in Science supports the role of reovirus as a trigger for celiac disease and results from the TEDDY study group published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology suggest that rotavirus vaccination could reduce celiac disease autoimmunity in susceptible children.

While the mechanisms underlying nonceliac gluten sensitivity or wheat sensitivity are still unclear, the terms “encompass individuals who report symptoms or alterations in health that are related to perceived gluten or wheat ingestion.” These symptoms could stem from fructose or fructans in wheat starch (FODMAPs), which could lead to symptoms similar to irritable bowel syndrome or other functional GI disorders. North American data show that more and more people without a diagnosis of celiac disease are consuming gluten-free products. Researchers have postulated that the pathophysiology of these conditions could include activation of the innate immune system, increased permeability, mucosal inflammation, basophil and eosinophil activation, antigliadin antibody elevation, and wheat amyloid trypsin inhibitors, but data have been inconsistent. The recommendation for diagnosing nonceliac gluten or wheat sensitivity is a double-blind placebo-controlled gluten trial to assess gluten-induced symptoms after excluding celiac disease or wheat allergy, but this testing is rarely available in North America. A recent study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology demonstrated the limitations of this testing. The gluten-free diet is now very popular, but some drawbacks have emerged. These include an increased risk for cardiovascular disorders linked to the diet according to a recent study published in BMJ, and increased levels of heavy metals in urine and blood found in insecticide used on rice, according to a recent study published in Epidemiology. Further studies are needed to corroborate these recall diet studies.

Dr. Crowe is a clinical professor of medicine in the department of gastroenterology, University of California, San Diego. She reports financial relationships with UpToDate, Ferring, and Otsuka. She made her comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the Annual Digestive Disease Week.

NLR useful for predicting 1-year mortality in PBC patients

An elevated baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was associated with a poor 1-year mortality rate in hospitalized primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) patients, according to Lin Lin, MD, of Tianjin (China) Medical University General Hospital and the Tianjin Institute of Digestive Diseases and associates.

A retrospective analysis of 88 PBC patients hospitalized between June 2009 and January 2014 was performed for the study. NLR was a significant predictor of survival, with an odds ratio of 1.5, a sensitivity of 100%, and a specificity of 67.1%. A baseline NLR value of 2.18 was selected as the cutoff for 1-year mortality. Of the 33 patients above this value at initial hospitalization, 6 died, whereas none of the 55 patients below this value died.

The results of the retrospective study were confirmed in a prospective 1-year cohort that included 63 people with PBC. The patients with a baseline NLR of less than 2.18 had significantly longer survival times than those who had a baseline NLR of 2.18 or higher.

“NLR – an affordable, widely available and reproducible index – is closely related to short-term mortality in patients with PBC. Further studies are warranted to externally cross-validate our findings in other populations,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in BMJ Open (2017. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015304).

An elevated baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was associated with a poor 1-year mortality rate in hospitalized primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) patients, according to Lin Lin, MD, of Tianjin (China) Medical University General Hospital and the Tianjin Institute of Digestive Diseases and associates.

A retrospective analysis of 88 PBC patients hospitalized between June 2009 and January 2014 was performed for the study. NLR was a significant predictor of survival, with an odds ratio of 1.5, a sensitivity of 100%, and a specificity of 67.1%. A baseline NLR value of 2.18 was selected as the cutoff for 1-year mortality. Of the 33 patients above this value at initial hospitalization, 6 died, whereas none of the 55 patients below this value died.

The results of the retrospective study were confirmed in a prospective 1-year cohort that included 63 people with PBC. The patients with a baseline NLR of less than 2.18 had significantly longer survival times than those who had a baseline NLR of 2.18 or higher.

“NLR – an affordable, widely available and reproducible index – is closely related to short-term mortality in patients with PBC. Further studies are warranted to externally cross-validate our findings in other populations,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in BMJ Open (2017. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015304).

An elevated baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was associated with a poor 1-year mortality rate in hospitalized primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) patients, according to Lin Lin, MD, of Tianjin (China) Medical University General Hospital and the Tianjin Institute of Digestive Diseases and associates.

A retrospective analysis of 88 PBC patients hospitalized between June 2009 and January 2014 was performed for the study. NLR was a significant predictor of survival, with an odds ratio of 1.5, a sensitivity of 100%, and a specificity of 67.1%. A baseline NLR value of 2.18 was selected as the cutoff for 1-year mortality. Of the 33 patients above this value at initial hospitalization, 6 died, whereas none of the 55 patients below this value died.

The results of the retrospective study were confirmed in a prospective 1-year cohort that included 63 people with PBC. The patients with a baseline NLR of less than 2.18 had significantly longer survival times than those who had a baseline NLR of 2.18 or higher.

“NLR – an affordable, widely available and reproducible index – is closely related to short-term mortality in patients with PBC. Further studies are warranted to externally cross-validate our findings in other populations,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in BMJ Open (2017. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015304).

FROM BMJ OPEN

VA cohort study: Individualize SSI prophylaxis based on patient factors

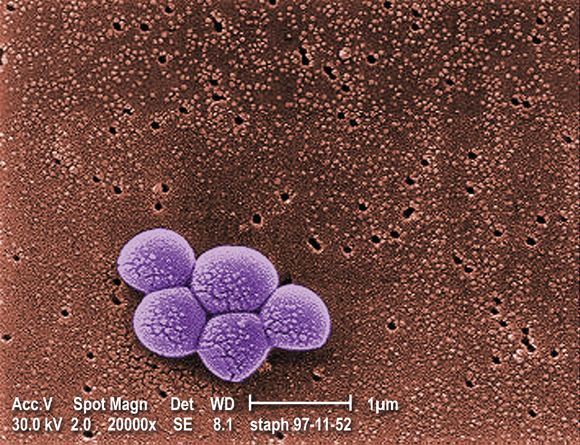

The combined use of vancomycin and a beta-lactam antibiotic for prophylaxis against surgical site infections is associated with both benefits and harms, according to findings from a national propensity-score–adjusted retrospective cohort study.

For example, the combination treatment reduced surgical site infections (SSIs) 30 days after cardiac surgical procedures but increased the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) in some patients, Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, of the VA Boston Healthcare System and her colleagues reported online July 10 in PLOS Medicine.

Among cardiac surgery patients, the incidence of surgical site infections was significantly lower for the 6,953 patients treated with both drugs vs. the 12,834 treated with a single agent (0.95% vs. 1.48%), the investigators found (PLOS Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002340).

SSI benefit with combination therapy

“After controlling for age, diabetes, ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] score, mupirocin administration, current smoking status, and preoperative MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] colonization status, receipt of combination antimicrobial prophylaxis was associated with reduced SSI risk following cardiac surgical procedures (adjusted risk ratio, 0.61),” they wrote, noting that, when combination therapy was compared with either of the agents alone, the associations were similar and that no association between SSI reduction and the combination regimen was seen for the other types of surgical procedures assessed.

Secondary analyses showed that, among the cardiac patients, differences in the rates of SSIs were seen based on MRSA status in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Among MRSA-colonized patients, SSIs occurred in 8 of 346 patients (2.3%) who received combination prophylaxis vs. 4 of 100 patients (4%) who received vancomycin alone (aRR, 0.53), and, among MRSA-negative and MRSA-unknown cardiac surgery patients, SSIs occurred in 58 of 6,607 patients (0.88%) receiving combination prophylaxis and 146 of 10,215 patients (1.4%) receiving a beta-lactam alone (aRR, 0.60).

“Among MRSA-colonized patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the associated absolute risk reduction for SSI was approximately triple that of the absolute risk reduction in MRSA-negative or -unknown patients, with a [number needed to treat] to prevent 1 SSI of 53 for the MRSA-colonized group, compared with 176 for the MRSA-negative or -unknown groups,” they wrote.

The incidence of Clostridium difficile infection was similar in both exposure groups (0.72% and 0.81% with combination and single agent prophylaxis, respectively).

Higher AKI risk with combination therapy

“In contrast, combination versus single prophylaxis was associated with higher relative risk of AKI in the 7-day postoperative period after adjusting for prophylaxis regimen duration, age, diabetes, ASA score, and smoking,” they said.

The rate of AKI was 23.75% among patients receiving combination prophylaxis, compared with 20.79% and 13.93% among those receiving vancomycin alone and a beta-lactam alone, respectively.

Significant associations between absolute risk of AKI and receipt of combination regimens were seen across all types of procedures, the investigators said.

“Overall, the NNH [number needed to harm] to cause one episode of AKI in cardiac surgery patients receiving combination therapy was 22, and, for stage 3 AKI, 167. The NNH associated with one additional episode of any postoperative AKI after receipt of combination therapy was 76 following orthopedic procedures and 25 following vascular surgical procedures,” they said.

The optimal approach for preventing SSIs is unclear. Although the multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery recommend single agent prophylaxis most often, with a beta-lactam antibiotic, for most surgical procedures, the use of vancomycin alone is a consideration in MRSA-colonized patients and in centers with a high MRSA incidence, and combination prophylaxis with a beta-lactam plus vancomycin is increasing. However, the relative risks and benefit of this strategy have not been carefully studied, the investigators said.

Thus, the investigators used a propensity-adjusted, log-binomial regression model stratified by type of surgical procedure among the cases identified in the Veterans Affairs cohort to assess the association between SSIs and receipt of combination prophylaxis versus single agent prophylaxis.

Though limited by the observational study design and by factors such as a predominantly male and slightly older and more rural population, the findings suggest that “clinicians may need to individualize prophylaxis strategy based on patient-specific factors that influence the risk-versus-benefit equation,” they said, concluding that “future studies are needed to evaluate the utility of MRSA screening protocols for optimizing and individualizing surgical prophylaxis regimen.”

This study was funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Branch-Elliman reported having no disclosures. One other author, Eli Perencevich, MD, received an investigator initiated Grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2013.

The combined use of vancomycin and a beta-lactam antibiotic for prophylaxis against surgical site infections is associated with both benefits and harms, according to findings from a national propensity-score–adjusted retrospective cohort study.

For example, the combination treatment reduced surgical site infections (SSIs) 30 days after cardiac surgical procedures but increased the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) in some patients, Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, of the VA Boston Healthcare System and her colleagues reported online July 10 in PLOS Medicine.

Among cardiac surgery patients, the incidence of surgical site infections was significantly lower for the 6,953 patients treated with both drugs vs. the 12,834 treated with a single agent (0.95% vs. 1.48%), the investigators found (PLOS Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002340).

SSI benefit with combination therapy

“After controlling for age, diabetes, ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] score, mupirocin administration, current smoking status, and preoperative MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] colonization status, receipt of combination antimicrobial prophylaxis was associated with reduced SSI risk following cardiac surgical procedures (adjusted risk ratio, 0.61),” they wrote, noting that, when combination therapy was compared with either of the agents alone, the associations were similar and that no association between SSI reduction and the combination regimen was seen for the other types of surgical procedures assessed.

Secondary analyses showed that, among the cardiac patients, differences in the rates of SSIs were seen based on MRSA status in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Among MRSA-colonized patients, SSIs occurred in 8 of 346 patients (2.3%) who received combination prophylaxis vs. 4 of 100 patients (4%) who received vancomycin alone (aRR, 0.53), and, among MRSA-negative and MRSA-unknown cardiac surgery patients, SSIs occurred in 58 of 6,607 patients (0.88%) receiving combination prophylaxis and 146 of 10,215 patients (1.4%) receiving a beta-lactam alone (aRR, 0.60).