User login

Lasers still play a role in treatment of dermatologic conditions in children

CHICAGO – Multiple laser and light options are available to treat children with infantile hemangiomas, port wine birthmarks, and angiofibromas, according to Kristen M. Kelly, MD.

“Combination treatments with procedures and medications can improve treatment in many cases,” Dr. Kelly said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

Dr. Kelly, professor of dermatology and surgery at the University of California, Irvine, said that the use of lasers and other light sources for infantile hemangiomas has dramatically decreased since propranolol, timolol, and other beta-blockers have become available. Most children are candidates for beta-blocker therapy, she said, but for those who are not, the pulsed dye laser (PDL) may be a good option. She also considers using the PDL for ulcerated lesions. “Of course concern comes up, because lasers can sometimes cause ulcerations, so you have to be aware of that,” she said.

“For the more proliferative phase of infantile hemangiomas, I’ll use a larger spot size: 10-12 mm, and short pulse durations: 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds, and low energies,” Dr. Kelly said. “I would start with an energy of 5 or 5.5 J/cm2. I may creep that up a little with time, but I don’t feel that you need to use very high energies. For lesions that are starting to involute, you could consider higher energies.”

Consider the combination of PDL and propranolol for patients who have a superficial component, for ulcerated lesions, or for rapidly progressing lesions that are not responding to your treatment. “You can also use the combination of PDL and timolol,” she said. “Starting treatment can avoid the need for reconstruction later.”

Dr. Kelly then discussed her approach to treating port wine birthmarks. She almost exclusively uses the PDL and the 755-nm Alexandrite lasers for these lesions. “For some of the resistant lesions, I’ll consider some of the combined treatments, like the combined 1064/532 nm system,” she said. “If I have really young patients, I use the PDL almost exclusively. I find the Alexandrite laser useful when I have thicker lesions that have hypertrophied.”

For optimal effect, she recommends treating lesions as early as possible and increasing chromophore target by placing patients with facial lesions in the Trendelenburg position during treatment sessions. Her preferred PDL parameters are a wavelength of 585 nm or 595 nm with a pulse duration of 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds for the vast majority of lesions. “I try to vary the pulse duration over time, so if I’m getting a great result with 0.45 milliseconds, I’ll do that a couple of times,” Dr. Kelly said. “Once I feel I’ve reached a plateau, I might change to 1.5 milliseconds, or consider doing a second pass.”

Whenever possible she uses larger spot sizes and chooses the level of energy based on the type of lesion she’s treating. “I think it’s important to look for an endpoint,” she said. “I like to see deep purpura but I don’t like to see gray, because I feel that’s where you’re going to get epidermal injury or [there is] the chance for scarring and dyspigmentation, which can be permanent in some patients.”

Patients with port wine birthmarks require 3-15 treatments or more, typically 4 weeks apart. “Some people do 2- or 3-week intervals; that’s something to consider,” Dr. Kelly said. “In a darker-skinned patient with hyperpigmentation, I will use longer intervals, especially on an extremity that may take a little longer to heal.”

Alternative treatments are being studied, including the use of lasers in combination with antiangiogenic agents. “Rapamycin has been looked at most extensively, and it’s been shown to have a significant benefit,” she said.

According to Dr. Kelly, a new device for treating port wine birthmarks is being developed that combines pulse dye laser, Nd:YAG, and radiofrequency. “The potential advantage of this is that when we use the PDL alone, we probably cannot get very deep into those vessels,” she said. “The combination of the PDL and radiofrequency may allow us to more completely coagulate these vessels and get better response.”

Dr. Kelly closed her presentation by discussing angiofibromas, disfiguring skin lesions that are associated with tuberous sclerosis and have a fairly rapid recurrence. Topical and/or oral rapamycin are treatment options, but so are laser and light sources. She cited approaches published by Roy Geronemus MD, of the Laser and Skin Surgery Center of New York, and his associates, which included PDL treatment with a 10-mm spot size delivered at 7.5 J/cm2 with a pulse duration of 1.5 ms, and dynamic cooling spray duration of 30 ms (Lasers Surg Med 2013;45:555-7). This was followed by ablative fractional resurfacing with a 15-mm spot size at 70 mJ per pulse and 40% coverage. Other treatment options for angiofibromas include pinpoint electrosurgery to papular, fibrotic lesions and topical rapamycin ointment twice a day.

Dr. Kelly disclosed having drugs or devices donated by Light Sciences Oncology, Solta Medical, Cynosure, Syneron Candela, and Novartis. She is a consultant for MundiPharma, Allergan, and Syneron Candela, and has received research funding from the American Society of Laser Medicine and Surgery, the National Institutes of Health, the Sturge-Weber Foundation, and the UC Irvine Institute of Clinical and Translational Science.

CHICAGO – Multiple laser and light options are available to treat children with infantile hemangiomas, port wine birthmarks, and angiofibromas, according to Kristen M. Kelly, MD.

“Combination treatments with procedures and medications can improve treatment in many cases,” Dr. Kelly said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

Dr. Kelly, professor of dermatology and surgery at the University of California, Irvine, said that the use of lasers and other light sources for infantile hemangiomas has dramatically decreased since propranolol, timolol, and other beta-blockers have become available. Most children are candidates for beta-blocker therapy, she said, but for those who are not, the pulsed dye laser (PDL) may be a good option. She also considers using the PDL for ulcerated lesions. “Of course concern comes up, because lasers can sometimes cause ulcerations, so you have to be aware of that,” she said.

“For the more proliferative phase of infantile hemangiomas, I’ll use a larger spot size: 10-12 mm, and short pulse durations: 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds, and low energies,” Dr. Kelly said. “I would start with an energy of 5 or 5.5 J/cm2. I may creep that up a little with time, but I don’t feel that you need to use very high energies. For lesions that are starting to involute, you could consider higher energies.”

Consider the combination of PDL and propranolol for patients who have a superficial component, for ulcerated lesions, or for rapidly progressing lesions that are not responding to your treatment. “You can also use the combination of PDL and timolol,” she said. “Starting treatment can avoid the need for reconstruction later.”

Dr. Kelly then discussed her approach to treating port wine birthmarks. She almost exclusively uses the PDL and the 755-nm Alexandrite lasers for these lesions. “For some of the resistant lesions, I’ll consider some of the combined treatments, like the combined 1064/532 nm system,” she said. “If I have really young patients, I use the PDL almost exclusively. I find the Alexandrite laser useful when I have thicker lesions that have hypertrophied.”

For optimal effect, she recommends treating lesions as early as possible and increasing chromophore target by placing patients with facial lesions in the Trendelenburg position during treatment sessions. Her preferred PDL parameters are a wavelength of 585 nm or 595 nm with a pulse duration of 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds for the vast majority of lesions. “I try to vary the pulse duration over time, so if I’m getting a great result with 0.45 milliseconds, I’ll do that a couple of times,” Dr. Kelly said. “Once I feel I’ve reached a plateau, I might change to 1.5 milliseconds, or consider doing a second pass.”

Whenever possible she uses larger spot sizes and chooses the level of energy based on the type of lesion she’s treating. “I think it’s important to look for an endpoint,” she said. “I like to see deep purpura but I don’t like to see gray, because I feel that’s where you’re going to get epidermal injury or [there is] the chance for scarring and dyspigmentation, which can be permanent in some patients.”

Patients with port wine birthmarks require 3-15 treatments or more, typically 4 weeks apart. “Some people do 2- or 3-week intervals; that’s something to consider,” Dr. Kelly said. “In a darker-skinned patient with hyperpigmentation, I will use longer intervals, especially on an extremity that may take a little longer to heal.”

Alternative treatments are being studied, including the use of lasers in combination with antiangiogenic agents. “Rapamycin has been looked at most extensively, and it’s been shown to have a significant benefit,” she said.

According to Dr. Kelly, a new device for treating port wine birthmarks is being developed that combines pulse dye laser, Nd:YAG, and radiofrequency. “The potential advantage of this is that when we use the PDL alone, we probably cannot get very deep into those vessels,” she said. “The combination of the PDL and radiofrequency may allow us to more completely coagulate these vessels and get better response.”

Dr. Kelly closed her presentation by discussing angiofibromas, disfiguring skin lesions that are associated with tuberous sclerosis and have a fairly rapid recurrence. Topical and/or oral rapamycin are treatment options, but so are laser and light sources. She cited approaches published by Roy Geronemus MD, of the Laser and Skin Surgery Center of New York, and his associates, which included PDL treatment with a 10-mm spot size delivered at 7.5 J/cm2 with a pulse duration of 1.5 ms, and dynamic cooling spray duration of 30 ms (Lasers Surg Med 2013;45:555-7). This was followed by ablative fractional resurfacing with a 15-mm spot size at 70 mJ per pulse and 40% coverage. Other treatment options for angiofibromas include pinpoint electrosurgery to papular, fibrotic lesions and topical rapamycin ointment twice a day.

Dr. Kelly disclosed having drugs or devices donated by Light Sciences Oncology, Solta Medical, Cynosure, Syneron Candela, and Novartis. She is a consultant for MundiPharma, Allergan, and Syneron Candela, and has received research funding from the American Society of Laser Medicine and Surgery, the National Institutes of Health, the Sturge-Weber Foundation, and the UC Irvine Institute of Clinical and Translational Science.

CHICAGO – Multiple laser and light options are available to treat children with infantile hemangiomas, port wine birthmarks, and angiofibromas, according to Kristen M. Kelly, MD.

“Combination treatments with procedures and medications can improve treatment in many cases,” Dr. Kelly said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

Dr. Kelly, professor of dermatology and surgery at the University of California, Irvine, said that the use of lasers and other light sources for infantile hemangiomas has dramatically decreased since propranolol, timolol, and other beta-blockers have become available. Most children are candidates for beta-blocker therapy, she said, but for those who are not, the pulsed dye laser (PDL) may be a good option. She also considers using the PDL for ulcerated lesions. “Of course concern comes up, because lasers can sometimes cause ulcerations, so you have to be aware of that,” she said.

“For the more proliferative phase of infantile hemangiomas, I’ll use a larger spot size: 10-12 mm, and short pulse durations: 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds, and low energies,” Dr. Kelly said. “I would start with an energy of 5 or 5.5 J/cm2. I may creep that up a little with time, but I don’t feel that you need to use very high energies. For lesions that are starting to involute, you could consider higher energies.”

Consider the combination of PDL and propranolol for patients who have a superficial component, for ulcerated lesions, or for rapidly progressing lesions that are not responding to your treatment. “You can also use the combination of PDL and timolol,” she said. “Starting treatment can avoid the need for reconstruction later.”

Dr. Kelly then discussed her approach to treating port wine birthmarks. She almost exclusively uses the PDL and the 755-nm Alexandrite lasers for these lesions. “For some of the resistant lesions, I’ll consider some of the combined treatments, like the combined 1064/532 nm system,” she said. “If I have really young patients, I use the PDL almost exclusively. I find the Alexandrite laser useful when I have thicker lesions that have hypertrophied.”

For optimal effect, she recommends treating lesions as early as possible and increasing chromophore target by placing patients with facial lesions in the Trendelenburg position during treatment sessions. Her preferred PDL parameters are a wavelength of 585 nm or 595 nm with a pulse duration of 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds for the vast majority of lesions. “I try to vary the pulse duration over time, so if I’m getting a great result with 0.45 milliseconds, I’ll do that a couple of times,” Dr. Kelly said. “Once I feel I’ve reached a plateau, I might change to 1.5 milliseconds, or consider doing a second pass.”

Whenever possible she uses larger spot sizes and chooses the level of energy based on the type of lesion she’s treating. “I think it’s important to look for an endpoint,” she said. “I like to see deep purpura but I don’t like to see gray, because I feel that’s where you’re going to get epidermal injury or [there is] the chance for scarring and dyspigmentation, which can be permanent in some patients.”

Patients with port wine birthmarks require 3-15 treatments or more, typically 4 weeks apart. “Some people do 2- or 3-week intervals; that’s something to consider,” Dr. Kelly said. “In a darker-skinned patient with hyperpigmentation, I will use longer intervals, especially on an extremity that may take a little longer to heal.”

Alternative treatments are being studied, including the use of lasers in combination with antiangiogenic agents. “Rapamycin has been looked at most extensively, and it’s been shown to have a significant benefit,” she said.

According to Dr. Kelly, a new device for treating port wine birthmarks is being developed that combines pulse dye laser, Nd:YAG, and radiofrequency. “The potential advantage of this is that when we use the PDL alone, we probably cannot get very deep into those vessels,” she said. “The combination of the PDL and radiofrequency may allow us to more completely coagulate these vessels and get better response.”

Dr. Kelly closed her presentation by discussing angiofibromas, disfiguring skin lesions that are associated with tuberous sclerosis and have a fairly rapid recurrence. Topical and/or oral rapamycin are treatment options, but so are laser and light sources. She cited approaches published by Roy Geronemus MD, of the Laser and Skin Surgery Center of New York, and his associates, which included PDL treatment with a 10-mm spot size delivered at 7.5 J/cm2 with a pulse duration of 1.5 ms, and dynamic cooling spray duration of 30 ms (Lasers Surg Med 2013;45:555-7). This was followed by ablative fractional resurfacing with a 15-mm spot size at 70 mJ per pulse and 40% coverage. Other treatment options for angiofibromas include pinpoint electrosurgery to papular, fibrotic lesions and topical rapamycin ointment twice a day.

Dr. Kelly disclosed having drugs or devices donated by Light Sciences Oncology, Solta Medical, Cynosure, Syneron Candela, and Novartis. She is a consultant for MundiPharma, Allergan, and Syneron Candela, and has received research funding from the American Society of Laser Medicine and Surgery, the National Institutes of Health, the Sturge-Weber Foundation, and the UC Irvine Institute of Clinical and Translational Science.

AT WCPD 2017

CT scoring system may improve sacroiliitis treatment in IBD

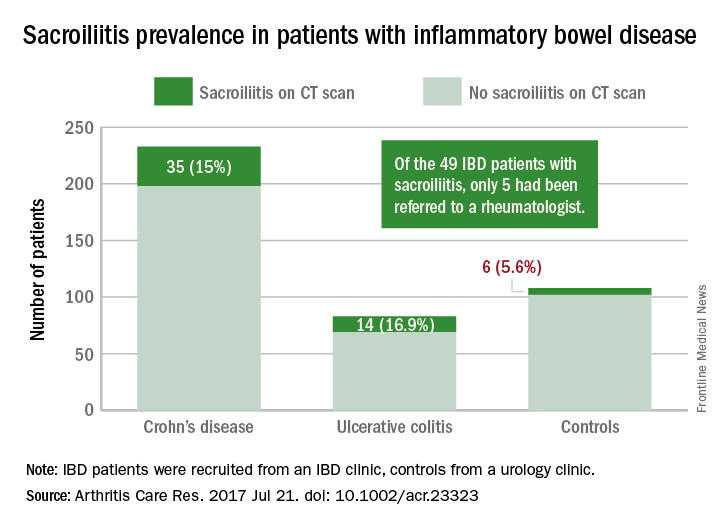

A standardized scoring system to identify sacroiliitis could enable patients with inflammatory bowel disease to get earlier rheumatology referrals and improve treatment, according to an analysis of IBD patients with pre-existing abdominal CT scans.

Of the 316 patients recruited from an IBD clinic in Toronto, the validated CT scan scoring system identified 49 with sacroiliitis, of whom only 5 had been referred to an outpatient rheumatology clinic in the city. Rates of sacroiliitis were similar between the 233 patients with Crohn’s disease (15%) and the 83 with ulcerative colitis (16.9%). The scoring system indicated sacroiliitis in 6 (5.6%) of the 108 control subjects, who were recruited from a urology clinic and had no prior history of chronic back pain, reported Jonathan Chan, MD, of the University of Toronto and his associates (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Jul 21. doi: 10.1002/acr.23323).“Previous studies using CT scan to detect sacroiliitis have relied upon an adaptation of the [modified New York] criteria or a radiologist’s gestalt. Such an adaptation may not be appropriate since changes suggestive of sacroiliitis can be found in the healthy population due to the increased sensitivity of CT scans,” the investigators said. They developed a CT-scan scoring system in which the sacroiliac joints are divided into left/right and iliac/sacral segments. The slice with the greatest number of erosions in each of the four segments contributes that value to the total erosion score, with a score of 3 or greater identifying the presence of sacroiliitis.

By demonstrating that sacroiliitis is three times more prevalent among IBD patients and can be reliably detected in CT scans performed in the clinical care of those patients, this study suggests that “more timely referral for rheumatology assessment” could avoid unnecessary treatment with biologics, Dr. Chan and his associates wrote.

The study was supported in part by a fellowship grant from the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society and in part by Janssen. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest for the study.

A standardized scoring system to identify sacroiliitis could enable patients with inflammatory bowel disease to get earlier rheumatology referrals and improve treatment, according to an analysis of IBD patients with pre-existing abdominal CT scans.

Of the 316 patients recruited from an IBD clinic in Toronto, the validated CT scan scoring system identified 49 with sacroiliitis, of whom only 5 had been referred to an outpatient rheumatology clinic in the city. Rates of sacroiliitis were similar between the 233 patients with Crohn’s disease (15%) and the 83 with ulcerative colitis (16.9%). The scoring system indicated sacroiliitis in 6 (5.6%) of the 108 control subjects, who were recruited from a urology clinic and had no prior history of chronic back pain, reported Jonathan Chan, MD, of the University of Toronto and his associates (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Jul 21. doi: 10.1002/acr.23323).“Previous studies using CT scan to detect sacroiliitis have relied upon an adaptation of the [modified New York] criteria or a radiologist’s gestalt. Such an adaptation may not be appropriate since changes suggestive of sacroiliitis can be found in the healthy population due to the increased sensitivity of CT scans,” the investigators said. They developed a CT-scan scoring system in which the sacroiliac joints are divided into left/right and iliac/sacral segments. The slice with the greatest number of erosions in each of the four segments contributes that value to the total erosion score, with a score of 3 or greater identifying the presence of sacroiliitis.

By demonstrating that sacroiliitis is three times more prevalent among IBD patients and can be reliably detected in CT scans performed in the clinical care of those patients, this study suggests that “more timely referral for rheumatology assessment” could avoid unnecessary treatment with biologics, Dr. Chan and his associates wrote.

The study was supported in part by a fellowship grant from the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society and in part by Janssen. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest for the study.

A standardized scoring system to identify sacroiliitis could enable patients with inflammatory bowel disease to get earlier rheumatology referrals and improve treatment, according to an analysis of IBD patients with pre-existing abdominal CT scans.

Of the 316 patients recruited from an IBD clinic in Toronto, the validated CT scan scoring system identified 49 with sacroiliitis, of whom only 5 had been referred to an outpatient rheumatology clinic in the city. Rates of sacroiliitis were similar between the 233 patients with Crohn’s disease (15%) and the 83 with ulcerative colitis (16.9%). The scoring system indicated sacroiliitis in 6 (5.6%) of the 108 control subjects, who were recruited from a urology clinic and had no prior history of chronic back pain, reported Jonathan Chan, MD, of the University of Toronto and his associates (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Jul 21. doi: 10.1002/acr.23323).“Previous studies using CT scan to detect sacroiliitis have relied upon an adaptation of the [modified New York] criteria or a radiologist’s gestalt. Such an adaptation may not be appropriate since changes suggestive of sacroiliitis can be found in the healthy population due to the increased sensitivity of CT scans,” the investigators said. They developed a CT-scan scoring system in which the sacroiliac joints are divided into left/right and iliac/sacral segments. The slice with the greatest number of erosions in each of the four segments contributes that value to the total erosion score, with a score of 3 or greater identifying the presence of sacroiliitis.

By demonstrating that sacroiliitis is three times more prevalent among IBD patients and can be reliably detected in CT scans performed in the clinical care of those patients, this study suggests that “more timely referral for rheumatology assessment” could avoid unnecessary treatment with biologics, Dr. Chan and his associates wrote.

The study was supported in part by a fellowship grant from the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society and in part by Janssen. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest for the study.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Potential new role for FFR

Paris – Fractional flow reserve is under study for a potential major application: guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) optimization immediately after stent placement, Roberto Diletti, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

At the end of the procedure, FFR measurement using a novel monorail optical pressure sensor catheter revealed that 43% of the lesions had a suboptimal FFR value of 0.90 or less.

“Just this year, two meta-analyses showed that a cutoff of 0.90 is important to define a group of patients at high risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and revascularization,” noted Dr. Diletti of Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Using the older, more conservative cutoff of an FFR of 0.85 or less, 20% of the lesions would potentially benefit from further action to optimize the physiologic result, most often in the form of additional expansion of the stent.

“We are used to thinking of FFR as a tool to understand whether a lesion has to be treated or not. Now we can also start thinking about FFR as a tool to guide PCI optimization,” the cardiologist said.

Optimization wasn’t actually performed in this observational registry. That will be the focus of FFR-REACT, a planned randomized trial investigating the clinical impact of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS)-directed FFR optimization of PCI.

In a per-patient analysis, 48% of FFR-SEARCH participants had a poststent FFR of 0.90 or less in one or more treated lesions. Another 22% had a postprocedure FFR of 0.85 or less in at least one treated lesion, while 8.9% had an FFR of 0.80, which is below the threshold for ischemia.

The primary endpoint in the ongoing FFR-SEARCH study is the 2-year composite rate of major adverse cardiovascular events, defined as MI, any revascularization, or all-cause mortality. Only the 30-day MACE rate was available at the time of Dr. Diletti’s presentation in Paris. The rate was 1.5% in patients with a postprocedure FFR greater than 0.90, 2.0% in those with an FFR of 0.86-0.90, 2.6% with an FFR of 0.81-0.85, and 2.8% with a poststent FFR of 0.80 or less. While those early between-group differences weren’t statistically significant, the trend is encouraging, he noted.

Postprocedure FFR measurement took an average of 5 minutes. The procedure was simple and safe, according to Dr. Diletti. There were no complications related to the use of the Navvus MicroCatheter technology. He explained that the device profile is comparable to a 0.022-inch diameter at the lesion site. Wire access to the vessel was maintained throughout. The rapid-exchange monorail microcatheter was inserted over the previously used standard 0.014-inch coronary guidewire. The optical pressure sensor was positioned roughly 20 mm distal to the distal stent edge. Manual pullback with measurements obtained at various locations in the vicinity of the stented lesion was repeated as necessary in order to identify where optimization, if appropriate, should be focused.

Operators were unable to crossover the microcatheter in 3.5% of cases, mostly because of vessel tortuosity or calcification.

Audience members commented that many of the low FFRs after stenting may reflect diffuse coronary disease, which can be corrected only by placing numerous additional stents, creating its own problems. Dr. Diletti offered reassurance on that score. He explained that in an IVUS substudy of FFR-SEARCH, an unstented physiologically important focal lesion or stent underexpansion was identified in 86% of the cases of low FFR.

“That means you can do something about it. In the other 14% of cases, in my opinion, you cannot do a lot because of very diffuse disease distally,” he said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest in connection with the study, supported by ACIST Medical Systems. The Navvus MicroCatheter is approved by both the Food and Drug Administration and the European regulatory agency.

Paris – Fractional flow reserve is under study for a potential major application: guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) optimization immediately after stent placement, Roberto Diletti, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

At the end of the procedure, FFR measurement using a novel monorail optical pressure sensor catheter revealed that 43% of the lesions had a suboptimal FFR value of 0.90 or less.

“Just this year, two meta-analyses showed that a cutoff of 0.90 is important to define a group of patients at high risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and revascularization,” noted Dr. Diletti of Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Using the older, more conservative cutoff of an FFR of 0.85 or less, 20% of the lesions would potentially benefit from further action to optimize the physiologic result, most often in the form of additional expansion of the stent.

“We are used to thinking of FFR as a tool to understand whether a lesion has to be treated or not. Now we can also start thinking about FFR as a tool to guide PCI optimization,” the cardiologist said.

Optimization wasn’t actually performed in this observational registry. That will be the focus of FFR-REACT, a planned randomized trial investigating the clinical impact of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS)-directed FFR optimization of PCI.

In a per-patient analysis, 48% of FFR-SEARCH participants had a poststent FFR of 0.90 or less in one or more treated lesions. Another 22% had a postprocedure FFR of 0.85 or less in at least one treated lesion, while 8.9% had an FFR of 0.80, which is below the threshold for ischemia.

The primary endpoint in the ongoing FFR-SEARCH study is the 2-year composite rate of major adverse cardiovascular events, defined as MI, any revascularization, or all-cause mortality. Only the 30-day MACE rate was available at the time of Dr. Diletti’s presentation in Paris. The rate was 1.5% in patients with a postprocedure FFR greater than 0.90, 2.0% in those with an FFR of 0.86-0.90, 2.6% with an FFR of 0.81-0.85, and 2.8% with a poststent FFR of 0.80 or less. While those early between-group differences weren’t statistically significant, the trend is encouraging, he noted.

Postprocedure FFR measurement took an average of 5 minutes. The procedure was simple and safe, according to Dr. Diletti. There were no complications related to the use of the Navvus MicroCatheter technology. He explained that the device profile is comparable to a 0.022-inch diameter at the lesion site. Wire access to the vessel was maintained throughout. The rapid-exchange monorail microcatheter was inserted over the previously used standard 0.014-inch coronary guidewire. The optical pressure sensor was positioned roughly 20 mm distal to the distal stent edge. Manual pullback with measurements obtained at various locations in the vicinity of the stented lesion was repeated as necessary in order to identify where optimization, if appropriate, should be focused.

Operators were unable to crossover the microcatheter in 3.5% of cases, mostly because of vessel tortuosity or calcification.

Audience members commented that many of the low FFRs after stenting may reflect diffuse coronary disease, which can be corrected only by placing numerous additional stents, creating its own problems. Dr. Diletti offered reassurance on that score. He explained that in an IVUS substudy of FFR-SEARCH, an unstented physiologically important focal lesion or stent underexpansion was identified in 86% of the cases of low FFR.

“That means you can do something about it. In the other 14% of cases, in my opinion, you cannot do a lot because of very diffuse disease distally,” he said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest in connection with the study, supported by ACIST Medical Systems. The Navvus MicroCatheter is approved by both the Food and Drug Administration and the European regulatory agency.

Paris – Fractional flow reserve is under study for a potential major application: guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) optimization immediately after stent placement, Roberto Diletti, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

At the end of the procedure, FFR measurement using a novel monorail optical pressure sensor catheter revealed that 43% of the lesions had a suboptimal FFR value of 0.90 or less.

“Just this year, two meta-analyses showed that a cutoff of 0.90 is important to define a group of patients at high risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and revascularization,” noted Dr. Diletti of Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Using the older, more conservative cutoff of an FFR of 0.85 or less, 20% of the lesions would potentially benefit from further action to optimize the physiologic result, most often in the form of additional expansion of the stent.

“We are used to thinking of FFR as a tool to understand whether a lesion has to be treated or not. Now we can also start thinking about FFR as a tool to guide PCI optimization,” the cardiologist said.

Optimization wasn’t actually performed in this observational registry. That will be the focus of FFR-REACT, a planned randomized trial investigating the clinical impact of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS)-directed FFR optimization of PCI.

In a per-patient analysis, 48% of FFR-SEARCH participants had a poststent FFR of 0.90 or less in one or more treated lesions. Another 22% had a postprocedure FFR of 0.85 or less in at least one treated lesion, while 8.9% had an FFR of 0.80, which is below the threshold for ischemia.

The primary endpoint in the ongoing FFR-SEARCH study is the 2-year composite rate of major adverse cardiovascular events, defined as MI, any revascularization, or all-cause mortality. Only the 30-day MACE rate was available at the time of Dr. Diletti’s presentation in Paris. The rate was 1.5% in patients with a postprocedure FFR greater than 0.90, 2.0% in those with an FFR of 0.86-0.90, 2.6% with an FFR of 0.81-0.85, and 2.8% with a poststent FFR of 0.80 or less. While those early between-group differences weren’t statistically significant, the trend is encouraging, he noted.

Postprocedure FFR measurement took an average of 5 minutes. The procedure was simple and safe, according to Dr. Diletti. There were no complications related to the use of the Navvus MicroCatheter technology. He explained that the device profile is comparable to a 0.022-inch diameter at the lesion site. Wire access to the vessel was maintained throughout. The rapid-exchange monorail microcatheter was inserted over the previously used standard 0.014-inch coronary guidewire. The optical pressure sensor was positioned roughly 20 mm distal to the distal stent edge. Manual pullback with measurements obtained at various locations in the vicinity of the stented lesion was repeated as necessary in order to identify where optimization, if appropriate, should be focused.

Operators were unable to crossover the microcatheter in 3.5% of cases, mostly because of vessel tortuosity or calcification.

Audience members commented that many of the low FFRs after stenting may reflect diffuse coronary disease, which can be corrected only by placing numerous additional stents, creating its own problems. Dr. Diletti offered reassurance on that score. He explained that in an IVUS substudy of FFR-SEARCH, an unstented physiologically important focal lesion or stent underexpansion was identified in 86% of the cases of low FFR.

“That means you can do something about it. In the other 14% of cases, in my opinion, you cannot do a lot because of very diffuse disease distally,” he said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest in connection with the study, supported by ACIST Medical Systems. The Navvus MicroCatheter is approved by both the Food and Drug Administration and the European regulatory agency.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM EuroPCR

It's Not Appealing, But It Is A-Peeling

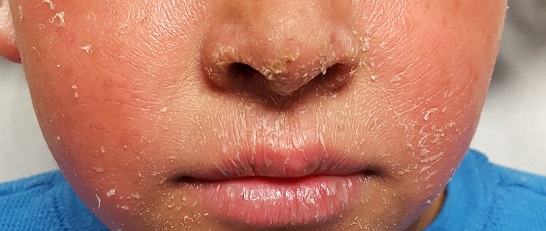

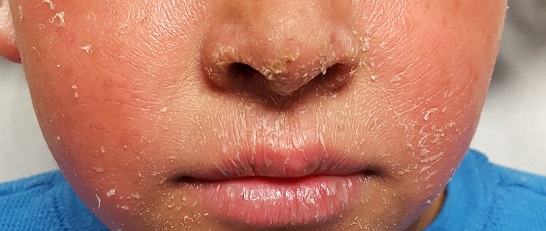

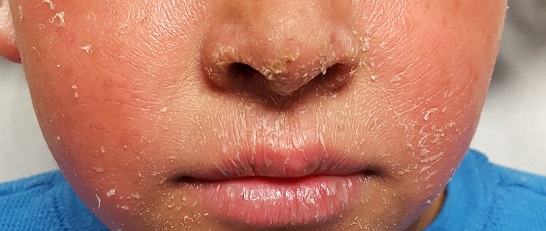

A 6-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation of his dry, thin skin. Since birth, it has frequently torn, and it burns with the application of almost any product or soap. Neither OTC nor prescription products have helped.

The boy is reportedly in good health otherwise and is not atopic. Nonetheless, two of his siblings are similarly affected, and there is a strong family history of similar dermatologic problems on his father’s side. He and his family are from Mexico and have type IV skin.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress but does complain about his skin problems. His skin is quite thin and dry, and fine scaling covers his palms, face, legs, trunk, and scalp. In short, none of his skin looks normal. The skin on his legs is especially scaly and has a pronounced reticulated appearance.

His fingernails are dystrophic, with transverse ridging and a loss of connection between the cuticles and nail plates.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Ichthyosis vulgaris (IV) is one of a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together. This breakdown can lead to excessive water loss, as well as vulnerability of skin to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

IV is by far the most common variation, comprising at least 95% of all ichthyosiform dermatoses. It results from an inherited abnormality of epidermal differentiation or metabolism; affected patients have a higher incidence of eye problems (eg, keratitis, cataracts) in addition to their skin problems.

A total of 28 types of ichthyosis have been described, many of which are part of larger syndromes (such as keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome or Netherton syndrome). Another uncommon type, X-linked recessive ichthyosis, manifests in about 1 in 5,000 births; these patients improve dramatically in the summertime with additional sun exposure.

Ichthyosis manifests with varying degrees of severity. While this case is fairly severe, the worst cases (Harlequin and lamellar forms) begin at birth with a nearly absent stratum corneum.

This patient and his family were advised on the use of emollients and avoidance of excessive drying of skin. They were also strongly encouraged to seek genetic counseling.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ichthyosis is a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together.

- The resultant water loss can leave skin vulnerable to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

- Ichthyosis vulgaris is by far the most common member of this family of disorders, comprising more than 95% of cases.

- Heavy emollients and avoidance of drying constitute the bulk of treatment efforts.

A 6-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation of his dry, thin skin. Since birth, it has frequently torn, and it burns with the application of almost any product or soap. Neither OTC nor prescription products have helped.

The boy is reportedly in good health otherwise and is not atopic. Nonetheless, two of his siblings are similarly affected, and there is a strong family history of similar dermatologic problems on his father’s side. He and his family are from Mexico and have type IV skin.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress but does complain about his skin problems. His skin is quite thin and dry, and fine scaling covers his palms, face, legs, trunk, and scalp. In short, none of his skin looks normal. The skin on his legs is especially scaly and has a pronounced reticulated appearance.

His fingernails are dystrophic, with transverse ridging and a loss of connection between the cuticles and nail plates.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Ichthyosis vulgaris (IV) is one of a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together. This breakdown can lead to excessive water loss, as well as vulnerability of skin to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

IV is by far the most common variation, comprising at least 95% of all ichthyosiform dermatoses. It results from an inherited abnormality of epidermal differentiation or metabolism; affected patients have a higher incidence of eye problems (eg, keratitis, cataracts) in addition to their skin problems.

A total of 28 types of ichthyosis have been described, many of which are part of larger syndromes (such as keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome or Netherton syndrome). Another uncommon type, X-linked recessive ichthyosis, manifests in about 1 in 5,000 births; these patients improve dramatically in the summertime with additional sun exposure.

Ichthyosis manifests with varying degrees of severity. While this case is fairly severe, the worst cases (Harlequin and lamellar forms) begin at birth with a nearly absent stratum corneum.

This patient and his family were advised on the use of emollients and avoidance of excessive drying of skin. They were also strongly encouraged to seek genetic counseling.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ichthyosis is a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together.

- The resultant water loss can leave skin vulnerable to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

- Ichthyosis vulgaris is by far the most common member of this family of disorders, comprising more than 95% of cases.

- Heavy emollients and avoidance of drying constitute the bulk of treatment efforts.

A 6-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation of his dry, thin skin. Since birth, it has frequently torn, and it burns with the application of almost any product or soap. Neither OTC nor prescription products have helped.

The boy is reportedly in good health otherwise and is not atopic. Nonetheless, two of his siblings are similarly affected, and there is a strong family history of similar dermatologic problems on his father’s side. He and his family are from Mexico and have type IV skin.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress but does complain about his skin problems. His skin is quite thin and dry, and fine scaling covers his palms, face, legs, trunk, and scalp. In short, none of his skin looks normal. The skin on his legs is especially scaly and has a pronounced reticulated appearance.

His fingernails are dystrophic, with transverse ridging and a loss of connection between the cuticles and nail plates.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Ichthyosis vulgaris (IV) is one of a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together. This breakdown can lead to excessive water loss, as well as vulnerability of skin to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

IV is by far the most common variation, comprising at least 95% of all ichthyosiform dermatoses. It results from an inherited abnormality of epidermal differentiation or metabolism; affected patients have a higher incidence of eye problems (eg, keratitis, cataracts) in addition to their skin problems.

A total of 28 types of ichthyosis have been described, many of which are part of larger syndromes (such as keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome or Netherton syndrome). Another uncommon type, X-linked recessive ichthyosis, manifests in about 1 in 5,000 births; these patients improve dramatically in the summertime with additional sun exposure.

Ichthyosis manifests with varying degrees of severity. While this case is fairly severe, the worst cases (Harlequin and lamellar forms) begin at birth with a nearly absent stratum corneum.

This patient and his family were advised on the use of emollients and avoidance of excessive drying of skin. They were also strongly encouraged to seek genetic counseling.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ichthyosis is a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together.

- The resultant water loss can leave skin vulnerable to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

- Ichthyosis vulgaris is by far the most common member of this family of disorders, comprising more than 95% of cases.

- Heavy emollients and avoidance of drying constitute the bulk of treatment efforts.

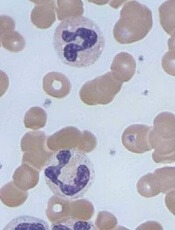

Decreasing RBC transfusions saves center $1 million

Researchers have reported that interventions designed to decrease the need for red blood cell (RBC) transfusions proved effective when implemented at an academic medical center, and they resulted in an annual cost savings of more than $1 million.

The interventions included educational tools, a “best practice advisory,” and changes to the computerized provider order entry system.

They enabled the medical center to reduce multi-unit transfusions by 67.1% and transfusions for patients with hemoglobin (Hb) values of at least 7 g/dL by 47.4%.

Ian Jenkins, MD, of University of California San Diego (UCSD) Health, and his colleagues reported these results in The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

This work began with a multidisciplinary team at UCSD Health reviewing the transfusion literature on clinical trials, meta-analyses, guidelines, and improvement efforts.

The team used the information gleaned from this review and implemented the following interventions in an attempt to reduce unnecessary RBC transfusions:

- Educational tools (handouts, a video, PowerPoint presentations, etc)

- Enhancements to the health system’s computerized provider order entry system (eg, changing default RBC dose from 2 units to 1 unit)

- A “best practice advisory” intended to reduce unnecessary blood product use and costs by using real-time clinical decision support, a process for providing information at the point of care to help inform decisions about a patient’s care.

To assess the impact of their interventions, the researchers evaluated data on most non-infant, inpatient RBC transfusions given at UCSD Health between January 1, 2014, and September 30, 2016.

They excluded units given to patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and units given within 12 hours of a surgical procedure. The team said they excluded these transfusions because of the higher probability of unstable blood volume or special circumstances that might justify off-protocol transfusion.

The researchers then calculated the rate of inpatient RBC units transfused per 1000 patient-days (without exclusions), the percentage of inpatient RBC units transfused for patients with Hb ≥ 7 g/dL, and the percentage of multi-unit RBC transfusions, divided into 3 periods:

- Pre-intervention or baseline (January 1, 2014–September 30, 2014)

- During the intervention (October 1, 2014–April 30, 2015)

- Post-intervention (May 1, 2015–September 30, 2016).

There were 36,386 RBC units administered during the study period, which was 464,424 patient days.

Multi-unit transfusions decreased from 59.9% at baseline to 41.7% during the intervention period and 19.7% during the post-intervention period (P<0.0001).

Transfusions in patients with Hb values ≥ 7 g/dL decreased from 72.3% at baseline to 57.8% during the intervention period and 38.0% during the post-intervention period (P<0.0001).

The total RBC transfusion rate (units per 1000 patient-days) decreased from 89.8 at baseline to 78.1 during the intervention period and 72.7 during the post-intervention period (P<0.0001).

The estimated savings, based on a cost of $250 per RBC unit, was about $1,050,750 per year. ![]()

Researchers have reported that interventions designed to decrease the need for red blood cell (RBC) transfusions proved effective when implemented at an academic medical center, and they resulted in an annual cost savings of more than $1 million.

The interventions included educational tools, a “best practice advisory,” and changes to the computerized provider order entry system.

They enabled the medical center to reduce multi-unit transfusions by 67.1% and transfusions for patients with hemoglobin (Hb) values of at least 7 g/dL by 47.4%.

Ian Jenkins, MD, of University of California San Diego (UCSD) Health, and his colleagues reported these results in The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

This work began with a multidisciplinary team at UCSD Health reviewing the transfusion literature on clinical trials, meta-analyses, guidelines, and improvement efforts.

The team used the information gleaned from this review and implemented the following interventions in an attempt to reduce unnecessary RBC transfusions:

- Educational tools (handouts, a video, PowerPoint presentations, etc)

- Enhancements to the health system’s computerized provider order entry system (eg, changing default RBC dose from 2 units to 1 unit)

- A “best practice advisory” intended to reduce unnecessary blood product use and costs by using real-time clinical decision support, a process for providing information at the point of care to help inform decisions about a patient’s care.

To assess the impact of their interventions, the researchers evaluated data on most non-infant, inpatient RBC transfusions given at UCSD Health between January 1, 2014, and September 30, 2016.

They excluded units given to patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and units given within 12 hours of a surgical procedure. The team said they excluded these transfusions because of the higher probability of unstable blood volume or special circumstances that might justify off-protocol transfusion.

The researchers then calculated the rate of inpatient RBC units transfused per 1000 patient-days (without exclusions), the percentage of inpatient RBC units transfused for patients with Hb ≥ 7 g/dL, and the percentage of multi-unit RBC transfusions, divided into 3 periods:

- Pre-intervention or baseline (January 1, 2014–September 30, 2014)

- During the intervention (October 1, 2014–April 30, 2015)

- Post-intervention (May 1, 2015–September 30, 2016).

There were 36,386 RBC units administered during the study period, which was 464,424 patient days.

Multi-unit transfusions decreased from 59.9% at baseline to 41.7% during the intervention period and 19.7% during the post-intervention period (P<0.0001).

Transfusions in patients with Hb values ≥ 7 g/dL decreased from 72.3% at baseline to 57.8% during the intervention period and 38.0% during the post-intervention period (P<0.0001).

The total RBC transfusion rate (units per 1000 patient-days) decreased from 89.8 at baseline to 78.1 during the intervention period and 72.7 during the post-intervention period (P<0.0001).

The estimated savings, based on a cost of $250 per RBC unit, was about $1,050,750 per year. ![]()

Researchers have reported that interventions designed to decrease the need for red blood cell (RBC) transfusions proved effective when implemented at an academic medical center, and they resulted in an annual cost savings of more than $1 million.

The interventions included educational tools, a “best practice advisory,” and changes to the computerized provider order entry system.

They enabled the medical center to reduce multi-unit transfusions by 67.1% and transfusions for patients with hemoglobin (Hb) values of at least 7 g/dL by 47.4%.

Ian Jenkins, MD, of University of California San Diego (UCSD) Health, and his colleagues reported these results in The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

This work began with a multidisciplinary team at UCSD Health reviewing the transfusion literature on clinical trials, meta-analyses, guidelines, and improvement efforts.

The team used the information gleaned from this review and implemented the following interventions in an attempt to reduce unnecessary RBC transfusions:

- Educational tools (handouts, a video, PowerPoint presentations, etc)

- Enhancements to the health system’s computerized provider order entry system (eg, changing default RBC dose from 2 units to 1 unit)

- A “best practice advisory” intended to reduce unnecessary blood product use and costs by using real-time clinical decision support, a process for providing information at the point of care to help inform decisions about a patient’s care.

To assess the impact of their interventions, the researchers evaluated data on most non-infant, inpatient RBC transfusions given at UCSD Health between January 1, 2014, and September 30, 2016.

They excluded units given to patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and units given within 12 hours of a surgical procedure. The team said they excluded these transfusions because of the higher probability of unstable blood volume or special circumstances that might justify off-protocol transfusion.

The researchers then calculated the rate of inpatient RBC units transfused per 1000 patient-days (without exclusions), the percentage of inpatient RBC units transfused for patients with Hb ≥ 7 g/dL, and the percentage of multi-unit RBC transfusions, divided into 3 periods:

- Pre-intervention or baseline (January 1, 2014–September 30, 2014)

- During the intervention (October 1, 2014–April 30, 2015)

- Post-intervention (May 1, 2015–September 30, 2016).

There were 36,386 RBC units administered during the study period, which was 464,424 patient days.

Multi-unit transfusions decreased from 59.9% at baseline to 41.7% during the intervention period and 19.7% during the post-intervention period (P<0.0001).

Transfusions in patients with Hb values ≥ 7 g/dL decreased from 72.3% at baseline to 57.8% during the intervention period and 38.0% during the post-intervention period (P<0.0001).

The total RBC transfusion rate (units per 1000 patient-days) decreased from 89.8 at baseline to 78.1 during the intervention period and 72.7 during the post-intervention period (P<0.0001).

The estimated savings, based on a cost of $250 per RBC unit, was about $1,050,750 per year. ![]()

GEP classifier predicts risk in MM

A gene expression profiling (GEP) classifier can accurately identify high- and low-risk patients with multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

The GEP classifier is known as SKY92, and researchers found they could accurately identify high-risk MM patients using SKY92 alone.

By combining SKY92 with the International Staging System (ISS), the team was able to identify low-risk MM patients as well.

“We have demonstrated the prognostic value of SKY92 not only as a marker of high risk, but also as a marker of low risk when combined with ISS,” said study author Erik H. van Beers, PhD, vice president of genomics at SkylineDx, the company that developed SKY92.

“Both validated markers may serve as the basis for the discovery of improved individualized therapies for patients with multiple myeloma.”

Dr van Beers and his colleagues compared 8 risk-assessment platforms to analyze gene expression data from 91 newly diagnosed MM patients. The patients were included in an independent dataset amassed by the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation and the Multiple Myeloma Genomics Initiative (MMRF/MMGI).

The researchers used the GEP classifiers SKY92, UAMS70, UAMS80, IFM15, HM19, Cancer Testis Antigen, Centrosome Index, and Proliferation Index to identify high-risk patients.

Of the 8 classifiers, SKY92 identified the largest proportion (21%) of high-risk cases and also attained the highest Cox proportional hazard ratio (8.2) for overall survival (OS).

Additionally, SKY92 predicted 9 of the 13 (60%) deaths that occurred at 2 years and 16 of the 31 (52%) deaths at 5 years, a predictive rate that was higher than any of the other classifiers.

Dr van Beers and his colleagues also combined the SKY92 standard-risk classifier with the ISS to identify low-risk patients in the MMRF/MMGI cohort. This combination was recently identified as a marker for detecting low-risk MM.*

The SKY92/ISS marker identified 42% of patients as low risk, with their median OS not reached at 96 months. The low-risk classification was strongly supported by the achieved hazard ratio of 10.

“The MMRF/MMGI dataset was not part of our previous discovery*, which demonstrated that the combination of SKY92 and ISS identifies the lowest-risk patients with high accuracy and leaves the smallest proportion of patients identified as intermediate risk,” Dr van Beers said. “Thus, the dataset remained available for independent validation—an important factor in the adoption of gene expression profiling tools.”

“We are pleased to have validated the SKY92/ISS low-risk marker by applying it to the well-characterized MMRF/MMGI cohort,” added study author Rafael Fonseca, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. “Our findings further strengthen the prognostic utility of the combination marker.” ![]()

*Kuiper R, van Duin M, van Vliet, MH, et al. Prediction of high- and low-risk multiple myeloma based on gene expression and the International Staging System. Blood. 2015;126(17):1996-2004.

A gene expression profiling (GEP) classifier can accurately identify high- and low-risk patients with multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

The GEP classifier is known as SKY92, and researchers found they could accurately identify high-risk MM patients using SKY92 alone.

By combining SKY92 with the International Staging System (ISS), the team was able to identify low-risk MM patients as well.

“We have demonstrated the prognostic value of SKY92 not only as a marker of high risk, but also as a marker of low risk when combined with ISS,” said study author Erik H. van Beers, PhD, vice president of genomics at SkylineDx, the company that developed SKY92.

“Both validated markers may serve as the basis for the discovery of improved individualized therapies for patients with multiple myeloma.”

Dr van Beers and his colleagues compared 8 risk-assessment platforms to analyze gene expression data from 91 newly diagnosed MM patients. The patients were included in an independent dataset amassed by the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation and the Multiple Myeloma Genomics Initiative (MMRF/MMGI).

The researchers used the GEP classifiers SKY92, UAMS70, UAMS80, IFM15, HM19, Cancer Testis Antigen, Centrosome Index, and Proliferation Index to identify high-risk patients.

Of the 8 classifiers, SKY92 identified the largest proportion (21%) of high-risk cases and also attained the highest Cox proportional hazard ratio (8.2) for overall survival (OS).

Additionally, SKY92 predicted 9 of the 13 (60%) deaths that occurred at 2 years and 16 of the 31 (52%) deaths at 5 years, a predictive rate that was higher than any of the other classifiers.

Dr van Beers and his colleagues also combined the SKY92 standard-risk classifier with the ISS to identify low-risk patients in the MMRF/MMGI cohort. This combination was recently identified as a marker for detecting low-risk MM.*

The SKY92/ISS marker identified 42% of patients as low risk, with their median OS not reached at 96 months. The low-risk classification was strongly supported by the achieved hazard ratio of 10.

“The MMRF/MMGI dataset was not part of our previous discovery*, which demonstrated that the combination of SKY92 and ISS identifies the lowest-risk patients with high accuracy and leaves the smallest proportion of patients identified as intermediate risk,” Dr van Beers said. “Thus, the dataset remained available for independent validation—an important factor in the adoption of gene expression profiling tools.”

“We are pleased to have validated the SKY92/ISS low-risk marker by applying it to the well-characterized MMRF/MMGI cohort,” added study author Rafael Fonseca, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. “Our findings further strengthen the prognostic utility of the combination marker.” ![]()

*Kuiper R, van Duin M, van Vliet, MH, et al. Prediction of high- and low-risk multiple myeloma based on gene expression and the International Staging System. Blood. 2015;126(17):1996-2004.

A gene expression profiling (GEP) classifier can accurately identify high- and low-risk patients with multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

The GEP classifier is known as SKY92, and researchers found they could accurately identify high-risk MM patients using SKY92 alone.

By combining SKY92 with the International Staging System (ISS), the team was able to identify low-risk MM patients as well.

“We have demonstrated the prognostic value of SKY92 not only as a marker of high risk, but also as a marker of low risk when combined with ISS,” said study author Erik H. van Beers, PhD, vice president of genomics at SkylineDx, the company that developed SKY92.

“Both validated markers may serve as the basis for the discovery of improved individualized therapies for patients with multiple myeloma.”

Dr van Beers and his colleagues compared 8 risk-assessment platforms to analyze gene expression data from 91 newly diagnosed MM patients. The patients were included in an independent dataset amassed by the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation and the Multiple Myeloma Genomics Initiative (MMRF/MMGI).

The researchers used the GEP classifiers SKY92, UAMS70, UAMS80, IFM15, HM19, Cancer Testis Antigen, Centrosome Index, and Proliferation Index to identify high-risk patients.

Of the 8 classifiers, SKY92 identified the largest proportion (21%) of high-risk cases and also attained the highest Cox proportional hazard ratio (8.2) for overall survival (OS).

Additionally, SKY92 predicted 9 of the 13 (60%) deaths that occurred at 2 years and 16 of the 31 (52%) deaths at 5 years, a predictive rate that was higher than any of the other classifiers.

Dr van Beers and his colleagues also combined the SKY92 standard-risk classifier with the ISS to identify low-risk patients in the MMRF/MMGI cohort. This combination was recently identified as a marker for detecting low-risk MM.*

The SKY92/ISS marker identified 42% of patients as low risk, with their median OS not reached at 96 months. The low-risk classification was strongly supported by the achieved hazard ratio of 10.

“The MMRF/MMGI dataset was not part of our previous discovery*, which demonstrated that the combination of SKY92 and ISS identifies the lowest-risk patients with high accuracy and leaves the smallest proportion of patients identified as intermediate risk,” Dr van Beers said. “Thus, the dataset remained available for independent validation—an important factor in the adoption of gene expression profiling tools.”

“We are pleased to have validated the SKY92/ISS low-risk marker by applying it to the well-characterized MMRF/MMGI cohort,” added study author Rafael Fonseca, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. “Our findings further strengthen the prognostic utility of the combination marker.” ![]()

*Kuiper R, van Duin M, van Vliet, MH, et al. Prediction of high- and low-risk multiple myeloma based on gene expression and the International Staging System. Blood. 2015;126(17):1996-2004.

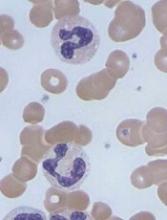

Product granted fast track designation for aTTP

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to caplacizumab, an anti-von Willebrand factor (vWF) nanobody being developed for the treatment of acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP).

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the new drug application or biologics license application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

About caplacizumab

Caplacizumab is a bivalent anti-vWF nanobody being developed by Ablynx. Caplacizumab works by blocking the interaction of ultra-large vWF multimers with platelets, having an immediate effect on platelet aggregation and the ensuing formation and accumulation of the micro-clots that cause the severe thrombocytopenia, tissue ischemia, and organ dysfunction that occurs in patients with aTTP.

Researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of caplacizumab, given with standard care for aTTP, in the phase 2 TITAN trial.

The trial enrolled 75 patients with aTTP. They all received the standard of care—daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy. Thirty-six patients were randomized to receive caplacizumab as well, and 39 were randomized to placebo.

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. Relapse was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively. Exacerbation was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required re-initiation of daily exchange.

The rate of adverse events thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of events that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively.

A lower proportion of subjects in the caplacizumab arm experienced one or more major thromboembolic events or died, compared to the placebo arm—11.4% and 43.2%, respectively.

In addition, fewer caplacizumab-treated patients were refractory to treatment—5.7% vs 21.6%.

There were 2 deaths in the placebo arm, and both of those patients were refractory to treatment. There were no deaths reported in the caplacizumab arm.

Now, researchers are evaluating caplacizumab in the phase 3 HERCULES trial (NCT02553317). Results from this study are anticipated in the second half of 2017 are expected to support a planned biologics license application filing in the US in 2018. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to caplacizumab, an anti-von Willebrand factor (vWF) nanobody being developed for the treatment of acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP).

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the new drug application or biologics license application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

About caplacizumab

Caplacizumab is a bivalent anti-vWF nanobody being developed by Ablynx. Caplacizumab works by blocking the interaction of ultra-large vWF multimers with platelets, having an immediate effect on platelet aggregation and the ensuing formation and accumulation of the micro-clots that cause the severe thrombocytopenia, tissue ischemia, and organ dysfunction that occurs in patients with aTTP.

Researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of caplacizumab, given with standard care for aTTP, in the phase 2 TITAN trial.

The trial enrolled 75 patients with aTTP. They all received the standard of care—daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy. Thirty-six patients were randomized to receive caplacizumab as well, and 39 were randomized to placebo.

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. Relapse was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively. Exacerbation was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required re-initiation of daily exchange.

The rate of adverse events thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of events that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively.

A lower proportion of subjects in the caplacizumab arm experienced one or more major thromboembolic events or died, compared to the placebo arm—11.4% and 43.2%, respectively.

In addition, fewer caplacizumab-treated patients were refractory to treatment—5.7% vs 21.6%.

There were 2 deaths in the placebo arm, and both of those patients were refractory to treatment. There were no deaths reported in the caplacizumab arm.

Now, researchers are evaluating caplacizumab in the phase 3 HERCULES trial (NCT02553317). Results from this study are anticipated in the second half of 2017 are expected to support a planned biologics license application filing in the US in 2018. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to caplacizumab, an anti-von Willebrand factor (vWF) nanobody being developed for the treatment of acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP).

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the new drug application or biologics license application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

About caplacizumab

Caplacizumab is a bivalent anti-vWF nanobody being developed by Ablynx. Caplacizumab works by blocking the interaction of ultra-large vWF multimers with platelets, having an immediate effect on platelet aggregation and the ensuing formation and accumulation of the micro-clots that cause the severe thrombocytopenia, tissue ischemia, and organ dysfunction that occurs in patients with aTTP.

Researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of caplacizumab, given with standard care for aTTP, in the phase 2 TITAN trial.

The trial enrolled 75 patients with aTTP. They all received the standard of care—daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy. Thirty-six patients were randomized to receive caplacizumab as well, and 39 were randomized to placebo.

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. Relapse was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively. Exacerbation was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required re-initiation of daily exchange.

The rate of adverse events thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of events that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively.

A lower proportion of subjects in the caplacizumab arm experienced one or more major thromboembolic events or died, compared to the placebo arm—11.4% and 43.2%, respectively.

In addition, fewer caplacizumab-treated patients were refractory to treatment—5.7% vs 21.6%.

There were 2 deaths in the placebo arm, and both of those patients were refractory to treatment. There were no deaths reported in the caplacizumab arm.

Now, researchers are evaluating caplacizumab in the phase 3 HERCULES trial (NCT02553317). Results from this study are anticipated in the second half of 2017 are expected to support a planned biologics license application filing in the US in 2018. ![]()

Bilateral axillary rash

The FP diagnosed inverse psoriasis. Important clues that pointed to the diagnosis included the history of the rash not resolving with antifungal medications or after stopping use of deodorant (evidence that this was unlikely to be contact dermatitis), along with the fingernail pits.

Inverse psoriasis is found in the intertriginous areas of the axillae, groin, inframammary folds, and intergluteal fold. “Inverse” refers to the fact that the distribution is not on extensor surfaces, but in areas of body folds. Morphologically, the lesions have little to no visible scale and, therefore, are not easily recognized as psoriasis. The color is generally pink to red, but can be hyperpigmented in dark-skinned individuals.

Inverse psoriasis often mimics Candida and tinea infections; when antifungal medicines are not working, always consider inverse psoriasis. Not all erythematous plaques in the axillae are fungal. It helps to look for clues such as nail changes (such as the pits noted with this patient) or subtle plaques on the elbows, knees, or umbilicus to make the diagnosis of psoriasis.

Treatment consists of a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. The choice of vehicle can be based on patient preference; creams and ointments both work to treat inverse psoriasis.

In this case, the FP prescribed a mid-potency topical corticosteroid (0.1% triamcinolone ointment) to be applied twice daily. Both the FP and the patient agreed that an ointment, rather than a cream, would be the better option. While the ointment can be greasy, creams often have an alcohol base and are thus more likely than a petrolatum ointment to sting.

The FP also checked for psoriasis risk factors and discovered that the patient was neither smoking nor drinking alcohol. However, the patient was overweight and agreed to improve her diet and exercise for reasonable weight loss.

At her follow-up 2 months later, the patient’s psoriasis was 90% better. She had also lost 5 pounds. While discussing treatment options, a joint decision was made to try a higher-potency topical steroid ointment with the goal of 100% clearance. The patient understood the risk of skin atrophy and was given instructions to return to the mid-potency steroid once the higher-potency steroid achieved satisfactory results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed inverse psoriasis. Important clues that pointed to the diagnosis included the history of the rash not resolving with antifungal medications or after stopping use of deodorant (evidence that this was unlikely to be contact dermatitis), along with the fingernail pits.

Inverse psoriasis is found in the intertriginous areas of the axillae, groin, inframammary folds, and intergluteal fold. “Inverse” refers to the fact that the distribution is not on extensor surfaces, but in areas of body folds. Morphologically, the lesions have little to no visible scale and, therefore, are not easily recognized as psoriasis. The color is generally pink to red, but can be hyperpigmented in dark-skinned individuals.

Inverse psoriasis often mimics Candida and tinea infections; when antifungal medicines are not working, always consider inverse psoriasis. Not all erythematous plaques in the axillae are fungal. It helps to look for clues such as nail changes (such as the pits noted with this patient) or subtle plaques on the elbows, knees, or umbilicus to make the diagnosis of psoriasis.

Treatment consists of a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. The choice of vehicle can be based on patient preference; creams and ointments both work to treat inverse psoriasis.

In this case, the FP prescribed a mid-potency topical corticosteroid (0.1% triamcinolone ointment) to be applied twice daily. Both the FP and the patient agreed that an ointment, rather than a cream, would be the better option. While the ointment can be greasy, creams often have an alcohol base and are thus more likely than a petrolatum ointment to sting.

The FP also checked for psoriasis risk factors and discovered that the patient was neither smoking nor drinking alcohol. However, the patient was overweight and agreed to improve her diet and exercise for reasonable weight loss.

At her follow-up 2 months later, the patient’s psoriasis was 90% better. She had also lost 5 pounds. While discussing treatment options, a joint decision was made to try a higher-potency topical steroid ointment with the goal of 100% clearance. The patient understood the risk of skin atrophy and was given instructions to return to the mid-potency steroid once the higher-potency steroid achieved satisfactory results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed inverse psoriasis. Important clues that pointed to the diagnosis included the history of the rash not resolving with antifungal medications or after stopping use of deodorant (evidence that this was unlikely to be contact dermatitis), along with the fingernail pits.

Inverse psoriasis is found in the intertriginous areas of the axillae, groin, inframammary folds, and intergluteal fold. “Inverse” refers to the fact that the distribution is not on extensor surfaces, but in areas of body folds. Morphologically, the lesions have little to no visible scale and, therefore, are not easily recognized as psoriasis. The color is generally pink to red, but can be hyperpigmented in dark-skinned individuals.