User login

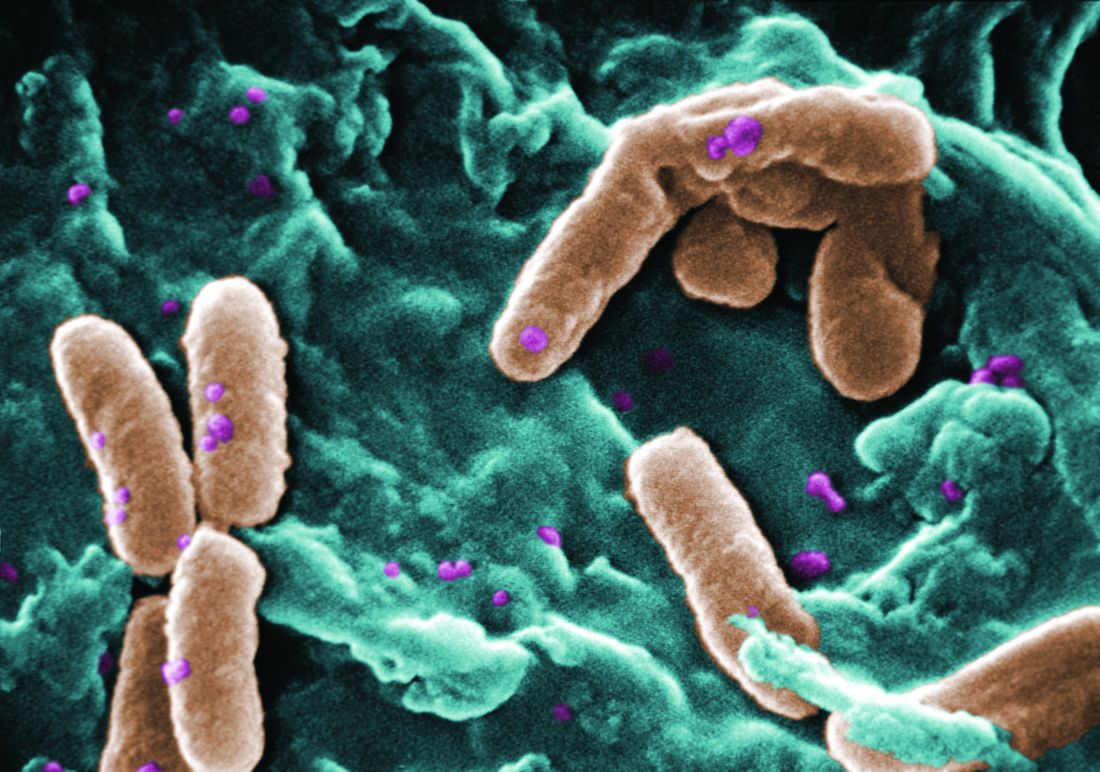

Rate of resistant P. aeruginosa in children rising steadily

The rate of infection with resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa among children has risen steadily about 4% per year since 1999, according to a report.

Infections with P aeruginosa in children occur most often associated with pulmonary disease in patients with cystic fibrosis, but healthy children also can experience a variety of P aeruginosa infection types.

They focused on 77,349 P. aeruginosa isolates that were tested for resistance for all five antibiotic classes: cephalosporins, beta-lactam and beta-lactamase inhibitors, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides. The investigators were specifically interested in multidrug- and carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. They described the organism as “arguably the most resistance-prone health care–related pathogen.”

The study samples were obtained from the respiratory tract, urinary tract, ear, sinuses, wounds, skin, and connective tissues of children aged 1-17 years who were treated in 1999-2012; 2012 was the last year for which this information was collected in this database. Patients were treated in ambulatory, inpatient, ICU, and long-term-care settings. The study excluded children with cystic fibrosis and children under 1 year of age, so as to improve the applicability of the results to the general pediatric population.

The proportion of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa samples rose from 15% to 26% during the 13-year study period, and the proportion of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa samples rose from 9% to 20%. This represents an average annual increase of approximately 4% for both types of resistance, Dr. Logan and her associates said (J Ped Infect Dis. 2016 Nov 16. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw064).

These increases were consistent across all but one age group and all but one treatment setting, the exception being inpatients aged 13-17 years. The prevalence of resistant P. aeruginosa was highest among adolescents in ambulatory, ICU, or long-term-care settings; their rates were three times higher than those in children aged 1 year and two times higher than those in children aged 5 years. It is possible that this pattern reflects “an increasing number of older children with a medically complex condition who have frequent exposure to the health care environment,” the investigators noted.

“The results of our study highlight the need for bacterial surveillance, strategies for implementing effective infection prevention, and antimicrobial stewardship programs.” In addition, all health care facilities should consider using rapid molecular diagnostic platforms to guide antibiotic treatment decisions, “to reduce the burden of the persistent and continually evolving global threat of extensively drug-resistant organisms,” Dr. Logan and her associates added.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and the Health Grand Challenges Program at Princeton University. Dr. Logan and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The rate of infection with resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa among children has risen steadily about 4% per year since 1999, according to a report.

Infections with P aeruginosa in children occur most often associated with pulmonary disease in patients with cystic fibrosis, but healthy children also can experience a variety of P aeruginosa infection types.

They focused on 77,349 P. aeruginosa isolates that were tested for resistance for all five antibiotic classes: cephalosporins, beta-lactam and beta-lactamase inhibitors, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides. The investigators were specifically interested in multidrug- and carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. They described the organism as “arguably the most resistance-prone health care–related pathogen.”

The study samples were obtained from the respiratory tract, urinary tract, ear, sinuses, wounds, skin, and connective tissues of children aged 1-17 years who were treated in 1999-2012; 2012 was the last year for which this information was collected in this database. Patients were treated in ambulatory, inpatient, ICU, and long-term-care settings. The study excluded children with cystic fibrosis and children under 1 year of age, so as to improve the applicability of the results to the general pediatric population.

The proportion of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa samples rose from 15% to 26% during the 13-year study period, and the proportion of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa samples rose from 9% to 20%. This represents an average annual increase of approximately 4% for both types of resistance, Dr. Logan and her associates said (J Ped Infect Dis. 2016 Nov 16. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw064).

These increases were consistent across all but one age group and all but one treatment setting, the exception being inpatients aged 13-17 years. The prevalence of resistant P. aeruginosa was highest among adolescents in ambulatory, ICU, or long-term-care settings; their rates were three times higher than those in children aged 1 year and two times higher than those in children aged 5 years. It is possible that this pattern reflects “an increasing number of older children with a medically complex condition who have frequent exposure to the health care environment,” the investigators noted.

“The results of our study highlight the need for bacterial surveillance, strategies for implementing effective infection prevention, and antimicrobial stewardship programs.” In addition, all health care facilities should consider using rapid molecular diagnostic platforms to guide antibiotic treatment decisions, “to reduce the burden of the persistent and continually evolving global threat of extensively drug-resistant organisms,” Dr. Logan and her associates added.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and the Health Grand Challenges Program at Princeton University. Dr. Logan and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The rate of infection with resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa among children has risen steadily about 4% per year since 1999, according to a report.

Infections with P aeruginosa in children occur most often associated with pulmonary disease in patients with cystic fibrosis, but healthy children also can experience a variety of P aeruginosa infection types.

They focused on 77,349 P. aeruginosa isolates that were tested for resistance for all five antibiotic classes: cephalosporins, beta-lactam and beta-lactamase inhibitors, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides. The investigators were specifically interested in multidrug- and carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. They described the organism as “arguably the most resistance-prone health care–related pathogen.”

The study samples were obtained from the respiratory tract, urinary tract, ear, sinuses, wounds, skin, and connective tissues of children aged 1-17 years who were treated in 1999-2012; 2012 was the last year for which this information was collected in this database. Patients were treated in ambulatory, inpatient, ICU, and long-term-care settings. The study excluded children with cystic fibrosis and children under 1 year of age, so as to improve the applicability of the results to the general pediatric population.

The proportion of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa samples rose from 15% to 26% during the 13-year study period, and the proportion of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa samples rose from 9% to 20%. This represents an average annual increase of approximately 4% for both types of resistance, Dr. Logan and her associates said (J Ped Infect Dis. 2016 Nov 16. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw064).

These increases were consistent across all but one age group and all but one treatment setting, the exception being inpatients aged 13-17 years. The prevalence of resistant P. aeruginosa was highest among adolescents in ambulatory, ICU, or long-term-care settings; their rates were three times higher than those in children aged 1 year and two times higher than those in children aged 5 years. It is possible that this pattern reflects “an increasing number of older children with a medically complex condition who have frequent exposure to the health care environment,” the investigators noted.

“The results of our study highlight the need for bacterial surveillance, strategies for implementing effective infection prevention, and antimicrobial stewardship programs.” In addition, all health care facilities should consider using rapid molecular diagnostic platforms to guide antibiotic treatment decisions, “to reduce the burden of the persistent and continually evolving global threat of extensively drug-resistant organisms,” Dr. Logan and her associates added.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and the Health Grand Challenges Program at Princeton University. Dr. Logan and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The proportion of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa samples rose from 15% to 26% during the 13-year study period, and the proportion of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa samples rose from 9% to 20%.

Data source: A longitudinal analysis of information in a nationally representative database of microbiology laboratories serving approximately 300 U.S. hospitals.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and the Health Grand Challenges Program at Princeton University. Dr. Logan and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

How social media solved a skin outbreak

Several teens who came home from a trip abroad with ugly ulcerated skin lesions in 2014 got vague and unhelpful diagnoses: Physicians thought they had bug bites. True, but that was only part of the story. It took an alert dermatologist and Facebook to identify the true cause, spread the word, and stop the outbreak.

“Social media facilitated communication between patients, crowd sourcing a diagnosis,” said Kanokporn Mongkolrattanothai, MD, who treated three of the teens at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

What did the kids have? Read on and see if you can make the diagnosis yourself.

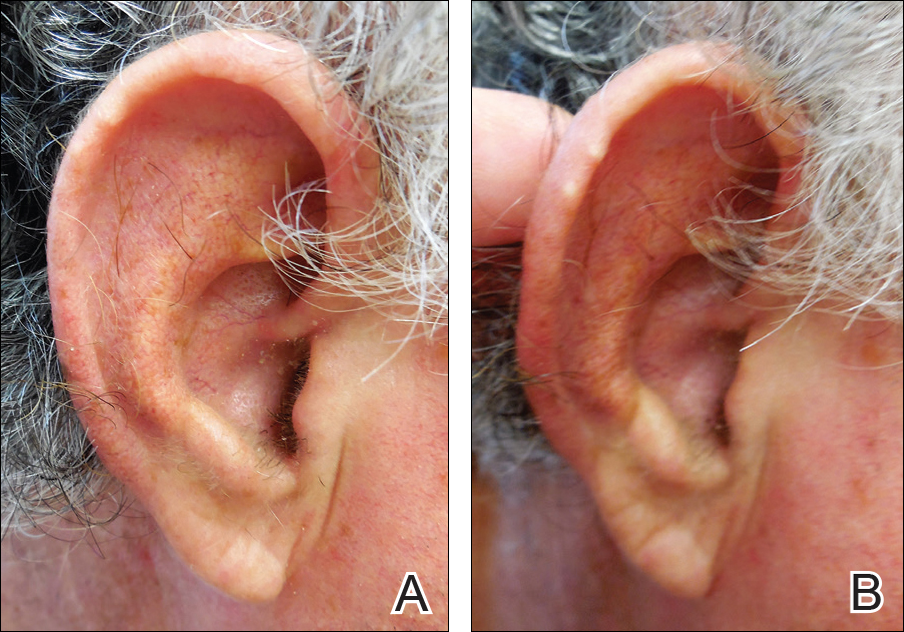

Upon their return, pruritic red papules appeared on a 16-year-old girl’s ankle and thigh. They transformed into ulcers with raised edges and a central crater, according to a report that published online in Pediatric Dermatology (2016 Sep;33[5]:e276-7. doi: 10.1111/pde.12910). At least 12 teens from the trip had similar ulcerated lesions, mostly in exposed areas like arms and legs, said Dr. Mongkolrattanothai, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and a coauthor of the report.

Six patients received a diagnosis of insect bites, and one was diagnosed with a bacterial skin infection, noted Dr. Mongkolrattanothai of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. But these diagnoses were incorrect.

“The light bulb really came on when she mentioned that the lesions were still present several months after the trip to Israel,” said Dr. Krakowski, who was at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego at the time. “On physical exam, the lesions were ulcerated and eroded and did not look to be typical bug bite reactions.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the diagnosis.

On Facebook, the teenager posted a picture of a T-shirt with the words “I went to Israel, and all I got was leishmaniasis.” At the same time, another traveler on the same trip posted pictures of lesions. This set off a wave of awareness that sent affected teens to seek care at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Mattel Children’s Hospital UCLA, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente Woodland Hills Medical Center, and Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego.

“It is likely that our patients became infected with leishmaniasis while camping in the Negev Desert, sleeping on sand dunes at night without use of mosquito netting or tents,” Dr. Mongkolrattanothai said in an interview. “Most of the affected teens did not take precautions against insect bites, which would have included appropriate clothing to minimize areas of exposed skin and the use of repellent products. This placed them at risk for sand fly bites, as sand flies are most active in twilight, evening, and nighttime hours.”

Cutaneous leishmaniasis can lead to permanent scarring, and another form, visceral leishmaniasis, can be fatal.

What helped Dr. Krakowski crack the case? “Training at the University of California at San Diego, in such close proximity to the Navy’s Balboa Medical Center, we are taught from day 1 to think outside of the box because ‘there are zebras in Africa,’ ” he said. “With so much international travel in and out of the region, including to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic, it is warranted to consider that specific diagnosis on the differential. Normally, I do not have to biopsy ‘bug bites,’ but considering the patient’s entire presentation, you almost have to do a biopsy to make sure the lesions were not leishmaniasis.”

Dr. Krakowski praised the CDC. “They have a tremendous amount of resources dedicated to helping investigators work through diagnostic dilemmas such as this, and they helped us – free of charge – to confirm the diagnosis, type the leishmaniasis, and plot a treatment course to resolution,” he said. “They also were instrumental in helping us identify and educate other potentially exposed patients from the camping trip.”

In November, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene published new guidelines about leishmaniasis in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw670). The societies warn that leishmaniasis is becoming more common in the United States, in part because of ecotourists infected in Central and South America and returning soldiers infected in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Dr. Mongkolrattanothai and Dr. Krakowski reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Several teens who came home from a trip abroad with ugly ulcerated skin lesions in 2014 got vague and unhelpful diagnoses: Physicians thought they had bug bites. True, but that was only part of the story. It took an alert dermatologist and Facebook to identify the true cause, spread the word, and stop the outbreak.

“Social media facilitated communication between patients, crowd sourcing a diagnosis,” said Kanokporn Mongkolrattanothai, MD, who treated three of the teens at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

What did the kids have? Read on and see if you can make the diagnosis yourself.

Upon their return, pruritic red papules appeared on a 16-year-old girl’s ankle and thigh. They transformed into ulcers with raised edges and a central crater, according to a report that published online in Pediatric Dermatology (2016 Sep;33[5]:e276-7. doi: 10.1111/pde.12910). At least 12 teens from the trip had similar ulcerated lesions, mostly in exposed areas like arms and legs, said Dr. Mongkolrattanothai, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and a coauthor of the report.

Six patients received a diagnosis of insect bites, and one was diagnosed with a bacterial skin infection, noted Dr. Mongkolrattanothai of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. But these diagnoses were incorrect.

“The light bulb really came on when she mentioned that the lesions were still present several months after the trip to Israel,” said Dr. Krakowski, who was at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego at the time. “On physical exam, the lesions were ulcerated and eroded and did not look to be typical bug bite reactions.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the diagnosis.

On Facebook, the teenager posted a picture of a T-shirt with the words “I went to Israel, and all I got was leishmaniasis.” At the same time, another traveler on the same trip posted pictures of lesions. This set off a wave of awareness that sent affected teens to seek care at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Mattel Children’s Hospital UCLA, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente Woodland Hills Medical Center, and Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego.

“It is likely that our patients became infected with leishmaniasis while camping in the Negev Desert, sleeping on sand dunes at night without use of mosquito netting or tents,” Dr. Mongkolrattanothai said in an interview. “Most of the affected teens did not take precautions against insect bites, which would have included appropriate clothing to minimize areas of exposed skin and the use of repellent products. This placed them at risk for sand fly bites, as sand flies are most active in twilight, evening, and nighttime hours.”

Cutaneous leishmaniasis can lead to permanent scarring, and another form, visceral leishmaniasis, can be fatal.

What helped Dr. Krakowski crack the case? “Training at the University of California at San Diego, in such close proximity to the Navy’s Balboa Medical Center, we are taught from day 1 to think outside of the box because ‘there are zebras in Africa,’ ” he said. “With so much international travel in and out of the region, including to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic, it is warranted to consider that specific diagnosis on the differential. Normally, I do not have to biopsy ‘bug bites,’ but considering the patient’s entire presentation, you almost have to do a biopsy to make sure the lesions were not leishmaniasis.”

Dr. Krakowski praised the CDC. “They have a tremendous amount of resources dedicated to helping investigators work through diagnostic dilemmas such as this, and they helped us – free of charge – to confirm the diagnosis, type the leishmaniasis, and plot a treatment course to resolution,” he said. “They also were instrumental in helping us identify and educate other potentially exposed patients from the camping trip.”

In November, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene published new guidelines about leishmaniasis in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw670). The societies warn that leishmaniasis is becoming more common in the United States, in part because of ecotourists infected in Central and South America and returning soldiers infected in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Dr. Mongkolrattanothai and Dr. Krakowski reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Several teens who came home from a trip abroad with ugly ulcerated skin lesions in 2014 got vague and unhelpful diagnoses: Physicians thought they had bug bites. True, but that was only part of the story. It took an alert dermatologist and Facebook to identify the true cause, spread the word, and stop the outbreak.

“Social media facilitated communication between patients, crowd sourcing a diagnosis,” said Kanokporn Mongkolrattanothai, MD, who treated three of the teens at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

What did the kids have? Read on and see if you can make the diagnosis yourself.

Upon their return, pruritic red papules appeared on a 16-year-old girl’s ankle and thigh. They transformed into ulcers with raised edges and a central crater, according to a report that published online in Pediatric Dermatology (2016 Sep;33[5]:e276-7. doi: 10.1111/pde.12910). At least 12 teens from the trip had similar ulcerated lesions, mostly in exposed areas like arms and legs, said Dr. Mongkolrattanothai, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and a coauthor of the report.

Six patients received a diagnosis of insect bites, and one was diagnosed with a bacterial skin infection, noted Dr. Mongkolrattanothai of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. But these diagnoses were incorrect.

“The light bulb really came on when she mentioned that the lesions were still present several months after the trip to Israel,” said Dr. Krakowski, who was at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego at the time. “On physical exam, the lesions were ulcerated and eroded and did not look to be typical bug bite reactions.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the diagnosis.

On Facebook, the teenager posted a picture of a T-shirt with the words “I went to Israel, and all I got was leishmaniasis.” At the same time, another traveler on the same trip posted pictures of lesions. This set off a wave of awareness that sent affected teens to seek care at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Mattel Children’s Hospital UCLA, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente Woodland Hills Medical Center, and Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego.

“It is likely that our patients became infected with leishmaniasis while camping in the Negev Desert, sleeping on sand dunes at night without use of mosquito netting or tents,” Dr. Mongkolrattanothai said in an interview. “Most of the affected teens did not take precautions against insect bites, which would have included appropriate clothing to minimize areas of exposed skin and the use of repellent products. This placed them at risk for sand fly bites, as sand flies are most active in twilight, evening, and nighttime hours.”

Cutaneous leishmaniasis can lead to permanent scarring, and another form, visceral leishmaniasis, can be fatal.

What helped Dr. Krakowski crack the case? “Training at the University of California at San Diego, in such close proximity to the Navy’s Balboa Medical Center, we are taught from day 1 to think outside of the box because ‘there are zebras in Africa,’ ” he said. “With so much international travel in and out of the region, including to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic, it is warranted to consider that specific diagnosis on the differential. Normally, I do not have to biopsy ‘bug bites,’ but considering the patient’s entire presentation, you almost have to do a biopsy to make sure the lesions were not leishmaniasis.”

Dr. Krakowski praised the CDC. “They have a tremendous amount of resources dedicated to helping investigators work through diagnostic dilemmas such as this, and they helped us – free of charge – to confirm the diagnosis, type the leishmaniasis, and plot a treatment course to resolution,” he said. “They also were instrumental in helping us identify and educate other potentially exposed patients from the camping trip.”

In November, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene published new guidelines about leishmaniasis in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw670). The societies warn that leishmaniasis is becoming more common in the United States, in part because of ecotourists infected in Central and South America and returning soldiers infected in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Dr. Mongkolrattanothai and Dr. Krakowski reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Influences and beliefs on vaccine hesitancy remain complex

ATLANTA – Before clinicians can learn new and effective strategies on addressing vaccine hesitancy in their practices, they need to understand both the “forest” and the “trees.” That is, it helps to understand the big picture in terms of national trends, and it’s equally important to understand the motivations and psychology of parents who refuse or remain hesitant about vaccines.

Paula Frew, PhD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, pointed out that vaccination coverage of children under 3 years old in the United States remains consistently high. An estimated 93% of children have received at least three doses of the polio vaccine, 92% have received at least one dose of the MMR vaccine, 92% have received at least three doses of the hepatitis B vaccine, and 91% have received at least one dose of the varicella vaccine.

In fact, less than 1% of parents selectively or completely refuse all vaccines – but an estimated 13%-22% of parents intentionally delay vaccines, Dr. Frew said at a conference sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention..

She described findings from a study she and colleagues conducted to assess the influence of vaccination decisions among parents of children under age 7 years. They categorized the parents as nonhesitant acceptors of vaccines, hesitant acceptors, delayers, or refusers. Surveys of 2,603 parents in 2012 and 2,518 parents in 2014 revealed that parents overwhelmingly cite their health care provider as their most trusted source of information on vaccines, including 99% of acceptors and 71% of refusers. Among hesitant acceptors, 49% of parents in 2012 and 48% of parents in 2014 said their doctor positively influenced their vaccination decision.

Qualitative findings from focus groups

Still, hesitancy is common enough that qualitative research is seeking to understand parents’ vaccine concerns. One such study involved focus groups with vaccine-hesitant mothers because mothers or other female guardians are the caregivers most often involved in their children’s health care decisions, according to Judith Mendel, MPH, of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Ms. Mendel’s study aimed to understand what drives vaccine-related confidence, how to overcome hesitancy over vaccines, and what messaging approaches might work most effectively. She and her colleagues recruited 61 women who participated in one of four groups in the Philadelphia area or one of four in the San Francisco area during April and May 2016. The women all were responsible for the health decisions of at least one child age 5 years or younger and had previously delayed or declined a recommended vaccine for their child.

Each group included six to nine women and involved a 2-hour semistructured discussion about health concerns; what vaccine confidence is; the mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about vaccines and immunization; and feedback on videos and info-graphics designed to educate others about immunization. The focus groups defined having confidence about vaccines as feeling trust, feeling good about a decision, having many years of research or practice, and being informed and knowledgeable.

“Three themes bubbled up together from the groups,” Ms. Mendel said. “Women had concerns about vaccine ingredients and their effects on physiology, about the recommended schedule, and about the medical system.”

Their concerns about vaccine ingredients and physiology would be familiar to pediatric providers:

• A persistent belief that autism is caused by vaccines.

• Concerns about vaccines made from weakened pathogens.

• Belief that vaccines replace a function that the body is equipped to handle on its own.

• Fears about short-term and long-term side effects.

• Little tolerance for established minor reactions to vaccines.

The mothers were accepting of the vaccines that had been on the schedule when they were children, such as polio, but they did not understand why vaccination starts so young and preferred “alternative” or catch-up schedules.

“They believed that when they were younger, the schedule started later,” Ms. Mendel said. “Some women felt there were too many injections given, while other women preferred not to use combination vaccines.”

Their concerns about the medical system, meanwhile, involved a general lack of trust for mainstream medicine and anyone involved in the immunization system. They believed that interactions with doctors today differ significantly from the way it was when they were children.

“They did not like feeling pressured by health care providers to vaccinate their kid,” Ms. Mendel said. “If they thought the provider was providing a somewhat authoritative or paternalistic stance with their recommendation, some of these women really shied from that and were dissuaded by that.”

What messages work?

The researchers then tested several messaging approaches with the women that included videos and printouts about vaccine safety, herd immunity, and how vaccines work. The materials received high ratings for being informative, coalescing around 4 on a Likert scale of 1-5, but “in terms of really swaying the needle on confidence, it was barely middle ground,” Ms. Mendel said, referring to scores ranging from 3.1 to 3.4.

“Despite someone thinking something was informative, it doesn’t necessarily change their attitudes or perceptions,” she said.

What the women liked about the materials were clear messaging with a respectful tone that was not patronizing, as well as statistics.

“They wanted information on both the pros and cons, the risks as well as the benefits,” Ms. Mendel said. “They also wanted to believe the information they were interacting with was coming from a reliable source,” although she added that “what we may consider a reliable source may not necessarily be what they consider a reliable source.”

Ultimately, no single message or approach worked well for all the mothers, but they all wanted “balanced messages,” although it wasn’t clear if giving more attention to possible risks would positively influence their beliefs about immunization.

“It’s clear that many sources really shape these views and perceptions around vaccines and immunization for these women,” Ms. Mendel said. “It’s really clear that these women are doing the best they can, or believe they can, to make the best health and wellness decisions for their children. However, as health communicators, I think there remains a lot of opportunities for us to help them do a better job.”

The researchers reported no disclosures and did not report external funding sources.

ATLANTA – Before clinicians can learn new and effective strategies on addressing vaccine hesitancy in their practices, they need to understand both the “forest” and the “trees.” That is, it helps to understand the big picture in terms of national trends, and it’s equally important to understand the motivations and psychology of parents who refuse or remain hesitant about vaccines.

Paula Frew, PhD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, pointed out that vaccination coverage of children under 3 years old in the United States remains consistently high. An estimated 93% of children have received at least three doses of the polio vaccine, 92% have received at least one dose of the MMR vaccine, 92% have received at least three doses of the hepatitis B vaccine, and 91% have received at least one dose of the varicella vaccine.

In fact, less than 1% of parents selectively or completely refuse all vaccines – but an estimated 13%-22% of parents intentionally delay vaccines, Dr. Frew said at a conference sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention..

She described findings from a study she and colleagues conducted to assess the influence of vaccination decisions among parents of children under age 7 years. They categorized the parents as nonhesitant acceptors of vaccines, hesitant acceptors, delayers, or refusers. Surveys of 2,603 parents in 2012 and 2,518 parents in 2014 revealed that parents overwhelmingly cite their health care provider as their most trusted source of information on vaccines, including 99% of acceptors and 71% of refusers. Among hesitant acceptors, 49% of parents in 2012 and 48% of parents in 2014 said their doctor positively influenced their vaccination decision.

Qualitative findings from focus groups

Still, hesitancy is common enough that qualitative research is seeking to understand parents’ vaccine concerns. One such study involved focus groups with vaccine-hesitant mothers because mothers or other female guardians are the caregivers most often involved in their children’s health care decisions, according to Judith Mendel, MPH, of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Ms. Mendel’s study aimed to understand what drives vaccine-related confidence, how to overcome hesitancy over vaccines, and what messaging approaches might work most effectively. She and her colleagues recruited 61 women who participated in one of four groups in the Philadelphia area or one of four in the San Francisco area during April and May 2016. The women all were responsible for the health decisions of at least one child age 5 years or younger and had previously delayed or declined a recommended vaccine for their child.

Each group included six to nine women and involved a 2-hour semistructured discussion about health concerns; what vaccine confidence is; the mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about vaccines and immunization; and feedback on videos and info-graphics designed to educate others about immunization. The focus groups defined having confidence about vaccines as feeling trust, feeling good about a decision, having many years of research or practice, and being informed and knowledgeable.

“Three themes bubbled up together from the groups,” Ms. Mendel said. “Women had concerns about vaccine ingredients and their effects on physiology, about the recommended schedule, and about the medical system.”

Their concerns about vaccine ingredients and physiology would be familiar to pediatric providers:

• A persistent belief that autism is caused by vaccines.

• Concerns about vaccines made from weakened pathogens.

• Belief that vaccines replace a function that the body is equipped to handle on its own.

• Fears about short-term and long-term side effects.

• Little tolerance for established minor reactions to vaccines.

The mothers were accepting of the vaccines that had been on the schedule when they were children, such as polio, but they did not understand why vaccination starts so young and preferred “alternative” or catch-up schedules.

“They believed that when they were younger, the schedule started later,” Ms. Mendel said. “Some women felt there were too many injections given, while other women preferred not to use combination vaccines.”

Their concerns about the medical system, meanwhile, involved a general lack of trust for mainstream medicine and anyone involved in the immunization system. They believed that interactions with doctors today differ significantly from the way it was when they were children.

“They did not like feeling pressured by health care providers to vaccinate their kid,” Ms. Mendel said. “If they thought the provider was providing a somewhat authoritative or paternalistic stance with their recommendation, some of these women really shied from that and were dissuaded by that.”

What messages work?

The researchers then tested several messaging approaches with the women that included videos and printouts about vaccine safety, herd immunity, and how vaccines work. The materials received high ratings for being informative, coalescing around 4 on a Likert scale of 1-5, but “in terms of really swaying the needle on confidence, it was barely middle ground,” Ms. Mendel said, referring to scores ranging from 3.1 to 3.4.

“Despite someone thinking something was informative, it doesn’t necessarily change their attitudes or perceptions,” she said.

What the women liked about the materials were clear messaging with a respectful tone that was not patronizing, as well as statistics.

“They wanted information on both the pros and cons, the risks as well as the benefits,” Ms. Mendel said. “They also wanted to believe the information they were interacting with was coming from a reliable source,” although she added that “what we may consider a reliable source may not necessarily be what they consider a reliable source.”

Ultimately, no single message or approach worked well for all the mothers, but they all wanted “balanced messages,” although it wasn’t clear if giving more attention to possible risks would positively influence their beliefs about immunization.

“It’s clear that many sources really shape these views and perceptions around vaccines and immunization for these women,” Ms. Mendel said. “It’s really clear that these women are doing the best they can, or believe they can, to make the best health and wellness decisions for their children. However, as health communicators, I think there remains a lot of opportunities for us to help them do a better job.”

The researchers reported no disclosures and did not report external funding sources.

ATLANTA – Before clinicians can learn new and effective strategies on addressing vaccine hesitancy in their practices, they need to understand both the “forest” and the “trees.” That is, it helps to understand the big picture in terms of national trends, and it’s equally important to understand the motivations and psychology of parents who refuse or remain hesitant about vaccines.

Paula Frew, PhD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, pointed out that vaccination coverage of children under 3 years old in the United States remains consistently high. An estimated 93% of children have received at least three doses of the polio vaccine, 92% have received at least one dose of the MMR vaccine, 92% have received at least three doses of the hepatitis B vaccine, and 91% have received at least one dose of the varicella vaccine.

In fact, less than 1% of parents selectively or completely refuse all vaccines – but an estimated 13%-22% of parents intentionally delay vaccines, Dr. Frew said at a conference sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention..

She described findings from a study she and colleagues conducted to assess the influence of vaccination decisions among parents of children under age 7 years. They categorized the parents as nonhesitant acceptors of vaccines, hesitant acceptors, delayers, or refusers. Surveys of 2,603 parents in 2012 and 2,518 parents in 2014 revealed that parents overwhelmingly cite their health care provider as their most trusted source of information on vaccines, including 99% of acceptors and 71% of refusers. Among hesitant acceptors, 49% of parents in 2012 and 48% of parents in 2014 said their doctor positively influenced their vaccination decision.

Qualitative findings from focus groups

Still, hesitancy is common enough that qualitative research is seeking to understand parents’ vaccine concerns. One such study involved focus groups with vaccine-hesitant mothers because mothers or other female guardians are the caregivers most often involved in their children’s health care decisions, according to Judith Mendel, MPH, of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Ms. Mendel’s study aimed to understand what drives vaccine-related confidence, how to overcome hesitancy over vaccines, and what messaging approaches might work most effectively. She and her colleagues recruited 61 women who participated in one of four groups in the Philadelphia area or one of four in the San Francisco area during April and May 2016. The women all were responsible for the health decisions of at least one child age 5 years or younger and had previously delayed or declined a recommended vaccine for their child.

Each group included six to nine women and involved a 2-hour semistructured discussion about health concerns; what vaccine confidence is; the mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about vaccines and immunization; and feedback on videos and info-graphics designed to educate others about immunization. The focus groups defined having confidence about vaccines as feeling trust, feeling good about a decision, having many years of research or practice, and being informed and knowledgeable.

“Three themes bubbled up together from the groups,” Ms. Mendel said. “Women had concerns about vaccine ingredients and their effects on physiology, about the recommended schedule, and about the medical system.”

Their concerns about vaccine ingredients and physiology would be familiar to pediatric providers:

• A persistent belief that autism is caused by vaccines.

• Concerns about vaccines made from weakened pathogens.

• Belief that vaccines replace a function that the body is equipped to handle on its own.

• Fears about short-term and long-term side effects.

• Little tolerance for established minor reactions to vaccines.

The mothers were accepting of the vaccines that had been on the schedule when they were children, such as polio, but they did not understand why vaccination starts so young and preferred “alternative” or catch-up schedules.

“They believed that when they were younger, the schedule started later,” Ms. Mendel said. “Some women felt there were too many injections given, while other women preferred not to use combination vaccines.”

Their concerns about the medical system, meanwhile, involved a general lack of trust for mainstream medicine and anyone involved in the immunization system. They believed that interactions with doctors today differ significantly from the way it was when they were children.

“They did not like feeling pressured by health care providers to vaccinate their kid,” Ms. Mendel said. “If they thought the provider was providing a somewhat authoritative or paternalistic stance with their recommendation, some of these women really shied from that and were dissuaded by that.”

What messages work?

The researchers then tested several messaging approaches with the women that included videos and printouts about vaccine safety, herd immunity, and how vaccines work. The materials received high ratings for being informative, coalescing around 4 on a Likert scale of 1-5, but “in terms of really swaying the needle on confidence, it was barely middle ground,” Ms. Mendel said, referring to scores ranging from 3.1 to 3.4.

“Despite someone thinking something was informative, it doesn’t necessarily change their attitudes or perceptions,” she said.

What the women liked about the materials were clear messaging with a respectful tone that was not patronizing, as well as statistics.

“They wanted information on both the pros and cons, the risks as well as the benefits,” Ms. Mendel said. “They also wanted to believe the information they were interacting with was coming from a reliable source,” although she added that “what we may consider a reliable source may not necessarily be what they consider a reliable source.”

Ultimately, no single message or approach worked well for all the mothers, but they all wanted “balanced messages,” although it wasn’t clear if giving more attention to possible risks would positively influence their beliefs about immunization.

“It’s clear that many sources really shape these views and perceptions around vaccines and immunization for these women,” Ms. Mendel said. “It’s really clear that these women are doing the best they can, or believe they can, to make the best health and wellness decisions for their children. However, as health communicators, I think there remains a lot of opportunities for us to help them do a better job.”

The researchers reported no disclosures and did not report external funding sources.

Targeted interventions aid in HPV vaccination uptake

ATLANTA – Holly Groom, MPH, of the Center for Health Research at Kaiser Permanente Northwest, described the intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates within the Kaiser Permanente NW health care system involving two hospitals and 31 medical offices, which serves 44,000 adolescents aged 11-17 years. About a quarter of patients reside in Washington, with the remainder in Oregon.

In addition to two in-person provider education and feedback sessions, the intervention included quarterly vaccine coverage, missed vaccination opportunity assessment reports, and a mailed parent survey. The staff education sessions covered six different cancers caused by HPV – cervical, anal, oropharyngeal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar – and their annual incidence, such as an estimated 10,000 oropharyngeal cancer cases in males and more than 11,000 cervical cancer cases in females each year.

One of the tip sheets distributed during provider and staff education offered specific language that providers could use to recommend the vaccine to parents and educate them about what HPV disease is and what cancers it can cause. For parents who are confused or concerned about why the vaccine is recommended at ages 11-12 years, for example, providers can respond, “We’re vaccinating today so your child will have the best protection possible long before the start of any kind of sexual activity. We vaccinate people well before they are exposed to an infection, as is the case with measles and the other recommended childhood vaccines.”

For those providers uneasy about mentioning sexual activity, Ms. Groom said, they can stick with telling parents the vaccine should be administered “long before the risk of infection” without mentioning the mechanism of infection.

Ms. Groom provided three other recommended statements as well:

• “I strongly believe in the importance of this cancer-preventing vaccine.”

• “I have given HPV vaccine to my son/daughter (or grandchild/niece/nephew/friend’s children).”

• “Experts, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, cancer doctors, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, also agree that getting the HPV vaccine is very important for your child.”

Feedback from the training sessions was “overwhelmingly positive,” with 87% of the respondents stating that they planned to implement the strategies and tools discussed and an additional 12% said they were already using those strategies and tools.

The parental survey, although it had only a 12% response rate, initially revealed that just over a third (36%) of parents weren’t sure if they were going to vaccinate their child when they went in for a well visit, but more than 90% of these parents did vaccinate their children.

Ms. Groom reported no disclosures. No external funding was reported.

Communication strategies to improve HPV immunization

Several communication strategies have been developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to help providers overcome barriers to improving HPV immunization coverage, Yvonne Garcia said at the National Immunization Conference.

Among providers’ barriers are hesitancy to make a recommendation for the HPV vaccine, and the need to understand the burden of the disease and the need for the vaccine, said Ms. Garcia, a health communications specialist for the CDC.

“Also, they overestimate parents’ concerns about the vaccine when what we have learned from parents is that they value the HPV vaccine, but they’re not hearing their child’s doctor recommend it,” she said.

Overcoming these barriers requires patient outreach and awareness of HPV coverage rates at the city and state levels, as well as their individual and practice rates. Providers should bundle their recommendation with the other vaccines recommended by the CDC at the ages of 11 and 12 years: “Your child is due for three vaccines today that offer protection against meningitis, HPV cancers, and whooping cough,” is one example of language to use, Ms. Garcia said.

“Effective patient outreach for HPV vaccination includes the reminder/recall system, scheduling remaining doses at the time of receiving the first doses, and creating parental expectation that HPV vaccination is a very normal part of the immunization process, and that it occurs at ages 11 and 12,” she said.

She also reviewed the barriers among parents for HPV vaccination that providers can address. To respond to parents’ lack of knowledge about the vaccine or the need for it, providers “need to stress that it’s needed for cancer prevention,” Ms. Garcia said.

Providers also can reassure parents with concerns about safety and side effects that extensive safety research exists regarding HPV immunization from the past 10 years.

For those worried that HPV vaccination gives “permission for sexual activity” or that kids are too young, providers can reassure parents that the shot is not linked with increased sexual activity, and that it’s recommended at ages 11 and 12 years because the vaccine induces a better immune response at those ages than later on, she said.

Ms. Garcia reported no disclosures. No external funding was reported.

This article was updated Dec. 2, 2016.

ATLANTA – Holly Groom, MPH, of the Center for Health Research at Kaiser Permanente Northwest, described the intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates within the Kaiser Permanente NW health care system involving two hospitals and 31 medical offices, which serves 44,000 adolescents aged 11-17 years. About a quarter of patients reside in Washington, with the remainder in Oregon.

In addition to two in-person provider education and feedback sessions, the intervention included quarterly vaccine coverage, missed vaccination opportunity assessment reports, and a mailed parent survey. The staff education sessions covered six different cancers caused by HPV – cervical, anal, oropharyngeal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar – and their annual incidence, such as an estimated 10,000 oropharyngeal cancer cases in males and more than 11,000 cervical cancer cases in females each year.

One of the tip sheets distributed during provider and staff education offered specific language that providers could use to recommend the vaccine to parents and educate them about what HPV disease is and what cancers it can cause. For parents who are confused or concerned about why the vaccine is recommended at ages 11-12 years, for example, providers can respond, “We’re vaccinating today so your child will have the best protection possible long before the start of any kind of sexual activity. We vaccinate people well before they are exposed to an infection, as is the case with measles and the other recommended childhood vaccines.”

For those providers uneasy about mentioning sexual activity, Ms. Groom said, they can stick with telling parents the vaccine should be administered “long before the risk of infection” without mentioning the mechanism of infection.

Ms. Groom provided three other recommended statements as well:

• “I strongly believe in the importance of this cancer-preventing vaccine.”

• “I have given HPV vaccine to my son/daughter (or grandchild/niece/nephew/friend’s children).”

• “Experts, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, cancer doctors, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, also agree that getting the HPV vaccine is very important for your child.”

Feedback from the training sessions was “overwhelmingly positive,” with 87% of the respondents stating that they planned to implement the strategies and tools discussed and an additional 12% said they were already using those strategies and tools.

The parental survey, although it had only a 12% response rate, initially revealed that just over a third (36%) of parents weren’t sure if they were going to vaccinate their child when they went in for a well visit, but more than 90% of these parents did vaccinate their children.

Ms. Groom reported no disclosures. No external funding was reported.

Communication strategies to improve HPV immunization

Several communication strategies have been developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to help providers overcome barriers to improving HPV immunization coverage, Yvonne Garcia said at the National Immunization Conference.

Among providers’ barriers are hesitancy to make a recommendation for the HPV vaccine, and the need to understand the burden of the disease and the need for the vaccine, said Ms. Garcia, a health communications specialist for the CDC.

“Also, they overestimate parents’ concerns about the vaccine when what we have learned from parents is that they value the HPV vaccine, but they’re not hearing their child’s doctor recommend it,” she said.

Overcoming these barriers requires patient outreach and awareness of HPV coverage rates at the city and state levels, as well as their individual and practice rates. Providers should bundle their recommendation with the other vaccines recommended by the CDC at the ages of 11 and 12 years: “Your child is due for three vaccines today that offer protection against meningitis, HPV cancers, and whooping cough,” is one example of language to use, Ms. Garcia said.

“Effective patient outreach for HPV vaccination includes the reminder/recall system, scheduling remaining doses at the time of receiving the first doses, and creating parental expectation that HPV vaccination is a very normal part of the immunization process, and that it occurs at ages 11 and 12,” she said.

She also reviewed the barriers among parents for HPV vaccination that providers can address. To respond to parents’ lack of knowledge about the vaccine or the need for it, providers “need to stress that it’s needed for cancer prevention,” Ms. Garcia said.

Providers also can reassure parents with concerns about safety and side effects that extensive safety research exists regarding HPV immunization from the past 10 years.

For those worried that HPV vaccination gives “permission for sexual activity” or that kids are too young, providers can reassure parents that the shot is not linked with increased sexual activity, and that it’s recommended at ages 11 and 12 years because the vaccine induces a better immune response at those ages than later on, she said.

Ms. Garcia reported no disclosures. No external funding was reported.

This article was updated Dec. 2, 2016.

ATLANTA – Holly Groom, MPH, of the Center for Health Research at Kaiser Permanente Northwest, described the intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates within the Kaiser Permanente NW health care system involving two hospitals and 31 medical offices, which serves 44,000 adolescents aged 11-17 years. About a quarter of patients reside in Washington, with the remainder in Oregon.

In addition to two in-person provider education and feedback sessions, the intervention included quarterly vaccine coverage, missed vaccination opportunity assessment reports, and a mailed parent survey. The staff education sessions covered six different cancers caused by HPV – cervical, anal, oropharyngeal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar – and their annual incidence, such as an estimated 10,000 oropharyngeal cancer cases in males and more than 11,000 cervical cancer cases in females each year.

One of the tip sheets distributed during provider and staff education offered specific language that providers could use to recommend the vaccine to parents and educate them about what HPV disease is and what cancers it can cause. For parents who are confused or concerned about why the vaccine is recommended at ages 11-12 years, for example, providers can respond, “We’re vaccinating today so your child will have the best protection possible long before the start of any kind of sexual activity. We vaccinate people well before they are exposed to an infection, as is the case with measles and the other recommended childhood vaccines.”

For those providers uneasy about mentioning sexual activity, Ms. Groom said, they can stick with telling parents the vaccine should be administered “long before the risk of infection” without mentioning the mechanism of infection.

Ms. Groom provided three other recommended statements as well:

• “I strongly believe in the importance of this cancer-preventing vaccine.”

• “I have given HPV vaccine to my son/daughter (or grandchild/niece/nephew/friend’s children).”

• “Experts, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, cancer doctors, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, also agree that getting the HPV vaccine is very important for your child.”

Feedback from the training sessions was “overwhelmingly positive,” with 87% of the respondents stating that they planned to implement the strategies and tools discussed and an additional 12% said they were already using those strategies and tools.

The parental survey, although it had only a 12% response rate, initially revealed that just over a third (36%) of parents weren’t sure if they were going to vaccinate their child when they went in for a well visit, but more than 90% of these parents did vaccinate their children.

Ms. Groom reported no disclosures. No external funding was reported.

Communication strategies to improve HPV immunization

Several communication strategies have been developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to help providers overcome barriers to improving HPV immunization coverage, Yvonne Garcia said at the National Immunization Conference.

Among providers’ barriers are hesitancy to make a recommendation for the HPV vaccine, and the need to understand the burden of the disease and the need for the vaccine, said Ms. Garcia, a health communications specialist for the CDC.

“Also, they overestimate parents’ concerns about the vaccine when what we have learned from parents is that they value the HPV vaccine, but they’re not hearing their child’s doctor recommend it,” she said.

Overcoming these barriers requires patient outreach and awareness of HPV coverage rates at the city and state levels, as well as their individual and practice rates. Providers should bundle their recommendation with the other vaccines recommended by the CDC at the ages of 11 and 12 years: “Your child is due for three vaccines today that offer protection against meningitis, HPV cancers, and whooping cough,” is one example of language to use, Ms. Garcia said.

“Effective patient outreach for HPV vaccination includes the reminder/recall system, scheduling remaining doses at the time of receiving the first doses, and creating parental expectation that HPV vaccination is a very normal part of the immunization process, and that it occurs at ages 11 and 12,” she said.

She also reviewed the barriers among parents for HPV vaccination that providers can address. To respond to parents’ lack of knowledge about the vaccine or the need for it, providers “need to stress that it’s needed for cancer prevention,” Ms. Garcia said.

Providers also can reassure parents with concerns about safety and side effects that extensive safety research exists regarding HPV immunization from the past 10 years.

For those worried that HPV vaccination gives “permission for sexual activity” or that kids are too young, providers can reassure parents that the shot is not linked with increased sexual activity, and that it’s recommended at ages 11 and 12 years because the vaccine induces a better immune response at those ages than later on, she said.

Ms. Garcia reported no disclosures. No external funding was reported.

This article was updated Dec. 2, 2016.

AT THE NATIONAL IMMUNIZATION CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Targeted interventions to improve HPV vaccination can be effective.

Major finding: In one health care system’s intervention, 87% of providers found the tools and strategies for increasing HPV vaccination uptake helpful and worth using.

Data source: A study within the Kaiser Permanente NW health care system involving two hospitals and 31 medical offices, which serves 44,000 adolescents aged 11-17 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Groom reported no disclosures. No external funding was reported.

Checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer figure prominently at WCLC 2016

Oncology Practice will be on-site this coming week at the 17th World Conference on Lung Cancer in Vienna with the latest on checkpoint inhibitors and other treatments for lung cancer. Look for coverage of the best clinical presentations at the conference, hosted by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, including the following and more, beginning Sunday, Dec. 4.

OA03.01 - First-Line Nivolumab Monotherapy and Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced NSCLC: Long-Term Outcomes from CheckMate 012.

OA03.02 - Atezolizumab as 1L Therapy for Advanced NSCLC in PD-L1–Selected Patients: Updated ORR, PFS, and OS Data From the BIRCH Study.

OA03.03 - JAVELIN Solid Tumor: Safety and Clinical Activity of Avelumab (Anti–PD-L1) as First-Line Treatment in Patients With Advanced NSCLC.

OA03.05 - Analysis of Early Survival in Patients With Advanced Nonsquamous NSCLC Treated With Nivolumab vs. Docetaxel in CheckMate 057.

OA03.07 - KEYNOTE-010: Durable Clinical Benefit in Patients With Previously Treated, PD-L1–Expressing NSCLC Who Completed Pembrolizumab.

OA05.01 - Pembrolizumab in Patients With Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer: Updated Survival Results from KEYNOTE-028.

OA13.03 - Long-Term Overall Survival for Patients With Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma on Pembrolizumab Enrolled in KEYNOTE-028.

PL03.03 - Randomised Phase III Study of Osimertinib vs. Platinum-Pemetrexed for EGFR T790M-Positive Advanced NSCLC (AURA3).

PL03.05 - BRAIN: A Phase III Trial Comparing WBI and Chemotherapy With Icotinib in NSCLC With Brain Metastases Harboring EGFR Mutations (CTONG 1201).

PL03.07 - First-line Ceritinib Versus Chemotherapy in Patients With ALK-Rearranged (ALK+) NSCLC: A Randomized, Phase III Study (ASCEND-4).

PL03.09 - Phase III Study of Ganetespib, a Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor, With Docetaxel versus Docetaxel in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer (GALAXY-2).

PL04a.01 - Health-Related Quality of Life for Pembrolizumab vs. Chemotherapy in Advanced NSCLC With PD-L1 TPS Greater Than or Equal to 50%: Data From KEYNOTE-024.

PL04a.02 - OAK, a Randomized Phase III Study of Atezolizumab vs. Docetaxel in Patients With Advanced NSCLC: Results From Subgroup Analyses.

PL04a.03 - Durvalumab in 3rd-Line Locally Advanced or Metastatic, EGFR/ALK Wild-Type NSCLC: Results from the Phase II ATLANTIC Study.

MA09.02 - Pembrolizumab + Carboplatin and Pemetrexed as 1st-Line Therapy for Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: KEYNOTE-021.

MA09.11 - Efficacy and Safety of Necitumumab and Pembrolizumab Combination Therapy in Stage IV Nonsquamous Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer.

Oncology Practice will be on-site this coming week at the 17th World Conference on Lung Cancer in Vienna with the latest on checkpoint inhibitors and other treatments for lung cancer. Look for coverage of the best clinical presentations at the conference, hosted by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, including the following and more, beginning Sunday, Dec. 4.

OA03.01 - First-Line Nivolumab Monotherapy and Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced NSCLC: Long-Term Outcomes from CheckMate 012.

OA03.02 - Atezolizumab as 1L Therapy for Advanced NSCLC in PD-L1–Selected Patients: Updated ORR, PFS, and OS Data From the BIRCH Study.

OA03.03 - JAVELIN Solid Tumor: Safety and Clinical Activity of Avelumab (Anti–PD-L1) as First-Line Treatment in Patients With Advanced NSCLC.

OA03.05 - Analysis of Early Survival in Patients With Advanced Nonsquamous NSCLC Treated With Nivolumab vs. Docetaxel in CheckMate 057.

OA03.07 - KEYNOTE-010: Durable Clinical Benefit in Patients With Previously Treated, PD-L1–Expressing NSCLC Who Completed Pembrolizumab.

OA05.01 - Pembrolizumab in Patients With Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer: Updated Survival Results from KEYNOTE-028.

OA13.03 - Long-Term Overall Survival for Patients With Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma on Pembrolizumab Enrolled in KEYNOTE-028.

PL03.03 - Randomised Phase III Study of Osimertinib vs. Platinum-Pemetrexed for EGFR T790M-Positive Advanced NSCLC (AURA3).

PL03.05 - BRAIN: A Phase III Trial Comparing WBI and Chemotherapy With Icotinib in NSCLC With Brain Metastases Harboring EGFR Mutations (CTONG 1201).

PL03.07 - First-line Ceritinib Versus Chemotherapy in Patients With ALK-Rearranged (ALK+) NSCLC: A Randomized, Phase III Study (ASCEND-4).

PL03.09 - Phase III Study of Ganetespib, a Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor, With Docetaxel versus Docetaxel in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer (GALAXY-2).

PL04a.01 - Health-Related Quality of Life for Pembrolizumab vs. Chemotherapy in Advanced NSCLC With PD-L1 TPS Greater Than or Equal to 50%: Data From KEYNOTE-024.

PL04a.02 - OAK, a Randomized Phase III Study of Atezolizumab vs. Docetaxel in Patients With Advanced NSCLC: Results From Subgroup Analyses.

PL04a.03 - Durvalumab in 3rd-Line Locally Advanced or Metastatic, EGFR/ALK Wild-Type NSCLC: Results from the Phase II ATLANTIC Study.

MA09.02 - Pembrolizumab + Carboplatin and Pemetrexed as 1st-Line Therapy for Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: KEYNOTE-021.

MA09.11 - Efficacy and Safety of Necitumumab and Pembrolizumab Combination Therapy in Stage IV Nonsquamous Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer.

Oncology Practice will be on-site this coming week at the 17th World Conference on Lung Cancer in Vienna with the latest on checkpoint inhibitors and other treatments for lung cancer. Look for coverage of the best clinical presentations at the conference, hosted by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, including the following and more, beginning Sunday, Dec. 4.

OA03.01 - First-Line Nivolumab Monotherapy and Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced NSCLC: Long-Term Outcomes from CheckMate 012.

OA03.02 - Atezolizumab as 1L Therapy for Advanced NSCLC in PD-L1–Selected Patients: Updated ORR, PFS, and OS Data From the BIRCH Study.

OA03.03 - JAVELIN Solid Tumor: Safety and Clinical Activity of Avelumab (Anti–PD-L1) as First-Line Treatment in Patients With Advanced NSCLC.

OA03.05 - Analysis of Early Survival in Patients With Advanced Nonsquamous NSCLC Treated With Nivolumab vs. Docetaxel in CheckMate 057.

OA03.07 - KEYNOTE-010: Durable Clinical Benefit in Patients With Previously Treated, PD-L1–Expressing NSCLC Who Completed Pembrolizumab.

OA05.01 - Pembrolizumab in Patients With Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer: Updated Survival Results from KEYNOTE-028.

OA13.03 - Long-Term Overall Survival for Patients With Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma on Pembrolizumab Enrolled in KEYNOTE-028.

PL03.03 - Randomised Phase III Study of Osimertinib vs. Platinum-Pemetrexed for EGFR T790M-Positive Advanced NSCLC (AURA3).

PL03.05 - BRAIN: A Phase III Trial Comparing WBI and Chemotherapy With Icotinib in NSCLC With Brain Metastases Harboring EGFR Mutations (CTONG 1201).

PL03.07 - First-line Ceritinib Versus Chemotherapy in Patients With ALK-Rearranged (ALK+) NSCLC: A Randomized, Phase III Study (ASCEND-4).

PL03.09 - Phase III Study of Ganetespib, a Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor, With Docetaxel versus Docetaxel in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer (GALAXY-2).

PL04a.01 - Health-Related Quality of Life for Pembrolizumab vs. Chemotherapy in Advanced NSCLC With PD-L1 TPS Greater Than or Equal to 50%: Data From KEYNOTE-024.

PL04a.02 - OAK, a Randomized Phase III Study of Atezolizumab vs. Docetaxel in Patients With Advanced NSCLC: Results From Subgroup Analyses.

PL04a.03 - Durvalumab in 3rd-Line Locally Advanced or Metastatic, EGFR/ALK Wild-Type NSCLC: Results from the Phase II ATLANTIC Study.

MA09.02 - Pembrolizumab + Carboplatin and Pemetrexed as 1st-Line Therapy for Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: KEYNOTE-021.

MA09.11 - Efficacy and Safety of Necitumumab and Pembrolizumab Combination Therapy in Stage IV Nonsquamous Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer.

FROM WCLC 2016

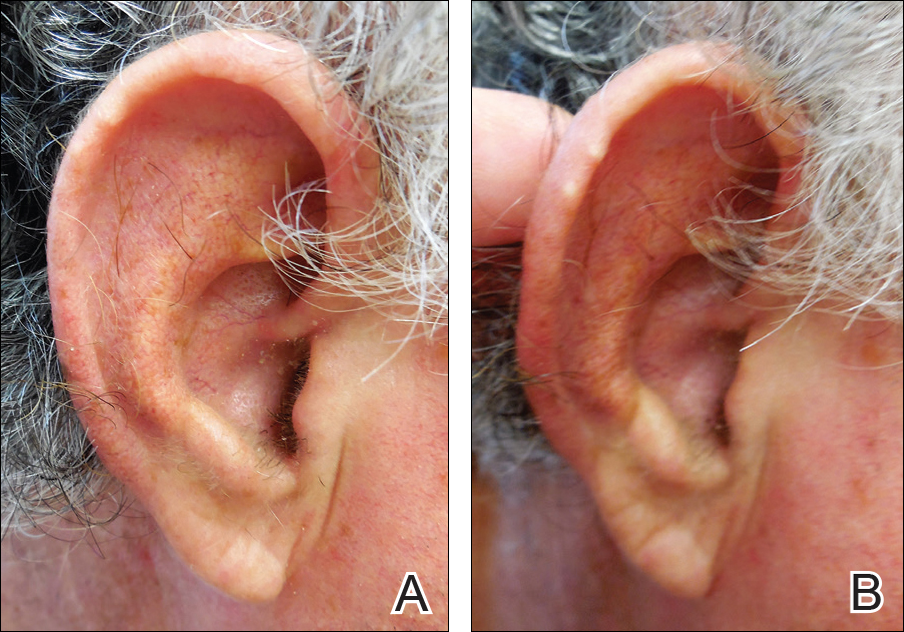

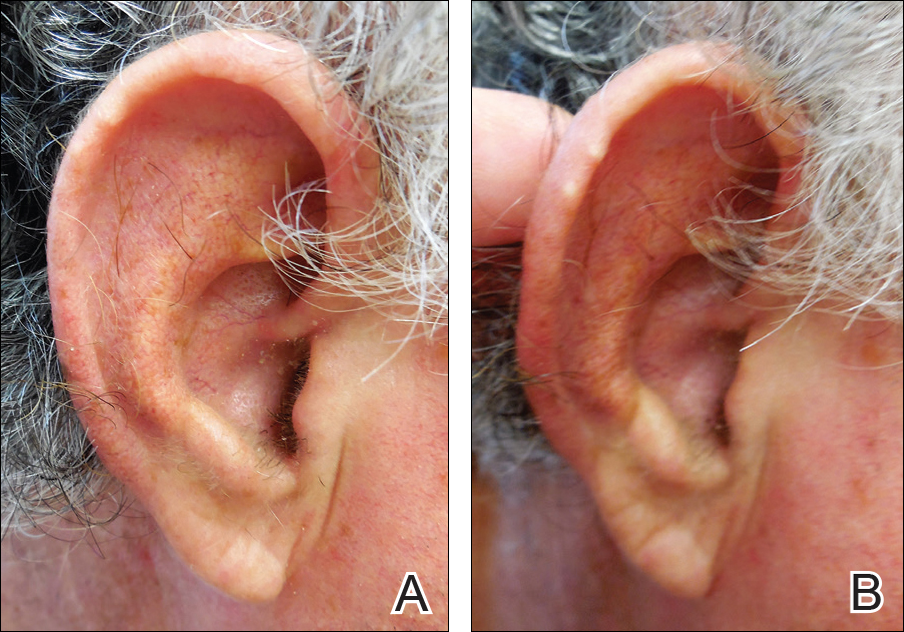

Prenatal exposure to hydroxychloroquine cuts risk of neonatal cutaneous lupus

WASHINGTON – Prenatal hydroxychloroquine reduces the risk of cutaneous neonatal lupus by 60% among the infants of women with a systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease.

The medication easily passes the placental barrier and confers significant protection to neonates born to women who have anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies, Julie Barsalou, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Toll-like receptors 7 and 9 have been implicated in the initiation and maintenance of interface dermatitis, and hydroxychloroquine inhibits these receptors. In mouse studies, the drug has led to improvement of this type of dermatitis. Hydroxychloroquine also works well in treating subacute cutaneous lupus, she said, and because it can travel across the placenta, it could be an effective means of preventing this disorder in at-risk neonates.

To examine any potential benefit, Dr. Barsalou looked at three pediatric lupus databases: the SickKids NLE database from Toronto, the U.S. Research Registry for Neonatal Lupus, and the French Registry for Neonatal Lupus.

These registries include infants born to mothers with anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies, and a diagnosis of lupus, dermatomyositis, Sjögren’s syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or rheumatic arthritis. No infants with cardiac neonatal lupus were included in the study.

In addition to hydroxychloroquine, Dr. Barsalou examined the use of prenatal azathioprine, nonfluorinated and fluorinated steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin.

The cohort comprised 545 neonates born to 535 mothers. Among these, 112 developed cNLE. The remaining 433 infants were used as controls.

Mothers of both cases and controls were a mean age of 31 years. Among cases, the most common diagnosis was Sjögren’s syndrome (53%), followed by systemic lupus erythematosus (46%). Among controls, the most common maternal diagnosis was SLE (62%), followed by Sjögren’s (31%).

All mothers of cases were positive for anti-Ro antibodies; 72% were positive for anti-La antibodies. Among mothers of controls, 99% had anti-Ro antibodies and 48% had anti-La antibodies.

Mothers of cases took hydroxychloroquine (17%), fluorinated steroids (6%), and nonfluorinated steroids with or without azathioprine (28%). Mothers of controls took hydroxychloroquine (34%), fluorinated steroids (4%), and nonfluorinated steroids with or without azathioprine (44%),

There were significantly more female than male infants in the case group (65%). The median age at rash onset was 6 weeks.

Dr. Barsalou performed several multivariate analyses on the entire cohort, as well as two subgroup analyses: one on infants who developed the cNLE rash within the first 4 weeks of life and one on only the infants of mothers with SLE.

In the primary analysis, maternal anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies more than doubled the risk of an infant developing cNLE (odds ratio, 2.5). The use of hydroxychloroquine decreased this risk by 60% (OR, 0.4). Being a female infant increased the risk by 70% (OR, 1.7).

In the group of infants with early-onset rash, maternal anti-La antibodies more than tripled the risk (OR, 3.5), while the use of hydroxychloroquine decreased the risk by 80% (OR, 0.2).

Among the infants born to women with SLE, concomitant secondary Sjögren’s syndrome increased the risk of cNLE by more than threefold (OR, 3.5). Anti-La antibodies more than doubled the risk (OR, 2.5), and the use of hydroxychloroquine decreased it by 60% (OR, 0.4).

“This is the first study to address the prevention of cutaneous neonatal lupus,” Dr. Barsalou said. “We found that prenatal exposure to hydroxychloroquine is likely protective.”

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

WASHINGTON – Prenatal hydroxychloroquine reduces the risk of cutaneous neonatal lupus by 60% among the infants of women with a systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease.

The medication easily passes the placental barrier and confers significant protection to neonates born to women who have anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies, Julie Barsalou, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Toll-like receptors 7 and 9 have been implicated in the initiation and maintenance of interface dermatitis, and hydroxychloroquine inhibits these receptors. In mouse studies, the drug has led to improvement of this type of dermatitis. Hydroxychloroquine also works well in treating subacute cutaneous lupus, she said, and because it can travel across the placenta, it could be an effective means of preventing this disorder in at-risk neonates.

To examine any potential benefit, Dr. Barsalou looked at three pediatric lupus databases: the SickKids NLE database from Toronto, the U.S. Research Registry for Neonatal Lupus, and the French Registry for Neonatal Lupus.

These registries include infants born to mothers with anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies, and a diagnosis of lupus, dermatomyositis, Sjögren’s syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or rheumatic arthritis. No infants with cardiac neonatal lupus were included in the study.

In addition to hydroxychloroquine, Dr. Barsalou examined the use of prenatal azathioprine, nonfluorinated and fluorinated steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin.

The cohort comprised 545 neonates born to 535 mothers. Among these, 112 developed cNLE. The remaining 433 infants were used as controls.

Mothers of both cases and controls were a mean age of 31 years. Among cases, the most common diagnosis was Sjögren’s syndrome (53%), followed by systemic lupus erythematosus (46%). Among controls, the most common maternal diagnosis was SLE (62%), followed by Sjögren’s (31%).

All mothers of cases were positive for anti-Ro antibodies; 72% were positive for anti-La antibodies. Among mothers of controls, 99% had anti-Ro antibodies and 48% had anti-La antibodies.

Mothers of cases took hydroxychloroquine (17%), fluorinated steroids (6%), and nonfluorinated steroids with or without azathioprine (28%). Mothers of controls took hydroxychloroquine (34%), fluorinated steroids (4%), and nonfluorinated steroids with or without azathioprine (44%),

There were significantly more female than male infants in the case group (65%). The median age at rash onset was 6 weeks.

Dr. Barsalou performed several multivariate analyses on the entire cohort, as well as two subgroup analyses: one on infants who developed the cNLE rash within the first 4 weeks of life and one on only the infants of mothers with SLE.

In the primary analysis, maternal anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies more than doubled the risk of an infant developing cNLE (odds ratio, 2.5). The use of hydroxychloroquine decreased this risk by 60% (OR, 0.4). Being a female infant increased the risk by 70% (OR, 1.7).

In the group of infants with early-onset rash, maternal anti-La antibodies more than tripled the risk (OR, 3.5), while the use of hydroxychloroquine decreased the risk by 80% (OR, 0.2).

Among the infants born to women with SLE, concomitant secondary Sjögren’s syndrome increased the risk of cNLE by more than threefold (OR, 3.5). Anti-La antibodies more than doubled the risk (OR, 2.5), and the use of hydroxychloroquine decreased it by 60% (OR, 0.4).

“This is the first study to address the prevention of cutaneous neonatal lupus,” Dr. Barsalou said. “We found that prenatal exposure to hydroxychloroquine is likely protective.”

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

WASHINGTON – Prenatal hydroxychloroquine reduces the risk of cutaneous neonatal lupus by 60% among the infants of women with a systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease.

The medication easily passes the placental barrier and confers significant protection to neonates born to women who have anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies, Julie Barsalou, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Toll-like receptors 7 and 9 have been implicated in the initiation and maintenance of interface dermatitis, and hydroxychloroquine inhibits these receptors. In mouse studies, the drug has led to improvement of this type of dermatitis. Hydroxychloroquine also works well in treating subacute cutaneous lupus, she said, and because it can travel across the placenta, it could be an effective means of preventing this disorder in at-risk neonates.

To examine any potential benefit, Dr. Barsalou looked at three pediatric lupus databases: the SickKids NLE database from Toronto, the U.S. Research Registry for Neonatal Lupus, and the French Registry for Neonatal Lupus.

These registries include infants born to mothers with anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies, and a diagnosis of lupus, dermatomyositis, Sjögren’s syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or rheumatic arthritis. No infants with cardiac neonatal lupus were included in the study.

In addition to hydroxychloroquine, Dr. Barsalou examined the use of prenatal azathioprine, nonfluorinated and fluorinated steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin.

The cohort comprised 545 neonates born to 535 mothers. Among these, 112 developed cNLE. The remaining 433 infants were used as controls.

Mothers of both cases and controls were a mean age of 31 years. Among cases, the most common diagnosis was Sjögren’s syndrome (53%), followed by systemic lupus erythematosus (46%). Among controls, the most common maternal diagnosis was SLE (62%), followed by Sjögren’s (31%).

All mothers of cases were positive for anti-Ro antibodies; 72% were positive for anti-La antibodies. Among mothers of controls, 99% had anti-Ro antibodies and 48% had anti-La antibodies.

Mothers of cases took hydroxychloroquine (17%), fluorinated steroids (6%), and nonfluorinated steroids with or without azathioprine (28%). Mothers of controls took hydroxychloroquine (34%), fluorinated steroids (4%), and nonfluorinated steroids with or without azathioprine (44%),

There were significantly more female than male infants in the case group (65%). The median age at rash onset was 6 weeks.

Dr. Barsalou performed several multivariate analyses on the entire cohort, as well as two subgroup analyses: one on infants who developed the cNLE rash within the first 4 weeks of life and one on only the infants of mothers with SLE.

In the primary analysis, maternal anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies more than doubled the risk of an infant developing cNLE (odds ratio, 2.5). The use of hydroxychloroquine decreased this risk by 60% (OR, 0.4). Being a female infant increased the risk by 70% (OR, 1.7).

In the group of infants with early-onset rash, maternal anti-La antibodies more than tripled the risk (OR, 3.5), while the use of hydroxychloroquine decreased the risk by 80% (OR, 0.2).

Among the infants born to women with SLE, concomitant secondary Sjögren’s syndrome increased the risk of cNLE by more than threefold (OR, 3.5). Anti-La antibodies more than doubled the risk (OR, 2.5), and the use of hydroxychloroquine decreased it by 60% (OR, 0.4).