User login

Emergency Imaging: Facial Trauma After a Fall

An 89-year-old man presented to the ED with facial trauma due to a mechanical fall after losing his balance on uneven pavement and hitting the right side of his face. Physical examination revealed an ecchymosis inferior to the right eye and tenderness to palpation at the right maxilla and bilateral nasolabial folds. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) was ordered for further evaluation; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

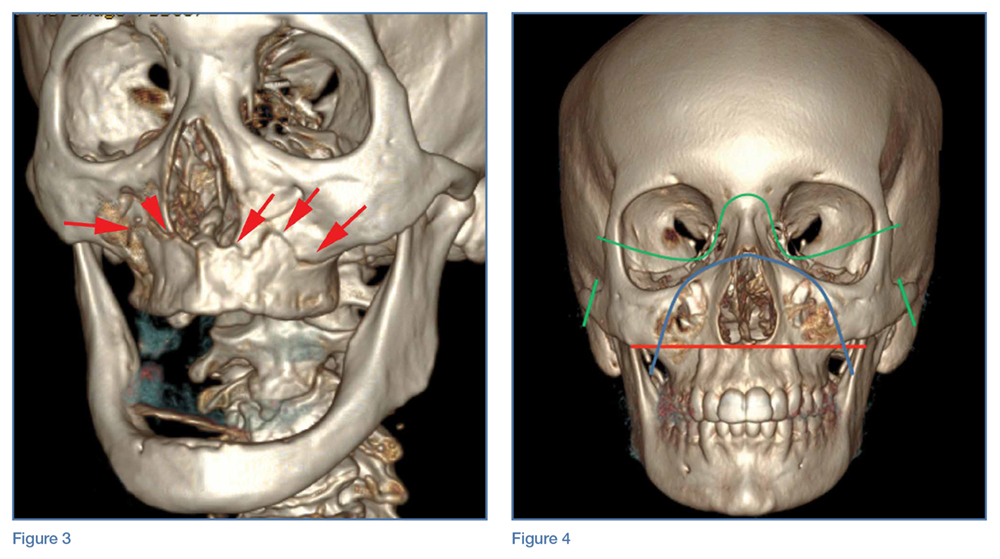

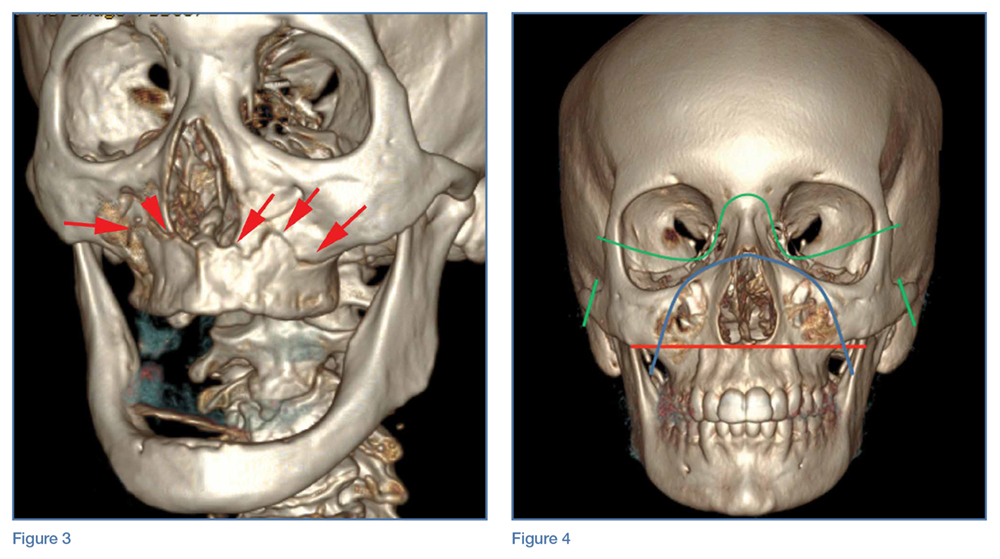

A noncontrast CT of the maxillofacial bones demonstrated acute fractures through the bilateral pterygoid plates (white arrows, Figure 2a). The fractures extended through the medial and lateral walls of the bilateral maxillary sinuses (red arrows, Figure 2a), and propagated to the frontal processes of the maxilla (red arrows, Figure 2b), extending toward the alveolar process, indicating involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa. The full extent of the fracture is best seen on a 3D-reconstructed image (red arrows, Figure 3). Additional images (not presented here) confirmed no fracture involvement of the orbital floors, nasal bones, or zygomatic arches. Expected posttraumatic hemorrhage was appreciated within the maxillary sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a).

Le Fort Fractures

The findings described above are characteristic of a Le Fort I fracture pattern. Initially described in 1901 by René Le Fort, a French surgeon, the Le Fort classification system details somewhat predictable midface fracture patterns resulting in various degrees of craniofacial disassociation.1 Using weights that were dropped on cadaveric heads, Le Fort discovered that the pterygoid plates must be disrupted in order for the midface facial bones to separate from the skull base. As such, when diagnosing a Le Fort fracture, fracture of the pterygoid plate must be present, regardless of the fracture type (Le Fort I, II, and III).2

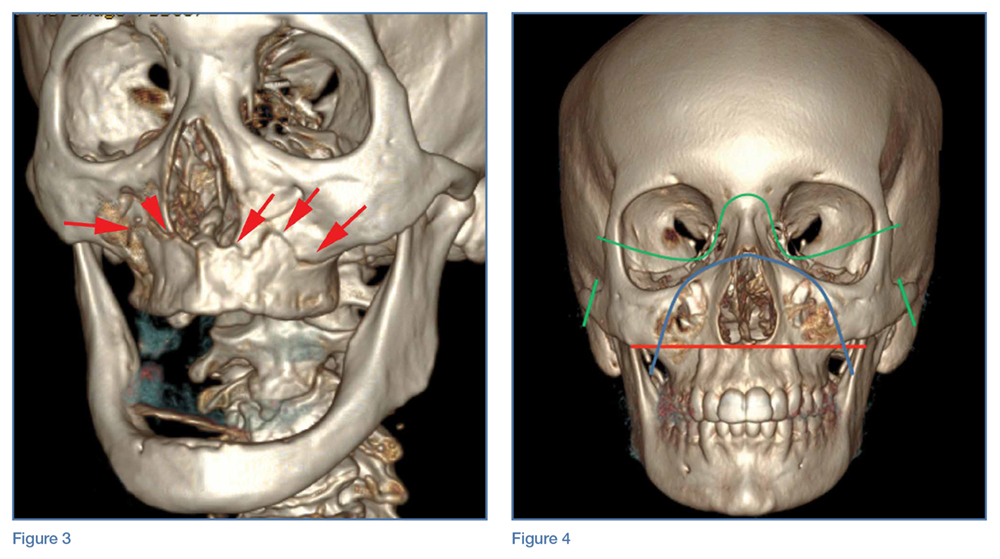

Le Fort I Fracture. This fracture pattern (red line, Figure 4) is referred to as a “floating palate” and involves separation of the hard palate from the skull base via fracture extension from the pterygoid plates into the maxillary sinus walls, as demonstrated in this case. The key distinguisher of the Le Fort I pattern is involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.2

Le Fort II Fracture. This fracture pattern (blue line, Figure 4) describes a “floating maxilla” wherein the pterygoid plate fractures are met with a pyramidal-type fracture pattern of the midface. The maxillary teeth form the base of the pyramid, and the fracture extends superiorly through the infraorbital rims bilaterally and toward the nasofrontal suture.2,3 Le Fort II fractures result in the maxilla floating freely from the rest of the midface and skull base.

Le Fort III Fracture. This fracture pattern (green lines, Figure 4) describes a “floating face” with complete craniofacial disjunction resulting from fracture of the pterygoid plates, nasofrontal suture, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, and zygomatic arch/zygomaticofrontal suture.2,3

It is important to note that midface trauma represents a complex spectrum of injuries, and Le Fort fractures only account for a small percentage of facial bone fractures that present through Level 1 trauma centers.2 Le Fort fracture patterns can coexist with other fracture patterns and also can be seen in combination with each other. For example, one side of the face may demonstrate a Le Fort II pattern while the other side concurrently demonstrates a Le Fort III pattern. Though not robust enough for complete description of and surgical planning for facial fractures, this classification system is a succinct and well-accepted means of describing major fracture planes.

1. Le Fort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901;23:208-227, 360-379, 479-507.

2. Rhea JT, Novelline RA. How to simplify the CT diagnosis of Le Fort fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1700-1705.

3. Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):783-793.

An 89-year-old man presented to the ED with facial trauma due to a mechanical fall after losing his balance on uneven pavement and hitting the right side of his face. Physical examination revealed an ecchymosis inferior to the right eye and tenderness to palpation at the right maxilla and bilateral nasolabial folds. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) was ordered for further evaluation; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

A noncontrast CT of the maxillofacial bones demonstrated acute fractures through the bilateral pterygoid plates (white arrows, Figure 2a). The fractures extended through the medial and lateral walls of the bilateral maxillary sinuses (red arrows, Figure 2a), and propagated to the frontal processes of the maxilla (red arrows, Figure 2b), extending toward the alveolar process, indicating involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa. The full extent of the fracture is best seen on a 3D-reconstructed image (red arrows, Figure 3). Additional images (not presented here) confirmed no fracture involvement of the orbital floors, nasal bones, or zygomatic arches. Expected posttraumatic hemorrhage was appreciated within the maxillary sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a).

Le Fort Fractures

The findings described above are characteristic of a Le Fort I fracture pattern. Initially described in 1901 by René Le Fort, a French surgeon, the Le Fort classification system details somewhat predictable midface fracture patterns resulting in various degrees of craniofacial disassociation.1 Using weights that were dropped on cadaveric heads, Le Fort discovered that the pterygoid plates must be disrupted in order for the midface facial bones to separate from the skull base. As such, when diagnosing a Le Fort fracture, fracture of the pterygoid plate must be present, regardless of the fracture type (Le Fort I, II, and III).2

Le Fort I Fracture. This fracture pattern (red line, Figure 4) is referred to as a “floating palate” and involves separation of the hard palate from the skull base via fracture extension from the pterygoid plates into the maxillary sinus walls, as demonstrated in this case. The key distinguisher of the Le Fort I pattern is involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.2

Le Fort II Fracture. This fracture pattern (blue line, Figure 4) describes a “floating maxilla” wherein the pterygoid plate fractures are met with a pyramidal-type fracture pattern of the midface. The maxillary teeth form the base of the pyramid, and the fracture extends superiorly through the infraorbital rims bilaterally and toward the nasofrontal suture.2,3 Le Fort II fractures result in the maxilla floating freely from the rest of the midface and skull base.

Le Fort III Fracture. This fracture pattern (green lines, Figure 4) describes a “floating face” with complete craniofacial disjunction resulting from fracture of the pterygoid plates, nasofrontal suture, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, and zygomatic arch/zygomaticofrontal suture.2,3

It is important to note that midface trauma represents a complex spectrum of injuries, and Le Fort fractures only account for a small percentage of facial bone fractures that present through Level 1 trauma centers.2 Le Fort fracture patterns can coexist with other fracture patterns and also can be seen in combination with each other. For example, one side of the face may demonstrate a Le Fort II pattern while the other side concurrently demonstrates a Le Fort III pattern. Though not robust enough for complete description of and surgical planning for facial fractures, this classification system is a succinct and well-accepted means of describing major fracture planes.

An 89-year-old man presented to the ED with facial trauma due to a mechanical fall after losing his balance on uneven pavement and hitting the right side of his face. Physical examination revealed an ecchymosis inferior to the right eye and tenderness to palpation at the right maxilla and bilateral nasolabial folds. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) was ordered for further evaluation; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

A noncontrast CT of the maxillofacial bones demonstrated acute fractures through the bilateral pterygoid plates (white arrows, Figure 2a). The fractures extended through the medial and lateral walls of the bilateral maxillary sinuses (red arrows, Figure 2a), and propagated to the frontal processes of the maxilla (red arrows, Figure 2b), extending toward the alveolar process, indicating involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa. The full extent of the fracture is best seen on a 3D-reconstructed image (red arrows, Figure 3). Additional images (not presented here) confirmed no fracture involvement of the orbital floors, nasal bones, or zygomatic arches. Expected posttraumatic hemorrhage was appreciated within the maxillary sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a).

Le Fort Fractures

The findings described above are characteristic of a Le Fort I fracture pattern. Initially described in 1901 by René Le Fort, a French surgeon, the Le Fort classification system details somewhat predictable midface fracture patterns resulting in various degrees of craniofacial disassociation.1 Using weights that were dropped on cadaveric heads, Le Fort discovered that the pterygoid plates must be disrupted in order for the midface facial bones to separate from the skull base. As such, when diagnosing a Le Fort fracture, fracture of the pterygoid plate must be present, regardless of the fracture type (Le Fort I, II, and III).2

Le Fort I Fracture. This fracture pattern (red line, Figure 4) is referred to as a “floating palate” and involves separation of the hard palate from the skull base via fracture extension from the pterygoid plates into the maxillary sinus walls, as demonstrated in this case. The key distinguisher of the Le Fort I pattern is involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.2

Le Fort II Fracture. This fracture pattern (blue line, Figure 4) describes a “floating maxilla” wherein the pterygoid plate fractures are met with a pyramidal-type fracture pattern of the midface. The maxillary teeth form the base of the pyramid, and the fracture extends superiorly through the infraorbital rims bilaterally and toward the nasofrontal suture.2,3 Le Fort II fractures result in the maxilla floating freely from the rest of the midface and skull base.

Le Fort III Fracture. This fracture pattern (green lines, Figure 4) describes a “floating face” with complete craniofacial disjunction resulting from fracture of the pterygoid plates, nasofrontal suture, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, and zygomatic arch/zygomaticofrontal suture.2,3

It is important to note that midface trauma represents a complex spectrum of injuries, and Le Fort fractures only account for a small percentage of facial bone fractures that present through Level 1 trauma centers.2 Le Fort fracture patterns can coexist with other fracture patterns and also can be seen in combination with each other. For example, one side of the face may demonstrate a Le Fort II pattern while the other side concurrently demonstrates a Le Fort III pattern. Though not robust enough for complete description of and surgical planning for facial fractures, this classification system is a succinct and well-accepted means of describing major fracture planes.

1. Le Fort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901;23:208-227, 360-379, 479-507.

2. Rhea JT, Novelline RA. How to simplify the CT diagnosis of Le Fort fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1700-1705.

3. Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):783-793.

1. Le Fort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901;23:208-227, 360-379, 479-507.

2. Rhea JT, Novelline RA. How to simplify the CT diagnosis of Le Fort fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1700-1705.

3. Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):783-793.

First EDition: Retail Clinics and Rate of ED Visits, more

Retail Clinics Have Not Decreased the Rate of Low-Acuity ED Visits

BY JEFF BAUER

The number of retail clinics—those located in pharmacies, supermarkets, and other retail settings—in the United States increased from 130 in 2006 to nearly 1,400 in 2012. However, this proliferation of retail clinics has not lead to a meaningful reduction in low-acuity ED visits, according to a recent observational study published in Annals of Emergency Medicine.1

Using information from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Emergency Department Databases, which include data on more than 2,000 EDs in 23 states from 2006 through 2013, researchers looked at the association between retail clinic penetration and the rate of treat-and-release ED visits for 11 low-acuity conditions (allergic rhinitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, other eye conditions, influenza, otitis externa, otitis media, pharyngitis, upper respiratory infections/sinusitis, urinary tract infections, and viral infections).

Retail clinic penetration was defined as the percentage of an ED’s catchment area (areas that accounted for up to 75% of patients who visited for low-acuity conditions) that overlapped with the 10-minute-drive radius of a retail clinic. The results were calculated as a rate ratio, which reflected the change in the rate of low-acuity ED visits associated with an ED having no retail clinic penetration to having approximately the average penetration rate within 2012. Results were controlled for the number of urgent care centers that were present in each ED catchment area, but only for hospital-associated urgent care centers, as there are no reliable data to identify all urgent care centers.

Retail clinic penetration more than doubled during the study period. Overall, increased retail clinic penetration was not associated with a change in the rate of low-acuity ED visits. Among patients with private insurance, there was a small reduction (0.3% per calendar quarter) in ED visits for low-acuity conditions, but this translated into an estimated 17 fewer ED visits by privately insured patients over 1 year for the average ED, assuming the retail clinic penetration rate increased by 40% in that year.

In an accompanying editorial,2 Jesse M. Pines, MD, suggests that visits to retail clinics may be mostly “new-use” visits, meaning many individuals who would not have otherwise received treatment seek care in a retail clinic because such clinics are available. Dr Pines proposed three reasons retail clinics may create new-use visits: they meet unmet demands for care; motivations for seeking care differ in EDs and retail clinics; and people who are more likely to use EDs for low-acuity conditions do so because they have limited access to other types of care, including retail clinics.

1. Martsolf G, Fingar KR, Coffey R, et al. Association between the opening of retail clinics and low-acuity emergency department visits. Ann Emerg Med. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.462.

2. Pines JM. Why retail clinics do not substitute for emergency department visits and what this means for value-based care. Ann Emerg Med. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.09.047.

Hypotension During Transport to ED Drives Mortality in Traumatic Brain Injury

MITCHEL L. ZOLER

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

The severity and duration of hypotension in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients during emergency medical service (EMS) transport to an ED has a tight and essentially linear relationship to mortality rate during subsequent weeks of recovery, according to an analysis of more than 7,500 brain-injured patients.

For each doubling of the combined severity and duration of hypotension during the prehospital period, when systolic blood pressure (BP) was <90 mm Hg, patient mortality rose by 19%, Daniel W. Spaite, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

However, the results do not address whether aggressive treatment of hypotension by EMS technicians in a patient with TBI leads to reduced mortality. That question is being assessed as part of the primary endpoint of the Excellence in Prehospital Injury Care-Traumatic Brain Injury (EPIC-TBI) study, which should be completed by the end of 2017, said Dr Spaite, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona in Tucson.Results from prior studies have clearly linked prehospital hypotension with worse survival in TBI patients. Until now, however, there was no appreciation of the fact that not all hypotensive episodes are equal, and that both the severity of hypotension and its duration incrementally contribute to mortality as the “dose” of hypotension a patient experiences increases. In large part, this is because prehospital hypotension has been recorded simply as a dichotomous, yes/no condition.

The innovation introduced by Dr Spaite and his associates in their analysis of the EPIC-TBI data was to drill down into each patient’s hypotensive event, made possible by the 16,711 patients enrolled in EPIC-TBI. Their calculations were limited to patients with EMS records of at least two BP measurements during prehospital transport. These data allowed Spaite et al to utilize both the extent to which systolic BP dropped below 90 mm Hg and the amount of time systolic BP was below this threshold to better define the total hypotension exposure each patient received.

This meant that a patient with a TBI and a systolic BP of 80 mm Hg for 10 minutes had twice the hypotension exposure of both a patient with a systolic BP of 85 mm Hg for 10 minutes and a patient with a systolic BP of 80 mm Hg for 5 minutes.

The analysis by Spaite et al also adjusted the relationship of total hypotensive severity and duration and subsequent mortality based on several baseline demographic and clinical variables, including age, sex, injury severity, trauma type, and head-region severity score. After adjustment, the researchers found a “strikingly linear relationship” between hypotension severity and duration and mortality, Dr Spaite said.

The EPIC-TBI enrolled TBI patients aged 10 years or older during 2007 to 2014 through participation of dozens of EMS providers throughout Arizona. For the current analysis, the researchers identified 7,521 patients from the total group who had at least two BP measurements taken during their prehospital EMS care and also met other inclusion criteria.

The best way to manage hypotension in TBI patients during the prehospital period remains unclear. Simply raising BP via intravenous (IV) fluid infusion may not necessarily help, because it could exacerbate a patient’s bleeding, Dr Spaite noted during an interview.

The primary goal of EPIC-TBI is to assess the implementation of the third edition of the TBI guidelines released in 2007 by the Brain Trauma Foundation. (The fourth edition of these guidelines came out in August 2016.) The new finding by Dr Spaite and his associates will allow the full EPIC-TBI analysis to correlate patient outcomes with the impact that acute, prehospital treatment had on the hypotension severity and duration each patient experienced, he noted.

“What’s remarkable is that the single prehospital parameter of hypotension for just a few minutes during transport can have such a strong impact on survival, given all the other factors that can influence outcomes” in TBI patients once they reach a hospital and during the period they remain hospitalized, Dr Spaite said.

1. Spaite DW. Presentation at: American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2016. November 12-16, 2016; New Orleans, LA.

Fluid Administration in Sepsis Did Not Increase Need for Dialysis

M. Alexander Otto

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Fluid administration of at least 1 L did not increase the incidence of acute respiratory or heart failure in severe sepsis, and actually seemed to decrease the need for dialysis in a review of 164 patients at Scott and White Memorial Hospital in Temple, Texas.

For every 1 mL of fluid administered per kilogram of body weight, the likelihood of dialysis decreased by 8.5% (odds ratio [OR], 0.915; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.854-0.980; P = .0111), with no increase in heart or respiratory failure on univariate analysis. The 126 patients (77%) who received at least 1 L of fluid had a 68% reduction in the need for dialysis (OR, 0.32; CI, 0.117-0.890; P = .0288).

These findings come from a quality improvement project the hospital launched after researchers there realized that the benchmark Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines were not being met. The patients in the study had a systolic BP below 90 mm Hg or lactate level of at least 4 mmol/L. The guidelines would have called for these patients to receive 30 mL/kg of crystalloid fluids within 3 hours of presentation, but only 28 patients (17%) met that mark.

“The No. 1 reason we weren’t meeting benchmarks was fluid administration,” explained lead investigator Aruna Jahoor, MD, a pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine fellow at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

Seventeen percent of patients received ≥30 mL/kg of fluid resuscitation, while 28% received ≥20 mL/kg of IV fluid resuscitation. It turned out that staff in the ED—where most of the patients were treated in the critical first 6 hours—were concerned about fluid overload and putting patients into respiratory, heart, or renal failure, Dr Jahoor said. The team found no difference in mortality rates when patients received 30 mL/kg—just over 2 L in a patient weighing 70 kg—vs 20 mL/kg or 1 L. The patients’ in-hospital mortality rate and 28-day mortality rate were 27% and 32%, respectively.

There also were no increased rates of heart failure, acute respiratory failure, or mechanical ventilation when patients received at least 1 L of fluid. “There were [also] lower rates of dialysis, which indicated that we weren’t overloading patients. Even when we looked at fluid as a continuous variable, we still didn’t see” complications, Dr Jahoor said.

The findings should be reassuring to treating physicians. “When you have pushback against 30-mL/kg administration, you can say ‘well, at least let’s give a liter.’ You don’t have to worry as much about some of the complications you are citing,’ ” she said.

For very obese patients, “it can get a little uncomfortable to be given” enough fluid to meet the 30-mL/kg goal, “but you can give at least a liter” without having to worry too much, she said. The patients in the study were treated from 2010 to 2013; normal saline was the most common resuscitation fluid. The hospital has since added the 30-mL/kg fluid resuscitation to its sepsis admission orders, and compliance has increased significantly.

A multivariate analysis is in the works to control for confounders. “We will probably [still] see you are not having increased rates of congestive heart or respiratory failure, or needing dialysis,” Dr Jahoor said. The protective effect against dialysis might drop out, “but I am hoping it doesn’t,” she said.

1. Jahoor A, Delmas T, Giri B, et al. Fluid resuscitation of at least 1 liter in septic patients decreases the need for renal replacement therapy without increasing the risk of acute congestive heart failure or acute respiratory failure. Chest. 2016;150(4_S):349A. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.362.

Survey: Antibiotic Shortages Are the New Norm

SHARON WORCESTER

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Antibiotic shortages reported by the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) in 2011 persist in 2016, according to a Web-based follow-up survey of infectious disease physicians.

Of 701 network members who responded to the EIN survey in early 2016, 70% reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years. They did so by using broader-spectrum agents (75% of respondents), more costly agents (58%), less effective second-line agents (45%), and more toxic agents (37%), Adi Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In addition, 73% of respondents reported that the shortages affected patient care or outcomes, reported Dr Gundlapalli of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The percentage of respondents reporting adverse patient outcomes related to shortages increased from 2011 to 2016 (51% vs 73%), he noted at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

In the 2016 survey, the top 10 antimicrobials reported as being in short supply over the past 2 years were piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), doxycycline, imipenem, acyclovir, and amikacin. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and acyclovir were in short supply in 2011 and 2016.

According to respondents, the most common ways they learned about drug shortages were from hospital notification (76%), from a colleague (56%), from a pharmacy that contacted them regarding a prescription for the agent (53%), or from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Web site or another Web site (23%). The most common ways of learning about a shortage changed—from notification after trying to prescribe a drug in 2011, to proactive hospital/system (local) notification in 2016; 71% of respondents said that communications in 2016 were sufficient.

Most respondents (83%) reported that guidelines for dealing with shortages had been developed by an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) at their institution.

“This, I think, is one of the highlight results,” said Dr Gundlapalli, who is also a staff physician at the VA Salt Lake City Health System. “In 2011, we had no specific question or comments received about [ASPs], and here in 2016, 83% of respondents’ institutions had developed guidelines related to drug shortages.”

Respondents also had the opportunity to submit free-text responses, and among the themes that emerged was concern regarding toxicity and adverse outcomes associated with increased use of aminoglycosides because of the shortage of piperacillin-tazobactam. Another was the shortage of meropenem, which led one ASP to “institute restrictions on its use, which have continued,” he said.

“Another theme was ‘simpler agents seem more likely to be in shortage,’ ” Dr Gundlapalli said, noting ampicillin-sulbactam in 2016 and penicillin G procaine as examples.

“And then, of course, the other theme across the board...was our new asset,” he said, explaining that some respondents commented on the value of ASP pharmacists and programs to help with drug shortage issues.

The overall theme of this follow-up survey, in the context of prior surveys in 2001 and 2011, is that antibiotic shortages are the “new normal—a way of life,” Dr Gundlapalli said.

“The concerns do persist, and we feel there is further work to be done here,” he said. He specifically noted that there is a need to inform and educate fellows and colleagues in hospitals, increase awareness generally, improve communication strategies, and conduct detailed studies on adverse effects and outcomes.

“And now, since ASPs are very pervasive...maybe it’s time to formalize and delineate the role of ASPs in antimicrobial shortages,” he said.

Donald Graham, MD, one of the study’s coauthors, said he believes the problem is in part the result of economics, and in part because of “the higher standards that the FDA imposes upon these manufacturing concerns.” These drugs often are low-profit items, and it is not always in the financial best interest of a pharmaceutical company to upgrade their facilities.

1. Gundlapalli A. Presentation at: IDWeek 2016. October 26-30, 2016. New Orleans, LA.

Hospitalizations for Opioid Poisoning Tripled in Preschool Children

Richard Franki

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

From 1997 to 2012, the annual number of hospitalizations for opioid poisoning rose 178% among children aged 1 to 19 years, according to data from 13,052 discharges in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Kids’ Inpatient Database.

In 2012, there were 2,918 hospitalizations for opioid poisoning among children aged 1 to 19 years, compared with 1,049 in 1997, reported Julie R. Gaither, PhD, MPH, RN, and her associates at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

The greatest change occurred among the youngest children, as the number of those aged 1 to 4 years rose from 133 in 1997 to 421 in 2012—an increase of 217%. For those aged 15 to 19 years, the annual number of hospitalizations went from 715 to 2,171 (204%) over that time period, which included a slight drop from 2009 to 2012, according to the investigators,

The increase in hospitalizations for prescription opioid poisoning in children aged 10 to 14 years was 58% from 1997 to 2012 (rising from 171 to 272), while estimates for 5- to 9-year-old children did not meet the criteria for statistical reliability and were not included in the analysis, Dr Gaither and her associates said.

1. Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, Camenga DR. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Oct 31. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2154.

Pelvic Fracture Pattern Predicts the Need for Hemorrhage Control

Doug Brunk

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Blunt trauma patients admitted in shock with anterior posterior compression III or vertical shear fracture patterns, or patients with open pelvic fracture are at greatest risk of severe bleeding requiring pelvic hemorrhage-control intervention, results from a multicenter trial demonstrated.

Thirty years ago, researchers defined a classification of pelvic fracture based on a pattern of force applied to the pelvis, Todd W. Costantini, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST). They identified three main force patterns: lateral compression, anterior posterior compression, and vertical shear.

“They were able to show that certain pelvic fractures were associated with soft-tissue injury and pelvic hemorrhage,” said Dr Costantini, of the division of trauma, surgical critical care, burns and acute care surgery at the University of California, San Diego. “Since then, several single-center studies have been conducted in an attempt to correlate fracture pattern with the risk of pelvic hemorrhage. A majority of these studies evaluated angiogram [and embolization] as the endpoint for hemorrhage control. Modern trauma care has evolved to include multiple modalities to control hemorrhage, which include pelvic external fixator placement, pelvic angiography and embolization, preperitoneal pelvic packing, and the use of the REBOA [Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta] catheter as an adjunct to hemorrhage control.”

In a recently published study, Dr Costantini and his associates found wide variability in the use of pelvic hemorrhage-control methods.1 “While angioembolization alone and external fixator placement alone were the most common methods used, there were various combinations of these methods used at different times by different institutions,” he said.

These results prompted the researchers to prospectively evaluate the correlation between pelvic fracture pattern and modern care of pelvic hemorrhage control at 11 Level 1 trauma centers over a 2-year period.2 Inclusion criteria for the study, which was sponsored by the AAST Multi-institutional Trials Committee, were patients over age 18 years, blunt mechanism of injury, and shock on admission defined as “...systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or heart rate >120 beats per minute or base deficit <-5.”1 Exclusion criteria included isolated hip fracture, pregnancy, and lack of pelvic imaging.

The researchers evaluated the pelvic fracture pattern for each patient in the study. “Each pelvic image was evaluated by a trauma surgeon, orthopedic surgeon, or radiologist and classified using the Young-Burgess Classification system,” Dr Costantini said. Next, they used univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to examine predictors for hemorrhage control intervention and mortality. The objective was to determine whether pelvic fracture pattern would predict the need for a hemorrhage control intervention.

Of the 46,716 trauma patients admitted over the 2-year period, 1,339 sustained a pelvic fracture. Of these, 178 met criteria for shock. The researchers excluded 15 patients due to lack of pelvic imaging, which left 163 patients in the final analysis. Their mean age was 44 years and 58% were male. On admission, their mean systolic BP was 93 mm Hg, their mean HR was 117 beats/min, and their median Injury Severity Score was 28. The mean hospital length of stay was 12 days and the mortality rate was 30%. The three most common mechanisms of injury were motor vehicle crash (42%), followed by pedestrian vs auto (23%), and falls (18%).

Compared with patients who did not require hemorrhage-control intervention, those who did received more transfusion of packed red blood cells (13 vs 7 units, respectively; P < .01) and fresh frozen plasma (10 U vs 5 U; P = .01). In addition, 67% of patients with open pelvic fracture required a hemorrhage control intervention. The rate of mortality was similar between the patients who required a pelvic hemorrhage control intervention and those who did not (34% vs 28%; P = .47).

The three most common types of pelvic fracture patterns were lateral compression I (36%) and II (23%), followed by vertical shear (13%). Patients with lateral compression I and II fractures were least likely to require hemorrhage-control intervention (22% and 19%, respectively). However, on univariate analysis, patients with anterior posterior compression III fractures and those with vertical shear fractures were more likely to require a pelvic hemorrhage control intervention, compared with those who sustained other types of pelvic fractures (83% and 55%, respectively).

On multivariate analysis, the three main independent predictors of need for a hemorrhagic control intervention were anterior posterior compression III fracture (OR, 109.43; P < .001), open pelvic fracture (OR, 7.36; P = .014), and vertical shear fracture (OR, 6.99; P = .002). Pelvic fracture pattern did not predict mortality on multivariate analysis.

The invited discussant, Joseph M. Galante, MD, trauma medical director for the University of California, Davis Health System, characterized the study as important “because it examines all forms of hemorrhage control, not just arterioembolism in the treatment of pelvic fractures,” he said. “The ability to predict who will need hemorrhage control allows for earlier mobilization to resources, both in the operating room or interventional suite and in the resuscitation bay.”

1. Costantini TW, Coimbra R, Holcomb JB, et al. Current management of hemorrhage from severe pelvic fractures: Results of an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma multi-institutional trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(5):717-723; discussion 723-725. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001034.2. Costantini TW. Presentation at: 75th Annual Meeting of American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) and Clinical Congress of Acute Care Surgery. September 14-17, 2016. Waikoloa, Hawaii.

Retail Clinics Have Not Decreased the Rate of Low-Acuity ED Visits

BY JEFF BAUER

The number of retail clinics—those located in pharmacies, supermarkets, and other retail settings—in the United States increased from 130 in 2006 to nearly 1,400 in 2012. However, this proliferation of retail clinics has not lead to a meaningful reduction in low-acuity ED visits, according to a recent observational study published in Annals of Emergency Medicine.1

Using information from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Emergency Department Databases, which include data on more than 2,000 EDs in 23 states from 2006 through 2013, researchers looked at the association between retail clinic penetration and the rate of treat-and-release ED visits for 11 low-acuity conditions (allergic rhinitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, other eye conditions, influenza, otitis externa, otitis media, pharyngitis, upper respiratory infections/sinusitis, urinary tract infections, and viral infections).

Retail clinic penetration was defined as the percentage of an ED’s catchment area (areas that accounted for up to 75% of patients who visited for low-acuity conditions) that overlapped with the 10-minute-drive radius of a retail clinic. The results were calculated as a rate ratio, which reflected the change in the rate of low-acuity ED visits associated with an ED having no retail clinic penetration to having approximately the average penetration rate within 2012. Results were controlled for the number of urgent care centers that were present in each ED catchment area, but only for hospital-associated urgent care centers, as there are no reliable data to identify all urgent care centers.

Retail clinic penetration more than doubled during the study period. Overall, increased retail clinic penetration was not associated with a change in the rate of low-acuity ED visits. Among patients with private insurance, there was a small reduction (0.3% per calendar quarter) in ED visits for low-acuity conditions, but this translated into an estimated 17 fewer ED visits by privately insured patients over 1 year for the average ED, assuming the retail clinic penetration rate increased by 40% in that year.

In an accompanying editorial,2 Jesse M. Pines, MD, suggests that visits to retail clinics may be mostly “new-use” visits, meaning many individuals who would not have otherwise received treatment seek care in a retail clinic because such clinics are available. Dr Pines proposed three reasons retail clinics may create new-use visits: they meet unmet demands for care; motivations for seeking care differ in EDs and retail clinics; and people who are more likely to use EDs for low-acuity conditions do so because they have limited access to other types of care, including retail clinics.

1. Martsolf G, Fingar KR, Coffey R, et al. Association between the opening of retail clinics and low-acuity emergency department visits. Ann Emerg Med. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.462.

2. Pines JM. Why retail clinics do not substitute for emergency department visits and what this means for value-based care. Ann Emerg Med. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.09.047.

Hypotension During Transport to ED Drives Mortality in Traumatic Brain Injury

MITCHEL L. ZOLER

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

The severity and duration of hypotension in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients during emergency medical service (EMS) transport to an ED has a tight and essentially linear relationship to mortality rate during subsequent weeks of recovery, according to an analysis of more than 7,500 brain-injured patients.

For each doubling of the combined severity and duration of hypotension during the prehospital period, when systolic blood pressure (BP) was <90 mm Hg, patient mortality rose by 19%, Daniel W. Spaite, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

However, the results do not address whether aggressive treatment of hypotension by EMS technicians in a patient with TBI leads to reduced mortality. That question is being assessed as part of the primary endpoint of the Excellence in Prehospital Injury Care-Traumatic Brain Injury (EPIC-TBI) study, which should be completed by the end of 2017, said Dr Spaite, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona in Tucson.Results from prior studies have clearly linked prehospital hypotension with worse survival in TBI patients. Until now, however, there was no appreciation of the fact that not all hypotensive episodes are equal, and that both the severity of hypotension and its duration incrementally contribute to mortality as the “dose” of hypotension a patient experiences increases. In large part, this is because prehospital hypotension has been recorded simply as a dichotomous, yes/no condition.

The innovation introduced by Dr Spaite and his associates in their analysis of the EPIC-TBI data was to drill down into each patient’s hypotensive event, made possible by the 16,711 patients enrolled in EPIC-TBI. Their calculations were limited to patients with EMS records of at least two BP measurements during prehospital transport. These data allowed Spaite et al to utilize both the extent to which systolic BP dropped below 90 mm Hg and the amount of time systolic BP was below this threshold to better define the total hypotension exposure each patient received.

This meant that a patient with a TBI and a systolic BP of 80 mm Hg for 10 minutes had twice the hypotension exposure of both a patient with a systolic BP of 85 mm Hg for 10 minutes and a patient with a systolic BP of 80 mm Hg for 5 minutes.

The analysis by Spaite et al also adjusted the relationship of total hypotensive severity and duration and subsequent mortality based on several baseline demographic and clinical variables, including age, sex, injury severity, trauma type, and head-region severity score. After adjustment, the researchers found a “strikingly linear relationship” between hypotension severity and duration and mortality, Dr Spaite said.

The EPIC-TBI enrolled TBI patients aged 10 years or older during 2007 to 2014 through participation of dozens of EMS providers throughout Arizona. For the current analysis, the researchers identified 7,521 patients from the total group who had at least two BP measurements taken during their prehospital EMS care and also met other inclusion criteria.

The best way to manage hypotension in TBI patients during the prehospital period remains unclear. Simply raising BP via intravenous (IV) fluid infusion may not necessarily help, because it could exacerbate a patient’s bleeding, Dr Spaite noted during an interview.

The primary goal of EPIC-TBI is to assess the implementation of the third edition of the TBI guidelines released in 2007 by the Brain Trauma Foundation. (The fourth edition of these guidelines came out in August 2016.) The new finding by Dr Spaite and his associates will allow the full EPIC-TBI analysis to correlate patient outcomes with the impact that acute, prehospital treatment had on the hypotension severity and duration each patient experienced, he noted.

“What’s remarkable is that the single prehospital parameter of hypotension for just a few minutes during transport can have such a strong impact on survival, given all the other factors that can influence outcomes” in TBI patients once they reach a hospital and during the period they remain hospitalized, Dr Spaite said.

1. Spaite DW. Presentation at: American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2016. November 12-16, 2016; New Orleans, LA.

Fluid Administration in Sepsis Did Not Increase Need for Dialysis

M. Alexander Otto

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Fluid administration of at least 1 L did not increase the incidence of acute respiratory or heart failure in severe sepsis, and actually seemed to decrease the need for dialysis in a review of 164 patients at Scott and White Memorial Hospital in Temple, Texas.

For every 1 mL of fluid administered per kilogram of body weight, the likelihood of dialysis decreased by 8.5% (odds ratio [OR], 0.915; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.854-0.980; P = .0111), with no increase in heart or respiratory failure on univariate analysis. The 126 patients (77%) who received at least 1 L of fluid had a 68% reduction in the need for dialysis (OR, 0.32; CI, 0.117-0.890; P = .0288).

These findings come from a quality improvement project the hospital launched after researchers there realized that the benchmark Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines were not being met. The patients in the study had a systolic BP below 90 mm Hg or lactate level of at least 4 mmol/L. The guidelines would have called for these patients to receive 30 mL/kg of crystalloid fluids within 3 hours of presentation, but only 28 patients (17%) met that mark.

“The No. 1 reason we weren’t meeting benchmarks was fluid administration,” explained lead investigator Aruna Jahoor, MD, a pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine fellow at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

Seventeen percent of patients received ≥30 mL/kg of fluid resuscitation, while 28% received ≥20 mL/kg of IV fluid resuscitation. It turned out that staff in the ED—where most of the patients were treated in the critical first 6 hours—were concerned about fluid overload and putting patients into respiratory, heart, or renal failure, Dr Jahoor said. The team found no difference in mortality rates when patients received 30 mL/kg—just over 2 L in a patient weighing 70 kg—vs 20 mL/kg or 1 L. The patients’ in-hospital mortality rate and 28-day mortality rate were 27% and 32%, respectively.

There also were no increased rates of heart failure, acute respiratory failure, or mechanical ventilation when patients received at least 1 L of fluid. “There were [also] lower rates of dialysis, which indicated that we weren’t overloading patients. Even when we looked at fluid as a continuous variable, we still didn’t see” complications, Dr Jahoor said.

The findings should be reassuring to treating physicians. “When you have pushback against 30-mL/kg administration, you can say ‘well, at least let’s give a liter.’ You don’t have to worry as much about some of the complications you are citing,’ ” she said.

For very obese patients, “it can get a little uncomfortable to be given” enough fluid to meet the 30-mL/kg goal, “but you can give at least a liter” without having to worry too much, she said. The patients in the study were treated from 2010 to 2013; normal saline was the most common resuscitation fluid. The hospital has since added the 30-mL/kg fluid resuscitation to its sepsis admission orders, and compliance has increased significantly.

A multivariate analysis is in the works to control for confounders. “We will probably [still] see you are not having increased rates of congestive heart or respiratory failure, or needing dialysis,” Dr Jahoor said. The protective effect against dialysis might drop out, “but I am hoping it doesn’t,” she said.

1. Jahoor A, Delmas T, Giri B, et al. Fluid resuscitation of at least 1 liter in septic patients decreases the need for renal replacement therapy without increasing the risk of acute congestive heart failure or acute respiratory failure. Chest. 2016;150(4_S):349A. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.362.

Survey: Antibiotic Shortages Are the New Norm

SHARON WORCESTER

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Antibiotic shortages reported by the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) in 2011 persist in 2016, according to a Web-based follow-up survey of infectious disease physicians.

Of 701 network members who responded to the EIN survey in early 2016, 70% reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years. They did so by using broader-spectrum agents (75% of respondents), more costly agents (58%), less effective second-line agents (45%), and more toxic agents (37%), Adi Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In addition, 73% of respondents reported that the shortages affected patient care or outcomes, reported Dr Gundlapalli of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The percentage of respondents reporting adverse patient outcomes related to shortages increased from 2011 to 2016 (51% vs 73%), he noted at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

In the 2016 survey, the top 10 antimicrobials reported as being in short supply over the past 2 years were piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), doxycycline, imipenem, acyclovir, and amikacin. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and acyclovir were in short supply in 2011 and 2016.

According to respondents, the most common ways they learned about drug shortages were from hospital notification (76%), from a colleague (56%), from a pharmacy that contacted them regarding a prescription for the agent (53%), or from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Web site or another Web site (23%). The most common ways of learning about a shortage changed—from notification after trying to prescribe a drug in 2011, to proactive hospital/system (local) notification in 2016; 71% of respondents said that communications in 2016 were sufficient.

Most respondents (83%) reported that guidelines for dealing with shortages had been developed by an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) at their institution.

“This, I think, is one of the highlight results,” said Dr Gundlapalli, who is also a staff physician at the VA Salt Lake City Health System. “In 2011, we had no specific question or comments received about [ASPs], and here in 2016, 83% of respondents’ institutions had developed guidelines related to drug shortages.”

Respondents also had the opportunity to submit free-text responses, and among the themes that emerged was concern regarding toxicity and adverse outcomes associated with increased use of aminoglycosides because of the shortage of piperacillin-tazobactam. Another was the shortage of meropenem, which led one ASP to “institute restrictions on its use, which have continued,” he said.

“Another theme was ‘simpler agents seem more likely to be in shortage,’ ” Dr Gundlapalli said, noting ampicillin-sulbactam in 2016 and penicillin G procaine as examples.

“And then, of course, the other theme across the board...was our new asset,” he said, explaining that some respondents commented on the value of ASP pharmacists and programs to help with drug shortage issues.

The overall theme of this follow-up survey, in the context of prior surveys in 2001 and 2011, is that antibiotic shortages are the “new normal—a way of life,” Dr Gundlapalli said.

“The concerns do persist, and we feel there is further work to be done here,” he said. He specifically noted that there is a need to inform and educate fellows and colleagues in hospitals, increase awareness generally, improve communication strategies, and conduct detailed studies on adverse effects and outcomes.

“And now, since ASPs are very pervasive...maybe it’s time to formalize and delineate the role of ASPs in antimicrobial shortages,” he said.

Donald Graham, MD, one of the study’s coauthors, said he believes the problem is in part the result of economics, and in part because of “the higher standards that the FDA imposes upon these manufacturing concerns.” These drugs often are low-profit items, and it is not always in the financial best interest of a pharmaceutical company to upgrade their facilities.

1. Gundlapalli A. Presentation at: IDWeek 2016. October 26-30, 2016. New Orleans, LA.

Hospitalizations for Opioid Poisoning Tripled in Preschool Children

Richard Franki

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

From 1997 to 2012, the annual number of hospitalizations for opioid poisoning rose 178% among children aged 1 to 19 years, according to data from 13,052 discharges in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Kids’ Inpatient Database.

In 2012, there were 2,918 hospitalizations for opioid poisoning among children aged 1 to 19 years, compared with 1,049 in 1997, reported Julie R. Gaither, PhD, MPH, RN, and her associates at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

The greatest change occurred among the youngest children, as the number of those aged 1 to 4 years rose from 133 in 1997 to 421 in 2012—an increase of 217%. For those aged 15 to 19 years, the annual number of hospitalizations went from 715 to 2,171 (204%) over that time period, which included a slight drop from 2009 to 2012, according to the investigators,

The increase in hospitalizations for prescription opioid poisoning in children aged 10 to 14 years was 58% from 1997 to 2012 (rising from 171 to 272), while estimates for 5- to 9-year-old children did not meet the criteria for statistical reliability and were not included in the analysis, Dr Gaither and her associates said.

1. Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, Camenga DR. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Oct 31. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2154.

Pelvic Fracture Pattern Predicts the Need for Hemorrhage Control

Doug Brunk

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Blunt trauma patients admitted in shock with anterior posterior compression III or vertical shear fracture patterns, or patients with open pelvic fracture are at greatest risk of severe bleeding requiring pelvic hemorrhage-control intervention, results from a multicenter trial demonstrated.

Thirty years ago, researchers defined a classification of pelvic fracture based on a pattern of force applied to the pelvis, Todd W. Costantini, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST). They identified three main force patterns: lateral compression, anterior posterior compression, and vertical shear.

“They were able to show that certain pelvic fractures were associated with soft-tissue injury and pelvic hemorrhage,” said Dr Costantini, of the division of trauma, surgical critical care, burns and acute care surgery at the University of California, San Diego. “Since then, several single-center studies have been conducted in an attempt to correlate fracture pattern with the risk of pelvic hemorrhage. A majority of these studies evaluated angiogram [and embolization] as the endpoint for hemorrhage control. Modern trauma care has evolved to include multiple modalities to control hemorrhage, which include pelvic external fixator placement, pelvic angiography and embolization, preperitoneal pelvic packing, and the use of the REBOA [Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta] catheter as an adjunct to hemorrhage control.”

In a recently published study, Dr Costantini and his associates found wide variability in the use of pelvic hemorrhage-control methods.1 “While angioembolization alone and external fixator placement alone were the most common methods used, there were various combinations of these methods used at different times by different institutions,” he said.

These results prompted the researchers to prospectively evaluate the correlation between pelvic fracture pattern and modern care of pelvic hemorrhage control at 11 Level 1 trauma centers over a 2-year period.2 Inclusion criteria for the study, which was sponsored by the AAST Multi-institutional Trials Committee, were patients over age 18 years, blunt mechanism of injury, and shock on admission defined as “...systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or heart rate >120 beats per minute or base deficit <-5.”1 Exclusion criteria included isolated hip fracture, pregnancy, and lack of pelvic imaging.

The researchers evaluated the pelvic fracture pattern for each patient in the study. “Each pelvic image was evaluated by a trauma surgeon, orthopedic surgeon, or radiologist and classified using the Young-Burgess Classification system,” Dr Costantini said. Next, they used univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to examine predictors for hemorrhage control intervention and mortality. The objective was to determine whether pelvic fracture pattern would predict the need for a hemorrhage control intervention.

Of the 46,716 trauma patients admitted over the 2-year period, 1,339 sustained a pelvic fracture. Of these, 178 met criteria for shock. The researchers excluded 15 patients due to lack of pelvic imaging, which left 163 patients in the final analysis. Their mean age was 44 years and 58% were male. On admission, their mean systolic BP was 93 mm Hg, their mean HR was 117 beats/min, and their median Injury Severity Score was 28. The mean hospital length of stay was 12 days and the mortality rate was 30%. The three most common mechanisms of injury were motor vehicle crash (42%), followed by pedestrian vs auto (23%), and falls (18%).

Compared with patients who did not require hemorrhage-control intervention, those who did received more transfusion of packed red blood cells (13 vs 7 units, respectively; P < .01) and fresh frozen plasma (10 U vs 5 U; P = .01). In addition, 67% of patients with open pelvic fracture required a hemorrhage control intervention. The rate of mortality was similar between the patients who required a pelvic hemorrhage control intervention and those who did not (34% vs 28%; P = .47).

The three most common types of pelvic fracture patterns were lateral compression I (36%) and II (23%), followed by vertical shear (13%). Patients with lateral compression I and II fractures were least likely to require hemorrhage-control intervention (22% and 19%, respectively). However, on univariate analysis, patients with anterior posterior compression III fractures and those with vertical shear fractures were more likely to require a pelvic hemorrhage control intervention, compared with those who sustained other types of pelvic fractures (83% and 55%, respectively).

On multivariate analysis, the three main independent predictors of need for a hemorrhagic control intervention were anterior posterior compression III fracture (OR, 109.43; P < .001), open pelvic fracture (OR, 7.36; P = .014), and vertical shear fracture (OR, 6.99; P = .002). Pelvic fracture pattern did not predict mortality on multivariate analysis.

The invited discussant, Joseph M. Galante, MD, trauma medical director for the University of California, Davis Health System, characterized the study as important “because it examines all forms of hemorrhage control, not just arterioembolism in the treatment of pelvic fractures,” he said. “The ability to predict who will need hemorrhage control allows for earlier mobilization to resources, both in the operating room or interventional suite and in the resuscitation bay.”

1. Costantini TW, Coimbra R, Holcomb JB, et al. Current management of hemorrhage from severe pelvic fractures: Results of an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma multi-institutional trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(5):717-723; discussion 723-725. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001034.2. Costantini TW. Presentation at: 75th Annual Meeting of American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) and Clinical Congress of Acute Care Surgery. September 14-17, 2016. Waikoloa, Hawaii.

Retail Clinics Have Not Decreased the Rate of Low-Acuity ED Visits

BY JEFF BAUER

The number of retail clinics—those located in pharmacies, supermarkets, and other retail settings—in the United States increased from 130 in 2006 to nearly 1,400 in 2012. However, this proliferation of retail clinics has not lead to a meaningful reduction in low-acuity ED visits, according to a recent observational study published in Annals of Emergency Medicine.1

Using information from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Emergency Department Databases, which include data on more than 2,000 EDs in 23 states from 2006 through 2013, researchers looked at the association between retail clinic penetration and the rate of treat-and-release ED visits for 11 low-acuity conditions (allergic rhinitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, other eye conditions, influenza, otitis externa, otitis media, pharyngitis, upper respiratory infections/sinusitis, urinary tract infections, and viral infections).

Retail clinic penetration was defined as the percentage of an ED’s catchment area (areas that accounted for up to 75% of patients who visited for low-acuity conditions) that overlapped with the 10-minute-drive radius of a retail clinic. The results were calculated as a rate ratio, which reflected the change in the rate of low-acuity ED visits associated with an ED having no retail clinic penetration to having approximately the average penetration rate within 2012. Results were controlled for the number of urgent care centers that were present in each ED catchment area, but only for hospital-associated urgent care centers, as there are no reliable data to identify all urgent care centers.

Retail clinic penetration more than doubled during the study period. Overall, increased retail clinic penetration was not associated with a change in the rate of low-acuity ED visits. Among patients with private insurance, there was a small reduction (0.3% per calendar quarter) in ED visits for low-acuity conditions, but this translated into an estimated 17 fewer ED visits by privately insured patients over 1 year for the average ED, assuming the retail clinic penetration rate increased by 40% in that year.

In an accompanying editorial,2 Jesse M. Pines, MD, suggests that visits to retail clinics may be mostly “new-use” visits, meaning many individuals who would not have otherwise received treatment seek care in a retail clinic because such clinics are available. Dr Pines proposed three reasons retail clinics may create new-use visits: they meet unmet demands for care; motivations for seeking care differ in EDs and retail clinics; and people who are more likely to use EDs for low-acuity conditions do so because they have limited access to other types of care, including retail clinics.

1. Martsolf G, Fingar KR, Coffey R, et al. Association between the opening of retail clinics and low-acuity emergency department visits. Ann Emerg Med. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.462.

2. Pines JM. Why retail clinics do not substitute for emergency department visits and what this means for value-based care. Ann Emerg Med. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.09.047.

Hypotension During Transport to ED Drives Mortality in Traumatic Brain Injury

MITCHEL L. ZOLER

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

The severity and duration of hypotension in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients during emergency medical service (EMS) transport to an ED has a tight and essentially linear relationship to mortality rate during subsequent weeks of recovery, according to an analysis of more than 7,500 brain-injured patients.

For each doubling of the combined severity and duration of hypotension during the prehospital period, when systolic blood pressure (BP) was <90 mm Hg, patient mortality rose by 19%, Daniel W. Spaite, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

However, the results do not address whether aggressive treatment of hypotension by EMS technicians in a patient with TBI leads to reduced mortality. That question is being assessed as part of the primary endpoint of the Excellence in Prehospital Injury Care-Traumatic Brain Injury (EPIC-TBI) study, which should be completed by the end of 2017, said Dr Spaite, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona in Tucson.Results from prior studies have clearly linked prehospital hypotension with worse survival in TBI patients. Until now, however, there was no appreciation of the fact that not all hypotensive episodes are equal, and that both the severity of hypotension and its duration incrementally contribute to mortality as the “dose” of hypotension a patient experiences increases. In large part, this is because prehospital hypotension has been recorded simply as a dichotomous, yes/no condition.

The innovation introduced by Dr Spaite and his associates in their analysis of the EPIC-TBI data was to drill down into each patient’s hypotensive event, made possible by the 16,711 patients enrolled in EPIC-TBI. Their calculations were limited to patients with EMS records of at least two BP measurements during prehospital transport. These data allowed Spaite et al to utilize both the extent to which systolic BP dropped below 90 mm Hg and the amount of time systolic BP was below this threshold to better define the total hypotension exposure each patient received.

This meant that a patient with a TBI and a systolic BP of 80 mm Hg for 10 minutes had twice the hypotension exposure of both a patient with a systolic BP of 85 mm Hg for 10 minutes and a patient with a systolic BP of 80 mm Hg for 5 minutes.

The analysis by Spaite et al also adjusted the relationship of total hypotensive severity and duration and subsequent mortality based on several baseline demographic and clinical variables, including age, sex, injury severity, trauma type, and head-region severity score. After adjustment, the researchers found a “strikingly linear relationship” between hypotension severity and duration and mortality, Dr Spaite said.

The EPIC-TBI enrolled TBI patients aged 10 years or older during 2007 to 2014 through participation of dozens of EMS providers throughout Arizona. For the current analysis, the researchers identified 7,521 patients from the total group who had at least two BP measurements taken during their prehospital EMS care and also met other inclusion criteria.

The best way to manage hypotension in TBI patients during the prehospital period remains unclear. Simply raising BP via intravenous (IV) fluid infusion may not necessarily help, because it could exacerbate a patient’s bleeding, Dr Spaite noted during an interview.

The primary goal of EPIC-TBI is to assess the implementation of the third edition of the TBI guidelines released in 2007 by the Brain Trauma Foundation. (The fourth edition of these guidelines came out in August 2016.) The new finding by Dr Spaite and his associates will allow the full EPIC-TBI analysis to correlate patient outcomes with the impact that acute, prehospital treatment had on the hypotension severity and duration each patient experienced, he noted.

“What’s remarkable is that the single prehospital parameter of hypotension for just a few minutes during transport can have such a strong impact on survival, given all the other factors that can influence outcomes” in TBI patients once they reach a hospital and during the period they remain hospitalized, Dr Spaite said.

1. Spaite DW. Presentation at: American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2016. November 12-16, 2016; New Orleans, LA.

Fluid Administration in Sepsis Did Not Increase Need for Dialysis

M. Alexander Otto

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Fluid administration of at least 1 L did not increase the incidence of acute respiratory or heart failure in severe sepsis, and actually seemed to decrease the need for dialysis in a review of 164 patients at Scott and White Memorial Hospital in Temple, Texas.

For every 1 mL of fluid administered per kilogram of body weight, the likelihood of dialysis decreased by 8.5% (odds ratio [OR], 0.915; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.854-0.980; P = .0111), with no increase in heart or respiratory failure on univariate analysis. The 126 patients (77%) who received at least 1 L of fluid had a 68% reduction in the need for dialysis (OR, 0.32; CI, 0.117-0.890; P = .0288).

These findings come from a quality improvement project the hospital launched after researchers there realized that the benchmark Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines were not being met. The patients in the study had a systolic BP below 90 mm Hg or lactate level of at least 4 mmol/L. The guidelines would have called for these patients to receive 30 mL/kg of crystalloid fluids within 3 hours of presentation, but only 28 patients (17%) met that mark.

“The No. 1 reason we weren’t meeting benchmarks was fluid administration,” explained lead investigator Aruna Jahoor, MD, a pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine fellow at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

Seventeen percent of patients received ≥30 mL/kg of fluid resuscitation, while 28% received ≥20 mL/kg of IV fluid resuscitation. It turned out that staff in the ED—where most of the patients were treated in the critical first 6 hours—were concerned about fluid overload and putting patients into respiratory, heart, or renal failure, Dr Jahoor said. The team found no difference in mortality rates when patients received 30 mL/kg—just over 2 L in a patient weighing 70 kg—vs 20 mL/kg or 1 L. The patients’ in-hospital mortality rate and 28-day mortality rate were 27% and 32%, respectively.

There also were no increased rates of heart failure, acute respiratory failure, or mechanical ventilation when patients received at least 1 L of fluid. “There were [also] lower rates of dialysis, which indicated that we weren’t overloading patients. Even when we looked at fluid as a continuous variable, we still didn’t see” complications, Dr Jahoor said.

The findings should be reassuring to treating physicians. “When you have pushback against 30-mL/kg administration, you can say ‘well, at least let’s give a liter.’ You don’t have to worry as much about some of the complications you are citing,’ ” she said.

For very obese patients, “it can get a little uncomfortable to be given” enough fluid to meet the 30-mL/kg goal, “but you can give at least a liter” without having to worry too much, she said. The patients in the study were treated from 2010 to 2013; normal saline was the most common resuscitation fluid. The hospital has since added the 30-mL/kg fluid resuscitation to its sepsis admission orders, and compliance has increased significantly.

A multivariate analysis is in the works to control for confounders. “We will probably [still] see you are not having increased rates of congestive heart or respiratory failure, or needing dialysis,” Dr Jahoor said. The protective effect against dialysis might drop out, “but I am hoping it doesn’t,” she said.

1. Jahoor A, Delmas T, Giri B, et al. Fluid resuscitation of at least 1 liter in septic patients decreases the need for renal replacement therapy without increasing the risk of acute congestive heart failure or acute respiratory failure. Chest. 2016;150(4_S):349A. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.362.

Survey: Antibiotic Shortages Are the New Norm

SHARON WORCESTER

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Antibiotic shortages reported by the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) in 2011 persist in 2016, according to a Web-based follow-up survey of infectious disease physicians.

Of 701 network members who responded to the EIN survey in early 2016, 70% reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years. They did so by using broader-spectrum agents (75% of respondents), more costly agents (58%), less effective second-line agents (45%), and more toxic agents (37%), Adi Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In addition, 73% of respondents reported that the shortages affected patient care or outcomes, reported Dr Gundlapalli of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The percentage of respondents reporting adverse patient outcomes related to shortages increased from 2011 to 2016 (51% vs 73%), he noted at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

In the 2016 survey, the top 10 antimicrobials reported as being in short supply over the past 2 years were piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), doxycycline, imipenem, acyclovir, and amikacin. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and acyclovir were in short supply in 2011 and 2016.

According to respondents, the most common ways they learned about drug shortages were from hospital notification (76%), from a colleague (56%), from a pharmacy that contacted them regarding a prescription for the agent (53%), or from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Web site or another Web site (23%). The most common ways of learning about a shortage changed—from notification after trying to prescribe a drug in 2011, to proactive hospital/system (local) notification in 2016; 71% of respondents said that communications in 2016 were sufficient.

Most respondents (83%) reported that guidelines for dealing with shortages had been developed by an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) at their institution.

“This, I think, is one of the highlight results,” said Dr Gundlapalli, who is also a staff physician at the VA Salt Lake City Health System. “In 2011, we had no specific question or comments received about [ASPs], and here in 2016, 83% of respondents’ institutions had developed guidelines related to drug shortages.”

Respondents also had the opportunity to submit free-text responses, and among the themes that emerged was concern regarding toxicity and adverse outcomes associated with increased use of aminoglycosides because of the shortage of piperacillin-tazobactam. Another was the shortage of meropenem, which led one ASP to “institute restrictions on its use, which have continued,” he said.

“Another theme was ‘simpler agents seem more likely to be in shortage,’ ” Dr Gundlapalli said, noting ampicillin-sulbactam in 2016 and penicillin G procaine as examples.

“And then, of course, the other theme across the board...was our new asset,” he said, explaining that some respondents commented on the value of ASP pharmacists and programs to help with drug shortage issues.

The overall theme of this follow-up survey, in the context of prior surveys in 2001 and 2011, is that antibiotic shortages are the “new normal—a way of life,” Dr Gundlapalli said.

“The concerns do persist, and we feel there is further work to be done here,” he said. He specifically noted that there is a need to inform and educate fellows and colleagues in hospitals, increase awareness generally, improve communication strategies, and conduct detailed studies on adverse effects and outcomes.

“And now, since ASPs are very pervasive...maybe it’s time to formalize and delineate the role of ASPs in antimicrobial shortages,” he said.

Donald Graham, MD, one of the study’s coauthors, said he believes the problem is in part the result of economics, and in part because of “the higher standards that the FDA imposes upon these manufacturing concerns.” These drugs often are low-profit items, and it is not always in the financial best interest of a pharmaceutical company to upgrade their facilities.

1. Gundlapalli A. Presentation at: IDWeek 2016. October 26-30, 2016. New Orleans, LA.

Hospitalizations for Opioid Poisoning Tripled in Preschool Children

Richard Franki

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

From 1997 to 2012, the annual number of hospitalizations for opioid poisoning rose 178% among children aged 1 to 19 years, according to data from 13,052 discharges in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Kids’ Inpatient Database.

In 2012, there were 2,918 hospitalizations for opioid poisoning among children aged 1 to 19 years, compared with 1,049 in 1997, reported Julie R. Gaither, PhD, MPH, RN, and her associates at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

The greatest change occurred among the youngest children, as the number of those aged 1 to 4 years rose from 133 in 1997 to 421 in 2012—an increase of 217%. For those aged 15 to 19 years, the annual number of hospitalizations went from 715 to 2,171 (204%) over that time period, which included a slight drop from 2009 to 2012, according to the investigators,

The increase in hospitalizations for prescription opioid poisoning in children aged 10 to 14 years was 58% from 1997 to 2012 (rising from 171 to 272), while estimates for 5- to 9-year-old children did not meet the criteria for statistical reliability and were not included in the analysis, Dr Gaither and her associates said.

1. Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, Camenga DR. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Oct 31. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2154.

Pelvic Fracture Pattern Predicts the Need for Hemorrhage Control

Doug Brunk

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Blunt trauma patients admitted in shock with anterior posterior compression III or vertical shear fracture patterns, or patients with open pelvic fracture are at greatest risk of severe bleeding requiring pelvic hemorrhage-control intervention, results from a multicenter trial demonstrated.

Thirty years ago, researchers defined a classification of pelvic fracture based on a pattern of force applied to the pelvis, Todd W. Costantini, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST). They identified three main force patterns: lateral compression, anterior posterior compression, and vertical shear.

“They were able to show that certain pelvic fractures were associated with soft-tissue injury and pelvic hemorrhage,” said Dr Costantini, of the division of trauma, surgical critical care, burns and acute care surgery at the University of California, San Diego. “Since then, several single-center studies have been conducted in an attempt to correlate fracture pattern with the risk of pelvic hemorrhage. A majority of these studies evaluated angiogram [and embolization] as the endpoint for hemorrhage control. Modern trauma care has evolved to include multiple modalities to control hemorrhage, which include pelvic external fixator placement, pelvic angiography and embolization, preperitoneal pelvic packing, and the use of the REBOA [Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta] catheter as an adjunct to hemorrhage control.”

In a recently published study, Dr Costantini and his associates found wide variability in the use of pelvic hemorrhage-control methods.1 “While angioembolization alone and external fixator placement alone were the most common methods used, there were various combinations of these methods used at different times by different institutions,” he said.