User login

Exophytic Scaly Nodule on the Wrist

Exophytic Scaly Nodule on the Wrist

THE DIAGNOSIS: Atypical Spitz Tumor

The shave biopsy revealed extensive dermal proliferation with spitzoid cytomorphology containing large, spindled nuclei; prominent nucleoli; and abundant homogenous cytoplasm arranged in haphazard fascicles. The proliferation was associated with prominent pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epidermis, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase immunohistochemistry showed diffuse strong positivity. Fluorescence in situ hybridization confirmed fusion of the tropomyosin 3 (TPM3) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) genes, which finalized the diagnosis of an ALK-mutated atypical spitz tumor. Due to the location and size of the lesion, Mohs micrographic surgery was performed to excise the tumor and clear the margins.

Spitz nevi are uncommon benign melanocytic neoplasms that typically occur in pediatric populations.1 Atypical spitz nevi comprised fewer than 17% of all childhood melanocytic nevi in the United States and can be considered in the broader category of spitzoid tumors. Spitz nevi are divided into 3 classes: Spitz nevus, atypical Spitz nevus, and spitzoid melanoma. Atypical Spitz nevi have typical Spitz nevus and spitzoid melanoma features and often can be difficult to distinguish on dermoscopy. Malignant Spitz tumors typically occur in the fifth decade of life, though the age distribution can vary widely.1

Black patients are less likely to be diagnosed with Spitz nevi, potentially due to a lower prevalence in this population, thus limiting the clinician’s clinical exposure and leading to increased rates of misdiagnoses.2 Spitz nevi usually manifest as well-circumscribed, dome-shaped papules and frequently are described as pink to red due to increased vascularity and limited melanin content1; however, these lesions may appear more violaceous, dusky, or dark brown in darker skin types. Additionally, approximately 71% of patients in a clinical review of Spitz nevi had a pigmented lesion, ranging from light brown to black.3 It is important for dermatologists to understand that the contrast in color between the nevus and the surrounding skin may not be as striking, prominent, or clinically concerning, particularly in darker skin types, such as in our patient.

Spitz nevi frequently manifest as rapidly growing solitary lesions most frequently developing in the lower legs (shown in 41% of lesions in one report).4 However, a recent retrospective review indicated that Spitz nevi in Black patients most commonly were found on the upper extremities, as was seen in our patient.2 Compared to typical and common Spitz nevi, atypical Spitz nevi often are greater than 10 mm in diameter and have features of ulceration.

Diagnosing atypical spitzoid melanocytic lesions requires adequate clinical suspicion and confirmation via biopsy. Under dermoscopy, typical Spitz nevi often display a starburst or globular pattern with pinpoint vessels, though it can have variable manifestations of both patterns. Atypical Spitz nevi can be challenging to distinguish from melanoma on dermoscopy since both conditions can have atypical pigment networks or structureless homogenous areas.1 Consequently, there often is a lower threshold for biopsy and possible follow-up excision for atypical Spitz nevi. Histopathology of atypical Spitz nevi includes epithelioid and spindle melanocytes but can share features of melanomas, including areas of prominent pagetoid spread, asymmetry, and poor circumscription.5 Furthermore, atypical Spitz nevi with ALK gene fusion, as seen in our patient, have been shown in the literature to demonstrate distinct histopathologic features, such as wedge-shaped extension into the dermis or a bulbous lower border that can resemble pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.6

The differential diagnosis for this rapidly growing scaly nodule also should include pyogenic granuloma, bacillary angiomatosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and amelanotic melanoma. Pyogenic granuloma is a rapidly growing, benign, vascular tumor that often becomes ulcerated and can occur in any age group.7 Pyogenic granuloma frequently appears at sites of trauma as a solitary, bright pink to red, friable, pedunculated papule and often manifests on the arms, hands, and face, similar to atypical Spitz nevi, though they can appear anywhere on the body. Histology shows a lobular capillary network with a central feeder vessel.7

Bacillary angiomatosis is an uncommon cutaneous infection associated with vascular proliferation and neovascularization due to the gram-negative organism Bartonella henselae.8 Bacillary nodules typically are reddish to purple and appear on the arms, sometimes with central ulceration and bleeding. Patients may present with multiple papules and nodules of varying sizes, as the lesions can arise in crops and follow a sporotrichoid pattern. Most patients with bacillary angiomatosis are immunosuppressed, though it rarely can affect immunocompetent patients. Histologically, bacillary angiomatosis is similar to pyogenic granuloma, though Gram or Warthin-Starry stains can help differentiate B henselae.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a malignant vascular neoplasm that often manifests in immunocompromised patients as violaceous, purple, or red patches, plaques, and nodules on the skin or oral mucosa. Histopathology shows spindle cell proliferation of irregular complex vascular channels dissecting through the dermis. Human herpesvirus 8 immunohistochemistry can be used to confirm diagnosis on histopathology.9 In contrast, amelanotic melanoma consists of lack of pigmentation, asymmetry with polymorphous vascular pattern, and high mitotic rate and is commonly found in sun-exposed areas. Dermoscopic features include irregular globules with blue-whitish veil.10

Treatment of atypical Spitz nevi depends mainly on the age of the patient and the histologic features of the nevus. Adults with atypical Spitz nevi frequently require excision, while the preferred choice for treatment in children with common Spitz nevi is regular clinical monitoring when there are no concerning clinical, dermoscopic, or histologic features.8 Compared to common Spitz nevi, atypical Spitz nevi have more melanoma-like features, resulting in a stronger recommendation for excision. Excision allows for a more thorough histologic evaluation and minimizes the likelihood of a recurrent atypical lesion.11 In all cases, close clinical follow-up is recommended to monitor for reoccurrence.

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part I. background and diagnoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1073-1084. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.040

- Farid YI, Honda KS. Spitz nevi in African Americans: a retrospective chart review of 11 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:511-518. doi:10.1111 /cup.13903

- Dal Pozzo V, Benelli C, Restano L, et al. Clinical review of 247 case records of Spitz nevus (epithelioid cell and/or spindle cell nevus). Dermatology 1997;194:20-25. doi: 10.1159/000246051

- Berlingeri-Ramos AC, Morales-Burgos A, Sanchez JL, et al. Spitz nevus in a Hispanic population: a clinicopathological study of 130 cases. Am J Dermatopathol 2010;32:267-275. doi: 10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181c52b99

- Brown A, Sawyer JD, Neumeister MW. Spitz nevus: review and update. Clin Plast Surg 2021;48:677-686. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2021.06.002 [published Online First: 20210818]

- Yeh I, de la Fouchardiere A, Pissaloux D, et al. Clinical, histopathologic, and genomic features of Spitz tumors with ALK fusions. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:581-91. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000387

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556077/

- Akram SM, Anwar MY, Thandra KC, et al. Bacillary angiomatosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated July 4, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448092/

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Pizzichetta MA, Talamini R, Stanganelli I, et al. Amelanotic/ hypomelanotic melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features. Br J Dermatol 2004;150(6):1117-1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05928.x

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part II. natural history and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:1087-1092. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.045

THE DIAGNOSIS: Atypical Spitz Tumor

The shave biopsy revealed extensive dermal proliferation with spitzoid cytomorphology containing large, spindled nuclei; prominent nucleoli; and abundant homogenous cytoplasm arranged in haphazard fascicles. The proliferation was associated with prominent pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epidermis, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase immunohistochemistry showed diffuse strong positivity. Fluorescence in situ hybridization confirmed fusion of the tropomyosin 3 (TPM3) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) genes, which finalized the diagnosis of an ALK-mutated atypical spitz tumor. Due to the location and size of the lesion, Mohs micrographic surgery was performed to excise the tumor and clear the margins.

Spitz nevi are uncommon benign melanocytic neoplasms that typically occur in pediatric populations.1 Atypical spitz nevi comprised fewer than 17% of all childhood melanocytic nevi in the United States and can be considered in the broader category of spitzoid tumors. Spitz nevi are divided into 3 classes: Spitz nevus, atypical Spitz nevus, and spitzoid melanoma. Atypical Spitz nevi have typical Spitz nevus and spitzoid melanoma features and often can be difficult to distinguish on dermoscopy. Malignant Spitz tumors typically occur in the fifth decade of life, though the age distribution can vary widely.1

Black patients are less likely to be diagnosed with Spitz nevi, potentially due to a lower prevalence in this population, thus limiting the clinician’s clinical exposure and leading to increased rates of misdiagnoses.2 Spitz nevi usually manifest as well-circumscribed, dome-shaped papules and frequently are described as pink to red due to increased vascularity and limited melanin content1; however, these lesions may appear more violaceous, dusky, or dark brown in darker skin types. Additionally, approximately 71% of patients in a clinical review of Spitz nevi had a pigmented lesion, ranging from light brown to black.3 It is important for dermatologists to understand that the contrast in color between the nevus and the surrounding skin may not be as striking, prominent, or clinically concerning, particularly in darker skin types, such as in our patient.

Spitz nevi frequently manifest as rapidly growing solitary lesions most frequently developing in the lower legs (shown in 41% of lesions in one report).4 However, a recent retrospective review indicated that Spitz nevi in Black patients most commonly were found on the upper extremities, as was seen in our patient.2 Compared to typical and common Spitz nevi, atypical Spitz nevi often are greater than 10 mm in diameter and have features of ulceration.

Diagnosing atypical spitzoid melanocytic lesions requires adequate clinical suspicion and confirmation via biopsy. Under dermoscopy, typical Spitz nevi often display a starburst or globular pattern with pinpoint vessels, though it can have variable manifestations of both patterns. Atypical Spitz nevi can be challenging to distinguish from melanoma on dermoscopy since both conditions can have atypical pigment networks or structureless homogenous areas.1 Consequently, there often is a lower threshold for biopsy and possible follow-up excision for atypical Spitz nevi. Histopathology of atypical Spitz nevi includes epithelioid and spindle melanocytes but can share features of melanomas, including areas of prominent pagetoid spread, asymmetry, and poor circumscription.5 Furthermore, atypical Spitz nevi with ALK gene fusion, as seen in our patient, have been shown in the literature to demonstrate distinct histopathologic features, such as wedge-shaped extension into the dermis or a bulbous lower border that can resemble pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.6

The differential diagnosis for this rapidly growing scaly nodule also should include pyogenic granuloma, bacillary angiomatosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and amelanotic melanoma. Pyogenic granuloma is a rapidly growing, benign, vascular tumor that often becomes ulcerated and can occur in any age group.7 Pyogenic granuloma frequently appears at sites of trauma as a solitary, bright pink to red, friable, pedunculated papule and often manifests on the arms, hands, and face, similar to atypical Spitz nevi, though they can appear anywhere on the body. Histology shows a lobular capillary network with a central feeder vessel.7

Bacillary angiomatosis is an uncommon cutaneous infection associated with vascular proliferation and neovascularization due to the gram-negative organism Bartonella henselae.8 Bacillary nodules typically are reddish to purple and appear on the arms, sometimes with central ulceration and bleeding. Patients may present with multiple papules and nodules of varying sizes, as the lesions can arise in crops and follow a sporotrichoid pattern. Most patients with bacillary angiomatosis are immunosuppressed, though it rarely can affect immunocompetent patients. Histologically, bacillary angiomatosis is similar to pyogenic granuloma, though Gram or Warthin-Starry stains can help differentiate B henselae.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a malignant vascular neoplasm that often manifests in immunocompromised patients as violaceous, purple, or red patches, plaques, and nodules on the skin or oral mucosa. Histopathology shows spindle cell proliferation of irregular complex vascular channels dissecting through the dermis. Human herpesvirus 8 immunohistochemistry can be used to confirm diagnosis on histopathology.9 In contrast, amelanotic melanoma consists of lack of pigmentation, asymmetry with polymorphous vascular pattern, and high mitotic rate and is commonly found in sun-exposed areas. Dermoscopic features include irregular globules with blue-whitish veil.10

Treatment of atypical Spitz nevi depends mainly on the age of the patient and the histologic features of the nevus. Adults with atypical Spitz nevi frequently require excision, while the preferred choice for treatment in children with common Spitz nevi is regular clinical monitoring when there are no concerning clinical, dermoscopic, or histologic features.8 Compared to common Spitz nevi, atypical Spitz nevi have more melanoma-like features, resulting in a stronger recommendation for excision. Excision allows for a more thorough histologic evaluation and minimizes the likelihood of a recurrent atypical lesion.11 In all cases, close clinical follow-up is recommended to monitor for reoccurrence.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Atypical Spitz Tumor

The shave biopsy revealed extensive dermal proliferation with spitzoid cytomorphology containing large, spindled nuclei; prominent nucleoli; and abundant homogenous cytoplasm arranged in haphazard fascicles. The proliferation was associated with prominent pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epidermis, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase immunohistochemistry showed diffuse strong positivity. Fluorescence in situ hybridization confirmed fusion of the tropomyosin 3 (TPM3) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) genes, which finalized the diagnosis of an ALK-mutated atypical spitz tumor. Due to the location and size of the lesion, Mohs micrographic surgery was performed to excise the tumor and clear the margins.

Spitz nevi are uncommon benign melanocytic neoplasms that typically occur in pediatric populations.1 Atypical spitz nevi comprised fewer than 17% of all childhood melanocytic nevi in the United States and can be considered in the broader category of spitzoid tumors. Spitz nevi are divided into 3 classes: Spitz nevus, atypical Spitz nevus, and spitzoid melanoma. Atypical Spitz nevi have typical Spitz nevus and spitzoid melanoma features and often can be difficult to distinguish on dermoscopy. Malignant Spitz tumors typically occur in the fifth decade of life, though the age distribution can vary widely.1

Black patients are less likely to be diagnosed with Spitz nevi, potentially due to a lower prevalence in this population, thus limiting the clinician’s clinical exposure and leading to increased rates of misdiagnoses.2 Spitz nevi usually manifest as well-circumscribed, dome-shaped papules and frequently are described as pink to red due to increased vascularity and limited melanin content1; however, these lesions may appear more violaceous, dusky, or dark brown in darker skin types. Additionally, approximately 71% of patients in a clinical review of Spitz nevi had a pigmented lesion, ranging from light brown to black.3 It is important for dermatologists to understand that the contrast in color between the nevus and the surrounding skin may not be as striking, prominent, or clinically concerning, particularly in darker skin types, such as in our patient.

Spitz nevi frequently manifest as rapidly growing solitary lesions most frequently developing in the lower legs (shown in 41% of lesions in one report).4 However, a recent retrospective review indicated that Spitz nevi in Black patients most commonly were found on the upper extremities, as was seen in our patient.2 Compared to typical and common Spitz nevi, atypical Spitz nevi often are greater than 10 mm in diameter and have features of ulceration.

Diagnosing atypical spitzoid melanocytic lesions requires adequate clinical suspicion and confirmation via biopsy. Under dermoscopy, typical Spitz nevi often display a starburst or globular pattern with pinpoint vessels, though it can have variable manifestations of both patterns. Atypical Spitz nevi can be challenging to distinguish from melanoma on dermoscopy since both conditions can have atypical pigment networks or structureless homogenous areas.1 Consequently, there often is a lower threshold for biopsy and possible follow-up excision for atypical Spitz nevi. Histopathology of atypical Spitz nevi includes epithelioid and spindle melanocytes but can share features of melanomas, including areas of prominent pagetoid spread, asymmetry, and poor circumscription.5 Furthermore, atypical Spitz nevi with ALK gene fusion, as seen in our patient, have been shown in the literature to demonstrate distinct histopathologic features, such as wedge-shaped extension into the dermis or a bulbous lower border that can resemble pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.6

The differential diagnosis for this rapidly growing scaly nodule also should include pyogenic granuloma, bacillary angiomatosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and amelanotic melanoma. Pyogenic granuloma is a rapidly growing, benign, vascular tumor that often becomes ulcerated and can occur in any age group.7 Pyogenic granuloma frequently appears at sites of trauma as a solitary, bright pink to red, friable, pedunculated papule and often manifests on the arms, hands, and face, similar to atypical Spitz nevi, though they can appear anywhere on the body. Histology shows a lobular capillary network with a central feeder vessel.7

Bacillary angiomatosis is an uncommon cutaneous infection associated with vascular proliferation and neovascularization due to the gram-negative organism Bartonella henselae.8 Bacillary nodules typically are reddish to purple and appear on the arms, sometimes with central ulceration and bleeding. Patients may present with multiple papules and nodules of varying sizes, as the lesions can arise in crops and follow a sporotrichoid pattern. Most patients with bacillary angiomatosis are immunosuppressed, though it rarely can affect immunocompetent patients. Histologically, bacillary angiomatosis is similar to pyogenic granuloma, though Gram or Warthin-Starry stains can help differentiate B henselae.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a malignant vascular neoplasm that often manifests in immunocompromised patients as violaceous, purple, or red patches, plaques, and nodules on the skin or oral mucosa. Histopathology shows spindle cell proliferation of irregular complex vascular channels dissecting through the dermis. Human herpesvirus 8 immunohistochemistry can be used to confirm diagnosis on histopathology.9 In contrast, amelanotic melanoma consists of lack of pigmentation, asymmetry with polymorphous vascular pattern, and high mitotic rate and is commonly found in sun-exposed areas. Dermoscopic features include irregular globules with blue-whitish veil.10

Treatment of atypical Spitz nevi depends mainly on the age of the patient and the histologic features of the nevus. Adults with atypical Spitz nevi frequently require excision, while the preferred choice for treatment in children with common Spitz nevi is regular clinical monitoring when there are no concerning clinical, dermoscopic, or histologic features.8 Compared to common Spitz nevi, atypical Spitz nevi have more melanoma-like features, resulting in a stronger recommendation for excision. Excision allows for a more thorough histologic evaluation and minimizes the likelihood of a recurrent atypical lesion.11 In all cases, close clinical follow-up is recommended to monitor for reoccurrence.

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part I. background and diagnoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1073-1084. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.040

- Farid YI, Honda KS. Spitz nevi in African Americans: a retrospective chart review of 11 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:511-518. doi:10.1111 /cup.13903

- Dal Pozzo V, Benelli C, Restano L, et al. Clinical review of 247 case records of Spitz nevus (epithelioid cell and/or spindle cell nevus). Dermatology 1997;194:20-25. doi: 10.1159/000246051

- Berlingeri-Ramos AC, Morales-Burgos A, Sanchez JL, et al. Spitz nevus in a Hispanic population: a clinicopathological study of 130 cases. Am J Dermatopathol 2010;32:267-275. doi: 10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181c52b99

- Brown A, Sawyer JD, Neumeister MW. Spitz nevus: review and update. Clin Plast Surg 2021;48:677-686. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2021.06.002 [published Online First: 20210818]

- Yeh I, de la Fouchardiere A, Pissaloux D, et al. Clinical, histopathologic, and genomic features of Spitz tumors with ALK fusions. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:581-91. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000387

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556077/

- Akram SM, Anwar MY, Thandra KC, et al. Bacillary angiomatosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated July 4, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448092/

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Pizzichetta MA, Talamini R, Stanganelli I, et al. Amelanotic/ hypomelanotic melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features. Br J Dermatol 2004;150(6):1117-1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05928.x

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part II. natural history and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:1087-1092. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.045

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part I. background and diagnoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1073-1084. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.040

- Farid YI, Honda KS. Spitz nevi in African Americans: a retrospective chart review of 11 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:511-518. doi:10.1111 /cup.13903

- Dal Pozzo V, Benelli C, Restano L, et al. Clinical review of 247 case records of Spitz nevus (epithelioid cell and/or spindle cell nevus). Dermatology 1997;194:20-25. doi: 10.1159/000246051

- Berlingeri-Ramos AC, Morales-Burgos A, Sanchez JL, et al. Spitz nevus in a Hispanic population: a clinicopathological study of 130 cases. Am J Dermatopathol 2010;32:267-275. doi: 10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181c52b99

- Brown A, Sawyer JD, Neumeister MW. Spitz nevus: review and update. Clin Plast Surg 2021;48:677-686. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2021.06.002 [published Online First: 20210818]

- Yeh I, de la Fouchardiere A, Pissaloux D, et al. Clinical, histopathologic, and genomic features of Spitz tumors with ALK fusions. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:581-91. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000387

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556077/

- Akram SM, Anwar MY, Thandra KC, et al. Bacillary angiomatosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated July 4, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448092/

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Pizzichetta MA, Talamini R, Stanganelli I, et al. Amelanotic/ hypomelanotic melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features. Br J Dermatol 2004;150(6):1117-1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05928.x

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part II. natural history and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:1087-1092. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.045

Exophytic Scaly Nodule on the Wrist

Exophytic Scaly Nodule on the Wrist

A 30-year-old Black man presented to the dermatology clinic with a rapidly growing, exophytic, scaly nodule on the right volar wrist of 2 months’ duration. The patient’s medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Physical examination revealed an irregularly bordered, red to violaceous, scaly, eroded, exophytic nodule on the wrist that was 2 cm in diameter with a surrounding adherent white-yellow crust. The patient had presumed the nodule was a wart and had been self-treating with over-the-counter salicylic acid and cryotherapy with no relief. He denied any bleeding or pruritus. The rest of the skin examination was unremarkable. A shave biopsy was performed for further evaluation.

Psoriasis Treatment Considerations in Military Patients: Unique Patients, Unique Drugs

Psoriasis is a common dermatologic problem with nearly 5% prevalence in the United States. There is a bimodal distribution with peak onset between 20 and 30 years of age and 50 and 60 years, which means that this condition can arise before, during, or after military service.1 Unfortunately, for many prospective recruits psoriasis is a medically disqualifying condition that can prevent entry into active duty unless a medical waiver is granted. For active-duty military, new-onset psoriasis and its treatment can impair affected service members’ ability to perform mission-critical work and can prevent them from deploying to remote or austere locations. In this way, psoriasis presents a unique challenge for active-duty service members.

Many therapies are available that can effectively treat psoriasis, but these treatments often carry a side-effect profile that limits their use during travel or in austere settings. Herein, we discuss the unique challenges of treating psoriasis patients who are in the military at a time when global mobility is critical to mission success. Although in some ways these challenges truly are unique to the military population, we strongly believe that similar but perhaps underappreciated challenges exist in the civilian sector. Close examination of these challenges may reveal that alternative treatment choices are sometimes indicated for reasons beyond just efficacy, side-effect profile, and cost.

Treatment Considerations

The medical treatment of psoriasis has undergone substantial change in recent decades. Before the turn of the century, the mainstays of medical treatment were steroids, methotrexate, and phototherapy. Today, a wide array of biologics and other systemic drugs are altering the impact of psoriasis in our society. With so many treatment options currently available, the question becomes, “Which one is best for my patient?” Immediate considerations are efficacy versus side effects as well as cost; however, in military dermatology, the ability to store, transport, and administer the treatment can be just as important.

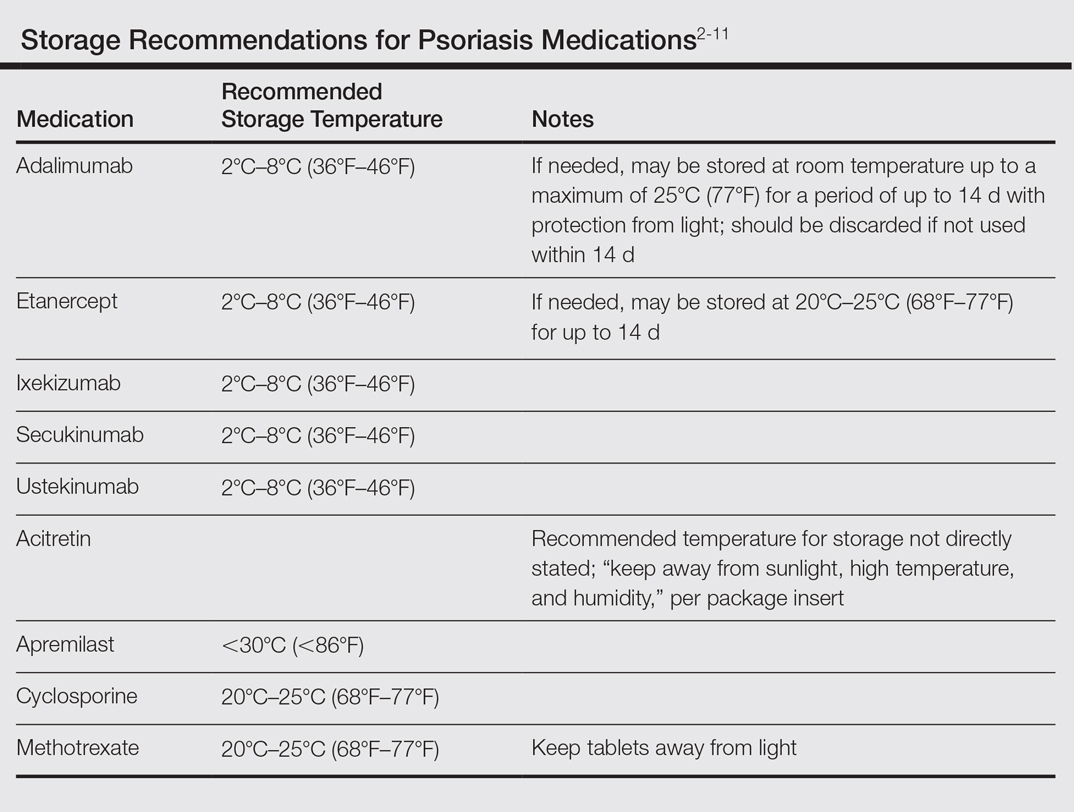

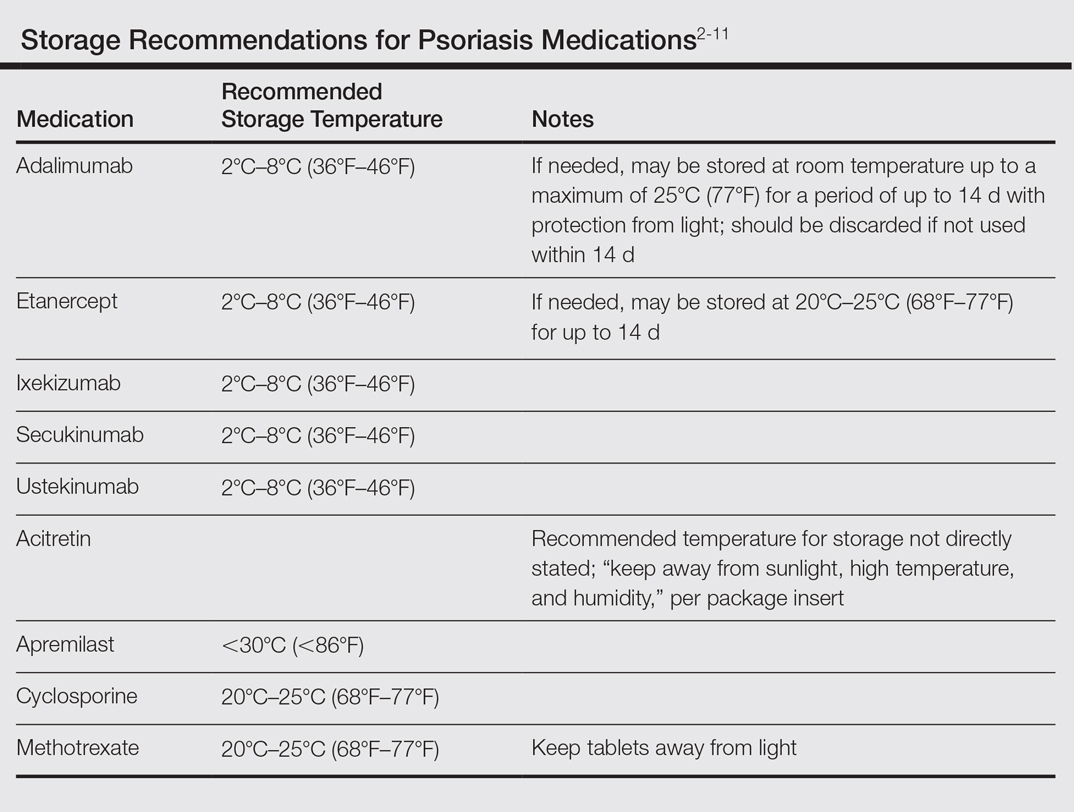

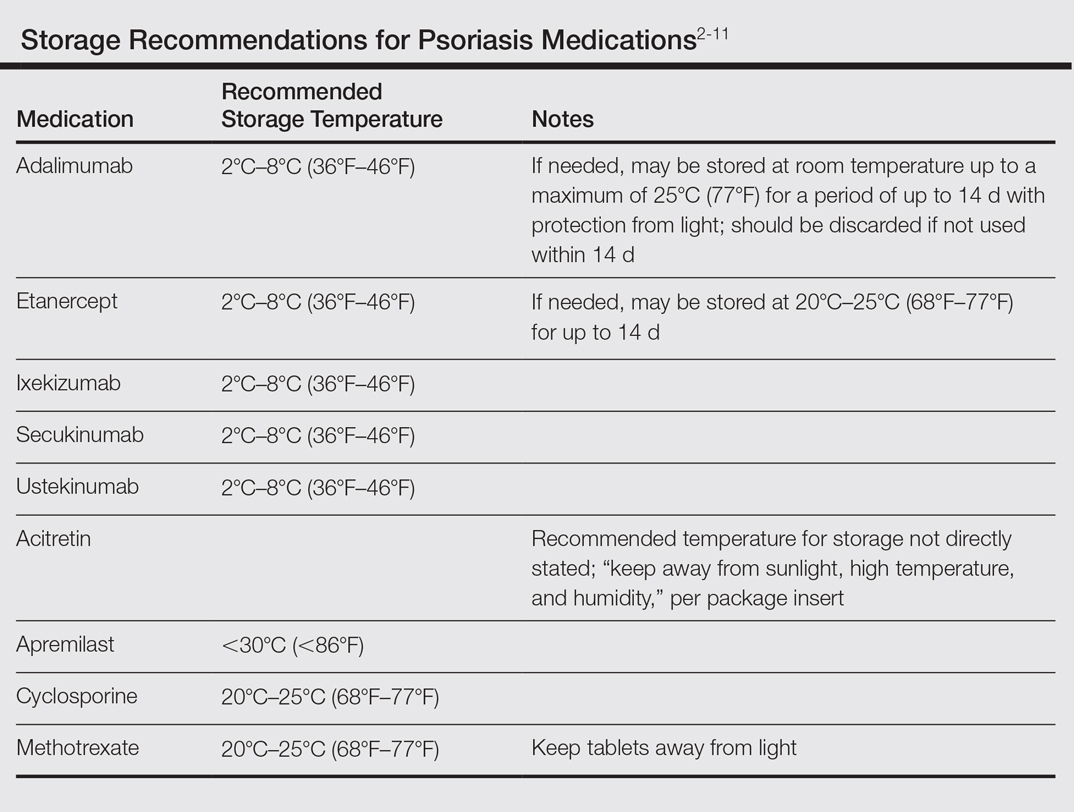

Although these problems may at first seem unique to active-duty military members, they also affect a substantial segment of the civilian sector. Take for instance the government contractor who deploys in support of military contingency actions, or the foreign aid workers, international businessmen, and diplomats around the world. In fact, any person who travels extensively might have difficulty carrying and storing their medications (Table) or encounter barriers that prevent routine access to care. Travel also may increase the risk of exposure to virulent pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which may further limit treatment options. This group of world travelers together comprises a minority of psoriasis patients who may be better treated with novel agents rather than with what might be considered the standard of care in a domestic setting.

Options for Care

Methotrexate

In many ways, methotrexate is the gold standard of psoriasis treatment. It is a first-line medication for many patients because it is typically well tolerated, has well-established efficacy, is easy to administer, and is relatively inexpensive.12 Although it is easy to store, transport, and administer, it requires regular laboratory monitoring at 3-month intervals or more frequently with dosage changes. It also is contraindicated in women of childbearing age who plan to become pregnant, which can be a considerable hindrance in the young active-duty population.

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine is another inexpensive medication that can produce excellent results in the treatment of psoriasis.1,12 Although long-term use of cyclosporine in transplant patients has been well studied, its use for the treatment of dermatologic conditions is usually limited to 1 year. The need for monthly blood pressure checks and at least quarterly laboratory monitoring means it is not an optimal choice for a deployed service member.

Acitretin

Acitretin is another systemic medication with an established track record in psoriasis treatment. Although close follow-up and laboratory monitoring is required for both males and females, use of this medication can have a greater effect on women of childbearing age, as it is absolutely contraindicated in any female trying to conceive.13 In addition, acitretin is stored in fat cells, and traces of the drug can be found in the blood for up to 3 years. During this period, patients are advised to strictly avoid pregnancy and are even restricted from donating blood.13 Given these concerns, acitretin is not always a reasonable treatment option for the military service member.

Biologics

Biologics are the newest agents in the treatment of psoriasis. They require less laboratory monitoring and can provide excellent results. Adalimumab is a reasonable first-line biologic treatment for some patients. We find the laboratory monitoring is minimally obtrusive, side effects usually are limited, and the efficacy is great enough that most patients elect to continue treatment. Unfortunately, adalimumab has some major drawbacks in our specific use scenario in that it requires nearly continuous refrigeration and is never to exceed 25°C (77°F), it has a relatively close-interval dosing schedule, and it can cause immunosuppression. However, for short trips to nonaustere locations with an acceptable risk for pathogenic exposure, adalimumab may remain a viable option for many travelers, as it can be stored at room temperature for up to 14 days.2 Ustekinumab also is a reasonable choice for many travelers because dosing is every 12 weeks and it carries a lower risk of immunosuppression.2,3 Ustekinumab, however, has the major drawback of high cost.12 Newer IL-17A inhibitors such as secukinumab or ixekizumab also can offer excellent results, but long-term infection rates have not been reported. Overall, the infection rates are comparable to ustekinumab.14,15 After the loading phase, secukinumab is dosed monthly and logistically could still pose a problem due to the need for continued refrigeration.14

Apremilast

Although it is not the best first-line treatment for every patient, apremilast carries 3 distinct advantages in treating the military patient population: (1) laboratory monitoring is required only once per year, (2) it is easy to store, and (3) it is easy to administer. However, the major downside is that apremilast is less effective than other systemic agents in the treatment of psoriasis.16 As with other systemic drugs, adjunctive topical treatment can provide additional therapeutic effects, and for many patients, this combined approach is sufficient to reach their therapeutic goals.

For these reasons, in the special case of deployable, active-duty military members we often consider starting treatment with apremilast versus other systemic agents. As with all systemic psoriasis treatments, we generally advise patients to return 16 weeks after initiating treatment to assess efficacy and evaluate their deployment status. Although apremilast may take longer to reach full efficacy than many other systemic agents, one clinical trial suggested this time frame is sufficient to evaluate response to treatment.16 After this initial assessment, we revert to yearly monitoring, and the patient is usually cleared to deploy with minimal restrictions.

Final Considerations

The manifestation of psoriasis is different in every patient, and military service poses additional treatment challenges. For all of our military patients, we recommend an initial period of close follow-up after starting any new systemic agent, which is necessary to ensure the treatment is effective and well tolerated and also that we are good stewards of our resources. Once efficacy is established and side effects remain tolerable, we generally endorse continued treatment without specific travel or work restrictions.

We are cognizant of the unique nature of military service, and all too often we find ourselves trying to practice good medicine in bad places. As military physicians, we serve a population that is eager to do their job and willing to make incredible sacrifices to do so. After considering the wide range of circumstances unique to the military, our responsibility as providers is to do our best to improve service members’ quality of life as they carry out their missions.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Stelara [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2009.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2007.

- Cosentyx [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2016.

- Otezla [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2014.

- Enbrel [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen; 2015.

- Taltz [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2016.

- Methotrexate [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2016.

- Gengraf [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: Abbvie Inc; 2015.

- Acitretin [package insert]. Mason, OH: Prasco Laboratories; 2015.

- Beyer V, Wolverton SE. Recent trends in systemic psoriasis treatment costs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:46-54.

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [published online June 8, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, anoral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

Psoriasis is a common dermatologic problem with nearly 5% prevalence in the United States. There is a bimodal distribution with peak onset between 20 and 30 years of age and 50 and 60 years, which means that this condition can arise before, during, or after military service.1 Unfortunately, for many prospective recruits psoriasis is a medically disqualifying condition that can prevent entry into active duty unless a medical waiver is granted. For active-duty military, new-onset psoriasis and its treatment can impair affected service members’ ability to perform mission-critical work and can prevent them from deploying to remote or austere locations. In this way, psoriasis presents a unique challenge for active-duty service members.

Many therapies are available that can effectively treat psoriasis, but these treatments often carry a side-effect profile that limits their use during travel or in austere settings. Herein, we discuss the unique challenges of treating psoriasis patients who are in the military at a time when global mobility is critical to mission success. Although in some ways these challenges truly are unique to the military population, we strongly believe that similar but perhaps underappreciated challenges exist in the civilian sector. Close examination of these challenges may reveal that alternative treatment choices are sometimes indicated for reasons beyond just efficacy, side-effect profile, and cost.

Treatment Considerations

The medical treatment of psoriasis has undergone substantial change in recent decades. Before the turn of the century, the mainstays of medical treatment were steroids, methotrexate, and phototherapy. Today, a wide array of biologics and other systemic drugs are altering the impact of psoriasis in our society. With so many treatment options currently available, the question becomes, “Which one is best for my patient?” Immediate considerations are efficacy versus side effects as well as cost; however, in military dermatology, the ability to store, transport, and administer the treatment can be just as important.

Although these problems may at first seem unique to active-duty military members, they also affect a substantial segment of the civilian sector. Take for instance the government contractor who deploys in support of military contingency actions, or the foreign aid workers, international businessmen, and diplomats around the world. In fact, any person who travels extensively might have difficulty carrying and storing their medications (Table) or encounter barriers that prevent routine access to care. Travel also may increase the risk of exposure to virulent pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which may further limit treatment options. This group of world travelers together comprises a minority of psoriasis patients who may be better treated with novel agents rather than with what might be considered the standard of care in a domestic setting.

Options for Care

Methotrexate

In many ways, methotrexate is the gold standard of psoriasis treatment. It is a first-line medication for many patients because it is typically well tolerated, has well-established efficacy, is easy to administer, and is relatively inexpensive.12 Although it is easy to store, transport, and administer, it requires regular laboratory monitoring at 3-month intervals or more frequently with dosage changes. It also is contraindicated in women of childbearing age who plan to become pregnant, which can be a considerable hindrance in the young active-duty population.

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine is another inexpensive medication that can produce excellent results in the treatment of psoriasis.1,12 Although long-term use of cyclosporine in transplant patients has been well studied, its use for the treatment of dermatologic conditions is usually limited to 1 year. The need for monthly blood pressure checks and at least quarterly laboratory monitoring means it is not an optimal choice for a deployed service member.

Acitretin

Acitretin is another systemic medication with an established track record in psoriasis treatment. Although close follow-up and laboratory monitoring is required for both males and females, use of this medication can have a greater effect on women of childbearing age, as it is absolutely contraindicated in any female trying to conceive.13 In addition, acitretin is stored in fat cells, and traces of the drug can be found in the blood for up to 3 years. During this period, patients are advised to strictly avoid pregnancy and are even restricted from donating blood.13 Given these concerns, acitretin is not always a reasonable treatment option for the military service member.

Biologics

Biologics are the newest agents in the treatment of psoriasis. They require less laboratory monitoring and can provide excellent results. Adalimumab is a reasonable first-line biologic treatment for some patients. We find the laboratory monitoring is minimally obtrusive, side effects usually are limited, and the efficacy is great enough that most patients elect to continue treatment. Unfortunately, adalimumab has some major drawbacks in our specific use scenario in that it requires nearly continuous refrigeration and is never to exceed 25°C (77°F), it has a relatively close-interval dosing schedule, and it can cause immunosuppression. However, for short trips to nonaustere locations with an acceptable risk for pathogenic exposure, adalimumab may remain a viable option for many travelers, as it can be stored at room temperature for up to 14 days.2 Ustekinumab also is a reasonable choice for many travelers because dosing is every 12 weeks and it carries a lower risk of immunosuppression.2,3 Ustekinumab, however, has the major drawback of high cost.12 Newer IL-17A inhibitors such as secukinumab or ixekizumab also can offer excellent results, but long-term infection rates have not been reported. Overall, the infection rates are comparable to ustekinumab.14,15 After the loading phase, secukinumab is dosed monthly and logistically could still pose a problem due to the need for continued refrigeration.14

Apremilast

Although it is not the best first-line treatment for every patient, apremilast carries 3 distinct advantages in treating the military patient population: (1) laboratory monitoring is required only once per year, (2) it is easy to store, and (3) it is easy to administer. However, the major downside is that apremilast is less effective than other systemic agents in the treatment of psoriasis.16 As with other systemic drugs, adjunctive topical treatment can provide additional therapeutic effects, and for many patients, this combined approach is sufficient to reach their therapeutic goals.

For these reasons, in the special case of deployable, active-duty military members we often consider starting treatment with apremilast versus other systemic agents. As with all systemic psoriasis treatments, we generally advise patients to return 16 weeks after initiating treatment to assess efficacy and evaluate their deployment status. Although apremilast may take longer to reach full efficacy than many other systemic agents, one clinical trial suggested this time frame is sufficient to evaluate response to treatment.16 After this initial assessment, we revert to yearly monitoring, and the patient is usually cleared to deploy with minimal restrictions.

Final Considerations

The manifestation of psoriasis is different in every patient, and military service poses additional treatment challenges. For all of our military patients, we recommend an initial period of close follow-up after starting any new systemic agent, which is necessary to ensure the treatment is effective and well tolerated and also that we are good stewards of our resources. Once efficacy is established and side effects remain tolerable, we generally endorse continued treatment without specific travel or work restrictions.

We are cognizant of the unique nature of military service, and all too often we find ourselves trying to practice good medicine in bad places. As military physicians, we serve a population that is eager to do their job and willing to make incredible sacrifices to do so. After considering the wide range of circumstances unique to the military, our responsibility as providers is to do our best to improve service members’ quality of life as they carry out their missions.

Psoriasis is a common dermatologic problem with nearly 5% prevalence in the United States. There is a bimodal distribution with peak onset between 20 and 30 years of age and 50 and 60 years, which means that this condition can arise before, during, or after military service.1 Unfortunately, for many prospective recruits psoriasis is a medically disqualifying condition that can prevent entry into active duty unless a medical waiver is granted. For active-duty military, new-onset psoriasis and its treatment can impair affected service members’ ability to perform mission-critical work and can prevent them from deploying to remote or austere locations. In this way, psoriasis presents a unique challenge for active-duty service members.

Many therapies are available that can effectively treat psoriasis, but these treatments often carry a side-effect profile that limits their use during travel or in austere settings. Herein, we discuss the unique challenges of treating psoriasis patients who are in the military at a time when global mobility is critical to mission success. Although in some ways these challenges truly are unique to the military population, we strongly believe that similar but perhaps underappreciated challenges exist in the civilian sector. Close examination of these challenges may reveal that alternative treatment choices are sometimes indicated for reasons beyond just efficacy, side-effect profile, and cost.

Treatment Considerations

The medical treatment of psoriasis has undergone substantial change in recent decades. Before the turn of the century, the mainstays of medical treatment were steroids, methotrexate, and phototherapy. Today, a wide array of biologics and other systemic drugs are altering the impact of psoriasis in our society. With so many treatment options currently available, the question becomes, “Which one is best for my patient?” Immediate considerations are efficacy versus side effects as well as cost; however, in military dermatology, the ability to store, transport, and administer the treatment can be just as important.

Although these problems may at first seem unique to active-duty military members, they also affect a substantial segment of the civilian sector. Take for instance the government contractor who deploys in support of military contingency actions, or the foreign aid workers, international businessmen, and diplomats around the world. In fact, any person who travels extensively might have difficulty carrying and storing their medications (Table) or encounter barriers that prevent routine access to care. Travel also may increase the risk of exposure to virulent pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which may further limit treatment options. This group of world travelers together comprises a minority of psoriasis patients who may be better treated with novel agents rather than with what might be considered the standard of care in a domestic setting.

Options for Care

Methotrexate

In many ways, methotrexate is the gold standard of psoriasis treatment. It is a first-line medication for many patients because it is typically well tolerated, has well-established efficacy, is easy to administer, and is relatively inexpensive.12 Although it is easy to store, transport, and administer, it requires regular laboratory monitoring at 3-month intervals or more frequently with dosage changes. It also is contraindicated in women of childbearing age who plan to become pregnant, which can be a considerable hindrance in the young active-duty population.

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine is another inexpensive medication that can produce excellent results in the treatment of psoriasis.1,12 Although long-term use of cyclosporine in transplant patients has been well studied, its use for the treatment of dermatologic conditions is usually limited to 1 year. The need for monthly blood pressure checks and at least quarterly laboratory monitoring means it is not an optimal choice for a deployed service member.

Acitretin

Acitretin is another systemic medication with an established track record in psoriasis treatment. Although close follow-up and laboratory monitoring is required for both males and females, use of this medication can have a greater effect on women of childbearing age, as it is absolutely contraindicated in any female trying to conceive.13 In addition, acitretin is stored in fat cells, and traces of the drug can be found in the blood for up to 3 years. During this period, patients are advised to strictly avoid pregnancy and are even restricted from donating blood.13 Given these concerns, acitretin is not always a reasonable treatment option for the military service member.

Biologics

Biologics are the newest agents in the treatment of psoriasis. They require less laboratory monitoring and can provide excellent results. Adalimumab is a reasonable first-line biologic treatment for some patients. We find the laboratory monitoring is minimally obtrusive, side effects usually are limited, and the efficacy is great enough that most patients elect to continue treatment. Unfortunately, adalimumab has some major drawbacks in our specific use scenario in that it requires nearly continuous refrigeration and is never to exceed 25°C (77°F), it has a relatively close-interval dosing schedule, and it can cause immunosuppression. However, for short trips to nonaustere locations with an acceptable risk for pathogenic exposure, adalimumab may remain a viable option for many travelers, as it can be stored at room temperature for up to 14 days.2 Ustekinumab also is a reasonable choice for many travelers because dosing is every 12 weeks and it carries a lower risk of immunosuppression.2,3 Ustekinumab, however, has the major drawback of high cost.12 Newer IL-17A inhibitors such as secukinumab or ixekizumab also can offer excellent results, but long-term infection rates have not been reported. Overall, the infection rates are comparable to ustekinumab.14,15 After the loading phase, secukinumab is dosed monthly and logistically could still pose a problem due to the need for continued refrigeration.14

Apremilast

Although it is not the best first-line treatment for every patient, apremilast carries 3 distinct advantages in treating the military patient population: (1) laboratory monitoring is required only once per year, (2) it is easy to store, and (3) it is easy to administer. However, the major downside is that apremilast is less effective than other systemic agents in the treatment of psoriasis.16 As with other systemic drugs, adjunctive topical treatment can provide additional therapeutic effects, and for many patients, this combined approach is sufficient to reach their therapeutic goals.

For these reasons, in the special case of deployable, active-duty military members we often consider starting treatment with apremilast versus other systemic agents. As with all systemic psoriasis treatments, we generally advise patients to return 16 weeks after initiating treatment to assess efficacy and evaluate their deployment status. Although apremilast may take longer to reach full efficacy than many other systemic agents, one clinical trial suggested this time frame is sufficient to evaluate response to treatment.16 After this initial assessment, we revert to yearly monitoring, and the patient is usually cleared to deploy with minimal restrictions.

Final Considerations

The manifestation of psoriasis is different in every patient, and military service poses additional treatment challenges. For all of our military patients, we recommend an initial period of close follow-up after starting any new systemic agent, which is necessary to ensure the treatment is effective and well tolerated and also that we are good stewards of our resources. Once efficacy is established and side effects remain tolerable, we generally endorse continued treatment without specific travel or work restrictions.

We are cognizant of the unique nature of military service, and all too often we find ourselves trying to practice good medicine in bad places. As military physicians, we serve a population that is eager to do their job and willing to make incredible sacrifices to do so. After considering the wide range of circumstances unique to the military, our responsibility as providers is to do our best to improve service members’ quality of life as they carry out their missions.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Stelara [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2009.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2007.

- Cosentyx [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2016.

- Otezla [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2014.

- Enbrel [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen; 2015.

- Taltz [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2016.

- Methotrexate [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2016.

- Gengraf [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: Abbvie Inc; 2015.

- Acitretin [package insert]. Mason, OH: Prasco Laboratories; 2015.

- Beyer V, Wolverton SE. Recent trends in systemic psoriasis treatment costs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:46-54.

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [published online June 8, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, anoral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Stelara [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2009.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2007.

- Cosentyx [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2016.

- Otezla [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2014.

- Enbrel [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen; 2015.

- Taltz [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2016.

- Methotrexate [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2016.

- Gengraf [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: Abbvie Inc; 2015.

- Acitretin [package insert]. Mason, OH: Prasco Laboratories; 2015.

- Beyer V, Wolverton SE. Recent trends in systemic psoriasis treatment costs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:46-54.

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [published online June 8, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, anoral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

Practice Points

- Establishing goals of treatment with each patient is a critical step in treating the patient rather than the diagnosis.

- A good social history can reveal job-related impact of disease and potential logistical roadblocks to treatment.

- Efficacy must be weighed against the burden of logistical constraints for each patient; potential issues include difficulty complying with follow-up visits, access to laboratory monitoring, exposure to pathogens, and adequacy of medication transport and storage.