User login

Fecal calprotectin tops CRP as Crohn’s marker

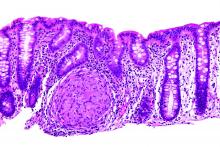

Stool calprotectin correlates with severity of small-bowel Crohn’s disease, as measured against balloon-assisted enteroscopy and computed tomography enterography, according to a review reported in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology of 89 patients at Toho University in Chiba, Japan.

Although the correlation was moderate, the findings suggest that fecal calprotectin (FC), with additional work, might turn out to be a good biomarker for tracking small-bowel Crohn’s disease (CD) and its response to tumor necrosis factor blockers. “Currently, it is not widely accepted that FC relates to disease activity in patients with small-intestinal CD,” said investigators led by Tsunetaka Arai of Toho University’s division of gastroenterology and hepatology (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Aug 23. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.08.015).

Gastroenterologists need a decent biomarker for small-bowel Crohn’s because old-school endoscopy falls short. Adhesions and strictures block endoscopes, and sometimes scopes simply can’t reach the disease site.

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE) and computed tomography enterography (CTE) have emerged in recent years as alternatives, but, even so, the need persists for a noninvasive and inexpensive biomarker that’s better than the current standard of C-reactive protein (CRP), which can be thrown off by systemic inflammation, among other problems. The Toho investigators “believe that FC could be a relevant surrogate marker of disease activity in small-bowel CD.” Stool calprotectin paralleled disease activity in their study, while “neither the CDAI [CD activity index] score nor serum CRP showed similar correlation,” they said.

However, elevations in FC – a calcium- and zinc-binding protein released when neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages inflame the intestinal mucosa – was independent of CD location, which signals the need for further investigation.

Meanwhile, the decent correlation between FC and CTE in the study “should [also] mean that” they could be used together to reliably define mucosal healing. CTE on its own “showed good correlation” with BAE; a CTE score/segment less than 2 [was] associated with endoscopic mucosal healing” on BAE, the investigators said.

The study subjects were an average of 32 years old, and had CD for 9 years; most were men. They had highly active disease at their first endoscopy (average CDAI of 120 points), and an average CRP of 1.09 mg/dL. Twenty-seven patients (30.3%) had small-bowel CD, 50 (56.2%) had ileocolonic CD, and 12 (13.5%) had colonic CD.

They all had endoscopic exams, BAE, and FC stool testing; those with strictures (17) went on to CTE; CTE detected every lesion despite the strictures.

The authors had no conflicts of interest.

Stool calprotectin correlates with severity of small-bowel Crohn’s disease, as measured against balloon-assisted enteroscopy and computed tomography enterography, according to a review reported in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology of 89 patients at Toho University in Chiba, Japan.

Although the correlation was moderate, the findings suggest that fecal calprotectin (FC), with additional work, might turn out to be a good biomarker for tracking small-bowel Crohn’s disease (CD) and its response to tumor necrosis factor blockers. “Currently, it is not widely accepted that FC relates to disease activity in patients with small-intestinal CD,” said investigators led by Tsunetaka Arai of Toho University’s division of gastroenterology and hepatology (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Aug 23. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.08.015).

Gastroenterologists need a decent biomarker for small-bowel Crohn’s because old-school endoscopy falls short. Adhesions and strictures block endoscopes, and sometimes scopes simply can’t reach the disease site.

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE) and computed tomography enterography (CTE) have emerged in recent years as alternatives, but, even so, the need persists for a noninvasive and inexpensive biomarker that’s better than the current standard of C-reactive protein (CRP), which can be thrown off by systemic inflammation, among other problems. The Toho investigators “believe that FC could be a relevant surrogate marker of disease activity in small-bowel CD.” Stool calprotectin paralleled disease activity in their study, while “neither the CDAI [CD activity index] score nor serum CRP showed similar correlation,” they said.

However, elevations in FC – a calcium- and zinc-binding protein released when neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages inflame the intestinal mucosa – was independent of CD location, which signals the need for further investigation.

Meanwhile, the decent correlation between FC and CTE in the study “should [also] mean that” they could be used together to reliably define mucosal healing. CTE on its own “showed good correlation” with BAE; a CTE score/segment less than 2 [was] associated with endoscopic mucosal healing” on BAE, the investigators said.

The study subjects were an average of 32 years old, and had CD for 9 years; most were men. They had highly active disease at their first endoscopy (average CDAI of 120 points), and an average CRP of 1.09 mg/dL. Twenty-seven patients (30.3%) had small-bowel CD, 50 (56.2%) had ileocolonic CD, and 12 (13.5%) had colonic CD.

They all had endoscopic exams, BAE, and FC stool testing; those with strictures (17) went on to CTE; CTE detected every lesion despite the strictures.

The authors had no conflicts of interest.

Stool calprotectin correlates with severity of small-bowel Crohn’s disease, as measured against balloon-assisted enteroscopy and computed tomography enterography, according to a review reported in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology of 89 patients at Toho University in Chiba, Japan.

Although the correlation was moderate, the findings suggest that fecal calprotectin (FC), with additional work, might turn out to be a good biomarker for tracking small-bowel Crohn’s disease (CD) and its response to tumor necrosis factor blockers. “Currently, it is not widely accepted that FC relates to disease activity in patients with small-intestinal CD,” said investigators led by Tsunetaka Arai of Toho University’s division of gastroenterology and hepatology (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Aug 23. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.08.015).

Gastroenterologists need a decent biomarker for small-bowel Crohn’s because old-school endoscopy falls short. Adhesions and strictures block endoscopes, and sometimes scopes simply can’t reach the disease site.

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE) and computed tomography enterography (CTE) have emerged in recent years as alternatives, but, even so, the need persists for a noninvasive and inexpensive biomarker that’s better than the current standard of C-reactive protein (CRP), which can be thrown off by systemic inflammation, among other problems. The Toho investigators “believe that FC could be a relevant surrogate marker of disease activity in small-bowel CD.” Stool calprotectin paralleled disease activity in their study, while “neither the CDAI [CD activity index] score nor serum CRP showed similar correlation,” they said.

However, elevations in FC – a calcium- and zinc-binding protein released when neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages inflame the intestinal mucosa – was independent of CD location, which signals the need for further investigation.

Meanwhile, the decent correlation between FC and CTE in the study “should [also] mean that” they could be used together to reliably define mucosal healing. CTE on its own “showed good correlation” with BAE; a CTE score/segment less than 2 [was] associated with endoscopic mucosal healing” on BAE, the investigators said.

The study subjects were an average of 32 years old, and had CD for 9 years; most were men. They had highly active disease at their first endoscopy (average CDAI of 120 points), and an average CRP of 1.09 mg/dL. Twenty-seven patients (30.3%) had small-bowel CD, 50 (56.2%) had ileocolonic CD, and 12 (13.5%) had colonic CD.

They all had endoscopic exams, BAE, and FC stool testing; those with strictures (17) went on to CTE; CTE detected every lesion despite the strictures.

The authors had no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A fecal calprotectin cutoff of 215 mcg/g identified mucosal healing with 82.8% sensitivity, 71.4% specificity, and an AUC of 0.81.

Data source: Review of 89 Crohn’s patients

Disclosures: The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

PrEP adoption lagging behind awareness in high-risk population

NEW ORLEANS – Awareness about preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is steadily increasing among men who have sex with men at high risk for HIV infection, but that increased knowledge did not translate into greater willingness to take the daily pill nor did it increase engagement in high-risk behaviors.

Using questions from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System (NHBS), investigators surveyed men who have sex with men in urban settings in 3-year cycles. Awareness about HIV PrEP, once-daily emtricitabine/tenofovir (Truvada) increased from 21% in 2008 to 28% in 2011 to 46% in 2014.

The increase from 2011 to 2014 was statistically significant (P less than .001). The Food and Drug Administration approved the preventive regimen in 2012.

Increased knowledge did not translate to greater willingness to take the daily pill – which has held steady at about 60% of over time.

The number of men who self-reported as HIV negative and sexually active in the previous 12 months included in the survey varied from 421 in 2008, to 461 in 2011, to 451 in 2014.

For people at elevated risk for HIV infection, PrEP also represents an opportunity to take greater control over behavior, according to a recent review (Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11:3-9). “When you get people in for counseling or condoms, you give them a sense of control,” said Dr. Krotchko of Denver Health Medical Center.

Most survey respondents said they anticipated they would use condoms just as frequently as before if taking PrEP (82%, 78%, and 78%, in 2008, 2011, and 2014, respectively). Similarly, the majority of respondents anticipated having the same number of sexual partners if taking PrEP (92%, 85%, and 89%). These differences were not statistically significant.

The findings indicate availability of HIV PrEP is not increasing unhealthy behaviors, as some may fear. “Riskier behavior while on PrEP has not been borne out by the literature,” Dr. Krotchko said.

Strengths of the study include directly targeting a high-risk population and identifying those with high-risk behaviors who could benefit from use of HIV PrEP. Self-reported anticipated changes may not reflect future behavior in all cases, a potential limitation, Dr. Krotchko pointed out.

The NHBS survey is funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. IDWeek 2016 comprises the combined meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

NEW ORLEANS – Awareness about preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is steadily increasing among men who have sex with men at high risk for HIV infection, but that increased knowledge did not translate into greater willingness to take the daily pill nor did it increase engagement in high-risk behaviors.

Using questions from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System (NHBS), investigators surveyed men who have sex with men in urban settings in 3-year cycles. Awareness about HIV PrEP, once-daily emtricitabine/tenofovir (Truvada) increased from 21% in 2008 to 28% in 2011 to 46% in 2014.

The increase from 2011 to 2014 was statistically significant (P less than .001). The Food and Drug Administration approved the preventive regimen in 2012.

Increased knowledge did not translate to greater willingness to take the daily pill – which has held steady at about 60% of over time.

The number of men who self-reported as HIV negative and sexually active in the previous 12 months included in the survey varied from 421 in 2008, to 461 in 2011, to 451 in 2014.

For people at elevated risk for HIV infection, PrEP also represents an opportunity to take greater control over behavior, according to a recent review (Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11:3-9). “When you get people in for counseling or condoms, you give them a sense of control,” said Dr. Krotchko of Denver Health Medical Center.

Most survey respondents said they anticipated they would use condoms just as frequently as before if taking PrEP (82%, 78%, and 78%, in 2008, 2011, and 2014, respectively). Similarly, the majority of respondents anticipated having the same number of sexual partners if taking PrEP (92%, 85%, and 89%). These differences were not statistically significant.

The findings indicate availability of HIV PrEP is not increasing unhealthy behaviors, as some may fear. “Riskier behavior while on PrEP has not been borne out by the literature,” Dr. Krotchko said.

Strengths of the study include directly targeting a high-risk population and identifying those with high-risk behaviors who could benefit from use of HIV PrEP. Self-reported anticipated changes may not reflect future behavior in all cases, a potential limitation, Dr. Krotchko pointed out.

The NHBS survey is funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. IDWeek 2016 comprises the combined meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

NEW ORLEANS – Awareness about preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is steadily increasing among men who have sex with men at high risk for HIV infection, but that increased knowledge did not translate into greater willingness to take the daily pill nor did it increase engagement in high-risk behaviors.

Using questions from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System (NHBS), investigators surveyed men who have sex with men in urban settings in 3-year cycles. Awareness about HIV PrEP, once-daily emtricitabine/tenofovir (Truvada) increased from 21% in 2008 to 28% in 2011 to 46% in 2014.

The increase from 2011 to 2014 was statistically significant (P less than .001). The Food and Drug Administration approved the preventive regimen in 2012.

Increased knowledge did not translate to greater willingness to take the daily pill – which has held steady at about 60% of over time.

The number of men who self-reported as HIV negative and sexually active in the previous 12 months included in the survey varied from 421 in 2008, to 461 in 2011, to 451 in 2014.

For people at elevated risk for HIV infection, PrEP also represents an opportunity to take greater control over behavior, according to a recent review (Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11:3-9). “When you get people in for counseling or condoms, you give them a sense of control,” said Dr. Krotchko of Denver Health Medical Center.

Most survey respondents said they anticipated they would use condoms just as frequently as before if taking PrEP (82%, 78%, and 78%, in 2008, 2011, and 2014, respectively). Similarly, the majority of respondents anticipated having the same number of sexual partners if taking PrEP (92%, 85%, and 89%). These differences were not statistically significant.

The findings indicate availability of HIV PrEP is not increasing unhealthy behaviors, as some may fear. “Riskier behavior while on PrEP has not been borne out by the literature,” Dr. Krotchko said.

Strengths of the study include directly targeting a high-risk population and identifying those with high-risk behaviors who could benefit from use of HIV PrEP. Self-reported anticipated changes may not reflect future behavior in all cases, a potential limitation, Dr. Krotchko pointed out.

The NHBS survey is funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. IDWeek 2016 comprises the combined meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

AT IDWEEK 2016

Key clinical point: Adoption and use of HIV PrEP continues to lag behind studies showing its effectiveness in the high-risk population of men who have sex with men.

Major finding: Despite increasing awareness, willingness to use HIV PrEP among MSM remained steady at about 60% over time in a series of national behavioral health surveys.

Data source: The National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System.

Disclosures: Dr. Krotchko had no relevant disclosures.

Thank You to Our 2016 Peer Reviewers

The editors of Emergency Medicine acknowledge the help of the journal’s editorial board members, other emergency physicians, and colleagues in other specialties who reviewed manuscripts in 2016. On behalf of our readers, who are the beneficiaries of your efforts, we thank you.

Alfred Z. Abuhamad, MD

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Eastern Virginia Medical School

John E. Arbo, MD

Division of Emergency Medicine and Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

David P. Calfee, MD

Division of Infectious Diseases

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Richard M. Cantor, MD, FAAP, FACEP

Emergency Department, Pediatrics

Upstate Medical University

Wallace A. Carter, MD, FACEP

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Sunday Clark, ScD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Theodore R. Delbridge, MD

Department of Emergency

Medicine East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine

Joseph J. Fins, MD

Division of Medical Ethics Internal Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Ron W. Flenner, MD

Department of Internal Medicine

Eastern Virginia Medical School

E. John Gallagher, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Marianne Gausche-Hill, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Keith D. Hentel, MD

Department of Radiology

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Barry J. Knapp, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Eastern Virginia Medical School

Richard I. Lapin, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Anthony C. Mustalish, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Lewis S. Nelson, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

Debra Perina, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Constance Peterson, MA

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Shari L. Platt, MD, FAAP

Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Rama B. Rao, MD

Division of Toxicology

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Earl J. Reisdorff, MD

Executive Director

American Board of Emergency Medicine

Thomas M. Scalea, MD, FACS, FCCM

Program in Trauma

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Edward J. Schenk, MD

Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Christopher K. Schott, MD, MS

Department of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care Medicine

University of Pittsburgh

Adam J Singer, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Stony Brook University and Medical Center

Sarah A. Stahmer, MD, FACEP

Division of Emergency Medicine

Duke University Medical Center

Michael E. Stern, MD

Division of Geriatric Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Susan Stone, MD

Emergency Medicine/Palliative Care

University of California, Los Angeles

Todd Taylor, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Emory University School of Medicine

The editors of Emergency Medicine acknowledge the help of the journal’s editorial board members, other emergency physicians, and colleagues in other specialties who reviewed manuscripts in 2016. On behalf of our readers, who are the beneficiaries of your efforts, we thank you.

Alfred Z. Abuhamad, MD

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Eastern Virginia Medical School

John E. Arbo, MD

Division of Emergency Medicine and Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

David P. Calfee, MD

Division of Infectious Diseases

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Richard M. Cantor, MD, FAAP, FACEP

Emergency Department, Pediatrics

Upstate Medical University

Wallace A. Carter, MD, FACEP

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Sunday Clark, ScD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Theodore R. Delbridge, MD

Department of Emergency

Medicine East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine

Joseph J. Fins, MD

Division of Medical Ethics Internal Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Ron W. Flenner, MD

Department of Internal Medicine

Eastern Virginia Medical School

E. John Gallagher, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Marianne Gausche-Hill, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Keith D. Hentel, MD

Department of Radiology

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Barry J. Knapp, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Eastern Virginia Medical School

Richard I. Lapin, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Anthony C. Mustalish, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Lewis S. Nelson, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

Debra Perina, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Constance Peterson, MA

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Shari L. Platt, MD, FAAP

Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Rama B. Rao, MD

Division of Toxicology

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Earl J. Reisdorff, MD

Executive Director

American Board of Emergency Medicine

Thomas M. Scalea, MD, FACS, FCCM

Program in Trauma

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Edward J. Schenk, MD

Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Christopher K. Schott, MD, MS

Department of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care Medicine

University of Pittsburgh

Adam J Singer, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Stony Brook University and Medical Center

Sarah A. Stahmer, MD, FACEP

Division of Emergency Medicine

Duke University Medical Center

Michael E. Stern, MD

Division of Geriatric Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Susan Stone, MD

Emergency Medicine/Palliative Care

University of California, Los Angeles

Todd Taylor, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Emory University School of Medicine

The editors of Emergency Medicine acknowledge the help of the journal’s editorial board members, other emergency physicians, and colleagues in other specialties who reviewed manuscripts in 2016. On behalf of our readers, who are the beneficiaries of your efforts, we thank you.

Alfred Z. Abuhamad, MD

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Eastern Virginia Medical School

John E. Arbo, MD

Division of Emergency Medicine and Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

David P. Calfee, MD

Division of Infectious Diseases

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Richard M. Cantor, MD, FAAP, FACEP

Emergency Department, Pediatrics

Upstate Medical University

Wallace A. Carter, MD, FACEP

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Sunday Clark, ScD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Theodore R. Delbridge, MD

Department of Emergency

Medicine East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine

Joseph J. Fins, MD

Division of Medical Ethics Internal Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Ron W. Flenner, MD

Department of Internal Medicine

Eastern Virginia Medical School

E. John Gallagher, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Marianne Gausche-Hill, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Keith D. Hentel, MD

Department of Radiology

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Barry J. Knapp, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Eastern Virginia Medical School

Richard I. Lapin, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Anthony C. Mustalish, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Lewis S. Nelson, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

Debra Perina, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Constance Peterson, MA

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Shari L. Platt, MD, FAAP

Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Rama B. Rao, MD

Division of Toxicology

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Earl J. Reisdorff, MD

Executive Director

American Board of Emergency Medicine

Thomas M. Scalea, MD, FACS, FCCM

Program in Trauma

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Edward J. Schenk, MD

Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Christopher K. Schott, MD, MS

Department of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care Medicine

University of Pittsburgh

Adam J Singer, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Stony Brook University and Medical Center

Sarah A. Stahmer, MD, FACEP

Division of Emergency Medicine

Duke University Medical Center

Michael E. Stern, MD

Division of Geriatric Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University

Susan Stone, MD

Emergency Medicine/Palliative Care

University of California, Los Angeles

Todd Taylor, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Emory University School of Medicine

Screening tool spots teens headed for substance-dependent adulthood

VIENNA – The creation of a simple risk score that accurately predicts which adolescents in the general population will develop persistent substance dependence as adults has been one of the highlights of the year in addiction medicine, Wim van den Brink, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“These predictors are not very difficult to assess. Clinicians will be interested to know that the positive predictive value of the screen is threefold greater than the persistent prevalence rate,” noted Dr. van den Brink, professor of psychiatry and addiction at the University of Amsterdam and director of the Amsterdam Institute for Addiction Research.

The New Zealand researchers developed what they call “a universal screening tool” by working backward in an analysis of a representative group of 1,037 individuals born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in 1972-1973 and prospectively followed to age 38 years, with a 95% study retention rate. Along the way, participants were assessed for dependence on alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, or hard drugs at ages 21, 26, 32, and 38.

Persistent substance dependence in adulthood, defined as dependence at a minimum of three of the assessments, was present in 19% of subjects.

The investigators found that the presence in childhood or adolescence of any four of nine risk factors had an area under the curve of 80% for persistent substance dependence as an adult. The sensitivity was 43%, with a 93% specificity. The positive predictive value was 60%, and the negative predictive value was 87% (Psychol Med. 2016 Mar;46[4]:877-89).

The nine risk factors are low family socioeconomic status, a family history of substance dependence, childhood depression, childhood conduct disorder, early exposure to substances, adolescent frequent alcohol use, adolescent frequent cannabis use, male gender, and adolescent frequent tobacco use.

The single least potent predictor was low family socioeconomic status, with an associated 1.73-fold increased risk. The strongest predictors were adolescent frequent tobacco use, which conferred a 5.41-fold increased risk; adolescent frequent cannabis use, with a 4.25-fold risk; and childhood conduct disorder, with a 3.2-fold increased risk.

The investigators also analyzed the screening tool’s performance in predicting a modified outcome consisting of adult persistent dependence on any of the target substances except for tobacco. The predictive power of having any four of the risk factors was similar to that found in the main analysis; however, the two strongest predictors now became adolescent frequent cannabis use, with a 9.5-fold increased risk, and childhood conduct disorder, with a relative risk of 5.42.

Regarding childhood conduct disorder as a risk factor, Dr. van den Brink said, “If you are a child with conduct disorder, your chances of becoming substance dependent in coming years is more than fivefold greater than in a child without conduct disorder.”

This raises the question of whether effective treatment of childhood conduct disorder might prevent later development of persistent substance dependence in adulthood. The answer remains unknown. Although there is no approved drug therapy for conduct disorder, methylphenidate is widely prescribed, especially in young patients with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Several years ago a meta-analysis of 15 longitudinal studies with more than 2,500 participants concluded that stimulant therapy of childhood ADHD neither increased nor reduced the risk of subsequent substance use disorders (JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 Jul;70[7]:740-9). Prescribing physicians were happy to hear they weren’t causing iatrogenic injury, but Dr. van den Brink said he was never comfortable with the investigators’ conclusion.

“There was a lot of heterogeneity in the data, so the overall conclusion might not be the best conclusion,” he said.

He said has become more convinced of that than ever as a result of a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled MRI study of cerebral blood flow in response to methylphenidate in stimulant-naive patients with childhood or adult AHDH. The investigators found that MRIs obtained 1 week after the conclusion of 16 weeks of methylphenidate therapy showed increased blood flow in the strial and thalamic areas in the pediatric ADHD patients but not in the adults with ADHD (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 1;73[9]:955-62).

This is evidence of an age-dependent sustained effect of methylphenidate therapy on dopamine striatal-thalamic circuitry in children that’s not related to the drug’s clinical effects, which were gone after a week off therapy. The question is, Does this effect represent neurotoxicity, or is it an expression of enhanced brain maturation? Dr. van den Brink said he suspects it’s the latter but cannot exclude the former possibility.

VIENNA – The creation of a simple risk score that accurately predicts which adolescents in the general population will develop persistent substance dependence as adults has been one of the highlights of the year in addiction medicine, Wim van den Brink, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“These predictors are not very difficult to assess. Clinicians will be interested to know that the positive predictive value of the screen is threefold greater than the persistent prevalence rate,” noted Dr. van den Brink, professor of psychiatry and addiction at the University of Amsterdam and director of the Amsterdam Institute for Addiction Research.

The New Zealand researchers developed what they call “a universal screening tool” by working backward in an analysis of a representative group of 1,037 individuals born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in 1972-1973 and prospectively followed to age 38 years, with a 95% study retention rate. Along the way, participants were assessed for dependence on alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, or hard drugs at ages 21, 26, 32, and 38.

Persistent substance dependence in adulthood, defined as dependence at a minimum of three of the assessments, was present in 19% of subjects.

The investigators found that the presence in childhood or adolescence of any four of nine risk factors had an area under the curve of 80% for persistent substance dependence as an adult. The sensitivity was 43%, with a 93% specificity. The positive predictive value was 60%, and the negative predictive value was 87% (Psychol Med. 2016 Mar;46[4]:877-89).

The nine risk factors are low family socioeconomic status, a family history of substance dependence, childhood depression, childhood conduct disorder, early exposure to substances, adolescent frequent alcohol use, adolescent frequent cannabis use, male gender, and adolescent frequent tobacco use.

The single least potent predictor was low family socioeconomic status, with an associated 1.73-fold increased risk. The strongest predictors were adolescent frequent tobacco use, which conferred a 5.41-fold increased risk; adolescent frequent cannabis use, with a 4.25-fold risk; and childhood conduct disorder, with a 3.2-fold increased risk.

The investigators also analyzed the screening tool’s performance in predicting a modified outcome consisting of adult persistent dependence on any of the target substances except for tobacco. The predictive power of having any four of the risk factors was similar to that found in the main analysis; however, the two strongest predictors now became adolescent frequent cannabis use, with a 9.5-fold increased risk, and childhood conduct disorder, with a relative risk of 5.42.

Regarding childhood conduct disorder as a risk factor, Dr. van den Brink said, “If you are a child with conduct disorder, your chances of becoming substance dependent in coming years is more than fivefold greater than in a child without conduct disorder.”

This raises the question of whether effective treatment of childhood conduct disorder might prevent later development of persistent substance dependence in adulthood. The answer remains unknown. Although there is no approved drug therapy for conduct disorder, methylphenidate is widely prescribed, especially in young patients with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Several years ago a meta-analysis of 15 longitudinal studies with more than 2,500 participants concluded that stimulant therapy of childhood ADHD neither increased nor reduced the risk of subsequent substance use disorders (JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 Jul;70[7]:740-9). Prescribing physicians were happy to hear they weren’t causing iatrogenic injury, but Dr. van den Brink said he was never comfortable with the investigators’ conclusion.

“There was a lot of heterogeneity in the data, so the overall conclusion might not be the best conclusion,” he said.

He said has become more convinced of that than ever as a result of a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled MRI study of cerebral blood flow in response to methylphenidate in stimulant-naive patients with childhood or adult AHDH. The investigators found that MRIs obtained 1 week after the conclusion of 16 weeks of methylphenidate therapy showed increased blood flow in the strial and thalamic areas in the pediatric ADHD patients but not in the adults with ADHD (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 1;73[9]:955-62).

This is evidence of an age-dependent sustained effect of methylphenidate therapy on dopamine striatal-thalamic circuitry in children that’s not related to the drug’s clinical effects, which were gone after a week off therapy. The question is, Does this effect represent neurotoxicity, or is it an expression of enhanced brain maturation? Dr. van den Brink said he suspects it’s the latter but cannot exclude the former possibility.

VIENNA – The creation of a simple risk score that accurately predicts which adolescents in the general population will develop persistent substance dependence as adults has been one of the highlights of the year in addiction medicine, Wim van den Brink, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“These predictors are not very difficult to assess. Clinicians will be interested to know that the positive predictive value of the screen is threefold greater than the persistent prevalence rate,” noted Dr. van den Brink, professor of psychiatry and addiction at the University of Amsterdam and director of the Amsterdam Institute for Addiction Research.

The New Zealand researchers developed what they call “a universal screening tool” by working backward in an analysis of a representative group of 1,037 individuals born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in 1972-1973 and prospectively followed to age 38 years, with a 95% study retention rate. Along the way, participants were assessed for dependence on alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, or hard drugs at ages 21, 26, 32, and 38.

Persistent substance dependence in adulthood, defined as dependence at a minimum of three of the assessments, was present in 19% of subjects.

The investigators found that the presence in childhood or adolescence of any four of nine risk factors had an area under the curve of 80% for persistent substance dependence as an adult. The sensitivity was 43%, with a 93% specificity. The positive predictive value was 60%, and the negative predictive value was 87% (Psychol Med. 2016 Mar;46[4]:877-89).

The nine risk factors are low family socioeconomic status, a family history of substance dependence, childhood depression, childhood conduct disorder, early exposure to substances, adolescent frequent alcohol use, adolescent frequent cannabis use, male gender, and adolescent frequent tobacco use.

The single least potent predictor was low family socioeconomic status, with an associated 1.73-fold increased risk. The strongest predictors were adolescent frequent tobacco use, which conferred a 5.41-fold increased risk; adolescent frequent cannabis use, with a 4.25-fold risk; and childhood conduct disorder, with a 3.2-fold increased risk.

The investigators also analyzed the screening tool’s performance in predicting a modified outcome consisting of adult persistent dependence on any of the target substances except for tobacco. The predictive power of having any four of the risk factors was similar to that found in the main analysis; however, the two strongest predictors now became adolescent frequent cannabis use, with a 9.5-fold increased risk, and childhood conduct disorder, with a relative risk of 5.42.

Regarding childhood conduct disorder as a risk factor, Dr. van den Brink said, “If you are a child with conduct disorder, your chances of becoming substance dependent in coming years is more than fivefold greater than in a child without conduct disorder.”

This raises the question of whether effective treatment of childhood conduct disorder might prevent later development of persistent substance dependence in adulthood. The answer remains unknown. Although there is no approved drug therapy for conduct disorder, methylphenidate is widely prescribed, especially in young patients with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Several years ago a meta-analysis of 15 longitudinal studies with more than 2,500 participants concluded that stimulant therapy of childhood ADHD neither increased nor reduced the risk of subsequent substance use disorders (JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 Jul;70[7]:740-9). Prescribing physicians were happy to hear they weren’t causing iatrogenic injury, but Dr. van den Brink said he was never comfortable with the investigators’ conclusion.

“There was a lot of heterogeneity in the data, so the overall conclusion might not be the best conclusion,” he said.

He said has become more convinced of that than ever as a result of a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled MRI study of cerebral blood flow in response to methylphenidate in stimulant-naive patients with childhood or adult AHDH. The investigators found that MRIs obtained 1 week after the conclusion of 16 weeks of methylphenidate therapy showed increased blood flow in the strial and thalamic areas in the pediatric ADHD patients but not in the adults with ADHD (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 1;73[9]:955-62).

This is evidence of an age-dependent sustained effect of methylphenidate therapy on dopamine striatal-thalamic circuitry in children that’s not related to the drug’s clinical effects, which were gone after a week off therapy. The question is, Does this effect represent neurotoxicity, or is it an expression of enhanced brain maturation? Dr. van den Brink said he suspects it’s the latter but cannot exclude the former possibility.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Ocular rosacea remains a stubborn foe

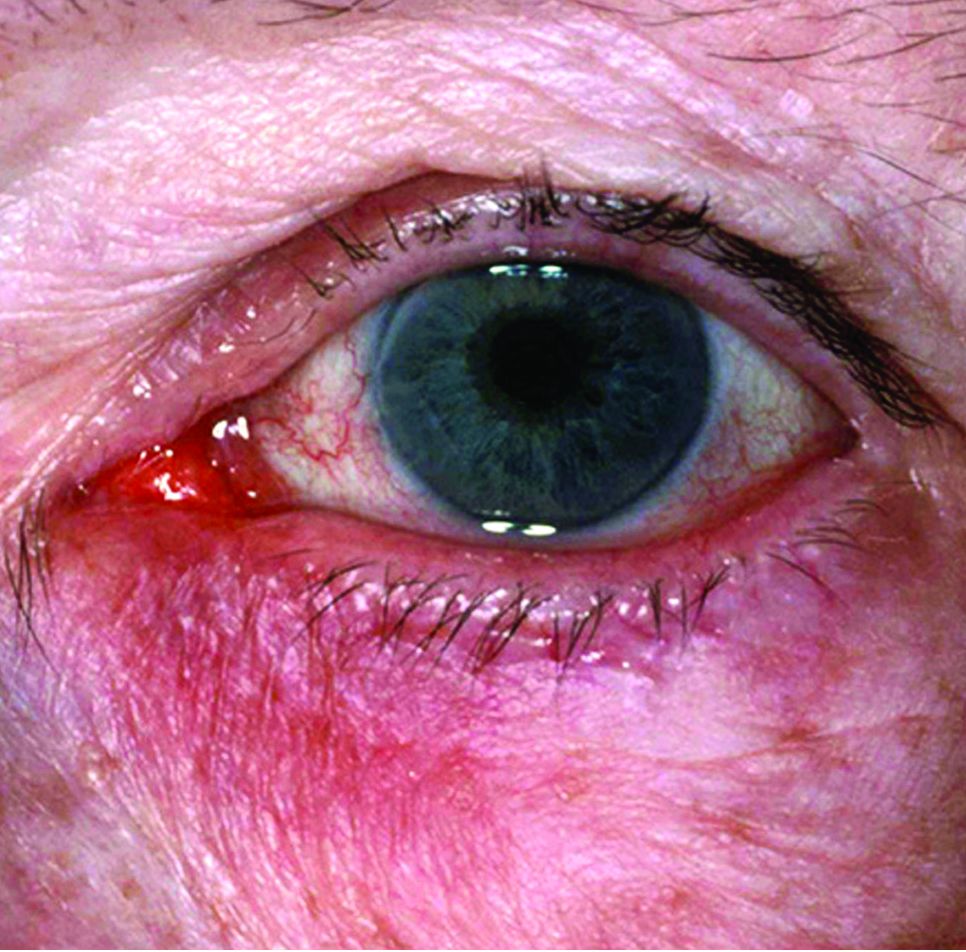

Few skin disorders have the power to devastate lives like ocular rosacea, a painful condition that disrupts vision and can lead to blindness, according to ophthalmologist Edward Wladis, MD.

“Patients really suffer from this diagnosis,” said Dr. Wladis, who practices in Slingerlands, N.Y.

Charles Slonim, MD, an ophthalmologist who practices in Tampa, Fla., put it this way: “We control the condition more than 50 percent of the time, but frequently patients go into periods of remission only to have a recurrence or exacerbation of their ocular rosacea.”

Dr. Wladis coauthored a 2013 report that examined treatments for ocular rosacea, which noted that estimates of the proportion of people with rosacea in the United States who develop ocular rosacea vary, ranging from 58% to 72% (US Ophthalmic Review, 2013;6[2]:86-8).

“Ocular rosacea is one of the subtypes of this disease of cutaneous inflammation,” Dr. Wladis said. “Once the skin becomes so severely inflamed, the glands that lubricate the eye become damaged, and the tear film evaporates rapidly. As a result, patients complain of the effects of a dry ocular surface, and they suffer from blurred vision, tearing, pain, and problems with glare.”

Dr. Slonim suggests that dermatologists refer rosacea patients to an ophthalmologist if they present with any eye symptom, such as dryness, burning, or itching, foreign body sensation in one or both eyes, or chronic redness of either the eyes or the eyelid margins. “They should be seen should be seen by an ophthalmologist to rule out ocular rosacea,” he said. “The ophthalmologist’s ability to look at the eye and eyelids under high magnification – a slit lamp examination – gives us an advantage in the diagnosis of ocular rosacea.”

If these patients do have ocular rosacea, their prognosis is unclear. “Unfortunately, many of our treatments haven’t been carefully vetted,” Dr. Wladis said.

He tends to begin with simpler treatments to heal the ocular surface, such as artificial tears and plugs in the tear drainage ducts to keep tears from leaving the eye quickly. Eyelid scrubs and warm compresses can also be helpful, he said, along with suggestions about lifestyle modifications to avoid the triggers that may exacerbate rosacea.

If those treatments fail, antibiotics are an option.

A 2015 Cochrane Review of studies of rosacea treatments suggested that for treating ocular rosacea, cyclosporine 0.05% ophthalmic emulsion “appeared to be more effective than artificial tears” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 28;[3]:CD003262). And a 2015 study of 38 patients with ocular rosacea concluded that topical cyclosporine was significantly more effective in relieving symptoms and in the treatment of eyelid signs, compared with oral doxycycline (Int J Ophthalmol. 2015 Jun 18;8[3]:544-9).

Antibiotics seem to improve the eyelid’s health, “although some studies have documented that the cornea often doesn’t benefit from antibiotics, and patients’ visual acuity may not improve,” Dr. Wladis said.

Ophthalmologists also may prescribe nonsteroidal and steroidal anti-inflammatory drops, Dr. Slonim added, although “the use of topical ophthalmic steroids do carry the risk of secondary glaucoma with increased intraocular pressures.”

There are even more alternatives. “Dietary modification with omega-3 fatty acids appears to benefit the quality of the tear film,” Dr. Wladis said, referring to the results of a prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of patients with dry eye (Int J Ophthalmol. 2013 Dec 18;[6]:811-6). “Intraductal meibomian gland probing and intense pulsed light therapy have both been shown to improve ocular surface–related quality of life, although these treatments are relatively invasive and can rapidly become quite expensive for the patient.”

What’s on the horizon? Researchers have “started to unlock the mysteries of rosacea at the cellular level,” Dr. Wladis said. “Our efforts have recently focused on the cellular changes in the skin of rosacea patients. Using several methods, we assayed the activation of a wide variety of signals within the cells of the skin of these patients and found a consistent elevation of two specific signals.”

The researchers were especially pleased, he said, “that these signals appear to be activated in the outer layers of the skin, meaning that a topical preparation could be developed to selectively suppress these cell signals to turn off the disease without interfering with normal skin structure and function and without the side effects of oral or intravenous medications.”

His team is now working on a topical medication. “Ideally,” he noted, “future clinicians will be able to shift their focus from nonspecific therapies like antibiotics and steroids to really powerful, meaningful cellular therapeutics.”

Dr. Slonim reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Wladis shares a provisional patent for the use of topical kinase inhibitors in the management of rosacea and recently co-started a biotechnology company called Praxis Biotechnology that aims to develop and test therapies for the condition. He serves as a consultant for both Bausch & Lomb and Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

Few skin disorders have the power to devastate lives like ocular rosacea, a painful condition that disrupts vision and can lead to blindness, according to ophthalmologist Edward Wladis, MD.

“Patients really suffer from this diagnosis,” said Dr. Wladis, who practices in Slingerlands, N.Y.

Charles Slonim, MD, an ophthalmologist who practices in Tampa, Fla., put it this way: “We control the condition more than 50 percent of the time, but frequently patients go into periods of remission only to have a recurrence or exacerbation of their ocular rosacea.”

Dr. Wladis coauthored a 2013 report that examined treatments for ocular rosacea, which noted that estimates of the proportion of people with rosacea in the United States who develop ocular rosacea vary, ranging from 58% to 72% (US Ophthalmic Review, 2013;6[2]:86-8).

“Ocular rosacea is one of the subtypes of this disease of cutaneous inflammation,” Dr. Wladis said. “Once the skin becomes so severely inflamed, the glands that lubricate the eye become damaged, and the tear film evaporates rapidly. As a result, patients complain of the effects of a dry ocular surface, and they suffer from blurred vision, tearing, pain, and problems with glare.”

Dr. Slonim suggests that dermatologists refer rosacea patients to an ophthalmologist if they present with any eye symptom, such as dryness, burning, or itching, foreign body sensation in one or both eyes, or chronic redness of either the eyes or the eyelid margins. “They should be seen should be seen by an ophthalmologist to rule out ocular rosacea,” he said. “The ophthalmologist’s ability to look at the eye and eyelids under high magnification – a slit lamp examination – gives us an advantage in the diagnosis of ocular rosacea.”

If these patients do have ocular rosacea, their prognosis is unclear. “Unfortunately, many of our treatments haven’t been carefully vetted,” Dr. Wladis said.

He tends to begin with simpler treatments to heal the ocular surface, such as artificial tears and plugs in the tear drainage ducts to keep tears from leaving the eye quickly. Eyelid scrubs and warm compresses can also be helpful, he said, along with suggestions about lifestyle modifications to avoid the triggers that may exacerbate rosacea.

If those treatments fail, antibiotics are an option.

A 2015 Cochrane Review of studies of rosacea treatments suggested that for treating ocular rosacea, cyclosporine 0.05% ophthalmic emulsion “appeared to be more effective than artificial tears” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 28;[3]:CD003262). And a 2015 study of 38 patients with ocular rosacea concluded that topical cyclosporine was significantly more effective in relieving symptoms and in the treatment of eyelid signs, compared with oral doxycycline (Int J Ophthalmol. 2015 Jun 18;8[3]:544-9).

Antibiotics seem to improve the eyelid’s health, “although some studies have documented that the cornea often doesn’t benefit from antibiotics, and patients’ visual acuity may not improve,” Dr. Wladis said.

Ophthalmologists also may prescribe nonsteroidal and steroidal anti-inflammatory drops, Dr. Slonim added, although “the use of topical ophthalmic steroids do carry the risk of secondary glaucoma with increased intraocular pressures.”

There are even more alternatives. “Dietary modification with omega-3 fatty acids appears to benefit the quality of the tear film,” Dr. Wladis said, referring to the results of a prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of patients with dry eye (Int J Ophthalmol. 2013 Dec 18;[6]:811-6). “Intraductal meibomian gland probing and intense pulsed light therapy have both been shown to improve ocular surface–related quality of life, although these treatments are relatively invasive and can rapidly become quite expensive for the patient.”

What’s on the horizon? Researchers have “started to unlock the mysteries of rosacea at the cellular level,” Dr. Wladis said. “Our efforts have recently focused on the cellular changes in the skin of rosacea patients. Using several methods, we assayed the activation of a wide variety of signals within the cells of the skin of these patients and found a consistent elevation of two specific signals.”

The researchers were especially pleased, he said, “that these signals appear to be activated in the outer layers of the skin, meaning that a topical preparation could be developed to selectively suppress these cell signals to turn off the disease without interfering with normal skin structure and function and without the side effects of oral or intravenous medications.”

His team is now working on a topical medication. “Ideally,” he noted, “future clinicians will be able to shift their focus from nonspecific therapies like antibiotics and steroids to really powerful, meaningful cellular therapeutics.”

Dr. Slonim reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Wladis shares a provisional patent for the use of topical kinase inhibitors in the management of rosacea and recently co-started a biotechnology company called Praxis Biotechnology that aims to develop and test therapies for the condition. He serves as a consultant for both Bausch & Lomb and Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

Few skin disorders have the power to devastate lives like ocular rosacea, a painful condition that disrupts vision and can lead to blindness, according to ophthalmologist Edward Wladis, MD.

“Patients really suffer from this diagnosis,” said Dr. Wladis, who practices in Slingerlands, N.Y.

Charles Slonim, MD, an ophthalmologist who practices in Tampa, Fla., put it this way: “We control the condition more than 50 percent of the time, but frequently patients go into periods of remission only to have a recurrence or exacerbation of their ocular rosacea.”

Dr. Wladis coauthored a 2013 report that examined treatments for ocular rosacea, which noted that estimates of the proportion of people with rosacea in the United States who develop ocular rosacea vary, ranging from 58% to 72% (US Ophthalmic Review, 2013;6[2]:86-8).

“Ocular rosacea is one of the subtypes of this disease of cutaneous inflammation,” Dr. Wladis said. “Once the skin becomes so severely inflamed, the glands that lubricate the eye become damaged, and the tear film evaporates rapidly. As a result, patients complain of the effects of a dry ocular surface, and they suffer from blurred vision, tearing, pain, and problems with glare.”

Dr. Slonim suggests that dermatologists refer rosacea patients to an ophthalmologist if they present with any eye symptom, such as dryness, burning, or itching, foreign body sensation in one or both eyes, or chronic redness of either the eyes or the eyelid margins. “They should be seen should be seen by an ophthalmologist to rule out ocular rosacea,” he said. “The ophthalmologist’s ability to look at the eye and eyelids under high magnification – a slit lamp examination – gives us an advantage in the diagnosis of ocular rosacea.”

If these patients do have ocular rosacea, their prognosis is unclear. “Unfortunately, many of our treatments haven’t been carefully vetted,” Dr. Wladis said.

He tends to begin with simpler treatments to heal the ocular surface, such as artificial tears and plugs in the tear drainage ducts to keep tears from leaving the eye quickly. Eyelid scrubs and warm compresses can also be helpful, he said, along with suggestions about lifestyle modifications to avoid the triggers that may exacerbate rosacea.

If those treatments fail, antibiotics are an option.

A 2015 Cochrane Review of studies of rosacea treatments suggested that for treating ocular rosacea, cyclosporine 0.05% ophthalmic emulsion “appeared to be more effective than artificial tears” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 28;[3]:CD003262). And a 2015 study of 38 patients with ocular rosacea concluded that topical cyclosporine was significantly more effective in relieving symptoms and in the treatment of eyelid signs, compared with oral doxycycline (Int J Ophthalmol. 2015 Jun 18;8[3]:544-9).

Antibiotics seem to improve the eyelid’s health, “although some studies have documented that the cornea often doesn’t benefit from antibiotics, and patients’ visual acuity may not improve,” Dr. Wladis said.

Ophthalmologists also may prescribe nonsteroidal and steroidal anti-inflammatory drops, Dr. Slonim added, although “the use of topical ophthalmic steroids do carry the risk of secondary glaucoma with increased intraocular pressures.”

There are even more alternatives. “Dietary modification with omega-3 fatty acids appears to benefit the quality of the tear film,” Dr. Wladis said, referring to the results of a prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of patients with dry eye (Int J Ophthalmol. 2013 Dec 18;[6]:811-6). “Intraductal meibomian gland probing and intense pulsed light therapy have both been shown to improve ocular surface–related quality of life, although these treatments are relatively invasive and can rapidly become quite expensive for the patient.”

What’s on the horizon? Researchers have “started to unlock the mysteries of rosacea at the cellular level,” Dr. Wladis said. “Our efforts have recently focused on the cellular changes in the skin of rosacea patients. Using several methods, we assayed the activation of a wide variety of signals within the cells of the skin of these patients and found a consistent elevation of two specific signals.”

The researchers were especially pleased, he said, “that these signals appear to be activated in the outer layers of the skin, meaning that a topical preparation could be developed to selectively suppress these cell signals to turn off the disease without interfering with normal skin structure and function and without the side effects of oral or intravenous medications.”

His team is now working on a topical medication. “Ideally,” he noted, “future clinicians will be able to shift their focus from nonspecific therapies like antibiotics and steroids to really powerful, meaningful cellular therapeutics.”

Dr. Slonim reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Wladis shares a provisional patent for the use of topical kinase inhibitors in the management of rosacea and recently co-started a biotechnology company called Praxis Biotechnology that aims to develop and test therapies for the condition. He serves as a consultant for both Bausch & Lomb and Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

Emergency Imaging: Facial Trauma After a Fall

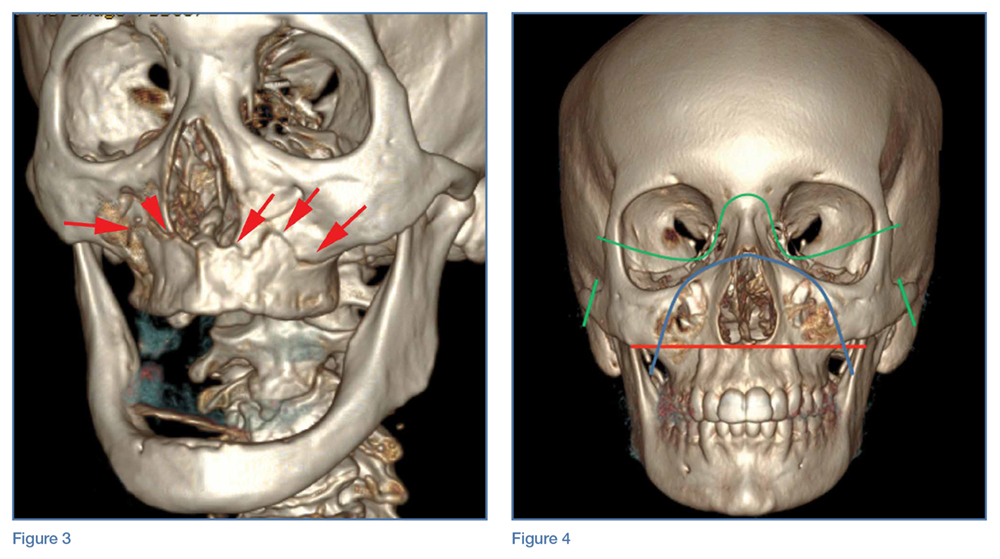

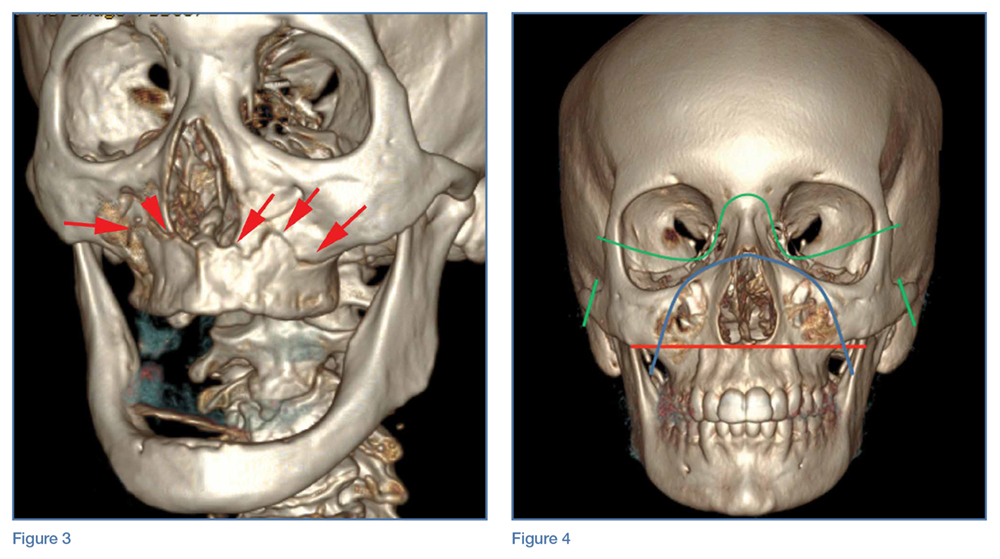

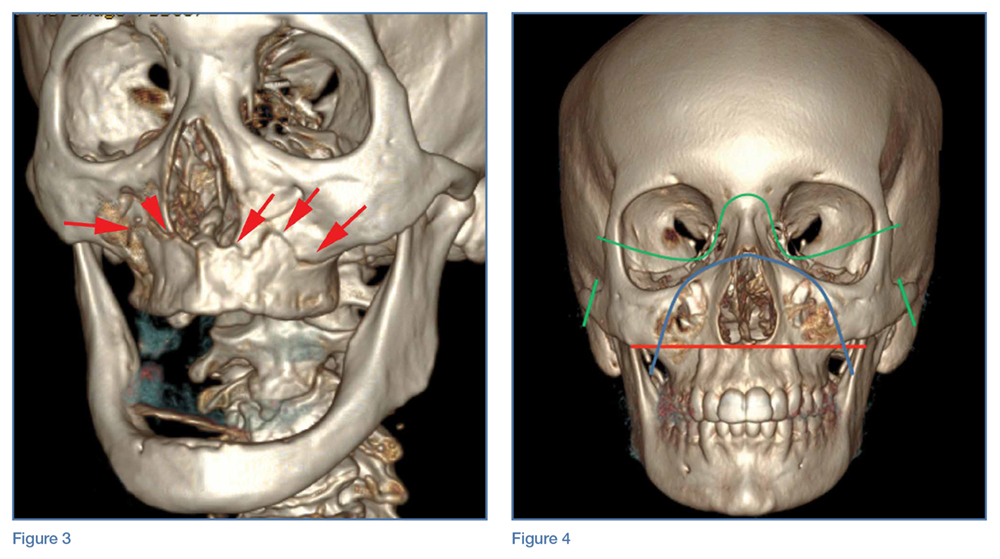

An 89-year-old man presented to the ED with facial trauma due to a mechanical fall after losing his balance on uneven pavement and hitting the right side of his face. Physical examination revealed an ecchymosis inferior to the right eye and tenderness to palpation at the right maxilla and bilateral nasolabial folds. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) was ordered for further evaluation; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

A noncontrast CT of the maxillofacial bones demonstrated acute fractures through the bilateral pterygoid plates (white arrows, Figure 2a). The fractures extended through the medial and lateral walls of the bilateral maxillary sinuses (red arrows, Figure 2a), and propagated to the frontal processes of the maxilla (red arrows, Figure 2b), extending toward the alveolar process, indicating involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa. The full extent of the fracture is best seen on a 3D-reconstructed image (red arrows, Figure 3). Additional images (not presented here) confirmed no fracture involvement of the orbital floors, nasal bones, or zygomatic arches. Expected posttraumatic hemorrhage was appreciated within the maxillary sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a).

Le Fort Fractures

The findings described above are characteristic of a Le Fort I fracture pattern. Initially described in 1901 by René Le Fort, a French surgeon, the Le Fort classification system details somewhat predictable midface fracture patterns resulting in various degrees of craniofacial disassociation.1 Using weights that were dropped on cadaveric heads, Le Fort discovered that the pterygoid plates must be disrupted in order for the midface facial bones to separate from the skull base. As such, when diagnosing a Le Fort fracture, fracture of the pterygoid plate must be present, regardless of the fracture type (Le Fort I, II, and III).2

Le Fort I Fracture. This fracture pattern (red line, Figure 4) is referred to as a “floating palate” and involves separation of the hard palate from the skull base via fracture extension from the pterygoid plates into the maxillary sinus walls, as demonstrated in this case. The key distinguisher of the Le Fort I pattern is involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.2

Le Fort II Fracture. This fracture pattern (blue line, Figure 4) describes a “floating maxilla” wherein the pterygoid plate fractures are met with a pyramidal-type fracture pattern of the midface. The maxillary teeth form the base of the pyramid, and the fracture extends superiorly through the infraorbital rims bilaterally and toward the nasofrontal suture.2,3 Le Fort II fractures result in the maxilla floating freely from the rest of the midface and skull base.

Le Fort III Fracture. This fracture pattern (green lines, Figure 4) describes a “floating face” with complete craniofacial disjunction resulting from fracture of the pterygoid plates, nasofrontal suture, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, and zygomatic arch/zygomaticofrontal suture.2,3

It is important to note that midface trauma represents a complex spectrum of injuries, and Le Fort fractures only account for a small percentage of facial bone fractures that present through Level 1 trauma centers.2 Le Fort fracture patterns can coexist with other fracture patterns and also can be seen in combination with each other. For example, one side of the face may demonstrate a Le Fort II pattern while the other side concurrently demonstrates a Le Fort III pattern. Though not robust enough for complete description of and surgical planning for facial fractures, this classification system is a succinct and well-accepted means of describing major fracture planes.

1. Le Fort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901;23:208-227, 360-379, 479-507.

2. Rhea JT, Novelline RA. How to simplify the CT diagnosis of Le Fort fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1700-1705.

3. Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):783-793.

An 89-year-old man presented to the ED with facial trauma due to a mechanical fall after losing his balance on uneven pavement and hitting the right side of his face. Physical examination revealed an ecchymosis inferior to the right eye and tenderness to palpation at the right maxilla and bilateral nasolabial folds. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) was ordered for further evaluation; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

A noncontrast CT of the maxillofacial bones demonstrated acute fractures through the bilateral pterygoid plates (white arrows, Figure 2a). The fractures extended through the medial and lateral walls of the bilateral maxillary sinuses (red arrows, Figure 2a), and propagated to the frontal processes of the maxilla (red arrows, Figure 2b), extending toward the alveolar process, indicating involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa. The full extent of the fracture is best seen on a 3D-reconstructed image (red arrows, Figure 3). Additional images (not presented here) confirmed no fracture involvement of the orbital floors, nasal bones, or zygomatic arches. Expected posttraumatic hemorrhage was appreciated within the maxillary sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a).

Le Fort Fractures

The findings described above are characteristic of a Le Fort I fracture pattern. Initially described in 1901 by René Le Fort, a French surgeon, the Le Fort classification system details somewhat predictable midface fracture patterns resulting in various degrees of craniofacial disassociation.1 Using weights that were dropped on cadaveric heads, Le Fort discovered that the pterygoid plates must be disrupted in order for the midface facial bones to separate from the skull base. As such, when diagnosing a Le Fort fracture, fracture of the pterygoid plate must be present, regardless of the fracture type (Le Fort I, II, and III).2

Le Fort I Fracture. This fracture pattern (red line, Figure 4) is referred to as a “floating palate” and involves separation of the hard palate from the skull base via fracture extension from the pterygoid plates into the maxillary sinus walls, as demonstrated in this case. The key distinguisher of the Le Fort I pattern is involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.2

Le Fort II Fracture. This fracture pattern (blue line, Figure 4) describes a “floating maxilla” wherein the pterygoid plate fractures are met with a pyramidal-type fracture pattern of the midface. The maxillary teeth form the base of the pyramid, and the fracture extends superiorly through the infraorbital rims bilaterally and toward the nasofrontal suture.2,3 Le Fort II fractures result in the maxilla floating freely from the rest of the midface and skull base.

Le Fort III Fracture. This fracture pattern (green lines, Figure 4) describes a “floating face” with complete craniofacial disjunction resulting from fracture of the pterygoid plates, nasofrontal suture, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, and zygomatic arch/zygomaticofrontal suture.2,3

It is important to note that midface trauma represents a complex spectrum of injuries, and Le Fort fractures only account for a small percentage of facial bone fractures that present through Level 1 trauma centers.2 Le Fort fracture patterns can coexist with other fracture patterns and also can be seen in combination with each other. For example, one side of the face may demonstrate a Le Fort II pattern while the other side concurrently demonstrates a Le Fort III pattern. Though not robust enough for complete description of and surgical planning for facial fractures, this classification system is a succinct and well-accepted means of describing major fracture planes.

An 89-year-old man presented to the ED with facial trauma due to a mechanical fall after losing his balance on uneven pavement and hitting the right side of his face. Physical examination revealed an ecchymosis inferior to the right eye and tenderness to palpation at the right maxilla and bilateral nasolabial folds. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) was ordered for further evaluation; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

A noncontrast CT of the maxillofacial bones demonstrated acute fractures through the bilateral pterygoid plates (white arrows, Figure 2a). The fractures extended through the medial and lateral walls of the bilateral maxillary sinuses (red arrows, Figure 2a), and propagated to the frontal processes of the maxilla (red arrows, Figure 2b), extending toward the alveolar process, indicating involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa. The full extent of the fracture is best seen on a 3D-reconstructed image (red arrows, Figure 3). Additional images (not presented here) confirmed no fracture involvement of the orbital floors, nasal bones, or zygomatic arches. Expected posttraumatic hemorrhage was appreciated within the maxillary sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a).

Le Fort Fractures

The findings described above are characteristic of a Le Fort I fracture pattern. Initially described in 1901 by René Le Fort, a French surgeon, the Le Fort classification system details somewhat predictable midface fracture patterns resulting in various degrees of craniofacial disassociation.1 Using weights that were dropped on cadaveric heads, Le Fort discovered that the pterygoid plates must be disrupted in order for the midface facial bones to separate from the skull base. As such, when diagnosing a Le Fort fracture, fracture of the pterygoid plate must be present, regardless of the fracture type (Le Fort I, II, and III).2

Le Fort I Fracture. This fracture pattern (red line, Figure 4) is referred to as a “floating palate” and involves separation of the hard palate from the skull base via fracture extension from the pterygoid plates into the maxillary sinus walls, as demonstrated in this case. The key distinguisher of the Le Fort I pattern is involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.2

Le Fort II Fracture. This fracture pattern (blue line, Figure 4) describes a “floating maxilla” wherein the pterygoid plate fractures are met with a pyramidal-type fracture pattern of the midface. The maxillary teeth form the base of the pyramid, and the fracture extends superiorly through the infraorbital rims bilaterally and toward the nasofrontal suture.2,3 Le Fort II fractures result in the maxilla floating freely from the rest of the midface and skull base.

Le Fort III Fracture. This fracture pattern (green lines, Figure 4) describes a “floating face” with complete craniofacial disjunction resulting from fracture of the pterygoid plates, nasofrontal suture, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, and zygomatic arch/zygomaticofrontal suture.2,3

It is important to note that midface trauma represents a complex spectrum of injuries, and Le Fort fractures only account for a small percentage of facial bone fractures that present through Level 1 trauma centers.2 Le Fort fracture patterns can coexist with other fracture patterns and also can be seen in combination with each other. For example, one side of the face may demonstrate a Le Fort II pattern while the other side concurrently demonstrates a Le Fort III pattern. Though not robust enough for complete description of and surgical planning for facial fractures, this classification system is a succinct and well-accepted means of describing major fracture planes.

1. Le Fort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901;23:208-227, 360-379, 479-507.

2. Rhea JT, Novelline RA. How to simplify the CT diagnosis of Le Fort fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1700-1705.

3. Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):783-793.

1. Le Fort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901;23:208-227, 360-379, 479-507.

2. Rhea JT, Novelline RA. How to simplify the CT diagnosis of Le Fort fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1700-1705.

3. Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):783-793.

First EDition: Retail Clinics and Rate of ED Visits, more

Retail Clinics Have Not Decreased the Rate of Low-Acuity ED Visits

BY JEFF BAUER

The number of retail clinics—those located in pharmacies, supermarkets, and other retail settings—in the United States increased from 130 in 2006 to nearly 1,400 in 2012. However, this proliferation of retail clinics has not lead to a meaningful reduction in low-acuity ED visits, according to a recent observational study published in Annals of Emergency Medicine.1

Using information from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Emergency Department Databases, which include data on more than 2,000 EDs in 23 states from 2006 through 2013, researchers looked at the association between retail clinic penetration and the rate of treat-and-release ED visits for 11 low-acuity conditions (allergic rhinitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, other eye conditions, influenza, otitis externa, otitis media, pharyngitis, upper respiratory infections/sinusitis, urinary tract infections, and viral infections).

Retail clinic penetration was defined as the percentage of an ED’s catchment area (areas that accounted for up to 75% of patients who visited for low-acuity conditions) that overlapped with the 10-minute-drive radius of a retail clinic. The results were calculated as a rate ratio, which reflected the change in the rate of low-acuity ED visits associated with an ED having no retail clinic penetration to having approximately the average penetration rate within 2012. Results were controlled for the number of urgent care centers that were present in each ED catchment area, but only for hospital-associated urgent care centers, as there are no reliable data to identify all urgent care centers.

Retail clinic penetration more than doubled during the study period. Overall, increased retail clinic penetration was not associated with a change in the rate of low-acuity ED visits. Among patients with private insurance, there was a small reduction (0.3% per calendar quarter) in ED visits for low-acuity conditions, but this translated into an estimated 17 fewer ED visits by privately insured patients over 1 year for the average ED, assuming the retail clinic penetration rate increased by 40% in that year.

In an accompanying editorial,2 Jesse M. Pines, MD, suggests that visits to retail clinics may be mostly “new-use” visits, meaning many individuals who would not have otherwise received treatment seek care in a retail clinic because such clinics are available. Dr Pines proposed three reasons retail clinics may create new-use visits: they meet unmet demands for care; motivations for seeking care differ in EDs and retail clinics; and people who are more likely to use EDs for low-acuity conditions do so because they have limited access to other types of care, including retail clinics.

1. Martsolf G, Fingar KR, Coffey R, et al. Association between the opening of retail clinics and low-acuity emergency department visits. Ann Emerg Med. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.462.

2. Pines JM. Why retail clinics do not substitute for emergency department visits and what this means for value-based care. Ann Emerg Med. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.09.047.

Hypotension During Transport to ED Drives Mortality in Traumatic Brain Injury

MITCHEL L. ZOLER

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

The severity and duration of hypotension in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients during emergency medical service (EMS) transport to an ED has a tight and essentially linear relationship to mortality rate during subsequent weeks of recovery, according to an analysis of more than 7,500 brain-injured patients.

For each doubling of the combined severity and duration of hypotension during the prehospital period, when systolic blood pressure (BP) was <90 mm Hg, patient mortality rose by 19%, Daniel W. Spaite, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

However, the results do not address whether aggressive treatment of hypotension by EMS technicians in a patient with TBI leads to reduced mortality. That question is being assessed as part of the primary endpoint of the Excellence in Prehospital Injury Care-Traumatic Brain Injury (EPIC-TBI) study, which should be completed by the end of 2017, said Dr Spaite, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona in Tucson.Results from prior studies have clearly linked prehospital hypotension with worse survival in TBI patients. Until now, however, there was no appreciation of the fact that not all hypotensive episodes are equal, and that both the severity of hypotension and its duration incrementally contribute to mortality as the “dose” of hypotension a patient experiences increases. In large part, this is because prehospital hypotension has been recorded simply as a dichotomous, yes/no condition.

The innovation introduced by Dr Spaite and his associates in their analysis of the EPIC-TBI data was to drill down into each patient’s hypotensive event, made possible by the 16,711 patients enrolled in EPIC-TBI. Their calculations were limited to patients with EMS records of at least two BP measurements during prehospital transport. These data allowed Spaite et al to utilize both the extent to which systolic BP dropped below 90 mm Hg and the amount of time systolic BP was below this threshold to better define the total hypotension exposure each patient received.

This meant that a patient with a TBI and a systolic BP of 80 mm Hg for 10 minutes had twice the hypotension exposure of both a patient with a systolic BP of 85 mm Hg for 10 minutes and a patient with a systolic BP of 80 mm Hg for 5 minutes.

The analysis by Spaite et al also adjusted the relationship of total hypotensive severity and duration and subsequent mortality based on several baseline demographic and clinical variables, including age, sex, injury severity, trauma type, and head-region severity score. After adjustment, the researchers found a “strikingly linear relationship” between hypotension severity and duration and mortality, Dr Spaite said.

The EPIC-TBI enrolled TBI patients aged 10 years or older during 2007 to 2014 through participation of dozens of EMS providers throughout Arizona. For the current analysis, the researchers identified 7,521 patients from the total group who had at least two BP measurements taken during their prehospital EMS care and also met other inclusion criteria.

The best way to manage hypotension in TBI patients during the prehospital period remains unclear. Simply raising BP via intravenous (IV) fluid infusion may not necessarily help, because it could exacerbate a patient’s bleeding, Dr Spaite noted during an interview.

The primary goal of EPIC-TBI is to assess the implementation of the third edition of the TBI guidelines released in 2007 by the Brain Trauma Foundation. (The fourth edition of these guidelines came out in August 2016.) The new finding by Dr Spaite and his associates will allow the full EPIC-TBI analysis to correlate patient outcomes with the impact that acute, prehospital treatment had on the hypotension severity and duration each patient experienced, he noted.

“What’s remarkable is that the single prehospital parameter of hypotension for just a few minutes during transport can have such a strong impact on survival, given all the other factors that can influence outcomes” in TBI patients once they reach a hospital and during the period they remain hospitalized, Dr Spaite said.

1. Spaite DW. Presentation at: American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2016. November 12-16, 2016; New Orleans, LA.

Fluid Administration in Sepsis Did Not Increase Need for Dialysis

M. Alexander Otto

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Fluid administration of at least 1 L did not increase the incidence of acute respiratory or heart failure in severe sepsis, and actually seemed to decrease the need for dialysis in a review of 164 patients at Scott and White Memorial Hospital in Temple, Texas.