User login

Emergency Imaging: Facial Trauma After a Fall

An 89-year-old man presented to the ED with facial trauma due to a mechanical fall after losing his balance on uneven pavement and hitting the right side of his face. Physical examination revealed an ecchymosis inferior to the right eye and tenderness to palpation at the right maxilla and bilateral nasolabial folds. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) was ordered for further evaluation; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

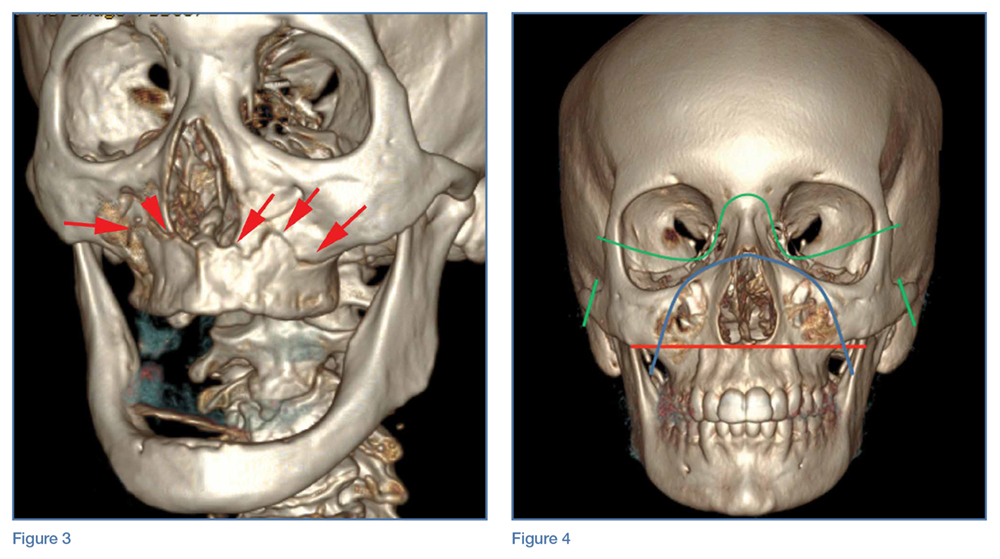

A noncontrast CT of the maxillofacial bones demonstrated acute fractures through the bilateral pterygoid plates (white arrows, Figure 2a). The fractures extended through the medial and lateral walls of the bilateral maxillary sinuses (red arrows, Figure 2a), and propagated to the frontal processes of the maxilla (red arrows, Figure 2b), extending toward the alveolar process, indicating involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa. The full extent of the fracture is best seen on a 3D-reconstructed image (red arrows, Figure 3). Additional images (not presented here) confirmed no fracture involvement of the orbital floors, nasal bones, or zygomatic arches. Expected posttraumatic hemorrhage was appreciated within the maxillary sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a).

Le Fort Fractures

The findings described above are characteristic of a Le Fort I fracture pattern. Initially described in 1901 by René Le Fort, a French surgeon, the Le Fort classification system details somewhat predictable midface fracture patterns resulting in various degrees of craniofacial disassociation.1 Using weights that were dropped on cadaveric heads, Le Fort discovered that the pterygoid plates must be disrupted in order for the midface facial bones to separate from the skull base. As such, when diagnosing a Le Fort fracture, fracture of the pterygoid plate must be present, regardless of the fracture type (Le Fort I, II, and III).2

Le Fort I Fracture. This fracture pattern (red line, Figure 4) is referred to as a “floating palate” and involves separation of the hard palate from the skull base via fracture extension from the pterygoid plates into the maxillary sinus walls, as demonstrated in this case. The key distinguisher of the Le Fort I pattern is involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.2

Le Fort II Fracture. This fracture pattern (blue line, Figure 4) describes a “floating maxilla” wherein the pterygoid plate fractures are met with a pyramidal-type fracture pattern of the midface. The maxillary teeth form the base of the pyramid, and the fracture extends superiorly through the infraorbital rims bilaterally and toward the nasofrontal suture.2,3 Le Fort II fractures result in the maxilla floating freely from the rest of the midface and skull base.

Le Fort III Fracture. This fracture pattern (green lines, Figure 4) describes a “floating face” with complete craniofacial disjunction resulting from fracture of the pterygoid plates, nasofrontal suture, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, and zygomatic arch/zygomaticofrontal suture.2,3

It is important to note that midface trauma represents a complex spectrum of injuries, and Le Fort fractures only account for a small percentage of facial bone fractures that present through Level 1 trauma centers.2 Le Fort fracture patterns can coexist with other fracture patterns and also can be seen in combination with each other. For example, one side of the face may demonstrate a Le Fort II pattern while the other side concurrently demonstrates a Le Fort III pattern. Though not robust enough for complete description of and surgical planning for facial fractures, this classification system is a succinct and well-accepted means of describing major fracture planes.

1. Le Fort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901;23:208-227, 360-379, 479-507.

2. Rhea JT, Novelline RA. How to simplify the CT diagnosis of Le Fort fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1700-1705.

3. Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):783-793.

An 89-year-old man presented to the ED with facial trauma due to a mechanical fall after losing his balance on uneven pavement and hitting the right side of his face. Physical examination revealed an ecchymosis inferior to the right eye and tenderness to palpation at the right maxilla and bilateral nasolabial folds. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) was ordered for further evaluation; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

A noncontrast CT of the maxillofacial bones demonstrated acute fractures through the bilateral pterygoid plates (white arrows, Figure 2a). The fractures extended through the medial and lateral walls of the bilateral maxillary sinuses (red arrows, Figure 2a), and propagated to the frontal processes of the maxilla (red arrows, Figure 2b), extending toward the alveolar process, indicating involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa. The full extent of the fracture is best seen on a 3D-reconstructed image (red arrows, Figure 3). Additional images (not presented here) confirmed no fracture involvement of the orbital floors, nasal bones, or zygomatic arches. Expected posttraumatic hemorrhage was appreciated within the maxillary sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a).

Le Fort Fractures

The findings described above are characteristic of a Le Fort I fracture pattern. Initially described in 1901 by René Le Fort, a French surgeon, the Le Fort classification system details somewhat predictable midface fracture patterns resulting in various degrees of craniofacial disassociation.1 Using weights that were dropped on cadaveric heads, Le Fort discovered that the pterygoid plates must be disrupted in order for the midface facial bones to separate from the skull base. As such, when diagnosing a Le Fort fracture, fracture of the pterygoid plate must be present, regardless of the fracture type (Le Fort I, II, and III).2

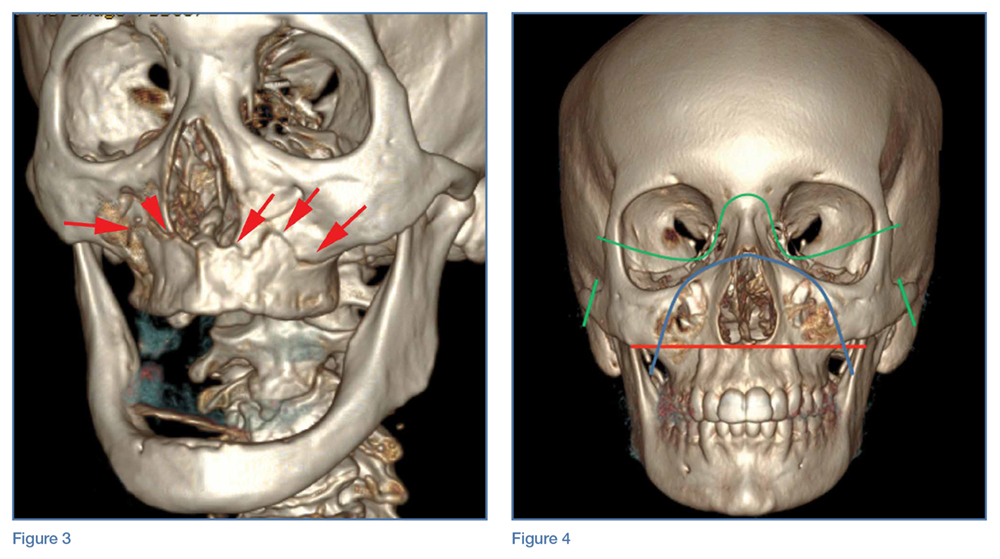

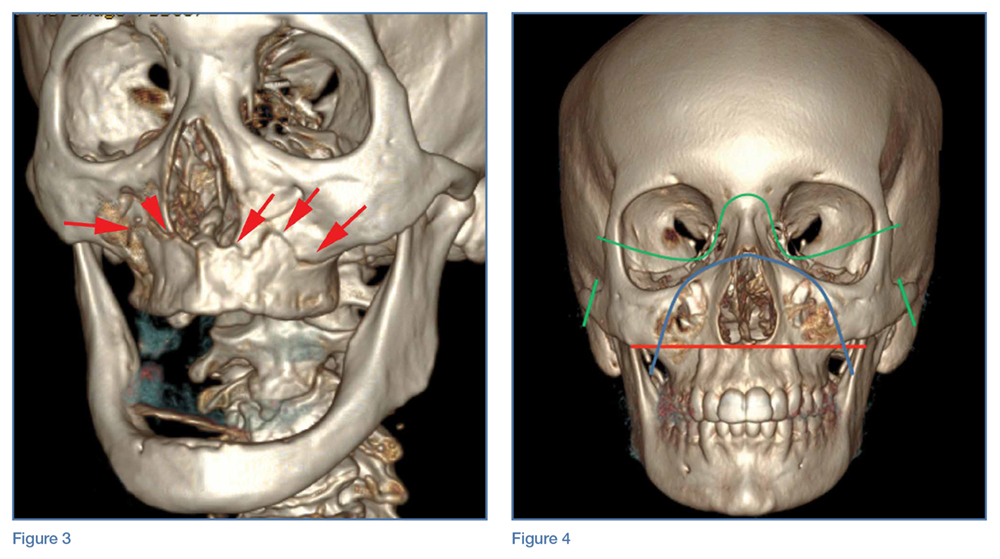

Le Fort I Fracture. This fracture pattern (red line, Figure 4) is referred to as a “floating palate” and involves separation of the hard palate from the skull base via fracture extension from the pterygoid plates into the maxillary sinus walls, as demonstrated in this case. The key distinguisher of the Le Fort I pattern is involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.2

Le Fort II Fracture. This fracture pattern (blue line, Figure 4) describes a “floating maxilla” wherein the pterygoid plate fractures are met with a pyramidal-type fracture pattern of the midface. The maxillary teeth form the base of the pyramid, and the fracture extends superiorly through the infraorbital rims bilaterally and toward the nasofrontal suture.2,3 Le Fort II fractures result in the maxilla floating freely from the rest of the midface and skull base.

Le Fort III Fracture. This fracture pattern (green lines, Figure 4) describes a “floating face” with complete craniofacial disjunction resulting from fracture of the pterygoid plates, nasofrontal suture, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, and zygomatic arch/zygomaticofrontal suture.2,3

It is important to note that midface trauma represents a complex spectrum of injuries, and Le Fort fractures only account for a small percentage of facial bone fractures that present through Level 1 trauma centers.2 Le Fort fracture patterns can coexist with other fracture patterns and also can be seen in combination with each other. For example, one side of the face may demonstrate a Le Fort II pattern while the other side concurrently demonstrates a Le Fort III pattern. Though not robust enough for complete description of and surgical planning for facial fractures, this classification system is a succinct and well-accepted means of describing major fracture planes.

An 89-year-old man presented to the ED with facial trauma due to a mechanical fall after losing his balance on uneven pavement and hitting the right side of his face. Physical examination revealed an ecchymosis inferior to the right eye and tenderness to palpation at the right maxilla and bilateral nasolabial folds. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) was ordered for further evaluation; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

A noncontrast CT of the maxillofacial bones demonstrated acute fractures through the bilateral pterygoid plates (white arrows, Figure 2a). The fractures extended through the medial and lateral walls of the bilateral maxillary sinuses (red arrows, Figure 2a), and propagated to the frontal processes of the maxilla (red arrows, Figure 2b), extending toward the alveolar process, indicating involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa. The full extent of the fracture is best seen on a 3D-reconstructed image (red arrows, Figure 3). Additional images (not presented here) confirmed no fracture involvement of the orbital floors, nasal bones, or zygomatic arches. Expected posttraumatic hemorrhage was appreciated within the maxillary sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a).

Le Fort Fractures

The findings described above are characteristic of a Le Fort I fracture pattern. Initially described in 1901 by René Le Fort, a French surgeon, the Le Fort classification system details somewhat predictable midface fracture patterns resulting in various degrees of craniofacial disassociation.1 Using weights that were dropped on cadaveric heads, Le Fort discovered that the pterygoid plates must be disrupted in order for the midface facial bones to separate from the skull base. As such, when diagnosing a Le Fort fracture, fracture of the pterygoid plate must be present, regardless of the fracture type (Le Fort I, II, and III).2

Le Fort I Fracture. This fracture pattern (red line, Figure 4) is referred to as a “floating palate” and involves separation of the hard palate from the skull base via fracture extension from the pterygoid plates into the maxillary sinus walls, as demonstrated in this case. The key distinguisher of the Le Fort I pattern is involvement of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.2

Le Fort II Fracture. This fracture pattern (blue line, Figure 4) describes a “floating maxilla” wherein the pterygoid plate fractures are met with a pyramidal-type fracture pattern of the midface. The maxillary teeth form the base of the pyramid, and the fracture extends superiorly through the infraorbital rims bilaterally and toward the nasofrontal suture.2,3 Le Fort II fractures result in the maxilla floating freely from the rest of the midface and skull base.

Le Fort III Fracture. This fracture pattern (green lines, Figure 4) describes a “floating face” with complete craniofacial disjunction resulting from fracture of the pterygoid plates, nasofrontal suture, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, and zygomatic arch/zygomaticofrontal suture.2,3

It is important to note that midface trauma represents a complex spectrum of injuries, and Le Fort fractures only account for a small percentage of facial bone fractures that present through Level 1 trauma centers.2 Le Fort fracture patterns can coexist with other fracture patterns and also can be seen in combination with each other. For example, one side of the face may demonstrate a Le Fort II pattern while the other side concurrently demonstrates a Le Fort III pattern. Though not robust enough for complete description of and surgical planning for facial fractures, this classification system is a succinct and well-accepted means of describing major fracture planes.

1. Le Fort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901;23:208-227, 360-379, 479-507.

2. Rhea JT, Novelline RA. How to simplify the CT diagnosis of Le Fort fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1700-1705.

3. Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):783-793.

1. Le Fort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901;23:208-227, 360-379, 479-507.

2. Rhea JT, Novelline RA. How to simplify the CT diagnosis of Le Fort fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1700-1705.

3. Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):783-793.

Emergency Imaging: Acute abdominal pain

An 89-year-old woman with a history of coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic constipation, and glaucoma presented to the ED for evaluation of chest pain and headache. Upon arrival at the ED, the patient also began to experience unrelenting abdominal pain. Abdominal examination showed mild tenderness in the right lower quadrant upon palpation. An abdominal radiograph and a computed tomography (CT) scan were ordered; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What is the preferred management for this patient?

Answer

The abdominal radiograph showed no evidence of bowel obstruction. There was, however, a round area of increased density in the pelvis, suggesting the presence of a soft-tissue mass (white arrows, Figure 2) directly adjacent to the sigmoid colon (white asterisk, Figure 2).

Giant Colonic Diverticula

Giant colonic diverticula (GCD) are diverticula larger than 4 cm. This is a rare manifestation of diverticular disease of the bowel and most commonly occurs within the sigmoid colon. The majority of patients who develop GCD are older than age 60 years.1

The clinical presentation of GCD is nonspecific but can include abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, and fever in the acute setting.2 Chronic presentations of GCD include intermittent abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation. In two-thirds of patients, a palpable abdominal mass is found on physical examination.3

Diagnosis

Due to the nonspecific presentation of GCD, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Although radiographs may show a dilated air-filled structure in the abdomen, differentiation from a normal air-filled bowel may be difficult. Computed tomography is the imaging modality of choice based on its ability to demonstrate the presence of a smooth-walled gas-containing structure that communicates with the bowel lumen. In addition, CT has the ability to visualize the fluid and stool that are often present within the diverticulum. In cases of acute inflammation, diverticular wall thickening also may be present on CT.

Though no longer routinely used, barium enema is another option for diagnosing GCD because it can also demonstrate communication between the giant diverticula and the bowel lumen. However, barium enema is not often used in the emergency setting due to an increased risk of perforation and peritonitis.1

Management

Complications caused by GCD occur in 15% to 35% of cases and most commonly include perforation with associated peritonitis and abscess formation.4 Due to associated morbidity, the preferred treatment is surgical management—even when GCD is found incidentally in asymptomatic patients. In uncomplicated cases, surgical resection of the diverticulum and adjacent colon is performed with primary colic anastomosis. In some cases, a diverting ileostomy is created. In the presence of perforation and/or abscess, percutaneous catheter drainage and two-stage colectomy with colostomy typically is performed.5

1. Zeina AR, Mahamid A, Nachtigal A, Ashkenazi I, Shapira-Rootman M. Giant colonic diverticulum: radiographic and MDCT characteristics. Insights Imaging. 2015;6(6):659-664. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0433-x.

2. Custer TJ, Blevins DV, Vara TM. Giant colonic diverticulum: a rare manifestation of a common disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3(5):543-548.

3. de Oliveira NC, Welch JP. Giant diverticula of the colon: a clinical assessment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(7):1092-1096.

4. Majeski J, Durst G Jr. Obstructing giant colonic diverticulum. South Med J. 2000;93(8):797-799.

5. Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Giannini G, et al. Giant colonic diverticulum: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment: systematic review of 166 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(1):360-368. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.360.

An 89-year-old woman with a history of coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic constipation, and glaucoma presented to the ED for evaluation of chest pain and headache. Upon arrival at the ED, the patient also began to experience unrelenting abdominal pain. Abdominal examination showed mild tenderness in the right lower quadrant upon palpation. An abdominal radiograph and a computed tomography (CT) scan were ordered; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What is the preferred management for this patient?

Answer

The abdominal radiograph showed no evidence of bowel obstruction. There was, however, a round area of increased density in the pelvis, suggesting the presence of a soft-tissue mass (white arrows, Figure 2) directly adjacent to the sigmoid colon (white asterisk, Figure 2).

Giant Colonic Diverticula

Giant colonic diverticula (GCD) are diverticula larger than 4 cm. This is a rare manifestation of diverticular disease of the bowel and most commonly occurs within the sigmoid colon. The majority of patients who develop GCD are older than age 60 years.1

The clinical presentation of GCD is nonspecific but can include abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, and fever in the acute setting.2 Chronic presentations of GCD include intermittent abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation. In two-thirds of patients, a palpable abdominal mass is found on physical examination.3

Diagnosis

Due to the nonspecific presentation of GCD, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Although radiographs may show a dilated air-filled structure in the abdomen, differentiation from a normal air-filled bowel may be difficult. Computed tomography is the imaging modality of choice based on its ability to demonstrate the presence of a smooth-walled gas-containing structure that communicates with the bowel lumen. In addition, CT has the ability to visualize the fluid and stool that are often present within the diverticulum. In cases of acute inflammation, diverticular wall thickening also may be present on CT.

Though no longer routinely used, barium enema is another option for diagnosing GCD because it can also demonstrate communication between the giant diverticula and the bowel lumen. However, barium enema is not often used in the emergency setting due to an increased risk of perforation and peritonitis.1

Management

Complications caused by GCD occur in 15% to 35% of cases and most commonly include perforation with associated peritonitis and abscess formation.4 Due to associated morbidity, the preferred treatment is surgical management—even when GCD is found incidentally in asymptomatic patients. In uncomplicated cases, surgical resection of the diverticulum and adjacent colon is performed with primary colic anastomosis. In some cases, a diverting ileostomy is created. In the presence of perforation and/or abscess, percutaneous catheter drainage and two-stage colectomy with colostomy typically is performed.5

An 89-year-old woman with a history of coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic constipation, and glaucoma presented to the ED for evaluation of chest pain and headache. Upon arrival at the ED, the patient also began to experience unrelenting abdominal pain. Abdominal examination showed mild tenderness in the right lower quadrant upon palpation. An abdominal radiograph and a computed tomography (CT) scan were ordered; representative images are presented above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What is the preferred management for this patient?

Answer

The abdominal radiograph showed no evidence of bowel obstruction. There was, however, a round area of increased density in the pelvis, suggesting the presence of a soft-tissue mass (white arrows, Figure 2) directly adjacent to the sigmoid colon (white asterisk, Figure 2).

Giant Colonic Diverticula

Giant colonic diverticula (GCD) are diverticula larger than 4 cm. This is a rare manifestation of diverticular disease of the bowel and most commonly occurs within the sigmoid colon. The majority of patients who develop GCD are older than age 60 years.1

The clinical presentation of GCD is nonspecific but can include abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, and fever in the acute setting.2 Chronic presentations of GCD include intermittent abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation. In two-thirds of patients, a palpable abdominal mass is found on physical examination.3

Diagnosis

Due to the nonspecific presentation of GCD, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Although radiographs may show a dilated air-filled structure in the abdomen, differentiation from a normal air-filled bowel may be difficult. Computed tomography is the imaging modality of choice based on its ability to demonstrate the presence of a smooth-walled gas-containing structure that communicates with the bowel lumen. In addition, CT has the ability to visualize the fluid and stool that are often present within the diverticulum. In cases of acute inflammation, diverticular wall thickening also may be present on CT.

Though no longer routinely used, barium enema is another option for diagnosing GCD because it can also demonstrate communication between the giant diverticula and the bowel lumen. However, barium enema is not often used in the emergency setting due to an increased risk of perforation and peritonitis.1

Management

Complications caused by GCD occur in 15% to 35% of cases and most commonly include perforation with associated peritonitis and abscess formation.4 Due to associated morbidity, the preferred treatment is surgical management—even when GCD is found incidentally in asymptomatic patients. In uncomplicated cases, surgical resection of the diverticulum and adjacent colon is performed with primary colic anastomosis. In some cases, a diverting ileostomy is created. In the presence of perforation and/or abscess, percutaneous catheter drainage and two-stage colectomy with colostomy typically is performed.5

1. Zeina AR, Mahamid A, Nachtigal A, Ashkenazi I, Shapira-Rootman M. Giant colonic diverticulum: radiographic and MDCT characteristics. Insights Imaging. 2015;6(6):659-664. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0433-x.

2. Custer TJ, Blevins DV, Vara TM. Giant colonic diverticulum: a rare manifestation of a common disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3(5):543-548.

3. de Oliveira NC, Welch JP. Giant diverticula of the colon: a clinical assessment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(7):1092-1096.

4. Majeski J, Durst G Jr. Obstructing giant colonic diverticulum. South Med J. 2000;93(8):797-799.

5. Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Giannini G, et al. Giant colonic diverticulum: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment: systematic review of 166 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(1):360-368. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.360.

1. Zeina AR, Mahamid A, Nachtigal A, Ashkenazi I, Shapira-Rootman M. Giant colonic diverticulum: radiographic and MDCT characteristics. Insights Imaging. 2015;6(6):659-664. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0433-x.

2. Custer TJ, Blevins DV, Vara TM. Giant colonic diverticulum: a rare manifestation of a common disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3(5):543-548.

3. de Oliveira NC, Welch JP. Giant diverticula of the colon: a clinical assessment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(7):1092-1096.

4. Majeski J, Durst G Jr. Obstructing giant colonic diverticulum. South Med J. 2000;93(8):797-799.

5. Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Giannini G, et al. Giant colonic diverticulum: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment: systematic review of 166 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(1):360-368. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.360.