User login

FDA puts pembrolizumab trials on clinical hold

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed clinical holds on 3 trials testing combination therapy with pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in patients with multiple myeloma (MM)—KEYNOTE-183, KEYNOTE-185, and KEYNOTE-023.

In 2 of these trials—KEYNOTE-183 and -185—there were more deaths among patients receiving pembrolizumab than among patients receiving comparator treatments.

KEYNOTE-183 is a phase 3 study of pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone with or without pembrolizumab in refractory or relapsed and refractory MM.

KEYNOTE-185 is a phase 3 study of lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone with or without pembrolizumab in newly diagnosed and treatment-naïve MM.

The excess deaths in the pembrolizumab arms of KEYNOTE-183 and -185 led to a pause in enrollment for both trials, which was announced last month.

Now, the FDA says available data suggest the risks of pembrolizumab plus pomalidomide or lenalidomide outweigh any potential benefit for MM patients.

Therefore, all patients enrolled in KEYNOTE-183 and -185 will discontinue investigational treatment with pembrolizumab.

The same applies to patients in the pembrolizumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone cohort of KEYNOTE-023.

KEYNOTE-023 is a phase 1 trial of pembrolizumab in combination with backbone treatments. Cohort 1 of this trial was designed to evaluate pembrolizumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in MM patients who received prior treatment with an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide).

Pembrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks interaction between the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its receptor ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2.

Pembrolizumab is FDA-approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, head and neck cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high solid tumors. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed clinical holds on 3 trials testing combination therapy with pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in patients with multiple myeloma (MM)—KEYNOTE-183, KEYNOTE-185, and KEYNOTE-023.

In 2 of these trials—KEYNOTE-183 and -185—there were more deaths among patients receiving pembrolizumab than among patients receiving comparator treatments.

KEYNOTE-183 is a phase 3 study of pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone with or without pembrolizumab in refractory or relapsed and refractory MM.

KEYNOTE-185 is a phase 3 study of lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone with or without pembrolizumab in newly diagnosed and treatment-naïve MM.

The excess deaths in the pembrolizumab arms of KEYNOTE-183 and -185 led to a pause in enrollment for both trials, which was announced last month.

Now, the FDA says available data suggest the risks of pembrolizumab plus pomalidomide or lenalidomide outweigh any potential benefit for MM patients.

Therefore, all patients enrolled in KEYNOTE-183 and -185 will discontinue investigational treatment with pembrolizumab.

The same applies to patients in the pembrolizumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone cohort of KEYNOTE-023.

KEYNOTE-023 is a phase 1 trial of pembrolizumab in combination with backbone treatments. Cohort 1 of this trial was designed to evaluate pembrolizumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in MM patients who received prior treatment with an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide).

Pembrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks interaction between the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its receptor ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2.

Pembrolizumab is FDA-approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, head and neck cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high solid tumors. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed clinical holds on 3 trials testing combination therapy with pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in patients with multiple myeloma (MM)—KEYNOTE-183, KEYNOTE-185, and KEYNOTE-023.

In 2 of these trials—KEYNOTE-183 and -185—there were more deaths among patients receiving pembrolizumab than among patients receiving comparator treatments.

KEYNOTE-183 is a phase 3 study of pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone with or without pembrolizumab in refractory or relapsed and refractory MM.

KEYNOTE-185 is a phase 3 study of lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone with or without pembrolizumab in newly diagnosed and treatment-naïve MM.

The excess deaths in the pembrolizumab arms of KEYNOTE-183 and -185 led to a pause in enrollment for both trials, which was announced last month.

Now, the FDA says available data suggest the risks of pembrolizumab plus pomalidomide or lenalidomide outweigh any potential benefit for MM patients.

Therefore, all patients enrolled in KEYNOTE-183 and -185 will discontinue investigational treatment with pembrolizumab.

The same applies to patients in the pembrolizumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone cohort of KEYNOTE-023.

KEYNOTE-023 is a phase 1 trial of pembrolizumab in combination with backbone treatments. Cohort 1 of this trial was designed to evaluate pembrolizumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in MM patients who received prior treatment with an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide).

Pembrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks interaction between the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its receptor ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2.

Pembrolizumab is FDA-approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, head and neck cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high solid tumors. ![]()

What’s Her Dry-agnosis?

ANSWER

The correct answer is eczema/atopic dermatitis (choice “c”).

Patients with eczema have a low threshold for itching, so they scratch, often making the condition appear far worse than it really is. In such cases, it’s typical for the problem to be mistaken for impetigo (choice “a”) or yeast infection (choice “d”). The latter, much like psoriasis (choice “b”), is quite rare in the perioral area. Furthermore, the patient had no indicative signs of psoriasis.

DISCUSSION

Eczema is one of several manifestations of atopic dermatitis, a syndrome that affects more than 20% of newborns in this country. These children have extraordinarily dry, thin skin that overreacts to wetting and drying, as well as scratching. Certain areas are especially prone to these changes and consequently develop scaling and itching.

The perioral area is one, in large part because it is kept moist by food, drink, nasal secretions, and saliva (due to habitual lip licking). The scaly rash becomes inflamed; on people with skin of color, this frequently manifests with hyperpigmentation.

When picked enough, this type of rash can become impetiginized—that is, superficially infected with staph or strep. But in this patient’s case, antibiotics were of no practical use.

A topical steroid ointment (hydrocortisone 2.5%) was used, and the patient was urged to stop picking (or licking!) and to use moisturizers (eg, petroleum jelly). The family was educated about the problem and its origins, and the parents were reassured of the self-limiting nature of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (a major source of concern).

In this case, the key to making the correct diagnosis was the significance of the personal and family history of atopy—and an appre

ANSWER

The correct answer is eczema/atopic dermatitis (choice “c”).

Patients with eczema have a low threshold for itching, so they scratch, often making the condition appear far worse than it really is. In such cases, it’s typical for the problem to be mistaken for impetigo (choice “a”) or yeast infection (choice “d”). The latter, much like psoriasis (choice “b”), is quite rare in the perioral area. Furthermore, the patient had no indicative signs of psoriasis.

DISCUSSION

Eczema is one of several manifestations of atopic dermatitis, a syndrome that affects more than 20% of newborns in this country. These children have extraordinarily dry, thin skin that overreacts to wetting and drying, as well as scratching. Certain areas are especially prone to these changes and consequently develop scaling and itching.

The perioral area is one, in large part because it is kept moist by food, drink, nasal secretions, and saliva (due to habitual lip licking). The scaly rash becomes inflamed; on people with skin of color, this frequently manifests with hyperpigmentation.

When picked enough, this type of rash can become impetiginized—that is, superficially infected with staph or strep. But in this patient’s case, antibiotics were of no practical use.

A topical steroid ointment (hydrocortisone 2.5%) was used, and the patient was urged to stop picking (or licking!) and to use moisturizers (eg, petroleum jelly). The family was educated about the problem and its origins, and the parents were reassured of the self-limiting nature of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (a major source of concern).

In this case, the key to making the correct diagnosis was the significance of the personal and family history of atopy—and an appre

ANSWER

The correct answer is eczema/atopic dermatitis (choice “c”).

Patients with eczema have a low threshold for itching, so they scratch, often making the condition appear far worse than it really is. In such cases, it’s typical for the problem to be mistaken for impetigo (choice “a”) or yeast infection (choice “d”). The latter, much like psoriasis (choice “b”), is quite rare in the perioral area. Furthermore, the patient had no indicative signs of psoriasis.

DISCUSSION

Eczema is one of several manifestations of atopic dermatitis, a syndrome that affects more than 20% of newborns in this country. These children have extraordinarily dry, thin skin that overreacts to wetting and drying, as well as scratching. Certain areas are especially prone to these changes and consequently develop scaling and itching.

The perioral area is one, in large part because it is kept moist by food, drink, nasal secretions, and saliva (due to habitual lip licking). The scaly rash becomes inflamed; on people with skin of color, this frequently manifests with hyperpigmentation.

When picked enough, this type of rash can become impetiginized—that is, superficially infected with staph or strep. But in this patient’s case, antibiotics were of no practical use.

A topical steroid ointment (hydrocortisone 2.5%) was used, and the patient was urged to stop picking (or licking!) and to use moisturizers (eg, petroleum jelly). The family was educated about the problem and its origins, and the parents were reassured of the self-limiting nature of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (a major source of concern).

In this case, the key to making the correct diagnosis was the significance of the personal and family history of atopy—and an appre

The persistent rash around this 5-year-old African-American girl’s mouth is causing a great deal of concern for her parents, who request referral to dermatology after four months of attempted treatment. Oral and topical antibiotics, as well as antifungal products (nystatin and fluconazole), have been used to no good effect.

The patient is often seen licking her lips, which dries and irritates them. Fine crusting surrounds her mouth, particularly the left lateral oral commissure. The skin in the affected areas is darker than the rest.

Elsewhere, her type IV skin is quite dry, with focal areas of scaling on the arms and antecubital region. No rash is seen on extensor areas, nor are there any changes in her nails.

The child is markedly atopic, as are her siblings, who are present for the exam. The patient and her siblings are all congested, breathing through their mouths (“allergies,” according to their parents).

Loop ileostomy tops colectomy for IBD rescue

SEATTLE – Diverting loop ileostomies save patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with severe colitis from rushed total abdominal colectomies, buying time for patient optimization before surgery, and perhaps even saving colons, according to a report from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Urgent colectomy is the standard of care, but it’s a big operation when patients aren’t doing well. Immunosuppression, malnutrition, and other problems lead to high rates of complications.

In 2013, UCLA physicians decided to try rescue diverting loop ileostomies (DLIs), a relatively quick, minimally invasive option to temporarily divert the fecal stream, instead. The idea is to give the colon a chance to heal and the patient another shot at medical management and recovery before definitive surgery. There’s even a chance of colon salvage.

The approach has been working well at UCLA. Investigators previously reported good results for their first eight patients. They presented updated results for the series – now up to 34 patients – at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

So far, DLI allowed 91% of patients (31/34) to avoid urgent total colectomies. It’s “a safe alternative. Patients undergoing DLI have acceptably low complication rates and most are afforded time for medical and nutritional optimization prior to proceeding with their definitive surgical care,” said presenter Tara Russell, MD, a UCLA surgery resident.

“Currently, [almost every] patient presenting with acute colitis who we aren’t able to get to the point of discharge with medical optimization” is now offered rescue DLI at the university, and patients have been eager for a chance at avoiding total colectomy. The only patients who are not offered DLI are those with, for instance, fulminant toxic megacolon, Dr. Russell said.

The DLI approach failed in just 2 of the 18 ulcerative colitis patients and 1 of the 16 Crohn’s patients in the series. All three went on to emergent total colectomies 11-53 days after the procedure.

The majority of DLI patients tolerated oral intake by postop day 1, and the median time to resuming a regular diet was 2 days. Most people were discharged within a day or 2 of diversion, and a few took longer to achieve medical rescue. Almost 90% had an improvement in nutritional status, and over 80% went on to elective laparoscopic definitive procedures or colon salvage.

Two patients had postop wound infections, “but there were no other complications” with DLI, Dr. Russell said.

All DLIs were performed with a single-incision laparoscopic approach and took an average of about a half hour. Most of the diversions were in the right lower abdominal quadrant.

The mean age of the patients was 36 years, with a range of 16-81 years. Just over half were men. Of 21 patients who met systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria at the time of operation, 13 (62%) resolved within 24 hours of DLI.

SEATTLE – Diverting loop ileostomies save patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with severe colitis from rushed total abdominal colectomies, buying time for patient optimization before surgery, and perhaps even saving colons, according to a report from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Urgent colectomy is the standard of care, but it’s a big operation when patients aren’t doing well. Immunosuppression, malnutrition, and other problems lead to high rates of complications.

In 2013, UCLA physicians decided to try rescue diverting loop ileostomies (DLIs), a relatively quick, minimally invasive option to temporarily divert the fecal stream, instead. The idea is to give the colon a chance to heal and the patient another shot at medical management and recovery before definitive surgery. There’s even a chance of colon salvage.

The approach has been working well at UCLA. Investigators previously reported good results for their first eight patients. They presented updated results for the series – now up to 34 patients – at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

So far, DLI allowed 91% of patients (31/34) to avoid urgent total colectomies. It’s “a safe alternative. Patients undergoing DLI have acceptably low complication rates and most are afforded time for medical and nutritional optimization prior to proceeding with their definitive surgical care,” said presenter Tara Russell, MD, a UCLA surgery resident.

“Currently, [almost every] patient presenting with acute colitis who we aren’t able to get to the point of discharge with medical optimization” is now offered rescue DLI at the university, and patients have been eager for a chance at avoiding total colectomy. The only patients who are not offered DLI are those with, for instance, fulminant toxic megacolon, Dr. Russell said.

The DLI approach failed in just 2 of the 18 ulcerative colitis patients and 1 of the 16 Crohn’s patients in the series. All three went on to emergent total colectomies 11-53 days after the procedure.

The majority of DLI patients tolerated oral intake by postop day 1, and the median time to resuming a regular diet was 2 days. Most people were discharged within a day or 2 of diversion, and a few took longer to achieve medical rescue. Almost 90% had an improvement in nutritional status, and over 80% went on to elective laparoscopic definitive procedures or colon salvage.

Two patients had postop wound infections, “but there were no other complications” with DLI, Dr. Russell said.

All DLIs were performed with a single-incision laparoscopic approach and took an average of about a half hour. Most of the diversions were in the right lower abdominal quadrant.

The mean age of the patients was 36 years, with a range of 16-81 years. Just over half were men. Of 21 patients who met systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria at the time of operation, 13 (62%) resolved within 24 hours of DLI.

SEATTLE – Diverting loop ileostomies save patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with severe colitis from rushed total abdominal colectomies, buying time for patient optimization before surgery, and perhaps even saving colons, according to a report from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Urgent colectomy is the standard of care, but it’s a big operation when patients aren’t doing well. Immunosuppression, malnutrition, and other problems lead to high rates of complications.

In 2013, UCLA physicians decided to try rescue diverting loop ileostomies (DLIs), a relatively quick, minimally invasive option to temporarily divert the fecal stream, instead. The idea is to give the colon a chance to heal and the patient another shot at medical management and recovery before definitive surgery. There’s even a chance of colon salvage.

The approach has been working well at UCLA. Investigators previously reported good results for their first eight patients. They presented updated results for the series – now up to 34 patients – at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

So far, DLI allowed 91% of patients (31/34) to avoid urgent total colectomies. It’s “a safe alternative. Patients undergoing DLI have acceptably low complication rates and most are afforded time for medical and nutritional optimization prior to proceeding with their definitive surgical care,” said presenter Tara Russell, MD, a UCLA surgery resident.

“Currently, [almost every] patient presenting with acute colitis who we aren’t able to get to the point of discharge with medical optimization” is now offered rescue DLI at the university, and patients have been eager for a chance at avoiding total colectomy. The only patients who are not offered DLI are those with, for instance, fulminant toxic megacolon, Dr. Russell said.

The DLI approach failed in just 2 of the 18 ulcerative colitis patients and 1 of the 16 Crohn’s patients in the series. All three went on to emergent total colectomies 11-53 days after the procedure.

The majority of DLI patients tolerated oral intake by postop day 1, and the median time to resuming a regular diet was 2 days. Most people were discharged within a day or 2 of diversion, and a few took longer to achieve medical rescue. Almost 90% had an improvement in nutritional status, and over 80% went on to elective laparoscopic definitive procedures or colon salvage.

Two patients had postop wound infections, “but there were no other complications” with DLI, Dr. Russell said.

All DLIs were performed with a single-incision laparoscopic approach and took an average of about a half hour. Most of the diversions were in the right lower abdominal quadrant.

The mean age of the patients was 36 years, with a range of 16-81 years. Just over half were men. Of 21 patients who met systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria at the time of operation, 13 (62%) resolved within 24 hours of DLI.

AT ASCRS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: DLI allowed 91% of patients (31/34) to avoid urgent total colectomies.

Data source: A report on 34 patients with severe, acute inflammatory bowel disease colitis.

Disclosures: The presenter had no disclosures.

Coaching ‘No’

In a recent column entitled “To the limit,” I tried to make the case that the negative consequences of permissive parenting are numerous enough to warrant the attention of primary care pediatricians and family physicians. The evidence linking atypical sensory adaptation, behavior difficulties, sleep deprivation, and obesity to a permissive parenting style is just beginning to appear in the literature, but the numbers are in sync with the anecdotal observations of many experienced pediatricians like me. In that previous column,

First, let me make it clear that I don’t consider parenting style to be a topic that needs to occur on the checklist of every patient at every health maintenance visit. You already are overburdened with the demands of experts who have lobbied to have their favorite hot button issues included in your 15 minutes of face-to-face time with your young patients.

We also must accept our limited role as advisors. There are many ways to skin a cat and to raise a child. Homogeneity is not our goal. We must respect the cultural and philosophical differences that exist in our society. However, in my opinion, the unhealthy consequences of permissive parenting deserve a sensitive attempt at education and some gentle anticipatory guidance ... hopefully without an aroma of condescension.

The opportunities for our input begin in the first few months of life when parents are faced with the difficult questions of whether it is safe and appropriate to allow their infant to cry himself to sleep and whether a mom must allow her infant to use her breast as a pacifier. With the transition to solid food comes the challenge of how to manage the inevitable rejection of new tastes, colors, and textures. Of course, most parents find these issues challenging, but to what degree a parent can internalize your reassurance and advice is a good reflection on where he or she sits on the permissive to authoritarian spectrum of parenting.

With an infant’s rapidly advancing motor skills comes the question of when, where, and how to create boundaries to keep the child safe ... and to protect the environment from the surprisingly destructive power of an inquisitive toddler. Here the permissive parent will be continually challenged when he or she finds that simply saying “No” or “Don’t” doesn’t always work ... to some extent because, up to this point, the child has never encountered a situation in which s/he hasn’t gotten what s/he wants.

This is not an issue in which we should allow ourselves to get bogged down in circuitous philosophical arguments. We must keep our advice practical and focused on issues of safety and health. I have found that a significant number of permissive parents can learn the difficult skill of saying “No” to their children. It takes time, but it is time well spent.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In a recent column entitled “To the limit,” I tried to make the case that the negative consequences of permissive parenting are numerous enough to warrant the attention of primary care pediatricians and family physicians. The evidence linking atypical sensory adaptation, behavior difficulties, sleep deprivation, and obesity to a permissive parenting style is just beginning to appear in the literature, but the numbers are in sync with the anecdotal observations of many experienced pediatricians like me. In that previous column,

First, let me make it clear that I don’t consider parenting style to be a topic that needs to occur on the checklist of every patient at every health maintenance visit. You already are overburdened with the demands of experts who have lobbied to have their favorite hot button issues included in your 15 minutes of face-to-face time with your young patients.

We also must accept our limited role as advisors. There are many ways to skin a cat and to raise a child. Homogeneity is not our goal. We must respect the cultural and philosophical differences that exist in our society. However, in my opinion, the unhealthy consequences of permissive parenting deserve a sensitive attempt at education and some gentle anticipatory guidance ... hopefully without an aroma of condescension.

The opportunities for our input begin in the first few months of life when parents are faced with the difficult questions of whether it is safe and appropriate to allow their infant to cry himself to sleep and whether a mom must allow her infant to use her breast as a pacifier. With the transition to solid food comes the challenge of how to manage the inevitable rejection of new tastes, colors, and textures. Of course, most parents find these issues challenging, but to what degree a parent can internalize your reassurance and advice is a good reflection on where he or she sits on the permissive to authoritarian spectrum of parenting.

With an infant’s rapidly advancing motor skills comes the question of when, where, and how to create boundaries to keep the child safe ... and to protect the environment from the surprisingly destructive power of an inquisitive toddler. Here the permissive parent will be continually challenged when he or she finds that simply saying “No” or “Don’t” doesn’t always work ... to some extent because, up to this point, the child has never encountered a situation in which s/he hasn’t gotten what s/he wants.

This is not an issue in which we should allow ourselves to get bogged down in circuitous philosophical arguments. We must keep our advice practical and focused on issues of safety and health. I have found that a significant number of permissive parents can learn the difficult skill of saying “No” to their children. It takes time, but it is time well spent.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In a recent column entitled “To the limit,” I tried to make the case that the negative consequences of permissive parenting are numerous enough to warrant the attention of primary care pediatricians and family physicians. The evidence linking atypical sensory adaptation, behavior difficulties, sleep deprivation, and obesity to a permissive parenting style is just beginning to appear in the literature, but the numbers are in sync with the anecdotal observations of many experienced pediatricians like me. In that previous column,

First, let me make it clear that I don’t consider parenting style to be a topic that needs to occur on the checklist of every patient at every health maintenance visit. You already are overburdened with the demands of experts who have lobbied to have their favorite hot button issues included in your 15 minutes of face-to-face time with your young patients.

We also must accept our limited role as advisors. There are many ways to skin a cat and to raise a child. Homogeneity is not our goal. We must respect the cultural and philosophical differences that exist in our society. However, in my opinion, the unhealthy consequences of permissive parenting deserve a sensitive attempt at education and some gentle anticipatory guidance ... hopefully without an aroma of condescension.

The opportunities for our input begin in the first few months of life when parents are faced with the difficult questions of whether it is safe and appropriate to allow their infant to cry himself to sleep and whether a mom must allow her infant to use her breast as a pacifier. With the transition to solid food comes the challenge of how to manage the inevitable rejection of new tastes, colors, and textures. Of course, most parents find these issues challenging, but to what degree a parent can internalize your reassurance and advice is a good reflection on where he or she sits on the permissive to authoritarian spectrum of parenting.

With an infant’s rapidly advancing motor skills comes the question of when, where, and how to create boundaries to keep the child safe ... and to protect the environment from the surprisingly destructive power of an inquisitive toddler. Here the permissive parent will be continually challenged when he or she finds that simply saying “No” or “Don’t” doesn’t always work ... to some extent because, up to this point, the child has never encountered a situation in which s/he hasn’t gotten what s/he wants.

This is not an issue in which we should allow ourselves to get bogged down in circuitous philosophical arguments. We must keep our advice practical and focused on issues of safety and health. I have found that a significant number of permissive parents can learn the difficult skill of saying “No” to their children. It takes time, but it is time well spent.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

To the limit

Do you believe that children whose parents can make and enforce rules are more likely to thrive than those children whose parents are hesitant to set limits? If you don’t see limit setting as a critical function of parenting, you and I are not only marching to different drummers, we aren’t even in the same parade.

You may be tempted to write me off as just another old school ranter because I believe that limit setting is one of the cornerstones of parenting. But, let’s look at some of the evidence. There are several studies demonstrating that children whose parents set bedtimes get more sleep. One recent survey also found that teenagers who got more sleep as a result of enforced bedtimes functioned better in school (Sleep. 2011 Jun 1;34[6]:797-800).

An important question is whether permissive parenting is a problem that warrants our concern as pediatricians. We always are on alert for the red flags of abusive parenting, and, obviously, failure to intervene in cases of abuse can be disastrous. However, if we can believe the results from the studies that have already been completed, it seems pretty clear that permissive parenting can spawn behavioral problems, sleep problems, and the myriad of downstream effects that can result from sleep deprivation. And I haven’t even touched on the possible relationship between permissive parenting and the obesity epidemic.

If we still consider ourselves the preventive medicine specialists, shouldn’t pediatricians and family medicine physicians be more invested in minimizing the unhealthy consequences of permissive parenting? If we can agree on a firm “Yes!” the next question is, When and how should we address the issue?

A more nuanced discussion can be the germ of a future Letters from Maine, but the short answer is that we need to sound as nonjudgmental as possible as we present our case for limit setting. We need to start early before the die is cast, and we should be better about publicizing our supporting evidence. Setting a bedtime can begin in the first 6 months of life. Helping parents learn to say, “No, we aren’t going to feed you only what you like to eat!” can start as an infant makes what can be an unsettling transition to solid food.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Do you believe that children whose parents can make and enforce rules are more likely to thrive than those children whose parents are hesitant to set limits? If you don’t see limit setting as a critical function of parenting, you and I are not only marching to different drummers, we aren’t even in the same parade.

You may be tempted to write me off as just another old school ranter because I believe that limit setting is one of the cornerstones of parenting. But, let’s look at some of the evidence. There are several studies demonstrating that children whose parents set bedtimes get more sleep. One recent survey also found that teenagers who got more sleep as a result of enforced bedtimes functioned better in school (Sleep. 2011 Jun 1;34[6]:797-800).

An important question is whether permissive parenting is a problem that warrants our concern as pediatricians. We always are on alert for the red flags of abusive parenting, and, obviously, failure to intervene in cases of abuse can be disastrous. However, if we can believe the results from the studies that have already been completed, it seems pretty clear that permissive parenting can spawn behavioral problems, sleep problems, and the myriad of downstream effects that can result from sleep deprivation. And I haven’t even touched on the possible relationship between permissive parenting and the obesity epidemic.

If we still consider ourselves the preventive medicine specialists, shouldn’t pediatricians and family medicine physicians be more invested in minimizing the unhealthy consequences of permissive parenting? If we can agree on a firm “Yes!” the next question is, When and how should we address the issue?

A more nuanced discussion can be the germ of a future Letters from Maine, but the short answer is that we need to sound as nonjudgmental as possible as we present our case for limit setting. We need to start early before the die is cast, and we should be better about publicizing our supporting evidence. Setting a bedtime can begin in the first 6 months of life. Helping parents learn to say, “No, we aren’t going to feed you only what you like to eat!” can start as an infant makes what can be an unsettling transition to solid food.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Do you believe that children whose parents can make and enforce rules are more likely to thrive than those children whose parents are hesitant to set limits? If you don’t see limit setting as a critical function of parenting, you and I are not only marching to different drummers, we aren’t even in the same parade.

You may be tempted to write me off as just another old school ranter because I believe that limit setting is one of the cornerstones of parenting. But, let’s look at some of the evidence. There are several studies demonstrating that children whose parents set bedtimes get more sleep. One recent survey also found that teenagers who got more sleep as a result of enforced bedtimes functioned better in school (Sleep. 2011 Jun 1;34[6]:797-800).

An important question is whether permissive parenting is a problem that warrants our concern as pediatricians. We always are on alert for the red flags of abusive parenting, and, obviously, failure to intervene in cases of abuse can be disastrous. However, if we can believe the results from the studies that have already been completed, it seems pretty clear that permissive parenting can spawn behavioral problems, sleep problems, and the myriad of downstream effects that can result from sleep deprivation. And I haven’t even touched on the possible relationship between permissive parenting and the obesity epidemic.

If we still consider ourselves the preventive medicine specialists, shouldn’t pediatricians and family medicine physicians be more invested in minimizing the unhealthy consequences of permissive parenting? If we can agree on a firm “Yes!” the next question is, When and how should we address the issue?

A more nuanced discussion can be the germ of a future Letters from Maine, but the short answer is that we need to sound as nonjudgmental as possible as we present our case for limit setting. We need to start early before the die is cast, and we should be better about publicizing our supporting evidence. Setting a bedtime can begin in the first 6 months of life. Helping parents learn to say, “No, we aren’t going to feed you only what you like to eat!” can start as an infant makes what can be an unsettling transition to solid food.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

NF-kB inhibitor IT-901 shows promise in Richter syndrome

NEW YORK – The novel NF-kB inhibitor IT-901 appears active against Richter syndrome, according to in vitro analyses of primary leukemic cells and in vivo analyses in patient-derived xenograft models.

The findings suggest that NF-kB inhibition should be considered as a therapeutic strategy for Richter syndrome patients, Tiziana Vaisitti, PhD, said at the annual International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia.

Several factors have been shown to be associated with the development of Richter syndrome (RS), including somatic and germline genetic characteristics, biologic and clinical features, and certain CLL therapies. Recent studies have identified a critical role of mutations in specific genes, such as CKN2A, TP53, and NOTCH1 in the transformation of CLL to RS, which ultimately results in the aberrant activation of selected pathways – including NF-kB, Dr. Vaisitti of the University of Turin and the Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine, Turin, Italy explained.

In an ongoing study on the effects of IT-901 in CLL, she and her colleagues showed that “this compound was able to interfere with NF-kB transcriptional activity.”

That effect is followed by rapid and marked reduction in “the oxidative phosphorylation capacity of CLL cells, determined also by the transcriptional regulation of genes that control this process.”

“Moreover, this compound induces a significant increase and release of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species,” she said, adding: “The final result of this cascade of events is that IT-901 is able to rapidly induce apoptosis selectively in primary CLL cells, independently of the clinical subgroup of patients we are considering, and with very little toxicity on normal lymphocytes.”

The experimental data indicated that IT-901 is effective not only on the leukemic side, but it also acts on the stromal bystander component of the disease, mainly on nurse-like cells, by modulating the expression of molecules critical for CLL survival, she said.

Those findings were reported at the 2016 American Society of Hematology annual meeting (Blood. 2016;128:304).

For the current analyses, she and her colleagues tested the effects of IT-901 in RS, which affects up to 10% of patients with CLL, and for which there is an unmet therapeutic need. They looked at the mechanisms of action of the compound in leukemic cells both in vitro and in vivo.

In line with previous data, NF-kB was “constitutively highly active in RS cells freshly isolated from patients,” she reported.

Exposure to IT-901 at a 5 microM dose for 6 hours significantly decreased binding of p50 and p65 to DNA, and western blotting analyses on nuclear extracts indicated impaired translocation of those subunits in the nucleus, and compromised expression of the whole NF-kB complex, she said.

IT-901 also induced apoptosis in primary RS cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner; significant efficacy was seen after 24 hours of treatment, with more than half of the cells dead.

These results were then confirmed in an RS cell line established in the lab from a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model, and even in the presence of a protective stromal layer IT-901 was able to induce apoptosis, she said.

The effects of IT-901 treatment were then analyzed in vivo using 3 different PDX models established from primary cells of RS patients and characterized by different molecular and genetic features. RS cells obtained from the PDX-tumor mass, were subcutaneously injected in severely immune-compromised mice and left to engraft until a palpable mass was present. IT-901 was then administered at a dose of 15 mg/kg, every day for 2 weeks, with a 2 day break after 5 days of administration.

Tumor size was significantly reduced, and as was demonstrated in vitro, immune-histochemical analyses of the tumor mass showed diminished expression and localization of the p65 subunit into the nucleus of tumor cells and increased cleavage of Caspase-3 in the treated mice as compared with vehicle-treated mice.

The findings provide proof-of-principle that IT-901 is effective in RS cells, diminishing NF-kB transcriptional activity and expression, and finally inducing apoptosis, Dr. Vaisitti said.

Dr. Vaisitti has received research funding from Immune Target.

NEW YORK – The novel NF-kB inhibitor IT-901 appears active against Richter syndrome, according to in vitro analyses of primary leukemic cells and in vivo analyses in patient-derived xenograft models.

The findings suggest that NF-kB inhibition should be considered as a therapeutic strategy for Richter syndrome patients, Tiziana Vaisitti, PhD, said at the annual International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia.

Several factors have been shown to be associated with the development of Richter syndrome (RS), including somatic and germline genetic characteristics, biologic and clinical features, and certain CLL therapies. Recent studies have identified a critical role of mutations in specific genes, such as CKN2A, TP53, and NOTCH1 in the transformation of CLL to RS, which ultimately results in the aberrant activation of selected pathways – including NF-kB, Dr. Vaisitti of the University of Turin and the Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine, Turin, Italy explained.

In an ongoing study on the effects of IT-901 in CLL, she and her colleagues showed that “this compound was able to interfere with NF-kB transcriptional activity.”

That effect is followed by rapid and marked reduction in “the oxidative phosphorylation capacity of CLL cells, determined also by the transcriptional regulation of genes that control this process.”

“Moreover, this compound induces a significant increase and release of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species,” she said, adding: “The final result of this cascade of events is that IT-901 is able to rapidly induce apoptosis selectively in primary CLL cells, independently of the clinical subgroup of patients we are considering, and with very little toxicity on normal lymphocytes.”

The experimental data indicated that IT-901 is effective not only on the leukemic side, but it also acts on the stromal bystander component of the disease, mainly on nurse-like cells, by modulating the expression of molecules critical for CLL survival, she said.

Those findings were reported at the 2016 American Society of Hematology annual meeting (Blood. 2016;128:304).

For the current analyses, she and her colleagues tested the effects of IT-901 in RS, which affects up to 10% of patients with CLL, and for which there is an unmet therapeutic need. They looked at the mechanisms of action of the compound in leukemic cells both in vitro and in vivo.

In line with previous data, NF-kB was “constitutively highly active in RS cells freshly isolated from patients,” she reported.

Exposure to IT-901 at a 5 microM dose for 6 hours significantly decreased binding of p50 and p65 to DNA, and western blotting analyses on nuclear extracts indicated impaired translocation of those subunits in the nucleus, and compromised expression of the whole NF-kB complex, she said.

IT-901 also induced apoptosis in primary RS cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner; significant efficacy was seen after 24 hours of treatment, with more than half of the cells dead.

These results were then confirmed in an RS cell line established in the lab from a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model, and even in the presence of a protective stromal layer IT-901 was able to induce apoptosis, she said.

The effects of IT-901 treatment were then analyzed in vivo using 3 different PDX models established from primary cells of RS patients and characterized by different molecular and genetic features. RS cells obtained from the PDX-tumor mass, were subcutaneously injected in severely immune-compromised mice and left to engraft until a palpable mass was present. IT-901 was then administered at a dose of 15 mg/kg, every day for 2 weeks, with a 2 day break after 5 days of administration.

Tumor size was significantly reduced, and as was demonstrated in vitro, immune-histochemical analyses of the tumor mass showed diminished expression and localization of the p65 subunit into the nucleus of tumor cells and increased cleavage of Caspase-3 in the treated mice as compared with vehicle-treated mice.

The findings provide proof-of-principle that IT-901 is effective in RS cells, diminishing NF-kB transcriptional activity and expression, and finally inducing apoptosis, Dr. Vaisitti said.

Dr. Vaisitti has received research funding from Immune Target.

NEW YORK – The novel NF-kB inhibitor IT-901 appears active against Richter syndrome, according to in vitro analyses of primary leukemic cells and in vivo analyses in patient-derived xenograft models.

The findings suggest that NF-kB inhibition should be considered as a therapeutic strategy for Richter syndrome patients, Tiziana Vaisitti, PhD, said at the annual International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia.

Several factors have been shown to be associated with the development of Richter syndrome (RS), including somatic and germline genetic characteristics, biologic and clinical features, and certain CLL therapies. Recent studies have identified a critical role of mutations in specific genes, such as CKN2A, TP53, and NOTCH1 in the transformation of CLL to RS, which ultimately results in the aberrant activation of selected pathways – including NF-kB, Dr. Vaisitti of the University of Turin and the Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine, Turin, Italy explained.

In an ongoing study on the effects of IT-901 in CLL, she and her colleagues showed that “this compound was able to interfere with NF-kB transcriptional activity.”

That effect is followed by rapid and marked reduction in “the oxidative phosphorylation capacity of CLL cells, determined also by the transcriptional regulation of genes that control this process.”

“Moreover, this compound induces a significant increase and release of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species,” she said, adding: “The final result of this cascade of events is that IT-901 is able to rapidly induce apoptosis selectively in primary CLL cells, independently of the clinical subgroup of patients we are considering, and with very little toxicity on normal lymphocytes.”

The experimental data indicated that IT-901 is effective not only on the leukemic side, but it also acts on the stromal bystander component of the disease, mainly on nurse-like cells, by modulating the expression of molecules critical for CLL survival, she said.

Those findings were reported at the 2016 American Society of Hematology annual meeting (Blood. 2016;128:304).

For the current analyses, she and her colleagues tested the effects of IT-901 in RS, which affects up to 10% of patients with CLL, and for which there is an unmet therapeutic need. They looked at the mechanisms of action of the compound in leukemic cells both in vitro and in vivo.

In line with previous data, NF-kB was “constitutively highly active in RS cells freshly isolated from patients,” she reported.

Exposure to IT-901 at a 5 microM dose for 6 hours significantly decreased binding of p50 and p65 to DNA, and western blotting analyses on nuclear extracts indicated impaired translocation of those subunits in the nucleus, and compromised expression of the whole NF-kB complex, she said.

IT-901 also induced apoptosis in primary RS cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner; significant efficacy was seen after 24 hours of treatment, with more than half of the cells dead.

These results were then confirmed in an RS cell line established in the lab from a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model, and even in the presence of a protective stromal layer IT-901 was able to induce apoptosis, she said.

The effects of IT-901 treatment were then analyzed in vivo using 3 different PDX models established from primary cells of RS patients and characterized by different molecular and genetic features. RS cells obtained from the PDX-tumor mass, were subcutaneously injected in severely immune-compromised mice and left to engraft until a palpable mass was present. IT-901 was then administered at a dose of 15 mg/kg, every day for 2 weeks, with a 2 day break after 5 days of administration.

Tumor size was significantly reduced, and as was demonstrated in vitro, immune-histochemical analyses of the tumor mass showed diminished expression and localization of the p65 subunit into the nucleus of tumor cells and increased cleavage of Caspase-3 in the treated mice as compared with vehicle-treated mice.

The findings provide proof-of-principle that IT-901 is effective in RS cells, diminishing NF-kB transcriptional activity and expression, and finally inducing apoptosis, Dr. Vaisitti said.

Dr. Vaisitti has received research funding from Immune Target.

AT THE iwCLL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: IT-901 induced apoptosis in primary RS cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner; significant efficacy was seen after 24 hours of treatment, with more than half of the cells dead.

Data source: In vitro and in vivo analyses.

Disclosures: Dr. Vaisitti has received research funding from Immune Target.

Consequence of change? Medicaid disenrollment delayed breast cancer diagnosis

A spike in later-stage breast cancers is a potential byproduct of the Republican-proposed Medicaid reductions, according to Wafa Tarazi, PhD, and her colleagues.

The team looked at breast cancer stage at diagnosis following the 2005 Medicaid disenrollment of nearly 170,000 nonelderly adults in Tennessee that occurred because of state financial issues.

“Overall, nonelderly women in Tennessee were diagnosed at later stages of disease and experienced more delays in treatment in the period after disenrollment,” wrote Dr. Tarazi of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. “Disenrollment was found to be associated with a 3.3 percentage point increase in late stage of disease at the time of diagnosis” (Cancer 2016 June 26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30771).

The investigators offered a few explanations for why this could be the case.

While disenrollment was associated with later stage of breast cancer at diagnosis, it also was associated with a 1.9 percentage-point decrease in a 60-day–plus delay in surgical treatment and a 1.4 percentage-point decrease in a greater-than-90-day–plus delay in treatment for women living in low-income ZIP codes, compared with women living in high-income ZIP codes.

Contractions “in the availability of Medicaid coverage have important health consequences for low-income women, and may increase income-related disparities, morbidity, and mortality for those diagnosed with breast cancer,” the authors wrote. “These negative health consequences should be considered by policymakers who weigh the costs and benefits of implementing or discontinuing expanded Medicaid coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and future federal and state policies.”

The Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A spike in later-stage breast cancers is a potential byproduct of the Republican-proposed Medicaid reductions, according to Wafa Tarazi, PhD, and her colleagues.

The team looked at breast cancer stage at diagnosis following the 2005 Medicaid disenrollment of nearly 170,000 nonelderly adults in Tennessee that occurred because of state financial issues.

“Overall, nonelderly women in Tennessee were diagnosed at later stages of disease and experienced more delays in treatment in the period after disenrollment,” wrote Dr. Tarazi of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. “Disenrollment was found to be associated with a 3.3 percentage point increase in late stage of disease at the time of diagnosis” (Cancer 2016 June 26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30771).

The investigators offered a few explanations for why this could be the case.

While disenrollment was associated with later stage of breast cancer at diagnosis, it also was associated with a 1.9 percentage-point decrease in a 60-day–plus delay in surgical treatment and a 1.4 percentage-point decrease in a greater-than-90-day–plus delay in treatment for women living in low-income ZIP codes, compared with women living in high-income ZIP codes.

Contractions “in the availability of Medicaid coverage have important health consequences for low-income women, and may increase income-related disparities, morbidity, and mortality for those diagnosed with breast cancer,” the authors wrote. “These negative health consequences should be considered by policymakers who weigh the costs and benefits of implementing or discontinuing expanded Medicaid coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and future federal and state policies.”

The Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A spike in later-stage breast cancers is a potential byproduct of the Republican-proposed Medicaid reductions, according to Wafa Tarazi, PhD, and her colleagues.

The team looked at breast cancer stage at diagnosis following the 2005 Medicaid disenrollment of nearly 170,000 nonelderly adults in Tennessee that occurred because of state financial issues.

“Overall, nonelderly women in Tennessee were diagnosed at later stages of disease and experienced more delays in treatment in the period after disenrollment,” wrote Dr. Tarazi of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. “Disenrollment was found to be associated with a 3.3 percentage point increase in late stage of disease at the time of diagnosis” (Cancer 2016 June 26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30771).

The investigators offered a few explanations for why this could be the case.

While disenrollment was associated with later stage of breast cancer at diagnosis, it also was associated with a 1.9 percentage-point decrease in a 60-day–plus delay in surgical treatment and a 1.4 percentage-point decrease in a greater-than-90-day–plus delay in treatment for women living in low-income ZIP codes, compared with women living in high-income ZIP codes.

Contractions “in the availability of Medicaid coverage have important health consequences for low-income women, and may increase income-related disparities, morbidity, and mortality for those diagnosed with breast cancer,” the authors wrote. “These negative health consequences should be considered by policymakers who weigh the costs and benefits of implementing or discontinuing expanded Medicaid coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and future federal and state policies.”

The Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM CANCER

Meta-analysis: Bisphosphonates mitigate glucocorticoid-induced bone loss

MADRID – Bisphosphonates mitigate the damaging effects of glucocorticoid on bone, boosting bone mineral density and reducing the risk of fracture by up to 33%, compared with placebo, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

The review of 11 randomized, controlled trials found that bisphosphonates consistently improved bone outcomes among patients taking prednisone, Anas Makhzoum, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

The primary outcomes of these trials were mean percentage change in bone mineral density at lumbar spine and femoral neck, and fracture incidence.

The drugs examined were ibandronate, alendronate, risedronate, etidronate, and clodronate. The mean duration of these trials was 71 weeks. Patients took a mean steroid dose of 15 mg.

Dr. Makhzoum, a resident at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., pooled nine of these trials for the outcome of mean percentage change in lumbar spine bone mineral density. The pooled mean percentage change of lumbar spine consistently favored bisphosphonates, compared with placebo, with a mean, statistically significant difference of approximately 4%.

Six studies were pooled for the outcome of mean percentage change in femoral neck bone mineral density. The pooled mean percentage change consistently favored bisphosphonates, with a mean, statistically significant difference of 2.95% relative to placebo.

Seven studies were pooled for outcome of incident fracture and the results consistently favored bisphosphonates, with a mean, statistically significant 33% decrease in the risk of a new fracture, compared with the placebo group (relative risk, 0.66).

“Bisphosphonates remain the standard of care for prevention and treatment of bone loss in patients on chronic steroids treatment,” Dr. Makhzoum noted.

He had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

MADRID – Bisphosphonates mitigate the damaging effects of glucocorticoid on bone, boosting bone mineral density and reducing the risk of fracture by up to 33%, compared with placebo, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

The review of 11 randomized, controlled trials found that bisphosphonates consistently improved bone outcomes among patients taking prednisone, Anas Makhzoum, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

The primary outcomes of these trials were mean percentage change in bone mineral density at lumbar spine and femoral neck, and fracture incidence.

The drugs examined were ibandronate, alendronate, risedronate, etidronate, and clodronate. The mean duration of these trials was 71 weeks. Patients took a mean steroid dose of 15 mg.

Dr. Makhzoum, a resident at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., pooled nine of these trials for the outcome of mean percentage change in lumbar spine bone mineral density. The pooled mean percentage change of lumbar spine consistently favored bisphosphonates, compared with placebo, with a mean, statistically significant difference of approximately 4%.

Six studies were pooled for the outcome of mean percentage change in femoral neck bone mineral density. The pooled mean percentage change consistently favored bisphosphonates, with a mean, statistically significant difference of 2.95% relative to placebo.

Seven studies were pooled for outcome of incident fracture and the results consistently favored bisphosphonates, with a mean, statistically significant 33% decrease in the risk of a new fracture, compared with the placebo group (relative risk, 0.66).

“Bisphosphonates remain the standard of care for prevention and treatment of bone loss in patients on chronic steroids treatment,” Dr. Makhzoum noted.

He had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

MADRID – Bisphosphonates mitigate the damaging effects of glucocorticoid on bone, boosting bone mineral density and reducing the risk of fracture by up to 33%, compared with placebo, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

The review of 11 randomized, controlled trials found that bisphosphonates consistently improved bone outcomes among patients taking prednisone, Anas Makhzoum, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

The primary outcomes of these trials were mean percentage change in bone mineral density at lumbar spine and femoral neck, and fracture incidence.

The drugs examined were ibandronate, alendronate, risedronate, etidronate, and clodronate. The mean duration of these trials was 71 weeks. Patients took a mean steroid dose of 15 mg.

Dr. Makhzoum, a resident at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., pooled nine of these trials for the outcome of mean percentage change in lumbar spine bone mineral density. The pooled mean percentage change of lumbar spine consistently favored bisphosphonates, compared with placebo, with a mean, statistically significant difference of approximately 4%.

Six studies were pooled for the outcome of mean percentage change in femoral neck bone mineral density. The pooled mean percentage change consistently favored bisphosphonates, with a mean, statistically significant difference of 2.95% relative to placebo.

Seven studies were pooled for outcome of incident fracture and the results consistently favored bisphosphonates, with a mean, statistically significant 33% decrease in the risk of a new fracture, compared with the placebo group (relative risk, 0.66).

“Bisphosphonates remain the standard of care for prevention and treatment of bone loss in patients on chronic steroids treatment,” Dr. Makhzoum noted.

He had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE EULAR 2017 CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Relative to placebo, bisphosphonates reduced the risk of fracture by up to 33%.

Data source: A meta-analysis comprising 11 randomized, placebo-controlled trials with more than 2,000 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Makhzoum had no financial disclosures.

Large Hyperpigmented Nodule on the Leg

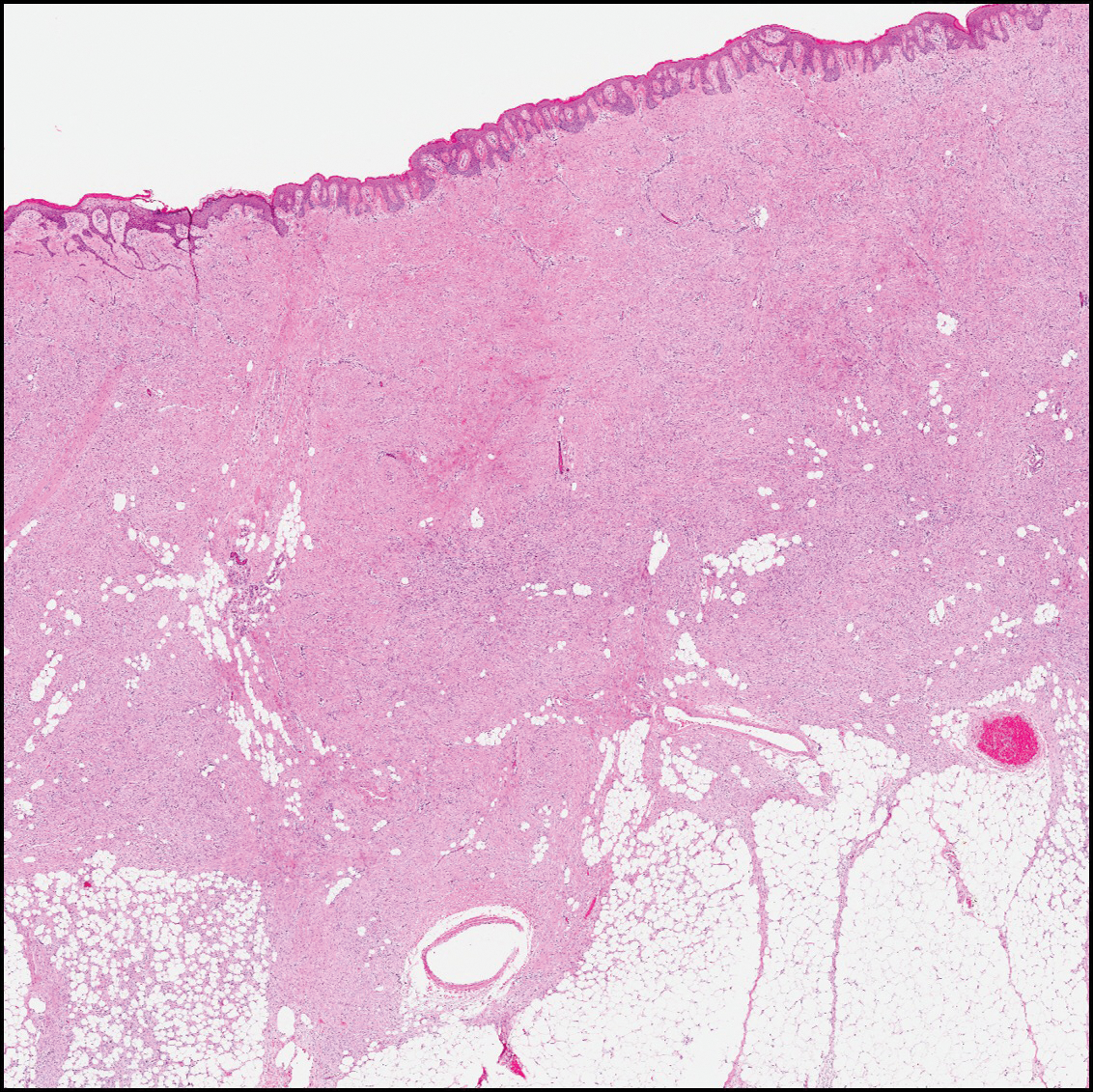

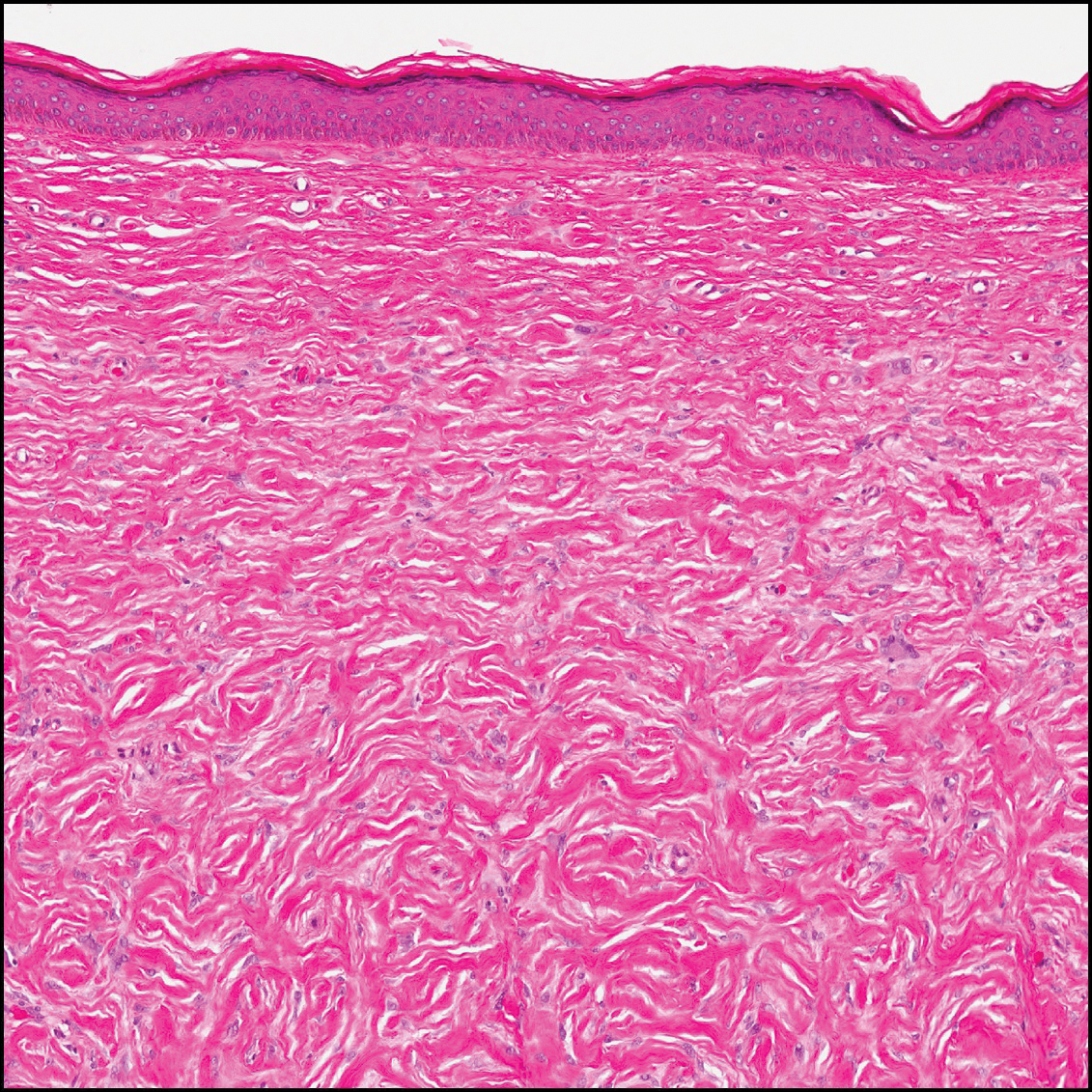

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10