User login

QI enthusiast to QI leader: Jonathan Bae, MD, SFHM

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Jonathan Bae, MD, SFHM, associate chief medical officer for patient and clinical quality at Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C.

With a father and two sisters in medicine, Jonathan Bae was destined to become a physician – or something completely different, as he explains.

“Either outcome is common when you have a parent who is a doctor,” said Dr. Bae, who has two siblings who chose a different career path. But while Dr. Bae’s desire to be a clinician was set at an early age, his interest in quality improvement work came much later.

Twelve years ago, Dr. Bae matched in Duke’s Medicine-Pediatrics residency program because he wanted to be well equipped to treat patients across the age spectrum. Completing residency in 2009, Dr. Bae enjoyed providing clinical care as a hospitalist, but discovered that he also enjoyed teaching. To enhance his skills as a clinician educator, Dr. Bae enrolled in the Academic Hospitalist Academy, where the curriculum introduced him to quality improvement and patient safety, and some aspects of hospital administration. “Jeff Glasheen’s talk on the drivers of medicine, and how to find your unique voice and identity … brought together my interest in education and quality work,” Dr. Bae recalled.

“I left the meeting energized with new information, and then the opportunity came up to lead a QI initiative here,” he said. The project focused on improving improve care delivery to diabetic patients, specifically the completion of foot exams. “We saw our rates of screening go from less than 50% to greater than 80%,” Dr. Bae said. “I found it to be extremely gratifying to be involved in implementing changes that could lead to care improvement for patients.”

Once Dr. Bae made his interests in QI work known to colleagues and administrators, the projects came readily. Following his chief residency year, Dr. Bae remained with Duke Medicine Residency Program as an associate program director for QI, “which was a great platform for doing project work that aligned my interests in teaching and doing QI work,” he said. In addition to developing a residency curriculum in QI, Dr. Bae initiated a program to incentivize GME trainees across the health system in performance metrics such as readmissions, patient satisfaction, hand hygiene, and safety event reporting. The outcomes, Dr. Bae said, “have had an improved quality and safety impact on our organization.”

From there, Dr. Bae initiated multiple projects focused on reducing readmissions and mortality. Currently, he is standardizing the mortality review process across three hospitals in Duke’s health system. Consistent methodology and language will allow for more accurate analysis and comparison of factors contributing to patient mortality in the system, Dr. Bae said, adding, “We have already learned a lot about care delivery and operations, and measures that can be taken to reduce gaps in care delivery and keep patients safe.”

Looking back on the days when he only thought about providing care, Dr. Bae said, “my world view has changed but my desire to change the world hasn’t. I now do more quality work because I find it so gratifying. In the QI space, I’m affecting not one, but many people at a time.”

He encourages hospitalists with similar interests to seek out colleagues and leaders – internal and external to their institutions – that will help them initiate and implement projects that feed their passions. Getting to know the QI basics is the simple part, Dr. Bae said.

“There’s no magic behind PDSA cycles or models of improvement,” he said. “It’s the team and people you pull together that makes a project successful.”

His current work centers on understanding and building health care provider resiliency at Duke. “I feel this … is going to make a tremendous difference for our organization,” Dr. Bae said. “The system should be designed to promote well-being, not just prevent burnout.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Jonathan Bae, MD, SFHM, associate chief medical officer for patient and clinical quality at Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C.

With a father and two sisters in medicine, Jonathan Bae was destined to become a physician – or something completely different, as he explains.

“Either outcome is common when you have a parent who is a doctor,” said Dr. Bae, who has two siblings who chose a different career path. But while Dr. Bae’s desire to be a clinician was set at an early age, his interest in quality improvement work came much later.

Twelve years ago, Dr. Bae matched in Duke’s Medicine-Pediatrics residency program because he wanted to be well equipped to treat patients across the age spectrum. Completing residency in 2009, Dr. Bae enjoyed providing clinical care as a hospitalist, but discovered that he also enjoyed teaching. To enhance his skills as a clinician educator, Dr. Bae enrolled in the Academic Hospitalist Academy, where the curriculum introduced him to quality improvement and patient safety, and some aspects of hospital administration. “Jeff Glasheen’s talk on the drivers of medicine, and how to find your unique voice and identity … brought together my interest in education and quality work,” Dr. Bae recalled.

“I left the meeting energized with new information, and then the opportunity came up to lead a QI initiative here,” he said. The project focused on improving improve care delivery to diabetic patients, specifically the completion of foot exams. “We saw our rates of screening go from less than 50% to greater than 80%,” Dr. Bae said. “I found it to be extremely gratifying to be involved in implementing changes that could lead to care improvement for patients.”

Once Dr. Bae made his interests in QI work known to colleagues and administrators, the projects came readily. Following his chief residency year, Dr. Bae remained with Duke Medicine Residency Program as an associate program director for QI, “which was a great platform for doing project work that aligned my interests in teaching and doing QI work,” he said. In addition to developing a residency curriculum in QI, Dr. Bae initiated a program to incentivize GME trainees across the health system in performance metrics such as readmissions, patient satisfaction, hand hygiene, and safety event reporting. The outcomes, Dr. Bae said, “have had an improved quality and safety impact on our organization.”

From there, Dr. Bae initiated multiple projects focused on reducing readmissions and mortality. Currently, he is standardizing the mortality review process across three hospitals in Duke’s health system. Consistent methodology and language will allow for more accurate analysis and comparison of factors contributing to patient mortality in the system, Dr. Bae said, adding, “We have already learned a lot about care delivery and operations, and measures that can be taken to reduce gaps in care delivery and keep patients safe.”

Looking back on the days when he only thought about providing care, Dr. Bae said, “my world view has changed but my desire to change the world hasn’t. I now do more quality work because I find it so gratifying. In the QI space, I’m affecting not one, but many people at a time.”

He encourages hospitalists with similar interests to seek out colleagues and leaders – internal and external to their institutions – that will help them initiate and implement projects that feed their passions. Getting to know the QI basics is the simple part, Dr. Bae said.

“There’s no magic behind PDSA cycles or models of improvement,” he said. “It’s the team and people you pull together that makes a project successful.”

His current work centers on understanding and building health care provider resiliency at Duke. “I feel this … is going to make a tremendous difference for our organization,” Dr. Bae said. “The system should be designed to promote well-being, not just prevent burnout.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Jonathan Bae, MD, SFHM, associate chief medical officer for patient and clinical quality at Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C.

With a father and two sisters in medicine, Jonathan Bae was destined to become a physician – or something completely different, as he explains.

“Either outcome is common when you have a parent who is a doctor,” said Dr. Bae, who has two siblings who chose a different career path. But while Dr. Bae’s desire to be a clinician was set at an early age, his interest in quality improvement work came much later.

Twelve years ago, Dr. Bae matched in Duke’s Medicine-Pediatrics residency program because he wanted to be well equipped to treat patients across the age spectrum. Completing residency in 2009, Dr. Bae enjoyed providing clinical care as a hospitalist, but discovered that he also enjoyed teaching. To enhance his skills as a clinician educator, Dr. Bae enrolled in the Academic Hospitalist Academy, where the curriculum introduced him to quality improvement and patient safety, and some aspects of hospital administration. “Jeff Glasheen’s talk on the drivers of medicine, and how to find your unique voice and identity … brought together my interest in education and quality work,” Dr. Bae recalled.

“I left the meeting energized with new information, and then the opportunity came up to lead a QI initiative here,” he said. The project focused on improving improve care delivery to diabetic patients, specifically the completion of foot exams. “We saw our rates of screening go from less than 50% to greater than 80%,” Dr. Bae said. “I found it to be extremely gratifying to be involved in implementing changes that could lead to care improvement for patients.”

Once Dr. Bae made his interests in QI work known to colleagues and administrators, the projects came readily. Following his chief residency year, Dr. Bae remained with Duke Medicine Residency Program as an associate program director for QI, “which was a great platform for doing project work that aligned my interests in teaching and doing QI work,” he said. In addition to developing a residency curriculum in QI, Dr. Bae initiated a program to incentivize GME trainees across the health system in performance metrics such as readmissions, patient satisfaction, hand hygiene, and safety event reporting. The outcomes, Dr. Bae said, “have had an improved quality and safety impact on our organization.”

From there, Dr. Bae initiated multiple projects focused on reducing readmissions and mortality. Currently, he is standardizing the mortality review process across three hospitals in Duke’s health system. Consistent methodology and language will allow for more accurate analysis and comparison of factors contributing to patient mortality in the system, Dr. Bae said, adding, “We have already learned a lot about care delivery and operations, and measures that can be taken to reduce gaps in care delivery and keep patients safe.”

Looking back on the days when he only thought about providing care, Dr. Bae said, “my world view has changed but my desire to change the world hasn’t. I now do more quality work because I find it so gratifying. In the QI space, I’m affecting not one, but many people at a time.”

He encourages hospitalists with similar interests to seek out colleagues and leaders – internal and external to their institutions – that will help them initiate and implement projects that feed their passions. Getting to know the QI basics is the simple part, Dr. Bae said.

“There’s no magic behind PDSA cycles or models of improvement,” he said. “It’s the team and people you pull together that makes a project successful.”

His current work centers on understanding and building health care provider resiliency at Duke. “I feel this … is going to make a tremendous difference for our organization,” Dr. Bae said. “The system should be designed to promote well-being, not just prevent burnout.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

QI enthusiast to QI leader: Luci Leykum, MD

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

QI enthusiast to QI leader: John Bulger, DO

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of John Bulger, DO, chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan.

As chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan, John Bulger, DO, MBA, is intimately acquainted with the daily challenges that intersect with the delivery of safe, quality-driven care in the hospital system.

He’s also very familiar with the intricacies of carving out a professional road map. When Dr. Bulger began practicing as an internist at Geisinger Health System in the late 1990s, there wasn’t a formal hospitalist designation. He created one and became director of the hospital medicine program. Years later, when the opportunity arose to become chief quality officer, Dr. Bulger was a natural fit for the position, having led many improvement-centered committees and projects while running the hospital medicine group.

Early in his QI immersion, Dr. Bulger sought training where available from sources such as ACP and SHM, while familiarizing himself with methodologies such as PDSA and Lean. There are far more QI training opportunities available to hospitalists today than when Dr. Bulger began his journey, but the fundamentals of success come back to finding the right mentors, team building, and implementing projects built around SMART goals.

Getting started, Dr. Bulger suggests to “pick something within your scope, like medical reconciliation for every patient, or ensuring that every patient who leaves the hospital gets an appointment with their primary physician within 7 days. Early on, we were working on issues like pneumonia core measures and providing discharge instructions.”

He cautions those starting out in QI against viewing unintended outcomes or project setbacks as failure. “If your goal is to take a (scenario) from bad to perfect, you’ll end up getting discouraged. Any effort toward making things better is helpful. If it doesn’t work you try something else.”

While Dr. Bulger is fully supportive of the impact that quality improvement projects make at the institutional level, he encourages clinicians and researchers to always keep the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim in sight.

“We need better measures and more discussion about what is best for patients,” Dr. Bulger said. “The things we talk about in (health care) – readmission rates, glycemic control – have a minimal impact on people’s health, but the social determinants of health – the patient’s housing and economic situation – play a bigger role than anything else. As we move from provider- to patient-centric communities by fixing the Triple Aim, the experience will be better for both providers and patients.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of John Bulger, DO, chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan.

As chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan, John Bulger, DO, MBA, is intimately acquainted with the daily challenges that intersect with the delivery of safe, quality-driven care in the hospital system.

He’s also very familiar with the intricacies of carving out a professional road map. When Dr. Bulger began practicing as an internist at Geisinger Health System in the late 1990s, there wasn’t a formal hospitalist designation. He created one and became director of the hospital medicine program. Years later, when the opportunity arose to become chief quality officer, Dr. Bulger was a natural fit for the position, having led many improvement-centered committees and projects while running the hospital medicine group.

Early in his QI immersion, Dr. Bulger sought training where available from sources such as ACP and SHM, while familiarizing himself with methodologies such as PDSA and Lean. There are far more QI training opportunities available to hospitalists today than when Dr. Bulger began his journey, but the fundamentals of success come back to finding the right mentors, team building, and implementing projects built around SMART goals.

Getting started, Dr. Bulger suggests to “pick something within your scope, like medical reconciliation for every patient, or ensuring that every patient who leaves the hospital gets an appointment with their primary physician within 7 days. Early on, we were working on issues like pneumonia core measures and providing discharge instructions.”

He cautions those starting out in QI against viewing unintended outcomes or project setbacks as failure. “If your goal is to take a (scenario) from bad to perfect, you’ll end up getting discouraged. Any effort toward making things better is helpful. If it doesn’t work you try something else.”

While Dr. Bulger is fully supportive of the impact that quality improvement projects make at the institutional level, he encourages clinicians and researchers to always keep the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim in sight.

“We need better measures and more discussion about what is best for patients,” Dr. Bulger said. “The things we talk about in (health care) – readmission rates, glycemic control – have a minimal impact on people’s health, but the social determinants of health – the patient’s housing and economic situation – play a bigger role than anything else. As we move from provider- to patient-centric communities by fixing the Triple Aim, the experience will be better for both providers and patients.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of John Bulger, DO, chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan.

As chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan, John Bulger, DO, MBA, is intimately acquainted with the daily challenges that intersect with the delivery of safe, quality-driven care in the hospital system.

He’s also very familiar with the intricacies of carving out a professional road map. When Dr. Bulger began practicing as an internist at Geisinger Health System in the late 1990s, there wasn’t a formal hospitalist designation. He created one and became director of the hospital medicine program. Years later, when the opportunity arose to become chief quality officer, Dr. Bulger was a natural fit for the position, having led many improvement-centered committees and projects while running the hospital medicine group.

Early in his QI immersion, Dr. Bulger sought training where available from sources such as ACP and SHM, while familiarizing himself with methodologies such as PDSA and Lean. There are far more QI training opportunities available to hospitalists today than when Dr. Bulger began his journey, but the fundamentals of success come back to finding the right mentors, team building, and implementing projects built around SMART goals.

Getting started, Dr. Bulger suggests to “pick something within your scope, like medical reconciliation for every patient, or ensuring that every patient who leaves the hospital gets an appointment with their primary physician within 7 days. Early on, we were working on issues like pneumonia core measures and providing discharge instructions.”

He cautions those starting out in QI against viewing unintended outcomes or project setbacks as failure. “If your goal is to take a (scenario) from bad to perfect, you’ll end up getting discouraged. Any effort toward making things better is helpful. If it doesn’t work you try something else.”

While Dr. Bulger is fully supportive of the impact that quality improvement projects make at the institutional level, he encourages clinicians and researchers to always keep the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim in sight.

“We need better measures and more discussion about what is best for patients,” Dr. Bulger said. “The things we talk about in (health care) – readmission rates, glycemic control – have a minimal impact on people’s health, but the social determinants of health – the patient’s housing and economic situation – play a bigger role than anything else. As we move from provider- to patient-centric communities by fixing the Triple Aim, the experience will be better for both providers and patients.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Crossing the personal quality chasm: QI enthusiast to QI leader

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

For Eric Howell, MD, MHM, the journey to becoming a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, past president of SHM, and director of SHM’s Leadership Academies commenced with a major quality improvement (QI) challenge.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center was struggling with throughput from the emergency department when Dr. Howell began practicing there in the early days of hospital medicine. “The ED said the medicine service was too slow, and the hospitalists said, ‘We’re working as fast as we can,’ ” Dr. Howell recalled of his real-world introduction to implementation science. “So, I took on triage oversight in 2000 and began streamlining flow.”

With a growing reputation for finding solutions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions, Dr. Howell joined the Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (Project BOOST) project team in 2007 to codevelop one of SHM’s most successful programs. He humbly attributes some of this success to luck. “I happened to be at the right place at the right time. There was a problem, opportunity knocked, and I opened the door,” he said.

After some reflection, he pinpoints more tangible factors – a gift for innovative thinking and finding options that unify, rather than polarize, people and departments.

“I always ensure a solution makes the pie bigger, so that everyone benefits from it,” he said. “I don’t approach a problem like a sporting event, where one group wins and another loses.”

Dr. Howell says that an inclusive mindset is an important characteristic for anyone on a QI track because “it encourages buy-in from everyone who is impacted by a problem, and their investment in making the outcome successful.”

Skill development in areas such as leadership principles and processes such as lean will benefit those on a QI pathway, but finding the right mentors is just as critical. Dr. Howell looked to multiple people from diverse backgrounds, none of which included QI, to “help me move my skill set forward,” he said. “A clinical educator helped me to interact with other people, learn to facilitate an educational initiative, and lead people to change.”

Another mentor, he recalled, was an engineer who helped him figure out how to measure the success of his projects. And a third mentor cleared the pathway of obstructions, providing access to the people who would make his projects successful.

Being able to pivot is also important, Dr. Howell said. “Whether it is looking at data or the people you need to approach to solve a problem, be able to change your approach. Flip-flopping is a good thing in QI, because you’re always adjusting your tactics based on new information.”

Today, as SHM’s senior physician advisor to its Center for Quality Improvement, Dr. Howell holds multiple roles within the Johns Hopkins system and has received numerous awards for excellence in teaching and practice. The core principles that he started with on the path remain the same: “Be humble,” he said, “and give away credit. We are often collaborating with other professionals, so shining a light on the great work that they do will make projects more successful and improve the likelihood that they will want to collaborate with you in the future.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

For Eric Howell, MD, MHM, the journey to becoming a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, past president of SHM, and director of SHM’s Leadership Academies commenced with a major quality improvement (QI) challenge.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center was struggling with throughput from the emergency department when Dr. Howell began practicing there in the early days of hospital medicine. “The ED said the medicine service was too slow, and the hospitalists said, ‘We’re working as fast as we can,’ ” Dr. Howell recalled of his real-world introduction to implementation science. “So, I took on triage oversight in 2000 and began streamlining flow.”

With a growing reputation for finding solutions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions, Dr. Howell joined the Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (Project BOOST) project team in 2007 to codevelop one of SHM’s most successful programs. He humbly attributes some of this success to luck. “I happened to be at the right place at the right time. There was a problem, opportunity knocked, and I opened the door,” he said.

After some reflection, he pinpoints more tangible factors – a gift for innovative thinking and finding options that unify, rather than polarize, people and departments.

“I always ensure a solution makes the pie bigger, so that everyone benefits from it,” he said. “I don’t approach a problem like a sporting event, where one group wins and another loses.”

Dr. Howell says that an inclusive mindset is an important characteristic for anyone on a QI track because “it encourages buy-in from everyone who is impacted by a problem, and their investment in making the outcome successful.”

Skill development in areas such as leadership principles and processes such as lean will benefit those on a QI pathway, but finding the right mentors is just as critical. Dr. Howell looked to multiple people from diverse backgrounds, none of which included QI, to “help me move my skill set forward,” he said. “A clinical educator helped me to interact with other people, learn to facilitate an educational initiative, and lead people to change.”

Another mentor, he recalled, was an engineer who helped him figure out how to measure the success of his projects. And a third mentor cleared the pathway of obstructions, providing access to the people who would make his projects successful.

Being able to pivot is also important, Dr. Howell said. “Whether it is looking at data or the people you need to approach to solve a problem, be able to change your approach. Flip-flopping is a good thing in QI, because you’re always adjusting your tactics based on new information.”

Today, as SHM’s senior physician advisor to its Center for Quality Improvement, Dr. Howell holds multiple roles within the Johns Hopkins system and has received numerous awards for excellence in teaching and practice. The core principles that he started with on the path remain the same: “Be humble,” he said, “and give away credit. We are often collaborating with other professionals, so shining a light on the great work that they do will make projects more successful and improve the likelihood that they will want to collaborate with you in the future.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

For Eric Howell, MD, MHM, the journey to becoming a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, past president of SHM, and director of SHM’s Leadership Academies commenced with a major quality improvement (QI) challenge.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center was struggling with throughput from the emergency department when Dr. Howell began practicing there in the early days of hospital medicine. “The ED said the medicine service was too slow, and the hospitalists said, ‘We’re working as fast as we can,’ ” Dr. Howell recalled of his real-world introduction to implementation science. “So, I took on triage oversight in 2000 and began streamlining flow.”

With a growing reputation for finding solutions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions, Dr. Howell joined the Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (Project BOOST) project team in 2007 to codevelop one of SHM’s most successful programs. He humbly attributes some of this success to luck. “I happened to be at the right place at the right time. There was a problem, opportunity knocked, and I opened the door,” he said.

After some reflection, he pinpoints more tangible factors – a gift for innovative thinking and finding options that unify, rather than polarize, people and departments.

“I always ensure a solution makes the pie bigger, so that everyone benefits from it,” he said. “I don’t approach a problem like a sporting event, where one group wins and another loses.”

Dr. Howell says that an inclusive mindset is an important characteristic for anyone on a QI track because “it encourages buy-in from everyone who is impacted by a problem, and their investment in making the outcome successful.”

Skill development in areas such as leadership principles and processes such as lean will benefit those on a QI pathway, but finding the right mentors is just as critical. Dr. Howell looked to multiple people from diverse backgrounds, none of which included QI, to “help me move my skill set forward,” he said. “A clinical educator helped me to interact with other people, learn to facilitate an educational initiative, and lead people to change.”

Another mentor, he recalled, was an engineer who helped him figure out how to measure the success of his projects. And a third mentor cleared the pathway of obstructions, providing access to the people who would make his projects successful.

Being able to pivot is also important, Dr. Howell said. “Whether it is looking at data or the people you need to approach to solve a problem, be able to change your approach. Flip-flopping is a good thing in QI, because you’re always adjusting your tactics based on new information.”

Today, as SHM’s senior physician advisor to its Center for Quality Improvement, Dr. Howell holds multiple roles within the Johns Hopkins system and has received numerous awards for excellence in teaching and practice. The core principles that he started with on the path remain the same: “Be humble,” he said, “and give away credit. We are often collaborating with other professionals, so shining a light on the great work that they do will make projects more successful and improve the likelihood that they will want to collaborate with you in the future.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Crossing the personal quality chasm: QI enthusiast to QI leader

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Jennifer Myers, director of quality and safety education at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Even as a junior physician, Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, embraced the complexities of the hospital system and the opportunity to transform patient care. She was one of the first hospitalists to participate in and lead quality improvement (QI) work at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center more than 10 years ago, where, “in that role, I got to know almost everyone in the hospital and got an up-close view of how the hospital works administratively,” she recalled.

The experience taught Dr. Myers how little she knew at that time about hospital operations, and she convinced hospital administrators that a mechanism was needed to prepare the next generation of leaders in QI and patient safety. In 2011, with the support of a career development award from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Dr. Myers formulated a quality and patient safety curriculum for residents of Penn Medicine, as well as a more basic introductory program for medical students.

“You will always do your best in work that you are passionate about,” she said, advising others to do the same when choosing their career pathways. “Find others who are interested in – or frustrated by – the same things that you are, and work with them as you begin to shape your projects. If it’s the opioid epidemic, partner with someone in the hospital with an interest in making informed prescribing decisions. If it’s working with residents in quality, find a chief resident to help you develop an educational pathway or elective.”

Dr. Myers says that hospitalists who function at the intersection of the ICU, the ER, and inpatient care are naturally suited for leadership positions in quality and patient safety, “but, if you are a hospitalist aspiring to be a chief quality or medical officer or (someone) who wants to know the field more deeply, I recommend getting advanced training.”

Hospitalists now have multiple educational opportunities in QI to choose from, but that was not the case 7 years ago when SHM leaders invited Dr. Myers to develop and lead the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA). The 2.5-day program trains medical educators to develop curricula that incorporate quality improvement and safety principles into their local institutions. “We give them the core quality and safety knowledge but also the skills to develop and assess curricula,” Dr. Myers said. “The program also focuses on professional development and community building.”

While education is important, Dr. Myers says that a willingness to take risks is a greater predictor of success in QI. “It’s a very experiential field where you learn by doing. What you have done, and are willing to do, is more important than the training that you’ve had. Can you lead an initiative? Do you communicate well with people and teams? Can you articulate the value equation?”

She also advises hospitalists to find multiple mentors in quality work. “We talk a lot about that at QSEA,” Dr. Myers said. “It’s important to have the perspectives of people inside and outside of your institution. That’s also where the SHM network is helpful. Mentorship is a pillar of [many activities] at the annual meeting ... and [at] programs like the Academic Hospitalist Academy and QSEA.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Jennifer Myers, director of quality and safety education at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Even as a junior physician, Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, embraced the complexities of the hospital system and the opportunity to transform patient care. She was one of the first hospitalists to participate in and lead quality improvement (QI) work at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center more than 10 years ago, where, “in that role, I got to know almost everyone in the hospital and got an up-close view of how the hospital works administratively,” she recalled.

The experience taught Dr. Myers how little she knew at that time about hospital operations, and she convinced hospital administrators that a mechanism was needed to prepare the next generation of leaders in QI and patient safety. In 2011, with the support of a career development award from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Dr. Myers formulated a quality and patient safety curriculum for residents of Penn Medicine, as well as a more basic introductory program for medical students.

“You will always do your best in work that you are passionate about,” she said, advising others to do the same when choosing their career pathways. “Find others who are interested in – or frustrated by – the same things that you are, and work with them as you begin to shape your projects. If it’s the opioid epidemic, partner with someone in the hospital with an interest in making informed prescribing decisions. If it’s working with residents in quality, find a chief resident to help you develop an educational pathway or elective.”

Dr. Myers says that hospitalists who function at the intersection of the ICU, the ER, and inpatient care are naturally suited for leadership positions in quality and patient safety, “but, if you are a hospitalist aspiring to be a chief quality or medical officer or (someone) who wants to know the field more deeply, I recommend getting advanced training.”

Hospitalists now have multiple educational opportunities in QI to choose from, but that was not the case 7 years ago when SHM leaders invited Dr. Myers to develop and lead the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA). The 2.5-day program trains medical educators to develop curricula that incorporate quality improvement and safety principles into their local institutions. “We give them the core quality and safety knowledge but also the skills to develop and assess curricula,” Dr. Myers said. “The program also focuses on professional development and community building.”

While education is important, Dr. Myers says that a willingness to take risks is a greater predictor of success in QI. “It’s a very experiential field where you learn by doing. What you have done, and are willing to do, is more important than the training that you’ve had. Can you lead an initiative? Do you communicate well with people and teams? Can you articulate the value equation?”

She also advises hospitalists to find multiple mentors in quality work. “We talk a lot about that at QSEA,” Dr. Myers said. “It’s important to have the perspectives of people inside and outside of your institution. That’s also where the SHM network is helpful. Mentorship is a pillar of [many activities] at the annual meeting ... and [at] programs like the Academic Hospitalist Academy and QSEA.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Jennifer Myers, director of quality and safety education at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Even as a junior physician, Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, embraced the complexities of the hospital system and the opportunity to transform patient care. She was one of the first hospitalists to participate in and lead quality improvement (QI) work at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center more than 10 years ago, where, “in that role, I got to know almost everyone in the hospital and got an up-close view of how the hospital works administratively,” she recalled.

The experience taught Dr. Myers how little she knew at that time about hospital operations, and she convinced hospital administrators that a mechanism was needed to prepare the next generation of leaders in QI and patient safety. In 2011, with the support of a career development award from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Dr. Myers formulated a quality and patient safety curriculum for residents of Penn Medicine, as well as a more basic introductory program for medical students.

“You will always do your best in work that you are passionate about,” she said, advising others to do the same when choosing their career pathways. “Find others who are interested in – or frustrated by – the same things that you are, and work with them as you begin to shape your projects. If it’s the opioid epidemic, partner with someone in the hospital with an interest in making informed prescribing decisions. If it’s working with residents in quality, find a chief resident to help you develop an educational pathway or elective.”

Dr. Myers says that hospitalists who function at the intersection of the ICU, the ER, and inpatient care are naturally suited for leadership positions in quality and patient safety, “but, if you are a hospitalist aspiring to be a chief quality or medical officer or (someone) who wants to know the field more deeply, I recommend getting advanced training.”

Hospitalists now have multiple educational opportunities in QI to choose from, but that was not the case 7 years ago when SHM leaders invited Dr. Myers to develop and lead the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA). The 2.5-day program trains medical educators to develop curricula that incorporate quality improvement and safety principles into their local institutions. “We give them the core quality and safety knowledge but also the skills to develop and assess curricula,” Dr. Myers said. “The program also focuses on professional development and community building.”

While education is important, Dr. Myers says that a willingness to take risks is a greater predictor of success in QI. “It’s a very experiential field where you learn by doing. What you have done, and are willing to do, is more important than the training that you’ve had. Can you lead an initiative? Do you communicate well with people and teams? Can you articulate the value equation?”

She also advises hospitalists to find multiple mentors in quality work. “We talk a lot about that at QSEA,” Dr. Myers said. “It’s important to have the perspectives of people inside and outside of your institution. That’s also where the SHM network is helpful. Mentorship is a pillar of [many activities] at the annual meeting ... and [at] programs like the Academic Hospitalist Academy and QSEA.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

QI enthusiast turns QI leader

Editor’s note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chose a career path in hospital medicine for the reasons that attract many to the specialty – a love of “a little bit of everything, clinically” and the opportunity to problem-solve a diverse range of professional challenges on a daily basis.

“I was frustrated with our internal inefficiencies, and motivated by wanting to provide optimal care to patients,” Dr. O’Leary said, recalling his entry into the world of quality improvement. “It was the first time as a physician that I felt like quality was a problem that I owned – and if anyone was going to address it, it would have to be a hospitalist.”

That epiphany 16 years ago led Dr. O’Leary, now chief of hospital medicine at the same institution, on a path of enacting change. He began volunteering on small improvement projects around the hospital, which led to an invitation to chair the Quality Management Committee in the hospital medicine department. He continued to build his skills by enrolling in Six Sigma training and in Northwestern University’s Master in Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety program.

“That was transformative,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The master’s program, coupled with performance training, changed the trajectory of my career in quality improvement.”

While he encourages anyone with an interest in QI to seek additional training opportunities, he says personal qualities – tenacity, curiosity, and a willingness to collaborate—are better predictors of success. For those wondering how to get started, “look for a niche, an unmet need that is valuable to your organization, and fill it,” he advised. “You don’t have to be an expert in that area, but you can become one.”

Making strong connections within the hospital system is essential. Reach out to the contacts you know, he said, and if they are not the ones to help you solve the problem, they often know who can.

“That’s key to quality improvement success, as well as career success,” he said. “Find a mentor. It might be someone who is more senior within the hospitalist group, in medicine, or even outside the hospital. Meet with them regularly and ask them for feedback on your ideas.”

Newcomers to QI should embrace opportunities to change care and not get discouraged when a project has unintended outcomes.

“Failure is when a team never gets to the point of implementing the intervention or when a team doesn’t know whether the intervention has actually changed results,” he said. “Learning why an intervention isn’t effective can be as valuable as implementing one that is. If every project is successful, it just means that you’re not taking enough risks.”

Dr. O’Leary spends about 25% of his professional time providing clinical care, and another 15% meeting his responsibilities as division chief. He uses the other protected time in his schedule to lead QI and teach QI skills in programs like Northwestern Medicine’s Academy for Quality and Safety Improvement (AQSI).

As a former faculty member in SHM’s Quality and Safety Educator’s Academy (QSEA), he has trained medical educators to develop curricula in quality improvement and patient safety. He says both AQSI and QSEA are especially effective because they encourage interaction, which is valuable to professionals at all levels looking to advance their skill in QI.

“Even in a teaching capacity,” he noted, “what I learned from other faculty and participants in QSEA was critical.”

Residents and junior hospitalists often have the impression that they lack the skills to lead quality initiatives, but Dr. O’Leary says medical school provides the nuts and bolts – analytical skills, statistical knowledge, critical thinking. He encouraged hospitalists to move ahead, even without formal QI training.

“If you have strong interpersonal skills – the willingness to make friends and build connections – you will be successful,” he said.

It’s also an excellent way to learn about the ins and outs of the hospital system and the work of other departments and specialties. Dr. O’Leary especially enjoys that aspect of his work, as well as the ability to address systemic issues that he values.

“I get the greatest fulfillment from the opportunity to be creative … and to implement projects that are important to me and help patients,” he said. “As long as the projects align with organizational goals, I can usually find the support we need to be successful.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chose a career path in hospital medicine for the reasons that attract many to the specialty – a love of “a little bit of everything, clinically” and the opportunity to problem-solve a diverse range of professional challenges on a daily basis.

“I was frustrated with our internal inefficiencies, and motivated by wanting to provide optimal care to patients,” Dr. O’Leary said, recalling his entry into the world of quality improvement. “It was the first time as a physician that I felt like quality was a problem that I owned – and if anyone was going to address it, it would have to be a hospitalist.”

That epiphany 16 years ago led Dr. O’Leary, now chief of hospital medicine at the same institution, on a path of enacting change. He began volunteering on small improvement projects around the hospital, which led to an invitation to chair the Quality Management Committee in the hospital medicine department. He continued to build his skills by enrolling in Six Sigma training and in Northwestern University’s Master in Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety program.

“That was transformative,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The master’s program, coupled with performance training, changed the trajectory of my career in quality improvement.”

While he encourages anyone with an interest in QI to seek additional training opportunities, he says personal qualities – tenacity, curiosity, and a willingness to collaborate—are better predictors of success. For those wondering how to get started, “look for a niche, an unmet need that is valuable to your organization, and fill it,” he advised. “You don’t have to be an expert in that area, but you can become one.”

Making strong connections within the hospital system is essential. Reach out to the contacts you know, he said, and if they are not the ones to help you solve the problem, they often know who can.

“That’s key to quality improvement success, as well as career success,” he said. “Find a mentor. It might be someone who is more senior within the hospitalist group, in medicine, or even outside the hospital. Meet with them regularly and ask them for feedback on your ideas.”

Newcomers to QI should embrace opportunities to change care and not get discouraged when a project has unintended outcomes.

“Failure is when a team never gets to the point of implementing the intervention or when a team doesn’t know whether the intervention has actually changed results,” he said. “Learning why an intervention isn’t effective can be as valuable as implementing one that is. If every project is successful, it just means that you’re not taking enough risks.”

Dr. O’Leary spends about 25% of his professional time providing clinical care, and another 15% meeting his responsibilities as division chief. He uses the other protected time in his schedule to lead QI and teach QI skills in programs like Northwestern Medicine’s Academy for Quality and Safety Improvement (AQSI).

As a former faculty member in SHM’s Quality and Safety Educator’s Academy (QSEA), he has trained medical educators to develop curricula in quality improvement and patient safety. He says both AQSI and QSEA are especially effective because they encourage interaction, which is valuable to professionals at all levels looking to advance their skill in QI.

“Even in a teaching capacity,” he noted, “what I learned from other faculty and participants in QSEA was critical.”

Residents and junior hospitalists often have the impression that they lack the skills to lead quality initiatives, but Dr. O’Leary says medical school provides the nuts and bolts – analytical skills, statistical knowledge, critical thinking. He encouraged hospitalists to move ahead, even without formal QI training.

“If you have strong interpersonal skills – the willingness to make friends and build connections – you will be successful,” he said.

It’s also an excellent way to learn about the ins and outs of the hospital system and the work of other departments and specialties. Dr. O’Leary especially enjoys that aspect of his work, as well as the ability to address systemic issues that he values.

“I get the greatest fulfillment from the opportunity to be creative … and to implement projects that are important to me and help patients,” he said. “As long as the projects align with organizational goals, I can usually find the support we need to be successful.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chose a career path in hospital medicine for the reasons that attract many to the specialty – a love of “a little bit of everything, clinically” and the opportunity to problem-solve a diverse range of professional challenges on a daily basis.

“I was frustrated with our internal inefficiencies, and motivated by wanting to provide optimal care to patients,” Dr. O’Leary said, recalling his entry into the world of quality improvement. “It was the first time as a physician that I felt like quality was a problem that I owned – and if anyone was going to address it, it would have to be a hospitalist.”

That epiphany 16 years ago led Dr. O’Leary, now chief of hospital medicine at the same institution, on a path of enacting change. He began volunteering on small improvement projects around the hospital, which led to an invitation to chair the Quality Management Committee in the hospital medicine department. He continued to build his skills by enrolling in Six Sigma training and in Northwestern University’s Master in Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety program.

“That was transformative,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The master’s program, coupled with performance training, changed the trajectory of my career in quality improvement.”

While he encourages anyone with an interest in QI to seek additional training opportunities, he says personal qualities – tenacity, curiosity, and a willingness to collaborate—are better predictors of success. For those wondering how to get started, “look for a niche, an unmet need that is valuable to your organization, and fill it,” he advised. “You don’t have to be an expert in that area, but you can become one.”

Making strong connections within the hospital system is essential. Reach out to the contacts you know, he said, and if they are not the ones to help you solve the problem, they often know who can.

“That’s key to quality improvement success, as well as career success,” he said. “Find a mentor. It might be someone who is more senior within the hospitalist group, in medicine, or even outside the hospital. Meet with them regularly and ask them for feedback on your ideas.”

Newcomers to QI should embrace opportunities to change care and not get discouraged when a project has unintended outcomes.

“Failure is when a team never gets to the point of implementing the intervention or when a team doesn’t know whether the intervention has actually changed results,” he said. “Learning why an intervention isn’t effective can be as valuable as implementing one that is. If every project is successful, it just means that you’re not taking enough risks.”

Dr. O’Leary spends about 25% of his professional time providing clinical care, and another 15% meeting his responsibilities as division chief. He uses the other protected time in his schedule to lead QI and teach QI skills in programs like Northwestern Medicine’s Academy for Quality and Safety Improvement (AQSI).

As a former faculty member in SHM’s Quality and Safety Educator’s Academy (QSEA), he has trained medical educators to develop curricula in quality improvement and patient safety. He says both AQSI and QSEA are especially effective because they encourage interaction, which is valuable to professionals at all levels looking to advance their skill in QI.

“Even in a teaching capacity,” he noted, “what I learned from other faculty and participants in QSEA was critical.”

Residents and junior hospitalists often have the impression that they lack the skills to lead quality initiatives, but Dr. O’Leary says medical school provides the nuts and bolts – analytical skills, statistical knowledge, critical thinking. He encouraged hospitalists to move ahead, even without formal QI training.

“If you have strong interpersonal skills – the willingness to make friends and build connections – you will be successful,” he said.

It’s also an excellent way to learn about the ins and outs of the hospital system and the work of other departments and specialties. Dr. O’Leary especially enjoys that aspect of his work, as well as the ability to address systemic issues that he values.

“I get the greatest fulfillment from the opportunity to be creative … and to implement projects that are important to me and help patients,” he said. “As long as the projects align with organizational goals, I can usually find the support we need to be successful.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

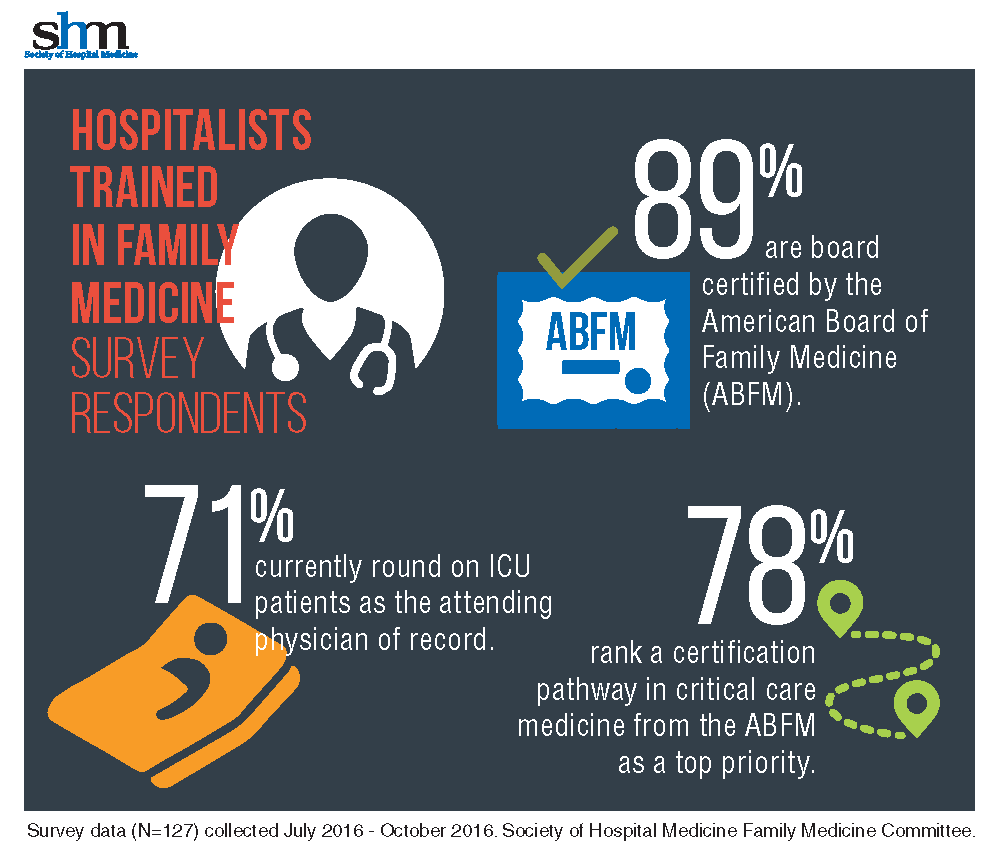

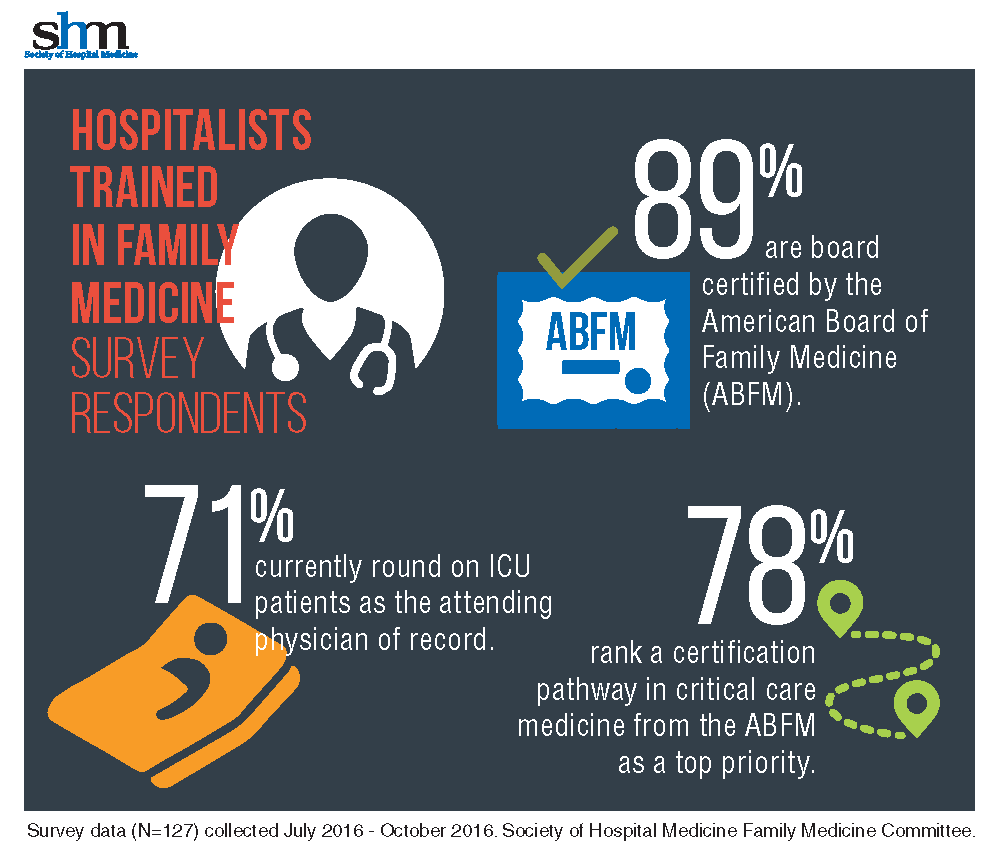

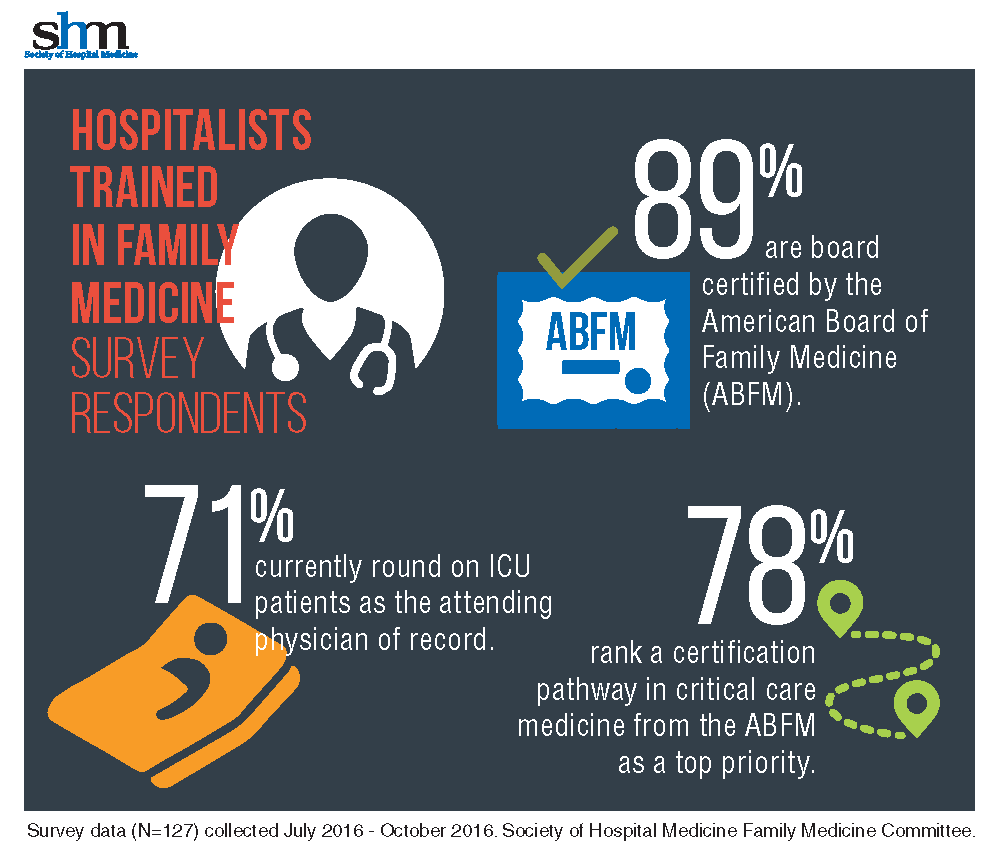

Hospitalists trained in family medicine seek critical care training pathway

A nationwide shortage of intensivists has more hospitalists stepping into the critical care arena, but not all with the level of preparation and comfort of David Aymond, MD, a Louisiana-based hospitalist trained in family medicine (HTFM).

Dr. Aymond gained his ICU experience in a fellowship with the University of Alabama, where hospitalists also “were responsible for ICU patients,” he said. Years later, as an employee of both small and large hospitals with busy ICU services, and a faculty member for a family medicine residency with a busy ICU, Dr. Aymond moves seamlessly between roles.

“It was eye-opening to learn how many [HTFM] are not only caring for patients in the ICU, but also are requesting additional training,” said Dr. Aymond, a member of the SHM Family Medicine Committee. “A critical care pathway would provide them with a level of expertise already available to physicians in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and surgery.”

With 71% of HTFM reporting that they round on ICU as the attending physician, the strong endorsement (78%) for critical care certification is not surprising.

“I am currently practicing as a full time intensivist and take consults from other providers, yet I only have a certificate from fellowship, no formal board certification in critical care,” noted a survey respondent.

Other participants stated, “it makes perfect sense to have a pathway to critical care if both family medicine and internal medicine coexist as hospitalists,” that certification is “imperative at rural and underserved hospitals,” and also “helpful for those …who work in larger hospitals and take care of critically ill patients.” More than half of those surveyed want the Family Medicine Committee to work with ABFM to create the pathway.

The majority (87%) of the HTFM survey respondents are certified by the ABFM, and 8% have attained Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine. Common pathways for additional credentialing include SHM’s Fellow of Hospital Medicine program (38%), a fellowship in hospital medicine (19%), and certification in hospice and palliative care (15%). More than 38% reported “other qualifications,” such as years of work experience, certification by the American Osteopathic Board of Family Physicians, and prior training in internal medicine.

The survey also found that certification differences in internal medicine and family medicine hospitalists, which may have posed employment obstacles in the past for HTFM, are not as much of an issue.

“The critical care pathway is the bigger concern,” Dr. Aymond said.

SHM’s Family Medicine Committee will be working on a proposal to ABFM to create the training pathway in the coming months. Dr. Aymond wants intensivists to know that this not an attempt to encroach on their professional domain, “but an opportunity to fill the existing professional gap.

Family medicine physicians are already providing critical care services, so a pathway to obtain formal training makes sense,” he adds. “If a family medicine doc completes the fellowship and takes it back to a residency program [the residents] will be more prepared for their potential careers in hospital and ICU medicine and much more comfortable with high-acuity patients.”

Claudia Stahl is SHM’s content manager.

A nationwide shortage of intensivists has more hospitalists stepping into the critical care arena, but not all with the level of preparation and comfort of David Aymond, MD, a Louisiana-based hospitalist trained in family medicine (HTFM).

Dr. Aymond gained his ICU experience in a fellowship with the University of Alabama, where hospitalists also “were responsible for ICU patients,” he said. Years later, as an employee of both small and large hospitals with busy ICU services, and a faculty member for a family medicine residency with a busy ICU, Dr. Aymond moves seamlessly between roles.

“It was eye-opening to learn how many [HTFM] are not only caring for patients in the ICU, but also are requesting additional training,” said Dr. Aymond, a member of the SHM Family Medicine Committee. “A critical care pathway would provide them with a level of expertise already available to physicians in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and surgery.”

With 71% of HTFM reporting that they round on ICU as the attending physician, the strong endorsement (78%) for critical care certification is not surprising.

“I am currently practicing as a full time intensivist and take consults from other providers, yet I only have a certificate from fellowship, no formal board certification in critical care,” noted a survey respondent.

Other participants stated, “it makes perfect sense to have a pathway to critical care if both family medicine and internal medicine coexist as hospitalists,” that certification is “imperative at rural and underserved hospitals,” and also “helpful for those …who work in larger hospitals and take care of critically ill patients.” More than half of those surveyed want the Family Medicine Committee to work with ABFM to create the pathway.

The majority (87%) of the HTFM survey respondents are certified by the ABFM, and 8% have attained Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine. Common pathways for additional credentialing include SHM’s Fellow of Hospital Medicine program (38%), a fellowship in hospital medicine (19%), and certification in hospice and palliative care (15%). More than 38% reported “other qualifications,” such as years of work experience, certification by the American Osteopathic Board of Family Physicians, and prior training in internal medicine.

The survey also found that certification differences in internal medicine and family medicine hospitalists, which may have posed employment obstacles in the past for HTFM, are not as much of an issue.

“The critical care pathway is the bigger concern,” Dr. Aymond said.

SHM’s Family Medicine Committee will be working on a proposal to ABFM to create the training pathway in the coming months. Dr. Aymond wants intensivists to know that this not an attempt to encroach on their professional domain, “but an opportunity to fill the existing professional gap.

Family medicine physicians are already providing critical care services, so a pathway to obtain formal training makes sense,” he adds. “If a family medicine doc completes the fellowship and takes it back to a residency program [the residents] will be more prepared for their potential careers in hospital and ICU medicine and much more comfortable with high-acuity patients.”

Claudia Stahl is SHM’s content manager.

A nationwide shortage of intensivists has more hospitalists stepping into the critical care arena, but not all with the level of preparation and comfort of David Aymond, MD, a Louisiana-based hospitalist trained in family medicine (HTFM).

Dr. Aymond gained his ICU experience in a fellowship with the University of Alabama, where hospitalists also “were responsible for ICU patients,” he said. Years later, as an employee of both small and large hospitals with busy ICU services, and a faculty member for a family medicine residency with a busy ICU, Dr. Aymond moves seamlessly between roles.

“It was eye-opening to learn how many [HTFM] are not only caring for patients in the ICU, but also are requesting additional training,” said Dr. Aymond, a member of the SHM Family Medicine Committee. “A critical care pathway would provide them with a level of expertise already available to physicians in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and surgery.”

With 71% of HTFM reporting that they round on ICU as the attending physician, the strong endorsement (78%) for critical care certification is not surprising.

“I am currently practicing as a full time intensivist and take consults from other providers, yet I only have a certificate from fellowship, no formal board certification in critical care,” noted a survey respondent.