User login

VIDEO: Meta-analysis favors anticoagulation for patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis

Patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) who received anticoagulation therapy had nearly fivefold greater odds of recanalization compared with untreated patients, and were no more likely to experience major or minor bleeding, in a pooled analysis of eight studies published in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.042).

Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001), wrote Lorenzo Loffredo, MD, of Sapienza University, Rome, and his coinvestigators. Rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group. Together, the findings “show that anticoagulants are efficacious and safe for treatment of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients,” although larger, interventional clinical trials are needed to pinpoint the clinical role of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients with PVT, the reviewers reported.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Bleeding from portal hypertension is a major complication in cirrhosis, but PVT affects about 20% of patients and predicts poor outcomes, they noted. Anticoagulation in this setting can be difficult because patients often have concurrent coagulopathies that are hard to assess with standard techniques, such as PT-INR (international normalized ratio). Although some studies support anticoagulating these patients, data are limited. Therefore, the reviewers searched PubMed, the ISI Web of Science, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane database through Feb. 14, 2017, for trials comparing anticoagulation with no treatment in patients with cirrhosis and PVT.

This search yielded eight trials of 353 patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or no treatment for about 6 months, with a typical follow-up period of 2 years. The reviewers found no evidence of publication bias or significant heterogeneity among the trials. Six studies evaluated complete recanalization, another set of six studies tracked progression of PVT, a third set of six studies evaluated major or minor bleeding events, and four studies evaluated spontaneous variceal bleeding. Compared with no treatment, anticoagulation was tied to a significantly greater likelihood of complete recanalization (pooled odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-7.4; P = .002), a significantly lower chance of PVT progressing (9% vs. 33%; pooled odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06-0.31; P less than .0001), no difference in bleeding rates (11% in each pooled group), and a significantly lower risk of spontaneous variceal bleeding (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.94; P = .04).

“Metaregression analysis showed that duration of anticoagulation did not influence outcomes,” the reviewers wrote. “Low-molecular-weight heparin, but not warfarin, was significantly associated with a complete PVT resolution as compared to untreated patients, while both low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin were effective in reducing PVT progression.” That finding merits careful interpretation, however, because most studies on warfarin were retrospective and lacked data on the quality of anticoagulation, they added.

“It is a challenge to treat patients with cirrhosis using anticoagulants because of the perception that the coexistent coagulopathy could promote bleeding,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, their analysis suggests that anticoagulation has significant benefits and does not increase bleeding risk, regardless of the severity of liver failure, they concluded.

The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) who received anticoagulation therapy had nearly fivefold greater odds of recanalization compared with untreated patients, and were no more likely to experience major or minor bleeding, in a pooled analysis of eight studies published in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.042).

Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001), wrote Lorenzo Loffredo, MD, of Sapienza University, Rome, and his coinvestigators. Rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group. Together, the findings “show that anticoagulants are efficacious and safe for treatment of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients,” although larger, interventional clinical trials are needed to pinpoint the clinical role of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients with PVT, the reviewers reported.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Bleeding from portal hypertension is a major complication in cirrhosis, but PVT affects about 20% of patients and predicts poor outcomes, they noted. Anticoagulation in this setting can be difficult because patients often have concurrent coagulopathies that are hard to assess with standard techniques, such as PT-INR (international normalized ratio). Although some studies support anticoagulating these patients, data are limited. Therefore, the reviewers searched PubMed, the ISI Web of Science, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane database through Feb. 14, 2017, for trials comparing anticoagulation with no treatment in patients with cirrhosis and PVT.

This search yielded eight trials of 353 patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or no treatment for about 6 months, with a typical follow-up period of 2 years. The reviewers found no evidence of publication bias or significant heterogeneity among the trials. Six studies evaluated complete recanalization, another set of six studies tracked progression of PVT, a third set of six studies evaluated major or minor bleeding events, and four studies evaluated spontaneous variceal bleeding. Compared with no treatment, anticoagulation was tied to a significantly greater likelihood of complete recanalization (pooled odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-7.4; P = .002), a significantly lower chance of PVT progressing (9% vs. 33%; pooled odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06-0.31; P less than .0001), no difference in bleeding rates (11% in each pooled group), and a significantly lower risk of spontaneous variceal bleeding (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.94; P = .04).

“Metaregression analysis showed that duration of anticoagulation did not influence outcomes,” the reviewers wrote. “Low-molecular-weight heparin, but not warfarin, was significantly associated with a complete PVT resolution as compared to untreated patients, while both low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin were effective in reducing PVT progression.” That finding merits careful interpretation, however, because most studies on warfarin were retrospective and lacked data on the quality of anticoagulation, they added.

“It is a challenge to treat patients with cirrhosis using anticoagulants because of the perception that the coexistent coagulopathy could promote bleeding,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, their analysis suggests that anticoagulation has significant benefits and does not increase bleeding risk, regardless of the severity of liver failure, they concluded.

The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) who received anticoagulation therapy had nearly fivefold greater odds of recanalization compared with untreated patients, and were no more likely to experience major or minor bleeding, in a pooled analysis of eight studies published in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.042).

Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001), wrote Lorenzo Loffredo, MD, of Sapienza University, Rome, and his coinvestigators. Rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group. Together, the findings “show that anticoagulants are efficacious and safe for treatment of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients,” although larger, interventional clinical trials are needed to pinpoint the clinical role of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients with PVT, the reviewers reported.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Bleeding from portal hypertension is a major complication in cirrhosis, but PVT affects about 20% of patients and predicts poor outcomes, they noted. Anticoagulation in this setting can be difficult because patients often have concurrent coagulopathies that are hard to assess with standard techniques, such as PT-INR (international normalized ratio). Although some studies support anticoagulating these patients, data are limited. Therefore, the reviewers searched PubMed, the ISI Web of Science, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane database through Feb. 14, 2017, for trials comparing anticoagulation with no treatment in patients with cirrhosis and PVT.

This search yielded eight trials of 353 patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or no treatment for about 6 months, with a typical follow-up period of 2 years. The reviewers found no evidence of publication bias or significant heterogeneity among the trials. Six studies evaluated complete recanalization, another set of six studies tracked progression of PVT, a third set of six studies evaluated major or minor bleeding events, and four studies evaluated spontaneous variceal bleeding. Compared with no treatment, anticoagulation was tied to a significantly greater likelihood of complete recanalization (pooled odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-7.4; P = .002), a significantly lower chance of PVT progressing (9% vs. 33%; pooled odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06-0.31; P less than .0001), no difference in bleeding rates (11% in each pooled group), and a significantly lower risk of spontaneous variceal bleeding (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.94; P = .04).

“Metaregression analysis showed that duration of anticoagulation did not influence outcomes,” the reviewers wrote. “Low-molecular-weight heparin, but not warfarin, was significantly associated with a complete PVT resolution as compared to untreated patients, while both low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin were effective in reducing PVT progression.” That finding merits careful interpretation, however, because most studies on warfarin were retrospective and lacked data on the quality of anticoagulation, they added.

“It is a challenge to treat patients with cirrhosis using anticoagulants because of the perception that the coexistent coagulopathy could promote bleeding,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, their analysis suggests that anticoagulation has significant benefits and does not increase bleeding risk, regardless of the severity of liver failure, they concluded.

The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Anticoagulation produced favorable outcomes with no increase in bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis.

Major finding: Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001); rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group.

Data source: A systematic review and meta-analysis of eight studies of 353 patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis.

Disclosures: The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Cosmeceuticals and Alternative Therapies for Rosacea

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

Debunking Acne Myths: Is Itching a Symptom of Acne?

Myth: Itching is not a symptom of acne

Acne vulgaris typically is not considered to be a pruritic disease; however, many patients experience itching, which leads them to scratch their acne lesions, causing secondary bacterial infections and subsequent scarring, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation of the involved skin. Although itching rarely is mentioned as a clinical feature of acne, pruritus can be an important contributory factor to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life in acne patients of all ages, and acne itching may be an important target for therapy.

In a descriptive study of 120 consecutive acne patients in Singapore, itch was found to be a common (70% of patients) and debilitating symptom of acne. The majority of patients (83%) reported itch at noon with severity that was comparable to a mosquito bite, and the most common physical descriptor was tickling (68%). Common aggravating factors included sweat (71%), heat (62%), and stress (31%). Fifty-five percent of patients said itching had a negative impact on their mood, and 52% reported that they had scratched or rubbed the affected area.

A study of 108 adolescents with acne limited to the face yielded half who reported itching within acne lesions. The presence of itching was unrelated to age, gender, where they lived, positive family history, or acne severity. In most patients, pruritus appeared relatively infrequently and for a short period of time: 7.4% reported itching every day, 24.1% on a weekly basis, 29.6% at least once a month, and 37.7% even less frequently. Itch episodes lasted less than 1 minute in most participants. However, 31.5% of participants sought medical treatment to reduce itching. The most important factors aggravating the intensity of itching were sweat, stress, physical effort, heat, fatigue, and dry air, respectively.

Regarding the impact of acne itching on quality of life, 29.6% of participants felt depressed and 1.8% were anxious because of their itching. Some participants also noted that itching caused difficulties in falling asleep and awakening from itching.

The pathogenesis of localized itching in acne could be connected with the change in pH of the microenvironment of the acne follicle, providing an optimal environment for the production of histamine or histaminelike products by Propionibacterium acnes. Pruritus also may be a complication of certain acne therapies. Increased awareness among patients of this potential side effect may be helpful in preventing the unnecessary discontinuation of an otherwise effective acne therapy. Understanding factors that may aggravate itching in acne lesions also may be helpful to patients.

Lim YL, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G, et al. Pruritus is a common and significant symptom of acne [published online July 8, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1332-1336.

Reich A, Trybucka K, Tracinska A, et al. Acne itch: do acne patients suffer from itching? Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:38-42.

Myth: Itching is not a symptom of acne

Acne vulgaris typically is not considered to be a pruritic disease; however, many patients experience itching, which leads them to scratch their acne lesions, causing secondary bacterial infections and subsequent scarring, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation of the involved skin. Although itching rarely is mentioned as a clinical feature of acne, pruritus can be an important contributory factor to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life in acne patients of all ages, and acne itching may be an important target for therapy.

In a descriptive study of 120 consecutive acne patients in Singapore, itch was found to be a common (70% of patients) and debilitating symptom of acne. The majority of patients (83%) reported itch at noon with severity that was comparable to a mosquito bite, and the most common physical descriptor was tickling (68%). Common aggravating factors included sweat (71%), heat (62%), and stress (31%). Fifty-five percent of patients said itching had a negative impact on their mood, and 52% reported that they had scratched or rubbed the affected area.

A study of 108 adolescents with acne limited to the face yielded half who reported itching within acne lesions. The presence of itching was unrelated to age, gender, where they lived, positive family history, or acne severity. In most patients, pruritus appeared relatively infrequently and for a short period of time: 7.4% reported itching every day, 24.1% on a weekly basis, 29.6% at least once a month, and 37.7% even less frequently. Itch episodes lasted less than 1 minute in most participants. However, 31.5% of participants sought medical treatment to reduce itching. The most important factors aggravating the intensity of itching were sweat, stress, physical effort, heat, fatigue, and dry air, respectively.

Regarding the impact of acne itching on quality of life, 29.6% of participants felt depressed and 1.8% were anxious because of their itching. Some participants also noted that itching caused difficulties in falling asleep and awakening from itching.

The pathogenesis of localized itching in acne could be connected with the change in pH of the microenvironment of the acne follicle, providing an optimal environment for the production of histamine or histaminelike products by Propionibacterium acnes. Pruritus also may be a complication of certain acne therapies. Increased awareness among patients of this potential side effect may be helpful in preventing the unnecessary discontinuation of an otherwise effective acne therapy. Understanding factors that may aggravate itching in acne lesions also may be helpful to patients.

Myth: Itching is not a symptom of acne

Acne vulgaris typically is not considered to be a pruritic disease; however, many patients experience itching, which leads them to scratch their acne lesions, causing secondary bacterial infections and subsequent scarring, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation of the involved skin. Although itching rarely is mentioned as a clinical feature of acne, pruritus can be an important contributory factor to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life in acne patients of all ages, and acne itching may be an important target for therapy.

In a descriptive study of 120 consecutive acne patients in Singapore, itch was found to be a common (70% of patients) and debilitating symptom of acne. The majority of patients (83%) reported itch at noon with severity that was comparable to a mosquito bite, and the most common physical descriptor was tickling (68%). Common aggravating factors included sweat (71%), heat (62%), and stress (31%). Fifty-five percent of patients said itching had a negative impact on their mood, and 52% reported that they had scratched or rubbed the affected area.

A study of 108 adolescents with acne limited to the face yielded half who reported itching within acne lesions. The presence of itching was unrelated to age, gender, where they lived, positive family history, or acne severity. In most patients, pruritus appeared relatively infrequently and for a short period of time: 7.4% reported itching every day, 24.1% on a weekly basis, 29.6% at least once a month, and 37.7% even less frequently. Itch episodes lasted less than 1 minute in most participants. However, 31.5% of participants sought medical treatment to reduce itching. The most important factors aggravating the intensity of itching were sweat, stress, physical effort, heat, fatigue, and dry air, respectively.

Regarding the impact of acne itching on quality of life, 29.6% of participants felt depressed and 1.8% were anxious because of their itching. Some participants also noted that itching caused difficulties in falling asleep and awakening from itching.

The pathogenesis of localized itching in acne could be connected with the change in pH of the microenvironment of the acne follicle, providing an optimal environment for the production of histamine or histaminelike products by Propionibacterium acnes. Pruritus also may be a complication of certain acne therapies. Increased awareness among patients of this potential side effect may be helpful in preventing the unnecessary discontinuation of an otherwise effective acne therapy. Understanding factors that may aggravate itching in acne lesions also may be helpful to patients.

Lim YL, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G, et al. Pruritus is a common and significant symptom of acne [published online July 8, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1332-1336.

Reich A, Trybucka K, Tracinska A, et al. Acne itch: do acne patients suffer from itching? Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:38-42.

Lim YL, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G, et al. Pruritus is a common and significant symptom of acne [published online July 8, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1332-1336.

Reich A, Trybucka K, Tracinska A, et al. Acne itch: do acne patients suffer from itching? Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:38-42.

Emergency Ultrasound: Ultrasound-Guided Arthrocentesis of the Ankle

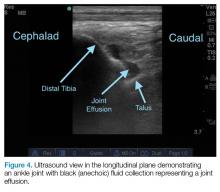

Ankle effusions can be quite debilitating, causing band-like swelling and stiffness to the anterior aspect of ankle at the tibiotalar joint. Significant swelling can impair ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The differential diagnosis for joint effusions is wide, and includes traumatic effusion; gout; osteoarthritis; rheumatoid arthritis; and septic arthritis, which is one of the most important diagnoses for the emergency physician (EP) to identify and initiate prompt treatment to reduce the risk of serious morbidity and mortality. Differentiating these conditions requires joint aspiration and synovial fluid analysis. While a large effusion will be palpable and likely ballotable, smaller effusions are more challenging clinically. In such cases, point-of-care (POC) ultrasound can be a valuable tool in confirming a joint effusion.

Identifying Landmarks and Tibiotalar Joint

To access the tibiotalar joint space, it is important to identify useful landmarks.1 This is best accomplished by having the patient in the supine position, with the affected knee flexed approximately 90° and plantar surface of the foot lying flat on the bed (Figure 1).

Performing the Arthrocentesis

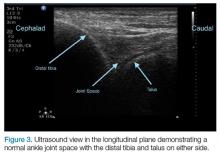

The arthrocentesis is performed under sterile conditions using the high-frequency linear probe. A sterile probe cover is highly recommended if the operator will be using ultrasound to guide the procedure in real time.2 Using the palpable landmarks as a guide, the clinician should align the probe just medial to the tibialis anterior tendon with the probe marker oriented cephalad; scanning should begin superior to the ankle joint. The tibia will appear as a hyperechoic stripe just under a thin soft tissue layer. When the tibia is visible, the clinician should then slide the probe distally. The joint space will demonstrated by visualization of the distal tibia and talus bone (Figure 3).

Pearls and Pitfalls

Point-of-care ultrasound is not only useful to guide arthrocentesis of joint effusions, but also to confirm the presence of an effusion prior to aspiration. At our institution, we have had many cases in which POC ultrasound demonstrated an absence of effusion, and we were able to avoid an unnecessary joint aspiration. Moreover, when an effusion is present, POC ultrasound-guided aspiration avoids complications. The use of POC ultrasound can also increase the confidence of the provider performing arthrocentesis of joints less commonly aspirated.

Summary

Joint aspiration is an important procedural tool for EPs, especially when used to rule out life-threatening conditions such as septic arthritis. Deeper joints and small fluid collections, however, can be difficult to access without image guidance. In the ED setting, POC ultrasound provides a widely available, easy-to-use, low-cost tool to increase the likelihood of success while minimizing damage to adjacent structures.

1. Nagdev A. Ultrasound-guided ankle arthrocentesis. Highland General Hospital Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Web site. http://highlandultrasound.com/ankle-arthrocentesis. Accessed June 8, 2017.

2. Reichman EF, Simon RR. Arthrocentesis. In: Reichman EF, Simon RR, eds. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY; 2013.

Ankle effusions can be quite debilitating, causing band-like swelling and stiffness to the anterior aspect of ankle at the tibiotalar joint. Significant swelling can impair ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The differential diagnosis for joint effusions is wide, and includes traumatic effusion; gout; osteoarthritis; rheumatoid arthritis; and septic arthritis, which is one of the most important diagnoses for the emergency physician (EP) to identify and initiate prompt treatment to reduce the risk of serious morbidity and mortality. Differentiating these conditions requires joint aspiration and synovial fluid analysis. While a large effusion will be palpable and likely ballotable, smaller effusions are more challenging clinically. In such cases, point-of-care (POC) ultrasound can be a valuable tool in confirming a joint effusion.

Identifying Landmarks and Tibiotalar Joint

To access the tibiotalar joint space, it is important to identify useful landmarks.1 This is best accomplished by having the patient in the supine position, with the affected knee flexed approximately 90° and plantar surface of the foot lying flat on the bed (Figure 1).

Performing the Arthrocentesis

The arthrocentesis is performed under sterile conditions using the high-frequency linear probe. A sterile probe cover is highly recommended if the operator will be using ultrasound to guide the procedure in real time.2 Using the palpable landmarks as a guide, the clinician should align the probe just medial to the tibialis anterior tendon with the probe marker oriented cephalad; scanning should begin superior to the ankle joint. The tibia will appear as a hyperechoic stripe just under a thin soft tissue layer. When the tibia is visible, the clinician should then slide the probe distally. The joint space will demonstrated by visualization of the distal tibia and talus bone (Figure 3).

Pearls and Pitfalls

Point-of-care ultrasound is not only useful to guide arthrocentesis of joint effusions, but also to confirm the presence of an effusion prior to aspiration. At our institution, we have had many cases in which POC ultrasound demonstrated an absence of effusion, and we were able to avoid an unnecessary joint aspiration. Moreover, when an effusion is present, POC ultrasound-guided aspiration avoids complications. The use of POC ultrasound can also increase the confidence of the provider performing arthrocentesis of joints less commonly aspirated.

Summary

Joint aspiration is an important procedural tool for EPs, especially when used to rule out life-threatening conditions such as septic arthritis. Deeper joints and small fluid collections, however, can be difficult to access without image guidance. In the ED setting, POC ultrasound provides a widely available, easy-to-use, low-cost tool to increase the likelihood of success while minimizing damage to adjacent structures.

Ankle effusions can be quite debilitating, causing band-like swelling and stiffness to the anterior aspect of ankle at the tibiotalar joint. Significant swelling can impair ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The differential diagnosis for joint effusions is wide, and includes traumatic effusion; gout; osteoarthritis; rheumatoid arthritis; and septic arthritis, which is one of the most important diagnoses for the emergency physician (EP) to identify and initiate prompt treatment to reduce the risk of serious morbidity and mortality. Differentiating these conditions requires joint aspiration and synovial fluid analysis. While a large effusion will be palpable and likely ballotable, smaller effusions are more challenging clinically. In such cases, point-of-care (POC) ultrasound can be a valuable tool in confirming a joint effusion.

Identifying Landmarks and Tibiotalar Joint

To access the tibiotalar joint space, it is important to identify useful landmarks.1 This is best accomplished by having the patient in the supine position, with the affected knee flexed approximately 90° and plantar surface of the foot lying flat on the bed (Figure 1).

Performing the Arthrocentesis

The arthrocentesis is performed under sterile conditions using the high-frequency linear probe. A sterile probe cover is highly recommended if the operator will be using ultrasound to guide the procedure in real time.2 Using the palpable landmarks as a guide, the clinician should align the probe just medial to the tibialis anterior tendon with the probe marker oriented cephalad; scanning should begin superior to the ankle joint. The tibia will appear as a hyperechoic stripe just under a thin soft tissue layer. When the tibia is visible, the clinician should then slide the probe distally. The joint space will demonstrated by visualization of the distal tibia and talus bone (Figure 3).

Pearls and Pitfalls

Point-of-care ultrasound is not only useful to guide arthrocentesis of joint effusions, but also to confirm the presence of an effusion prior to aspiration. At our institution, we have had many cases in which POC ultrasound demonstrated an absence of effusion, and we were able to avoid an unnecessary joint aspiration. Moreover, when an effusion is present, POC ultrasound-guided aspiration avoids complications. The use of POC ultrasound can also increase the confidence of the provider performing arthrocentesis of joints less commonly aspirated.

Summary

Joint aspiration is an important procedural tool for EPs, especially when used to rule out life-threatening conditions such as septic arthritis. Deeper joints and small fluid collections, however, can be difficult to access without image guidance. In the ED setting, POC ultrasound provides a widely available, easy-to-use, low-cost tool to increase the likelihood of success while minimizing damage to adjacent structures.

1. Nagdev A. Ultrasound-guided ankle arthrocentesis. Highland General Hospital Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Web site. http://highlandultrasound.com/ankle-arthrocentesis. Accessed June 8, 2017.

2. Reichman EF, Simon RR. Arthrocentesis. In: Reichman EF, Simon RR, eds. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY; 2013.

1. Nagdev A. Ultrasound-guided ankle arthrocentesis. Highland General Hospital Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Web site. http://highlandultrasound.com/ankle-arthrocentesis. Accessed June 8, 2017.

2. Reichman EF, Simon RR. Arthrocentesis. In: Reichman EF, Simon RR, eds. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY; 2013.

Heritability of colorectal cancer estimated at 40%

Thus, CRC “has a substantial heritable component, and may be more heritable in women than men,” Rebecca E. Graff, ScD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues wrote. “Siblings, and particularly monozygotic cotwins, of individuals with colon or rectal cancer should consider personalized screening,” they added.

The model that best fits the data accounted for additive genetic and environmental effects, the researchers said. Based on this model, genetic factors explained about 40% (95% CI, 33%-48%) of variation in the risk of CRC. Thus, the heritability of CRC was about 40%. The estimated heritability of colon cancer was 16% and that of rectal cancer was 15%, but confidence intervals were wide, ranging from 0% to 47% or 50%, respectively. Individual environmental factors accounted for most of the remaining risk of colon and rectal cancers.

“Heritability was greater among women than men and greatest when colorectal cancer combining all subsites together was analyzed,” the researchers noted. Monozygotic twins of CRC patients were at greater risk of both colon and rectal cancers than were same-sex dizygotic twins, indicating that both types of cancer might share inherited genetic risk factors, they added. Variants identified by genomewide association studies “do not come close to accounting for the disease’s heritability,” but, in the meantime, twins of affected cotwins “might benefit particularly from diligent screening, given their excess risk relative to the general population.”

Funders included the Ellison Foundation, the Odense University Hospital AgeCare program, the Academy of Finland, and US BioSHaRE-EU, and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, BioSHaRE-EU, the Swedish Ministry for Higher Education, and the Karolinska Institutet, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Graff had no conflicts of interest.

Thus, CRC “has a substantial heritable component, and may be more heritable in women than men,” Rebecca E. Graff, ScD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues wrote. “Siblings, and particularly monozygotic cotwins, of individuals with colon or rectal cancer should consider personalized screening,” they added.

The model that best fits the data accounted for additive genetic and environmental effects, the researchers said. Based on this model, genetic factors explained about 40% (95% CI, 33%-48%) of variation in the risk of CRC. Thus, the heritability of CRC was about 40%. The estimated heritability of colon cancer was 16% and that of rectal cancer was 15%, but confidence intervals were wide, ranging from 0% to 47% or 50%, respectively. Individual environmental factors accounted for most of the remaining risk of colon and rectal cancers.

“Heritability was greater among women than men and greatest when colorectal cancer combining all subsites together was analyzed,” the researchers noted. Monozygotic twins of CRC patients were at greater risk of both colon and rectal cancers than were same-sex dizygotic twins, indicating that both types of cancer might share inherited genetic risk factors, they added. Variants identified by genomewide association studies “do not come close to accounting for the disease’s heritability,” but, in the meantime, twins of affected cotwins “might benefit particularly from diligent screening, given their excess risk relative to the general population.”

Funders included the Ellison Foundation, the Odense University Hospital AgeCare program, the Academy of Finland, and US BioSHaRE-EU, and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, BioSHaRE-EU, the Swedish Ministry for Higher Education, and the Karolinska Institutet, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Graff had no conflicts of interest.

Thus, CRC “has a substantial heritable component, and may be more heritable in women than men,” Rebecca E. Graff, ScD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues wrote. “Siblings, and particularly monozygotic cotwins, of individuals with colon or rectal cancer should consider personalized screening,” they added.

The model that best fits the data accounted for additive genetic and environmental effects, the researchers said. Based on this model, genetic factors explained about 40% (95% CI, 33%-48%) of variation in the risk of CRC. Thus, the heritability of CRC was about 40%. The estimated heritability of colon cancer was 16% and that of rectal cancer was 15%, but confidence intervals were wide, ranging from 0% to 47% or 50%, respectively. Individual environmental factors accounted for most of the remaining risk of colon and rectal cancers.

“Heritability was greater among women than men and greatest when colorectal cancer combining all subsites together was analyzed,” the researchers noted. Monozygotic twins of CRC patients were at greater risk of both colon and rectal cancers than were same-sex dizygotic twins, indicating that both types of cancer might share inherited genetic risk factors, they added. Variants identified by genomewide association studies “do not come close to accounting for the disease’s heritability,” but, in the meantime, twins of affected cotwins “might benefit particularly from diligent screening, given their excess risk relative to the general population.”

Funders included the Ellison Foundation, the Odense University Hospital AgeCare program, the Academy of Finland, and US BioSHaRE-EU, and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, BioSHaRE-EU, the Swedish Ministry for Higher Education, and the Karolinska Institutet, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Graff had no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: If a monozygotic twin developed colorectal cancer, his or her twin had about a threefold higher risk of CRC than did the overall cohort (familial risk ratio, 3.1; 95% CI, 2.4-3.8).

Major finding: Genetic factors explained about 40% (95% CI, 33%-48%) of variation in the risk of colorectal cancer.

Data source: An analysis of 39,990 monozygotic and 61,443 same-sex dizygotic twins from the Nordic Twin Study of Cancer.

Disclosures: Funders included the Ellison Foundation, the Odense University Hospital AgeCare program, the Academy of Finland, US BioSHaRE-EU, and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, BioSHaRE-EU, the Swedish Ministry for Higher Education, and the Karolinska Institutet, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Graff had no conflicts of interest.

Endoscopists who took 1 minute longer detected significantly more upper GI neoplasms

Endoscopists who took about a minute longer during screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) detected significantly more upper gastrointestinal neoplasms than their quicker colleagues, in a retrospective study reported in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.009).

Detection rates were 0.28% and 0.20%, respectively (P = .005), and this difference remained statistically significant after the investigators controlled for numerous factors that also can affect the chances of detecting gastric neoplasms during upper endoscopy, reported Jae Myung Park, MD, and his colleagues at Seoul (Korea) St. Mary’s Hospital.

Gastric cancer is the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, they noted. Although EGD has been practiced globally for decades, there is no consensus on which performance metrics optimize diagnostic yield. Both Korea and Japan have adopted screening EGD to help diagnose gastric cancer, but interval cancers and false-positive results remain concerns, and the field lacks rigorous analyses comparing EGD time with gastric cancer detection rates. Therefore, the researchers studied 111,962 consecutive patients who underwent EGD at one hospital in Seoul from 2009 through 2015. Fourteen board-certified endoscopists performed these procedures at a single endoscopy unit.A total of 262 patients (0.23%) were diagnosed with gastric neoplasia or dysplasia, duodenal neoplasia, or esophageal carcinoma. This finding closely resembled a prior report from Korea, the investigators noted. Detection rates among individual endoscopists ranged from 0.14% to 0.32%, and longer EGD time was associated with a higher detection rate with an R value of 0.54 (P = .046). During the first year of the study, EGDs without biopsies averaged 2 minutes, 53 seconds. Based on this finding, the researchers set a cutoff time of 3 minutes and classified eight endoscopists as fast (mean EGD duration, 2 minutes and 38 seconds; standard deviation, 21 seconds) and six endoscopists as slow (mean duration, 3 minutes and 25 seconds; SD, 19 seconds). Slower endoscopists were significantly more likely to detect gastric adenomas or carcinomas, even after the investigators controlled for the biopsy rates and experience level of these endoscopists and patients’ age, sex, smoking status, alcohol use, and family history of cancer (odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.97; P = .0018).

Older age, male sex, and smoking also were significant correlates of cancer detection in the multivariable model. Biopsy rates among endoscopists ranged from 7% to 28%, and taking a biopsy was an even stronger predictor of detecting an upper GI neoplasm than was EGD duration, with an R value of 0.76 (P = .002). Although this study was observational and retrospective and lacked data on prior EGD examinations, surveillance intervals, and rates of false-negative results, it “supports the hypothesis that examination duration affects the diagnostic accuracy of EGD,” Dr. Park and his coinvestigators reported. “Prolonging the examination time will allow more careful examination by the endoscopist, which will enable the detection of more subtle lesions. Based on our data, we believe that these indicators can improve the quality of EGD.”

Funders included the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology; the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning; and the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Screening and surveillance practices remain one of the major indications for performing upper endoscopy in patients to detect esophageal (adenocarcinoma in the West; squamous cell in the East) and gastric cancer (in the East). The goal of the initial endoscopy is to detect precancerous lesions (such as Barrett's esophagus and gastric intestinal metaplasia) and, if detected, to grade them properly and evaluate for the presence of dysplasia and cancer in subsequent surveillance examinations.

Prateek Sharma, MD, is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, University of Kansas, Kansas City, Mo. He has no conflicts of interest.

Screening and surveillance practices remain one of the major indications for performing upper endoscopy in patients to detect esophageal (adenocarcinoma in the West; squamous cell in the East) and gastric cancer (in the East). The goal of the initial endoscopy is to detect precancerous lesions (such as Barrett's esophagus and gastric intestinal metaplasia) and, if detected, to grade them properly and evaluate for the presence of dysplasia and cancer in subsequent surveillance examinations.

Prateek Sharma, MD, is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, University of Kansas, Kansas City, Mo. He has no conflicts of interest.

Screening and surveillance practices remain one of the major indications for performing upper endoscopy in patients to detect esophageal (adenocarcinoma in the West; squamous cell in the East) and gastric cancer (in the East). The goal of the initial endoscopy is to detect precancerous lesions (such as Barrett's esophagus and gastric intestinal metaplasia) and, if detected, to grade them properly and evaluate for the presence of dysplasia and cancer in subsequent surveillance examinations.

Prateek Sharma, MD, is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, University of Kansas, Kansas City, Mo. He has no conflicts of interest.

Endoscopists who took about a minute longer during screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) detected significantly more upper gastrointestinal neoplasms than their quicker colleagues, in a retrospective study reported in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.009).

Detection rates were 0.28% and 0.20%, respectively (P = .005), and this difference remained statistically significant after the investigators controlled for numerous factors that also can affect the chances of detecting gastric neoplasms during upper endoscopy, reported Jae Myung Park, MD, and his colleagues at Seoul (Korea) St. Mary’s Hospital.

Gastric cancer is the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, they noted. Although EGD has been practiced globally for decades, there is no consensus on which performance metrics optimize diagnostic yield. Both Korea and Japan have adopted screening EGD to help diagnose gastric cancer, but interval cancers and false-positive results remain concerns, and the field lacks rigorous analyses comparing EGD time with gastric cancer detection rates. Therefore, the researchers studied 111,962 consecutive patients who underwent EGD at one hospital in Seoul from 2009 through 2015. Fourteen board-certified endoscopists performed these procedures at a single endoscopy unit.A total of 262 patients (0.23%) were diagnosed with gastric neoplasia or dysplasia, duodenal neoplasia, or esophageal carcinoma. This finding closely resembled a prior report from Korea, the investigators noted. Detection rates among individual endoscopists ranged from 0.14% to 0.32%, and longer EGD time was associated with a higher detection rate with an R value of 0.54 (P = .046). During the first year of the study, EGDs without biopsies averaged 2 minutes, 53 seconds. Based on this finding, the researchers set a cutoff time of 3 minutes and classified eight endoscopists as fast (mean EGD duration, 2 minutes and 38 seconds; standard deviation, 21 seconds) and six endoscopists as slow (mean duration, 3 minutes and 25 seconds; SD, 19 seconds). Slower endoscopists were significantly more likely to detect gastric adenomas or carcinomas, even after the investigators controlled for the biopsy rates and experience level of these endoscopists and patients’ age, sex, smoking status, alcohol use, and family history of cancer (odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.97; P = .0018).

Older age, male sex, and smoking also were significant correlates of cancer detection in the multivariable model. Biopsy rates among endoscopists ranged from 7% to 28%, and taking a biopsy was an even stronger predictor of detecting an upper GI neoplasm than was EGD duration, with an R value of 0.76 (P = .002). Although this study was observational and retrospective and lacked data on prior EGD examinations, surveillance intervals, and rates of false-negative results, it “supports the hypothesis that examination duration affects the diagnostic accuracy of EGD,” Dr. Park and his coinvestigators reported. “Prolonging the examination time will allow more careful examination by the endoscopist, which will enable the detection of more subtle lesions. Based on our data, we believe that these indicators can improve the quality of EGD.”

Funders included the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology; the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning; and the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Endoscopists who took about a minute longer during screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) detected significantly more upper gastrointestinal neoplasms than their quicker colleagues, in a retrospective study reported in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.009).

Detection rates were 0.28% and 0.20%, respectively (P = .005), and this difference remained statistically significant after the investigators controlled for numerous factors that also can affect the chances of detecting gastric neoplasms during upper endoscopy, reported Jae Myung Park, MD, and his colleagues at Seoul (Korea) St. Mary’s Hospital.

Gastric cancer is the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, they noted. Although EGD has been practiced globally for decades, there is no consensus on which performance metrics optimize diagnostic yield. Both Korea and Japan have adopted screening EGD to help diagnose gastric cancer, but interval cancers and false-positive results remain concerns, and the field lacks rigorous analyses comparing EGD time with gastric cancer detection rates. Therefore, the researchers studied 111,962 consecutive patients who underwent EGD at one hospital in Seoul from 2009 through 2015. Fourteen board-certified endoscopists performed these procedures at a single endoscopy unit.A total of 262 patients (0.23%) were diagnosed with gastric neoplasia or dysplasia, duodenal neoplasia, or esophageal carcinoma. This finding closely resembled a prior report from Korea, the investigators noted. Detection rates among individual endoscopists ranged from 0.14% to 0.32%, and longer EGD time was associated with a higher detection rate with an R value of 0.54 (P = .046). During the first year of the study, EGDs without biopsies averaged 2 minutes, 53 seconds. Based on this finding, the researchers set a cutoff time of 3 minutes and classified eight endoscopists as fast (mean EGD duration, 2 minutes and 38 seconds; standard deviation, 21 seconds) and six endoscopists as slow (mean duration, 3 minutes and 25 seconds; SD, 19 seconds). Slower endoscopists were significantly more likely to detect gastric adenomas or carcinomas, even after the investigators controlled for the biopsy rates and experience level of these endoscopists and patients’ age, sex, smoking status, alcohol use, and family history of cancer (odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.97; P = .0018).

Older age, male sex, and smoking also were significant correlates of cancer detection in the multivariable model. Biopsy rates among endoscopists ranged from 7% to 28%, and taking a biopsy was an even stronger predictor of detecting an upper GI neoplasm than was EGD duration, with an R value of 0.76 (P = .002). Although this study was observational and retrospective and lacked data on prior EGD examinations, surveillance intervals, and rates of false-negative results, it “supports the hypothesis that examination duration affects the diagnostic accuracy of EGD,” Dr. Park and his coinvestigators reported. “Prolonging the examination time will allow more careful examination by the endoscopist, which will enable the detection of more subtle lesions. Based on our data, we believe that these indicators can improve the quality of EGD.”

Funders included the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology; the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning; and the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Adding about 1 minute to an upper endoscopy might significantly increase the detection of upper gastrointestinal neoplasms.

Major finding: Slow endoscopists (with a mean duration for the procedure of 3 minutes and 25 seconds) had a detection rate of 0.28%, while fast endoscopists (2 minutes and 38 seconds) had a detection rate of 0.20% (P = .005).

Data source: A single-center retrospective study of 111,962 individuals who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy in Korea between 2009 and 2015.

Disclosures: Funders included the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology; the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning; and the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Teen suicide risk significant among screened nonresponders

SAN FRANCISCO – Teens who answered “no response” for one or more questions during a standard suicide screening in the ED typically have a risk of suicide nearly on par with those who answered “yes” to at least one question, results of a study showed.

“Risk for suicidality was substantial among both groups,” Tricia Hengehold of the University of Cincinnati reported at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “About half of each group fit the medium-risk category, although the yes group had more teens in the high-risk category comparatively.”

In their study, she and her coinvestigators compared all teens who answered yes or no response (NR) to any question on the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ). A total of 3,386 adolescents, aged 12-17 years, were screened when each presented to the ED with a complaint other than a psychiatric one. The data came from a preexisting study not initially designed for studying nonresponders.

The majority of teens (93%) answered no to all ASQ questions: 5% answered yes to at least one ASQ question, regardless of other answers, and 2% answered no response on at least one of the ASQ questions, but did not answer yes to any of them.

The average age of participants was 14 years among all response groups, but females were overrepresented in the yes and NR groups: 74% of females answered yes to one of the ASQ questions, compared with just 26% of males. Similarly, 79% of females were classified as nonresponders, vs. 21% of males. In the negative screen group, however, females (54%) and males (46%) were much more evenly represented.

Patients who answered yes or NR also were more likely to have Medicaid or Medicare than commercial insurance or a self-pay arrangement. Within the yes group, 56% had public insurance, and 39% had private insurance. In the NR group, 43% had public insurance, and 53% had private insurance.

Any teens who answered yes or NR should have undergone evaluation by a mental health professional, but those answering yes were more likely to get this evaluation than nonresponders. Nearly all (93%) of those answering yes received the evaluation, compared with 79% of nonresponders. Yet half of the nonresponders who were evaluated were recommended for further follow-up, not far behind the 65% recommended from among the yes group.

A clinically significant risk of suicide existed among 93% of those answering yes and 85% of nonresponders, the investigators found. About a third (33%) of the yes group were classified as high risk – suicidal ideation within the past week or no treatment after a previous attempt – while 16% of the nonresponders were.

“The NR group was more often in an earlier stage of change than the yes group, presenting with a greater percentage of teens in the precontemplation category,” Ms. Hengehold said. The precontemplation category, which included 27% of the NR group and 17% of the yes group, referred to teens who did not believe they would benefit from working with a mental health professional.

The contemplation category referred to teens who said they were still thinking about whether to meet with a mental health professional or that they would seek treatment if their suicidality worsened. This category included 9% of yes responders and 14% of nonresponders.

A higher proportion of yes responders (56%) than nonresponders (41%) had reached the preparation stage, which meant they had agreed to set up treatment or had received a referral within a month after their ED visit. A similar percentage of yes responders and nonresponders were currently in treatment, seeing a mental health professional intermittently, or had successfully received therapy.

“The sociodemographic characteristics of teens that endorse a no response are very similar to those of positive endorsers,” she concluded. She noted the potential importance of including an NR option on suicide-screening instruments.

Although nonresponders had clinically significant mental health concerns that indicated a need for further evaluation, these adolescents were less ready to engage in mental health services than those answering yes.

“This may be important when designing suicide risk interventions for each group,” she reported.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Hengehold and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Teens who answered “no response” for one or more questions during a standard suicide screening in the ED typically have a risk of suicide nearly on par with those who answered “yes” to at least one question, results of a study showed.

“Risk for suicidality was substantial among both groups,” Tricia Hengehold of the University of Cincinnati reported at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “About half of each group fit the medium-risk category, although the yes group had more teens in the high-risk category comparatively.”

In their study, she and her coinvestigators compared all teens who answered yes or no response (NR) to any question on the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ). A total of 3,386 adolescents, aged 12-17 years, were screened when each presented to the ED with a complaint other than a psychiatric one. The data came from a preexisting study not initially designed for studying nonresponders.

The majority of teens (93%) answered no to all ASQ questions: 5% answered yes to at least one ASQ question, regardless of other answers, and 2% answered no response on at least one of the ASQ questions, but did not answer yes to any of them.

The average age of participants was 14 years among all response groups, but females were overrepresented in the yes and NR groups: 74% of females answered yes to one of the ASQ questions, compared with just 26% of males. Similarly, 79% of females were classified as nonresponders, vs. 21% of males. In the negative screen group, however, females (54%) and males (46%) were much more evenly represented.

Patients who answered yes or NR also were more likely to have Medicaid or Medicare than commercial insurance or a self-pay arrangement. Within the yes group, 56% had public insurance, and 39% had private insurance. In the NR group, 43% had public insurance, and 53% had private insurance.

Any teens who answered yes or NR should have undergone evaluation by a mental health professional, but those answering yes were more likely to get this evaluation than nonresponders. Nearly all (93%) of those answering yes received the evaluation, compared with 79% of nonresponders. Yet half of the nonresponders who were evaluated were recommended for further follow-up, not far behind the 65% recommended from among the yes group.

A clinically significant risk of suicide existed among 93% of those answering yes and 85% of nonresponders, the investigators found. About a third (33%) of the yes group were classified as high risk – suicidal ideation within the past week or no treatment after a previous attempt – while 16% of the nonresponders were.

“The NR group was more often in an earlier stage of change than the yes group, presenting with a greater percentage of teens in the precontemplation category,” Ms. Hengehold said. The precontemplation category, which included 27% of the NR group and 17% of the yes group, referred to teens who did not believe they would benefit from working with a mental health professional.

The contemplation category referred to teens who said they were still thinking about whether to meet with a mental health professional or that they would seek treatment if their suicidality worsened. This category included 9% of yes responders and 14% of nonresponders.

A higher proportion of yes responders (56%) than nonresponders (41%) had reached the preparation stage, which meant they had agreed to set up treatment or had received a referral within a month after their ED visit. A similar percentage of yes responders and nonresponders were currently in treatment, seeing a mental health professional intermittently, or had successfully received therapy.

“The sociodemographic characteristics of teens that endorse a no response are very similar to those of positive endorsers,” she concluded. She noted the potential importance of including an NR option on suicide-screening instruments.

Although nonresponders had clinically significant mental health concerns that indicated a need for further evaluation, these adolescents were less ready to engage in mental health services than those answering yes.

“This may be important when designing suicide risk interventions for each group,” she reported.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Hengehold and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Teens who answered “no response” for one or more questions during a standard suicide screening in the ED typically have a risk of suicide nearly on par with those who answered “yes” to at least one question, results of a study showed.

“Risk for suicidality was substantial among both groups,” Tricia Hengehold of the University of Cincinnati reported at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “About half of each group fit the medium-risk category, although the yes group had more teens in the high-risk category comparatively.”

In their study, she and her coinvestigators compared all teens who answered yes or no response (NR) to any question on the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ). A total of 3,386 adolescents, aged 12-17 years, were screened when each presented to the ED with a complaint other than a psychiatric one. The data came from a preexisting study not initially designed for studying nonresponders.

The majority of teens (93%) answered no to all ASQ questions: 5% answered yes to at least one ASQ question, regardless of other answers, and 2% answered no response on at least one of the ASQ questions, but did not answer yes to any of them.

The average age of participants was 14 years among all response groups, but females were overrepresented in the yes and NR groups: 74% of females answered yes to one of the ASQ questions, compared with just 26% of males. Similarly, 79% of females were classified as nonresponders, vs. 21% of males. In the negative screen group, however, females (54%) and males (46%) were much more evenly represented.

Patients who answered yes or NR also were more likely to have Medicaid or Medicare than commercial insurance or a self-pay arrangement. Within the yes group, 56% had public insurance, and 39% had private insurance. In the NR group, 43% had public insurance, and 53% had private insurance.

Any teens who answered yes or NR should have undergone evaluation by a mental health professional, but those answering yes were more likely to get this evaluation than nonresponders. Nearly all (93%) of those answering yes received the evaluation, compared with 79% of nonresponders. Yet half of the nonresponders who were evaluated were recommended for further follow-up, not far behind the 65% recommended from among the yes group.

A clinically significant risk of suicide existed among 93% of those answering yes and 85% of nonresponders, the investigators found. About a third (33%) of the yes group were classified as high risk – suicidal ideation within the past week or no treatment after a previous attempt – while 16% of the nonresponders were.

“The NR group was more often in an earlier stage of change than the yes group, presenting with a greater percentage of teens in the precontemplation category,” Ms. Hengehold said. The precontemplation category, which included 27% of the NR group and 17% of the yes group, referred to teens who did not believe they would benefit from working with a mental health professional.

The contemplation category referred to teens who said they were still thinking about whether to meet with a mental health professional or that they would seek treatment if their suicidality worsened. This category included 9% of yes responders and 14% of nonresponders.

A higher proportion of yes responders (56%) than nonresponders (41%) had reached the preparation stage, which meant they had agreed to set up treatment or had received a referral within a month after their ED visit. A similar percentage of yes responders and nonresponders were currently in treatment, seeing a mental health professional intermittently, or had successfully received therapy.

“The sociodemographic characteristics of teens that endorse a no response are very similar to those of positive endorsers,” she concluded. She noted the potential importance of including an NR option on suicide-screening instruments.

Although nonresponders had clinically significant mental health concerns that indicated a need for further evaluation, these adolescents were less ready to engage in mental health services than those answering yes.

“This may be important when designing suicide risk interventions for each group,” she reported.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Hengehold and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

AT PAS 17

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Eighty-five percent of teens who were nonresponders on at least one suicide-screening question had a clinically significant risk of suicide, compared with 93% of those answering yes.

Data source: The findings are based on an analysis of responses from 3,386 adolescents screened for suicidality during a nonpsychiatric emergency department visit.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Hengehold and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Case Studies in Toxicology: An Unlikely Cause of Paralysis

Case

An Asian man in his third decade, with a medical history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia, and who had recently been involved in a motor vehicle collision (MVC), presented to the ED with a chief complaint of severe bilateral upper and lower extremity weakness. The patient noted that the weakness had begun the previous evening and became progressively worse throughout the night, to the point that he was unable to move any of his extremities on the morning of presentation.

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient was awake, alert, and oriented to self, time, and place; he also spoke in full sentences without distress. He denied fever, chills, difficulty breathing, or preceding viral illness. The patient stated that he was not taking any medications and denied a history of alcohol, tobacco, or drug abuse.

Initial vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 141/50 mm Hg; heart rate, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; and temperature, 97.4°F. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. On physical examination, the patient was in no acute distress and had a normal mental status. His pupils were normally reactive and his other cranial nerves were normal. Muscle strength in the upper and lower extremities was 1/5 with 1+ reflexes bilaterally, and there was no sensory deficit. The patient was placed on continuous cardiac monitoring with pulse oximetry.

What is the differential diagnosis for acute extremity weakness or paralysis?

The differential diagnosis for acute symmetrical extremity weakness or paralysis is broad and includes conditions of neurological, inflammatory, and toxic/metabolic etiologies.1 Neurological diagnoses to consider include acute stroke, specifically of the anterior cerebral or middle cerebral artery territories; Guillain-Barré syndrome; myasthenia gravis; spinal cord compression; and tick paralysis. Acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke most frequently presents with unilateral upper or lower extremity weakness accompanied by garbled speech and sensory deficits. Patients who have suffered a brainstem or cerebellar stroke commonly present with alterations of consciousness, visual changes, and ataxia. Posterior circulation strokes are also characterized by crossed neurological deficits, such as motor deficits on one side of the body and sensory deficits on the other.

Spinal Cord Pathology. Signs and symptoms of spinal cord compression or inflammation vary widely depending on the level affected. Motor and sensory findings of spinal cord pathology include muscle weakness, spasticity, hyper- or hyporeflexia, and a discrete level below which sensation is absent or reduced.