User login

Monthly fitusiran showed promise in small phase I hemophilia trial

and increased thrombin production, according to the results of a small phase I dose-escalation study.

Compared with baseline, levels of antithrombin dropped by 70%-89%, K. John Pasi, MB, ChB, PhD, of the Royal London Haemophilia Centre and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry and his associates reported at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress and simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine. There were no thromboembolic events during the study, and the most common adverse events were mild injection-site reactions, they added.

Patients with hemophilia typically need frequent infusions of clotting factors, creating an urgent need for new therapies. Fitusiran is an investigational RNA interference (RNAi) therapy that targets antithrombin. This multicenter, open-label, phase I study included four healthy volunteers and 25 patients with moderate or severe hemophilia A or B without inhibitors. The healthy participants received a single subcutaneous injection of fitusiran (0.03 mg/kg) or placebo. The hemophilia patients received three injections of fitusiran either once weekly (0.015, 0.045, or 0.075 mg/kg) or once monthly (0.225, 0.45, 0.9, or 1.8 mg/kg, or a fixed dose of 80 mg (N Engl J Med. 2017 July 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616569).

The single fitusiran dose and the weekly treatment regimens both produced consistent, sustained drops in plasma antithrombin levels, which supported a longer interval between doses, the researchers said. A monthly dose of 0.225 mg/kg cut antithrombin levels by about 70%, compared with baseline (standard deviation, ±9%), while a monthly dose of 1.8 mg/kg produced about an 89% (standard deviation, ±1%) drop in antithrombin levels. The fixed 80-mg dose consistently lowered antithrombin levels by about 87%, compared with baseline. The decreases in antithrombin varied little during the weeks between doses and were associated with increased thrombin generation, regardless of whether patients had hemophilia A or B, Dr. Pasi and his associates said.

One patient stopped treatment because of severe chest pain, but the investigators ruled out thrombosis as a cause. Fitusiran targets the liver, and 36% of patients developed transient increases in liver aminotransferase levels, they noted. Most of these patients had a history of hepatitis C virus infection. An extension study (NCT02554773) is ongoing to assess longer-term safety and efficacy findings. The investigators also are studying fitusiran in patients with inhibitory alloantibodies.

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals provided funding. Dr. Pasi disclosed research funding, advisory board fees, and travel grants from Alnylam and Genzyme. Four coinvestigators also disclosed receiving support from Alnylam during the conduct of the study.

and increased thrombin production, according to the results of a small phase I dose-escalation study.

Compared with baseline, levels of antithrombin dropped by 70%-89%, K. John Pasi, MB, ChB, PhD, of the Royal London Haemophilia Centre and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry and his associates reported at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress and simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine. There were no thromboembolic events during the study, and the most common adverse events were mild injection-site reactions, they added.

Patients with hemophilia typically need frequent infusions of clotting factors, creating an urgent need for new therapies. Fitusiran is an investigational RNA interference (RNAi) therapy that targets antithrombin. This multicenter, open-label, phase I study included four healthy volunteers and 25 patients with moderate or severe hemophilia A or B without inhibitors. The healthy participants received a single subcutaneous injection of fitusiran (0.03 mg/kg) or placebo. The hemophilia patients received three injections of fitusiran either once weekly (0.015, 0.045, or 0.075 mg/kg) or once monthly (0.225, 0.45, 0.9, or 1.8 mg/kg, or a fixed dose of 80 mg (N Engl J Med. 2017 July 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616569).

The single fitusiran dose and the weekly treatment regimens both produced consistent, sustained drops in plasma antithrombin levels, which supported a longer interval between doses, the researchers said. A monthly dose of 0.225 mg/kg cut antithrombin levels by about 70%, compared with baseline (standard deviation, ±9%), while a monthly dose of 1.8 mg/kg produced about an 89% (standard deviation, ±1%) drop in antithrombin levels. The fixed 80-mg dose consistently lowered antithrombin levels by about 87%, compared with baseline. The decreases in antithrombin varied little during the weeks between doses and were associated with increased thrombin generation, regardless of whether patients had hemophilia A or B, Dr. Pasi and his associates said.

One patient stopped treatment because of severe chest pain, but the investigators ruled out thrombosis as a cause. Fitusiran targets the liver, and 36% of patients developed transient increases in liver aminotransferase levels, they noted. Most of these patients had a history of hepatitis C virus infection. An extension study (NCT02554773) is ongoing to assess longer-term safety and efficacy findings. The investigators also are studying fitusiran in patients with inhibitory alloantibodies.

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals provided funding. Dr. Pasi disclosed research funding, advisory board fees, and travel grants from Alnylam and Genzyme. Four coinvestigators also disclosed receiving support from Alnylam during the conduct of the study.

and increased thrombin production, according to the results of a small phase I dose-escalation study.

Compared with baseline, levels of antithrombin dropped by 70%-89%, K. John Pasi, MB, ChB, PhD, of the Royal London Haemophilia Centre and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry and his associates reported at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress and simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine. There were no thromboembolic events during the study, and the most common adverse events were mild injection-site reactions, they added.

Patients with hemophilia typically need frequent infusions of clotting factors, creating an urgent need for new therapies. Fitusiran is an investigational RNA interference (RNAi) therapy that targets antithrombin. This multicenter, open-label, phase I study included four healthy volunteers and 25 patients with moderate or severe hemophilia A or B without inhibitors. The healthy participants received a single subcutaneous injection of fitusiran (0.03 mg/kg) or placebo. The hemophilia patients received three injections of fitusiran either once weekly (0.015, 0.045, or 0.075 mg/kg) or once monthly (0.225, 0.45, 0.9, or 1.8 mg/kg, or a fixed dose of 80 mg (N Engl J Med. 2017 July 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616569).

The single fitusiran dose and the weekly treatment regimens both produced consistent, sustained drops in plasma antithrombin levels, which supported a longer interval between doses, the researchers said. A monthly dose of 0.225 mg/kg cut antithrombin levels by about 70%, compared with baseline (standard deviation, ±9%), while a monthly dose of 1.8 mg/kg produced about an 89% (standard deviation, ±1%) drop in antithrombin levels. The fixed 80-mg dose consistently lowered antithrombin levels by about 87%, compared with baseline. The decreases in antithrombin varied little during the weeks between doses and were associated with increased thrombin generation, regardless of whether patients had hemophilia A or B, Dr. Pasi and his associates said.

One patient stopped treatment because of severe chest pain, but the investigators ruled out thrombosis as a cause. Fitusiran targets the liver, and 36% of patients developed transient increases in liver aminotransferase levels, they noted. Most of these patients had a history of hepatitis C virus infection. An extension study (NCT02554773) is ongoing to assess longer-term safety and efficacy findings. The investigators also are studying fitusiran in patients with inhibitory alloantibodies.

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals provided funding. Dr. Pasi disclosed research funding, advisory board fees, and travel grants from Alnylam and Genzyme. Four coinvestigators also disclosed receiving support from Alnylam during the conduct of the study.

FROM THE 2017 ISTH CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Once-monthly subcutaneous treatment with fitusiran led to dose-dependent lowering of antithrombin levels and increased thrombin production among patients with hemophilia A or B without inhibitors.

Major finding: Compared with baseline, levels of antithrombin dropped by 70%-89%. There were no episodes of thrombosis, and the most common adverse events were injection-site reactions.

Data source: A phase I dose-escalation study.

Disclosures: Alnylam Pharmaceuticals provided funding. Dr. Pasi disclosed research funding, advisory board fees, and travel grants from Alnylam and Genzyme. Four coinvestigators also disclosed receiving support from Alnylam during the conduct of the study.

Obesity medicine: How to incorporate it into your practice

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Resources

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Resources

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Resources

Prophylactic emicizumab cut bleeds by 87% in hemophilia A with inhibitors

Once-weekly prophylactic therapy with emicizumab (ACE910) was associated an 87% lower rate of treated bleeding than no prophylaxis among patients with hemophilia A with inhibitors in the open-label, phase III HAVEN 1 trial.

After a median 24 weeks of treatment (range, 3-48 weeks), the 35 patients who were randomly assigned to prophylactic emicizumab (3.0 mg per kg for 4 weeks, followed by 1.5 mg per kg) had an annualized bleeding rate of 2.9 events, compared with an annualized rate of 23.3 events among the 18 patients who received no prophylaxis. The difference was statistically significant, reported Johannes Oldenburg, MD, PhD, and his associates at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress and simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703068).

In addition, 63% of patients who received prophylactic emicizumab had no bleeding events, compared with only 6% of the comparison group, said Dr. Oldenburg of Universitaetsklinikum Bonn, Germany. Emicizumab also was associated with a 79% lower rate of treated bleeds, compared with the historic rate among 24 patients who previously had been on prophylactic bypassing agents (P less than .001). No patient developed detectable antidrug antibodies.

The most common adverse events were injection site reactions (15% of patients), followed by headache, upper respiratory tract infection, arthralgia, and fatigue. Four patients developed thrombotic microangiopathy or cavernous sinus thrombosis and skin necrosis, all of whom had experienced breakthrough bleeding for which they had received multiple infusions of activated prothrombin complex concentrate at doses averaging more than 100 U per kg per day.

Patients with severe hemophilia A typically require prophylactic factor VIII infusions two to three times a week, but 30% develop neutralizing antibodies against factor VIII (inhibitors), which increases care burden, costs, and complication rates.

Emicizumab is a recombinant humanized bispecific monoclonal antibody that restores the function of missing active factor VIII by bridging activated factor IX and factor X, the investigators noted. A phase I study linked once-weekly emicizumab prophylaxis to markedly lower bleeding rates without dose-limiting toxicities (N Engl J Med 2016;374:2044-53). Subsequently, the phase III HAVEN 1 study (NCT02622321) compared once-weekly subcutaneous prophylactic emicizumab with on-demand (episodic) and prophylactic use of bypassing agents (BPAs) in 109 adults and adolescents (12 years and older) with hemophilia A with inhibitors. The primary endpoint was the difference in rates of treated bleeds between the groups. Patients had a median age of 28 years, all were male, and most had severe hemophilia at baseline. They typically had more than nine bleeding events in the 6 months before enrollment, with bleeding in more than one target joint and factor VIII titers of 180 Bethesda units per mL.

HAVEN 1 was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Chugai Pharmaceutical. Dr. Oldenburg and 13 coinvestigators disclosed ties to Chugai, Roche, and other pharmaceutical companies. The remaining coinvestigator had no disclosures.

The results of this phase III trial are of great importance to patients with for hemophilia A, offering “an elegant new solution for treatment.” Although it is not clear how best to treat the infrequent events of breakthrough bleeding when administering emicizumab, it is evident that repeated high doses of activated prothrombin complex concentrate should be avoided. Also, how to integrate emicizumab prophylaxis with current schedules for the induction of immune tolerance to factor VIII remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, weekly subcutaneous emicizumab prophylaxis offer great reductions in bleeding rates and improve quality of life “for this very challenging patient group.” Additional studies already are underway to ascertain the benefit of emicizumab prophylaxis in children with hemophilia with inhibitors, and a study for patients with hemophilia A without inhibitors is planned.

“These are extraordinary times for innovation in hemophilia therapy, and the introduction of emicizumab represents a major contribution toward achieving an enhanced standard of care for this lifelong bleeding disorder.”

David Lillicrap, MD, is with the department of pathology and molecular medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario. He reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments are from his accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2017 June 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1707802).

The results of this phase III trial are of great importance to patients with for hemophilia A, offering “an elegant new solution for treatment.” Although it is not clear how best to treat the infrequent events of breakthrough bleeding when administering emicizumab, it is evident that repeated high doses of activated prothrombin complex concentrate should be avoided. Also, how to integrate emicizumab prophylaxis with current schedules for the induction of immune tolerance to factor VIII remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, weekly subcutaneous emicizumab prophylaxis offer great reductions in bleeding rates and improve quality of life “for this very challenging patient group.” Additional studies already are underway to ascertain the benefit of emicizumab prophylaxis in children with hemophilia with inhibitors, and a study for patients with hemophilia A without inhibitors is planned.

“These are extraordinary times for innovation in hemophilia therapy, and the introduction of emicizumab represents a major contribution toward achieving an enhanced standard of care for this lifelong bleeding disorder.”

David Lillicrap, MD, is with the department of pathology and molecular medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario. He reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments are from his accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2017 June 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1707802).

The results of this phase III trial are of great importance to patients with for hemophilia A, offering “an elegant new solution for treatment.” Although it is not clear how best to treat the infrequent events of breakthrough bleeding when administering emicizumab, it is evident that repeated high doses of activated prothrombin complex concentrate should be avoided. Also, how to integrate emicizumab prophylaxis with current schedules for the induction of immune tolerance to factor VIII remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, weekly subcutaneous emicizumab prophylaxis offer great reductions in bleeding rates and improve quality of life “for this very challenging patient group.” Additional studies already are underway to ascertain the benefit of emicizumab prophylaxis in children with hemophilia with inhibitors, and a study for patients with hemophilia A without inhibitors is planned.

“These are extraordinary times for innovation in hemophilia therapy, and the introduction of emicizumab represents a major contribution toward achieving an enhanced standard of care for this lifelong bleeding disorder.”

David Lillicrap, MD, is with the department of pathology and molecular medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario. He reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments are from his accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2017 June 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1707802).

Once-weekly prophylactic therapy with emicizumab (ACE910) was associated an 87% lower rate of treated bleeding than no prophylaxis among patients with hemophilia A with inhibitors in the open-label, phase III HAVEN 1 trial.

After a median 24 weeks of treatment (range, 3-48 weeks), the 35 patients who were randomly assigned to prophylactic emicizumab (3.0 mg per kg for 4 weeks, followed by 1.5 mg per kg) had an annualized bleeding rate of 2.9 events, compared with an annualized rate of 23.3 events among the 18 patients who received no prophylaxis. The difference was statistically significant, reported Johannes Oldenburg, MD, PhD, and his associates at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress and simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703068).

In addition, 63% of patients who received prophylactic emicizumab had no bleeding events, compared with only 6% of the comparison group, said Dr. Oldenburg of Universitaetsklinikum Bonn, Germany. Emicizumab also was associated with a 79% lower rate of treated bleeds, compared with the historic rate among 24 patients who previously had been on prophylactic bypassing agents (P less than .001). No patient developed detectable antidrug antibodies.

The most common adverse events were injection site reactions (15% of patients), followed by headache, upper respiratory tract infection, arthralgia, and fatigue. Four patients developed thrombotic microangiopathy or cavernous sinus thrombosis and skin necrosis, all of whom had experienced breakthrough bleeding for which they had received multiple infusions of activated prothrombin complex concentrate at doses averaging more than 100 U per kg per day.

Patients with severe hemophilia A typically require prophylactic factor VIII infusions two to three times a week, but 30% develop neutralizing antibodies against factor VIII (inhibitors), which increases care burden, costs, and complication rates.

Emicizumab is a recombinant humanized bispecific monoclonal antibody that restores the function of missing active factor VIII by bridging activated factor IX and factor X, the investigators noted. A phase I study linked once-weekly emicizumab prophylaxis to markedly lower bleeding rates without dose-limiting toxicities (N Engl J Med 2016;374:2044-53). Subsequently, the phase III HAVEN 1 study (NCT02622321) compared once-weekly subcutaneous prophylactic emicizumab with on-demand (episodic) and prophylactic use of bypassing agents (BPAs) in 109 adults and adolescents (12 years and older) with hemophilia A with inhibitors. The primary endpoint was the difference in rates of treated bleeds between the groups. Patients had a median age of 28 years, all were male, and most had severe hemophilia at baseline. They typically had more than nine bleeding events in the 6 months before enrollment, with bleeding in more than one target joint and factor VIII titers of 180 Bethesda units per mL.

HAVEN 1 was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Chugai Pharmaceutical. Dr. Oldenburg and 13 coinvestigators disclosed ties to Chugai, Roche, and other pharmaceutical companies. The remaining coinvestigator had no disclosures.

Once-weekly prophylactic therapy with emicizumab (ACE910) was associated an 87% lower rate of treated bleeding than no prophylaxis among patients with hemophilia A with inhibitors in the open-label, phase III HAVEN 1 trial.

After a median 24 weeks of treatment (range, 3-48 weeks), the 35 patients who were randomly assigned to prophylactic emicizumab (3.0 mg per kg for 4 weeks, followed by 1.5 mg per kg) had an annualized bleeding rate of 2.9 events, compared with an annualized rate of 23.3 events among the 18 patients who received no prophylaxis. The difference was statistically significant, reported Johannes Oldenburg, MD, PhD, and his associates at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress and simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703068).

In addition, 63% of patients who received prophylactic emicizumab had no bleeding events, compared with only 6% of the comparison group, said Dr. Oldenburg of Universitaetsklinikum Bonn, Germany. Emicizumab also was associated with a 79% lower rate of treated bleeds, compared with the historic rate among 24 patients who previously had been on prophylactic bypassing agents (P less than .001). No patient developed detectable antidrug antibodies.

The most common adverse events were injection site reactions (15% of patients), followed by headache, upper respiratory tract infection, arthralgia, and fatigue. Four patients developed thrombotic microangiopathy or cavernous sinus thrombosis and skin necrosis, all of whom had experienced breakthrough bleeding for which they had received multiple infusions of activated prothrombin complex concentrate at doses averaging more than 100 U per kg per day.

Patients with severe hemophilia A typically require prophylactic factor VIII infusions two to three times a week, but 30% develop neutralizing antibodies against factor VIII (inhibitors), which increases care burden, costs, and complication rates.

Emicizumab is a recombinant humanized bispecific monoclonal antibody that restores the function of missing active factor VIII by bridging activated factor IX and factor X, the investigators noted. A phase I study linked once-weekly emicizumab prophylaxis to markedly lower bleeding rates without dose-limiting toxicities (N Engl J Med 2016;374:2044-53). Subsequently, the phase III HAVEN 1 study (NCT02622321) compared once-weekly subcutaneous prophylactic emicizumab with on-demand (episodic) and prophylactic use of bypassing agents (BPAs) in 109 adults and adolescents (12 years and older) with hemophilia A with inhibitors. The primary endpoint was the difference in rates of treated bleeds between the groups. Patients had a median age of 28 years, all were male, and most had severe hemophilia at baseline. They typically had more than nine bleeding events in the 6 months before enrollment, with bleeding in more than one target joint and factor VIII titers of 180 Bethesda units per mL.

HAVEN 1 was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Chugai Pharmaceutical. Dr. Oldenburg and 13 coinvestigators disclosed ties to Chugai, Roche, and other pharmaceutical companies. The remaining coinvestigator had no disclosures.

From 2017 ISTH CONGRESS

Key clinical point: .

Major finding: After a median 24 weeks of treatment, the intervention group averaged 2.9 bleeds per year vs. 23.3 events in the control group.

Data source: A phase III randomized multicenter open-label trial of 109 male adolescents and adults with hemophilia A and factor VIII inhibitors.

Disclosures: HAVEN 1 was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Chugai Pharmaceutical. Dr. Oldenburg and 13 coinvestigators disclosed ties to Chugai, Roche, and other pharmaceutical companies. The remaining coinvestigator had no disclosures.

Antibody could reduce bone fractures in MM

Preclinical research suggests a targeted therapy may be able to rebuild and strengthen bone in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

Researchers tested an antibody targeting the protein sclerostin, an important regulator of bone formation, in mouse models of MM.

The antibody prevented bone loss and even increased bone volume in the mice.

The treatment also made bones more resistant to fracture and worked synergistically with zoledronic acid.

Michelle McDonald, PhD, of the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and her colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

“Multiple myeloma is a cancer that grows in bone, and, in most patients, it is associated with widespread bone loss and recurrent bone fractures, which can be extremely painful and debilitating,” Dr McDonald said.

“The current treatment for myeloma-associated bone disease with bisphosphonate drugs prevents further bone loss, but it doesn’t fix damaged bones, so patients continue to fracture. We wanted to re-stimulate bone formation and increase bone strength and resistance to fracture.”

So the researchers tested an antibody that targets and neutralizes sclerostin. In clinical studies of osteoporosis, such antibodies have been shown to increase bone mass and reduce fracture incidence.

In the mouse models of MM, the antibody prevented further bone loss and even doubled bone volume in some of the mice.

“When we looked at the bones before and after treatment, the difference was remarkable,” Dr McDonald said. “We saw less lesions or ‘holes’ in the bones after anti-sclerostin treatment. These lesions are the primary cause of bone pain, so this is an extremely important result.”

The treatment also made the bones substantially stronger, with more than double the resistance to fracture observed in many of the tests.

The researchers then combined the antibody with the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid and observed positive results.

“Bisphosphonates work by preventing bone breakdown, so we combined zoledronic acid with the new anti-sclerostin antibody that rebuilds bone,” Dr McDonald said. “Together, the impact on bone thickness, strength, and resistance to fracture was greater than either treatment alone.”

The researchers said these findings suggest a potential new strategy for reducing fractures in patients with MM.

“[M]yelomas, like other cancers, vary from individual to individual and can therefore be difficult to target,” said study author Peter I. Croucher, PhD, of the Garvan Institute of Medical Research.

“By targeting sclerostin, we are blocking a protein that is active in every person’s bones and not something unique to a person’s cancer. Therefore, in the future, when we test this antibody in humans, we are hopeful to see a response in most, if not all, patients.”

“We are now looking towards clinical trials for this antibody and, in the future, development of this type of therapy for the clinical treatment of multiple myeloma. This therapeutic approach has the potential to transform the prognosis for myeloma patients, enhancing quality of life, and ultimately reducing mortality. It also has clinical implications for the treatment of other cancers that develop in the skeleton.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests a targeted therapy may be able to rebuild and strengthen bone in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

Researchers tested an antibody targeting the protein sclerostin, an important regulator of bone formation, in mouse models of MM.

The antibody prevented bone loss and even increased bone volume in the mice.

The treatment also made bones more resistant to fracture and worked synergistically with zoledronic acid.

Michelle McDonald, PhD, of the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and her colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

“Multiple myeloma is a cancer that grows in bone, and, in most patients, it is associated with widespread bone loss and recurrent bone fractures, which can be extremely painful and debilitating,” Dr McDonald said.

“The current treatment for myeloma-associated bone disease with bisphosphonate drugs prevents further bone loss, but it doesn’t fix damaged bones, so patients continue to fracture. We wanted to re-stimulate bone formation and increase bone strength and resistance to fracture.”

So the researchers tested an antibody that targets and neutralizes sclerostin. In clinical studies of osteoporosis, such antibodies have been shown to increase bone mass and reduce fracture incidence.

In the mouse models of MM, the antibody prevented further bone loss and even doubled bone volume in some of the mice.

“When we looked at the bones before and after treatment, the difference was remarkable,” Dr McDonald said. “We saw less lesions or ‘holes’ in the bones after anti-sclerostin treatment. These lesions are the primary cause of bone pain, so this is an extremely important result.”

The treatment also made the bones substantially stronger, with more than double the resistance to fracture observed in many of the tests.

The researchers then combined the antibody with the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid and observed positive results.

“Bisphosphonates work by preventing bone breakdown, so we combined zoledronic acid with the new anti-sclerostin antibody that rebuilds bone,” Dr McDonald said. “Together, the impact on bone thickness, strength, and resistance to fracture was greater than either treatment alone.”

The researchers said these findings suggest a potential new strategy for reducing fractures in patients with MM.

“[M]yelomas, like other cancers, vary from individual to individual and can therefore be difficult to target,” said study author Peter I. Croucher, PhD, of the Garvan Institute of Medical Research.

“By targeting sclerostin, we are blocking a protein that is active in every person’s bones and not something unique to a person’s cancer. Therefore, in the future, when we test this antibody in humans, we are hopeful to see a response in most, if not all, patients.”

“We are now looking towards clinical trials for this antibody and, in the future, development of this type of therapy for the clinical treatment of multiple myeloma. This therapeutic approach has the potential to transform the prognosis for myeloma patients, enhancing quality of life, and ultimately reducing mortality. It also has clinical implications for the treatment of other cancers that develop in the skeleton.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests a targeted therapy may be able to rebuild and strengthen bone in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

Researchers tested an antibody targeting the protein sclerostin, an important regulator of bone formation, in mouse models of MM.

The antibody prevented bone loss and even increased bone volume in the mice.

The treatment also made bones more resistant to fracture and worked synergistically with zoledronic acid.

Michelle McDonald, PhD, of the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and her colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

“Multiple myeloma is a cancer that grows in bone, and, in most patients, it is associated with widespread bone loss and recurrent bone fractures, which can be extremely painful and debilitating,” Dr McDonald said.

“The current treatment for myeloma-associated bone disease with bisphosphonate drugs prevents further bone loss, but it doesn’t fix damaged bones, so patients continue to fracture. We wanted to re-stimulate bone formation and increase bone strength and resistance to fracture.”

So the researchers tested an antibody that targets and neutralizes sclerostin. In clinical studies of osteoporosis, such antibodies have been shown to increase bone mass and reduce fracture incidence.

In the mouse models of MM, the antibody prevented further bone loss and even doubled bone volume in some of the mice.

“When we looked at the bones before and after treatment, the difference was remarkable,” Dr McDonald said. “We saw less lesions or ‘holes’ in the bones after anti-sclerostin treatment. These lesions are the primary cause of bone pain, so this is an extremely important result.”

The treatment also made the bones substantially stronger, with more than double the resistance to fracture observed in many of the tests.

The researchers then combined the antibody with the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid and observed positive results.

“Bisphosphonates work by preventing bone breakdown, so we combined zoledronic acid with the new anti-sclerostin antibody that rebuilds bone,” Dr McDonald said. “Together, the impact on bone thickness, strength, and resistance to fracture was greater than either treatment alone.”

The researchers said these findings suggest a potential new strategy for reducing fractures in patients with MM.

“[M]yelomas, like other cancers, vary from individual to individual and can therefore be difficult to target,” said study author Peter I. Croucher, PhD, of the Garvan Institute of Medical Research.

“By targeting sclerostin, we are blocking a protein that is active in every person’s bones and not something unique to a person’s cancer. Therefore, in the future, when we test this antibody in humans, we are hopeful to see a response in most, if not all, patients.”

“We are now looking towards clinical trials for this antibody and, in the future, development of this type of therapy for the clinical treatment of multiple myeloma. This therapeutic approach has the potential to transform the prognosis for myeloma patients, enhancing quality of life, and ultimately reducing mortality. It also has clinical implications for the treatment of other cancers that develop in the skeleton.” ![]()

From Revved Up to Banged Up

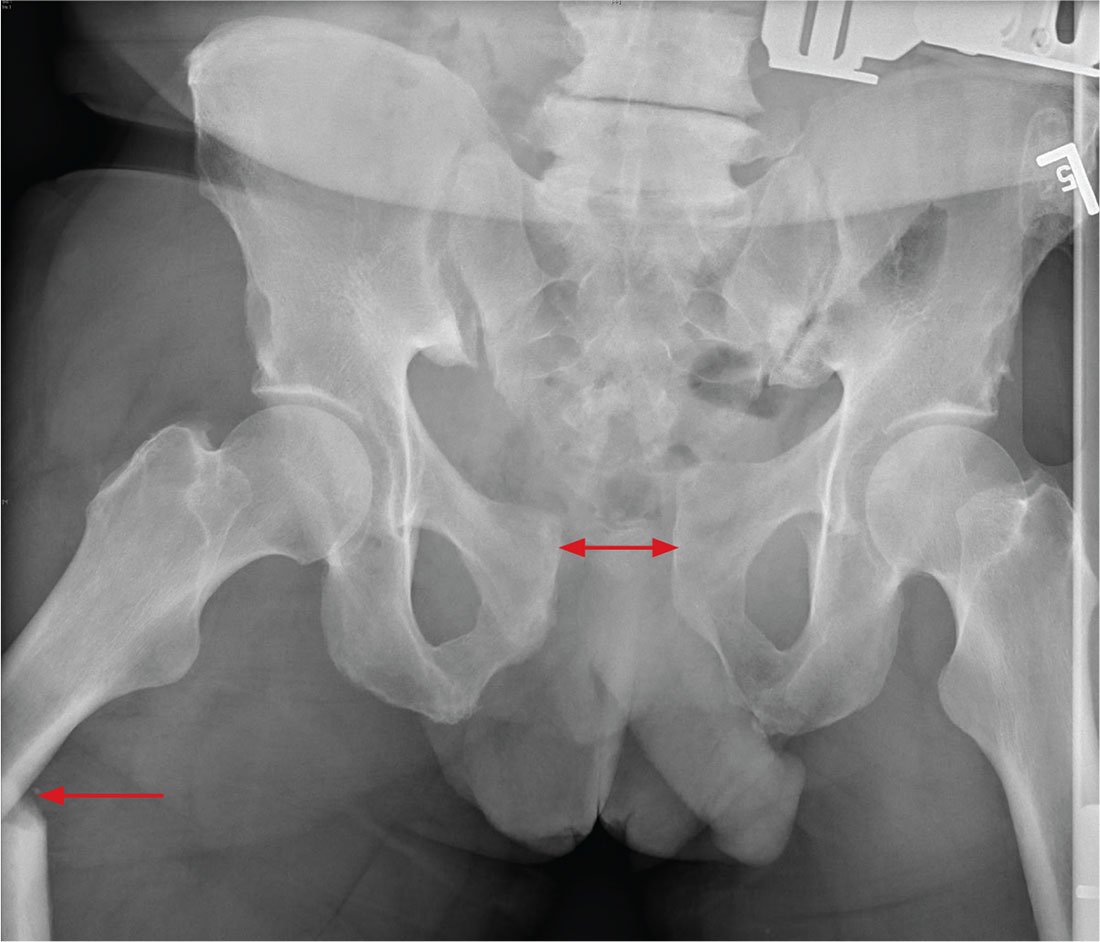

ANSWER

There is significant diastasis of the pubic symphysis, measuring nearly 4 cm. No obvious fractures of the hip or pelvis are seen, but there is malalignment of the rami. There is also evidence of a proximal right femur fracture, although this area is not fully imaged.

Such radiographic findings are typically referred to as an open book pelvic fracture. Usually the result of a shear injury, these fractures are not uncommon and carry an increased risk for pelvic vascular injury.

Emergent orthopedic and vascular consults were obtained, and the patient was placed in a pelvic binder to help reduce the distraction and tamponade any potential vascular injuries.

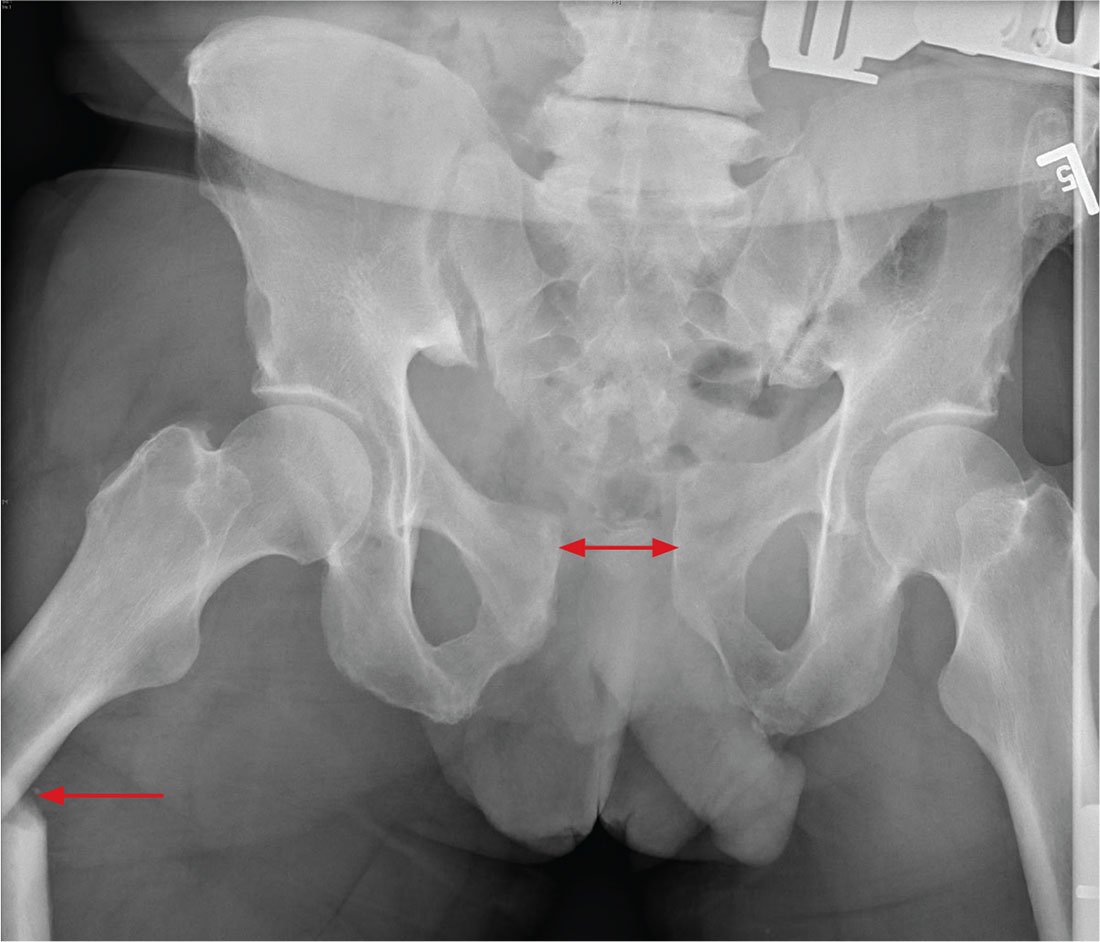

ANSWER

There is significant diastasis of the pubic symphysis, measuring nearly 4 cm. No obvious fractures of the hip or pelvis are seen, but there is malalignment of the rami. There is also evidence of a proximal right femur fracture, although this area is not fully imaged.

Such radiographic findings are typically referred to as an open book pelvic fracture. Usually the result of a shear injury, these fractures are not uncommon and carry an increased risk for pelvic vascular injury.

Emergent orthopedic and vascular consults were obtained, and the patient was placed in a pelvic binder to help reduce the distraction and tamponade any potential vascular injuries.

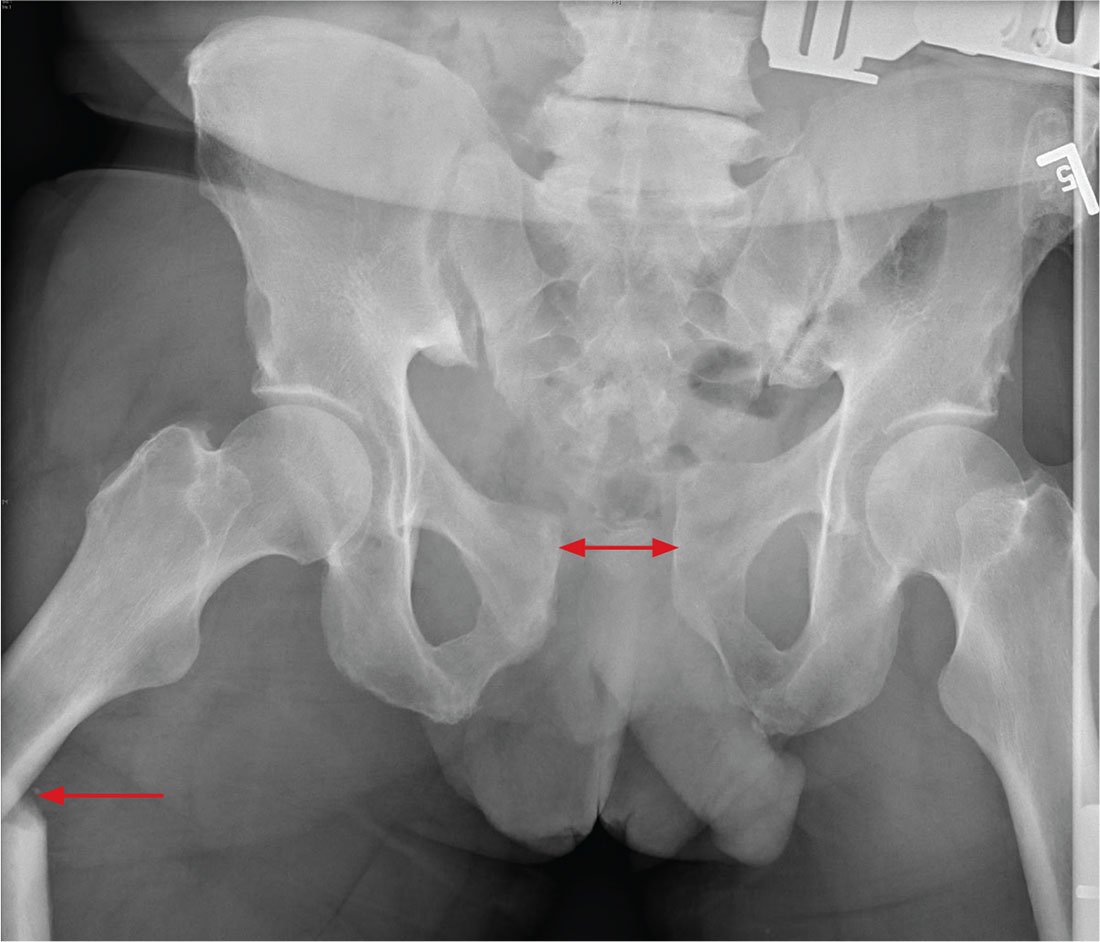

ANSWER

There is significant diastasis of the pubic symphysis, measuring nearly 4 cm. No obvious fractures of the hip or pelvis are seen, but there is malalignment of the rami. There is also evidence of a proximal right femur fracture, although this area is not fully imaged.

Such radiographic findings are typically referred to as an open book pelvic fracture. Usually the result of a shear injury, these fractures are not uncommon and carry an increased risk for pelvic vascular injury.

Emergent orthopedic and vascular consults were obtained, and the patient was placed in a pelvic binder to help reduce the distraction and tamponade any potential vascular injuries.

A man, approximately 60 years old, is brought to your facility as a trauma code following a vehicular accident. He was riding a motorcycle when he crashed into another vehicle and was thrown off. Emergency medical personnel report that the patient has obvious head, facial, and extremity trauma. Due to decreased level of consciousness, he was intubated en route. History is otherwise unknown.

Upon arrival, he has two large-bore IVs in place, with fluids going wide open. Despite that, his systolic blood pressure is 90 mm Hg and his heart rate is in the range of 150-160 beats/min. The massive transfusion protocol has been initiated to aid in the aggressive resuscitation efforts.

Portable radiographs of the chest and pelvis are obtained; the latter is shown. What is your impression?

Lithoplasty tames heavily calcified coronary lesions

PARIS – A novel therapeutic ultrasound-based technology known as lithoplasty is turning heads in interventional cardiology and vascular medicine because it addresses the bane of interventionalists’ existence: complex, heavily calcified coronary and peripheral artery lesions.

“Calcification is something we deal with every day in interventional cardiology. It makes the procedures more expensive, longer, and in fact several recent studies have shown that the complication rate for calcified lesions is higher than for any other lesion subtype. Calcification is the next big thing that we’re trying to take on in interventional cardiology,” Todd J. Brinton, MD, observed at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

At EuroPCR, he presented the results of DISRUPT CAD, a seven-center study in which 60 patients with heavily calcified coronary lesions underwent lithoplasty in order to facilitate stent placement. The study met all of its safety and performance endpoints. As a result, the week prior to EuroPCR the European regulatory agency granted marketing approval for Shockwave Medical’s coronary lithoplasty system; the indication is for coronary vessel preparation prior to stenting. A large phase III U.S. trial aimed at gaining FDA approval is planned.

Moreover, on the basis of the earlier favorable DISRUPT PAD trial, lithoplasty has already been approved for treatment of peripheral artery disease (PAD) in Europe since late 2015 and by the FDA since September 2016. Now underway is DISRUPT PAD III, a large postmarketing randomized trial comparing lithoplasty with conventional balloon angioplasty in patients with heavily calcified PAD, added Dr. Brinton, an interventional cardiologist at Stanford (Calif.) University and cofounder of Shockwave Medical.

Lithoplasty is a potentially transformative technology which he described as “lithotripsy inside a balloon.” Lithotripsy has an established 30-year track record for the safe treatment of kidney stones. However, lithotripsy utilizes focused ultrasound, while lithoplasty relies upon circumferential unfocused therapeutic ultrasound delivered by miniaturized emitters placed inside a 12-mm intravascular balloon. The balloon is crossed to the target lesion, inflated to a modest pressure of 4 atmospheres, then the operator delivers lithoplasty pulses lasting over 1 microsec in duration at a rate of 1/sec for 10 seconds in order to fracture the thick intramedial calcium plaque, allowing the lesion to open up and thereby normalize vessel compliance.

“Once you’ve cracked the calcium you can easily dilate the lesion. It’s the calcium that’s restricting the ability to dilate. The real fundamental need here is to maximize acute gain to get really good stent apposition. We’re trying to get expansion,” the cardiologist explained.

That was readily achieved in the DISRUPT CAD study. The 60 participants had reference vessel diameters of 2.5-4.0 mm, with an average target lesion length of 20 mm. The calcification was heavy, covering on average 270 degrees of the vessel circumference as measured by optical coherence tomography, with an average calcium thickness of 0.97 mm and a calcified segment length of 22.3 mm.

The mean stent expansion was 112%. The minimum luminal diameter improved from 0.9 mm pretreatment to 2.6 mm post treatment, for an acute gain of 1.7 mm. The amount of acute gain was similar across the full range of vessel diameters.

The mean diameter stenosis went from 68% pretreatment to 13% post-treatment.

The primary safety endpoint was the 30-day rate of MACE, defined as cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization. The rate was 5%, consisting of 3 patients with mild non–Q-wave MI defined by creatine kinase–MB elevations more than three times the upper limit of normal. The 6-month MACE rate was 8.5%, which included the three non–Q-wave MIs plus two cardiac deaths not related to the procedure or technology.

Final angiographic results adjudicated in a central core laboratory showed no perforations, abrupt closures, slow or no reflow events, or residual dissections. These are complications commonly seen with debulking devices such as rotational or orbital atherectomy, Dr. Brinton noted.

The primary performance endpoint in DISRUPT CAD was clinical success, defined as a residual stenosis of less than 50% post PCI with no in-hospital MACE. This was achieved in 57 of 60 patients, or 95%. The device was successfully delivered to the target lesion with subsequent performance of lithoplasty in 59 of 60 patients. An even more flexible and deliverable device will be released in the coming year, according to the cardiologist.

“I’d say the take-home is that the disease has changed,” Dr. Brinton commented. “It’s not the same disease that we had when Gruentzig did his first balloon angioplasty. These lesions are more calcified, more complex, yet for the most part we use the same balloon we’ve been using for the last 40 years. So lithoplasty is really an attempt to modernize the therapy in a new patient subset we now take care of who are much more complicated than the patients we originally took care of.”

“The reality is, we’re having difficulty taking care of these patients. For myself as an interventionalist, it’s not uncommon to look around the table and see a massive amount of tools when we’re doing these complex cases. Lithoplasty is intended to bring the simplicity. I would say it’s not necessarily to make the best operators better, it’s to bring all operators up to the ability to take on these complex lesions that are now usually reserved for high-volume centers that can do debulking,” he added.

Session cochair David R. Holmes Jr., MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., pronounced lithoplasty “tremendously exciting.” He and the other panelists focused on questions of safety and potential collateral damage: Where does the calcified debris go? What are the effects of the unfocused sonic pressure waves on noncalcified plaque? How hot does the vessel get?

Dr. Brinton replied that thick calcium plaque is located mostly in the medial vessel wall and stays there after fracturing. That’s why distal embolization wasn’t an issue in DISRUPT CAD. In animal studies, even at 20 times the energy dose used in clinical practice, lithoplasty had no effect on softer, noncalcified plaque or normal tissue. Vessel temperature increases by about 1.2 degrees C during lithoplasty, which isn’t sufficient to cause injury or drive restenosis.

Elsewhere at EuroPCR, Alberto Cremonesi, MD, who chaired a press conference where Dr. Brinton presented highlights of DISRUPT CAD, declared lithoplasty is “in my mind a real breakthrough, not only for coronary disease but also for PAD.”

Is it possible that stand-alone lithoplasty could reduce the need for multiple stents in longer coronary lesions, instead making possible more focal stenting? asked Dr. Cremonesi of Maria Cecilia Hospital in Cotignola, Italy.

That’s one of several possibilities worthy of future investigation, Dr. Brinton replied. Lithoplasty might also facilitate the results obtainable with bioresorbable coronary scaffolds or drug-coated balloons, he added.

He noted that as cofounder of and a consultant to Shockwave Medical, he has a sizable financial involvement with the company.

PARIS – A novel therapeutic ultrasound-based technology known as lithoplasty is turning heads in interventional cardiology and vascular medicine because it addresses the bane of interventionalists’ existence: complex, heavily calcified coronary and peripheral artery lesions.

“Calcification is something we deal with every day in interventional cardiology. It makes the procedures more expensive, longer, and in fact several recent studies have shown that the complication rate for calcified lesions is higher than for any other lesion subtype. Calcification is the next big thing that we’re trying to take on in interventional cardiology,” Todd J. Brinton, MD, observed at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

At EuroPCR, he presented the results of DISRUPT CAD, a seven-center study in which 60 patients with heavily calcified coronary lesions underwent lithoplasty in order to facilitate stent placement. The study met all of its safety and performance endpoints. As a result, the week prior to EuroPCR the European regulatory agency granted marketing approval for Shockwave Medical’s coronary lithoplasty system; the indication is for coronary vessel preparation prior to stenting. A large phase III U.S. trial aimed at gaining FDA approval is planned.

Moreover, on the basis of the earlier favorable DISRUPT PAD trial, lithoplasty has already been approved for treatment of peripheral artery disease (PAD) in Europe since late 2015 and by the FDA since September 2016. Now underway is DISRUPT PAD III, a large postmarketing randomized trial comparing lithoplasty with conventional balloon angioplasty in patients with heavily calcified PAD, added Dr. Brinton, an interventional cardiologist at Stanford (Calif.) University and cofounder of Shockwave Medical.

Lithoplasty is a potentially transformative technology which he described as “lithotripsy inside a balloon.” Lithotripsy has an established 30-year track record for the safe treatment of kidney stones. However, lithotripsy utilizes focused ultrasound, while lithoplasty relies upon circumferential unfocused therapeutic ultrasound delivered by miniaturized emitters placed inside a 12-mm intravascular balloon. The balloon is crossed to the target lesion, inflated to a modest pressure of 4 atmospheres, then the operator delivers lithoplasty pulses lasting over 1 microsec in duration at a rate of 1/sec for 10 seconds in order to fracture the thick intramedial calcium plaque, allowing the lesion to open up and thereby normalize vessel compliance.

“Once you’ve cracked the calcium you can easily dilate the lesion. It’s the calcium that’s restricting the ability to dilate. The real fundamental need here is to maximize acute gain to get really good stent apposition. We’re trying to get expansion,” the cardiologist explained.

That was readily achieved in the DISRUPT CAD study. The 60 participants had reference vessel diameters of 2.5-4.0 mm, with an average target lesion length of 20 mm. The calcification was heavy, covering on average 270 degrees of the vessel circumference as measured by optical coherence tomography, with an average calcium thickness of 0.97 mm and a calcified segment length of 22.3 mm.

The mean stent expansion was 112%. The minimum luminal diameter improved from 0.9 mm pretreatment to 2.6 mm post treatment, for an acute gain of 1.7 mm. The amount of acute gain was similar across the full range of vessel diameters.

The mean diameter stenosis went from 68% pretreatment to 13% post-treatment.

The primary safety endpoint was the 30-day rate of MACE, defined as cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization. The rate was 5%, consisting of 3 patients with mild non–Q-wave MI defined by creatine kinase–MB elevations more than three times the upper limit of normal. The 6-month MACE rate was 8.5%, which included the three non–Q-wave MIs plus two cardiac deaths not related to the procedure or technology.

Final angiographic results adjudicated in a central core laboratory showed no perforations, abrupt closures, slow or no reflow events, or residual dissections. These are complications commonly seen with debulking devices such as rotational or orbital atherectomy, Dr. Brinton noted.

The primary performance endpoint in DISRUPT CAD was clinical success, defined as a residual stenosis of less than 50% post PCI with no in-hospital MACE. This was achieved in 57 of 60 patients, or 95%. The device was successfully delivered to the target lesion with subsequent performance of lithoplasty in 59 of 60 patients. An even more flexible and deliverable device will be released in the coming year, according to the cardiologist.

“I’d say the take-home is that the disease has changed,” Dr. Brinton commented. “It’s not the same disease that we had when Gruentzig did his first balloon angioplasty. These lesions are more calcified, more complex, yet for the most part we use the same balloon we’ve been using for the last 40 years. So lithoplasty is really an attempt to modernize the therapy in a new patient subset we now take care of who are much more complicated than the patients we originally took care of.”

“The reality is, we’re having difficulty taking care of these patients. For myself as an interventionalist, it’s not uncommon to look around the table and see a massive amount of tools when we’re doing these complex cases. Lithoplasty is intended to bring the simplicity. I would say it’s not necessarily to make the best operators better, it’s to bring all operators up to the ability to take on these complex lesions that are now usually reserved for high-volume centers that can do debulking,” he added.

Session cochair David R. Holmes Jr., MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., pronounced lithoplasty “tremendously exciting.” He and the other panelists focused on questions of safety and potential collateral damage: Where does the calcified debris go? What are the effects of the unfocused sonic pressure waves on noncalcified plaque? How hot does the vessel get?

Dr. Brinton replied that thick calcium plaque is located mostly in the medial vessel wall and stays there after fracturing. That’s why distal embolization wasn’t an issue in DISRUPT CAD. In animal studies, even at 20 times the energy dose used in clinical practice, lithoplasty had no effect on softer, noncalcified plaque or normal tissue. Vessel temperature increases by about 1.2 degrees C during lithoplasty, which isn’t sufficient to cause injury or drive restenosis.

Elsewhere at EuroPCR, Alberto Cremonesi, MD, who chaired a press conference where Dr. Brinton presented highlights of DISRUPT CAD, declared lithoplasty is “in my mind a real breakthrough, not only for coronary disease but also for PAD.”

Is it possible that stand-alone lithoplasty could reduce the need for multiple stents in longer coronary lesions, instead making possible more focal stenting? asked Dr. Cremonesi of Maria Cecilia Hospital in Cotignola, Italy.

That’s one of several possibilities worthy of future investigation, Dr. Brinton replied. Lithoplasty might also facilitate the results obtainable with bioresorbable coronary scaffolds or drug-coated balloons, he added.

He noted that as cofounder of and a consultant to Shockwave Medical, he has a sizable financial involvement with the company.

PARIS – A novel therapeutic ultrasound-based technology known as lithoplasty is turning heads in interventional cardiology and vascular medicine because it addresses the bane of interventionalists’ existence: complex, heavily calcified coronary and peripheral artery lesions.

“Calcification is something we deal with every day in interventional cardiology. It makes the procedures more expensive, longer, and in fact several recent studies have shown that the complication rate for calcified lesions is higher than for any other lesion subtype. Calcification is the next big thing that we’re trying to take on in interventional cardiology,” Todd J. Brinton, MD, observed at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

At EuroPCR, he presented the results of DISRUPT CAD, a seven-center study in which 60 patients with heavily calcified coronary lesions underwent lithoplasty in order to facilitate stent placement. The study met all of its safety and performance endpoints. As a result, the week prior to EuroPCR the European regulatory agency granted marketing approval for Shockwave Medical’s coronary lithoplasty system; the indication is for coronary vessel preparation prior to stenting. A large phase III U.S. trial aimed at gaining FDA approval is planned.

Moreover, on the basis of the earlier favorable DISRUPT PAD trial, lithoplasty has already been approved for treatment of peripheral artery disease (PAD) in Europe since late 2015 and by the FDA since September 2016. Now underway is DISRUPT PAD III, a large postmarketing randomized trial comparing lithoplasty with conventional balloon angioplasty in patients with heavily calcified PAD, added Dr. Brinton, an interventional cardiologist at Stanford (Calif.) University and cofounder of Shockwave Medical.

Lithoplasty is a potentially transformative technology which he described as “lithotripsy inside a balloon.” Lithotripsy has an established 30-year track record for the safe treatment of kidney stones. However, lithotripsy utilizes focused ultrasound, while lithoplasty relies upon circumferential unfocused therapeutic ultrasound delivered by miniaturized emitters placed inside a 12-mm intravascular balloon. The balloon is crossed to the target lesion, inflated to a modest pressure of 4 atmospheres, then the operator delivers lithoplasty pulses lasting over 1 microsec in duration at a rate of 1/sec for 10 seconds in order to fracture the thick intramedial calcium plaque, allowing the lesion to open up and thereby normalize vessel compliance.

“Once you’ve cracked the calcium you can easily dilate the lesion. It’s the calcium that’s restricting the ability to dilate. The real fundamental need here is to maximize acute gain to get really good stent apposition. We’re trying to get expansion,” the cardiologist explained.

That was readily achieved in the DISRUPT CAD study. The 60 participants had reference vessel diameters of 2.5-4.0 mm, with an average target lesion length of 20 mm. The calcification was heavy, covering on average 270 degrees of the vessel circumference as measured by optical coherence tomography, with an average calcium thickness of 0.97 mm and a calcified segment length of 22.3 mm.

The mean stent expansion was 112%. The minimum luminal diameter improved from 0.9 mm pretreatment to 2.6 mm post treatment, for an acute gain of 1.7 mm. The amount of acute gain was similar across the full range of vessel diameters.

The mean diameter stenosis went from 68% pretreatment to 13% post-treatment.

The primary safety endpoint was the 30-day rate of MACE, defined as cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization. The rate was 5%, consisting of 3 patients with mild non–Q-wave MI defined by creatine kinase–MB elevations more than three times the upper limit of normal. The 6-month MACE rate was 8.5%, which included the three non–Q-wave MIs plus two cardiac deaths not related to the procedure or technology.

Final angiographic results adjudicated in a central core laboratory showed no perforations, abrupt closures, slow or no reflow events, or residual dissections. These are complications commonly seen with debulking devices such as rotational or orbital atherectomy, Dr. Brinton noted.

The primary performance endpoint in DISRUPT CAD was clinical success, defined as a residual stenosis of less than 50% post PCI with no in-hospital MACE. This was achieved in 57 of 60 patients, or 95%. The device was successfully delivered to the target lesion with subsequent performance of lithoplasty in 59 of 60 patients. An even more flexible and deliverable device will be released in the coming year, according to the cardiologist.

“I’d say the take-home is that the disease has changed,” Dr. Brinton commented. “It’s not the same disease that we had when Gruentzig did his first balloon angioplasty. These lesions are more calcified, more complex, yet for the most part we use the same balloon we’ve been using for the last 40 years. So lithoplasty is really an attempt to modernize the therapy in a new patient subset we now take care of who are much more complicated than the patients we originally took care of.”

“The reality is, we’re having difficulty taking care of these patients. For myself as an interventionalist, it’s not uncommon to look around the table and see a massive amount of tools when we’re doing these complex cases. Lithoplasty is intended to bring the simplicity. I would say it’s not necessarily to make the best operators better, it’s to bring all operators up to the ability to take on these complex lesions that are now usually reserved for high-volume centers that can do debulking,” he added.

Session cochair David R. Holmes Jr., MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., pronounced lithoplasty “tremendously exciting.” He and the other panelists focused on questions of safety and potential collateral damage: Where does the calcified debris go? What are the effects of the unfocused sonic pressure waves on noncalcified plaque? How hot does the vessel get?

Dr. Brinton replied that thick calcium plaque is located mostly in the medial vessel wall and stays there after fracturing. That’s why distal embolization wasn’t an issue in DISRUPT CAD. In animal studies, even at 20 times the energy dose used in clinical practice, lithoplasty had no effect on softer, noncalcified plaque or normal tissue. Vessel temperature increases by about 1.2 degrees C during lithoplasty, which isn’t sufficient to cause injury or drive restenosis.

Elsewhere at EuroPCR, Alberto Cremonesi, MD, who chaired a press conference where Dr. Brinton presented highlights of DISRUPT CAD, declared lithoplasty is “in my mind a real breakthrough, not only for coronary disease but also for PAD.”

Is it possible that stand-alone lithoplasty could reduce the need for multiple stents in longer coronary lesions, instead making possible more focal stenting? asked Dr. Cremonesi of Maria Cecilia Hospital in Cotignola, Italy.

That’s one of several possibilities worthy of future investigation, Dr. Brinton replied. Lithoplasty might also facilitate the results obtainable with bioresorbable coronary scaffolds or drug-coated balloons, he added.

He noted that as cofounder of and a consultant to Shockwave Medical, he has a sizable financial involvement with the company.

AT EUROPCR

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Lithoplasty of heavily calcified coronary lesions improved the minimum luminal diameter from 0.9 mm pretreatment to 2.6 mm post-treatment, for an immediate gain of 1.7 mm prior to stent placement.

Data source: This study featured 6-month follow-up of 60 patients with heavily calcified coronary lesions who underwent lithoplasty followed by stenting.

Disclosures: The DISRUPT CAD study was sponsored by Shockwave Medical, which is developing lithoplasty. The presenter cofounded the company.

Common insurance plans exclude NCI, NCCN cancer centers

Narrow insurance plan coverage may prevent US cancer patients from receiving care at “high-quality” cancer centers, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Researchers found that “narrow network” insurance plans—lower-premium plans with reduced access to certain providers—are more likely to exclude doctors associated with National Cancer Institute (NCI) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) cancer centers.

These centers are recognized for their scientific and research leadership, quality and safety initiatives, and access to expert physicians and clinical trials.

NCCN member institutions are particularly recognized for higher-quality care, and treatment at NCI-designated cancer centers is associated with lower mortality than other hospitals, particularly among more severely ill patients and those with more advanced disease.

For this study, researchers examined cancer provider networks offered on the 2014 individual health insurance exchanges and then determined which oncologists were affiliated with NCI-designated and NCCN cancer centers.

The researchers found that narrower networks were less likely to include physicians associated with NCI-designated and NCCN member institutions.

“To see such a robust result was surprising,” said study author Laura Yasaitis, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“The finding that narrower networks were more likely to exclude NCI and NCCN oncologists was consistent no matter how we looked at it. This is not just a few networks. It’s a clear trend.”

The researchers said the results point to 2 major problems—transparency and access.

“Patients should be able to easily figure out whether the physicians they might need will be covered under a given plan,” said study author Justin E. Bekelman, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania.

The researchers suggested that insurers report doctor’s affiliations with NCI and NCCN cancer centers so that consumers can make more informed choices.

The team also suggested that insurers offer mechanisms that would allow patients to seek care out of network without incurring penalties in exceptional circumstances.

“If patients have narrow network plans and absolutely need the kind of complex cancer care that they can only receive from one of these providers, there should be a standard exception process to allow patients to access the care they need,” Dr Bekelman said. ![]()

Narrow insurance plan coverage may prevent US cancer patients from receiving care at “high-quality” cancer centers, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Researchers found that “narrow network” insurance plans—lower-premium plans with reduced access to certain providers—are more likely to exclude doctors associated with National Cancer Institute (NCI) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) cancer centers.

These centers are recognized for their scientific and research leadership, quality and safety initiatives, and access to expert physicians and clinical trials.

NCCN member institutions are particularly recognized for higher-quality care, and treatment at NCI-designated cancer centers is associated with lower mortality than other hospitals, particularly among more severely ill patients and those with more advanced disease.

For this study, researchers examined cancer provider networks offered on the 2014 individual health insurance exchanges and then determined which oncologists were affiliated with NCI-designated and NCCN cancer centers.

The researchers found that narrower networks were less likely to include physicians associated with NCI-designated and NCCN member institutions.

“To see such a robust result was surprising,” said study author Laura Yasaitis, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“The finding that narrower networks were more likely to exclude NCI and NCCN oncologists was consistent no matter how we looked at it. This is not just a few networks. It’s a clear trend.”

The researchers said the results point to 2 major problems—transparency and access.

“Patients should be able to easily figure out whether the physicians they might need will be covered under a given plan,” said study author Justin E. Bekelman, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania.

The researchers suggested that insurers report doctor’s affiliations with NCI and NCCN cancer centers so that consumers can make more informed choices.

The team also suggested that insurers offer mechanisms that would allow patients to seek care out of network without incurring penalties in exceptional circumstances.

“If patients have narrow network plans and absolutely need the kind of complex cancer care that they can only receive from one of these providers, there should be a standard exception process to allow patients to access the care they need,” Dr Bekelman said. ![]()

Narrow insurance plan coverage may prevent US cancer patients from receiving care at “high-quality” cancer centers, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Researchers found that “narrow network” insurance plans—lower-premium plans with reduced access to certain providers—are more likely to exclude doctors associated with National Cancer Institute (NCI) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) cancer centers.

These centers are recognized for their scientific and research leadership, quality and safety initiatives, and access to expert physicians and clinical trials.

NCCN member institutions are particularly recognized for higher-quality care, and treatment at NCI-designated cancer centers is associated with lower mortality than other hospitals, particularly among more severely ill patients and those with more advanced disease.

For this study, researchers examined cancer provider networks offered on the 2014 individual health insurance exchanges and then determined which oncologists were affiliated with NCI-designated and NCCN cancer centers.

The researchers found that narrower networks were less likely to include physicians associated with NCI-designated and NCCN member institutions.

“To see such a robust result was surprising,” said study author Laura Yasaitis, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“The finding that narrower networks were more likely to exclude NCI and NCCN oncologists was consistent no matter how we looked at it. This is not just a few networks. It’s a clear trend.”

The researchers said the results point to 2 major problems—transparency and access.

“Patients should be able to easily figure out whether the physicians they might need will be covered under a given plan,” said study author Justin E. Bekelman, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania.

The researchers suggested that insurers report doctor’s affiliations with NCI and NCCN cancer centers so that consumers can make more informed choices.

The team also suggested that insurers offer mechanisms that would allow patients to seek care out of network without incurring penalties in exceptional circumstances.

“If patients have narrow network plans and absolutely need the kind of complex cancer care that they can only receive from one of these providers, there should be a standard exception process to allow patients to access the care they need,” Dr Bekelman said. ![]()

New one-time treatment for head lice found safe for children

CHICAGO – A novel one-time topical treatment for head lice, abametapir, was well tolerated in children as young as 6 months, according to pooled results from 11 clinical trials.

The pooled safety data included results from 11 clinical trials including 1,372 patients. Of these, 700 were aged 6 months to 17 years, and patients were exposed to the novel metalloproteinase inhibitor for 10-20 minutes.

In examining safety data from the pooled trials, Lydie Hazan, MD, of Axis Clinical Trials and her collaborators found that for pediatric patients, most treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were skin and subcutaneous tissue-related. The most common AEs were erythema, rash, a burning sensation on the skin, and contact dermatitis.

Data for the three phase II pharmacokinetic trials, the phase II ovicidal efficacy trial, and the two phase III trials were reported separately by Dr. Hazan and her coauthors in a poster presentation at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. The overall incidence of treatment-emergent AEs in the studies ranged from 20% to 29% for patients in the active arms of the trials. For patients who received the vehicle lotion only, the incidence of AEs ranged from 16% to 57%.

Of the 11 trials, 6 involved pediatric patients, with one phase IIB trial, one phase II ovicidal trial, two maximal-use open-label trials, and two phase III randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials. Of the 920 patients, in most of the trials they received a 10-minute exposure to the study drug (489 received abametapir lotion 0.74%, 431 received vehicle lotion).

Looking just at the phase III trials, 24% of patients in the abametapir arm reported AEs, while 19% of those receiving vehicle reported any AE.

In the two maximal-use pediatric trials, drug exposure ranged from 3.3 g to 200.8 g; AEs in these two trials occurred in 23% of participants.

Safety data collected for all studies also included vital signs, results of physical exams, and laboratory tests; no “clinically meaningful” changes were seen in any of the trials for any of these values, according to Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

“AEs were mild, not age-related, and primarily in the system organ class of skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders,” said Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

Abematapir 0.74% lotion had previously been shown to be an effective ovicidal treatment for head lice when used in a single application; the lotion is intended to be applied at home by the patient or caregiver (J Med Entomol. 2017. 54[1]:167-72).*

Dr. Hazan is employed by Axis clinical trials. Other study authors were employed by Hatchtech, which developed abametapir, and by Promius Pharma/Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, which plans to market abametapir lotion.

*Correction, 8/7/17: An earlier version of this article had an incorrect citation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – A novel one-time topical treatment for head lice, abametapir, was well tolerated in children as young as 6 months, according to pooled results from 11 clinical trials.

The pooled safety data included results from 11 clinical trials including 1,372 patients. Of these, 700 were aged 6 months to 17 years, and patients were exposed to the novel metalloproteinase inhibitor for 10-20 minutes.

In examining safety data from the pooled trials, Lydie Hazan, MD, of Axis Clinical Trials and her collaborators found that for pediatric patients, most treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were skin and subcutaneous tissue-related. The most common AEs were erythema, rash, a burning sensation on the skin, and contact dermatitis.

Data for the three phase II pharmacokinetic trials, the phase II ovicidal efficacy trial, and the two phase III trials were reported separately by Dr. Hazan and her coauthors in a poster presentation at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. The overall incidence of treatment-emergent AEs in the studies ranged from 20% to 29% for patients in the active arms of the trials. For patients who received the vehicle lotion only, the incidence of AEs ranged from 16% to 57%.

Of the 11 trials, 6 involved pediatric patients, with one phase IIB trial, one phase II ovicidal trial, two maximal-use open-label trials, and two phase III randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials. Of the 920 patients, in most of the trials they received a 10-minute exposure to the study drug (489 received abametapir lotion 0.74%, 431 received vehicle lotion).

Looking just at the phase III trials, 24% of patients in the abametapir arm reported AEs, while 19% of those receiving vehicle reported any AE.

In the two maximal-use pediatric trials, drug exposure ranged from 3.3 g to 200.8 g; AEs in these two trials occurred in 23% of participants.

Safety data collected for all studies also included vital signs, results of physical exams, and laboratory tests; no “clinically meaningful” changes were seen in any of the trials for any of these values, according to Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

“AEs were mild, not age-related, and primarily in the system organ class of skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders,” said Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

Abematapir 0.74% lotion had previously been shown to be an effective ovicidal treatment for head lice when used in a single application; the lotion is intended to be applied at home by the patient or caregiver (J Med Entomol. 2017. 54[1]:167-72).*

Dr. Hazan is employed by Axis clinical trials. Other study authors were employed by Hatchtech, which developed abametapir, and by Promius Pharma/Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, which plans to market abametapir lotion.

*Correction, 8/7/17: An earlier version of this article had an incorrect citation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – A novel one-time topical treatment for head lice, abametapir, was well tolerated in children as young as 6 months, according to pooled results from 11 clinical trials.

The pooled safety data included results from 11 clinical trials including 1,372 patients. Of these, 700 were aged 6 months to 17 years, and patients were exposed to the novel metalloproteinase inhibitor for 10-20 minutes.

In examining safety data from the pooled trials, Lydie Hazan, MD, of Axis Clinical Trials and her collaborators found that for pediatric patients, most treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were skin and subcutaneous tissue-related. The most common AEs were erythema, rash, a burning sensation on the skin, and contact dermatitis.

Data for the three phase II pharmacokinetic trials, the phase II ovicidal efficacy trial, and the two phase III trials were reported separately by Dr. Hazan and her coauthors in a poster presentation at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. The overall incidence of treatment-emergent AEs in the studies ranged from 20% to 29% for patients in the active arms of the trials. For patients who received the vehicle lotion only, the incidence of AEs ranged from 16% to 57%.

Of the 11 trials, 6 involved pediatric patients, with one phase IIB trial, one phase II ovicidal trial, two maximal-use open-label trials, and two phase III randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials. Of the 920 patients, in most of the trials they received a 10-minute exposure to the study drug (489 received abametapir lotion 0.74%, 431 received vehicle lotion).

Looking just at the phase III trials, 24% of patients in the abametapir arm reported AEs, while 19% of those receiving vehicle reported any AE.

In the two maximal-use pediatric trials, drug exposure ranged from 3.3 g to 200.8 g; AEs in these two trials occurred in 23% of participants.

Safety data collected for all studies also included vital signs, results of physical exams, and laboratory tests; no “clinically meaningful” changes were seen in any of the trials for any of these values, according to Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

“AEs were mild, not age-related, and primarily in the system organ class of skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders,” said Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

Abematapir 0.74% lotion had previously been shown to be an effective ovicidal treatment for head lice when used in a single application; the lotion is intended to be applied at home by the patient or caregiver (J Med Entomol. 2017. 54[1]:167-72).*

Dr. Hazan is employed by Axis clinical trials. Other study authors were employed by Hatchtech, which developed abametapir, and by Promius Pharma/Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, which plans to market abametapir lotion.

*Correction, 8/7/17: An earlier version of this article had an incorrect citation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT WCPD 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In pooled clinical trial data, pediatric patients had adverse events at the same rate as adult patients, with overall rates ranging from 20% to 57%.

Data source: Pooled data from 11 clinical trials including 1,372 patients, 700 of whom were aged 6 months to 17 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Hazan is employed by Axis Clinical Trials. Other study authors were employed by Hatchtech, which developed abametapir, and by Promius Pharma/Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, which plans to market abametapir lotion.

Isotretinoin patients need not postpone skin surgery

Skin procedures including superficial chemical peels, laser hair removal, minor cutaneous surgery, manual dermabrasion, and fractional ablative and fractional nonablative laser procedures can be performed safely on patients who have recently been or are currently being treated with isotretinoin, according to new recommendations from a consensus panel.

The recommendations were published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Postponing surgical procedures in patients taking isotretinoin because of the potential for keloid formation and delayed wound healing “has persisted despite increasing reports to the contrary,” wrote Leah K. Spring, DO, of Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, Camp Lejeune, N.C., and her colleagues (JAMA Dermatol. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2077).

This protocol is based on 11 patients with delayed healing and keloids, the researchers noted. “In our consensus-based assessment, these initial cases presented a hypothesis to be tested, rather than the foundation for medical dogma on which more than 30 years of clinical practice was built,” they wrote.

To establish the current level of evidence for delaying procedures in isotretinoin patients and to make recommendations, an expert panel reviewed data from 32 publications and more than 1,485 procedures. The literature was divided into five areas: dermabrasion, chemical peels, cutaneous surgery, laser hair removal, and ablative/nonablative laser treatments.

The researchers determined that evidence does not support the safety of mechanical dermabrasion or fully ablative laser surgeries for current or recent isotretinoin users. Manual dermabrasion and microdermabrasion were deemed safe for isotretinoin patients based on the latest evidence, however, as were fractional ablative and fractional nonablative procedures.

In addition, the evidence did not support refraining from chemical peels, laser hair removal, or cutaneous surgery for current and recent isotretinoin patients, although the panel recommended additional prospective, controlled clinical trials in these areas.

In the area of cutaneous surgery, the consensus panel also noted the need for “a rigorous evaluation of the aforementioned specific warning that muscle flap insertion should be delayed until the patient displays normal [creatine phosphokinase (CPK)] levels or, at least, CPK levels below twofold of normal.”