User login

Optimal age for cardiovascular disease screening remains elusive

SAN FRANCISCO – In the United States, deaths from cardiovascular disease fell by about 50% in men and women between 1980 and 2000, and fell an additional 31% between 2000 and 2010, according to Robert Baron, MD.

That’s the good news, driven largely by the introduction of statin therapy and by risk-factor modifications. The not-so-great news? The optimal screening age for CVD risk remains elusive.

“We’ve been arguing about this for at least 30 years,” he said at the UCSF Annual Advances in Internal Medicine.

The 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk recommends screening at age 21 years to identify those with an LDL cholesterol level greater than 190 mg/dL, while a more recent draft recommendation statement from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening at age 35 in men and 45 in women for most cases, or at age 20 in people deemed to be at increased risk. Both sets of guidelines recommend the use of statins in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and LDL of 190 mg/dL or greater, and/or diabetes.

“In essence, the USPSTF guidelines are saying definitely use statins for primary prevention in high-risk people; they’re just creating a little more gray area as to what exactly constitutes high risk,” said Dr. Baron, an internist who is associate dean at UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco. “The question is, how do you draw the line? I would argue that depends on the patient preference.”

In a recently published analysis, researchers set out to determine how the USPSTF guidelines compare with the ACC/AHA guidelines in terms of the proportion of U.S. adults potentially treated (JAMA. 2017 Apr 18; 317[15]:1563-7). After using estimates based on data from 3,416 participants in the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the researchers found that USPSTF recommendations would be associated with statin initiation in 16% of U.S. adults aged 40-75 years without prior CVD, compared with 24% according to the ACC/AHA guidelines.

Among those adults for whom therapy would no longer be recommended under the USPSTF recommendations, 55% are aged 40-59 years with a mean 30-year cardiovascular risk exceeding 30%, and 28% have diabetes. According to Dr. Baron, the comparison “reinforces the primary prevention message. It gives the patient a bit more flexibility.”

After starting patients on a statin, the best available evidence recommends monitoring adherence but not treating to a specific LDL goal, he said. Statins should not be used in patients older than age 75 unless they have existing ASCVD. The addition of other lipid-modifying drugs is generally not recommended, but it may be needed in patients who demonstrate intolerance to statins. Patients should also avoid using NSAIDS, which raise CVD risk, and instead use medications that lower it, such as aspirin, he said.

Dr. Baron reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – In the United States, deaths from cardiovascular disease fell by about 50% in men and women between 1980 and 2000, and fell an additional 31% between 2000 and 2010, according to Robert Baron, MD.

That’s the good news, driven largely by the introduction of statin therapy and by risk-factor modifications. The not-so-great news? The optimal screening age for CVD risk remains elusive.

“We’ve been arguing about this for at least 30 years,” he said at the UCSF Annual Advances in Internal Medicine.

The 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk recommends screening at age 21 years to identify those with an LDL cholesterol level greater than 190 mg/dL, while a more recent draft recommendation statement from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening at age 35 in men and 45 in women for most cases, or at age 20 in people deemed to be at increased risk. Both sets of guidelines recommend the use of statins in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and LDL of 190 mg/dL or greater, and/or diabetes.

“In essence, the USPSTF guidelines are saying definitely use statins for primary prevention in high-risk people; they’re just creating a little more gray area as to what exactly constitutes high risk,” said Dr. Baron, an internist who is associate dean at UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco. “The question is, how do you draw the line? I would argue that depends on the patient preference.”

In a recently published analysis, researchers set out to determine how the USPSTF guidelines compare with the ACC/AHA guidelines in terms of the proportion of U.S. adults potentially treated (JAMA. 2017 Apr 18; 317[15]:1563-7). After using estimates based on data from 3,416 participants in the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the researchers found that USPSTF recommendations would be associated with statin initiation in 16% of U.S. adults aged 40-75 years without prior CVD, compared with 24% according to the ACC/AHA guidelines.

Among those adults for whom therapy would no longer be recommended under the USPSTF recommendations, 55% are aged 40-59 years with a mean 30-year cardiovascular risk exceeding 30%, and 28% have diabetes. According to Dr. Baron, the comparison “reinforces the primary prevention message. It gives the patient a bit more flexibility.”

After starting patients on a statin, the best available evidence recommends monitoring adherence but not treating to a specific LDL goal, he said. Statins should not be used in patients older than age 75 unless they have existing ASCVD. The addition of other lipid-modifying drugs is generally not recommended, but it may be needed in patients who demonstrate intolerance to statins. Patients should also avoid using NSAIDS, which raise CVD risk, and instead use medications that lower it, such as aspirin, he said.

Dr. Baron reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – In the United States, deaths from cardiovascular disease fell by about 50% in men and women between 1980 and 2000, and fell an additional 31% between 2000 and 2010, according to Robert Baron, MD.

That’s the good news, driven largely by the introduction of statin therapy and by risk-factor modifications. The not-so-great news? The optimal screening age for CVD risk remains elusive.

“We’ve been arguing about this for at least 30 years,” he said at the UCSF Annual Advances in Internal Medicine.

The 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk recommends screening at age 21 years to identify those with an LDL cholesterol level greater than 190 mg/dL, while a more recent draft recommendation statement from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening at age 35 in men and 45 in women for most cases, or at age 20 in people deemed to be at increased risk. Both sets of guidelines recommend the use of statins in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and LDL of 190 mg/dL or greater, and/or diabetes.

“In essence, the USPSTF guidelines are saying definitely use statins for primary prevention in high-risk people; they’re just creating a little more gray area as to what exactly constitutes high risk,” said Dr. Baron, an internist who is associate dean at UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco. “The question is, how do you draw the line? I would argue that depends on the patient preference.”

In a recently published analysis, researchers set out to determine how the USPSTF guidelines compare with the ACC/AHA guidelines in terms of the proportion of U.S. adults potentially treated (JAMA. 2017 Apr 18; 317[15]:1563-7). After using estimates based on data from 3,416 participants in the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the researchers found that USPSTF recommendations would be associated with statin initiation in 16% of U.S. adults aged 40-75 years without prior CVD, compared with 24% according to the ACC/AHA guidelines.

Among those adults for whom therapy would no longer be recommended under the USPSTF recommendations, 55% are aged 40-59 years with a mean 30-year cardiovascular risk exceeding 30%, and 28% have diabetes. According to Dr. Baron, the comparison “reinforces the primary prevention message. It gives the patient a bit more flexibility.”

After starting patients on a statin, the best available evidence recommends monitoring adherence but not treating to a specific LDL goal, he said. Statins should not be used in patients older than age 75 unless they have existing ASCVD. The addition of other lipid-modifying drugs is generally not recommended, but it may be needed in patients who demonstrate intolerance to statins. Patients should also avoid using NSAIDS, which raise CVD risk, and instead use medications that lower it, such as aspirin, he said.

Dr. Baron reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL ADVANCES IN INTERNAL MEDICINE

Higher ADHD risk seen in children with migraine

BOSTON – Children aged 5-12 years with signs of migraine headache were as much as seven times as likely as other children to also appear to have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but those with tension-type headaches didn’t face a higher risk of ADHD, a Brazilian study showed.

It’s not clear why the apparent link between migraines and ADHD exists. However, lead study author Marco Antônio Arruda, MD, PhD, a pediatric neurologist in São Paulo (Brazil) University, said in an interview that other research has linked migraine to mental health problems.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology and published online in the Journal of Attention Disorders (2017. doi: 10.1177/1087054717710767), was launched to better understand the connection between migraine and ADHD, which are thought to each affect as many as 1 in 10 children.

The study analyzes data from mothers and teachers of 5,671 children aged 5-12 years who answered questions as part of a Brazil-wide epidemiologic study called the Attention Brazil Project. Just over half of the participants were boys, and about half were from the Brazilian middle class.

Based on answers from mothers and teachers, the researchers estimated that 9% of the children had episodic migraine and 0.6% had chronic migraine. The level of episodic tension-type headache was estimated at 12.8%, with a lower rate in the two poorest vs. the two richest quintiles (8.6% vs. 14.4%, respectively; relative risk, 0.6; 95% confidence interval, 0.5-0.8).

The researchers estimated that 5.3% of the children overall showed signs of ADHD (7.5% in boys vs. 3.1% in girls; RR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.9-3.1).

There was no sign that children with tension-type headaches had a significantly higher risk of ADHD than other children. However, compared with controls, those with various types of migraine headaches did have a higher risk of ADHD. Nearly 11% of those with migraine overall showed signs of ADHD, compared with 2.6% of the control group (RR, 4.1; 95% CI, 2.7-6.2). The numbers for episodic migraine were nearly identical to those for migraine overall: 10.2% vs. 2.6% (RR, 3.8; 95% CI, 2.5-5.9).

Just over 19% of kids in a third migraine group – those with chronic migraine, defined as headaches appearing more than 14 days per month for the last 3 months – showed signs of ADHD, compared with just 2.6% of the control group (RR = 7.3; 95% CI, 3.5-15.5).

“A number of risk factors to the association were identified, including male gender, prenatal exposure to tobacco, high headache frequency, and below average school performance,” Dr. Arruda said. “However, we did not find a significant influence of age, race, city density, national region where a child lives, income class, and prenatal exposure to alcohol in the comorbidity of ADHD and migraine in this sample. These results help us to identify risk groups allowing early interventions.”

Regarding an explanation for the links between migraines and ADHD, Dr. Arruda pointed to genetic and epigenetic factors that affect brain neurotransmitters and said he believes that stress and other stimuli could be influencing dopamine and noradrenergic processes.

Dr. Arruda said his next step is to examine whether stimulant drugs – the class used to treat ADHD – may help reduce headaches too.

“My clinical experience strongly indicates that psychostimulants have a highly positive effect on migraine prophylaxis, although headache occurs in the very beginning of the treatment,” Dr. Arruda said. “So, we are looking for financial support to conduct a randomized, double-blind, placebo control study to check this hypothesis.”

The study received no specific funding, and Dr. Arruda reported no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Children aged 5-12 years with signs of migraine headache were as much as seven times as likely as other children to also appear to have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but those with tension-type headaches didn’t face a higher risk of ADHD, a Brazilian study showed.

It’s not clear why the apparent link between migraines and ADHD exists. However, lead study author Marco Antônio Arruda, MD, PhD, a pediatric neurologist in São Paulo (Brazil) University, said in an interview that other research has linked migraine to mental health problems.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology and published online in the Journal of Attention Disorders (2017. doi: 10.1177/1087054717710767), was launched to better understand the connection between migraine and ADHD, which are thought to each affect as many as 1 in 10 children.

The study analyzes data from mothers and teachers of 5,671 children aged 5-12 years who answered questions as part of a Brazil-wide epidemiologic study called the Attention Brazil Project. Just over half of the participants were boys, and about half were from the Brazilian middle class.

Based on answers from mothers and teachers, the researchers estimated that 9% of the children had episodic migraine and 0.6% had chronic migraine. The level of episodic tension-type headache was estimated at 12.8%, with a lower rate in the two poorest vs. the two richest quintiles (8.6% vs. 14.4%, respectively; relative risk, 0.6; 95% confidence interval, 0.5-0.8).

The researchers estimated that 5.3% of the children overall showed signs of ADHD (7.5% in boys vs. 3.1% in girls; RR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.9-3.1).

There was no sign that children with tension-type headaches had a significantly higher risk of ADHD than other children. However, compared with controls, those with various types of migraine headaches did have a higher risk of ADHD. Nearly 11% of those with migraine overall showed signs of ADHD, compared with 2.6% of the control group (RR, 4.1; 95% CI, 2.7-6.2). The numbers for episodic migraine were nearly identical to those for migraine overall: 10.2% vs. 2.6% (RR, 3.8; 95% CI, 2.5-5.9).

Just over 19% of kids in a third migraine group – those with chronic migraine, defined as headaches appearing more than 14 days per month for the last 3 months – showed signs of ADHD, compared with just 2.6% of the control group (RR = 7.3; 95% CI, 3.5-15.5).

“A number of risk factors to the association were identified, including male gender, prenatal exposure to tobacco, high headache frequency, and below average school performance,” Dr. Arruda said. “However, we did not find a significant influence of age, race, city density, national region where a child lives, income class, and prenatal exposure to alcohol in the comorbidity of ADHD and migraine in this sample. These results help us to identify risk groups allowing early interventions.”

Regarding an explanation for the links between migraines and ADHD, Dr. Arruda pointed to genetic and epigenetic factors that affect brain neurotransmitters and said he believes that stress and other stimuli could be influencing dopamine and noradrenergic processes.

Dr. Arruda said his next step is to examine whether stimulant drugs – the class used to treat ADHD – may help reduce headaches too.

“My clinical experience strongly indicates that psychostimulants have a highly positive effect on migraine prophylaxis, although headache occurs in the very beginning of the treatment,” Dr. Arruda said. “So, we are looking for financial support to conduct a randomized, double-blind, placebo control study to check this hypothesis.”

The study received no specific funding, and Dr. Arruda reported no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Children aged 5-12 years with signs of migraine headache were as much as seven times as likely as other children to also appear to have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but those with tension-type headaches didn’t face a higher risk of ADHD, a Brazilian study showed.

It’s not clear why the apparent link between migraines and ADHD exists. However, lead study author Marco Antônio Arruda, MD, PhD, a pediatric neurologist in São Paulo (Brazil) University, said in an interview that other research has linked migraine to mental health problems.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology and published online in the Journal of Attention Disorders (2017. doi: 10.1177/1087054717710767), was launched to better understand the connection between migraine and ADHD, which are thought to each affect as many as 1 in 10 children.

The study analyzes data from mothers and teachers of 5,671 children aged 5-12 years who answered questions as part of a Brazil-wide epidemiologic study called the Attention Brazil Project. Just over half of the participants were boys, and about half were from the Brazilian middle class.

Based on answers from mothers and teachers, the researchers estimated that 9% of the children had episodic migraine and 0.6% had chronic migraine. The level of episodic tension-type headache was estimated at 12.8%, with a lower rate in the two poorest vs. the two richest quintiles (8.6% vs. 14.4%, respectively; relative risk, 0.6; 95% confidence interval, 0.5-0.8).

The researchers estimated that 5.3% of the children overall showed signs of ADHD (7.5% in boys vs. 3.1% in girls; RR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.9-3.1).

There was no sign that children with tension-type headaches had a significantly higher risk of ADHD than other children. However, compared with controls, those with various types of migraine headaches did have a higher risk of ADHD. Nearly 11% of those with migraine overall showed signs of ADHD, compared with 2.6% of the control group (RR, 4.1; 95% CI, 2.7-6.2). The numbers for episodic migraine were nearly identical to those for migraine overall: 10.2% vs. 2.6% (RR, 3.8; 95% CI, 2.5-5.9).

Just over 19% of kids in a third migraine group – those with chronic migraine, defined as headaches appearing more than 14 days per month for the last 3 months – showed signs of ADHD, compared with just 2.6% of the control group (RR = 7.3; 95% CI, 3.5-15.5).

“A number of risk factors to the association were identified, including male gender, prenatal exposure to tobacco, high headache frequency, and below average school performance,” Dr. Arruda said. “However, we did not find a significant influence of age, race, city density, national region where a child lives, income class, and prenatal exposure to alcohol in the comorbidity of ADHD and migraine in this sample. These results help us to identify risk groups allowing early interventions.”

Regarding an explanation for the links between migraines and ADHD, Dr. Arruda pointed to genetic and epigenetic factors that affect brain neurotransmitters and said he believes that stress and other stimuli could be influencing dopamine and noradrenergic processes.

Dr. Arruda said his next step is to examine whether stimulant drugs – the class used to treat ADHD – may help reduce headaches too.

“My clinical experience strongly indicates that psychostimulants have a highly positive effect on migraine prophylaxis, although headache occurs in the very beginning of the treatment,” Dr. Arruda said. “So, we are looking for financial support to conduct a randomized, double-blind, placebo control study to check this hypothesis.”

The study received no specific funding, and Dr. Arruda reported no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAN 2017

Key clinical point: , but there’s no excess risk in children with tension-type headaches.

Major finding: Of children with chronic migraine, 19.4% (0.6% of the total) showed signs of ADHD, vs. 2.6% of the control group (RR, 7.3; 95% CI, 3.5-15.5).

Data source: Surveys of mothers and teachers of 5,671 Brazilian children aged 5-12 years.

Disclosures: The study received no specific funding, and Dr. Arruda reported no relevant financial disclosures.

How to get through the tough talks about alopecia areata

CHICAGO – If you can’t set the temptation to hurry aside and take the time to listen, things may not go well, said Neil Prose, MD.

With the caveat that Janus kinase inhibitors show promise, Dr. Prose said that “most children who are destined to lose their hair will probably do so despite all of our best efforts.” Figuring out how to engage children and parents and frame a positive conversation about alopecia can present a real challenge, especially in the context of a busy practice, said Dr. Prose, professor of dermatology and medical director of Patterson Place Pediatric Dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“These are very culturally-specific suggestions, but see which ones work for you,” said Dr. Prose, speaking to an international audience at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

Dr. Prose depicted two opposing images. In one, he said, the patient and you are sitting on opposite sides of the table, with the prospect of hair loss looming between them. By contrast, “imagine what it would take to be on the same side of the table, looking at the problem together,” he said.

There are many barriers that stand in the way of getting you and the patient on the same side of the issue of dealing with severe alopecia areata. The high emotional content of the discussion can be big factor, not just for the patient and family members, but also for you.

“We are often dealing with patient disappointment and, frankly, with our own sense of personal failure” when there isn’t always a good set of options, said Dr. Prose. Other specific aspects of severe pediatric alopecia areata that make the conversation difficult include the high degree of uncertainty that any particular treatment will succeed and a knowledge of how to give patients and family members hope without raising expectations unrealistically.

Coming back to the important first steps of not rushing the visit and being sure to listen, Dr. Prose said that, for him, the process begins before he enters the room, when he takes a moment to clear his mind. “It starts for me just before I open the door to the examining room. As human beings, we are infinitely distractible. It’s very hard for us to simply pay attention.”

Yet, this is vitally important, he said, because families need to be heard. Citing the oft-quoted statistic that, on average, a physician interrupts a patient in the first 17 seconds of the office visit, Dr. Prose said, “Many of us are ‘explainaholics,’ ’’ spending precious visit time talking about what the physician thinks is important.

Still, it’s important to validate parents’ concerns and to alleviate guilt. “Patients’ families sometimes feel guilty because they are so upset and worried – and it’s not cancer,” said Dr. Prose. Potential impacts on quality of life are still huge, and all parents want the best for their children, he pointed out.

One way he likes to begin a follow-up visit is simply to ask, “So, how’s everyone doing?” This opens the door to allow the child and the family to talk about what’s important to them. These may be symptom-related, but social issues also may be what’s looming largest.

In order to decipher how hair loss is affecting a particular child, Dr. Prose said he likes to say, “I need to understand how this is affecting you, so we can decide together where to go from here.” This gives the family control in setting the agenda and begins the process of bringing you to the same side of the table.

Specific prompts that can help you understand how alopecia is affecting a child can include asking about how things are going at school, what the child’s friends know about his or her alopecia, whether there is mocking or bullying occurring, and how the patient, family, and teachers are addressing the global picture.

Parents can be asked whether they are noticing changes in behavior, and it’s a good idea to check in on how parents are coping as well, said Dr. Prose.

To ensure that families feel they’re being heard, and to make sure you are understanding correctly, it’s useful to mirror what’s been said, beginning with a phrase like, “So, what you’re saying is …” Putting a name to the emotions that emerge during the visit also can be useful, using phrases like, “I can imagine that this has been disappointing,” or “It feels like everyone is very worried.”

But, said Dr. Prose, don’t forget about opportunities to praise patients and their families when they’ve come through a tough time well. This validation is important, he said.

When treatment isn’t working, a first place to start is to acknowledge that you, along with the family, wish that things were turning out differently. Then, said Dr. Prose, it can be really important to reappraise treatment goals. After taking the emotional temperature of the room, it may be appropriate to ask, “Is it time to talk about not doing any more treatments?” This question can be put within the framework that hair may or may not regrow spontaneously anyway and that new treatments are emerging that may help in future.

When giving advice or talking about difficult issues, it can be helpful to ask permission, said Dr. Prose. He likes to begin with, “Would it be okay if I ...?” Then, he said, the door can be opened to give advice about school issues, to ask about difficult treatment decisions, or even to share tips learned from other families’ coping methods.

Don’t forget, said Dr. Prose, to refer patients to high-quality information and online support resources, such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. The Internet is full of inaccurate and scary information, and patients and families need help with this navigation, he said.

The very last question Dr. Prose asks during a visit is “What other questions do you have?” The question is always framed exactly like this, he said, because it assumes there will be more questions, and it gives families permission to ask more. Although most of the time there aren’t any further questions, Dr. Prose said, “Do not ask the question with your hand on the doorknob!”

Dr. Prose had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – If you can’t set the temptation to hurry aside and take the time to listen, things may not go well, said Neil Prose, MD.

With the caveat that Janus kinase inhibitors show promise, Dr. Prose said that “most children who are destined to lose their hair will probably do so despite all of our best efforts.” Figuring out how to engage children and parents and frame a positive conversation about alopecia can present a real challenge, especially in the context of a busy practice, said Dr. Prose, professor of dermatology and medical director of Patterson Place Pediatric Dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“These are very culturally-specific suggestions, but see which ones work for you,” said Dr. Prose, speaking to an international audience at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

Dr. Prose depicted two opposing images. In one, he said, the patient and you are sitting on opposite sides of the table, with the prospect of hair loss looming between them. By contrast, “imagine what it would take to be on the same side of the table, looking at the problem together,” he said.

There are many barriers that stand in the way of getting you and the patient on the same side of the issue of dealing with severe alopecia areata. The high emotional content of the discussion can be big factor, not just for the patient and family members, but also for you.

“We are often dealing with patient disappointment and, frankly, with our own sense of personal failure” when there isn’t always a good set of options, said Dr. Prose. Other specific aspects of severe pediatric alopecia areata that make the conversation difficult include the high degree of uncertainty that any particular treatment will succeed and a knowledge of how to give patients and family members hope without raising expectations unrealistically.

Coming back to the important first steps of not rushing the visit and being sure to listen, Dr. Prose said that, for him, the process begins before he enters the room, when he takes a moment to clear his mind. “It starts for me just before I open the door to the examining room. As human beings, we are infinitely distractible. It’s very hard for us to simply pay attention.”

Yet, this is vitally important, he said, because families need to be heard. Citing the oft-quoted statistic that, on average, a physician interrupts a patient in the first 17 seconds of the office visit, Dr. Prose said, “Many of us are ‘explainaholics,’ ’’ spending precious visit time talking about what the physician thinks is important.

Still, it’s important to validate parents’ concerns and to alleviate guilt. “Patients’ families sometimes feel guilty because they are so upset and worried – and it’s not cancer,” said Dr. Prose. Potential impacts on quality of life are still huge, and all parents want the best for their children, he pointed out.

One way he likes to begin a follow-up visit is simply to ask, “So, how’s everyone doing?” This opens the door to allow the child and the family to talk about what’s important to them. These may be symptom-related, but social issues also may be what’s looming largest.

In order to decipher how hair loss is affecting a particular child, Dr. Prose said he likes to say, “I need to understand how this is affecting you, so we can decide together where to go from here.” This gives the family control in setting the agenda and begins the process of bringing you to the same side of the table.

Specific prompts that can help you understand how alopecia is affecting a child can include asking about how things are going at school, what the child’s friends know about his or her alopecia, whether there is mocking or bullying occurring, and how the patient, family, and teachers are addressing the global picture.

Parents can be asked whether they are noticing changes in behavior, and it’s a good idea to check in on how parents are coping as well, said Dr. Prose.

To ensure that families feel they’re being heard, and to make sure you are understanding correctly, it’s useful to mirror what’s been said, beginning with a phrase like, “So, what you’re saying is …” Putting a name to the emotions that emerge during the visit also can be useful, using phrases like, “I can imagine that this has been disappointing,” or “It feels like everyone is very worried.”

But, said Dr. Prose, don’t forget about opportunities to praise patients and their families when they’ve come through a tough time well. This validation is important, he said.

When treatment isn’t working, a first place to start is to acknowledge that you, along with the family, wish that things were turning out differently. Then, said Dr. Prose, it can be really important to reappraise treatment goals. After taking the emotional temperature of the room, it may be appropriate to ask, “Is it time to talk about not doing any more treatments?” This question can be put within the framework that hair may or may not regrow spontaneously anyway and that new treatments are emerging that may help in future.

When giving advice or talking about difficult issues, it can be helpful to ask permission, said Dr. Prose. He likes to begin with, “Would it be okay if I ...?” Then, he said, the door can be opened to give advice about school issues, to ask about difficult treatment decisions, or even to share tips learned from other families’ coping methods.

Don’t forget, said Dr. Prose, to refer patients to high-quality information and online support resources, such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. The Internet is full of inaccurate and scary information, and patients and families need help with this navigation, he said.

The very last question Dr. Prose asks during a visit is “What other questions do you have?” The question is always framed exactly like this, he said, because it assumes there will be more questions, and it gives families permission to ask more. Although most of the time there aren’t any further questions, Dr. Prose said, “Do not ask the question with your hand on the doorknob!”

Dr. Prose had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – If you can’t set the temptation to hurry aside and take the time to listen, things may not go well, said Neil Prose, MD.

With the caveat that Janus kinase inhibitors show promise, Dr. Prose said that “most children who are destined to lose their hair will probably do so despite all of our best efforts.” Figuring out how to engage children and parents and frame a positive conversation about alopecia can present a real challenge, especially in the context of a busy practice, said Dr. Prose, professor of dermatology and medical director of Patterson Place Pediatric Dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“These are very culturally-specific suggestions, but see which ones work for you,” said Dr. Prose, speaking to an international audience at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

Dr. Prose depicted two opposing images. In one, he said, the patient and you are sitting on opposite sides of the table, with the prospect of hair loss looming between them. By contrast, “imagine what it would take to be on the same side of the table, looking at the problem together,” he said.

There are many barriers that stand in the way of getting you and the patient on the same side of the issue of dealing with severe alopecia areata. The high emotional content of the discussion can be big factor, not just for the patient and family members, but also for you.

“We are often dealing with patient disappointment and, frankly, with our own sense of personal failure” when there isn’t always a good set of options, said Dr. Prose. Other specific aspects of severe pediatric alopecia areata that make the conversation difficult include the high degree of uncertainty that any particular treatment will succeed and a knowledge of how to give patients and family members hope without raising expectations unrealistically.

Coming back to the important first steps of not rushing the visit and being sure to listen, Dr. Prose said that, for him, the process begins before he enters the room, when he takes a moment to clear his mind. “It starts for me just before I open the door to the examining room. As human beings, we are infinitely distractible. It’s very hard for us to simply pay attention.”

Yet, this is vitally important, he said, because families need to be heard. Citing the oft-quoted statistic that, on average, a physician interrupts a patient in the first 17 seconds of the office visit, Dr. Prose said, “Many of us are ‘explainaholics,’ ’’ spending precious visit time talking about what the physician thinks is important.

Still, it’s important to validate parents’ concerns and to alleviate guilt. “Patients’ families sometimes feel guilty because they are so upset and worried – and it’s not cancer,” said Dr. Prose. Potential impacts on quality of life are still huge, and all parents want the best for their children, he pointed out.

One way he likes to begin a follow-up visit is simply to ask, “So, how’s everyone doing?” This opens the door to allow the child and the family to talk about what’s important to them. These may be symptom-related, but social issues also may be what’s looming largest.

In order to decipher how hair loss is affecting a particular child, Dr. Prose said he likes to say, “I need to understand how this is affecting you, so we can decide together where to go from here.” This gives the family control in setting the agenda and begins the process of bringing you to the same side of the table.

Specific prompts that can help you understand how alopecia is affecting a child can include asking about how things are going at school, what the child’s friends know about his or her alopecia, whether there is mocking or bullying occurring, and how the patient, family, and teachers are addressing the global picture.

Parents can be asked whether they are noticing changes in behavior, and it’s a good idea to check in on how parents are coping as well, said Dr. Prose.

To ensure that families feel they’re being heard, and to make sure you are understanding correctly, it’s useful to mirror what’s been said, beginning with a phrase like, “So, what you’re saying is …” Putting a name to the emotions that emerge during the visit also can be useful, using phrases like, “I can imagine that this has been disappointing,” or “It feels like everyone is very worried.”

But, said Dr. Prose, don’t forget about opportunities to praise patients and their families when they’ve come through a tough time well. This validation is important, he said.

When treatment isn’t working, a first place to start is to acknowledge that you, along with the family, wish that things were turning out differently. Then, said Dr. Prose, it can be really important to reappraise treatment goals. After taking the emotional temperature of the room, it may be appropriate to ask, “Is it time to talk about not doing any more treatments?” This question can be put within the framework that hair may or may not regrow spontaneously anyway and that new treatments are emerging that may help in future.

When giving advice or talking about difficult issues, it can be helpful to ask permission, said Dr. Prose. He likes to begin with, “Would it be okay if I ...?” Then, he said, the door can be opened to give advice about school issues, to ask about difficult treatment decisions, or even to share tips learned from other families’ coping methods.

Don’t forget, said Dr. Prose, to refer patients to high-quality information and online support resources, such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. The Internet is full of inaccurate and scary information, and patients and families need help with this navigation, he said.

The very last question Dr. Prose asks during a visit is “What other questions do you have?” The question is always framed exactly like this, he said, because it assumes there will be more questions, and it gives families permission to ask more. Although most of the time there aren’t any further questions, Dr. Prose said, “Do not ask the question with your hand on the doorknob!”

Dr. Prose had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCPD 2017

Common malaria diagnostic test also can predict treatment-related anemia

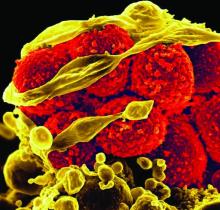

While the drug artesunate remains the gold standard for patients with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria, it also can induce anemia within days or weeks of starting treatment.

In research published online in Science Translational Medicine, a team of researchers led by Papa Alioune Ndour, PhD, of the Université Paris Descartes, presented findings on how a cheap, widely available diagnostic test for malaria infection can be used, under a modified protocol, to predict a form of anemia known as postartesunate delayed hemolysis (PADH) (Sci Transl Med. 2017 Jul 5;9[397]. pii: eaaf9377).

Dr. Ndour and his colleagues discovered, studying prospective cohorts of 95 artesunate-treated malaria patients in Bangladesh and 53 in France, that, if they administered an HRP2 test on day 3 of treatment, a positive result predicted PADH with 89% sensitivity and 73% specificity. However, while the diagnostic test uses a whole blood sample, blood must be diluted 1:500 for the same test to predict PADH. The investigators also studied a comparison cohort of 49 quinine-treated patients in France, in whom HRP2 persistence was much lower.

Using the HRP2-based tests for PADH prediction is more complex than using it for malaria diagnosis, as blood samples must be diluted and because assessment “involves a quantitative element” to determine whether once-infected red blood cells have reached a concentration associated with a high risk of hemolysis, Dr. Ndour and his colleagues cautioned.

“Future large prospective studies will more precisely determine the robustness of prediction in different geographic and logistical settings,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

The study was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the French National Research Agency, and the Wellcome Trust. Five investigators, including Dr. Ndour, disclosed research grants from pharmaceutical firms for artesunate studies, two disclosed advisory board relationships with a Sigma Tau Laboratories, and another reported industry funding for anemia research related to artesunate.

While the drug artesunate remains the gold standard for patients with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria, it also can induce anemia within days or weeks of starting treatment.

In research published online in Science Translational Medicine, a team of researchers led by Papa Alioune Ndour, PhD, of the Université Paris Descartes, presented findings on how a cheap, widely available diagnostic test for malaria infection can be used, under a modified protocol, to predict a form of anemia known as postartesunate delayed hemolysis (PADH) (Sci Transl Med. 2017 Jul 5;9[397]. pii: eaaf9377).

Dr. Ndour and his colleagues discovered, studying prospective cohorts of 95 artesunate-treated malaria patients in Bangladesh and 53 in France, that, if they administered an HRP2 test on day 3 of treatment, a positive result predicted PADH with 89% sensitivity and 73% specificity. However, while the diagnostic test uses a whole blood sample, blood must be diluted 1:500 for the same test to predict PADH. The investigators also studied a comparison cohort of 49 quinine-treated patients in France, in whom HRP2 persistence was much lower.

Using the HRP2-based tests for PADH prediction is more complex than using it for malaria diagnosis, as blood samples must be diluted and because assessment “involves a quantitative element” to determine whether once-infected red blood cells have reached a concentration associated with a high risk of hemolysis, Dr. Ndour and his colleagues cautioned.

“Future large prospective studies will more precisely determine the robustness of prediction in different geographic and logistical settings,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

The study was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the French National Research Agency, and the Wellcome Trust. Five investigators, including Dr. Ndour, disclosed research grants from pharmaceutical firms for artesunate studies, two disclosed advisory board relationships with a Sigma Tau Laboratories, and another reported industry funding for anemia research related to artesunate.

While the drug artesunate remains the gold standard for patients with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria, it also can induce anemia within days or weeks of starting treatment.

In research published online in Science Translational Medicine, a team of researchers led by Papa Alioune Ndour, PhD, of the Université Paris Descartes, presented findings on how a cheap, widely available diagnostic test for malaria infection can be used, under a modified protocol, to predict a form of anemia known as postartesunate delayed hemolysis (PADH) (Sci Transl Med. 2017 Jul 5;9[397]. pii: eaaf9377).

Dr. Ndour and his colleagues discovered, studying prospective cohorts of 95 artesunate-treated malaria patients in Bangladesh and 53 in France, that, if they administered an HRP2 test on day 3 of treatment, a positive result predicted PADH with 89% sensitivity and 73% specificity. However, while the diagnostic test uses a whole blood sample, blood must be diluted 1:500 for the same test to predict PADH. The investigators also studied a comparison cohort of 49 quinine-treated patients in France, in whom HRP2 persistence was much lower.

Using the HRP2-based tests for PADH prediction is more complex than using it for malaria diagnosis, as blood samples must be diluted and because assessment “involves a quantitative element” to determine whether once-infected red blood cells have reached a concentration associated with a high risk of hemolysis, Dr. Ndour and his colleagues cautioned.

“Future large prospective studies will more precisely determine the robustness of prediction in different geographic and logistical settings,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

The study was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the French National Research Agency, and the Wellcome Trust. Five investigators, including Dr. Ndour, disclosed research grants from pharmaceutical firms for artesunate studies, two disclosed advisory board relationships with a Sigma Tau Laboratories, and another reported industry funding for anemia research related to artesunate.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A positive result on an HRP2 test with diluted blood was 89% sensitive and 73% specific in predicting treatment-related anemia.

Data source: Two prospective cohorts of 95 artesunate-treated malaria patients in Bangladesh and 53 in France, plus a comparison cohort of 49 quinine-treated patients in France.

Disclosures: International foundations sponsored the study. Six of the investigators disclosed research support or other financial conflicts.

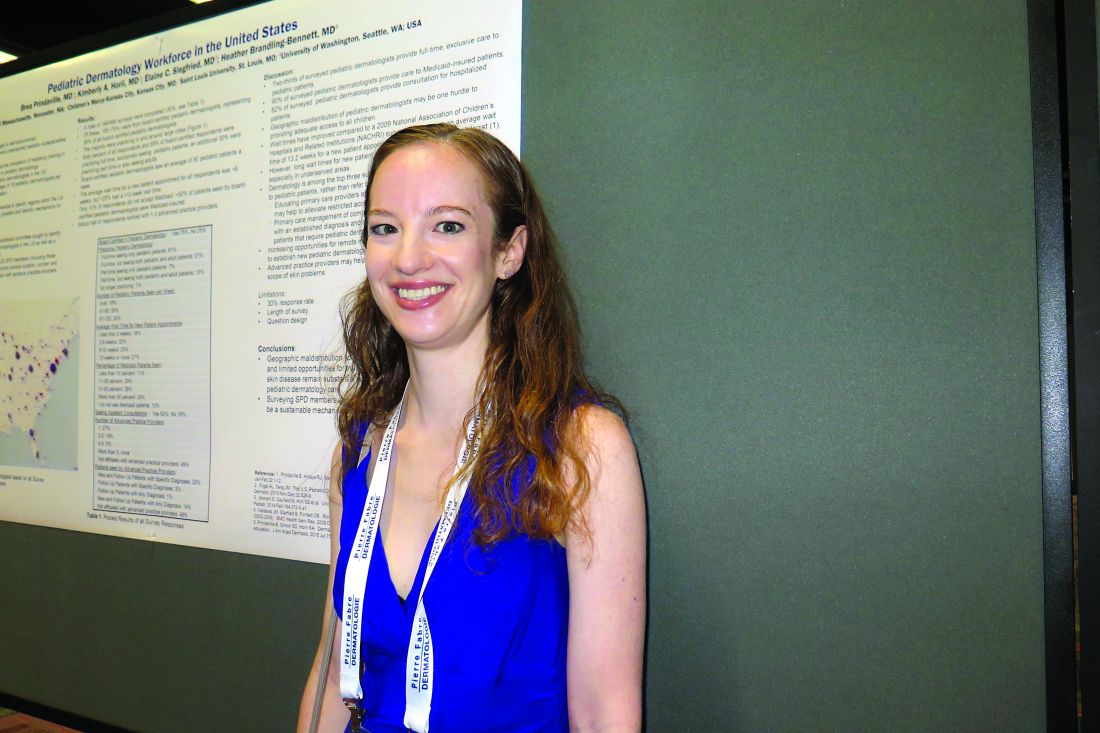

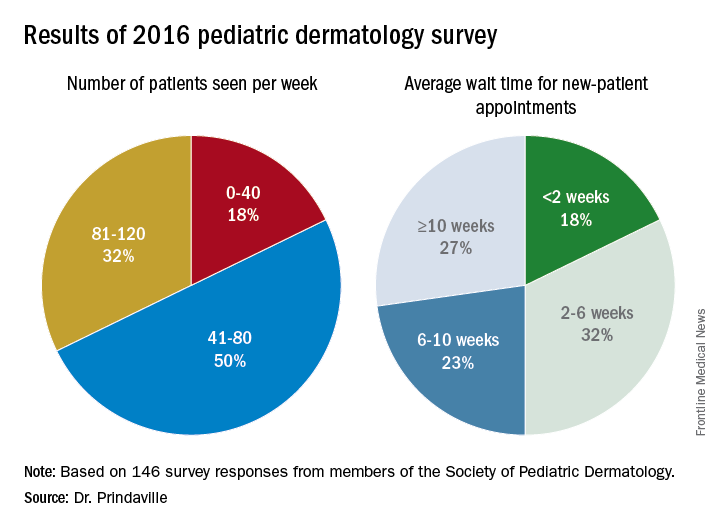

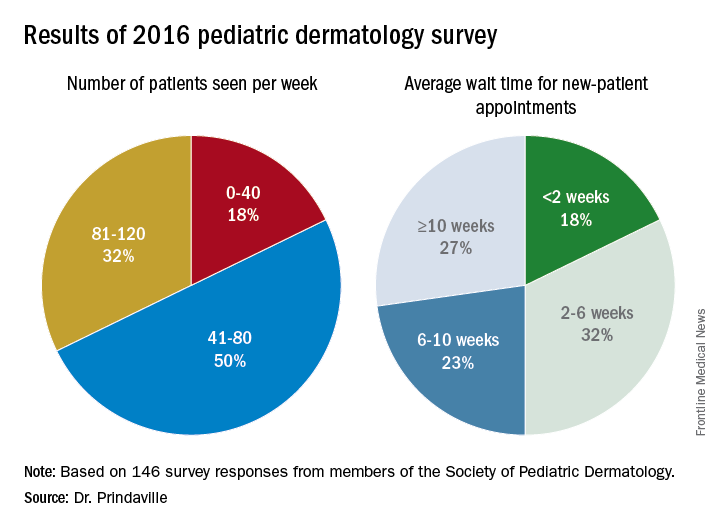

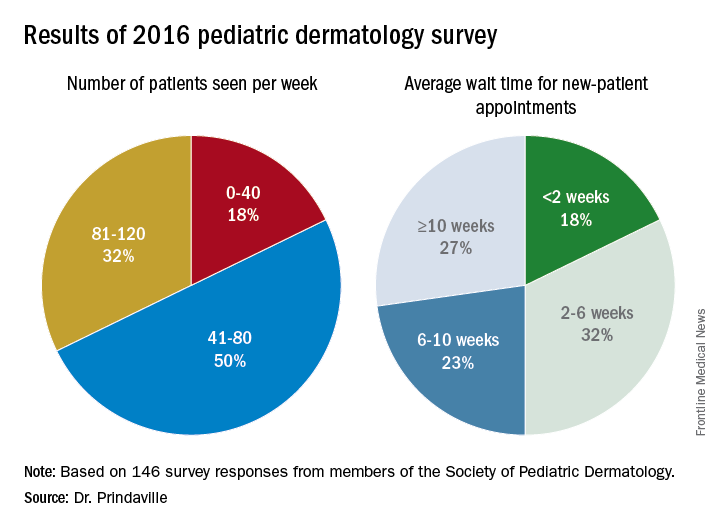

Study spotlights pediatric dermatology workplace trends

CHICAGO – Geographic maldistribution of trained pediatric dermatologists and long wait times for new-patient appointments are two key hurdles impacting patient access to pediatric dermatology care, according to a survey of workforce trends.

“There are large areas of the country that don’t have any pediatric dermatologists, which influences how we can train dermatologists, pediatricians, and medical students who want to do pediatric dermatology,” study author Brea Prindaville, MD, said in an interview at the World Congress for Pediatric Dermatology. “We’re trying to keep an eye on how that’s going, and how we can improve not only the geographic distribution, but also the numbers that we have in the workforce.”

In a project spearheaded by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) workforce committee, Dr. Prindaville of Children’s Mercy-Kansas City (Mo.) and her associates emailed a nine-question survey to the 484 SPD members in the United States to determine practice location, number and types of patients seen, wait times, and association with advance practice providers between November and December of 2016. In all, 146 surveys were completed, for a response rate of 30%. Of these, 75% were from board-certified pediatric dermatologists. The majority of survey respondents were practicing in and around large cities, while 60% of all respondents and 68% of board-certified respondents were practicing full-time, seeing pediatric patients exclusively. An additional 30% were practicing part-time or also seeing adults. Board-certified pediatric dermatologists saw an average of 80 pediatric patients per week.

Only 10% of survey respondents did not accept Medicaid, and about 50% of patients seen by board-certified pediatric dermatologists were insured by Medicaid. In addition, about half of respondents worked with one to three advanced practice providers.

Dr. Prindaville, who helped conduct the study during her pediatric dermatology fellowship at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its low response rate, the limited number of survey questions, and the question design. Going forward, she and her associates hope to keep a pulse on workplace trends by surveying SPD members annually, perhaps with membership renewal.

The survey was supported by the SPD. Dr. Prindaville reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Geographic maldistribution of trained pediatric dermatologists and long wait times for new-patient appointments are two key hurdles impacting patient access to pediatric dermatology care, according to a survey of workforce trends.

“There are large areas of the country that don’t have any pediatric dermatologists, which influences how we can train dermatologists, pediatricians, and medical students who want to do pediatric dermatology,” study author Brea Prindaville, MD, said in an interview at the World Congress for Pediatric Dermatology. “We’re trying to keep an eye on how that’s going, and how we can improve not only the geographic distribution, but also the numbers that we have in the workforce.”

In a project spearheaded by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) workforce committee, Dr. Prindaville of Children’s Mercy-Kansas City (Mo.) and her associates emailed a nine-question survey to the 484 SPD members in the United States to determine practice location, number and types of patients seen, wait times, and association with advance practice providers between November and December of 2016. In all, 146 surveys were completed, for a response rate of 30%. Of these, 75% were from board-certified pediatric dermatologists. The majority of survey respondents were practicing in and around large cities, while 60% of all respondents and 68% of board-certified respondents were practicing full-time, seeing pediatric patients exclusively. An additional 30% were practicing part-time or also seeing adults. Board-certified pediatric dermatologists saw an average of 80 pediatric patients per week.

Only 10% of survey respondents did not accept Medicaid, and about 50% of patients seen by board-certified pediatric dermatologists were insured by Medicaid. In addition, about half of respondents worked with one to three advanced practice providers.

Dr. Prindaville, who helped conduct the study during her pediatric dermatology fellowship at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its low response rate, the limited number of survey questions, and the question design. Going forward, she and her associates hope to keep a pulse on workplace trends by surveying SPD members annually, perhaps with membership renewal.

The survey was supported by the SPD. Dr. Prindaville reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Geographic maldistribution of trained pediatric dermatologists and long wait times for new-patient appointments are two key hurdles impacting patient access to pediatric dermatology care, according to a survey of workforce trends.

“There are large areas of the country that don’t have any pediatric dermatologists, which influences how we can train dermatologists, pediatricians, and medical students who want to do pediatric dermatology,” study author Brea Prindaville, MD, said in an interview at the World Congress for Pediatric Dermatology. “We’re trying to keep an eye on how that’s going, and how we can improve not only the geographic distribution, but also the numbers that we have in the workforce.”

In a project spearheaded by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) workforce committee, Dr. Prindaville of Children’s Mercy-Kansas City (Mo.) and her associates emailed a nine-question survey to the 484 SPD members in the United States to determine practice location, number and types of patients seen, wait times, and association with advance practice providers between November and December of 2016. In all, 146 surveys were completed, for a response rate of 30%. Of these, 75% were from board-certified pediatric dermatologists. The majority of survey respondents were practicing in and around large cities, while 60% of all respondents and 68% of board-certified respondents were practicing full-time, seeing pediatric patients exclusively. An additional 30% were practicing part-time or also seeing adults. Board-certified pediatric dermatologists saw an average of 80 pediatric patients per week.

Only 10% of survey respondents did not accept Medicaid, and about 50% of patients seen by board-certified pediatric dermatologists were insured by Medicaid. In addition, about half of respondents worked with one to three advanced practice providers.

Dr. Prindaville, who helped conduct the study during her pediatric dermatology fellowship at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its low response rate, the limited number of survey questions, and the question design. Going forward, she and her associates hope to keep a pulse on workplace trends by surveying SPD members annually, perhaps with membership renewal.

The survey was supported by the SPD. Dr. Prindaville reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT WCPD 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The majority of survey respondents were practicing in and around large cities, and the average wait time for a new-patient appointment for all respondents was about 6 weeks.

Data source: Online survey completed by 146 Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) members in the United States.

Disclosures: The survey was supported by the SPD. Dr. Prindaville reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis have decreased over decades

MADRID – Recent improvements in the management of rheumatoid arthritis may have had a positive impact on common cardiovascular comorbidities, according to the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Risk ratios (RR) for several CV events in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients were found to be lower for data published after 2000 and up to March 2016 when compared with data published up until 2000. Indeed, comparing these two time periods, French researchers found that the RR for myocardial infarction (MI) were a respective 1.32 and 1.18, for heart failure a respective 1.25 and 1.17, and for CV mortality a respective 1.21 and 1.07.

“Systemic inflammation is the cornerstone of both rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis,” Cécile Gaujoux-Viala, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at Montpellier University, Nîmes, France, and chief of the rheumatology service at Nîmes University Hospital, said during a press briefing at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“Over the past 15 years, new treatment strategies such as ‘tight control,’ ‘treat-to-target,’ methotrexate optimization, and use of biologic DMARDs [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] have led to better control of this inflammation,” Dr. Gaujoux-Viala added.

The aim of the meta-analysis was to look at the overall risk for CV events in RA patients versus the general population, she said, as well as to see if there had been any temporal shift by analyzing data obtained within two time periods – before 2000 and after 2000.

A systematic literature review was performed using the PubMed and Cochrane Library databases to search for observational studies that provided data about the occurrence of CV events in RA patients and controls. Of 5,714 papers that included reports of stroke, MI, heart failure, or CV death, 28 had the necessary data that could be used for the meta-analysis. Overall, the 28 studies included 227,871 RA patients, with a mean age of 55 years.

Results showed that RA patients had a 17% increased risk for stroke versus controls overall (P = .002), with a RR of 1.17. The RRs were 1.12 before 2000 and 1.23 after 2000, making stroke the only CV event that did not appear to show a downward trend.

Compared with the general population, RA patients had a 24% excess risk of MI, a 22% excess risk of heart failure, and a 18% excess risk of dying from a CV event (all P less than .00001).

These data provide “confirmation of an increased CV risk in RA patients compared to the general population,” said Dr. Gaujoux-Viala, who also discussed the study and its implications in a video interview.

Commenting on the study, Philip J. Mease, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, wondered where the studies used in the meta-analysis had been performed because of the potential impact that reduced access to CV medications or prevention strategies in certain countries could have on the results. However, the investigators did not determine where each of the studies used in the review took place.

Dr. Gaujoux-Viala had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MADRID – Recent improvements in the management of rheumatoid arthritis may have had a positive impact on common cardiovascular comorbidities, according to the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Risk ratios (RR) for several CV events in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients were found to be lower for data published after 2000 and up to March 2016 when compared with data published up until 2000. Indeed, comparing these two time periods, French researchers found that the RR for myocardial infarction (MI) were a respective 1.32 and 1.18, for heart failure a respective 1.25 and 1.17, and for CV mortality a respective 1.21 and 1.07.

“Systemic inflammation is the cornerstone of both rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis,” Cécile Gaujoux-Viala, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at Montpellier University, Nîmes, France, and chief of the rheumatology service at Nîmes University Hospital, said during a press briefing at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“Over the past 15 years, new treatment strategies such as ‘tight control,’ ‘treat-to-target,’ methotrexate optimization, and use of biologic DMARDs [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] have led to better control of this inflammation,” Dr. Gaujoux-Viala added.

The aim of the meta-analysis was to look at the overall risk for CV events in RA patients versus the general population, she said, as well as to see if there had been any temporal shift by analyzing data obtained within two time periods – before 2000 and after 2000.

A systematic literature review was performed using the PubMed and Cochrane Library databases to search for observational studies that provided data about the occurrence of CV events in RA patients and controls. Of 5,714 papers that included reports of stroke, MI, heart failure, or CV death, 28 had the necessary data that could be used for the meta-analysis. Overall, the 28 studies included 227,871 RA patients, with a mean age of 55 years.

Results showed that RA patients had a 17% increased risk for stroke versus controls overall (P = .002), with a RR of 1.17. The RRs were 1.12 before 2000 and 1.23 after 2000, making stroke the only CV event that did not appear to show a downward trend.

Compared with the general population, RA patients had a 24% excess risk of MI, a 22% excess risk of heart failure, and a 18% excess risk of dying from a CV event (all P less than .00001).

These data provide “confirmation of an increased CV risk in RA patients compared to the general population,” said Dr. Gaujoux-Viala, who also discussed the study and its implications in a video interview.

Commenting on the study, Philip J. Mease, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, wondered where the studies used in the meta-analysis had been performed because of the potential impact that reduced access to CV medications or prevention strategies in certain countries could have on the results. However, the investigators did not determine where each of the studies used in the review took place.

Dr. Gaujoux-Viala had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MADRID – Recent improvements in the management of rheumatoid arthritis may have had a positive impact on common cardiovascular comorbidities, according to the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Risk ratios (RR) for several CV events in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients were found to be lower for data published after 2000 and up to March 2016 when compared with data published up until 2000. Indeed, comparing these two time periods, French researchers found that the RR for myocardial infarction (MI) were a respective 1.32 and 1.18, for heart failure a respective 1.25 and 1.17, and for CV mortality a respective 1.21 and 1.07.

“Systemic inflammation is the cornerstone of both rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis,” Cécile Gaujoux-Viala, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at Montpellier University, Nîmes, France, and chief of the rheumatology service at Nîmes University Hospital, said during a press briefing at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“Over the past 15 years, new treatment strategies such as ‘tight control,’ ‘treat-to-target,’ methotrexate optimization, and use of biologic DMARDs [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] have led to better control of this inflammation,” Dr. Gaujoux-Viala added.

The aim of the meta-analysis was to look at the overall risk for CV events in RA patients versus the general population, she said, as well as to see if there had been any temporal shift by analyzing data obtained within two time periods – before 2000 and after 2000.

A systematic literature review was performed using the PubMed and Cochrane Library databases to search for observational studies that provided data about the occurrence of CV events in RA patients and controls. Of 5,714 papers that included reports of stroke, MI, heart failure, or CV death, 28 had the necessary data that could be used for the meta-analysis. Overall, the 28 studies included 227,871 RA patients, with a mean age of 55 years.

Results showed that RA patients had a 17% increased risk for stroke versus controls overall (P = .002), with a RR of 1.17. The RRs were 1.12 before 2000 and 1.23 after 2000, making stroke the only CV event that did not appear to show a downward trend.

Compared with the general population, RA patients had a 24% excess risk of MI, a 22% excess risk of heart failure, and a 18% excess risk of dying from a CV event (all P less than .00001).

These data provide “confirmation of an increased CV risk in RA patients compared to the general population,” said Dr. Gaujoux-Viala, who also discussed the study and its implications in a video interview.

Commenting on the study, Philip J. Mease, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, wondered where the studies used in the meta-analysis had been performed because of the potential impact that reduced access to CV medications or prevention strategies in certain countries could have on the results. However, the investigators did not determine where each of the studies used in the review took place.

Dr. Gaujoux-Viala had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE EULAR 2017 CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Risk ratios for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and CV mortality were lower between the period of 2000-2016 than for the period up to 2000.

Data source: Meta-analysis of 28 studies published up to March 2016 that provided data on CV event rates in RA patients and the general population.

Disclosures: Dr. Gaujoux-Viala had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ceftaroline shortens duration of MRSA bacteremia

NEW ORLEANS – Ceftaroline fosamil reduced the median duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia by 2 days in Veterans Administration patients, a retrospective study showed.

Investigators identified 219 patients with MRSA within the Veterans Affairs (VA) medical system nationwide from 2011 to 2015. All patients received at least 48 hours of ceftaroline fosamil (Teflaro) therapy to treat MRSA bacteremia. “We know it has good activity against MRSA in vitro. We use it in bacteremia, but we don’t have a lot of clinical data to support or refute its use,” said Nicholas S. Britt, PharmD, a PGY2 infectious diseases resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

“Ceftaroline was primarily used as second-line or salvage therapy … which is basically what we expected, based on how it’s used in clinical practice,” Dr. Britt said.

Treatment failures

A total of 88 of the 219 (40%) patients experienced treatment failure. This rate “seems kind of high, but, if you look at some of the other MRSA agents for bacteremia (vancomycin, for example), it usually has a treatment failure rate around 60%,” Dr. Britt said. “The outcomes were not as poor as I would expect with [patients] using it for second- and third-line therapy.”

Hospital-acquired infection (odds ratio, 2.11; P = .013), ICU admission (OR, 3.95; P less than .001) and infective endocarditis (OR, 4.77; P = .002) were significantly associated with treatment failure in a univariate analysis. “Admissions to the ICU and endocarditis were the big ones, factors you would associate with failure for most antibiotics,” Dr. Britt said. In a multivariate analysis, only ICU admission remained significantly associated with treatment failure (adjusted OR, 2.24; P = .028).

The investigators also looked at treatment failure with ceftaroline monotherapy, compared with its use in combination. There is in vitro data showing synergy when you add ceftaroline to daptomycin, vancomycin, or some of these other agents,” Dr. Britt said. However, he added, “We didn’t find any significant difference in outcomes when you added another agent.” Treatment failure with monotherapy was 35%, versus 46%, with combination treatment (P = .107).

“This could be because the sicker patients are the ones getting combination therapy.”

No observed differences by dosing

Dr. Britt and his colleagues also looked for any differences by dosing interval, “which hasn’t been evaluated extensively.”

The Food and Drug Administration labeled it for use every 12 hours, but treatment of MRSA bacteremia is an off-label use, Dr. Britt explained. Dosing every 8 hours instead improves the achievement of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters in in vitro studies. “Clinically, we’re almost always using it q8. They’re sick patients, so you don’t want to under-dose them. And ceftaroline is pretty well tolerated overall.”

“But, we didn’t really see any difference between the q8 and the q12” in terms of treatment failure. The rates were 36% and 42%, respectively, and not significantly different (P = .440). “Granted, patients who are sicker are probably going to get treated more aggressively,” Dr. Britt added.

The current research only focused on outcomes associated with ceftaroline. Going forward, Dr. Britt said, “We’re hoping to use this data to compare ceftaroline to other agents as well, probably as second-line therapy, since that’s how it’s used most often.”

Dr. Britt had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Ceftaroline fosamil reduced the median duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia by 2 days in Veterans Administration patients, a retrospective study showed.

Investigators identified 219 patients with MRSA within the Veterans Affairs (VA) medical system nationwide from 2011 to 2015. All patients received at least 48 hours of ceftaroline fosamil (Teflaro) therapy to treat MRSA bacteremia. “We know it has good activity against MRSA in vitro. We use it in bacteremia, but we don’t have a lot of clinical data to support or refute its use,” said Nicholas S. Britt, PharmD, a PGY2 infectious diseases resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

“Ceftaroline was primarily used as second-line or salvage therapy … which is basically what we expected, based on how it’s used in clinical practice,” Dr. Britt said.

Treatment failures

A total of 88 of the 219 (40%) patients experienced treatment failure. This rate “seems kind of high, but, if you look at some of the other MRSA agents for bacteremia (vancomycin, for example), it usually has a treatment failure rate around 60%,” Dr. Britt said. “The outcomes were not as poor as I would expect with [patients] using it for second- and third-line therapy.”

Hospital-acquired infection (odds ratio, 2.11; P = .013), ICU admission (OR, 3.95; P less than .001) and infective endocarditis (OR, 4.77; P = .002) were significantly associated with treatment failure in a univariate analysis. “Admissions to the ICU and endocarditis were the big ones, factors you would associate with failure for most antibiotics,” Dr. Britt said. In a multivariate analysis, only ICU admission remained significantly associated with treatment failure (adjusted OR, 2.24; P = .028).

The investigators also looked at treatment failure with ceftaroline monotherapy, compared with its use in combination. There is in vitro data showing synergy when you add ceftaroline to daptomycin, vancomycin, or some of these other agents,” Dr. Britt said. However, he added, “We didn’t find any significant difference in outcomes when you added another agent.” Treatment failure with monotherapy was 35%, versus 46%, with combination treatment (P = .107).

“This could be because the sicker patients are the ones getting combination therapy.”

No observed differences by dosing

Dr. Britt and his colleagues also looked for any differences by dosing interval, “which hasn’t been evaluated extensively.”

The Food and Drug Administration labeled it for use every 12 hours, but treatment of MRSA bacteremia is an off-label use, Dr. Britt explained. Dosing every 8 hours instead improves the achievement of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters in in vitro studies. “Clinically, we’re almost always using it q8. They’re sick patients, so you don’t want to under-dose them. And ceftaroline is pretty well tolerated overall.”

“But, we didn’t really see any difference between the q8 and the q12” in terms of treatment failure. The rates were 36% and 42%, respectively, and not significantly different (P = .440). “Granted, patients who are sicker are probably going to get treated more aggressively,” Dr. Britt added.

The current research only focused on outcomes associated with ceftaroline. Going forward, Dr. Britt said, “We’re hoping to use this data to compare ceftaroline to other agents as well, probably as second-line therapy, since that’s how it’s used most often.”

Dr. Britt had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Ceftaroline fosamil reduced the median duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia by 2 days in Veterans Administration patients, a retrospective study showed.

Investigators identified 219 patients with MRSA within the Veterans Affairs (VA) medical system nationwide from 2011 to 2015. All patients received at least 48 hours of ceftaroline fosamil (Teflaro) therapy to treat MRSA bacteremia. “We know it has good activity against MRSA in vitro. We use it in bacteremia, but we don’t have a lot of clinical data to support or refute its use,” said Nicholas S. Britt, PharmD, a PGY2 infectious diseases resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

“Ceftaroline was primarily used as second-line or salvage therapy … which is basically what we expected, based on how it’s used in clinical practice,” Dr. Britt said.

Treatment failures

A total of 88 of the 219 (40%) patients experienced treatment failure. This rate “seems kind of high, but, if you look at some of the other MRSA agents for bacteremia (vancomycin, for example), it usually has a treatment failure rate around 60%,” Dr. Britt said. “The outcomes were not as poor as I would expect with [patients] using it for second- and third-line therapy.”

Hospital-acquired infection (odds ratio, 2.11; P = .013), ICU admission (OR, 3.95; P less than .001) and infective endocarditis (OR, 4.77; P = .002) were significantly associated with treatment failure in a univariate analysis. “Admissions to the ICU and endocarditis were the big ones, factors you would associate with failure for most antibiotics,” Dr. Britt said. In a multivariate analysis, only ICU admission remained significantly associated with treatment failure (adjusted OR, 2.24; P = .028).

The investigators also looked at treatment failure with ceftaroline monotherapy, compared with its use in combination. There is in vitro data showing synergy when you add ceftaroline to daptomycin, vancomycin, or some of these other agents,” Dr. Britt said. However, he added, “We didn’t find any significant difference in outcomes when you added another agent.” Treatment failure with monotherapy was 35%, versus 46%, with combination treatment (P = .107).

“This could be because the sicker patients are the ones getting combination therapy.”

No observed differences by dosing

Dr. Britt and his colleagues also looked for any differences by dosing interval, “which hasn’t been evaluated extensively.”

The Food and Drug Administration labeled it for use every 12 hours, but treatment of MRSA bacteremia is an off-label use, Dr. Britt explained. Dosing every 8 hours instead improves the achievement of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters in in vitro studies. “Clinically, we’re almost always using it q8. They’re sick patients, so you don’t want to under-dose them. And ceftaroline is pretty well tolerated overall.”

“But, we didn’t really see any difference between the q8 and the q12” in terms of treatment failure. The rates were 36% and 42%, respectively, and not significantly different (P = .440). “Granted, patients who are sicker are probably going to get treated more aggressively,” Dr. Britt added.

The current research only focused on outcomes associated with ceftaroline. Going forward, Dr. Britt said, “We’re hoping to use this data to compare ceftaroline to other agents as well, probably as second-line therapy, since that’s how it’s used most often.”

Dr. Britt had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ASM MICROBE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Median duration of MRSA bacteremia dropped from 2.79 days before to 1.18 days after initiation of ceftaroline (P less than .001).

Data source: A retrospective study of 219 hospitalized VA patients initiating ceftaroline for MRSA bacteremia.

Disclosures: Dr. Britt had no relevant financial disclosures.

Carbapenem-resistant sepsis risk factors vary significantly

NEW ORLEANS – Investigators discovered significant differences in risk factors when comparing 603 people hospitalized with carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative sepsis with either Enterobacteriaceae-caused or non-Enterobacteriaceae–caused infection.

“We know some of the virulence factors and the resistance mechanisms can differ between those two groups. We really wanted to see if that would influence outcomes,” said Nicholas S. Britt, PharmD, a PGY2 infectious disease resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. Mortality rates, however, did not differ significantly.

“Patients who had Enterobacteriaceae infections were more likely to have urinary tract infections, to be older patients, and to have higher APACHE (Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation) II scores,” Dr. Britt said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. These differences all were statistically significant, compared with those of the CRNE group (P less than .05).

In contrast, the non-Enterobacteriaceae patients tended to have more respiratory infections and more frequent central venous catheter use. This group also was more likely to have a history of carbapenem use and more frequent antimicrobial exposures overall and to present after solid organ transplantation. “The cystic fibrosis patients were more likely to get non-Enterobacteriaceae infections as well,” Dr. Britt added. These differences also were statistically significant (all P less than .05).

“I think the biggest takeaway from this study, honestly, is the number of patients infected with CRE, versus CRNE,” Dr. Britt said. “We know CRE are a serious public health threat, one of the biggest threats out there, but, if you look at the burden on carbapenem-resistant disease, it’s primarily the non-Enterobacteriaceae.”

In fact, more than three-quarters of the patient studied (78%) had CRNE infections, and Pseudomonas was a major driver, he added. “Carbapenem resistance in this group of patients is something we should be focusing on – not only the CRE – because we’re seeing more of the non-CRE clinically.”

Patient age, presence of bloodstream infection, and use of mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, and immunosuppression was associated with hospital mortality in the study. After adjusting for potential confounders, however, CRNE infection was not associated with increased hospital mortality, compared with CRE cases (adjusted odds ratio, 0.97; P = .917).

“Our mortality rate was 16%, which is comparable to [that of] other studies,” Dr. Britt said. “There doesn’t seem to be any difference in this outcome between the two groups.” Mortality was 16.4% in the CRE cohort, versus 16.5% in the CRNE cohort (P = 0.965).

NEW ORLEANS – Investigators discovered significant differences in risk factors when comparing 603 people hospitalized with carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative sepsis with either Enterobacteriaceae-caused or non-Enterobacteriaceae–caused infection.

“We know some of the virulence factors and the resistance mechanisms can differ between those two groups. We really wanted to see if that would influence outcomes,” said Nicholas S. Britt, PharmD, a PGY2 infectious disease resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. Mortality rates, however, did not differ significantly.