User login

How primary care physicians can hit the mark on contraceptive counseling

SAN FRANCISCO – When it comes to counseling women about contraceptive care and family planning, many primary care physicians fall short, according to Christine Dehlendorf, MD.

“Providing contraceptive care and family planning care is part of what we do as preventive care for women of reproductive age, but we don’t always do it as often as we should,” Dr. Dehlendorf said at the UCSF Annual Advances in Internal Medicine meeting. “We don’t often take the initiative of making sure that women’s contraceptive needs are being met at all visits when we engage with them.”

“Many of you might think that’s okay, because we’re only talking about it when women come in for family planning visits,” said Dr. Dehlendorf of the departments of family and community medicine and obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. “In fact, this is something that is an ongoing need for women. We should be using every opportunity to make sure we’re helping them, even if it’s just by initiating the conversation and providing referrals as appropriate.”

Some might think that the best approach to contraceptive decision making involves recommending the most highly effective methods, such as long-acting reversible contraceptives, which have a risk of failure that’s 20 times lower than that of short-acting hormonal methods. Examples of counseling approaches used in that context include tiered effectiveness, in which the clinician presents methods in order of effectiveness, and motivational interviewing, a counseling approach developed for use in people with addictions.

However, Dr. Dehlendorf said she prefers to view contraceptive choice as a decision driven by women’s values and preferences.

“We know that effectiveness is very important to women, but we also know that things like side-effect profile and control over the [contraceptive] method are important as well,” she explained. “These strong features reflect women’s different assessments of the desirability of different outcomes associated with contraceptive use.

“For example, some women think that the possibility of amenorrhea with progestin IUDs or Depo-Provera is a great thing, and other people think it would be horrible,” Dr. Dehlendorf noted. “It has nothing to do with safety or effectiveness; this has to do with how women view that characteristic in the context of their own values and preferences.”

The differential value that women may place on contraceptive effectiveness also relates to different perceptions they have of the possibility of an unplanned pregnancy in their lives, and how important that is to avoid.

“In general, in the public health and clinical dialogue, the idea is that an unplanned pregnancy is an inherently bad pregnancy,” Dr. Dehlendorf said. “The conventional dialogue involves the notion of intentions and plans: Are they intending or planning to get pregnant? Intentions being timing-based ideas of when to get pregnant, and plans being concrete steps they take to act on those intentions.”

However, an emerging body of literature has shown that there are other dimensions of how women think about the possibility of pregnancy in their lives that are distinct from intentions and plans, she said, such as desire, which is how strongly they intend or don’t intend to have a pregnancy, and feelings, their emotional orientation around the potential for a pregnancy in their life.

“You could argue that this is overcomplicating things, but that is not true,” Dr. Dehlendorf said. “Plans, intentions, desires, and feelings are all different concepts, and some of them are more or less relevant to individual women, and they don’t always align with each other. That’s very much in conflict with how we conventionally talk about pregnancy in women’s lives.”

Examples from qualitative research have fleshed this out.

In one recently published study, researchers led by Jenny A. Higgins, PhD, of the department of gender and women’s studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, asked women about their views on IUDs. One woman said, “I guess one of the reasons that I haven’t gotten an IUD yet is like, I don’t know, having one kid already and being in a long-term committed relationship, it takes the element of surprise out of when we would have our next kid, which I kind of want. I’m in that weird position. I just don’t want to put too much thought and planning into when I have my next kid.”

Other women view an unplanned pregnancy as emotionally welcome.

In a longitudinal study that measured prospective pregnancy intentions and feelings among 403 women in Austin, Tex., one woman said, “Another pregnancy is definitely not the right path for me, and I’m being very careful with birth control. But if I somehow ended up pregnant, would I embrace it and think it’s for the best? Absolutely.”

Another study participant said, “I don’t want more kids and was hoping to get my tubes tied. We can’t afford another one. But if it happened, I’d still be happy. I’d be really excited. We’d rise to the occasion. Nothing would really change” (Soc Sci Med. 2015 May;132:149-155).

According to Dr. Dehlendorf, the lesson from such studies is that women are going to assess the importance of the efficacy of their contraceptive method differently, depending on how important it is for them to prevent an unintended pregnancy.

“They’re not going to make a decision about effectiveness the way we as clinicians might think that they should,” she said. “So, assuming that highly effective methods are the best methods for all women because of their effectiveness ignores the variability in preferences, and it also doesn’t take into account women’s strong feelings about other aspects of contraceptive use, such as bleeding profiles and control over their methods.”

Shared decision making may be the best way to help women make a choice based on their preferences. In a study that Dr. Dehlendorf and her associates conducted in 348 women who were seen for contraceptive care in the San Francisco Bay area, two habits were associated with contraceptive continuation: investing in the beginning, and eliciting the patient’s perspective (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;215[1]:78.e1-9). “Investing in the beginning consists of greeting the patient warmly, making small talk, and treating the patient as a person,” she said. “That was the most highly influential aspect of the interaction. Building rapport and decision support helps women choose a method that’s a good fit for them.

“We also know that women like this method of counseling, but this approach might not be for everyone,” Dr. Dehlendorf cautioned. “Some women don’t want your suggestions, even if it’s grounded in their preferences. They just want to get the method that they came in for. The right thing is to acknowledge that, but you can also ask women if they want to hear about other methods, because some women might not know about all of their options.”

Dr. Dehlendorf reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – When it comes to counseling women about contraceptive care and family planning, many primary care physicians fall short, according to Christine Dehlendorf, MD.

“Providing contraceptive care and family planning care is part of what we do as preventive care for women of reproductive age, but we don’t always do it as often as we should,” Dr. Dehlendorf said at the UCSF Annual Advances in Internal Medicine meeting. “We don’t often take the initiative of making sure that women’s contraceptive needs are being met at all visits when we engage with them.”

“Many of you might think that’s okay, because we’re only talking about it when women come in for family planning visits,” said Dr. Dehlendorf of the departments of family and community medicine and obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. “In fact, this is something that is an ongoing need for women. We should be using every opportunity to make sure we’re helping them, even if it’s just by initiating the conversation and providing referrals as appropriate.”

Some might think that the best approach to contraceptive decision making involves recommending the most highly effective methods, such as long-acting reversible contraceptives, which have a risk of failure that’s 20 times lower than that of short-acting hormonal methods. Examples of counseling approaches used in that context include tiered effectiveness, in which the clinician presents methods in order of effectiveness, and motivational interviewing, a counseling approach developed for use in people with addictions.

However, Dr. Dehlendorf said she prefers to view contraceptive choice as a decision driven by women’s values and preferences.

“We know that effectiveness is very important to women, but we also know that things like side-effect profile and control over the [contraceptive] method are important as well,” she explained. “These strong features reflect women’s different assessments of the desirability of different outcomes associated with contraceptive use.

“For example, some women think that the possibility of amenorrhea with progestin IUDs or Depo-Provera is a great thing, and other people think it would be horrible,” Dr. Dehlendorf noted. “It has nothing to do with safety or effectiveness; this has to do with how women view that characteristic in the context of their own values and preferences.”

The differential value that women may place on contraceptive effectiveness also relates to different perceptions they have of the possibility of an unplanned pregnancy in their lives, and how important that is to avoid.

“In general, in the public health and clinical dialogue, the idea is that an unplanned pregnancy is an inherently bad pregnancy,” Dr. Dehlendorf said. “The conventional dialogue involves the notion of intentions and plans: Are they intending or planning to get pregnant? Intentions being timing-based ideas of when to get pregnant, and plans being concrete steps they take to act on those intentions.”

However, an emerging body of literature has shown that there are other dimensions of how women think about the possibility of pregnancy in their lives that are distinct from intentions and plans, she said, such as desire, which is how strongly they intend or don’t intend to have a pregnancy, and feelings, their emotional orientation around the potential for a pregnancy in their life.

“You could argue that this is overcomplicating things, but that is not true,” Dr. Dehlendorf said. “Plans, intentions, desires, and feelings are all different concepts, and some of them are more or less relevant to individual women, and they don’t always align with each other. That’s very much in conflict with how we conventionally talk about pregnancy in women’s lives.”

Examples from qualitative research have fleshed this out.

In one recently published study, researchers led by Jenny A. Higgins, PhD, of the department of gender and women’s studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, asked women about their views on IUDs. One woman said, “I guess one of the reasons that I haven’t gotten an IUD yet is like, I don’t know, having one kid already and being in a long-term committed relationship, it takes the element of surprise out of when we would have our next kid, which I kind of want. I’m in that weird position. I just don’t want to put too much thought and planning into when I have my next kid.”

Other women view an unplanned pregnancy as emotionally welcome.

In a longitudinal study that measured prospective pregnancy intentions and feelings among 403 women in Austin, Tex., one woman said, “Another pregnancy is definitely not the right path for me, and I’m being very careful with birth control. But if I somehow ended up pregnant, would I embrace it and think it’s for the best? Absolutely.”

Another study participant said, “I don’t want more kids and was hoping to get my tubes tied. We can’t afford another one. But if it happened, I’d still be happy. I’d be really excited. We’d rise to the occasion. Nothing would really change” (Soc Sci Med. 2015 May;132:149-155).

According to Dr. Dehlendorf, the lesson from such studies is that women are going to assess the importance of the efficacy of their contraceptive method differently, depending on how important it is for them to prevent an unintended pregnancy.

“They’re not going to make a decision about effectiveness the way we as clinicians might think that they should,” she said. “So, assuming that highly effective methods are the best methods for all women because of their effectiveness ignores the variability in preferences, and it also doesn’t take into account women’s strong feelings about other aspects of contraceptive use, such as bleeding profiles and control over their methods.”

Shared decision making may be the best way to help women make a choice based on their preferences. In a study that Dr. Dehlendorf and her associates conducted in 348 women who were seen for contraceptive care in the San Francisco Bay area, two habits were associated with contraceptive continuation: investing in the beginning, and eliciting the patient’s perspective (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;215[1]:78.e1-9). “Investing in the beginning consists of greeting the patient warmly, making small talk, and treating the patient as a person,” she said. “That was the most highly influential aspect of the interaction. Building rapport and decision support helps women choose a method that’s a good fit for them.

“We also know that women like this method of counseling, but this approach might not be for everyone,” Dr. Dehlendorf cautioned. “Some women don’t want your suggestions, even if it’s grounded in their preferences. They just want to get the method that they came in for. The right thing is to acknowledge that, but you can also ask women if they want to hear about other methods, because some women might not know about all of their options.”

Dr. Dehlendorf reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – When it comes to counseling women about contraceptive care and family planning, many primary care physicians fall short, according to Christine Dehlendorf, MD.

“Providing contraceptive care and family planning care is part of what we do as preventive care for women of reproductive age, but we don’t always do it as often as we should,” Dr. Dehlendorf said at the UCSF Annual Advances in Internal Medicine meeting. “We don’t often take the initiative of making sure that women’s contraceptive needs are being met at all visits when we engage with them.”

“Many of you might think that’s okay, because we’re only talking about it when women come in for family planning visits,” said Dr. Dehlendorf of the departments of family and community medicine and obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. “In fact, this is something that is an ongoing need for women. We should be using every opportunity to make sure we’re helping them, even if it’s just by initiating the conversation and providing referrals as appropriate.”

Some might think that the best approach to contraceptive decision making involves recommending the most highly effective methods, such as long-acting reversible contraceptives, which have a risk of failure that’s 20 times lower than that of short-acting hormonal methods. Examples of counseling approaches used in that context include tiered effectiveness, in which the clinician presents methods in order of effectiveness, and motivational interviewing, a counseling approach developed for use in people with addictions.

However, Dr. Dehlendorf said she prefers to view contraceptive choice as a decision driven by women’s values and preferences.

“We know that effectiveness is very important to women, but we also know that things like side-effect profile and control over the [contraceptive] method are important as well,” she explained. “These strong features reflect women’s different assessments of the desirability of different outcomes associated with contraceptive use.

“For example, some women think that the possibility of amenorrhea with progestin IUDs or Depo-Provera is a great thing, and other people think it would be horrible,” Dr. Dehlendorf noted. “It has nothing to do with safety or effectiveness; this has to do with how women view that characteristic in the context of their own values and preferences.”

The differential value that women may place on contraceptive effectiveness also relates to different perceptions they have of the possibility of an unplanned pregnancy in their lives, and how important that is to avoid.

“In general, in the public health and clinical dialogue, the idea is that an unplanned pregnancy is an inherently bad pregnancy,” Dr. Dehlendorf said. “The conventional dialogue involves the notion of intentions and plans: Are they intending or planning to get pregnant? Intentions being timing-based ideas of when to get pregnant, and plans being concrete steps they take to act on those intentions.”

However, an emerging body of literature has shown that there are other dimensions of how women think about the possibility of pregnancy in their lives that are distinct from intentions and plans, she said, such as desire, which is how strongly they intend or don’t intend to have a pregnancy, and feelings, their emotional orientation around the potential for a pregnancy in their life.

“You could argue that this is overcomplicating things, but that is not true,” Dr. Dehlendorf said. “Plans, intentions, desires, and feelings are all different concepts, and some of them are more or less relevant to individual women, and they don’t always align with each other. That’s very much in conflict with how we conventionally talk about pregnancy in women’s lives.”

Examples from qualitative research have fleshed this out.

In one recently published study, researchers led by Jenny A. Higgins, PhD, of the department of gender and women’s studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, asked women about their views on IUDs. One woman said, “I guess one of the reasons that I haven’t gotten an IUD yet is like, I don’t know, having one kid already and being in a long-term committed relationship, it takes the element of surprise out of when we would have our next kid, which I kind of want. I’m in that weird position. I just don’t want to put too much thought and planning into when I have my next kid.”

Other women view an unplanned pregnancy as emotionally welcome.

In a longitudinal study that measured prospective pregnancy intentions and feelings among 403 women in Austin, Tex., one woman said, “Another pregnancy is definitely not the right path for me, and I’m being very careful with birth control. But if I somehow ended up pregnant, would I embrace it and think it’s for the best? Absolutely.”

Another study participant said, “I don’t want more kids and was hoping to get my tubes tied. We can’t afford another one. But if it happened, I’d still be happy. I’d be really excited. We’d rise to the occasion. Nothing would really change” (Soc Sci Med. 2015 May;132:149-155).

According to Dr. Dehlendorf, the lesson from such studies is that women are going to assess the importance of the efficacy of their contraceptive method differently, depending on how important it is for them to prevent an unintended pregnancy.

“They’re not going to make a decision about effectiveness the way we as clinicians might think that they should,” she said. “So, assuming that highly effective methods are the best methods for all women because of their effectiveness ignores the variability in preferences, and it also doesn’t take into account women’s strong feelings about other aspects of contraceptive use, such as bleeding profiles and control over their methods.”

Shared decision making may be the best way to help women make a choice based on their preferences. In a study that Dr. Dehlendorf and her associates conducted in 348 women who were seen for contraceptive care in the San Francisco Bay area, two habits were associated with contraceptive continuation: investing in the beginning, and eliciting the patient’s perspective (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;215[1]:78.e1-9). “Investing in the beginning consists of greeting the patient warmly, making small talk, and treating the patient as a person,” she said. “That was the most highly influential aspect of the interaction. Building rapport and decision support helps women choose a method that’s a good fit for them.

“We also know that women like this method of counseling, but this approach might not be for everyone,” Dr. Dehlendorf cautioned. “Some women don’t want your suggestions, even if it’s grounded in their preferences. They just want to get the method that they came in for. The right thing is to acknowledge that, but you can also ask women if they want to hear about other methods, because some women might not know about all of their options.”

Dr. Dehlendorf reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL ADVANCES IN INTERNAL MEDICINE

Point/Counterpoint: Is intraoperative drain placement essential during pancreatectomy?

Yes, placing drains is essential.

It’s important to look at the evidence in the literature, starting with a randomized controlled trial of 179 patients from 2001 that showed no reduction in death or complication rate associated with use of surgical intraperitoneal closed suction drainage (Ann. Surg. 2001;234:487-94). Interestingly, even though this study showed there was no benefit to using drains, they address the use of closed suction drainage. The investigators were not claiming all drains are unnecessary.

Why drain placement? The argument for drains includes evacuation of blood, pancreatic juice, bile, and chyle. In addition, assessing drainage can act as a warning sign for anastomotic leak or hemorrhage, so patients can potentially avoid additional interventions.

A study from University of Tokyo researchers found three drains were more effective than one. In addition, the investigators argued against early removal, pointing out that the risk for infection associated with drains only increased after day 10. The researchers were not only in favor of drains but in favor of multiple drains (World J Surg. 2016;40:1226-35).

A multicenter, randomized prospective trial conducted in the United States compared 68 patients with drains to 69 others without during pancreaticoduodenectomy. They reported an increase in the frequency and severity of complications when drains were omitted, including the number of grade 2 or greater complications. Furthermore, the safety monitoring board stopped the study early because mortality among patients in the drain group was 3%, compared with 12% in the no-drain group. (Ann. Surg. 2014:259:605-12).

Another set of researchers in Germany conducted a prospective, randomized study that favored omission of drains. However, a closer look at demographics shows that about one-fourth of participants had chronic pancreatitis, which is associated with a low risk of fistula (Ann Surg. 2016;263:440-9). In addition, they found no significant difference in fistula rates between patients who underwent pancreaticojejunostomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy. Interestingly, the authors noted that surgeons were reluctant to omit drains in many situations, even in a clinical trial context.

Furthermore, a systematic review of nine studies with nearly 3,000 patients suggests it is still necessary to place abdominal drains during pancreatic resection, researchers at the Medical College of Xi’an Jiaotong University in China reported (World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5719-34). The authors cited a significant increase in morbidity among patients in whom drains were omitted (odds ratio, 2.39).

Perhaps the cleverest way to address this controversy with drains during pancreatic resection comes from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. They looked at surgical risk factors to gain a more nuanced view. They used the Fistula Risk Score (FRS) to stratify patients and re-examined the outcomes of the multicenter U.S. study I cited earlier that was stopped early because of differences in mortality rates. The University of Pennsylvania research found that FRS correlated well with outcomes, suggesting its use as a mitigation strategy in patients at moderate to high risk for developing clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula (J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:21-30). In other words, they suggest routine prophylactic drainage for patients at moderate to high risk but also suggest that there may be no need for prophylactic drainage for negligible to low risk patients.

I would like to conclude that drains appear essential in many cases, including for moderate to higher risk patients. We need to tailor our practices as surgeons regarding placement of drains during pancreatectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy. Our goal remains to create opportunities for prolonged survival and better quality of life for our patients.

Dr. Dervenis is head of the Department of Surgical Oncology at the Metropolitan Hospital in Athens, Greece. He is also chair of the hepato-pancreato-biliary surgical unit. He reported no disclosures.

No, drain placement is not always necessary.

Drain placement is not essential during all pancreatectomies. The practice is so historically entrenched in our specialty that I need you to check your dogma at the door and take a look at the data with an open mind.

There are many, many retrospective studies that examine drainage versus no drainage. All of these studies have shown the same thing: There is no difference in many outcomes, including mortality. There may be a difference in terms of complicated, postoperative fistulae, which are difficult to manage in patients who have drains.

Another prospective randomized trial from Germany compared the reintervention rate, an endpoint I like, among 439 patients (Ann Surg. 2016;264:528-37). There was no statistically significant difference between the drain or no drain groups, further suggesting that drains are not essential in all cases.

We also need to take a closer look at the study Dr. Dervenis cited (Ann Surg. 2014:259:605-12). It’s true this trial was stopped early because of a higher mortality rate of 12% in the no drain group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .097). There was no difference in the fistula rate.

When you look at these data, there are a couple of conclusions you can reach. One conclusion is that a trial of 130 people designed for 750 found something uniquely different that had never been reported in any retrospective series, including one by the study’s senior author that demonstrated drains are essential (HPB [Oxford]. 2011;13:503-10). Another conclusion is that drains are not needed, and there is a very good chance this is a false positive finding. Look at the reasons the 10 participants died. I’m not sure a drain would have helped some of the patients without them, and some of the patients who had drains still died.

A study looking at practice at my institution, MSKCC, shows that drains are still used about half the time, indicating they are not essential. (Ann. Surg. 2013 Dec;258[6]:1051-8). Drains were more commonly used for pancreaticoduodenectomy and when the surgeon thought there might be a problem, such as a soft gland, difficult time in the OR, or a small pancreatic duct.

If you look at these data, this pans out in every retrospective study I’ve seen comparing drain versus no drain – the patients with drains tend to have higher morbidity. Among the 1,122 resection patients in the MSKCC study, those without operative drains had significantly lower rates of grade 3 complications and overall morbidity and fewer readmissions and lower rates of grade 3 or higher pancreatic fistula. Mortality and reintervention rates were no different.

I also looked at our most recent data, between 2010 and 2015. Now we are using intraoperative drains even less often. They are not considered essential at this point.

There are multiple retrospective and well-designed prospective, randomized trials that show no benefit to routine drainage following pancreatectomy. Acceptance of randomized clinical data is slow, particularly when it flies in the face of what you were taught by your mentors over the past 40 or 50 years. I encourage you to look at these data carefully and utilize them in your practice.

Dr. Allen is associate director for clinical programs at David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research and the Murray F. Brennan chair in surgery at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. He reported no disclosures.

Yes, placing drains is essential.

It’s important to look at the evidence in the literature, starting with a randomized controlled trial of 179 patients from 2001 that showed no reduction in death or complication rate associated with use of surgical intraperitoneal closed suction drainage (Ann. Surg. 2001;234:487-94). Interestingly, even though this study showed there was no benefit to using drains, they address the use of closed suction drainage. The investigators were not claiming all drains are unnecessary.

Why drain placement? The argument for drains includes evacuation of blood, pancreatic juice, bile, and chyle. In addition, assessing drainage can act as a warning sign for anastomotic leak or hemorrhage, so patients can potentially avoid additional interventions.

A study from University of Tokyo researchers found three drains were more effective than one. In addition, the investigators argued against early removal, pointing out that the risk for infection associated with drains only increased after day 10. The researchers were not only in favor of drains but in favor of multiple drains (World J Surg. 2016;40:1226-35).

A multicenter, randomized prospective trial conducted in the United States compared 68 patients with drains to 69 others without during pancreaticoduodenectomy. They reported an increase in the frequency and severity of complications when drains were omitted, including the number of grade 2 or greater complications. Furthermore, the safety monitoring board stopped the study early because mortality among patients in the drain group was 3%, compared with 12% in the no-drain group. (Ann. Surg. 2014:259:605-12).

Another set of researchers in Germany conducted a prospective, randomized study that favored omission of drains. However, a closer look at demographics shows that about one-fourth of participants had chronic pancreatitis, which is associated with a low risk of fistula (Ann Surg. 2016;263:440-9). In addition, they found no significant difference in fistula rates between patients who underwent pancreaticojejunostomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy. Interestingly, the authors noted that surgeons were reluctant to omit drains in many situations, even in a clinical trial context.

Furthermore, a systematic review of nine studies with nearly 3,000 patients suggests it is still necessary to place abdominal drains during pancreatic resection, researchers at the Medical College of Xi’an Jiaotong University in China reported (World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5719-34). The authors cited a significant increase in morbidity among patients in whom drains were omitted (odds ratio, 2.39).

Perhaps the cleverest way to address this controversy with drains during pancreatic resection comes from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. They looked at surgical risk factors to gain a more nuanced view. They used the Fistula Risk Score (FRS) to stratify patients and re-examined the outcomes of the multicenter U.S. study I cited earlier that was stopped early because of differences in mortality rates. The University of Pennsylvania research found that FRS correlated well with outcomes, suggesting its use as a mitigation strategy in patients at moderate to high risk for developing clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula (J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:21-30). In other words, they suggest routine prophylactic drainage for patients at moderate to high risk but also suggest that there may be no need for prophylactic drainage for negligible to low risk patients.

I would like to conclude that drains appear essential in many cases, including for moderate to higher risk patients. We need to tailor our practices as surgeons regarding placement of drains during pancreatectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy. Our goal remains to create opportunities for prolonged survival and better quality of life for our patients.

Dr. Dervenis is head of the Department of Surgical Oncology at the Metropolitan Hospital in Athens, Greece. He is also chair of the hepato-pancreato-biliary surgical unit. He reported no disclosures.

No, drain placement is not always necessary.

Drain placement is not essential during all pancreatectomies. The practice is so historically entrenched in our specialty that I need you to check your dogma at the door and take a look at the data with an open mind.

There are many, many retrospective studies that examine drainage versus no drainage. All of these studies have shown the same thing: There is no difference in many outcomes, including mortality. There may be a difference in terms of complicated, postoperative fistulae, which are difficult to manage in patients who have drains.

Another prospective randomized trial from Germany compared the reintervention rate, an endpoint I like, among 439 patients (Ann Surg. 2016;264:528-37). There was no statistically significant difference between the drain or no drain groups, further suggesting that drains are not essential in all cases.

We also need to take a closer look at the study Dr. Dervenis cited (Ann Surg. 2014:259:605-12). It’s true this trial was stopped early because of a higher mortality rate of 12% in the no drain group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .097). There was no difference in the fistula rate.

When you look at these data, there are a couple of conclusions you can reach. One conclusion is that a trial of 130 people designed for 750 found something uniquely different that had never been reported in any retrospective series, including one by the study’s senior author that demonstrated drains are essential (HPB [Oxford]. 2011;13:503-10). Another conclusion is that drains are not needed, and there is a very good chance this is a false positive finding. Look at the reasons the 10 participants died. I’m not sure a drain would have helped some of the patients without them, and some of the patients who had drains still died.

A study looking at practice at my institution, MSKCC, shows that drains are still used about half the time, indicating they are not essential. (Ann. Surg. 2013 Dec;258[6]:1051-8). Drains were more commonly used for pancreaticoduodenectomy and when the surgeon thought there might be a problem, such as a soft gland, difficult time in the OR, or a small pancreatic duct.

If you look at these data, this pans out in every retrospective study I’ve seen comparing drain versus no drain – the patients with drains tend to have higher morbidity. Among the 1,122 resection patients in the MSKCC study, those without operative drains had significantly lower rates of grade 3 complications and overall morbidity and fewer readmissions and lower rates of grade 3 or higher pancreatic fistula. Mortality and reintervention rates were no different.

I also looked at our most recent data, between 2010 and 2015. Now we are using intraoperative drains even less often. They are not considered essential at this point.

There are multiple retrospective and well-designed prospective, randomized trials that show no benefit to routine drainage following pancreatectomy. Acceptance of randomized clinical data is slow, particularly when it flies in the face of what you were taught by your mentors over the past 40 or 50 years. I encourage you to look at these data carefully and utilize them in your practice.

Dr. Allen is associate director for clinical programs at David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research and the Murray F. Brennan chair in surgery at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. He reported no disclosures.

Yes, placing drains is essential.

It’s important to look at the evidence in the literature, starting with a randomized controlled trial of 179 patients from 2001 that showed no reduction in death or complication rate associated with use of surgical intraperitoneal closed suction drainage (Ann. Surg. 2001;234:487-94). Interestingly, even though this study showed there was no benefit to using drains, they address the use of closed suction drainage. The investigators were not claiming all drains are unnecessary.

Why drain placement? The argument for drains includes evacuation of blood, pancreatic juice, bile, and chyle. In addition, assessing drainage can act as a warning sign for anastomotic leak or hemorrhage, so patients can potentially avoid additional interventions.

A study from University of Tokyo researchers found three drains were more effective than one. In addition, the investigators argued against early removal, pointing out that the risk for infection associated with drains only increased after day 10. The researchers were not only in favor of drains but in favor of multiple drains (World J Surg. 2016;40:1226-35).

A multicenter, randomized prospective trial conducted in the United States compared 68 patients with drains to 69 others without during pancreaticoduodenectomy. They reported an increase in the frequency and severity of complications when drains were omitted, including the number of grade 2 or greater complications. Furthermore, the safety monitoring board stopped the study early because mortality among patients in the drain group was 3%, compared with 12% in the no-drain group. (Ann. Surg. 2014:259:605-12).

Another set of researchers in Germany conducted a prospective, randomized study that favored omission of drains. However, a closer look at demographics shows that about one-fourth of participants had chronic pancreatitis, which is associated with a low risk of fistula (Ann Surg. 2016;263:440-9). In addition, they found no significant difference in fistula rates between patients who underwent pancreaticojejunostomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy. Interestingly, the authors noted that surgeons were reluctant to omit drains in many situations, even in a clinical trial context.

Furthermore, a systematic review of nine studies with nearly 3,000 patients suggests it is still necessary to place abdominal drains during pancreatic resection, researchers at the Medical College of Xi’an Jiaotong University in China reported (World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5719-34). The authors cited a significant increase in morbidity among patients in whom drains were omitted (odds ratio, 2.39).

Perhaps the cleverest way to address this controversy with drains during pancreatic resection comes from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. They looked at surgical risk factors to gain a more nuanced view. They used the Fistula Risk Score (FRS) to stratify patients and re-examined the outcomes of the multicenter U.S. study I cited earlier that was stopped early because of differences in mortality rates. The University of Pennsylvania research found that FRS correlated well with outcomes, suggesting its use as a mitigation strategy in patients at moderate to high risk for developing clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula (J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:21-30). In other words, they suggest routine prophylactic drainage for patients at moderate to high risk but also suggest that there may be no need for prophylactic drainage for negligible to low risk patients.

I would like to conclude that drains appear essential in many cases, including for moderate to higher risk patients. We need to tailor our practices as surgeons regarding placement of drains during pancreatectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy. Our goal remains to create opportunities for prolonged survival and better quality of life for our patients.

Dr. Dervenis is head of the Department of Surgical Oncology at the Metropolitan Hospital in Athens, Greece. He is also chair of the hepato-pancreato-biliary surgical unit. He reported no disclosures.

No, drain placement is not always necessary.

Drain placement is not essential during all pancreatectomies. The practice is so historically entrenched in our specialty that I need you to check your dogma at the door and take a look at the data with an open mind.

There are many, many retrospective studies that examine drainage versus no drainage. All of these studies have shown the same thing: There is no difference in many outcomes, including mortality. There may be a difference in terms of complicated, postoperative fistulae, which are difficult to manage in patients who have drains.

Another prospective randomized trial from Germany compared the reintervention rate, an endpoint I like, among 439 patients (Ann Surg. 2016;264:528-37). There was no statistically significant difference between the drain or no drain groups, further suggesting that drains are not essential in all cases.

We also need to take a closer look at the study Dr. Dervenis cited (Ann Surg. 2014:259:605-12). It’s true this trial was stopped early because of a higher mortality rate of 12% in the no drain group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .097). There was no difference in the fistula rate.

When you look at these data, there are a couple of conclusions you can reach. One conclusion is that a trial of 130 people designed for 750 found something uniquely different that had never been reported in any retrospective series, including one by the study’s senior author that demonstrated drains are essential (HPB [Oxford]. 2011;13:503-10). Another conclusion is that drains are not needed, and there is a very good chance this is a false positive finding. Look at the reasons the 10 participants died. I’m not sure a drain would have helped some of the patients without them, and some of the patients who had drains still died.

A study looking at practice at my institution, MSKCC, shows that drains are still used about half the time, indicating they are not essential. (Ann. Surg. 2013 Dec;258[6]:1051-8). Drains were more commonly used for pancreaticoduodenectomy and when the surgeon thought there might be a problem, such as a soft gland, difficult time in the OR, or a small pancreatic duct.

If you look at these data, this pans out in every retrospective study I’ve seen comparing drain versus no drain – the patients with drains tend to have higher morbidity. Among the 1,122 resection patients in the MSKCC study, those without operative drains had significantly lower rates of grade 3 complications and overall morbidity and fewer readmissions and lower rates of grade 3 or higher pancreatic fistula. Mortality and reintervention rates were no different.

I also looked at our most recent data, between 2010 and 2015. Now we are using intraoperative drains even less often. They are not considered essential at this point.

There are multiple retrospective and well-designed prospective, randomized trials that show no benefit to routine drainage following pancreatectomy. Acceptance of randomized clinical data is slow, particularly when it flies in the face of what you were taught by your mentors over the past 40 or 50 years. I encourage you to look at these data carefully and utilize them in your practice.

Dr. Allen is associate director for clinical programs at David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research and the Murray F. Brennan chair in surgery at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. He reported no disclosures.

Temporary tissue expanders optimize radiotherapy after mastectomy

LAS VEGAS – Radiation oncologists at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, were able to complete 98% of their radiotherapy plans when women received temporary tissue expanders, instead of immediate reconstructions, at the time of skin-sparing mastectomy, in a series of 384 women, most with stage 2-3 breast cancer.

The expanders – saline-filled bags commonly used in plastic surgery to create new skin – were kept in place but deflated for radiotherapy, which allowed for optimal access to treatment fields; the final reconstruction, successful in 90% of women, came a median of 7 months following radiation.

“The shape and volume of the reconstruction” – and the need to avoid damaging the new breast – “got in the way of putting radiation where we wanted it to be. We ended up having bad radiotherapy plans, patients not getting skin-sparing mastectomies, and high probabilities of radiation complications to the reconstruction,” said investigator Eric Strom, MD, professor of radiation oncology at MD Anderson.

Radiologists and plastic and oncologic surgeons collaborated to try tissue expanders instead. “We wanted the advantage of skin-sparing mastectomy without the disadvantages” of immediate reconstruction, Dr. Strom said at the American Society of Breast Surgeons annual meeting.

With the new approach, “radiotherapy is superior. We don’t have to compromise our plans. I can put radiation everywhere it needs to be, without frying the heart” and almost completely avoiding the lungs, he said.

The 5-year rates of locoregional control, disease-free survival, and overall survival were 99.2%, 86.1%, and 92.4%, respectively, which “is extraordinary” in patients with stage 2-3 breast cancer, and likely due at least in part to optimal radiotherapy, he said.

Tissue expanders also keep the skin envelope open so it’s able to receive a graft at final reconstruction; abdominal skin doesn’t have to brought up to recreate the breast.

“This approach lessens negative interactions between breast reconstruction and [radiotherapy] and offers patients what they most desire: a high probability of freedom from cancer and optimal final aesthetic outcome,” said Zeina Ayoub, MD, a radiation oncology fellow at Anderson who presented the findings.

The median age of the women was 44 years, and almost all were node positive. Radiation was delivered to the chest wall and regional lymphatics, including the internal mammary chain.

Fifty women (13.0%) required explantation after radiation but before reconstruction, most commonly because of cellulitis; even so, more than half went on to final reconstruction.

Abdominal autologous reconstruction was the most common type, followed by latissimus dorsi–based reconstruction, and exchange of the tissue expander with an implant.

Dr. Ayoub and Dr. Strom had no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Radiation oncologists at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, were able to complete 98% of their radiotherapy plans when women received temporary tissue expanders, instead of immediate reconstructions, at the time of skin-sparing mastectomy, in a series of 384 women, most with stage 2-3 breast cancer.

The expanders – saline-filled bags commonly used in plastic surgery to create new skin – were kept in place but deflated for radiotherapy, which allowed for optimal access to treatment fields; the final reconstruction, successful in 90% of women, came a median of 7 months following radiation.

“The shape and volume of the reconstruction” – and the need to avoid damaging the new breast – “got in the way of putting radiation where we wanted it to be. We ended up having bad radiotherapy plans, patients not getting skin-sparing mastectomies, and high probabilities of radiation complications to the reconstruction,” said investigator Eric Strom, MD, professor of radiation oncology at MD Anderson.

Radiologists and plastic and oncologic surgeons collaborated to try tissue expanders instead. “We wanted the advantage of skin-sparing mastectomy without the disadvantages” of immediate reconstruction, Dr. Strom said at the American Society of Breast Surgeons annual meeting.

With the new approach, “radiotherapy is superior. We don’t have to compromise our plans. I can put radiation everywhere it needs to be, without frying the heart” and almost completely avoiding the lungs, he said.

The 5-year rates of locoregional control, disease-free survival, and overall survival were 99.2%, 86.1%, and 92.4%, respectively, which “is extraordinary” in patients with stage 2-3 breast cancer, and likely due at least in part to optimal radiotherapy, he said.

Tissue expanders also keep the skin envelope open so it’s able to receive a graft at final reconstruction; abdominal skin doesn’t have to brought up to recreate the breast.

“This approach lessens negative interactions between breast reconstruction and [radiotherapy] and offers patients what they most desire: a high probability of freedom from cancer and optimal final aesthetic outcome,” said Zeina Ayoub, MD, a radiation oncology fellow at Anderson who presented the findings.

The median age of the women was 44 years, and almost all were node positive. Radiation was delivered to the chest wall and regional lymphatics, including the internal mammary chain.

Fifty women (13.0%) required explantation after radiation but before reconstruction, most commonly because of cellulitis; even so, more than half went on to final reconstruction.

Abdominal autologous reconstruction was the most common type, followed by latissimus dorsi–based reconstruction, and exchange of the tissue expander with an implant.

Dr. Ayoub and Dr. Strom had no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Radiation oncologists at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, were able to complete 98% of their radiotherapy plans when women received temporary tissue expanders, instead of immediate reconstructions, at the time of skin-sparing mastectomy, in a series of 384 women, most with stage 2-3 breast cancer.

The expanders – saline-filled bags commonly used in plastic surgery to create new skin – were kept in place but deflated for radiotherapy, which allowed for optimal access to treatment fields; the final reconstruction, successful in 90% of women, came a median of 7 months following radiation.

“The shape and volume of the reconstruction” – and the need to avoid damaging the new breast – “got in the way of putting radiation where we wanted it to be. We ended up having bad radiotherapy plans, patients not getting skin-sparing mastectomies, and high probabilities of radiation complications to the reconstruction,” said investigator Eric Strom, MD, professor of radiation oncology at MD Anderson.

Radiologists and plastic and oncologic surgeons collaborated to try tissue expanders instead. “We wanted the advantage of skin-sparing mastectomy without the disadvantages” of immediate reconstruction, Dr. Strom said at the American Society of Breast Surgeons annual meeting.

With the new approach, “radiotherapy is superior. We don’t have to compromise our plans. I can put radiation everywhere it needs to be, without frying the heart” and almost completely avoiding the lungs, he said.

The 5-year rates of locoregional control, disease-free survival, and overall survival were 99.2%, 86.1%, and 92.4%, respectively, which “is extraordinary” in patients with stage 2-3 breast cancer, and likely due at least in part to optimal radiotherapy, he said.

Tissue expanders also keep the skin envelope open so it’s able to receive a graft at final reconstruction; abdominal skin doesn’t have to brought up to recreate the breast.

“This approach lessens negative interactions between breast reconstruction and [radiotherapy] and offers patients what they most desire: a high probability of freedom from cancer and optimal final aesthetic outcome,” said Zeina Ayoub, MD, a radiation oncology fellow at Anderson who presented the findings.

The median age of the women was 44 years, and almost all were node positive. Radiation was delivered to the chest wall and regional lymphatics, including the internal mammary chain.

Fifty women (13.0%) required explantation after radiation but before reconstruction, most commonly because of cellulitis; even so, more than half went on to final reconstruction.

Abdominal autologous reconstruction was the most common type, followed by latissimus dorsi–based reconstruction, and exchange of the tissue expander with an implant.

Dr. Ayoub and Dr. Strom had no relevant disclosures.

AT ASBS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 5-year rates of locoregional control, disease-free survival, and overall survival were 99.2%, 86.1%, and 92.4%, respectively, likely due at least in part to optimal radiotherapy.

Data source: Review of 384 patients.

Disclosures: The investigators said they had no relevant disclosures.

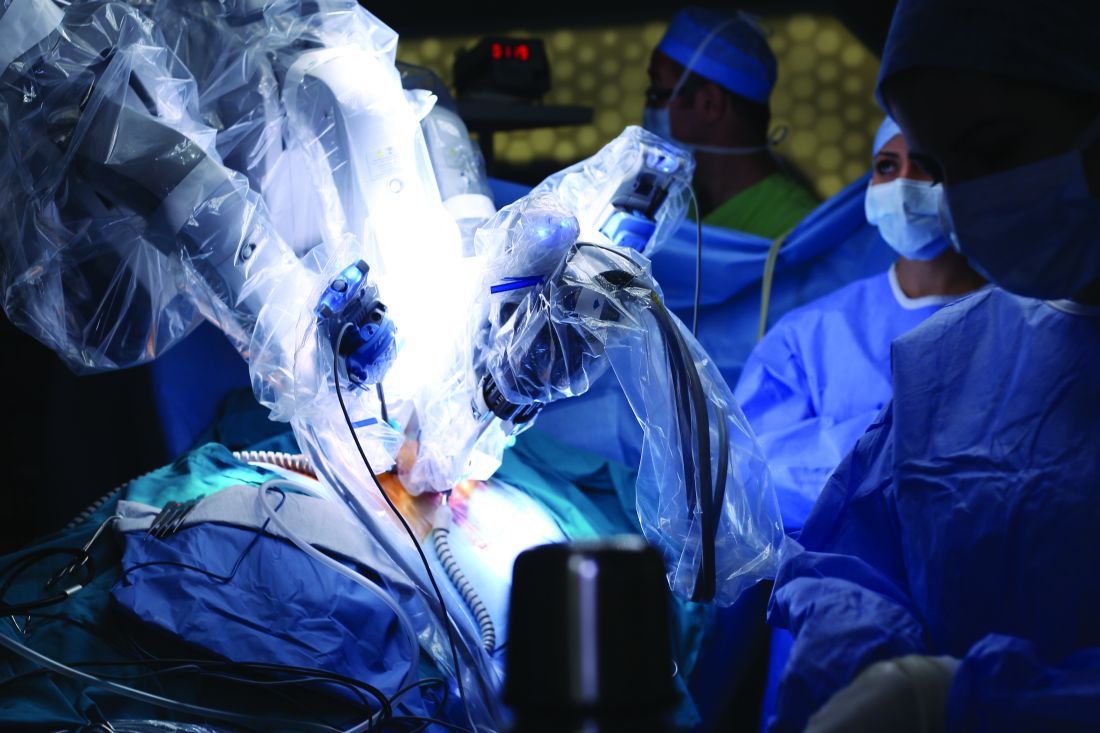

Robotic-assisted IHR causes fewer complications in obese patients

Obese people undergoing inguinal hernia repair experienced fewer complications when the surgery was robotic assisted, compared to open repairs, according to Ramachandra Kolachalam, MD, and his associates.

A total of 148 robotic-assisted repairs (RHRs) and 113 open repairs were included in the study. Of open repair (OHR) patients, 11.5% experienced postoperative complications post discharge, compared with only 2.7% of RHR patients. OHR patients also had lower rates of concomitant procedures (16.8% vs. 29.7%) and bilateral repairs (11.5% vs. 35.1%). Morbidity rates did not differ significantly between the groups.

“Robotic-assisted inguinal hernia repair could lead to increased acceptance of minimally invasive hernia repair with the associated clinical benefits to patients, including those who are obese with higher comorbidities and higher American Surgery Association scores. A prospective study of obesity in RHR is warranted to confirm our findings,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Surgical Endoscopy (2017. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5665-z).

Obese people undergoing inguinal hernia repair experienced fewer complications when the surgery was robotic assisted, compared to open repairs, according to Ramachandra Kolachalam, MD, and his associates.

A total of 148 robotic-assisted repairs (RHRs) and 113 open repairs were included in the study. Of open repair (OHR) patients, 11.5% experienced postoperative complications post discharge, compared with only 2.7% of RHR patients. OHR patients also had lower rates of concomitant procedures (16.8% vs. 29.7%) and bilateral repairs (11.5% vs. 35.1%). Morbidity rates did not differ significantly between the groups.

“Robotic-assisted inguinal hernia repair could lead to increased acceptance of minimally invasive hernia repair with the associated clinical benefits to patients, including those who are obese with higher comorbidities and higher American Surgery Association scores. A prospective study of obesity in RHR is warranted to confirm our findings,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Surgical Endoscopy (2017. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5665-z).

Obese people undergoing inguinal hernia repair experienced fewer complications when the surgery was robotic assisted, compared to open repairs, according to Ramachandra Kolachalam, MD, and his associates.

A total of 148 robotic-assisted repairs (RHRs) and 113 open repairs were included in the study. Of open repair (OHR) patients, 11.5% experienced postoperative complications post discharge, compared with only 2.7% of RHR patients. OHR patients also had lower rates of concomitant procedures (16.8% vs. 29.7%) and bilateral repairs (11.5% vs. 35.1%). Morbidity rates did not differ significantly between the groups.

“Robotic-assisted inguinal hernia repair could lead to increased acceptance of minimally invasive hernia repair with the associated clinical benefits to patients, including those who are obese with higher comorbidities and higher American Surgery Association scores. A prospective study of obesity in RHR is warranted to confirm our findings,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Surgical Endoscopy (2017. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5665-z).

FROM SURGICAL ENDOSCOPY

VA/DOD elevate psychotherapy over medication in updated PTSD guidelines

MIAMI – New federal clinical practice guidelines for treating posttraumatic stress disorder move trauma-focused psychotherapy ahead of pharmacotherapy as first-line treatment.

“That is quite a statement that is being made, and it’s a big shift in our treatment guidelines,” Lori L. Davis, MD, said at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting. Dr. Davis, who coauthored the update for the Departments of Veterans Affairs and of Defense, discussed the guidelines at the meeting in advance of their release this summer.

The guidelines, dated June 2017 and based on evidence reviewed through March 2016, specify that evidence is strong for first-line psychotherapy that includes some form of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring. Such therapies include prolonged exposure, cognitive processing, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, narrative exposure therapy, brief eclectic psychotherapy, and PTSD-specific cognitive-behavioral therapy.

The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Work Group found that evidence was weakest for non–trauma-focused therapies, such as stress inoculation training and present-centered and interpersonal psychotherapy. Manualized group therapy also was rated as weak, but insufficient evidence was found to rate one type of group therapy over another.

Insufficient evidence also was cited for psychotherapies not specified in other recommendations, such as dialectical behavior therapy, skills training in affect and interpersonal regulation, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), seeking safety therapy, or supportive counseling.

“Some of these treatments have been found to be effective for the treatment of other disorders (e.g., ACT for [major depressive disorder]),” the work group members wrote, “but do not have evidence of efficacy in patients with PTSD.”

The recommendations are based on a review of literature from the past 20 years and are congruent with other treatment guidelines internationally, according to Sheila A.M. Rausch, PhD, who directs mental health research and program evaluation for the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System in Michigan, is a work group member, and served as a panelist at the meeting.

“What is striking is that, based on people reviewing all the evidence out there – and there are different methodologies for doing so – regardless, [the different groups] tend to come to the same conclusions,” Dr. Rausch said.

The updated guidelines cite insufficient evidence for making any recommendations for augmented or combined treatments of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

Medications considered to have a strong evidence base for monotherapy were sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine, and venlafaxine. In cases in which a person declines psychotherapy, those medications are recommended as first-line treatment.

Prazosin, typically used to managing nightmares tied to PTSD, received a “suggest against” recommendation, in part because of the discovery of a publication bias, according to Dr. Davis, who is associate chief of staff for research and development at the Tuscaloosa (Ala.) VA Medical Center and a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurobiology at the University of Alabama in Birmingham and Tuscaloosa. She noted that the work group remained unsure of “how to grapple with this” news that the study drug did not break from placebo in the treatment of nightmares in more than 300 combat veterans with PTSD.

“We are not trying to tell you not to use antidepressants for major depressive disorder or panic disorders that are often comorbid with PTSD, so you have to keep that in mind as you read these guidelines,” Dr. Davis said. Many patients already take antidepressants because they are easily accessed in primary care practices, she added.

The work group found that evidence generally was weak against atypical antipsychotics – particularly in light of the known adverse side effects of those drugs. However, the group singled out risperidone. “We suggest against treatment of PTSD with quetiapine, olanzapine, and other atypical antipsychotics (except for risperidone, which is a ‘strong against,’ see recommendation 20),” the guidelines suggest.

They also “suggested against” two antidepressants – citalopram and amitriptyline, a tricyclic. The quality of evidence for those drugs was deemed low. Two drugs – lamotrigine and topiramate – also received “suggested against” rankings, and the evidence for the use of those drugs was deemed very low.

Meanwhile, the work group wrote that the quality of evidence was low and “recommended against” the use of three other drugs: divalproex, tiagabine, and guanfacine. They also found the quality of evidence to be very low for the drug class of benzodiazepines and four drugs – risperidone, D-cycloserine, ketamine, and hydrocortisone. They also found insufficient evidence to recommend complementary and integrative health (CIH) practices such as meditation and yoga for treating PTSD. The work group did offer a caveat, however. “It is important to clarify that we are not recommending against the treatments but rather are saying that, at this time, the research does not support the use of any CIH practice for the primary treatment of PTSD.”

Cannabis and its derivatives also were recommended against by the work group because of a “lack of evidence for their efficacy, known adverse effects, and associated risks.”

Dr. Davis said the work group’s findings underscored a crisis in pharmacotherapeutic research in PTSD. Since 2006, there have been only four industry-sponsored drugs for PTSD. “I find it kind of sad,” she said.

Currently, Dr. Rausch’s own study for the VA focuses on comparing the effects of combination therapies for PTSD in the context of patient preferences, in order to tailor the treatments accordingly. In 223 returning veterans with PTSD, she and her colleagues are conducting a head-to-head comparison of prolonged exposure therapy plus placebo, prolonged exposure plus sertraline, and sertraline plus emotion memory management therapy to determine how starting a patient on both kinds of treatments simultaneously affect response.

“It’s clinically important to find out what is really going on in the brain and body,” she said. “Although we know we have therapies that work, we need to find answers for partial responders ... and how to increase the speed and magnitude of response.”

Dr. Davis’s research is funded in part by the VA, Forest, Merck, Tonix, and Otsuka, for whom she also acts as a consultant. Dr. Rausch did not have any disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

MIAMI – New federal clinical practice guidelines for treating posttraumatic stress disorder move trauma-focused psychotherapy ahead of pharmacotherapy as first-line treatment.

“That is quite a statement that is being made, and it’s a big shift in our treatment guidelines,” Lori L. Davis, MD, said at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting. Dr. Davis, who coauthored the update for the Departments of Veterans Affairs and of Defense, discussed the guidelines at the meeting in advance of their release this summer.

The guidelines, dated June 2017 and based on evidence reviewed through March 2016, specify that evidence is strong for first-line psychotherapy that includes some form of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring. Such therapies include prolonged exposure, cognitive processing, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, narrative exposure therapy, brief eclectic psychotherapy, and PTSD-specific cognitive-behavioral therapy.

The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Work Group found that evidence was weakest for non–trauma-focused therapies, such as stress inoculation training and present-centered and interpersonal psychotherapy. Manualized group therapy also was rated as weak, but insufficient evidence was found to rate one type of group therapy over another.

Insufficient evidence also was cited for psychotherapies not specified in other recommendations, such as dialectical behavior therapy, skills training in affect and interpersonal regulation, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), seeking safety therapy, or supportive counseling.

“Some of these treatments have been found to be effective for the treatment of other disorders (e.g., ACT for [major depressive disorder]),” the work group members wrote, “but do not have evidence of efficacy in patients with PTSD.”

The recommendations are based on a review of literature from the past 20 years and are congruent with other treatment guidelines internationally, according to Sheila A.M. Rausch, PhD, who directs mental health research and program evaluation for the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System in Michigan, is a work group member, and served as a panelist at the meeting.

“What is striking is that, based on people reviewing all the evidence out there – and there are different methodologies for doing so – regardless, [the different groups] tend to come to the same conclusions,” Dr. Rausch said.

The updated guidelines cite insufficient evidence for making any recommendations for augmented or combined treatments of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

Medications considered to have a strong evidence base for monotherapy were sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine, and venlafaxine. In cases in which a person declines psychotherapy, those medications are recommended as first-line treatment.

Prazosin, typically used to managing nightmares tied to PTSD, received a “suggest against” recommendation, in part because of the discovery of a publication bias, according to Dr. Davis, who is associate chief of staff for research and development at the Tuscaloosa (Ala.) VA Medical Center and a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurobiology at the University of Alabama in Birmingham and Tuscaloosa. She noted that the work group remained unsure of “how to grapple with this” news that the study drug did not break from placebo in the treatment of nightmares in more than 300 combat veterans with PTSD.

“We are not trying to tell you not to use antidepressants for major depressive disorder or panic disorders that are often comorbid with PTSD, so you have to keep that in mind as you read these guidelines,” Dr. Davis said. Many patients already take antidepressants because they are easily accessed in primary care practices, she added.

The work group found that evidence generally was weak against atypical antipsychotics – particularly in light of the known adverse side effects of those drugs. However, the group singled out risperidone. “We suggest against treatment of PTSD with quetiapine, olanzapine, and other atypical antipsychotics (except for risperidone, which is a ‘strong against,’ see recommendation 20),” the guidelines suggest.

They also “suggested against” two antidepressants – citalopram and amitriptyline, a tricyclic. The quality of evidence for those drugs was deemed low. Two drugs – lamotrigine and topiramate – also received “suggested against” rankings, and the evidence for the use of those drugs was deemed very low.

Meanwhile, the work group wrote that the quality of evidence was low and “recommended against” the use of three other drugs: divalproex, tiagabine, and guanfacine. They also found the quality of evidence to be very low for the drug class of benzodiazepines and four drugs – risperidone, D-cycloserine, ketamine, and hydrocortisone. They also found insufficient evidence to recommend complementary and integrative health (CIH) practices such as meditation and yoga for treating PTSD. The work group did offer a caveat, however. “It is important to clarify that we are not recommending against the treatments but rather are saying that, at this time, the research does not support the use of any CIH practice for the primary treatment of PTSD.”

Cannabis and its derivatives also were recommended against by the work group because of a “lack of evidence for their efficacy, known adverse effects, and associated risks.”

Dr. Davis said the work group’s findings underscored a crisis in pharmacotherapeutic research in PTSD. Since 2006, there have been only four industry-sponsored drugs for PTSD. “I find it kind of sad,” she said.

Currently, Dr. Rausch’s own study for the VA focuses on comparing the effects of combination therapies for PTSD in the context of patient preferences, in order to tailor the treatments accordingly. In 223 returning veterans with PTSD, she and her colleagues are conducting a head-to-head comparison of prolonged exposure therapy plus placebo, prolonged exposure plus sertraline, and sertraline plus emotion memory management therapy to determine how starting a patient on both kinds of treatments simultaneously affect response.

“It’s clinically important to find out what is really going on in the brain and body,” she said. “Although we know we have therapies that work, we need to find answers for partial responders ... and how to increase the speed and magnitude of response.”

Dr. Davis’s research is funded in part by the VA, Forest, Merck, Tonix, and Otsuka, for whom she also acts as a consultant. Dr. Rausch did not have any disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

MIAMI – New federal clinical practice guidelines for treating posttraumatic stress disorder move trauma-focused psychotherapy ahead of pharmacotherapy as first-line treatment.

“That is quite a statement that is being made, and it’s a big shift in our treatment guidelines,” Lori L. Davis, MD, said at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting. Dr. Davis, who coauthored the update for the Departments of Veterans Affairs and of Defense, discussed the guidelines at the meeting in advance of their release this summer.

The guidelines, dated June 2017 and based on evidence reviewed through March 2016, specify that evidence is strong for first-line psychotherapy that includes some form of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring. Such therapies include prolonged exposure, cognitive processing, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, narrative exposure therapy, brief eclectic psychotherapy, and PTSD-specific cognitive-behavioral therapy.

The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Work Group found that evidence was weakest for non–trauma-focused therapies, such as stress inoculation training and present-centered and interpersonal psychotherapy. Manualized group therapy also was rated as weak, but insufficient evidence was found to rate one type of group therapy over another.

Insufficient evidence also was cited for psychotherapies not specified in other recommendations, such as dialectical behavior therapy, skills training in affect and interpersonal regulation, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), seeking safety therapy, or supportive counseling.

“Some of these treatments have been found to be effective for the treatment of other disorders (e.g., ACT for [major depressive disorder]),” the work group members wrote, “but do not have evidence of efficacy in patients with PTSD.”

The recommendations are based on a review of literature from the past 20 years and are congruent with other treatment guidelines internationally, according to Sheila A.M. Rausch, PhD, who directs mental health research and program evaluation for the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System in Michigan, is a work group member, and served as a panelist at the meeting.

“What is striking is that, based on people reviewing all the evidence out there – and there are different methodologies for doing so – regardless, [the different groups] tend to come to the same conclusions,” Dr. Rausch said.

The updated guidelines cite insufficient evidence for making any recommendations for augmented or combined treatments of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

Medications considered to have a strong evidence base for monotherapy were sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine, and venlafaxine. In cases in which a person declines psychotherapy, those medications are recommended as first-line treatment.

Prazosin, typically used to managing nightmares tied to PTSD, received a “suggest against” recommendation, in part because of the discovery of a publication bias, according to Dr. Davis, who is associate chief of staff for research and development at the Tuscaloosa (Ala.) VA Medical Center and a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurobiology at the University of Alabama in Birmingham and Tuscaloosa. She noted that the work group remained unsure of “how to grapple with this” news that the study drug did not break from placebo in the treatment of nightmares in more than 300 combat veterans with PTSD.

“We are not trying to tell you not to use antidepressants for major depressive disorder or panic disorders that are often comorbid with PTSD, so you have to keep that in mind as you read these guidelines,” Dr. Davis said. Many patients already take antidepressants because they are easily accessed in primary care practices, she added.

The work group found that evidence generally was weak against atypical antipsychotics – particularly in light of the known adverse side effects of those drugs. However, the group singled out risperidone. “We suggest against treatment of PTSD with quetiapine, olanzapine, and other atypical antipsychotics (except for risperidone, which is a ‘strong against,’ see recommendation 20),” the guidelines suggest.

They also “suggested against” two antidepressants – citalopram and amitriptyline, a tricyclic. The quality of evidence for those drugs was deemed low. Two drugs – lamotrigine and topiramate – also received “suggested against” rankings, and the evidence for the use of those drugs was deemed very low.

Meanwhile, the work group wrote that the quality of evidence was low and “recommended against” the use of three other drugs: divalproex, tiagabine, and guanfacine. They also found the quality of evidence to be very low for the drug class of benzodiazepines and four drugs – risperidone, D-cycloserine, ketamine, and hydrocortisone. They also found insufficient evidence to recommend complementary and integrative health (CIH) practices such as meditation and yoga for treating PTSD. The work group did offer a caveat, however. “It is important to clarify that we are not recommending against the treatments but rather are saying that, at this time, the research does not support the use of any CIH practice for the primary treatment of PTSD.”

Cannabis and its derivatives also were recommended against by the work group because of a “lack of evidence for their efficacy, known adverse effects, and associated risks.”

Dr. Davis said the work group’s findings underscored a crisis in pharmacotherapeutic research in PTSD. Since 2006, there have been only four industry-sponsored drugs for PTSD. “I find it kind of sad,” she said.

Currently, Dr. Rausch’s own study for the VA focuses on comparing the effects of combination therapies for PTSD in the context of patient preferences, in order to tailor the treatments accordingly. In 223 returning veterans with PTSD, she and her colleagues are conducting a head-to-head comparison of prolonged exposure therapy plus placebo, prolonged exposure plus sertraline, and sertraline plus emotion memory management therapy to determine how starting a patient on both kinds of treatments simultaneously affect response.

“It’s clinically important to find out what is really going on in the brain and body,” she said. “Although we know we have therapies that work, we need to find answers for partial responders ... and how to increase the speed and magnitude of response.”

Dr. Davis’s research is funded in part by the VA, Forest, Merck, Tonix, and Otsuka, for whom she also acts as a consultant. Dr. Rausch did not have any disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ASCP ANNUAL MEETING

Prior resections increase anastomotic leak risk in Crohn’s

SEATTLE – The risk of anastomotic leaks after bowel resection for Crohn’s disease is more than three times higher in patients who have had prior resections, according to a review of 206 patients at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

There were 20 anastomotic leaks within 30 days of resection in those patients, giving an overall leakage rate of 10%. Among the 123 patients who were having their first resection, however, the rate was 5% (6/123). The risk jumped to 17% in the 83 who had prior resections (14/83) and 23% (7) among the 30 patients who had two or more prior resections, which is “substantially higher than we talk about in the clinic when we are counseling these people,” said lead investigator Forrest Johnston, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at Lahey.

The findings are important because prior resections have not, until now, been formally recognized as a risk factor for anastomotic leaks, and repeat resections are common in Crohn’s. “When you see patients for repeat intestinal resections, you have to look at them as a higher risk population in terms of your counseling and algorithms,” Dr. Johnston said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting. In addition, to mitigate the increased risk, Crohn’s patients who have repeat resections need additional attention to correct modifiable risk factors before surgery, such as steroid use and malnutrition. “Some of these patients are pushed through the clinic,” but “they deserve a bit more time.”

The heightened risk is also “another factor that might tip you one way or another” in choosing surgical options. “It’s certainly something to think about,” he said.

The new and prior resection patients in the study were well matched in terms of known risk factors for leakage, including age, sex, preoperative serum albumin, and use of immune suppressing medications. “The increased risk of leak is not explained by preoperative nutritional status or medication use,” Dr. Johnston said.

Estimated blood loss, OR time, types of procedures, hand-sewn versus stapled anastomoses, and other surgical variables were also similar.