User login

Black Adherence Nodules on the Scalp Hair Shaft

The Diagnosis: Piedra

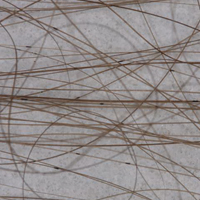

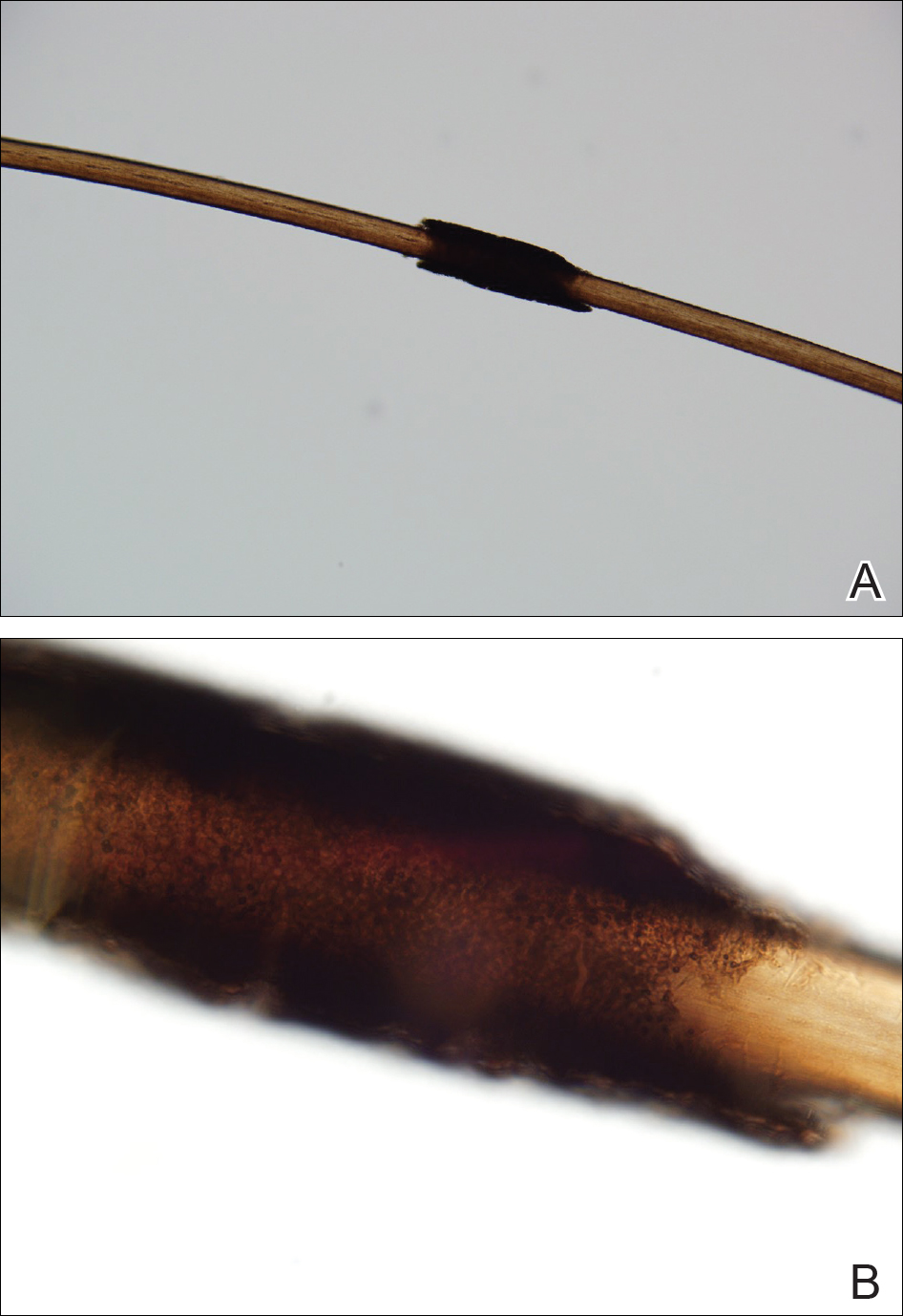

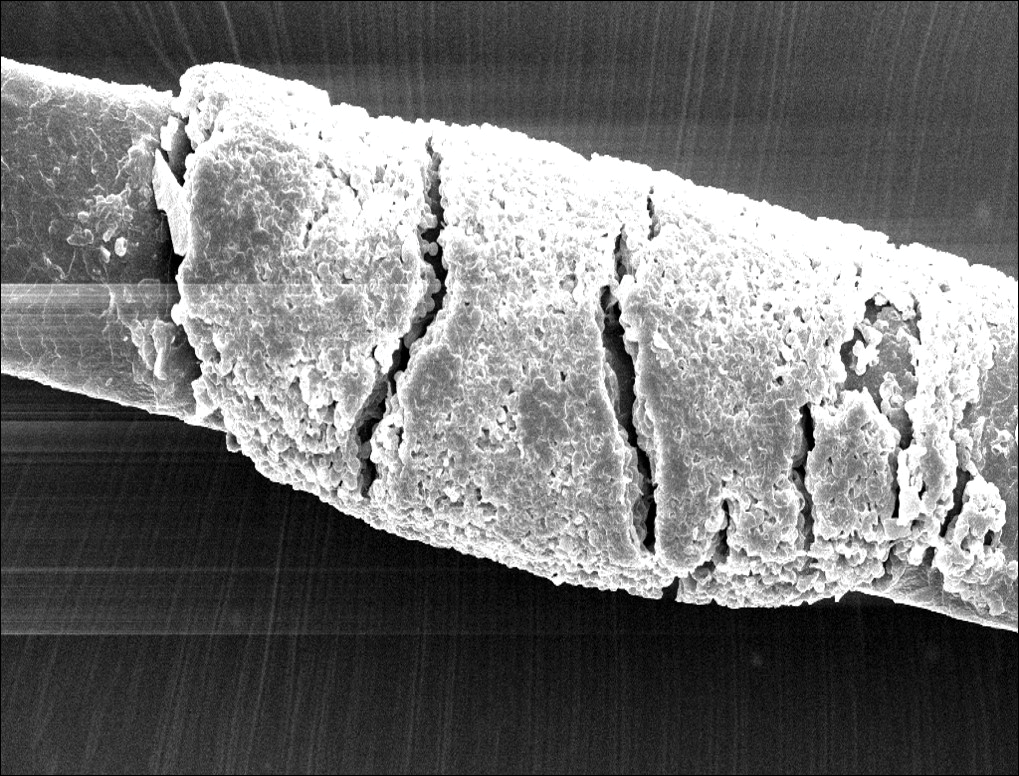

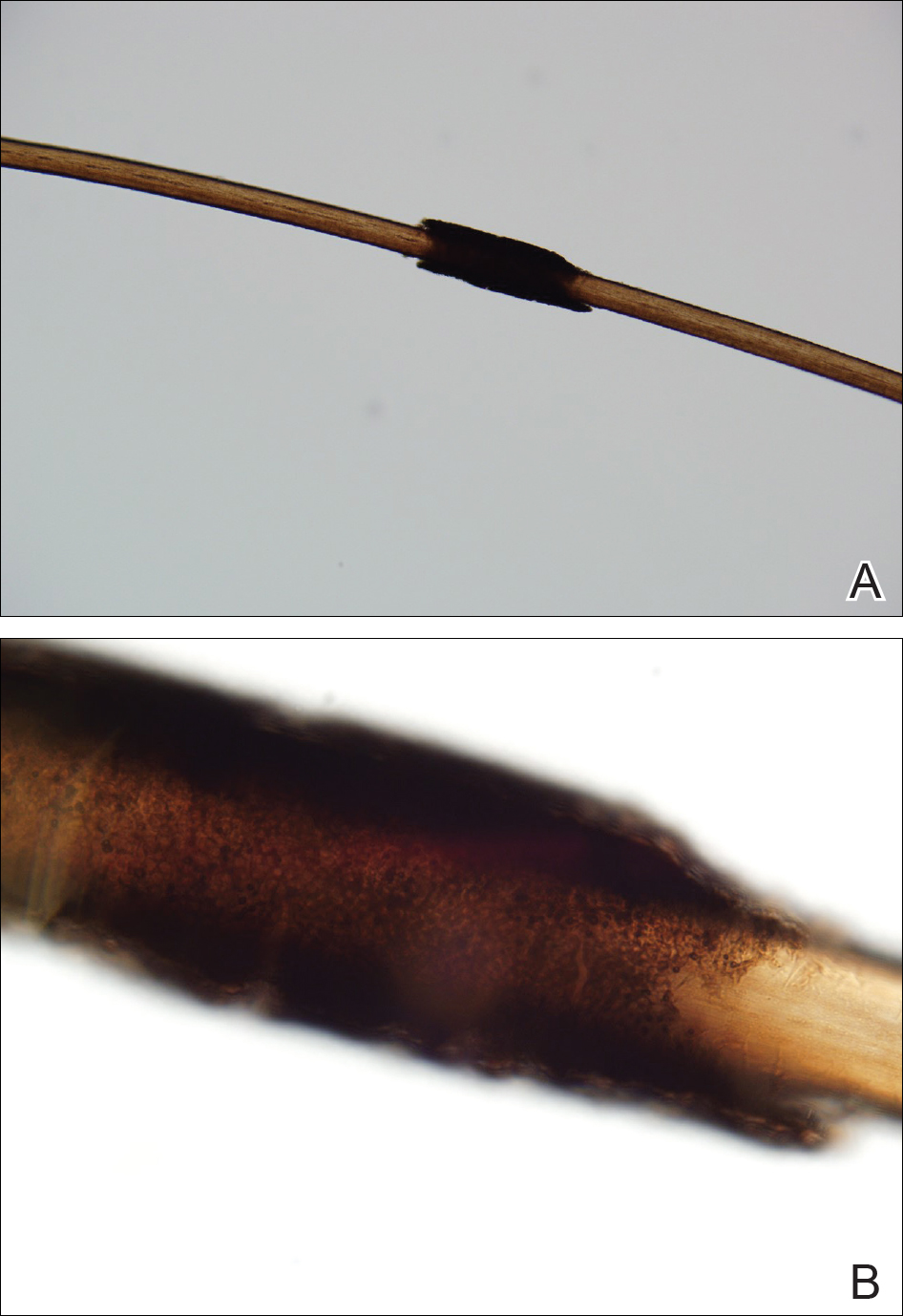

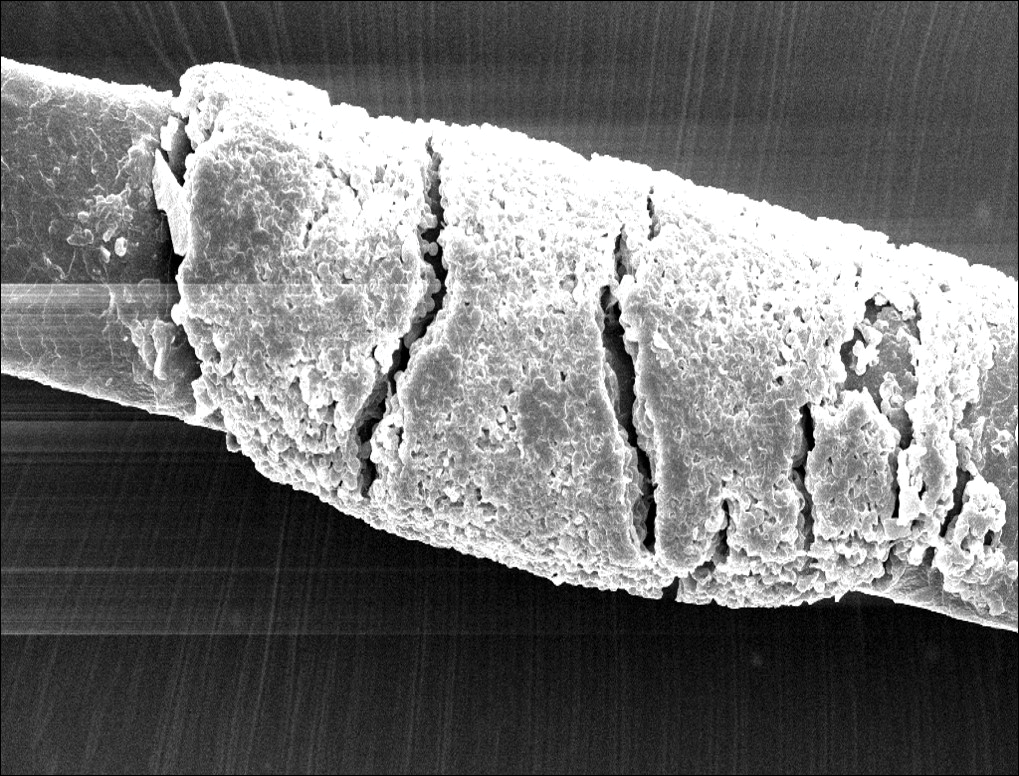

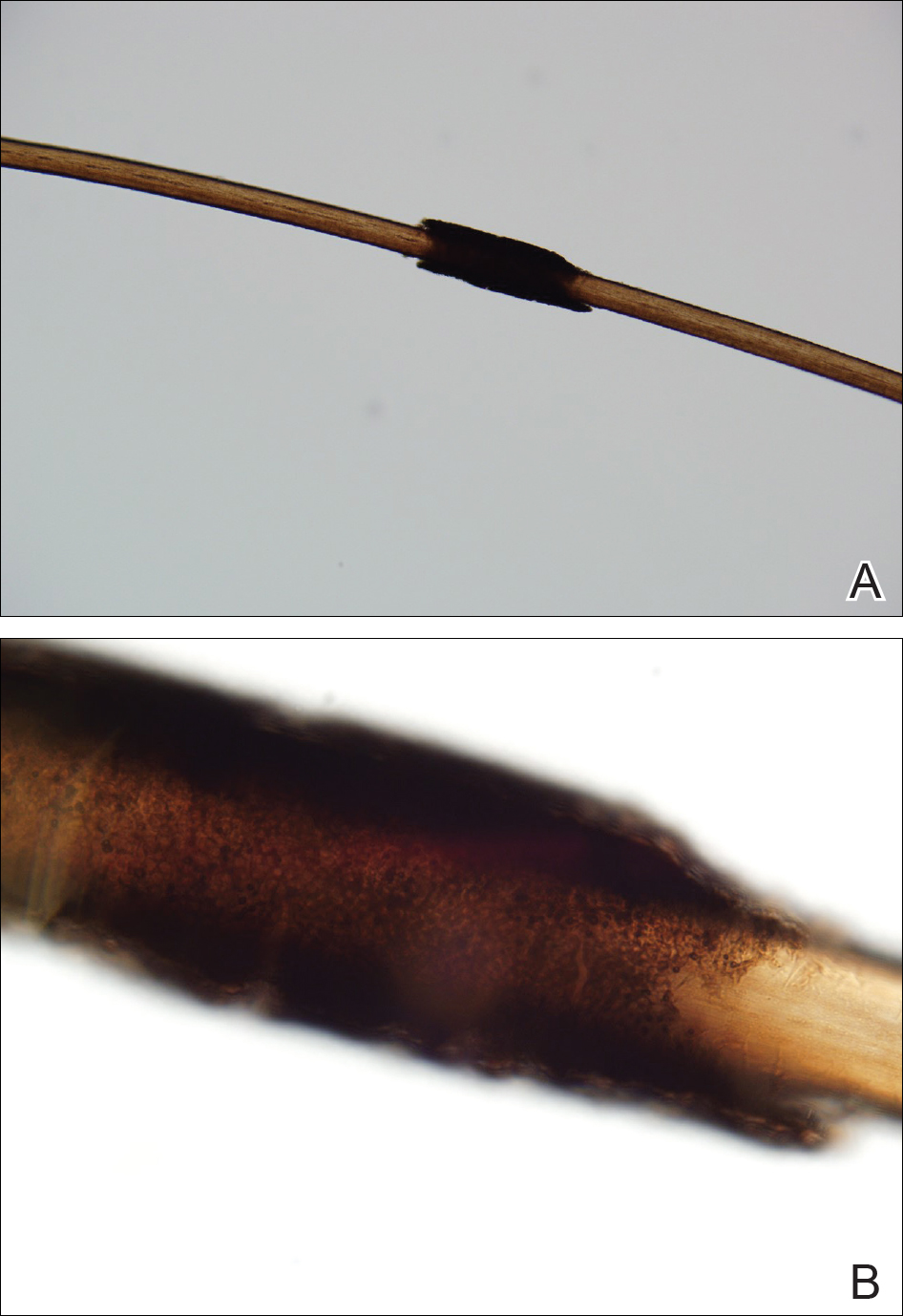

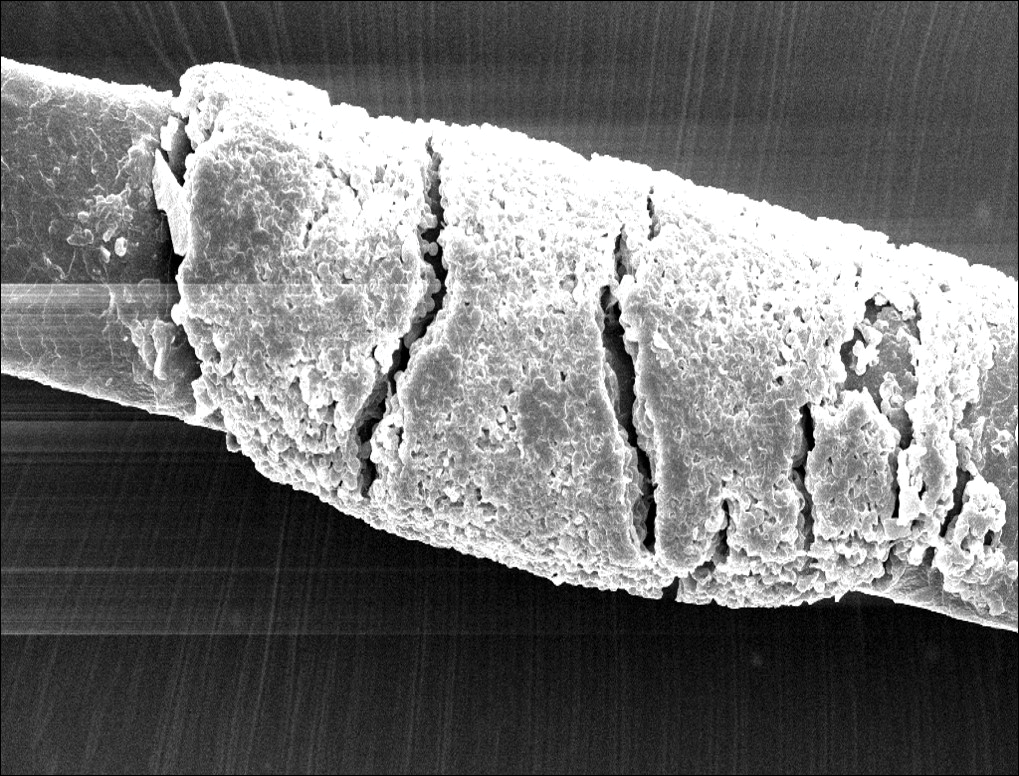

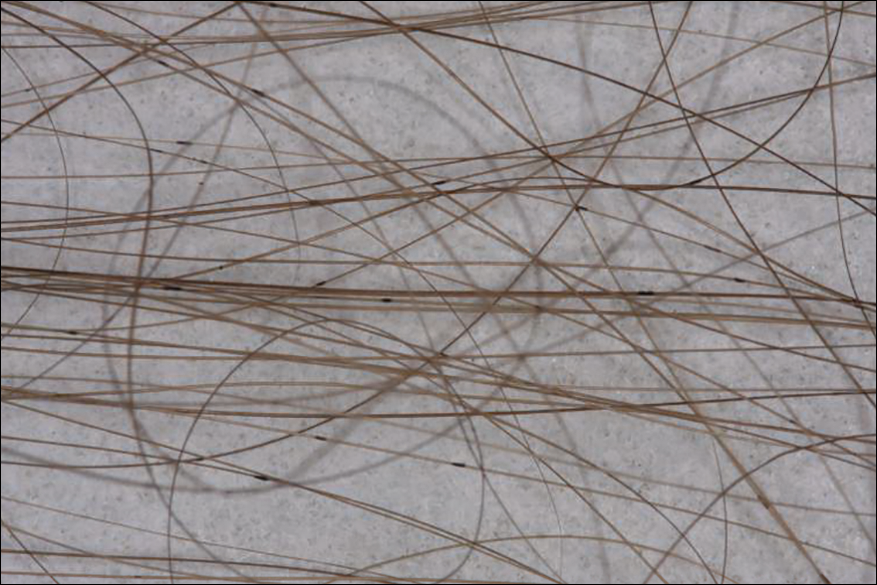

Microscopic examination of the hair shafts revealed brown to black, firmly adherent concretions (Figure 1). Scanning electron microscopy of the nodules was performed, which allowed for greater definition of the constituent hyphae and arthrospores (Figure 2).

Fungal cultures grew Trichosporon inkin along with other dematiaceous molds. The patient initially was treated with a combination of ketoconazole shampoo and weekly application of topical terbinafine. She trimmed 15.2 cm of the hair of her own volition. At 2-month follow-up the nodules were still present, though smaller and less numerous. Repeat cultures were obtained, which again grew T inkin. She then began taking oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks.

This case of piedra is unique in that our patient presented with black nodules clinically, but cultures grew only the causative agent of white piedra, T inkin. A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms black piedra, white piedra, or piedra, and mixed infection or coinfection yielded one other similar case.1 Kanitakis et al1 speculated that perhaps there was coinfection of black and white piedra and that Piedraia hortae, the causative agent of black piedra, was unable to flourish in culture facing competition from other fungi. This scenario also could apply to our patient. However, the original culture taken from our patient also grew other dematiaceous molds including Cladosporium and Exophiala species. It also is possible that these other fungi could have contributed pigment to the nodules, giving it the appearance of black piedra when only T inkin was present as the true pathogen.

White piedra is a rare fungal infection of the hair shaft caused by organisms of the genus Trichosporon, with Trichosporon ovoides most likely to infect the scalp.2 Black piedra is a similar fungal infection caused by P hortae. Piedra means stone in Spanish, reflecting the appearance of these organisms on the hair shaft. It is common in tropical regions of the world such as Southeast Asia and South America, flourishing in the high temperatures and humidity.2 Both infectious agents are found in the soil or in standing water.3 White piedra most commonly is found in facial, axilla, or pubic hair, while black piedra most often is found in the hair of the scalp.2,4 Local cultural practices may contribute to transfer of Trichosporon or P hortae to the scalp, including the use of Brazilian plant oils in the hair or tying a veil or hijab to wet hair. Interestingly, some groups intentionally introduce the fungus to their hair for cosmetic reasons in endemic areas.2,3,5

Patients with white or black piedra generally are asymptomatic.4 Some may notice a rough texture to the hair or hear a characteristic metallic rattling sound as the nodules make contact with brush bristles.2,3 On inspection of the scalp, white piedra will appear to be white to light brown nodules, while black piedra presents as brown to black in color. The nodules are often firm on palpation.2,3 The nodules of white piedra generally are easy to remove in contrast to black piedra, which involves nodules that securely attach to the hair shaft but can be removed with pressure.3,5 Piedra has natural keratolytic activities and with prolonged infection can penetrate the hair cuticle, causing weakness and eventual breakage of the hair. This invasion into the hair cortex also can complicate treatment regimens, contributing to the chronic course of these infections.6

Diagnosis is based on clinical and microscopic findings. Nodules on hair shafts can be prepared with potassium hydroxide and placed on glass slides for examination.4 Dyes such as toluidine blue or chlorazol black E stain can be used to assist in identifying fungal structures.2 Sabouraud agar with cycloheximide may be the best choice for culture medium.2 Black piedra slowly grows into small dome-shaped colonies. White piedra will grow more quickly into cream-colored colonies with wrinkles and sometimes mucinous characteristics.3

The best treatment of black or white piedra is to cut the hair, thereby eliminating the fungi,7 which is not an easy option for many patients, such as ours, because of the aesthetic implications. Alternative treatments include azole shampoos such as ketoconazole.2,4 Treatment with oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks has been successfully used for black piedra.7 Patients must be careful to thoroughly clean or discard hairbrushes, as they can serve as reservoirs of fungi to reinfect patients or spread to others.5,7

- Kanitakis J, Persat F, Piens MA, et al. Black piedra: report of a French case associated with Trichosporon asahii. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1258-1260.

- Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

- Khatu SS, Poojary SA, Nagpur NG. Nodules on the hair: a rare case of mixed piedra. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:220-223.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Sobera JO, et al. Fungal diseases. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012:1251-1284.

- Desai DH, Nadkarni NJ. Piedra: an ethnicity-related trichosis? Int J Dermatol. 2013;53:1008-1011.

- Figueras M, Guarro J, Zaror L. New findings in black piedra infection. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:157-158.

- Gip L. Black piedra: the first case treated with terbinafine (Lamisil). Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(suppl 43):26-28.

The Diagnosis: Piedra

Microscopic examination of the hair shafts revealed brown to black, firmly adherent concretions (Figure 1). Scanning electron microscopy of the nodules was performed, which allowed for greater definition of the constituent hyphae and arthrospores (Figure 2).

Fungal cultures grew Trichosporon inkin along with other dematiaceous molds. The patient initially was treated with a combination of ketoconazole shampoo and weekly application of topical terbinafine. She trimmed 15.2 cm of the hair of her own volition. At 2-month follow-up the nodules were still present, though smaller and less numerous. Repeat cultures were obtained, which again grew T inkin. She then began taking oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks.

This case of piedra is unique in that our patient presented with black nodules clinically, but cultures grew only the causative agent of white piedra, T inkin. A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms black piedra, white piedra, or piedra, and mixed infection or coinfection yielded one other similar case.1 Kanitakis et al1 speculated that perhaps there was coinfection of black and white piedra and that Piedraia hortae, the causative agent of black piedra, was unable to flourish in culture facing competition from other fungi. This scenario also could apply to our patient. However, the original culture taken from our patient also grew other dematiaceous molds including Cladosporium and Exophiala species. It also is possible that these other fungi could have contributed pigment to the nodules, giving it the appearance of black piedra when only T inkin was present as the true pathogen.

White piedra is a rare fungal infection of the hair shaft caused by organisms of the genus Trichosporon, with Trichosporon ovoides most likely to infect the scalp.2 Black piedra is a similar fungal infection caused by P hortae. Piedra means stone in Spanish, reflecting the appearance of these organisms on the hair shaft. It is common in tropical regions of the world such as Southeast Asia and South America, flourishing in the high temperatures and humidity.2 Both infectious agents are found in the soil or in standing water.3 White piedra most commonly is found in facial, axilla, or pubic hair, while black piedra most often is found in the hair of the scalp.2,4 Local cultural practices may contribute to transfer of Trichosporon or P hortae to the scalp, including the use of Brazilian plant oils in the hair or tying a veil or hijab to wet hair. Interestingly, some groups intentionally introduce the fungus to their hair for cosmetic reasons in endemic areas.2,3,5

Patients with white or black piedra generally are asymptomatic.4 Some may notice a rough texture to the hair or hear a characteristic metallic rattling sound as the nodules make contact with brush bristles.2,3 On inspection of the scalp, white piedra will appear to be white to light brown nodules, while black piedra presents as brown to black in color. The nodules are often firm on palpation.2,3 The nodules of white piedra generally are easy to remove in contrast to black piedra, which involves nodules that securely attach to the hair shaft but can be removed with pressure.3,5 Piedra has natural keratolytic activities and with prolonged infection can penetrate the hair cuticle, causing weakness and eventual breakage of the hair. This invasion into the hair cortex also can complicate treatment regimens, contributing to the chronic course of these infections.6

Diagnosis is based on clinical and microscopic findings. Nodules on hair shafts can be prepared with potassium hydroxide and placed on glass slides for examination.4 Dyes such as toluidine blue or chlorazol black E stain can be used to assist in identifying fungal structures.2 Sabouraud agar with cycloheximide may be the best choice for culture medium.2 Black piedra slowly grows into small dome-shaped colonies. White piedra will grow more quickly into cream-colored colonies with wrinkles and sometimes mucinous characteristics.3

The best treatment of black or white piedra is to cut the hair, thereby eliminating the fungi,7 which is not an easy option for many patients, such as ours, because of the aesthetic implications. Alternative treatments include azole shampoos such as ketoconazole.2,4 Treatment with oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks has been successfully used for black piedra.7 Patients must be careful to thoroughly clean or discard hairbrushes, as they can serve as reservoirs of fungi to reinfect patients or spread to others.5,7

The Diagnosis: Piedra

Microscopic examination of the hair shafts revealed brown to black, firmly adherent concretions (Figure 1). Scanning electron microscopy of the nodules was performed, which allowed for greater definition of the constituent hyphae and arthrospores (Figure 2).

Fungal cultures grew Trichosporon inkin along with other dematiaceous molds. The patient initially was treated with a combination of ketoconazole shampoo and weekly application of topical terbinafine. She trimmed 15.2 cm of the hair of her own volition. At 2-month follow-up the nodules were still present, though smaller and less numerous. Repeat cultures were obtained, which again grew T inkin. She then began taking oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks.

This case of piedra is unique in that our patient presented with black nodules clinically, but cultures grew only the causative agent of white piedra, T inkin. A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms black piedra, white piedra, or piedra, and mixed infection or coinfection yielded one other similar case.1 Kanitakis et al1 speculated that perhaps there was coinfection of black and white piedra and that Piedraia hortae, the causative agent of black piedra, was unable to flourish in culture facing competition from other fungi. This scenario also could apply to our patient. However, the original culture taken from our patient also grew other dematiaceous molds including Cladosporium and Exophiala species. It also is possible that these other fungi could have contributed pigment to the nodules, giving it the appearance of black piedra when only T inkin was present as the true pathogen.

White piedra is a rare fungal infection of the hair shaft caused by organisms of the genus Trichosporon, with Trichosporon ovoides most likely to infect the scalp.2 Black piedra is a similar fungal infection caused by P hortae. Piedra means stone in Spanish, reflecting the appearance of these organisms on the hair shaft. It is common in tropical regions of the world such as Southeast Asia and South America, flourishing in the high temperatures and humidity.2 Both infectious agents are found in the soil or in standing water.3 White piedra most commonly is found in facial, axilla, or pubic hair, while black piedra most often is found in the hair of the scalp.2,4 Local cultural practices may contribute to transfer of Trichosporon or P hortae to the scalp, including the use of Brazilian plant oils in the hair or tying a veil or hijab to wet hair. Interestingly, some groups intentionally introduce the fungus to their hair for cosmetic reasons in endemic areas.2,3,5

Patients with white or black piedra generally are asymptomatic.4 Some may notice a rough texture to the hair or hear a characteristic metallic rattling sound as the nodules make contact with brush bristles.2,3 On inspection of the scalp, white piedra will appear to be white to light brown nodules, while black piedra presents as brown to black in color. The nodules are often firm on palpation.2,3 The nodules of white piedra generally are easy to remove in contrast to black piedra, which involves nodules that securely attach to the hair shaft but can be removed with pressure.3,5 Piedra has natural keratolytic activities and with prolonged infection can penetrate the hair cuticle, causing weakness and eventual breakage of the hair. This invasion into the hair cortex also can complicate treatment regimens, contributing to the chronic course of these infections.6

Diagnosis is based on clinical and microscopic findings. Nodules on hair shafts can be prepared with potassium hydroxide and placed on glass slides for examination.4 Dyes such as toluidine blue or chlorazol black E stain can be used to assist in identifying fungal structures.2 Sabouraud agar with cycloheximide may be the best choice for culture medium.2 Black piedra slowly grows into small dome-shaped colonies. White piedra will grow more quickly into cream-colored colonies with wrinkles and sometimes mucinous characteristics.3

The best treatment of black or white piedra is to cut the hair, thereby eliminating the fungi,7 which is not an easy option for many patients, such as ours, because of the aesthetic implications. Alternative treatments include azole shampoos such as ketoconazole.2,4 Treatment with oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks has been successfully used for black piedra.7 Patients must be careful to thoroughly clean or discard hairbrushes, as they can serve as reservoirs of fungi to reinfect patients or spread to others.5,7

- Kanitakis J, Persat F, Piens MA, et al. Black piedra: report of a French case associated with Trichosporon asahii. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1258-1260.

- Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

- Khatu SS, Poojary SA, Nagpur NG. Nodules on the hair: a rare case of mixed piedra. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:220-223.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Sobera JO, et al. Fungal diseases. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012:1251-1284.

- Desai DH, Nadkarni NJ. Piedra: an ethnicity-related trichosis? Int J Dermatol. 2013;53:1008-1011.

- Figueras M, Guarro J, Zaror L. New findings in black piedra infection. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:157-158.

- Gip L. Black piedra: the first case treated with terbinafine (Lamisil). Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(suppl 43):26-28.

- Kanitakis J, Persat F, Piens MA, et al. Black piedra: report of a French case associated with Trichosporon asahii. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1258-1260.

- Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

- Khatu SS, Poojary SA, Nagpur NG. Nodules on the hair: a rare case of mixed piedra. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:220-223.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Sobera JO, et al. Fungal diseases. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012:1251-1284.

- Desai DH, Nadkarni NJ. Piedra: an ethnicity-related trichosis? Int J Dermatol. 2013;53:1008-1011.

- Figueras M, Guarro J, Zaror L. New findings in black piedra infection. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:157-158.

- Gip L. Black piedra: the first case treated with terbinafine (Lamisil). Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(suppl 43):26-28.

A 21-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with what she described as small black dots in her hair that she first noted 3 months prior to presentation. The black nodules were asymptomatic, but the patient noted that they seemed to be moving up the hair shaft. They were firmly attached and great effort was required to remove them. The patient's sister recently developed similar nodules. The patient and her sister work as missionaries and had spent time in India, Southeast Asia, and Central America within the last few years. Physical examination revealed firmly adherent black nodules involving the mid to distal portions of the hair shafts on the scalp. There were no nail or skin findings. Cultures were obtained, and microscopic examination was performed.

Statins might protect against rectal anastomotic leaks

SEATTLE – Statins appeared to decrease the risk of sepsis after colorectal surgery and of anastomotic leak after rectal resection in a review of 7,285 elective colorectal surgery patients at 64 Michigan hospitals.

Overall, 2,515 patients (34.5%) were on statins preoperatively and received at least one dose while in the hospital post op. Their outcomes were compared with those of the 4,770 patients (65.5%) who were not on statins.

Statin patients were older (mean, 68 vs. 59 years) with more comorbidities (mean, 2.4 vs. 1.1), including diabetes (34% vs.12%) and hypertension (78% vs. 41%). The majority of statin patients were American Society of Anesthesiologists class 3, and the majority of nonstatin patients were class 1 or 2. The investigators controlled for those and other confounders by multivariate logistic regression and propensity scoring.

“We believe that statin medications can reduce sepsis in the colorectal patient population and may improve anastomotic leak rates for rectal resections,” concluded investigators led by David Disbrow, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Mich.

The immediate take-home from the study is to make sure that patients who should be on statins for hypercholesterolemia or other reasons are actually taking the drugs prior to colorectal surgery. It just might improve their surgical outcomes. “I think that would be a good way to start,” Dr. Disbrow said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

If statins truly do help reduce postop sepsis and rectal anastomotic leaks, he said, it’s probably because of their anti-inflammatory effects, which have been demonstrated in previous studies. New Zealand investigators, for instance, randomized 65 patients to 40 mg oral simvastatin for up to a week before elective colorectal resections or Hartmann’s procedure reversals and for 2 weeks afterwards; 67 patients were randomized to placebo. The simvastatin group had significantly lower postop plasma concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha (J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Aug;223[2]:308-20.e1).

Even so, there were no between-group differences in postoperative complications in that study, and, in general, the impact of statins on postop complications has been mixed in the literature. Some studies have shown benefits, others have suggested harm, and a few have shown nothing either way.

It’s the same situation with prior looks at anastomotic leaks. A Danish review of 2,766 patients who had colorectal anastomoses – 496 (19%) treated perioperatively with statins, some in high-dose – found no difference in leakage rates (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.84-2.05; P = 0.23)(Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 Aug;56[8]:980-6). On the other hand, a more recent British review of 144 patients – 45 (39.4%) on preoperative statins – found that “although patients taking statins did not have a significantly reduced leak risk, compared to nonstatin users, high-risk patients taking statins had the same leak risk as non–high risk patients; therefore, it is plausible that statins normalize the risk of anastomotic leak in high-risk patients” (Gut. 2015;64:A162-3).

In the new Michigan study, there were no differences in surgical site infections or 30-day mortality between statin and nonstatin patients, but patients on statins were less likely to get pneumonia, which might help account for their lower sepsis risk, Dr. Disbrow said.

Data for the study came from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative database.

Dr. Disbrow had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Statins appeared to decrease the risk of sepsis after colorectal surgery and of anastomotic leak after rectal resection in a review of 7,285 elective colorectal surgery patients at 64 Michigan hospitals.

Overall, 2,515 patients (34.5%) were on statins preoperatively and received at least one dose while in the hospital post op. Their outcomes were compared with those of the 4,770 patients (65.5%) who were not on statins.

Statin patients were older (mean, 68 vs. 59 years) with more comorbidities (mean, 2.4 vs. 1.1), including diabetes (34% vs.12%) and hypertension (78% vs. 41%). The majority of statin patients were American Society of Anesthesiologists class 3, and the majority of nonstatin patients were class 1 or 2. The investigators controlled for those and other confounders by multivariate logistic regression and propensity scoring.

“We believe that statin medications can reduce sepsis in the colorectal patient population and may improve anastomotic leak rates for rectal resections,” concluded investigators led by David Disbrow, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Mich.

The immediate take-home from the study is to make sure that patients who should be on statins for hypercholesterolemia or other reasons are actually taking the drugs prior to colorectal surgery. It just might improve their surgical outcomes. “I think that would be a good way to start,” Dr. Disbrow said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

If statins truly do help reduce postop sepsis and rectal anastomotic leaks, he said, it’s probably because of their anti-inflammatory effects, which have been demonstrated in previous studies. New Zealand investigators, for instance, randomized 65 patients to 40 mg oral simvastatin for up to a week before elective colorectal resections or Hartmann’s procedure reversals and for 2 weeks afterwards; 67 patients were randomized to placebo. The simvastatin group had significantly lower postop plasma concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha (J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Aug;223[2]:308-20.e1).

Even so, there were no between-group differences in postoperative complications in that study, and, in general, the impact of statins on postop complications has been mixed in the literature. Some studies have shown benefits, others have suggested harm, and a few have shown nothing either way.

It’s the same situation with prior looks at anastomotic leaks. A Danish review of 2,766 patients who had colorectal anastomoses – 496 (19%) treated perioperatively with statins, some in high-dose – found no difference in leakage rates (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.84-2.05; P = 0.23)(Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 Aug;56[8]:980-6). On the other hand, a more recent British review of 144 patients – 45 (39.4%) on preoperative statins – found that “although patients taking statins did not have a significantly reduced leak risk, compared to nonstatin users, high-risk patients taking statins had the same leak risk as non–high risk patients; therefore, it is plausible that statins normalize the risk of anastomotic leak in high-risk patients” (Gut. 2015;64:A162-3).

In the new Michigan study, there were no differences in surgical site infections or 30-day mortality between statin and nonstatin patients, but patients on statins were less likely to get pneumonia, which might help account for their lower sepsis risk, Dr. Disbrow said.

Data for the study came from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative database.

Dr. Disbrow had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Statins appeared to decrease the risk of sepsis after colorectal surgery and of anastomotic leak after rectal resection in a review of 7,285 elective colorectal surgery patients at 64 Michigan hospitals.

Overall, 2,515 patients (34.5%) were on statins preoperatively and received at least one dose while in the hospital post op. Their outcomes were compared with those of the 4,770 patients (65.5%) who were not on statins.

Statin patients were older (mean, 68 vs. 59 years) with more comorbidities (mean, 2.4 vs. 1.1), including diabetes (34% vs.12%) and hypertension (78% vs. 41%). The majority of statin patients were American Society of Anesthesiologists class 3, and the majority of nonstatin patients were class 1 or 2. The investigators controlled for those and other confounders by multivariate logistic regression and propensity scoring.

“We believe that statin medications can reduce sepsis in the colorectal patient population and may improve anastomotic leak rates for rectal resections,” concluded investigators led by David Disbrow, MD, a colorectal surgery fellow at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Mich.

The immediate take-home from the study is to make sure that patients who should be on statins for hypercholesterolemia or other reasons are actually taking the drugs prior to colorectal surgery. It just might improve their surgical outcomes. “I think that would be a good way to start,” Dr. Disbrow said at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons annual meeting.

If statins truly do help reduce postop sepsis and rectal anastomotic leaks, he said, it’s probably because of their anti-inflammatory effects, which have been demonstrated in previous studies. New Zealand investigators, for instance, randomized 65 patients to 40 mg oral simvastatin for up to a week before elective colorectal resections or Hartmann’s procedure reversals and for 2 weeks afterwards; 67 patients were randomized to placebo. The simvastatin group had significantly lower postop plasma concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha (J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Aug;223[2]:308-20.e1).

Even so, there were no between-group differences in postoperative complications in that study, and, in general, the impact of statins on postop complications has been mixed in the literature. Some studies have shown benefits, others have suggested harm, and a few have shown nothing either way.

It’s the same situation with prior looks at anastomotic leaks. A Danish review of 2,766 patients who had colorectal anastomoses – 496 (19%) treated perioperatively with statins, some in high-dose – found no difference in leakage rates (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.84-2.05; P = 0.23)(Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 Aug;56[8]:980-6). On the other hand, a more recent British review of 144 patients – 45 (39.4%) on preoperative statins – found that “although patients taking statins did not have a significantly reduced leak risk, compared to nonstatin users, high-risk patients taking statins had the same leak risk as non–high risk patients; therefore, it is plausible that statins normalize the risk of anastomotic leak in high-risk patients” (Gut. 2015;64:A162-3).

In the new Michigan study, there were no differences in surgical site infections or 30-day mortality between statin and nonstatin patients, but patients on statins were less likely to get pneumonia, which might help account for their lower sepsis risk, Dr. Disbrow said.

Data for the study came from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative database.

Dr. Disbrow had no disclosures.

AT ASCRS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The statin group had a reduced risk of sepsis (OR, 0.712; 95% CI, 0.535-0.948; P = .020), and, while statins were not associated with a reduction in anastomotic leaks overall, they were protective in subgroup analysis of patients who had rectal resections, which are especially prone to leakage (OR, 0.260; 95% CI, 0.112-0.605, P = .002).

Data source: A review of 7,285 elective colorectal surgery patients.

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no disclosures.

VIDEO: Meta-analysis favors anticoagulation for patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis

Patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) who received anticoagulation therapy had nearly fivefold greater odds of recanalization compared with untreated patients, and were no more likely to experience major or minor bleeding, in a pooled analysis of eight studies published in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.042).

Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001), wrote Lorenzo Loffredo, MD, of Sapienza University, Rome, and his coinvestigators. Rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group. Together, the findings “show that anticoagulants are efficacious and safe for treatment of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients,” although larger, interventional clinical trials are needed to pinpoint the clinical role of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients with PVT, the reviewers reported.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Bleeding from portal hypertension is a major complication in cirrhosis, but PVT affects about 20% of patients and predicts poor outcomes, they noted. Anticoagulation in this setting can be difficult because patients often have concurrent coagulopathies that are hard to assess with standard techniques, such as PT-INR (international normalized ratio). Although some studies support anticoagulating these patients, data are limited. Therefore, the reviewers searched PubMed, the ISI Web of Science, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane database through Feb. 14, 2017, for trials comparing anticoagulation with no treatment in patients with cirrhosis and PVT.

This search yielded eight trials of 353 patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or no treatment for about 6 months, with a typical follow-up period of 2 years. The reviewers found no evidence of publication bias or significant heterogeneity among the trials. Six studies evaluated complete recanalization, another set of six studies tracked progression of PVT, a third set of six studies evaluated major or minor bleeding events, and four studies evaluated spontaneous variceal bleeding. Compared with no treatment, anticoagulation was tied to a significantly greater likelihood of complete recanalization (pooled odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-7.4; P = .002), a significantly lower chance of PVT progressing (9% vs. 33%; pooled odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06-0.31; P less than .0001), no difference in bleeding rates (11% in each pooled group), and a significantly lower risk of spontaneous variceal bleeding (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.94; P = .04).

“Metaregression analysis showed that duration of anticoagulation did not influence outcomes,” the reviewers wrote. “Low-molecular-weight heparin, but not warfarin, was significantly associated with a complete PVT resolution as compared to untreated patients, while both low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin were effective in reducing PVT progression.” That finding merits careful interpretation, however, because most studies on warfarin were retrospective and lacked data on the quality of anticoagulation, they added.

“It is a challenge to treat patients with cirrhosis using anticoagulants because of the perception that the coexistent coagulopathy could promote bleeding,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, their analysis suggests that anticoagulation has significant benefits and does not increase bleeding risk, regardless of the severity of liver failure, they concluded.

The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) who received anticoagulation therapy had nearly fivefold greater odds of recanalization compared with untreated patients, and were no more likely to experience major or minor bleeding, in a pooled analysis of eight studies published in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.042).

Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001), wrote Lorenzo Loffredo, MD, of Sapienza University, Rome, and his coinvestigators. Rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group. Together, the findings “show that anticoagulants are efficacious and safe for treatment of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients,” although larger, interventional clinical trials are needed to pinpoint the clinical role of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients with PVT, the reviewers reported.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Bleeding from portal hypertension is a major complication in cirrhosis, but PVT affects about 20% of patients and predicts poor outcomes, they noted. Anticoagulation in this setting can be difficult because patients often have concurrent coagulopathies that are hard to assess with standard techniques, such as PT-INR (international normalized ratio). Although some studies support anticoagulating these patients, data are limited. Therefore, the reviewers searched PubMed, the ISI Web of Science, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane database through Feb. 14, 2017, for trials comparing anticoagulation with no treatment in patients with cirrhosis and PVT.

This search yielded eight trials of 353 patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or no treatment for about 6 months, with a typical follow-up period of 2 years. The reviewers found no evidence of publication bias or significant heterogeneity among the trials. Six studies evaluated complete recanalization, another set of six studies tracked progression of PVT, a third set of six studies evaluated major or minor bleeding events, and four studies evaluated spontaneous variceal bleeding. Compared with no treatment, anticoagulation was tied to a significantly greater likelihood of complete recanalization (pooled odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-7.4; P = .002), a significantly lower chance of PVT progressing (9% vs. 33%; pooled odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06-0.31; P less than .0001), no difference in bleeding rates (11% in each pooled group), and a significantly lower risk of spontaneous variceal bleeding (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.94; P = .04).

“Metaregression analysis showed that duration of anticoagulation did not influence outcomes,” the reviewers wrote. “Low-molecular-weight heparin, but not warfarin, was significantly associated with a complete PVT resolution as compared to untreated patients, while both low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin were effective in reducing PVT progression.” That finding merits careful interpretation, however, because most studies on warfarin were retrospective and lacked data on the quality of anticoagulation, they added.

“It is a challenge to treat patients with cirrhosis using anticoagulants because of the perception that the coexistent coagulopathy could promote bleeding,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, their analysis suggests that anticoagulation has significant benefits and does not increase bleeding risk, regardless of the severity of liver failure, they concluded.

The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) who received anticoagulation therapy had nearly fivefold greater odds of recanalization compared with untreated patients, and were no more likely to experience major or minor bleeding, in a pooled analysis of eight studies published in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.042).

Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001), wrote Lorenzo Loffredo, MD, of Sapienza University, Rome, and his coinvestigators. Rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group. Together, the findings “show that anticoagulants are efficacious and safe for treatment of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients,” although larger, interventional clinical trials are needed to pinpoint the clinical role of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients with PVT, the reviewers reported.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Bleeding from portal hypertension is a major complication in cirrhosis, but PVT affects about 20% of patients and predicts poor outcomes, they noted. Anticoagulation in this setting can be difficult because patients often have concurrent coagulopathies that are hard to assess with standard techniques, such as PT-INR (international normalized ratio). Although some studies support anticoagulating these patients, data are limited. Therefore, the reviewers searched PubMed, the ISI Web of Science, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane database through Feb. 14, 2017, for trials comparing anticoagulation with no treatment in patients with cirrhosis and PVT.

This search yielded eight trials of 353 patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or no treatment for about 6 months, with a typical follow-up period of 2 years. The reviewers found no evidence of publication bias or significant heterogeneity among the trials. Six studies evaluated complete recanalization, another set of six studies tracked progression of PVT, a third set of six studies evaluated major or minor bleeding events, and four studies evaluated spontaneous variceal bleeding. Compared with no treatment, anticoagulation was tied to a significantly greater likelihood of complete recanalization (pooled odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-7.4; P = .002), a significantly lower chance of PVT progressing (9% vs. 33%; pooled odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06-0.31; P less than .0001), no difference in bleeding rates (11% in each pooled group), and a significantly lower risk of spontaneous variceal bleeding (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.94; P = .04).

“Metaregression analysis showed that duration of anticoagulation did not influence outcomes,” the reviewers wrote. “Low-molecular-weight heparin, but not warfarin, was significantly associated with a complete PVT resolution as compared to untreated patients, while both low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin were effective in reducing PVT progression.” That finding merits careful interpretation, however, because most studies on warfarin were retrospective and lacked data on the quality of anticoagulation, they added.

“It is a challenge to treat patients with cirrhosis using anticoagulants because of the perception that the coexistent coagulopathy could promote bleeding,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, their analysis suggests that anticoagulation has significant benefits and does not increase bleeding risk, regardless of the severity of liver failure, they concluded.

The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Anticoagulation produced favorable outcomes with no increase in bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis.

Major finding: Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001); rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group.

Data source: A systematic review and meta-analysis of eight studies of 353 patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis.

Disclosures: The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Cosmeceuticals and Alternative Therapies for Rosacea

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

Debunking Acne Myths: Is Itching a Symptom of Acne?

Myth: Itching is not a symptom of acne

Acne vulgaris typically is not considered to be a pruritic disease; however, many patients experience itching, which leads them to scratch their acne lesions, causing secondary bacterial infections and subsequent scarring, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation of the involved skin. Although itching rarely is mentioned as a clinical feature of acne, pruritus can be an important contributory factor to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life in acne patients of all ages, and acne itching may be an important target for therapy.

In a descriptive study of 120 consecutive acne patients in Singapore, itch was found to be a common (70% of patients) and debilitating symptom of acne. The majority of patients (83%) reported itch at noon with severity that was comparable to a mosquito bite, and the most common physical descriptor was tickling (68%). Common aggravating factors included sweat (71%), heat (62%), and stress (31%). Fifty-five percent of patients said itching had a negative impact on their mood, and 52% reported that they had scratched or rubbed the affected area.

A study of 108 adolescents with acne limited to the face yielded half who reported itching within acne lesions. The presence of itching was unrelated to age, gender, where they lived, positive family history, or acne severity. In most patients, pruritus appeared relatively infrequently and for a short period of time: 7.4% reported itching every day, 24.1% on a weekly basis, 29.6% at least once a month, and 37.7% even less frequently. Itch episodes lasted less than 1 minute in most participants. However, 31.5% of participants sought medical treatment to reduce itching. The most important factors aggravating the intensity of itching were sweat, stress, physical effort, heat, fatigue, and dry air, respectively.

Regarding the impact of acne itching on quality of life, 29.6% of participants felt depressed and 1.8% were anxious because of their itching. Some participants also noted that itching caused difficulties in falling asleep and awakening from itching.

The pathogenesis of localized itching in acne could be connected with the change in pH of the microenvironment of the acne follicle, providing an optimal environment for the production of histamine or histaminelike products by Propionibacterium acnes. Pruritus also may be a complication of certain acne therapies. Increased awareness among patients of this potential side effect may be helpful in preventing the unnecessary discontinuation of an otherwise effective acne therapy. Understanding factors that may aggravate itching in acne lesions also may be helpful to patients.

Lim YL, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G, et al. Pruritus is a common and significant symptom of acne [published online July 8, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1332-1336.

Reich A, Trybucka K, Tracinska A, et al. Acne itch: do acne patients suffer from itching? Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:38-42.

Myth: Itching is not a symptom of acne

Acne vulgaris typically is not considered to be a pruritic disease; however, many patients experience itching, which leads them to scratch their acne lesions, causing secondary bacterial infections and subsequent scarring, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation of the involved skin. Although itching rarely is mentioned as a clinical feature of acne, pruritus can be an important contributory factor to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life in acne patients of all ages, and acne itching may be an important target for therapy.

In a descriptive study of 120 consecutive acne patients in Singapore, itch was found to be a common (70% of patients) and debilitating symptom of acne. The majority of patients (83%) reported itch at noon with severity that was comparable to a mosquito bite, and the most common physical descriptor was tickling (68%). Common aggravating factors included sweat (71%), heat (62%), and stress (31%). Fifty-five percent of patients said itching had a negative impact on their mood, and 52% reported that they had scratched or rubbed the affected area.

A study of 108 adolescents with acne limited to the face yielded half who reported itching within acne lesions. The presence of itching was unrelated to age, gender, where they lived, positive family history, or acne severity. In most patients, pruritus appeared relatively infrequently and for a short period of time: 7.4% reported itching every day, 24.1% on a weekly basis, 29.6% at least once a month, and 37.7% even less frequently. Itch episodes lasted less than 1 minute in most participants. However, 31.5% of participants sought medical treatment to reduce itching. The most important factors aggravating the intensity of itching were sweat, stress, physical effort, heat, fatigue, and dry air, respectively.

Regarding the impact of acne itching on quality of life, 29.6% of participants felt depressed and 1.8% were anxious because of their itching. Some participants also noted that itching caused difficulties in falling asleep and awakening from itching.

The pathogenesis of localized itching in acne could be connected with the change in pH of the microenvironment of the acne follicle, providing an optimal environment for the production of histamine or histaminelike products by Propionibacterium acnes. Pruritus also may be a complication of certain acne therapies. Increased awareness among patients of this potential side effect may be helpful in preventing the unnecessary discontinuation of an otherwise effective acne therapy. Understanding factors that may aggravate itching in acne lesions also may be helpful to patients.

Myth: Itching is not a symptom of acne

Acne vulgaris typically is not considered to be a pruritic disease; however, many patients experience itching, which leads them to scratch their acne lesions, causing secondary bacterial infections and subsequent scarring, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation of the involved skin. Although itching rarely is mentioned as a clinical feature of acne, pruritus can be an important contributory factor to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life in acne patients of all ages, and acne itching may be an important target for therapy.

In a descriptive study of 120 consecutive acne patients in Singapore, itch was found to be a common (70% of patients) and debilitating symptom of acne. The majority of patients (83%) reported itch at noon with severity that was comparable to a mosquito bite, and the most common physical descriptor was tickling (68%). Common aggravating factors included sweat (71%), heat (62%), and stress (31%). Fifty-five percent of patients said itching had a negative impact on their mood, and 52% reported that they had scratched or rubbed the affected area.

A study of 108 adolescents with acne limited to the face yielded half who reported itching within acne lesions. The presence of itching was unrelated to age, gender, where they lived, positive family history, or acne severity. In most patients, pruritus appeared relatively infrequently and for a short period of time: 7.4% reported itching every day, 24.1% on a weekly basis, 29.6% at least once a month, and 37.7% even less frequently. Itch episodes lasted less than 1 minute in most participants. However, 31.5% of participants sought medical treatment to reduce itching. The most important factors aggravating the intensity of itching were sweat, stress, physical effort, heat, fatigue, and dry air, respectively.

Regarding the impact of acne itching on quality of life, 29.6% of participants felt depressed and 1.8% were anxious because of their itching. Some participants also noted that itching caused difficulties in falling asleep and awakening from itching.

The pathogenesis of localized itching in acne could be connected with the change in pH of the microenvironment of the acne follicle, providing an optimal environment for the production of histamine or histaminelike products by Propionibacterium acnes. Pruritus also may be a complication of certain acne therapies. Increased awareness among patients of this potential side effect may be helpful in preventing the unnecessary discontinuation of an otherwise effective acne therapy. Understanding factors that may aggravate itching in acne lesions also may be helpful to patients.

Lim YL, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G, et al. Pruritus is a common and significant symptom of acne [published online July 8, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1332-1336.

Reich A, Trybucka K, Tracinska A, et al. Acne itch: do acne patients suffer from itching? Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:38-42.

Lim YL, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G, et al. Pruritus is a common and significant symptom of acne [published online July 8, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1332-1336.

Reich A, Trybucka K, Tracinska A, et al. Acne itch: do acne patients suffer from itching? Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:38-42.

Emergency Ultrasound: Ultrasound-Guided Arthrocentesis of the Ankle

Ankle effusions can be quite debilitating, causing band-like swelling and stiffness to the anterior aspect of ankle at the tibiotalar joint. Significant swelling can impair ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The differential diagnosis for joint effusions is wide, and includes traumatic effusion; gout; osteoarthritis; rheumatoid arthritis; and septic arthritis, which is one of the most important diagnoses for the emergency physician (EP) to identify and initiate prompt treatment to reduce the risk of serious morbidity and mortality. Differentiating these conditions requires joint aspiration and synovial fluid analysis. While a large effusion will be palpable and likely ballotable, smaller effusions are more challenging clinically. In such cases, point-of-care (POC) ultrasound can be a valuable tool in confirming a joint effusion.

Identifying Landmarks and Tibiotalar Joint

To access the tibiotalar joint space, it is important to identify useful landmarks.1 This is best accomplished by having the patient in the supine position, with the affected knee flexed approximately 90° and plantar surface of the foot lying flat on the bed (Figure 1).

Performing the Arthrocentesis

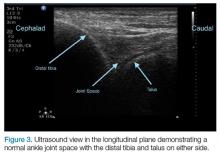

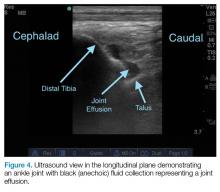

The arthrocentesis is performed under sterile conditions using the high-frequency linear probe. A sterile probe cover is highly recommended if the operator will be using ultrasound to guide the procedure in real time.2 Using the palpable landmarks as a guide, the clinician should align the probe just medial to the tibialis anterior tendon with the probe marker oriented cephalad; scanning should begin superior to the ankle joint. The tibia will appear as a hyperechoic stripe just under a thin soft tissue layer. When the tibia is visible, the clinician should then slide the probe distally. The joint space will demonstrated by visualization of the distal tibia and talus bone (Figure 3).

Pearls and Pitfalls

Point-of-care ultrasound is not only useful to guide arthrocentesis of joint effusions, but also to confirm the presence of an effusion prior to aspiration. At our institution, we have had many cases in which POC ultrasound demonstrated an absence of effusion, and we were able to avoid an unnecessary joint aspiration. Moreover, when an effusion is present, POC ultrasound-guided aspiration avoids complications. The use of POC ultrasound can also increase the confidence of the provider performing arthrocentesis of joints less commonly aspirated.

Summary

Joint aspiration is an important procedural tool for EPs, especially when used to rule out life-threatening conditions such as septic arthritis. Deeper joints and small fluid collections, however, can be difficult to access without image guidance. In the ED setting, POC ultrasound provides a widely available, easy-to-use, low-cost tool to increase the likelihood of success while minimizing damage to adjacent structures.

1. Nagdev A. Ultrasound-guided ankle arthrocentesis. Highland General Hospital Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Web site. http://highlandultrasound.com/ankle-arthrocentesis. Accessed June 8, 2017.

2. Reichman EF, Simon RR. Arthrocentesis. In: Reichman EF, Simon RR, eds. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY; 2013.

Ankle effusions can be quite debilitating, causing band-like swelling and stiffness to the anterior aspect of ankle at the tibiotalar joint. Significant swelling can impair ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The differential diagnosis for joint effusions is wide, and includes traumatic effusion; gout; osteoarthritis; rheumatoid arthritis; and septic arthritis, which is one of the most important diagnoses for the emergency physician (EP) to identify and initiate prompt treatment to reduce the risk of serious morbidity and mortality. Differentiating these conditions requires joint aspiration and synovial fluid analysis. While a large effusion will be palpable and likely ballotable, smaller effusions are more challenging clinically. In such cases, point-of-care (POC) ultrasound can be a valuable tool in confirming a joint effusion.

Identifying Landmarks and Tibiotalar Joint

To access the tibiotalar joint space, it is important to identify useful landmarks.1 This is best accomplished by having the patient in the supine position, with the affected knee flexed approximately 90° and plantar surface of the foot lying flat on the bed (Figure 1).

Performing the Arthrocentesis

The arthrocentesis is performed under sterile conditions using the high-frequency linear probe. A sterile probe cover is highly recommended if the operator will be using ultrasound to guide the procedure in real time.2 Using the palpable landmarks as a guide, the clinician should align the probe just medial to the tibialis anterior tendon with the probe marker oriented cephalad; scanning should begin superior to the ankle joint. The tibia will appear as a hyperechoic stripe just under a thin soft tissue layer. When the tibia is visible, the clinician should then slide the probe distally. The joint space will demonstrated by visualization of the distal tibia and talus bone (Figure 3).

Pearls and Pitfalls

Point-of-care ultrasound is not only useful to guide arthrocentesis of joint effusions, but also to confirm the presence of an effusion prior to aspiration. At our institution, we have had many cases in which POC ultrasound demonstrated an absence of effusion, and we were able to avoid an unnecessary joint aspiration. Moreover, when an effusion is present, POC ultrasound-guided aspiration avoids complications. The use of POC ultrasound can also increase the confidence of the provider performing arthrocentesis of joints less commonly aspirated.

Summary

Joint aspiration is an important procedural tool for EPs, especially when used to rule out life-threatening conditions such as septic arthritis. Deeper joints and small fluid collections, however, can be difficult to access without image guidance. In the ED setting, POC ultrasound provides a widely available, easy-to-use, low-cost tool to increase the likelihood of success while minimizing damage to adjacent structures.

Ankle effusions can be quite debilitating, causing band-like swelling and stiffness to the anterior aspect of ankle at the tibiotalar joint. Significant swelling can impair ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The differential diagnosis for joint effusions is wide, and includes traumatic effusion; gout; osteoarthritis; rheumatoid arthritis; and septic arthritis, which is one of the most important diagnoses for the emergency physician (EP) to identify and initiate prompt treatment to reduce the risk of serious morbidity and mortality. Differentiating these conditions requires joint aspiration and synovial fluid analysis. While a large effusion will be palpable and likely ballotable, smaller effusions are more challenging clinically. In such cases, point-of-care (POC) ultrasound can be a valuable tool in confirming a joint effusion.

Identifying Landmarks and Tibiotalar Joint

To access the tibiotalar joint space, it is important to identify useful landmarks.1 This is best accomplished by having the patient in the supine position, with the affected knee flexed approximately 90° and plantar surface of the foot lying flat on the bed (Figure 1).

Performing the Arthrocentesis

The arthrocentesis is performed under sterile conditions using the high-frequency linear probe. A sterile probe cover is highly recommended if the operator will be using ultrasound to guide the procedure in real time.2 Using the palpable landmarks as a guide, the clinician should align the probe just medial to the tibialis anterior tendon with the probe marker oriented cephalad; scanning should begin superior to the ankle joint. The tibia will appear as a hyperechoic stripe just under a thin soft tissue layer. When the tibia is visible, the clinician should then slide the probe distally. The joint space will demonstrated by visualization of the distal tibia and talus bone (Figure 3).

Pearls and Pitfalls

Point-of-care ultrasound is not only useful to guide arthrocentesis of joint effusions, but also to confirm the presence of an effusion prior to aspiration. At our institution, we have had many cases in which POC ultrasound demonstrated an absence of effusion, and we were able to avoid an unnecessary joint aspiration. Moreover, when an effusion is present, POC ultrasound-guided aspiration avoids complications. The use of POC ultrasound can also increase the confidence of the provider performing arthrocentesis of joints less commonly aspirated.

Summary

Joint aspiration is an important procedural tool for EPs, especially when used to rule out life-threatening conditions such as septic arthritis. Deeper joints and small fluid collections, however, can be difficult to access without image guidance. In the ED setting, POC ultrasound provides a widely available, easy-to-use, low-cost tool to increase the likelihood of success while minimizing damage to adjacent structures.

1. Nagdev A. Ultrasound-guided ankle arthrocentesis. Highland General Hospital Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Web site. http://highlandultrasound.com/ankle-arthrocentesis. Accessed June 8, 2017.

2. Reichman EF, Simon RR. Arthrocentesis. In: Reichman EF, Simon RR, eds. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY; 2013.

1. Nagdev A. Ultrasound-guided ankle arthrocentesis. Highland General Hospital Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Web site. http://highlandultrasound.com/ankle-arthrocentesis. Accessed June 8, 2017.

2. Reichman EF, Simon RR. Arthrocentesis. In: Reichman EF, Simon RR, eds. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY; 2013.

Heritability of colorectal cancer estimated at 40%

Thus, CRC “has a substantial heritable component, and may be more heritable in women than men,” Rebecca E. Graff, ScD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues wrote. “Siblings, and particularly monozygotic cotwins, of individuals with colon or rectal cancer should consider personalized screening,” they added.

The model that best fits the data accounted for additive genetic and environmental effects, the researchers said. Based on this model, genetic factors explained about 40% (95% CI, 33%-48%) of variation in the risk of CRC. Thus, the heritability of CRC was about 40%. The estimated heritability of colon cancer was 16% and that of rectal cancer was 15%, but confidence intervals were wide, ranging from 0% to 47% or 50%, respectively. Individual environmental factors accounted for most of the remaining risk of colon and rectal cancers.

“Heritability was greater among women than men and greatest when colorectal cancer combining all subsites together was analyzed,” the researchers noted. Monozygotic twins of CRC patients were at greater risk of both colon and rectal cancers than were same-sex dizygotic twins, indicating that both types of cancer might share inherited genetic risk factors, they added. Variants identified by genomewide association studies “do not come close to accounting for the disease’s heritability,” but, in the meantime, twins of affected cotwins “might benefit particularly from diligent screening, given their excess risk relative to the general population.”

Funders included the Ellison Foundation, the Odense University Hospital AgeCare program, the Academy of Finland, and US BioSHaRE-EU, and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, BioSHaRE-EU, the Swedish Ministry for Higher Education, and the Karolinska Institutet, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Graff had no conflicts of interest.

Thus, CRC “has a substantial heritable component, and may be more heritable in women than men,” Rebecca E. Graff, ScD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues wrote. “Siblings, and particularly monozygotic cotwins, of individuals with colon or rectal cancer should consider personalized screening,” they added.

The model that best fits the data accounted for additive genetic and environmental effects, the researchers said. Based on this model, genetic factors explained about 40% (95% CI, 33%-48%) of variation in the risk of CRC. Thus, the heritability of CRC was about 40%. The estimated heritability of colon cancer was 16% and that of rectal cancer was 15%, but confidence intervals were wide, ranging from 0% to 47% or 50%, respectively. Individual environmental factors accounted for most of the remaining risk of colon and rectal cancers.

“Heritability was greater among women than men and greatest when colorectal cancer combining all subsites together was analyzed,” the researchers noted. Monozygotic twins of CRC patients were at greater risk of both colon and rectal cancers than were same-sex dizygotic twins, indicating that both types of cancer might share inherited genetic risk factors, they added. Variants identified by genomewide association studies “do not come close to accounting for the disease’s heritability,” but, in the meantime, twins of affected cotwins “might benefit particularly from diligent screening, given their excess risk relative to the general population.”

Funders included the Ellison Foundation, the Odense University Hospital AgeCare program, the Academy of Finland, and US BioSHaRE-EU, and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, BioSHaRE-EU, the Swedish Ministry for Higher Education, and the Karolinska Institutet, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Graff had no conflicts of interest.

Thus, CRC “has a substantial heritable component, and may be more heritable in women than men,” Rebecca E. Graff, ScD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues wrote. “Siblings, and particularly monozygotic cotwins, of individuals with colon or rectal cancer should consider personalized screening,” they added.

The model that best fits the data accounted for additive genetic and environmental effects, the researchers said. Based on this model, genetic factors explained about 40% (95% CI, 33%-48%) of variation in the risk of CRC. Thus, the heritability of CRC was about 40%. The estimated heritability of colon cancer was 16% and that of rectal cancer was 15%, but confidence intervals were wide, ranging from 0% to 47% or 50%, respectively. Individual environmental factors accounted for most of the remaining risk of colon and rectal cancers.

“Heritability was greater among women than men and greatest when colorectal cancer combining all subsites together was analyzed,” the researchers noted. Monozygotic twins of CRC patients were at greater risk of both colon and rectal cancers than were same-sex dizygotic twins, indicating that both types of cancer might share inherited genetic risk factors, they added. Variants identified by genomewide association studies “do not come close to accounting for the disease’s heritability,” but, in the meantime, twins of affected cotwins “might benefit particularly from diligent screening, given their excess risk relative to the general population.”

Funders included the Ellison Foundation, the Odense University Hospital AgeCare program, the Academy of Finland, and US BioSHaRE-EU, and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, BioSHaRE-EU, the Swedish Ministry for Higher Education, and the Karolinska Institutet, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Graff had no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: If a monozygotic twin developed colorectal cancer, his or her twin had about a threefold higher risk of CRC than did the overall cohort (familial risk ratio, 3.1; 95% CI, 2.4-3.8).

Major finding: Genetic factors explained about 40% (95% CI, 33%-48%) of variation in the risk of colorectal cancer.

Data source: An analysis of 39,990 monozygotic and 61,443 same-sex dizygotic twins from the Nordic Twin Study of Cancer.

Disclosures: Funders included the Ellison Foundation, the Odense University Hospital AgeCare program, the Academy of Finland, US BioSHaRE-EU, and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, BioSHaRE-EU, the Swedish Ministry for Higher Education, and the Karolinska Institutet, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Graff had no conflicts of interest.

Endoscopists who took 1 minute longer detected significantly more upper GI neoplasms

Endoscopists who took about a minute longer during screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) detected significantly more upper gastrointestinal neoplasms than their quicker colleagues, in a retrospective study reported in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.009).

Detection rates were 0.28% and 0.20%, respectively (P = .005), and this difference remained statistically significant after the investigators controlled for numerous factors that also can affect the chances of detecting gastric neoplasms during upper endoscopy, reported Jae Myung Park, MD, and his colleagues at Seoul (Korea) St. Mary’s Hospital.