User login

Do sleep interventions prevent atrial fibrillation?

WASHINGTON – If patients have sleep disordered breathing with obstructive sleep apnea, will its treatment have cardiovascular disease benefits, especially in terms of the incidence or severity of atrial fibrillation?

Observational evidence suggests that apnea interventions may help these patients, but no clear case yet exists to prove that a breathing intervention works, experts say, and, as a result, U.S. practice is mixed when it comes to using treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), specifically continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), to prevent or treat atrial fibrillation.

“Only a very small number of patients with atrial fibrillation undergo a sleep study,” he said in an interview. “Before I’d send my mother for atrial fibrillation ablation, I would first look for sleep disordered breathing [SDB],” but this generally isn’t happening routinely. Patients with other types of cardiovascular disease who could potentially benefit from sleep disordered breathing diagnosis and treatment are those with hypertension, especially patients who don’t fully respond to three or more antihypertensive drugs and patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, he added.

Dr. Oldenburg also echoed Dr. Mehra in saying that the evidence supporting this approach for managing atrial fibrillation is less than conclusive.

“We need more precise phenotyping of patients” to better focus on patients with cardiovascular disease and sleep disordered breathing who clearly benefit from CPAP intervention, he said.

Results from the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) trial, reported in September 2016, especially tarnished the notion that treating sleep disordered breathing in patients with various cardiovascular diseases can help avoid future cardiovascular events. The multicenter trial enrolled 2,717 adults with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease to receive either CPAP plus optimal routine care or optimal routine care only. After an average follow-up of close to 4 years, the patients treated with CPAP showed no benefit in terms of reduced cardiovascular events (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 8;375[10]:919-31).

An editorial that ran with this report suggested that the neutral outcome may have occurred because the average nightly duration of CPAP that patients in the trial self administered was just over 3 hours, arguably an inadequate dose. Other possible reasons for the lack of benefit include the time during their sleep cycle when patients administered CPAP (at the start of sleep rather than later) and that CPAP may have a reduced ability to avert new cardiovascular events in patients with established cardiovascular disease (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 8;375[8]:994-6).

Regardless of the reasons, the SAVE results, coupled with the neutral results and suggestion of harm from using adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and central sleep apnea in the SERVE-HF trial (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sept 17;373[12]:1095-105), have thrust the management of SDB in patients with cardiovascular disease back to the point where SDB interventions have no well-proven indications for cardiovascular disease patients.

“With the SERVE-HF and SAVE trials not showing benefit, we now have equipoise” for using or not using SDB interventions in these patients, Dr. Mehra said. “It’s not clear that treating OSA improves outcomes. That allows us to randomize patients to a control placebo arm” in future trials.

An important issue in the failure to clearly establish a role for treating OSA in patients with atrial fibrillation or other cardiovascular diseases may have been over reliance on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) as the arbiter of OSA severity, Dr. Oldenburg said. “Maybe there are parameters to look at aside from AHI, perhaps hypoxemia burden or desaturation time. AHI is not the whole truth; we need to look at other parameters. AHI may not be the correct metric to look at in patients with various cardiovascular diseases.”

Her analysis also showed that patients with at least 10 minutes of sleep time with an oxygen saturation rate of 90% or less had a 64% increased rate of later atrial fibrillation hospitalizations, compared with those with fewer than 10 minutes spent in this state. Nearly a quarter of the patients studied fell into this category.

“Nocturnal oxygen desaturation may be stronger than AHI for predicting atrial fibrillation development,” Dr. Kendzerska concluded. “The severity of OSA-related intermittent hypoxia may be more important than sleep fragmentation in the development of atrial fibrillation. These findings support a relationship between OSA, chronic nocturnal hypoxemia, and new onset atrial fibrillation.”

However, using oxygen desaturation instead of AHI to gauge the severity of OSA won’t solve all the challenges that sleep researchers currently face in trying to determine the efficacy of breathing interventions to prevent or treat cardiovascular disease. In the neutral SAVE trial, researchers used nocturnal oxygen saturation levels to select patients with clinically meaningful OSA.

Dr. Mehra and Dr. Kendzerska had no disclosures. Dr. Oldenburg has received consultant fees, honoraria, and/or research support from ResMed, Respicardia, and Weinmann.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This article was updated on 7/10/17.

WASHINGTON – If patients have sleep disordered breathing with obstructive sleep apnea, will its treatment have cardiovascular disease benefits, especially in terms of the incidence or severity of atrial fibrillation?

Observational evidence suggests that apnea interventions may help these patients, but no clear case yet exists to prove that a breathing intervention works, experts say, and, as a result, U.S. practice is mixed when it comes to using treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), specifically continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), to prevent or treat atrial fibrillation.

“Only a very small number of patients with atrial fibrillation undergo a sleep study,” he said in an interview. “Before I’d send my mother for atrial fibrillation ablation, I would first look for sleep disordered breathing [SDB],” but this generally isn’t happening routinely. Patients with other types of cardiovascular disease who could potentially benefit from sleep disordered breathing diagnosis and treatment are those with hypertension, especially patients who don’t fully respond to three or more antihypertensive drugs and patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, he added.

Dr. Oldenburg also echoed Dr. Mehra in saying that the evidence supporting this approach for managing atrial fibrillation is less than conclusive.

“We need more precise phenotyping of patients” to better focus on patients with cardiovascular disease and sleep disordered breathing who clearly benefit from CPAP intervention, he said.

Results from the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) trial, reported in September 2016, especially tarnished the notion that treating sleep disordered breathing in patients with various cardiovascular diseases can help avoid future cardiovascular events. The multicenter trial enrolled 2,717 adults with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease to receive either CPAP plus optimal routine care or optimal routine care only. After an average follow-up of close to 4 years, the patients treated with CPAP showed no benefit in terms of reduced cardiovascular events (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 8;375[10]:919-31).

An editorial that ran with this report suggested that the neutral outcome may have occurred because the average nightly duration of CPAP that patients in the trial self administered was just over 3 hours, arguably an inadequate dose. Other possible reasons for the lack of benefit include the time during their sleep cycle when patients administered CPAP (at the start of sleep rather than later) and that CPAP may have a reduced ability to avert new cardiovascular events in patients with established cardiovascular disease (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 8;375[8]:994-6).

Regardless of the reasons, the SAVE results, coupled with the neutral results and suggestion of harm from using adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and central sleep apnea in the SERVE-HF trial (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sept 17;373[12]:1095-105), have thrust the management of SDB in patients with cardiovascular disease back to the point where SDB interventions have no well-proven indications for cardiovascular disease patients.

“With the SERVE-HF and SAVE trials not showing benefit, we now have equipoise” for using or not using SDB interventions in these patients, Dr. Mehra said. “It’s not clear that treating OSA improves outcomes. That allows us to randomize patients to a control placebo arm” in future trials.

An important issue in the failure to clearly establish a role for treating OSA in patients with atrial fibrillation or other cardiovascular diseases may have been over reliance on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) as the arbiter of OSA severity, Dr. Oldenburg said. “Maybe there are parameters to look at aside from AHI, perhaps hypoxemia burden or desaturation time. AHI is not the whole truth; we need to look at other parameters. AHI may not be the correct metric to look at in patients with various cardiovascular diseases.”

Her analysis also showed that patients with at least 10 minutes of sleep time with an oxygen saturation rate of 90% or less had a 64% increased rate of later atrial fibrillation hospitalizations, compared with those with fewer than 10 minutes spent in this state. Nearly a quarter of the patients studied fell into this category.

“Nocturnal oxygen desaturation may be stronger than AHI for predicting atrial fibrillation development,” Dr. Kendzerska concluded. “The severity of OSA-related intermittent hypoxia may be more important than sleep fragmentation in the development of atrial fibrillation. These findings support a relationship between OSA, chronic nocturnal hypoxemia, and new onset atrial fibrillation.”

However, using oxygen desaturation instead of AHI to gauge the severity of OSA won’t solve all the challenges that sleep researchers currently face in trying to determine the efficacy of breathing interventions to prevent or treat cardiovascular disease. In the neutral SAVE trial, researchers used nocturnal oxygen saturation levels to select patients with clinically meaningful OSA.

Dr. Mehra and Dr. Kendzerska had no disclosures. Dr. Oldenburg has received consultant fees, honoraria, and/or research support from ResMed, Respicardia, and Weinmann.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This article was updated on 7/10/17.

WASHINGTON – If patients have sleep disordered breathing with obstructive sleep apnea, will its treatment have cardiovascular disease benefits, especially in terms of the incidence or severity of atrial fibrillation?

Observational evidence suggests that apnea interventions may help these patients, but no clear case yet exists to prove that a breathing intervention works, experts say, and, as a result, U.S. practice is mixed when it comes to using treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), specifically continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), to prevent or treat atrial fibrillation.

“Only a very small number of patients with atrial fibrillation undergo a sleep study,” he said in an interview. “Before I’d send my mother for atrial fibrillation ablation, I would first look for sleep disordered breathing [SDB],” but this generally isn’t happening routinely. Patients with other types of cardiovascular disease who could potentially benefit from sleep disordered breathing diagnosis and treatment are those with hypertension, especially patients who don’t fully respond to three or more antihypertensive drugs and patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, he added.

Dr. Oldenburg also echoed Dr. Mehra in saying that the evidence supporting this approach for managing atrial fibrillation is less than conclusive.

“We need more precise phenotyping of patients” to better focus on patients with cardiovascular disease and sleep disordered breathing who clearly benefit from CPAP intervention, he said.

Results from the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) trial, reported in September 2016, especially tarnished the notion that treating sleep disordered breathing in patients with various cardiovascular diseases can help avoid future cardiovascular events. The multicenter trial enrolled 2,717 adults with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease to receive either CPAP plus optimal routine care or optimal routine care only. After an average follow-up of close to 4 years, the patients treated with CPAP showed no benefit in terms of reduced cardiovascular events (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 8;375[10]:919-31).

An editorial that ran with this report suggested that the neutral outcome may have occurred because the average nightly duration of CPAP that patients in the trial self administered was just over 3 hours, arguably an inadequate dose. Other possible reasons for the lack of benefit include the time during their sleep cycle when patients administered CPAP (at the start of sleep rather than later) and that CPAP may have a reduced ability to avert new cardiovascular events in patients with established cardiovascular disease (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 8;375[8]:994-6).

Regardless of the reasons, the SAVE results, coupled with the neutral results and suggestion of harm from using adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and central sleep apnea in the SERVE-HF trial (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sept 17;373[12]:1095-105), have thrust the management of SDB in patients with cardiovascular disease back to the point where SDB interventions have no well-proven indications for cardiovascular disease patients.

“With the SERVE-HF and SAVE trials not showing benefit, we now have equipoise” for using or not using SDB interventions in these patients, Dr. Mehra said. “It’s not clear that treating OSA improves outcomes. That allows us to randomize patients to a control placebo arm” in future trials.

An important issue in the failure to clearly establish a role for treating OSA in patients with atrial fibrillation or other cardiovascular diseases may have been over reliance on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) as the arbiter of OSA severity, Dr. Oldenburg said. “Maybe there are parameters to look at aside from AHI, perhaps hypoxemia burden or desaturation time. AHI is not the whole truth; we need to look at other parameters. AHI may not be the correct metric to look at in patients with various cardiovascular diseases.”

Her analysis also showed that patients with at least 10 minutes of sleep time with an oxygen saturation rate of 90% or less had a 64% increased rate of later atrial fibrillation hospitalizations, compared with those with fewer than 10 minutes spent in this state. Nearly a quarter of the patients studied fell into this category.

“Nocturnal oxygen desaturation may be stronger than AHI for predicting atrial fibrillation development,” Dr. Kendzerska concluded. “The severity of OSA-related intermittent hypoxia may be more important than sleep fragmentation in the development of atrial fibrillation. These findings support a relationship between OSA, chronic nocturnal hypoxemia, and new onset atrial fibrillation.”

However, using oxygen desaturation instead of AHI to gauge the severity of OSA won’t solve all the challenges that sleep researchers currently face in trying to determine the efficacy of breathing interventions to prevent or treat cardiovascular disease. In the neutral SAVE trial, researchers used nocturnal oxygen saturation levels to select patients with clinically meaningful OSA.

Dr. Mehra and Dr. Kendzerska had no disclosures. Dr. Oldenburg has received consultant fees, honoraria, and/or research support from ResMed, Respicardia, and Weinmann.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This article was updated on 7/10/17.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ATS 2017

Vascular Injury Following a Fall Onto an Outstretched Hand

A 46-year-old man with a remote history of general tonic-clonic seizures, for which he was taking phenytoin, presented to the ED 30 minutes after sustaining a witnessed mechanical fall. The patient had fallen onto his nondominant left hand, which resulted in an injury to his elbow. He reported neither losing consciousness nor experiencing any seizures following the incident. He denied dislocating the joint or sustaining any other injuries from the fall. He also denied a history of past left elbow injury.

The patient was alert, oriented, and provided a full history of the incident. Regarding medical history, he stated that his last seizure had occurred 10 years prior. Except for the left elbow pain, a review of his systems was negative. The patient appeared in no acute distress, and supported his left upper extremity with a bandana and his right hand.

The patient’s vital signs were normal. The physical examination was negative except for the left elbow, which had significant swelling and limited range of motion without skin break, leading to suspicion for a prehospital dislocation with self-reduction. The joints above, below, and at the injury site were assessed for neurovascular injury.

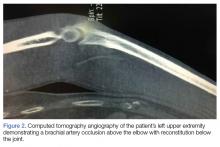

Computed tomography angiography of the left upper extremity showed a brachial artery occlusion above the elbow, with reconstitution below the joint (Figure 2).

Discussion

There is a paucity of information on vascular injury from elbow dislocation in the emergency medicine literature. A recent literature search referenced orthopedic pitfalls in the ED,1 but most data appear in the orthopedic and vascular literature. A case report from the orthopedic literature in Brazil cites a vascular injury after ED relocation of a dislocated elbow following an assault.2

The elbow is the second most commonly dislocated joint (not including the patella) after the shoulder.3 Posterior dislocations make up the majority of these injuries. Simple versus complex injuries can be differentiated by the presence or absence of fracture.4 Simple complications include stiffness; loss of mobility, especially with full extension; neurovascular injuries; and compartment syndrome. Complex injuries involve fractures and potential neurovascular injuries, stiffness, pain, and loss of mobility.

Soft tissue injuries, fractures, and neurovascular complaints represent the majority of ED encounters, and are commonly related to falls. The elbow is the articulation of the humerus, ulna, and radius bones. Range of motion includes, but is not limited to, flexion, extension, supination, and pronation. Tears in the lateral ulnar ligament, joint capsule, and medial collateral ligament lead to instability of the joint and increase risk of dislocation.

Fractures make up to 20% of injuries to the elbow. These include fractures of the radial head and neck (most common), olecranon, and distal humerus.5 Open elbow fractures are rare, as are vascular injuries (5%-13% of cases).6 When present, vascular elbow injuries usually involve the brachial artery, and display abnormal palpable and Doppler assessment of the brachial and radial arteries.6

Nerve injuries may include injury to the radial nerve. Manifestations of radial nerve injury include abnormal sensation to the dorsum of the hand, trouble straightening the arm, and wrist-drop. Ulnar nerve injury typically presents with abnormal sensation to the fourth and fifth digits and decreased grip strength.

Conclusion

Vascular abnormalities are rare complications following elbow injuries. Our patient sustained a lacerated brachial artery, which was repaired via saphenous graft; brachial and basilic vein lacerations, which were ligated; and an avulsion fracture with an unstable joint, which was stabilized with external fixation and stabilization. He was discharged the following day with full neurovascular function.

A methodical approach to assessing patients presenting with elbow injury is essential to making the correct diagnosis. This should include a careful evaluation of the joints above and below the area of injury, as well as attention to the neurovascular examination, with a heightened suspicion for a vascular abnormality in complex injuries. Doppler and ultrasound evaluation with multiple rechecks can assist with the diagnosis. Our patient was rapidly assessed with a concern for a vascular injury, and was emergently referred to vascular surgery for repair of the brachial artery and stabilization of the joint.

1. Carter SJ, Germann CA, Dacus AA, Sweeney TW, Perron AD. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: neurovascular injury associated with posterior elbow dislocations. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(8):960-965. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.05.024.

2. Miyazaki AN, Fregoneze M, Santos PD, do Val Sella G, Checchia CS, Checchia SL. Brachial artery injury due to closed posterior elbow dislocation: case report. Rev Bras Ortop. 2016;51(2):239-243. doi:10.1016/j.rboe.2016.02.007.

3. Beingessner J, Pollock W, King GJW. Elbow fractures and dislocations. In: Court-Brown CM, Heckman JD, McQueen MM, Ricci WM, Tornetta P, eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015:1179-1228.

4. McCabe MP, Savoie FH 3rd. Simple elbow dislocations: evaluation, management, and outcomes. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40(1):62-71. doi:10.3810/psm.2012.02.1952.

5. Jungbluth P, Hakimi M, Linhart W, Windolf J. Current concepts: simple and complex elbow dislocations—acute and definitive treatment. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2008;34(2):120-130. doi:10.1007/s00068-008-8033-9.

6. Marcheix B, Chaufour X, Ayel J, et al. Transection of the brachial artery after closed posterior elbow dislocation. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(6):1230-1232. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2005.07.046.

A 46-year-old man with a remote history of general tonic-clonic seizures, for which he was taking phenytoin, presented to the ED 30 minutes after sustaining a witnessed mechanical fall. The patient had fallen onto his nondominant left hand, which resulted in an injury to his elbow. He reported neither losing consciousness nor experiencing any seizures following the incident. He denied dislocating the joint or sustaining any other injuries from the fall. He also denied a history of past left elbow injury.

The patient was alert, oriented, and provided a full history of the incident. Regarding medical history, he stated that his last seizure had occurred 10 years prior. Except for the left elbow pain, a review of his systems was negative. The patient appeared in no acute distress, and supported his left upper extremity with a bandana and his right hand.

The patient’s vital signs were normal. The physical examination was negative except for the left elbow, which had significant swelling and limited range of motion without skin break, leading to suspicion for a prehospital dislocation with self-reduction. The joints above, below, and at the injury site were assessed for neurovascular injury.

Computed tomography angiography of the left upper extremity showed a brachial artery occlusion above the elbow, with reconstitution below the joint (Figure 2).

Discussion

There is a paucity of information on vascular injury from elbow dislocation in the emergency medicine literature. A recent literature search referenced orthopedic pitfalls in the ED,1 but most data appear in the orthopedic and vascular literature. A case report from the orthopedic literature in Brazil cites a vascular injury after ED relocation of a dislocated elbow following an assault.2

The elbow is the second most commonly dislocated joint (not including the patella) after the shoulder.3 Posterior dislocations make up the majority of these injuries. Simple versus complex injuries can be differentiated by the presence or absence of fracture.4 Simple complications include stiffness; loss of mobility, especially with full extension; neurovascular injuries; and compartment syndrome. Complex injuries involve fractures and potential neurovascular injuries, stiffness, pain, and loss of mobility.

Soft tissue injuries, fractures, and neurovascular complaints represent the majority of ED encounters, and are commonly related to falls. The elbow is the articulation of the humerus, ulna, and radius bones. Range of motion includes, but is not limited to, flexion, extension, supination, and pronation. Tears in the lateral ulnar ligament, joint capsule, and medial collateral ligament lead to instability of the joint and increase risk of dislocation.

Fractures make up to 20% of injuries to the elbow. These include fractures of the radial head and neck (most common), olecranon, and distal humerus.5 Open elbow fractures are rare, as are vascular injuries (5%-13% of cases).6 When present, vascular elbow injuries usually involve the brachial artery, and display abnormal palpable and Doppler assessment of the brachial and radial arteries.6

Nerve injuries may include injury to the radial nerve. Manifestations of radial nerve injury include abnormal sensation to the dorsum of the hand, trouble straightening the arm, and wrist-drop. Ulnar nerve injury typically presents with abnormal sensation to the fourth and fifth digits and decreased grip strength.

Conclusion

Vascular abnormalities are rare complications following elbow injuries. Our patient sustained a lacerated brachial artery, which was repaired via saphenous graft; brachial and basilic vein lacerations, which were ligated; and an avulsion fracture with an unstable joint, which was stabilized with external fixation and stabilization. He was discharged the following day with full neurovascular function.

A methodical approach to assessing patients presenting with elbow injury is essential to making the correct diagnosis. This should include a careful evaluation of the joints above and below the area of injury, as well as attention to the neurovascular examination, with a heightened suspicion for a vascular abnormality in complex injuries. Doppler and ultrasound evaluation with multiple rechecks can assist with the diagnosis. Our patient was rapidly assessed with a concern for a vascular injury, and was emergently referred to vascular surgery for repair of the brachial artery and stabilization of the joint.

A 46-year-old man with a remote history of general tonic-clonic seizures, for which he was taking phenytoin, presented to the ED 30 minutes after sustaining a witnessed mechanical fall. The patient had fallen onto his nondominant left hand, which resulted in an injury to his elbow. He reported neither losing consciousness nor experiencing any seizures following the incident. He denied dislocating the joint or sustaining any other injuries from the fall. He also denied a history of past left elbow injury.

The patient was alert, oriented, and provided a full history of the incident. Regarding medical history, he stated that his last seizure had occurred 10 years prior. Except for the left elbow pain, a review of his systems was negative. The patient appeared in no acute distress, and supported his left upper extremity with a bandana and his right hand.

The patient’s vital signs were normal. The physical examination was negative except for the left elbow, which had significant swelling and limited range of motion without skin break, leading to suspicion for a prehospital dislocation with self-reduction. The joints above, below, and at the injury site were assessed for neurovascular injury.

Computed tomography angiography of the left upper extremity showed a brachial artery occlusion above the elbow, with reconstitution below the joint (Figure 2).

Discussion

There is a paucity of information on vascular injury from elbow dislocation in the emergency medicine literature. A recent literature search referenced orthopedic pitfalls in the ED,1 but most data appear in the orthopedic and vascular literature. A case report from the orthopedic literature in Brazil cites a vascular injury after ED relocation of a dislocated elbow following an assault.2

The elbow is the second most commonly dislocated joint (not including the patella) after the shoulder.3 Posterior dislocations make up the majority of these injuries. Simple versus complex injuries can be differentiated by the presence or absence of fracture.4 Simple complications include stiffness; loss of mobility, especially with full extension; neurovascular injuries; and compartment syndrome. Complex injuries involve fractures and potential neurovascular injuries, stiffness, pain, and loss of mobility.

Soft tissue injuries, fractures, and neurovascular complaints represent the majority of ED encounters, and are commonly related to falls. The elbow is the articulation of the humerus, ulna, and radius bones. Range of motion includes, but is not limited to, flexion, extension, supination, and pronation. Tears in the lateral ulnar ligament, joint capsule, and medial collateral ligament lead to instability of the joint and increase risk of dislocation.

Fractures make up to 20% of injuries to the elbow. These include fractures of the radial head and neck (most common), olecranon, and distal humerus.5 Open elbow fractures are rare, as are vascular injuries (5%-13% of cases).6 When present, vascular elbow injuries usually involve the brachial artery, and display abnormal palpable and Doppler assessment of the brachial and radial arteries.6

Nerve injuries may include injury to the radial nerve. Manifestations of radial nerve injury include abnormal sensation to the dorsum of the hand, trouble straightening the arm, and wrist-drop. Ulnar nerve injury typically presents with abnormal sensation to the fourth and fifth digits and decreased grip strength.

Conclusion

Vascular abnormalities are rare complications following elbow injuries. Our patient sustained a lacerated brachial artery, which was repaired via saphenous graft; brachial and basilic vein lacerations, which were ligated; and an avulsion fracture with an unstable joint, which was stabilized with external fixation and stabilization. He was discharged the following day with full neurovascular function.

A methodical approach to assessing patients presenting with elbow injury is essential to making the correct diagnosis. This should include a careful evaluation of the joints above and below the area of injury, as well as attention to the neurovascular examination, with a heightened suspicion for a vascular abnormality in complex injuries. Doppler and ultrasound evaluation with multiple rechecks can assist with the diagnosis. Our patient was rapidly assessed with a concern for a vascular injury, and was emergently referred to vascular surgery for repair of the brachial artery and stabilization of the joint.

1. Carter SJ, Germann CA, Dacus AA, Sweeney TW, Perron AD. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: neurovascular injury associated with posterior elbow dislocations. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(8):960-965. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.05.024.

2. Miyazaki AN, Fregoneze M, Santos PD, do Val Sella G, Checchia CS, Checchia SL. Brachial artery injury due to closed posterior elbow dislocation: case report. Rev Bras Ortop. 2016;51(2):239-243. doi:10.1016/j.rboe.2016.02.007.

3. Beingessner J, Pollock W, King GJW. Elbow fractures and dislocations. In: Court-Brown CM, Heckman JD, McQueen MM, Ricci WM, Tornetta P, eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015:1179-1228.

4. McCabe MP, Savoie FH 3rd. Simple elbow dislocations: evaluation, management, and outcomes. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40(1):62-71. doi:10.3810/psm.2012.02.1952.

5. Jungbluth P, Hakimi M, Linhart W, Windolf J. Current concepts: simple and complex elbow dislocations—acute and definitive treatment. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2008;34(2):120-130. doi:10.1007/s00068-008-8033-9.

6. Marcheix B, Chaufour X, Ayel J, et al. Transection of the brachial artery after closed posterior elbow dislocation. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(6):1230-1232. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2005.07.046.

1. Carter SJ, Germann CA, Dacus AA, Sweeney TW, Perron AD. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: neurovascular injury associated with posterior elbow dislocations. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(8):960-965. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.05.024.

2. Miyazaki AN, Fregoneze M, Santos PD, do Val Sella G, Checchia CS, Checchia SL. Brachial artery injury due to closed posterior elbow dislocation: case report. Rev Bras Ortop. 2016;51(2):239-243. doi:10.1016/j.rboe.2016.02.007.

3. Beingessner J, Pollock W, King GJW. Elbow fractures and dislocations. In: Court-Brown CM, Heckman JD, McQueen MM, Ricci WM, Tornetta P, eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015:1179-1228.

4. McCabe MP, Savoie FH 3rd. Simple elbow dislocations: evaluation, management, and outcomes. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40(1):62-71. doi:10.3810/psm.2012.02.1952.

5. Jungbluth P, Hakimi M, Linhart W, Windolf J. Current concepts: simple and complex elbow dislocations—acute and definitive treatment. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2008;34(2):120-130. doi:10.1007/s00068-008-8033-9.

6. Marcheix B, Chaufour X, Ayel J, et al. Transection of the brachial artery after closed posterior elbow dislocation. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(6):1230-1232. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2005.07.046.

What's Eating You? Sticktight Flea Revisited

Identifying Characteristics

The sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea) earns its name by embedding its head in the host's skin using broad and serrated laciniae and can feed at one site for up to 19 days.1 It differs in morphology from dog (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat (Ctenocephalides felis) fleas, lacking genal (mustache area) and promotal (back of the head) ctenidia (combs), and is half the size of the cat flea. It has 2 pairs of setae (hairs) behind the antennae with an anteriorly flattened head (Figure).

Disease Transmission

Although its primary host is poultry and it also is known as the stickfast or chicken flea, the sticktight flea has been found in many species of birds and mammals, including humans. It is becoming more common in dogs in many parts of the world, including the United States,2-5 and has been found to be the most common flea on dogs in areas of South Africa.6 Other noted hosts of E gallinacea are rodents, cottontail rabbits, cats, ground squirrels, and pigs.7-14 Human infestation occurs from exposure to affected animals.15 As blood feeders, fleas have long been known to serve as vectors for many diseases, including bubonic plague, typhus, and tularemia, as well as an intermediate host of the dog tapeworm (Dipylidium caninum).5 Rickettsia felis, belonging to the spotted fever group, is an emerging infectious disease in humans commonly found in the cat flea (C felis) but also has been detected in E gallinacea.7 Echidnophaga gallinacea is found worldwide in the tropics, subtropics, and temperate zones, and it is the only representative of the genus found in the United States.1 Given the wide range of wild and domestic animal hosts and wide geographic distribution for E gallinacea, it represents an increasing risk for humans.

Echidnophaga gallinacea favors feeding from fleshy areas without thick fur or plumage. In birds, the area around the eyes, comb, and wattles is included; in dogs, it can be the eyes, in between the toes, and in the genital area.1 Flea bites cause irritation and itching for hosts including humans, typically resulting in clusters of firm, pruritic, erythematous papules with a central punctum.15 Severe bites also may lead to bullous lesions. In birds, symptoms can be extreme, with infestation around the eyes leading to swelling and blindness, a decline in egg production, weight loss, and death in young birds.1 Similar to other fleas, E gallinacea is wingless and depends on jumping onto a host for transmission, which can be from the ground, carpeting and flooring, furniture, or another host. Fleas are champion jumpers (relative to body size) and can jump 100 times their length.16

Management

Treating sticktight fleas can be tricky, as they embed tightly into the host's skin. Animals should be treated by a qualified veterinarian. Removal of attached fleas in humans requires grasping the flea firmly with tweezers and pulling from the skin. If the infestation is considerable, malathion 5% liquid or gel can be applied. Patients can treat itching with topical steroids and antipruritic creams, and oral antihistamines can be used to relieve symptoms and reduce the likelihood of damaged skin as well as the potential for secondary infection. The flea-infested environment should be treated with insecticides. For treatment of hard surfaces, dichlorvos and propetamphos are effective. Organophosphates work well on fabric and carpeting. Domestic pets and livestock may be treated by a veterinarian with agents such as fipronil, selamectin, imidacloprid, metaflumizone, nitenpyram, lufenuron, methoprene, and pyriproxyfen.

- Gyimesi ZS, Hayden ER, Greiner EC. Sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea) infestation in a Victoria crowned pigeon (Goura victoria). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2007;38:594-596.

- Kalkofen UP, Greenberg J. Echidnophaga gallinacea infestation in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1974;165:447-448.

- Harman DW, Halliwell RE, Greiner EC. Flea species from dogs and cats in north-central Florida. Vet Parasitol. 1987;23:135-140.

- Boughton RK, Atwell JW, Schoech SJ. An introduced generalist parasite, the sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea), and its pathology in the threatened Florida scrub-jay (Aphelocoma coerulescens). J Parasitol. 2006;92:941-948.

- Durden LA, Judy TN, Martin JE, et al. Fleas parasitizing domestic dogs in Georgia, USA: species composition and seasonal abundance. Vet Parasitol. 2005;130:157-162.

- Rautenbach GH, Boomker J, de Villiers IL. A descriptive study of the canine population in a rural town in southern Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1991;62:158-162.

- Leulmi H, Socolovschi C, Laudisoit A, et al. Detection of Rickettsia felis, Rickettsia typhi, Bartonella species and Yersinia pestis in fleas (Siphonaptera) from Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3152.

- Guernier V, Lagadec E, LeMinter G, et al. Fleas of small mammals on Reunion Island: diversity, distribution and epidemiological consequences. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3129.

- Cantó GJ, Guerrero RI, Olvera-Ramírez AM, et al. Prevalence of fleas and gastrointestinal parasites in free-roaming cats in central Mexico [published online April 3, 2013]. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60744.

- Akucewich LH, Philman K, Clark A, et al. Prevalence of ectoparasites in a population of feral cats from north central Florida during the summer. Vet Parasitol. 2002;109:129-139.

- Linardi PM, Gomes AF, Botelho JR, et al. Some ectoparasites of commensal rodents from Huambo, Angola. J Med Entomol. 1994;31:754-756.

- Pfaffenberger GS, Valencia VB. Ectoparasites of sympatric cottontails (Sylvilagus audubonii Nelson) and jack rabbits (Lepus californicus Mearns) from the high plains of eastern New Mexico. J Parasitol. 1988;74:842-846.

- Hubbart JA, Jachowski DS, Eads DA. Seasonal and among-site variation in the occurrence and abundance of fleas on California ground squirrels (Otospermophilus beecheyi). J Vector Ecol. 2011;36:117-123.

- Braae UC, Ngowi HA, Johansen MV. Smallholder pig production: prevalence and risk factors of ectoparasites. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:241-244.

- Carlson JC, Fox MS. A sticktight flea removed from the cheek of a two-year-old boy from Los Angeles. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:4.

- Rothschild M, Schlein Y, Parker K, et al. The flying leap of the flea. Scientific American. 1973;229:92.

Identifying Characteristics

The sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea) earns its name by embedding its head in the host's skin using broad and serrated laciniae and can feed at one site for up to 19 days.1 It differs in morphology from dog (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat (Ctenocephalides felis) fleas, lacking genal (mustache area) and promotal (back of the head) ctenidia (combs), and is half the size of the cat flea. It has 2 pairs of setae (hairs) behind the antennae with an anteriorly flattened head (Figure).

Disease Transmission

Although its primary host is poultry and it also is known as the stickfast or chicken flea, the sticktight flea has been found in many species of birds and mammals, including humans. It is becoming more common in dogs in many parts of the world, including the United States,2-5 and has been found to be the most common flea on dogs in areas of South Africa.6 Other noted hosts of E gallinacea are rodents, cottontail rabbits, cats, ground squirrels, and pigs.7-14 Human infestation occurs from exposure to affected animals.15 As blood feeders, fleas have long been known to serve as vectors for many diseases, including bubonic plague, typhus, and tularemia, as well as an intermediate host of the dog tapeworm (Dipylidium caninum).5 Rickettsia felis, belonging to the spotted fever group, is an emerging infectious disease in humans commonly found in the cat flea (C felis) but also has been detected in E gallinacea.7 Echidnophaga gallinacea is found worldwide in the tropics, subtropics, and temperate zones, and it is the only representative of the genus found in the United States.1 Given the wide range of wild and domestic animal hosts and wide geographic distribution for E gallinacea, it represents an increasing risk for humans.

Echidnophaga gallinacea favors feeding from fleshy areas without thick fur or plumage. In birds, the area around the eyes, comb, and wattles is included; in dogs, it can be the eyes, in between the toes, and in the genital area.1 Flea bites cause irritation and itching for hosts including humans, typically resulting in clusters of firm, pruritic, erythematous papules with a central punctum.15 Severe bites also may lead to bullous lesions. In birds, symptoms can be extreme, with infestation around the eyes leading to swelling and blindness, a decline in egg production, weight loss, and death in young birds.1 Similar to other fleas, E gallinacea is wingless and depends on jumping onto a host for transmission, which can be from the ground, carpeting and flooring, furniture, or another host. Fleas are champion jumpers (relative to body size) and can jump 100 times their length.16

Management

Treating sticktight fleas can be tricky, as they embed tightly into the host's skin. Animals should be treated by a qualified veterinarian. Removal of attached fleas in humans requires grasping the flea firmly with tweezers and pulling from the skin. If the infestation is considerable, malathion 5% liquid or gel can be applied. Patients can treat itching with topical steroids and antipruritic creams, and oral antihistamines can be used to relieve symptoms and reduce the likelihood of damaged skin as well as the potential for secondary infection. The flea-infested environment should be treated with insecticides. For treatment of hard surfaces, dichlorvos and propetamphos are effective. Organophosphates work well on fabric and carpeting. Domestic pets and livestock may be treated by a veterinarian with agents such as fipronil, selamectin, imidacloprid, metaflumizone, nitenpyram, lufenuron, methoprene, and pyriproxyfen.

Identifying Characteristics

The sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea) earns its name by embedding its head in the host's skin using broad and serrated laciniae and can feed at one site for up to 19 days.1 It differs in morphology from dog (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat (Ctenocephalides felis) fleas, lacking genal (mustache area) and promotal (back of the head) ctenidia (combs), and is half the size of the cat flea. It has 2 pairs of setae (hairs) behind the antennae with an anteriorly flattened head (Figure).

Disease Transmission

Although its primary host is poultry and it also is known as the stickfast or chicken flea, the sticktight flea has been found in many species of birds and mammals, including humans. It is becoming more common in dogs in many parts of the world, including the United States,2-5 and has been found to be the most common flea on dogs in areas of South Africa.6 Other noted hosts of E gallinacea are rodents, cottontail rabbits, cats, ground squirrels, and pigs.7-14 Human infestation occurs from exposure to affected animals.15 As blood feeders, fleas have long been known to serve as vectors for many diseases, including bubonic plague, typhus, and tularemia, as well as an intermediate host of the dog tapeworm (Dipylidium caninum).5 Rickettsia felis, belonging to the spotted fever group, is an emerging infectious disease in humans commonly found in the cat flea (C felis) but also has been detected in E gallinacea.7 Echidnophaga gallinacea is found worldwide in the tropics, subtropics, and temperate zones, and it is the only representative of the genus found in the United States.1 Given the wide range of wild and domestic animal hosts and wide geographic distribution for E gallinacea, it represents an increasing risk for humans.

Echidnophaga gallinacea favors feeding from fleshy areas without thick fur or plumage. In birds, the area around the eyes, comb, and wattles is included; in dogs, it can be the eyes, in between the toes, and in the genital area.1 Flea bites cause irritation and itching for hosts including humans, typically resulting in clusters of firm, pruritic, erythematous papules with a central punctum.15 Severe bites also may lead to bullous lesions. In birds, symptoms can be extreme, with infestation around the eyes leading to swelling and blindness, a decline in egg production, weight loss, and death in young birds.1 Similar to other fleas, E gallinacea is wingless and depends on jumping onto a host for transmission, which can be from the ground, carpeting and flooring, furniture, or another host. Fleas are champion jumpers (relative to body size) and can jump 100 times their length.16

Management

Treating sticktight fleas can be tricky, as they embed tightly into the host's skin. Animals should be treated by a qualified veterinarian. Removal of attached fleas in humans requires grasping the flea firmly with tweezers and pulling from the skin. If the infestation is considerable, malathion 5% liquid or gel can be applied. Patients can treat itching with topical steroids and antipruritic creams, and oral antihistamines can be used to relieve symptoms and reduce the likelihood of damaged skin as well as the potential for secondary infection. The flea-infested environment should be treated with insecticides. For treatment of hard surfaces, dichlorvos and propetamphos are effective. Organophosphates work well on fabric and carpeting. Domestic pets and livestock may be treated by a veterinarian with agents such as fipronil, selamectin, imidacloprid, metaflumizone, nitenpyram, lufenuron, methoprene, and pyriproxyfen.

- Gyimesi ZS, Hayden ER, Greiner EC. Sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea) infestation in a Victoria crowned pigeon (Goura victoria). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2007;38:594-596.

- Kalkofen UP, Greenberg J. Echidnophaga gallinacea infestation in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1974;165:447-448.

- Harman DW, Halliwell RE, Greiner EC. Flea species from dogs and cats in north-central Florida. Vet Parasitol. 1987;23:135-140.

- Boughton RK, Atwell JW, Schoech SJ. An introduced generalist parasite, the sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea), and its pathology in the threatened Florida scrub-jay (Aphelocoma coerulescens). J Parasitol. 2006;92:941-948.

- Durden LA, Judy TN, Martin JE, et al. Fleas parasitizing domestic dogs in Georgia, USA: species composition and seasonal abundance. Vet Parasitol. 2005;130:157-162.

- Rautenbach GH, Boomker J, de Villiers IL. A descriptive study of the canine population in a rural town in southern Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1991;62:158-162.

- Leulmi H, Socolovschi C, Laudisoit A, et al. Detection of Rickettsia felis, Rickettsia typhi, Bartonella species and Yersinia pestis in fleas (Siphonaptera) from Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3152.

- Guernier V, Lagadec E, LeMinter G, et al. Fleas of small mammals on Reunion Island: diversity, distribution and epidemiological consequences. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3129.

- Cantó GJ, Guerrero RI, Olvera-Ramírez AM, et al. Prevalence of fleas and gastrointestinal parasites in free-roaming cats in central Mexico [published online April 3, 2013]. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60744.

- Akucewich LH, Philman K, Clark A, et al. Prevalence of ectoparasites in a population of feral cats from north central Florida during the summer. Vet Parasitol. 2002;109:129-139.

- Linardi PM, Gomes AF, Botelho JR, et al. Some ectoparasites of commensal rodents from Huambo, Angola. J Med Entomol. 1994;31:754-756.

- Pfaffenberger GS, Valencia VB. Ectoparasites of sympatric cottontails (Sylvilagus audubonii Nelson) and jack rabbits (Lepus californicus Mearns) from the high plains of eastern New Mexico. J Parasitol. 1988;74:842-846.

- Hubbart JA, Jachowski DS, Eads DA. Seasonal and among-site variation in the occurrence and abundance of fleas on California ground squirrels (Otospermophilus beecheyi). J Vector Ecol. 2011;36:117-123.

- Braae UC, Ngowi HA, Johansen MV. Smallholder pig production: prevalence and risk factors of ectoparasites. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:241-244.

- Carlson JC, Fox MS. A sticktight flea removed from the cheek of a two-year-old boy from Los Angeles. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:4.

- Rothschild M, Schlein Y, Parker K, et al. The flying leap of the flea. Scientific American. 1973;229:92.

- Gyimesi ZS, Hayden ER, Greiner EC. Sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea) infestation in a Victoria crowned pigeon (Goura victoria). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2007;38:594-596.

- Kalkofen UP, Greenberg J. Echidnophaga gallinacea infestation in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1974;165:447-448.

- Harman DW, Halliwell RE, Greiner EC. Flea species from dogs and cats in north-central Florida. Vet Parasitol. 1987;23:135-140.

- Boughton RK, Atwell JW, Schoech SJ. An introduced generalist parasite, the sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea), and its pathology in the threatened Florida scrub-jay (Aphelocoma coerulescens). J Parasitol. 2006;92:941-948.

- Durden LA, Judy TN, Martin JE, et al. Fleas parasitizing domestic dogs in Georgia, USA: species composition and seasonal abundance. Vet Parasitol. 2005;130:157-162.

- Rautenbach GH, Boomker J, de Villiers IL. A descriptive study of the canine population in a rural town in southern Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1991;62:158-162.

- Leulmi H, Socolovschi C, Laudisoit A, et al. Detection of Rickettsia felis, Rickettsia typhi, Bartonella species and Yersinia pestis in fleas (Siphonaptera) from Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3152.

- Guernier V, Lagadec E, LeMinter G, et al. Fleas of small mammals on Reunion Island: diversity, distribution and epidemiological consequences. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3129.

- Cantó GJ, Guerrero RI, Olvera-Ramírez AM, et al. Prevalence of fleas and gastrointestinal parasites in free-roaming cats in central Mexico [published online April 3, 2013]. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60744.

- Akucewich LH, Philman K, Clark A, et al. Prevalence of ectoparasites in a population of feral cats from north central Florida during the summer. Vet Parasitol. 2002;109:129-139.

- Linardi PM, Gomes AF, Botelho JR, et al. Some ectoparasites of commensal rodents from Huambo, Angola. J Med Entomol. 1994;31:754-756.

- Pfaffenberger GS, Valencia VB. Ectoparasites of sympatric cottontails (Sylvilagus audubonii Nelson) and jack rabbits (Lepus californicus Mearns) from the high plains of eastern New Mexico. J Parasitol. 1988;74:842-846.

- Hubbart JA, Jachowski DS, Eads DA. Seasonal and among-site variation in the occurrence and abundance of fleas on California ground squirrels (Otospermophilus beecheyi). J Vector Ecol. 2011;36:117-123.

- Braae UC, Ngowi HA, Johansen MV. Smallholder pig production: prevalence and risk factors of ectoparasites. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:241-244.

- Carlson JC, Fox MS. A sticktight flea removed from the cheek of a two-year-old boy from Los Angeles. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:4.

- Rothschild M, Schlein Y, Parker K, et al. The flying leap of the flea. Scientific American. 1973;229:92.

Practice Points

- Although the primary host of the sticktight flea is poultry, it has been found in many species of birds and mammals, including humans.

- Flea bites cause irritation and itching for hosts, typically resulting in clusters of firm, pruritic, erythematous papules with a central punctum.

- Removal of attached fleas in humans requires grasping the flea firmly with tweezers and pulling from the skin.

Some adjuvant endocrine therapies better than others for young breast cancer patients

Young women treated for early hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer fare better if their adjuvant endocrine therapy includes ovarian function suppression (OFS), according to a new analysis published online.

Senior author Gini F. Fleming, MD, director of the medical oncology breast program at the University of Chicago Medical Center, and her colleagues analyzed data from a pair of international phase III randomized adjuvant trials: the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial (SOFT) and the Tamoxifen and Exemestane Trial (TEXT).

Main analyses were based on a respective 240 and 145 women younger than 35 years who had undergone surgery for early hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer, received chemotherapy, and were randomly assigned to 5 years of various adjuvant endocrine therapies.

In SOFT, the 5-year breast cancer–free interval was 67.1% (95% CI, 54.6%-76.9%) with tamoxifen (Nolvadex) alone, 75.9% (64.0%-84.4%) with tamoxifen plus OFS, and 83.2% (72.7%-90.0%) with exemestane (Aromasin) plus OFS (J Clin Oncol. 2017 June 27 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0946). In TEXT, it was 79.2% (66.2%-87.7%) with tamoxifen plus OFS and 81.6% (69.8%-89.2%) with exemestane plus OFS.

In a quality of life analysis among women receiving OFS, vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and sweats) showed greatest increase from baseline (roughly 30-40 points) in the first 6 months of therapy. Loss of sexual interest and difficulties in becoming aroused were also noteworthy (8 points or greater). However, scores for global quality of life (physical well-being, mood, coping effort, and health perception) showed little change from baseline and were essentially the same as those seen among premenopausal women aged 35 or older in the same trials.

Overall, 19.8% of the young women in SOFT and TEXT stopped all protocol-assigned endocrine therapy early. The proportion rose with time and was higher than that among the older premenopausal group.

“There was a meaningful clinical benefit in breast cancer outcomes with the addition of OFS to tamoxifen and some additional benefit from use of an aromatase inhibitor with OFS. Longer follow-up is critical to clarify potential survival benefits,” the investigators wrote. “There were substantial adverse effects from these combined endocrine treatments, but they were not different in the younger and older than 35 years populations. Despite this, rates of nonadherence were slightly higher in women younger than 35 years.

“Availability of these age-specific data regarding risks and benefits of combined endocrine therapy will support shared decision making regarding OFS among young women at high risk for recurrence and death from breast cancer and, it is hoped, improve adherence among those who select OFS,” they concluded.

Young women treated for early hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer fare better if their adjuvant endocrine therapy includes ovarian function suppression (OFS), according to a new analysis published online.

Senior author Gini F. Fleming, MD, director of the medical oncology breast program at the University of Chicago Medical Center, and her colleagues analyzed data from a pair of international phase III randomized adjuvant trials: the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial (SOFT) and the Tamoxifen and Exemestane Trial (TEXT).

Main analyses were based on a respective 240 and 145 women younger than 35 years who had undergone surgery for early hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer, received chemotherapy, and were randomly assigned to 5 years of various adjuvant endocrine therapies.

In SOFT, the 5-year breast cancer–free interval was 67.1% (95% CI, 54.6%-76.9%) with tamoxifen (Nolvadex) alone, 75.9% (64.0%-84.4%) with tamoxifen plus OFS, and 83.2% (72.7%-90.0%) with exemestane (Aromasin) plus OFS (J Clin Oncol. 2017 June 27 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0946). In TEXT, it was 79.2% (66.2%-87.7%) with tamoxifen plus OFS and 81.6% (69.8%-89.2%) with exemestane plus OFS.

In a quality of life analysis among women receiving OFS, vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and sweats) showed greatest increase from baseline (roughly 30-40 points) in the first 6 months of therapy. Loss of sexual interest and difficulties in becoming aroused were also noteworthy (8 points or greater). However, scores for global quality of life (physical well-being, mood, coping effort, and health perception) showed little change from baseline and were essentially the same as those seen among premenopausal women aged 35 or older in the same trials.

Overall, 19.8% of the young women in SOFT and TEXT stopped all protocol-assigned endocrine therapy early. The proportion rose with time and was higher than that among the older premenopausal group.

“There was a meaningful clinical benefit in breast cancer outcomes with the addition of OFS to tamoxifen and some additional benefit from use of an aromatase inhibitor with OFS. Longer follow-up is critical to clarify potential survival benefits,” the investigators wrote. “There were substantial adverse effects from these combined endocrine treatments, but they were not different in the younger and older than 35 years populations. Despite this, rates of nonadherence were slightly higher in women younger than 35 years.

“Availability of these age-specific data regarding risks and benefits of combined endocrine therapy will support shared decision making regarding OFS among young women at high risk for recurrence and death from breast cancer and, it is hoped, improve adherence among those who select OFS,” they concluded.

Young women treated for early hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer fare better if their adjuvant endocrine therapy includes ovarian function suppression (OFS), according to a new analysis published online.

Senior author Gini F. Fleming, MD, director of the medical oncology breast program at the University of Chicago Medical Center, and her colleagues analyzed data from a pair of international phase III randomized adjuvant trials: the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial (SOFT) and the Tamoxifen and Exemestane Trial (TEXT).

Main analyses were based on a respective 240 and 145 women younger than 35 years who had undergone surgery for early hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer, received chemotherapy, and were randomly assigned to 5 years of various adjuvant endocrine therapies.

In SOFT, the 5-year breast cancer–free interval was 67.1% (95% CI, 54.6%-76.9%) with tamoxifen (Nolvadex) alone, 75.9% (64.0%-84.4%) with tamoxifen plus OFS, and 83.2% (72.7%-90.0%) with exemestane (Aromasin) plus OFS (J Clin Oncol. 2017 June 27 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0946). In TEXT, it was 79.2% (66.2%-87.7%) with tamoxifen plus OFS and 81.6% (69.8%-89.2%) with exemestane plus OFS.

In a quality of life analysis among women receiving OFS, vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and sweats) showed greatest increase from baseline (roughly 30-40 points) in the first 6 months of therapy. Loss of sexual interest and difficulties in becoming aroused were also noteworthy (8 points or greater). However, scores for global quality of life (physical well-being, mood, coping effort, and health perception) showed little change from baseline and were essentially the same as those seen among premenopausal women aged 35 or older in the same trials.

Overall, 19.8% of the young women in SOFT and TEXT stopped all protocol-assigned endocrine therapy early. The proportion rose with time and was higher than that among the older premenopausal group.

“There was a meaningful clinical benefit in breast cancer outcomes with the addition of OFS to tamoxifen and some additional benefit from use of an aromatase inhibitor with OFS. Longer follow-up is critical to clarify potential survival benefits,” the investigators wrote. “There were substantial adverse effects from these combined endocrine treatments, but they were not different in the younger and older than 35 years populations. Despite this, rates of nonadherence were slightly higher in women younger than 35 years.

“Availability of these age-specific data regarding risks and benefits of combined endocrine therapy will support shared decision making regarding OFS among young women at high risk for recurrence and death from breast cancer and, it is hoped, improve adherence among those who select OFS,” they concluded.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In SOFT, the 5-year breast cancer–free interval was 67.1% with tamoxifen alone, 75.9% with tamoxifen plus OFS, and 83.2% with exemestane plus OFS. In TEXT, it was 79.2% with tamoxifen plus OFS and 81.6% with exemestane plus OFS.

Data source: An analysis of women younger than 35 years treated for early hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer and given adjuvant endocrine therapy in the phase III randomized SOFT trial (240 women) or TEXT trial (145 women).

Disclosures: Dr. Fleming disclosed that she receives research funding from Corcept Therapeutics (institutional) and has a relationship with Aeterna Zentaris.

Cognitive declines tied to stress in older African Americans

Higher levels of perceived stress appear to be associated with faster declines in two cognitive domains – episodic memory and visuospatial ability – among older African Americans without dementia, results from a longitudinal study of 467 participants suggest.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between perceived stress and cognition in specific cognitive domains in general and in a minority population in particular,” reported Arlener D. Turner, PhD, of the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center and the department of behavioral sciences at Rush University, Chicago, and her associates.

Each participant took a battery of neuropsychological tests, including the MMSE, annually for up to 9 years. The participants’ stress levels were assessed using a 4-item version of Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), “an index of the degree to which a person finds their lives unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloading – characteristics central to the evaluation of stress” (Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25[1]:25-34).

Dr. Turner and her associates found that participants with a mean age and education level, and a PSS score 1 point above the mean experienced annual declines in episodic memory of 0.022 points (P = .047) and in visuospatial ability of 0.021 points (P = .017). No such associations were found for semantic or working memory or for perceptual speed.

The investigators said that the study did not pinpoint the mechanisms that link stress to cognition. “The well-established mechanism of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis dysregulation in chronic stress may play a role,” they wrote. Another contributing factor could be inflammation, they said, citing research showing that discrimination is “a persistent stressor in African Americans and that perceived discrimination is associated with elevated levels of C-reactive protein.” Future studies are needed, they said, to test which mechanisms might be pathways between perceived stress and cognitive decline.

They cited several limitations. For example, because less educational attainment is associated with higher levels of stress and this cohort had achieved educational levels that were relatively high, this cohort’s reports of perceived stress might have been modest. In addition, “perception of stress is, by nature, a self-report measure,” the investigators wrote.

The National Institute on Aging and the Illinois Department of Public Health funded the study. Neither Dr. Turner nor her associates had any conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @ginahenderson

Higher levels of perceived stress appear to be associated with faster declines in two cognitive domains – episodic memory and visuospatial ability – among older African Americans without dementia, results from a longitudinal study of 467 participants suggest.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between perceived stress and cognition in specific cognitive domains in general and in a minority population in particular,” reported Arlener D. Turner, PhD, of the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center and the department of behavioral sciences at Rush University, Chicago, and her associates.

Each participant took a battery of neuropsychological tests, including the MMSE, annually for up to 9 years. The participants’ stress levels were assessed using a 4-item version of Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), “an index of the degree to which a person finds their lives unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloading – characteristics central to the evaluation of stress” (Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25[1]:25-34).

Dr. Turner and her associates found that participants with a mean age and education level, and a PSS score 1 point above the mean experienced annual declines in episodic memory of 0.022 points (P = .047) and in visuospatial ability of 0.021 points (P = .017). No such associations were found for semantic or working memory or for perceptual speed.

The investigators said that the study did not pinpoint the mechanisms that link stress to cognition. “The well-established mechanism of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis dysregulation in chronic stress may play a role,” they wrote. Another contributing factor could be inflammation, they said, citing research showing that discrimination is “a persistent stressor in African Americans and that perceived discrimination is associated with elevated levels of C-reactive protein.” Future studies are needed, they said, to test which mechanisms might be pathways between perceived stress and cognitive decline.

They cited several limitations. For example, because less educational attainment is associated with higher levels of stress and this cohort had achieved educational levels that were relatively high, this cohort’s reports of perceived stress might have been modest. In addition, “perception of stress is, by nature, a self-report measure,” the investigators wrote.

The National Institute on Aging and the Illinois Department of Public Health funded the study. Neither Dr. Turner nor her associates had any conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @ginahenderson

Higher levels of perceived stress appear to be associated with faster declines in two cognitive domains – episodic memory and visuospatial ability – among older African Americans without dementia, results from a longitudinal study of 467 participants suggest.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between perceived stress and cognition in specific cognitive domains in general and in a minority population in particular,” reported Arlener D. Turner, PhD, of the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center and the department of behavioral sciences at Rush University, Chicago, and her associates.

Each participant took a battery of neuropsychological tests, including the MMSE, annually for up to 9 years. The participants’ stress levels were assessed using a 4-item version of Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), “an index of the degree to which a person finds their lives unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloading – characteristics central to the evaluation of stress” (Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25[1]:25-34).

Dr. Turner and her associates found that participants with a mean age and education level, and a PSS score 1 point above the mean experienced annual declines in episodic memory of 0.022 points (P = .047) and in visuospatial ability of 0.021 points (P = .017). No such associations were found for semantic or working memory or for perceptual speed.

The investigators said that the study did not pinpoint the mechanisms that link stress to cognition. “The well-established mechanism of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis dysregulation in chronic stress may play a role,” they wrote. Another contributing factor could be inflammation, they said, citing research showing that discrimination is “a persistent stressor in African Americans and that perceived discrimination is associated with elevated levels of C-reactive protein.” Future studies are needed, they said, to test which mechanisms might be pathways between perceived stress and cognitive decline.

They cited several limitations. For example, because less educational attainment is associated with higher levels of stress and this cohort had achieved educational levels that were relatively high, this cohort’s reports of perceived stress might have been modest. In addition, “perception of stress is, by nature, a self-report measure,” the investigators wrote.

The National Institute on Aging and the Illinois Department of Public Health funded the study. Neither Dr. Turner nor her associates had any conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @ginahenderson

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GERIATRIC PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Participants with a mean age of 73.4 years and education level of 15 years and a score 1 point above the mean on Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale experienced annual declines in episodic memory of 0.022 points (P = .047) and in visuospatial ability of 0.021 points (P = .017).

Data source: An analysis of 467 African Americans enrolled in the longitudinal Minority Aging Research Study.

Disclosures: The National Institute on Aging and the Illinois Department of Public Health funded the study. Neither Dr. Turner nor her associates had any conflicts of interest.

Low-fat diet reduces risk of death if breast cancer is diagnosed

Women can reduce their risk of dying should they receive a breast cancer diagnosis by following a low-fat diet, suggests an analysis from the phase III multicenter randomized Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification trial.

Investigators led by Rowan T. Chlebowski, MD, PhD, formerly of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California, and now at City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, California, analyzed data from 48,835 postmenopausal women who had never had breast cancer and had normal mammograms. The women were randomly assigned 2:3 to a diet aimed at reducing fat intake to 20% of energy and increasing intake of fruits, vegetables, and grains or to a usual diet.

However, the rate of deaths after breast cancer from any cause was 0.025% per year in the former group and 0.038% per year in the latter group, a difference that translated to a more than one-third reduction in risk (hazard ratio, 0.65; P = .02).

Similarly, during the median 16.1-year total follow-up, the rate of deaths attributed to breast cancer was 0.035% per year in the low-fat diet group and 0.039% per year in the usual diet group, a difference that was not significant (P =. 41). However, the rate of deaths after breast cancer from any cause was 0.085% per year in the former group and 0.11% per year in the latter group, a difference that translated to a nearly one-fifth reduction in the risk of death (HR, 0.82; P = .01).

In subgroup analyses, there were significant interactions whereby benefit was greater for women who had a baseline waist circumference of at least 88 cm and increased with the baseline percentage of total energy from fat.

“The lower risk of poor prognosis, ER+, PR– breast cancers … in the dietary group contributed to the favorable dietary effect on death after breast cancer,” the investigators noted. “An additional factor that potentially influenced deaths after breast cancer could be a favorable dietary influence on mortality as a result of other causes, including cardiovascular disease.”

“Future studies of other lifestyle interventions on breast cancer incidence and outcome could incorporate some form of a low-fat dietary pattern as a base,” they concluded.

Women can reduce their risk of dying should they receive a breast cancer diagnosis by following a low-fat diet, suggests an analysis from the phase III multicenter randomized Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification trial.

Investigators led by Rowan T. Chlebowski, MD, PhD, formerly of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California, and now at City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, California, analyzed data from 48,835 postmenopausal women who had never had breast cancer and had normal mammograms. The women were randomly assigned 2:3 to a diet aimed at reducing fat intake to 20% of energy and increasing intake of fruits, vegetables, and grains or to a usual diet.

However, the rate of deaths after breast cancer from any cause was 0.025% per year in the former group and 0.038% per year in the latter group, a difference that translated to a more than one-third reduction in risk (hazard ratio, 0.65; P = .02).

Similarly, during the median 16.1-year total follow-up, the rate of deaths attributed to breast cancer was 0.035% per year in the low-fat diet group and 0.039% per year in the usual diet group, a difference that was not significant (P =. 41). However, the rate of deaths after breast cancer from any cause was 0.085% per year in the former group and 0.11% per year in the latter group, a difference that translated to a nearly one-fifth reduction in the risk of death (HR, 0.82; P = .01).

In subgroup analyses, there were significant interactions whereby benefit was greater for women who had a baseline waist circumference of at least 88 cm and increased with the baseline percentage of total energy from fat.

“The lower risk of poor prognosis, ER+, PR– breast cancers … in the dietary group contributed to the favorable dietary effect on death after breast cancer,” the investigators noted. “An additional factor that potentially influenced deaths after breast cancer could be a favorable dietary influence on mortality as a result of other causes, including cardiovascular disease.”

“Future studies of other lifestyle interventions on breast cancer incidence and outcome could incorporate some form of a low-fat dietary pattern as a base,” they concluded.

Women can reduce their risk of dying should they receive a breast cancer diagnosis by following a low-fat diet, suggests an analysis from the phase III multicenter randomized Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification trial.

Investigators led by Rowan T. Chlebowski, MD, PhD, formerly of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California, and now at City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, California, analyzed data from 48,835 postmenopausal women who had never had breast cancer and had normal mammograms. The women were randomly assigned 2:3 to a diet aimed at reducing fat intake to 20% of energy and increasing intake of fruits, vegetables, and grains or to a usual diet.

However, the rate of deaths after breast cancer from any cause was 0.025% per year in the former group and 0.038% per year in the latter group, a difference that translated to a more than one-third reduction in risk (hazard ratio, 0.65; P = .02).

Similarly, during the median 16.1-year total follow-up, the rate of deaths attributed to breast cancer was 0.035% per year in the low-fat diet group and 0.039% per year in the usual diet group, a difference that was not significant (P =. 41). However, the rate of deaths after breast cancer from any cause was 0.085% per year in the former group and 0.11% per year in the latter group, a difference that translated to a nearly one-fifth reduction in the risk of death (HR, 0.82; P = .01).

In subgroup analyses, there were significant interactions whereby benefit was greater for women who had a baseline waist circumference of at least 88 cm and increased with the baseline percentage of total energy from fat.

“The lower risk of poor prognosis, ER+, PR– breast cancers … in the dietary group contributed to the favorable dietary effect on death after breast cancer,” the investigators noted. “An additional factor that potentially influenced deaths after breast cancer could be a favorable dietary influence on mortality as a result of other causes, including cardiovascular disease.”

“Future studies of other lifestyle interventions on breast cancer incidence and outcome could incorporate some form of a low-fat dietary pattern as a base,” they concluded.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Compared with peers assigned to a usual diet, women assigned to a low-fat diet were less likely to die after breast cancer diagnosis from any cause during both the 8.5-year intervention (HR 0.65) and the 16.1-year total follow-up (HR, 0.82).

Data source: A posthoc analysis of a phase III randomized controlled trial among 48,835 postmenopausal women who had never had breast cancer and had normal mammograms (Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification trial).

Disclosures: Dr. Chlebowski disclosed consulting or advisory roles with Novartis, Genentech, Amgen, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. He is also on the Speakers’ Bureau for Novartis and Genentech.

Phototherapy Coding and Documentation in the Time of Biologics