User login

Gradual vs abrupt smoking cessation: Each has its place

In the article by Smith et al, “ ‘Cold turkey’ works best for smoking cessation” (J Fam Pract. 2017;66:174-176), the authors highlighted a study by Lindson-Hawley et al showing that abrupt cessation was as

While I agree with Smith et al’s assessment of abrupt cessation for patients in the preparation and action stages of change as created by DiClemente and Prochaska,2 most clinical patients are in the pre-contemplative and contemplative stages of change. A bias of the study was that all recruited participants were willing to quit within 2 weeks.

A systematic review by the same authors (Lindson-Hawley et al) compared gradual reduction of smoking with abrupt cessation and found comparable quit rates.3 Smith et al commented that the reason for this conclusion was limitations in the studies, including differences in patient populations, outcome definitions, and types of interventions.

Because a large subset of clinical patients are in the pre-contemplative and contemplative stages of change, I believe gradual cessation remains an important technique to use while patients transition their beliefs.

Jeff Ebel, DO

Toledo, Ohio

Author’s response:

I appreciate Dr. Ebel’s input and perspective. My co-authors and I acknowledge that the previous systematic review noted comparable quit rates, but there were significant limitations to the studies, which Dr. Ebel noted. The highlight from the 2016 randomized, controlled trial by Lindson-Hawley et al is that patients are more likely to quit from abrupt cessation, even if they initially prefer gradual cessation. As Dr. Ebel notes (and we highlighted in the PURL), our role as family physicians is to inform patients of the data, but support them in whatever method of cessation they choose.

Dustin K. Smith, DO

Jacksonville, Fla.

1. Lindson-Hawley N, Banting M, West R, et al. Gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation: a randomized, controlled noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:585-592.

2. DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO. Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: a comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addict Behav. 1982;7:133-142.

3. Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P, Hughes JR. Reduction versus abrupt cessation in smokers who want to quit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD008033.

In the article by Smith et al, “ ‘Cold turkey’ works best for smoking cessation” (J Fam Pract. 2017;66:174-176), the authors highlighted a study by Lindson-Hawley et al showing that abrupt cessation was as

While I agree with Smith et al’s assessment of abrupt cessation for patients in the preparation and action stages of change as created by DiClemente and Prochaska,2 most clinical patients are in the pre-contemplative and contemplative stages of change. A bias of the study was that all recruited participants were willing to quit within 2 weeks.

A systematic review by the same authors (Lindson-Hawley et al) compared gradual reduction of smoking with abrupt cessation and found comparable quit rates.3 Smith et al commented that the reason for this conclusion was limitations in the studies, including differences in patient populations, outcome definitions, and types of interventions.

Because a large subset of clinical patients are in the pre-contemplative and contemplative stages of change, I believe gradual cessation remains an important technique to use while patients transition their beliefs.

Jeff Ebel, DO

Toledo, Ohio

Author’s response:

I appreciate Dr. Ebel’s input and perspective. My co-authors and I acknowledge that the previous systematic review noted comparable quit rates, but there were significant limitations to the studies, which Dr. Ebel noted. The highlight from the 2016 randomized, controlled trial by Lindson-Hawley et al is that patients are more likely to quit from abrupt cessation, even if they initially prefer gradual cessation. As Dr. Ebel notes (and we highlighted in the PURL), our role as family physicians is to inform patients of the data, but support them in whatever method of cessation they choose.

Dustin K. Smith, DO

Jacksonville, Fla.

In the article by Smith et al, “ ‘Cold turkey’ works best for smoking cessation” (J Fam Pract. 2017;66:174-176), the authors highlighted a study by Lindson-Hawley et al showing that abrupt cessation was as

While I agree with Smith et al’s assessment of abrupt cessation for patients in the preparation and action stages of change as created by DiClemente and Prochaska,2 most clinical patients are in the pre-contemplative and contemplative stages of change. A bias of the study was that all recruited participants were willing to quit within 2 weeks.

A systematic review by the same authors (Lindson-Hawley et al) compared gradual reduction of smoking with abrupt cessation and found comparable quit rates.3 Smith et al commented that the reason for this conclusion was limitations in the studies, including differences in patient populations, outcome definitions, and types of interventions.

Because a large subset of clinical patients are in the pre-contemplative and contemplative stages of change, I believe gradual cessation remains an important technique to use while patients transition their beliefs.

Jeff Ebel, DO

Toledo, Ohio

Author’s response:

I appreciate Dr. Ebel’s input and perspective. My co-authors and I acknowledge that the previous systematic review noted comparable quit rates, but there were significant limitations to the studies, which Dr. Ebel noted. The highlight from the 2016 randomized, controlled trial by Lindson-Hawley et al is that patients are more likely to quit from abrupt cessation, even if they initially prefer gradual cessation. As Dr. Ebel notes (and we highlighted in the PURL), our role as family physicians is to inform patients of the data, but support them in whatever method of cessation they choose.

Dustin K. Smith, DO

Jacksonville, Fla.

1. Lindson-Hawley N, Banting M, West R, et al. Gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation: a randomized, controlled noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:585-592.

2. DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO. Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: a comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addict Behav. 1982;7:133-142.

3. Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P, Hughes JR. Reduction versus abrupt cessation in smokers who want to quit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD008033.

1. Lindson-Hawley N, Banting M, West R, et al. Gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation: a randomized, controlled noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:585-592.

2. DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO. Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: a comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addict Behav. 1982;7:133-142.

3. Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P, Hughes JR. Reduction versus abrupt cessation in smokers who want to quit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD008033.

What effects—if any—does marijuana use during pregnancy have on the fetus or child?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

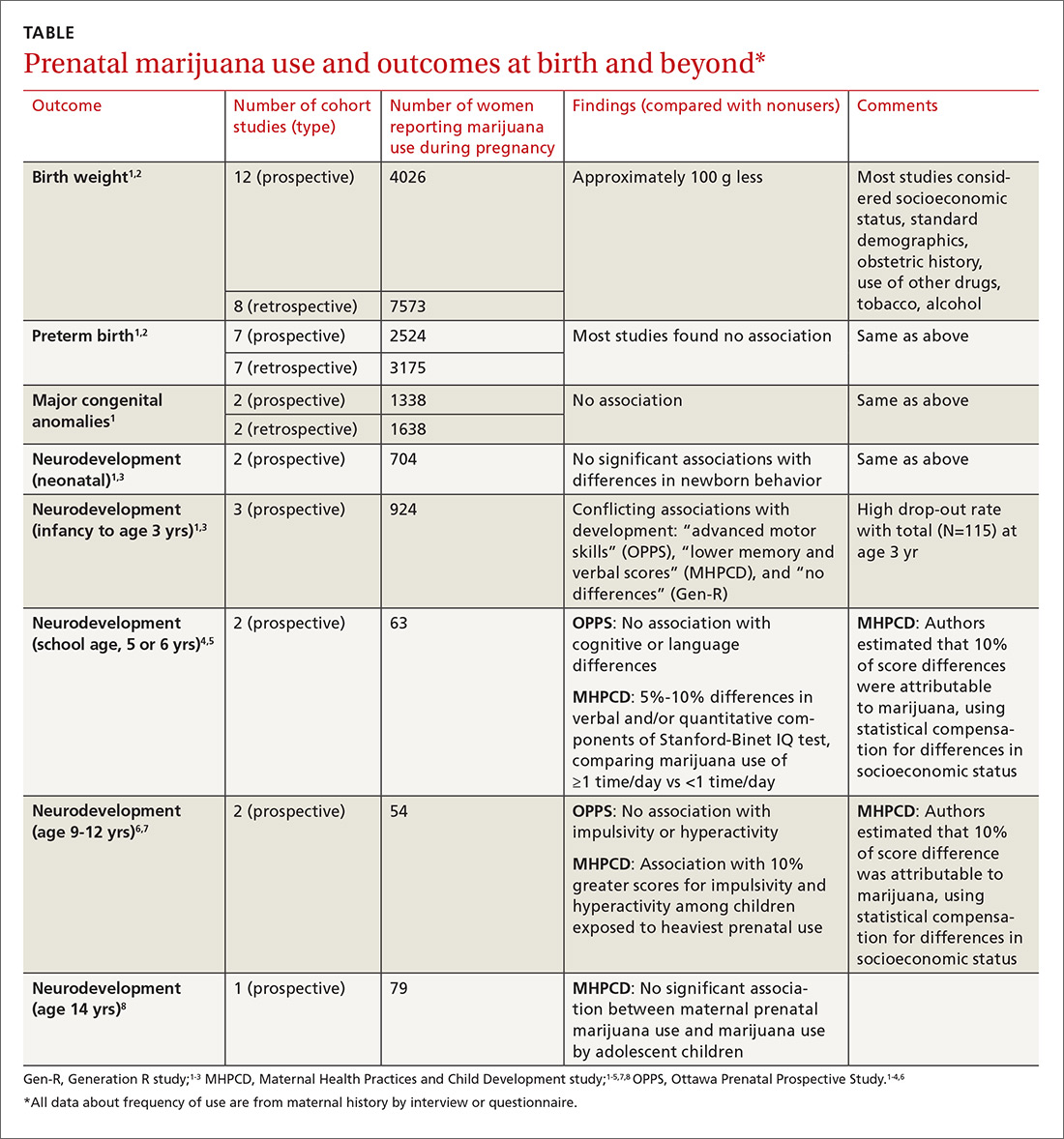

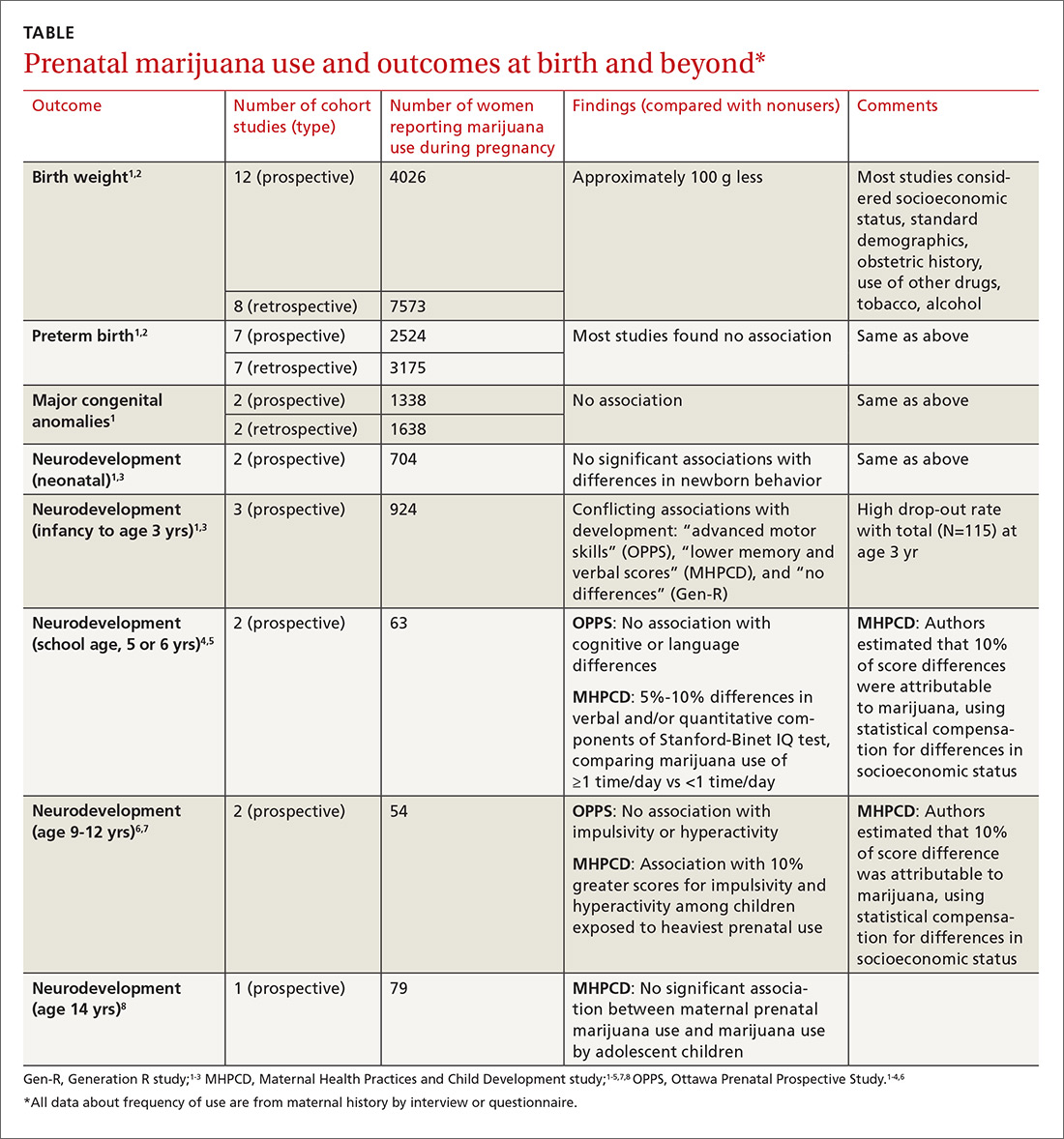

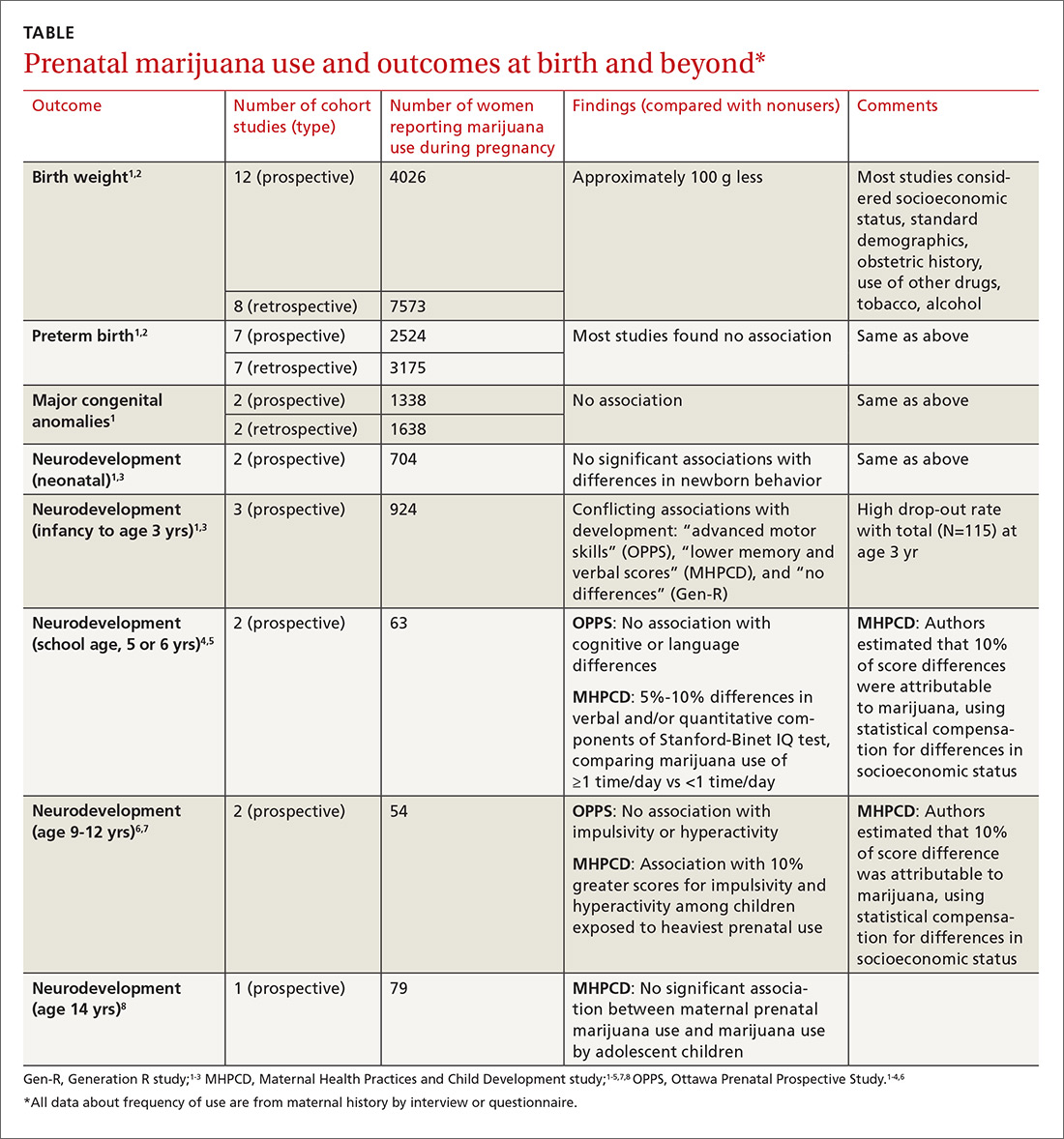

A large systematic review of prospective and retrospective cohort studies found little or no effect of maternal marijuana use on birth weight, stillbirths, preterm births, or congenital anomalies (TABLE1-8). Some studies found lower birth weights and some found higher birth weights. The authors couldn’t perform a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity, but estimated a clinically insignificant difference of 100 g. Most studies were limited by failure to account for concurrent maternal tobacco smoking.

Moreover, all studies used interview data to determine maternal prenatal marijuana use, which can be subject to large recall bias. A multicenter prospective study of 585 pregnant women that compared interview data with serum screening to identify tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) found poor correlation between history and laboratory validation, for example.1 Only 31% of pregnant women with positive THC testing self-reported marijuana use (31% sensitivity), and only 43% of women who reported marijuana use had a positive THC screen (43% specificity). Most studies didn’t quantify marijuana use well and didn’t associate use with trimester of exposure.

The authors also point out that marijuana potency has increased substantially since the 1980s when many of the studies were done (THC content was 3.2% in 1983 and 13% in 2008); prenatal marijuana use in the present day may expose the fetus to larger amounts of THC.1

A 2016 retrospective cohort study of 56 mothers who reported prenatal marijuana use found no differences in preterm birth, low birth weight, or Apgar scores.2

Neurodevelopmental effects on infants, long-term effects on children, teens

Three prospective cohort studies evaluated neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates and infants, and 2 studies continued to follow children into adolescence.1,3 All found essentially no differences associated with prenatal marijuana at birth, throughout infancy, and through age 3 years. The studies had the same limitations as those described previously (potential recall bias for identifying which children were exposed to marijuana prenatally and poorly quantified marijuana use not well-associated with trimester of exposure).

The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS) examined 140 low-risk pregnancies in white women of higher socioeconomic status who used marijuana during pregnancy.1,3-7 Investigators considered: socioeconomic status, standard demographics, obstetric history, and use of other drugs, tobacco, and alcohol. Using a standardized newborn assessment scale, they found subtle behavioral differences at one week but not 9 days. Investigators evaluated children again at 3 years of age, school entry (5 or 6 years), and 9 to 12 years.

The Maternal Health Practices and Child Development study (MHPCD) of 564 high-risk pregnancies in predominantly minority women of low socioeconomic status followed infants from birth through 14 years of age.1,3-5,7,8 It found some small differences in outcomes among children exposed to marijuana prenatally. Of note, when investigators evaluated marijuana use at age 14 years, they compared adolescent self-report history with urine THC testing (specificity 78%).

The MHPCD study was limited because, compared with the nonusing group, mothers who used marijuana were also 20% to 25% more likely to be single and poor, to live in poorer quality homes, and to use alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Investigators used statistical modeling to account for these environmental differences and estimated that 10% of the difference in outcomes was attributable to prenatal marijuana exposure.

The Generation R study (Gen R) enrolled 220 lower-risk pregnancies in multiethnic European women of higher socioeconomic status, followed children to 3 years of age, and found no marijuana-associated differences in any parameter.1,3,4 The final assessment included only 51 children.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening all women for tobacco, alcohol, and drug use (including marijuana) during early pregnancy.9 Women who report marijuana use should be counseled regarding potential adverse consequences to fetal health and be encouraged to discontinue use.

ACOG says that insufficient data exist to evaluate the effects of marijuana use on infants during lactation and breastfeeding and recommends against it.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine also recommends screening pregnant women for drug use and making appropriate referrals for substance use treatment.10

1. Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:761-778.

2. Chabarria KC, Racusin DA, Antony KM, et al. Marijuana use and its effects in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:506.e1-e7.

3. Warner TD, Roussos-Ross D, Behnke M. It’s not your mother’s marijuana: effects on maternal-fetal health and the developing child. Clinical Perinatology. 2014;41:877-894.

4. Huizink AC. Prenatal cannabis exposure and infant outcomes: overview of studies. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;52:45-52.

5. Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Willford J, et al. Prenatal marijuana exposure and intelligence test performance at age 6. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:254-263.

6. Fried PA. The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS): methodological issues and findings—it’s easy to throw the baby out with the bath water. Life Sci. 1995;56:2159-2168.

7. Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Richardson GA. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325-336.

8. Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Thomas CA. Prenatal marijuana exposure contributes to the prediction of marijuana use at age 14. Addiction. 2006;101:1313-1322.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 637: Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:234-238.

10. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public policy statement on women, alcohol and other drugs, and pregnancy. Chevy Chase MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2011. Available at: http://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/1womenandpregnancy_7-11.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2016.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A large systematic review of prospective and retrospective cohort studies found little or no effect of maternal marijuana use on birth weight, stillbirths, preterm births, or congenital anomalies (TABLE1-8). Some studies found lower birth weights and some found higher birth weights. The authors couldn’t perform a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity, but estimated a clinically insignificant difference of 100 g. Most studies were limited by failure to account for concurrent maternal tobacco smoking.

Moreover, all studies used interview data to determine maternal prenatal marijuana use, which can be subject to large recall bias. A multicenter prospective study of 585 pregnant women that compared interview data with serum screening to identify tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) found poor correlation between history and laboratory validation, for example.1 Only 31% of pregnant women with positive THC testing self-reported marijuana use (31% sensitivity), and only 43% of women who reported marijuana use had a positive THC screen (43% specificity). Most studies didn’t quantify marijuana use well and didn’t associate use with trimester of exposure.

The authors also point out that marijuana potency has increased substantially since the 1980s when many of the studies were done (THC content was 3.2% in 1983 and 13% in 2008); prenatal marijuana use in the present day may expose the fetus to larger amounts of THC.1

A 2016 retrospective cohort study of 56 mothers who reported prenatal marijuana use found no differences in preterm birth, low birth weight, or Apgar scores.2

Neurodevelopmental effects on infants, long-term effects on children, teens

Three prospective cohort studies evaluated neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates and infants, and 2 studies continued to follow children into adolescence.1,3 All found essentially no differences associated with prenatal marijuana at birth, throughout infancy, and through age 3 years. The studies had the same limitations as those described previously (potential recall bias for identifying which children were exposed to marijuana prenatally and poorly quantified marijuana use not well-associated with trimester of exposure).

The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS) examined 140 low-risk pregnancies in white women of higher socioeconomic status who used marijuana during pregnancy.1,3-7 Investigators considered: socioeconomic status, standard demographics, obstetric history, and use of other drugs, tobacco, and alcohol. Using a standardized newborn assessment scale, they found subtle behavioral differences at one week but not 9 days. Investigators evaluated children again at 3 years of age, school entry (5 or 6 years), and 9 to 12 years.

The Maternal Health Practices and Child Development study (MHPCD) of 564 high-risk pregnancies in predominantly minority women of low socioeconomic status followed infants from birth through 14 years of age.1,3-5,7,8 It found some small differences in outcomes among children exposed to marijuana prenatally. Of note, when investigators evaluated marijuana use at age 14 years, they compared adolescent self-report history with urine THC testing (specificity 78%).

The MHPCD study was limited because, compared with the nonusing group, mothers who used marijuana were also 20% to 25% more likely to be single and poor, to live in poorer quality homes, and to use alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Investigators used statistical modeling to account for these environmental differences and estimated that 10% of the difference in outcomes was attributable to prenatal marijuana exposure.

The Generation R study (Gen R) enrolled 220 lower-risk pregnancies in multiethnic European women of higher socioeconomic status, followed children to 3 years of age, and found no marijuana-associated differences in any parameter.1,3,4 The final assessment included only 51 children.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening all women for tobacco, alcohol, and drug use (including marijuana) during early pregnancy.9 Women who report marijuana use should be counseled regarding potential adverse consequences to fetal health and be encouraged to discontinue use.

ACOG says that insufficient data exist to evaluate the effects of marijuana use on infants during lactation and breastfeeding and recommends against it.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine also recommends screening pregnant women for drug use and making appropriate referrals for substance use treatment.10

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A large systematic review of prospective and retrospective cohort studies found little or no effect of maternal marijuana use on birth weight, stillbirths, preterm births, or congenital anomalies (TABLE1-8). Some studies found lower birth weights and some found higher birth weights. The authors couldn’t perform a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity, but estimated a clinically insignificant difference of 100 g. Most studies were limited by failure to account for concurrent maternal tobacco smoking.

Moreover, all studies used interview data to determine maternal prenatal marijuana use, which can be subject to large recall bias. A multicenter prospective study of 585 pregnant women that compared interview data with serum screening to identify tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) found poor correlation between history and laboratory validation, for example.1 Only 31% of pregnant women with positive THC testing self-reported marijuana use (31% sensitivity), and only 43% of women who reported marijuana use had a positive THC screen (43% specificity). Most studies didn’t quantify marijuana use well and didn’t associate use with trimester of exposure.

The authors also point out that marijuana potency has increased substantially since the 1980s when many of the studies were done (THC content was 3.2% in 1983 and 13% in 2008); prenatal marijuana use in the present day may expose the fetus to larger amounts of THC.1

A 2016 retrospective cohort study of 56 mothers who reported prenatal marijuana use found no differences in preterm birth, low birth weight, or Apgar scores.2

Neurodevelopmental effects on infants, long-term effects on children, teens

Three prospective cohort studies evaluated neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates and infants, and 2 studies continued to follow children into adolescence.1,3 All found essentially no differences associated with prenatal marijuana at birth, throughout infancy, and through age 3 years. The studies had the same limitations as those described previously (potential recall bias for identifying which children were exposed to marijuana prenatally and poorly quantified marijuana use not well-associated with trimester of exposure).

The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS) examined 140 low-risk pregnancies in white women of higher socioeconomic status who used marijuana during pregnancy.1,3-7 Investigators considered: socioeconomic status, standard demographics, obstetric history, and use of other drugs, tobacco, and alcohol. Using a standardized newborn assessment scale, they found subtle behavioral differences at one week but not 9 days. Investigators evaluated children again at 3 years of age, school entry (5 or 6 years), and 9 to 12 years.

The Maternal Health Practices and Child Development study (MHPCD) of 564 high-risk pregnancies in predominantly minority women of low socioeconomic status followed infants from birth through 14 years of age.1,3-5,7,8 It found some small differences in outcomes among children exposed to marijuana prenatally. Of note, when investigators evaluated marijuana use at age 14 years, they compared adolescent self-report history with urine THC testing (specificity 78%).

The MHPCD study was limited because, compared with the nonusing group, mothers who used marijuana were also 20% to 25% more likely to be single and poor, to live in poorer quality homes, and to use alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Investigators used statistical modeling to account for these environmental differences and estimated that 10% of the difference in outcomes was attributable to prenatal marijuana exposure.

The Generation R study (Gen R) enrolled 220 lower-risk pregnancies in multiethnic European women of higher socioeconomic status, followed children to 3 years of age, and found no marijuana-associated differences in any parameter.1,3,4 The final assessment included only 51 children.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening all women for tobacco, alcohol, and drug use (including marijuana) during early pregnancy.9 Women who report marijuana use should be counseled regarding potential adverse consequences to fetal health and be encouraged to discontinue use.

ACOG says that insufficient data exist to evaluate the effects of marijuana use on infants during lactation and breastfeeding and recommends against it.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine also recommends screening pregnant women for drug use and making appropriate referrals for substance use treatment.10

1. Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:761-778.

2. Chabarria KC, Racusin DA, Antony KM, et al. Marijuana use and its effects in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:506.e1-e7.

3. Warner TD, Roussos-Ross D, Behnke M. It’s not your mother’s marijuana: effects on maternal-fetal health and the developing child. Clinical Perinatology. 2014;41:877-894.

4. Huizink AC. Prenatal cannabis exposure and infant outcomes: overview of studies. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;52:45-52.

5. Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Willford J, et al. Prenatal marijuana exposure and intelligence test performance at age 6. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:254-263.

6. Fried PA. The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS): methodological issues and findings—it’s easy to throw the baby out with the bath water. Life Sci. 1995;56:2159-2168.

7. Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Richardson GA. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325-336.

8. Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Thomas CA. Prenatal marijuana exposure contributes to the prediction of marijuana use at age 14. Addiction. 2006;101:1313-1322.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 637: Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:234-238.

10. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public policy statement on women, alcohol and other drugs, and pregnancy. Chevy Chase MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2011. Available at: http://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/1womenandpregnancy_7-11.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2016.

1. Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:761-778.

2. Chabarria KC, Racusin DA, Antony KM, et al. Marijuana use and its effects in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:506.e1-e7.

3. Warner TD, Roussos-Ross D, Behnke M. It’s not your mother’s marijuana: effects on maternal-fetal health and the developing child. Clinical Perinatology. 2014;41:877-894.

4. Huizink AC. Prenatal cannabis exposure and infant outcomes: overview of studies. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;52:45-52.

5. Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Willford J, et al. Prenatal marijuana exposure and intelligence test performance at age 6. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:254-263.

6. Fried PA. The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS): methodological issues and findings—it’s easy to throw the baby out with the bath water. Life Sci. 1995;56:2159-2168.

7. Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Richardson GA. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325-336.

8. Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Thomas CA. Prenatal marijuana exposure contributes to the prediction of marijuana use at age 14. Addiction. 2006;101:1313-1322.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 637: Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:234-238.

10. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public policy statement on women, alcohol and other drugs, and pregnancy. Chevy Chase MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2011. Available at: http://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/1womenandpregnancy_7-11.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2016.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

The effects are unclear. Marijuana use during pregnancy is associated with clinically unimportant lower birth weights (growth differences of approximately 100 g), but no differences in preterm births or congenital anomalies (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, prospective and retrospective cohort studies with methodologic flaws).

Similarly, prenatal marijuana use isn’t associated with differences in neurodevelopmental outcomes (behavior problems, intellect, visual perception, language, or sustained attention and memory tasks) at birth, in the neonatal period, or in childhood through age 3 years. However, it may be associated with minimally lower verbal/quantitative IQ scores (1%) at age 6 years and increased impulsivity and hyperactivity (1%) at 10 years. Prenatal use isn’t linked to increased substance use at age 14 years (SOR: B, conflicting long-term prospective and retrospective cohort studies with methodologic flaws).

Rewriting the script on polypharmacy

Drugs are valuable when they effectively relieve symptoms or prevent illness, but we all know they are double-edged swords when it comes to cost, adverse effects, and drug interactions. This “downside” is not lost on older Americans—especially when you consider that more than a third of Americans, ages 62 to 85 years, take 5 or more prescription medications daily.1

Too often patients take prescription drugs that they either don’t need or that are harming them. That’s where deprescribing comes in. As this month’s feature article by McGrath and colleagues explains, deprescribing is the process of reducing or stopping unnecessary prescription medications.

The power of deprescribing. About a decade ago, a geriatrician/family physician friend of mine took over as medical director of a 160-bed nursing home. He lamented that the average number of prescription medications taken by the patients in the nursing home was 9.5. He and his team went to work deprescribing, and one year later, the average number of prescription medications per patient was 5.3. As far as he and the nursing staff could tell, the patients were doing just fine and were more alert and functional.

Another specialist, another Rx. In clinic, I saw a 54-year-old woman with the chief complaint of chronic, dry cough for which she had been on a specialist pilgrimage. A GI specialist prescribed omeprazole, an ENT physician prescribed fluticasone nasal spray and cetirizine, and a pulmonologist added an inhaled corticosteroid to the mix. (I’m not making this up!) I reviewed her medication list carefully and noted she had been placed on amitriptyline for insomnia shortly before the cough began. I was suspicious because the properties of anticholinergics can contribute to a cough. At my suggestion, she agreed to stop the amitriptyline (and endure some sleeplessness). Two weeks later, she returned with no cough. Over the next month, she stopped all 4 other medications, and the cough did not return.

Today in the office, a 64-year-old man complained of lightheadedness and fatigue and told me his blood pressure on home monitoring was consistently around 105/50 mm Hg. In addition to taking 3 antihypertensive medications, I discovered he had been prescribed doxazosin—an alpha blocker, which also lowers blood pressure—

I’m certain that you, too, have stories of successful deprescribing. Let’s remain alert to the problem of polypharmacy, keep meticulous medication lists, and deprescribe whenever it makes good sense. Doing so is essential to our roles as family physicians.

1. Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, et al. Changes in prescription and over-the-counter medication and dietary supplement use among older adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:473-482.

Drugs are valuable when they effectively relieve symptoms or prevent illness, but we all know they are double-edged swords when it comes to cost, adverse effects, and drug interactions. This “downside” is not lost on older Americans—especially when you consider that more than a third of Americans, ages 62 to 85 years, take 5 or more prescription medications daily.1

Too often patients take prescription drugs that they either don’t need or that are harming them. That’s where deprescribing comes in. As this month’s feature article by McGrath and colleagues explains, deprescribing is the process of reducing or stopping unnecessary prescription medications.

The power of deprescribing. About a decade ago, a geriatrician/family physician friend of mine took over as medical director of a 160-bed nursing home. He lamented that the average number of prescription medications taken by the patients in the nursing home was 9.5. He and his team went to work deprescribing, and one year later, the average number of prescription medications per patient was 5.3. As far as he and the nursing staff could tell, the patients were doing just fine and were more alert and functional.

Another specialist, another Rx. In clinic, I saw a 54-year-old woman with the chief complaint of chronic, dry cough for which she had been on a specialist pilgrimage. A GI specialist prescribed omeprazole, an ENT physician prescribed fluticasone nasal spray and cetirizine, and a pulmonologist added an inhaled corticosteroid to the mix. (I’m not making this up!) I reviewed her medication list carefully and noted she had been placed on amitriptyline for insomnia shortly before the cough began. I was suspicious because the properties of anticholinergics can contribute to a cough. At my suggestion, she agreed to stop the amitriptyline (and endure some sleeplessness). Two weeks later, she returned with no cough. Over the next month, she stopped all 4 other medications, and the cough did not return.

Today in the office, a 64-year-old man complained of lightheadedness and fatigue and told me his blood pressure on home monitoring was consistently around 105/50 mm Hg. In addition to taking 3 antihypertensive medications, I discovered he had been prescribed doxazosin—an alpha blocker, which also lowers blood pressure—

I’m certain that you, too, have stories of successful deprescribing. Let’s remain alert to the problem of polypharmacy, keep meticulous medication lists, and deprescribe whenever it makes good sense. Doing so is essential to our roles as family physicians.

Drugs are valuable when they effectively relieve symptoms or prevent illness, but we all know they are double-edged swords when it comes to cost, adverse effects, and drug interactions. This “downside” is not lost on older Americans—especially when you consider that more than a third of Americans, ages 62 to 85 years, take 5 or more prescription medications daily.1

Too often patients take prescription drugs that they either don’t need or that are harming them. That’s where deprescribing comes in. As this month’s feature article by McGrath and colleagues explains, deprescribing is the process of reducing or stopping unnecessary prescription medications.

The power of deprescribing. About a decade ago, a geriatrician/family physician friend of mine took over as medical director of a 160-bed nursing home. He lamented that the average number of prescription medications taken by the patients in the nursing home was 9.5. He and his team went to work deprescribing, and one year later, the average number of prescription medications per patient was 5.3. As far as he and the nursing staff could tell, the patients were doing just fine and were more alert and functional.

Another specialist, another Rx. In clinic, I saw a 54-year-old woman with the chief complaint of chronic, dry cough for which she had been on a specialist pilgrimage. A GI specialist prescribed omeprazole, an ENT physician prescribed fluticasone nasal spray and cetirizine, and a pulmonologist added an inhaled corticosteroid to the mix. (I’m not making this up!) I reviewed her medication list carefully and noted she had been placed on amitriptyline for insomnia shortly before the cough began. I was suspicious because the properties of anticholinergics can contribute to a cough. At my suggestion, she agreed to stop the amitriptyline (and endure some sleeplessness). Two weeks later, she returned with no cough. Over the next month, she stopped all 4 other medications, and the cough did not return.

Today in the office, a 64-year-old man complained of lightheadedness and fatigue and told me his blood pressure on home monitoring was consistently around 105/50 mm Hg. In addition to taking 3 antihypertensive medications, I discovered he had been prescribed doxazosin—an alpha blocker, which also lowers blood pressure—

I’m certain that you, too, have stories of successful deprescribing. Let’s remain alert to the problem of polypharmacy, keep meticulous medication lists, and deprescribe whenever it makes good sense. Doing so is essential to our roles as family physicians.

1. Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, et al. Changes in prescription and over-the-counter medication and dietary supplement use among older adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:473-482.

1. Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, et al. Changes in prescription and over-the-counter medication and dietary supplement use among older adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:473-482.

HCV on the Rise Among Women Giving Birth

Between 2009 and 2014, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among women giving birth rose 89%, from 1.8 to 3.4 per live births, according to a study published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The researchers say, geographically, the increase in maternal HCV infection mirrors increases in HCV incidence among adults. The highest infection rate was in West Virginia, which had 22.6 per 1,000 live births. Next was Tennessee with 10.1. State infection rates varied widely: Hawaii had the lowest rate, of 0.7.

In Tennessee, the prevalence of maternal HCV infection increased 163%, from 3.8 per 1,000 in 2009 to 10 in 2014. But even among the 95 Tennessee counties, rates varied substantially. The highest rates were in the 52 Appalachian counties. Campbell County had 78 per 1,000 births. Compared with women in urban areas, pregnant women from rural areas had triple the odds of HCV infection. The rise in infection among pregnant women coincides with the rises in heroin and prescription opioid epidemics, which also disproportionately affect rural populations.

Analyzing the Tennessee births, researchers found that the odds of HCV infection were about 5 times higher among women who smoked cigarettes during pregnancy. Concurrent infections were another serious risk factor, with hepatitis B virus infection boosting the odds of HCV infection by nearly 17 times.

HCV infection is a growing—but modifiable—threat among pregnant women, the researchers say. The rise in infection is “particularly concerning,” in light of recent research that has found poor follow-up of HCV-exposed infants. The researchers cite a Philadelphia study that found only 16% of HCV-exposed infants were appropriately followed. That could mean that infected infants are going undetected, the researchers say. The rate of transmission from mothers to infants is estimated at 6%; it’s important for exposed infants to be followed for evidence of seroconversion. But anti-HCV antibody tests can’t be completed until 18 months because passively acquired maternal antibodies can persist. Testing for HCV ribonucleic acid can be performed earlier.

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend selective screening of pregnant women at high risk for HCV infection, particularly those with a history of injection drug use or long-term hemodialysis.

Between 2009 and 2014, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among women giving birth rose 89%, from 1.8 to 3.4 per live births, according to a study published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The researchers say, geographically, the increase in maternal HCV infection mirrors increases in HCV incidence among adults. The highest infection rate was in West Virginia, which had 22.6 per 1,000 live births. Next was Tennessee with 10.1. State infection rates varied widely: Hawaii had the lowest rate, of 0.7.

In Tennessee, the prevalence of maternal HCV infection increased 163%, from 3.8 per 1,000 in 2009 to 10 in 2014. But even among the 95 Tennessee counties, rates varied substantially. The highest rates were in the 52 Appalachian counties. Campbell County had 78 per 1,000 births. Compared with women in urban areas, pregnant women from rural areas had triple the odds of HCV infection. The rise in infection among pregnant women coincides with the rises in heroin and prescription opioid epidemics, which also disproportionately affect rural populations.

Analyzing the Tennessee births, researchers found that the odds of HCV infection were about 5 times higher among women who smoked cigarettes during pregnancy. Concurrent infections were another serious risk factor, with hepatitis B virus infection boosting the odds of HCV infection by nearly 17 times.

HCV infection is a growing—but modifiable—threat among pregnant women, the researchers say. The rise in infection is “particularly concerning,” in light of recent research that has found poor follow-up of HCV-exposed infants. The researchers cite a Philadelphia study that found only 16% of HCV-exposed infants were appropriately followed. That could mean that infected infants are going undetected, the researchers say. The rate of transmission from mothers to infants is estimated at 6%; it’s important for exposed infants to be followed for evidence of seroconversion. But anti-HCV antibody tests can’t be completed until 18 months because passively acquired maternal antibodies can persist. Testing for HCV ribonucleic acid can be performed earlier.

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend selective screening of pregnant women at high risk for HCV infection, particularly those with a history of injection drug use or long-term hemodialysis.

Between 2009 and 2014, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among women giving birth rose 89%, from 1.8 to 3.4 per live births, according to a study published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The researchers say, geographically, the increase in maternal HCV infection mirrors increases in HCV incidence among adults. The highest infection rate was in West Virginia, which had 22.6 per 1,000 live births. Next was Tennessee with 10.1. State infection rates varied widely: Hawaii had the lowest rate, of 0.7.

In Tennessee, the prevalence of maternal HCV infection increased 163%, from 3.8 per 1,000 in 2009 to 10 in 2014. But even among the 95 Tennessee counties, rates varied substantially. The highest rates were in the 52 Appalachian counties. Campbell County had 78 per 1,000 births. Compared with women in urban areas, pregnant women from rural areas had triple the odds of HCV infection. The rise in infection among pregnant women coincides with the rises in heroin and prescription opioid epidemics, which also disproportionately affect rural populations.

Analyzing the Tennessee births, researchers found that the odds of HCV infection were about 5 times higher among women who smoked cigarettes during pregnancy. Concurrent infections were another serious risk factor, with hepatitis B virus infection boosting the odds of HCV infection by nearly 17 times.

HCV infection is a growing—but modifiable—threat among pregnant women, the researchers say. The rise in infection is “particularly concerning,” in light of recent research that has found poor follow-up of HCV-exposed infants. The researchers cite a Philadelphia study that found only 16% of HCV-exposed infants were appropriately followed. That could mean that infected infants are going undetected, the researchers say. The rate of transmission from mothers to infants is estimated at 6%; it’s important for exposed infants to be followed for evidence of seroconversion. But anti-HCV antibody tests can’t be completed until 18 months because passively acquired maternal antibodies can persist. Testing for HCV ribonucleic acid can be performed earlier.

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend selective screening of pregnant women at high risk for HCV infection, particularly those with a history of injection drug use or long-term hemodialysis.

EC approves therapy for relapsed/refractory BCP-ALL

The European Commission (EC) has approved inotuzumab ozogamicin (BESPONSA®) as monotherapy for adults with relapsed or refractory, CD22-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL).

Adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive, relapsed/refractory, CD22-positive BCP-ALL should have failed treatment with at least one tyrosine kinase inhibitor before receiving inotuzumab ozogamicin.

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 and a cytotoxic agent known as calicheamicin.

The product originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech (now UCB), but Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing and clinical development activities.

The EC’s approval of inotuzumab ozogamicin is supported by results from a phase 3 trial, which were published in NEJM in June 2016.

The trial enrolled 326 adult patients with relapsed or refractory BCP-ALL and compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard of care chemotherapy.

The rate of complete remission, including incomplete hematologic recovery, was 80.7% in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 29.4% in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001). The median duration of remission was 4.6 months and 3.1 months, respectively (P=0.03).

Forty-one percent of patients treated with inotuzumab ozogamicin and 11% of those who received chemotherapy proceeded to stem cell transplant directly after treatment (P<0.001).

The median progression-free survival was 5.0 months in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1.8 months in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001).

The median overall survival was 7.7 months and 6.7 months, respectively (P=0.04). This did not meet the prespecified boundary of significance (P=0.0208).

Liver-related adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm than the chemotherapy arm. The most frequent of these were increased aspartate aminotransferase level (20% vs 10%), hyperbilirubinemia (15% vs 10%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (14% vs 11%).

Veno-occlusive liver disease occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 17 deaths during treatment in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 11 in the chemotherapy arm. Four deaths were considered related to inotuzumab ozogamicin, and 2 were thought to be related to chemotherapy. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has approved inotuzumab ozogamicin (BESPONSA®) as monotherapy for adults with relapsed or refractory, CD22-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL).

Adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive, relapsed/refractory, CD22-positive BCP-ALL should have failed treatment with at least one tyrosine kinase inhibitor before receiving inotuzumab ozogamicin.

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 and a cytotoxic agent known as calicheamicin.

The product originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech (now UCB), but Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing and clinical development activities.

The EC’s approval of inotuzumab ozogamicin is supported by results from a phase 3 trial, which were published in NEJM in June 2016.

The trial enrolled 326 adult patients with relapsed or refractory BCP-ALL and compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard of care chemotherapy.

The rate of complete remission, including incomplete hematologic recovery, was 80.7% in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 29.4% in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001). The median duration of remission was 4.6 months and 3.1 months, respectively (P=0.03).

Forty-one percent of patients treated with inotuzumab ozogamicin and 11% of those who received chemotherapy proceeded to stem cell transplant directly after treatment (P<0.001).

The median progression-free survival was 5.0 months in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1.8 months in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001).

The median overall survival was 7.7 months and 6.7 months, respectively (P=0.04). This did not meet the prespecified boundary of significance (P=0.0208).

Liver-related adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm than the chemotherapy arm. The most frequent of these were increased aspartate aminotransferase level (20% vs 10%), hyperbilirubinemia (15% vs 10%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (14% vs 11%).

Veno-occlusive liver disease occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 17 deaths during treatment in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 11 in the chemotherapy arm. Four deaths were considered related to inotuzumab ozogamicin, and 2 were thought to be related to chemotherapy. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has approved inotuzumab ozogamicin (BESPONSA®) as monotherapy for adults with relapsed or refractory, CD22-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL).

Adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive, relapsed/refractory, CD22-positive BCP-ALL should have failed treatment with at least one tyrosine kinase inhibitor before receiving inotuzumab ozogamicin.

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 and a cytotoxic agent known as calicheamicin.

The product originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech (now UCB), but Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing and clinical development activities.

The EC’s approval of inotuzumab ozogamicin is supported by results from a phase 3 trial, which were published in NEJM in June 2016.

The trial enrolled 326 adult patients with relapsed or refractory BCP-ALL and compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard of care chemotherapy.

The rate of complete remission, including incomplete hematologic recovery, was 80.7% in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 29.4% in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001). The median duration of remission was 4.6 months and 3.1 months, respectively (P=0.03).

Forty-one percent of patients treated with inotuzumab ozogamicin and 11% of those who received chemotherapy proceeded to stem cell transplant directly after treatment (P<0.001).

The median progression-free survival was 5.0 months in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1.8 months in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001).

The median overall survival was 7.7 months and 6.7 months, respectively (P=0.04). This did not meet the prespecified boundary of significance (P=0.0208).

Liver-related adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm than the chemotherapy arm. The most frequent of these were increased aspartate aminotransferase level (20% vs 10%), hyperbilirubinemia (15% vs 10%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (14% vs 11%).

Veno-occlusive liver disease occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 17 deaths during treatment in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 11 in the chemotherapy arm. Four deaths were considered related to inotuzumab ozogamicin, and 2 were thought to be related to chemotherapy. ![]()

A sheep in wolf’s clothing?

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

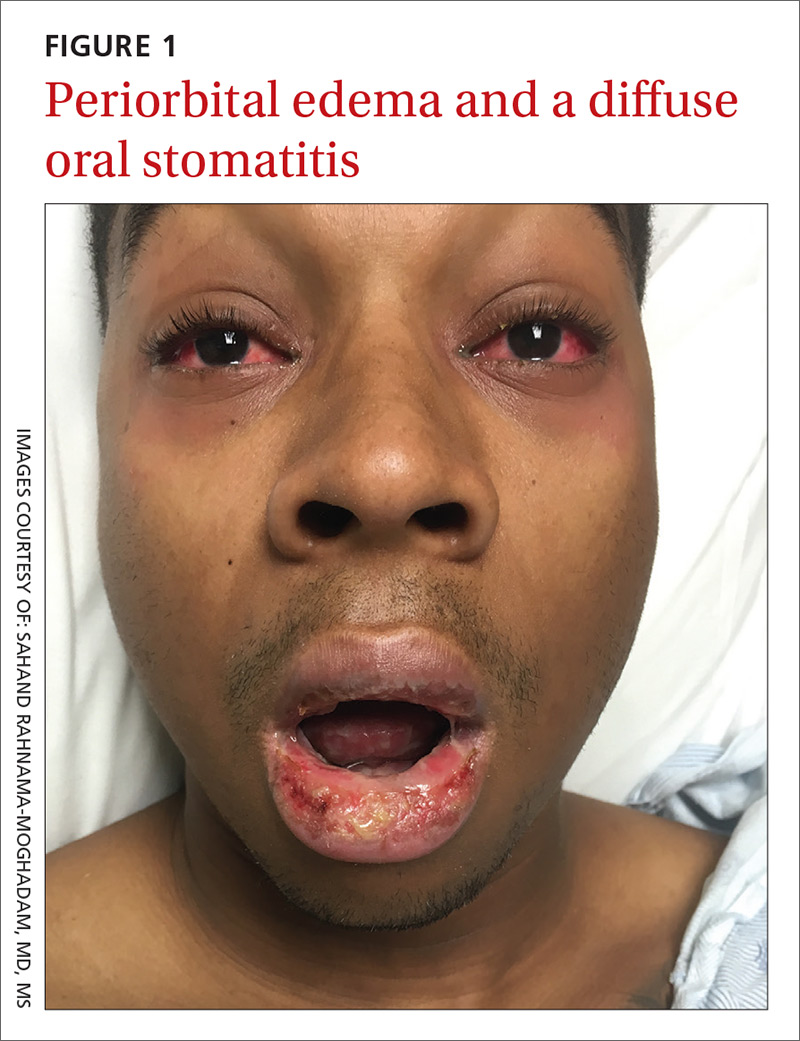

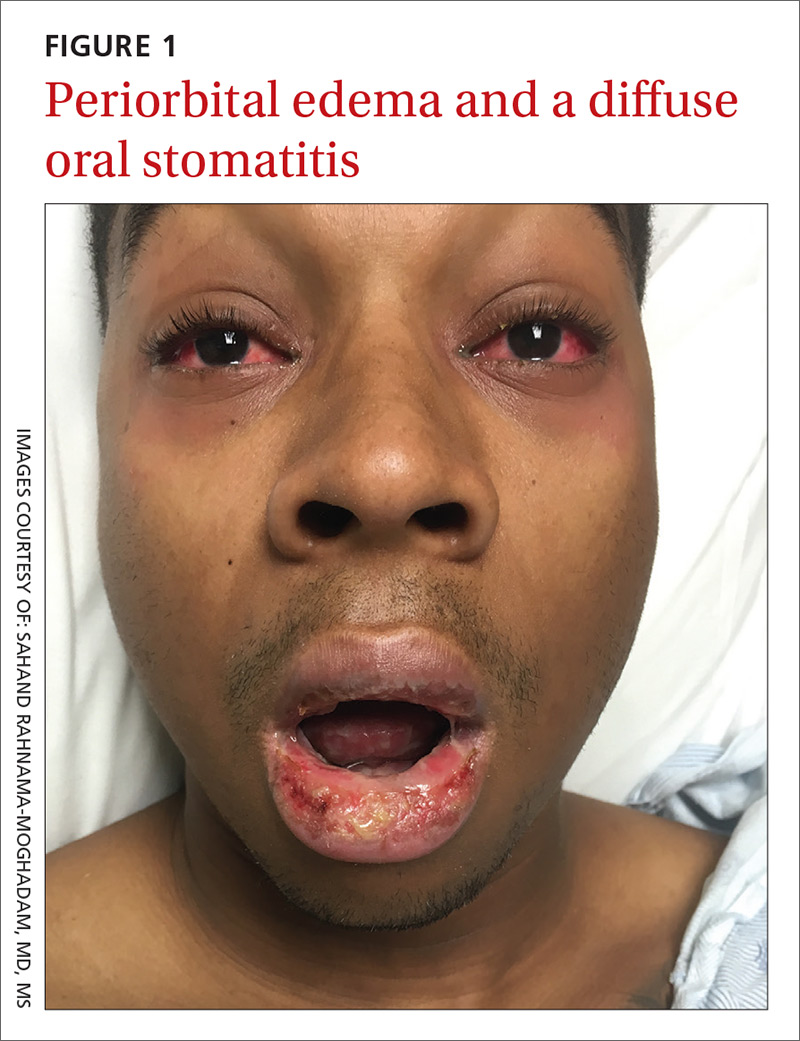

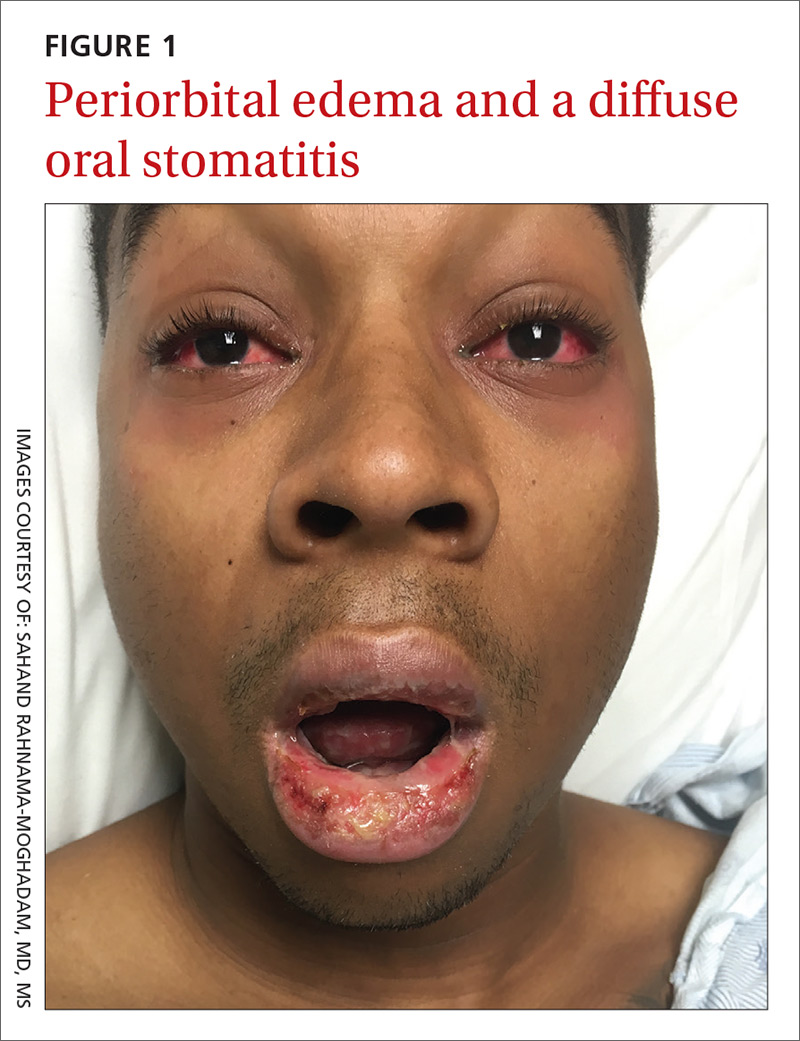

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

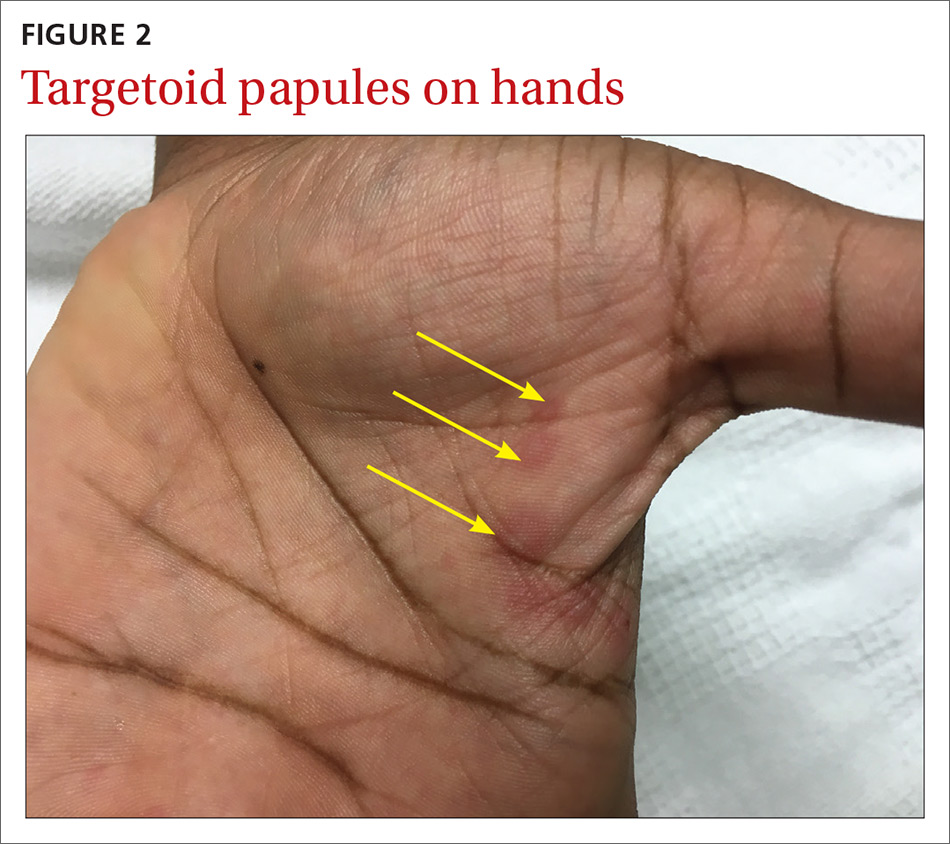

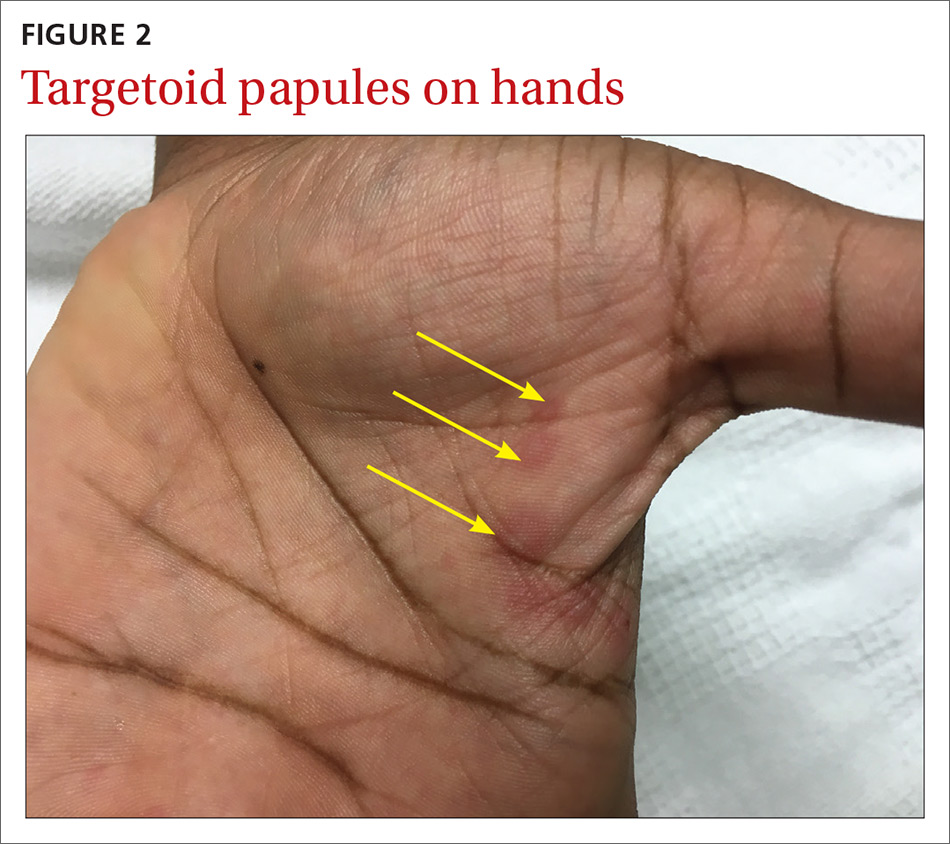

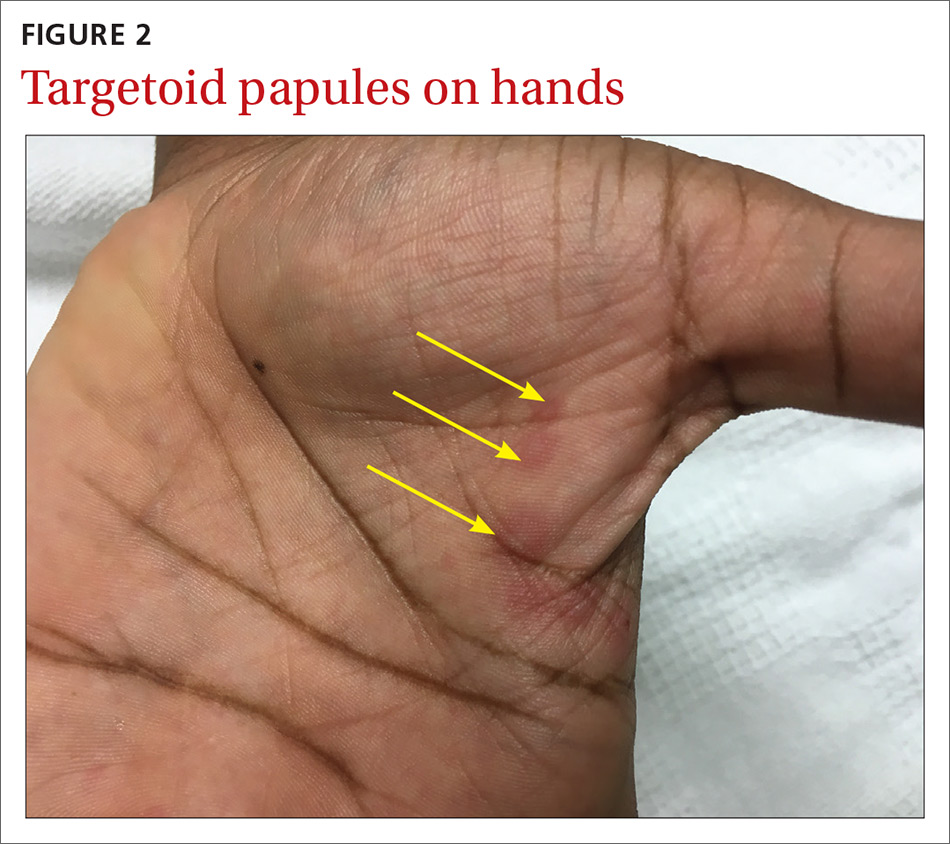

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis

The patient was admitted for observation to rule out Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). We felt that the degree of mucositis (extensive) compared to the number of targetoid papules on the hands (minimal) suggested a diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM), a subtype of erythema multiforme (EM) major. The patient’s prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise also supported a “walking pneumonia” diagnosis, such as MPAM.

Further testing. The patient had a normal chest x-ray and a negative respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but IgM serologies for Mycoplasma were elevated. Although the patient developed targetoid lesions on his hands during his first 24 hours in the hospital, he felt his constitutional symptoms had improved.

Exposure to Mycoplasma leads to an immune response

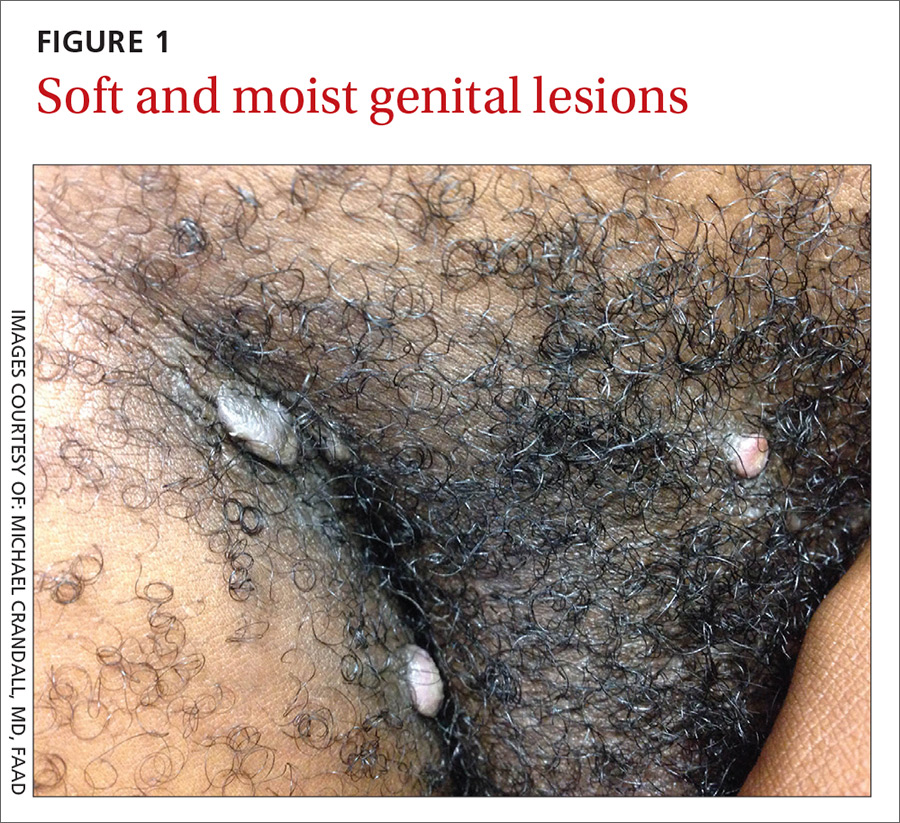

MPAM (also known as Fuchs’ syndrome and mycoplasma-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations) appears at some point during infection with M pneumoniae and causes severe ocular, oral, and sometimes genital symptoms with minimal skin manifestations.

MPAM is primarily seen in young males. In one systemic review of 202 cases, the average age of the patients was 11.9 years and 66% were male.1 Exposure to M pneumoniae is theorized to result in the production of autoantibodies to mycoplasma p1-adhesion molecules and to molecular mimicry of keratinocyte antigens located in the mucosa.1-3

Mycoplasma organisms have not been isolated from the cutaneous lesions of patients with MPAM; they have only been isolated from the respiratory tract, supporting the theory that MPAM is the body’s immune response to Mycoplasma, rather than a direct pathologic effect.4 This pathogenesis is distinct from that of SJS/TEN, which is thought to involve CD8+ T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis (programed cell death). In addition, SJS/TEN is almost always drug induced.

First up in the differential: Rule out SJS/TEN

When evaluating a patient like ours with a blistering eruption, the most important diagnosis to exclude is SJS/TEN. This condition is usually triggered by a medication, which was absent in this case. SJS/TEN begins with a host of constitutional symptoms and an erythematous blistering eruption, which may be preceded by atypical targetoid (2-zoned) flat papules along with erosions on 2 or more mucosal surfaces.

Patients with SJS/TEN are usually critically ill and may have a guarded prognosis. Patients with MPAM have a more favorable prognosis and are unlikely to be critically ill—as was the case with our patient.

EM major is often associated with Mycoplasma infections. Patients with EM major may have fever and arthralgias, as well as extensive mucous membrane involvement including that of the lips/mouth, eyes, and genitals.

Experts agree that EM is separate from the SJS/TEN continuum, and that patients with EM major, including those with MPAM, are not at risk of developing SJS/TEN.5 EM is characterized by the presence of the more characteristic ‘target’ or ‘iris’ 3-zoned lesion—a central dusky purpura, surrounded by an elevated edematous pale ring, rimmed by a red macular outer ring. EM major is defined as EM along with involvement of one or more mucosal regions.

In this case, the patient had acral target lesions and oral and ocular mucosal involvement characteristic of EM major, without widespread skin erosions or sloughing commonly seen with SJS/TEN.

Kawasaki’s disease occurs in young children and presents with conjunctivitis and oral changes. However, patients with Kawasaki’s disease generally have a fever for >5 days, a strawberry tongue (not a part of the morphology of EM major or MPAM), and palmoplantar erythema and desquamation that are not common with EM major or MPAM.1

Pemphigus vulgaris is uncommon in children and young adults. The disease does not present with diffuse mucositis nor diffuse blistering of the skin, but rather with discrete shallow erosions on the mucosa and the trunk along with flaccid bullae and erosions on the skin.

The morphologies of a fixed drug eruption (round purpuric patch) and toxic shock syndrome (diffuse macular erythema and widespread skin sloughing) are inconsistent with this patient’s diffuse mucositis, conjunctivitis, and targetoid lesions.

Confirm exposure to M pneumoniae

Testing with the purpose of ruling in MPAM is directed toward proving that the patient has been exposed to M pneumoniae. (Of note: M pneumoniae cannot be detected via routine commercial blood cultures.)

Serologic testing for elevated IgM antibodies to Mycoplasma is the most specific method. Various studies have found it to be positive in 100% of cases, but detection may be delayed for a couple of weeks while the body develops the requisite antibodies.4

Respiratory PCR for Mycoplasma is rapid and usually appropriately positive, but may be negative in cases where the patient has spontaneously cleared the infection or has been exposed to antibiotics before development of the eruption.4 An infiltrate on chest imaging is supportive of the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy will demonstrate either mucositis and necrosis of keratinocytes or EM-like necrosis, but does not suggest an etiology.

Strikingly different paths of care

Distinguishing between SJS/TEN and EM major (including MPAM) is crucial to guiding management. Patients with SJS/TEN need critical care, particularly of their eyes and genitourinary and respiratory systems. Specialist consultation is often required.

For EM major, patients require supportive care along with ongoing assurances that the eruption has a benign prognosis. Hospital admission is not mandatory as long as adequate supportive care and symptom control can be provided on an outpatient basis. Early consultation with Ophthalmology, Oral Medicine, and Urology may also be key.

Keep in mind that patients may have severe stomatitis and pain that alter their ability to eat and perform normal activities. Thus, managing pain and ensuring adequate nutrition are crucial for successful support. While antibiotics treat active Mycoplasma infection, there is no clear evidence that antibiotics alter the course of the eruption, which is also consistent with the hypothesized pathogenesis.3,4

While there is no clear statistical evidence that systemic immune suppression alters the disease course, a large proportion (31%) of patients in a recent systematic review of MPAM were treated with corticosteroids, and a smaller, but noteworthy, percentage (9%) were treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG).4 There are reports of severe stomatitis that didn’t improve with supportive care, but that showed dramatic improvement with IVIG treatment.6,7

Our patient had difficulty controlling secretions and managing the painful mucositis of his mouth; he was initially unable to tolerate solid foods. Topical lidocaine solution for his mucositis caused burning and more discomfort, but acetaminophen-hydrocodone 300 mg-5 mg every 6 hours did relieve his pain. Wound care with a bland emollient and the application of non-stick dressings to his lips at night also helped to relieve some of the pain.

Because the patient’s oropharyngeal swelling made it hard for him to swallow, he received oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d, which provided him with relief within 24 hours. The acute inflammation and eruption also subsided within 48 hours and the patient was discharged after 5 days of being hospitalized. He continued to recover as an outpatient, seeing his primary care physician within 2 weeks for final nutrition and wound care support. Two weeks after that, he had a dermatology appointment, and all of his lesions had re-epithelialized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, MS, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7323 Snowden Road, Apt. 1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; [email protected].

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.

2. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

3. Dinulos JG. What’s new with common, uncommon and rare rashes in childhood. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:261-266.

4. Meyer Sauteur PM, Goetschel P, Lautenschlager S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and mucositis–part of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome spectrum. J Dtsh Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:740-746.

5. Figueira-Coelho J, Lourenço S, Pires AC, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:399-403.

6. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

7. Zipitis CS, Thalange N. Intravenous immunoglobulins for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with minimal skin manifestations. Eur J Pediatr.2007;166:585-588.

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis

The patient was admitted for observation to rule out Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). We felt that the degree of mucositis (extensive) compared to the number of targetoid papules on the hands (minimal) suggested a diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM), a subtype of erythema multiforme (EM) major. The patient’s prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise also supported a “walking pneumonia” diagnosis, such as MPAM.

Further testing. The patient had a normal chest x-ray and a negative respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but IgM serologies for Mycoplasma were elevated. Although the patient developed targetoid lesions on his hands during his first 24 hours in the hospital, he felt his constitutional symptoms had improved.

Exposure to Mycoplasma leads to an immune response

MPAM (also known as Fuchs’ syndrome and mycoplasma-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations) appears at some point during infection with M pneumoniae and causes severe ocular, oral, and sometimes genital symptoms with minimal skin manifestations.

MPAM is primarily seen in young males. In one systemic review of 202 cases, the average age of the patients was 11.9 years and 66% were male.1 Exposure to M pneumoniae is theorized to result in the production of autoantibodies to mycoplasma p1-adhesion molecules and to molecular mimicry of keratinocyte antigens located in the mucosa.1-3

Mycoplasma organisms have not been isolated from the cutaneous lesions of patients with MPAM; they have only been isolated from the respiratory tract, supporting the theory that MPAM is the body’s immune response to Mycoplasma, rather than a direct pathologic effect.4 This pathogenesis is distinct from that of SJS/TEN, which is thought to involve CD8+ T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis (programed cell death). In addition, SJS/TEN is almost always drug induced.

First up in the differential: Rule out SJS/TEN

When evaluating a patient like ours with a blistering eruption, the most important diagnosis to exclude is SJS/TEN. This condition is usually triggered by a medication, which was absent in this case. SJS/TEN begins with a host of constitutional symptoms and an erythematous blistering eruption, which may be preceded by atypical targetoid (2-zoned) flat papules along with erosions on 2 or more mucosal surfaces.

Patients with SJS/TEN are usually critically ill and may have a guarded prognosis. Patients with MPAM have a more favorable prognosis and are unlikely to be critically ill—as was the case with our patient.

EM major is often associated with Mycoplasma infections. Patients with EM major may have fever and arthralgias, as well as extensive mucous membrane involvement including that of the lips/mouth, eyes, and genitals.

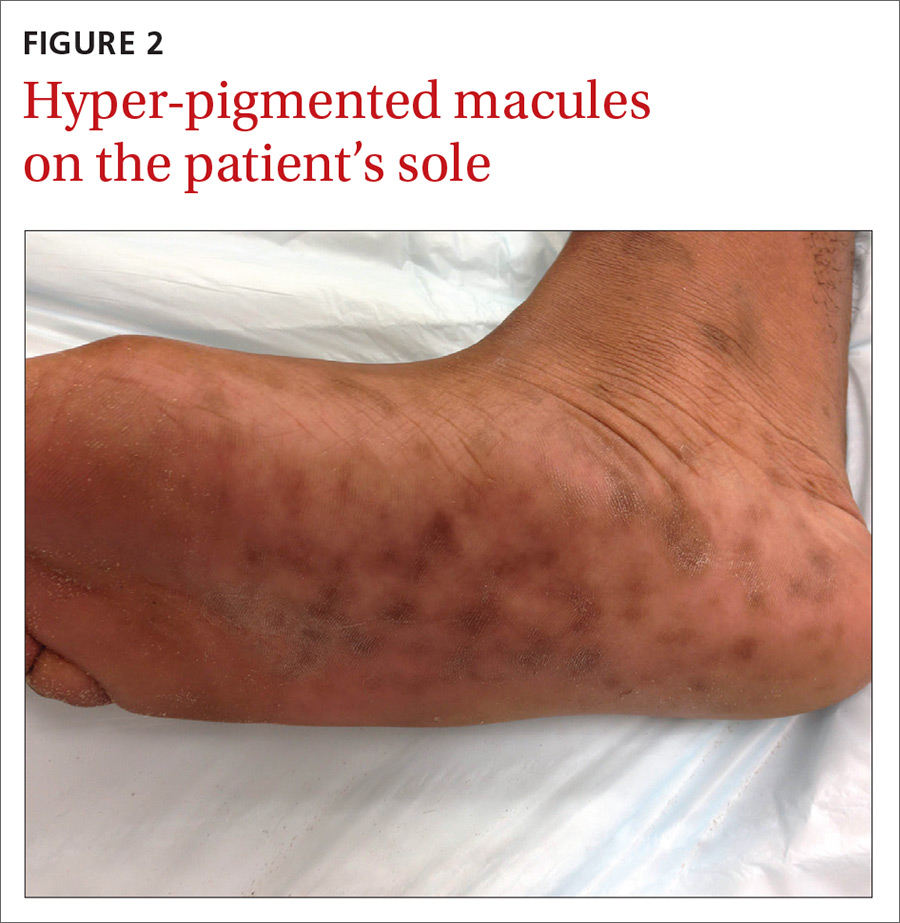

Experts agree that EM is separate from the SJS/TEN continuum, and that patients with EM major, including those with MPAM, are not at risk of developing SJS/TEN.5 EM is characterized by the presence of the more characteristic ‘target’ or ‘iris’ 3-zoned lesion—a central dusky purpura, surrounded by an elevated edematous pale ring, rimmed by a red macular outer ring. EM major is defined as EM along with involvement of one or more mucosal regions.

In this case, the patient had acral target lesions and oral and ocular mucosal involvement characteristic of EM major, without widespread skin erosions or sloughing commonly seen with SJS/TEN.

Kawasaki’s disease occurs in young children and presents with conjunctivitis and oral changes. However, patients with Kawasaki’s disease generally have a fever for >5 days, a strawberry tongue (not a part of the morphology of EM major or MPAM), and palmoplantar erythema and desquamation that are not common with EM major or MPAM.1

Pemphigus vulgaris is uncommon in children and young adults. The disease does not present with diffuse mucositis nor diffuse blistering of the skin, but rather with discrete shallow erosions on the mucosa and the trunk along with flaccid bullae and erosions on the skin.

The morphologies of a fixed drug eruption (round purpuric patch) and toxic shock syndrome (diffuse macular erythema and widespread skin sloughing) are inconsistent with this patient’s diffuse mucositis, conjunctivitis, and targetoid lesions.

Confirm exposure to M pneumoniae

Testing with the purpose of ruling in MPAM is directed toward proving that the patient has been exposed to M pneumoniae. (Of note: M pneumoniae cannot be detected via routine commercial blood cultures.)

Serologic testing for elevated IgM antibodies to Mycoplasma is the most specific method. Various studies have found it to be positive in 100% of cases, but detection may be delayed for a couple of weeks while the body develops the requisite antibodies.4

Respiratory PCR for Mycoplasma is rapid and usually appropriately positive, but may be negative in cases where the patient has spontaneously cleared the infection or has been exposed to antibiotics before development of the eruption.4 An infiltrate on chest imaging is supportive of the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy will demonstrate either mucositis and necrosis of keratinocytes or EM-like necrosis, but does not suggest an etiology.

Strikingly different paths of care

Distinguishing between SJS/TEN and EM major (including MPAM) is crucial to guiding management. Patients with SJS/TEN need critical care, particularly of their eyes and genitourinary and respiratory systems. Specialist consultation is often required.

For EM major, patients require supportive care along with ongoing assurances that the eruption has a benign prognosis. Hospital admission is not mandatory as long as adequate supportive care and symptom control can be provided on an outpatient basis. Early consultation with Ophthalmology, Oral Medicine, and Urology may also be key.

Keep in mind that patients may have severe stomatitis and pain that alter their ability to eat and perform normal activities. Thus, managing pain and ensuring adequate nutrition are crucial for successful support. While antibiotics treat active Mycoplasma infection, there is no clear evidence that antibiotics alter the course of the eruption, which is also consistent with the hypothesized pathogenesis.3,4

While there is no clear statistical evidence that systemic immune suppression alters the disease course, a large proportion (31%) of patients in a recent systematic review of MPAM were treated with corticosteroids, and a smaller, but noteworthy, percentage (9%) were treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG).4 There are reports of severe stomatitis that didn’t improve with supportive care, but that showed dramatic improvement with IVIG treatment.6,7

Our patient had difficulty controlling secretions and managing the painful mucositis of his mouth; he was initially unable to tolerate solid foods. Topical lidocaine solution for his mucositis caused burning and more discomfort, but acetaminophen-hydrocodone 300 mg-5 mg every 6 hours did relieve his pain. Wound care with a bland emollient and the application of non-stick dressings to his lips at night also helped to relieve some of the pain.

Because the patient’s oropharyngeal swelling made it hard for him to swallow, he received oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d, which provided him with relief within 24 hours. The acute inflammation and eruption also subsided within 48 hours and the patient was discharged after 5 days of being hospitalized. He continued to recover as an outpatient, seeing his primary care physician within 2 weeks for final nutrition and wound care support. Two weeks after that, he had a dermatology appointment, and all of his lesions had re-epithelialized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, MS, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7323 Snowden Road, Apt. 1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; [email protected].

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis

The patient was admitted for observation to rule out Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). We felt that the degree of mucositis (extensive) compared to the number of targetoid papules on the hands (minimal) suggested a diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM), a subtype of erythema multiforme (EM) major. The patient’s prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise also supported a “walking pneumonia” diagnosis, such as MPAM.

Further testing. The patient had a normal chest x-ray and a negative respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but IgM serologies for Mycoplasma were elevated. Although the patient developed targetoid lesions on his hands during his first 24 hours in the hospital, he felt his constitutional symptoms had improved.

Exposure to Mycoplasma leads to an immune response

MPAM (also known as Fuchs’ syndrome and mycoplasma-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations) appears at some point during infection with M pneumoniae and causes severe ocular, oral, and sometimes genital symptoms with minimal skin manifestations.

MPAM is primarily seen in young males. In one systemic review of 202 cases, the average age of the patients was 11.9 years and 66% were male.1 Exposure to M pneumoniae is theorized to result in the production of autoantibodies to mycoplasma p1-adhesion molecules and to molecular mimicry of keratinocyte antigens located in the mucosa.1-3

Mycoplasma organisms have not been isolated from the cutaneous lesions of patients with MPAM; they have only been isolated from the respiratory tract, supporting the theory that MPAM is the body’s immune response to Mycoplasma, rather than a direct pathologic effect.4 This pathogenesis is distinct from that of SJS/TEN, which is thought to involve CD8+ T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis (programed cell death). In addition, SJS/TEN is almost always drug induced.

First up in the differential: Rule out SJS/TEN

When evaluating a patient like ours with a blistering eruption, the most important diagnosis to exclude is SJS/TEN. This condition is usually triggered by a medication, which was absent in this case. SJS/TEN begins with a host of constitutional symptoms and an erythematous blistering eruption, which may be preceded by atypical targetoid (2-zoned) flat papules along with erosions on 2 or more mucosal surfaces.

Patients with SJS/TEN are usually critically ill and may have a guarded prognosis. Patients with MPAM have a more favorable prognosis and are unlikely to be critically ill—as was the case with our patient.

EM major is often associated with Mycoplasma infections. Patients with EM major may have fever and arthralgias, as well as extensive mucous membrane involvement including that of the lips/mouth, eyes, and genitals.

Experts agree that EM is separate from the SJS/TEN continuum, and that patients with EM major, including those with MPAM, are not at risk of developing SJS/TEN.5 EM is characterized by the presence of the more characteristic ‘target’ or ‘iris’ 3-zoned lesion—a central dusky purpura, surrounded by an elevated edematous pale ring, rimmed by a red macular outer ring. EM major is defined as EM along with involvement of one or more mucosal regions.

In this case, the patient had acral target lesions and oral and ocular mucosal involvement characteristic of EM major, without widespread skin erosions or sloughing commonly seen with SJS/TEN.

Kawasaki’s disease occurs in young children and presents with conjunctivitis and oral changes. However, patients with Kawasaki’s disease generally have a fever for >5 days, a strawberry tongue (not a part of the morphology of EM major or MPAM), and palmoplantar erythema and desquamation that are not common with EM major or MPAM.1

Pemphigus vulgaris is uncommon in children and young adults. The disease does not present with diffuse mucositis nor diffuse blistering of the skin, but rather with discrete shallow erosions on the mucosa and the trunk along with flaccid bullae and erosions on the skin.

The morphologies of a fixed drug eruption (round purpuric patch) and toxic shock syndrome (diffuse macular erythema and widespread skin sloughing) are inconsistent with this patient’s diffuse mucositis, conjunctivitis, and targetoid lesions.

Confirm exposure to M pneumoniae

Testing with the purpose of ruling in MPAM is directed toward proving that the patient has been exposed to M pneumoniae. (Of note: M pneumoniae cannot be detected via routine commercial blood cultures.)

Serologic testing for elevated IgM antibodies to Mycoplasma is the most specific method. Various studies have found it to be positive in 100% of cases, but detection may be delayed for a couple of weeks while the body develops the requisite antibodies.4

Respiratory PCR for Mycoplasma is rapid and usually appropriately positive, but may be negative in cases where the patient has spontaneously cleared the infection or has been exposed to antibiotics before development of the eruption.4 An infiltrate on chest imaging is supportive of the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy will demonstrate either mucositis and necrosis of keratinocytes or EM-like necrosis, but does not suggest an etiology.

Strikingly different paths of care

Distinguishing between SJS/TEN and EM major (including MPAM) is crucial to guiding management. Patients with SJS/TEN need critical care, particularly of their eyes and genitourinary and respiratory systems. Specialist consultation is often required.

For EM major, patients require supportive care along with ongoing assurances that the eruption has a benign prognosis. Hospital admission is not mandatory as long as adequate supportive care and symptom control can be provided on an outpatient basis. Early consultation with Ophthalmology, Oral Medicine, and Urology may also be key.

Keep in mind that patients may have severe stomatitis and pain that alter their ability to eat and perform normal activities. Thus, managing pain and ensuring adequate nutrition are crucial for successful support. While antibiotics treat active Mycoplasma infection, there is no clear evidence that antibiotics alter the course of the eruption, which is also consistent with the hypothesized pathogenesis.3,4

While there is no clear statistical evidence that systemic immune suppression alters the disease course, a large proportion (31%) of patients in a recent systematic review of MPAM were treated with corticosteroids, and a smaller, but noteworthy, percentage (9%) were treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG).4 There are reports of severe stomatitis that didn’t improve with supportive care, but that showed dramatic improvement with IVIG treatment.6,7

Our patient had difficulty controlling secretions and managing the painful mucositis of his mouth; he was initially unable to tolerate solid foods. Topical lidocaine solution for his mucositis caused burning and more discomfort, but acetaminophen-hydrocodone 300 mg-5 mg every 6 hours did relieve his pain. Wound care with a bland emollient and the application of non-stick dressings to his lips at night also helped to relieve some of the pain.

Because the patient’s oropharyngeal swelling made it hard for him to swallow, he received oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d, which provided him with relief within 24 hours. The acute inflammation and eruption also subsided within 48 hours and the patient was discharged after 5 days of being hospitalized. He continued to recover as an outpatient, seeing his primary care physician within 2 weeks for final nutrition and wound care support. Two weeks after that, he had a dermatology appointment, and all of his lesions had re-epithelialized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, MS, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7323 Snowden Road, Apt. 1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; [email protected].

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.

2. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

3. Dinulos JG. What’s new with common, uncommon and rare rashes in childhood. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:261-266.