User login

The Integration of Extended Reality in Arthroplasty: Reviewing Technological Progress and Clinical Benefits

The Integration of Extended Reality in Arthroplasty: Reviewing Technological Progress and Clinical Benefits

The introduction of extended reality (XR) to the operating room (OR) has proved promising for enhancing surgical precision and improving patient outcomes. In the field of orthopedic surgery, precise alignment of implants is integral to maintaining functional range of motion and preventing impingement of adjacent neurovascular structures. XR systems have shown promise in arthroplasty including by improving precision and streamlining surgery by allowing surgeons to create 3D preoperative plans that are accessible intraoperatively. This article explores the current applications of XR in arthroplasty, highlights recent advancements and benefits, and describes limitations in comparison to traditional techniques.

Methods

A literature search identified studies involving the use of XR in arthroplasty and current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved XR systems. Multiple electronic databases were used, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and IEEE Xplore. Search terms included: extended reality, augmented reality, virtual reality, arthroplasty, joint replacement, total knee arthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. The study design, intervention details, outcomes, and comparisons with traditional surgical techniques were thematically analyzed, with identification of common ideas associated with XR use in arthroplasty. This narrative report highlights the integration of XR in arthroplasty.

Extended Reality Fundamentals

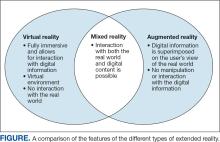

XR encompasses augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and mixed reality (MR). AR involves superimposing digitally rendered information and images onto the surgeon’s view of the real world, typically through the use of a headset and smart glasses.1 AR allows the surgeon to move and interact freely within the OR, removing the need for additional screens or devices to display patient information or imaging. VR is a fully immersive simulation using a headset that obstructs the view of the real world but allows the user to move freely within this virtual setting, often with audio or other sensory stimuli. MR combines AR and VR to create a digital model that allows for real-world interaction, with the advantage of adapting information and models in real time.2 Whereas in AR the surgeon can view the data projected from the headset, MR provides the ability to interact with and manipulate the digital content (Figure). Both AR and MR have been adapted for use in the OR, while VR has been adapted for use in surgical planning and training.

Extended Reality Use in Orthopedics

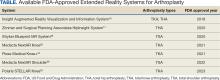

The HipNav system was introduced in 1995 to create preoperative plans that assist surgeons in accurately implanting the acetabular cup during total hip arthroplasty (THA).3 Although not commercially successful, this system spurred surgeons to experiment with XR to improve the accuracy and alignment of orthopedic implants. Systems capable of displaying the desired intraoperative implant placement have flourished, with applications in fracture reduction, arthroplasty, solid tumor resection, and hardware placement.4-7 Accurate alignment has been linked to improvements in patient outcomes.8-10 XR has great potential within the field of arthroplasty, with multiple new systems approved by the FDA and currently available in the US (Table).

Hip Arthroplasty

Orientation of the acetabular cup is a technically challenging part of THA. Accuracy in the anteversion and inclination angles of the acetabular cup is required to maintain implant stability, preserve functional range of motion (ROM), and prevent precocious wear.11,12 Despite preoperative planning, surgeons often overestimate the inclination angle and underestimate anteversion.13 Improper implantation of the acetabular cup can lead to joint instability caused by aseptic loosening, increasing the risk of dislocation and the need for revision surgery.14,15 Dislocations typically present to the emergency department, but primary care practitioners may encounter patients with pain or diminished sensation due to impingement or instability.16

The introduction of XR into the OR has provided the opportunity for real-time navigation and adjustment of the acetabular cup to maximize anteversion and inclination angles. Currently, 2 FDA-approved systems are available for THA: the Zimmer and Surgical Planning Associates HipInsight system, and the Insight Augmented Reality Visualization and Information System (ARVIS). The HipInsight system consists of a hologram projection using the Microsoft HoloLens2 device and optimizes preoperative planning, producing accuracy of anteversion and inclination angles within 3°.17 ARVIS employs existing surgical helmets and 2 mounted tracking cameras to provide navigation intraoperatively. ARVIS has also been approved for use in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty.18

HipInsight has shown utility in increasing the accuracy of acetabular cup placement along with the use of biplanar radiographic scans.19 However, there are no studies validating the efficacy of ARVIS and HipInsight and assessing long-term disease-oriented or patient-oriented outcomes.

Knee Arthroplasty

In the setting of TKA, XR is most effective in ensuring accurate resection of the tibial and femoral components. Achieving the planned femoral coronal, axial, and sagittal angles allows the prosthesis to be on the femoral axis of rotation, improving functional outcomes. XR systems for TKA have been shown to increase the accuracy of distal femoral resection with a limited increase in surgery duration.20,21 For TKA in particular, patients are often less satisfied with the result than surgeons expect.22 Accurate alignment can improve patient satisfaction and reduce return-to-clinic rates for postoperative pain management, a factor that primary care practitioners should consider when recommending a patient for TKA.23

Along with ARVIS, 3 additional XR systems are FDA-approved for use in TKA. The Pixee Medical Knee+ system uses smart glasses and trackers to aid in the positioning of instruments for improved accuracy while allowing real-time navigation.24 The Medacta NextAR Knee’s single-use tracking system allows for intraoperative navigation with the use of AR glasses.25 The Polaris STELLAR Knee uses MR and avoids the need for preoperative imaging by capturing real-time anatomic data.26

The Pixee Medical Knee+ system was commercially available in Europe for several years prior to FDA approval, so more research exists on its efficacy. One study found that the Pixee Medical Knee+ system initially demonstrated an inferior clinical outcome, attributed to the learning curve associated with using the system.27 However, more recent studies have shown its utility in improving alignment, regardless of implant specifications.28,29 The Medacta NextAR Knee system has been shown to improve accuracy of tibial rotation and soft tissue balance and even increase OR efficiency.30,31 The Polaris STELLAR Knee system received FDA approval in 2023; no published research exists on its accuracy and outcomes.26

Shoulder Arthroplasty

Minimally invasive techniques are favored in total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) due to the vitality of maintaining the surrounding soft tissue to maximize preservation of motility and strength.32 However, this complicates the procedure by decreasing the ability to effectively access and visualize key structures of the shoulder. Accordingly, issues with implant positioning and alignment are more common with TSA than other joint arthroplasties, making XR particularly promising.33 Some studies report that up to 67% of patients experience glenohumeral instability, which can clinically present as weakness, decreased range of motion, and persistent shoulder pain.34,35 The use of preoperative computed tomography to improve understanding of glenoid anatomy and glenohumeral subluxation is becoming increasingly common, and it can be combined with XR to improve accuracy.36,37

Two FDA-approved systems are available. The Stryker Blueprint MR system is used for intraoperative guidance and integration for patient imaging used for preoperative planning. The Medacta NextAR Shoulder system is a parallel of the company’s TKA system. The Stryker Blueprint MR system combines the Microsoft HoloLens 2 headset to display preoperative plans with a secondary display for coordination with the rest of the surgical team.38 Similar to the Medacta NextAR Knee, the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system uses the same single-use tracking system and AR glasses for intraoperative guidance.39

Data on the long-term outcomes of using these systems are still limited, but the Stryker Blueprint MR system has not been shown to accurately predict postoperative ROM.40 Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system can provide accurate inclination, retroversion, entry point, depth, and rotation values based on the preoperative planned values.41,42 However, this accuracy has yet to be confirmed in vivo, and the impact of using XR in TSA on long-term outcomes is still unknown.

Challenges and Limitations

Though XR has proven to be promising in arthroplasty, several limitations regarding widespread implementation exist. In particular, there is a steep learning curve associated with the use of XR systems, which can cause increased operative time and even initial inferior outcomes, as demonstrated with the Pixee Medical Knee+ system. The need for extensive practice and training prior to use could delay widespread adoption and may cause discrepancies in surgical outcomes. Unfamiliarity with the system and technological difficulties that may require troubleshooting can also increase operative time, particularly for surgeons new to using the XR system. Though intraoperative navigation is expected to improve accuracy of implant alignment, its added complexity may also result in longer surgeries.

In addition to the steep learning curve and increased operative time, there is a high upfront cost associated with XR systems. Exact costs of XR systems are not typically disclosed, but available estimates suggest an average sales price of about $1000 per case. Given the proprietary nature of these technologies, publicly available cost data are limited, making it challenging to fully assess the financial burden on health care institutions. Though some systems, such as ARVIS, can be integrated with existing surgical helmets, many require the purchase of AR glasses and secondary displays. This can cause further variation in the total expense for each system. In low-resource settings, this represents a significant challenge to widespread implementation. To justify this cost, additional research on long-term patient outcomes is needed to ensure the benefits of XR systems outweigh the cost.

Although early studies on XR systems in arthroplasty have shown improvements in precision and short-term outcomes, long-term data regarding effectiveness remains. Even systems such as ARVIS and HipInsight have limited long-term follow-up, making it difficult to assess whether the improved accuracy with these XR systems translates into improved patient outcomes compared with traditional arthroplasty.

CONCLUSIONS

XR technologies have shown significant potential in enhancing precision and patient outcomes. Through the integration of XR in the OR, surgeons can visualize preoperative plans and even make intraoperative changes, with the benefit of improving implant alignment.

There are some disadvantages to its use, however, including high cost and increased operative time. Despite this, the integration of XR into surgical practice can deliver more precise implant alignment and address other challenges faced with conventional techniques. As these technologies evolve and studies on long-term outcomes validate their utility, XR has the potential to transform the field of arthroplasty.

Azuma RT. A survey of augmented reality. Presence-Teleop Virt. 1997;6:355-385. doi:10.1162/pres.1997.6.4.355

Speicher M, Hall BD, Nebeling M. What is Mixed Reality? In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery; 2019:1-15. doi:10.1145/3290605.3300767

Digioia AM, Jaramaz B, Nikou C, et al. Surgical navigation for total hip replacement with the use of hipnav. Oper Tech Orthop. 2000;10:3-8. doi:10.1016/S1048-6666(00)80036-1

Ogawa H, Hasegawa S, Tsukada S, et al. A pilot study of augmented reality technology applied to the acetabular cup placement during total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1833-1837. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.067

Shen F, Chen B, Guo Q, et al. Augmented reality patient-specific reconstruction plate design for pelvic and acetabular fracture surgery. Int J CARS. 2013;8:169-179. doi:10.1007/s11548-012-0775-5

Cho HS, Park YK, Gupta S, et al. Augmented reality in bone tumour resection: an experimental study. Bone Joint Res. 2017;6:137-143. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.63.bjr-2016-0289.r1

Wu X, Liu R, Yu J, et al. Mixed reality technology launches in orthopedic surgery for comprehensive preoperative management of complicated cervical fractures. Surg Innov. 2018;25:421-422. doi:10.1177/1553350618761758

Dossett HG, Arthur JR, Makovicka JL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasties: long-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S209-S214. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.03.065

Kazarian GS, Haddad FS, Donaldson MJ, et al. Implant malalignment may be a risk factor for poor patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S129-S133. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2022.02.087

Peng Y, Arauz P, An S, et al. Does component alignment affect patient reported outcomes following bicruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty? An in vivo three-dimensional analysis. J Knee Surg. 2020;33:798-803. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1688500

D’Lima DD, Urquhart AG, Buehler KO, et al. The effect of the orientation of the acetabular and femoral components on the range of motion of the hip at different head-neck ratios. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:315-321. doi:10.2106/00004623-200003000-00003

Yamaguchi M, Akisue T, Bauer TW, et al. The spatial location of impingement in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:305-313. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(00)90601-6

Grammatopoulos G, Alvand A, Monk AP, et al. Surgeons’ accuracy in achieving their desired acetabular component orientation. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:e72. doi:10.2106/JBJS.15.01080

Kennedy JG, Rogers WB, Soffe KE, et al. Effect of acetabular component orientation on recurrent dislocation, pelvic osteolysis, polyethylene wear, and component migration. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:530-534. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90052-3

Del Schutte H, Lipman AJ, Bannar SM, et al. Effects of acetabular abduction on cup wear rates in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:621-626. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)80003-X

Aresti N, Kassam J, Bartlett D, et al. Primary care management of postoperative shoulder, hip, and knee arthroplasty. BMJ. 2017;359:j4431. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4431

HipInsightTM System. Zimmer Biomet. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.zimmerbiomet.com/en/products-and-solutions/zb-edge/mixed-reality-portfolio/hipinsight-system.html

ARVIS. Insight Medical Systems. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.insightmedsys.com/arvis

Sun DC, Murphy WS, Amundson AJ, et al. Validation of a novel method of measuring cup orientation using biplanar simultaneous radiographic images. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S252-S256. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.04.011

Tsukada S, Ogawa H, Nishino M, et al. Augmented reality-assisted femoral bone resection in total knee arthroplasty. JBJS Open Access. 2021;6:e21.00001. doi:10.2106/JBJS.OA.21.00001

Castellarin G, Bori E, Barbieux E, et al. Is total knee arthroplasty surgical performance enhanced using augmented reality? A single-center study on 76 consecutive patients. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:332-335. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.08.013

Choi YJ, Ra HJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016;28:1. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.1.1

Hazratwala K, Gouk C, Wilkinson MPR, et al. Navigated functional alignment total knee arthroplasty achieves reliable, reproducible and accurate results with high patient satisfaction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:3861-3870. doi:10.1007/s00167-023-07327-w

Knee+. Pixee Medical. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.pixee-medical.com/en/products/knee-nexsight/

KNEE | NEXTAR. Nextar. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/knee

POLARIS AR receives clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for STELLAR Knee. News release. PRNewswire. November 3, 2023. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/polarisar-receives-clearance-from-the-us-food-and-drug-administration-for-stellar-knee-301976747.html

van Overschelde P, Vansintjan P, Byn P, Lapierre C, van Lysebettens W. Does augmented reality improve clinical outcome in TKA? A prospective observational report. In: The 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Computer Assisted Orthopaedic Surgery. 2022:170-174.

Sakellariou E, Alevrogiannis P, Alevrogianni F, et al. Single-center experience with Knee+TM augmented reality navigation system in primary total knee arthroplasty. World J Orthop. 2024;15:247-256. doi:10.5312/wjo.v15.i3.247

León-Muñoz VJ, Moya-Angeler J, López-López M, et al. Integration of square fiducial markers in patient-specific instrumentation and their applicability in knee surgery. J Pers Med. 2023;13:727. doi:10.3390/jpm13050727

Fucentese SF, Koch PP. A novel augmented reality-based surgical guidance system for total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141:2227-2233. doi:10.1007/s00402-021-04204-4

Sabatini L, Ascani D, Vezza D, et al. Novel surgical technique for total knee arthroplasty integrating kinematic alignment and real-time elongation of the ligaments using the NextAR system. J Pers Med. 2024;14:794. doi:10.3390/jpm14080794

Daher M, Ghanimeh J, Otayek J, et al. Augmented reality and shoulder replacement: a state-of-the-art review article. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2023;3:274-278. doi:10.1016/j.xrrt.2023.01.008

Atmani H, Merienne F, Fofi D, et al. Computer aided surgery system for shoulder prosthesis placement. Comput Aided Surg. 2007;12:60-70. doi:10.3109/10929080701210832

Eichinger JK, Galvin JW. Management of complications after total shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8:83-91. doi:10.1007/s12178-014-9251-x

Bonnevialle N, Melis B, Neyton L, et al. Aseptic glenoid loosening or failure in total shoulder arthroplasty: revision with glenoid reimplantation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:745-751. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.009

Erickson BJ, Chalmers PN, Denard P, et al. Does commercially available shoulder arthroplasty preoperative planning software agree with surgeon measurements of version, inclination, and subluxation? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:413-420. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.027

Werner BS, Hudek R, Burkhart KJ, et al. The influence of three-dimensional planning on decision-making in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:1477-1483. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.006

Blueprint. Stryker. Updated August 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.stryker.com/us/en/trauma-and-extremities/products/blueprint.html

NextAR Shoulder. Medacta. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/shoulder

Baumgarten KM. Accuracy of Blueprint software in predicting range of motion 1 year after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:1088-1094. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2022.12.009

Rojas JT, Jost B, Zipeto C, et al. Glenoid component placement in reverse shoulder arthroplasty assisted with augmented reality through a head-mounted display leads to low deviation between planned and postoperative parameters. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:e587-e596. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2023.05.002

Dey Hazra RO, Paksoy A, Imiolczyk JP, et al. Augmented reality–assisted intraoperative navigation increases precision of glenoid inclination in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2025;34(2):577-583. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2024.05.039

The introduction of extended reality (XR) to the operating room (OR) has proved promising for enhancing surgical precision and improving patient outcomes. In the field of orthopedic surgery, precise alignment of implants is integral to maintaining functional range of motion and preventing impingement of adjacent neurovascular structures. XR systems have shown promise in arthroplasty including by improving precision and streamlining surgery by allowing surgeons to create 3D preoperative plans that are accessible intraoperatively. This article explores the current applications of XR in arthroplasty, highlights recent advancements and benefits, and describes limitations in comparison to traditional techniques.

Methods

A literature search identified studies involving the use of XR in arthroplasty and current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved XR systems. Multiple electronic databases were used, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and IEEE Xplore. Search terms included: extended reality, augmented reality, virtual reality, arthroplasty, joint replacement, total knee arthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. The study design, intervention details, outcomes, and comparisons with traditional surgical techniques were thematically analyzed, with identification of common ideas associated with XR use in arthroplasty. This narrative report highlights the integration of XR in arthroplasty.

Extended Reality Fundamentals

XR encompasses augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and mixed reality (MR). AR involves superimposing digitally rendered information and images onto the surgeon’s view of the real world, typically through the use of a headset and smart glasses.1 AR allows the surgeon to move and interact freely within the OR, removing the need for additional screens or devices to display patient information or imaging. VR is a fully immersive simulation using a headset that obstructs the view of the real world but allows the user to move freely within this virtual setting, often with audio or other sensory stimuli. MR combines AR and VR to create a digital model that allows for real-world interaction, with the advantage of adapting information and models in real time.2 Whereas in AR the surgeon can view the data projected from the headset, MR provides the ability to interact with and manipulate the digital content (Figure). Both AR and MR have been adapted for use in the OR, while VR has been adapted for use in surgical planning and training.

Extended Reality Use in Orthopedics

The HipNav system was introduced in 1995 to create preoperative plans that assist surgeons in accurately implanting the acetabular cup during total hip arthroplasty (THA).3 Although not commercially successful, this system spurred surgeons to experiment with XR to improve the accuracy and alignment of orthopedic implants. Systems capable of displaying the desired intraoperative implant placement have flourished, with applications in fracture reduction, arthroplasty, solid tumor resection, and hardware placement.4-7 Accurate alignment has been linked to improvements in patient outcomes.8-10 XR has great potential within the field of arthroplasty, with multiple new systems approved by the FDA and currently available in the US (Table).

Hip Arthroplasty

Orientation of the acetabular cup is a technically challenging part of THA. Accuracy in the anteversion and inclination angles of the acetabular cup is required to maintain implant stability, preserve functional range of motion (ROM), and prevent precocious wear.11,12 Despite preoperative planning, surgeons often overestimate the inclination angle and underestimate anteversion.13 Improper implantation of the acetabular cup can lead to joint instability caused by aseptic loosening, increasing the risk of dislocation and the need for revision surgery.14,15 Dislocations typically present to the emergency department, but primary care practitioners may encounter patients with pain or diminished sensation due to impingement or instability.16

The introduction of XR into the OR has provided the opportunity for real-time navigation and adjustment of the acetabular cup to maximize anteversion and inclination angles. Currently, 2 FDA-approved systems are available for THA: the Zimmer and Surgical Planning Associates HipInsight system, and the Insight Augmented Reality Visualization and Information System (ARVIS). The HipInsight system consists of a hologram projection using the Microsoft HoloLens2 device and optimizes preoperative planning, producing accuracy of anteversion and inclination angles within 3°.17 ARVIS employs existing surgical helmets and 2 mounted tracking cameras to provide navigation intraoperatively. ARVIS has also been approved for use in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty.18

HipInsight has shown utility in increasing the accuracy of acetabular cup placement along with the use of biplanar radiographic scans.19 However, there are no studies validating the efficacy of ARVIS and HipInsight and assessing long-term disease-oriented or patient-oriented outcomes.

Knee Arthroplasty

In the setting of TKA, XR is most effective in ensuring accurate resection of the tibial and femoral components. Achieving the planned femoral coronal, axial, and sagittal angles allows the prosthesis to be on the femoral axis of rotation, improving functional outcomes. XR systems for TKA have been shown to increase the accuracy of distal femoral resection with a limited increase in surgery duration.20,21 For TKA in particular, patients are often less satisfied with the result than surgeons expect.22 Accurate alignment can improve patient satisfaction and reduce return-to-clinic rates for postoperative pain management, a factor that primary care practitioners should consider when recommending a patient for TKA.23

Along with ARVIS, 3 additional XR systems are FDA-approved for use in TKA. The Pixee Medical Knee+ system uses smart glasses and trackers to aid in the positioning of instruments for improved accuracy while allowing real-time navigation.24 The Medacta NextAR Knee’s single-use tracking system allows for intraoperative navigation with the use of AR glasses.25 The Polaris STELLAR Knee uses MR and avoids the need for preoperative imaging by capturing real-time anatomic data.26

The Pixee Medical Knee+ system was commercially available in Europe for several years prior to FDA approval, so more research exists on its efficacy. One study found that the Pixee Medical Knee+ system initially demonstrated an inferior clinical outcome, attributed to the learning curve associated with using the system.27 However, more recent studies have shown its utility in improving alignment, regardless of implant specifications.28,29 The Medacta NextAR Knee system has been shown to improve accuracy of tibial rotation and soft tissue balance and even increase OR efficiency.30,31 The Polaris STELLAR Knee system received FDA approval in 2023; no published research exists on its accuracy and outcomes.26

Shoulder Arthroplasty

Minimally invasive techniques are favored in total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) due to the vitality of maintaining the surrounding soft tissue to maximize preservation of motility and strength.32 However, this complicates the procedure by decreasing the ability to effectively access and visualize key structures of the shoulder. Accordingly, issues with implant positioning and alignment are more common with TSA than other joint arthroplasties, making XR particularly promising.33 Some studies report that up to 67% of patients experience glenohumeral instability, which can clinically present as weakness, decreased range of motion, and persistent shoulder pain.34,35 The use of preoperative computed tomography to improve understanding of glenoid anatomy and glenohumeral subluxation is becoming increasingly common, and it can be combined with XR to improve accuracy.36,37

Two FDA-approved systems are available. The Stryker Blueprint MR system is used for intraoperative guidance and integration for patient imaging used for preoperative planning. The Medacta NextAR Shoulder system is a parallel of the company’s TKA system. The Stryker Blueprint MR system combines the Microsoft HoloLens 2 headset to display preoperative plans with a secondary display for coordination with the rest of the surgical team.38 Similar to the Medacta NextAR Knee, the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system uses the same single-use tracking system and AR glasses for intraoperative guidance.39

Data on the long-term outcomes of using these systems are still limited, but the Stryker Blueprint MR system has not been shown to accurately predict postoperative ROM.40 Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system can provide accurate inclination, retroversion, entry point, depth, and rotation values based on the preoperative planned values.41,42 However, this accuracy has yet to be confirmed in vivo, and the impact of using XR in TSA on long-term outcomes is still unknown.

Challenges and Limitations

Though XR has proven to be promising in arthroplasty, several limitations regarding widespread implementation exist. In particular, there is a steep learning curve associated with the use of XR systems, which can cause increased operative time and even initial inferior outcomes, as demonstrated with the Pixee Medical Knee+ system. The need for extensive practice and training prior to use could delay widespread adoption and may cause discrepancies in surgical outcomes. Unfamiliarity with the system and technological difficulties that may require troubleshooting can also increase operative time, particularly for surgeons new to using the XR system. Though intraoperative navigation is expected to improve accuracy of implant alignment, its added complexity may also result in longer surgeries.

In addition to the steep learning curve and increased operative time, there is a high upfront cost associated with XR systems. Exact costs of XR systems are not typically disclosed, but available estimates suggest an average sales price of about $1000 per case. Given the proprietary nature of these technologies, publicly available cost data are limited, making it challenging to fully assess the financial burden on health care institutions. Though some systems, such as ARVIS, can be integrated with existing surgical helmets, many require the purchase of AR glasses and secondary displays. This can cause further variation in the total expense for each system. In low-resource settings, this represents a significant challenge to widespread implementation. To justify this cost, additional research on long-term patient outcomes is needed to ensure the benefits of XR systems outweigh the cost.

Although early studies on XR systems in arthroplasty have shown improvements in precision and short-term outcomes, long-term data regarding effectiveness remains. Even systems such as ARVIS and HipInsight have limited long-term follow-up, making it difficult to assess whether the improved accuracy with these XR systems translates into improved patient outcomes compared with traditional arthroplasty.

CONCLUSIONS

XR technologies have shown significant potential in enhancing precision and patient outcomes. Through the integration of XR in the OR, surgeons can visualize preoperative plans and even make intraoperative changes, with the benefit of improving implant alignment.

There are some disadvantages to its use, however, including high cost and increased operative time. Despite this, the integration of XR into surgical practice can deliver more precise implant alignment and address other challenges faced with conventional techniques. As these technologies evolve and studies on long-term outcomes validate their utility, XR has the potential to transform the field of arthroplasty.

The introduction of extended reality (XR) to the operating room (OR) has proved promising for enhancing surgical precision and improving patient outcomes. In the field of orthopedic surgery, precise alignment of implants is integral to maintaining functional range of motion and preventing impingement of adjacent neurovascular structures. XR systems have shown promise in arthroplasty including by improving precision and streamlining surgery by allowing surgeons to create 3D preoperative plans that are accessible intraoperatively. This article explores the current applications of XR in arthroplasty, highlights recent advancements and benefits, and describes limitations in comparison to traditional techniques.

Methods

A literature search identified studies involving the use of XR in arthroplasty and current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved XR systems. Multiple electronic databases were used, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and IEEE Xplore. Search terms included: extended reality, augmented reality, virtual reality, arthroplasty, joint replacement, total knee arthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. The study design, intervention details, outcomes, and comparisons with traditional surgical techniques were thematically analyzed, with identification of common ideas associated with XR use in arthroplasty. This narrative report highlights the integration of XR in arthroplasty.

Extended Reality Fundamentals

XR encompasses augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and mixed reality (MR). AR involves superimposing digitally rendered information and images onto the surgeon’s view of the real world, typically through the use of a headset and smart glasses.1 AR allows the surgeon to move and interact freely within the OR, removing the need for additional screens or devices to display patient information or imaging. VR is a fully immersive simulation using a headset that obstructs the view of the real world but allows the user to move freely within this virtual setting, often with audio or other sensory stimuli. MR combines AR and VR to create a digital model that allows for real-world interaction, with the advantage of adapting information and models in real time.2 Whereas in AR the surgeon can view the data projected from the headset, MR provides the ability to interact with and manipulate the digital content (Figure). Both AR and MR have been adapted for use in the OR, while VR has been adapted for use in surgical planning and training.

Extended Reality Use in Orthopedics

The HipNav system was introduced in 1995 to create preoperative plans that assist surgeons in accurately implanting the acetabular cup during total hip arthroplasty (THA).3 Although not commercially successful, this system spurred surgeons to experiment with XR to improve the accuracy and alignment of orthopedic implants. Systems capable of displaying the desired intraoperative implant placement have flourished, with applications in fracture reduction, arthroplasty, solid tumor resection, and hardware placement.4-7 Accurate alignment has been linked to improvements in patient outcomes.8-10 XR has great potential within the field of arthroplasty, with multiple new systems approved by the FDA and currently available in the US (Table).

Hip Arthroplasty

Orientation of the acetabular cup is a technically challenging part of THA. Accuracy in the anteversion and inclination angles of the acetabular cup is required to maintain implant stability, preserve functional range of motion (ROM), and prevent precocious wear.11,12 Despite preoperative planning, surgeons often overestimate the inclination angle and underestimate anteversion.13 Improper implantation of the acetabular cup can lead to joint instability caused by aseptic loosening, increasing the risk of dislocation and the need for revision surgery.14,15 Dislocations typically present to the emergency department, but primary care practitioners may encounter patients with pain or diminished sensation due to impingement or instability.16

The introduction of XR into the OR has provided the opportunity for real-time navigation and adjustment of the acetabular cup to maximize anteversion and inclination angles. Currently, 2 FDA-approved systems are available for THA: the Zimmer and Surgical Planning Associates HipInsight system, and the Insight Augmented Reality Visualization and Information System (ARVIS). The HipInsight system consists of a hologram projection using the Microsoft HoloLens2 device and optimizes preoperative planning, producing accuracy of anteversion and inclination angles within 3°.17 ARVIS employs existing surgical helmets and 2 mounted tracking cameras to provide navigation intraoperatively. ARVIS has also been approved for use in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty.18

HipInsight has shown utility in increasing the accuracy of acetabular cup placement along with the use of biplanar radiographic scans.19 However, there are no studies validating the efficacy of ARVIS and HipInsight and assessing long-term disease-oriented or patient-oriented outcomes.

Knee Arthroplasty

In the setting of TKA, XR is most effective in ensuring accurate resection of the tibial and femoral components. Achieving the planned femoral coronal, axial, and sagittal angles allows the prosthesis to be on the femoral axis of rotation, improving functional outcomes. XR systems for TKA have been shown to increase the accuracy of distal femoral resection with a limited increase in surgery duration.20,21 For TKA in particular, patients are often less satisfied with the result than surgeons expect.22 Accurate alignment can improve patient satisfaction and reduce return-to-clinic rates for postoperative pain management, a factor that primary care practitioners should consider when recommending a patient for TKA.23

Along with ARVIS, 3 additional XR systems are FDA-approved for use in TKA. The Pixee Medical Knee+ system uses smart glasses and trackers to aid in the positioning of instruments for improved accuracy while allowing real-time navigation.24 The Medacta NextAR Knee’s single-use tracking system allows for intraoperative navigation with the use of AR glasses.25 The Polaris STELLAR Knee uses MR and avoids the need for preoperative imaging by capturing real-time anatomic data.26

The Pixee Medical Knee+ system was commercially available in Europe for several years prior to FDA approval, so more research exists on its efficacy. One study found that the Pixee Medical Knee+ system initially demonstrated an inferior clinical outcome, attributed to the learning curve associated with using the system.27 However, more recent studies have shown its utility in improving alignment, regardless of implant specifications.28,29 The Medacta NextAR Knee system has been shown to improve accuracy of tibial rotation and soft tissue balance and even increase OR efficiency.30,31 The Polaris STELLAR Knee system received FDA approval in 2023; no published research exists on its accuracy and outcomes.26

Shoulder Arthroplasty

Minimally invasive techniques are favored in total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) due to the vitality of maintaining the surrounding soft tissue to maximize preservation of motility and strength.32 However, this complicates the procedure by decreasing the ability to effectively access and visualize key structures of the shoulder. Accordingly, issues with implant positioning and alignment are more common with TSA than other joint arthroplasties, making XR particularly promising.33 Some studies report that up to 67% of patients experience glenohumeral instability, which can clinically present as weakness, decreased range of motion, and persistent shoulder pain.34,35 The use of preoperative computed tomography to improve understanding of glenoid anatomy and glenohumeral subluxation is becoming increasingly common, and it can be combined with XR to improve accuracy.36,37

Two FDA-approved systems are available. The Stryker Blueprint MR system is used for intraoperative guidance and integration for patient imaging used for preoperative planning. The Medacta NextAR Shoulder system is a parallel of the company’s TKA system. The Stryker Blueprint MR system combines the Microsoft HoloLens 2 headset to display preoperative plans with a secondary display for coordination with the rest of the surgical team.38 Similar to the Medacta NextAR Knee, the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system uses the same single-use tracking system and AR glasses for intraoperative guidance.39

Data on the long-term outcomes of using these systems are still limited, but the Stryker Blueprint MR system has not been shown to accurately predict postoperative ROM.40 Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system can provide accurate inclination, retroversion, entry point, depth, and rotation values based on the preoperative planned values.41,42 However, this accuracy has yet to be confirmed in vivo, and the impact of using XR in TSA on long-term outcomes is still unknown.

Challenges and Limitations

Though XR has proven to be promising in arthroplasty, several limitations regarding widespread implementation exist. In particular, there is a steep learning curve associated with the use of XR systems, which can cause increased operative time and even initial inferior outcomes, as demonstrated with the Pixee Medical Knee+ system. The need for extensive practice and training prior to use could delay widespread adoption and may cause discrepancies in surgical outcomes. Unfamiliarity with the system and technological difficulties that may require troubleshooting can also increase operative time, particularly for surgeons new to using the XR system. Though intraoperative navigation is expected to improve accuracy of implant alignment, its added complexity may also result in longer surgeries.

In addition to the steep learning curve and increased operative time, there is a high upfront cost associated with XR systems. Exact costs of XR systems are not typically disclosed, but available estimates suggest an average sales price of about $1000 per case. Given the proprietary nature of these technologies, publicly available cost data are limited, making it challenging to fully assess the financial burden on health care institutions. Though some systems, such as ARVIS, can be integrated with existing surgical helmets, many require the purchase of AR glasses and secondary displays. This can cause further variation in the total expense for each system. In low-resource settings, this represents a significant challenge to widespread implementation. To justify this cost, additional research on long-term patient outcomes is needed to ensure the benefits of XR systems outweigh the cost.

Although early studies on XR systems in arthroplasty have shown improvements in precision and short-term outcomes, long-term data regarding effectiveness remains. Even systems such as ARVIS and HipInsight have limited long-term follow-up, making it difficult to assess whether the improved accuracy with these XR systems translates into improved patient outcomes compared with traditional arthroplasty.

CONCLUSIONS

XR technologies have shown significant potential in enhancing precision and patient outcomes. Through the integration of XR in the OR, surgeons can visualize preoperative plans and even make intraoperative changes, with the benefit of improving implant alignment.

There are some disadvantages to its use, however, including high cost and increased operative time. Despite this, the integration of XR into surgical practice can deliver more precise implant alignment and address other challenges faced with conventional techniques. As these technologies evolve and studies on long-term outcomes validate their utility, XR has the potential to transform the field of arthroplasty.

Azuma RT. A survey of augmented reality. Presence-Teleop Virt. 1997;6:355-385. doi:10.1162/pres.1997.6.4.355

Speicher M, Hall BD, Nebeling M. What is Mixed Reality? In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery; 2019:1-15. doi:10.1145/3290605.3300767

Digioia AM, Jaramaz B, Nikou C, et al. Surgical navigation for total hip replacement with the use of hipnav. Oper Tech Orthop. 2000;10:3-8. doi:10.1016/S1048-6666(00)80036-1

Ogawa H, Hasegawa S, Tsukada S, et al. A pilot study of augmented reality technology applied to the acetabular cup placement during total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1833-1837. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.067

Shen F, Chen B, Guo Q, et al. Augmented reality patient-specific reconstruction plate design for pelvic and acetabular fracture surgery. Int J CARS. 2013;8:169-179. doi:10.1007/s11548-012-0775-5

Cho HS, Park YK, Gupta S, et al. Augmented reality in bone tumour resection: an experimental study. Bone Joint Res. 2017;6:137-143. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.63.bjr-2016-0289.r1

Wu X, Liu R, Yu J, et al. Mixed reality technology launches in orthopedic surgery for comprehensive preoperative management of complicated cervical fractures. Surg Innov. 2018;25:421-422. doi:10.1177/1553350618761758

Dossett HG, Arthur JR, Makovicka JL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasties: long-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S209-S214. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.03.065

Kazarian GS, Haddad FS, Donaldson MJ, et al. Implant malalignment may be a risk factor for poor patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S129-S133. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2022.02.087

Peng Y, Arauz P, An S, et al. Does component alignment affect patient reported outcomes following bicruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty? An in vivo three-dimensional analysis. J Knee Surg. 2020;33:798-803. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1688500

D’Lima DD, Urquhart AG, Buehler KO, et al. The effect of the orientation of the acetabular and femoral components on the range of motion of the hip at different head-neck ratios. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:315-321. doi:10.2106/00004623-200003000-00003

Yamaguchi M, Akisue T, Bauer TW, et al. The spatial location of impingement in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:305-313. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(00)90601-6

Grammatopoulos G, Alvand A, Monk AP, et al. Surgeons’ accuracy in achieving their desired acetabular component orientation. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:e72. doi:10.2106/JBJS.15.01080

Kennedy JG, Rogers WB, Soffe KE, et al. Effect of acetabular component orientation on recurrent dislocation, pelvic osteolysis, polyethylene wear, and component migration. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:530-534. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90052-3

Del Schutte H, Lipman AJ, Bannar SM, et al. Effects of acetabular abduction on cup wear rates in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:621-626. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)80003-X

Aresti N, Kassam J, Bartlett D, et al. Primary care management of postoperative shoulder, hip, and knee arthroplasty. BMJ. 2017;359:j4431. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4431

HipInsightTM System. Zimmer Biomet. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.zimmerbiomet.com/en/products-and-solutions/zb-edge/mixed-reality-portfolio/hipinsight-system.html

ARVIS. Insight Medical Systems. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.insightmedsys.com/arvis

Sun DC, Murphy WS, Amundson AJ, et al. Validation of a novel method of measuring cup orientation using biplanar simultaneous radiographic images. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S252-S256. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.04.011

Tsukada S, Ogawa H, Nishino M, et al. Augmented reality-assisted femoral bone resection in total knee arthroplasty. JBJS Open Access. 2021;6:e21.00001. doi:10.2106/JBJS.OA.21.00001

Castellarin G, Bori E, Barbieux E, et al. Is total knee arthroplasty surgical performance enhanced using augmented reality? A single-center study on 76 consecutive patients. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:332-335. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.08.013

Choi YJ, Ra HJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016;28:1. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.1.1

Hazratwala K, Gouk C, Wilkinson MPR, et al. Navigated functional alignment total knee arthroplasty achieves reliable, reproducible and accurate results with high patient satisfaction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:3861-3870. doi:10.1007/s00167-023-07327-w

Knee+. Pixee Medical. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.pixee-medical.com/en/products/knee-nexsight/

KNEE | NEXTAR. Nextar. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/knee

POLARIS AR receives clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for STELLAR Knee. News release. PRNewswire. November 3, 2023. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/polarisar-receives-clearance-from-the-us-food-and-drug-administration-for-stellar-knee-301976747.html

van Overschelde P, Vansintjan P, Byn P, Lapierre C, van Lysebettens W. Does augmented reality improve clinical outcome in TKA? A prospective observational report. In: The 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Computer Assisted Orthopaedic Surgery. 2022:170-174.

Sakellariou E, Alevrogiannis P, Alevrogianni F, et al. Single-center experience with Knee+TM augmented reality navigation system in primary total knee arthroplasty. World J Orthop. 2024;15:247-256. doi:10.5312/wjo.v15.i3.247

León-Muñoz VJ, Moya-Angeler J, López-López M, et al. Integration of square fiducial markers in patient-specific instrumentation and their applicability in knee surgery. J Pers Med. 2023;13:727. doi:10.3390/jpm13050727

Fucentese SF, Koch PP. A novel augmented reality-based surgical guidance system for total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141:2227-2233. doi:10.1007/s00402-021-04204-4

Sabatini L, Ascani D, Vezza D, et al. Novel surgical technique for total knee arthroplasty integrating kinematic alignment and real-time elongation of the ligaments using the NextAR system. J Pers Med. 2024;14:794. doi:10.3390/jpm14080794

Daher M, Ghanimeh J, Otayek J, et al. Augmented reality and shoulder replacement: a state-of-the-art review article. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2023;3:274-278. doi:10.1016/j.xrrt.2023.01.008

Atmani H, Merienne F, Fofi D, et al. Computer aided surgery system for shoulder prosthesis placement. Comput Aided Surg. 2007;12:60-70. doi:10.3109/10929080701210832

Eichinger JK, Galvin JW. Management of complications after total shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8:83-91. doi:10.1007/s12178-014-9251-x

Bonnevialle N, Melis B, Neyton L, et al. Aseptic glenoid loosening or failure in total shoulder arthroplasty: revision with glenoid reimplantation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:745-751. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.009

Erickson BJ, Chalmers PN, Denard P, et al. Does commercially available shoulder arthroplasty preoperative planning software agree with surgeon measurements of version, inclination, and subluxation? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:413-420. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.027

Werner BS, Hudek R, Burkhart KJ, et al. The influence of three-dimensional planning on decision-making in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:1477-1483. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.006

Blueprint. Stryker. Updated August 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.stryker.com/us/en/trauma-and-extremities/products/blueprint.html

NextAR Shoulder. Medacta. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/shoulder

Baumgarten KM. Accuracy of Blueprint software in predicting range of motion 1 year after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:1088-1094. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2022.12.009

Rojas JT, Jost B, Zipeto C, et al. Glenoid component placement in reverse shoulder arthroplasty assisted with augmented reality through a head-mounted display leads to low deviation between planned and postoperative parameters. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:e587-e596. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2023.05.002

Dey Hazra RO, Paksoy A, Imiolczyk JP, et al. Augmented reality–assisted intraoperative navigation increases precision of glenoid inclination in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2025;34(2):577-583. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2024.05.039

Azuma RT. A survey of augmented reality. Presence-Teleop Virt. 1997;6:355-385. doi:10.1162/pres.1997.6.4.355

Speicher M, Hall BD, Nebeling M. What is Mixed Reality? In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery; 2019:1-15. doi:10.1145/3290605.3300767

Digioia AM, Jaramaz B, Nikou C, et al. Surgical navigation for total hip replacement with the use of hipnav. Oper Tech Orthop. 2000;10:3-8. doi:10.1016/S1048-6666(00)80036-1

Ogawa H, Hasegawa S, Tsukada S, et al. A pilot study of augmented reality technology applied to the acetabular cup placement during total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1833-1837. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.067

Shen F, Chen B, Guo Q, et al. Augmented reality patient-specific reconstruction plate design for pelvic and acetabular fracture surgery. Int J CARS. 2013;8:169-179. doi:10.1007/s11548-012-0775-5

Cho HS, Park YK, Gupta S, et al. Augmented reality in bone tumour resection: an experimental study. Bone Joint Res. 2017;6:137-143. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.63.bjr-2016-0289.r1

Wu X, Liu R, Yu J, et al. Mixed reality technology launches in orthopedic surgery for comprehensive preoperative management of complicated cervical fractures. Surg Innov. 2018;25:421-422. doi:10.1177/1553350618761758

Dossett HG, Arthur JR, Makovicka JL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasties: long-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S209-S214. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.03.065

Kazarian GS, Haddad FS, Donaldson MJ, et al. Implant malalignment may be a risk factor for poor patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S129-S133. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2022.02.087

Peng Y, Arauz P, An S, et al. Does component alignment affect patient reported outcomes following bicruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty? An in vivo three-dimensional analysis. J Knee Surg. 2020;33:798-803. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1688500

D’Lima DD, Urquhart AG, Buehler KO, et al. The effect of the orientation of the acetabular and femoral components on the range of motion of the hip at different head-neck ratios. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:315-321. doi:10.2106/00004623-200003000-00003

Yamaguchi M, Akisue T, Bauer TW, et al. The spatial location of impingement in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:305-313. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(00)90601-6

Grammatopoulos G, Alvand A, Monk AP, et al. Surgeons’ accuracy in achieving their desired acetabular component orientation. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:e72. doi:10.2106/JBJS.15.01080

Kennedy JG, Rogers WB, Soffe KE, et al. Effect of acetabular component orientation on recurrent dislocation, pelvic osteolysis, polyethylene wear, and component migration. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:530-534. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90052-3

Del Schutte H, Lipman AJ, Bannar SM, et al. Effects of acetabular abduction on cup wear rates in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:621-626. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)80003-X

Aresti N, Kassam J, Bartlett D, et al. Primary care management of postoperative shoulder, hip, and knee arthroplasty. BMJ. 2017;359:j4431. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4431

HipInsightTM System. Zimmer Biomet. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.zimmerbiomet.com/en/products-and-solutions/zb-edge/mixed-reality-portfolio/hipinsight-system.html

ARVIS. Insight Medical Systems. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.insightmedsys.com/arvis

Sun DC, Murphy WS, Amundson AJ, et al. Validation of a novel method of measuring cup orientation using biplanar simultaneous radiographic images. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S252-S256. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.04.011

Tsukada S, Ogawa H, Nishino M, et al. Augmented reality-assisted femoral bone resection in total knee arthroplasty. JBJS Open Access. 2021;6:e21.00001. doi:10.2106/JBJS.OA.21.00001

Castellarin G, Bori E, Barbieux E, et al. Is total knee arthroplasty surgical performance enhanced using augmented reality? A single-center study on 76 consecutive patients. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:332-335. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.08.013

Choi YJ, Ra HJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016;28:1. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.1.1

Hazratwala K, Gouk C, Wilkinson MPR, et al. Navigated functional alignment total knee arthroplasty achieves reliable, reproducible and accurate results with high patient satisfaction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:3861-3870. doi:10.1007/s00167-023-07327-w

Knee+. Pixee Medical. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.pixee-medical.com/en/products/knee-nexsight/

KNEE | NEXTAR. Nextar. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/knee

POLARIS AR receives clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for STELLAR Knee. News release. PRNewswire. November 3, 2023. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/polarisar-receives-clearance-from-the-us-food-and-drug-administration-for-stellar-knee-301976747.html

van Overschelde P, Vansintjan P, Byn P, Lapierre C, van Lysebettens W. Does augmented reality improve clinical outcome in TKA? A prospective observational report. In: The 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Computer Assisted Orthopaedic Surgery. 2022:170-174.

Sakellariou E, Alevrogiannis P, Alevrogianni F, et al. Single-center experience with Knee+TM augmented reality navigation system in primary total knee arthroplasty. World J Orthop. 2024;15:247-256. doi:10.5312/wjo.v15.i3.247

León-Muñoz VJ, Moya-Angeler J, López-López M, et al. Integration of square fiducial markers in patient-specific instrumentation and their applicability in knee surgery. J Pers Med. 2023;13:727. doi:10.3390/jpm13050727

Fucentese SF, Koch PP. A novel augmented reality-based surgical guidance system for total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141:2227-2233. doi:10.1007/s00402-021-04204-4

Sabatini L, Ascani D, Vezza D, et al. Novel surgical technique for total knee arthroplasty integrating kinematic alignment and real-time elongation of the ligaments using the NextAR system. J Pers Med. 2024;14:794. doi:10.3390/jpm14080794

Daher M, Ghanimeh J, Otayek J, et al. Augmented reality and shoulder replacement: a state-of-the-art review article. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2023;3:274-278. doi:10.1016/j.xrrt.2023.01.008

Atmani H, Merienne F, Fofi D, et al. Computer aided surgery system for shoulder prosthesis placement. Comput Aided Surg. 2007;12:60-70. doi:10.3109/10929080701210832

Eichinger JK, Galvin JW. Management of complications after total shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8:83-91. doi:10.1007/s12178-014-9251-x

Bonnevialle N, Melis B, Neyton L, et al. Aseptic glenoid loosening or failure in total shoulder arthroplasty: revision with glenoid reimplantation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:745-751. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.009

Erickson BJ, Chalmers PN, Denard P, et al. Does commercially available shoulder arthroplasty preoperative planning software agree with surgeon measurements of version, inclination, and subluxation? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:413-420. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.027

Werner BS, Hudek R, Burkhart KJ, et al. The influence of three-dimensional planning on decision-making in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:1477-1483. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.006

Blueprint. Stryker. Updated August 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.stryker.com/us/en/trauma-and-extremities/products/blueprint.html

NextAR Shoulder. Medacta. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/shoulder

Baumgarten KM. Accuracy of Blueprint software in predicting range of motion 1 year after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:1088-1094. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2022.12.009

Rojas JT, Jost B, Zipeto C, et al. Glenoid component placement in reverse shoulder arthroplasty assisted with augmented reality through a head-mounted display leads to low deviation between planned and postoperative parameters. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:e587-e596. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2023.05.002

Dey Hazra RO, Paksoy A, Imiolczyk JP, et al. Augmented reality–assisted intraoperative navigation increases precision of glenoid inclination in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2025;34(2):577-583. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2024.05.039

The Integration of Extended Reality in Arthroplasty: Reviewing Technological Progress and Clinical Benefits

The Integration of Extended Reality in Arthroplasty: Reviewing Technological Progress and Clinical Benefits

Effects of Lumbar Fusion and Dual-Mobility Liners on Dislocation Rates Following Total Hip Arthroplasty in a Veteran Population

Effects of Lumbar Fusion and Dual-Mobility Liners on Dislocation Rates Following Total Hip Arthroplasty in a Veteran Population

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is among the most common elective orthopedic procedures performed annually in the United States, with an estimated 635,000 to 909,000 THAs expected each year by 2030.1 Consequently, complication rates and revision surgeries related to THA have been increasing, along with the financial burden on the health care system.2-4 Optimizing outcomes for patients undergoing THA and identifying risk factors for treatment failure have become areas of focus.

Over the last decade, there has been a renewed interest in the effect of previous lumbar spine fusion (LSF) surgery on THA outcomes. Studies have explored the rates of complications, postoperative mobility, and THA implant impingement.5-8 However, the outcome receiving the most attention in recent literature is the rate and effect of dislocation in patients with lumbar fusion surgery. Large Medicare database analyses have discovered an association with increased rates of dislocations in patients with lumbar fusion surgeries compared with those without.9,10 Prosthetic hip dislocation is an expensive complication of THA and is projected to have greater impact through 2035 due to a growing number of THA procedures.11 Identifying risk factors associated with hip dislocation is paramount to mitigating its effect on patients who have undergone THA.

Recent research has found increased rates of THA dislocation and revision surgery in patients with LSF, with some studies showing previous LSF as the strongest independent predictor.6-16 However, controversy surrounds this relationship, including the sequence of procedures (LSF before or after THA), the time between procedures, and involvement of the sacrum in LSF. One study found that patients had a 106% increased risk of dislocation when LSF was performed before THA compared with patients who underwent LSF 5 years after undergoing THA, while another study showed no significant difference in dislocations pre- vs post-LSF.16,17 An additional study showed no significant difference in the rate of dislocation in patients without sacral involvement in the LSF, while also showing significantly higher rates of dislocation in LSF with sacral involvement.12 The researchers also found a trend toward more dislocations in longer lumbosacral fusions. Recent studies have also examined dislocation rates with lumbar fusion in patients treated with dual-mobility liners.18-20 The consensus from these studies is that dual-mobility liners significantly decrease the rate of dislocation in primary THAs with lumbar fusion.

The present study sought to determine the rates of hip dislocations in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital setting. To the authors’ knowledge, no retrospective study focusing on THAs in the veteran population has been performed. This study benefits from controlling for various surgeon techniques and surgical preferences when compared to large Medicare database studies because the orthopedic surgeon (ABK) only performed the posterior approach for all patients during the study period.

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether the rates of hip dislocation would, in fact, be higher in patients with lumbar fusion surgery, as recent database studies suggest. Secondary objectives included determining whether patient characteristics, comorbidities, number of levels fused, or inclusion of the sacrum in the fusion construct influenced dislocation rates. Furthermore, VA Dayton Healthcare System (VADHS) began routine use of dual-mobility liners for lumbar fusion patients in 2018, allowing for examination of these patients.

Methods

The Wright State University and VADHS Institutional Review Board approved this study design. A retrospective review of all primary THAs at VADHS was performed to investigate the relationship between previous lumbar spine fusion and the incidence of THA revision. Manual chart review was performed for patients who underwent primary THA between January 2003, and December 2022. One surgeon performed all surgeries using only the posterior approach. Patients were not excluded if they had bilateral procedures and all eligible hips were included. Patients with a concomitant diagnosis of fracture of the femoral head or femoral neck at the time of surgery were excluded. Additionally, only patients with ≥ 12 months of follow-up data were included.

The primary outcome was dislocation within 12 months of THA; the primary independent variable was LSF prior to THA. Covariates included patient demographics (age, sex, body mass index [BMI]) and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, with additional data collected on the number of levels fused, sacral spine involvement, revision rates, and use of dual-mobility liners. Year of surgery was also included in analyses to account for any changes that may have occurred during the study period.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4. Patients were grouped into 2 cohorts, depending on whether they had received LSF prior to THA. Analyses were adjusted for repeated measures to account for the small percentage of patients with bilateral procedures.

Univariate comparisons between cohorts for covariates, as well as rates of dislocation and revision, were performed using the independent samples t test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for dichotomous categorical variables. Significant comorbidities, as well as age, sex, BMI, liner type, LSF cohort, and surgery year, were included in a logistic regression model to determine what effect, if any, they had on the likelihood of dislocation. Variables were removed using a backward stepwise approach, starting with the nonsignificant variable effect with the lowest χ2 value, and continuing until reaching a final model where all remaining variable effects were significant. For the variables retained in the final model, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were derived, with dislocation designated as the event. Individual comorbidity subcomponents of the CCI were also analyzed for their effects on dislocation using backward stepwise logistic regression. A secondary analysis among patients with LSF tested for the influence of the number of vertebral levels fused, the presence or absence of sacral involvement in the fusion, and the use of dual-mobility liners on the likelihood of hip dislocation.

Results

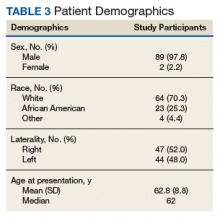

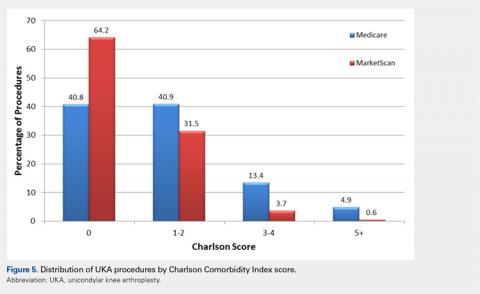

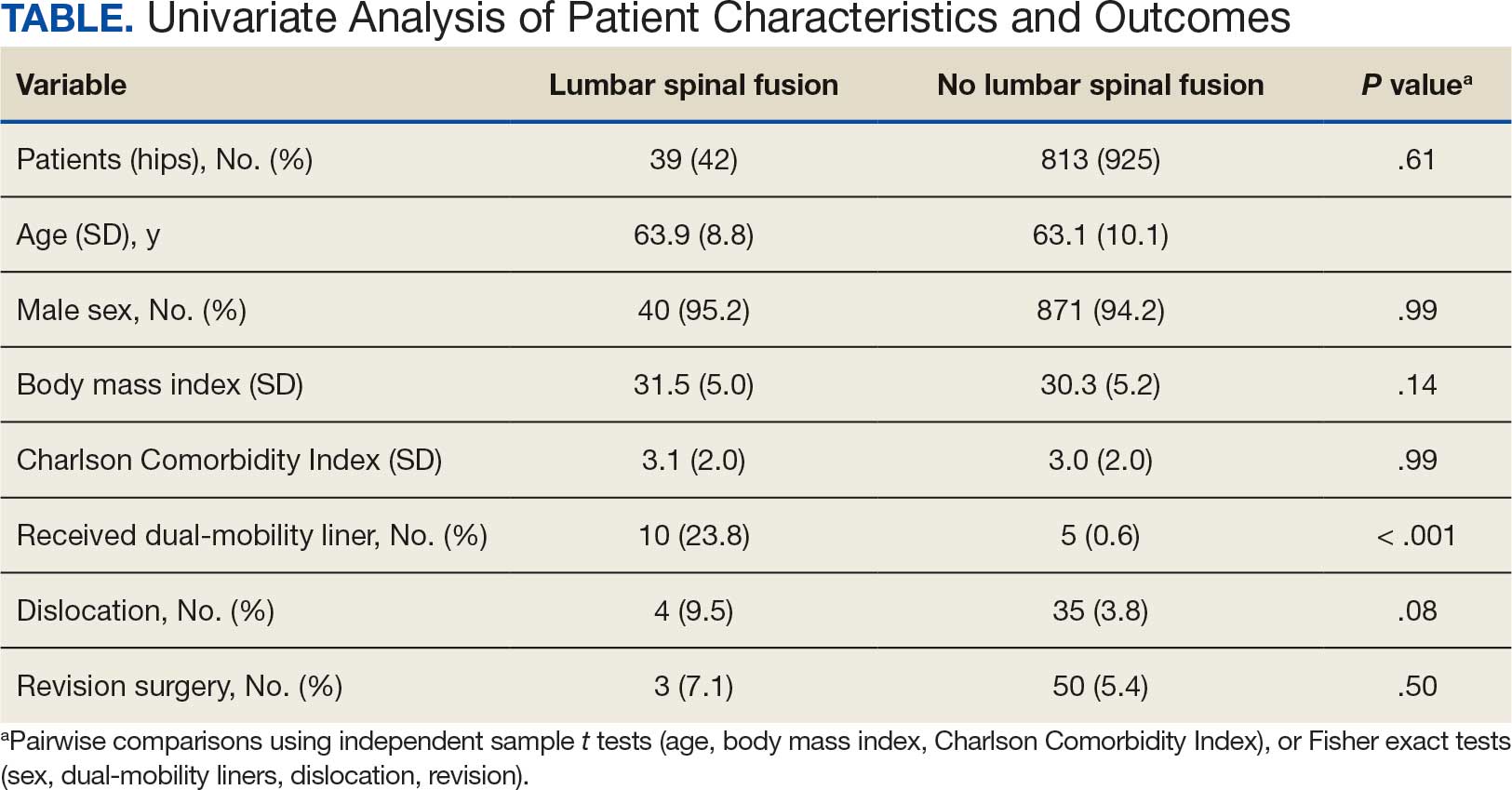

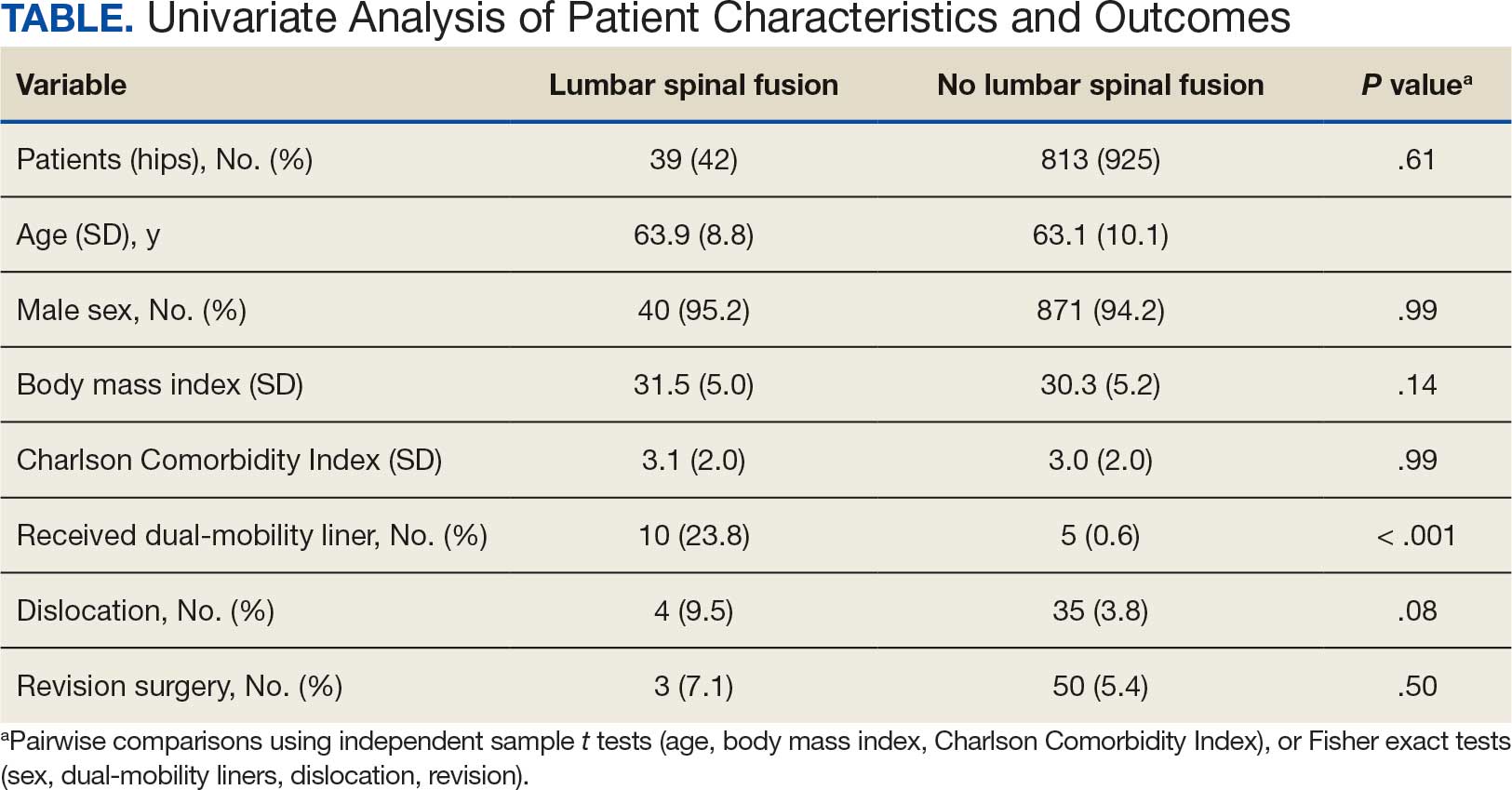

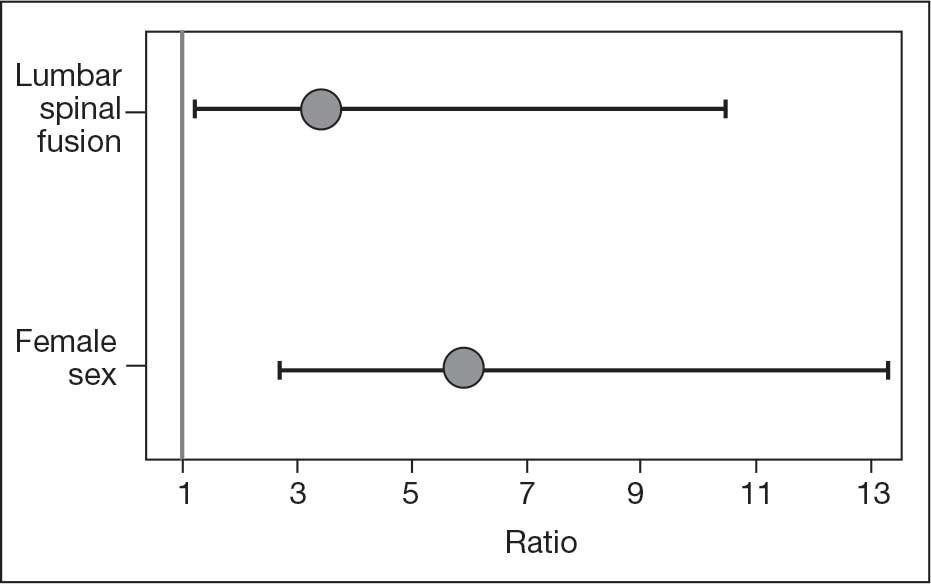

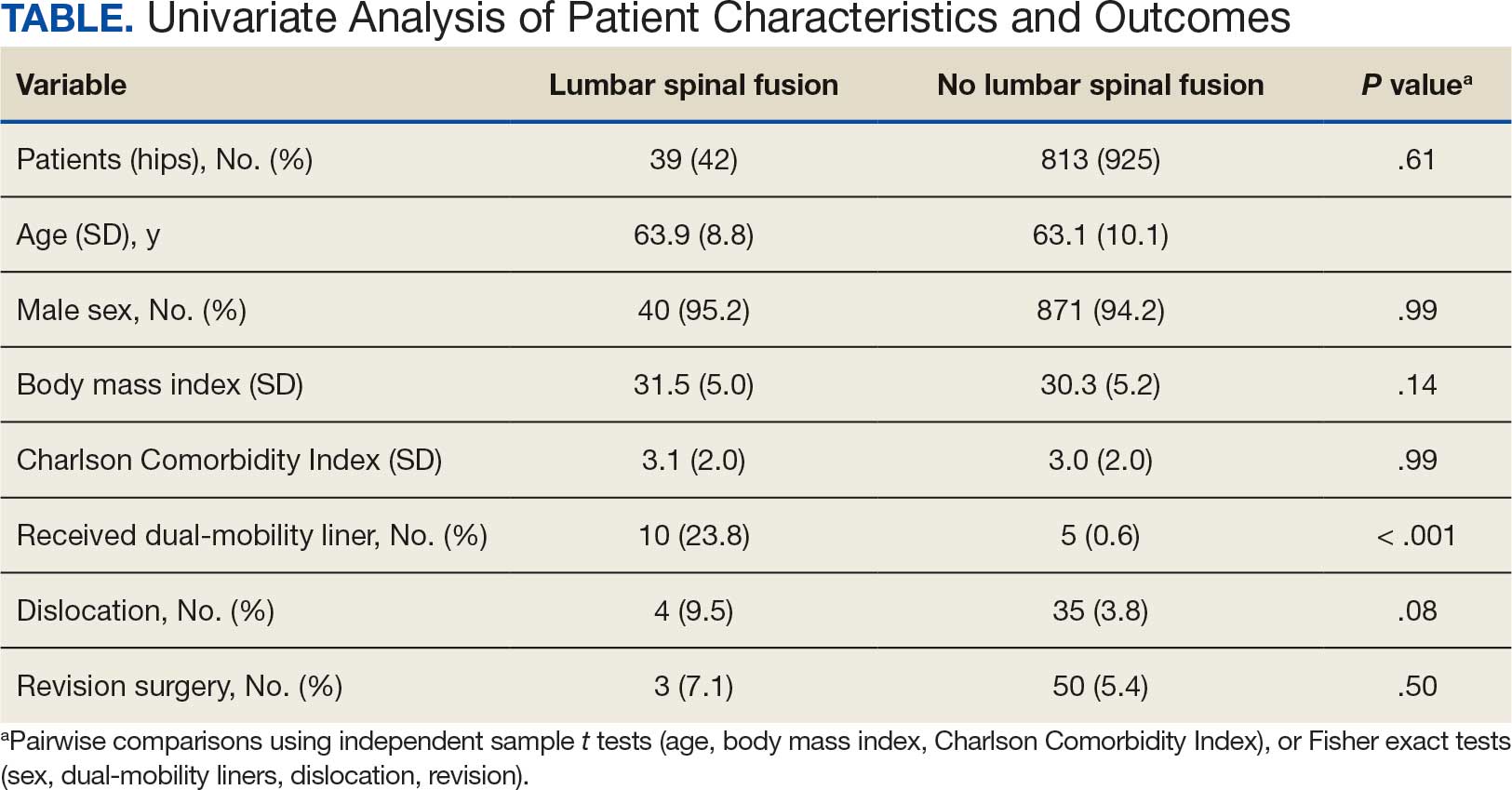

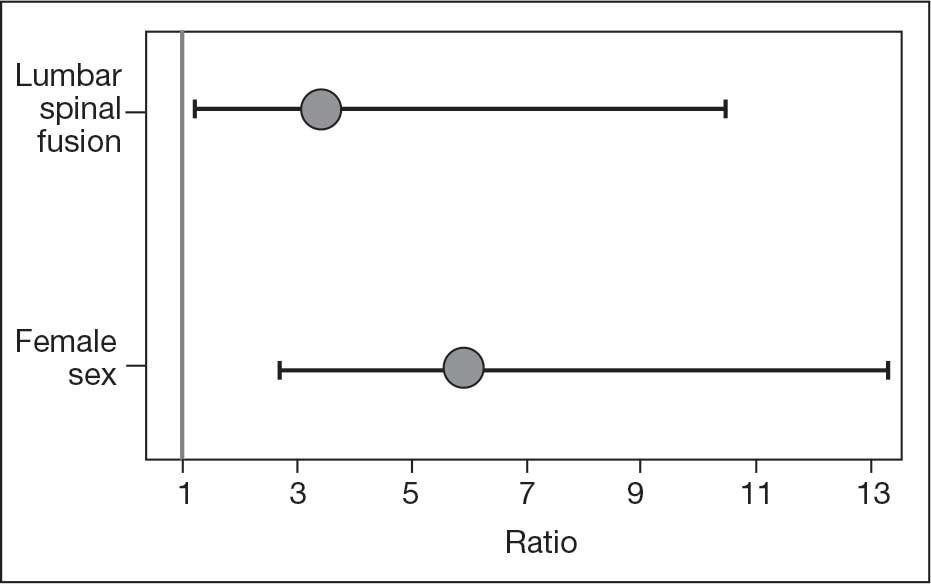

The LSF cohort included 39 patients with THA and prior LSF, 3 of whom had bilateral procedures, for a total of 42 hips. The non-LSF cohort included 813 patients with THA, 112 of whom had bilateral procedures, for a total of 925 hips. The LSF and non-LSF cohorts did not differ significantly in age, sex, BMI, CCI, or revision rates (Table). The LSF cohort included a significantly higher percentage of hips receiving dual-mobility liners than did the non-LSF cohort (23.8% vs 0.6%; P < .001) and had more than twice the rate of dislocation (4 of 42 hips [9.5%] vs 35 of 925 hips [3.8%]), although this difference was not statistically significant (P = .08).

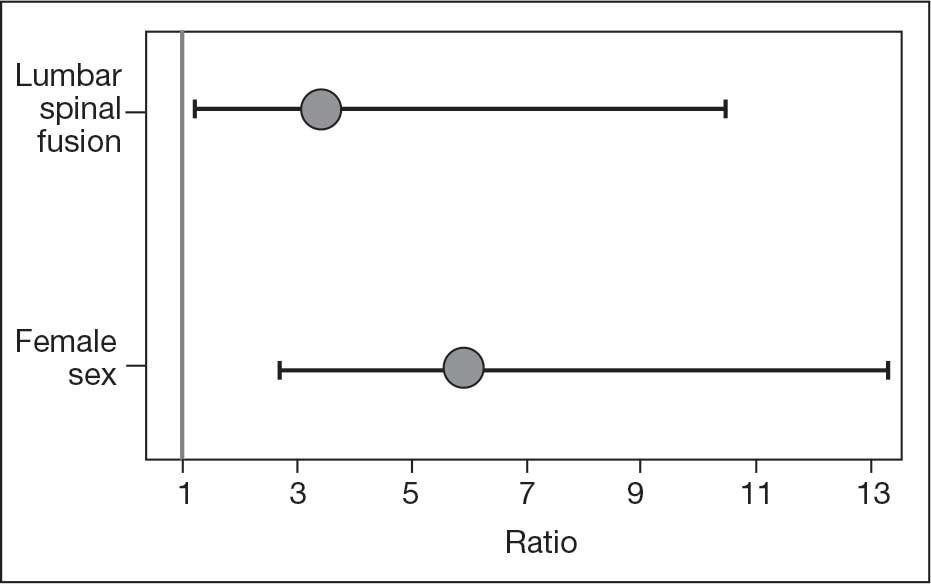

The final logistic regression model with dislocation as the outcome was statistically significant (χ2, 17.47; P < .001) and retained 2 significant predictor variables: LSF cohort (χ2, 4.63; P = .03), and sex (χ2, 18.27; P < .001). Females were more likely than males to experience dislocation (OR, 5.84; 95% CI, 2.60-13.13; P < .001) as were patients who had LSF prior to THA (OR, 3.42; 95% CI, 1.12-10.47; P = .03) (Figure). None of the CCI subcomponent comorbidities significantly affected the probability of dislocation (myocardial infarction, P = .46; congestive heart failure, P = .47; peripheral vascular disease, P = .97; stroke, P = .51; dementia, P = .99; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, P = .95; connective tissue disease, P = .25; peptic ulcer, P = .41; liver disease, P = .30; diabetes, P = .06; hemiplegia, P = .99; chronic kidney disease, P = .82; solid tumor, P = .90; leukemia, P = .99; lymphoma, P = .99; AIDS, P = .99). Within the LSF cohort, neither the number of levels fused (P = .83) nor sacral involvement (P = .42), significantly affected the probability of hip dislocation. None of the patients in either cohort who received dual-mobility liners subsequently dislocated their hips, nor did any of them require revision surgery.

Discussion

Spinopelvic biomechanics have been an area of increasing interest and research. Spinal fusion has been shown to alter the mobility of the pelvis and has been associated with decreased stability of THA implants.21 For example, in the setting of a fused spine, the lack of compensatory changes in pelvic tilt or acetabular anteversion when adjusting to a seated or standing position may predispose patients to impingement because the acetabular component is not properly positioned. Dual-mobility constructs mitigate this risk by providing an additional articulation, which increases jump distance and range of motion prior to impingement, thereby enhancing stability.

The use of dual-mobility liners in patients with LSF has also been examined.18-20 These studies demonstrate a reduced risk of postoperative THA dislocation in patients with previous LSF. The rate of postoperative complications and revisions for LSF patients with dual-mobility liners was also found to be similar to that of THAs without dual-mobility in patients without prior LSF. This study focused on a veteran population to demonstrate the efficacy of dual-mobility liners in patients with LSF. The results indicate that LSF prior to THA and female sex were predictors for prosthetic hip dislocations in the 12-month postoperative period in this patient population, which aligns with the current literature.

The dislocation rate in the LSF-THA group (9.5%) was higher than the dislocation rate in the control group (3.8%). Although not statistically significant in the univariate analysis, LSF was shown to be a significant risk factor after controlling for patient sex. Other studies have found the dislocation rate to be 3% to 7%, which is lower than the dislocation rate observed in this study.8,10,16

The reasons for this higher rate of dislocation are not entirely clear. A veteran population has poorer overall health than the general population, which may contribute to the higher than previously reported dislocation rates.22 These results can be applied to the management of veterans seeking THA.

There have been conflicting reports regarding the impact a patient’s sex has on THA outcomes in the general population.23-26 This study found that female patients had higher rates of dislocation within 1 year of THA than male patients. This difference, which could be due to differences in baseline anatomic hip morphology between the sexes; females tend to have smaller femoral head sizes and less offset compared with males.27,28 However, this finding could have been confounded by the small number of female veterans in the study cohort.

A type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) diagnosis, which is a component of CCI, trended toward increased risk of prosthetic hip dislocation. Multiple studies have also discussed the increased risk of postoperative infections and revisions following THA in patients with T2DM.29-31 One study found T2DM to be an independent risk factor for immediate in-hospital postoperative complications following hip arthroplasty.32

Another factor that may influence postoperative dislocation risk is surgical approach. The posterior approach has historically been associated with higher rates of instability when compared to anterior or lateral THA.33 Researchers have also looked at the role that surgical approach plays in patients with prior LSF. Huebschmann et al confirmed that not only is LSF a significant risk factor for dislocation following THA, but anterior and laterally based surgical approaches may mitigate this risk.34

Limitations

As a retrospective cohort study, the reliability of the data hinges on complete documentation. Documentation of all encounters for dislocations was obtained from the VA Computerized Patient Record System, which may have led to some dislocation events being missed. However, as long as there was adequate postoperative follow-up, it was assumed all events outside the VA were included. Another limitation of this study was that male patients greatly outnumbered female patients, and this fact could limit the generalizability of findings to the population as a whole.

Conclusions

This study in a veteran population found that prior LSF and female sex were significant predictors for postoperative dislocation within 1 year of THA surgery. Additionally, the use of a dual-mobility liner was found to be protective against postoperative dislocation events. These data allow clinicians to better counsel veterans on the risk factors associated with postoperative dislocation and strategies to mitigate this risk.

- Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1455-1460. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.01617

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:128-133. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00155

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, et al. Future clinical and economic impact of revision total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:144-151. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00587

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, et al. Primary and revision arthroplasty surgery caseloads in the United States from 1990 to 2004. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:195-203. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.015

- Yamato Y, Furuhashi H, Hasegawa T, et al. Simulation of implant impingement after spinal corrective fusion surgery in patients with previous total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective case series. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021;46:512-519. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003836

- Mudrick CA, Melvin JS, Springer BD. Late posterior hip instability after lumbar spinopelvic fusion. Arthroplast Today. 2015;1:25-29. doi:10.1016/j.artd.2015.05.002

- Diebo BG, Beyer GA, Grieco PW, et al. Complications in patients undergoing spinal fusion after THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:412-417.doi:10.1007/s11999.0000000000000009 8.

- Sing DC, Barry JJ, Aguilar TU, et al. Prior lumbar spinal arthrodesis increases risk of prosthetic-related complication in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:227-232.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.069

- King CA, Landy DC, Martell JM, et al. Time to dislocation analysis of lumbar spine fusion following total hip arthroplasty: breaking up a happy home. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3768-3772. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.029

- Buckland AJ, Puvanesarajah V, Vigdorchik J, et al. Dislocation of a primary total hip arthroplasty is more common in patients with a lumbar spinal fusion. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:585-591.doi:10.1302/0301-620X.99B5.BJJ-2016-0657.R1

- Pirruccio K, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. The burden of prosthetic hip dislocations in the United States is projected to significantly increase by 2035. Hip Int. 2021;31:714-721. doi:10.1177/1120700020923619

- Salib CG, Reina N, Perry KI, et al. Lumbar fusion involving the sacrum increases dislocation risk in primary total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B:198-206. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.101B2.BJJ-2018-0754.R1

- An VVG, Phan K, Sivakumar BS, et al. Prior lumbar spinal fusion is associated with an increased risk of dislocation and revision in total hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:297-300. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.040

- Klemt C, Padmanabha A, Tirumala V, et al. Lumbar spine fusion before revision total hip arthroplasty is associated with increased dislocation rates. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:e860-e868. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00824

- Gausden EB, Parhar HS, Popper JE, et al. Risk factors for early dislocation following primary elective total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1567-1571. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.034

- Malkani AL, Himschoot KJ, Ong KL, et al. Does timing of primary total hip arthroplasty prior to or after lumbar spine fusion have an effect on dislocation and revision rates?. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:907-911. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.009

- Parilla FW, Shah RR, Gordon AC, et al. Does it matter: total hip arthroplasty or lumbar spinal fusion first? Preoperative sagittal spinopelvic measurements guide patient-specific surgical strategies in patients requiring both. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2652-2662. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.053

- Chalmers BP, Syku M, Sculco TP, et al. Dual-mobility constructs in primary total hip arthroplasty in high-risk patients with spinal fusions: our institutional experience. Arthroplast Today. 2020;6:749-754. doi:10.1016/j.artd.2020.07.024

- Nessler JM, Malkani AL, Sachdeva S, et al. Use of dual mobility cups in patients undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty with prior lumbar spine fusion. Int Orthop. 2020;44:857-862. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04507-y