User login

Current pneumococcal vaccines knock out many serotypes, but others take their place

The introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines 7 (PCV7) and 13 (PCV13) has significantly reduced pneumococcal colonization of the serotypes targeted by the vaccines, but serotypes not covered by these vaccines have picked up the slack, according to an analysis of more than 6,000 young Massachusetts children tested at well child or acute care visits over 15 years.

In the past 15 years, use of pneumococcal vaccines in the United States has led to dramatic declines in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in young children, reductions in pneumonia hospitalizations, and herd protection in older adults against disease that otherwise would be caused by the vaccinated serotypes, studies have found. But not all serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae are covered by the vaccines.

The data used in the Massachusetts study included results from nasopharyngeal swabs taken from 6,537 children younger than 7 years of age in various Massachusetts communities during six respiratory illness seasons during 2000-2001, 2003-2004, 2006-2007, 2008-2009, 2010-2011, and 2013-2014. The highest rate of pneumococcal colonization was in 2011 at 32%, and the lowest was in 2004 at 23%, Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, of the Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, both in Boston, and her associates reported (Pediatrics. 2017;140[3]:e20170001).

In 2001, PCV7 serotypes were the most common, but after the rapid introduction of the vaccine, infection rates for those serotypes quickly declined, nearly disappearing by 2007. Serotype 19A became the most common serotype in 2004, but after the introduction of PCV13 in 2010, it and other serotypes targeted by PCV13 also began to decline. In 2014, the most common serotypes were 15B/C, 35B, 23B, 11A, and 23A.

Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for about a third of observed Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizations in 2001, but by 2014 they accounted for nearly all colonizations. In addition, the overall rate of infection did not decrease over the study period. While a reduction was seen from 2011 to 2014, it remains to be seen whether this drop is transient.

“Replacement with nonincluded serotypes remains a risk with vaccines that do not cover the full range of serotype diversity. As new selective pressures are applied, such as the introduction of a vaccine into a community, the void may be filled by nontargeted serotypes,” as was observed after PCV7, Dr. Lee and her fellow researchers noted.

Nonsusceptibility to erythromycin was most common in 2014, with 35% of pneumococcal isolates displaying either moderate susceptibility or resistance. Nonsusceptibility to ceftriaxone (12%), clindamycin (9%), and penicillin (6%) was significantly less common, and no isolates were found to have vancomycin resistance.

“First-line penicillins continue to be the most frequently prescribed antibiotic across all age groups among young children in Massachusetts, which may result in the continued success of 19A associated with penicillin resistance,” the researchers said.

Risk factors associated with colonization by either PCV13 serotypes or non-PCV13 serotypes include younger age, more hours of child care exposure, and having a respiratory tract infection on the day of sampling. The presence of a smoker in the house and recent usage of antibiotics was associated with colonization by PCV13 serotypes but not by non-PCV13 serotypes.

“As newer pneumococcal vaccines are developed, there will continue to be a need for monitoring both the intended and unintended consequences of altering the nasopharyngeal niche through immunization,” Dr. Lee and her associates concluded.

This work was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and the National Institutes of Health. Marc Lipsitch, PhD; William P. Hanage, PhD; Ken Kleinman; Stephen Pelton, MD; and Susan S. Huang, MD, MPH, reported various conflicts of interest. Dr. Lee and the remaining investigators indicated that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

“The hope that IPD and antibiotic resistance would disappear after widespread use of PCV vaccines has yet to be realized,” Douglas S. Swanson, MD, and Christopher J. Harrison, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2017;140[5]:e20172034).

While some invasive pneumococcal diseases, such as occult bacteremia and meningitis, have been significantly reduced due to PCV7 and PCV13, “one concern is whether some replacement serotypes could have invasive disease potential. For example, post-PCV7, there was increased severity of IPD from non-PCV7 serogroup organisms among children in the Intermountain West of the United States,” the authors noted. Newly dominant strains, such as post-PCV13 serotype 35B, could cause increased IPD in vulnerable populations, becoming the equivalent of a post-PCV7 serotype 19A.

While addressing emerging serotypes in additional PCVs is possible, reformulating the vaccine and obtaining Food and Drug Administration approval would take time and resources, with no clear guarantee of ultimate success, making “this strategy seem like playing a game of whack-a-mole. To overcome the phenomenon of serotype replacement, vaccine strategies need to expand beyond serotype specificity by identifying antigens common to all Streptococcus pneumoniae, regardless of serotype,” Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison said.

“Shifts back to less penicillin resistance may soon preclude the need for high dose amoxicillin for acute otitis media, and the near absence of occult Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia may drastically reduce empirical ceftriaxone for fever without a focus. To assist providers in ongoing vigilance for the now less frequent IPD, algorithms based on new epidemiologic data are in development and should decrease the number of ‘sepsis work-ups’ performed,” they said.

On-time PCV13 vaccination would help address the risk factor of young age, and judicious antibiotic use could further reduce antibiotic resistance. Social engineering approaches, although difficult, also might help. These approaches include continued parent education to restrict secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization, as well as having young children spend fewer hours in day care in order to reduce two other risk factors – pathogen exposure and frequency of viral upper respiratory tract infections.

Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison are with the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Both reported conducting pneumococcal research supported by funding from Pfizer.

“The hope that IPD and antibiotic resistance would disappear after widespread use of PCV vaccines has yet to be realized,” Douglas S. Swanson, MD, and Christopher J. Harrison, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2017;140[5]:e20172034).

While some invasive pneumococcal diseases, such as occult bacteremia and meningitis, have been significantly reduced due to PCV7 and PCV13, “one concern is whether some replacement serotypes could have invasive disease potential. For example, post-PCV7, there was increased severity of IPD from non-PCV7 serogroup organisms among children in the Intermountain West of the United States,” the authors noted. Newly dominant strains, such as post-PCV13 serotype 35B, could cause increased IPD in vulnerable populations, becoming the equivalent of a post-PCV7 serotype 19A.

While addressing emerging serotypes in additional PCVs is possible, reformulating the vaccine and obtaining Food and Drug Administration approval would take time and resources, with no clear guarantee of ultimate success, making “this strategy seem like playing a game of whack-a-mole. To overcome the phenomenon of serotype replacement, vaccine strategies need to expand beyond serotype specificity by identifying antigens common to all Streptococcus pneumoniae, regardless of serotype,” Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison said.

“Shifts back to less penicillin resistance may soon preclude the need for high dose amoxicillin for acute otitis media, and the near absence of occult Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia may drastically reduce empirical ceftriaxone for fever without a focus. To assist providers in ongoing vigilance for the now less frequent IPD, algorithms based on new epidemiologic data are in development and should decrease the number of ‘sepsis work-ups’ performed,” they said.

On-time PCV13 vaccination would help address the risk factor of young age, and judicious antibiotic use could further reduce antibiotic resistance. Social engineering approaches, although difficult, also might help. These approaches include continued parent education to restrict secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization, as well as having young children spend fewer hours in day care in order to reduce two other risk factors – pathogen exposure and frequency of viral upper respiratory tract infections.

Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison are with the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Both reported conducting pneumococcal research supported by funding from Pfizer.

“The hope that IPD and antibiotic resistance would disappear after widespread use of PCV vaccines has yet to be realized,” Douglas S. Swanson, MD, and Christopher J. Harrison, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2017;140[5]:e20172034).

While some invasive pneumococcal diseases, such as occult bacteremia and meningitis, have been significantly reduced due to PCV7 and PCV13, “one concern is whether some replacement serotypes could have invasive disease potential. For example, post-PCV7, there was increased severity of IPD from non-PCV7 serogroup organisms among children in the Intermountain West of the United States,” the authors noted. Newly dominant strains, such as post-PCV13 serotype 35B, could cause increased IPD in vulnerable populations, becoming the equivalent of a post-PCV7 serotype 19A.

While addressing emerging serotypes in additional PCVs is possible, reformulating the vaccine and obtaining Food and Drug Administration approval would take time and resources, with no clear guarantee of ultimate success, making “this strategy seem like playing a game of whack-a-mole. To overcome the phenomenon of serotype replacement, vaccine strategies need to expand beyond serotype specificity by identifying antigens common to all Streptococcus pneumoniae, regardless of serotype,” Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison said.

“Shifts back to less penicillin resistance may soon preclude the need for high dose amoxicillin for acute otitis media, and the near absence of occult Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia may drastically reduce empirical ceftriaxone for fever without a focus. To assist providers in ongoing vigilance for the now less frequent IPD, algorithms based on new epidemiologic data are in development and should decrease the number of ‘sepsis work-ups’ performed,” they said.

On-time PCV13 vaccination would help address the risk factor of young age, and judicious antibiotic use could further reduce antibiotic resistance. Social engineering approaches, although difficult, also might help. These approaches include continued parent education to restrict secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization, as well as having young children spend fewer hours in day care in order to reduce two other risk factors – pathogen exposure and frequency of viral upper respiratory tract infections.

Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison are with the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Both reported conducting pneumococcal research supported by funding from Pfizer.

The introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines 7 (PCV7) and 13 (PCV13) has significantly reduced pneumococcal colonization of the serotypes targeted by the vaccines, but serotypes not covered by these vaccines have picked up the slack, according to an analysis of more than 6,000 young Massachusetts children tested at well child or acute care visits over 15 years.

In the past 15 years, use of pneumococcal vaccines in the United States has led to dramatic declines in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in young children, reductions in pneumonia hospitalizations, and herd protection in older adults against disease that otherwise would be caused by the vaccinated serotypes, studies have found. But not all serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae are covered by the vaccines.

The data used in the Massachusetts study included results from nasopharyngeal swabs taken from 6,537 children younger than 7 years of age in various Massachusetts communities during six respiratory illness seasons during 2000-2001, 2003-2004, 2006-2007, 2008-2009, 2010-2011, and 2013-2014. The highest rate of pneumococcal colonization was in 2011 at 32%, and the lowest was in 2004 at 23%, Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, of the Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, both in Boston, and her associates reported (Pediatrics. 2017;140[3]:e20170001).

In 2001, PCV7 serotypes were the most common, but after the rapid introduction of the vaccine, infection rates for those serotypes quickly declined, nearly disappearing by 2007. Serotype 19A became the most common serotype in 2004, but after the introduction of PCV13 in 2010, it and other serotypes targeted by PCV13 also began to decline. In 2014, the most common serotypes were 15B/C, 35B, 23B, 11A, and 23A.

Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for about a third of observed Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizations in 2001, but by 2014 they accounted for nearly all colonizations. In addition, the overall rate of infection did not decrease over the study period. While a reduction was seen from 2011 to 2014, it remains to be seen whether this drop is transient.

“Replacement with nonincluded serotypes remains a risk with vaccines that do not cover the full range of serotype diversity. As new selective pressures are applied, such as the introduction of a vaccine into a community, the void may be filled by nontargeted serotypes,” as was observed after PCV7, Dr. Lee and her fellow researchers noted.

Nonsusceptibility to erythromycin was most common in 2014, with 35% of pneumococcal isolates displaying either moderate susceptibility or resistance. Nonsusceptibility to ceftriaxone (12%), clindamycin (9%), and penicillin (6%) was significantly less common, and no isolates were found to have vancomycin resistance.

“First-line penicillins continue to be the most frequently prescribed antibiotic across all age groups among young children in Massachusetts, which may result in the continued success of 19A associated with penicillin resistance,” the researchers said.

Risk factors associated with colonization by either PCV13 serotypes or non-PCV13 serotypes include younger age, more hours of child care exposure, and having a respiratory tract infection on the day of sampling. The presence of a smoker in the house and recent usage of antibiotics was associated with colonization by PCV13 serotypes but not by non-PCV13 serotypes.

“As newer pneumococcal vaccines are developed, there will continue to be a need for monitoring both the intended and unintended consequences of altering the nasopharyngeal niche through immunization,” Dr. Lee and her associates concluded.

This work was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and the National Institutes of Health. Marc Lipsitch, PhD; William P. Hanage, PhD; Ken Kleinman; Stephen Pelton, MD; and Susan S. Huang, MD, MPH, reported various conflicts of interest. Dr. Lee and the remaining investigators indicated that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

The introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines 7 (PCV7) and 13 (PCV13) has significantly reduced pneumococcal colonization of the serotypes targeted by the vaccines, but serotypes not covered by these vaccines have picked up the slack, according to an analysis of more than 6,000 young Massachusetts children tested at well child or acute care visits over 15 years.

In the past 15 years, use of pneumococcal vaccines in the United States has led to dramatic declines in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in young children, reductions in pneumonia hospitalizations, and herd protection in older adults against disease that otherwise would be caused by the vaccinated serotypes, studies have found. But not all serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae are covered by the vaccines.

The data used in the Massachusetts study included results from nasopharyngeal swabs taken from 6,537 children younger than 7 years of age in various Massachusetts communities during six respiratory illness seasons during 2000-2001, 2003-2004, 2006-2007, 2008-2009, 2010-2011, and 2013-2014. The highest rate of pneumococcal colonization was in 2011 at 32%, and the lowest was in 2004 at 23%, Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, of the Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, both in Boston, and her associates reported (Pediatrics. 2017;140[3]:e20170001).

In 2001, PCV7 serotypes were the most common, but after the rapid introduction of the vaccine, infection rates for those serotypes quickly declined, nearly disappearing by 2007. Serotype 19A became the most common serotype in 2004, but after the introduction of PCV13 in 2010, it and other serotypes targeted by PCV13 also began to decline. In 2014, the most common serotypes were 15B/C, 35B, 23B, 11A, and 23A.

Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for about a third of observed Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizations in 2001, but by 2014 they accounted for nearly all colonizations. In addition, the overall rate of infection did not decrease over the study period. While a reduction was seen from 2011 to 2014, it remains to be seen whether this drop is transient.

“Replacement with nonincluded serotypes remains a risk with vaccines that do not cover the full range of serotype diversity. As new selective pressures are applied, such as the introduction of a vaccine into a community, the void may be filled by nontargeted serotypes,” as was observed after PCV7, Dr. Lee and her fellow researchers noted.

Nonsusceptibility to erythromycin was most common in 2014, with 35% of pneumococcal isolates displaying either moderate susceptibility or resistance. Nonsusceptibility to ceftriaxone (12%), clindamycin (9%), and penicillin (6%) was significantly less common, and no isolates were found to have vancomycin resistance.

“First-line penicillins continue to be the most frequently prescribed antibiotic across all age groups among young children in Massachusetts, which may result in the continued success of 19A associated with penicillin resistance,” the researchers said.

Risk factors associated with colonization by either PCV13 serotypes or non-PCV13 serotypes include younger age, more hours of child care exposure, and having a respiratory tract infection on the day of sampling. The presence of a smoker in the house and recent usage of antibiotics was associated with colonization by PCV13 serotypes but not by non-PCV13 serotypes.

“As newer pneumococcal vaccines are developed, there will continue to be a need for monitoring both the intended and unintended consequences of altering the nasopharyngeal niche through immunization,” Dr. Lee and her associates concluded.

This work was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and the National Institutes of Health. Marc Lipsitch, PhD; William P. Hanage, PhD; Ken Kleinman; Stephen Pelton, MD; and Susan S. Huang, MD, MPH, reported various conflicts of interest. Dr. Lee and the remaining investigators indicated that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Serotype 19A became the most dominant serotype in 2004 but was significantly reduced by 2014 and replaced largely by serotypes 15B/C and 35B.

Data source: An analysis of pneumococcal serotypes in 6,537 children younger than 7 years of age who had well-child or acute care visits during six surveillance periods from 2000 to 2014.

Disclosures: This work was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and the National Institutes of Health. Marc Lipsitch, PhD; William P. Hanage, PhD; Ken Kleinman; Stephen I. Pelton, MD; and Susan S. Huang, MD, MPH, reported various conflicts of interest. Dr. Lee and the remaining investigators indicated that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

Taking One for the Team

ANSWER

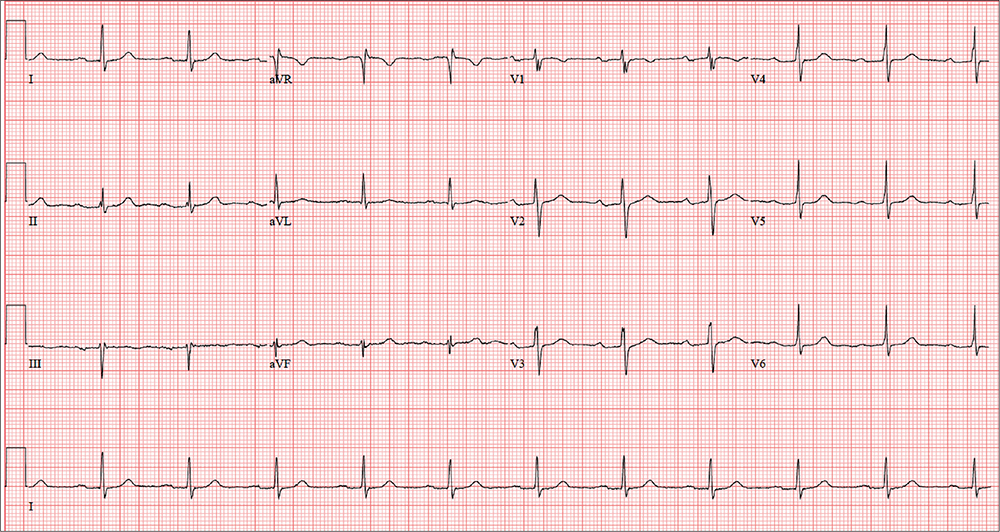

The correct interpretation of this patient’s ECG includes sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, otherwise within normal limits. A first-degree AV block is diagnosed based on a PR interval > 200 ms, which represents a prolonged conduction time from the sinus node to the ventricles. A 1:1 ratio of P waves to QRS complexes with consistent PR intervals eliminates the possibility of a second- or third-degree heart block.

First-degree AV block is generally a benign finding. However, care should be taken if the patient ever needs medications to slow AV nodal conduction (ie, ß-blockers, calcium channel blockers).

Finally, it may be tempting to consider Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome based on the delta wave seen in leads V4 to V6. But this possibility is ruled out by the presence of a first-degree AV block.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this patient’s ECG includes sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, otherwise within normal limits. A first-degree AV block is diagnosed based on a PR interval > 200 ms, which represents a prolonged conduction time from the sinus node to the ventricles. A 1:1 ratio of P waves to QRS complexes with consistent PR intervals eliminates the possibility of a second- or third-degree heart block.

First-degree AV block is generally a benign finding. However, care should be taken if the patient ever needs medications to slow AV nodal conduction (ie, ß-blockers, calcium channel blockers).

Finally, it may be tempting to consider Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome based on the delta wave seen in leads V4 to V6. But this possibility is ruled out by the presence of a first-degree AV block.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this patient’s ECG includes sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, otherwise within normal limits. A first-degree AV block is diagnosed based on a PR interval > 200 ms, which represents a prolonged conduction time from the sinus node to the ventricles. A 1:1 ratio of P waves to QRS complexes with consistent PR intervals eliminates the possibility of a second- or third-degree heart block.

First-degree AV block is generally a benign finding. However, care should be taken if the patient ever needs medications to slow AV nodal conduction (ie, ß-blockers, calcium channel blockers).

Finally, it may be tempting to consider Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome based on the delta wave seen in leads V4 to V6. But this possibility is ruled out by the presence of a first-degree AV block.

In an effort to detect cardiopulmonary abnormalities in student athletes, a local university holds a screening event in which an

On exam, he appears in excellent health and has no medical or physical complaints. His medical history is unremarkable. He has participated in sports for most of his life and has never had symptoms of chest pain, dyspnea, shortness of breath, syncope, or near-syncope. An annual physical exam with his primary care provider four months ago provided him with a “clean bill of health.”

His surgical history includes an open reduction and internal fixation of a high ankle fracture, sustained while playing football in college.

The patient is married and has two children, both of whom are in good health. Family history is positive for hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and endometrial cancer. He has never smoked cigarettes and denies illicit drug use aside from trying marijuana in college. He rarely consumes alcohol (just at social events). He is not taking any medications and has no known drug allergies.

The review of systems is significant for a recent (now resolved) upper respiratory illness. He denies any changes in bowel or bladder function, as well as any endocrine, neurologic, or constitutional symptoms.

Vital signs include a blood pressure of 108/64 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 12 breaths/min-1. His height is 76 in and his weight, 204 lb. Since this is a screening event and not a standard appointment, a complete physical exam is not performed.

The patient’s ECG shows a ventricular rate of 66 beats/min; PR interval, 266 ms; QRS duration, 98 ms; QT/QTc interval, 410/429 ms; P axis, 26°; R axis, –6°; and T axis, 43°. What is your interpretation?

Use of BZD and sedative-hypnotics among hospitalized elderly

Clinical question: Which hospitalized older patients are inappropriately prescribed benzodiazepines or sedative hypnotics post discharge, and who is prescribing these medications?

Background: During hospitalization, older patients commonly suffer from agitation and insomnia. Unfortunately, benzodiazepines and sedative hypnotics are commonly used as first-line treatments for these conditions despite significant risk which includes cognitive impairment, postural instability, increased risk of falls and hip fracture as well as lack of effectiveness. The purpose of this study is to determine the magnitude of the issue, discover root causes, and determine the type or types of corrective action needed.

Study Design: Single-center retrospective observational study.

Setting: Urban academic medical center in Toronto.

There was significant increase in these prescriptions if the patient was admitted to a surgical or specialty service compared to the general internal medicine service (odds ratio, 6.61; 95% confidence interval, 2.70-16.17). First-year trainees prescribed these medications more than did attending or fellows (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.08-0.93).

Study limitations include being from a single institution, not being blinded, and inadequate statistical power. Therefore, it may lack generalizability, may be subjected to observer bias, and may not detect significant effects of covariates.

Bottom line: Sleep disruption and poor quality of sleep were the primary reason for the majority of potentially inappropriate newly prescribed benzodiazepines and sedative hypnotics, with first-year trainees being more likely to prescribe these medications compared to attendings and fellows.

Citation: Pek EA, Ramfry A, Pendrith C, et al. High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2017 May;12(5):310-6.

Dr. Choe is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Clinical question: Which hospitalized older patients are inappropriately prescribed benzodiazepines or sedative hypnotics post discharge, and who is prescribing these medications?

Background: During hospitalization, older patients commonly suffer from agitation and insomnia. Unfortunately, benzodiazepines and sedative hypnotics are commonly used as first-line treatments for these conditions despite significant risk which includes cognitive impairment, postural instability, increased risk of falls and hip fracture as well as lack of effectiveness. The purpose of this study is to determine the magnitude of the issue, discover root causes, and determine the type or types of corrective action needed.

Study Design: Single-center retrospective observational study.

Setting: Urban academic medical center in Toronto.

There was significant increase in these prescriptions if the patient was admitted to a surgical or specialty service compared to the general internal medicine service (odds ratio, 6.61; 95% confidence interval, 2.70-16.17). First-year trainees prescribed these medications more than did attending or fellows (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.08-0.93).

Study limitations include being from a single institution, not being blinded, and inadequate statistical power. Therefore, it may lack generalizability, may be subjected to observer bias, and may not detect significant effects of covariates.

Bottom line: Sleep disruption and poor quality of sleep were the primary reason for the majority of potentially inappropriate newly prescribed benzodiazepines and sedative hypnotics, with first-year trainees being more likely to prescribe these medications compared to attendings and fellows.

Citation: Pek EA, Ramfry A, Pendrith C, et al. High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2017 May;12(5):310-6.

Dr. Choe is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Clinical question: Which hospitalized older patients are inappropriately prescribed benzodiazepines or sedative hypnotics post discharge, and who is prescribing these medications?

Background: During hospitalization, older patients commonly suffer from agitation and insomnia. Unfortunately, benzodiazepines and sedative hypnotics are commonly used as first-line treatments for these conditions despite significant risk which includes cognitive impairment, postural instability, increased risk of falls and hip fracture as well as lack of effectiveness. The purpose of this study is to determine the magnitude of the issue, discover root causes, and determine the type or types of corrective action needed.

Study Design: Single-center retrospective observational study.

Setting: Urban academic medical center in Toronto.

There was significant increase in these prescriptions if the patient was admitted to a surgical or specialty service compared to the general internal medicine service (odds ratio, 6.61; 95% confidence interval, 2.70-16.17). First-year trainees prescribed these medications more than did attending or fellows (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.08-0.93).

Study limitations include being from a single institution, not being blinded, and inadequate statistical power. Therefore, it may lack generalizability, may be subjected to observer bias, and may not detect significant effects of covariates.

Bottom line: Sleep disruption and poor quality of sleep were the primary reason for the majority of potentially inappropriate newly prescribed benzodiazepines and sedative hypnotics, with first-year trainees being more likely to prescribe these medications compared to attendings and fellows.

Citation: Pek EA, Ramfry A, Pendrith C, et al. High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2017 May;12(5):310-6.

Dr. Choe is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Fasting glucose fluctuations, severe hypoglycemia up T2DM death risk

AT EASD 2017

LISBON –

A second wave of results from the DEVOTE study, which compared the cardiovascular safety of insulin degludec (Tresiba, Novo Nordisk) versus insulin glargine, found that day-to-day variability in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) versus no FPG variability was significantly associated with both severe hypoglycemia (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.37; 95% confidence interval, 2.52-4.50; P less than .001), and all-cause mortality (aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.01-1.75; P = .00432).

In addition, severe hypoglycemia was linked to all-cause mortality, with a temporal relationship seen such that the risk for death was higher the more recent the episode of severe hypoglycemia had been. Indeed, while the risk of death was 2.5 times higher at any time after an episode of severe hypoglycemia than if no prior severe hypoglycemia occurred (HR, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.35-13.09), it was four times higher 15 days after severe hypoglycemia than after no such event (HR, 4.20; 95% CI, 1.9-3.50).

These results of DEVOTE 2 and DEVOTE 3 were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and published in Diabetologia on Sept. 15.

What do the results mean for current practice?

“There’s great interest in knowing whether glucose variability and severe hypoglycemia are associated with cardiovascular risk and mortality; these data are therefore important and timely,” said the invited commentator and editorialist for the study Martin Rutter, MD, a senior lecturer in cardiometabolic medicine at the University of Manchester and an honorary consultant physician at Manchester Royal Infirmary, England.

“Only further clinical trials can genuinely guide clinicians on whether to target glucose variability and risk for severe hypos to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes. My hope is that these data will help to build a case for such trials,” Dr. Rutter said.

DEVOTE: main findings and secondary analyses

The main findings from the DEVOTE study were reported in June during the American Diabetes Association’s Annual Scientific Sessions and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2017 Aug 24;377[8]:723-32). These showed that insulin degludec was noninferior to insulin glargine, with a similar rate of major cardiovascular events (MACE), which comprised nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and cardiovascular death (8.5% vs. 9.3%; HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.78-1.06; P less than .001). The rate of severe hypoglycemia was significantly (P less than .001) lower in the degludec than glargine arm, however, occurring in a respective 4.9% and 6.6% of patients in each group (odds ratio, 0.73).

“DEVOTE confirms the cardiovascular safety of insulin degludec, compared with glargine,” said DEVOTE study investigator, Neil Poulter, MD, FMedSci, of the Imperial Clinical Trials Unit at Imperial College London. “The rate of severe hypoglycemia was significantly reduced [with insulin degludec vs. glargine] in the DEVOTE trial.”

Role of glycemic variability

“It is well established that there is a relationship between glycemic variability and hypoglycemia,” said Bernard Zinman, MD, director of the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, who presented the DEVOTE 2 findings. He commented that the “very dense data” collected during the main study had enabled a fuller analysis of glycemic variability. Dr. Zinman was keen to emphasize that it was the fasting variability that was studied.

Looking at outcomes, there was a dose relationship seen from low to high glycemic variability with increasing rates of severe hypoglycemia, MACE, and all-cause mortality the higher the variability, Dr. Zinman reported.

Although initially there was an increased risk for MACE with increasing glycemic variability, “the association was not maintained after adjusting for baseline characteristics and the most recent A1c,” Dr. Zinman said.

Timing of severe hypoglycemia could be vital

Severe hypoglycemia is under-reported and there is still concern over inducing hypoglycemia, which “conflicts with treatment success,” observed Thomas Pieber, MD, who presented the DEVOTE 3 findings on the relationship between severe hypoglycemia and outcomes.

“Up to 80% of us are concerned about the risk of hypoglycemia and we are not treating glycemic control as aggressively as we would do if there was not any worry about hypoglycemia,” Dr. Pieber said, referring to primary care physicians and diabetes specialists.

Talking about the DEVOTE 3 results, Dr. Pieber noted: “There was no significant association between severe hypoglycemia and MACE, but there was a significantly higher risk of cardiovascular death following a severe hypoglycemia event.” He reminded the audience that an episode of severe hypoglycemia was one which required the assistance of another person, as defined by International Hypoglycemia Study Group which has been acknowledged by both the ADA and EASD.

“These data we have analyzed support a temporal relationship between severe hypoglycemia and all-cause mortality,” Dr. Pieber, adding “the findings indicate that severe hypoglycemia is associated with higher subsequent mortality.”

Predicting severe hypos

“There are well-known factors that influence the risk of having a severe hypoglycemic event,” commented another of the DEVOTE study investigators, John Buse, MD, PhD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine at Chapel Hill. These include the insulin treatment regimen, the duration of diabetes, sex, and baseline HbA1c, to pick the more traditional ones. Additional ones that a post-hoc analysis of the DEVOTE data identified are baseline renal function, prior stroke, low-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio, diastolic blood pressure, hepatic impairment, and smoking status. Age, another traditional risk factor, was identified as well and all these went in to create the DEVOTE severe hypoglycemia risk prediction model.

The DEVOTE hypoglycemia risk score is currently a work in progress; the app can be seen at http://www.hyporiskscore.com/. DEVOTE was funded by Novo Nordisk. Slides presented at the EASD meeting are available for download at https://tracs.unc.edu/DEVOTE.

Dr. Rutter disclosed receiving honoraria and funding to attend educational meetings from Novo Nordisk and honoraria and consulting fees from Ascensia, Cell Catapult, and Roche Diabetes Care.

Dr. Poulter has received speaker fees and consultancy fees from Novo Nordisk, Servier, Takeda, and AstraZeneca; and grants for his research group relating to type 2 diabetes mellitus from Diabetes UK, the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation, and the Julius Clinical and the British Heart Foundation.

Dr. Zinman has received grant support from Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca. He disclosed receiving consulting fees from Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and Sanofi.

Dr. Pieber disclosed receiving received research support from Novo Nordisk and AstraZeneca paid directly to his institution and personal honoraria from Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Roche Diabetes Care. Dr. Pieber is the Chief Scientific Officer of the Center for Biomarker Research in Medicine, a publicly funded biomarker research company.

Dr. Buse reported receiving contracted consulting fees, paid to his institution, and travel support from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly and Company, GI Dynamics, Elcelyx, Merck, Metavention, vTv Pharma, PhaseBio, AstraZeneca, Dance Biopharm, Sanofi, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Orexigen, Takeda, Adocia, Roche, NovaTarg, Shenzhen High Tide, Fractyl, and Dexcom. He has also received consultancy fees and grant support from Eli Lilly and Company, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GI Dynamics, Merck, PhaseBio, AstraZeneca, Medtronic Minimed, Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Andromeda, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, MacroGenics, Intarcia Therapeutics, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Scion NeuroStim, Orexigen, Takeda, Theracos, and Bayer. Dr. Buse has also received fees and holds stock options in PhaseBio and Insulin Algorithm, as well as serving on the board of the AstraZeneca Healthcare Foundation.

AT EASD 2017

LISBON –

A second wave of results from the DEVOTE study, which compared the cardiovascular safety of insulin degludec (Tresiba, Novo Nordisk) versus insulin glargine, found that day-to-day variability in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) versus no FPG variability was significantly associated with both severe hypoglycemia (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.37; 95% confidence interval, 2.52-4.50; P less than .001), and all-cause mortality (aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.01-1.75; P = .00432).

In addition, severe hypoglycemia was linked to all-cause mortality, with a temporal relationship seen such that the risk for death was higher the more recent the episode of severe hypoglycemia had been. Indeed, while the risk of death was 2.5 times higher at any time after an episode of severe hypoglycemia than if no prior severe hypoglycemia occurred (HR, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.35-13.09), it was four times higher 15 days after severe hypoglycemia than after no such event (HR, 4.20; 95% CI, 1.9-3.50).

These results of DEVOTE 2 and DEVOTE 3 were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and published in Diabetologia on Sept. 15.

What do the results mean for current practice?

“There’s great interest in knowing whether glucose variability and severe hypoglycemia are associated with cardiovascular risk and mortality; these data are therefore important and timely,” said the invited commentator and editorialist for the study Martin Rutter, MD, a senior lecturer in cardiometabolic medicine at the University of Manchester and an honorary consultant physician at Manchester Royal Infirmary, England.

“Only further clinical trials can genuinely guide clinicians on whether to target glucose variability and risk for severe hypos to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes. My hope is that these data will help to build a case for such trials,” Dr. Rutter said.

DEVOTE: main findings and secondary analyses

The main findings from the DEVOTE study were reported in June during the American Diabetes Association’s Annual Scientific Sessions and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2017 Aug 24;377[8]:723-32). These showed that insulin degludec was noninferior to insulin glargine, with a similar rate of major cardiovascular events (MACE), which comprised nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and cardiovascular death (8.5% vs. 9.3%; HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.78-1.06; P less than .001). The rate of severe hypoglycemia was significantly (P less than .001) lower in the degludec than glargine arm, however, occurring in a respective 4.9% and 6.6% of patients in each group (odds ratio, 0.73).

“DEVOTE confirms the cardiovascular safety of insulin degludec, compared with glargine,” said DEVOTE study investigator, Neil Poulter, MD, FMedSci, of the Imperial Clinical Trials Unit at Imperial College London. “The rate of severe hypoglycemia was significantly reduced [with insulin degludec vs. glargine] in the DEVOTE trial.”

Role of glycemic variability

“It is well established that there is a relationship between glycemic variability and hypoglycemia,” said Bernard Zinman, MD, director of the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, who presented the DEVOTE 2 findings. He commented that the “very dense data” collected during the main study had enabled a fuller analysis of glycemic variability. Dr. Zinman was keen to emphasize that it was the fasting variability that was studied.

Looking at outcomes, there was a dose relationship seen from low to high glycemic variability with increasing rates of severe hypoglycemia, MACE, and all-cause mortality the higher the variability, Dr. Zinman reported.

Although initially there was an increased risk for MACE with increasing glycemic variability, “the association was not maintained after adjusting for baseline characteristics and the most recent A1c,” Dr. Zinman said.

Timing of severe hypoglycemia could be vital

Severe hypoglycemia is under-reported and there is still concern over inducing hypoglycemia, which “conflicts with treatment success,” observed Thomas Pieber, MD, who presented the DEVOTE 3 findings on the relationship between severe hypoglycemia and outcomes.

“Up to 80% of us are concerned about the risk of hypoglycemia and we are not treating glycemic control as aggressively as we would do if there was not any worry about hypoglycemia,” Dr. Pieber said, referring to primary care physicians and diabetes specialists.

Talking about the DEVOTE 3 results, Dr. Pieber noted: “There was no significant association between severe hypoglycemia and MACE, but there was a significantly higher risk of cardiovascular death following a severe hypoglycemia event.” He reminded the audience that an episode of severe hypoglycemia was one which required the assistance of another person, as defined by International Hypoglycemia Study Group which has been acknowledged by both the ADA and EASD.

“These data we have analyzed support a temporal relationship between severe hypoglycemia and all-cause mortality,” Dr. Pieber, adding “the findings indicate that severe hypoglycemia is associated with higher subsequent mortality.”

Predicting severe hypos

“There are well-known factors that influence the risk of having a severe hypoglycemic event,” commented another of the DEVOTE study investigators, John Buse, MD, PhD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine at Chapel Hill. These include the insulin treatment regimen, the duration of diabetes, sex, and baseline HbA1c, to pick the more traditional ones. Additional ones that a post-hoc analysis of the DEVOTE data identified are baseline renal function, prior stroke, low-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio, diastolic blood pressure, hepatic impairment, and smoking status. Age, another traditional risk factor, was identified as well and all these went in to create the DEVOTE severe hypoglycemia risk prediction model.

The DEVOTE hypoglycemia risk score is currently a work in progress; the app can be seen at http://www.hyporiskscore.com/. DEVOTE was funded by Novo Nordisk. Slides presented at the EASD meeting are available for download at https://tracs.unc.edu/DEVOTE.

Dr. Rutter disclosed receiving honoraria and funding to attend educational meetings from Novo Nordisk and honoraria and consulting fees from Ascensia, Cell Catapult, and Roche Diabetes Care.

Dr. Poulter has received speaker fees and consultancy fees from Novo Nordisk, Servier, Takeda, and AstraZeneca; and grants for his research group relating to type 2 diabetes mellitus from Diabetes UK, the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation, and the Julius Clinical and the British Heart Foundation.

Dr. Zinman has received grant support from Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca. He disclosed receiving consulting fees from Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and Sanofi.

Dr. Pieber disclosed receiving received research support from Novo Nordisk and AstraZeneca paid directly to his institution and personal honoraria from Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Roche Diabetes Care. Dr. Pieber is the Chief Scientific Officer of the Center for Biomarker Research in Medicine, a publicly funded biomarker research company.

Dr. Buse reported receiving contracted consulting fees, paid to his institution, and travel support from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly and Company, GI Dynamics, Elcelyx, Merck, Metavention, vTv Pharma, PhaseBio, AstraZeneca, Dance Biopharm, Sanofi, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Orexigen, Takeda, Adocia, Roche, NovaTarg, Shenzhen High Tide, Fractyl, and Dexcom. He has also received consultancy fees and grant support from Eli Lilly and Company, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GI Dynamics, Merck, PhaseBio, AstraZeneca, Medtronic Minimed, Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Andromeda, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, MacroGenics, Intarcia Therapeutics, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Scion NeuroStim, Orexigen, Takeda, Theracos, and Bayer. Dr. Buse has also received fees and holds stock options in PhaseBio and Insulin Algorithm, as well as serving on the board of the AstraZeneca Healthcare Foundation.

AT EASD 2017

LISBON –

A second wave of results from the DEVOTE study, which compared the cardiovascular safety of insulin degludec (Tresiba, Novo Nordisk) versus insulin glargine, found that day-to-day variability in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) versus no FPG variability was significantly associated with both severe hypoglycemia (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.37; 95% confidence interval, 2.52-4.50; P less than .001), and all-cause mortality (aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.01-1.75; P = .00432).

In addition, severe hypoglycemia was linked to all-cause mortality, with a temporal relationship seen such that the risk for death was higher the more recent the episode of severe hypoglycemia had been. Indeed, while the risk of death was 2.5 times higher at any time after an episode of severe hypoglycemia than if no prior severe hypoglycemia occurred (HR, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.35-13.09), it was four times higher 15 days after severe hypoglycemia than after no such event (HR, 4.20; 95% CI, 1.9-3.50).

These results of DEVOTE 2 and DEVOTE 3 were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and published in Diabetologia on Sept. 15.

What do the results mean for current practice?

“There’s great interest in knowing whether glucose variability and severe hypoglycemia are associated with cardiovascular risk and mortality; these data are therefore important and timely,” said the invited commentator and editorialist for the study Martin Rutter, MD, a senior lecturer in cardiometabolic medicine at the University of Manchester and an honorary consultant physician at Manchester Royal Infirmary, England.

“Only further clinical trials can genuinely guide clinicians on whether to target glucose variability and risk for severe hypos to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes. My hope is that these data will help to build a case for such trials,” Dr. Rutter said.

DEVOTE: main findings and secondary analyses

The main findings from the DEVOTE study were reported in June during the American Diabetes Association’s Annual Scientific Sessions and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2017 Aug 24;377[8]:723-32). These showed that insulin degludec was noninferior to insulin glargine, with a similar rate of major cardiovascular events (MACE), which comprised nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and cardiovascular death (8.5% vs. 9.3%; HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.78-1.06; P less than .001). The rate of severe hypoglycemia was significantly (P less than .001) lower in the degludec than glargine arm, however, occurring in a respective 4.9% and 6.6% of patients in each group (odds ratio, 0.73).

“DEVOTE confirms the cardiovascular safety of insulin degludec, compared with glargine,” said DEVOTE study investigator, Neil Poulter, MD, FMedSci, of the Imperial Clinical Trials Unit at Imperial College London. “The rate of severe hypoglycemia was significantly reduced [with insulin degludec vs. glargine] in the DEVOTE trial.”

Role of glycemic variability

“It is well established that there is a relationship between glycemic variability and hypoglycemia,” said Bernard Zinman, MD, director of the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, who presented the DEVOTE 2 findings. He commented that the “very dense data” collected during the main study had enabled a fuller analysis of glycemic variability. Dr. Zinman was keen to emphasize that it was the fasting variability that was studied.

Looking at outcomes, there was a dose relationship seen from low to high glycemic variability with increasing rates of severe hypoglycemia, MACE, and all-cause mortality the higher the variability, Dr. Zinman reported.

Although initially there was an increased risk for MACE with increasing glycemic variability, “the association was not maintained after adjusting for baseline characteristics and the most recent A1c,” Dr. Zinman said.

Timing of severe hypoglycemia could be vital

Severe hypoglycemia is under-reported and there is still concern over inducing hypoglycemia, which “conflicts with treatment success,” observed Thomas Pieber, MD, who presented the DEVOTE 3 findings on the relationship between severe hypoglycemia and outcomes.

“Up to 80% of us are concerned about the risk of hypoglycemia and we are not treating glycemic control as aggressively as we would do if there was not any worry about hypoglycemia,” Dr. Pieber said, referring to primary care physicians and diabetes specialists.

Talking about the DEVOTE 3 results, Dr. Pieber noted: “There was no significant association between severe hypoglycemia and MACE, but there was a significantly higher risk of cardiovascular death following a severe hypoglycemia event.” He reminded the audience that an episode of severe hypoglycemia was one which required the assistance of another person, as defined by International Hypoglycemia Study Group which has been acknowledged by both the ADA and EASD.

“These data we have analyzed support a temporal relationship between severe hypoglycemia and all-cause mortality,” Dr. Pieber, adding “the findings indicate that severe hypoglycemia is associated with higher subsequent mortality.”

Predicting severe hypos

“There are well-known factors that influence the risk of having a severe hypoglycemic event,” commented another of the DEVOTE study investigators, John Buse, MD, PhD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine at Chapel Hill. These include the insulin treatment regimen, the duration of diabetes, sex, and baseline HbA1c, to pick the more traditional ones. Additional ones that a post-hoc analysis of the DEVOTE data identified are baseline renal function, prior stroke, low-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio, diastolic blood pressure, hepatic impairment, and smoking status. Age, another traditional risk factor, was identified as well and all these went in to create the DEVOTE severe hypoglycemia risk prediction model.

The DEVOTE hypoglycemia risk score is currently a work in progress; the app can be seen at http://www.hyporiskscore.com/. DEVOTE was funded by Novo Nordisk. Slides presented at the EASD meeting are available for download at https://tracs.unc.edu/DEVOTE.

Dr. Rutter disclosed receiving honoraria and funding to attend educational meetings from Novo Nordisk and honoraria and consulting fees from Ascensia, Cell Catapult, and Roche Diabetes Care.

Dr. Poulter has received speaker fees and consultancy fees from Novo Nordisk, Servier, Takeda, and AstraZeneca; and grants for his research group relating to type 2 diabetes mellitus from Diabetes UK, the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation, and the Julius Clinical and the British Heart Foundation.

Dr. Zinman has received grant support from Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca. He disclosed receiving consulting fees from Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and Sanofi.

Dr. Pieber disclosed receiving received research support from Novo Nordisk and AstraZeneca paid directly to his institution and personal honoraria from Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Roche Diabetes Care. Dr. Pieber is the Chief Scientific Officer of the Center for Biomarker Research in Medicine, a publicly funded biomarker research company.

Dr. Buse reported receiving contracted consulting fees, paid to his institution, and travel support from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly and Company, GI Dynamics, Elcelyx, Merck, Metavention, vTv Pharma, PhaseBio, AstraZeneca, Dance Biopharm, Sanofi, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Orexigen, Takeda, Adocia, Roche, NovaTarg, Shenzhen High Tide, Fractyl, and Dexcom. He has also received consultancy fees and grant support from Eli Lilly and Company, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GI Dynamics, Merck, PhaseBio, AstraZeneca, Medtronic Minimed, Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Andromeda, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, MacroGenics, Intarcia Therapeutics, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Scion NeuroStim, Orexigen, Takeda, Theracos, and Bayer. Dr. Buse has also received fees and holds stock options in PhaseBio and Insulin Algorithm, as well as serving on the board of the AstraZeneca Healthcare Foundation.

Key clinical point: Evenly maintained blood glucose levels may save lives in T2DM.

Major finding: Patients with greater fluctuations of fasting plasma glucose were more likely to die than were those with more episodes of severe hypoglycemia.

Data source: Further analysis of data from both DEVOTE 2 and DEVOTE 3, involving 7,637 patients with type 2 diabetes who were treated with either insulin degludec or insulin glargine.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Novo Nordisk. All presenters have received consulting fees from Novo Nordisk among other pharmaceutical companies. Two presenters (Dr. Zinman and Dr. Pieber) also disclosed receiving research support from the company.

Make the Diagnosis - October 2017

Palmoplantar keratoderma

Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is made of a group of benign disorders that cause thickening of the palms and soles. It is generally divided into three categories: diffuse PPK, with involvement of the whole palmoplantar surface; focal and striate PPK, usually located mainly on pressure points; and punctate PPK, featuring multiple small hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, or spicules. This patient’s lesions are most consistent with punctate palmoplantar keratoderma (PPPK).

PPPK is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, although acquired cases can be seen. It is also called Buschke-Fischer-Brauer syndrome, or keratodermia palmoplantaris papulosa. The condition affects men and women equally. Lesions usually appear during adolescence or after, unlike other forms of keratoderma, which may occur during childhood. While any race may be affected, in those of African descent, lesions are more common in the palmar creases. The condition is likely due to an aberration in proteins involved in keratin filament assembly. A mutation in the AAGAB gene can be at fault. PPPK can be associated with Darier’s disease and Cowden disease. Familial PPPK may be associated with Hodgkin disease, squamous cell carcinoma, kidney, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer.

Upon physical exam, multiple keratotic, punctate papules are present on the palms and soles, which may appear clear or more opaque. They may also have a verrucous appearance. Some lesions may have a central keratotic core and appear more comedonal. Most often, lesions are nontransgradient, meaning they only involve the palms and soles. Sometimes lesions may extend to the top of the hands and feet as well, which is called transgradient. Lesions are typically asymptomatic, although larger lesions can become painful with friction. Other types of PPPKs include filiform keratoderma and marginal keratoderma.

Histologic evaluation reveals columns of hyperkeratosis with an increased granular layer. There is no dermal inflammation. Clinically, the differential diagnosis is limited. Verruca vulgaris will reveal bleeding points upon paring with a blade. In spiny keratoderma, also called punctate porokeratosis of the palms and soles, lesions protrude more and resemble “music box spines.” Histologically, columnar parakeratosis is seen. Pitted keratolysis have reduced stratum corneum and a distinct clinical appearance.

If treatment is desired, emollients, keratolytics such as topical retinoids, salicylic acid, lactic acid, and urea may be used. Oral retinoids may be useful in symptomatic patients. Surgery and CO2 laser may be an option for resistant lesions.

This case and photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Palmoplantar keratoderma

Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is made of a group of benign disorders that cause thickening of the palms and soles. It is generally divided into three categories: diffuse PPK, with involvement of the whole palmoplantar surface; focal and striate PPK, usually located mainly on pressure points; and punctate PPK, featuring multiple small hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, or spicules. This patient’s lesions are most consistent with punctate palmoplantar keratoderma (PPPK).

PPPK is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, although acquired cases can be seen. It is also called Buschke-Fischer-Brauer syndrome, or keratodermia palmoplantaris papulosa. The condition affects men and women equally. Lesions usually appear during adolescence or after, unlike other forms of keratoderma, which may occur during childhood. While any race may be affected, in those of African descent, lesions are more common in the palmar creases. The condition is likely due to an aberration in proteins involved in keratin filament assembly. A mutation in the AAGAB gene can be at fault. PPPK can be associated with Darier’s disease and Cowden disease. Familial PPPK may be associated with Hodgkin disease, squamous cell carcinoma, kidney, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer.

Upon physical exam, multiple keratotic, punctate papules are present on the palms and soles, which may appear clear or more opaque. They may also have a verrucous appearance. Some lesions may have a central keratotic core and appear more comedonal. Most often, lesions are nontransgradient, meaning they only involve the palms and soles. Sometimes lesions may extend to the top of the hands and feet as well, which is called transgradient. Lesions are typically asymptomatic, although larger lesions can become painful with friction. Other types of PPPKs include filiform keratoderma and marginal keratoderma.

Histologic evaluation reveals columns of hyperkeratosis with an increased granular layer. There is no dermal inflammation. Clinically, the differential diagnosis is limited. Verruca vulgaris will reveal bleeding points upon paring with a blade. In spiny keratoderma, also called punctate porokeratosis of the palms and soles, lesions protrude more and resemble “music box spines.” Histologically, columnar parakeratosis is seen. Pitted keratolysis have reduced stratum corneum and a distinct clinical appearance.

If treatment is desired, emollients, keratolytics such as topical retinoids, salicylic acid, lactic acid, and urea may be used. Oral retinoids may be useful in symptomatic patients. Surgery and CO2 laser may be an option for resistant lesions.

This case and photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Palmoplantar keratoderma

Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is made of a group of benign disorders that cause thickening of the palms and soles. It is generally divided into three categories: diffuse PPK, with involvement of the whole palmoplantar surface; focal and striate PPK, usually located mainly on pressure points; and punctate PPK, featuring multiple small hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, or spicules. This patient’s lesions are most consistent with punctate palmoplantar keratoderma (PPPK).

PPPK is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, although acquired cases can be seen. It is also called Buschke-Fischer-Brauer syndrome, or keratodermia palmoplantaris papulosa. The condition affects men and women equally. Lesions usually appear during adolescence or after, unlike other forms of keratoderma, which may occur during childhood. While any race may be affected, in those of African descent, lesions are more common in the palmar creases. The condition is likely due to an aberration in proteins involved in keratin filament assembly. A mutation in the AAGAB gene can be at fault. PPPK can be associated with Darier’s disease and Cowden disease. Familial PPPK may be associated with Hodgkin disease, squamous cell carcinoma, kidney, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer.

Upon physical exam, multiple keratotic, punctate papules are present on the palms and soles, which may appear clear or more opaque. They may also have a verrucous appearance. Some lesions may have a central keratotic core and appear more comedonal. Most often, lesions are nontransgradient, meaning they only involve the palms and soles. Sometimes lesions may extend to the top of the hands and feet as well, which is called transgradient. Lesions are typically asymptomatic, although larger lesions can become painful with friction. Other types of PPPKs include filiform keratoderma and marginal keratoderma.

Histologic evaluation reveals columns of hyperkeratosis with an increased granular layer. There is no dermal inflammation. Clinically, the differential diagnosis is limited. Verruca vulgaris will reveal bleeding points upon paring with a blade. In spiny keratoderma, also called punctate porokeratosis of the palms and soles, lesions protrude more and resemble “music box spines.” Histologically, columnar parakeratosis is seen. Pitted keratolysis have reduced stratum corneum and a distinct clinical appearance.

If treatment is desired, emollients, keratolytics such as topical retinoids, salicylic acid, lactic acid, and urea may be used. Oral retinoids may be useful in symptomatic patients. Surgery and CO2 laser may be an option for resistant lesions.

This case and photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

FDA approves higher dose brigatinib tablet for advanced ALK+ NSCLC

The Food and Drug Administration has approved 180 mg brigatinib (Alunbrig) tablets for treatment of anaplastic lymphoma kinase–positive (ALK+) metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), expanding on previously available 30-mg tablets.*

“With the approval of a 180-mg tablet, Alunbrig has become the only ALK inhibitor available as a one tablet per day dose that can be taken with or without food,” Ryan Cohlhepp, PharmD, vice president, U.S. Commercial, at Takeda Oncology said in a press release.

Approval of the regimen was based on objective response in the ongoing, two-arm, open-label, multicenter phase 2 ALTA trial, which enrolled 222 patients with metastatic or locally advanced ALK+ NSCLC who had progressed on crizotinib. Patients were randomized to brigatinib orally either 90 mg once daily or 180 mg once daily following a 7-day lead-in at 90 mg once daily. Of those in the 180-mg arm, 53% had an objective response, compared with 48% in the 90-mg arm.

Adverse reactions occurred in 40% of the patients in the 180-mg arm, compared with 38% in the 90-mg arm. The most common serious adverse reactions were pneumonia and interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis. Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 3.7% of the patients, caused by pneumonia (two patients), sudden death, dyspnea, respiratory failure, pulmonary embolism, bacterial meningitis and urosepsis (one patient each).

The ALTA trial is ongoing, and updated results will be presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer in Yokohama, Japan, on Oct. 15-18, the company said in the press release.

*Correction, 10/4/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the previously available tablet sizes.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved 180 mg brigatinib (Alunbrig) tablets for treatment of anaplastic lymphoma kinase–positive (ALK+) metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), expanding on previously available 30-mg tablets.*

“With the approval of a 180-mg tablet, Alunbrig has become the only ALK inhibitor available as a one tablet per day dose that can be taken with or without food,” Ryan Cohlhepp, PharmD, vice president, U.S. Commercial, at Takeda Oncology said in a press release.

Approval of the regimen was based on objective response in the ongoing, two-arm, open-label, multicenter phase 2 ALTA trial, which enrolled 222 patients with metastatic or locally advanced ALK+ NSCLC who had progressed on crizotinib. Patients were randomized to brigatinib orally either 90 mg once daily or 180 mg once daily following a 7-day lead-in at 90 mg once daily. Of those in the 180-mg arm, 53% had an objective response, compared with 48% in the 90-mg arm.

Adverse reactions occurred in 40% of the patients in the 180-mg arm, compared with 38% in the 90-mg arm. The most common serious adverse reactions were pneumonia and interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis. Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 3.7% of the patients, caused by pneumonia (two patients), sudden death, dyspnea, respiratory failure, pulmonary embolism, bacterial meningitis and urosepsis (one patient each).

The ALTA trial is ongoing, and updated results will be presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer in Yokohama, Japan, on Oct. 15-18, the company said in the press release.

*Correction, 10/4/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the previously available tablet sizes.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved 180 mg brigatinib (Alunbrig) tablets for treatment of anaplastic lymphoma kinase–positive (ALK+) metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), expanding on previously available 30-mg tablets.*

“With the approval of a 180-mg tablet, Alunbrig has become the only ALK inhibitor available as a one tablet per day dose that can be taken with or without food,” Ryan Cohlhepp, PharmD, vice president, U.S. Commercial, at Takeda Oncology said in a press release.

Approval of the regimen was based on objective response in the ongoing, two-arm, open-label, multicenter phase 2 ALTA trial, which enrolled 222 patients with metastatic or locally advanced ALK+ NSCLC who had progressed on crizotinib. Patients were randomized to brigatinib orally either 90 mg once daily or 180 mg once daily following a 7-day lead-in at 90 mg once daily. Of those in the 180-mg arm, 53% had an objective response, compared with 48% in the 90-mg arm.

Adverse reactions occurred in 40% of the patients in the 180-mg arm, compared with 38% in the 90-mg arm. The most common serious adverse reactions were pneumonia and interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis. Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 3.7% of the patients, caused by pneumonia (two patients), sudden death, dyspnea, respiratory failure, pulmonary embolism, bacterial meningitis and urosepsis (one patient each).

The ALTA trial is ongoing, and updated results will be presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer in Yokohama, Japan, on Oct. 15-18, the company said in the press release.

*Correction, 10/4/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the previously available tablet sizes.

HCA is the country’s highest-volume health system

HCA of Nashville, Tenn., had more discharges in 2016 than any other health system in the United States, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

HCA’s 192 hospitals recorded over 1.7 million discharges last year, more than twice as many as Ascension Health in St. Louis, which discharged almost 860,000 patients from its 136 hospitals. Tennessee is also the home of the nation’s third-largest health system, Community Health Systems of Franklin, which totaled just over 805,000 discharges in 2016. Tenet Healthcare Corporation in Dallas was fourth with 752,000 discharges, and Trinity Health in Livonia, Mich., was fifth with 737,000 discharges, the AHRQ said in its Compendium of U.S. Health Systems, 2016.

HCA of Nashville, Tenn., had more discharges in 2016 than any other health system in the United States, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

HCA’s 192 hospitals recorded over 1.7 million discharges last year, more than twice as many as Ascension Health in St. Louis, which discharged almost 860,000 patients from its 136 hospitals. Tennessee is also the home of the nation’s third-largest health system, Community Health Systems of Franklin, which totaled just over 805,000 discharges in 2016. Tenet Healthcare Corporation in Dallas was fourth with 752,000 discharges, and Trinity Health in Livonia, Mich., was fifth with 737,000 discharges, the AHRQ said in its Compendium of U.S. Health Systems, 2016.

HCA of Nashville, Tenn., had more discharges in 2016 than any other health system in the United States, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

HCA’s 192 hospitals recorded over 1.7 million discharges last year, more than twice as many as Ascension Health in St. Louis, which discharged almost 860,000 patients from its 136 hospitals. Tennessee is also the home of the nation’s third-largest health system, Community Health Systems of Franklin, which totaled just over 805,000 discharges in 2016. Tenet Healthcare Corporation in Dallas was fourth with 752,000 discharges, and Trinity Health in Livonia, Mich., was fifth with 737,000 discharges, the AHRQ said in its Compendium of U.S. Health Systems, 2016.

DDSEP® 8 Quick quiz - October 2017 Question 1

Q1: Answer: A

Campylobacter species are a major cause of diarrheal illness in the world. The organism inhabits the intestinal tracts of a wide range of animal hosts, notably poultry; contamination from these sources can lead to foodborne disease. Given the self-limited nature of most Campylobacter infections and the limited efficacy of routine antimicrobial therapy, treatment is warranted only for patients with features of severe disease or risk for severe disease.

Patients with severe disease include individuals with bloody stools, high fever, extra-intestinal infection, worsening or relapsing symptoms, or symptoms lasting longer than 1 week. Those at risk for severe disease include patients who are elderly, pregnant, or immunocompromised. First-line agents for treatment of Campylobacter infection include fluoroquinolones (if sensitive) or azithromycin. Campylobacter is inherently resistant to trimethoprim and beta-lactam antibiotics, including penicillin and most cephalosporins.

In the United States, the rate of resistance to fluoroquinolones is also increasing. The rate of ciprofloxacin resistance among Campylobacter isolated in the United States increased from 0% to 19% between 1989 and 2001. Inappropriate and overprescription of fluoroquinolones in humans combined with increased fluoroquinolone use in the poultry industry in particular have contributed to the increased prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance.

The rate of macrolide-resistance among Campylobacter has remained stable at less than 5% in most parts of the world.

References

1. Dasti J.I., Tareen A.M., Lugert R., et al. Campylobacter jejuni: A brief overview on pathogenicity-associated factors and disease-mediating mechanisms. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:205–11.

2. Gupta A., Nelson J.M., Barrett T.J., et al. Antimicrobial resistance among Campylobacter strains, United States, 1997-2001. Emerging infectious diseases. Jun 2004;10(6):1102-9.

Q1: Answer: A

Campylobacter species are a major cause of diarrheal illness in the world. The organism inhabits the intestinal tracts of a wide range of animal hosts, notably poultry; contamination from these sources can lead to foodborne disease. Given the self-limited nature of most Campylobacter infections and the limited efficacy of routine antimicrobial therapy, treatment is warranted only for patients with features of severe disease or risk for severe disease.

Patients with severe disease include individuals with bloody stools, high fever, extra-intestinal infection, worsening or relapsing symptoms, or symptoms lasting longer than 1 week. Those at risk for severe disease include patients who are elderly, pregnant, or immunocompromised. First-line agents for treatment of Campylobacter infection include fluoroquinolones (if sensitive) or azithromycin. Campylobacter is inherently resistant to trimethoprim and beta-lactam antibiotics, including penicillin and most cephalosporins.

In the United States, the rate of resistance to fluoroquinolones is also increasing. The rate of ciprofloxacin resistance among Campylobacter isolated in the United States increased from 0% to 19% between 1989 and 2001. Inappropriate and overprescription of fluoroquinolones in humans combined with increased fluoroquinolone use in the poultry industry in particular have contributed to the increased prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance.

The rate of macrolide-resistance among Campylobacter has remained stable at less than 5% in most parts of the world.

References

1. Dasti J.I., Tareen A.M., Lugert R., et al. Campylobacter jejuni: A brief overview on pathogenicity-associated factors and disease-mediating mechanisms. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:205–11.

2. Gupta A., Nelson J.M., Barrett T.J., et al. Antimicrobial resistance among Campylobacter strains, United States, 1997-2001. Emerging infectious diseases. Jun 2004;10(6):1102-9.

Q1: Answer: A

Campylobacter species are a major cause of diarrheal illness in the world. The organism inhabits the intestinal tracts of a wide range of animal hosts, notably poultry; contamination from these sources can lead to foodborne disease. Given the self-limited nature of most Campylobacter infections and the limited efficacy of routine antimicrobial therapy, treatment is warranted only for patients with features of severe disease or risk for severe disease.

Patients with severe disease include individuals with bloody stools, high fever, extra-intestinal infection, worsening or relapsing symptoms, or symptoms lasting longer than 1 week. Those at risk for severe disease include patients who are elderly, pregnant, or immunocompromised. First-line agents for treatment of Campylobacter infection include fluoroquinolones (if sensitive) or azithromycin. Campylobacter is inherently resistant to trimethoprim and beta-lactam antibiotics, including penicillin and most cephalosporins.

In the United States, the rate of resistance to fluoroquinolones is also increasing. The rate of ciprofloxacin resistance among Campylobacter isolated in the United States increased from 0% to 19% between 1989 and 2001. Inappropriate and overprescription of fluoroquinolones in humans combined with increased fluoroquinolone use in the poultry industry in particular have contributed to the increased prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance.

The rate of macrolide-resistance among Campylobacter has remained stable at less than 5% in most parts of the world.

References

1. Dasti J.I., Tareen A.M., Lugert R., et al. Campylobacter jejuni: A brief overview on pathogenicity-associated factors and disease-mediating mechanisms. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:205–11.

2. Gupta A., Nelson J.M., Barrett T.J., et al. Antimicrobial resistance among Campylobacter strains, United States, 1997-2001. Emerging infectious diseases. Jun 2004;10(6):1102-9.