User login

Ideals of Facial Beauty

Several concepts of ideal aesthetic measurements can be traced back to ancient Greek and European Renaissance art. In examining canons of beauty, these classical ideals often are compared to modern-day standards, allowing clinicians to delineate the parameters of an attractive facial appearance and facilitate the planning of cosmetic procedures.

Given the growing number of available cosmetic interventions, dermatologists have a powerful ability to modify facial proportions; however, changes to individual structures should be made with a mindful approach to improving overall facial harmony. This article reviews the established parameters of facial beauty to assist the clinician in enhancing cosmetic outcomes.

Canons of Facial Aesthetics

Horizontal Thirds

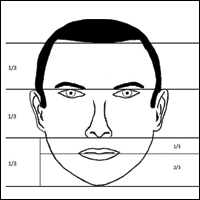

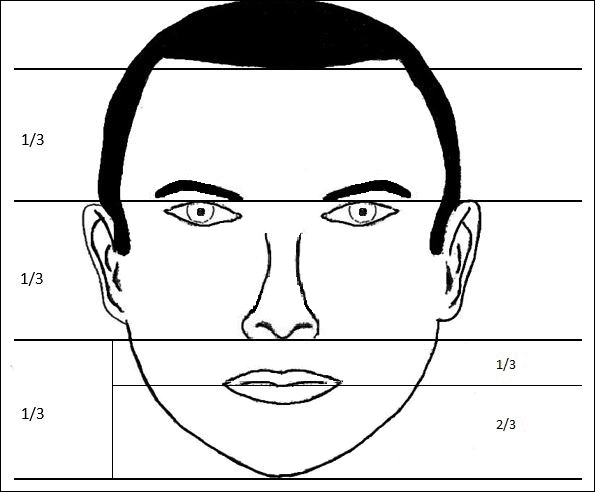

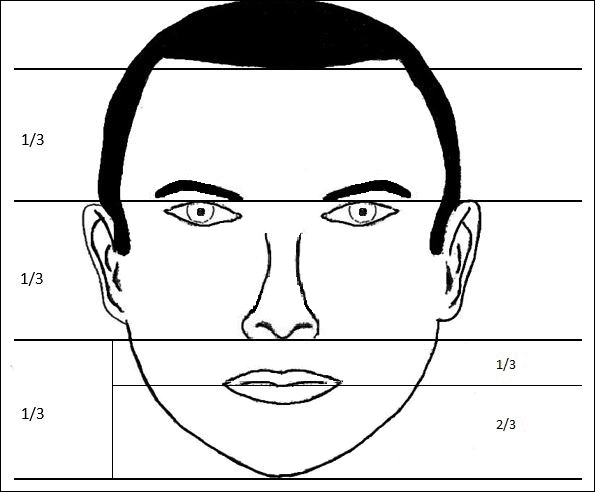

In his writings on human anatomy, Leonardo da Vinci described dividing the face into equal thirds (Figure 1). The upper third measures from the trichion (the midline point of the normal hairline) to the glabella (the smooth prominence between the eyebrows). The middle third measures from the glabella to the subnasale (the midline point where the nasal septum meets the upper lip). The lower third measures from the subnasale to the menton (the most inferior point of the chin).1

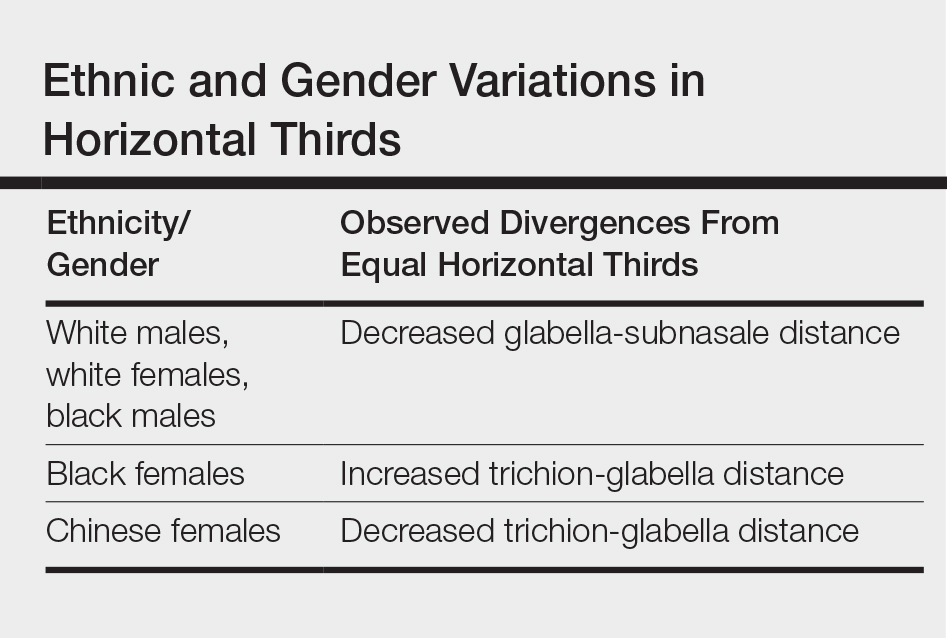

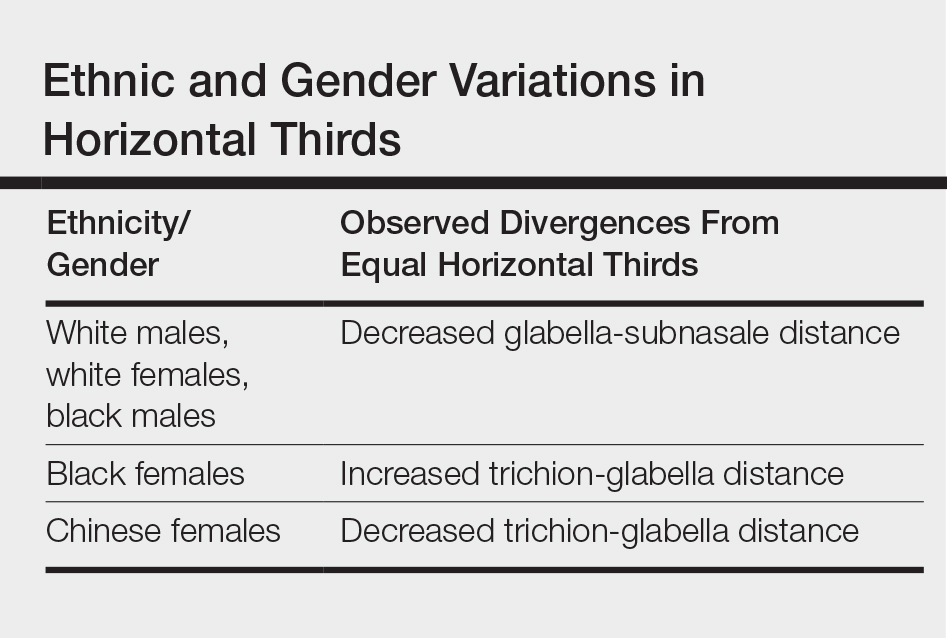

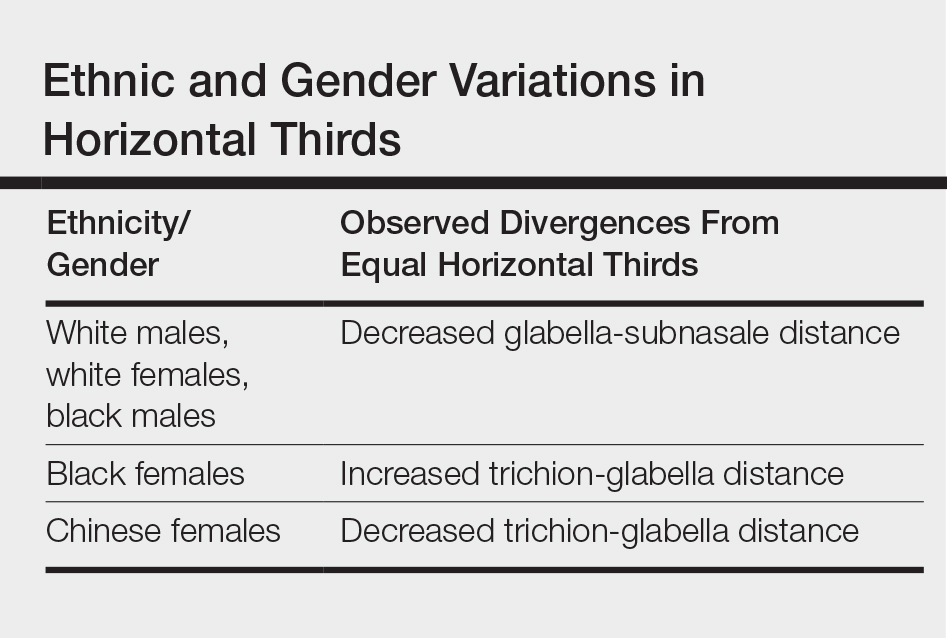

Although the validity of the canon is intended to apply across race and gender, these proportions may vary by ethnicity (Table). In white individuals, the middle third of the face tends to be shorter than the upper and lower thirds.2 This same relationship has been observed in black males.3 In Chinese females, the upper third commonly is shorter than the middle and lower thirds, correlating with a less prominent forehead. In contrast, black females tend to have a relatively longer upper third.4

The relationship between modern perceptions of attractiveness and the neoclassical norm of equal thirds remains a topic of interest. Milutinovic et al1 examined facial thirds in white female celebrities from beauty and fashion magazines and compared them to a group of anonymous white females from the general population. The group of anonymous females showed statistically significant (P<.05) differences between the sizes of the 3 facial segments, whereas the group of celebrity faces demonstrated uniformity between the facial thirds.1

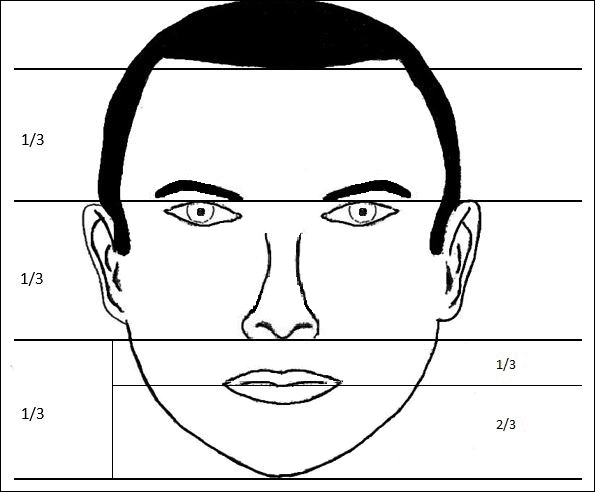

The lower face can itself be divided into thirds, with the upper third measured from the subnasale to the stomion (the midline point of the oral fissure when the lips are closed), and the lower two-thirds measured from the stomion to the menton (Figure 1). Mommaerts and Moerenhout5 examined photographs of 105 attractive celebrity faces and compared their proportions to those of classical sculptures of gods and goddesses (antique faces). The authors identified an upper one-third to lower two-thirds ratio of 69.8% in celebrity females and 69.1% in celebrity males; these ratios were not significantly different from the 72.4% seen in antique females and 73.1% in antique males. The authors concluded that a 30% upper lip to 70% lower lip-chin proportion may be the most appropriate to describe contemporary standards.5

Vertical Fifths

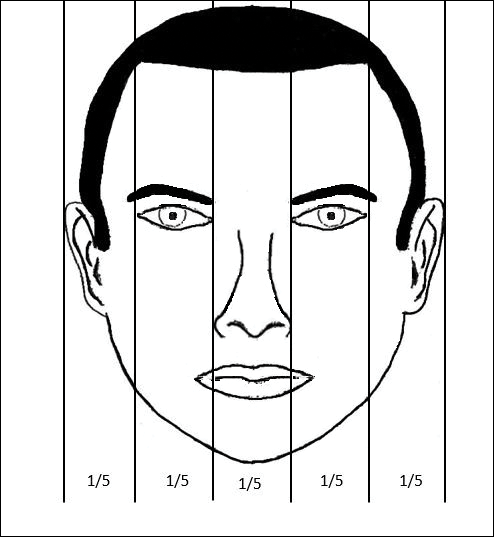

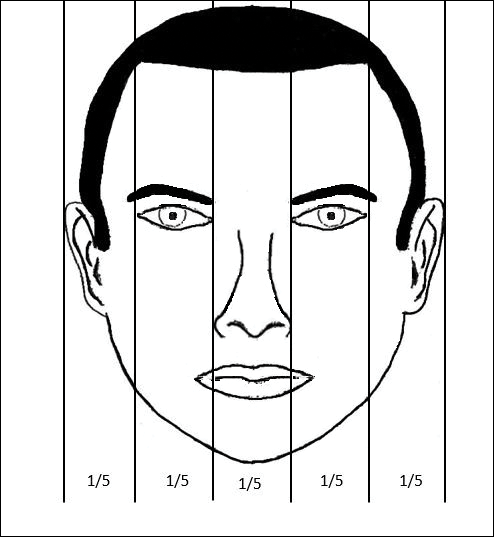

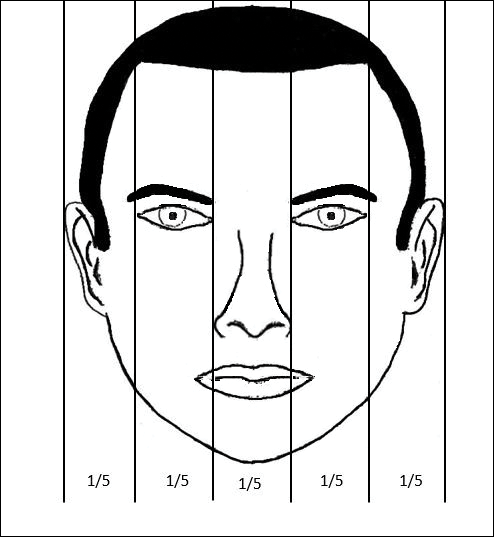

In the vertical dimension, the neoclassical canon of facial proportions divides the face into equal fifths (Figure 2).6 The 2 most lateral fifths are measured from the lateral helix of each ear to the exocanthus of each eye. The eye fissure lengths (measured between the endocanthion and exocanthion of each eye) represent one-fifth. The middle fifth is measured between the medial canthi of both eyes (endocanthion to endocanthion). This distance is equal to the width of the nose, as measured between both alae. Finally, the width of the mouth represents 1.5-times the width of the nose. These ratios of the vertical fifths apply to both males and females.6

Anthropometric studies have examined deviations from the neoclassical canon according to ethnicity. Wang et al7 compared the measurements of North American white and Han Chinese patients to these standards. White patients demonstrated a greater ratio of mouth width to nose width relative to the canon. In contrast, Han Chinese patients demonstrated a relatively wider nose and narrower mouth.7

In black individuals, it has been observed that the dimensions of most facial segments correspond to the neoclassical standards; however, nose width is relatively wider in black individuals relative to the canon as well as relative to white individuals.8

Milutinovic et al1 also compared vertical fifths between white celebrities and anonymous females. In the anonymous female group, statistically significant (P<.05) variations were found between the sizes of the different facial components. In contrast, the celebrity female group showed balance between the widths of vertical fifths.1

Lips

In the lower facial third, the lips represent a key element of attractiveness. Recently, lip augmentation, aimed at creating fuller and plumper lips, has dominated the popular culture and social media landscape.9 Although the aesthetic ideal of lips continues to evolve over time, recent studies have aimed at quantifying modern notions of attractive lip appearance.

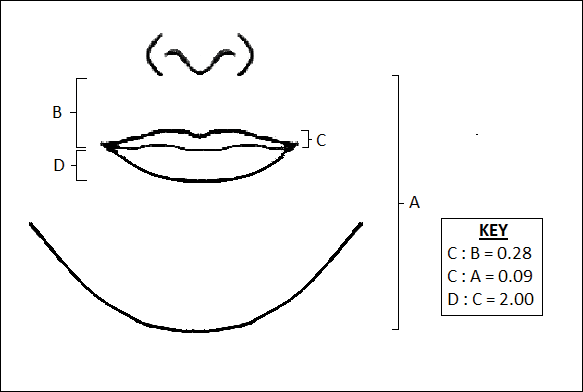

Popenko et al10 examined lip measurements using computer-generated images of white women with different variations of lip sizes and lower face proportions. Computer-generated faces were graded on attractiveness by more than 400 individuals from focus groups. An upper lip to lower lip ratio of 1:2 was judged to be the most attractive, while a ratio of 2:1 was judged to be the least attractive. Results also showed that the surface area of the most attractive lips comprised roughly 10% of the lower third of the face.10

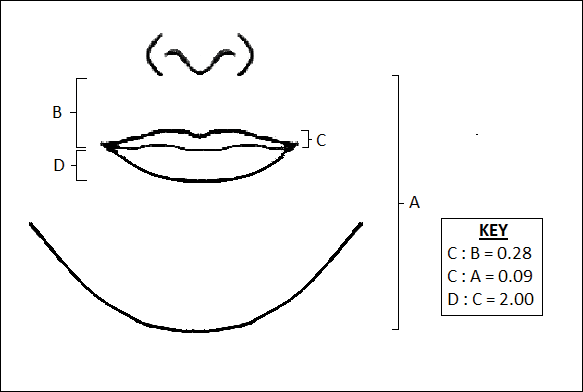

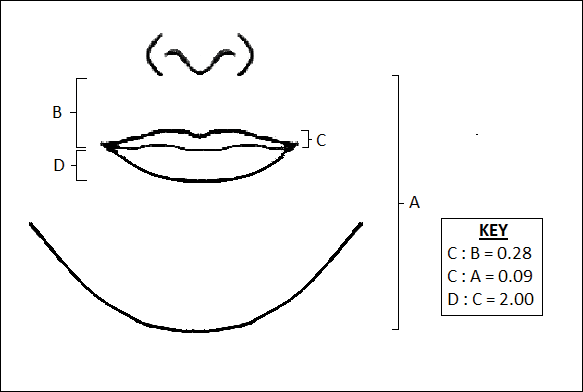

Penna et al11 analyzed various parameters of the lips and lower facial third using photographs of 176 white males and females that were judged on attractiveness by 250 volunteer evaluators. Faces were graded on a scale from 1 (absolutely attractive) to 7 (absolutely unattractive). Attractive males and females (grades 1 and 2) both demonstrated an average ratio of upper vermilion height to nose-mouth distance (measured from the subnasalae to the lower edge of the upper vermilion border) of 0.28, which was significantly greater than the average ratio observed in less attractive individuals (grades 6 or 7)(P<.05). In addition, attractive males and females demonstrated a ratio of upper vermilion height to nose-chin distance (measured from the subnasalae to the menton) of 0.09, which again was larger than the average ratio seen in less attractive individuals. Figure 3 demonstrates an aesthetic ideal of the lips derived from these 2 studies, though consideration should be given to the fact that these studies were based in white populations.

Golden Ratio

The golden ratio, also known as Phi, can be observed in nature, art, and architecture. Approximately equal to 1.618, the golden ratio also has been identified as a possible marker of beauty in the human face and has garnered attention in the lay press. The ratio has been applied to several proportions and structures in the face, such as the ratio of mouth width to nose width or the ratio of tooth height to tooth width, with investigation providing varying levels of validation about whether these ratios truly correlate with perceptions of beauty.12 Swift and Remington13 advocated for application of the golden ratio toward a comprehensive set of facial proportions. Marquardt14 used the golden ratio to create a 3-dimensional representation of an idealized face, known as the golden decagon mask. Although the golden ratio and the golden decagon mask have been proposed as analytic tools, their utility in clinical practice may be limited. Firstly, due to its popularity in the lay press, the golden ratio has been inconsistently applied to a wide range of facial ratios, which may undermine confidence in its representation as truth rather than coincidence. Secondly, although some authors have found validity of the golden decagon mask in representing unified ratios of attractiveness, others have asserted that it characterizes a masculinized white female and fails to account for ethnic differences.15-19

Age-Related Changes

In addition to the facial proportions guided by genetics, several changes occur with increased age. Over the course of a lifetime, predictable patterns emerge in the dimensions of the skin, soft tissue, and bone. These alterations in structural proportions may ultimately lead to an unevenness in facial aesthetics.

In skeletal structure, gradual bone resorption and expansion causes a reduction in facial height as well as an increase in facial width and depth.20 Fat atrophy and hypertrophy affect soft tissue proportions, visualized as hollowing at the temples, cheeks, and around the eyes, along with fullness in the submental region and jowls.21 Finally, decreases in skin elasticity and collagen exacerbate the appearance of rhytides and sagging. In older patients who desire a more youthful appearance, various applications of dermal fillers, fat grafting, liposuction, and skin tightening techniques can help to mitigate these changes.

Conclusion

Improving facial aesthetics relies on an understanding of the norms of facial proportions. Although cosmetic interventions commonly are advertised or described based on a single anatomical unit, it is important to appreciate the relationships between facial structures. Most notably, clinicians should be mindful of facial ratios when considering the introduction of filler materials or implants. Augmentation procedures at the temples, zygomatic arch, jaw, chin, and lips all have the possibility to alter facial ratios. Changes should therefore be considered in the context of improving overall facial harmony, with the clinician remaining cognizant of the ideal vertical and horizontal divisions of the face. Understanding such concepts and communicating them to patients can help in appropriately addressing all target areas, thereby leading to greater patient satisfaction.

- Milutinovic J, Zelic K, Nedeljkovic N. Evaluation of facial beauty using anthropometric proportions. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:428250. doi:10.1155/2014/428250.

- Farkas LG, Hreczko TA, Kolar JC, et al. Vertical and horizontal proportions of the face in young-adult North-American Caucasians: revision of neoclassical canons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:328-338.

- Porter JP. The average African American male face: an anthropometric analysis. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6:78-81.

- Porter JP, Olson KL. Anthropometric facial analysis of the African American woman. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:191-197.

- Mommaerts MY, Moerenhout BA. Ideal proportions in full face front view, contemporary versus antique. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39:107-110.

- Vegter F, Hage JJ. Clinical anthropometry and canons of the face in historical perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:1090-1096.

- Wang D, Qian G, Zhang M, et al. Differences in horizontal, neoclassical facial canons in Chinese (Han) and North American Caucasian populations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21:265-269.

- Farkas LG, Forrest CR, Litsas L. Revision of neoclassical facial canons in young adult Afro-Americans. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000;24:179-184.

- Coleman GG, Lindauer SJ, Tüfekçi E, et al. Influence of chin prominence on esthetic lip profile preferences. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:36-42.

- Popenko NA, Tripathi PB, Devcic Z, et al. A quantitative approach to determining the ideal female lip aesthetic and its effect on facial attractiveness. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19:261-267.

- Penna V, Fricke A, Iblher N, et al. The attractive lip: a photomorphometric analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:920-929.

- Prokopakis EP, Vlastos IM, Picavet VA, et al. The golden ratio in facial symmetry. Rhinology. 2013;51:18-21.

- Swift A, Remington K. BeautiPHIcationTM: a global approach to facial beauty. Clin Plast Surg. 2011;38:247-277.

- Marquardt SR. Dr. Stephen R. Marquardt on the Golden Decagon and human facial beauty. interview by Dr. Gottlieb. J Clin Orthod. 2002;36:339-347.

- Veerala G, Gandikota CS, Yadagiri PK, et al. Marquardt’s facial Golden Decagon mask and its fitness with South Indian facial traits. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC49-ZC52.

- Holland E. Marquardt’s Phi mask: pitfalls of relying on fashion models and the golden ratio to describe a beautiful face. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:200-208.

- Alam MK, Mohd Noor NF, Basri R, et al. Multiracial facial golden ratio and evaluation of facial appearance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142914.

- Kim YH. Easy facial analysis using the facial golden mask. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:643-649.

- Bashour M. An objective system for measuring facial attractiveness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:757-774; discussion 775-776.

- Bartlett SP, Grossman R, Whitaker LA. Age-related changes of the craniofacial skeleton: an anthropometric and histologic analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:592-600.

- Donofrio LM. Fat distribution: a morphologic study of the aging face. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1107-1112.

Several concepts of ideal aesthetic measurements can be traced back to ancient Greek and European Renaissance art. In examining canons of beauty, these classical ideals often are compared to modern-day standards, allowing clinicians to delineate the parameters of an attractive facial appearance and facilitate the planning of cosmetic procedures.

Given the growing number of available cosmetic interventions, dermatologists have a powerful ability to modify facial proportions; however, changes to individual structures should be made with a mindful approach to improving overall facial harmony. This article reviews the established parameters of facial beauty to assist the clinician in enhancing cosmetic outcomes.

Canons of Facial Aesthetics

Horizontal Thirds

In his writings on human anatomy, Leonardo da Vinci described dividing the face into equal thirds (Figure 1). The upper third measures from the trichion (the midline point of the normal hairline) to the glabella (the smooth prominence between the eyebrows). The middle third measures from the glabella to the subnasale (the midline point where the nasal septum meets the upper lip). The lower third measures from the subnasale to the menton (the most inferior point of the chin).1

Although the validity of the canon is intended to apply across race and gender, these proportions may vary by ethnicity (Table). In white individuals, the middle third of the face tends to be shorter than the upper and lower thirds.2 This same relationship has been observed in black males.3 In Chinese females, the upper third commonly is shorter than the middle and lower thirds, correlating with a less prominent forehead. In contrast, black females tend to have a relatively longer upper third.4

The relationship between modern perceptions of attractiveness and the neoclassical norm of equal thirds remains a topic of interest. Milutinovic et al1 examined facial thirds in white female celebrities from beauty and fashion magazines and compared them to a group of anonymous white females from the general population. The group of anonymous females showed statistically significant (P<.05) differences between the sizes of the 3 facial segments, whereas the group of celebrity faces demonstrated uniformity between the facial thirds.1

The lower face can itself be divided into thirds, with the upper third measured from the subnasale to the stomion (the midline point of the oral fissure when the lips are closed), and the lower two-thirds measured from the stomion to the menton (Figure 1). Mommaerts and Moerenhout5 examined photographs of 105 attractive celebrity faces and compared their proportions to those of classical sculptures of gods and goddesses (antique faces). The authors identified an upper one-third to lower two-thirds ratio of 69.8% in celebrity females and 69.1% in celebrity males; these ratios were not significantly different from the 72.4% seen in antique females and 73.1% in antique males. The authors concluded that a 30% upper lip to 70% lower lip-chin proportion may be the most appropriate to describe contemporary standards.5

Vertical Fifths

In the vertical dimension, the neoclassical canon of facial proportions divides the face into equal fifths (Figure 2).6 The 2 most lateral fifths are measured from the lateral helix of each ear to the exocanthus of each eye. The eye fissure lengths (measured between the endocanthion and exocanthion of each eye) represent one-fifth. The middle fifth is measured between the medial canthi of both eyes (endocanthion to endocanthion). This distance is equal to the width of the nose, as measured between both alae. Finally, the width of the mouth represents 1.5-times the width of the nose. These ratios of the vertical fifths apply to both males and females.6

Anthropometric studies have examined deviations from the neoclassical canon according to ethnicity. Wang et al7 compared the measurements of North American white and Han Chinese patients to these standards. White patients demonstrated a greater ratio of mouth width to nose width relative to the canon. In contrast, Han Chinese patients demonstrated a relatively wider nose and narrower mouth.7

In black individuals, it has been observed that the dimensions of most facial segments correspond to the neoclassical standards; however, nose width is relatively wider in black individuals relative to the canon as well as relative to white individuals.8

Milutinovic et al1 also compared vertical fifths between white celebrities and anonymous females. In the anonymous female group, statistically significant (P<.05) variations were found between the sizes of the different facial components. In contrast, the celebrity female group showed balance between the widths of vertical fifths.1

Lips

In the lower facial third, the lips represent a key element of attractiveness. Recently, lip augmentation, aimed at creating fuller and plumper lips, has dominated the popular culture and social media landscape.9 Although the aesthetic ideal of lips continues to evolve over time, recent studies have aimed at quantifying modern notions of attractive lip appearance.

Popenko et al10 examined lip measurements using computer-generated images of white women with different variations of lip sizes and lower face proportions. Computer-generated faces were graded on attractiveness by more than 400 individuals from focus groups. An upper lip to lower lip ratio of 1:2 was judged to be the most attractive, while a ratio of 2:1 was judged to be the least attractive. Results also showed that the surface area of the most attractive lips comprised roughly 10% of the lower third of the face.10

Penna et al11 analyzed various parameters of the lips and lower facial third using photographs of 176 white males and females that were judged on attractiveness by 250 volunteer evaluators. Faces were graded on a scale from 1 (absolutely attractive) to 7 (absolutely unattractive). Attractive males and females (grades 1 and 2) both demonstrated an average ratio of upper vermilion height to nose-mouth distance (measured from the subnasalae to the lower edge of the upper vermilion border) of 0.28, which was significantly greater than the average ratio observed in less attractive individuals (grades 6 or 7)(P<.05). In addition, attractive males and females demonstrated a ratio of upper vermilion height to nose-chin distance (measured from the subnasalae to the menton) of 0.09, which again was larger than the average ratio seen in less attractive individuals. Figure 3 demonstrates an aesthetic ideal of the lips derived from these 2 studies, though consideration should be given to the fact that these studies were based in white populations.

Golden Ratio

The golden ratio, also known as Phi, can be observed in nature, art, and architecture. Approximately equal to 1.618, the golden ratio also has been identified as a possible marker of beauty in the human face and has garnered attention in the lay press. The ratio has been applied to several proportions and structures in the face, such as the ratio of mouth width to nose width or the ratio of tooth height to tooth width, with investigation providing varying levels of validation about whether these ratios truly correlate with perceptions of beauty.12 Swift and Remington13 advocated for application of the golden ratio toward a comprehensive set of facial proportions. Marquardt14 used the golden ratio to create a 3-dimensional representation of an idealized face, known as the golden decagon mask. Although the golden ratio and the golden decagon mask have been proposed as analytic tools, their utility in clinical practice may be limited. Firstly, due to its popularity in the lay press, the golden ratio has been inconsistently applied to a wide range of facial ratios, which may undermine confidence in its representation as truth rather than coincidence. Secondly, although some authors have found validity of the golden decagon mask in representing unified ratios of attractiveness, others have asserted that it characterizes a masculinized white female and fails to account for ethnic differences.15-19

Age-Related Changes

In addition to the facial proportions guided by genetics, several changes occur with increased age. Over the course of a lifetime, predictable patterns emerge in the dimensions of the skin, soft tissue, and bone. These alterations in structural proportions may ultimately lead to an unevenness in facial aesthetics.

In skeletal structure, gradual bone resorption and expansion causes a reduction in facial height as well as an increase in facial width and depth.20 Fat atrophy and hypertrophy affect soft tissue proportions, visualized as hollowing at the temples, cheeks, and around the eyes, along with fullness in the submental region and jowls.21 Finally, decreases in skin elasticity and collagen exacerbate the appearance of rhytides and sagging. In older patients who desire a more youthful appearance, various applications of dermal fillers, fat grafting, liposuction, and skin tightening techniques can help to mitigate these changes.

Conclusion

Improving facial aesthetics relies on an understanding of the norms of facial proportions. Although cosmetic interventions commonly are advertised or described based on a single anatomical unit, it is important to appreciate the relationships between facial structures. Most notably, clinicians should be mindful of facial ratios when considering the introduction of filler materials or implants. Augmentation procedures at the temples, zygomatic arch, jaw, chin, and lips all have the possibility to alter facial ratios. Changes should therefore be considered in the context of improving overall facial harmony, with the clinician remaining cognizant of the ideal vertical and horizontal divisions of the face. Understanding such concepts and communicating them to patients can help in appropriately addressing all target areas, thereby leading to greater patient satisfaction.

Several concepts of ideal aesthetic measurements can be traced back to ancient Greek and European Renaissance art. In examining canons of beauty, these classical ideals often are compared to modern-day standards, allowing clinicians to delineate the parameters of an attractive facial appearance and facilitate the planning of cosmetic procedures.

Given the growing number of available cosmetic interventions, dermatologists have a powerful ability to modify facial proportions; however, changes to individual structures should be made with a mindful approach to improving overall facial harmony. This article reviews the established parameters of facial beauty to assist the clinician in enhancing cosmetic outcomes.

Canons of Facial Aesthetics

Horizontal Thirds

In his writings on human anatomy, Leonardo da Vinci described dividing the face into equal thirds (Figure 1). The upper third measures from the trichion (the midline point of the normal hairline) to the glabella (the smooth prominence between the eyebrows). The middle third measures from the glabella to the subnasale (the midline point where the nasal septum meets the upper lip). The lower third measures from the subnasale to the menton (the most inferior point of the chin).1

Although the validity of the canon is intended to apply across race and gender, these proportions may vary by ethnicity (Table). In white individuals, the middle third of the face tends to be shorter than the upper and lower thirds.2 This same relationship has been observed in black males.3 In Chinese females, the upper third commonly is shorter than the middle and lower thirds, correlating with a less prominent forehead. In contrast, black females tend to have a relatively longer upper third.4

The relationship between modern perceptions of attractiveness and the neoclassical norm of equal thirds remains a topic of interest. Milutinovic et al1 examined facial thirds in white female celebrities from beauty and fashion magazines and compared them to a group of anonymous white females from the general population. The group of anonymous females showed statistically significant (P<.05) differences between the sizes of the 3 facial segments, whereas the group of celebrity faces demonstrated uniformity between the facial thirds.1

The lower face can itself be divided into thirds, with the upper third measured from the subnasale to the stomion (the midline point of the oral fissure when the lips are closed), and the lower two-thirds measured from the stomion to the menton (Figure 1). Mommaerts and Moerenhout5 examined photographs of 105 attractive celebrity faces and compared their proportions to those of classical sculptures of gods and goddesses (antique faces). The authors identified an upper one-third to lower two-thirds ratio of 69.8% in celebrity females and 69.1% in celebrity males; these ratios were not significantly different from the 72.4% seen in antique females and 73.1% in antique males. The authors concluded that a 30% upper lip to 70% lower lip-chin proportion may be the most appropriate to describe contemporary standards.5

Vertical Fifths

In the vertical dimension, the neoclassical canon of facial proportions divides the face into equal fifths (Figure 2).6 The 2 most lateral fifths are measured from the lateral helix of each ear to the exocanthus of each eye. The eye fissure lengths (measured between the endocanthion and exocanthion of each eye) represent one-fifth. The middle fifth is measured between the medial canthi of both eyes (endocanthion to endocanthion). This distance is equal to the width of the nose, as measured between both alae. Finally, the width of the mouth represents 1.5-times the width of the nose. These ratios of the vertical fifths apply to both males and females.6

Anthropometric studies have examined deviations from the neoclassical canon according to ethnicity. Wang et al7 compared the measurements of North American white and Han Chinese patients to these standards. White patients demonstrated a greater ratio of mouth width to nose width relative to the canon. In contrast, Han Chinese patients demonstrated a relatively wider nose and narrower mouth.7

In black individuals, it has been observed that the dimensions of most facial segments correspond to the neoclassical standards; however, nose width is relatively wider in black individuals relative to the canon as well as relative to white individuals.8

Milutinovic et al1 also compared vertical fifths between white celebrities and anonymous females. In the anonymous female group, statistically significant (P<.05) variations were found between the sizes of the different facial components. In contrast, the celebrity female group showed balance between the widths of vertical fifths.1

Lips

In the lower facial third, the lips represent a key element of attractiveness. Recently, lip augmentation, aimed at creating fuller and plumper lips, has dominated the popular culture and social media landscape.9 Although the aesthetic ideal of lips continues to evolve over time, recent studies have aimed at quantifying modern notions of attractive lip appearance.

Popenko et al10 examined lip measurements using computer-generated images of white women with different variations of lip sizes and lower face proportions. Computer-generated faces were graded on attractiveness by more than 400 individuals from focus groups. An upper lip to lower lip ratio of 1:2 was judged to be the most attractive, while a ratio of 2:1 was judged to be the least attractive. Results also showed that the surface area of the most attractive lips comprised roughly 10% of the lower third of the face.10

Penna et al11 analyzed various parameters of the lips and lower facial third using photographs of 176 white males and females that were judged on attractiveness by 250 volunteer evaluators. Faces were graded on a scale from 1 (absolutely attractive) to 7 (absolutely unattractive). Attractive males and females (grades 1 and 2) both demonstrated an average ratio of upper vermilion height to nose-mouth distance (measured from the subnasalae to the lower edge of the upper vermilion border) of 0.28, which was significantly greater than the average ratio observed in less attractive individuals (grades 6 or 7)(P<.05). In addition, attractive males and females demonstrated a ratio of upper vermilion height to nose-chin distance (measured from the subnasalae to the menton) of 0.09, which again was larger than the average ratio seen in less attractive individuals. Figure 3 demonstrates an aesthetic ideal of the lips derived from these 2 studies, though consideration should be given to the fact that these studies were based in white populations.

Golden Ratio

The golden ratio, also known as Phi, can be observed in nature, art, and architecture. Approximately equal to 1.618, the golden ratio also has been identified as a possible marker of beauty in the human face and has garnered attention in the lay press. The ratio has been applied to several proportions and structures in the face, such as the ratio of mouth width to nose width or the ratio of tooth height to tooth width, with investigation providing varying levels of validation about whether these ratios truly correlate with perceptions of beauty.12 Swift and Remington13 advocated for application of the golden ratio toward a comprehensive set of facial proportions. Marquardt14 used the golden ratio to create a 3-dimensional representation of an idealized face, known as the golden decagon mask. Although the golden ratio and the golden decagon mask have been proposed as analytic tools, their utility in clinical practice may be limited. Firstly, due to its popularity in the lay press, the golden ratio has been inconsistently applied to a wide range of facial ratios, which may undermine confidence in its representation as truth rather than coincidence. Secondly, although some authors have found validity of the golden decagon mask in representing unified ratios of attractiveness, others have asserted that it characterizes a masculinized white female and fails to account for ethnic differences.15-19

Age-Related Changes

In addition to the facial proportions guided by genetics, several changes occur with increased age. Over the course of a lifetime, predictable patterns emerge in the dimensions of the skin, soft tissue, and bone. These alterations in structural proportions may ultimately lead to an unevenness in facial aesthetics.

In skeletal structure, gradual bone resorption and expansion causes a reduction in facial height as well as an increase in facial width and depth.20 Fat atrophy and hypertrophy affect soft tissue proportions, visualized as hollowing at the temples, cheeks, and around the eyes, along with fullness in the submental region and jowls.21 Finally, decreases in skin elasticity and collagen exacerbate the appearance of rhytides and sagging. In older patients who desire a more youthful appearance, various applications of dermal fillers, fat grafting, liposuction, and skin tightening techniques can help to mitigate these changes.

Conclusion

Improving facial aesthetics relies on an understanding of the norms of facial proportions. Although cosmetic interventions commonly are advertised or described based on a single anatomical unit, it is important to appreciate the relationships between facial structures. Most notably, clinicians should be mindful of facial ratios when considering the introduction of filler materials or implants. Augmentation procedures at the temples, zygomatic arch, jaw, chin, and lips all have the possibility to alter facial ratios. Changes should therefore be considered in the context of improving overall facial harmony, with the clinician remaining cognizant of the ideal vertical and horizontal divisions of the face. Understanding such concepts and communicating them to patients can help in appropriately addressing all target areas, thereby leading to greater patient satisfaction.

- Milutinovic J, Zelic K, Nedeljkovic N. Evaluation of facial beauty using anthropometric proportions. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:428250. doi:10.1155/2014/428250.

- Farkas LG, Hreczko TA, Kolar JC, et al. Vertical and horizontal proportions of the face in young-adult North-American Caucasians: revision of neoclassical canons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:328-338.

- Porter JP. The average African American male face: an anthropometric analysis. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6:78-81.

- Porter JP, Olson KL. Anthropometric facial analysis of the African American woman. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:191-197.

- Mommaerts MY, Moerenhout BA. Ideal proportions in full face front view, contemporary versus antique. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39:107-110.

- Vegter F, Hage JJ. Clinical anthropometry and canons of the face in historical perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:1090-1096.

- Wang D, Qian G, Zhang M, et al. Differences in horizontal, neoclassical facial canons in Chinese (Han) and North American Caucasian populations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21:265-269.

- Farkas LG, Forrest CR, Litsas L. Revision of neoclassical facial canons in young adult Afro-Americans. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000;24:179-184.

- Coleman GG, Lindauer SJ, Tüfekçi E, et al. Influence of chin prominence on esthetic lip profile preferences. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:36-42.

- Popenko NA, Tripathi PB, Devcic Z, et al. A quantitative approach to determining the ideal female lip aesthetic and its effect on facial attractiveness. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19:261-267.

- Penna V, Fricke A, Iblher N, et al. The attractive lip: a photomorphometric analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:920-929.

- Prokopakis EP, Vlastos IM, Picavet VA, et al. The golden ratio in facial symmetry. Rhinology. 2013;51:18-21.

- Swift A, Remington K. BeautiPHIcationTM: a global approach to facial beauty. Clin Plast Surg. 2011;38:247-277.

- Marquardt SR. Dr. Stephen R. Marquardt on the Golden Decagon and human facial beauty. interview by Dr. Gottlieb. J Clin Orthod. 2002;36:339-347.

- Veerala G, Gandikota CS, Yadagiri PK, et al. Marquardt’s facial Golden Decagon mask and its fitness with South Indian facial traits. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC49-ZC52.

- Holland E. Marquardt’s Phi mask: pitfalls of relying on fashion models and the golden ratio to describe a beautiful face. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:200-208.

- Alam MK, Mohd Noor NF, Basri R, et al. Multiracial facial golden ratio and evaluation of facial appearance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142914.

- Kim YH. Easy facial analysis using the facial golden mask. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:643-649.

- Bashour M. An objective system for measuring facial attractiveness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:757-774; discussion 775-776.

- Bartlett SP, Grossman R, Whitaker LA. Age-related changes of the craniofacial skeleton: an anthropometric and histologic analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:592-600.

- Donofrio LM. Fat distribution: a morphologic study of the aging face. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1107-1112.

- Milutinovic J, Zelic K, Nedeljkovic N. Evaluation of facial beauty using anthropometric proportions. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:428250. doi:10.1155/2014/428250.

- Farkas LG, Hreczko TA, Kolar JC, et al. Vertical and horizontal proportions of the face in young-adult North-American Caucasians: revision of neoclassical canons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:328-338.

- Porter JP. The average African American male face: an anthropometric analysis. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6:78-81.

- Porter JP, Olson KL. Anthropometric facial analysis of the African American woman. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:191-197.

- Mommaerts MY, Moerenhout BA. Ideal proportions in full face front view, contemporary versus antique. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39:107-110.

- Vegter F, Hage JJ. Clinical anthropometry and canons of the face in historical perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:1090-1096.

- Wang D, Qian G, Zhang M, et al. Differences in horizontal, neoclassical facial canons in Chinese (Han) and North American Caucasian populations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21:265-269.

- Farkas LG, Forrest CR, Litsas L. Revision of neoclassical facial canons in young adult Afro-Americans. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000;24:179-184.

- Coleman GG, Lindauer SJ, Tüfekçi E, et al. Influence of chin prominence on esthetic lip profile preferences. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:36-42.

- Popenko NA, Tripathi PB, Devcic Z, et al. A quantitative approach to determining the ideal female lip aesthetic and its effect on facial attractiveness. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19:261-267.

- Penna V, Fricke A, Iblher N, et al. The attractive lip: a photomorphometric analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:920-929.

- Prokopakis EP, Vlastos IM, Picavet VA, et al. The golden ratio in facial symmetry. Rhinology. 2013;51:18-21.

- Swift A, Remington K. BeautiPHIcationTM: a global approach to facial beauty. Clin Plast Surg. 2011;38:247-277.

- Marquardt SR. Dr. Stephen R. Marquardt on the Golden Decagon and human facial beauty. interview by Dr. Gottlieb. J Clin Orthod. 2002;36:339-347.

- Veerala G, Gandikota CS, Yadagiri PK, et al. Marquardt’s facial Golden Decagon mask and its fitness with South Indian facial traits. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC49-ZC52.

- Holland E. Marquardt’s Phi mask: pitfalls of relying on fashion models and the golden ratio to describe a beautiful face. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:200-208.

- Alam MK, Mohd Noor NF, Basri R, et al. Multiracial facial golden ratio and evaluation of facial appearance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142914.

- Kim YH. Easy facial analysis using the facial golden mask. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:643-649.

- Bashour M. An objective system for measuring facial attractiveness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:757-774; discussion 775-776.

- Bartlett SP, Grossman R, Whitaker LA. Age-related changes of the craniofacial skeleton: an anthropometric and histologic analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:592-600.

- Donofrio LM. Fat distribution: a morphologic study of the aging face. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1107-1112.

Practice Points

- Canons of ideal facial dimensions have existed since antiquity and remain relevant in modern times.

- Horizontal and vertical anatomical ratios can provide a useful framework for cosmetic interventions.

- To maximize aesthetic results, alterations to individual cosmetic units should be made with thoughtful consideration of overall facial harmony.

Do Infants Fed Rice and Rice Products Have an Increased Risk for Skin Cancer?

To the Editor:

Rice and rice products, such as rice cereal and rice snacks, contain inorganic arsenic. Exposure to arsenicin utero and during early life may be associated with adverse fetal growth, adverse infant and child immune response, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Therefore, the World Health Organization, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the European Union, and the US Food and Drug Administration have suggested maximum arsenic ingestion recommendations for infants: 100 ng/g for inorganic arsenic in products geared toward infants. However, infants consuming only a few servings of rice products may exceed the weekly tolerable intake of arsenic.

Karagas et al1 obtained dietary data on 759 infants who were enrolled in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study from 2011 to 2014. They noted that 80% of the infants had been introduced to rice cereal during the first year. Additional data on diet and total urinary arsenic at 12 months was available for 129 infants: 32.6% of these infants were fed rice snacks. In addition, the total urinary arsenic concentration was higher among infants who ate rice cereal or rice snacks as compared to infants who did not eat rice or rice products.

Chronic arsenic exposure can result in patchy dark brown hyperpigmentation with scattered pale spots referred to as “raindrops on a dusty road.” The axilla, eyelids, groin, neck, nipples, and temples often are affected. However, the hyperpigmentation can extend across the chest, abdomen, and back in severe cases.

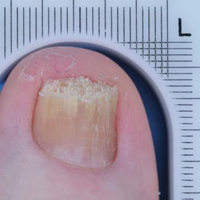

Horizontal white lines across the nails (Mees lines) may develop. Keratoses, often on the palms (arsenic keratoses), may appear; they persist and may progress to skin cancers. In addition, patients with arsenic exposure are more susceptible to developing nonmelanoma skin cancers.2

It is unknown if exposure to inorganic arsenic in infancy predisposes these individuals to skin cancer when they become adults. Long-term longitudinal follow-up of the participants in this study may provide additional insight. Perhaps infants should not receive rice cereals and rice snacks or their parents should more carefully monitor the amount of rice and rice products that they ingest.

- Karagas MR, Punshon T, Sayarath V, et al. Association of rice and rice-product consumption with arsenic exposure early in life. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:609-616.

- Mayer JE, Goldman RH. Arsenic and skin cancer in the USA: the current evidence regarding arsenic-contaminated drinking water. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55;e585-e591.

To the Editor:

Rice and rice products, such as rice cereal and rice snacks, contain inorganic arsenic. Exposure to arsenicin utero and during early life may be associated with adverse fetal growth, adverse infant and child immune response, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Therefore, the World Health Organization, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the European Union, and the US Food and Drug Administration have suggested maximum arsenic ingestion recommendations for infants: 100 ng/g for inorganic arsenic in products geared toward infants. However, infants consuming only a few servings of rice products may exceed the weekly tolerable intake of arsenic.

Karagas et al1 obtained dietary data on 759 infants who were enrolled in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study from 2011 to 2014. They noted that 80% of the infants had been introduced to rice cereal during the first year. Additional data on diet and total urinary arsenic at 12 months was available for 129 infants: 32.6% of these infants were fed rice snacks. In addition, the total urinary arsenic concentration was higher among infants who ate rice cereal or rice snacks as compared to infants who did not eat rice or rice products.

Chronic arsenic exposure can result in patchy dark brown hyperpigmentation with scattered pale spots referred to as “raindrops on a dusty road.” The axilla, eyelids, groin, neck, nipples, and temples often are affected. However, the hyperpigmentation can extend across the chest, abdomen, and back in severe cases.

Horizontal white lines across the nails (Mees lines) may develop. Keratoses, often on the palms (arsenic keratoses), may appear; they persist and may progress to skin cancers. In addition, patients with arsenic exposure are more susceptible to developing nonmelanoma skin cancers.2

It is unknown if exposure to inorganic arsenic in infancy predisposes these individuals to skin cancer when they become adults. Long-term longitudinal follow-up of the participants in this study may provide additional insight. Perhaps infants should not receive rice cereals and rice snacks or their parents should more carefully monitor the amount of rice and rice products that they ingest.

To the Editor:

Rice and rice products, such as rice cereal and rice snacks, contain inorganic arsenic. Exposure to arsenicin utero and during early life may be associated with adverse fetal growth, adverse infant and child immune response, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Therefore, the World Health Organization, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the European Union, and the US Food and Drug Administration have suggested maximum arsenic ingestion recommendations for infants: 100 ng/g for inorganic arsenic in products geared toward infants. However, infants consuming only a few servings of rice products may exceed the weekly tolerable intake of arsenic.

Karagas et al1 obtained dietary data on 759 infants who were enrolled in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study from 2011 to 2014. They noted that 80% of the infants had been introduced to rice cereal during the first year. Additional data on diet and total urinary arsenic at 12 months was available for 129 infants: 32.6% of these infants were fed rice snacks. In addition, the total urinary arsenic concentration was higher among infants who ate rice cereal or rice snacks as compared to infants who did not eat rice or rice products.

Chronic arsenic exposure can result in patchy dark brown hyperpigmentation with scattered pale spots referred to as “raindrops on a dusty road.” The axilla, eyelids, groin, neck, nipples, and temples often are affected. However, the hyperpigmentation can extend across the chest, abdomen, and back in severe cases.

Horizontal white lines across the nails (Mees lines) may develop. Keratoses, often on the palms (arsenic keratoses), may appear; they persist and may progress to skin cancers. In addition, patients with arsenic exposure are more susceptible to developing nonmelanoma skin cancers.2

It is unknown if exposure to inorganic arsenic in infancy predisposes these individuals to skin cancer when they become adults. Long-term longitudinal follow-up of the participants in this study may provide additional insight. Perhaps infants should not receive rice cereals and rice snacks or their parents should more carefully monitor the amount of rice and rice products that they ingest.

- Karagas MR, Punshon T, Sayarath V, et al. Association of rice and rice-product consumption with arsenic exposure early in life. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:609-616.

- Mayer JE, Goldman RH. Arsenic and skin cancer in the USA: the current evidence regarding arsenic-contaminated drinking water. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55;e585-e591.

- Karagas MR, Punshon T, Sayarath V, et al. Association of rice and rice-product consumption with arsenic exposure early in life. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:609-616.

- Mayer JE, Goldman RH. Arsenic and skin cancer in the USA: the current evidence regarding arsenic-contaminated drinking water. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55;e585-e591.

Biologic may bring relief for children and adults with XLH syndrome

DENVER – Two studies provide hope for a new treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), a genetic disorder that leads to low phosphorus levels, which can cause rickets in children and a host of bone and other problems in adulthood.

The studies evaluated the use of burosumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). FGF23 is a hormone that reduces serum levels of phosphorus and vitamin D through its effects on the kidney.

“For the first time, this establishes the efficacy of any treatment in adults with XLH,” said Karl L. Insogna, MD, professor of medicine (endocrinology), at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who presented the phase III study results during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. “Even in adults who have a lot of underlying disease burden, which is not likely to be completely reversed by this drug, you can address the underlying pathophysiology of the disease and show not only symptomatic improvement but also healing of fractures and pseudofractures,” he added.

XLH patients may be treated with calcitriol and phosphate, but this requires dosing 3-5 times a day, with side effects that can be onerous. “If you were dealing with a shot, you’d have 100% compliance and (fewer) side effects. It’s going to be a whole lot better,” he noted.

In the phase 3 adult trial, 134 patients were randomized to subcutaneous burosumab (at a dose of 1 mg/kg) or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. Among those treated with burosumab, 94.1% achieved serum phosphatase levels in the normal range, compared with 7.6% of those on placebo. Among patients taking burosumab, 36.9% of fractures and pseudofractures present at baseline had healed by the end of the study, compared with 9.9% of the fractures and pseudofractures in the placebo group (odds ratio, 7.76; P =.0001).

The two groups had similar safety profiles, with no differences in serum or urine calcium, serum intact parathyroid hormone, or nephrocalcinosis severity score.

In the phase 2 pediatric trial, 52 patients aged 5-12 years received subcutaneous burosumab every other week or once a month for 64 weeks. Although the patients had received vitamin D/phosphate therapy for an average of 7 years before enrollment, rickets was present at baseline (mean Thatcher Rickets Severity Score, 1.8). The dose of burosumab was titrated (maximum dose 2 mg/kg) to achieve age-appropriate fasting serum phosphate. All of the subjects achieved normal fasting serum phosphatase levels, but the values were more stable in the dose treated every other week.

The Thatcher RSS improved overall (–0.92; P less than .0001) in the group dosed every other week (–1.00; P less than .0001) and the group dosed monthly (–0.84; P less than .0001). These changes were more notable in patients with more severe rickets at baseline (RSS, 1.5 or higher), which had a change of –1.44 (P less than .0001).

Similar improvements were seen with the Radiographic Global Impression of Change (RGI-C). Among children with an RSS value of 1.5 or higher, substantial healing (an increase in RGI-C equal to or greater that 2) occurred in the group dosed every other week (82.4%) and the group dosed monthly (70.6%).

There was no evidence of hyperphosphatemia or hypercalcemia, and there were no clinically meaningful changes in urine calcium or serum intact parathyroid hormone levels.

The studies were funded by Ultragenyx and Kyowa Kirin International. Dr. Insogna reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – Two studies provide hope for a new treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), a genetic disorder that leads to low phosphorus levels, which can cause rickets in children and a host of bone and other problems in adulthood.

The studies evaluated the use of burosumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). FGF23 is a hormone that reduces serum levels of phosphorus and vitamin D through its effects on the kidney.

“For the first time, this establishes the efficacy of any treatment in adults with XLH,” said Karl L. Insogna, MD, professor of medicine (endocrinology), at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who presented the phase III study results during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. “Even in adults who have a lot of underlying disease burden, which is not likely to be completely reversed by this drug, you can address the underlying pathophysiology of the disease and show not only symptomatic improvement but also healing of fractures and pseudofractures,” he added.

XLH patients may be treated with calcitriol and phosphate, but this requires dosing 3-5 times a day, with side effects that can be onerous. “If you were dealing with a shot, you’d have 100% compliance and (fewer) side effects. It’s going to be a whole lot better,” he noted.

In the phase 3 adult trial, 134 patients were randomized to subcutaneous burosumab (at a dose of 1 mg/kg) or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. Among those treated with burosumab, 94.1% achieved serum phosphatase levels in the normal range, compared with 7.6% of those on placebo. Among patients taking burosumab, 36.9% of fractures and pseudofractures present at baseline had healed by the end of the study, compared with 9.9% of the fractures and pseudofractures in the placebo group (odds ratio, 7.76; P =.0001).

The two groups had similar safety profiles, with no differences in serum or urine calcium, serum intact parathyroid hormone, or nephrocalcinosis severity score.

In the phase 2 pediatric trial, 52 patients aged 5-12 years received subcutaneous burosumab every other week or once a month for 64 weeks. Although the patients had received vitamin D/phosphate therapy for an average of 7 years before enrollment, rickets was present at baseline (mean Thatcher Rickets Severity Score, 1.8). The dose of burosumab was titrated (maximum dose 2 mg/kg) to achieve age-appropriate fasting serum phosphate. All of the subjects achieved normal fasting serum phosphatase levels, but the values were more stable in the dose treated every other week.

The Thatcher RSS improved overall (–0.92; P less than .0001) in the group dosed every other week (–1.00; P less than .0001) and the group dosed monthly (–0.84; P less than .0001). These changes were more notable in patients with more severe rickets at baseline (RSS, 1.5 or higher), which had a change of –1.44 (P less than .0001).

Similar improvements were seen with the Radiographic Global Impression of Change (RGI-C). Among children with an RSS value of 1.5 or higher, substantial healing (an increase in RGI-C equal to or greater that 2) occurred in the group dosed every other week (82.4%) and the group dosed monthly (70.6%).

There was no evidence of hyperphosphatemia or hypercalcemia, and there were no clinically meaningful changes in urine calcium or serum intact parathyroid hormone levels.

The studies were funded by Ultragenyx and Kyowa Kirin International. Dr. Insogna reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – Two studies provide hope for a new treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), a genetic disorder that leads to low phosphorus levels, which can cause rickets in children and a host of bone and other problems in adulthood.

The studies evaluated the use of burosumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). FGF23 is a hormone that reduces serum levels of phosphorus and vitamin D through its effects on the kidney.

“For the first time, this establishes the efficacy of any treatment in adults with XLH,” said Karl L. Insogna, MD, professor of medicine (endocrinology), at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who presented the phase III study results during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. “Even in adults who have a lot of underlying disease burden, which is not likely to be completely reversed by this drug, you can address the underlying pathophysiology of the disease and show not only symptomatic improvement but also healing of fractures and pseudofractures,” he added.

XLH patients may be treated with calcitriol and phosphate, but this requires dosing 3-5 times a day, with side effects that can be onerous. “If you were dealing with a shot, you’d have 100% compliance and (fewer) side effects. It’s going to be a whole lot better,” he noted.

In the phase 3 adult trial, 134 patients were randomized to subcutaneous burosumab (at a dose of 1 mg/kg) or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. Among those treated with burosumab, 94.1% achieved serum phosphatase levels in the normal range, compared with 7.6% of those on placebo. Among patients taking burosumab, 36.9% of fractures and pseudofractures present at baseline had healed by the end of the study, compared with 9.9% of the fractures and pseudofractures in the placebo group (odds ratio, 7.76; P =.0001).

The two groups had similar safety profiles, with no differences in serum or urine calcium, serum intact parathyroid hormone, or nephrocalcinosis severity score.

In the phase 2 pediatric trial, 52 patients aged 5-12 years received subcutaneous burosumab every other week or once a month for 64 weeks. Although the patients had received vitamin D/phosphate therapy for an average of 7 years before enrollment, rickets was present at baseline (mean Thatcher Rickets Severity Score, 1.8). The dose of burosumab was titrated (maximum dose 2 mg/kg) to achieve age-appropriate fasting serum phosphate. All of the subjects achieved normal fasting serum phosphatase levels, but the values were more stable in the dose treated every other week.

The Thatcher RSS improved overall (–0.92; P less than .0001) in the group dosed every other week (–1.00; P less than .0001) and the group dosed monthly (–0.84; P less than .0001). These changes were more notable in patients with more severe rickets at baseline (RSS, 1.5 or higher), which had a change of –1.44 (P less than .0001).

Similar improvements were seen with the Radiographic Global Impression of Change (RGI-C). Among children with an RSS value of 1.5 or higher, substantial healing (an increase in RGI-C equal to or greater that 2) occurred in the group dosed every other week (82.4%) and the group dosed monthly (70.6%).

There was no evidence of hyperphosphatemia or hypercalcemia, and there were no clinically meaningful changes in urine calcium or serum intact parathyroid hormone levels.

The studies were funded by Ultragenyx and Kyowa Kirin International. Dr. Insogna reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ASBMR

Key clinical point: An investigational biologic targeting fibroblast growth factor 23 improved symptoms in both adults and children.

Major finding: Normal serum phosphatase levels were achieved in 94.1% of adults and in all children treated with burosumab

Data source: A prospective phase 2 trial in 52 children with XLH and a randomized, controlled phase 3 trial in 134 adults with XLH.

Disclosures: The studies were funded by Ultragenyx and Kyowa Kirin International. Dr. Insogna reported having no financial disclosures.

Clinical Trial Designs for Topical Antifungal Treatments of Onychomycosis and Implications on Clinical Practice

Onychomycosis is a fungal nail infection primarily caused by dermatophytes.1 If left untreated, the infection can cause nail destruction and deformities,1 resulting in pain and discomfort,2 impaired foot mobility,3 and an overall reduced quality of life.1 Onychomycosis is a chronic condition that requires long treatment periods due to the slow growth rates of toenails.1 To successfully cure the condition, fungal eradication must be achieved.

Prior to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of tavaborole and efinaconazole, ciclopirox was the only approved topical treatment for onychomycosis.4 The recent approval of tavaborole and efinaconazole has increased treatment options available to patients and has started to pave the way for future topical treatments. This article discusses the 3 approved topical treatments for onychomycosis and focuses on the design of the phase 3 clinical trials that led to their approval.

Topical Agents Used to Treat Onychomycosis

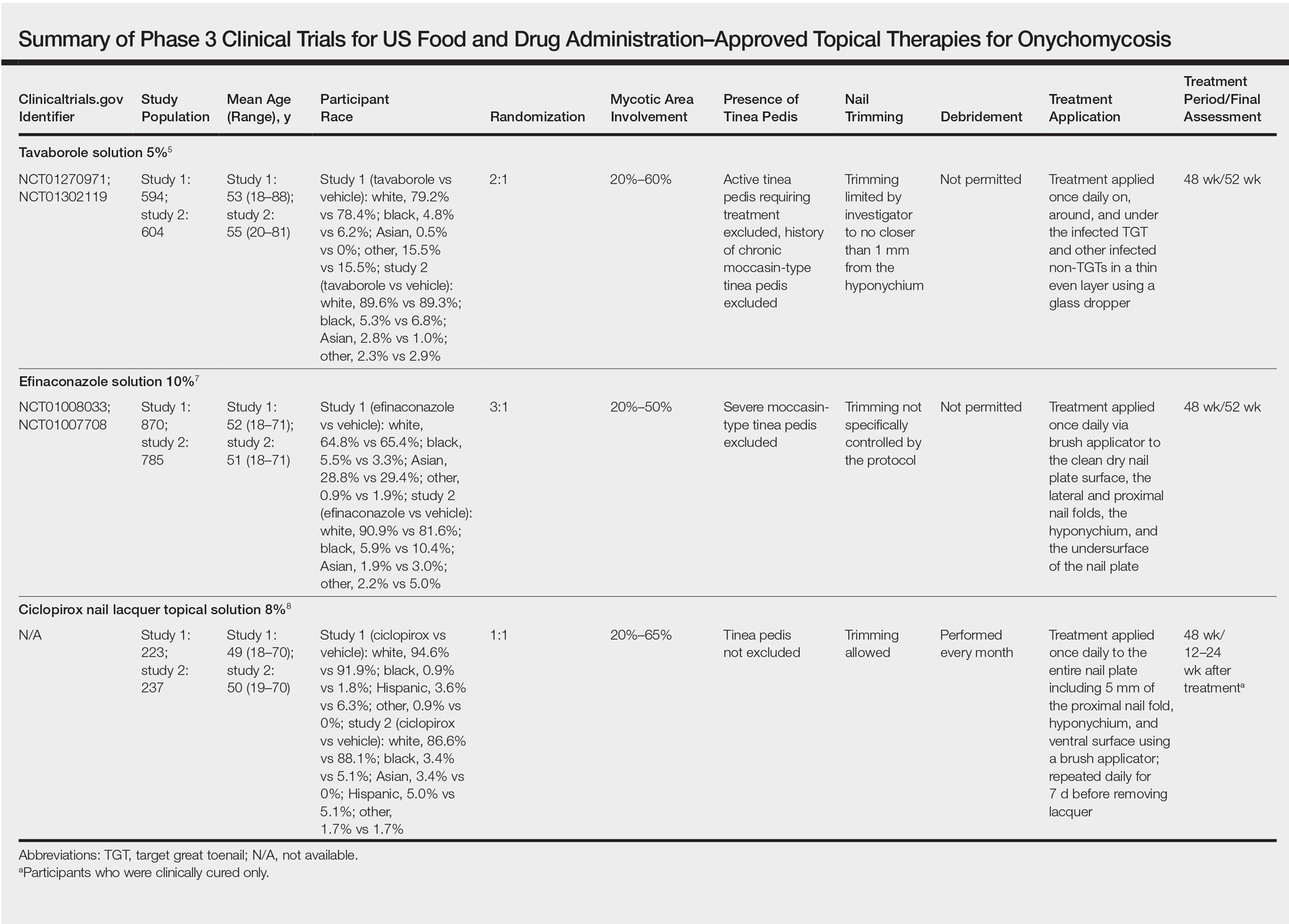

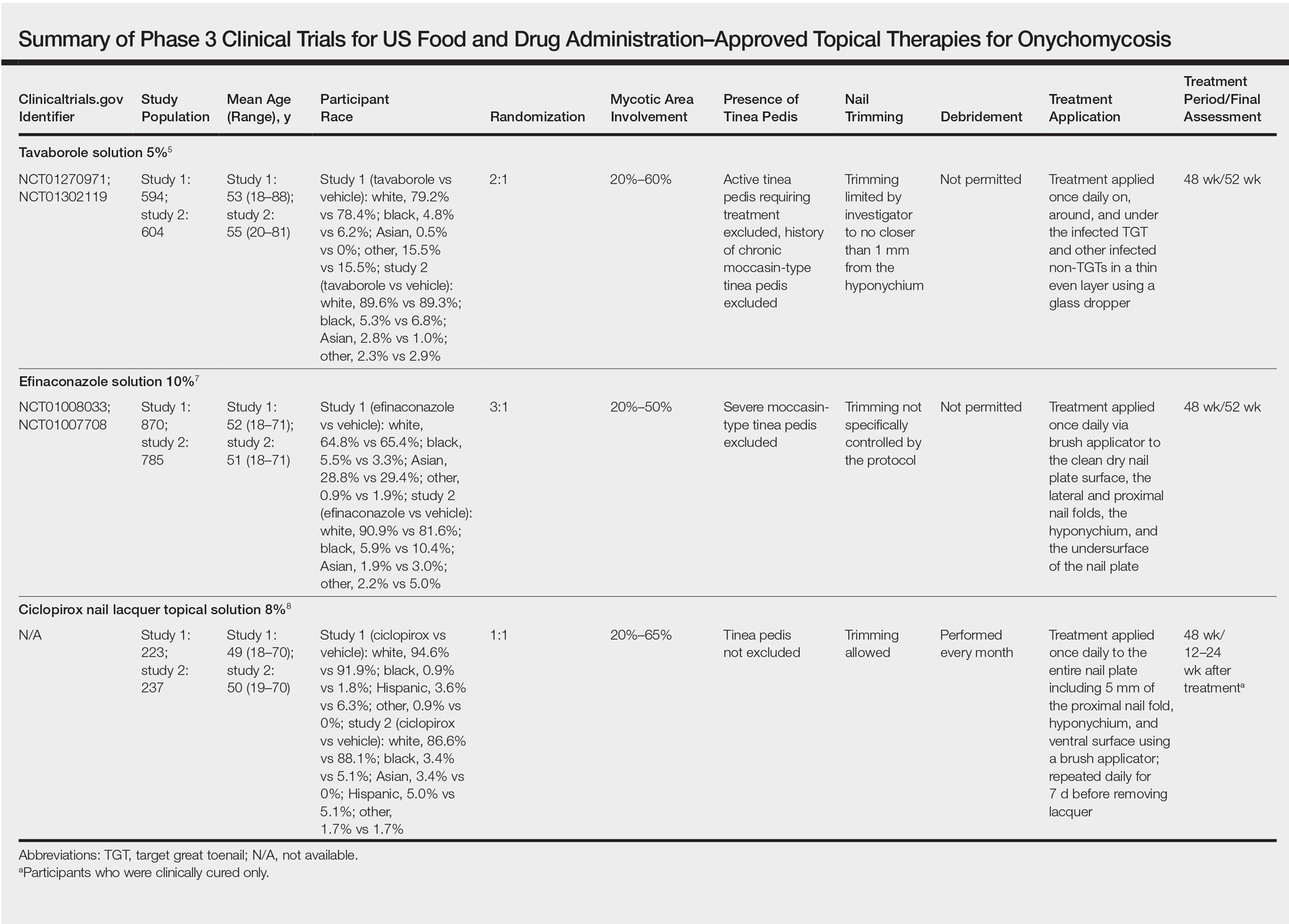

Tavaborole, efinaconazole, and ciclopirox have undergone extensive clinical investigation to receive FDA approval. Results from pivotal phase 3 studies establishing the efficacy and safety of each agent formed the basis for regulatory submission. Although it may seem intuitive to compare the relative performance of these agents based on their respective phase 3 clinical trial data, there are important differences in study methodology, conduct, and populations that prevent direct comparisons. The FDA provides limited guidance to the pharmaceutical industry on how to conduct clinical trials for potential onychomycosis treatments. Comparative efficacy and safety claims are limited based on cross-study comparisons. The details of the phase 3 trial designs are summarized in the Table.

Tavaborole

Tavaborole is a boron-based treatment with a novel mechanism of action.5 Tavaborole binds to the editing domain of leucyl–transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase via an integrated boron atom and inhibits fungal protein synthesis.6 Two identical randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 clinical trials evaluating tavaborole were performed.5 The first study (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT01270971) included 594 participants from27 sites in the United States and Mexico and was conducted between December 2010 and November 2012. The second study (NCT01302119) included 604 participants from 32 sites in the United States and Canada and was conducted between February 2011 and January 2013.

Eligible participants 18 years and older had distal subungual onychomycosis (DSO) of the toenails affecting 20% to 60% of 1 or more target great toenails (TGTs), tested positive for fungus using potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mounts and positive for Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes on fungal culture diagnostic tests, had distal TGT thickness of 3 mm or less, and had 3 mm or more of clear nail between the proximal nail fold and the most proximal visible mycotic border.5 Those with active tinea pedis requiring treatment or with a history of chronic moccasin-type tinea pedis were excluded. Participants were randomized to receive either tavaborole or vehicle (2:1). Treatments were applied once daily to all infected toenails for a total of 48 weeks, and nail debridement (defined as partial or complete removal of the toenail) was not permitted. Notably, controlled trimming of the nail was allowed to 1 mm of the leading nail edge. Regular assessments of each toenail for disease involvement, onycholysis, and subungual hyperkeratosis were made at screening, baseline, week 2, week 6, and every 6 weeks thereafter until week 52. Subungual TGT samples were taken at screening and every 12 weeks during the study for examination at a mycology laboratory, which performed KOH and fungal culture tests. A follow-up assessment was made at week 52.5

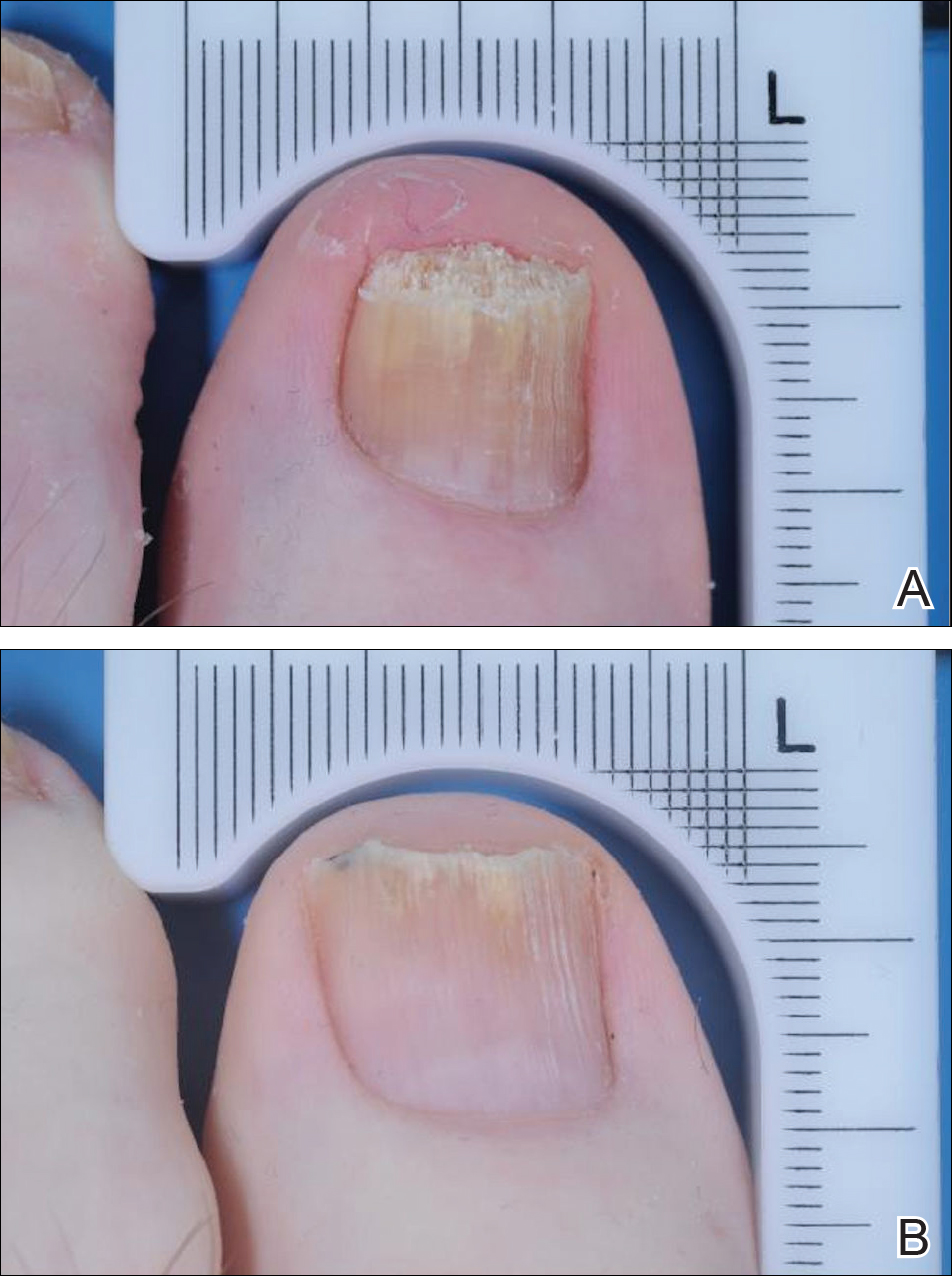

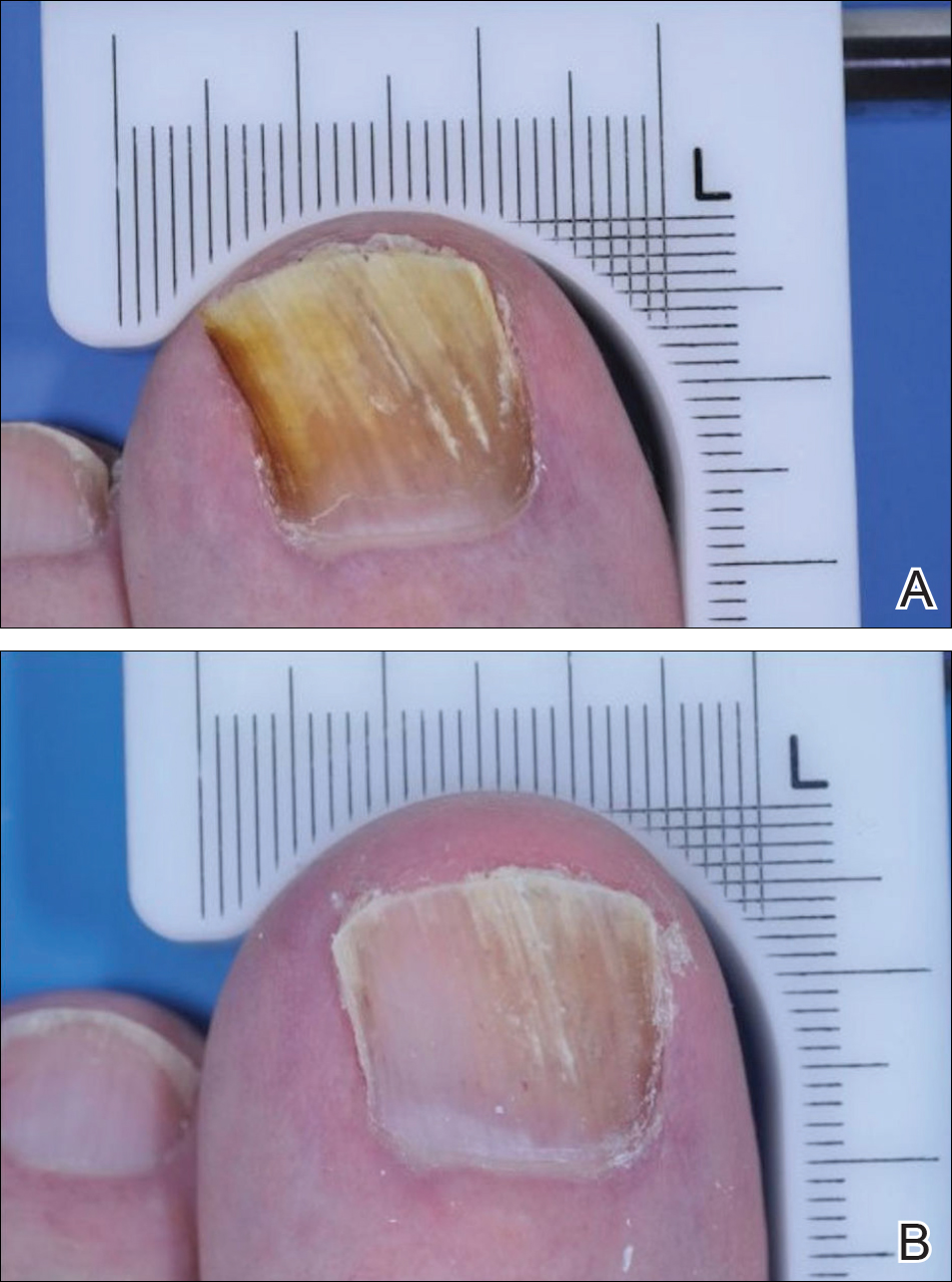

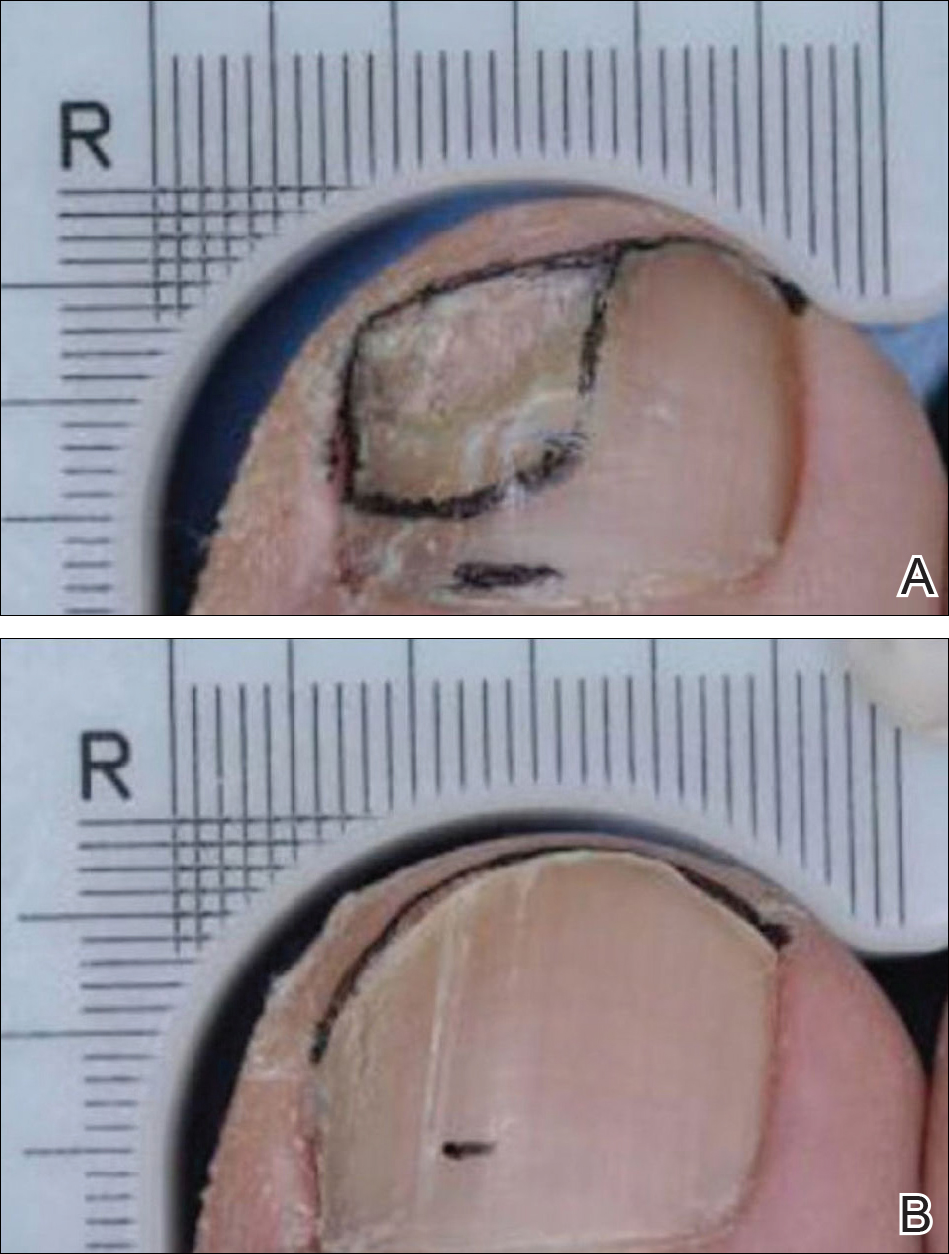

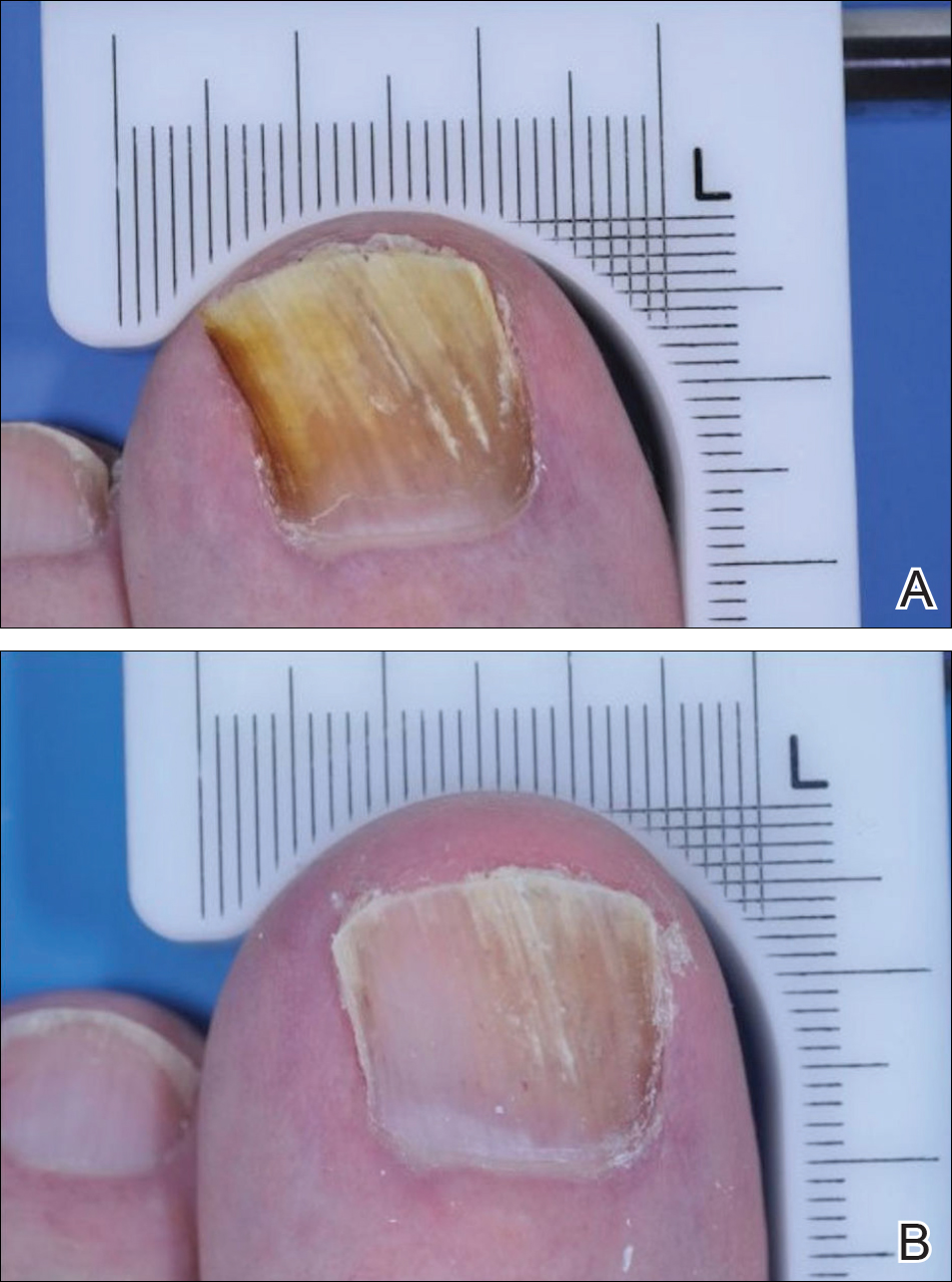

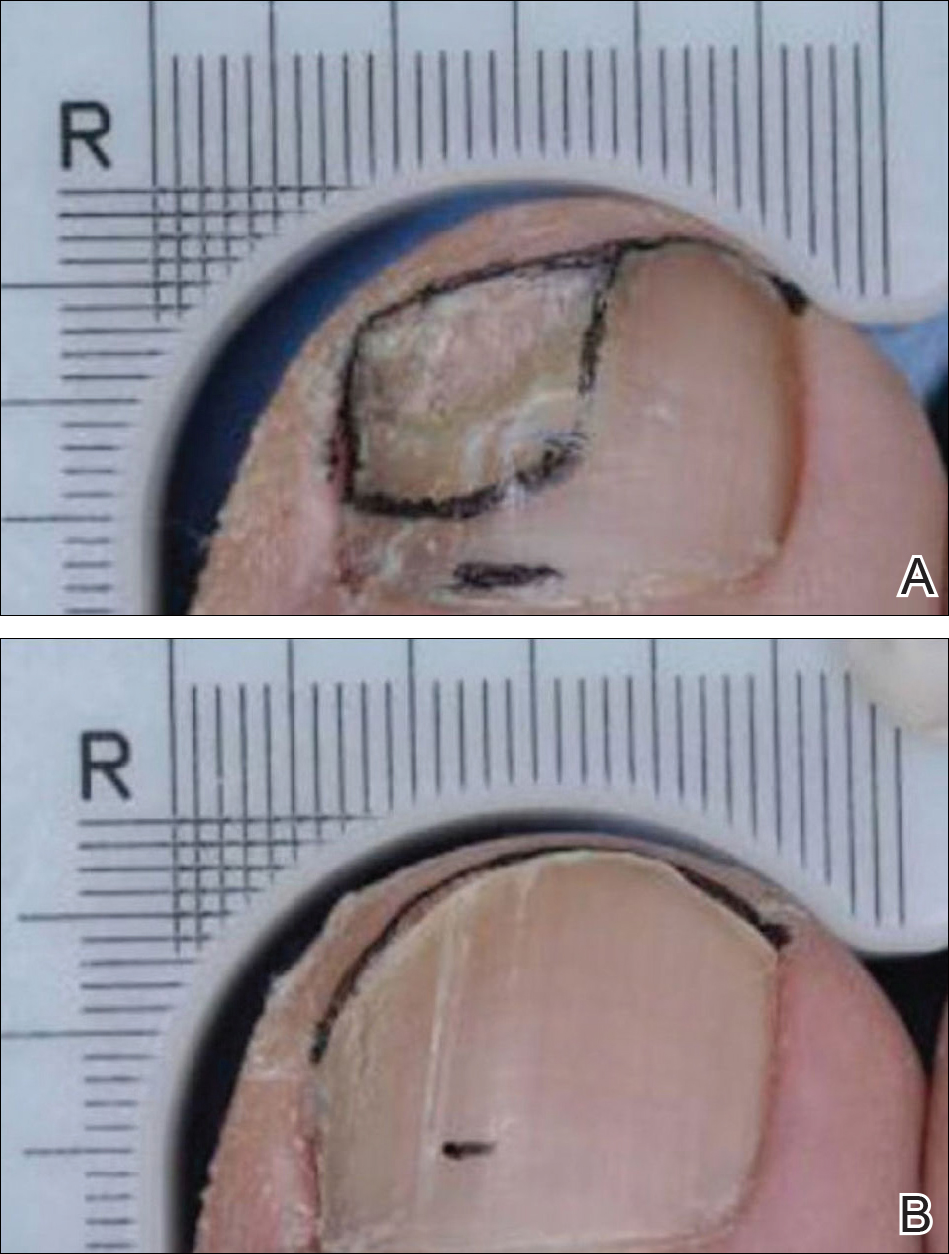

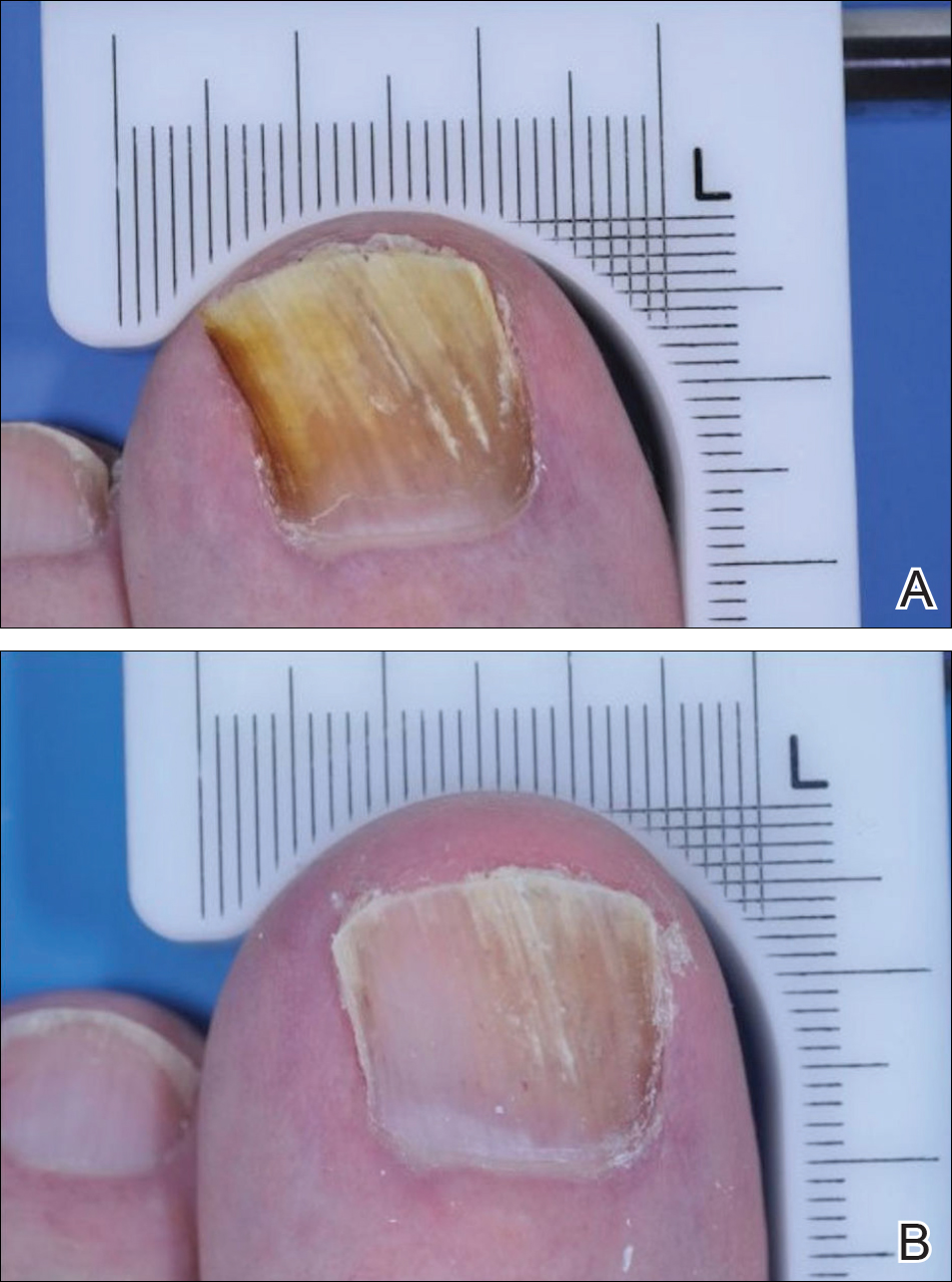

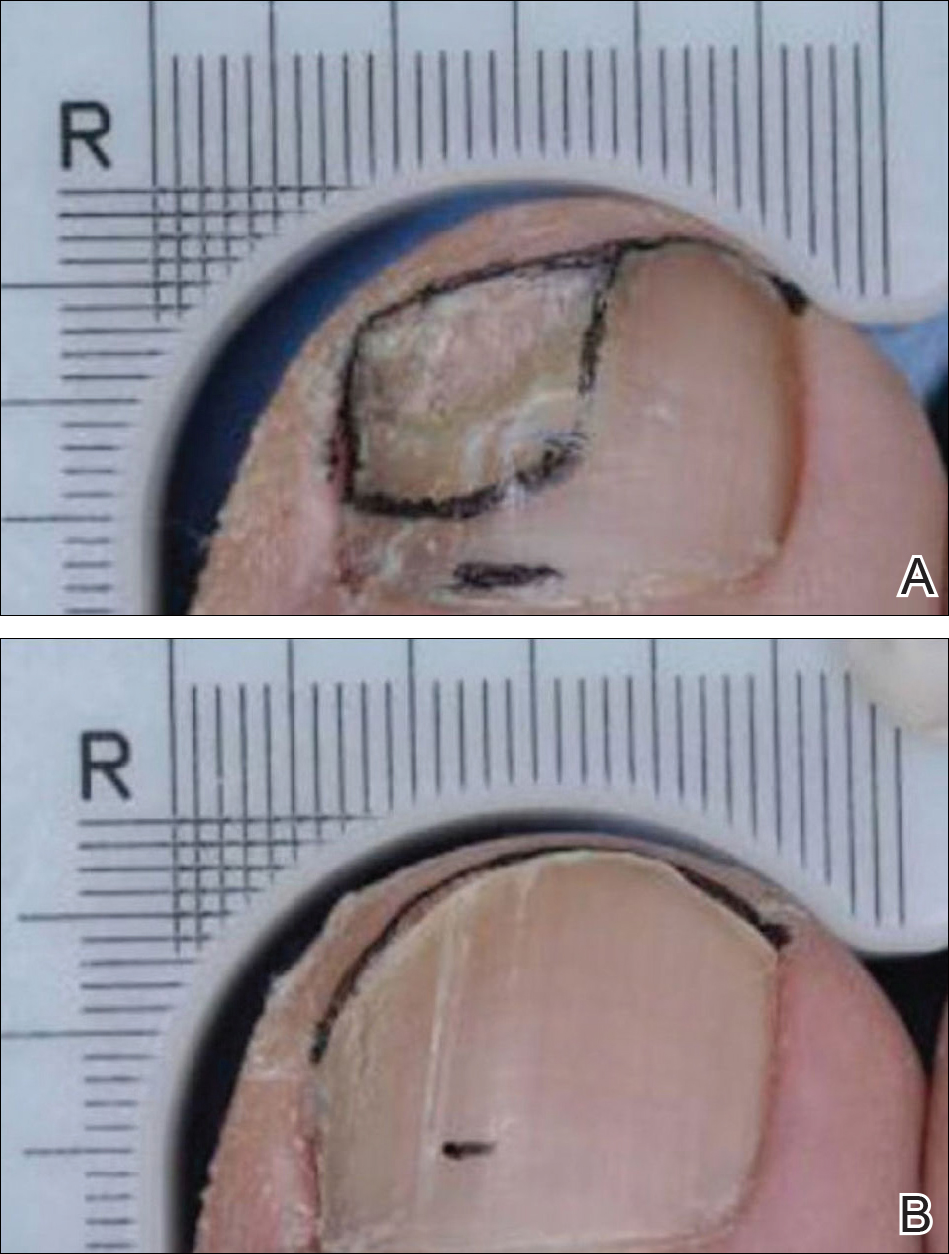

The primary end point was complete cure of the TGT at week 52, with secondary end points of completely or almost clear TGT nail (≤10% dystrophic nail), completely or almost clear TGT nail (≤10% dystrophic nail) plus negative mycology, and negative mycology of TGT.5 Examples of TGTs in participants who achieved complete cure and almost clear nails with negative mycology before and after treatment with tavaborole are shown in Figure 1. An example of a patient considered to have treatment failure is shown in Figure 2. This patient showed marked improvement in nail appearance and had a negative culture result but had a positive KOH test, which demonstrates the stringency in which topical agents are judged in onychomycosis trials.5

Efinaconazole

Efinaconazole is a topical triazole antifungal specifically indicated to treat onychomycosis. Two identical randomized, vehicle-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trials were performed to assess the safety and efficacy of efinaconazole solution 10%.7 The first study (NCT01008033) involved 870 participants and was conducted at a total of 74 sites in Japan (33 sites), Canada (7 sites), and the United States (34 sites) between December 2009 and September 2011. The second study (NCT01007708) had 785 participants and was conducted at 44 sites in Canada (8 sites) and the United States (36 sites) between December 2009 and October 2011.

Participants aged 18 to 70 years with a clinical diagnosis of DSO affecting 1 or more TGT were eligible to participate.7 Other eligibility criteria included an uninfected toenail length 3 mm or more from the proximal nail fold, a maximum toenail thickness of 3 mm, positive KOH wet mounts, and positive dermatophyte or mixed dermatophyte/candida cultures. Dermatophytes included T rubrum and T mentagrophytes. Those with severe moccasin-type tinea pedis were excluded. Participants were randomized to receive efinaconazole or vehicle (3:1). Once-daily treatments were self-applied to nails for 48 weeks. Clinical assessments were made at baseline and every 12 weeks until week 48, with a follow-up assessment at week 52. No nail trimming protocol was provided.7

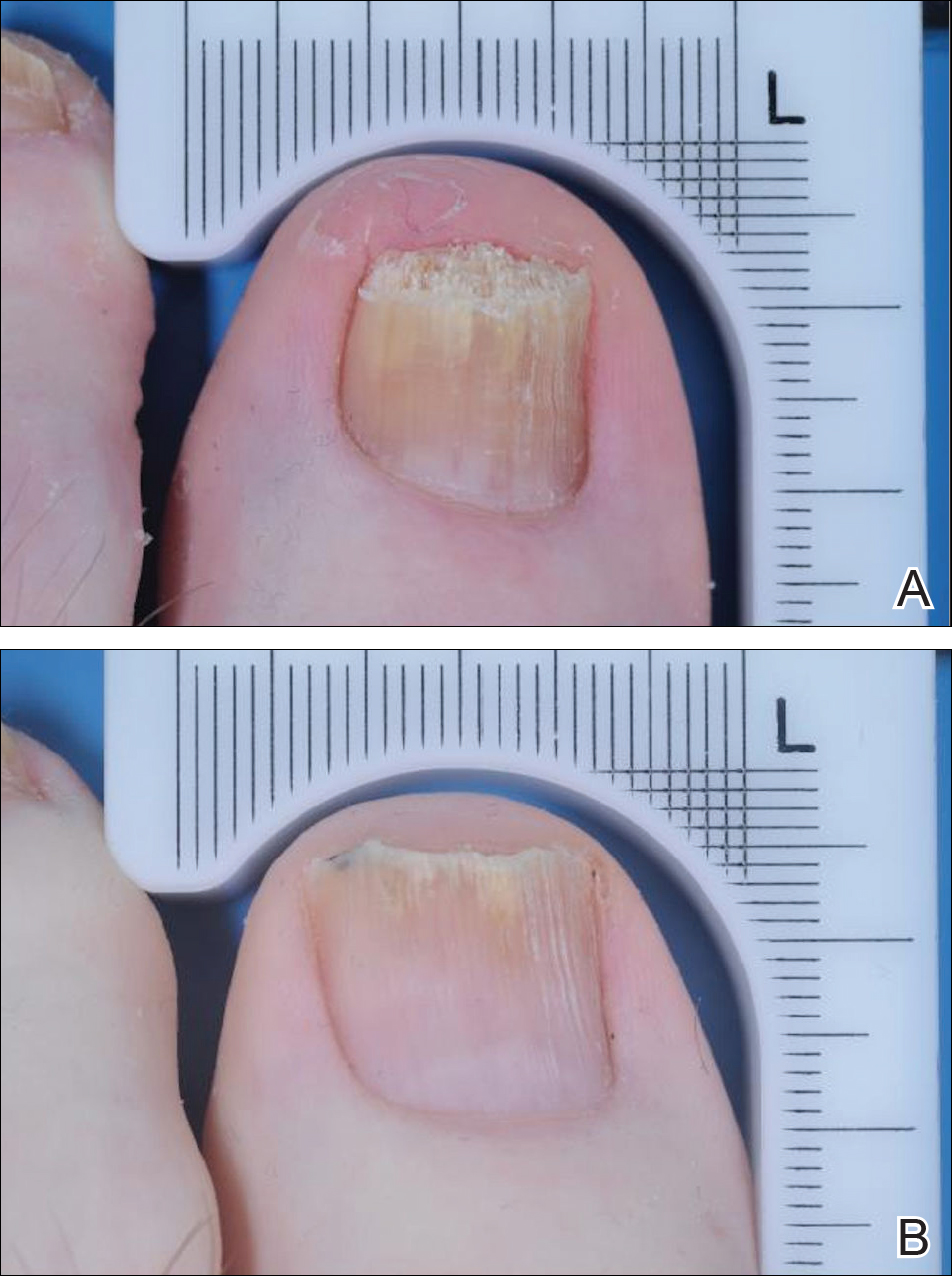

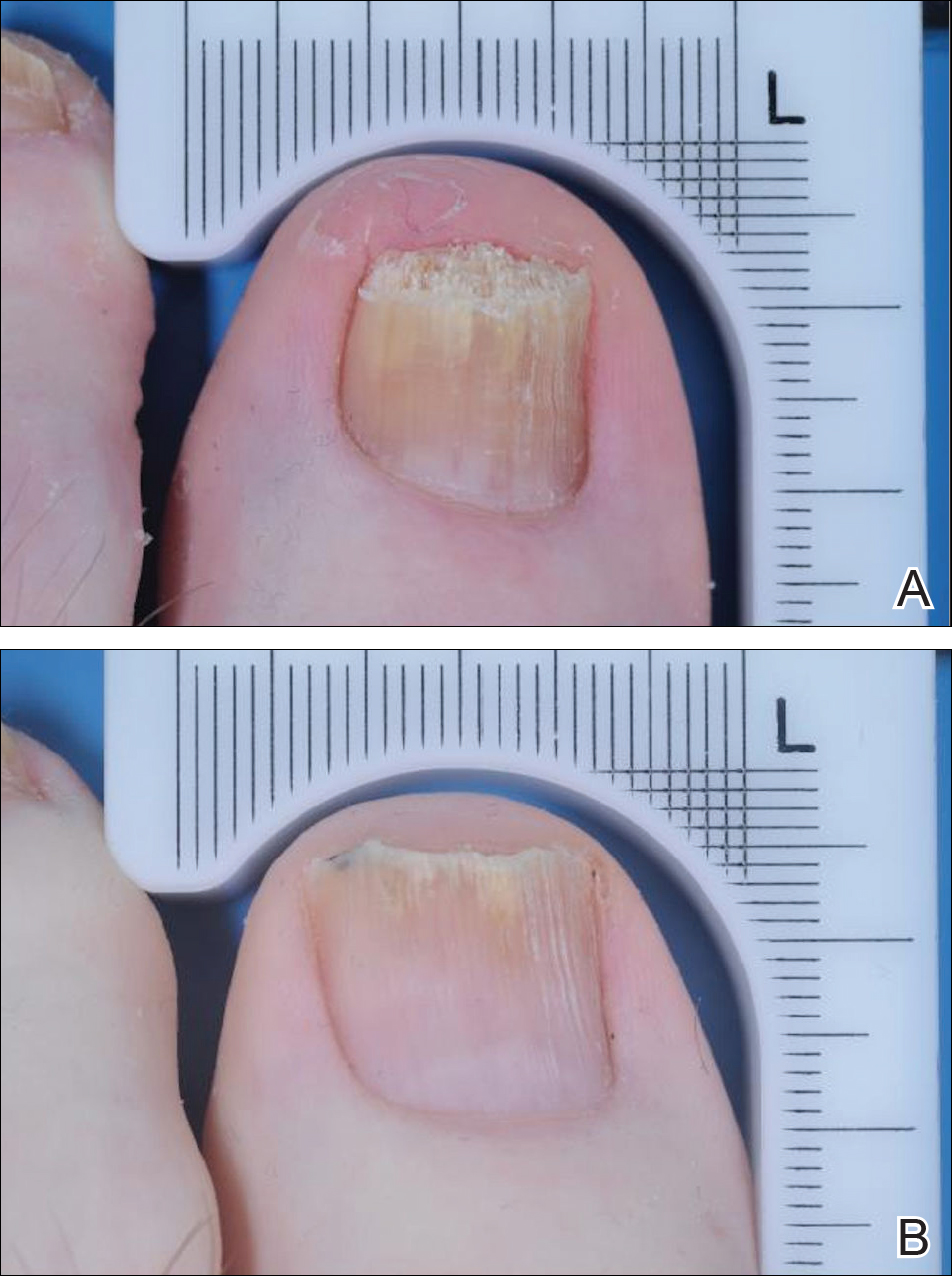

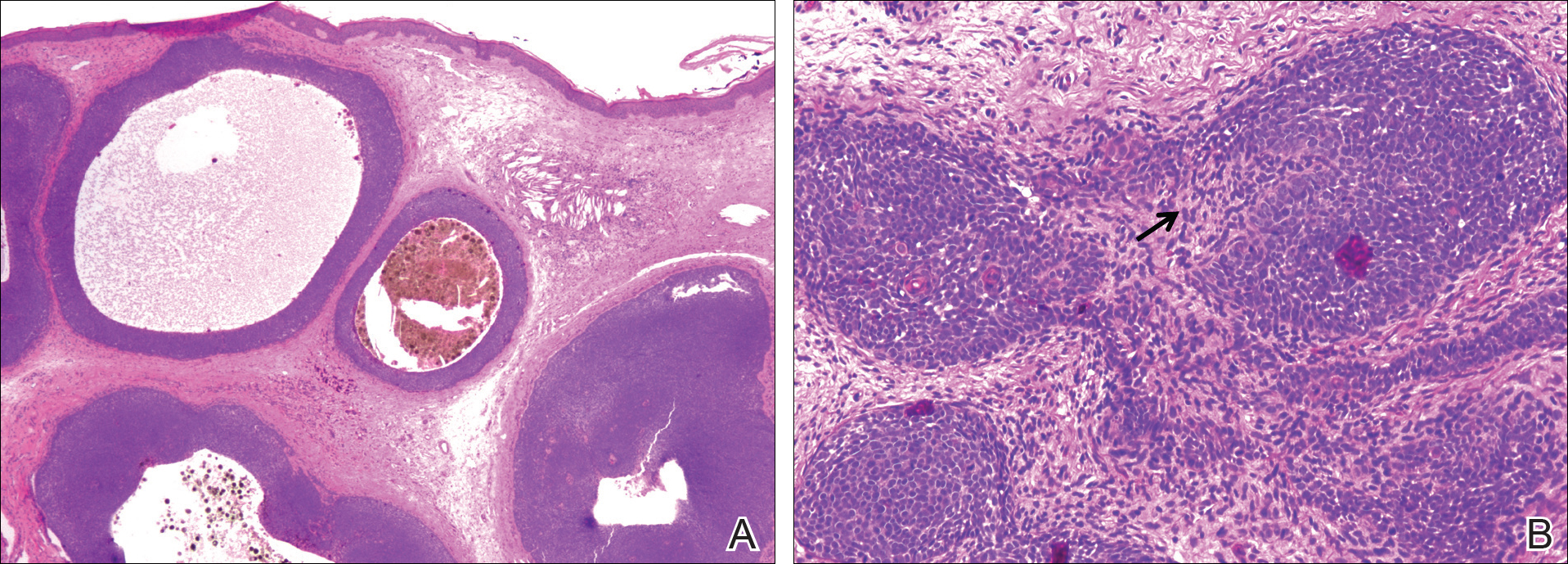

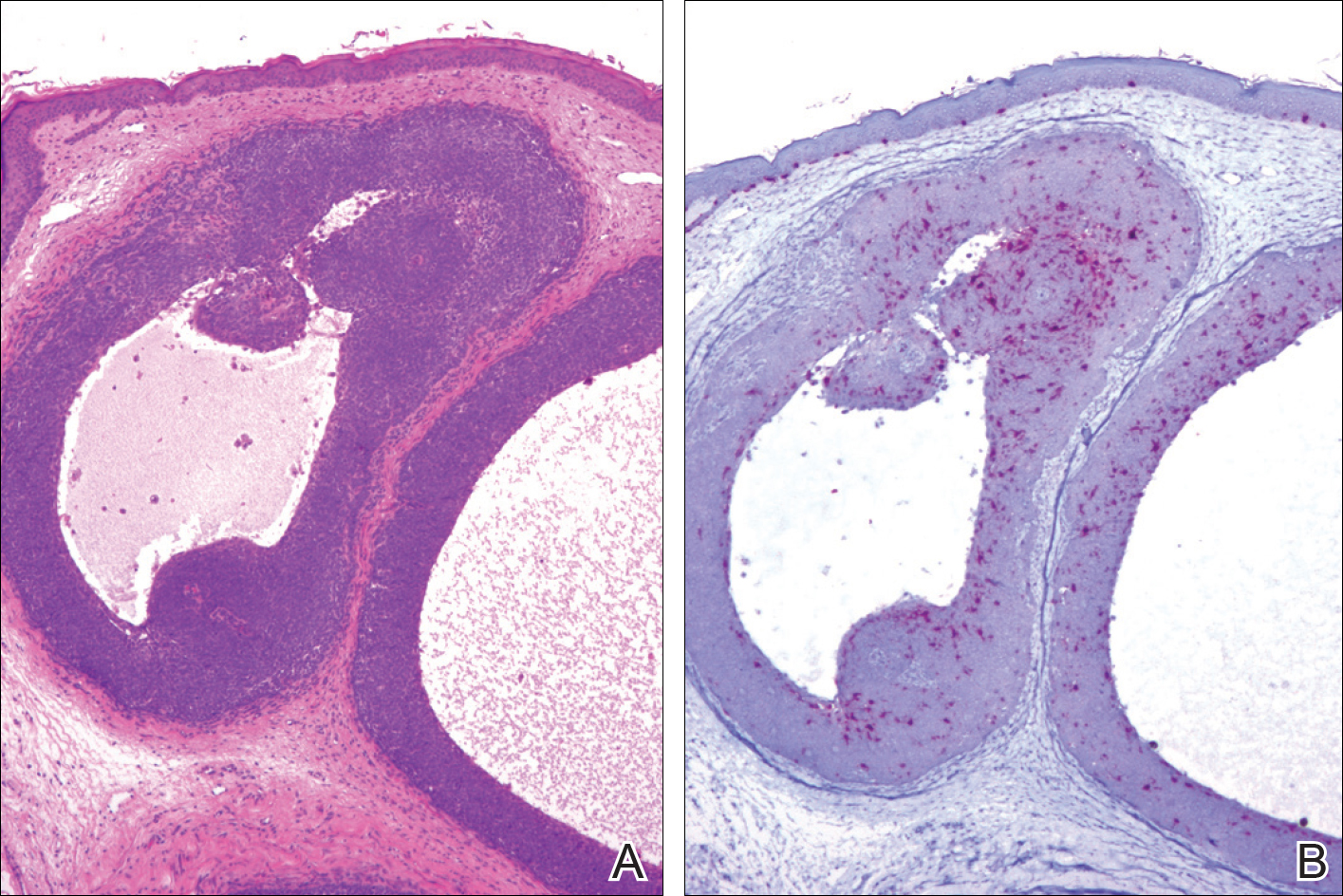

The primary end point of the efinaconazole phase 3 trials was complete cure at week 52, with secondary end points including mycologic cure, treatment success (≤5% mycotic nail), and complete or almost complete cure (negative culture and KOH, ≤5% mycotic nail). An example of a complete cure from baseline to week 52 is shown in Figure 3.7

Ciclopirox

Ciclopirox was the first topical therapy to be approved for the treatment of onychomycosis. Ciclopirox is a broad-spectrum antifungal agent that inhibits metal-dependent enzymes, which are responsible for the degradation of toxic peroxides in fungal cells. The safety and efficacy of ciclopirox nail lacquer topical solution 8% also was investigated in 2 identical phase 3 clinical trials.8 The first study was conducted at 9 sites in the United States between June 1994 and June 1996 and included 223 participants. The second study was conducted at 9 sites in the United States between July 1994 and April 1996 and included 237 participants.

Eligible participants were required to have DSO in at least one TGT, positive KOH wet mount with positive dermatophyte culture, and 20% to 65% nail involvement.8 Those with tinea pedis were not excluded. Participants were randomized to receive once-daily treatment with ciclopirox or vehicle (1:1)(applied to all toenails and affected fingernails) for 48 weeks. The product was to be removed by the patient with alcohol on a weekly basis. Trimming was allowed as necessary, and mechanical debridement by the physician could be performed monthly. Assessments were made every 4 weeks, and mycologic examinations were performed every 12 weeks. Participants who were clinically cured were assessed further in a 12- to 24-week posttreatment follow-up period.8

The primary end point of complete cure and secondary end points of treatment success (negative culture and KOH, ≤10% mycotic nail), mycologic cure, and negative mycologic culture were assessed at week 48.8

Phase 3 Clinical Trial Similarities and Differences

The phase 3 clinical trials used to investigate the safety and efficacy of tavaborole,5 efinaconazole,7 and ciclopirox8 were similar in their overall design. All trials were randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies in patients with DSO. Each agent was assessed using a once-daily application for a treatment period of 48 weeks.

Primary differences among study designs included the age range of participants, the range of mycotic nail involvement, the presence/absence of tinea pedis, and the nail trimming/debridement protocols used. Differences were observed in the patient eligibility criteria of these trials. Both mycotic area and participant age range were inconsistent for each agent (eTable). Participants with larger mycotic areas usually have a poorer prognosis, as they tend to have a greater fungal load.9 A baseline mycotic area of 20% to 60%,5 20% to 50%,7 and 20% to 65%8 at baseline was required for the tavaborole, efinaconazole, and ciclopirox trials, respectively. Variations in mycotic area between trials can affect treatment efficacy, as clinical cures can be reached quicker by patients with smaller areas of infection. Of note, the average mycotic area of involvement was not reported in the tavaborole studies but was 36% and 40% for the efinaconazole and ciclopirox studies, respectively.5,8 It also is more difficult to achieve complete cure in older patients, as they have poor circulation and reduced nail growth rates.1,10 The participant age range was 18 to 88 years in the tavaborole trials, with 8% of the participants older than 70 years,5 compared to 18 to 71 years in both the efinaconazole and ciclopirox trials.7,8 The average age of participants in each study was approximately 54, 51, and 50 years for tavaborole, efinaconazole, and ciclopirox, respectively. Because factors impacting treatment failure can increase with age, efficacy results can be confounded by differing age distributions across different studies.

Another important feature that differed between the clinical trials was the approach to nail trimming—defined as shortening of the free edge of the nail distal to the hyponychium—which varies from debridement in that the nail plate is removed or reduced in thickness proximal to the hyponychium. In the tavaborole trials, trimming was controlled to within 1 mm of the free edge of the nail,5 whereas the protocol used for the ciclopirox trials allowed nail trimming as necessary as well as moderate debridement before treatment application and on a monthly basis.8 Debridement is an important component in all ciclopirox trials, as it is used to reduce fungal load.11 No trimming control was provided during the efinaconazole trials; however, debridement was prohibited.7 These differences can dramatically affect the study results, as residual fungal elements and portions of infected nails are removed during the trimming process in an uncontrolled manner, which can affect mycologic testing results as well as the clinical efficacy results determined through investigator evaluation. Discrepancies regarding nail trimming approach inevitably makes the trial results difficult to compare, as mycologic cure is not translatable between studies.

Furthermore, somewhat unusually, complete cure rate variations were observed between different study centers in the efinaconazole trials. Japanese centers in the first efinaconazole study (NCT01008033) had higher complete cure rates in both the efinaconazole and vehicle treatment arms, which is notable because approximately 29% of participants in this study were Asian, mostly hailing from 33 Japanese centers. The reason for these confounding results is unknown and requires further analysis.

Lastly, the presence or absence of tinea pedis can affect the response to onychomycosis treatment. In the tavaborole trials, patients with active interdigital tinea pedis or exclusively plantar tinea pedis or chronic moccasin-type tinea pedis requiring treatment were excluded from the studies.5 In contrast, only patients with severe moccasin-type tinea pedis were excluded in efinaconazole trials.7 The ciclopirox studies had no exclusions based on presence of tinea pedis.8 These differences are noteworthy, as tinea pedis can serve as a reservoir for fungal infection if not treated and can lead to recurrence of onychomycosis.12

Conclusion

In recent years, disappointing efficacy has resulted in the failure of several topical agents for onychomycosis during their development; however, there are several aspects to consider when examining efficacy data in onychomycosis studies. Obtaining a complete cure in onychomycosis is difficult. Because patients applying treatments at home are unlikely to undergo mycologic testing to confirm complete cure, visual inspections are helpful to determine treatment efficacy.

Despite similar overall designs, notable differences in the study designs of the phase 3 clinical trials investigating tavaborole, efinaconazole, and ciclopirox are likely to have had an effect on the reported results, making the efficacy of the agents difficult to compare. It is particularly tempting to compare the primary end point results of each trial, especially considering tavaborole and efinaconazole had primary end points with the same parameters; however, there are several other factors (eg, age range of study population, extent of infection, nail trimming, patient demographics) that may have affected the outcomes of the studies and precluded a direct comparison of any end points. Without head-to-head investigations, there is room for prescribing clinicians to interpret results differently.

Acknowledgment

Writing and editorial assistance was provided by ApotheCom Associates, LLC, Yardley, Pennsylvania, and was supported by Sandoz, a Novartis division.

- Elewski BE. Onychomycosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:415-429.

- Thomas J, Jacobson GA, Narkowicz CK, et al. Toenail onychomycosis: an important global disease burden. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2010;35:497-519.

- Scher RK. Onychomycosis: a significant medical disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 2):S2-S5.

- Del Rosso JQ. The role of topical antifungal therapy for onychomycosis and the emergence of newer agents. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-18.

- Elewski BE, Aly R, Baldwin SL, et al. Efficacy and safety of tavaborole topical solution, 5%, a novel boron-based antifungal agent, for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: results from 2 randomized phase-III studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:62-69.

- Rock FL, Mao W, Yaremchuk A, et al. An antifungal agent inhibits an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by trapping tRNA in the editing site. Science. 2007;316:1759-1761.

- Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

- Gupta AK, Joseph WS. Ciclopirox 8% nail lacquer in the treatment of onychomycosis of the toenails in the United States. J Am Pod Med Assoc. 2000;90:495-501.

- Carney C, Tosti A, Daniel R, et al. A new classification system for grading the severity of onychomycosis: Onychomycosis Severity Index. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1277-1282.

- Gupta AK. Onychomycosis in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2000;16:397-407.

- Gupta AK, Malkin KF. Ciclopirox nail lacquer and podiatric practice. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2000;90:502-507.

- Scher RK, Baran R. Onychomycosis in clinical practice: factors contributing to recurrence. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):5-9.

Onychomycosis is a fungal nail infection primarily caused by dermatophytes.1 If left untreated, the infection can cause nail destruction and deformities,1 resulting in pain and discomfort,2 impaired foot mobility,3 and an overall reduced quality of life.1 Onychomycosis is a chronic condition that requires long treatment periods due to the slow growth rates of toenails.1 To successfully cure the condition, fungal eradication must be achieved.

Prior to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of tavaborole and efinaconazole, ciclopirox was the only approved topical treatment for onychomycosis.4 The recent approval of tavaborole and efinaconazole has increased treatment options available to patients and has started to pave the way for future topical treatments. This article discusses the 3 approved topical treatments for onychomycosis and focuses on the design of the phase 3 clinical trials that led to their approval.

Topical Agents Used to Treat Onychomycosis

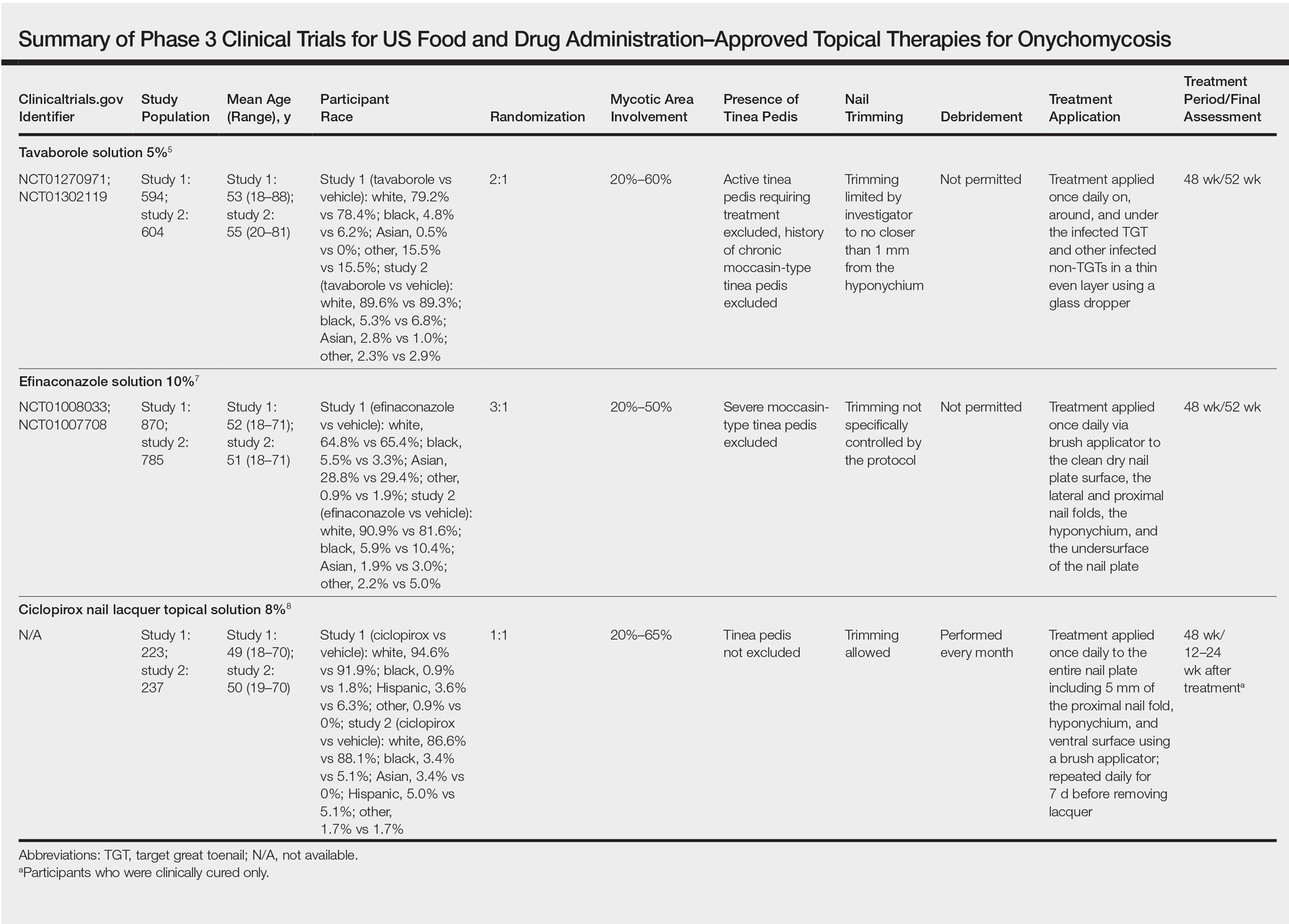

Tavaborole, efinaconazole, and ciclopirox have undergone extensive clinical investigation to receive FDA approval. Results from pivotal phase 3 studies establishing the efficacy and safety of each agent formed the basis for regulatory submission. Although it may seem intuitive to compare the relative performance of these agents based on their respective phase 3 clinical trial data, there are important differences in study methodology, conduct, and populations that prevent direct comparisons. The FDA provides limited guidance to the pharmaceutical industry on how to conduct clinical trials for potential onychomycosis treatments. Comparative efficacy and safety claims are limited based on cross-study comparisons. The details of the phase 3 trial designs are summarized in the Table.

Tavaborole

Tavaborole is a boron-based treatment with a novel mechanism of action.5 Tavaborole binds to the editing domain of leucyl–transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase via an integrated boron atom and inhibits fungal protein synthesis.6 Two identical randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 clinical trials evaluating tavaborole were performed.5 The first study (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT01270971) included 594 participants from27 sites in the United States and Mexico and was conducted between December 2010 and November 2012. The second study (NCT01302119) included 604 participants from 32 sites in the United States and Canada and was conducted between February 2011 and January 2013.

Eligible participants 18 years and older had distal subungual onychomycosis (DSO) of the toenails affecting 20% to 60% of 1 or more target great toenails (TGTs), tested positive for fungus using potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mounts and positive for Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes on fungal culture diagnostic tests, had distal TGT thickness of 3 mm or less, and had 3 mm or more of clear nail between the proximal nail fold and the most proximal visible mycotic border.5 Those with active tinea pedis requiring treatment or with a history of chronic moccasin-type tinea pedis were excluded. Participants were randomized to receive either tavaborole or vehicle (2:1). Treatments were applied once daily to all infected toenails for a total of 48 weeks, and nail debridement (defined as partial or complete removal of the toenail) was not permitted. Notably, controlled trimming of the nail was allowed to 1 mm of the leading nail edge. Regular assessments of each toenail for disease involvement, onycholysis, and subungual hyperkeratosis were made at screening, baseline, week 2, week 6, and every 6 weeks thereafter until week 52. Subungual TGT samples were taken at screening and every 12 weeks during the study for examination at a mycology laboratory, which performed KOH and fungal culture tests. A follow-up assessment was made at week 52.5