User login

A multidisciplinary approach to diaphragmatic endometriosis

Endometriosis affects approximately 11% of women; the disease can be categorized as pelvic endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis, based on anatomic presentation. It is estimated that about 12% of extrapelvic disease involves the diaphragm or thoracic cavity.

While diaphragmatic endometriosis often is asymptomatic, patients who are symptomatic can experience progressive and incapacitating pain. because of a traditional focus on the lower pelvic region. Some cases are misdiagnosed as other conditions involving the gastrointestinal tract or of cardiothoracic origin, because of the propensity of diaphragmatic disease to occur posteriorly and hide behind the liver. The variable appearance of endometriotic lesions and the lack of reliable diagnostic or imaging tests also can contribute to delayed diagnosis.

Symptoms usually occur cyclically with the onset of menses, but sometimes are unrelated to menses. Most diaphragmatic lesions occur on the abdominal side and right hemidiaphragm, which may offer evidence for the theory that retrograde menstruation drives the development of endometriosis because of the clockwise flow of peritoneal fluid. However, lesions have been found on all parts of the diaphragm, including the left side only, the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm, and the phrenic nerve. There is no correlation between the size/number of lesions and either pneumothorax or hemothorax, nor pain.

The best diagnostic method is thorough surveillance intraoperatively. In our practice, we routinely inspect the diaphragm for endometriosis at the time of video laparoscopy.

In women who have symptoms, it is important to ensure the best exposure of the diaphragm by properly considering the patient’s positioning and port placement, and by using an atraumatic liver retractor or grasping forceps to gently push the liver down and away from the visual/operative field. Posterior diaphragm viewing can also be enhanced by utilizing a 30-degree laparoscope angled toward the back. At times, it is helpful to cut the falciform ligament near the liver to expose the right side of the diaphragm completely while the patient is in steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

Most lesions in symptomatic patients can be successfully removed with hydrodissection and vaporization or excision. For asymptomatic patients with an incidental finding of diaphragmatic endometriosis, the suggestion is not to treat lesions in order to avoid the potential risk of injury to the diaphragm, phrenic nerve, lungs, or heart – especially when an adequate multidisciplinary team is not available.

Pathophysiology

In addition to retrograde menstruation, there are two other common theories regarding the pathophysiology of thoracic endometriosis. First, high prostaglandin F2-alpha at ovulation may result in vasospasm and ischemia of the lungs (resulting, in turn, in alveolar rupture and subsequent pneumothorax). Second, the loss of a mucus plug during menses may result in communication between the environment and peritoneal cavity.

What is clear is that patients who have symptoms consistent with pelvic endometriosis and chest complaints should be evaluated for both diaphragmatic and pelvic endometriosis. It’s also increasing clear that a multidisciplinary approach utilizing combined laparoscopy and thoracoscopy is a safe and effective method for addressing pelvic, diaphragmatic, and other thoracic endometriosis when other treatments have failed.

A multidisciplinary approach

Since the introduction of video laparoscopy and ease of evaluation of the upper abdomen, more extrapelvic endometriosis – including disease in the upper abdomen and diaphragm – is being diagnosed. The thoracic and visceral diaphragm are the most commonly described sites of thoracic endometriosis, and disease is often right sided, with parenchymal involvement less commonly reported.

Abdominopelvic and visceral diaphragmatic endometriosis are treated endoscopically with hydrodissection followed by excision or ablation. Superficial lesions away from the central diaphragm can be coagulated using bipolar current.

Thoracoscopic treatment varies, involving ablation or excision of smaller diaphragmatic lesions, pulmonary wedge resection of deep parenchymal nodules (using a stapling device), diaphragm resection of deep diaphragmatic lesions using a stapling device, or by excision and manual suturing.

Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment begins by introducing a 10-mm port at the umbilicus and placing three additional ports in the upper quadrant (right or left, depending on implant location). The arrangement (similar to that of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy or splenectomy) allows for examination of the posterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm and almost the entire left hemidiaphragm in addition to routine abdominopelvic exploration.

For better laparoscopic visualization, the patient is repositioned in steep reverse Trendelenburg, and the liver is gently pushed caudally to view the adjacent diaphragm. The upper abdominal walls and the liver also may be evaluated while in this position.

Bluish pigmented lesions are the most commonly reported form of diaphragmatic endometriosis, followed by lesions with a reddish-purple appearance. However, lesions can present with various colors and morphologic appearances, such as fibrotic white lesions or adhesions to the liver.

In our practice, we recommend using the CO2 laser (set at 20-25 watts) with hydrodissection for superficial lesions. The CO2 laser is much more precise and has a smaller depth of penetration and less thermal spread, compared with electrocautery. The CO2 laser beam also reaches otherwise hard-to-access areas behind the liver and has proven to be safe for vaporizing and/or excising many types of diaphragmatic lesions. We have successfully treated diaphragmatic endometriosis in the vicinity of the phrenic nerve and directly in line with the left ventricle.

Watch a video from Dr. Ceana Nezhat demonstrating a step wise vaporization and excision of diaphragmatic endometriosis utilizing different techniques.

(Courtesy Dr. Ceana Nezhat)

Plasma jet energy and ultrasonic energy are good alternatives when a CO2 laser is not available and are preferable to the use of cold scissors because of subsequent bleeding, which requires bipolar hemostasis.

Monopolar electrocautery is not as good a choice for treating diaphragmatic endometriosis because of higher depth of penetration, which may cause tissue necrosis and subsequent delayed diaphragmatic fenestrations. It also may cause unpredictable diaphragmatic muscular contractions and electrical conduction transmitted to the heart, inducing arrhythmia.

For patients treated via combined VALS and VATS procedures, endometriotic lesions involving the entire thickness of the diaphragm should be completely resected, and the defect can be repaired with either sutures or staples.

In all cases, special anesthesia considerations must be made given the inability to completely ventilate the lung. In our practice, we use a double-lumen endotracheal tube for single lung ventilation, if needed. A bronchial blocker is used to isolate the lung when the double-lumen endotracheal tube cannot be inserted.

It is important to note that we do not recommend VATS with VALS in all suspicious cases. We reserve VATS only for patients with catamenial pneumothorax, catamenial hemothorax, hemoptysis, and pulmonary nodules, defined as Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. We usually start with medical management first, then proceed to VALS, and finally, VATS, with the intention to treat if the patient fails nonsurgical treatments. It is better to avoid VATS, if possible, because it is associated with longer recovery and more pain; it should be done if all else fails.

If the patient has completed childbearing or passed reproductive age, bilateral salpingectomy, or hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, may be considered as the first step prior to more aggressive excisional procedures. This is especially true for widespread lesions, as branches of the phrenic nerve are difficult to see and injury could result in paralysis of the diaphragm. It’s important to appreciate that if estrogen stimulation to the diaphragmatic lesions is to cease for the long term, hormonal suppression or surgical treatment including bilateral oophorectomy should be utilized.

My colleagues and I have reported on our experience with a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of diaphragmatic endometriosis in 25 patients. All had both pelvic and thoracic symptoms, and the majority had endometrial implants on both the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm.

There were two postoperative complications: a diaphragmatic hernia and a vaginal cuff hematoma. Over a follow-up period of 3-18 months, all 25 patients had significant improvement or resolution of their chest complaints, and most remained asymptomatic for more than 6 months (JSLS. 2014 Jul-Sep;18[3]. pii: e2014.00312. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00312).

Dr. Ceana Nezhat is the fellowship director of Nezhat Medical Center, the medical director of training and education at Northside Hospital, and an adjunct clinical professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, all in Atlanta. He is president of SRS (Society of Reproductive Surgeons) and past president of AAGL (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists). Dr. Nezhat is a consultant for Novuson Surgical, Karl Storz Endoscopy, Lumenis, and AbbVie; a medical advisor for Plasma Surgical, and a member of the scientific advisory board for SurgiQuest.

Suggested readings

1. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Nezhat’s Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy with Hysteroscopy. Fourth Edition. Cambridge University Press. 2013.

2. Am J Med. 1996 Feb;100(2):164-70.

3. Fertil Steril. 1998 Jun;69(6):1048-55.

4. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Sep;42(3):699-711.

5. JSLS. 2012 Jan-Mar; 16(1):140-2.

Endometriosis affects approximately 11% of women; the disease can be categorized as pelvic endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis, based on anatomic presentation. It is estimated that about 12% of extrapelvic disease involves the diaphragm or thoracic cavity.

While diaphragmatic endometriosis often is asymptomatic, patients who are symptomatic can experience progressive and incapacitating pain. because of a traditional focus on the lower pelvic region. Some cases are misdiagnosed as other conditions involving the gastrointestinal tract or of cardiothoracic origin, because of the propensity of diaphragmatic disease to occur posteriorly and hide behind the liver. The variable appearance of endometriotic lesions and the lack of reliable diagnostic or imaging tests also can contribute to delayed diagnosis.

Symptoms usually occur cyclically with the onset of menses, but sometimes are unrelated to menses. Most diaphragmatic lesions occur on the abdominal side and right hemidiaphragm, which may offer evidence for the theory that retrograde menstruation drives the development of endometriosis because of the clockwise flow of peritoneal fluid. However, lesions have been found on all parts of the diaphragm, including the left side only, the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm, and the phrenic nerve. There is no correlation between the size/number of lesions and either pneumothorax or hemothorax, nor pain.

The best diagnostic method is thorough surveillance intraoperatively. In our practice, we routinely inspect the diaphragm for endometriosis at the time of video laparoscopy.

In women who have symptoms, it is important to ensure the best exposure of the diaphragm by properly considering the patient’s positioning and port placement, and by using an atraumatic liver retractor or grasping forceps to gently push the liver down and away from the visual/operative field. Posterior diaphragm viewing can also be enhanced by utilizing a 30-degree laparoscope angled toward the back. At times, it is helpful to cut the falciform ligament near the liver to expose the right side of the diaphragm completely while the patient is in steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

Most lesions in symptomatic patients can be successfully removed with hydrodissection and vaporization or excision. For asymptomatic patients with an incidental finding of diaphragmatic endometriosis, the suggestion is not to treat lesions in order to avoid the potential risk of injury to the diaphragm, phrenic nerve, lungs, or heart – especially when an adequate multidisciplinary team is not available.

Pathophysiology

In addition to retrograde menstruation, there are two other common theories regarding the pathophysiology of thoracic endometriosis. First, high prostaglandin F2-alpha at ovulation may result in vasospasm and ischemia of the lungs (resulting, in turn, in alveolar rupture and subsequent pneumothorax). Second, the loss of a mucus plug during menses may result in communication between the environment and peritoneal cavity.

What is clear is that patients who have symptoms consistent with pelvic endometriosis and chest complaints should be evaluated for both diaphragmatic and pelvic endometriosis. It’s also increasing clear that a multidisciplinary approach utilizing combined laparoscopy and thoracoscopy is a safe and effective method for addressing pelvic, diaphragmatic, and other thoracic endometriosis when other treatments have failed.

A multidisciplinary approach

Since the introduction of video laparoscopy and ease of evaluation of the upper abdomen, more extrapelvic endometriosis – including disease in the upper abdomen and diaphragm – is being diagnosed. The thoracic and visceral diaphragm are the most commonly described sites of thoracic endometriosis, and disease is often right sided, with parenchymal involvement less commonly reported.

Abdominopelvic and visceral diaphragmatic endometriosis are treated endoscopically with hydrodissection followed by excision or ablation. Superficial lesions away from the central diaphragm can be coagulated using bipolar current.

Thoracoscopic treatment varies, involving ablation or excision of smaller diaphragmatic lesions, pulmonary wedge resection of deep parenchymal nodules (using a stapling device), diaphragm resection of deep diaphragmatic lesions using a stapling device, or by excision and manual suturing.

Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment begins by introducing a 10-mm port at the umbilicus and placing three additional ports in the upper quadrant (right or left, depending on implant location). The arrangement (similar to that of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy or splenectomy) allows for examination of the posterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm and almost the entire left hemidiaphragm in addition to routine abdominopelvic exploration.

For better laparoscopic visualization, the patient is repositioned in steep reverse Trendelenburg, and the liver is gently pushed caudally to view the adjacent diaphragm. The upper abdominal walls and the liver also may be evaluated while in this position.

Bluish pigmented lesions are the most commonly reported form of diaphragmatic endometriosis, followed by lesions with a reddish-purple appearance. However, lesions can present with various colors and morphologic appearances, such as fibrotic white lesions or adhesions to the liver.

In our practice, we recommend using the CO2 laser (set at 20-25 watts) with hydrodissection for superficial lesions. The CO2 laser is much more precise and has a smaller depth of penetration and less thermal spread, compared with electrocautery. The CO2 laser beam also reaches otherwise hard-to-access areas behind the liver and has proven to be safe for vaporizing and/or excising many types of diaphragmatic lesions. We have successfully treated diaphragmatic endometriosis in the vicinity of the phrenic nerve and directly in line with the left ventricle.

Watch a video from Dr. Ceana Nezhat demonstrating a step wise vaporization and excision of diaphragmatic endometriosis utilizing different techniques.

(Courtesy Dr. Ceana Nezhat)

Plasma jet energy and ultrasonic energy are good alternatives when a CO2 laser is not available and are preferable to the use of cold scissors because of subsequent bleeding, which requires bipolar hemostasis.

Monopolar electrocautery is not as good a choice for treating diaphragmatic endometriosis because of higher depth of penetration, which may cause tissue necrosis and subsequent delayed diaphragmatic fenestrations. It also may cause unpredictable diaphragmatic muscular contractions and electrical conduction transmitted to the heart, inducing arrhythmia.

For patients treated via combined VALS and VATS procedures, endometriotic lesions involving the entire thickness of the diaphragm should be completely resected, and the defect can be repaired with either sutures or staples.

In all cases, special anesthesia considerations must be made given the inability to completely ventilate the lung. In our practice, we use a double-lumen endotracheal tube for single lung ventilation, if needed. A bronchial blocker is used to isolate the lung when the double-lumen endotracheal tube cannot be inserted.

It is important to note that we do not recommend VATS with VALS in all suspicious cases. We reserve VATS only for patients with catamenial pneumothorax, catamenial hemothorax, hemoptysis, and pulmonary nodules, defined as Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. We usually start with medical management first, then proceed to VALS, and finally, VATS, with the intention to treat if the patient fails nonsurgical treatments. It is better to avoid VATS, if possible, because it is associated with longer recovery and more pain; it should be done if all else fails.

If the patient has completed childbearing or passed reproductive age, bilateral salpingectomy, or hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, may be considered as the first step prior to more aggressive excisional procedures. This is especially true for widespread lesions, as branches of the phrenic nerve are difficult to see and injury could result in paralysis of the diaphragm. It’s important to appreciate that if estrogen stimulation to the diaphragmatic lesions is to cease for the long term, hormonal suppression or surgical treatment including bilateral oophorectomy should be utilized.

My colleagues and I have reported on our experience with a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of diaphragmatic endometriosis in 25 patients. All had both pelvic and thoracic symptoms, and the majority had endometrial implants on both the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm.

There were two postoperative complications: a diaphragmatic hernia and a vaginal cuff hematoma. Over a follow-up period of 3-18 months, all 25 patients had significant improvement or resolution of their chest complaints, and most remained asymptomatic for more than 6 months (JSLS. 2014 Jul-Sep;18[3]. pii: e2014.00312. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00312).

Dr. Ceana Nezhat is the fellowship director of Nezhat Medical Center, the medical director of training and education at Northside Hospital, and an adjunct clinical professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, all in Atlanta. He is president of SRS (Society of Reproductive Surgeons) and past president of AAGL (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists). Dr. Nezhat is a consultant for Novuson Surgical, Karl Storz Endoscopy, Lumenis, and AbbVie; a medical advisor for Plasma Surgical, and a member of the scientific advisory board for SurgiQuest.

Suggested readings

1. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Nezhat’s Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy with Hysteroscopy. Fourth Edition. Cambridge University Press. 2013.

2. Am J Med. 1996 Feb;100(2):164-70.

3. Fertil Steril. 1998 Jun;69(6):1048-55.

4. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Sep;42(3):699-711.

5. JSLS. 2012 Jan-Mar; 16(1):140-2.

Endometriosis affects approximately 11% of women; the disease can be categorized as pelvic endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis, based on anatomic presentation. It is estimated that about 12% of extrapelvic disease involves the diaphragm or thoracic cavity.

While diaphragmatic endometriosis often is asymptomatic, patients who are symptomatic can experience progressive and incapacitating pain. because of a traditional focus on the lower pelvic region. Some cases are misdiagnosed as other conditions involving the gastrointestinal tract or of cardiothoracic origin, because of the propensity of diaphragmatic disease to occur posteriorly and hide behind the liver. The variable appearance of endometriotic lesions and the lack of reliable diagnostic or imaging tests also can contribute to delayed diagnosis.

Symptoms usually occur cyclically with the onset of menses, but sometimes are unrelated to menses. Most diaphragmatic lesions occur on the abdominal side and right hemidiaphragm, which may offer evidence for the theory that retrograde menstruation drives the development of endometriosis because of the clockwise flow of peritoneal fluid. However, lesions have been found on all parts of the diaphragm, including the left side only, the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm, and the phrenic nerve. There is no correlation between the size/number of lesions and either pneumothorax or hemothorax, nor pain.

The best diagnostic method is thorough surveillance intraoperatively. In our practice, we routinely inspect the diaphragm for endometriosis at the time of video laparoscopy.

In women who have symptoms, it is important to ensure the best exposure of the diaphragm by properly considering the patient’s positioning and port placement, and by using an atraumatic liver retractor or grasping forceps to gently push the liver down and away from the visual/operative field. Posterior diaphragm viewing can also be enhanced by utilizing a 30-degree laparoscope angled toward the back. At times, it is helpful to cut the falciform ligament near the liver to expose the right side of the diaphragm completely while the patient is in steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

Most lesions in symptomatic patients can be successfully removed with hydrodissection and vaporization or excision. For asymptomatic patients with an incidental finding of diaphragmatic endometriosis, the suggestion is not to treat lesions in order to avoid the potential risk of injury to the diaphragm, phrenic nerve, lungs, or heart – especially when an adequate multidisciplinary team is not available.

Pathophysiology

In addition to retrograde menstruation, there are two other common theories regarding the pathophysiology of thoracic endometriosis. First, high prostaglandin F2-alpha at ovulation may result in vasospasm and ischemia of the lungs (resulting, in turn, in alveolar rupture and subsequent pneumothorax). Second, the loss of a mucus plug during menses may result in communication between the environment and peritoneal cavity.

What is clear is that patients who have symptoms consistent with pelvic endometriosis and chest complaints should be evaluated for both diaphragmatic and pelvic endometriosis. It’s also increasing clear that a multidisciplinary approach utilizing combined laparoscopy and thoracoscopy is a safe and effective method for addressing pelvic, diaphragmatic, and other thoracic endometriosis when other treatments have failed.

A multidisciplinary approach

Since the introduction of video laparoscopy and ease of evaluation of the upper abdomen, more extrapelvic endometriosis – including disease in the upper abdomen and diaphragm – is being diagnosed. The thoracic and visceral diaphragm are the most commonly described sites of thoracic endometriosis, and disease is often right sided, with parenchymal involvement less commonly reported.

Abdominopelvic and visceral diaphragmatic endometriosis are treated endoscopically with hydrodissection followed by excision or ablation. Superficial lesions away from the central diaphragm can be coagulated using bipolar current.

Thoracoscopic treatment varies, involving ablation or excision of smaller diaphragmatic lesions, pulmonary wedge resection of deep parenchymal nodules (using a stapling device), diaphragm resection of deep diaphragmatic lesions using a stapling device, or by excision and manual suturing.

Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment begins by introducing a 10-mm port at the umbilicus and placing three additional ports in the upper quadrant (right or left, depending on implant location). The arrangement (similar to that of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy or splenectomy) allows for examination of the posterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm and almost the entire left hemidiaphragm in addition to routine abdominopelvic exploration.

For better laparoscopic visualization, the patient is repositioned in steep reverse Trendelenburg, and the liver is gently pushed caudally to view the adjacent diaphragm. The upper abdominal walls and the liver also may be evaluated while in this position.

Bluish pigmented lesions are the most commonly reported form of diaphragmatic endometriosis, followed by lesions with a reddish-purple appearance. However, lesions can present with various colors and morphologic appearances, such as fibrotic white lesions or adhesions to the liver.

In our practice, we recommend using the CO2 laser (set at 20-25 watts) with hydrodissection for superficial lesions. The CO2 laser is much more precise and has a smaller depth of penetration and less thermal spread, compared with electrocautery. The CO2 laser beam also reaches otherwise hard-to-access areas behind the liver and has proven to be safe for vaporizing and/or excising many types of diaphragmatic lesions. We have successfully treated diaphragmatic endometriosis in the vicinity of the phrenic nerve and directly in line with the left ventricle.

Watch a video from Dr. Ceana Nezhat demonstrating a step wise vaporization and excision of diaphragmatic endometriosis utilizing different techniques.

(Courtesy Dr. Ceana Nezhat)

Plasma jet energy and ultrasonic energy are good alternatives when a CO2 laser is not available and are preferable to the use of cold scissors because of subsequent bleeding, which requires bipolar hemostasis.

Monopolar electrocautery is not as good a choice for treating diaphragmatic endometriosis because of higher depth of penetration, which may cause tissue necrosis and subsequent delayed diaphragmatic fenestrations. It also may cause unpredictable diaphragmatic muscular contractions and electrical conduction transmitted to the heart, inducing arrhythmia.

For patients treated via combined VALS and VATS procedures, endometriotic lesions involving the entire thickness of the diaphragm should be completely resected, and the defect can be repaired with either sutures or staples.

In all cases, special anesthesia considerations must be made given the inability to completely ventilate the lung. In our practice, we use a double-lumen endotracheal tube for single lung ventilation, if needed. A bronchial blocker is used to isolate the lung when the double-lumen endotracheal tube cannot be inserted.

It is important to note that we do not recommend VATS with VALS in all suspicious cases. We reserve VATS only for patients with catamenial pneumothorax, catamenial hemothorax, hemoptysis, and pulmonary nodules, defined as Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. We usually start with medical management first, then proceed to VALS, and finally, VATS, with the intention to treat if the patient fails nonsurgical treatments. It is better to avoid VATS, if possible, because it is associated with longer recovery and more pain; it should be done if all else fails.

If the patient has completed childbearing or passed reproductive age, bilateral salpingectomy, or hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, may be considered as the first step prior to more aggressive excisional procedures. This is especially true for widespread lesions, as branches of the phrenic nerve are difficult to see and injury could result in paralysis of the diaphragm. It’s important to appreciate that if estrogen stimulation to the diaphragmatic lesions is to cease for the long term, hormonal suppression or surgical treatment including bilateral oophorectomy should be utilized.

My colleagues and I have reported on our experience with a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of diaphragmatic endometriosis in 25 patients. All had both pelvic and thoracic symptoms, and the majority had endometrial implants on both the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm.

There were two postoperative complications: a diaphragmatic hernia and a vaginal cuff hematoma. Over a follow-up period of 3-18 months, all 25 patients had significant improvement or resolution of their chest complaints, and most remained asymptomatic for more than 6 months (JSLS. 2014 Jul-Sep;18[3]. pii: e2014.00312. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00312).

Dr. Ceana Nezhat is the fellowship director of Nezhat Medical Center, the medical director of training and education at Northside Hospital, and an adjunct clinical professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, all in Atlanta. He is president of SRS (Society of Reproductive Surgeons) and past president of AAGL (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists). Dr. Nezhat is a consultant for Novuson Surgical, Karl Storz Endoscopy, Lumenis, and AbbVie; a medical advisor for Plasma Surgical, and a member of the scientific advisory board for SurgiQuest.

Suggested readings

1. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Nezhat’s Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy with Hysteroscopy. Fourth Edition. Cambridge University Press. 2013.

2. Am J Med. 1996 Feb;100(2):164-70.

3. Fertil Steril. 1998 Jun;69(6):1048-55.

4. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Sep;42(3):699-711.

5. JSLS. 2012 Jan-Mar; 16(1):140-2.

Diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis

The first case of diaphragmatic endometriosis was reported by Alan Brews in 19541. Unfortunately, no guidelines exist to enhance the recognition and treatment.

Diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis often is overlooked by the gynecologist, not only because of lack of appreciation of the symptoms but also because of the failure to properly work-up the patient and evaluate the diaphragm at time of surgery. In a retrospective review of 3,008 patients with pelvic endometriosis published in Surgical Endoscopy in 2013, Marcello Ceccaroni, MD, PhD, and his colleagues found 46 cases (1.53%) with the intraoperative diagnosis of diaphragmatic endometriosis, six with liver involvement. Multiple diaphragmatic endometriosis lesions were seen in 70% of patients and, the vast majority being right-sided lesions (87%), with 11% of cases having bilateral lesions.2 While in the study, superficial lesions were generally vaporized using the argon beam coagulator, deep lesions were removed by sharp dissection, highlighting the need to have adequately trained minimally invasive surgeons treating diaphragmatic lesions via incision. If a pneumothorax occurred, and reabsorbable suture was placed after adequate expansion of the lung via positive pressure ventilation and progressive air suctioning with complete evacuation of the pneumothorax prior to the final closure (i.e., a purse string around the suction device), then the integrity of the closure could be proven using a bubble test with 500cc of saline placed at the diaphragm.

As the gynecologic surgeon studies Dr. Nezhat’s thorough discourse, it is obvious that, at times, a multidisciplinary team must be involved. Although possible, it would appear that risk of diaphragm paralysis secondary to injury of the phrenic nerve is indeed rare. This likely is because of the greater incidence of right-sided disease, rather than involving the central tendon, and lower likelihood that the lesion penetrates deeply. Nevertheless, a prudent multidisciplinary approach and knowledge of the anatomy will inevitably further reduce this rare complication.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He reported having no financial disclosures related to this column.

References

1. Proc R Soc Med. 1954 Jun; 47(6):461-8.

2. Surg Endosc. 2013 Feb;27(2):625-32.

The first case of diaphragmatic endometriosis was reported by Alan Brews in 19541. Unfortunately, no guidelines exist to enhance the recognition and treatment.

Diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis often is overlooked by the gynecologist, not only because of lack of appreciation of the symptoms but also because of the failure to properly work-up the patient and evaluate the diaphragm at time of surgery. In a retrospective review of 3,008 patients with pelvic endometriosis published in Surgical Endoscopy in 2013, Marcello Ceccaroni, MD, PhD, and his colleagues found 46 cases (1.53%) with the intraoperative diagnosis of diaphragmatic endometriosis, six with liver involvement. Multiple diaphragmatic endometriosis lesions were seen in 70% of patients and, the vast majority being right-sided lesions (87%), with 11% of cases having bilateral lesions.2 While in the study, superficial lesions were generally vaporized using the argon beam coagulator, deep lesions were removed by sharp dissection, highlighting the need to have adequately trained minimally invasive surgeons treating diaphragmatic lesions via incision. If a pneumothorax occurred, and reabsorbable suture was placed after adequate expansion of the lung via positive pressure ventilation and progressive air suctioning with complete evacuation of the pneumothorax prior to the final closure (i.e., a purse string around the suction device), then the integrity of the closure could be proven using a bubble test with 500cc of saline placed at the diaphragm.

As the gynecologic surgeon studies Dr. Nezhat’s thorough discourse, it is obvious that, at times, a multidisciplinary team must be involved. Although possible, it would appear that risk of diaphragm paralysis secondary to injury of the phrenic nerve is indeed rare. This likely is because of the greater incidence of right-sided disease, rather than involving the central tendon, and lower likelihood that the lesion penetrates deeply. Nevertheless, a prudent multidisciplinary approach and knowledge of the anatomy will inevitably further reduce this rare complication.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He reported having no financial disclosures related to this column.

References

1. Proc R Soc Med. 1954 Jun; 47(6):461-8.

2. Surg Endosc. 2013 Feb;27(2):625-32.

The first case of diaphragmatic endometriosis was reported by Alan Brews in 19541. Unfortunately, no guidelines exist to enhance the recognition and treatment.

Diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis often is overlooked by the gynecologist, not only because of lack of appreciation of the symptoms but also because of the failure to properly work-up the patient and evaluate the diaphragm at time of surgery. In a retrospective review of 3,008 patients with pelvic endometriosis published in Surgical Endoscopy in 2013, Marcello Ceccaroni, MD, PhD, and his colleagues found 46 cases (1.53%) with the intraoperative diagnosis of diaphragmatic endometriosis, six with liver involvement. Multiple diaphragmatic endometriosis lesions were seen in 70% of patients and, the vast majority being right-sided lesions (87%), with 11% of cases having bilateral lesions.2 While in the study, superficial lesions were generally vaporized using the argon beam coagulator, deep lesions were removed by sharp dissection, highlighting the need to have adequately trained minimally invasive surgeons treating diaphragmatic lesions via incision. If a pneumothorax occurred, and reabsorbable suture was placed after adequate expansion of the lung via positive pressure ventilation and progressive air suctioning with complete evacuation of the pneumothorax prior to the final closure (i.e., a purse string around the suction device), then the integrity of the closure could be proven using a bubble test with 500cc of saline placed at the diaphragm.

As the gynecologic surgeon studies Dr. Nezhat’s thorough discourse, it is obvious that, at times, a multidisciplinary team must be involved. Although possible, it would appear that risk of diaphragm paralysis secondary to injury of the phrenic nerve is indeed rare. This likely is because of the greater incidence of right-sided disease, rather than involving the central tendon, and lower likelihood that the lesion penetrates deeply. Nevertheless, a prudent multidisciplinary approach and knowledge of the anatomy will inevitably further reduce this rare complication.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He reported having no financial disclosures related to this column.

References

1. Proc R Soc Med. 1954 Jun; 47(6):461-8.

2. Surg Endosc. 2013 Feb;27(2):625-32.

Optimal Treatment of Patients With Diabetes

Click here to access Optimal Treatment of Patients With Diabetes

Table of Contents

- Overview of the 2017 VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes

- Roundtable Discussion: Implementing the 2017 VA/DoD Diabetes Clinical Practice Guideline

- Bolus Insulin Prescribing Recommendations for Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

- Serious Mental Illness and Its Impact on Diabetes Care in a VA Nurse/Pharmacist-Managed Population

- Concentrated Insulins: A Review and Recommendations

- Glycemic Control After Discontinuation of Metformin in Patients With Elevated Serum Creatinine

Click here to access Optimal Treatment of Patients With Diabetes

Table of Contents

- Overview of the 2017 VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes

- Roundtable Discussion: Implementing the 2017 VA/DoD Diabetes Clinical Practice Guideline

- Bolus Insulin Prescribing Recommendations for Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

- Serious Mental Illness and Its Impact on Diabetes Care in a VA Nurse/Pharmacist-Managed Population

- Concentrated Insulins: A Review and Recommendations

- Glycemic Control After Discontinuation of Metformin in Patients With Elevated Serum Creatinine

Click here to access Optimal Treatment of Patients With Diabetes

Table of Contents

- Overview of the 2017 VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes

- Roundtable Discussion: Implementing the 2017 VA/DoD Diabetes Clinical Practice Guideline

- Bolus Insulin Prescribing Recommendations for Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

- Serious Mental Illness and Its Impact on Diabetes Care in a VA Nurse/Pharmacist-Managed Population

- Concentrated Insulins: A Review and Recommendations

- Glycemic Control After Discontinuation of Metformin in Patients With Elevated Serum Creatinine

Navigating the anticoagulant landscape in 2017

This article reviews recommendations and evidence concerning current anticoagulant management for venous thromboembolism and perioperative care, with an emphasis on individualizing treatment for real-world patients.

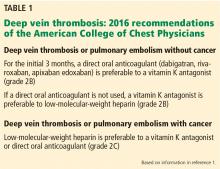

TREATING ACUTE VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM

Case 1: Deep vein thrombosis in an otherwise healthy man

A 40-year-old man presents with 7 days of progressive right leg swelling. He has no antecedent risk factors for deep vein thrombosis or other medical problems. Venous ultrasonography reveals an iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. How should he be managed?

- Outpatient treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin for 4 to 6 days plus warfarin

- Outpatient treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant, ie, apixaban, dabigatran (which requires 4 to 6 days of initial treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin), or rivaroxaban

- Catheter-directed thrombolysis followed by low-molecular-weight heparin, then warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant

- Inpatient intravenous heparin for 7 to 10 days, then warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant

All of these are acceptable for managing acute venous thromboembolism, but the clinician’s role is to identify which treatment is most appropriate for an individual patient.

Deep vein thrombosis is not a single condition

Multiple guidelines exist to help decide on a management strategy. Those of the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP)1 are used most often.

That said, guidelines are established for “average” patients, so it is important to look beyond guidelines and individualize management. Venous thromboembolism is not a single entity; it has a myriad of clinical presentations that could call for different treatments. Most patients have submassive deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, which is not limb-threatening nor associated with hemodynamic instability. It can also differ in terms of etiology and can be unprovoked (or idiopathic), cancer-related, catheter-associated, or provoked by surgery or immobility.

Deep vein thrombosis has a wide spectrum of presentations. It can involve the veins of the calf only, or it can involve the femoral and iliac veins and other locations including the splanchnic veins, the cerebral sinuses, and upper extremities. Pulmonary embolism can be massive (defined as being associated with hemodynamic instability or impending respiratory failure) or submassive. Similarly, patients differ in terms of baseline medical conditions, mobility, and lifestyle. Anticoagulant management decisions should take all these factors into account.

Consider clot location

Our patient with iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis is best managed differently than a more typical patient with less extensive thrombosis that would involve the popliteal or femoral vein segments, or both. A clot that involves the iliac vein is more likely to lead to postthrombotic chronic pain and swelling as the lack of venous outflow bypass channels to circumvent the clot location creates higher venous pressure within the affected leg. Therefore, for our patient, catheter-directed thrombolysis is an option that should be considered.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis trials

According to the “open-vein hypothesis,” quickly eliminating the thrombus and restoring unobstructed venous flow may mitigate the risk not only of recurrent thrombosis, but also of postthrombotic syndrome, which is often not given much consideration acutely but can cause significant, life-altering chronic disability.

The “valve-integrity hypothesis” is also important; it considers whether lytic therapy may help prevent damage to such valves in an attempt to mitigate the amount of venous hypertension.

Thus, catheter-directed thrombolysis offers theoretical benefits, and recent trials have assessed it against standard anticoagulation treatments.

The CaVenT trial (Catheter-Directed Venous Thrombolysis),2 conducted in Norway, randomized 209 patients with midfemoral to iliac deep vein thrombosis to conventional treatment (anticoagulation alone) or anticoagulation plus catheter-directed thrombolysis. At 2 years, postthrombotic syndrome had occurred in 41% of the catheter-directed thrombolysis group compared with 56% of the conventional treatment group (P = .047). At 5 years, the difference widened to 43% vs 71% (P < .01, number needed to treat = 4).3 Despite the superiority of lytic therapy, the incidence of postthrombotic syndrome remained high in patients who received this treatment.

The ATTRACT trial (Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal With Adjunctive Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis),4 a US multicenter, open-label, assessor-blind study, randomized 698 patients with femoral or more-proximal deep vein thrombosis to either standard care (anticoagulant therapy and graduated elastic compression stockings) or standard care plus catheter-directed thrombolysis. In preliminary results presented at the Society of Interventional Radiology meeting in March 2017, although no difference was found in the primary outcome (postthrombotic syndrome at 24 months), catheter-directed thrombolysis for iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis led to a 25% reduction in moderate to severe postthrombotic syndrome.

Although it is too early to draw conclusions before publication of the ATTRACT study, the preliminary results highlight the need to individualize treatment and to be selective about using catheter-directed thrombolysis. The trials provide reassurance that catheter-directed lysis is a reasonable and safe intervention when performed by physicians experienced in the procedure. The risk of major bleeding appears to be low (about 2%) and that for intracranial hemorrhage even lower (< 0.5%).

Catheter-directed thrombolysis is appropriate in some cases

The 2016 ACCP guidelines1 recommend anticoagulant therapy alone over catheter-directed thrombolysis for patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis of the leg. However, it is a grade 2C (weak) recommendation.

They provide no specific recommendation as to the clinical indications for catheter-directed thrombolysis, but identify patients who would be most likely to benefit, ie, those who have:

- Iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis

- Symptoms for less than 14 days

- Good functional status

- Life expectancy of more than 1 year

- Low risk of bleeding.

Our patient satisfies these criteria, suggesting that catheter-directed thrombolysis is a reasonable option for him.

Timing is important. Catheter-directed lysis is more likely to be beneficial if used before fibrin deposits form and stiffen the venous valves, causing irreversible damage that leads to postthrombotic syndrome.

Role of direct oral anticoagulants

The availability of direct oral anticoagulants has generated interest in defining their therapeutic role in patients with venous thromboembolism.

In a meta-analysis5 of major trials comparing direct oral anticoagulants and vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin, no significant difference was found for the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism or venous thromboembolism-related deaths. However, fewer patients experienced major bleeding with direct oral anticoagulants (relative risk 0.61, P = .002). Although significant, the absolute risk reduction was small; the incidence of major bleeding was 1.1% with direct oral anticoagulants vs 1.8% with vitamin K antagonists.

The main advantage of direct oral anticoagulants is greater convenience for the patient.

WHICH PATIENTS ON WARFARIN NEED BRIDGING PREOPERATIVELY?

Many patients still take warfarin, particularly those with atrial fibrillation, a mechanical heart valve, or venous thromboembolism. In many countries, warfarin remains the dominant anticoagulant for stroke prevention. Whether these patients need heparin during the period of perioperative warfarin interruption is a frequently encountered scenario that, until recently, was controversial. Recent studies have helped to inform the need for heparin bridging in many of these patients.

Case 2: An elderly woman on warfarin facing cancer surgery

A 75-year-old woman weighing 65 kg is scheduled for elective colon resection for incidentally found colon cancer. She is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. She also has hypertension and diabetes and had a transient ischemic attack 10 years ago.

One doctor told her she needs to be assessed for heparin bridging, but another told her she does not need bridging.

The default management should be not to bridge patients who have atrial fibrillation, but to consider bridging in selected patients, such as those with recent stroke or transient ischemic attack or a prior thromboembolic event during warfarin interruption. However, decisions about bridging should not be made on the basis of the CHADS2 score alone. For the patient described here, I would recommend not bridging.

Complex factors contribute to stroke risk

Stroke risk for patients with atrial fibrillation can be quickly estimated with the CHADS2 score, based on:

- Congestive heart failure (1 point)

- Hypertension (1 point)

- Age at least 75 (1 point)

- Diabetes (1 point)

- Stroke or transient ischemic attack (2 points).

Our patient has a score of 5, corresponding to an annual adjusted stroke risk of 12.5%. Whether her transient ischemic attack of 10 years ago is comparable in significance to a recent stroke is debatable and highlights a weakness of clinical prediction rules. Moreover, such prediction scores were developed to estimate the long-term risk of stroke if anticoagulants are not given, and they have not been assessed in a perioperative setting where there is short-term interruption of anticoagulants. Also, the perioperative milieu is associated with additional factors not captured in these clinical prediction rules that may affect the risk of stroke.

Thus, the risk of perioperative stroke likely involves the interplay of multiple factors, including the type of surgery the patient is undergoing. Some factors may be mitigated:

- Rebound hypercoagulability after stopping an oral anticoagulant can be prevented by intraoperative blood pressure and volume control

- Elevated biochemical factors (eg, D-dimer, B-type natriuretic peptide, troponin) may be lowered with perioperative aspirin therapy

- Lipid and genetic factors may be mitigated with perioperative statin use.

Can heparin bridging also mitigate the risk?

Bridging in patients with atrial fibrillation

Most patients who are taking warfarin are doing so because of atrial fibrillation, so most evidence about perioperative bridging was developed in such patients.

The BRIDGE trial (Bridging Anticoagulation in Patients Who Require Temporary Interruption of Warfarin Therapy for an Elective Invasive Procedure or Surgery)6 was the first randomized controlled trial to compare a bridging and no-bridging strategy for patients with atrial fibrillation who required warfarin interruption for elective surgery. Nearly 2,000 patients were given either low-molecular-weight heparin or placebo starting 3 days before until 24 hours before a procedure, and then for 5 to 10 days afterwards. For all patients, warfarin was stopped 5 days before the procedure and was resumed within 24 hours afterwards.

A no-bridging strategy was noninferior to bridging: the risk of perioperative arterial thromboembolism was 0.4% without bridging vs 0.3% with bridging (P = .01 for noninferiority). In addition, a no-bridging strategy conferred a lower risk of major bleeding than bridging: 1.3% vs 3.2% (relative risk 0.41, P = .005 for superiority).

Although the difference in absolute bleeding risk was small, bleeding rates were lower than those seen outside of clinical trials, as the bridging protocol used in BRIDGE was designed to minimize the risk of bleeding. Also, although only 5% of patients had a CHADS2 score of 5 or 6, such patients are infrequent in clinical practice, and BRIDGE did include a considerable proportion (17%) of patients with a prior stroke or transient ischemic attack who would be considered at high risk.

Other evidence about heparin bridging is derived from observational studies, more than 10 of which have been conducted. In general, they have found that not bridging is associated with low rates of arterial thromboembolism (< 0.5%) and that bridging is associated with high rates of major bleeding (4%–7%).7–12

Bridging in patients with a mechanical heart valve

Warfarin is the only anticoagulant option for patients who have a mechanical heart valve. No randomized controlled trials have evaluated the benefits of perioperative bridging vs no bridging in this setting.

Observational (cohort) studies suggest that the risk of perioperative arterial thromboembolism is similar with or without bridging anticoagulation, although most patients studied were bridged and those not bridged were considered at low risk (eg, with a bileaflet aortic valve and no additional risk factors).13 However, without stronger evidence from randomized controlled trials, bridging should be the default management for patients with a mechanical heart valve. In our practice, we bridge most patients who have a mechanical heart valve unless they are considered to be at low risk, such as those who have a bileaflet aortic valve.

Bridging in patients with prior venous thromboembolism

Even less evidence is available for periprocedural management of patients who have a history of venous thromboembolism. No randomized controlled trials exist evaluating bridging vs no bridging. In 1 cohort study in which more than 90% of patients had had thromboembolism more than 3 months before the procedure, the rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism without bridging was less than 0.5%.14

It is reasonable to bridge patients who need anticoagulant interruption within 3 months of diagnosis of a deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, and to consider using a temporary inferior vena cava filter for patients who have had a clot who need treatment interruption during the initial 3 to 4 weeks after diagnosis.

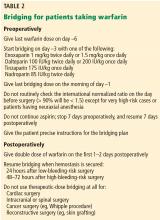

Practice guidelines: Perioperative anticoagulation

Guidance for preoperative and postoperative bridging for patients taking warfarin is summarized in Table 2.

CARDIAC PROCEDURES

For patients facing a procedure to implant an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) or pacemaker, a procedure-specific concern is the avoidance of pocket hematoma.

Patients on warfarin: Do not bridge

The BRUISE CONTROL-1 trial (Bridge or Continue Coumadin for Device Surgery Randomized Controlled Trial)19 randomized patients undergoing pacemaker or ICD implantation to either continued anticoagulation therapy and not bridging (ie, continued warfarin so long as the international normalized ratio was < 3) vs conventional bridging treatment (ie, stopping warfarin and bridging with low-molecular-weight heparin). A clinically significant device-pocket hematoma occurred in 3.5% of the continued-warfarin group vs 16.0% in the heparin-bridging group (P < .001). Thromboembolic complications were rare, and rates did not differ between the 2 groups.

Results of the BRUISE CONTROL-1 trial serve as a caution to at least not be too aggressive with bridging. The study design involved resuming heparin 24 hours after surgery, which is perhaps more aggressive than standard practice. In our practice, we wait at least 24 hours to reinstate heparin after minor surgery, and 48 to 72 hours after surgery with higher bleeding risk.

These results are perhaps not surprising if one considers how carefully surgeons try to control bleeding during surgery for patients taking anticoagulants. For patients who are not on an anticoagulant, small bleeding may be less of a concern during a procedure. When high doses of heparin are introduced soon after surgery, small concerns during surgery may become big problems afterward.

Based on these results, it is reasonable to undertake device implantation without interruption of a vitamin K antagonist such as warfarin.

Patients on direct oral anticoagulants: The jury is still out

The similar BRUISE CONTROL-2 trial is currently under way, comparing interruption vs continuation of dabigatran for patients undergoing cardiac device surgery.

In Europe, surgeons are less concerned than those in the United States about operating while a patient is on anticoagulant therapy. But the safety of this practice is not backed by strong evidence.

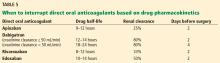

Direct oral anticoagulants: Consider pharmacokinetics

Direct oral anticoagulants are potent and fast-acting, with a peak effect 1 to 3 hours after intake. This rapid anticoagulant action is similar to that of bridging with low-molecular-weight heparin, and caution is needed when administering direct oral anticoagulants, especially after major surgery or surgery with a high bleeding risk.

Frost et al20 compared the pharmacokinetics of apixaban (with twice-daily dosing) and rivaroxaban (once-daily dosing) and found that peak anticoagulant activity is faster and higher with rivaroxaban. This is important, because many patients will take their anticoagulant first thing in the morning. Consequently, if patients require any kind of procedure (including dental), they should skip the morning dose of the direct oral anticoagulant to avoid having the procedure done during the peak anticoagulant effect, and they should either not take that day’s dose or defer the dose until the evening after the procedure.

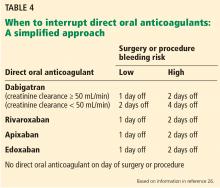

MANAGING SURGERY FOR PATIENTS ON A DIRECT ORAL ANTICOAGULANT

Case 3: An elderly woman on apixaban facing surgery

Let us imagine that our previous patient takes apixaban instead of warfarin. She is 75 years old, has atrial fibrillation, and is about to undergo elective colon resection for cancer. One doctor advises her to simply stop apixaban for 2 days, while another says she should go off apixaban for 5 days and will need bridging. Which plan is best?

In the perioperative setting, our goal is to interrupt patients’ anticoagulant therapy for the shortest time that results in no residual anticoagulant effect at the time of the procedure.

They further recommend that if the risk of venous thromboembolism is high, low-molecular-weight heparin bridging should be done while stopping the direct oral anticoagulant, with the heparin discontinued 24 hours before the procedure. This recommendation seems counterintuitive, as it is advising replacing a short-acting anticoagulant with low-molecular-weight heparin, another short-acting anticoagulant.

The guidelines committee was unable to provide strength and grading of their recommendations, as too few well-designed studies are available to support them. The doctor in case 3 who advised stopping apixaban for 5 days and bridging is following the guidelines, but without much evidence to support this strategy.

Is bridging needed during interruption of a direct oral anticoagulant?

There are no randomized, controlled trials of bridging vs no bridging in patients taking direct oral anticoagulants. Substudies exist of patients taking these drugs for atrial fibrillation who had treatment interrupted for procedures, but the studies did not randomize bridging vs no bridging, nor were bridging regimens standardized. Three of the four atrial fibrillation trials had a blinded design (warfarin vs direct oral anticoagulants), making perioperative management difficult, as physicians did not know the pharmacokinetics of the drugs their patients were taking.22–24

We used the database from the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial22 to evaluate bridging in patients taking either warfarin or dabigatran. With an open-label study design (the blinding was only for the 110 mg and 150 mg dabigatran doses), clinicians were aware of whether patients were receiving warfarin or dabigatran, thereby facilitating perioperative management. Among dabigatran-treated patients, those who were bridged had significantly more major bleeding than those not bridged (6.5% vs 1.8%, P < .001), with no difference between the groups for stroke or systemic embolism. Although it is not a randomized controlled trial, it does provide evidence that bridging may not be advisable for patients taking a direct oral anticoagulant.

The 2017 American College of Cardiology guidelines25 conclude that parenteral bridging is not indicated for direct oral anticoagulants. Although this is not based on strong evidence, the guidance appears reasonable according to the evidence at hand.

The 2017 American Heart Association Guidelines16 recommend a somewhat complex approach based on periprocedural bleeding risk and thromboembolic risk.

How long to interrupt direct oral anticoagulants?

Evidence for this approach comes from a prospective cohort study27 of 541 patients being treated with dabigatran who were having an elective surgery or invasive procedure. Patients received standard perioperative management, with the timing of the last dabigatran dose before the procedure (24 hours, 48 hours, or 96 hours) based on the bleeding risk of surgery and the patient’s creatinine clearance. Dabigatran was resumed 24 to 72 hours after the procedure. No heparin bridging was done. Patients were followed for up to 30 days postoperatively. The results were favorable with few complications: one transient ischemic attack (0.2%), 10 major bleeding episodes (1.8%), and 28 minor bleeding episodes (5.2%).

A subgroup of 181 patients in this study28 had a plasma sample drawn just before surgery, allowing the investigators to assess the level of coagulation factors after dabigatran interruption. Results were as follows:

- 93% had a normal prothrombin time

- 80% had a normal activated partial thromboplastin time

- 33% had a normal thrombin time

- 81% had a normal dilute thrombin time.

The dilute thrombin time is considered the most reliable test of the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran but is not widely available. The activated partial thromboplastin time can provide a more widely used coagulation test to assess (in a less precise manner) whether there is an anticoagulant effect of dabigatran present, and more sensitive activated partial thromboplastin time assays can be used to better detect any residual dabigatran effect.

Dabigatran levels were also measured. Although 66% of patients had low drug levels just before surgery, the others still had substantial dabigatran on board. The fact that bleeding event rates were so low in this study despite the presence of dabigatran in many patients raises the question of whether having some drug on board is a good predictor of bleeding risk.

An interruption protocol with a longer interruption interval—12 to 14 hours longer than in the previous study (3 days for high-bleed risk procedures, 2 days for low-bleed risk procedures)—brought the activated partial thromboplastin time and dilute thrombin time to normal levels for 100% of patients with the protocol for high-bleeding-risk surgery. This study was based on small numbers and its interruption strategy needs further investigation.29

Case 3 continued

The PAUSE study (NCT02228798), a multicenter, prospective cohort study, is designed to establish a safe, standardized protocol for the perioperative management of patients with atrial fibrillation taking dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban and will include 3,300 patients.

PATIENTS WITH A CORONARY STENT WHO NEED SURGERY

Case 4: A woman with a stent facing surgery

A 70-year-old woman needs breast cancer resection. She has coronary artery disease and had a drug-eluting stent placed 5 months ago after elective cardiac catheterization. She also has hypertension, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Her medications include an angiotensin II receptor blocker, hydrochlorothiazide, insulin, and an oral hypoglycemic. She is also taking aspirin 81 mg daily and ticagrelor (a P2Y12 receptor antagonist) 90 mg twice daily.

Her cardiologist is concerned that stopping antiplatelet therapy could trigger acute stent thrombosis, which has a 50% or higher mortality rate.

Should she stop taking aspirin before surgery? What about the ticagrelor?

Is aspirin safe during surgery?

Evidence concerning aspirin during surgery comes from Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2 (POISE-2), a double-blind, randomized controlled trial.30 Patients who had known cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease and were about to undergo noncardiac surgery were stratified according to whether they had been taking aspirin before the study (patients taking aspirin within 72 hours of the surgery were excluded from randomization). Participants in each group were randomized to take either aspirin or placebo just before surgery. The primary outcome was the combined rate of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction 30 days after randomization.

The study found no differences in the primary end point between the two groups. However, major bleeding occurred significantly more often in the aspirin group (4.6% vs 3.8%, hazard ratio 1.2, 95% confidence interval 1.0–1.5).

Moreover, only 4% of the patients in this trial had a cardiac stent. The trial excluded patients who had had a bare-metal stent placed within 6 weeks or a drug-eluting stent placed within 1 year, so it does not help us answer whether aspirin should be stopped for our current patient.

Is surgery safe for patients with stents?

The safety of undergoing surgery with a stent was investigated in a large US Veterans Administration retrospective cohort study.31 More than 20,000 patients with stents who underwent noncardiac surgery within 2 years of stent placement were compared with a control group of more than 41,000 patients with stents who did not undergo surgery. Patients were matched by stent type and cardiac risk factors at the time of stent placement.

The risk of an adverse cardiac event in both the surgical and nonsurgical cohorts was highest in the initial 6 weeks after stent placement and plateaued 6 months after stent placement, when the risk difference between the surgical and nonsurgical groups leveled off to 1%.

The risk of a major adverse cardiac event postoperatively was much more dependent on the timing of stent placement in complex and inpatient surgeries. For outpatient surgeries, the risk of a major cardiac event was very low and the timing of stent placement did not matter.

A Danish observational study32 compared more than 4,000 patients with drug-eluting stents having surgery to more than 20,000 matched controls without coronary heart disease having similar surgery. The risk of myocardial infarction or cardiac death was much higher for patients undergoing surgery within 1 month after drug-eluting stent placement compared with controls without heart disease and patients with stent placement longer than 1 month before surgery.

Our practice is to continue aspirin for surgery in patients with coronary stents regardless of the timing of placement. Although there is a small increased risk of bleeding, this must be balanced against thrombotic risk. We typically stop clopidogrel 5 to 7 days before surgery and ticagrelor 3 to 5 days before surgery. We may decide to give platelets before very-high-risk surgery (eg, intracranial, spinal) if there is a decision to continue both antiplatelet drugs—for example, in a patient who recently received a drug-eluting stent (ie, within 3 months). It is essential to involve the cardiologist and surgeon in these decisions.

BOTTOM LINE

- Kearon C, Aki EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016; 149:315–352.

- Enden T, Haig Y, Klow NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 379:31–38.

- Haig Y, Enden T, Grotta O, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Post-thrombotic syndrome after catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep vein thrombosis (CaVenT): 5-year follow-up results of an open-label, randomized controlled trial. Lancet Haematol 2016; 3:e64–e71.

- Vedantham S, Goldhaber SZ, Kahn SR, et al. Rationale and design of the ATTRACT Study: a multicenter randomized trial to evaluate pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for the prevention of postthrombotic syndrome in patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis. Am Heart J 2013; 165:523–530.

- Van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, Middeldorp S, Buller HR. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood 2014; 124:1968–1975.

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, et al; BRIDGE Investigators. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:823–833.

- Douketis J, Johnson JA, Turpie AG. Low-molecular-weight heparin as bridging anticoagulation during interruption of warfarin: assessment of a standardized periprocedural anticoagulation regimen. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164:1319–1326.

- Dunn AS, Spyropoulos AC, Turpie AG. Bridging therapy in patients on long-term oral anticoagulants who require surgery: the Prospective Peri-operative Enoxaparin Cohort Trial (PROSPECT). J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5:2211–2218.

- Kovacs MJ, Kearon C, Rodger M, et al. Single-arm study of bridging therapy with low-molecular-weight heparin for patients at risk of arterial embolism who require temporary interruption of warfarin. Circulation 2004; 110:1658–1663.

- Spyropoulos AC, Turpie AG, Dunn AS, et al; REGIMEN Investigators. Clinical outcomes with unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin as bridging therapy in patients on long-term oral anticoagulants: the REGIMEN registry. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:1246–1252.

- Douketis JD, Woods K, Foster GA, Crowther MA. Bridging anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin after interruption of warfarin therapy is associated with a residual anticoagulant effect prior to surgery. Thromb Haemost 2005; 94:528–531.

- Schulman S, Hwang HG, Eikelboom JW, Kearon C, Pai M, Delaney J. Loading dose vs. maintenance dose of warfarin for reinitiation after invasive procedures: a randomized trial. J Thromb Haemost 2014; 12:1254-1259.

- Siegal D, Yudin J, Kaatz S, Douketis JD, Lim W, Spyropoulos AC. Periprocedural heparin bridging in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists: systematic review and meta-analysis of bleeding and thromboembolic rates. Circulation 2012; 126:1630–1639.

- Skeith L, Taylor J, Lazo-Langner A, Kovacs MJ. Conservative perioperative anticoagulation management in patients with chronic venous thromboembolic disease: a cohort study. J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10:2298–2304.

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2012; 141(2 suppl):e326S–e350S.

- Doherty JU, Gluckman TJ, Hucker WJ, et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69:871–898.

- Raval AN, Cigarroa JE, Chung MK, et al; American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology Subcommittee of the Acute Cardiac Care and General Cardiology Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Management of patients on non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in the acute care and periprocedural setting: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 135:e604–e633.

- Tafur A, Douketis J. Perioperative anticoagulant management in patients with atrial fibrillation: practical implications of recent clinical trials. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2015; 125:666–671.

- Birnie DH, Healey JS, Wells GA, et al: BRUISE CONTROL Investigators. Pacemaker or defibrillator surgery without interruption of anticoagulation. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:2084–2093.

- Frost C, Song Y, Barrett YC, et al. A randomized direct comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of apixaban and rivaroxaban. Clin Pharmacol 2014; 6:179–187.

- Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano DA, et al. Interventional spine and pain procedures in patients on antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications: guidelines from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World institute of Pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2015; 40:182–212.

- Douketis JD, Healey JS, Brueckmann M, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation during dabigatran or warfarin interruption among patients who had an elective surgery or procedure. Substudy of the RE-LY trial. Thromb Haemost 2015; 113:625–632.

- Steinberg BA, Peterson ED, Kim S, et al; Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators and Patients. Use and outcomes associated with bridging during anticoagulation interruptions in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF). Circulation 2015; 131:488–494.

- Garcia D, Alexander JH, Wallentin L, et al. Management and clinical outcomes in patients treated with apixaban vs warfarin undergoing procedures. Blood 2014; 124:3692–3698.

- Doherty JU, Gluckman TJ, Hucker WJ, et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69:871–898.

- Thrombosis Canada. NOACs/DOACs: Peri-operative management. http://thrombosiscanada.ca/?page_id=18#. Accessed August 30, 2017.

- Schulman S, Carrier M, Lee AY, et al; Periop Dabigatran Study Group. Perioperative management of dabigatran: a prospective cohort study. Circulation 2015; 132:167–173.

- Douketis JD, Wang G, Chan N, et al. Effect of standardized perioperative dabigatran interruption on the residual anticoagulation effect at the time of surgery or procedure. J Thromb Haemost 2016; 14:89–97.

- Douketis JD, Syed S, Schulman S. Periprocedural management of direct oral anticoagulants: comment on the 2015 American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine guidelines. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016; 41:127–129.

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al; POISE-2 Investigators. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1494–1503.

- Holcomb CN, Graham LA, Richman JS, et al. The incremental risk of noncardiac surgery on adverse cardiac events following coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:2730–2739.

- Egholm G, Kristensen SD, Thim T, et al. Risk associated with surgery within 12 months after coronary drug-eluting stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68:2622–2632.

This article reviews recommendations and evidence concerning current anticoagulant management for venous thromboembolism and perioperative care, with an emphasis on individualizing treatment for real-world patients.

TREATING ACUTE VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM

Case 1: Deep vein thrombosis in an otherwise healthy man

A 40-year-old man presents with 7 days of progressive right leg swelling. He has no antecedent risk factors for deep vein thrombosis or other medical problems. Venous ultrasonography reveals an iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. How should he be managed?

- Outpatient treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin for 4 to 6 days plus warfarin

- Outpatient treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant, ie, apixaban, dabigatran (which requires 4 to 6 days of initial treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin), or rivaroxaban

- Catheter-directed thrombolysis followed by low-molecular-weight heparin, then warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant

- Inpatient intravenous heparin for 7 to 10 days, then warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant

All of these are acceptable for managing acute venous thromboembolism, but the clinician’s role is to identify which treatment is most appropriate for an individual patient.

Deep vein thrombosis is not a single condition

Multiple guidelines exist to help decide on a management strategy. Those of the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP)1 are used most often.

That said, guidelines are established for “average” patients, so it is important to look beyond guidelines and individualize management. Venous thromboembolism is not a single entity; it has a myriad of clinical presentations that could call for different treatments. Most patients have submassive deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, which is not limb-threatening nor associated with hemodynamic instability. It can also differ in terms of etiology and can be unprovoked (or idiopathic), cancer-related, catheter-associated, or provoked by surgery or immobility.

Deep vein thrombosis has a wide spectrum of presentations. It can involve the veins of the calf only, or it can involve the femoral and iliac veins and other locations including the splanchnic veins, the cerebral sinuses, and upper extremities. Pulmonary embolism can be massive (defined as being associated with hemodynamic instability or impending respiratory failure) or submassive. Similarly, patients differ in terms of baseline medical conditions, mobility, and lifestyle. Anticoagulant management decisions should take all these factors into account.

Consider clot location

Our patient with iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis is best managed differently than a more typical patient with less extensive thrombosis that would involve the popliteal or femoral vein segments, or both. A clot that involves the iliac vein is more likely to lead to postthrombotic chronic pain and swelling as the lack of venous outflow bypass channels to circumvent the clot location creates higher venous pressure within the affected leg. Therefore, for our patient, catheter-directed thrombolysis is an option that should be considered.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis trials