User login

VIDEO: Trial posts null results for Helicobacter screening, eradication

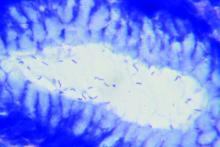

Compared with usual care, screening for and the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection did not significantly improve the risk of dyspepsia or peptic ulcer disease, use of health care services, or quality of life in a large randomized, controlled trial reported in the November issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.006).

After 13 years of follow-up, the prevalence of dyspepsia was 19% in both arms (adjusted odds ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.82-1.04), reported Maria Bomme, MD, of University of Southern Denmark (Odense), and her associates. The cumulative risk of the coprimary endpoint, peptic ulcer disease, was 3% in both groups (risk ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.09). Screening and eradication also did not affect secondary endpoints such as rates of gastroesophageal reflux, endoscopy, antacid use, or health care utilization, or mental and physical quality of life.

The study “was designed to provide evidence on the effect of H. pylori screening at a population scale,” the researchers wrote. “It showed no significant long-term effect of population screening when compared with current clinical practice in a low-prevalence area.”

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Prior studies have suggested that eradicating H. pylori infection might help prevent peptic ulcers and dyspepsia and could reduce the risk of gastric cancer, the researchers noted. For this trial, they randomly assigned 20,011 adults aged 40-65 years from a single county in Denmark to receive H. pylori screening or usual care. Screening consisted of an outpatient blood test for H. pylori, which was confirmed by 13C-urea breath test (UBT) if positive. Individuals with confirmed infections were offered triple eradication therapy (20 mg omeprazole, 500 mg clarithromycin, and either 1 g amoxicillin or 500 mg metronidazole) twice daily for 1 week. This regimen eradicated 95% of infections, based on UBT results from a subset of 200 individuals.

Compared with nonparticipants, the 12,530 (63%) study enrollees were significantly more likely to be female, 50 years or older, married, and to have a history of peptic ulcer disease. Rates of follow-up were 92% at 1 year, 83% at 5 years, and 69% (8,658 individuals) at 13 years. Among 5,749 screened participants, 17.5% tested positive for H. pylori. Nearly all underwent eradication therapy. At 5 years, screening and eradication were associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of peptic ulcers and associated complications and with modest improvements in dyspepsia, health care visits for dyspepsia, and sick leave days, compared with usual care. But the prevalence of dyspepsia waned in both groups over time and did not significantly differ between groups at 13 years in either the intention-to-treat or per-protocol analysis. Likewise, annual rates of peptic ulcer disease were very similar (1.9 cases/1,000 screened individuals and 2.2 cases/1,000 controls; incidence rate ratio, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.69-1.10). Rates of gastroesophageal cancer also were similar among groups throughout the study.

Screening for and eradicating H. pylori also did not affect the likelihood of dyspepsia or peptic ulcer disease at 13 years among individuals who were dyspeptic at baseline, the researchers said. The relatively low prevalence of H. pylori infection in Denmark might have diluted the effects of screening and eradication, they added.

Funders included the Region of Southern Denmark, the department of clinical research at the University of Southern Denmark, the Odense University Hospital research board, and the Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation, Beckett- Fonden, and Helsefonden. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Compared with usual care, screening for and the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection did not significantly improve the risk of dyspepsia or peptic ulcer disease, use of health care services, or quality of life in a large randomized, controlled trial reported in the November issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.006).

After 13 years of follow-up, the prevalence of dyspepsia was 19% in both arms (adjusted odds ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.82-1.04), reported Maria Bomme, MD, of University of Southern Denmark (Odense), and her associates. The cumulative risk of the coprimary endpoint, peptic ulcer disease, was 3% in both groups (risk ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.09). Screening and eradication also did not affect secondary endpoints such as rates of gastroesophageal reflux, endoscopy, antacid use, or health care utilization, or mental and physical quality of life.

The study “was designed to provide evidence on the effect of H. pylori screening at a population scale,” the researchers wrote. “It showed no significant long-term effect of population screening when compared with current clinical practice in a low-prevalence area.”

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Prior studies have suggested that eradicating H. pylori infection might help prevent peptic ulcers and dyspepsia and could reduce the risk of gastric cancer, the researchers noted. For this trial, they randomly assigned 20,011 adults aged 40-65 years from a single county in Denmark to receive H. pylori screening or usual care. Screening consisted of an outpatient blood test for H. pylori, which was confirmed by 13C-urea breath test (UBT) if positive. Individuals with confirmed infections were offered triple eradication therapy (20 mg omeprazole, 500 mg clarithromycin, and either 1 g amoxicillin or 500 mg metronidazole) twice daily for 1 week. This regimen eradicated 95% of infections, based on UBT results from a subset of 200 individuals.

Compared with nonparticipants, the 12,530 (63%) study enrollees were significantly more likely to be female, 50 years or older, married, and to have a history of peptic ulcer disease. Rates of follow-up were 92% at 1 year, 83% at 5 years, and 69% (8,658 individuals) at 13 years. Among 5,749 screened participants, 17.5% tested positive for H. pylori. Nearly all underwent eradication therapy. At 5 years, screening and eradication were associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of peptic ulcers and associated complications and with modest improvements in dyspepsia, health care visits for dyspepsia, and sick leave days, compared with usual care. But the prevalence of dyspepsia waned in both groups over time and did not significantly differ between groups at 13 years in either the intention-to-treat or per-protocol analysis. Likewise, annual rates of peptic ulcer disease were very similar (1.9 cases/1,000 screened individuals and 2.2 cases/1,000 controls; incidence rate ratio, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.69-1.10). Rates of gastroesophageal cancer also were similar among groups throughout the study.

Screening for and eradicating H. pylori also did not affect the likelihood of dyspepsia or peptic ulcer disease at 13 years among individuals who were dyspeptic at baseline, the researchers said. The relatively low prevalence of H. pylori infection in Denmark might have diluted the effects of screening and eradication, they added.

Funders included the Region of Southern Denmark, the department of clinical research at the University of Southern Denmark, the Odense University Hospital research board, and the Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation, Beckett- Fonden, and Helsefonden. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Compared with usual care, screening for and the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection did not significantly improve the risk of dyspepsia or peptic ulcer disease, use of health care services, or quality of life in a large randomized, controlled trial reported in the November issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.006).

After 13 years of follow-up, the prevalence of dyspepsia was 19% in both arms (adjusted odds ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.82-1.04), reported Maria Bomme, MD, of University of Southern Denmark (Odense), and her associates. The cumulative risk of the coprimary endpoint, peptic ulcer disease, was 3% in both groups (risk ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.09). Screening and eradication also did not affect secondary endpoints such as rates of gastroesophageal reflux, endoscopy, antacid use, or health care utilization, or mental and physical quality of life.

The study “was designed to provide evidence on the effect of H. pylori screening at a population scale,” the researchers wrote. “It showed no significant long-term effect of population screening when compared with current clinical practice in a low-prevalence area.”

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Prior studies have suggested that eradicating H. pylori infection might help prevent peptic ulcers and dyspepsia and could reduce the risk of gastric cancer, the researchers noted. For this trial, they randomly assigned 20,011 adults aged 40-65 years from a single county in Denmark to receive H. pylori screening or usual care. Screening consisted of an outpatient blood test for H. pylori, which was confirmed by 13C-urea breath test (UBT) if positive. Individuals with confirmed infections were offered triple eradication therapy (20 mg omeprazole, 500 mg clarithromycin, and either 1 g amoxicillin or 500 mg metronidazole) twice daily for 1 week. This regimen eradicated 95% of infections, based on UBT results from a subset of 200 individuals.

Compared with nonparticipants, the 12,530 (63%) study enrollees were significantly more likely to be female, 50 years or older, married, and to have a history of peptic ulcer disease. Rates of follow-up were 92% at 1 year, 83% at 5 years, and 69% (8,658 individuals) at 13 years. Among 5,749 screened participants, 17.5% tested positive for H. pylori. Nearly all underwent eradication therapy. At 5 years, screening and eradication were associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of peptic ulcers and associated complications and with modest improvements in dyspepsia, health care visits for dyspepsia, and sick leave days, compared with usual care. But the prevalence of dyspepsia waned in both groups over time and did not significantly differ between groups at 13 years in either the intention-to-treat or per-protocol analysis. Likewise, annual rates of peptic ulcer disease were very similar (1.9 cases/1,000 screened individuals and 2.2 cases/1,000 controls; incidence rate ratio, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.69-1.10). Rates of gastroesophageal cancer also were similar among groups throughout the study.

Screening for and eradicating H. pylori also did not affect the likelihood of dyspepsia or peptic ulcer disease at 13 years among individuals who were dyspeptic at baseline, the researchers said. The relatively low prevalence of H. pylori infection in Denmark might have diluted the effects of screening and eradication, they added.

Funders included the Region of Southern Denmark, the department of clinical research at the University of Southern Denmark, the Odense University Hospital research board, and the Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation, Beckett- Fonden, and Helsefonden. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Screening for and eradicating H. pylori infections did not significantly improve long-term prevalence of dyspepsia, incidence of peptic ulcer disease, use of health care services, or quality of life.

Major finding: At 13-year follow-up, both arms had a 19% prevalence of dyspepsia (aOR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.82-1.04) and a 3% cumulative incidence of peptic ulcer disease (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.79-1.09).

Data source: A randomized controlled trial of 8,658 adults aged 40-65 years

Disclosures: Funders included the Region of Southern Denmark, the department of clinical research at the University of Southern Denmark, the Odense University Hospital research board, and the Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation, Beckett- Fonden, and Helsefonden. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Alcohol showed no cardiovascular benefits in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Alcohol consumption produced no apparent cardiovascular benefits among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, according to a study of 570 white and black adults from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) longitudinal cohort.

After researchers controlled for multiple demographic and clinical confounders, alcohol use was not associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia, nor with homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, C-reactive protein level, total cholesterol, systolic or diastolic blood pressure, coronary artery calcification, E/A ratio, or global longitudinal strain among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), reported Lisa B. VanWagner, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and her associates. “[A] recommendation of cardiovascular disease risk benefit of alcohol use in persons with NAFLD cannot be made based on the current findings,” they wrote. They advocated for prospective, long-term studies to better understand how various types and doses of alcohol affect hard cardiovascular endpoints in patients with NAFLD. Their study was published in Gastroenterology.

CARDIA enrolled 5,115 black and white adults aged 18-30 years from four cities in the United States, and followed them long term. Participants were asked about alcohol consumption at study entry and again at 15, 20, and 25 years of follow-up. At year 25, participants underwent computed tomography (CT) examinations of the thorax and abdomen and tissue Doppler echocardiography with myocardial strain measured by speckle tracking (Gastroenterology. 2017 Aug 9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.012).

The 570 participants with NAFLD averaged 50 years of age, 54% were black, 46% were female, and 58% consumed at least one alcoholic drink per week, said the researchers. Compared with nondrinkers, drinkers had attained significantly higher education levels, were significantly more likely to be white and male, and had a significantly lower average body mass index (34.4 kg/m2 vs. 37.3 kg/m2) and C-reactive protein level (4.2 vs. 6.1 mg per L), and a significantly lower prevalence of diabetes (23% vs. 37%), impaired glucose tolerance (42% vs. 49%), obesity (75% vs. 83%) and metabolic syndrome (55% vs. 66%) (P less than .05 for all comparisons). Drinkers and nondrinkers resembled each other in terms of lipid profiles, use of lipid-lowering medications, liver attenuation scores, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures, although significantly more nondrinkers used antihypertensive medications (46% vs.35%; P = .005).

Drinkers had a higher prevalence of coronary artery calcification, defined as Agatston score above 0 (42% vs. 34%), and the difference approached statistical significance (P = .05). However, after they adjusted for multiple potential confounders, the researchers found no link between alcohol consumption and risk factors for cardiovascular disease or between alcohol consumption and measures of subclinical cardiovascular disease. This finding persisted in sensitivity analyses that examined alcohol dose, binge drinking, history of cardiovascular events, and former heavy alcohol use.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Taken together, the findings “challenge the belief that alcohol use may reduce cardiovascular disease risk in persons with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,” the investigators concluded. Clinical heart failure was too rare to reliably assess, but “we failed to observe an association between alcohol use and multiple markers of subclinical changes in cardiac structure and function that may be precursors of incident heart failure in NAFLD,” they wrote. More longitudinal studies would be needed to clarify how moderate alcohol use in NAFLD affects coronary artery calcification or changes in myocardial structure and function, they cautioned.

The National Institutes of Health supported the work. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Alcohol consumption produced no apparent cardiovascular benefits among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, according to a study of 570 white and black adults from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) longitudinal cohort.

After researchers controlled for multiple demographic and clinical confounders, alcohol use was not associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia, nor with homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, C-reactive protein level, total cholesterol, systolic or diastolic blood pressure, coronary artery calcification, E/A ratio, or global longitudinal strain among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), reported Lisa B. VanWagner, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and her associates. “[A] recommendation of cardiovascular disease risk benefit of alcohol use in persons with NAFLD cannot be made based on the current findings,” they wrote. They advocated for prospective, long-term studies to better understand how various types and doses of alcohol affect hard cardiovascular endpoints in patients with NAFLD. Their study was published in Gastroenterology.

CARDIA enrolled 5,115 black and white adults aged 18-30 years from four cities in the United States, and followed them long term. Participants were asked about alcohol consumption at study entry and again at 15, 20, and 25 years of follow-up. At year 25, participants underwent computed tomography (CT) examinations of the thorax and abdomen and tissue Doppler echocardiography with myocardial strain measured by speckle tracking (Gastroenterology. 2017 Aug 9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.012).

The 570 participants with NAFLD averaged 50 years of age, 54% were black, 46% were female, and 58% consumed at least one alcoholic drink per week, said the researchers. Compared with nondrinkers, drinkers had attained significantly higher education levels, were significantly more likely to be white and male, and had a significantly lower average body mass index (34.4 kg/m2 vs. 37.3 kg/m2) and C-reactive protein level (4.2 vs. 6.1 mg per L), and a significantly lower prevalence of diabetes (23% vs. 37%), impaired glucose tolerance (42% vs. 49%), obesity (75% vs. 83%) and metabolic syndrome (55% vs. 66%) (P less than .05 for all comparisons). Drinkers and nondrinkers resembled each other in terms of lipid profiles, use of lipid-lowering medications, liver attenuation scores, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures, although significantly more nondrinkers used antihypertensive medications (46% vs.35%; P = .005).

Drinkers had a higher prevalence of coronary artery calcification, defined as Agatston score above 0 (42% vs. 34%), and the difference approached statistical significance (P = .05). However, after they adjusted for multiple potential confounders, the researchers found no link between alcohol consumption and risk factors for cardiovascular disease or between alcohol consumption and measures of subclinical cardiovascular disease. This finding persisted in sensitivity analyses that examined alcohol dose, binge drinking, history of cardiovascular events, and former heavy alcohol use.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Taken together, the findings “challenge the belief that alcohol use may reduce cardiovascular disease risk in persons with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,” the investigators concluded. Clinical heart failure was too rare to reliably assess, but “we failed to observe an association between alcohol use and multiple markers of subclinical changes in cardiac structure and function that may be precursors of incident heart failure in NAFLD,” they wrote. More longitudinal studies would be needed to clarify how moderate alcohol use in NAFLD affects coronary artery calcification or changes in myocardial structure and function, they cautioned.

The National Institutes of Health supported the work. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Alcohol consumption produced no apparent cardiovascular benefits among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, according to a study of 570 white and black adults from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) longitudinal cohort.

After researchers controlled for multiple demographic and clinical confounders, alcohol use was not associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia, nor with homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, C-reactive protein level, total cholesterol, systolic or diastolic blood pressure, coronary artery calcification, E/A ratio, or global longitudinal strain among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), reported Lisa B. VanWagner, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and her associates. “[A] recommendation of cardiovascular disease risk benefit of alcohol use in persons with NAFLD cannot be made based on the current findings,” they wrote. They advocated for prospective, long-term studies to better understand how various types and doses of alcohol affect hard cardiovascular endpoints in patients with NAFLD. Their study was published in Gastroenterology.

CARDIA enrolled 5,115 black and white adults aged 18-30 years from four cities in the United States, and followed them long term. Participants were asked about alcohol consumption at study entry and again at 15, 20, and 25 years of follow-up. At year 25, participants underwent computed tomography (CT) examinations of the thorax and abdomen and tissue Doppler echocardiography with myocardial strain measured by speckle tracking (Gastroenterology. 2017 Aug 9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.012).

The 570 participants with NAFLD averaged 50 years of age, 54% were black, 46% were female, and 58% consumed at least one alcoholic drink per week, said the researchers. Compared with nondrinkers, drinkers had attained significantly higher education levels, were significantly more likely to be white and male, and had a significantly lower average body mass index (34.4 kg/m2 vs. 37.3 kg/m2) and C-reactive protein level (4.2 vs. 6.1 mg per L), and a significantly lower prevalence of diabetes (23% vs. 37%), impaired glucose tolerance (42% vs. 49%), obesity (75% vs. 83%) and metabolic syndrome (55% vs. 66%) (P less than .05 for all comparisons). Drinkers and nondrinkers resembled each other in terms of lipid profiles, use of lipid-lowering medications, liver attenuation scores, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures, although significantly more nondrinkers used antihypertensive medications (46% vs.35%; P = .005).

Drinkers had a higher prevalence of coronary artery calcification, defined as Agatston score above 0 (42% vs. 34%), and the difference approached statistical significance (P = .05). However, after they adjusted for multiple potential confounders, the researchers found no link between alcohol consumption and risk factors for cardiovascular disease or between alcohol consumption and measures of subclinical cardiovascular disease. This finding persisted in sensitivity analyses that examined alcohol dose, binge drinking, history of cardiovascular events, and former heavy alcohol use.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Taken together, the findings “challenge the belief that alcohol use may reduce cardiovascular disease risk in persons with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,” the investigators concluded. Clinical heart failure was too rare to reliably assess, but “we failed to observe an association between alcohol use and multiple markers of subclinical changes in cardiac structure and function that may be precursors of incident heart failure in NAFLD,” they wrote. More longitudinal studies would be needed to clarify how moderate alcohol use in NAFLD affects coronary artery calcification or changes in myocardial structure and function, they cautioned.

The National Institutes of Health supported the work. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: No cardioprotective effects were shown with alcohol consumption in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Major finding: After researchers adjusted for multiple confounders, alcohol use was not associated with risk factors for cardiovascular disease or with indicators of subclinical cardiovascular disease.

Data source: A longitudinal, population-based study of 570 individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health supported the work. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

For treatment-resistant hypertension, drug urine screen advised

SAN FRANCISCO – The best way to make sure that patients are taking their blood pressure medications is to screen their urine for the drugs and metabolites, according to Robert Carey, MD, professor of medicine and dean emeritus of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Dr. Carey shared his thoughts on the matter during his presentation on treatment resistant hypertension, at the joint scientific sessions of the AHA Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

In up to about half the cases of apparent resistant hypertension, people simply aren’t taking their medications. Urine screening, “I believe, is the most accurate and best method of verifying adherence,” far more reliable than asking patients, or counting prescription refills, he said.

“I’m sort of a mad dog on documenting adherence because I think if we don’t document it and treat it, we will be stuck with a lot of inertia, and things won’t get better,” Dr. Carey said. He recommended speaking with patients, getting their permission to check urine levels, and reporting back results. It won’t make a difference in every case, but sometimes it will, especially if there’s an intervention to improve adherence, he noted.

Urine screening is available in most teaching hospitals and in commercial labs. “I think we will be seeing more and more availability. It has been demonstrated to be cost effective,” he said.

If adherence isn’t a problem, obesity, high sodium intake, and other lifestyle issues should be addressed, as well as the use of drugs that can raise blood pressure, especially NSAIDS, contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapies.

A workup for secondary causes also is in order. About 20% of patients will have primary aldosteronism, so all patients should be screened. Renal parenchymal disease and renal vascular disease also are common. Renal artery stenosis usually can be managed medically and rarely requires stenting. “One might take the tack of nonscreening until there’s a reduction in renal function or blood pressure goes way out of control,” Dr. Carey said.

Pheochromocytoma and Cushing’s syndrome are rare causes. Obstructive sleep apnea also is on the list “but I’m not sure it should be there. For one thing, CPAP [continuous positive airway pressure] only lowers blood pressure 1 or 2 mm. Secondly, CPAP does not prevent cardiovascular disease events in patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and established cardiovascular risk,” he said.

If there’s no secondary cause that can be addressed, “the first thing to do is check the diuretic, and substitute in a long-acting, thiazide-like diuretic, either chlorthalidone or indapamide.” They lower blood pressure more effectively than do the thiazide diuretics, such as chlorothiazide and hydrochlorothiazide. They also provide better protection against cardiovascular events. “Once you make that substitution, you need to add a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, spironolactone or eplerenone. We have excellent data for both [classes of] diuretics to be added,” Dr. Carey said.

“Once we get beyond that point, we have to search the literature, and generally, we’ll come up with a goose egg in terms of randomized clinical trials. Another step is to add a beta-blocker or a vasodilating beta-blocker, [but] you would need to know precisely the mechanism of vasodilation,” he noted. After that, “you could add hydralazine or minoxidil,” a more potent vasodilator, but they have to be given with a beta-blocker and diuretic. If those approaches fail, “consider referring to a hypertension specialist,” he said.

Dr. Carey did not report any industry ties.

SAN FRANCISCO – The best way to make sure that patients are taking their blood pressure medications is to screen their urine for the drugs and metabolites, according to Robert Carey, MD, professor of medicine and dean emeritus of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Dr. Carey shared his thoughts on the matter during his presentation on treatment resistant hypertension, at the joint scientific sessions of the AHA Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

In up to about half the cases of apparent resistant hypertension, people simply aren’t taking their medications. Urine screening, “I believe, is the most accurate and best method of verifying adherence,” far more reliable than asking patients, or counting prescription refills, he said.

“I’m sort of a mad dog on documenting adherence because I think if we don’t document it and treat it, we will be stuck with a lot of inertia, and things won’t get better,” Dr. Carey said. He recommended speaking with patients, getting their permission to check urine levels, and reporting back results. It won’t make a difference in every case, but sometimes it will, especially if there’s an intervention to improve adherence, he noted.

Urine screening is available in most teaching hospitals and in commercial labs. “I think we will be seeing more and more availability. It has been demonstrated to be cost effective,” he said.

If adherence isn’t a problem, obesity, high sodium intake, and other lifestyle issues should be addressed, as well as the use of drugs that can raise blood pressure, especially NSAIDS, contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapies.

A workup for secondary causes also is in order. About 20% of patients will have primary aldosteronism, so all patients should be screened. Renal parenchymal disease and renal vascular disease also are common. Renal artery stenosis usually can be managed medically and rarely requires stenting. “One might take the tack of nonscreening until there’s a reduction in renal function or blood pressure goes way out of control,” Dr. Carey said.

Pheochromocytoma and Cushing’s syndrome are rare causes. Obstructive sleep apnea also is on the list “but I’m not sure it should be there. For one thing, CPAP [continuous positive airway pressure] only lowers blood pressure 1 or 2 mm. Secondly, CPAP does not prevent cardiovascular disease events in patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and established cardiovascular risk,” he said.

If there’s no secondary cause that can be addressed, “the first thing to do is check the diuretic, and substitute in a long-acting, thiazide-like diuretic, either chlorthalidone or indapamide.” They lower blood pressure more effectively than do the thiazide diuretics, such as chlorothiazide and hydrochlorothiazide. They also provide better protection against cardiovascular events. “Once you make that substitution, you need to add a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, spironolactone or eplerenone. We have excellent data for both [classes of] diuretics to be added,” Dr. Carey said.

“Once we get beyond that point, we have to search the literature, and generally, we’ll come up with a goose egg in terms of randomized clinical trials. Another step is to add a beta-blocker or a vasodilating beta-blocker, [but] you would need to know precisely the mechanism of vasodilation,” he noted. After that, “you could add hydralazine or minoxidil,” a more potent vasodilator, but they have to be given with a beta-blocker and diuretic. If those approaches fail, “consider referring to a hypertension specialist,” he said.

Dr. Carey did not report any industry ties.

SAN FRANCISCO – The best way to make sure that patients are taking their blood pressure medications is to screen their urine for the drugs and metabolites, according to Robert Carey, MD, professor of medicine and dean emeritus of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Dr. Carey shared his thoughts on the matter during his presentation on treatment resistant hypertension, at the joint scientific sessions of the AHA Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

In up to about half the cases of apparent resistant hypertension, people simply aren’t taking their medications. Urine screening, “I believe, is the most accurate and best method of verifying adherence,” far more reliable than asking patients, or counting prescription refills, he said.

“I’m sort of a mad dog on documenting adherence because I think if we don’t document it and treat it, we will be stuck with a lot of inertia, and things won’t get better,” Dr. Carey said. He recommended speaking with patients, getting their permission to check urine levels, and reporting back results. It won’t make a difference in every case, but sometimes it will, especially if there’s an intervention to improve adherence, he noted.

Urine screening is available in most teaching hospitals and in commercial labs. “I think we will be seeing more and more availability. It has been demonstrated to be cost effective,” he said.

If adherence isn’t a problem, obesity, high sodium intake, and other lifestyle issues should be addressed, as well as the use of drugs that can raise blood pressure, especially NSAIDS, contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapies.

A workup for secondary causes also is in order. About 20% of patients will have primary aldosteronism, so all patients should be screened. Renal parenchymal disease and renal vascular disease also are common. Renal artery stenosis usually can be managed medically and rarely requires stenting. “One might take the tack of nonscreening until there’s a reduction in renal function or blood pressure goes way out of control,” Dr. Carey said.

Pheochromocytoma and Cushing’s syndrome are rare causes. Obstructive sleep apnea also is on the list “but I’m not sure it should be there. For one thing, CPAP [continuous positive airway pressure] only lowers blood pressure 1 or 2 mm. Secondly, CPAP does not prevent cardiovascular disease events in patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and established cardiovascular risk,” he said.

If there’s no secondary cause that can be addressed, “the first thing to do is check the diuretic, and substitute in a long-acting, thiazide-like diuretic, either chlorthalidone or indapamide.” They lower blood pressure more effectively than do the thiazide diuretics, such as chlorothiazide and hydrochlorothiazide. They also provide better protection against cardiovascular events. “Once you make that substitution, you need to add a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, spironolactone or eplerenone. We have excellent data for both [classes of] diuretics to be added,” Dr. Carey said.

“Once we get beyond that point, we have to search the literature, and generally, we’ll come up with a goose egg in terms of randomized clinical trials. Another step is to add a beta-blocker or a vasodilating beta-blocker, [but] you would need to know precisely the mechanism of vasodilation,” he noted. After that, “you could add hydralazine or minoxidil,” a more potent vasodilator, but they have to be given with a beta-blocker and diuretic. If those approaches fail, “consider referring to a hypertension specialist,” he said.

Dr. Carey did not report any industry ties.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM JOINT HYPERTENSION 2017

October 2017 Digital Edition

Click here to access the October 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- A Mission for Graduate Medical Education at VA

- Trends in Hysterectomy Rates and Approaches in the VA

- A Severe Case of Paliperidone Palmitate-Induced Parkinsonism: Opportunities for Improvement

- A Case of Streptococcus pyogenes Sepsis of Possible Oral Origin

- Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

- Improving Care and Reducing Length of Stay in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Replacement

- Restoring Function in Veterans With Complex Chronic Pain

- Bearing the Standard

- FDA Updates

- NOVA Updates

Click here to access the October 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- A Mission for Graduate Medical Education at VA

- Trends in Hysterectomy Rates and Approaches in the VA

- A Severe Case of Paliperidone Palmitate-Induced Parkinsonism: Opportunities for Improvement

- A Case of Streptococcus pyogenes Sepsis of Possible Oral Origin

- Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

- Improving Care and Reducing Length of Stay in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Replacement

- Restoring Function in Veterans With Complex Chronic Pain

- Bearing the Standard

- FDA Updates

- NOVA Updates

Click here to access the October 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- A Mission for Graduate Medical Education at VA

- Trends in Hysterectomy Rates and Approaches in the VA

- A Severe Case of Paliperidone Palmitate-Induced Parkinsonism: Opportunities for Improvement

- A Case of Streptococcus pyogenes Sepsis of Possible Oral Origin

- Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

- Improving Care and Reducing Length of Stay in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Replacement

- Restoring Function in Veterans With Complex Chronic Pain

- Bearing the Standard

- FDA Updates

- NOVA Updates

Prescribing antipsychotics in geriatric patients: Focus on schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

Antipsychotics are FDA-approved as a primary treatment for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and as adjunctive therapy for major depressive disorder. In the United States, approximately 26% of antipsychotic prescriptions written for these indications are for individuals age >65.1 Additionally, antipsychotics are widely used to treat behavioral symptoms associated with dementia.1 The rapid expansion of the use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), in particular, has been driven in part by their lower risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) compared with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs).1 However, a growing body of data indicates that all antipsychotics have a range of adverse effects in older patients. This focus is critical in light of demographic trends—in the next 10 to 15 years, the population age >60 will grow 3.5 times more rapidly than the general population.2

In this context, psychiatrists need information on the relative risks of antipsychotics for older patients. This 3-part series summarizes findings and recommendations on safety and tolerability when prescribing antipsychotics in older individuals with chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and dementia. This review aims to:

- briefly summarize the major studies and analyses relevant to older patients with these diagnoses

- provide a summative opinion on safety and tolerability issues in these older adults

- highlight the gaps in the evidence base and areas that need additional research.

Part 1 focuses on older adults with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Subsequent articles will focus on prescribing antipsychotics to older adults with depression and those with dementia.

Schizophrenia

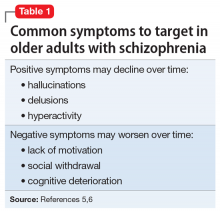

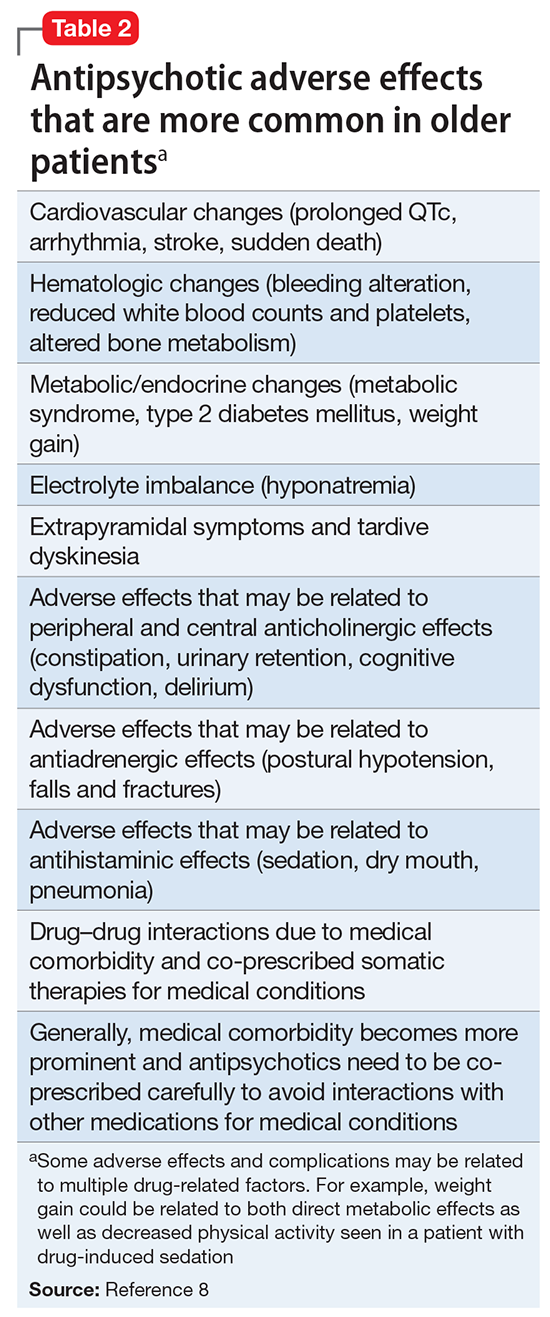

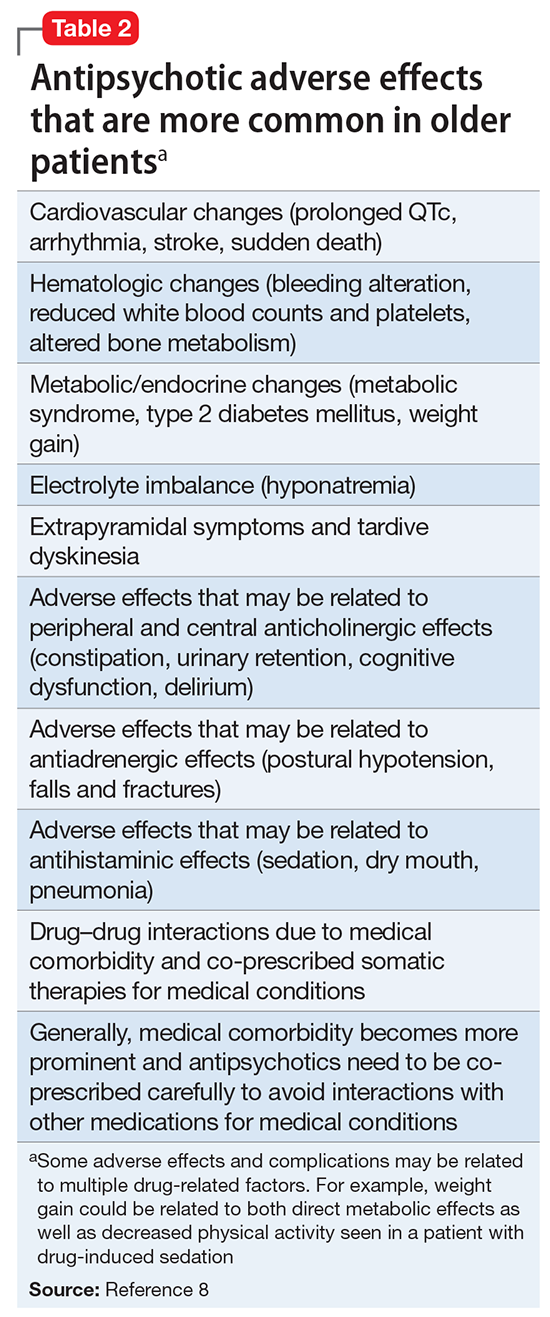

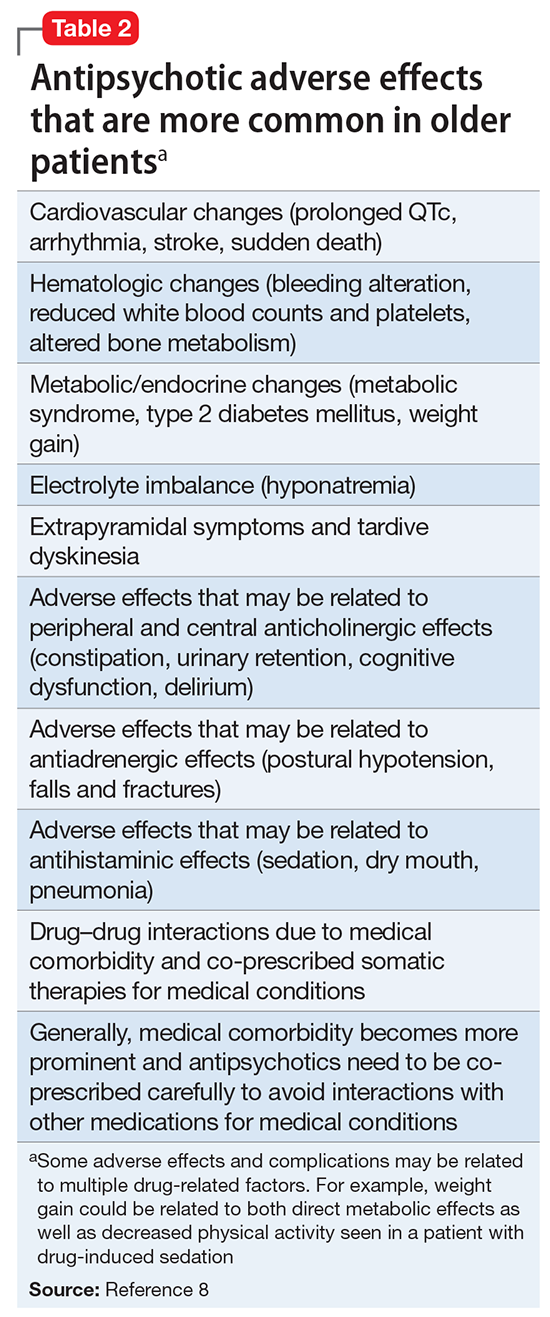

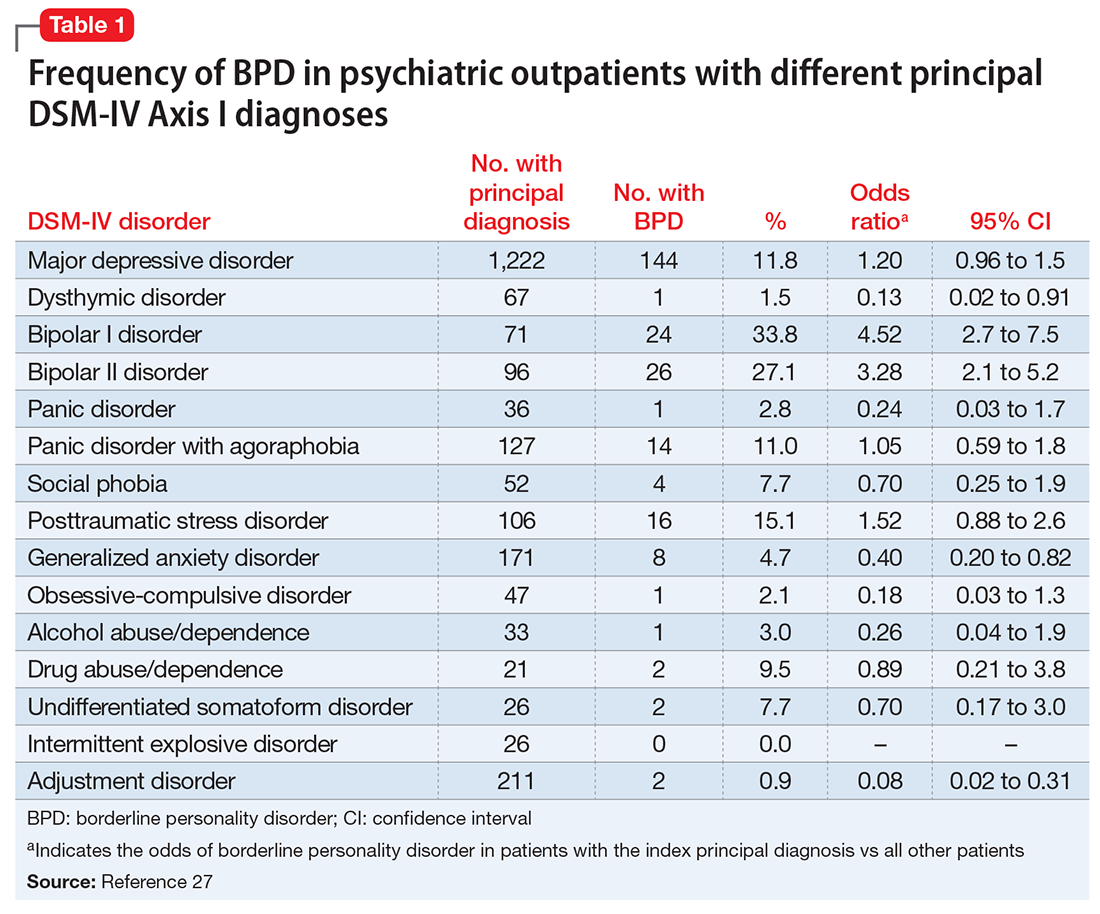

Summary of benefits, place in treatment armamentarium. Individuals with schizophrenia have a shorter life expectancy than that of the general population mostly as a result of suicide and comorbid physical illnesses,3 but the number of patients with schizophrenia age >55 will double over the next 2 decades.4 With aging, both positive and negative symptoms may be a focus of treatment (Table 1).5,6 Antipsychotics are a first-line treatment for older patients with schizophrenia with few medication alternatives.7 Safety risks associated with antipsychotics in older people span a broad spectrum (Table 2).8

A 6-week prospective RCT evaluated paliperidone extended-release vs placebo in 114 older adults (age ≥65 years; mean age, 70 years) with schizophrenia.14 There was an optional 24-week extension of open-label treatment with paliperidone. Mean daily dose of paliperidone was 8.4 mg. Efficacy measures did not show consistent statistically significant differences between treatment groups. Discontinuation rates were similar between paliperidone (7%) vs placebo (8%). Serious adverse events occurred in 3% of paliperidone-treated vs 8% of placebo-treated patients. Elevated prolactin levels occurred in one-half of paliperidone-treated patients. There were no prolactin or glucose treatment-related adverse events or significant mean changes in body weight for either paliperidone-treated or placebo-treated patients. Safety findings in the 24-week, open-label extension group were consistent with the RCT results.

Howanitz et al15 conducted a 12-week, prospective RCT that compared clozapine (mean dose, 300 mg/d) with chlorpromazine (mean dose, 600 mg/d) in 42 older adults (mean age, 67 years) with schizophrenia. Drop-out rate prior to 5 weeks was 19% and similar between groups. Common adverse effects included sialorrhea, hematologic abnormalities, sedation, tachycardia, EPS, and weight gain. Although both drugs were effective, more patients taking clozapine had tachycardia and weight gain, while more chlorpromazine patients reported sedation.

There have been other, less rigorous studies.7,8 Most of these studies evaluated risperidone and olanzapine, and most were conducted in “younger” geriatric patients (age <75 years). Although patients who participate in clinical trials may be healthier than “typical” patients, adverse effects such as EPS, sedation, and weight gain were still relatively common in these studies.

Other clinical data. A major consideration in treating older adults with schizophrenia is balancing the need to administer an antipsychotic dose high enough to alleviate psychotic symptoms while minimizing dose-dependent adverse effects. There is a U-shaped relationship between age and vulnerability to antipsychotic adverse effects,16,17 wherein adverse effects are highest at younger and older ages. Evidence supports using the lowest effective antipsychotic dose for geriatric patients with schizophrenia. Positive emission tomography (PET) studies suggest that older patients develop EPS with lower doses despite lower receptor occupancy.17,18 A recent study of 35 older patients (mean age, 60.1 years) with schizophrenia obtained PET, clinical measures, and blood pharmacokinetic measures before and after reduction of risperidone or olanzapine doses.18 A ≥40% reduction in dose was associated with reduced adverse effects, particularly EPS and elevation of prolactin levels. Moreover, the therapeutic window of striatal D2/D3 receptor occupancy appeared to be 50% to 60% in these older patients, compared with 65% to 80% in younger patients.

Long-term risks of antipsychotic treatment across the lifespan are less clear, with evidence suggesting both lower and higher mortality risk.19,20 It is difficult to fully disentangle the long-term risks of antipsychotics from the cumulative effects of lifestyle and comorbidity among individuals who have lived with schizophrenia for decades. Large naturalistic studies that include substantial numbers of older people with schizophrenia might be a way to elicit more information on long-term safety. The Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcome (SOHO) study was a large naturalistic trial that recruited >10,000 individuals with schizophrenia in 10 European countries.21 Although the SOHO study found differences between antipsychotics and adverse effects, such as EPS, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction, because the mean age of these patients was approximately 40 years and the follow-up period was only 3 years, it is difficult to draw conclusions that could be relevant to older individuals who have had schizophrenia for decades.

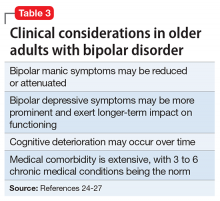

Bipolar Disorder

Clinical trials: Bipolar depression. A post hoc, secondary analysis of two 8-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies in bipolar depression compared 2 dosages of quetiapine (300 mg/d and 600 mg/d) with placebo in mixed-age patients.31 In a subgroup of 72 patients, ages 55 to 65, remission occurred more often with quetiapine than with placebo. Study discontinuation rates were similar between older people and younger people (age <55 years): quetiapine, 300 mg/d, 29.2%; quetiapine, 600 mg/d, 48.1%; and placebo, 29.6% in older adults, compared with 37.1%, 45.8%, and 38.1%, respectively, in younger adults. In all patients, the most common reason for discontinuation was adverse events with quetiapine and lack of efficacy for placebo. Adverse event rates were similar in older and younger adults. Dry mouth and dizziness were more common in older adults. Proportions of adults experiencing clinically significant weight gain (≥7% of body weight) were 5.3%, 8.3%, and 0% in older adults receiving quetiapine, 300 mg/d, quetiapine, 600 mg/d, and placebo, respectively, compared with 7.2%, 10.1%, and 2.6% in younger adults. EPS and treatment-emergent mania were minimal.

A secondary analysis of mixed-age, RCTs examined response in older adults (age ≥55 years) with bipolar I depression who received lurasidone as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.32 In the monotherapy study, these patients were randomized to 6 weeks of lurasidone 20 to 60 mg/d, lurasidone 80 to 120 mg/d, or placebo. In the adjunctive therapy study, they were randomized to lurasidone 20 to 120 mg/d or placebo with either lithium or valproate. There were 83 older adults (17.1% of the sample) in the monotherapy study and 53 (15.6%) in the adjunctive therapy study. Mean improvement in depression was significantly higher for both doses of lurasidone monotherapy than placebo. Adjunctive lurasidone was not associated with statistically significant improvement vs placebo. The most frequent adverse events in older patients on lurasidone monotherapy 20 to 60 mg/d or 80 to 120 mg/d were nausea (18.5% and 9.7%, respectively) and somnolence (11.1% and 0%, respectively). Akathisia (9.7%) and insomnia (9.7%) were the most common adverse events in the group receiving 80 to 120 mg/d, with the rate of akathisia exhibiting a dose-related increase. Weight change with lurasidone was similar to placebo, and there were no clinically meaningful group changes in vital signs, electrocardiography, or laboratory parameters.

A small (N = 20) open study found improvement in older adults with bipolar depression with aripiprazole (mean dose, 10.3 mg/d).33 Adverse effects included restlessness and weight gain (n = 3, 9% each), sedation (n = 2, 10%), and drooling and diarrhea/loose stools (n = 1, 5% each). In another small study (N = 15) using asenapine (mean dose, 11.2 mg/d) in mainly older bipolar patients with depression, the most common adverse effects were gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort (n = 5, 33%) and restlessness, tremors, cognitive difficulties, and sluggishness (n = 2, 13% each).34

Clinical trials: Bipolar mania. Researchers conducted a pooled analysis of two 12-week randomized trials comparing quetiapine with placebo in a mixed-age sample with bipolar mania.35 In a subgroup of 59 older patients (mean age, 62.9 years), manic symptoms improved significantly more with quetiapine (modal dose, 550 mg/d) than with placebo. Adverse effects reported by >10% of older patients were dry mouth, somnolence, postural hypotension, insomnia, weight gain, and dizziness. Insomnia was reported by >10% of patients receiving placebo.

In a case series of 11 elderly patients with mania receiving asenapine, Baruch et al36 reported a 63% remission rate. One patient discontinued the study because of a new rash, 1 discontinued after developing peripheral edema, and 3 patients reported mild sedation.

Beyer et al37 reported on a post hoc analysis of 94 older adults (mean age, 57.1 years; range, 50.1 to 74.8 years) with acute bipolar mania receiving olanzapine (n = 47), divalproex (n = 31), or placebo (n = 16) in a pooled olanzapine clinical trials database. Patients receiving olanzapine or divalproex had improvement in mania; those receiving placebo did not improve. Safety findings were comparable with reports in younger patients with mania.

Other clinical data. Adverse effects found in mixed-age samples using secondary analyses of clinical trials need to be interpreted with caution because these types of studies usually exclude individuals with significant medical comorbidity. Medical burden, cognitive impairment, or concomitant medications generally necessitate slower drug titration and lower total daily dosing. For example, a secondary analysis of the U.S. National Institute of Health-funded Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder study, which had broader inclusion criteria than most clinical trials, reported that, although recovery rates in older adults with bipolar disorder were fairly good (78.5%), lower doses of risperidone were used in older vs younger patients.38

Clinical considerations

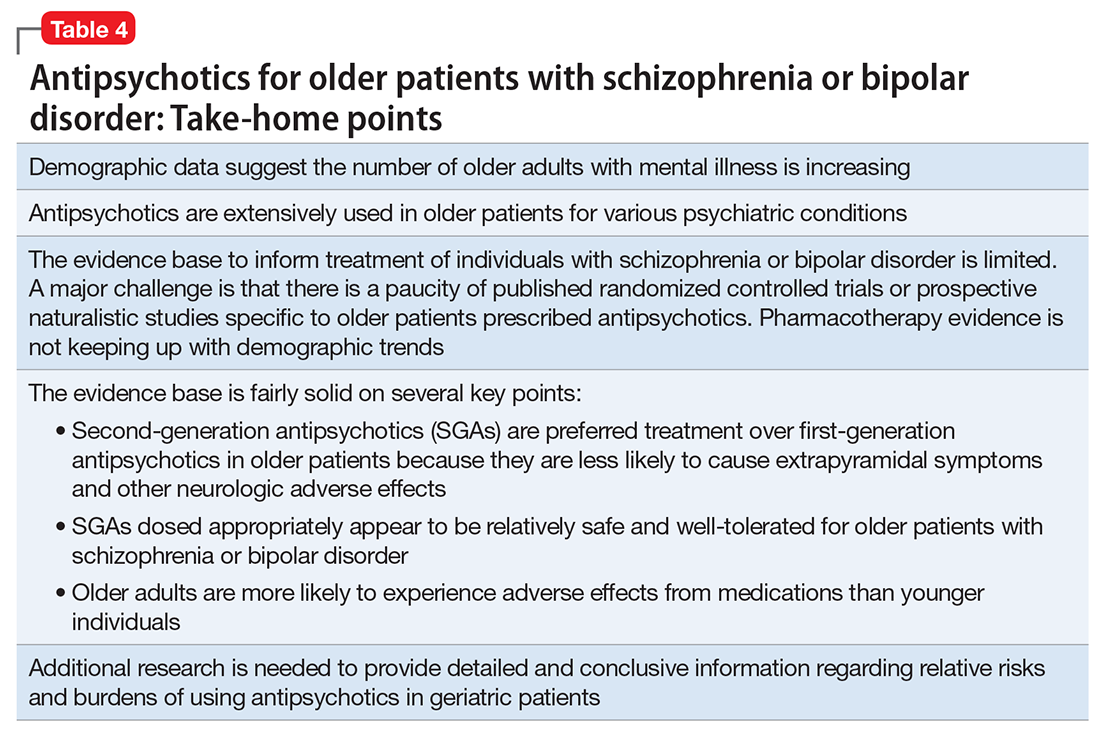

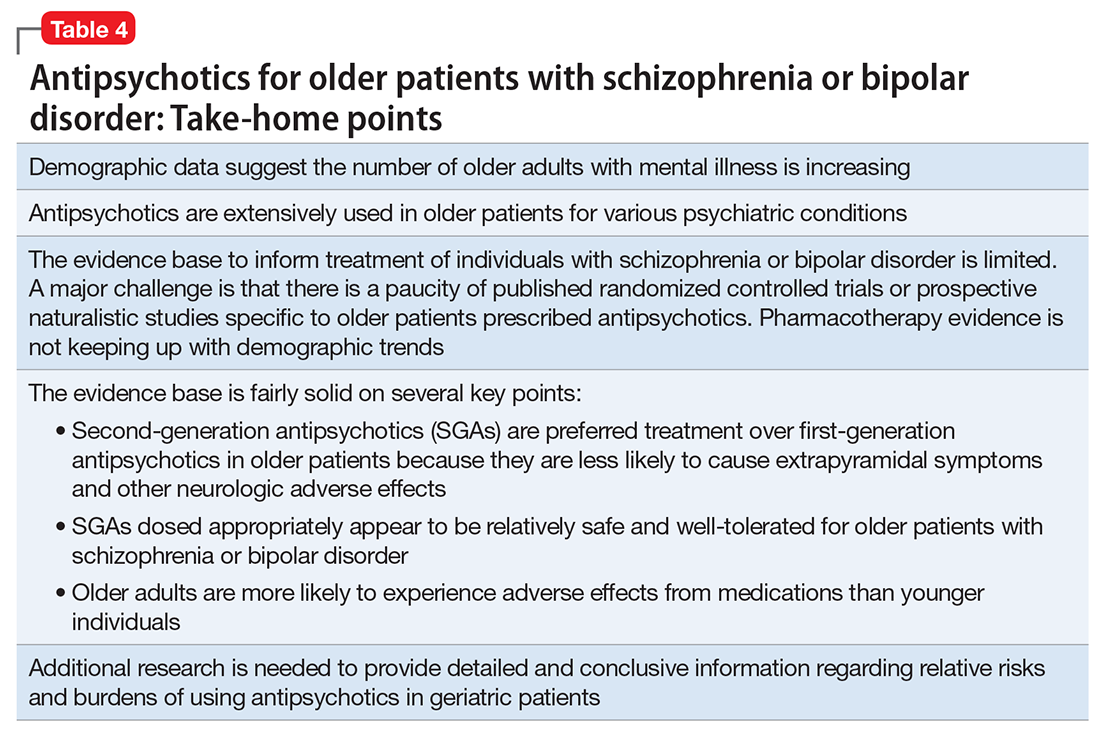

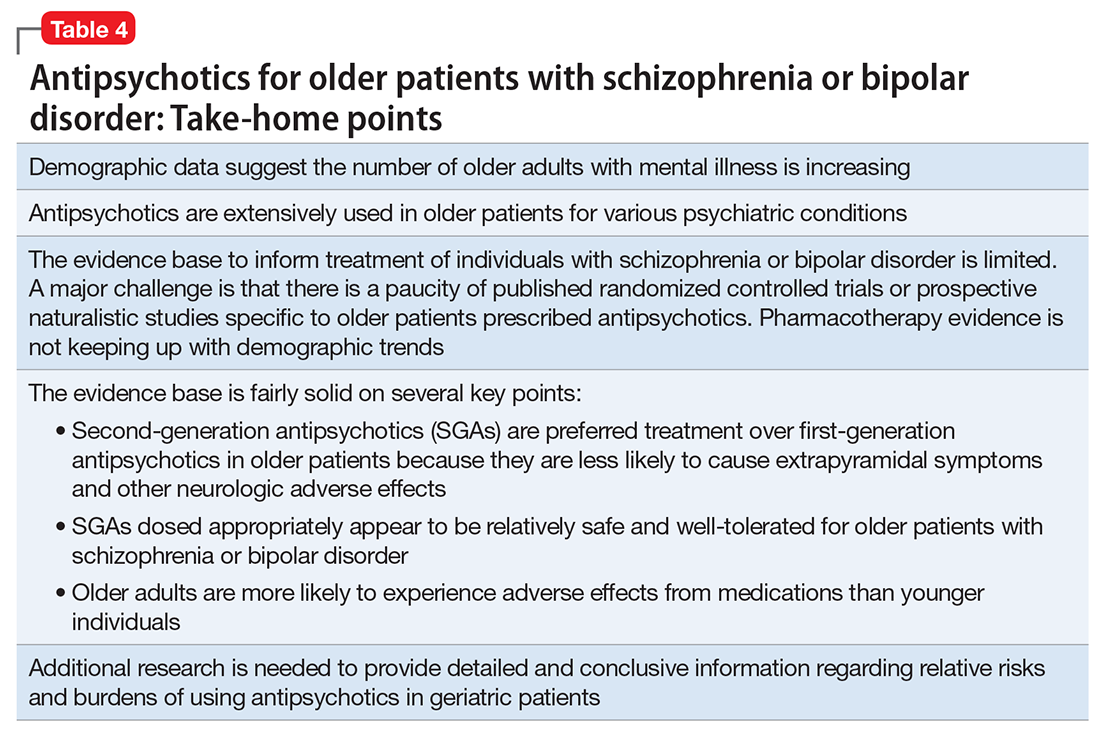

Interpretation of the relative risks of antipsychotics in older people must be tempered by the caveat that there is limited high-quality data (Table 4). Antipsychotics are the first-line therapy for older patients with schizophrenia, although their use is supported by a small number of prospective RCTs. SGAs are preferred because of their lower propensity to cause EPS and other motor adverse effects. Older persons with schizophrenia have an EPS threshold lower than younger patients and determining the lowest effective dosage may minimize EPS and cognitive adverse effects. As individuals with long-standing schizophrenia get older, their antipsychotic dosages may need to be reduced, and clinicians need to monitor for adverse effects that are more common among older people, such as tardive dyskinesia and metabolic abnormalities. In healthy, “younger” geriatric patients, monitoring for adverse effects may be similar to monitoring of younger patients. Patients who are older or frail may need more frequent assessment.

Like older adults with schizophrenia, geriatric patients with bipolar disorder have reduced drug tolerability and experience more adverse effects than younger patients. There are no prospective controlled studies that evaluated using antipsychotics in older patients with bipolar disorder. In older bipolar patients, the most problematic adverse effects of antipsychotics are akathisia, parkinsonism, other EPS, sedation and dizziness (which may increase fall risk), and GI discomfort. A key tolerability and safety consideration when treating older adults with bipolar disorder is the role of antipsychotics in relation to the use of lithium and mood stabilizers. Some studies have suggested that lithium has neuroprotective effects when used long-term; however, at least 1 report suggested that long-term antipsychotic treatment may be associated with neurodegeneration.39

The literature does not provide strong evidence on the many clinical variations that we see in routine practice settings, such as combinations of drug treatments or drugs prescribed to patients with specific comorbid conditions. There is a need for large cohort studies that monitor treatment course, medical comorbidity, and prognosis. Additionally, well-designed clinical trials such as the DART-AD, which investigated longer-term trajectories of people with dementia taking antipsychotics, should serve as a model for the type of research that is needed to better understand outcome variability among older people with chronic psychotic or bipolar disorders.40

1. Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, et al. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995-2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(2):177-184.

2. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population ageing: 1950-2050. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/worldageing19502050. Accessed September 1, 2017.

3. Lawrence D, Kisely S, Pais J. The epidemiology of excess mortality in people with mental illness. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(12):752-760.

4. Cohen CI, Vahia I, Reyes P, et al. Focus on geriatric psychiatry: schizophrenia in later life: clinical symptoms and social well-being. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(3):232-234.

5. Jeste DV, Barak Y, Madhusoodanan S, et al. International multisite double-blind trial of the atypical antipsychotics risperidone and olanzapine in 175 elderly patients with chronic schizophrenia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(6):638-647.

6. Kalache SM, Mulsant BH, Davies SJ, et al. The impact of aging, cognition, and symptoms on functional competence in individuals with schizophrenia across the lifespan. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(2):374-381.

7. Suzuki T, Remington G, Uchida H, et al. Management of schizophrenia in late life with antipsychotic medications: a qualitative review. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(12):961-980.

8. Mulsant BH, Pollock BG. Psychopharmacology. In: David C. Steffens DC, Blazer DG, Thakur ME (eds). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Geriatric Psychiatry, 5th Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:527-587.

9. Cohen CI, Meesters PD, Zhao J. New perspectives on schizophrenia in later life: implications for treatment, policy, and research. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(4):340-350.

10. Marriott RG, Neil W, Waddingham S. Antipsychotic medication for elderly people with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005580.

11. Essali A, Ali G. Antipsychotic drug treatment for elderly people with late-onset schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(2):CD004162.

12. Scott J, Greenwald BS, Kramer E, et al. Atypical (second generation) antipsychotic treatment response in very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(5):742-748.

13. Rado J, Janicak PG. Pharmacological and clinical profile of recently approved second-generation antipsychotics: implications for treatment of schizophrenia in older patients. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(10):783-791.

14. Tzimos A, Samokhvalov V, Kramer M, et al. Safety and tolerability of oral paliperidone extended-release tablets in elderly patients with schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study with six-month open-label extension. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(1):31-43.

15. Howanitz E, Pardo M, Smelson DA, et al. The efficacy and safety of clozapine versus chlorpromazine in geriatric schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):41-44.

16. Sproule BA, Lake J, Mamo DC, et al. Are antipsychotic prescribing patterns different in older and younger adults?: a survey of 1357 psychiatric inpatients in Toronto. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(4):248-254.

17. Uchida H, Suzuki T, Mamo DC, et al. Effects of age and age of onset on prescribed antipsychotic dose in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a survey of 1,418 patients in Japan. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(7):584-593.

18. Graff-Guerrero A, Rajji TK, Mulsant BH, et al. Evaluation of antipsychotic dose reduction in late-life schizophrenia: a prospective dopamine D2/3 occupancy study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(9):927-934.

19. Khan A, Schwartz K, Stern C, et al. Mortality risk in patients with schizophrenia participating in premarketing atypical antipsychotic clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(12):1828-1833.

20. Weinmann S, Read J, Aderhold V. Influence of antipsychotics on mortality in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(1):1-11.

21. Novick D, Haro JM, Perrin E, et al. Tolerability of outpatient antipsychotic treatment: 36-month results from the European Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes (SOHO) study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19(8):542-550.

22. Sajatovic M, Blow FC, Ignacio RV, et al. Age-related modifiers of clinical presentation and health service use among veterans with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(9):1014-1021.

23. Jeste DV, Alexopoulos GS, Bartels SJ, et al. Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: research agenda for the next 2 decades. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(9):848-853.

24. Sajatovic M, Chen P. Geriatric bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34(2):319-333,vii.

25. Sajatovic M, Strejilevich SA, Gildengers AG, et al. A report on older-age bipolar disorder from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(7):689-704.

26. Lala SV, Sajatovic M. Medical and psychiatric comorbidities among elderly individuals with bipolar disorder: a literature review. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(1):20-25.

27. Dols A, Rhebergen D, Beekman A, et al. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities: results from a bipolar elderly cohort study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(11):1066-1074.

28. Pillarella J, Higashi A, Alexander GC, et al. Trends in use of second-generation antipsychotics for treatment of bipolar disorder in the United States, 1998-2009. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(1):83-86.

29. De Fruyt J, Deschepper E, Audenaert K, et al. Second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(5):603-617.

30. Nivoli AM, Murru A, Goikolea JM, et al. New treatment guidelines for acute bipolar mania: a critical review. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(2):125-141.

31. Sajatovic M, Paulsson B. Quetiapine for the treatment of depressive episodes in adults aged 55 to 65 years with bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry Annual Meeting; 2007; New Orleans, LA.

32. Sajatovic M, Forester B, Tsai J, et al. Efficacy and safety of lurasidone in older adults with bipolar depression: analysis of two double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Paper presented at: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP) 53rd Annual Meeting; 2014; Phoenix, AZ.

33. Sajatovic M, Coconcea N, Ignacio RV, et al. Aripiprazole therapy in 20 older adults with bipolar disorder: a 12-week, open-label trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):41-46.

34. Sajatovic M, Dines P, Fuentes-Casiano E, et al. Asenapine in the treatment of older adults with bipolar disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(7):710-719.

35. Sajatovic M, Calabrese JR, Mullen J. Quetiapine for the treatment of bipolar mania in older adults. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(6):662-671.

36. Baruch Y, Tadger S, Plopski I, et al. Asenapine for elderly bipolar manic patients. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(1):130-132.

37. Beyer JL, Siegal A, Kennedy JS. Olanzapine, divalproex and placebo treatment, non-head to head comparisons of older adults acute mania. Paper presented at: 10th Congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association; 2001; Nice, France.

38. Al Jurdi RK, Marangell LB, Petersen NJ, et al. Prescription patterns of psychotropic medications in elderly compared with younger participants who achieved a “recovered” status in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(11):922-933.

39. Gildengers AG, Chung KH, Huang SH, et al. Neuroprogressive effects of lifetime illness duration in older adults with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(6):617-623.

40. Ballard C, Lana MM, Theodoulou M, et al. A randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled trial in dementia patients continuing or stopping neuroleptics (the DART-AD trial). PLoS Med. 2008;5(4):e76.

Antipsychotics are FDA-approved as a primary treatment for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and as adjunctive therapy for major depressive disorder. In the United States, approximately 26% of antipsychotic prescriptions written for these indications are for individuals age >65.1 Additionally, antipsychotics are widely used to treat behavioral symptoms associated with dementia.1 The rapid expansion of the use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), in particular, has been driven in part by their lower risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) compared with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs).1 However, a growing body of data indicates that all antipsychotics have a range of adverse effects in older patients. This focus is critical in light of demographic trends—in the next 10 to 15 years, the population age >60 will grow 3.5 times more rapidly than the general population.2

In this context, psychiatrists need information on the relative risks of antipsychotics for older patients. This 3-part series summarizes findings and recommendations on safety and tolerability when prescribing antipsychotics in older individuals with chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and dementia. This review aims to:

- briefly summarize the major studies and analyses relevant to older patients with these diagnoses

- provide a summative opinion on safety and tolerability issues in these older adults

- highlight the gaps in the evidence base and areas that need additional research.

Part 1 focuses on older adults with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Subsequent articles will focus on prescribing antipsychotics to older adults with depression and those with dementia.

Schizophrenia

Summary of benefits, place in treatment armamentarium. Individuals with schizophrenia have a shorter life expectancy than that of the general population mostly as a result of suicide and comorbid physical illnesses,3 but the number of patients with schizophrenia age >55 will double over the next 2 decades.4 With aging, both positive and negative symptoms may be a focus of treatment (Table 1).5,6 Antipsychotics are a first-line treatment for older patients with schizophrenia with few medication alternatives.7 Safety risks associated with antipsychotics in older people span a broad spectrum (Table 2).8

A 6-week prospective RCT evaluated paliperidone extended-release vs placebo in 114 older adults (age ≥65 years; mean age, 70 years) with schizophrenia.14 There was an optional 24-week extension of open-label treatment with paliperidone. Mean daily dose of paliperidone was 8.4 mg. Efficacy measures did not show consistent statistically significant differences between treatment groups. Discontinuation rates were similar between paliperidone (7%) vs placebo (8%). Serious adverse events occurred in 3% of paliperidone-treated vs 8% of placebo-treated patients. Elevated prolactin levels occurred in one-half of paliperidone-treated patients. There were no prolactin or glucose treatment-related adverse events or significant mean changes in body weight for either paliperidone-treated or placebo-treated patients. Safety findings in the 24-week, open-label extension group were consistent with the RCT results.

Howanitz et al15 conducted a 12-week, prospective RCT that compared clozapine (mean dose, 300 mg/d) with chlorpromazine (mean dose, 600 mg/d) in 42 older adults (mean age, 67 years) with schizophrenia. Drop-out rate prior to 5 weeks was 19% and similar between groups. Common adverse effects included sialorrhea, hematologic abnormalities, sedation, tachycardia, EPS, and weight gain. Although both drugs were effective, more patients taking clozapine had tachycardia and weight gain, while more chlorpromazine patients reported sedation.

There have been other, less rigorous studies.7,8 Most of these studies evaluated risperidone and olanzapine, and most were conducted in “younger” geriatric patients (age <75 years). Although patients who participate in clinical trials may be healthier than “typical” patients, adverse effects such as EPS, sedation, and weight gain were still relatively common in these studies.

Other clinical data. A major consideration in treating older adults with schizophrenia is balancing the need to administer an antipsychotic dose high enough to alleviate psychotic symptoms while minimizing dose-dependent adverse effects. There is a U-shaped relationship between age and vulnerability to antipsychotic adverse effects,16,17 wherein adverse effects are highest at younger and older ages. Evidence supports using the lowest effective antipsychotic dose for geriatric patients with schizophrenia. Positive emission tomography (PET) studies suggest that older patients develop EPS with lower doses despite lower receptor occupancy.17,18 A recent study of 35 older patients (mean age, 60.1 years) with schizophrenia obtained PET, clinical measures, and blood pharmacokinetic measures before and after reduction of risperidone or olanzapine doses.18 A ≥40% reduction in dose was associated with reduced adverse effects, particularly EPS and elevation of prolactin levels. Moreover, the therapeutic window of striatal D2/D3 receptor occupancy appeared to be 50% to 60% in these older patients, compared with 65% to 80% in younger patients.

Long-term risks of antipsychotic treatment across the lifespan are less clear, with evidence suggesting both lower and higher mortality risk.19,20 It is difficult to fully disentangle the long-term risks of antipsychotics from the cumulative effects of lifestyle and comorbidity among individuals who have lived with schizophrenia for decades. Large naturalistic studies that include substantial numbers of older people with schizophrenia might be a way to elicit more information on long-term safety. The Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcome (SOHO) study was a large naturalistic trial that recruited >10,000 individuals with schizophrenia in 10 European countries.21 Although the SOHO study found differences between antipsychotics and adverse effects, such as EPS, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction, because the mean age of these patients was approximately 40 years and the follow-up period was only 3 years, it is difficult to draw conclusions that could be relevant to older individuals who have had schizophrenia for decades.

Bipolar Disorder

Clinical trials: Bipolar depression. A post hoc, secondary analysis of two 8-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies in bipolar depression compared 2 dosages of quetiapine (300 mg/d and 600 mg/d) with placebo in mixed-age patients.31 In a subgroup of 72 patients, ages 55 to 65, remission occurred more often with quetiapine than with placebo. Study discontinuation rates were similar between older people and younger people (age <55 years): quetiapine, 300 mg/d, 29.2%; quetiapine, 600 mg/d, 48.1%; and placebo, 29.6% in older adults, compared with 37.1%, 45.8%, and 38.1%, respectively, in younger adults. In all patients, the most common reason for discontinuation was adverse events with quetiapine and lack of efficacy for placebo. Adverse event rates were similar in older and younger adults. Dry mouth and dizziness were more common in older adults. Proportions of adults experiencing clinically significant weight gain (≥7% of body weight) were 5.3%, 8.3%, and 0% in older adults receiving quetiapine, 300 mg/d, quetiapine, 600 mg/d, and placebo, respectively, compared with 7.2%, 10.1%, and 2.6% in younger adults. EPS and treatment-emergent mania were minimal.

A secondary analysis of mixed-age, RCTs examined response in older adults (age ≥55 years) with bipolar I depression who received lurasidone as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.32 In the monotherapy study, these patients were randomized to 6 weeks of lurasidone 20 to 60 mg/d, lurasidone 80 to 120 mg/d, or placebo. In the adjunctive therapy study, they were randomized to lurasidone 20 to 120 mg/d or placebo with either lithium or valproate. There were 83 older adults (17.1% of the sample) in the monotherapy study and 53 (15.6%) in the adjunctive therapy study. Mean improvement in depression was significantly higher for both doses of lurasidone monotherapy than placebo. Adjunctive lurasidone was not associated with statistically significant improvement vs placebo. The most frequent adverse events in older patients on lurasidone monotherapy 20 to 60 mg/d or 80 to 120 mg/d were nausea (18.5% and 9.7%, respectively) and somnolence (11.1% and 0%, respectively). Akathisia (9.7%) and insomnia (9.7%) were the most common adverse events in the group receiving 80 to 120 mg/d, with the rate of akathisia exhibiting a dose-related increase. Weight change with lurasidone was similar to placebo, and there were no clinically meaningful group changes in vital signs, electrocardiography, or laboratory parameters.

A small (N = 20) open study found improvement in older adults with bipolar depression with aripiprazole (mean dose, 10.3 mg/d).33 Adverse effects included restlessness and weight gain (n = 3, 9% each), sedation (n = 2, 10%), and drooling and diarrhea/loose stools (n = 1, 5% each). In another small study (N = 15) using asenapine (mean dose, 11.2 mg/d) in mainly older bipolar patients with depression, the most common adverse effects were gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort (n = 5, 33%) and restlessness, tremors, cognitive difficulties, and sluggishness (n = 2, 13% each).34

Clinical trials: Bipolar mania. Researchers conducted a pooled analysis of two 12-week randomized trials comparing quetiapine with placebo in a mixed-age sample with bipolar mania.35 In a subgroup of 59 older patients (mean age, 62.9 years), manic symptoms improved significantly more with quetiapine (modal dose, 550 mg/d) than with placebo. Adverse effects reported by >10% of older patients were dry mouth, somnolence, postural hypotension, insomnia, weight gain, and dizziness. Insomnia was reported by >10% of patients receiving placebo.

In a case series of 11 elderly patients with mania receiving asenapine, Baruch et al36 reported a 63% remission rate. One patient discontinued the study because of a new rash, 1 discontinued after developing peripheral edema, and 3 patients reported mild sedation.

Beyer et al37 reported on a post hoc analysis of 94 older adults (mean age, 57.1 years; range, 50.1 to 74.8 years) with acute bipolar mania receiving olanzapine (n = 47), divalproex (n = 31), or placebo (n = 16) in a pooled olanzapine clinical trials database. Patients receiving olanzapine or divalproex had improvement in mania; those receiving placebo did not improve. Safety findings were comparable with reports in younger patients with mania.

Other clinical data. Adverse effects found in mixed-age samples using secondary analyses of clinical trials need to be interpreted with caution because these types of studies usually exclude individuals with significant medical comorbidity. Medical burden, cognitive impairment, or concomitant medications generally necessitate slower drug titration and lower total daily dosing. For example, a secondary analysis of the U.S. National Institute of Health-funded Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder study, which had broader inclusion criteria than most clinical trials, reported that, although recovery rates in older adults with bipolar disorder were fairly good (78.5%), lower doses of risperidone were used in older vs younger patients.38

Clinical considerations

Interpretation of the relative risks of antipsychotics in older people must be tempered by the caveat that there is limited high-quality data (Table 4). Antipsychotics are the first-line therapy for older patients with schizophrenia, although their use is supported by a small number of prospective RCTs. SGAs are preferred because of their lower propensity to cause EPS and other motor adverse effects. Older persons with schizophrenia have an EPS threshold lower than younger patients and determining the lowest effective dosage may minimize EPS and cognitive adverse effects. As individuals with long-standing schizophrenia get older, their antipsychotic dosages may need to be reduced, and clinicians need to monitor for adverse effects that are more common among older people, such as tardive dyskinesia and metabolic abnormalities. In healthy, “younger” geriatric patients, monitoring for adverse effects may be similar to monitoring of younger patients. Patients who are older or frail may need more frequent assessment.

Like older adults with schizophrenia, geriatric patients with bipolar disorder have reduced drug tolerability and experience more adverse effects than younger patients. There are no prospective controlled studies that evaluated using antipsychotics in older patients with bipolar disorder. In older bipolar patients, the most problematic adverse effects of antipsychotics are akathisia, parkinsonism, other EPS, sedation and dizziness (which may increase fall risk), and GI discomfort. A key tolerability and safety consideration when treating older adults with bipolar disorder is the role of antipsychotics in relation to the use of lithium and mood stabilizers. Some studies have suggested that lithium has neuroprotective effects when used long-term; however, at least 1 report suggested that long-term antipsychotic treatment may be associated with neurodegeneration.39

The literature does not provide strong evidence on the many clinical variations that we see in routine practice settings, such as combinations of drug treatments or drugs prescribed to patients with specific comorbid conditions. There is a need for large cohort studies that monitor treatment course, medical comorbidity, and prognosis. Additionally, well-designed clinical trials such as the DART-AD, which investigated longer-term trajectories of people with dementia taking antipsychotics, should serve as a model for the type of research that is needed to better understand outcome variability among older people with chronic psychotic or bipolar disorders.40

Antipsychotics are FDA-approved as a primary treatment for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and as adjunctive therapy for major depressive disorder. In the United States, approximately 26% of antipsychotic prescriptions written for these indications are for individuals age >65.1 Additionally, antipsychotics are widely used to treat behavioral symptoms associated with dementia.1 The rapid expansion of the use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), in particular, has been driven in part by their lower risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) compared with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs).1 However, a growing body of data indicates that all antipsychotics have a range of adverse effects in older patients. This focus is critical in light of demographic trends—in the next 10 to 15 years, the population age >60 will grow 3.5 times more rapidly than the general population.2

In this context, psychiatrists need information on the relative risks of antipsychotics for older patients. This 3-part series summarizes findings and recommendations on safety and tolerability when prescribing antipsychotics in older individuals with chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and dementia. This review aims to:

- briefly summarize the major studies and analyses relevant to older patients with these diagnoses

- provide a summative opinion on safety and tolerability issues in these older adults

- highlight the gaps in the evidence base and areas that need additional research.

Part 1 focuses on older adults with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Subsequent articles will focus on prescribing antipsychotics to older adults with depression and those with dementia.

Schizophrenia

Summary of benefits, place in treatment armamentarium. Individuals with schizophrenia have a shorter life expectancy than that of the general population mostly as a result of suicide and comorbid physical illnesses,3 but the number of patients with schizophrenia age >55 will double over the next 2 decades.4 With aging, both positive and negative symptoms may be a focus of treatment (Table 1).5,6 Antipsychotics are a first-line treatment for older patients with schizophrenia with few medication alternatives.7 Safety risks associated with antipsychotics in older people span a broad spectrum (Table 2).8

A 6-week prospective RCT evaluated paliperidone extended-release vs placebo in 114 older adults (age ≥65 years; mean age, 70 years) with schizophrenia.14 There was an optional 24-week extension of open-label treatment with paliperidone. Mean daily dose of paliperidone was 8.4 mg. Efficacy measures did not show consistent statistically significant differences between treatment groups. Discontinuation rates were similar between paliperidone (7%) vs placebo (8%). Serious adverse events occurred in 3% of paliperidone-treated vs 8% of placebo-treated patients. Elevated prolactin levels occurred in one-half of paliperidone-treated patients. There were no prolactin or glucose treatment-related adverse events or significant mean changes in body weight for either paliperidone-treated or placebo-treated patients. Safety findings in the 24-week, open-label extension group were consistent with the RCT results.

Howanitz et al15 conducted a 12-week, prospective RCT that compared clozapine (mean dose, 300 mg/d) with chlorpromazine (mean dose, 600 mg/d) in 42 older adults (mean age, 67 years) with schizophrenia. Drop-out rate prior to 5 weeks was 19% and similar between groups. Common adverse effects included sialorrhea, hematologic abnormalities, sedation, tachycardia, EPS, and weight gain. Although both drugs were effective, more patients taking clozapine had tachycardia and weight gain, while more chlorpromazine patients reported sedation.

There have been other, less rigorous studies.7,8 Most of these studies evaluated risperidone and olanzapine, and most were conducted in “younger” geriatric patients (age <75 years). Although patients who participate in clinical trials may be healthier than “typical” patients, adverse effects such as EPS, sedation, and weight gain were still relatively common in these studies.