User login

Orphan designation recommended for PCM-075

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) has recommended that PCM-075 receive orphan drug designation as a treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

PCM-075 is an oral adenosine triphosphate competitive inhibitor of the serine/threonine Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) enzyme, which is overexpressed in hematologic and solid tumor malignancies.

The COMP’s recommendation for PCM-075 is expected to be adopted by the European Commission at the end of this month.

Orphan drug designation in Europe is available to companies developing products intended to treat a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition that affects fewer than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union (EU).

The designation allows for financial and regulatory incentives that include 10 years of marketing exclusivity in the EU after product approval, eligibility for conditional marketing authorization, protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency at reduced fees during the product development phase, and direct access to centralized marketing authorization in the EU.

PCM-075 research

PCM-075 only targets the PLK1 isoform (not PLK2 or PLK3) and has a 24-hour drug half-life with reversible, on-target hematologic toxicities, according to Trovagene, Inc., the company developing PCM-075.

Trovagene believes that PCM-075’s reversible, on-target activity, combined with an improved dose/scheduling protocol, could mean that PCM-075 will improve upon long-term outcomes observed in previous studies with a PLK inhibitor in AML.

This includes a phase 2 study in which AML patients who received a PLK inhibitor plus low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) had a higher response rate than patients who received LDAC alone—31% and 13.3%, respectively.

Trovagene said preclinical studies have shown that PCM-075 synergizes with more than 10 drugs used to treat hematologic and solid tumor malignancies. This includes FLT3 and HDAC inhibitors, taxanes, and cytotoxins.

Trovagene is now conducting a phase 1b/2 trial of PCM-075 in combination with standard care (LDAC or decitabine) in patients with AML (NCT03303339).

The company has already completed a phase 1 dose-escalation study of PCM-075 in patients with advanced metastatic solid tumor malignancies. Results from this study were published in Investigational New Drugs.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) has recommended that PCM-075 receive orphan drug designation as a treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

PCM-075 is an oral adenosine triphosphate competitive inhibitor of the serine/threonine Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) enzyme, which is overexpressed in hematologic and solid tumor malignancies.

The COMP’s recommendation for PCM-075 is expected to be adopted by the European Commission at the end of this month.

Orphan drug designation in Europe is available to companies developing products intended to treat a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition that affects fewer than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union (EU).

The designation allows for financial and regulatory incentives that include 10 years of marketing exclusivity in the EU after product approval, eligibility for conditional marketing authorization, protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency at reduced fees during the product development phase, and direct access to centralized marketing authorization in the EU.

PCM-075 research

PCM-075 only targets the PLK1 isoform (not PLK2 or PLK3) and has a 24-hour drug half-life with reversible, on-target hematologic toxicities, according to Trovagene, Inc., the company developing PCM-075.

Trovagene believes that PCM-075’s reversible, on-target activity, combined with an improved dose/scheduling protocol, could mean that PCM-075 will improve upon long-term outcomes observed in previous studies with a PLK inhibitor in AML.

This includes a phase 2 study in which AML patients who received a PLK inhibitor plus low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) had a higher response rate than patients who received LDAC alone—31% and 13.3%, respectively.

Trovagene said preclinical studies have shown that PCM-075 synergizes with more than 10 drugs used to treat hematologic and solid tumor malignancies. This includes FLT3 and HDAC inhibitors, taxanes, and cytotoxins.

Trovagene is now conducting a phase 1b/2 trial of PCM-075 in combination with standard care (LDAC or decitabine) in patients with AML (NCT03303339).

The company has already completed a phase 1 dose-escalation study of PCM-075 in patients with advanced metastatic solid tumor malignancies. Results from this study were published in Investigational New Drugs.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) has recommended that PCM-075 receive orphan drug designation as a treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

PCM-075 is an oral adenosine triphosphate competitive inhibitor of the serine/threonine Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) enzyme, which is overexpressed in hematologic and solid tumor malignancies.

The COMP’s recommendation for PCM-075 is expected to be adopted by the European Commission at the end of this month.

Orphan drug designation in Europe is available to companies developing products intended to treat a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition that affects fewer than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union (EU).

The designation allows for financial and regulatory incentives that include 10 years of marketing exclusivity in the EU after product approval, eligibility for conditional marketing authorization, protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency at reduced fees during the product development phase, and direct access to centralized marketing authorization in the EU.

PCM-075 research

PCM-075 only targets the PLK1 isoform (not PLK2 or PLK3) and has a 24-hour drug half-life with reversible, on-target hematologic toxicities, according to Trovagene, Inc., the company developing PCM-075.

Trovagene believes that PCM-075’s reversible, on-target activity, combined with an improved dose/scheduling protocol, could mean that PCM-075 will improve upon long-term outcomes observed in previous studies with a PLK inhibitor in AML.

This includes a phase 2 study in which AML patients who received a PLK inhibitor plus low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) had a higher response rate than patients who received LDAC alone—31% and 13.3%, respectively.

Trovagene said preclinical studies have shown that PCM-075 synergizes with more than 10 drugs used to treat hematologic and solid tumor malignancies. This includes FLT3 and HDAC inhibitors, taxanes, and cytotoxins.

Trovagene is now conducting a phase 1b/2 trial of PCM-075 in combination with standard care (LDAC or decitabine) in patients with AML (NCT03303339).

The company has already completed a phase 1 dose-escalation study of PCM-075 in patients with advanced metastatic solid tumor malignancies. Results from this study were published in Investigational New Drugs.

Conditional OS estimates show upfront TKI benefit in mRCC

An analysis of conditional survival outcomes for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) has suggested that first-line therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) can result in improved survival odds over time.

Patients with mRCC treated with a TKI upfront had gradual increases over time in conditional overall survival estimates when compared with baseline survival predictions, a retrospective review has indicated.

Patients who survived at least 36 months after the start of therapy had an estimated 36-month conditional overall survival (OS) rate that was 7.3% higher than the predicted survival at the initiation of therapy, reported Seong Il Seo, MD, PhD, from Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, North Korea, and his colleagues.

The investigators also found that, while predictors of survival changed over time, previous metastasectomy was a key prognosticator of conditional overall survival throughout 36 months of follow-up, they reported in The Journal of Urology.

“To our knowledge, our data are the first to reveal the beneficial role of metastasectomy on conditional OS probabilities with time since an initial survival estimation, particularly in patients at intermediate and poor risk. [Conditional survival] estimates can be beneficial to counsel patients with mRCC about more practical prognoses and helpful to continuously adjust surveillance planning in these patients,” they wrote.

Conditional survival is an analytical method for providing more accurate estimates of how prognoses change over time when patients with aggressive metastatic disease, such as mRCC, are exposed to therapies such as nephrectomy or TKIs.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed records for 1,131 patients with mRCC in the Korean Renal Cancer Study Group database. They calculated conditional OS using a nomogram that indicated the likelihood that a patient would survive an additional number of years given that he or she had already survived a certain number of years. They also created a multivariate regression model to identify predictors of conditional survival over time.

They found that, at all survival times after the start of TKI therapy (6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months), conditional overall survival gradually increased when compared with baseline survival estimates.

“While the actual overall survival rate decreased with time, the 36-month conditional overall survival rate was calculated as 7.3% higher in patients who had already survived 36 months compared to baseline estimations at the time of initial tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment,” they wrote.

In the multivariate model, prognostic factors such as gender, pathologic T stage, and Heng risk classification became nonsignificant over time, but previous metastasectomy remained a significant independent predictor of survival after TKI therapy at all time points except for 18 months.

“This study largely corroborates previous data from the IMDC (International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium), and it provides useful information on prognostication,” commented Adam B. Weiner, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago, in a brief accompanying editorial.

The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea research grant funded by the Ministry of Science and Information and Communications Technology and by a Korea Health Technology R&D Project grant through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in South Korea. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Kang M et al. J Urol. 2018 June 22. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.06.030.

An analysis of conditional survival outcomes for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) has suggested that first-line therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) can result in improved survival odds over time.

Patients with mRCC treated with a TKI upfront had gradual increases over time in conditional overall survival estimates when compared with baseline survival predictions, a retrospective review has indicated.

Patients who survived at least 36 months after the start of therapy had an estimated 36-month conditional overall survival (OS) rate that was 7.3% higher than the predicted survival at the initiation of therapy, reported Seong Il Seo, MD, PhD, from Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, North Korea, and his colleagues.

The investigators also found that, while predictors of survival changed over time, previous metastasectomy was a key prognosticator of conditional overall survival throughout 36 months of follow-up, they reported in The Journal of Urology.

“To our knowledge, our data are the first to reveal the beneficial role of metastasectomy on conditional OS probabilities with time since an initial survival estimation, particularly in patients at intermediate and poor risk. [Conditional survival] estimates can be beneficial to counsel patients with mRCC about more practical prognoses and helpful to continuously adjust surveillance planning in these patients,” they wrote.

Conditional survival is an analytical method for providing more accurate estimates of how prognoses change over time when patients with aggressive metastatic disease, such as mRCC, are exposed to therapies such as nephrectomy or TKIs.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed records for 1,131 patients with mRCC in the Korean Renal Cancer Study Group database. They calculated conditional OS using a nomogram that indicated the likelihood that a patient would survive an additional number of years given that he or she had already survived a certain number of years. They also created a multivariate regression model to identify predictors of conditional survival over time.

They found that, at all survival times after the start of TKI therapy (6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months), conditional overall survival gradually increased when compared with baseline survival estimates.

“While the actual overall survival rate decreased with time, the 36-month conditional overall survival rate was calculated as 7.3% higher in patients who had already survived 36 months compared to baseline estimations at the time of initial tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment,” they wrote.

In the multivariate model, prognostic factors such as gender, pathologic T stage, and Heng risk classification became nonsignificant over time, but previous metastasectomy remained a significant independent predictor of survival after TKI therapy at all time points except for 18 months.

“This study largely corroborates previous data from the IMDC (International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium), and it provides useful information on prognostication,” commented Adam B. Weiner, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago, in a brief accompanying editorial.

The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea research grant funded by the Ministry of Science and Information and Communications Technology and by a Korea Health Technology R&D Project grant through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in South Korea. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Kang M et al. J Urol. 2018 June 22. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.06.030.

An analysis of conditional survival outcomes for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) has suggested that first-line therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) can result in improved survival odds over time.

Patients with mRCC treated with a TKI upfront had gradual increases over time in conditional overall survival estimates when compared with baseline survival predictions, a retrospective review has indicated.

Patients who survived at least 36 months after the start of therapy had an estimated 36-month conditional overall survival (OS) rate that was 7.3% higher than the predicted survival at the initiation of therapy, reported Seong Il Seo, MD, PhD, from Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, North Korea, and his colleagues.

The investigators also found that, while predictors of survival changed over time, previous metastasectomy was a key prognosticator of conditional overall survival throughout 36 months of follow-up, they reported in The Journal of Urology.

“To our knowledge, our data are the first to reveal the beneficial role of metastasectomy on conditional OS probabilities with time since an initial survival estimation, particularly in patients at intermediate and poor risk. [Conditional survival] estimates can be beneficial to counsel patients with mRCC about more practical prognoses and helpful to continuously adjust surveillance planning in these patients,” they wrote.

Conditional survival is an analytical method for providing more accurate estimates of how prognoses change over time when patients with aggressive metastatic disease, such as mRCC, are exposed to therapies such as nephrectomy or TKIs.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed records for 1,131 patients with mRCC in the Korean Renal Cancer Study Group database. They calculated conditional OS using a nomogram that indicated the likelihood that a patient would survive an additional number of years given that he or she had already survived a certain number of years. They also created a multivariate regression model to identify predictors of conditional survival over time.

They found that, at all survival times after the start of TKI therapy (6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months), conditional overall survival gradually increased when compared with baseline survival estimates.

“While the actual overall survival rate decreased with time, the 36-month conditional overall survival rate was calculated as 7.3% higher in patients who had already survived 36 months compared to baseline estimations at the time of initial tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment,” they wrote.

In the multivariate model, prognostic factors such as gender, pathologic T stage, and Heng risk classification became nonsignificant over time, but previous metastasectomy remained a significant independent predictor of survival after TKI therapy at all time points except for 18 months.

“This study largely corroborates previous data from the IMDC (International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium), and it provides useful information on prognostication,” commented Adam B. Weiner, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago, in a brief accompanying editorial.

The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea research grant funded by the Ministry of Science and Information and Communications Technology and by a Korea Health Technology R&D Project grant through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in South Korea. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Kang M et al. J Urol. 2018 June 22. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.06.030.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF UROLOGY

Key clinical point: Conditional overall survival estimates may help clinicians adjust surveillance planning in patients with mRCC.

Major finding: At all survival times after the start of TKI therapy, conditional overall survival gradually increased when compared with baseline survival estimates.

Study details: Retrospective review of records on 1,131 patients with mRCC.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea research grant funded by the Ministry of Science and Information and Communications Technology and by a Korea Health Technology R&D Project grant through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in South Korea. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Kang M et al. J Urol. 2018 June 22. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.06.030.

How Does Migraine Affect a Patient’s Relationships?

Compared with episodic migraine, chronic migraine is more likely to have detrimental effects on family life.

SAN FRANCISCO—Patients with chronic migraine are significantly more likely than those with episodic migraine to report that headaches contribute to relationship problems and have a detrimental effect on family life, researchers said at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. Negative effects on family life include a delay in having children and having fewer children.

Migraine can detract from many aspects of family life and affect all members of the patient’s family. Dawn C. Buse, PhD, Clinical Professor of Neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York, and colleagues analyzed data from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study to understand the effects of episodic and chronic migraine on a person’s relationships and family life.

An Analysis of CaMEO Data

The CaMEO study is a prospective, longitudinal, web-based survey designed to characterize the impact of migraine, among other objectives, in a systematic US sample of people meeting modified ICHD-2R criteria. A total of 19,891 respondents met study criteria, including criteria for migraine, and were invited to complete the Family Burden Module (FBM), which assessed the impact, perception, and emotions related to living with migraine among people with migraine and their family members.

Dr. Buse and colleagues presented the results of migraineurs’ responses to the FBM regarding relationships with spouses or significant others and relationships with children living at home. The investigators stratified migraineurs by episodic migraine (ie, those with fewer than 14 headache days per month) and chronic migraine (ie, those with 15 or more headache days per month). Migraineurs were asked about their current relationship status (ie, in a current relationship or not, living together or not). Questions evaluated how headaches had affected past or current relationships with Likert-type response options that corresponded to degrees of disagreement or agreement. Dr. Buse’s group analyzed items by relationship status, episodic or chronic migraine status, and gender.

Women and Men Were Affected Similarly

In all, 13,064 respondents provided valid data. Of this population, 11,938 (91.4%) had episodic migraine and 1,126 (8.6%) had chronic migraine. Of those not currently in a relationship (n = 3,189), respondents with chronic migraine were significantly more likely to indicate that headaches had contributed to relationship problems (37.0%), compared with patients with episodic migraine (15.0%). Of those in a relationship but not living together (n = 1,323), 43.9% of respondents with chronic migraine indicated that headaches were causing relationship concerns or were preventing a closer relationship, such as moving in together or getting married, compared with 15.8% of patients with episodic migraine. The responses were similar among men (18.0%) and women (17.8%).

About 47% of respondents with chronic migraine reported that headaches have caused one or more previous relationship to end or have other problems, compared with 18.2% of respondents with episodic migraine. Headache contributions to relationship problems (ie, breakup or other difficulties) were similar among men (20.6%) and women (19.9%).

Of those in a relationship and living together (n = 8,127), 78.2% of respondents with chronic migraine agreed that they would be a better partner if they did not have headaches, compared with 46.2% of respondents with episodic migraine. Furthermore, 9.6% of patients with chronic migraine had delayed having children or had fewer children, compared with 2.6% of patients with episodic migraine. The researchers observed no differences between men and women.

Compared with episodic migraine, chronic migraine is more likely to have detrimental effects on family life.

Compared with episodic migraine, chronic migraine is more likely to have detrimental effects on family life.

SAN FRANCISCO—Patients with chronic migraine are significantly more likely than those with episodic migraine to report that headaches contribute to relationship problems and have a detrimental effect on family life, researchers said at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. Negative effects on family life include a delay in having children and having fewer children.

Migraine can detract from many aspects of family life and affect all members of the patient’s family. Dawn C. Buse, PhD, Clinical Professor of Neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York, and colleagues analyzed data from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study to understand the effects of episodic and chronic migraine on a person’s relationships and family life.

An Analysis of CaMEO Data

The CaMEO study is a prospective, longitudinal, web-based survey designed to characterize the impact of migraine, among other objectives, in a systematic US sample of people meeting modified ICHD-2R criteria. A total of 19,891 respondents met study criteria, including criteria for migraine, and were invited to complete the Family Burden Module (FBM), which assessed the impact, perception, and emotions related to living with migraine among people with migraine and their family members.

Dr. Buse and colleagues presented the results of migraineurs’ responses to the FBM regarding relationships with spouses or significant others and relationships with children living at home. The investigators stratified migraineurs by episodic migraine (ie, those with fewer than 14 headache days per month) and chronic migraine (ie, those with 15 or more headache days per month). Migraineurs were asked about their current relationship status (ie, in a current relationship or not, living together or not). Questions evaluated how headaches had affected past or current relationships with Likert-type response options that corresponded to degrees of disagreement or agreement. Dr. Buse’s group analyzed items by relationship status, episodic or chronic migraine status, and gender.

Women and Men Were Affected Similarly

In all, 13,064 respondents provided valid data. Of this population, 11,938 (91.4%) had episodic migraine and 1,126 (8.6%) had chronic migraine. Of those not currently in a relationship (n = 3,189), respondents with chronic migraine were significantly more likely to indicate that headaches had contributed to relationship problems (37.0%), compared with patients with episodic migraine (15.0%). Of those in a relationship but not living together (n = 1,323), 43.9% of respondents with chronic migraine indicated that headaches were causing relationship concerns or were preventing a closer relationship, such as moving in together or getting married, compared with 15.8% of patients with episodic migraine. The responses were similar among men (18.0%) and women (17.8%).

About 47% of respondents with chronic migraine reported that headaches have caused one or more previous relationship to end or have other problems, compared with 18.2% of respondents with episodic migraine. Headache contributions to relationship problems (ie, breakup or other difficulties) were similar among men (20.6%) and women (19.9%).

Of those in a relationship and living together (n = 8,127), 78.2% of respondents with chronic migraine agreed that they would be a better partner if they did not have headaches, compared with 46.2% of respondents with episodic migraine. Furthermore, 9.6% of patients with chronic migraine had delayed having children or had fewer children, compared with 2.6% of patients with episodic migraine. The researchers observed no differences between men and women.

SAN FRANCISCO—Patients with chronic migraine are significantly more likely than those with episodic migraine to report that headaches contribute to relationship problems and have a detrimental effect on family life, researchers said at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. Negative effects on family life include a delay in having children and having fewer children.

Migraine can detract from many aspects of family life and affect all members of the patient’s family. Dawn C. Buse, PhD, Clinical Professor of Neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York, and colleagues analyzed data from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study to understand the effects of episodic and chronic migraine on a person’s relationships and family life.

An Analysis of CaMEO Data

The CaMEO study is a prospective, longitudinal, web-based survey designed to characterize the impact of migraine, among other objectives, in a systematic US sample of people meeting modified ICHD-2R criteria. A total of 19,891 respondents met study criteria, including criteria for migraine, and were invited to complete the Family Burden Module (FBM), which assessed the impact, perception, and emotions related to living with migraine among people with migraine and their family members.

Dr. Buse and colleagues presented the results of migraineurs’ responses to the FBM regarding relationships with spouses or significant others and relationships with children living at home. The investigators stratified migraineurs by episodic migraine (ie, those with fewer than 14 headache days per month) and chronic migraine (ie, those with 15 or more headache days per month). Migraineurs were asked about their current relationship status (ie, in a current relationship or not, living together or not). Questions evaluated how headaches had affected past or current relationships with Likert-type response options that corresponded to degrees of disagreement or agreement. Dr. Buse’s group analyzed items by relationship status, episodic or chronic migraine status, and gender.

Women and Men Were Affected Similarly

In all, 13,064 respondents provided valid data. Of this population, 11,938 (91.4%) had episodic migraine and 1,126 (8.6%) had chronic migraine. Of those not currently in a relationship (n = 3,189), respondents with chronic migraine were significantly more likely to indicate that headaches had contributed to relationship problems (37.0%), compared with patients with episodic migraine (15.0%). Of those in a relationship but not living together (n = 1,323), 43.9% of respondents with chronic migraine indicated that headaches were causing relationship concerns or were preventing a closer relationship, such as moving in together or getting married, compared with 15.8% of patients with episodic migraine. The responses were similar among men (18.0%) and women (17.8%).

About 47% of respondents with chronic migraine reported that headaches have caused one or more previous relationship to end or have other problems, compared with 18.2% of respondents with episodic migraine. Headache contributions to relationship problems (ie, breakup or other difficulties) were similar among men (20.6%) and women (19.9%).

Of those in a relationship and living together (n = 8,127), 78.2% of respondents with chronic migraine agreed that they would be a better partner if they did not have headaches, compared with 46.2% of respondents with episodic migraine. Furthermore, 9.6% of patients with chronic migraine had delayed having children or had fewer children, compared with 2.6% of patients with episodic migraine. The researchers observed no differences between men and women.

Are Posttraumatic Headaches Different Than Nontraumatic Headaches?

Over time, headache frequency diminished in those with mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic headache.

SAN FRANCISCO—Among a cohort of recently deployed soldiers, headaches were frequent but were more severe, frequent, and migrainous if associated with concussion, according to a report presented at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. At one-year follow-up, headache frequency had decreased in soldiers with posttraumatic headache (PTH) but remained higher in this group than in those whose headaches were presumed to be unrelated to head injury, said Ann I. Scher, PhD, Director and Professor of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, and colleagues.

“There are limited data on the phenotypic differences between headaches related to mild traumatic brain injury and ‘regular’ headaches,” Dr. Scher said. “A better understanding of the posttraumatic headache phenotype will inform the design of interventional studies for this difficult to treat population.”

Dr. Scher and colleagues designed a study to compare headache features and one-year prognosis in a cohort of recently deployed soldiers with and without a recent history of a deployment-related mild traumatic brain injury (ie, concussion).

In all, 1,567 soldiers were randomly recruited at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Fort Carson, Colorado, within a few days of return from Iraq or Afghanistan. Soldiers with mild traumatic brain injury (ie, cases) and controls were identified based on whether they reported sustaining a mild traumatic brain injury during their most recent deployment. Participants completed a detailed self-administered headache questionnaire. Cases who reported having headaches that started or worsened after a head injury were defined as cases with PTH, and all other cases were defined as cases without PTH. Headache and migraine features assessed were unilateral location, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, exacerbation, pulsatility, visual aura, sensory aura, pain level, frequency, and allodynia. Headaches were assessed again at three months and 12 months.

Soldiers were primarily young men (mean age, 27; 92% male). Most controls (64%) and mild traumatic brain injury cases (80%) reported having headaches in the past year. Among those with headaches, daily or continuous headache was reported by 5% of controls, 7% of cases without PTH, and 24% of cases with PTH. All headache and migraine features were less common in controls than in cases and less common in cases without PTH than in cases with PTH. Finally, cases without PTH and controls had a similar prevalence of most headache and migraine features, with the exceptions of sensory aura and headache frequency.

At three months, mean annualized headache frequency decreased by about 20 days among cases with PTH but remained unchanged in the other groups. Results were similar at 12 months. Baseline visual or sensory aura and pulsatility were positive prognostic factors associated with reduced headache frequency at 12 months. Baseline headache pain was a negative prognostic factor.

Over time, headache frequency diminished in those with mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic headache.

Over time, headache frequency diminished in those with mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic headache.

SAN FRANCISCO—Among a cohort of recently deployed soldiers, headaches were frequent but were more severe, frequent, and migrainous if associated with concussion, according to a report presented at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. At one-year follow-up, headache frequency had decreased in soldiers with posttraumatic headache (PTH) but remained higher in this group than in those whose headaches were presumed to be unrelated to head injury, said Ann I. Scher, PhD, Director and Professor of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, and colleagues.

“There are limited data on the phenotypic differences between headaches related to mild traumatic brain injury and ‘regular’ headaches,” Dr. Scher said. “A better understanding of the posttraumatic headache phenotype will inform the design of interventional studies for this difficult to treat population.”

Dr. Scher and colleagues designed a study to compare headache features and one-year prognosis in a cohort of recently deployed soldiers with and without a recent history of a deployment-related mild traumatic brain injury (ie, concussion).

In all, 1,567 soldiers were randomly recruited at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Fort Carson, Colorado, within a few days of return from Iraq or Afghanistan. Soldiers with mild traumatic brain injury (ie, cases) and controls were identified based on whether they reported sustaining a mild traumatic brain injury during their most recent deployment. Participants completed a detailed self-administered headache questionnaire. Cases who reported having headaches that started or worsened after a head injury were defined as cases with PTH, and all other cases were defined as cases without PTH. Headache and migraine features assessed were unilateral location, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, exacerbation, pulsatility, visual aura, sensory aura, pain level, frequency, and allodynia. Headaches were assessed again at three months and 12 months.

Soldiers were primarily young men (mean age, 27; 92% male). Most controls (64%) and mild traumatic brain injury cases (80%) reported having headaches in the past year. Among those with headaches, daily or continuous headache was reported by 5% of controls, 7% of cases without PTH, and 24% of cases with PTH. All headache and migraine features were less common in controls than in cases and less common in cases without PTH than in cases with PTH. Finally, cases without PTH and controls had a similar prevalence of most headache and migraine features, with the exceptions of sensory aura and headache frequency.

At three months, mean annualized headache frequency decreased by about 20 days among cases with PTH but remained unchanged in the other groups. Results were similar at 12 months. Baseline visual or sensory aura and pulsatility were positive prognostic factors associated with reduced headache frequency at 12 months. Baseline headache pain was a negative prognostic factor.

SAN FRANCISCO—Among a cohort of recently deployed soldiers, headaches were frequent but were more severe, frequent, and migrainous if associated with concussion, according to a report presented at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. At one-year follow-up, headache frequency had decreased in soldiers with posttraumatic headache (PTH) but remained higher in this group than in those whose headaches were presumed to be unrelated to head injury, said Ann I. Scher, PhD, Director and Professor of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, and colleagues.

“There are limited data on the phenotypic differences between headaches related to mild traumatic brain injury and ‘regular’ headaches,” Dr. Scher said. “A better understanding of the posttraumatic headache phenotype will inform the design of interventional studies for this difficult to treat population.”

Dr. Scher and colleagues designed a study to compare headache features and one-year prognosis in a cohort of recently deployed soldiers with and without a recent history of a deployment-related mild traumatic brain injury (ie, concussion).

In all, 1,567 soldiers were randomly recruited at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Fort Carson, Colorado, within a few days of return from Iraq or Afghanistan. Soldiers with mild traumatic brain injury (ie, cases) and controls were identified based on whether they reported sustaining a mild traumatic brain injury during their most recent deployment. Participants completed a detailed self-administered headache questionnaire. Cases who reported having headaches that started or worsened after a head injury were defined as cases with PTH, and all other cases were defined as cases without PTH. Headache and migraine features assessed were unilateral location, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, exacerbation, pulsatility, visual aura, sensory aura, pain level, frequency, and allodynia. Headaches were assessed again at three months and 12 months.

Soldiers were primarily young men (mean age, 27; 92% male). Most controls (64%) and mild traumatic brain injury cases (80%) reported having headaches in the past year. Among those with headaches, daily or continuous headache was reported by 5% of controls, 7% of cases without PTH, and 24% of cases with PTH. All headache and migraine features were less common in controls than in cases and less common in cases without PTH than in cases with PTH. Finally, cases without PTH and controls had a similar prevalence of most headache and migraine features, with the exceptions of sensory aura and headache frequency.

At three months, mean annualized headache frequency decreased by about 20 days among cases with PTH but remained unchanged in the other groups. Results were similar at 12 months. Baseline visual or sensory aura and pulsatility were positive prognostic factors associated with reduced headache frequency at 12 months. Baseline headache pain was a negative prognostic factor.

Osteochondritis Dissecans Lesion of the Radial Head

ABSTRACT

This case shows an atypical presentation of an osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesion of the radial head with detachment diagnosed on plain radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). OCD lesions are rather uncommon in the elbow joint; however, when present, these lesions are typically seen in throwing athletes or gymnasts who engage in activities involving repetitive trauma to the elbow. Involvement of the radial head is extremely rare, accounting for <5% of all elbow OCD lesions. Conventional radiographs have low sensitivity for detecting OCD lesions and may frequently miss these lesions in the early stages. MRI, the imaging modality of choice, can detect these lesions at the earliest stage and provide a clear picture of the involved articular cartilage and underlying bone. Treatment options can vary between nonoperative and operative management depending on several factors, including age and activity level of the patient, size and type of lesion, and clinical presentation. This case represents a radial head OCD lesion managed by arthroscopic débridement alone, resulting in a positive outcome.

Continue to: Case Report...

CASE REPORT

A healthy, 14-year-old, left-hand-dominant adolescent boy presented to the office with a chief complaint of pain localized to the posterolateral aspect of his elbow. He described an injury where he felt a “pop” in his elbow followed by immediate pain in the posterolateral elbow after throwing a pitch during a baseball game. Since the injury, the patient had experienced difficulty extending his elbow and a sharp, throbbing pain during forearm rotation. The patient also reported an intermittent clicking feeling in the elbow. Prior to this injury, he had no elbow pain. He presented in an otherwise normal state of health with no reported past medical or surgical history and no previous trauma to the left upper extremity.

Physical examination demonstrated a mild effusion of the left elbow in the region of the posterolateral corner or “soft spot” with tenderness to palpation over the radial head. The patient had restricted elbow motion with 30° to 135° of flexion. He had 90° of pronation and supination. Ligamentous examination revealed stability of the elbow to both varus and valgus stress at 30° of flexion. No deficits were observed upon upper-extremity neurovascular examination.

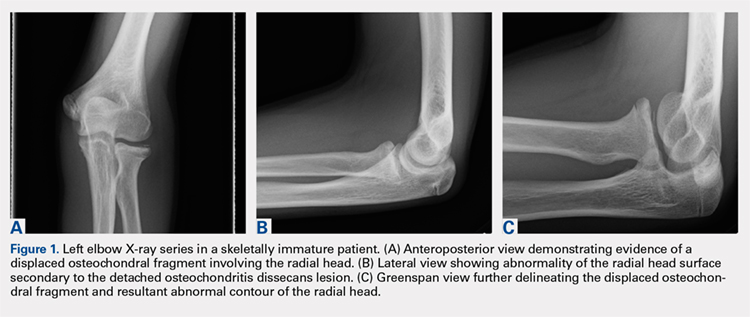

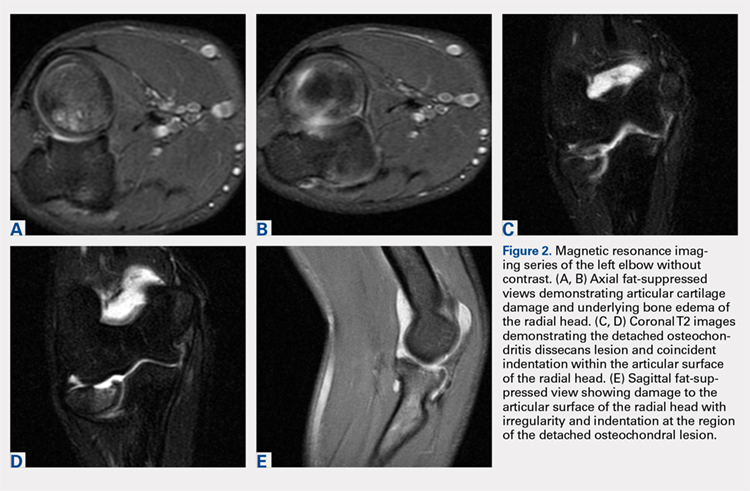

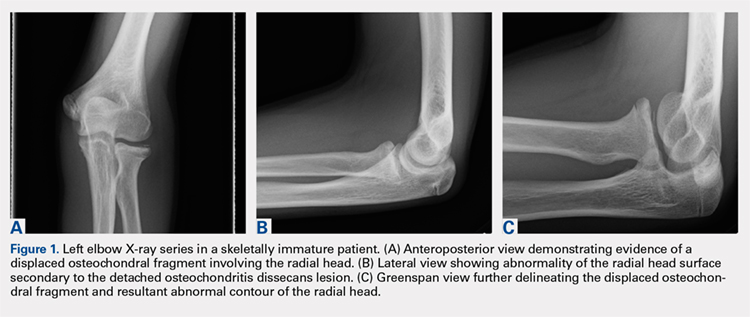

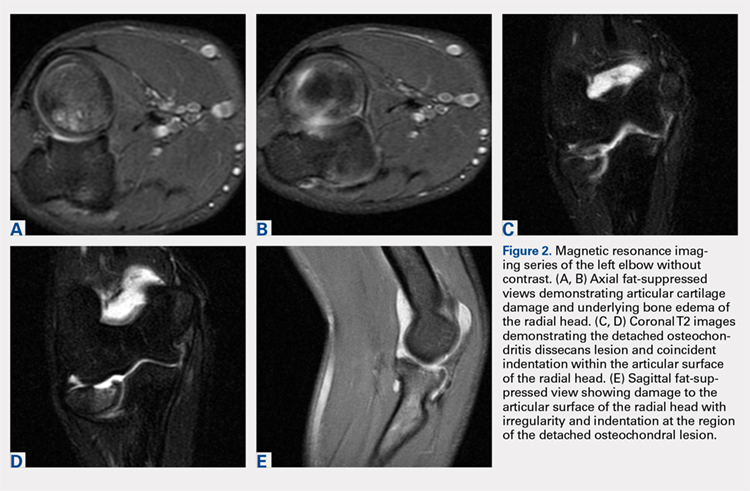

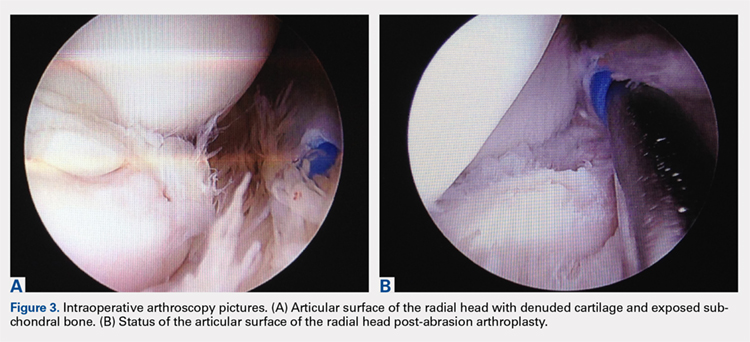

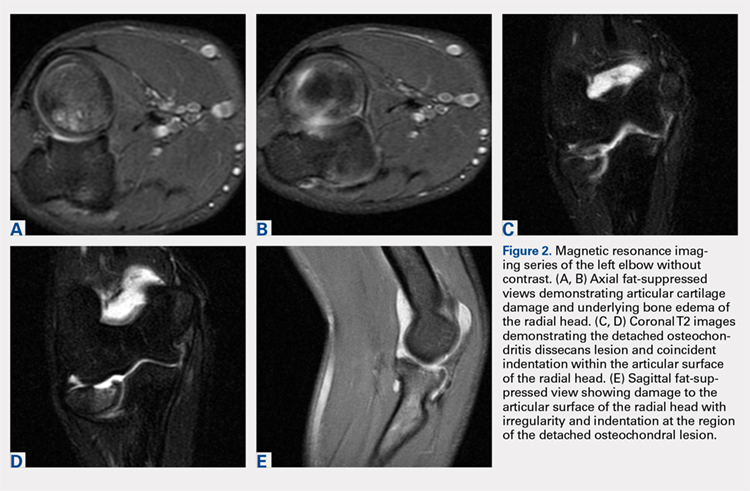

Plain radiographs of the left elbow were initially taken. Anteroposterior, lateral, and Greenspan views revealed evidence of a displaced osteochondral fragment of the radial head in this skeletally immature patient. No involvement of the capitellum was apparent (Figures 1A-1C). Non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left elbow was subsequently obtained to evaluate the lesion further, and the images confirmed an unstable osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesion of the radial head with a detached fragment entrapped within the elbow joint (Figures 2A-2E).

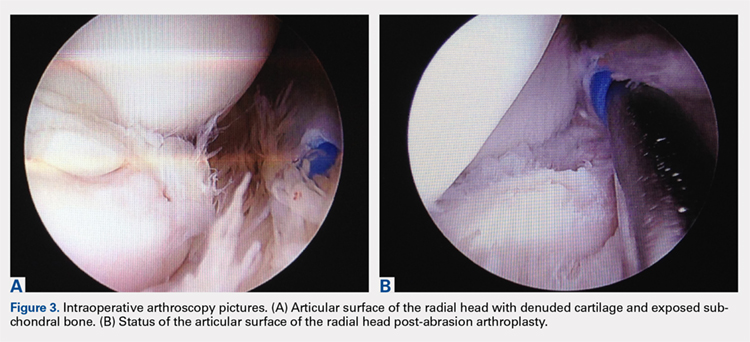

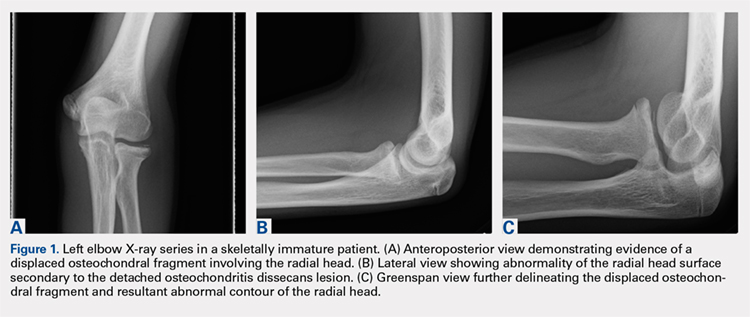

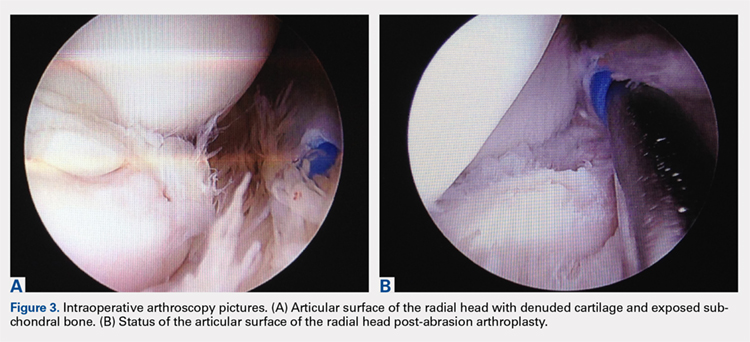

Elbow arthroscopy was performed to evaluate the extent of the OCD lesion to enable determination of the integrity of the cartilaginous surface and remove the loose body entrapped within the elbow joint. Multiple loose bodies (all <5 mm in size) were removed from the elbow joint. Visualization of the radiocapitellar joint revealed extensive cartilage damage to the radial head with multiple areas of denuded cartilage and exposed bone. The main chondral defect measured approximately 4 mm in size. Probing of the lesion confirmed no stable edge; thus, abrasion arthroplasty was performed to stabilize the lesion and stimulate future fibrous cartilage growth (Figures 3A, 3B).

The patient was started on physical therapy consisting of active and active-assisted elbow ranges of motion on postoperative day 10. At the 6-week follow up, the patient presented to the office with pain-free motion of the left elbow ranging from −5° to 135° of flexion. He maintained full pronation and supination. At this point, the patient was advised to begin a throwing program. Three months after treatment, the patient resumed baseball activities, including throwing, with pain-free, full range of motion of the elbow. The patient and the patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION

Elbow pain is a common complaint among young baseball players. OCD lesions, however, are an uncommon entity associated with elbow pathology.1 The overall incidence of OCD lesions is between 15 to 30 per 100,000 people.2-3 Specifically in patients aged 2 to 19 years, the incidence of elbow OCD lesions is 2.2 per 100,000 patients and 3.8 and 0.6 per 100,000 for males and females, respectively.4 Radial head OCD lesions are extremely rare, occurring in <5% of all elbow OCD cases.1 The majority of these lesions are asymptomatic and typically seen in patients who engage in repetitive overhead and upper-extremity weight-bearing activities. Reports indicate that the incidence of these lesions is on the rise and the age of presentation is decreasing, likely because of increased awareness of the disease and increasing involvement of young athletes in competitive athletics.4-5 Most patients with elbow OCD have a history of repetitive overuse of the elbow, as seen in baseball players, leading to excessive compressive and shear forces across the radiocapitellar joint and progression of the dissecans lesion.6

Patients with OCD lesions of the elbow typically present with inflammatory type symptoms and lateral elbow pain. The pain tends to be mild at rest and becomes more pronounced with activity. Patients often wait until mechanical symptoms ensue (eg, clicking, catching, or locking) before presenting to the office. On physical examination, pain in the region of the OCD lesion is usually accompanied by a mild effusion. Stiffness, particularly a loss of terminal extension, may accompany the mechanical symptoms on range of motion testing.7

Workup of elbow OCD lesions begins with obtaining plain radiographs of the elbow. Plain films are of limited use in evaluating these lesions but can help determine separation and the approximate size of the fragment.8 Further work-up must include MRI sequences, which allow for the best evaluation of the articular cartilage, underlying bone, and, specifically, the size and degree of separation of the OCD lesion.9

Nonoperative treatment of OCD lesions is usually successful if diagnosed early. Such treatment consists of activity modification, rest, anti-inflammatory medications, and a gradual return to athletic activities over the next 3 to 6 months provided the symptoms abate.10-11 During this interval, physical therapy may be employed to preserve or regain range of motion in the elbow. Clinical evidence has demonstrated improved outcomes in younger athletes with open physes.12 Returning to athletic activities is advised only when complete resolution of symptoms has been achieved and full motion about the elbow and shoulder girdle has been regained.6

If symptoms persist despite nonoperative management, or if evidence of an unstable lesion (ie, detached fragment) is obtained, operative intervention is appropriate. Operative management includes diagnostic arthroscopy of the entire elbow, removal of any small, loose bodies, and synovectomy as needed. Thereafter, the OCD lesion must be addressed. In cases of capitellar OCD lesions, if the articular cartilage surface is intact, antegrade or retrograde drilling of the subchondral bone is appropriate and will likely result in a good-to-excellent functional outcome.13-14 If disruption to the articular cartilage fissures is found or the lesion appears to be separating from the native bone, fixation of the fragment can be attempted, provided an adequate portion of the subchondral bone remains attached to the OCD lesion.6,14 Oftentimes, the bony bed must be prepared prior to fixation by removal of any fibrous tissue overlying the subchondral bone and ensuring adequate bleeding across the entire bed. Care should be taken to remove any fibrous tissue underlying the OCD lesion. If the OCD lesion is completely loose and/or the bone stock is insufficient or fragmented, arthroscopic removal of the OCD lesion followed by débridement and abrasion arthroplasty of subchondral bone is recommended.15 Improved functional outcomes from this procedure can be expected in contained lesions.15 If the patient continues to be symptomatic, osteochondral autograft or allograft procedures can be attempted depending on the size of the remaining defect.16-18

Other cases of radial head OCD lesions have been reported in the literature.19-20 In 2009, Dotzis and colleagues19 reported a case of an OCD lesion that was managed nonsurgically with observation alone as the lesion was stable and non-detached. Tatebe and colleagues20 reported 4 cases in which OCD involved the radial head and was accompanied by radial head subluxation. All lesions were located at the posteromedial aspect of the radial head with anterior subluxation of the radial head.20 Three of the cases were managed surgically via ulnar osteotomy (2 cases) and fragment removal (1 case).20 All except the 1 case treated by fragment excision revealed a good outcome.20 The patient in this case presented with a detached lesion, confirmed on MRI, with pain, mechanical symptoms, and of loss of terminal extension. Given the chronicity of the injury and the presence of mechanical symptoms, the decision was made to proceed with operative intervention. During elbow arthroscopy, multiple loose bodies were removed from the elbow joint, and inspection of the radiocapitellar joint revealed extensive cartilage damage to the radial head with multiple areas of denuded cartilage and exposed bone. Since the OCD lesion was completely loose and the bone stock was insufficient and too fragmented to attempt fixation, abrasion arthroplasty was performed to stabilize the lesion and stimulate future fibrous cartilage growth. At the 6-week follow up, the patient regained full range of motion of this elbow with no complaints of pain. At the 3-month follow up, the patient reported no pain after returning to throwing and all baseball-related activities.

CONCLUSION

This report presents an extremely rare case of an OCD lesion involving the radial head. Diagnosis and treatment of this lesion followed a protocol similar to that used for the management of capitellar OCD lesions. When dealing with elbow OCD lesions, especially in the skeletally immature patient population, nonsurgical management and a gradual return to activities should be attempted. If symptoms persist despite nonoperative management or evidence of an unstable lesion (as presented in this case) is obtained, operative intervention is appropriate.

- Jans LB, Ditchfield M, Anna G, Jaremko JL, Verstraete KL. MR imaging findings and MR criteria for instability in osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow in children. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(6):1306-1310. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.007.

- Hughston JC, Hergenroeder PT, Courtenay BG. Osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66(9):1340-1348. doi:10.2106/00004623-198466090-00003.

- Lindén B. The incidence of osteochondritis dissecans in the condyles of the femur. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47(6):664-667. doi:10.3109/17453677608988756.

- Kessler JI, Nikizad H, Shea KG, Jacobs JC, Bebchuk JD, Weiss JM. The demographics and epidemiology of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee in children and adolescents. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):320-326. doi:10.1177/0363546513510390.

- Kocher MS, Tucker R, Ganley TJ, Flynn JM. Management of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: current Concepts Review. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(7):1181-1191. doi:10.1177/0363546506290127.

- Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1205-1214. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00622.

- Takahara M, Ogino T, Takagi M, Tsuchida H, Orui H, Nambu T. Natural progression of osteo Chondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum: initial observations. Radiology. 2000;216(1):207-212. doi:10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl29207.

- Kijowski R, De Smet AA. Radiography of the elbow for evaluation of patients with osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(5):266-271. doi:10.1007/s00256-005-0899-6.

- Kijowski R, De Smet AA. MRI findings of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum with surgical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1453-1459. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1570.

- Takahara M, Ogino T, Fukushima S, Tsuchida H, Kaneda K. Nonoperative treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(6):728-732. doi:10.1177/03635465990270060701.

- Takahara M, Ogino T, Sasaki I, Kato H, Minami A, Kaneda K. Long term outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;363(363):108-115. doi:10.1097/00003086-199906000-00014.

- Pill SG, Ganley TJ, Milam RA, Lou JE, Meyer JS, Flynn JM. Role of magnetic resonance imaging and clinical criteria in predicting successful nonoperative treatment of osteochondritis dissecans in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(1):102-108. doi:10.1097/01241398-200301000-00021.

- Mihara K, Suzuki K, Makiuchi D, Nishinaka N, Yamaguchi K, Tsutsui H. Surgical treatment for osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):31-37. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.007.

- Byrd JWT, Jones KS. Arthroscopic surgery for isolated capitellar osteochondritis dissecans in adolescent baseball players: minimum three-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(4):474-478. doi:10.1177/03635465020300040401.

- Krijnen MR, Lim L, Willems WJ. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum: report of 5 female athletes. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(2):210-214. doi:10.1053/jars.2003.50052.

- Mihara K, Suzuki K, Makiuchi D, Nishinaka N, Yamaguchi K, Tsutsui H. Surgical treatment for osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):31-37. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.007.

- Yamamoto Y, Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, Sato H, Toh S. Osteochondral autograft transplantation for osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow in juvenile baseball players: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(5):714-720. doi:10.1177/0363546505282620.

- Ahmad CS, ElAttrache NS. Mosaicplasty for capitellar osteochondritis dissecans. In: Yamaguchi K, O'Driscoll S, King G, McKee M, eds. [In press] Advanced Reconstruction Elbow. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

- Dotzis A, Galissier B, Peyrou P, Longis B, Moulies D. Osteochondritis dissecans of the radial head: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):e18-e21. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.04.009.

- Tatebe M, Hirata H, Shinohara T, Yamamoto M, Morita A, Horii E. Pathomechanical significance of radial head subluxation in the onset of osteochondritis dissecans of the radial head. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(1):e4-e6. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e318214d678.

ABSTRACT

This case shows an atypical presentation of an osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesion of the radial head with detachment diagnosed on plain radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). OCD lesions are rather uncommon in the elbow joint; however, when present, these lesions are typically seen in throwing athletes or gymnasts who engage in activities involving repetitive trauma to the elbow. Involvement of the radial head is extremely rare, accounting for <5% of all elbow OCD lesions. Conventional radiographs have low sensitivity for detecting OCD lesions and may frequently miss these lesions in the early stages. MRI, the imaging modality of choice, can detect these lesions at the earliest stage and provide a clear picture of the involved articular cartilage and underlying bone. Treatment options can vary between nonoperative and operative management depending on several factors, including age and activity level of the patient, size and type of lesion, and clinical presentation. This case represents a radial head OCD lesion managed by arthroscopic débridement alone, resulting in a positive outcome.

Continue to: Case Report...

CASE REPORT

A healthy, 14-year-old, left-hand-dominant adolescent boy presented to the office with a chief complaint of pain localized to the posterolateral aspect of his elbow. He described an injury where he felt a “pop” in his elbow followed by immediate pain in the posterolateral elbow after throwing a pitch during a baseball game. Since the injury, the patient had experienced difficulty extending his elbow and a sharp, throbbing pain during forearm rotation. The patient also reported an intermittent clicking feeling in the elbow. Prior to this injury, he had no elbow pain. He presented in an otherwise normal state of health with no reported past medical or surgical history and no previous trauma to the left upper extremity.

Physical examination demonstrated a mild effusion of the left elbow in the region of the posterolateral corner or “soft spot” with tenderness to palpation over the radial head. The patient had restricted elbow motion with 30° to 135° of flexion. He had 90° of pronation and supination. Ligamentous examination revealed stability of the elbow to both varus and valgus stress at 30° of flexion. No deficits were observed upon upper-extremity neurovascular examination.

Plain radiographs of the left elbow were initially taken. Anteroposterior, lateral, and Greenspan views revealed evidence of a displaced osteochondral fragment of the radial head in this skeletally immature patient. No involvement of the capitellum was apparent (Figures 1A-1C). Non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left elbow was subsequently obtained to evaluate the lesion further, and the images confirmed an unstable osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesion of the radial head with a detached fragment entrapped within the elbow joint (Figures 2A-2E).

Elbow arthroscopy was performed to evaluate the extent of the OCD lesion to enable determination of the integrity of the cartilaginous surface and remove the loose body entrapped within the elbow joint. Multiple loose bodies (all <5 mm in size) were removed from the elbow joint. Visualization of the radiocapitellar joint revealed extensive cartilage damage to the radial head with multiple areas of denuded cartilage and exposed bone. The main chondral defect measured approximately 4 mm in size. Probing of the lesion confirmed no stable edge; thus, abrasion arthroplasty was performed to stabilize the lesion and stimulate future fibrous cartilage growth (Figures 3A, 3B).

The patient was started on physical therapy consisting of active and active-assisted elbow ranges of motion on postoperative day 10. At the 6-week follow up, the patient presented to the office with pain-free motion of the left elbow ranging from −5° to 135° of flexion. He maintained full pronation and supination. At this point, the patient was advised to begin a throwing program. Three months after treatment, the patient resumed baseball activities, including throwing, with pain-free, full range of motion of the elbow. The patient and the patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION

Elbow pain is a common complaint among young baseball players. OCD lesions, however, are an uncommon entity associated with elbow pathology.1 The overall incidence of OCD lesions is between 15 to 30 per 100,000 people.2-3 Specifically in patients aged 2 to 19 years, the incidence of elbow OCD lesions is 2.2 per 100,000 patients and 3.8 and 0.6 per 100,000 for males and females, respectively.4 Radial head OCD lesions are extremely rare, occurring in <5% of all elbow OCD cases.1 The majority of these lesions are asymptomatic and typically seen in patients who engage in repetitive overhead and upper-extremity weight-bearing activities. Reports indicate that the incidence of these lesions is on the rise and the age of presentation is decreasing, likely because of increased awareness of the disease and increasing involvement of young athletes in competitive athletics.4-5 Most patients with elbow OCD have a history of repetitive overuse of the elbow, as seen in baseball players, leading to excessive compressive and shear forces across the radiocapitellar joint and progression of the dissecans lesion.6

Patients with OCD lesions of the elbow typically present with inflammatory type symptoms and lateral elbow pain. The pain tends to be mild at rest and becomes more pronounced with activity. Patients often wait until mechanical symptoms ensue (eg, clicking, catching, or locking) before presenting to the office. On physical examination, pain in the region of the OCD lesion is usually accompanied by a mild effusion. Stiffness, particularly a loss of terminal extension, may accompany the mechanical symptoms on range of motion testing.7

Workup of elbow OCD lesions begins with obtaining plain radiographs of the elbow. Plain films are of limited use in evaluating these lesions but can help determine separation and the approximate size of the fragment.8 Further work-up must include MRI sequences, which allow for the best evaluation of the articular cartilage, underlying bone, and, specifically, the size and degree of separation of the OCD lesion.9

Nonoperative treatment of OCD lesions is usually successful if diagnosed early. Such treatment consists of activity modification, rest, anti-inflammatory medications, and a gradual return to athletic activities over the next 3 to 6 months provided the symptoms abate.10-11 During this interval, physical therapy may be employed to preserve or regain range of motion in the elbow. Clinical evidence has demonstrated improved outcomes in younger athletes with open physes.12 Returning to athletic activities is advised only when complete resolution of symptoms has been achieved and full motion about the elbow and shoulder girdle has been regained.6

If symptoms persist despite nonoperative management, or if evidence of an unstable lesion (ie, detached fragment) is obtained, operative intervention is appropriate. Operative management includes diagnostic arthroscopy of the entire elbow, removal of any small, loose bodies, and synovectomy as needed. Thereafter, the OCD lesion must be addressed. In cases of capitellar OCD lesions, if the articular cartilage surface is intact, antegrade or retrograde drilling of the subchondral bone is appropriate and will likely result in a good-to-excellent functional outcome.13-14 If disruption to the articular cartilage fissures is found or the lesion appears to be separating from the native bone, fixation of the fragment can be attempted, provided an adequate portion of the subchondral bone remains attached to the OCD lesion.6,14 Oftentimes, the bony bed must be prepared prior to fixation by removal of any fibrous tissue overlying the subchondral bone and ensuring adequate bleeding across the entire bed. Care should be taken to remove any fibrous tissue underlying the OCD lesion. If the OCD lesion is completely loose and/or the bone stock is insufficient or fragmented, arthroscopic removal of the OCD lesion followed by débridement and abrasion arthroplasty of subchondral bone is recommended.15 Improved functional outcomes from this procedure can be expected in contained lesions.15 If the patient continues to be symptomatic, osteochondral autograft or allograft procedures can be attempted depending on the size of the remaining defect.16-18

Other cases of radial head OCD lesions have been reported in the literature.19-20 In 2009, Dotzis and colleagues19 reported a case of an OCD lesion that was managed nonsurgically with observation alone as the lesion was stable and non-detached. Tatebe and colleagues20 reported 4 cases in which OCD involved the radial head and was accompanied by radial head subluxation. All lesions were located at the posteromedial aspect of the radial head with anterior subluxation of the radial head.20 Three of the cases were managed surgically via ulnar osteotomy (2 cases) and fragment removal (1 case).20 All except the 1 case treated by fragment excision revealed a good outcome.20 The patient in this case presented with a detached lesion, confirmed on MRI, with pain, mechanical symptoms, and of loss of terminal extension. Given the chronicity of the injury and the presence of mechanical symptoms, the decision was made to proceed with operative intervention. During elbow arthroscopy, multiple loose bodies were removed from the elbow joint, and inspection of the radiocapitellar joint revealed extensive cartilage damage to the radial head with multiple areas of denuded cartilage and exposed bone. Since the OCD lesion was completely loose and the bone stock was insufficient and too fragmented to attempt fixation, abrasion arthroplasty was performed to stabilize the lesion and stimulate future fibrous cartilage growth. At the 6-week follow up, the patient regained full range of motion of this elbow with no complaints of pain. At the 3-month follow up, the patient reported no pain after returning to throwing and all baseball-related activities.

CONCLUSION

This report presents an extremely rare case of an OCD lesion involving the radial head. Diagnosis and treatment of this lesion followed a protocol similar to that used for the management of capitellar OCD lesions. When dealing with elbow OCD lesions, especially in the skeletally immature patient population, nonsurgical management and a gradual return to activities should be attempted. If symptoms persist despite nonoperative management or evidence of an unstable lesion (as presented in this case) is obtained, operative intervention is appropriate.

ABSTRACT

This case shows an atypical presentation of an osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesion of the radial head with detachment diagnosed on plain radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). OCD lesions are rather uncommon in the elbow joint; however, when present, these lesions are typically seen in throwing athletes or gymnasts who engage in activities involving repetitive trauma to the elbow. Involvement of the radial head is extremely rare, accounting for <5% of all elbow OCD lesions. Conventional radiographs have low sensitivity for detecting OCD lesions and may frequently miss these lesions in the early stages. MRI, the imaging modality of choice, can detect these lesions at the earliest stage and provide a clear picture of the involved articular cartilage and underlying bone. Treatment options can vary between nonoperative and operative management depending on several factors, including age and activity level of the patient, size and type of lesion, and clinical presentation. This case represents a radial head OCD lesion managed by arthroscopic débridement alone, resulting in a positive outcome.

Continue to: Case Report...

CASE REPORT

A healthy, 14-year-old, left-hand-dominant adolescent boy presented to the office with a chief complaint of pain localized to the posterolateral aspect of his elbow. He described an injury where he felt a “pop” in his elbow followed by immediate pain in the posterolateral elbow after throwing a pitch during a baseball game. Since the injury, the patient had experienced difficulty extending his elbow and a sharp, throbbing pain during forearm rotation. The patient also reported an intermittent clicking feeling in the elbow. Prior to this injury, he had no elbow pain. He presented in an otherwise normal state of health with no reported past medical or surgical history and no previous trauma to the left upper extremity.

Physical examination demonstrated a mild effusion of the left elbow in the region of the posterolateral corner or “soft spot” with tenderness to palpation over the radial head. The patient had restricted elbow motion with 30° to 135° of flexion. He had 90° of pronation and supination. Ligamentous examination revealed stability of the elbow to both varus and valgus stress at 30° of flexion. No deficits were observed upon upper-extremity neurovascular examination.

Plain radiographs of the left elbow were initially taken. Anteroposterior, lateral, and Greenspan views revealed evidence of a displaced osteochondral fragment of the radial head in this skeletally immature patient. No involvement of the capitellum was apparent (Figures 1A-1C). Non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left elbow was subsequently obtained to evaluate the lesion further, and the images confirmed an unstable osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesion of the radial head with a detached fragment entrapped within the elbow joint (Figures 2A-2E).

Elbow arthroscopy was performed to evaluate the extent of the OCD lesion to enable determination of the integrity of the cartilaginous surface and remove the loose body entrapped within the elbow joint. Multiple loose bodies (all <5 mm in size) were removed from the elbow joint. Visualization of the radiocapitellar joint revealed extensive cartilage damage to the radial head with multiple areas of denuded cartilage and exposed bone. The main chondral defect measured approximately 4 mm in size. Probing of the lesion confirmed no stable edge; thus, abrasion arthroplasty was performed to stabilize the lesion and stimulate future fibrous cartilage growth (Figures 3A, 3B).

The patient was started on physical therapy consisting of active and active-assisted elbow ranges of motion on postoperative day 10. At the 6-week follow up, the patient presented to the office with pain-free motion of the left elbow ranging from −5° to 135° of flexion. He maintained full pronation and supination. At this point, the patient was advised to begin a throwing program. Three months after treatment, the patient resumed baseball activities, including throwing, with pain-free, full range of motion of the elbow. The patient and the patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION

Elbow pain is a common complaint among young baseball players. OCD lesions, however, are an uncommon entity associated with elbow pathology.1 The overall incidence of OCD lesions is between 15 to 30 per 100,000 people.2-3 Specifically in patients aged 2 to 19 years, the incidence of elbow OCD lesions is 2.2 per 100,000 patients and 3.8 and 0.6 per 100,000 for males and females, respectively.4 Radial head OCD lesions are extremely rare, occurring in <5% of all elbow OCD cases.1 The majority of these lesions are asymptomatic and typically seen in patients who engage in repetitive overhead and upper-extremity weight-bearing activities. Reports indicate that the incidence of these lesions is on the rise and the age of presentation is decreasing, likely because of increased awareness of the disease and increasing involvement of young athletes in competitive athletics.4-5 Most patients with elbow OCD have a history of repetitive overuse of the elbow, as seen in baseball players, leading to excessive compressive and shear forces across the radiocapitellar joint and progression of the dissecans lesion.6

Patients with OCD lesions of the elbow typically present with inflammatory type symptoms and lateral elbow pain. The pain tends to be mild at rest and becomes more pronounced with activity. Patients often wait until mechanical symptoms ensue (eg, clicking, catching, or locking) before presenting to the office. On physical examination, pain in the region of the OCD lesion is usually accompanied by a mild effusion. Stiffness, particularly a loss of terminal extension, may accompany the mechanical symptoms on range of motion testing.7

Workup of elbow OCD lesions begins with obtaining plain radiographs of the elbow. Plain films are of limited use in evaluating these lesions but can help determine separation and the approximate size of the fragment.8 Further work-up must include MRI sequences, which allow for the best evaluation of the articular cartilage, underlying bone, and, specifically, the size and degree of separation of the OCD lesion.9

Nonoperative treatment of OCD lesions is usually successful if diagnosed early. Such treatment consists of activity modification, rest, anti-inflammatory medications, and a gradual return to athletic activities over the next 3 to 6 months provided the symptoms abate.10-11 During this interval, physical therapy may be employed to preserve or regain range of motion in the elbow. Clinical evidence has demonstrated improved outcomes in younger athletes with open physes.12 Returning to athletic activities is advised only when complete resolution of symptoms has been achieved and full motion about the elbow and shoulder girdle has been regained.6

If symptoms persist despite nonoperative management, or if evidence of an unstable lesion (ie, detached fragment) is obtained, operative intervention is appropriate. Operative management includes diagnostic arthroscopy of the entire elbow, removal of any small, loose bodies, and synovectomy as needed. Thereafter, the OCD lesion must be addressed. In cases of capitellar OCD lesions, if the articular cartilage surface is intact, antegrade or retrograde drilling of the subchondral bone is appropriate and will likely result in a good-to-excellent functional outcome.13-14 If disruption to the articular cartilage fissures is found or the lesion appears to be separating from the native bone, fixation of the fragment can be attempted, provided an adequate portion of the subchondral bone remains attached to the OCD lesion.6,14 Oftentimes, the bony bed must be prepared prior to fixation by removal of any fibrous tissue overlying the subchondral bone and ensuring adequate bleeding across the entire bed. Care should be taken to remove any fibrous tissue underlying the OCD lesion. If the OCD lesion is completely loose and/or the bone stock is insufficient or fragmented, arthroscopic removal of the OCD lesion followed by débridement and abrasion arthroplasty of subchondral bone is recommended.15 Improved functional outcomes from this procedure can be expected in contained lesions.15 If the patient continues to be symptomatic, osteochondral autograft or allograft procedures can be attempted depending on the size of the remaining defect.16-18

Other cases of radial head OCD lesions have been reported in the literature.19-20 In 2009, Dotzis and colleagues19 reported a case of an OCD lesion that was managed nonsurgically with observation alone as the lesion was stable and non-detached. Tatebe and colleagues20 reported 4 cases in which OCD involved the radial head and was accompanied by radial head subluxation. All lesions were located at the posteromedial aspect of the radial head with anterior subluxation of the radial head.20 Three of the cases were managed surgically via ulnar osteotomy (2 cases) and fragment removal (1 case).20 All except the 1 case treated by fragment excision revealed a good outcome.20 The patient in this case presented with a detached lesion, confirmed on MRI, with pain, mechanical symptoms, and of loss of terminal extension. Given the chronicity of the injury and the presence of mechanical symptoms, the decision was made to proceed with operative intervention. During elbow arthroscopy, multiple loose bodies were removed from the elbow joint, and inspection of the radiocapitellar joint revealed extensive cartilage damage to the radial head with multiple areas of denuded cartilage and exposed bone. Since the OCD lesion was completely loose and the bone stock was insufficient and too fragmented to attempt fixation, abrasion arthroplasty was performed to stabilize the lesion and stimulate future fibrous cartilage growth. At the 6-week follow up, the patient regained full range of motion of this elbow with no complaints of pain. At the 3-month follow up, the patient reported no pain after returning to throwing and all baseball-related activities.

CONCLUSION

This report presents an extremely rare case of an OCD lesion involving the radial head. Diagnosis and treatment of this lesion followed a protocol similar to that used for the management of capitellar OCD lesions. When dealing with elbow OCD lesions, especially in the skeletally immature patient population, nonsurgical management and a gradual return to activities should be attempted. If symptoms persist despite nonoperative management or evidence of an unstable lesion (as presented in this case) is obtained, operative intervention is appropriate.

- Jans LB, Ditchfield M, Anna G, Jaremko JL, Verstraete KL. MR imaging findings and MR criteria for instability in osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow in children. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(6):1306-1310. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.007.

- Hughston JC, Hergenroeder PT, Courtenay BG. Osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66(9):1340-1348. doi:10.2106/00004623-198466090-00003.

- Lindén B. The incidence of osteochondritis dissecans in the condyles of the femur. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47(6):664-667. doi:10.3109/17453677608988756.

- Kessler JI, Nikizad H, Shea KG, Jacobs JC, Bebchuk JD, Weiss JM. The demographics and epidemiology of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee in children and adolescents. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):320-326. doi:10.1177/0363546513510390.

- Kocher MS, Tucker R, Ganley TJ, Flynn JM. Management of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: current Concepts Review. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(7):1181-1191. doi:10.1177/0363546506290127.

- Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1205-1214. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00622.

- Takahara M, Ogino T, Takagi M, Tsuchida H, Orui H, Nambu T. Natural progression of osteo Chondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum: initial observations. Radiology. 2000;216(1):207-212. doi:10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl29207.

- Kijowski R, De Smet AA. Radiography of the elbow for evaluation of patients with osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(5):266-271. doi:10.1007/s00256-005-0899-6.

- Kijowski R, De Smet AA. MRI findings of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum with surgical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1453-1459. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1570.

- Takahara M, Ogino T, Fukushima S, Tsuchida H, Kaneda K. Nonoperative treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(6):728-732. doi:10.1177/03635465990270060701.