User login

Lay health workers improve end-of-life care

Lay health workers (LHWs) can improve documentation of cancer patients’ care preferences in the aftermath of their diagnosis, investigators report.

Physicians, palliative care workers, and other health professionals can help cancer patients understand their prognosis and establish end-of-life care preferences, but busy schedules and professional reluctance often prevent this. Nonclinical, nonprofessional LHWs often are employed to assist with screening and adherence, but little work has been done to use them in end-of-life care, Manali I. Patel, MD, MPH, and her associates wrote in JAMA Oncology.

To investigate their potential in this role, the researchers randomized 213 patients with stage 3 or 4 recurrent cancer to usual care or the LHW intervention, which included a 6-month structured program delivered by a single LHW who was enrolled in a part-time graduate health education program. The LHWs received an 80-hour online skills-based seminar and 4 weeks’ observation training with a palliative care team.

The LHWs helped patients with advanced care planning, including: education about goals of care, establishment of care preferences, establishment of a surrogate decision maker, creation of an advanced directive, and encouragement to discuss the patient’s care with the clinician.

In the intervention arm, 92.4% of patients successfully had their goals of care documented in the electronic health record within 6 months of randomization, compared with 17.6% of the usual care group (P less than .001). They also were more likely to have created an advanced directive (67.6% vs. 25.9%; P less than .001), Dr. Patel, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and her associates reported.

Patient satisfaction was also greater in the intervention arm, as measured by the Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers & Systems “satisfaction with provider” item (mean score, 9.16 vs. 7.83; P less than .001). At 6 months, with respect to their oncology provider, patients in the intervention arm registered a mean increase in satisfaction score of 1.53 (P less than .001).

Patients who died were more likely to receive hospice care if they were in the LHW group (76.7% vs. 48.3%; P =.002). Those in the LHW group also had lower health care costs during the final 30 days of their lives ($1,048 vs. $23,482; P less than .001).

Overall, the study shows that LHWs may be one mechanism for delivering high-value care and avoiding unnecessary, burdensome late-life treatments, at least in cancer patients.

SOURCE: Patel MI et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Jul 26doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2446.

Lay health workers (LHWs) can improve documentation of cancer patients’ care preferences in the aftermath of their diagnosis, investigators report.

Physicians, palliative care workers, and other health professionals can help cancer patients understand their prognosis and establish end-of-life care preferences, but busy schedules and professional reluctance often prevent this. Nonclinical, nonprofessional LHWs often are employed to assist with screening and adherence, but little work has been done to use them in end-of-life care, Manali I. Patel, MD, MPH, and her associates wrote in JAMA Oncology.

To investigate their potential in this role, the researchers randomized 213 patients with stage 3 or 4 recurrent cancer to usual care or the LHW intervention, which included a 6-month structured program delivered by a single LHW who was enrolled in a part-time graduate health education program. The LHWs received an 80-hour online skills-based seminar and 4 weeks’ observation training with a palliative care team.

The LHWs helped patients with advanced care planning, including: education about goals of care, establishment of care preferences, establishment of a surrogate decision maker, creation of an advanced directive, and encouragement to discuss the patient’s care with the clinician.

In the intervention arm, 92.4% of patients successfully had their goals of care documented in the electronic health record within 6 months of randomization, compared with 17.6% of the usual care group (P less than .001). They also were more likely to have created an advanced directive (67.6% vs. 25.9%; P less than .001), Dr. Patel, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and her associates reported.

Patient satisfaction was also greater in the intervention arm, as measured by the Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers & Systems “satisfaction with provider” item (mean score, 9.16 vs. 7.83; P less than .001). At 6 months, with respect to their oncology provider, patients in the intervention arm registered a mean increase in satisfaction score of 1.53 (P less than .001).

Patients who died were more likely to receive hospice care if they were in the LHW group (76.7% vs. 48.3%; P =.002). Those in the LHW group also had lower health care costs during the final 30 days of their lives ($1,048 vs. $23,482; P less than .001).

Overall, the study shows that LHWs may be one mechanism for delivering high-value care and avoiding unnecessary, burdensome late-life treatments, at least in cancer patients.

SOURCE: Patel MI et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Jul 26doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2446.

Lay health workers (LHWs) can improve documentation of cancer patients’ care preferences in the aftermath of their diagnosis, investigators report.

Physicians, palliative care workers, and other health professionals can help cancer patients understand their prognosis and establish end-of-life care preferences, but busy schedules and professional reluctance often prevent this. Nonclinical, nonprofessional LHWs often are employed to assist with screening and adherence, but little work has been done to use them in end-of-life care, Manali I. Patel, MD, MPH, and her associates wrote in JAMA Oncology.

To investigate their potential in this role, the researchers randomized 213 patients with stage 3 or 4 recurrent cancer to usual care or the LHW intervention, which included a 6-month structured program delivered by a single LHW who was enrolled in a part-time graduate health education program. The LHWs received an 80-hour online skills-based seminar and 4 weeks’ observation training with a palliative care team.

The LHWs helped patients with advanced care planning, including: education about goals of care, establishment of care preferences, establishment of a surrogate decision maker, creation of an advanced directive, and encouragement to discuss the patient’s care with the clinician.

In the intervention arm, 92.4% of patients successfully had their goals of care documented in the electronic health record within 6 months of randomization, compared with 17.6% of the usual care group (P less than .001). They also were more likely to have created an advanced directive (67.6% vs. 25.9%; P less than .001), Dr. Patel, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and her associates reported.

Patient satisfaction was also greater in the intervention arm, as measured by the Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers & Systems “satisfaction with provider” item (mean score, 9.16 vs. 7.83; P less than .001). At 6 months, with respect to their oncology provider, patients in the intervention arm registered a mean increase in satisfaction score of 1.53 (P less than .001).

Patients who died were more likely to receive hospice care if they were in the LHW group (76.7% vs. 48.3%; P =.002). Those in the LHW group also had lower health care costs during the final 30 days of their lives ($1,048 vs. $23,482; P less than .001).

Overall, the study shows that LHWs may be one mechanism for delivering high-value care and avoiding unnecessary, burdensome late-life treatments, at least in cancer patients.

SOURCE: Patel MI et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Jul 26doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2446.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Lay health workers helped advanced cancer patients document their treatment preferences and reduced end of life costs.

Major finding: 92.4% of patients working with LHWs had their preferences recorded at 6 months, compared with 17.6% of controls.

Study details: Randomized, controlled trial of 213 patients with stage 3 or 4 recurrent cancer.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, and the California Healthcare Foundation.

Source: Patel MI et al. JAMA Oncology. 2018 Jul 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2446.

Asystole Following Nitroglycerin: A Review of Two Cases

Case reports of a 54-year-old man with angina and a 69-year-old woman demonstrate an underreported, self-limiting side effect associated with nitroglycerin.

Nitroglycerin (NTG), or glyceryl trinitrate, was first introduced into the medical community by Murrell,1,2 who reported on anecdotal observations of its antianginal properties by workers within manufacturing plants refining the product for its explosive properties. While the route of administration of NTG has changed from this incidental environmental exposure to the now formulated therapies available, its benefit as an outpatient, abortive treatment for stable angina has been validated beyond early subjective observations in the literature.1-3 In fact, its successful use over the years for angina has produced an expansive pharmacopeia, including its use for undifferentiated chest pain and exacerbation of congestive heart failure.3-5

Despite the extensive history of NTG as a proven vasodilator, emerging uses continue to be explored in equal measure with technological advances.2,6 Though morbidity and mortality reductions are dependent on its use within clinical practice, NTG is not an innocuous drug.5 Most of the reported side effects associated with NTG are well established and include hypotension, tachycardia, flushing, nausea, vomiting, and headache.3,6,7 An often forgotten side effect associated with NTG use is asystole. We present the following two cases to highlight both common uses of NTG as well as this underreported side effect.

Case 1: Nitroglycerin for Stable Anginal Chest Pain

A 54-year-old man with a history of hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia (HLP), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) presented to the ED for evaluation of a 3-hour history of intermittent, retrosternal, left-sided, nonradiating chest “pressure and tightness.” The patient stated that the chest discomfort began at rest but was exacerbated by exertion with episodes lasting 10 to 15 minutes. The patient rated the peak pain associated with these episodes as a “7” on a pain scale of 1 to 10. He further noted that his symptoms abated and he became “pain-free” when at rest.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 156/87 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 68 beats/min; respiratory rate (RR), 18 beats/min; and temperature (T), 98.4°F. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air.

The patient, who performed regular BP checks at home, noted that his recent BP readings had been very high. A review of the patient’s systems was positive for shortness of breath and diaphoresis; symptoms were otherwise negative, including any prior episodes. His social history was noncontributory and negative for tobacco, alcohol, or drug use. The patient did report that he had taken an uneventful 6-hour car ride the previous week.

On physical examination, the patient was nontoxic and resting comfortably, without signs of acute distress or pain. Cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, and radial pulses were 2+ and symmetric. The abdominal examination was benign and the neurological examination was nonfocal. There was no evidence of peripheral edema or asymmetry of the calves, which were nontender to palpation.

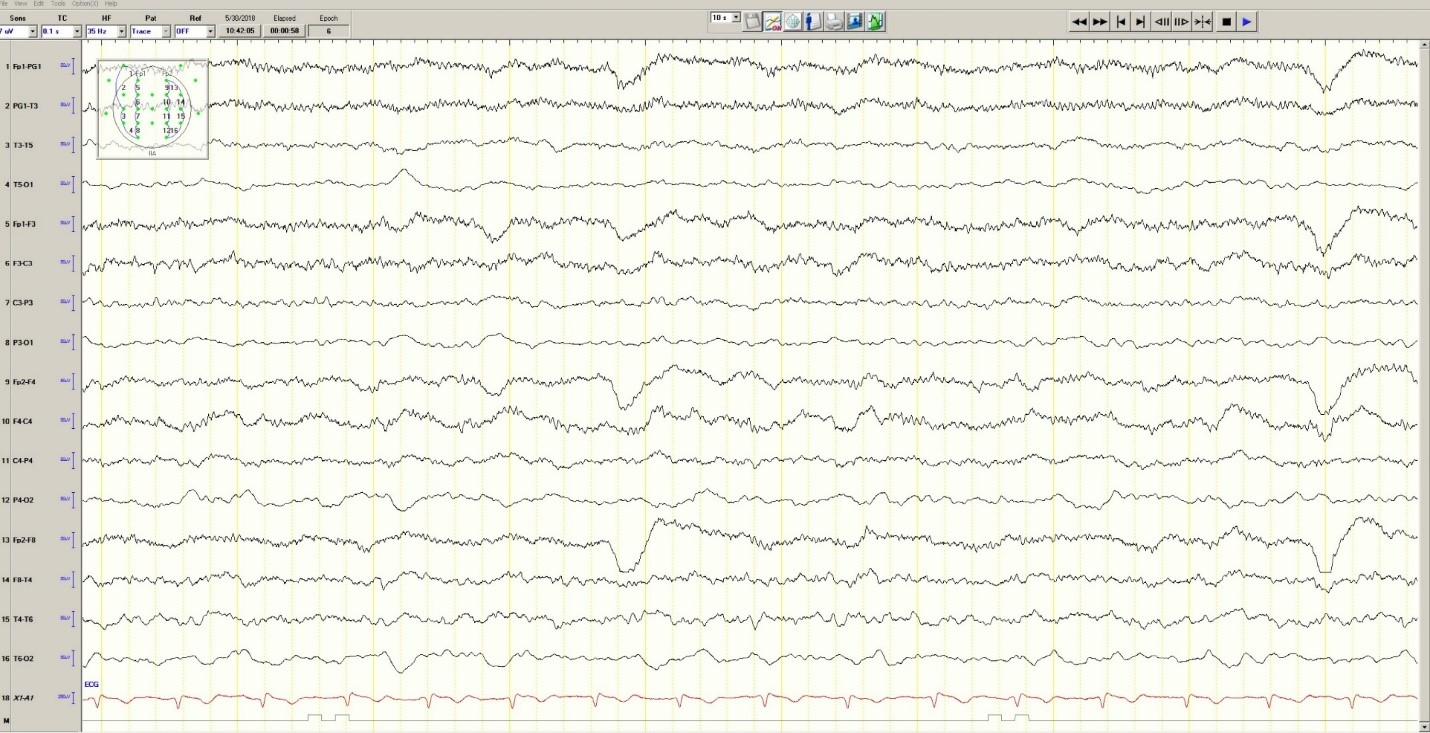

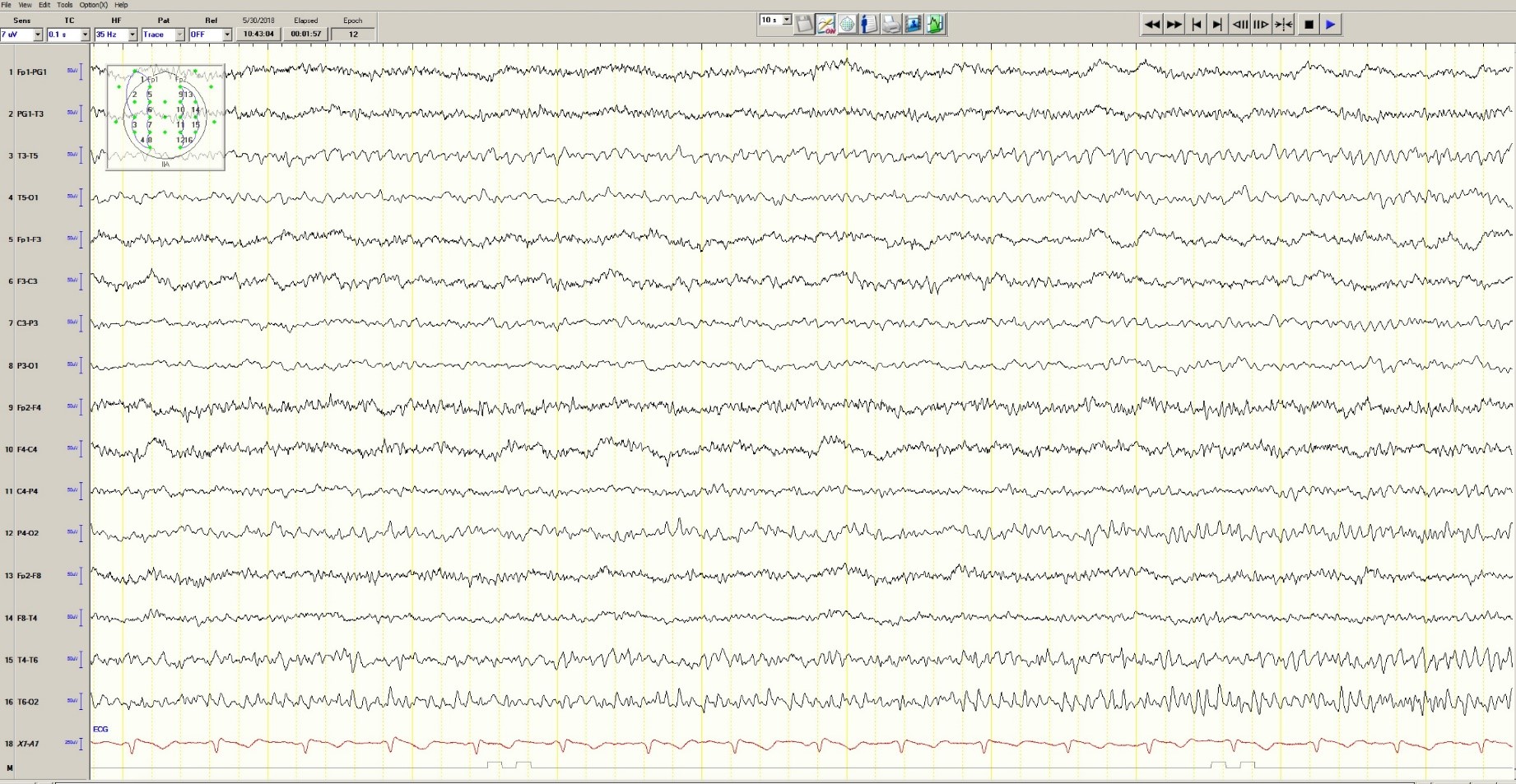

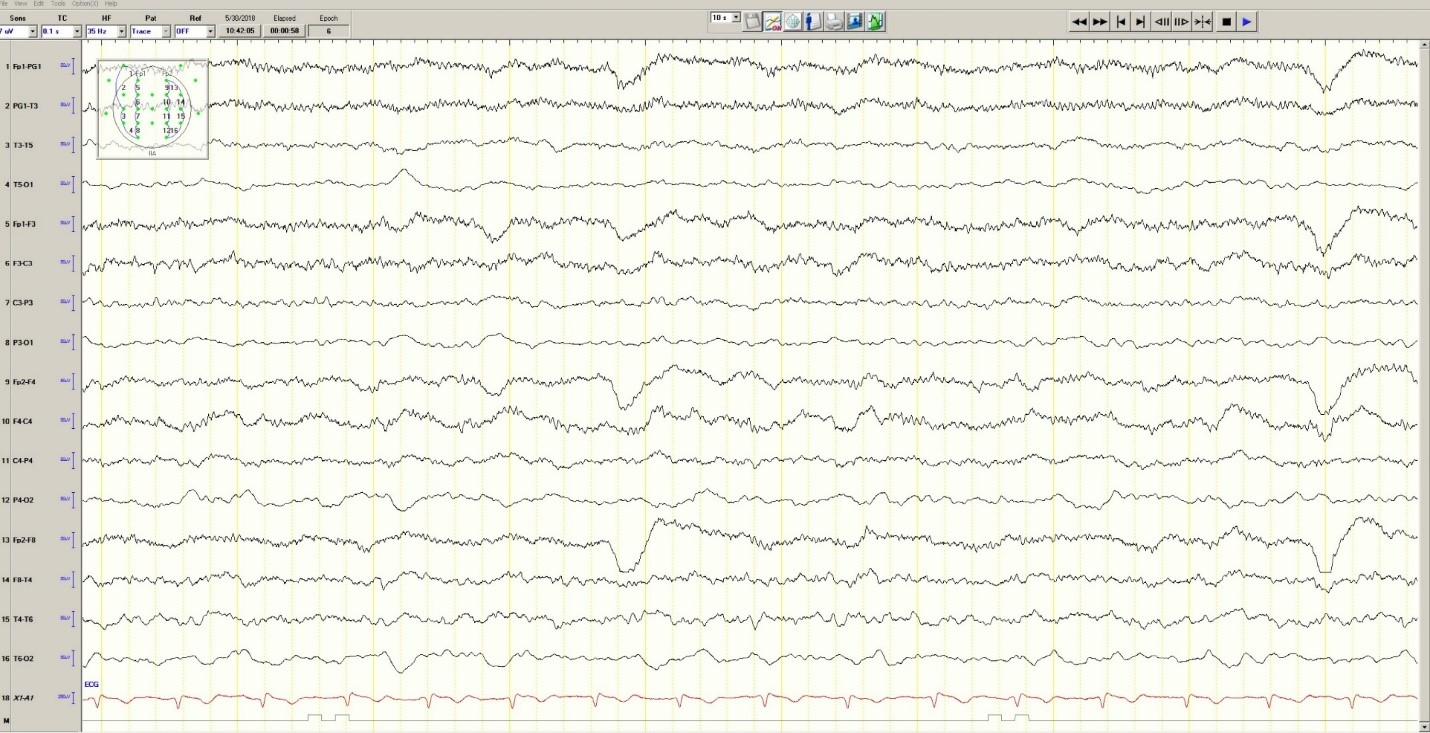

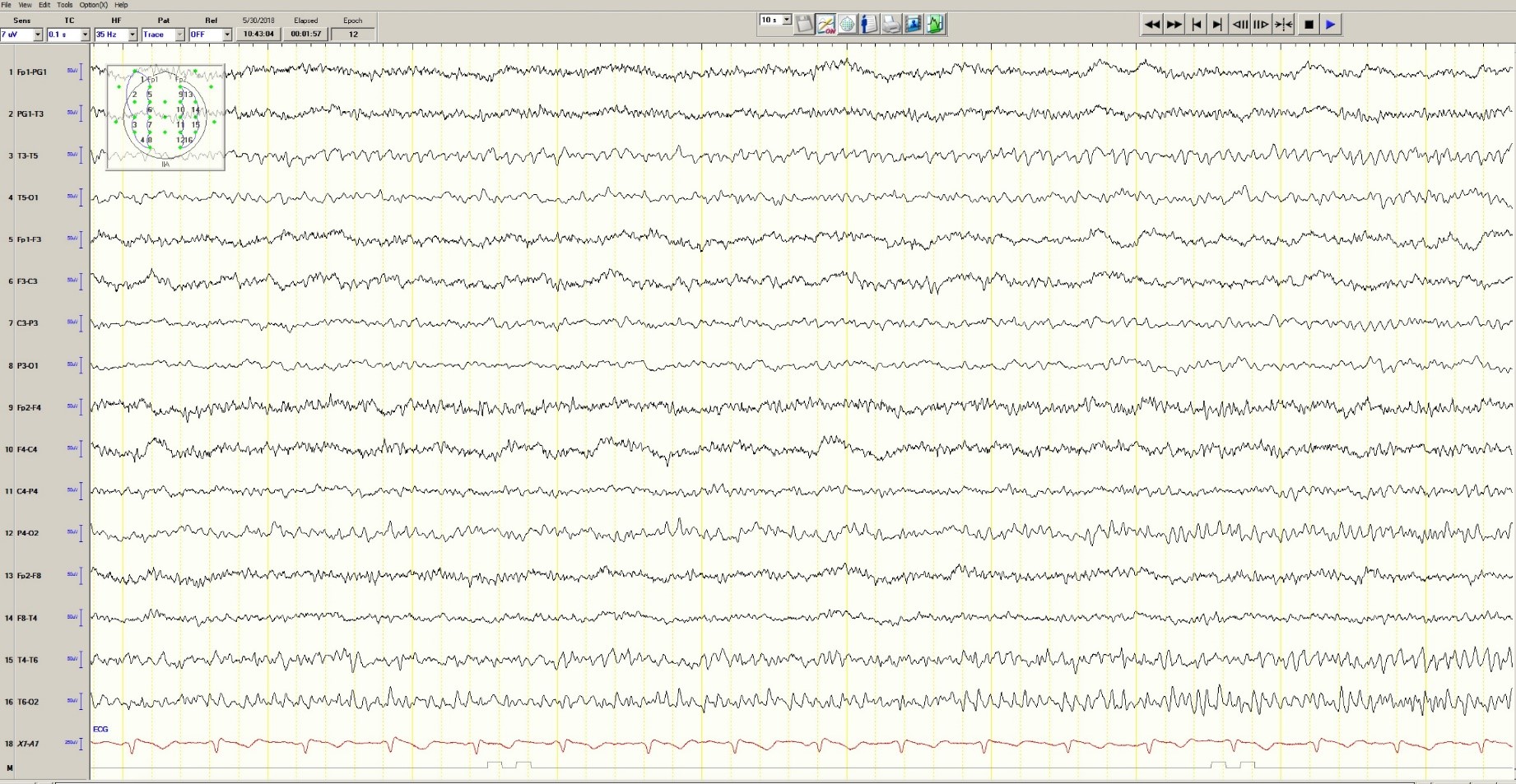

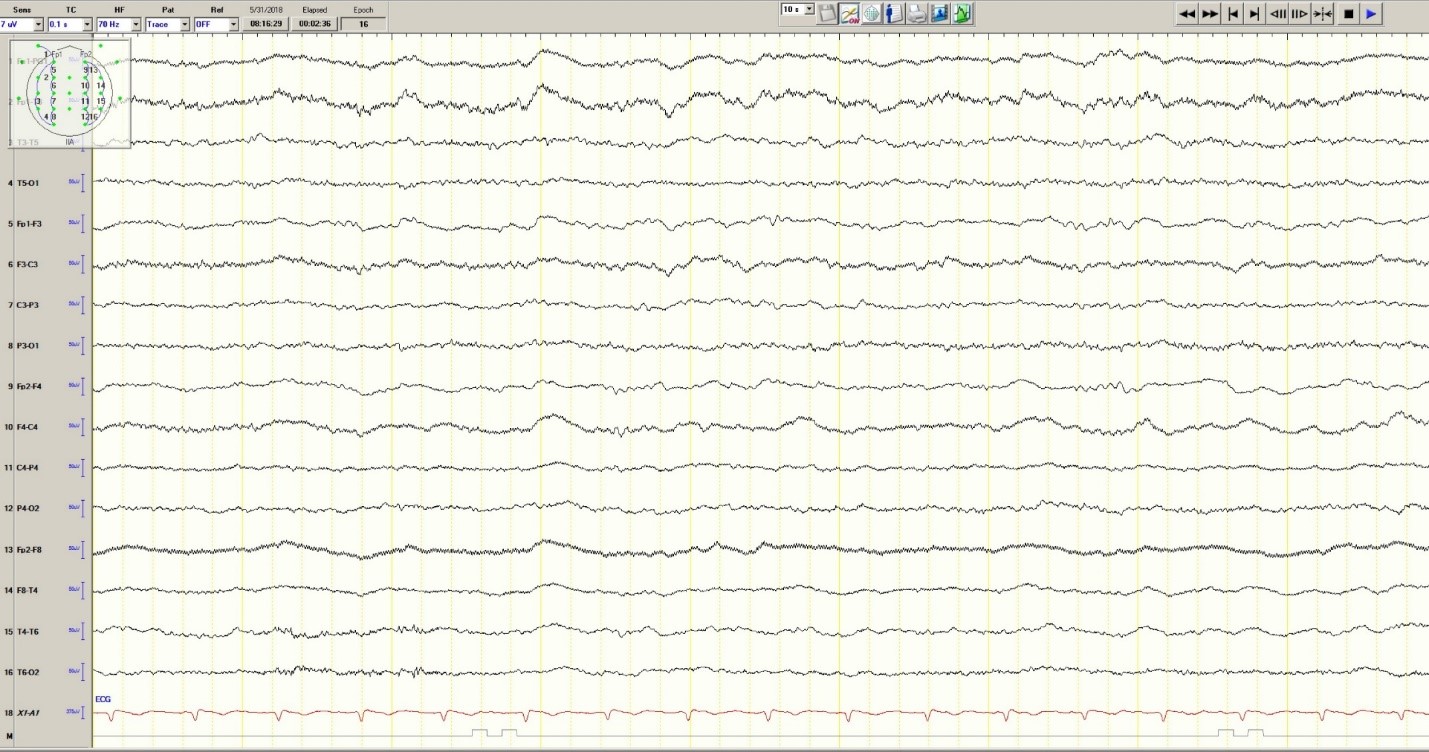

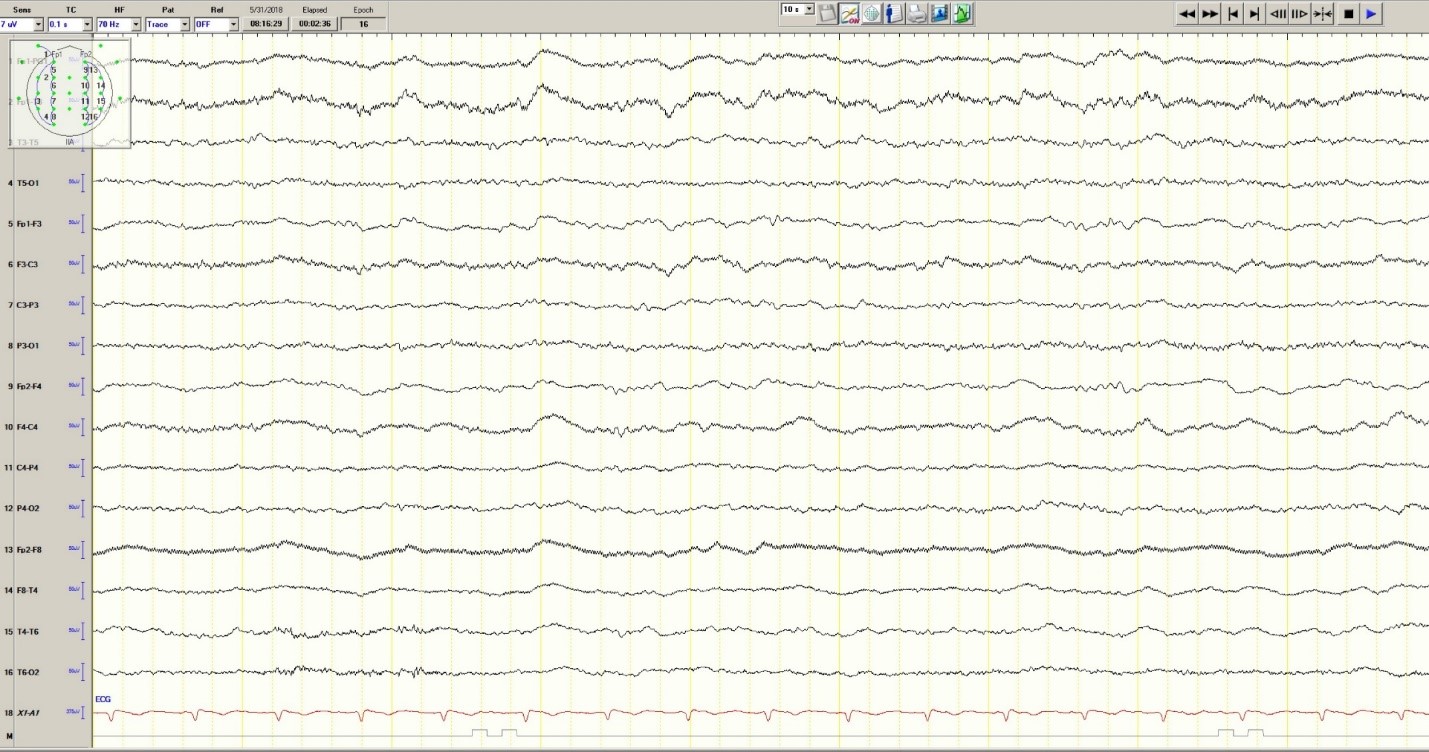

The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 1) showed a normal sinus rhythm of 65 beats/min, left axis deviation, and normal intervals; there was no acute ST-segment elevation or depression.

Case 2: Nitroglycerin for Unstable Anginal Chest Pain

A 69-year-old obese woman with a medical history significant for HTN, HLP, and GERD presented to the ED for evaluation of nausea and chest pressure. She described the chest pressure as feeling dull and heavy. She further noted that the discomfort had been occurring intermittently upon exertion, but that this recent episode started while at rest and persisted.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: BP, 183/80 mm Hg; HR, 94 beats/min; RR, 20 beats/min; and T, 98.0°F. Oxygen saturation was 92% on room air. On a review of systems, the patient denied any associated symptoms; she likewise denied a history of any recent surgeries, immobilization, active malignancy, or recent travel. Her social history was noncontributory and was negative for tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drug use.

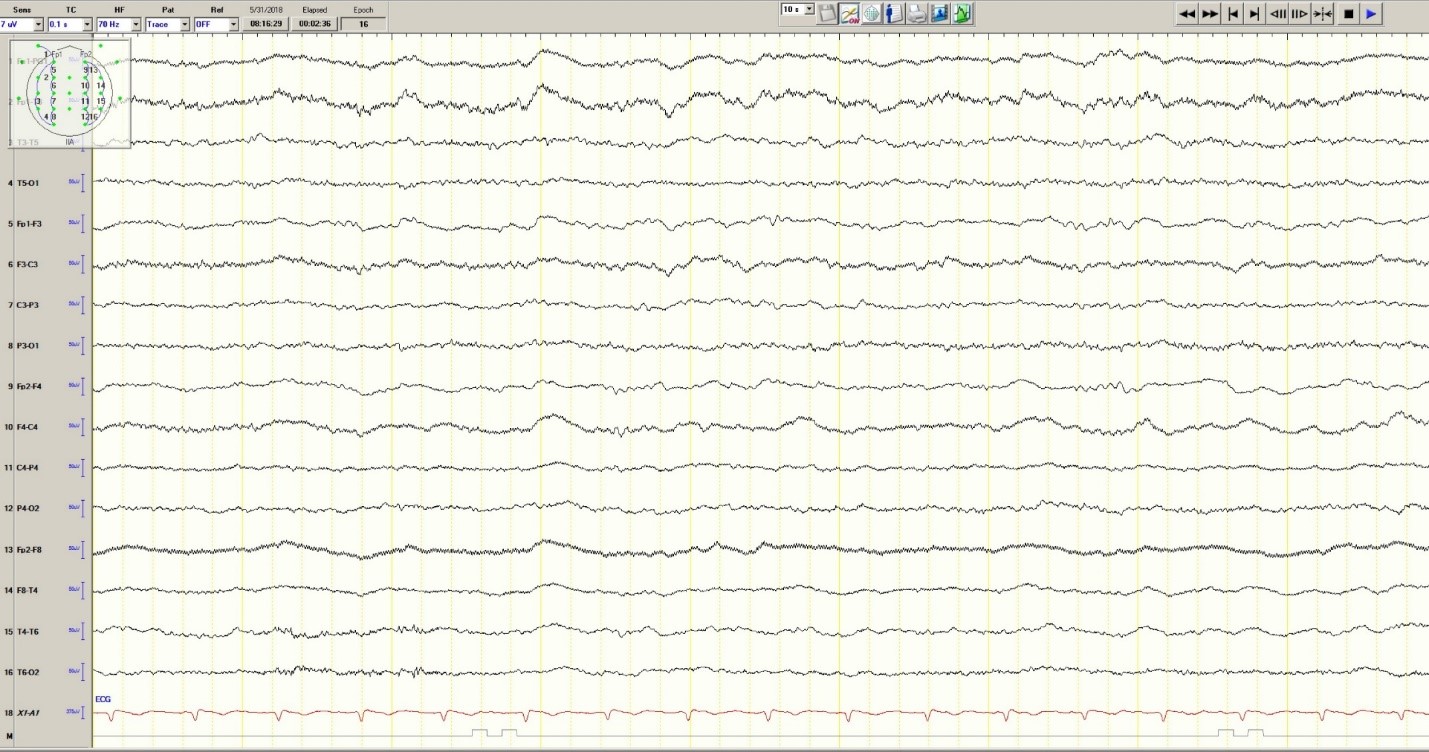

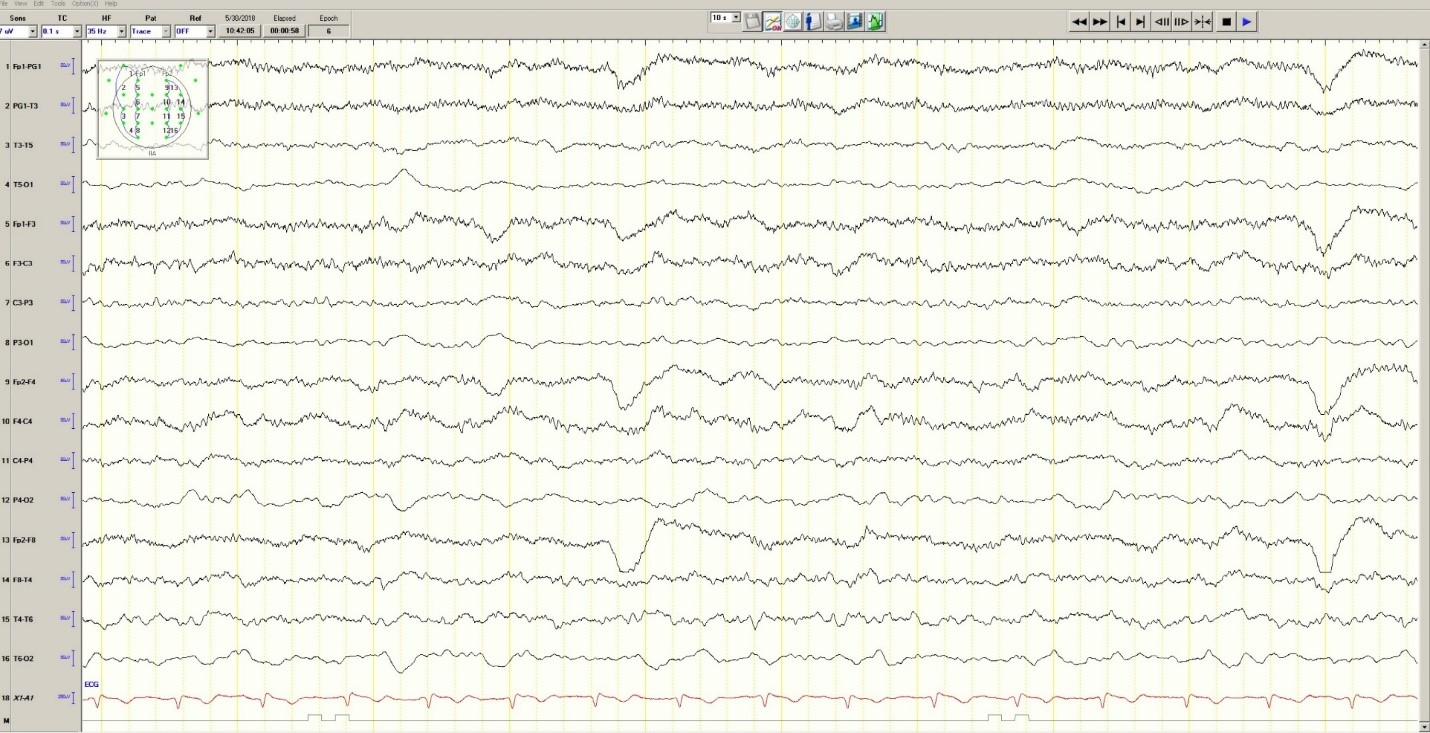

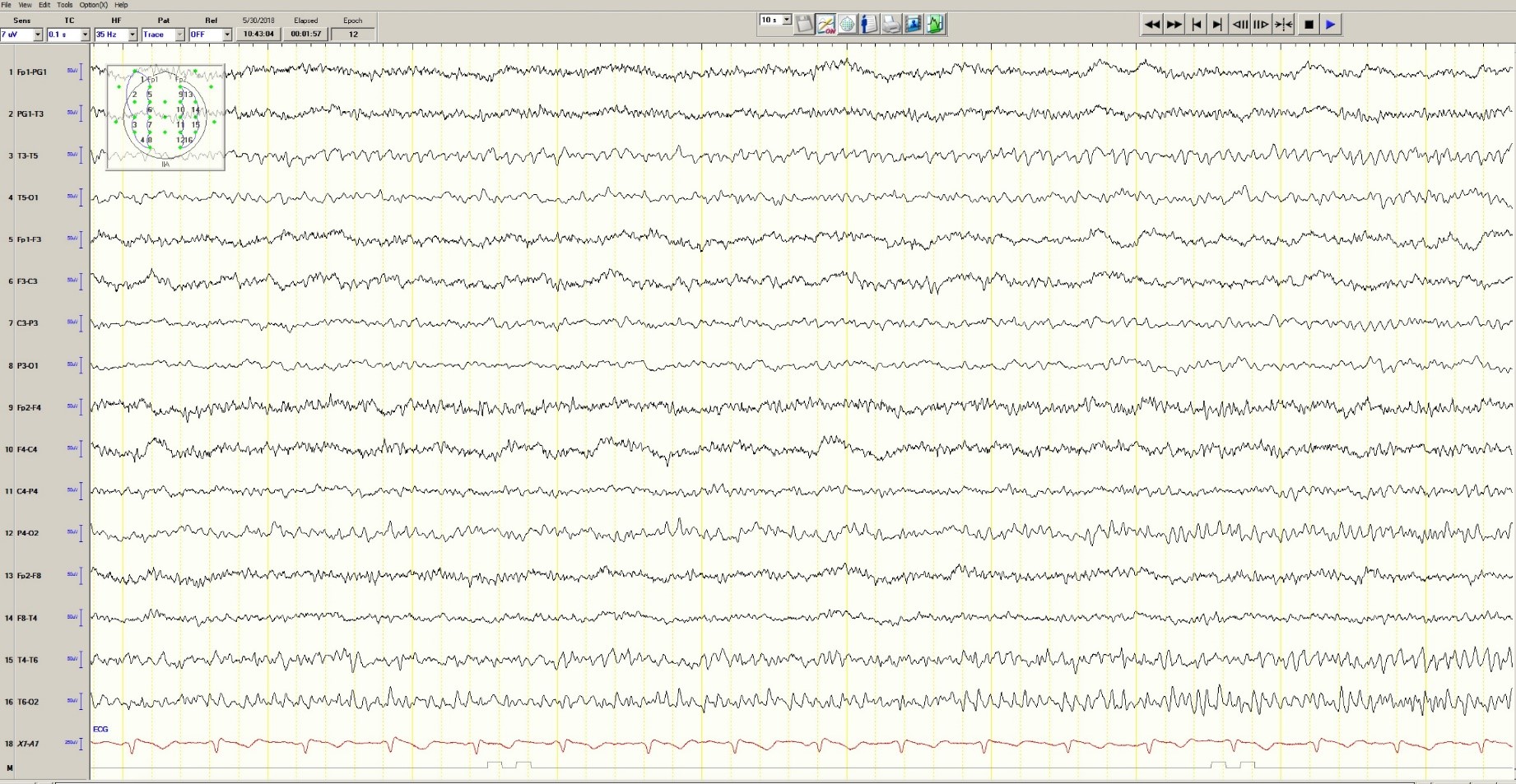

On physical examination the patient was nontoxic and resting comfortably, without signs of acute distress or diaphoresis. The cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, and radial pulses were 2+ and symmetric. The patient had trace pedal edema bilaterally, but her calves were symmetric and nontender. The abdomen was benign and the neurological examination was nonfocal. An ECG (Figure 2) showed a normal sinus rhythm with no signs of ischemia (eg, no ST-segment changes or T-wave inversions were present).

Cases 1 and 2: Shared Clinical Course

In both of the two cases presented, ECGs were obtained for the patients upon arrival at the ED. Both patients were placed on telemetry with continuous monitoring, and intravenous (IV) access was obtained. Baseline laboratory evaluation for each of these patients included a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and cardiac enzyme measurement. A D-dimer test was also ordered for the patient in Case 1 based on his concerning history and low-pretest probability for a pulmonary embolism (ie, positive pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria). Portable chest X-ray imaging on each of the patients showed no acute pathology, and all of their laboratory results were within normal ranges. Both of the patients in Case 1 and 2 received a 324-mg chewable aspirin and an IV fluid bolus.

Case 1

During evaluation, the patient in Case 1 developed unprovoked chest pain, which he rated as a “7,” for which he was given 400 mcg NTG sublingually (SL). After administration of NTG, the patient reported that his pain reduced to a “4.” Repeat ECG and vital signs remained unchanged. Though Case 1 patient’s pain abated, since it persisted, he was given a second dose of SL NTG. Within 2 minutes of receiving the second dose of NTG, the patient became bradycardic (30 beats/min) with a stable BP and then became unresponsive, converting to asystolic rhythm. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated, with a successful return of vital signs and baseline cognition following 20 seconds of compressions. Despite success following critical interventions, his HR persisted at 30 beats/min with a narrow regular complex, and normal BP. Because of the persistent bradycardia and preceding asystolic rhythm, he was given 0.5 mg of atropine IV, which increased his HR to 80 beats/min. Cardiology service was consulted, and the patient was admitted following an otherwise stable course. Since the cardiologist did not feel emergent cardiac catheterization was indicated, the patient was observed and subsequently discharged home following an uneventful hospitalization, including a normal stress test.

Case 2

The patient in Case 2, had chest pain upon arrival at the ED and was administered SL NTG, with notable improvement in chest pain, but not complete resolution. With serial examinations, including a review of pain scale scores, she was given two subsequent doses of SL NTG. Within 1 minute from receiving the third dose of NTG, the patient complained of lightheadedness and nausea, and became pale and diaphoretic. Telemetry revealed bradycardia, which progressed to junctional escape beats, followed by ventricular escape beats, and then asystole, at which point she became unresponsive and pulseless. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated, with a return of spontaneous circulation within 15 seconds of intervention; she gradually returned to her baseline with observation. Repeat vital signs were: BP, 155/70 mm Hg; HR, 99 beats/min; RR, 20 breaths/min; and she was afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 99% on 15 liters of oxygen/min, which was weaned prior to hospital admission. A repeat ECG demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm without evidence of ischemia. Cardiology service was consulted and the patient was admitted for further evaluation, including a 3-day inpatient observation, serial cardiac enzymes, thyroid panel, contrast chest computed tomography scan, echocardiogram, and cardiac stress test. All studies were within normal limits, except for an incidental minor pectus excavatum attributed to the quality CPR. In addition, a nuclear medicine perfusion imaging study was obtained, which revealed no evidence of myocardial ischemia or scar, consistent with the patient’s stable course. The patient’s symptoms resolved early in her inpatient stay, and she was discharged home with prescriptions for antihypertensive and antihyperlipidemia agents and instructed to follow-up with her primary care physician.

Discussion

Nitroglycerin is commonly used to treat various symptoms of cardiac origin, namely relief of chest pain due to suspected acute coronary syndromes.2,3The mechanism of action of NTG is predominantly through potent smooth muscle relaxation of the venous and arterial systems, reducing both preload and afterload.2,3 This results in reduced myocardial oxygen demand, potentiating the relief of myocardial ischemia.

Contraindications

Contraindications to NTG include known allergy, pericardial tamponade, restrictive cardiomyopathy, increased intracranial pressure, and concomitant use of phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Moreover, NTG should not be given to treat conditions wherein cardiac output is dependent on venous return, as in the setting of inferior myocardial infarction (MI) with right ventricular involvement. Furthermore, there is no evidence in the literature to support the erroneous use of NTG as a diagnostic therapy, with limited sensitivity yields for conclusive cardiac-associated chest pain.8

Adverse Effects and Events

The common side effects of NTG are well documented and include hypotension, tachycardia, flushing, nausea, vomiting, and headache.7,3,6 Syncope, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest following the administration of NTG are rare events, as evidenced by the paucity of literature describing these complications. Rather, it appears that these side effects are observed only in the setting of myocardial ischemia or MI.3,9-11 Fewer cases of ventricular fibrillation, responsive to defibrillation, and asystole also have been observed.9The exact mechanism for bradycardia without hypotension and subsequent asystole following NTG administration remains elusive, though this response is thought to be associated with the Bezold-Jarisch reflex.

Bezold-Jarisch Reflex

The Bezold-Jarisch reflex is a cardiovascular response consisting of bradycardia and hypotension that is believed to be from stimulation of inhibitory cardiac receptors by stretch, chemical, or pharmacological stimulation.12 The earliest cases of Bezold-Jarisch reflex following NTG occurred in the setting of MI and were attributed to ongoing myocardial ischemia.13 Recent studies have revealed that coronary stenosis without concurrent ischemia is actually not a sensitizing factor, and that bradycardia and asystole following NTG have occurred in patients without evidence of coronary artery disease.9,14 As part of this response, it is theorized that the development of bradycardia is related to vasovagal stimulation, a centrally mediated response to the headache or nausea following NTG administration.10,11,15

Despite these observational studies and after thorough review of the available cases, no unifying factors exist to predict with certainty the patient population in which this response is likely to occur.12,16Based on a literature review, it appears that asystole following NTG is self-limited; however, in most cases, bradycardia was treated with atropine without adverse side effects.12,15,16

Conclusion

The two cases presented involved a middle-aged male patient and an elderly female patient, both of whom had several cardiac risk factors but no evidence of acute ischemia or infarction on ECG or laboratory studies. It is well established that NTG can cause hypotension without bradycardia; however, the development of bradycardia without, or even preceding, hypotension is less recognized. Several mechanisms have been postulated but none fully explain this reaction; moreover, no anticipatory risk factors have been consistently observed. Even though the patients in Case 1 and 2 underwent extensive evaluation, no specific etiology of the observed reaction was identified, though neither patient underwent cardiac catheterization to definitively exclude abnormal coronary artery pathology as a precipitating factor.

These cases illustrate the unpredictable adverse reaction to a common medication used for a ubiquitous complaint. The explanation as to the source for this reaction is lacking, the literature has consistently described the transient and self-limiting effect of asystole following NTG.9,12,14,16Bradycardia, though self-limiting, remains responsive to appropriately dosed atropine when NTG-induced.3,12,16 The authors wish to stress the importance of establishing IV access and being prepared for adverse events whenever administering sublingual nitroglycerin to a patient.

1. Miura T, Nishinaka T, Terada T, Yonezawa K. Vasodilatory effect of nitroglycerin in Japanese subjects with different aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) genotypes. Chem Biol Interact. 2017;276:40-45. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2017.03.012.

2. Noonan PK, Williams RL, Benet LZ. Dose dependent pharmacokinetics of nitroglycerin after multiple intravenous infusions in healthy volunteers. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1985;13(2):143-157.

3. Proulx MH, de Montigny L, Ross D, Vacon C, Juste LE, Segal E. Prehospital nitroglycerin in tachycardic chest pain patients: a risk for hypotension or not? Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;21(1):68-73. doi:10.1080/10903127.2016.1194929.

4. Huis In ‘t Veld MA, Cullen L, Mahler SA, Backus BE, Dezman ZDW, Mattu A. The fast and the furious: low-risk chest pain and the rapid rule-out protocol. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(3):474-478. doi:10.5811/westjem.2016.12.32676.

5. Pasupathy S, Tavella R, Grover S, et al. Early use of N-acetylcysteine with nitrate therapy in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction reduces myocardial infarct size (the NACIAM Trial [N-acetylcysteine in Acute Myocardial Infarction]). Circulation. 2017;136(10):894-903. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027575.

6. Turan B, Daşlı T, Erkol A, Erden İ. Effectiveness of sublingual nitroglycerin before puncture compared with conventional intra-carterial nitroglycerin in transradial procedures: a randomized trial. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16(7):391-396. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2015.07.006.

7. Nagy-Grócz G, Bohár Z, Fejes-Szabó A, et al. Nitroglycerin increases serotonin transporter expression in rat spinal cord but anandamide modulated this effect. J Chem Neuroanat. 2017;85:13-20. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2017.06.002.

8. Steele R, McNaughton T, McConahy M, Lam J. Chest pain in emergency department patients: if the pain is relieved by nitroglycerin, is it more likely to be cardiac chest pain? CJEM. 2006;8(3):164-169.

9. Dettorre K, Brywczynski J, McKinney J, Slovis C. Not the nitro? Patient goes into prehospital V-fib arrest following nitroglycerin. JEMS. 2009;34(5):34,36. doi:10.1016/S0197-2510(09)70124-X.

10. Buckley R, Roberts R. Symptomatic bradycardia following the administration of sublingual nitroglycerin. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11(3):253-255.

11. Takase B, Uehata A, Nishioka T, et al. Different mechanisms of isoproterenol-induced and nitroglycerin-induced syncope during head-up tilt in patients with unexplained syncope: important role of epinephrine in nitroglycerin-induced syncope. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12(7):791-796.

12. Brandes W, Santiago T, Limacher M. Nitroglycerin-induced hypotension, bradycardia, and asystole: report of a case and review of the literature. Clin Cardiol. 1990;13(10):741-744.

13. Ong EA, Canlas C, Smith W. Nitroglycerin-induced asystole. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(5):954.

14. Shah SP, Waxman S. Two cases of Bezold-Jarisch reflex induced by intra-arterial nitroglycerin in critical left main coronary artery stenosis. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40(4):484-486.

15. Mark AL. The Bezold-Jarisch reflex revisited: clinical implications of inhibitory reflexes originating in the heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;1(1):90-102.

16. Younas F, Janjua M, Badshah A, DeGregorio M, Patel KC, Cotant JF. Transient complete heart block and isolated ventricular asystole with nitroglycerin. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2012;13(8):533-535. doi:10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283416b8b.

Case reports of a 54-year-old man with angina and a 69-year-old woman demonstrate an underreported, self-limiting side effect associated with nitroglycerin.

Case reports of a 54-year-old man with angina and a 69-year-old woman demonstrate an underreported, self-limiting side effect associated with nitroglycerin.

Nitroglycerin (NTG), or glyceryl trinitrate, was first introduced into the medical community by Murrell,1,2 who reported on anecdotal observations of its antianginal properties by workers within manufacturing plants refining the product for its explosive properties. While the route of administration of NTG has changed from this incidental environmental exposure to the now formulated therapies available, its benefit as an outpatient, abortive treatment for stable angina has been validated beyond early subjective observations in the literature.1-3 In fact, its successful use over the years for angina has produced an expansive pharmacopeia, including its use for undifferentiated chest pain and exacerbation of congestive heart failure.3-5

Despite the extensive history of NTG as a proven vasodilator, emerging uses continue to be explored in equal measure with technological advances.2,6 Though morbidity and mortality reductions are dependent on its use within clinical practice, NTG is not an innocuous drug.5 Most of the reported side effects associated with NTG are well established and include hypotension, tachycardia, flushing, nausea, vomiting, and headache.3,6,7 An often forgotten side effect associated with NTG use is asystole. We present the following two cases to highlight both common uses of NTG as well as this underreported side effect.

Case 1: Nitroglycerin for Stable Anginal Chest Pain

A 54-year-old man with a history of hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia (HLP), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) presented to the ED for evaluation of a 3-hour history of intermittent, retrosternal, left-sided, nonradiating chest “pressure and tightness.” The patient stated that the chest discomfort began at rest but was exacerbated by exertion with episodes lasting 10 to 15 minutes. The patient rated the peak pain associated with these episodes as a “7” on a pain scale of 1 to 10. He further noted that his symptoms abated and he became “pain-free” when at rest.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 156/87 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 68 beats/min; respiratory rate (RR), 18 beats/min; and temperature (T), 98.4°F. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air.

The patient, who performed regular BP checks at home, noted that his recent BP readings had been very high. A review of the patient’s systems was positive for shortness of breath and diaphoresis; symptoms were otherwise negative, including any prior episodes. His social history was noncontributory and negative for tobacco, alcohol, or drug use. The patient did report that he had taken an uneventful 6-hour car ride the previous week.

On physical examination, the patient was nontoxic and resting comfortably, without signs of acute distress or pain. Cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, and radial pulses were 2+ and symmetric. The abdominal examination was benign and the neurological examination was nonfocal. There was no evidence of peripheral edema or asymmetry of the calves, which were nontender to palpation.

The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 1) showed a normal sinus rhythm of 65 beats/min, left axis deviation, and normal intervals; there was no acute ST-segment elevation or depression.

Case 2: Nitroglycerin for Unstable Anginal Chest Pain

A 69-year-old obese woman with a medical history significant for HTN, HLP, and GERD presented to the ED for evaluation of nausea and chest pressure. She described the chest pressure as feeling dull and heavy. She further noted that the discomfort had been occurring intermittently upon exertion, but that this recent episode started while at rest and persisted.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: BP, 183/80 mm Hg; HR, 94 beats/min; RR, 20 beats/min; and T, 98.0°F. Oxygen saturation was 92% on room air. On a review of systems, the patient denied any associated symptoms; she likewise denied a history of any recent surgeries, immobilization, active malignancy, or recent travel. Her social history was noncontributory and was negative for tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drug use.

On physical examination the patient was nontoxic and resting comfortably, without signs of acute distress or diaphoresis. The cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, and radial pulses were 2+ and symmetric. The patient had trace pedal edema bilaterally, but her calves were symmetric and nontender. The abdomen was benign and the neurological examination was nonfocal. An ECG (Figure 2) showed a normal sinus rhythm with no signs of ischemia (eg, no ST-segment changes or T-wave inversions were present).

Cases 1 and 2: Shared Clinical Course

In both of the two cases presented, ECGs were obtained for the patients upon arrival at the ED. Both patients were placed on telemetry with continuous monitoring, and intravenous (IV) access was obtained. Baseline laboratory evaluation for each of these patients included a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and cardiac enzyme measurement. A D-dimer test was also ordered for the patient in Case 1 based on his concerning history and low-pretest probability for a pulmonary embolism (ie, positive pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria). Portable chest X-ray imaging on each of the patients showed no acute pathology, and all of their laboratory results were within normal ranges. Both of the patients in Case 1 and 2 received a 324-mg chewable aspirin and an IV fluid bolus.

Case 1

During evaluation, the patient in Case 1 developed unprovoked chest pain, which he rated as a “7,” for which he was given 400 mcg NTG sublingually (SL). After administration of NTG, the patient reported that his pain reduced to a “4.” Repeat ECG and vital signs remained unchanged. Though Case 1 patient’s pain abated, since it persisted, he was given a second dose of SL NTG. Within 2 minutes of receiving the second dose of NTG, the patient became bradycardic (30 beats/min) with a stable BP and then became unresponsive, converting to asystolic rhythm. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated, with a successful return of vital signs and baseline cognition following 20 seconds of compressions. Despite success following critical interventions, his HR persisted at 30 beats/min with a narrow regular complex, and normal BP. Because of the persistent bradycardia and preceding asystolic rhythm, he was given 0.5 mg of atropine IV, which increased his HR to 80 beats/min. Cardiology service was consulted, and the patient was admitted following an otherwise stable course. Since the cardiologist did not feel emergent cardiac catheterization was indicated, the patient was observed and subsequently discharged home following an uneventful hospitalization, including a normal stress test.

Case 2

The patient in Case 2, had chest pain upon arrival at the ED and was administered SL NTG, with notable improvement in chest pain, but not complete resolution. With serial examinations, including a review of pain scale scores, she was given two subsequent doses of SL NTG. Within 1 minute from receiving the third dose of NTG, the patient complained of lightheadedness and nausea, and became pale and diaphoretic. Telemetry revealed bradycardia, which progressed to junctional escape beats, followed by ventricular escape beats, and then asystole, at which point she became unresponsive and pulseless. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated, with a return of spontaneous circulation within 15 seconds of intervention; she gradually returned to her baseline with observation. Repeat vital signs were: BP, 155/70 mm Hg; HR, 99 beats/min; RR, 20 breaths/min; and she was afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 99% on 15 liters of oxygen/min, which was weaned prior to hospital admission. A repeat ECG demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm without evidence of ischemia. Cardiology service was consulted and the patient was admitted for further evaluation, including a 3-day inpatient observation, serial cardiac enzymes, thyroid panel, contrast chest computed tomography scan, echocardiogram, and cardiac stress test. All studies were within normal limits, except for an incidental minor pectus excavatum attributed to the quality CPR. In addition, a nuclear medicine perfusion imaging study was obtained, which revealed no evidence of myocardial ischemia or scar, consistent with the patient’s stable course. The patient’s symptoms resolved early in her inpatient stay, and she was discharged home with prescriptions for antihypertensive and antihyperlipidemia agents and instructed to follow-up with her primary care physician.

Discussion

Nitroglycerin is commonly used to treat various symptoms of cardiac origin, namely relief of chest pain due to suspected acute coronary syndromes.2,3The mechanism of action of NTG is predominantly through potent smooth muscle relaxation of the venous and arterial systems, reducing both preload and afterload.2,3 This results in reduced myocardial oxygen demand, potentiating the relief of myocardial ischemia.

Contraindications

Contraindications to NTG include known allergy, pericardial tamponade, restrictive cardiomyopathy, increased intracranial pressure, and concomitant use of phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Moreover, NTG should not be given to treat conditions wherein cardiac output is dependent on venous return, as in the setting of inferior myocardial infarction (MI) with right ventricular involvement. Furthermore, there is no evidence in the literature to support the erroneous use of NTG as a diagnostic therapy, with limited sensitivity yields for conclusive cardiac-associated chest pain.8

Adverse Effects and Events

The common side effects of NTG are well documented and include hypotension, tachycardia, flushing, nausea, vomiting, and headache.7,3,6 Syncope, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest following the administration of NTG are rare events, as evidenced by the paucity of literature describing these complications. Rather, it appears that these side effects are observed only in the setting of myocardial ischemia or MI.3,9-11 Fewer cases of ventricular fibrillation, responsive to defibrillation, and asystole also have been observed.9The exact mechanism for bradycardia without hypotension and subsequent asystole following NTG administration remains elusive, though this response is thought to be associated with the Bezold-Jarisch reflex.

Bezold-Jarisch Reflex

The Bezold-Jarisch reflex is a cardiovascular response consisting of bradycardia and hypotension that is believed to be from stimulation of inhibitory cardiac receptors by stretch, chemical, or pharmacological stimulation.12 The earliest cases of Bezold-Jarisch reflex following NTG occurred in the setting of MI and were attributed to ongoing myocardial ischemia.13 Recent studies have revealed that coronary stenosis without concurrent ischemia is actually not a sensitizing factor, and that bradycardia and asystole following NTG have occurred in patients without evidence of coronary artery disease.9,14 As part of this response, it is theorized that the development of bradycardia is related to vasovagal stimulation, a centrally mediated response to the headache or nausea following NTG administration.10,11,15

Despite these observational studies and after thorough review of the available cases, no unifying factors exist to predict with certainty the patient population in which this response is likely to occur.12,16Based on a literature review, it appears that asystole following NTG is self-limited; however, in most cases, bradycardia was treated with atropine without adverse side effects.12,15,16

Conclusion

The two cases presented involved a middle-aged male patient and an elderly female patient, both of whom had several cardiac risk factors but no evidence of acute ischemia or infarction on ECG or laboratory studies. It is well established that NTG can cause hypotension without bradycardia; however, the development of bradycardia without, or even preceding, hypotension is less recognized. Several mechanisms have been postulated but none fully explain this reaction; moreover, no anticipatory risk factors have been consistently observed. Even though the patients in Case 1 and 2 underwent extensive evaluation, no specific etiology of the observed reaction was identified, though neither patient underwent cardiac catheterization to definitively exclude abnormal coronary artery pathology as a precipitating factor.

These cases illustrate the unpredictable adverse reaction to a common medication used for a ubiquitous complaint. The explanation as to the source for this reaction is lacking, the literature has consistently described the transient and self-limiting effect of asystole following NTG.9,12,14,16Bradycardia, though self-limiting, remains responsive to appropriately dosed atropine when NTG-induced.3,12,16 The authors wish to stress the importance of establishing IV access and being prepared for adverse events whenever administering sublingual nitroglycerin to a patient.

Nitroglycerin (NTG), or glyceryl trinitrate, was first introduced into the medical community by Murrell,1,2 who reported on anecdotal observations of its antianginal properties by workers within manufacturing plants refining the product for its explosive properties. While the route of administration of NTG has changed from this incidental environmental exposure to the now formulated therapies available, its benefit as an outpatient, abortive treatment for stable angina has been validated beyond early subjective observations in the literature.1-3 In fact, its successful use over the years for angina has produced an expansive pharmacopeia, including its use for undifferentiated chest pain and exacerbation of congestive heart failure.3-5

Despite the extensive history of NTG as a proven vasodilator, emerging uses continue to be explored in equal measure with technological advances.2,6 Though morbidity and mortality reductions are dependent on its use within clinical practice, NTG is not an innocuous drug.5 Most of the reported side effects associated with NTG are well established and include hypotension, tachycardia, flushing, nausea, vomiting, and headache.3,6,7 An often forgotten side effect associated with NTG use is asystole. We present the following two cases to highlight both common uses of NTG as well as this underreported side effect.

Case 1: Nitroglycerin for Stable Anginal Chest Pain

A 54-year-old man with a history of hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia (HLP), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) presented to the ED for evaluation of a 3-hour history of intermittent, retrosternal, left-sided, nonradiating chest “pressure and tightness.” The patient stated that the chest discomfort began at rest but was exacerbated by exertion with episodes lasting 10 to 15 minutes. The patient rated the peak pain associated with these episodes as a “7” on a pain scale of 1 to 10. He further noted that his symptoms abated and he became “pain-free” when at rest.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 156/87 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 68 beats/min; respiratory rate (RR), 18 beats/min; and temperature (T), 98.4°F. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air.

The patient, who performed regular BP checks at home, noted that his recent BP readings had been very high. A review of the patient’s systems was positive for shortness of breath and diaphoresis; symptoms were otherwise negative, including any prior episodes. His social history was noncontributory and negative for tobacco, alcohol, or drug use. The patient did report that he had taken an uneventful 6-hour car ride the previous week.

On physical examination, the patient was nontoxic and resting comfortably, without signs of acute distress or pain. Cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, and radial pulses were 2+ and symmetric. The abdominal examination was benign and the neurological examination was nonfocal. There was no evidence of peripheral edema or asymmetry of the calves, which were nontender to palpation.

The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 1) showed a normal sinus rhythm of 65 beats/min, left axis deviation, and normal intervals; there was no acute ST-segment elevation or depression.

Case 2: Nitroglycerin for Unstable Anginal Chest Pain

A 69-year-old obese woman with a medical history significant for HTN, HLP, and GERD presented to the ED for evaluation of nausea and chest pressure. She described the chest pressure as feeling dull and heavy. She further noted that the discomfort had been occurring intermittently upon exertion, but that this recent episode started while at rest and persisted.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: BP, 183/80 mm Hg; HR, 94 beats/min; RR, 20 beats/min; and T, 98.0°F. Oxygen saturation was 92% on room air. On a review of systems, the patient denied any associated symptoms; she likewise denied a history of any recent surgeries, immobilization, active malignancy, or recent travel. Her social history was noncontributory and was negative for tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drug use.

On physical examination the patient was nontoxic and resting comfortably, without signs of acute distress or diaphoresis. The cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, and radial pulses were 2+ and symmetric. The patient had trace pedal edema bilaterally, but her calves were symmetric and nontender. The abdomen was benign and the neurological examination was nonfocal. An ECG (Figure 2) showed a normal sinus rhythm with no signs of ischemia (eg, no ST-segment changes or T-wave inversions were present).

Cases 1 and 2: Shared Clinical Course

In both of the two cases presented, ECGs were obtained for the patients upon arrival at the ED. Both patients were placed on telemetry with continuous monitoring, and intravenous (IV) access was obtained. Baseline laboratory evaluation for each of these patients included a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and cardiac enzyme measurement. A D-dimer test was also ordered for the patient in Case 1 based on his concerning history and low-pretest probability for a pulmonary embolism (ie, positive pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria). Portable chest X-ray imaging on each of the patients showed no acute pathology, and all of their laboratory results were within normal ranges. Both of the patients in Case 1 and 2 received a 324-mg chewable aspirin and an IV fluid bolus.

Case 1

During evaluation, the patient in Case 1 developed unprovoked chest pain, which he rated as a “7,” for which he was given 400 mcg NTG sublingually (SL). After administration of NTG, the patient reported that his pain reduced to a “4.” Repeat ECG and vital signs remained unchanged. Though Case 1 patient’s pain abated, since it persisted, he was given a second dose of SL NTG. Within 2 minutes of receiving the second dose of NTG, the patient became bradycardic (30 beats/min) with a stable BP and then became unresponsive, converting to asystolic rhythm. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated, with a successful return of vital signs and baseline cognition following 20 seconds of compressions. Despite success following critical interventions, his HR persisted at 30 beats/min with a narrow regular complex, and normal BP. Because of the persistent bradycardia and preceding asystolic rhythm, he was given 0.5 mg of atropine IV, which increased his HR to 80 beats/min. Cardiology service was consulted, and the patient was admitted following an otherwise stable course. Since the cardiologist did not feel emergent cardiac catheterization was indicated, the patient was observed and subsequently discharged home following an uneventful hospitalization, including a normal stress test.

Case 2

The patient in Case 2, had chest pain upon arrival at the ED and was administered SL NTG, with notable improvement in chest pain, but not complete resolution. With serial examinations, including a review of pain scale scores, she was given two subsequent doses of SL NTG. Within 1 minute from receiving the third dose of NTG, the patient complained of lightheadedness and nausea, and became pale and diaphoretic. Telemetry revealed bradycardia, which progressed to junctional escape beats, followed by ventricular escape beats, and then asystole, at which point she became unresponsive and pulseless. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated, with a return of spontaneous circulation within 15 seconds of intervention; she gradually returned to her baseline with observation. Repeat vital signs were: BP, 155/70 mm Hg; HR, 99 beats/min; RR, 20 breaths/min; and she was afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 99% on 15 liters of oxygen/min, which was weaned prior to hospital admission. A repeat ECG demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm without evidence of ischemia. Cardiology service was consulted and the patient was admitted for further evaluation, including a 3-day inpatient observation, serial cardiac enzymes, thyroid panel, contrast chest computed tomography scan, echocardiogram, and cardiac stress test. All studies were within normal limits, except for an incidental minor pectus excavatum attributed to the quality CPR. In addition, a nuclear medicine perfusion imaging study was obtained, which revealed no evidence of myocardial ischemia or scar, consistent with the patient’s stable course. The patient’s symptoms resolved early in her inpatient stay, and she was discharged home with prescriptions for antihypertensive and antihyperlipidemia agents and instructed to follow-up with her primary care physician.

Discussion

Nitroglycerin is commonly used to treat various symptoms of cardiac origin, namely relief of chest pain due to suspected acute coronary syndromes.2,3The mechanism of action of NTG is predominantly through potent smooth muscle relaxation of the venous and arterial systems, reducing both preload and afterload.2,3 This results in reduced myocardial oxygen demand, potentiating the relief of myocardial ischemia.

Contraindications

Contraindications to NTG include known allergy, pericardial tamponade, restrictive cardiomyopathy, increased intracranial pressure, and concomitant use of phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Moreover, NTG should not be given to treat conditions wherein cardiac output is dependent on venous return, as in the setting of inferior myocardial infarction (MI) with right ventricular involvement. Furthermore, there is no evidence in the literature to support the erroneous use of NTG as a diagnostic therapy, with limited sensitivity yields for conclusive cardiac-associated chest pain.8

Adverse Effects and Events

The common side effects of NTG are well documented and include hypotension, tachycardia, flushing, nausea, vomiting, and headache.7,3,6 Syncope, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest following the administration of NTG are rare events, as evidenced by the paucity of literature describing these complications. Rather, it appears that these side effects are observed only in the setting of myocardial ischemia or MI.3,9-11 Fewer cases of ventricular fibrillation, responsive to defibrillation, and asystole also have been observed.9The exact mechanism for bradycardia without hypotension and subsequent asystole following NTG administration remains elusive, though this response is thought to be associated with the Bezold-Jarisch reflex.

Bezold-Jarisch Reflex

The Bezold-Jarisch reflex is a cardiovascular response consisting of bradycardia and hypotension that is believed to be from stimulation of inhibitory cardiac receptors by stretch, chemical, or pharmacological stimulation.12 The earliest cases of Bezold-Jarisch reflex following NTG occurred in the setting of MI and were attributed to ongoing myocardial ischemia.13 Recent studies have revealed that coronary stenosis without concurrent ischemia is actually not a sensitizing factor, and that bradycardia and asystole following NTG have occurred in patients without evidence of coronary artery disease.9,14 As part of this response, it is theorized that the development of bradycardia is related to vasovagal stimulation, a centrally mediated response to the headache or nausea following NTG administration.10,11,15

Despite these observational studies and after thorough review of the available cases, no unifying factors exist to predict with certainty the patient population in which this response is likely to occur.12,16Based on a literature review, it appears that asystole following NTG is self-limited; however, in most cases, bradycardia was treated with atropine without adverse side effects.12,15,16

Conclusion

The two cases presented involved a middle-aged male patient and an elderly female patient, both of whom had several cardiac risk factors but no evidence of acute ischemia or infarction on ECG or laboratory studies. It is well established that NTG can cause hypotension without bradycardia; however, the development of bradycardia without, or even preceding, hypotension is less recognized. Several mechanisms have been postulated but none fully explain this reaction; moreover, no anticipatory risk factors have been consistently observed. Even though the patients in Case 1 and 2 underwent extensive evaluation, no specific etiology of the observed reaction was identified, though neither patient underwent cardiac catheterization to definitively exclude abnormal coronary artery pathology as a precipitating factor.

These cases illustrate the unpredictable adverse reaction to a common medication used for a ubiquitous complaint. The explanation as to the source for this reaction is lacking, the literature has consistently described the transient and self-limiting effect of asystole following NTG.9,12,14,16Bradycardia, though self-limiting, remains responsive to appropriately dosed atropine when NTG-induced.3,12,16 The authors wish to stress the importance of establishing IV access and being prepared for adverse events whenever administering sublingual nitroglycerin to a patient.

1. Miura T, Nishinaka T, Terada T, Yonezawa K. Vasodilatory effect of nitroglycerin in Japanese subjects with different aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) genotypes. Chem Biol Interact. 2017;276:40-45. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2017.03.012.

2. Noonan PK, Williams RL, Benet LZ. Dose dependent pharmacokinetics of nitroglycerin after multiple intravenous infusions in healthy volunteers. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1985;13(2):143-157.

3. Proulx MH, de Montigny L, Ross D, Vacon C, Juste LE, Segal E. Prehospital nitroglycerin in tachycardic chest pain patients: a risk for hypotension or not? Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;21(1):68-73. doi:10.1080/10903127.2016.1194929.

4. Huis In ‘t Veld MA, Cullen L, Mahler SA, Backus BE, Dezman ZDW, Mattu A. The fast and the furious: low-risk chest pain and the rapid rule-out protocol. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(3):474-478. doi:10.5811/westjem.2016.12.32676.

5. Pasupathy S, Tavella R, Grover S, et al. Early use of N-acetylcysteine with nitrate therapy in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction reduces myocardial infarct size (the NACIAM Trial [N-acetylcysteine in Acute Myocardial Infarction]). Circulation. 2017;136(10):894-903. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027575.

6. Turan B, Daşlı T, Erkol A, Erden İ. Effectiveness of sublingual nitroglycerin before puncture compared with conventional intra-carterial nitroglycerin in transradial procedures: a randomized trial. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16(7):391-396. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2015.07.006.

7. Nagy-Grócz G, Bohár Z, Fejes-Szabó A, et al. Nitroglycerin increases serotonin transporter expression in rat spinal cord but anandamide modulated this effect. J Chem Neuroanat. 2017;85:13-20. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2017.06.002.

8. Steele R, McNaughton T, McConahy M, Lam J. Chest pain in emergency department patients: if the pain is relieved by nitroglycerin, is it more likely to be cardiac chest pain? CJEM. 2006;8(3):164-169.

9. Dettorre K, Brywczynski J, McKinney J, Slovis C. Not the nitro? Patient goes into prehospital V-fib arrest following nitroglycerin. JEMS. 2009;34(5):34,36. doi:10.1016/S0197-2510(09)70124-X.

10. Buckley R, Roberts R. Symptomatic bradycardia following the administration of sublingual nitroglycerin. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11(3):253-255.

11. Takase B, Uehata A, Nishioka T, et al. Different mechanisms of isoproterenol-induced and nitroglycerin-induced syncope during head-up tilt in patients with unexplained syncope: important role of epinephrine in nitroglycerin-induced syncope. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12(7):791-796.

12. Brandes W, Santiago T, Limacher M. Nitroglycerin-induced hypotension, bradycardia, and asystole: report of a case and review of the literature. Clin Cardiol. 1990;13(10):741-744.

13. Ong EA, Canlas C, Smith W. Nitroglycerin-induced asystole. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(5):954.

14. Shah SP, Waxman S. Two cases of Bezold-Jarisch reflex induced by intra-arterial nitroglycerin in critical left main coronary artery stenosis. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40(4):484-486.

15. Mark AL. The Bezold-Jarisch reflex revisited: clinical implications of inhibitory reflexes originating in the heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;1(1):90-102.

16. Younas F, Janjua M, Badshah A, DeGregorio M, Patel KC, Cotant JF. Transient complete heart block and isolated ventricular asystole with nitroglycerin. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2012;13(8):533-535. doi:10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283416b8b.

1. Miura T, Nishinaka T, Terada T, Yonezawa K. Vasodilatory effect of nitroglycerin in Japanese subjects with different aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) genotypes. Chem Biol Interact. 2017;276:40-45. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2017.03.012.

2. Noonan PK, Williams RL, Benet LZ. Dose dependent pharmacokinetics of nitroglycerin after multiple intravenous infusions in healthy volunteers. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1985;13(2):143-157.

3. Proulx MH, de Montigny L, Ross D, Vacon C, Juste LE, Segal E. Prehospital nitroglycerin in tachycardic chest pain patients: a risk for hypotension or not? Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;21(1):68-73. doi:10.1080/10903127.2016.1194929.

4. Huis In ‘t Veld MA, Cullen L, Mahler SA, Backus BE, Dezman ZDW, Mattu A. The fast and the furious: low-risk chest pain and the rapid rule-out protocol. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(3):474-478. doi:10.5811/westjem.2016.12.32676.

5. Pasupathy S, Tavella R, Grover S, et al. Early use of N-acetylcysteine with nitrate therapy in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction reduces myocardial infarct size (the NACIAM Trial [N-acetylcysteine in Acute Myocardial Infarction]). Circulation. 2017;136(10):894-903. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027575.

6. Turan B, Daşlı T, Erkol A, Erden İ. Effectiveness of sublingual nitroglycerin before puncture compared with conventional intra-carterial nitroglycerin in transradial procedures: a randomized trial. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16(7):391-396. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2015.07.006.

7. Nagy-Grócz G, Bohár Z, Fejes-Szabó A, et al. Nitroglycerin increases serotonin transporter expression in rat spinal cord but anandamide modulated this effect. J Chem Neuroanat. 2017;85:13-20. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2017.06.002.

8. Steele R, McNaughton T, McConahy M, Lam J. Chest pain in emergency department patients: if the pain is relieved by nitroglycerin, is it more likely to be cardiac chest pain? CJEM. 2006;8(3):164-169.

9. Dettorre K, Brywczynski J, McKinney J, Slovis C. Not the nitro? Patient goes into prehospital V-fib arrest following nitroglycerin. JEMS. 2009;34(5):34,36. doi:10.1016/S0197-2510(09)70124-X.

10. Buckley R, Roberts R. Symptomatic bradycardia following the administration of sublingual nitroglycerin. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11(3):253-255.

11. Takase B, Uehata A, Nishioka T, et al. Different mechanisms of isoproterenol-induced and nitroglycerin-induced syncope during head-up tilt in patients with unexplained syncope: important role of epinephrine in nitroglycerin-induced syncope. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12(7):791-796.

12. Brandes W, Santiago T, Limacher M. Nitroglycerin-induced hypotension, bradycardia, and asystole: report of a case and review of the literature. Clin Cardiol. 1990;13(10):741-744.

13. Ong EA, Canlas C, Smith W. Nitroglycerin-induced asystole. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(5):954.

14. Shah SP, Waxman S. Two cases of Bezold-Jarisch reflex induced by intra-arterial nitroglycerin in critical left main coronary artery stenosis. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40(4):484-486.

15. Mark AL. The Bezold-Jarisch reflex revisited: clinical implications of inhibitory reflexes originating in the heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;1(1):90-102.

16. Younas F, Janjua M, Badshah A, DeGregorio M, Patel KC, Cotant JF. Transient complete heart block and isolated ventricular asystole with nitroglycerin. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2012;13(8):533-535. doi:10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283416b8b.

Neoadjuvant-treated N2 rectal cancer linked to PCR failure

Orlando – Clinical an analysis of a large, multicenter database has suggested.

In multivariate regression, pretreatment N2 stage was the only variable significantly associated with failure of achieving pathologic complete response, according to Ebram Salama, MD, of Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital at McGill University, Montreal.

“We should be reconsidering putting these patients in watch-and-wait protocols,” Dr. Salama said in an oral abstract presentation at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

The analysis included 369 elective cases of cT2-4 N0-2 rectal cancer that were treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy during 2016 from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) proctectomy-specific database.

Of those cases, 53 (14.4%) achieved PCR, a proportion consistent with what has been reported previously in medical literature, Dr. Salama noted during his presentation.

The multivariate analysis revealed that pretreatment N2 stage was a negative predictor of PCR with an odds ratio of 0.18 (95% confidence interval, 0.04-0.82; P = .026), according to presented data.

By contrast, Dr. Salama said, there were no significant associations between response and other variables, including pretreatment N1 stage, pretreatment T stage, tumor location, gender, or body mass index.

Dr. Salama acknowledged limitations of this retrospective study, including a lack of data on other variables of interest, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, tumor size, imaging characteristics, molecular markers, and the time interval between chemoradiotherapy and surgery.

“We obviously need more data to evaluate other predictive factors in achieving a complete pathological response,” he said, adding that it’s also unclear whether the results of the present study could be generalized to institutions not participating in ACS NSQIP.

Dr. Salama presented the research on behalf of Nathalie Wong-Chong, MD, also of McGill University. He had no conflicts of interest to report for his presentation.

Orlando – Clinical an analysis of a large, multicenter database has suggested.

In multivariate regression, pretreatment N2 stage was the only variable significantly associated with failure of achieving pathologic complete response, according to Ebram Salama, MD, of Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital at McGill University, Montreal.

“We should be reconsidering putting these patients in watch-and-wait protocols,” Dr. Salama said in an oral abstract presentation at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

The analysis included 369 elective cases of cT2-4 N0-2 rectal cancer that were treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy during 2016 from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) proctectomy-specific database.

Of those cases, 53 (14.4%) achieved PCR, a proportion consistent with what has been reported previously in medical literature, Dr. Salama noted during his presentation.

The multivariate analysis revealed that pretreatment N2 stage was a negative predictor of PCR with an odds ratio of 0.18 (95% confidence interval, 0.04-0.82; P = .026), according to presented data.

By contrast, Dr. Salama said, there were no significant associations between response and other variables, including pretreatment N1 stage, pretreatment T stage, tumor location, gender, or body mass index.

Dr. Salama acknowledged limitations of this retrospective study, including a lack of data on other variables of interest, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, tumor size, imaging characteristics, molecular markers, and the time interval between chemoradiotherapy and surgery.

“We obviously need more data to evaluate other predictive factors in achieving a complete pathological response,” he said, adding that it’s also unclear whether the results of the present study could be generalized to institutions not participating in ACS NSQIP.

Dr. Salama presented the research on behalf of Nathalie Wong-Chong, MD, also of McGill University. He had no conflicts of interest to report for his presentation.

Orlando – Clinical an analysis of a large, multicenter database has suggested.

In multivariate regression, pretreatment N2 stage was the only variable significantly associated with failure of achieving pathologic complete response, according to Ebram Salama, MD, of Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital at McGill University, Montreal.

“We should be reconsidering putting these patients in watch-and-wait protocols,” Dr. Salama said in an oral abstract presentation at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

The analysis included 369 elective cases of cT2-4 N0-2 rectal cancer that were treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy during 2016 from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) proctectomy-specific database.

Of those cases, 53 (14.4%) achieved PCR, a proportion consistent with what has been reported previously in medical literature, Dr. Salama noted during his presentation.

The multivariate analysis revealed that pretreatment N2 stage was a negative predictor of PCR with an odds ratio of 0.18 (95% confidence interval, 0.04-0.82; P = .026), according to presented data.

By contrast, Dr. Salama said, there were no significant associations between response and other variables, including pretreatment N1 stage, pretreatment T stage, tumor location, gender, or body mass index.

Dr. Salama acknowledged limitations of this retrospective study, including a lack of data on other variables of interest, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, tumor size, imaging characteristics, molecular markers, and the time interval between chemoradiotherapy and surgery.

“We obviously need more data to evaluate other predictive factors in achieving a complete pathological response,” he said, adding that it’s also unclear whether the results of the present study could be generalized to institutions not participating in ACS NSQIP.

Dr. Salama presented the research on behalf of Nathalie Wong-Chong, MD, also of McGill University. He had no conflicts of interest to report for his presentation.

REPORTING FROM ACSQSC 2018

Key clinical point: N2 disease may be a negative predictor of pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer.

Major finding: Pretreatment N2 stage was a negative predictor of complete pathological response, with an odds ratio of 0.18 (95% confidence interval, 0.04-0.82; P = .026).

Study details: A study of 369 elective cases of cT2-4 N0-2 rectal cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy from 2016 in the ACS NSQIP proctectomy-specific database.

Disclosures: Dr. Salama had no conflicts of interest to report for his presentation.

PET/CT accurately predicts MCL stage

Bone marrow involvement in mantle cell lymphoma could be assessed using just 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET/CT, according to findings from a small, retrospective study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

Rustain Morgan, MD, of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and his colleagues found that, at a certain threshold of bone marrow voxels in standard uptake value (SUV), there was 100% sensitivity and 80% specificity in determining bone marrow involvement in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

Currently, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines call for bone marrow biopsy and whole body FDG PET/CT scan to complete an initial diagnosis of MCL.

“One of the most important factors for correct staging is the identification of bone marrow involvement, occurring in approximately 55% of patients with MCL, which classifies patients as advanced stage. However, accurate analysis of bone marrow involvement can be challenging due to sampling error,” the researchers wrote. “While bone marrow biopsy remains the gold standard, it is not a perfect standard given unilateral variability.”

In previous studies, FDG PET/CT was not considered sensitive enough to detect gastrointestinal or bone marrow involvement. However, these earlier studies used SUV maximum or mean or a visual assessment of the bone marrow activity, compared with hepatic uptake. To address this issue, the researchers developed a new method of examining SUV distribution throughout the pelvic bones by analyzing thousands of bone marrow voxels within the bilateral iliacs.

During the developmental phase, an institutional dataset of 11 patients with MCL was used to define the voxel-based analysis. These patients had undergone both unilateral iliac bone marrow biopsy and FDG PET/CT at the initial diagnosis. Then, FDG PET/CT scans from another 12 patients with MCL from a different institution were used to validate the developmental phase findings. Finally, a control group of 5 people with no known malignancy were referred for FDG PET/CT pulmonary nodule evaluation.

“The hypothesis of the study was that, if the bone marrow was involved by lymphoma, then there would be a small increase in the SUV of each voxel, reflecting involvement by the lymphoma. In order to capture such changes, we analyzed the percent of total voxels in SUV ranging from 0.75 to 1.20, in increments of 0.05, as this is where the greatest divergence was visually identified,” the researchers wrote. “The goal was to identify if a percentage of voxels at a set SUV could detect lymphomatous involvement.”

The researchers identified 10 candidate thresholds in the developmental phase; 4 of these performed better than the others in the validation phase. Using those thresholds, 10 of the 12 patients in the validation cohort could be correctly staged using FDG PET/CT.

Further analysis identified a single threshold that performed best: If greater than 38% of the voxels (averaging 1,734 voxels) demonstrated an SUV of less than 0.95, the sensitivity was 100% and the specificity was 80%.

The researchers acknowledged that the findings are limited because of the study’s small sample size and said the results should be validated in a larger trial.

There was no external funding for the study and the researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Morgan R et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.024.

Bone marrow involvement in mantle cell lymphoma could be assessed using just 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET/CT, according to findings from a small, retrospective study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

Rustain Morgan, MD, of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and his colleagues found that, at a certain threshold of bone marrow voxels in standard uptake value (SUV), there was 100% sensitivity and 80% specificity in determining bone marrow involvement in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

Currently, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines call for bone marrow biopsy and whole body FDG PET/CT scan to complete an initial diagnosis of MCL.

“One of the most important factors for correct staging is the identification of bone marrow involvement, occurring in approximately 55% of patients with MCL, which classifies patients as advanced stage. However, accurate analysis of bone marrow involvement can be challenging due to sampling error,” the researchers wrote. “While bone marrow biopsy remains the gold standard, it is not a perfect standard given unilateral variability.”

In previous studies, FDG PET/CT was not considered sensitive enough to detect gastrointestinal or bone marrow involvement. However, these earlier studies used SUV maximum or mean or a visual assessment of the bone marrow activity, compared with hepatic uptake. To address this issue, the researchers developed a new method of examining SUV distribution throughout the pelvic bones by analyzing thousands of bone marrow voxels within the bilateral iliacs.

During the developmental phase, an institutional dataset of 11 patients with MCL was used to define the voxel-based analysis. These patients had undergone both unilateral iliac bone marrow biopsy and FDG PET/CT at the initial diagnosis. Then, FDG PET/CT scans from another 12 patients with MCL from a different institution were used to validate the developmental phase findings. Finally, a control group of 5 people with no known malignancy were referred for FDG PET/CT pulmonary nodule evaluation.

“The hypothesis of the study was that, if the bone marrow was involved by lymphoma, then there would be a small increase in the SUV of each voxel, reflecting involvement by the lymphoma. In order to capture such changes, we analyzed the percent of total voxels in SUV ranging from 0.75 to 1.20, in increments of 0.05, as this is where the greatest divergence was visually identified,” the researchers wrote. “The goal was to identify if a percentage of voxels at a set SUV could detect lymphomatous involvement.”

The researchers identified 10 candidate thresholds in the developmental phase; 4 of these performed better than the others in the validation phase. Using those thresholds, 10 of the 12 patients in the validation cohort could be correctly staged using FDG PET/CT.

Further analysis identified a single threshold that performed best: If greater than 38% of the voxels (averaging 1,734 voxels) demonstrated an SUV of less than 0.95, the sensitivity was 100% and the specificity was 80%.

The researchers acknowledged that the findings are limited because of the study’s small sample size and said the results should be validated in a larger trial.

There was no external funding for the study and the researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Morgan R et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.024.

Bone marrow involvement in mantle cell lymphoma could be assessed using just 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET/CT, according to findings from a small, retrospective study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

Rustain Morgan, MD, of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and his colleagues found that, at a certain threshold of bone marrow voxels in standard uptake value (SUV), there was 100% sensitivity and 80% specificity in determining bone marrow involvement in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

Currently, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines call for bone marrow biopsy and whole body FDG PET/CT scan to complete an initial diagnosis of MCL.

“One of the most important factors for correct staging is the identification of bone marrow involvement, occurring in approximately 55% of patients with MCL, which classifies patients as advanced stage. However, accurate analysis of bone marrow involvement can be challenging due to sampling error,” the researchers wrote. “While bone marrow biopsy remains the gold standard, it is not a perfect standard given unilateral variability.”

In previous studies, FDG PET/CT was not considered sensitive enough to detect gastrointestinal or bone marrow involvement. However, these earlier studies used SUV maximum or mean or a visual assessment of the bone marrow activity, compared with hepatic uptake. To address this issue, the researchers developed a new method of examining SUV distribution throughout the pelvic bones by analyzing thousands of bone marrow voxels within the bilateral iliacs.

During the developmental phase, an institutional dataset of 11 patients with MCL was used to define the voxel-based analysis. These patients had undergone both unilateral iliac bone marrow biopsy and FDG PET/CT at the initial diagnosis. Then, FDG PET/CT scans from another 12 patients with MCL from a different institution were used to validate the developmental phase findings. Finally, a control group of 5 people with no known malignancy were referred for FDG PET/CT pulmonary nodule evaluation.

“The hypothesis of the study was that, if the bone marrow was involved by lymphoma, then there would be a small increase in the SUV of each voxel, reflecting involvement by the lymphoma. In order to capture such changes, we analyzed the percent of total voxels in SUV ranging from 0.75 to 1.20, in increments of 0.05, as this is where the greatest divergence was visually identified,” the researchers wrote. “The goal was to identify if a percentage of voxels at a set SUV could detect lymphomatous involvement.”

The researchers identified 10 candidate thresholds in the developmental phase; 4 of these performed better than the others in the validation phase. Using those thresholds, 10 of the 12 patients in the validation cohort could be correctly staged using FDG PET/CT.

Further analysis identified a single threshold that performed best: If greater than 38% of the voxels (averaging 1,734 voxels) demonstrated an SUV of less than 0.95, the sensitivity was 100% and the specificity was 80%.

The researchers acknowledged that the findings are limited because of the study’s small sample size and said the results should be validated in a larger trial.

There was no external funding for the study and the researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Morgan R et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.024.

REPORTING FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA & LEUKEMIA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: If greater than 38% of the voxels demonstrated an standard uptake value of less than 0.95, there was a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 80%.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 23 patients with mantle cell leukemia and 5 controls.

Disclosures: There was no external funding for the study and the researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Morgan R et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.024.

Plantar Ulcerative Lichen Planus: Rapid Improvement With a Novel Triple-Therapy Approach

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.