User login

Treatment of relapsing progressive MS may reduce disability progression

Superimposed relapses were associated with a significantly reduced risk of disability progression in a longitudinal, prospective cohort study of 1,419 multiple sclerosis patients (MS) of the progressive-onset type.

To determine the role of inflammatory relapses on disability in the progressive-relapsing phenotype of progressive-onset MS, the researchers collected data from MSBase, an international, observational cohort of MS patients, from January 1995 to February 2017. The study population included 1,419 adults with MS (553 in the relapse subgroup, 866 in a nonrelapse subgroup) from 83 centers in 28 countries; the median prospective follow-up period was 5 years. The patients included in the analysis had adult-onset disease, at least three clinic visits with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score recorded, and a time frame of more than 3 months between the second and last visit.

Overall, patients with relapses had significantly less risk of disability progression after adjusting for confounding variables (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.94; P = .003). Disease progression was defined as worsening of the EDSS score.

In addition, the researchers examined the data in a stratified model and found a 4% relative decrease in the hazard of confirmed disability progression events for each 10% increment of follow-up time for receiving disease-modifying therapy (DMT). However, DMT did not reduce disease progression risk in progressive-onset MS patients without relapse.

“This suggests that relapses in progressive-onset MS, as a clinical correlate of episodic inflammatory activity, represent a positive prognostic marker and provide an opportunity to improve disease outcomes through prevention of relapse-related disability accrual,” the researchers wrote.

Interferon-beta was the most common DMT, given to 73% of the relapse patients and 56% of the nonrelapse patients, followed by glatiramer acetate (20% and 13%, respectively), and fingolimod (12% and 16%, respectively).

The study’s main limitation was the use of the EDSS as a measure of disability, as well as the absence of quantifiable disability change to confirm relapse, the researchers noted. However, “these findings provide further evidence for a progressive-onset MS phenotype with acute episodic inflammatory changes, thereby identifying patients who may respond to existing immunotherapies.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the MSBase Foundation, a nonprofit organization that itself receives support from multiple companies, including Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi. Dr. Hughes had no financial conflicts to disclose, but most coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Novartis, Sanofi. Genzyme, and Biogen.

SOURCE: Hughes J et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2109.

This study is important because it addresses an area of controversy in management of patients with a progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) phenotype. The role of superimposed relapses in patients with progressive MS has long been debated, with some studies reporting no impact on long-term disability accrual and other reporting a negative impact of relapses. Treatment of progressive MS remains controversial as well, with only one therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration for any form of progressive MS. There is considerable ongoing debate about whether MS disease-modifying therapies (MSDMT) are effective in progressive forms of MS, and whether clinical or MRI evidence of active inflammation predicts a better chance of response.

This study has several important strengths and limitations. The large sample size allowed statistical power to detect relatively small differences in disability progression risk between progressive MS subtypes. The better prognosis in progressive patients with superimposed relapses contradicts some earlier studies that suggested a worse prognosis or no difference in prognosis between progressive patients with and without relapses. This study also supports a role for MSDMT in progressive MS patients, at least those with clinical evidence of relapses, and possibly MRI evidence of inflammatory disease activity (although this was not specifically addressed in the current study). Limitations of the study include the observational nature of the database, variable periods of follow-up, lack of objective verification of recorded relapses either with EDSS scores or MRI confirmation, and lack of an untreated control group. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn as to whether MSDMT exposure had a favorable impact on the whole cohort of progressive patients versus no treatment.

Jonathan L. Carter, MD , is an MS specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He had no relevant disclosures to report.

This study is important because it addresses an area of controversy in management of patients with a progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) phenotype. The role of superimposed relapses in patients with progressive MS has long been debated, with some studies reporting no impact on long-term disability accrual and other reporting a negative impact of relapses. Treatment of progressive MS remains controversial as well, with only one therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration for any form of progressive MS. There is considerable ongoing debate about whether MS disease-modifying therapies (MSDMT) are effective in progressive forms of MS, and whether clinical or MRI evidence of active inflammation predicts a better chance of response.

This study has several important strengths and limitations. The large sample size allowed statistical power to detect relatively small differences in disability progression risk between progressive MS subtypes. The better prognosis in progressive patients with superimposed relapses contradicts some earlier studies that suggested a worse prognosis or no difference in prognosis between progressive patients with and without relapses. This study also supports a role for MSDMT in progressive MS patients, at least those with clinical evidence of relapses, and possibly MRI evidence of inflammatory disease activity (although this was not specifically addressed in the current study). Limitations of the study include the observational nature of the database, variable periods of follow-up, lack of objective verification of recorded relapses either with EDSS scores or MRI confirmation, and lack of an untreated control group. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn as to whether MSDMT exposure had a favorable impact on the whole cohort of progressive patients versus no treatment.

Jonathan L. Carter, MD , is an MS specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He had no relevant disclosures to report.

This study is important because it addresses an area of controversy in management of patients with a progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) phenotype. The role of superimposed relapses in patients with progressive MS has long been debated, with some studies reporting no impact on long-term disability accrual and other reporting a negative impact of relapses. Treatment of progressive MS remains controversial as well, with only one therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration for any form of progressive MS. There is considerable ongoing debate about whether MS disease-modifying therapies (MSDMT) are effective in progressive forms of MS, and whether clinical or MRI evidence of active inflammation predicts a better chance of response.

This study has several important strengths and limitations. The large sample size allowed statistical power to detect relatively small differences in disability progression risk between progressive MS subtypes. The better prognosis in progressive patients with superimposed relapses contradicts some earlier studies that suggested a worse prognosis or no difference in prognosis between progressive patients with and without relapses. This study also supports a role for MSDMT in progressive MS patients, at least those with clinical evidence of relapses, and possibly MRI evidence of inflammatory disease activity (although this was not specifically addressed in the current study). Limitations of the study include the observational nature of the database, variable periods of follow-up, lack of objective verification of recorded relapses either with EDSS scores or MRI confirmation, and lack of an untreated control group. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn as to whether MSDMT exposure had a favorable impact on the whole cohort of progressive patients versus no treatment.

Jonathan L. Carter, MD , is an MS specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He had no relevant disclosures to report.

Superimposed relapses were associated with a significantly reduced risk of disability progression in a longitudinal, prospective cohort study of 1,419 multiple sclerosis patients (MS) of the progressive-onset type.

To determine the role of inflammatory relapses on disability in the progressive-relapsing phenotype of progressive-onset MS, the researchers collected data from MSBase, an international, observational cohort of MS patients, from January 1995 to February 2017. The study population included 1,419 adults with MS (553 in the relapse subgroup, 866 in a nonrelapse subgroup) from 83 centers in 28 countries; the median prospective follow-up period was 5 years. The patients included in the analysis had adult-onset disease, at least three clinic visits with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score recorded, and a time frame of more than 3 months between the second and last visit.

Overall, patients with relapses had significantly less risk of disability progression after adjusting for confounding variables (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.94; P = .003). Disease progression was defined as worsening of the EDSS score.

In addition, the researchers examined the data in a stratified model and found a 4% relative decrease in the hazard of confirmed disability progression events for each 10% increment of follow-up time for receiving disease-modifying therapy (DMT). However, DMT did not reduce disease progression risk in progressive-onset MS patients without relapse.

“This suggests that relapses in progressive-onset MS, as a clinical correlate of episodic inflammatory activity, represent a positive prognostic marker and provide an opportunity to improve disease outcomes through prevention of relapse-related disability accrual,” the researchers wrote.

Interferon-beta was the most common DMT, given to 73% of the relapse patients and 56% of the nonrelapse patients, followed by glatiramer acetate (20% and 13%, respectively), and fingolimod (12% and 16%, respectively).

The study’s main limitation was the use of the EDSS as a measure of disability, as well as the absence of quantifiable disability change to confirm relapse, the researchers noted. However, “these findings provide further evidence for a progressive-onset MS phenotype with acute episodic inflammatory changes, thereby identifying patients who may respond to existing immunotherapies.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the MSBase Foundation, a nonprofit organization that itself receives support from multiple companies, including Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi. Dr. Hughes had no financial conflicts to disclose, but most coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Novartis, Sanofi. Genzyme, and Biogen.

SOURCE: Hughes J et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2109.

Superimposed relapses were associated with a significantly reduced risk of disability progression in a longitudinal, prospective cohort study of 1,419 multiple sclerosis patients (MS) of the progressive-onset type.

To determine the role of inflammatory relapses on disability in the progressive-relapsing phenotype of progressive-onset MS, the researchers collected data from MSBase, an international, observational cohort of MS patients, from January 1995 to February 2017. The study population included 1,419 adults with MS (553 in the relapse subgroup, 866 in a nonrelapse subgroup) from 83 centers in 28 countries; the median prospective follow-up period was 5 years. The patients included in the analysis had adult-onset disease, at least three clinic visits with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score recorded, and a time frame of more than 3 months between the second and last visit.

Overall, patients with relapses had significantly less risk of disability progression after adjusting for confounding variables (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.94; P = .003). Disease progression was defined as worsening of the EDSS score.

In addition, the researchers examined the data in a stratified model and found a 4% relative decrease in the hazard of confirmed disability progression events for each 10% increment of follow-up time for receiving disease-modifying therapy (DMT). However, DMT did not reduce disease progression risk in progressive-onset MS patients without relapse.

“This suggests that relapses in progressive-onset MS, as a clinical correlate of episodic inflammatory activity, represent a positive prognostic marker and provide an opportunity to improve disease outcomes through prevention of relapse-related disability accrual,” the researchers wrote.

Interferon-beta was the most common DMT, given to 73% of the relapse patients and 56% of the nonrelapse patients, followed by glatiramer acetate (20% and 13%, respectively), and fingolimod (12% and 16%, respectively).

The study’s main limitation was the use of the EDSS as a measure of disability, as well as the absence of quantifiable disability change to confirm relapse, the researchers noted. However, “these findings provide further evidence for a progressive-onset MS phenotype with acute episodic inflammatory changes, thereby identifying patients who may respond to existing immunotherapies.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the MSBase Foundation, a nonprofit organization that itself receives support from multiple companies, including Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi. Dr. Hughes had no financial conflicts to disclose, but most coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Novartis, Sanofi. Genzyme, and Biogen.

SOURCE: Hughes J et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2109.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Disease-modifying therapy was significantly associated with less disability progression in multiple sclerosis patients with superimposed relapses, compared with those without relapses.

Major finding: Progressive-onset multiple sclerosis patients with superimposed relapses were significantly less likely to have confirmed disability progression (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.83).

Study details: The data came from a longitudinal, prospective cohort study of 1,419 adults with progressive-onset multiple sclerosis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the MSBase Foundation, a nonprofit organization that itself receives support from multiple companies, including Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi. Dr. Hughes had no financial conflicts to disclose, but most coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies, including Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Genzyme, and Biogen.

Source: Hughes J et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2109.

Help Develop 3 SVS Guidelines

The Society for Vascular Surgery needs members to participate in guideline writing groups on three topics: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery, Trauma and Genetic Aneurysms/Dissections. SVS welcomes applicants with expertise and experience in diverse practice settings. Visit here for more information and the survey/application forms for each guideline. Completed forms are due Aug. 15.

The Society for Vascular Surgery needs members to participate in guideline writing groups on three topics: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery, Trauma and Genetic Aneurysms/Dissections. SVS welcomes applicants with expertise and experience in diverse practice settings. Visit here for more information and the survey/application forms for each guideline. Completed forms are due Aug. 15.

The Society for Vascular Surgery needs members to participate in guideline writing groups on three topics: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery, Trauma and Genetic Aneurysms/Dissections. SVS welcomes applicants with expertise and experience in diverse practice settings. Visit here for more information and the survey/application forms for each guideline. Completed forms are due Aug. 15.

Submit Ideas for VAM 2019

Do you have an idea for an informative session at the 2019 Vascular Annual Meeting? The Society for Vascular Surgery is seeking proposals for invited sessions — postgraduate courses; breakfast, concurrent or small-group sessions; and/or Tips and Tricks and Ask the Experts sessions — for next year’s meeting. Suggestions are due by Aug. 27. See more information and find the submission form here. The 2019 VAM will be June 12-15 at the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just outside Washington, D.C.

Do you have an idea for an informative session at the 2019 Vascular Annual Meeting? The Society for Vascular Surgery is seeking proposals for invited sessions — postgraduate courses; breakfast, concurrent or small-group sessions; and/or Tips and Tricks and Ask the Experts sessions — for next year’s meeting. Suggestions are due by Aug. 27. See more information and find the submission form here. The 2019 VAM will be June 12-15 at the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just outside Washington, D.C.

Do you have an idea for an informative session at the 2019 Vascular Annual Meeting? The Society for Vascular Surgery is seeking proposals for invited sessions — postgraduate courses; breakfast, concurrent or small-group sessions; and/or Tips and Tricks and Ask the Experts sessions — for next year’s meeting. Suggestions are due by Aug. 27. See more information and find the submission form here. The 2019 VAM will be June 12-15 at the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just outside Washington, D.C.

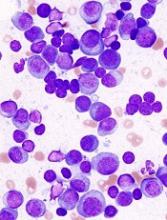

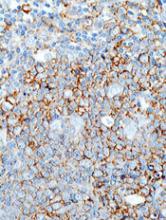

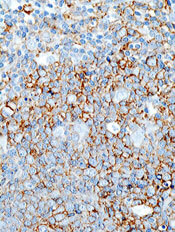

Insurance is a matter of life or death for lymphoma patients

Having health insurance can mean the difference between life and death for patients with follicular lymphoma, suggest results of a study showing that patients with private health insurance had nearly twofold better survival outcomes than patients without insurance or those who were covered by Medicare or Medicaid.

A review of records on more than 43,000 patients with follicular lymphoma (FL) in a national cancer registry showed that, compared with patients under age 65 with private insurance, the hazard ratios (HR) for death among patients in the same age bracket with either no insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare were, respectively, 1.96, 1.83, and 1.96 (P less than .0001 for each comparison).

“Our study finds that insurance status contributes to survival disparities in FL. Future studies on outcomes in FL should include insurance status as an important predictor,” Christopher R. Flowers, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta and his colleagues wrote in Blood.

“Further research on prognosis for FL should examine the impact of public policy, such as the passage of the [Affordable Care Act], on FL outcomes, as well as examine other factors that influence access to care, such as individual-level socioeconomic status, regular primary care visits, access to prescription medications, and care affordability,” they added.

The investigators noted that earlier research found that patients with Medicaid or no insurance were more likely than privately-insured patients to be diagnosed with cancers at advanced stages, and that some patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas have been shown to have insurance-related disparities in treatments and outcomes.

To see whether the same could be true for patients with indolent-histology lymphomas such as FL, they extracted data from the National Cancer Database, a nationwide hospital-based cancer registry sponsored jointly by the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society.

They identified a total of 43,648 patients aged 18 years or older who were diagnosed with FL from 2004 through 2014. They looked at both patients 18-64 years and those 65 years and older to account for changes in insurance with Medicare eligibility.

Overall survival among patients younger than age 65 was significantly worse for patients with public insurance (Medicaid or Medicare) or no insurance in Cox proportional hazard models controlling for available data on sociodemographic factors and prognostic indicators.

However, compared with patients aged 65 and older with private insurance, only patients with Medicare as their sole source of insurance had significantly worse overall survival (HR, 1.28; P less than .0001).

Patients who were uninsured or had Medicaid were more likely than others to have lower socioeconomic status, present with advanced-stage disease, have systemic symptoms, and have multiple comorbidities that persisted after controlling for known sociodemographic and prognostic factors.

The investigators found that, among patients under age 65, those with a comorbidity score of 1 had an HR for death of 1.71, compared with patients with no comorbidities, and that patients with a score of 2 or greater had a HR of 3.1 (P less than .0001 for each comparison).

“The findings of the study indicate that improving access to affordable, quality health care may reduce disparities in survival for those currently lacking coverage,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by Emory University, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Flowers reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Spectrum, Celgene, and several other companies. The other authors reported having nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Goldstein JS et al. Blood. 2018 Jul 24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-03-839035.

Having health insurance can mean the difference between life and death for patients with follicular lymphoma, suggest results of a study showing that patients with private health insurance had nearly twofold better survival outcomes than patients without insurance or those who were covered by Medicare or Medicaid.

A review of records on more than 43,000 patients with follicular lymphoma (FL) in a national cancer registry showed that, compared with patients under age 65 with private insurance, the hazard ratios (HR) for death among patients in the same age bracket with either no insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare were, respectively, 1.96, 1.83, and 1.96 (P less than .0001 for each comparison).

“Our study finds that insurance status contributes to survival disparities in FL. Future studies on outcomes in FL should include insurance status as an important predictor,” Christopher R. Flowers, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta and his colleagues wrote in Blood.

“Further research on prognosis for FL should examine the impact of public policy, such as the passage of the [Affordable Care Act], on FL outcomes, as well as examine other factors that influence access to care, such as individual-level socioeconomic status, regular primary care visits, access to prescription medications, and care affordability,” they added.

The investigators noted that earlier research found that patients with Medicaid or no insurance were more likely than privately-insured patients to be diagnosed with cancers at advanced stages, and that some patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas have been shown to have insurance-related disparities in treatments and outcomes.

To see whether the same could be true for patients with indolent-histology lymphomas such as FL, they extracted data from the National Cancer Database, a nationwide hospital-based cancer registry sponsored jointly by the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society.

They identified a total of 43,648 patients aged 18 years or older who were diagnosed with FL from 2004 through 2014. They looked at both patients 18-64 years and those 65 years and older to account for changes in insurance with Medicare eligibility.

Overall survival among patients younger than age 65 was significantly worse for patients with public insurance (Medicaid or Medicare) or no insurance in Cox proportional hazard models controlling for available data on sociodemographic factors and prognostic indicators.

However, compared with patients aged 65 and older with private insurance, only patients with Medicare as their sole source of insurance had significantly worse overall survival (HR, 1.28; P less than .0001).

Patients who were uninsured or had Medicaid were more likely than others to have lower socioeconomic status, present with advanced-stage disease, have systemic symptoms, and have multiple comorbidities that persisted after controlling for known sociodemographic and prognostic factors.

The investigators found that, among patients under age 65, those with a comorbidity score of 1 had an HR for death of 1.71, compared with patients with no comorbidities, and that patients with a score of 2 or greater had a HR of 3.1 (P less than .0001 for each comparison).

“The findings of the study indicate that improving access to affordable, quality health care may reduce disparities in survival for those currently lacking coverage,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by Emory University, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Flowers reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Spectrum, Celgene, and several other companies. The other authors reported having nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Goldstein JS et al. Blood. 2018 Jul 24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-03-839035.

Having health insurance can mean the difference between life and death for patients with follicular lymphoma, suggest results of a study showing that patients with private health insurance had nearly twofold better survival outcomes than patients without insurance or those who were covered by Medicare or Medicaid.

A review of records on more than 43,000 patients with follicular lymphoma (FL) in a national cancer registry showed that, compared with patients under age 65 with private insurance, the hazard ratios (HR) for death among patients in the same age bracket with either no insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare were, respectively, 1.96, 1.83, and 1.96 (P less than .0001 for each comparison).

“Our study finds that insurance status contributes to survival disparities in FL. Future studies on outcomes in FL should include insurance status as an important predictor,” Christopher R. Flowers, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta and his colleagues wrote in Blood.

“Further research on prognosis for FL should examine the impact of public policy, such as the passage of the [Affordable Care Act], on FL outcomes, as well as examine other factors that influence access to care, such as individual-level socioeconomic status, regular primary care visits, access to prescription medications, and care affordability,” they added.

The investigators noted that earlier research found that patients with Medicaid or no insurance were more likely than privately-insured patients to be diagnosed with cancers at advanced stages, and that some patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas have been shown to have insurance-related disparities in treatments and outcomes.

To see whether the same could be true for patients with indolent-histology lymphomas such as FL, they extracted data from the National Cancer Database, a nationwide hospital-based cancer registry sponsored jointly by the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society.

They identified a total of 43,648 patients aged 18 years or older who were diagnosed with FL from 2004 through 2014. They looked at both patients 18-64 years and those 65 years and older to account for changes in insurance with Medicare eligibility.

Overall survival among patients younger than age 65 was significantly worse for patients with public insurance (Medicaid or Medicare) or no insurance in Cox proportional hazard models controlling for available data on sociodemographic factors and prognostic indicators.

However, compared with patients aged 65 and older with private insurance, only patients with Medicare as their sole source of insurance had significantly worse overall survival (HR, 1.28; P less than .0001).

Patients who were uninsured or had Medicaid were more likely than others to have lower socioeconomic status, present with advanced-stage disease, have systemic symptoms, and have multiple comorbidities that persisted after controlling for known sociodemographic and prognostic factors.

The investigators found that, among patients under age 65, those with a comorbidity score of 1 had an HR for death of 1.71, compared with patients with no comorbidities, and that patients with a score of 2 or greater had a HR of 3.1 (P less than .0001 for each comparison).

“The findings of the study indicate that improving access to affordable, quality health care may reduce disparities in survival for those currently lacking coverage,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by Emory University, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Flowers reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Spectrum, Celgene, and several other companies. The other authors reported having nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Goldstein JS et al. Blood. 2018 Jul 24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-03-839035.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The risk for death among patients under age 65 with no insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare was nearly twice that of similar patients with private health insurance.

Study details: Review of data on 43,648 patients with follicular lymphoma in the National Cancer Database.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Emory University, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Flowers reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Spectrum, Celgene, and several other companies. The other authors reported having nothing to disclose.

Source: Goldstein JS et al. Blood. 2018 Jul 24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-03-839035.

A Veteran With Fibromyalgia Presenting With Dyspnea

Case Presentation. A 64-year-old US Army veteran with a history of colorectal cancer, melanoma, and fibrinolytic presented with dyspnea to VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS). Seven years prior to the current presentation, at the time of her diagnosis of colorectal cancer, the patient was found to be HIV negative but to have a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test. She was treated with isoniazid (INH) therapy for 9 months. Sputum cultures collected prior to initiation of therapy grew Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) in 1 of 3 samples, with these results reported several months after initiation of therapy. She was a never smoker with no known travel or exposure. At the time of the current presentation, her medications included bupropion, levothyroxine, capsaicin, cyclobenzaprine, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen.

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Monach, this patient is on a variety of pain medications and has a diagnosis of fibromyalgia. This diagnosis often frustrates doctors and patients alike. Can you tell us about fibromyalgia from the rheumatologist’s perspective and what you think of her current treatment regimen?

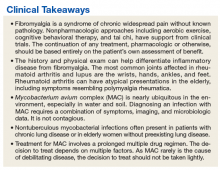

►Paul A. Monach, MD, PhD, Chief, Section of Rheumatology, VABHS and Associate Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Fibromyalgia is a syndrome of chronic widespread pain without known pathology in the musculoskeletal system. It is thought to be caused by chronic dysfunction of pain-processing pathways in the central nervous system (CNS). It is often accompanied by other somatic symptoms such as chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain. It is a common condition, affecting up to 5% of otherwise healthy women. It is particularly common in persons with chronic nonrestorative sleep or posttraumatic stress disorder from a wide range of causes. However, it also is more common in persons with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as lupus, Sjögren syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis. Concern for one of these diseases is the main reason to consider referring a patient for evaluation by a rheumatologist. Often rheumatologists participate in the management of fibromyalgia. A patient should be given appropriate expectations by the referring physician.

Effectiveness of treatment varies widely among patients. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as aerobic exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and tai chi have support from clinical trials, and yoga and aquatherapy also are widely used.1,2 The classes of drugs used are the same as for neuropathic pain: tricyclics, including cyclobenzaprine; serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); and gabapentinoids. In contrast, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids are ineffective unless there is a superimposed mechanical or inflammatory cause in the periphery. The key point is that continuation of any treatment should be based entirely on the patient’s own assessment of benefit.

►Dr. Swamy. Seven years later, the patient returned to her primary care provider, reporting increased dyspnea on exertion as well as significant fatigue. She was referred to the pulmonary department and had repeat computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, which indicated persistent right middle lobe (RML) bronchiectasis. She then underwent bronchoscopy with a subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture growing MAC. Dr. Fine, please interpret the baseline and follow-up CT scans and help us understand the significance of the MAC on sputum and BAL cultures.

►Alan Fine, MD, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS and Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Prior to this presentation, the patient had a pleural-based area of fibrosis with possible associated RML bronchiectasis. This appears to be a postinflammatory process without classic features of malignant or metastatic disease. She then had a sputum, which grew MAC in only 1 of 3 samples and in liquid media only. Importantly, the sputum was not smear positive. All of this suggests a low organism burden. One possibility is that this could reflect colonization with MAC; it is not uncommon for patients with underlying chronic changes in their lung to grow MAC, and it is often difficult to tell whether it is indicative of active disease. Structural lung disease, such as bronchiectasis, predisposes a patient to MAC, but chronic MAC also may cause bronchiectasis. This chicken-and-egg scenario comes up frequently. She may have a MAC infection, but as she is HIV negative and asymptomatic, there is no urgent indication to treat, especially as the burden of therapy is not insignificant.

►Dr. Swamy. Do we need to worry about Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)?

►Dr. Fine. Although she was previously PPD positive, she had already completed 1 year of isoniazid (INH) therapy, making active MTB less likely. From an infection control standpoint, it is important to distinguish MAC from MTB. The former is not contagious, and there is no need for airborne isolation.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, where does MAC come from? Does it commonly cause disease?

►Dr. Fine. In the environment, MAC is nearly ubiquitous , especially in water and soil. In one study, 20% of showerheads were positive for MAC; when patients are infected, we may suggest changing/bleaching the showerhead, but there are no definitive recommendations.3 Because MAC is so common in the environment, it is unlikely that measures to target MAC colonization will be clinically meaningful. On the other hand, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections is increasing across the US, and it may be a common and frequently underdiagnosed cause of chronic cough, especially in postmenopausal women.

►Dr. Swamy. Four years prior to the current presentation, the patient developed a cough after an upper respiratory tract infection that persisted for more than 2 weeks. Given her history, she underwent a repeat chest CT, which noted a slight increase in nodularity and ground-glass opacity restricted to the RML. She also reported dyspnea on exertion and was referred to the pulmonary medicine department. By the time she arrived, her dyspnea had largely resolved, but she reported persistent fatigue without other systemic symptoms, such as fevers or chills. Dr. Fine, does MAC explain this patient’s dyspnea?

►Dr. Fine. As her pulmonary symptoms resolved in a short period of time with only azithromycin, it is very unlikely that her symptoms were related to her prior disease. The MAC infection is not likely to cause dyspnea on exertion and fatigue and should be worked up more broadly before attributing it to MAC. In view of this, it would not be unreasonable to follow her clinically and see her again in 6 to 8 weeks. In this context, we also should consider the untoward impact of repeated radiation exposure derived from multiple CT scans. When a patient has an abnormality on CT scan, it often leads to further scans even if the symptoms do not match the previous findings, as in this case.

►Dr. Swamy. Given her ongoing fatigue and systemic symptoms (morning stiffness of the shoulders, legs, and thighs, and leg cramps), she was referred to the rheumatology department where the physical examination revealed muscle tenderness in her proximal arms and legs with normal strength, tender points at the elbows and medial side of the bilateral knees, significant tenderness of lower legs, and no synovitis.

Dr. Monach, can you walk us through your approach to this patient? Are we seeing manifestations of fibromyalgia? What diagnoses concerns you and how would you proceed?

►Dr. Monach. The history and exam are most helpful in raising or reducing suspicion for an underlying inflammatory disease. Areas of tenderness described in her case are typical of fibromyalgia, although it can be difficult to interpret symptoms in the hip girdle and shoulder girdle because objective findings are often absent on exam in patients with inflammatory arthritis or bursitis. Similarly, tenderness at sites of tendon insertion (enthuses) without objective abnormalities is common in different forms of spondyloarthritis, so tenderness at the elbow, knee, lateral hip, and low back can be difficult to interpret. What this patient is lacking is prominent subjective or objective findings in the joints most commonly affected in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus: wrists, hands, ankles, and feet.

►Dr. Swamy. Initial laboratory data include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 79 with a normal C-reactive protein. A tentative diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatic is made with consideration of a trial treatment of prednisone.

Dr. Monach, this patient has an indolent infection and is about to be given glucocorticoids. Could you describe the situations in which you feel that glucocorticoids cause a relative immunosuppression?

►Dr. Monach. Glucocorticoids are considered safe in a patient whose infection is not intrinsically dangerous or who has started appropriate antibiotics for that infection. Although all toxicities of glucocorticoids are dose dependent, the long-standing assertion that doses below 10 mg to 15 mg do not increase risk of infection is contradicted by data published in the past 10 to 15 years, with the caveat that these patients were on long-term treatment.

►Dr. Swamy. The patient was started on prednisone 15 mg per day for 15 days. She returned to the clinic after 1 week of prednisone troutment and noted “significant improvement in fatigue, morning stiffness of shoulders, thighs, leg, back is better, leg cramps resolved, shooting pain in many joints resolved.” Further laboratory results were notable for a negative rheumatoid factor, negative antinuclear antibody, and a cyclic citrullinated peptide of 60. A presumptive diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was made and plaquenil 200 mg twice daily was started.

Dr. Monach, can you explain why RA comes up now on serology but was not considered initially? Why does this presentation fit RA, and was her response to treatment typical? How does this fit in with her previous diagnosis of fibromyalgia? Was that just an atypical, indolent presentation of RA?

►Dr. Monach. Though her presentation is atypical for RA, in elderly patients, RA can present with symptoms resembling polymyalgia rheumatica. The question is whether she had RA all along (in which case “elderly onset” would not apply) or had fibromyalgia and developed RA more recently. The response to empiric glucocorticoid therapy is helpful, since fibromyalgia should not improve with prednisone even in a patient with RA unless treatment of RA would allow better sleep and ability to exercise. Rheumatoid arthritis typically responds very well to prednisone in the 5-mg to 15-mg range.

►Dr. Swamy. Given the new diagnosis of an inflammatory arthritis requiring immunosuppression, bronchoscopy with BAL is performed to evaluate for the presence of MAC. These cultures were positive for MAC.

Dr. Fine, does the positive BAL culture indicate an active MAC infection?

►Dr. Fine. Yes, based on these updated data, the patient has an active MAC infection. Active infection is defined as symptoms or imaging consistent with the diagnosis, supporting microbiology data (either 2 sputum or 1 BAL sample growing MAC) and the exclusion of other causes. Previously, this patient grew MAC in just one expectorated sputum; this did not meet the microbiologic criteria. Now sputum has grown in the BAL sample; along with the CT imaging, this is enough to diagnosis active MAC infection.

Treatment for MAC must consider the details of each case. First, this is not an emergency; treatment decisions should be made with the rheumatologist to consider the planned immunosuppression. For example, we must consider potential drug interactions. A specific point should be made of the use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibition, which data indicate can reactivate TB and may inhibit mechanisms that restrain mycobacterial disease. Serious cases of MAC infection have been reported in the literature in the setting of TNF-α inhibition.5,6 Despite these concerns, there is not a contraindication to using these therapies from the perspective of the active MAC disease. All of these decisions will impact the need to commit the patient to MAC therapy.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, what do you consider prior to initiating MAC therapy?

► Dr. Fine. The decision to pursue MAC therapy should not be taken lightly. Therapy often entails prolonged multidrug regimens, usually spanning more than a year, with frequent adverse effects. Outside of very specific cases, such as TNF-β inhibition, MAC is rarely a life-threatening disease, so the benefit may be limited. Treatment for MAC is certainly unlikely to be fruitful without a diligent and motivated patient able to handle the high and prolonged pill burden. Of note, it is also important to keep this patient up-to-date with influenza and pneumonia vaccination given her structural lung disease.

►Dr. Swamy. The decision is made to treat MAC with azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol. The disease is noted to be nonfibrocavitary. The patient underwent monthly liver function test monitoring and visual acuity testing, which were unremarkable. Dr. Fine, can you describe the phenotypes of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) disease?

►Dr. Fine. There are 3 main phenotypes of NTM.3 First, we see the elderly man with preexisting lung disease—usually chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—with fibrocavitary and/or reticulonodular appearance. Second, we see the slim, elderly woman often without any preexisting lung disease presenting with focal bronchiectasis and nodular lesions in right middle lobe and lingula—the Lady Windermere syndrome. This eponym is derived from Oscar Wilde’s play “Lady Windermere’s Fan, a Play About a Good Woman,” and was first associated with this disease in 1992.7 At the time, it was thought that the voluntary suppression of cough led to poorly draining lung regions, vulnerable to engraftment by atypical mycobacteria. Infection with atypical mycobacteria are associated with this population; however, it is no longer thought to be due to the voluntary suppression of cough.7,8 Third, we do occasionally see atypical presentations, such as focal masses and solitary nodules.

►Dr. Swamy. At 1-year follow-up she successfully completed MAC therapy and noted ongoing control of rheumatoid symptoms.

1. Bernardy K, Klose P, Welsch P, Häuser W. Efficacy, acceptability and safety of cognitive behavioural therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(2):242-260.

2. Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011279.

3. Aksamit TR, Philley JV, Griffith DE. Nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) lung disease: the top ten essentials. Respir Med. 2014;108(3):417-425.

4. Aucott JN. Glucocorticoids and infection. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23(3):655-670.

5. Curtis JR, Yang S, Patkar NM, et al. Risk of hospitalized bacterial infections associated with biologic treatment among US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(7):990-997.

6. Lane MA, McDonald JR, Zeringue AL, et al. TNF-α antagonist use and risk of hospitalization for infection in a national cohort of veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90(2):139-145.

7. Reich JM, Johnson RE. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease presenting as an isolated lingular or middle lobe pattern. The Lady Windermere syndrome. Chest. 1992;101(6):1605-1609.

8. Kasthoori JJ, Liam CK, Wastie ML. Lady Windermere syndrome: an inappropriate eponym for an increasingly important condition. Singapore Med J. 2008;49(2):e47-e49.

Case Presentation. A 64-year-old US Army veteran with a history of colorectal cancer, melanoma, and fibrinolytic presented with dyspnea to VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS). Seven years prior to the current presentation, at the time of her diagnosis of colorectal cancer, the patient was found to be HIV negative but to have a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test. She was treated with isoniazid (INH) therapy for 9 months. Sputum cultures collected prior to initiation of therapy grew Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) in 1 of 3 samples, with these results reported several months after initiation of therapy. She was a never smoker with no known travel or exposure. At the time of the current presentation, her medications included bupropion, levothyroxine, capsaicin, cyclobenzaprine, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen.

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Monach, this patient is on a variety of pain medications and has a diagnosis of fibromyalgia. This diagnosis often frustrates doctors and patients alike. Can you tell us about fibromyalgia from the rheumatologist’s perspective and what you think of her current treatment regimen?

►Paul A. Monach, MD, PhD, Chief, Section of Rheumatology, VABHS and Associate Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Fibromyalgia is a syndrome of chronic widespread pain without known pathology in the musculoskeletal system. It is thought to be caused by chronic dysfunction of pain-processing pathways in the central nervous system (CNS). It is often accompanied by other somatic symptoms such as chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain. It is a common condition, affecting up to 5% of otherwise healthy women. It is particularly common in persons with chronic nonrestorative sleep or posttraumatic stress disorder from a wide range of causes. However, it also is more common in persons with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as lupus, Sjögren syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis. Concern for one of these diseases is the main reason to consider referring a patient for evaluation by a rheumatologist. Often rheumatologists participate in the management of fibromyalgia. A patient should be given appropriate expectations by the referring physician.

Effectiveness of treatment varies widely among patients. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as aerobic exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and tai chi have support from clinical trials, and yoga and aquatherapy also are widely used.1,2 The classes of drugs used are the same as for neuropathic pain: tricyclics, including cyclobenzaprine; serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); and gabapentinoids. In contrast, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids are ineffective unless there is a superimposed mechanical or inflammatory cause in the periphery. The key point is that continuation of any treatment should be based entirely on the patient’s own assessment of benefit.

►Dr. Swamy. Seven years later, the patient returned to her primary care provider, reporting increased dyspnea on exertion as well as significant fatigue. She was referred to the pulmonary department and had repeat computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, which indicated persistent right middle lobe (RML) bronchiectasis. She then underwent bronchoscopy with a subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture growing MAC. Dr. Fine, please interpret the baseline and follow-up CT scans and help us understand the significance of the MAC on sputum and BAL cultures.

►Alan Fine, MD, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS and Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Prior to this presentation, the patient had a pleural-based area of fibrosis with possible associated RML bronchiectasis. This appears to be a postinflammatory process without classic features of malignant or metastatic disease. She then had a sputum, which grew MAC in only 1 of 3 samples and in liquid media only. Importantly, the sputum was not smear positive. All of this suggests a low organism burden. One possibility is that this could reflect colonization with MAC; it is not uncommon for patients with underlying chronic changes in their lung to grow MAC, and it is often difficult to tell whether it is indicative of active disease. Structural lung disease, such as bronchiectasis, predisposes a patient to MAC, but chronic MAC also may cause bronchiectasis. This chicken-and-egg scenario comes up frequently. She may have a MAC infection, but as she is HIV negative and asymptomatic, there is no urgent indication to treat, especially as the burden of therapy is not insignificant.

►Dr. Swamy. Do we need to worry about Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)?

►Dr. Fine. Although she was previously PPD positive, she had already completed 1 year of isoniazid (INH) therapy, making active MTB less likely. From an infection control standpoint, it is important to distinguish MAC from MTB. The former is not contagious, and there is no need for airborne isolation.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, where does MAC come from? Does it commonly cause disease?

►Dr. Fine. In the environment, MAC is nearly ubiquitous , especially in water and soil. In one study, 20% of showerheads were positive for MAC; when patients are infected, we may suggest changing/bleaching the showerhead, but there are no definitive recommendations.3 Because MAC is so common in the environment, it is unlikely that measures to target MAC colonization will be clinically meaningful. On the other hand, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections is increasing across the US, and it may be a common and frequently underdiagnosed cause of chronic cough, especially in postmenopausal women.

►Dr. Swamy. Four years prior to the current presentation, the patient developed a cough after an upper respiratory tract infection that persisted for more than 2 weeks. Given her history, she underwent a repeat chest CT, which noted a slight increase in nodularity and ground-glass opacity restricted to the RML. She also reported dyspnea on exertion and was referred to the pulmonary medicine department. By the time she arrived, her dyspnea had largely resolved, but she reported persistent fatigue without other systemic symptoms, such as fevers or chills. Dr. Fine, does MAC explain this patient’s dyspnea?

►Dr. Fine. As her pulmonary symptoms resolved in a short period of time with only azithromycin, it is very unlikely that her symptoms were related to her prior disease. The MAC infection is not likely to cause dyspnea on exertion and fatigue and should be worked up more broadly before attributing it to MAC. In view of this, it would not be unreasonable to follow her clinically and see her again in 6 to 8 weeks. In this context, we also should consider the untoward impact of repeated radiation exposure derived from multiple CT scans. When a patient has an abnormality on CT scan, it often leads to further scans even if the symptoms do not match the previous findings, as in this case.

►Dr. Swamy. Given her ongoing fatigue and systemic symptoms (morning stiffness of the shoulders, legs, and thighs, and leg cramps), she was referred to the rheumatology department where the physical examination revealed muscle tenderness in her proximal arms and legs with normal strength, tender points at the elbows and medial side of the bilateral knees, significant tenderness of lower legs, and no synovitis.

Dr. Monach, can you walk us through your approach to this patient? Are we seeing manifestations of fibromyalgia? What diagnoses concerns you and how would you proceed?

►Dr. Monach. The history and exam are most helpful in raising or reducing suspicion for an underlying inflammatory disease. Areas of tenderness described in her case are typical of fibromyalgia, although it can be difficult to interpret symptoms in the hip girdle and shoulder girdle because objective findings are often absent on exam in patients with inflammatory arthritis or bursitis. Similarly, tenderness at sites of tendon insertion (enthuses) without objective abnormalities is common in different forms of spondyloarthritis, so tenderness at the elbow, knee, lateral hip, and low back can be difficult to interpret. What this patient is lacking is prominent subjective or objective findings in the joints most commonly affected in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus: wrists, hands, ankles, and feet.

►Dr. Swamy. Initial laboratory data include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 79 with a normal C-reactive protein. A tentative diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatic is made with consideration of a trial treatment of prednisone.

Dr. Monach, this patient has an indolent infection and is about to be given glucocorticoids. Could you describe the situations in which you feel that glucocorticoids cause a relative immunosuppression?

►Dr. Monach. Glucocorticoids are considered safe in a patient whose infection is not intrinsically dangerous or who has started appropriate antibiotics for that infection. Although all toxicities of glucocorticoids are dose dependent, the long-standing assertion that doses below 10 mg to 15 mg do not increase risk of infection is contradicted by data published in the past 10 to 15 years, with the caveat that these patients were on long-term treatment.

►Dr. Swamy. The patient was started on prednisone 15 mg per day for 15 days. She returned to the clinic after 1 week of prednisone troutment and noted “significant improvement in fatigue, morning stiffness of shoulders, thighs, leg, back is better, leg cramps resolved, shooting pain in many joints resolved.” Further laboratory results were notable for a negative rheumatoid factor, negative antinuclear antibody, and a cyclic citrullinated peptide of 60. A presumptive diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was made and plaquenil 200 mg twice daily was started.

Dr. Monach, can you explain why RA comes up now on serology but was not considered initially? Why does this presentation fit RA, and was her response to treatment typical? How does this fit in with her previous diagnosis of fibromyalgia? Was that just an atypical, indolent presentation of RA?

►Dr. Monach. Though her presentation is atypical for RA, in elderly patients, RA can present with symptoms resembling polymyalgia rheumatica. The question is whether she had RA all along (in which case “elderly onset” would not apply) or had fibromyalgia and developed RA more recently. The response to empiric glucocorticoid therapy is helpful, since fibromyalgia should not improve with prednisone even in a patient with RA unless treatment of RA would allow better sleep and ability to exercise. Rheumatoid arthritis typically responds very well to prednisone in the 5-mg to 15-mg range.

►Dr. Swamy. Given the new diagnosis of an inflammatory arthritis requiring immunosuppression, bronchoscopy with BAL is performed to evaluate for the presence of MAC. These cultures were positive for MAC.

Dr. Fine, does the positive BAL culture indicate an active MAC infection?

►Dr. Fine. Yes, based on these updated data, the patient has an active MAC infection. Active infection is defined as symptoms or imaging consistent with the diagnosis, supporting microbiology data (either 2 sputum or 1 BAL sample growing MAC) and the exclusion of other causes. Previously, this patient grew MAC in just one expectorated sputum; this did not meet the microbiologic criteria. Now sputum has grown in the BAL sample; along with the CT imaging, this is enough to diagnosis active MAC infection.

Treatment for MAC must consider the details of each case. First, this is not an emergency; treatment decisions should be made with the rheumatologist to consider the planned immunosuppression. For example, we must consider potential drug interactions. A specific point should be made of the use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibition, which data indicate can reactivate TB and may inhibit mechanisms that restrain mycobacterial disease. Serious cases of MAC infection have been reported in the literature in the setting of TNF-α inhibition.5,6 Despite these concerns, there is not a contraindication to using these therapies from the perspective of the active MAC disease. All of these decisions will impact the need to commit the patient to MAC therapy.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, what do you consider prior to initiating MAC therapy?

► Dr. Fine. The decision to pursue MAC therapy should not be taken lightly. Therapy often entails prolonged multidrug regimens, usually spanning more than a year, with frequent adverse effects. Outside of very specific cases, such as TNF-β inhibition, MAC is rarely a life-threatening disease, so the benefit may be limited. Treatment for MAC is certainly unlikely to be fruitful without a diligent and motivated patient able to handle the high and prolonged pill burden. Of note, it is also important to keep this patient up-to-date with influenza and pneumonia vaccination given her structural lung disease.

►Dr. Swamy. The decision is made to treat MAC with azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol. The disease is noted to be nonfibrocavitary. The patient underwent monthly liver function test monitoring and visual acuity testing, which were unremarkable. Dr. Fine, can you describe the phenotypes of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) disease?

►Dr. Fine. There are 3 main phenotypes of NTM.3 First, we see the elderly man with preexisting lung disease—usually chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—with fibrocavitary and/or reticulonodular appearance. Second, we see the slim, elderly woman often without any preexisting lung disease presenting with focal bronchiectasis and nodular lesions in right middle lobe and lingula—the Lady Windermere syndrome. This eponym is derived from Oscar Wilde’s play “Lady Windermere’s Fan, a Play About a Good Woman,” and was first associated with this disease in 1992.7 At the time, it was thought that the voluntary suppression of cough led to poorly draining lung regions, vulnerable to engraftment by atypical mycobacteria. Infection with atypical mycobacteria are associated with this population; however, it is no longer thought to be due to the voluntary suppression of cough.7,8 Third, we do occasionally see atypical presentations, such as focal masses and solitary nodules.

►Dr. Swamy. At 1-year follow-up she successfully completed MAC therapy and noted ongoing control of rheumatoid symptoms.

Case Presentation. A 64-year-old US Army veteran with a history of colorectal cancer, melanoma, and fibrinolytic presented with dyspnea to VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS). Seven years prior to the current presentation, at the time of her diagnosis of colorectal cancer, the patient was found to be HIV negative but to have a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test. She was treated with isoniazid (INH) therapy for 9 months. Sputum cultures collected prior to initiation of therapy grew Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) in 1 of 3 samples, with these results reported several months after initiation of therapy. She was a never smoker with no known travel or exposure. At the time of the current presentation, her medications included bupropion, levothyroxine, capsaicin, cyclobenzaprine, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen.

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Monach, this patient is on a variety of pain medications and has a diagnosis of fibromyalgia. This diagnosis often frustrates doctors and patients alike. Can you tell us about fibromyalgia from the rheumatologist’s perspective and what you think of her current treatment regimen?

►Paul A. Monach, MD, PhD, Chief, Section of Rheumatology, VABHS and Associate Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Fibromyalgia is a syndrome of chronic widespread pain without known pathology in the musculoskeletal system. It is thought to be caused by chronic dysfunction of pain-processing pathways in the central nervous system (CNS). It is often accompanied by other somatic symptoms such as chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain. It is a common condition, affecting up to 5% of otherwise healthy women. It is particularly common in persons with chronic nonrestorative sleep or posttraumatic stress disorder from a wide range of causes. However, it also is more common in persons with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as lupus, Sjögren syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis. Concern for one of these diseases is the main reason to consider referring a patient for evaluation by a rheumatologist. Often rheumatologists participate in the management of fibromyalgia. A patient should be given appropriate expectations by the referring physician.

Effectiveness of treatment varies widely among patients. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as aerobic exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and tai chi have support from clinical trials, and yoga and aquatherapy also are widely used.1,2 The classes of drugs used are the same as for neuropathic pain: tricyclics, including cyclobenzaprine; serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); and gabapentinoids. In contrast, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids are ineffective unless there is a superimposed mechanical or inflammatory cause in the periphery. The key point is that continuation of any treatment should be based entirely on the patient’s own assessment of benefit.

►Dr. Swamy. Seven years later, the patient returned to her primary care provider, reporting increased dyspnea on exertion as well as significant fatigue. She was referred to the pulmonary department and had repeat computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, which indicated persistent right middle lobe (RML) bronchiectasis. She then underwent bronchoscopy with a subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture growing MAC. Dr. Fine, please interpret the baseline and follow-up CT scans and help us understand the significance of the MAC on sputum and BAL cultures.

►Alan Fine, MD, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS and Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Prior to this presentation, the patient had a pleural-based area of fibrosis with possible associated RML bronchiectasis. This appears to be a postinflammatory process without classic features of malignant or metastatic disease. She then had a sputum, which grew MAC in only 1 of 3 samples and in liquid media only. Importantly, the sputum was not smear positive. All of this suggests a low organism burden. One possibility is that this could reflect colonization with MAC; it is not uncommon for patients with underlying chronic changes in their lung to grow MAC, and it is often difficult to tell whether it is indicative of active disease. Structural lung disease, such as bronchiectasis, predisposes a patient to MAC, but chronic MAC also may cause bronchiectasis. This chicken-and-egg scenario comes up frequently. She may have a MAC infection, but as she is HIV negative and asymptomatic, there is no urgent indication to treat, especially as the burden of therapy is not insignificant.

►Dr. Swamy. Do we need to worry about Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)?

►Dr. Fine. Although she was previously PPD positive, she had already completed 1 year of isoniazid (INH) therapy, making active MTB less likely. From an infection control standpoint, it is important to distinguish MAC from MTB. The former is not contagious, and there is no need for airborne isolation.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, where does MAC come from? Does it commonly cause disease?

►Dr. Fine. In the environment, MAC is nearly ubiquitous , especially in water and soil. In one study, 20% of showerheads were positive for MAC; when patients are infected, we may suggest changing/bleaching the showerhead, but there are no definitive recommendations.3 Because MAC is so common in the environment, it is unlikely that measures to target MAC colonization will be clinically meaningful. On the other hand, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections is increasing across the US, and it may be a common and frequently underdiagnosed cause of chronic cough, especially in postmenopausal women.

►Dr. Swamy. Four years prior to the current presentation, the patient developed a cough after an upper respiratory tract infection that persisted for more than 2 weeks. Given her history, she underwent a repeat chest CT, which noted a slight increase in nodularity and ground-glass opacity restricted to the RML. She also reported dyspnea on exertion and was referred to the pulmonary medicine department. By the time she arrived, her dyspnea had largely resolved, but she reported persistent fatigue without other systemic symptoms, such as fevers or chills. Dr. Fine, does MAC explain this patient’s dyspnea?

►Dr. Fine. As her pulmonary symptoms resolved in a short period of time with only azithromycin, it is very unlikely that her symptoms were related to her prior disease. The MAC infection is not likely to cause dyspnea on exertion and fatigue and should be worked up more broadly before attributing it to MAC. In view of this, it would not be unreasonable to follow her clinically and see her again in 6 to 8 weeks. In this context, we also should consider the untoward impact of repeated radiation exposure derived from multiple CT scans. When a patient has an abnormality on CT scan, it often leads to further scans even if the symptoms do not match the previous findings, as in this case.

►Dr. Swamy. Given her ongoing fatigue and systemic symptoms (morning stiffness of the shoulders, legs, and thighs, and leg cramps), she was referred to the rheumatology department where the physical examination revealed muscle tenderness in her proximal arms and legs with normal strength, tender points at the elbows and medial side of the bilateral knees, significant tenderness of lower legs, and no synovitis.

Dr. Monach, can you walk us through your approach to this patient? Are we seeing manifestations of fibromyalgia? What diagnoses concerns you and how would you proceed?

►Dr. Monach. The history and exam are most helpful in raising or reducing suspicion for an underlying inflammatory disease. Areas of tenderness described in her case are typical of fibromyalgia, although it can be difficult to interpret symptoms in the hip girdle and shoulder girdle because objective findings are often absent on exam in patients with inflammatory arthritis or bursitis. Similarly, tenderness at sites of tendon insertion (enthuses) without objective abnormalities is common in different forms of spondyloarthritis, so tenderness at the elbow, knee, lateral hip, and low back can be difficult to interpret. What this patient is lacking is prominent subjective or objective findings in the joints most commonly affected in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus: wrists, hands, ankles, and feet.

►Dr. Swamy. Initial laboratory data include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 79 with a normal C-reactive protein. A tentative diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatic is made with consideration of a trial treatment of prednisone.

Dr. Monach, this patient has an indolent infection and is about to be given glucocorticoids. Could you describe the situations in which you feel that glucocorticoids cause a relative immunosuppression?

►Dr. Monach. Glucocorticoids are considered safe in a patient whose infection is not intrinsically dangerous or who has started appropriate antibiotics for that infection. Although all toxicities of glucocorticoids are dose dependent, the long-standing assertion that doses below 10 mg to 15 mg do not increase risk of infection is contradicted by data published in the past 10 to 15 years, with the caveat that these patients were on long-term treatment.

►Dr. Swamy. The patient was started on prednisone 15 mg per day for 15 days. She returned to the clinic after 1 week of prednisone troutment and noted “significant improvement in fatigue, morning stiffness of shoulders, thighs, leg, back is better, leg cramps resolved, shooting pain in many joints resolved.” Further laboratory results were notable for a negative rheumatoid factor, negative antinuclear antibody, and a cyclic citrullinated peptide of 60. A presumptive diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was made and plaquenil 200 mg twice daily was started.

Dr. Monach, can you explain why RA comes up now on serology but was not considered initially? Why does this presentation fit RA, and was her response to treatment typical? How does this fit in with her previous diagnosis of fibromyalgia? Was that just an atypical, indolent presentation of RA?

►Dr. Monach. Though her presentation is atypical for RA, in elderly patients, RA can present with symptoms resembling polymyalgia rheumatica. The question is whether she had RA all along (in which case “elderly onset” would not apply) or had fibromyalgia and developed RA more recently. The response to empiric glucocorticoid therapy is helpful, since fibromyalgia should not improve with prednisone even in a patient with RA unless treatment of RA would allow better sleep and ability to exercise. Rheumatoid arthritis typically responds very well to prednisone in the 5-mg to 15-mg range.

►Dr. Swamy. Given the new diagnosis of an inflammatory arthritis requiring immunosuppression, bronchoscopy with BAL is performed to evaluate for the presence of MAC. These cultures were positive for MAC.

Dr. Fine, does the positive BAL culture indicate an active MAC infection?

►Dr. Fine. Yes, based on these updated data, the patient has an active MAC infection. Active infection is defined as symptoms or imaging consistent with the diagnosis, supporting microbiology data (either 2 sputum or 1 BAL sample growing MAC) and the exclusion of other causes. Previously, this patient grew MAC in just one expectorated sputum; this did not meet the microbiologic criteria. Now sputum has grown in the BAL sample; along with the CT imaging, this is enough to diagnosis active MAC infection.

Treatment for MAC must consider the details of each case. First, this is not an emergency; treatment decisions should be made with the rheumatologist to consider the planned immunosuppression. For example, we must consider potential drug interactions. A specific point should be made of the use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibition, which data indicate can reactivate TB and may inhibit mechanisms that restrain mycobacterial disease. Serious cases of MAC infection have been reported in the literature in the setting of TNF-α inhibition.5,6 Despite these concerns, there is not a contraindication to using these therapies from the perspective of the active MAC disease. All of these decisions will impact the need to commit the patient to MAC therapy.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, what do you consider prior to initiating MAC therapy?

► Dr. Fine. The decision to pursue MAC therapy should not be taken lightly. Therapy often entails prolonged multidrug regimens, usually spanning more than a year, with frequent adverse effects. Outside of very specific cases, such as TNF-β inhibition, MAC is rarely a life-threatening disease, so the benefit may be limited. Treatment for MAC is certainly unlikely to be fruitful without a diligent and motivated patient able to handle the high and prolonged pill burden. Of note, it is also important to keep this patient up-to-date with influenza and pneumonia vaccination given her structural lung disease.

►Dr. Swamy. The decision is made to treat MAC with azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol. The disease is noted to be nonfibrocavitary. The patient underwent monthly liver function test monitoring and visual acuity testing, which were unremarkable. Dr. Fine, can you describe the phenotypes of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) disease?

►Dr. Fine. There are 3 main phenotypes of NTM.3 First, we see the elderly man with preexisting lung disease—usually chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—with fibrocavitary and/or reticulonodular appearance. Second, we see the slim, elderly woman often without any preexisting lung disease presenting with focal bronchiectasis and nodular lesions in right middle lobe and lingula—the Lady Windermere syndrome. This eponym is derived from Oscar Wilde’s play “Lady Windermere’s Fan, a Play About a Good Woman,” and was first associated with this disease in 1992.7 At the time, it was thought that the voluntary suppression of cough led to poorly draining lung regions, vulnerable to engraftment by atypical mycobacteria. Infection with atypical mycobacteria are associated with this population; however, it is no longer thought to be due to the voluntary suppression of cough.7,8 Third, we do occasionally see atypical presentations, such as focal masses and solitary nodules.

►Dr. Swamy. At 1-year follow-up she successfully completed MAC therapy and noted ongoing control of rheumatoid symptoms.

1. Bernardy K, Klose P, Welsch P, Häuser W. Efficacy, acceptability and safety of cognitive behavioural therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(2):242-260.

2. Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011279.

3. Aksamit TR, Philley JV, Griffith DE. Nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) lung disease: the top ten essentials. Respir Med. 2014;108(3):417-425.

4. Aucott JN. Glucocorticoids and infection. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23(3):655-670.

5. Curtis JR, Yang S, Patkar NM, et al. Risk of hospitalized bacterial infections associated with biologic treatment among US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(7):990-997.

6. Lane MA, McDonald JR, Zeringue AL, et al. TNF-α antagonist use and risk of hospitalization for infection in a national cohort of veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90(2):139-145.

7. Reich JM, Johnson RE. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease presenting as an isolated lingular or middle lobe pattern. The Lady Windermere syndrome. Chest. 1992;101(6):1605-1609.

8. Kasthoori JJ, Liam CK, Wastie ML. Lady Windermere syndrome: an inappropriate eponym for an increasingly important condition. Singapore Med J. 2008;49(2):e47-e49.

1. Bernardy K, Klose P, Welsch P, Häuser W. Efficacy, acceptability and safety of cognitive behavioural therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(2):242-260.

2. Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011279.

3. Aksamit TR, Philley JV, Griffith DE. Nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) lung disease: the top ten essentials. Respir Med. 2014;108(3):417-425.

4. Aucott JN. Glucocorticoids and infection. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23(3):655-670.

5. Curtis JR, Yang S, Patkar NM, et al. Risk of hospitalized bacterial infections associated with biologic treatment among US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(7):990-997.

6. Lane MA, McDonald JR, Zeringue AL, et al. TNF-α antagonist use and risk of hospitalization for infection in a national cohort of veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90(2):139-145.

7. Reich JM, Johnson RE. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease presenting as an isolated lingular or middle lobe pattern. The Lady Windermere syndrome. Chest. 1992;101(6):1605-1609.

8. Kasthoori JJ, Liam CK, Wastie ML. Lady Windermere syndrome: an inappropriate eponym for an increasingly important condition. Singapore Med J. 2008;49(2):e47-e49.

Company stops development of drug for MM

MorphoSys AG has decided to stop developing MOR202 as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).