User login

Herceptin linked to doubling of HF risk in women with breast cancer

Adding more evidence to an ongoing debate, a large new study suggests that patients with breast cancer who take trastuzumab (Herceptin) may face double the adjusted risk of developing heart failure, with older women at highest risk.

The study also found that most patients who took trastuzumab didn’t receive recommended cardiac screening.

The researchers said their findings are unique because they tracked both younger and older patients. “By examining the rates of both cardiac monitoring and cardiotoxicity, we could begin to address the controversial issue of whether cardiac monitoring is warranted in young breast cancer patients,” wrote Mariana Chavez-MacGregor, MD, MSC, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and her associates. The report was published in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

While Trastuzumab has boosted breast cancer survival rates for patients with HER2-positive tumors, it’s also raised concerns about cardiotoxicity that could be an indicator of subsequent congestive heart failure (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jun 12;(6):CD006242).

According to the new study, the risk of trastuzumab risk is linked to damage to cardiac myocytes that can cause reversible cardiotoxicity.

The prescribing information for trastuzumab advises patients to undergo cardiac monitoring before treatment with trastuzumab and every 3 months during treatment. Recommendations by medical organizations have varied.

Now, as a 2016 report put it, it’s “increasingly unclear” whether frequent routine monitoring is appropriate for all patients (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 1;34[10]:1030-3).

For the current study, Dr. Chavez-MacGregor and her associates identified 16,456 adult women in the United States who were diagnosed with nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer from 2009 to 2014. Researchers tracked the group, with a median age of 56, through as late as 2015.

The women were treated with chemotherapy within 6 months of diagnosis, and 4,325 received trastuzumab.

Of all the subjects, 692 patients (4.2%) developed heart failure following chemotherapy. The rate among patients treated with trastuzumab was higher, at 8.3%, compared with 2.7% for those not treated with trastuzumab (P less than .001).

The researchers also looked at anthracycline users and found that they were slightly more likely to develop HF (4.6% vs. 4.0% among nonusers, P = .048).

Increased age boosted the risk of HF in the trastuzumab-treated patients, and the risk was highest in those treated with both anthracyclines and trastuzumab. Other factors linked to more risk were comorbidities, hypertension, and valve disease.

After adjusting for confounders, the researchers estimated that those treated with trastuzumab were 2.01 times more likely to develop HF (HR, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.72-2.36), and those who took anthracycline were 1.53 times more likely (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.30-1.80)

The researchers also examined medical records for evidence that subjects underwent cardiac screening at least once every 4 months, not 3 months, as the prescribing information recommends. The study team chose to focus on 4-month intervals “to compensate for differences in scheduling, resources, or levels of accessibility to medical care.”

Medical records suggest that 73.5% of patients who took trastuzumab underwent cardiac screening at the beginning of therapy, but only 46.2% continued to do so at least every 4 months.

An adjusted model linked more screening to the use of anthracyclines and taxanes, radiation treatment, and living in the Northeast vs. the West.

“HF was more frequently identified among patients undergoing recommended cardiac monitoring (10.4% compared with 6.5%, respectively; P less than.001), suggesting that, as more patients are screened, more patients are likely to be found having HF,” the researchers reported.

However, they added that “our sensitivity analysis using inpatient claims allowed us to determine that the HF identified using cardiac monitoring was not severe enough to require hospitalization and was likely asymptomatic. The clinical implications of the diagnosis of asymptomatic HF are hard to determine and are beyond the scope of this study.”

The researchers also noted that the findings suggest that screening has become more common in recent years.

“The number of cancer survivors is expected to increase over time, and we will continue to see patients develop treatment-related cardiotoxicity,” the researchers wrote. “Thus, more research, evidence-based guidelines, and tools for prediction of cancer treatment–related cardiotoxicity are needed.”

The National Cancer Institute and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas funded the study. Two study authors reported grant funding from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, and one reports consulting for Pfizer and Roche. The other authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavez-MacGregor M et al. JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Aug;11[8]1084-93.

While trastuzumab clearly benefits patients with HER2-positive breast cancer at various stages of progression, concerns about heart failure persist. Studies have suggested that the drug doesn’t boost the risk of late cardiac events, but it’s not clear if this is due to mandated screening in these trials. The new study provides more evidence that adherence to screening guidelines is limited, and recent trials offer evidence that the general cardiac risk may be overblown. Future studies could be designed to offer insight into the wisdom of adjusting screening regimens based on stratification of risk. A meta-analysis could also be helpful, and the upcoming results of the SAFE-HEART study will provide information about the safety of anti-HER2 antibody therapy in patients with low but asymptomatic left-ventricular ejection fraction.

These comments are excerpted from a commentary by Chau T. Dang, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and her associates (JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Aug;11[8]:1094-7). Most of the commentary authors report various disclosures.

While trastuzumab clearly benefits patients with HER2-positive breast cancer at various stages of progression, concerns about heart failure persist. Studies have suggested that the drug doesn’t boost the risk of late cardiac events, but it’s not clear if this is due to mandated screening in these trials. The new study provides more evidence that adherence to screening guidelines is limited, and recent trials offer evidence that the general cardiac risk may be overblown. Future studies could be designed to offer insight into the wisdom of adjusting screening regimens based on stratification of risk. A meta-analysis could also be helpful, and the upcoming results of the SAFE-HEART study will provide information about the safety of anti-HER2 antibody therapy in patients with low but asymptomatic left-ventricular ejection fraction.

These comments are excerpted from a commentary by Chau T. Dang, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and her associates (JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Aug;11[8]:1094-7). Most of the commentary authors report various disclosures.

While trastuzumab clearly benefits patients with HER2-positive breast cancer at various stages of progression, concerns about heart failure persist. Studies have suggested that the drug doesn’t boost the risk of late cardiac events, but it’s not clear if this is due to mandated screening in these trials. The new study provides more evidence that adherence to screening guidelines is limited, and recent trials offer evidence that the general cardiac risk may be overblown. Future studies could be designed to offer insight into the wisdom of adjusting screening regimens based on stratification of risk. A meta-analysis could also be helpful, and the upcoming results of the SAFE-HEART study will provide information about the safety of anti-HER2 antibody therapy in patients with low but asymptomatic left-ventricular ejection fraction.

These comments are excerpted from a commentary by Chau T. Dang, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and her associates (JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Aug;11[8]:1094-7). Most of the commentary authors report various disclosures.

Adding more evidence to an ongoing debate, a large new study suggests that patients with breast cancer who take trastuzumab (Herceptin) may face double the adjusted risk of developing heart failure, with older women at highest risk.

The study also found that most patients who took trastuzumab didn’t receive recommended cardiac screening.

The researchers said their findings are unique because they tracked both younger and older patients. “By examining the rates of both cardiac monitoring and cardiotoxicity, we could begin to address the controversial issue of whether cardiac monitoring is warranted in young breast cancer patients,” wrote Mariana Chavez-MacGregor, MD, MSC, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and her associates. The report was published in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

While Trastuzumab has boosted breast cancer survival rates for patients with HER2-positive tumors, it’s also raised concerns about cardiotoxicity that could be an indicator of subsequent congestive heart failure (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jun 12;(6):CD006242).

According to the new study, the risk of trastuzumab risk is linked to damage to cardiac myocytes that can cause reversible cardiotoxicity.

The prescribing information for trastuzumab advises patients to undergo cardiac monitoring before treatment with trastuzumab and every 3 months during treatment. Recommendations by medical organizations have varied.

Now, as a 2016 report put it, it’s “increasingly unclear” whether frequent routine monitoring is appropriate for all patients (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 1;34[10]:1030-3).

For the current study, Dr. Chavez-MacGregor and her associates identified 16,456 adult women in the United States who were diagnosed with nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer from 2009 to 2014. Researchers tracked the group, with a median age of 56, through as late as 2015.

The women were treated with chemotherapy within 6 months of diagnosis, and 4,325 received trastuzumab.

Of all the subjects, 692 patients (4.2%) developed heart failure following chemotherapy. The rate among patients treated with trastuzumab was higher, at 8.3%, compared with 2.7% for those not treated with trastuzumab (P less than .001).

The researchers also looked at anthracycline users and found that they were slightly more likely to develop HF (4.6% vs. 4.0% among nonusers, P = .048).

Increased age boosted the risk of HF in the trastuzumab-treated patients, and the risk was highest in those treated with both anthracyclines and trastuzumab. Other factors linked to more risk were comorbidities, hypertension, and valve disease.

After adjusting for confounders, the researchers estimated that those treated with trastuzumab were 2.01 times more likely to develop HF (HR, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.72-2.36), and those who took anthracycline were 1.53 times more likely (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.30-1.80)

The researchers also examined medical records for evidence that subjects underwent cardiac screening at least once every 4 months, not 3 months, as the prescribing information recommends. The study team chose to focus on 4-month intervals “to compensate for differences in scheduling, resources, or levels of accessibility to medical care.”

Medical records suggest that 73.5% of patients who took trastuzumab underwent cardiac screening at the beginning of therapy, but only 46.2% continued to do so at least every 4 months.

An adjusted model linked more screening to the use of anthracyclines and taxanes, radiation treatment, and living in the Northeast vs. the West.

“HF was more frequently identified among patients undergoing recommended cardiac monitoring (10.4% compared with 6.5%, respectively; P less than.001), suggesting that, as more patients are screened, more patients are likely to be found having HF,” the researchers reported.

However, they added that “our sensitivity analysis using inpatient claims allowed us to determine that the HF identified using cardiac monitoring was not severe enough to require hospitalization and was likely asymptomatic. The clinical implications of the diagnosis of asymptomatic HF are hard to determine and are beyond the scope of this study.”

The researchers also noted that the findings suggest that screening has become more common in recent years.

“The number of cancer survivors is expected to increase over time, and we will continue to see patients develop treatment-related cardiotoxicity,” the researchers wrote. “Thus, more research, evidence-based guidelines, and tools for prediction of cancer treatment–related cardiotoxicity are needed.”

The National Cancer Institute and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas funded the study. Two study authors reported grant funding from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, and one reports consulting for Pfizer and Roche. The other authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavez-MacGregor M et al. JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Aug;11[8]1084-93.

Adding more evidence to an ongoing debate, a large new study suggests that patients with breast cancer who take trastuzumab (Herceptin) may face double the adjusted risk of developing heart failure, with older women at highest risk.

The study also found that most patients who took trastuzumab didn’t receive recommended cardiac screening.

The researchers said their findings are unique because they tracked both younger and older patients. “By examining the rates of both cardiac monitoring and cardiotoxicity, we could begin to address the controversial issue of whether cardiac monitoring is warranted in young breast cancer patients,” wrote Mariana Chavez-MacGregor, MD, MSC, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and her associates. The report was published in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

While Trastuzumab has boosted breast cancer survival rates for patients with HER2-positive tumors, it’s also raised concerns about cardiotoxicity that could be an indicator of subsequent congestive heart failure (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jun 12;(6):CD006242).

According to the new study, the risk of trastuzumab risk is linked to damage to cardiac myocytes that can cause reversible cardiotoxicity.

The prescribing information for trastuzumab advises patients to undergo cardiac monitoring before treatment with trastuzumab and every 3 months during treatment. Recommendations by medical organizations have varied.

Now, as a 2016 report put it, it’s “increasingly unclear” whether frequent routine monitoring is appropriate for all patients (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 1;34[10]:1030-3).

For the current study, Dr. Chavez-MacGregor and her associates identified 16,456 adult women in the United States who were diagnosed with nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer from 2009 to 2014. Researchers tracked the group, with a median age of 56, through as late as 2015.

The women were treated with chemotherapy within 6 months of diagnosis, and 4,325 received trastuzumab.

Of all the subjects, 692 patients (4.2%) developed heart failure following chemotherapy. The rate among patients treated with trastuzumab was higher, at 8.3%, compared with 2.7% for those not treated with trastuzumab (P less than .001).

The researchers also looked at anthracycline users and found that they were slightly more likely to develop HF (4.6% vs. 4.0% among nonusers, P = .048).

Increased age boosted the risk of HF in the trastuzumab-treated patients, and the risk was highest in those treated with both anthracyclines and trastuzumab. Other factors linked to more risk were comorbidities, hypertension, and valve disease.

After adjusting for confounders, the researchers estimated that those treated with trastuzumab were 2.01 times more likely to develop HF (HR, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.72-2.36), and those who took anthracycline were 1.53 times more likely (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.30-1.80)

The researchers also examined medical records for evidence that subjects underwent cardiac screening at least once every 4 months, not 3 months, as the prescribing information recommends. The study team chose to focus on 4-month intervals “to compensate for differences in scheduling, resources, or levels of accessibility to medical care.”

Medical records suggest that 73.5% of patients who took trastuzumab underwent cardiac screening at the beginning of therapy, but only 46.2% continued to do so at least every 4 months.

An adjusted model linked more screening to the use of anthracyclines and taxanes, radiation treatment, and living in the Northeast vs. the West.

“HF was more frequently identified among patients undergoing recommended cardiac monitoring (10.4% compared with 6.5%, respectively; P less than.001), suggesting that, as more patients are screened, more patients are likely to be found having HF,” the researchers reported.

However, they added that “our sensitivity analysis using inpatient claims allowed us to determine that the HF identified using cardiac monitoring was not severe enough to require hospitalization and was likely asymptomatic. The clinical implications of the diagnosis of asymptomatic HF are hard to determine and are beyond the scope of this study.”

The researchers also noted that the findings suggest that screening has become more common in recent years.

“The number of cancer survivors is expected to increase over time, and we will continue to see patients develop treatment-related cardiotoxicity,” the researchers wrote. “Thus, more research, evidence-based guidelines, and tools for prediction of cancer treatment–related cardiotoxicity are needed.”

The National Cancer Institute and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas funded the study. Two study authors reported grant funding from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, and one reports consulting for Pfizer and Roche. The other authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavez-MacGregor M et al. JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Aug;11[8]1084-93.

FROM JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING

Key clinical point: Women with breast cancer who take trastuzumab (Herceptin) may face double the adjusted risk of heart failure, but most aren’t screened frequently.

Major finding: Patients who took trastuzumab were 2.01 times more likely to develop HF (HR, 95% CI, 1.72-2.36) than were those who didn’t. Of all patients who took the drug, fewer than half received recommended frequency of screening.

Study details: Analysis of 16,456 U.S. adult women with nonmetastatic breast cancer diagnosed from 2009 to 2014 and tracked through 2015. Of those, 4.2% developed HF.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas funded the study. Two study authors report grant funding from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, and one reports consulting for Pfizer and Roche. The other authors report no disclosures.

Source: Chavez-MacGregor M et al. JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging 2018 Aug;11[8]1084-93.

FDA warning shines light on vaginal rejuvenation

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a stern warning to several manufacturers and a statement of caution to the public concerning “vaginal rejuvenation,” an umbrella term for a host of procedures to alter vaginal tissue for therapeutic or cosmetic purposes.

Lasers and other energy-based devices have been approved to treat abnormal or precancerous cervical or vaginal tissue and general warts, but the FDA has not approved any to treat vaginal atrophy, urinary incontinence, or reduced sexual function.

Device manufacturers claim lasers can address these conditions despite limited scientific evidence for their safety or efficacy. Insurers do not reimburse the procedures, considering them to be cosmetic.

In a July 30 statement, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, slammed “deceptive” marketing practices on the part of manufacturers.

The FDA has reviewed 12 complaints since December 2015 of adverse effects related to vaginal procedures using the devices. Two were from manufacturers reporting pain and bleeding in patients following treatment, FDA spokeswoman Deborah Kotz said in an interview. “The FDA has also received voluntary MedWatch reports from individual patients who experienced significant pain and discomfort from procedures performed with these devices.”

The agency has targeted seven firms: Alma Lasers, BTL Aesthetics, BTL Industries, Cynosure, InMode, Sciton, and ThermiGen, with letters demanding evidence of FDA approval, clearance, or intent to seek clearance for use of their products on female genitalia. They also asked for evidence backing specific claims.

In a July 26 letter to BTL Industries, for example, the FDA demanded to know why the firm was marketing its Exilis laser device, approved for the treatment of facial wrinkles, as “Ultra Femme 360,” which it called “a whole new approach to women’s intimate health.” The device, according to the manufacturer, “provides the shortest noninvasive radio-frequency treatment available for female intimate parts” and “is proven to increase elastin and collagen in the treatment area.”

The FDA asked Cynosure, the maker of the Mona Lisa Touch, a system marketed as an FDA-approved treatment for vaginal atrophy, for evidence to support its claims that Mona Lisa Touch “is the only technology for vaginal and vulvar health with over 18+ published clinical studies” and is clinically proven to treat “painful symptoms of menopause, including intimacy.” They also asked for information about a modification to the originally approved device that was not brought to the FDA’s attention.

In a letter to Alma Lasers, whose Pixel CO2 Laser System was approved for use in a broad use of surgical applications including gynecologic surgery, the FDA noted that the device was being marketed as “FEMILIFT,” a laser procedure designed to “improve vaginal irregularities” and to assist “in vaginal mucosa revitalization.” The FDA demanded evidence for those claims.

The manufacturers have 30 days to respond to the FDA, which has not ruled out seeking enforcement action against firms with unsatisfactory responses.

For more than a decade, researchers have shown that healthy vaginal morphology is exceptionally wide ranging, including a recent study in more than 650 women, the largest to date (BJOG. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15387). Nonetheless, interest in elective vaginal procedures has only increased, with an industry report from the International Society of Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery describing a 45% increase in the use of one surgery, vaginal labiaplasty, between 2014 and 2016. Most procedures were performed in Brazil and the United States.

While plastic surgery societies support vaginal rejuvenation procedures, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has long frowned on them, with its first critique issued in a 2007 committee opinion. “No adequate studies have been published assessing the long-term satisfaction, safety, and complication rates for these procedures,” the association said last year in its most recent update on the subject.

Gynecologist David M. Jaspan, DO, of the Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia, echoed ACOG’s views and said he welcomed FDA interest in vaginal rejuvenation.

The practice has “never been endorsed by the College or a board. It’s been considered a cosmetic procedure and it’s been under scrutiny for at least a decade,” Dr. Jaspan said. “I have reservations about the clinical outcomes and the training surrounds these procedures and I anxiously await randomized controlled trials to further evaluate them.”

Gynecologists who offer the procedures caution that they may have a role, and that randomized trials are underway to determine which groups of women might be best helped.

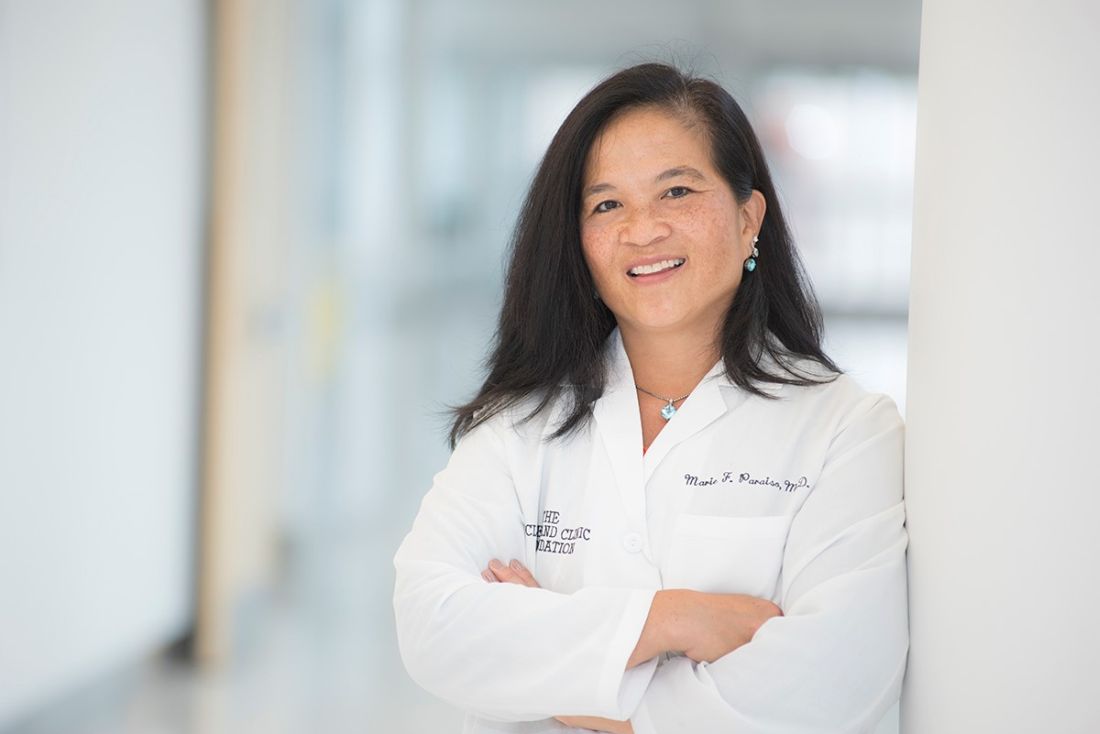

Marie Paraiso, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic, said she uses the Mona Lisa Touch, a CO2 fractionated laser, to treat patients with genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). These patients, Dr. Paraiso said, “complain of vaginal dryness and are unable to have intercourse or experience significant pain during or after intercourse. Some of them also may have irritative voiding, urinary frequency and urgency, or mild stress incontinence.”

Dr. Paraiso’s group has performed some 300 treatments with the laser and “we have fortunately not had patients complaining of persistent vaginal pain or scarring.” About 80%-90% of patients respond, she said, with some 20%-25% seeking retreatment within a year. “I believe for women who have contraindications to hormonal therapy or do not tolerate or cannot afford prolonged hormonal therapy, the CO2 fractional vaginal laser has been effective.”

Dr. Paraiso is also leading a multisite clinical trial randomizing about 200 patients with GSM to the laser treatment or estrogen-based vaginal creams, and following them for 6 months; thus far, she said, 6 of 89 patients, half in the laser arm, have reported mild to moderate adverse events.

Dr. Paraiso said she does not have a financial relationship with the manufacturer of Mona Lisa Touch, and that the trial was funded by the Foundation for Female Health Awareness, which receives unrestricted research grants from some device makers. “Our institute owns the laser and I have never been paid to train anyone to perform these procedures,” Dr. Paraiso added. “Our onus was to study the laser in order to improve the lives of our patients.”

Other trials comparing vaginal lasers with sham treatment are currently underway or in planning.

The North American Menopause Society struck a cautious note in response to the FDA criticism. In a statement issued August 1, JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, the society’s executive director, said the field needed prospective, randomized, sham-controlled trials of the laser and energy therapies. The therapies “may turn out to be an appropriate choice for many women, particularly for those concerned about breast cancer risk” associated with hormonal treatments. But until more robust data are available, doctors should “discuss the benefits and risks of all available treatment options for vaginal symptoms, including over-the-counter lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, and FDA-approved vaginal therapies such as vaginal estrogen and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone and oral therapies such as hormone therapy and ospemifene to determine the best treatment for women with GSM.”

Any discussion of vaginal energy-based therapies, should include the disclosure that these have not been approved for the specific indication, Dr. Pinkerton cautioned.

The term “vaginal rejuvenation,” coined by cosmetic gynecologists, incorporates surgeries designed to modify the appearance of the vulva, reduce the redundancy of vaginal tissue, and improve vaginal tone.

Endorsed by some well-known academic gynecologists, these devices have been promoted as “safe and effective” without any prospective, randomized studies and without accountability for conflicts of interest including “educational stipends” from device manufacturers and clinicians’ need to recoup the high cost of the devices themselves.

Studies have generally been limited to fewer than 100 patients followed for 12 weeks or less. Companies are not informing doctors that the devices may not be FDA approved for the purposes advertised, nor are they providing adverse effects reports. Laser and radio-frequency procedures at best demonstrate temporary, marginal improvement in vaginal tone and dyspareunia, and at worst are associated with increased pelvic pain and dyspareunia, as well as vaginal, rectal, and bladder thermal burns. For those of us who specialize in cosmetic surgery, they have very limited benefit with a significant risk of injury to the patient even when properly used.

Julio Cesar Novoa, MD, is a private practice ob.gyn from El Paso, Tex. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The term “vaginal rejuvenation,” coined by cosmetic gynecologists, incorporates surgeries designed to modify the appearance of the vulva, reduce the redundancy of vaginal tissue, and improve vaginal tone.

Endorsed by some well-known academic gynecologists, these devices have been promoted as “safe and effective” without any prospective, randomized studies and without accountability for conflicts of interest including “educational stipends” from device manufacturers and clinicians’ need to recoup the high cost of the devices themselves.

Studies have generally been limited to fewer than 100 patients followed for 12 weeks or less. Companies are not informing doctors that the devices may not be FDA approved for the purposes advertised, nor are they providing adverse effects reports. Laser and radio-frequency procedures at best demonstrate temporary, marginal improvement in vaginal tone and dyspareunia, and at worst are associated with increased pelvic pain and dyspareunia, as well as vaginal, rectal, and bladder thermal burns. For those of us who specialize in cosmetic surgery, they have very limited benefit with a significant risk of injury to the patient even when properly used.

Julio Cesar Novoa, MD, is a private practice ob.gyn from El Paso, Tex. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The term “vaginal rejuvenation,” coined by cosmetic gynecologists, incorporates surgeries designed to modify the appearance of the vulva, reduce the redundancy of vaginal tissue, and improve vaginal tone.

Endorsed by some well-known academic gynecologists, these devices have been promoted as “safe and effective” without any prospective, randomized studies and without accountability for conflicts of interest including “educational stipends” from device manufacturers and clinicians’ need to recoup the high cost of the devices themselves.

Studies have generally been limited to fewer than 100 patients followed for 12 weeks or less. Companies are not informing doctors that the devices may not be FDA approved for the purposes advertised, nor are they providing adverse effects reports. Laser and radio-frequency procedures at best demonstrate temporary, marginal improvement in vaginal tone and dyspareunia, and at worst are associated with increased pelvic pain and dyspareunia, as well as vaginal, rectal, and bladder thermal burns. For those of us who specialize in cosmetic surgery, they have very limited benefit with a significant risk of injury to the patient even when properly used.

Julio Cesar Novoa, MD, is a private practice ob.gyn from El Paso, Tex. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a stern warning to several manufacturers and a statement of caution to the public concerning “vaginal rejuvenation,” an umbrella term for a host of procedures to alter vaginal tissue for therapeutic or cosmetic purposes.

Lasers and other energy-based devices have been approved to treat abnormal or precancerous cervical or vaginal tissue and general warts, but the FDA has not approved any to treat vaginal atrophy, urinary incontinence, or reduced sexual function.

Device manufacturers claim lasers can address these conditions despite limited scientific evidence for their safety or efficacy. Insurers do not reimburse the procedures, considering them to be cosmetic.

In a July 30 statement, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, slammed “deceptive” marketing practices on the part of manufacturers.

The FDA has reviewed 12 complaints since December 2015 of adverse effects related to vaginal procedures using the devices. Two were from manufacturers reporting pain and bleeding in patients following treatment, FDA spokeswoman Deborah Kotz said in an interview. “The FDA has also received voluntary MedWatch reports from individual patients who experienced significant pain and discomfort from procedures performed with these devices.”

The agency has targeted seven firms: Alma Lasers, BTL Aesthetics, BTL Industries, Cynosure, InMode, Sciton, and ThermiGen, with letters demanding evidence of FDA approval, clearance, or intent to seek clearance for use of their products on female genitalia. They also asked for evidence backing specific claims.

In a July 26 letter to BTL Industries, for example, the FDA demanded to know why the firm was marketing its Exilis laser device, approved for the treatment of facial wrinkles, as “Ultra Femme 360,” which it called “a whole new approach to women’s intimate health.” The device, according to the manufacturer, “provides the shortest noninvasive radio-frequency treatment available for female intimate parts” and “is proven to increase elastin and collagen in the treatment area.”

The FDA asked Cynosure, the maker of the Mona Lisa Touch, a system marketed as an FDA-approved treatment for vaginal atrophy, for evidence to support its claims that Mona Lisa Touch “is the only technology for vaginal and vulvar health with over 18+ published clinical studies” and is clinically proven to treat “painful symptoms of menopause, including intimacy.” They also asked for information about a modification to the originally approved device that was not brought to the FDA’s attention.

In a letter to Alma Lasers, whose Pixel CO2 Laser System was approved for use in a broad use of surgical applications including gynecologic surgery, the FDA noted that the device was being marketed as “FEMILIFT,” a laser procedure designed to “improve vaginal irregularities” and to assist “in vaginal mucosa revitalization.” The FDA demanded evidence for those claims.

The manufacturers have 30 days to respond to the FDA, which has not ruled out seeking enforcement action against firms with unsatisfactory responses.

For more than a decade, researchers have shown that healthy vaginal morphology is exceptionally wide ranging, including a recent study in more than 650 women, the largest to date (BJOG. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15387). Nonetheless, interest in elective vaginal procedures has only increased, with an industry report from the International Society of Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery describing a 45% increase in the use of one surgery, vaginal labiaplasty, between 2014 and 2016. Most procedures were performed in Brazil and the United States.

While plastic surgery societies support vaginal rejuvenation procedures, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has long frowned on them, with its first critique issued in a 2007 committee opinion. “No adequate studies have been published assessing the long-term satisfaction, safety, and complication rates for these procedures,” the association said last year in its most recent update on the subject.

Gynecologist David M. Jaspan, DO, of the Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia, echoed ACOG’s views and said he welcomed FDA interest in vaginal rejuvenation.

The practice has “never been endorsed by the College or a board. It’s been considered a cosmetic procedure and it’s been under scrutiny for at least a decade,” Dr. Jaspan said. “I have reservations about the clinical outcomes and the training surrounds these procedures and I anxiously await randomized controlled trials to further evaluate them.”

Gynecologists who offer the procedures caution that they may have a role, and that randomized trials are underway to determine which groups of women might be best helped.

Marie Paraiso, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic, said she uses the Mona Lisa Touch, a CO2 fractionated laser, to treat patients with genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). These patients, Dr. Paraiso said, “complain of vaginal dryness and are unable to have intercourse or experience significant pain during or after intercourse. Some of them also may have irritative voiding, urinary frequency and urgency, or mild stress incontinence.”

Dr. Paraiso’s group has performed some 300 treatments with the laser and “we have fortunately not had patients complaining of persistent vaginal pain or scarring.” About 80%-90% of patients respond, she said, with some 20%-25% seeking retreatment within a year. “I believe for women who have contraindications to hormonal therapy or do not tolerate or cannot afford prolonged hormonal therapy, the CO2 fractional vaginal laser has been effective.”

Dr. Paraiso is also leading a multisite clinical trial randomizing about 200 patients with GSM to the laser treatment or estrogen-based vaginal creams, and following them for 6 months; thus far, she said, 6 of 89 patients, half in the laser arm, have reported mild to moderate adverse events.

Dr. Paraiso said she does not have a financial relationship with the manufacturer of Mona Lisa Touch, and that the trial was funded by the Foundation for Female Health Awareness, which receives unrestricted research grants from some device makers. “Our institute owns the laser and I have never been paid to train anyone to perform these procedures,” Dr. Paraiso added. “Our onus was to study the laser in order to improve the lives of our patients.”

Other trials comparing vaginal lasers with sham treatment are currently underway or in planning.

The North American Menopause Society struck a cautious note in response to the FDA criticism. In a statement issued August 1, JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, the society’s executive director, said the field needed prospective, randomized, sham-controlled trials of the laser and energy therapies. The therapies “may turn out to be an appropriate choice for many women, particularly for those concerned about breast cancer risk” associated with hormonal treatments. But until more robust data are available, doctors should “discuss the benefits and risks of all available treatment options for vaginal symptoms, including over-the-counter lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, and FDA-approved vaginal therapies such as vaginal estrogen and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone and oral therapies such as hormone therapy and ospemifene to determine the best treatment for women with GSM.”

Any discussion of vaginal energy-based therapies, should include the disclosure that these have not been approved for the specific indication, Dr. Pinkerton cautioned.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a stern warning to several manufacturers and a statement of caution to the public concerning “vaginal rejuvenation,” an umbrella term for a host of procedures to alter vaginal tissue for therapeutic or cosmetic purposes.

Lasers and other energy-based devices have been approved to treat abnormal or precancerous cervical or vaginal tissue and general warts, but the FDA has not approved any to treat vaginal atrophy, urinary incontinence, or reduced sexual function.

Device manufacturers claim lasers can address these conditions despite limited scientific evidence for their safety or efficacy. Insurers do not reimburse the procedures, considering them to be cosmetic.

In a July 30 statement, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, slammed “deceptive” marketing practices on the part of manufacturers.

The FDA has reviewed 12 complaints since December 2015 of adverse effects related to vaginal procedures using the devices. Two were from manufacturers reporting pain and bleeding in patients following treatment, FDA spokeswoman Deborah Kotz said in an interview. “The FDA has also received voluntary MedWatch reports from individual patients who experienced significant pain and discomfort from procedures performed with these devices.”

The agency has targeted seven firms: Alma Lasers, BTL Aesthetics, BTL Industries, Cynosure, InMode, Sciton, and ThermiGen, with letters demanding evidence of FDA approval, clearance, or intent to seek clearance for use of their products on female genitalia. They also asked for evidence backing specific claims.

In a July 26 letter to BTL Industries, for example, the FDA demanded to know why the firm was marketing its Exilis laser device, approved for the treatment of facial wrinkles, as “Ultra Femme 360,” which it called “a whole new approach to women’s intimate health.” The device, according to the manufacturer, “provides the shortest noninvasive radio-frequency treatment available for female intimate parts” and “is proven to increase elastin and collagen in the treatment area.”

The FDA asked Cynosure, the maker of the Mona Lisa Touch, a system marketed as an FDA-approved treatment for vaginal atrophy, for evidence to support its claims that Mona Lisa Touch “is the only technology for vaginal and vulvar health with over 18+ published clinical studies” and is clinically proven to treat “painful symptoms of menopause, including intimacy.” They also asked for information about a modification to the originally approved device that was not brought to the FDA’s attention.

In a letter to Alma Lasers, whose Pixel CO2 Laser System was approved for use in a broad use of surgical applications including gynecologic surgery, the FDA noted that the device was being marketed as “FEMILIFT,” a laser procedure designed to “improve vaginal irregularities” and to assist “in vaginal mucosa revitalization.” The FDA demanded evidence for those claims.

The manufacturers have 30 days to respond to the FDA, which has not ruled out seeking enforcement action against firms with unsatisfactory responses.

For more than a decade, researchers have shown that healthy vaginal morphology is exceptionally wide ranging, including a recent study in more than 650 women, the largest to date (BJOG. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15387). Nonetheless, interest in elective vaginal procedures has only increased, with an industry report from the International Society of Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery describing a 45% increase in the use of one surgery, vaginal labiaplasty, between 2014 and 2016. Most procedures were performed in Brazil and the United States.

While plastic surgery societies support vaginal rejuvenation procedures, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has long frowned on them, with its first critique issued in a 2007 committee opinion. “No adequate studies have been published assessing the long-term satisfaction, safety, and complication rates for these procedures,” the association said last year in its most recent update on the subject.

Gynecologist David M. Jaspan, DO, of the Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia, echoed ACOG’s views and said he welcomed FDA interest in vaginal rejuvenation.

The practice has “never been endorsed by the College or a board. It’s been considered a cosmetic procedure and it’s been under scrutiny for at least a decade,” Dr. Jaspan said. “I have reservations about the clinical outcomes and the training surrounds these procedures and I anxiously await randomized controlled trials to further evaluate them.”

Gynecologists who offer the procedures caution that they may have a role, and that randomized trials are underway to determine which groups of women might be best helped.

Marie Paraiso, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic, said she uses the Mona Lisa Touch, a CO2 fractionated laser, to treat patients with genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). These patients, Dr. Paraiso said, “complain of vaginal dryness and are unable to have intercourse or experience significant pain during or after intercourse. Some of them also may have irritative voiding, urinary frequency and urgency, or mild stress incontinence.”

Dr. Paraiso’s group has performed some 300 treatments with the laser and “we have fortunately not had patients complaining of persistent vaginal pain or scarring.” About 80%-90% of patients respond, she said, with some 20%-25% seeking retreatment within a year. “I believe for women who have contraindications to hormonal therapy or do not tolerate or cannot afford prolonged hormonal therapy, the CO2 fractional vaginal laser has been effective.”

Dr. Paraiso is also leading a multisite clinical trial randomizing about 200 patients with GSM to the laser treatment or estrogen-based vaginal creams, and following them for 6 months; thus far, she said, 6 of 89 patients, half in the laser arm, have reported mild to moderate adverse events.

Dr. Paraiso said she does not have a financial relationship with the manufacturer of Mona Lisa Touch, and that the trial was funded by the Foundation for Female Health Awareness, which receives unrestricted research grants from some device makers. “Our institute owns the laser and I have never been paid to train anyone to perform these procedures,” Dr. Paraiso added. “Our onus was to study the laser in order to improve the lives of our patients.”

Other trials comparing vaginal lasers with sham treatment are currently underway or in planning.

The North American Menopause Society struck a cautious note in response to the FDA criticism. In a statement issued August 1, JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, the society’s executive director, said the field needed prospective, randomized, sham-controlled trials of the laser and energy therapies. The therapies “may turn out to be an appropriate choice for many women, particularly for those concerned about breast cancer risk” associated with hormonal treatments. But until more robust data are available, doctors should “discuss the benefits and risks of all available treatment options for vaginal symptoms, including over-the-counter lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, and FDA-approved vaginal therapies such as vaginal estrogen and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone and oral therapies such as hormone therapy and ospemifene to determine the best treatment for women with GSM.”

Any discussion of vaginal energy-based therapies, should include the disclosure that these have not been approved for the specific indication, Dr. Pinkerton cautioned.

CMS proposal to level E/M payments raises concerns

Citing the need to reduce paperwork hassles, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are proposing to flatten the payment for evaluation and management (E/M) visits coded at levels 2-5.

The CMS outlined how the proposal would affect payment using 2018 rates to model the change. The proposal would set the payment rate for level 1 E/M office visits for new patients at $44, down from the $45 using the current methodology. Levels 2-5 would receive $135. Currently, payments for level 2 visits are set at $76, level 3 at $110, level 4 at $167, and level 5 at $211.

For office visits with established patients, the proposed rate would be $24, up from the current payment of $22 for a level 1 visit. Levels 2-5 would receive $93. Under the current methodology, payments for level 2 visits are set at $45, level 3 at $74, level 4 at $109, and level 5 at $148.

The change also comes with a reduced documentation burden, so the same documentation is needed regardless of which level between 2 and 5 the office visit is, a move that is expected to save some time each day.

The CMS outlined its vision for changes to the E/M payment in the proposed update to the 2019 Medicare physician fee schedule. Comments on the proposal are due Sept. 10, 2018.

The agency estimated that for most specialties, there would be minimal effect on this proposed change. However, for 10 specialties, payment reductions could result from this change.

Specialties identified as potentially losing less than 3% of their overall payment include allergy/immunology, audiologists, hematology/oncology, neurology, otolaryngology, pulmonary disease, and radiation oncology and radiation therapy centers.

Rheumatologists are expected to lose 3% of their pay from the proposal, while dermatologists and podiatrists are expected to lose 4%.

On the flip side, obstetricians/gynecologists are expected to see a 4% bump because of this proposal, while nurse practitioners could see a 3% increase. Specialties expected to see an increase of less than 3% include hand surgery, interventional pain management, optometry, physician assistants, psychiatry, and urology.

The proposal is raising concerns, particularly from those who stand to see their pay reduced by the proposal.

CMS "has proposed a disastrous plan that would force most neurologists not just to abandon Medicare participation, but also to refuse treatment to Medicare patients," Marc Raphaelson, MD, chair of the American Academy of Neurology's Coding Subcommittee and the Academy's representative to the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, wrote in a report. "The AAN is responding vigorously that one size does not fit all. One visit type does not fit our patients or our practices. Neurologists could not sustain our practices at the proposed payment rates."

Dr. Raphaelson noted that the AAN applauds the agency's "willingness to abandon medically irrelevant charting that contributes to our frustration and burnout. CMS has brought payment and documentation reform into a bright light. In return, it is up to the AAN, and our collegial medical societies, to propose a fair and transparent way to pay doctors for the work we really do."

The AAN recently joined the Americal College of Rheumatology (ACR) on Capitol Hill to raise awareness of the proposed cuts.

“Rheumatologists are pretty concerned about this,” Angus B. Worthing, MD, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Government Affairs, said in an interview. “Being a cognitive specialty ... we see patients who have complex or multiple issues and we focus more in the clinic on cognitive services, instead of procedural services.” He noted that rheumatologists bill across the E/M levels so it would be difficult to suggest a flat fee that would keep them from losing money.

Dr. Worthing, whose practice is in the Washington, D.C., metro area, said that about 70% of the Medicare payment covers overhead for the practice, leaving 30% to go toward the rheumatologist’s salary. To illustrate the impact of the proposed 3% cut, Dr. Worthing used the hypothetical of a current $100 payment turning into a $97 payment under the proposal. The overhead doesn’t change, so the physician’s portion that goes toward his salary drops 10% when it decreases from $30 to $27.

The Community Oncology Alliance made a similar observation.

“CMS is proposing to drastically cut payment for the critical evaluation and management of more complex cancer cases from $172 to $135 (a 22% payment cut) for a new patient and from $148 to $93 (a 37% payment cut) for an existing patient. Although CMS is proposing to streamline the reporting of these cases, the proposal severely undervalues the thorough and critical evaluation and management of seniors with cancer, especially life-threatening complex cases,” the organization said in a statement.

Dr. Worthing said the proposal has implications for recruiting medical trainees into rheumatology and for physicians in practice who may be considering whether to stop seeing Medicare patients. “Since we already have a shortage of rheumatologists in the U.S. that, per the ACR’s recent study, appears to be worsening, we are pretty concerned that if this proposal is finalized, we could be facing a situation with longer wait times to see a rheumatologist,” he said.

But Dr. Worthing praised the proposed reduction of documentation and said that it could save physicians some time. “If this proposal were finalized, I might be able to spend a minute or two less typing or documenting in a typical patient visit,” he said. “That might add up over time to seeing more patients.”

CMS officials estimate the proposal would save a lot more time. CMS Administrator Seema Verma said that the documentation change would result in an additional 51 hours for patient care per clinician per year.

However, Dr. Worthing said he was doubtful that any increase in volume would offset the losses from the proposed flat payment across levels 2-5 E/M visits, especially if the pay decrease results in access issues. “If doctors were seeing less and having a harder time covering their business expenses seeing Medicare patients, they might be incentivized to see more commercially insured patients and maintain their practice’s viability that way and not participate in Medicare anymore,” he said.

***This story was updated 8/8/2018.

SOURCE: CMS proposed rule, CMS-1693-P.

Citing the need to reduce paperwork hassles, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are proposing to flatten the payment for evaluation and management (E/M) visits coded at levels 2-5.

The CMS outlined how the proposal would affect payment using 2018 rates to model the change. The proposal would set the payment rate for level 1 E/M office visits for new patients at $44, down from the $45 using the current methodology. Levels 2-5 would receive $135. Currently, payments for level 2 visits are set at $76, level 3 at $110, level 4 at $167, and level 5 at $211.

For office visits with established patients, the proposed rate would be $24, up from the current payment of $22 for a level 1 visit. Levels 2-5 would receive $93. Under the current methodology, payments for level 2 visits are set at $45, level 3 at $74, level 4 at $109, and level 5 at $148.

The change also comes with a reduced documentation burden, so the same documentation is needed regardless of which level between 2 and 5 the office visit is, a move that is expected to save some time each day.

The CMS outlined its vision for changes to the E/M payment in the proposed update to the 2019 Medicare physician fee schedule. Comments on the proposal are due Sept. 10, 2018.

The agency estimated that for most specialties, there would be minimal effect on this proposed change. However, for 10 specialties, payment reductions could result from this change.

Specialties identified as potentially losing less than 3% of their overall payment include allergy/immunology, audiologists, hematology/oncology, neurology, otolaryngology, pulmonary disease, and radiation oncology and radiation therapy centers.

Rheumatologists are expected to lose 3% of their pay from the proposal, while dermatologists and podiatrists are expected to lose 4%.

On the flip side, obstetricians/gynecologists are expected to see a 4% bump because of this proposal, while nurse practitioners could see a 3% increase. Specialties expected to see an increase of less than 3% include hand surgery, interventional pain management, optometry, physician assistants, psychiatry, and urology.

The proposal is raising concerns, particularly from those who stand to see their pay reduced by the proposal.

CMS "has proposed a disastrous plan that would force most neurologists not just to abandon Medicare participation, but also to refuse treatment to Medicare patients," Marc Raphaelson, MD, chair of the American Academy of Neurology's Coding Subcommittee and the Academy's representative to the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, wrote in a report. "The AAN is responding vigorously that one size does not fit all. One visit type does not fit our patients or our practices. Neurologists could not sustain our practices at the proposed payment rates."

Dr. Raphaelson noted that the AAN applauds the agency's "willingness to abandon medically irrelevant charting that contributes to our frustration and burnout. CMS has brought payment and documentation reform into a bright light. In return, it is up to the AAN, and our collegial medical societies, to propose a fair and transparent way to pay doctors for the work we really do."

The AAN recently joined the Americal College of Rheumatology (ACR) on Capitol Hill to raise awareness of the proposed cuts.

“Rheumatologists are pretty concerned about this,” Angus B. Worthing, MD, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Government Affairs, said in an interview. “Being a cognitive specialty ... we see patients who have complex or multiple issues and we focus more in the clinic on cognitive services, instead of procedural services.” He noted that rheumatologists bill across the E/M levels so it would be difficult to suggest a flat fee that would keep them from losing money.

Dr. Worthing, whose practice is in the Washington, D.C., metro area, said that about 70% of the Medicare payment covers overhead for the practice, leaving 30% to go toward the rheumatologist’s salary. To illustrate the impact of the proposed 3% cut, Dr. Worthing used the hypothetical of a current $100 payment turning into a $97 payment under the proposal. The overhead doesn’t change, so the physician’s portion that goes toward his salary drops 10% when it decreases from $30 to $27.

The Community Oncology Alliance made a similar observation.

“CMS is proposing to drastically cut payment for the critical evaluation and management of more complex cancer cases from $172 to $135 (a 22% payment cut) for a new patient and from $148 to $93 (a 37% payment cut) for an existing patient. Although CMS is proposing to streamline the reporting of these cases, the proposal severely undervalues the thorough and critical evaluation and management of seniors with cancer, especially life-threatening complex cases,” the organization said in a statement.

Dr. Worthing said the proposal has implications for recruiting medical trainees into rheumatology and for physicians in practice who may be considering whether to stop seeing Medicare patients. “Since we already have a shortage of rheumatologists in the U.S. that, per the ACR’s recent study, appears to be worsening, we are pretty concerned that if this proposal is finalized, we could be facing a situation with longer wait times to see a rheumatologist,” he said.

But Dr. Worthing praised the proposed reduction of documentation and said that it could save physicians some time. “If this proposal were finalized, I might be able to spend a minute or two less typing or documenting in a typical patient visit,” he said. “That might add up over time to seeing more patients.”

CMS officials estimate the proposal would save a lot more time. CMS Administrator Seema Verma said that the documentation change would result in an additional 51 hours for patient care per clinician per year.

However, Dr. Worthing said he was doubtful that any increase in volume would offset the losses from the proposed flat payment across levels 2-5 E/M visits, especially if the pay decrease results in access issues. “If doctors were seeing less and having a harder time covering their business expenses seeing Medicare patients, they might be incentivized to see more commercially insured patients and maintain their practice’s viability that way and not participate in Medicare anymore,” he said.

***This story was updated 8/8/2018.

SOURCE: CMS proposed rule, CMS-1693-P.

Citing the need to reduce paperwork hassles, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are proposing to flatten the payment for evaluation and management (E/M) visits coded at levels 2-5.

The CMS outlined how the proposal would affect payment using 2018 rates to model the change. The proposal would set the payment rate for level 1 E/M office visits for new patients at $44, down from the $45 using the current methodology. Levels 2-5 would receive $135. Currently, payments for level 2 visits are set at $76, level 3 at $110, level 4 at $167, and level 5 at $211.

For office visits with established patients, the proposed rate would be $24, up from the current payment of $22 for a level 1 visit. Levels 2-5 would receive $93. Under the current methodology, payments for level 2 visits are set at $45, level 3 at $74, level 4 at $109, and level 5 at $148.

The change also comes with a reduced documentation burden, so the same documentation is needed regardless of which level between 2 and 5 the office visit is, a move that is expected to save some time each day.

The CMS outlined its vision for changes to the E/M payment in the proposed update to the 2019 Medicare physician fee schedule. Comments on the proposal are due Sept. 10, 2018.

The agency estimated that for most specialties, there would be minimal effect on this proposed change. However, for 10 specialties, payment reductions could result from this change.

Specialties identified as potentially losing less than 3% of their overall payment include allergy/immunology, audiologists, hematology/oncology, neurology, otolaryngology, pulmonary disease, and radiation oncology and radiation therapy centers.

Rheumatologists are expected to lose 3% of their pay from the proposal, while dermatologists and podiatrists are expected to lose 4%.

On the flip side, obstetricians/gynecologists are expected to see a 4% bump because of this proposal, while nurse practitioners could see a 3% increase. Specialties expected to see an increase of less than 3% include hand surgery, interventional pain management, optometry, physician assistants, psychiatry, and urology.

The proposal is raising concerns, particularly from those who stand to see their pay reduced by the proposal.

CMS "has proposed a disastrous plan that would force most neurologists not just to abandon Medicare participation, but also to refuse treatment to Medicare patients," Marc Raphaelson, MD, chair of the American Academy of Neurology's Coding Subcommittee and the Academy's representative to the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, wrote in a report. "The AAN is responding vigorously that one size does not fit all. One visit type does not fit our patients or our practices. Neurologists could not sustain our practices at the proposed payment rates."

Dr. Raphaelson noted that the AAN applauds the agency's "willingness to abandon medically irrelevant charting that contributes to our frustration and burnout. CMS has brought payment and documentation reform into a bright light. In return, it is up to the AAN, and our collegial medical societies, to propose a fair and transparent way to pay doctors for the work we really do."

The AAN recently joined the Americal College of Rheumatology (ACR) on Capitol Hill to raise awareness of the proposed cuts.

“Rheumatologists are pretty concerned about this,” Angus B. Worthing, MD, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Government Affairs, said in an interview. “Being a cognitive specialty ... we see patients who have complex or multiple issues and we focus more in the clinic on cognitive services, instead of procedural services.” He noted that rheumatologists bill across the E/M levels so it would be difficult to suggest a flat fee that would keep them from losing money.

Dr. Worthing, whose practice is in the Washington, D.C., metro area, said that about 70% of the Medicare payment covers overhead for the practice, leaving 30% to go toward the rheumatologist’s salary. To illustrate the impact of the proposed 3% cut, Dr. Worthing used the hypothetical of a current $100 payment turning into a $97 payment under the proposal. The overhead doesn’t change, so the physician’s portion that goes toward his salary drops 10% when it decreases from $30 to $27.

The Community Oncology Alliance made a similar observation.

“CMS is proposing to drastically cut payment for the critical evaluation and management of more complex cancer cases from $172 to $135 (a 22% payment cut) for a new patient and from $148 to $93 (a 37% payment cut) for an existing patient. Although CMS is proposing to streamline the reporting of these cases, the proposal severely undervalues the thorough and critical evaluation and management of seniors with cancer, especially life-threatening complex cases,” the organization said in a statement.

Dr. Worthing said the proposal has implications for recruiting medical trainees into rheumatology and for physicians in practice who may be considering whether to stop seeing Medicare patients. “Since we already have a shortage of rheumatologists in the U.S. that, per the ACR’s recent study, appears to be worsening, we are pretty concerned that if this proposal is finalized, we could be facing a situation with longer wait times to see a rheumatologist,” he said.

But Dr. Worthing praised the proposed reduction of documentation and said that it could save physicians some time. “If this proposal were finalized, I might be able to spend a minute or two less typing or documenting in a typical patient visit,” he said. “That might add up over time to seeing more patients.”

CMS officials estimate the proposal would save a lot more time. CMS Administrator Seema Verma said that the documentation change would result in an additional 51 hours for patient care per clinician per year.

However, Dr. Worthing said he was doubtful that any increase in volume would offset the losses from the proposed flat payment across levels 2-5 E/M visits, especially if the pay decrease results in access issues. “If doctors were seeing less and having a harder time covering their business expenses seeing Medicare patients, they might be incentivized to see more commercially insured patients and maintain their practice’s viability that way and not participate in Medicare anymore,” he said.

***This story was updated 8/8/2018.

SOURCE: CMS proposed rule, CMS-1693-P.

Key clinical point: Some specialties would be paid less under proposed payment changes for 2019.

Major finding: New patient visits (levels 2-5) would be paid at $135 and established patient visits (levels 2-5) would be paid at $93.

Study details: The physician fee schedule proposal would pay level 2-5 E/M visits at the same rate, and reduce some documentation requirements.

Disclosures: No relevant financial disclosures were reported.

Source: CMS proposed rule, CMS-1693-P.

Medical associations want withdrawal of Title X changes

Leading medical societies are calling on the Trump administration to withdraw its proposed changes to the federal Title X family planning program, calling the modifications a threat to essential health care for women.

In late May, the Department of Health & Human Services proposed broad changes to Title X, including no longer allowing staff at Title X clinics to counsel, refer, or provide information to women about abortions and mandating that Title X clinics that offer abortions maintain a separate facility for abortion services. The proposed changes aim to “refocus” the Title X program and ensure that all Title X services align with its family planning mission, according to the proposed rule published June 1.

In a July 31 letter to HHS, the American Medical Association requested that HHS withdraw the proposal, citing concerns from the medical community.

“We are very concerned that the proposed changes, if implemented, would undermine patients’ access to high-quality medical care and information, dangerously interfere with the patient-physician relationship and conflict with physicians’ ethical obligations, exclude qualified providers, and jeopardize public health,” James L. Madara, MD, chief executive officer and vice president of the AMA, wrote in a letter. “We urge HHS to withdraw this [proposal].”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Psychiatric Association, and 13 other health care associations also have called on the HHS to rescind its proposed rule. According to a statement from these associations, the proposal endangers women’s lives by restricting access to medically accurate information and preventive health care.

Title X is a long-standing federal program that provides funding for women’s health care and comprehensive family planning services, primarily to low-income and uninsured patients. Federal law prohibits the use of Title X funds to pay for abortions.

Under the proposed regulations, the Trump administration would define “family planning” as the voluntary process of identifying goals and developing a plan for the number and spacing of children and the means by which those goals may be achieved. This includes planning methods and services “to limit or enhance the likelihood of conception, including contraceptive methods and natural family planning or other fertility awareness-based methods,” according to the proposal. HHS specifies that family planning does not include postconception care, obstetric or prenatal care, or abortion as a method of family planning. HHS has proposed that, if a woman comes to a Title X–funded clinic and is pregnant, she be referred externally for pregnancy services. However, the proposed rule would no longer allow Title X programs to provide abortion counseling and/or referral.

According to HHS, requiring separate facilities for abortion-related care would ensure that Title X funds are used for the purposes expressly mandated by Congress – to offer family planning methods and services – and that any infrastructure built with Title X funds would not be used for impermissible purposes.

More than 100,000 comments have been submitted on the proposed rule since June. Antiabortion organizations, such as the Susan B. Anthony List, have expressed strong support for the proposed rule.

“The American people have repeatedly expressed their predominant policy preferences by supporting Congressional enactments designed to distinguish and separate abortion from family planning,” SBA List President Marjorie Dannenfelser wrote in a comment. “Abortion is not health care, nor is abortion family planning. The Clinton administration and subsequent presidential administrations have erroneously allowed the blatant distribution of Title X funding to abortion centers and abortion-referral facilities for years and in direct violation of the original purpose of Title X funding.”

A group of 14 state governors, meanwhile, has threatened legal action if the Trump administration moves forward with finalizing its rule. In a May 31 letter, the 14 Democratic governors urged HHS to halt its changes to the Title X program and said they would explore all options, including legal avenues, to protect patients’ access to care. More recently, Democratic governors in Washington, Oregon, Hawaii, and New York have said they will refuse all Title X funding if the Trump administration does not rescind its proposed changes to the program.

“This is not an issue about life or choices. This is an issue about the rights of millions of individuals who deserve the best health care available,” Hawaii governor David Ige said in a July 30 statement. “Hawaii will not accept federal funds for these programs if the proposed rules are implemented.”

Public comment on the proposed rule closed on July 31.

Leading medical societies are calling on the Trump administration to withdraw its proposed changes to the federal Title X family planning program, calling the modifications a threat to essential health care for women.

In late May, the Department of Health & Human Services proposed broad changes to Title X, including no longer allowing staff at Title X clinics to counsel, refer, or provide information to women about abortions and mandating that Title X clinics that offer abortions maintain a separate facility for abortion services. The proposed changes aim to “refocus” the Title X program and ensure that all Title X services align with its family planning mission, according to the proposed rule published June 1.

In a July 31 letter to HHS, the American Medical Association requested that HHS withdraw the proposal, citing concerns from the medical community.

“We are very concerned that the proposed changes, if implemented, would undermine patients’ access to high-quality medical care and information, dangerously interfere with the patient-physician relationship and conflict with physicians’ ethical obligations, exclude qualified providers, and jeopardize public health,” James L. Madara, MD, chief executive officer and vice president of the AMA, wrote in a letter. “We urge HHS to withdraw this [proposal].”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Psychiatric Association, and 13 other health care associations also have called on the HHS to rescind its proposed rule. According to a statement from these associations, the proposal endangers women’s lives by restricting access to medically accurate information and preventive health care.

Title X is a long-standing federal program that provides funding for women’s health care and comprehensive family planning services, primarily to low-income and uninsured patients. Federal law prohibits the use of Title X funds to pay for abortions.

Under the proposed regulations, the Trump administration would define “family planning” as the voluntary process of identifying goals and developing a plan for the number and spacing of children and the means by which those goals may be achieved. This includes planning methods and services “to limit or enhance the likelihood of conception, including contraceptive methods and natural family planning or other fertility awareness-based methods,” according to the proposal. HHS specifies that family planning does not include postconception care, obstetric or prenatal care, or abortion as a method of family planning. HHS has proposed that, if a woman comes to a Title X–funded clinic and is pregnant, she be referred externally for pregnancy services. However, the proposed rule would no longer allow Title X programs to provide abortion counseling and/or referral.

According to HHS, requiring separate facilities for abortion-related care would ensure that Title X funds are used for the purposes expressly mandated by Congress – to offer family planning methods and services – and that any infrastructure built with Title X funds would not be used for impermissible purposes.

More than 100,000 comments have been submitted on the proposed rule since June. Antiabortion organizations, such as the Susan B. Anthony List, have expressed strong support for the proposed rule.

“The American people have repeatedly expressed their predominant policy preferences by supporting Congressional enactments designed to distinguish and separate abortion from family planning,” SBA List President Marjorie Dannenfelser wrote in a comment. “Abortion is not health care, nor is abortion family planning. The Clinton administration and subsequent presidential administrations have erroneously allowed the blatant distribution of Title X funding to abortion centers and abortion-referral facilities for years and in direct violation of the original purpose of Title X funding.”

A group of 14 state governors, meanwhile, has threatened legal action if the Trump administration moves forward with finalizing its rule. In a May 31 letter, the 14 Democratic governors urged HHS to halt its changes to the Title X program and said they would explore all options, including legal avenues, to protect patients’ access to care. More recently, Democratic governors in Washington, Oregon, Hawaii, and New York have said they will refuse all Title X funding if the Trump administration does not rescind its proposed changes to the program.

“This is not an issue about life or choices. This is an issue about the rights of millions of individuals who deserve the best health care available,” Hawaii governor David Ige said in a July 30 statement. “Hawaii will not accept federal funds for these programs if the proposed rules are implemented.”

Public comment on the proposed rule closed on July 31.

Leading medical societies are calling on the Trump administration to withdraw its proposed changes to the federal Title X family planning program, calling the modifications a threat to essential health care for women.

In late May, the Department of Health & Human Services proposed broad changes to Title X, including no longer allowing staff at Title X clinics to counsel, refer, or provide information to women about abortions and mandating that Title X clinics that offer abortions maintain a separate facility for abortion services. The proposed changes aim to “refocus” the Title X program and ensure that all Title X services align with its family planning mission, according to the proposed rule published June 1.

In a July 31 letter to HHS, the American Medical Association requested that HHS withdraw the proposal, citing concerns from the medical community.

“We are very concerned that the proposed changes, if implemented, would undermine patients’ access to high-quality medical care and information, dangerously interfere with the patient-physician relationship and conflict with physicians’ ethical obligations, exclude qualified providers, and jeopardize public health,” James L. Madara, MD, chief executive officer and vice president of the AMA, wrote in a letter. “We urge HHS to withdraw this [proposal].”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Psychiatric Association, and 13 other health care associations also have called on the HHS to rescind its proposed rule. According to a statement from these associations, the proposal endangers women’s lives by restricting access to medically accurate information and preventive health care.

Title X is a long-standing federal program that provides funding for women’s health care and comprehensive family planning services, primarily to low-income and uninsured patients. Federal law prohibits the use of Title X funds to pay for abortions.

Under the proposed regulations, the Trump administration would define “family planning” as the voluntary process of identifying goals and developing a plan for the number and spacing of children and the means by which those goals may be achieved. This includes planning methods and services “to limit or enhance the likelihood of conception, including contraceptive methods and natural family planning or other fertility awareness-based methods,” according to the proposal. HHS specifies that family planning does not include postconception care, obstetric or prenatal care, or abortion as a method of family planning. HHS has proposed that, if a woman comes to a Title X–funded clinic and is pregnant, she be referred externally for pregnancy services. However, the proposed rule would no longer allow Title X programs to provide abortion counseling and/or referral.