User login

Real-world study: 8 weeks of two-drug combo highly effective against HCV

Eight weeks of a two-drug combination led to sustained viral response (SVR) in 94% of noncirrhotic, treatment-naive, genotype 1 hepatitis C virus–infected patients, based on a retrospective study of Veterans Affairs health system data presented in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

But VA clinicians prescribed the 8-week regimen to less than half of eligible patients, said George Ioannou, MD, of the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle. Increasing its use, when appropriate, “could save on costs,” although the currently available interferon-free regimens “leave substantial room for improvement in SVRs among persons with cirrhosis and genotype 2 or 3 infections,” he and his associates wrote.

The two-drug regimen contained sofosbuvir and ledipasvir. Clinical trials of sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, and paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir (PrOD) have reported SVR rates well above 90%, “with the exception of certain subgroups, such as patients with Child’s B or C cirrhosis and those infected with genotype 3 HCV,” the researchers noted. However, older interferon-based regimens did not perform as well in the real world as in trials, and “it is unclear if this is the case for current interferon-free regimens, or whether the relative ease of administration of these regimens has narrowed the SVR gap between clinical trials and clinical practice.” Questions also persist about how effective the interferon-free regimens are in various HCV genotypes and subgroups, they added (Gastroenterology 2016 Jul 18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.05.049). To help answer these questions, they analyzed data from more than 17,000 HCV patients in the VA health care system who received sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir between January 2014 and June 2015. The cohort included about 14,000 patients with genotype 1 infections, about 2,100 patients with genotype 2 infections, about 1,200 patients with genotype 3 infections, and 135 patients with genotype 4 infections. Patients averaged 62 years of age, about half were non-Hispanic white, 29% were non-Hispanic black, and nearly a third had been diagnosed with cirrhosis, including 10% with decompensated cirrhosis.

The VA guidelines recommended 8 weeks instead of 12 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for treatment-naive, noncirrhotic, genotype 1 patients with a viral load under 6 million IU/mL, although that recommendation was not FDA approved and was based only on a post hoc analysis of the ION-3 trial, the investigators noted. These concerns seemed to affect practice – of 4,066 eligible patients, only 1,975 (49%) received the 8-week regimen. Notably, however, their rate of SVR 12 weeks after treatment (SVR12) was 95.1% (95% confidence interval, 94% to 96%) – nearly identical to that of patients with the same characteristics who received 12 weeks of treatment (95.8%; 94.7% to 96.8%; P = .6).

Rates of SVR12 did not significantly differ between ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and PrOD regimens, including in multivariable and propensity score–adjusted analyses, the researchers reported. Rates of SVR12 also exceeded 90% in subgroups of treatment-experienced and cirrhotic genotype 1 patients, they added. However, rates of SVR12 were lower for nongenotype 1 infections, as has been observed in trials. Specifically, rates of SVR12 were 90% for genotype 4 patients, 86% for genotype 2 patients who received sofosbuvir and ribavirin, and 75% for genotype 3 patients (including 78% for patients given ledipasvir/sofosbuvir plus ribavirin, 87% for patients given sofosbuvir and pegylated interferon plus ribavirin, and 71% for patients given sofosbuvir monotherapy). For cirrhotic patients, rates of SVR12 were 91% for genotype 1, 77% for genotype 2, 66% for genotype 3, and 84% for genotype 4.

The findings confirm that the new interferon-free regimens “can achieve remarkably high SVR rates in real-world clinical practice, especially in genotype 1–infected patients,” the researchers wrote. The cost of these regimens is “the main obstacle to curing HCV” in as many patients as possible, but is expected to “decline dramatically” as the FDA approves new regimens, they noted. “In fact, costs decreased dramatically within the VA after the completion of our study and after the FDA approved elbasvir/grazoprevir in January 2016.”

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The investigators had no disclosures.

Eight weeks of a two-drug combination led to sustained viral response (SVR) in 94% of noncirrhotic, treatment-naive, genotype 1 hepatitis C virus–infected patients, based on a retrospective study of Veterans Affairs health system data presented in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

But VA clinicians prescribed the 8-week regimen to less than half of eligible patients, said George Ioannou, MD, of the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle. Increasing its use, when appropriate, “could save on costs,” although the currently available interferon-free regimens “leave substantial room for improvement in SVRs among persons with cirrhosis and genotype 2 or 3 infections,” he and his associates wrote.

The two-drug regimen contained sofosbuvir and ledipasvir. Clinical trials of sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, and paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir (PrOD) have reported SVR rates well above 90%, “with the exception of certain subgroups, such as patients with Child’s B or C cirrhosis and those infected with genotype 3 HCV,” the researchers noted. However, older interferon-based regimens did not perform as well in the real world as in trials, and “it is unclear if this is the case for current interferon-free regimens, or whether the relative ease of administration of these regimens has narrowed the SVR gap between clinical trials and clinical practice.” Questions also persist about how effective the interferon-free regimens are in various HCV genotypes and subgroups, they added (Gastroenterology 2016 Jul 18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.05.049). To help answer these questions, they analyzed data from more than 17,000 HCV patients in the VA health care system who received sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir between January 2014 and June 2015. The cohort included about 14,000 patients with genotype 1 infections, about 2,100 patients with genotype 2 infections, about 1,200 patients with genotype 3 infections, and 135 patients with genotype 4 infections. Patients averaged 62 years of age, about half were non-Hispanic white, 29% were non-Hispanic black, and nearly a third had been diagnosed with cirrhosis, including 10% with decompensated cirrhosis.

The VA guidelines recommended 8 weeks instead of 12 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for treatment-naive, noncirrhotic, genotype 1 patients with a viral load under 6 million IU/mL, although that recommendation was not FDA approved and was based only on a post hoc analysis of the ION-3 trial, the investigators noted. These concerns seemed to affect practice – of 4,066 eligible patients, only 1,975 (49%) received the 8-week regimen. Notably, however, their rate of SVR 12 weeks after treatment (SVR12) was 95.1% (95% confidence interval, 94% to 96%) – nearly identical to that of patients with the same characteristics who received 12 weeks of treatment (95.8%; 94.7% to 96.8%; P = .6).

Rates of SVR12 did not significantly differ between ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and PrOD regimens, including in multivariable and propensity score–adjusted analyses, the researchers reported. Rates of SVR12 also exceeded 90% in subgroups of treatment-experienced and cirrhotic genotype 1 patients, they added. However, rates of SVR12 were lower for nongenotype 1 infections, as has been observed in trials. Specifically, rates of SVR12 were 90% for genotype 4 patients, 86% for genotype 2 patients who received sofosbuvir and ribavirin, and 75% for genotype 3 patients (including 78% for patients given ledipasvir/sofosbuvir plus ribavirin, 87% for patients given sofosbuvir and pegylated interferon plus ribavirin, and 71% for patients given sofosbuvir monotherapy). For cirrhotic patients, rates of SVR12 were 91% for genotype 1, 77% for genotype 2, 66% for genotype 3, and 84% for genotype 4.

The findings confirm that the new interferon-free regimens “can achieve remarkably high SVR rates in real-world clinical practice, especially in genotype 1–infected patients,” the researchers wrote. The cost of these regimens is “the main obstacle to curing HCV” in as many patients as possible, but is expected to “decline dramatically” as the FDA approves new regimens, they noted. “In fact, costs decreased dramatically within the VA after the completion of our study and after the FDA approved elbasvir/grazoprevir in January 2016.”

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The investigators had no disclosures.

Eight weeks of a two-drug combination led to sustained viral response (SVR) in 94% of noncirrhotic, treatment-naive, genotype 1 hepatitis C virus–infected patients, based on a retrospective study of Veterans Affairs health system data presented in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

But VA clinicians prescribed the 8-week regimen to less than half of eligible patients, said George Ioannou, MD, of the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle. Increasing its use, when appropriate, “could save on costs,” although the currently available interferon-free regimens “leave substantial room for improvement in SVRs among persons with cirrhosis and genotype 2 or 3 infections,” he and his associates wrote.

The two-drug regimen contained sofosbuvir and ledipasvir. Clinical trials of sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, and paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir (PrOD) have reported SVR rates well above 90%, “with the exception of certain subgroups, such as patients with Child’s B or C cirrhosis and those infected with genotype 3 HCV,” the researchers noted. However, older interferon-based regimens did not perform as well in the real world as in trials, and “it is unclear if this is the case for current interferon-free regimens, or whether the relative ease of administration of these regimens has narrowed the SVR gap between clinical trials and clinical practice.” Questions also persist about how effective the interferon-free regimens are in various HCV genotypes and subgroups, they added (Gastroenterology 2016 Jul 18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.05.049). To help answer these questions, they analyzed data from more than 17,000 HCV patients in the VA health care system who received sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir between January 2014 and June 2015. The cohort included about 14,000 patients with genotype 1 infections, about 2,100 patients with genotype 2 infections, about 1,200 patients with genotype 3 infections, and 135 patients with genotype 4 infections. Patients averaged 62 years of age, about half were non-Hispanic white, 29% were non-Hispanic black, and nearly a third had been diagnosed with cirrhosis, including 10% with decompensated cirrhosis.

The VA guidelines recommended 8 weeks instead of 12 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for treatment-naive, noncirrhotic, genotype 1 patients with a viral load under 6 million IU/mL, although that recommendation was not FDA approved and was based only on a post hoc analysis of the ION-3 trial, the investigators noted. These concerns seemed to affect practice – of 4,066 eligible patients, only 1,975 (49%) received the 8-week regimen. Notably, however, their rate of SVR 12 weeks after treatment (SVR12) was 95.1% (95% confidence interval, 94% to 96%) – nearly identical to that of patients with the same characteristics who received 12 weeks of treatment (95.8%; 94.7% to 96.8%; P = .6).

Rates of SVR12 did not significantly differ between ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and PrOD regimens, including in multivariable and propensity score–adjusted analyses, the researchers reported. Rates of SVR12 also exceeded 90% in subgroups of treatment-experienced and cirrhotic genotype 1 patients, they added. However, rates of SVR12 were lower for nongenotype 1 infections, as has been observed in trials. Specifically, rates of SVR12 were 90% for genotype 4 patients, 86% for genotype 2 patients who received sofosbuvir and ribavirin, and 75% for genotype 3 patients (including 78% for patients given ledipasvir/sofosbuvir plus ribavirin, 87% for patients given sofosbuvir and pegylated interferon plus ribavirin, and 71% for patients given sofosbuvir monotherapy). For cirrhotic patients, rates of SVR12 were 91% for genotype 1, 77% for genotype 2, 66% for genotype 3, and 84% for genotype 4.

The findings confirm that the new interferon-free regimens “can achieve remarkably high SVR rates in real-world clinical practice, especially in genotype 1–infected patients,” the researchers wrote. The cost of these regimens is “the main obstacle to curing HCV” in as many patients as possible, but is expected to “decline dramatically” as the FDA approves new regimens, they noted. “In fact, costs decreased dramatically within the VA after the completion of our study and after the FDA approved elbasvir/grazoprevir in January 2016.”

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The investigators had no disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Eight-week and 12-week regimens of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir achieved similarly high rates of sustained viral response (SVR) among noncirrhotic, treatment-naive, genotype 1 hepatitis C virus–infected patients with viral loads under 6 million IU/mL.

Major finding: Twelve weeks after treatment, rates of SVR were 95.1% for the 8-week regimen and 95.8% for the 12-week regimen (P = .6).

Data source: A retrospective analysis of data from 17,487 patients with HCV infection.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The investigators had no disclosures.

Fecal immunochemical testing, colonoscopy outperformed multitarget stool DNA testing

Fecal immunochemical testing and colonoscopy detected colorectal cancer (CRC) more effectively and cheaply than did multitarget stool DNA testing, based on a Markov model that assumed equal rates of participation in the three strategies, according to a report in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

Multitarget stool DNA testing (MT-sDNA) “may be a cost-effective alternative if it can achieve patient participation rates that are high enough compared with those of FIT [fecal immunochemical testing] that paying for its higher test cost can be justified,” wrote Uri Ladabaum, MD, and Ajitha Mannalithara, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University.

Studies have yielded mixed results about whether FIT or fecal DNA testing are preferable for CRC detection. In one recent large prospective study of patients at average CRC risk, a MT-sDNA test that included KRAS mutations, aberrant NDRG4 and BMP3 methylation, and hemoglobin outperformed FIT for detecting CRC and precancerous lesions but also yielded more false positives, the researchers noted.

Although many decision analyses have examined the efficacy and cost of CRC screening strategies, they have not delved into “the complex patterns of screening participation over time that are now being described (consistent screeners, late entrants, dropouts, intermittent screeners, consistent non-responders),” accounted for variable participation in organized and opportunistic screening programs, or controlled for differential reimbursement rates for public versus private insurance, they added (Gastroenterology 2016 Jun 7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.003).

Dr. Ladabaum and Dr. Mannalithara therefore constructed a Markov model of patients at average risk for CRC to compare the efficacy and costs of MT-sDNA, colonoscopy, and FIT. The model included numerous variables, such as disease states ranging from a small adenomatous polyp to disseminated CRC, longitudinal changes in rates of participation for both opportunistic screening and organized screening programs, and different rates of commercial and Medicare reimbursement.

Assuming optimal adherence, an annual FIT test and colonoscopy every 10 years were more effective and less costly than MT-sDNA every 3 years, the researchers found. Compared with successful FIT screening programs – which have a 50% rate of consistent participation and a 27% rate of intermittent participation and cost about $153 per patient per testing cycle – an MT-sDNA program would need to have at least a 68% rate of consistent participation and a 32% rate of intermittent (every 3 years) participation, or would need to cost 60% less than it does now ($260 for commercial payment and $197 for Medicare payment in 2015) to be preferable when assuming a threshold of $100,000 for every extra quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. MT-sDNA every 3 years, however, would be more cost-effective than opportunistic FIT screening if participation rates were more than 1.7 times those that are typical of opportunistic FIT (15% consistent participation and 30% intermittent participation).

These results held up in various subgroup analyses, and FIT was preferred in 99% of iterations in a Monte Carlo simulation that assumed equal participation rates and the same $100,000 per QALY threshold. “For the MT-sDNA test to be cost-effective, the patient support program included in its cost would need to achieve substantially higher participation rates than those of FIT, whether in organized programs or under the opportunistic screening setting more common in the U.S. than in the rest of the world,” they concluded.

The study was funded by an unrestricted research grant from Exact Science Corp. Dr. Ladabaum reported consulting for ESC in 2014 and disclosed current consulting or advisory relationships with Given Imaging and Mauna Kea Technologies. Dr. Mannalithara had no disclosures.

Fecal immunochemical testing and colonoscopy detected colorectal cancer (CRC) more effectively and cheaply than did multitarget stool DNA testing, based on a Markov model that assumed equal rates of participation in the three strategies, according to a report in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

Multitarget stool DNA testing (MT-sDNA) “may be a cost-effective alternative if it can achieve patient participation rates that are high enough compared with those of FIT [fecal immunochemical testing] that paying for its higher test cost can be justified,” wrote Uri Ladabaum, MD, and Ajitha Mannalithara, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University.

Studies have yielded mixed results about whether FIT or fecal DNA testing are preferable for CRC detection. In one recent large prospective study of patients at average CRC risk, a MT-sDNA test that included KRAS mutations, aberrant NDRG4 and BMP3 methylation, and hemoglobin outperformed FIT for detecting CRC and precancerous lesions but also yielded more false positives, the researchers noted.

Although many decision analyses have examined the efficacy and cost of CRC screening strategies, they have not delved into “the complex patterns of screening participation over time that are now being described (consistent screeners, late entrants, dropouts, intermittent screeners, consistent non-responders),” accounted for variable participation in organized and opportunistic screening programs, or controlled for differential reimbursement rates for public versus private insurance, they added (Gastroenterology 2016 Jun 7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.003).

Dr. Ladabaum and Dr. Mannalithara therefore constructed a Markov model of patients at average risk for CRC to compare the efficacy and costs of MT-sDNA, colonoscopy, and FIT. The model included numerous variables, such as disease states ranging from a small adenomatous polyp to disseminated CRC, longitudinal changes in rates of participation for both opportunistic screening and organized screening programs, and different rates of commercial and Medicare reimbursement.

Assuming optimal adherence, an annual FIT test and colonoscopy every 10 years were more effective and less costly than MT-sDNA every 3 years, the researchers found. Compared with successful FIT screening programs – which have a 50% rate of consistent participation and a 27% rate of intermittent participation and cost about $153 per patient per testing cycle – an MT-sDNA program would need to have at least a 68% rate of consistent participation and a 32% rate of intermittent (every 3 years) participation, or would need to cost 60% less than it does now ($260 for commercial payment and $197 for Medicare payment in 2015) to be preferable when assuming a threshold of $100,000 for every extra quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. MT-sDNA every 3 years, however, would be more cost-effective than opportunistic FIT screening if participation rates were more than 1.7 times those that are typical of opportunistic FIT (15% consistent participation and 30% intermittent participation).

These results held up in various subgroup analyses, and FIT was preferred in 99% of iterations in a Monte Carlo simulation that assumed equal participation rates and the same $100,000 per QALY threshold. “For the MT-sDNA test to be cost-effective, the patient support program included in its cost would need to achieve substantially higher participation rates than those of FIT, whether in organized programs or under the opportunistic screening setting more common in the U.S. than in the rest of the world,” they concluded.

The study was funded by an unrestricted research grant from Exact Science Corp. Dr. Ladabaum reported consulting for ESC in 2014 and disclosed current consulting or advisory relationships with Given Imaging and Mauna Kea Technologies. Dr. Mannalithara had no disclosures.

Fecal immunochemical testing and colonoscopy detected colorectal cancer (CRC) more effectively and cheaply than did multitarget stool DNA testing, based on a Markov model that assumed equal rates of participation in the three strategies, according to a report in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

Multitarget stool DNA testing (MT-sDNA) “may be a cost-effective alternative if it can achieve patient participation rates that are high enough compared with those of FIT [fecal immunochemical testing] that paying for its higher test cost can be justified,” wrote Uri Ladabaum, MD, and Ajitha Mannalithara, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University.

Studies have yielded mixed results about whether FIT or fecal DNA testing are preferable for CRC detection. In one recent large prospective study of patients at average CRC risk, a MT-sDNA test that included KRAS mutations, aberrant NDRG4 and BMP3 methylation, and hemoglobin outperformed FIT for detecting CRC and precancerous lesions but also yielded more false positives, the researchers noted.

Although many decision analyses have examined the efficacy and cost of CRC screening strategies, they have not delved into “the complex patterns of screening participation over time that are now being described (consistent screeners, late entrants, dropouts, intermittent screeners, consistent non-responders),” accounted for variable participation in organized and opportunistic screening programs, or controlled for differential reimbursement rates for public versus private insurance, they added (Gastroenterology 2016 Jun 7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.003).

Dr. Ladabaum and Dr. Mannalithara therefore constructed a Markov model of patients at average risk for CRC to compare the efficacy and costs of MT-sDNA, colonoscopy, and FIT. The model included numerous variables, such as disease states ranging from a small adenomatous polyp to disseminated CRC, longitudinal changes in rates of participation for both opportunistic screening and organized screening programs, and different rates of commercial and Medicare reimbursement.

Assuming optimal adherence, an annual FIT test and colonoscopy every 10 years were more effective and less costly than MT-sDNA every 3 years, the researchers found. Compared with successful FIT screening programs – which have a 50% rate of consistent participation and a 27% rate of intermittent participation and cost about $153 per patient per testing cycle – an MT-sDNA program would need to have at least a 68% rate of consistent participation and a 32% rate of intermittent (every 3 years) participation, or would need to cost 60% less than it does now ($260 for commercial payment and $197 for Medicare payment in 2015) to be preferable when assuming a threshold of $100,000 for every extra quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. MT-sDNA every 3 years, however, would be more cost-effective than opportunistic FIT screening if participation rates were more than 1.7 times those that are typical of opportunistic FIT (15% consistent participation and 30% intermittent participation).

These results held up in various subgroup analyses, and FIT was preferred in 99% of iterations in a Monte Carlo simulation that assumed equal participation rates and the same $100,000 per QALY threshold. “For the MT-sDNA test to be cost-effective, the patient support program included in its cost would need to achieve substantially higher participation rates than those of FIT, whether in organized programs or under the opportunistic screening setting more common in the U.S. than in the rest of the world,” they concluded.

The study was funded by an unrestricted research grant from Exact Science Corp. Dr. Ladabaum reported consulting for ESC in 2014 and disclosed current consulting or advisory relationships with Given Imaging and Mauna Kea Technologies. Dr. Mannalithara had no disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Fecal immunochemical testing and colonoscopy were more effective and less costly than multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal cancer screening.

Major finding: Annual fecal immunochemical testing and colonoscopy every 10 years were more efficacious and cost-effective than multitarget stool DNA testing, given optimal adherence rates.

Data source: A decision analytic health economic evaluation of the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the three modalities.

Disclosures: The study was funded by an unrestricted research grant from Exact Science Corp. Dr. Ladabaum reported consulting for ESC in 2014 and disclosed current consulting or advisory relationships with Given Imaging and Mauna Kea Technologies. Dr. Mannalithara had no disclosures.

Study reinforced value of preconception IBD care

Targeted and regular outpatient care before conception helped prevent relapse of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) during pregnancy, according to a single-center prospective observational study reported in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Women who received such care had about 50% lower odds of relapse while pregnant compared with women seen only after conception, said Alison de Lima, MD, PhD, of Erasmus MC–University Medical Hospital Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and her associates. “Preconception care seems effective in achieving desirable behavioral modifications in IBD women in terms of folic acid intake, smoking cessation, and correct IBD medication adherence, eventually reducing disease relapse during pregnancy. Most importantly, preconception care positively influences birth outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Several recent studies have reported “incorrect beliefs, unfounded fears, and insufficient knowledge” among women with IBD when it comes to pregnancy, the researchers noted. These beliefs can undermine medication adherence, potentially increasing the risk of complications and poor birth outcomes, they added. Studies have confirmed the value of preconception care for chronic diseases such as diabetes, but none had done so for IBD (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Mar 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.018). Therefore, Dr. de Lima and her associates prospectively followed 317 women seen at the IBD preconception outpatient clinic at a tertiary referral hospital during 2008-2014. A total of 155 patients first visited the clinic before becoming pregnant, while the other 162 patients did so only after conception. New patient visits lasted about 30-45 minutes and included fecal calprotectin testing to assess disease activity, education about the need to avoid conceiving during a disease flare, and general advice about taking folic acid, quitting smoking, and avoiding alcohol during pregnancy. Follow-up visits, which occurred every 3 months before pregnancy and every 2 months thereafter, included clinical assessments of disease activity, maternal serum testing to assess compliance with antitumor necrosis factor and thiopurine therapy, and assessments of folic acid supplementation, smoking, and alcohol use.

Patients who received such care before conceiving tended to be younger (29.7 vs. 31.4 years; P = .001), were more often nulliparous (76% vs. 51%; P = .0001), and had a shorter history of IBD (5.1 vs. 8 years; P = .0001), compared with the postconception care group, the researchers said. However, after researchers controlled for parity, disease duration, and the number of relapses in the year before pregnancy, the preconception care group had a nearly sixfold greater odds of adhering to IBD medications during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.3), about a fivefold greater odds of sufficient folic acid intake (aOR, 5.3; 95% CI, 2.7-10.3), and a more than fourfold odds of smoking cessation during pregnancy (aOR, 4.63; 95% CI, 1.2-17.6). Notably, preconception care was tied to a 49% lower odds of disease relapse during pregnancy (aOR, 0.51; 95% CI; 0.28-0.95) and to a nearly 50% lower rate of low birth weight (birth weight less than 2,500 g).

“To our surprise, this study did not detect an effect of preconception care on periconceptional disease activity,” the researchers said – even though they strove to educate patients on this concept. “We can only speculate about the explanation for this finding, but we believe this could be a result of a discrepancy between physician-declared disease remission and the patient’s own feeling of well-being combined with a strong reproductive desire.”

The investigators reported no funding sources, and Dr. de Lima had no disclosures. Two coinvestigators reported ties to Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, Shire, and Ferring.

Targeted and regular outpatient care before conception helped prevent relapse of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) during pregnancy, according to a single-center prospective observational study reported in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Women who received such care had about 50% lower odds of relapse while pregnant compared with women seen only after conception, said Alison de Lima, MD, PhD, of Erasmus MC–University Medical Hospital Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and her associates. “Preconception care seems effective in achieving desirable behavioral modifications in IBD women in terms of folic acid intake, smoking cessation, and correct IBD medication adherence, eventually reducing disease relapse during pregnancy. Most importantly, preconception care positively influences birth outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Several recent studies have reported “incorrect beliefs, unfounded fears, and insufficient knowledge” among women with IBD when it comes to pregnancy, the researchers noted. These beliefs can undermine medication adherence, potentially increasing the risk of complications and poor birth outcomes, they added. Studies have confirmed the value of preconception care for chronic diseases such as diabetes, but none had done so for IBD (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Mar 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.018). Therefore, Dr. de Lima and her associates prospectively followed 317 women seen at the IBD preconception outpatient clinic at a tertiary referral hospital during 2008-2014. A total of 155 patients first visited the clinic before becoming pregnant, while the other 162 patients did so only after conception. New patient visits lasted about 30-45 minutes and included fecal calprotectin testing to assess disease activity, education about the need to avoid conceiving during a disease flare, and general advice about taking folic acid, quitting smoking, and avoiding alcohol during pregnancy. Follow-up visits, which occurred every 3 months before pregnancy and every 2 months thereafter, included clinical assessments of disease activity, maternal serum testing to assess compliance with antitumor necrosis factor and thiopurine therapy, and assessments of folic acid supplementation, smoking, and alcohol use.

Patients who received such care before conceiving tended to be younger (29.7 vs. 31.4 years; P = .001), were more often nulliparous (76% vs. 51%; P = .0001), and had a shorter history of IBD (5.1 vs. 8 years; P = .0001), compared with the postconception care group, the researchers said. However, after researchers controlled for parity, disease duration, and the number of relapses in the year before pregnancy, the preconception care group had a nearly sixfold greater odds of adhering to IBD medications during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.3), about a fivefold greater odds of sufficient folic acid intake (aOR, 5.3; 95% CI, 2.7-10.3), and a more than fourfold odds of smoking cessation during pregnancy (aOR, 4.63; 95% CI, 1.2-17.6). Notably, preconception care was tied to a 49% lower odds of disease relapse during pregnancy (aOR, 0.51; 95% CI; 0.28-0.95) and to a nearly 50% lower rate of low birth weight (birth weight less than 2,500 g).

“To our surprise, this study did not detect an effect of preconception care on periconceptional disease activity,” the researchers said – even though they strove to educate patients on this concept. “We can only speculate about the explanation for this finding, but we believe this could be a result of a discrepancy between physician-declared disease remission and the patient’s own feeling of well-being combined with a strong reproductive desire.”

The investigators reported no funding sources, and Dr. de Lima had no disclosures. Two coinvestigators reported ties to Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, Shire, and Ferring.

Targeted and regular outpatient care before conception helped prevent relapse of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) during pregnancy, according to a single-center prospective observational study reported in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Women who received such care had about 50% lower odds of relapse while pregnant compared with women seen only after conception, said Alison de Lima, MD, PhD, of Erasmus MC–University Medical Hospital Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and her associates. “Preconception care seems effective in achieving desirable behavioral modifications in IBD women in terms of folic acid intake, smoking cessation, and correct IBD medication adherence, eventually reducing disease relapse during pregnancy. Most importantly, preconception care positively influences birth outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Several recent studies have reported “incorrect beliefs, unfounded fears, and insufficient knowledge” among women with IBD when it comes to pregnancy, the researchers noted. These beliefs can undermine medication adherence, potentially increasing the risk of complications and poor birth outcomes, they added. Studies have confirmed the value of preconception care for chronic diseases such as diabetes, but none had done so for IBD (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Mar 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.018). Therefore, Dr. de Lima and her associates prospectively followed 317 women seen at the IBD preconception outpatient clinic at a tertiary referral hospital during 2008-2014. A total of 155 patients first visited the clinic before becoming pregnant, while the other 162 patients did so only after conception. New patient visits lasted about 30-45 minutes and included fecal calprotectin testing to assess disease activity, education about the need to avoid conceiving during a disease flare, and general advice about taking folic acid, quitting smoking, and avoiding alcohol during pregnancy. Follow-up visits, which occurred every 3 months before pregnancy and every 2 months thereafter, included clinical assessments of disease activity, maternal serum testing to assess compliance with antitumor necrosis factor and thiopurine therapy, and assessments of folic acid supplementation, smoking, and alcohol use.

Patients who received such care before conceiving tended to be younger (29.7 vs. 31.4 years; P = .001), were more often nulliparous (76% vs. 51%; P = .0001), and had a shorter history of IBD (5.1 vs. 8 years; P = .0001), compared with the postconception care group, the researchers said. However, after researchers controlled for parity, disease duration, and the number of relapses in the year before pregnancy, the preconception care group had a nearly sixfold greater odds of adhering to IBD medications during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.3), about a fivefold greater odds of sufficient folic acid intake (aOR, 5.3; 95% CI, 2.7-10.3), and a more than fourfold odds of smoking cessation during pregnancy (aOR, 4.63; 95% CI, 1.2-17.6). Notably, preconception care was tied to a 49% lower odds of disease relapse during pregnancy (aOR, 0.51; 95% CI; 0.28-0.95) and to a nearly 50% lower rate of low birth weight (birth weight less than 2,500 g).

“To our surprise, this study did not detect an effect of preconception care on periconceptional disease activity,” the researchers said – even though they strove to educate patients on this concept. “We can only speculate about the explanation for this finding, but we believe this could be a result of a discrepancy between physician-declared disease remission and the patient’s own feeling of well-being combined with a strong reproductive desire.”

The investigators reported no funding sources, and Dr. de Lima had no disclosures. Two coinvestigators reported ties to Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, Shire, and Ferring.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Preconception care with intensive follow-up seems to help prevent relapse of IBD during pregnancy.

Major finding: Women who were seen and followed before pregnancy had about a 50% lower odds of relapse while pregnant than did women who did not seek care until after becoming pregnant.

Data source: A single-center prospective observational study of 317 women with IBD seen at a university outpatient clinic.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no funding sources, and Dr. de Lima had no disclosures. Two coinvestigators reported ties to Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, Shire, and Ferring.

Use these tips to choose the best neuroimaging modality for your pediatric patient

Social media: Potential pitfalls for psychiatrists

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

‘Enough!’ We need to take back our profession; More unresolved questions about psychiatry

‘Enough!’ We need to take back our profession

Every day, I am grateful that I became a physician and a psychiatrist. Every minute that I spend with patients is an honor and a privilege. I have never forgotten that. But it is heartbreaking to see my precious profession being destroyed by bureaucrats.

An example: I am concerned about the effect that passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) will have on physicians. I read articles telling us how we should handle this new plan for reimbursement, but I also read that 86% of physicians are not in favor of MACRA. How did we get stuck with it?

Another example of why it has become virtually impossible to do our job: I spend a fair amount of time obtaining prior authorization for generic medications that are available at big-box stores for $10 or $15; often, these authorizations need approval by the medical director. I have been beaten down enough over the years to learn that I should no longer prescribe brand-name medications—only generic medications (which still require authorization!), even when my patient has been taking the medication for 10 or 15 years. The last time I sought authorization to prescribe a medication, the reviewer asked me why I had not tried 3 different generics over the past year. I had to remind her that I had an active prior authorization in place from the year before, and so why would I do what she was proposing?

Physicians are some of the most highly trained professionals. It takes 7 to 15 years to be able to be somewhat proficient at the job, then another 30 or 40 years of practice to become really good at it. But we’ve become technicians at the mercy of business executives: We go to our office and spend our time checking off boxes, trying to figure out proper coding and the proper diagnosis, so that we can get an appropriate amount of money for the service we’re providing. How has it come to this? Why can’t we take back our profession?

Another problem is that physicians are being paid for their performance and the outcomes they produce. But people are not refrigerators: We can do everything right and the patient still dies. I have a number of patients who have no insight into their psychiatric illness; no matter what I say, or do, or how much time I spend with them, they are nonadherent. How is this my fault?

Physicians are not given the opportunity to think for themselves, or to prescribe treatments that they see fit and document in ways that they were trained. Where is the American Medical Association, the Connecticut State Medical Society, the Hartford County Medical Association, and all the other associations that supposedly represent us? How have they allowed this to happen?

In the future, health care will be provided by physician assistants and nurse practitioners; physicians will provide background supervision, or perform surgery, but the patient will never meet them. I respect NPs and PAs, but they do not have the rigorous training that physicians have. But they’re less expensive—and isn’t that what it’s all about?

If we are not going to speak up, or if we are not going to elect officials to truly represent us and advocate for us, then we have nobody to blame but ourselves.

Carole Black Cohen, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Farmington, Connecticut

More unresolved questions about psychiatry

In Dr. Nasrallah’s August essay (From the Editor,

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Retired Tenured Professor of Psychiatry

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Dr. Moffic is spot-on about the escalating rate of burnout among physicians, including psychiatrists. The reason I did not include burnout in the list of questions is because I intended to pose questions related to external forces that interfere with patient care. Burnout is a vicious internal typhoon of emotional turmoil that might be related to multiple idiosyncratic personal variables and only partially to frustrations in clinical practice.

Burnout is, one might say, a subcortical event (generated in the amygdala?)—not a cortical process like the “why” questions that beg for answers. Admittedly, however, the cumulative burden of practice frustrations—especially the inability to erase the personal, social, financial, and vocational stigmata that plague our patients’ lives—can, eventually, take a toll on our morale and quality of life.

Fortunately, we psychiatrists generally are a resilient breed. We can manage personal stress using techniques that we employ in our practices. That might be why burnout is lower in psychiatry than it is in other medical specialties.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

‘Enough!’ We need to take back our profession

Every day, I am grateful that I became a physician and a psychiatrist. Every minute that I spend with patients is an honor and a privilege. I have never forgotten that. But it is heartbreaking to see my precious profession being destroyed by bureaucrats.

An example: I am concerned about the effect that passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) will have on physicians. I read articles telling us how we should handle this new plan for reimbursement, but I also read that 86% of physicians are not in favor of MACRA. How did we get stuck with it?

Another example of why it has become virtually impossible to do our job: I spend a fair amount of time obtaining prior authorization for generic medications that are available at big-box stores for $10 or $15; often, these authorizations need approval by the medical director. I have been beaten down enough over the years to learn that I should no longer prescribe brand-name medications—only generic medications (which still require authorization!), even when my patient has been taking the medication for 10 or 15 years. The last time I sought authorization to prescribe a medication, the reviewer asked me why I had not tried 3 different generics over the past year. I had to remind her that I had an active prior authorization in place from the year before, and so why would I do what she was proposing?

Physicians are some of the most highly trained professionals. It takes 7 to 15 years to be able to be somewhat proficient at the job, then another 30 or 40 years of practice to become really good at it. But we’ve become technicians at the mercy of business executives: We go to our office and spend our time checking off boxes, trying to figure out proper coding and the proper diagnosis, so that we can get an appropriate amount of money for the service we’re providing. How has it come to this? Why can’t we take back our profession?

Another problem is that physicians are being paid for their performance and the outcomes they produce. But people are not refrigerators: We can do everything right and the patient still dies. I have a number of patients who have no insight into their psychiatric illness; no matter what I say, or do, or how much time I spend with them, they are nonadherent. How is this my fault?

Physicians are not given the opportunity to think for themselves, or to prescribe treatments that they see fit and document in ways that they were trained. Where is the American Medical Association, the Connecticut State Medical Society, the Hartford County Medical Association, and all the other associations that supposedly represent us? How have they allowed this to happen?

In the future, health care will be provided by physician assistants and nurse practitioners; physicians will provide background supervision, or perform surgery, but the patient will never meet them. I respect NPs and PAs, but they do not have the rigorous training that physicians have. But they’re less expensive—and isn’t that what it’s all about?

If we are not going to speak up, or if we are not going to elect officials to truly represent us and advocate for us, then we have nobody to blame but ourselves.

Carole Black Cohen, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Farmington, Connecticut

More unresolved questions about psychiatry

In Dr. Nasrallah’s August essay (From the Editor,

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Retired Tenured Professor of Psychiatry

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Dr. Moffic is spot-on about the escalating rate of burnout among physicians, including psychiatrists. The reason I did not include burnout in the list of questions is because I intended to pose questions related to external forces that interfere with patient care. Burnout is a vicious internal typhoon of emotional turmoil that might be related to multiple idiosyncratic personal variables and only partially to frustrations in clinical practice.

Burnout is, one might say, a subcortical event (generated in the amygdala?)—not a cortical process like the “why” questions that beg for answers. Admittedly, however, the cumulative burden of practice frustrations—especially the inability to erase the personal, social, financial, and vocational stigmata that plague our patients’ lives—can, eventually, take a toll on our morale and quality of life.

Fortunately, we psychiatrists generally are a resilient breed. We can manage personal stress using techniques that we employ in our practices. That might be why burnout is lower in psychiatry than it is in other medical specialties.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

‘Enough!’ We need to take back our profession

Every day, I am grateful that I became a physician and a psychiatrist. Every minute that I spend with patients is an honor and a privilege. I have never forgotten that. But it is heartbreaking to see my precious profession being destroyed by bureaucrats.

An example: I am concerned about the effect that passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) will have on physicians. I read articles telling us how we should handle this new plan for reimbursement, but I also read that 86% of physicians are not in favor of MACRA. How did we get stuck with it?

Another example of why it has become virtually impossible to do our job: I spend a fair amount of time obtaining prior authorization for generic medications that are available at big-box stores for $10 or $15; often, these authorizations need approval by the medical director. I have been beaten down enough over the years to learn that I should no longer prescribe brand-name medications—only generic medications (which still require authorization!), even when my patient has been taking the medication for 10 or 15 years. The last time I sought authorization to prescribe a medication, the reviewer asked me why I had not tried 3 different generics over the past year. I had to remind her that I had an active prior authorization in place from the year before, and so why would I do what she was proposing?

Physicians are some of the most highly trained professionals. It takes 7 to 15 years to be able to be somewhat proficient at the job, then another 30 or 40 years of practice to become really good at it. But we’ve become technicians at the mercy of business executives: We go to our office and spend our time checking off boxes, trying to figure out proper coding and the proper diagnosis, so that we can get an appropriate amount of money for the service we’re providing. How has it come to this? Why can’t we take back our profession?

Another problem is that physicians are being paid for their performance and the outcomes they produce. But people are not refrigerators: We can do everything right and the patient still dies. I have a number of patients who have no insight into their psychiatric illness; no matter what I say, or do, or how much time I spend with them, they are nonadherent. How is this my fault?

Physicians are not given the opportunity to think for themselves, or to prescribe treatments that they see fit and document in ways that they were trained. Where is the American Medical Association, the Connecticut State Medical Society, the Hartford County Medical Association, and all the other associations that supposedly represent us? How have they allowed this to happen?

In the future, health care will be provided by physician assistants and nurse practitioners; physicians will provide background supervision, or perform surgery, but the patient will never meet them. I respect NPs and PAs, but they do not have the rigorous training that physicians have. But they’re less expensive—and isn’t that what it’s all about?

If we are not going to speak up, or if we are not going to elect officials to truly represent us and advocate for us, then we have nobody to blame but ourselves.

Carole Black Cohen, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Farmington, Connecticut

More unresolved questions about psychiatry

In Dr. Nasrallah’s August essay (From the Editor,

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Retired Tenured Professor of Psychiatry

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Dr. Moffic is spot-on about the escalating rate of burnout among physicians, including psychiatrists. The reason I did not include burnout in the list of questions is because I intended to pose questions related to external forces that interfere with patient care. Burnout is a vicious internal typhoon of emotional turmoil that might be related to multiple idiosyncratic personal variables and only partially to frustrations in clinical practice.

Burnout is, one might say, a subcortical event (generated in the amygdala?)—not a cortical process like the “why” questions that beg for answers. Admittedly, however, the cumulative burden of practice frustrations—especially the inability to erase the personal, social, financial, and vocational stigmata that plague our patients’ lives—can, eventually, take a toll on our morale and quality of life.

Fortunately, we psychiatrists generally are a resilient breed. We can manage personal stress using techniques that we employ in our practices. That might be why burnout is lower in psychiatry than it is in other medical specialties.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

The psychiatry workforce pool is shrinking. What are we doing about it?

The dilemma of a diminishing workforce pool might seem more the province of medical school deans, psychiatry department chairs, and psychiatry residency training directors, but our ability to recruit and retain psychiatrists is, in reality, everyone’s concern—including hospitals, clinics, and, especially, patients and their families. Even without knowledge of the specialty or any numerical appraisal, for example, it is common knowledge that we have a dire shortage of child and adolescent and geriatric psychiatrists—a topic of widespread interest and great consequence for access to mental health care.

Tracking a decline

The very title of a recent provocative paper1 in Health Affairs says it all: “Population of US practicing psychiatrists declined 2003-13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care.” In an elegant analysis, the authors expose (1) a 10% decline in the number of psychiatrists for every 100,000 people and (2) wide regional variability in the availability of psychiatrists. In stark contrast, the number of neurologists increased by >15% and the primary care workforce remained stable, with a 1.3% increase in the number of physicians, over the same 10 years.

At the beginning of the psychiatry workforce pipeline, the number of medical students who choose psychiatry remains both small (typically, slightly more than 4% of graduating students) and remarkably stable over time. Wilbanks et al,2 in a thoughtful analysis of the 2011 to 2013 Medical School Graduation Questionnaire of the Association of American Medical Colleges, affirm and, in part, explain this consistent pattern. They note that the 4 most important considerations among students who select psychiatry are:

- personality fit

- specialty content

- work–life balance

- role model influences.

Some of these considerations also overlap with those of students in other specialties; the authors also note that older medical students and women are more likely to choose psychiatry.

Here is what we must do to erase the shortage

It does appear that, despite scientific advances in brain and behavior, expanding therapeutic options, and unique patient interactions that, taken together, should make a career in psychiatry exciting and appealing, there are simply not enough of us to meet the population’s mental health needs. This is a serious problem. It is our professional obligation—all of us—that we take on this shortage and develop solutions to it.

At its zenith, only about 7% of medical students chose psychiatry. We need to proactively prime the pump for our specialty by encouraging more observerships and promoting mental health careers through community outreach to high school students.

We must be diligent and effective mentors to medical students; mentorship is a powerful catalyst for career decision-making.

We need to make psychiatry clerkships exciting, to show off the best of what our specialty has to offer, and to cultivate sustained interest among our students in the brain and its psychiatric disorders.

We need to highlight the momentous advances in knowledge, biology, and treatments that now characterize our psychiatric profession. We need to advocate for more of these accomplishments.

We must be public stigma-busters! (Our patients need us to do this, too.)

And there is more to do:

Collaborate. In delivering psychiatric health care, we need to expand our effectiveness to achieve more collaboration, greater extension of effect, and broader outreach. Collaborative care has come of age as a delivery model; it should be embraced more broadly. We need to continue our efforts to bridge the many sister mental health disciplines—psychology, nursing, social work, counseling—that collectively provide mental health care.

Unite. Given the inadequate workforce numbers and enormous need, we will diminish ourselves by “guild infighting” and, consequently, weaken our legislative advocacy and leverage. We need to embrace and support all medical specialties and have them support us as well. We need to grow closer to primary care and support this specialty as the true front line of mental health. We also need to bridge the gap between addiction medicine and psychiatry, especially given the high level of addiction comorbidity in many psychiatric disorders.

Foster innovation. The deficit of psychiatric workers might be buffered by innovations in how we leverage our expertise. Telepsychiatry, for example, is clearly advancing, and brings psychiatry to remote areas where psychiatrists are scarce. Mobile health also has great potential for mental health. As one of us (H.A.N.) highlighted recently,3 as genetics become more molecular, what has been the potential of clinically applicable pharmacogenomics might become reality. Psychiatry needs to make progress toward personalized medicine because the disorders we treat are extremely heterogeneous in their etiology, phenomenology, treatment response, and outcomes.

The appeal of working with mind and brain

The extent to which we can convey unfettered optimism about the role of psychiatry in medicine and the relentless progress in neurobiological research, together, will go a long way toward attracting the best and brightest newly minted physicians to our specialty. The brain is the last frontier in medicine; psychiatry is intimately tethered to its unfolding complexity. With millennials placing a higher premium on work–life issues, the enviable balance and quality of life of a psychiatric career might now be particularly opportune, enhancing the quantity and quality of professionals that we can attract to psychiatry.

1. Bishop TF, Seirup JK, Pincus HA, et al. Population of US practicing psychiatrist declined, 2003-13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1271-1277.

2. Wilbanks L, Spollen J, Messias E. Factors influencing medical school graduates toward a career in psychiatry: analysis from the 2011-2013 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(2):255-260.

3. Nasrallah HA. ‘Druggable’ genes, promiscuous drugs, repurposed medications. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(5):23,41.

The dilemma of a diminishing workforce pool might seem more the province of medical school deans, psychiatry department chairs, and psychiatry residency training directors, but our ability to recruit and retain psychiatrists is, in reality, everyone’s concern—including hospitals, clinics, and, especially, patients and their families. Even without knowledge of the specialty or any numerical appraisal, for example, it is common knowledge that we have a dire shortage of child and adolescent and geriatric psychiatrists—a topic of widespread interest and great consequence for access to mental health care.

Tracking a decline

The very title of a recent provocative paper1 in Health Affairs says it all: “Population of US practicing psychiatrists declined 2003-13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care.” In an elegant analysis, the authors expose (1) a 10% decline in the number of psychiatrists for every 100,000 people and (2) wide regional variability in the availability of psychiatrists. In stark contrast, the number of neurologists increased by >15% and the primary care workforce remained stable, with a 1.3% increase in the number of physicians, over the same 10 years.

At the beginning of the psychiatry workforce pipeline, the number of medical students who choose psychiatry remains both small (typically, slightly more than 4% of graduating students) and remarkably stable over time. Wilbanks et al,2 in a thoughtful analysis of the 2011 to 2013 Medical School Graduation Questionnaire of the Association of American Medical Colleges, affirm and, in part, explain this consistent pattern. They note that the 4 most important considerations among students who select psychiatry are:

- personality fit

- specialty content

- work–life balance

- role model influences.

Some of these considerations also overlap with those of students in other specialties; the authors also note that older medical students and women are more likely to choose psychiatry.

Here is what we must do to erase the shortage

It does appear that, despite scientific advances in brain and behavior, expanding therapeutic options, and unique patient interactions that, taken together, should make a career in psychiatry exciting and appealing, there are simply not enough of us to meet the population’s mental health needs. This is a serious problem. It is our professional obligation—all of us—that we take on this shortage and develop solutions to it.

At its zenith, only about 7% of medical students chose psychiatry. We need to proactively prime the pump for our specialty by encouraging more observerships and promoting mental health careers through community outreach to high school students.

We must be diligent and effective mentors to medical students; mentorship is a powerful catalyst for career decision-making.

We need to make psychiatry clerkships exciting, to show off the best of what our specialty has to offer, and to cultivate sustained interest among our students in the brain and its psychiatric disorders.

We need to highlight the momentous advances in knowledge, biology, and treatments that now characterize our psychiatric profession. We need to advocate for more of these accomplishments.

We must be public stigma-busters! (Our patients need us to do this, too.)

And there is more to do:

Collaborate. In delivering psychiatric health care, we need to expand our effectiveness to achieve more collaboration, greater extension of effect, and broader outreach. Collaborative care has come of age as a delivery model; it should be embraced more broadly. We need to continue our efforts to bridge the many sister mental health disciplines—psychology, nursing, social work, counseling—that collectively provide mental health care.

Unite. Given the inadequate workforce numbers and enormous need, we will diminish ourselves by “guild infighting” and, consequently, weaken our legislative advocacy and leverage. We need to embrace and support all medical specialties and have them support us as well. We need to grow closer to primary care and support this specialty as the true front line of mental health. We also need to bridge the gap between addiction medicine and psychiatry, especially given the high level of addiction comorbidity in many psychiatric disorders.

Foster innovation. The deficit of psychiatric workers might be buffered by innovations in how we leverage our expertise. Telepsychiatry, for example, is clearly advancing, and brings psychiatry to remote areas where psychiatrists are scarce. Mobile health also has great potential for mental health. As one of us (H.A.N.) highlighted recently,3 as genetics become more molecular, what has been the potential of clinically applicable pharmacogenomics might become reality. Psychiatry needs to make progress toward personalized medicine because the disorders we treat are extremely heterogeneous in their etiology, phenomenology, treatment response, and outcomes.

The appeal of working with mind and brain

The extent to which we can convey unfettered optimism about the role of psychiatry in medicine and the relentless progress in neurobiological research, together, will go a long way toward attracting the best and brightest newly minted physicians to our specialty. The brain is the last frontier in medicine; psychiatry is intimately tethered to its unfolding complexity. With millennials placing a higher premium on work–life issues, the enviable balance and quality of life of a psychiatric career might now be particularly opportune, enhancing the quantity and quality of professionals that we can attract to psychiatry.

The dilemma of a diminishing workforce pool might seem more the province of medical school deans, psychiatry department chairs, and psychiatry residency training directors, but our ability to recruit and retain psychiatrists is, in reality, everyone’s concern—including hospitals, clinics, and, especially, patients and their families. Even without knowledge of the specialty or any numerical appraisal, for example, it is common knowledge that we have a dire shortage of child and adolescent and geriatric psychiatrists—a topic of widespread interest and great consequence for access to mental health care.

Tracking a decline

The very title of a recent provocative paper1 in Health Affairs says it all: “Population of US practicing psychiatrists declined 2003-13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care.” In an elegant analysis, the authors expose (1) a 10% decline in the number of psychiatrists for every 100,000 people and (2) wide regional variability in the availability of psychiatrists. In stark contrast, the number of neurologists increased by >15% and the primary care workforce remained stable, with a 1.3% increase in the number of physicians, over the same 10 years.

At the beginning of the psychiatry workforce pipeline, the number of medical students who choose psychiatry remains both small (typically, slightly more than 4% of graduating students) and remarkably stable over time. Wilbanks et al,2 in a thoughtful analysis of the 2011 to 2013 Medical School Graduation Questionnaire of the Association of American Medical Colleges, affirm and, in part, explain this consistent pattern. They note that the 4 most important considerations among students who select psychiatry are:

- personality fit

- specialty content

- work–life balance

- role model influences.

Some of these considerations also overlap with those of students in other specialties; the authors also note that older medical students and women are more likely to choose psychiatry.

Here is what we must do to erase the shortage

It does appear that, despite scientific advances in brain and behavior, expanding therapeutic options, and unique patient interactions that, taken together, should make a career in psychiatry exciting and appealing, there are simply not enough of us to meet the population’s mental health needs. This is a serious problem. It is our professional obligation—all of us—that we take on this shortage and develop solutions to it.

At its zenith, only about 7% of medical students chose psychiatry. We need to proactively prime the pump for our specialty by encouraging more observerships and promoting mental health careers through community outreach to high school students.

We must be diligent and effective mentors to medical students; mentorship is a powerful catalyst for career decision-making.

We need to make psychiatry clerkships exciting, to show off the best of what our specialty has to offer, and to cultivate sustained interest among our students in the brain and its psychiatric disorders.

We need to highlight the momentous advances in knowledge, biology, and treatments that now characterize our psychiatric profession. We need to advocate for more of these accomplishments.

We must be public stigma-busters! (Our patients need us to do this, too.)

And there is more to do:

Collaborate. In delivering psychiatric health care, we need to expand our effectiveness to achieve more collaboration, greater extension of effect, and broader outreach. Collaborative care has come of age as a delivery model; it should be embraced more broadly. We need to continue our efforts to bridge the many sister mental health disciplines—psychology, nursing, social work, counseling—that collectively provide mental health care.

Unite. Given the inadequate workforce numbers and enormous need, we will diminish ourselves by “guild infighting” and, consequently, weaken our legislative advocacy and leverage. We need to embrace and support all medical specialties and have them support us as well. We need to grow closer to primary care and support this specialty as the true front line of mental health. We also need to bridge the gap between addiction medicine and psychiatry, especially given the high level of addiction comorbidity in many psychiatric disorders.

Foster innovation. The deficit of psychiatric workers might be buffered by innovations in how we leverage our expertise. Telepsychiatry, for example, is clearly advancing, and brings psychiatry to remote areas where psychiatrists are scarce. Mobile health also has great potential for mental health. As one of us (H.A.N.) highlighted recently,3 as genetics become more molecular, what has been the potential of clinically applicable pharmacogenomics might become reality. Psychiatry needs to make progress toward personalized medicine because the disorders we treat are extremely heterogeneous in their etiology, phenomenology, treatment response, and outcomes.

The appeal of working with mind and brain

The extent to which we can convey unfettered optimism about the role of psychiatry in medicine and the relentless progress in neurobiological research, together, will go a long way toward attracting the best and brightest newly minted physicians to our specialty. The brain is the last frontier in medicine; psychiatry is intimately tethered to its unfolding complexity. With millennials placing a higher premium on work–life issues, the enviable balance and quality of life of a psychiatric career might now be particularly opportune, enhancing the quantity and quality of professionals that we can attract to psychiatry.

1. Bishop TF, Seirup JK, Pincus HA, et al. Population of US practicing psychiatrist declined, 2003-13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1271-1277.

2. Wilbanks L, Spollen J, Messias E. Factors influencing medical school graduates toward a career in psychiatry: analysis from the 2011-2013 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(2):255-260.

3. Nasrallah HA. ‘Druggable’ genes, promiscuous drugs, repurposed medications. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(5):23,41.

1. Bishop TF, Seirup JK, Pincus HA, et al. Population of US practicing psychiatrist declined, 2003-13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1271-1277.

2. Wilbanks L, Spollen J, Messias E. Factors influencing medical school graduates toward a career in psychiatry: analysis from the 2011-2013 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(2):255-260.

3. Nasrallah HA. ‘Druggable’ genes, promiscuous drugs, repurposed medications. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(5):23,41.

Neuroimaging in children and adolescents: When do you scan? With which modalities?

The first 15 years of the new millennium have seen a great increase in research on neuroimaging in children and adolescents who have a psychiatric disorder. In addition, imaging modalities continue to evolve, and are becoming increasingly accessible and informative. The literature is now replete with reports of neurostructural differences between patients and healthy subjects in a variety of common pediatric psychiatric conditions, including anxiety disorders, mood disorders, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Historically, the clinical utility of neuroimaging was restricted to the identification of structural pathology. Today, accumulating data reveal novel roles for neuroimaging; these revelations are supported by studies demonstrating that treatment response for psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacotherapeutic interventions can be predicted by neurochemical and neurofunctional characteristics assessed by advanced imaging technologies, such as magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and functional MRI.

However, such advanced techniques are (at least at present) not ready for routine clinical use for this purpose. Instead, neuroimaging in the child and adolescent psychiatric clinic remains largely focused on ruling out neurostructural, neurologic, “nonpsychiatric” causes of our patients’ symptoms.

Understanding the role and limitations of major imaging modalities is key to guiding efficient and appropriate neuroimaging selection for pediatric patients. In this article, we describe and review:

- neuroimaging approaches for children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders

- the role of neuroimaging in (1) the differential diagnosis and workup of common psychiatric disorders and (2) urgent clinical situations

- how to determine what type of imaging to obtain.

Computed tomography

CT, which utilizes ionizing radiation, often is reserved, in the pediatric setting, for (1) emergency evaluation and (2) excluding potentially catastrophic neurologic injury resulting from:

- ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke

- herniation

- intracerebral hemorrhage

- subdural and epidural hematoma

- large intracranial mass with mass effect

- increased intracranial pressure

- acute skull fracture.

Although a CT scan is, typically, quick and has excellent sensitivity for acute bleeding and bony pathology, it exposes the patient to radiation and provides poor resolution compared with MRI.

In pediatrics, there has been practice-changing recognition of the importance of limiting lifetime radiation exposure incurred from medical procedures and imaging. As a result, most providers now agree that use of MRI in lieu of CT is appropriate in many, if not most, non-emergent situations. In an emergent situation, however, CT imaging is appropriate and should not be delayed. Moreover, in an emergent situation, you should not hesitate to use head CT in children, although timely discussion with the radiologist is recommended to review your differential diagnosis to better determine the preferred imaging modality.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Over the past several decades, MRI has been increasingly available in most pediatric health care facilities. The modality offers specific advantages for pediatric patients, including:

- better spatial resolution

- the ability to concurrently assess multiple pathologic processes

- lack of exposure to ionizing radiation.1

A number of MRI sequences, described below, can be used to assess vascular, inflammatory, structural, and metabolic processes.

A look inside. Comprehensive review of the physics that underlies MRI is beyond the scope of this article; several important principles are relevant to clinicians, however. Image contrast is dependent on intrinsic properties of tissue with regard to proton density, longitudinal relaxation time (T1), and transverse relaxation time (T2). Pulse sequences, which describe the strength and timing of the radiofrequency pulse and gradient pulses, define imaging acquisition parameters (eg, repetition time between the radio frequency pulse and echo time).

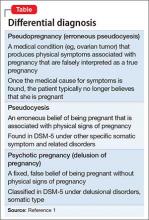

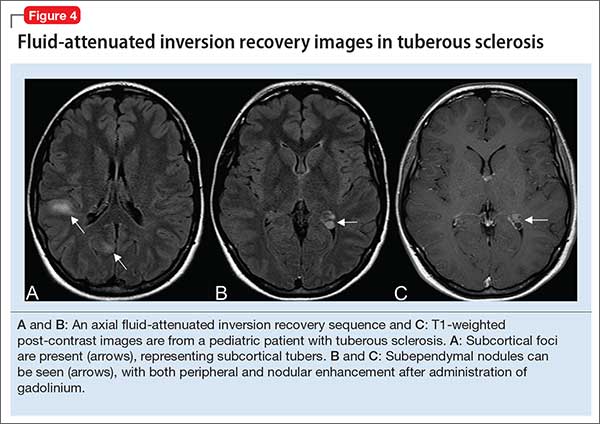

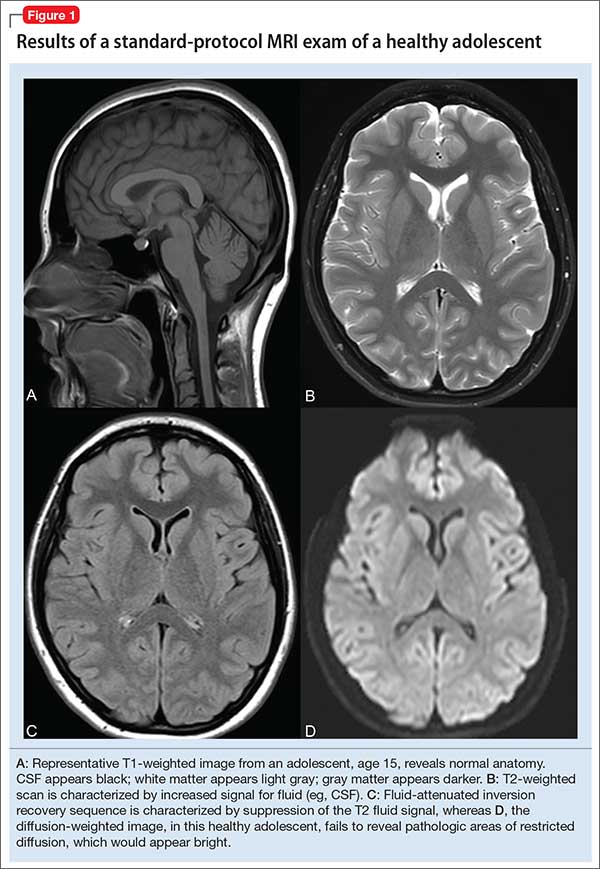

In turn, the intensity of the signal that is “seen” with various pulse sequences is differentially affected by intrinsic properties of tissue. At most pediatric institutions, the standard MRI-examination protocol includes: a T1-weighted image (Figure 1A); a T2-weighted scan (Figure 1B); fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (Figure 1C); and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (Figure 1D).

Specific MRI sequences

T1 images. T1 sequences, or so-called anatomy sequences, are ideally suited for detailed neuroanatomic evaluations. They are generated in such a way that structures containing fluid are dark (hypo-intense), whereas other structures, with higher fat or protein content, are brighter (iso-intense, even hyper-intense). For this reason, CSF in the intracranial ventricles is dark, and white matter is brighter than the cortex because of lipid in myelin sheaths.

In addition, to view structural abnormalities that are characterized by altered vascular supply or flow, such as tumors and infections (abscesses), contrast imaging can be particularly helpful; such images generally are obtained as T1 sequences.

T2 images. By contrast to the T1-weighted sequence, the T2-weighted sequences emphasize fluid signal; structures such as the ventricles, which contain CSF, therefore will be bright (hyper-intense). Pathology that produces edema or fluid, such as edema surrounding demyelinating lesions or infections, also will show bright hyper-intense signal. In T2-weighted images of the brain, white matter shows lower signal intensity than the cortex because of the relatively lower water content in white matter tracts and myelin sheaths.