User login

Pimavanserin for psychosis in patients with Parkinson’s disease

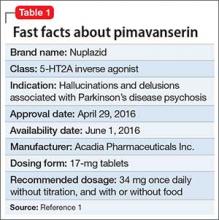

Pimavanserin is a potent 5-HT2A inverse agonist and 5-HT2C inverse agonist, with 5-fold greater affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor.1 Although antagonists block agonist actions at the receptor site, inverse agonists reduce the level of baseline constitutive activity seen in many G protein-coupled receptors. This medication is FDA approved for treating hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD) psychosis (Table 1).1

In the pivotal 6-week clinical trial, pimavanserin significantly reduced positive symptoms seen in PD patients with psychosis (effect size = 0.50), with no evident impairment of motor function.2 Only 2 adverse effects occurred in ≥5% of pimavanserin-treated patients and at ≥2 times the rate of placebo: peripheral edema (7% vs 3% for placebo) and confusion (6% vs 3% for placebo). There was a mean increase in the QTc of 7.3 milliseconds compared with placebo in the pivotal phase III study.

Clinical implications

Despite numerous developments in the pharmacotherapeutics of psychotic disorders, patients with psychosis related to PD previously responded in a robust manner to only 1 antipsychotic, low-dosage clozapine (mean effect size, 0.80),2 with numerous failed trials for other atypical antipsychotics, including quetiapine.3,4 The pathophysiology of psychosis in PD patients is not related to dopamine agonist treatment, but is caused by the accumulation of cortical Lewy body burden, which results in loss of serotonergic signaling from dorsal raphe neurons. The net effect is up-regulation of postsynaptic 5-HT2A receptors.5 Psychosis is the most common cause of nursing home placement among PD patients without dementia.6

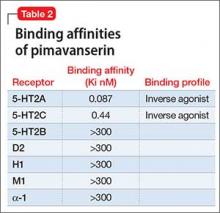

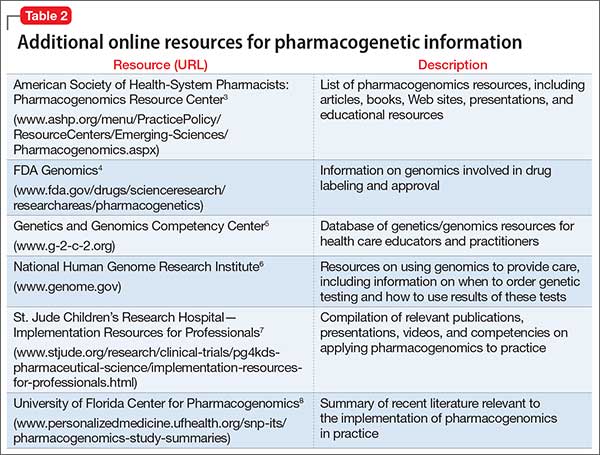

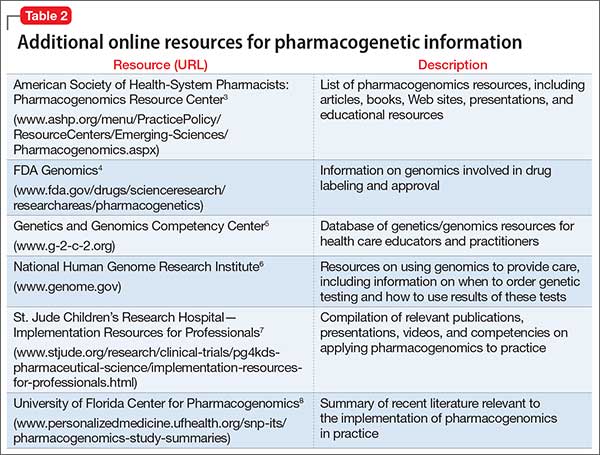

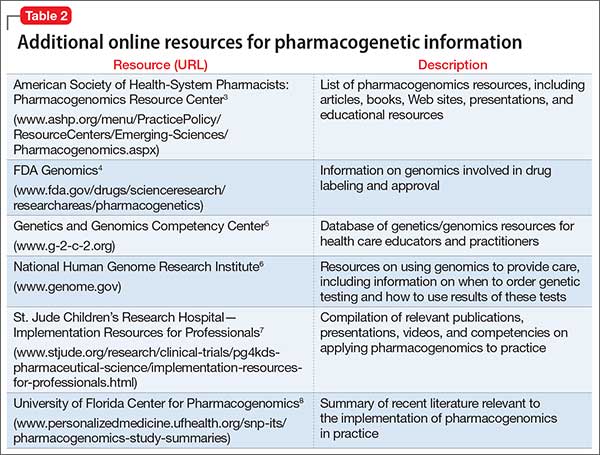

Receptor blocking. Based on the finding that clozapine in low dosages acts at 5-HT2A receptors,7 pimavanserin was designed to be a potent 5-HT2A inverse agonist, with more than 5-fold higher selectivity over 5-HT2C receptors, and no appreciable affinity for other serotonergic, adrenergic, dopaminergic, muscarinic, or histaminergic receptors8 (Table 2). The concept that 5-HT2A receptor stimulation can cause psychosis with prominent visual hallucinations is known from studies of LSD and other hallucinogenic compounds whose activity is blocked by 5-HT2A antagonists.

As an agent devoid of dopamine D2 antagonism, pimavanserin carries no risk of exacerbating motor symptoms, which was commonly seen with most atypical antipsychotics studied for psychosis in PD patients, except for clozapine and quetiapine.3 Although quetiapine did not cause motor effects, it proved ineffective in multiple studies (n = 153), likely because of the near absence of potent 5-HT2A binding.4

Pimavanserin also lacks:

- the hematologic monitoring requirement of clozapine

- clozapine’s risks of sedation, orthostasis, and anticholinergic and metabolic adverse effects.

Pimavanserin is significantly more potent than other non-antipsychotic psychotropics at the 5-HT2Areceptor, including doxepin (26 nM), trazodone (36 nM), and mirtazapine (60 nM).

Use in psychosis associated with PD. Recommended dosage is 34 mg once daily without titration (with or without food), based on results from a phase III clinical trial2 (because of the FDA breakthrough therapy designation for this compound, only 1 phase III trial was required). Pimavanserin produced significant improvement on the PD-adapted Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS-PD), a 9-item instrument extracted from the larger SAPS used in schizophrenia research. Specifically, pimavanserin was effective for both the hallucinations and delusions components of the SAPS-PD.

Pharmacologic profile, adverse effects. Pimavanserin lacks affinity for receptors other than 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C, leading to an absence of significant anticholinergic effects, orthostasis, or sedation in clinical trials.2 In all short-term clinical trials, the only common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were peripheral edema (7% vs 2% placebo) and confusional state (6% vs 3% placebo).2 More than 300 patients have been treated for >6 months, >270 have been treated for at least 12 months, and >150 have been treated for at least 24 months with no adverse effects other than those seen in the short-term trials.1

There is a measurable impact on cardiac conduction seen in phase III data and in the thorough QT study. In the thorough QT study, 252 healthy participants received multiple dosages in a randomized, double-blind manner with positive controls.1 The maximum mean change from baseline was 13.5 milliseconds at dosages twice the recommended dosage, and the upper limit of the 90% CI was only slightly greater at 16.6 milliseconds. Subsequent kinetic analyses suggested concentration-dependent QTc interval prolongation in the therapeutic range, with a recommendation to halve the daily dosage in patients taking potent cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inhibitors.

In the 6-week, placebo-controlled effectiveness studies, mean increases in QTc interval were in the range of 5 to 8 milliseconds. There were sporadic reports of QTcF values ≥500 milliseconds, or changes from baseline QTc values ≥60 milliseconds in pimavanserin-treated participants, although the incidence generally was the same for pimavanserin and placebo groups. There were no reports of torsades de pointes or any differences from placebo in the incidence of adverse reactions associated with delayed ventricular repolarization.

How it works

The theory behind development of pimavanserin rests in the finding that low-dosage clozapine (6.25 to 50 mg/d) was effective for PD patients with psychosis (effect size 0.80).8 Although clozapine has high affinity for multiple sites, including histamine H1 receptors (Ki = 1.13 nM), α-1A and a α-2C adrenergic receptors (Ki = 1.62 nM and 6 nM, respectively), 5-HT2A receptors (Ki = 5.35 nM), and muscarinic M1 receptors (Ki = 6 nM), the hypothesized primary mechanism of clozapine’s effectiveness for PD psychosis at low dosages focused on the 5-HT2Areceptor. This idea was based on the knowledge that hallucinogens such as mescaline, psilocybin, and LSD are 5-HT2A agonists.9 This hallucinogenic activity can be blocked with 5-HT2A antagonists. Because of pimavanserin’s binding profile, the compound was studied as a treatment for psychosis in PD patients.

Pharmacokinetics

Pimavanserin demonstrates dose-proportional pharmacokinetics after a single oral dose as much as 7.5 times the recommended dosage. The pharmacokinetics of pimavanserin were similar in study participants (mean age, 72.4) and healthy controls, and a high-fat meal had no impact on the maximum blood levels (Cmax) or total drug exposure (area under the curve [AUC]).

The mean plasma half-lives for pimavanserin and its metabolite N-desmethyl-pimavanserin (AC-279) are 57 hours and 200 hours, respectively. Although the metabolite appears active in in vitro assays, it does not cross the blood-brain barrier to any appreciable extent, therefore contributing little to the clinical effect. The median time to maximum concentration (Tmax) of pimavanserin is 6 hours with a range of 4 to 24 hours, while the median Tmax of the primary metabolite AC-279 is 6 hours. The bioavailability of pimavanserin in an oral tablet or solution essentially is identical.

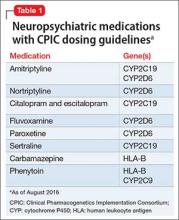

Pimavanserin is primarily metabolized via CYP3A4 to AC-279, and strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (eg, ketoconazole, itraconazole, clarithromycin, indinavir) increase pimavanserin Cmax by 1.5-fold, and AUC by 3-fold. In patients taking strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, the dosage of pimavanserin should be reduced by 50% to 17 mg/d. Conversely, patients on CYP3A4 inducers (eg, rifampin, carbamazepine, phenytoin) should be monitored for lack of efficacy; consider a dosage increase as necessary. Neither pimavanserin nor its metabolite, AC-279, are inhibitors or inducers of major CYP enzymes or drug transporters.

Efficacy in PD psychosis

Study 1. This 6-week, fixed dosage, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was performed in adult PD patients age ≥40 with PD psychosis.2 Participants had to have (1) a PD diagnosis for at least 1 year and (2) psychotic symptoms that developed after diagnosis. Psychotic symptoms had to be present for at least 1 month, occurring at least weekly in the month before screening, and severe enough to warrant antipsychotic treatment. Baseline Mini-Mental State Examination score had to be ≥21 out of 30, with no evidence of delirium. Patients with dementia preceding or concurrent with the PD diagnosis were excluded. Antipsychotic treatments were not permitted during the trial.

After a 2-week nonpharmacotherapeutic lead-in phase that included a brief, daily psychosocial intervention by a caregiver, 199 patients who still met severity criteria were randomly allocated in a 1:1 manner to pimavanserin (34 mg of active drug, reported in the paper as 40 mg of pimavanserin tartrate) or matched placebo. Based on kinetic modeling and earlier clinical data, lower dosages (ie, 17 mg) were not explored, because they achieved only 50% of the steady state plasma levels thought to be required for efficacy.

The primary outcome was assessed by central, independent raters using the PD-adapted SAPS-PD. The efficacy analysis included 95 pimavanserin-treated individuals and 90 taking placebo. Baseline SAPS-PD scores were 14.7 ± 5.55 in the placebo group, and 15.9 ± 6.12 in the pimavanserin arm. Participants had a mean age of 72.4 and 94% white ethnicity across both cohorts; 42% of the placebo group and 33% of the pimavanserin group were female. Antipsychotic exposure in the 21 days prior to study entry were reported in 17% (n = 15) and 19% (n = 18) of the placebo and pimavanserin groups, respectively, with the most common agent being quetiapine (13 of 15, placebo, 16 of 18, pimavanserin). Approximately one-third of all participants were taking a cholinesterase inhibitor throughout the study.

Efficacy outcome. Pimavanserin was associated with a 5.79-point decrease in SAPS-PD scores compared with 2.73-point decrease for placebo (difference −3.06, 95% CI −4.91 to −1.20; P = .001). The effect size for this difference (Cohen’s d) was 0.50. The significant effect of pimavanserin vs placebo also was seen in separate analyses of the SAPS-PD subscore for hallucinations and delusions (effect size 0.50), and individually for hallucinations (effect size 0.45) and delusions (effect size 0.33). Separation from placebo appeared after the second week of pimavanserin treatment, and continued through the end of the study. There is unpublished data showing efficacy through week 10, and longer term, uncontrolled data consistent with sustained response. An exploratory analysis of caregiver burden demonstrated an effect size of 0.50.

Tolerability

The discontinuation rate because of adverse events for pimavanserin and placebo-treated patients was 10 patients in the pimavanserin group (4 due to psychotic symptoms within 10 days of starting the study drug) compared with 2 in the placebo group. There was no evidence of motor worsening in either group, demonstrated by the score on part II of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) that captures self-reported activities of daily living, or on UPDRS part III (motor examination). Pimavanserin has no contraindications.

Unique clinical issues

Binding properties. Pimavanserin possesses potent 5-HT2A inverse agonist properties required to manage psychosis in PD patients, but lacks clozapine’s affinities for α-1 adrenergic, muscarinic, or histaminergic receptors that contribute to clozapine’s poor tolerability. Moreover, pimavanserin has no appreciable affinity for dopaminergic receptors, and therefore does not induce motor adverse effects.

Clozapine aside, all available atypical antipsychotics have proved ineffective for psychosis in PD patients, and most caused significant motor worsening.3 Although quetiapine does not cause motor effects, it has been shown to be ineffective for psychosis in PD patients in multiple trials.4

The effect size for clozapine response is large (0.80) in PD patients with psychosis, but tolerability issues and administrative burdens regarding patient and prescriber registration and routine hematological monitoring pose significant clinical barriers. Clozapine also lacks an FDA indication for this purpose, which may pose a hurdle to its use in certain treatment settings.

Why Rx? The reasons to prescribe pimavanserin for PD patients with psychosis likely include:

- absence of tolerability issues seen with the only other effective agent, clozapine

- lack of motor effects

- lack of administrative and monitoring burden related to clozapine prescribing

- only agent with FDA approval for hallucinations and delusions in PD patients with psychosis.

Dosing

The recommended dosage of pimavanserin is 34 mg/d administered as a single dose with or without food. There is no need for titration, and none was performed in the pivotal clinical trial. Given the long half-life (57 hours), steady state is not achieved until day 12, therefore initiation with a lower dosage might prolong the time to efficacy. There is no dosage adjustment required in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment, but pimavanserin treatment is not recommended in patients with severe renal impairment. Pimavanserin has not been evaluated in patients with hepatic impairment (using Child-Pugh criteria), and is not recommended for these patients.

Other key aspects of dosing to keep in mind.

- Because pimavanserin is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor; the recommended dosage is 17 mg/d when administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.

- Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of pimavanserin with CYP3A4 inducers, patients should be monitored for lack of efficacy during concomitant use with a CYP3A4 inducer, and consideration given to a dosage increase.

Use in pregnancy and lactation. There are no data on the use of pimavanserin in pregnant women, but no developmental effects were seen when the drug was administered orally at 10 or 12 times the maximum recommended human dosage to rats or rabbits during organogenesis. Pimavanserin was not teratogenic in pregnant rats and rabbits. There is no information regarding the presence of pimavanserin in human breast milk.

Geriatric patients. No dosage adjustment is required for older patients. The study population in the pivotal trial was mean age 72.4 years.

Summing up

Before development of pimavanserin, clozapine was the only effective treatment for psychosis in PD patients. Despite clozapine’s robust effects across several trials, patients often were given ineffective medications, such as quetiapine, because of the administrative and tolerability barriers posed by clozapine use. Because psychosis is the most common cause of nursing home placement in non-demented PD patients, an agent with demonstrated efficacy and without the adverse effect profile of clozapine or monitoring requirements represents an enormous advance in the treatment of psychosis in PD patients.

1. Nuplazid [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2016.

2. Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, et al. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. [Erratum in Lancet. 2014;384(9937):28]. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):533-540.

3. Borek LL, Friedman JH. Treating psychosis in movement disorder patients: a review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(11):1553-1564.

4. Desmarais P, Massoud F, Filion J, et al. Quetiapine for psychosis in Parkinson disease and neurodegenerative parkinsonian disorders: a systematic review. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2016;29(4):227-236.

5. Ballanger B, Strafella AP, van Eimeren T, et al. Serotonin 2A receptors and visual hallucinations in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(4):416-421.

6. Ravina B, Marder K, Fernandez HH, et al. Diagnostic criteria for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: report of an NINDS, NIMH work group. Mov Disord. 2007;22(8):1061-1068.

7. Nordström AL, Farde L, Nyberg S, et al. D1, D2, and 5-HT2 receptor occupancy in relation to clozapine serum concentration: a PET study of schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(10):1444-1449.

8. Hacksell U, Burstein ES, McFarland K, et al. On the discovery and development of pimavanserin: a novel drug candidate for Parkinson’s psychosis. Neurochem Res. 2014;39(10):2008-2017.

9. Moreno JL, Holloway T, Albizu L, et al. Metabotropic glutamate mGlu2 receptor is necessary for the pharmacological and behavioral effects induced by hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists. Neurosci Lett. 2011;493(3):76-79.

Pimavanserin is a potent 5-HT2A inverse agonist and 5-HT2C inverse agonist, with 5-fold greater affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor.1 Although antagonists block agonist actions at the receptor site, inverse agonists reduce the level of baseline constitutive activity seen in many G protein-coupled receptors. This medication is FDA approved for treating hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD) psychosis (Table 1).1

In the pivotal 6-week clinical trial, pimavanserin significantly reduced positive symptoms seen in PD patients with psychosis (effect size = 0.50), with no evident impairment of motor function.2 Only 2 adverse effects occurred in ≥5% of pimavanserin-treated patients and at ≥2 times the rate of placebo: peripheral edema (7% vs 3% for placebo) and confusion (6% vs 3% for placebo). There was a mean increase in the QTc of 7.3 milliseconds compared with placebo in the pivotal phase III study.

Clinical implications

Despite numerous developments in the pharmacotherapeutics of psychotic disorders, patients with psychosis related to PD previously responded in a robust manner to only 1 antipsychotic, low-dosage clozapine (mean effect size, 0.80),2 with numerous failed trials for other atypical antipsychotics, including quetiapine.3,4 The pathophysiology of psychosis in PD patients is not related to dopamine agonist treatment, but is caused by the accumulation of cortical Lewy body burden, which results in loss of serotonergic signaling from dorsal raphe neurons. The net effect is up-regulation of postsynaptic 5-HT2A receptors.5 Psychosis is the most common cause of nursing home placement among PD patients without dementia.6

Receptor blocking. Based on the finding that clozapine in low dosages acts at 5-HT2A receptors,7 pimavanserin was designed to be a potent 5-HT2A inverse agonist, with more than 5-fold higher selectivity over 5-HT2C receptors, and no appreciable affinity for other serotonergic, adrenergic, dopaminergic, muscarinic, or histaminergic receptors8 (Table 2). The concept that 5-HT2A receptor stimulation can cause psychosis with prominent visual hallucinations is known from studies of LSD and other hallucinogenic compounds whose activity is blocked by 5-HT2A antagonists.

As an agent devoid of dopamine D2 antagonism, pimavanserin carries no risk of exacerbating motor symptoms, which was commonly seen with most atypical antipsychotics studied for psychosis in PD patients, except for clozapine and quetiapine.3 Although quetiapine did not cause motor effects, it proved ineffective in multiple studies (n = 153), likely because of the near absence of potent 5-HT2A binding.4

Pimavanserin also lacks:

- the hematologic monitoring requirement of clozapine

- clozapine’s risks of sedation, orthostasis, and anticholinergic and metabolic adverse effects.

Pimavanserin is significantly more potent than other non-antipsychotic psychotropics at the 5-HT2Areceptor, including doxepin (26 nM), trazodone (36 nM), and mirtazapine (60 nM).

Use in psychosis associated with PD. Recommended dosage is 34 mg once daily without titration (with or without food), based on results from a phase III clinical trial2 (because of the FDA breakthrough therapy designation for this compound, only 1 phase III trial was required). Pimavanserin produced significant improvement on the PD-adapted Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS-PD), a 9-item instrument extracted from the larger SAPS used in schizophrenia research. Specifically, pimavanserin was effective for both the hallucinations and delusions components of the SAPS-PD.

Pharmacologic profile, adverse effects. Pimavanserin lacks affinity for receptors other than 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C, leading to an absence of significant anticholinergic effects, orthostasis, or sedation in clinical trials.2 In all short-term clinical trials, the only common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were peripheral edema (7% vs 2% placebo) and confusional state (6% vs 3% placebo).2 More than 300 patients have been treated for >6 months, >270 have been treated for at least 12 months, and >150 have been treated for at least 24 months with no adverse effects other than those seen in the short-term trials.1

There is a measurable impact on cardiac conduction seen in phase III data and in the thorough QT study. In the thorough QT study, 252 healthy participants received multiple dosages in a randomized, double-blind manner with positive controls.1 The maximum mean change from baseline was 13.5 milliseconds at dosages twice the recommended dosage, and the upper limit of the 90% CI was only slightly greater at 16.6 milliseconds. Subsequent kinetic analyses suggested concentration-dependent QTc interval prolongation in the therapeutic range, with a recommendation to halve the daily dosage in patients taking potent cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inhibitors.

In the 6-week, placebo-controlled effectiveness studies, mean increases in QTc interval were in the range of 5 to 8 milliseconds. There were sporadic reports of QTcF values ≥500 milliseconds, or changes from baseline QTc values ≥60 milliseconds in pimavanserin-treated participants, although the incidence generally was the same for pimavanserin and placebo groups. There were no reports of torsades de pointes or any differences from placebo in the incidence of adverse reactions associated with delayed ventricular repolarization.

How it works

The theory behind development of pimavanserin rests in the finding that low-dosage clozapine (6.25 to 50 mg/d) was effective for PD patients with psychosis (effect size 0.80).8 Although clozapine has high affinity for multiple sites, including histamine H1 receptors (Ki = 1.13 nM), α-1A and a α-2C adrenergic receptors (Ki = 1.62 nM and 6 nM, respectively), 5-HT2A receptors (Ki = 5.35 nM), and muscarinic M1 receptors (Ki = 6 nM), the hypothesized primary mechanism of clozapine’s effectiveness for PD psychosis at low dosages focused on the 5-HT2Areceptor. This idea was based on the knowledge that hallucinogens such as mescaline, psilocybin, and LSD are 5-HT2A agonists.9 This hallucinogenic activity can be blocked with 5-HT2A antagonists. Because of pimavanserin’s binding profile, the compound was studied as a treatment for psychosis in PD patients.

Pharmacokinetics

Pimavanserin demonstrates dose-proportional pharmacokinetics after a single oral dose as much as 7.5 times the recommended dosage. The pharmacokinetics of pimavanserin were similar in study participants (mean age, 72.4) and healthy controls, and a high-fat meal had no impact on the maximum blood levels (Cmax) or total drug exposure (area under the curve [AUC]).

The mean plasma half-lives for pimavanserin and its metabolite N-desmethyl-pimavanserin (AC-279) are 57 hours and 200 hours, respectively. Although the metabolite appears active in in vitro assays, it does not cross the blood-brain barrier to any appreciable extent, therefore contributing little to the clinical effect. The median time to maximum concentration (Tmax) of pimavanserin is 6 hours with a range of 4 to 24 hours, while the median Tmax of the primary metabolite AC-279 is 6 hours. The bioavailability of pimavanserin in an oral tablet or solution essentially is identical.

Pimavanserin is primarily metabolized via CYP3A4 to AC-279, and strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (eg, ketoconazole, itraconazole, clarithromycin, indinavir) increase pimavanserin Cmax by 1.5-fold, and AUC by 3-fold. In patients taking strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, the dosage of pimavanserin should be reduced by 50% to 17 mg/d. Conversely, patients on CYP3A4 inducers (eg, rifampin, carbamazepine, phenytoin) should be monitored for lack of efficacy; consider a dosage increase as necessary. Neither pimavanserin nor its metabolite, AC-279, are inhibitors or inducers of major CYP enzymes or drug transporters.

Efficacy in PD psychosis

Study 1. This 6-week, fixed dosage, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was performed in adult PD patients age ≥40 with PD psychosis.2 Participants had to have (1) a PD diagnosis for at least 1 year and (2) psychotic symptoms that developed after diagnosis. Psychotic symptoms had to be present for at least 1 month, occurring at least weekly in the month before screening, and severe enough to warrant antipsychotic treatment. Baseline Mini-Mental State Examination score had to be ≥21 out of 30, with no evidence of delirium. Patients with dementia preceding or concurrent with the PD diagnosis were excluded. Antipsychotic treatments were not permitted during the trial.

After a 2-week nonpharmacotherapeutic lead-in phase that included a brief, daily psychosocial intervention by a caregiver, 199 patients who still met severity criteria were randomly allocated in a 1:1 manner to pimavanserin (34 mg of active drug, reported in the paper as 40 mg of pimavanserin tartrate) or matched placebo. Based on kinetic modeling and earlier clinical data, lower dosages (ie, 17 mg) were not explored, because they achieved only 50% of the steady state plasma levels thought to be required for efficacy.

The primary outcome was assessed by central, independent raters using the PD-adapted SAPS-PD. The efficacy analysis included 95 pimavanserin-treated individuals and 90 taking placebo. Baseline SAPS-PD scores were 14.7 ± 5.55 in the placebo group, and 15.9 ± 6.12 in the pimavanserin arm. Participants had a mean age of 72.4 and 94% white ethnicity across both cohorts; 42% of the placebo group and 33% of the pimavanserin group were female. Antipsychotic exposure in the 21 days prior to study entry were reported in 17% (n = 15) and 19% (n = 18) of the placebo and pimavanserin groups, respectively, with the most common agent being quetiapine (13 of 15, placebo, 16 of 18, pimavanserin). Approximately one-third of all participants were taking a cholinesterase inhibitor throughout the study.

Efficacy outcome. Pimavanserin was associated with a 5.79-point decrease in SAPS-PD scores compared with 2.73-point decrease for placebo (difference −3.06, 95% CI −4.91 to −1.20; P = .001). The effect size for this difference (Cohen’s d) was 0.50. The significant effect of pimavanserin vs placebo also was seen in separate analyses of the SAPS-PD subscore for hallucinations and delusions (effect size 0.50), and individually for hallucinations (effect size 0.45) and delusions (effect size 0.33). Separation from placebo appeared after the second week of pimavanserin treatment, and continued through the end of the study. There is unpublished data showing efficacy through week 10, and longer term, uncontrolled data consistent with sustained response. An exploratory analysis of caregiver burden demonstrated an effect size of 0.50.

Tolerability

The discontinuation rate because of adverse events for pimavanserin and placebo-treated patients was 10 patients in the pimavanserin group (4 due to psychotic symptoms within 10 days of starting the study drug) compared with 2 in the placebo group. There was no evidence of motor worsening in either group, demonstrated by the score on part II of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) that captures self-reported activities of daily living, or on UPDRS part III (motor examination). Pimavanserin has no contraindications.

Unique clinical issues

Binding properties. Pimavanserin possesses potent 5-HT2A inverse agonist properties required to manage psychosis in PD patients, but lacks clozapine’s affinities for α-1 adrenergic, muscarinic, or histaminergic receptors that contribute to clozapine’s poor tolerability. Moreover, pimavanserin has no appreciable affinity for dopaminergic receptors, and therefore does not induce motor adverse effects.

Clozapine aside, all available atypical antipsychotics have proved ineffective for psychosis in PD patients, and most caused significant motor worsening.3 Although quetiapine does not cause motor effects, it has been shown to be ineffective for psychosis in PD patients in multiple trials.4

The effect size for clozapine response is large (0.80) in PD patients with psychosis, but tolerability issues and administrative burdens regarding patient and prescriber registration and routine hematological monitoring pose significant clinical barriers. Clozapine also lacks an FDA indication for this purpose, which may pose a hurdle to its use in certain treatment settings.

Why Rx? The reasons to prescribe pimavanserin for PD patients with psychosis likely include:

- absence of tolerability issues seen with the only other effective agent, clozapine

- lack of motor effects

- lack of administrative and monitoring burden related to clozapine prescribing

- only agent with FDA approval for hallucinations and delusions in PD patients with psychosis.

Dosing

The recommended dosage of pimavanserin is 34 mg/d administered as a single dose with or without food. There is no need for titration, and none was performed in the pivotal clinical trial. Given the long half-life (57 hours), steady state is not achieved until day 12, therefore initiation with a lower dosage might prolong the time to efficacy. There is no dosage adjustment required in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment, but pimavanserin treatment is not recommended in patients with severe renal impairment. Pimavanserin has not been evaluated in patients with hepatic impairment (using Child-Pugh criteria), and is not recommended for these patients.

Other key aspects of dosing to keep in mind.

- Because pimavanserin is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor; the recommended dosage is 17 mg/d when administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.

- Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of pimavanserin with CYP3A4 inducers, patients should be monitored for lack of efficacy during concomitant use with a CYP3A4 inducer, and consideration given to a dosage increase.

Use in pregnancy and lactation. There are no data on the use of pimavanserin in pregnant women, but no developmental effects were seen when the drug was administered orally at 10 or 12 times the maximum recommended human dosage to rats or rabbits during organogenesis. Pimavanserin was not teratogenic in pregnant rats and rabbits. There is no information regarding the presence of pimavanserin in human breast milk.

Geriatric patients. No dosage adjustment is required for older patients. The study population in the pivotal trial was mean age 72.4 years.

Summing up

Before development of pimavanserin, clozapine was the only effective treatment for psychosis in PD patients. Despite clozapine’s robust effects across several trials, patients often were given ineffective medications, such as quetiapine, because of the administrative and tolerability barriers posed by clozapine use. Because psychosis is the most common cause of nursing home placement in non-demented PD patients, an agent with demonstrated efficacy and without the adverse effect profile of clozapine or monitoring requirements represents an enormous advance in the treatment of psychosis in PD patients.

Pimavanserin is a potent 5-HT2A inverse agonist and 5-HT2C inverse agonist, with 5-fold greater affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor.1 Although antagonists block agonist actions at the receptor site, inverse agonists reduce the level of baseline constitutive activity seen in many G protein-coupled receptors. This medication is FDA approved for treating hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD) psychosis (Table 1).1

In the pivotal 6-week clinical trial, pimavanserin significantly reduced positive symptoms seen in PD patients with psychosis (effect size = 0.50), with no evident impairment of motor function.2 Only 2 adverse effects occurred in ≥5% of pimavanserin-treated patients and at ≥2 times the rate of placebo: peripheral edema (7% vs 3% for placebo) and confusion (6% vs 3% for placebo). There was a mean increase in the QTc of 7.3 milliseconds compared with placebo in the pivotal phase III study.

Clinical implications

Despite numerous developments in the pharmacotherapeutics of psychotic disorders, patients with psychosis related to PD previously responded in a robust manner to only 1 antipsychotic, low-dosage clozapine (mean effect size, 0.80),2 with numerous failed trials for other atypical antipsychotics, including quetiapine.3,4 The pathophysiology of psychosis in PD patients is not related to dopamine agonist treatment, but is caused by the accumulation of cortical Lewy body burden, which results in loss of serotonergic signaling from dorsal raphe neurons. The net effect is up-regulation of postsynaptic 5-HT2A receptors.5 Psychosis is the most common cause of nursing home placement among PD patients without dementia.6

Receptor blocking. Based on the finding that clozapine in low dosages acts at 5-HT2A receptors,7 pimavanserin was designed to be a potent 5-HT2A inverse agonist, with more than 5-fold higher selectivity over 5-HT2C receptors, and no appreciable affinity for other serotonergic, adrenergic, dopaminergic, muscarinic, or histaminergic receptors8 (Table 2). The concept that 5-HT2A receptor stimulation can cause psychosis with prominent visual hallucinations is known from studies of LSD and other hallucinogenic compounds whose activity is blocked by 5-HT2A antagonists.

As an agent devoid of dopamine D2 antagonism, pimavanserin carries no risk of exacerbating motor symptoms, which was commonly seen with most atypical antipsychotics studied for psychosis in PD patients, except for clozapine and quetiapine.3 Although quetiapine did not cause motor effects, it proved ineffective in multiple studies (n = 153), likely because of the near absence of potent 5-HT2A binding.4

Pimavanserin also lacks:

- the hematologic monitoring requirement of clozapine

- clozapine’s risks of sedation, orthostasis, and anticholinergic and metabolic adverse effects.

Pimavanserin is significantly more potent than other non-antipsychotic psychotropics at the 5-HT2Areceptor, including doxepin (26 nM), trazodone (36 nM), and mirtazapine (60 nM).

Use in psychosis associated with PD. Recommended dosage is 34 mg once daily without titration (with or without food), based on results from a phase III clinical trial2 (because of the FDA breakthrough therapy designation for this compound, only 1 phase III trial was required). Pimavanserin produced significant improvement on the PD-adapted Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS-PD), a 9-item instrument extracted from the larger SAPS used in schizophrenia research. Specifically, pimavanserin was effective for both the hallucinations and delusions components of the SAPS-PD.

Pharmacologic profile, adverse effects. Pimavanserin lacks affinity for receptors other than 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C, leading to an absence of significant anticholinergic effects, orthostasis, or sedation in clinical trials.2 In all short-term clinical trials, the only common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were peripheral edema (7% vs 2% placebo) and confusional state (6% vs 3% placebo).2 More than 300 patients have been treated for >6 months, >270 have been treated for at least 12 months, and >150 have been treated for at least 24 months with no adverse effects other than those seen in the short-term trials.1

There is a measurable impact on cardiac conduction seen in phase III data and in the thorough QT study. In the thorough QT study, 252 healthy participants received multiple dosages in a randomized, double-blind manner with positive controls.1 The maximum mean change from baseline was 13.5 milliseconds at dosages twice the recommended dosage, and the upper limit of the 90% CI was only slightly greater at 16.6 milliseconds. Subsequent kinetic analyses suggested concentration-dependent QTc interval prolongation in the therapeutic range, with a recommendation to halve the daily dosage in patients taking potent cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inhibitors.

In the 6-week, placebo-controlled effectiveness studies, mean increases in QTc interval were in the range of 5 to 8 milliseconds. There were sporadic reports of QTcF values ≥500 milliseconds, or changes from baseline QTc values ≥60 milliseconds in pimavanserin-treated participants, although the incidence generally was the same for pimavanserin and placebo groups. There were no reports of torsades de pointes or any differences from placebo in the incidence of adverse reactions associated with delayed ventricular repolarization.

How it works

The theory behind development of pimavanserin rests in the finding that low-dosage clozapine (6.25 to 50 mg/d) was effective for PD patients with psychosis (effect size 0.80).8 Although clozapine has high affinity for multiple sites, including histamine H1 receptors (Ki = 1.13 nM), α-1A and a α-2C adrenergic receptors (Ki = 1.62 nM and 6 nM, respectively), 5-HT2A receptors (Ki = 5.35 nM), and muscarinic M1 receptors (Ki = 6 nM), the hypothesized primary mechanism of clozapine’s effectiveness for PD psychosis at low dosages focused on the 5-HT2Areceptor. This idea was based on the knowledge that hallucinogens such as mescaline, psilocybin, and LSD are 5-HT2A agonists.9 This hallucinogenic activity can be blocked with 5-HT2A antagonists. Because of pimavanserin’s binding profile, the compound was studied as a treatment for psychosis in PD patients.

Pharmacokinetics

Pimavanserin demonstrates dose-proportional pharmacokinetics after a single oral dose as much as 7.5 times the recommended dosage. The pharmacokinetics of pimavanserin were similar in study participants (mean age, 72.4) and healthy controls, and a high-fat meal had no impact on the maximum blood levels (Cmax) or total drug exposure (area under the curve [AUC]).

The mean plasma half-lives for pimavanserin and its metabolite N-desmethyl-pimavanserin (AC-279) are 57 hours and 200 hours, respectively. Although the metabolite appears active in in vitro assays, it does not cross the blood-brain barrier to any appreciable extent, therefore contributing little to the clinical effect. The median time to maximum concentration (Tmax) of pimavanserin is 6 hours with a range of 4 to 24 hours, while the median Tmax of the primary metabolite AC-279 is 6 hours. The bioavailability of pimavanserin in an oral tablet or solution essentially is identical.

Pimavanserin is primarily metabolized via CYP3A4 to AC-279, and strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (eg, ketoconazole, itraconazole, clarithromycin, indinavir) increase pimavanserin Cmax by 1.5-fold, and AUC by 3-fold. In patients taking strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, the dosage of pimavanserin should be reduced by 50% to 17 mg/d. Conversely, patients on CYP3A4 inducers (eg, rifampin, carbamazepine, phenytoin) should be monitored for lack of efficacy; consider a dosage increase as necessary. Neither pimavanserin nor its metabolite, AC-279, are inhibitors or inducers of major CYP enzymes or drug transporters.

Efficacy in PD psychosis

Study 1. This 6-week, fixed dosage, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was performed in adult PD patients age ≥40 with PD psychosis.2 Participants had to have (1) a PD diagnosis for at least 1 year and (2) psychotic symptoms that developed after diagnosis. Psychotic symptoms had to be present for at least 1 month, occurring at least weekly in the month before screening, and severe enough to warrant antipsychotic treatment. Baseline Mini-Mental State Examination score had to be ≥21 out of 30, with no evidence of delirium. Patients with dementia preceding or concurrent with the PD diagnosis were excluded. Antipsychotic treatments were not permitted during the trial.

After a 2-week nonpharmacotherapeutic lead-in phase that included a brief, daily psychosocial intervention by a caregiver, 199 patients who still met severity criteria were randomly allocated in a 1:1 manner to pimavanserin (34 mg of active drug, reported in the paper as 40 mg of pimavanserin tartrate) or matched placebo. Based on kinetic modeling and earlier clinical data, lower dosages (ie, 17 mg) were not explored, because they achieved only 50% of the steady state plasma levels thought to be required for efficacy.

The primary outcome was assessed by central, independent raters using the PD-adapted SAPS-PD. The efficacy analysis included 95 pimavanserin-treated individuals and 90 taking placebo. Baseline SAPS-PD scores were 14.7 ± 5.55 in the placebo group, and 15.9 ± 6.12 in the pimavanserin arm. Participants had a mean age of 72.4 and 94% white ethnicity across both cohorts; 42% of the placebo group and 33% of the pimavanserin group were female. Antipsychotic exposure in the 21 days prior to study entry were reported in 17% (n = 15) and 19% (n = 18) of the placebo and pimavanserin groups, respectively, with the most common agent being quetiapine (13 of 15, placebo, 16 of 18, pimavanserin). Approximately one-third of all participants were taking a cholinesterase inhibitor throughout the study.

Efficacy outcome. Pimavanserin was associated with a 5.79-point decrease in SAPS-PD scores compared with 2.73-point decrease for placebo (difference −3.06, 95% CI −4.91 to −1.20; P = .001). The effect size for this difference (Cohen’s d) was 0.50. The significant effect of pimavanserin vs placebo also was seen in separate analyses of the SAPS-PD subscore for hallucinations and delusions (effect size 0.50), and individually for hallucinations (effect size 0.45) and delusions (effect size 0.33). Separation from placebo appeared after the second week of pimavanserin treatment, and continued through the end of the study. There is unpublished data showing efficacy through week 10, and longer term, uncontrolled data consistent with sustained response. An exploratory analysis of caregiver burden demonstrated an effect size of 0.50.

Tolerability

The discontinuation rate because of adverse events for pimavanserin and placebo-treated patients was 10 patients in the pimavanserin group (4 due to psychotic symptoms within 10 days of starting the study drug) compared with 2 in the placebo group. There was no evidence of motor worsening in either group, demonstrated by the score on part II of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) that captures self-reported activities of daily living, or on UPDRS part III (motor examination). Pimavanserin has no contraindications.

Unique clinical issues

Binding properties. Pimavanserin possesses potent 5-HT2A inverse agonist properties required to manage psychosis in PD patients, but lacks clozapine’s affinities for α-1 adrenergic, muscarinic, or histaminergic receptors that contribute to clozapine’s poor tolerability. Moreover, pimavanserin has no appreciable affinity for dopaminergic receptors, and therefore does not induce motor adverse effects.

Clozapine aside, all available atypical antipsychotics have proved ineffective for psychosis in PD patients, and most caused significant motor worsening.3 Although quetiapine does not cause motor effects, it has been shown to be ineffective for psychosis in PD patients in multiple trials.4

The effect size for clozapine response is large (0.80) in PD patients with psychosis, but tolerability issues and administrative burdens regarding patient and prescriber registration and routine hematological monitoring pose significant clinical barriers. Clozapine also lacks an FDA indication for this purpose, which may pose a hurdle to its use in certain treatment settings.

Why Rx? The reasons to prescribe pimavanserin for PD patients with psychosis likely include:

- absence of tolerability issues seen with the only other effective agent, clozapine

- lack of motor effects

- lack of administrative and monitoring burden related to clozapine prescribing

- only agent with FDA approval for hallucinations and delusions in PD patients with psychosis.

Dosing

The recommended dosage of pimavanserin is 34 mg/d administered as a single dose with or without food. There is no need for titration, and none was performed in the pivotal clinical trial. Given the long half-life (57 hours), steady state is not achieved until day 12, therefore initiation with a lower dosage might prolong the time to efficacy. There is no dosage adjustment required in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment, but pimavanserin treatment is not recommended in patients with severe renal impairment. Pimavanserin has not been evaluated in patients with hepatic impairment (using Child-Pugh criteria), and is not recommended for these patients.

Other key aspects of dosing to keep in mind.

- Because pimavanserin is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor; the recommended dosage is 17 mg/d when administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.

- Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of pimavanserin with CYP3A4 inducers, patients should be monitored for lack of efficacy during concomitant use with a CYP3A4 inducer, and consideration given to a dosage increase.

Use in pregnancy and lactation. There are no data on the use of pimavanserin in pregnant women, but no developmental effects were seen when the drug was administered orally at 10 or 12 times the maximum recommended human dosage to rats or rabbits during organogenesis. Pimavanserin was not teratogenic in pregnant rats and rabbits. There is no information regarding the presence of pimavanserin in human breast milk.

Geriatric patients. No dosage adjustment is required for older patients. The study population in the pivotal trial was mean age 72.4 years.

Summing up

Before development of pimavanserin, clozapine was the only effective treatment for psychosis in PD patients. Despite clozapine’s robust effects across several trials, patients often were given ineffective medications, such as quetiapine, because of the administrative and tolerability barriers posed by clozapine use. Because psychosis is the most common cause of nursing home placement in non-demented PD patients, an agent with demonstrated efficacy and without the adverse effect profile of clozapine or monitoring requirements represents an enormous advance in the treatment of psychosis in PD patients.

1. Nuplazid [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2016.

2. Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, et al. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. [Erratum in Lancet. 2014;384(9937):28]. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):533-540.

3. Borek LL, Friedman JH. Treating psychosis in movement disorder patients: a review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(11):1553-1564.

4. Desmarais P, Massoud F, Filion J, et al. Quetiapine for psychosis in Parkinson disease and neurodegenerative parkinsonian disorders: a systematic review. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2016;29(4):227-236.

5. Ballanger B, Strafella AP, van Eimeren T, et al. Serotonin 2A receptors and visual hallucinations in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(4):416-421.

6. Ravina B, Marder K, Fernandez HH, et al. Diagnostic criteria for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: report of an NINDS, NIMH work group. Mov Disord. 2007;22(8):1061-1068.

7. Nordström AL, Farde L, Nyberg S, et al. D1, D2, and 5-HT2 receptor occupancy in relation to clozapine serum concentration: a PET study of schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(10):1444-1449.

8. Hacksell U, Burstein ES, McFarland K, et al. On the discovery and development of pimavanserin: a novel drug candidate for Parkinson’s psychosis. Neurochem Res. 2014;39(10):2008-2017.

9. Moreno JL, Holloway T, Albizu L, et al. Metabotropic glutamate mGlu2 receptor is necessary for the pharmacological and behavioral effects induced by hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists. Neurosci Lett. 2011;493(3):76-79.

1. Nuplazid [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2016.

2. Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, et al. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. [Erratum in Lancet. 2014;384(9937):28]. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):533-540.

3. Borek LL, Friedman JH. Treating psychosis in movement disorder patients: a review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(11):1553-1564.

4. Desmarais P, Massoud F, Filion J, et al. Quetiapine for psychosis in Parkinson disease and neurodegenerative parkinsonian disorders: a systematic review. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2016;29(4):227-236.

5. Ballanger B, Strafella AP, van Eimeren T, et al. Serotonin 2A receptors and visual hallucinations in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(4):416-421.

6. Ravina B, Marder K, Fernandez HH, et al. Diagnostic criteria for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: report of an NINDS, NIMH work group. Mov Disord. 2007;22(8):1061-1068.

7. Nordström AL, Farde L, Nyberg S, et al. D1, D2, and 5-HT2 receptor occupancy in relation to clozapine serum concentration: a PET study of schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(10):1444-1449.

8. Hacksell U, Burstein ES, McFarland K, et al. On the discovery and development of pimavanserin: a novel drug candidate for Parkinson’s psychosis. Neurochem Res. 2014;39(10):2008-2017.

9. Moreno JL, Holloway T, Albizu L, et al. Metabotropic glutamate mGlu2 receptor is necessary for the pharmacological and behavioral effects induced by hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists. Neurosci Lett. 2011;493(3):76-79.

Online dating and personal information: Pause before you post

Most adults want to have happy romantic relationships. But meeting eligible companions and finding the time to date can feel nearly impossible to many physicians, especially residents, whose 80-hour work weeks limit opportunities to meet potential partners.1

So it’s no surprise that Dr. R’s friends have suggested that she try online dating. If she does, she would be far from alone: 15% of U.S. adults have sought relationships online, and one-fourth of people in their 20s have used a mobile dating app.2,3 Online dating might work well for Dr. R, too. Between 2005 and 2012, more than one-third of U.S. marriages started online, and these marriages seemed happier and ended in separation or divorce less often than marriages that started in more traditional ways.4

Online dating is just one example of how “the permeation of online and social media into everyday life is placing doctors in new situations that they find difficult to navigate.”5 Many physicians—psychiatrists among them—date online. Yet, like Dr. R, physicians are cautious about using social media because of worries about public exposure and legal concerns.5 Moreover, medical associations haven’t developed guidelines that would help physicians reconcile their professional and personal lives if they seek companionship online.6

Although we don’t have complete answers to Dr. R’s questions, we have gathered some ideas and information that she might find helpful. Read on as we explore:

- potential benefits for psychiatrists who try online dating

- problems when physicians use social media

- how to minimize mishaps if you seek companionship online.

Advantages and benefits

Online dating is most popular among young adults. But singles and divorcees of all ages, sexual orientations, and backgrounds are increasingly seeking long-term relationships with internet-based dating tools rather than hoping to meet people through family, friends, church, and the workplace. It has become common—and no longer stigmatizing—for couples to say they met online.2,7

A dating Web site or app is a simple, fast, low-investment way to increase your opportunities to meet other singles and to make contact with more potential partners than you would meet otherwise. This is particularly helpful for people in thinner dating markets (eg, gays, lesbians, middle-age heterosexuals, and rural dwellers) or people seeking a companion of a particular type or lifestyle.7,8 Many internet dating tools claim that their matching algorithms can increase your chances of meeting someone you will find compatible (although research questions whether the algorithms really work8). Dating sites and apps also let users engage in brief, computer-mediated communications that can foster greater attraction and comfort before meeting for a first date.8

Appeal to psychiatrists

Online dating may have special appeal to young psychiatrists such as Dr. R. Oddly enough, being a mental health professional can leave you socially isolated. Many people react cautiously when they learn you are a psychiatrist—they think you are evaluating them (and let’s face it: often, this is true).9 Psychiatrists should be cordial but circumspect in conducting work relationships, which limits the type and amount of social life they might generate in the setting where many people meet their future spouses.10

Online dating can help single psychiatrists overcome these barriers. Scientifically minded physicians can find plenty of research-grounded advice for improving online dating chances.11-14 Two medical researchers even published a meta-analysis of evidence-based methods that can improve the chances of converting online contacts to a first date.15

Caution: Hazards ahead

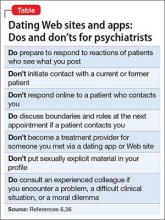

When seeking romance online, psychiatrists shouldn’t forget their professional obligations, including the duty to maintain clear boundaries between their social and work lives.16 If Dr. R decides to try online dating, she will be making it possible for curious patients to gain access to some of her personal information. She will have to figure out how to avoid jeopardizing her professional reputation or inadvertently opening the door to sexual misconduct.17

Boundaries online. Psychiatrists use the term “boundaries” to refer to how they structure appointments and monitor their behavior during therapy to keep the treatment relationship free of personal, sexual, and romantic influences. Keeping one’s emotional life out of treatment helps prevent exploitation of patients and fosters a sense of safety and assurance that the physician is acting solely with the patient’s interest in mind. Breaching boundaries in ways that exploit patients or serve the doctor’s needs can undermine treatment, harm patients, and result in serious professional consequences.18

Maintaining appropriate boundaries can be challenging for psychiatrists who want to date online because the outside-the-office context can muddy the distinction between one’s professional and personal identity. Online dating environments make it easier for physicians to inadvertently initiate social or romantic interactions with people they have treated but don’t recognize (something the authors know has happened to colleagues). Additionally, the internet’s anonymity leaves users vulnerable to being lured into interactions with someone who is using a fictional online persona—an activity colloquially called “catfishing.”19

Although patients may play an active role in boundary breaches, the physician bears sole responsibility for maintaining proper limits within the therapeutic relationship.18 For many psychiatrists, innocuous but non-professional interactions with patients have been the first steps down a “slippery slope” toward serious boundary violations, including sexual contact—an activity that both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Psychiatric Association deem categorically unethical and that can lead to malpractice lawsuits, sanctions by medical license boards, and (in some jurisdictions) criminal prosecution.20 When using social media and online dating tools, psychiatrists should avoid even seemingly minor boundary violations as a safeguard against more serious transgressions.20,21

Reports of online misconduct by medical trainees and practitioners are plentiful.22,23 In response, several medical organizations, including the AMA and the American College of Physicians, have developed professional guidelines for appropriate behavior on social media by physicians.24,25 These guidelines stress the importance of maintaining a professional presence when one’s online activity is publicly viewable.

How much self-disclosure is appropriate?

Traditionally, psychiatrists (including psychoanalysts) have felt that occasional, limited, well-considered references to oneself are acceptable and even helpful in treatment.26 The majority of therapists report using therapy-relevant self-disclosure, but they are cautious about what they say. Conscientious therapists avoid self-disclosure to satisfy their own needs, and they avoid self-disclosure with patients for whom it would have detrimental effects.18,27

Dating Web sites contain a lot of personal information that physicians don’t usually share with patients. Although physicians who use social media are advised to be careful about the information they make available to the public,28 this is more difficult to do with dating applications, where revealing some information about yourself is necessary for making meaningful connections. Creating an online dating profile means that you are potentially letting patients or patients’ relatives know about your place of residence, income, sexual orientation, number of children, and interests. You will need to think about how you will respond if a patient unexpectedly comments on your dating profile during a session or asks you out.

Beyond creating awkward situations, self-disclosure can have treatment implications, and it’s impossible to know how a particular comment will affect a particular client in a particular situation.29 Psychiatrists who engage in online dating may want to limit their posted personal information only to what they would feel reasonably comfortable with having patients know about them, and hope this will suffice to capture the attention of potential partners.

Sustaining professionalism while remaining human. The term “medical professionalism” originally referred to ethical conduct during the practice of medicine30 and to sustaining one’s commitment to patients, fellow professionals, and the institutions within which health care is provided.31 More recently, however, discussions of medical professionalism have encompassed how physicians comport themselves away from work. Physicians’ actions outside the office or hospital—and especially what they say, do, or post online—have a powerful effect on perceptions of their institutions and the medical profession as a whole.25,32

Photos and comments posted by physicians can be seen by millions and can have major repercussions for employment prospects and public perceptions.25 Questionable postings by physicians on social media outlets have resulted in disciplinary actions by licensing authorities and have damaged physicians’ careers.23

What seems appropriate for a dating Web site varies from person to person. A suggestive smile or flirtatious joke that most people would find harmless may strike others as provocative. Derogatory language, depictions of intoxication or substance abuse, and inappropriate patient-related comments are clear-cut mistakes.32-34 But also keep in mind that what medical professionals find acceptable to post on social networking sites does not always match what the general public thinks.35

Bottom Line

1. Miller JA. Romance in residency: is dating even possible? Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/844059. Published May 5, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

2. Smith A, Anderson M. 5 facts about online dating. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/02/29/5-facts-about-online-dating. Published February 29, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

3. Smith A. 15% of American adults have used online dating sites or mobile dating apps. http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/02/11/15-percent-of-american-adults-have-used-online-dating-sites-or-mobile-dating-apps/. Published February 11, 2016. Accessed June 27, 2016.

4. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Gonzaga GC, et al. Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(25):10135-10140.

5. Brown J, Ryan C, Harris A. How doctors view and use social media: a national survey. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(12):e267.

6. Berlin R. The professional ethics of online dating: need for guidance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(9):935-937.

7. Rosenfeld MJ, Thomas RJ. Searching for a mate: the rise of the Internet as a social intermediary. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(4):523-547.

8. Finkel EJ, Eastwick PW, Karney BR, et al. Online dating: a critical analysis from the perspective of psychological science. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2012;13(1):3-66.

9. Pierre J. A mad world: a diagnosis of mental illness is more common than ever—did psychiatrists create the problem, or just recognise it? Aeon.co. https://aeon.co/essays/do-psychiatrists-really-think-that-everyone-is-crazy. Published March 19, 2014. Accessed June 28, 2016.

10. Pearce A, Gambrell D. This chart shows who marries CEOs, doctors, chefs and janitors. Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2016-who-marries-whom. February 11, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

11. Lowin R. Proofread that text before sending! Bad grammar is a dating deal breaker, most say. Today. http://www.today.com/health/can-your-awesome-grammar-really-get-you-date-according-new-t77376. Published March 2, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

12. Reilly K. This strategy will make your Tinder game much stronger. Time. http://time.com/4263598/tinder-gif-messages-response-rate. Published March 17, 2016. Accessed June 28, 2016.

13. Wotipka CD, High AC. Providing a foundation for a satisfying relationship: a direct test of warranting versus selective self-presentation as predictors of attraction to online dating profiles. Presentation at the 101st Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association; November 20, 2014; Chicago, IL.

14. Vacharkulksemsuk T, Reit E, Khambatta P, et al. Dominant, open nonverbal displays are attractive at zero-acquaintance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(15):4009-4014.

15. Khan KS, Chaudhry S. An evidence-based approach to an ancient pursuit: systematic review on converting online contact into a first date. Evid Based Med. 2015;20(2):48-56.

16. Chretien KC, Tuck MG. Online professionalism: a synthetic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(2):106-117.

17. Jackson WC. When patients are normal people: strategies for managing dual relationships. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(3):100-103.

18. Gutheil TG, Gabbard GO. The concept of boundaries in clinical practice: theoretical and risk-management dimensions. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(2):188-196.

19. D’Costa K. Catfishing: the truth about deception online. ScientificAmerican.com. http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/anthropology-in-practice/catfishing-the-truth-about-deception-online. Published April 25, 2014. Accessed June 29, 2016.

20. Sarkar SP. Boundary violation and sexual exploitation in psychiatry and psychotherapy: a review. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10(4):312-320.

21. Nadelson C, Notman MT. Boundaries in the doctor-patient relationship. Theor Med Bioeth. 2002;23(3):191-201.

22. Walton JM, White J, Ross S. What’s on YOUR Facebook profile? Evaluation of an educational intervention to promote appropriate use of privacy settings by medical students on social networking sites. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:28708. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28708.

23. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, et al. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142.

24. Decamp M. Physicians, social media, and conflict of interest. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):299-303.

25. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al; American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee; American College of Physicians Council of Associates; Federation of State Medical Boards Special Committee on Ethics and Professionalism. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):620-627.

26. Meissner WW. The problem of self-disclosure in psychoanalysis. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2002;50(3):827-867.

27. Henretty JR, Levitt HM. The role of therapist self-disclosure in psychotherapy: a qualitative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(1):63-77.

28. Ponce BA, Determann JR, Boohaker HA, et al. Social networking profiles and professionalism issues in residency applicants: an original study-cohort study. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(4):502-507.

29. Peterson ZD. More than a mirror: the ethics of therapist self-disclosure. Psychotherapy: Theory Research & Practice. 2002;39(1):21-31.

30. Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226-235.

31. Wass V. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. Clin Med (Lond). 2006;6(1):109-113.

32. Langenfeld SJ, Cook G, Sudbeck C, et al. An assessment of unprofessional behavior among surgical residents on Facebook: a warning of the dangers of social media. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e28-e32.

33. Chauhan B, George R, Coffin J. Social media and you: what every physician needs to know. J Med Pract Manage. 2012;28(3):206-209.

34. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, et al. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142.

35. Jain A, Petty EM, Jaber RM, et al. What is appropriate to post on social media? Ratings from students, faculty members and the public. Med Educ. 2014;48(2):157-169.

36. Gabbard GO, Roberts LW, Crisp-Han H, et al. Professionalism in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2012.

Most adults want to have happy romantic relationships. But meeting eligible companions and finding the time to date can feel nearly impossible to many physicians, especially residents, whose 80-hour work weeks limit opportunities to meet potential partners.1

So it’s no surprise that Dr. R’s friends have suggested that she try online dating. If she does, she would be far from alone: 15% of U.S. adults have sought relationships online, and one-fourth of people in their 20s have used a mobile dating app.2,3 Online dating might work well for Dr. R, too. Between 2005 and 2012, more than one-third of U.S. marriages started online, and these marriages seemed happier and ended in separation or divorce less often than marriages that started in more traditional ways.4

Online dating is just one example of how “the permeation of online and social media into everyday life is placing doctors in new situations that they find difficult to navigate.”5 Many physicians—psychiatrists among them—date online. Yet, like Dr. R, physicians are cautious about using social media because of worries about public exposure and legal concerns.5 Moreover, medical associations haven’t developed guidelines that would help physicians reconcile their professional and personal lives if they seek companionship online.6

Although we don’t have complete answers to Dr. R’s questions, we have gathered some ideas and information that she might find helpful. Read on as we explore:

- potential benefits for psychiatrists who try online dating

- problems when physicians use social media

- how to minimize mishaps if you seek companionship online.

Advantages and benefits

Online dating is most popular among young adults. But singles and divorcees of all ages, sexual orientations, and backgrounds are increasingly seeking long-term relationships with internet-based dating tools rather than hoping to meet people through family, friends, church, and the workplace. It has become common—and no longer stigmatizing—for couples to say they met online.2,7

A dating Web site or app is a simple, fast, low-investment way to increase your opportunities to meet other singles and to make contact with more potential partners than you would meet otherwise. This is particularly helpful for people in thinner dating markets (eg, gays, lesbians, middle-age heterosexuals, and rural dwellers) or people seeking a companion of a particular type or lifestyle.7,8 Many internet dating tools claim that their matching algorithms can increase your chances of meeting someone you will find compatible (although research questions whether the algorithms really work8). Dating sites and apps also let users engage in brief, computer-mediated communications that can foster greater attraction and comfort before meeting for a first date.8

Appeal to psychiatrists

Online dating may have special appeal to young psychiatrists such as Dr. R. Oddly enough, being a mental health professional can leave you socially isolated. Many people react cautiously when they learn you are a psychiatrist—they think you are evaluating them (and let’s face it: often, this is true).9 Psychiatrists should be cordial but circumspect in conducting work relationships, which limits the type and amount of social life they might generate in the setting where many people meet their future spouses.10

Online dating can help single psychiatrists overcome these barriers. Scientifically minded physicians can find plenty of research-grounded advice for improving online dating chances.11-14 Two medical researchers even published a meta-analysis of evidence-based methods that can improve the chances of converting online contacts to a first date.15

Caution: Hazards ahead

When seeking romance online, psychiatrists shouldn’t forget their professional obligations, including the duty to maintain clear boundaries between their social and work lives.16 If Dr. R decides to try online dating, she will be making it possible for curious patients to gain access to some of her personal information. She will have to figure out how to avoid jeopardizing her professional reputation or inadvertently opening the door to sexual misconduct.17

Boundaries online. Psychiatrists use the term “boundaries” to refer to how they structure appointments and monitor their behavior during therapy to keep the treatment relationship free of personal, sexual, and romantic influences. Keeping one’s emotional life out of treatment helps prevent exploitation of patients and fosters a sense of safety and assurance that the physician is acting solely with the patient’s interest in mind. Breaching boundaries in ways that exploit patients or serve the doctor’s needs can undermine treatment, harm patients, and result in serious professional consequences.18

Maintaining appropriate boundaries can be challenging for psychiatrists who want to date online because the outside-the-office context can muddy the distinction between one’s professional and personal identity. Online dating environments make it easier for physicians to inadvertently initiate social or romantic interactions with people they have treated but don’t recognize (something the authors know has happened to colleagues). Additionally, the internet’s anonymity leaves users vulnerable to being lured into interactions with someone who is using a fictional online persona—an activity colloquially called “catfishing.”19

Although patients may play an active role in boundary breaches, the physician bears sole responsibility for maintaining proper limits within the therapeutic relationship.18 For many psychiatrists, innocuous but non-professional interactions with patients have been the first steps down a “slippery slope” toward serious boundary violations, including sexual contact—an activity that both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Psychiatric Association deem categorically unethical and that can lead to malpractice lawsuits, sanctions by medical license boards, and (in some jurisdictions) criminal prosecution.20 When using social media and online dating tools, psychiatrists should avoid even seemingly minor boundary violations as a safeguard against more serious transgressions.20,21

Reports of online misconduct by medical trainees and practitioners are plentiful.22,23 In response, several medical organizations, including the AMA and the American College of Physicians, have developed professional guidelines for appropriate behavior on social media by physicians.24,25 These guidelines stress the importance of maintaining a professional presence when one’s online activity is publicly viewable.

How much self-disclosure is appropriate?

Traditionally, psychiatrists (including psychoanalysts) have felt that occasional, limited, well-considered references to oneself are acceptable and even helpful in treatment.26 The majority of therapists report using therapy-relevant self-disclosure, but they are cautious about what they say. Conscientious therapists avoid self-disclosure to satisfy their own needs, and they avoid self-disclosure with patients for whom it would have detrimental effects.18,27

Dating Web sites contain a lot of personal information that physicians don’t usually share with patients. Although physicians who use social media are advised to be careful about the information they make available to the public,28 this is more difficult to do with dating applications, where revealing some information about yourself is necessary for making meaningful connections. Creating an online dating profile means that you are potentially letting patients or patients’ relatives know about your place of residence, income, sexual orientation, number of children, and interests. You will need to think about how you will respond if a patient unexpectedly comments on your dating profile during a session or asks you out.

Beyond creating awkward situations, self-disclosure can have treatment implications, and it’s impossible to know how a particular comment will affect a particular client in a particular situation.29 Psychiatrists who engage in online dating may want to limit their posted personal information only to what they would feel reasonably comfortable with having patients know about them, and hope this will suffice to capture the attention of potential partners.

Sustaining professionalism while remaining human. The term “medical professionalism” originally referred to ethical conduct during the practice of medicine30 and to sustaining one’s commitment to patients, fellow professionals, and the institutions within which health care is provided.31 More recently, however, discussions of medical professionalism have encompassed how physicians comport themselves away from work. Physicians’ actions outside the office or hospital—and especially what they say, do, or post online—have a powerful effect on perceptions of their institutions and the medical profession as a whole.25,32

Photos and comments posted by physicians can be seen by millions and can have major repercussions for employment prospects and public perceptions.25 Questionable postings by physicians on social media outlets have resulted in disciplinary actions by licensing authorities and have damaged physicians’ careers.23

What seems appropriate for a dating Web site varies from person to person. A suggestive smile or flirtatious joke that most people would find harmless may strike others as provocative. Derogatory language, depictions of intoxication or substance abuse, and inappropriate patient-related comments are clear-cut mistakes.32-34 But also keep in mind that what medical professionals find acceptable to post on social networking sites does not always match what the general public thinks.35

Bottom Line

Most adults want to have happy romantic relationships. But meeting eligible companions and finding the time to date can feel nearly impossible to many physicians, especially residents, whose 80-hour work weeks limit opportunities to meet potential partners.1

So it’s no surprise that Dr. R’s friends have suggested that she try online dating. If she does, she would be far from alone: 15% of U.S. adults have sought relationships online, and one-fourth of people in their 20s have used a mobile dating app.2,3 Online dating might work well for Dr. R, too. Between 2005 and 2012, more than one-third of U.S. marriages started online, and these marriages seemed happier and ended in separation or divorce less often than marriages that started in more traditional ways.4

Online dating is just one example of how “the permeation of online and social media into everyday life is placing doctors in new situations that they find difficult to navigate.”5 Many physicians—psychiatrists among them—date online. Yet, like Dr. R, physicians are cautious about using social media because of worries about public exposure and legal concerns.5 Moreover, medical associations haven’t developed guidelines that would help physicians reconcile their professional and personal lives if they seek companionship online.6

Although we don’t have complete answers to Dr. R’s questions, we have gathered some ideas and information that she might find helpful. Read on as we explore:

- potential benefits for psychiatrists who try online dating

- problems when physicians use social media

- how to minimize mishaps if you seek companionship online.

Advantages and benefits

Online dating is most popular among young adults. But singles and divorcees of all ages, sexual orientations, and backgrounds are increasingly seeking long-term relationships with internet-based dating tools rather than hoping to meet people through family, friends, church, and the workplace. It has become common—and no longer stigmatizing—for couples to say they met online.2,7