User login

A Melting Pot of Mail

VAPING DANGERS: CLEARING THE AIR

The liquid base of an e-cigarette contains either vegetable glycerin (VG) or propylene glycol, or more commonly, a proprietary combination of both. Each of these ingredients has varying effects on the body.

However, the first paragraph of Randy D. Danielsen’s editorial alluded to what I consider a bigger concern regarding the future medical complications of vaping. The description of a “… huge puff of cherry-scented smoke …” indicates that vapes are not puffed on the way cigarettes are.

Cigarette smoking is similar to drinking through a straw—the smoke is first captured in the mouth, then cooled and inhaled. In contrast, vaping involves inhaling smoke directly into the lungs. This action, along with the thick VG base, produces a high volume of smoke. Vape shops even sponsor contests to see who can produce the largest cloud of smoke.

Therefore, my concern regarding vaping is not limited to the toxicity of the ingredients; it extends to how the toxicants are delivered to the poor, unsuspecting alveoli.

Gary Dula, FNP-C

Houston, TX

Continue for Millenials: Not All Sitting at the Kids' Table >>

MILLENIALS: NOT ALL SITTING AT THE KIDS' TABLES

I received my master’s degree in 2015 and am nearing completion of a year-long FNP fellowship program. I was an Army nurse for four years and a float nurse at various hospitals for five. I am a “millennial”—and, according to the published letters about precepting, am hated by older nurses because of it. Considering I have practiced with many hard-working people my age who would lay down their lives for this country, I find this unprecedented.

I work hard, but the school I attended for my FNP did not prepare me well; it was difficult to get people to teach and precept me during school. This led me to apply for my current fellowship.

Throughout my nine-year nursing career, I have precepted many nurses, including those with associate degrees. I will continue to mentor and precept as an APRN. I take issue with the portrayal of millennials as lazy and unable to work hard. Why? Because we will not work for free, would like to collaboratively learn, and need help to develop our skills?

One day, you will grow old and need someone to take care of you. Why on earth would you berate the people who will be doing just that? Complaining about this generation is not going to change the fact that they are here and present in the workforce. We need more providers, and chastising the younger generation is not going to solve that problem.

Stephanie Butler-Cleland, FNP-BC

Colorado Springs, CO

Continue for The Pros of Precepting >>

THE PROS OF PRECEPTING

I am an urgent care NP in urban communities on the West Coast of Florida. I had taken a break from precepting as a result of negative experiences, but I recently resumed to precept my first NP student in years.

Prior to accepting the student I precepted, I received requests from two other students. One asked if I could change my schedule to be closer to where she lived. The other clearly didn’t want to commit to the drive or the hours I was available, and asked if I would work more weekends to accommodate her schedule. Needless to say, I refused both students.

Instead, I precepted a smart 28-year-old student from my alma mater, one of the Florida state universities. She was attentive, prepared, and eager. I was very, very impressed with her. She had been a nurse for four years and was a second-semester student. It was a pleasure to have her; I like being questioned and challenged. It was fun to see her enjoying my job, and it reminded me of why I love what I do.

Anne Conklin, MS, ARNP-C

Bradenton, FL

Continue for A Scheming Industry >>

A SCHEMING INDUSTRY

Intelligent health care policy has been frustrated by the enormous amount of money brought to bear on Congress by the insurance and pharmaceutical industries. Each dollar paid to an insurance company is used to construct buildings, hire workers, create a sales staff, and ultimately pay their shareholders a profit.

Since the insurance industry obtained an antitrust exemption in the 1940s, they are essentially immune from prosecution for price collusion. Until recently, it was difficult to know how much of the money paid was returned in the form of medical benefits. In order to keep profits rising, they must enroll more people. Promising coverage while impeding medical workups and care, making great profits, and needing more and more enrollees fits the definition of a Ponzi scheme.

Several years ago in California, the state insurance commission (under threat of decertification) got an industry representative to admit that the maximum percentage of dollars used for services was 70%. In other words, for each dollar spent, a patient would be lucky to get 70 cents worth of services.

All of us who practice know how the companies do this: We request a needed diagnostic test or treatment and are denied. I have interrupted my schedule on many days to call for a “peer to peer” review—only once was I denied. This is a roadblock that many busy practitioners will not challenge. Since insurance companies market how great their coverage is, patients often get angry at the provider.

The repeated argument is that the market forces will lower medical costs. This fallacy is easily debunked by noting the ever-escalating costs and comparing health care costs as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in our country versus others. France, for example, expends 12% of GDP on health and ranks first in health care outcomes by world standards. In the US, we are approaching 20% of GDP.

Since insurance adds nothing to care and increases costs dramatically (every provider has to have billers for the various insurance companies, since each has its own requirements), a single-payer system is the only system that will lower costs. Those who benefit from the current system declare that we can’t have “socialized medicine.” To which I would respond, fine; we’ll continue to pay 30% to 50% more so that insurance companies can have their profits at our expense.

Nelson Herilhy, PA-C, MHS

Concord, CA

VAPING DANGERS: CLEARING THE AIR

The liquid base of an e-cigarette contains either vegetable glycerin (VG) or propylene glycol, or more commonly, a proprietary combination of both. Each of these ingredients has varying effects on the body.

However, the first paragraph of Randy D. Danielsen’s editorial alluded to what I consider a bigger concern regarding the future medical complications of vaping. The description of a “… huge puff of cherry-scented smoke …” indicates that vapes are not puffed on the way cigarettes are.

Cigarette smoking is similar to drinking through a straw—the smoke is first captured in the mouth, then cooled and inhaled. In contrast, vaping involves inhaling smoke directly into the lungs. This action, along with the thick VG base, produces a high volume of smoke. Vape shops even sponsor contests to see who can produce the largest cloud of smoke.

Therefore, my concern regarding vaping is not limited to the toxicity of the ingredients; it extends to how the toxicants are delivered to the poor, unsuspecting alveoli.

Gary Dula, FNP-C

Houston, TX

Continue for Millenials: Not All Sitting at the Kids' Table >>

MILLENIALS: NOT ALL SITTING AT THE KIDS' TABLES

I received my master’s degree in 2015 and am nearing completion of a year-long FNP fellowship program. I was an Army nurse for four years and a float nurse at various hospitals for five. I am a “millennial”—and, according to the published letters about precepting, am hated by older nurses because of it. Considering I have practiced with many hard-working people my age who would lay down their lives for this country, I find this unprecedented.

I work hard, but the school I attended for my FNP did not prepare me well; it was difficult to get people to teach and precept me during school. This led me to apply for my current fellowship.

Throughout my nine-year nursing career, I have precepted many nurses, including those with associate degrees. I will continue to mentor and precept as an APRN. I take issue with the portrayal of millennials as lazy and unable to work hard. Why? Because we will not work for free, would like to collaboratively learn, and need help to develop our skills?

One day, you will grow old and need someone to take care of you. Why on earth would you berate the people who will be doing just that? Complaining about this generation is not going to change the fact that they are here and present in the workforce. We need more providers, and chastising the younger generation is not going to solve that problem.

Stephanie Butler-Cleland, FNP-BC

Colorado Springs, CO

Continue for The Pros of Precepting >>

THE PROS OF PRECEPTING

I am an urgent care NP in urban communities on the West Coast of Florida. I had taken a break from precepting as a result of negative experiences, but I recently resumed to precept my first NP student in years.

Prior to accepting the student I precepted, I received requests from two other students. One asked if I could change my schedule to be closer to where she lived. The other clearly didn’t want to commit to the drive or the hours I was available, and asked if I would work more weekends to accommodate her schedule. Needless to say, I refused both students.

Instead, I precepted a smart 28-year-old student from my alma mater, one of the Florida state universities. She was attentive, prepared, and eager. I was very, very impressed with her. She had been a nurse for four years and was a second-semester student. It was a pleasure to have her; I like being questioned and challenged. It was fun to see her enjoying my job, and it reminded me of why I love what I do.

Anne Conklin, MS, ARNP-C

Bradenton, FL

Continue for A Scheming Industry >>

A SCHEMING INDUSTRY

Intelligent health care policy has been frustrated by the enormous amount of money brought to bear on Congress by the insurance and pharmaceutical industries. Each dollar paid to an insurance company is used to construct buildings, hire workers, create a sales staff, and ultimately pay their shareholders a profit.

Since the insurance industry obtained an antitrust exemption in the 1940s, they are essentially immune from prosecution for price collusion. Until recently, it was difficult to know how much of the money paid was returned in the form of medical benefits. In order to keep profits rising, they must enroll more people. Promising coverage while impeding medical workups and care, making great profits, and needing more and more enrollees fits the definition of a Ponzi scheme.

Several years ago in California, the state insurance commission (under threat of decertification) got an industry representative to admit that the maximum percentage of dollars used for services was 70%. In other words, for each dollar spent, a patient would be lucky to get 70 cents worth of services.

All of us who practice know how the companies do this: We request a needed diagnostic test or treatment and are denied. I have interrupted my schedule on many days to call for a “peer to peer” review—only once was I denied. This is a roadblock that many busy practitioners will not challenge. Since insurance companies market how great their coverage is, patients often get angry at the provider.

The repeated argument is that the market forces will lower medical costs. This fallacy is easily debunked by noting the ever-escalating costs and comparing health care costs as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in our country versus others. France, for example, expends 12% of GDP on health and ranks first in health care outcomes by world standards. In the US, we are approaching 20% of GDP.

Since insurance adds nothing to care and increases costs dramatically (every provider has to have billers for the various insurance companies, since each has its own requirements), a single-payer system is the only system that will lower costs. Those who benefit from the current system declare that we can’t have “socialized medicine.” To which I would respond, fine; we’ll continue to pay 30% to 50% more so that insurance companies can have their profits at our expense.

Nelson Herilhy, PA-C, MHS

Concord, CA

VAPING DANGERS: CLEARING THE AIR

The liquid base of an e-cigarette contains either vegetable glycerin (VG) or propylene glycol, or more commonly, a proprietary combination of both. Each of these ingredients has varying effects on the body.

However, the first paragraph of Randy D. Danielsen’s editorial alluded to what I consider a bigger concern regarding the future medical complications of vaping. The description of a “… huge puff of cherry-scented smoke …” indicates that vapes are not puffed on the way cigarettes are.

Cigarette smoking is similar to drinking through a straw—the smoke is first captured in the mouth, then cooled and inhaled. In contrast, vaping involves inhaling smoke directly into the lungs. This action, along with the thick VG base, produces a high volume of smoke. Vape shops even sponsor contests to see who can produce the largest cloud of smoke.

Therefore, my concern regarding vaping is not limited to the toxicity of the ingredients; it extends to how the toxicants are delivered to the poor, unsuspecting alveoli.

Gary Dula, FNP-C

Houston, TX

Continue for Millenials: Not All Sitting at the Kids' Table >>

MILLENIALS: NOT ALL SITTING AT THE KIDS' TABLES

I received my master’s degree in 2015 and am nearing completion of a year-long FNP fellowship program. I was an Army nurse for four years and a float nurse at various hospitals for five. I am a “millennial”—and, according to the published letters about precepting, am hated by older nurses because of it. Considering I have practiced with many hard-working people my age who would lay down their lives for this country, I find this unprecedented.

I work hard, but the school I attended for my FNP did not prepare me well; it was difficult to get people to teach and precept me during school. This led me to apply for my current fellowship.

Throughout my nine-year nursing career, I have precepted many nurses, including those with associate degrees. I will continue to mentor and precept as an APRN. I take issue with the portrayal of millennials as lazy and unable to work hard. Why? Because we will not work for free, would like to collaboratively learn, and need help to develop our skills?

One day, you will grow old and need someone to take care of you. Why on earth would you berate the people who will be doing just that? Complaining about this generation is not going to change the fact that they are here and present in the workforce. We need more providers, and chastising the younger generation is not going to solve that problem.

Stephanie Butler-Cleland, FNP-BC

Colorado Springs, CO

Continue for The Pros of Precepting >>

THE PROS OF PRECEPTING

I am an urgent care NP in urban communities on the West Coast of Florida. I had taken a break from precepting as a result of negative experiences, but I recently resumed to precept my first NP student in years.

Prior to accepting the student I precepted, I received requests from two other students. One asked if I could change my schedule to be closer to where she lived. The other clearly didn’t want to commit to the drive or the hours I was available, and asked if I would work more weekends to accommodate her schedule. Needless to say, I refused both students.

Instead, I precepted a smart 28-year-old student from my alma mater, one of the Florida state universities. She was attentive, prepared, and eager. I was very, very impressed with her. She had been a nurse for four years and was a second-semester student. It was a pleasure to have her; I like being questioned and challenged. It was fun to see her enjoying my job, and it reminded me of why I love what I do.

Anne Conklin, MS, ARNP-C

Bradenton, FL

Continue for A Scheming Industry >>

A SCHEMING INDUSTRY

Intelligent health care policy has been frustrated by the enormous amount of money brought to bear on Congress by the insurance and pharmaceutical industries. Each dollar paid to an insurance company is used to construct buildings, hire workers, create a sales staff, and ultimately pay their shareholders a profit.

Since the insurance industry obtained an antitrust exemption in the 1940s, they are essentially immune from prosecution for price collusion. Until recently, it was difficult to know how much of the money paid was returned in the form of medical benefits. In order to keep profits rising, they must enroll more people. Promising coverage while impeding medical workups and care, making great profits, and needing more and more enrollees fits the definition of a Ponzi scheme.

Several years ago in California, the state insurance commission (under threat of decertification) got an industry representative to admit that the maximum percentage of dollars used for services was 70%. In other words, for each dollar spent, a patient would be lucky to get 70 cents worth of services.

All of us who practice know how the companies do this: We request a needed diagnostic test or treatment and are denied. I have interrupted my schedule on many days to call for a “peer to peer” review—only once was I denied. This is a roadblock that many busy practitioners will not challenge. Since insurance companies market how great their coverage is, patients often get angry at the provider.

The repeated argument is that the market forces will lower medical costs. This fallacy is easily debunked by noting the ever-escalating costs and comparing health care costs as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in our country versus others. France, for example, expends 12% of GDP on health and ranks first in health care outcomes by world standards. In the US, we are approaching 20% of GDP.

Since insurance adds nothing to care and increases costs dramatically (every provider has to have billers for the various insurance companies, since each has its own requirements), a single-payer system is the only system that will lower costs. Those who benefit from the current system declare that we can’t have “socialized medicine.” To which I would respond, fine; we’ll continue to pay 30% to 50% more so that insurance companies can have their profits at our expense.

Nelson Herilhy, PA-C, MHS

Concord, CA

“Unprecedented” VA Proposal? We Don’t Think So

On May 25, 2016, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) published a proposed rule change in the Federal Register under the simple heading “Advanced Practice Registered Nurses.” From such modest beginnings stemmed a potential game-changer for advanced practice clinicians in this country: In summary, the VA proposed to “amend its medical regulations to permit full practice authority of all VA advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) when they are acting within the scope of their VA employment.”1

The impetus for the VA’s proposal is that 505,000 veterans wait 30 days to access care within the VA system—and 300,000 wait between 31 and 60 days for health services.2 Granting plenary practice to VA APRNs would enable them to respond to this backlog of patients, since veterans would have direct access to APRNs who practice within the VA system, regardless of their state of licensure.

More than 4,800 NPs work within the VA; they provide clinical assessments, order appropriate tests and medications, and develop patient-centered care plans.2,3 Research has documented that outcomes for patients whose care is managed by NPs are equal to or better than outcomes for similar patients who are managed by physicians.4 As Major General Vincent Boles of the US Army (retired) stated, “Veterans rely on VA health care to take care of them, and the VA’s nurse practitioners are qualified to provide our veterans with the care they need and deserve.”4

Allowing veterans access to high-quality care is a 21st century solution that is “zero risk, zero cost, zero delay,” according to Dr. Cindy Cooke, President of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP).4 And it is not just the AANP that supports this rule change. Ninety-one percent of US households that are home to a veteran, and 88% of Americans overall, express support for the VA proposal. In a Mellman Group survey of more than 1,000 adults, strong support was noted across party lines (91% of Republicans; 90% of Democrats)—a rarity in our current political climate.4

Support for full practice authority for NPs at the VA has come from more than 60 organizations, including the Military Officers’ Association of America, the Air Force Sergeants Association, AARP (with 3.7 million veteran households in its membership), and 80 bipartisan members of Congress.5 At the AANP annual conference in San Antonio, Dr. Cooke was joined by leaders from the local American Legion and retired military officers who announced their support for this “change in practice.”3

However, among the more than 162,000 comments received by the VA during the public comment period, there were dissenting opinions. On July 13, 2016, Dr. Robert Wergin, Chair of the Board of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), sent a letter to Dr. David Shulkin, the Undersecretary of Health in the VA, stating that there were “significant concerns” about the rule change. His main point was that granting full practice authority to NPs would “alter the consistent standards of care for veterans over nonveterans in the states; further fragment the health care system; and dismantle physician-led team-based health care models.” He also stated that “the AAFP strongly opposes the unprecedented proposal to dismiss state practice authority regarding the authority of NPs.”6

Unprecedented? I don’t think so. I practiced as a family NP in the Navy for more than 20 years. I had my own patient panel, cared for active duty members and their families, and evaluated outcomes the same way my physician colleagues did. We practiced collaboratively and respectfully. We discussed patient plan issues, provided peer review on one another’s charts, and accepted new patients into our panels. It was a true collaborative practice.

Military nurses only need to be licensed in one state. The guidelines for NP practice were not based on the rules of the state in which we were licensed but were established by our professional practice association—just as the guidelines for physician practice were not based on the rules extant in their licensing state. I practiced successfully in many states and overseas, although I was licensed in a state that did not recognize plenary practice at the time.

The VA is attempting to respond to veterans’ need for access to care by adopting a model similar to what the military employs. It’s not a matter of superseding state regulations; it’s a matter of recognizing the education and training of health care professionals who can improve patient outcomes.

The opportunity to respond to the proposed amendment has now closed. Through its grassroots Veterans Deserve Care campaign, the AANP and its partners and supporters—clinicians, veterans, families, and others—submitted nearly 60,000 comments.2 Now we wait for the VA to review the abundance of feedback and issue their final decision.

I am hopeful that the VA will acknowledge the overwhelming evidence that our veterans deserve access to care led by highly qualified professionals. The old system isn’t working. Einstein said that the definition of insanity was to do the same thing over and over and expect a different outcome; maintaining a faulty system fits that description. NPs have a well-tested, evidence-based, high-quality education that encourages their ability to lead health care teams, perform collaboratively, and improve outcomes for those who have served our country.

Caring for active duty military and veterans is in the DNA of nurses. Florence Nightingale spent much of her post-Crimea life using evidence-based proposals and political influence to improve the health care of the soldiers and veterans of the British Empire. In Notes on Nursing, she spurred nurses to political action: “Let whoever [sic] is in charge keep this simple question in her [sic] head (not how can I always do this right thing myself, but) how can I provide for this right thing to be always done?”7 This advice should be taken to heart by all health care professionals: We can honor our veterans by advocating for and providing the health care access they need.

To share your thoughts, please contact us at [email protected]

1. Advanced practice registered nurses [2016-12338]. Fed Regist. May 25, 2016. https://federalregister.gov/a/2016-12338.

2. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. AANP and Air Force Sergeants Association urge VA to swiftly enact proposed rule. July 25, 2016. www.aanp.org/legislation-regu lation/federal-legislation/va-proposed-rule/173-press-room/2016-press-releases/ 1987-aanp-and-air-force-sergeants-associa tion-urge-va-to-swiftly-enact-proposed-rule. Accessed August 9, 2016.

3. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. AANP and veterans groups call for streamlined access to veteran’s health care. June 23, 2016. www.aanp.org/press-room/press-releases/173-press-room/2016-press-releases/1959-aanp-veteran-groups-call-for-streamlined-access-to-veterans-health-care. Accessed August 9, 2016.

4. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. National survey finds overwhelming support for VA rule granting veterans direct access to nurse practitioner care. July 20, 2016. www.aanp.org/press-room/press-releases/173-press-room/2016-press-releases/1986-national-survey-finds-overwhelming-support-for-va-rule-granting-veterans-direct-access-to-nurse-practition er-care. Accessed August 9, 2016.

5. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. Nursing coalition and veterans groups join forces in unprecedented response to VA proposed rule to increase veterans’ access to care. June 28, 2016. www.aana.com/newsandjournal/News/Pages/062816-Nursing-Coalition-and-Veterans-Groups-Join-Forces-in-Unprecedented-Response-to-VA-Proposed-Rule.aspx. Accessed August 9, 2016.

6. Wergin RL. Letter to David Shulkin. July 13, 2016. www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/docu ments/advocacy/workforce/scope/LT-VHA-APRN-071316.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016 .

7. Nightingale F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company; 1860.

On May 25, 2016, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) published a proposed rule change in the Federal Register under the simple heading “Advanced Practice Registered Nurses.” From such modest beginnings stemmed a potential game-changer for advanced practice clinicians in this country: In summary, the VA proposed to “amend its medical regulations to permit full practice authority of all VA advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) when they are acting within the scope of their VA employment.”1

The impetus for the VA’s proposal is that 505,000 veterans wait 30 days to access care within the VA system—and 300,000 wait between 31 and 60 days for health services.2 Granting plenary practice to VA APRNs would enable them to respond to this backlog of patients, since veterans would have direct access to APRNs who practice within the VA system, regardless of their state of licensure.

More than 4,800 NPs work within the VA; they provide clinical assessments, order appropriate tests and medications, and develop patient-centered care plans.2,3 Research has documented that outcomes for patients whose care is managed by NPs are equal to or better than outcomes for similar patients who are managed by physicians.4 As Major General Vincent Boles of the US Army (retired) stated, “Veterans rely on VA health care to take care of them, and the VA’s nurse practitioners are qualified to provide our veterans with the care they need and deserve.”4

Allowing veterans access to high-quality care is a 21st century solution that is “zero risk, zero cost, zero delay,” according to Dr. Cindy Cooke, President of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP).4 And it is not just the AANP that supports this rule change. Ninety-one percent of US households that are home to a veteran, and 88% of Americans overall, express support for the VA proposal. In a Mellman Group survey of more than 1,000 adults, strong support was noted across party lines (91% of Republicans; 90% of Democrats)—a rarity in our current political climate.4

Support for full practice authority for NPs at the VA has come from more than 60 organizations, including the Military Officers’ Association of America, the Air Force Sergeants Association, AARP (with 3.7 million veteran households in its membership), and 80 bipartisan members of Congress.5 At the AANP annual conference in San Antonio, Dr. Cooke was joined by leaders from the local American Legion and retired military officers who announced their support for this “change in practice.”3

However, among the more than 162,000 comments received by the VA during the public comment period, there were dissenting opinions. On July 13, 2016, Dr. Robert Wergin, Chair of the Board of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), sent a letter to Dr. David Shulkin, the Undersecretary of Health in the VA, stating that there were “significant concerns” about the rule change. His main point was that granting full practice authority to NPs would “alter the consistent standards of care for veterans over nonveterans in the states; further fragment the health care system; and dismantle physician-led team-based health care models.” He also stated that “the AAFP strongly opposes the unprecedented proposal to dismiss state practice authority regarding the authority of NPs.”6

Unprecedented? I don’t think so. I practiced as a family NP in the Navy for more than 20 years. I had my own patient panel, cared for active duty members and their families, and evaluated outcomes the same way my physician colleagues did. We practiced collaboratively and respectfully. We discussed patient plan issues, provided peer review on one another’s charts, and accepted new patients into our panels. It was a true collaborative practice.

Military nurses only need to be licensed in one state. The guidelines for NP practice were not based on the rules of the state in which we were licensed but were established by our professional practice association—just as the guidelines for physician practice were not based on the rules extant in their licensing state. I practiced successfully in many states and overseas, although I was licensed in a state that did not recognize plenary practice at the time.

The VA is attempting to respond to veterans’ need for access to care by adopting a model similar to what the military employs. It’s not a matter of superseding state regulations; it’s a matter of recognizing the education and training of health care professionals who can improve patient outcomes.

The opportunity to respond to the proposed amendment has now closed. Through its grassroots Veterans Deserve Care campaign, the AANP and its partners and supporters—clinicians, veterans, families, and others—submitted nearly 60,000 comments.2 Now we wait for the VA to review the abundance of feedback and issue their final decision.

I am hopeful that the VA will acknowledge the overwhelming evidence that our veterans deserve access to care led by highly qualified professionals. The old system isn’t working. Einstein said that the definition of insanity was to do the same thing over and over and expect a different outcome; maintaining a faulty system fits that description. NPs have a well-tested, evidence-based, high-quality education that encourages their ability to lead health care teams, perform collaboratively, and improve outcomes for those who have served our country.

Caring for active duty military and veterans is in the DNA of nurses. Florence Nightingale spent much of her post-Crimea life using evidence-based proposals and political influence to improve the health care of the soldiers and veterans of the British Empire. In Notes on Nursing, she spurred nurses to political action: “Let whoever [sic] is in charge keep this simple question in her [sic] head (not how can I always do this right thing myself, but) how can I provide for this right thing to be always done?”7 This advice should be taken to heart by all health care professionals: We can honor our veterans by advocating for and providing the health care access they need.

To share your thoughts, please contact us at [email protected]

On May 25, 2016, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) published a proposed rule change in the Federal Register under the simple heading “Advanced Practice Registered Nurses.” From such modest beginnings stemmed a potential game-changer for advanced practice clinicians in this country: In summary, the VA proposed to “amend its medical regulations to permit full practice authority of all VA advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) when they are acting within the scope of their VA employment.”1

The impetus for the VA’s proposal is that 505,000 veterans wait 30 days to access care within the VA system—and 300,000 wait between 31 and 60 days for health services.2 Granting plenary practice to VA APRNs would enable them to respond to this backlog of patients, since veterans would have direct access to APRNs who practice within the VA system, regardless of their state of licensure.

More than 4,800 NPs work within the VA; they provide clinical assessments, order appropriate tests and medications, and develop patient-centered care plans.2,3 Research has documented that outcomes for patients whose care is managed by NPs are equal to or better than outcomes for similar patients who are managed by physicians.4 As Major General Vincent Boles of the US Army (retired) stated, “Veterans rely on VA health care to take care of them, and the VA’s nurse practitioners are qualified to provide our veterans with the care they need and deserve.”4

Allowing veterans access to high-quality care is a 21st century solution that is “zero risk, zero cost, zero delay,” according to Dr. Cindy Cooke, President of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP).4 And it is not just the AANP that supports this rule change. Ninety-one percent of US households that are home to a veteran, and 88% of Americans overall, express support for the VA proposal. In a Mellman Group survey of more than 1,000 adults, strong support was noted across party lines (91% of Republicans; 90% of Democrats)—a rarity in our current political climate.4

Support for full practice authority for NPs at the VA has come from more than 60 organizations, including the Military Officers’ Association of America, the Air Force Sergeants Association, AARP (with 3.7 million veteran households in its membership), and 80 bipartisan members of Congress.5 At the AANP annual conference in San Antonio, Dr. Cooke was joined by leaders from the local American Legion and retired military officers who announced their support for this “change in practice.”3

However, among the more than 162,000 comments received by the VA during the public comment period, there were dissenting opinions. On July 13, 2016, Dr. Robert Wergin, Chair of the Board of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), sent a letter to Dr. David Shulkin, the Undersecretary of Health in the VA, stating that there were “significant concerns” about the rule change. His main point was that granting full practice authority to NPs would “alter the consistent standards of care for veterans over nonveterans in the states; further fragment the health care system; and dismantle physician-led team-based health care models.” He also stated that “the AAFP strongly opposes the unprecedented proposal to dismiss state practice authority regarding the authority of NPs.”6

Unprecedented? I don’t think so. I practiced as a family NP in the Navy for more than 20 years. I had my own patient panel, cared for active duty members and their families, and evaluated outcomes the same way my physician colleagues did. We practiced collaboratively and respectfully. We discussed patient plan issues, provided peer review on one another’s charts, and accepted new patients into our panels. It was a true collaborative practice.

Military nurses only need to be licensed in one state. The guidelines for NP practice were not based on the rules of the state in which we were licensed but were established by our professional practice association—just as the guidelines for physician practice were not based on the rules extant in their licensing state. I practiced successfully in many states and overseas, although I was licensed in a state that did not recognize plenary practice at the time.

The VA is attempting to respond to veterans’ need for access to care by adopting a model similar to what the military employs. It’s not a matter of superseding state regulations; it’s a matter of recognizing the education and training of health care professionals who can improve patient outcomes.

The opportunity to respond to the proposed amendment has now closed. Through its grassroots Veterans Deserve Care campaign, the AANP and its partners and supporters—clinicians, veterans, families, and others—submitted nearly 60,000 comments.2 Now we wait for the VA to review the abundance of feedback and issue their final decision.

I am hopeful that the VA will acknowledge the overwhelming evidence that our veterans deserve access to care led by highly qualified professionals. The old system isn’t working. Einstein said that the definition of insanity was to do the same thing over and over and expect a different outcome; maintaining a faulty system fits that description. NPs have a well-tested, evidence-based, high-quality education that encourages their ability to lead health care teams, perform collaboratively, and improve outcomes for those who have served our country.

Caring for active duty military and veterans is in the DNA of nurses. Florence Nightingale spent much of her post-Crimea life using evidence-based proposals and political influence to improve the health care of the soldiers and veterans of the British Empire. In Notes on Nursing, she spurred nurses to political action: “Let whoever [sic] is in charge keep this simple question in her [sic] head (not how can I always do this right thing myself, but) how can I provide for this right thing to be always done?”7 This advice should be taken to heart by all health care professionals: We can honor our veterans by advocating for and providing the health care access they need.

To share your thoughts, please contact us at [email protected]

1. Advanced practice registered nurses [2016-12338]. Fed Regist. May 25, 2016. https://federalregister.gov/a/2016-12338.

2. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. AANP and Air Force Sergeants Association urge VA to swiftly enact proposed rule. July 25, 2016. www.aanp.org/legislation-regu lation/federal-legislation/va-proposed-rule/173-press-room/2016-press-releases/ 1987-aanp-and-air-force-sergeants-associa tion-urge-va-to-swiftly-enact-proposed-rule. Accessed August 9, 2016.

3. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. AANP and veterans groups call for streamlined access to veteran’s health care. June 23, 2016. www.aanp.org/press-room/press-releases/173-press-room/2016-press-releases/1959-aanp-veteran-groups-call-for-streamlined-access-to-veterans-health-care. Accessed August 9, 2016.

4. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. National survey finds overwhelming support for VA rule granting veterans direct access to nurse practitioner care. July 20, 2016. www.aanp.org/press-room/press-releases/173-press-room/2016-press-releases/1986-national-survey-finds-overwhelming-support-for-va-rule-granting-veterans-direct-access-to-nurse-practition er-care. Accessed August 9, 2016.

5. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. Nursing coalition and veterans groups join forces in unprecedented response to VA proposed rule to increase veterans’ access to care. June 28, 2016. www.aana.com/newsandjournal/News/Pages/062816-Nursing-Coalition-and-Veterans-Groups-Join-Forces-in-Unprecedented-Response-to-VA-Proposed-Rule.aspx. Accessed August 9, 2016.

6. Wergin RL. Letter to David Shulkin. July 13, 2016. www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/docu ments/advocacy/workforce/scope/LT-VHA-APRN-071316.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016 .

7. Nightingale F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company; 1860.

1. Advanced practice registered nurses [2016-12338]. Fed Regist. May 25, 2016. https://federalregister.gov/a/2016-12338.

2. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. AANP and Air Force Sergeants Association urge VA to swiftly enact proposed rule. July 25, 2016. www.aanp.org/legislation-regu lation/federal-legislation/va-proposed-rule/173-press-room/2016-press-releases/ 1987-aanp-and-air-force-sergeants-associa tion-urge-va-to-swiftly-enact-proposed-rule. Accessed August 9, 2016.

3. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. AANP and veterans groups call for streamlined access to veteran’s health care. June 23, 2016. www.aanp.org/press-room/press-releases/173-press-room/2016-press-releases/1959-aanp-veteran-groups-call-for-streamlined-access-to-veterans-health-care. Accessed August 9, 2016.

4. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. National survey finds overwhelming support for VA rule granting veterans direct access to nurse practitioner care. July 20, 2016. www.aanp.org/press-room/press-releases/173-press-room/2016-press-releases/1986-national-survey-finds-overwhelming-support-for-va-rule-granting-veterans-direct-access-to-nurse-practition er-care. Accessed August 9, 2016.

5. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. Nursing coalition and veterans groups join forces in unprecedented response to VA proposed rule to increase veterans’ access to care. June 28, 2016. www.aana.com/newsandjournal/News/Pages/062816-Nursing-Coalition-and-Veterans-Groups-Join-Forces-in-Unprecedented-Response-to-VA-Proposed-Rule.aspx. Accessed August 9, 2016.

6. Wergin RL. Letter to David Shulkin. July 13, 2016. www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/docu ments/advocacy/workforce/scope/LT-VHA-APRN-071316.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016 .

7. Nightingale F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company; 1860.

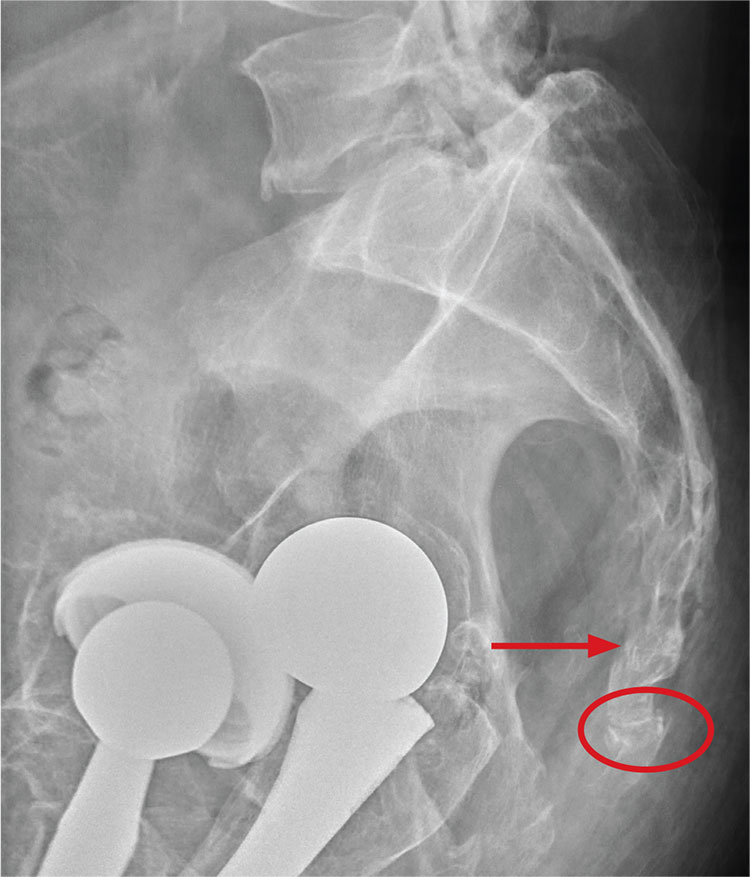

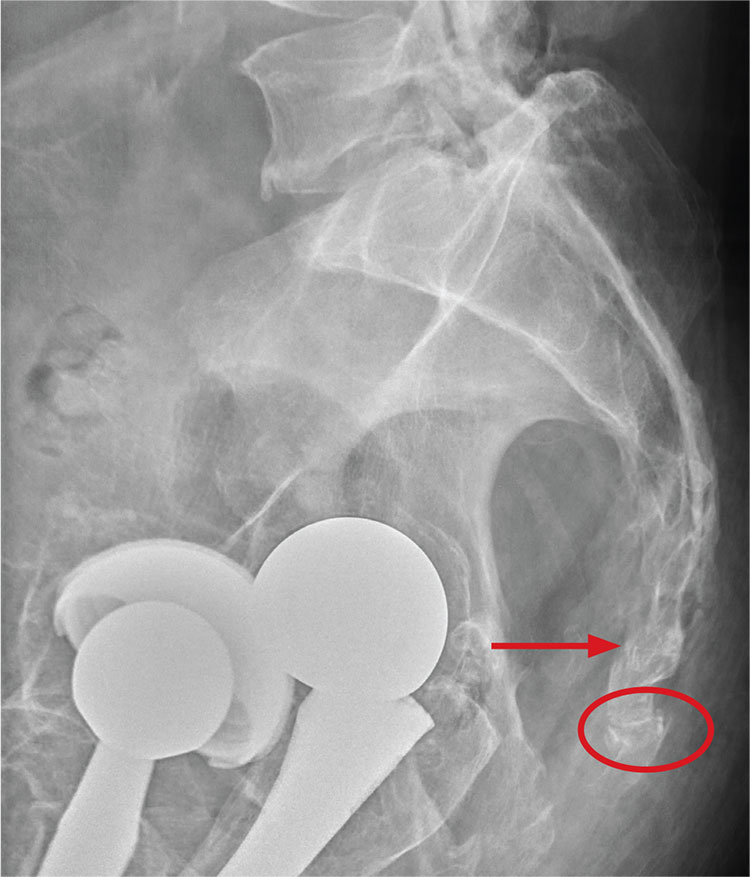

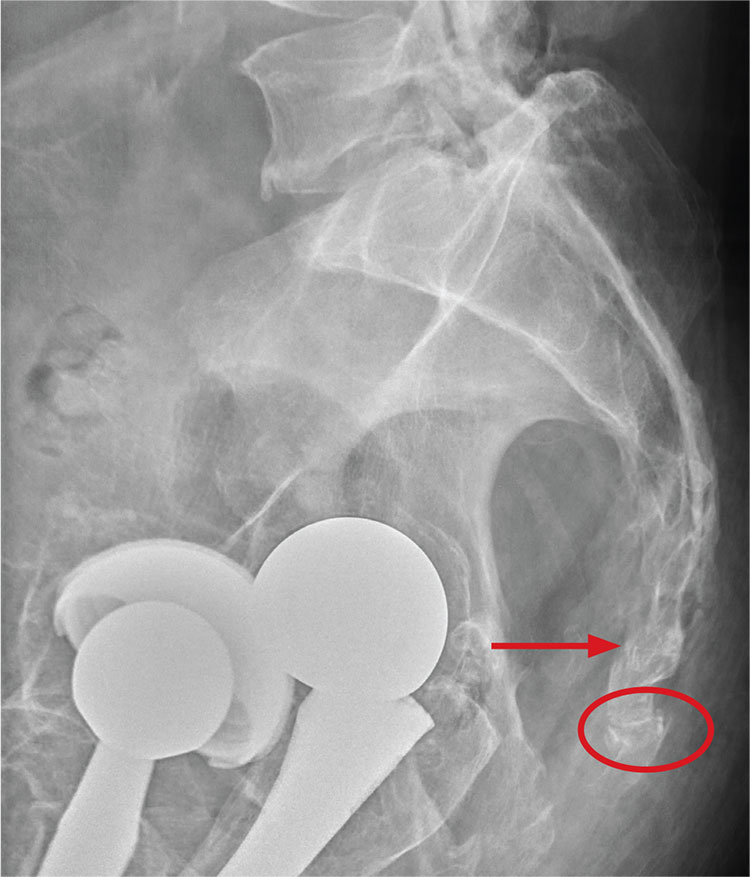

When Man’s Legs “Give Out,” His Buttocks Takes the Brunt

ANSWER

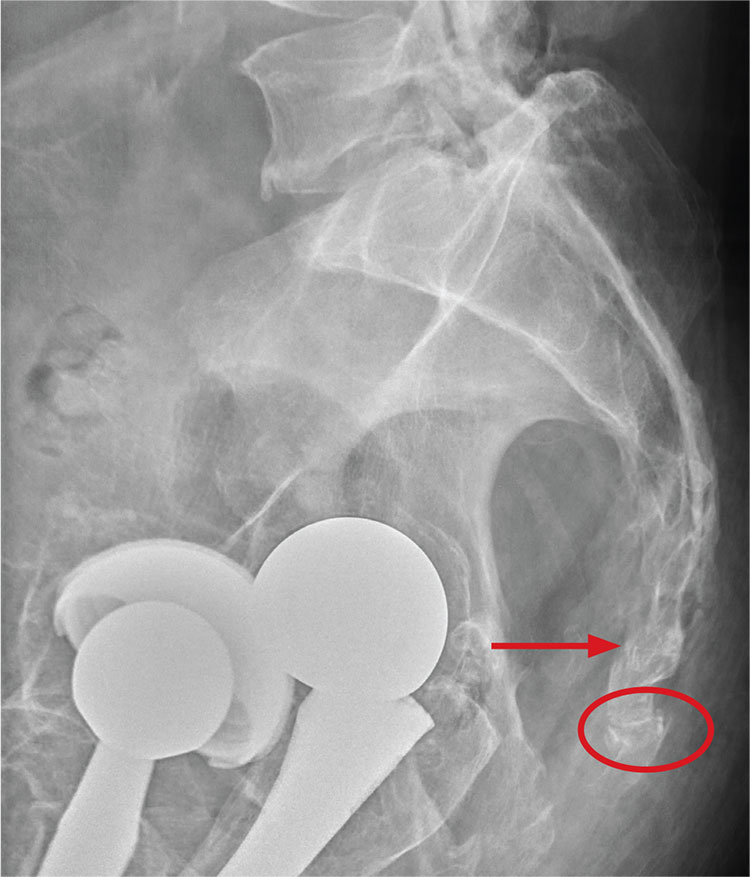

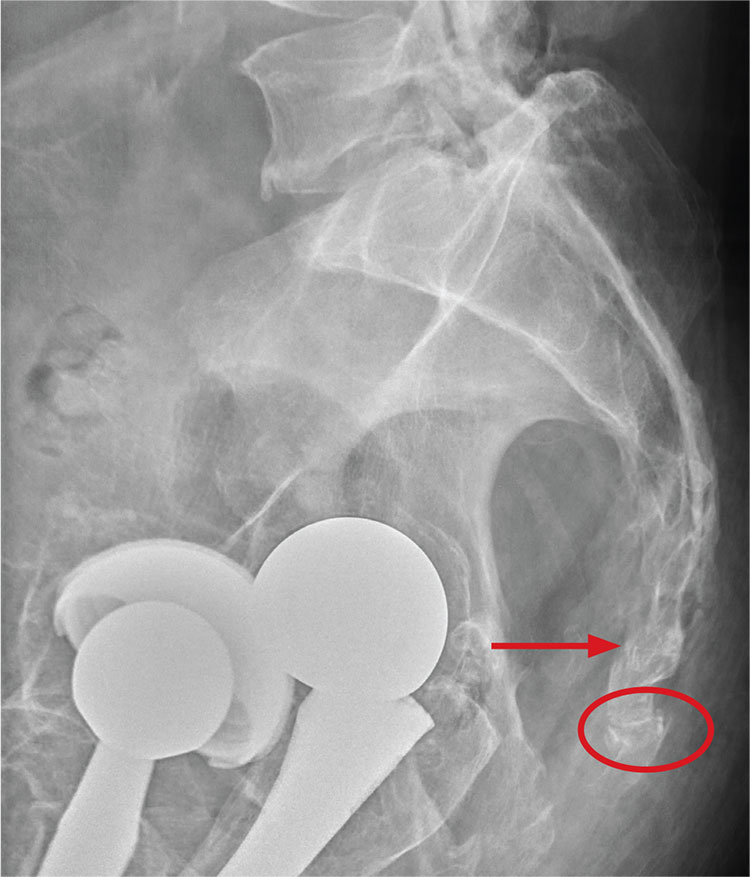

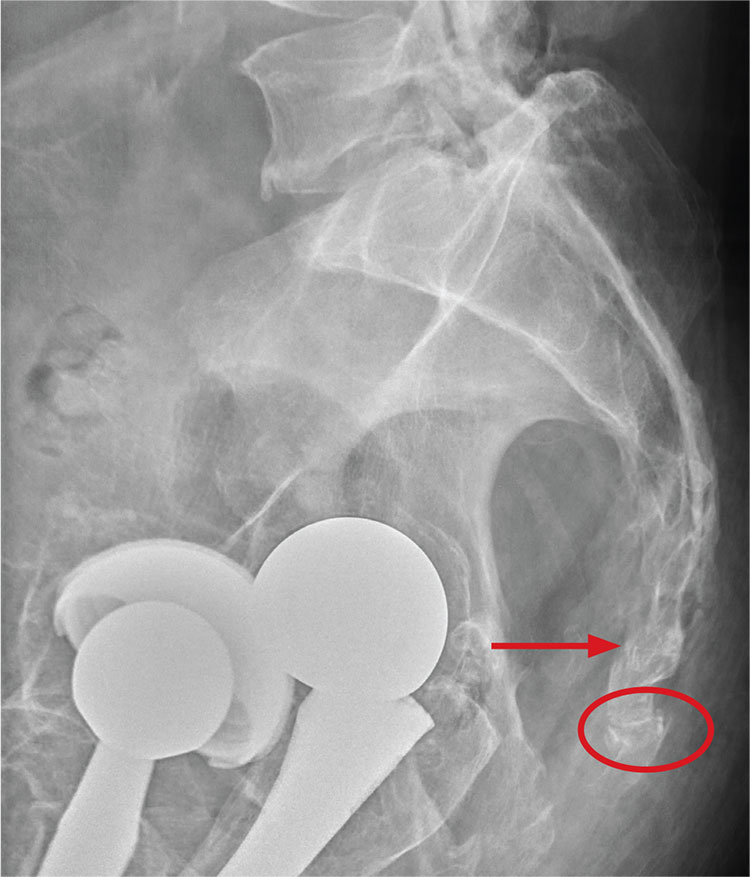

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

ANSWER

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

ANSWER

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

A 75-year-old man presents to the urgent care center for evaluation of pain in his buttocks after a fall. He states he was walking when his “legs gave out” and he hit the ground. He landed squarely on his buttocks, causing immediate pain. He was eventually able to get up with some assistance. He denies current weakness or any bowel or bladder complaints.

His medical/surgical history is significant for coronary artery disease, hypertension, and bilateral hip replacements. Physical exam reveals an elderly male who is uncomfortable but in no obvious distress. His vital signs are stable. He has moderate point tenderness over his sacrum but is able to move all his extremities well, with normal strength.

Radiograph of his sacrum/coccyx is shown. What is your impression?

Maybe it is all in your head

Origin of pain: Brain vs body. Recent research provides strong evidence that in some cases of intractable chronic pain, the origin of the pain signal is in the brain—rather than the body. In this issue of JFP, Davis and Vanderah discuss this type of pain as “a third kind” that needs to be treated in a manner that completely differs from that for peripherally generated pain. They refer to the traditional kinds of pain as either nociceptive (resulting from tissue damage or insult), or neuropathic (due to dysfunctional stimulation of peripheral nerves). The neurophysiology of the third kind of pain, which I will call “centrally generated pain,” is not fully understood, but neuroimaging and other sophisticated methods are identifying areas of the brain that become activated by psychological trauma, leading to significant painful suffering in the absence of tissue damage, or that is far out of proportion to physical insult.

The bad news for primary care physicians is that this third kind of pain is difficult, if not impossible, to treat with our traditional armamentarium of pain medications and physical modalities. In fact, these patients are often at risk for addiction, as doses of ineffective narcotics are escalated.

The good news is that clinical researchers have begun to identify ways to effectively treat centrally generated pain. For example, Schubiner et al used a novel psychological approach that involved helping patients "learn that their pain is influenced primarily by central nervous system psychological processes, and to enhance awareness and expression of emotions related to psychological trauma or conflict."1 Thirty percent of the 72 participants in the preliminary, uncontrolled trial experienced a 70% reduction in pain. Dr. Schubiner’s research is ongoing and supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Proper diagnosis is paramount. Of course, proper diagnosis is paramount because an individual may suffer from more than one of the 3 kinds of pain and require different approaches for each. Thorough evaluation at a multidisciplinary pain clinic is a good place to start. Once the diagnoses are sorted out, it will then be possible to treat each component of pain appropriately.

Dr. Schubiner’s methods and other new and developing treatment approaches to chronic pain will help us better relieve patients’ suffering, reduce narcotic overuse, and relieve our own anxiety about caring for these challenging patients.

1. Burger AJ, Lumley MA, Carty JN, et al. The effects of a novel psychological attribution and emotional awareness and expression therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a preliminary, uncontrolled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2016;81:1-8.

Origin of pain: Brain vs body. Recent research provides strong evidence that in some cases of intractable chronic pain, the origin of the pain signal is in the brain—rather than the body. In this issue of JFP, Davis and Vanderah discuss this type of pain as “a third kind” that needs to be treated in a manner that completely differs from that for peripherally generated pain. They refer to the traditional kinds of pain as either nociceptive (resulting from tissue damage or insult), or neuropathic (due to dysfunctional stimulation of peripheral nerves). The neurophysiology of the third kind of pain, which I will call “centrally generated pain,” is not fully understood, but neuroimaging and other sophisticated methods are identifying areas of the brain that become activated by psychological trauma, leading to significant painful suffering in the absence of tissue damage, or that is far out of proportion to physical insult.

The bad news for primary care physicians is that this third kind of pain is difficult, if not impossible, to treat with our traditional armamentarium of pain medications and physical modalities. In fact, these patients are often at risk for addiction, as doses of ineffective narcotics are escalated.

The good news is that clinical researchers have begun to identify ways to effectively treat centrally generated pain. For example, Schubiner et al used a novel psychological approach that involved helping patients "learn that their pain is influenced primarily by central nervous system psychological processes, and to enhance awareness and expression of emotions related to psychological trauma or conflict."1 Thirty percent of the 72 participants in the preliminary, uncontrolled trial experienced a 70% reduction in pain. Dr. Schubiner’s research is ongoing and supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Proper diagnosis is paramount. Of course, proper diagnosis is paramount because an individual may suffer from more than one of the 3 kinds of pain and require different approaches for each. Thorough evaluation at a multidisciplinary pain clinic is a good place to start. Once the diagnoses are sorted out, it will then be possible to treat each component of pain appropriately.

Dr. Schubiner’s methods and other new and developing treatment approaches to chronic pain will help us better relieve patients’ suffering, reduce narcotic overuse, and relieve our own anxiety about caring for these challenging patients.

1. Burger AJ, Lumley MA, Carty JN, et al. The effects of a novel psychological attribution and emotional awareness and expression therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a preliminary, uncontrolled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2016;81:1-8.

Origin of pain: Brain vs body. Recent research provides strong evidence that in some cases of intractable chronic pain, the origin of the pain signal is in the brain—rather than the body. In this issue of JFP, Davis and Vanderah discuss this type of pain as “a third kind” that needs to be treated in a manner that completely differs from that for peripherally generated pain. They refer to the traditional kinds of pain as either nociceptive (resulting from tissue damage or insult), or neuropathic (due to dysfunctional stimulation of peripheral nerves). The neurophysiology of the third kind of pain, which I will call “centrally generated pain,” is not fully understood, but neuroimaging and other sophisticated methods are identifying areas of the brain that become activated by psychological trauma, leading to significant painful suffering in the absence of tissue damage, or that is far out of proportion to physical insult.

The bad news for primary care physicians is that this third kind of pain is difficult, if not impossible, to treat with our traditional armamentarium of pain medications and physical modalities. In fact, these patients are often at risk for addiction, as doses of ineffective narcotics are escalated.

The good news is that clinical researchers have begun to identify ways to effectively treat centrally generated pain. For example, Schubiner et al used a novel psychological approach that involved helping patients "learn that their pain is influenced primarily by central nervous system psychological processes, and to enhance awareness and expression of emotions related to psychological trauma or conflict."1 Thirty percent of the 72 participants in the preliminary, uncontrolled trial experienced a 70% reduction in pain. Dr. Schubiner’s research is ongoing and supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Proper diagnosis is paramount. Of course, proper diagnosis is paramount because an individual may suffer from more than one of the 3 kinds of pain and require different approaches for each. Thorough evaluation at a multidisciplinary pain clinic is a good place to start. Once the diagnoses are sorted out, it will then be possible to treat each component of pain appropriately.

Dr. Schubiner’s methods and other new and developing treatment approaches to chronic pain will help us better relieve patients’ suffering, reduce narcotic overuse, and relieve our own anxiety about caring for these challenging patients.

1. Burger AJ, Lumley MA, Carty JN, et al. The effects of a novel psychological attribution and emotional awareness and expression therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a preliminary, uncontrolled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2016;81:1-8.

Why did testing stop at EKG—especially given family history? ... More

Why did testing stop at EKG—especially given family history?

AFTER COMPLAINING OF CHEST PAIN, a 37-year-old man underwent an electrocardiogram (EKG) examination. The doctor concluded that the pain was not cardiac in nature. Two years later, the patient died of a sudden cardiac event associated with coronary atherosclerotic disease.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The decedent suffered from high cholesterol and had a family history of cardiac issues, yet no additional testing was performed when the patient’s complaints continued.

THE DEFENSE No information on the defense is available.

VERDICT $3 million settlement.

COMMENT This is déjà vu for me. A colleague of mine had a nearly identical case a few years ago, but the patient died several days later. In the case described here, the high cholesterol and family history were red flags. A normal EKG does not rule out angina. I do wonder what happened, however, in the 2 years between the office visit and the patient’s sudden death. The chest pain at the office visit may well have been non-cardiac, but it appears the jury was not convinced.

2 FPs overlook boy’s proteinuria; delay in Dx costs him a kidney

AN 11-YEAR-OLD BOY underwent a laparoscopic appendectomy that included a urinalysis. Following the surgery, the surgeon notified the family physician (FP) that the patient’s urinalysis showed >300 mg/dL of protein. The result was unusual and required follow-up. The surgeon felt that the urinalysis result might be related to the proximity of the appendicitis to the boy’s ureter. The boy was evaluated on several other occasions by the FP, but no work-up was performed.

Three years later, the boy saw a different FP, who noted that the child had elevated blood pressure and blurry vision—among other symptoms. The boy’s renal function tests were documented as abnormal; however, the patient and his mother were never notified of this. Also, the patient was never referred to a nephrologist or neurologist and there was no intervention for a potential kidney abnormality.

Two years later, an associate of the FP ordered further blood tests that showed a clear abnormality with regard to the integrity of the child’s kidney function. The boy was evaluated at a hospital and diagnosed with end-stage renal disease. He received a kidney transplant 3 months later and requires lifetime medical care as a result of the transplant. The boy will likely require further transplants in 10-year increments.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM Both FPs deviated from the accepted standard of care when they failed to order further testing as a result of the abnormal laboratory tests. Earlier intervention may have prolonged the life of the boy’s kidney, thereby postponing the need for kidney replacements.

THE DEFENSE No information on the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.25 million Massachusetts settlement.

COMMENT 300 mg/dL is a significant amount of proteinuria and requires further testing. Why didn’t the FP follow up? Was a summary of the hospitalization sent to him/her? Certainly the diagnosis should have been made by the second FP, and the patient should’ve been referred to a nephrologist. A lawsuit would most likely have been averted had this happened. Delayed diagnosis accounts for a high proportion of malpractice suits against FPs.

Duodenal ulcer mistakenly attributed to Crohn’s disease

A 47-YEAR-OLD MAN with a history of Crohn’s disease began experiencing persistent abdominal pain. He hadn’t had symptoms of his Crohn’s disease in over 12 years. Nevertheless, doctors diagnosed his pain as an aggravation of the disease and gave him treatment based on this diagnosis. In fact, though, the man had an acute duodenal ulcer that had progressed and perforated. The patient underwent 12 surgeries (with complications) and almost 2 years of near-constant hospitalization as a result of the misdiagnosis. He now requires 24-hour care in all aspects of his life.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The doctors were negligent in their failure to consider and diagnose a peptic ulcer when the plaintiff’s symptoms indicated issues other than Crohn’s disease.

THE DEFENSE No information on the defense is available.

VERDICT $28 million Maryland verdict.

COMMENT I suspect this was a tough diagnosis, given the patient’s prior history of Crohn’s disease. We are not told the nature of the abdominal pain. If the patient had classic epigastric pain, peptic ulcer disease should have been investigated. This case serves as a reminder that patients can have more than one disease of an organ system, and it reminds us of the need for a careful history and close follow-up if a complaint does not resolve.

Why did testing stop at EKG—especially given family history?

AFTER COMPLAINING OF CHEST PAIN, a 37-year-old man underwent an electrocardiogram (EKG) examination. The doctor concluded that the pain was not cardiac in nature. Two years later, the patient died of a sudden cardiac event associated with coronary atherosclerotic disease.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The decedent suffered from high cholesterol and had a family history of cardiac issues, yet no additional testing was performed when the patient’s complaints continued.

THE DEFENSE No information on the defense is available.

VERDICT $3 million settlement.

COMMENT This is déjà vu for me. A colleague of mine had a nearly identical case a few years ago, but the patient died several days later. In the case described here, the high cholesterol and family history were red flags. A normal EKG does not rule out angina. I do wonder what happened, however, in the 2 years between the office visit and the patient’s sudden death. The chest pain at the office visit may well have been non-cardiac, but it appears the jury was not convinced.

2 FPs overlook boy’s proteinuria; delay in Dx costs him a kidney

AN 11-YEAR-OLD BOY underwent a laparoscopic appendectomy that included a urinalysis. Following the surgery, the surgeon notified the family physician (FP) that the patient’s urinalysis showed >300 mg/dL of protein. The result was unusual and required follow-up. The surgeon felt that the urinalysis result might be related to the proximity of the appendicitis to the boy’s ureter. The boy was evaluated on several other occasions by the FP, but no work-up was performed.

Three years later, the boy saw a different FP, who noted that the child had elevated blood pressure and blurry vision—among other symptoms. The boy’s renal function tests were documented as abnormal; however, the patient and his mother were never notified of this. Also, the patient was never referred to a nephrologist or neurologist and there was no intervention for a potential kidney abnormality.

Two years later, an associate of the FP ordered further blood tests that showed a clear abnormality with regard to the integrity of the child’s kidney function. The boy was evaluated at a hospital and diagnosed with end-stage renal disease. He received a kidney transplant 3 months later and requires lifetime medical care as a result of the transplant. The boy will likely require further transplants in 10-year increments.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM Both FPs deviated from the accepted standard of care when they failed to order further testing as a result of the abnormal laboratory tests. Earlier intervention may have prolonged the life of the boy’s kidney, thereby postponing the need for kidney replacements.

THE DEFENSE No information on the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.25 million Massachusetts settlement.

COMMENT 300 mg/dL is a significant amount of proteinuria and requires further testing. Why didn’t the FP follow up? Was a summary of the hospitalization sent to him/her? Certainly the diagnosis should have been made by the second FP, and the patient should’ve been referred to a nephrologist. A lawsuit would most likely have been averted had this happened. Delayed diagnosis accounts for a high proportion of malpractice suits against FPs.

Duodenal ulcer mistakenly attributed to Crohn’s disease

A 47-YEAR-OLD MAN with a history of Crohn’s disease began experiencing persistent abdominal pain. He hadn’t had symptoms of his Crohn’s disease in over 12 years. Nevertheless, doctors diagnosed his pain as an aggravation of the disease and gave him treatment based on this diagnosis. In fact, though, the man had an acute duodenal ulcer that had progressed and perforated. The patient underwent 12 surgeries (with complications) and almost 2 years of near-constant hospitalization as a result of the misdiagnosis. He now requires 24-hour care in all aspects of his life.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The doctors were negligent in their failure to consider and diagnose a peptic ulcer when the plaintiff’s symptoms indicated issues other than Crohn’s disease.

THE DEFENSE No information on the defense is available.

VERDICT $28 million Maryland verdict.

COMMENT I suspect this was a tough diagnosis, given the patient’s prior history of Crohn’s disease. We are not told the nature of the abdominal pain. If the patient had classic epigastric pain, peptic ulcer disease should have been investigated. This case serves as a reminder that patients can have more than one disease of an organ system, and it reminds us of the need for a careful history and close follow-up if a complaint does not resolve.

Why did testing stop at EKG—especially given family history?

AFTER COMPLAINING OF CHEST PAIN, a 37-year-old man underwent an electrocardiogram (EKG) examination. The doctor concluded that the pain was not cardiac in nature. Two years later, the patient died of a sudden cardiac event associated with coronary atherosclerotic disease.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The decedent suffered from high cholesterol and had a family history of cardiac issues, yet no additional testing was performed when the patient’s complaints continued.

THE DEFENSE No information on the defense is available.

VERDICT $3 million settlement.

COMMENT This is déjà vu for me. A colleague of mine had a nearly identical case a few years ago, but the patient died several days later. In the case described here, the high cholesterol and family history were red flags. A normal EKG does not rule out angina. I do wonder what happened, however, in the 2 years between the office visit and the patient’s sudden death. The chest pain at the office visit may well have been non-cardiac, but it appears the jury was not convinced.

2 FPs overlook boy’s proteinuria; delay in Dx costs him a kidney

AN 11-YEAR-OLD BOY underwent a laparoscopic appendectomy that included a urinalysis. Following the surgery, the surgeon notified the family physician (FP) that the patient’s urinalysis showed >300 mg/dL of protein. The result was unusual and required follow-up. The surgeon felt that the urinalysis result might be related to the proximity of the appendicitis to the boy’s ureter. The boy was evaluated on several other occasions by the FP, but no work-up was performed.

Three years later, the boy saw a different FP, who noted that the child had elevated blood pressure and blurry vision—among other symptoms. The boy’s renal function tests were documented as abnormal; however, the patient and his mother were never notified of this. Also, the patient was never referred to a nephrologist or neurologist and there was no intervention for a potential kidney abnormality.

Two years later, an associate of the FP ordered further blood tests that showed a clear abnormality with regard to the integrity of the child’s kidney function. The boy was evaluated at a hospital and diagnosed with end-stage renal disease. He received a kidney transplant 3 months later and requires lifetime medical care as a result of the transplant. The boy will likely require further transplants in 10-year increments.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM Both FPs deviated from the accepted standard of care when they failed to order further testing as a result of the abnormal laboratory tests. Earlier intervention may have prolonged the life of the boy’s kidney, thereby postponing the need for kidney replacements.

THE DEFENSE No information on the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.25 million Massachusetts settlement.

COMMENT 300 mg/dL is a significant amount of proteinuria and requires further testing. Why didn’t the FP follow up? Was a summary of the hospitalization sent to him/her? Certainly the diagnosis should have been made by the second FP, and the patient should’ve been referred to a nephrologist. A lawsuit would most likely have been averted had this happened. Delayed diagnosis accounts for a high proportion of malpractice suits against FPs.

Duodenal ulcer mistakenly attributed to Crohn’s disease

A 47-YEAR-OLD MAN with a history of Crohn’s disease began experiencing persistent abdominal pain. He hadn’t had symptoms of his Crohn’s disease in over 12 years. Nevertheless, doctors diagnosed his pain as an aggravation of the disease and gave him treatment based on this diagnosis. In fact, though, the man had an acute duodenal ulcer that had progressed and perforated. The patient underwent 12 surgeries (with complications) and almost 2 years of near-constant hospitalization as a result of the misdiagnosis. He now requires 24-hour care in all aspects of his life.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The doctors were negligent in their failure to consider and diagnose a peptic ulcer when the plaintiff’s symptoms indicated issues other than Crohn’s disease.

THE DEFENSE No information on the defense is available.

VERDICT $28 million Maryland verdict.

COMMENT I suspect this was a tough diagnosis, given the patient’s prior history of Crohn’s disease. We are not told the nature of the abdominal pain. If the patient had classic epigastric pain, peptic ulcer disease should have been investigated. This case serves as a reminder that patients can have more than one disease of an organ system, and it reminds us of the need for a careful history and close follow-up if a complaint does not resolve.

Need-to-know information for the 2016-2017 flu season

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) took the unusual step at its June 2016 meeting of recommending against using a currently licensed vaccine, live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), in the 2016-2017 influenza season.1 ACIP based its recommendation on surveillance data collected by the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which showed poor effectiveness by the LAIV vaccine among children and adolescents during the past 3 years.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), however, has chosen not to take any action on this matter, saying on its Web site it “has determined that specific regulatory action is not warranted at this time. This determination is based on FDA’s review of manufacturing and clinical data supporting licensure … the totality of the evidence presented at the ACIP meeting, taking into account the inherent limitations of observational studies conducted to evaluate influenza vaccine effectiveness, as well as the well-known variability of influenza vaccine effectiveness across influenza seasons.”2

CDC data for the 2015-2016 flu season showed the effectiveness of LAIV to be just 3% among children 2 years through 17 years of age.3 The reason for this apparent lack of effectiveness is unknown. Other LAIV-effectiveness studies conducted in the 2015-2016 season—one each, in the United States, United Kingdom, and Finland—had results that differed from the CDC surveillance data, with effectiveness ranging from 46% to 58% against all strains combined.2 These results are comparable to vaccine effectiveness found in observational studies in children for both LAIV and inactivated influenza vaccines (IIV) in prior seasons.2

Vaccine manufacturers had projected that 171 to 176 million doses of flu vaccine, in all forms, would be available in the United States during the 2016-2017 season.3 LAIV accounts for about 8% of the total supply of influenza vaccine in the United States,3 and ACIP’s recommendation is not expected to create shortages of other options for the upcoming season. However, the LAIV accounts for one-third of flu vaccines administered to children, and clinicians who provide vaccinations to children have already ordered their vaccine supplies for the upcoming season. Also, it is not clear if children who have previously received the LAIV product will now accept other options for influenza vaccination—all of which involve an injection.

Whether the recommendation against LAIV will continue after this season is also unknown.

What happened during the 2015-2016 influenza season?

The 2015-2016 influenza season was relatively mild with the peak activity occurring in March, somewhat later than in previous years. The circulating influenza strains matched closely to those in the vaccine, making it more effective than the previous year’s vaccine. The predominant circulating strain was A (H1N1), accounting for 58% of illness; A (H3N2) caused 6% of cases and all B types together accounted for 34%.4 The hospitalization rate for all ages was 31.3/100,000 compared with 64.1 the year before.5 There were 85 pediatric deaths compared with 148 in 2014-2015.6

Vaccine effectiveness among all age groups and against all circulating strains was 47%.4 No major vaccine safety concerns were detected. Among those who received IIV3, there was a slight increase in the incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome of 2.6 cases per one million vaccines.7

Other recommendations for 2016-2017

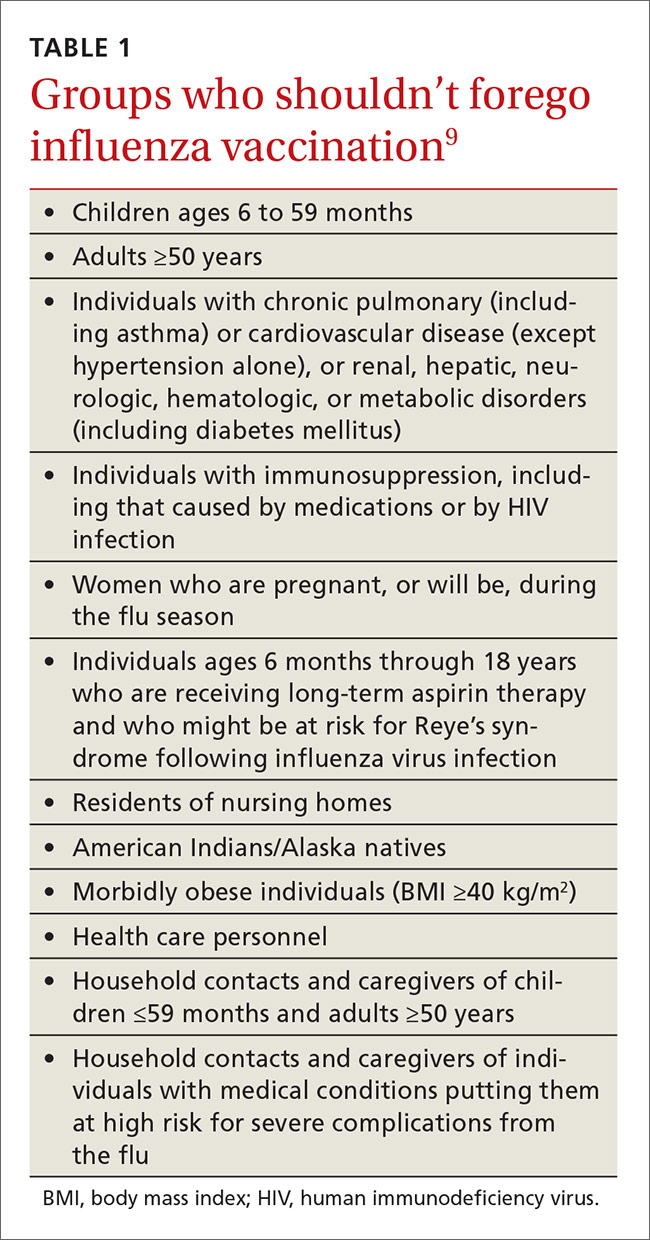

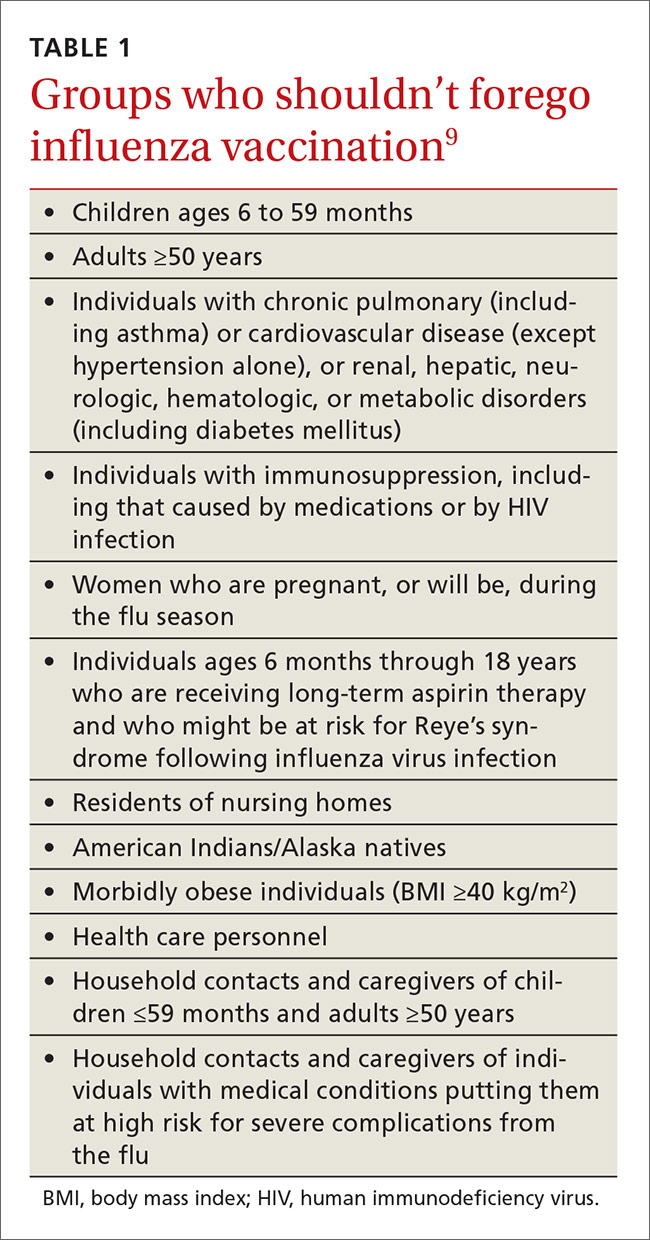

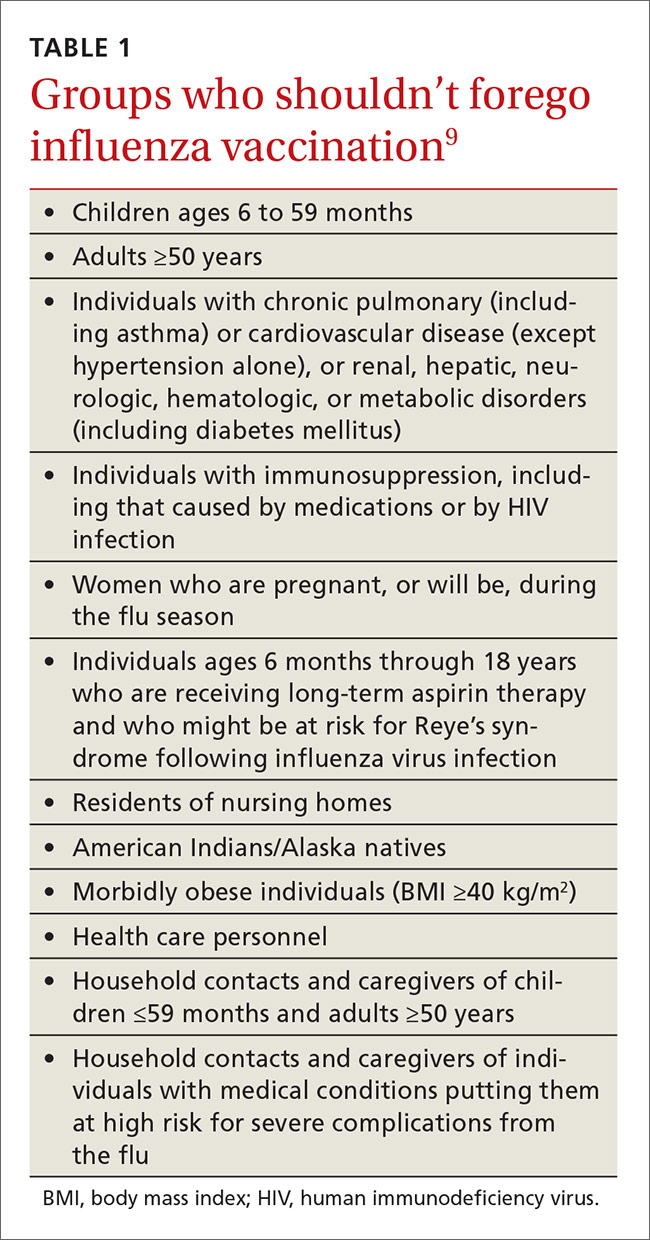

Once again, ACIP recommends influenza vaccine for all individuals 6 months and older.8 The CDC additionally specifies particular groups that should not skip vaccination given that they are at high risk of complications from influenza infection or because they could expose high-risk individuals to infection (TABLE 1).9

There will continue to be a selection of trivalent and quadrivalent influenza vaccine products in 2016-2017. Trivalent products will contain 3 viral strains: A/California/7/2009 (H1N1), A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2) and B/Brisbane/60/2008.10 The quadrivalent products will contain those 3 antigens plus B/Phuket/3073/2013.10 The H3N2 strain is different from the one in last year’s vaccine. Each year, influenza experts analyze surveillance data to predict which circulating strains will predominate in North America, and these antigens constitute the vaccine formulation. The accuracy of this prediction in large part determines how effective the vaccine will be that season.

Two new vaccines have been approved for use in the United States. A quadrivalent cell culture inactivated vaccine (CCIV4), Flucelvax, was licensed in May 2016. It is prepared from virus propagated in canine kidney cells, not with an egg-based production process. It is approved for use in individuals 4 years of age and older.8 Fluad, an adjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, was licensed in late 2015 for individuals 65 years of age and older.8 This is the first adjuvanted influenza vaccine licensed in the United States and will compete with high-dose quadrivalent vaccine for use in older adults. ACIP does not express a preference for any vaccine in this age group.

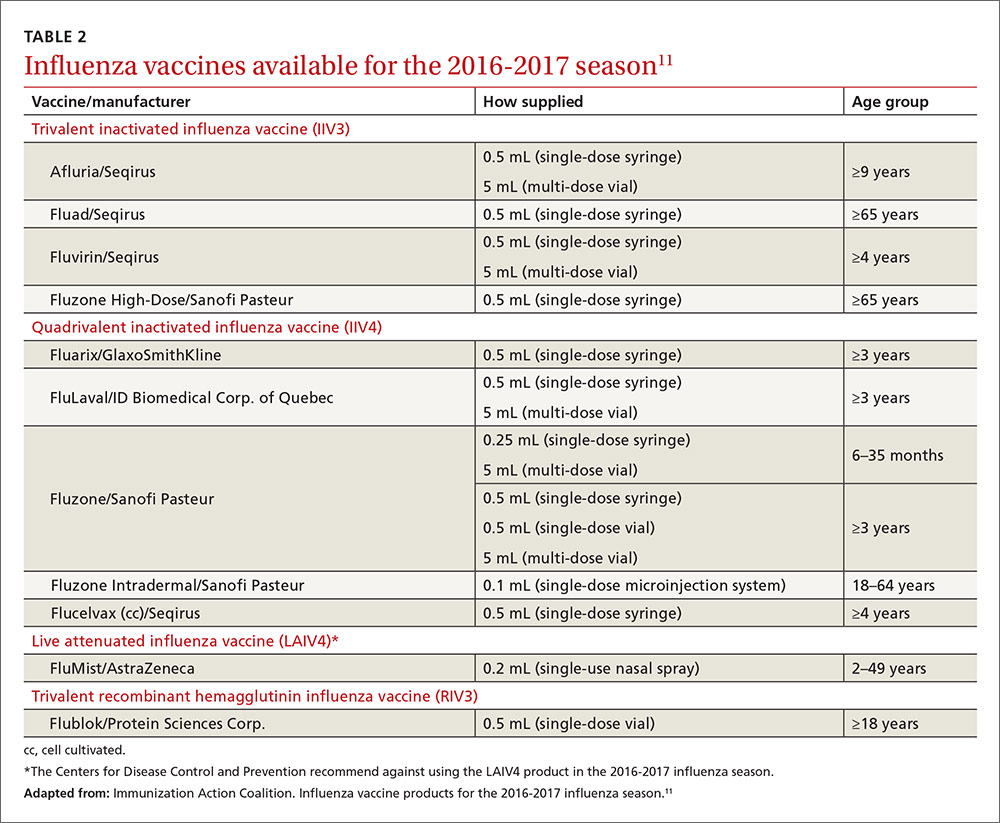

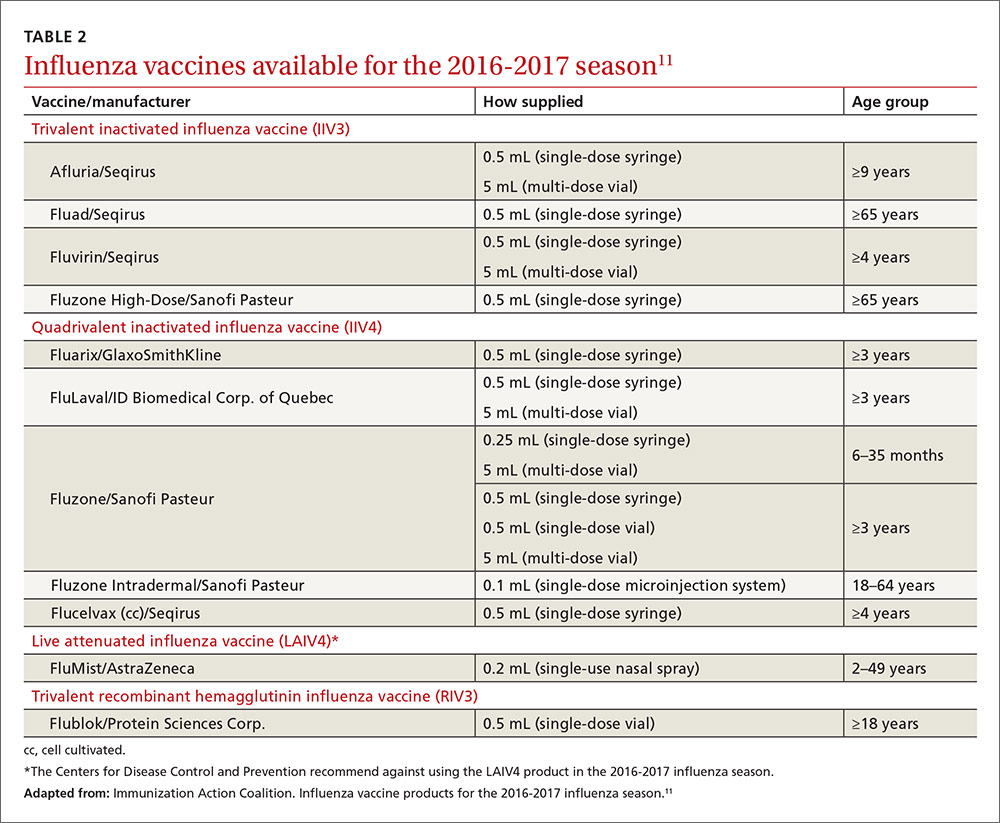

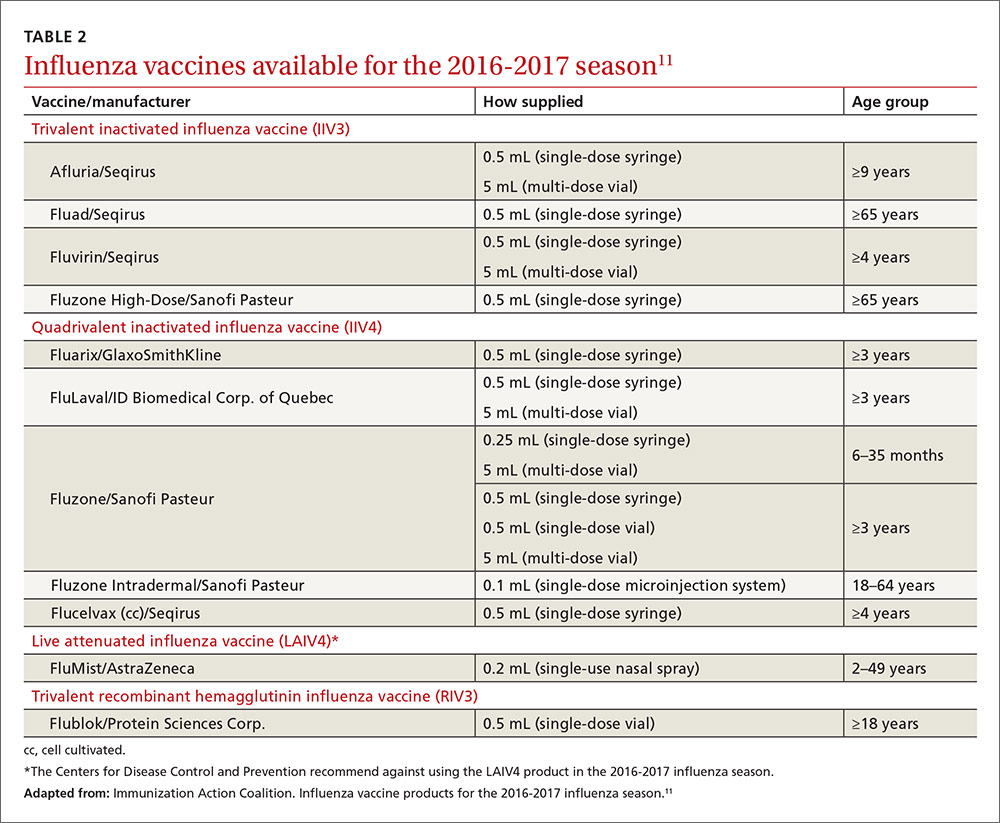

Two other vaccines should also be available by this fall: Flublok, a quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine for individuals 18 years and older, and Flulaval, a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, for individuals 6 months of age and older. TABLE 211 lists approved influenza vaccines.

Issues specific to children

Deciding how many vaccine doses children need has been further simplified. Children younger than 9 years need 2 doses if they have received fewer than 2 doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2016. The interval between the 2 doses should be at least 4 weeks. The 2 doses do not have to be the same product; importantly, do not delay a second dose just to obtain the same product used for the first dose. Also, one dose can be trivalent and the other one quadrivalent, although this offers less-than-optimal protection against the B-virus that is only in the quadrivalent product.

Children younger than 9 years require only one dose if they have received 2 or more total doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2016. The 2 previous doses need not have been received during the same influenza season or consecutive influenza seasons.

In children ages 6 through 23 months there is a slight increased risk of febrile seizure if the influenza vaccine is co-administered with other vaccines, specifically pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV 13) and diphtheria-tetanus-acellular-pertussis (DTaP). The 3 vaccines administered at the same time result in 30 febrile seizures per 100,000 children;12 the rate is lower when influenza vaccine is co-administered with only one of the others. ACIP believes that the risk of a febrile seizure, which does no long-term harm, does not warrant delaying vaccines that could be co-administered.13

Egg allergy requires no special precautions

Evidence continues to grow that influenza vaccine products do not contain enough egg protein to cause significant problems in those with a history of egg allergies. This year’s recommendations state that no special precautions are needed regarding the anatomic site of immunization or the length of observation after administering influenza vaccine in those with a history of allergies to eggs, no matter how severe. All vaccine-administration facilities should be able to respond to any hypersensitivity reaction, and the standard waiting time for observation after all vaccinations is 15 minutes.

Antiviral medications for treatment or prevention

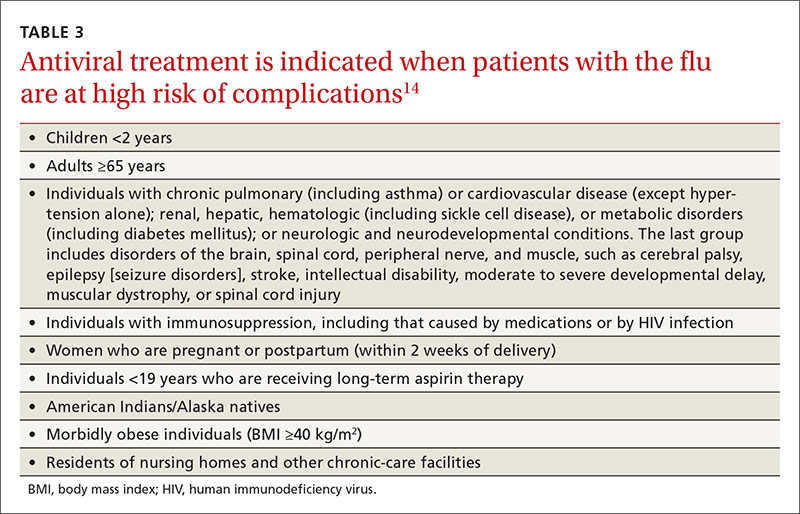

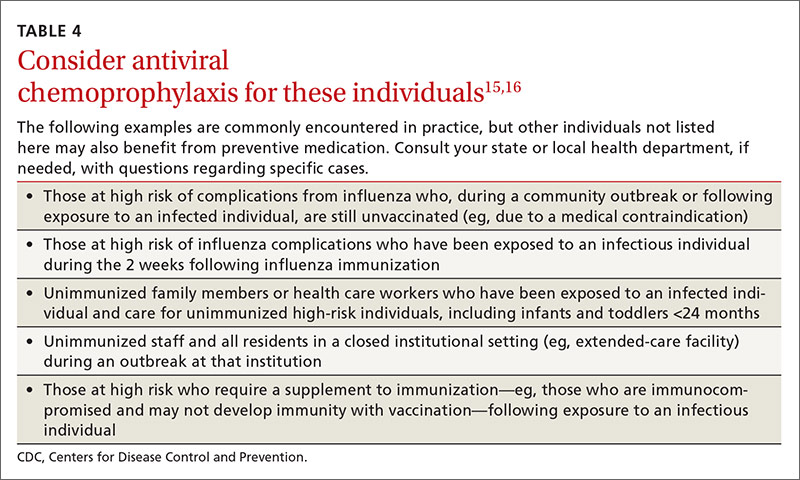

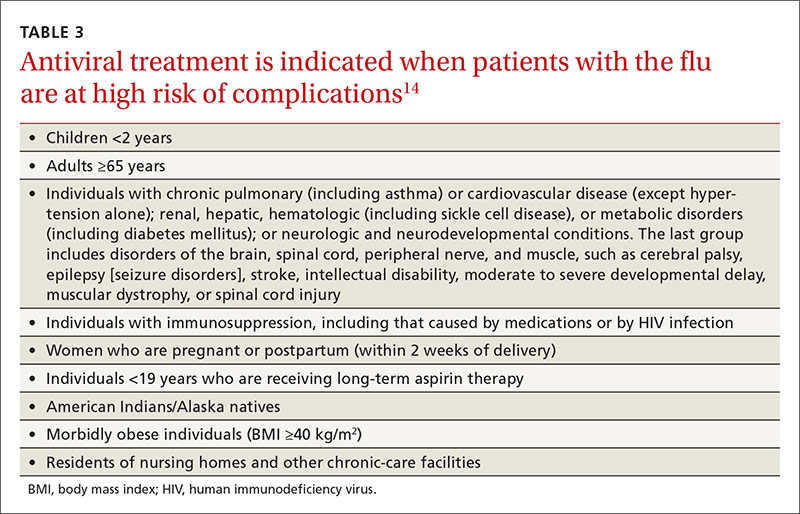

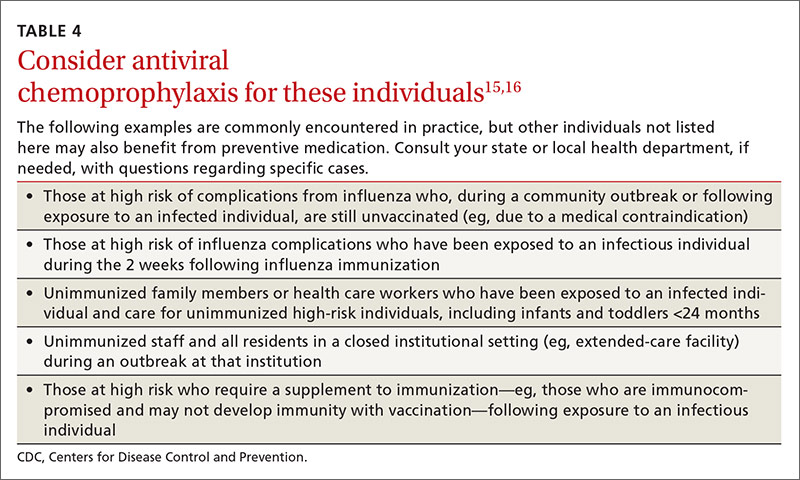

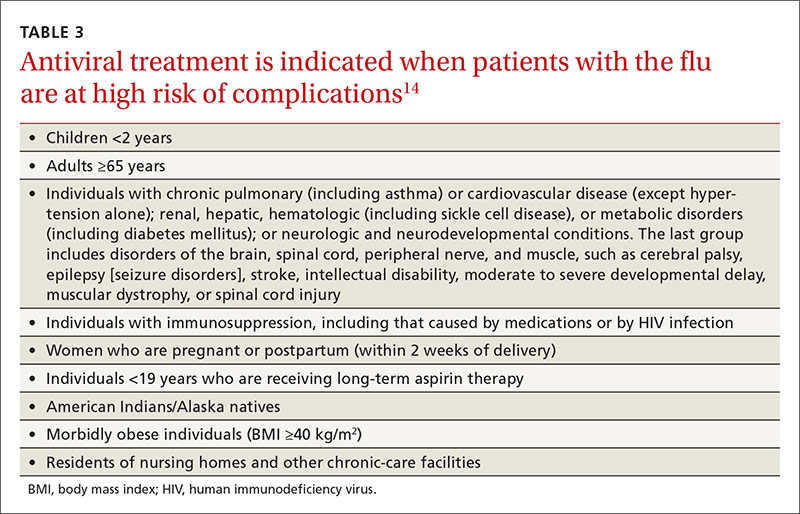

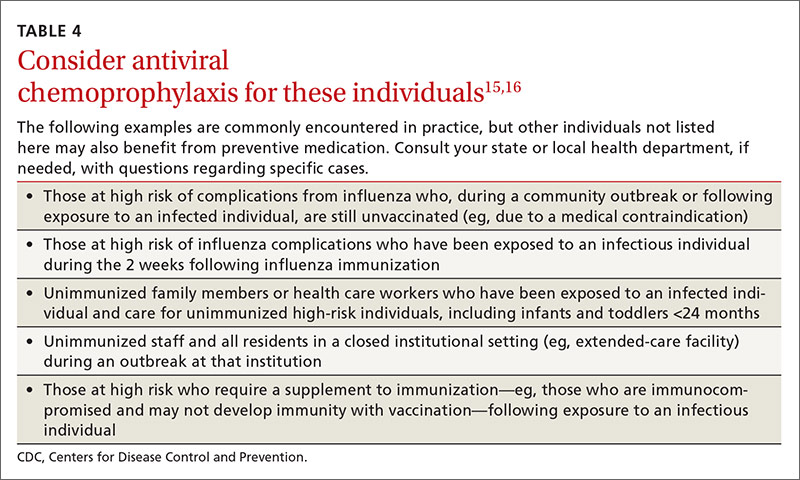

Most influenza strains circulating in 2016-2017 are expected to remain sensitive to oseltamivir and zanamivir, which can be used for treatment or disease prevention. A third neuraminidase inhibitor, peramivir, is available for intravenous use in adults 18 and older. Treatment is recommended for those who have confirmed or suspected influenza and are at high risk for complications (TABLE 3).14 Consideration of antiviral chemoprevention is recommended under certain circumstances (TABLE 4).15,16 The CDC influenza Web site lists recommended doses and duration for each antiviral for treatment and chemoprevention.15

1. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2016-17 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-54.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA information regarding FluMist quadrivalent vaccine. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm508761.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0622-laiv-flu.html. Accessed July 13, 2016.

4. Flannery B, Chung J. Influenza vaccine effectiveness, including LAIV vs IIV in children and adolescents, US Flu VE Network, 2015-2016. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-05-flannery.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluView. Laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations. Available at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/FluHospRates.html. Accessed July 25, 2016.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluView. Number of influenza-associated pediatric deaths by week of death. Available at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/PedFluDeath.html. Accessed July 25, 2016.

7. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2015-2016 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-04-shimabukuro.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

8. Grohskopf L. Proposed recommendations 2016-2017 influenza season. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-08-grohskopf.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination: a summary for clinicians. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vax-summary.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What you should know for the 2016-2017 influenza season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season-2016-2017.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

11. Immunization Action Coalition. Influenza vaccine products for the 2016-2017 influenza season. Available at: http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4072.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2016.

12. Duffy J, Weintraub E, Hambidge SJ, et al. Febrile seizure risk after vaccination in children 6 to 23 months. Pediatrics. 2016;138.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood vaccines and febrile seizures. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/febrile-seizures.html. Accessed August 11, 2016.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of antivirals. Background and guidance on the use of influenza antiviral agents. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.