User login

Decoding AFib recurrence: PCPs’ role in personalized care

One in three patients who experience their first bout of atrial fibrillation (AFib) during hospitalization can expect to experience a recurrence of the arrhythmia within the year, new research shows.

The findings, reported in Annals of Internal Medicine, suggest these patients may be good candidates for oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk for stroke.

“Atrial fibrillation is very common in patients for the very first time in their life when they’re sick and in the hospital,” said William F. McIntyre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., who led the study. These new insights into AFib management suggest there is a need for primary care physicians to be on the lookout for potential recurrence.

AFib is strongly linked to stroke, and patients at greater risk for stroke may be prescribed oral anticoagulants. Although the arrhythmia can be reversed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, risk for recurrence was unclear, Dr. McIntyre said.

“We wanted to know if the patient was in atrial fibrillation because of the physiologic stress that they were under, or if they just have the disease called atrial fibrillation, which should usually be followed lifelong by a specialist,” Dr. McIntyre said.

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues followed 139 patients (mean age, 71 years) at three medical centers in Ontario who experienced new-onset AFib during their hospital stay, along with an equal number of patients who had no history of AFib and who served as controls. The research team used a Holter monitor to record study participants’ heart rhythm for 14 days to detect incident AFib at 1 and 6 months after discharge. They also followed up with periodic phone calls for up to 12 months. Among the study participants, half were admitted for noncardiac surgeries, and the other half were admitted for medical illnesses, including infections and pneumonia. Participants with a prior history of AFib were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study was an episode of AFib that lasted at least 30 seconds on the monitor or one detected during routine care at the 12-month mark.

Patients who experienced AFib for the first time in the hospital had roughly a 33% risk for recurrence within a year, nearly sevenfold higher than their age- and sex-matched counterparts who had not had an arrhythmia during their hospital stay (3%; confidence interval, 0%-6.4%).

“This study has important implications for management of patients who have a first presentation of AFib that is concurrent with a reversible physiologic stressor,” the authors wrote. “An AFib recurrence risk of 33.1% at 1 year is neither low enough to conclude that transient new-onset AFib in the setting of another illness is benign nor high enough that all such transient new-onset AFib can be assumed to be paroxysmal AFib. Instead, these results call for risk stratification and follow-up in these patients.”

The researchers reported that among people with recurrent AFib in the study, the median total time in arrhythmia was 9 hours. “This far exceeds the cutoff of 6 minutes that was established as being associated with stroke using simulated AFib screening in patients with implanted continuous monitors,” they wrote. “These results suggest that the patients in our study who had AFib detected in follow-up are similar to contemporary patients with AFib for whom evidence-based therapies, including oral anticoagulation, are warranted.”

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues were able to track outcomes and treatments for the patients in the study. In the group with recurrent AFib, 1 had a stroke, 2 experienced systemic embolism, 3 had a heart failure event, 6 experienced bleeding, and 11 died. In the other group, there was one case of stroke, one of heart failure, four cases involving bleeding, and seven deaths. “The proportion of participants with new-onset AFib during their initial hospitalization who were taking oral anticoagulants was 47.1% at 6 months and 49.2% at 12 months. This included 73% of participants with AFib detected during follow-up and 39% who did not have AFib detected during follow-up,” they wrote.

The uncertain nature of AFib recurrence complicates predictions about patients’ posthospitalization experiences within the following year. “We cannot just say: ‘Hey, this is just a reversible illness, and now we can forget about it,’ ” Dr. McIntyre said. “Nor is the risk of recurrence so strong in the other direction that you can give patients a lifelong diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.”

Role for primary care

Without that certainty, physicians cannot refer everyone who experiences new-onset AFib to a cardiologist for long-term care. The variability in recurrence rates necessitates a more nuanced and personalized approach. Here, primary care physicians step in, offering tailored care based on their established, long-term patient relationships, Dr. McIntyre said.

The study participants already have chronic health conditions that bring them into regular contact with their family physician. This gives primary care physicians a golden opportunity to be on lookout and to recommend care from a cardiologist at the appropriate time if it becomes necessary, he said.

“I have certainly seen cases of recurrent atrial fibrillation in patients who had an episode while hospitalized, and consistent with this study, this is a common clinical occurrence,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. Primary care physicians must remain vigilant and avoid the temptation to attribute AFib solely to illness or surgery

“Ideally, we would have randomized clinical trial data to guide the decision about whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation,” said Dr. Bhatt, who added that a cardiology consultation may also be appropriate.

Dr. McIntyre reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous relationships with industry.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

One in three patients who experience their first bout of atrial fibrillation (AFib) during hospitalization can expect to experience a recurrence of the arrhythmia within the year, new research shows.

The findings, reported in Annals of Internal Medicine, suggest these patients may be good candidates for oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk for stroke.

“Atrial fibrillation is very common in patients for the very first time in their life when they’re sick and in the hospital,” said William F. McIntyre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., who led the study. These new insights into AFib management suggest there is a need for primary care physicians to be on the lookout for potential recurrence.

AFib is strongly linked to stroke, and patients at greater risk for stroke may be prescribed oral anticoagulants. Although the arrhythmia can be reversed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, risk for recurrence was unclear, Dr. McIntyre said.

“We wanted to know if the patient was in atrial fibrillation because of the physiologic stress that they were under, or if they just have the disease called atrial fibrillation, which should usually be followed lifelong by a specialist,” Dr. McIntyre said.

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues followed 139 patients (mean age, 71 years) at three medical centers in Ontario who experienced new-onset AFib during their hospital stay, along with an equal number of patients who had no history of AFib and who served as controls. The research team used a Holter monitor to record study participants’ heart rhythm for 14 days to detect incident AFib at 1 and 6 months after discharge. They also followed up with periodic phone calls for up to 12 months. Among the study participants, half were admitted for noncardiac surgeries, and the other half were admitted for medical illnesses, including infections and pneumonia. Participants with a prior history of AFib were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study was an episode of AFib that lasted at least 30 seconds on the monitor or one detected during routine care at the 12-month mark.

Patients who experienced AFib for the first time in the hospital had roughly a 33% risk for recurrence within a year, nearly sevenfold higher than their age- and sex-matched counterparts who had not had an arrhythmia during their hospital stay (3%; confidence interval, 0%-6.4%).

“This study has important implications for management of patients who have a first presentation of AFib that is concurrent with a reversible physiologic stressor,” the authors wrote. “An AFib recurrence risk of 33.1% at 1 year is neither low enough to conclude that transient new-onset AFib in the setting of another illness is benign nor high enough that all such transient new-onset AFib can be assumed to be paroxysmal AFib. Instead, these results call for risk stratification and follow-up in these patients.”

The researchers reported that among people with recurrent AFib in the study, the median total time in arrhythmia was 9 hours. “This far exceeds the cutoff of 6 minutes that was established as being associated with stroke using simulated AFib screening in patients with implanted continuous monitors,” they wrote. “These results suggest that the patients in our study who had AFib detected in follow-up are similar to contemporary patients with AFib for whom evidence-based therapies, including oral anticoagulation, are warranted.”

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues were able to track outcomes and treatments for the patients in the study. In the group with recurrent AFib, 1 had a stroke, 2 experienced systemic embolism, 3 had a heart failure event, 6 experienced bleeding, and 11 died. In the other group, there was one case of stroke, one of heart failure, four cases involving bleeding, and seven deaths. “The proportion of participants with new-onset AFib during their initial hospitalization who were taking oral anticoagulants was 47.1% at 6 months and 49.2% at 12 months. This included 73% of participants with AFib detected during follow-up and 39% who did not have AFib detected during follow-up,” they wrote.

The uncertain nature of AFib recurrence complicates predictions about patients’ posthospitalization experiences within the following year. “We cannot just say: ‘Hey, this is just a reversible illness, and now we can forget about it,’ ” Dr. McIntyre said. “Nor is the risk of recurrence so strong in the other direction that you can give patients a lifelong diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.”

Role for primary care

Without that certainty, physicians cannot refer everyone who experiences new-onset AFib to a cardiologist for long-term care. The variability in recurrence rates necessitates a more nuanced and personalized approach. Here, primary care physicians step in, offering tailored care based on their established, long-term patient relationships, Dr. McIntyre said.

The study participants already have chronic health conditions that bring them into regular contact with their family physician. This gives primary care physicians a golden opportunity to be on lookout and to recommend care from a cardiologist at the appropriate time if it becomes necessary, he said.

“I have certainly seen cases of recurrent atrial fibrillation in patients who had an episode while hospitalized, and consistent with this study, this is a common clinical occurrence,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. Primary care physicians must remain vigilant and avoid the temptation to attribute AFib solely to illness or surgery

“Ideally, we would have randomized clinical trial data to guide the decision about whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation,” said Dr. Bhatt, who added that a cardiology consultation may also be appropriate.

Dr. McIntyre reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous relationships with industry.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

One in three patients who experience their first bout of atrial fibrillation (AFib) during hospitalization can expect to experience a recurrence of the arrhythmia within the year, new research shows.

The findings, reported in Annals of Internal Medicine, suggest these patients may be good candidates for oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk for stroke.

“Atrial fibrillation is very common in patients for the very first time in their life when they’re sick and in the hospital,” said William F. McIntyre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., who led the study. These new insights into AFib management suggest there is a need for primary care physicians to be on the lookout for potential recurrence.

AFib is strongly linked to stroke, and patients at greater risk for stroke may be prescribed oral anticoagulants. Although the arrhythmia can be reversed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, risk for recurrence was unclear, Dr. McIntyre said.

“We wanted to know if the patient was in atrial fibrillation because of the physiologic stress that they were under, or if they just have the disease called atrial fibrillation, which should usually be followed lifelong by a specialist,” Dr. McIntyre said.

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues followed 139 patients (mean age, 71 years) at three medical centers in Ontario who experienced new-onset AFib during their hospital stay, along with an equal number of patients who had no history of AFib and who served as controls. The research team used a Holter monitor to record study participants’ heart rhythm for 14 days to detect incident AFib at 1 and 6 months after discharge. They also followed up with periodic phone calls for up to 12 months. Among the study participants, half were admitted for noncardiac surgeries, and the other half were admitted for medical illnesses, including infections and pneumonia. Participants with a prior history of AFib were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study was an episode of AFib that lasted at least 30 seconds on the monitor or one detected during routine care at the 12-month mark.

Patients who experienced AFib for the first time in the hospital had roughly a 33% risk for recurrence within a year, nearly sevenfold higher than their age- and sex-matched counterparts who had not had an arrhythmia during their hospital stay (3%; confidence interval, 0%-6.4%).

“This study has important implications for management of patients who have a first presentation of AFib that is concurrent with a reversible physiologic stressor,” the authors wrote. “An AFib recurrence risk of 33.1% at 1 year is neither low enough to conclude that transient new-onset AFib in the setting of another illness is benign nor high enough that all such transient new-onset AFib can be assumed to be paroxysmal AFib. Instead, these results call for risk stratification and follow-up in these patients.”

The researchers reported that among people with recurrent AFib in the study, the median total time in arrhythmia was 9 hours. “This far exceeds the cutoff of 6 minutes that was established as being associated with stroke using simulated AFib screening in patients with implanted continuous monitors,” they wrote. “These results suggest that the patients in our study who had AFib detected in follow-up are similar to contemporary patients with AFib for whom evidence-based therapies, including oral anticoagulation, are warranted.”

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues were able to track outcomes and treatments for the patients in the study. In the group with recurrent AFib, 1 had a stroke, 2 experienced systemic embolism, 3 had a heart failure event, 6 experienced bleeding, and 11 died. In the other group, there was one case of stroke, one of heart failure, four cases involving bleeding, and seven deaths. “The proportion of participants with new-onset AFib during their initial hospitalization who were taking oral anticoagulants was 47.1% at 6 months and 49.2% at 12 months. This included 73% of participants with AFib detected during follow-up and 39% who did not have AFib detected during follow-up,” they wrote.

The uncertain nature of AFib recurrence complicates predictions about patients’ posthospitalization experiences within the following year. “We cannot just say: ‘Hey, this is just a reversible illness, and now we can forget about it,’ ” Dr. McIntyre said. “Nor is the risk of recurrence so strong in the other direction that you can give patients a lifelong diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.”

Role for primary care

Without that certainty, physicians cannot refer everyone who experiences new-onset AFib to a cardiologist for long-term care. The variability in recurrence rates necessitates a more nuanced and personalized approach. Here, primary care physicians step in, offering tailored care based on their established, long-term patient relationships, Dr. McIntyre said.

The study participants already have chronic health conditions that bring them into regular contact with their family physician. This gives primary care physicians a golden opportunity to be on lookout and to recommend care from a cardiologist at the appropriate time if it becomes necessary, he said.

“I have certainly seen cases of recurrent atrial fibrillation in patients who had an episode while hospitalized, and consistent with this study, this is a common clinical occurrence,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. Primary care physicians must remain vigilant and avoid the temptation to attribute AFib solely to illness or surgery

“Ideally, we would have randomized clinical trial data to guide the decision about whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation,” said Dr. Bhatt, who added that a cardiology consultation may also be appropriate.

Dr. McIntyre reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous relationships with industry.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

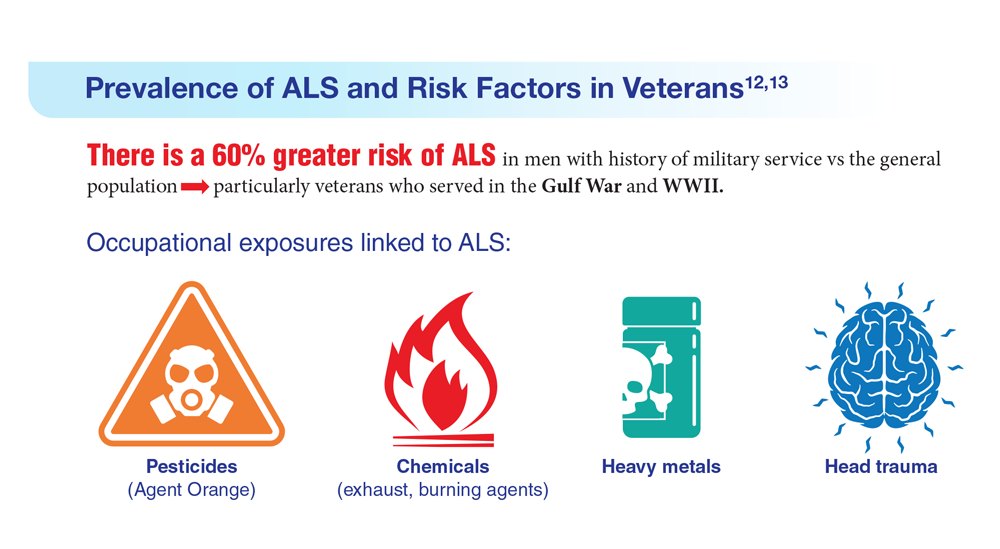

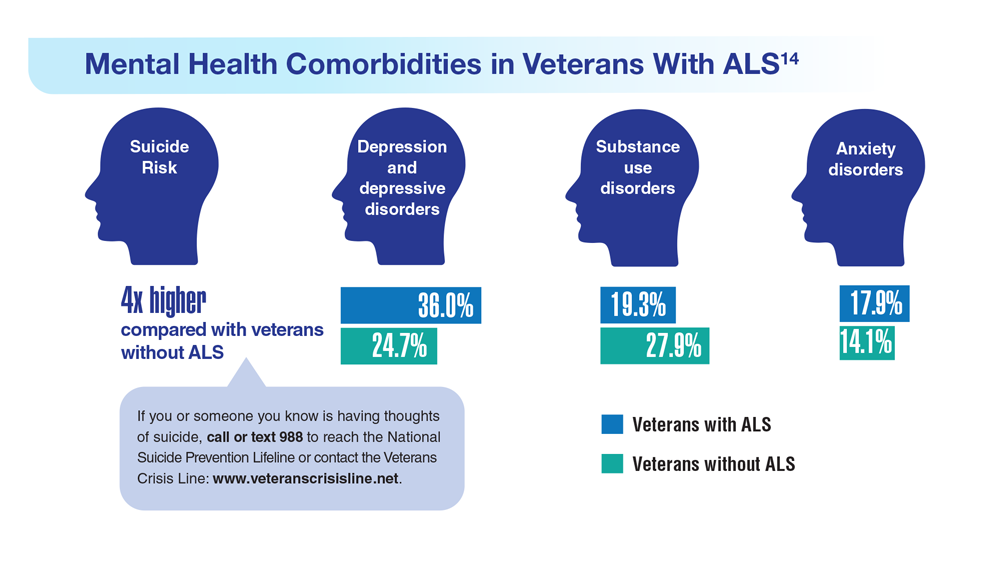

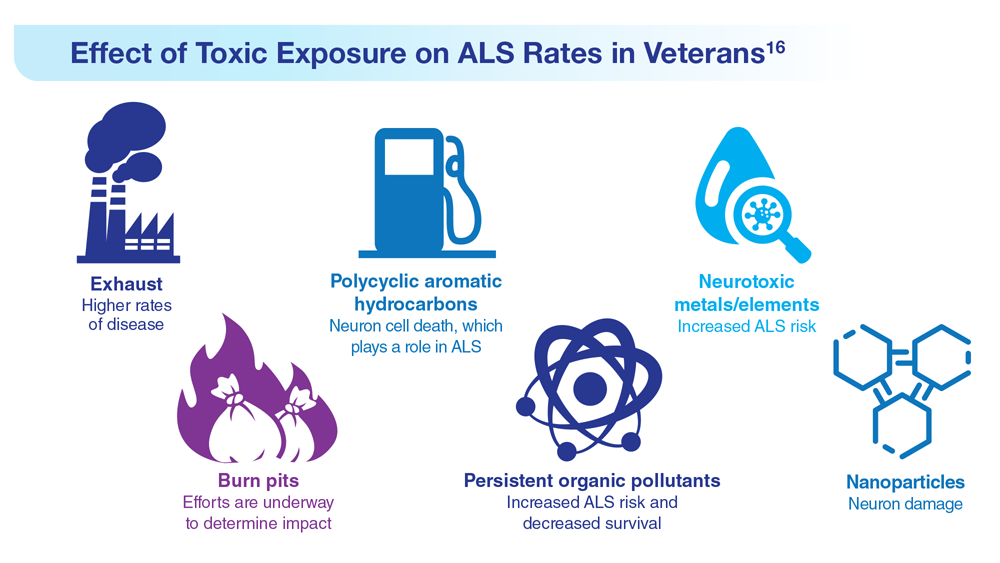

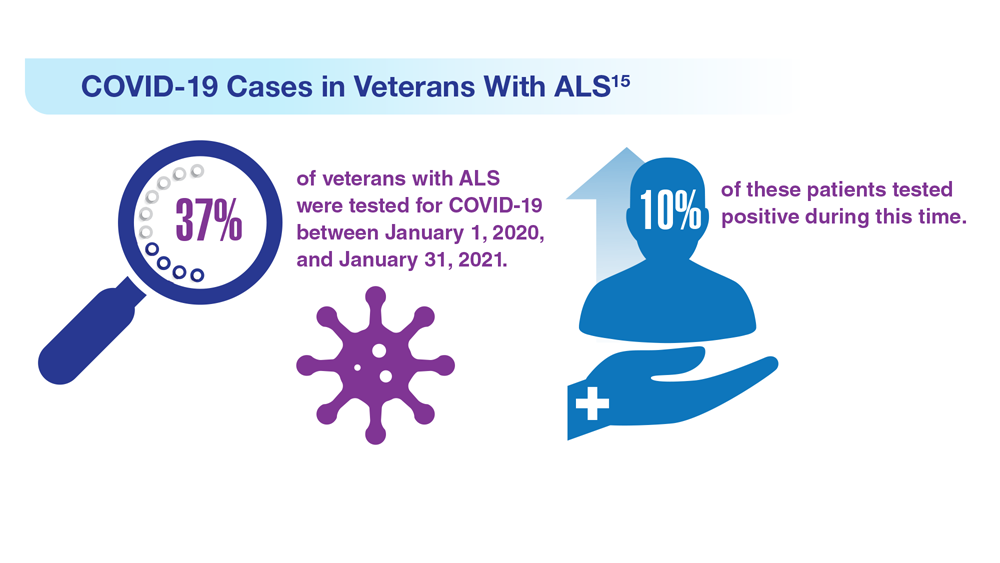

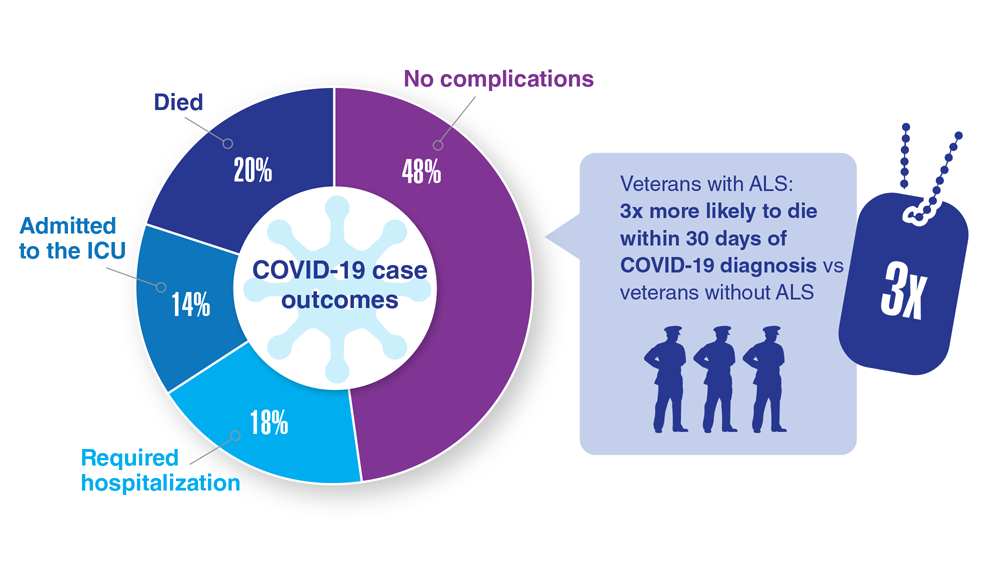

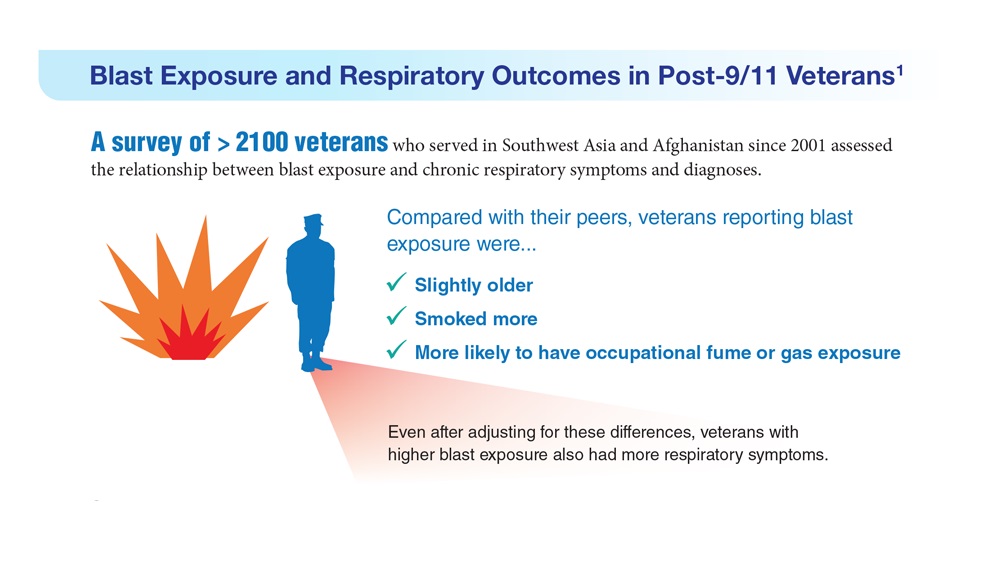

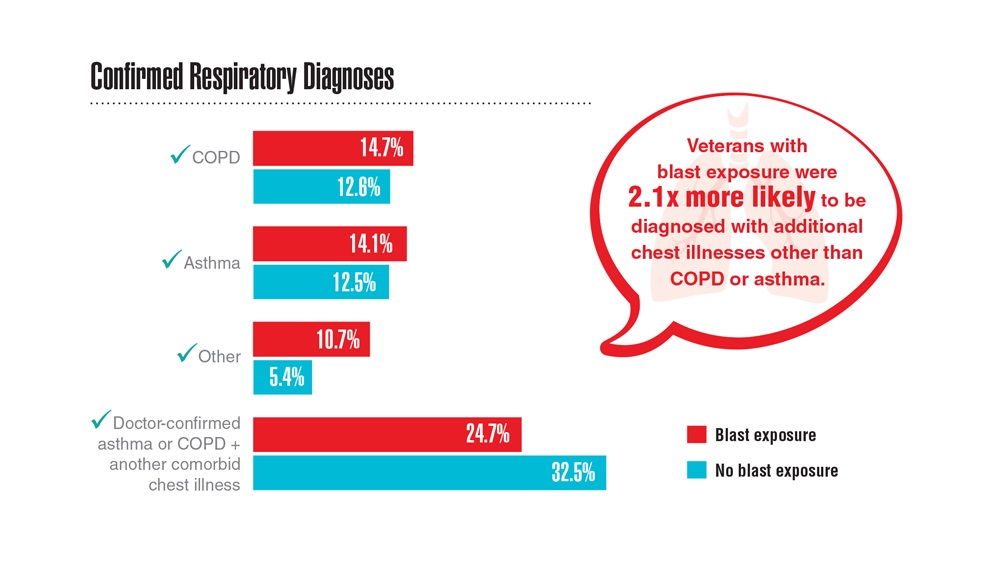

Data Trends 2023: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

12. The ALS Association. ALS in the military. https://www.als.org/navigating-als/military-veterans/ALS-in-the-Military

13. McKay KA et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;143(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/ane.13345

14. Lund EM et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):807-811. doi:10.1002/mus.27181

15. Galea MD et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(4):E18-E20. doi:10.1002/mus.27373

16. Re DB et al. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2359-2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10928-5

12. The ALS Association. ALS in the military. https://www.als.org/navigating-als/military-veterans/ALS-in-the-Military

13. McKay KA et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;143(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/ane.13345

14. Lund EM et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):807-811. doi:10.1002/mus.27181

15. Galea MD et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(4):E18-E20. doi:10.1002/mus.27373

16. Re DB et al. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2359-2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10928-5

12. The ALS Association. ALS in the military. https://www.als.org/navigating-als/military-veterans/ALS-in-the-Military

13. McKay KA et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;143(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/ane.13345

14. Lund EM et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):807-811. doi:10.1002/mus.27181

15. Galea MD et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(4):E18-E20. doi:10.1002/mus.27373

16. Re DB et al. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2359-2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10928-5

Spironolactone safe, effective option for women with hidradenitis suppurativa

CARLSBAD, CALIF. –

Those are the key findings from a single-center retrospective study that Jennifer L. Hsiao, MD, and colleagues presented during a poster session at the annual symposium of the California Society of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery.

In an interview after the meeting, Dr. Hsiao, a dermatologist who directs the hidradenitis suppurativa clinic at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that hormones are thought to play a role in HS pathogenesis given the typical HS symptom onset around puberty and fluctuations in disease activity with menses (typically premenstrual flares) and pregnancy. “Spironolactone, an anti-androgenic agent, is used to treat HS in women; however, there is a paucity of data on the efficacy of spironolactone for HS and whether certain patient characteristics may influence treatment response,” she told this news organization. “This study is unique in that we contribute to existing literature regarding spironolactone efficacy in HS and we also investigate whether the presence of menstrual HS flares or polycystic ovarian syndrome influences the likelihood of response to spironolactone.”

For the analysis, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 53 adult women with HS who were prescribed spironolactone and who received care at USC’s HS clinic between January 2015 and December 2021. They collected data on demographics, comorbidities, HS medications, treatment response at 3 and 6 months, as well as adverse events. They also evaluated physician-assessed response to treatment when available.

The mean age of patients was 31 years, 37% were White, 30.4% were Black, 21.7% were Hispanic, 6.5% were Asian, and the remainder were biracial. The mean age at HS diagnosis was 25.1 years and the three most common comorbidities were acne (50.9%), obesity (45.3%), and anemia (37.7%). As for menstrual history, 56.6% had perimenstrual HS flares and 37.7% had irregular menstrual cycles. The top three classes of concomitant medications were antibiotics (58.5%), oral contraceptives (50.9%), and other birth control methods (18.9%).

The mean spironolactone dose was 104 mg/day; 84.1% of the women experienced improvement of HS 3 months after starting the drug, while 81.8% had improvement of their HS 6 months after starting the drug. The researchers also found that 56.6% of women had documented perimenstrual HS flares and 7.5% had PCOS.

“Spironolactone is often thought of as a helpful medication to consider if a patient reports having HS flares around menses or features of PCOS,” Dr. Hsiao said. However, she added, “our study found that there was no statistically significant difference in the response to spironolactone based on the presence of premenstrual flares or concomitant PCOS.” She said that spironolactone may be used as an adjunct therapeutic option in patients with more severe disease in addition to other medical and surgical therapies for HS. “Combining different treatment options that target different pathophysiologic factors is usually required to achieve adequate disease control in HS,” she said.

Dr. Hsiao acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and small sample size. “A confounding variable is that some patients were on other medications in addition to spironolactone, which may have influenced treatment outcomes,” she noted. “Larger prospective studies are needed to identify optimal dosing for spironolactone therapy in HS as well as predictors of treatment response.”

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study, said that with only one FDA-approved systemic medication for the management of HS (adalimumab), “we off-label bandits must be creative to curtail the incredibly painful impact this chronic, destructive inflammatory disease can have on our patients.”

“The evidence supporting our approaches, whether it be antibiotics, immunomodulators, or in this case, antihormonal therapies, is limited, so more data is always welcome,” said Dr. Friedman, who was not involved with the study. “One very interesting point raised by the authors, one I share with my trainees frequently from my own experience, is that regardless of menstrual cycle abnormalities, spironolactone can be impactful. This is important to remember, in that overt signs of hormonal influences is not a requisite for the use or effectiveness of antihormonal therapy.”

Dr. Hsiao disclosed that she is a member of board of directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. She has also served as a consultant for AbbVie, Aclaris, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, UCB, as a speaker for AbbVie, and as an investigator for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Incyte. Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CARLSBAD, CALIF. –

Those are the key findings from a single-center retrospective study that Jennifer L. Hsiao, MD, and colleagues presented during a poster session at the annual symposium of the California Society of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery.

In an interview after the meeting, Dr. Hsiao, a dermatologist who directs the hidradenitis suppurativa clinic at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that hormones are thought to play a role in HS pathogenesis given the typical HS symptom onset around puberty and fluctuations in disease activity with menses (typically premenstrual flares) and pregnancy. “Spironolactone, an anti-androgenic agent, is used to treat HS in women; however, there is a paucity of data on the efficacy of spironolactone for HS and whether certain patient characteristics may influence treatment response,” she told this news organization. “This study is unique in that we contribute to existing literature regarding spironolactone efficacy in HS and we also investigate whether the presence of menstrual HS flares or polycystic ovarian syndrome influences the likelihood of response to spironolactone.”

For the analysis, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 53 adult women with HS who were prescribed spironolactone and who received care at USC’s HS clinic between January 2015 and December 2021. They collected data on demographics, comorbidities, HS medications, treatment response at 3 and 6 months, as well as adverse events. They also evaluated physician-assessed response to treatment when available.

The mean age of patients was 31 years, 37% were White, 30.4% were Black, 21.7% were Hispanic, 6.5% were Asian, and the remainder were biracial. The mean age at HS diagnosis was 25.1 years and the three most common comorbidities were acne (50.9%), obesity (45.3%), and anemia (37.7%). As for menstrual history, 56.6% had perimenstrual HS flares and 37.7% had irregular menstrual cycles. The top three classes of concomitant medications were antibiotics (58.5%), oral contraceptives (50.9%), and other birth control methods (18.9%).

The mean spironolactone dose was 104 mg/day; 84.1% of the women experienced improvement of HS 3 months after starting the drug, while 81.8% had improvement of their HS 6 months after starting the drug. The researchers also found that 56.6% of women had documented perimenstrual HS flares and 7.5% had PCOS.

“Spironolactone is often thought of as a helpful medication to consider if a patient reports having HS flares around menses or features of PCOS,” Dr. Hsiao said. However, she added, “our study found that there was no statistically significant difference in the response to spironolactone based on the presence of premenstrual flares or concomitant PCOS.” She said that spironolactone may be used as an adjunct therapeutic option in patients with more severe disease in addition to other medical and surgical therapies for HS. “Combining different treatment options that target different pathophysiologic factors is usually required to achieve adequate disease control in HS,” she said.

Dr. Hsiao acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and small sample size. “A confounding variable is that some patients were on other medications in addition to spironolactone, which may have influenced treatment outcomes,” she noted. “Larger prospective studies are needed to identify optimal dosing for spironolactone therapy in HS as well as predictors of treatment response.”

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study, said that with only one FDA-approved systemic medication for the management of HS (adalimumab), “we off-label bandits must be creative to curtail the incredibly painful impact this chronic, destructive inflammatory disease can have on our patients.”

“The evidence supporting our approaches, whether it be antibiotics, immunomodulators, or in this case, antihormonal therapies, is limited, so more data is always welcome,” said Dr. Friedman, who was not involved with the study. “One very interesting point raised by the authors, one I share with my trainees frequently from my own experience, is that regardless of menstrual cycle abnormalities, spironolactone can be impactful. This is important to remember, in that overt signs of hormonal influences is not a requisite for the use or effectiveness of antihormonal therapy.”

Dr. Hsiao disclosed that she is a member of board of directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. She has also served as a consultant for AbbVie, Aclaris, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, UCB, as a speaker for AbbVie, and as an investigator for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Incyte. Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CARLSBAD, CALIF. –

Those are the key findings from a single-center retrospective study that Jennifer L. Hsiao, MD, and colleagues presented during a poster session at the annual symposium of the California Society of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery.

In an interview after the meeting, Dr. Hsiao, a dermatologist who directs the hidradenitis suppurativa clinic at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that hormones are thought to play a role in HS pathogenesis given the typical HS symptom onset around puberty and fluctuations in disease activity with menses (typically premenstrual flares) and pregnancy. “Spironolactone, an anti-androgenic agent, is used to treat HS in women; however, there is a paucity of data on the efficacy of spironolactone for HS and whether certain patient characteristics may influence treatment response,” she told this news organization. “This study is unique in that we contribute to existing literature regarding spironolactone efficacy in HS and we also investigate whether the presence of menstrual HS flares or polycystic ovarian syndrome influences the likelihood of response to spironolactone.”

For the analysis, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 53 adult women with HS who were prescribed spironolactone and who received care at USC’s HS clinic between January 2015 and December 2021. They collected data on demographics, comorbidities, HS medications, treatment response at 3 and 6 months, as well as adverse events. They also evaluated physician-assessed response to treatment when available.

The mean age of patients was 31 years, 37% were White, 30.4% were Black, 21.7% were Hispanic, 6.5% were Asian, and the remainder were biracial. The mean age at HS diagnosis was 25.1 years and the three most common comorbidities were acne (50.9%), obesity (45.3%), and anemia (37.7%). As for menstrual history, 56.6% had perimenstrual HS flares and 37.7% had irregular menstrual cycles. The top three classes of concomitant medications were antibiotics (58.5%), oral contraceptives (50.9%), and other birth control methods (18.9%).

The mean spironolactone dose was 104 mg/day; 84.1% of the women experienced improvement of HS 3 months after starting the drug, while 81.8% had improvement of their HS 6 months after starting the drug. The researchers also found that 56.6% of women had documented perimenstrual HS flares and 7.5% had PCOS.

“Spironolactone is often thought of as a helpful medication to consider if a patient reports having HS flares around menses or features of PCOS,” Dr. Hsiao said. However, she added, “our study found that there was no statistically significant difference in the response to spironolactone based on the presence of premenstrual flares or concomitant PCOS.” She said that spironolactone may be used as an adjunct therapeutic option in patients with more severe disease in addition to other medical and surgical therapies for HS. “Combining different treatment options that target different pathophysiologic factors is usually required to achieve adequate disease control in HS,” she said.

Dr. Hsiao acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and small sample size. “A confounding variable is that some patients were on other medications in addition to spironolactone, which may have influenced treatment outcomes,” she noted. “Larger prospective studies are needed to identify optimal dosing for spironolactone therapy in HS as well as predictors of treatment response.”

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study, said that with only one FDA-approved systemic medication for the management of HS (adalimumab), “we off-label bandits must be creative to curtail the incredibly painful impact this chronic, destructive inflammatory disease can have on our patients.”

“The evidence supporting our approaches, whether it be antibiotics, immunomodulators, or in this case, antihormonal therapies, is limited, so more data is always welcome,” said Dr. Friedman, who was not involved with the study. “One very interesting point raised by the authors, one I share with my trainees frequently from my own experience, is that regardless of menstrual cycle abnormalities, spironolactone can be impactful. This is important to remember, in that overt signs of hormonal influences is not a requisite for the use or effectiveness of antihormonal therapy.”

Dr. Hsiao disclosed that she is a member of board of directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. She has also served as a consultant for AbbVie, Aclaris, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, UCB, as a speaker for AbbVie, and as an investigator for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Incyte. Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT CALDERM 2023

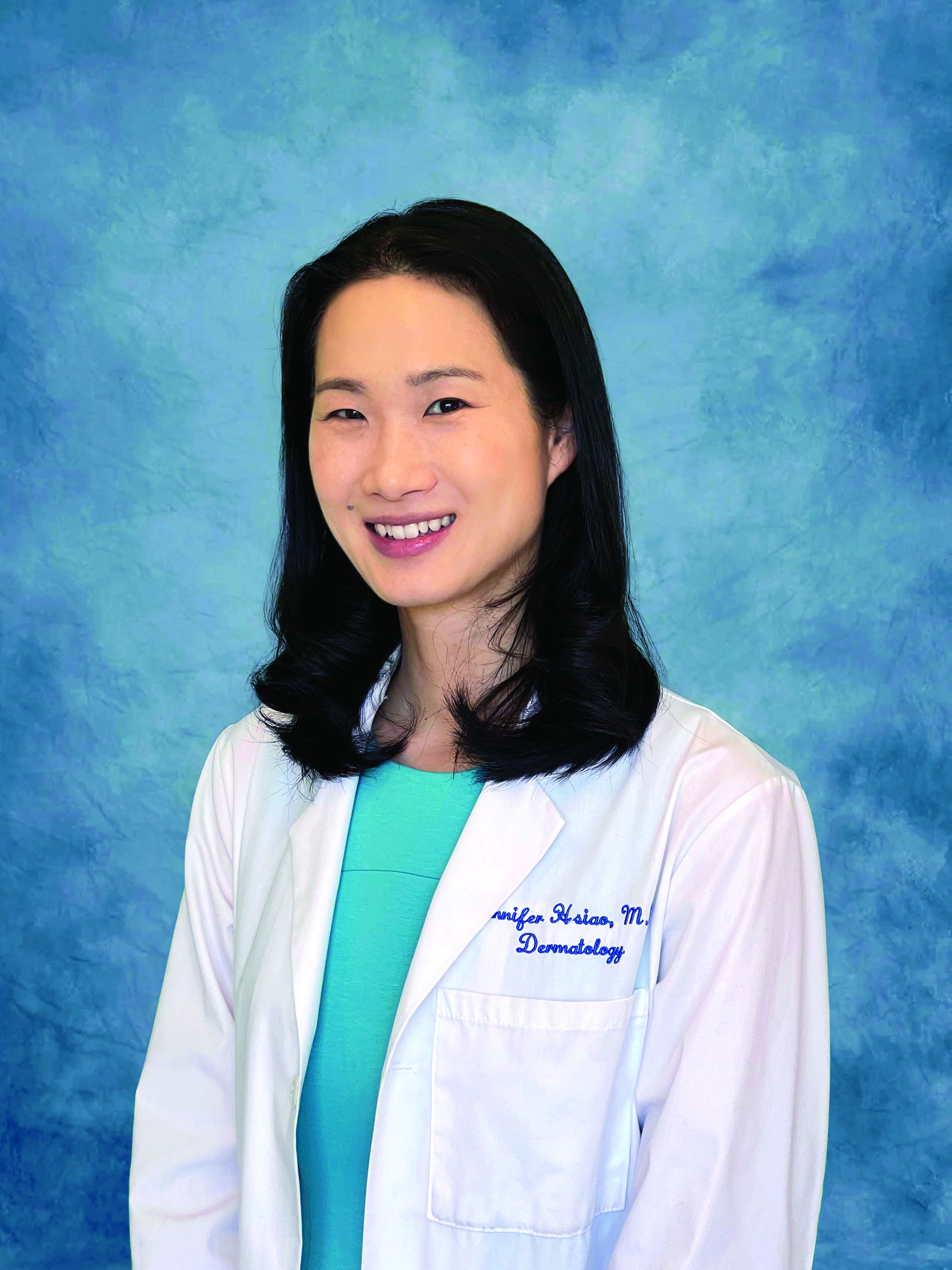

Data Trends 2023: Alzheimer’s and Dementia

6. Zhu CW, Sano M. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:610334. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610334

7. Nianogo RA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):584-591. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976

8. Logue MW et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec 22. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/alz.12870

9. Kempuraj D et al. Clin Ther. 2020;42(6):974-982. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.018

10. Martinez S et al. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5011

11. Verger A et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1553-1555. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06177-5

6. Zhu CW, Sano M. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:610334. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610334

7. Nianogo RA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):584-591. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976

8. Logue MW et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec 22. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/alz.12870

9. Kempuraj D et al. Clin Ther. 2020;42(6):974-982. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.018

10. Martinez S et al. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5011

11. Verger A et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1553-1555. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06177-5

6. Zhu CW, Sano M. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:610334. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610334

7. Nianogo RA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):584-591. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976

8. Logue MW et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec 22. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/alz.12870

9. Kempuraj D et al. Clin Ther. 2020;42(6):974-982. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.018

10. Martinez S et al. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5011

11. Verger A et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1553-1555. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06177-5

More data support heart donation after circulatory death

TOPLINE:

There are no significant differences in 1-year mortality, survival to hospital discharge, severe primary graft dysfunction (PGD), and other outcomes post heart transplant between patients who receive a heart obtained by donation after circulatory death (DCD) and patients who receive a heart by donation after brain death (DBD), a new study has shown.

METHODOLOGY:

- The retrospective review included 385 patients (median age, 57.4 years; 26% women; 72.5% White) who underwent a heart transplant at Vanderbilt University Medical Center from January 2020 to January 2023. Of these, 263 received DBD hearts, and 122 received DCD hearts.

- In the DCD group, 17% of hearts were recovered by use of ex vivo machine perfusion (EVP), and 83% by use of normothermic regional perfusion followed by static cold storage; 4% of DBD hearts were recovered by use of EVP, and 96% by use of static cold storage.

- The primary outcome was survival at 1 year after transplantation; key secondary outcomes included survival to hospital discharge, survival at 30 days and 6 months after transplantation, and severe PGD.

TAKEAWAY:

- (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-1.81; P = .54), a finding that was unchanged when adjusted for recipient age.

- There were no significant differences in survival to hospital discharge (93.4% DBD vs. 94.5% DCD; HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.26-1.99; P = .53), to 30 days (95.1% DBD vs. 96.7% DCD; HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.22-2.05; P = .48), or to 6 months (92.8% DBD vs. 94.3% DCD; HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.25-1.85; P = .45) after transplantation.

- The incidence of severe PGD was similar between groups (5.7% DCD vs. 5.7% DBD; HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.41-2.4; P = .99).

- There were no significant between-group differences in other outcomes, including incidence of treated rejection and cases of cardiac allograft vasculopathy of grade 1 or greater on the International Society for scale at 1 year.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings add to the growing body of evidence in support of DCD heart transplantation,” the authors write, potentially expanding the heart donor pool. They note that outcomes remained similar between groups despite higher-risk patients being overrepresented in the DCD cohort.

In an accompanying editorial, Sean P. Pinney, MD, Center for Cardiovascular Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and a colleague called the results “impressive” and “encouraging,” although there are still “important unknowns,” including longer-term outcomes, the financial impact of DCD, and whether results can be replicated in other centers.

“These results provide confidence that DCD can be safely and effectively performed without compromising outcomes, at least in a large-volume center of excellence,” and help provide evidence “to support the spreading acceptance of DCD among heart transplant programs.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Hasan K. Siddiqi, MD, department of medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues. It was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was conducted at a single center and had a retrospective design and a modest sample size that prevented adjustment for all potentially confounding variables. Meaningful differences among DCD recipients could not be explored with regard to organ recovery technique, and small but statistically meaningful differences in outcomes could not be detected, the authors note. Follow-up was limited to 1 year after transplantation.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Pinney has received consulting fees from Abbott, ADI, Ancora, CareDx, ImpulseDynamics, Medtronic, Nuwellis, Procyrion, Restore Medical, Transmedics, and Valgen Medtech.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

There are no significant differences in 1-year mortality, survival to hospital discharge, severe primary graft dysfunction (PGD), and other outcomes post heart transplant between patients who receive a heart obtained by donation after circulatory death (DCD) and patients who receive a heart by donation after brain death (DBD), a new study has shown.

METHODOLOGY:

- The retrospective review included 385 patients (median age, 57.4 years; 26% women; 72.5% White) who underwent a heart transplant at Vanderbilt University Medical Center from January 2020 to January 2023. Of these, 263 received DBD hearts, and 122 received DCD hearts.

- In the DCD group, 17% of hearts were recovered by use of ex vivo machine perfusion (EVP), and 83% by use of normothermic regional perfusion followed by static cold storage; 4% of DBD hearts were recovered by use of EVP, and 96% by use of static cold storage.

- The primary outcome was survival at 1 year after transplantation; key secondary outcomes included survival to hospital discharge, survival at 30 days and 6 months after transplantation, and severe PGD.

TAKEAWAY:

- (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-1.81; P = .54), a finding that was unchanged when adjusted for recipient age.

- There were no significant differences in survival to hospital discharge (93.4% DBD vs. 94.5% DCD; HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.26-1.99; P = .53), to 30 days (95.1% DBD vs. 96.7% DCD; HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.22-2.05; P = .48), or to 6 months (92.8% DBD vs. 94.3% DCD; HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.25-1.85; P = .45) after transplantation.

- The incidence of severe PGD was similar between groups (5.7% DCD vs. 5.7% DBD; HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.41-2.4; P = .99).

- There were no significant between-group differences in other outcomes, including incidence of treated rejection and cases of cardiac allograft vasculopathy of grade 1 or greater on the International Society for scale at 1 year.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings add to the growing body of evidence in support of DCD heart transplantation,” the authors write, potentially expanding the heart donor pool. They note that outcomes remained similar between groups despite higher-risk patients being overrepresented in the DCD cohort.

In an accompanying editorial, Sean P. Pinney, MD, Center for Cardiovascular Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and a colleague called the results “impressive” and “encouraging,” although there are still “important unknowns,” including longer-term outcomes, the financial impact of DCD, and whether results can be replicated in other centers.

“These results provide confidence that DCD can be safely and effectively performed without compromising outcomes, at least in a large-volume center of excellence,” and help provide evidence “to support the spreading acceptance of DCD among heart transplant programs.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Hasan K. Siddiqi, MD, department of medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues. It was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was conducted at a single center and had a retrospective design and a modest sample size that prevented adjustment for all potentially confounding variables. Meaningful differences among DCD recipients could not be explored with regard to organ recovery technique, and small but statistically meaningful differences in outcomes could not be detected, the authors note. Follow-up was limited to 1 year after transplantation.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Pinney has received consulting fees from Abbott, ADI, Ancora, CareDx, ImpulseDynamics, Medtronic, Nuwellis, Procyrion, Restore Medical, Transmedics, and Valgen Medtech.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

There are no significant differences in 1-year mortality, survival to hospital discharge, severe primary graft dysfunction (PGD), and other outcomes post heart transplant between patients who receive a heart obtained by donation after circulatory death (DCD) and patients who receive a heart by donation after brain death (DBD), a new study has shown.

METHODOLOGY:

- The retrospective review included 385 patients (median age, 57.4 years; 26% women; 72.5% White) who underwent a heart transplant at Vanderbilt University Medical Center from January 2020 to January 2023. Of these, 263 received DBD hearts, and 122 received DCD hearts.

- In the DCD group, 17% of hearts were recovered by use of ex vivo machine perfusion (EVP), and 83% by use of normothermic regional perfusion followed by static cold storage; 4% of DBD hearts were recovered by use of EVP, and 96% by use of static cold storage.

- The primary outcome was survival at 1 year after transplantation; key secondary outcomes included survival to hospital discharge, survival at 30 days and 6 months after transplantation, and severe PGD.

TAKEAWAY:

- (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-1.81; P = .54), a finding that was unchanged when adjusted for recipient age.

- There were no significant differences in survival to hospital discharge (93.4% DBD vs. 94.5% DCD; HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.26-1.99; P = .53), to 30 days (95.1% DBD vs. 96.7% DCD; HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.22-2.05; P = .48), or to 6 months (92.8% DBD vs. 94.3% DCD; HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.25-1.85; P = .45) after transplantation.

- The incidence of severe PGD was similar between groups (5.7% DCD vs. 5.7% DBD; HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.41-2.4; P = .99).

- There were no significant between-group differences in other outcomes, including incidence of treated rejection and cases of cardiac allograft vasculopathy of grade 1 or greater on the International Society for scale at 1 year.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings add to the growing body of evidence in support of DCD heart transplantation,” the authors write, potentially expanding the heart donor pool. They note that outcomes remained similar between groups despite higher-risk patients being overrepresented in the DCD cohort.

In an accompanying editorial, Sean P. Pinney, MD, Center for Cardiovascular Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and a colleague called the results “impressive” and “encouraging,” although there are still “important unknowns,” including longer-term outcomes, the financial impact of DCD, and whether results can be replicated in other centers.

“These results provide confidence that DCD can be safely and effectively performed without compromising outcomes, at least in a large-volume center of excellence,” and help provide evidence “to support the spreading acceptance of DCD among heart transplant programs.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Hasan K. Siddiqi, MD, department of medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues. It was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was conducted at a single center and had a retrospective design and a modest sample size that prevented adjustment for all potentially confounding variables. Meaningful differences among DCD recipients could not be explored with regard to organ recovery technique, and small but statistically meaningful differences in outcomes could not be detected, the authors note. Follow-up was limited to 1 year after transplantation.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Pinney has received consulting fees from Abbott, ADI, Ancora, CareDx, ImpulseDynamics, Medtronic, Nuwellis, Procyrion, Restore Medical, Transmedics, and Valgen Medtech.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary aspergillosis predicts poor outcomes in critically ill flu patients

Critically ill influenza patients with associated pulmonary aspergillosis were more than twice as likely to die in intensive care than those without the added infection, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 1,700 individuals.

Reports of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) are rising in critically ill patients, but data on risk factors, clinical features, and outcomes are limited, Lawrence Y. Lu, MD, of The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues wrote. In addition, diagnosis of IAPA can be challenging, and many clinicians report low awareness of the condition.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 10 observational studies including 1,720 critically ill influenza patients aged 16 years and older; of these, 331 had IAPA, for a prevalence of 19.2%. The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality in the hospital and in the ICU. Secondary outcomes included ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, and the need for supportive care (invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, pressor support, and extracorporeal membranous oxygenation).

Overall, mortality among flu patients in the ICU was significantly higher for those with IAPA than those without IAPA (45.0% vs. 23.8%, respectively), as was all-cause mortality (46.4% vs. 26.2%, respectively; odds ratio, 2.6 and P < .001 for both ICU and all-cause mortality).

Factors significantly associated with an increased risk for IAPA included organ transplant (OR, 4.8), hematogenous malignancy (OR, 2.5), being immunocompromised in some way (OR, 2.2), and prolonged corticosteroid use prior to hospital admission (OR, 2.4).

IAPA also was associated with more severe disease, a higher rate of complications, longer ICU stays, and a greater need for organ supports, the researchers noted. Clinical features not significantly more common in patients with IAPA included fever, hemoptysis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design of the included studies and inability to control for all potential confounders, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the variations in study design, variability of practice patterns across locations, and inclusion of data mainly from countries of high socioeconomic status.

“Given the apparent waning of the COVID-19 pandemic and re-emergence of influenza, our analysis also revealed other gaps in the current literature, including the need to validate newer diagnostic methods and to develop a system to measure severity of IAPA,” the researchers added.

However, the current study results reflect IAPA prevalence from previous studies, and support the need to have a lower threshold for IAPA testing and initiation of antifungal treatment, even with limited data for clinical guidance, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Critically ill influenza patients with associated pulmonary aspergillosis were more than twice as likely to die in intensive care than those without the added infection, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 1,700 individuals.

Reports of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) are rising in critically ill patients, but data on risk factors, clinical features, and outcomes are limited, Lawrence Y. Lu, MD, of The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues wrote. In addition, diagnosis of IAPA can be challenging, and many clinicians report low awareness of the condition.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 10 observational studies including 1,720 critically ill influenza patients aged 16 years and older; of these, 331 had IAPA, for a prevalence of 19.2%. The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality in the hospital and in the ICU. Secondary outcomes included ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, and the need for supportive care (invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, pressor support, and extracorporeal membranous oxygenation).

Overall, mortality among flu patients in the ICU was significantly higher for those with IAPA than those without IAPA (45.0% vs. 23.8%, respectively), as was all-cause mortality (46.4% vs. 26.2%, respectively; odds ratio, 2.6 and P < .001 for both ICU and all-cause mortality).

Factors significantly associated with an increased risk for IAPA included organ transplant (OR, 4.8), hematogenous malignancy (OR, 2.5), being immunocompromised in some way (OR, 2.2), and prolonged corticosteroid use prior to hospital admission (OR, 2.4).

IAPA also was associated with more severe disease, a higher rate of complications, longer ICU stays, and a greater need for organ supports, the researchers noted. Clinical features not significantly more common in patients with IAPA included fever, hemoptysis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design of the included studies and inability to control for all potential confounders, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the variations in study design, variability of practice patterns across locations, and inclusion of data mainly from countries of high socioeconomic status.

“Given the apparent waning of the COVID-19 pandemic and re-emergence of influenza, our analysis also revealed other gaps in the current literature, including the need to validate newer diagnostic methods and to develop a system to measure severity of IAPA,” the researchers added.

However, the current study results reflect IAPA prevalence from previous studies, and support the need to have a lower threshold for IAPA testing and initiation of antifungal treatment, even with limited data for clinical guidance, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Critically ill influenza patients with associated pulmonary aspergillosis were more than twice as likely to die in intensive care than those without the added infection, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 1,700 individuals.

Reports of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) are rising in critically ill patients, but data on risk factors, clinical features, and outcomes are limited, Lawrence Y. Lu, MD, of The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues wrote. In addition, diagnosis of IAPA can be challenging, and many clinicians report low awareness of the condition.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 10 observational studies including 1,720 critically ill influenza patients aged 16 years and older; of these, 331 had IAPA, for a prevalence of 19.2%. The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality in the hospital and in the ICU. Secondary outcomes included ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, and the need for supportive care (invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, pressor support, and extracorporeal membranous oxygenation).

Overall, mortality among flu patients in the ICU was significantly higher for those with IAPA than those without IAPA (45.0% vs. 23.8%, respectively), as was all-cause mortality (46.4% vs. 26.2%, respectively; odds ratio, 2.6 and P < .001 for both ICU and all-cause mortality).

Factors significantly associated with an increased risk for IAPA included organ transplant (OR, 4.8), hematogenous malignancy (OR, 2.5), being immunocompromised in some way (OR, 2.2), and prolonged corticosteroid use prior to hospital admission (OR, 2.4).

IAPA also was associated with more severe disease, a higher rate of complications, longer ICU stays, and a greater need for organ supports, the researchers noted. Clinical features not significantly more common in patients with IAPA included fever, hemoptysis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design of the included studies and inability to control for all potential confounders, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the variations in study design, variability of practice patterns across locations, and inclusion of data mainly from countries of high socioeconomic status.

“Given the apparent waning of the COVID-19 pandemic and re-emergence of influenza, our analysis also revealed other gaps in the current literature, including the need to validate newer diagnostic methods and to develop a system to measure severity of IAPA,” the researchers added.

However, the current study results reflect IAPA prevalence from previous studies, and support the need to have a lower threshold for IAPA testing and initiation of antifungal treatment, even with limited data for clinical guidance, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL CHEST

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

THE COMPARISON

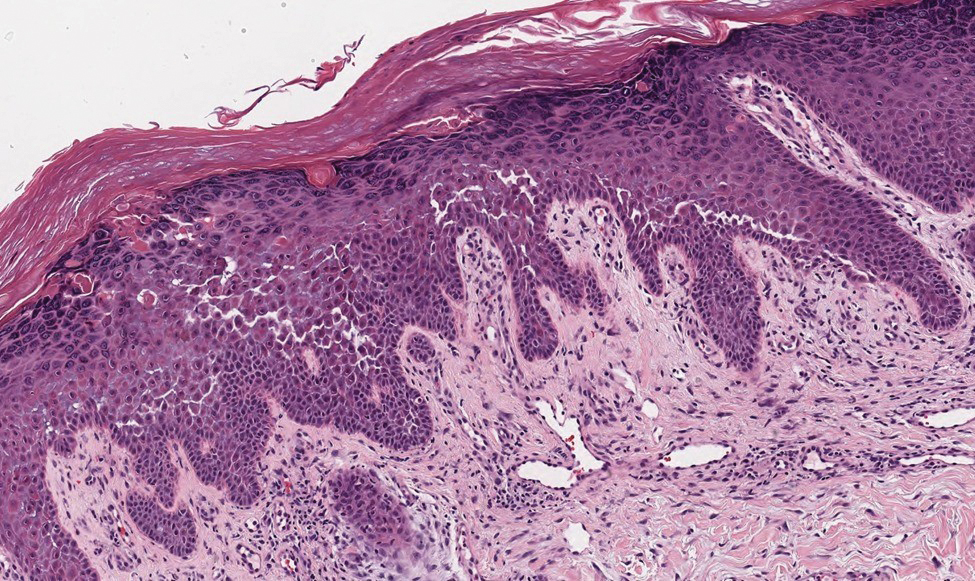

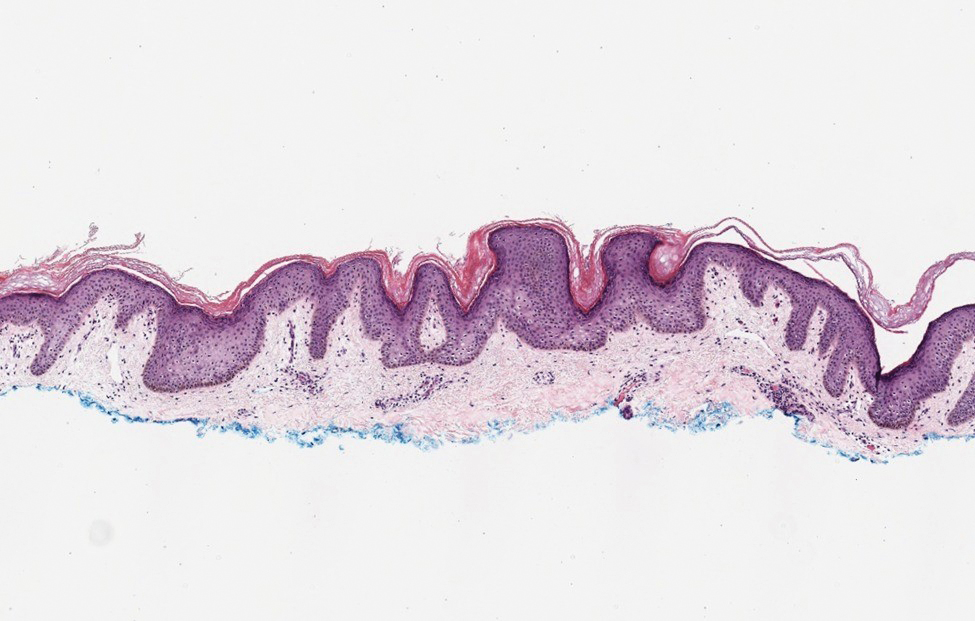

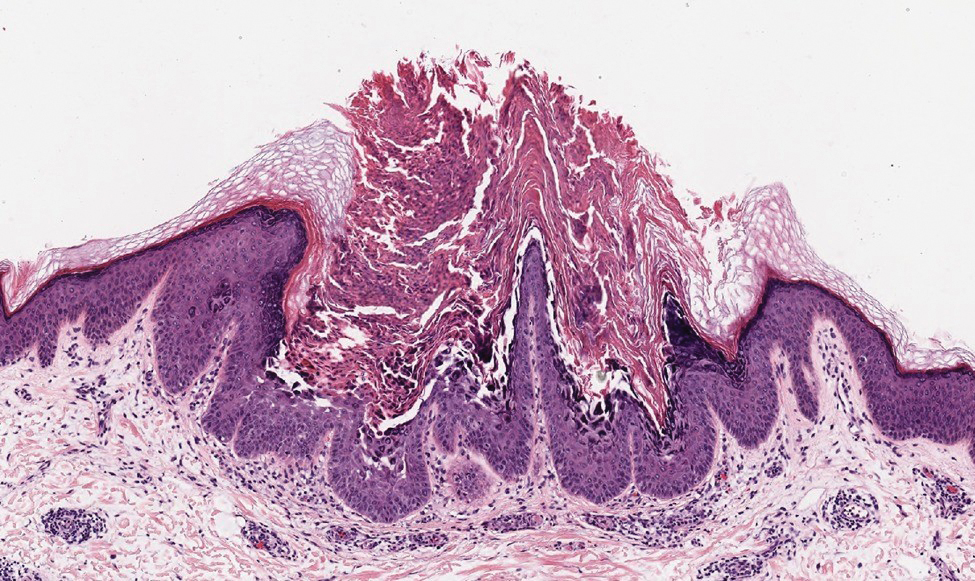

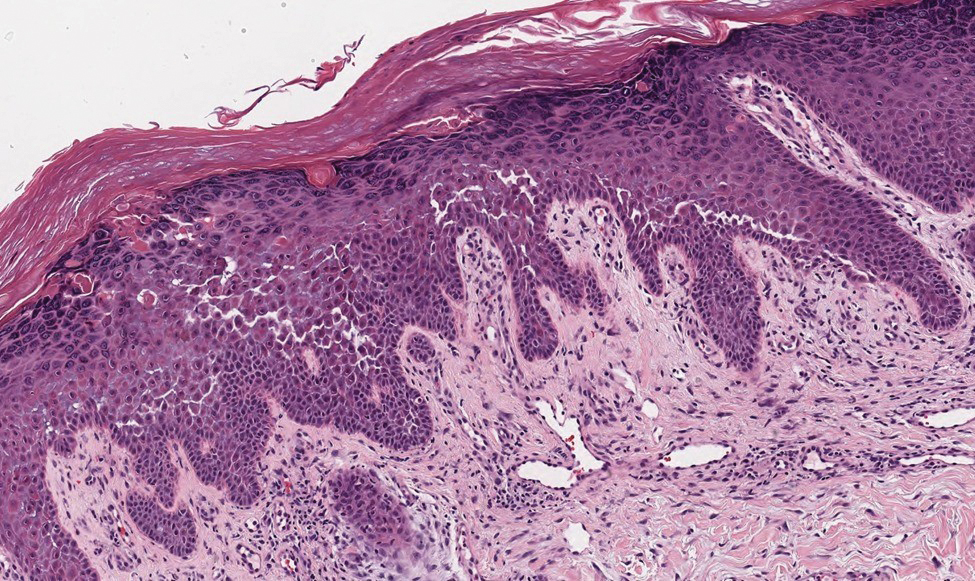

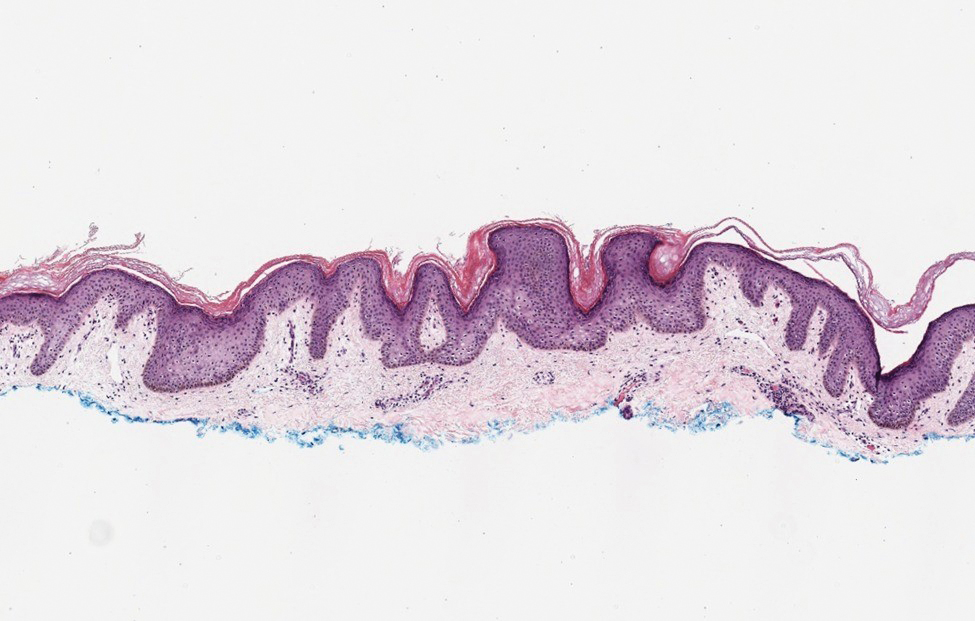

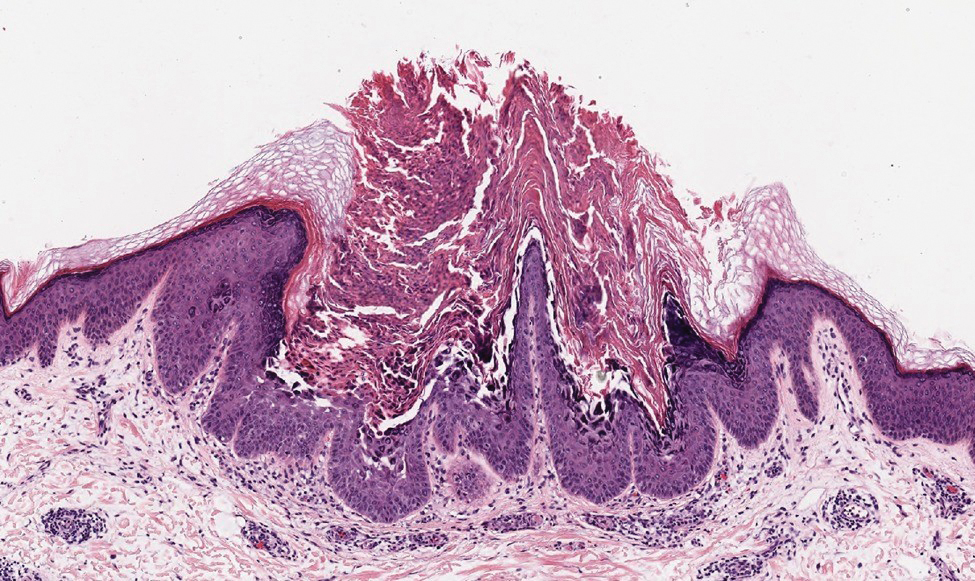

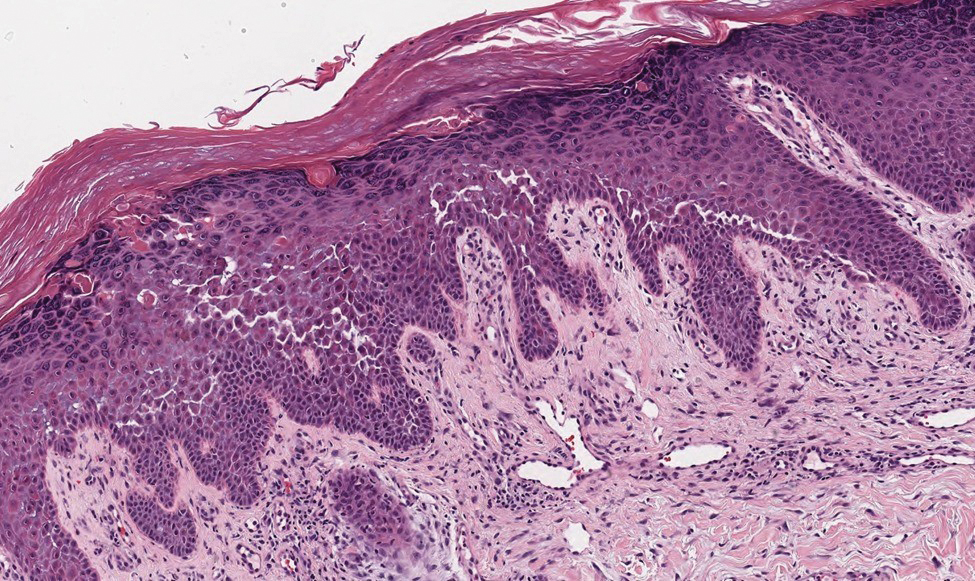

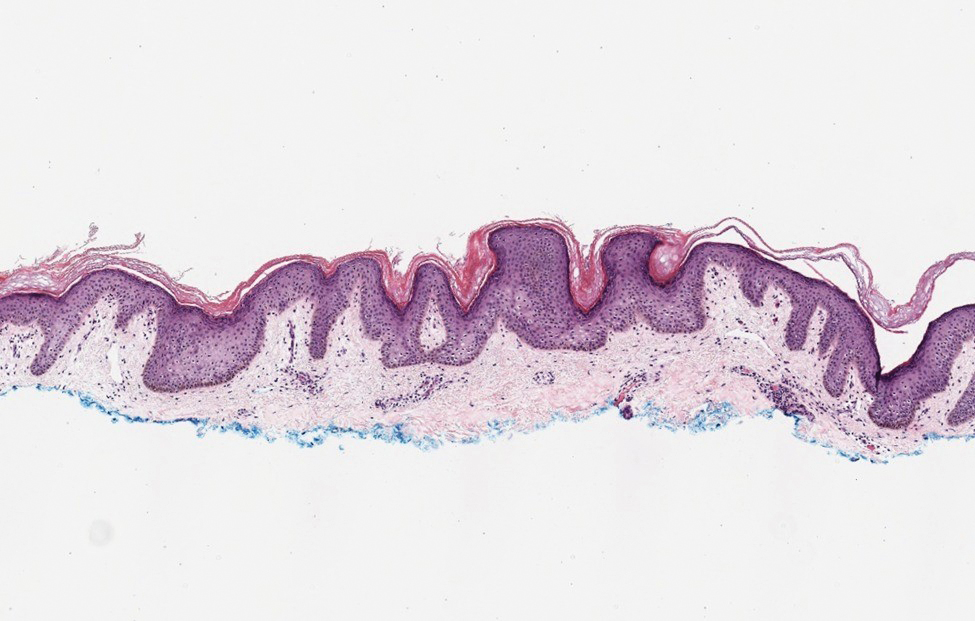

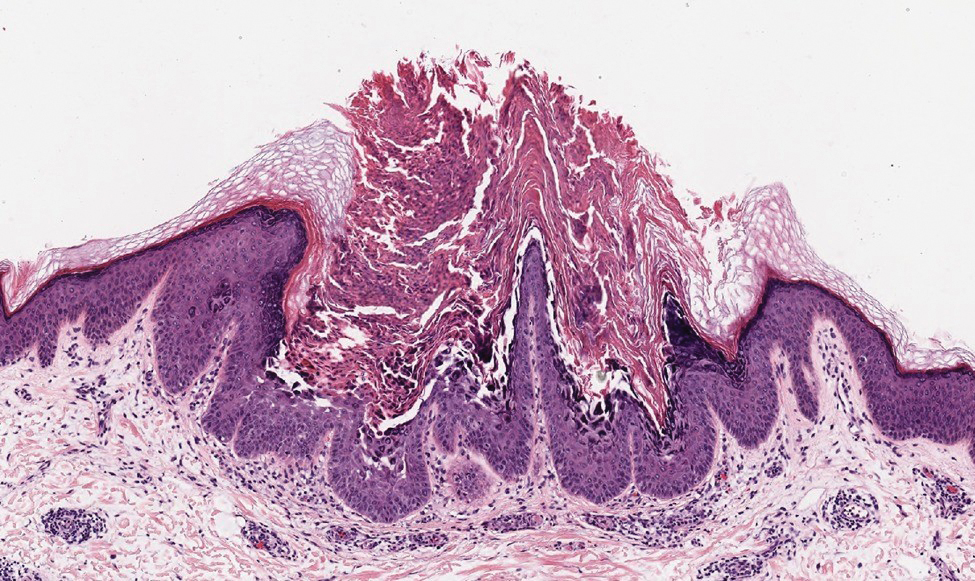

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas on the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to one or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is reexposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 Allergic contact dermatitis is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%- 23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N=19,457); 17,803 (92.9%) of these patients were White and only 1360 (7.1%) were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

Allergic contact dermatitis is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (Figure, A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (Figure, B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD)(a common component of hair dye) (Figure, C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. Allergic contact dermatitis due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on day 1 and covered. Then, on day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight

Clinical photographs of ACD and patch test results in patients with SOC are not commonplace in the literature. Positive patch test results in patients with darker skin tones vary from those of patients with lighter skin tones, and if the clinician reading the patch test result is not familiar with the findings in darker skin tones, the diagnosis may be delayed or missed.15

Furthermore, Scott et al15 highlighted that many dermatology residency training programs have a paucity of SOC education in their curriculum. This lack of representation may contribute to the diagnostic challenges encountered by health care providers.

Timely access to health care and education as well as economic stability are essential for the successful management of patients with ACD. Some individuals with SOC have been disproportionately affected by social determinants of health. Rodriguez-Homs et al19 demonstrated that the distance needed to travel to a clinic and the poverty rate of the county the patient lives in play a role in referral to a clinician specializing in contact dermatitis.

A retrospective registry review of 2310 patients undergoing patch testing at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston revealed that 2.5% were Black, 5.5% were Latinx, 8.3% were Asian, and the remaining 83.7% were White.20 Qian et al21 also looked at patch testing patterns among various sociodemographic groups (N=1,107,530) and found that 69% of patients were White and 59% were female. Rates of patch testing among patients who were Black, lesser educated, male, lower income, and younger (children aged 0–12 years) were significantly lower than for other groups when ACD was suspected (P<.0001).21 The lower rates of patch testing in patients with SOC may be due to low suspicion of diagnosis, low referral rates due to limited medical insurance, and financial instability, as well as other socioeconomic factors.20

Tamazian et al16 reviewed pediatric populations at 13 US centers and found that Black children received patch testing less frequently than White and Hispanic children. Another review of pediatric patch testing in patients with SOC found that a less comprehensive panel of allergens was used in this population.22

The key to resolution of ACD is removal of the offending antigen, and if patients are not being tested, then they risk having a prolonged and complicated course of ACD with a poor prognosis. Patients with SOC also experience greater negative psychosocial impact due to ACD disease burden.21,23

The lower rates of patch testing in Black patients cannot solely be attributed to difficulty diagnosing ACD in darker skin tones; it is likely due to the impact of social determinants of health. Alleviating health disparities will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74: 1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Bertoli MJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Autoeczematization: a strange id reaction of the skin. Cutis. 2021;108:163-166. doi:10.12788/cutis.0342

- Johansen JD, Bonefeld CM, Schwensen JFB, et al. Novel insights into contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149:1162-1171. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.02.002

- Karagounis TK, Cohen DE. Occupational hand dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023;23:201-212. doi:10.1007/s11882-023-01070-5

- Cvetkovski RS, Rothman KJ, Olsen J, et al. Relation between diagnoses on severity, sick leave and loss of job among patients with occupational hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:93-98. doi:10.1111/j .1365-2133.2005.06415.x

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Brites GS, Ferreira I, Sebastião AI, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to development of new preventive strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;162:105282. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105282

- Nielsen NH, Menne T. The relationship between IgE‐mediated and cell‐mediated hypersensitivities in an unselected Danish population: the Glostrup Allergy Study, Denmark. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:669-672. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06967.x

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeLeo VA, Alexis A, Warshaw EM, et al. The association of race/ethnicity and patch test results: North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1998- 2006. Dermatitis. 2016;27:288-292. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000220

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis to personal care products is increasing (but different!) in males and females: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1996-2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1446-1455. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.003

- Dickel H, Taylor JS, Evey P, et al. Comparison of patch test results with a standard series among white and black racial groups. Am J Contact Dermatol. 2001;12:77-82. doi:10.1053/ajcd.2001.20110

- DeLeo VA, Taylor SC, Belsito DV, et al. The effect of race and ethnicity on patch test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S107-S112. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120792

- Scott I, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Update on contact dermatitis and patch testing in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2021;108:10-12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0292

- Tamazian S, Oboite M, Treat JR. Patch testing in skin of color: a brief report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:952-953. doi:10.1111/pde.14578

- Litchman G, Nair PA, Atwater AR, et al. Contact dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459230/

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.049

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Liu B, Green CL, et al. Duration of dermatitis before patch test appointment is associated with distance to clinic and county poverty rate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:259-264. doi:10.1097 /DER.0000000000000581

- Foschi CM, Tam I, Schalock PC, et al. Patch testing results in skin of color: a retrospective review from the Massachusetts General Hospital contact dermatitis clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:452-454. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.022

- Qian MF, Li S, Honari G, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in patch testing for commercially insured patients with dermatitis: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1411-1413. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.041

- Young K, Collis RW, Sheinbein D, et al. Retrospective review of pediatric patch testing results in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:953-954. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.031

- Kadyk DL, Hall S, Belsito DV. Quality of life of patients with allergic contact dermatitis: an exploratory analysis by gender, ethnicity, age, and occupation. Dermatitis. 2004;15:117-124.

THE COMPARISON

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas on the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to one or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is reexposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 Allergic contact dermatitis is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%- 23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N=19,457); 17,803 (92.9%) of these patients were White and only 1360 (7.1%) were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

Allergic contact dermatitis is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (Figure, A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (Figure, B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD)(a common component of hair dye) (Figure, C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. Allergic contact dermatitis due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on day 1 and covered. Then, on day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight