User login

Study provides new insight into B-cell metabolism

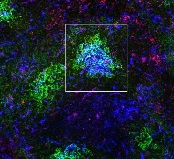

the spleen of a mouse, showing

inactivated GSK3 (magenta)

in B cells (blue) near follicular

dendritic cells (green).

Image from the lab of

Robert Rickert, PhD

Research published in Nature Immunology helps explain how B-cell metabolism adapts to different environments.

The study suggests the protein GSK3 acts as a metabolic checkpoint regulator in B cells, promoting the survival of circulating B cells while limiting the growth and proliferation of B cells in germinal centers.

“Our research shows that the protein GSK3 plays a crucial role in helping B cells meet the energy needs of their distinct states,” said study author Robert Rickert, PhD, of Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California.

“The findings are particularly relevant for certain B-cell pathologies, including lymphoma subtypes, where there is an increased demand for energy to support the hyperproliferation of cells in a microenvironment that may be limited in nutrients.”

Dr Rickert and his colleagues noted that B cells predominate in a quiescent state until they encounter an antigen, which prompts the cells to grow, proliferate, and differentiate.

The team’s new study showed that GSK3 adjusts B-cell metabolism to match the needs of these different cell states.

In circulating B cells, GSK3 limits overall metabolic activity. In proliferating B cells in germinal centers, GSK3 slows glycolysis and the production of mitochondria.

In fact, GSK3 function is essential for B-cell survival in germinal centers. To understand why, the researchers looked at how B cells in these regions generate energy.

The team found that because these B cells are so metabolically active, they consume nearly all available glucose. That switches on glycolysis.

High glycolytic activity leads to an accumulation of toxic reactive oxygen species, as does rapid manufacture of mitochondria, which tend to leak the same chemicals.

Thus, by restraining the metabolism in specific ways, GSK3 prevents cell death induced by reactive oxygen species.

“Our results were really surprising,” Dr Rickert said. “Until now, we would have thought that slowing metabolism would only be important for preventing B cells from becoming cancerous, which it indeed may be. These studies provide insight into the dynamic nature of B-cell metabolism that literally ‘fuels’ differentiation in the germinal center to produce an effective antibody response.”

“It’s not yet clear whether or how GSK3 might be a target for future therapies for B cell-related diseases, but this research opens a lot of doors for further studies. To start with, we plan to investigate how GSK3 is regulated in lymphoma and how that relates to changes in metabolism. That research could lead to new approaches to treating lymphoma.”

This research was performed in collaboration with scientists at Eli Lilly and the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at the University of Toronto. Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Lilly Research Award Program, the Arthritis National Research Foundation, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. ![]()

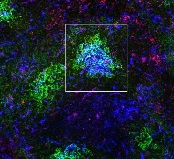

the spleen of a mouse, showing

inactivated GSK3 (magenta)

in B cells (blue) near follicular

dendritic cells (green).

Image from the lab of

Robert Rickert, PhD

Research published in Nature Immunology helps explain how B-cell metabolism adapts to different environments.

The study suggests the protein GSK3 acts as a metabolic checkpoint regulator in B cells, promoting the survival of circulating B cells while limiting the growth and proliferation of B cells in germinal centers.

“Our research shows that the protein GSK3 plays a crucial role in helping B cells meet the energy needs of their distinct states,” said study author Robert Rickert, PhD, of Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California.

“The findings are particularly relevant for certain B-cell pathologies, including lymphoma subtypes, where there is an increased demand for energy to support the hyperproliferation of cells in a microenvironment that may be limited in nutrients.”

Dr Rickert and his colleagues noted that B cells predominate in a quiescent state until they encounter an antigen, which prompts the cells to grow, proliferate, and differentiate.

The team’s new study showed that GSK3 adjusts B-cell metabolism to match the needs of these different cell states.

In circulating B cells, GSK3 limits overall metabolic activity. In proliferating B cells in germinal centers, GSK3 slows glycolysis and the production of mitochondria.

In fact, GSK3 function is essential for B-cell survival in germinal centers. To understand why, the researchers looked at how B cells in these regions generate energy.

The team found that because these B cells are so metabolically active, they consume nearly all available glucose. That switches on glycolysis.

High glycolytic activity leads to an accumulation of toxic reactive oxygen species, as does rapid manufacture of mitochondria, which tend to leak the same chemicals.

Thus, by restraining the metabolism in specific ways, GSK3 prevents cell death induced by reactive oxygen species.

“Our results were really surprising,” Dr Rickert said. “Until now, we would have thought that slowing metabolism would only be important for preventing B cells from becoming cancerous, which it indeed may be. These studies provide insight into the dynamic nature of B-cell metabolism that literally ‘fuels’ differentiation in the germinal center to produce an effective antibody response.”

“It’s not yet clear whether or how GSK3 might be a target for future therapies for B cell-related diseases, but this research opens a lot of doors for further studies. To start with, we plan to investigate how GSK3 is regulated in lymphoma and how that relates to changes in metabolism. That research could lead to new approaches to treating lymphoma.”

This research was performed in collaboration with scientists at Eli Lilly and the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at the University of Toronto. Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Lilly Research Award Program, the Arthritis National Research Foundation, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. ![]()

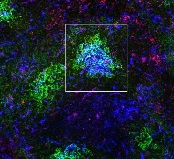

the spleen of a mouse, showing

inactivated GSK3 (magenta)

in B cells (blue) near follicular

dendritic cells (green).

Image from the lab of

Robert Rickert, PhD

Research published in Nature Immunology helps explain how B-cell metabolism adapts to different environments.

The study suggests the protein GSK3 acts as a metabolic checkpoint regulator in B cells, promoting the survival of circulating B cells while limiting the growth and proliferation of B cells in germinal centers.

“Our research shows that the protein GSK3 plays a crucial role in helping B cells meet the energy needs of their distinct states,” said study author Robert Rickert, PhD, of Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California.

“The findings are particularly relevant for certain B-cell pathologies, including lymphoma subtypes, where there is an increased demand for energy to support the hyperproliferation of cells in a microenvironment that may be limited in nutrients.”

Dr Rickert and his colleagues noted that B cells predominate in a quiescent state until they encounter an antigen, which prompts the cells to grow, proliferate, and differentiate.

The team’s new study showed that GSK3 adjusts B-cell metabolism to match the needs of these different cell states.

In circulating B cells, GSK3 limits overall metabolic activity. In proliferating B cells in germinal centers, GSK3 slows glycolysis and the production of mitochondria.

In fact, GSK3 function is essential for B-cell survival in germinal centers. To understand why, the researchers looked at how B cells in these regions generate energy.

The team found that because these B cells are so metabolically active, they consume nearly all available glucose. That switches on glycolysis.

High glycolytic activity leads to an accumulation of toxic reactive oxygen species, as does rapid manufacture of mitochondria, which tend to leak the same chemicals.

Thus, by restraining the metabolism in specific ways, GSK3 prevents cell death induced by reactive oxygen species.

“Our results were really surprising,” Dr Rickert said. “Until now, we would have thought that slowing metabolism would only be important for preventing B cells from becoming cancerous, which it indeed may be. These studies provide insight into the dynamic nature of B-cell metabolism that literally ‘fuels’ differentiation in the germinal center to produce an effective antibody response.”

“It’s not yet clear whether or how GSK3 might be a target for future therapies for B cell-related diseases, but this research opens a lot of doors for further studies. To start with, we plan to investigate how GSK3 is regulated in lymphoma and how that relates to changes in metabolism. That research could lead to new approaches to treating lymphoma.”

This research was performed in collaboration with scientists at Eli Lilly and the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at the University of Toronto. Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Lilly Research Award Program, the Arthritis National Research Foundation, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. ![]()

HAART may contribute to profound escalation in syphilis

Highly active antiretroviral therapy taken by HIV-positive men who have sex with men may be contributing to the profound escalation in syphilis infections recently observed worldwide, a recent report suggests.

After noting reports of a substantial and rapid rise in syphilis infections around the globe, which have been largely confined to HIV-positive men taking HAART, researchers constructed mathematical models to test the possibility that HAART may inadvertently alter immune responses in ways that enhance the patient’s vulnerability to Treponema pallidum.

If these findings are verified in further studies, it will be “imperative” to address this unforeseen sequela before implementing global pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) programs, they noted.

The investigators devised their mathematical models to account for the possibility that either HAART itself, or the use of HAART as a surrogate marker for high-risk sex, or both factors together could influence the association with syphilis. The first model assumed that one or more components of HAART could impair the immune response to T. pallidum, and the second assumed that men taking HAART would perceive themselves as low risk and increase their number of partners, thus heightening their ability to transmit the organism.

Each model demonstrated that immunologic changes or behavioral changes could produce syphilis outbreaks similar to those reported in the literature.

“Strikingly, the peak prevalence of the syphilis outbreak produced by both behavioral and immunologic changes [acting together] is larger than the sum of the peaks of outbreaks produced independently by either type of change,” Dr. Rekart and his associates said (Sex Transm Infect. 2017 Jan 16. doi: 10.1136/sextrans.2016.052870).

In other words, HAART-associated immunologic and behavioral changes “can in principle act synergistically to increase syphilis prevalence by amounts comparable with that observed in ongoing outbreaks,” they said.

It is notable that the rates of two other STDs, gonorrhea and chlamydia, have either failed to increase as much or as rapidly as syphilis, or have actually decreased, in the same patient populations. So, the researchers also examined the biological plausibility that HAART could increase patients’ susceptibility to syphilis but not to gonorrhea and chlamydia.

The immune system’s primary clearance mechanism of T. pallidum, macrophage-mediated opsonophagocytosis, requires “unperturbed mitochondrial function to ensure peak metabolic activity within macrophages, opsonic antibody production, and ... macrophage activation.” But HIV infection reduces the quality of opsonic antibodies, and some components of HAART significantly suppress mitochondrial function, the proinflammatory response, and macrophage activation. Theoretically, the combination of these factors could impair treponemal clearance via opsonophagocytosis, Dr. Rekart and his associates said.

In contrast, gonorrhea and chlamydia are caused by pathogens that are not so reliant on opsonophagocytosis to be cleared by the immune system. So, HAART would not lead to similar surges in the rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia infection.

Further studies are needed to corroborate these findings. If they are confirmed, the use of both HAART and PrEP will require changes in patient management to mitigate this increased risk for acquiring syphilis and perhaps other disorders, the researchers noted.

“A retrospective case-control and/or a prospective cohort study comparing the prevalence and epidemiological features of infectious syphilis cases among patients who are HIV-1 positive and treated with HAART, patients who are HIV-1 positive and untreated, and patients who are HIV-1-negative ... would be enlightening,” the investigators added.

Thie study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Rekart and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The novel hypothesis proposed by Dr. Michael L. Rekart and his associates is intriguing, and warrants careful consideration.

But it is critical to emphasize that the authors are in no way suggesting that antiretroviral therapy be reconsidered for the treatment and prevention of HIV. Rather, their aim is to stimulate discussion, inform research, and address the staggering increases in syphilis rates.

The focus on HIV appears to have tempered the urgency to control other STDs. But history has shown many times over that that would be a costly mistake. This study demonstrates why screening for, diagnosing, and treating all sexually transmitted infections must be a priority.

Susan Tuddenham, MD, is in the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tuddenham and her associates made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Rekart’s study (Sex Transm Infect. 2017 Jan 16. doi: 10.1136/sextrans.2016.052940).

The novel hypothesis proposed by Dr. Michael L. Rekart and his associates is intriguing, and warrants careful consideration.

But it is critical to emphasize that the authors are in no way suggesting that antiretroviral therapy be reconsidered for the treatment and prevention of HIV. Rather, their aim is to stimulate discussion, inform research, and address the staggering increases in syphilis rates.

The focus on HIV appears to have tempered the urgency to control other STDs. But history has shown many times over that that would be a costly mistake. This study demonstrates why screening for, diagnosing, and treating all sexually transmitted infections must be a priority.

Susan Tuddenham, MD, is in the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tuddenham and her associates made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Rekart’s study (Sex Transm Infect. 2017 Jan 16. doi: 10.1136/sextrans.2016.052940).

The novel hypothesis proposed by Dr. Michael L. Rekart and his associates is intriguing, and warrants careful consideration.

But it is critical to emphasize that the authors are in no way suggesting that antiretroviral therapy be reconsidered for the treatment and prevention of HIV. Rather, their aim is to stimulate discussion, inform research, and address the staggering increases in syphilis rates.

The focus on HIV appears to have tempered the urgency to control other STDs. But history has shown many times over that that would be a costly mistake. This study demonstrates why screening for, diagnosing, and treating all sexually transmitted infections must be a priority.

Susan Tuddenham, MD, is in the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tuddenham and her associates made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Rekart’s study (Sex Transm Infect. 2017 Jan 16. doi: 10.1136/sextrans.2016.052940).

Highly active antiretroviral therapy taken by HIV-positive men who have sex with men may be contributing to the profound escalation in syphilis infections recently observed worldwide, a recent report suggests.

After noting reports of a substantial and rapid rise in syphilis infections around the globe, which have been largely confined to HIV-positive men taking HAART, researchers constructed mathematical models to test the possibility that HAART may inadvertently alter immune responses in ways that enhance the patient’s vulnerability to Treponema pallidum.

If these findings are verified in further studies, it will be “imperative” to address this unforeseen sequela before implementing global pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) programs, they noted.

The investigators devised their mathematical models to account for the possibility that either HAART itself, or the use of HAART as a surrogate marker for high-risk sex, or both factors together could influence the association with syphilis. The first model assumed that one or more components of HAART could impair the immune response to T. pallidum, and the second assumed that men taking HAART would perceive themselves as low risk and increase their number of partners, thus heightening their ability to transmit the organism.

Each model demonstrated that immunologic changes or behavioral changes could produce syphilis outbreaks similar to those reported in the literature.

“Strikingly, the peak prevalence of the syphilis outbreak produced by both behavioral and immunologic changes [acting together] is larger than the sum of the peaks of outbreaks produced independently by either type of change,” Dr. Rekart and his associates said (Sex Transm Infect. 2017 Jan 16. doi: 10.1136/sextrans.2016.052870).

In other words, HAART-associated immunologic and behavioral changes “can in principle act synergistically to increase syphilis prevalence by amounts comparable with that observed in ongoing outbreaks,” they said.

It is notable that the rates of two other STDs, gonorrhea and chlamydia, have either failed to increase as much or as rapidly as syphilis, or have actually decreased, in the same patient populations. So, the researchers also examined the biological plausibility that HAART could increase patients’ susceptibility to syphilis but not to gonorrhea and chlamydia.

The immune system’s primary clearance mechanism of T. pallidum, macrophage-mediated opsonophagocytosis, requires “unperturbed mitochondrial function to ensure peak metabolic activity within macrophages, opsonic antibody production, and ... macrophage activation.” But HIV infection reduces the quality of opsonic antibodies, and some components of HAART significantly suppress mitochondrial function, the proinflammatory response, and macrophage activation. Theoretically, the combination of these factors could impair treponemal clearance via opsonophagocytosis, Dr. Rekart and his associates said.

In contrast, gonorrhea and chlamydia are caused by pathogens that are not so reliant on opsonophagocytosis to be cleared by the immune system. So, HAART would not lead to similar surges in the rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia infection.

Further studies are needed to corroborate these findings. If they are confirmed, the use of both HAART and PrEP will require changes in patient management to mitigate this increased risk for acquiring syphilis and perhaps other disorders, the researchers noted.

“A retrospective case-control and/or a prospective cohort study comparing the prevalence and epidemiological features of infectious syphilis cases among patients who are HIV-1 positive and treated with HAART, patients who are HIV-1 positive and untreated, and patients who are HIV-1-negative ... would be enlightening,” the investigators added.

Thie study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Rekart and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy taken by HIV-positive men who have sex with men may be contributing to the profound escalation in syphilis infections recently observed worldwide, a recent report suggests.

After noting reports of a substantial and rapid rise in syphilis infections around the globe, which have been largely confined to HIV-positive men taking HAART, researchers constructed mathematical models to test the possibility that HAART may inadvertently alter immune responses in ways that enhance the patient’s vulnerability to Treponema pallidum.

If these findings are verified in further studies, it will be “imperative” to address this unforeseen sequela before implementing global pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) programs, they noted.

The investigators devised their mathematical models to account for the possibility that either HAART itself, or the use of HAART as a surrogate marker for high-risk sex, or both factors together could influence the association with syphilis. The first model assumed that one or more components of HAART could impair the immune response to T. pallidum, and the second assumed that men taking HAART would perceive themselves as low risk and increase their number of partners, thus heightening their ability to transmit the organism.

Each model demonstrated that immunologic changes or behavioral changes could produce syphilis outbreaks similar to those reported in the literature.

“Strikingly, the peak prevalence of the syphilis outbreak produced by both behavioral and immunologic changes [acting together] is larger than the sum of the peaks of outbreaks produced independently by either type of change,” Dr. Rekart and his associates said (Sex Transm Infect. 2017 Jan 16. doi: 10.1136/sextrans.2016.052870).

In other words, HAART-associated immunologic and behavioral changes “can in principle act synergistically to increase syphilis prevalence by amounts comparable with that observed in ongoing outbreaks,” they said.

It is notable that the rates of two other STDs, gonorrhea and chlamydia, have either failed to increase as much or as rapidly as syphilis, or have actually decreased, in the same patient populations. So, the researchers also examined the biological plausibility that HAART could increase patients’ susceptibility to syphilis but not to gonorrhea and chlamydia.

The immune system’s primary clearance mechanism of T. pallidum, macrophage-mediated opsonophagocytosis, requires “unperturbed mitochondrial function to ensure peak metabolic activity within macrophages, opsonic antibody production, and ... macrophage activation.” But HIV infection reduces the quality of opsonic antibodies, and some components of HAART significantly suppress mitochondrial function, the proinflammatory response, and macrophage activation. Theoretically, the combination of these factors could impair treponemal clearance via opsonophagocytosis, Dr. Rekart and his associates said.

In contrast, gonorrhea and chlamydia are caused by pathogens that are not so reliant on opsonophagocytosis to be cleared by the immune system. So, HAART would not lead to similar surges in the rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia infection.

Further studies are needed to corroborate these findings. If they are confirmed, the use of both HAART and PrEP will require changes in patient management to mitigate this increased risk for acquiring syphilis and perhaps other disorders, the researchers noted.

“A retrospective case-control and/or a prospective cohort study comparing the prevalence and epidemiological features of infectious syphilis cases among patients who are HIV-1 positive and treated with HAART, patients who are HIV-1 positive and untreated, and patients who are HIV-1-negative ... would be enlightening,” the investigators added.

Thie study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Rekart and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

Key clinical point: HAART may be contributing to the profound escalation in syphilis infections worldwide, perhaps by impairing immunity to Treponema pallidum.

Major finding: HAART-associated immunologic and behavioral changes can in principle act synergistically to increase syphilis prevalence by amounts comparable with that observed in ongoing outbreaks.

Data source: Mathematical modeling studies of potential HAART-induced changes in immune function and behavior among HIV-positive men who have sex with men.

Disclosures: This study supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Rekart and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae occurs in 25% of long-term acute care hospital cultures

Nearly one-quarter of Klebsiella pneumoniae cultures in a network of U.S. long-term acute care hospitals are resistant to carbapenem, according to Jennifer H. Han, MD, and her associates.

From a sample of 3,846 K. pneumoniae cultures taken from 64 long-term acute care hospitals in 16 states, 946, or 24.6%, of the cultures were carbapenem-resistant, and were taken from 821 patients. Just under 54% of CRKP isolates were taken from a respiratory source, with 37% coming from urine and the remaining 9.4% coming from blood. Nearly all CRKP isolates were resistant to fluoroquinolones, and 59.2% were resistant to amikacin.

Of the 16 states where cultures were taken from, California had the highest rate of carbapenem resistance, with 45.5% of K. pneumoniae cultures showing resistance. Other states with high rates of CRKP included South Carolina, Kentucky, and Indiana.

“Given the chronically, critically ill population, with convergence of at-risk patients from multiple facilities, future studies of optimal infection prevention strategies are urgently needed for this setting. In addition, expansion of national surveillance efforts and improved communication between [long-term acute care hospitals] and acute care hospitals will be critical for reducing the continued emergence and dissemination of CRKP across the health care continuum,” Dr. Han and her associates concluded.

Find the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1 LTACHs 093/cid/ciw856)

Nearly one-quarter of Klebsiella pneumoniae cultures in a network of U.S. long-term acute care hospitals are resistant to carbapenem, according to Jennifer H. Han, MD, and her associates.

From a sample of 3,846 K. pneumoniae cultures taken from 64 long-term acute care hospitals in 16 states, 946, or 24.6%, of the cultures were carbapenem-resistant, and were taken from 821 patients. Just under 54% of CRKP isolates were taken from a respiratory source, with 37% coming from urine and the remaining 9.4% coming from blood. Nearly all CRKP isolates were resistant to fluoroquinolones, and 59.2% were resistant to amikacin.

Of the 16 states where cultures were taken from, California had the highest rate of carbapenem resistance, with 45.5% of K. pneumoniae cultures showing resistance. Other states with high rates of CRKP included South Carolina, Kentucky, and Indiana.

“Given the chronically, critically ill population, with convergence of at-risk patients from multiple facilities, future studies of optimal infection prevention strategies are urgently needed for this setting. In addition, expansion of national surveillance efforts and improved communication between [long-term acute care hospitals] and acute care hospitals will be critical for reducing the continued emergence and dissemination of CRKP across the health care continuum,” Dr. Han and her associates concluded.

Find the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1 LTACHs 093/cid/ciw856)

Nearly one-quarter of Klebsiella pneumoniae cultures in a network of U.S. long-term acute care hospitals are resistant to carbapenem, according to Jennifer H. Han, MD, and her associates.

From a sample of 3,846 K. pneumoniae cultures taken from 64 long-term acute care hospitals in 16 states, 946, or 24.6%, of the cultures were carbapenem-resistant, and were taken from 821 patients. Just under 54% of CRKP isolates were taken from a respiratory source, with 37% coming from urine and the remaining 9.4% coming from blood. Nearly all CRKP isolates were resistant to fluoroquinolones, and 59.2% were resistant to amikacin.

Of the 16 states where cultures were taken from, California had the highest rate of carbapenem resistance, with 45.5% of K. pneumoniae cultures showing resistance. Other states with high rates of CRKP included South Carolina, Kentucky, and Indiana.

“Given the chronically, critically ill population, with convergence of at-risk patients from multiple facilities, future studies of optimal infection prevention strategies are urgently needed for this setting. In addition, expansion of national surveillance efforts and improved communication between [long-term acute care hospitals] and acute care hospitals will be critical for reducing the continued emergence and dissemination of CRKP across the health care continuum,” Dr. Han and her associates concluded.

Find the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1 LTACHs 093/cid/ciw856)

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Asymptomatic carriage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae ‘considerable’

Asymptomatic carriage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae is “considerable,” according to genetic analyses of bacterial isolates obtained from patients at four large U.S. hospitals.

To better understand the “urgent threat” of carbapenem resistance – specifically, to obtain a “snapshot” of how the resistant enterobacteria evolve, diversify, and spread – the researchers performed genetic analyses on 122 carbapenem-resistant and 141 carbapenem-susceptible bacterial isolates from patients hospitalized during a 16-month period at three Boston and one California medical centers. The isolates were obtained from urine (44%), respiratory tract (16%), blood (11%), wound (11%), and other samples, said Gustavo C. Cerqueira, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., and his associates.

They found 8 species of bacteria that exhibited carbapenem resistance, chiefly Klebsiella pneumoniae. There also was a significant degree of diversity among resistant Enterobacteria. Most importantly, the investigators found evidence of substantial asymptomatic carriage of resistant bacteria and discovered several previously unrecognized mechanisms that produced resistance. Taken together, the findings indicate “continued innovation by these organisms to thwart the action of this important class of antibiotics,” reported Dr. Cerqueira, also affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his associates (Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2017 Jan 16 [doi:10.1073/pnas.1616248114]).

The study findings underscore the need for “an aggressive approach to surveillance and isolation” to control this continuing threat, they added.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Cerqueira and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Asymptomatic carriage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae is “considerable,” according to genetic analyses of bacterial isolates obtained from patients at four large U.S. hospitals.

To better understand the “urgent threat” of carbapenem resistance – specifically, to obtain a “snapshot” of how the resistant enterobacteria evolve, diversify, and spread – the researchers performed genetic analyses on 122 carbapenem-resistant and 141 carbapenem-susceptible bacterial isolates from patients hospitalized during a 16-month period at three Boston and one California medical centers. The isolates were obtained from urine (44%), respiratory tract (16%), blood (11%), wound (11%), and other samples, said Gustavo C. Cerqueira, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., and his associates.

They found 8 species of bacteria that exhibited carbapenem resistance, chiefly Klebsiella pneumoniae. There also was a significant degree of diversity among resistant Enterobacteria. Most importantly, the investigators found evidence of substantial asymptomatic carriage of resistant bacteria and discovered several previously unrecognized mechanisms that produced resistance. Taken together, the findings indicate “continued innovation by these organisms to thwart the action of this important class of antibiotics,” reported Dr. Cerqueira, also affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his associates (Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2017 Jan 16 [doi:10.1073/pnas.1616248114]).

The study findings underscore the need for “an aggressive approach to surveillance and isolation” to control this continuing threat, they added.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Cerqueira and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Asymptomatic carriage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae is “considerable,” according to genetic analyses of bacterial isolates obtained from patients at four large U.S. hospitals.

To better understand the “urgent threat” of carbapenem resistance – specifically, to obtain a “snapshot” of how the resistant enterobacteria evolve, diversify, and spread – the researchers performed genetic analyses on 122 carbapenem-resistant and 141 carbapenem-susceptible bacterial isolates from patients hospitalized during a 16-month period at three Boston and one California medical centers. The isolates were obtained from urine (44%), respiratory tract (16%), blood (11%), wound (11%), and other samples, said Gustavo C. Cerqueira, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., and his associates.

They found 8 species of bacteria that exhibited carbapenem resistance, chiefly Klebsiella pneumoniae. There also was a significant degree of diversity among resistant Enterobacteria. Most importantly, the investigators found evidence of substantial asymptomatic carriage of resistant bacteria and discovered several previously unrecognized mechanisms that produced resistance. Taken together, the findings indicate “continued innovation by these organisms to thwart the action of this important class of antibiotics,” reported Dr. Cerqueira, also affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his associates (Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2017 Jan 16 [doi:10.1073/pnas.1616248114]).

The study findings underscore the need for “an aggressive approach to surveillance and isolation” to control this continuing threat, they added.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Cerqueira and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

Key clinical point: Asymptomatic carriage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae is “considerable.”

Major finding: Researchers found eight species of bacteria that exhibited carbapenem resistance, a significant degree of diversity among resistant enterobacteria, evidence of substantial asymptomatic carriage of resistant bacteria, and several previously unrecognized mechanisms that produced resistance.

Data source: Genetic analyses of 122 carbapenem-resistant and 141 carbapenem-susceptible bacterial isolates obtained from patients at 4 large U.S. hospitals.

Disclosures: This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Cerqueira and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Older women with remitted depression show attention bias for negative information

Older women with a history of major depressive disorder are more likely to direct their attention to negative images than women without history of MDD, researchers report. The findings follow previous research showing that individuals currently depressed or at-risk show a similar attention bias.

The current study examined 33 postmenopausal women aged 45-75 years with an emotion dot probe (EDP) task combined with fMRI scans, in addition to cognitive and depression history screening and several self-rated measures.

“We examined resting-state functional connectivity before the EDP task to assess differences in intrinsic amygdala functional connections to other brain areas between the groups,” wrote Kimberly Albert, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and her coauthors (J Affect Disord. 2017 Mar 1;210:49-52).

The women in the study with a history of MDD showed greater attention facilitation to negative images, greater amygdala activity, and greater amygdala-hippocampal functional connectivity than women without a history of MDD.

“Attention bias for negative information can be seen in individuals with past MDD without inducing a negative mood state. Attention bias for negative information may be an ongoing vulnerability for MDD recurrence independent of mood state,” Dr. Albert and her coauthors wrote.

Older women with a history of major depressive disorder are more likely to direct their attention to negative images than women without history of MDD, researchers report. The findings follow previous research showing that individuals currently depressed or at-risk show a similar attention bias.

The current study examined 33 postmenopausal women aged 45-75 years with an emotion dot probe (EDP) task combined with fMRI scans, in addition to cognitive and depression history screening and several self-rated measures.

“We examined resting-state functional connectivity before the EDP task to assess differences in intrinsic amygdala functional connections to other brain areas between the groups,” wrote Kimberly Albert, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and her coauthors (J Affect Disord. 2017 Mar 1;210:49-52).

The women in the study with a history of MDD showed greater attention facilitation to negative images, greater amygdala activity, and greater amygdala-hippocampal functional connectivity than women without a history of MDD.

“Attention bias for negative information can be seen in individuals with past MDD without inducing a negative mood state. Attention bias for negative information may be an ongoing vulnerability for MDD recurrence independent of mood state,” Dr. Albert and her coauthors wrote.

Older women with a history of major depressive disorder are more likely to direct their attention to negative images than women without history of MDD, researchers report. The findings follow previous research showing that individuals currently depressed or at-risk show a similar attention bias.

The current study examined 33 postmenopausal women aged 45-75 years with an emotion dot probe (EDP) task combined with fMRI scans, in addition to cognitive and depression history screening and several self-rated measures.

“We examined resting-state functional connectivity before the EDP task to assess differences in intrinsic amygdala functional connections to other brain areas between the groups,” wrote Kimberly Albert, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and her coauthors (J Affect Disord. 2017 Mar 1;210:49-52).

The women in the study with a history of MDD showed greater attention facilitation to negative images, greater amygdala activity, and greater amygdala-hippocampal functional connectivity than women without a history of MDD.

“Attention bias for negative information can be seen in individuals with past MDD without inducing a negative mood state. Attention bias for negative information may be an ongoing vulnerability for MDD recurrence independent of mood state,” Dr. Albert and her coauthors wrote.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Triclosan sutures halve surgical site infections in children

The use of triclosan-impregnated sutures reduced by half the incidence of surgical site infections in children, a large randomized study has determined.

Overall, the antibiotic-treated sutures cut the number of these infections by 52%, but they were particularly effective in reducing the risk of deep surgical site infections (SSIs), Marjo Renko, MD, wrote (Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17[1]:50-7).

The study was conducted in clean wounds in healthy children and in a center that already had a very low rate of surgical site infections (just 5%) – showing that improvement is possible even in optimal care settings, wrote Dr. Renko, of the University of Oulu, Finland, and her colleagues.

“This randomized, controlled study shows that even in low-risk settings, where other prophylactic measures are available to use, triclosan-containing sutures effectively prevented the occurrence of SSIs in children,” the team wrote.

The study cohort comprised 1,633 children aged 7-17 who underwent surgery at a single Finnish hospital from 2010-2014. Most were there for planned surgery (87%); the remainder had emergency surgery. The most common surgical site was musculoskeletal (40%), followed by abdominal wall surgery (about 25%), and urogenital surgery (about 13%). The rest were intraabdominal or procedures on the nervous system, chest, and skin or subcutaneous tissue.

The children were randomized to either plain or triclosan-impregnated sutures. The primary outcome was the occurrence of a superficial or deep surgical site infection, based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria. The procedures were performed by 69 surgeons.

In a modified intent-to-treat analysis, a surgical site infection occurred in 3% of the triclosan-suture group (20 children) and in 5% of the control suture group (42 children). In the control group, these infections were most often of chest incisions (15%), followed by skin incisions (10%) and nervous system, intraabdominal, and musculoskeletal incisions (8% each). In the triclosan group, the most common site of infection was skin (10%), followed by musculoskeletal (4%), nervous system (2%), and urogenital and abdominal wall incisions (1% each).

Compared with control sutures, triclosan sutures reduced the overall risk of a surgical site infection by 52% (relative risk, 0.48; 95% confidence interval, 0.28-0.80). The number needed to treat to avoid one infection was 36.

The sutures were significantly more effective in reducing deep infections than superficial infections. Superficial infections occurred in 2% of the triclosan group (17) and 4% of the control group (28) – a risk reduction of 39% (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.34-1.09) Deep infections occurred in less than 1% of the triclosan group (3) and 2% of the control group (14) – a risk reduction of 79% (RR, 0.21’ CI, 0.07-0.66).

Infections were associated with an increased incidence of wound dehiscence in the control group (6% vs. 4%), the need for additional antimicrobial agents (7% vs. 2%), and wound revisions (2% vs. less than 1%). Children in the control group also had more outpatient visits (8% vs. 4%) and were more often readmitted because of their infection (2% vs. 1%).

The authors noted that triclosan, in the setting of increased household use, “has raised concerns about the toxic effects of the drug on the human body. Observational studies have reported associations between triclosan exposures and altered thyroid hormone levels, body mass index, and waist circumference.”

Two Norwegian studies found that the drug was associated with inhalation allergies and seasonal allergies.

“Because of the agent’s suspected toxicity and to prevent further development of resistant bacteria, use of triclosan should be restricted and reserved only for medical procedures with adequate evidence,” they noted. However, “SSIs cause much morbidity and mortality after surgical procedures, and economic evaluations recommend the use of triclosan-containing material.”

Dr. Renko received grants from the Alma and K.A. Snellman Foundation, the Finnish Medical Foundation, and the Foundation for Pediatric Research.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

The study by Dr. Marjo Renko and her colleagues is impressive in its sheer numbers, if not so much in its findings, Felix J. Hüttner, MD, and Markus K. Diener, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17[1]:3-4).

“We congratulate the authors on successfully doing a pragmatic, large-scale trial in a difficult setting; randomized controlled trials in children are known to pose specific challenges to researchers. However, the monocenter design raises some concerns about the generalizability of the results.”

Single-center trials can overestimate treatment effects, the colleagues noted. Dr. Renko’s conclusions don’t line up with their own metaanalysis of triclosan-containing sutures for abdominal wall closure. In it, three single-center trials found in favor of the triclosan sutures, but two multicenter trials did not.

The variation in infection rates in each type of surgery is a clue to the difficulty of a one-size-fits-all intervention like the treated sutures. “The differences between the intervention group and the control group vary widely by surgery type – for example, 0% versus 15% for thoracic surgery, compared with 1% versus 1% for surgery of the urinary system and genitals. Thus, triclosan-containing sutures might only be beneficial for specific types of operations and in our opinion, it cannot be concluded that triclosan-containing sutures reduce surgical site infections in all of these indications. Future trials should focus at individual types of pediatric surgery to evaluate a potential beneficial effect.”

Dr. Hüttner and Dr. Diener are surgeons at the University of Heidelberg, Germany. Dr. Hüttner had no financial disclosures. Dr. Diener has received grants from Johnson & Johnson Medical Limited.

The study by Dr. Marjo Renko and her colleagues is impressive in its sheer numbers, if not so much in its findings, Felix J. Hüttner, MD, and Markus K. Diener, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17[1]:3-4).

“We congratulate the authors on successfully doing a pragmatic, large-scale trial in a difficult setting; randomized controlled trials in children are known to pose specific challenges to researchers. However, the monocenter design raises some concerns about the generalizability of the results.”

Single-center trials can overestimate treatment effects, the colleagues noted. Dr. Renko’s conclusions don’t line up with their own metaanalysis of triclosan-containing sutures for abdominal wall closure. In it, three single-center trials found in favor of the triclosan sutures, but two multicenter trials did not.

The variation in infection rates in each type of surgery is a clue to the difficulty of a one-size-fits-all intervention like the treated sutures. “The differences between the intervention group and the control group vary widely by surgery type – for example, 0% versus 15% for thoracic surgery, compared with 1% versus 1% for surgery of the urinary system and genitals. Thus, triclosan-containing sutures might only be beneficial for specific types of operations and in our opinion, it cannot be concluded that triclosan-containing sutures reduce surgical site infections in all of these indications. Future trials should focus at individual types of pediatric surgery to evaluate a potential beneficial effect.”

Dr. Hüttner and Dr. Diener are surgeons at the University of Heidelberg, Germany. Dr. Hüttner had no financial disclosures. Dr. Diener has received grants from Johnson & Johnson Medical Limited.

The study by Dr. Marjo Renko and her colleagues is impressive in its sheer numbers, if not so much in its findings, Felix J. Hüttner, MD, and Markus K. Diener, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17[1]:3-4).

“We congratulate the authors on successfully doing a pragmatic, large-scale trial in a difficult setting; randomized controlled trials in children are known to pose specific challenges to researchers. However, the monocenter design raises some concerns about the generalizability of the results.”

Single-center trials can overestimate treatment effects, the colleagues noted. Dr. Renko’s conclusions don’t line up with their own metaanalysis of triclosan-containing sutures for abdominal wall closure. In it, three single-center trials found in favor of the triclosan sutures, but two multicenter trials did not.

The variation in infection rates in each type of surgery is a clue to the difficulty of a one-size-fits-all intervention like the treated sutures. “The differences between the intervention group and the control group vary widely by surgery type – for example, 0% versus 15% for thoracic surgery, compared with 1% versus 1% for surgery of the urinary system and genitals. Thus, triclosan-containing sutures might only be beneficial for specific types of operations and in our opinion, it cannot be concluded that triclosan-containing sutures reduce surgical site infections in all of these indications. Future trials should focus at individual types of pediatric surgery to evaluate a potential beneficial effect.”

Dr. Hüttner and Dr. Diener are surgeons at the University of Heidelberg, Germany. Dr. Hüttner had no financial disclosures. Dr. Diener has received grants from Johnson & Johnson Medical Limited.

The use of triclosan-impregnated sutures reduced by half the incidence of surgical site infections in children, a large randomized study has determined.

Overall, the antibiotic-treated sutures cut the number of these infections by 52%, but they were particularly effective in reducing the risk of deep surgical site infections (SSIs), Marjo Renko, MD, wrote (Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17[1]:50-7).

The study was conducted in clean wounds in healthy children and in a center that already had a very low rate of surgical site infections (just 5%) – showing that improvement is possible even in optimal care settings, wrote Dr. Renko, of the University of Oulu, Finland, and her colleagues.

“This randomized, controlled study shows that even in low-risk settings, where other prophylactic measures are available to use, triclosan-containing sutures effectively prevented the occurrence of SSIs in children,” the team wrote.

The study cohort comprised 1,633 children aged 7-17 who underwent surgery at a single Finnish hospital from 2010-2014. Most were there for planned surgery (87%); the remainder had emergency surgery. The most common surgical site was musculoskeletal (40%), followed by abdominal wall surgery (about 25%), and urogenital surgery (about 13%). The rest were intraabdominal or procedures on the nervous system, chest, and skin or subcutaneous tissue.

The children were randomized to either plain or triclosan-impregnated sutures. The primary outcome was the occurrence of a superficial or deep surgical site infection, based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria. The procedures were performed by 69 surgeons.

In a modified intent-to-treat analysis, a surgical site infection occurred in 3% of the triclosan-suture group (20 children) and in 5% of the control suture group (42 children). In the control group, these infections were most often of chest incisions (15%), followed by skin incisions (10%) and nervous system, intraabdominal, and musculoskeletal incisions (8% each). In the triclosan group, the most common site of infection was skin (10%), followed by musculoskeletal (4%), nervous system (2%), and urogenital and abdominal wall incisions (1% each).

Compared with control sutures, triclosan sutures reduced the overall risk of a surgical site infection by 52% (relative risk, 0.48; 95% confidence interval, 0.28-0.80). The number needed to treat to avoid one infection was 36.

The sutures were significantly more effective in reducing deep infections than superficial infections. Superficial infections occurred in 2% of the triclosan group (17) and 4% of the control group (28) – a risk reduction of 39% (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.34-1.09) Deep infections occurred in less than 1% of the triclosan group (3) and 2% of the control group (14) – a risk reduction of 79% (RR, 0.21’ CI, 0.07-0.66).

Infections were associated with an increased incidence of wound dehiscence in the control group (6% vs. 4%), the need for additional antimicrobial agents (7% vs. 2%), and wound revisions (2% vs. less than 1%). Children in the control group also had more outpatient visits (8% vs. 4%) and were more often readmitted because of their infection (2% vs. 1%).

The authors noted that triclosan, in the setting of increased household use, “has raised concerns about the toxic effects of the drug on the human body. Observational studies have reported associations between triclosan exposures and altered thyroid hormone levels, body mass index, and waist circumference.”

Two Norwegian studies found that the drug was associated with inhalation allergies and seasonal allergies.

“Because of the agent’s suspected toxicity and to prevent further development of resistant bacteria, use of triclosan should be restricted and reserved only for medical procedures with adequate evidence,” they noted. However, “SSIs cause much morbidity and mortality after surgical procedures, and economic evaluations recommend the use of triclosan-containing material.”

Dr. Renko received grants from the Alma and K.A. Snellman Foundation, the Finnish Medical Foundation, and the Foundation for Pediatric Research.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

The use of triclosan-impregnated sutures reduced by half the incidence of surgical site infections in children, a large randomized study has determined.

Overall, the antibiotic-treated sutures cut the number of these infections by 52%, but they were particularly effective in reducing the risk of deep surgical site infections (SSIs), Marjo Renko, MD, wrote (Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17[1]:50-7).

The study was conducted in clean wounds in healthy children and in a center that already had a very low rate of surgical site infections (just 5%) – showing that improvement is possible even in optimal care settings, wrote Dr. Renko, of the University of Oulu, Finland, and her colleagues.

“This randomized, controlled study shows that even in low-risk settings, where other prophylactic measures are available to use, triclosan-containing sutures effectively prevented the occurrence of SSIs in children,” the team wrote.

The study cohort comprised 1,633 children aged 7-17 who underwent surgery at a single Finnish hospital from 2010-2014. Most were there for planned surgery (87%); the remainder had emergency surgery. The most common surgical site was musculoskeletal (40%), followed by abdominal wall surgery (about 25%), and urogenital surgery (about 13%). The rest were intraabdominal or procedures on the nervous system, chest, and skin or subcutaneous tissue.

The children were randomized to either plain or triclosan-impregnated sutures. The primary outcome was the occurrence of a superficial or deep surgical site infection, based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria. The procedures were performed by 69 surgeons.

In a modified intent-to-treat analysis, a surgical site infection occurred in 3% of the triclosan-suture group (20 children) and in 5% of the control suture group (42 children). In the control group, these infections were most often of chest incisions (15%), followed by skin incisions (10%) and nervous system, intraabdominal, and musculoskeletal incisions (8% each). In the triclosan group, the most common site of infection was skin (10%), followed by musculoskeletal (4%), nervous system (2%), and urogenital and abdominal wall incisions (1% each).

Compared with control sutures, triclosan sutures reduced the overall risk of a surgical site infection by 52% (relative risk, 0.48; 95% confidence interval, 0.28-0.80). The number needed to treat to avoid one infection was 36.

The sutures were significantly more effective in reducing deep infections than superficial infections. Superficial infections occurred in 2% of the triclosan group (17) and 4% of the control group (28) – a risk reduction of 39% (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.34-1.09) Deep infections occurred in less than 1% of the triclosan group (3) and 2% of the control group (14) – a risk reduction of 79% (RR, 0.21’ CI, 0.07-0.66).

Infections were associated with an increased incidence of wound dehiscence in the control group (6% vs. 4%), the need for additional antimicrobial agents (7% vs. 2%), and wound revisions (2% vs. less than 1%). Children in the control group also had more outpatient visits (8% vs. 4%) and were more often readmitted because of their infection (2% vs. 1%).

The authors noted that triclosan, in the setting of increased household use, “has raised concerns about the toxic effects of the drug on the human body. Observational studies have reported associations between triclosan exposures and altered thyroid hormone levels, body mass index, and waist circumference.”

Two Norwegian studies found that the drug was associated with inhalation allergies and seasonal allergies.

“Because of the agent’s suspected toxicity and to prevent further development of resistant bacteria, use of triclosan should be restricted and reserved only for medical procedures with adequate evidence,” they noted. However, “SSIs cause much morbidity and mortality after surgical procedures, and economic evaluations recommend the use of triclosan-containing material.”

Dr. Renko received grants from the Alma and K.A. Snellman Foundation, the Finnish Medical Foundation, and the Foundation for Pediatric Research.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

FROM LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall, the sutures were associated with a 52% decrease in SSIs.

Data source: The study randomized 1,633 children undergoing surgery to the triclosan sutures or to a control suture.

Disclosures: Dr. Renko received grants from the Alma and K.A. Snellman Foundation, the Finnish Medical Foundation, and the Foundation for Pediatric Research.

West Nile virus accounted for 95% of domestic arboviral disease in 2015

West Nile virus was the most common cause of domestically acquired arboviral disease in the United States in 2015, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A total of 2,282 cases of arboviral disease were reported to the CDC in 2015. Of those, 2,175 cases were caused by the West Nile virus. Of the patients with WNV, 1,616 were hospitalized because of the disease, and 146 died. Neuroinvasive WNV, which occurred in 1,455 cases, accounted for 1,382 of 1,616 WNV hospitalizations and 142 of 146 deaths.

Of the 107 non-WNV arbovirus cases reported to the CDC, 55 were La Crosse virus, 23 were St. Louis encephalitis, 11 were Jamestown Canyon virus, 7 were Powassan virus, and 6 were eastern equine encephalitis. In addition to La Crosse and Jamestown Canyon, 4 cases of additional California serogroup viruses were reported, as was 1 case of Cache Valley virus.

“Health care providers should consider arboviral infections in the differential diagnosis of cases of aseptic meningitis and encephalitis, obtain appropriate specimens for laboratory testing, and promptly report cases to public health authorities. Because human vaccines against domestic arboviruses are not available, prevention depends on community and household efforts to reduce vector populations, personal protective measures to decrease exposure to mosquitoes and ticks, and screening of blood donors,” the CDC investigators concluded.

Find the full report in the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6602a3).

West Nile virus was the most common cause of domestically acquired arboviral disease in the United States in 2015, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A total of 2,282 cases of arboviral disease were reported to the CDC in 2015. Of those, 2,175 cases were caused by the West Nile virus. Of the patients with WNV, 1,616 were hospitalized because of the disease, and 146 died. Neuroinvasive WNV, which occurred in 1,455 cases, accounted for 1,382 of 1,616 WNV hospitalizations and 142 of 146 deaths.

Of the 107 non-WNV arbovirus cases reported to the CDC, 55 were La Crosse virus, 23 were St. Louis encephalitis, 11 were Jamestown Canyon virus, 7 were Powassan virus, and 6 were eastern equine encephalitis. In addition to La Crosse and Jamestown Canyon, 4 cases of additional California serogroup viruses were reported, as was 1 case of Cache Valley virus.

“Health care providers should consider arboviral infections in the differential diagnosis of cases of aseptic meningitis and encephalitis, obtain appropriate specimens for laboratory testing, and promptly report cases to public health authorities. Because human vaccines against domestic arboviruses are not available, prevention depends on community and household efforts to reduce vector populations, personal protective measures to decrease exposure to mosquitoes and ticks, and screening of blood donors,” the CDC investigators concluded.

Find the full report in the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6602a3).

West Nile virus was the most common cause of domestically acquired arboviral disease in the United States in 2015, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A total of 2,282 cases of arboviral disease were reported to the CDC in 2015. Of those, 2,175 cases were caused by the West Nile virus. Of the patients with WNV, 1,616 were hospitalized because of the disease, and 146 died. Neuroinvasive WNV, which occurred in 1,455 cases, accounted for 1,382 of 1,616 WNV hospitalizations and 142 of 146 deaths.

Of the 107 non-WNV arbovirus cases reported to the CDC, 55 were La Crosse virus, 23 were St. Louis encephalitis, 11 were Jamestown Canyon virus, 7 were Powassan virus, and 6 were eastern equine encephalitis. In addition to La Crosse and Jamestown Canyon, 4 cases of additional California serogroup viruses were reported, as was 1 case of Cache Valley virus.

“Health care providers should consider arboviral infections in the differential diagnosis of cases of aseptic meningitis and encephalitis, obtain appropriate specimens for laboratory testing, and promptly report cases to public health authorities. Because human vaccines against domestic arboviruses are not available, prevention depends on community and household efforts to reduce vector populations, personal protective measures to decrease exposure to mosquitoes and ticks, and screening of blood donors,” the CDC investigators concluded.

Find the full report in the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6602a3).

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY REPORT

Marijuana calms children with autism

SAN FRANCISCO – About once a month, Antonio Y. Hardan, MD, and his colleagues at the Stanford (Calif.) University Autism and Developmental Disorders Clinic see an autistic child who is using or being prescribed marijuana.

“There are two types or responses we see with marijuana,” said Dr. Hardan, director of the clinic. “Most of the time, it calms the kid down for 2 or 3 hours, which is what you’d expect from marijuana. In one out of 10, I am hearing that parents see improvements in the core features of autism. We have several families who would swear by marijuana, but then 4 or 6 months later, they will change their mind and say it’s not helping as much.

Marijuana is just one of many alternatives families and doctors are trying to improve upon the usual medications and therapies for autism; the range of options being tried speaks to the desperation and frustration of families looking for help. There’s no home run so far; the common denominator for alternatives is anecdotal support but little evidence. Stanford has tried to address the evidence gap and continues to do so.

In 2012, for instance, Dr. Hardan and his colleagues reported a 33 patient study that found that N-acetylcysteine (NAC) – another hopeful candidate in recent years – might curb irritability (Biol Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 1;71[11]:956-61).

The tricky part about NAC is that it’s a dietary supplement, so you can’t be sure of what you’re getting in the store. There were questions at the talk about dose and formulations.

“The one we used in the study is made by BioAdvantex,” a Canadian company. “That’s the one that worked for us. One of the advantages is that every dose is wrapped individually.” NAC is an antioxidant, “so if you expose [it] to oxygen or light, it will get oxidized, and over time be less effective,” said Dr. Hardan, also a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the university.

Most of the time, NAC is very well tolerated, with only a little bit of flatulence and upset stomach.

Dr. Hardan and his colleagues started with 900 mg in one dose once a day for 4 weeks, then one dose twice a day for 4 weeks, followed by one dose three times daily, in children aged 2-12 years old. With experience, they are going faster now, cutting the 4 week interval to 2. “Some people are [even] more aggressive, which is okay,” he said.

Propranolol is another fashionable option, prescribed by a lot of doctors.

It’s not a new option; about 20 years ago, “we used it in very high dosages, 700-800 mg a day for self-injurious behavior. People wonder how you can go that high; above a dose of 200 mg, there is what we call an ‘escape phenomena’ where the heart will stop responding, and the effects on blood pressure and pulse are minimal,” Dr. Hardan said.

Interest in propranolol over the past 5 years has expanded to anxiety, sensory abnormalities, and other non-specific autism symptoms. “Unfortunately, there are no clinical trials to support that,” he said. The only evidence so far is from a functional MRI study in adults that suggested a little bit more efficient processing on a language task; further investigation is underway.

A lot of parents also are asking for oxytocin, and doctors are prescribing it. Someone in the audience wondered whether it had a role in everyday practice.

“Not at this time,” Dr. Hardan said. “I would suggest waiting a little bit until” results are reported from an ongoing trial. They are due soon, and there might be a subgroup of kids who benefit. Oxytocin seemed to help all-comers recognize facial cues.

Arginine vasopressin might do that, too, and be more specific for autism; Stanford is planning a study to look into it.

Attendees also wanted to know what to do about sleep problems, a common issue in autism.

“I’m aggressive in the treatment of insomnia, especially in single-parent households, because if the kid isn’t sleeping, the parent isn’t sleeping” and they may get irritable and moody, which raises the risk of abuse, Dr. Hardan said.

He starts with melatonin, 1 mg in the evening, and increases it by 1 mg every week to hit a target of 6 mg per night. He hasn’t seen much benefit of going higher. It’s important to remember that melatonin might take up to a week to see the full effect.

If melatonin fails, Dr. Hardan goes up the ladder. Diphenhydramine (Benadryl), benzodiazepines, trazodone (Oleptro), and mirtazapine (Remeron) are among the options. Rarely, there’s a need for quetiapine (Seroquel).

To counter benzodiazepine disinhibition, he asks parents to try them on a good day at home, so the effect of environmental stressors like going to the dentist can be divided out from the drug.

Dr. Hardan cautioned that there is “no evidence at this time to support the use of” lamotrigine (Lamictal). “Please don’t use it; somebody will end up developing” Stevens-Johnson syndrome. “It will be difficult to defend against that.”

Dr. Hardan is an adviser for Roche.

SAN FRANCISCO – About once a month, Antonio Y. Hardan, MD, and his colleagues at the Stanford (Calif.) University Autism and Developmental Disorders Clinic see an autistic child who is using or being prescribed marijuana.

“There are two types or responses we see with marijuana,” said Dr. Hardan, director of the clinic. “Most of the time, it calms the kid down for 2 or 3 hours, which is what you’d expect from marijuana. In one out of 10, I am hearing that parents see improvements in the core features of autism. We have several families who would swear by marijuana, but then 4 or 6 months later, they will change their mind and say it’s not helping as much.

Marijuana is just one of many alternatives families and doctors are trying to improve upon the usual medications and therapies for autism; the range of options being tried speaks to the desperation and frustration of families looking for help. There’s no home run so far; the common denominator for alternatives is anecdotal support but little evidence. Stanford has tried to address the evidence gap and continues to do so.

In 2012, for instance, Dr. Hardan and his colleagues reported a 33 patient study that found that N-acetylcysteine (NAC) – another hopeful candidate in recent years – might curb irritability (Biol Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 1;71[11]:956-61).

The tricky part about NAC is that it’s a dietary supplement, so you can’t be sure of what you’re getting in the store. There were questions at the talk about dose and formulations.

“The one we used in the study is made by BioAdvantex,” a Canadian company. “That’s the one that worked for us. One of the advantages is that every dose is wrapped individually.” NAC is an antioxidant, “so if you expose [it] to oxygen or light, it will get oxidized, and over time be less effective,” said Dr. Hardan, also a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the university.

Most of the time, NAC is very well tolerated, with only a little bit of flatulence and upset stomach.

Dr. Hardan and his colleagues started with 900 mg in one dose once a day for 4 weeks, then one dose twice a day for 4 weeks, followed by one dose three times daily, in children aged 2-12 years old. With experience, they are going faster now, cutting the 4 week interval to 2. “Some people are [even] more aggressive, which is okay,” he said.

Propranolol is another fashionable option, prescribed by a lot of doctors.

It’s not a new option; about 20 years ago, “we used it in very high dosages, 700-800 mg a day for self-injurious behavior. People wonder how you can go that high; above a dose of 200 mg, there is what we call an ‘escape phenomena’ where the heart will stop responding, and the effects on blood pressure and pulse are minimal,” Dr. Hardan said.

Interest in propranolol over the past 5 years has expanded to anxiety, sensory abnormalities, and other non-specific autism symptoms. “Unfortunately, there are no clinical trials to support that,” he said. The only evidence so far is from a functional MRI study in adults that suggested a little bit more efficient processing on a language task; further investigation is underway.

A lot of parents also are asking for oxytocin, and doctors are prescribing it. Someone in the audience wondered whether it had a role in everyday practice.

“Not at this time,” Dr. Hardan said. “I would suggest waiting a little bit until” results are reported from an ongoing trial. They are due soon, and there might be a subgroup of kids who benefit. Oxytocin seemed to help all-comers recognize facial cues.

Arginine vasopressin might do that, too, and be more specific for autism; Stanford is planning a study to look into it.

Attendees also wanted to know what to do about sleep problems, a common issue in autism.

“I’m aggressive in the treatment of insomnia, especially in single-parent households, because if the kid isn’t sleeping, the parent isn’t sleeping” and they may get irritable and moody, which raises the risk of abuse, Dr. Hardan said.

He starts with melatonin, 1 mg in the evening, and increases it by 1 mg every week to hit a target of 6 mg per night. He hasn’t seen much benefit of going higher. It’s important to remember that melatonin might take up to a week to see the full effect.

If melatonin fails, Dr. Hardan goes up the ladder. Diphenhydramine (Benadryl), benzodiazepines, trazodone (Oleptro), and mirtazapine (Remeron) are among the options. Rarely, there’s a need for quetiapine (Seroquel).

To counter benzodiazepine disinhibition, he asks parents to try them on a good day at home, so the effect of environmental stressors like going to the dentist can be divided out from the drug.

Dr. Hardan cautioned that there is “no evidence at this time to support the use of” lamotrigine (Lamictal). “Please don’t use it; somebody will end up developing” Stevens-Johnson syndrome. “It will be difficult to defend against that.”

Dr. Hardan is an adviser for Roche.

SAN FRANCISCO – About once a month, Antonio Y. Hardan, MD, and his colleagues at the Stanford (Calif.) University Autism and Developmental Disorders Clinic see an autistic child who is using or being prescribed marijuana.

“There are two types or responses we see with marijuana,” said Dr. Hardan, director of the clinic. “Most of the time, it calms the kid down for 2 or 3 hours, which is what you’d expect from marijuana. In one out of 10, I am hearing that parents see improvements in the core features of autism. We have several families who would swear by marijuana, but then 4 or 6 months later, they will change their mind and say it’s not helping as much.

Marijuana is just one of many alternatives families and doctors are trying to improve upon the usual medications and therapies for autism; the range of options being tried speaks to the desperation and frustration of families looking for help. There’s no home run so far; the common denominator for alternatives is anecdotal support but little evidence. Stanford has tried to address the evidence gap and continues to do so.

In 2012, for instance, Dr. Hardan and his colleagues reported a 33 patient study that found that N-acetylcysteine (NAC) – another hopeful candidate in recent years – might curb irritability (Biol Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 1;71[11]:956-61).

The tricky part about NAC is that it’s a dietary supplement, so you can’t be sure of what you’re getting in the store. There were questions at the talk about dose and formulations.

“The one we used in the study is made by BioAdvantex,” a Canadian company. “That’s the one that worked for us. One of the advantages is that every dose is wrapped individually.” NAC is an antioxidant, “so if you expose [it] to oxygen or light, it will get oxidized, and over time be less effective,” said Dr. Hardan, also a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the university.

Most of the time, NAC is very well tolerated, with only a little bit of flatulence and upset stomach.

Dr. Hardan and his colleagues started with 900 mg in one dose once a day for 4 weeks, then one dose twice a day for 4 weeks, followed by one dose three times daily, in children aged 2-12 years old. With experience, they are going faster now, cutting the 4 week interval to 2. “Some people are [even] more aggressive, which is okay,” he said.

Propranolol is another fashionable option, prescribed by a lot of doctors.

It’s not a new option; about 20 years ago, “we used it in very high dosages, 700-800 mg a day for self-injurious behavior. People wonder how you can go that high; above a dose of 200 mg, there is what we call an ‘escape phenomena’ where the heart will stop responding, and the effects on blood pressure and pulse are minimal,” Dr. Hardan said.

Interest in propranolol over the past 5 years has expanded to anxiety, sensory abnormalities, and other non-specific autism symptoms. “Unfortunately, there are no clinical trials to support that,” he said. The only evidence so far is from a functional MRI study in adults that suggested a little bit more efficient processing on a language task; further investigation is underway.

A lot of parents also are asking for oxytocin, and doctors are prescribing it. Someone in the audience wondered whether it had a role in everyday practice.

“Not at this time,” Dr. Hardan said. “I would suggest waiting a little bit until” results are reported from an ongoing trial. They are due soon, and there might be a subgroup of kids who benefit. Oxytocin seemed to help all-comers recognize facial cues.

Arginine vasopressin might do that, too, and be more specific for autism; Stanford is planning a study to look into it.

Attendees also wanted to know what to do about sleep problems, a common issue in autism.

“I’m aggressive in the treatment of insomnia, especially in single-parent households, because if the kid isn’t sleeping, the parent isn’t sleeping” and they may get irritable and moody, which raises the risk of abuse, Dr. Hardan said.

He starts with melatonin, 1 mg in the evening, and increases it by 1 mg every week to hit a target of 6 mg per night. He hasn’t seen much benefit of going higher. It’s important to remember that melatonin might take up to a week to see the full effect.

If melatonin fails, Dr. Hardan goes up the ladder. Diphenhydramine (Benadryl), benzodiazepines, trazodone (Oleptro), and mirtazapine (Remeron) are among the options. Rarely, there’s a need for quetiapine (Seroquel).

To counter benzodiazepine disinhibition, he asks parents to try them on a good day at home, so the effect of environmental stressors like going to the dentist can be divided out from the drug.

Dr. Hardan cautioned that there is “no evidence at this time to support the use of” lamotrigine (Lamictal). “Please don’t use it; somebody will end up developing” Stevens-Johnson syndrome. “It will be difficult to defend against that.”

Dr. Hardan is an adviser for Roche.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE INSTITUTE

Postpartum depression risk 20 times greater among women with depression history