User login

Observation works for most smaller splanchnic artery aneurysms

CHICAGO – Guidelines for the management of splanchnic artery aneurysms have been hard to come by because of their rarity, but investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, have surveyed their 20-year experience to conclude that surveillance is appropriate for most cases of aneurysms smaller than 25 mm, and selective open or endovascular repair is indicated for larger lesions, depending on their location.

“Most of the small splanchnic artery aneurysms (SAAs) of less than 25 mm did not grow or rupture over time and can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years,” Mark F. Conrad, MD, reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

The predominant sites of aneurysm were the splenic artery (95, 36%) and the celiac artery (78, 30%), followed by the hepatic artery (34, 13%), pancreaticoduodenal artery (PDA; 25, 9.6%), superior mesenteric artery (SMA; 17, 6%), gastroduodenal artery (GDA; 11, 4%), jejunal artery (3, 1%) and inferior mesenteric artery (1, 0.4%).

Surveillance consisted of imaging every 3 years. Of the surveillance cohort, 138 patients had longer-term follow-up. The average aneurysm size was 16.3 mm, “so they’re small,” Dr. Conrad said. Of that whole group, only 12 (9%), of SAAs grew in size, and of those, 8 were 25 mm or smaller when they were identified; 8 of the 12 required repair. “The average time to repair was 2 years,” Dr. Conrad said. “There were no ruptures in the surveillance cohort.”

Among the early repair group, 13 (14.7%) had rupture upon presentation, 3 of which (23%) were pseudoaneurysms. The majority of aneurysms in this group were in either the splenic artery, PDA, or GDA. “Their average size was 31 mm – much larger than the patients that we watched,” he said. A total of 70% of all repairs were endovascular in nature, the remainder open, but endovascular comprised a higher percentage of rupture repairs: 10 (77%) vs. 3 (23%) that underwent open procedures.

The outcomes for endovascular and open repair were similar based on the small number of subjects, Dr. Conrad said: 30-day morbidity of 17% for endovascular repair and 22.2% for open; and 30-day mortality of 3.5% and 4.5%, respectively. However, for ruptured lesions, the outcomes were starkly significant: 54% morbidity and 8% mortality at 30 days.

The researchers performed a univariate analysis of predictors for aneurysm. They were aneurysm size with an odds ratio of 1.04 for every 1 mm of growth; PDA or GDA lesions with an OR of 11.2; and Ehlers-Danlos type IV syndrome with an OR of 32.5. The latter included all the three study patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Among patients who had splenic SAAs, 99 (93%) were asymptomatic and 5 (5.3%) had pseudoaneurysm, and almost half (47) went into surveillance. Over a mean observation period of 35 months, six (12.8%) grew in size, comprising half of the growing SAAs in the observation group. Thirty-two had endovascular repair and four open repair, with a 30-day morbidity of 22% and 30-day mortality of 2.7%.

Celiac SAAs proved most problematic in terms of symptomatology; all 78 patients with this variant were asymptomatic, and 12 (15%) had dissection. Sixty patients went into surveillance with a mean time of 43 months, and three (5) had aneurysms that grew in size. Five had intervention, four with open repair, with 30-day morbidity of 20% and no 30-day mortality.

Hepatic SAAs affected 34 study subjects, 29 (85%) of whom were asymptomatic, 4 (15%) who had dissection, and 7 (21%) with pseudoaneurysm. Eleven entered surveillance for an average of 28 months, but none showed any aneurysmal growth. The 16 who had intervention were evenly split between open and endovascular repair with 30-day morbidity of 25% and 30-day morality of 12.5%.

The PDA and GDA aneurysms “are really interesting,” Dr. Conrad said. “I think they’re different in nature than the other aneurysms,” he said, noting that 12 (33%) of these aneurysms were symptomatic and 6 (17%) were pseudoaneurysms. Because of the high rate of rupture of PDA/GDA aneurysms, Dr. Conrad advised repair at diagnosis: “97% of these patients had a celiac stenosis, and of those, two-thirds were atherosclerosis related and one-third related to the median arcuate ligament compression.” The rupture rate was comparatively high – 20%. Twenty cases underwent endovascular repair with a 90% success rate while four cases had open repair. Thirty-day morbidity for intact lesions was 11% with no deaths, and 50% with 14% mortality rate for ruptured lesions.

Of the SMA aneurysms in the study population, only 17% were mycotic with the remainder asymptomatic, Dr. Conrad said. Nine underwent surveillance, with one growing in size over a mean observation period of 28 months, four had open repair, and two endovascular repair. Morbidity was 17% at 30 days with no deaths.

The guidelines Dr. Conrad and his group developed recommend treatment for symptomatic patients and a more nuanced approach for asymptomatic patients, depending on the location and size of SAA. All lesions 25 mm or smaller, except those of the PDA/GDA, can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years, he said; intervention is indicated for all larger lesions. Endovascular repair is in order for all splenic SAAs in pregnancy, liver transplantation, and pseudoaneurysm. For hepatic SAAs, open or endovascular repair is indicated for pseudoaneurysm, but open repair only is indicated for asymptomatic celiac SAAs with pseudoaneurysm. Endovascular intervention can address most SAA aneurysms of the PDA and GDA.

Dr. Conrad disclosed he is a consultant to Medtronic and Volcano and is a member of Bard’s clinical events committee.

CHICAGO – Guidelines for the management of splanchnic artery aneurysms have been hard to come by because of their rarity, but investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, have surveyed their 20-year experience to conclude that surveillance is appropriate for most cases of aneurysms smaller than 25 mm, and selective open or endovascular repair is indicated for larger lesions, depending on their location.

“Most of the small splanchnic artery aneurysms (SAAs) of less than 25 mm did not grow or rupture over time and can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years,” Mark F. Conrad, MD, reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

The predominant sites of aneurysm were the splenic artery (95, 36%) and the celiac artery (78, 30%), followed by the hepatic artery (34, 13%), pancreaticoduodenal artery (PDA; 25, 9.6%), superior mesenteric artery (SMA; 17, 6%), gastroduodenal artery (GDA; 11, 4%), jejunal artery (3, 1%) and inferior mesenteric artery (1, 0.4%).

Surveillance consisted of imaging every 3 years. Of the surveillance cohort, 138 patients had longer-term follow-up. The average aneurysm size was 16.3 mm, “so they’re small,” Dr. Conrad said. Of that whole group, only 12 (9%), of SAAs grew in size, and of those, 8 were 25 mm or smaller when they were identified; 8 of the 12 required repair. “The average time to repair was 2 years,” Dr. Conrad said. “There were no ruptures in the surveillance cohort.”

Among the early repair group, 13 (14.7%) had rupture upon presentation, 3 of which (23%) were pseudoaneurysms. The majority of aneurysms in this group were in either the splenic artery, PDA, or GDA. “Their average size was 31 mm – much larger than the patients that we watched,” he said. A total of 70% of all repairs were endovascular in nature, the remainder open, but endovascular comprised a higher percentage of rupture repairs: 10 (77%) vs. 3 (23%) that underwent open procedures.

The outcomes for endovascular and open repair were similar based on the small number of subjects, Dr. Conrad said: 30-day morbidity of 17% for endovascular repair and 22.2% for open; and 30-day mortality of 3.5% and 4.5%, respectively. However, for ruptured lesions, the outcomes were starkly significant: 54% morbidity and 8% mortality at 30 days.

The researchers performed a univariate analysis of predictors for aneurysm. They were aneurysm size with an odds ratio of 1.04 for every 1 mm of growth; PDA or GDA lesions with an OR of 11.2; and Ehlers-Danlos type IV syndrome with an OR of 32.5. The latter included all the three study patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Among patients who had splenic SAAs, 99 (93%) were asymptomatic and 5 (5.3%) had pseudoaneurysm, and almost half (47) went into surveillance. Over a mean observation period of 35 months, six (12.8%) grew in size, comprising half of the growing SAAs in the observation group. Thirty-two had endovascular repair and four open repair, with a 30-day morbidity of 22% and 30-day mortality of 2.7%.

Celiac SAAs proved most problematic in terms of symptomatology; all 78 patients with this variant were asymptomatic, and 12 (15%) had dissection. Sixty patients went into surveillance with a mean time of 43 months, and three (5) had aneurysms that grew in size. Five had intervention, four with open repair, with 30-day morbidity of 20% and no 30-day mortality.

Hepatic SAAs affected 34 study subjects, 29 (85%) of whom were asymptomatic, 4 (15%) who had dissection, and 7 (21%) with pseudoaneurysm. Eleven entered surveillance for an average of 28 months, but none showed any aneurysmal growth. The 16 who had intervention were evenly split between open and endovascular repair with 30-day morbidity of 25% and 30-day morality of 12.5%.

The PDA and GDA aneurysms “are really interesting,” Dr. Conrad said. “I think they’re different in nature than the other aneurysms,” he said, noting that 12 (33%) of these aneurysms were symptomatic and 6 (17%) were pseudoaneurysms. Because of the high rate of rupture of PDA/GDA aneurysms, Dr. Conrad advised repair at diagnosis: “97% of these patients had a celiac stenosis, and of those, two-thirds were atherosclerosis related and one-third related to the median arcuate ligament compression.” The rupture rate was comparatively high – 20%. Twenty cases underwent endovascular repair with a 90% success rate while four cases had open repair. Thirty-day morbidity for intact lesions was 11% with no deaths, and 50% with 14% mortality rate for ruptured lesions.

Of the SMA aneurysms in the study population, only 17% were mycotic with the remainder asymptomatic, Dr. Conrad said. Nine underwent surveillance, with one growing in size over a mean observation period of 28 months, four had open repair, and two endovascular repair. Morbidity was 17% at 30 days with no deaths.

The guidelines Dr. Conrad and his group developed recommend treatment for symptomatic patients and a more nuanced approach for asymptomatic patients, depending on the location and size of SAA. All lesions 25 mm or smaller, except those of the PDA/GDA, can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years, he said; intervention is indicated for all larger lesions. Endovascular repair is in order for all splenic SAAs in pregnancy, liver transplantation, and pseudoaneurysm. For hepatic SAAs, open or endovascular repair is indicated for pseudoaneurysm, but open repair only is indicated for asymptomatic celiac SAAs with pseudoaneurysm. Endovascular intervention can address most SAA aneurysms of the PDA and GDA.

Dr. Conrad disclosed he is a consultant to Medtronic and Volcano and is a member of Bard’s clinical events committee.

CHICAGO – Guidelines for the management of splanchnic artery aneurysms have been hard to come by because of their rarity, but investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, have surveyed their 20-year experience to conclude that surveillance is appropriate for most cases of aneurysms smaller than 25 mm, and selective open or endovascular repair is indicated for larger lesions, depending on their location.

“Most of the small splanchnic artery aneurysms (SAAs) of less than 25 mm did not grow or rupture over time and can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years,” Mark F. Conrad, MD, reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

The predominant sites of aneurysm were the splenic artery (95, 36%) and the celiac artery (78, 30%), followed by the hepatic artery (34, 13%), pancreaticoduodenal artery (PDA; 25, 9.6%), superior mesenteric artery (SMA; 17, 6%), gastroduodenal artery (GDA; 11, 4%), jejunal artery (3, 1%) and inferior mesenteric artery (1, 0.4%).

Surveillance consisted of imaging every 3 years. Of the surveillance cohort, 138 patients had longer-term follow-up. The average aneurysm size was 16.3 mm, “so they’re small,” Dr. Conrad said. Of that whole group, only 12 (9%), of SAAs grew in size, and of those, 8 were 25 mm or smaller when they were identified; 8 of the 12 required repair. “The average time to repair was 2 years,” Dr. Conrad said. “There were no ruptures in the surveillance cohort.”

Among the early repair group, 13 (14.7%) had rupture upon presentation, 3 of which (23%) were pseudoaneurysms. The majority of aneurysms in this group were in either the splenic artery, PDA, or GDA. “Their average size was 31 mm – much larger than the patients that we watched,” he said. A total of 70% of all repairs were endovascular in nature, the remainder open, but endovascular comprised a higher percentage of rupture repairs: 10 (77%) vs. 3 (23%) that underwent open procedures.

The outcomes for endovascular and open repair were similar based on the small number of subjects, Dr. Conrad said: 30-day morbidity of 17% for endovascular repair and 22.2% for open; and 30-day mortality of 3.5% and 4.5%, respectively. However, for ruptured lesions, the outcomes were starkly significant: 54% morbidity and 8% mortality at 30 days.

The researchers performed a univariate analysis of predictors for aneurysm. They were aneurysm size with an odds ratio of 1.04 for every 1 mm of growth; PDA or GDA lesions with an OR of 11.2; and Ehlers-Danlos type IV syndrome with an OR of 32.5. The latter included all the three study patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Among patients who had splenic SAAs, 99 (93%) were asymptomatic and 5 (5.3%) had pseudoaneurysm, and almost half (47) went into surveillance. Over a mean observation period of 35 months, six (12.8%) grew in size, comprising half of the growing SAAs in the observation group. Thirty-two had endovascular repair and four open repair, with a 30-day morbidity of 22% and 30-day mortality of 2.7%.

Celiac SAAs proved most problematic in terms of symptomatology; all 78 patients with this variant were asymptomatic, and 12 (15%) had dissection. Sixty patients went into surveillance with a mean time of 43 months, and three (5) had aneurysms that grew in size. Five had intervention, four with open repair, with 30-day morbidity of 20% and no 30-day mortality.

Hepatic SAAs affected 34 study subjects, 29 (85%) of whom were asymptomatic, 4 (15%) who had dissection, and 7 (21%) with pseudoaneurysm. Eleven entered surveillance for an average of 28 months, but none showed any aneurysmal growth. The 16 who had intervention were evenly split between open and endovascular repair with 30-day morbidity of 25% and 30-day morality of 12.5%.

The PDA and GDA aneurysms “are really interesting,” Dr. Conrad said. “I think they’re different in nature than the other aneurysms,” he said, noting that 12 (33%) of these aneurysms were symptomatic and 6 (17%) were pseudoaneurysms. Because of the high rate of rupture of PDA/GDA aneurysms, Dr. Conrad advised repair at diagnosis: “97% of these patients had a celiac stenosis, and of those, two-thirds were atherosclerosis related and one-third related to the median arcuate ligament compression.” The rupture rate was comparatively high – 20%. Twenty cases underwent endovascular repair with a 90% success rate while four cases had open repair. Thirty-day morbidity for intact lesions was 11% with no deaths, and 50% with 14% mortality rate for ruptured lesions.

Of the SMA aneurysms in the study population, only 17% were mycotic with the remainder asymptomatic, Dr. Conrad said. Nine underwent surveillance, with one growing in size over a mean observation period of 28 months, four had open repair, and two endovascular repair. Morbidity was 17% at 30 days with no deaths.

The guidelines Dr. Conrad and his group developed recommend treatment for symptomatic patients and a more nuanced approach for asymptomatic patients, depending on the location and size of SAA. All lesions 25 mm or smaller, except those of the PDA/GDA, can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years, he said; intervention is indicated for all larger lesions. Endovascular repair is in order for all splenic SAAs in pregnancy, liver transplantation, and pseudoaneurysm. For hepatic SAAs, open or endovascular repair is indicated for pseudoaneurysm, but open repair only is indicated for asymptomatic celiac SAAs with pseudoaneurysm. Endovascular intervention can address most SAA aneurysms of the PDA and GDA.

Dr. Conrad disclosed he is a consultant to Medtronic and Volcano and is a member of Bard’s clinical events committee.

AT THE NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Surveillance imaging every three years may be adequate to manage splanchnic artery aneurysms (SAA) smaller than 25 mm, because they rarely expand significantly.

Major finding: In the surveillance group that had long-term follow-up, 9% had SAAs that grew in size.

Data source: Analysis of 250 patients with 264 SAAs during 1994-2014 in the Research Patient Data Registry at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Conrad disclosed he is a consultant to Medtronic and Volcano and is a member of Bard’s clinical events committee.

Pairing vascular reconstruction, pancreatic cancer resection

CHICAGO – More than 53,000 people will develop pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in the United States this year, and upwards of 41,000 will die from the disease, many of them with tumors considered unresectable because they involve adjacent vessels. However, researchers at the University of California, Irvine, have found that careful removal of the tumor around involved veins and arteries, even in borderline cases, can improve outcomes for these patients.

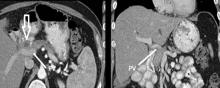

Roy M. Fujitani, MD, updated previously published data on a single-center study he coauthored in 2015 of 270 patients who had undergone a Whipple operation, 183 for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:475-80) at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Resection of pancreatic tumors without vascular involvement is fairly straightforward for surgical oncologists to perform, Dr. Fujitani said, but pancreatic tumors enter the borderline resectable category when preoperative CT scan shows portal vein abutment, for which vascular surgery should provide counsel and assist. However, even in some cases when preoperative CT scan shows unresectable, locally advanced pancreatic tumor with celiac artery encasement, neoadjuvant therapy may downstage the disease into the borderline category, he said.

“Patients with borderline resectable or stage II disease are those one should consider for reconstruction,” Dr. Fujitani said. Resectable findings of borderline disease include encasement of the portal vein, superior mesenteric vein and the confluence of the portal venous system (with suitable proximal and distal targets for reconstruction); and less-than-circumferential involvement of the common hepatic artery or right hepatic artery – but without involvement of the superior mesenteric artery or the celiac axis and “certainly not” the aorta. “This would account for about one-fourth of patients in high-volume centers as being able to receive concomitant vascular reconstruction,” Dr. Fujitani said.

In the UCI series, 60 patients with borderline lesions underwent vascular reconstruction. “As it turned out, there was no significant difference in survival between the reconstruction group and the nonreconstruction group,” Dr. Fujitani said, “but it’s important to note that these patients who had the reconstruction would never have been operated on if we were not able to do the reconstruction.” Thirty-day mortality was around 5% and 1-year survival around 70% in both groups, he said. However, at about 1.5 years the Kaplan-Meier survival curves between the two groups diverged, which Dr. Fujitani attributed to more advanced disease in the reconstruction group.

“We found lymph node status and tumor margins were most important in determining survival of these patients,” he said. “Gaining an R0 resection is the most important thing that determines favorable survivability.”

Dr. Fujitani also reviewed different techniques for vascular reconstruction, and while differences in complication rates or 1-, 2-, or 3-year survival were not statistically significant, he did note that mean survival with lateral venorrhaphy exceeded that of primary anastomosis and interposition graft – 21 months vs. 13 months vs. 4 months, suggesting the merits of a more aggressive approach to vascular resection and reconstruction.

“Improvement of survival outcomes may be achieved with concomitant advanced vascular reconstruction in carefully selected patients,” Dr. Fujitani said. “There are multiple options for vascular reconstruction for mesenteric portal venous and visceral arterial involvement using standard vascular surgical techniques.” He added that a dedicated team of experienced surgical oncologists and vascular surgeons for these reconstructions “is essential for successful outcomes.”

Dr. Fujitani had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CHICAGO – More than 53,000 people will develop pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in the United States this year, and upwards of 41,000 will die from the disease, many of them with tumors considered unresectable because they involve adjacent vessels. However, researchers at the University of California, Irvine, have found that careful removal of the tumor around involved veins and arteries, even in borderline cases, can improve outcomes for these patients.

Roy M. Fujitani, MD, updated previously published data on a single-center study he coauthored in 2015 of 270 patients who had undergone a Whipple operation, 183 for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:475-80) at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Resection of pancreatic tumors without vascular involvement is fairly straightforward for surgical oncologists to perform, Dr. Fujitani said, but pancreatic tumors enter the borderline resectable category when preoperative CT scan shows portal vein abutment, for which vascular surgery should provide counsel and assist. However, even in some cases when preoperative CT scan shows unresectable, locally advanced pancreatic tumor with celiac artery encasement, neoadjuvant therapy may downstage the disease into the borderline category, he said.

“Patients with borderline resectable or stage II disease are those one should consider for reconstruction,” Dr. Fujitani said. Resectable findings of borderline disease include encasement of the portal vein, superior mesenteric vein and the confluence of the portal venous system (with suitable proximal and distal targets for reconstruction); and less-than-circumferential involvement of the common hepatic artery or right hepatic artery – but without involvement of the superior mesenteric artery or the celiac axis and “certainly not” the aorta. “This would account for about one-fourth of patients in high-volume centers as being able to receive concomitant vascular reconstruction,” Dr. Fujitani said.

In the UCI series, 60 patients with borderline lesions underwent vascular reconstruction. “As it turned out, there was no significant difference in survival between the reconstruction group and the nonreconstruction group,” Dr. Fujitani said, “but it’s important to note that these patients who had the reconstruction would never have been operated on if we were not able to do the reconstruction.” Thirty-day mortality was around 5% and 1-year survival around 70% in both groups, he said. However, at about 1.5 years the Kaplan-Meier survival curves between the two groups diverged, which Dr. Fujitani attributed to more advanced disease in the reconstruction group.

“We found lymph node status and tumor margins were most important in determining survival of these patients,” he said. “Gaining an R0 resection is the most important thing that determines favorable survivability.”

Dr. Fujitani also reviewed different techniques for vascular reconstruction, and while differences in complication rates or 1-, 2-, or 3-year survival were not statistically significant, he did note that mean survival with lateral venorrhaphy exceeded that of primary anastomosis and interposition graft – 21 months vs. 13 months vs. 4 months, suggesting the merits of a more aggressive approach to vascular resection and reconstruction.

“Improvement of survival outcomes may be achieved with concomitant advanced vascular reconstruction in carefully selected patients,” Dr. Fujitani said. “There are multiple options for vascular reconstruction for mesenteric portal venous and visceral arterial involvement using standard vascular surgical techniques.” He added that a dedicated team of experienced surgical oncologists and vascular surgeons for these reconstructions “is essential for successful outcomes.”

Dr. Fujitani had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CHICAGO – More than 53,000 people will develop pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in the United States this year, and upwards of 41,000 will die from the disease, many of them with tumors considered unresectable because they involve adjacent vessels. However, researchers at the University of California, Irvine, have found that careful removal of the tumor around involved veins and arteries, even in borderline cases, can improve outcomes for these patients.

Roy M. Fujitani, MD, updated previously published data on a single-center study he coauthored in 2015 of 270 patients who had undergone a Whipple operation, 183 for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:475-80) at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Resection of pancreatic tumors without vascular involvement is fairly straightforward for surgical oncologists to perform, Dr. Fujitani said, but pancreatic tumors enter the borderline resectable category when preoperative CT scan shows portal vein abutment, for which vascular surgery should provide counsel and assist. However, even in some cases when preoperative CT scan shows unresectable, locally advanced pancreatic tumor with celiac artery encasement, neoadjuvant therapy may downstage the disease into the borderline category, he said.

“Patients with borderline resectable or stage II disease are those one should consider for reconstruction,” Dr. Fujitani said. Resectable findings of borderline disease include encasement of the portal vein, superior mesenteric vein and the confluence of the portal venous system (with suitable proximal and distal targets for reconstruction); and less-than-circumferential involvement of the common hepatic artery or right hepatic artery – but without involvement of the superior mesenteric artery or the celiac axis and “certainly not” the aorta. “This would account for about one-fourth of patients in high-volume centers as being able to receive concomitant vascular reconstruction,” Dr. Fujitani said.

In the UCI series, 60 patients with borderline lesions underwent vascular reconstruction. “As it turned out, there was no significant difference in survival between the reconstruction group and the nonreconstruction group,” Dr. Fujitani said, “but it’s important to note that these patients who had the reconstruction would never have been operated on if we were not able to do the reconstruction.” Thirty-day mortality was around 5% and 1-year survival around 70% in both groups, he said. However, at about 1.5 years the Kaplan-Meier survival curves between the two groups diverged, which Dr. Fujitani attributed to more advanced disease in the reconstruction group.

“We found lymph node status and tumor margins were most important in determining survival of these patients,” he said. “Gaining an R0 resection is the most important thing that determines favorable survivability.”

Dr. Fujitani also reviewed different techniques for vascular reconstruction, and while differences in complication rates or 1-, 2-, or 3-year survival were not statistically significant, he did note that mean survival with lateral venorrhaphy exceeded that of primary anastomosis and interposition graft – 21 months vs. 13 months vs. 4 months, suggesting the merits of a more aggressive approach to vascular resection and reconstruction.

“Improvement of survival outcomes may be achieved with concomitant advanced vascular reconstruction in carefully selected patients,” Dr. Fujitani said. “There are multiple options for vascular reconstruction for mesenteric portal venous and visceral arterial involvement using standard vascular surgical techniques.” He added that a dedicated team of experienced surgical oncologists and vascular surgeons for these reconstructions “is essential for successful outcomes.”

Dr. Fujitani had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

AT THE NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: A more aggressive vascular resection and reconstruction in pancreatic cancer may improve outcomes and palliation in these patients.

Major finding: Mean survival with lateral venorrhaphy exceeded primary anastomosis and interposition graft (21 months vs. 13 months vs. 4 months).

Data source: Updated data of previously published single-center retrospective review of 183 patients who had Whipple procedure for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Disclosures: Dr. Fujitani reported having no financial disclosures.

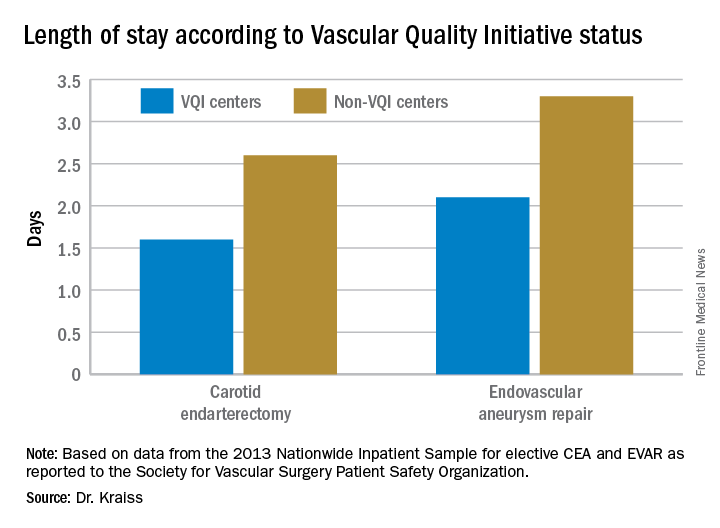

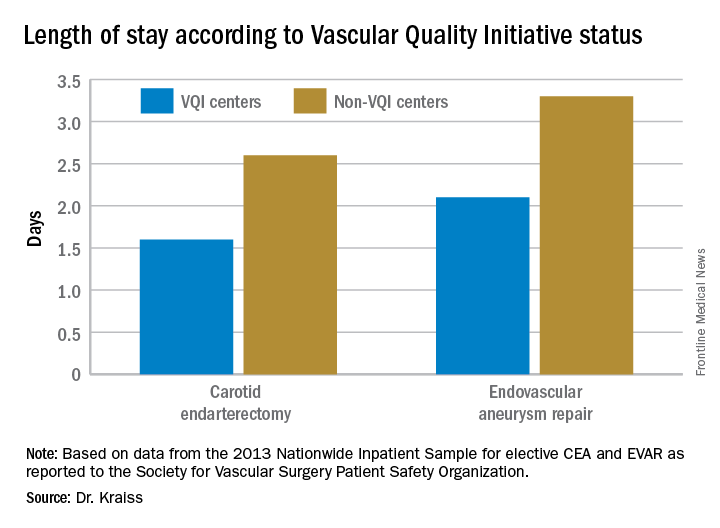

VQI confirms improvements in vascular practice

CHICAGO – Five years after the Society for Vascular Surgery launched the Vascular Quality Initiative, participating centers are more likely to use chlorhexidine and have also cut their surgery times and reduced their transfusion rates, according to results presented at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

But more drastic have been the improvements once low-performing centers have made in these measures and others, Larry Kraiss, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in reporting an update on VQI. “If you look at centers that had a big change in not using chlorhexidine to using chlorhexidine, the reduction of surgical site infections [SSI] in that subgroup was actually pretty significant,” said Dr. Kraiss, chair of the governing council of the SVS Patient Safety Organization, which oversees VQI.

These pivotal improvements came about after the VQI distributed what it calls COPI reports – for Center Opportunity Profile for Improvement – to participating centers. Currently, 379 centers in 46 states and Ontario participate in VQI, feeding data into 12 different vascular procedure registries ranging from peripheral vascular interventions to lower-extremity amputations. As of Nov. 1, 2016, 330,400 procedures had been submitted to VQI.

Dr. Kraiss called the COPI report the “workhorse” of the VQI. “It can give participating centers insight into what they can do to improve outcomes,” he said. It is one of three types of reports VQI provides. The others are benchmarking reports that show the masked ratings for all participating centers but confidentially highlight the rating of the individual center receiving the report; and reports for individual providers.

The most recent readout of the SSI COPI report compared measures in two periods: 2011-2012 and 2013-2014. In those periods, overall use of chlorhexidine rose from 66.6% to 81.2%; transfusion rates of more than 2 units fell from 14.4% to 11.5%; the share of procedures lasting 220 minutes or more fell from 50.2% to 47.7%; and SSI rate overall fell from 3.4% to 3.1%. While the change in SSI was not statistically significant, Dr. Kraiss said the 17 centers that had a large increase in chlorhexidine use did see statistically significant declines in SSI.

VQI also showed a 5-year survival rate of 79% of patients discharged with both statin and aspirin therapy vs. 61% for patients discharged without (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61[4]:1010-9). “This represents an opportunity to inform individual providers about how often they discharge patients on an aspirin and statin,” Dr. Kraiss said. Provider-targeted reports show how individual physicians rate in their region and nationwide.

VQI is more than a registry, Dr. Kraiss said; it’s also organized into 17 regional quality groups that provide surgeons a safe place to discuss VQI data and how to use that to encourage best practices. “There’s no risk of compromising or making the information identifiable,” he said. “It’s a matter of just getting together and trying to share best practices in a relatively informal environment, and hopefully through that drive quality improvement.

Other benefits of participating in VQI are that it can help surgeons comply with requirements for Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). VQI also offers opportunities to enroll in industry-sponsored clinical trials, which can help defray the cost of VQI participation, he said.

Dr. Kraiss had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CHICAGO – Five years after the Society for Vascular Surgery launched the Vascular Quality Initiative, participating centers are more likely to use chlorhexidine and have also cut their surgery times and reduced their transfusion rates, according to results presented at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

But more drastic have been the improvements once low-performing centers have made in these measures and others, Larry Kraiss, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in reporting an update on VQI. “If you look at centers that had a big change in not using chlorhexidine to using chlorhexidine, the reduction of surgical site infections [SSI] in that subgroup was actually pretty significant,” said Dr. Kraiss, chair of the governing council of the SVS Patient Safety Organization, which oversees VQI.

These pivotal improvements came about after the VQI distributed what it calls COPI reports – for Center Opportunity Profile for Improvement – to participating centers. Currently, 379 centers in 46 states and Ontario participate in VQI, feeding data into 12 different vascular procedure registries ranging from peripheral vascular interventions to lower-extremity amputations. As of Nov. 1, 2016, 330,400 procedures had been submitted to VQI.

Dr. Kraiss called the COPI report the “workhorse” of the VQI. “It can give participating centers insight into what they can do to improve outcomes,” he said. It is one of three types of reports VQI provides. The others are benchmarking reports that show the masked ratings for all participating centers but confidentially highlight the rating of the individual center receiving the report; and reports for individual providers.

The most recent readout of the SSI COPI report compared measures in two periods: 2011-2012 and 2013-2014. In those periods, overall use of chlorhexidine rose from 66.6% to 81.2%; transfusion rates of more than 2 units fell from 14.4% to 11.5%; the share of procedures lasting 220 minutes or more fell from 50.2% to 47.7%; and SSI rate overall fell from 3.4% to 3.1%. While the change in SSI was not statistically significant, Dr. Kraiss said the 17 centers that had a large increase in chlorhexidine use did see statistically significant declines in SSI.

VQI also showed a 5-year survival rate of 79% of patients discharged with both statin and aspirin therapy vs. 61% for patients discharged without (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61[4]:1010-9). “This represents an opportunity to inform individual providers about how often they discharge patients on an aspirin and statin,” Dr. Kraiss said. Provider-targeted reports show how individual physicians rate in their region and nationwide.

VQI is more than a registry, Dr. Kraiss said; it’s also organized into 17 regional quality groups that provide surgeons a safe place to discuss VQI data and how to use that to encourage best practices. “There’s no risk of compromising or making the information identifiable,” he said. “It’s a matter of just getting together and trying to share best practices in a relatively informal environment, and hopefully through that drive quality improvement.

Other benefits of participating in VQI are that it can help surgeons comply with requirements for Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). VQI also offers opportunities to enroll in industry-sponsored clinical trials, which can help defray the cost of VQI participation, he said.

Dr. Kraiss had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CHICAGO – Five years after the Society for Vascular Surgery launched the Vascular Quality Initiative, participating centers are more likely to use chlorhexidine and have also cut their surgery times and reduced their transfusion rates, according to results presented at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

But more drastic have been the improvements once low-performing centers have made in these measures and others, Larry Kraiss, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in reporting an update on VQI. “If you look at centers that had a big change in not using chlorhexidine to using chlorhexidine, the reduction of surgical site infections [SSI] in that subgroup was actually pretty significant,” said Dr. Kraiss, chair of the governing council of the SVS Patient Safety Organization, which oversees VQI.

These pivotal improvements came about after the VQI distributed what it calls COPI reports – for Center Opportunity Profile for Improvement – to participating centers. Currently, 379 centers in 46 states and Ontario participate in VQI, feeding data into 12 different vascular procedure registries ranging from peripheral vascular interventions to lower-extremity amputations. As of Nov. 1, 2016, 330,400 procedures had been submitted to VQI.

Dr. Kraiss called the COPI report the “workhorse” of the VQI. “It can give participating centers insight into what they can do to improve outcomes,” he said. It is one of three types of reports VQI provides. The others are benchmarking reports that show the masked ratings for all participating centers but confidentially highlight the rating of the individual center receiving the report; and reports for individual providers.

The most recent readout of the SSI COPI report compared measures in two periods: 2011-2012 and 2013-2014. In those periods, overall use of chlorhexidine rose from 66.6% to 81.2%; transfusion rates of more than 2 units fell from 14.4% to 11.5%; the share of procedures lasting 220 minutes or more fell from 50.2% to 47.7%; and SSI rate overall fell from 3.4% to 3.1%. While the change in SSI was not statistically significant, Dr. Kraiss said the 17 centers that had a large increase in chlorhexidine use did see statistically significant declines in SSI.

VQI also showed a 5-year survival rate of 79% of patients discharged with both statin and aspirin therapy vs. 61% for patients discharged without (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61[4]:1010-9). “This represents an opportunity to inform individual providers about how often they discharge patients on an aspirin and statin,” Dr. Kraiss said. Provider-targeted reports show how individual physicians rate in their region and nationwide.

VQI is more than a registry, Dr. Kraiss said; it’s also organized into 17 regional quality groups that provide surgeons a safe place to discuss VQI data and how to use that to encourage best practices. “There’s no risk of compromising or making the information identifiable,” he said. “It’s a matter of just getting together and trying to share best practices in a relatively informal environment, and hopefully through that drive quality improvement.

Other benefits of participating in VQI are that it can help surgeons comply with requirements for Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). VQI also offers opportunities to enroll in industry-sponsored clinical trials, which can help defray the cost of VQI participation, he said.

Dr. Kraiss had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

AT THE NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: The Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) provides comparative outcomes data that centers and surgeons can use to improve quality.

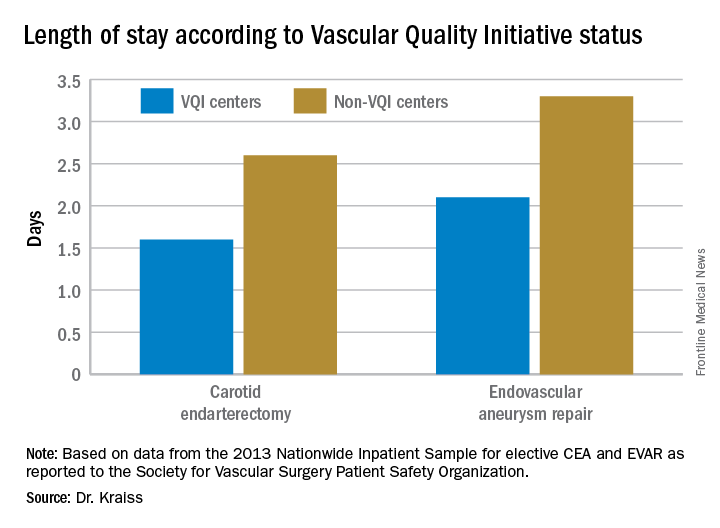

Major finding: Hospital length of stay for carotid endarterectomy averages 1.6 days for VQI centers vs. 2.6 days for nonparticipating centers.

Data source: VQI database.

Disclosures: Dr. Kraiss reported having no financial disclosures.

Vascular anomalies often misdiagnosed amidst confusion

CHICAGO – Thanks to convoluted terminology, not to mention confusion in the literature, physicians have been known to frequently misdiagnose vascular malformations as hemangiomas, but an evolving understanding of their differences may lead to more precise diagnoses, according to a report at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

“Historically there has been a great deal of confusion in the literature when it comes to the nomenclature used to describe vascular anomalies,” said Naiem Nassiri, MD, of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. He pointed out that the term hemangioma “or derivatives thereof” – cavernous hemangioma, cavernous angioma, lymphangioma and cystic hygroma – are “absolute misnomers and continue to be misused and applied almost haphazardly to any anomalous vascular lesion.”

He cited reports that 71% of vascular anomalies have been improperly called hemangiomas, 69% have initially been diagnosed incorrectly, and 21% received the wrong treatment (Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25[1]:7-12; Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011:127[1]:347-51). “Erroneous terminology has prognostic as well as diagnostic and therapeutic implications, and these can actually be quite devastating for the patient, not only clinically and physically but psychologically as well,” Dr. Nassiri said.

Using the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies classification for hemangiomas and vascular malformations can help physicians make the differential diagnosis, Dr. Nassiri said. Hemangiomas are neoplastic lesions of infancy, though not always congenital, with a finite growth phase, whereas vascular malformations (VMs) are nonneoplastic, congenital lesions that can appear at any age and do not regress spontaneously, he said.

Infantile hemangiomas typically appear as the classic strawberry birthmark in children, whereas VMs tend to appear later in life. “They require some environmental trigger, such as trauma, activity, or changes in the hormonal milieu to manifest onset,” he said of VMs.

Simply put, VMs fall into three broad categories: slow-flow malformations, which include lymphatic and venous malformations; high-flow arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and fistulas; and congenital mixed syndromes, which can include combinations thereof.

Dr. Nassiri noted that contrast-enhanced MRI is the standard imaging modality for diagnosis of VMs, and can differentiate between slow-flow and high-flow lesions. However, vascular specialists must be vigilant in ordering imaging for slow-flow lesions. “Orders can be changed to MR venography, and I’ve had patients who’ve gone decades with multiple MR venograms and no one can figure out what’s going on as no identifiable lesion is readily detected,” he said. “MR venograms are fantastic for detecting truncular blood flow where there typically are no anomalies in the vast majority of patients with isolated venous malformations, but on contrast-enhanced MRI these convoluted cluster of anomalous veins light up like Christmas trees.”

Lymphatic malformations affect the head and neck more so than the extremities, trunk or viscera, and are prone to infection and bleeding. “You can think of these as fluid-filled balloons, and the goal of treatment is fairly simple: You want to puncture the balloon and drain the fluid inside so as to obtain maximum wall collapse,” Dr. Nassiri said. Infusion of a sclerosant causes an inflammatory reaction leading to fibrosis, which then prevents balloon re-expansion. Surgical excision is best used as a secondary adjunct.

Venous malformations, comprising about 80% of all VMs, typically present as soft, spongy blue or purple compressible masses with associated pain that worsens with exertion, Dr. Nassiri said. “The most dangerous thing that is often overlooked, even by some of the physicians that treat these on a regular basis, is localized intravascular coagulopathy, which if left untreated can progress to fulminant disseminated intravascular coagulopathy,” he said. This tends to occur more in the more widespread varieties of venous malformations.

A common misnomer associated with venous malformations in adults is “liver hemangioma,” owing to the confusing nomenclature, Dr. Nassiri said. “When interrogated angiographically,” he said, “what is often labeled as a hepatic hemangioma is in fact a venous malformation. Natural history of the two entities is completely different.”

Dr. Nassiri described congenital high-flow AVMs as “convoluted networks of blood vessels with poorly differentiated endothelial cells that have neither a venous nor an arterial designation; this entity, otherwise known as a nidus, sits between the feeding arteries and the draining veins.” Treatment aims to eliminate the flow within that nidus.

Super-selective microcatheterization is the best option for nidus access and embolization using liquid embolic agents, preferably those that polymerize when infused. “This is probably the most potent angiogenic entity I’ve ever seen,” Dr. Nassiri said of the nidus.

“It’s like a low-pressure sump and it will recruit collaterals vigorously, so you have to eliminate that nidus.” A variety of different embolic agents, some off label, may be used for high flow AVMs.

For congenital mixed syndromes, the same diagnostic and therapeutic concepts hold true depending on the type of VM involved. Dr. Nassiri advised a multidisciplinary approach, and noted that early trials have investigated the use of sirolimus in severe, life-threatening cases (Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82[5]:1171-9. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13022).

Dr. Nassiri disclosed serving on the speakers bureaus for Boston Scientific, Penumbra, and Merritt Medical, and is a consultant to Merritt Medical.

CHICAGO – Thanks to convoluted terminology, not to mention confusion in the literature, physicians have been known to frequently misdiagnose vascular malformations as hemangiomas, but an evolving understanding of their differences may lead to more precise diagnoses, according to a report at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

“Historically there has been a great deal of confusion in the literature when it comes to the nomenclature used to describe vascular anomalies,” said Naiem Nassiri, MD, of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. He pointed out that the term hemangioma “or derivatives thereof” – cavernous hemangioma, cavernous angioma, lymphangioma and cystic hygroma – are “absolute misnomers and continue to be misused and applied almost haphazardly to any anomalous vascular lesion.”

He cited reports that 71% of vascular anomalies have been improperly called hemangiomas, 69% have initially been diagnosed incorrectly, and 21% received the wrong treatment (Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25[1]:7-12; Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011:127[1]:347-51). “Erroneous terminology has prognostic as well as diagnostic and therapeutic implications, and these can actually be quite devastating for the patient, not only clinically and physically but psychologically as well,” Dr. Nassiri said.

Using the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies classification for hemangiomas and vascular malformations can help physicians make the differential diagnosis, Dr. Nassiri said. Hemangiomas are neoplastic lesions of infancy, though not always congenital, with a finite growth phase, whereas vascular malformations (VMs) are nonneoplastic, congenital lesions that can appear at any age and do not regress spontaneously, he said.

Infantile hemangiomas typically appear as the classic strawberry birthmark in children, whereas VMs tend to appear later in life. “They require some environmental trigger, such as trauma, activity, or changes in the hormonal milieu to manifest onset,” he said of VMs.

Simply put, VMs fall into three broad categories: slow-flow malformations, which include lymphatic and venous malformations; high-flow arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and fistulas; and congenital mixed syndromes, which can include combinations thereof.

Dr. Nassiri noted that contrast-enhanced MRI is the standard imaging modality for diagnosis of VMs, and can differentiate between slow-flow and high-flow lesions. However, vascular specialists must be vigilant in ordering imaging for slow-flow lesions. “Orders can be changed to MR venography, and I’ve had patients who’ve gone decades with multiple MR venograms and no one can figure out what’s going on as no identifiable lesion is readily detected,” he said. “MR venograms are fantastic for detecting truncular blood flow where there typically are no anomalies in the vast majority of patients with isolated venous malformations, but on contrast-enhanced MRI these convoluted cluster of anomalous veins light up like Christmas trees.”

Lymphatic malformations affect the head and neck more so than the extremities, trunk or viscera, and are prone to infection and bleeding. “You can think of these as fluid-filled balloons, and the goal of treatment is fairly simple: You want to puncture the balloon and drain the fluid inside so as to obtain maximum wall collapse,” Dr. Nassiri said. Infusion of a sclerosant causes an inflammatory reaction leading to fibrosis, which then prevents balloon re-expansion. Surgical excision is best used as a secondary adjunct.

Venous malformations, comprising about 80% of all VMs, typically present as soft, spongy blue or purple compressible masses with associated pain that worsens with exertion, Dr. Nassiri said. “The most dangerous thing that is often overlooked, even by some of the physicians that treat these on a regular basis, is localized intravascular coagulopathy, which if left untreated can progress to fulminant disseminated intravascular coagulopathy,” he said. This tends to occur more in the more widespread varieties of venous malformations.

A common misnomer associated with venous malformations in adults is “liver hemangioma,” owing to the confusing nomenclature, Dr. Nassiri said. “When interrogated angiographically,” he said, “what is often labeled as a hepatic hemangioma is in fact a venous malformation. Natural history of the two entities is completely different.”

Dr. Nassiri described congenital high-flow AVMs as “convoluted networks of blood vessels with poorly differentiated endothelial cells that have neither a venous nor an arterial designation; this entity, otherwise known as a nidus, sits between the feeding arteries and the draining veins.” Treatment aims to eliminate the flow within that nidus.

Super-selective microcatheterization is the best option for nidus access and embolization using liquid embolic agents, preferably those that polymerize when infused. “This is probably the most potent angiogenic entity I’ve ever seen,” Dr. Nassiri said of the nidus.

“It’s like a low-pressure sump and it will recruit collaterals vigorously, so you have to eliminate that nidus.” A variety of different embolic agents, some off label, may be used for high flow AVMs.

For congenital mixed syndromes, the same diagnostic and therapeutic concepts hold true depending on the type of VM involved. Dr. Nassiri advised a multidisciplinary approach, and noted that early trials have investigated the use of sirolimus in severe, life-threatening cases (Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82[5]:1171-9. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13022).

Dr. Nassiri disclosed serving on the speakers bureaus for Boston Scientific, Penumbra, and Merritt Medical, and is a consultant to Merritt Medical.

CHICAGO – Thanks to convoluted terminology, not to mention confusion in the literature, physicians have been known to frequently misdiagnose vascular malformations as hemangiomas, but an evolving understanding of their differences may lead to more precise diagnoses, according to a report at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

“Historically there has been a great deal of confusion in the literature when it comes to the nomenclature used to describe vascular anomalies,” said Naiem Nassiri, MD, of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. He pointed out that the term hemangioma “or derivatives thereof” – cavernous hemangioma, cavernous angioma, lymphangioma and cystic hygroma – are “absolute misnomers and continue to be misused and applied almost haphazardly to any anomalous vascular lesion.”

He cited reports that 71% of vascular anomalies have been improperly called hemangiomas, 69% have initially been diagnosed incorrectly, and 21% received the wrong treatment (Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25[1]:7-12; Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011:127[1]:347-51). “Erroneous terminology has prognostic as well as diagnostic and therapeutic implications, and these can actually be quite devastating for the patient, not only clinically and physically but psychologically as well,” Dr. Nassiri said.

Using the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies classification for hemangiomas and vascular malformations can help physicians make the differential diagnosis, Dr. Nassiri said. Hemangiomas are neoplastic lesions of infancy, though not always congenital, with a finite growth phase, whereas vascular malformations (VMs) are nonneoplastic, congenital lesions that can appear at any age and do not regress spontaneously, he said.

Infantile hemangiomas typically appear as the classic strawberry birthmark in children, whereas VMs tend to appear later in life. “They require some environmental trigger, such as trauma, activity, or changes in the hormonal milieu to manifest onset,” he said of VMs.

Simply put, VMs fall into three broad categories: slow-flow malformations, which include lymphatic and venous malformations; high-flow arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and fistulas; and congenital mixed syndromes, which can include combinations thereof.

Dr. Nassiri noted that contrast-enhanced MRI is the standard imaging modality for diagnosis of VMs, and can differentiate between slow-flow and high-flow lesions. However, vascular specialists must be vigilant in ordering imaging for slow-flow lesions. “Orders can be changed to MR venography, and I’ve had patients who’ve gone decades with multiple MR venograms and no one can figure out what’s going on as no identifiable lesion is readily detected,” he said. “MR venograms are fantastic for detecting truncular blood flow where there typically are no anomalies in the vast majority of patients with isolated venous malformations, but on contrast-enhanced MRI these convoluted cluster of anomalous veins light up like Christmas trees.”

Lymphatic malformations affect the head and neck more so than the extremities, trunk or viscera, and are prone to infection and bleeding. “You can think of these as fluid-filled balloons, and the goal of treatment is fairly simple: You want to puncture the balloon and drain the fluid inside so as to obtain maximum wall collapse,” Dr. Nassiri said. Infusion of a sclerosant causes an inflammatory reaction leading to fibrosis, which then prevents balloon re-expansion. Surgical excision is best used as a secondary adjunct.

Venous malformations, comprising about 80% of all VMs, typically present as soft, spongy blue or purple compressible masses with associated pain that worsens with exertion, Dr. Nassiri said. “The most dangerous thing that is often overlooked, even by some of the physicians that treat these on a regular basis, is localized intravascular coagulopathy, which if left untreated can progress to fulminant disseminated intravascular coagulopathy,” he said. This tends to occur more in the more widespread varieties of venous malformations.

A common misnomer associated with venous malformations in adults is “liver hemangioma,” owing to the confusing nomenclature, Dr. Nassiri said. “When interrogated angiographically,” he said, “what is often labeled as a hepatic hemangioma is in fact a venous malformation. Natural history of the two entities is completely different.”

Dr. Nassiri described congenital high-flow AVMs as “convoluted networks of blood vessels with poorly differentiated endothelial cells that have neither a venous nor an arterial designation; this entity, otherwise known as a nidus, sits between the feeding arteries and the draining veins.” Treatment aims to eliminate the flow within that nidus.

Super-selective microcatheterization is the best option for nidus access and embolization using liquid embolic agents, preferably those that polymerize when infused. “This is probably the most potent angiogenic entity I’ve ever seen,” Dr. Nassiri said of the nidus.

“It’s like a low-pressure sump and it will recruit collaterals vigorously, so you have to eliminate that nidus.” A variety of different embolic agents, some off label, may be used for high flow AVMs.

For congenital mixed syndromes, the same diagnostic and therapeutic concepts hold true depending on the type of VM involved. Dr. Nassiri advised a multidisciplinary approach, and noted that early trials have investigated the use of sirolimus in severe, life-threatening cases (Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82[5]:1171-9. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13022).

Dr. Nassiri disclosed serving on the speakers bureaus for Boston Scientific, Penumbra, and Merritt Medical, and is a consultant to Merritt Medical.

AT THE NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Use of imaging and a clearer understanding of the lack of neoplastic activity are key to more precisely diagnosing vascular malformations.

Data source: Review of literature and center experience.

Disclosure: Dr. Nassiri disclosed serving on the speakers bureaus for Boston Scientific, Penumbra, and Merritt Medical, and is a consultant to Merritt Medical.

An alternative device for ESRD patients with central venous obstruction

CHICAGO – Catheter dependence is often the final option available for hemodialysis patients who have exhausted upper extremity access because of central venous obstruction. But an alternative device that combines a standard expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) arterial graft component with an entirely internalized central venous catheter component may provide an additional option that can help avoid catheters in selected patients, according to pooled results reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Virginia L. Wong, MD, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, reported on her group’s and others’ experience using the Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) graft (Merit Medical) to gain access to the superior vena cava (SVC), thus allowing for further upper extremity access options. The device has its limitations in patients with CVO, Dr. Wong noted, “but it can be an important tool for the dedicated access surgeon who is likely to be referred the most complicated patients who have run out of just about every other option.”

The Food and Drug Administration approved the HeRO graft for CVO in 2008, but a recent pooled analysis (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50[1]:108-13), which showed a 1-year primary patency rate of 22% and a secondary patency rate of 60%, may provide clarity on how the device can be used to treat CVO in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients when the care team desires an alternative to femoral arteriovenous graft, Dr. Wong said. “The 1-year primary patency rate overall was not very good, but with aggressive thrombectomy programs the 1-year patency rate was decent,” she said.

The pooled analysis involved eight series from 2009 to 2015, but the largest series, which involved 164 patients, reported primary and secondary patency rates of 48.8% and 90.8%, respectively (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44[1]:93-9). “Patency for these alternative accesses may not be quite what we can achieve with standard upper-extremity access,” Dr. Wong said, “but these patients do not have the standard access as an option.”

Dr. Wong explained where the HeRO fits into the existing vascular practice. “The current data suggest that we should try to exhaust all traditional upper extremity access options before considering anything else, but the HeRO could be considered as an acceptable option for suitable patients,” she said. However, to achieve those outcomes, “you need to have an aggressive thrombectomy program.”

HeRO may be an option for salvage of an existing arm access, plagued by recalcitrant CVO, while still preserving the femoral sites and for future hemodialysis access and/or renal transplantation, Dr. Wong said.

The HeRO also has been used in alternative configurations, taking advantage of axillary or subclavian routes to the SVC when both internal jugular veins are occluded. Dr. Wong has used the femoral route to the inferior vena cava (IVC) for salvaging the femoral AV graft in which iliofemoral venous outflow has been compromised.

Anatomically, the patient must be able to accept a large-bore (19-Fr) access catheter into the central vein. Physiologically, the patient must be able to maintain patency of the long, low-resistance HeRO circuit, which can be up to 50 cm in length, she said. The protocol at Dr. Wong’s institution recommends an inflow arterial diameter of at least 3 mm, along with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 20% or greater and a minimum systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg for HeRO on the right side, and possibly higher when coming from the left.

Chronic hypotension is a frequent disqualifier, although some of these patients may benefit from midodrine hydrochloride, she said. In any event, a review of medications and consultation with nephrology and the dialysis unit are mandatory elements of patient screening. “I usually request hemodialysis run sheets from the last three sessions to see what systolic blood pressure excursion is like over the course of treatment,” she said.

The basic principles of hemo-access care are important when considering the HeRO for CVO patients, Dr. Wong said. These include site/side preservation, catheter avoidance and “not to burn any bridges” for future access. “Individualization of care and careful patient selection are probably the best bets if you’re just starting out,” she said. “Choose good patients before resorting to HeRO as the last option for a fairly marginal candidate.”

Dr. Wong had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CHICAGO – Catheter dependence is often the final option available for hemodialysis patients who have exhausted upper extremity access because of central venous obstruction. But an alternative device that combines a standard expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) arterial graft component with an entirely internalized central venous catheter component may provide an additional option that can help avoid catheters in selected patients, according to pooled results reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Virginia L. Wong, MD, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, reported on her group’s and others’ experience using the Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) graft (Merit Medical) to gain access to the superior vena cava (SVC), thus allowing for further upper extremity access options. The device has its limitations in patients with CVO, Dr. Wong noted, “but it can be an important tool for the dedicated access surgeon who is likely to be referred the most complicated patients who have run out of just about every other option.”

The Food and Drug Administration approved the HeRO graft for CVO in 2008, but a recent pooled analysis (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50[1]:108-13), which showed a 1-year primary patency rate of 22% and a secondary patency rate of 60%, may provide clarity on how the device can be used to treat CVO in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients when the care team desires an alternative to femoral arteriovenous graft, Dr. Wong said. “The 1-year primary patency rate overall was not very good, but with aggressive thrombectomy programs the 1-year patency rate was decent,” she said.

The pooled analysis involved eight series from 2009 to 2015, but the largest series, which involved 164 patients, reported primary and secondary patency rates of 48.8% and 90.8%, respectively (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44[1]:93-9). “Patency for these alternative accesses may not be quite what we can achieve with standard upper-extremity access,” Dr. Wong said, “but these patients do not have the standard access as an option.”

Dr. Wong explained where the HeRO fits into the existing vascular practice. “The current data suggest that we should try to exhaust all traditional upper extremity access options before considering anything else, but the HeRO could be considered as an acceptable option for suitable patients,” she said. However, to achieve those outcomes, “you need to have an aggressive thrombectomy program.”

HeRO may be an option for salvage of an existing arm access, plagued by recalcitrant CVO, while still preserving the femoral sites and for future hemodialysis access and/or renal transplantation, Dr. Wong said.

The HeRO also has been used in alternative configurations, taking advantage of axillary or subclavian routes to the SVC when both internal jugular veins are occluded. Dr. Wong has used the femoral route to the inferior vena cava (IVC) for salvaging the femoral AV graft in which iliofemoral venous outflow has been compromised.

Anatomically, the patient must be able to accept a large-bore (19-Fr) access catheter into the central vein. Physiologically, the patient must be able to maintain patency of the long, low-resistance HeRO circuit, which can be up to 50 cm in length, she said. The protocol at Dr. Wong’s institution recommends an inflow arterial diameter of at least 3 mm, along with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 20% or greater and a minimum systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg for HeRO on the right side, and possibly higher when coming from the left.

Chronic hypotension is a frequent disqualifier, although some of these patients may benefit from midodrine hydrochloride, she said. In any event, a review of medications and consultation with nephrology and the dialysis unit are mandatory elements of patient screening. “I usually request hemodialysis run sheets from the last three sessions to see what systolic blood pressure excursion is like over the course of treatment,” she said.

The basic principles of hemo-access care are important when considering the HeRO for CVO patients, Dr. Wong said. These include site/side preservation, catheter avoidance and “not to burn any bridges” for future access. “Individualization of care and careful patient selection are probably the best bets if you’re just starting out,” she said. “Choose good patients before resorting to HeRO as the last option for a fairly marginal candidate.”

Dr. Wong had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CHICAGO – Catheter dependence is often the final option available for hemodialysis patients who have exhausted upper extremity access because of central venous obstruction. But an alternative device that combines a standard expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) arterial graft component with an entirely internalized central venous catheter component may provide an additional option that can help avoid catheters in selected patients, according to pooled results reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Virginia L. Wong, MD, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, reported on her group’s and others’ experience using the Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) graft (Merit Medical) to gain access to the superior vena cava (SVC), thus allowing for further upper extremity access options. The device has its limitations in patients with CVO, Dr. Wong noted, “but it can be an important tool for the dedicated access surgeon who is likely to be referred the most complicated patients who have run out of just about every other option.”

The Food and Drug Administration approved the HeRO graft for CVO in 2008, but a recent pooled analysis (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50[1]:108-13), which showed a 1-year primary patency rate of 22% and a secondary patency rate of 60%, may provide clarity on how the device can be used to treat CVO in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients when the care team desires an alternative to femoral arteriovenous graft, Dr. Wong said. “The 1-year primary patency rate overall was not very good, but with aggressive thrombectomy programs the 1-year patency rate was decent,” she said.

The pooled analysis involved eight series from 2009 to 2015, but the largest series, which involved 164 patients, reported primary and secondary patency rates of 48.8% and 90.8%, respectively (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44[1]:93-9). “Patency for these alternative accesses may not be quite what we can achieve with standard upper-extremity access,” Dr. Wong said, “but these patients do not have the standard access as an option.”

Dr. Wong explained where the HeRO fits into the existing vascular practice. “The current data suggest that we should try to exhaust all traditional upper extremity access options before considering anything else, but the HeRO could be considered as an acceptable option for suitable patients,” she said. However, to achieve those outcomes, “you need to have an aggressive thrombectomy program.”

HeRO may be an option for salvage of an existing arm access, plagued by recalcitrant CVO, while still preserving the femoral sites and for future hemodialysis access and/or renal transplantation, Dr. Wong said.

The HeRO also has been used in alternative configurations, taking advantage of axillary or subclavian routes to the SVC when both internal jugular veins are occluded. Dr. Wong has used the femoral route to the inferior vena cava (IVC) for salvaging the femoral AV graft in which iliofemoral venous outflow has been compromised.

Anatomically, the patient must be able to accept a large-bore (19-Fr) access catheter into the central vein. Physiologically, the patient must be able to maintain patency of the long, low-resistance HeRO circuit, which can be up to 50 cm in length, she said. The protocol at Dr. Wong’s institution recommends an inflow arterial diameter of at least 3 mm, along with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 20% or greater and a minimum systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg for HeRO on the right side, and possibly higher when coming from the left.

Chronic hypotension is a frequent disqualifier, although some of these patients may benefit from midodrine hydrochloride, she said. In any event, a review of medications and consultation with nephrology and the dialysis unit are mandatory elements of patient screening. “I usually request hemodialysis run sheets from the last three sessions to see what systolic blood pressure excursion is like over the course of treatment,” she said.

The basic principles of hemo-access care are important when considering the HeRO for CVO patients, Dr. Wong said. These include site/side preservation, catheter avoidance and “not to burn any bridges” for future access. “Individualization of care and careful patient selection are probably the best bets if you’re just starting out,” she said. “Choose good patients before resorting to HeRO as the last option for a fairly marginal candidate.”

Dr. Wong had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Key clinical point: Combined graft-catheter device may preserve femoral access for hemodialysis for patients with central venous obstruction.

Major finding: One-year primary potency rate was 22% and secondary patency rate 60% for device recipients.

Data source: Literature review, including pooled results from eight studies involving 408 subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Wong reported having no financial disclosures.

Now is time to embrace emerging PAD interventions

CHICAGO – Bioresorbable scaffolds, new drugs, adjuvant interventions, and stem and progenitor cell therapy will change how vascular surgeons treat peripheral artery disease in the next 5 years, so they must embrace these emerging treatments or run the risk of being displaced by other specialists, according to a presentation at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

“Vascular surgeons must position their practices to be the nexus for the evaluation and treatment of the patient and proactively engage in the critical trials of these new technologies,” said Patrick J. Geraghty, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis. “If our specialty fails to adapt to new treatment options, we risk getting sidelined as critical limb ischemia (CLI) treatment moves into a multimodality model.”

Dr. Geraghty focused on several future directions for PAD treatment: improved drug-eluting stents (DES) for superficial femoral artery disease; drug-coated balloons and modified DES for infrapopliteal disease; biologic modifiers for claudication and CLI; and bioresorbable, drug-eluting scaffolds for infrainguinal interventions.

“You’re not simply a plumber anymore; you’re a biological response modifier,” Dr. Geraghty said, explaining that biologic response modification technologies are the logical successor where standard surgical and endovascular techniques have either fallen short (as in early patency loss due to restenosis) or failed to offer effective alternatives (as in no-option advanced CLI patients). “And that takes many of us out of our comfort zone,” he said.

Dr. Geraghty noted the VIBRANT trial (J Vasc Surg. 2013;58[2]:386-95) and similar studies of non–drug eluting constructs identified early restenosis as the primary culprit in endovascular patency loss. “If you could reduce those early patency losses, you’d have an admirable primary patency rate for these complex lesions,” he said. “We’re able to reconstruct a vessel lumen. The question is, how to best maintain it?”

To answer that, Dr. Geraghty noted that the SIROCCO II trial (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16[3]:331-8) failed to show an advantage for a sirolimus-eluting stent over bare nitinol stent for superficial femoral artery (SFA) disease, but the subsequent Zilver PTX trial showed the benefits of paclitaxel-eluting stents over 5 years (Circulation. 2016;133[15]:1472-83).

He noted that drug-coated balloons (DCBs) trials have yielded mixed results in infrapopliteal intervention. Most notably, the multicenter In.Pact DEEP trial (Circulation. 2015;131[5]:495-502) failed to show treatment efficacy, Dr. Geraghty said. “The In.Pact DEEP results sharply contrasted with the positive data from trials of similar DCBs in the SFA” (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[2]:145-53).

With regard to DES for infrapopliteal disease, Dr. Geraghty noted the promise of positive results of the ACHILLES (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60[22]:2290-5) and DESTINY (J Vasc Surg. 2012;55[2]:390-9) trials, along with the modest structural changes needed to convert from coronary to proximal tibial applications.

Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) for CLI have also made recent advances. “It has been a slow road, but I’m happy that industry has pursued this aggressively,” Dr. Geraghty said. He pointed out that the ESPRIT I trial of bioresorbable everolimus-eluting vascular scaffolds in PAD involving the external iliac artery and SFA reported restenosis rates of 12.1% and 16.1% at 1 and 2 years, respectively (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[11]:1178-87). A trial of the Absorb BVS (Abbott) for short infrapopliteal lesions showed primary patency rates of 96% and 85% at 1 and 2 years, he said (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[7]:715-24).

“Vascular surgeons should be tracking BVS technology closely,” Dr. Geraghty said. “It achieves multiple desirable goals: immediate scaffolding for luminal restoration; mitigation of the restenotic stimulus via stent resorption; drug delivery for inhibition of restenosis; and the prospect of simpler re-interventions.”

Stem/progenitor cell therapies may also provide new solutions for no-option vasculature. One trial that showed “promising trends,” Dr. Geraghty said, is the RESTORE-CLI study of bone marrow aspiration (Mol Ther. 2012;20[6]:1280-6). “This trial reported a trend toward improved time to failure and reduced amputation-free survival, but did not meet its primary endpoint,” he said. “Likewise, the recently presented Biomet MOBILE data failed to meet its primary endpoint, but showed favorable trends in some treatment subgroups” (J Vasc Surg. 2011;54[6]:1650-8).

Dr. Geraghty noted that trial design in this field may need to change directions. “Look at the Delphi consensus matrices for the WIfI (Wound, Ischemia, foot Infection) Threatened limb Classification System (J Vasc Surg. 2014;59[1]:220-34). These show that complex wounds bear a significant risk of amputation, perhaps unmitigated by successful revascularization.” In addition, he called amputation-free survival “a rather blunt instrument” for evaluating how therapies impact limb outcomes and said it can confound the analysis of their effectiveness.

“Instead of confining the progenitor-cell therapies to no-option CLI trials, I’m eager to also see them investigated for treatment of claudication,” Dr. Geraghty said. “Can cell-based therapies possibly displace endovascular interventions as the first-line, least-harmful option for claudication?”

Dr. Geraghty also touched on intra/extravascular adjuvant therapies: antithrombin nanoparticles; inhibitory nanoparticles and polymeric wraps; and adventitial drug delivery techniques, among others.

“It’s critically important for vascular surgeons to position themselves for continued success in CLI treatment,” he said. “That involves aggressive practice branding, active trial participation, critical analysis of new technologies, and adoption of new, even disruptive, treatment modalities that show patient benefit.”