User login

Contraception for women taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptics

Topiramate, introduced as an antiepileptic drug (AED), is currently most widely used for prevention of migraine headaches.

Because reproductive-aged women represent a population in which migraines are prevalent, clinicians need guidance to help women taking topiramate make sound contraceptive choices.

Several issues are relevant here. First, women who have migraines with aura should avoid estrogen-containing contraceptive pills, patches, and rings. Instead, progestin-only methods, including the contraceptive implant, may be recommended to patients with migraines.

Second, because topiramate, as with a number of other AEDs, is a teratogen, women using this medication need highly effective contraception. This consideration may also lead clinicians to recommend use of the implant in women with migraines.

Finally, topiramate, along with other AEDs (phenytoin, carbamazepine, barbiturates, primidone, and oxcarbazepine) induces hepatic enzymes, which results in reduced serum contraceptive steroid levels.

Because there is uncertainty regarding the degree to which the use of topiramate reduces serum levels of etonogestrel (the progestin released by the implant), investigators performed a prospective study to assess the pharmacokinetic impact of topiramate in women with the implant.

Ongoing users of contraceptive implants who agreed to use additional nonhormonal contraception were recruited to a 6-week study, during which they took topiramate and periodically had blood drawn.

Overall, use of topiramate was found to lower serum etonogestrel levels from baseline on a dose-related basis. At study completion, almost one-third of study participants were found to have serum progestin levels lower than the threshold associated with predictable ovulation suppression.

The results of this carefully conducted study support guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that women seeking contraception and using topiramate or other enzyme-inducing AEDs should be encouraged to use intrauterine devices or injectable contraception. The contraceptive efficacy of these latter methods is not diminished by concomitant use of enzyme inducers.

I am Andrew Kaunitz. Please take care of yourself and each other.

Any views expressed above are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Andrew M. Kaunitz is a professor and Associate Chairman, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Florida, Jacksonville.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Topiramate, introduced as an antiepileptic drug (AED), is currently most widely used for prevention of migraine headaches.

Because reproductive-aged women represent a population in which migraines are prevalent, clinicians need guidance to help women taking topiramate make sound contraceptive choices.

Several issues are relevant here. First, women who have migraines with aura should avoid estrogen-containing contraceptive pills, patches, and rings. Instead, progestin-only methods, including the contraceptive implant, may be recommended to patients with migraines.

Second, because topiramate, as with a number of other AEDs, is a teratogen, women using this medication need highly effective contraception. This consideration may also lead clinicians to recommend use of the implant in women with migraines.

Finally, topiramate, along with other AEDs (phenytoin, carbamazepine, barbiturates, primidone, and oxcarbazepine) induces hepatic enzymes, which results in reduced serum contraceptive steroid levels.

Because there is uncertainty regarding the degree to which the use of topiramate reduces serum levels of etonogestrel (the progestin released by the implant), investigators performed a prospective study to assess the pharmacokinetic impact of topiramate in women with the implant.

Ongoing users of contraceptive implants who agreed to use additional nonhormonal contraception were recruited to a 6-week study, during which they took topiramate and periodically had blood drawn.

Overall, use of topiramate was found to lower serum etonogestrel levels from baseline on a dose-related basis. At study completion, almost one-third of study participants were found to have serum progestin levels lower than the threshold associated with predictable ovulation suppression.

The results of this carefully conducted study support guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that women seeking contraception and using topiramate or other enzyme-inducing AEDs should be encouraged to use intrauterine devices or injectable contraception. The contraceptive efficacy of these latter methods is not diminished by concomitant use of enzyme inducers.

I am Andrew Kaunitz. Please take care of yourself and each other.

Any views expressed above are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Andrew M. Kaunitz is a professor and Associate Chairman, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Florida, Jacksonville.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Topiramate, introduced as an antiepileptic drug (AED), is currently most widely used for prevention of migraine headaches.

Because reproductive-aged women represent a population in which migraines are prevalent, clinicians need guidance to help women taking topiramate make sound contraceptive choices.

Several issues are relevant here. First, women who have migraines with aura should avoid estrogen-containing contraceptive pills, patches, and rings. Instead, progestin-only methods, including the contraceptive implant, may be recommended to patients with migraines.

Second, because topiramate, as with a number of other AEDs, is a teratogen, women using this medication need highly effective contraception. This consideration may also lead clinicians to recommend use of the implant in women with migraines.

Finally, topiramate, along with other AEDs (phenytoin, carbamazepine, barbiturates, primidone, and oxcarbazepine) induces hepatic enzymes, which results in reduced serum contraceptive steroid levels.

Because there is uncertainty regarding the degree to which the use of topiramate reduces serum levels of etonogestrel (the progestin released by the implant), investigators performed a prospective study to assess the pharmacokinetic impact of topiramate in women with the implant.

Ongoing users of contraceptive implants who agreed to use additional nonhormonal contraception were recruited to a 6-week study, during which they took topiramate and periodically had blood drawn.

Overall, use of topiramate was found to lower serum etonogestrel levels from baseline on a dose-related basis. At study completion, almost one-third of study participants were found to have serum progestin levels lower than the threshold associated with predictable ovulation suppression.

The results of this carefully conducted study support guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that women seeking contraception and using topiramate or other enzyme-inducing AEDs should be encouraged to use intrauterine devices or injectable contraception. The contraceptive efficacy of these latter methods is not diminished by concomitant use of enzyme inducers.

I am Andrew Kaunitz. Please take care of yourself and each other.

Any views expressed above are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Andrew M. Kaunitz is a professor and Associate Chairman, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Florida, Jacksonville.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Belmont Stakes to support initiatives focused on improving the patient experience

There is a variety of ways to support the many impactful new programs the CHEST Foundation will launch in 2022, but one of the most anticipated options is the annual Belmont Stakes Dinner and Auction on June 11 in New York City. This fun-filled evening will include a viewing of the 154th running of “The Championship Track,” a cocktail reception and plated dinner, a silent auction, a rooftop party, and much more.

This year, the dinner and auction will support the CHEST Foundation’s work in patient education and CHEST initiatives to improve patient care. Two areas of focus are disparities in care delivery and improving patients’ quality of life through partnerships designed to encourage earlier diagnosis and treatment.

With these goals in mind, new initiatives include an extension of the 2020 Foundation Listening Tour designed to help clinicians increase trust, equity, and access to health care for patients in traditionally marginalized communities.

In addition, CHEST is partnering with the Three Lakes Foundation on a program dedicated to shortening the time to diagnosis for pulmonary fibrosis (PF). This initiative will bring together pulmonologists and primary care physicians to develop a strategy for identifying PF more quickly, ensuring treatment can begin earlier in the disease trajectory. Early detection of PF is associated with better quality of life for patients, so improving clinicians’ understanding of the signs and symptoms of this rare disease and formulating better guidance for diagnosing it could result in drastic improvements for those living with PF.

To highlight the importance of these efforts, the evening also will include speeches from two patient advocates who have turned their own experiences with living with chronic lung disease into incredible action on behalf of patients.

To learn more about the CHEST Foundation’s initiatives in 2022 and how you can attend the Belmont Stakes Dinner and Auction to support these efforts, visit foundation.chestnet.org.

There is a variety of ways to support the many impactful new programs the CHEST Foundation will launch in 2022, but one of the most anticipated options is the annual Belmont Stakes Dinner and Auction on June 11 in New York City. This fun-filled evening will include a viewing of the 154th running of “The Championship Track,” a cocktail reception and plated dinner, a silent auction, a rooftop party, and much more.

This year, the dinner and auction will support the CHEST Foundation’s work in patient education and CHEST initiatives to improve patient care. Two areas of focus are disparities in care delivery and improving patients’ quality of life through partnerships designed to encourage earlier diagnosis and treatment.

With these goals in mind, new initiatives include an extension of the 2020 Foundation Listening Tour designed to help clinicians increase trust, equity, and access to health care for patients in traditionally marginalized communities.

In addition, CHEST is partnering with the Three Lakes Foundation on a program dedicated to shortening the time to diagnosis for pulmonary fibrosis (PF). This initiative will bring together pulmonologists and primary care physicians to develop a strategy for identifying PF more quickly, ensuring treatment can begin earlier in the disease trajectory. Early detection of PF is associated with better quality of life for patients, so improving clinicians’ understanding of the signs and symptoms of this rare disease and formulating better guidance for diagnosing it could result in drastic improvements for those living with PF.

To highlight the importance of these efforts, the evening also will include speeches from two patient advocates who have turned their own experiences with living with chronic lung disease into incredible action on behalf of patients.

To learn more about the CHEST Foundation’s initiatives in 2022 and how you can attend the Belmont Stakes Dinner and Auction to support these efforts, visit foundation.chestnet.org.

There is a variety of ways to support the many impactful new programs the CHEST Foundation will launch in 2022, but one of the most anticipated options is the annual Belmont Stakes Dinner and Auction on June 11 in New York City. This fun-filled evening will include a viewing of the 154th running of “The Championship Track,” a cocktail reception and plated dinner, a silent auction, a rooftop party, and much more.

This year, the dinner and auction will support the CHEST Foundation’s work in patient education and CHEST initiatives to improve patient care. Two areas of focus are disparities in care delivery and improving patients’ quality of life through partnerships designed to encourage earlier diagnosis and treatment.

With these goals in mind, new initiatives include an extension of the 2020 Foundation Listening Tour designed to help clinicians increase trust, equity, and access to health care for patients in traditionally marginalized communities.

In addition, CHEST is partnering with the Three Lakes Foundation on a program dedicated to shortening the time to diagnosis for pulmonary fibrosis (PF). This initiative will bring together pulmonologists and primary care physicians to develop a strategy for identifying PF more quickly, ensuring treatment can begin earlier in the disease trajectory. Early detection of PF is associated with better quality of life for patients, so improving clinicians’ understanding of the signs and symptoms of this rare disease and formulating better guidance for diagnosing it could result in drastic improvements for those living with PF.

To highlight the importance of these efforts, the evening also will include speeches from two patient advocates who have turned their own experiences with living with chronic lung disease into incredible action on behalf of patients.

To learn more about the CHEST Foundation’s initiatives in 2022 and how you can attend the Belmont Stakes Dinner and Auction to support these efforts, visit foundation.chestnet.org.

What COVID-19 taught us: The challenge of maintaining contingency level care to proactively forestall crisis care

In 2014, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care (TFMCC) published a CHEST consensus statement on disaster preparedness principles in caring for the critically ill during disasters and pandemics (Christian et al. CHEST. 2014;146[4_suppl]:8s-34s). This publication attempted to guide preparedness for both single-event disasters and more prolonged events, including a feared influenza pandemic.

Despite the foundation of planning and support this guidance provided, the COVID-19 pandemic response revealed substantial gaps in our understanding and preparedness for these more prolonged and widespread events.

In New York City, as the first COVID-19 wave began in March and April of 2020, area hospitals responded with surge plans that prioritized what was felt to be most important (Griffin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 1;201[11]:1337-44). Tiered, creative staffing structures were rapidly created with intensivists supervising non-ICU physicians and APPs. Procedure teams were created for intubation, proning, and central line placement. ICU space was created with adaptations to ORs and PACUs, and rooms on med-surg floors and step-down units underwent emergency renovations to allow creation of new “pop-up” ICUs. Triage protocols were altered: patients on high levels of supplemental oxygen, who would under normal circumstances have been admitted to an ICU, were triaged to floors and stepdown units. Equipment was reused, modified, and substituted creatively to optimize care for the maximum number of patients.

In the face of all of these struggles, many around the country and the world felt the efforts, though heroic, resulted in less than standard of care. Two subsequent publications validated this concern (Kadri et al. Ann Int Med. 2021,174;9:1240-51; Bravata DM et al. JAMA Open Network. 2021;4[1]:e2034266), demonstrating during severe surge, COVID-19 patients’ mortality increased significantly beyond that seen in non-surging or less-severe surging times, demonstrating a mortality effect of surge itself. Though these studies observed COVID-19 patients only, there is every reason to believe the findings applied to all critically ill patients cared for during these surges.

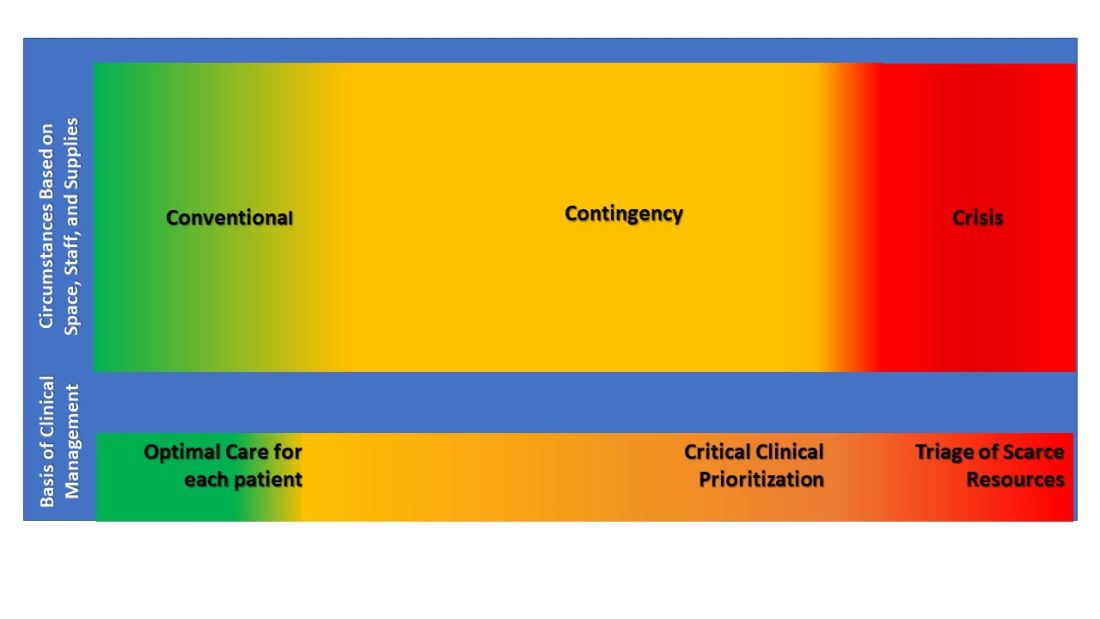

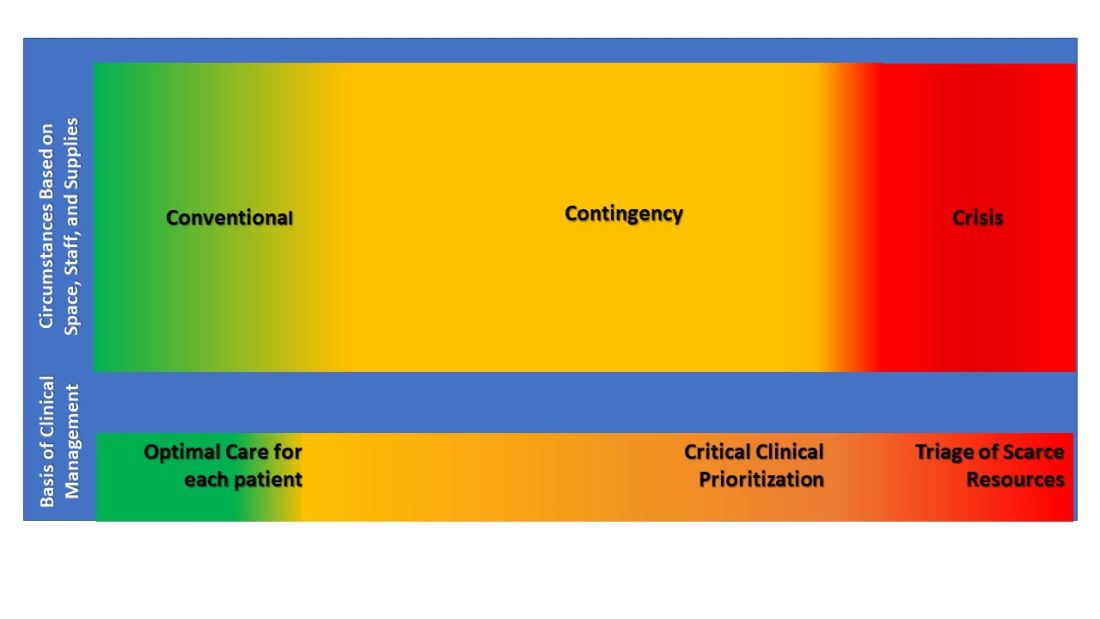

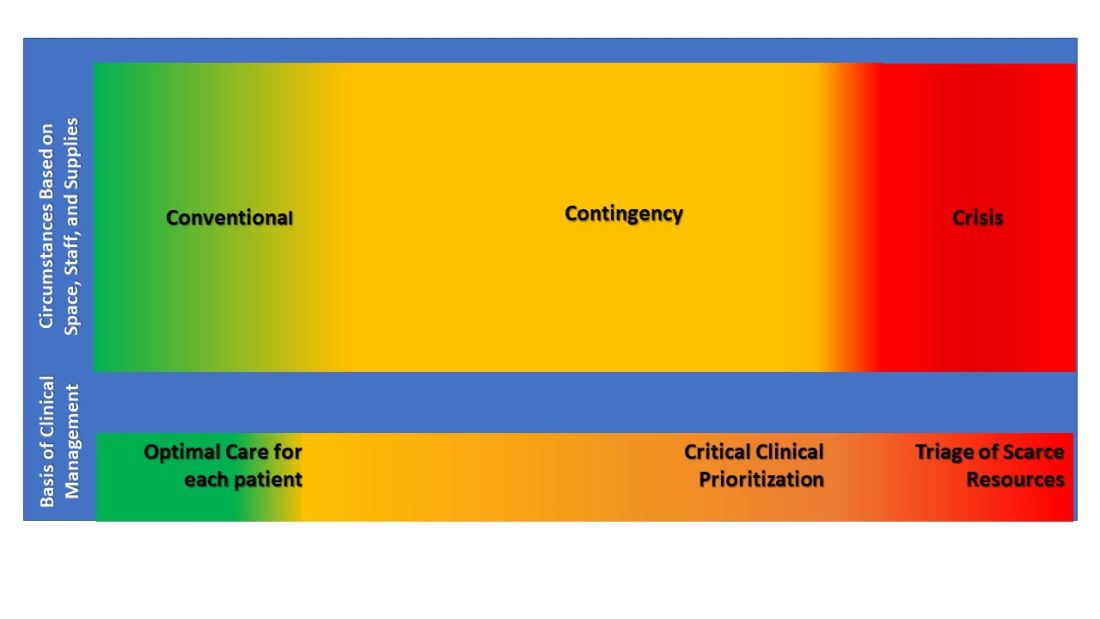

These experiences led the TFMCC to report updated strategies for remaining in contingency care levels and avoiding crisis care (Dichter JR et al. CHEST. 2022;161[2]:429-47). Contingency is equivalent to routine care though may require adaptations and employment of otherwise non-traditional resources. The ultimate goal of mass critical care in a public health emergency is to avoid crisis-operating conditions, crisis standards of care, and their associated challenging triage decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources.

The 10 suggestions included in the most recent TFMCC publication include staffing strategies and suggestions based on COVID-19 experiences for graded staff-to-patient ratios, and support processes to preserve the existing health care work force. Strategies also include reduction of redundant documentation, limiting overtime, and most importantly, approaches for improving teamwork and supporting psychological well-being and resilience. Examples include daily unit huddles to update care and share experiences, genuine intra-team recognition and appreciation, and embedding emotional health experts within teams to provide ongoing support.

Consistent communication between incident command and frontline clinicians was also a suggested priority, perhaps with a newly proposed position of physician clinical support supervisor. This would be a formal role within hospital incident command, a liaison between the two groups.

Surge strategies should include empowerment of bedside clinicians and leaders with both planning and real-time assessment of the clinical situation, as being at the front line of care enables the situational awareness to assess ICU strain most effectively. Further, ICU clinicians must recognize when progression deeper into contingency operations occurs and they become perilously close to crisis mode. At this point, decisions are made and scarce resources are modified beyond routine standards of care to preserve life. TFMCC designates this gray area between contingency and crisis as the Critical Clinical Prioritization level (Figure).

At this point, more resources must be provided, or patients must be transferred to other resourced hospitals.

Critical Clinical Prioritization is an illustration of necessity being the mother of invention, as these are adaptations clinicians devised under duress. Some particularly poignant examples are the spreading of 24 hours of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) resource between two and sometimes three patients to provide life sustainment to all; and when ventilators were in short supply, determining which patients required full ICU ventilator support vs those who could manage with lower functioning ventilators, and trading them between patients when demands changed.

These adaptations can only be done by experienced clinicians proactively managing bedside critical care under duress, further underscoring the importance of our suggestion that Critical Clinical Prioritization and ICU strain be managed by bedside clinicians and leaders.

The response of early transfer of patients – load-balancing - should be considered as soon as any hospital enters contingency conditions. This strategy is commonly implemented within larger health systems, ideally before reaching Critical Clinical Prioritization. Formal, organized state or regional load-balancing coordination, now referred to as medical operations command centers (MOCCs), were highly effective and proved lifesaving for those states that implemented them (including Arizona, Washington, California, Minnesota, and others). Support for establishment of MOCC’s is crucial in prolonging contingency operations and further helps support and protect disadvantaged populations (White et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[24]:2211-4).

Establishment of MOCCs has met resistance due to challenges that include interhospital/intersystem competition, logistics of moving critically ill patients sometimes across significant physical distance, and the costs of assuming care of uninsured or underinsured patients. Nevertheless, the benefits to the population as a whole necessitate working through these obstacles as successful MOCCs have done, usually with government and hospital association support.

In their final suggestion of the 2022 updated strategies, TFMCC suggests that hospitals use telemedicine technology both to expand specialists’ ability to provide care and facilitate families virtually visiting their critically ill loved one when safety precludes in-person visits.

These suggestions are pivotal in planning for future public health emergencies that include mass critical care, even during events that are limited in scope and duration.

Lastly, intensivists struggled with legal and ethical concerns when mired in crisis care circumstances and decisions of allocation, and potential reallocation, of scarce resources. These issues were not well addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining contingency level care and requiring further involvement from legal and medical ethics professionals for future planning.

The guiding principle of disaster preparedness is that we must do all the planning we can to ensure that we never need crisis standards of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020 Mar 28. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.).

We must be prepared. Guidelines and suggestions laid out through decades of experience gained a real-world test in the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we must all reorganize and create new plans or augment old ones with the information we have gained. The time is now. The work must continue.

Dr. Griffin is Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Dichter is Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota.

In 2014, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care (TFMCC) published a CHEST consensus statement on disaster preparedness principles in caring for the critically ill during disasters and pandemics (Christian et al. CHEST. 2014;146[4_suppl]:8s-34s). This publication attempted to guide preparedness for both single-event disasters and more prolonged events, including a feared influenza pandemic.

Despite the foundation of planning and support this guidance provided, the COVID-19 pandemic response revealed substantial gaps in our understanding and preparedness for these more prolonged and widespread events.

In New York City, as the first COVID-19 wave began in March and April of 2020, area hospitals responded with surge plans that prioritized what was felt to be most important (Griffin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 1;201[11]:1337-44). Tiered, creative staffing structures were rapidly created with intensivists supervising non-ICU physicians and APPs. Procedure teams were created for intubation, proning, and central line placement. ICU space was created with adaptations to ORs and PACUs, and rooms on med-surg floors and step-down units underwent emergency renovations to allow creation of new “pop-up” ICUs. Triage protocols were altered: patients on high levels of supplemental oxygen, who would under normal circumstances have been admitted to an ICU, were triaged to floors and stepdown units. Equipment was reused, modified, and substituted creatively to optimize care for the maximum number of patients.

In the face of all of these struggles, many around the country and the world felt the efforts, though heroic, resulted in less than standard of care. Two subsequent publications validated this concern (Kadri et al. Ann Int Med. 2021,174;9:1240-51; Bravata DM et al. JAMA Open Network. 2021;4[1]:e2034266), demonstrating during severe surge, COVID-19 patients’ mortality increased significantly beyond that seen in non-surging or less-severe surging times, demonstrating a mortality effect of surge itself. Though these studies observed COVID-19 patients only, there is every reason to believe the findings applied to all critically ill patients cared for during these surges.

These experiences led the TFMCC to report updated strategies for remaining in contingency care levels and avoiding crisis care (Dichter JR et al. CHEST. 2022;161[2]:429-47). Contingency is equivalent to routine care though may require adaptations and employment of otherwise non-traditional resources. The ultimate goal of mass critical care in a public health emergency is to avoid crisis-operating conditions, crisis standards of care, and their associated challenging triage decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources.

The 10 suggestions included in the most recent TFMCC publication include staffing strategies and suggestions based on COVID-19 experiences for graded staff-to-patient ratios, and support processes to preserve the existing health care work force. Strategies also include reduction of redundant documentation, limiting overtime, and most importantly, approaches for improving teamwork and supporting psychological well-being and resilience. Examples include daily unit huddles to update care and share experiences, genuine intra-team recognition and appreciation, and embedding emotional health experts within teams to provide ongoing support.

Consistent communication between incident command and frontline clinicians was also a suggested priority, perhaps with a newly proposed position of physician clinical support supervisor. This would be a formal role within hospital incident command, a liaison between the two groups.

Surge strategies should include empowerment of bedside clinicians and leaders with both planning and real-time assessment of the clinical situation, as being at the front line of care enables the situational awareness to assess ICU strain most effectively. Further, ICU clinicians must recognize when progression deeper into contingency operations occurs and they become perilously close to crisis mode. At this point, decisions are made and scarce resources are modified beyond routine standards of care to preserve life. TFMCC designates this gray area between contingency and crisis as the Critical Clinical Prioritization level (Figure).

At this point, more resources must be provided, or patients must be transferred to other resourced hospitals.

Critical Clinical Prioritization is an illustration of necessity being the mother of invention, as these are adaptations clinicians devised under duress. Some particularly poignant examples are the spreading of 24 hours of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) resource between two and sometimes three patients to provide life sustainment to all; and when ventilators were in short supply, determining which patients required full ICU ventilator support vs those who could manage with lower functioning ventilators, and trading them between patients when demands changed.

These adaptations can only be done by experienced clinicians proactively managing bedside critical care under duress, further underscoring the importance of our suggestion that Critical Clinical Prioritization and ICU strain be managed by bedside clinicians and leaders.

The response of early transfer of patients – load-balancing - should be considered as soon as any hospital enters contingency conditions. This strategy is commonly implemented within larger health systems, ideally before reaching Critical Clinical Prioritization. Formal, organized state or regional load-balancing coordination, now referred to as medical operations command centers (MOCCs), were highly effective and proved lifesaving for those states that implemented them (including Arizona, Washington, California, Minnesota, and others). Support for establishment of MOCC’s is crucial in prolonging contingency operations and further helps support and protect disadvantaged populations (White et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[24]:2211-4).

Establishment of MOCCs has met resistance due to challenges that include interhospital/intersystem competition, logistics of moving critically ill patients sometimes across significant physical distance, and the costs of assuming care of uninsured or underinsured patients. Nevertheless, the benefits to the population as a whole necessitate working through these obstacles as successful MOCCs have done, usually with government and hospital association support.

In their final suggestion of the 2022 updated strategies, TFMCC suggests that hospitals use telemedicine technology both to expand specialists’ ability to provide care and facilitate families virtually visiting their critically ill loved one when safety precludes in-person visits.

These suggestions are pivotal in planning for future public health emergencies that include mass critical care, even during events that are limited in scope and duration.

Lastly, intensivists struggled with legal and ethical concerns when mired in crisis care circumstances and decisions of allocation, and potential reallocation, of scarce resources. These issues were not well addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining contingency level care and requiring further involvement from legal and medical ethics professionals for future planning.

The guiding principle of disaster preparedness is that we must do all the planning we can to ensure that we never need crisis standards of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020 Mar 28. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.).

We must be prepared. Guidelines and suggestions laid out through decades of experience gained a real-world test in the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we must all reorganize and create new plans or augment old ones with the information we have gained. The time is now. The work must continue.

Dr. Griffin is Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Dichter is Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota.

In 2014, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care (TFMCC) published a CHEST consensus statement on disaster preparedness principles in caring for the critically ill during disasters and pandemics (Christian et al. CHEST. 2014;146[4_suppl]:8s-34s). This publication attempted to guide preparedness for both single-event disasters and more prolonged events, including a feared influenza pandemic.

Despite the foundation of planning and support this guidance provided, the COVID-19 pandemic response revealed substantial gaps in our understanding and preparedness for these more prolonged and widespread events.

In New York City, as the first COVID-19 wave began in March and April of 2020, area hospitals responded with surge plans that prioritized what was felt to be most important (Griffin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 1;201[11]:1337-44). Tiered, creative staffing structures were rapidly created with intensivists supervising non-ICU physicians and APPs. Procedure teams were created for intubation, proning, and central line placement. ICU space was created with adaptations to ORs and PACUs, and rooms on med-surg floors and step-down units underwent emergency renovations to allow creation of new “pop-up” ICUs. Triage protocols were altered: patients on high levels of supplemental oxygen, who would under normal circumstances have been admitted to an ICU, were triaged to floors and stepdown units. Equipment was reused, modified, and substituted creatively to optimize care for the maximum number of patients.

In the face of all of these struggles, many around the country and the world felt the efforts, though heroic, resulted in less than standard of care. Two subsequent publications validated this concern (Kadri et al. Ann Int Med. 2021,174;9:1240-51; Bravata DM et al. JAMA Open Network. 2021;4[1]:e2034266), demonstrating during severe surge, COVID-19 patients’ mortality increased significantly beyond that seen in non-surging or less-severe surging times, demonstrating a mortality effect of surge itself. Though these studies observed COVID-19 patients only, there is every reason to believe the findings applied to all critically ill patients cared for during these surges.

These experiences led the TFMCC to report updated strategies for remaining in contingency care levels and avoiding crisis care (Dichter JR et al. CHEST. 2022;161[2]:429-47). Contingency is equivalent to routine care though may require adaptations and employment of otherwise non-traditional resources. The ultimate goal of mass critical care in a public health emergency is to avoid crisis-operating conditions, crisis standards of care, and their associated challenging triage decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources.

The 10 suggestions included in the most recent TFMCC publication include staffing strategies and suggestions based on COVID-19 experiences for graded staff-to-patient ratios, and support processes to preserve the existing health care work force. Strategies also include reduction of redundant documentation, limiting overtime, and most importantly, approaches for improving teamwork and supporting psychological well-being and resilience. Examples include daily unit huddles to update care and share experiences, genuine intra-team recognition and appreciation, and embedding emotional health experts within teams to provide ongoing support.

Consistent communication between incident command and frontline clinicians was also a suggested priority, perhaps with a newly proposed position of physician clinical support supervisor. This would be a formal role within hospital incident command, a liaison between the two groups.

Surge strategies should include empowerment of bedside clinicians and leaders with both planning and real-time assessment of the clinical situation, as being at the front line of care enables the situational awareness to assess ICU strain most effectively. Further, ICU clinicians must recognize when progression deeper into contingency operations occurs and they become perilously close to crisis mode. At this point, decisions are made and scarce resources are modified beyond routine standards of care to preserve life. TFMCC designates this gray area between contingency and crisis as the Critical Clinical Prioritization level (Figure).

At this point, more resources must be provided, or patients must be transferred to other resourced hospitals.

Critical Clinical Prioritization is an illustration of necessity being the mother of invention, as these are adaptations clinicians devised under duress. Some particularly poignant examples are the spreading of 24 hours of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) resource between two and sometimes three patients to provide life sustainment to all; and when ventilators were in short supply, determining which patients required full ICU ventilator support vs those who could manage with lower functioning ventilators, and trading them between patients when demands changed.

These adaptations can only be done by experienced clinicians proactively managing bedside critical care under duress, further underscoring the importance of our suggestion that Critical Clinical Prioritization and ICU strain be managed by bedside clinicians and leaders.

The response of early transfer of patients – load-balancing - should be considered as soon as any hospital enters contingency conditions. This strategy is commonly implemented within larger health systems, ideally before reaching Critical Clinical Prioritization. Formal, organized state or regional load-balancing coordination, now referred to as medical operations command centers (MOCCs), were highly effective and proved lifesaving for those states that implemented them (including Arizona, Washington, California, Minnesota, and others). Support for establishment of MOCC’s is crucial in prolonging contingency operations and further helps support and protect disadvantaged populations (White et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[24]:2211-4).

Establishment of MOCCs has met resistance due to challenges that include interhospital/intersystem competition, logistics of moving critically ill patients sometimes across significant physical distance, and the costs of assuming care of uninsured or underinsured patients. Nevertheless, the benefits to the population as a whole necessitate working through these obstacles as successful MOCCs have done, usually with government and hospital association support.

In their final suggestion of the 2022 updated strategies, TFMCC suggests that hospitals use telemedicine technology both to expand specialists’ ability to provide care and facilitate families virtually visiting their critically ill loved one when safety precludes in-person visits.

These suggestions are pivotal in planning for future public health emergencies that include mass critical care, even during events that are limited in scope and duration.

Lastly, intensivists struggled with legal and ethical concerns when mired in crisis care circumstances and decisions of allocation, and potential reallocation, of scarce resources. These issues were not well addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining contingency level care and requiring further involvement from legal and medical ethics professionals for future planning.

The guiding principle of disaster preparedness is that we must do all the planning we can to ensure that we never need crisis standards of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020 Mar 28. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.).

We must be prepared. Guidelines and suggestions laid out through decades of experience gained a real-world test in the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we must all reorganize and create new plans or augment old ones with the information we have gained. The time is now. The work must continue.

Dr. Griffin is Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Dichter is Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota.

Building CHEST 2022: A look into the Scientific Program Committee Meeting

A quality educational meeting starts with a great slate of programs tailored to its audience, and CHEST 2022 is on-track to offer the highest tier of education for those in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine.

Although planning for the meeting started after CHEST 2021 wrapped up, the real magic started to happen a few months ago when the schedule began coming together. In mid-February, members of the Scientific Planning Committee gathered both virtually and in-person at the CHEST headquarters to solidify the schedule for the upcoming CHEST 2022 meeting taking place in Nashville, TN, October 16-19.

The excitement in the room was palpable as committee members gathered for the first time in over a year to plan what will be the first in-person meeting since CHEST 2019 in New Orleans.

Chair of CHEST 2022, Subani Chandra, MD, FCCP, has high expectations for the meeting and is excited for everyone to be together in Nashville. “There is something special about an in-person meeting and my goal for CHEST 2022 is to not only meet the academic needs of the attendees, but also to serve as a chance to recharge after a long haul in managing COVID-19,” says Dr. Chandra. “Many first-time CHEST attendees are fellows and, with the last two meetings being virtual, there are a lot of fellows who have yet to attend a meeting in-person, so that is a big responsibility for us and opportunity for them. We want to make sure they have a fun and productive meeting – learn from the best, understand how to apply the latest research, get to present their work, network, participate, and have fun doing it all!”

With something for everyone in chest medicine, the CHEST 2022 meeting will feature over 200 sessions covering eight curriculum groups:

- Obstructive lung disease

- Sleep

- Chest infections

- Cardiovascular/pulmonary vascular disease

- Pulmonary procedures/lung cancer/cardiothoracic surgery

- Interstitial lung disease/radiology

- Interdisciplinary/practice operations/education

- Critical care

Covering a large breadth of information, the sessions will include the latest trends in COVID-19 care – recommended protocols, surge-planning and best practices; deeper looks into the latest CHEST guidelines – thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19, antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease, and the guidelines for lung cancer screening; and sessions speaking to diversity, inclusion, and equity within medicine, including how lung disease affects populations differently.

Dr. Chandra says diversity was top of mind throughout the planning process. When submitting session ideas, it was noted that “submissions with speakers representing one gender and/or one institution will not be considered,” and that “selection priority will be given to outstanding submissions with proposed speakers who represent diversity of race, ethnicity, and professional status.”

During February’s meeting, as the committee members confirmed each of the sessions, they took the time to ensure every single one had presenters from a variety of backgrounds, including diversity of gender, race, credentialing, and years of experience in medicine.

It was important to the committee that this not be a physician-only meeting, because both CHEST and Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine feature an array of team members including physicians, advance practice providers, respiratory therapists, nurses and other members of the care team and the sessions will reflect that.

When asked what she hopes attendees will gain from CHEST 2022, Dr. Chandra says, “I want attendees to feel the joy that comes from not only being together, but learning together.”

She continued, “I want this meeting to remind clinicians why they fell in love with medicine and to remember why it is that we do what we do, especially after two grueling years. Attendees should leave feeling reinvigorated and charged with the latest literature and clinical expertise ready to be implemented into practice. Most of all, I want all of the attendees to have fun, because we are there to learn, but CHEST is also about enjoying medicine and those around you. I just cannot wait.”

A quality educational meeting starts with a great slate of programs tailored to its audience, and CHEST 2022 is on-track to offer the highest tier of education for those in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine.

Although planning for the meeting started after CHEST 2021 wrapped up, the real magic started to happen a few months ago when the schedule began coming together. In mid-February, members of the Scientific Planning Committee gathered both virtually and in-person at the CHEST headquarters to solidify the schedule for the upcoming CHEST 2022 meeting taking place in Nashville, TN, October 16-19.

The excitement in the room was palpable as committee members gathered for the first time in over a year to plan what will be the first in-person meeting since CHEST 2019 in New Orleans.

Chair of CHEST 2022, Subani Chandra, MD, FCCP, has high expectations for the meeting and is excited for everyone to be together in Nashville. “There is something special about an in-person meeting and my goal for CHEST 2022 is to not only meet the academic needs of the attendees, but also to serve as a chance to recharge after a long haul in managing COVID-19,” says Dr. Chandra. “Many first-time CHEST attendees are fellows and, with the last two meetings being virtual, there are a lot of fellows who have yet to attend a meeting in-person, so that is a big responsibility for us and opportunity for them. We want to make sure they have a fun and productive meeting – learn from the best, understand how to apply the latest research, get to present their work, network, participate, and have fun doing it all!”

With something for everyone in chest medicine, the CHEST 2022 meeting will feature over 200 sessions covering eight curriculum groups:

- Obstructive lung disease

- Sleep

- Chest infections

- Cardiovascular/pulmonary vascular disease

- Pulmonary procedures/lung cancer/cardiothoracic surgery

- Interstitial lung disease/radiology

- Interdisciplinary/practice operations/education

- Critical care

Covering a large breadth of information, the sessions will include the latest trends in COVID-19 care – recommended protocols, surge-planning and best practices; deeper looks into the latest CHEST guidelines – thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19, antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease, and the guidelines for lung cancer screening; and sessions speaking to diversity, inclusion, and equity within medicine, including how lung disease affects populations differently.

Dr. Chandra says diversity was top of mind throughout the planning process. When submitting session ideas, it was noted that “submissions with speakers representing one gender and/or one institution will not be considered,” and that “selection priority will be given to outstanding submissions with proposed speakers who represent diversity of race, ethnicity, and professional status.”

During February’s meeting, as the committee members confirmed each of the sessions, they took the time to ensure every single one had presenters from a variety of backgrounds, including diversity of gender, race, credentialing, and years of experience in medicine.

It was important to the committee that this not be a physician-only meeting, because both CHEST and Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine feature an array of team members including physicians, advance practice providers, respiratory therapists, nurses and other members of the care team and the sessions will reflect that.

When asked what she hopes attendees will gain from CHEST 2022, Dr. Chandra says, “I want attendees to feel the joy that comes from not only being together, but learning together.”

She continued, “I want this meeting to remind clinicians why they fell in love with medicine and to remember why it is that we do what we do, especially after two grueling years. Attendees should leave feeling reinvigorated and charged with the latest literature and clinical expertise ready to be implemented into practice. Most of all, I want all of the attendees to have fun, because we are there to learn, but CHEST is also about enjoying medicine and those around you. I just cannot wait.”

A quality educational meeting starts with a great slate of programs tailored to its audience, and CHEST 2022 is on-track to offer the highest tier of education for those in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine.

Although planning for the meeting started after CHEST 2021 wrapped up, the real magic started to happen a few months ago when the schedule began coming together. In mid-February, members of the Scientific Planning Committee gathered both virtually and in-person at the CHEST headquarters to solidify the schedule for the upcoming CHEST 2022 meeting taking place in Nashville, TN, October 16-19.

The excitement in the room was palpable as committee members gathered for the first time in over a year to plan what will be the first in-person meeting since CHEST 2019 in New Orleans.

Chair of CHEST 2022, Subani Chandra, MD, FCCP, has high expectations for the meeting and is excited for everyone to be together in Nashville. “There is something special about an in-person meeting and my goal for CHEST 2022 is to not only meet the academic needs of the attendees, but also to serve as a chance to recharge after a long haul in managing COVID-19,” says Dr. Chandra. “Many first-time CHEST attendees are fellows and, with the last two meetings being virtual, there are a lot of fellows who have yet to attend a meeting in-person, so that is a big responsibility for us and opportunity for them. We want to make sure they have a fun and productive meeting – learn from the best, understand how to apply the latest research, get to present their work, network, participate, and have fun doing it all!”

With something for everyone in chest medicine, the CHEST 2022 meeting will feature over 200 sessions covering eight curriculum groups:

- Obstructive lung disease

- Sleep

- Chest infections

- Cardiovascular/pulmonary vascular disease

- Pulmonary procedures/lung cancer/cardiothoracic surgery

- Interstitial lung disease/radiology

- Interdisciplinary/practice operations/education

- Critical care

Covering a large breadth of information, the sessions will include the latest trends in COVID-19 care – recommended protocols, surge-planning and best practices; deeper looks into the latest CHEST guidelines – thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19, antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease, and the guidelines for lung cancer screening; and sessions speaking to diversity, inclusion, and equity within medicine, including how lung disease affects populations differently.

Dr. Chandra says diversity was top of mind throughout the planning process. When submitting session ideas, it was noted that “submissions with speakers representing one gender and/or one institution will not be considered,” and that “selection priority will be given to outstanding submissions with proposed speakers who represent diversity of race, ethnicity, and professional status.”

During February’s meeting, as the committee members confirmed each of the sessions, they took the time to ensure every single one had presenters from a variety of backgrounds, including diversity of gender, race, credentialing, and years of experience in medicine.

It was important to the committee that this not be a physician-only meeting, because both CHEST and Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine feature an array of team members including physicians, advance practice providers, respiratory therapists, nurses and other members of the care team and the sessions will reflect that.

When asked what she hopes attendees will gain from CHEST 2022, Dr. Chandra says, “I want attendees to feel the joy that comes from not only being together, but learning together.”

She continued, “I want this meeting to remind clinicians why they fell in love with medicine and to remember why it is that we do what we do, especially after two grueling years. Attendees should leave feeling reinvigorated and charged with the latest literature and clinical expertise ready to be implemented into practice. Most of all, I want all of the attendees to have fun, because we are there to learn, but CHEST is also about enjoying medicine and those around you. I just cannot wait.”

Continuous remote patient monitoring

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic required health care systems around the world to rapidly innovate and adapt to unprecedented operational and clinical strain. Many health care systems leveraged virtual care capabilities as an innovative approach to safely and efficiently manage patients while reducing staff exposure and medical resource constraints (Healthcare [Basel]. 2020 Nov;8[4]:517; JMIR Form Res. 2021 Jan; 5[1]:e23190). With Medicare insurance claims data demonstrating a 30% reduction of in-person health visits, telemedicine has become an essential means to fill the gaps in providing essential medical services (JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Mar;181[3]:388-91). A vast majority of virtual health care visits come via telephonic encounters, which have inherent limitations in the ability to monitor patients with complex or critical medical conditions (Front Public Health. 2020;8:410; N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr;382[18]:1679-81). Remote patient monitoring (RPM) has been established in multiple clinical models as an effective adjunct in telemedicine encounters in order to ensure treatment regimen adherence, make real-time treatment adjustments, and identify patients at risk for early decompensation.

Long-term RPM data has demonstrated cost reduction, reduced burden of in-office visits, expedited management of significant clinical events, and decreased all-cause mortality rates. Previously RPM was limited to the care of patients with chronic conditions, particularly cardiac patients with congestive heart failure and invasive devices, such as pacemakers or implantable cardioverter–defibrillators (JMIR Form Res. 2021 Jan;5[1]:e23190; Front Public Health. 2020; 8:410). In response to the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) added RPM billing codes in 2019 and then included coverage of acute conditions in 2020 that permitted a more extensive role of RPM in telemedicine. This change in financial reimbursement led to a more aggressive expansion of RPM devices to assess physiologic parameters, such as weight, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and blood glucose levels for clinicians to review.

Currently, RPM devices fall within a low-risk FDA category that do not require clinical trials for validation prior to being cleared for CMS billing in a fee-for-service reimbursement model (N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr;384[15]:1384-6). A shortage of evidence-based publications to guide clinicians in this new landscape creates challenges from underuse, misuse, or abuse of RPM tools. In order to maximize the clinical benefits of RPM, standardized processes and device specifications derived from up-to-date research need to be established in professional society guidelines.

Formalized RPM protocols should play a key role in overcoming the hesitancy of health institutions becoming early adopters of RPM technologies. Some significant challenges leading to reluctance of executing an RPM program were recently highlighted at the REPROGRAM international consortium of telemedicine. These concerns involved building a technological infrastructure, training clinical staff, ensuring remote connectivity with broadband Internet, and working with patients of various technologic literacy (Front Public Health. 2020;8:410). We attempted to address these challenges by using a COVID-19 remote patient monitoring (CRPM) strategy within our Military Health System (MHS). By using the well-established responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed (RACI) matrix process mapping tool, we created a standardized enrollment process of high-risk patients across eight military treatment facilities (MTFs). High risk patients included those with COVID-19 pneumonia and persistent hypoxemia, those recovering from acute exacerbations of congestive heart failure, those with cardiopulmonary instability associated with malignancy, and other conditions that required continuous monitoring outside of the hospital setting.

In our CRPM process, the hospital inpatient unit or ED refer high-risk patients to a primary designated provider at each MTF for enrollment prior to discharge. Enrolled patients are equipped with an FDA-approved home monitoring kit that contains an electronic tablet, a network hub that operates independently of and/or in conjunction with Wi-Fi, and an armband containing a coin-sized monitor. The system has the capability to pair with additional smart-enabled accessories, such as a blood pressure cuff, temperature patch, and digital spirometer. With continuous bio-physiologic and symptom-based monitoring, a team of teleworking critical-care nurses monitor patients continuously. In case of a decompensation necessitating a higher level of care, an emergency action plan (EAP) is activated to ensure patients urgently receive emergency medical services. Once released from the CRPM program, discharged patients use prepaid shipping boxes to facilitate contactless repackaging, sanitization, and pickup for redistribution of devices to the MTF.

Given the increased number of hospital admissions noted during the COVID-19 global pandemic, the CRPM program has allowed us to address overutilization of hospital beds. Furthermore, it has allowed us to address issues of screening and resource utilization as we consider patients for safe implementation of home monitoring. While data concerning the outcome of the CRPM program are pending, we are encouraged about the ability to provide high quality care in a remote setting. To that end, we have addressed technologic difficulties, communication between remote providers and patients in the home environment, and communication between health care providers in various settings, such as the ED, inpatient wards, and the outpatient clinic.

To be sure, there are many challenges in making sure that CRPM adequately addresses the needs of patients, who may have persistent perturbations in cardiopulmonary status, tremendous anxiety about the progress or deterioration in their health status, and lack of understanding about their medical condition. Furthermore, providers face the challenge of making clinical decisions sometimes without the advantage of in-person examinations. Sometimes decisions must be made with incomplete information or when the status of the patient does not follow presupposed algorithms. Nevertheless, like many issues during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients and providers have evolved, pivoted, and made necessary adjustments to address an unprecedented time in recent history.

Ultimately, we believe that a continuous remote patient monitoring program can be designed, implemented, and maintained across a multifacility health care system for safe, effective, and efficient health care delivery. Limitations in implementing such a program might include lack of adequate Internet services, lack of telephonic communication, inadequate home facilities, lack of adequate home support, and, perhaps, lack of available emergency services. However, if the conditions for home monitoring are optimized, CRPM holds the promise of reducing the burden on emergency and inpatient hospital services, particularly when those services are strained in circumstances such as the ongoing global pandemic due to COVID-19. With further study, standardization, and evolution, remote monitoring will likely become a more acceptable and necessary form of health care delivery in the future.

Dr. Salomon is an Internal Medicine Resident (PGY-2); Dr. Muller is an Internal Medicine Resident (PGY-2); Dr. Boster is a Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellow; Dr. Loudermilk is a Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellow; and Dr. Kemp is Pulmonary and Critical Care staff, San Antonio Military Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic required health care systems around the world to rapidly innovate and adapt to unprecedented operational and clinical strain. Many health care systems leveraged virtual care capabilities as an innovative approach to safely and efficiently manage patients while reducing staff exposure and medical resource constraints (Healthcare [Basel]. 2020 Nov;8[4]:517; JMIR Form Res. 2021 Jan; 5[1]:e23190). With Medicare insurance claims data demonstrating a 30% reduction of in-person health visits, telemedicine has become an essential means to fill the gaps in providing essential medical services (JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Mar;181[3]:388-91). A vast majority of virtual health care visits come via telephonic encounters, which have inherent limitations in the ability to monitor patients with complex or critical medical conditions (Front Public Health. 2020;8:410; N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr;382[18]:1679-81). Remote patient monitoring (RPM) has been established in multiple clinical models as an effective adjunct in telemedicine encounters in order to ensure treatment regimen adherence, make real-time treatment adjustments, and identify patients at risk for early decompensation.

Long-term RPM data has demonstrated cost reduction, reduced burden of in-office visits, expedited management of significant clinical events, and decreased all-cause mortality rates. Previously RPM was limited to the care of patients with chronic conditions, particularly cardiac patients with congestive heart failure and invasive devices, such as pacemakers or implantable cardioverter–defibrillators (JMIR Form Res. 2021 Jan;5[1]:e23190; Front Public Health. 2020; 8:410). In response to the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) added RPM billing codes in 2019 and then included coverage of acute conditions in 2020 that permitted a more extensive role of RPM in telemedicine. This change in financial reimbursement led to a more aggressive expansion of RPM devices to assess physiologic parameters, such as weight, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and blood glucose levels for clinicians to review.

Currently, RPM devices fall within a low-risk FDA category that do not require clinical trials for validation prior to being cleared for CMS billing in a fee-for-service reimbursement model (N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr;384[15]:1384-6). A shortage of evidence-based publications to guide clinicians in this new landscape creates challenges from underuse, misuse, or abuse of RPM tools. In order to maximize the clinical benefits of RPM, standardized processes and device specifications derived from up-to-date research need to be established in professional society guidelines.

Formalized RPM protocols should play a key role in overcoming the hesitancy of health institutions becoming early adopters of RPM technologies. Some significant challenges leading to reluctance of executing an RPM program were recently highlighted at the REPROGRAM international consortium of telemedicine. These concerns involved building a technological infrastructure, training clinical staff, ensuring remote connectivity with broadband Internet, and working with patients of various technologic literacy (Front Public Health. 2020;8:410). We attempted to address these challenges by using a COVID-19 remote patient monitoring (CRPM) strategy within our Military Health System (MHS). By using the well-established responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed (RACI) matrix process mapping tool, we created a standardized enrollment process of high-risk patients across eight military treatment facilities (MTFs). High risk patients included those with COVID-19 pneumonia and persistent hypoxemia, those recovering from acute exacerbations of congestive heart failure, those with cardiopulmonary instability associated with malignancy, and other conditions that required continuous monitoring outside of the hospital setting.

In our CRPM process, the hospital inpatient unit or ED refer high-risk patients to a primary designated provider at each MTF for enrollment prior to discharge. Enrolled patients are equipped with an FDA-approved home monitoring kit that contains an electronic tablet, a network hub that operates independently of and/or in conjunction with Wi-Fi, and an armband containing a coin-sized monitor. The system has the capability to pair with additional smart-enabled accessories, such as a blood pressure cuff, temperature patch, and digital spirometer. With continuous bio-physiologic and symptom-based monitoring, a team of teleworking critical-care nurses monitor patients continuously. In case of a decompensation necessitating a higher level of care, an emergency action plan (EAP) is activated to ensure patients urgently receive emergency medical services. Once released from the CRPM program, discharged patients use prepaid shipping boxes to facilitate contactless repackaging, sanitization, and pickup for redistribution of devices to the MTF.

Given the increased number of hospital admissions noted during the COVID-19 global pandemic, the CRPM program has allowed us to address overutilization of hospital beds. Furthermore, it has allowed us to address issues of screening and resource utilization as we consider patients for safe implementation of home monitoring. While data concerning the outcome of the CRPM program are pending, we are encouraged about the ability to provide high quality care in a remote setting. To that end, we have addressed technologic difficulties, communication between remote providers and patients in the home environment, and communication between health care providers in various settings, such as the ED, inpatient wards, and the outpatient clinic.

To be sure, there are many challenges in making sure that CRPM adequately addresses the needs of patients, who may have persistent perturbations in cardiopulmonary status, tremendous anxiety about the progress or deterioration in their health status, and lack of understanding about their medical condition. Furthermore, providers face the challenge of making clinical decisions sometimes without the advantage of in-person examinations. Sometimes decisions must be made with incomplete information or when the status of the patient does not follow presupposed algorithms. Nevertheless, like many issues during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients and providers have evolved, pivoted, and made necessary adjustments to address an unprecedented time in recent history.

Ultimately, we believe that a continuous remote patient monitoring program can be designed, implemented, and maintained across a multifacility health care system for safe, effective, and efficient health care delivery. Limitations in implementing such a program might include lack of adequate Internet services, lack of telephonic communication, inadequate home facilities, lack of adequate home support, and, perhaps, lack of available emergency services. However, if the conditions for home monitoring are optimized, CRPM holds the promise of reducing the burden on emergency and inpatient hospital services, particularly when those services are strained in circumstances such as the ongoing global pandemic due to COVID-19. With further study, standardization, and evolution, remote monitoring will likely become a more acceptable and necessary form of health care delivery in the future.

Dr. Salomon is an Internal Medicine Resident (PGY-2); Dr. Muller is an Internal Medicine Resident (PGY-2); Dr. Boster is a Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellow; Dr. Loudermilk is a Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellow; and Dr. Kemp is Pulmonary and Critical Care staff, San Antonio Military Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic required health care systems around the world to rapidly innovate and adapt to unprecedented operational and clinical strain. Many health care systems leveraged virtual care capabilities as an innovative approach to safely and efficiently manage patients while reducing staff exposure and medical resource constraints (Healthcare [Basel]. 2020 Nov;8[4]:517; JMIR Form Res. 2021 Jan; 5[1]:e23190). With Medicare insurance claims data demonstrating a 30% reduction of in-person health visits, telemedicine has become an essential means to fill the gaps in providing essential medical services (JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Mar;181[3]:388-91). A vast majority of virtual health care visits come via telephonic encounters, which have inherent limitations in the ability to monitor patients with complex or critical medical conditions (Front Public Health. 2020;8:410; N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr;382[18]:1679-81). Remote patient monitoring (RPM) has been established in multiple clinical models as an effective adjunct in telemedicine encounters in order to ensure treatment regimen adherence, make real-time treatment adjustments, and identify patients at risk for early decompensation.

Long-term RPM data has demonstrated cost reduction, reduced burden of in-office visits, expedited management of significant clinical events, and decreased all-cause mortality rates. Previously RPM was limited to the care of patients with chronic conditions, particularly cardiac patients with congestive heart failure and invasive devices, such as pacemakers or implantable cardioverter–defibrillators (JMIR Form Res. 2021 Jan;5[1]:e23190; Front Public Health. 2020; 8:410). In response to the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) added RPM billing codes in 2019 and then included coverage of acute conditions in 2020 that permitted a more extensive role of RPM in telemedicine. This change in financial reimbursement led to a more aggressive expansion of RPM devices to assess physiologic parameters, such as weight, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and blood glucose levels for clinicians to review.

Currently, RPM devices fall within a low-risk FDA category that do not require clinical trials for validation prior to being cleared for CMS billing in a fee-for-service reimbursement model (N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr;384[15]:1384-6). A shortage of evidence-based publications to guide clinicians in this new landscape creates challenges from underuse, misuse, or abuse of RPM tools. In order to maximize the clinical benefits of RPM, standardized processes and device specifications derived from up-to-date research need to be established in professional society guidelines.

Formalized RPM protocols should play a key role in overcoming the hesitancy of health institutions becoming early adopters of RPM technologies. Some significant challenges leading to reluctance of executing an RPM program were recently highlighted at the REPROGRAM international consortium of telemedicine. These concerns involved building a technological infrastructure, training clinical staff, ensuring remote connectivity with broadband Internet, and working with patients of various technologic literacy (Front Public Health. 2020;8:410). We attempted to address these challenges by using a COVID-19 remote patient monitoring (CRPM) strategy within our Military Health System (MHS). By using the well-established responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed (RACI) matrix process mapping tool, we created a standardized enrollment process of high-risk patients across eight military treatment facilities (MTFs). High risk patients included those with COVID-19 pneumonia and persistent hypoxemia, those recovering from acute exacerbations of congestive heart failure, those with cardiopulmonary instability associated with malignancy, and other conditions that required continuous monitoring outside of the hospital setting.

In our CRPM process, the hospital inpatient unit or ED refer high-risk patients to a primary designated provider at each MTF for enrollment prior to discharge. Enrolled patients are equipped with an FDA-approved home monitoring kit that contains an electronic tablet, a network hub that operates independently of and/or in conjunction with Wi-Fi, and an armband containing a coin-sized monitor. The system has the capability to pair with additional smart-enabled accessories, such as a blood pressure cuff, temperature patch, and digital spirometer. With continuous bio-physiologic and symptom-based monitoring, a team of teleworking critical-care nurses monitor patients continuously. In case of a decompensation necessitating a higher level of care, an emergency action plan (EAP) is activated to ensure patients urgently receive emergency medical services. Once released from the CRPM program, discharged patients use prepaid shipping boxes to facilitate contactless repackaging, sanitization, and pickup for redistribution of devices to the MTF.

Given the increased number of hospital admissions noted during the COVID-19 global pandemic, the CRPM program has allowed us to address overutilization of hospital beds. Furthermore, it has allowed us to address issues of screening and resource utilization as we consider patients for safe implementation of home monitoring. While data concerning the outcome of the CRPM program are pending, we are encouraged about the ability to provide high quality care in a remote setting. To that end, we have addressed technologic difficulties, communication between remote providers and patients in the home environment, and communication between health care providers in various settings, such as the ED, inpatient wards, and the outpatient clinic.

To be sure, there are many challenges in making sure that CRPM adequately addresses the needs of patients, who may have persistent perturbations in cardiopulmonary status, tremendous anxiety about the progress or deterioration in their health status, and lack of understanding about their medical condition. Furthermore, providers face the challenge of making clinical decisions sometimes without the advantage of in-person examinations. Sometimes decisions must be made with incomplete information or when the status of the patient does not follow presupposed algorithms. Nevertheless, like many issues during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients and providers have evolved, pivoted, and made necessary adjustments to address an unprecedented time in recent history.

Ultimately, we believe that a continuous remote patient monitoring program can be designed, implemented, and maintained across a multifacility health care system for safe, effective, and efficient health care delivery. Limitations in implementing such a program might include lack of adequate Internet services, lack of telephonic communication, inadequate home facilities, lack of adequate home support, and, perhaps, lack of available emergency services. However, if the conditions for home monitoring are optimized, CRPM holds the promise of reducing the burden on emergency and inpatient hospital services, particularly when those services are strained in circumstances such as the ongoing global pandemic due to COVID-19. With further study, standardization, and evolution, remote monitoring will likely become a more acceptable and necessary form of health care delivery in the future.

Dr. Salomon is an Internal Medicine Resident (PGY-2); Dr. Muller is an Internal Medicine Resident (PGY-2); Dr. Boster is a Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellow; Dr. Loudermilk is a Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellow; and Dr. Kemp is Pulmonary and Critical Care staff, San Antonio Military Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

About ABIM’s Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment

Physicians from every specialty have stepped up in extraordinary ways during the pandemic; however, ABIM recognizes that pulmonary disease and critical care physicians, along with hospitalists and infectious disease specialists, have been especially burdened. ABIM has heard from many pulmonary disease and critical care medicine physicians asking for greater flexibility and choice in how they can maintain their board certifications.

For that reason, ABIM has extended deadlines for all Maintenance of Certification (MOC) requirements to 12/31/22 and to 2023 for Critical Care Medicine, Hospital Medicine, Infectious Disease, and Pulmonary Disease.

What assessment options does ABIM offer?

If you haven’t needed to take an MOC exam for a while, you might not be aware of ABIM’s current options and how they might work for you:

- The traditional, 10-year MOC assessment (a point-in-time exam taken at a test center)

- The new Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment (LKATM) (available in 12 specialties including Internal Medicine and Sleep Medicine now, and in Critical Care Medicine and Pulmonary Disease in 2023)

The 2-year Knowledge Check-In was retired at the end of 2021 with the introduction of the LKA.

How the new LKA works

As a longitudinal assessment, the LKA is designed to help you measure your medical knowledge over time and better melds assessment and learning. It consists of a 5-year cycle, during which you’ll be offered 30 questions each quarter, and need to open at least 500 out of 600 questions to meet the LKA Participation Requirement. You can choose not to open up to 100 questions over 5 years, allowing you to take breaks when you need them.

Once enrolled, you can take questions on your laptop, desktop, or smartphone. You’ll also be able to answer questions where and when it’s convenient for you, such as at your home or office – with no need to schedule an appointment or go to a test center. You can use all the same resources you use in practice – journals, apps, and your own personal notes—anything except another person. For most questions, you’ll find out immediately if your answer was correct or not, and you’ll receive a rationale explaining why, along with one or more references.

You’ll have 4 minutes to answer each question and can add extra time if needed by drawing from an annual 30-minute time bank. For each correct answer, you’ll earn 0.2 MOC points, and if you choose to participate in LKA for more than one of your certificates, you’ll have even more opportunities to earn points. In addition, beginning in your second year of participation, interim score reports will give you helpful information to let you know how you’re doing, so you can re-adjust your approach and focus your studies as needed. A pass/fail decision is made at the end of the 5-year cycle.

About eligibility

If you are currently certified in Critical Care Medicine or Pulmonary Disease and had an assessment due in 2020, 2021 or 2022, you don’t need to take an assessment this year and will be eligible to enroll in the LKA in 2023, or you can choose to take the traditional 10-year MOC exam.

Upon enrolling, you will continue to be reported as “Certified” as long as you are meeting the LKA Participation Requirement. If your next assessment isn’t due for a while, you will be able to enroll in the LKA in your assessment due year—not before then.

More information about eligibility can be found in a special section of ABIM’s website.

How much does it cost?

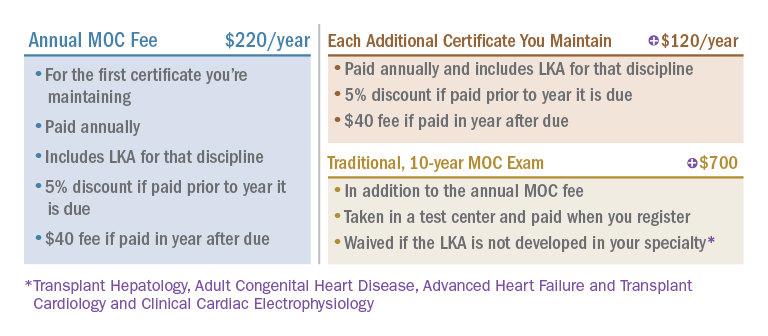

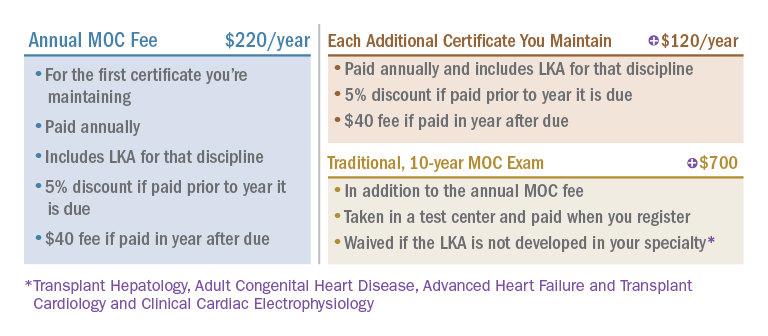

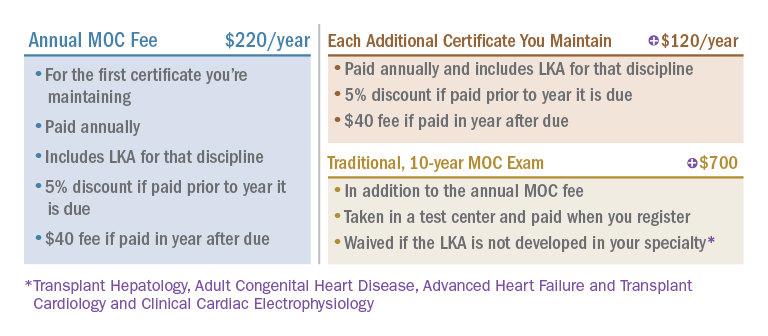

ABIM revised its MOC fees in 2022 to provide an option to pay less over time than previously, and the LKA will be included in your annual MOC fee at no additional cost. Here’s how it works:

In closing

Thousands of physicians have already started taking the LKA in 2022 and are reporting positive experiences with it. The ABIM is excited that physicians in additional disciplines, including Critical Care Medicine and Pulmonary Disease, will get to experience it themselves in 2023.

Physicians from every specialty have stepped up in extraordinary ways during the pandemic; however, ABIM recognizes that pulmonary disease and critical care physicians, along with hospitalists and infectious disease specialists, have been especially burdened. ABIM has heard from many pulmonary disease and critical care medicine physicians asking for greater flexibility and choice in how they can maintain their board certifications.

For that reason, ABIM has extended deadlines for all Maintenance of Certification (MOC) requirements to 12/31/22 and to 2023 for Critical Care Medicine, Hospital Medicine, Infectious Disease, and Pulmonary Disease.

What assessment options does ABIM offer?